For the Summer 2023 issue we have invited voices from the worlds of art, fashion, literature, and activism to reflect on the legendary career of Richard Avedon. Author and poet Jake Skeets has written a powerful and personal response to a photograph of his uncle, Benson James, from Avedon’s series In the American West . Skeets addresses the power dynamics and underlying tensions beneath the surface of the image and draws parallels to similar structures that endure in society today.

Harold Ancart and Katharina Grosse participate in illuminating conversations about the challenges of painting, articulating their unique concerns in the medium and describing how they push the limits of their distinctly different practices. And Péjú Oshin talks with Phoebe Boswell, Adelaide Damoah, and Julianknxx about artmaking that explores the function of ritual, the role of identity, and the blurring of cultural boundaries often defined by such constructs.

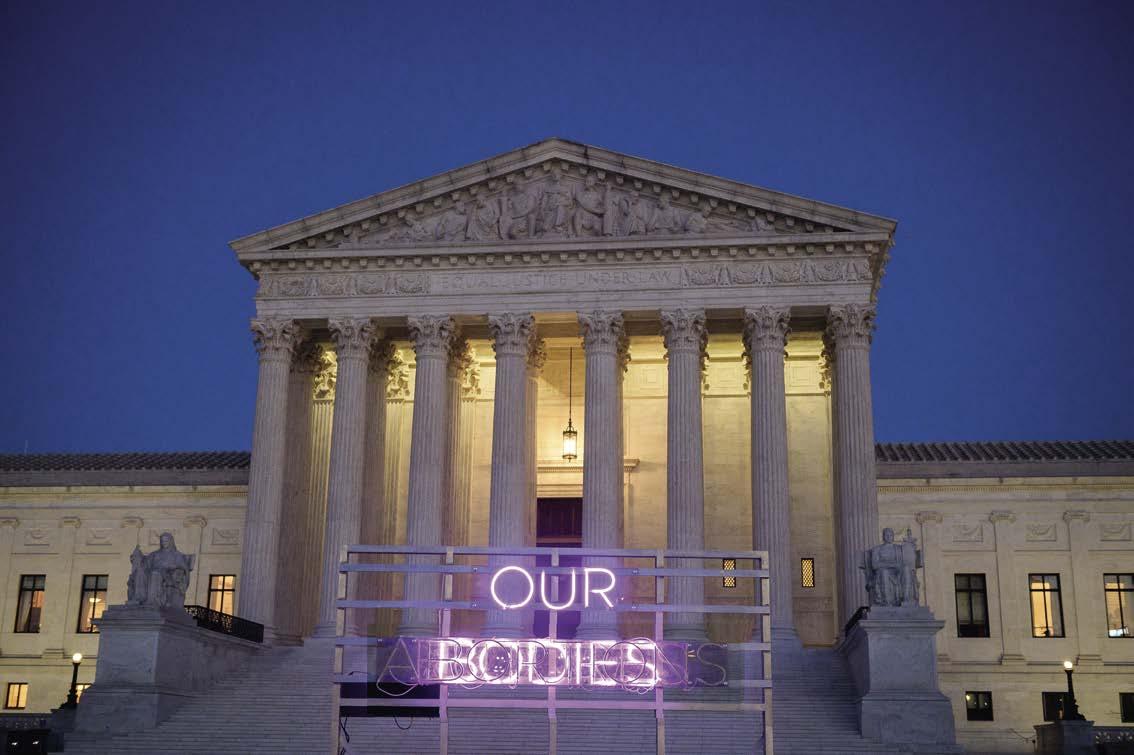

The fight for women’s rights—specifically for reproductive rights in the United States—has traced a long history through several generations of artists. Salomé Gómez-Upegui reflects on the power of these artists’ images, their ability to define and shape public opinion, their long-term influence, and the critical role of artists today in facing this conflict with heightened urgency.

We highlight the work of IntoUniversity, a British nonprofit that addresses systemic inequities, both in society at large and specifically in the art world, by creating educational opportunities for young people from disadvantaged communities.

The sudden and rapid proliferation of artificial intelligence—AI— in our world at this moment is both fascinating and disquieting. In this issue, Benjamín Labatut considers Bennett Miller’s engagement with AI as a partner in the act of creation. The possibilities of AI are truly limitless, yet the grave responsibility that accompanies those opportunities is as yet undefined and cannot be underestimated.

Alison McDonald, Editor-in-chief

Harold Ancart

In a wide-ranging conversation, Harold Ancart and novelist Andrew Winer cover a lot of artistic and philosophical ground, from being present to pathological escapism, and from portals and all-things-arepossible to palm trees.

44 Hans Ulrich Obrist’s Questionnaire: Lynn Hershman Leeson

The sixth installment of the series.

48 Avedon 100

In celebration of the centenary of Richard Avedon’s birth, almost 150 artists, designers, musicians, writers, curators, and representatives of the fashion world were asked to select a photograph by Avedon for an exhibition at Gagosian, New York, and to elaborate on the ways in which image and artist have affected them. We present a sampling of these images and writings.

66 Rites of Passage

Péjú Oshin speaks with Phoebe Boswell, Adelaide Damoah, and Julianknxx about their participation in the exhibition Rites of Passage at Gagosian, London, and about the complexities of community, performance, truth, and identity.

72 Fashion and Art, Part 14: Edward Enninful

Edward Enninful OBE has held the role of editor-in-chief of British Vogue since 2017. Here, Enninful meets with his longtime friend Derek Blasberg to discuss his recently published memoir, A Visible Man

78

Building a Legacy: Provenance

For this installment of the Building a Legacy series, Lisa Turvey met with Sharon Flescher and Lisa Duffy-Zeballos of the International Foundation for Art Research (ifar) to discuss the complexities of provenance research, the recent burgeoning of the field, and the multiple resources available for tracing the ownership history of artworks.

82

A Wild Wild Wind: Bennett Miller’s AI-Generated Art

Benjamín Labatut addresses Bennett Miller’s engagement with artificial intelligence as a partner in the creation of a series of new artworks, asking what this technology—and its hallucinations—can reveal about our own humanity.

88

Bigger Picture: IntoUniversity

Precious Adesina charts the development of the UK-based nonprofit organization IntoUniversity.

94 Tom Wesselman

Susan Davidson, the editor of the forthcoming monograph on The Great American Nudes , a series of works by Tom Wesselmann, explores the artist’s early experiments with collage, tracing their development from humble beginnings to the iconic series of paintings.

100

The African Desperate

Artist and filmmaker Martine Syms teamed up with writer and poet Rocket Caleshu to create the 2022 film The African Desperate . Starring the artist Diamond Stingily as Palace, the film received rave reviews for its honest and unflinching portrayal—and parody—of the art world. Syms, Caleshu, and Stingily met with Fiona Duncan to discuss the film’s creation.

106

All I Wanted to Do Was Paint: A Conversation between Katharina Grosse and Sabine Eckmann

Curator Sabine Eckmann met with Katharina Grosse to discuss the evolution of her practice.

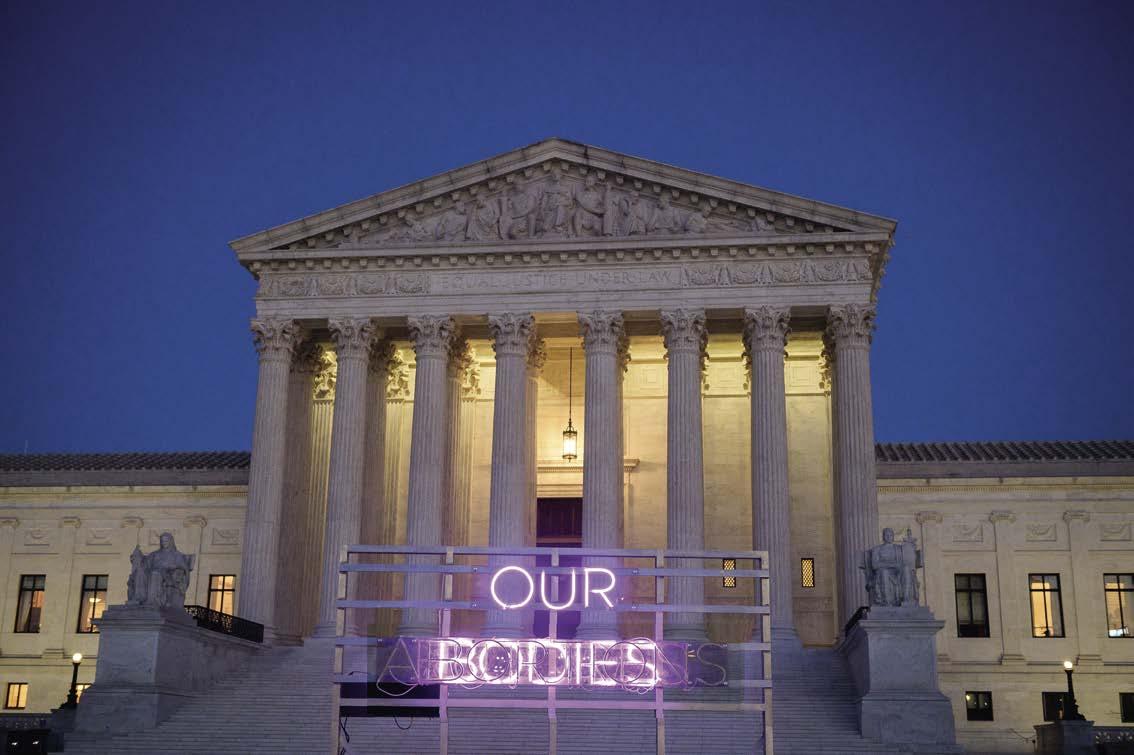

114 American Artists and Reproductive Justice

Salomé Gómez-Upegui traces the evolution of visual artists’ involvement in the fight for reproductive rights in the United States.

122

Soothing Sounds of Dread

Mike Stinavage profiles Weyes Blood during the musician’s world tour with a new record.

124 Still Life, Still

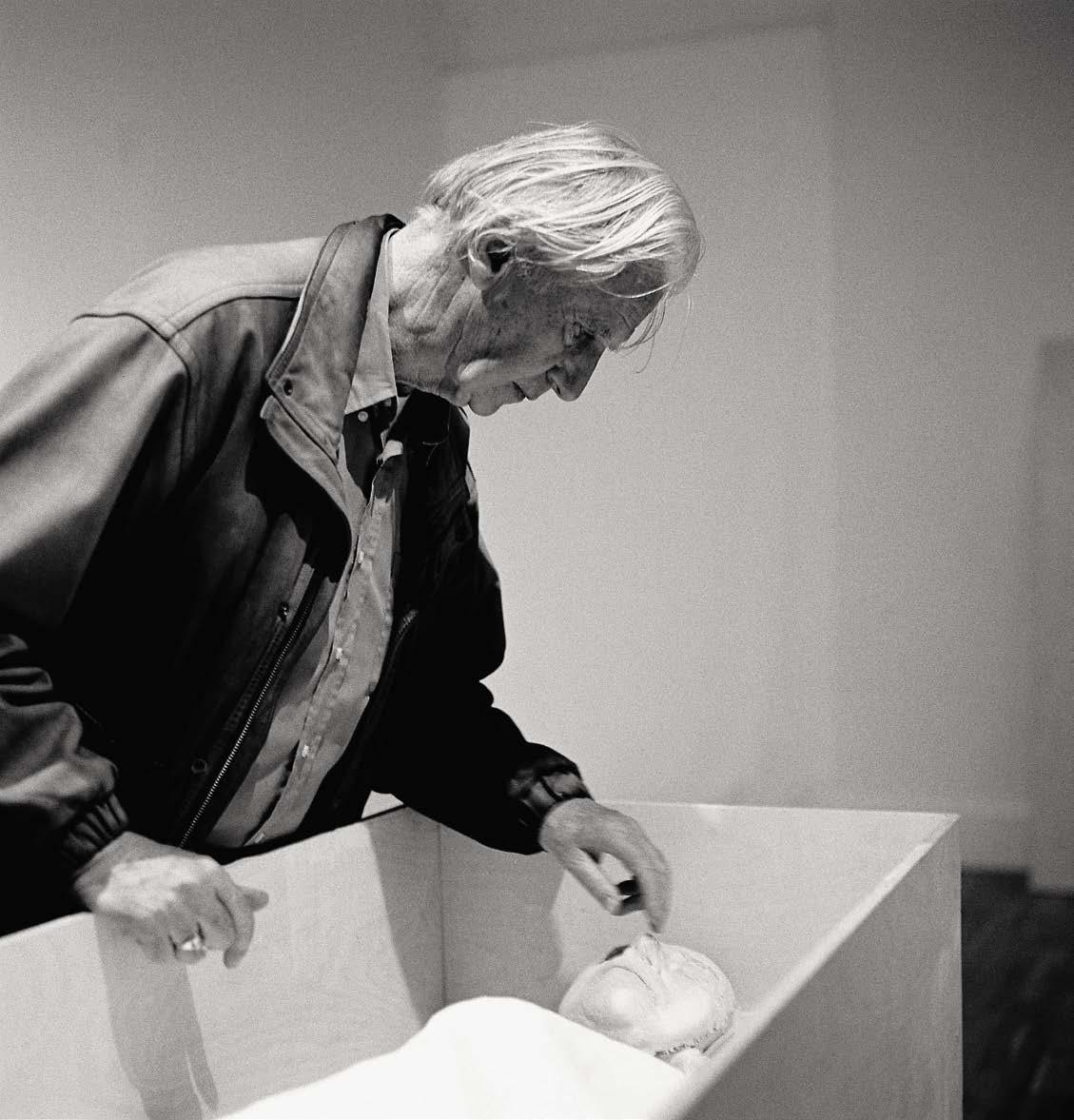

Harry Thorne reflects on the collaborations and friendship between Marcel Duchamp and the artist and author Brian O’Doherty.

130

Screen Time: Internet_Art

Ashley Overbeek speaks with Omar Kholeif about their new book Internet_Art: From the Birth of the Web to the Rise of NFTs

138

A Vera Tatum Novel by Leonora McCrae

by

The second installment of a short story by Percival Everett.

152 Copyright

Novelist Rachel Cusk responds to artist Taryn Simon’s Sleep (2020–21), exploring the fraught relationships between motherhood, artistic practice, mortality, and repetition.

156

Waiting for Clarice

Carlos Valladares marvels at the life and work of the prolific and peerless Brazilian author Clarice Lispector.

160

Out of Bounds: Marcia Tucker

Raymond Foye speaks with Lisa Phillips, the Toby Devan Lewis Director of the New Museum, New York, about Out of Bounds: The Collected Writings of Marcia Tucker, a comprehensive anthology of the writings of the museum’s founder.

180

Game Changer: Dorothy Miller

Scholar Wendy Jeffers is working on a comprehensive biography of Dorothy Miller, the groundbreaking curator who joined New York’s Museum of Modern Art in its early years and built a remarkable program, introducing many now-famous artists to the world. Here, Jeffers recounts key moments from Miller’s extraordinary life.

34

SUMMER 2023

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Front cover: Richard Avedon, Marilyn Monroe, actor, New York, May 6, 1957 © The Richard Avedon Foundation

HIGH JEWE LRY

Necklac e

Wh ite gold, sapphire, emer alds and diamond s

dior .com –800.929. dio r ( 3467)

loewe.c om

KAIA

WWW.MAISON-ALAIA

GERBER — LOS ANGELES, 10.2022 PHOTOGRAPHED AT STERLING RUBY STUDIO

COM

Editor-in-chief

Alison McDonald

Managing Editor

Wyatt Allgeier

Editor, Online and Print

Gillian Jakab

Text Editor

David Frankel

Executive Editor

Derek Blasberg

Digital and Video Production Assistant

Alanis Santiago-Rodriguez

Design Director

Paul Neale

Design

Alexander Ecob

Graphic Thought Facility

Website

Wolfram Wiedner Studio

Gagosian Quarterly, Summer 2023

Cover

Richard Avedon

Founder

Larry Gagosian

Published by Gagosian Media

Publisher

Jorge Garcia

Associate Publisher, Lifestyle

Priya Nat

For Advertising and Sponsorship Inquiries

Advertising@gagosian.com

Distribution David Renard

Distributed by Magazine Heaven

Distribution Manager Alexandra Samaras Prepress DL Imaging

Contributors

Precious Adesina

Harold Ancart

Derek Blasberg

Phoebe Boswell

Rocket Caleshu

Rachel Cusk

Adelaide Damoah

Susan Davidson

Lisa Duffy-Zeballos

Fiona Duncan

Sabine Eckmann

Edward Enninful

Percival Everett

Sharon Flescher

Raymond Foye

Salomé Gómez-Upegui

Katharina Grosse

Lynn Hershman Leeson

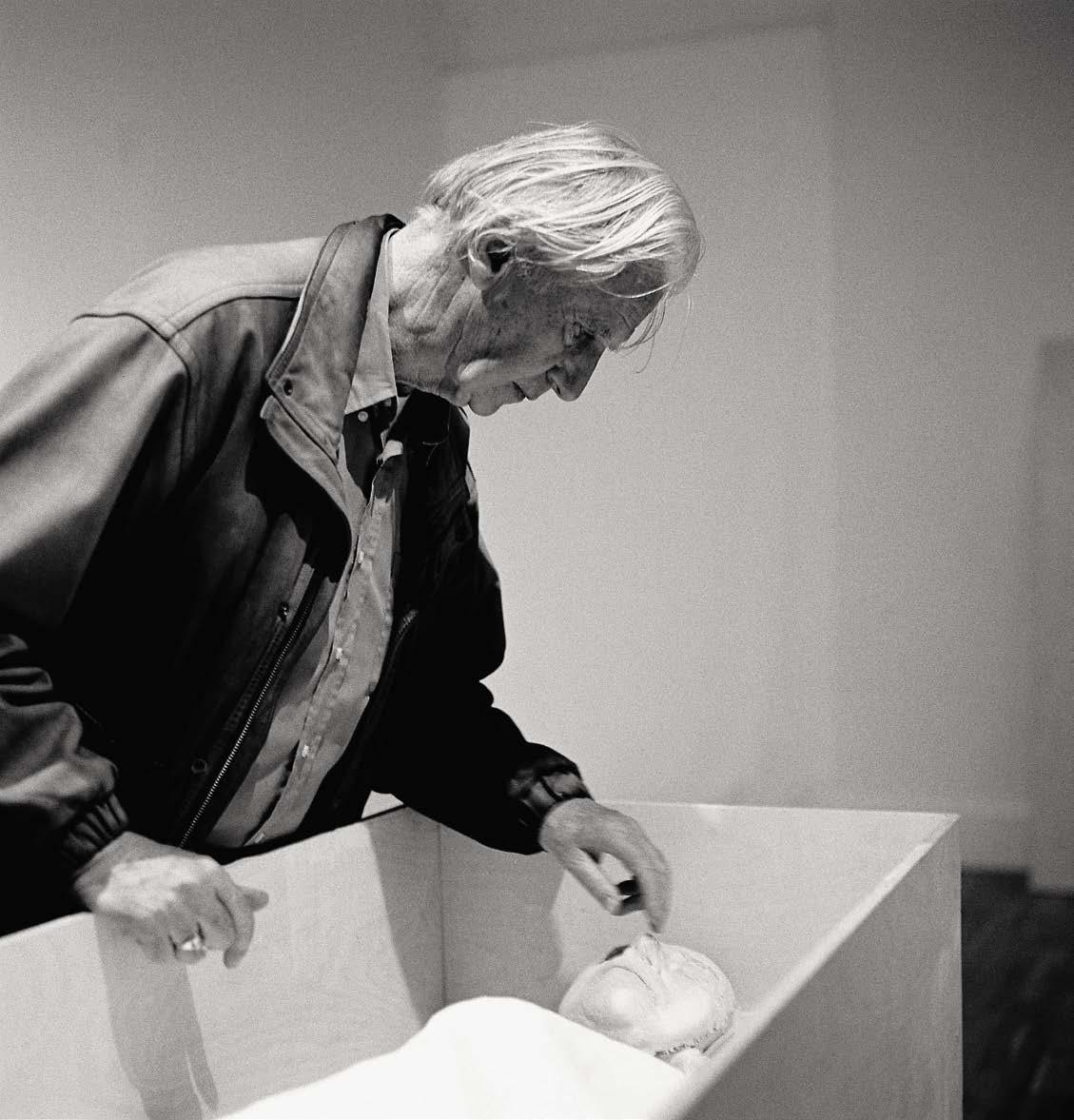

Wendy Jeffers

Julianknxx

Omar Kholeif

Benjamín Labatut

Hans Ulrich Obrist

Péjú Oshin

Ashley Overbeek

Lisa Phillips

Jake Skeets

Mike Stinavage

Diamond Stingily

Martine Syms

Harry Thorne

Lisa Turvey

Carlos Valladares

Andrew Winer

Thanks

Karrie Adamany

Richard Alwyn Fisher

Julia Arena

Laura Avedon

Andisheh Avini

Ashleigh Barice

Victoria Beard

Priya Bhatnagar

Michael Cary

Serena Cattaneo Adorno

Vittoria Ciaraldi

Maggie Dubinski

Poppy Edmonds

Andrew Fabricant

Paatela Fraga

Hallie Freer

Brett Garde

Jonathan Germaine

Lauren Gioia

Darlina Goldak

Séverine Gossart

Yasmine Hanni

Delphine Huisinga

Sarah Jones

Nina Joyce

Jennifer Knox White

Bernard Lagrange

Jona Lueddeckens

Lauren Mahony

James Martin

Constanza Martínez

Kelly McDaniel Quinn

James McKee

Rob McKeever

Bennett Miller

Jade Morgan

Olivia Mull

Kathy Paciello

Adam Rahman

Antwaun Sargent

Isabel Shorney

Taryn Simon

Diallo Simon-Ponte

Micol Spinazzi

Chandler Sterling

Putri Tan

Kara Vander Weg

Timothée Viale

Lily Walters

Lilias Wigan

Eva Wildes

Mimi Yiu

23

Printed by Pureprint Group

Adelaide Damoah, Nyɔŋma (Ten), 2023 (detail), cyanotype, ink, and gold on cotton and rag paper, in 2 parts, 11 ½ × 15 inches (29.2 × 38 cm) © Adelaide Damoah

CONTRIBUTORS

Harry Thorne

Harry Thorne is a writer and an editor at Gagosian. He lives in London.

Harold Ancart

Harold Ancart was born in Brussels in 1980 and lives and works in New York. His paintings, sculptures, and installations explore our experience of natural landscapes and built environments, alluding to a range of art-historical sources and often characterized by abstract passages of color. Focusing on recognizable subjects, Ancart isolates moments of poetry in everyday surroundings.

Susan Davidson

Curator and art historian Susan Davidson is an authority in the fields of Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, and Pop Art with a specialty in the art of Robert Rauschenberg. Davidson is also an accomplished museum professional with over thirty-year’s experience at two distinguished institutions: The Menil Collection, Houston, and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

Andrew Winer

Andrew Winer is the author of the novels The Marriage Artist (2010) and The Color Midnight Made (2002). He writes and lectures on art, philosophy, and literature. A recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in fiction, he is presently completing a novel and a book on the contemporary relevance of Friedrich Nietzsche’s central philosophical idea, the affirmation of life.

Wendy Jeffers

Wendy Jeffers is completing a biography of the legendary curator Dorothy Miller. She is past chair of the board of trustees of the Archives of American Art.

26

Percival Everett

Percival Everett is the author of twenty-two novels and four collections of stories. His novels include The Trees (2021), Telephone (2020), So Much Blue (2017), and Erasure (2001). He has received awards from the Guggenheim Foundation and Creative Capital. He lives in Los Angeles, where he is distinguished professor of English at the University of Southern California.

Jake Skeets

Jake Skeets is the author of Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers (2019), winner of the National Poetry Series, the Kate Tufts Discovery Award, the American Book Award, and the Whiting Award. He is from the Navajo Nation and teaches at the University of Oklahoma.

Katharina Grosse

Katharina Grosse is a German artist who lives and works in Berlin. Embracing the events and incidents that arise as she paints, Grosse opens up surfaces and spaces to the countless perceptual possibilities of the medium. While she is widely known for her temporary and permanent in situ work, which she paints directly onto architecture, interiors, and landscapes, her approach begins in the studio.

Sabine Eckmann

Sabine Eckmann joined the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University, Saint Louis, as curator in the fall of 1999 and also regularly teaches seminars in the university’s Department of Art History and Archaeology, School of Arts & Sciences. Eckmann, a native of Nuremberg, Germany, is a specialist in twentieth- and twenty-first-century European art and visual culture.

Precious Adesina

Precious Adesina is a London-based freelance journalist who specializes in arts and culture and often explores sociopolitical topics. She writes for a number of publications, including the New York Times , the Financial Times , the Economist , and BBC Culture , and has given many talks and panel discussions at British galleries on arts writing and research.

Mike Stinavage

Mike Stinavage is a writer and waste specialist from Michigan. He holds a master’s degree in political science from CUNY Graduate Center. As a Fulbright and Martin Kriesberg fellow, he researched the politics of waste management and wrote his second collection of short stories in Pamplona, Spain. His writings can be found in Slate , the Brooklyn Rail , the Riverdale Press , and more.

27

Photo: Bear Guerra

Photo: Max Vadukul

Martine Syms

Martine Syms obtained an MFA from Bard College, Annandale-onHudson, New York, in 2017 and a BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2007. Syms has earned wide recognition for a practice that combines conceptual grit, humor, and social commentary. Using a combination of video, installation, and performance, often interwoven with explorations of technique and narrative, Syms examines representations of Blackness and its relationship to vernacular, feminist thought, and radical traditions. Syms’s research-based practice often references and incorporates theoretical models concerning performed or imposed identities, the power of the gesture, and embedded assumptions concerning gender and racial inequalities.

Rocket Caleshu

Rocket Caleshu is a writer based in Los Angeles, where he is the director of Ashtanga Yoga Glassell.

Danielle Levitt

Fiona Duncan

Fiona Duncan is a Canadian-American author and organizer and the founder of the social literary practice Hard to Read. Duncan’s debut novel, Exquisite Mariposa (Soft Skull Press), won a 2020 Lambda Award. She is currently developing a narrative biography and critical study of the transdisciplinary American artist Pippa Garner.

Sharon Flescher

Sharon Flescher has been the executive director of the International Foundation for Art Research (ifar) since 1998 and is editor-in-chief of the award-winning ifar Journal . A graduate of Barnard College, Flescher holds master’s degrees in both English literature and art history and has a PhD in art history from Columbia University. She also attended the Wharton School of Business.

Diamond Stingily

Diamond Stingily is an artist and actress who was born in 1990 in Chicago, lives and works in New York, and is currently on a residency at the Art Explora foundation, Paris, in collaboration with the Cité internationale des arts. Her work has been presented in many institutions, including the Museum of Modern Art, New York (2022), the Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein (2022), the Kunstverein Munich (2019), the CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, San Francisco (2019), and the ICA Miami (2018). She acted in HBO’s Random Acts of Flyness and was the lead in Martine Syms’s debut feature film, The African Desperate . Photo: Farah Al Qasimi

Lisa Duffy-Zeballos

Lisa Duffy-Zeballos, PhD, is the art research director of the International Foundation for Art Research (ifar). Duffy-Zeballos received her PhD in art history from the Institute of Fine Arts at NYU. Since 2008, she has overseen the Art Authentication Research Service, the Provenance Research Service, and the Catalogues Raisonnés Database at ifar

28

Photo:

Photo: Danielle Levitt

Rachel Cusk

Rachel Cusk is the author of the Outline trilogy (2014–18), the memoirs A Life’s Work (2001) and Aftermath (2012), and several other works of fiction and nonfiction. A Guggenheim fellow, she lives in Paris. Photo: Siemon Scamell-Katz

Carlos Valladares

Carlos Valladares is a writer, critic, programmer, journalist, and video essayist from South Central Los Angeles, California. He studied film at Stanford and began his PhD in History of Art and Film and Media Studies at Yale University in the fall of 2019. He has written for the San Francisco Chronicle , Film Comment , and the Criterion Collection. Photo: Jerry Schatzberg

Benjamín Labatut

Benjamín Labatut is a Chilean writer born in the Netherlands in 1980. He is the author of The Maniac (2023), When We Cease to Understand the World (2020), La piedra de la locura (2021), Después de la luz (2016), and La Antártica empieza aquí (2012).

Salomé Gómez-Upegui

Salomé Gómez-Upegui is a Colombian-American writer and creative consultant based in Miami. She writes about art, gender, social justice, and climate change for a wide range of publications, and is the author of the book Feminista por accidente (Ariel, 2021).

Raymond Foye

Raymond Foye is a writer, publisher, and curator based in New York. In 2020 he received an American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation for his editing of The Collected Poems of Bob Kaufman for City Lights. He is presently editing The Collected Poems of Rene Ricard He is a consulting editor with the Brooklyn Rail Photo: Amy Grantham

Omar Kholeif

Dr. Omar Kholeif is an author, curator, broadcaster, and cultural historian who currently serves as Director of Collections and Senior Curator at Sharjah Art Foundation, UAE. Born in Cairo to Egyptian and Sudanese parents, Kholeif has curated over seventy exhibitions of visual art and has authored or coauthored over forty books, which collectively have been translated into twelve languages.

30

Photo: Juana Gómez

Phoebe Boswell

Phoebe Boswell is a multidisciplinary artist who lives and works in London. She embraces the fluidity of language and storytelling as a means to unpack the cultural associations with which bodies of water are imbued. Sharing new writing based on research for recent and ongoing work, Boswell explores the relentless dichotomy of water. Layers of historic violence and trauma attest to how it continues to bear witness to an inequitable society, while its ebb and flow, its surge and swell, posit water as a site for possible renewal, rebirth, reclamation—a healing, holding, place.

Péjú Oshin

Péjú Oshin is a British-Nigerian curator, writer, and lecturer born and raised in London. Sitting at the intersection of art, style, and culture, her work shows a keen interest in liminal theory and diasporic narratives. She is the author of Between Words & Space (2021), a collection of poetry and prose, and was shortlisted for the Forbes 30 Under 30 Europe list.

Julianknxx

Julianknxx’s work merges his poetic practice with films and performance, engaging in a form of existential inquiry that seeks at once to find ways of expressing the ineffable realities of human experiences and to examine the structures through which we live. In casting his practice as a “living archive” or a “history from below,” Julianknxx draws on West African traditions of oral history to reframe how we construct both local and global perspectives. His work challenges fixed ideas of identity and unravels linear Western historical and sociopolitical narratives, attempting to reconcile how it feels to exist primarily in liminal spaces.

Lynn Hershman Leeson

Lynn Hershman Leeson is widely recognized for her innovative work investigating issues that are now recognized as key to the workings of contemporary society: identity, surveillance, the relationship between humans and technology, and the use of media as a tool of empowerment against censorship and political repression.

Adelaide Damoah

British-Ghanaian artist Adelaide Damoah is a London-based multidisciplinary artist who uses investigative practices spanning painting, performance, collage, and photographic processes. Her key areas of interest are colonialism, joy, and feminism. She exhibits in national and international galleries and institutions including Gagosian, and serves on the boards of two art charities.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

Hans Ulrich Obrist is the artistic director of the Serpentine Galleries, London. He was previously curator at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Since his first show, World Soup (The Kitchen Show), in St. Gallen, Switzerland, in 1991, he has curated more than 300 exhibitions.

Tyler Mitchell

32

Photo: Marc Hibbert

Photo: Adenike Oke

Photo:

HAROLD

ANCART

Previous spread: Harold Ancart, Untitled , 2017 (detail), oil stick and pencil on canvas, in artist’s frame, 73 × 91 × 2 ¼ inches (185.4 × 231.1 × 5.7 cm), Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Opposite: Harold Ancart, Untitled , 2020 (detail), oil stick and pencil on paper, in artist’s frame, 31 × 23 5 8 × 1 ½ inches (78.7 × 60 × 3.8 cm)

This page: Harold Ancart, Untitled , 2021, oil stick and pencil on canvas, in artist’s frame, 24 × 31 × 1 ½ inches (61 × 78.7 × 3.8 cm)

Although, as the reader will see, Harold Ancart and I would have wished to be lost somewhere on a desert road, the two of us managed to have an enjoyable conversation about—well, getting lost. Getting lost, that is, from those aspects of society and the self that tend to fetter people to the familiar, harness them to what’s useful, and generally prevent them from becoming, as Nietzsche would have it, what they are. I spoke to the artist on the occasion of his first solo exhibition with Gagosian and found him to be warm, unassuming, and disarmingly honest. He was an ideal traveling companion and we covered a lot of artistic and philosophical ground, from being present to pathological escapism, and from portals and all-things-arepossible to palm trees. And, of course, painting.

—Andrew Winer

ANDREW WINER Too bad we aren’t conducting this interview on a road trip, Harold. I love the travel accounts that you’ve published—they’re so honest and intimate that they turn the reader into your traveling companion. We just met, but I already feel like we’ve logged all these hours in some tetchy and choleric Chevrolet Blazer from the ’90s.

HAROLD ANCART No, a GMC Yukon!

AW Oh yeah, that’s what it was. I was hoping the gallery would say you were waiting to meet me in some town like Joseph, Oregon.

HA I wish!

AW Right? I’d throw the easy questions at you first, on our way over to, what, Ely, Nevada?

HA Or we’d just look out at the desert.

AW Then, pulling into Hanksville, you know, down in Utah, we’d cover painting and drawing.

HA Then you’d hit me with the heavy stuff—

AW Right, about Existence and Being—when we’re heading up into Colorado’s Western Slope. We’d grab dinner at Natalia’s 1912 in Silverton. Of course, that would probably be too prescriptive for us! Sometimes I feel most free when I can tap into a way of being and working that isn’t governed by goals. It reminds me of what E. M. Forster asked: “How can I know what I think until I see what I say?” Does that speak to your experience of making a painting—to how much you know of what you want to do with a particular painting?

HA Yeah, I don’t know anything in advance. I’m relatively young, but I’ve learned, often the hard way, that I was lucky not to have reached the goals that I used to fixate on or set for myself when I was a young adult. It’s not out of many successes that I am who I am. Rather, it’s in spite of anything else, and through an innumerable amount of failures. I used to have a lot of opinions and a lot of prescriptive ideas about how life should be lived and about how painting should be done or what it should eventually look like. Those were difficult times of emotional conflict and physical and financial struggle. I remember being angry that things weren’t going my way.

AW My friends joke that I always say this, but you sound like Nietzsche! He wondered whether he had reason to be grateful for his failures and felt obligated to the hardest years of his life. He also cautioned against striving for a particular outcome, and even sort of mocked envisioning a “purpose” or a “wish.”

HA Yes, and luckily, as a result of these inner conflicts, I’ve come to realize that life, just like painting, has very little to do with what I thought I wanted. I came to realize that painting was about what I was doing, and subsequently about the observation of what had been done. That said, I always have some kind of an idea of where I want to go prior to starting a painting.

AW Ah, so you do have an idea . . .

HA But I tend to keep it simple: it can be an image, a shape, or the color blue. I know now, however, that these ideas, these things that the mind projects, are not to be fulfilled and that a particular destination is not to be reached. I guess that, just like Forster, I firmly believe that if you knew what you were going to paint before you actually painted it, painting would be of no interest at all. Same goes with writing or living, I would guess? Isn’t it by getting lost in writing them down that our ideas or our stories unfold? Almost as if our personal adventures, the accounts of a day, only begin when we start telling them or putting them into words?

AW I want to get lost in both the experience and my accounting of it. But by getting lost I paradoxically mean being present. Or maybe it isn’t a paradox, since being lost forces us to be very awake, doesn’t it? Awake to whatever will unfold. HA I agree, and while painting, I try as much as I can to welcome the unexpected. To consider failures, if not as blessings, then at least as opportunities for change or growth. I can then watch the painting unfold in front of me while making it. Working in that spirit allows the paint to become what the paint truly tends toward, not where I want it to go. Because of this, it’s very rare that I find myself conflicted after completing a painting. One

37

can only do what one does, after all. It’s in that spirit that I also try to live my life, with a vague idea of where I want to go, abandoning myself to it, watching it unfold in front of me as I walk through it.

AW Can you please be my life coach on the side?

HA Believe me, you wouldn’t want that.

AW But it’s very beautiful, what you’re saying, because you’re talking about something rare, I think, which is achieving a kind of freedom.

HA Or a nonchalance.

AW Sure, if by “nonchalance” you mean responding to reality in a way that involves actively doing something that gets you beyond the truncations of the familiar, the overly constructed, the duly reasoned, or even the named. It’s like Wallace Stevens telling us to see the sun again with an ignorant eye.

HA I’ve seen the moon many times and I’ve painted the moon many times, but it’s never the same moon when I look at it, nor is it ever the same moon when I’m done painting it.

AW Yeah—the moon is great. Can we stick to the sun for a second?

HA [Laughter ] You don’t need to get all California about it!

AW It’s not California! It’s Stevens! He writes, “The sun must bear no name, . . . but be in the difficulty of what it is to be.”

HA That’s pretty California, dude.

AW “What it is to be , man . . .”

HA Fine: the sun. Unlike with the moon, you can’t look at it. Or you can, but only in an unfocused way. Which is actually a way I like to look at things, as if they weren’t things. As if they were light. I like to get lost in sight and begin to account for what’s not in focus. To account for everything around the point of focus. Maybe that’s what Stevens means by seeing the sun with an ignorant eye. Other times, something comes into focus for me while everything else remains blurry. I try to pay equal attention to both: what’s in focus and what isn’t, for one cannot exist without the other. I try to consider both as whole.

AW I see this in your paintings! In your photos, too. And it makes me think of another Stevens poem, “July Mountain,” in which he writes, “We live in a constellation of patches and of pitches, not in a single world.”

HA I relate to that. I tend to look at the world as a formidable supermarket of colors, textures, and reflections. All the elements one needs to make a painting are out there.

AW Is that how you assemble a painting, then— the way, as Stevens writes at the end of that same poem, “when we climb a mountain, Vermont throws itself together”?

HA Well, through a process of distilling and recombining, which is the process by which all artistic activities come into shape. It’s through this process that I know whether I like a painting or not. If I look at a painting of the face of an old man, for example, I try to focus only on its color, texture, and light—the pitches and patches that the painting is made of—until it becomes that face again.

AW Which returns us to you watching the painting unfold in front of you while making it: the whole throws itself together before you, out of all these patches and fragments.

HA And by the way, that’s what makes the difference between a painting and an image: paintings are made of piles of patches and fragments.

AW But that can’t be easy, and to connect it back to conflicts and difficulties: I feel that one of the things that makes your paintings so generous is that they seem, in part, to be a record of your struggles. I sense that some sort of acquiescence has usually occurred during their making.

HA What do you mean?

AW Well, as in the work of Clyfford Still, for example, there’s often a sort of jagged beauty to your paintings: you see it in the edges, but also in the worked areas of color. Yet it seems to me that you get out just before the point where they’re overworked. What’s often left are traces of dissonance. My late friend the poet Adam Zagajewski wrote that “one must think against oneself, otherwise

Opposite:

one is not free.” Your paintings do give off a glow of freedom, yet they contain these frictions, and are made with these hard things—oil sticks—that are composed of thick, half-dry paint. And as with writing, as with any art form, the medium pushes back—pushes back against your freedom. It makes me wonder if, in addition to a kind of freedom when you’re painting, you also experience anxiety. Or even panic.

HA The only moment I feel anxious is when I pace the floor in the studio, smoking way too many cigarettes instead of working.

AW I feel anxious when I’m doing anything instead of working!

HA For me, this usually happens when I’m about to start a new work and the canvas is still untouched and I’m thinking about it too much. As if there was a risk that I would fuck it up . . . there’s no way one can fuck anything up beforehand. Perhaps the anxiety is because, beforehand, the realm of possibilities is vaster than it is once you’ve already started?

AW Yes!

HA I don’t know. It’s a bit like jumping into a lake on a hot summer day. If you try to enter the cold water gradually, you may take forever to enter. You must plunge into it, one way or another. Headfirst or not makes no difference—once you’re in it, you ultimately feel good. I call it “the zone.” A lot of things happen in there . . . some of them I’ll probably never be able to describe. But if there’s one thing that doesn’t belong there, it’s anxiety or self-esteem issues. There’s struggle, of course—I would even say that struggle is the necessary condition around which everything is built.

AW Tell me more about “the zone.”

HA It’s a zone of tension. That tension resides between two things: what the mind demands is one of them, and what the hand can do is another. It happens all the time that the mind rejects what the hand has done. This is where I find freedom.

AW Interesting. So freedom isn’t a willed thing—

HA No, it’s when something unexpected

38

This page: Harold Ancart, Untitled , 2017, oil stick and pencil on canvas, in artist’s frame, 80 × 96 × 2 ¼ inches (203.2 × 243.8 × 5.7 cm)

Harold Ancart, Untitled , 2017, oil stick and pencil on paper, in artist’s frame, 48 × 51 × 1 ½ inches (121.9 × 129.5 × 3.8 cm)

happens—when a terrible choice has been made, or when something happens to be poorly executed. When it doesn’t look how it usually does or when it doesn’t look how I think it should look. When one starts thinking against oneself, as Zagajewski says. The fact that you can only do what you do doesn’t exclude ending up doing something you usually wouldn’t.

AW That’s brilliant. And comforting, somehow. Do you think that, in this way, art can lead us to our longings?

HA I don’t know how to answer that question. As a young child, I was never satisfied with the here and now. I’ve always had a tendency to create some sort of alternate realm in which I was the almighty sovereign. Every child does that to a certain extent, I suppose? And that’s fine. Except that I’m no longer a child, and it hasn’t changed much.

AW For you and for many adults.

HA One must dream. I think it’s essential, but to what extent? I suffer from escapism. Pathologically. Sometimes I wonder if longing is actually a good thing . . . being here and wishing to be elsewhere. To ultimately realize, over and over again, that there’s no there there, and that reality belongs here and now—that’s brutal. The human condition is brutal. I don’t see how one could live if one didn’t have the ability to escape into one’s own thoughts. But to return to reality, this cruel reality with its physical rules and needs . . . it’s like trying to eat soup with a fork.

AW That’s what I was trying to ask before: should painting show us a world equal to our longings? Or should it change our longings? What I mean is, we often say that someone who dreams of the world being different from what it is—as in John Lennon’s “Imagine” or Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream”—is a person with imagination. Those are attempts, you might say, to impose what’s imagined on the world—in order to change it. Do you think there are painters like this? There’s also another kind of dreamer, who lets the world reveal and form itself around them, the kind of dreamer who

is capable of becoming enchanted with whatever appears. Do you identify with one of these kinds of dreamers?

HA I certainly do relate to both—to the first kind of dreamer, whose dreaming is so strong and persistent that it ends up altering their surroundings, and to the second kind, who finds enchanting moments in the ordinary. For me, they go hand in hand. The dream of a better life became true when I came to realize that everything is and always has been there, lingering, waiting for me to finally be able to see it. I personally believe that painting has to do with both the ability to dream of an elsewhere and the capacity to distill, or isolate and extract, elements of the everyday visual environment. These are the things that dreams are made of. This ability to recombine or reframe allows you to give shape to an elsewhere, whether it’s a human figure or a cloud, a window ledge, or an abstraction. AW What you say about painting—that it has to do with both the ability to dream of an elsewhere and the capacity to distill elements of the everyday—returns me to the Monet–Mitchell exhibition I just saw [at the Fondation Louis Vuitton] in Paris, and makes me think of the late Monets in particular, which have that quality without question, but which, stripped of their frames, also confront us with something shocking: their provisional nature. You can feel the speed with which Monet’s arm and wrist moved across the canvas, how fast and extemporaneously those paintings were made. After all, he was trying, in each of them, to capture the light of a particular part of the day—before it changed.

I happened to be at the Fondation Louis Vuitton with the painter David Salle; it was late, and we had only an hour before closing on a rainy cold night, so almost no one else was there, and we were able to move around the paintings as we pleased. I learned then that Salle is a fast looker: we did that place in forty minutes, and this, too, added to my sense that when it comes to making art, whether with paint or with words, there’s so little time. What’s that passage from the final volume of Proust’s In Search

of Lost Time , where he writes that the mind has its landscapes and almost no time is permitted for their contemplation? Proust tells us that his whole life has been equivalent to something like a painter hiking up a road over a lake that he wants to paint and that’s obstructed by rocks and trees. Brushes in hand, he can glimpse the lake through the gaps, but night is falling and he will soon have to stop painting, knowing that no day will ever break again. The Monets haunted me, but I couldn’t understand why until speaking with you now. It seems like we have so little to go by, that the whole enterprise is doubtful. Adam was referring to this, I think, when he wrote that doubt is more intelligent than poetry but that poetry surpasses doubt. In other words, we can’t get rid of doubt, and it can even be good for our art, but we need to trust that art, executed properly, overcomes doubt. Do you ever feel, when painting, that you’re answering to this kind of “I don’t know,” or managing it, say, with technique? HA Well, this is why I can say that, when it comes to my paintings, subject matter doesn’t hold as much significance as you might think. If I choose to make a painting that pictures flowers, for example, it pictures flowers almost in spite of all the meanings that we attach to flowers. The flowers in this case serve as a kind of alibi that allows me to push color onto the canvas. I don’t see myself as a painter of images, I see myself as a painter of color. When I think of all the figurative painters I admire—the list is long, spanning from Monet to Cézanne to Van Gogh to [Pablo] Picasso to [Henri] Matisse to [Philip] Guston to [Wayne] Thiebaud, to name a few—I also think about them as painters of color. It becomes more evident with the abstract painters I like, such as [Barnett] Newman or Still or [Richard] Diebenkorn (although he sits somewhere in between), that they are painters of color. I don’t know whether all these figurative painters were particularly attached to the images they were painting, but to me it feels secondary. The subject feels secondary. When you look at Van Gogh, who is the opposite of Seurat, it seems evident that very little is scripted or predetermined: he’s guided by some kind of a flux that allows him to open a door to somewhere beyond the subject of the painting itself, and this “beyond” is a place that even he could not see beforehand. I think it was his pragmatism, the very action of painting, that took him there. This also makes me think about this quote in [Carlos] Castaneda’s Teachings of Don Juan [1968]: “a man of knowledge lives by acting, not by thinking about acting.”

AW You mention Van Gogh opening a door to somewhere else, somewhere beyond the subject of the painting, which suggests that he saw alternate possibilities to what was immediately before him, both in the landscape, say, and on the canvas. It interests me because, a few days ago, I made a note for the novel I’m working on, in which I say that a finished painting, for all that it might have accomplished, paradoxically contains a paucity of alternate possibilities: this is how the painter knows it’s done, and how a painting gains an air of inevitability. Does finishing a painting feel this way to you—that there’s a closing down of other possibilities—even if it leaves open, or suggests, a path to another painting?

HA For me, to finish has everything to do with starting anew. As a matter of fact, I know that a painting is ready when it becomes a promise for another one, when whatever is in the painting, or whatever defines it, starts calling for even more that is not part of it, and that will never be part of

39

it, because it already belongs to the next one—the one that has not yet been painted.

AW That’s important, what you’re saying. It feels like a metaphor for the ongoingness of life—the way one moment dies into the next, or, to put it more positively, the way one moment’s end gives birth to a new moment. The idea that whatever is happening now is okay, ultimately, even if it feels negating, because it has a relationship, some direct connection, to what comes next, no matter how different what comes next will be.

HA Yes. What makes a work unique can be defined by everything that is the work as much as by everything that is not the work. Everything that is not the work but that could be the work constitutes its transformative potential. This transformative potential works as a promise for another work to come. This idea of a painting becoming a promise for another painting brings me back to what we were talking about earlier: the subject itself, and how it becomes secondary to what it’s made of. I think that it’s because the subject surrenders to paint that a thing can be painted over and over again without ever being the same thing. It shows us how Cézanne painted Mont SainteVictoire over and over again without ever repeating himself; how something as boring and banal as an apple never ceases to amaze us. It explains why every shadow of a plate longs for another shadow of another plate. How every painted cupcake begs for another painted cupcake. How every stroke of color demands another one, consecutively, endlessly, without ever being the same thing.

AW That thought is happy-making. Your paintings make me joyful. They’re like good memories. Something about the colors and the simplified forms—they make you think, I’ve seen these things before, I’ve been there . In his book Landscape and Memory [1995] Simon Schama writes something to the effect that landscape is the work of the mind before it can ever be trusted to the senses, that its scenery is built from layers of memory as much as from the strata of rock. Do you employ or think about memory in making these

paintings? Is memory important to them?

HA I like this idea of the landscape being made from memories as much as it’s made of rocks. In 2014, I took a road trip across the country. I bought a car and drove from east to west, back and forth. The car was a Jeep so the trunk sat high off the ground. I was painting out of that trunk along the way. I ended up making a lot of paintings—about twenty-seven, I think. I took the trip because I’d been living in New York for six or seven years and had never seen the rest of the country. I also read somewhere that one could never be a real American painter without having driven through and seen the country. I think it was [Jackson] Pollock who said that, and I guess I naively followed his advice, or maybe I just needed a good excuse to drive around—I love to drive, and I drove a lot during that journey, sometimes up to thirteen hours a day.

I believe you read the small essay I wrote afterward, which I used as an introduction to a book of photographs called Driving Is Awesome [2016]. I took the photos through the windshield while driving. I have the book right here. Let me read you just a small portion of the essay: “Around that time, I had already made a few drawings that were drying in the trunk. The car smelled of paint. My friend would ask me to stop here and there, so we could get out of the car and film. While he was filming, I drew. I drew anything. It does not matter. I have so many images in the eyes that I barely have to look around anymore.” As is the case for most of the landscapes I’ve painted since then, none of these road trip paintings (except for one of [Robert Smithson’s] Spiral Jetty [1970]) was of a particular place. These places don’t exist. They were created out of thin air. I think it’s because of their archetypal qualities that they induce a feeling of familiarity. Because they were made of piles of memories, of the many nowheres and everywheres that this world has to offer. This may be what makes them relatable.

AW The palm trees that make up your new show also induce a feeling of familiarity. Yet I’ve never

This page: Harold Ancart, Untitled , 2014, oil stick and pencil on paper, in artist’s frame, 15 ¾ × 19 ¾ × 1 ½ inches (40 × 50.2 × 3.8 cm)

Opposite: Harold Ancart, Untitled , 2023 (detail), oil stick and pencil on canvas, in artist’s frame, 81 × 71 × 2 ¼ inches (205.7 × 180.3 × 5.7 cm)

Following spread: Harold Ancart, driving is awesome, 2014–16, inkjet print, in 2 parts, each: 7 × 9 ½ inches (18 × 24 cm)

Artwork © Harold Ancart

Photos: JSP Art Photography

seen palm trees like them. How did you come to paint this series?

HA I painted the first one a long time ago. I think it was in 2014. I was living in my studio at the time, because I couldn’t afford both an apartment and a studio. The way I live and work now is very different: I come to the studio every day to work, and then I leave at the end of the day and do something else. There’s a clear separation between living and working, although I do carry most of the work with me, in spirit, even when I’m not in the studio. But back when I lived in my studio there was really no separation at all. I would sleep next to the paint that was drying and wake up in the middle of it. I wouldn’t say that it was healthy—in fact it was physically un healthy as much as psychologically disturbing not to be able to draw a line, or to have a physical separation. I was always in it; therefore, I couldn’t gain the necessary distance to determine whether what I was making was good or bad. I didn’t have the luxury to leave the studio and to come back to it with fresh eyes, to see what I’d done as if someone else had made these paintings and not myself. I was emotionally too involved in what I was making, therefore lacking perspective. My work was also very different: it was more abstract, mostly black and white, and very austere. I guess I reached a point where the pain I was in overcame the fear I felt about making a radical move. I began to want to make something completely different from these austere abstract works, and eventually to create a new window for myself, a more joyful window that I could project myself into, and that wasn’t just a reflection of the cold industrial environment that was surrounding me, which was Bushwick and its waste management. That’s how the first palm tree came. At first I thought it was ridiculous, but, since it brought joy and light inside my studio, I kept the painting up for a while, not as something serious but as a kind of a talisman I could look at. A promise for a brighter future. Then I came to realize that the people coming to visit me in the studio felt the same way about it— that it was bringing them a similar sense of joy and

40

lightness. I realized that just like me, they enjoyed looking at it.

I’ve made maybe ten of these palm trees over the past ten years, taking a lot of pleasure painting each one of them, for I knew that upon completion they would bring me instant gratification. Two of them belong to museum collections, one to the Hirshhorn Museum [and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC] and the other to the Beyeler Foundation [Basel], but somehow I never gave them their moment, I never made an exhibition out of them and always kept them on the back burner. Sometimes when you have the feeling of something being too good, you tend to be careful not to use it too much. You tend to be protective of it so that it doesn’t wear out. You save it for a great occasion.

AW Is painting a kind of sharing for you, then? Maybe a sharing in the delight of being around, of being here—a delight in what’s out there? I’m thinking of something Henry James wrote, and this I have to look up, because it’s impossible to paraphrase him. Here it is: “The very provocation offered to the artist by the universe, the provocation to him to be . . . an artist, and thereby supremely serve it; what do I take that for but the intense desire of being to get itself personally shared, to show itself for personally sharable, and thus foster the sublimest faith?”

HA From palm trees to the sublimest faith!

AW What do you think? Could this be an acceptable form of spirituality for the artist? Is there a place for this kind of calling, this kind of generosity—we almost could call it love —in what you do as an artist?

HA I love what I do, although I don’t really see myself as a supreme servant of the universe [laughter ]. I’m just a humble Belgian painter who happens to live in the here and the now. However, I do like the idea of paintings being portals that open onto a greater beyond. As I said earlier, I suffer from escapism. It doesn’t take much for me to start wandering around. What can I do? I often find myself thinking about paintings as vessels, or as a means of transportation that leads to the many elsewheres that are not the here and the now.

AW So you are sort of like old Henry!

HA Well, I wish for my paintings to do that for people—to transport them. To take them elsewhere. This is the intimate experience that I hope to share with others. To enter the world of paint, where

nothing resists and everything remains possible.

AW All Things Are Possible [1919]—that’s the name of an important book by the existentialist Lev Shestov, who was one of [Albert] Camus’s heroes and is also one of mine. I guess many of my writer heroes involve themselves in chasing the incalculable, including James. James wrote of things intimated by the deep, often hidden processes of living, things that, for this reason, can’t necessarily ever be fully known. Yet if it was seeable , James saw it. He once wrote to a struggling friend that experience, in this case sorrow, comes to us in great waves but is blind, whereas we see . Do you ever feel, when you’re painting, that you’re going after the incalculable or the unseeable, even as you’re making something that’s very much meant to be seen?

HA Yes.

AW [Laughs ] Let me try it this way: If I grant an openness to what’s around me—to that which is —I can sometimes feel that what’s out there possesses so much in excess of what I can perceive or determine. And every once in a while, I get a glimpse of that excess, but, almost immediately, words and names and meaning rush in to claim it. Do you think about this? Do you think painting can sometimes capture that ephemeral in-between moment, just before descriptions and meanings start to attach to what’s being perceived?

HA I’m familiar with these moments and with the sense of excess that you describe.

AW Phew!

HA It’s when a much deeper truth finds itself attached to a rather banal encounter. They often come to me when I’m completely detached. When I’m not trying to perceive anything—while peeling a potato, for example. They come to me as emotions, or as in a dream. But it’s almost impossible to hold on to these encounters because they change all the time and never maintain the same form. They’re grafted to the perceptual world but escape as we try to seize them or describe them.

AW They only exist as a flash.

HA Yes, and what I feel is that some paintings can revive these moments or feelings in me. They bring me back to a deeper truth when I look at them. Here I’m not talking about a deeper meaning but about an exhilarating moment that is the opposite of meaning—a great sense of silliness or obsolescence that is attached to all things. The reason

why I think painting or poetry or music can do that is that they’re among the very few activities on which meaning loses its grasp. They are in essence very silly and obsolete. They belong to a world in which rationality does not reign. Very few things can escape the shell of meaning like painting can; and when it does, historians and critics always do their best to bring it back to a rational sphere by describing and naming what should sometimes remain its own language: the unspoken language of paint. When I read about painting, I often feel that this sense of excess is being murdered by a cold and serious analytic language.

AW I pledge not to murder the deeper, silly, unseeable excess of your paintings.

HA Can we get that in writing?

AW Obsolescence and silliness: you’re reminding me of your countryman Simon Leys’s great collection of essays The Hall of Uselessness [2008], in which he quotes [the fourth-century bc Daoist philosopher] Zhuangzi as writing that everyone knows the usefulness of what is useful but few know the usefulness of what is useless. At the end of that book’s introduction, Leys writes that the sort of “uselessness” with which he, as a writer, has always concerned himself is the very ground that all the essential values of our common humanity rest on. Is painting “useless” in this way for you?

HA Society mostly recognizes a thing as being useful when it serves a practical function: a coffee machine, a cell phone, an airplane, a hair dryer. Poetry and painting don’t make coffee or dry your hair, so most consider them trivial and useless. What are these drawings going to do for you? Where is that going to take you, Mister Ancart? These are things I used to hear at school when I was caught “wasting my time” making drawings instead of doing whatever task was assigned to me. You’re a dreamer, a pariah, a good-for-nothing, you serve no purpose, and you’ll never be able to find a respectable position in society. For me, making purposeless things like paintings, or writing about nothing, is paramount. I still find hope in these things. They’re the opposite of what consumerism demands. Things that exist just for the sake of being, for the love of life, for the spirit. They are essential because they tend to stay away from the tyranny of meaning and the economic way in which the world supposedly turns. Ultimately, these are the things that will elevate us.

42

Ruby P eter

t

Pan collar necklace photogra phed in the studio of Rober

Guillot. judygeib.com

Hans Ulrich Obrist’s Questionnaire

Lynn

Leeson Hershman

44

Hans Ulrich Obrist Lynn Hershman Leeson

In this ongoing series, curator Hans Ulrich Obrist has devised a set of thirty-seven questions that invite artists, authors, musicians, and other visionaries to address key elements of their lives and creative practices. Respondents are invited to make a selection from the larger questionnaire and to reply in as many or as few words as they desire. For the second installment of 2023, we are honored to present the artist and filmmaker Lynn Hershman Lee. son

2. Does money corrupt art?

A: No, lack of money does.

5. What is your most recent work?

8. What was your first museum visit as a child?

A: The Cleveland Museum of Art, which I went to at least weekly.

A: They are all always unfinished, but the latest is about immortality. I’m working on the final part of The Cyborgian Rhapsody, a project I began in 1996 about the evolution of AI and how it affects identity and culture. Part 4 was written and performed by a GPT-3 chatbot that thinks it looks and sounds like me thirty years ago. I hope to have this complete by May. I’m also working on a much larger project about immortality, investigating the existence of immortality in certain plants, bacteria, and even jellyfish. I’m not certain what final form this will take yet—most likely a multimedia installation like The Infinity Engine (2014) or Twisted Gravity (2019–21).

7. What role does chance play?

A: Failure and chance are indispensable to complete a work.

17. Has the computer changed the way you work?

A: Hahahah. I live in the Bay Area mostly, where you breathe technologies and use the computer as your brain.

45

11. How did you come to art/How did art come to you?

A: I was born.

6. What is your unrealized project?

A: My life.

27. What was your biggest mistake?

A: Fretting about past mistakes.

9. What keeps you coming back to the studio?

A: Noise.

29. Do politics and art mingle?

A: Yes: one can’t exist without the other. Art is about change and perception in the context of current states of life, which politics defines.

23. What is time?

A: An invention to quantify reality.

34. What is your advice to a young artist?

A: Don’t throw anything away, and keep your sense of humor.

46

. christophegraber.com .

Photo Mathias Zuppig er Zurich Artw ork Karin Schiesser Zurich

Avedon 100

In celebration of the centenary of Richard Avedon’s birth, almost 150 artists, designers, musicians, writers, curators, and fashion world representatives were asked to select a photograph by Avedon and elaborate on the ways in which image and artist have made an impact on them for an exhibition at Gagosian, New York, this Spring. Participants include Hilton Als, Naomi Campbell, Elton John, Spike Lee, Sally Mann, Polly Mellen, Kate Moss, Chloë Sevigny, Taryn Simon, Christy Turlington, and Jonas Wood. A publication commemorating this exhibition consists of statements from these luminaries, as well as essays by Derek Blasberg, Larry Gagosian, Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, and Jake Skeets. We present a sampling of these materials here.

50

Everywhere Light

Jake Skeets reflects on Richard Avedon’s series

Oil. Rodeos. Drifters. A map to the American West, also called Frontier. We know the myth of it well. Open land for miles. Long horizons only broken by one or two mighty rivers. But there is little water still. There is dirt, and oil and rodeos and drifters. The open road is a metaphor for the opportunity that might exist out west . Out there Somewhere in the Frontier

One road is a vein through it all: US Highway 66, also known as Route 66. The Mother Road. According to the National Park Service, there are more than 250 sites along the road that are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It’s a road of both myth and history. The road was crucial to the US expansion in the West and contributed to several American industries, like fast food, roadside motels, and Native American jewelry. Entering any gas station or convenience store along the road still offers memorabilia of the all-American story. Richard Avedon entered this space while working on the series In the American West , stopping by several towns along the road, including small towns like Gallup, New Mexico. Travelers often speed through on their way to Las Vegas or Los Angeles. It’s a town that relies on this travel, both by road and train. One of the revenue streams for Gallup is (American) Indian Jewelry, earning it the nickname “The Indian Capital of the World.” And I consider it one of my hometowns. The other is Vanderwagen, New Mexico, just south of Gallup, located in the checkerboarded area of the Navajo Nation, also known as the Navajo Indian Reservation. For me, it’s Diné Bikeyah, the people’s land. It’s home. Gallup is a border town nestled between the homelands of the Navajo, Hopi, Laguna, Zuni, and Acoma people. It’s the nearest town for a lot of these communities, and families are often forced to travel into Gallup for groceries, supplies, and other amenities. For me, it was all of the above, even schooling. I know Gallup like the back of my hand. I know its history. I know its future.

Avedon visited Gallup in June of 1979. According to Laura Wilson, who worked with Avedon during In the American West , she would often approach subjects Avedon found interesting. While in Gallup, they encountered a man named Benson James. He was wearing a dirty shirt and they photographed him. His face is almost a mirror for the landscape. His face is a reflection of the American West. His hair is shoulder length, and he stands before the white backdrop with the weight of a century. James is holding some crumpled cash in his hand as he stares into the infinity of the camera lens and tells us a story without any words.

James and Avedon represent two histories colliding. In the photograph, we see the visible hand of James and the invisible hand of Avedon. We then see white as if a moment before blackout or death. White like the absent clouds above the western sky. White like foam on spilled beer outside a bar. White like the teeth of pageant queens in Texas or the large letters of small-town pride that are embedded in roadside hills. White like lightning. White like the story of the American West, all boom and roll. James represents the ones who were rolled, and Avedon represents the ones who do the rolling. And I mean this literally. James was murdered a year later in Gallup. Avedon went on to lead a life of celebrated photographs.

Avedon’s photographs tell so much of the American story. James’s death tells so much of the American story we all try to forget.

In 1985, my family received the finished book, In the American West . My grandmother had no idea

her son, my uncle, had been photographed. My aunt, Paula James, wrote a letter to Avedon, dated February 20, 1985, explaining that James was “stabbed about 40 times behind a Cedar Hills grocery store in Gallup.” My aunt sent the letter from the post office box she still uses today. The letter also inquired about the photo itself, asking if my uncle was paid for his photograph. My mother has a story about my grandmother charging people who wanted to take her picture whenever they traveled into Gallup. Many people wanted photographs of Native people back then. Avedon’s portrait feels different, however. It has a different texture. It has the stain of a forgotten side of American history. The side we lock our doors to, clutch our purses near, pretend we do not notice as we pump gas.

Avedon, in his erasure of background and the orientation of light, situates the American West in an infinite space, both past and present. Our only gesture of time is a face, a stare, a posture, the human body, all beautiful and true. Time is not an experiential element in Avedon’s work. Time is emotive. Time is physical. We can trace time along the photographs themselves. There is no history. There is no destiny. There is only story. And it was this story that moved me when I saw the portrait of my uncle.

I sent several e-mails to Laura Wilson, the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, and the Avedon Foundation during my research into the photograph of my uncle. I wanted to learn as much as I could. I even requested, if there were additional photos taken of my uncle, if I could view them privately. In a previous essay, I wrote about seeing the photograph as a child and again as an adult. I explained, then, that the photograph changed the direction of my first collection of poetry. My book became an investigation into the history of Gallup and my association with the violence that exists there. James’s story is not the only one. It belongs to a long legacy of people dying in Gallup because of alcoholism and racism. Those stories join the many others in various border towns across the United States and Canada. It even joins the hostility in borderlands across the world. Collision, after all, is violent. My first book attempted to write into the turbulence, to offer beauty within the chaos. I wrote to reclaim the story of my uncle in the way Avedon attempted to reclaim the forgotten stories that exist in the out there.

The frontier is my home. I’ve only known collision. My book was an attempt to let the sediment of that legacy settle and hope for a river stone somewhere in the future. Today, as I return to the portrait, I see only the story of my Uncle Benson. I hear the ghost hum of Gallup somewhere in the background. Beyond the white background exists a town that proves time is never what it seems. Time is a road. Time is a building. Time is a turquoise necklace. Time is a gas pump. Time is a body.

One of the kinds of artworks you can find in Gallup are rugs woven by Diné master weavers. They travel through space and time because of their beauty. The designs are everywhere today. One of the prominent designs is the Diné chief blanket with its famous bands of black and white wool. I asked once what the stripes mean. I was told by various people various things. The white and black can represent touch, as in the moment rain hits the ground, or the early morning when the sun is about to rise. And I trace the outline of my uncle’s figure on the white space and observe the same thing: rain, early morning. There is no tragedy in his portrait, only the world, plain as early morning light, an everywhere light.

51

In the American West, focusing on the portrait of his uncle, Benson James.

Opposite: Benson James, drifter, Route 66, Gallup, New Mexico, June 30, 1979

Opening spread: Deborah Willis

Photomat portrait of Richard Avedon, photographer, with a mask of James Baldwin, writer, New York, September 1, 1964

Framing a portrait of two artists who are also known as activists can be viewed as a complex production. The first time I saw the image it engaged my curiosity about masking, twinning, and storytelling. I selected this image because of the beauty of the constructed moment when I viewed it and the combination of the political and the personal merged in one single image. I have researched the philosophical writings of Baldwin and the aesthetic images of Avedon for years and find this pairing of identities an excellent example of hope, possibility, and friendship in the long rights struggle that included cultural transformations.

Spike Lee

Malcolm X, Black Nationalist leader, New York, March 27, 1963

To my dismay the great photographer Richard Avedon never took a portrait of me. It just never happened, but all was not lost. The New Yorker featured an Avedon portrait of Malcolm X with the review of my film. On my mantelpiece is that portrait of Malcolm signed to me by Avedon. I also have now on the walls of my 40 Acres and a Mule office in Brooklyn portraits of Lena Horne, Joe Louis’s right-hand fist, Marlon Brando, and Brando with Frank Sinatra. Richard Avedon was as great as the portraits he took of the greats.

Awol Erizku

Malcolm X, Black Nationalist leader, New York, March 27, 1963

Considering the fact that this particular portrait was made in the midst of the most tumultuous and divisive decade in world and American history, marked by the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War, political assassinations, and the emerging “generation gap,” I have a strong conviction Avedon was aiming to capture the spirit of Malcolm X and not just his image. Despite Avedon’s technical and conceptual intentions with this image, I find this portrait of Malcolm X abstruse and yet inherently compelling. The departure from his conventional portraits to this expressive style is perhaps indicative that this is (in fact) a psychological portrait or an attempt to express Malcolm’s dynamic within the country at this time.

52

Larry Gagosian

Marilyn Monroe, actor, New York, May 6, 1957

One of Richard Avedon’s most well-known portraits is of Marilyn Monroe in a moment of pensive introspection. Because she looks melancholy, and also because she would die less than five years after it was taken, it’s often referred to as “Sad Marilyn.” The world is less familiar with this mural of Marilyn, which Avedon produced using new advances in photography technology in 1994. This is what I find fascinating: it’s composed of images photographed in 1957, the same night as the iconic Sad Marilyn. Look closely and you’ll notice she’s wearing the same dress. Marilyn’s range as a performer is undeniable when you digest both images. In the mural, she is the opposite of sad: she’s a wild animal in her stride, a glamorous cascade of the ultimate female form, which has been immortalized for decades. It’s like choreographer Bob Fosse’s version of The Human Figure in Motion , Eadweard Muybridge’s 1901 book of photography that dissected human forms. For me, the most appealing part of this work is the notion that we are watching two legends at the peak of their powers: Avedon behind the camera and Marilyn in front of it. I’m a huge collector of Avedon’s portraits. In addition to the Sad Marilyn, I have acquired images of John Huston, Groucho Marx, Charlie Chaplin, Jean Renoir, and others. Avedon has a signature style and you know an Avedon when you see one. I admire his ability to keep someone in front of a camera until they exposed their true self, whether that meant waiting for them to crack and show a vulnerable side, or just cranking up the music and letting them go wild. With Marilyn, it seems he did both on the same night, which was surely one of the longest and most memorable of his career. (After all, he must have cherished the memory of that 1957 shoot to revisit it thirtyseven years later and make a new work out of it.)

I met Avedon many years after he photographed Marilyn. I’d visit him in Montauk and we’d have hard-boiled eggs and champagne, which he said was his favorite breakfast. He was always upbeat, bright, and talkative. I regret never asking him about Marilyn, because I’m still fascinated by her. But I find solace in knowing that now, years after they’ve both passed, the world is still reveling in their mysterious processes, epic careers, and undeniable mark on pop culture.

55

58

Amber Valletta

Twiggy, dress by Roberto Rojas, New York, April 3, 1967

I’ve always been drawn to this image of Twiggy because Avedon’s incredibly keen eye and mastery of composition are so clearly defined in it. The symmetry of the horizontal lines in the dress, her gentle facial expression, the demeanor of her body, the twilight of the studio light: it’s all exquisite. Avedon was a master of capturing a person’s interior world at the same time he was creating a specific moment in time. Though it is a fashion picture—with a fashion credit in its title— it’s even more moving as a portrait of Twiggy, the boundary-breaking, era-defining model who launched a fashion revolution. Avedon had an entirely modern view of photography, and so much of his work has defined the history of fashion photography and continues to inform much of its future. I’m honored to have worked with him and have been moved by his work since I first encountered it. He was and remains a true legend.

Kim Kardashian

Elizabeth Taylor, actor, cock feathers by Anello of Emme, New York, July 1, 1964

I’ve always been taken by Richard Avedon’s portrait of Elizabeth Taylor because it epitomizes her timeless beauty. In this image, he proves why she was such an icon of her era yet, at the same time, completely transcended it.

61

62

Denise Oliver-Velez

The Young Lords: Pablo Yoruba Guzmán, Minister of Information; Gloria González, Field Marshal; Juan González, Minister of Education; and Denise Oliver, Minister of Economic Development, New York, February 26, 1971

Looking at that photo reminds me of how very young we were to have the weight of leading a large group of members who were mostly younger than we were—and the amazing pressures we were faced with; we literally were Young Lords twenty-five hours a day—with a driving need to help our people while being harassed and spied on by multiple police agencies—local and federal.

63

Hilton Als

Truman Capote, writer, New York, January 21, 1949

When I was growing up, I admired Truman Capote’s unabashed queerness. He put it out there at a time when folks thought it best to keep it in. Back then, being out could get you arrested. It took a certain amount of toughness to be who you were if you were gay and unashamed in the 1940s, also a belief in what you could project as an out gay man: an effete stylishness, and a belief in fantasy. Dick captures that in this lovely, misty, and mystical portrait of a unique American artist.

Sally Mann

Ezra Pound, poet, at the home of William Carlos Williams, Rutherford, New Jersey, June 30, 1958

A few years ago, a picture of a man’s contorted face was used for the cover of a novel. I imagine it was chosen because of the ambiguity of the expression, although the title helpfully informs us that this was the subject’s expression at orgasm. So, unless something is terribly wrong with the guy, we can assume his face was contorted in pleasure.

The Avedon portrait of Ezra Pound is similarly ambiguous—as almost all good photographs are— although there is no mistaking what is on Pound’s face for orgasmic pleasure. At first glance it might appear to be anguish or deep grief, and that would not be an impossibility by any means. Ezra Pound was a man of oceanically deep sorrows, and he was also batshit crazy.

In 1958, the year this picture was taken, he had just been released from the bughouse, as he called it, at St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, DC. Shortly after this, he adopted his very public vow of total silence, which he steadfastly maintained, breaking it at long last by proclaiming, “I have never made a person happy in my life.” Interestingly, Cy Twombly told me that during this famous silence he happened to be sitting behind Pound in his private balcony at the Spoleto festival and clearly heard him speak to his wife, Olga; his voice was raspy and weak, but he was lucid. Or as lucid as a man can be who has been locked up outside like an animal in a 6-by-6-foot wire cage, keeping company with the doomed father of Emmett Till, while writing on pieces of toilet paper the uneven but often brilliant Pisan Cantos

In this moment captured by Avedon, Pound’s expression could reflect the exquisite intensity of concentration as he declaims those very cantos to his friend William Carlos Williams, or it could be the revelatory moment before the camera when he realized he was, in his own words from “Canto 115,” “A blown husk that is finished / But the light sings eternal.”

We can never know what this wounded, bitter, and confused man was feeling, and the unknowing, the question, the gift of ambiguity is what Avedon bestows on the viewer.

64

Artwork © The Richard Avedon Foundation

RITE S OF PASS -AGE

‘Rites of Passage’, an exhibition at Gagosian, London, this spring, explored the concept of “liminal space,” a coinage of the anthropologist Arnold van Gennep, through the work of nineteen contemporary artists who share a history of migration. Here, Péjú Oshin, associate director at Gagosian, London, speaks with Phoebe Boswell, Adelaide Damoah, and Julianknxx about their participation in the exhibition and about the complexities of community, performance, truth, and identity.

PÉJÚ OSHIN The show was titled Rites of Passage , and it considered the idea of liminal space. What are your experiences with this notion, conceptually as well as personally?

PHOEBE BOSWELL A lot of my work exists in the porous space between what we know and what we’re yet to know, what we’ve experienced and what hasn’t become yet. The idea of liminal space is really interesting: as a mental state, it can create a lot of tension because it’s a state of unknowing. But I think that the alternative reading of it, or the alternative sensation of it, is that it’s the space of massive possibility and radical hope. It becomes a space of immense knowledge, a space of everything that has been up till this moment, and also a space where the future hasn’t been tarnished yet, right? If you look at it in terms of who we are in this moment, it’s where we can place memory, and it’s also where we can dream.

JULIANKNXX It’s something I’m living out daily. I’ve been looking at the question of what it means to be Krio, from Africa, specifically West Africa, Sierra Leone. We’re made up of the African returnees who came back from Europe, the Caribbean, the Americas, and had to start a whole new identity and language. They had to reinvent modes of representing themselves. There’s this constant movement happening, but the excitement, as Phoebe was saying, lies in all that potential—the potential of shifting and drifting. The Krio people in Freetown created this identity of borrowing as they were moving along; they’ve borrowed literally everything that creates who they are today. And I’m here today because of this borrowed identity—that for me is exciting, and passing that on to my kids to think about feels positive. They are partly Sierra Leonean, partly Zimbabwean, but they were born in England. How they carry on this thing of what’s possible with humanity, how we can think of ourselves not just from a social/political lens, how we move as Black people and own spaces and take what we can without this limiting thought of, I’m this, therefore I should do X. . . . How do you say, No, I will take what I can wherever I’m at—I find that inspiring.

For an artist thinking about identity, thinking about how I present myself visually, there is a level of performance. I’m carrying these things with me into the ritual space, into the spiritual space, and into the physical space. I can bring my ancestors with me. In this space, for me, time and truth don’t matter. I don’t have to care about facts; I’m going to tell these stories in whatever way I can. Because when you look at how many stories white people tell about themselves, who cares about facts?