Studio visits, public art installations, interviews, and more on gagosian.com/quarterly

As part of Art Basel Paris’s public programming, Gagosian presented a new large-scale sculpture by Carsten Höller at Place Vendôme. In this video, the artist sits down to discuss the genesis of Giant Triple Mushroom (2024).

Join artist Peter Doig as he discusses the artists and works that inspired the creation of the exhibition The Street , at Gagosian, New York. Curated by Doig, and taking Balthus’s 1933 painting of the same title as its point of departure, the show is a portrait of urban life seen through the eyes of painters.

A conversation between Urs Fischer and film curator and writer Róisín Tapponi about fearless creativity and the artist’s most recent monograph, Urs Fischer: Monumental Sculpture

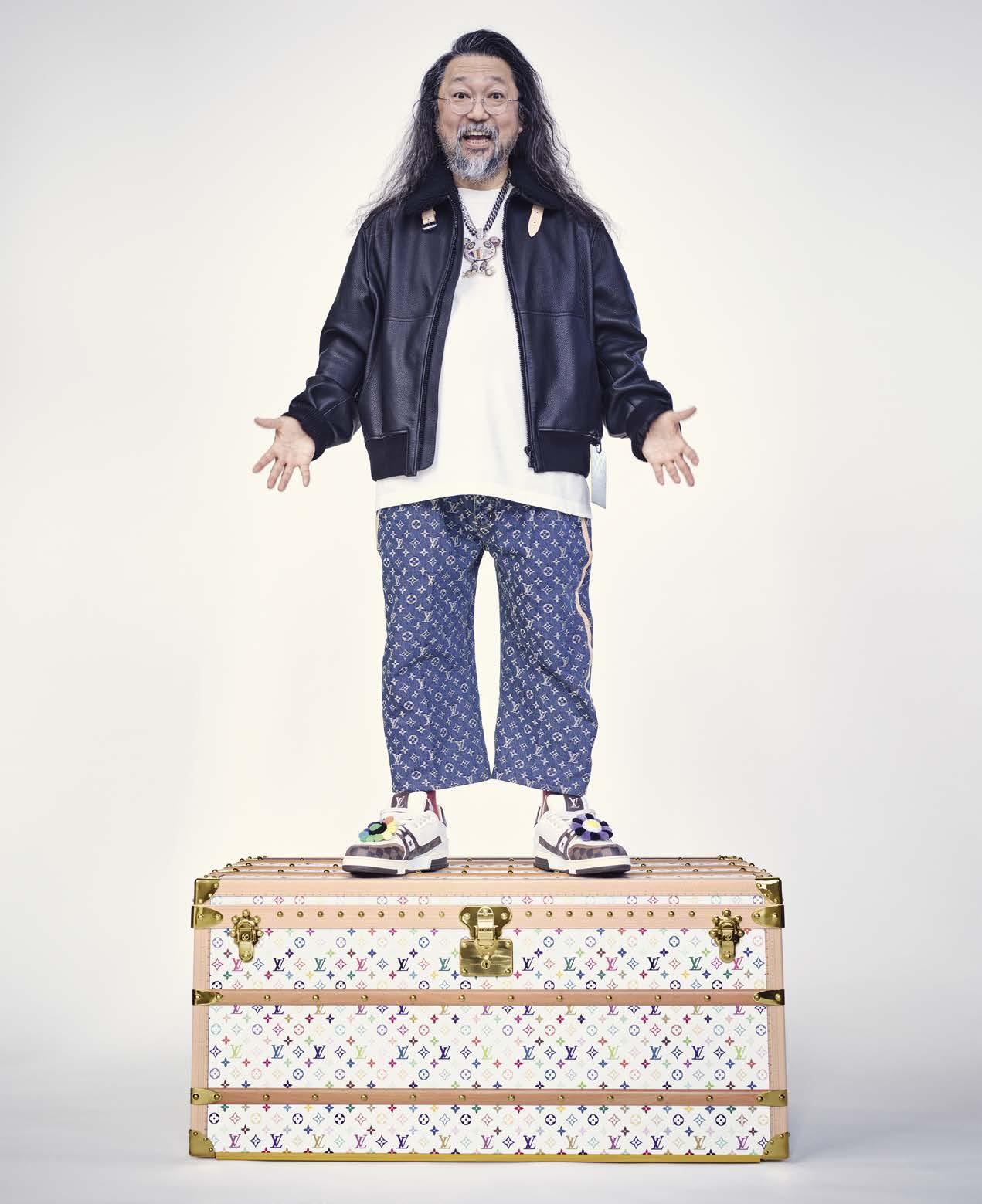

Join Gagosian for a conversation between Takashi Murakami and Hans Ulrich Obrist, curator and artistic director of Serpentine, at the Benjamin West Lecture Theatre at the Royal Academy of Art, London.

Editor-in-chief

Alison McDonald

Managing Editor

Wyatt Allgeier

Editor, Online and Print

Gillian Jakab

Text Editor

David Frankel

Executive Editor

Derek C. Blasberg

Digital and Video

Production Assistant

Alanis Santiago-Rodriguez

Design Director

Paul Neale

Design Alexander Ecob

Graphic Thought Facility

Website

Wolfram Wiedner Studio

Proofreading

Lindsey Westbrook

Founder Larry Gagosian

Publisher Jorge Garcia

Published by Gagosian Media

For Advertising and Sponsorship Inquiries

Advertising@gagosian.com

Distribution David Renard

Distributed by Magazine Heaven

Distribution Manager

Alexandra Samaras

Prepress DL Imaging

Printed by Pureprint Group

Contributors

Miriam Bale

Jane Bennett

Derek C. Blasberg

Richard Calvocoressi

Amber Collins

David Cronenberg

Walton Ford

Dan Fox

Tomás González Olavarría

Harmony Holiday

Christian House

Isabelle Huppert

Catherine Lacey

Nora Lawrence

Philip Lindsay

Myles Mellor

William Middleton

Ho Tzu Nyen

Hans Ulrich Obrist

Francine Prose

Alexander Provan

Francesco Risso

Jenny Saville

Ed Schad

Taryn Simon

Ross Simonini

Mike Stinavage

John Szwed

Masayoshi Takayama

Sam Wasson

Apichatpong Weerasethakul

Robert Wilson

Josh Zajdman

Thanks

Ben Acrish

Richard Alwyn Fisher

Julia Arena

Jin Auh

Lisa Ballard

Priya Bhatnagar

Yuko Burtless

Michael Cary

Serena Cattaneo Adorno

Vittoria Ciaraldi

Maggie Dubinski

Julia Erdman

Paatela Fraga

Mark Francis

Hallie Freer

Brett Garde

Eleanor Gibson

Lauren Gioia

Darlina Goldak

Rebecca Guerra

Anthony Hartley

Andrew Heyward

Delphine Huisinga

Lisa Immordino Vreeland

Alex Israel

Sarah Jones

Shiori Kawasaki

Léa Khayata

Bernard Lagrange

Lauren Mahony

James McKee

Adele Minardi

Sabine Moritz

Olivia Mull

Takashi Murakami

Kelly Quinn

Stefan Ratibor

Helen Redmond

Abram Scharf

Nick Simunovic

Putri Tan

Harry Thorne

Jess Topping

Kelsey Tyler

Philip Valles

Timothée Viale

Millicent Wilner

Penny Yeung

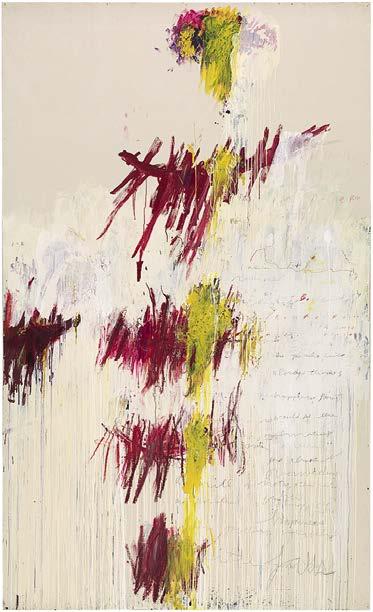

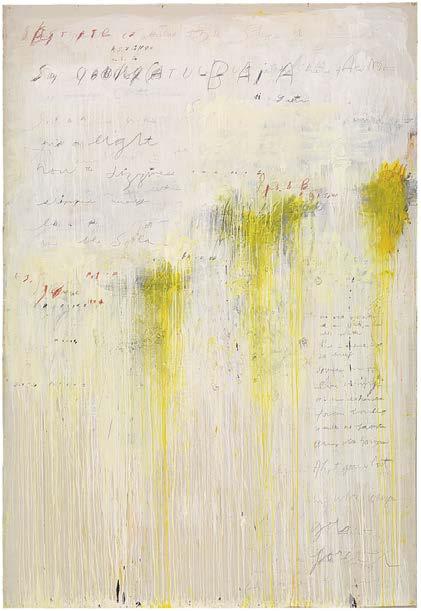

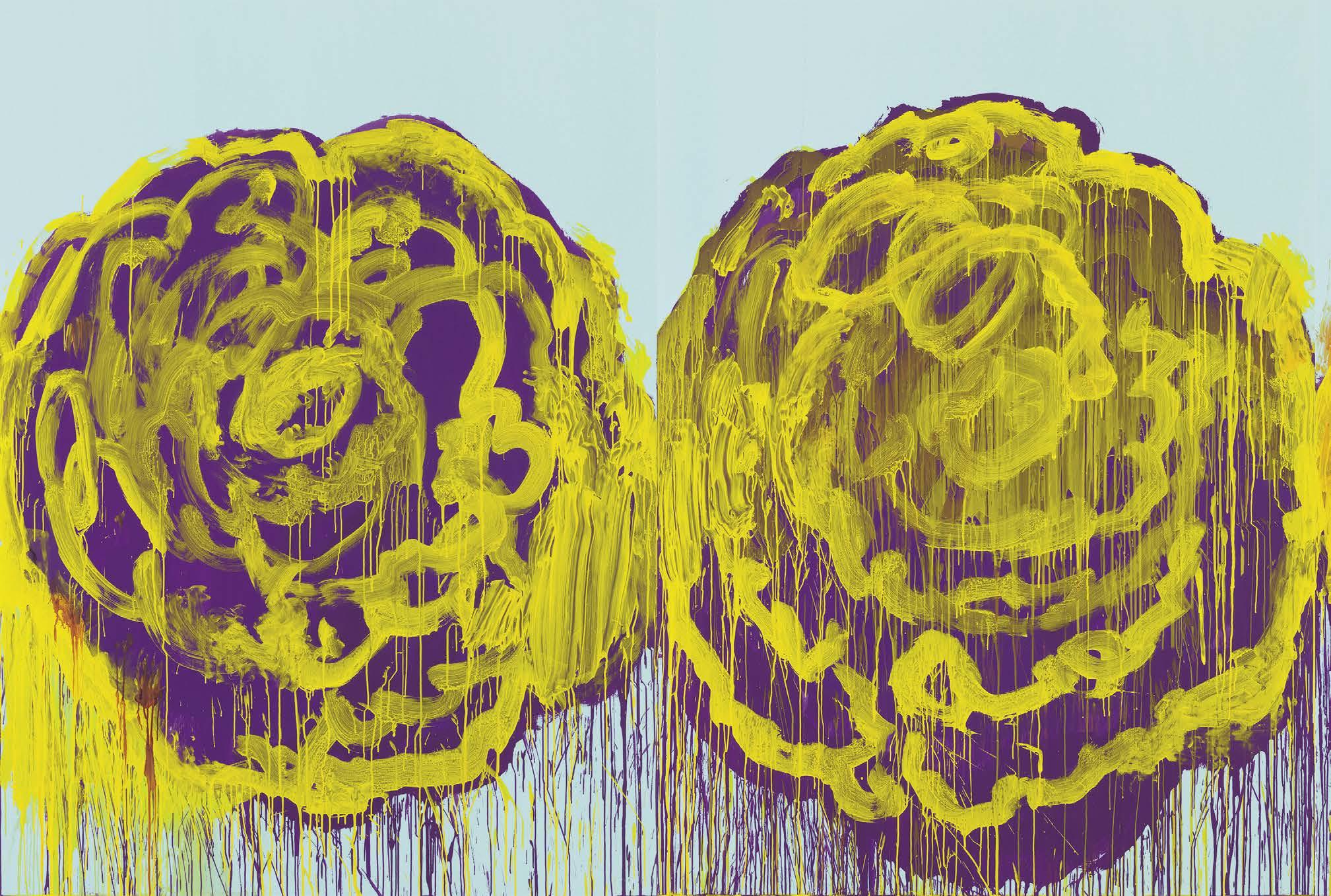

“The artists who become part of art history are the game-changers. They shift our perception of what art should be.” So says Jenny Saville about Cy Twombly, whose work appears on our cover. We are thrilled that Saville has shared with us her admiration for Twombly and her insights into the impact of his work on her practice. She speaks to what made Twombly so groundbreaking and profound, and to the way his innovations continue to shape the world of art.

Takashi Murakami is the subject of an essay by Ed Schad, who investigates the artist’s evolving engagement with historical touchpoints and the unique way his latest works bring Japanese art history into a contemporary dialogue. We continue our focus on painting with Francine Prose offering a fresh perspective on the bold new canvases of Sabine Moritz. The latest paintings by Alex Israel, an artist who finds endless inspiration in Los Angeles, take as their subject the city and the genre of film noir. Hollywood expert Sam Wasson

writes about the beauty at the heart of gritty noir films while considering Israel’s work and the way it honors Los Angeles.

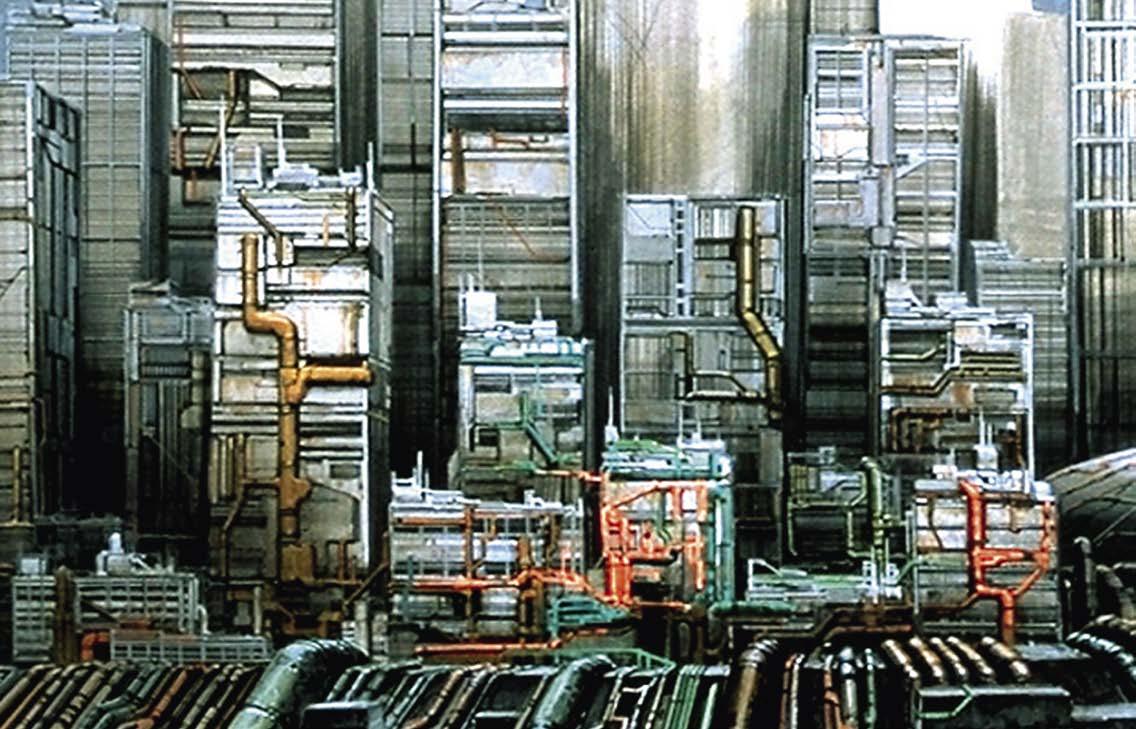

We have a deep dive into cinema with David Cronenberg speaking about his latest film, The Shrouds ; a discussion of an enlightening new documentary on Jean Cocteau; Dan Fox offering a creative take on cyberpunk; and director Apichatpong Weerasethakul reflecting on his artistic process.

The issue features conversations on a wide range of topics: Isabelle Huppert and Robert Wilson discuss their new collaboration with William Middleton; political theorist and philosopher Jane Bennett talks with Ross Simonini; and Harmony Holiday meets with Alexander Provan to discuss her latest exhibition and upcoming publications.

Alison McDonald, Editor-in-chief

48

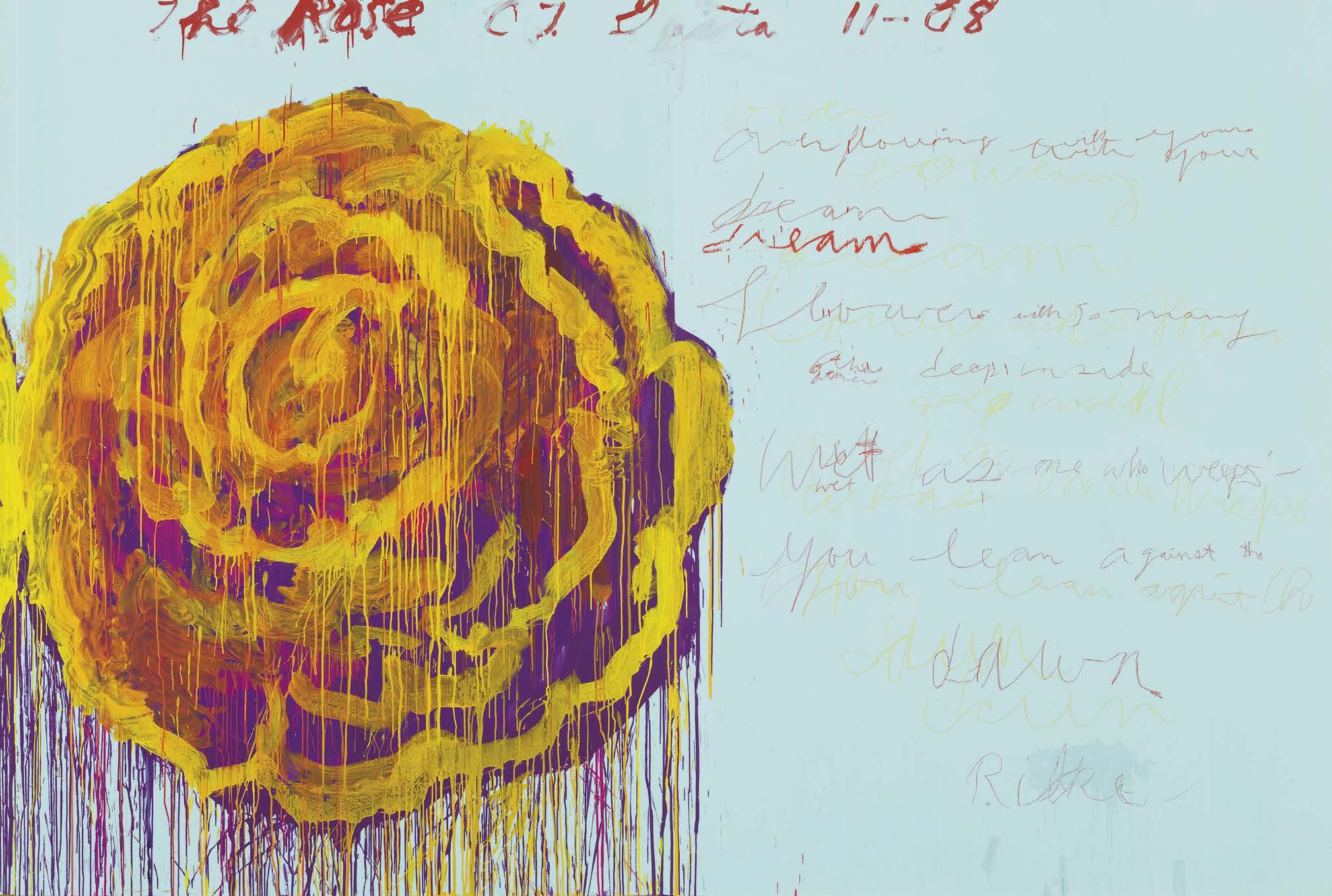

Cy Twombly by Jenny Saville: To Lift the Veil

In this excerpt from her Marion Barthelme Lecture presented at the Menil Collection, Houston, in 2024, Jenny Saville reflects on Cy Twombly’s poetic engagement with the world, with time and tension, and with growth.

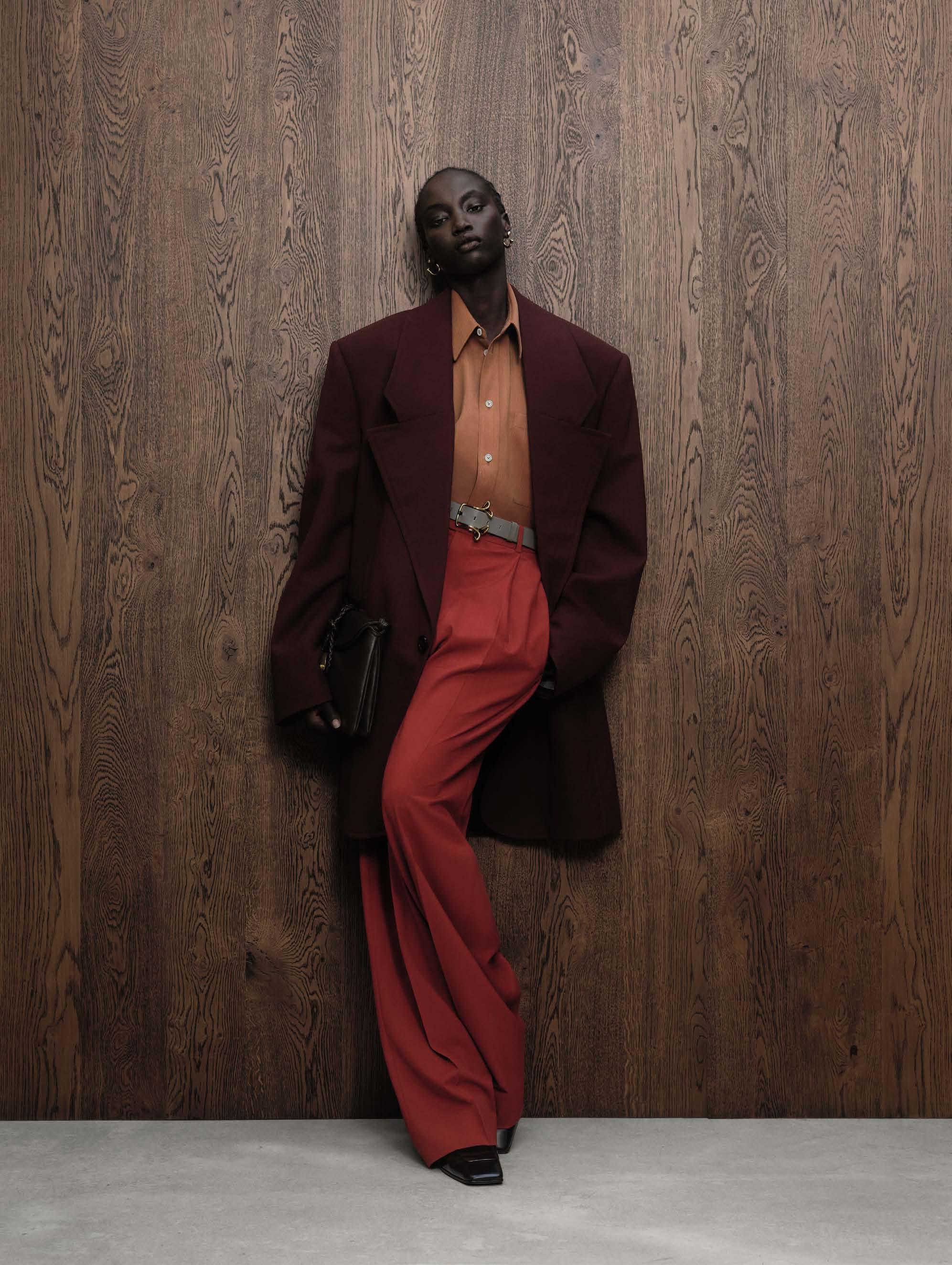

Francesco Risso, creative director of Marni since 2016, meets with the Quarterly ’s Derek C. Blasberg to discuss his symbiotic relationships with artists, childhood experiments with his family’s clothing, and the importance of the hand in creative pursuits.

62

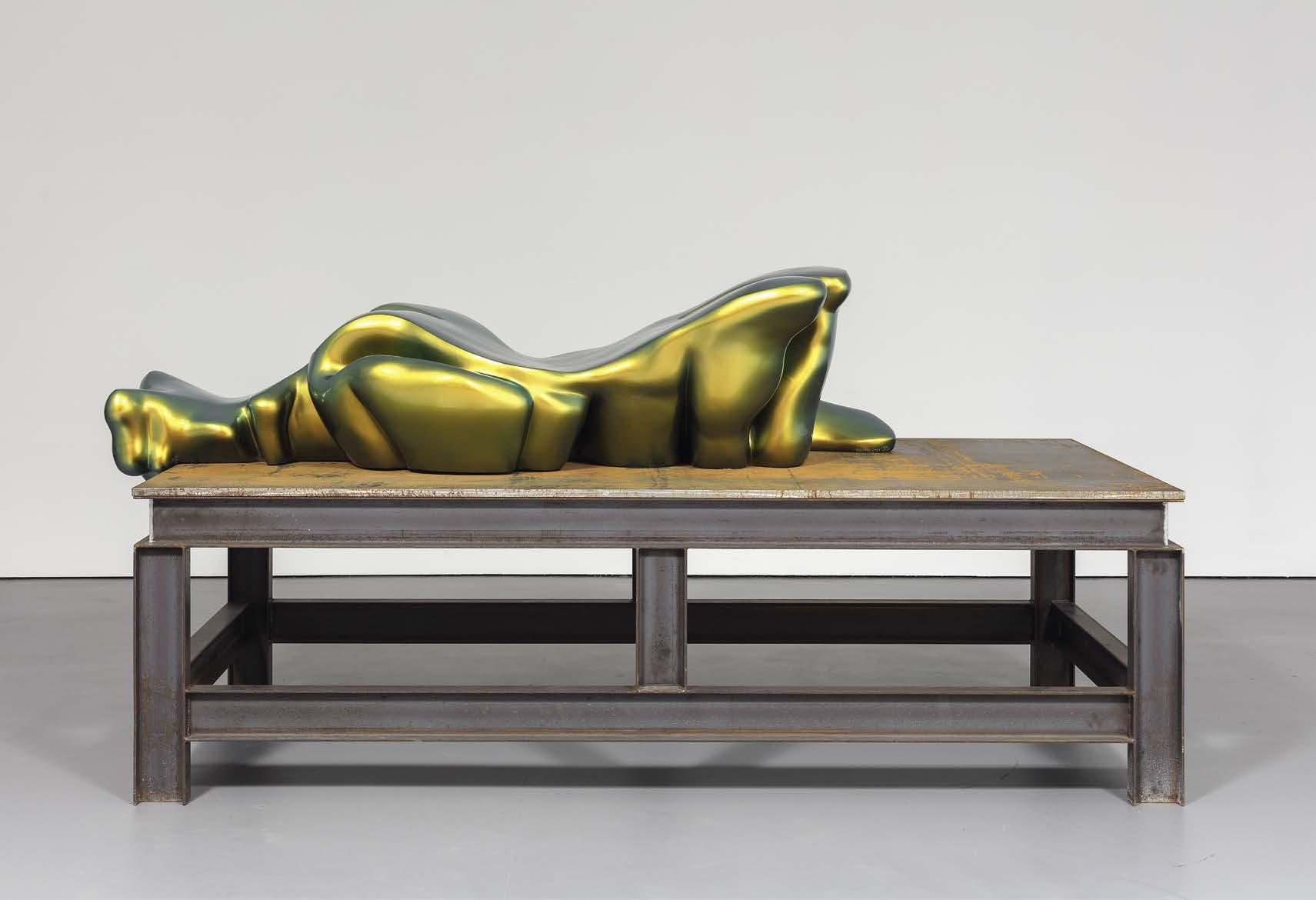

Amber Collins looks into the history of the artist’s Frauen series, eighteen works made between 1998 and 2006, and considers the artist’s radical explorations of the human body.

The first installment of a short story by Catherine Lacey.

78

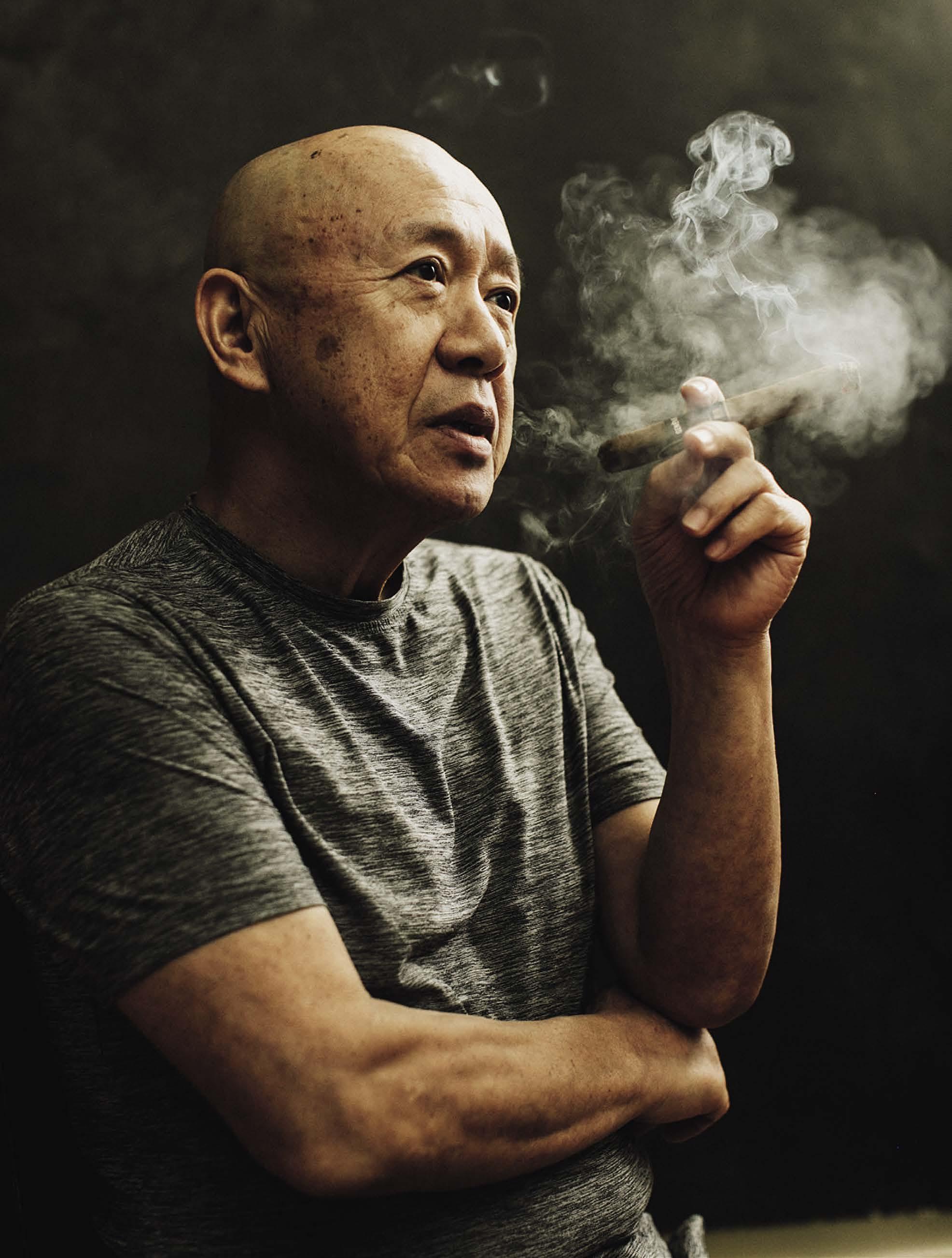

Ed Schad, curator and publications manager at the Broad, Los Angeles, examines Takashi Murakami’s interest in the copy and his innovations in its historical practice.

86

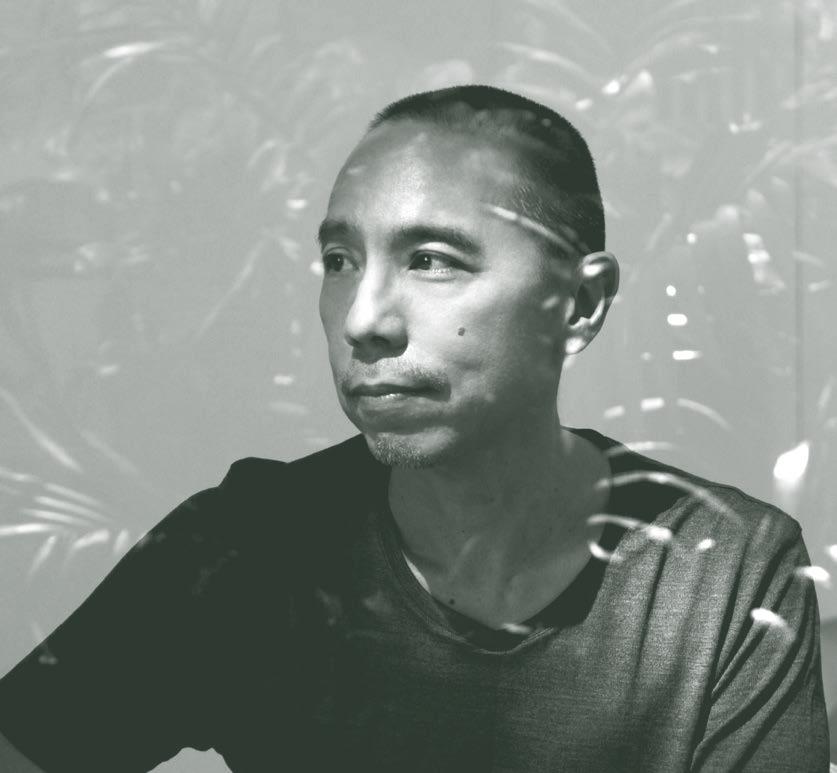

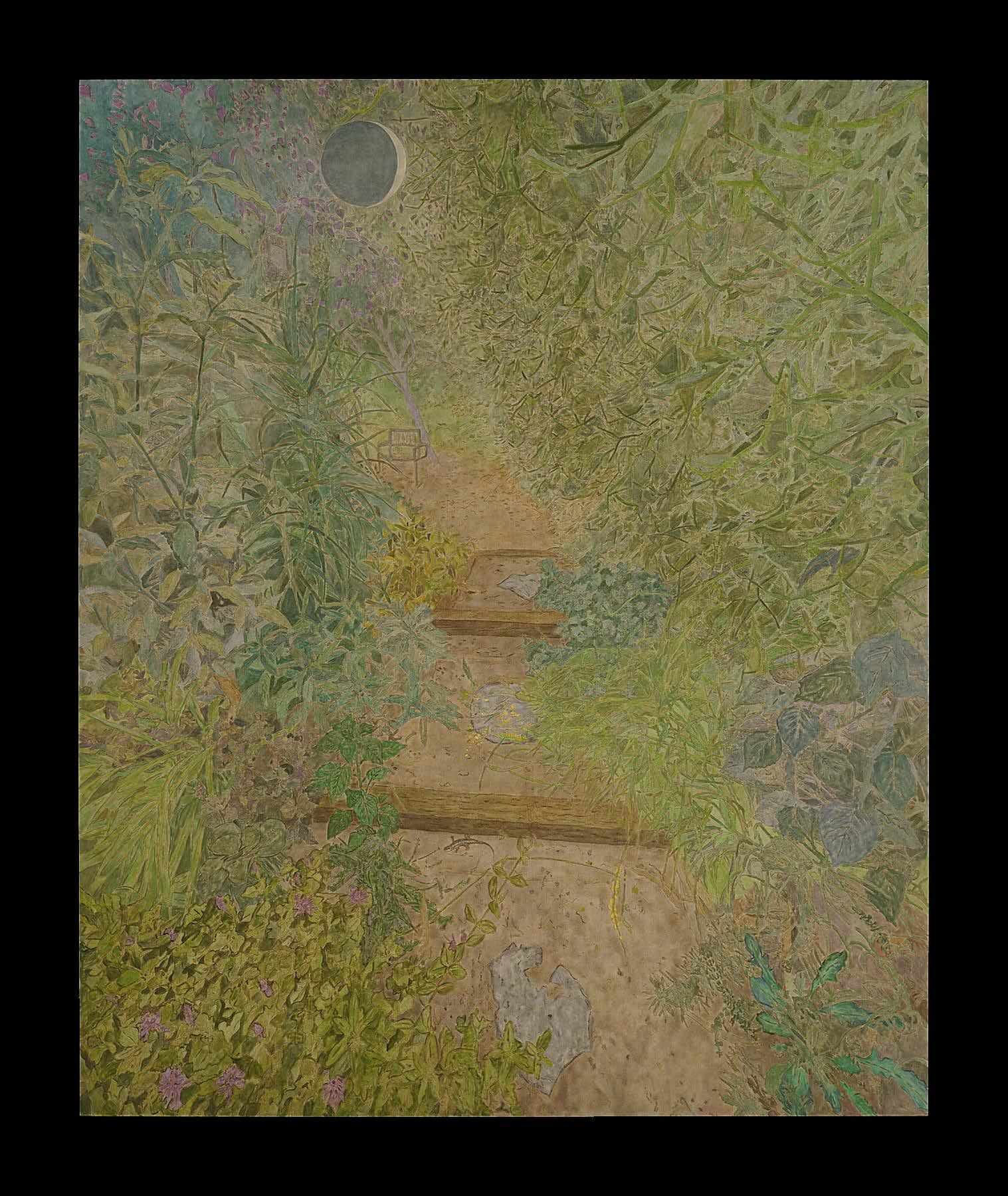

For the first installment of 2025, we are honored to present the artist and filmmaker Ho Tzu Nyen.

Celebrated chef and restaurateur

Masayoshi Takayama speaks with Gagosian Quarterly ’s Alison McDonald about the evolutions and continuities in his approach to food, design, and cigars on the recent anniversaries of his two New York establishments: Masa and Kappo Masa.

96

Filmmaker and author Lisa Immordino Vreeland has made a documentary on the life and art of Jean Cocteau. Here, Josh Zajdman reflects on the uncategorizable existence of this poet, filmmaker, artist, playwright, and novelist.

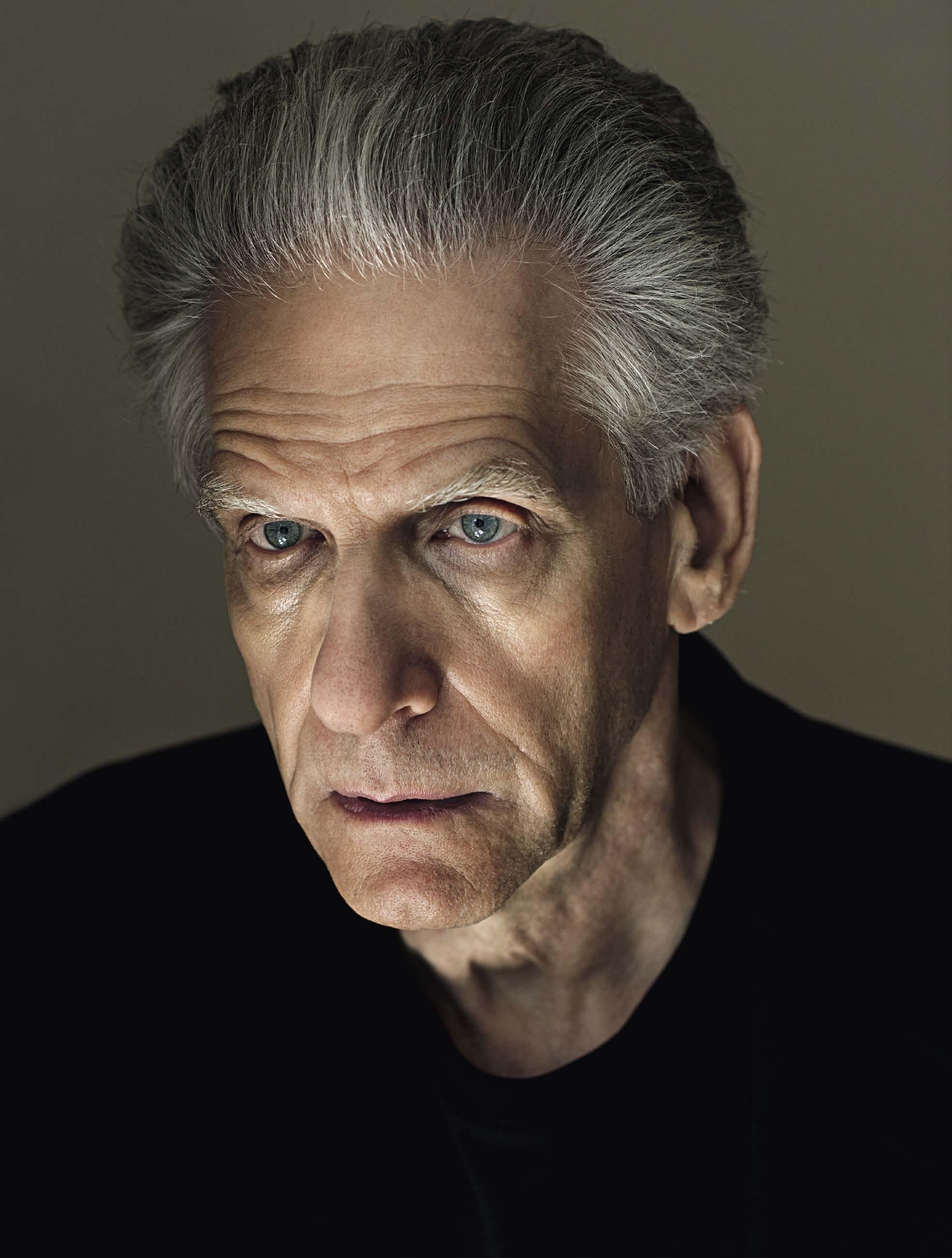

David Cronenberg’s film The Shrouds made its debut at last year’s Cannes Film Festival. Film writer and programmer Miriam Bale met with the auteur to discuss grieving, documentation, and the film’s cast.

Dan Fox travels through the matrix of cyberpunk.

Mike Stinavage meets with the film director Apichatpong Weerasethakul to discuss death and the artistic process.

Sam Wasson brings his deep knowledge of cinema, Hollywood, and film noir to Alex Israel’s new paintings of Los Angeles.

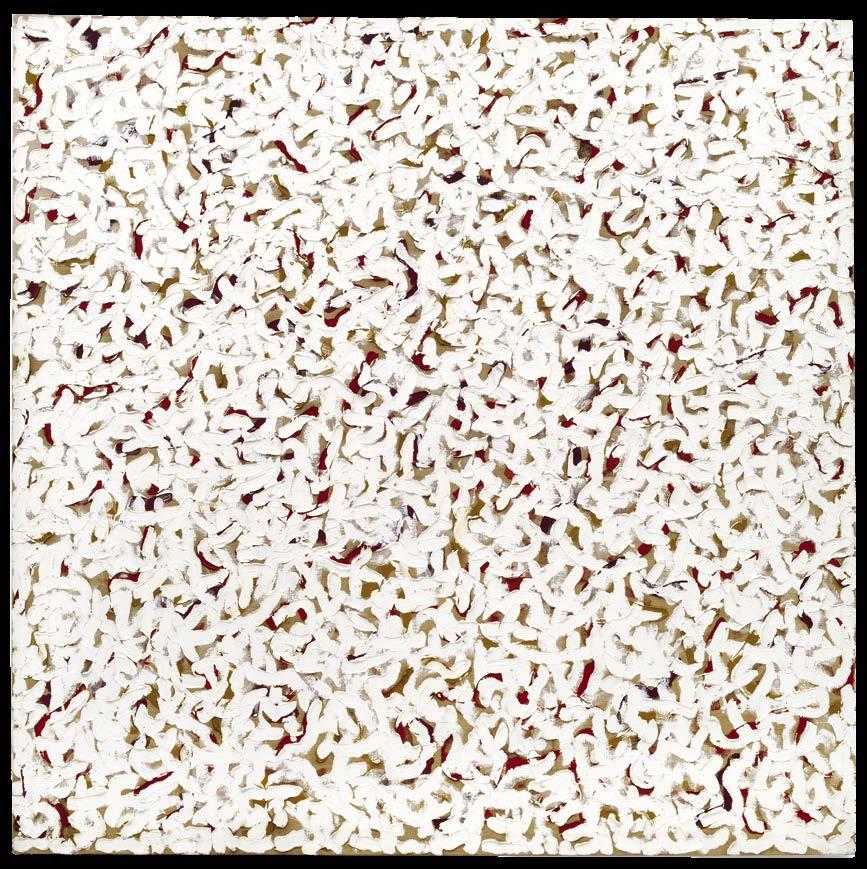

Previous spread, left to right: Sabine Moritz, Ferragosto I , 2023 (detail), oil on canvas, 78 ¾ × 118 ⅛ inches (200 × 300 cm) © Sabine Moritz. Photo: Georgios Michaloudis, farbanalyse, Cologne, Germany

Jean Cocteau, 1929 © Estate Germaine Krull, Museum Folkwang, Essen

Previous spread, right: Marni’s Spring/Summer 2024 fashion show in Paris. Photo: Saint-Ambroise

Above:

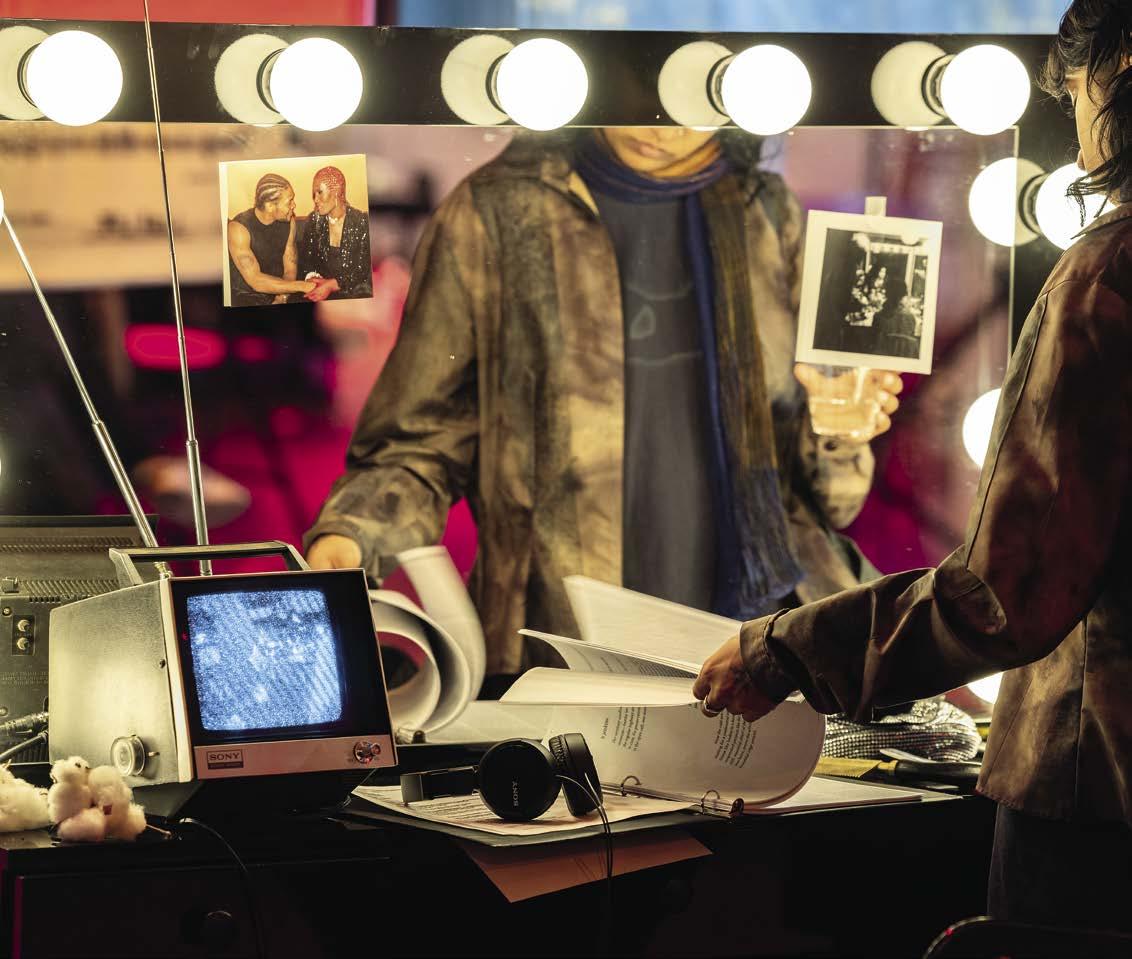

Installation view, Harmony Holiday: Black Backstage , The Kitchen at Westbeth, New York, March 21–May 25, 2024. Photo: Kyle Knodell

Below: Taryn Simon, Kleroterion 2024, installation view, Storm King Art Center, New Windsor, New York © Taryn Simon.

Photo: Eli Baden-Lasar

Francine Prose looks back to some of Moritz’s earlier graphite drawings, thinking through their relationship to the more recent explorations of color in oil paint.

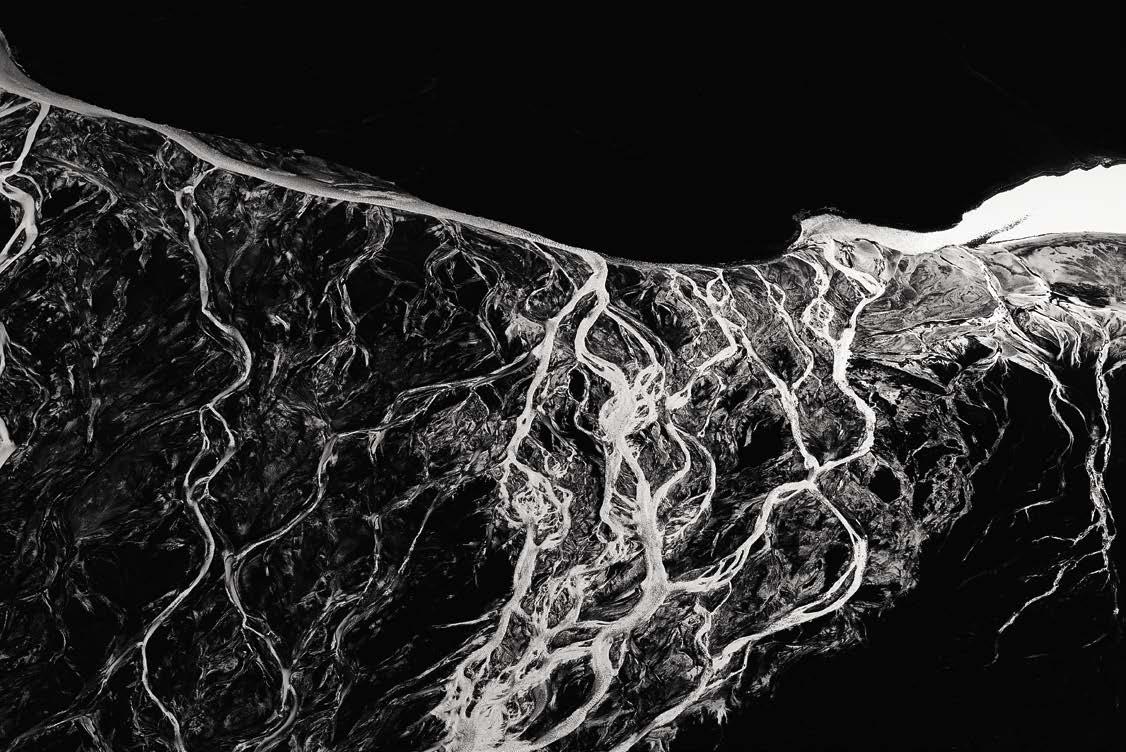

Christian House reports from Norway, where he has been considering the predominance of ice, and the variety of modes of depicting it, in Nordic art and literature.

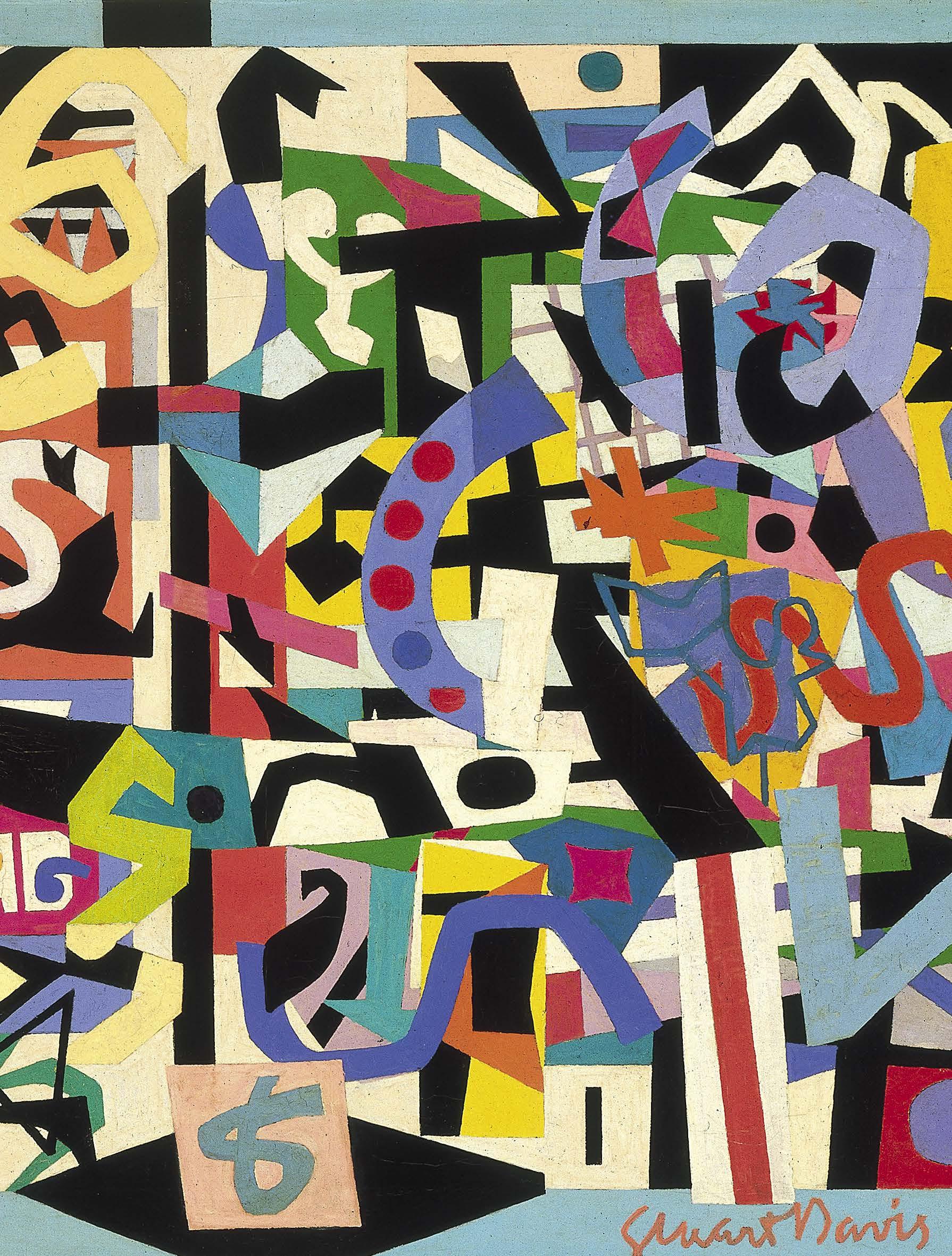

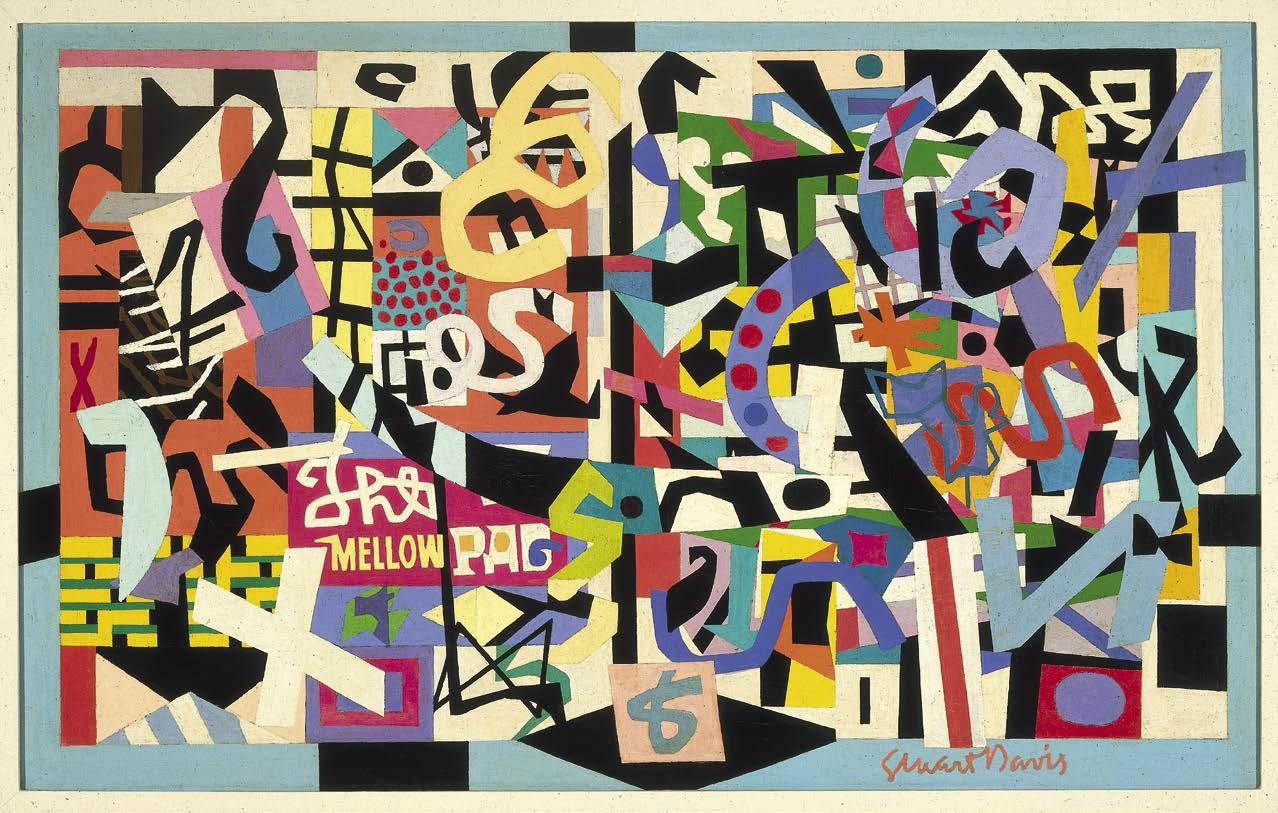

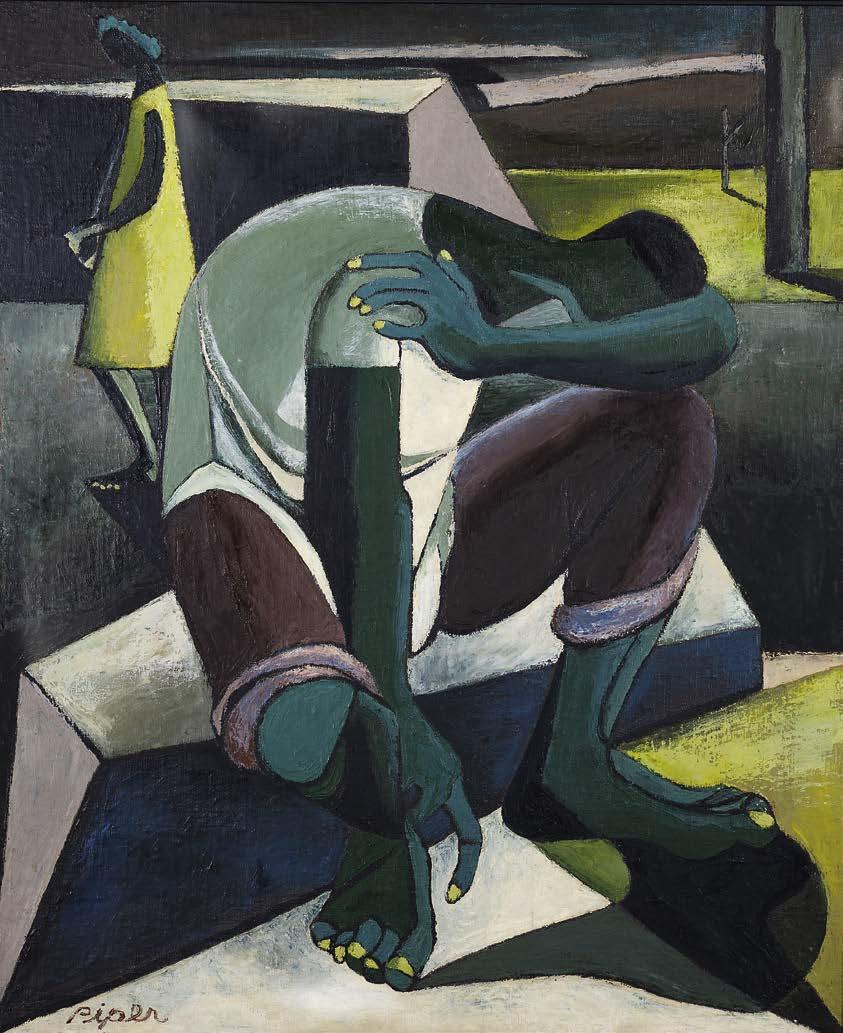

John Szwed identifies the crossrhythms between painters and jazz musicians throughout the twentieth century.

Last fall, Taryn Simon debuted an interactive sculpture entitled Kleroterion (2024). Based on a device from the beginnings of democracy in Athens, the work was installed at Storm King Art Center, New Windsor, New York. As part of that presentation, Simon participated in a panel discussion with Nora Lawrence, Tomás González Olavarría, and Philip Lindsay about democracy, sortition, and art’s place in politics.

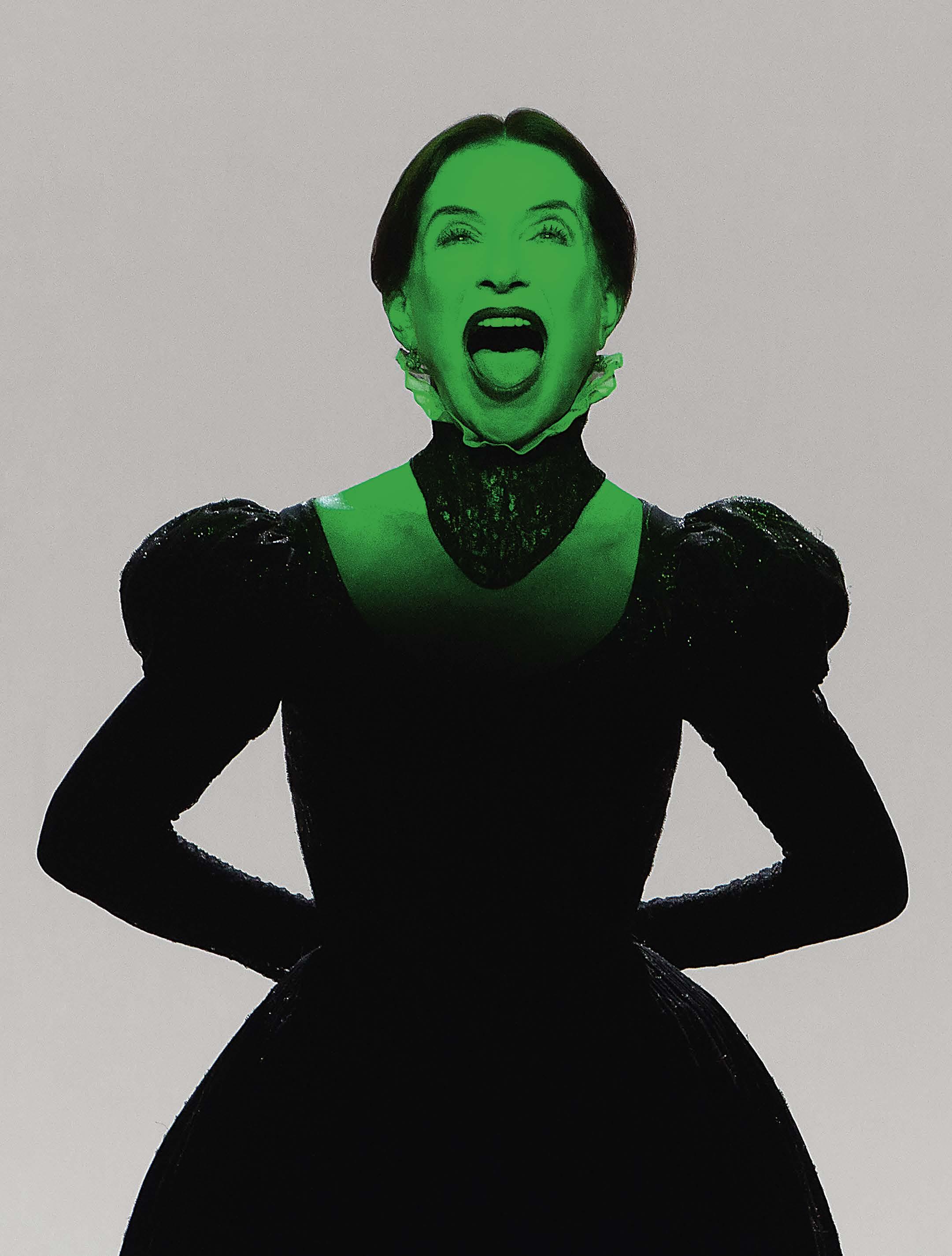

For over three decades, avant-garde theater and opera director Robert Wilson and actor Isabelle Huppert have shared a forceful and profound collaboration. Their latest piece is Mary Said What She Said . William Middleton caught up with the actor and the director in Paris.

Writer, dancer, and experimental filmmaker Harmony Holiday meets with Alexander Provan, author and editor of Triple Canopy, to discuss her 2024 exhibition Black Backstage at the Kitchen, New York.

Philosopher and political theorist

Jane Bennett corresponds with Ross Simonini about the development of her thought, the nature of material, and why she looks to literature and doodles for new perspectives on the liveliness of things.

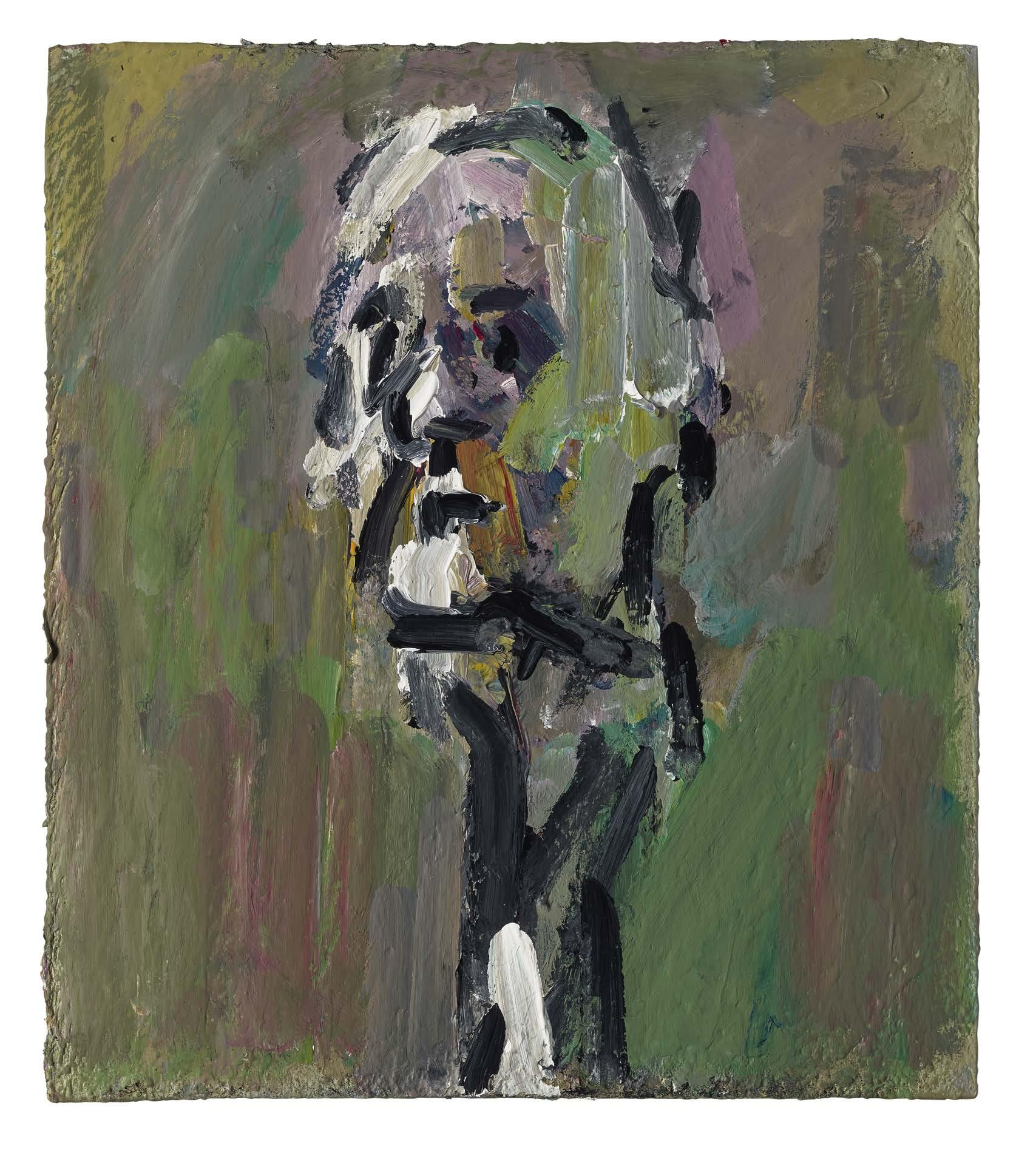

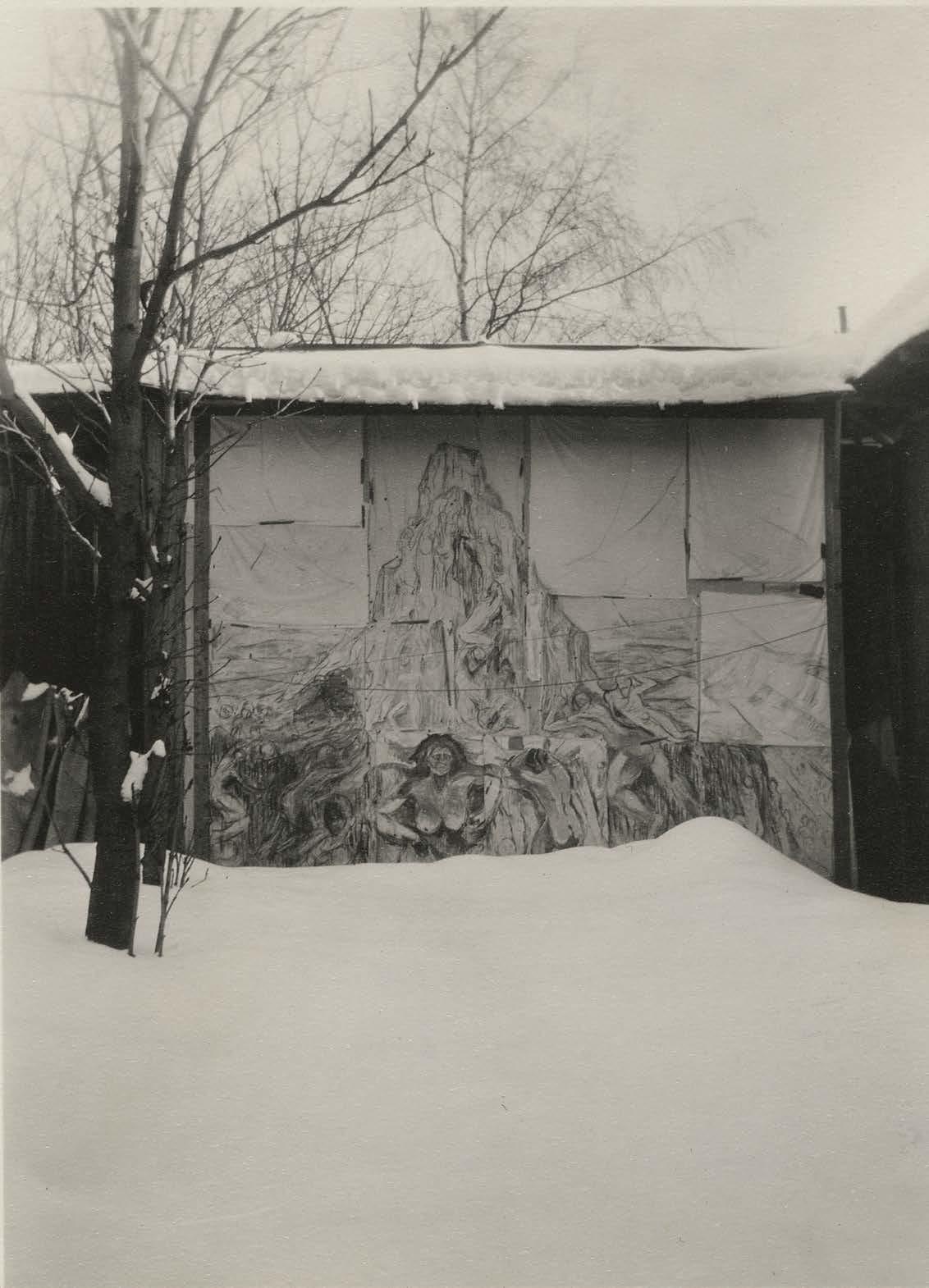

Curator Richard Calvocoressi remembers the extraordinary talent of Frank Auerbach.

Alexander Provan is the editor of Triple Canopy and a contributing editor of Bidoun . He is the recipient of a 2015 Creative Capital Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant and was a 2013–15 fellow at the Vera List Center for Art and Politics. Provan’s writing has appeared in the Nation , n+1, Art in America , Artforum , Frieze , and several exhibition catalogues.

Tomás González Olavarría is an economist, a fellow at the European University Institute, and the founder of Tribu, a nonprofit organization working to advance innovations and reforms in democracy. He led Latin America’s first national deliberativedemocracy process.

The Paris-based writer William Middleton is the author of Double Vision , a biography of the legendary art patrons and collectors Dominique and John de Menil, published in 2018 by Alfred A. Knopf. He has contributed to such publications as W, Vogue , Harper’s Bazaar, Architectural Digest , House & Garden , Departures , Town & Country, the New York Times , and T

Ross Simonini is an interdisciplinary artist, writer, and musician. His work comprises paintings, drawings, essays, dialogues, musical compositions, performance, and fiction.

Dan Fox is a writer, musician, and filmmaker. He is the author of the books Limbo (2018) and Pretentiousness: Why It Matters (2016), and codirector of the BBC documentary Other, Like Me: The Oral History of coum Transmissions and Throbbing Gristle (2020). He is a consulting editor for the Yale Review and lives in New York. Photo: Matthew Porter

Miriam Bale is a writer and film programmer based in California.

Jane Bennett is the Andrew W. Mellon Professor of the Humanities at Johns Hopkins University and specializes in the environmental humanities, political philosophy, nature writing, American romanticism, political rhetorics and affects, and contemporary social thought.

Sam Wasson is the best-selling author of many books on Hollywood. He was born and lives in Los Angeles.

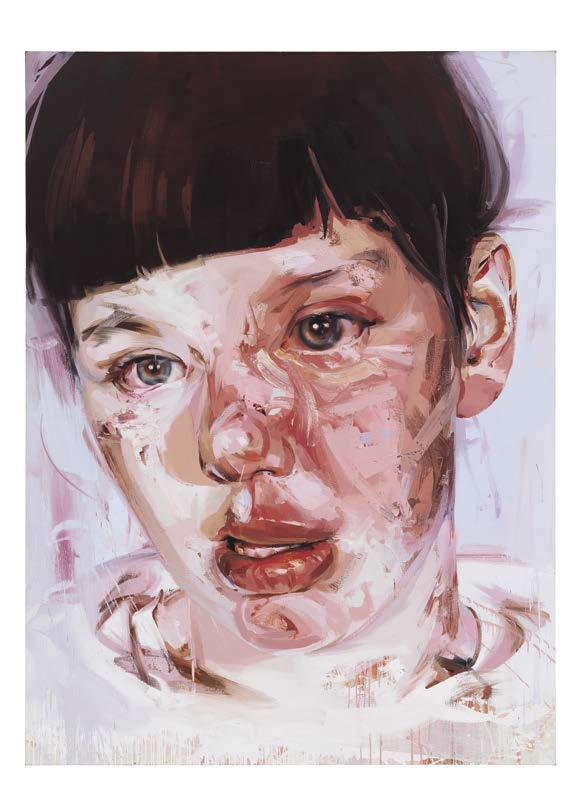

In her depictions of the human form, Jenny Saville transcends the boundaries of both classical figuration and modern abstraction. Applied in heavy layers, oil paint becomes as visceral as flesh itself, each painted mark maintaining a supple, mobile life of its own. As Saville pushes, smears, and scrapes her pigments over her large-scale canvases, the distinctions between living, breathing bodies and their painted representations begin to collapse. Photo: Paul Hansen/Getty Images

Ed Schad is curator and publications manager at the Broad in Los Angeles, where he has curated large-scale exhibitions of the work of Takashi Murakami, Shirin Neshat, William Kentridge, and Mickalene Thomas. His writing has appeared in Art Review, Frieze , the Brooklyn Rail , and the Los Angeles Review of Books

Isabelle Huppert is a French actress and producer. A collaborator with Claude Chabrol, Benoît Jacquot, and Michael Haneke, Huppert alternates between stage and screen, art-house cinema and mainstream films. She was introduced to the public by the Swiss director Claude Goretta in 1977 in the film The Lacemaker ; her theatrical career has led her to work with renowned directors such as Robert Wilson, Claude Régy, Krzysztof Warlikowski, Jacques Lassalle, and Luc Bondy, and to interpret contemporary authors such as Yasmina Reza and Florian Zeller.

Photo: JEP Celebrity Photos/Alamy Stock Photo.

Derek C. Blasberg is a writer, fashion editor, and New York Times best-selling author. He has been with Gagosian since 2014 and is the executive editor of Gagosian Quarterly

Robert Wilson’s productions have decisively shaped the look of theater and opera since the late 1960s. His signature use of light, his investigations into the structures of simple movements, and the classical rigor of his scene and furniture design have continuously articulated the force and originality of his vision. Wilson’s close ties and collaborations with leading artists, writers, and musicians continue to fascinate audiences worldwide.

Christian House worked as a proposals writer at Sotheby’s for a decade before a period as an obituarist for the Telegraph . He now writes on visual arts, literature, and history for publications such as the Financial Times , Canvas , and CNN Style

Philip Lindsay leads the Democracy Innovation Hub at the Hannah Arendt Center for Politics and Humanities at Bard College. Over the past three years, the Hub has hosted annual gatherings for advocates and practitioners of citizens’ assemblies in the United States. These gatherings led to the first major use of sortition in New York City, in 2023.

Mike Stinavage is a writer and waste specialist from Michigan. During his political science masters program at CUNY Graduate Center, he was awarded Fulbright and Martin Kriesberg fellowships to research the politics of waste in Northern Spain. He currently coordinates a European project on biowaste policy and writes fiction in Pamplona, Spain.

Masayoshi Takayama’s appreciation for food started at a young age, growing up working for his family’s fish market in a town of Tochigi Prefecture, Japan. Chef Masa is also chef/owner of Bar Masa (located next door to Masa), and is the chef at Kappo Masa (located at 976 Madison Avenue). Photo: Dacia Pierson

David Cronenberg has established his reputation as an auteur through his uniquely personal work as both film director and writer. Beginning his career in underground filmmaking, he has developed a dramatic oeuvre of outstanding depth and breadth and has been lauded as one of the world’s most influential filmmakers. Recognitions of his contributions to art and culture have included the Order of Canada and France’s Légion d’Honneur. Photo: Caitlin Cronenberg

Born in New York, where she lives and works, Taryn Simon received a BA in semiotics from Brown University in 1997. In 2001 she was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship for what would become her first major photo-and-text work, The Innocents (2002), which was exhibited at MoMA PS1, New York. Incorporating mediums ranging from photography and sculpture to text, sound, and performance, each of her projects is shaped by years of research and planning, including obtaining access from institutions as varied as the US Department of Homeland Security and Playboy Enterprises, Inc.

Nora Lawrence is the executive director of Storm King Art Center, New Windsor, New York. Lawrence has played an integral role in raising the center’s profile, seeing its audience grow four-fold and bringing in a new generation of artists. In 2023 she cocurated a site-specific commission by the artist Martin Puryear there. Lawrence has developed nearly twenty exhibitions with Storm King’s curatorial team, working with artists including Lynda Benglis, Mark Dion, Rashid Johnson, and Wangechi Mutu.

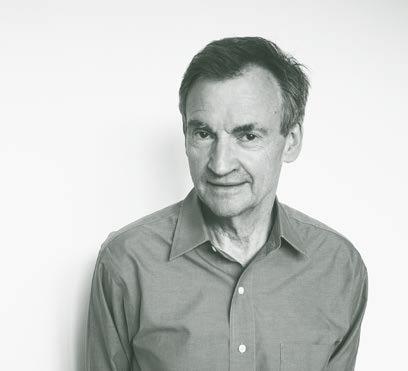

Hans Ulrich Obrist is artistic director of the Serpentine, London. He was previously the curator of the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Since his first show, World Soup (The Kitchen Show), in 1991, he has curated more than 350 exhibitions. Photo: Tyler Mitchell

When not writing about books or art, Josh Zajdman is doom-scrolling Instagram or working on his novel.

Catherine Lacey is the author of The Möbius Book , forthcoming from Farrar, Straus and Giroux in June 2025, and of five other books including Biography of X (2023). She has earned a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Whiting Award, the New York Public Library’s Young Lions Fiction Award, the Brooklyn Library Prize, and a Lambda Literary Award, and her work has been translated into a dozen languages.

Walton Ford recasts, reverses, and rearranges the conventions of animal art. He is a devout researcher, responding to everything from Hollywood horror movies to Indian fables, medieval bestiaries, colonial hunting narratives, and zookeepers’ manuals. He grew up in the Hudson Valley, graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design, and currently lives and works in New York.

Amber Collins is the associate director of research at Gagosian Art Advisory. An art history graduate of the University of Chicago, she will contribute essays to the forthcoming publications Thomas Schütte: Major Sculptures (winter 2025) and Amorelle Jacox: Color Keeping (spring 2025).

Apichatpong Weerasethakul is recognized as a major international filmmaker and visual artist. He began making films and video shorts in 1994 and completed his first feature in 2000. He has also mounted exhibitions and installations in many countries since 1998. His works are characterized by their use of nonlinear storytelling, often dealing with themes of memory, loss, identity, desire, and history. His films have won him widespread international recognition and numerous awards, including the Cannes Jury Prize for Memoria (2021), which featured Tilda Swinton and was his first film shot outside Thailand. His art prizes include the Sharjah Biennial Prize (2013), the Fukuoka Prize (2013), the Yanghyun Art Prize (2014), and the Artes Mundi Award (2019).

Photo: Chayaporn Maneesutham

John Szwed is the author and editor of many books, including biographies of Billie Holiday, Miles Davis, Sun Ra, and Alan Lomax. He has received fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation and in 2005 was awarded a Grammy for Doctor Jazz , a book included with the album Jelly Roll Morton: The Complete Library of Congress Recordings by Alan Lomax.

Alison McDonald is the Chief Creative Officer at Gagosian and has overseen marketing and publications at the gallery since 2002. During her tenure she has worked closely with Larry Gagosian to shape every aspect of the gallery’s extensive publishing program and has personally overseen more than five hundred books dedicated to the gallery’s artists.

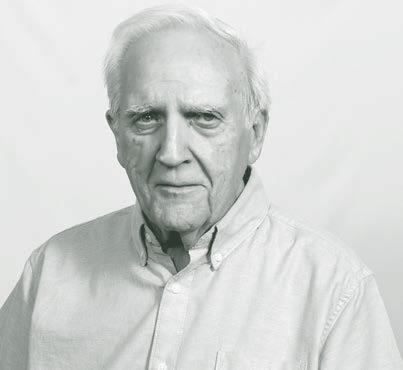

Richard Calvocoressi is a scholar and art historian. He has been a curator at Tate, London, director of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, and director of the Henry Moore Foundation. He joined Gagosian in 2015. Calvocoressi’s Georg Baselitz was published by Thames & Hudson in May 2021.

Francine Prose’s most recent novel is The Vixen (2021). Her other books include Caravaggio: Painter of Miracles (2005), Reading like a Writer (2012), Lovers at the Chameleon Club, Paris 1932 (2014), and Peggy Guggenheim: The Shock of the Modern (2015). The recipient of numerous grants and awards, she often writes about art. She is a distinguished writer in residence at Bard College.

Steeped in numerous Eastern and Western cultural references ranging from art history to theater and from cinema to music to philosophy, Ho Tzu Nyen’s works blend mythical narratives and historical facts to mobilize different understandings of history, its writing and transmission.

Harmony Holiday is a writer, dancer, archivist, filmmaker and author of five collections of poetry including Hollywood Forever and Maafa (2022). She curates an archive of griot poetics and a related performance series at Los Angeles’s MOCA and at a music and archive venue 2220 Arts, that she runs with several friends, also in Los Angeles. She has received the Motherwell Prize from Fence Books, a Ruth Lilly Fellowship, a NYFA fellowship, a Schomburg Fellowship, a California Book Award, a research fellowship from Harvard, and a teaching fellowship from Berkeley. She’s currently working on a collection of essays for Duke University Press and a biography of Abbey Lincoln, in addition to other writing, film, and curatorial projects.

Gagosian Quarterly presents a selection of new releases coming this spring.

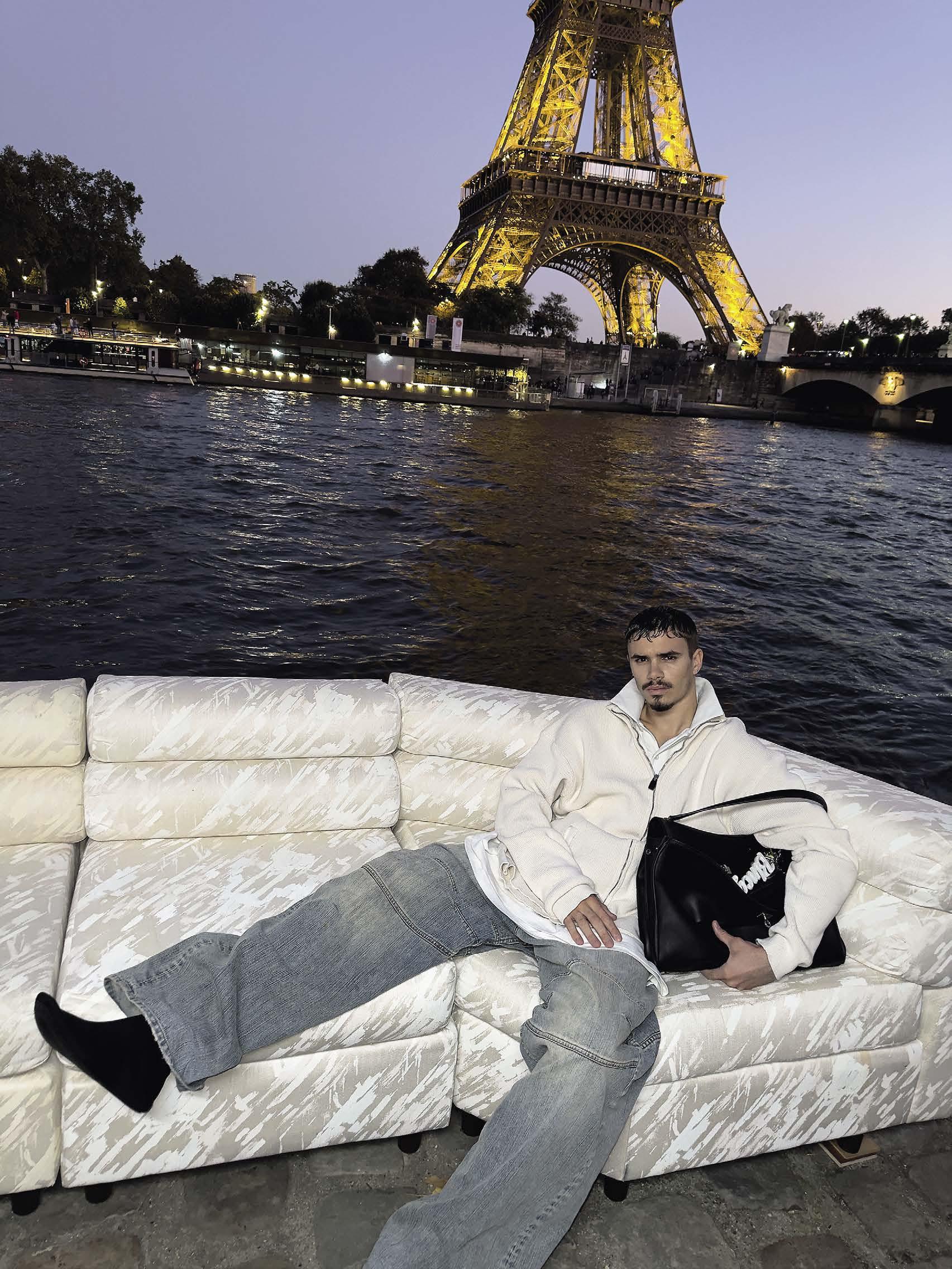

Collaboration

Louis Vuitton × Takashi Murakami

The celebrated artist and iconic luxury house reunite twenty years after their groundbreaking collaboration to launch the Louis Vuitton × Murakami reedition. This collection, featuring over 200 pieces, reimagines the vibrant motifs of the original, blending Murakami’s signature aesthetic with Louis Vuitton’s craftsmanship. From reworked Monogram bags to accessories, it celebrates creativity, technology, and a timeless artistic bond.

Photos: courtesy Louis Vuitton

Left: Perspective(s) (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2025)

Old Masters Perspective(s) by Laurent

Binet

Newly translated from the French by Sam Taylor, Laurent Binet’s Perspective(s) transforms the epistolary novel and Italian Renaissance history into a gripping mystery. When renowned artist Jacopo da Pontormo is found murdered in a church, a scandalous painting of Maria de’ Medici sparks further chaos. Art historian Giorgio Vasari is tasked with uncovering the killer, unraveling a web of political intrigue.

On December 12, pleats please issey miyake opened its new flagship store at 14 Kenmare Street, New York, in architect Tadao Ando’s debut New York building. With an interior designed by moment, the 2,224-square-foot space combines industrial elements with sleek pleated motifs. Exclusive pieces from the new soil & leaf collection marked the occasion, celebrating the brand’s light, functional beauty in this dynamic setting.

Above:

courtesy Issey Miyake

Right: Lauren Halsey: emajendat (Rizzoli International Publications, New York, 2024)

Exhibition Catalogue Lauren Halsey: emajendat

Published on the occasion of Lauren Halsey: emajendat at Serpentine, London, the artist’s first solo exhibition in the United Kingdom, this extensive volume includes images of Halsey’s stand-alone works and installations from 2018 through 2024, alongside texts analyzing her practice by Will Alexander, LeRonn P. Brooks, George Clinton, Harmony Holiday, Douglas Kearney, and Bettina Korek. A conversation between the artist, Lizzie Carey-Thomas, and Hans Ulrich Obrist is also included.

The publishing house Fitzcarraldo Editions, whose work with such authors as Svetlana Alexievich, Annie Ernaux, and Olga Tokarczuk belies its relative youth, has launched its inaugural poetry list. The series opens with Strange Beach , by Oluwaseun Olayiwola, and with two titles by Pulitzer Prize–winning poet Diane Seuss. As Seuss writes in her whip-smart collection Frank: Sonnets (2021), as if forecasting the ambitions of Fitzcarraldo’s poetry list: “The sonnet, like poverty, teaches you what you can do / without.”

Left: Frank: Sonnets (Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2025)

Right: Self Portraits: From 1800 to the Present (Assouline, 2025)

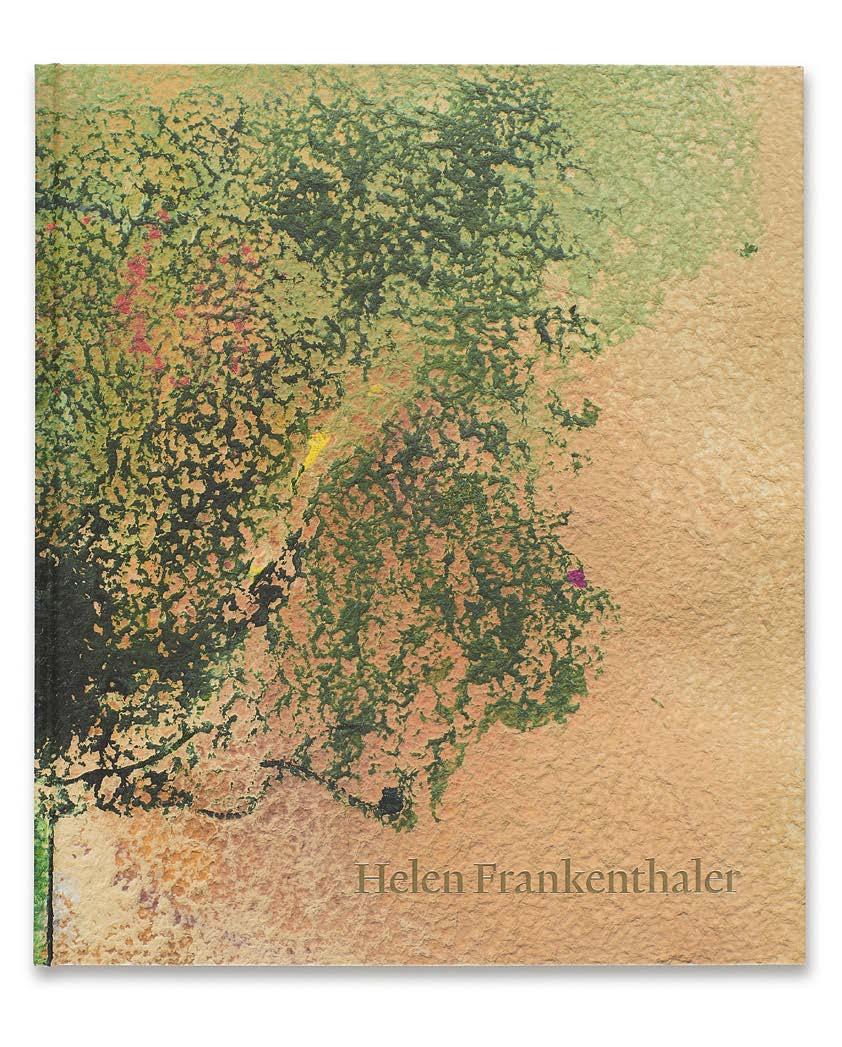

Below, left to right: Helen Frankenthaler: Painting on Paper, 1990–2002 (Gagosian, 2024)

The American No (Atria, 2024)

This new book from Assouline, edited by Philippe Ségalot and Morgane Guillet, offers a journey through the art of self-portraiture. Spanning centuries, it showcases over sixty works—from classic paintings to modern photography and found objects—revealing artists’ personal interpretations of identity. Featuring legends such as Monet and Caillebotte, it explores how selfreflection has evolved in art history.

This book was published on the occasion of Helen Frankenthaler: Painting on Paper, 1990–2002 , at Gagosian, Rome. The exhibition presented eighteen large-scale works from the last years of Frankenthaler’s career, when painting on paper became her primary means of expression. Reproductions of the paintings exhibited are accompanied by details revealing their physical presence and textures, as well as archival photographs of the artist and her studio at Shippan Point, in Stamford, Connecticut, in the 1990s. The book also features a new essay by Isabelle Dervaux analyzing the impetus for the works and the techniques that Frankenthaler employed when making them.

Short (Brilliant) Stories

The American No by Rupert Everett

Rupert Everett’s The American No, praised by critics since its UK release, arrives in the US this February. This captivating story collection offers darkly humorous and poignant tales drawn from Everett’s film and TV career.

Made by MSCHF, published by Phaidon, is an irreverent behindthe-scenes guide to the provocative Brooklyn-based art collective, known for boundary-pushing works that satirize popular culture. From the viral Big Red Boot to Jesus Shoes filled with holy water, the book explores twelve projects in depth, offering a glimpse into MSCHF’s creative process with never-before-seen images, essays, and a full archive of their audacious art.

This set of two porcelain plates produced by Howard Hodgkin Home features different details from the artist’s 1981 screen print Souvenir, which incorporates a wide variety of marks—including some made directly by the artist’s own hand—in five different shades of black.

Performance African Exodus by the Centre for the Less Good

The Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain presents the North American premiere of African Exodus , a performance from Johannesburg’s Centre for the Less Good Idea.

Running February 27–March 2, 2025, at PAC NYC, this musical odyssey blends African and Western choral traditions, exploring migration, language, and history through music, movement, and powerful storytelling.

Walton Ford’s exhibition Tutto opens on March 6, 2025, at Gagosian, New York. Here, the artist reflects on the life and passions of Marchesa Luisa Casati, the twentieth-century muse and patron of the arts.

The marchesa lived partly as a slave to her dream world. She was a great artist, but not understood by the common people or even her own friends, who were jealous spectators of her artistic successes.

—Alberto Martini, in Infinite Variety: The Life and Legend of the Marchesa Casati, 1999

In 1900, the newly married Marchese and Marchesa Casati were photographed perched side by side on a smooth boulder next to a waterfall. Camillo Casati wears a three-piece suit and sits in a confident and jaunty spread-legged pose, a proud crooked smile slanting beneath his waxed mustache. Luisa Casati sits by him ramrod straight, unsmiling, her large, melancholy eyes meeting ours. She is tightly corseted, trussed into a dark

Victorian outfit that completely covers her body save for her hands and face. She holds a riding crop and has donned a great floral hat. She does not steady herself by clasping her husband’s arm; instead she seems to be leaning on her unseen hand, touching the cool rock behind her back.

Thirteen years later, Luisa Casati was photographed in the center of a large crowd of costumed revelers, many in eighteenth-century dress. Now uncorseted, she wears an androgynous white harlequin costume, complete with loose high-waisted trousers and black mask, designed for her by Léon Bakst of the Ballets Russes. Again, her eyes look directly at the viewer. Her lipsticked mouth hints at a smile. One of her pet cheetahs sits calmly beside her and a large macaw rests on her hand. By that time she

had left her husband and had begun throwing massive parties at her halfruined palazzo in Venice.

Luisa made her palazzo into a kind of bohemian playground, hosting wild masquerades with live jazz, booze, opium, artists, writers, and socialites. She would dress outrageously and fearlessly, costumed as a fountain or as Catherine the Great, or covered with electric lights. She had lovers, both male and female, and ended up spending all of her vast wealth on clothes, jewels, artwork, parties, and exotic animals. The social events she created anticipated Andy Warhol’s Factory, artsy nightclubs, contemporary raves—in fact they propagated any idea we now have of a hot art scene.

In their book Infinite Variety: The Life and Legend of the Marchesa Casati

(1999), Scot D. Ryersson and Michael Orlando Yaccarino write, “More than one report details Luisa’s unusual nocturnal promenades: her spectral form, totally nude within the folds of a voluminous fur cloak, leading her pet cheetahs by jeweled leashes about the Piazza San Marco.” Having discovered only three rather blurred photos of Casati with her cheetahs, I found myself trying to imagine the cats’ life with the marchesa. These creatures contributed to the ferocity of Casati’s public image. They were also wild African animals caught up in a strange, frenetic world of parties, palazzos, gondola rides, and excess. I wanted to paint pictures about the world’s fastest animals living a fast life with a wild woman in Venice. The cheetahs got me invited to the party. Show me more.

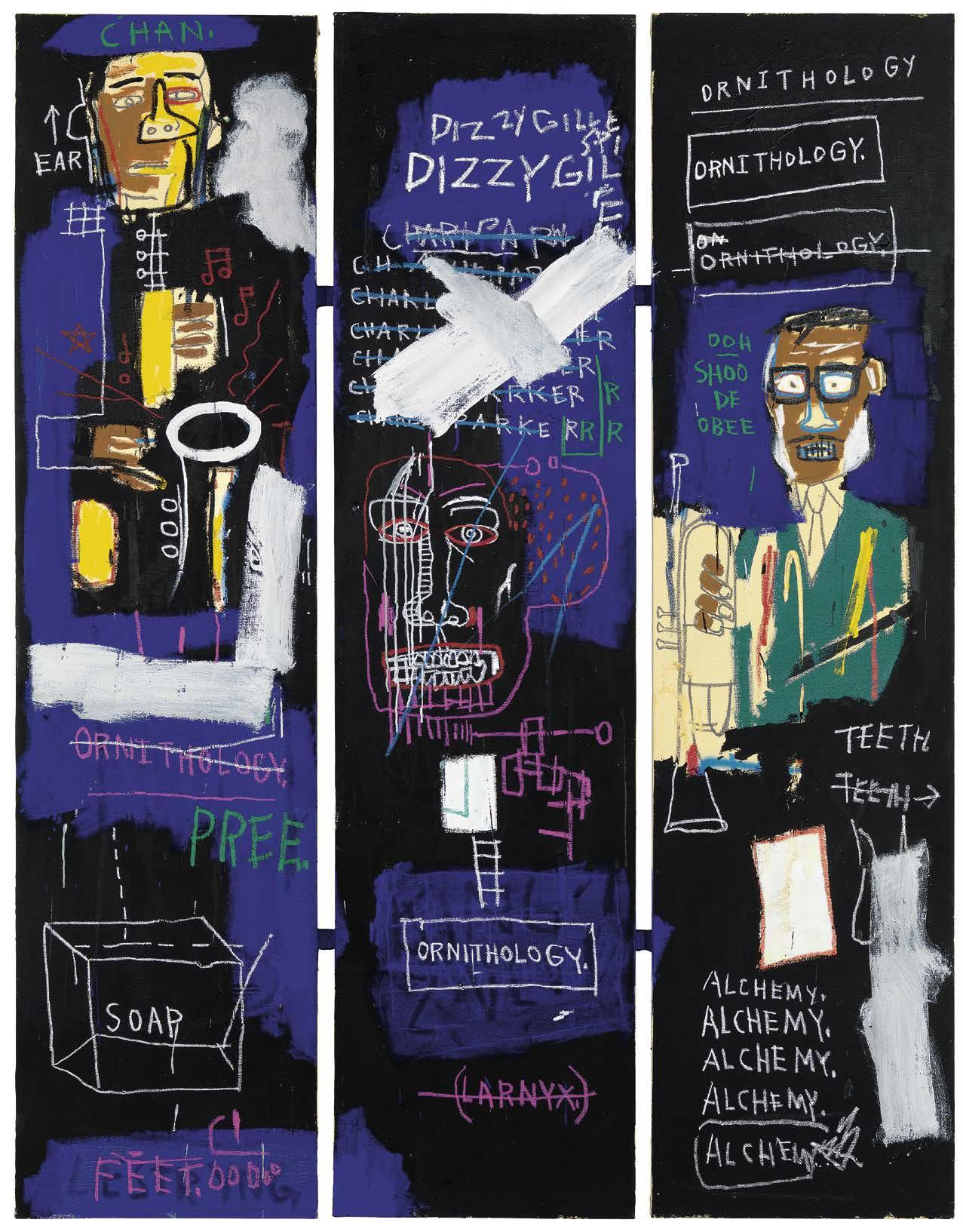

Vincent Gardner, trombonist, composer, and arranger in the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, speaks about the bebop genre and Jean-Michel Basquiat with the Quarterly ’s Alison McDonald on the occasion of “Bebop Revolution: JLCO with Wynton Marsalis,” two nights celebrating bebop at Jazz at Lincoln Center, New York. To read the full interview, visit gagosian.com/quarterly.

ALISON MCDONALD Please describe how the performance came together— illuminate a little bit about your process, from early ideas, inspirations, and conversations, to selecting music, rehearsals, and the final performance.

VINCENT GARDNER I’ve always been a fan of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, with Gillespie being one of my earliest musical references. My father, who was a trumpet player, showed me a picture of him when I first began to play trombone and was developing a bad habit and said, “He’s the ONLY one that can play an instrument looking like that. DON’T puff out your cheeks when you play!” As far as inspirations, I was thoroughly immersed in bebop by the amazing historian Phil Schaap and many of the older Brooklyn musicians and jazz fans I met when I lived there. The most prominent message that I learned from them is that the music was the statement from the youth of the 1940s on the way that they wanted music and the world to look in the years after World War II. It was to be based on both fun and virtuosity, and inclusive of everyone who had the skills to play it. This was the real “Bebop Revolution,” so in selecting music, I chose pieces that showcase not only the distinctive language that was only played during the bebop period but also pieces that were written by beboppers for some of the swing bands of the earlier era, showcasing how the music was being used to cross barriers of race and age. AMCD Bebop was groundbreaking when it emerged, and it has influenced generations of creators since. What impact did bebop specifically have on your work and early formation as a musician, and what thoughts might you have about jazz more generally and its traces in the works of Jean-Michel Basquiat?

VG First, I was astonished by the virtuosity of Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Max Roach, Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, and J.J. Johnson. As I learned more about jazz, I could hear that not only were they playing with astonishing technique and presence, but they were creating new language in jazz, putting notes and phrases together as no one had done before in earlier eras. They also did it at a time when the public, after a terrible war, would rather hear something familiar in their music instead of something new and innovative. Their integrity in proclaiming that this is the new music of that time and not bending to the pressure to conform is extremely inspiring. The cutting-edge nature of these new sounds, the bebop culture it created with the young people of the 1940s, and the folklore of Charlie Parker’s life influenced artists of all disciplines, and Basquiat created some of the most impactful references to it in his art.

My favorite out of those is Max Roach (1984). It has many clear layers to me that paint a powerful total statement. There are two ghostlike images in the painting, one which reminds us of Lester Young, clearly outlining the shape of his signature porkpie hat near the drums, and a larger, more menacing figure that seems to evoke how Roach’s influence took over all bebop drumming for a time and was the basis for the transition into the hard-bop style of the 1950s.

AMCD There is a conversational nature in improvised jazz, and I wonder if you see anything similar reflected in Basquiat’s work. There is an elevated harmonic language and rhythmic structure to bebop that you might also identify in the work of Basquiat. VG I do agree and see a parallel in Basquiat’s work. In anything improvisational there still must be both

balance between all of the contributing elements and also occasional moments of imbalance, which make it feel human and in realtime. I enjoy the interplay in Basquiat’s works between those features, sometimes reflected in color, texture, or a complete or partial reference to an image that may at first seem unrelated but only for a short time until you reexamine the work.…

Flo we r. Dendritic agat e, ameth ysts, gr een tourmalines and 1 8K gold. judygeib.co m

Spring

This puzzle, written by Myles Mellor, brings together clues from the worlds of art, dance, music, poetry, film, and beyond.

1 Siouxsie and the : postpunk band founded in the mid-’70s

5 African-American artist and musician known for assemblages and immersive environments, last name 11 Fermented malt beverage

12 Alicia Keys hit (two words) 13 Training Day star Mendes

15 Basquiat painting Untitled ( )

17 Brokeback Mountain director Lee

18 Flowers in a Van Gogh painting of 1888

21 First name of a prominent Mexican painter of murals

22 French word for soul

23 Actress Kunis of Black Swan

24 Caribbean music

27 Déjà (feeling of familiarity)

29 Memoirs of a movie

33 Epic Homer poem The

35 Belgian artist who lives and works in NYC, painter of Untitled (The Great Night), Harold

37 Elton John’s title

39 Life of , film about a boy and a tiger at sea

40 Celebrated New York– and

Hamptons-based interior designer Robert

41 “Bad Guy” singer Billie

44 Environmental watchdog org, abbr.

46 Repeated TV episode

48 Put two and two together

50 Subject of A Complete Unknown

51 Compass point, abbr.

52 Where the statue Cristo Redentor stands

53 Assist

54 24-hour period

55 “Queen of Pop” who dated Basquiat

Down

1 Hawking star Cumberbatch

2 Supermodel Campbell

3 Color

4 Role in Haydn’s The Creation

6 Military maneuvers, briefly

7 Last name of fashion designer and first name of a celebrated contemporary artist from South Central LA

8 Building addition

9 Georgia O’Keeffe painting

Sweet Peas

10 She starred alongside Angelina Jolie in Maleficent , Elle

14 Blue Ridge Mountains state, abbr.

16 Dates

19 Express verbally

20 Filled with intense emotion

21 Creator of Vitruvian Man (two words)

25 Global #1 hit for Chris de Burgh (commonly referred to in three words)

26 Ended

28 Los Angeles campus, for short

30 Electronic Arts, abbr.

31 Laughter sound

32 Dadaist artist Jean

34 Movie City, directed in part by Tarantino

36 Shakespeare’s fairy queen

38 India.Arie song “Strength, Courage, & ”

40 Legendary sculptor who created Thirty-Five Feet of Lead Rolled Up, Richard

42 Abstract Expressionist painter included in the 1964 exhibition Post-Painterly Abstraction , Frankenthaler

43 American painter who was a friend of Degas and was part of the Impressionist movement, Cassatt

45 Father, informally

47 World body, briefly

49 Lady (British princess)

50 Family man

Twombly by Jenny Saville

Jenny Saville reflects on Cy Twombly’s poetic engagement with the world, with time and tension, and with growth in this excerpt from her Marion Barthelme Lecture, presented at the Menil Collection, Houston, in 2024.

“Try and stay ignored for as long as possible.” This is what Cy Twombly said to me when I was twentynine years old. He was a hero of mine, so of course I thought, “This guy doesn’t like my work very much.” However, I know now that what he was saying was that a young painter needs time to learn, to develop. He was at the height of his powers when I met him, both artistically and in a career sense. Every artist wanted to know him and every museum wanted to buy his work. I was extraordinarily lucky that we were represented by the same gallery and for the last ten years of his life, I was around him and able to learn from him.

My first encounter with Twombly’s work was in my first term at the Glasgow School of Art, when I was eighteen years old. I saw two of his paintings in an art magazine—Suma from 1982 and an early-1960s work. I was a figurative painter, so I was only interested in depicting the body, but something about those images caught me and held me. From that moment on, I was hooked and sought out his work wherever and whenever I could.

Twombly spent his whole life with one foot in a cave and the other in a palace. He never left the cave really—he dealt with the fundamental themes of life, the need to survive, basic human desires, lustful needs, fears. Those foundational aspects of human nature are always there in his work. And he had an erudite love of the ancient world. This is already evident in the work he made at Black Mountain College in the 1950s. Seeing photographs from his travels, I suspect the whiteness of the buildings he encountered in North Africa and Greece must have influenced him.

Twombly showed the twelve-panel epic painting Lepanto (2001) at Gagosian, New York, in 2002, having made it for the Venice Biennale the year before. It depicts a battle between the Venetians and the Ottoman Turks, which took place on October 7, 1571, in the Gulf of Patras—a crushing victory for the Catholics of the Holy League Alliance. The work completely blew me away when I saw it; I couldn’t believe that painting could be this good in the current age. It changed my life and made me realize how hard you have to push as a painter if you want to do something significant. I was lucky enough to be at the gallery on the day the paintings were installed, and it was clear that this was history in the making.

For ten years, there was a challenge of sorts going on between Twombly and Larry Gagosian. Every time the latter opened a new space he would ask the former, “What paintings could you make to fill this space? And then if I open a space in Paris or Rome or London . . . ?” They had a one-upmanship between them that felt like a constant game and it was a thrill to witness two people being so expansive in their outlook. I’m not sure Twombly would have created this run of paintings without those spaces and that encouragement. And that he agreed to participate with this level of energy, at this moment in his life, made Gagosian the gallery it is today.

The artists who become part of art history are the game-changers. They shift our perception of what art should be. One of the reasons Twombly is so revered is the fact that he took avant-garde American painting and merged it

Previous spread:

Cy Twombly, Untitled , 1971 (detail), oil-based house paint and wax crayon on canvas, 79 1⁄8 × 134 ¾ inches (201 × 342.3 cm), Menil Collection, Houston. Gift of the artist © Cy Twombly Foundation

Above:

Cy Twombly, Untitled (Say Goodbye, Catullus, to the Shores of Asia Minor), 1994, oil, acrylic, wax crayon, oil stick, pencil, and colored pencil on canvas, 13 feet 1 ½ inches × 52 feet (4 × 15.9 m), Menil Collection, Houston. Gift of the artist © Cy Twombly Foundation

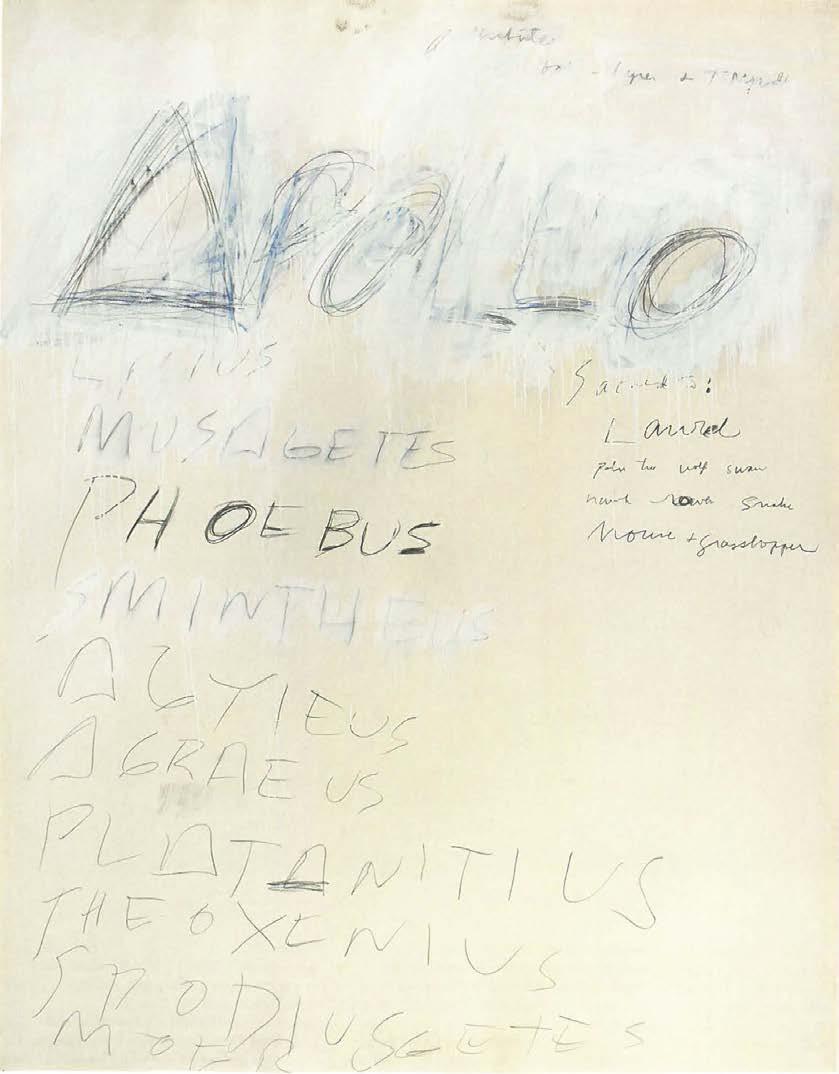

Left:

Cy Twombly, Apollo, 1975, pencil, oil, and oil stick on paper, 76 ¾ × 59 ½ inches (195 × 151.1 cm) © Cy Twombly Foundation

with ancient history. There’s nothing that tells you about that more than his Duchampian act of writing “Apollo” on a work from 1975. In that single gesture, he embodies four thousand years of Western culture in one word. When you read it, you think of all the poetic, literary, painted, and sculptural representations of Apollo throughout history. It’s an extraordinary act. Knowing Twombly, it was most likely instinctual—he probably just did it and thought, “Oh, that looks kind of good. I’ll write that again.” But, it is nonetheless a profound Duchampian statement that he’s making.

My favorite example of this is in Fifty Days at Iliam: House of Priam (1978). On the canvas he has repeatedly written, “Cassandra.” Cassandra was one of the daughters of King Priam of Troy, who proclaimed that the Trojan War was going to happen, but nobody believed her. There’s a kind of mania in the way Twombly has written “Cassandra, Cassandra, Cassandra,”—there’s a vibration to it. With this literal burying and dragging up of history, he creates a beautiful journey. By layering paint over text and inscribing the time needed for you to read the words, he plays with notions of time, balance, and tension. Twombly made language pictorial and artists like Basquiat followed him. You might never have had the same Basquiat without Twombly, without that decision to write “Apollo.”

What makes a great painting stand out forever? Tension. Any work from art history that has lasted has incredible tension within it. If you look at Michelangelo’s sculpture Moses (1513–15), it depicts an aged man from the Old Testament whose body is incredibly youthful. His arms have the muscles

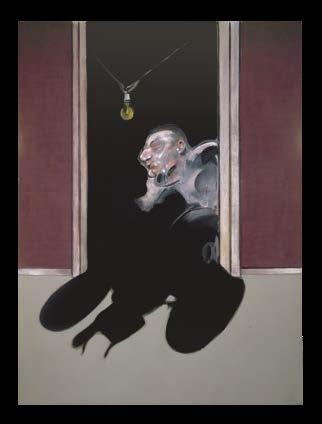

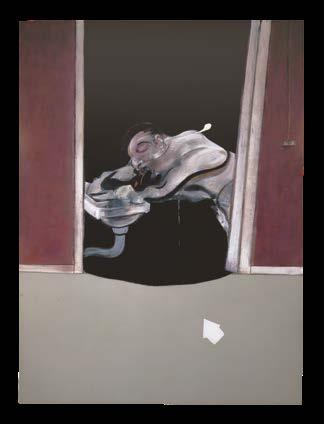

of a twenty-five-year-old, but you don’t realize it at first. When you first look, there is a believability to it. And that’s what art does—it creates tension by bringing improbable elements together. Another example is Francis Bacon’s painting of George Dyer, Triptych May–June (1973), with flat panels of organized design and areas of very thick paint. The tension lies in the juxtaposition of impastoed paint over clear modernist design and flat color— another layer that adds to the tension of the scene itself: the toilet and vomit, knowing the figure has died. It doesn’t matter whether a painting is a complicated figurative painting or a minimalist Barnett Newman Zip painting, it’s usually tension that makes the work powerful.

There is so much literature about Twombly, his love of poetry, and how he worked with ancient history. I think J. M. W. Turner and Claude Monet were major influences. When you look at Catullus , and read it from right to left, it’s a journey from a landmass in Asia Minor, but it’s also a passage through life and about the fleeting nature of life. You first see these incredible blossom shapes and you move through mistiness toward a battle. A journey through life, the epic battles and quests we know from ancient history—but also a journey that every human being has taken.

Twombly used a range of techniques—scraping and dripping paint, laying down different surfaces—to create different atmospheres. He had incredible hand skills when it came to dripping. We all know that a drip is actually part of nature— it’s the way rain works. With his drips he became a conductor of nature, harnessing its possibilities. He used drips to bury things within the painting, to give depth, or to bring things forward.

Sometimes he used very thinned-down white

paint, to apply over the top of text or an earlier image. If he started with yellow and then dripped white, that yellow would become misty, which is exactly what happens in traditional landscape painting, or indeed how we actually see things in nature. This “mistification” process was a device to create the feeling of space without having to depict anything at all. He used it throughout his career. There’s the horizontal canvas with the vertical drip, and the gravitational force that the drips harness create a dynamism within the painting. The misty nature adds a three-dimensional feeling. It is a very sophisticated approach that comes out of traditional painting techniques—laying down a hazy light to create a sense of illusionistic distance. The strongest contrast appears on the surface and it gives the structures three dimensions.

At the far right of Catullus , there is a bulbous shape. I’ve stared for ages at these forms thinking, “Cy, what on Earth are they? Are they blossoms? Are they stars? Are they going up or coming down?” I think they are the embodiment of fertility—the embodiment of spring. T. S. Eliot would call this “breeding.” They hint at blossoms, fruits, or a harvest. They have so many connotations in their color combinations. I find it interesting that Twombly painted Quattro Stagioni (A Painting in Four Parts) (1993–95), held in the collection of Tate, London, just before making this painting.

There is a text by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe that has driven my work for more than a decade now, which connects to Twombly. While he was in Sicily, Goethe discovered the mothers of Angion— ancient fertility goddesses who are responsible for the fertility of the world and for creation in all its forms. He invented a place called the “Realm of the Mothers.” It is somewhere outside of time

and place, and it is where all forms are created. In Goethe’s Faust Part II (1832), Mephistopheles says:

Take hold of it without disparaging. It shines and flashes, grows in my hand. How great its worth, will you now understand? The key will sense the right place from all others. Follow it down, t’will lead you to the Mothers. The Mothers like a shock, it smites my ear. What’s in this word I don’t like to hear? So limited in mind by each new word disturbed, will you only hear what you’ve always heard? Let naught perturb, however strange it rings, you’re long-accustomed to most wondrous things. In apathy I see no wheel for me. The thrill of all is man’s best quality. Whatever toll the world lays on this sense, enthralled, man deeply senses the immense. Descend then, or I could also say ascend. It’s all the same. Escape from the created into the unbound realm of forms. Delight in what long since was dissipated, like coursing clouds the throng is coiling around. Brandish the key and keep them out of bound. Good grasping it I feel new strength arise. My breast expands on to the enterprise. At last a glowing tripod tells you this that you’ve arrived in deepest deep abyss. You’ll see the Mothers in its radiant glow. Some sit, some stand, some wander to and fro, as it may chance. Formation, transformation, eternal minds, eternal recreation. Girt round by images of all things that be, they do not see you, forms alone they see. Do take courage then, for the peril’s great. And to the tripod go forth straight and touch it with the key.

Above: Francis Bacon, Triptych May–June, 1973, oil on canvas, in 3 parts, each: 78 × 58 inches (198.1 × 147.3 cm) © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved/ DACS, London/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2024

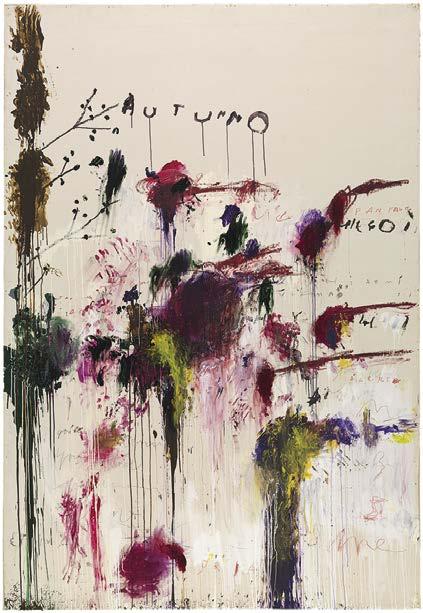

Below: Cy Twombly, Quattro Stagioni (A Painting in Four Parts), 1993–95; part 1: Primavera , acrylic, oil stick, wax crayon, colored pencil, and pencil on canvas, 123 × 74 ¾ inches (312.5 × 190 cm); part 2: Estate, acrylic, pencil, and colored pencil on canvas, 123 5 8 × 84 5⁄8 inches (314 × 215 cm); part 3: Autunno, acrylic, oil stick, wax crayon, and pencil on canvas, 123 ¼ × 84 5⁄8 inches (313 × 215 cm); part 4, Inverno, acrylic, oil stick, oil, and pencil on canvas, 123 3⁄8 × 86 ¾ inches (313.5 × 220.5 cm), Tate, London. Purchased with assistance from the American Fund for the Tate Gallery and Tate Member 2002 © Cy Twombly Foundation

When I’m working in my studio, trying to access something in my work by running colors together or almost being self-destructive and pushing at something, I feel a connection to this text and I think something in it also connects to Twombly’s fertile blossoms.

Twombly developed a whole vocabulary to get nature into painting. I often think of him as a child running toward a rainbow, trying to catch it in his hand. Once he’s got it, he puts it on the canvas and then he samples things—he takes a little bit of the sea, a little bit of the rainbow, and distills their essence, putting it all into paint. He had a keen sense for the way tonal transitions from nature occur. For example, we all have a relationship with sunsets—we all recognize them. When we see tones that are in tune with nature, we feel soulful. He could bring that into a painting the way others can hold a note. That was his gift. He didn’t have to be Turner or Monet, who spent their lives in nature, depicting what they were looking at. Instead he took aspects from both artists and used the potential of painting itself to show us the nature of things.

It’s similar to the way blossom works. There is a fleeting moment in spring of incredible abundance. It’s so beautiful and we can’t wait for it to come, but it only lasts a short time. And then there is a sense of sadness when it disappears. That arc of time wouldn’t be the same if we experienced blossom

all year round—the beauty exists in part because it is fleeting. And when Twombly created his, he tapped into our collective memory.

I’m a figurative painter but in summer I go to Greece and try to paint the sky without any forms, to observe the way light moves. I take the studies back to my studio and put them in my figurative paintings. There’s nothing more violent than a sunset at its peak. I’ve spent time in pathology rooms and anatomy rooms, I’ve seen heads that have been blown apart by shotgun fire, but nothing is as violent as a full sunset. As it begins you see blue and yellow, then fire, then comes the darkness and it grays off—things become misty, forms become soft, and you can no longer see the edges. I try to harness that through watercolor studies, and I can see Twombly’s influence in them.

Twombly uses ambiguity, which is king in modern contemporary painting. We love ambiguity— it’s where the poetry lies. He employs it time and again. And this brings me back to Lepanto, which references a battle. He used impasto and line, introducing a series of contradictions. I believe Turner’s Peace: Burial at Sea (1842) influenced this picture, particularly its quieter, mystical mistiness. I think he used Turner’s watercolor studies for inspiration. Twombly talked about his painting not having gravity; speaking with Robert Pincus-Witten in 1994 (and cited in Pincus-Witten’s essay in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition at Gagosian in 1994) he speaks of “a generic space, a loose gravitation, comparable to mythology itself, which also has no center of gravity.” His mistiness created a feeling of being ancient.

Twombly often employed impasto in his work, layering sections of paint on top of the canvas to give them a presence in themselves. This technique of using paint for its material quality is embedded in art history. Just look at the sleeve of the infanta at the top right-hand side of Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas (1656). The Spaniard used dots of pure white pigment on top of the painting. The last section of Catullus is one of the most magical parts of the piece. Two-thirds of the way across, the canvas changes tone. It goes from a mid-gray to a slightly lighter gray in the last third. It’s hard to imagine that he created a work on such a vast scale with a pencil nib—you can’t ask for more physical tension in a painting than that. He added boats using pencil and silver oil bar. The silver may have been a reference to Andy Warhol, because he was collecting the Pop artist’s work at the time, or to Delos, which was very important in the ancient world. The granite on the Greek island has silver flecks in it which shine, and it is referenced in poetry from ancient times. So many people have spoken about the references to poetry in Twombly’s work. He not only uses the words from poems but he employs them as blocks of text to act as a counterbalance to those circular blossoms. He uses text as horizon lines; he doesn’t create a true horizon because if he did, you wouldn’t buy into the blossoms—the painting would become too fixed in the real world. He can only suggest the real world. He plays with the tension of sequencing and time, and that in itself creates another world. Including text also transports you via the language and historical references it conjures.

Throughout his career, Twombly used devices that connect with time. People often talk about space in painting, but people talk less about time, and I think in fact it is one of the things that separates painting from the other arts. If you think about film, literature, and music, you need a certain sequence of time. In painting, you have a collection of present moments and the work is a document of those moments. Whether abstract or figurative, it’s a collection and record of time. In a way, a painting exists outside of time completely, and what you can do in the act of making is freeze a particular moment.

There’s a beautiful room of blackboard paintings in the Menil Collection. That body of work might be my favorite. In these Twombly tries to personify a line. When you’re standing in front of a surface making marks, you think in three dimensions, and those marks are never made by pulling, they’re always made by pushing into the surface. In a short statement published in the Italian journal L’Esperienza moderna in 1957 he explained, “Each line is now the actual experience with its own innate history. It doesn’t illustrate—it is the sensation of its own realization.” This comes from looking at Cezanne. It’s the kind of thinking that continues due to where and what it is and nothing else—it is of itself. Twombly epitomized this throughout his life—trying to find those moments, trying to embrace different ways of using materials. It’s also connected to the action of his body— the top is created by the rotation of the wrist, the

next line uses the rotation of the arm, and the bottom relies on the rotation of the torso. The association between the blackboard works and Leonardo da Vinci’s Deluge drawings is well-known (c. 1517–18). Da Vinci made a series of about ten works of a similar size in the last years of his life in France. They’re cataclysmic visions of studying water, which I think influenced Twombly. They also seem to be related to the Pyramid Texts—the oldest religious writings known to humans, located inside the temple of Unas in Egypt—which explain how to get to the afterlife. They’re made up of repetitive sounds, which Philip Glass used in a piece of music in the early 1980s, and I think Twombly probably tapped into that.

The ancient Egyptian goddess Isis was seen as the embodiment of fertility, all the secrets of nature were held within her. It has long been suggested by historians that over the course of time, the idea of Isis moves from Egypt to ancient Greece, where she becomes Artemis and later still Athena. She moves to Rome because sailors were going between there and Egypt. Then slowly, you see her become the Madonna and Child. So this journey, this hybridity, through Western history, which she embodies, is an allegory of nature. The Veil of Isis was made in ancient times in the north of Egypt and inscribed with these words: “I am all that was, all that is, and all that shall be and no mortal has lifted my veil.” If anybody tried to lift her veil and get us as close as possible to the secret of nature in our time, it was Cy Twombly.

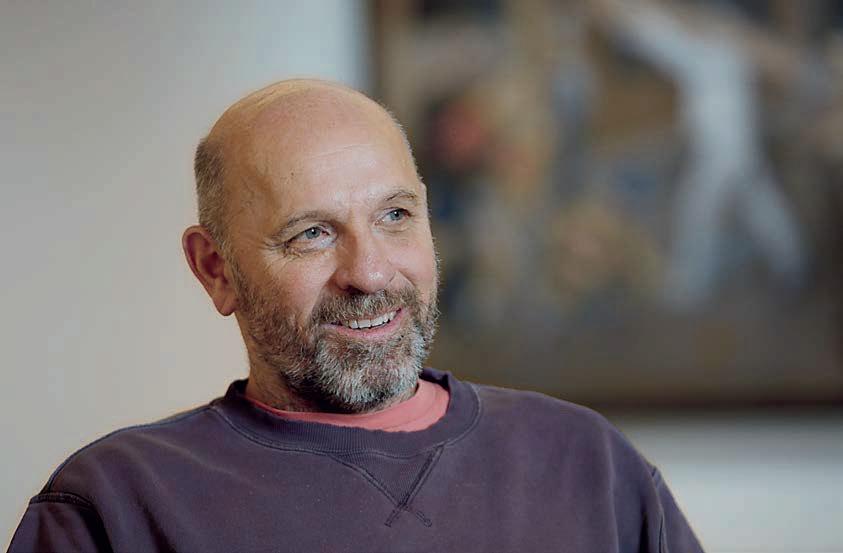

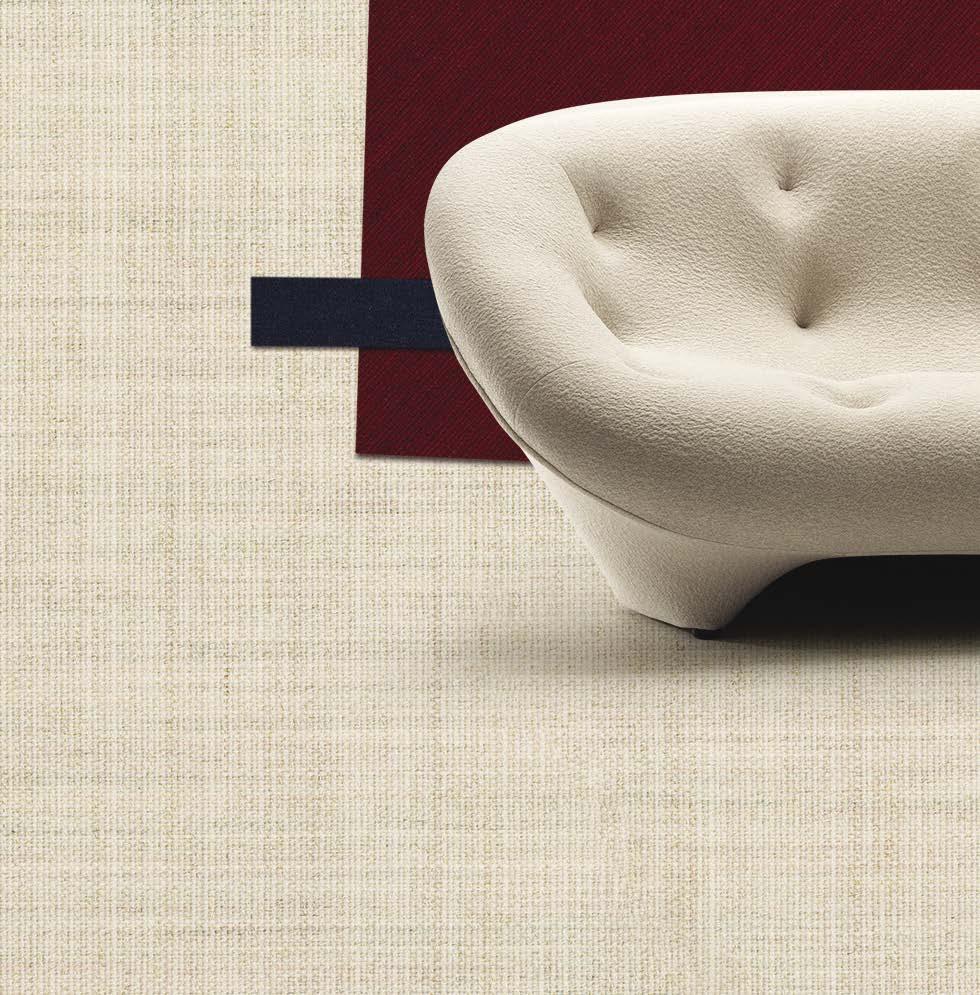

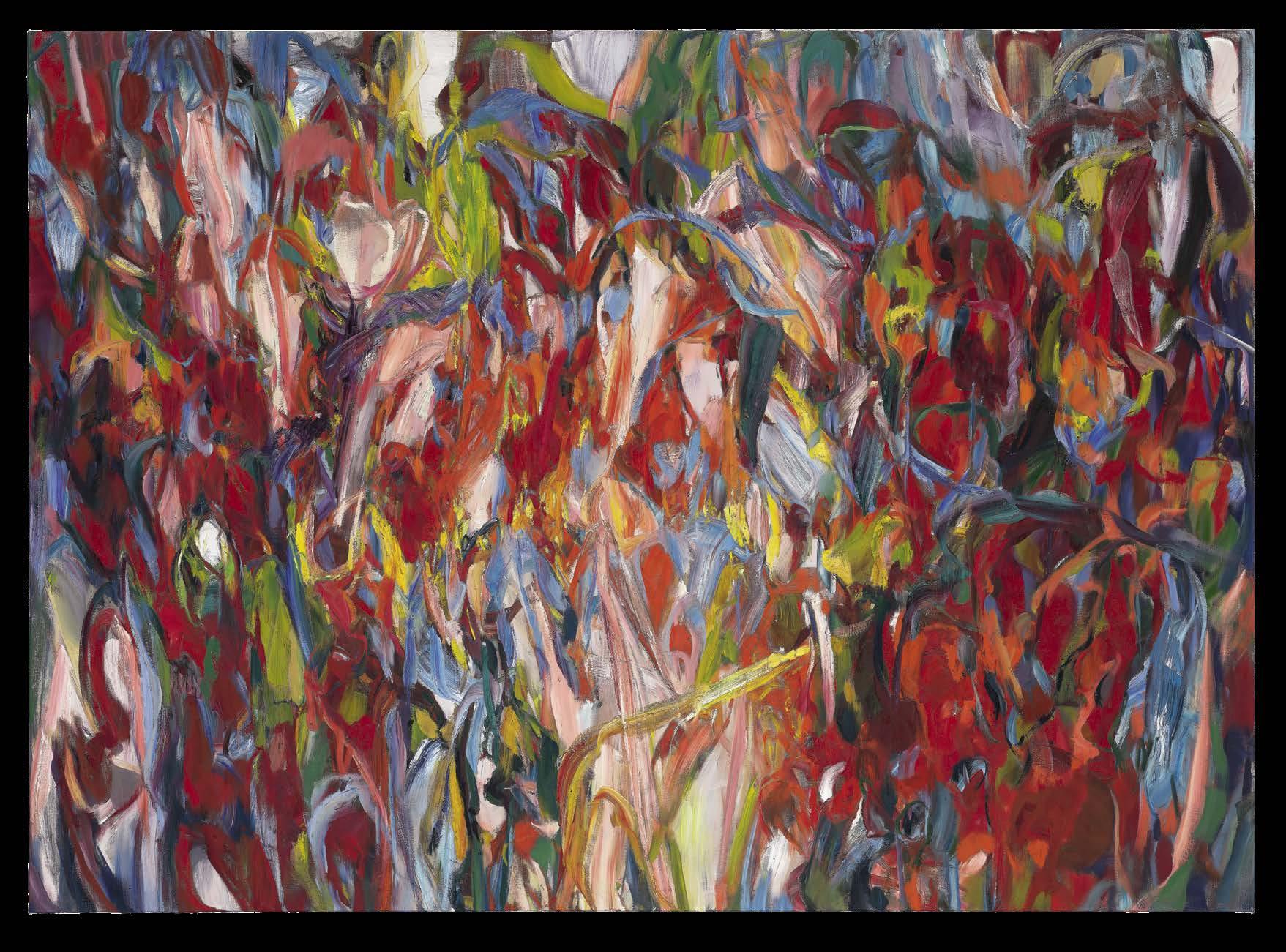

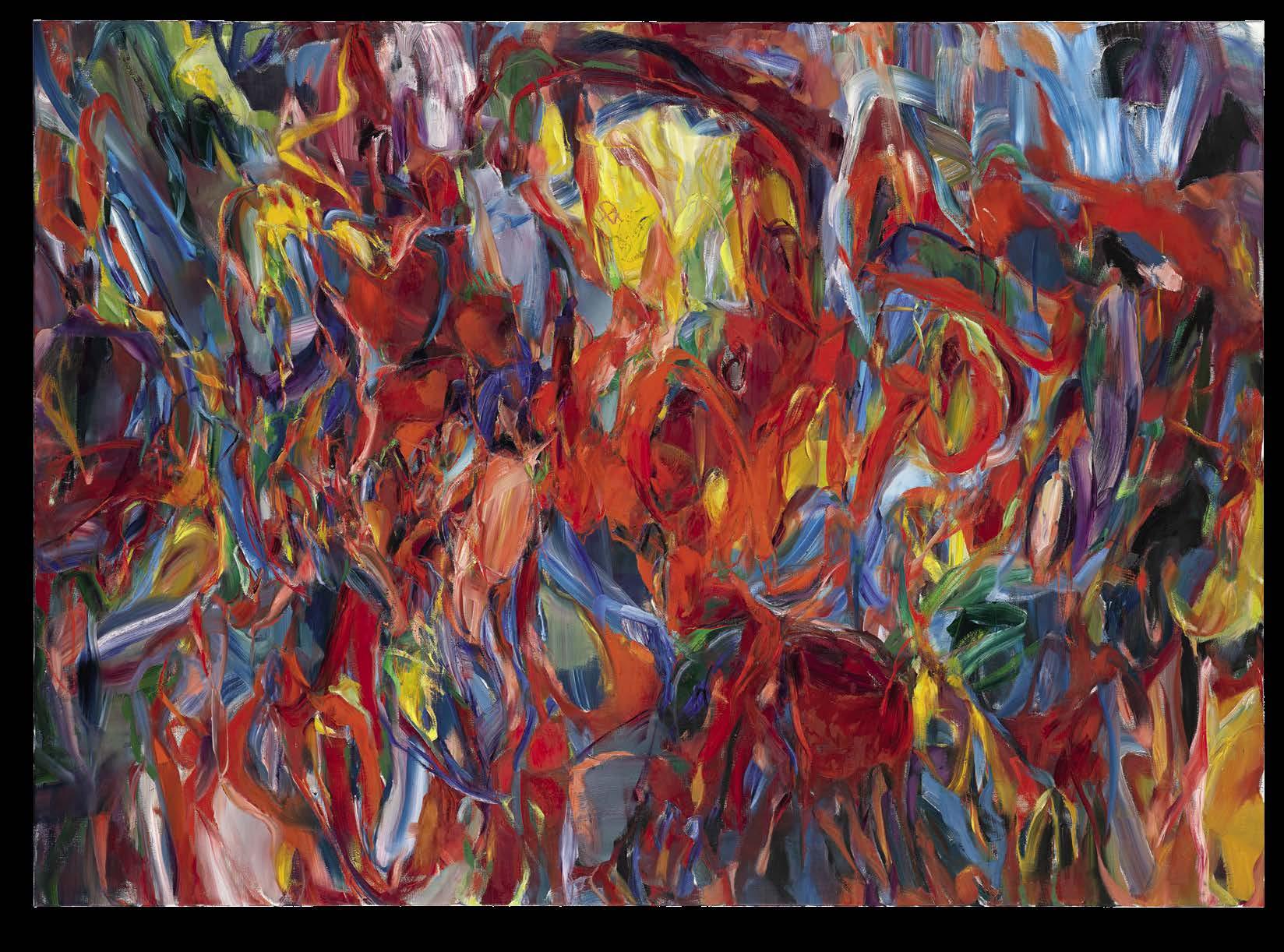

Francesco Risso, creative director of Marni since 2016, meets with the Quarterly ’s Derek C. Blasberg to discuss his symbiotic relationships with artists, childhood experiments with his family’s clothing, what he learned from his time working with Miuccia Prada, and the importance of the hand in creative pursuits.

Derek C. Blasberg: Ciao, Francesco! The last time I saw you was at Jadé [Fadojutimi]’s opening in New York, who you’ve become pals with. You made her a custom look for the night too.

Francesco Risso: I did! It’s funny, I met Jadé in Venice at the Biennale opening this year, but I wasn’t aware she’d come to so many Marni shows before that. I don’t know why I wasn’t aware because if there’s somebody I want to be aware of, it’s exactly someone like her. I’ve been following her work for a long time and it was incredible to realize that we were following each other.

DB: So she was a fan of your designs, and a client too?

FR: A huge client! And I was happy to realize that she was present at so many of my fashion shows. She was at the show in New York, she was even at the Tokyo show! We had a laugh because we were both like, “Oh my God, I know your work,” to each other. It was a nice epiphany.

DB: Tell me how the custom look she wore to the opening in New York came together. Is it fun for you to collaborate with someone like that?

FR: I love to do these kinds of things because, first of all, every person is different, and every person has a different lens on the brand and on me, and me on them. It generates curiosity and interesting conversations, and Jadé is an endless tunnel of creativity. Part of what I’ve been promoting at Marni is the idea of people wearing the brand, as opposed to the brand wearing

the people. The moment we sat down to think about what we could make, we started fleshing out her perspective around colors, shapes, ideas, even around the most stream-of-consciousness thoughts. She had a set list of songs, and she wanted what she wore to make her feel like those songs made her feel. It was a beautiful gesture. It’s so nice when you make clothes for people and it becomes a pleasurable tool. This is one side of my job that really makes me happy.

DB: When the exhibition opened, the New Yorker profiled Jadé and explained that she has a physical reaction to color, which I imagine for a designer is a perfect response.

FR: Yeah, absolutely. There’s something about the way she interplays and interlays multiple threads of colors. In the studio in London, she has assistants prepare her colors when she’s painting in the zone. I told her, “I want to be that assistant, just serving you the colors!” It would actually be a dream for me to do that.

DB: Maybe you guys can be interns for each other. You can come and help

her with the colors, and then she could help you choose fabrics.

FR: It’s a deal. Will you tell her?

DB: Are you friends with many artists?

FR: I’ve been at Marni for nearly a decade and I’ve had the chance to approach a lot of people to work with me on projects there. But I have to tell you, I never approached any of them like, “Oh, send me a PDF of some drawings and we’ll print it on a T-shirt.” That’s the opposite of what I want to do. I despise that method of art fusing with fashion. When we worked with Magdalena Suarez Frimkess, she had broken her arm while she was making ceramics, so she started drawing, and she said, “I’m having an epiphany with my left hand.” Those drawings, which were created in our activity together, were exhibited at LACMA [the Los Angeles County Museum of Art]. Piero Golia is one of my dearest friends, and this summer we were focused on reprocessing the way we collaborate, focusing less on just works and more on a process. We did a very extensive artist residency, which was beautiful. I like that I wasn’t just working with them as a Marni designer, I was painting with them too. We created something beautiful. That feels like part of the process but also part of the person that I am, and how I bring people toward work and life.

DB: Let’s go back before Marni, way back to your childhood. As you know, I grew up in an ordinary American family in the middle of the country, in the same house my whole childhood.

FR: Which is my fantasy!

DB: Because I know your childhood was much different. I fantasize about your childhood, living on a boat surrounded by such a colorful, complex family, with step-siblings and grandparents and everyone coming and going.

FR: Well, it was fascinating. My brothers and sisters are ten years older than I am, so when they were eighteen, I was just a child, and I had the luck to observe from another point of view. They were very loud, too! My father would come home unannounced with twenty people for lunch, and it would be so spontaneous, even messy. My grandparents from both sides of the family were living there too. It was really, really hectic. And I was rather silent.

DB: You were in the eye of the storm.

FR: It was chaos! When I was a kid in this chaotic environment, I started to make things. The use of the hand, for me, was the way to express myself, to talk, to say things. After so many years now, I discover that this is still what I love when I make clothes: it’s about making them with my hands. Even my own clothes never stay as they are—they always lose a piece, or I break a hem so that they can break even more over time.

DB: So you always knew you wanted to be a designer?

FR: I was nine years old when I started making clothes for myself, but I don’t think I knew what a fashion designer was until much later. I started with classical studies, then I did art school, thinking I loved literature, but I also loved to draw and I loved art, so it took me a while to say to myself, “I have to make clothes” as a career. It came as a surprise, in a way. But at that moment I fully dived into my mission, which I feel so lucky about now. My dad, for instance, was this incredibly good-looking, eclectic guy, who always had one crazy idea on top of another crazy idea, but I don’t think he ever knew what his mission was, I don’t think he ever used his creativity the way he had inside of him. So, for me, to feel that, yes, I found

my thing—it was a relief.

DB: You were very lucky to find a path to unleash this chaotic energy.

FR: Yes! Completely unleashed!

DB: When you’re eight or nine, and you’re working with your hands, are you only doing fashion and clothes, or are you also doing drawing and painting?

FR: The easiest elements I could play with were things I’d find in the wardrobes of my grandma, my mom, my sisters. I was literally Frankenstein, making my own version of their reality. I’ve tried to analyze this for a while with my shrink, but this was a drug for me. Of course it would make my sisters quite uncomfortable, and quite unhappy, because they couldn’t find their favorite skirt anymore because their skirt had become a shirt merged into a coat.

DB: Perhaps now they understand it was a sacrifice to the greater fashion good?

FR: An investment! Exactly. Fair enough.

DB: How did you transition from the Frankenstein kid in your family’s closets into the influential designer we know now?

FR: As a teenager I did classical studies in Italy, and then, when I was sixteen, I made my escape to New York. I came to FIT [the Fashion Institute of Technology] for my degree and then I went to London for an MA at Central Saint Martins.

DB: That’s when Louise Wilson, the infamous fashion professor who helped nurture talent like Alexander McQueen, was there, right?

FR: Yes. She hated me.

DB: Ha! Why?

FR: She hated me because I’d learned English in America, so I had a slight American accent. She couldn’t even talk to me. But I was grateful for how tough she was on me—on everyone—because she opened a gate for understanding what it means to not surrender, how to find creativity, and how to work around people. Her skills in that sense were incredible. So she was amazing, even if she didn’t let me speak in front of her.

DB: After Central Saint Martins did you move back to Italy?

FR: My first fashion job was for Anna Molinari. I spent some time in the outskirts of Modena, which coming from London was a shock. Then I moved to Milan. I worked for Alessandro Dell’Acqua for four years and then I had this incredible opportunity to work for ten years with Mrs. Prada.

DB: Of course Mrs. Prada is a creative director who has blurred the lines between fashion and art for years. How was it to be in her universe?

FR: She always referred to art, not in a direct way but more around what art brings as a thinking to society. Yes, she created the Fondazione Prada in Milan, but at times she was quite against the fusion of the two. I admired that because she didn’t want one to spoil the other. It was a great way of embracing all of it without spoiling either, which can happen in fashion when someone hires an artist to design a logo for a T-shirt. With Miuccia, it was completely different. What I treasure the most, which in a way is not far from what I learned from Louise, was the power of a concept. For example, at Prada there were months of sitting around a table and talking about ideas, and then making the clothes in one week, literally. That takes so much courage. [The design team] would have to be there in front of one of the most incredible people on the planet and talk about art and defend their position. I was so young, I was twenty-three or twenty-four, and you have to be brave at those tables and be able to express yourself. She would love it! I really treasure that surfing brain of hers. And yet it was always a balance around pushing. Some days we would push so much around creativity and create things that wouldn’t make any sense; then it was about stripping them down. One of the most important things is her passion to make clothes that are so impactful but also so applicable to reality, and therefore very human.

DB: The question that everyone ends up asking is, Can fashion be art? Can art be fashion?

FR: I hate speaking in that binary. This idea of fashion being art is reductive. The relationship I have with the making of clothes is completely different. And art and fashion are both marketed at the moment, but the message that one conveys is another landscape. Processes can be similar— the way you get to a place can be very similar to an artist’s. But whenever somebody comes up and says,

“Oh my God, this is a piece of art,” I want to vomit.

DB: You mentioned drawing on canvases and painting on canvases and painting on these dresses. Do you still work outside the design studio?

FR: I did for years, and then I stopped. To my surprise, throughout covid I became an obsessive writer. I’m not a good writer but I love to write! I love to compose things through writing.

DB: Do you write in English or in Italian?

FR: You know what’s funny? The best time I write is when I’m on a plane. There’s something about the pressure, or the fact that there are no phones. I have stuff that’s like half English and half Italian. I’m noticing that I have a harder time forming words in Italian. My boyfriend is French and we speak in

English. At the studio I speak English all the time because most of the people are from all over the world. I don’t speak so much Italian anymore; I’m actually kind of shy about it because sometimes I have to present things in Italian and my brain will occasionally go blank. Nowadays, when I’m not in the studio, I write. But I’d like to paint more and I think I will soon.

DB: Tell me about the residency you established. I know this is very personal to you, and it’s a project that you financed fifty-fifty with your own money and Marni’s investment.

FR: The residency was a journey, ha! Originally, it was going to happen in Milan last July with two artists who are Nigerian and live in London. They’re called Soldier and Slawn. I started this long and unnerving process with their visas. It was incredibly difficult to get them to Italy because whereas Nigeria and London have good agreements, that’s not the case for the rest of the world. I have to tell you that this was quite tough, and I finally said, “This is going to happen, even if it’s over my dead body.” After three months of their passport at the consulate, I said, “Fuck this,” canceled my summer holiday, and moved everything I’d built in Milan for the residency to London. I found a space online, rented it, and said, “Fine, we’ll just do it here.” I said, “It’s going to fucking happen” and I was so glad it did. The guys have such incredible personalities and are so talented and so soulful that they dragged me back into painting. We built a body of work that included more than a dozen triptychs, some of them painted alone and some painted all together. I had such an amazing time; it felt like when I was learning at school, or when I was making my clothes when I was a child. At times I was so shy, as if I was

a kid again, and at other times I’d stand in front of the canvas and think, “I can even just throw this out of the window and it’s fine.”

DB: Perhaps those feelings of nervousness and anxiety are motivational factors? When you took over Marni ten years ago, were you anxious or daunted?

FR: Oh my God, yes. Starting at Marni was a different type of fear. One of the things I feared most was my Prada history, and the fact that I was going to bring a part of that with me.

DB: Meaning, Would people say what he’s doing is too Prada?

FR: I was trying to refuse everything that I’d learned in order to be planted in a new garden and bloom with the rest of the people in the most honest way. I never tried to be somebody else. I never tried to be Consuelo [Castiglioni, the former designer of Marni]. And yet, I would say half the people say I’m the Antichrist of Marni and the other half say I’m very Marni. As you go from one family to a new family, you have to understand people’s language and people have to understand your language. More than fear, it was about trying to hold still and be patient about allowing these flowers to grow and bloom. I remember after the third year, one day I entered the studio and I felt, Wow, we’ve made this incredible synergy and group of people. So many times I felt goosebumps about what we’ve made through just holding hands and making peace and love. Does that sound so lame?

DB: No, it sounds like Woodstock, ha! You’ve done such an incredible job of building a Marni world. People are excited to come to one of your shows because people know that at a Marni show you’re going to have some sort of experience or sensation. That has to be intentional.

FR: Yes! I’m very aware that I want to use everyone’s energies for a good purpose, and of the money that a fashion show costs too. And for the editors and buyers and people who go to many shows, I know it’s an insane schedule, so there has to be a power of delivering emotionally. This comes from the incredible synergies that I have with the people I work with. What I do is extremely connected, and it starts and dies every season with [music producer] Dev Hynes. I don’t call him up and say, “Give me a song”; we work together from the start and talk about what we’re going to build. That plays a big role in even the most simple settings. Last season the models could decide where to walk among only pianos and spotlights, that was it. Simple, but it made such an incredible theater.

DB: My favorite Marni show was right after covid, the first time I’d been back to Milan, and you created sort of a religious experience in a theater in the round. You’d also asked to dress everyone who came to the show, as if we were one fashion congregation.

FR: When I had the first meeting with everyone back at the office [after covid], we said, “We have to get physical.” We’d been secluded for so long, and our work is so sensorial, we missed that sort of entanglement. We wrapped our rooms in canvas and we started painting for two weeks. From there everything kind of unraveled. I decided that I wanted to dress everyone, so everyone got an outfit we had painted. Everybody came in one week before—it was like 700 fittings plus the models—and it was such a memorable moment, running around to the changing rooms and greeting everyone. That show underlined in my head the purpose of what we do.

DB: I still have my outfit, Francesco.

FR: I’m glad!

DB: Francesco, when you talk, I can see the tattoos on your hand. What do the two moons mean?

FR: They symbolize symbiotic vision. Whatever mission I’m going for in terms of making and creativity is for me not an individual process. It’s about being in symbiosis with people and with brains. The tattoos remind me every day that my greatest passion is to learn. So I had them tattooed on my hand.

DB: So when you’re waving at someone, you’re signaling that life is about collaboration.

FR: By the way, it was the most painful thing I’ve ever done in my life.

DB: The tattoo or the symbiotic relationships?

FR: The tattoos! Working with people I love is a constant source of inspiration, the ultimate pleasure.

Thomas Schütte’s monumental sculptures were the subject of a recent exhibition at Gagosian, New York. Here, Amber Collins looks into the history of the artist’s Frauen series, eighteen works made between 1998 and 2006, and considers the artist’s radical explorations of the human body.

There is a quickness and a looseness to the fluidity of Schütte’s sculptures, but like the geology of a mountain, beach, or ocean, it couldn’t be any other way.

—Charles Ray 1

How does Thomas Schütte manage to simultaneously embrace and reject modernism in a single work? Tradition is invited, but only to a point. Suspended between distant pictorial realities, his sculptures can be fluid and elastic, strong and confined, buoyant and heavy, melting and coiled, playful and graceful, abstracted and whole. Schütte’s work, which spans sculpture, painting, drawing, printmaking, and architecture, is persistently contrarian and multidirectional—a place where past, present, and future are nonchronological, and where three left turns somehow never equal a right.

The Frauen sculptures, Schütte’s most ambitious and complex body of work to date, constitute a radical aesthetic statement on the figure in contemporary sculpture. The series, made between 1998 and 2006, is a sequence of eighteen works based on the female nude, each cast in bronze, steel, and aluminum. In them, the artist engages in a dialogue with the figurative tradition of the female nude, a subject that stretches back to antiquity. The works also build on the revolutionary iterations realized by such early modernist masters as Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and Henry Moore, casting their transformation of the figure and liberation of form into the contemporary landscape. Emphasizing both figuration and abstraction, the Frauen , with their vast range of poses and styles, propose a vision of sculpture tethered not

to representation, but to the fundamental possibilities of form.

The Frauen originated from brick-size blocks of clay rapidly formed by hand, then glazed and fired. Between 1997 and 1999, in the renowned ceramics workshop of Niels Dietrich in Cologne, Schütte created an astounding one hundred and twenty Ceramic Sketches . Describing the process, he said, “I was handed a small board with clay and given an hour to model it into a figure. It was sheer ambition: I made five, six, seven pieces a day.”2 The artist selected and scaled up eighteen of the one hundred and twenty Ceramic Sketches to make the Frauen . Thus each Ceramic Sketch , whether ultimately cast or not, belongs to a continuum within the series, as each assumed a new form in the passage from one to the next. In other words, the Ceramic Sketches are embedded in the DNA of every Frau

Often shown on shelves alongside the Frauen , the Ceramic Sketches are important in our consideration of the large-scale works. In 1999, Frauen (Nrs. 1–4) were first exhibited at Dia Center for the Arts in New York alongside seventy-five Ceramic Sketches . And the Frauen have been connected to their ceramic origins from that debut presentation onward—“every mistake in this quest for form, each blind alley, was just left there,” Schütte later said of the installation.3 Exhibiting the Ceramic Sketches with the Frauen invokes the sculptural thinking of Medardo Rosso, an Italian contemporary of Auguste Rodin. Rosso broke from the sculptural gravitas of late nineteenth-century Europe by elevating the bozzetto, or rough sketch, to the stature of a finished artwork. 4

Rosso’s sculpture and Schütte’s Ceramic Sketches

both manifest strong evidence of the artist’s hand. Rosso preserved the wax shell from the bronze casting process—a wax barrier is typically used to create a mold, then melted out and replaced by molten bronze—and reinforced it with plaster to create works such as Ecce Puer (Behold the Child , 1906, cast c. 1958–59). He worked up the wax by hand, leaving traces of his fingerprints and deliberately manipulating his surfaces to capture the fleeting and ephemeral qualities of light. In the last twenty years of his life, Rosso did not choose any new subjects, but continued to make new casts of existing models, reworking these in constantly different ways and ultimately producing roughly two hundred sculptural versions of just thirty-five different subjects. Though his work is aesthetically quite different from the Frauen , Rosso’s singular focus and transformation of each cast into a unique object parallels Schütte’s process.