GAGOSIAN & MUSIC

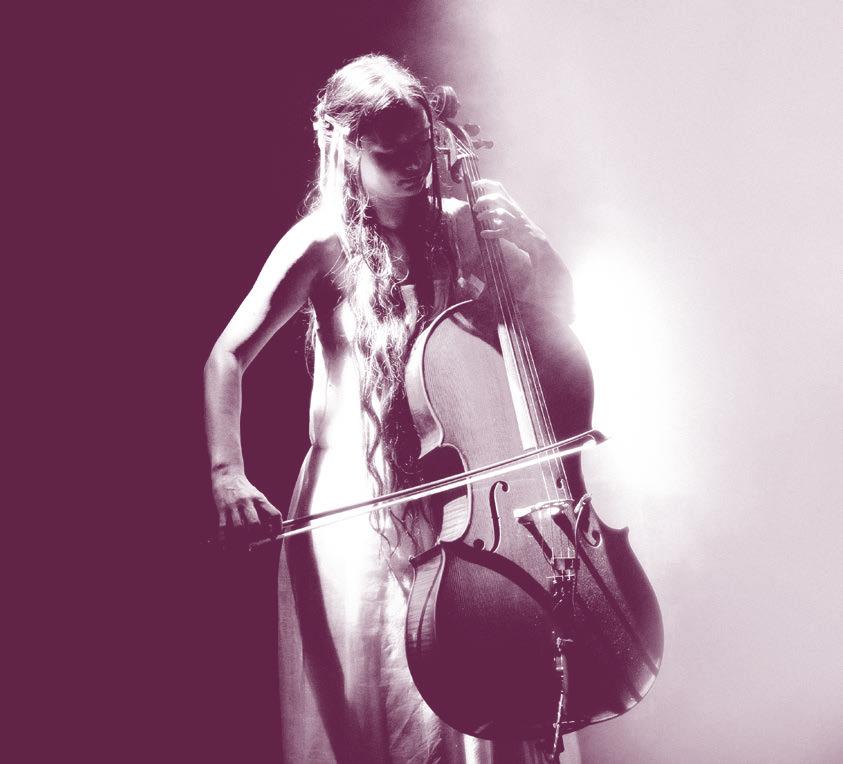

LUCINDA CHUA

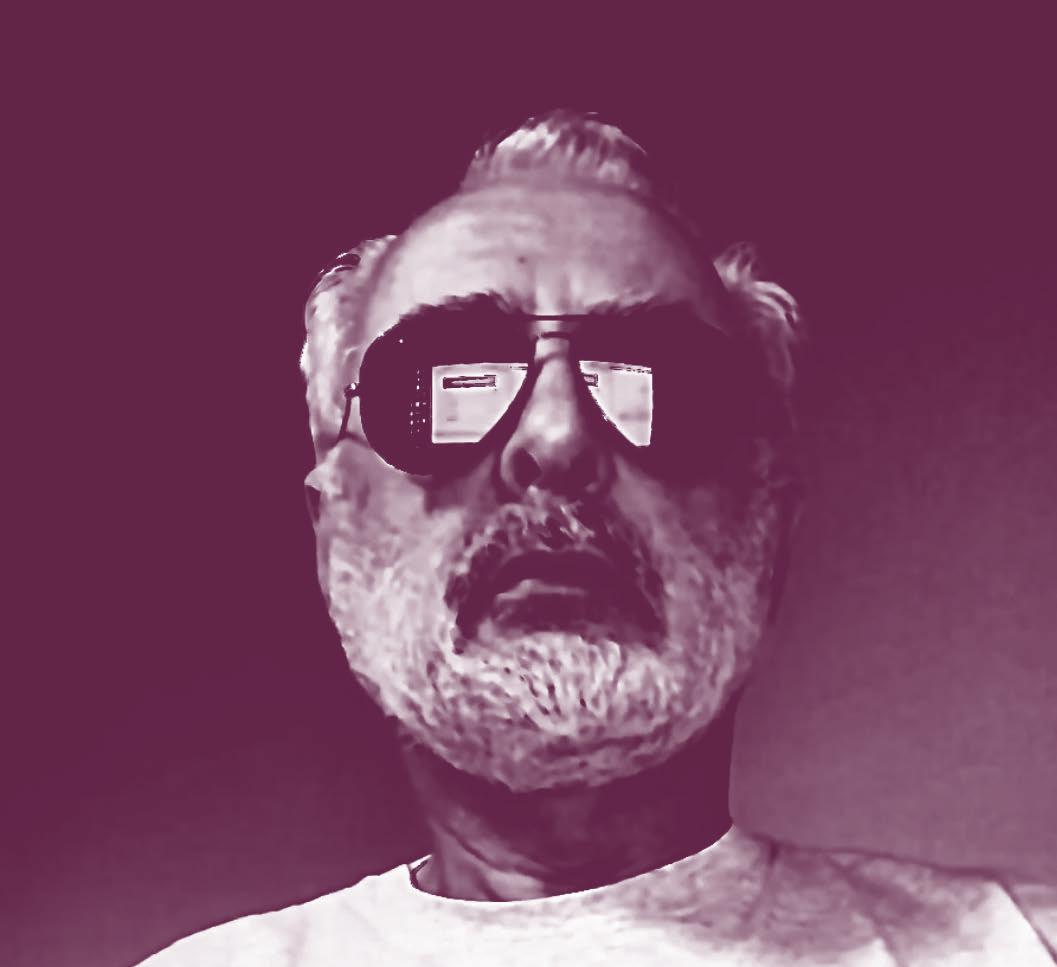

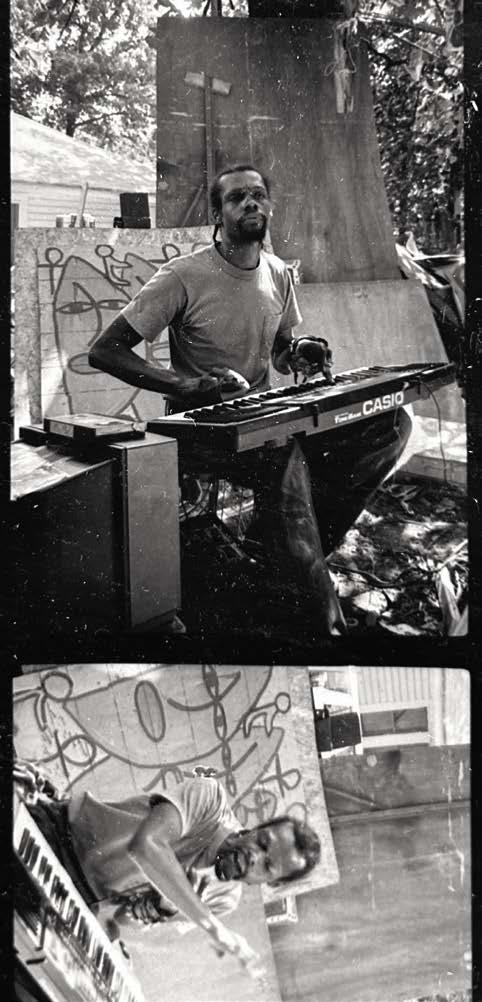

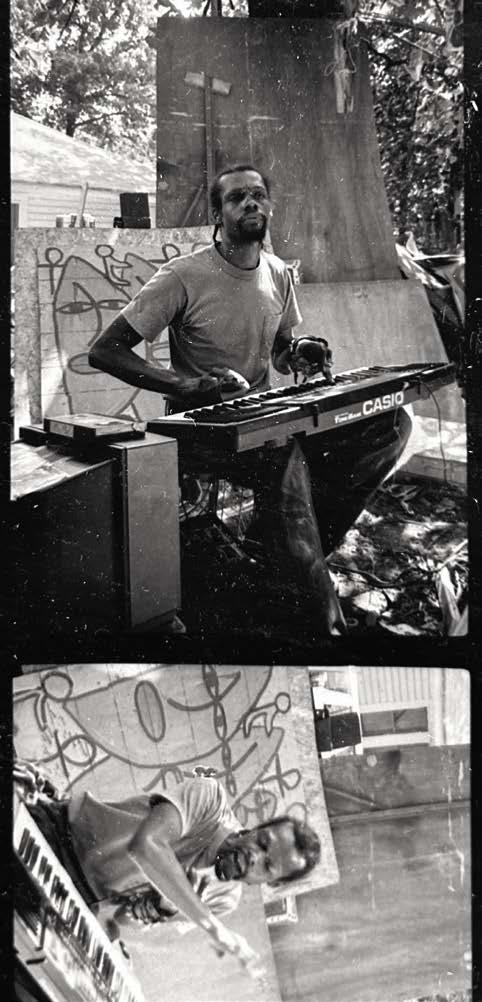

LONNIE HOLLEY

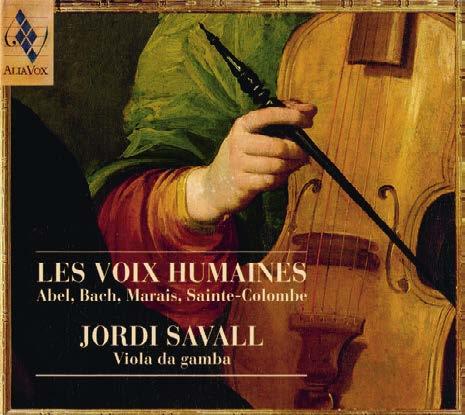

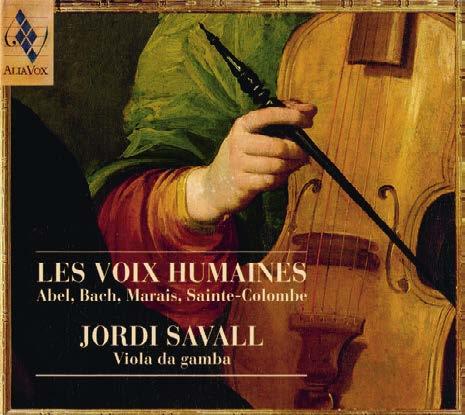

JORDI SAVALL

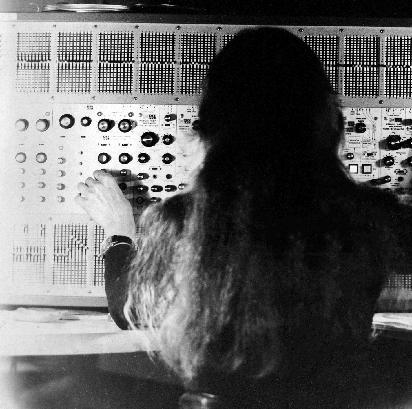

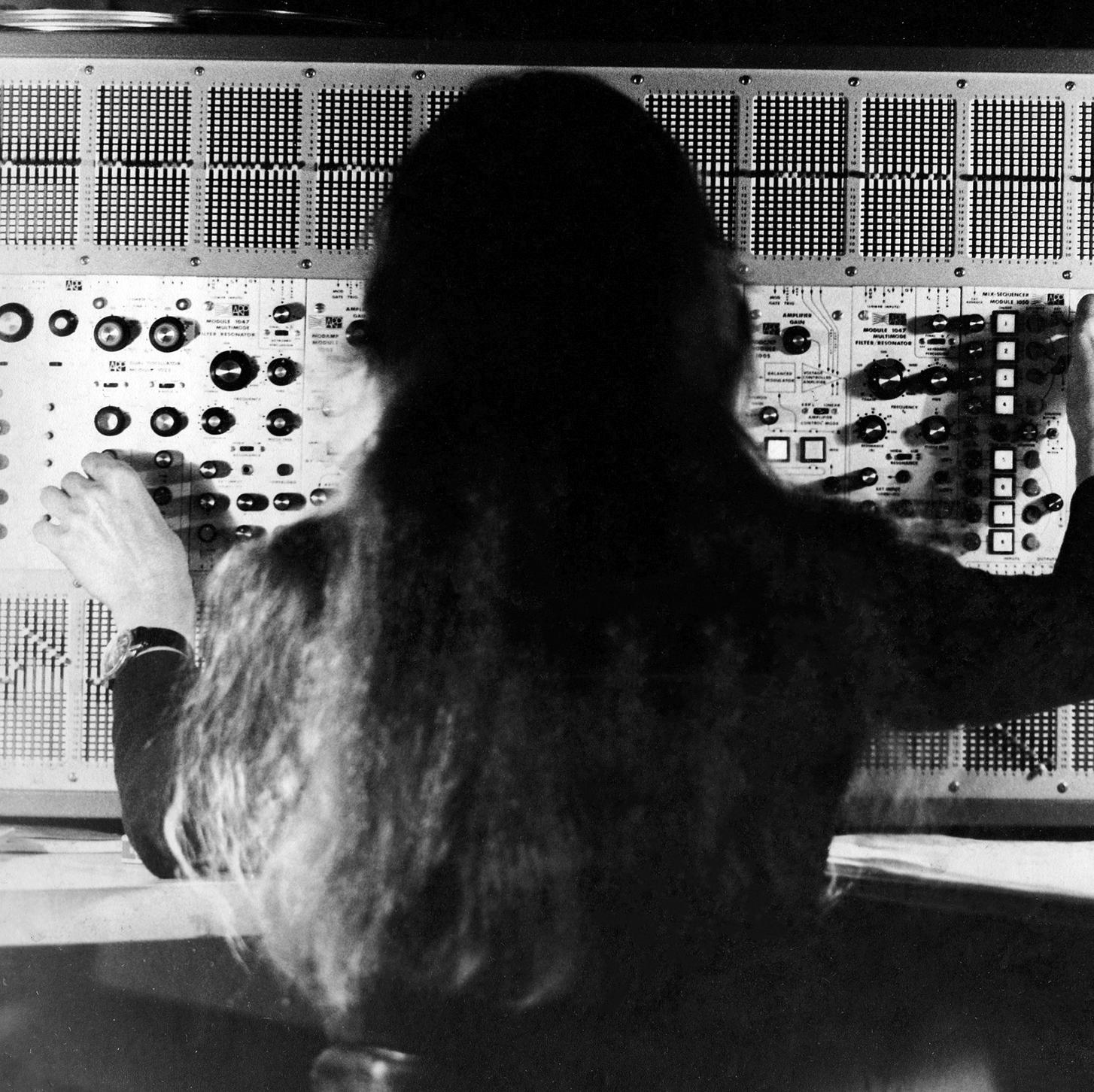

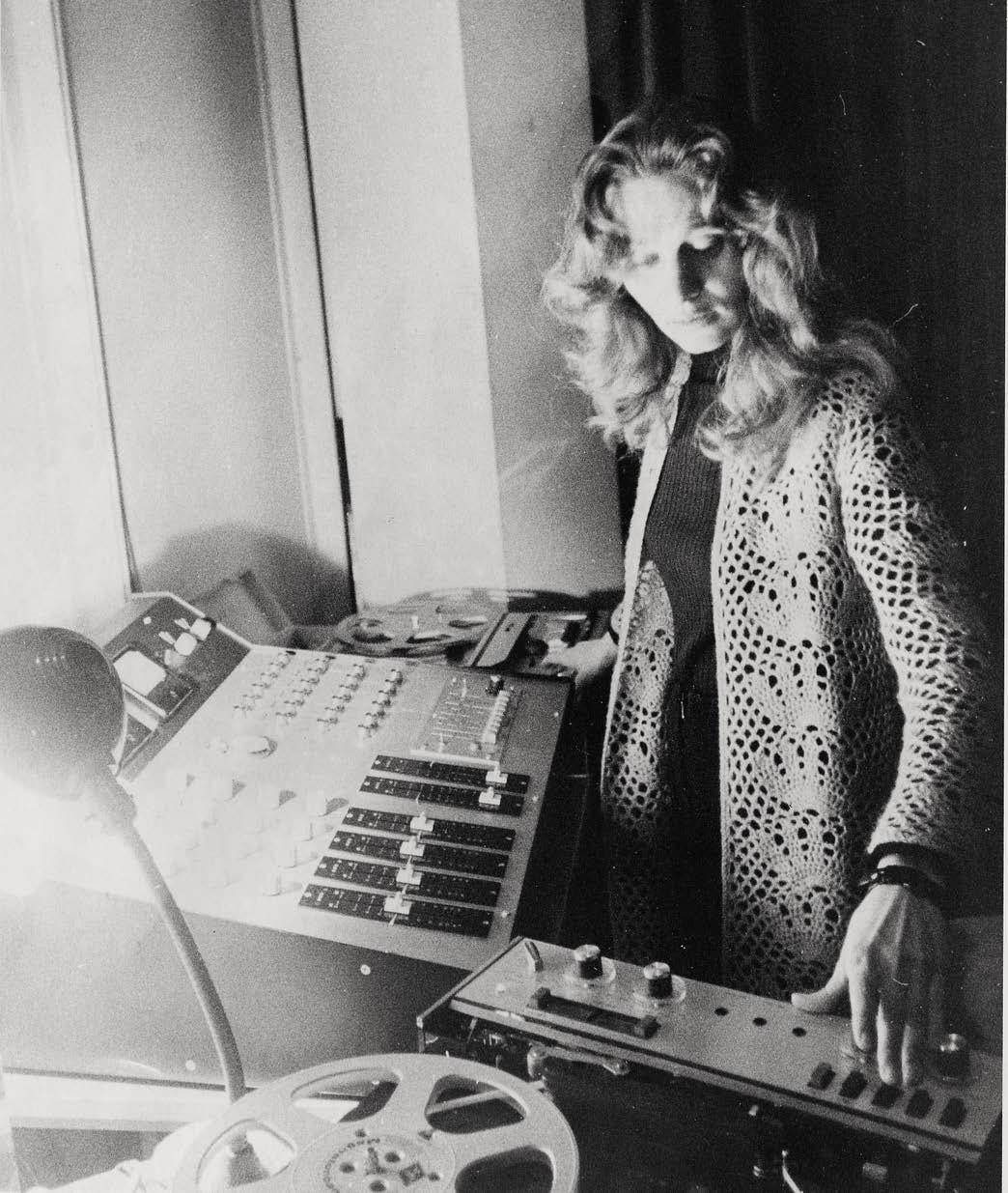

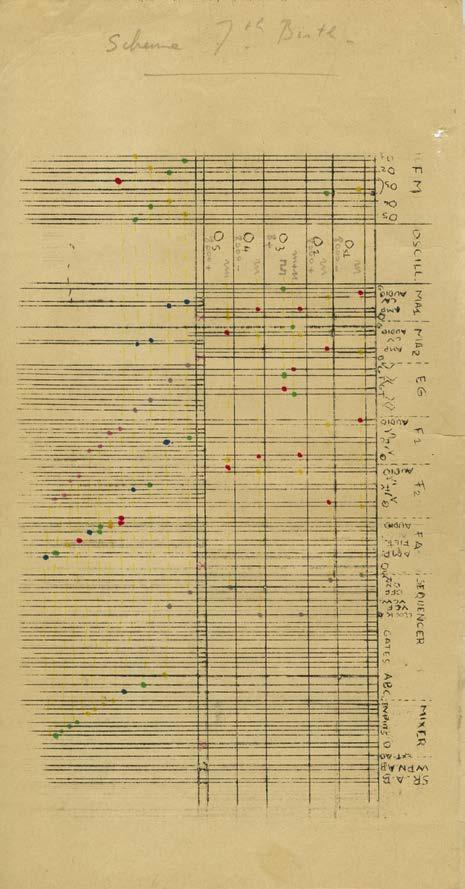

ÉLIANE RADIGUE

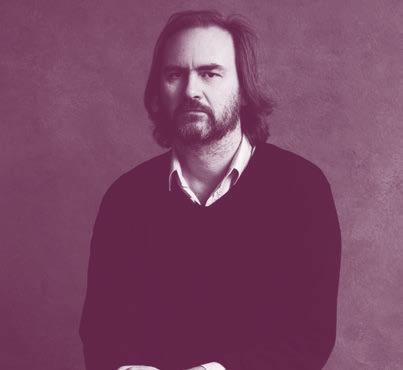

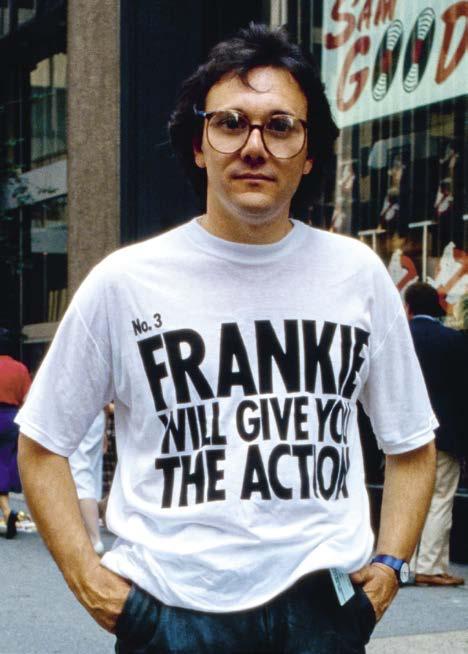

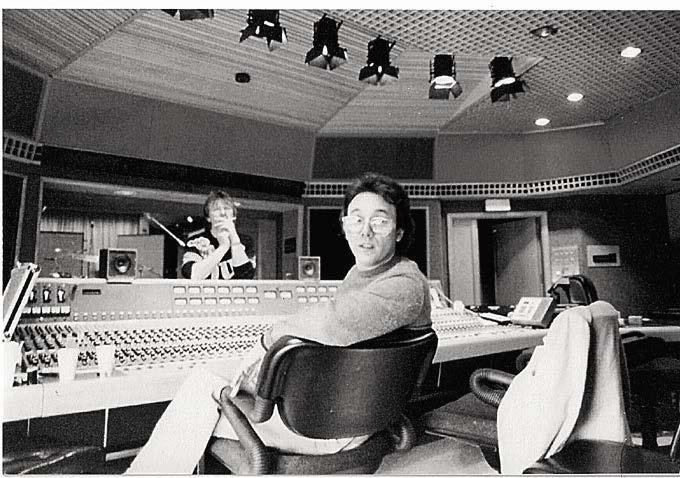

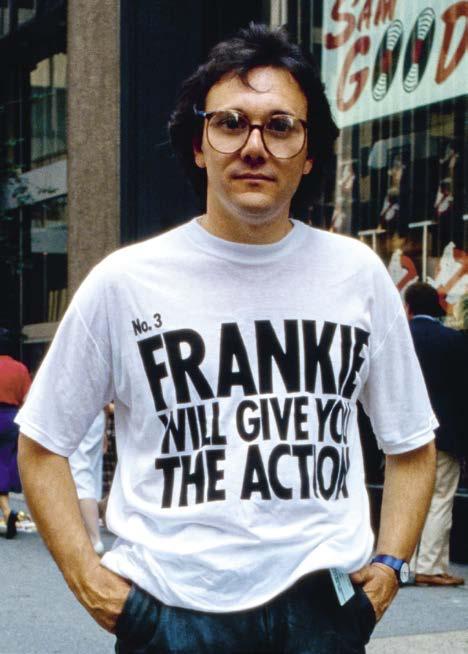

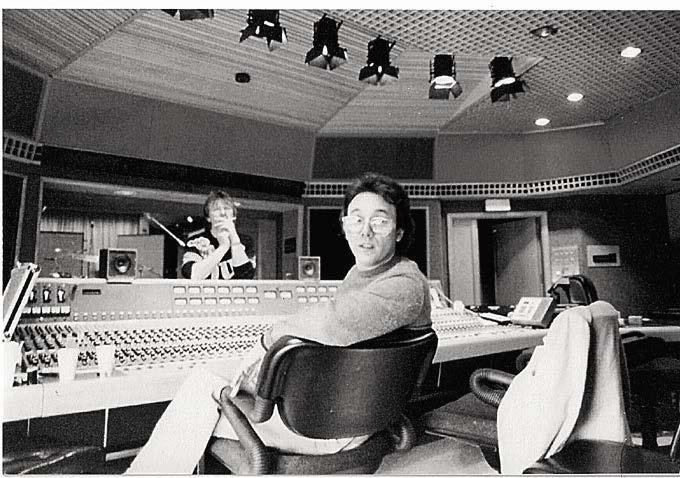

TREVOR HORN

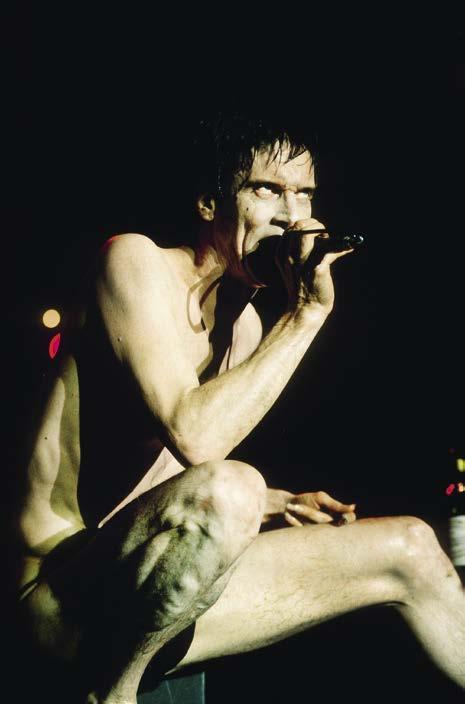

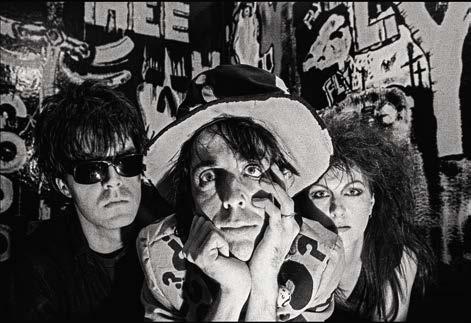

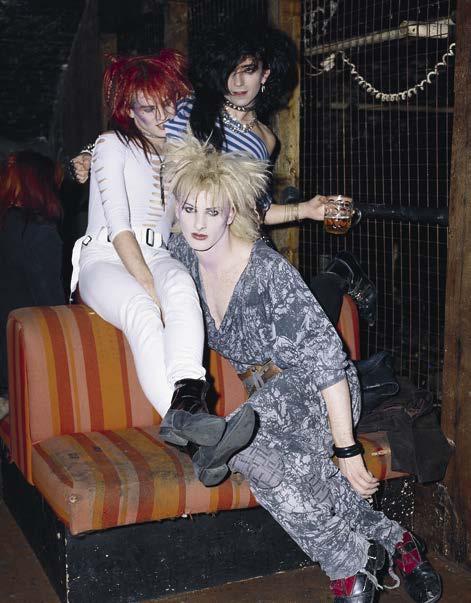

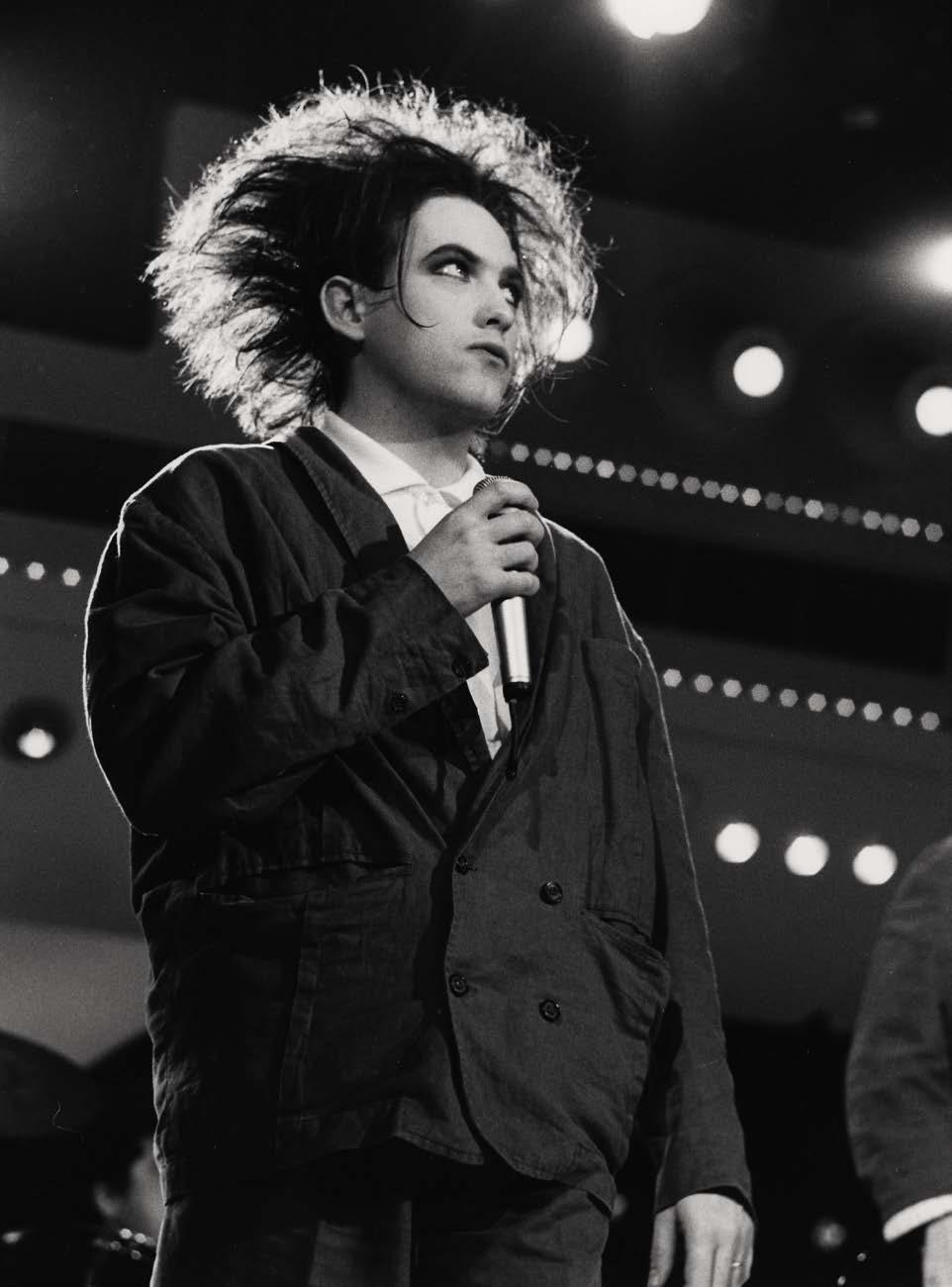

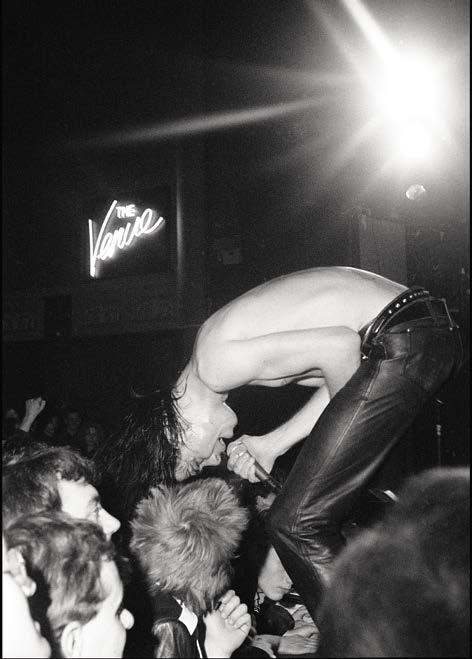

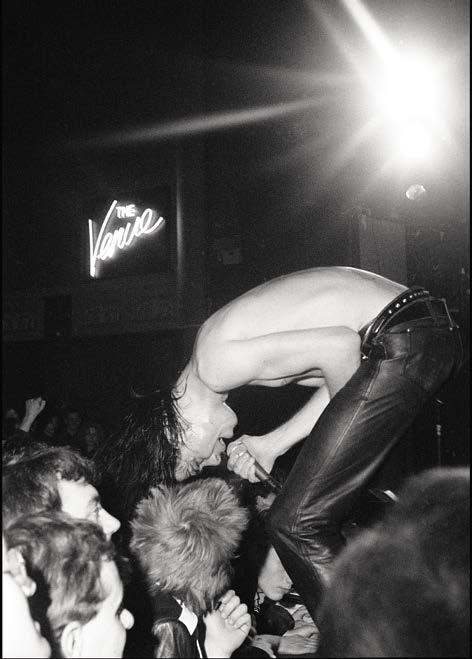

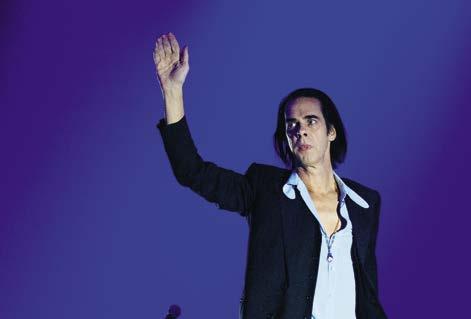

WHITE NOISE & GOTHS

BY:

DHRUVA BALRAM

HARRY THORNE

ARIANA REINES

LOUISE GRAY

YOUNG KIM

JACE CLAYTON & DAN FOX

Editor-in-chief

Alison McDonald

Managing Editor

Wyatt Allgeier

Editor, Online and Print

Gillian Jakab

Text Editor

David Frankel

Executive Editor

Derek Blasberg

Guest Editor, Music

Harry Thorne

Digital and Video

Production Assistant

Alanis Santiago-Rodriguez

Design Director

Paul Neale

Design

Alexander Ecob

Graphic Thought Facility

Website

Wolfram Wiedner Studio

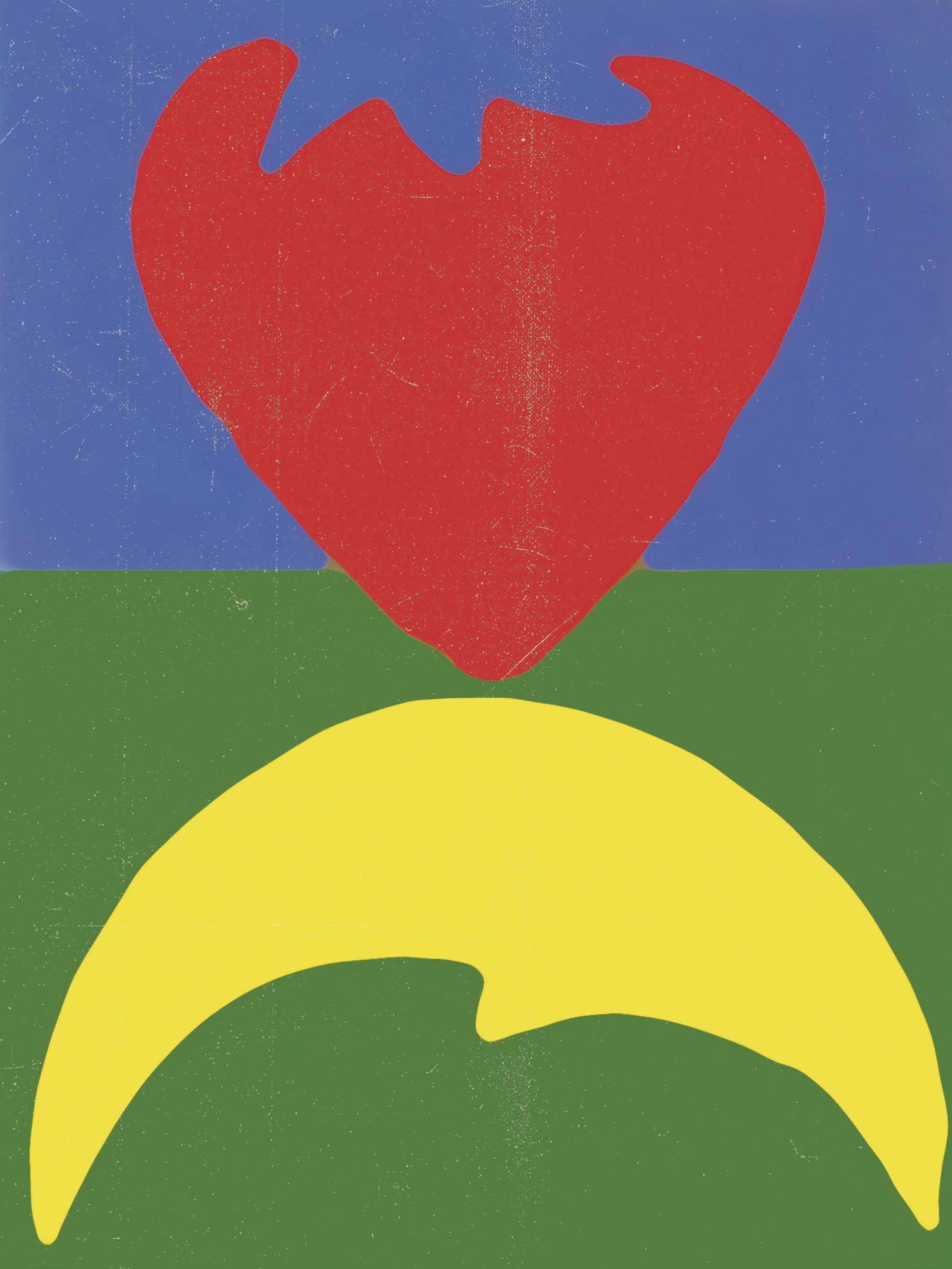

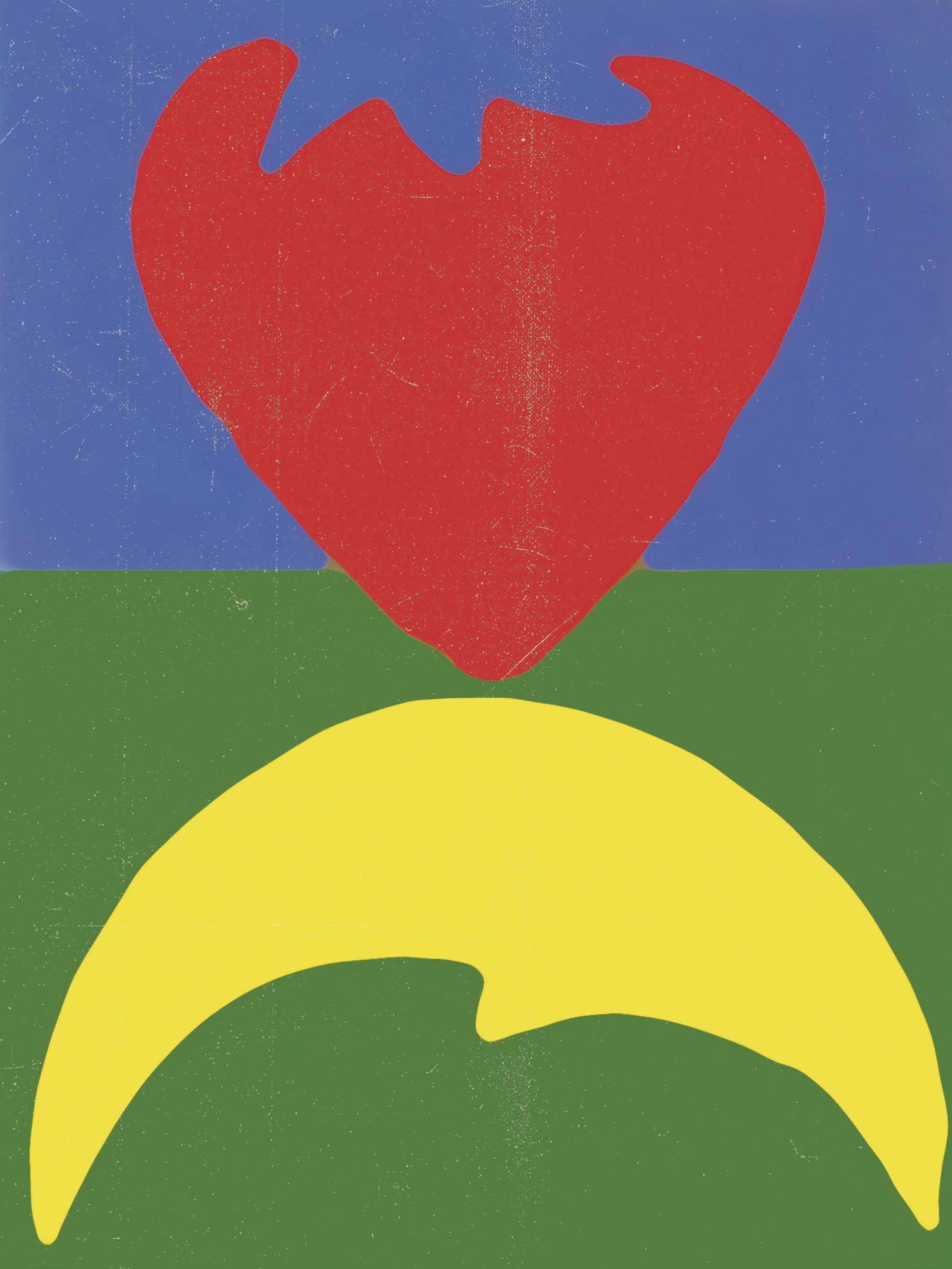

Cover

Roy Lichtenstein

Gagosian Quarterly, Summer 2024

Founder Larry Gagosian

Publisher Jorge Garcia

Published by Gagosian Media

Associate Publisher, Lifestyle Priya Nat

For Advertising and Sponsorship Inquiries

Advertising@gagosian.com

Distribution David Renard

Distributed by Magazine Heaven

Distribution Manager

Alexandra Samaras

Prepress

DL Imaging

Printed by Pureprint Group

Contributors

Valerie Balint

Dhruva Balram

Daniel Belasco

Derek Blasberg

Francesco Bonami

Marcantonio Brandolini

Cynthia Carr

Michael Cary

Lucinda Chua

Jace Clayton

Mario Codognato

Harry Cooper

Gemma De Angelis Testa

John Elderfield

Lauren Elkin

Charlie Fox

Dan Fox

Moeko Fujii

Gary Garrels

Alice Godwin

Louise Gray

Luca Guadagnino

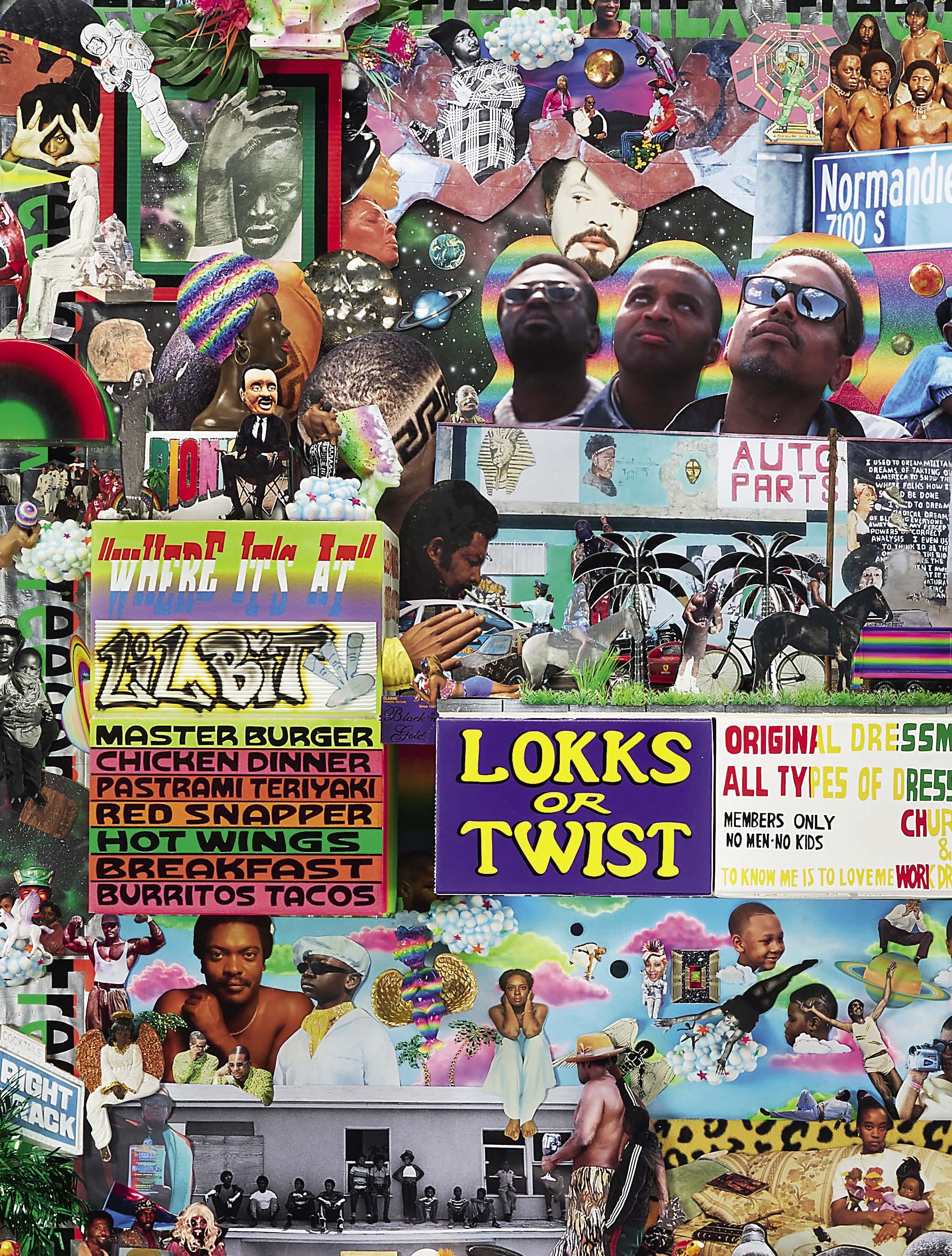

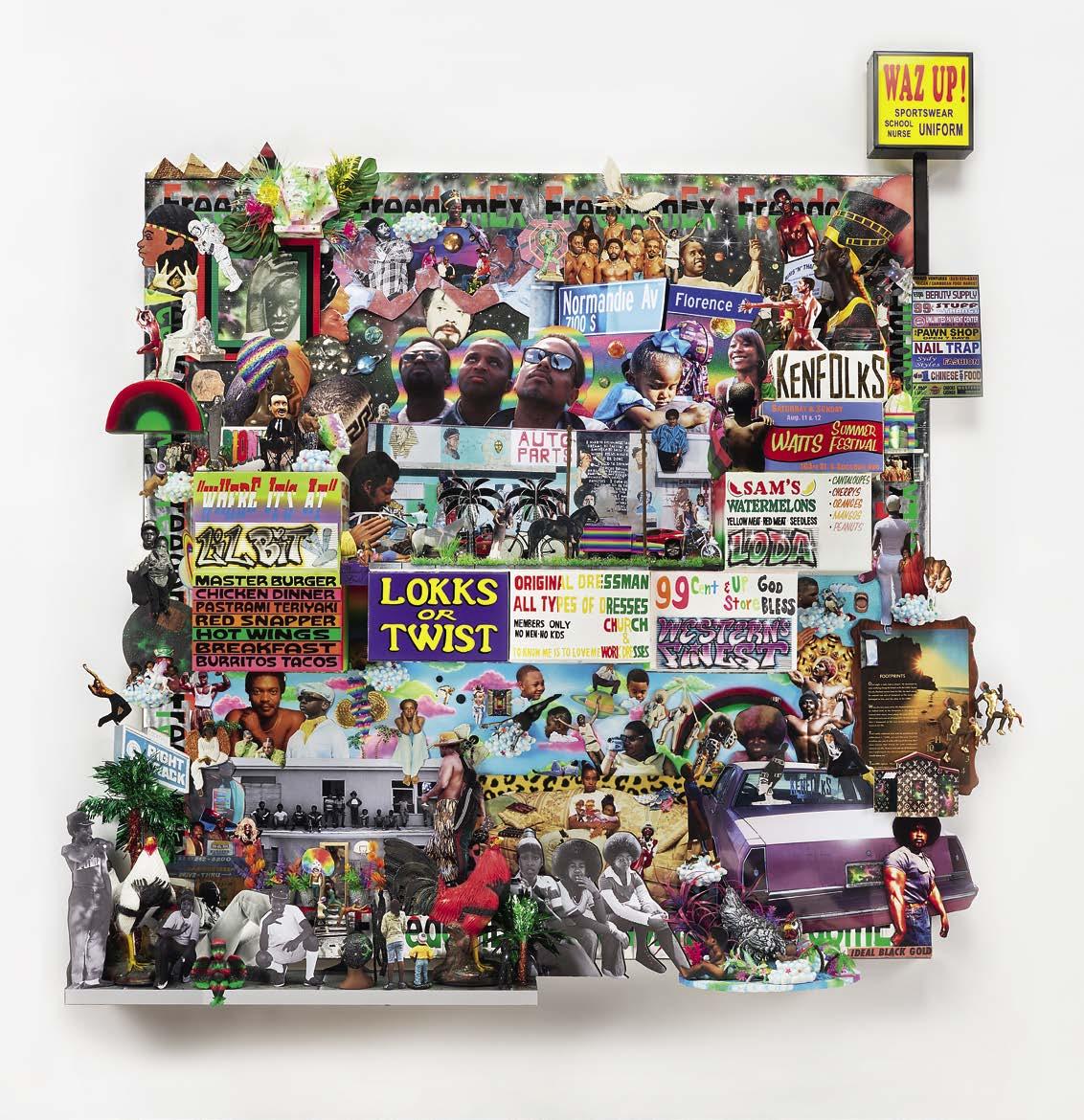

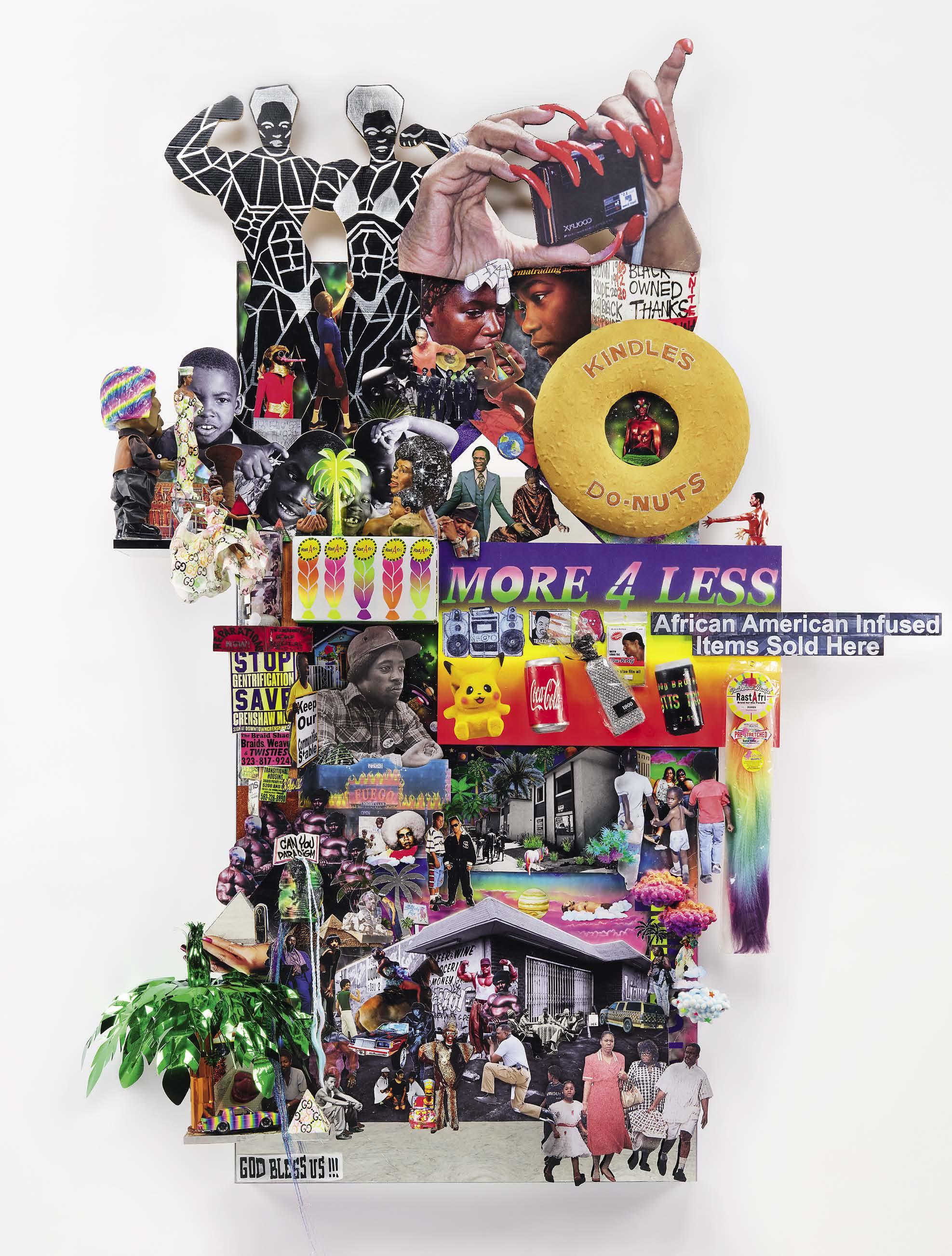

Lauren Halsey

Essence Harden

Karla Hiraldo Voleau

Lonnie Holley

Arinze Ifeakandu

Young Kim

Megan Kincaid

Lauren Mahony

Pepi Marchetti Franchi

Alison McDonald

Wayne McGregor

Oscar Murillo

Hans Ulrich Obrist

Michael Ovitz

Alessandro Rabottini

Ariana Reines

Dieter Roelstraete

Frank Stella

Harry Thorne

Nancy J. Troy

Carlos Valladares

Josh Zajdman

Thanks

Richard Alwyn Fisher

Julia Arena

Costanza Ballardini

Chloe Barter

Priya Bhatnagar

Serena Cattaneo Adorno

Maurizio Cattelan

Vittoria Ciaraldi

Heidi Coleman

Jeanne Collins

Maggie Dubinski

Andrew Fabricant

Mark Francis

Hallie Freer

Brett Garde

Eleanor Gibson

Lauren Gioia

Darlina Goldak

Nan Goldin

Leta Grzan

Andrew Heyward

Sarah Jones

Shiori Kawasaki

Léa Khayata

Shelley Lee

Rick Lowe

Rob McKeever

Olivia Mull

Kathy Paciello

Kelly Quinn

Helen Redmond

Antwaun Sargent

Ari Sarkisian

Jim Shaw

Diallo Simon-Ponte

Chandler Sterling

Sydney Stutterheim

Natasha Turk

Louis Vaccara

Timothée Viale

Lindsey Westbrook

Cover: Roy Lichtenstein, Bauhaus Stairway

on canvas, 26 feet 5 ¾ inches × 17 feet 11 ¾ inches (807.1 × 548 cm) © Estate

Mural , 1989 (detail), oil, Magna, acrylic, and graphite pencil

of

Roy

Lichtenstein. Photo: Rob McKeever

HIGH

JEWELR Y

LES JA RDINS DE LA COUTUR E COL LEC TION

Neck lace in pink gold, diamonds, rubies, pink sapphire s, pink and red spinels, spessa rt ite ga rnet s.

LES JA RDINS DE LA COUTUR E COL LEC TION

Neck lace in pink gold, diamonds, rubies, pink sapphire s, pink and red spinels, spessa rt ite ga rnet s.

SUMMER 2024 FROM THE EDITOR

Thirty-five years ago, the Hollywood superagent Michael Ovitz invited Roy Lichtenstein to create a mural as the centerpiece for the new headquarters of Creative Artists Agency, to be housed in a building designed for the purpose by I. M. Pei. In this issue of the Quarterly, Ovitz contributes a personal recollection of that invitation to punctuate an article on the result, Lichtenstein’s Bauhaus Stairway Mural , a storied project that cites an equally storied painting by Oskar Schlemmer from 1932.

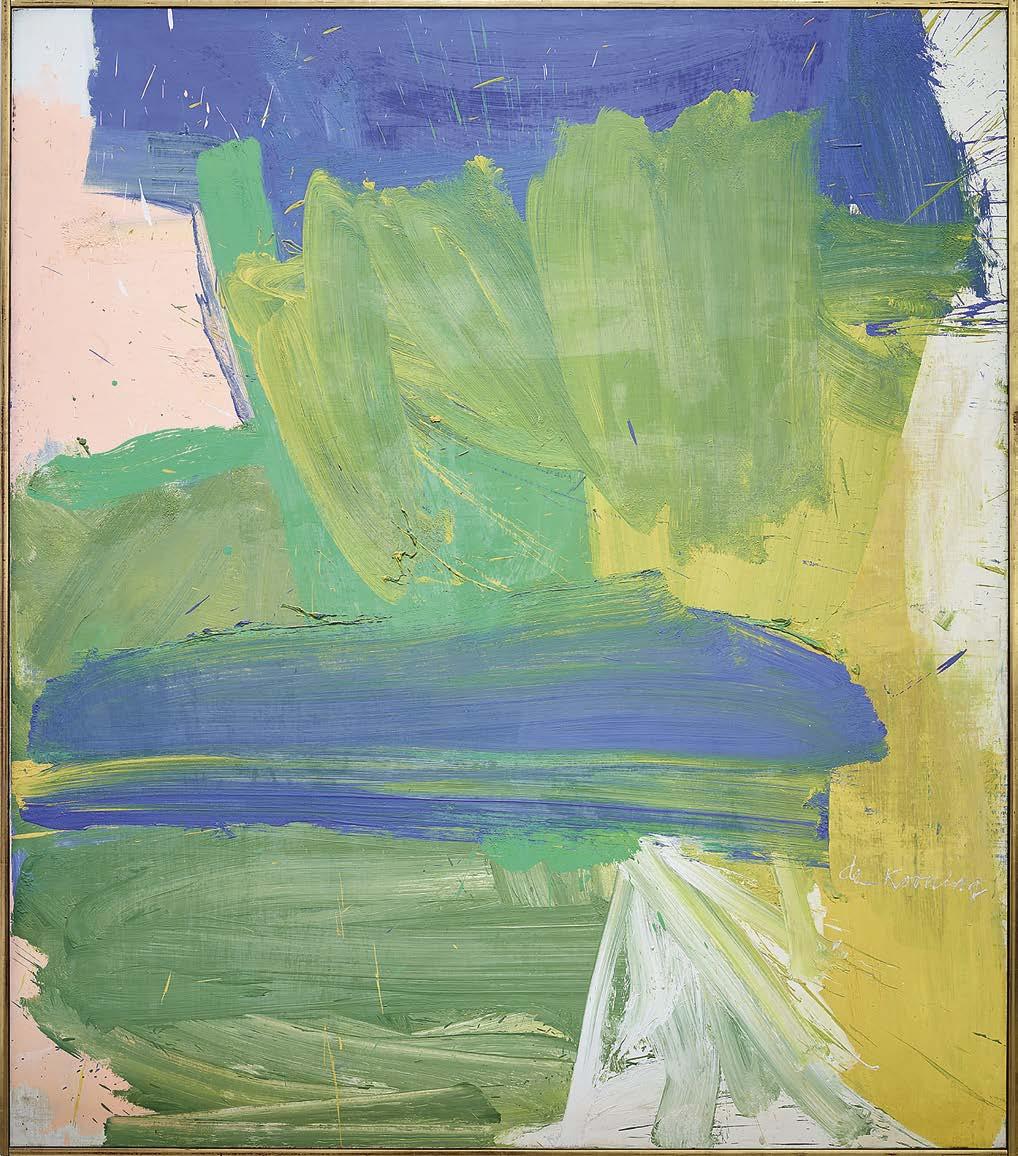

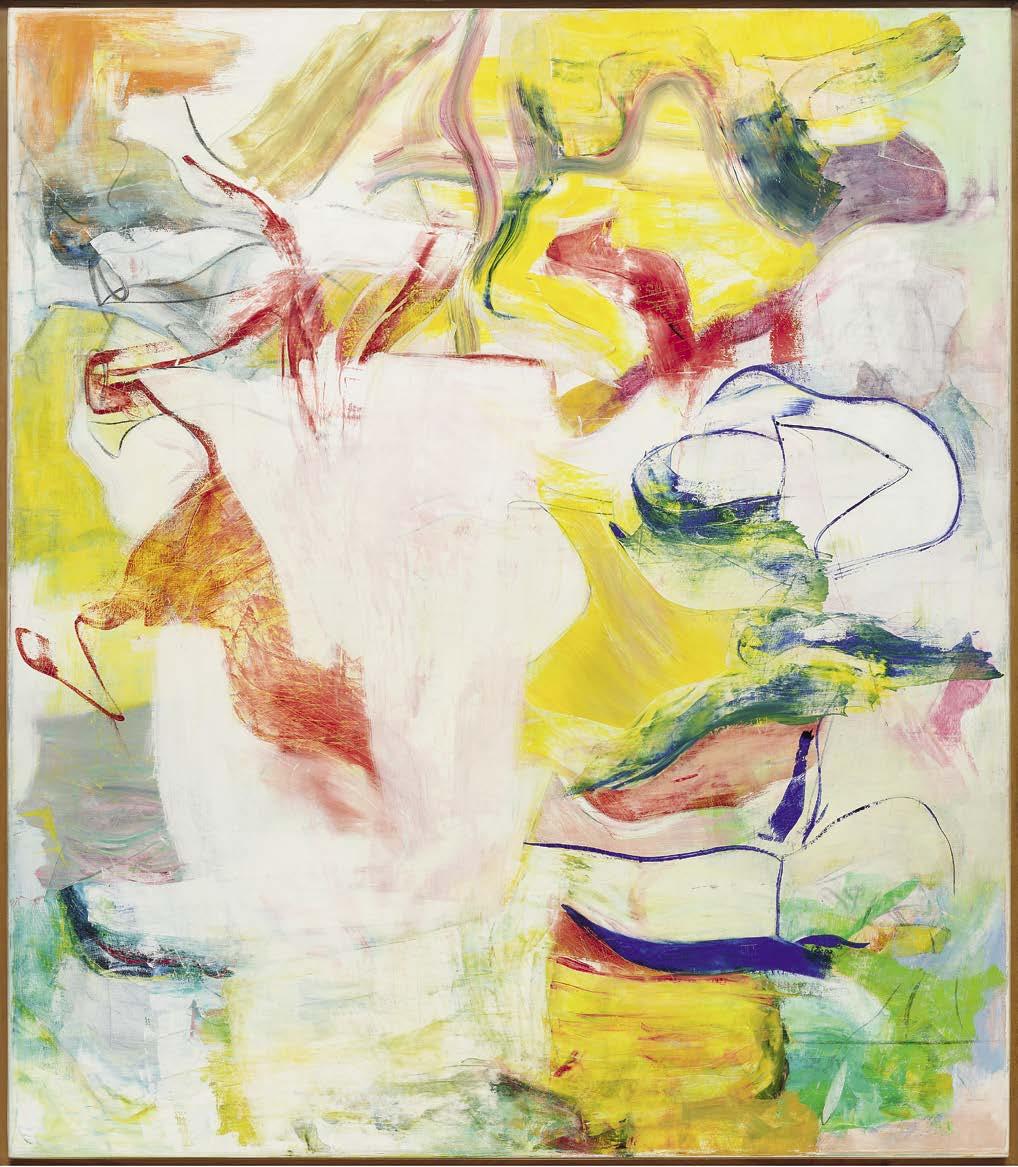

The second installment of our “Gagosian &” series of themed supplements centers on the world of music, highlighting songwriters, composers, performers, and deejays such as Lucinda Chua, Lonnie Holley, Jordi Savall, Jace Clayton, and Éliane Radigue. Exploring a wide range of musical genres, we include a personal account of the goth scene and a report on producer Trevor Horn’s memoir Adventures in Modern Recording . Projects staged to coincide with this year’s Venice Biennale are the subject of several articles, including an essay on Rick Lowe’s expansive practice on the occasion of his exhibition at the Palazzo Grimani and a conversation with the curators of Willem de Kooning and Italy, on view at the Gallerie dell’Accademia. Lauren Halsey, who will premiere a new installation on the occasion of the Biennale, talks with Essence Harden, and an

artful abecedarium annotates the work of Jim Shaw as he unveils a commission at Venice’s Berggruen Arts & Culture.

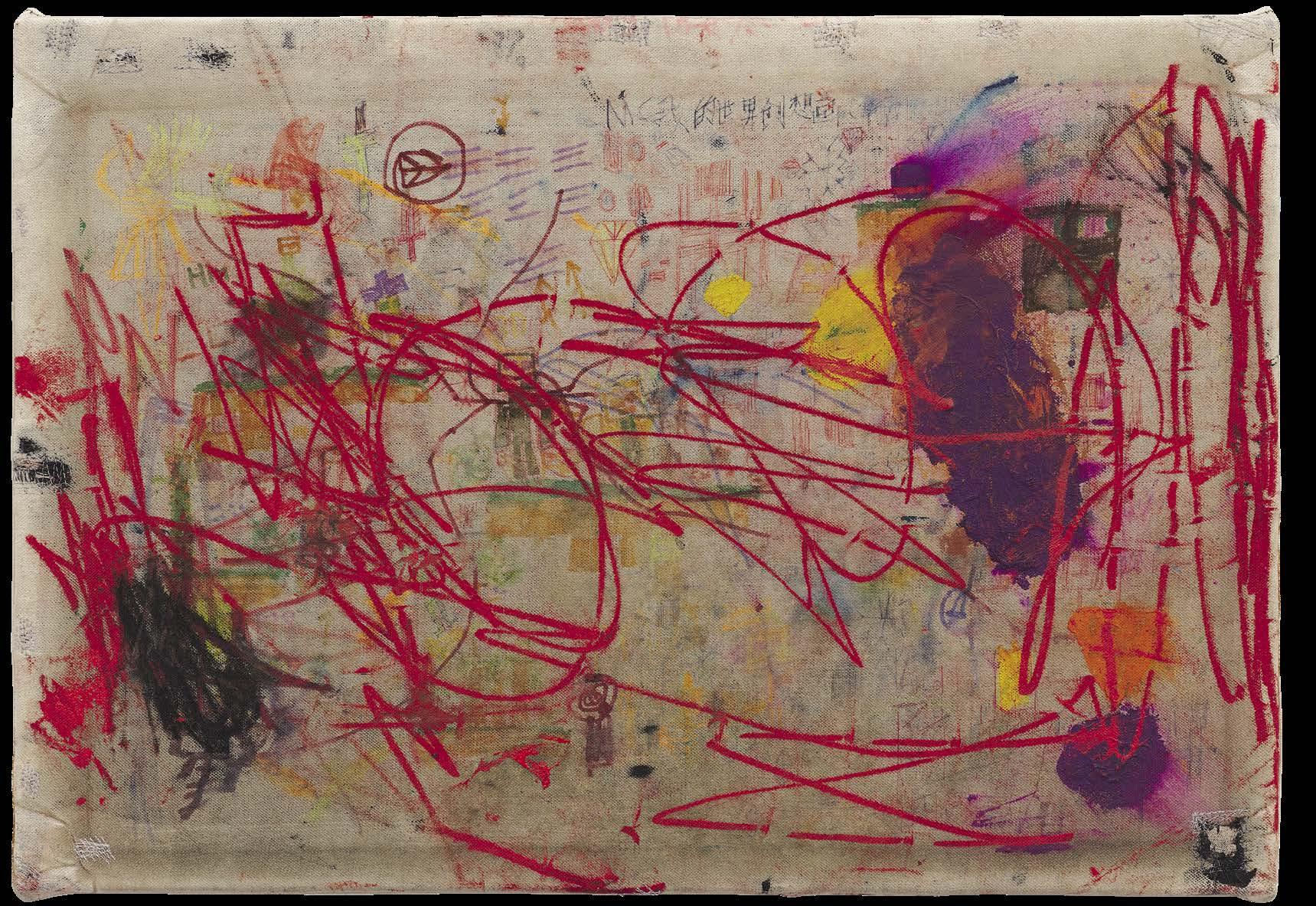

Michael Cary takes a poetic look at the power of Nan Goldin’s heartbreaking video triptych Sisters Saints Sibyls . We look at the work of Oscar Murillo ahead of two exhibitions of his, one at Tate Modern, London, and the other at Gagosian, Rome.

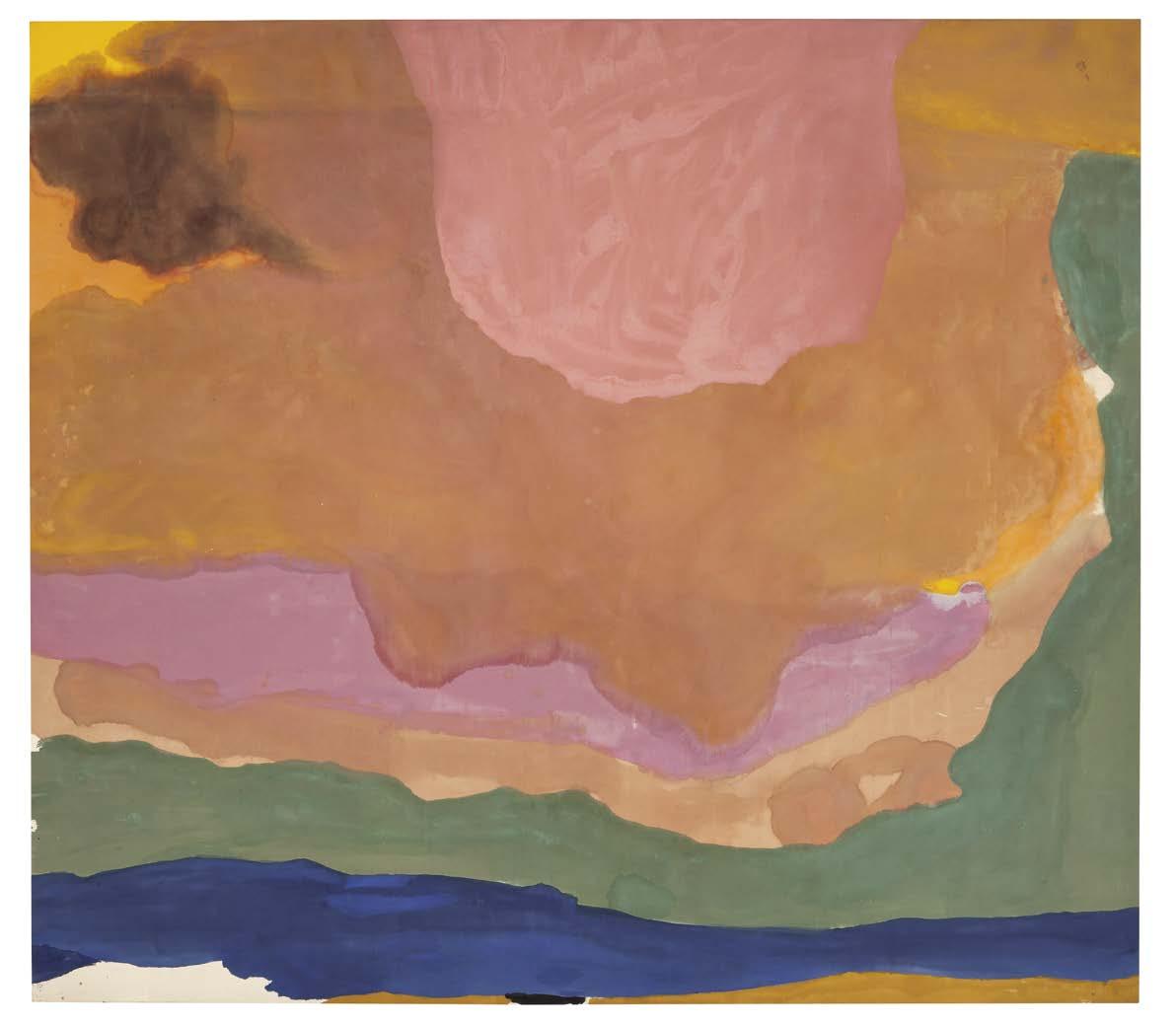

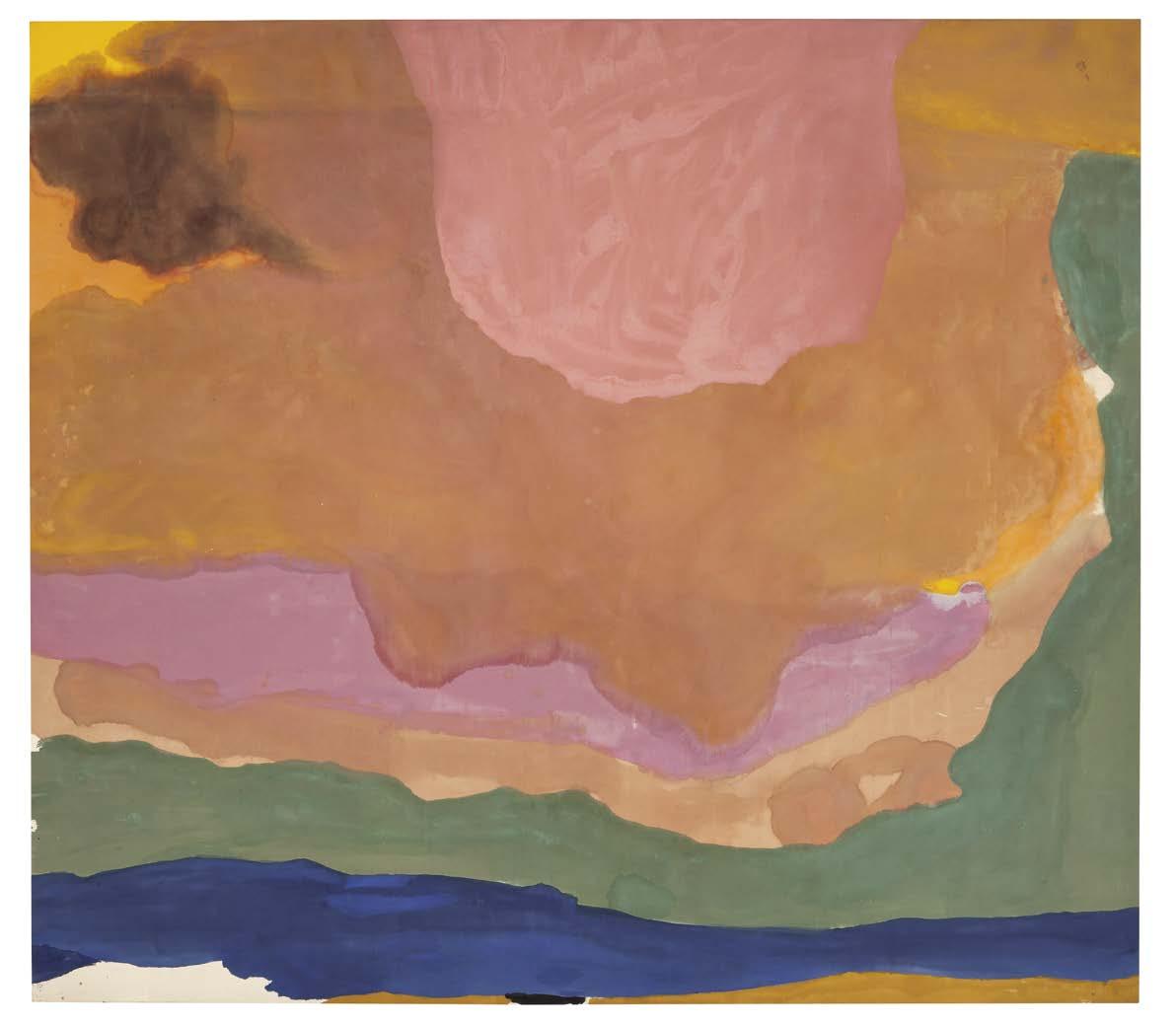

An expanded edition of John Elderfield’s celebrated 1989 monograph on Helen Frankenthaler will be published this summer. Here, Elderfield speaks with Harry Cooper and Lauren Mahony about the artist’s legacy, his own career-long engagement with her work, and new discoveries that await readers in the new book.

Francesco Bonami considers the political underlayer of Maurizio Cattelan’s work, looking beyond the humor that is such a potent aspect of his art even while quoting the great comic Charlie Chaplin: “Life is a tragedy when seen in close-up, but a comedy in long shot.”

We close the issue with an homage to the late Richard Marshall, curator at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art and arts editor of The Paris Review for over twenty years. In early periods when their futures were uncertain, Marshall championed many artists now recognized as leading figures of their time.

Alison McDonald, Editor-in-chief

42

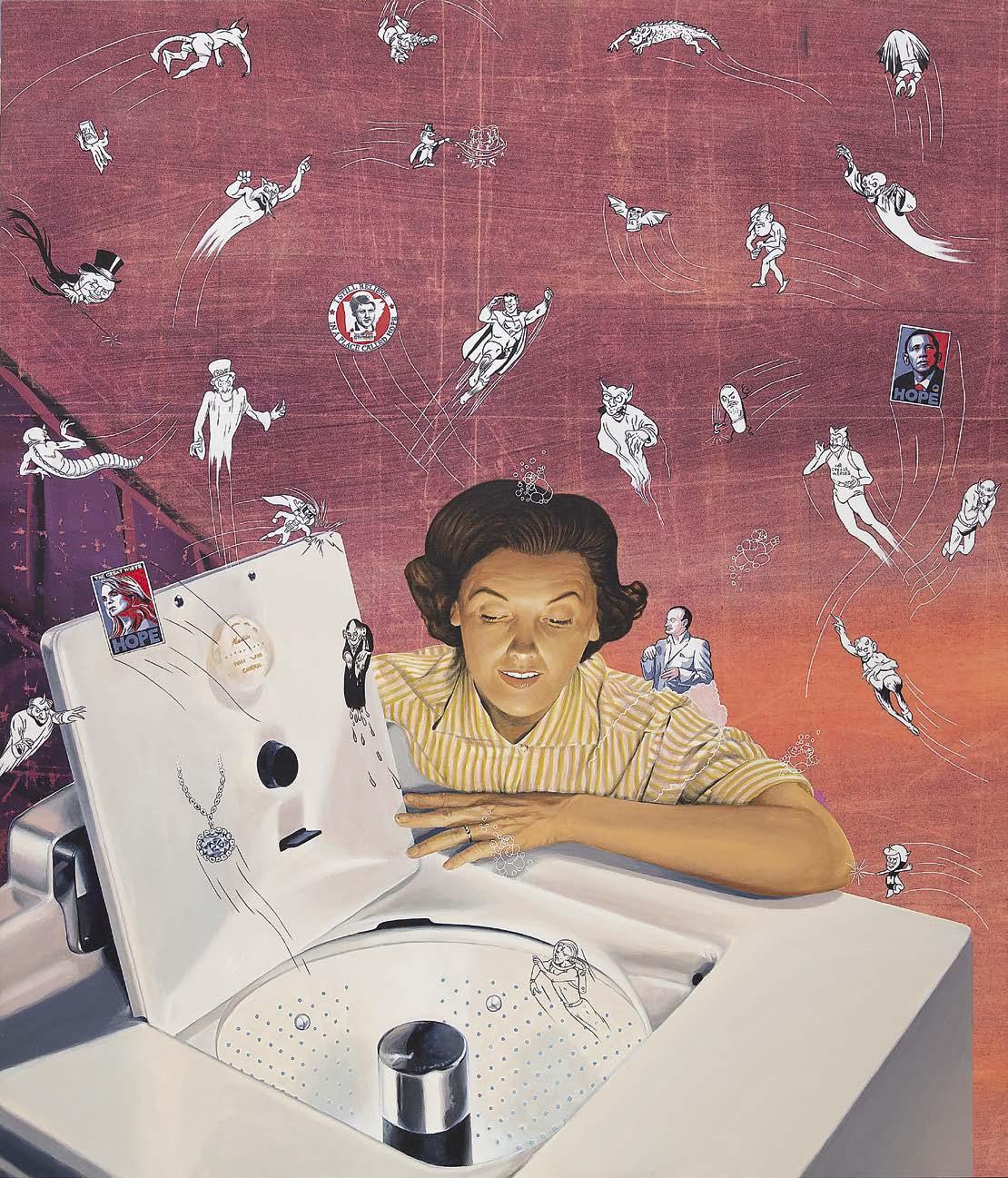

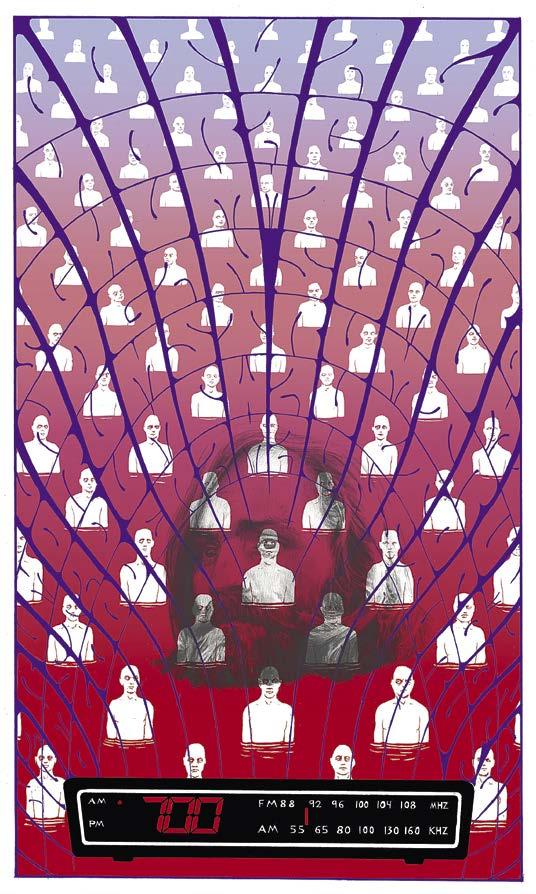

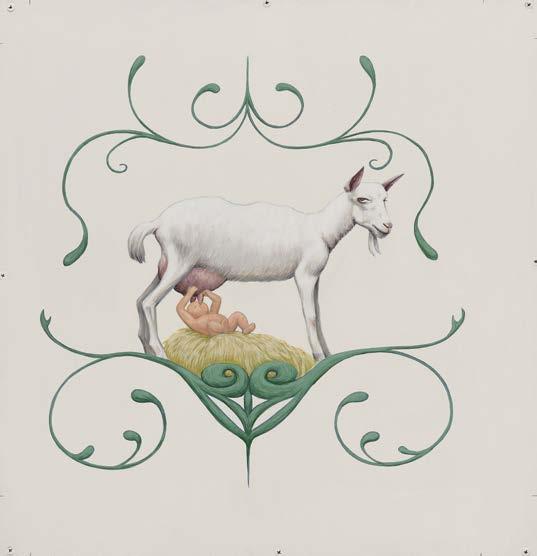

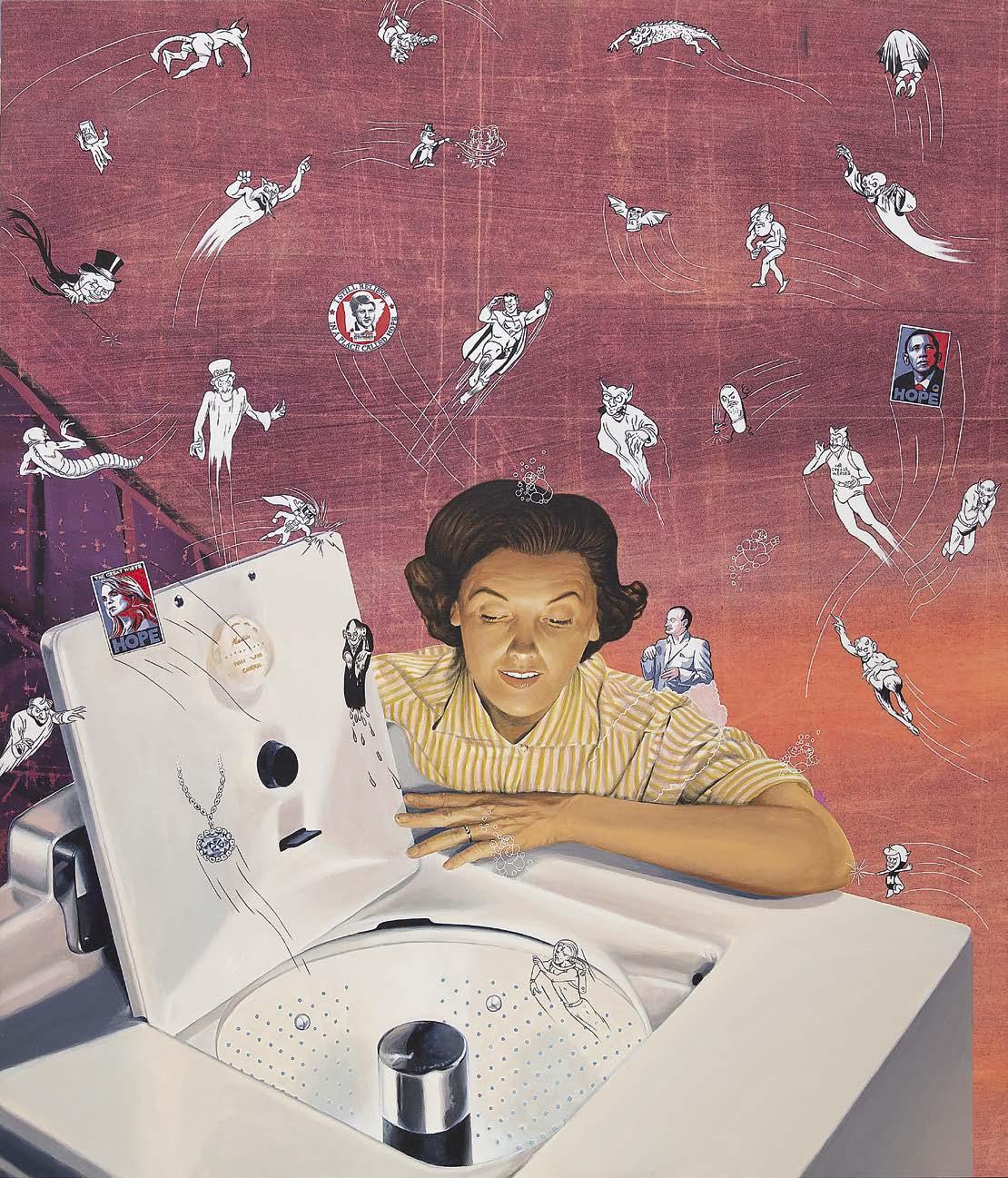

Maurizio Cattelan: Sunday Painter

An exhibition of new work by Maurizio Cattelan opened in New York earlier this spring. Curator Francesco Bonami asks us to consider Cattelan as a political artist, detailing the potent and clear observations at the core of these works.

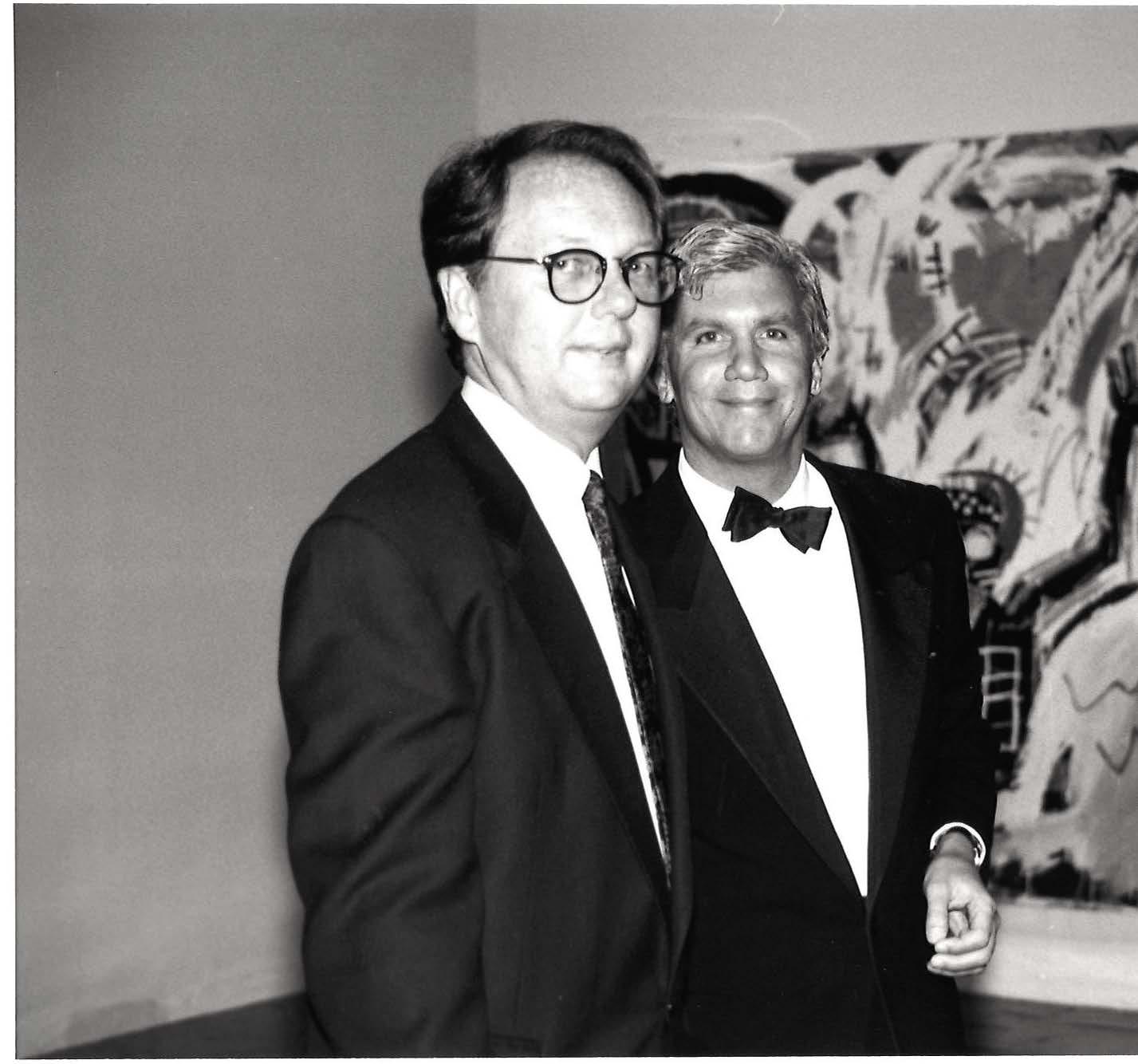

46 Bauhaus Stairway Mural

Alice Godwin and Alison McDonald explore the history of Roy Lichtenstein’s 1989 mural, contextualizing the work among the artist’s other mural projects as well as its inspiration: the German artist Oskar Schlemmer’s Bauhaus Stairway (Bauhaustreppe , 1932). Michael Ovitz, cofounder of Creative Artists Agency (CAA), looks back to 1989, when he commissioned Lichtenstein to create Bauhaus Stairway Mural for the new CAA Building in Beverly Hills, and reflects on the meaningful friendship he formed with the artist through the experience.

52 Hans Ulrich Obrist’s Questionnaire

For the second installment of 2024, we are honored to present the filmmaker Luca Guadagnino.

SUMMER 2024 TABLE OF CONTENTS

54

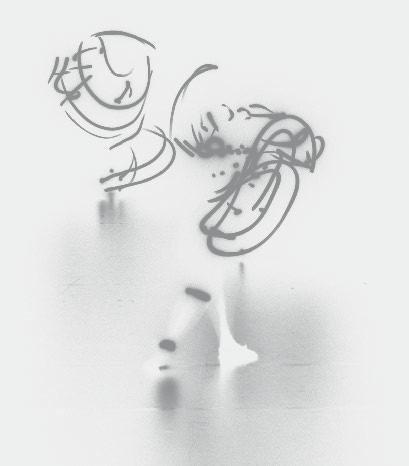

Nan Goldin: Sisters Saints Sibyls

Michael Cary explores the history behind, and power within, Nan Goldin’s video triptych Sisters Saints Sibyls (2004–22). The work will be on view at Soho Chapel, London, as part of the Gagosian Open exhibition from May 30 to June 16, 2024.

60

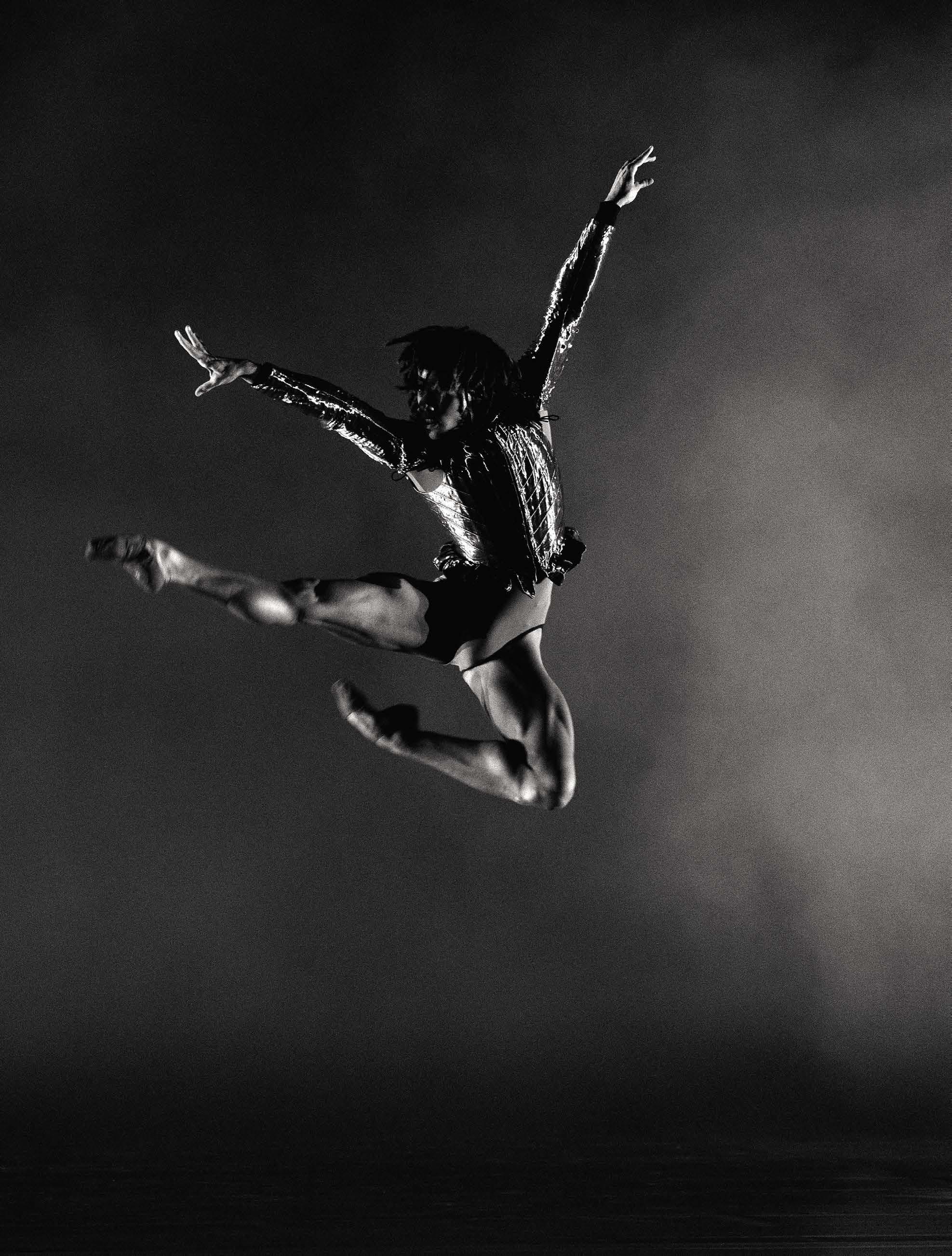

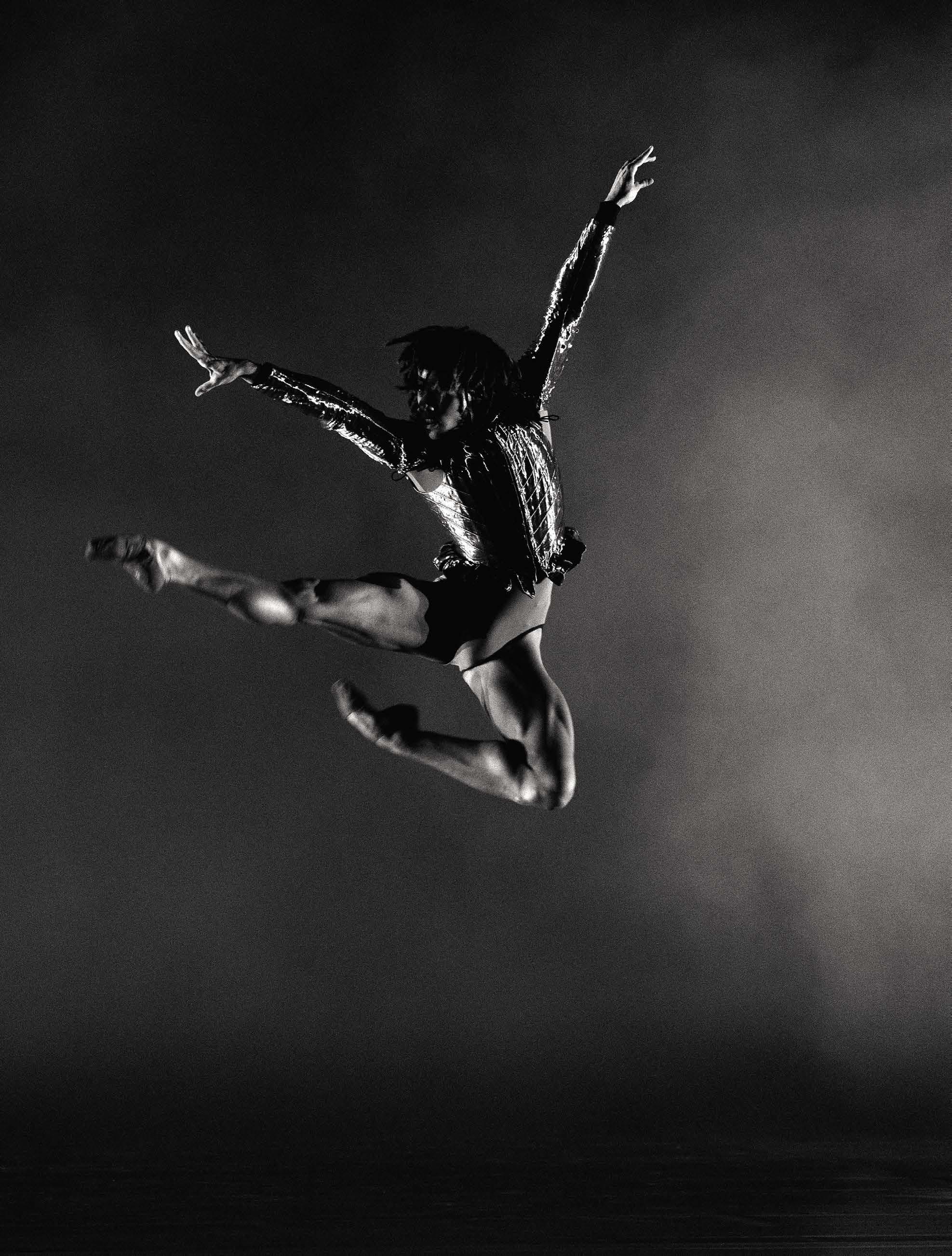

Wayne McGregor

Ahead of the US debut of Wayne McGregor’s Woolf Works , an acclaimed ballet inspired by the writings of Virginia Woolf, Alice Godwin talked with the choreographer about the challenge of translating great literary works for the theater.

66

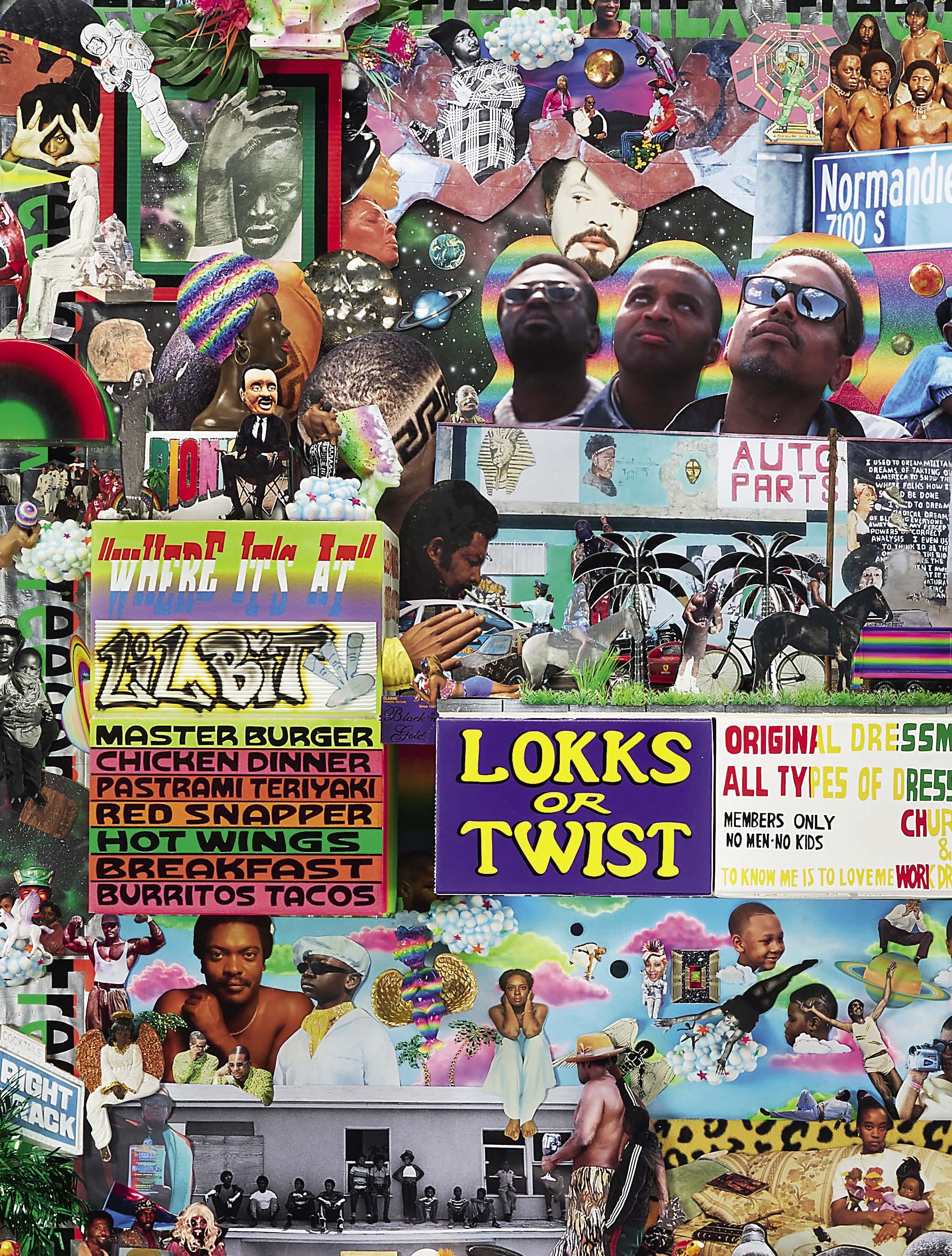

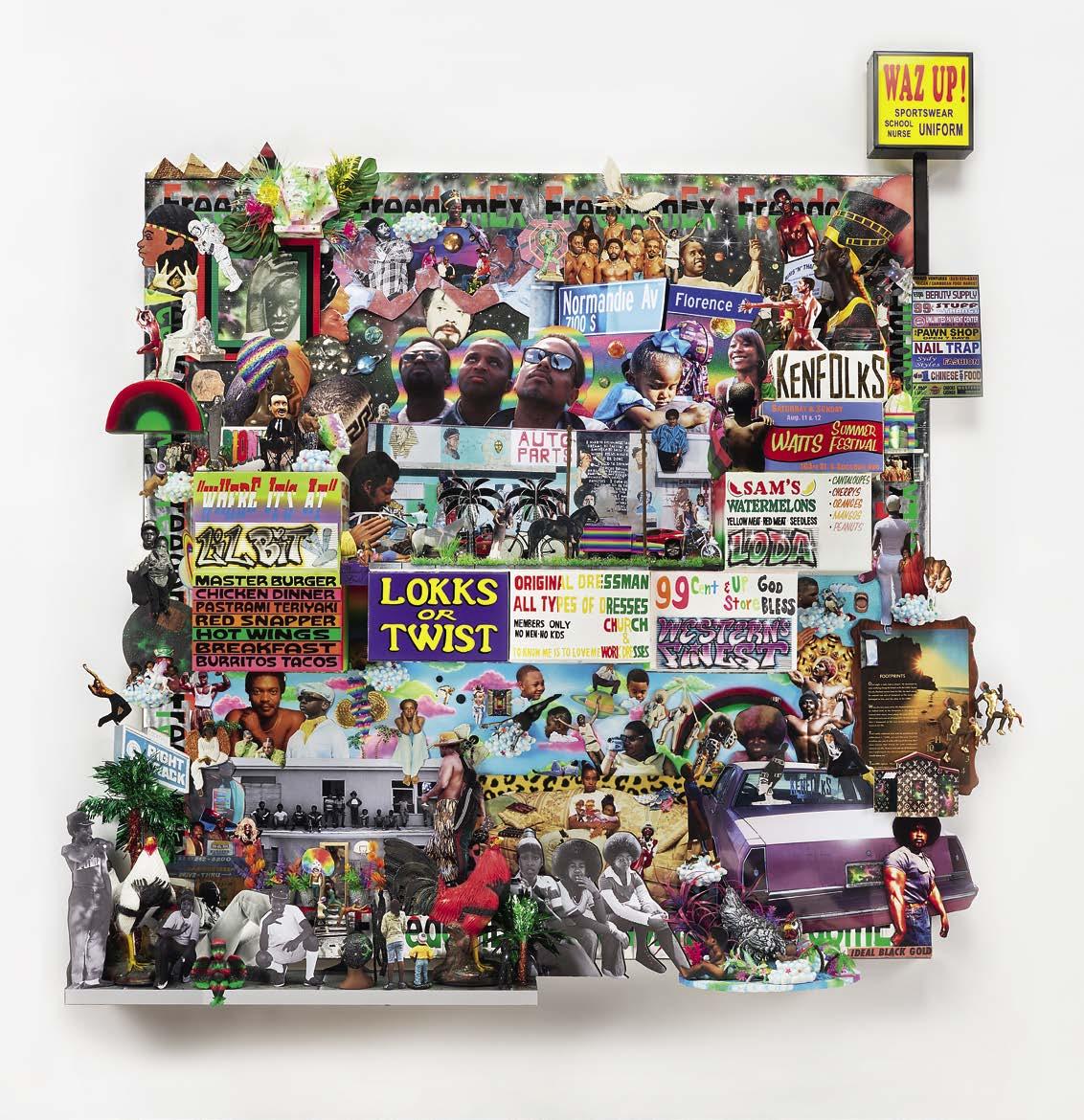

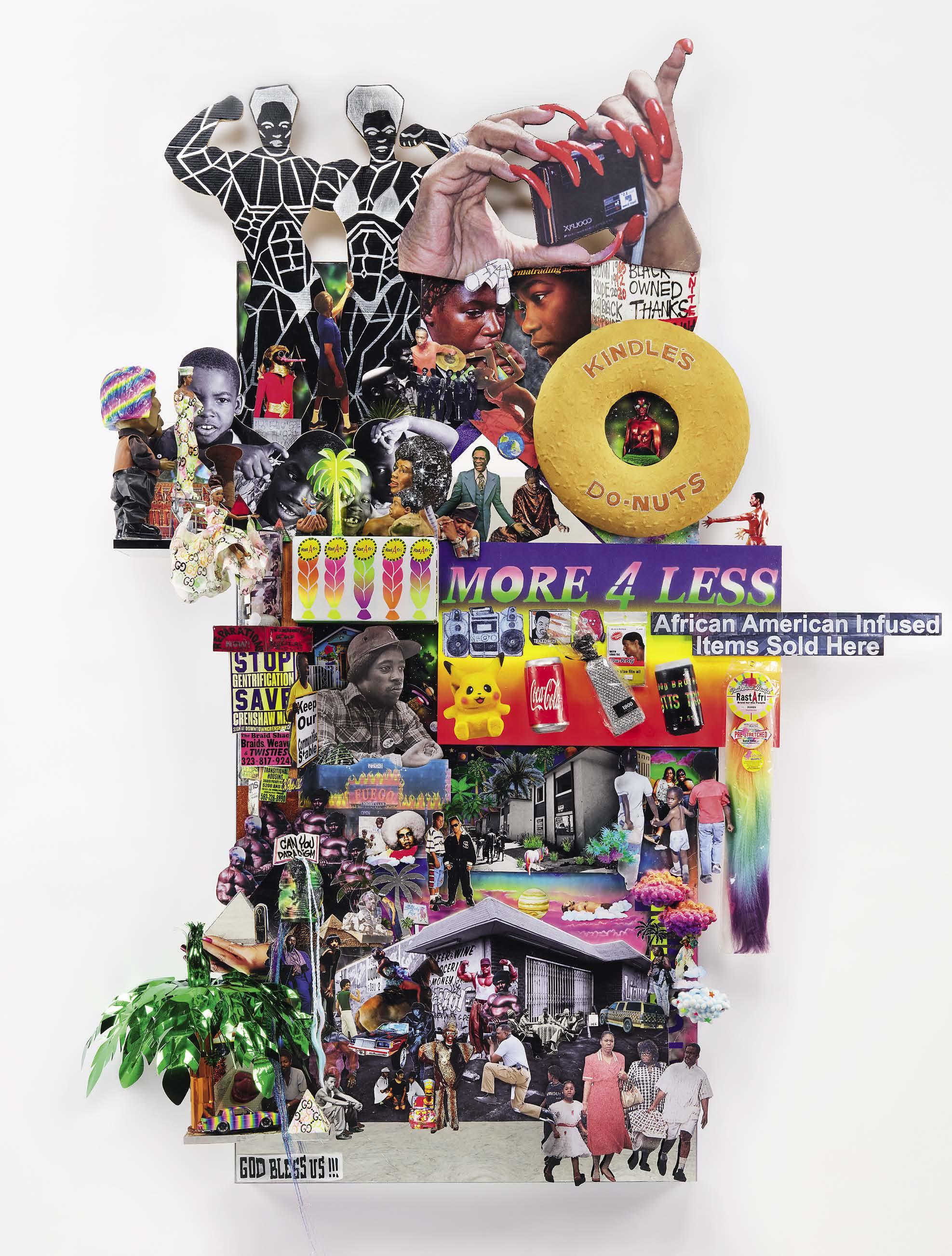

Lauren Halsey: Full and Complete Freedom

Essence Harden visited Lauren Halsey in her LA studio as the artist prepared for an exhibition in Paris and the premiere of her installation in the sixtieth Venice Biennale.

72

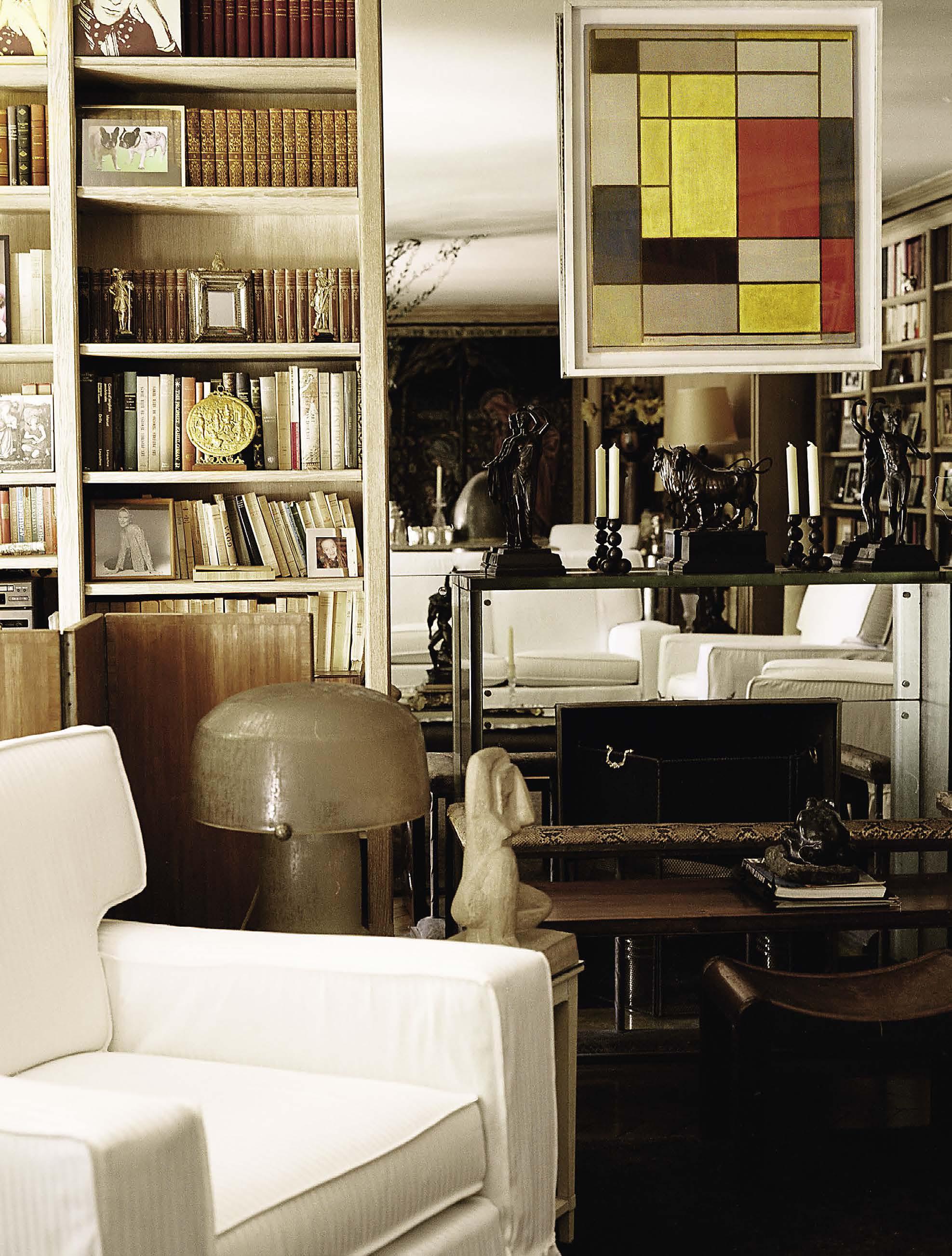

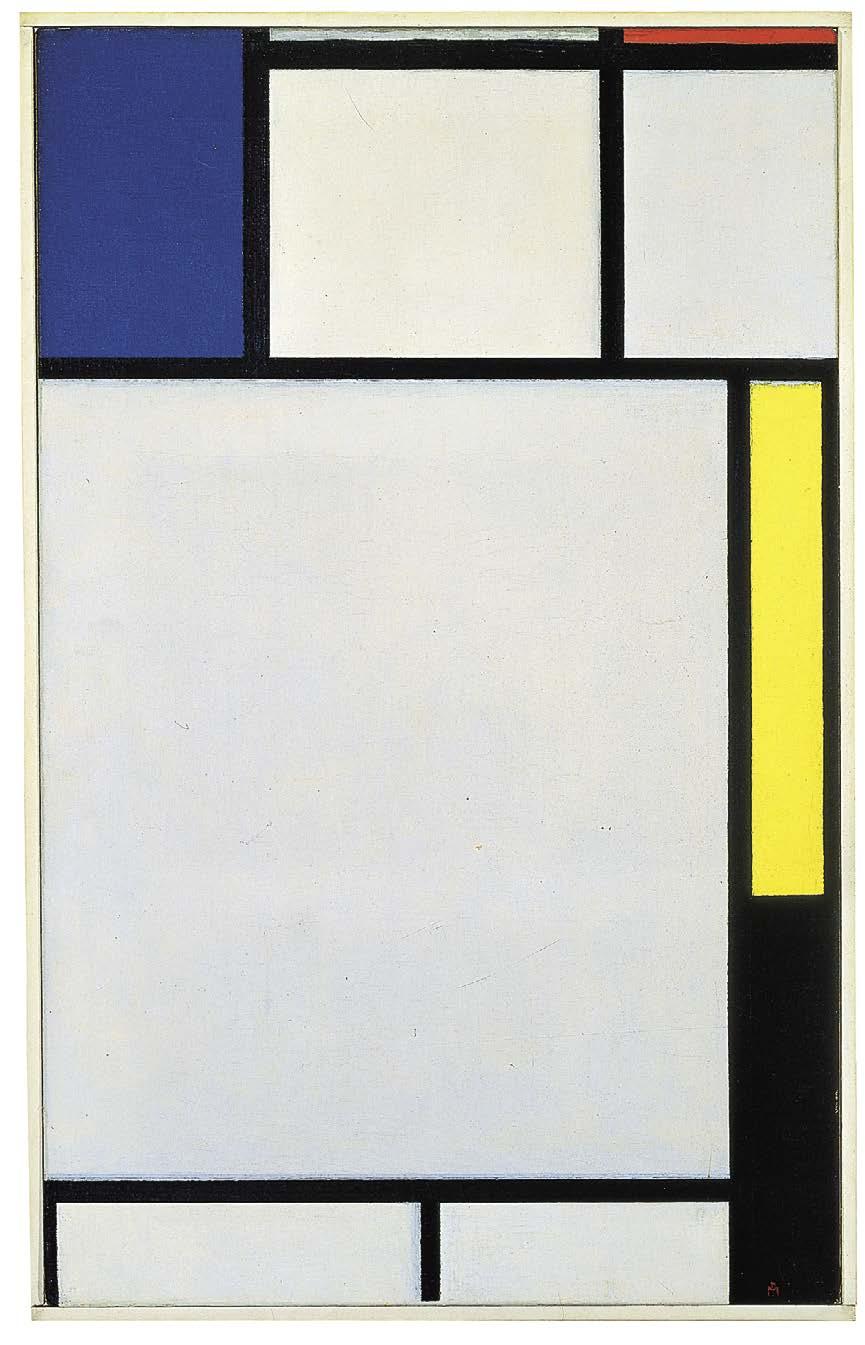

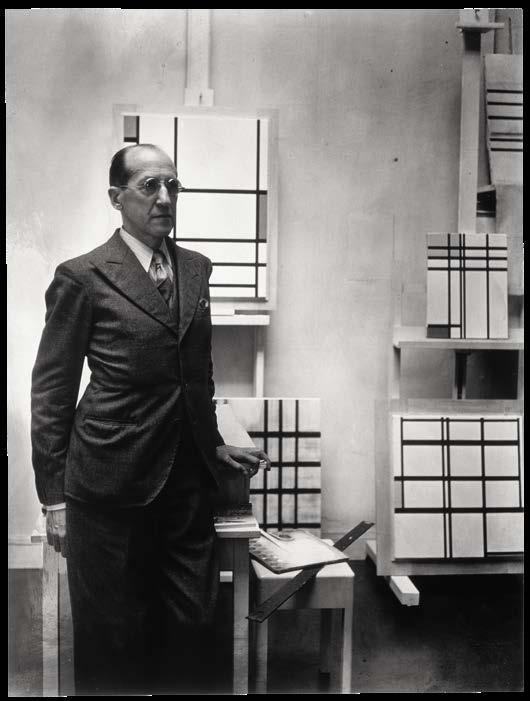

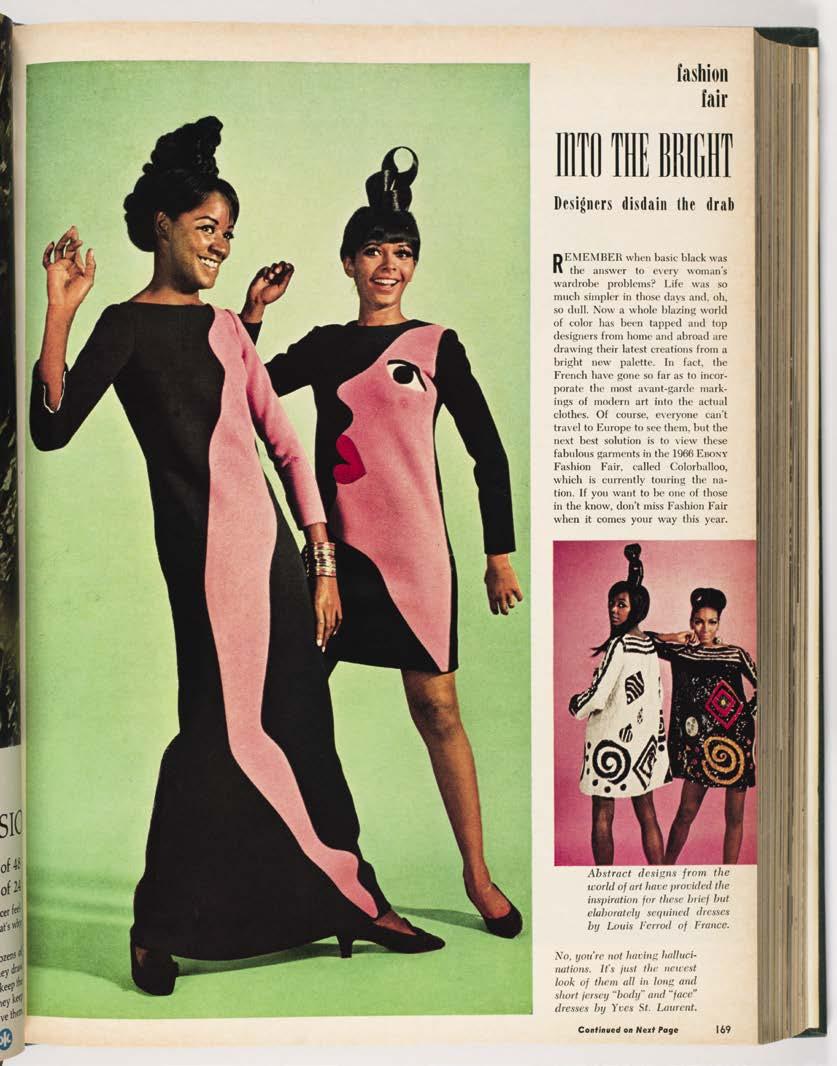

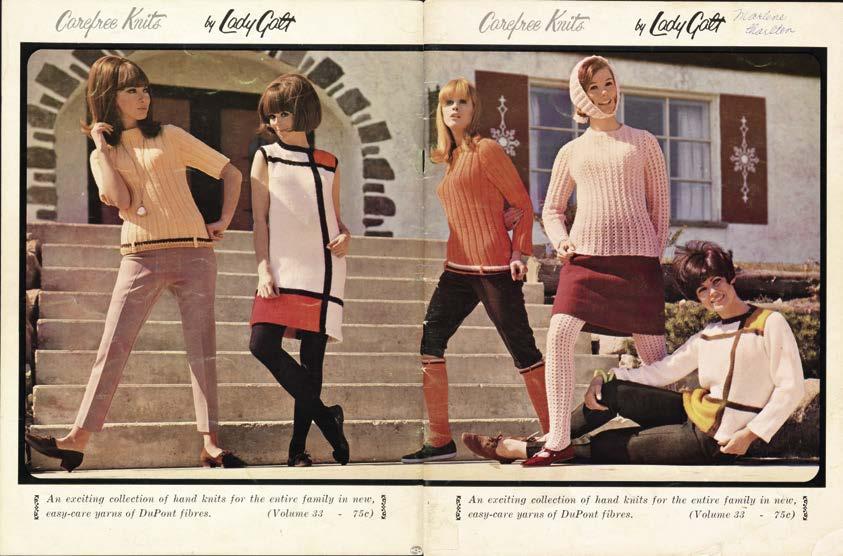

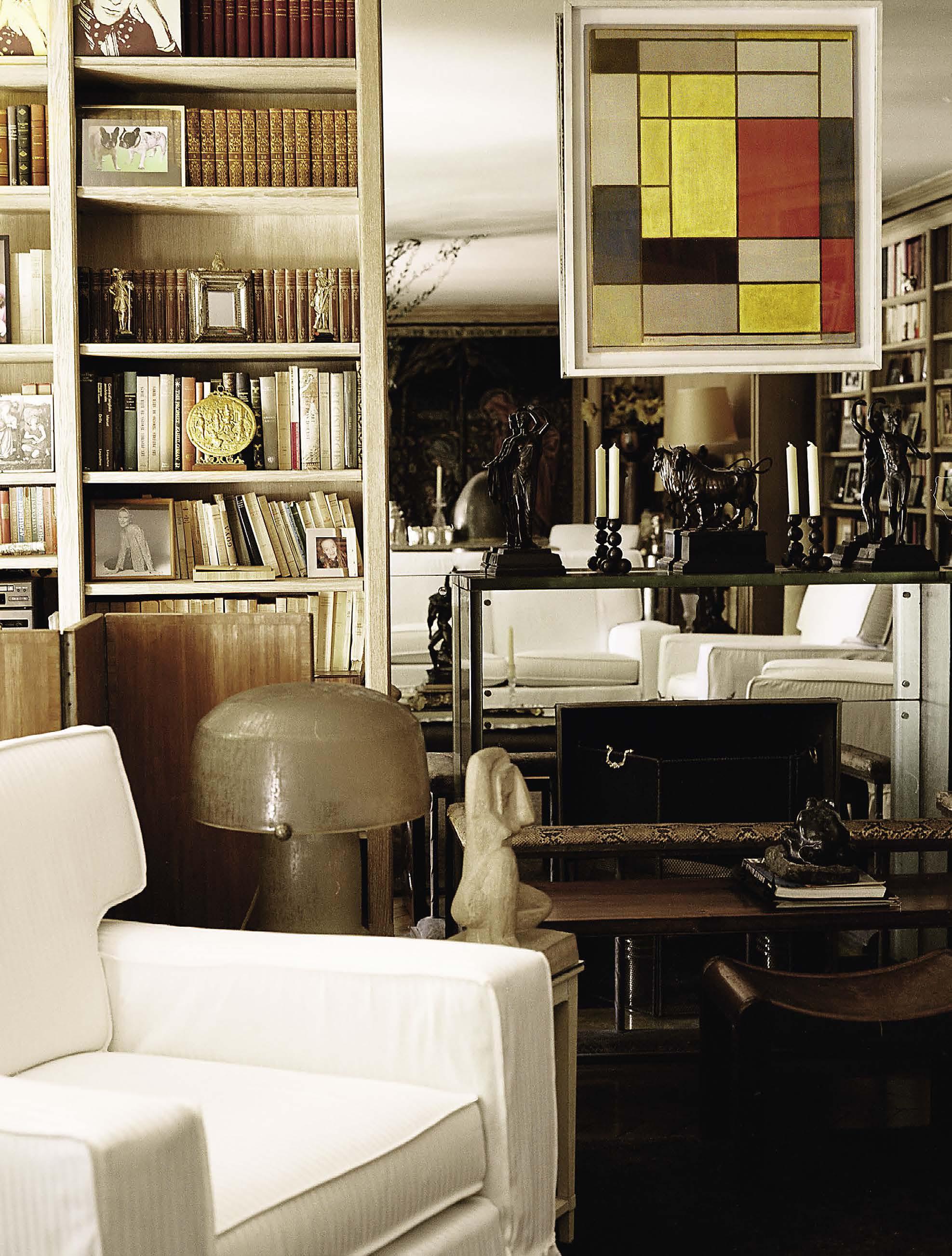

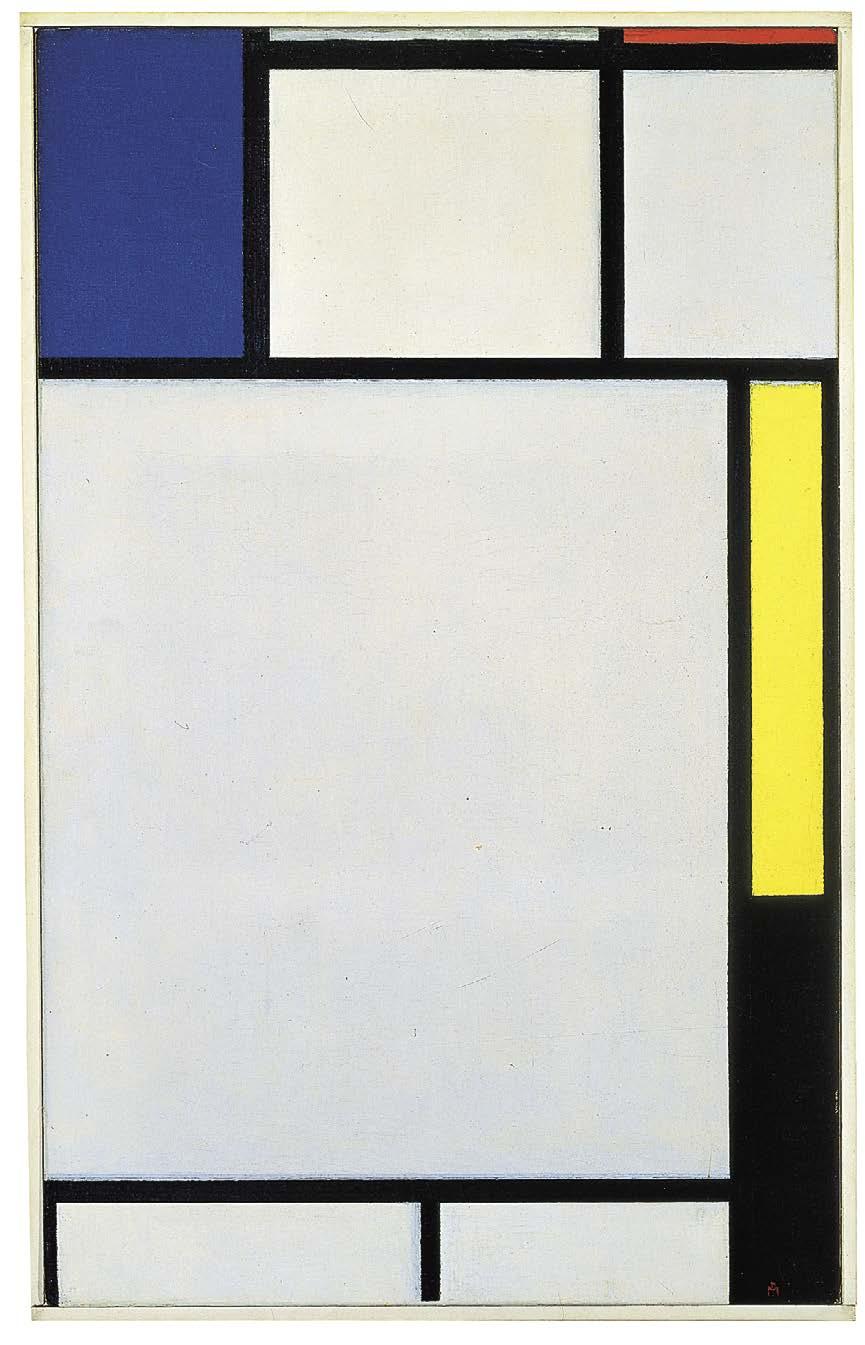

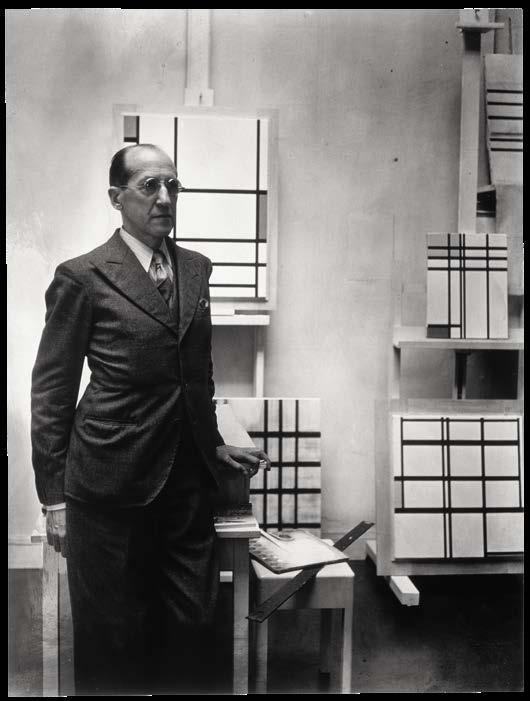

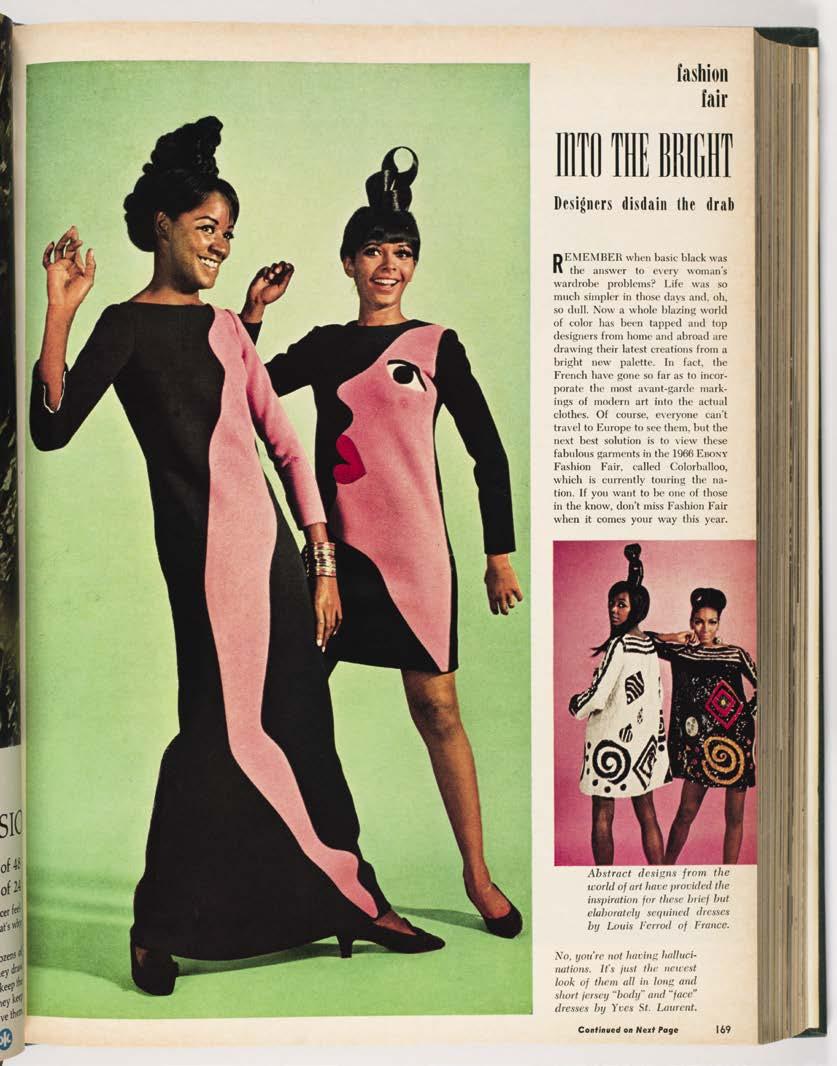

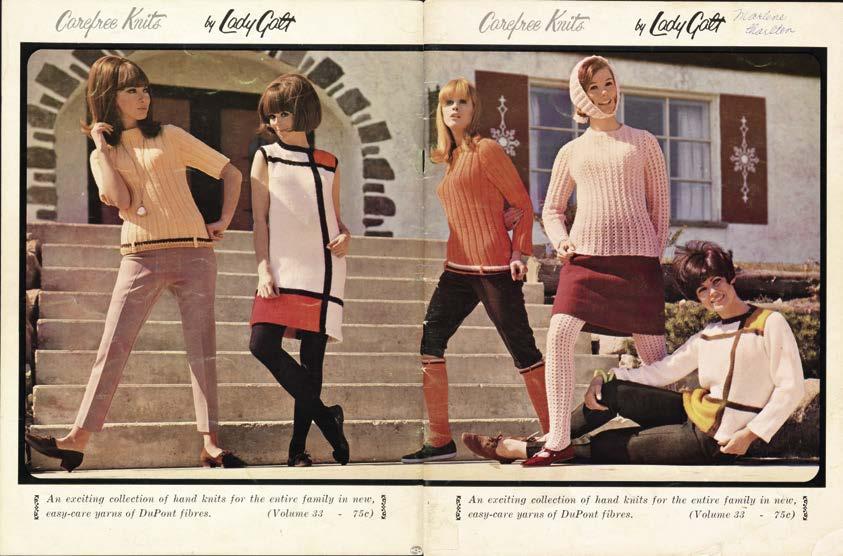

Fashion and Art, Part 18: Mondrian’s Dress

Nancy J. Troy, Victoria and Roger Sant Professor in Art Emerita, Stanford University, recently published Mondrian’s Dress: Yves Saint Laurent, Piet Mondrian, and Pop Art (MIT Press) with coauthor Ann Marguerite Tartsinis. The Quarterly ’s Derek Blasberg met with Troy to discuss.

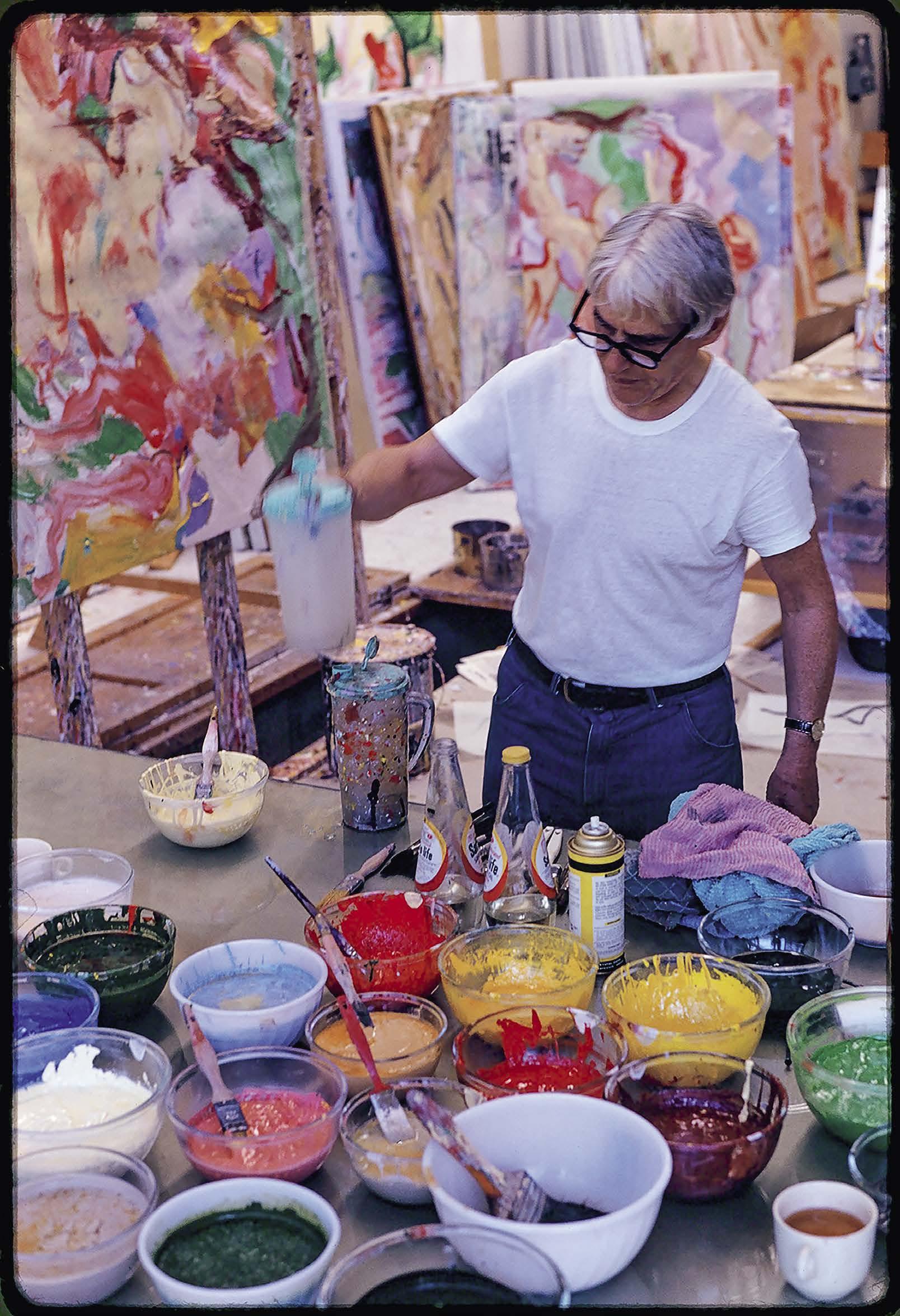

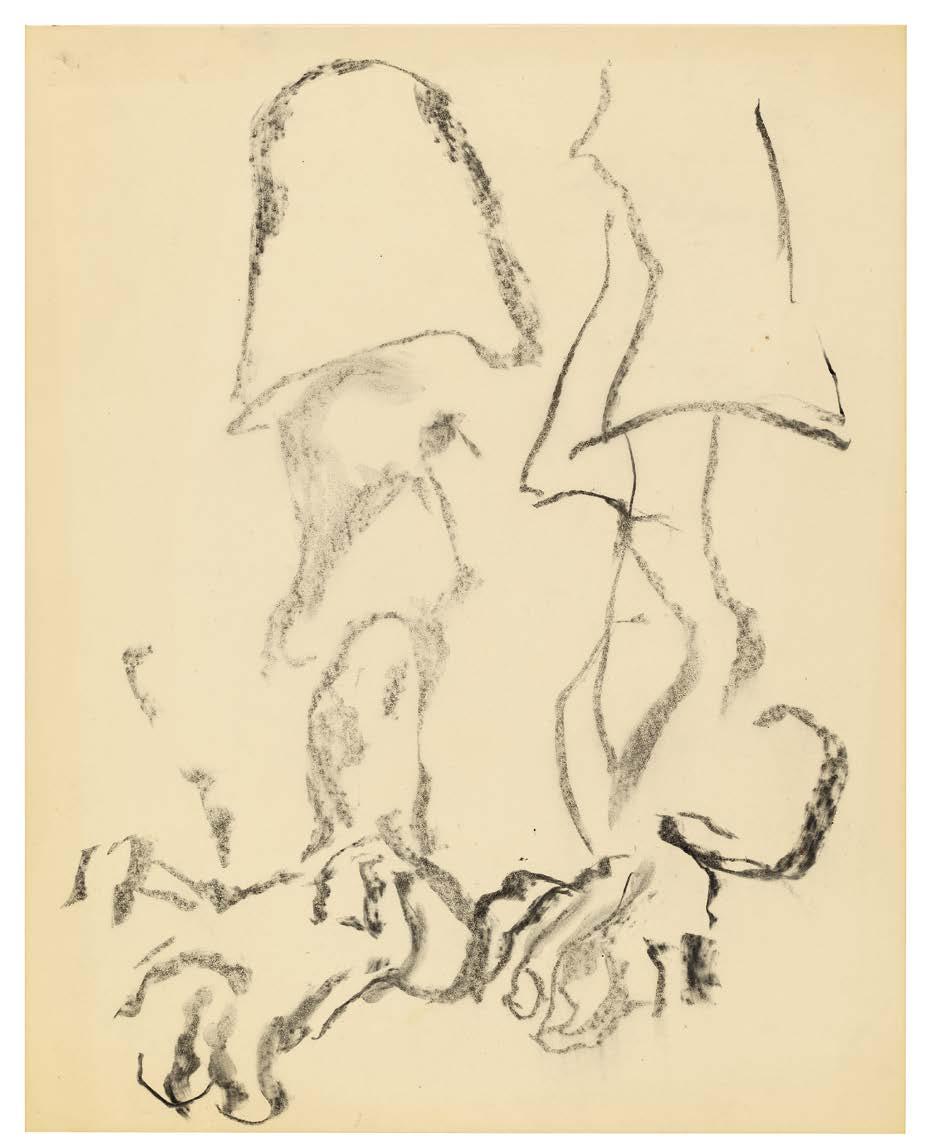

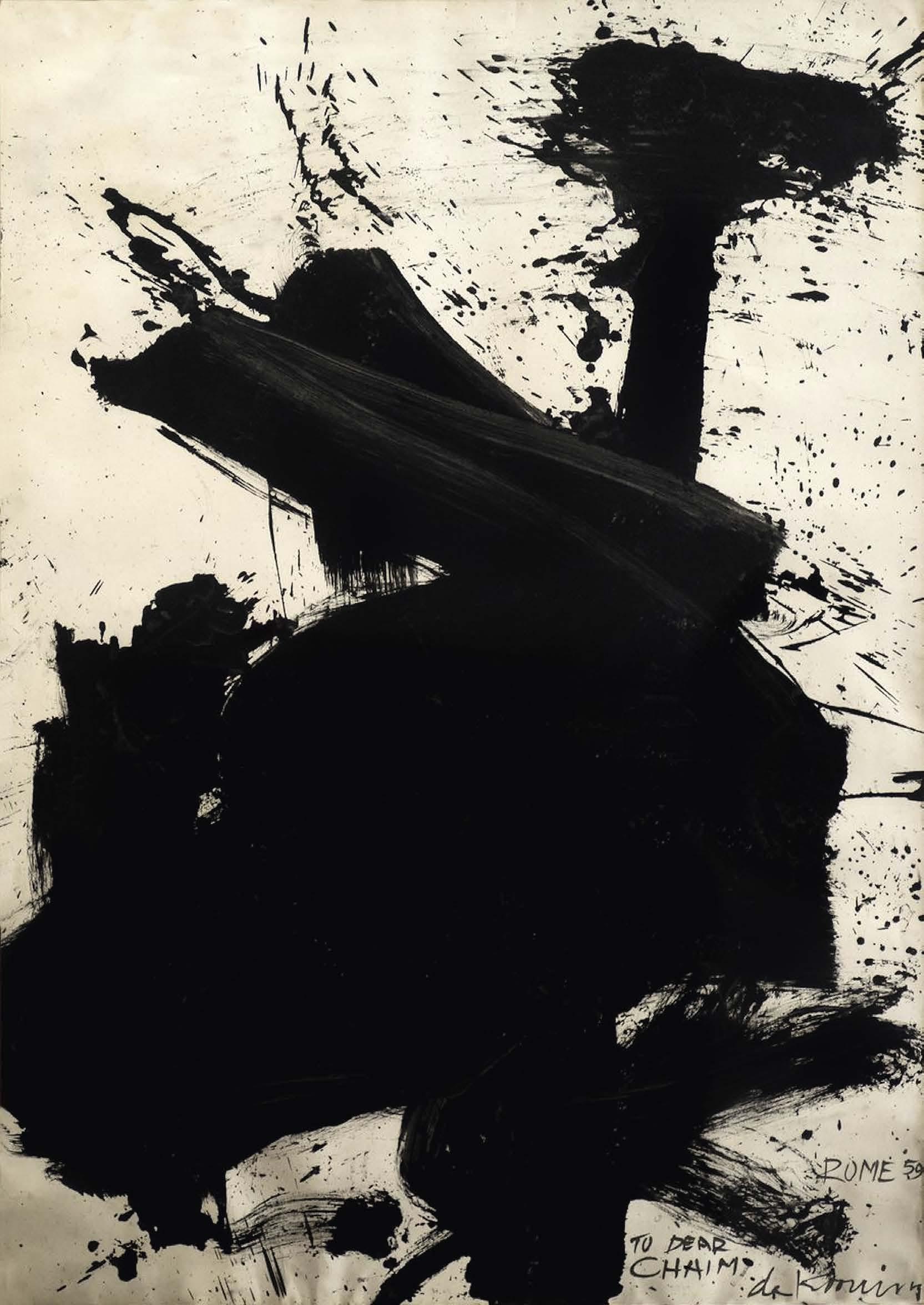

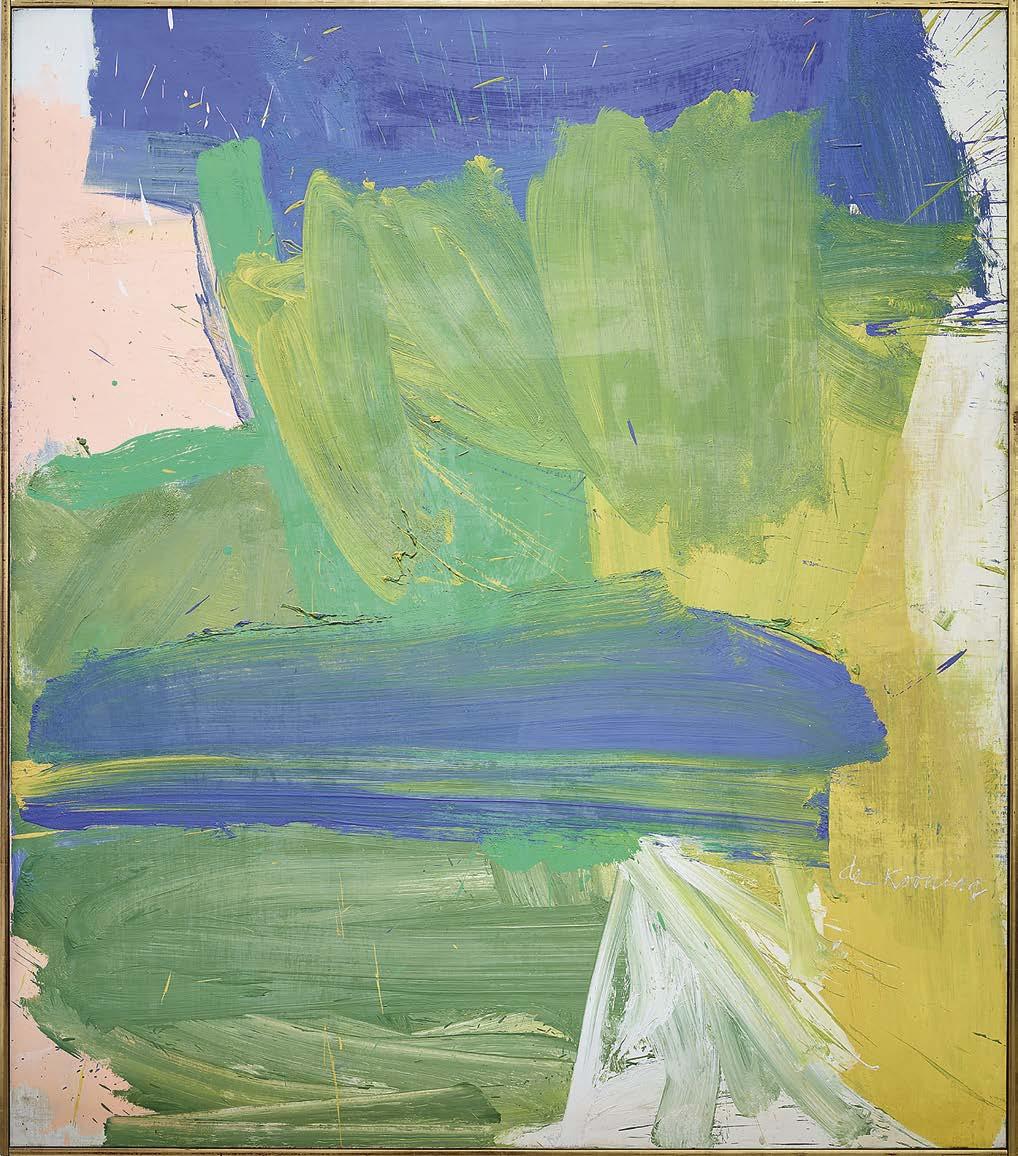

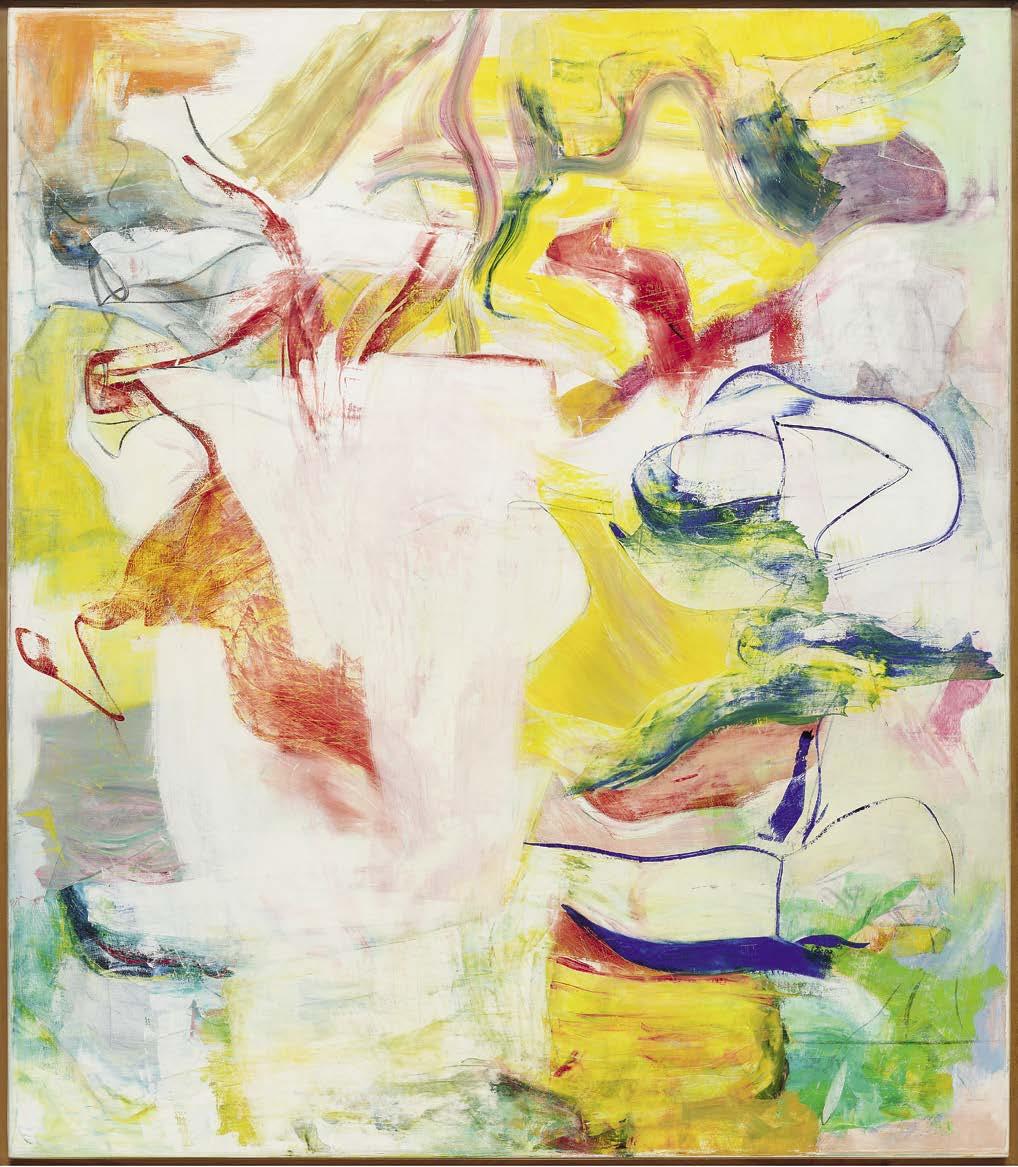

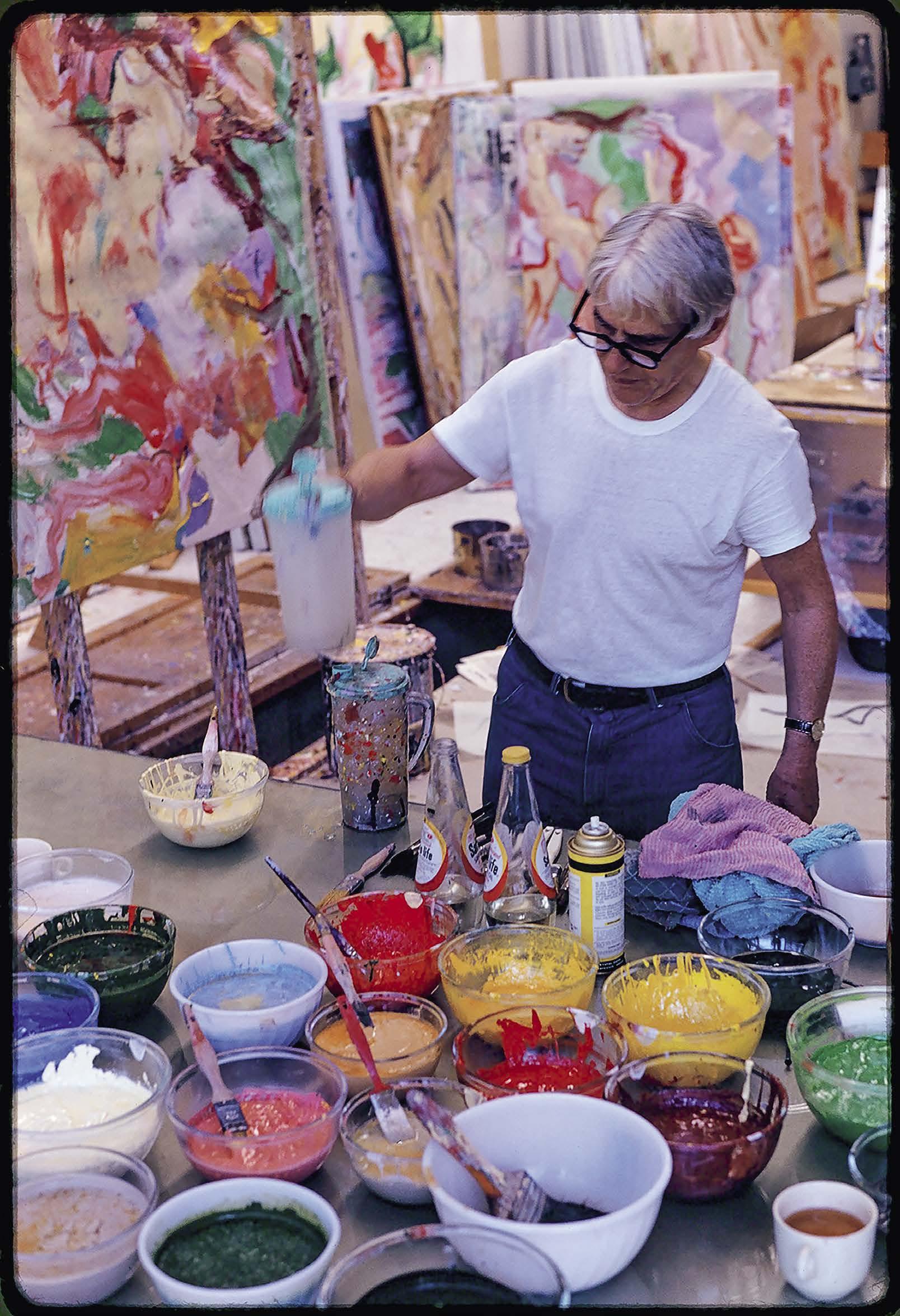

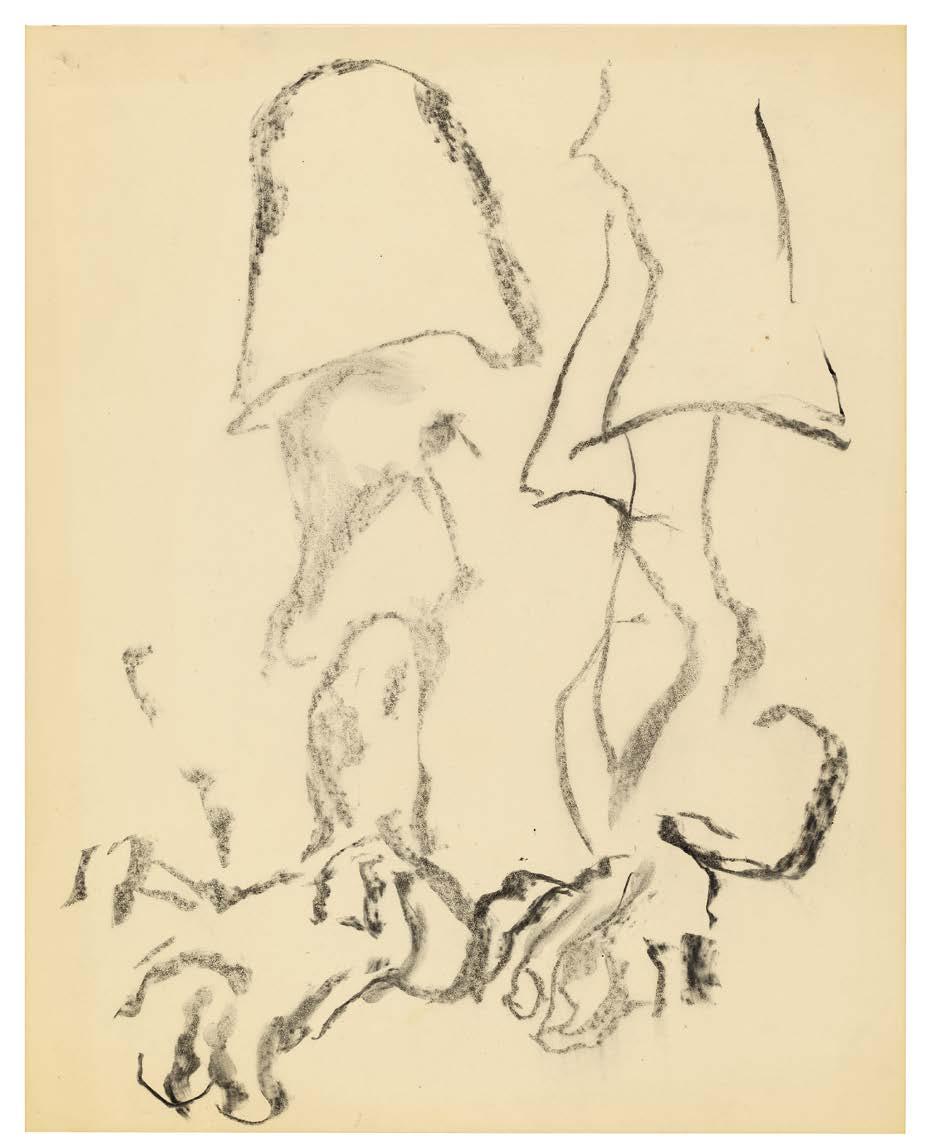

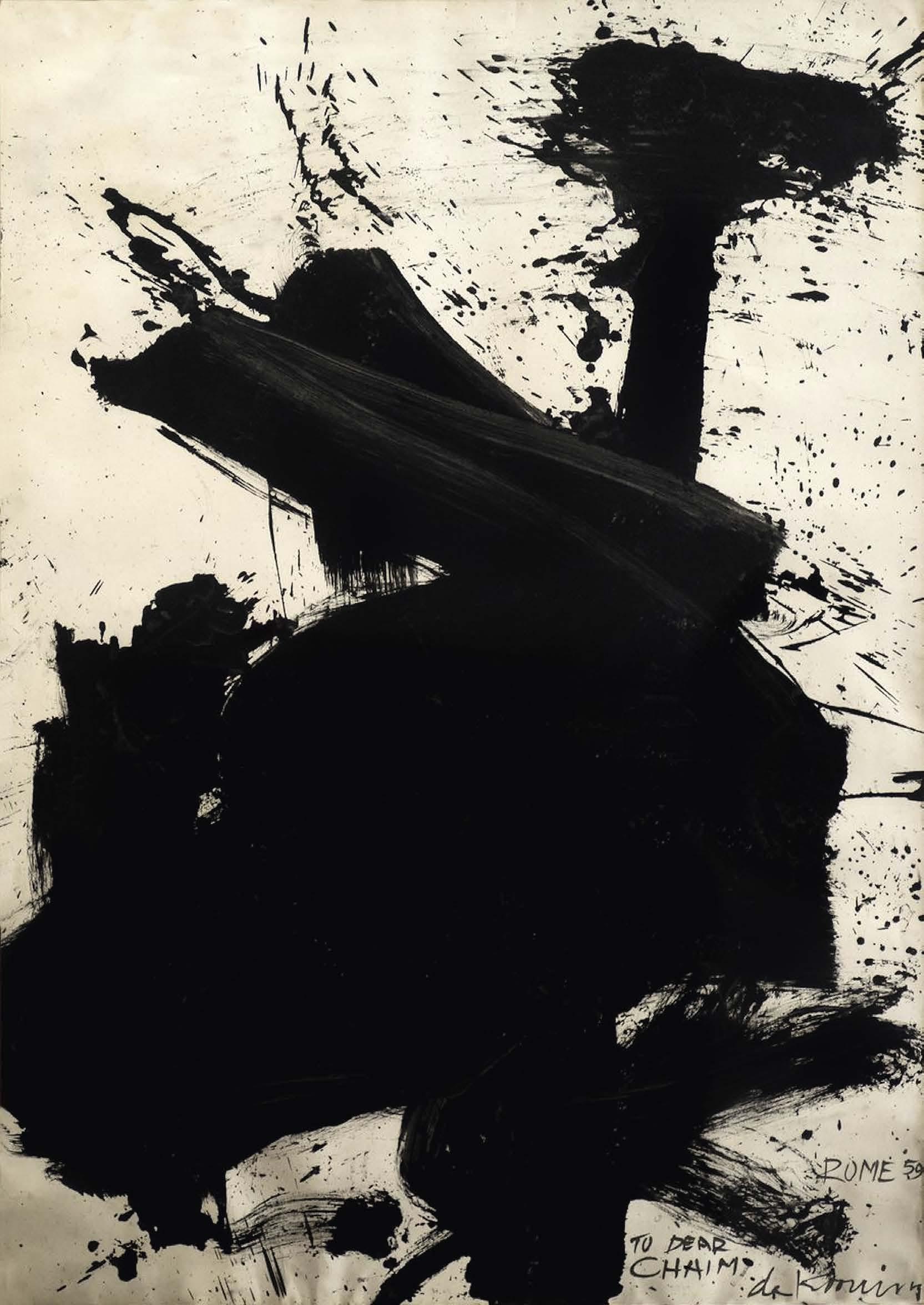

78 Willem de Kooning and Italy

In tandem with this year’s Venice Biennale, the city’s Gallerie dell’Accademia is featuring the exhibition Willem de Kooning and Italy, an in-depth examination of the artist’s time in Italy. The curators of the exhibition, Gary Garrels and Mario Codognato, speak about the project.

86

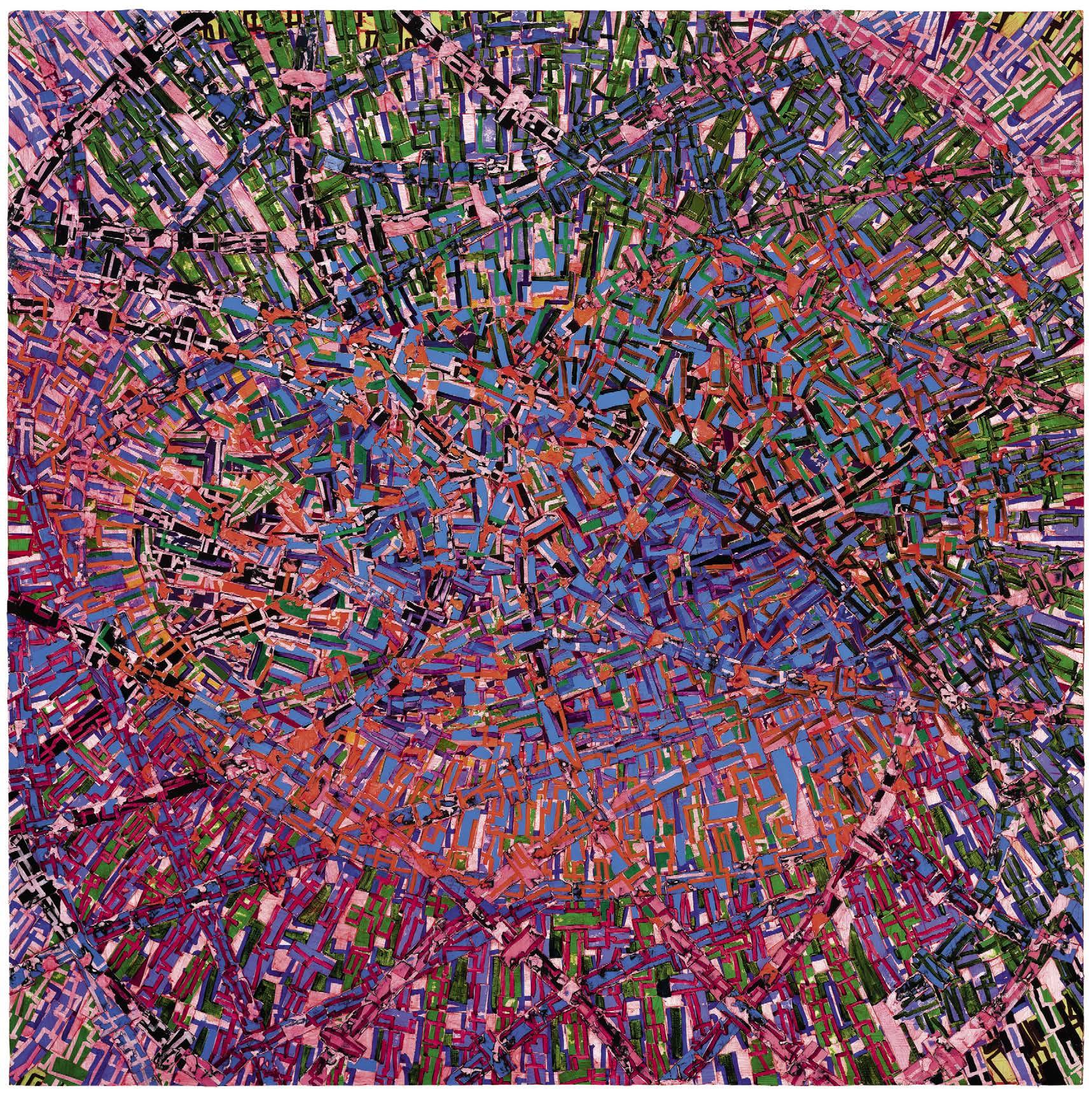

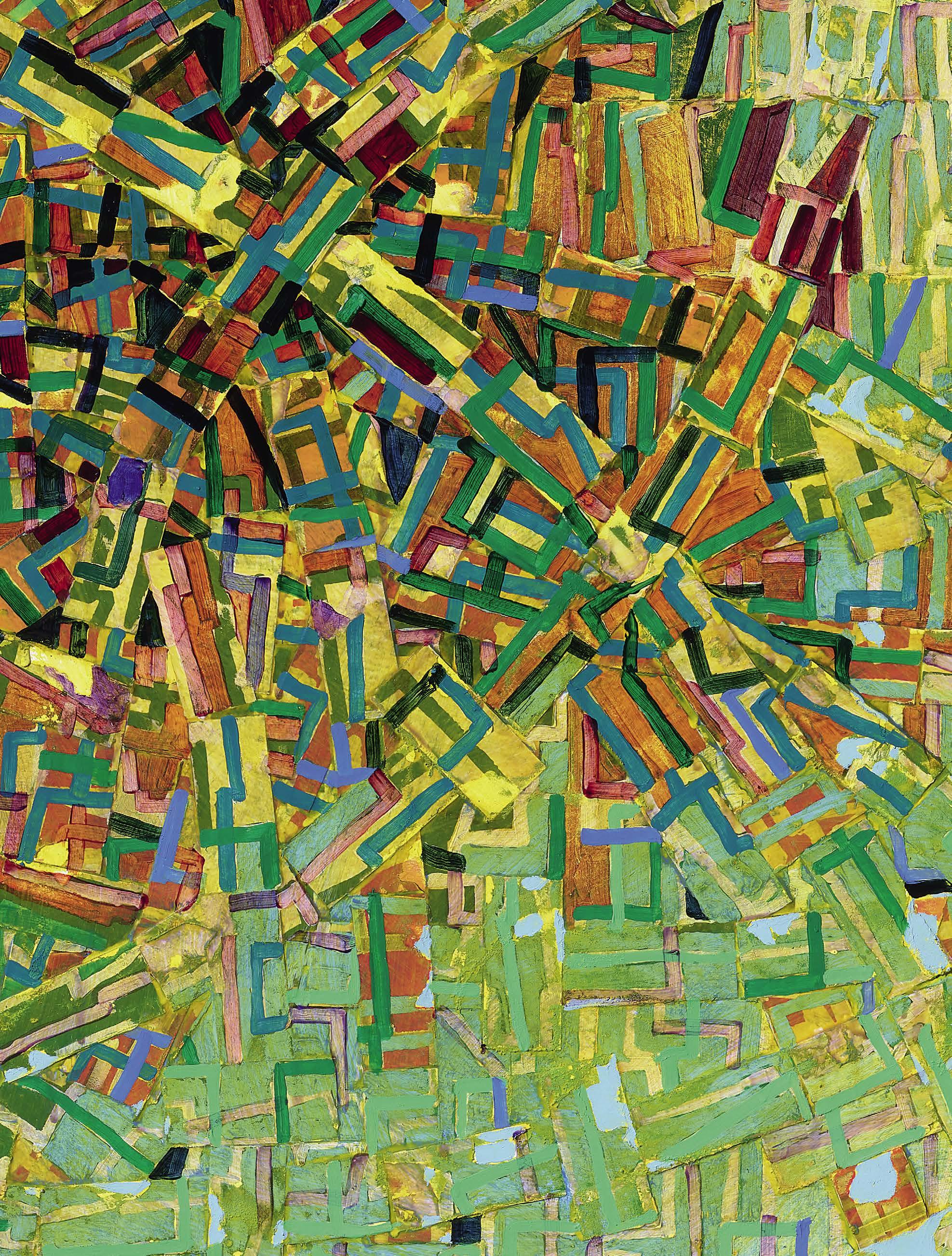

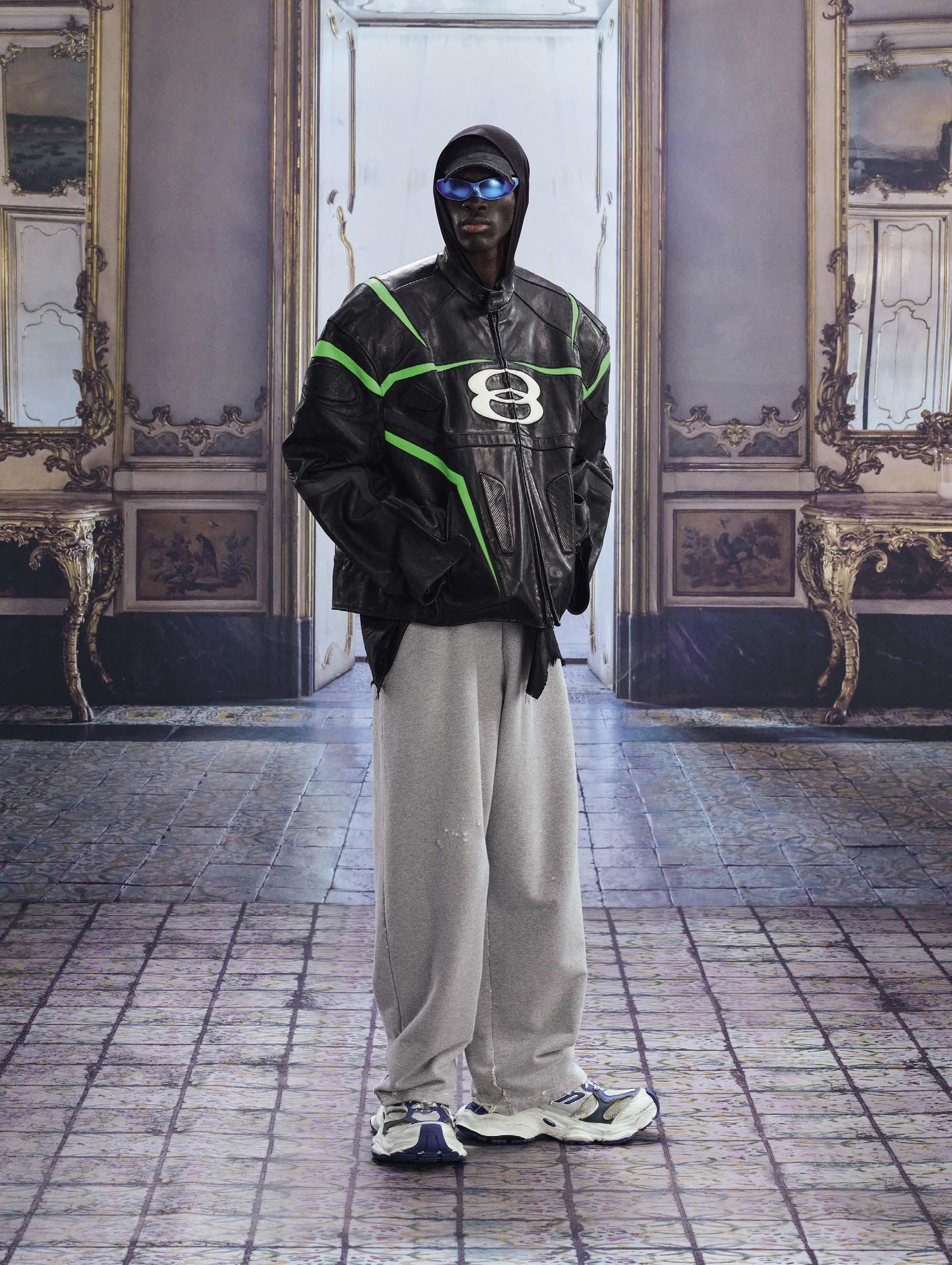

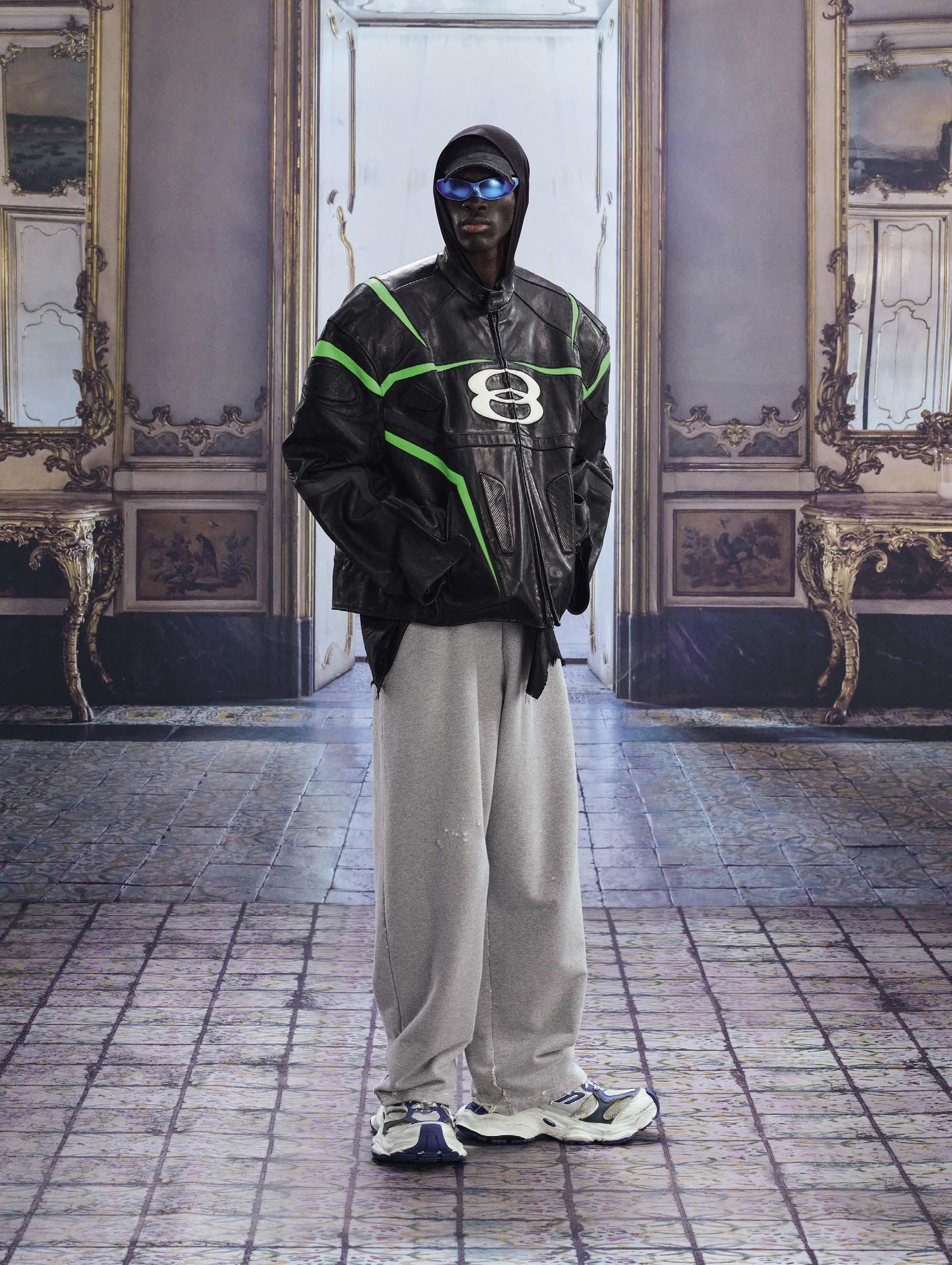

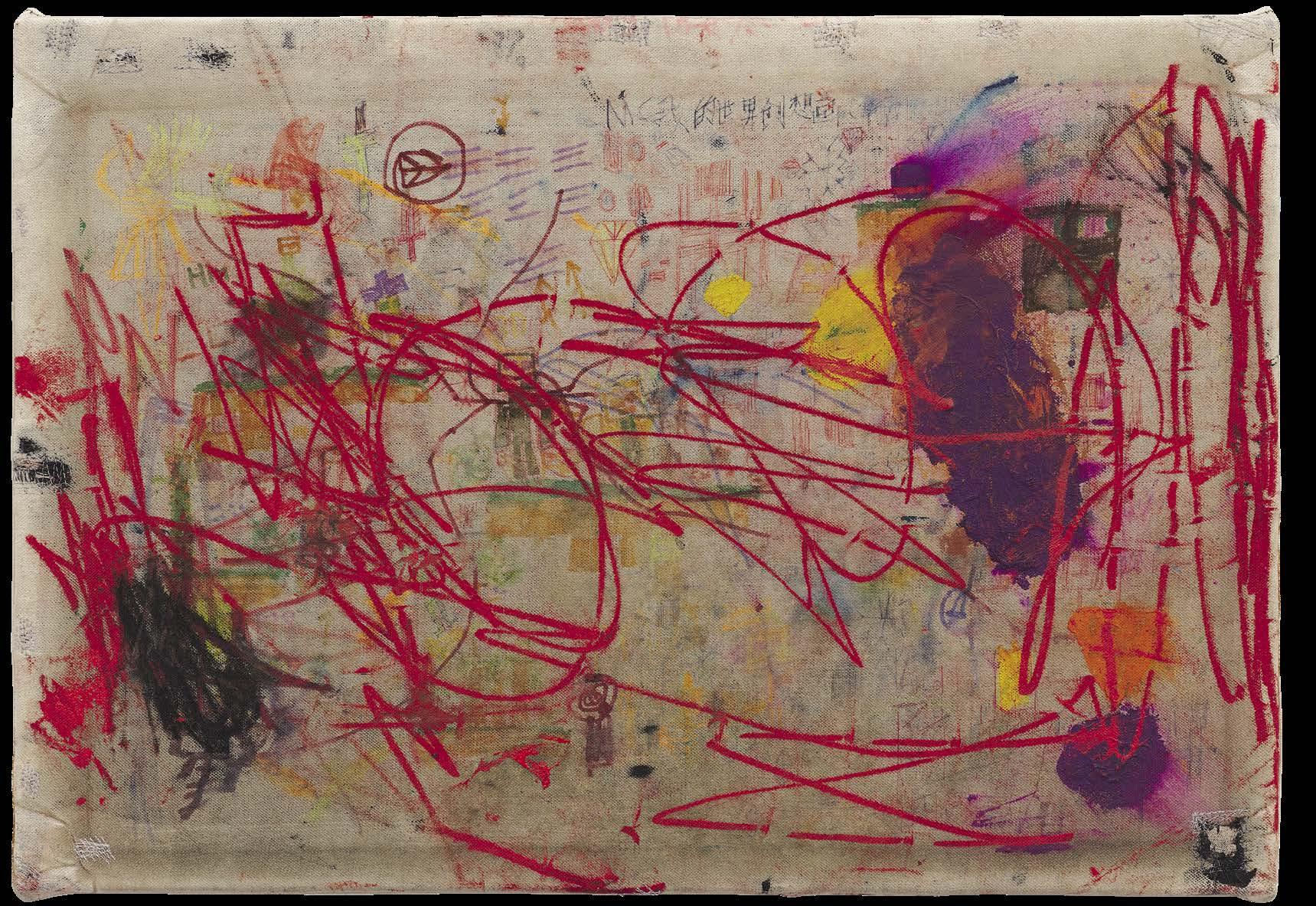

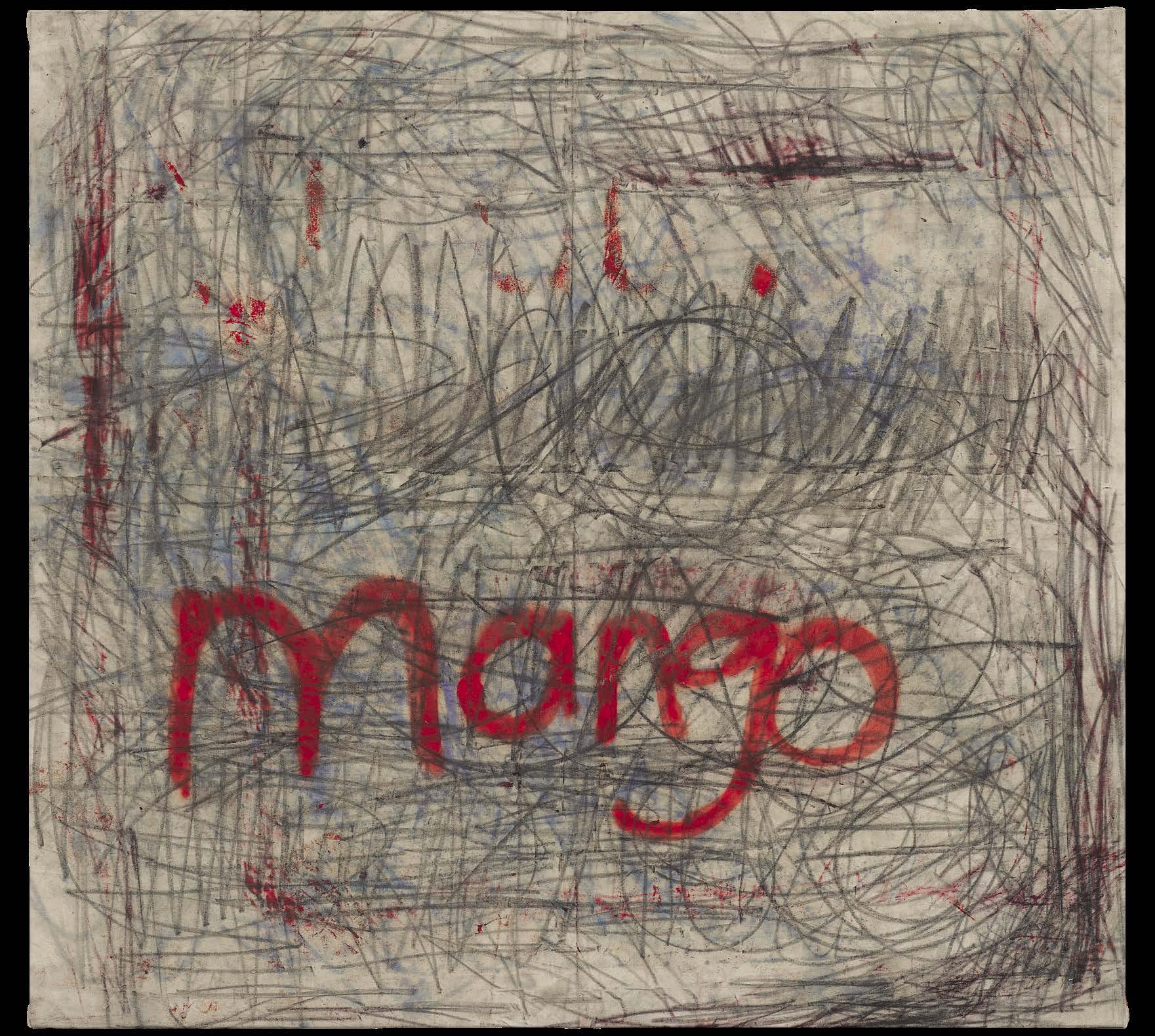

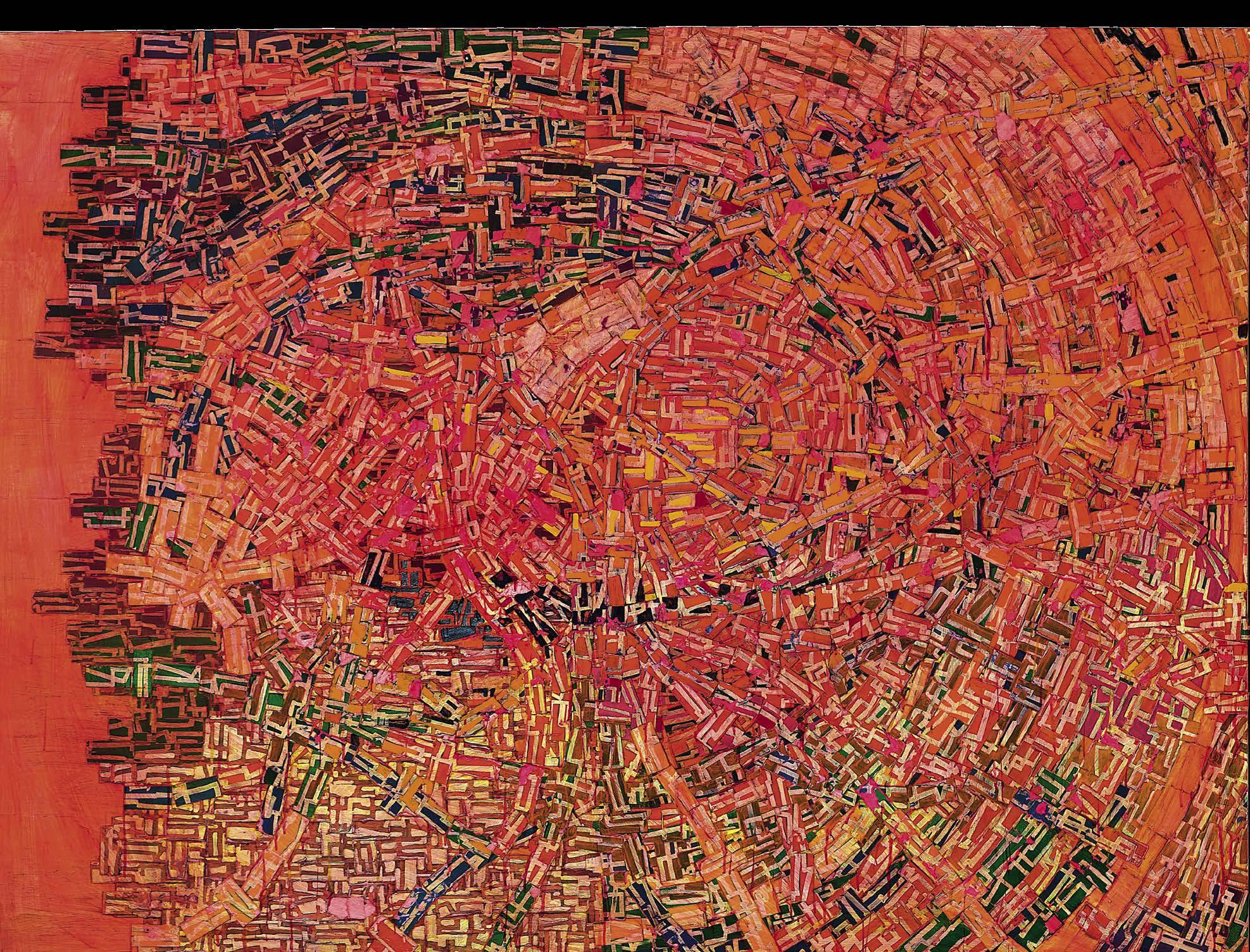

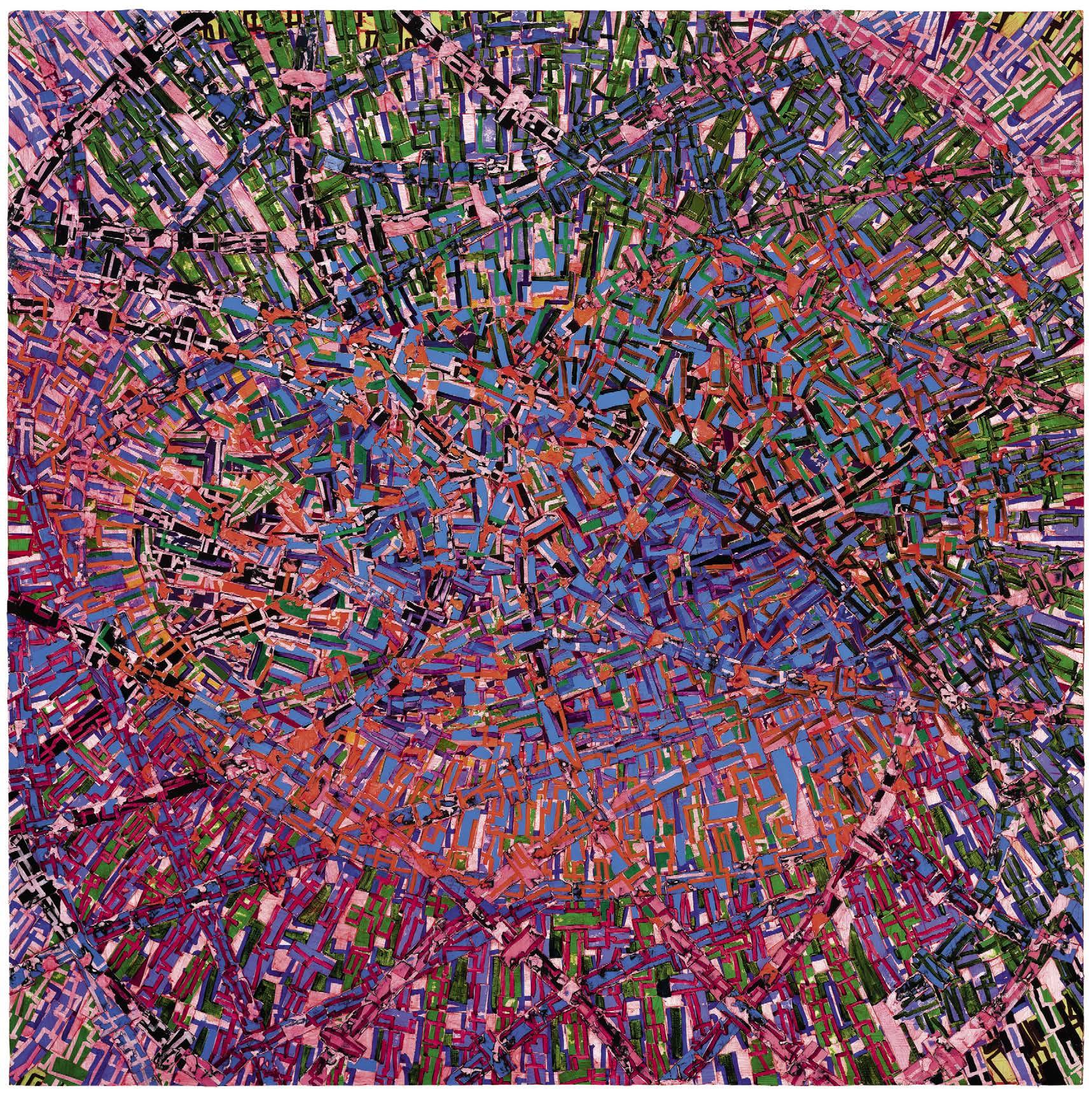

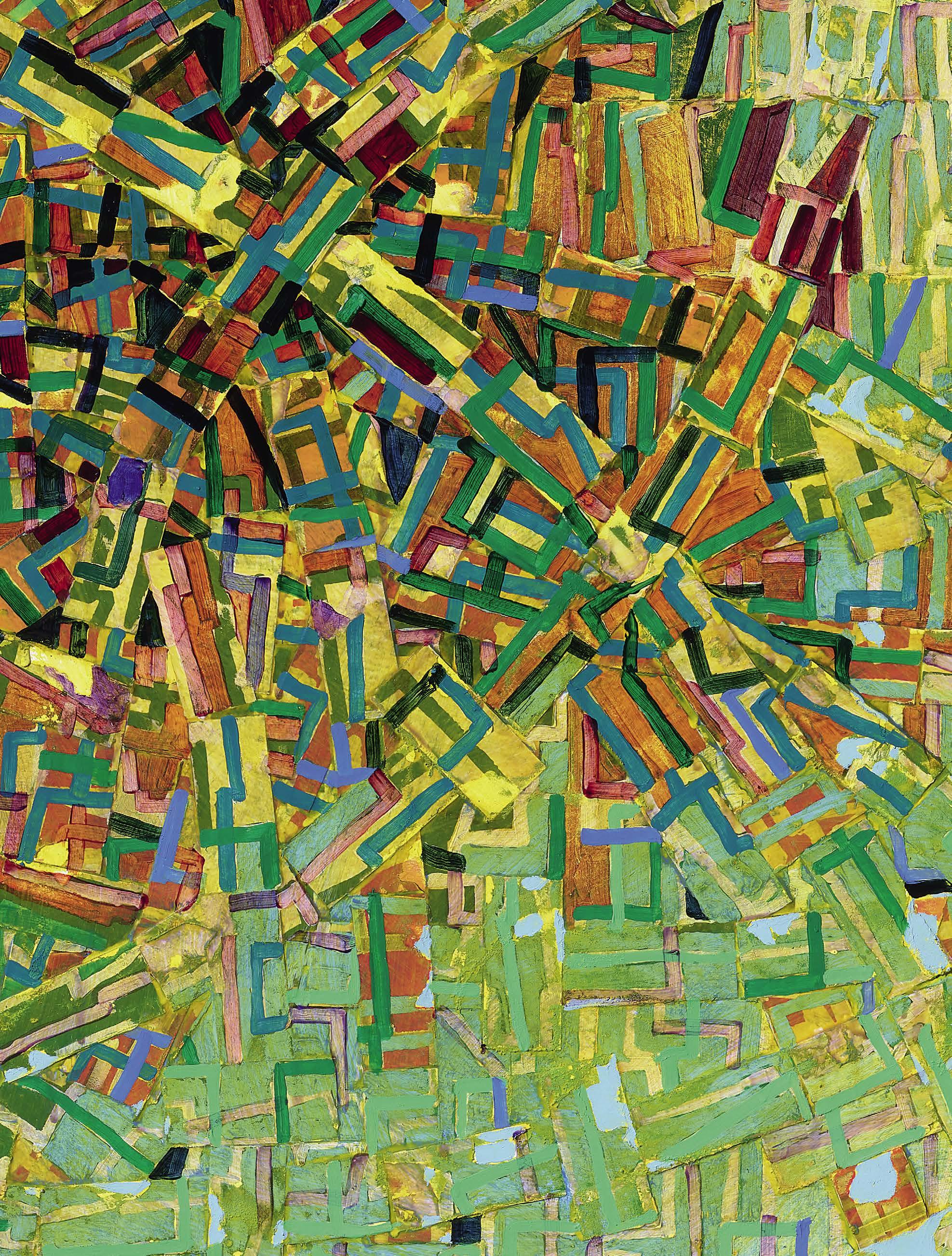

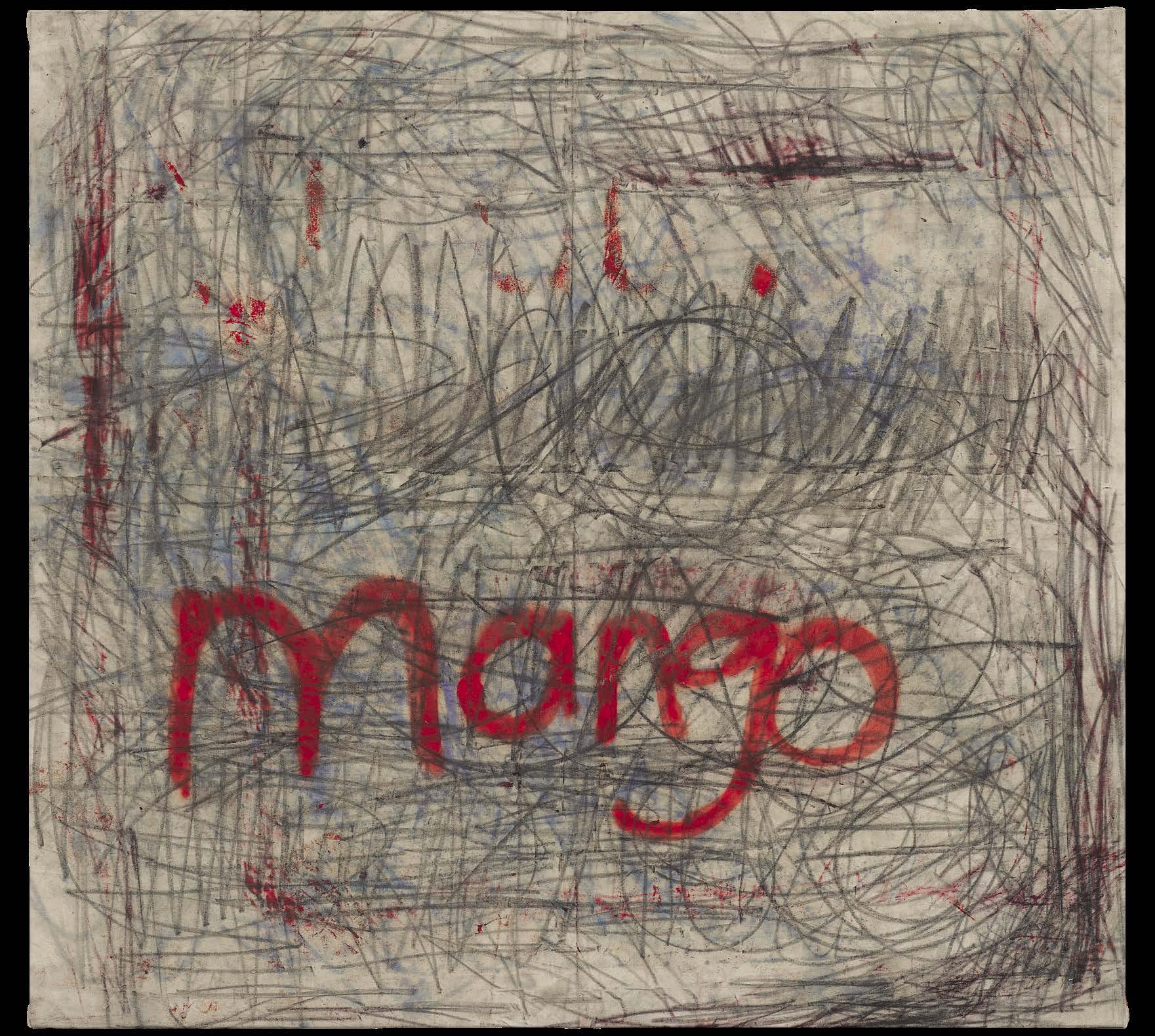

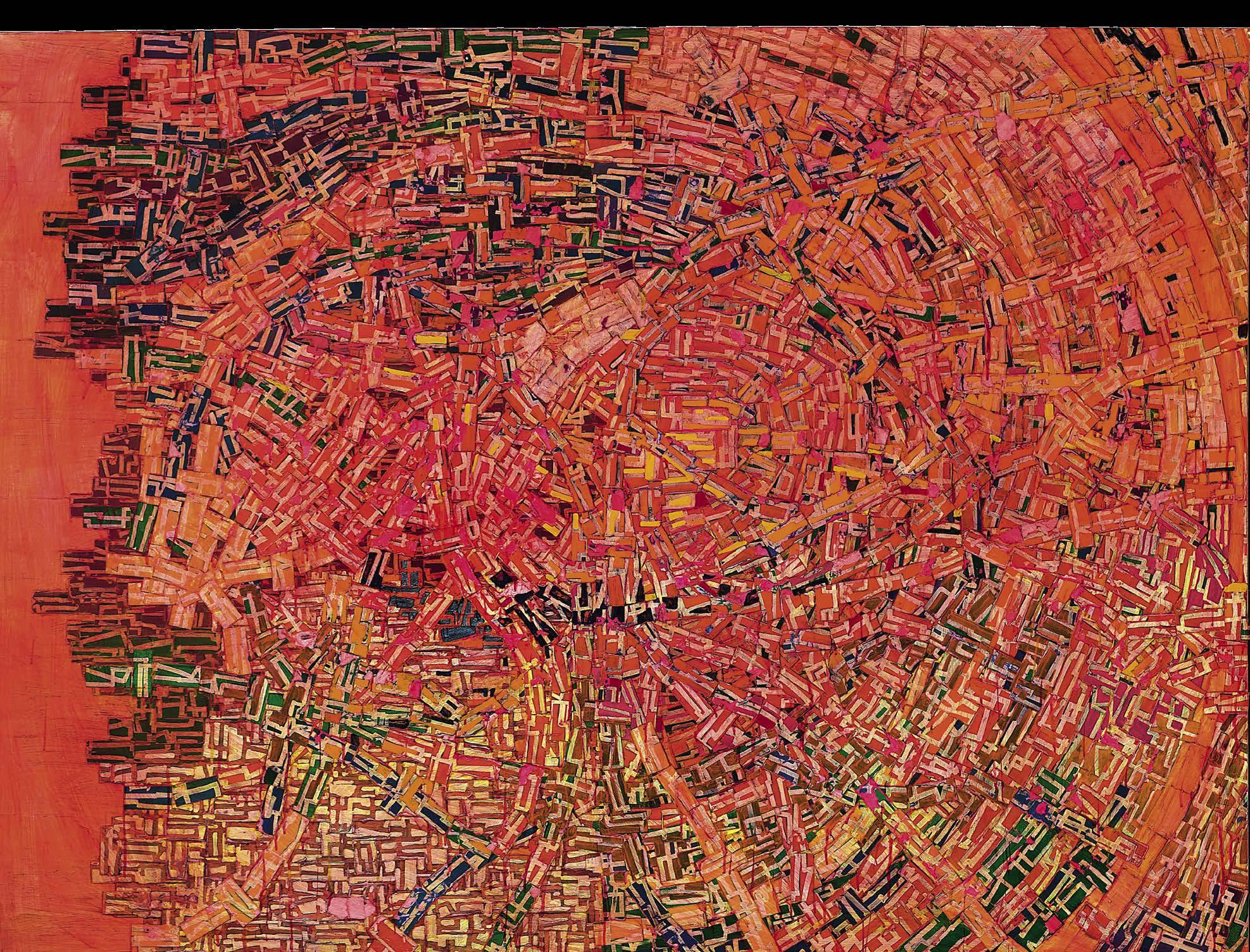

Oscar Murillo:

Marks and Whispers

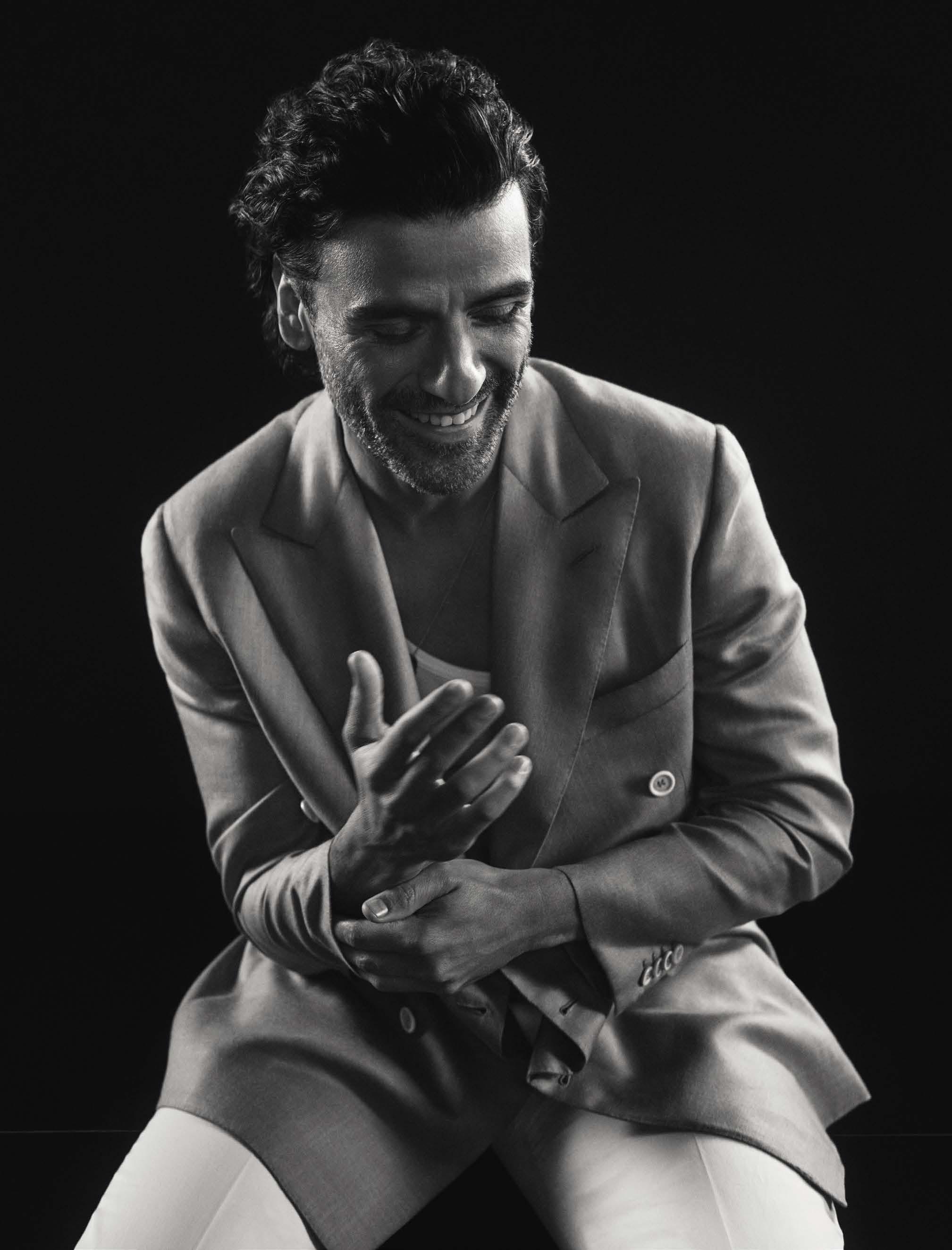

In advance of two exhibitions—The Flooded Garden at Tate Modern, London, and Marks and Whispers at Gagosian, Rome—curator Alessandro Rabottini visited Murillo’s London studio to discuss the connections between these projects.

21

92

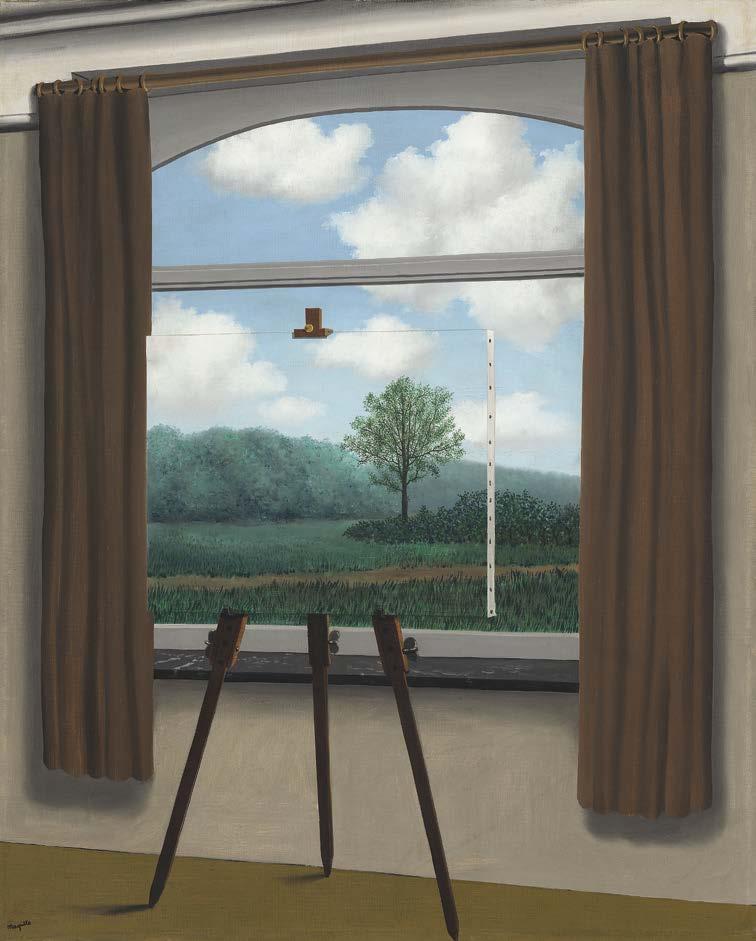

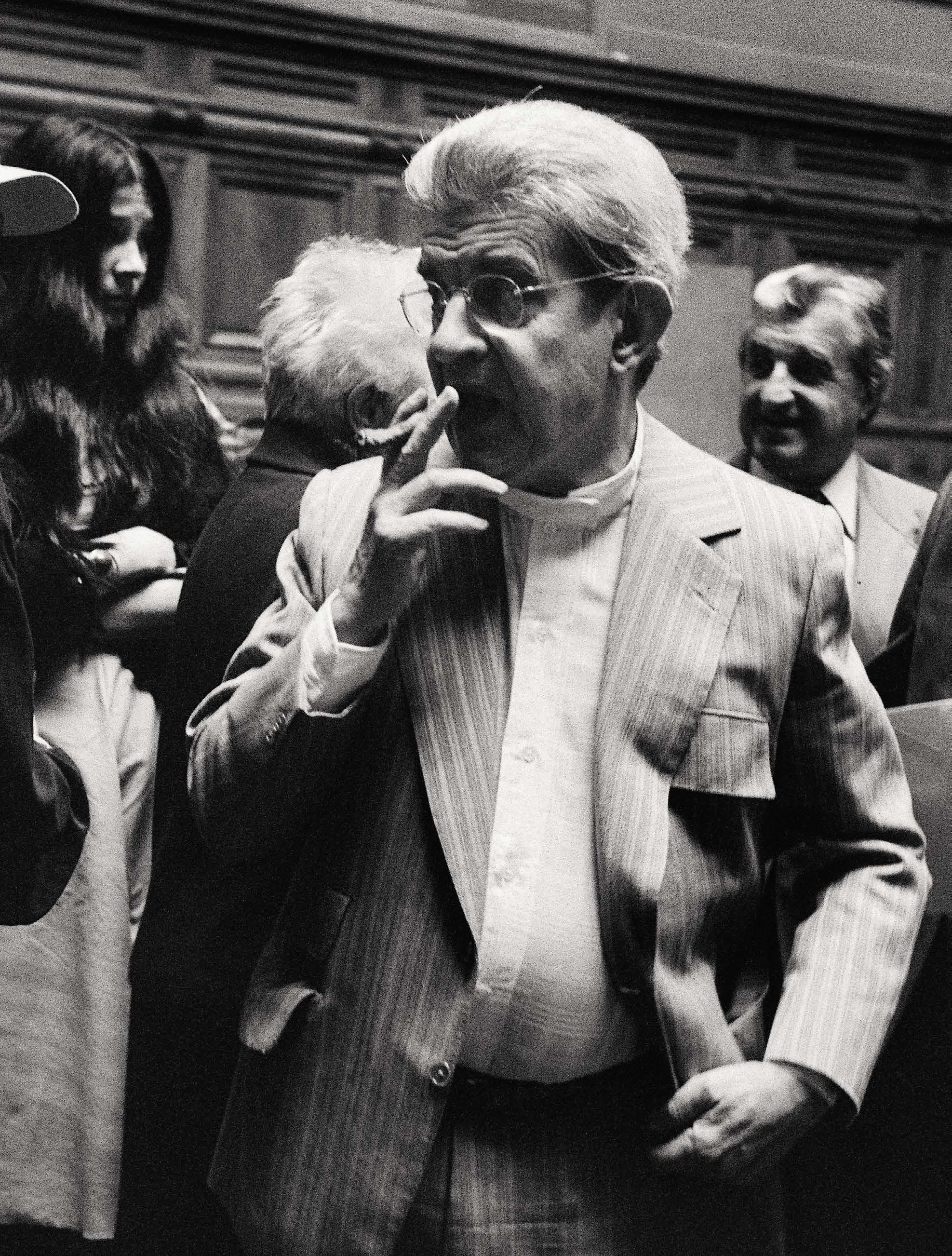

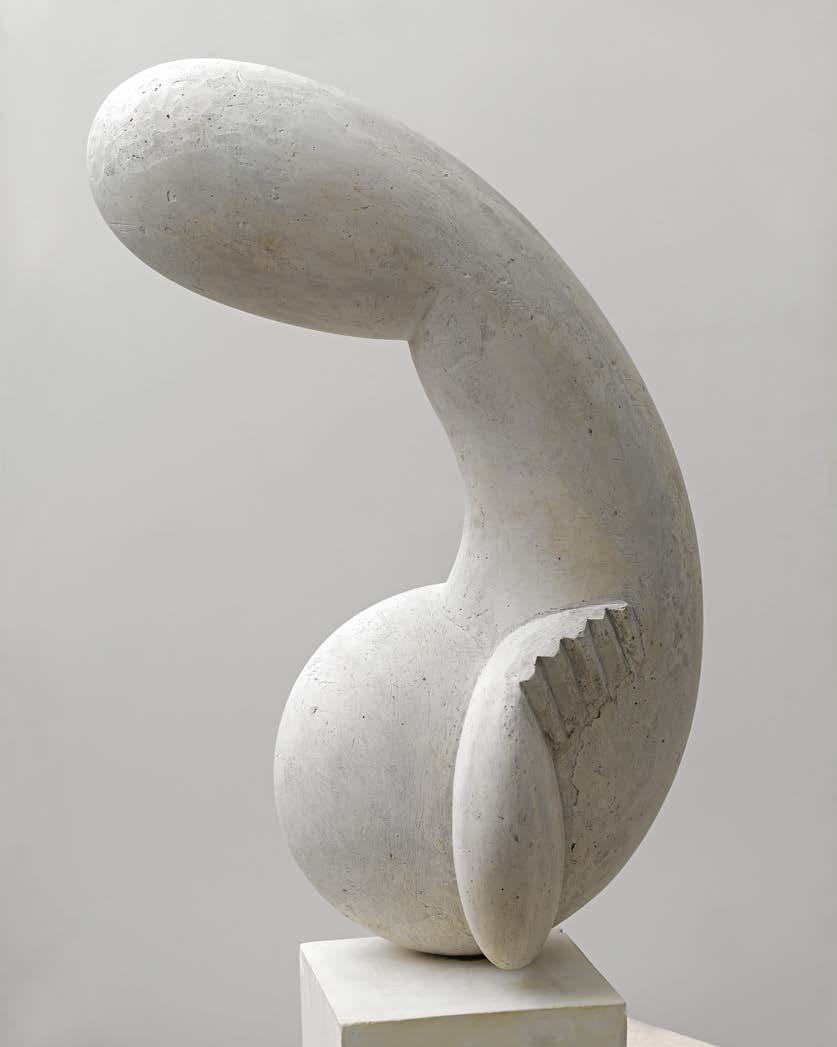

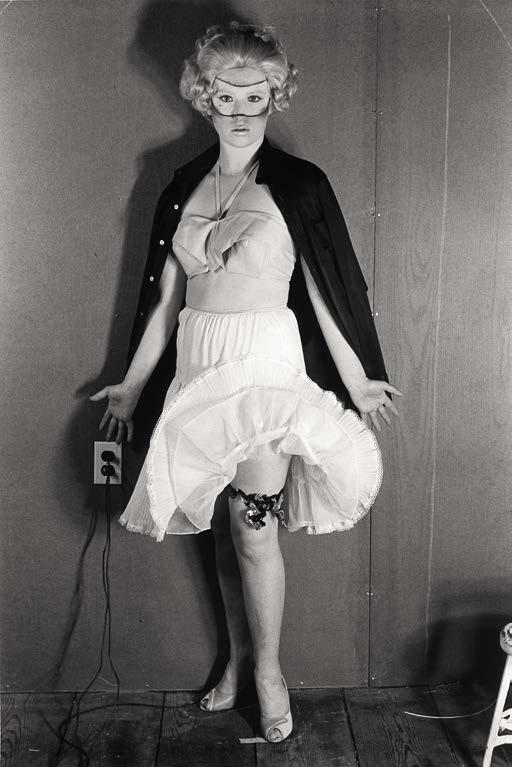

Lacan, the exhibition

On the heels of finishing a new novel, Scaffolding , that revolves around a Lacanian analyst, Lauren Elkin traveled to Metz, France, to take in Lacan, the exhibition. When art meets psychoanalysis at the Centre Pompidou satellite in that city.

98

Revisiting Frankenthaler

John Elderfield and Lauren Mahony speak with Harry Cooper about the new and expanded version of Elderfield’s 1989 monograph on Helen Frankenthaler that Gagosian will publish this summer.

104

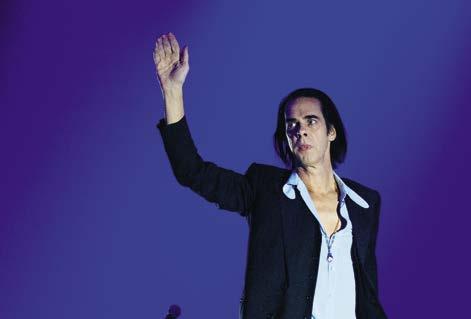

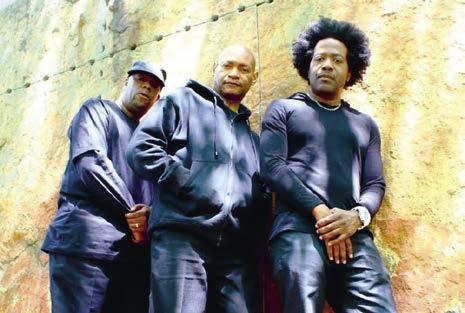

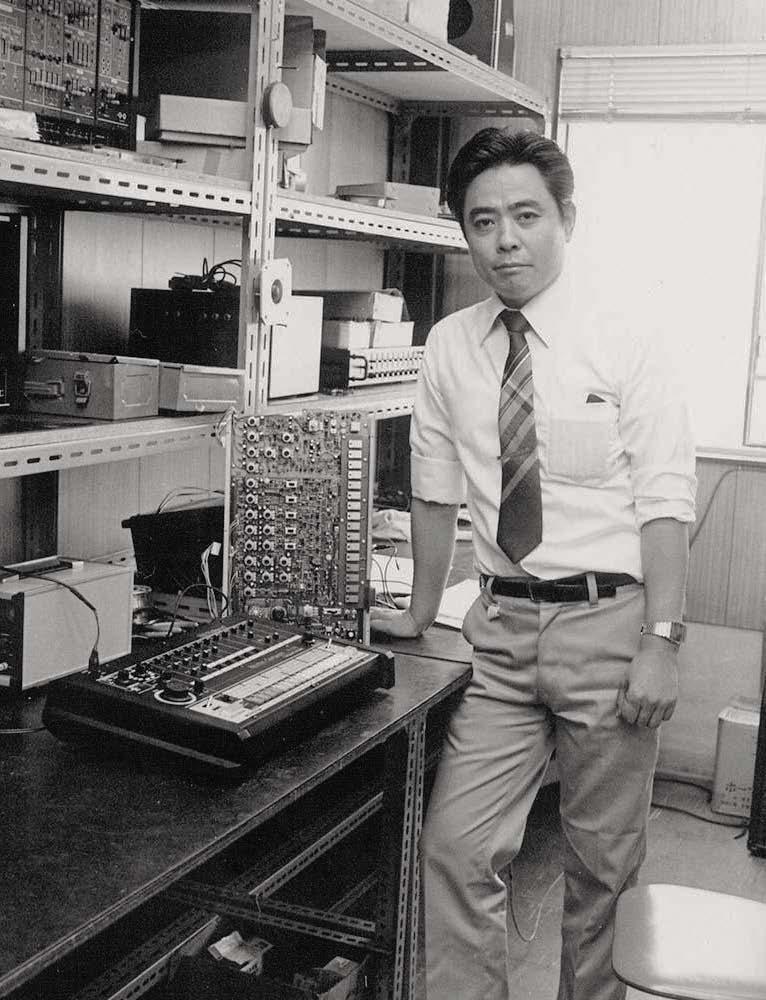

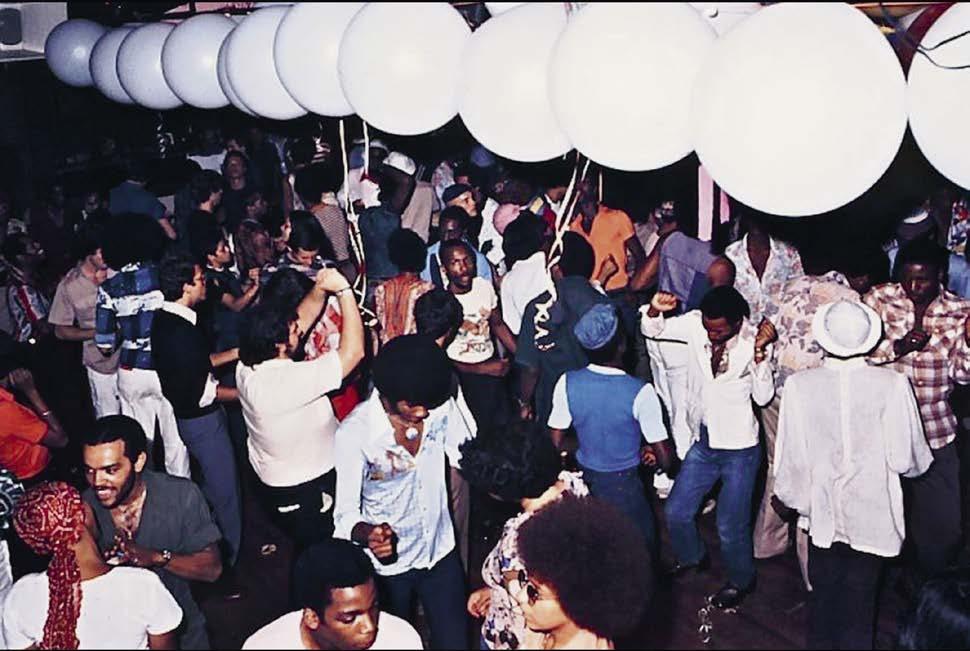

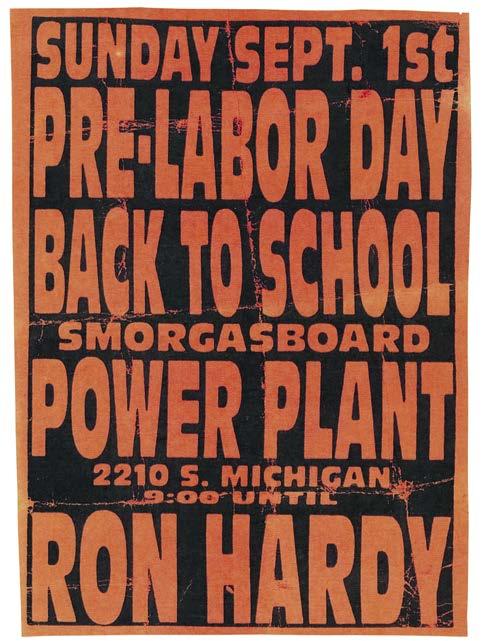

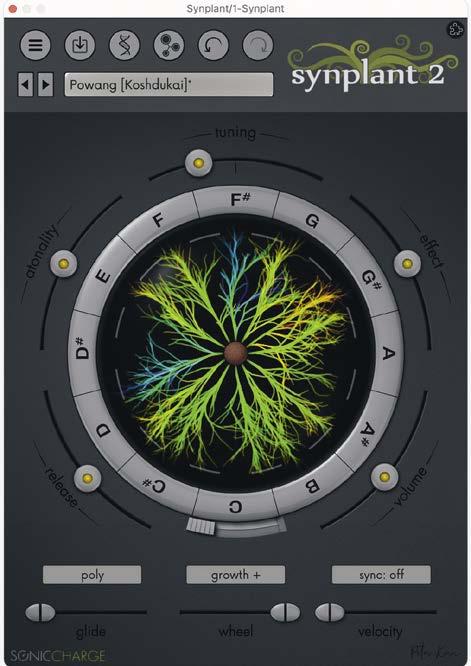

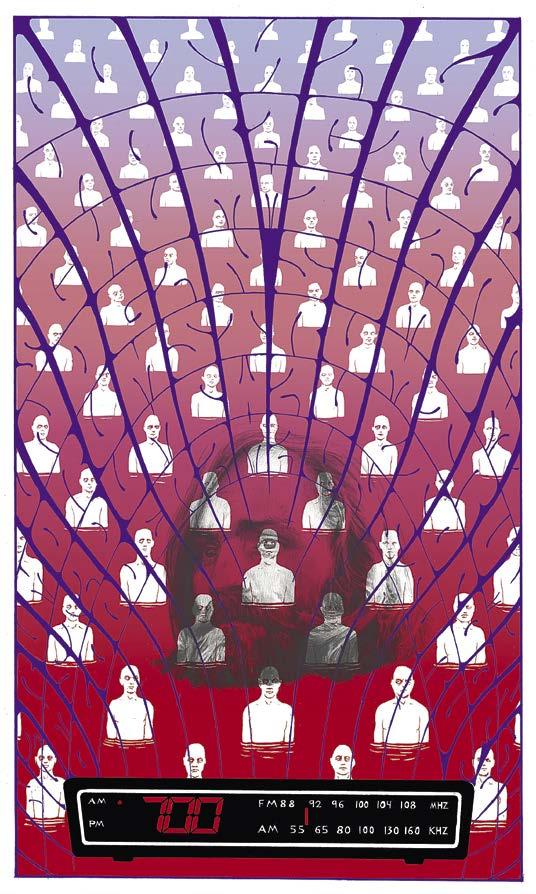

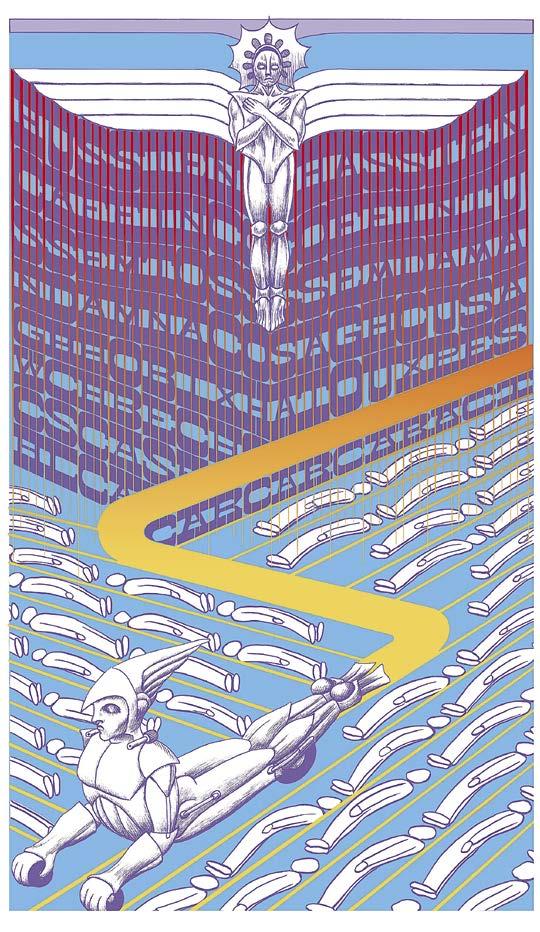

Gagosian & Music

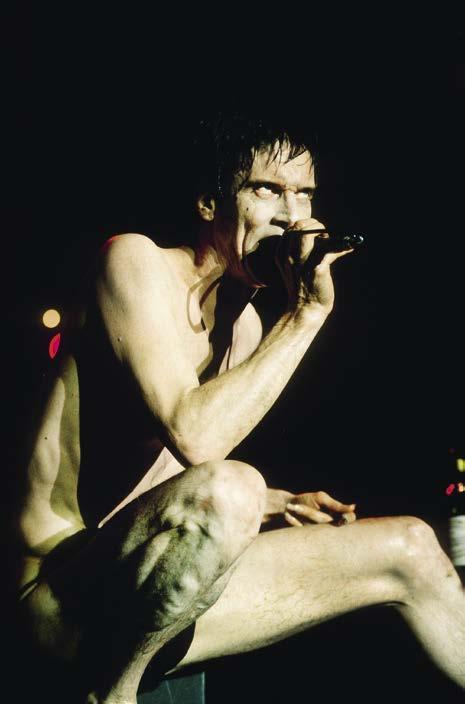

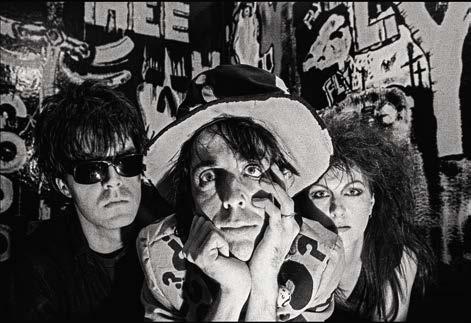

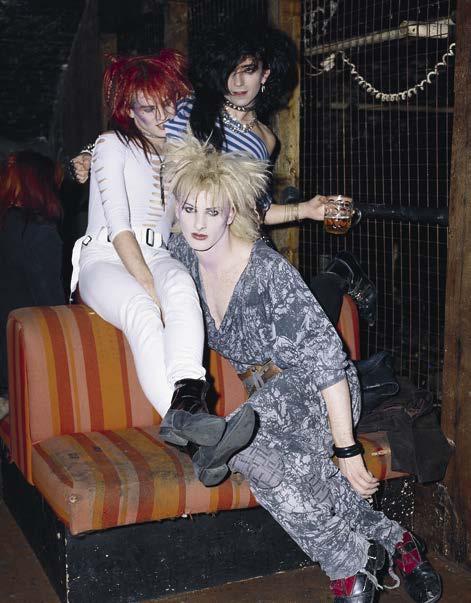

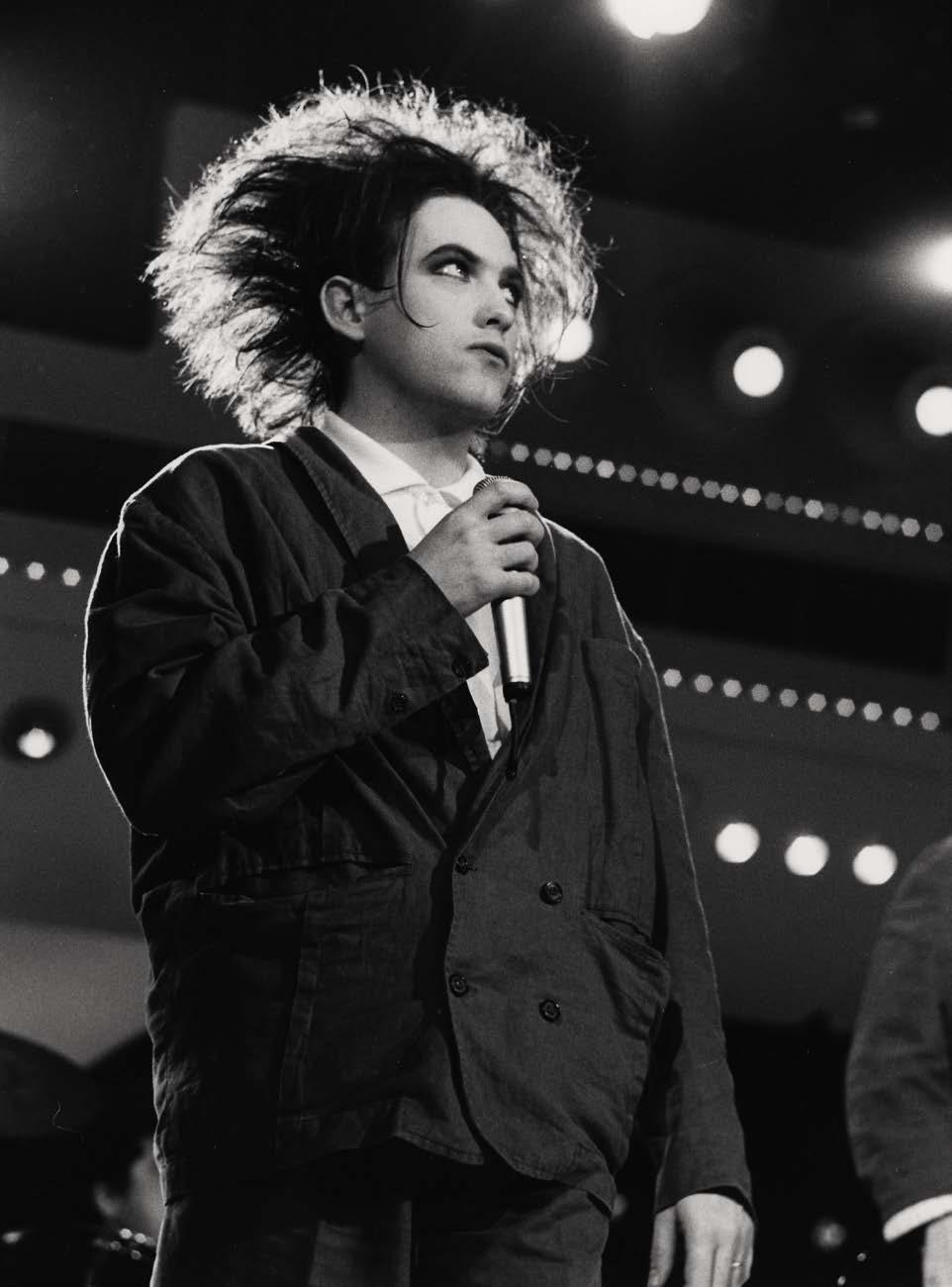

The second of the Quarterly ’s new themed supplements takes us into the world of music. We feature musicians Lucinda Chua, Lonnie Holley, Jordi Savall, and Éliane Radigue; share a sonic history of white noise; and learn about the personal history of a gothcurious writer.

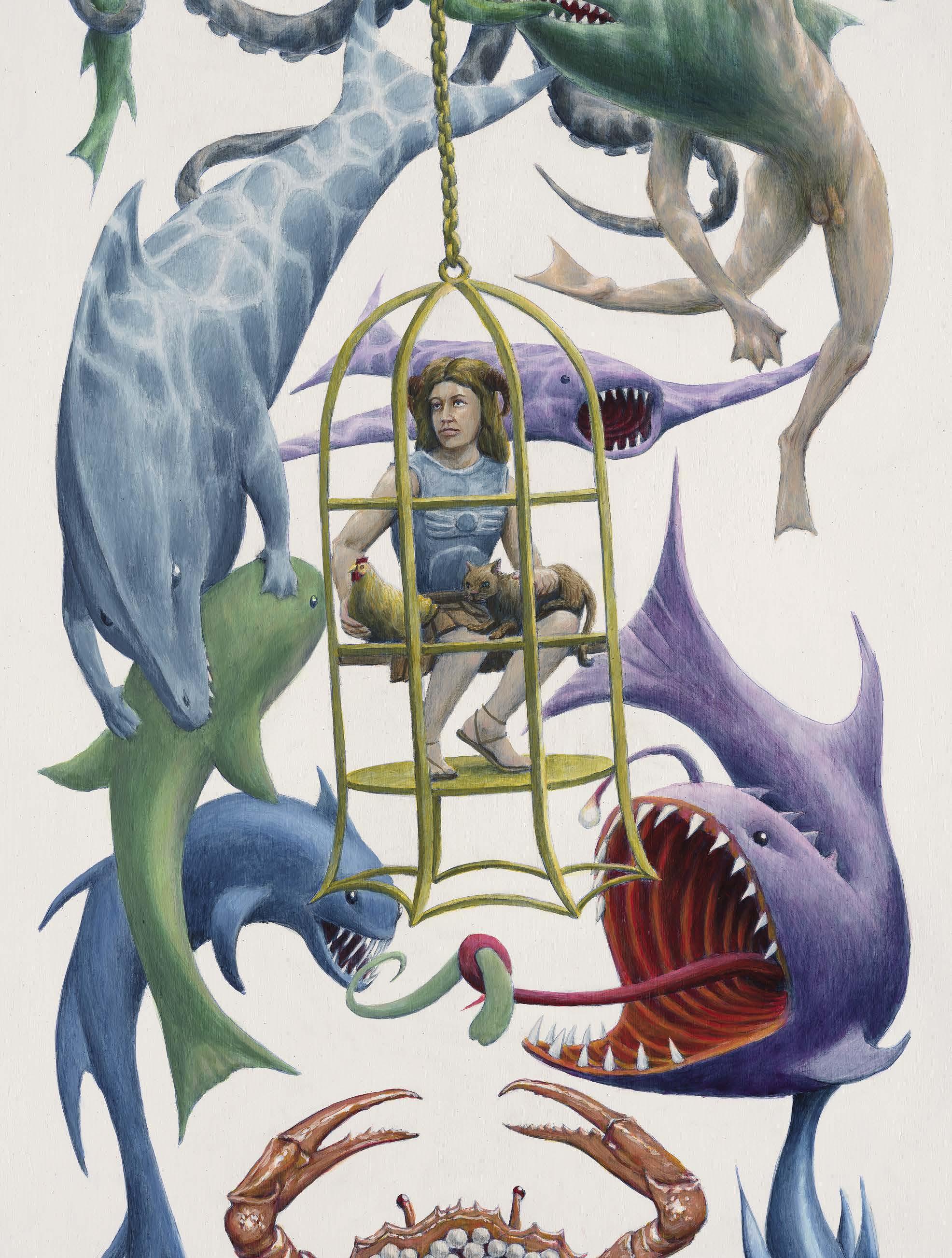

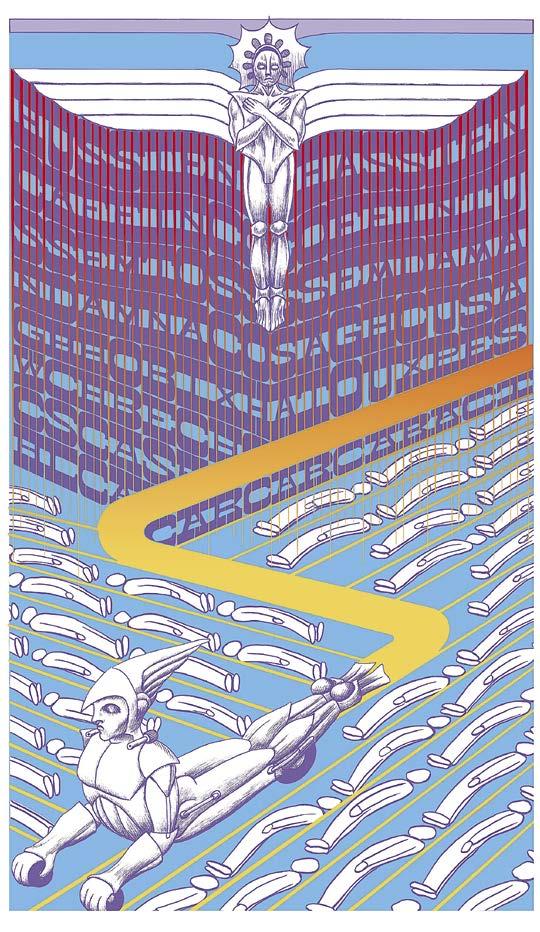

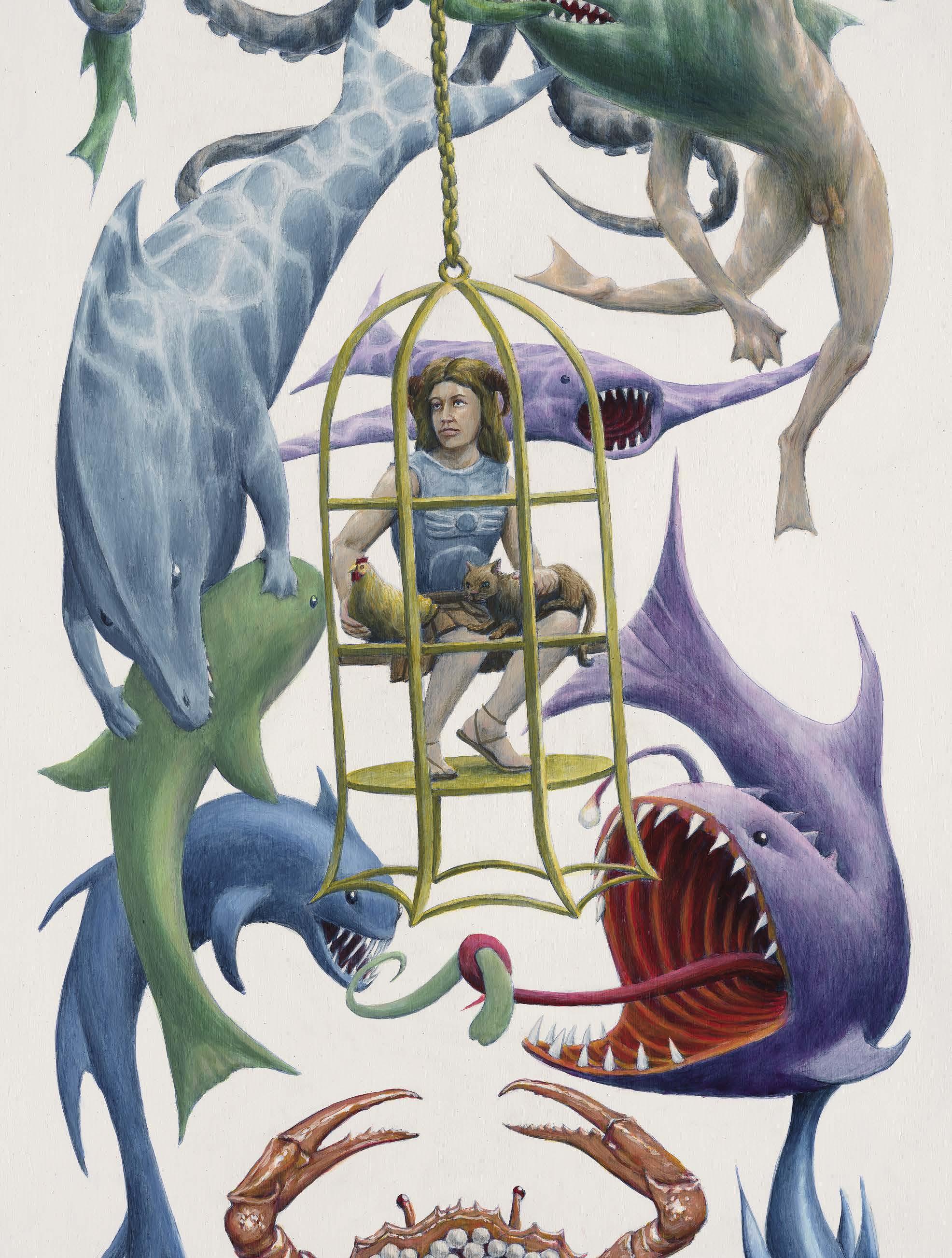

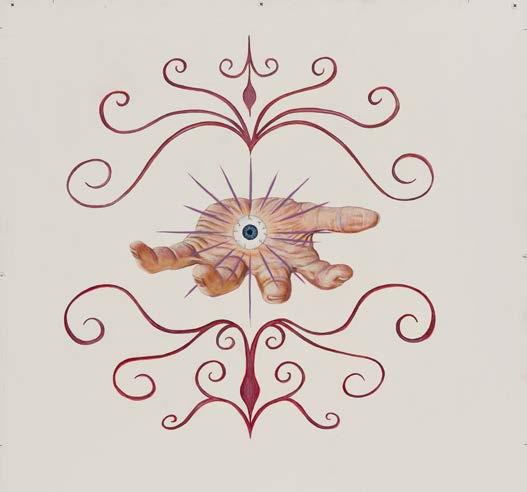

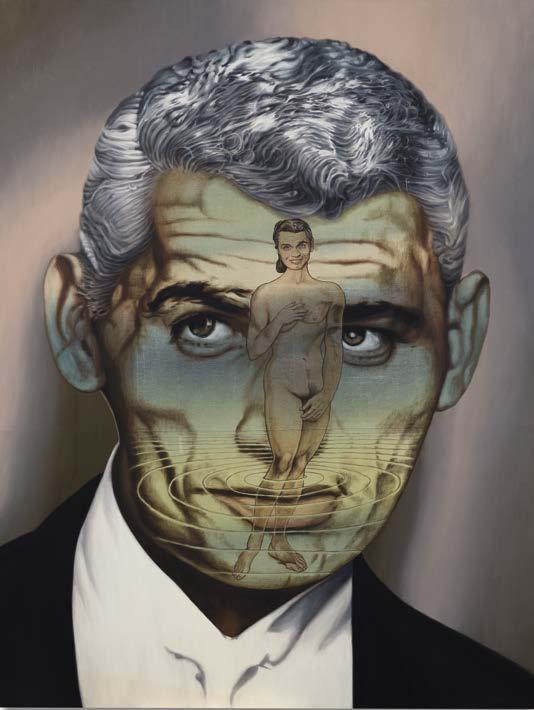

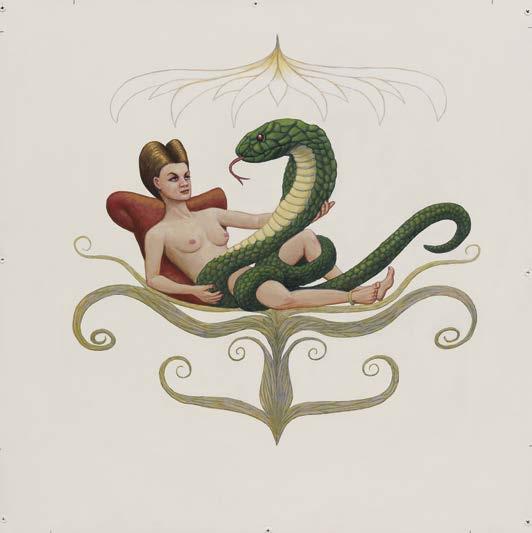

106

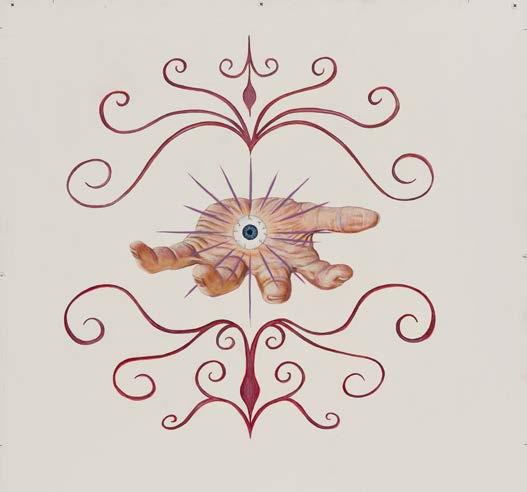

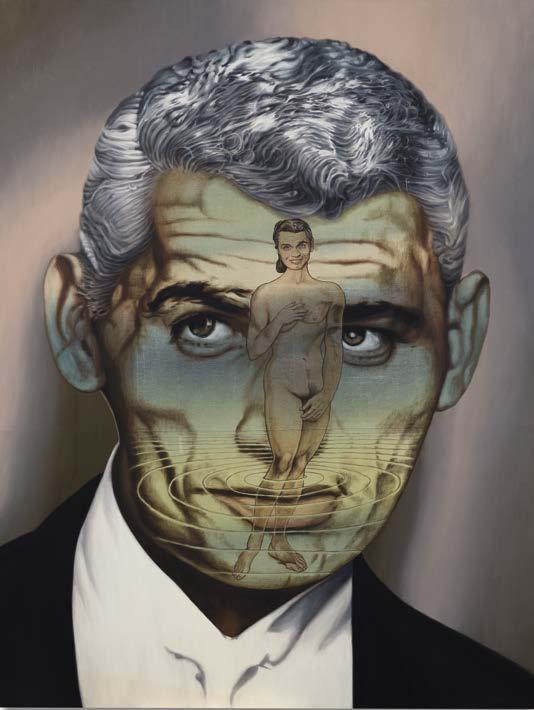

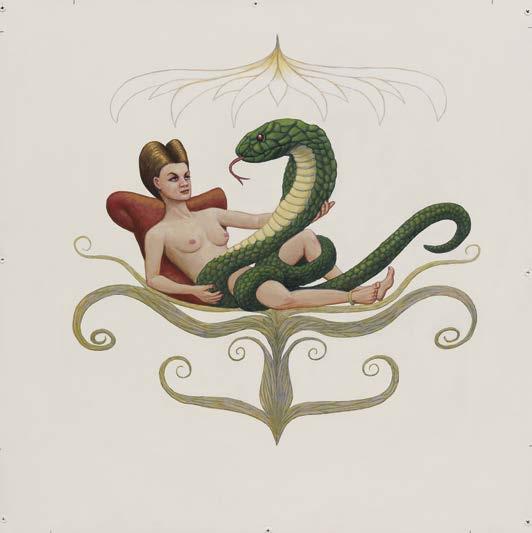

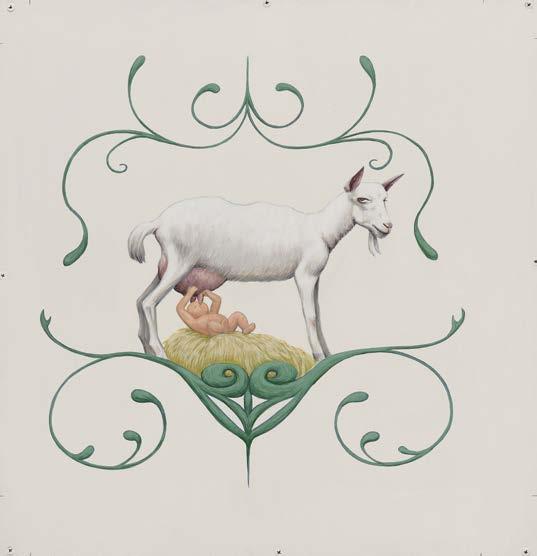

Jim Shaw A–Z

Charlie Fox takes a whirlwind trip through the Jim Shaw universe, traveling along the letters of the alphabet.

112

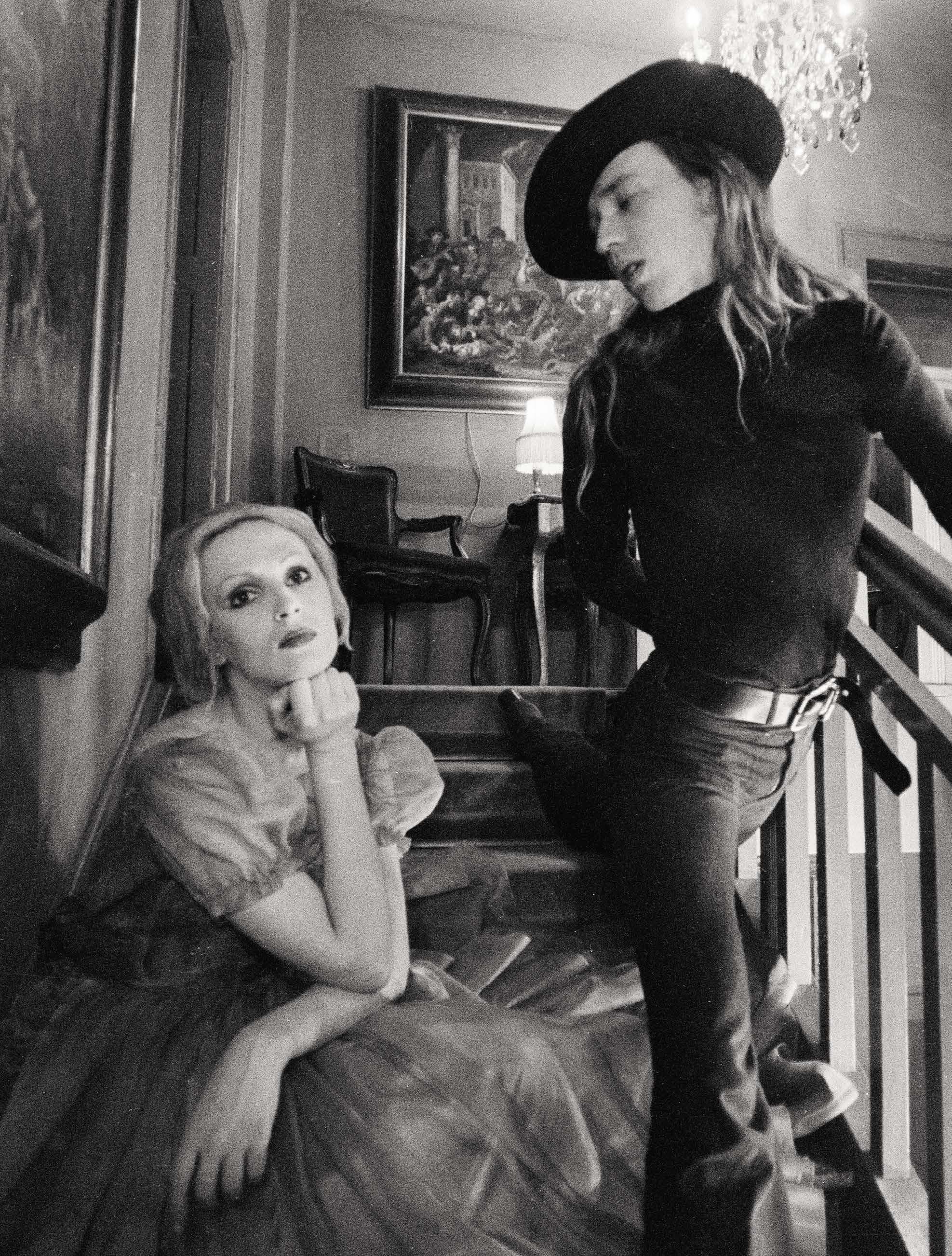

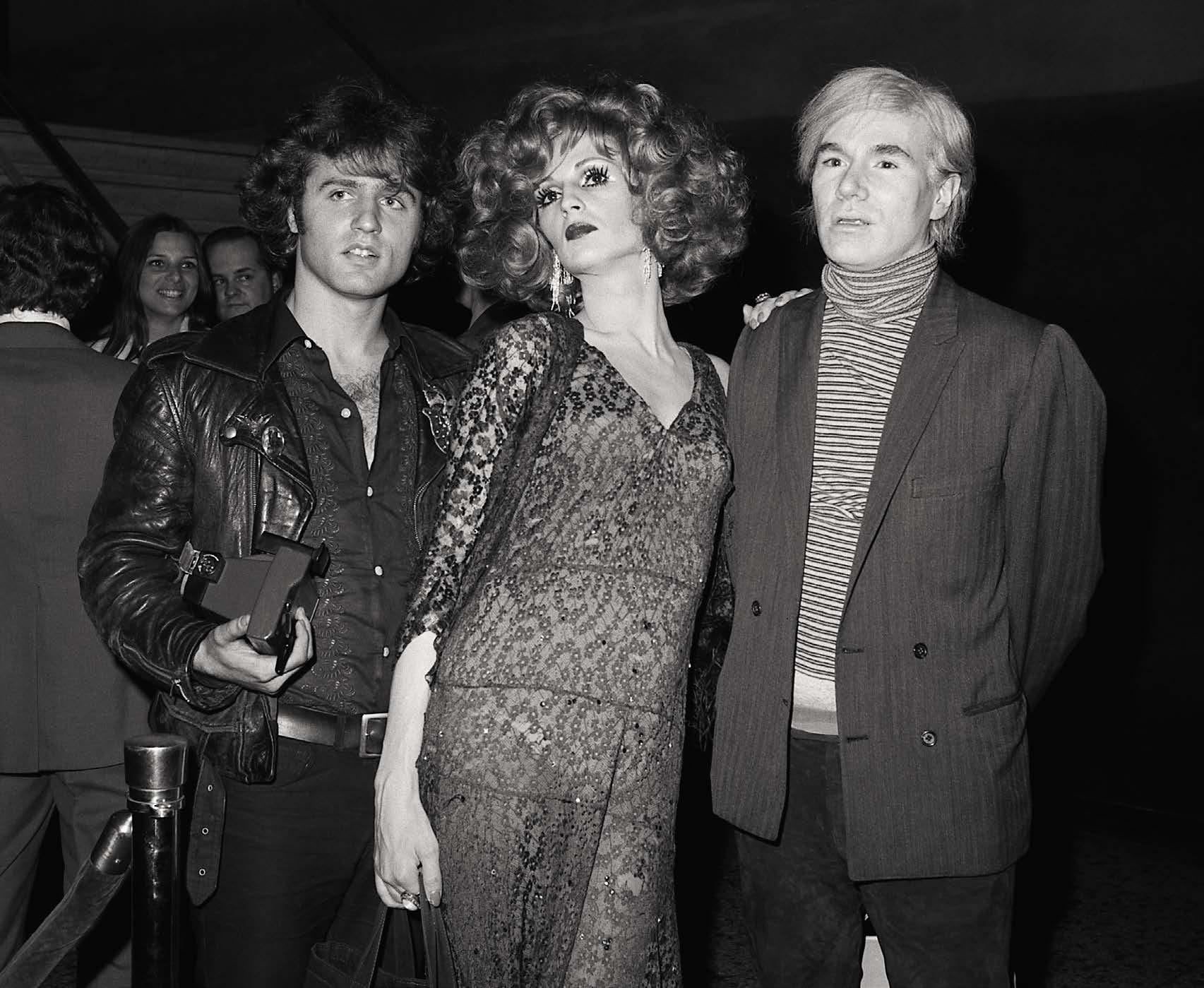

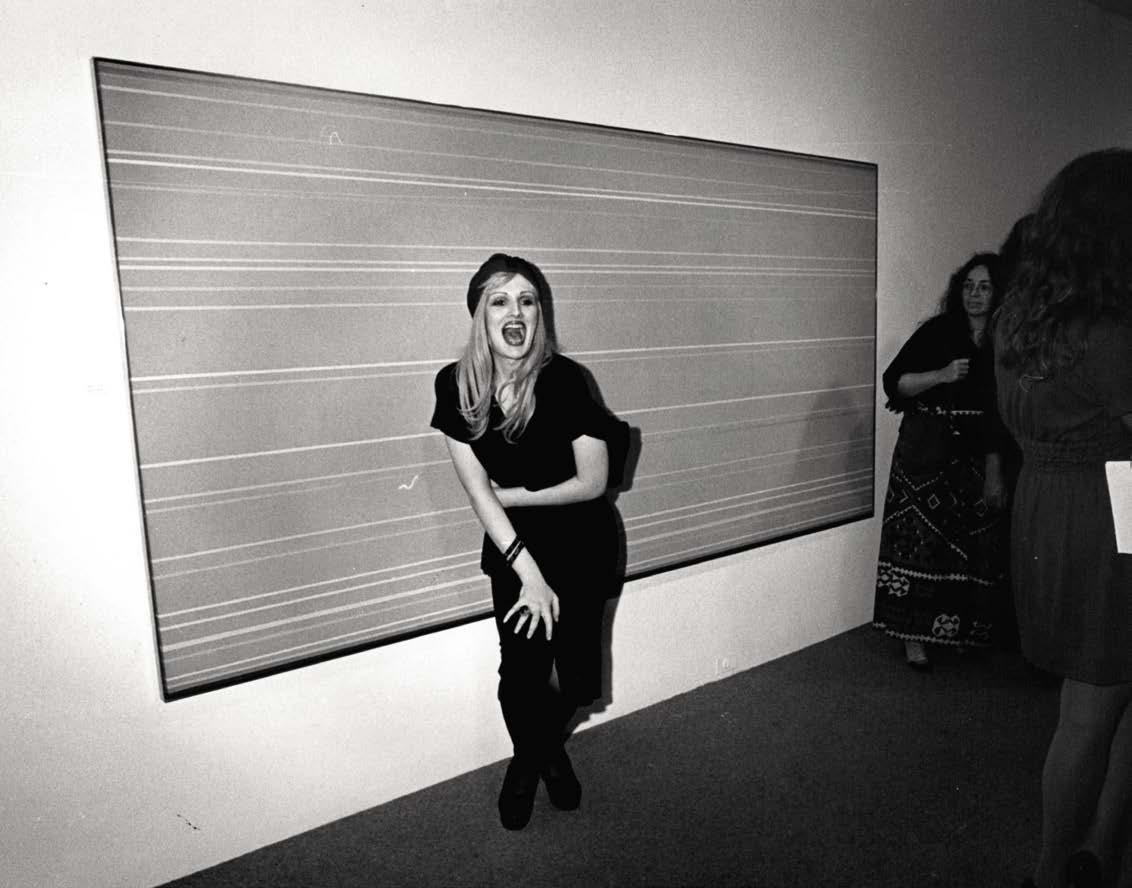

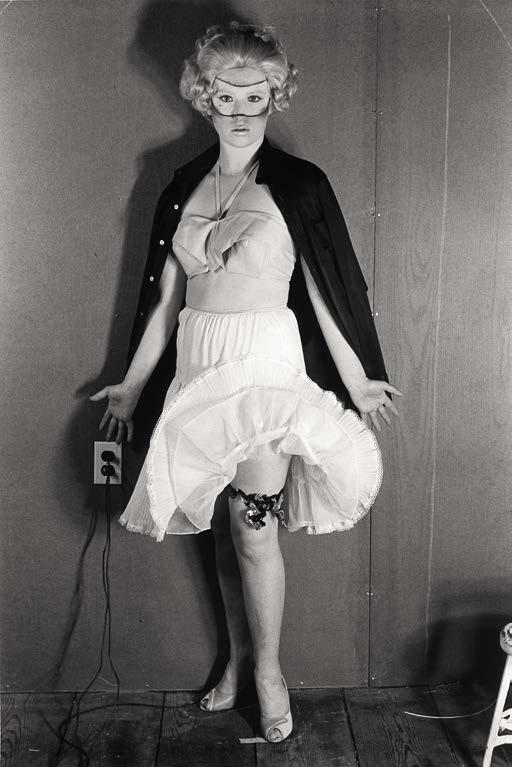

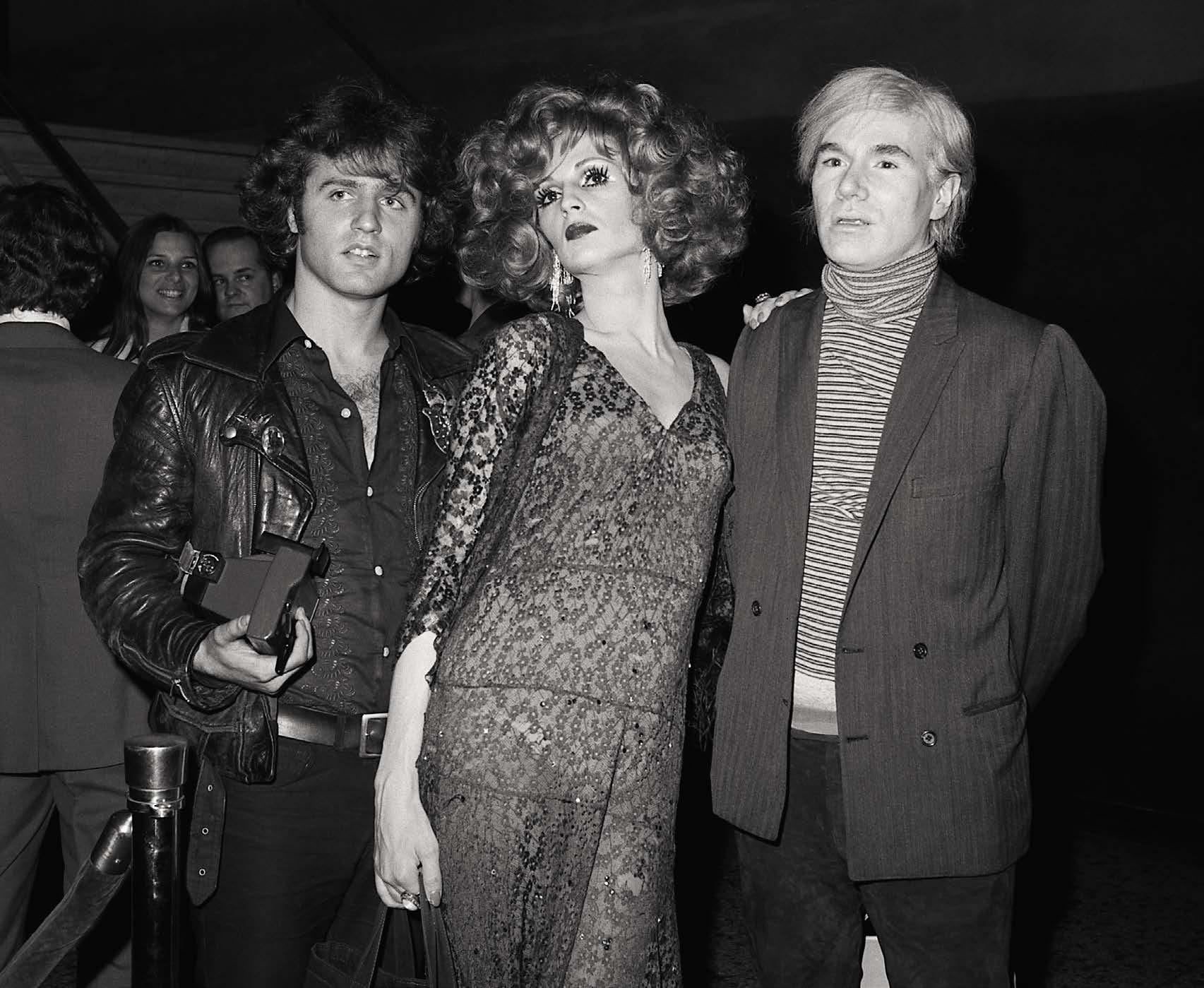

The Art of Biography: Candy Darling

Cynthia Carr’s latest biography recounts the life and work of the Warhol superstar and transgender trailblazer Candy Darling. Here, Carr tells Josh Zajdman about the origins of the book, her process, and what she hopes readers glean from the story.

118

Notes to Selves, Trains of Thought

Dieter Roelstraete, curator at the Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society at the University of Chicago and the coeditor of a recent monograph on Rick Lowe, writes on the artist’s journey from painting to community-based projects and back again in this essay from the publication.

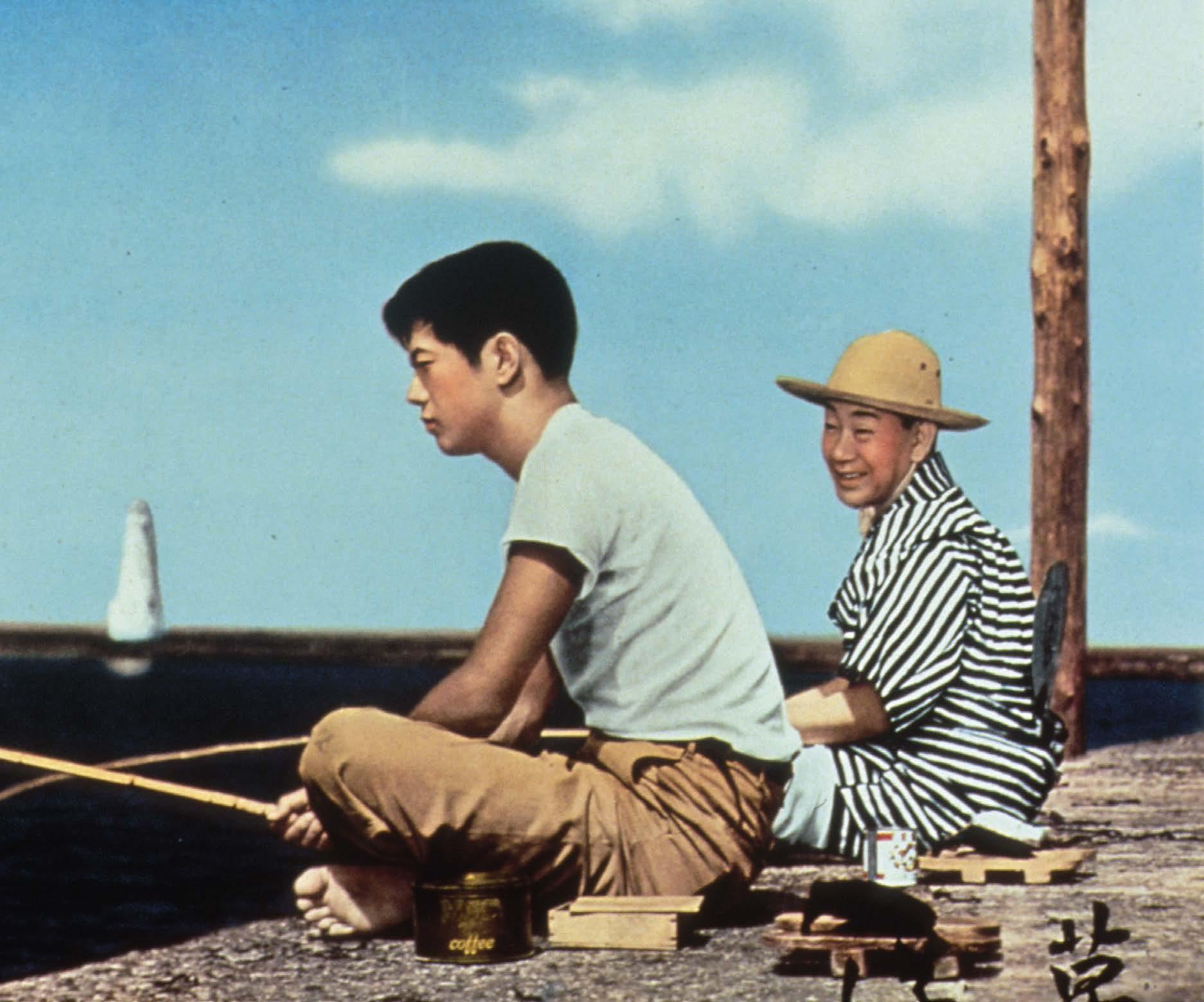

124 Museum of Gestures

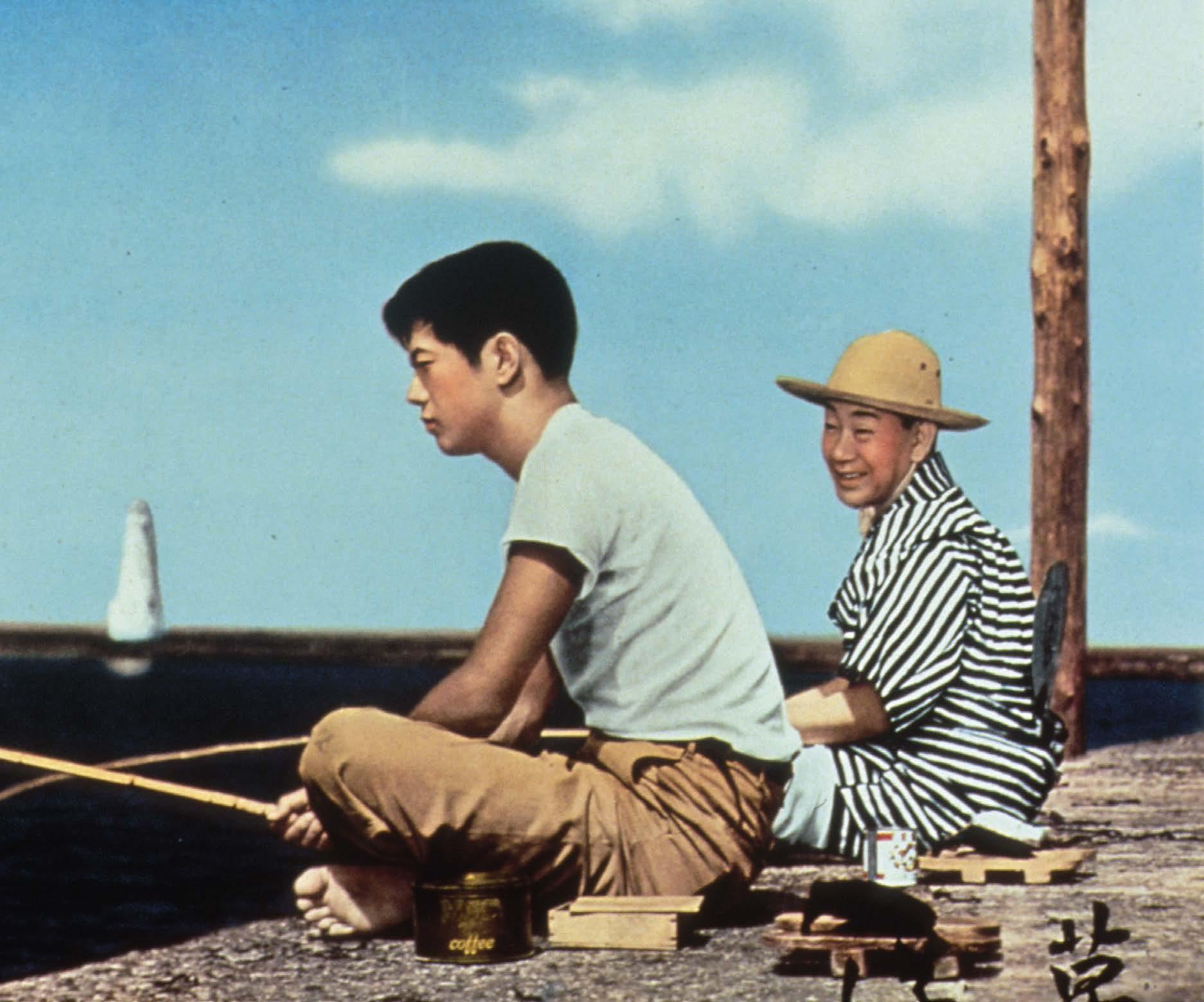

Moeko Fujii joins Carlos Valladares to celebrate a new English translation of Shiguéhiko Hasumi’s Directed by Yasujiro Ozu

130

Prosperity’s Long Song Part II: The Ripening

We present the second installment of a four-part short story by Arinze Ifeakandu.

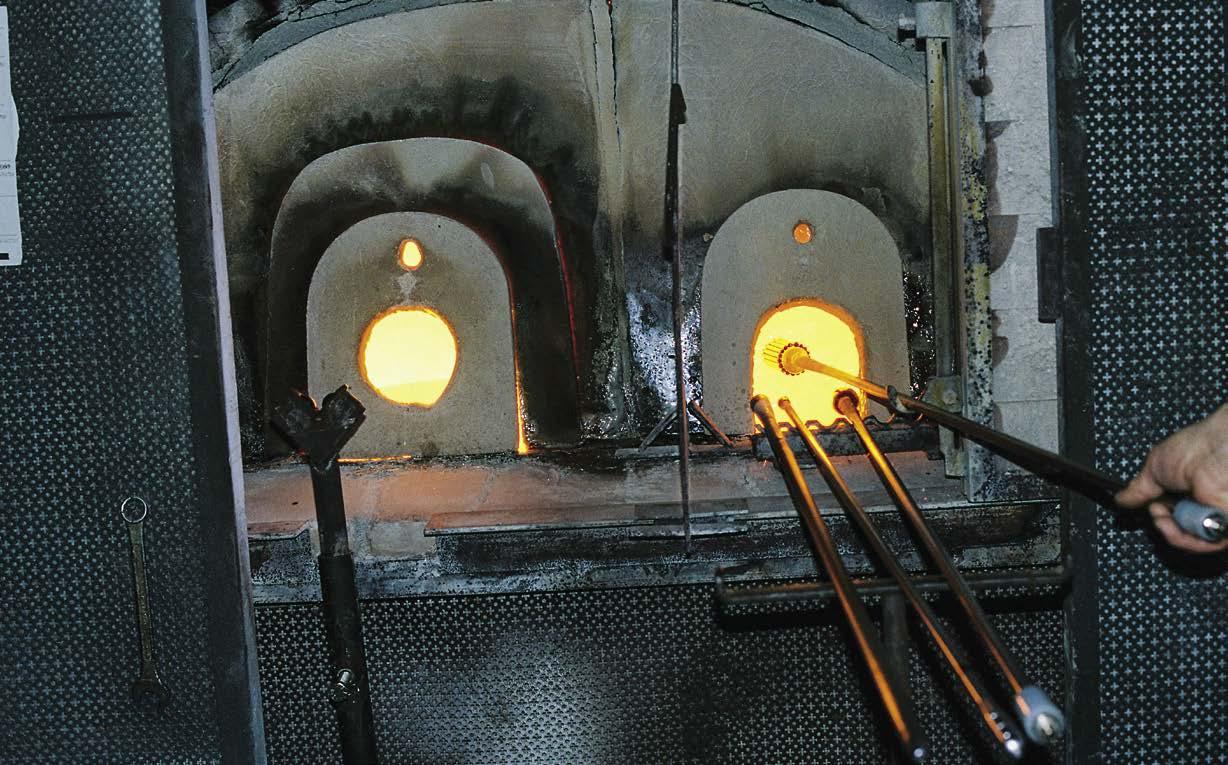

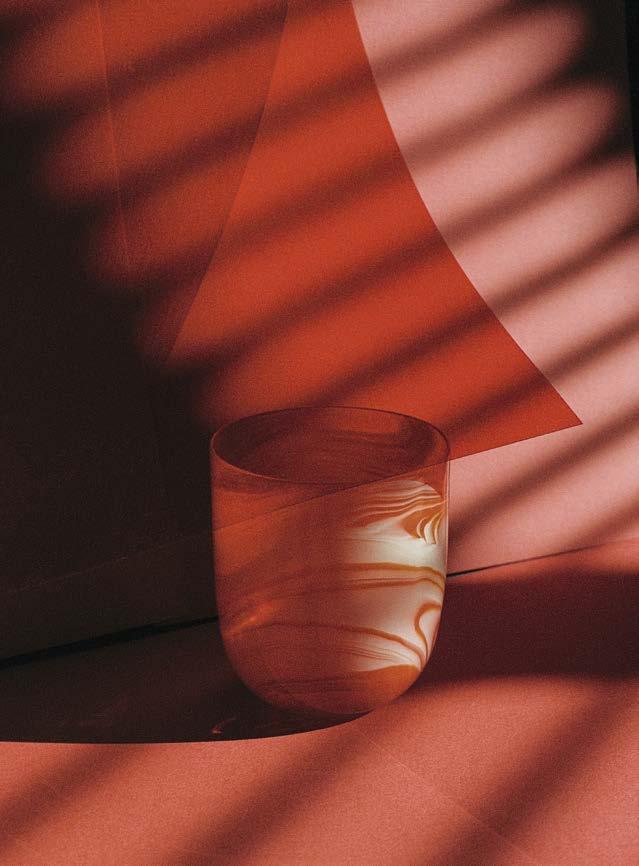

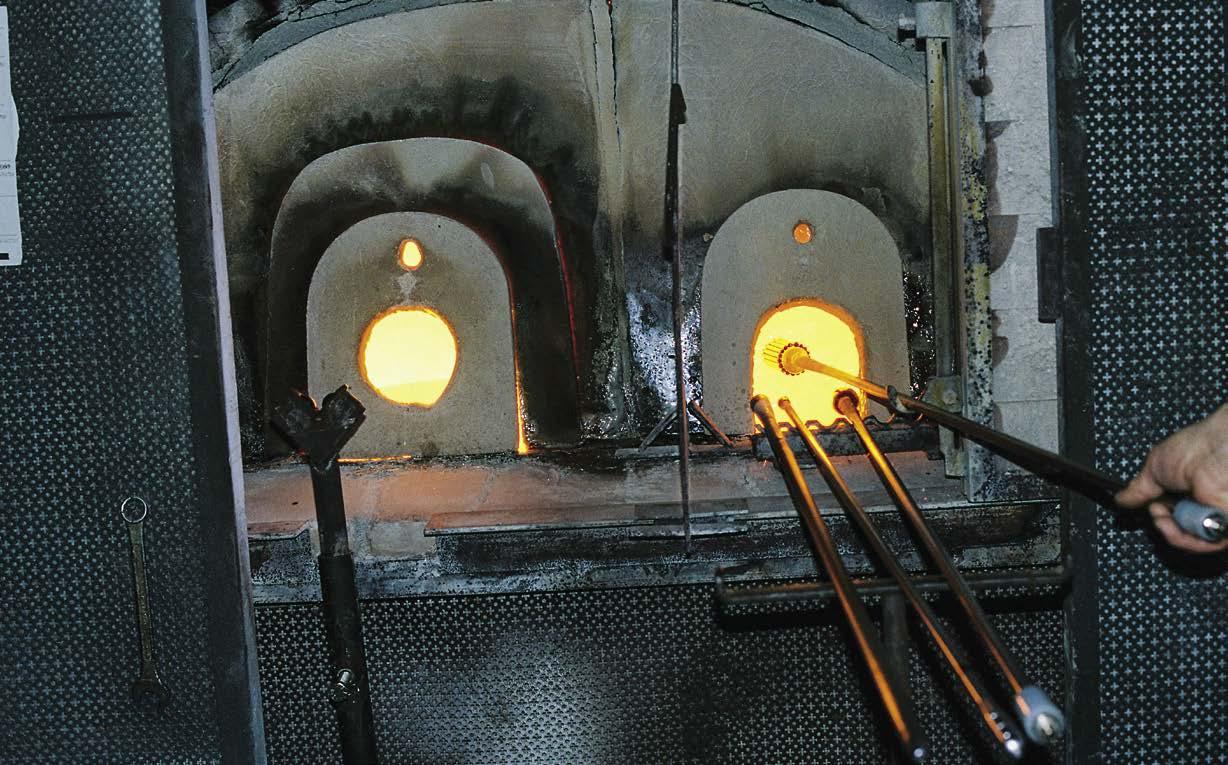

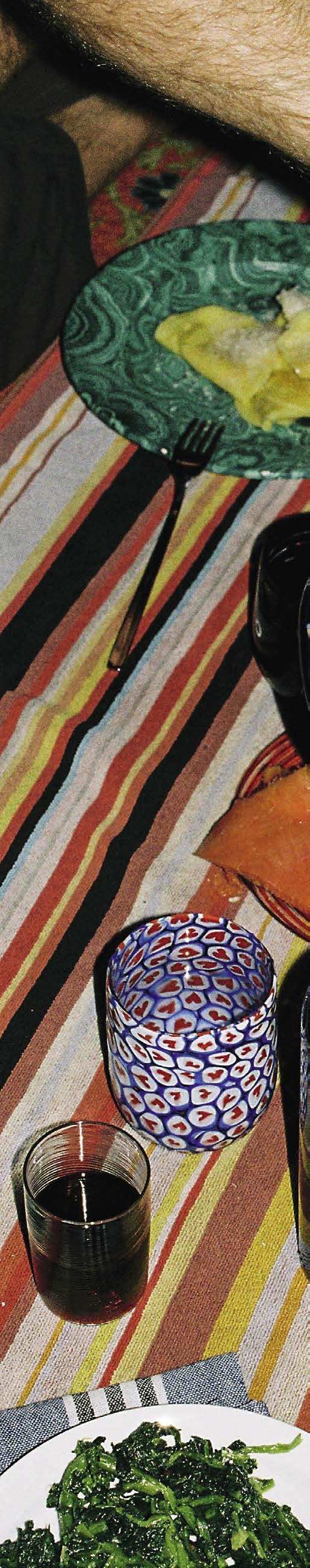

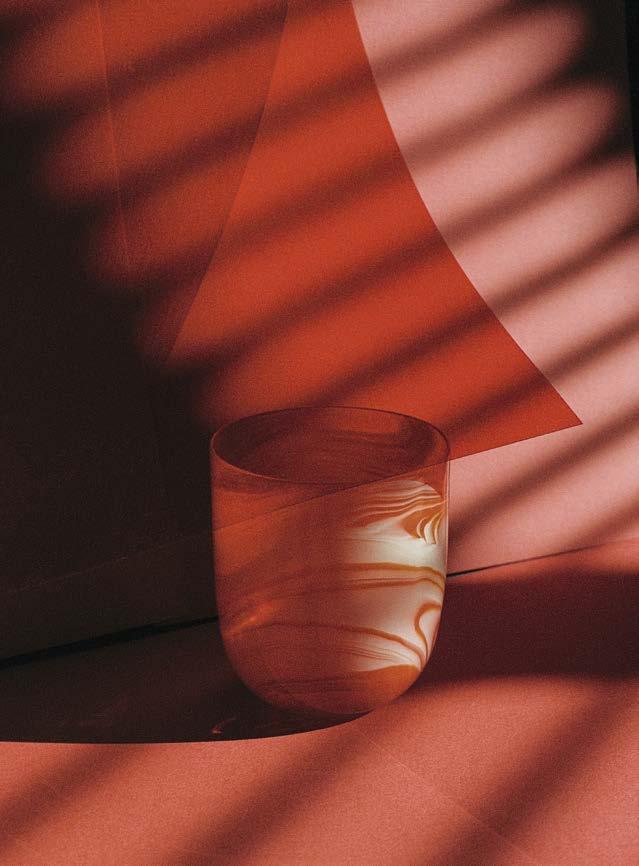

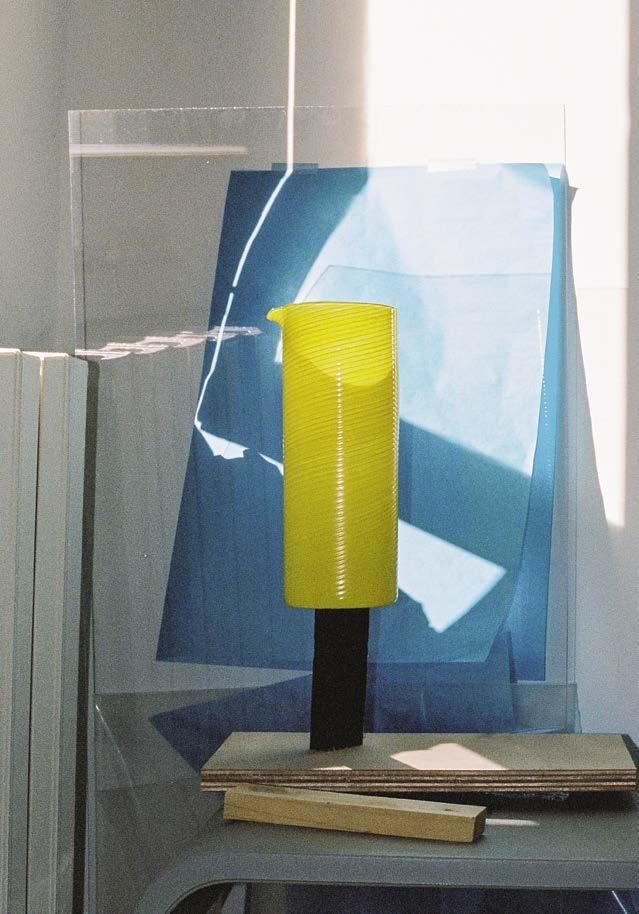

136 Laguna~B

An interview with Marcantonio Brandolini D’Adda, artist, designer, and CEO and art director of the Venice-based glassware company Laguna~B.

142

Building a Legacy: Historic Artists Homes and Studios

Daniel Belasco, executive director of the Al Held Foundation, meets with Valerie Balint, director of Historic Artists Homes and Studios (HAHS), to discuss the importance of preserving and engaging with artists’ personal and creative spaces.

144

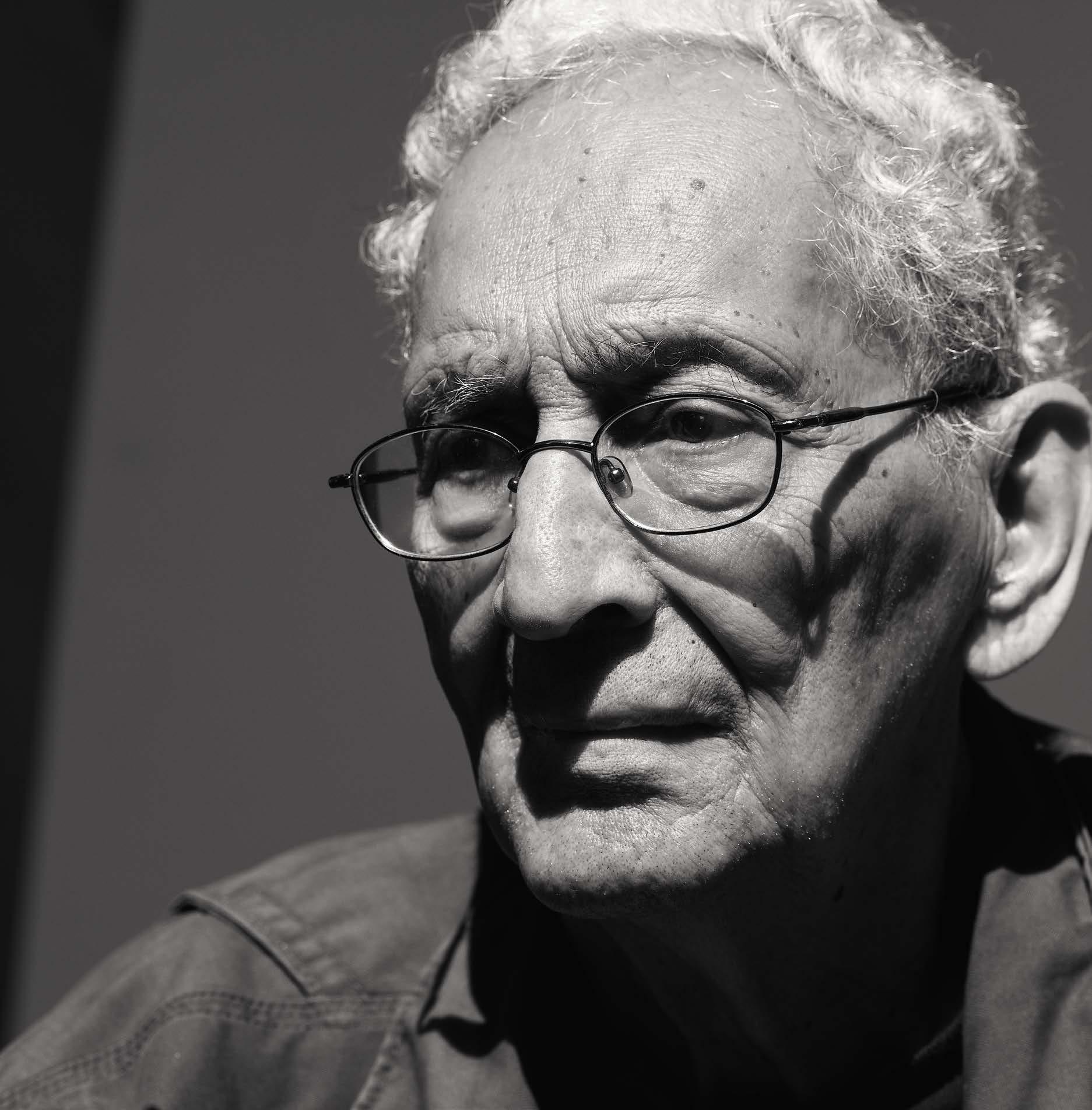

Frank Stella

An interview with Megan Kincaid.

150

Gemma De Angelis Testa

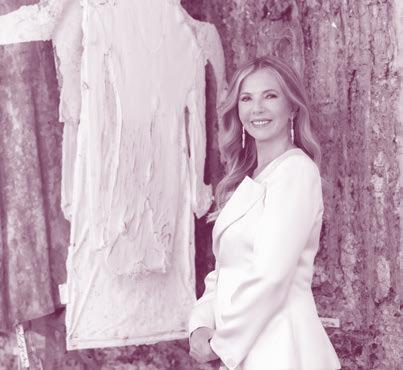

Gemma De Angelis Testa, collector and patron of the arts, met with Gagosian director Pepi Marchetti Franchi to discuss the genesis of her collection, the key role of her organization acacia (Friends of Italian contemporary art association) in enriching the world of contemporary Italian art, and what it means to share one’s collection with the public.

166

Game Changer: Richard Marshall

Alison McDonald celebrates the life of the curator Richard Marshall.

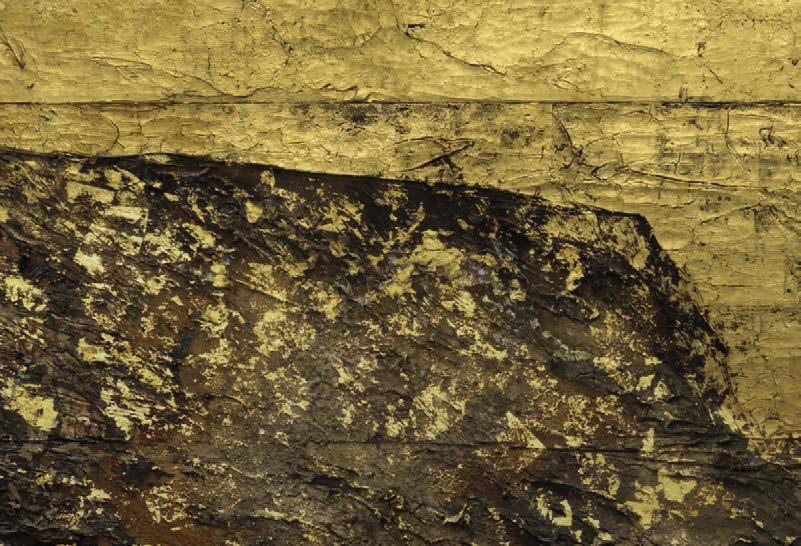

Previous spread, left: Rick Lowe, Untitled , 2023 (detail), acrylic and paper collage on canvas, 48 × 48 inches (121.9 × 121.9 cm) © Rick Lowe

Previous spread, center: Company Wayne McGregor and Paris Opera Ballet in Wayne McGregor’s Tree of Codes , 2015. Photo: Joel Chester Fildes

Previous spread, right: The 1966 Oldsmobile Toronado at the Detroit Auto Show, November–December 1965. Photographer unknown

This page, above: Still from Late Spring (1949), directed by Yasujiro Ozu. Photo: courtesy Janus Films/ The Criterion Collection

This page, left: Siouxsie Sioux, London, 1985 © Richard Haughton/ Bridgeman Images

22

Lauren Elkin

Lauren Elkin’s most recent book is Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art . Other books of hers include No. 91/92: Notes on a Parisian Commute and Flâneuse: Women Walk the City, which was a New York Times Notable Book of 2017 and a finalist for the PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel award for the art of the essay. She lives in London.

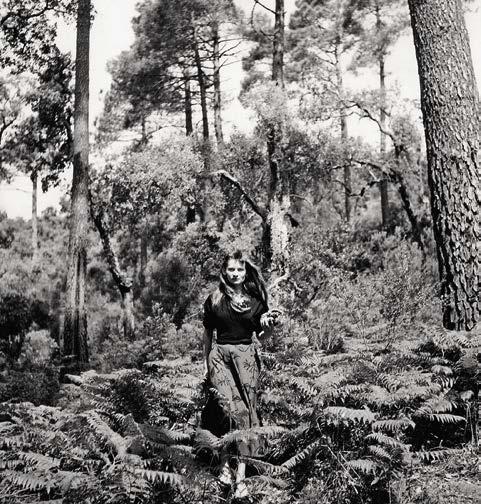

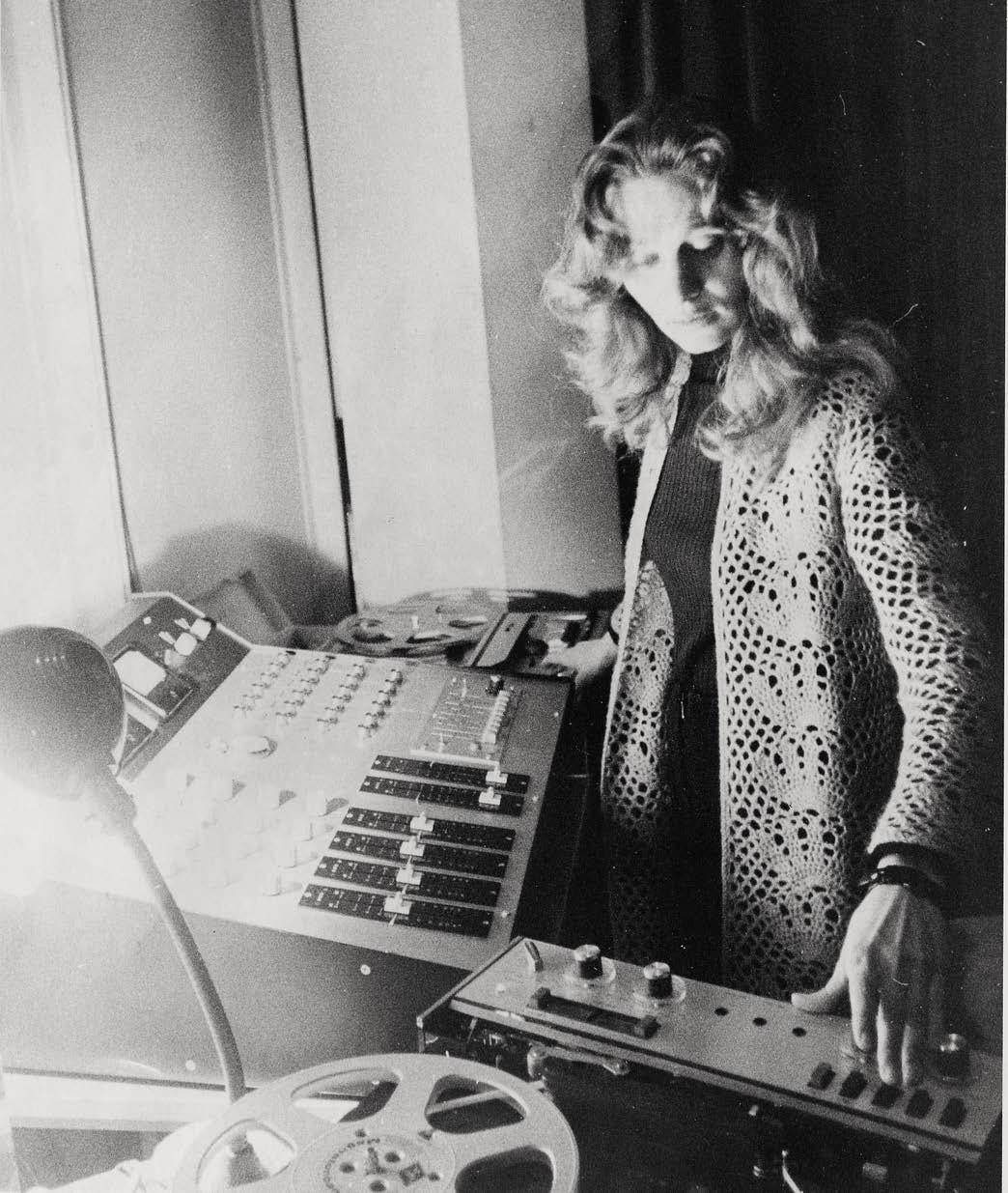

Louise Gray

Louise Gray writes on music and sound art for The Wire and other publications. Her recent writing has focused on ways of listening in the works of Éliane Radigue, Annea Lockwood, and Pauline Oliveros. She teaches the BA and MA Sound Arts courses at LCC, University of the Arts London. Photo: © D. Green

SPRING 2024 CONTRIBUTORS

Nancy J. Troy

Nancy J. Troy is Victoria and Roger Sant Professor in Art Emerita, Department of Art & Art History, Stanford University. She is the author of The De Stijl Environment , Modernism and the Decorative Arts in France: Art Nouveau to Le Corbusier, Couture Culture: A Study in Modern Art and Fashion , and, most recently, The Afterlife of Piet Mondrian

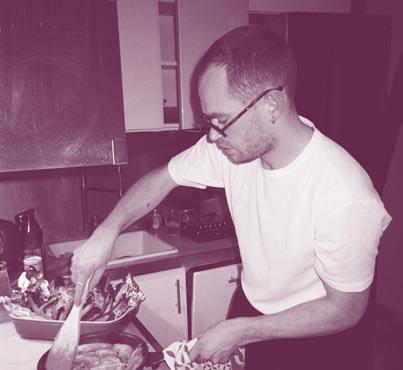

Dan Fox

Dan Fox is a writer, musician, and filmmaker. He is the author of the books Limbo and Pretentiousness: Why It Matters , and co-director of the BBC documentary Other, Like Me: The Oral History of COUM Transmissions and Throbbing Gristle . He is a consulting editor for The Yale Review and lives in New York. Photo: Matthew Porter

Jace Clayton

The artist and writer Jace Clayton is also known for his work as DJ/ rupture. He is the author of Uproot: Travels in 21st-Century Music and Digital Culture and is assistant professor of studio art and director of graduate studies at the Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts, Bard College, New York. Photo: Max Lakner

Ariana Reines

Ariana Reines is a poet, Obie-winning playwright, and performing artist. Her last book, A Sand Book , won the 2020 Kingsley Tufts Prize. Since 2020 she has run Invisible College, a platform for the study of sacred texts and poetry.

Cynthia Carr

Cynthia Carr is the author of Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz , winner of a Lambda Literary Award and a fi nalist for the J. Anthony Lukas Book Prize. Her previous books are Our Town: A Heartland Lynching, a Haunted Town, and the Hidden History of White America and On Edge: Performance at the End of the Twentieth Century Photo: Timothy Greenfield-Sanders

Josh Zajdman

When not writing about books or art, Josh Zajdman is doom-scrolling Instagram or working on his novel.

23

Charlie Fox

Charlie Fox is a writer and artist who lives in London. He wrote the book of essays This Young Monster, directed a music video for Oneohtrix Point Never with Emily Schubert, and curated the twin horror shows My Head Is a Haunted House and Dracula’s Wedding . His fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Dazed , The Paris Review, and the New York Times

Moeko Fujii

Moeko Fujii is an essayist and critic whose work has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books , Criterion , Aperture Magazine , and elsewhere. She currently writes a column on film for Orion Magazine

Mario Codognato

Mario Codognato was the first chief curator of madre , Naples, on its founding in 2005, curating retrospectives of the work of Jannis Kounellis, Rachel Whiteread, Thomas Struth, Franz West, and others there. Beginning in 2016, he was the director of the Anish Kapoor Foundation, and since 2022, the director of the Berggruen Arts & Culture Foundation, both in Venice.

Essence Harden

Essence Harden is the cocurator of Made in LA , 2025, curator of Frieze LA, Focus 2024, and a visual arts curator at the California African American Museum. Photo: Julia Johnson

Alessandro Rabottini

Alessandro Rabottini is an art critic and curator who lives and works between London and Milan. He has been the artistic director of MIART—International Modern and Contemporary Art Fair, Milan—since 2017. Rabottini has curated many exhibitions in European museums and institutions.

Gary Garrels

Gary Garrels is an independent curator who lives and works on the North Fork of Long Island. He previously held curatorial positions at the Dia Art Foundation, New York; the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; and the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Lauren Halsey

Lauren Halsey is rethinking the possibilities for art, architecture, and community engagement and producing both stand-alone artworks and sitespecific projects. Combining found, fabricated, and handmade objects, her work maintains a sense of civic urgency and free-flowing imagination, reflecting the lives of the people and places around her and addressing the crucial issues confronting people of color, queer populations, and the working class. Photo: Czariah Smith

Oscar Murillo

Born in La Paila, Colombia, Oscar Murillo emigrated to the United Kingdom with his family as a child. He studied at the Royal College of Art in London, working as an office cleaner to support himself. On graduating in 2012, Murillo quickly developed a reputation for his stitched paintings; since then, his work has expanded to include drawings, sculptures, installations, films, and performances, all guided by his fascination with the fluid concepts of identity, community, and the binary. Photo: Tim Bowditch

26

Hans Ulrich Obrist

Hans Ulrich Obrist is artistic director of the Serpentine, London. He was previously the curator of the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Since his first show, World Soup (The Kitchen Show), in 1991, he has curated more than 350 exhibitions. Photo: Tyler Mitchell

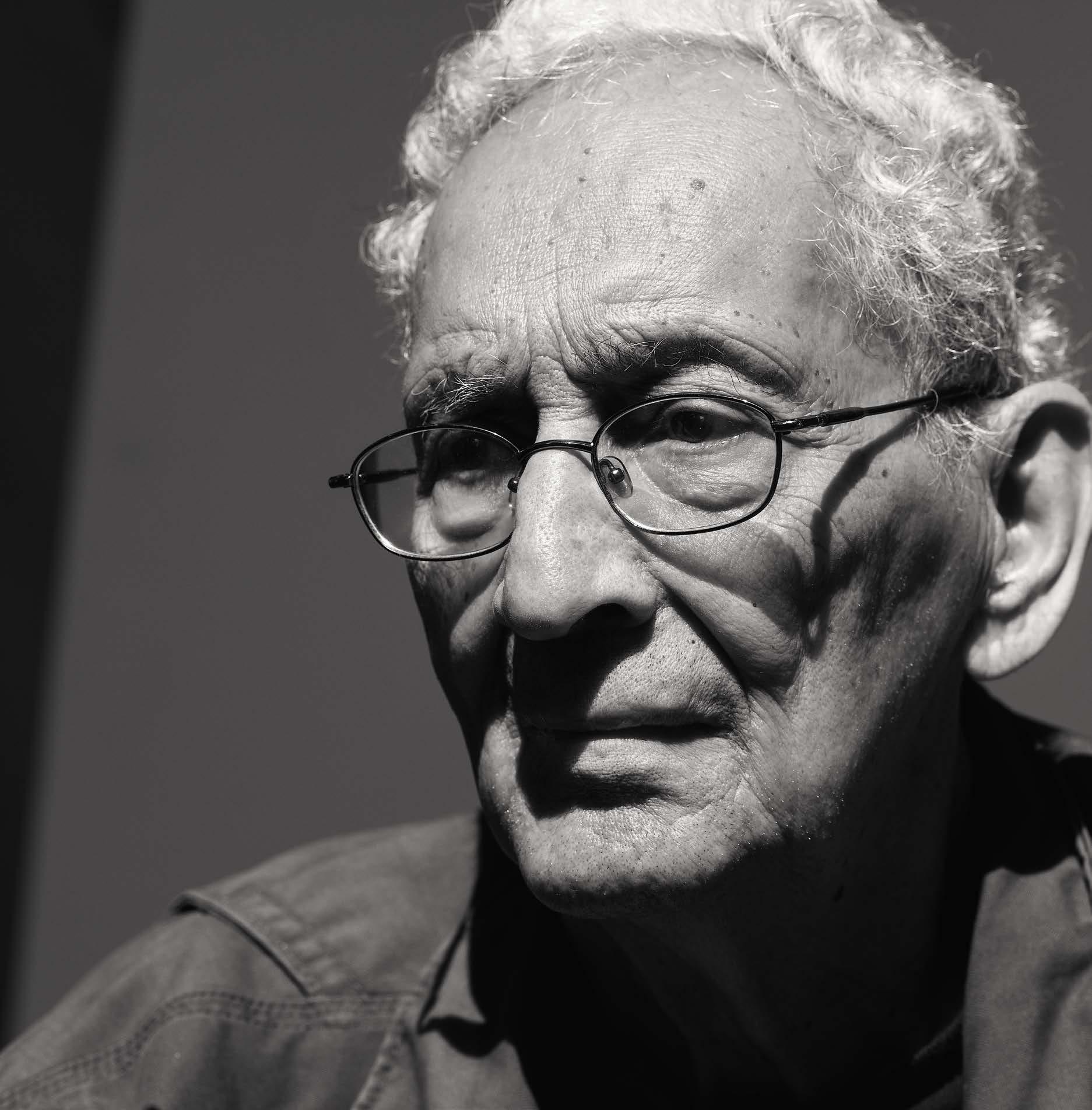

Gemma De Angelis Testa

Gemma De Angelis Testa is a collector of contemporary art and the widow of the artist and graphic designer Armando Testa. Since his death she has promoted and curated several exhibitions, as well as founding acacia (Associazione Amici Arte Contemporanea) in 2003, establishing a new form of collective patronage.

Pepi Marchetti Franchi

Founding director of Gagosian, Rome, Pepi Marchetti Franchi has overseen more than sixty exhibitions at the gallery since 2007. Raised in Rome, she has spent many years in New York, including eight years working at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. She is the vice president and cofounder of ITALICS.art.

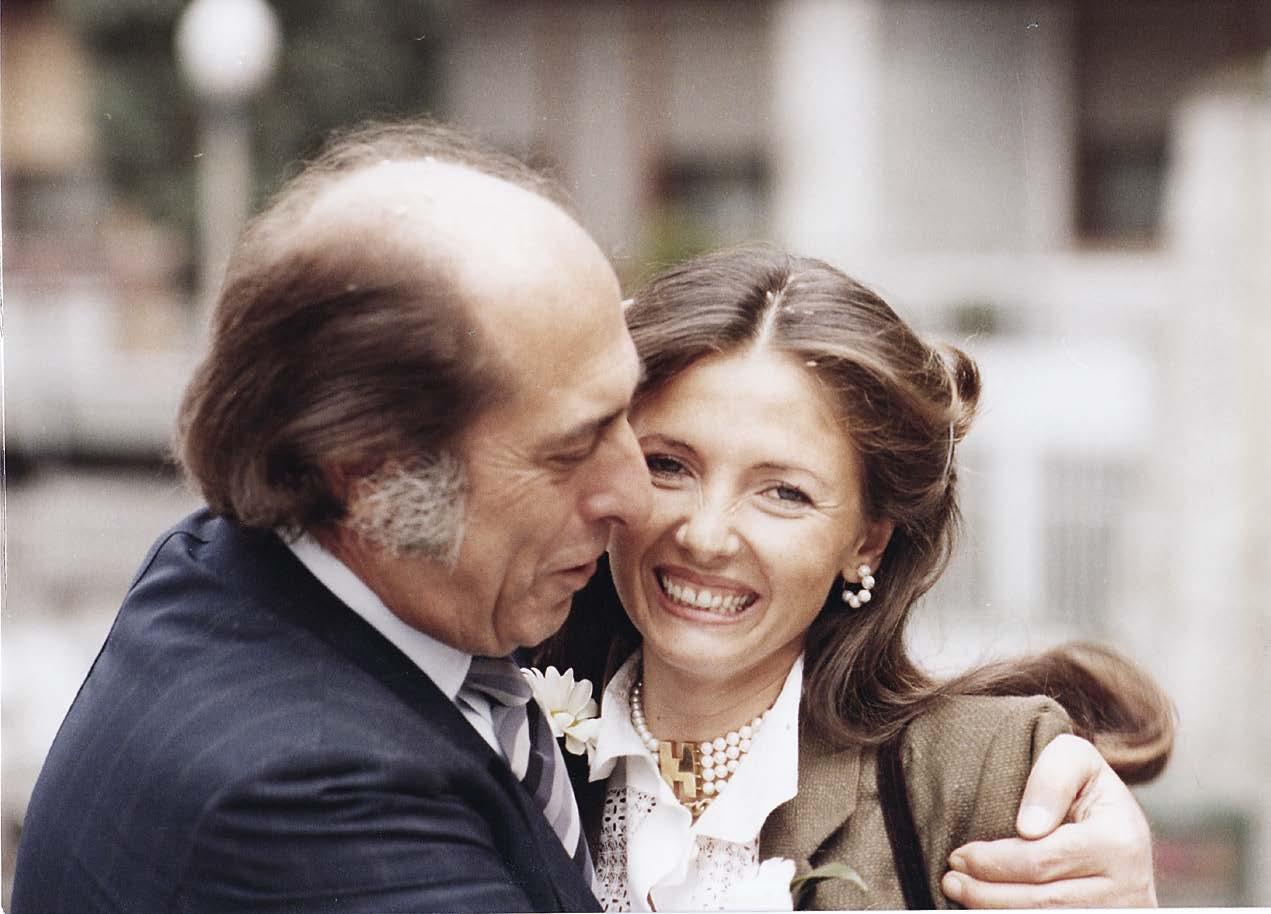

Young Kim

Young Kim is a writer who works in art, fashion, film, music, and literature while managing the estate of Malcolm McLaren, her late boyfriend and creative/business partner. Her first book, A Year on Earth with Mr. Hell (2020), is distributed by Omnibus Press. She is currently finishing a book on her years with McLaren and lives between Paris and New York.

Photo: Penny Slinger/Young Kim

Carlos Valladares

Carlos Valladares is a writer, critic, programmer, journalist, and video essayist from South Central Los Angeles. He studied film at Stanford University and began his PhD in the history of art and film and media studies at Yale University in the fall of 2019. He has written for the San Francisco Chronicle , Film Comment , and the Criterion Collection. Photo: Jerry Schatzberg

John Elderfield

John Elderfield is chief curator emeritus of painting and sculpture at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and was formerly the inaugural Allen R. Adler, Class of 1967, Distinguished Curator and Lecturer at the Princeton University Art Museum. He joined Gagosian in 2012 as a senior curator for special exhibitions.

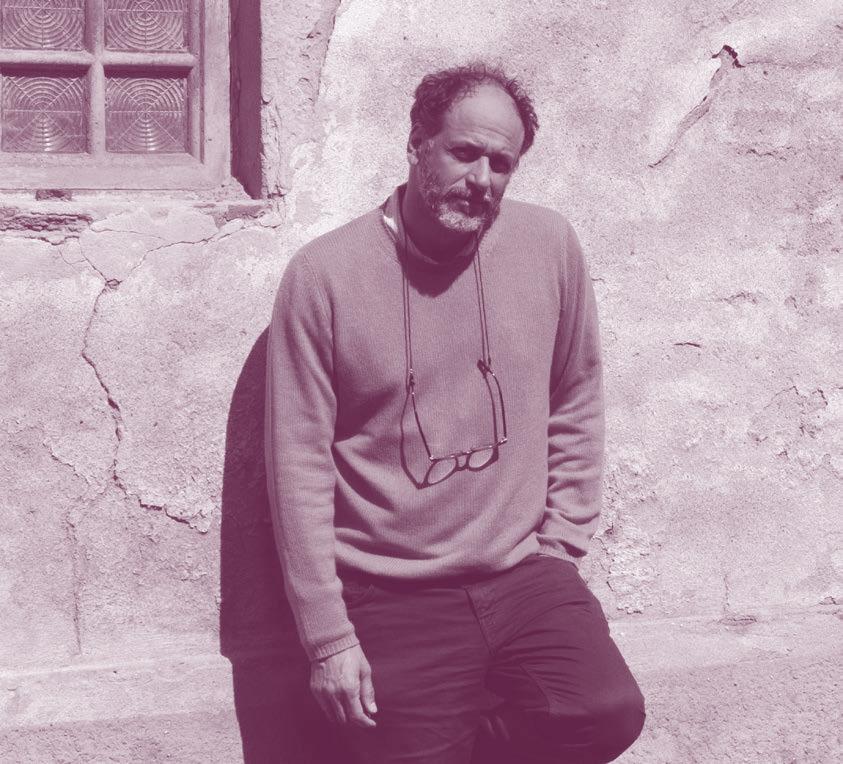

Luca Guadagnino

Luca Guadagnino was born in Palermo on August 10, 1971, to a Sicilian father and an Algerian mother. He is a director, producer, screenwriter, architect, and designer. An Academy Award nominee in 2018 and winner of the Silver Lion for Best Director at Venice Film Festival in 2022, he lives in Milan. Photo: Giulio Ghirardi.

Francesco Bonami

Francesco Bonami has curated more than 100 exhibitions, including the Venice Biennale in 2003 and the Whitney Biennial in 2010. He writes for La Repubblica , Artnews , and Vogue Italia . His most recent books include Post: L’opera d’arte nell’epoca della sua riproducibilità sociale and Mum, I Want to Be an Artist: How to Avoid Delusions (forthcoming).

27

Derek Blasberg

Derek Blasberg is a writer, fashion editor, and New York Times bestselling author. He has been with Gagosian since 2014 and is the executive editor of Gagosian Quarterly

Dieter Roelstraete

Dieter Roelstraete is the curator for the Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society at the University of Chicago, where he has organized exhibitions on Gelitin, Rick Lowe, Pope.L, Martha Rosler, and, most recently, Christopher Williams. Photo: Richard Pilnik

Megan Kincaid

Megan Kincaid is an art historian and curator. Kincaid has taught on modern art and critical theory at New York University and her scholarship has been published by the Museum of Modern Art, Duke University Press, and others. In May 2024 she will receive her PhD in art history from the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. She holds a BA from Columbia University.

Dhruva Balram

Dhruva Balram is a writer, editor, and creative producer. He is the cofounder of Dialled In, a South Asian–focused arts-and-culture grassroots organization. Balram coedited the book Haramacy and contributes to various online and print outlets.

Karla Hiraldo Voleau

Karla Hiraldo Voleau is a FrenchDominican artist and photographer. Through projects combining performance and photography, she often explores contemporary notions of intimacy, love, and the female gaze. Photo: © Jasmine Deporta

Marcantonio Brandolini d’Adda

Marcantonio Brandolini d’Adda is an Italian artist, designer, entrepreneur, and CEO and art director of Laguna~B. Photo: Karla Hiraldo Voleau

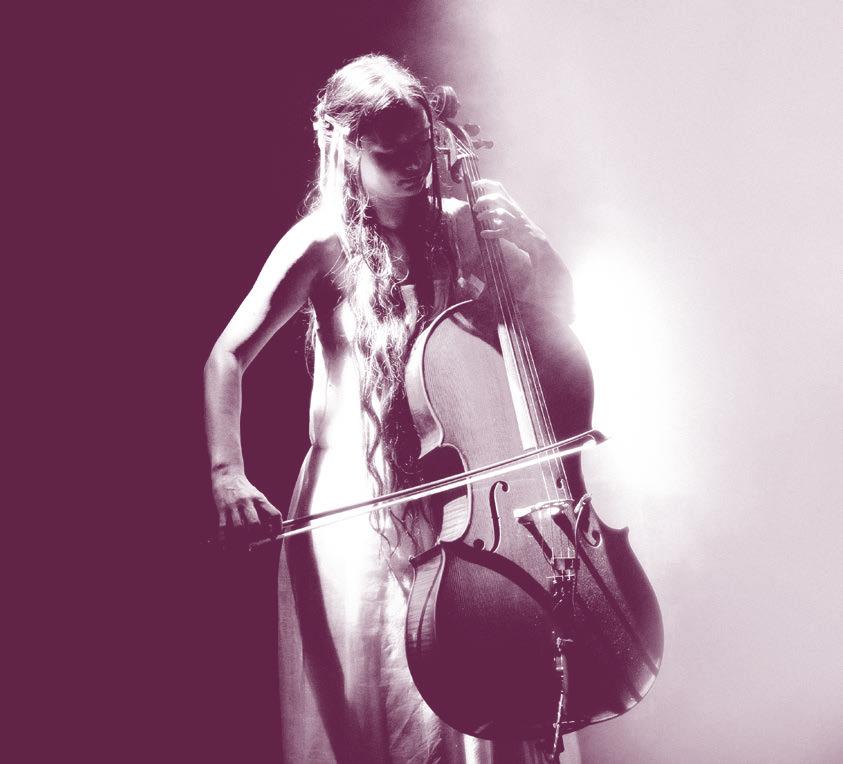

Lucinda Chua

Lucinda Chua is a London-based multi-instrumentalist, singer, songwriter, and composer. Her critically acclaimed debut album yian came out in 2023 and she performed songs from it, accompanied by the London Contemporary Orchestra, at the Barbican, London, this May.

Arinze Ifeakandu

Arinze Ifeakandu is the author of God’s Children Are Little Broken Things , which received the 2023 Dylan Thomas Prize, the Story Prize Spotlight Award, and the 2022 Republic of Consciousness Prize, and was a finalist for the 2022 Lambda Literary Award for Gay Fiction, the Kirkus Prize, and the CLMP Firecracker Award for Fiction. Photo: Bec Stupak Diop

28

Valerie Balint

Valerie Balint is the director of Historic Artists Homes and Studios (HAHS), a program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and author of Guide to Historic Artists Homes and Studios . Before heading HAHS, she served for seventeen years on the curatorial staff, most recently as interim director of collections and research, at Olana.

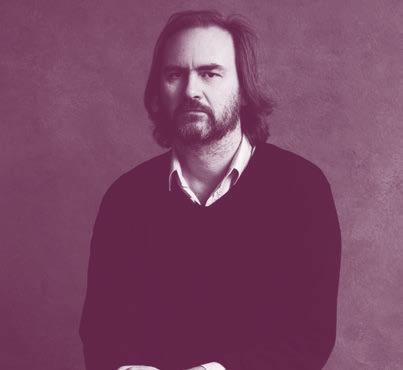

Harry Thorne

Harry Thorne is a writer and an editor at Gagosian. He lives in London.

Lauren Mahony

Lauren Mahony is a director in the publications department at Gagosian, where she has worked on exhibitions and publications devoted to Willem de Kooning, Helen Frankenthaler, Brice Marden, and David Reed, among others, since 2012. She previously worked as a curatorial assistant in the department of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Michael Cary

Michael Cary organizes exhibitions for Gagosian, including eight Picasso exhibitions in collaboration with John Richardson and members of the Picasso family. He joined Gagosian in 2008 after six years working with the late Kynaston McShine, then chief curator at large at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Alice Godwin

Alice Godwin is a British writer, researcher, and editor based in Copenhagen. An art-history graduate from the University of Oxford and the Courtauld Institute of Art, she penned an essay for the exhibition catalogue Damien Hirst: Fact Paintings and Fact Sculptures and has contributed to publications including Wallpaper, Artforum , Frieze , and the Brooklyn Rail

Daniel Belasco

Daniel Belasco is an art historian and curator. Executive director of the Al Held Foundation since 2016, he has discussed a variety of issues pertaining to artists’ legacies in conferences, symposia, and industry meetings. He is a trustee of the Association of Art Museum Curators Foundation.

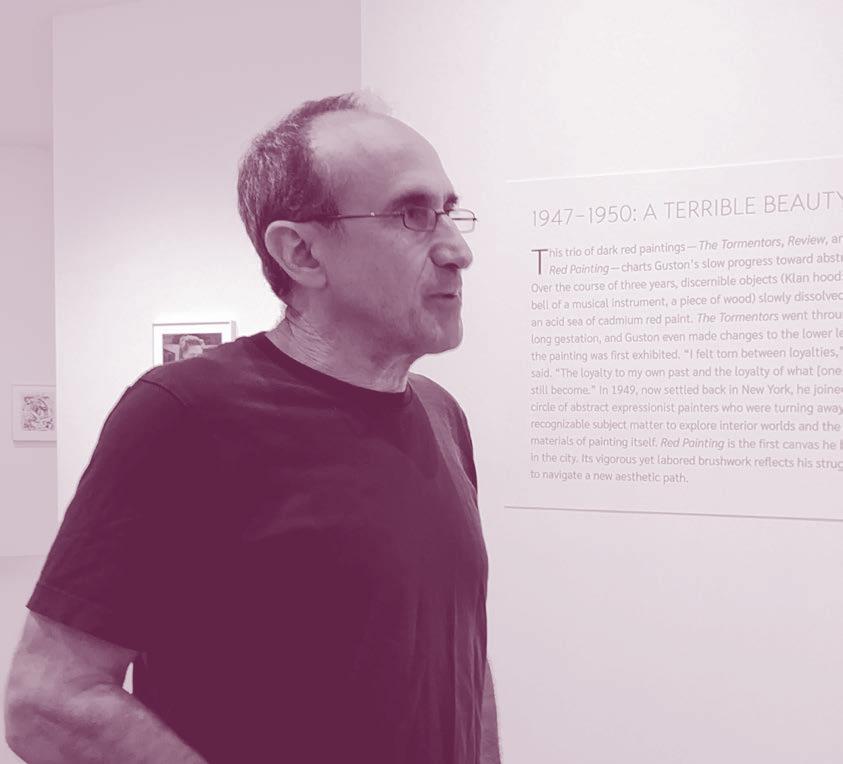

Harry Cooper

Harry Cooper was just appointed Bunny Mellon Curator of Modern Art at the National Gallery of Art, having served as head of modern and contemporary art there for the past sixteen years. His last exhibition, Philip Guston Now, appeared in Boston and Houston as well as Washington before concluding its run earlier this year at Tate Modern. An active writer, he has focused on issues of form and experience as well as word and image in the paintings of Stuart Davis, Juan Gris, Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly, Piet Mondrian, and Ed Ruscha, among others.

Wayne McGregor

Wayne McGregor CBE is a multi-award-winning British choreographer and director renowned for innovations that have redefined dance in the modern era. His touring company, Company Wayne McGregor, celebrated its thirtyyear anniversary in 2023. McGregor is also resident choreographer at the Royal Ballet, London, and director of dance for the Venice Biennale. He is regularly commissioned by dance companies around the world and his works are danced in their repertories. He choreographed ABBA Voyage , a concert that brought the ’70s pop group back onstage in a performance by virtual avatars. Photo: Pål Hansen

30

IN SEASON

Gagosian Quarterly presents a selection of new releases and events coming this summer.

Librairie Saint Laurent Babylone

Located at 9 rue de Grenelle, Paris, Saint Laurent Babylone is the newest project launched by the brand’s creative director, Anthony Vaccarello. Offering a carefully curated collection of books, art, and music, the store pays tribute to the past—with a nod to Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé’s ties to the SévresBabylone neighborhood, while providing a space for cultural events like author readings, signings, and DJ sessions for visitors today.

Below: Raven Halfmoon, Weeping Willow Women , 2022, ceramic and glaze, 7 ¼ × 4 ½ × 7 ¼ inches (18.3 × 11.7 × 18.3 cm).

Exhibition Loewe Foundation

Craft Prize 2024

From May 19–June 9, 2024, at Palais de Tokyo, Paris, the Loewe Foundation will exhibit work by the thirty finalists for their annual prize. The finalists, representing sixteen countries, work across a range of mediums, including ceramics, woodwork, textiles, furniture, paper, basketry, glass, metal, jewelry, lacquer, and leather.

32

Left: Interior of Saint Laurent Babylone, Paris. Photo: courtesy Saint Laurent

Photo: courtesy Loewe Foundation

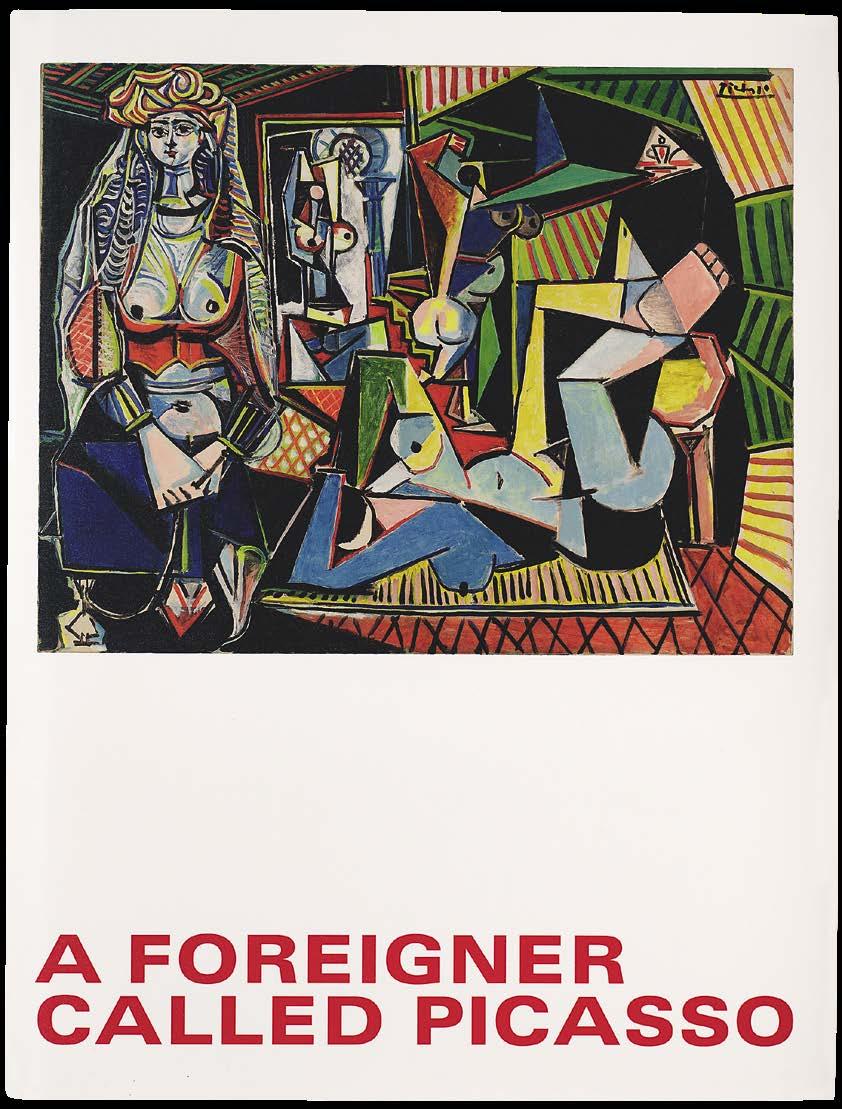

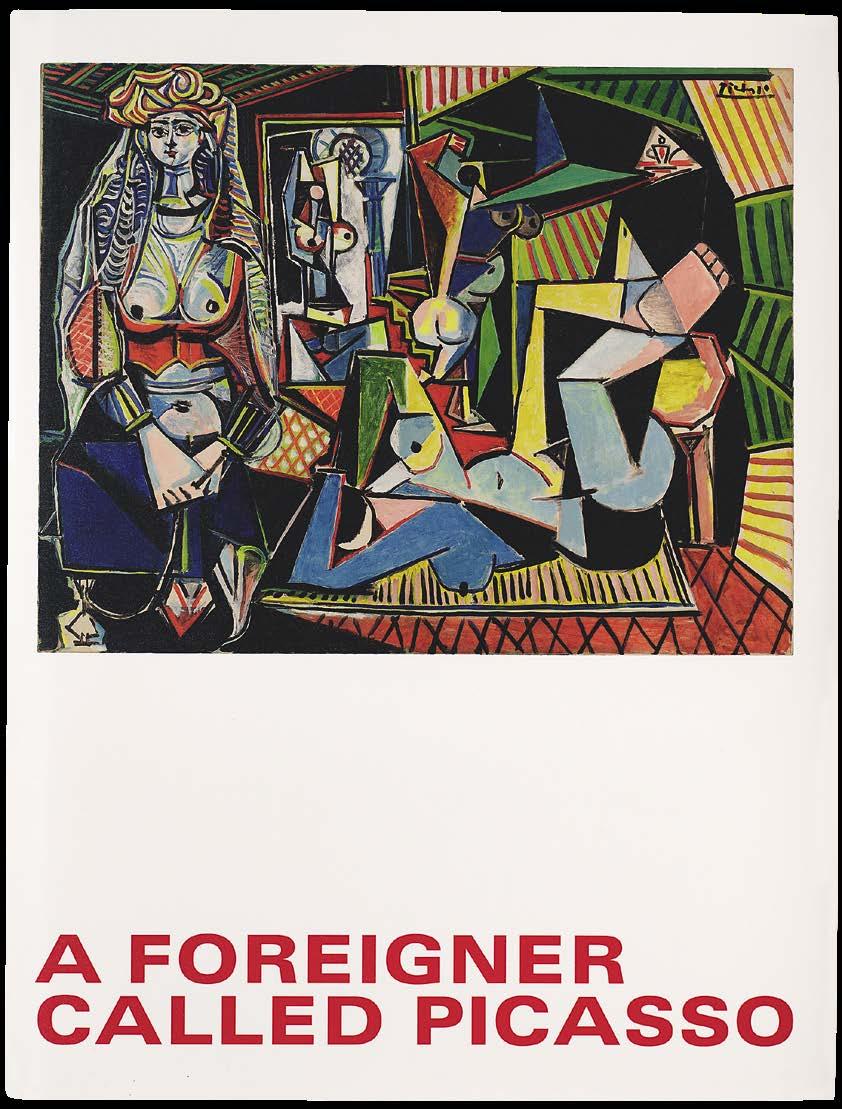

Exhibition Catalogue A Foreigner Called Picasso: Volume 1

This book was published on the occasion of A Foreigner Called Picasso at Gagosian, New York. Curated by Annie Cohen-Solal and Vérane Tasseau, the exhibition was organized in association with the Musée national Picasso–Paris and the Palais de la Porte Dorée–Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration, Paris. Spanning the entirety of Pablo Picasso’s career in France from 1900 through 1973, A Foreigner Called Picasso reframes our perception of Picasso with a focus on his status as a permanent foreigner in France. This volume includes an introduction by Larry Gagosian; a conversation between Cohen-Solal, Cécile Debray, director of Musée national Picasso–Paris, and Constance Rivière, director of the Palais de la Porte Dorée; and a text by Paloma Picasso. This publication is the first volume of a planned two-volume boxed set, with the second volume to include essays by the curators and contributions from leading international scholars— including Picasso experts, social scientists, and intellectuals at large— to further explore the important new perspectives opened up by this exhibition.

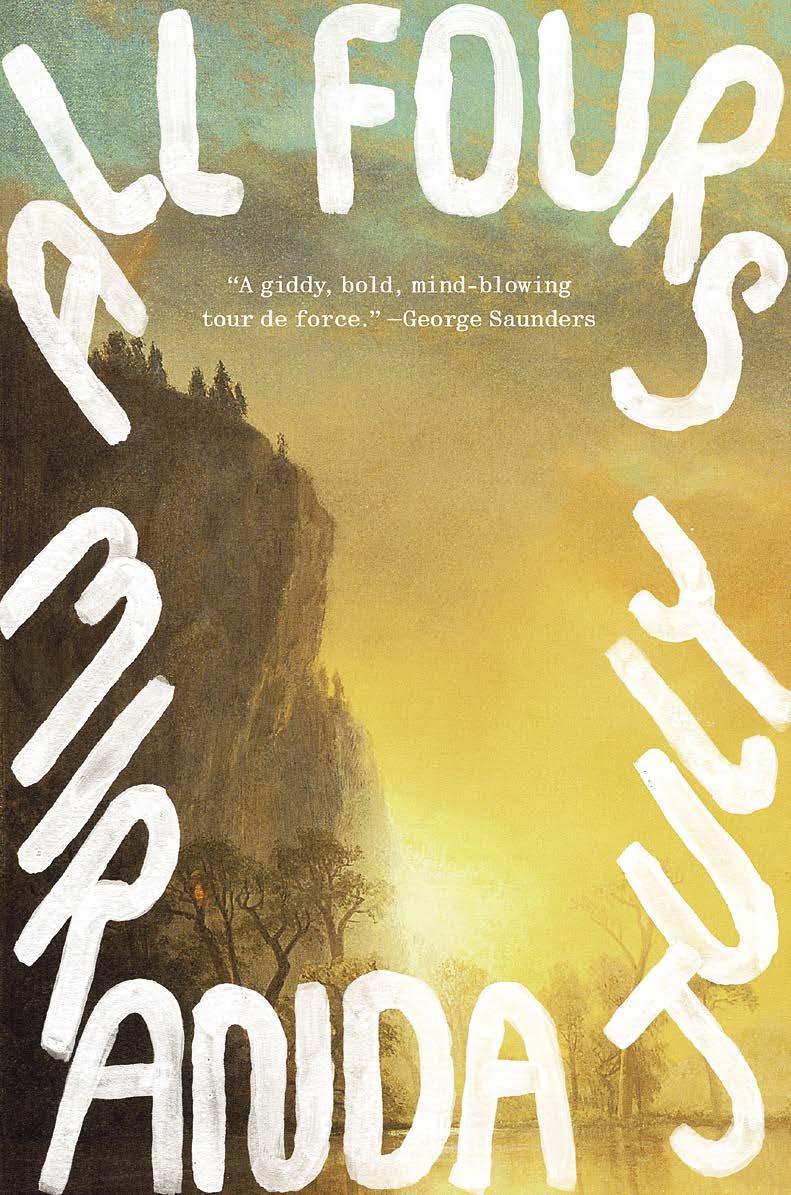

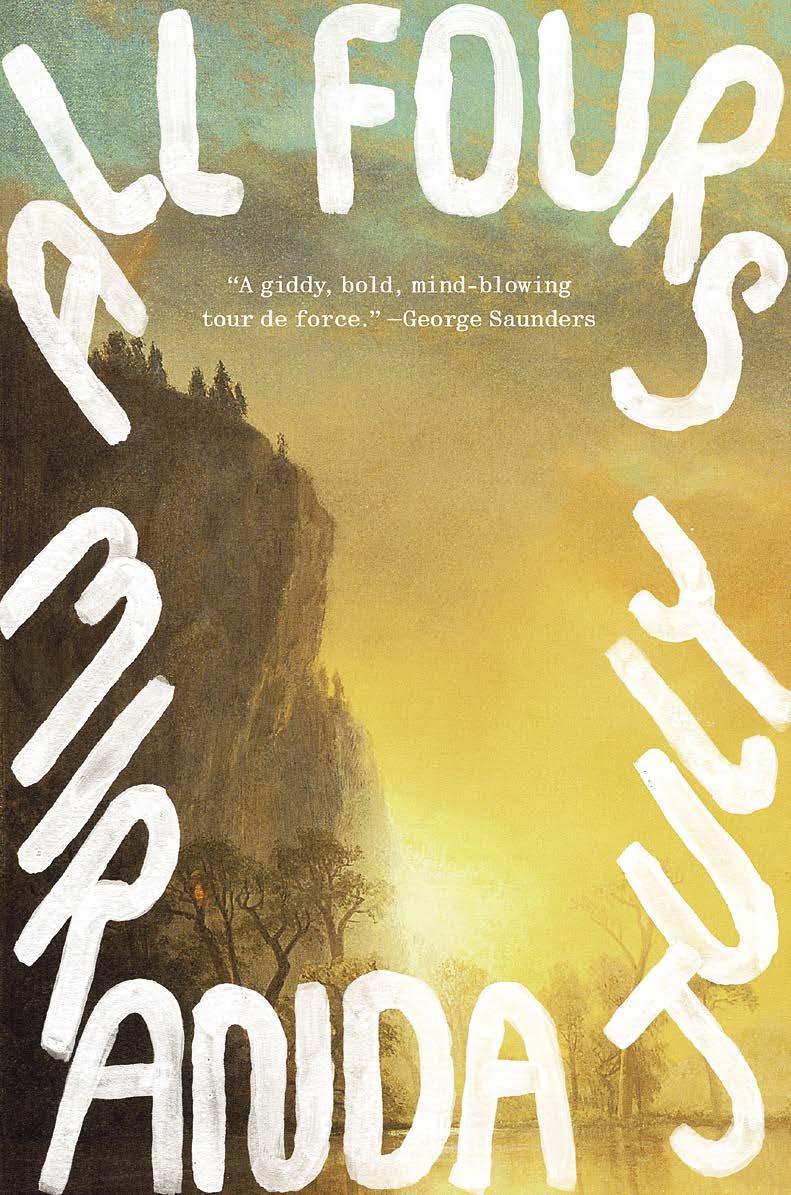

Novel Directions All Fours by Miranda July

The multihyphenate Miranda July returns with a new novel that pulses with intimacy and vulnerability in a manner characteristically her own. With every chapter, the life of the protagonist, a middle-aged artist and mother, veers in unanticipated directions on the wings of desire as she changes plans, holes up in a motel, gets dressed, and grapples with being known.

Left: Cover of A Foreigner Called Picasso: Volume 1 (Gagosian, 2024)

Right:

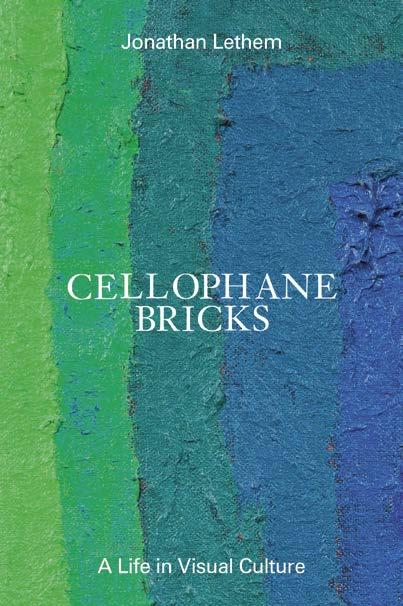

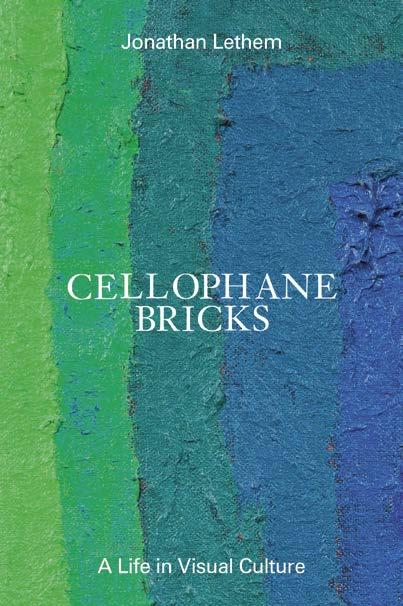

Cover of Jonathan Lethem’s Cellophane Bricks: A Life in Visual Culture (ZE Books, 2024)

Below:

Cover of Miranda July’s All Fours (Riverhead, 2024)

Essays on Art Cellophane Bricks: A Life in Visual Culture by Jonathan Lethem

Celebrated novelist Jonathan Lethem grew up in a world defined by visual culture—from a childhood in his father’s painting studio to his own education in art school—before finding his vocation in writing. In this collection of personal and critical essays, Lethem experiments with the genre of art-writing.

34

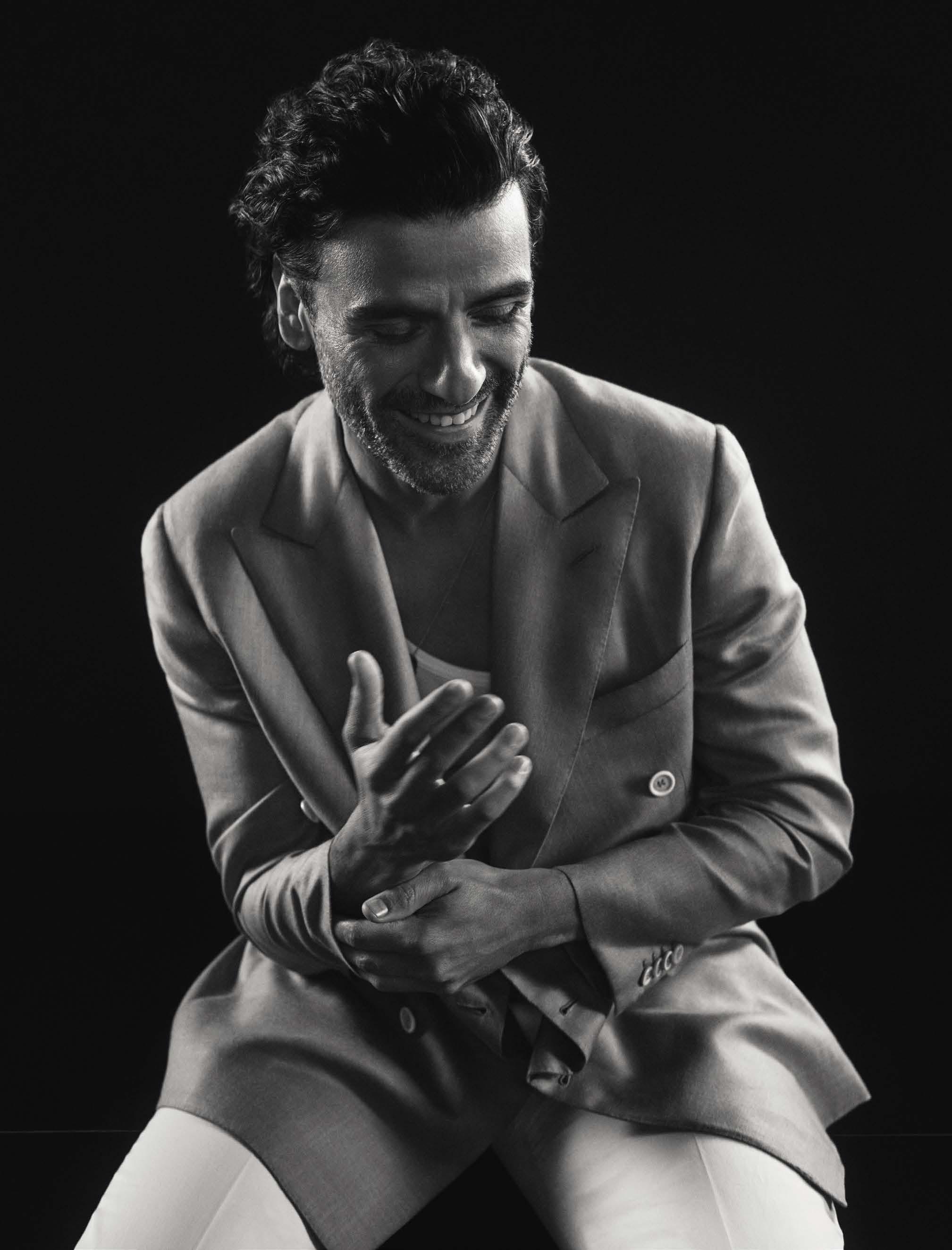

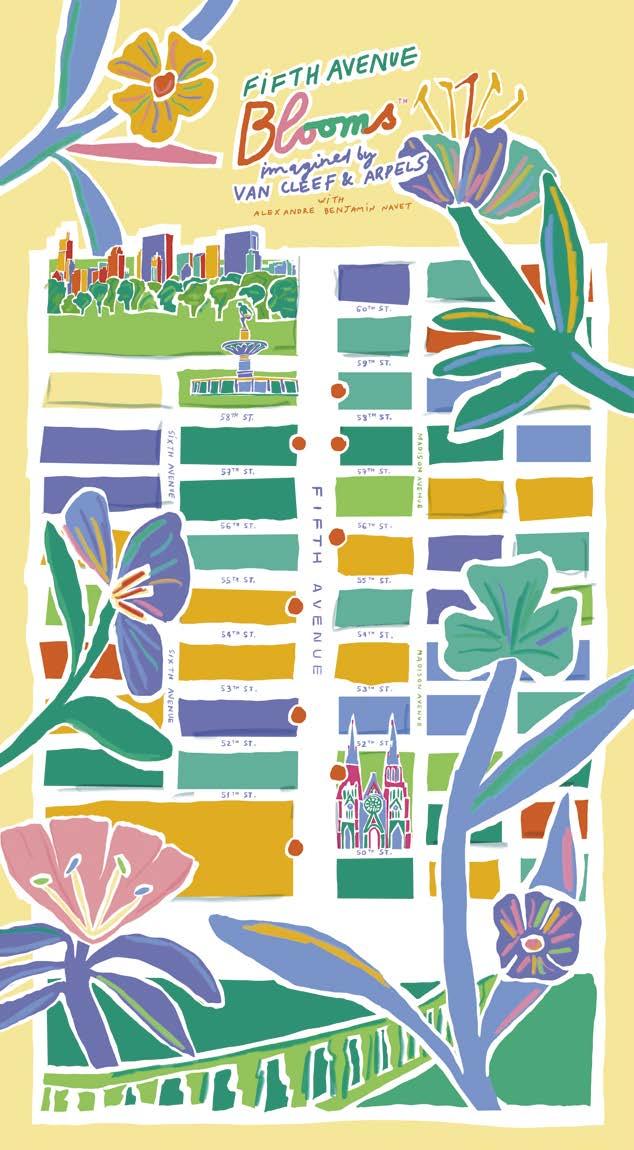

Urban Flowers Fifth Avenue Blooms, imagined by Van Cleef & Arpels

Through May 31, Van Cleef & Arpels has teamed up with French artist Alexandre Benjamin Navet to create colorful, sculptural installations that showcase flowers on the sidewalks of New York. The third consecutive year of this initiative will engage further sensorial elements, creating an unfolding garden with day-to-night visibility.

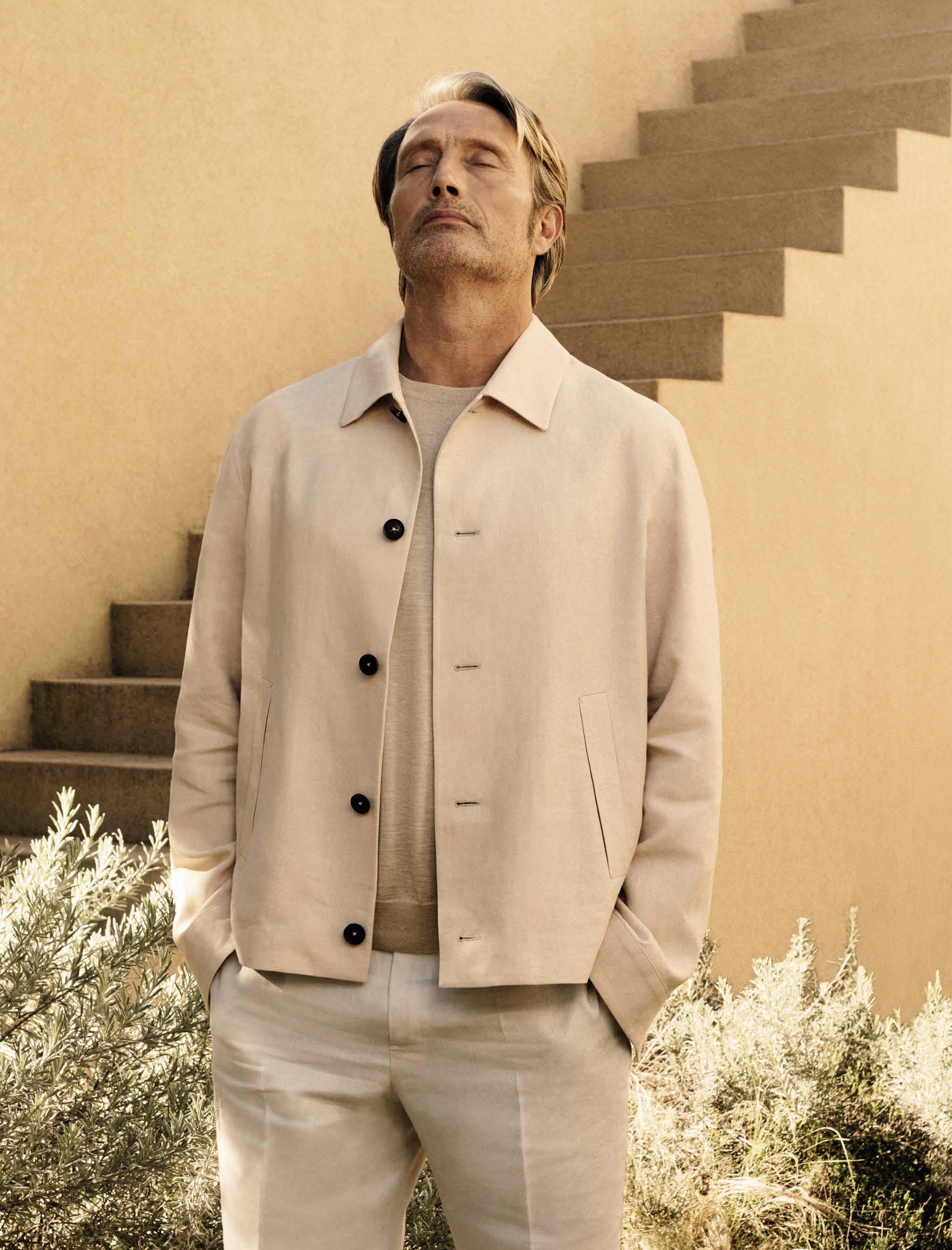

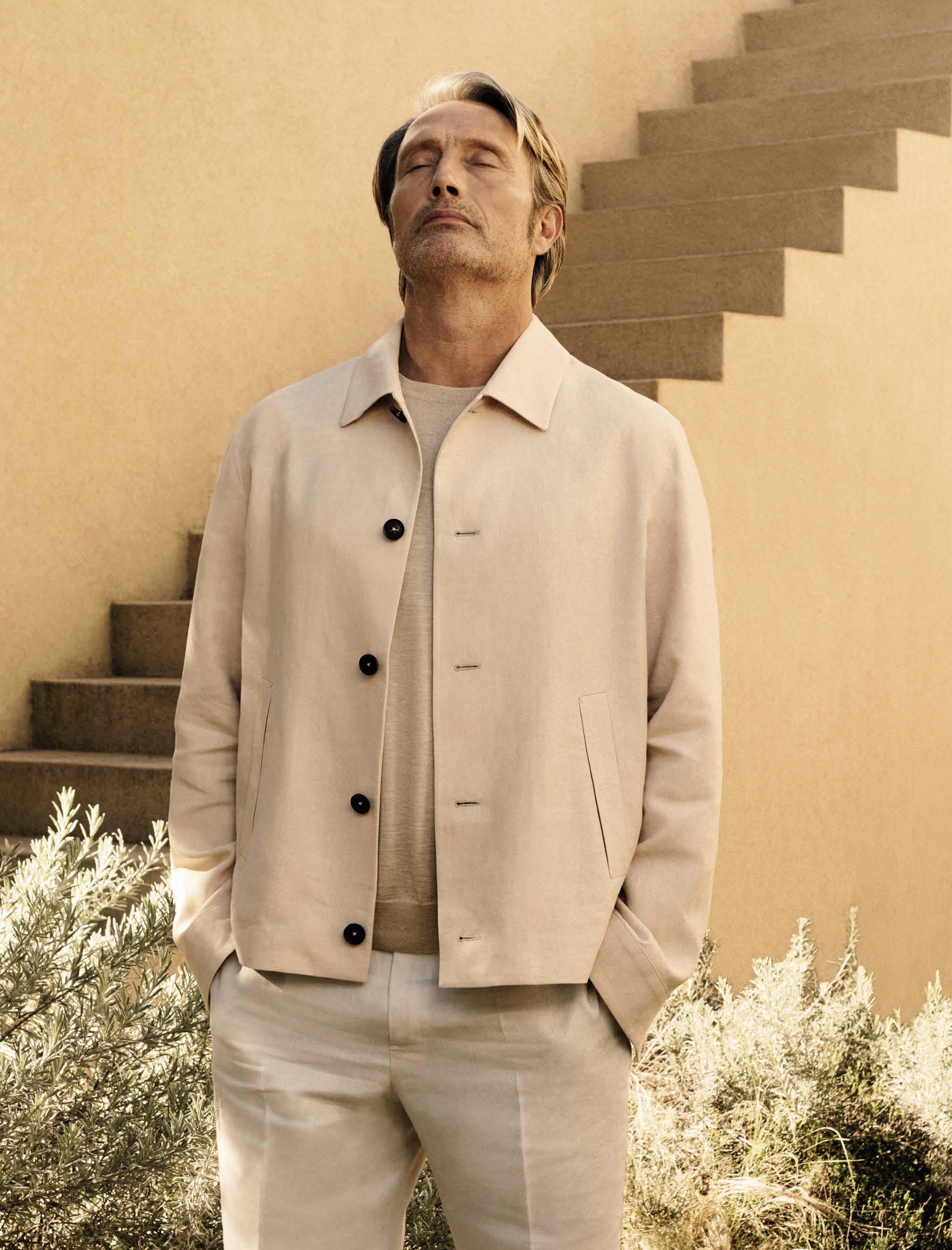

Tailor Made Born in Oasi Zegna

The result of a collaboration between Italian luxury brand Zegna, Rizzoli, the creative direction of Laura Decaminada, and text by Chidozie Obasi, this elaborate book evokes the richness of sensations that have come to define Zegna. Centering Oasi Zegna, the free-access natural territory established by the brand’s founder and maintained by his descendants in the Italian Alps, the book avoids biography and chronology, instead utilizing vivid imagery and poetic texts to celebrate this unique ecosystem.

Left: Image courtesy Van Cleef & Arpels

Right: Cover of Mary Ann Caws’s Symbolism, Dada, Surrealisms: Selected Writing of Mary Ann Caws (Reaktion Books, 2024)

Below: Cover and slipcase of Born in Oasi Zegna (Rizzoli, 2024)

Art History Symbolism, Dada, Surrealisms:

Selected Writing of Mary Ann Caws

For the centennial of the Surrealist movement, professor and author Mary Ann Caws returns with a compendium of essays that portray the key artists, writers, and artworks that came to define the avant-garde. From Antonin Artaud to Unica Zürn, the gathered texts paint a magic-infused portrait of these visionaries.

36

Visual Culture Black Meme: The History of the Images That Make U s by Legacy

Russell

Legacy Russell’s much-anticipated follow up to Glitch Feminism (2020) invites readers to think more critically about the semiotics and histories undergirding contemporary visual culture, from reaction gifs to viral memes. Behind the seemingly playful, Russell uncovers a brutal legacy of racism and exploited Black labor and pain.

Photobook United Kingdom by

Martin Parr

The newest installment of Éditions Louis Vuitton features the work of photographer Martin Parr, who brings his distinctive style to documenting the United Kingdom. From weddings to the Glastonbury Festival to the island’s shores and villages, the portfolio of images, taken between 1998 and today, showcases the faces and places that compose the country.

Left: Cover of Legacy Russell’s Black Meme: The History of the Images That Make Us (Verso, 2024)

Right: “Jean-Michel Basquiat: Venta Plate,” produced by Ligne Blanche, 2012

Below: Martin Parr’s United Kingdom (Éditions Louis Vuitton, 2024)

Jean-Michel Basquiat: Venta Plate

Produced by Ligne Blanche in Paris in collaboration with the Estate of JeanMichel Basquiat, this Limoges porcelain plate reproduces Basquiat’s painting The Mechanics That Always Have a Gear Left Over (1988).

38

Art at Home

1 Lonnie Holley’s AKA (two words)

6 The Starry Night backdrop

8 Mai

10 Painter of Discovery of the Body of St. Mark 11 Nicholas II, for example

12 Westminster or Fontenay 14 Egyptian cross 16 Summer cooler

18 Fruit captured in a Claude Monet painting, 1883

CROSSWORD

19 Houston’s Project Row Houses creator (two words)

Raise 23 Biographer of 49 across, Cynthia

Characteristic

Pronounced

Oism inventor Jim

Japanese Neo-Pop artist Yoshitomo 33 Out limb (two words)

Was ahead

Marina Rey, Ca.

Beatles label, once

Infrared, abbr.

Warhol superstar Candy

1 Painter of Pesaro Madonna

2 Elevates

3 Earlier

4 Occupation of David Guetta and Calvin Harris

5 “If the is concealed, it succeeds”: Ovid

6 Posed for a painting

7 Trevor Horn won a Grammy as the producer of this Seal song (four words)

9 Artist who used the soak-stain technique,

13 Desert plants with sword-shaped leaves

15 Vienna Secessionist

17 Draw roughly 20 Rhein II photographer

21 Titian’s Bacchus and 24 Managed

26 Contemporary American artist who uses architecture and installation art to demonstrate the realities of urban neighborhoods, Lauren

28 Dr (rapper)

30 You and I

32 Fashion house that created pieces inspired by Pablo Picasso’s original Tanagra ceramics

35 Contemporary artist who painted White Canoe

38 Compass point, abbr.

41 Mineo of Rebel without a Cause

42 Set up

45 Doctor title

40 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49

Down

together clues from the worlds of art, dance, music, poetry, film, and beyond.

This customized puzzle, written by Myles Mellor, brings

Across

27

36

37

40

43

44

46

47

48

49

Solution

22

25

29

31

34

For sure 39 Oprah’s network

Spartan

Half

Essential

Leave

An exhibition of new work by Maurizio Cattelan opened in New York earlier this spring. Curated by Francesco Bonami, this was the first solo presentation of new work by the artist in the city in over twenty years. Here, Bonami asks us to consider Cattelan as a political artist, detailing the potent and clear observations at the core of these works.

Maurizio Cattelan Sunday Painter

Frank and Jamie (2002): it sounds like Abbott and Costello or Laurel and Hardy. Since it is actually a sculpture by Maurizio Cattelan, the simile isn’t strange, for people often find his work slapstick and funny. In fact nothing could be farther from the truth. Cattelan is a political artist at heart—not in the vein of Hans Haacke or Barbara Kruger but more like Aristotle, a sort of craftsman of social issues and ultimately of social and collective feeling. His political stance is not moralistic, accusatory, or preachy; he presents the issues as they are, or as a general public could perceive them.

Frank and Jamie are two policemen, leaning upside down against a wall. They were the first work Cattelan showed in New York after 9/11 and his last in any private space in the United States, in that case the Marian Goodman Gallery, until this spring. Far from being funny, the two figures are a symbol of power subverted—the Twin Towers in human form. The work shows how contemporary history, or its chronicle, influences our understanding of the world and our daily life; how we deal daily with power without running the risk of having our lives disrupted by it.

Cattelan doesn’t really seek answers. As Marcel Duchamp used to say, “There are no solutions because there are no problems.” There are no answers because there are no real questions—life is what it is, unraveling under our feet. In our delusional state, we might wish we could change it, but we can’t. After Frank and Jamie came the triumph of the retrospective at the Guggenheim, New York, in 2012, to be followed by America (2016), the gold toilet installed in the museum at the mercy of the visitors’ number 1’s and 2’s, according to the need. The natural heir of Duchamp’s 1917 Fountain , America

made the cover of the New York Post , but the subtext was loaded: Donald Trump soon became president of the United States, making America rather more than a childish and expensive commentary on a world of luxury gone adrift.

While Cattelan’s infamous banana taped to the wall is called Comedian (2019), and a recent variation, a taped empty banana skin, is called Clown (2023), Cattelan is neither a comedian nor a clown but a combination of the two that produces a dramatic character, a kind of Robin Williams of art history, trapped in a body and fighting his true inner self. The result of this inner fight is a body of work that defies the conventional understanding of art, since it always refers to something outside the art world, even if art-world professionals can’t help but draw connections to other artists, from arte povera to Lucio Fontana. Such references are certainly possible, but are unintended and often serendipitous.

Besides being a closet political artist, Cattelan is also a bard of what I call “recreational violence,” or “RV.” Violence, like politics, is an intrinsic part of his language and philosophy, if often camouflaged under a veneer of humor. The new body of work is the logical expression of what was hidden in the too-obvious America : luxury and privilege can’t shield you from violence, articulated as some sort of ultimate entertainment, or the revenge of boredom and social resentment. You may be able to afford and enjoy making your daily no. 2 on a solid-gold toilet, but that pleasure can’t save you from someone with an assault rifle coming into your bathroom to interrupt your bowel movement.

Seen from a distance, that could be very funny. Charlie Chaplin used to say, “Life is a tragedy when

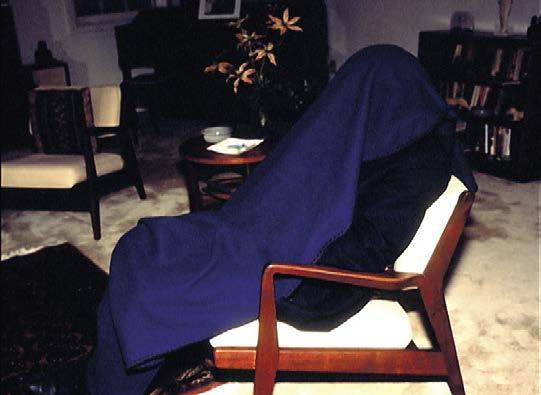

Previous spread: Photo: courtesy Maurizio Cattelan

This page, left: Maurizio Cattelan, Frank and Jamie, 2002, wax and clothes, dimensions variable

This page, below: Maurizio Cattelan, America , 2016, bowl: 18k gold; pipes and flushmeter: gold plated, 28 ½ × 14 × 27 inches (72.4 × 35.6 × 68.6 cm), installed at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Photo: Jacopo Zotti, courtesy Maurizio Cattelan Archive

Opposite: Maurizio Cattelan, You , 2021, platinum silicone, epoxy fiberglass, stainless steel, real hair, clothes, hemp rope, and flowers, 55 × 15 ¾ × 10 inches (140 × 40 × 25 cm).

Installation view, Maurizio Cattelan: Yo u, MASSIMODECARLO, Milan/ Lombardy. Photo: Zeno Zotti, courtesy the artist and MASSIMODECARLO

Artworks © Maurizio Cattelan

44

seen in close-up, but a comedy in long shot.” Cattelan similarly does a close-up, then a long shot, going in and out on reality. The last scene of Sam Peckinpah’s Wild Bunch (1969) may be enjoyable from a cinema seat, but the difference between the description of an action and the action itself can be dramatic and horrible. That gap between description and action, between entertainment and danger, is where Cattelan puts himself and the viewer. He and the viewer are in what we might call a Sunday state of mind, because Sunday is simultaneously a beautiful day and an ugly one, a holiday edging toward its own demise—edging toward Monday.

A gold panel covered with gunshot marks is like a Sunday: the background to a celebration gone bad, very bad. Shooting is not a novelty in art; we go from Manet’s The Execution of Emperor Maximilian (1867–69) to Goya’s Third of May 1808 (1814), from William Burroughs shooting everything and anybody around him to Chris Burden shooting at an airplane in flight, from Valerie Solanas’s attempt on the life of Andy Warhol in 1968 to Richard Avedon’s iconic photograph (1969) of the scars she left on Warhol’s body. But Cattelan’s Sunday (2024) goes a little farther, removing the presence of the shooter and transforming violence into a sort of pattern, a decoration, a memory of human folly. His wall could be the wall of some Las Vegas casino bullet-riddled by a disgruntled gambler. There is beauty in the aftermath of tragedy. The walls still standing from Beirut’s civil war look more like the ancient ruins of sandstone buildings than the rubble remaining from human insanity. Cattelan opens a way through this possible misunderstanding, speaking of the irresolvable contradictions

between freedom and violence, fun and horror. Like a variation on Colonel Kurtz in the last scenes of Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979), Cattelan seems to murmur not “The horror, the horror” but “The fun, the fun.” Not that he dismisses the horror, but he sees the other side of it— the fun. Obviously not the fun of the victims but the unimaginable but definitely present fun in the mind of the mass shooter.

What continues to puzzle Cattelan is the way fun can again and again produce horror, as is shown by the endless series of tragedies perpetrated in the name of the fictional freedom to be able to defend yourself. To the extent that Cattelan’s large shot wall makes vague reference to Duchamp’s Large Glass (1915–23) in the Philadelphia Museum— the victim stripped bare, rather than the bride— it invokes the artist’s submission to fate, chance, and the inscrutability of real meaning. Since there is no real meaning in violence, it is pointless to seek it; yet when recreational violence is part of the daily routine, with disposable victims and disposable murders, another kind of silent violence seeps through the seams of the social pattern and Cattelan unjudgmentally dives into it, creating a parallel world to the spectacle presented by recreational violence.

In that world, Cattelan analyzes how human degradation and humiliation, consistently pursued, can achieve a sort of classical dignity, the dignity of human subjects erased by the social structure yet still breathing, like mummified corpses not yet dead. All of this appears in November (2024), a fountain recalling the Manneken Pis (1619), the street-corner sculpture of a pissing kid that has long been a landmark of Brussels. The

difference is that what we see is not a playful child but a half-dozing male figure slouched on a bench with his penis in his hand, peeing on the ground. While it’s unclear whether the work is a monument to self-destruction or to survival, it certainly monumentalizes defiance of the written and unwritten laws of social and urban life; it is also another hymn to an awkward way of defining freedom. The male figure has no need of a gun to feel free or to avenge social injustice—his weapon is his own dick. He has no need to create horror, he is satisfied with inducing disgust. He dares you to take a selfie if you wish, and many will. In Cattelan’s work, repulsion, disgust, and violence are unavoidable backdrops to our detached and fictional lives. What’s the difference between a small child peeing in a fountain and a grown man peeing on the floor? It’s just a matter of convention. If you’re free to buy an assault rifle in a department store, what’s wrong with pissing in public? Sunday and November show an America gone adrift in the ocean of freedom while some kind of political hurricane is approaching.

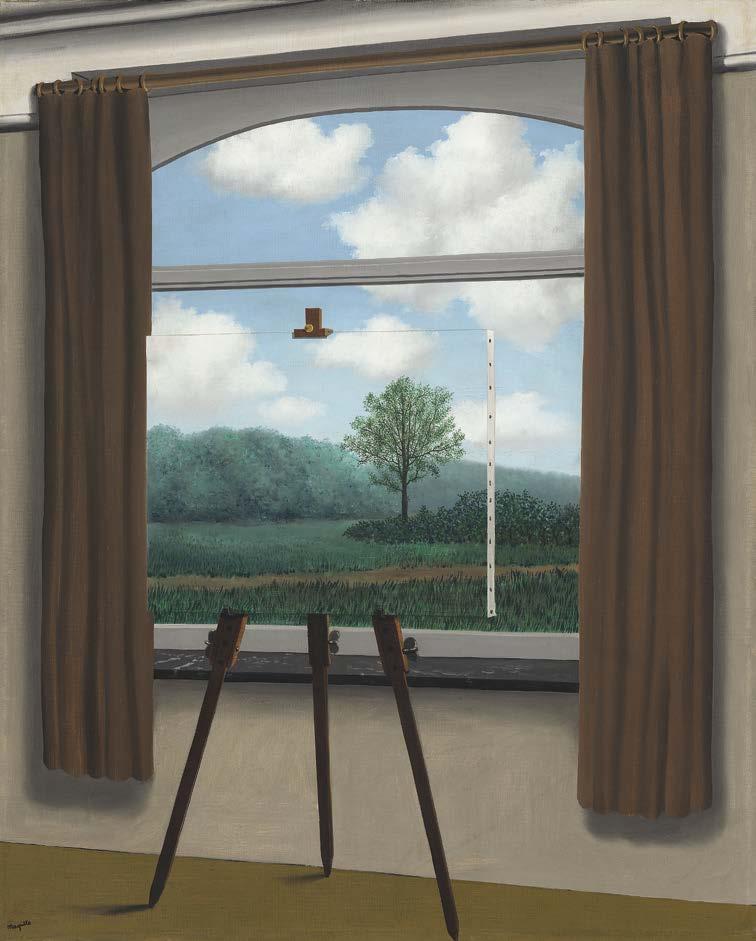

Cattelan is shy of addressing these issues explicitly; his work does not directly respond to or comment on what’s happening. He’s like a Sunday painter setting his easel on the sidewalk, unaware that a murder will soon occur there, or maybe that two people will fall in love there, or that something else will happen, including maybe nothing. He is a Sunday painter. His job is to paint, without judging it, whatever will happen that Sunday, on that sidewalk, at that time.

45

BAUHAUS STAIRWAY MURAL

Alice Godwin and Alison McDonald explore the history of Roy Lichtenstein’s mural of 1989, contextualizing the work among the artist’s other mural projects and reaching back to its inspiration: the Bauhaus Stairway painting of 1932 by the German artist Oskar Schlemmer.

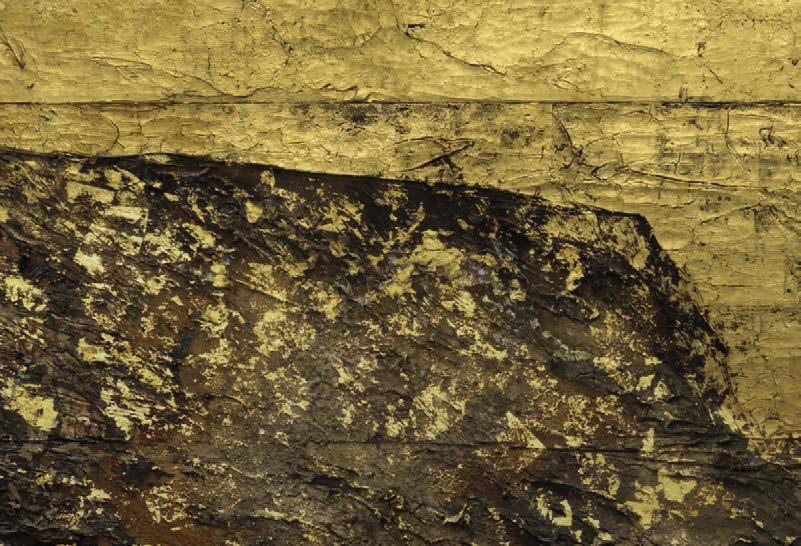

Soaring over twenty-six feet high, Roy Lichtenstein’s magnificent Bauhaus Stairway Mural from 1989 stands as a testament to his signature Pop style of benday dots, bold colors, and simplified forms, devices well suited to making a visual impact at a monumental scale. In contrast to the heroic or public themes of the Mexican muralists of the 1920s and the Works Progress Administration artists of Depression-era America, Lichtenstein’s murals fizz with the imagery of Pop and the pastiches of art history that also define his paintings. Over the years, he completed ten mural-sized installations (eleven if we include Super Sunset Billboard from 1967, which was later destroyed), producing these large-scale artworks from early to late in his career, from New York World’s Fair Mural (Girl in Window) of 1964 to Times Square Mural of 1994 (installed posthumously in 2002). He also made preparatory studies for four unrealized murals, ranging in date from 1968 to 1997. Having conceptualized working at large scale in the mid-1960s, Lichtenstein

approached mural projects in a variety of ways, sometimes enlarging a single image (as in New York World’s Fair Mural (Girl in Window) and University of Düsseldorf Brushstroke Mural [1980]), other times combining an accumulation of images from across his practice (as in Greene Street Mural [1983] and Mural with Blue Brushstroke [1986]). As Camille Morineau writes, he made his murals “a fairly systematic exploration of enlarging his own ‘tropes,’ as well as a tangential investigation of large genre paintings.”1

Bauhaus Stairway Mural , commissioned for the atrium of the I. M. Pei–designed headquarters of the Creative Artists Agency (CAA) in Beverly Hills, pays homage to just such a painting, Bauhaus Stairway ( Bauhaustreppe , 1932), which curator Diane Waldman has described as arguably the best single work by the German artist Oskar Schlemmer. 2 Schlemmer was a teacher at the revolutionary Bauhaus school in Weimar and later in Dessau, Germany, founded by Walter Gropius in 1919. The Bauhaus was devoted to a new type

of artistic education that united the fine and the applied arts—a mission that resonated profoundly with Lichtenstein’s intermingling of “high” and “low” art forms. Alongside other famed staff, including Marcel Breuer, Vasily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and László Moholy-Nagy, Schlemmer taught stage design, mural painting, and sculpture. A pioneer of abstract art, he was also a choreographer, most famously as the creator of the Triadisches Ballett (Triadic ballet) of 1922; he designed stage sets for Igor Stravinsky and Arnold Schoenberg operas in Berlin; and throughout the 1930s, he was known for his site-specific murals.

Facing mounting political pressure from the Nazi party, the Bauhaus left its purpose-built building in Dessau, designed for the school by Gropius, in 1932. Schlemmer, who had left the school three years earlier, painted Bauhaus Stairway on hearing the news of its closing. According to Christina Eliopoulos, Archives Fellow for Research and Reference at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), the painting’s present home, Schlemmer wanted, “to memorialize and pay tribute to the artists, students, and teachers who were part of this movement and who were coming under imminent attack from the Nazis during that time.”3

Showcasing the distinctive glass-fronted staircase of the Bauhaus’s modernist building, and its students moving up the steps, Schlemmer’s painting represents the Bauhaus in its ideal form. It was inspired by a photograph taken by Schlemmer’s fellow Bauhaus teacher T. Lux Feininger, the son of the artist Lyonel Feininger. Here, the staircase banister expresses both stability and progressive movement upward at a time of turmoil, while the stylized figures reflect Schlemmer’s belief in humanity as an organic as well as mechanical creation. Schlemmer made several paintings on this subject, including Treppenszene (Staircase scene, 1932), in the Hamburg Kunsthalle—among his last before the establishment of the Third Reich, in 1933, and his labeling as a degenerate artist by that regime, in 1937.

MoMA acquired Bauhaus Stairway after the founding director of the museum, Alfred H. Barr, saw it in a show at the Württembergischer Kunstverein during a visit to Stuttgart in 1933. Barr admired the painting and was shocked when the show was forced to close a few days later following a harsh review in the Nazi newspaper the

48

Previous spread, left: Roy Lichtenstein, Bauhaus Stairway Mural , 1989, oil, Magna, acrylic, and graphite pencil on canvas, 26 feet 5 ¾ inches × 17 feet 11 ¾ inches (807.1 × 548 cm) © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein. Photo: Rob McKeever

Previous spread, right: Roy Lichtenstein painting Bauhaus Stairway Mural (1989), Creative Artists Agency, Beverly Hills, California, 1989. Photo: © Sidney B. Felsen

Opposite, above: Oskar Schlemmer, Bauhaustreppe (Bauhaus Stairway ), 1932, oil on canvas, 63 ⅞ × 45 inches (162.3 × 114.3 cm), The Museum of Modern Art, New York; gift of Philip Johnson. Digital image: The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, New York

Opposite, below: Women from the Bauhaus weaving workshop on the staircase of the Bauhaus Building in Dessau, Germany, 1927 © Estate of T. Lux Feininger. Photo: T. Lux Feininger/BauhausArchiv, Berlin

Above: Roy Lichtenstein and his sons in front of New York World’s Fair Mural (Girl in Window), Flushing, New York, c. 1964. Photo: © Ken Heyman

National-Sozialistiches Kurier. The critic wrote menacingly, “This exhibition is doubtless the last chance the public will have to see painted Kunstbolschewismus [Bolshevik art] at large.”4 Within days of coming to power, the Nazi regime had begun to attack modern art and architecture, censor artworks, lock galleries, and eject modernists from the academies. Barr was a great admirer of the Bauhaus—indeed, the interdisciplinary nature of the school had served as a model for MoMA on its founding, in 1929—and he quickly persuaded a wealthy colleague, the architect Philip Johnson, to purchase Bauhaus Stairway for the museum. Since the opening of MoMA’s own purpose-built building in 1939, it has mostly hung in the stairwell there—a stairwell itself inspired by Gropius’s Bauhaus.

Lichtenstein was a native New Yorker who often cited art history, translating, distilling, even poking fun at art movements and individual artworks by filtering them through his distinctive Pop aesthetic. He knew museum collections well,

particularly those in New York, and certainly encountered Schlemmer’s painting at MoMA and understood the complexities of its history. In 1988, a year before creating the CAA mural, he made a smaller version of Bauhaus Stairway as a painting—though it still sits at 94 inches tall. That work and a study for it are part of the MoMA collection, where they speak quite directly to Schlemmer’s original. As Deborah Solomon wrote last fall in the New York Times , “It is not surprising that Lichtenstein was drawn to Schlemmer, who rejected the hot, romantic ethos of twentieth-century German Expressionism in much the same way that Lichtenstein rejected the emotive ethos of Abstract Expressionism a half-century later. . . . One of Lichtenstein’s enduring themes was the absurdity of utopian visions, and so the Schlemmer painting was perfect grist for his dot-pattern mill. Lichtenstein often seemed divided between admiration for his avant-garde predecessors and an opposing desire to parody their work.”5 Reimagining Bauhaus Stairway on a grand scale in Pop terms, and with the context of Hollywood emanating from the mural’s destined home in the CAA building, Lichtenstein drew parallels between the writers, directors, actors, and musicians entering these Los Angeles offices and the artists and students who filled the stairway at the Bauhaus so many generations earlier. He also tinkered playfully with the composition, his dry sense of humor responding to the mural’s destined longterm location. As Solomon notes, “Revealingly, in lieu of the male dancer that Schlemmer has positioned in the upper left of his painting, balancing en pointe , Lichtenstein has substituted an Oscar statuette. He thereby flattened the radical lessons of the Bauhaus into a race for an Academy Award.”6 Perhaps the Oscar is also a punning homage to Oskar Schlemmer—too much of a stretch, maybe, but the artist did have a playful spirit.

The painting of a mural is involved, requiring planning and preparation far more extensive than those for traditionally scaled canvases. This kind of execution suited Lichtenstein’s sensibilities. For Bauhaus Stairway Mural , he brought three assistants from New York to spend five weeks with him at CAA. To ensure the availability of the proper art supplies for the duration of the project, one of these assistants drove from New York to Los Angeles carrying materials that might be challenging to source at short notice. By the time everyone had arrived, the expansive canvas—backed with a layer of material to facilitate separating the work from the wall in the future if need be—was already installed but had not yet been primed. (It is amusing to wonder how many gallons of gesso it took to cover the canvas completely.) A projector was set on scaffolding across from the canvas, so that Lichtenstein could draw the composition from the projected image it cast. (Once the machine was aligned, an assistant needed to steady it for hours while Lichtenstein drew out the planned lines, as any shift or movement would misalign the projection.) Rob McKeever, a member of the Bauhaus Stairway Mural crew, recently recalled:

Once the image was scaled up, Lichtenstein would make a drawing directly on the canvas. Then we would apply tape to delineate the sections, we would paint to fill the colors in after that, then move the tape and apply black to fill the lines in. The dots on the murals would either be silk-screened or we would use a stencil (depending on the size, silk-screens were

49

hard to align, so stencils tended to be easier), which was often the most challenging part. Overall it was a pretty straightforward process and Roy was working alongside us every step of the way.7

was gifted by Philip Johnson in 1942 to MoMA, where it was enthroned at the top of the stairs until 1983. It was Johnson who commissioned Lichtenstein’s first mural in 1962 and who donated his wonderful painting Girl with Ball to MoMA. Each mural thus responded to a context where Lichtenstein tackled issues full throttle, regardless of how contentious they were.8

After seeing Bauhaus Stairway Mural in its most recent display, at Gagosian in Chelsea in 2023, David Whelan described his visual experience for the Brooklyn Rail : “At a distance, the various parts appear locked into place, but as you approach, the composition begins to move. Lichtenstein’s elongated curves took my vision for a ride before plunging into fields of Ben-Day dots, which produce a buzzing after-image that carries across the picture plane. Besides Lichtenstein’s dramatic optical effects, what held my attention most were moments in the composition where the artist went off-script, deviating from Schlemmer’s original painting.”9 The conical forms of the legs and arms in Schlemmer’s painting, for example, recall his designs for the stage—voluminous multicolored costumes that might force performers to modify their movements and test the relationship between body and space. Lichtenstein’s figures in the lower-right-hand and upper-left-hand corners of the mural seem to reference these costumes and Schlemmer’s volumetric rendering of the figure, as well as his interest in mechanical movement. But Lichtenstein injects Schlemmer’s vision of the Bauhaus with his own, electric Pop palette, bold outlines, and the two-dimensional modeling techniques of hatching and benday dots.

The Roy Lichtenstein Foundation Archives

Opposite: Bauhaus Stairway Mural , 1989, in the lobby of the Creative Artists Agency, Beverly Hills, California, 1989. Photo: © Paul Warchol Photography Inc.

Artworks © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein

Lichtenstein made several important murals in the 1980s, including Greene Street Mural , at Leo Castelli’s Greene Street Gallery (1983), and installations at AXA Equitable Center, New York (1984–86), and the Tel Aviv Museum of Art in 1989. It is interesting to note that Tel Aviv Museum of Art Mural was made in the same year Lichtenstein painted the CAA mural: it combines a variety of motifs from across the artist’s career, including a portion of Bauhaus Stairway. Morineau writes,

When Lichtenstein cites himself it is always clear, as seen in the Tel Aviv Museum of Art Mural , where Oskar Schlemmer’s stairway is paired with a sort of abstract double, to good effect: few people know that Tel Aviv is home to the largest collection of Bauhaus and International Style buildings in the world, all located in the city center. Incidentally, Lichtenstein’s citations in the Tel Aviv mural and others focus on political artists and wellknown mural artists—[Pablo] Picasso, [Fernand] Léger, [Marc] Chagall, Schlemmer—as well as on the loss of utopia, be it modern or contemporary. . . . [Schlemmer’s] Bauhaus Stairway

Speaking generally of Lichtenstein’s murals, Morineau writes, “The culture and life of museums and the history and politics of place are, more or less, directly evoked here. But also, more surprisingly, is the recurring religious metaphor of ascension, which may have helped to structure the compositions of Lichtenstein’s three largest murals ( Mural with Blue Brushstroke , Bauhaus Stairway Mural , and Tel Aviv Museum of Art Mural ).” 10 Waldman writes, “The subject of a stairway filled with people seems eminently suitable, and even manages to evoke something of the Bauhaus’s utopian belief in merging art and life. Here, this utopian ideal is joined with Lichtenstein’s democratizing aesthetic of replication, thus making art accessible to all and maintaining the connection between high art and consumer culture that underlies all his work.”11

1. Camille Morineau, “There Will Be Mural Painting,” Roy Lichtenstein: Greene Street Mural (New York: Gagosian, 2015), 79.

2. Diane Waldman, Roy Lichtenstein , exh. cat. (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1993), 271.

3. Christina Eliopoulos, in “UNIQLO ArtSpeaks: Christina Eliopoulos on Oskar Schlemmer’s Bauhaus Stairway,” MoMA post on Facebook #ArtSpeaks playlist, March 5, 2021. Available online at www.facebook.com/watch/?v=463274168200158 (accessed March 26, 2024).

4. Hugh Eakin, Picasso’s War: How Modern Art Came to America (New York: Crown, 2022), 266.

5. Deborah Solomon, “Heading Upstairs with Roy Lichtenstein,” New York Times , September 20, 2023. Available online at https:// www.nytimes.com/2023/09/20/arts/design/stairway-mural-roylichtenstein-gagosian.html (accessed March 26, 2024).

6. Ibid.

7. Rob McKeever, in conversation with Alison McDonald, March 18, 2024.

8. Morineau, “There Will Be Mural Painting,” 81.

9. David Whelan, “Roy Lichtenstein: Bauhaus Stairway Mural ,” Brooklyn Rail , November 2023. Available online at https:// brooklynrail.org/2023/11/artseen/Roy-Lichtenstein-BauhausStairway-Mural (accessed March 26, 2024).

10. Morineau, “There Will Be Mural Painting,” 81. 11. Waldman, Roy Lichtenstein , 353.

50

Above: Roy Lichtenstein with Bauhaus Stairway Mural (1989), in progress at the Creative Artists Agency, Beverly Hills, California, October 4, 1989. Photo: Betty Freeman, courtesy

ROY

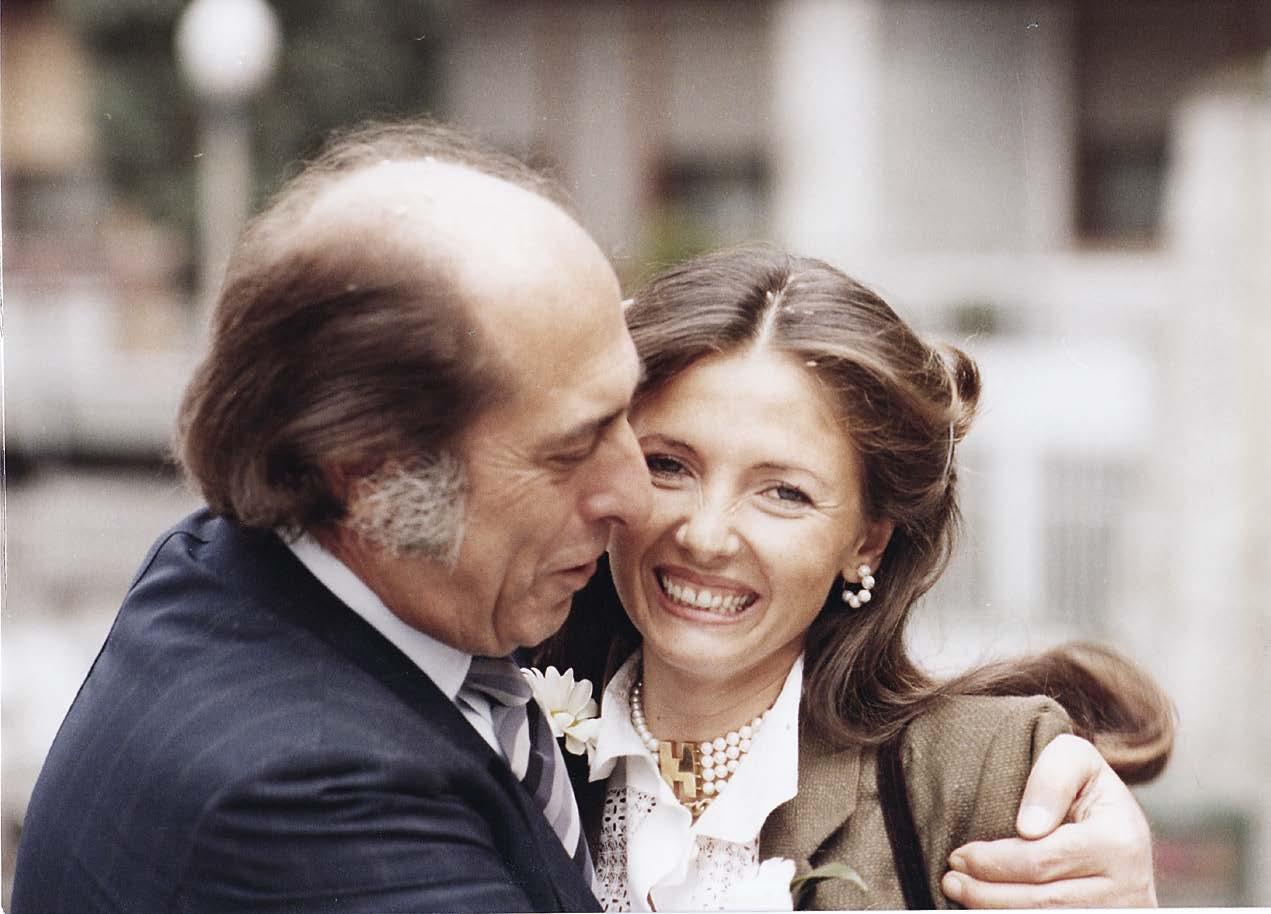

Michael Ovitz, cofounder of Creative Artists Agency (CAA), looks back to 1989, the year he and the architect I. M. Pei commissioned Roy Lichtenstein to create the Bauhaus Stairway Mural for the then new CAA Building in Los Angeles. Through the experience of working with Lichtenstein, Ovitz formed a meaningful friendship with the artist.

I spent one year trying to convince I. M. Pei to design the CAA Building. It was one of the most intense business challenges I ever encountered: I was trying to talk a world-class architect into working on a small building for a little-known entertainment company in Los Angeles, after he had just finished the 1,000,000-square-foot Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong. I was lucky enough to persuade him and in our initial design discussion we agreed that there was only one artist to paint the 30-foot-high entrance wall in the atrium. It needed bold color, relatable imagery, some connection to the theme of communication, and be a second Wow!, with the first one being the building.

A tall order.

Roy was the only choice.

I called Leo Castelli, Roy’s dealer, and asked to see him for ten minutes to discuss something about one of his artists. He kindly and quickly received me and I brought in a small model of the building to educate him on the site.

I told him that Roy was our first, second, and third choice and fortunately he loved the idea. He immediately put me into a meeting with Roy and Dorothy at their studio.

We agreed on the size of the work, but I told Roy to do whatever he felt comfortable with that signaled communication. He had “final cut,” a term directors use to make sure they have the last word on their film. For some reason, Leo put a clause in that if I didn’t like the maquette, I could withdraw. I never really remembered that and it wasn’t an option ever under consideration.

This started a journey for me as one of the best creative experiences and friendships I ever had the honor of having. I spent a lot of social time both with Roy alone and with Roy and Dorothy together, at many lunches and dinners with them and our other artist friends. I remember an epic lunch at Odeon with Roy, Dorothy, Chuck Close, Joel Shapiro, and others. I was in heaven.

Some months later, Roy called and asked me to come by. I showed up and a picture about five feet by four feet was neatly sitting on an easel, covered up. Roy totally ignored it and we talked about the work he was presently painting. After about an hour, I stood up and said I had to leave for another meeting. He casually stopped me and said, “So, do you want to see it?” Of course I couldn’t wait. He walked toward the easel and as I did too, he pulled the cloth cover off in one fell swoop, with intentional drama, like a magician unfolding his trick in an act.

As I was standing there stunned, looking at this image of Oskar Schlemmer’s Bauhaus Stairway (1932), totally modernized and in sixteen colors, Roy said, “Would you like to make any changes?”

I started laughing uncontrollably and then so did he. We both laughed for five minutes nonstop like two little kids. When it came to an end, I said, I’m canceling my meeting, let’s go to lunch. We went to some place in the Meatpacking District that he loved and laughed all through lunch about the fact that he’d asked me, someone without talent, if I wanted to change something in the drawing. I thought it was the ultimate offer—the idea that I might have any criticism of this modern masterpiece was so absurd that it became a common touch point for us in the future.

We flew Roy and Dorothy out to Beverly Hills and put them up at a great hotel and took them out consistently and gave multiple dinner parties for them. The company was their family in LA and the entertainment business embraced and respected them both.

Roy worked in the building for six weeks and we all watched the most unique example of creativity exploding daily in front of our eyes. I remember that Bob Rauschenberg, another friend of both of ours, came to see Roy work and Roy invited him up on the scaffolding and asked him to paint a section. Wow, what a thrill to watch two greats working together in our home, interacting with each other on a piece of art history.

The day Roy was finished, he asked all the staff to gather in the atrium and 400 or more people who were lucky enough to be in their offices gave him an ovation as he signed his name to the bottom.

51

Luca Guadagnino Hans Ulrich Obrist’s Questionnaire

52

Hans Ulrich Obrist

In this ongoing series, curator has devised a set of thirty-seven questions that invite artists, authors, musicians, and other visionaries to address key elements of their lives and creative practices. Respondents select from the larger questionnaire and reply in as many or as few words as they desire. For the second installment of 2024, we are honored to present the filmmaker .

Luca Guadagnino

6. What is your unrealized project?

A: The one that makes me sigh the most, and that I will fight to accomplish, is always the one I’m working on currently: Will it get made? And also a kitchen garden.

15. How would you like to die?

A: In a flash.

13. The future is . . . ?

A: Now. And it’s bleak.

16. What is your favorite color?

Imperial yellow.

18. Are there any quotes you live by?

A: “I am old and I cannot sleep,” by Alice Goodman, for the libretto of John Adams’s Nixon in China (1987).

36. What is your plan for the coming years?

A: Retire and harvest.

41. [Added by the author Joy Williams] In what guise does your worst nightmare appear?

A: Past loved ones.

53

A:

NAN GOLDIN SISTERS SAINTS SIBYLS

54

55

Michael Cary explores the history behind, and power within, Nan Goldin’s video triptych Sisters Saints Sibyls . The work will be on view at Soho Chapel, London, as part of Gagosian Open, from May 30 to June 16, 2024.

When Nan Goldin’s older sister Barbara was a teenager, she would go to the movies to make out with boys. Most teenagers do that at some point, a rite of passage for young Americans, skirting parental surveillance, testing maturity, flirting with dirty, exciting feelings in the dark. In that darkened space beneath projected images, we surrender

something. Cinema is subversive: it can touch us in ways that feel almost indecent. And filmmakers are tricksters, lulling us and seducing us with images, sound, and narrative so we don’t see their sucker punch of subtext approaching.

Goldin begins her film Sisters Saints Sibyls (2004–22) with a religious myth, the story of Saint Barbara. This does two things: it teaches us how to read what we are about to watch and indicates that unbelief may be a part of the equation. The film is presented as a three-channel projection—a triptych, the classical narrative form of religious painting. In this opening gambit, Goldin invites us to interpret and infer narrative from the still images of paintings, like the slides in an art history lecture, time-traveling from the Byzantine through the Renaissance, as the saint’s story is told in voiceover. Saint Barbara was locked away by her father to preserve her virginity, she secretly converted to Christianity in defiance of her pagan parent’s

beliefs and was tortured and executed because of it. The story is meant to serve as a lesson to believers— the lesson of an exemplary life which you should strive to emulate, knowing full well that you will be unable to, ensuring guilt and shame. This is not simply an introductory analogy to the real subject of Goldin’s film, but instruction on how to read the visual narrative Goldin sets forth.

America at mid-century: pious, prosperous, patriotic, proper. It’s a common trope in the United States to hark back to a simpler, better time, a time of conservative moral character and father knows best. Nostalgia is fantasy, of course; the 1950s weren’t a better time for Black folks, or for women. It wasn’t a better time for anyone who stepped out of line, for lefties, free spirits, homosexuals. In fact, looking back from the twenty-first century, it wasn’t the deviants who were the dark side of the ’50s, it was the perception and persecution of deviancy that in hindsight cast a shameful shadow across

56

that era. The flip side of all that conformity was a straining at the reins that gave rise to the full flowering of psychoanalysis in America. It became de rigueur and the rage to turn to the headshrinkers to explain society’s ills. We put everyone from veterans to criminals to Marilyn Monroe on the couch, and we were awash in bennies and Valium to get us through.

Barbara Holly Goldin reached the age of twelve in 1958. That was when the “trouble” between mother and daughter really began. Mother sent Barbara to a psychiatric detention center to fix her, to solve her. Barbara was in and out of facilities for the next six years, and Goldin presents us with the receipts: “Acting out, open defiance, sexually provocative behavior, association with undesirable friends, loud and coarse in speech”—all things a good girl shouldn’t be. Barbara went on dates with an older Black man. One psychiatric report states that she appeared to be confused about her sexual

identity and that she described being attracted to other girls. Barbara appeared awkward and ungainly and refused to shave her legs. She stirred up a perfect storm of middle-class, mid-century fears: race, deviant sexuality, failed femininity.

At about the time Barbara ran away and escaped her first confinement, Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s film of Tennessee Williams’s play Suddenly, Last Summer (1959) was released: Kate Hepburn, Monty Clift, and Liz Taylor, with a screenplay by Williams and Gore Vidal—another perfect storm. In the film, a family matriarch (Hepburn) implores a doctor (Clift) to have her niece (Taylor) institutionalized—to have her lobotomized, cutting out of her brain a vicious story that she won’t stop repeating. The offending story tells of an event “last summer” that exposed evidence of the homosexuality of the matriarch’s late son. The film dramatizes the panic surrounding behavior deemed unacceptable, unthinkable, and a mother’s hysterical inability to

live with the ordinary, ungovernable truth.

The truth is important to Goldin and she finds it by riding the waves of subtext, expertly calibrating the tension between what we see and what we hear: happy snapshots from a family album accompanying voice-overs reading the psychologists’ sober reports on Barbara’s condition; girls’ rooms in psychiatric wards, with happy, colorful bedspreads and a scrapbook titled “Joyful Memories,” accompanied by a soundtrack of a patient sobbing and negotiating with a caregiver; exterior shots of a lovely suburban home accompanied by Barbara’s “mother” screaming insults like slut and whore

It was in that home that Barbara and Nan grew up, in “the banality and deadening grip of suburbia.” Barbara was the elder sister by seven years, and Nan idolized her. Nan had a front-row seat to the “trouble” in that home: distant father, hysterical mother, the physical and psychic abuse that Barbara suffered, the effort to keep up appearances,

57

hiding from the neighbors what was really going on. Goldin reads in voice-over from another doctor’s report: “There is much evidence that it is not Miss Goldin who should be in the hospital, it’s Mrs. Goldin.”

The sibyls were prophetesses in ancient Greece, oracles of fate. They were the voices that revealed the subtext of a life. Barbara tells Nan that if Nan stays in that home, the psychiatrists say she will end up like her sister.

Barbara died by suicide in 1965, at the age of eighteen. Goldin revisits the scene of her death, framing the footage from Barbara’s perspective: on train tracks, a speeding Amtrak fast approaching, then roaring by. We hear a contemporaneous report of the suicide read aloud, but the images we see were shot recently. We imagine the historical event with the voice-over as our guide, but we also imagine Goldin’s presence at that site, what it must

feel like for her. We see a shot of a figure walking through trees, presumably near the train tracks. Is that Nan? She is there, but not necessarily behind the camera; she is not there alone. She’s there with us. We witness her witnessing.

Barbara’s suicide was a defining event in Nan’s life and prompted her to escape that home. The remainder of Sisters Saints Sibyls describes her trajectory in the aftermath—how the events in that suburban crucible affected her life. Nan rebelled, ran away, and found her own tribe of fellow rebels; “I wanna be evil, I wanna spit tacks.” We see familiar characters we know from Nan’s life: David, Brian, Cookie. She shows us the banality and deadening grip of addiction and her own journey of confinement in rehab. From the outside, Nan’s hospital looks like privilege, like a stately English manor, a stark contrast to the bleak bureaucratic facilities where Barbara was treated. But on the inside we

see Nan’s self-inflicted wounds and the bars on the windows, an interior reality that the neighbors don’t see.

So much of Goldin’s work is a kind of archaeology, reconstructing a historical milieu for us. We both see and imagine her in those spaces, at that time, not as documentarian but as participant. As a filmmaker, this is doubly so—not only is she a participant in historical events but we see her in the film examining those places in the present, in “reel” time, with us. Seeing Nan change and age through the film emphasizes what Barbara missed out on; she didn’t get the chance to mature, to grow older and wiser, to realize a life for herself. Nan did, and Barbara missed that too. But with living comes not only maturity, joy, ecstasy, and change but loss, pain, addiction. Trouble. It reminds us that living is brave, no matter how it turns out.

For the Gagosian Open presentation of Sisters

58

Saints Sibyls , Goldin chose the site of the Welsh Chapel, a deconsecrated church in the center of Soho, London. A triptych in a church: a natural home. Goldin’s first presentation of the film was in 2004, in the chapel of the Hôpital de la Salpêtrière, Paris, during the Festival d’automne. Salpêtrière was founded in 1656 as an asylum for poor women struggling with mental illness. In his book Madness and Civilization Michel Foucault describes the seventeenth-century origins of the “philanthropic” confining of “madness” to hospitals such as this one: “From the very start, one thing is clear: the Hôpital General is not a medical establishment. It is, rather, a sort of semijudicial structure, an administrative entity which, along with the already constituted powers, and outside of the courts, decides, judges, and executes. . . . A quasi-absolute sovereignty, jurisdiction without appeal, a writ of execution against which nothing can prevail.”

The hôpital was an institution designed not to treat and care for women but to confine, discipline, and punish them. Salpêtrière is also, of course, where Foucault himself died young, in 1984, from complications of aids, the disease so intimately entwined with the love that dare not speak its name. A disease surrounded by the silence of shame. Goldin’s life work has always been about addressing shame, diffusing it, renouncing it, refusing it. Attacking the powers that try to shame. Showing that shaming itself is shameful.

Goldin says that as a teen she suffered from crippling shyness: “My sister’s suicide silenced me.” Photography was the outlet that allowed her to “walk through fear—taking a picture was kind-of protective.” It was through photographing her friends that she connected with them, and it’s through her photographs that she connects with us.

Sisters Saints Sibyls reminds us how lucky we

are to be alive in the time of Nan Goldin. She is an archivist, constantly updating and revising her works, adding to them, altering them, and with each new work we feel we’ve been with her for decades. “Nan” is an artist whose work is so raw and honest that we feel we know her like a friend. Goldin is the journeyman, the maker of the experiences that allow us to know Nan. We imagine how Nan feels because we read it on her face, and we can read it on her face because Goldin has so skillfully arranged for us to do so. It’s an oeuvre of extraordinary generosity and empathy, though neither Nan nor Goldin wears her heart on her sleeve.

Sisters Saints Sibyls is a film as intimate as a diary, as deep as an archive, as hopeful as a prayer.

How do you make a life-affirming film about suicide, abuse, addiction, and constraint?

You look at the truth. Life ain’t pretty, but it is beautiful.

59

Throughout:

2004–22, three-channel video, 35 minutes, 17 seconds ©

Nan Goldin, Sisters Saints Sibyls ,

Nan Goldin

WAYNE MCGREGOR

Alice Godwin speaks with the choreographer about his inspirations from literature, visual art, music, and more.

Over the past three decades, the British choreographer Wayne McGregor has dazzled audiences with a restless curiosity about the potential of the moving body. His dances explore the possibilities of human creativity, from Dante’s Divine Comedy to artificial intelligence. This spring, the Royal Ballet choreographer brought his acclaimed performance Woolf Works to the United States. In preparation for the US debut of the production, which is inspired by the writings of Virginia Woolf, Alice Godwin talks with McGregor about the enduring legacy of the British staging, the challenge of translating great literary works for the theater, and his vital collaborations with visual artists, from Carmen Herrera and Edmund de Waal to Tacita Dean.

ALICE GODWIN Woolf Works is making its US debut with the American Ballet Theatre at the Segerstrom Center for the Arts, Costa Mesa, California, in April and will be traveling to New York’s Metropolitan Opera House in June. I saw the production when it premiered at the Royal Opera House in London in 2015 and I was completely blown away.

WAYNE MCGREGOR It’s crazy that it’s almost a decade old.

AG It was such a tremendous event at the time, winning a Laurence Olivier Award and a Critics’ Circle National Dance Award. I’m curious what effect the production had on your career?