26 56 Theaster Gates: The New World Amalgam of Charlotte William Whitney Perriand considers the artist’s art practices and social commitments.

34 Christopher Wool: Part II In this second installment of his two-part essay, Richard Hell explores Wool’s sculptural and photographic work made in Marfa, Texas.

50 Cut & Paste In this first installment of a two-part essay, John Elderfield tracks the oscillating states of unification and separation that Édouard Manet’s The Execution of Maximilian has endured since its creation, in 1868.

William Middleton writes on the legendary designer and her collaborative vision of modernism.

64 Building a Legacy: Multiples, Reproductions, and Editions Simon Stock, Marisa Cardinale, Hugues Herpin, and Jean-Jacques Neuer discuss originals, reproductions, and how best to preserve the artist’s intention when it comes to posthumous casting and printing.

76 Reading Nam June Paik Gregory Zinman, coeditor of We Are in Open Circuits: Writings by Nam June Paik, writes about his first exposure to the artist’s archives.

84 Perfect Balance Gillian Jakab considers the legacy of Sergei Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes in light of contemporary collaborations between visual artists and choreographers.

100 The Center of the Storm Carlos Valladares writes on filmmaker and photographer Jerry Schatzberg’s prolific career.

92

Rudolf Polanszky Hans Ulrich Obrist visits the artist at his studio outside Vienna to discover more about the origins of his practice, his experiments in freedom, and the importanc of drifting.

116 A Mythology of Forms: A Conversation about Carl Einstein Luise Mahler and Charles Haxthausen discuss the importance of this earlytwentieth-century critic’s theoretical projects.

120 Overture: Ridding the Passing Moments of Their Fat

68

Dirty Canvases Mark Loiacono situates Andy Warhol’s Piss and Oxidation paintings within the artist’s career.

Art historian Robert Farris Thompson has maintained a passion for Afro-Cuban dance and music since an early exposure, in 1944, to a conga line in his hometown of El Paso. Here, he tracks the spiritual, linguistic, and musical roots of mambo.

130 Huma Bhabha The artist tells Negar Azimi about her rooftop commission at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, her interest in the monstrous, and the influence of science fiction on her practice.

136 Rain Unraveled Tales Raymond Foye reminisces about his long-standing friendship with the poet Bob Kaufman.

Daniel Spaulding, prompted by an encounter with Piero di Cosimo’s Discovery of Honey by Bacchus (c. 1499), investigates the potential philosophical and political power embedded within the figure of the satyr.

Photo credits: Front cover: Christopher Wool, selection from Westtexaspsychosculpture, 2017 (detail) © Christopher Wool; courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York Top row, left to right: Rudolf Polanszky, Vienna, 2018 Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp, 1917, vintage gelatin silver print, 4 ⅞ × 3 ⅝ inches (12.2 × 9 cm) © Man Ray Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ ADAGP, Paris 2019

Bottom row, left to right: Andy Warhol, Oxidation Painting, 1978, urine and metallic pigment in acrylic medium on canvas, 28 × 30 inches (71.1 × 76.2 cm) © 2019 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

186 Game Changer Berit Potter describes the profound impact of museum director Grace McCann Morley (1900– 1985) on San Francisco and the art world at large.

Installation view, Richard Serra: Forged Rounds, Gagosian, West 24th Street, New York, September 17–December 7, 2019. © 2019 Richard Serra/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Cristiano Mascaro

142 Rachel Feinstein The artist discusses her life and work with Alan Yentob.

146 Casa Malaparte: A House Like Ourselves Wyatt Allgeier explores the legacy of Curzio Malaparte and corresponds with the avant-garde author’s youngest descendant, Tommaso Rositani Suckert.

152 Love Is Not a Flame: Part IV A short story by Mark Z. Danielewski.

44

Richard Serra A portfolio of the sculptor’s most recent works.

108

Man Ray: A Portrait of the Times In Man Ray’s 1963 autobiography, Self Portrait, he wrote about his time with various denizens of the Paris art world, detailing his meetings, photography sessions, and appreciation for these fellow artists. We present a selection of excerpts from these tales.

TABLE OF CONTENTS WINTER 2019

162 There’s Honey in the Hollows: Piero di Cosimo’s Form-of-Life

W

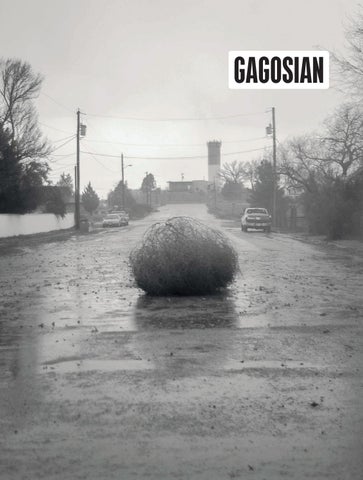

e wrap up our third year with a cover by Christopher Wool, a photograph from his recent Westtexaspsychosculpture series. Richard Hell’s captivating article on Wool describes how, in recent years, the artist has split his time between Marfa and New York, and the overall impact that the Texas landscape has had on his art making. This month marks an important anniversary for the gallery: in 1999, twenty years ago, Richard Serra’s Switch inaugurated Gagosian’s Chelsea space on West 24th Street in New York. Built specifically with the formidable weight of Serra’s massive steel sculptures in mind, the space quickly became a cornerstone of the neighborhood, which subsequently grew into the arts center it is today. We commemorate this occasion with a portfolio on the Serra sculptures currently on view in what are now our two Chelsea galleries. A few years later, in 2002, Gagosian was the first gallery to exhibit Andy Warhol’s Oxidation and Piss series, which have since become critical to scholars trying to understand the artist’s formal experiments. Mark Loiacono, curatorial researcher for the celebrated Warhol retrospective recently organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art, considers these works anew. We look at recent work by Theaster Gates that explores the social histories of migration and interracial relations by highlighting the specific history of Malaga, an island off the coast of Maine. This issue also spotlights Paris in the years after World War I, a period of rebuilding in which creative minds joined together to renew the spirit of the nation. We have articles on the dance collaborations of Sergei Diaghilev and his Ballets Russes and on Man Ray’s portraits of and writings on many great artists from this moment. We also look at the next generation through the work of Charlotte Perriand and her generous spirit of collaboration. We continue our examinations of legacy building and the clues it leaves for scholars, this time focusing on the archives of the video artist Nam June Paik. Our ongoing Building a Legacy feature examines questions around posthumous editions of artworks, particularly in sculpture and photography. Finally our Game Changer feature focuses on Grace McCann Morley, whose legacy is a vitally important institution of American culture: Morley was founding director of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Alison McDonald, Editor-in-chief

GAGOSIAN QUARTERLY ONLINE Weekly E-Newsletter For the latest updates on gallery shows, museum exhibitions, artist talks, art fairs, and more, sign up for our weekly e-newsletter, delivered to your inbox every Monday: gagosian.com/newsletter

Essay: Before the Smoke Has Cleared Angela Brown provides a glimpse into the charged ecologies of recent drawings and sculptures by Tatiana Trouvé, on view in On the Eve of Never Leaving at Gagosian, Beverly Hills.

Video: Nathaniel Mary Quinn The artist speaks to Q&A founder Troy Carter about deliverance, expression, and what drives him to make art. From top: Giuseppe Penone at Fort Mason, San Francisco, 2018 Tatiana Trouvé, Untitled, 2019, from the series Les Dessouvenus, 2013– © Tatiana Trouvé Nathaniel Mary Quinn and Troy Carter in conversation at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, September 2019

Video: Giuseppe Penone at Fort Mason On the occasion of the unveiling of a yearlong public installation in San Francisco’s Fort Mason, the artist discusses his large-scale bronze sculptures cast from trees.

"CAMÉLIA" NECKLACE IN WHITE GOLD, RUBY AND DIAMONDS "CAMÉLIA" RING IN WHITE GOLD AND DIAMONDS

CHANEL.COM

louisvuitton.com

CONTRIBUTORS William Middleton

Mark Loiacono

A Paris-based writer, William Middleton is the author of Double Vision, a biography of the legendary art patrons and collectors Dominique and John de Menil, published in 2018 by Alfred A. Knopf. He has contributed to such publications as W, Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Architectural Digest, House & Garden, Departures, Town & Country, the New York Times, and T.

Mark Loiacono is an independent art historian and curator. He holds a PhD in Art History from New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts. He has written extensively on Andy Warhol, and most recently served as the curatorial research associate for the blockbuster exhibition Andy Warhol—From A to B and Back Again at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Christopher Wool Christopher Wool may be best known for his paintings of large, black, stenciled letters on white canvases, but he actually works in a wide range of styles and with an array of painterly techniques, including spray painting, hand painting, and screen printing. Wool’s work sets up tensions between painting and erasing, gesture and removal, depth and flatness. He was born in 1955 in Chicago and lives and works in New York. Photo: Aubrey Mayer

Richard Hell Richard Hell and the Voidoids’ 1977 LP Blank Generation was rereleased in 2018 by Sire/Warner in a remastered facsimile edition. Hell’s books include two novels, Go Now (Scribner, 1996) and Godlike (Little House on the Bowery, 2005); his autobiography, I Dreamed I Was a Very Clean Tramp (Ecco, 2013); and the essay collection Massive Pissed Love: Nonfiction 2001– 2014 (Soft Skull Press, 2015).

John Elderfield John Elderfield, Chief Curator Emeritus of Painting and Sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, and formerly the inaugural Allen R. Adler, Class of 1967, Distinguished Curator and Lecturer at the Princeton University Art Museum, joined Gagosian in 2012 as a senior curator for special exhibitions.

Berit Potter Berit Potter is Assistant Professor of Art History and Museum and Gallery Practices at Humboldt State University, where she oversees the Museum and Gallery Practices Certificate Program. Her current book project, Widely Curious: Grace McCann Morley and the Origins of Global Contemporary Art, examines the career of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s first director and her pioneering advocacy for global perspectives.

16

Rachel Feinstein In richly detailed sculptures and multipart installations, Rachel Feinstein investigates and challenges the concept of luxury as expressed in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe, in the context of contemporary parallels. By synthesizing visual and societal opposites such as romance and pornography, elegance and kitsch, and the marvelous and the banal, she explores issues of taste and desire. Photo: Markus Jans, Architectural Digest © Condé Nast

Charles Haxthausen Charles Haxthausen is Robert Sterling Clark Professor of Art History, Emeritus, at Williams College and currently Distinguished Scholar at the Leonard A. Lauder Research Center for Modern Art at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. He is working on a book reassessing Paul Klee’s position within the early-twentieth-century European avant-garde.

Mark Z. Danielewski The New York Times has declared Mark Z. Danielewski “America’s foremost literary Magus.” He is the author of the award-winning and bestselling novel House of Leaves, National Book Award finalist Only Revolutions, as well as The Familiar and the novella The Fifty Year Sword, which became a performance at redcat, Los Angeles, for three consecutive years. thrown, his “signiconic” piece on Matthew Barney, was displayed at the Guggenheim Museum, New York, in 2015. His work has been translated and published throughout the world. Pantheon will release The Little Blue Kite in fall 2019. Photo: Nicolas Harvard

Gregory Zinman Gregory Zinman is an Assistant Professor in the School of Literature, Media, and Communication at the Georgia Institute of Technology. His writing on film and media has appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and October, among other publications. He is the editor, with John Hanhardt and Edith DeckerPhillips, of We Are in Open Circuits: Writings by Nam June Paik.

Luise Mahler Luise Mahler is an art historian specializing in modern art and its criticism. Her current project, a monographic book study, compares the different Cubisms that emerged from the German-language writings of such figures as Carl Einstein and Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler with those of their European contemporaries, Vincenc Kramář among them. Photo: annako, Berlin

Daniel Spaulding Daniel Spaulding is an art historian who lives in Los Angeles, where he works in the curatorial department of the Getty Research Institute and teaches at ArtCenter College of Design. He has a PhD from Yale. Writings of his have appeared in publications such as Art Journal, October, Radical Philosophy, and Mute Magazine.

17

R A LPH L AUR EN

Robert Farris Thompson A longtime art history professor at Yale, Robert Farris Thompson may be best known for his book Flash of the Spirit, published in 1983 and still in print today. Tracing continuities between the black cultures of Africa and the Americas, this hugely influential work was groundbreaking in both manner and method. The teenage Thompson was led to his love of Africa by popular music and dance. He has dreamed of a book on the mambo for literally decades; the manuscript is now in progress and we are proud to publish an excerpt.

Raymond Foye Raymond Foye is a writer, editor, publisher, and curator who lives in New York’s Chelsea Hotel. A former director of exhibitions and publications at Gagosian, he co-edited the forthcoming Collected Poems of Bob Kaufman for City Lights Books. He is Contributing Editor to the Brooklyn Rail, and is currently editing the Collected Poems of Rene Ricard, to be published in 2020.

Hans Ulrich Obrist Hans Ulrich Obrist is artistic director of the Serpentine Galleries in London. Prior to this, he was the curator of the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Since his first show, “World Soup” (The Kitchen Show) in 1991, he has curated more than 300 shows. Obrist’s recent publications include Ways of Curating (2015), The Age of Earthquakes (2015), Lives of the Artists, Lives of Architects (2015), Mondialité (2017), Somewhere Totally Else (2018), and The Athens Dialogues (2018). Photo: Wolfgang Tillmans

Carlos Valladares Carlos Valladares is a writer, critic, programmer, journalist, and video essayist from South Central Los Angeles, California. He studied film at Stanford and began his PhD in History of Art and Film & Media Studies at Yale University this fall. He has written for the San Francisco Chronicle, Film Comment, and the Criterion Collection. Photo: Cindy Shorney Pearson

Rudolf Polanszky Rudolf Polanszky is an artist who lives and works in Vienna, producing painting and sculpture using a variety of materials. His works have most recently been exhibited at the Vienna Secession, the 21er Haus, the Rubell Family Collection in Miami, and The Bunker in Palm Beach. They lie in the permanent collections of the Centre Pompidou, Paris, the Belvedere Museum, Vienna, the Artotek des Bundes, Vienna, and others.

Gillian Jakab Gillian Jakab works for La Napoule Art Foundation and has served, since 2016, as the dance editor of the Brooklyn Rail.

20

Simon Stock

Hugues Herpin

Simon Stock has been a director at Gagosian since 2018. Previously he was a senior international specialist for the Impressionist and Modern Art department at Sotheby’s. From 2008 to 2017 he curated the annual monumental sculpture exhibition Beyond Limits at Chatsworth House, England.

Hugues Herpin is the head of the Department for Strategic Affairs at the Musée Rodin, Paris. He joined the Musée Rodin in 1998, managing its cultural programs and then becoming assistant director, overseeing all events. Herpin has organized numerous Rodin exhibitions internationally and has written extensively about the artist’s work.

Alan Yentob

Marisa Cardinale

Alan Yentob has held many prestigious positions at the BBC. In addition to these various roles, he is on the boards of the South Bank and the International Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. He is also chairman of the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London.

Marisa Cardinale has been an advisor and consultant to artists and artists’ estates since 1995. She has created longevity plans for artists’ foundations, created and led strategies for artists’ transitions to multiple gallery representation, and facilitated the acquisition of substantial collections by major institutions for the Gordon Parks Foundation, the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, and others.

Negar Azimi

Jean-Jacques Neuer

William Whitney

Negar Azimi is a writer and the senior editor of Bidoun, a publishing and curatorial project. With Klaus Biesenbach, Tiffany Malakooti, and Babak Radboy, she recently curated the first retrospective of the Iranian avant-garde theater director and filmmaker Reza Abdoh at MoMA PS1, New York. She is at work on a book about the 1960s and ’70s.

Jean-Jacques Neuer is a Paris-based lawyer and a solicitor in London. He has been the official counsel of the Picasso Administration for more than twenty years, as well as of the Alberto Giacometti Foundation and the estates of Arman, Constantin Brancusi, and Yves Klein. He has also worked as a legal counselor for auction houses, art dealers, collectors, and experts.

William Whitney is a writer and critic currently based in New York. He is a candidate in the School of Visual Arts MFA Art Writing and Criticism program.

Huma Bhabha In expressive drawings on photographs as well as figurative sculptures carved from cork and Styrofoam, assembled from refuse and clay, or cast in bronze, Bhabha probes the tensions between time, memory, and displacement. References to science-fiction, archeological ruins, Roman antiquities, and postwar abstraction combine as she transforms the human figure into grimacing totems that are both unsettling and darkly humorous. Photo: Sean Thomas

22

D I O R .C O M

Gagosian Quarterly, Winter 2019

Editor-in-chief Alison McDonald

Founder Larry Gagosian

Managing Editor Wyatt Allgeier

Business Director Melissa Lazarov

Text Editor David Frankel

Published by Gagosian Media

Online Editor Jennifer Knox White

Publisher Jorge Garcia

Executive Editor Derek Blasberg Design Director Paul Neale Design Alexander Ecob Graphic Thought Facility Website Wolfram Wiedner Studio

Advertising Manager Mandi Garcia Advertising Representative Michael Bullock For Advertising and Sponsorship Inquiries Advertising@gagosian.com Distribution David Renard Distributed by Pineapple Media Ltd Distribution Manager Kelly McDaniel Prepress DL Imaging

Cover Christopher Wool

Printed by Pureprint Group

Contributors Wyatt Allgeier Negar Azimi Huma Bhabha Marisa Cardinale Mark Z. Danielewski John Elderfield Rachel Feinstein Raymond Foye Charles Haxthausen Richard Hell Hugues Herpin Gillian Jakab Mark Loiacono Luise Mahler William Middleton Jean-Jacques Neuer Hans Ulrich Obrist Rudolf Polanszky Berit Potter Daniel Spaulding Simon Stock Robert Farris Thompson Carlos Valladares William Whitney Christopher Wool Alan Yentob Gregory Zinman

Thanks Richard Alwyn Fisher Andréa Azéma Jennifer Belt Simon Bermeo-Ehmann Priya Bhatnagar Caroline Burghardt Michael Cary Serena Cattaneo Adorno Georgina Cohen Matthew Cross Rose Dergan Victoria Eatough Elsa Favreau Kate Fernandez-Lupino Lauren Fisher Douglas Flamm Emily Florido Mark Francis Jonas Fröhlich Brett Garde Theaster Gates Emma German Darlina Goldak Megan Goldman John Hanhardt Tiphaine Heron Delphine Huisinga Jacqueline Hulburd Noémie Husson Sarah Jones Lauren Mahony Susannah Maybank Rob McKeever Trina McKeever Gianni Melotti Olivia Mull

Louise Neri Ira Nowinski Hannah Pacious Jaimie Park Stefan Ratibor Michele Reverte Tommaso Rositani Suckert Alexandra Samaras Patrick Sarmiento Jerry Schatzberg Clara Serra Richard Serra Max Shackleton Nick Simunovic Rani Singh Rebecca Sternthal Anna Studebaker Quinn Max Teicher Sean Thomas Colin Torre Andie Trainer Peggy Tran-Le Daniel Umstaedter Timothée Viale Tabitha Walker Marcus Ward Ealan Wingate Kelso Wyeth Penny Yeung Jason Ysenburg

BOUTIQUES GENÈVE • PARIS • LONDON • BERLIN • NEW YORK MIAMI • BEVERLY HILLS • LAS VEGAS MOSCOW • DUBAI • TOKYO • HONG KONG SINGAPORE • SAINT-TROPEZ • CANNES COURCHEVEL • ZERMATT • ZÜRICH

CLASSIC FUSION ORLINSKI Sapphire case. In-house skeleton tourbillon movement with a 5-day power reserve. Limited to 30 pieces.

Theaster Gates’s exhibition Amalgam—originally on view at the Palais de Tokyo, Paris, in the spring of 2019, and traveling this December to Tate Liverpool—explores the social histories of migration and interracial relations by highlighting the specific history of the Maine island of Malaga. Here, William Whitney considers the exhibition in relation to Gates’s ongoing art practices and social commitments.

THEASTER GATES

AMALGAM

Theaster Gates’s 2019 exhibition, Amalgam, originally on view at the Palais de Tokyo, Paris—traveling this December to Tate Liverpool—explored the social histories of migration and interracial relations by highlighting the specific history of Malaga, Maine. Here, William Whitney considers the exhibition in relation to Gates’s ongoing practices and commitments.

28

In the context of the Negro problem neither whites nor blacks, for excellent reasons of their own, have the faintest desire to look back; but I think that the past is all that makes the present coherent, and further, that the past will remain horrible for exactly as long as we refuse to assess it honestly. —James Baldwin, “Autobiographical Notes,” 1955

Previous spread: Theaster Gates, Paris, France, 2019. Photo: Julien Faure/Paris Match/Contour by Getty Images Opposite: Installation view, Theaster Gates: Amalgam, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, February 20– May 12, 2019. Photo: Chris Strong Above: Theaster Gates, Dance of Malaga, 2019 (still), singlechannel video, color, sound, 35 minutes 4 seconds Following spread, top left and bottom right: Installation view, Theaster Gates: Amalgam, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, February 20– May 12, 2019. Photo: Chris Strong Following spread, top right: Installation view, Theaster Gates: The Black Monastic, Museu Serralves, Porto, Portugal, September 7–19, 2014

Seeking to reinvigorate forgotten objects and spaces through unorthodox methods, Theaster Gates aims to create platforms that will spark conversation and provide underserved communities with the means to participate in their own revitalization. Born in Chicago, the youngest of nine children, Gates still lives in the city, melding his reallife experiences with the skills and knowledge he acquired in academia, where he majored in urban planning as an undergraduate, then pursued an interdisciplinary combination of fine arts and religious studies two years later. Deeply cognizant of his role as both an artist in the world and a black artist in America, Gates has always understood the dynamics of capturing the public’s eye. His first major art project, Plates Convergence (2007), at Hyde Park Art Center, Chicago, saw him host a seated dinner for one hundred guests, serving traditional Southern food while introducing the audience to the work of Shoji Yamaguchi, a legendary Japanese ceramist whose plates are specifically designed for the food of African Americans. With each guest seated at a specific spot to ensure dynamic and thought-provoking conversations, the event was a resounding success, even as it became clear the story of Yamaguchi was entirely fabricated. Seeking to hone his practice to resonate as both object- and engagement-based, Plates Convergence deployed Gates’s status as an outsider to create a conversation around use value and locality, while also highlighting the power of art created without the influence of major institutions. Gates credits the project with helping him to establish an outsider practice, and to realize that working effectively outside major institutions could eventually be the key to attracting those institutions’ interest.1 Gates trained in pottery but he incorporates sculpture, painting, video, performance, and music into his practice, refusing to limit himself to a single medium in part because he believes that different issues require different platforms. In 2010, Gates was represented in both the Whitney Biennial and a solo exhibition at the Milwaukee Art Museum. For the Biennial, which served as his formal introduction to a larger public, he revamped

the museum’s sculpture court with found objects, transforming the space into a gathering area for performances, social engagement, and contemplation. Through the duration of the show, he used the space to meet with historians, artists, and street musicians, hosting a series of talks and musical performances. In Milwaukee, Gates’s show To Speculate Darkly: Theaster Gates and Dave the Potter featured a 250-person gospel choir singing musical adaptations of the poetic inscriptions that the nineteenth-century enslaved American ceramist Dave Drake left on pots he made. Accompanying the choir were original ceramic pieces from local artisans. The first artist to reinterpret Drake’s work and legacy, Gates connected the conditions for African Americans in the antebellum South to concerns regarding labor and craft in present-day America.2 Gates has also sought to create change outside his studio practice through his Rebuild Foundation, a nonprofit platform directed toward neighborhood regeneration and cultural development through the use of educational and arts programming. The foundation, established in 2010, develops affordable housing, studio, and live-work space, with many of its initiatives focusing on revitalizing Chicago’s South Side. While it isn’t necessary for artists to have more than one kind of practice in order to have an intellectual impact, Gates recognizes that in order to make a real impact with his community program, he requires a multitude. “In my case, I needed two, or three, or even four or five different platforms, because that seemed the truth of the devastating need in the community where I live,” Gates says. “If there is no community development corporation, if there is no bank that’s loaning locally, there are very few allies to black and brown artists.”3 Rather than running from the issues in his community, Gates does what he can to help, yet he insists that he is not an activist but rather just an artist, calling this kind of work one of the beauties of the profession: The beauty of being an artist, is that you have the freedom to talk about the things that you want to talk about, and to be generous in the direction of those things. There are times when I want to talk about homelessness and poverty, and then there are other times when I want to talk about the colour red, . . . [or] want to continue what had been a verbal conversation into the material world. Or there’s just a set of ideas that deal with my past. Having the freedom to materialize whatever I will is the gift of the 29

artist. It’s the gift that you have when you don’t have much else. 4 An eager mind with a keen eye for detail, Gates deals with topics that hover just beneath the surface of society’s collective consciousness. He created the Civil Tapestry series by cutting up and stitching decommissioned fire hoses over wooden supports to make singular works of abstract art. While the fire hoses reference the struggles of the Civil Rights Movement, Gates’s use of readymade objects recalls the practices initiated by Marcel Duchamp and followed through by many other artists. In providing the hoses with new meaning, Gates reminds viewers of the nuances of the fight for racial equality, asking them to grapple with how quickly relatively recent historical moments can turn vague, their presence acknowledged but no longer examined. In repurposing the fire hoses, he makes a charged statement through modest means, transforming readymade objects into a quiet demand that America’s history be remembered. What he calls his “acts of transformation” force viewers to contend with the power that objects can take on when placed in an artistic setting.5 Redemption is a key motivation for Gates, in terms of both materials and history, and as a way of extending art into issues of social justice and distribution. In his exhibition Amalgam Gates uses a wide spectrum of mediums, including sculpture, assemblage, video, and sound, to explore social histories of migration and interracial relations. An amalgam is a mixture or fusion of different elements, a fitting term for Gates’s revalidation of discarded materials. The exhibition focuses on the small island of Malaga, Maine, where in 1912 the state’s then 30

governor, Frederick W. Plaisted, expelled a population of forty-five people who were poor and either multiracial or in an interracial relationship. The origins of this community are believed to trace back to 1794, when Benjamin Darling, an African American married to a white woman, Sarah Proverbs, bought an island near Malaga, Horse Island (now called Harbor Island). One of Darling’s children sold Horse Island in 1847, when the family is thought to have moved to Malaga, which was unoccupied.6 In the early 1900s, Maine underwent drastic increases in real estate values and tourism. In this context the residents of Malaga Island were scorned for the unbecoming wooden huts in which they lived; at the same time, with the rise of the eugenics movement, they faced disdain for their darker skin and mixed-race features. The term “Malaga” became a stigma within the neighboring white communities. In 1903, the legislature placed Malaga in the township of Phippsburg, in Sagadahoc County.7 Fearing association with the island, the town sued successfully to repeal the legislation, leaving Malaga under state control and its residents wards of the state. Upon visiting the island in 1911, Governor Plaisted remarked, “The best plan would be to burn down the shacks with all their filth. Certainly the conditions are not creditable to our state, and we ought not to have such things near our front door, and I do not think that a like condition can be found in Maine, although there are some pretty bad localities elsewhere.”8 In a series of quick legal actions, the state awarded ownership of Malaga to the Perry family of Phippsburg, who proceeded to sell the island back to the state for $400.9 Following this purchase, the incumbent mixed-race community was informed of its eviction from the

island, to be scattered through the mainland. Some were involuntarily committed to psychiatric institutions, while others suffered internment. Originally planned to be a tourist destination, the island has remained uninhabited since this community was removed, as if haunted or damned. In 2018, Gates began a three-year residency at Colby College, Maine, as the school’s first distinguished visiting artist and as director of artist initiatives at its Lunder Institute for American Art. He learned of the island’s history in his first week at Colby while out on a weekend boat ride with friends. His experience in Maine aligned with earlier explorations he had made into broad questions about the conventions of history: how it is told, who it is told for, and what narratives and experiences it omits or elides (more often than not in the United States, those of African Americans). To Gates, “How we reckon with history is super important, and how we either choose to reconcile these deep complexities with honor or we choose not to says a lot about the character of our nation.”10 Colonialist practices are so deeply embedded in our society that they are often overlooked, and even when acknowledged, they are rarely scrutinized carefully. Yet what makes the story of Malaga so pertinent for an exhibition such as Amalgam is the discomfort one feels in learning what occurred there, and in imagining the horrific experience of Malaga’s residents. That discomfort is only intensified by the fact that the story remains largely suppressed a century later. The first work that viewers encountered in the Paris installation of Amalgam was Altar (2019), a giant slate-shingled section of a rooftop. While the work’s impact came from its powerful incongruity and surreality, the gesture reflected both the

houses destroyed on Malaga Island and the prevalence of slate rooftops all over Baron Haussmann’s Paris. The work also references Gates’s father, a roofer who left his son his tools upon passing away. Altars have religious meaning as places of sacrifice, and Gates’s Altar is no different, evoking the slaughter attached to the idea of racial purity. The author Richard Dyer, in his well-known 1997 essay “White,” discusses the rhetoric of whiteness built into the United States: “This property of whiteness, to be everything and nothing, is the source of its representational power. . . . if the invisibility of whiteness colonises the definition of other norms— class, gender, heterosexuality, nationality and so on—it also masks whiteness as itself a category.”11 In regards to Malaga Island, Gates acknowledges the role of whiteness, but rather than engage in an examination of what it is to be white, he probes the beauty and fear associated with being “the other,” using his artistic language to challenge viewers with an exhibition that highlights the dramatization of race. Gates’s multipart installation Island Modernity Institute and Department of Tourism (2019) unites traditional African artifacts with fictional archival documents depicting an imagined archaeological study of Malaga. A sign, enclosed in a vitrine elevated on a central podium, reads “In the end nothing is pure” in neon-green letters. Presented thus as a museological artifact, the sign exemplifies Gates’s ideas of beauty, referring both to interraciality and to his own combinatory art practices. Situated next to Island Modernity Institute . . . in Paris was a blackboard bearing a chalk sketch, a concise history of America’s relationship to black people, slavery, and miscegenation. The

blackboard also put forward the idea of a department of tourism for Malaga Island and presented a stream of consciousness regarding famous mixedrace and black people who can “pass”: actors Jesse Williams and Halle Berry, musician Alicia Keys, athlete Colin Kaepernick (dubbed “the kneeling football player”), and “some models like Winnie” (Harlow, who has vitiligo). Each medium combined with the other to envelop viewers in an immersive experience that was both educational and provocative. Gates conjoined the idea of the amalgam with

his own resistance, as an artist and thinker, to narrowness about what constitutes a work of art; each gallery offered disparate experiences thanks to his careful use of distinct mediums in a flurry of varied tones and emotional draws. Gates’s exploration of interracial identity serves as a reminder of a period when fear was rampant and difference was used as an excuse to subject others to cruelty and hate—issues still relevant under the current presidential administration. Coupled with that reminder is an open question

31

posed to Gates’s viewers regarding the beauty and strength of mixed-race people, whom society so often presents as enigmas. Such people have attachments to different histories that are typically not examined through collective discussion. This makes their existences unique, both blessing and curse, with few examples to follow in dealing with the conundrum of being biracial. Amalgam deals with the past in an unexpected way. The feeling throughout the exhibition is one not of outrage but rather of sorrowful and remorseful reflection, a haunting sadness tied to the unchallenged understanding of difference as abhorrent. The show touches a nerve in current society, where immigrants are demonized everywhere and tensions are growing among bordering countries. “Dépaysement,” one of many French words with no exact English equivalent, describes a feeling of homesickness or disorientation in being away from one’s home country. It came to mind as I reflected on Amalgam: the island’s residents were banished from their homes, unable to return because of the greed and fear that blinded some to their humanity. Gates has also made a film, Dance of Malaga (2019), in collaboration with the American choreographer Kyle Abraham. The work mixes interracial scenes from archival feature films selected by Gates with a performance choreographed and performed by Abraham on Malaga itself. The soundtrack—by the Black Monks of Mississippi, an experimental music ensemble, formed in 2008, led by Gates with the musicians Yaw Agyeman, Mikel Patrick Avery, Michael Drayton, and Khari Lemuel—is as eerie as it is enthralling, imparting a sense of both beauty and dread.12 The Black Monks experiment with the specifics of black sound, combining black music of 32

the South, such as the blues, gospel, and wailing, with East Asian monastic traditions to give life to the found objects that Gates collects. Their presence, in the film and in general, provides the audience with an understanding of the black voice in its utter uniqueness, and speaks to the experiences that Gates seeks to exemplify in his art. In the final station of the Paris exhibition, So Bitter, This Curse of Darkness (2019), bronze casts of African masks were set atop roughly hewn pillars of ash wood. On the wall adjacent to the works was a quote from Gates: “These trees were dying. A miller said they were not fit for timber. Useless. Somewhere in the death of a tree is the truth of its strength.” The installation foregrounded Gates’s preservationist determination to ensure that the memory of Malaga Island cannot be erased from historical dialogues again. Gates’s belief in the power of found objects, buildings, and communities allows a constant expansion in his work, as he explores different ideas and closely examines materials for potential new found meanings. In searching for perfection he became invested in the language of practice, ultimately finding joy in revitalizing everyday materials to present viewers with difficult questions, ranging from the complexities of the social and political world to the black experience. Rather than claim to supply answers, Gates looks to engage the public in a conversation, providing a starting point for discussions that need to occur for major change to happen. In a world in which everything is processed very quickly, Gates slows things down, challenging societal barriers while helping his community—a community so often excluded in so many ways—to benefit.

Installation view, Theaster Gates: Amalgam, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, February 20– May 12, 2019. Photo: Chris Strong Artwork © Theaster Gates

1. See Lilly Wei, “Theaster Gates,” Art in America, December 2011. Available online at www.artinamericamagazine.com/newsfeatures/magazines/theaster-gates/ (accessed August 27, 2019). 2. See the Milwaukee Art Museum’s website for To Speculate Darkly: Theaster Gates and Dave the Potter, online at https://mam. org/exhibitions/details/theasterGates.php (accessed August 27, 2019). 3. Gates, e-mail conversation with the author, July 7, 2019. 4. Ibid. 5. Gates, in Tim Marlow, interview with Theaster Gates (London: White Cube, 2012). Video available online at https://whitecube. com/channel/channel/theaster_gates_in_the_studio_2012 (accessed September 21, 2019). 6. See William David Barry, “The Shameful Story of Malaga Island,” DownEast Magazine, November 1980. Available online at www.malagaislandmaine.org/updates2013/The%20Shameful%20 Story%20of%20Malaga%20Island,%20DownEast%20 Magazine,%20November%201980.pdf (accessed August 28, 2019). 7. Ibid. 8. Frederick W. Plaisted, quoted in the Brunswick Times Record, July 21, 1911. Quoted in Maine State Museum, “The History,” available online at https://mainestatemuseum.org/learn/malagaisland-fragmented-lives-educational-materials/the-history/ (accessed August 28, 2019). 9. Maine State Museum, “The History.” 10. Gates, e-mail conversation with the author. 11. Richard Dyer, White (London and New York: Routledge, 1997, reprint ed. 2017), pp. 45–46. 12. See Laura Robertson, “The Black Charismatic,” Frieze, April 24, 2017. Available online at https://frieze.com/article/blackcharismatic (accessed August 29, 2019).

christopher wool part ii

gray turns to pink or his 21st century, much of it in texas text by richard hell

36

Previous spread: Christopher Wool, Untitled, 2018, oil and silkscreen on paper, 44 × 30 inches (111.8 × 76.2 cm) Opposite: Christopher Wool, Untitled, 2015, enamel and silkscreen ink on linen, 108 × 78 inches (274.3 × 198.1 cm) This page, all images: Christopher Wool, selections from Road, 2017

It took me a couple of years to fully appreciate Wool’s notorious early black-and-white paintroller and stencil-figure pattern paintings and giant panels of black-enamel-letter stencilings on whitepainted aluminum spelling such phrases as run dog run. When I encountered them in the mid’90s, ten years after he’d begun making them, I was innocent of recent painting. But I soon came to love them. They looked flat, like street signs or graffiti, and seemed preconceived—the act of painting them was apparently a formality once they were planned—and the graphic content was minimal. They felt aggressive but impassive and intelligent, while also often funny on levels. Wool made them for fifteen years. One might have assumed that this was his fundamental aesthetic. Then, around the turn of the century, he started making big, complex, black/white and gray, smeared and whorled and spray-paint-looped canvases that were partly about improvisation and largely about sophisticated composition—“the gray paintings.” As time goes on, things become less black and white. The paintings of the first two or three decades of Wool’s career had a particular, consistent, unusual quality, by my lights: they were uncanny. Almost all of them were black/white/gray; they seemed to eschew the sense of a human hand producing them. Even the smeary and graffiti-esque, highly elaborated gray paintings often used as their ground, or even their entire content, silk-screened photos of previous gray paintings, and after all, the reduction of all color to black and white and gray is not exactly humanistic, so to speak (though there’s always been humor in every period of Wool’s work). To me the paintings felt as if they’d simply appeared—like the writing on the wall, or like the world before you know anything about it—rather than painted by a person in time, despite the drips and the layering. I have to tell this story about a trippy twist on the experience of seeing that Wool enabled for me. For a year across 2006–07 I visited his studio every week to work with him at a computer monitor on a set of images we were creating together to make a book. In the process I was more and more humbled by his visual sense, the way he seemed to always know what looked interesting. I’d thought that the concept of a “visual person” was sloppy and goofy, like being a “feelings person” or an Aquarian or the beneficiary of “crystal power” or something. Being visual, I thought, was just a matter of educated taste. But Christopher had something extra, something innate, it seemed. Then, one late afternoon, returning home from working with him, I was walking through Tompkins Square Park in the East Village when the contents of my field of vision suddenly lost all meaning. There was no signification to anything before my eyes, just pattern and shape. A tree wasn’t a tree, it was a shape, and a building wasn’t a building, it was a pattern. Dimensionality was changed too, flattened, or made unnoticed, and color also diminished in effect. It was thrilling but also frightening. It was uncanny. It only lasted for a few seconds, but I felt like maybe this kind of seeing was part of what comprised a “visual person,” and that maybe it was in Christopher’s repertoire and helped explain his abilities. (The other paintings I’ve noticed reminding me of that walk in the park are Cézanne’s. It’s as if he wasn’t painting what he knew was there, but rather painting what he saw sans any influence of previously acquired information about it: it’s not an apple, it’s an area occurring in his field of vision.) 37

Oddly and probably not really relevantly, my mother had always picked up odd pieces of wire—often coat hangers—on the streets of Chicago. When I was first at Chinati I found a piece of wire that looked exactly like my drawing line only better and I thought it was funny to take this baroque piece of wire off the Judd landscape, so I sent it to my mother. As I started to find more pieces of wire that were like drawn line, I started saving them, for no particular reason. It was only years later that it dawned on me that these flattened balls of wire could be reconfigured in a three-dimensional way. The most recent part is realizing how important scale and setting are to sculpture—as opposed to the usual situation around painting. This led to the notion of designing sculpture for a specific environment—Marfa—and installing pieces around the property so I could try to see how these issues might work in situ. In the ’70s, sculptors, especially so-called modernist sculptors, were making work with the idea that what was important was internal formal dynamics; they tended to ignore setting or environment. And this came to be known derogatorily as plop sculpture for the seemingly casual way the sculptures looked once installed, often in urban plazas. With works like Tilted Arc Richard Serra and other sculptors of his generation specifically addressed the environment around the sculpture as part of the work, calling this idea 38

This page, top: Christopher Wool, Untitled, 2007, enamel on linen, 108 × 108 inches (274.3 × 274.3 cm) This page, bottom: Christopher Wool, Untitled, 2018, oil and silkscreen on paper, 44 × 30 inches (111.8 × 76.2 cm) Opposite: Christopher Wool, 2017

A strange sidebar semisupport of this occurred in an interview I recorded with Christopher in advance of something I was writing. He said of his painting, “You could almost say I’m picturing something in a nightmare, or a dream. . . . You know how nightmares can be so unbelievably powerful without really being about anything? Sometimes I have these terrible nightmares and I wake up and Charline asks, ‘Well, what were you dreaming?’ And I was sitting in the park and there was something—it was the scariest thing that ever could have happened. But nothing happened.” In the first years of the new century Wool began making the gray paintings, and he continued focusing on those up through the planning of his 2013–14 Guggenheim Museum retrospective in New York. In the mid-aughts he spent a period in Marfa, Texas, as an artist in residence at the Chinati Foundation, the complex of exhibition and installation spaces created there by Donald Judd, which opened to the public in the ’80s. Wool liked the environment. His wonderful-painter wife, Charline von Heyl, scored a residency too, and soon they decided to buy a house on the outskirts of town. So by 2010 they were spending a large part of the year in Texas. They continue to divide their time between New York and Marfa. Wool started organizing the Guggenheim exhibition with curator Katherine Brinson in 2011. During that period he also made his first large bronze sculpture. It was finished just in time to be installed in front of the museum for the show. He continues to make sculpture; to date he’s created ten large ones, two smaller, editioned works, and a piece in found barbed wire. The large sculptures are reminiscent of some of his canvases of loose spraypainted loops, but they were suggested to him by the lengths of discarded wire common in ranch country. The sculptures began as fencing wire that he bent and twisted into loose bundly shapes, though he was always conceiving of them as much larger pieces.

39

40

Opposite, top: Christopher Wool, 2018 Opposite, bottom: Christopher Wool, 2017 This page, all images: Christopher Wool, selections from Yard, 2018

site specificity, where sculptures didn’t exist as full works if they were removed from the specific site itself. And the appeal of thinking and working this way is pretty obvious, but much more complicated to actually accomplish than it sounds. Tilted Arc [on display in downtown Manhattan from 1981 to 1989, when complaints by some users of the site led to the work’s forced removal] was just blocks from my Chinatown loft and it really was a brilliant piece. But—the construction of the sculptures. . . . It’s not what I consider a great way of working, making something small and blowing it up. And in the past, until you could do it digitally, as things got larger they got more and more rounded at the edges and less and less detailed because you were basically doing it the Renaissance way, with a little thing moving here connected to a little bigger thing moving there, a rough mechanical enlargement. But now it can be done digitally with almost no loss of detail, which brings it back to a kind of handmade feeling. I left all the welds so you can see the process of assembly, and that, to me, is a lot like looking at a silk-screen painting where you can see that it’s handmade but it’s a mechanical hand. I really didn’t want them to look mechanically enlarged. And by leaving the welds and dispensing with patina, there’s really no way of seeing that they came from something small, which I think is important. They do tend to be quite flat, as much relief as sculpture. I’ve had trouble learning to work in three dimensions. They don’t stand up when they’re flat so there’s incentive to make them three-dimensional. I’m still a beginner. I’m a painter making sculptures, that’s clear. Personally, I love best the way the sculptures look in the wide-open Texas spaces, without any busyness crowding them or their internal view-framing. In the stolid glory of the Texas plains, they’re like funny tumbleweed, or doodles grown up, looming in droll homage like the landscape’s benevolent imps of the perverse, or its jesters. Early in my Marfa visits, pretty much contemporaneously with finding the wire, I had this strong notion that all the space and openness in Texas was kind of an ideal environment for sculpture. Just in the sense that sculpture is so much more physical than painting, and the landscape and access to material were almost calling for this. And that’s when I started taking pictures of things in the area that were sculptural, in a sense, without actually being art. Or at least not until I might have designated them as art. These photos—basically notes on sculpture—became the book Westtexaspsychosculpture [2017]. I took those photos over eight years before I put them together in a book. By then I had discovered what I could do with the wire and had opened that can of worms. The Texas photographs and the artist’s books in which they’re collected have things in common with, but are also strikingly different from, Wool’s prior photo books, such as Absent without Leave (1993) and East Broadway Breakdown (2003). East Broadway Breakdown was in part a tribute to Wool’s New York of the ’80s and ’90s. All the pictures were taken at night in the industrial/derelict neighborhood between his studio 41

42

This page, all images: Christopher Wool, selections from Westtexaspsychosculpture, 2017 All artwork © Christopher Wool; courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York

and his apartment. They’re grainy and cloudy but high contrast, black and white—all his photos have been black and white—and he shot them with flash without even looking through the viewfinder, then printed them via drugstore development services (though he adjusted for contrast in Photoshop afterward). There are no people in the pictures—just streets, puddles, garbage, buildings, fencing, battered cars, stains, and poles, reflecting flashbulb light at night. A stray dog or cat here and there. (Absent Without Leave is similar in approach and technique, but was shot on Wool’s travels overseas.) The Texas photos are also all exteriors and devoid of people, but they were deliberately framed with a digital camera in bright sunlight and then computer adjusted for clarity and emphasis with meticulous care. They’re radiantly crisp and subtle. As Wool said, his original motive was to conceive his choice of the clutter, debris, stackage, and storage around the small town of Marfa as sculpture, rather as Martin Kippenberger treated stray objects and specialized structures as buildings in his 1988 photo book Psychobuildings, or as Robert Smithson imagined industrial landscapes as sculpture. Another of Christopher’s Texas photo books, Yard (2018), combines images, as if doubly exposed, from the Westtexaspsychosculpture pictures and manipulates their tones to make intricate compositions. A third, Road (2017), is all photos of rutted, winding, rocky West Texas desert and mountain roads, and a fourth, Swamp (2019), combines pictures, as in Yard, but uses a wider variety of them and also adds a rust-brown color to areas of each image. These large books, with much white space per page to isolate the photos, are formatted and printed to the acknowledged highest standards, whereas his earlier books were done carefully but within a statement of values that downplayed classical “quality” picture-taking and printing. All the pictures in Absent without Leave, for instance, were photocopied for publication, degrading them extremely. Wool has also completed about forty large paintings in the last five or six years, as well as a series of smaller ones on paper and in oil paint, which medium is a radical departure for him, as is these works’ variety of mostly pastel colors, an outbreak of tint that may be an even greater departure. The large paintings are vintage Wool, but also, to me, seem done with a lighter touch than before. There’s humor: drips go sideways; a series uses arrangements of silk-screened typography that are then blotted and overpainted in a way that feels elegantly playful; Wool secretly includes his own profile in a silk-screened blot. If these paintings are less austere and impassive than his first couple of decades of paintings, the multicolored oil paintings on paper are positively sensuous. As is common with him, the papers underlying the oil paintings are silk-screens (of previous paintings) and etchings of his. The oil imagery is also recognizably Wool in its line, technique, and aesthetic, but newly warm and lush. There’s a little of the way Philip Guston handled paint in his later, cartoony, pink and gray works, though there’s no figuration in the Wools—they’re strictly abstract compositions, strong and lovely oil abstractions. So this twenty-first-century middle period of Wool’s is distinguished by a turn toward concentrating on deep composition, and toward the more warm and amused and serene—in contrast to the austere, aggressive, often gridlike appearance of much of his earlier work—without any loss in power or level of interest.

LO S A N G E L ES

N E W YO R K

LO N D O N

RICHARD SERRA

Weight is a value for me—not that it is any more compelling than lightness, but I simply know more about weight than about lightness and therefore I have more to say about it, more to say about the balancing of weight, the diminishing of weight, the addition and subtraction of weight, the concentration of weight, the rigging of weight, the propping of weight, the placement of weight, the locking of weight, the psychological effects of weight, the disorientation of weight, the disequilibrium of weight, the rotation of weight, the movement of weight, the directionality of weight, the shape of weight. —Richard Serra

46

47

48

Opening spread and previous spread: Richard Serra, Nine, 2019, forged steel, nine rounds, 7 feet × 6 feet 4 ¾ inches diameter (213.4 × 194.9 cm), 6 feet 6 inches × 6 feet 7 ¾ inches diameter (198.1 × 202.6 cm), 6 feet × 6 feet 11 inches diameter (182.9 × 210.8 cm), 5 feet 6 inches × 7 feet 2 inches diameter (167.6 × 218.4 cm), 5 feet × 7 feet 7 inches diameter

(152.4 × 231.1 cm), 4 feet 6 inches × 8 feet diameter (137.2 × 243.8 cm), 4 feet × 8 feet 6 inches diameter (121.9 × 259.1 cm), 3 feet 6 ½ inches × 9 feet diameter (108 × 274.3 cm), 3 feet 2 ¼ inches × 9 feet 6 inches diameter (97.2 × 289.6 cm) Opening spread photo: Rob McKeever Previous spread photo: Cristiano Mascaro

This spread: Richard Serra, Reverse Curve, 2005/19, weatherproof steel, 13 feet 1 ½ inches × 99 feet 9 inches × 19 feet 7 inches (4 × 30.4 × 6 m); plate: 2 inches (5 cm) thick Artwork © 2019 Richard Serra/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

49

CUT & PASTE In this first installment of a two-part essay, John Elderfield tracks the oscillating states of unification and separation that Édouard Manet’s The Execution of Maximilian has endured since its creation, in 1868.

Left: Fernand Lochard, photograph of Édouard Manet’s The Execution of Maximilian, December 1883, albumen print, 2 7⁄8 × 3 ¾ inches (7.2 × 9.5 cm). National Gallery, London Opposite: Édouard Manet, The Execution of Maximilian, 1867–68, oil on canvas, 6 feet 4 inches × 9 feet 4 inches (193 × 284 cm). National Gallery, London, Bought 1918

50

Ambroise Vollard was not only one of the most important French art dealers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—some would say the most important—he was also an extremely gifted writer who published biographies of Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, and Auguste Renoir: promotional vehicles for his artists, to be sure, but great reading nonetheless, full of wonderful firsthand anecdotes. Among the pleasures of his book on Degas are the half-dozen nicely rambling pages recording the artist’s thoughts on the subject of paintings being altered after their completion by those who had not made them. Degas was testy about his dislikes, and began by fulminating about a conservator wax-lining a painting: “giving it an ironing,” as he described it. Then he got to what was really on his mind: people cutting off from paintings a part they didn’t like. Someone he knew had said of the painting of a nude woman: “A good many society ladies come to my house, and I thought the lower part of the torso was not quite proper, so I cut it off.” Degas: “To think that an imbecile like that hasn’t been caught and locked up.” More alarmingly personal, Degas had painted a double portrait of his friend Édouard Manet and his wife in exchange for a still life of fruit. Visiting them, he “had a fearful shock”: Manet had “thought that the figure of Madame Manet detracted from the general effect,” and had cut it off. When Degas got home, he returned the still life with a stiff note: “Sir, I am sending back your Plums.” Then came the most interesting story. Vollard writes:

Sometime later I happened to meet Degas accompanied by a porter wheeling one of Manet’s pictures on a cart. It was one of the figures from the subject picture entitled, The Execution of Maximilian, and showed a sergeant loading his gun for the coup de grâce . . . [Then Degas shouted] “It’s an outrage! Think of anyone’s daring to cut up a picture like that. Some member of Manet’s family did it. All I can say, is never marry. I remember admiring this painting of the upper half of a soldier when I first visited the National Gallery in London as a teenager. The label said that it was a fragment of a large, damaged painting of the execution of the Emperor Maximilian in Mexico, on June 19, 1867; I hadn’t heard of this incident, the history then taught in British schools being almost exclusively British history. And the label had nothing to say about how the fragment got to the National Gallery. Little did I know, of course, that I would eventually learn a lot about both of these things while preparing an exhibition of Manet’s paintings on this subject—for there were more than this one—that opened at New York’s Museum of Modern Art late in 2006. Among the works shown there were photographs related to Maximilian’s execution that Manet would have seen. In an extraordinary irony, while the exhibition was on view, images of the execution of Saddam Hussein in Iraq were beamed around the world. T. S. Eliot famously wrote that the art of the past is altered by that of the present, as much as that of

the present is directed by the past. Looking back at Manet’s enterprise now, in a period of the production of far more art with a political message than a decade ago, does alter it. I will say something about that in the companion essay to this one to appear in the next issue of this magazine. Now, I will be arguing that the cutting up of this painting, deplored by Degas, now contributes to its delivery of its message. But let us first learn how the fragment showing the soldier got into the collection of the National Gallery in London. This is what happened: the painting was a fragment of, in fact, the second of Manet’s Execution of Maximilian paintings, abandoned by the artist in 1868—of this, more in a moment—and left rolled up at his wife’s home, where it languished in storage. Probably before Manet’s death, in 1883, the left side of the canvas was cut away, by Manet or someone unknown, perhaps because it was damaged, thereby removing the images of Maximilian and one of the two generals executed with him. That was when the only contemporaneous photograph we have of it was taken. “Some member of Manet’s family”—in fact Léon Leenhoff, who has been described both as Manet’s stepson and as his half-brother; his paternity has never been revealed—subsequently discarded and burned the by-then, he claimed, seriously damaged lower sections on either side of the composition, and cut up the remainder into four pieces. Then, in Degas’s words, “the sergeant loading his rifle . . . was hawked about and eventually sold 51

for 500 francs to [the art dealer Alphonse] Portier who let me have it.” (This was the delivery Vollard saw on the cart.) Degas then set about searching for the other pieces that remained of the picture: one large piece, depicting the remainder of the firing squad of soldiers, and two smaller ones, showing the upper part of the second general. He eventually found them, and now with all four, Vollard reported, “proceeded to glue them onto a canvas prepared for the purpose, leaving necessary space for the missing parts in case they should ever be recovered.” None others were recovered; and this was how the painting remained until Degas’s death, in 1917. The following year, the London National Gallery purchased it in the sale of Degas’s private collection—and, extraordinary though it now seems, proceeded to unglue the four pieces from the canvas on which Degas had so lovingly recomposed them. And so matters remained until another painter intervened. It is the National Gallery’s rule to itself that an artist should occupy a term position as one of its trustees; and when the painter Howard Hodgkin was appointed to that role, in 1978, he campaigned to have the painting returned to how Degas had left it, and eventually succeeded. The composition was first exhibited in that form in 1992. So, three artists—Degas and Hodgkin in addition to Manet—are responsible for the painting that now hangs as it is in London; as well as, of course, Léon Leenhoff.

52

W hat may be said in defense of what t he National Gallery did? First: there is no reason why, in principle, Manet would have objected to the exhibition of a figure removed from a composition with which he was dissatisfied. Leaving aside what he did to Degas’s double portrait of the Manets, when one of his own compositions, showing a death in a bullfight, was actually on the walls of the 1864 Salon, Manet “boldly took out a pocket knife and cut out the figure of the dead toreador,” a friend reported. And he made an independent painting of it. Second: if Manet was a divider, Degas was a combiner. In his later years he enjoyed making paintings from pasted-together pieces of paper. The work that the National Gallery acquired could be thought a joint production of Manet, the divider, and Degas, the combiner. And third: while the jigsaw that Degas assembled from the pieces of Manet’s painting would have fitted very comfortably into, say, the recent ecumenical exhibition of “unfinished” works of art at the Met Breuer, New York, it would not have done so on the walls of any major museum in 1918. Tastes have changed enormously since then, when the first modern collages had appeared only six years earlier. Now that collage techniques having persisted for almost seven decades—amazingly, longer than the entire period from Romanticism to

He then brought into his studio a squad of French infantry to pose, and also painted the face of the sergeant loading his rifle to resemble Napoleon III. This was sheer provocation on Manet’s part, and while his painting had been announced for exhibition in the official Salon due to open in May 1868, there was no way that he could have received permission to show it.

Opposite: Édouard Manet, Execution of the Emperor Maximilian, 1867, oil on canvas, 6 feet 5 1⁄8 inches × 8 feet 6 ¼ inches (195.9 × 259.7 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Frank Gair Macomber. Photo: © 2019 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Left: Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, The Third of May, 1808, 1814, oil on canvas, 8 feet 9 ½ inches × 11 feet 4 5⁄8 inches (268 × 347 cm). Museo del Prado, Madrid Below: Agustín Peraire, Maximilian’s Execution Squad Standing at Attention, June 1867, Albumen carte de visite, 2 × 3 inches (5.1 × 7.4 cm). Research Library, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

Cubism—the current appearance of Manet’s painting speaks to us anachronistically as an example of the art of assemblage. I said that the painting now in London was the second that Manet had painted on this subject. The first, now at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, would also qualify for an exhibition of “unfinished” works. It appears to have been begun within days of news reaching Paris, on July 1, 1867, of Maximilian’s execution in Querétaro, north of Mexico City—quick at that time for a distant event that had taken place less than two weeks before. It was begun, therefore, before engravings and photographs that pretended to show episodes or objects documenting the event started to appear, in August of that year; and it is generally agreed that when Manet eventually saw such images he abandoned this first painting, which would not be exhibited until 1905. As it stands, its unfinish in fact speaks of the uncertainty of the story it purports to tell, and of how Manet changed his mind about what to represent when he made the London painting. In shaping the Boston composition, Manet borrowed freely from Goya’s Third of May, 1808, a painting of 1814 in the Prado that depicts the execution of Spanish nationalists by invading French soldiers under the orders of Napoleon—the uncle of Napoleon III, the monarch of France in Manet’s time. Manet was imagining a situation that was, at face value, almost opposite to Goya’s subject: Mexican nationalists executing the representative of a French invasion. And he dressed his execution squad in flared pants and sombreros, which conformed to popular notions of what ordinary Mexican soldiers then looked like. Yet the borrowing from Goya suggests that he was beginning to implicate France. In the London painting that followed, the implication was made explicit. Manet learned from a report of August 11, 1867, in the newspaper Le

Figaro, that the uniform of the Mexican soldiers resembled the French uniform, and probably soon thereafter he saw photographs of the firing squad. He then brought into his studio a squad of French infantry to pose, and also painted the face of the sergeant loading his rifle to resemble Napoleon III. This was sheer provocation on Manet’s part, and while his painting had been announced for exhibition in the official Salon due to open in May 1868, there was no way that he could have received permission to show it. A photography dealer was jailed simply for being in possession of some of the photographs, by then in clandestine circulation. The painting therefore languished in Manet’s studio— what happened to it we already know—and Manet

eventually began a third and final large painting, which is now in the Kunsthalle Mannheim. I will defer to the second chapter of this story the changes in Manet’s imagining of this subject in that third painting, the extent to which they were influenced by incoming reports about what had actually happened in Querétaro, and how this relates to issues of political and polemical art and its censorship. To conclude now, I want to return to why I think the collage that Manet’s second painting became is such a compelling work. We are to imagine the artist making this composition poring over a succession of newspaper stories of a distant, horrifying event, hoping for

53

Right: Adrien Cordiglia, Commemorative picture of the Execution of Emperor Maximilian, 1867, glass plate negative, 3 3⁄8 × 4 ¾ inches (8.5 × 12 cm). Austrian National Library, Vienna, Picture Archive Below: Édouard Manet, Boy with a Sword, 1861, oil on canvas, 51 5⁄8 × 36 ¾ inches (131.1 × 93.4 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, gift of Erwin Davis, 1889

clarification and definitive truth, as we do now with such events, and either not finding it or disbelieving it, as we do now. We are also to imagine Manet piecing together fragments of news, knowing that they did not realistically or completely describe what had happened but offered, rather, the means of an imaginative act of rediscovery of something that was quickly receding into the past. It is purely accidental, of course, that the London canvas conveys something of this in its collagelike format, the parts not composing a complete picture and not

54

quite matching up with each other. Still, its incomplete status as a painting gives it particular power as an incomplete remembrance. And knowing that Manet drew on composite images of the execution, images themselves made by collaging together photographs of the victims and the firing squad, reinforces our awareness of the process of assembly that shaped its imagery. In the sky at the center of the London painting can be seen a diagonal motif, apparently a sword, that appears in neither of the other two compositions. It is especially puzzling because we cannot see the soldier holding it, Manet having hidden him behind the line of the soldiers who are firing their muskets. Late-nineteenth-century viewers would have known that it was customary in executions by firing squad that the command to fire be signaled by an officer either abruptly raising a sword or slowing raising and then abruptly lowering it. Now that that meaning has faded, the motif has become akin to what Roland Barthes famously called a “punctum,” something that catches our gaze without disclosing why it is there, even what it is, as opposed to the “studium,” the manifest meaning of a composition; therefore, inviting of subjective interpretation. I don’t think many people will associate the sword, this cutting device, with what happened to this painting, but it is there to wonder at in the sky; and perhaps some people will. What is unquestionably strange is that in 1861 Manet had painted a charming portrait, Boy with a Sword, now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which was in his possession when he put the sword in this Maximilian composition— perhaps even made him think of doing so. The boy portrayed in that canvas holding the sword was the young Léon Leenhoff, who would eventually cut up

the extraordinary painting that Degas then saved. Whether or not we know this, what remains unexplained is what precisely is happening in this cut-up painting. The muskets are firing, but one of the two generals who survived the cutting also seems to be surviving the execution; so presumably does the missing person—Maximilian?— whose hand he is holding. But why are there two left hands? And why is the general so unrealistically tall? And why is the soldier with a rifle so disengaged from the action as to seem almost to invite being cut off? In our age of assemblage, such narrative anomalies, far from further damaging the damaged painting, come across as entirely consonant with its now collaged format, the two forms of disjunction together fueling the excitement of unresolved recognition of what happened at Querétaro on June 19, 1867. But then, Manet himself did not know that when he made this painting; and when he did, he made yet another one. To be continued . . .

Bibliographical Note The information presented here is drawn from my Manet and the Execution of Maximilian (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2006), supplemented by my “Soldiers of Misfortune,” The Guardian, January 6, 2007, from which I have taken a few sentences. I also refer to Ambroise Vollard, Degas: An Intimate Portrait, translated by Randolph T. Weaver (New York: Greenberg, 1927); T. S. Eliot, “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” 1917, in his Selected Essays, 1917–1932 (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1932), and widely anthologized; and Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, 1980, translated by Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981).

THE NEW WORLD OF CHARLOTTE PERRIAND

Inspired by a visit to the Fondation Louis Vuitton’s exhibition Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World, William Middleton explores the life of this modernist pioneer and her impact on the worlds of design, art, and architecture.

58

A

rt is in everything,” insisted Charlotte Perriand, the pioneering French architect, designer, and multidisciplinary creative force. “It is in a gesture, a vase, a cooking pan, a glass, a sculpture, a piece of jewelry, a way of carrying yourself. Making love is an art.” Perriand, whose work is a high point of French modernism, had a broad vision of creativity. She termed it “synthesis of the arts,” an approach that expanded to include all of the fine and applied arts. Throughout the seven decades of her career, this idea became her manifesto. On the occasion of the twentieth anniversary of Perriand’s death, the Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, is giving her a major retrospective, Le Monde nouveau de Charlotte Perriand 1903–1999 (retitled in English Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World ), on view now and into February 2020. An ambitious exhibition four years in the making, it brings the full scale of her vision into focus for the first time. “Shortly after she died,” says Pernette Perriand Barsac, Perriand’s daughter and one of the show’s curators, “a friend of mine said that you have to wait fifteen or twenty years after the death of an artist to understand fully their place in art history.” The Fondation Vuitton’s Perriand exhibition incorporates a vast amount of design and architecture—200 objects, seven “reconstitutions” of historic rooms, four recreated structures, and twentyfive architectural models—as well as 200 works of art, lent by museums and private collectors around the world, by such artists as Georges Braque, Alexander Calder, Henri Laurens, Fernand Léger, Jacques Lipchitz, Joan Miró, and Pablo Picasso: paintings, sculptures, photographs, photomontages, and tapestries. “This is the largest exhibition we have ever dedicated to a single artist,” explains Jean-Paul Claverie, the director of the Fondation and for thirty years the cultural advisor to Bernard Arnault, chairman and CEO of the Vuitton parent company LVMH. “It marks the five-year anniversary of our Frank Gehry–designed building, which is itself a work of art. It is the first time we have focused on a female artist, and it is our first exhibition that incorporates design. If you ask me if this is a design exhibition, I will say that you are right. But I will also say that you are wrong.” One curatorial goal was to contextualize Perriand’s work. The Fondation Louis Vuitton has had a relationship with Pernette Perriand and with her husband, Jacques Barsac, who is overseeing the ongoing publication of a multivolume catalogue raisonné. “When Pernette mentioned to me that the anniversary of her mother’s death was approaching, I spoke with Bernard Arnault and he was immediately enthusiastic,” Claverie explains. “We worked very closely together because we agree that the genius of Perriand, her extraordinary designs, took place in the context of a variety of movements— intellectual, social, political, artistic, and philosophical—during a time of profound transformation, the birth of modern society in the twentieth century. This had been suggested in earlier exhibitions but not developed in detail.” The paintings and sculptures, selected for their connections with Perriand, explore her sense of a “synthesis of the arts”—in fact that was the exhibition’s working title. “The term is connected to the nineteenth-century utopian ideals of a total work of art,” says Olivier Michelon, the Fondation’s chief curator, “but Perriand makes the concept more precise. It is not a totality of art but a