ALVIN AILEY

REID BARTELME

MOEKO FUJII

LA(HORDE)

HARRIET JUNG

RENNIE MCDOUGALL

THOMAS NAIL

AMIT NOY

JACKIE SIBBLIES DRURY

ROSS SIMONINI

Editor-in-chief

Alison McDonald

Managing Editor

Wyatt Allgeier

Editor, Online and Print

Gillian Jakab

Text Editor David Frankel

Executive Editor Derek Blasberg

Digital and Video

Production Assistant

Alanis Santiago-Rodriguez

Design Director

Paul Neale

Design Alexander Ecob

Graphic Thought Facility

Website

Wolfram Wiedner Studio

Cover

Peter Doig

Founder Larry Gagosian

Publisher Jorge Garcia

Published by Gagosian Media

For Advertising and Sponsorship Inquiries

Advertising@gagosian.com

Distribution David Renard

Distributed by Magazine Heaven

Distribution Manager Alexandra Samaras

Prepress DL Imaging

Printed by Pureprint Group

Contributors

Miriam Bale

Reid Bartelme

Jessica Beck

Joanna Biggs

Derek C. Blasberg

Rosalind Brown

Ken Burns

Michael Craig-Martin

Sarah Crowner

Aria Darcella

Daria de Beauvais

Eli Diner

Peter Doig

Simone Farresin

Mark Francis

Moeko Fujii

Michel Gaubert

Zoë Hopkins

Arinze Ifeakandu

Harriet Jung

Pavel Kolesnikov

David Jacob Kramer

Alison McDonald

Rennie McDougall

Thomas Nail

Amit Noy

Hans Ulrich Obrist

Jenny Odell

Ashley Overbeek

John B. Ravenal

Scott Rothkopf

Michael Schmelling

Richard Shiff

Jackie Sibblies Drury

Ross Simonini

Sarah Sze

Rirkrit Tiravanija

Colm Tóibín

Andrea Trimarchi

Samson Tsoy

Jeff Wall

Lawrence Weschler

Thanks

Richard Alwyn Fisher

Julia Arena

Lisa Ballard

Mike Barnett

Priya Bhatnagar

Will Buckingham

Michael Cary

Serena Cattaneo Adorno

Vittoria Ciaraldi

Charlotte Dozier

Maggie Dubinski

Jill Feldman

Paatela Fraga

Hannah Freedberg

Hallie Freer

Bruno Fulcrand

Hilliary Gabryel

Brett Garde

Eleanor Gibson

Lauren Gioia

Darlina Goldak

Delphine Huisinga

Sarah Jones

Shiori Kawasaki

Léa Khayata

Bernard Lagrange

Lauren Mahony

Kelly McDaniel Quinn

Parinaz Mogadassi

Olivia Mull

Elizabeth Mullaney

Nu Nguyen

Samora Pinderhughes

Stefan Ratibor

Helen Redmond

Olga Rosen

Kathleen Ryan

Jasper Sharp

Rose Sheehan

Caitlin Sweeney

Putri Tan

Harry Thorne

Natasha Turk

Kelsey Tyler

Timothée Viale

Lindsey Westbrook

Felix Wimmer

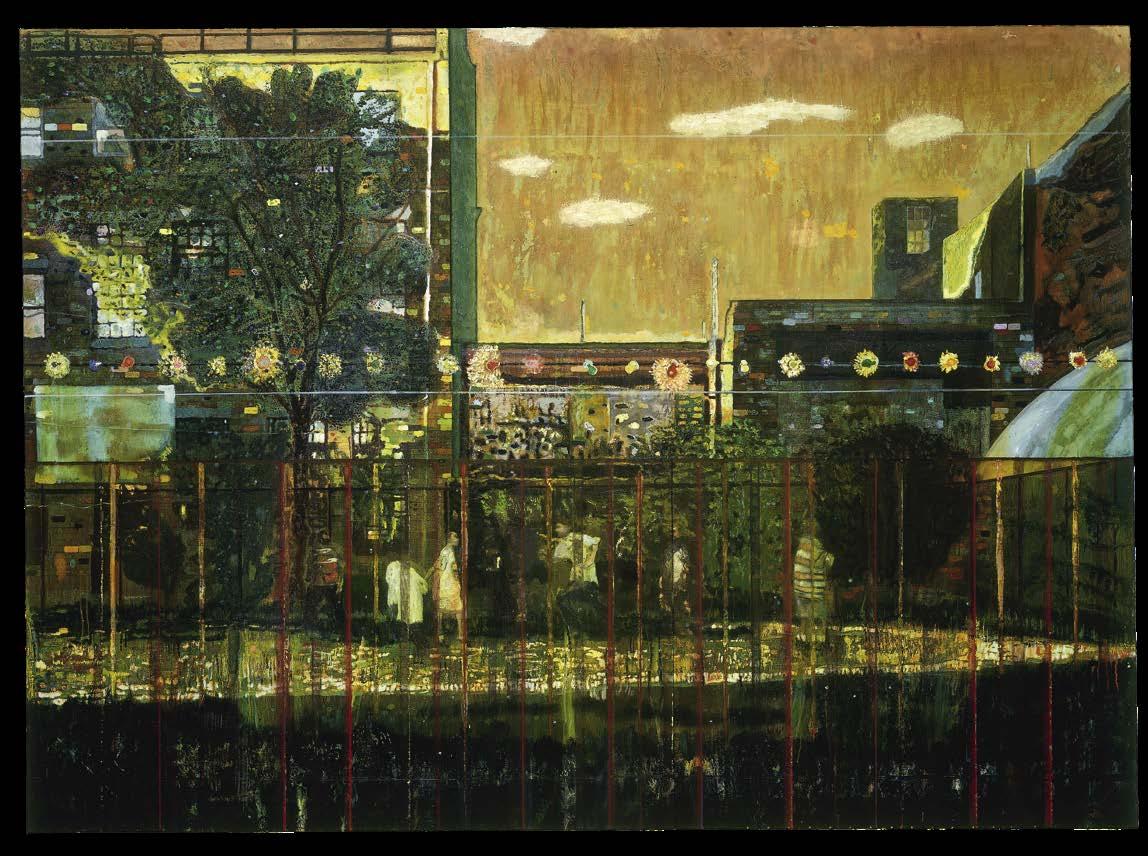

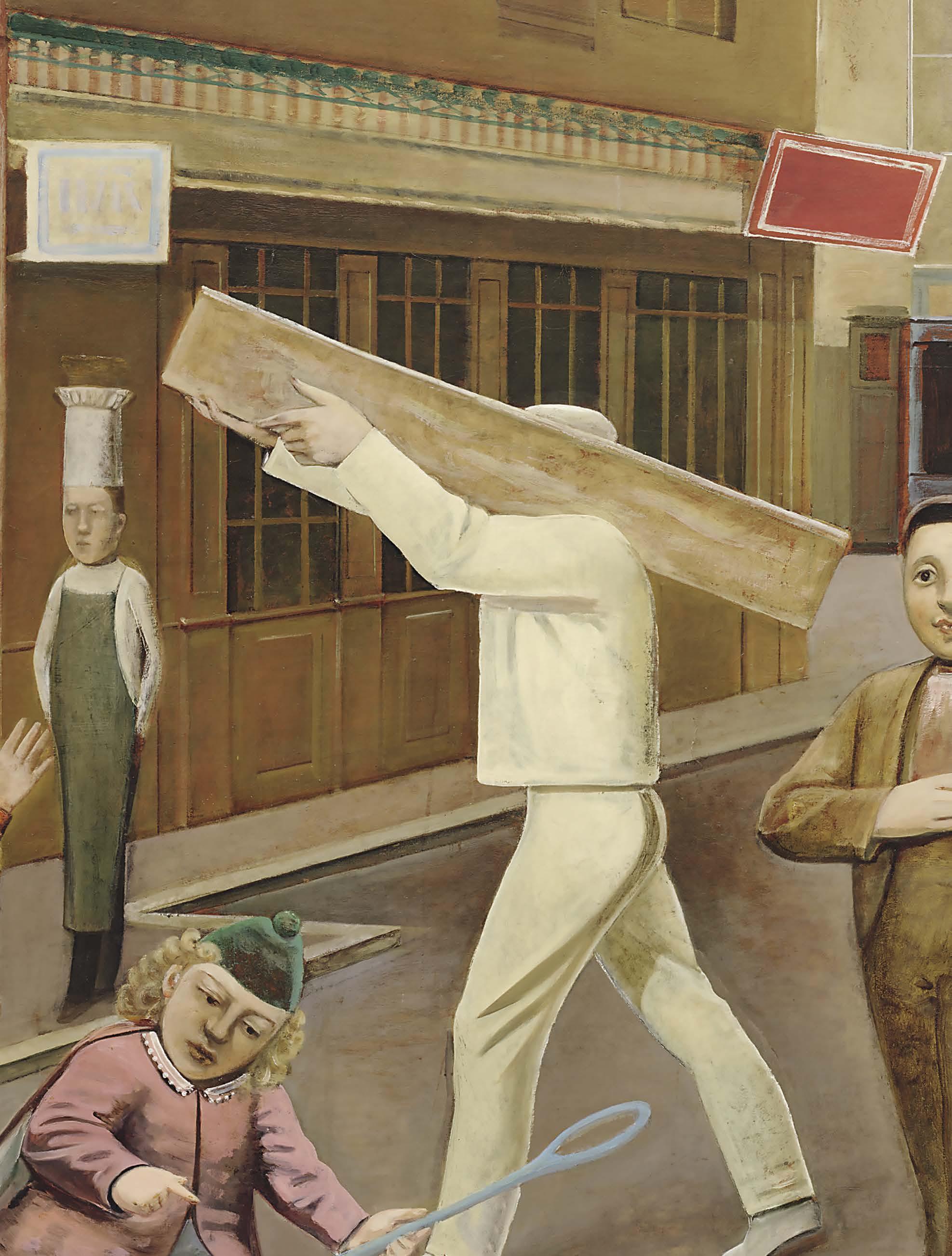

In this issue, Peter Doig, whose Night Playground (1997–98) appears on our cover, speaks with Richard Shiff about The Street (1933). Balthus’s surreal scene is the centerpiece of an exhibition in New York this November, curated by Doig and featuring paintings that have been touchstones for his own work over the years.

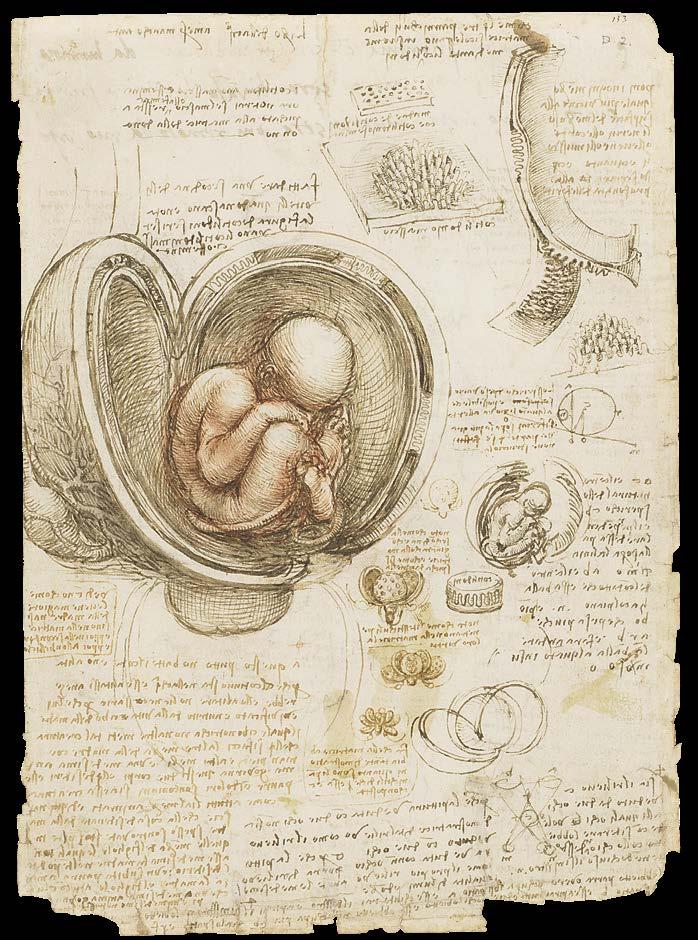

We connect with the legendary documentary filmmaker Ken Burns as he turns his attention to Leonardo da Vinci, whose insatiable curiosity and endless pursuit of knowledge produced discoveries that were centuries ahead of his time. And we look at three standouts from the Venice Film Festival with Miriam Bale.

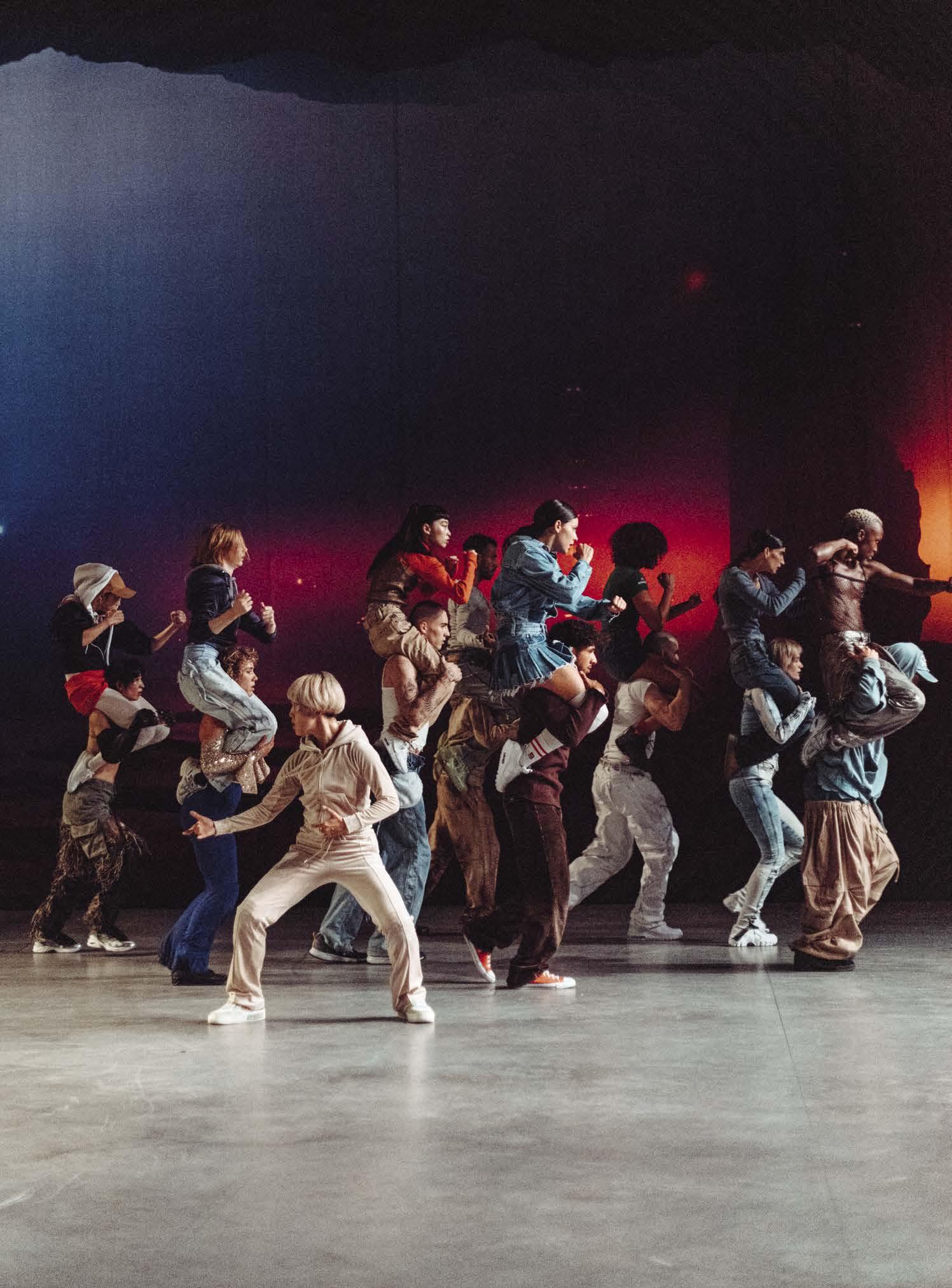

Our “Gagosian&” supplement, edited by Gillian Jakab, focuses on dance, with features on the French collective la(horde), the art of costuming, the philosophy of movement, and more.

We enter the world of music and fashion in a conversation with Michel Gaubert, who has long worked on the music behind runway shows around the world. And we discuss the cross-pollination of music and art with pianists Pavel Kolesnikov and Samson Tsoy.

We see new paintings in Jonas Wood’s studio ahead of a London exhibition. Sarah Crowner shares her latest works with Jenny Odell before a show in Athens. Jessica Beck surveys the career of Rudolf Stingel. Longtime friends Rirkrit Tiravanija and Sarah Sze discuss thriving in chaos, experiences in time, and their latest projects. We track Kathleen Ryan’s sustained and evolving engagement with sculpture and its depiction of the temporal.

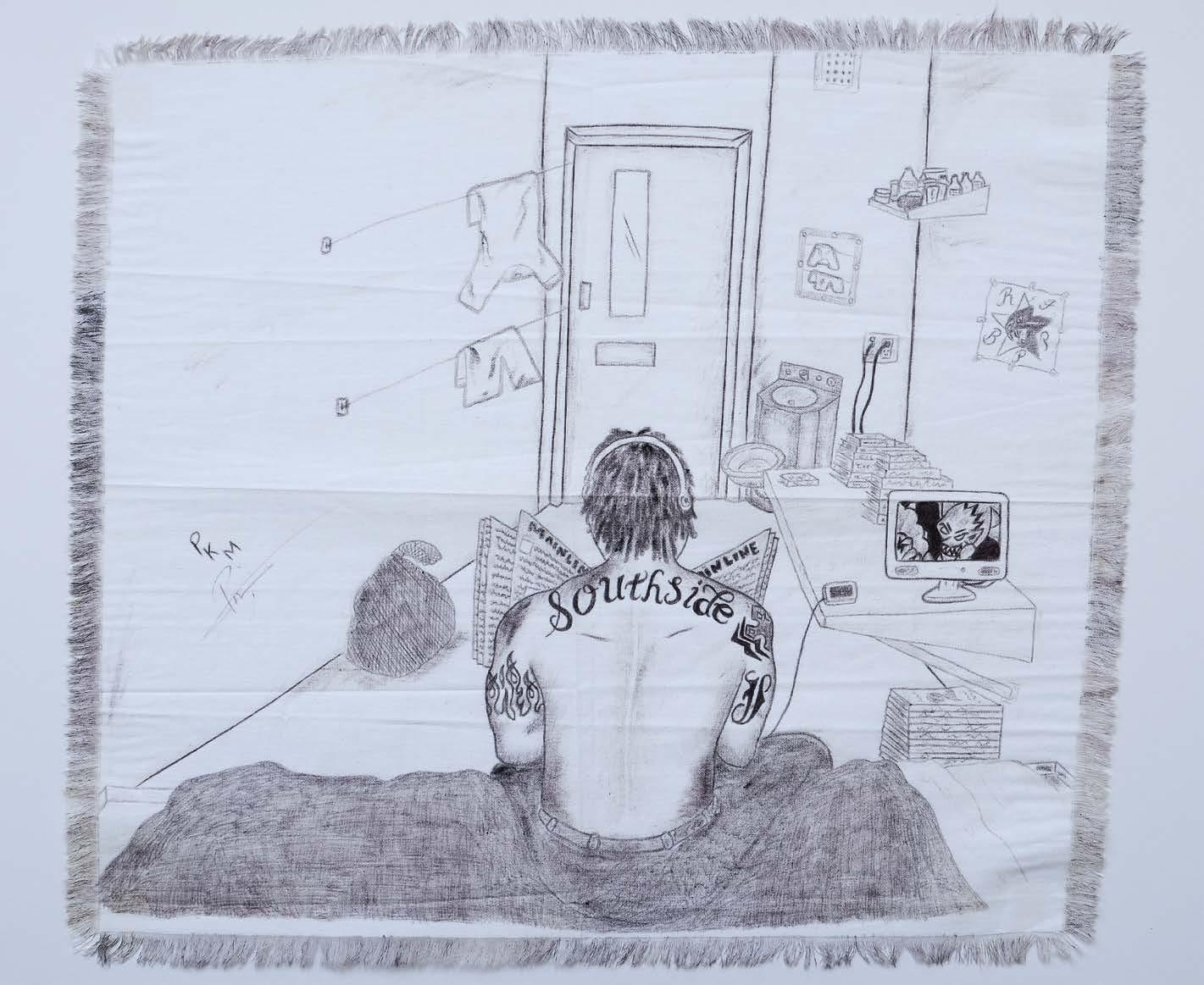

For our Bigger Picture series we focus on the Healing Project, a multidisciplinary art nonprofit founded by composer, activist, and artist Samora Pinderhughes.

This summer we lost Dorothy Lichtenstein, whose grace and generosity touched many of us. Scott Rothkopf remembers her as a dedicated philanthropist, a steward of the legacy of her husband Roy, and a person you always wanted to sit next to at dinners and whose generosity will benefit many generations to come.

Alison McDonald, Editor-in-chief

42 Game Changer: Kasper König

Mark Francis remembers his late friend, the indefatigable and radical curator Kasper König.

46 The Street: A Conversation between Peter Doig and Richard Shiff

A New York exhibition conceived and curated by the artist Peter Doig takes as its point of departure Balthus’s 1933 painting The Street , in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Ahead of the show, Doig and art historian Richard Shiff met up to look at Balthus’s painting together in person.

52

Leonardo da Vinci by Ken Burns

The fascinating life of Leonardo da Vinci is the subject of a new film by Ken Burns. The legendary filmmaker sat down with the Quarterly ’s Alison McDonald to discuss Leonardo’s insatiable curiosity, his passionate enchantment with nature, and his endless search for universal truths.

58

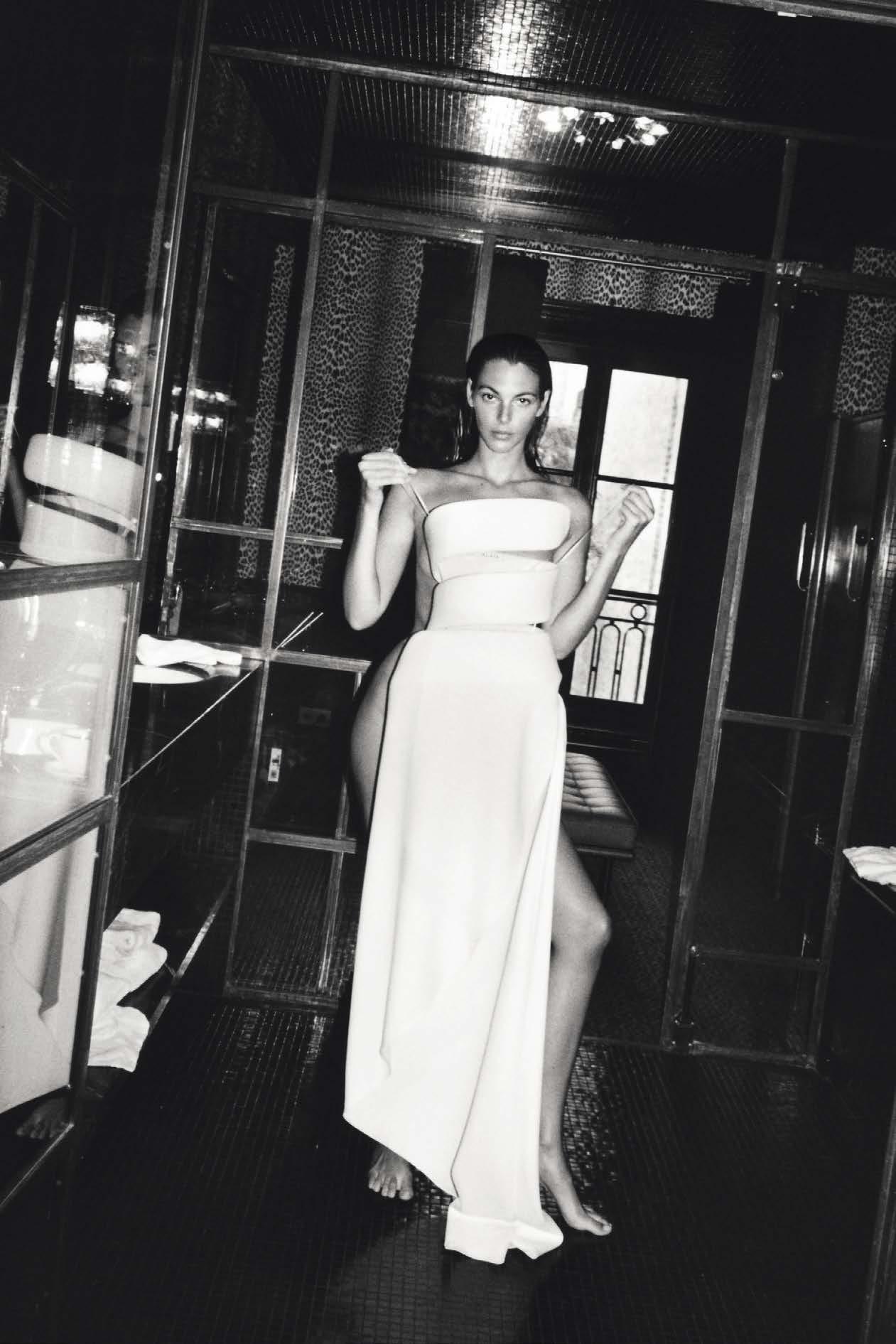

Michel Gaubert, the Paris-based music supervisor behind iconic runway shows across the globe, meets with the Quarterly ’s Derek C. Blasberg to discuss his first engagements with music and fashion, his fateful meeting with Karl Lagerfeld, and discovering sounds in unexpected places.

Art historian, curator, and writer Daria de Beauvais tracks the artist Kathleen Ryan’s sustained and evolving engagement with the temporal, the memento mori, Americana, and ecology.

Pavel Kolesnikov and Samson Tsoy are pianists, composers, and cofounders of Britain’s Ragged Music Festival. Lawrence Weschler speaks to the duo about the influence of visual aesthetics on their music, their engagements with Pop art and the work of Joseph Cornell and Richard Serra, and music’s ability to be infinitely specific.

Eli Diner visits Jonas Wood in his Los Angeles studio as the artist prepares for an exhibition of new paintings in London.

Miriam Bale considers three films that made their debut in Venice earlier this year.

Jessica Beck surveys the career of Rudolf Stingel, noting his sustained engagements with painting, environment, and memory.

Zoë Hopkins reports on the Healing Project, a multidisciplinary arts organization founded by the composer, artist, and activist Samora Pinderhughes in 2014.

For the fourth installment of 2024, we are honored to present Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin, founders of the research-based design studio FormaFantasma.

This past summer, Jenny Odell made a visit to Sarah Crowner’s studio in Red Hook, New York. Amid a series of new paintings that Crowner is making for an exhibition in Athens this November, the two discussed embodiment, honing attention, and what it means to enter vertical time.

This installment of the Quarterly ’s themed supplement dives into dance with features on the French collective la(horde), the art of costuming, the philosophy of movement, and more.

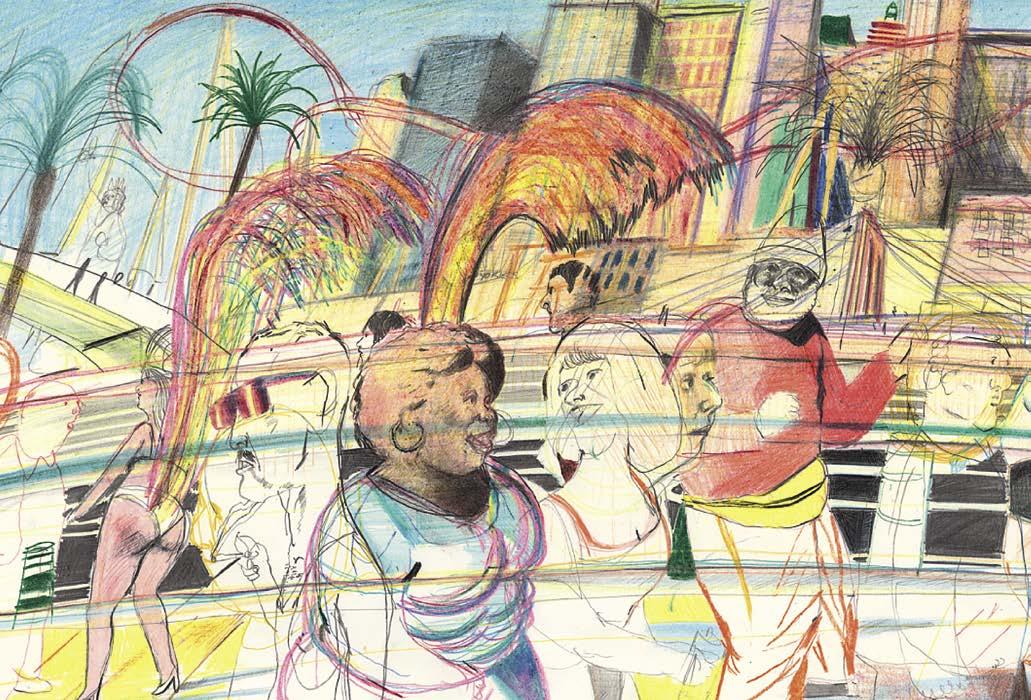

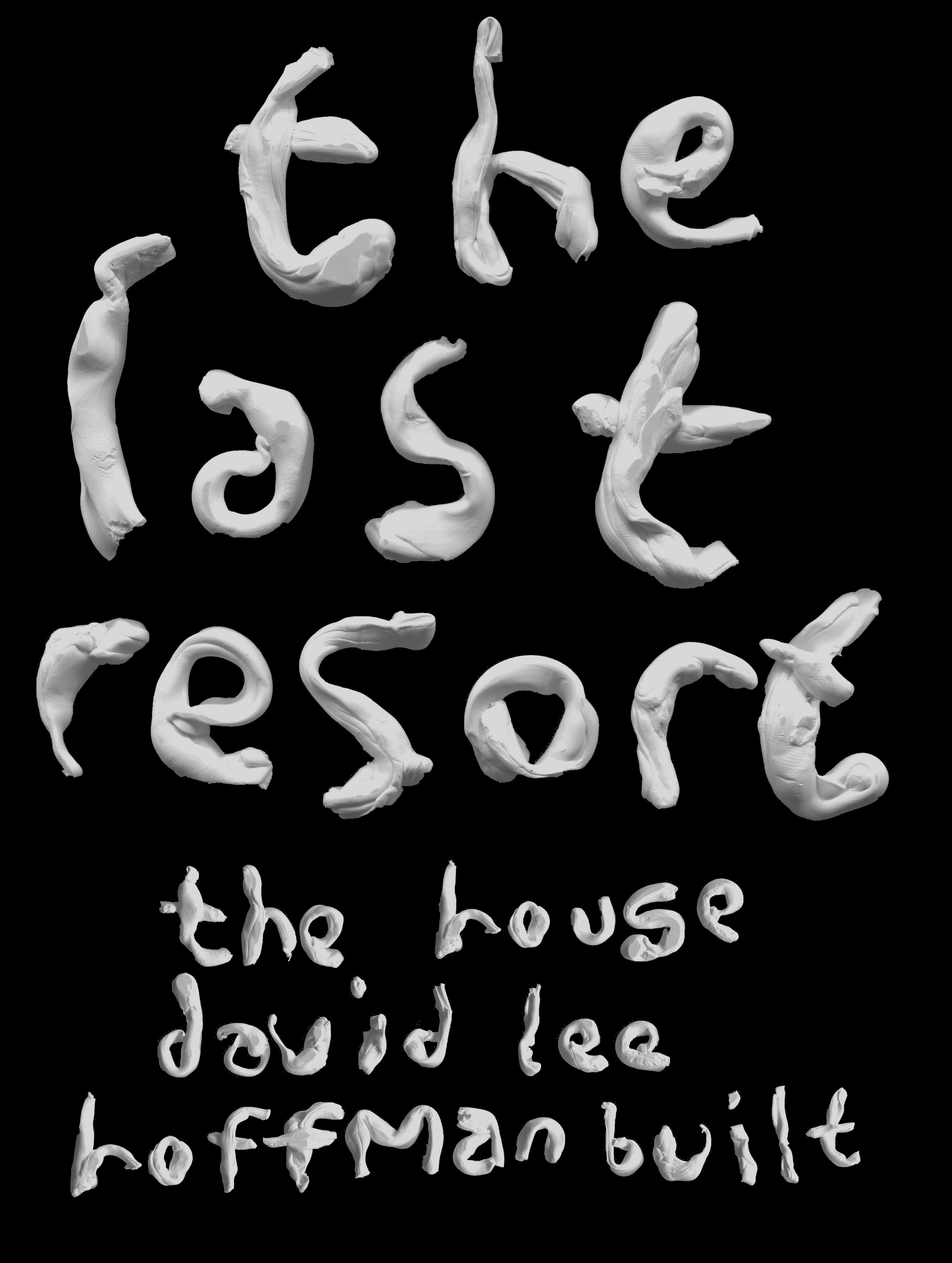

David Jacob Kramer and photographer Michael Schmelling take us to the Last Resort, the home and surrounding buildings created by David Lee Hoffman since 1973.

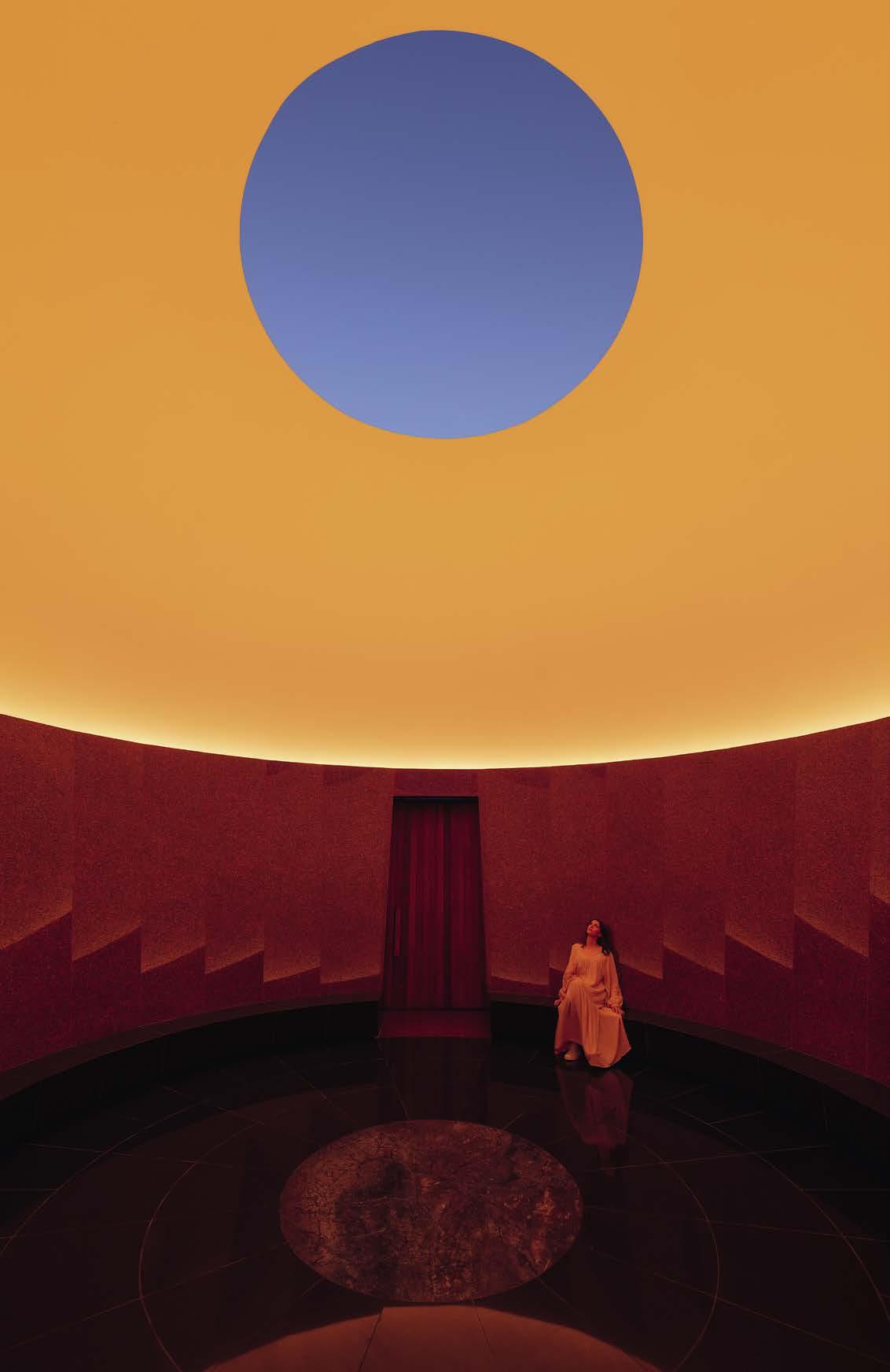

Ashley Overbeek takes us through the history, the contemporary culture, and some of the people of a coastal Uruguayan town that hosts worldclass museums and art installations.

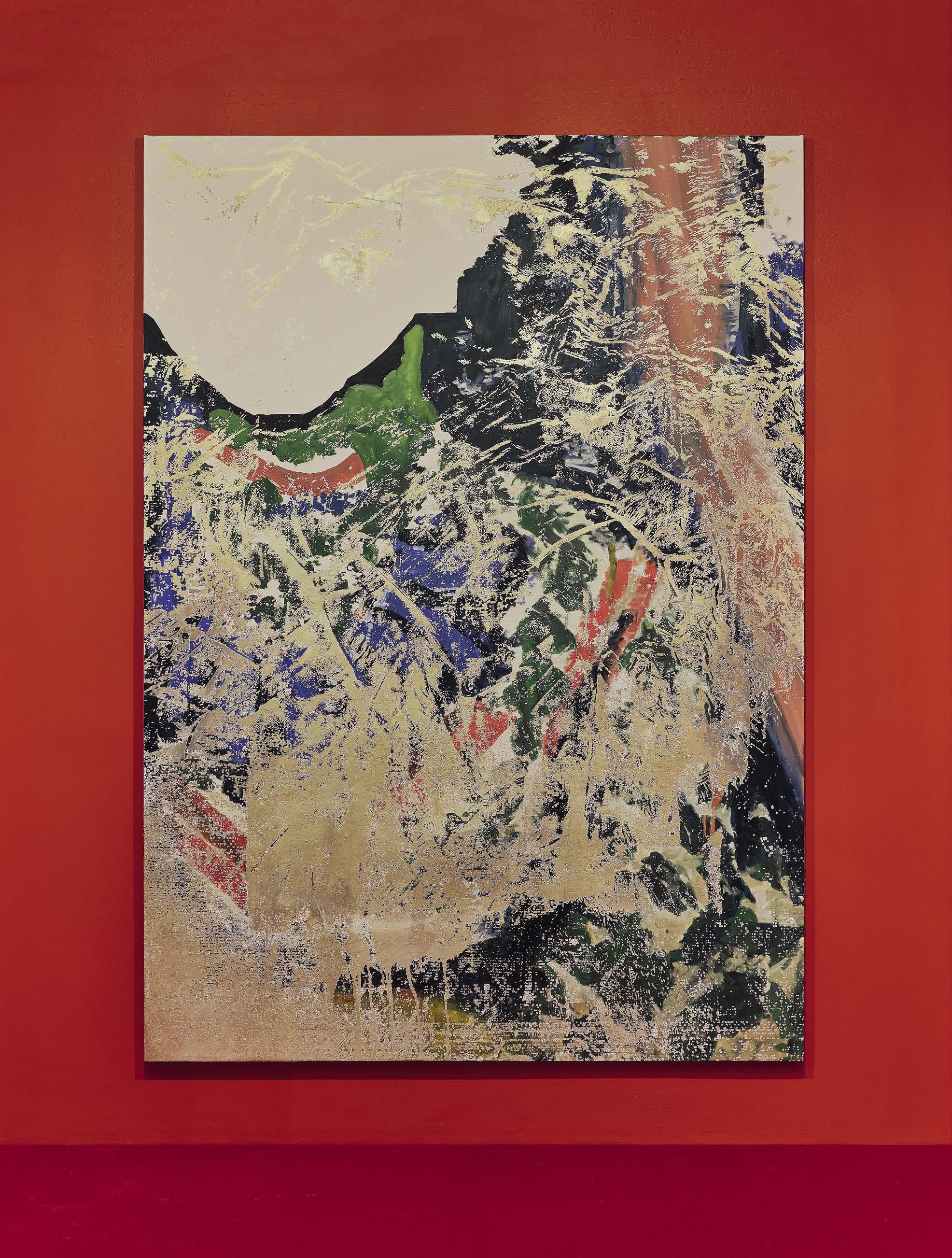

Previous spread, left: Kathleen Ryan, Bad Melon (Laid Back), 2020–24 (detail), cherry quartz, rose quartz, carnelian, agate, jasper, rhodonite, rhodochrosite, citrine, pink opal, glass, cast iron flies, brass flies, steel pins on coated polystyrene, and aluminum Airstream, 26 ½ × 29 ½ × 23 inches (67.3 × 74.9 × 58.4 cm) © Kathleen Ryan

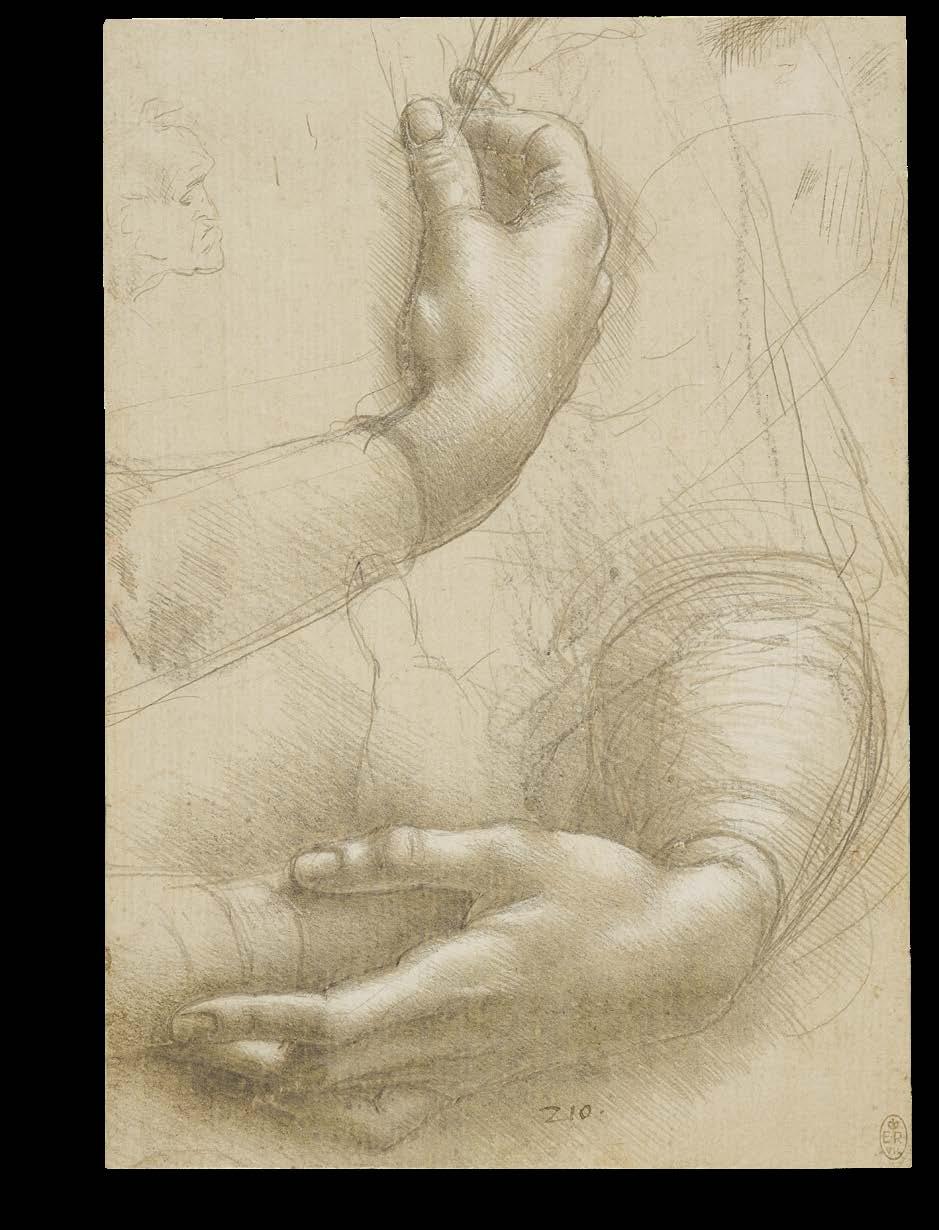

Previous spread, right: Leonardo da Vinci, Study for the Angel of the Virgin of the Rocks , c. 1478–85, by permission of MiC-Musei Reali, Biblioteca Reale. Photo: Ernani Orcorte

Above: The Last Resort, Marin County, California, 2024. Photo: Michael Schmelling

Below: Jonas Wood in his studio, Los Angeles, 2024. Photo: Laure Joliet

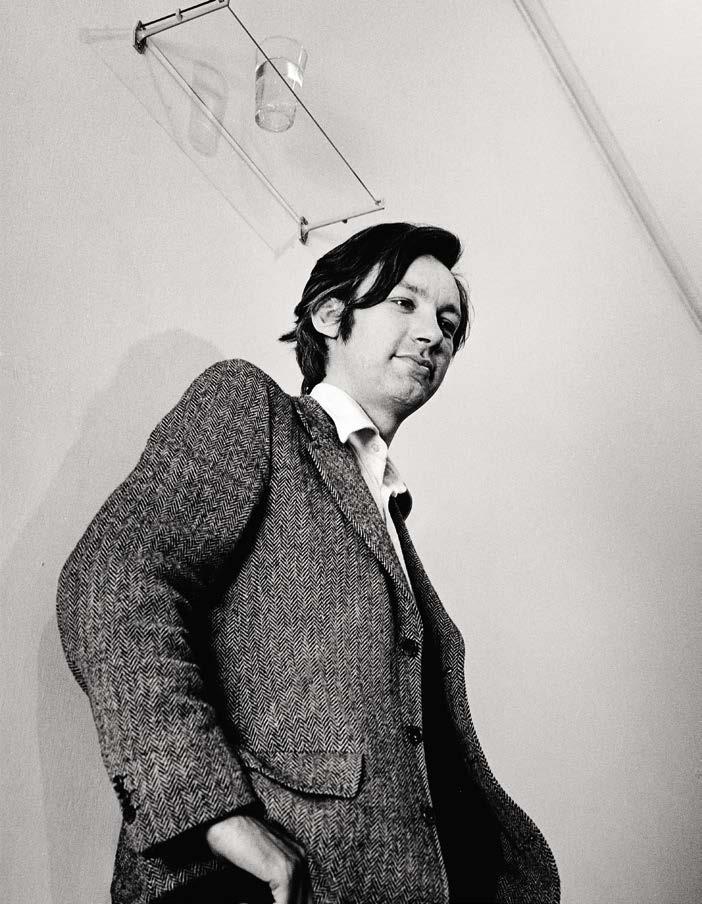

Michael Craig-Martin’s sixty-year career is the subject of a retrospective at the Royal Academy, London, on view through December 10, 2024. Ahead of the exhibition’s opening, the artist met with his longtime friend, the novelist Colm Tóibín, to discuss his materials and the generative inquiries at the heart of his practice.

Rosalind Brown discusses her debut novel, Practice, with author and senior editor of Harper’s Magazine Joanna Biggs.

Sarah Sze meets with Rirkrit Tiravanija to discuss thriving in chaos, making room for experiences in time, and her materials.

Aria Darcella ventures through the history of the French house’s bibliophilic engagement with travel, publishing, and art.

We present the final installment of a four-part short story by Arinze Ifeakandu.

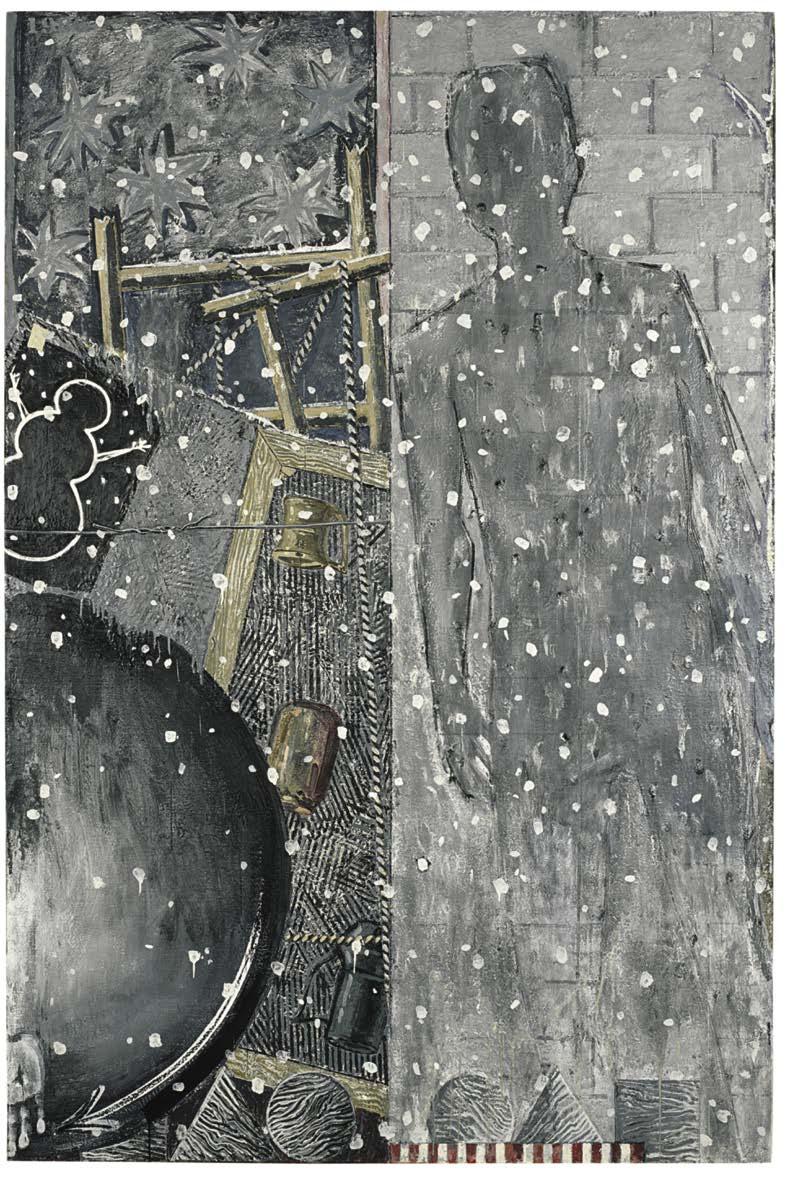

Jeff Wall explains the stories and literary allusions behind two photographs of his that will appear in an exhibition at Gagosian, New York, in November.

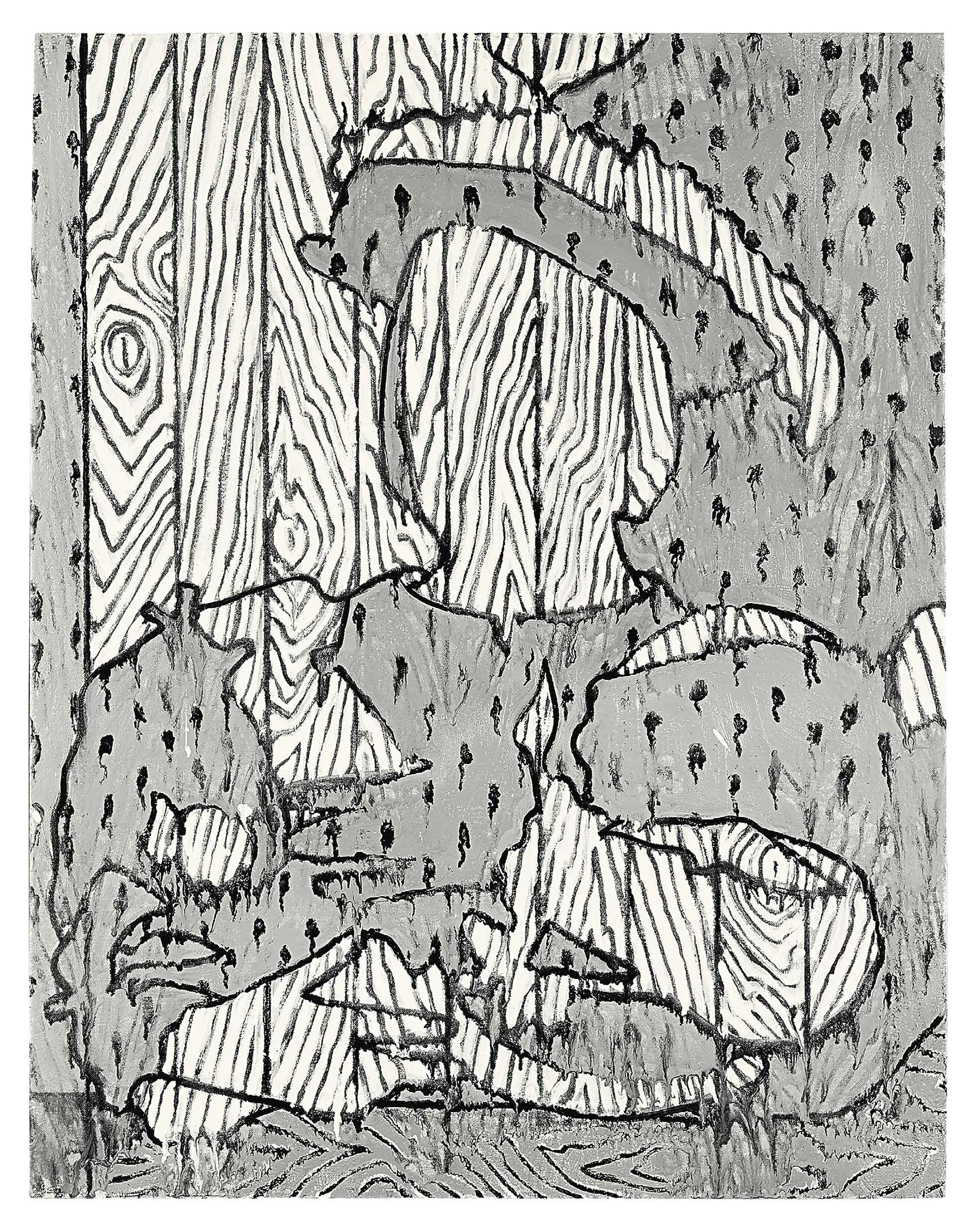

In the second part of a two-part essay, art historian John B. Ravenal considers Jasper Johns’s continued engagement with the motif of woodgrain.

Written by Scott Rothkopf.

Miriam Bale is a writer and film programmer based in California.

Aria Darcella is a fashion and culture writer based in New York. Photo: Zachary Headapohl

Arinze Ifeakandu is the author of God’s Children Are Little Broken Things , which received the 2023 Dylan Thomas Prize, the Story Prize Spotlight Award, and the 2022 Republic of Consciousness Prize. He was also a finalist for the 2022 Lambda Literary Award for Gay Fiction, the Kirkus Prize, and the CLMP Firecracker Award for Fiction. Photo: Bec Stupak Diop

John B. Ravenal is an independent curator and art historian based in Cambridge, Mass. He is the former executive director of the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, in Lincoln, Mass., and previously served as curator of modern and contemporary art at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond.

Jenny Odell is the author of the New York Times bestsellers How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy and Saving Time: Discovering a Life beyond the Clock , both of which have been translated into numerous languages. Odell has been an artist in residence at Recology SF (otherwise known as the dump), the San Francisco Planning Department, and the Internet Archive.

Daria de Beauvais is a Paris-based art historian, curator, writer, and lecturer. Senior curator at the Palais de Tokyo, she teaches at the PanthéonSorbonne university and is cohead of a research seminar at the École Normale Supérieure. She has curated exhibitions in Argentina, Australia, Belgium, France, the Netherlands, Romania, and the United States.

Photo: © François Bouchon

Zoë Hopkins is a writer and critic based in New York. She received her BA in art history and African American studies at Harvard University and is currently working on her MA in modern and contemporary art at Columbia University. Her writing has appeared in Artforum , the Brooklyn Rail , Cultured , and Hyperallergic

Hans Ulrich Obrist is the artistic director of the Serpentine, London. He was previously the curator of the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Since his first show, World Soup (The Kitchen Show), in St. Gallen, Switzerland, in 1991, he has curated more than 350 exhibitions. Photo: Tyler Mitchell

David Jacob Kramer is a Los Angeles–based writer. His most recent book is Heads Together: Weed and the Underground Press Syndicate, 1965–73 (Edition Patrick Frey).

Eli Diner is a Los Angeles–based writer. His work has appeared in publications including Artforum , Book Forum , Frieze , and Texte zur Kunst . He has a gossip column in the Los Angeles Review of Books . His book The Renaissance will be out in 2025 from Apogee Graphics.

Jessica Beck is a director at Gagosian, Beverly Hills. Formerly the Milton Fine Curator of Art at the Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, she has curated many projects, notably Andy Warhol: My Perfect Body, the first exhibition to explore the complexities of the body, through beauty, pain, and perfection, in Warhol’s practice.

Photo: Abby Warhola

Peter Doig was born in Edinburgh in 1959 and grew up in Trinidad and Canada before moving to London to study at Saint Martin’s School of Art and the Chelsea School of Art. Since 2002 he has divided his time between London and Trinidad. His work is represented in major public and private collections worldwide.

Richard Shiff is Effie Marie Cain Regents Chair in Art at the University of Texas at Austin. His Sensuous Thoughts: Essays on the Work of Donald Judd (2020) collects his writings on the artist over a twentyyear period. Many other essays on recent art appear in his Writings after Art (2023). For Gagosian he recently published “Haunting,” a text for the catalogue of David Reed’s exhibition of new paintings in 2020. He has published on Peter Doig on several occasions.

Sarah Crowner lives and works in Brooklyn. Her diverse practice incorporates two- and threedimensional works across a variety of media (painting, sculpture, installation, and set design). Crowner’s work points to an expanded field of painting, investigating the relationship between the element and the whole, and how parts build an entirety. In September 2023, the Pulitzer Arts Foundation opened Sarah Crowner: Around Orange , an exhibition of three new site-specific artworks responding to the architecture of the Pulitzer’s Tadao Ando building and Ellsworth Kelly’s monumental wall sculpture Blue Black . Other significant recent projects include a 2023 exhibition at the Hill Art Foundation in New York and a 2022 solo exhibition at Museo Amparo in Puebla, Mexico.

Lawrence Weschler, a graduate of Cowell College of the University of California at Santa Cruz, was for over twenty years a staff writer at The New Yorker, where his work shuttled between political tragedies and cultural comedies. He is a two-time winner of the George Polk Award and was also a recipient of Lannan Literary Award (1998).

Ross Simonini is an interdisciplinary artist, writer, and musician. His work includes paintings, drawings, essays, dialogues, musical composition, performance, and fiction.

Thomas Nail is a distinguished scholar and professor of philosophy at the University of Denver and the author of numerous books, including The Figure of the Migrant , Theory of the Border, Marx in Motion , Theory of the Image , Theory of the Object , Theory of the Earth , Lucretius I, II, III , Returning to Revolution , and Being and Motion . His research focuses on the philosophy of movement.

Jeff Wall was born in 1946 in Vancouver, where he continues to live and work. He has exhibited widely, including solo exhibitions at Tate Modern, London (2005); the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (2007); the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam and the Kunsthaus Bregenz (2014); and the Kunsthalle Mannheim, Germany (2018). Photo: Miro Kuzmanovic

Since the late 1990s, Sarah Sze has developed a distinct visual language that challenges the static nature of art. Widely recognized for expanding the boundaries between sculpture, painting, video, and installation, Sze uses a complex palette of materials, both analog and digital, to question how we mark time and space. Her work ranges from immersive installations that scale architectures to abstract canvases that explore a constantly evolving visual world. Sze was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship in 2003 and a Radcliffe Fellowship in 2005. She is a professor of visual art at Columbia University.

Rirkrit Tiravanija is known for a practice that overturns traditional exhibition formats in favor of social interactions through the sharing of everyday activities such as cooking, eating, and reading. Creating environments that reject the primacy of the art object and instead focus on use value and bringing people together through simple acts and environments of communal care, Tiravanija challenges expectations around labor and virtuosity. He is on the faculty of the School of the Arts at Columbia University and is a founding member and curator of Utopia Station, a collective project of artists, art historians, and curators.

Michael Craig-Martin depicts everyday items with a nuanced simplicity that exposes the tensions between objects and their representation. Distinguished by exceptional draftsmanship, vibrant color, and uninflected line, his work is intensely visual and rooted in an exploration of the relationships between perception, language, and meaning. Photo: Caroline True

Rosalind Brown grew up in Cambridge, England. She is the author of Practice , which was published in June by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Photo: Dougie Evans

Colm Tóibín was born in Enniscorthy, Ireland, in 1955. He is the author of eleven novels, including The Master, Brooklyn , The Testament of Mary, Nora Webster, House of Names , and The Magician . His work has been shortlisted for the Booker Prize three times and has won the Costa Novel Award and the IMPAC Award. He has also published two collections of stories and many works of nonfiction. Photo: Reynaldo Rivera

Joanna Biggs is the author A Life of One’s Own: Nine Women Writers Begin Again , which was published in paperback in August. Photo: Hillery Stone

Ken Burns has been making documentary films for almost fifty years. Since making the Academy Award–nominated Brooklyn Bridge of 1981, Burns has directed and produced some of the most acclaimed historical documentaries ever made, including The Civil War, Baseball , Jazz , The War, The National Parks: America’s Best Idea , Prohibition , The Roosevelts: An Intimate History, The Vietnam War, Country Music , The U.S. and the Holocaust , and, most recently, The American Buffalo Future film projects include Leonardo da Vinci , The American Revolution , Emancipation to Exodus , LBJ and the Great Society, and others. Burns’s films have been honored with dozens of major awards, including seventeen Emmy Awards, two Grammy Awards, and two Oscar nominations.

Ashley Overbeek is the director of strategic initiatives at Gagosian, where she has the pleasure of working with artists on digital projects. Overbeek is also a member of the advisory board of the Art and Antiquities Blockchain Consortium, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, and a guest speaker on the subject of art and technology at Stanford and Columbia University.

A director at Gagosian since 2002, Mark Francis was formerly founding director and chief curator of the Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh. He has been a curator at the Centre Pompidou, Paris; the Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh; the Whitechapel Art Gallery, London; and the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, England.

Alison McDonald is Chief Creative Officer at Gagosian and has overseen marketing and publications at the gallery since 2002. During her tenure she has worked closely with Larry Gagosian to shape every aspect of the gallery’s extensive publishing program and has personally overseen more than 500 books dedicated to the gallery’s artists.

Amit Noy is a choreographer, dancer, and writer who lives in Marseille, France. He makes performances (which often involve multiple generations of his own family), dances for the choreographer Michael Keegan-Dolan, and writes obsessively on dance for publications including Artforum , bomb , and the Brooklyn Rail

Moeko Fujii is an essayist and critic whose work has appeared in The New Yorker, the New York Review of Books , the Criterion’s Current , Aperture , and elsewhere. She currently writes a column on film for Orion Magazine

Scott Rothkopf is the Alice Pratt Brown Director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, where he previously served as the Nancy and Steve Crown Family Chief Curator. He joined the Whitney’s staff in 2009 and has curated and cocurated many exhibitions there, including Jasper Johns: Mind Mirror (2021), Glenn Ligon: AMERICA (2011), Wade Guyton OS (2012), Jeff Koons: A Retrospective (2014), America Is Hard to See (2015), Open Plan: Andrea Fraser (2016), Virginia Overton: Sculpture Gardens (2016), and Laura Owens (2017).

FormaFantasma is a research-based design studio investigating the ecological, historical, political, and social forces shaping the discipline of design today. The studio was founded in 2009 by Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin. Its aim is to facilitate a deeper understanding of both our natural and our built environments and to propose transformative interventions through design and its material, technical, social, and discursive possibilities. Working from studios in Milan and Rotterdam, the practice embraces a broad spectrum of typologies and methods, from product design through spatial design, strategic planning, and design consultancy. Trimarchi and Farresin also head the GEO–Design department at the Design Academy in Eindhoven, where they explore the social, economic, territorial, and geopolitical forces shaping design.

Jackie Sibblies Drury is a Brooklynbased playwright. Most recently she worked on Illinoise with Justin Peck, based on the album by Sufjan Stevens. Her plays include Marys Seacole (Obie Award), Fairview (Pulitzer Prize, Susan Smith Blackburn Prize), Really, Social Creatures , and We Are Proud to Present a Presentation. . . . Presenters of her plays include Soho Rep, Donmar Warehouse, the Young Vic, LCT3, New York City Players, Abrons Arts Center, and T: The New York Times Style Magazine

Rennie McDougall is a writer based in Brooklyn. His work has appeared in the Brooklyn Rail , frieze.com, Guernica , T Magazine , the Village Voice , and other publications. He received an Anthony Burgess Prize for Arts Journalism in 2018. His first book will be published by Abrams Press in 2026.

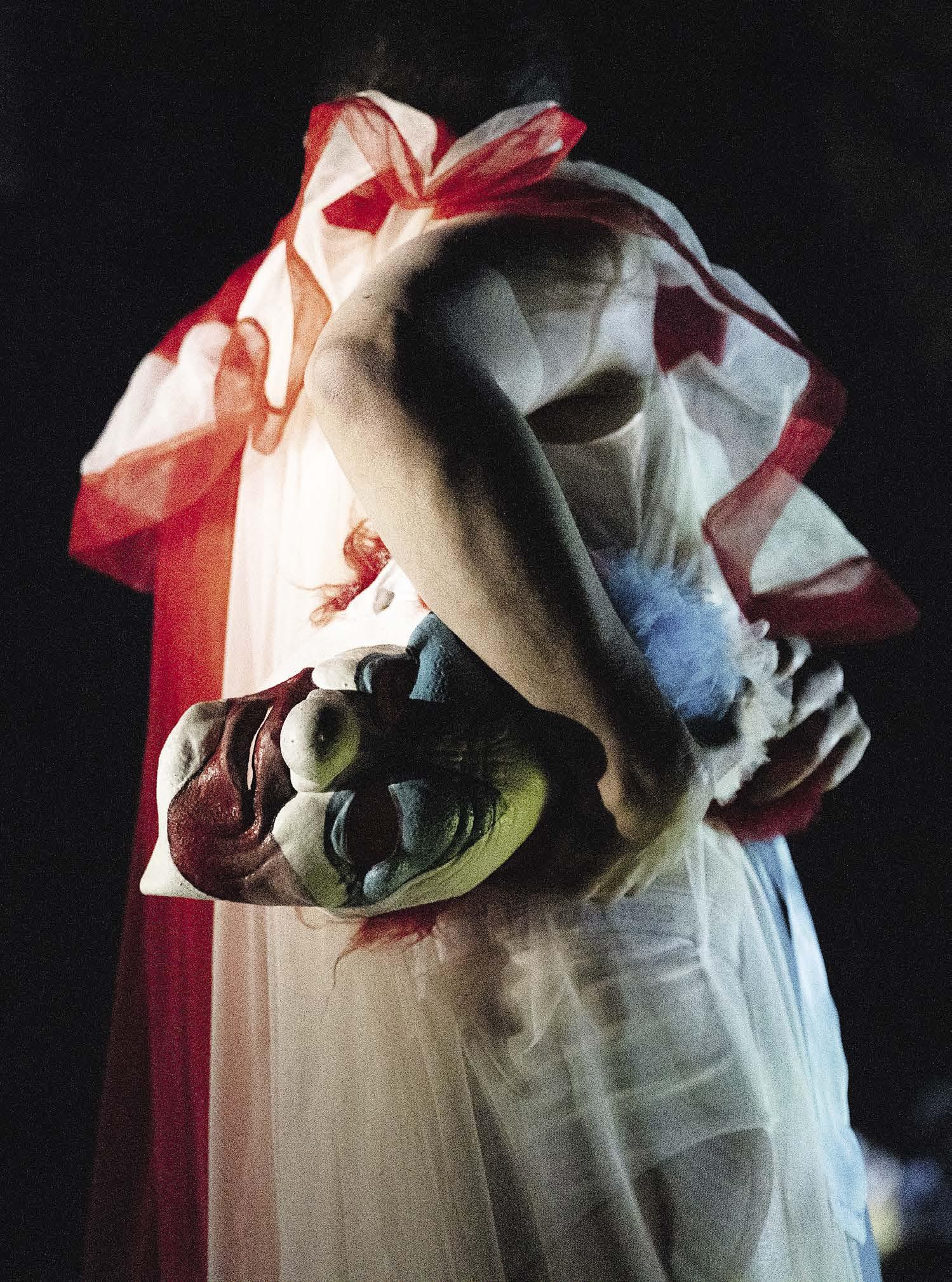

Harriet Jung and Reid Bartelme met in 2009 while pursuing fashion design degrees at the Fashion Institute of Technology, New York. They started designing collaboratively in 2011 and have focused their practice primarily on costuming dance. They work often with Justin Peck, Pam Tanowitz, and Kyle Abraham, and have devised costume-centric performances for commissions from the Museum of Art and Design and the Guggenheim Museum, New York. They made their Broadway design debut in 2023 with Bob Fosse’s Dancin’ and in 2024 designed Peck’s Broadway musical Illinoise . Jung and Bartelme have completed research fellowships at the Center for Ballet and the Arts at New York University and the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

Pavel Kolesnikov and Samson Tsoy have been living and working together since their early student days. For both artists, space and setting is a crucial element in their music-making. During the pandemic they performed Messiaen’s Visions de l’Amen at a former multistorey car park in London, while in the summer 2023, they brought back concerts at Aldeburgh’s historic Jubilee Theatre. Other presentations include Prokofiev’s Cinderella in the Muziekgebouw loading bay and performances in galleries across Europe. In 2019, Kolesnikov and Tsoy co-founded the Ragged Music Festival, which provides a strippeddown environment for artists to explore a dialogue between music, architecture, and visual arts. In 2024 the duo debuted at New York’s Carnegie Hall.

Michael Schmelling is the author of eight photo books, including The Plan , My Blank Pages , Your Blues , and Rise & Fall . Schmelling’s commissioned work has appeared in GQ , The Atlantic , the New York Times , M Le Monde , and Zeit Magazin .

Derek C. Blasberg is a writer, fashion editor, and New York Times best-selling author. He has been with Gagosian since 2014, and is the executive editor of Gagosian Quarterly

Gagosian Quarterly presents a selection of new releases coming this winter.

Louis Vuitton unveils Ocean BLVD, a collaboration with artist Alex Israel that transforms the Cologne Perfumes collection into a vibrant, immersive experience. This two-meter sculpture, inspired by California’s coastal charm, features contemporary architecture reflecting the spirit of Los Angeles and pays homage to Israel’s colorful aesthetic. Each scent embodies a unique stop along an imaginary boulevard, from the invigorating Pacific Chill spa to the nostalgic City of Stars cinema. Crafted by twenty artisans, this piece showcases luxurious materials and meticulous detail, celebrating the intersection of fragrance and art in a tribute to the Californian lifestyle.

This extensive monograph gathers nearly sixty large-scale sculptures and installations made by Urs Fischer over the past twenty-five years. The nearly four-hundredpage volume groups works under thematic headings such as “Holes,” “Lines,” and “Intersecting Objects,” illustrating how the Swiss artist has explored and returned to specific sculptural problems over decades, and how his approaches have changed with technology.

Oscar Murillo’s Arepas y Tamales printed shirts feature emblems from drawings the artist collected from schoolchildren’s desks around the world for his Frequencies project. The shirts were worn for the first time by the musicians of the Mar, Río y Cordillera group, from the Valle del Cauca region of Colombia, where Murillo was raised, when Murillo invited them to perform at Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt in the summer of 2023. Available in one size and ten different designs, the oversize, structured dress shirts are made of heavy cotton and feature mother-ofpearl buttons. Each has a label noting the country from which its drawing originates. In this one, a drawing of an ovoid green soccer field, surrounded by tiny red and blue houses, covers the shirt’s back.

This fall, Bottega Veneta unveils its debut fragrance collection under creative director Matthieu Blazy, capturing the essence of Venice. Inspired by the city’s rich tapestry of trade, each of the five fragrances weaves together global ingredients, reflecting the brand’s signature Intrecciato. From the sun-kissed Colpo di Sole to the sultry Déjà Minuit, these scents promise an evocative journey. Each bottle is a masterpiece of Murano-inspired design, emphasizing tactile pleasure and making these fragrances a treat as much for the hands as for the senses.

Bottom right: Wave of Blood (Divided Publishing, 2024)

Inspired by the To - jinbo - Cliffs of Fukui Prefecture in Japan, this hachi , or bowl, was designed by legendary chef Masayoshi Takayama, known as Masa, to serve as an ice basin for keeping an open sake bottle cold. It may also be used as a salad bowl. Each piece is unique in color and shape. Following the seven principles of the Japanese aesthetic concept of shibusa —simplicity, implicitness, modesty, naturalness, imperfection, everydayness, and silence—the Masa Designs collection is crafted to improve the aesthetics of everyday life. Markings and coloring will vary due to the unique nature of the production and firing processes.

Tiffany & Co. has unveiled the Tiffany Titan by Pharrell Williams collection, featuring high-luster freshwater pearls. Inspired by Poseidon’s trident and Pharrell’s roots in Virginia Beach, the collection embodies fearless individuality with its spearlike motifs and soft, curved links.

An epic poem, a memoir, a mystical transcription, a wild howl for honesty and diligence: Ariana Reines’s latest book defies categorization. Through a sustained engagement with the heart and with the powers and limitations of language, the poet asks nothing short of how to care for our souls in a world filled with grief and rage.

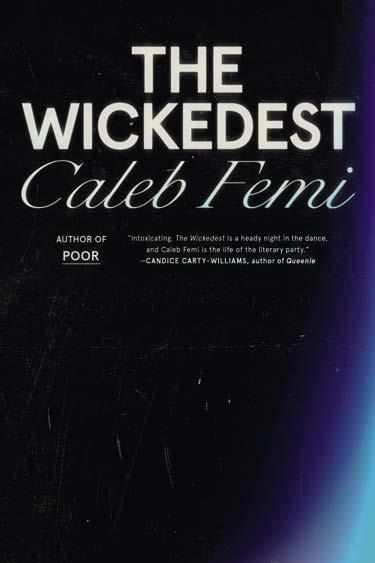

From the author of Poor (2020), this kinetic poem pulses, drops, climaxes, and carries the reader through one night in South London at a house party called “The Wickedest.” Femi’s euphoric approach imbues traditional poetic forms with new life, while exploring the power of the dance floor in sustaining community.

Below, left to right: Photo: courtesy

Photo: courtesy Vacheron Constantin

Photo: courtesy Cartier

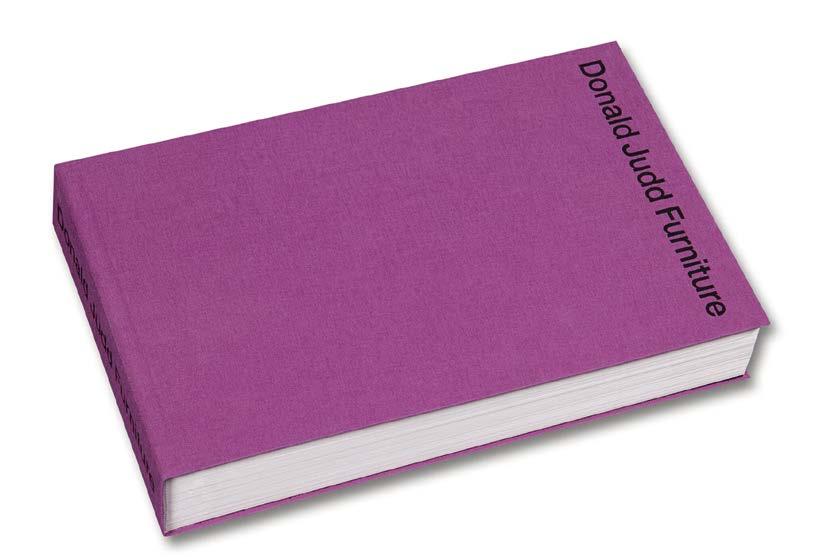

Donald Judd Furniture presents a selection of Donald Judd’s furniture in wood, metal, and plywood. In this new volume, more than 100 designs are presented through perspectival drawings organized by material in six chapters. Both newly commissioned and archival photographs explore the placement and function of furniture within Judd’s living and working spaces in New York, Texas, and Switzerland. These designs, spanning from 1970 to 1991, exemplify the directness of form and presence for which his work is celebrated.

Balenciaga has unveiled its latest flagship on Greene Street in SoHo, Manhattan. This two-story space, covering over 9,800 square feet, carries on the brand’s Raw Architecture concept, blending art and fashion in an “in-progress” aesthetic with elements reminiscent of Cristóbal Balenciaga’s original Paris atelier.

To celebrate the twentieth anniversary of its Patrimony collection, Vacheron Constantin introduces a limited edition self-winding timepiece in collaboration with designer Ora ïto. This vintage-inspired watch features a 40mm yellow-gold case and a toneon-tone dial adorned with concentric circles. Limited to just 100 pieces, it showcases the house’s watchmaking expertise and timeless aesthetic, perfectly complemented by Ora ïto’s marriage of simplicity and complexity.

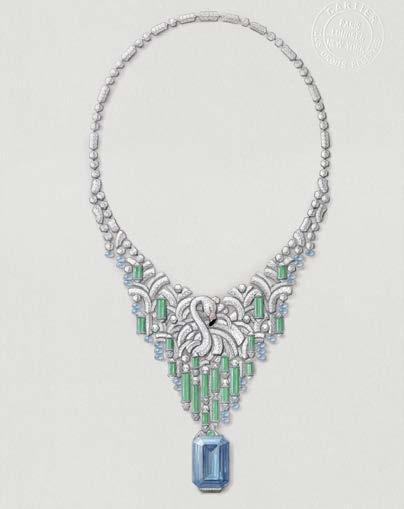

The latest jewelry collection from Cartier takes its cues from flora and fauna: turtles, flamingos, leopards, zebras, leaves, crocodiles, and more. Expertly designed and crafted, this series of necklaces, rings, and bracelets articulates the form and energy of the natural world with the finest materials.

Mark Francis remembers his late friend, the indefatigable and radical curator Kasper König.

It is a vivid indication of the meteoric trajectory of Kasper König’s career that his first experience of curating a museum exhibition was for the artist Claes Oldenburg, at Moderna Museet in Stockholm, in 1966, when König was only twenty-three years old. And he topped this a couple of years later when he organized an Andy Warhol exhibition, also at Moderna Museet, in 1968. He had proposed to Pontus Hultén, then the director of the museum, a popular exhibition that would cost almost nothing, and this was happily approved. Then he went to Warhol to suggest that they make the exhibition in Stockholm itself, rather than send works from the artist’s studio in New York: hundreds of Brillo Boxes (1964) and Silver Clouds (1966) would be fabricated on site, Cow wallpaper (1966) would be pasted to the museum’s exterior walls, and Warhol’s early films, such as Sleep (1964), would be projected in the galleries. It was a revolutionary way to present an artist’s work, entirely in the spirit of Warhol, and it proved highly successful: the museum claimed to have sold over

250,000 copies of the catalogue, a kind of artist’s book featuring the photographs of Billy Name.

König was born in 1943 in Mettingen, near Münster, Germany. In his late teens, still at school in Essen, he saw a Cy Twombly exhibition at Rudolf Zwirner’s gallery and briefly became an intern there. He soon moved to London, working for the gallerist Robert Fraser, and then on to New York, where he immersed himself in the downtown art, dance, and music worlds, meeting artists such as Oldenburg, Richard Artschwager, On Kawara, and Dan Graham, dancers Yvonne Rainer and Simone Forti, and many others.

In 1969, following the two precocious and well-received museum exhibitions in Stockholm, König somewhat mysteriously moved back to Europe and spent a year in Antwerp, becoming close to Marcel Broodthaers and Fluxus artists such as Robert Filliou and Addi Koepke. And then another move, to become the publisher of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design’s series of books with artists—

Bernhard Leitner’s The Architecture of Ludwig Wittgenstein (1973), Yvonne Rainer’s Work 1961–73 (1974), Donald Judd’s first Complete Writings (1975). He connected different strands of the avant-garde and became an essential conduit between the New York and European art worlds, especially those of Düsseldorf and Cologne.

For Harald Szeemann’s documenta exhibition in Kassel in 1972, König presented Oldenburg’s Mouse Museum as a single-artist museum within the larger exhibition. It should have been obvious by this point that König was one of the most brilliant and dynamic young curators in Germany, but he was notoriously never invited to curate documenta in the following years. Instead, he organized the first iteration of the Skulptur Projekte exhibitions in the town of Münster in 1977, coinciding with, and rather overshadowing, the documenta of the same year. It became his defining project, which he repeated in 1987 and expanded each decade until his final version, in 2017. Despite having no academic background and no institutional position, he independently curated the revisionist exhibition Westkunst. Zeitgenössische Kunst seit 1939 (West-art: Contemporary art since 1939), with the art historian Laszlo Glozer, in the trade fair halls in Cologne in 1981. The show was seen as provocative at the time, including overlooked work such as late paintings by Vasily Kandinsky and René Magritte’s Vache (Cow) paintings (1947–48), and it explicitly acknowledged the competitive hegemony of Western Europe and North America in the postwar period.

In 1984, König followed this enormous project with another, Von hier aus—Zwei Monate neue deutsche Kunst in Düsseldorf (Up from here—Two months of new German art in Düsseldorf), a survey of contemporary

German art. Only in the 1990s did he take a professional position, becoming the director of the Städelschule in Frankfurt, which rapidly became a dynamic art school, and founding Portikus, an associated Kunsthalle where he could present exhibitions of established and younger artists alike. One of the first, and most significant, was the exhibition of Gerhard Richter’s 18. Oktober 1977 series, made in 1988, which addressed the highly charged subject of the deaths in custody of members of the revolutionary group the Red Army Faction.

Then, in 2000, König became the director of the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, a final vindication of his distinguished status both nationally and internationally. He remained open to new ideas and to younger artists and became a mentor and supporter of the next generation of curators, such as Okwui Enwezor and Hans Ulrich Obrist. His energy was prodigious and he participated often in advisory committees, panels, and seminars.

Among my experiences over our long friendship, when I cocurated the Carnegie International exhibition in Pittsburgh in 1991 with Lynne Cooke, we invited Kasper to be on the jury for the Carnegie Prize. He insisted that On Kawara be awarded the prize, a decision not widely popular at the time, but certainly prescient and daring.

Kasper died in August. I last saw him in December in Berlin, where he lived after retiring from the Museum Ludwig and where he still had an office in the artist Douglas Gordon’s studio complex. We met at the Nationalgalerie, newly restored by David Chipperfield, and he had characteristically acute comments on the concurrent exhibitions of work by his old friends Richter and Isa Genzken. Kasper loved art and artists, and he retained his humor and anarchic spirit until the end.

This puzzle, written

by Myles Mellor,

brings together clues from the worlds of art, dance, music, poetry, film, and beyond.

1 Modernist sculptor who created Head

4 Mark Grotjahn painted a series based on this Italian island

9 Plastic Band, formed in 1969

10 Nancy , American sculptor and installation artist who works with salvaged objects

11 Empire star

13 Young lady

15 Roe , postmodernist photographer known for exploring the plastic nature of photography

18 “Earned it” singer the

19 Access requirement, often, abbr.

20 The Basket of by Salvador Dalí

22 Director of The Beach Bum , Korine

25 Gordon, artist known for luminous and hyperrealistic paintings, often featuring herself

26 Diving Boy I creator Richard

28 Country singer Tillis

30 Derrick , painter of Who Can I Run To (Xscape)

33 Conceive something in a different way

35 Ernie Barnes acrylic The Shack , later used as a Marvin Gaye album cover

36 Artistically unusual

38 Character in the musical Evita

40 Cereal grain

41 Poet’s evening, for short

42 Sistine Chapel ceiling figure

43 Hawaiian crooner Don

Down

1 Helen , painter whose vibrant works echo her travels to Greece, India, and Morocco

2 Crystal ball, e.g.

3 Very long time

4 Data-storage device

5 Cigar, to George Burns

6 Theaster Gates’s Black Corporation

7 Always Afternoon artist Howard

8 Lucinda Chua’s “Hold a ” song

12 Subject for an art historian in relation to artworks

14 Former SNL writer and cast member Samberg

16 Damien , painter of Veil of Unfolding Life

17 British installation artist and filmmaker Sir Julien

20 Manet work A at the Folies-Bergère

21 Confused expressions

23 Brokeback Mountain director, first name

24 First name of the artist known for paintings of subjects with big eyes

25 “Love Song” Grammy winner, first name

27 Creator of Marilyn Diptych

28 Richard , creator of the “Nurse Paintings”

29 Artist who has written obituaries for living celebrities, Adam

31 1973 Rolling Stones ballad

32 One of the collectors who supported and popularized Matisse, Stein

34 Van Morrison’s “ the Mystic”

35 Take a tour of

37 American artist who contributed to the Dadaist and Surrealist movements

39 Cut down

A New York exhibition conceived and curated by the artist Peter Doig takes as its point of departure Balthus’s 1933 painting The Street , in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art. Ahead of the show, Doig and art historian Richard Shiff met up to look at Balthus’s painting together in person.

RICHARD SHIFF From conversations over the years, I know that many people really like this painting. But to think of it in relation to your art specifically: the figural quality reminds me of your work, as does the complexity of the urban environment. These figures are iconic. They’re frozen in gesture, and the gestures are precise and enigmatic and meaningful all at once.

PETER DOIG That’s the mystery of the painting, and that’s why it has such a lasting resonance, because it presents a puzzle. It has a mixture of the real world, the world of painting, and the world of painting in the real world. When The Street was made, pretty much all shop fronts and their corresponding signs would have been hand painted; there would have been no photographic signage, et cetera. And I think Balthus was obviously aware and in some ways inspired by this painted world.

RS These figures have the character of the type of Renaissance painting that is defined as linear, where the shape of the body is very distinctive and essentially geometrical.

PD It’s as though he had absorbed almost everything that happened in painting from the Renaissance up to the Bauhaus. There’s an earlier version of this painting that Balthus made when he was twenty-one and that feels quite different, almost impressionistic, in the way it’s made.

RS Honestly, this work has always reminded me, vaguely but insistently, of Seurat’s [ A Sunday on ] La Grande Jatte [1884]. It’s a similar size. The figures are stiff. They’re very clearly outlined. But I’m also impressed by how it’s crisp and blurry at the same time.

PD It’s not afraid to look like a sign painting.

RS Yeah.

PD Fifteen years later, Balthus famously made a painting called The Mediterranean Cat —a cat sitting at a table with a fish on its plate, a rainbow over its head, and the sea behind it. It was like a painting you’d see in a restaurant. It has a similar sense of directness. In fact I think it was painted for a restaurant.

RS Yeah, now that you say that.

PD In a way, he was making a painting that wasn’t about being an expert painter. A lot of painters at that time would have thought The Street was, let’s not say amateurish, but a bit callow in its making. Not callow in its subject, though. And let’s not forget that he was in his twenties when he made this, he was a very young painter.

RS That’s right, but it doesn’t look like a young person’s painting. It’s too ambitious.

PD Yeah, it’s very ambitious.

RS There’s a figure on the left that resembles a signboard figure, the mannequin with the tall chef’s hat. All that’s missing is the menu. And the gesture of the central figure—

PD He looks like a bandleader, maybe of a marching band.

RS Except the other members of the band aren’t there. We simply have a bandleader. I just noticed that the curbing on the left side of the canvas disappears as it recedes into space behind the figures. It doesn’t turn the corner—a little bit of a liberty there. But Peter, in your painting—not to belittle what’s going on by calling it artful, but you’ve got artful remains of underpainting in your paintings, and that’s true here as well.

PD Well, I do enjoy that. Not just in this painting but in other artists’ paintings as well.

RS Why do you gravitate to this picture? It seems like you’ve been fascinated with it for a while.

PD I’m not the only one, by any means. It’s just a painting that I find endlessly beguiling. It needs to be seen. You feel like you’re witnessing something unfold before your eyes. It’s a kinetic painting that required a lot of decision-making on Balthus’s part. There’s a certain geometry to the painting as well, the underpinnings of a grid. You almost feel the presence of a T-square in its construction. A bold painting to have made, a street scene full of incidents from life both witnessed and imagined.

RS Compositionally, it’s full of geometric relationships. The girl’s elbow is virtually a right angle. And the shadow on the white pants of the

worker carrying the wood, that’s a geometric curve. And the tilt of the hat on the boy being carried, and the scarf of the nurse against the check pattern on her blouse. It’s rendered somewhat indistinct, because she’s in the background, but it’s a pretty skillful thing.

PD The hands are also very important. Every figure’s hands, except for the mannequin, remain active.

RS Yeah, they’re all gesturing or pointing in some way.

PD In looking at the green detailing that carries across the awning of the building on the center left, above the figures, you can see evidence of little spheres that he then painted out with one gestural stripe. And further down he hasn’t painted them all. They just cease to exist.

RS As if that’s a way of indicating depth. Or maybe he just stopped. There are lots of areas of incompletion that don’t seem to damage the painting, though you can’t see what’s being described there. It’s a bit of genius to put the pink in that green sign as a diagonal above the boy being carried, and it fits with everything else that’s happening on that side of the picture.

PD I had the opportunity to see the earlier version of this street scene this morning, which is compositionally similar but painted in such a different way. There’s so much more brushwork in that version. And it looks as though Balthus used the same brush to describe the boy’s face in the foreground as he did to paint a horse that’s in the background. He still allows himself quite a bit of looseness in this version, however; I guess because of its more ambitious scale, he wanted to turn this into more of a formal painting. The sketchy elements in the previous version are congealed into dark forms and silhouettes. Possibly the mostdescribed passages in the painting are the two heads on the far left.

RS Yeah. It’s interesting to think about taking out the elements that would be too sketchy to get away with at this scale, but leaving everything

very sketchy in the background, which matters less at this scale. By the way, what is this main figure wearing?

PD Looks like very high-waisted moleskin trousers.

RS Balthus produced a torso and legs in that figure with a minimal amount of articulation.

PD Almost the same color as the piece of wood.

RS Yeah. The wood is better described. That’s good sign painting, so to speak.

PD To be viewed from a distance.

RS There are all kinds of choices being made. For instance, the way a hand appears, the articulation of the fingers, seems to be a device to make the painting interesting in that place.

PD There seem to be a lot of devices used to make the painting, to make it right, as it were, to tie it together, to make it feel like it’s done. It’s a very open painting. It’s not pretending to be anything else.

RS Yeah. But I mean, we say the same about what you do.

PD I would hope so. There was an exhibition at the Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris recently, I don’t think Balthus was in it, but it included figurative artists he was associated with, such as the Berman brothers, Christian Bérard, and others. It was called Neo-Romantics: A Forgotten Moment in Modern Art 1926–1972 . There was a movement in figurative painting at the time that resisted the flow of modernism, and while Balthus was very much his own person, he remained connected to some of these other artists. He was part of the avant-garde, but he didn’t jump on any bandwagon. It was a great period for painting.

RS He’s a bit like Alex Katz is to us now, in terms of producing large-scale reductive and abstractive representational paintings.

PD I was in the National Gallery the other day in London to see this fantastic little show they had based around Degas’s Miss La La [at the Cirque

Fernando, 1879], you know, the acrobat, and they had gathered all of these studies, lots of really interesting works. Also on view was a small display of David Hockney’s responses to Piero della Francesca, specifically his Baptism of Christ painting [c. 1437–45]. There’s a figure in the background of the Piero painting that’s quite similar to the figure in the Balthus painting of the man carrying a piece of wood. In Piero’s painting, the man is bathing in the background, and he appears almost timeless. He looks like he’s wearing contemporary underpants, and then there are formal oddities— the reflection just doesn’t really make any sense at all. But the picture as a whole sings. There’s nothing realist about it but there are enough signs for us to believe it and want to enter it. And I think the Balthus painting has a very similar quality.

RS There was a real interest in Piero amongst British painters in the ’40s and ’50s, and I remember from my early art-historical education that a couple of generations before me, people I was instructed to read when I was a student, they were comparing everything to Piero. I mean, every modern painter had some connection to Piero. And there were certainly statements that connected Seurat to Piero. Some of it seemed tenuous to me, but the sensitivity was so strong that everything got compared to Piero or Poussin, one or the other, or to both. Do you think The Street could have been made by a British artist?

PD I don’t think so. It’s too French in the way it’s made—not just the scene, because British artists have painted Paris and all sorts of other places, but it feels like the painter is connected to France.

RS Too studied, maybe. Too logical. The way it’s organized.

PD I mean, this is an ambitious painting. It’s an ambitious scale. And he must have been thinking about contemporary paintings that he was seeing, perhaps ones made by the likes of Picasso and Matisse and Bonnard, who he was connected to.

Previous spread, and opposite: Balthus, The Street , 1933, oil on canvas, 76 ¾ × 94 ½ inches (195 × 240 cm), Museum of Modern Art, New York © 2024 Balthus/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris. Photo: © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, New York

This page: Peter Doig, Night Playground , 1997–98, oil on canvas, 78 ¾ × 108 ¼ inches (200 × 275 cm) © Peter Doig

He would have been motivated by the size of those paintings. He wasn’t going to resign himself to make paintings to hang above mantelpieces, let’s say. And I think the writers that he’s connected to, Georges Bataille among them, the kind of writing that was being published in their circles and being published in magazines like Minotaure —he wasn’t going to be making paintings that were tame or restrained.

RS You’re making me think that, of course, Surrealism is all over the place in this year, and this is the surreal of the commonplace, of the ordinary street, including the salacious scene of adolescent sexuality at the left.

PD The surrealism of The Street is maybe more surreal than that of Yves Tanguy or Max Ernst.

RS Exactly. More enigmatic because it isn’t fantastical. Because these are real people, but they don’t look real.

PD It’s not contrived in that respect.

RS So it’s Surrealism that’s more interesting than doctrinaire Surrealism.

PD I think he tried for and achieved a sense of timelessness with his work. What he was doing, which is clever, is looking at and taking cues from paintings he admired from the past and then tweaking aspects of them to use in his own work. And this made them believable in his time.

RS Yeah, some of those figures certainly look like they’re coming out of a nineteenth-century French painting, not a twentieth-century French painting. He returns to this scene in the early 1950s in Le Passage du Commerce Saint-Andre

PD Yes, that work is hanging at the Fondation Beyeler [in Riehen, Switzerland]. It’s often called his masterpiece but I actually prefer The Street

RS Why?

PD I find it more mysterious. It feels more filmic. More connected to the world of theater or dance rather than that of “pure” painting. I heard Federico Fellini was a huge admirer of Balthus and

actually wanted to make a film about him.

RS Well, he was a bit of a Fellini character. The people around him, also.

PD Something I read connected this work to his interest in [Lewis Carroll’s] Alice in Wonderland [1865].

RS When I first read that, I thought, yeah, that makes sense. Other scholars seemed to reject it, though. And there’s also his remark that this is all about children, right?

PD Well, the adults have either got their faces hidden or are walking away. The only faces you see are the faces of children.

You know, he altered this painting. The two figures on the far left were originally more provocative. Balthus changed the position of the boy’s hand at the request of the owner, who later donated the work to the Museum of Modern Art. And apparently he had no reservations about altering it. In response to being asked to make the changes to the painting, he said something along the lines of, When I was younger, I wanted to shock, but with the passage of time, that urge subsided.

It seems that, at this point in time, he wasn’t afraid to invent a way of depicting figures. They don’t seem particularly natural, which is similar to the way that I draw, actually. He was quite content with finding a figure that acts as a stand-in for his idea, for instance his chef figure, who, as you suggested, might be a mannequin outside a restaurant. It feels very worked out, almost as if he used silhouettes or cutouts to form the figures, which interests me and is something that I like to do.

RS You often reproduce, or take as a subject, sign painting or somebody painting on a wall.

PD Or sometimes I even pay homage to sign painters.

RS Maybe it’s in the literature somewhere, but the little girl on the lower left is a dwarfish figure,

which connects her to Velázquez. The complexity of this image is not only in Poussin and Seurat, it’s also Velázquez.

PD What about Oskar Schlemmer? Balthus spent time in Germany when he was a teenager. He claimed that he took no influence from German artists, but he would have been aware of them because of the circles he moved in and the people who came to the house.

RS As a painter, what do you think about the way Balthus made the painting?

PD I love the way it’s made. I love how open the painting is. The window frames and the signs, for instance: there’s a shoddiness to the way they’re rendered, but it’s very, very effective. He uses paint in a luscious way. I like what happens when he makes the paint quite thin, sort of bloodlike, like in the stripes on the pink-andwhite awning. To me that’s very exciting. It seems that what’s most important for him is not making a perfect painting, like Christian Schad, for instance, whose work I also like very much, but it’s so much more refined. This is like a pub sign as a fine-art painting.

RS He’s playing with transparency and opacity quite a bit, and there’s only enough opacity in there to produce a set of rhythmic highlights. There’s a spectrum that goes from opacity to transparency, different grades of it all the way through.

PD He wasn’t afraid to use devices. The highlighting on the little girl’s collar is irreverent in the way it’s made, in that he does attempt to conceal that it is in fact a device.

I think ultimately what’s interesting about this painting is that although he’s aware both of the history of art and of his contemporaries, Balthus paves his own course. It’s his own myth that possesses its own poetry. I think people will continue to try to decipher its many mysteries. And that’s why it still has life after so many years.

The fascinating life of Leonardo da Vinci is the subject of a new film by Ken Burns. The legendary filmmaker sat down with the Quarterly ’s Alison McDonald to discuss Leonardo’s insatiable curiosity, his passionate enchantment with nature, and his endless search for universal truths.

ALISON MCDONALD Your films tend to explore America’s greatest stories. What prompted you to make a film about Leonardo da Vinci?

KEN BURNS To be honest, I didn’t want to do it at first; as you mentioned, I’m an Americanist. But I’ve never been so inspired. My friend Walter Isaacson, who wrote a biography of Leonardo, made the suggestion. I mentioned it to my daughter, Sarah Burns, and her husband, David McMahon—we’ve worked on films together about the Central Park Five, Jackie Robinson, and Muhammad Ali. They were enthusiastic and thought a film on Leonardo would be great. While making this film, Sarah and Dave moved to Italy for a year with my two oldest grandkids.

AM Your films feel effortless for the viewer to engage with, but they are enormously complex puzzles that you layer together. And this must have been a bit of a different experience for you—while there are many notebooks, writings, and sources by and on Leonardo, it must have been a challenge not to have photographic or film sources from the period. How did you put this puzzle together?

KB It actually wasn’t that different from our other films—process is process. We had different materials to work with under different circumstances, but our approach was the same. As with any project, we arrived at it with preconceptions and quickly become aware of how little we actually knew, which is always a humbling experience. And then we just started building. Sarah and Dave wrote the script, so they were wrestling with the distillation, not just of all the visual material, but also with what we were going to say. To get [the Italian actor] Adriano Giannini to read the script was such a treat.

At some point we realized that, because of Leonardo’s capacious mind, we could keep a similar style—we could explode all the visuals, have split screens, and a single score. There’s one composer for the entire film, Caroline Shaw. And with Leonardo you can show video of rocket ships taking off and solar systems and beautiful images of nature.

AM How much did what you learned about Leonardo surprise you?

KB Every single day was a revelation.

AM Throughout all of Leonardo’s studies—painting, mathematics, physics, engineering—there’s a focus on nature. In the film, he is quoted saying, “The best gift that was given to me by the universe was the chance to question it.” His curiosity about nature was insatiable and he examined it often on both a macro level—water, wind, gravity—and on a human scale: skeletal structures, muscle movements, the way an eye works. Why do you think his fascination with nature plays such a central role in his thinking?

KB Leonardo was seeking a key to the cosmos, a way of better understanding all of human experience and knowledge. He studied the perfection of nature and he saw it as his primary teacher, as

Below:

Opposite: Leonardo da Vinci, The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, c. 1508–17, Musée du Louvre.

essentially the manifestation of God. For Leonardo it was a human responsibility to give nature life in a new way. We see him as a scientist, writer, inventor, theorist, painter, scholar, but he saw no division of labor: for him they were all one thing. He wanted to interrogate the universe. That was his divine duty. He asked the universe to yield up its subjects, to yield up its truth, and he was able to bring back so much to us in all of these various disciplines.

AM His discoveries are fascinating, especially considering that he was observing with only the human eye. He was way ahead of his time in examining and diagraming how blood pumps through heart valves, for instance.

KB He was 450 years ahead of his time in so many things. He studied the way heart valves work and his analysis wasn’t verified until we had MRIs, in the 1970s. He had no telescopes and no microscopes. He didn’t have calculus, which would have helped him with a lot of his mathematical stuff. Versing himself in mathematics, he was coming up with stuff about gravity well before Galileo (who didn’t have calculus either), before Isaac Newton (who did), and before Albert Einstein. He was getting to extraordinary places about gravity and fundamental principles of physics. He was an experimental physicist, a surgeon, an anatomist, a botanist. There’s this restless curiosity that’s able to synthesize knowledge and realize that knowledge is not enough. I went to Hampshire College in Massachusetts, and the school’s Latin motto was Non Satis Scire (To know is not enough). It means that you have to take something and put it into motion and practice it and synthesize that knowledge into something bigger that we might call understanding. And what you get when you spend time with Leonardo is just a sense that this may be the most incredible human being, having this gift of revelation in all these different areas.

AM In Florence at this moment, during the Renaissance, the arts were flourishing, there was a rediscovery of classical philosophy and literature, painters and sculptors were celebrated and in high demand. The Christian doctrine that had pervaded European art up to that point had been followed by humanism; it was an era of enlightenment when painting and culture were celebrated as the pinnacle of influence. If Leonardo had lived in a different era, do you think he would have been known as a painter or more celebrated for his scientific pursuits?

KB It’s such an interesting question. One we can’t answer. But let’s think about how he’s one of the great painters of all time, with only twenty works, half of them unfinished. Still, he made the most famous painting in the world today—a painting of the twenty-four-year-old wife of a well-to-do Florentine silk merchant, a woman who had had five kids by that age. And Leonardo never delivered the portrait. It’s unclear whether he ever considered it finished.

Giorgio Vasari, after describing the face in the Mona Lisa [c. 1503–06], drops down to the neck and says, I can see the blood flowing through her veins. I can see her heart beating. He’s rhapsodizing over the anatomy and the hair and the background and the mist and the texture of the skin and the sfumato technique that just, you cannot believe it when you get up close, what he’s doing with the translation between light and shade and gradations of various colors.

AM It’s interesting that there are so few paintings, because he made so many drawings and sketches, and articulated so many plans with illustrations.

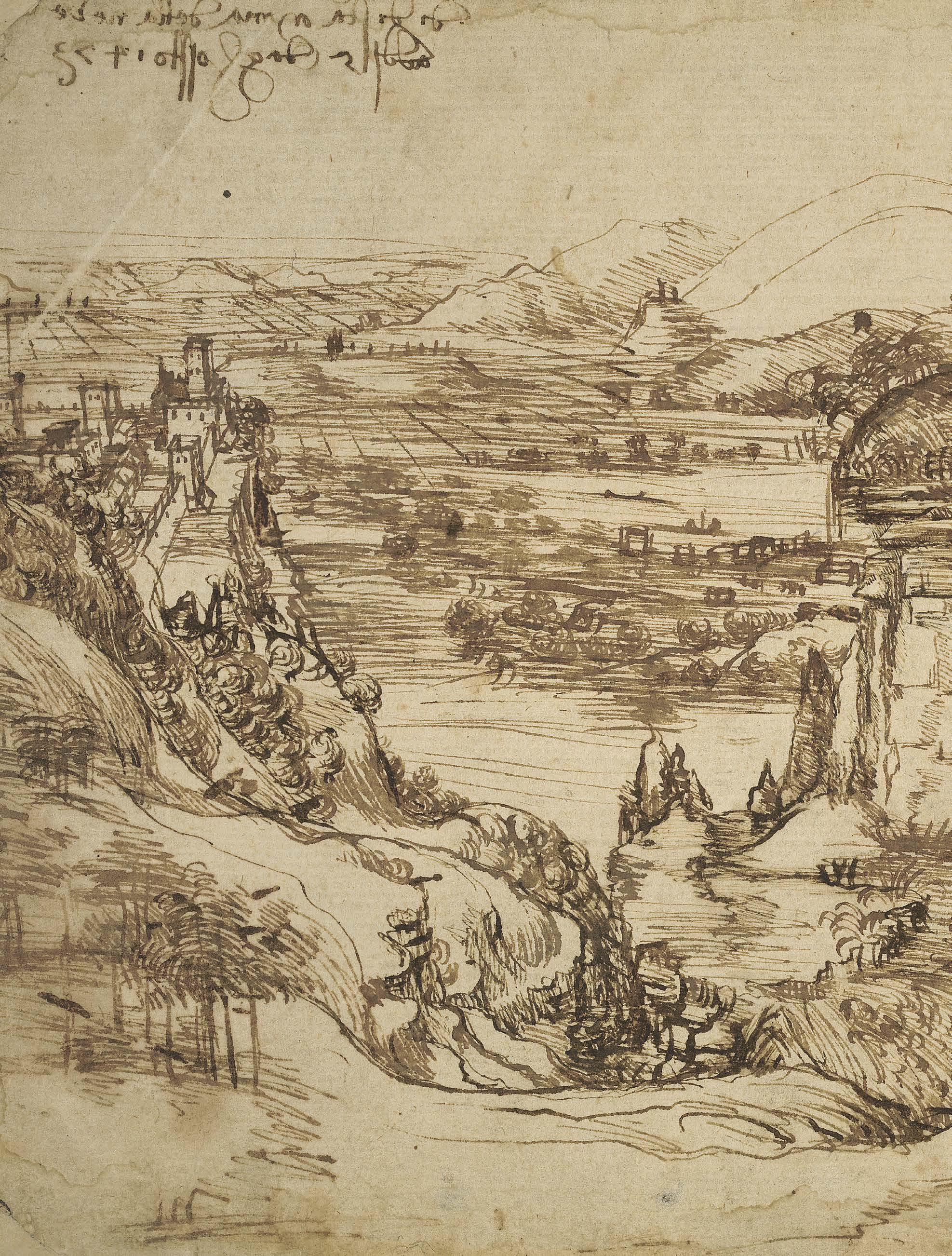

KB There are thousands of pages of codices and nearly all of them have some sort of illustration, some as simple as a Matisse or a Picasso, with only a couple of gestures. And in that gesture he has captured an emotion. Others are incredibly precise drawings in anticipation of even more complex paintings. And let’s not forget that he abandoned so many things because he’d already moved on from the problem. Still, he created what we believe is the first landscape drawing in Western art. He made the first experimental painting in his abandoned Adoration of the Magi [1481]. And you could also say that the Mona Lisa is a great work of science and that the drawings of embryos and anatomies are great works of art.

AM Patronage then had a completely different type of structure from the patronage we have today. How did shifts in patronage and politics impact Leonardo’s life, his scientific investigations, and the art he created?

KB As far as patronage, King Francis I of France offered Leonardo the best patronage of all, late in Leonardo’s life, which was by allowing him to study whatever he wanted. To be Aristotle to Francis’s Alexander.

AM Leonardo was born out of wedlock, which at that time meant that he could never attend university. He felt this was a blessing as it meant that his mind was totally open, his perspective wasn’t narrowed. And his notebooks, which he left for future generations to study, clearly connect directly with his thinking and provide insight into what preoccupied his mind.

KB That’s right. And there’s something organic about this. Adam Gopnik says that Leonardo was trying to crack the code of organic form—that’s where the study of nature came in. But you also have to understand the principles underlying all of this: they could be philosophical, could be spiritual, could be physical, could be architectural, could be all of these things—he felt determined to know everything. He wasn’t a scholar trapped in the ideas they teach at school.

AM What do you think sets his paintings apart and makes them stand the test of time?

KB When he died, his most famous painting was out of sight in the dining room of a monastery. And to me, he invented film with the Last Supper. He invented cinema, right? It’s not a frozen moment, the way painting is expected to be; there’s dynamic motion, it’s happening and it’s so spectacular. He took these familiar scenes and did them the way no one else ever has. Just look at Virgin of the Rocks [1483–86]: every painter is making their version of the Madonna and Child, but Leonardo’s is filled with the complex tension between a mother’s natural maternal instinct, a very humanist proposition, and the fact that she’s known through all time that she’s to bear the son of God and he’s going to be killed. There are two opposing forces: here’s John the Baptist to tell him of his future Passion, and there’s Jesus as a baby, accepting it. John is a baby and she’s trying to pull John back and trying to reach for her son with her other hand. But there’s an angel in the way. God gets it. God sees this. The fact that Leonardo could make such a complex painting relatively early in his career, and here we are marveling at it 550 years later . . . not just that he pulled it off, but that it’s moving.

AM I was looking at a painting with a scholar and an artist recently, and one of them said that the difference between a good painting and a great painting is that in a great painting, every detail holds time. It’s all there for a reason, and people in the future will continue to look at it and have it hold time, maybe

in a different way, from a different perspective, but it will be there and it’ll be active. One of the things that’s so remarkable about your film is that you make the viewer connect to him as a human. He’s not perfect. But also you bring in contemporaries of his who are, by the way, pretty exceptional artists themselves. Early on, Leonardo was an apprentice in the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio, who had trained many of Florence’s most celebrated artists. Returning to Florence after almost twenty years in Milan, he overlapped with Michelangelo. After that he was invited to join the Vatican court, where he encountered Raphael. These are just a few examples.

KB Yeah. I mean Raphael and Michelangelo, please.

AM And you explore the dynamics between them, which is compelling.

KB Well, there was some jealousy about Michelangelo’s David . Leonardo realized that David was great, but he wanted to put it behind a wall. And the Signoria, the town government, did not agree, so instead it was placed prominently outside, in front of everything. It was so spectacular. But Leonardo said no, the muscles look like a bag of walnuts, he’s not drawing them right. And Michelangelo himself was not an overly nice guy, whereas Leonardo was apparently very well liked, his jealousy notwithstanding. He had a great sense of humor and a protean intellect.

AM And he was so generous with his step-siblings after they behaved selfishly over and over again.

KB Yes, his step-siblings cut him out of various wills, but he still left generous sums to them in his will.

AM It’s rare to find that kindness.

KB It reminds me of a film I made many years ago about the Shakers. The Shakers discovered that their poorer neighbors were stealing their crops at night. They were master agriculturalists and their crops were blooming when others’ were not, so their poor neighbors were stealing their crops. You know what the Shakers did? They planted more crops. They said, We plant some for the Shakers, some for the thieves, and some for the crows—thieves and crows have to eat too. Magnanimity only makes you bigger and egotism makes you smaller.

AM That’s a wonderful anecdote. Do you feel closer to Leonardo now that you’ve made the film?

KB I love him. I feel like I know him, but I also feel like he’s unknowable. Last night I saw the film with an audience and I started to cry at scenes that I’ve watched hundreds of times. He gets you every time.

AM Did you expect to feel that sense of closeness when you started the film?

KB Well, I’ve always known that I was an emotional archaeologist. And I’m interested, not in nostalgia or sentimentality, but in higher emotions that may be produced. The difference between the whole and the sum of the parts. There’s a kind of emotional dynamic to all of that. This is a human story. It’s universal to all human beings.

AM He was such a unique and remarkable person.

KB He wakes you up and makes you want to be better. I mean, he wrote backwards in a mirror. Every single line of those codices—thousands and thousands of pages—are written backwards. Every time he picked up a pen to scratch, even a grocery list, he wrote backwards. Just think about what that means, the intentionality in every moment. He’s a citizen of the world and he’s virtuous and he’s always pursuing ever more knowledge. He’s doing a whirling dervish on about seven different planes of stuff at once, and he’s writing it all down backwards. I mean, come on. It’s just so great.

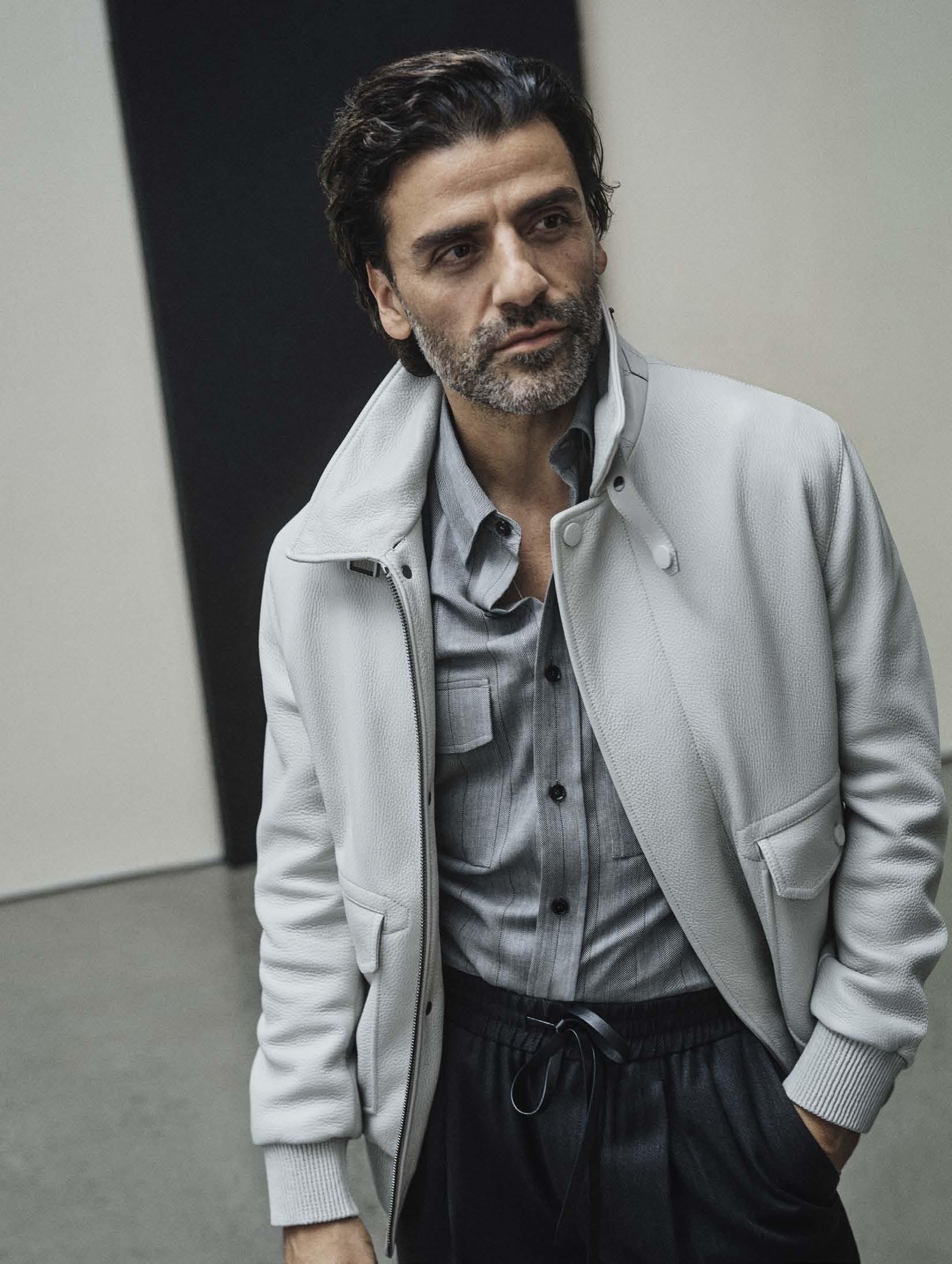

Michel Gaubert, the Paris-based music supervisor behind iconic runway shows across the globe, meets with the Quarterly ’s Derek C. Blasberg to discuss his first engagements with music and fashion, his fateful meeting with Karl Lagerfeld, and discovering sounds in unexpected places.

DEREK C. BLASBERG: My first question is about how I should ID you, Michel. I’ve called you a DJ, a sound designer, an audio architect. When you’re filling out your customs forms, how do you identify yourself?

MICHEL GAUBERT: Nowadays it’s “music supervisor.” I know “supervisor” is a bit strong as a word, but I do that because I work for commercials and films, and basically when I choose music for any event I work on, even the fashion shows, I’m really directing where the music should go. I’ve been called many things, but that sounds great to me.

DB: It’s like a conductor except you’re not in front of an orchestra.

MG: If you say “DJ,” it’s limiting because people think it’s me behind two turntables. If you say “sound engineer,” it’s another one thing. “Music supervisor” is a more global term, and I can do lots of things.

DB: Where did you grow up?

MG: I’m from Bougival, which is near Versailles, west of Paris.

DB: To an American that sounds incredibly exotic: “I grew up near Versailles.”

MG: Well, it’s very pretty. My mother still lives in Bougival and it’s beautiful. It’s only twenty minutes from [where I currently live in Paris] and you have the feeling you’re in the countryside, in Normandy or something. It’s very serene.

DB: When you were growing up, were you an arty kid? What was your childhood like?

MG: I was definitely into music. That started very early, maybe when I was five or six. It was something I had in common with my father, who loved Serge Gainsbourg and Billie Holiday. My mom owned bookstores and she was very into fashion. So I made my own little world, where I discovered I loved music, mainly from watching all the music shows on TV. I remember when the big British wave arrived, like the Stones and all that kind of stuff, I was into that right away. I liked the way they dressed. Specifically, I liked the fact that they used their style and their persona to highlight their music. Early on, I realized that they were made to be each other—the image and the sound were to be one thing.

DB: The look and feel of a band were related to the sound?

MG: Totally. There was this program in France that had a huge impact on me, Dim Dam Dom. I don’t know if you ever heard of it but if you haven’t you should try and find it, it’s incredible. It was on Sundays during lunchtime, and it was one of the first TV shows that showed music, art, fashion, cinema, all these kinds of things together. And a lot of it was made by artists like William Klein, who was there, Serge Gainsbourg, and there was Brigitte Bardot or Romy Schneider presenting the full collections, and all that kind of stuff. It was filmed in a very modern way, getting away from the old clichés of the ’60s. That really had a big influence on me.

DB: Did you have jobs as a kid? When did you discover that music could be a profession?

MG: In the early ’70s, when I was sixteen, I went to America for a year as an exchange student, and when I came back I worked with my mom in the bookstore. That was great for me because I could see all the books I wanted, and the magazines too. I had very easy access to all of this. Eventually I worked in a record shop called Clementine. In those days, specialty music shops in France had to import records, and we would get things that no other people had. At the end of the ’70s, when disco was going out, I went to work at Champs Disques on the Champs-Elysées, which was a milestone in Paris nightlife. It was a shop that was open eighteen hours a day, and it imported all kinds of important music, and basically it was supplying all the clubs of France and abroad. It understood the importance of dance culture and music being discovered as a joyful thing, something to share. And I was in charge! I had a lot of responsibility in that store, and we had a lot of people coming to the store, and that’s the first time I met Karl [Lagerfeld].

DB: Did you know who he was?

MG: Even then, he was already a collector. We all knew him as one of the biggest clients, in this case of records.

DB: I’m excited to talk to you about Karl, since he was the one who introduced us. But when we talk about the end of the ’70s and the early ’80s, I should also ask about designers like Claude Montana and Thierry Mugler, who were huge cultural forces in your early days. I think sometimes that era is glamorized and young people today feel nostalgic for those clothes. As someone

who was there, was it that great?

MG: I don’t know if I’m nostalgic for those days. I had a good time, but it was very different: there was no Internet, no cell phones, no nothing. The sense of time was different and everything felt less pressured. We had more time to go and have fun, go and do things. There weren’t a hundred shows in fashion week; there might have been thirty. And I feel like people retained a kind of openness because we didn’t have so much information coming at us all day. If we were going to a club or to a movie, we were more receptive, because we didn’t see a bunch of reviews and posts and hear a bunch of other people’s opinions about it.

DB: Did you ever go to one of those legendary Mugler shows?

MG: Mugler liked to be superextravagant and very bold, and there was a sense of humor about what he did, a sense of occasion. I didn’t work for him yet, but I saw one of his shows in 1984, and when I walked out of there, I said, “I want to do that. I want to do music for fashion shows.” It was incredible.

DB: There’s an element of performance art in that type of show. I watch those shows now on YouTube when I can’t sleep, and there are models coming out of the ceiling, models dressed as motorcycles. It was incredible.

MG: With Mugler it would all be sketched—each girl would have a specific light, specific music, specific hair. Every dress would be a whole production. And those shows lasted forever! Some were an hour long. As I told you earlier, attention spans were different back then. Now people at a show start to look for the exit after ten minutes.

DB: You worked with Karl for three decades, creating the music for his fashion shows. How would you guys share music tastes? Was it phone calls, text messages, emails?

MG: He was the king of faxing, don’t forget.

DB: I still have some of his faxes. I think after he passed away, everyone in fashion finally got rid of their fax machines.

MG: All of it was very complementary. I knew music he didn’t know and he knew music I didn’t know. In the beginning we’d just meet each other. On the first show I did with him he gave me this record by Malcolm McLaren called “House of the Blue Danube” and said “That’s what I want.” He turned me on to a lot of classical music and he was very, very savvy. For me he was a mindopener, because I realized early on I’d love everything he was showing me. In a way he was my teacher, which was what I liked. But then I was a good pupil, because I was responding to him with other things. My job was to find a way of mixing all this music together and making sense out of it.

DB: He collected so much stuff. He collected art, but also books, furniture, iPads. Do you collect anything?

MG: Yeah, I collect everything. But with Karl the passion was different. He would have an obsession. Like when he was in Biarritz, he was crazy about Ciboure pottery, and I think he bought everything that was available in the world. Basically there was none left for anybody else. Another time he went through his Memphis [design] era. He would devour, not like a collector but like an ogre.

DB: Was this hard to work with?

MG: In the beginning it was more instinctive, but then after maybe four or five years, we knew exactly what to expect from each other. We would share

ideas all the time and it was incredible. He would pull out everything from his ideas and his briefs and his resources, and he would share them very, very easily. And then I would answer, “Oh, look at this movie, because it reminds me of this,” and then we brought everything together. I would do little demos of music on movies and show him what I thought it should be like. It could be a mixture of Busby Berkeley and a little Alain Resnais and a video clip from Siouxsie and the Banshees. It was very much a traffic of influence.

DB: I like “traffic of influence.” That should be the name of your book, Michel. MG: I like that too. Maybe it will be!

DB: I know you’re still working with Chanel, and you often work with Jonathan Anderson at Loewe. Who else are you working with now?

MG: Everybody! I work with Sacai, a Japanese brand that I adore; Dior with Maria Grazia [Chiuri], who I like to work with; I also do Nensi Dojaka, a young designer who won the LVMH Prize a few years ago.

DB: What’s the process when you work with a designer? I imagine it’s different for everyone, but do you look at the collection, or do they send a mood board or something?

MG: It all depends. Everyone is a different thing. When I worked with Nicolas Ghesquière at Balenciaga, it was decided well in advance, maybe three months before the show.

DB: That’s a long time!

MG: Which was good for me. It would give us time to listen to a lot of things, see what we loved, and then funnel it down. Sometimes we would start with ten tracks or ten moods and finish with one. With Karl it was different because, after he started working at the Grand Palais, the decor was very important, as you know, so the music tone was often decided by the mood of the set.

DB: I’ve been to shows where you’ve created the music and I’ve heard spoken words, the sound of teeth being brushed, traffic. You’ve had what many would call nontraditional sounds. What do you think is the craziest thing you’ve put into a fashion-show soundtrack?

MG: I did one show with Raf Simons at Jil Sander and it was all about Lara Croft. She was the muse. Basically the show music was a soundtrack with all kinds of sounds generated from Tomb Raider. There was no music, basically. It was pretty wild. Some people loved it; some people thought, What the hell? That was a weird thing. I love working with Jonathan at Loewe, and we once

did a show that was very dark, very cold. So it began with the sound of air conditioning that turned into audio from the film Sunset Boulevard [1950], and then a piece of techno for thirty seconds that turned into something else.