di or .c om –80 0 92 9 .d io r ( 3 467 )

LA ROSE DIOR COL LEC TION Pink gold and diamonds.

LA ROSE DIOR COL LEC TION Pink gold and diamonds.

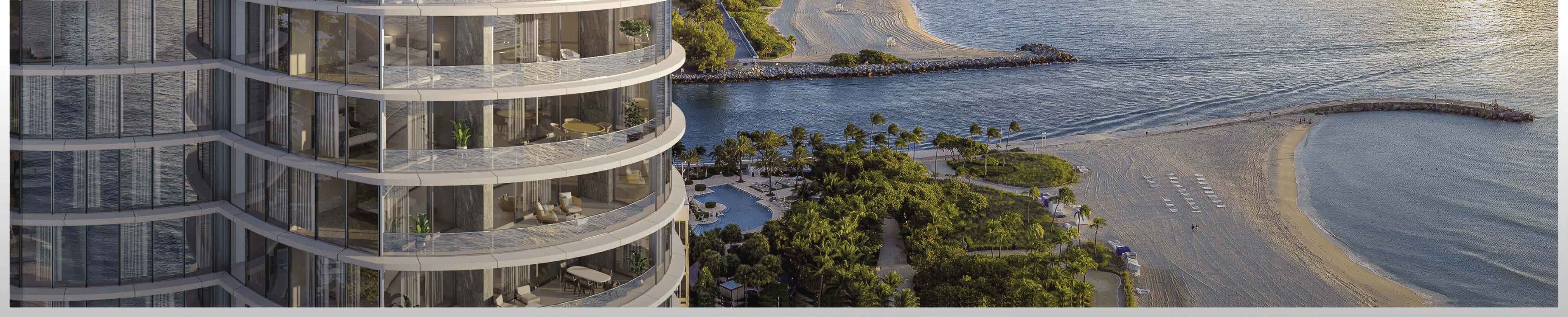

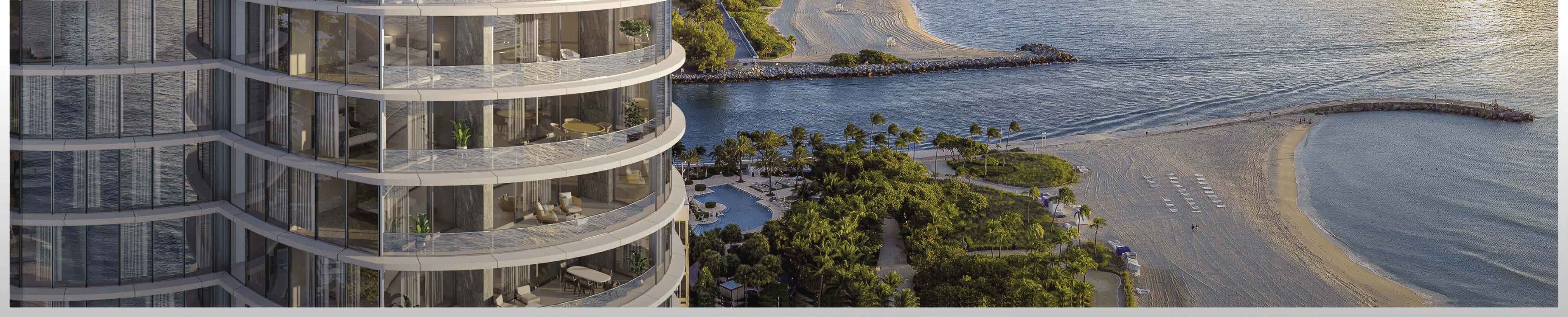

We are delighted to begin the new year with Roe Ethridge’s Two Kittens with Yarn Ball (2017–22) on our cover. Inside, our readers will find an exclusive artist’s book by Jim Shaw, who has long been inspired by comic books, pulp novels, and protest posters.

We invited Marc Newson, one of the most influential designers of his generation, to guestedit a series of articles in this issue. He has brought together an incredible section that covers a wide range of subjects, including concept cars, architecture, film, and more.

Next up for the Picture Books series, Emma Cline has invited painter Genieve Figgis to create a new artwork in response to an incredibly visual novella by author Lydia Millet. The inimitable author Joy Williams participates in Hans Ulrich Obrist’s questionnaire, and we kick off this year’s fiction serial with the first installment of a new story by Percival Everett.

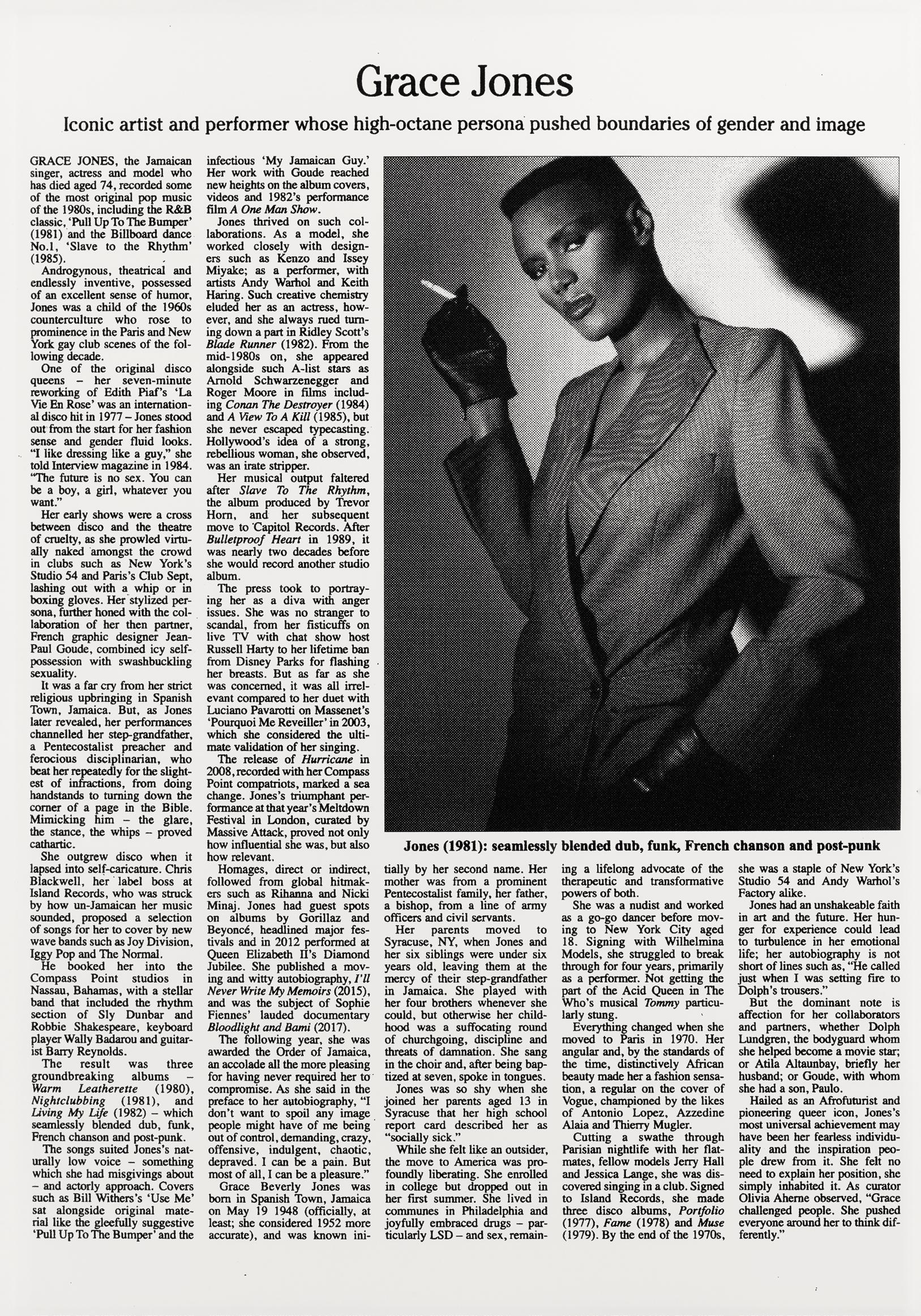

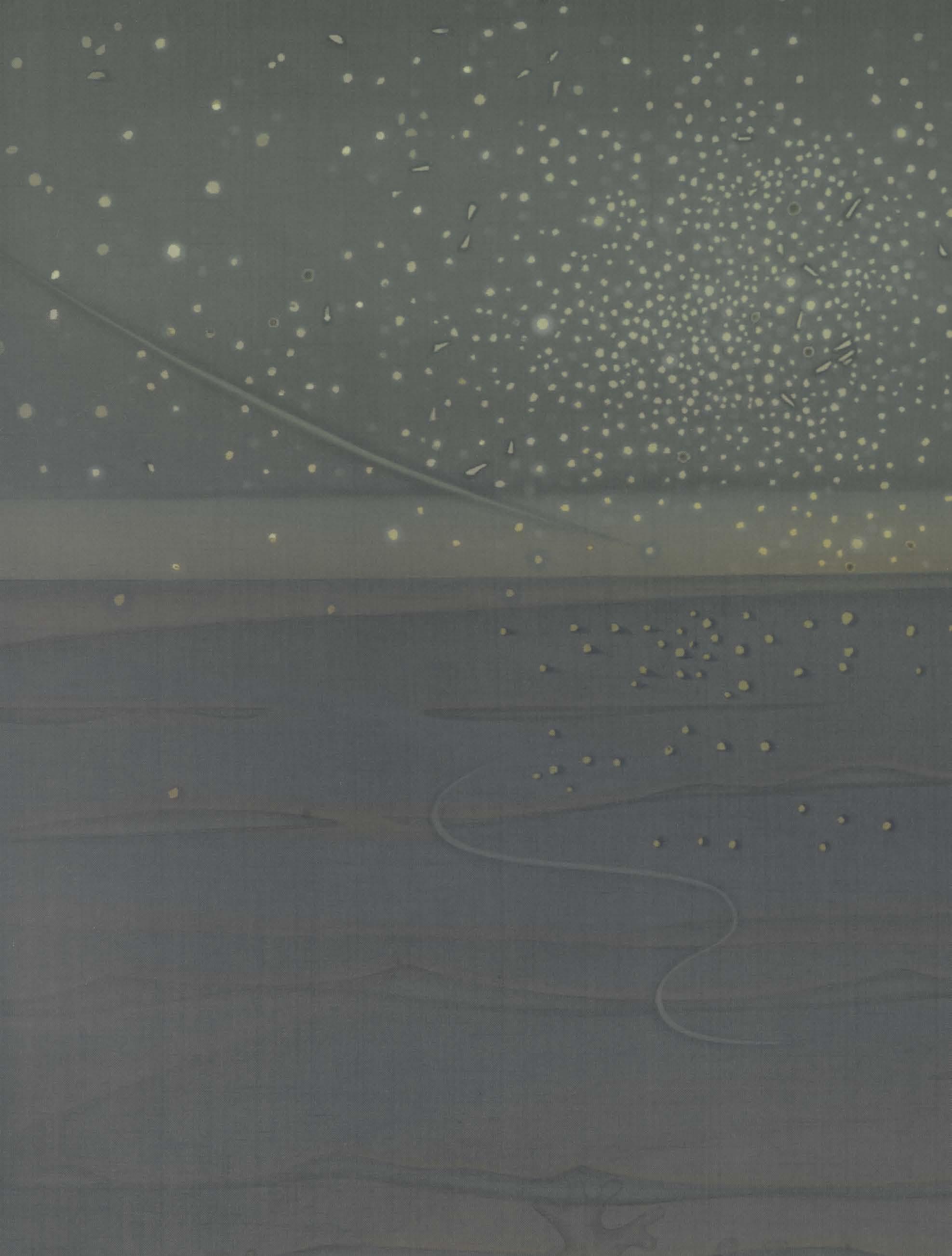

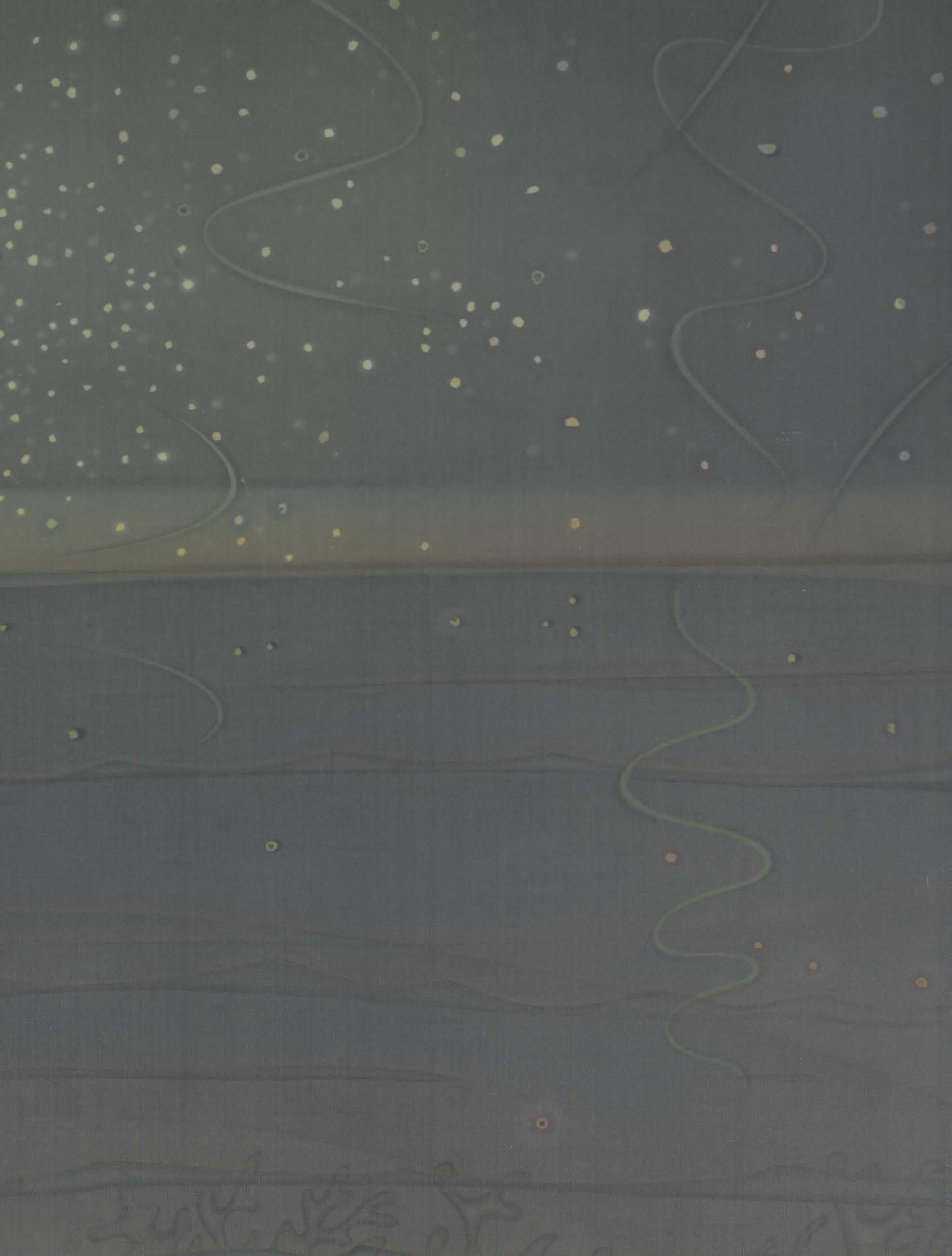

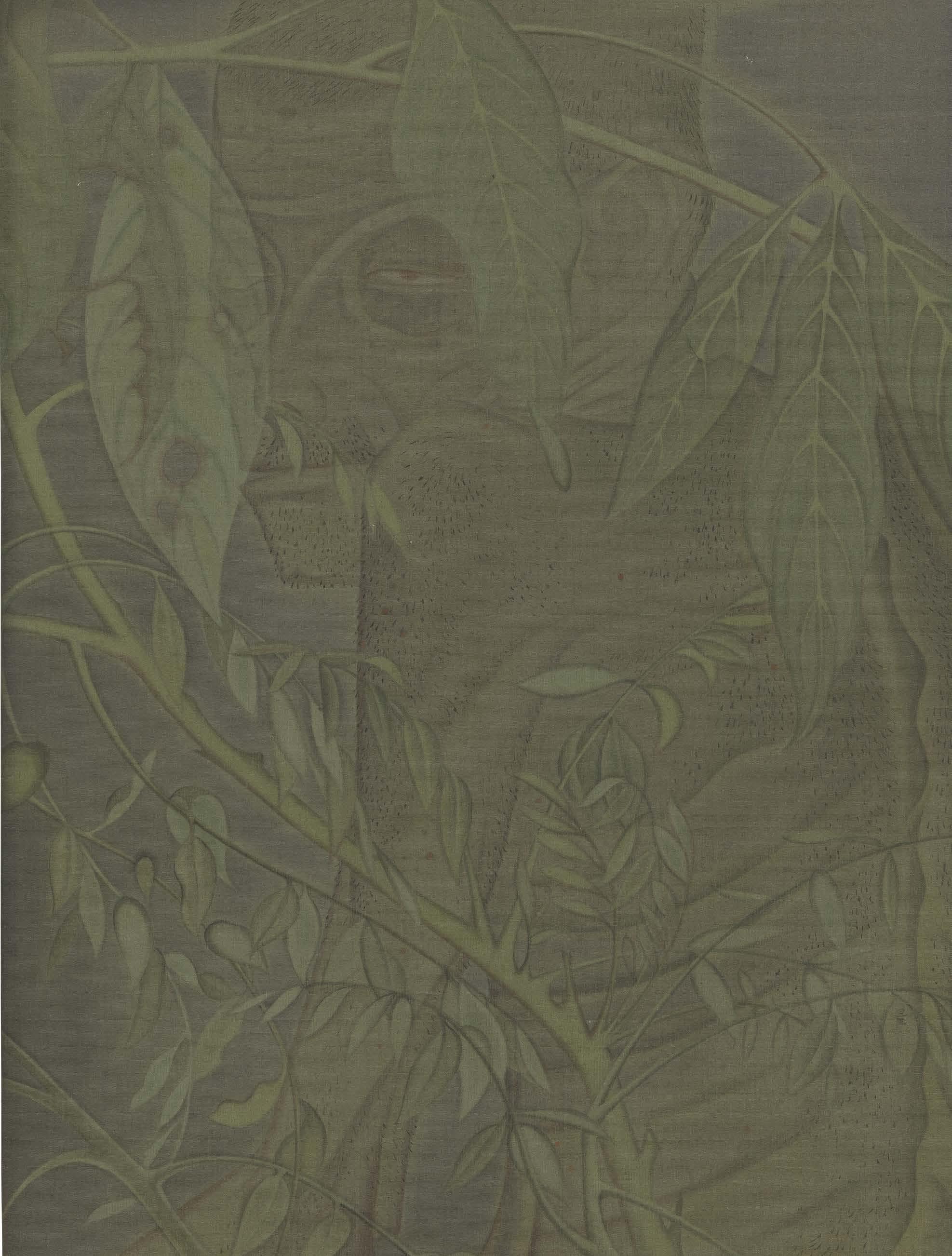

The issue features several articles on painters, all of whom approach their practices in radically different ways. On the occasion of an upcoming monograph, Richard Wright, an artist celebrated for site-specific and transient works, pens a personal and philosophical text about painting. Travis Diehl explores Hao Liang’s mastery of both traditional Chinese ink-wash painting and more contemporaneous considerations on the eve of Hao’s first solo exhibition in Europe. Novelist Andrew Winer expertly navigates the beauties and complexities at play in Glenn Brown’s latest works; Tiana Reid reports on her encounter with Cy Gavin’s new paintings; Ester Coen provides insight on the roots of Sterling Ruby’s recent colorful abstractions in early-twentieth-century avant-gardes including Futurism and Constructivism; and Adam McEwen speaks with Jeremy Deller about his obituaries for the living.

Finally, the photographer Sally Mann and the writer Benjamin Moser discuss biography, photography, and the responsibility of creators attempting to achieve honest portrayals of their subjects. Plus we have articles on legacy, biography, fashion, the future of the Internet, and harnessing the power of the blockchain for art and activism.

Alison McDonald, Editor-in-chief

Glenn Brown: From the Inside Out

Novelist Andrew Winer reports on the formal, conceptual, and philosophical perspectives embedded in Glenn Brown’s latest paintings and drawings. The two talked after the opening of the artist’s recent New York exhibition Glenn Brown: We’ll Keep On Dancing Till We Pay the Rent

52

The Art of Biography

William Middleton’s forthcoming biography of Karl Lagerfeld, Paradise Now, comes as a major follow-up to his lauded history of Dominique and John de Menil, Double Vision , from 2018. Here, curator Michael Cary talks with Middleton about the challenges, strategies, and revelations that went into telling the story of this larger-than-life visionary in the world of fashion.

58

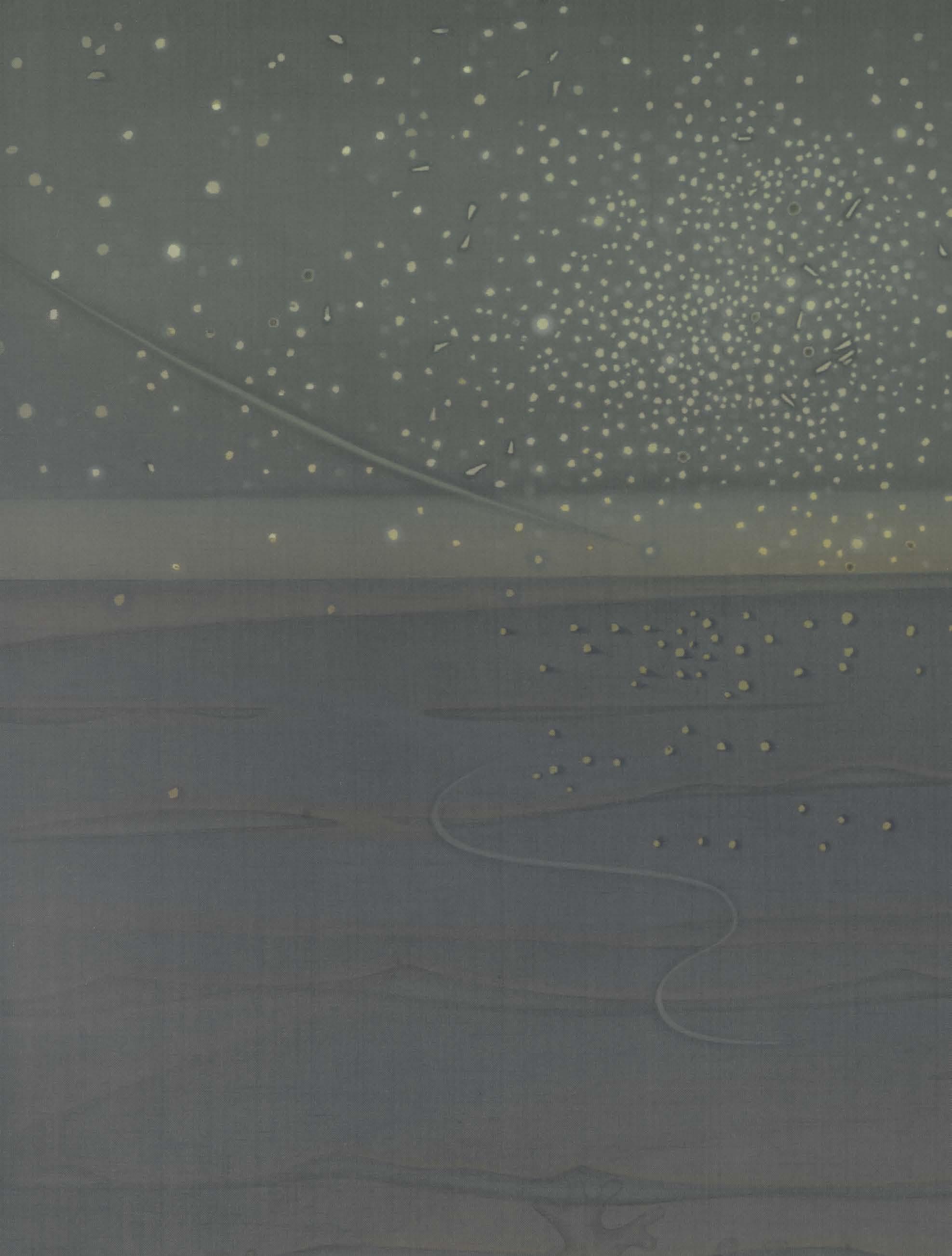

Cy Gavin: On the Other Side of the Limit

Tiana Reid reports on her encounter with the artist Cy Gavin’s new paintings.

64 Hans Ulrich Obrist’s Questionnaire: Joy Williams

The fifth installment of the series.

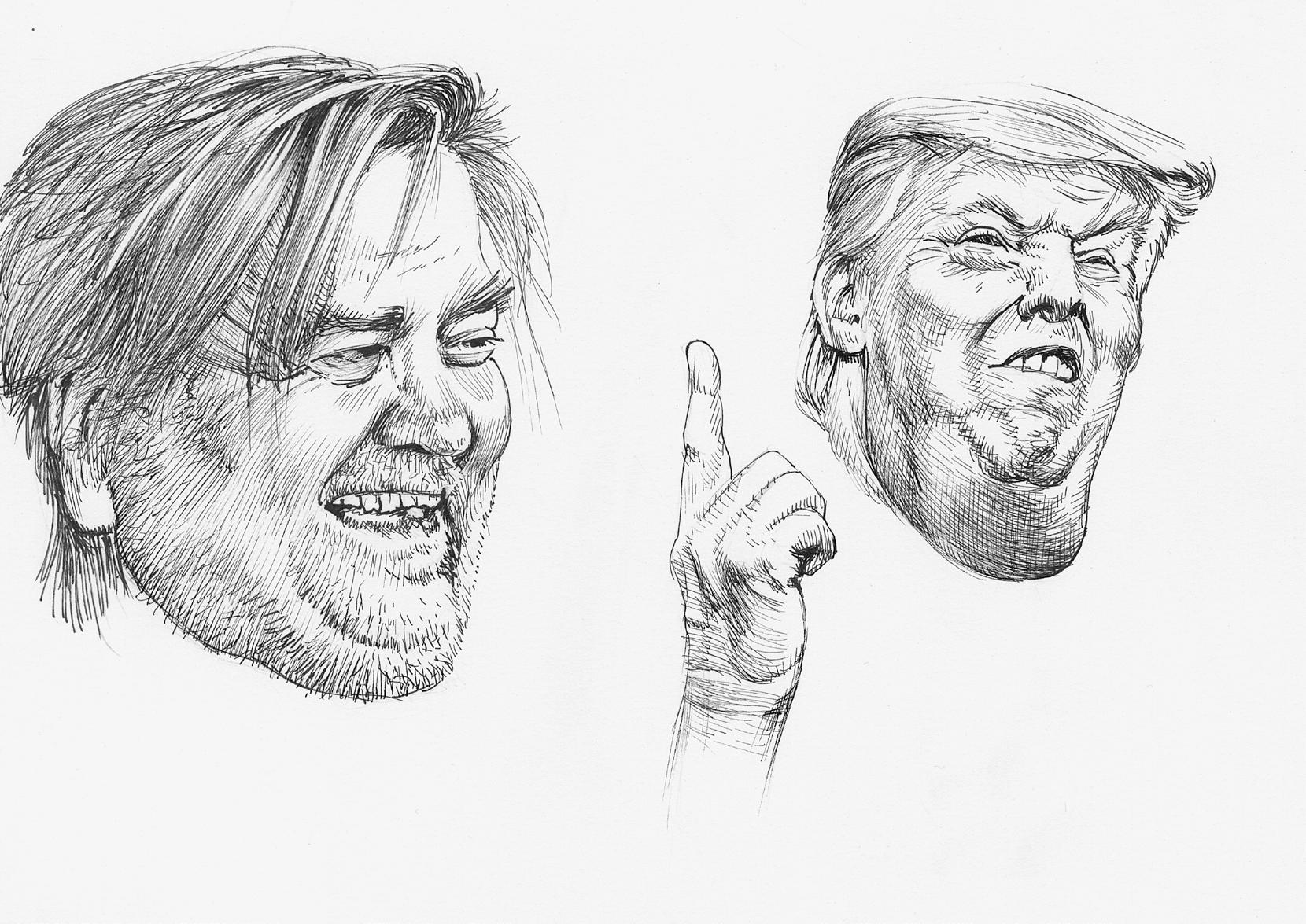

66 Adam McEwen: An Act of Love

Contemporary artists Adam McEwen and Jeremy Deller met up online over the holiday season to discuss McEwen’s upcoming exhibitions in London and Rome. McEwen delves into the motivations and criteria behind his work, as well as the challenges and complexities of memorializing the living.

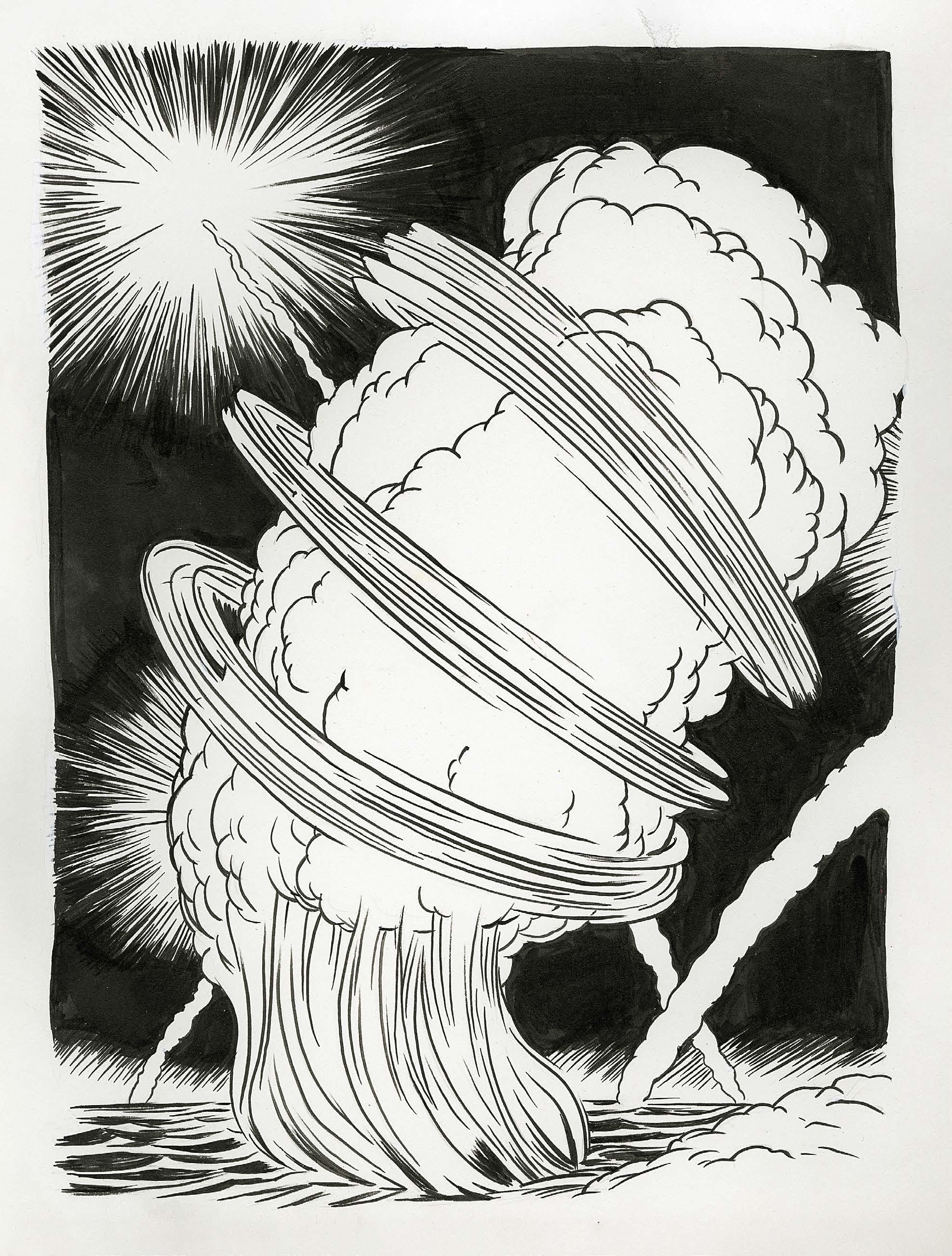

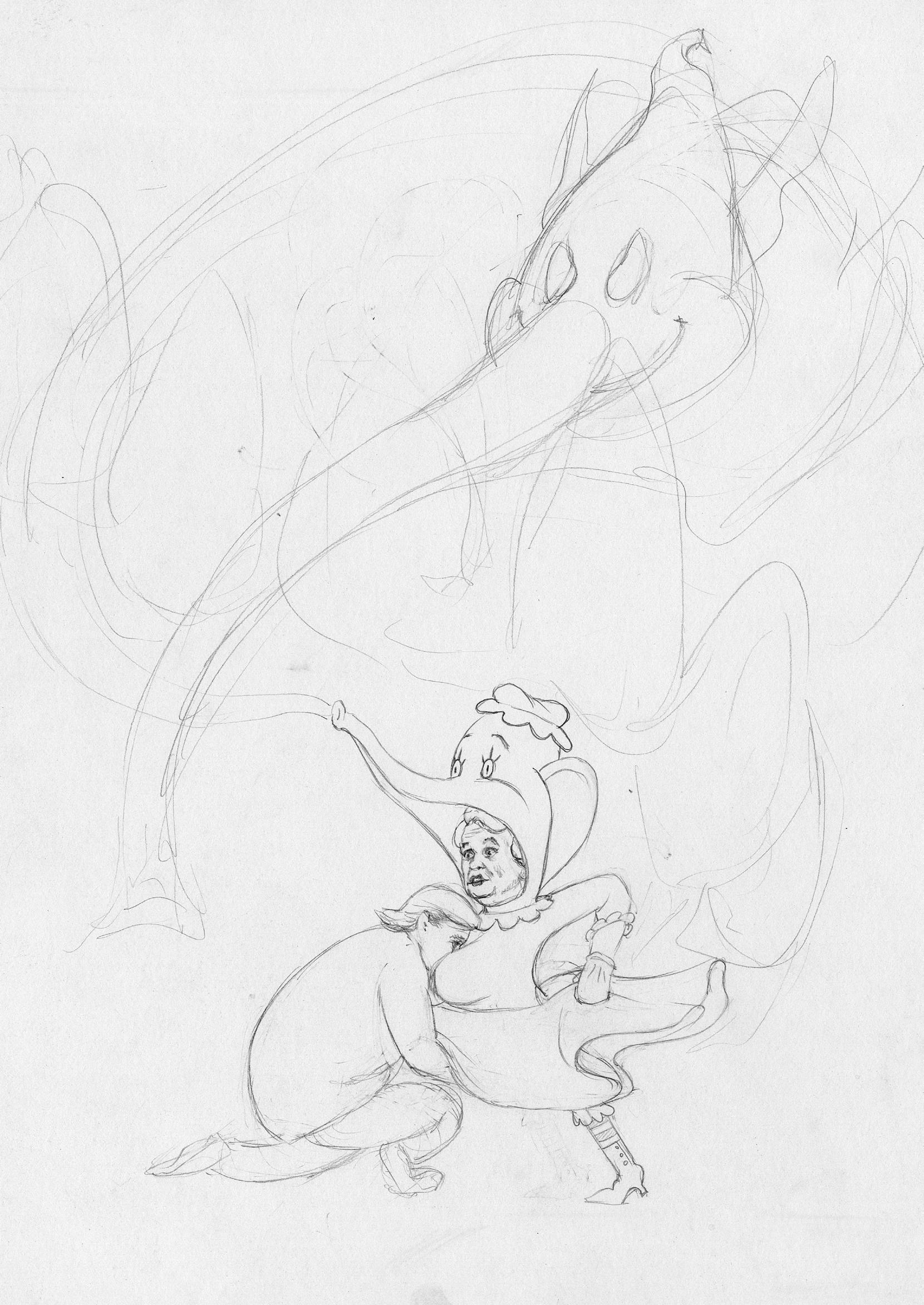

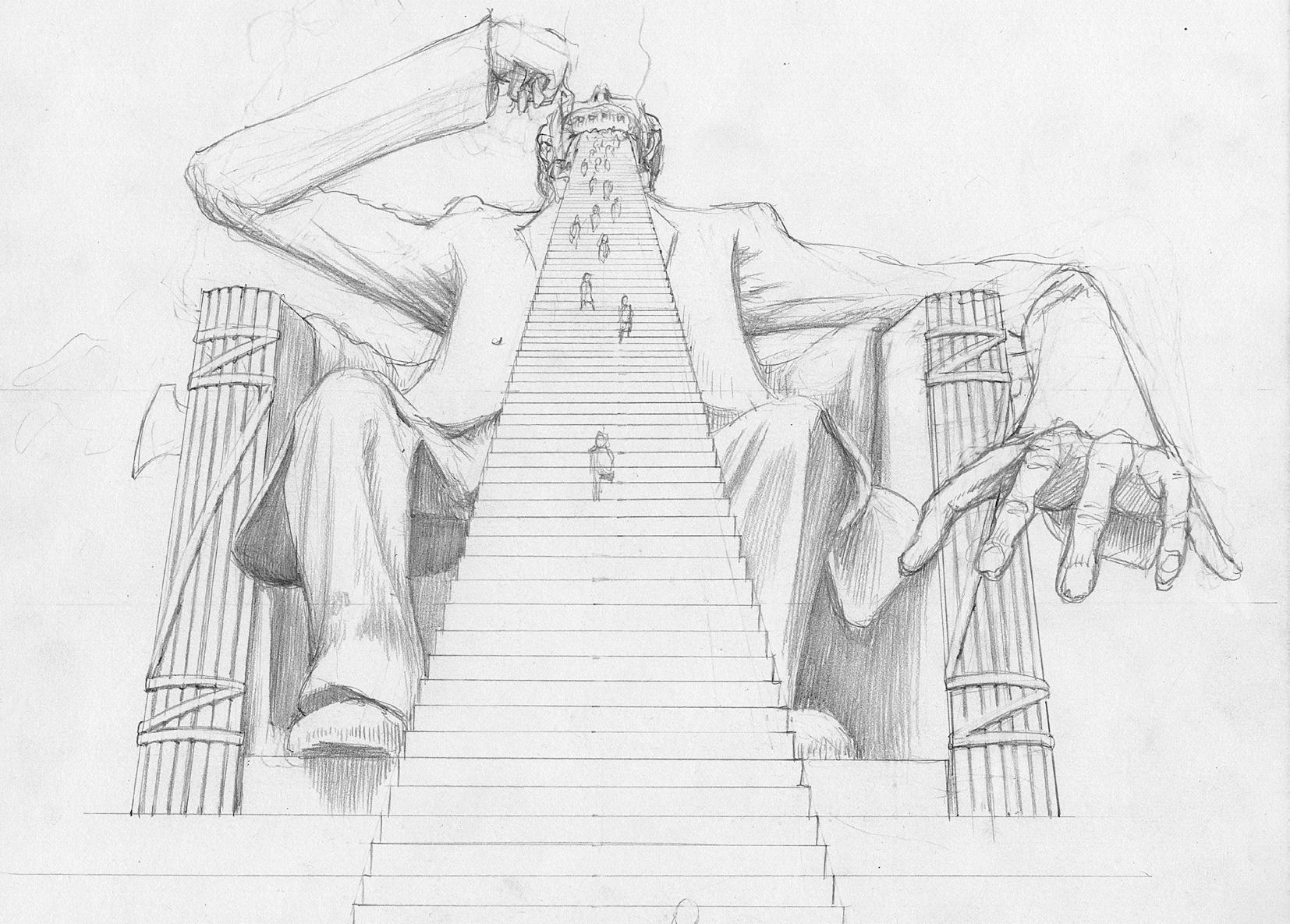

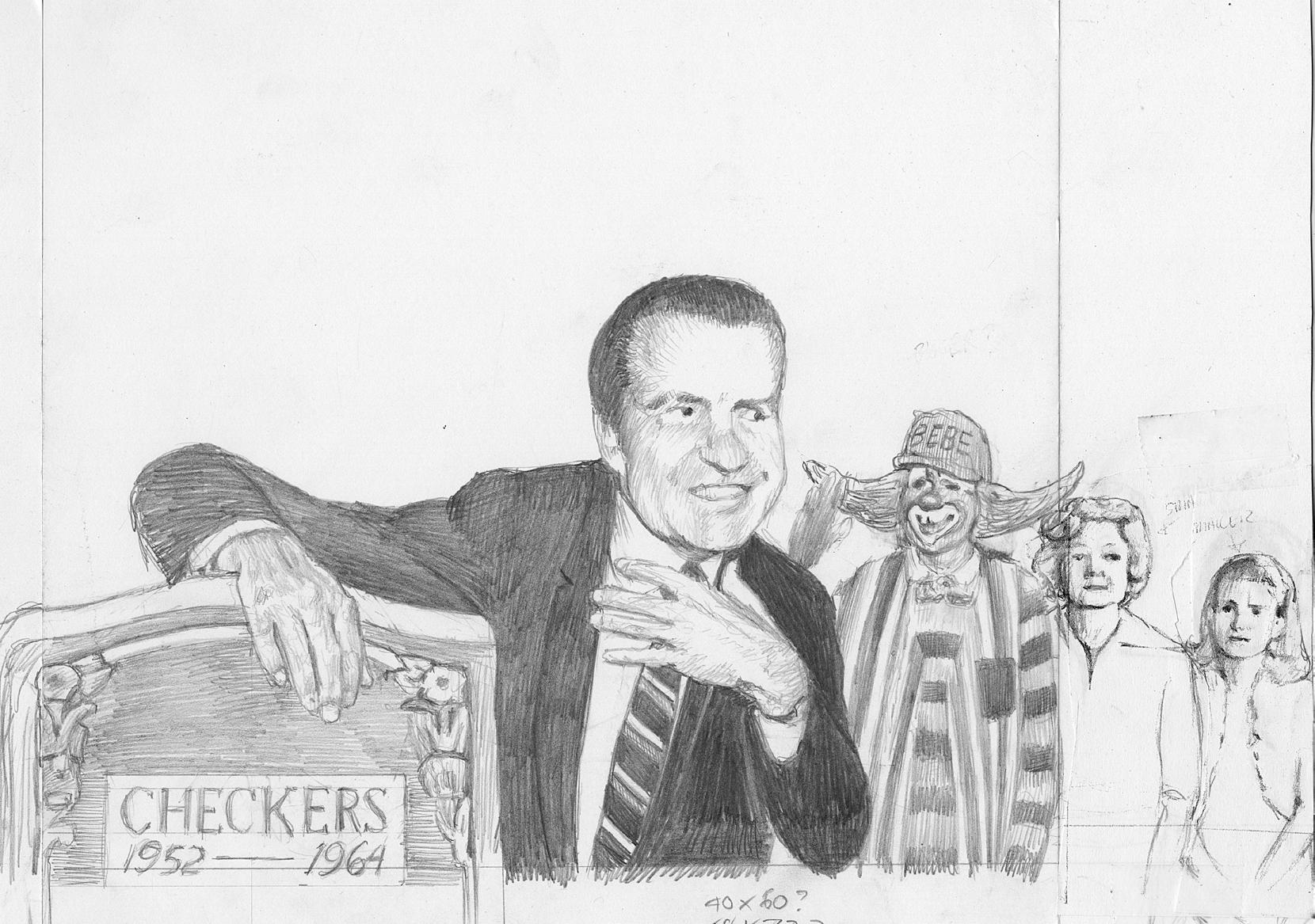

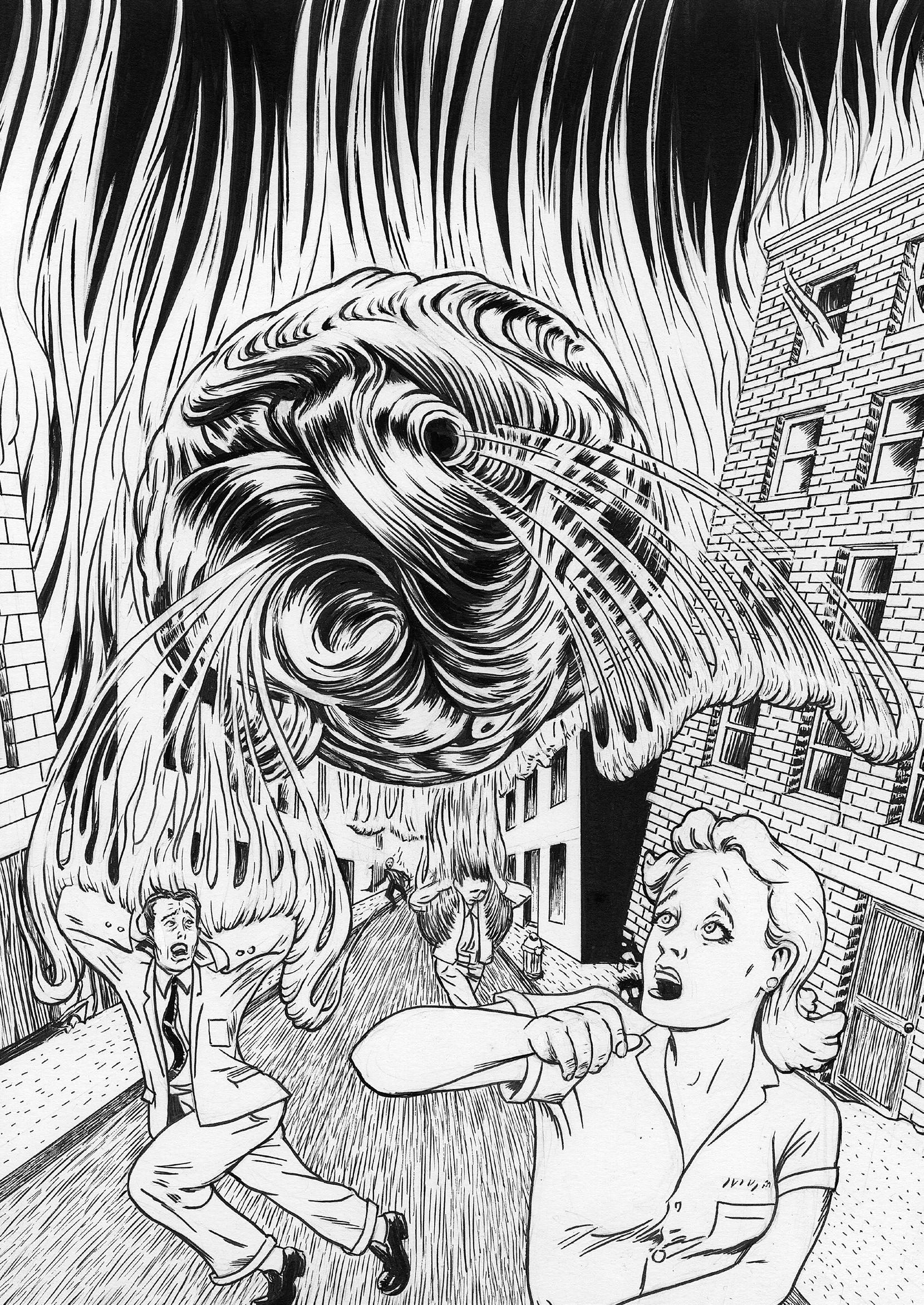

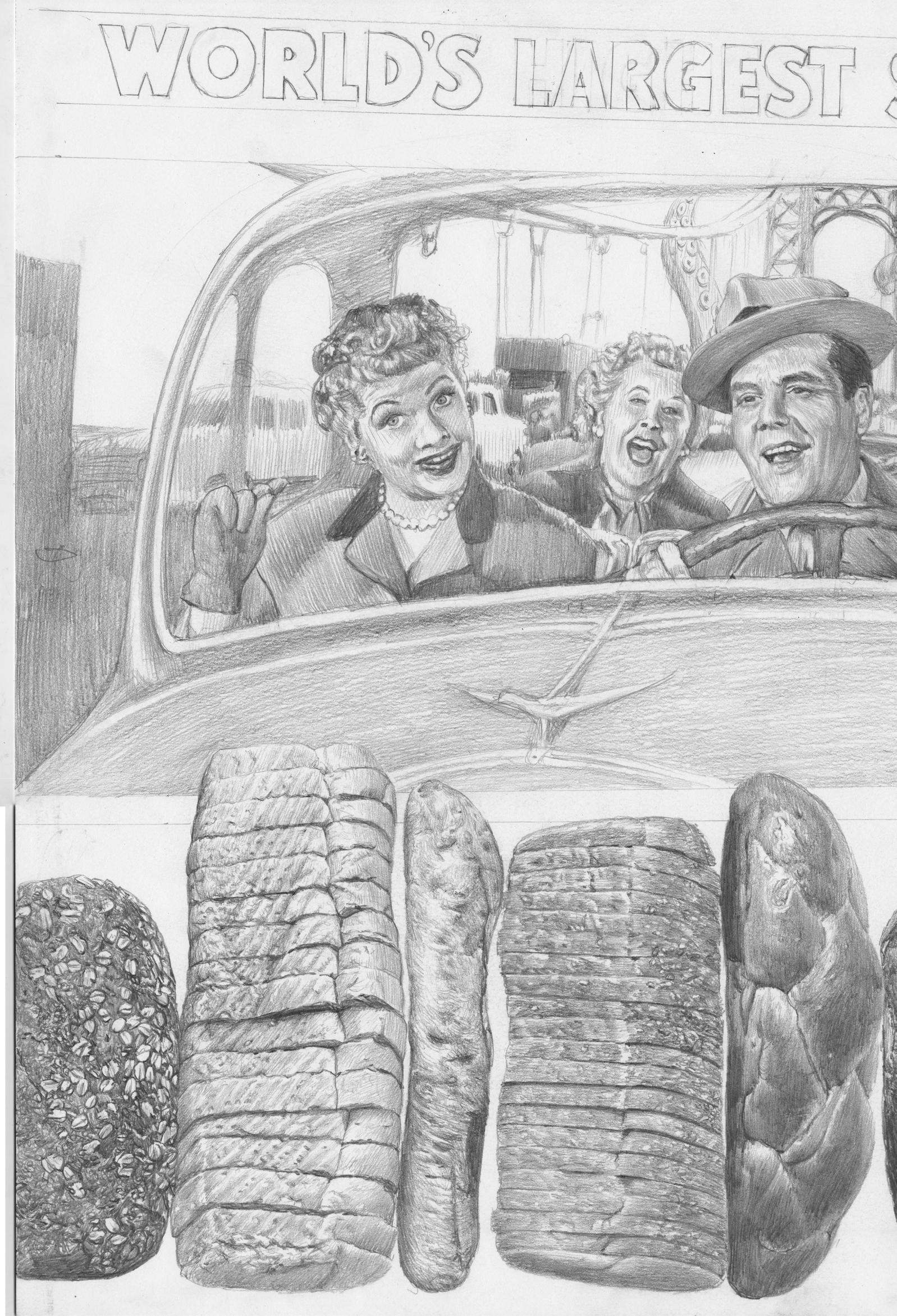

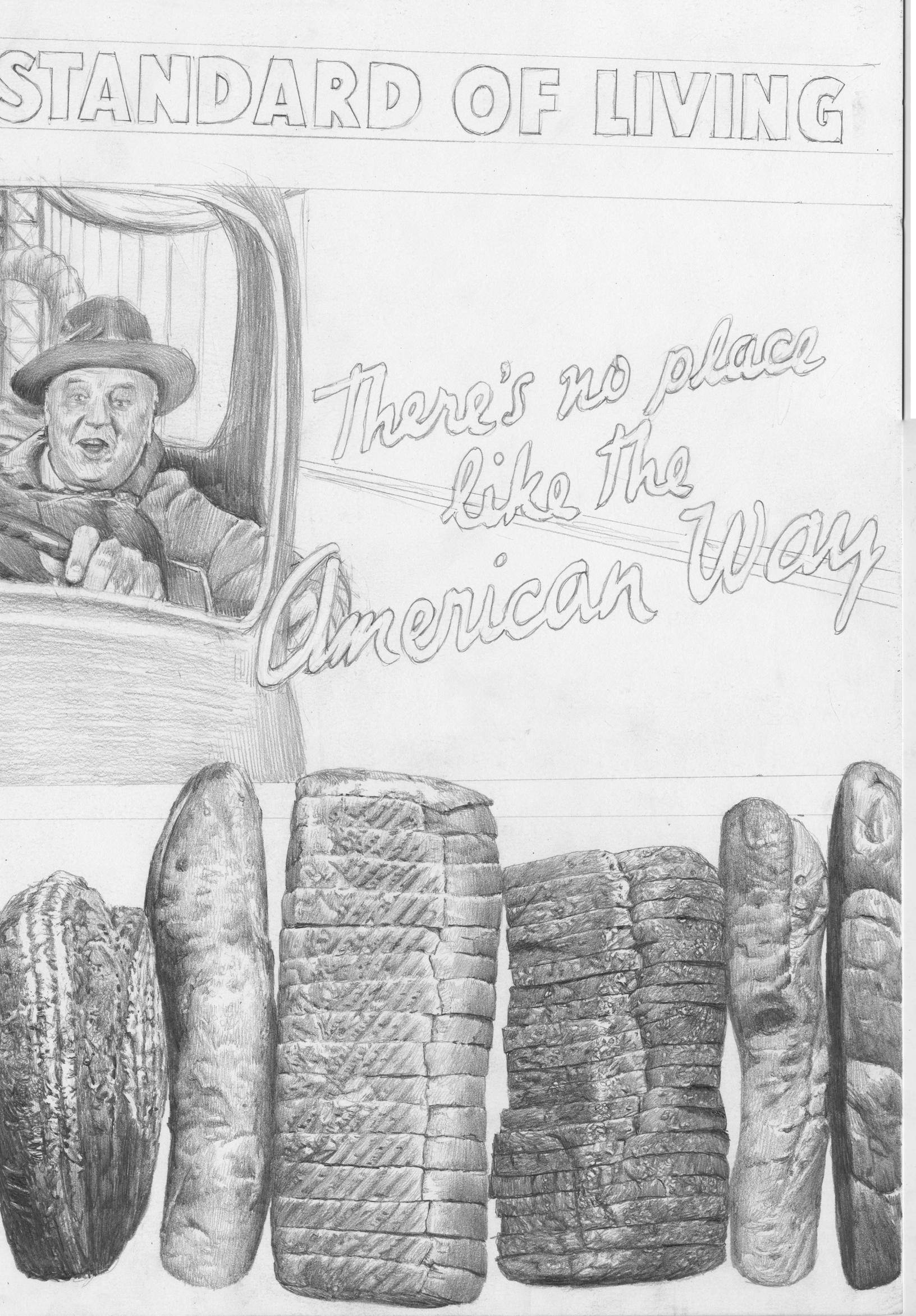

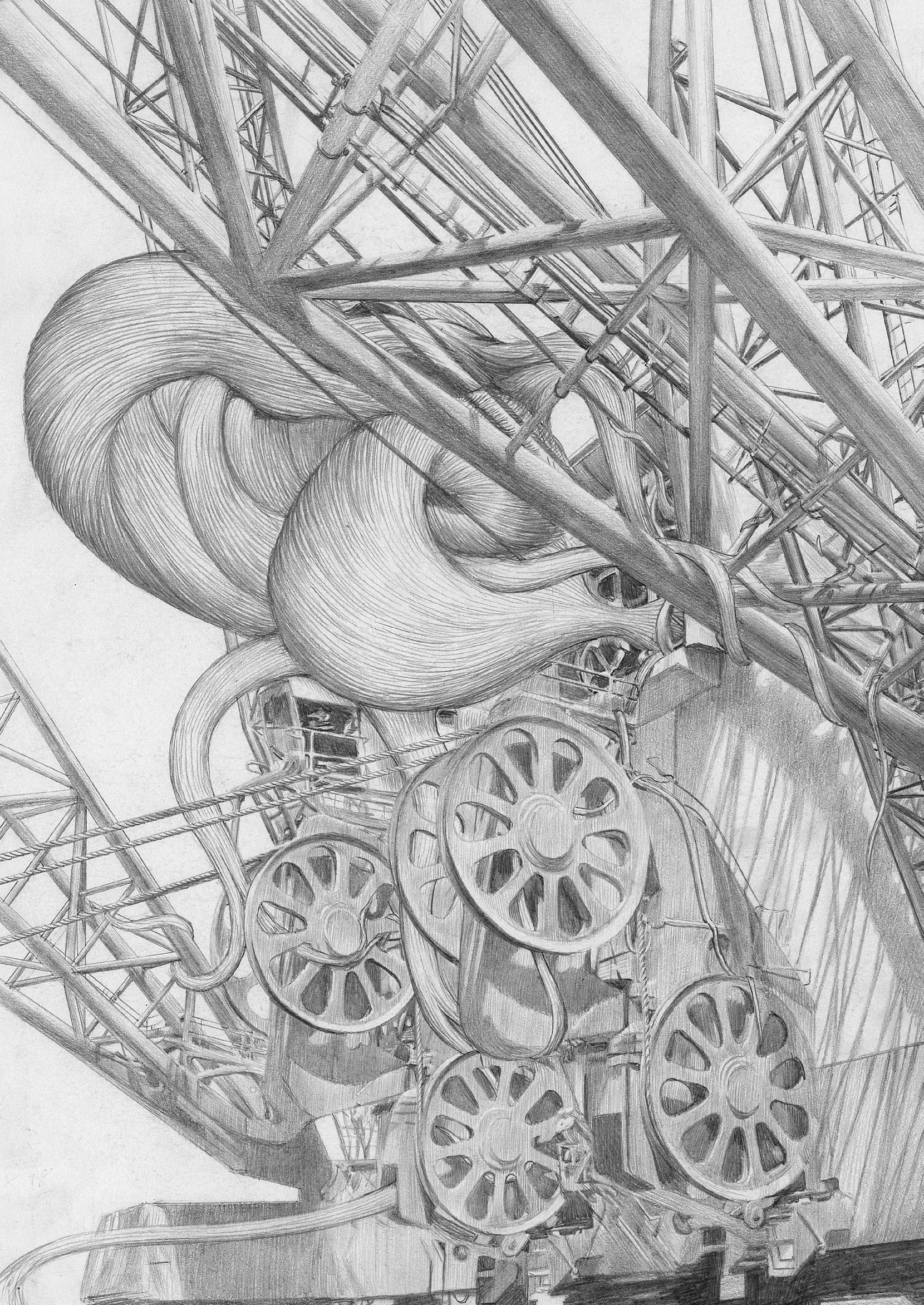

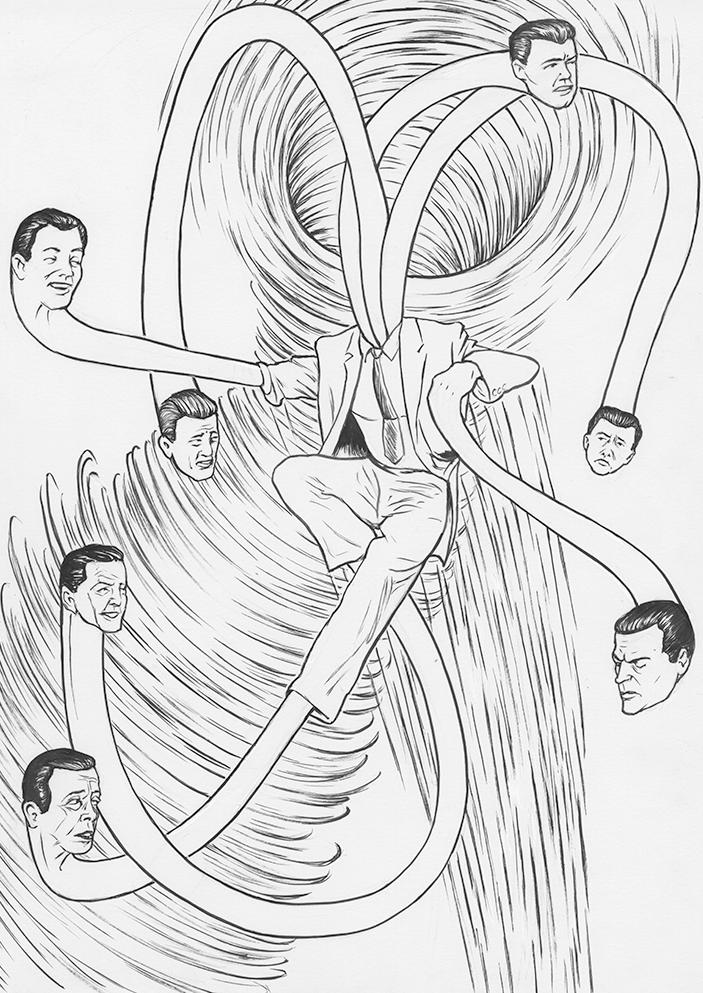

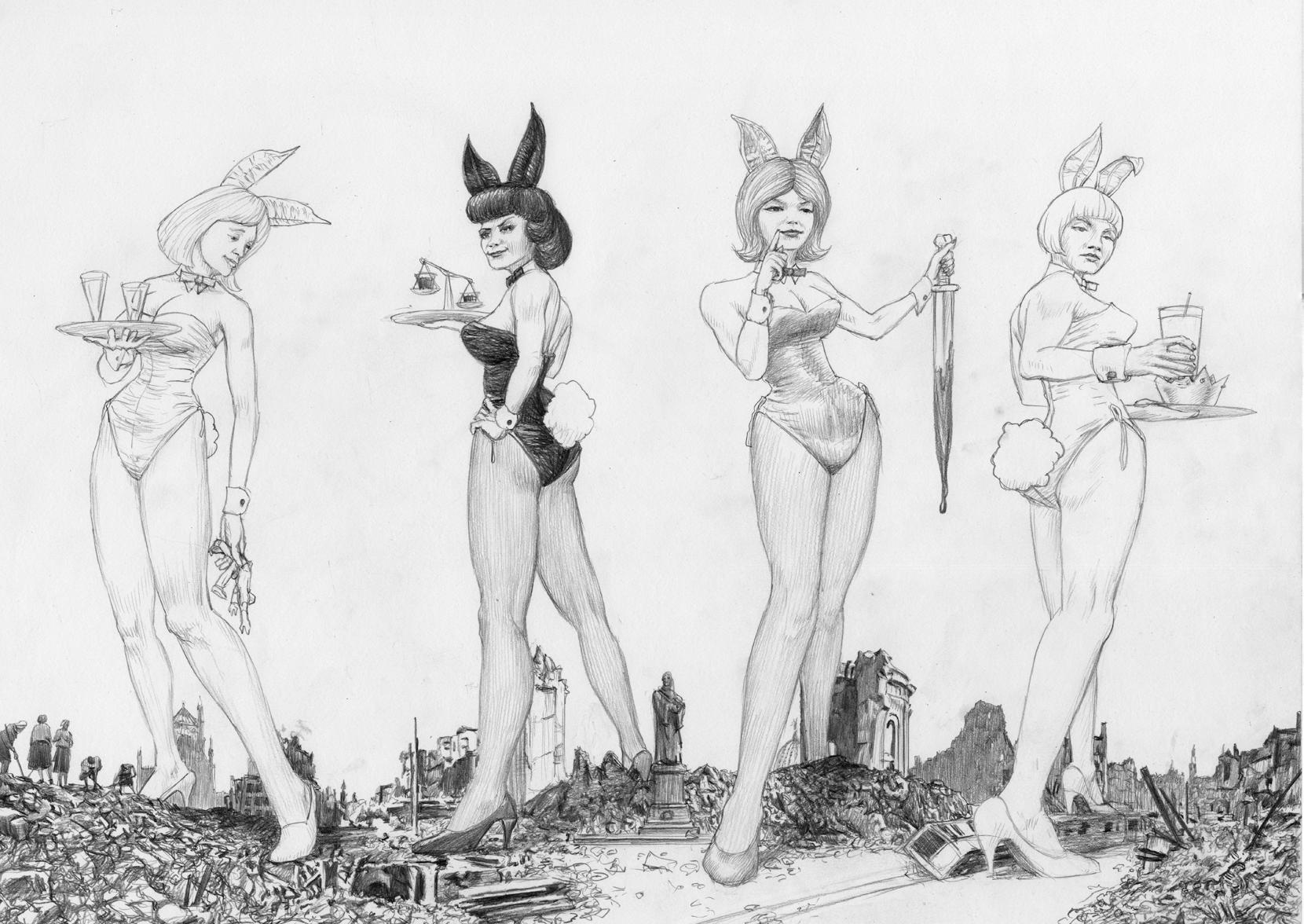

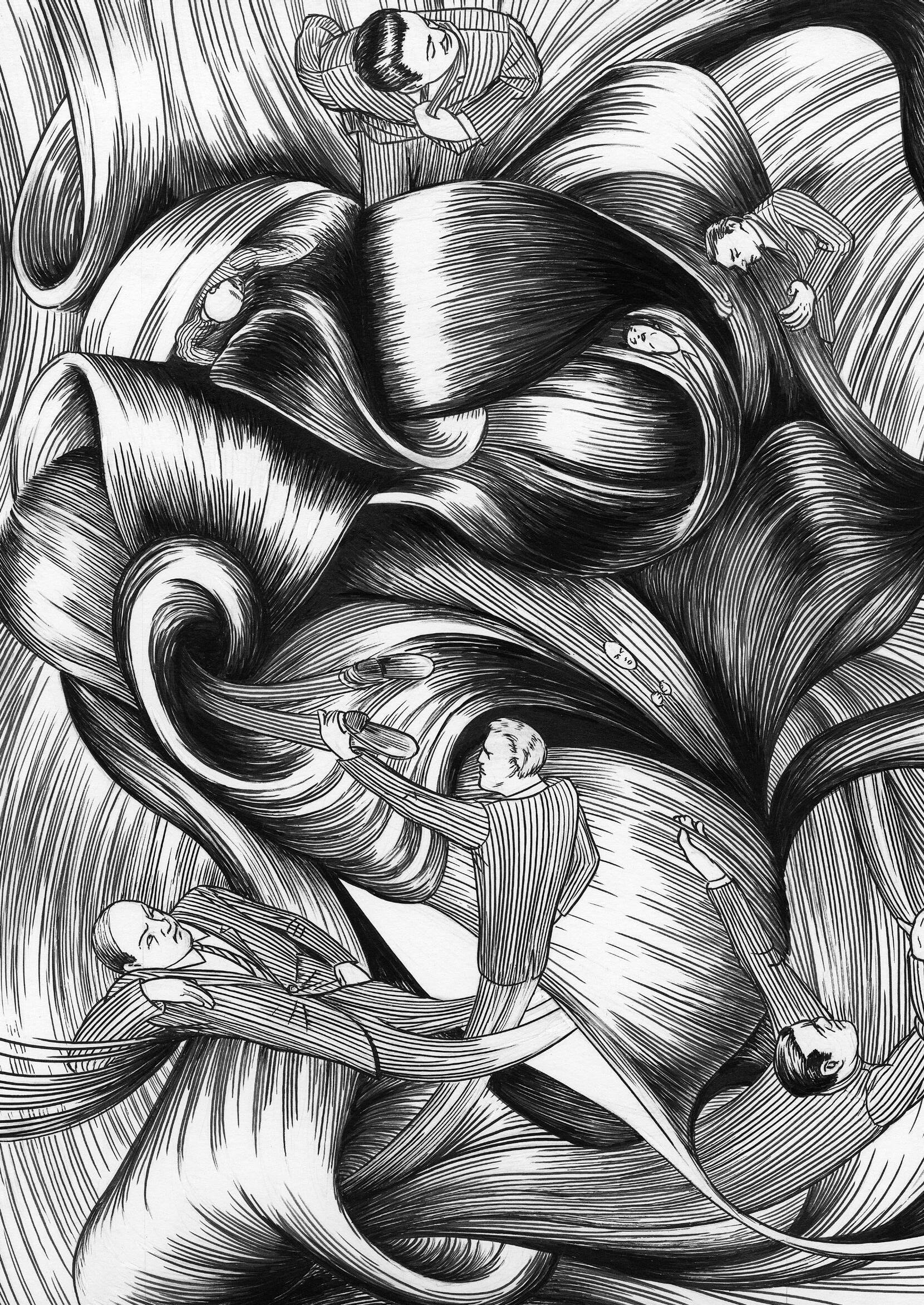

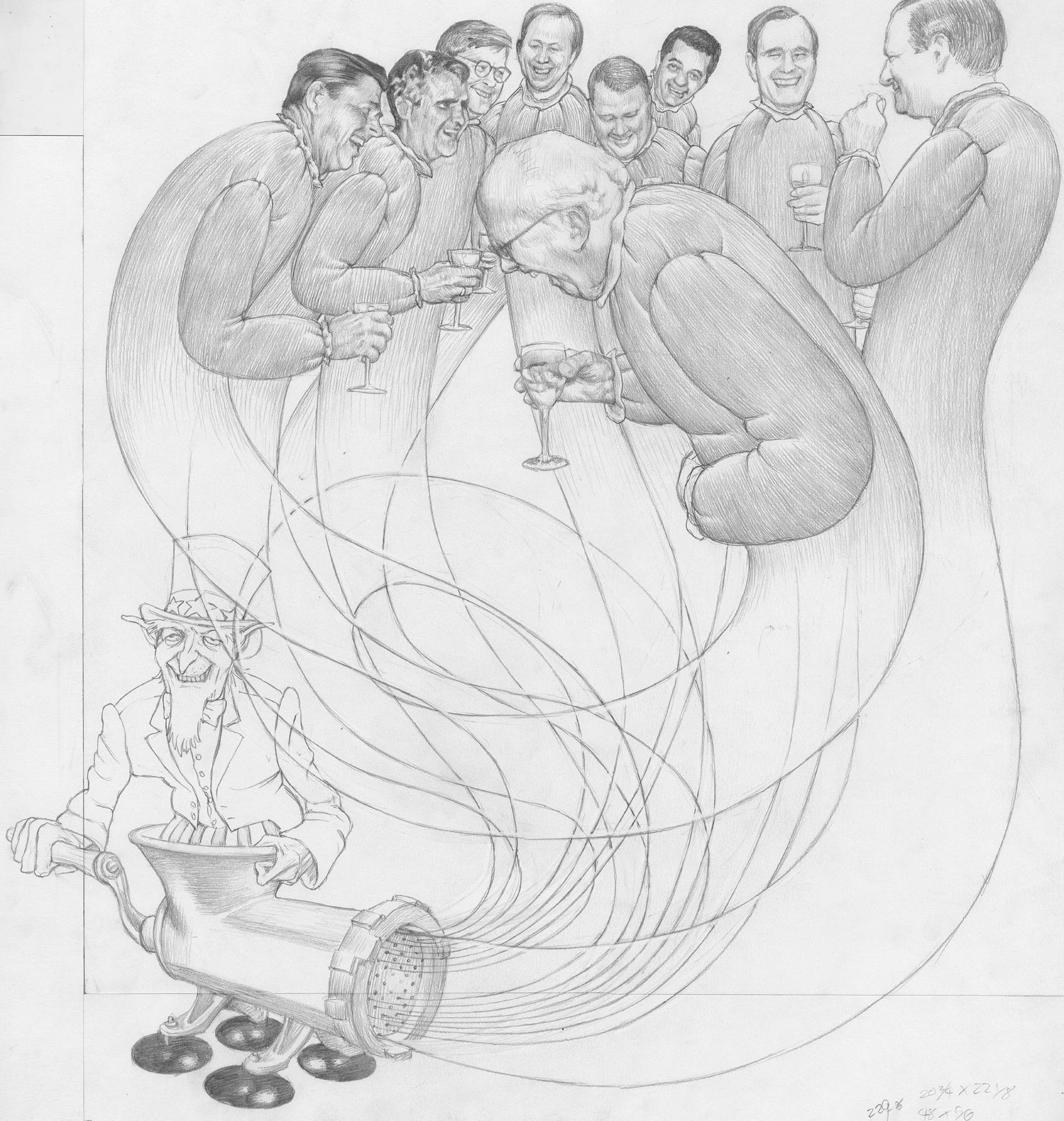

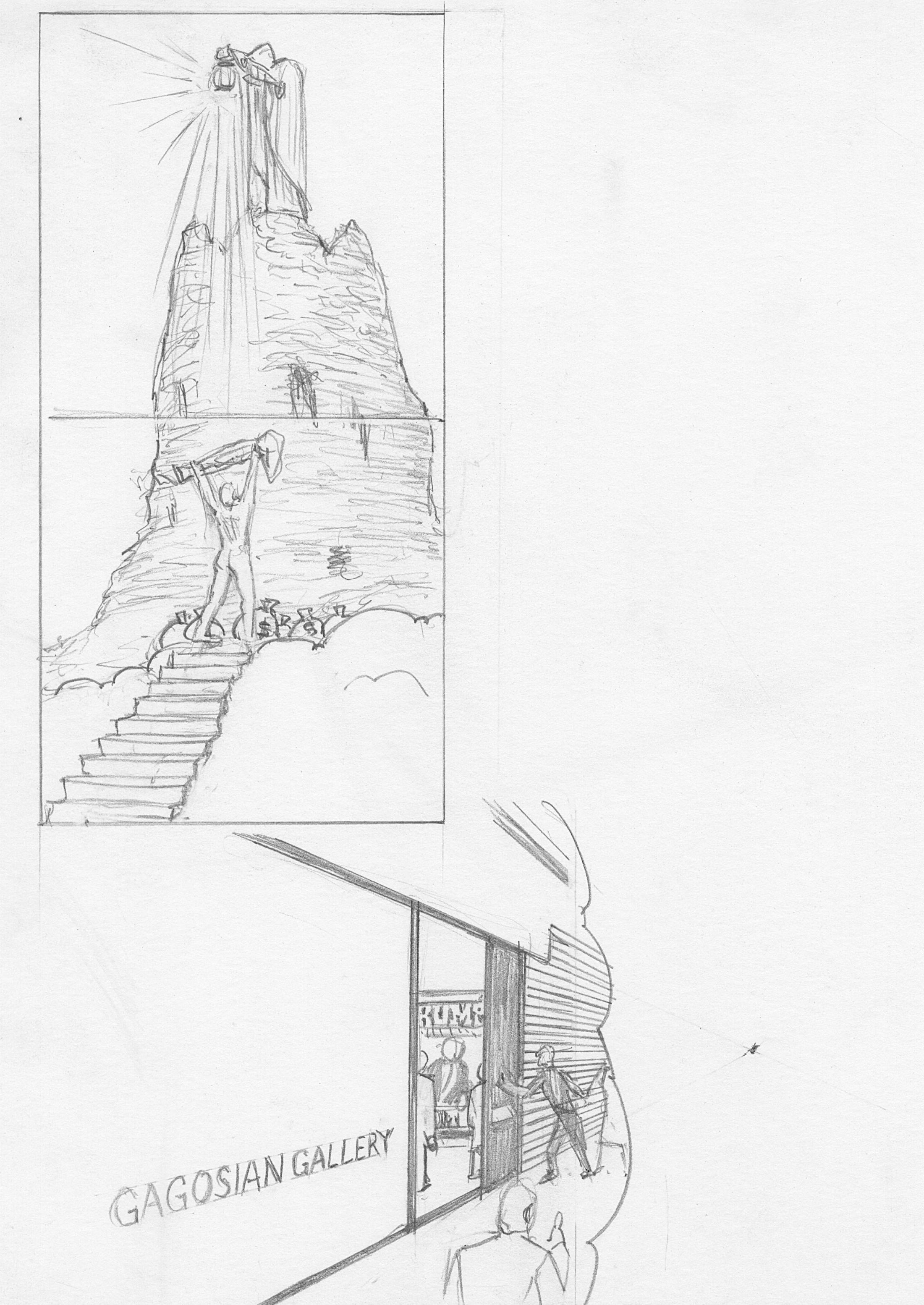

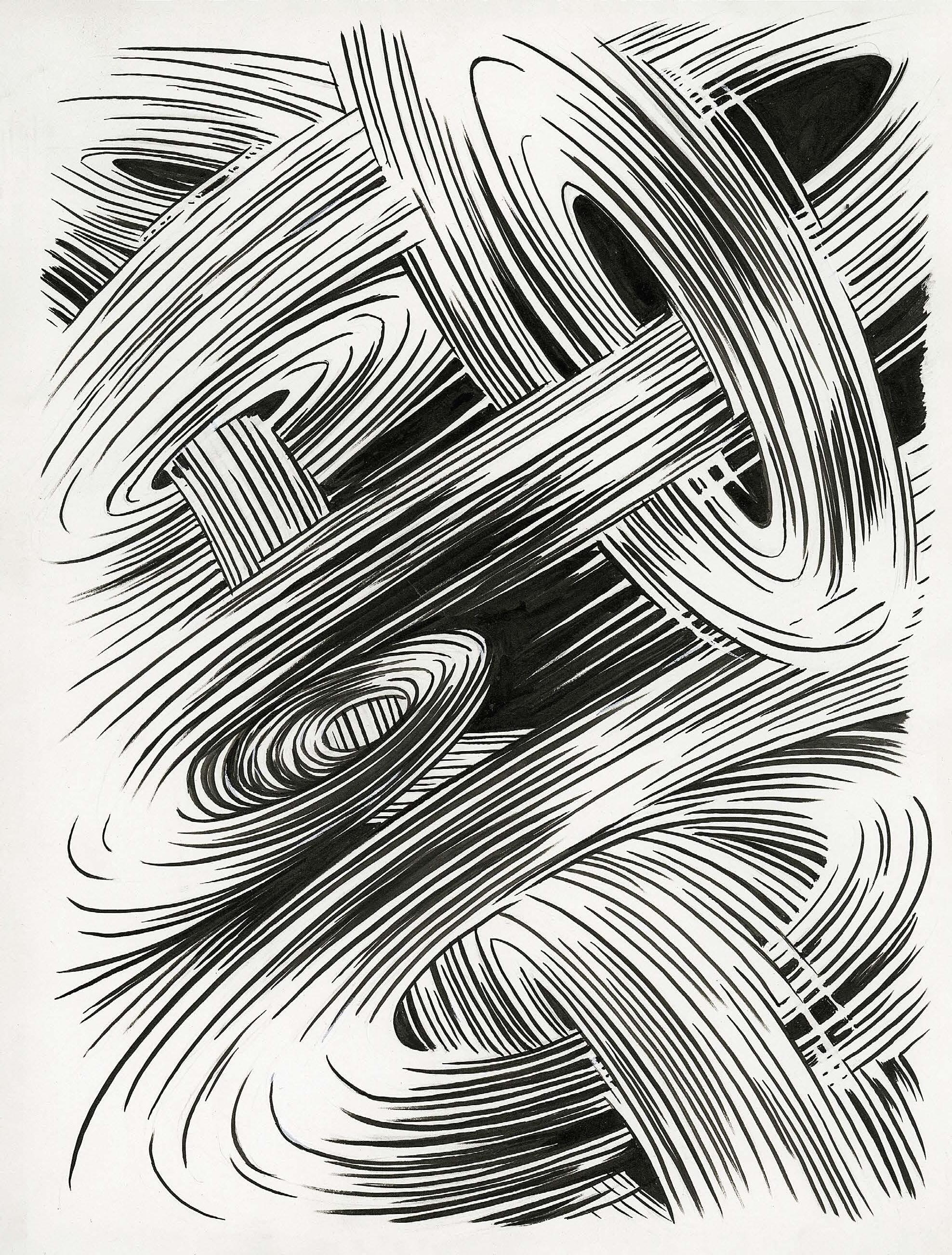

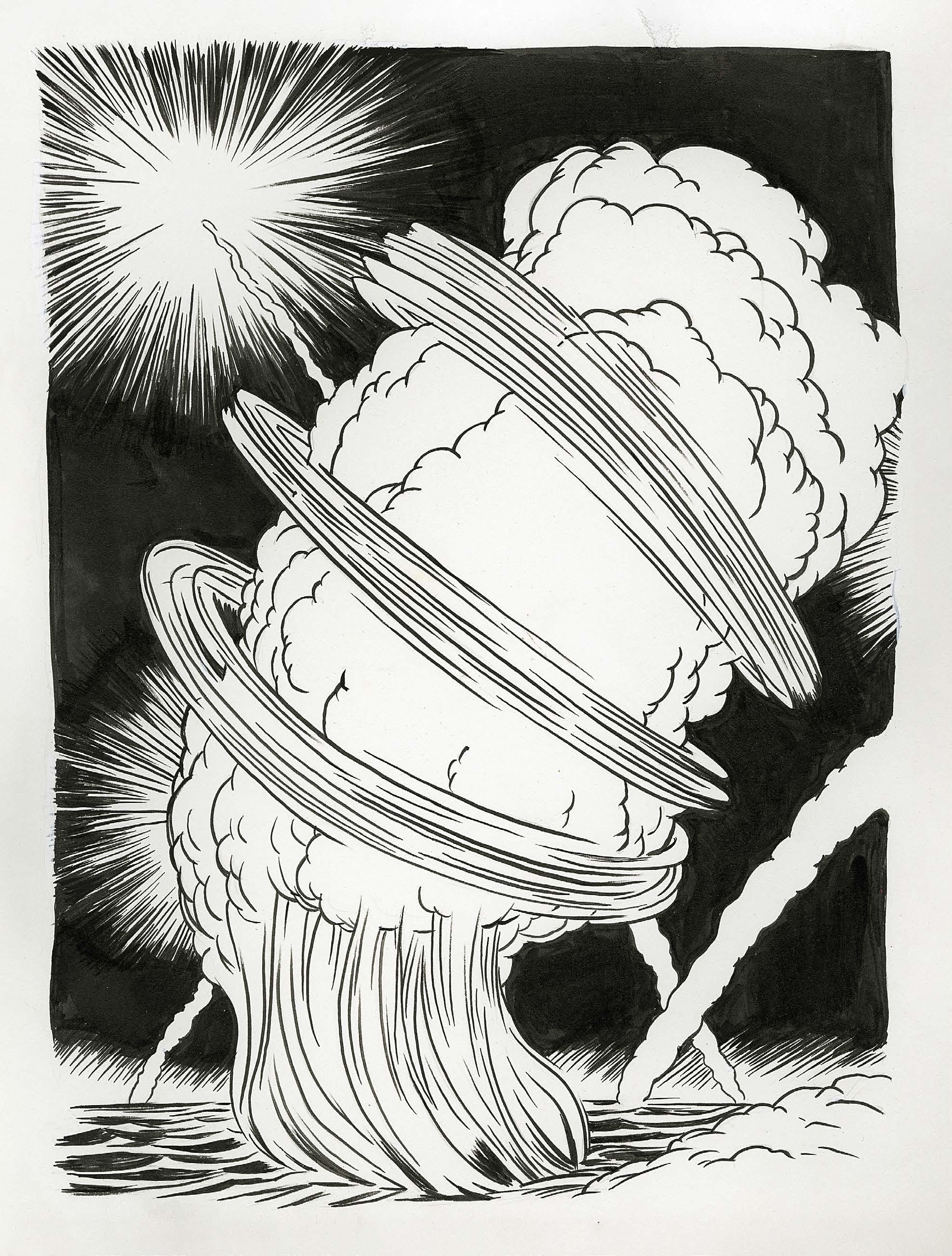

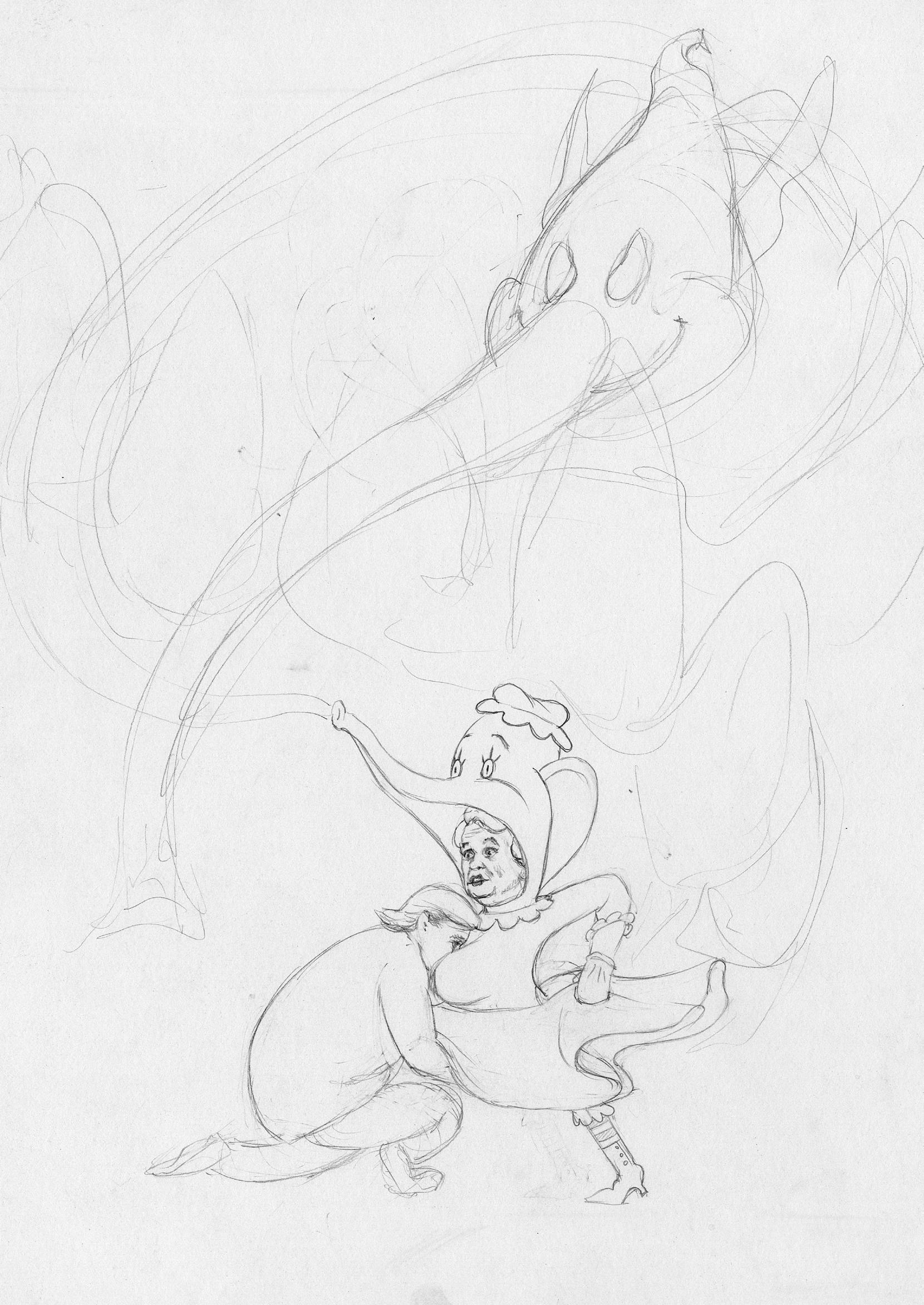

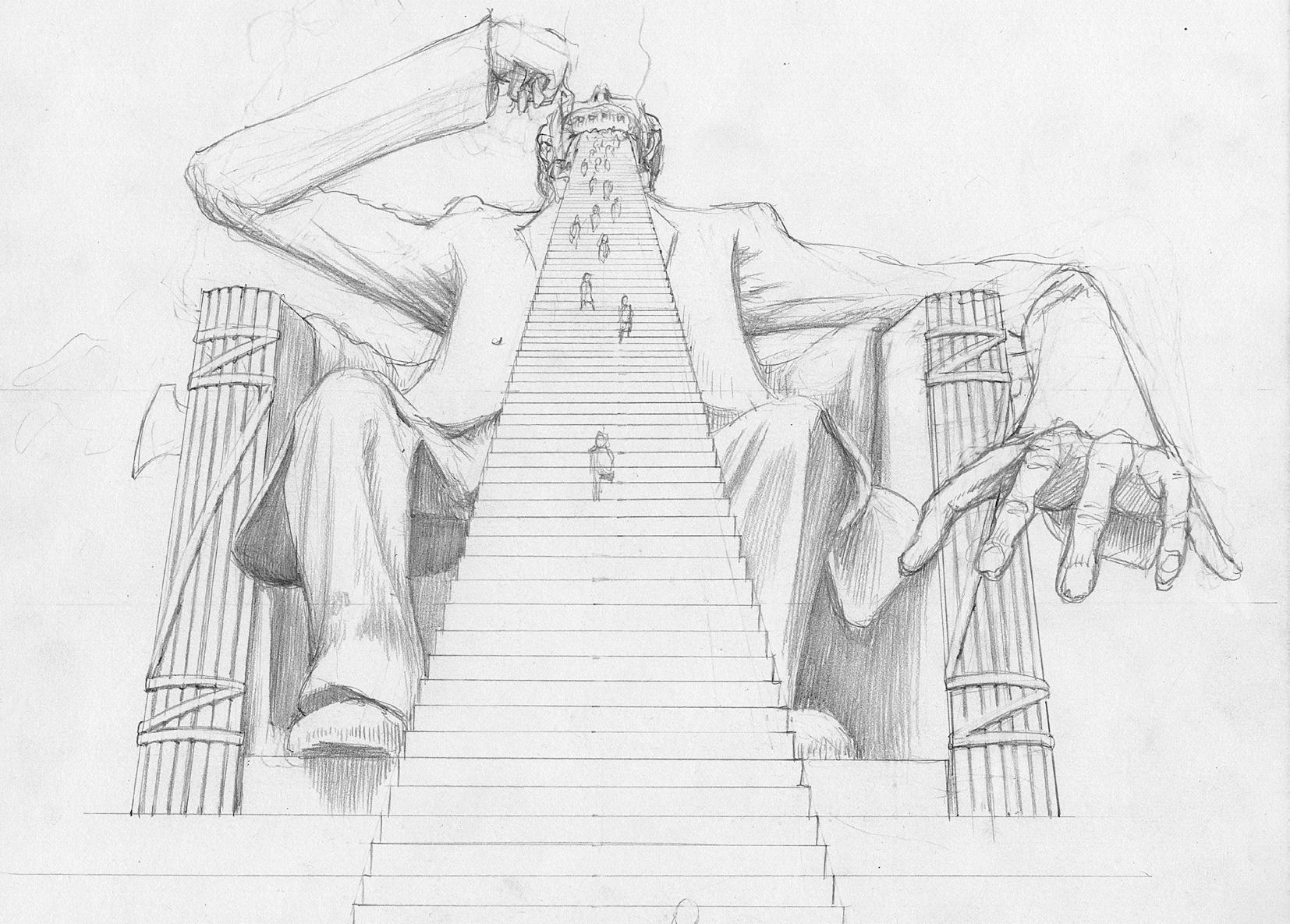

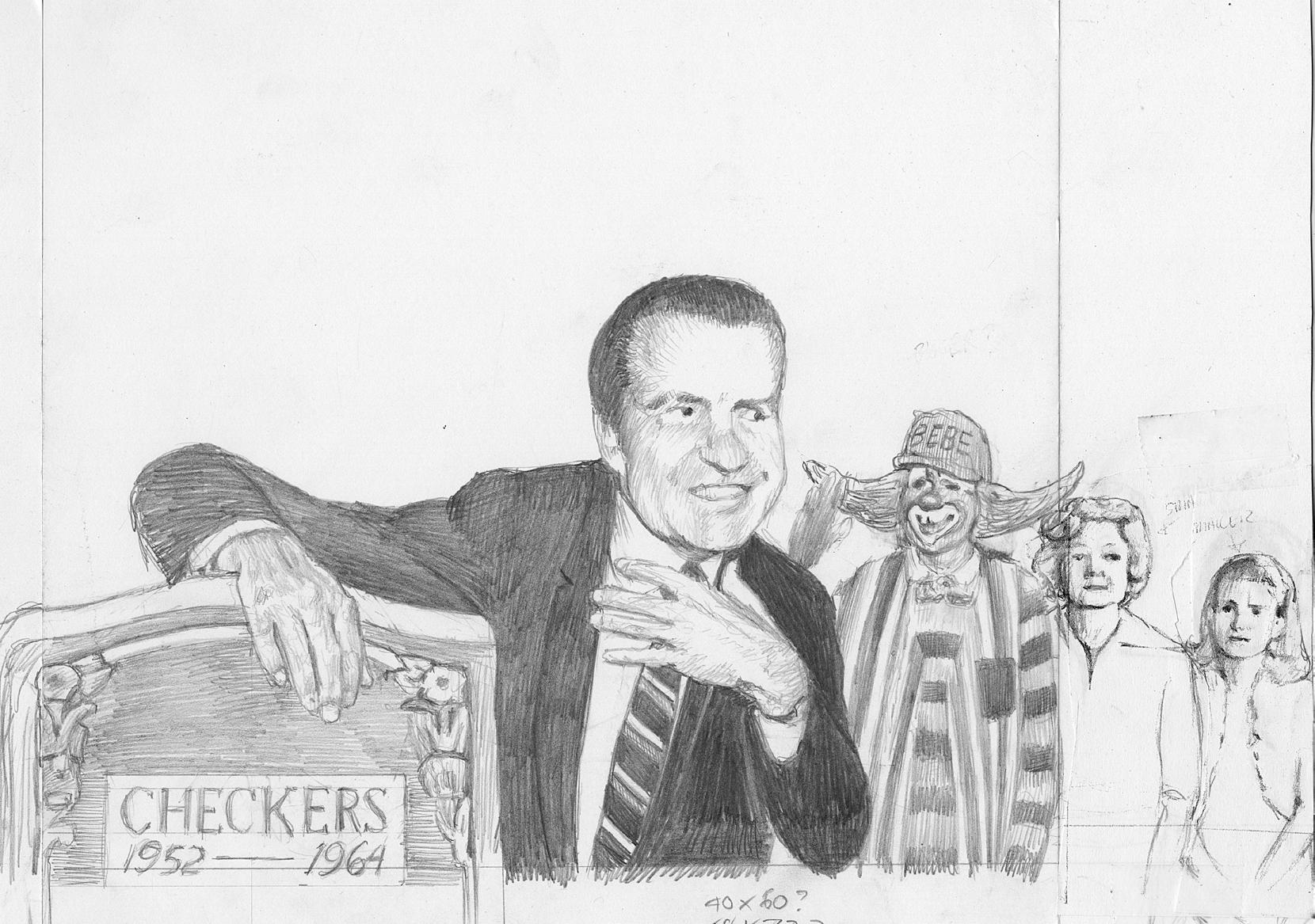

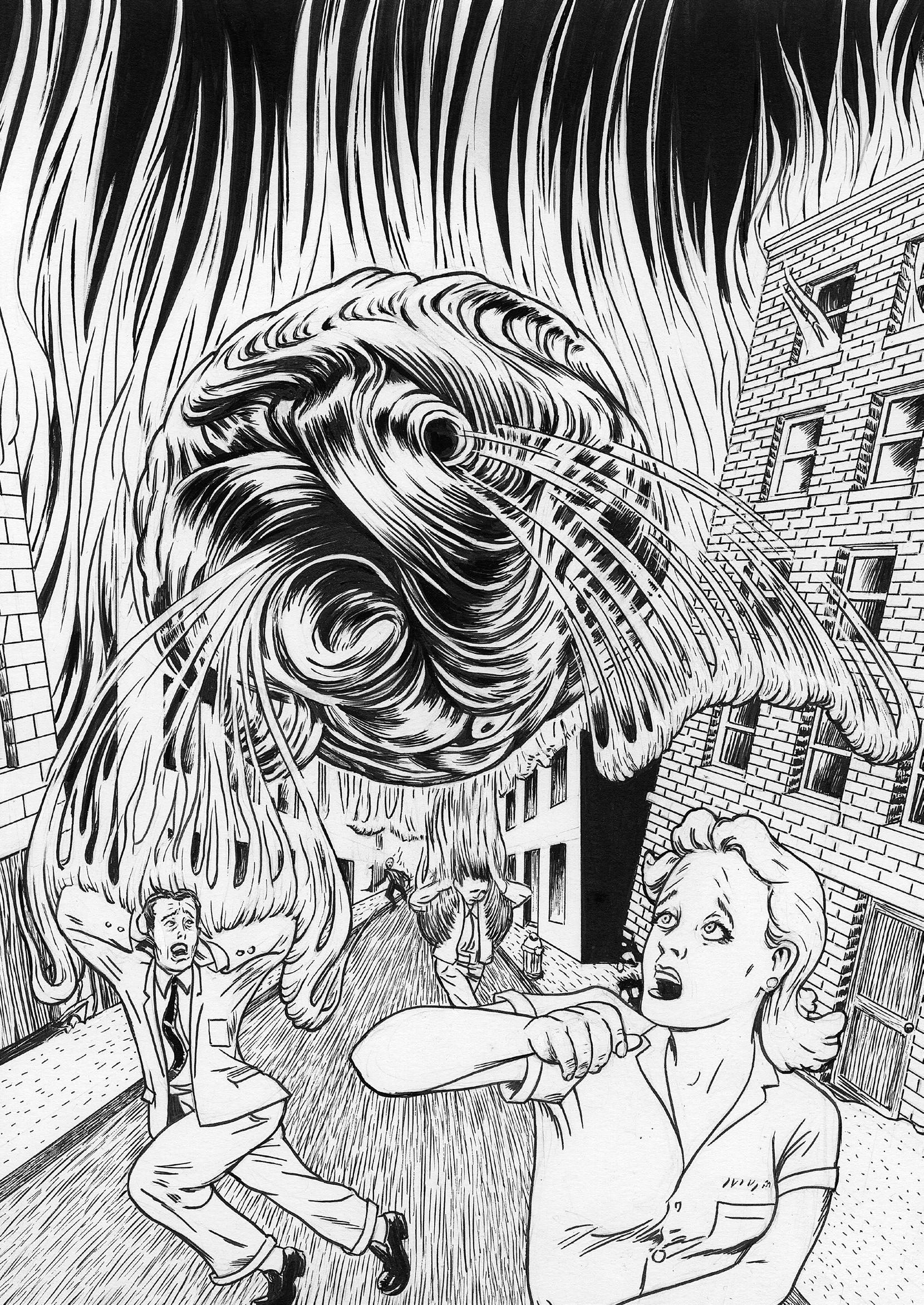

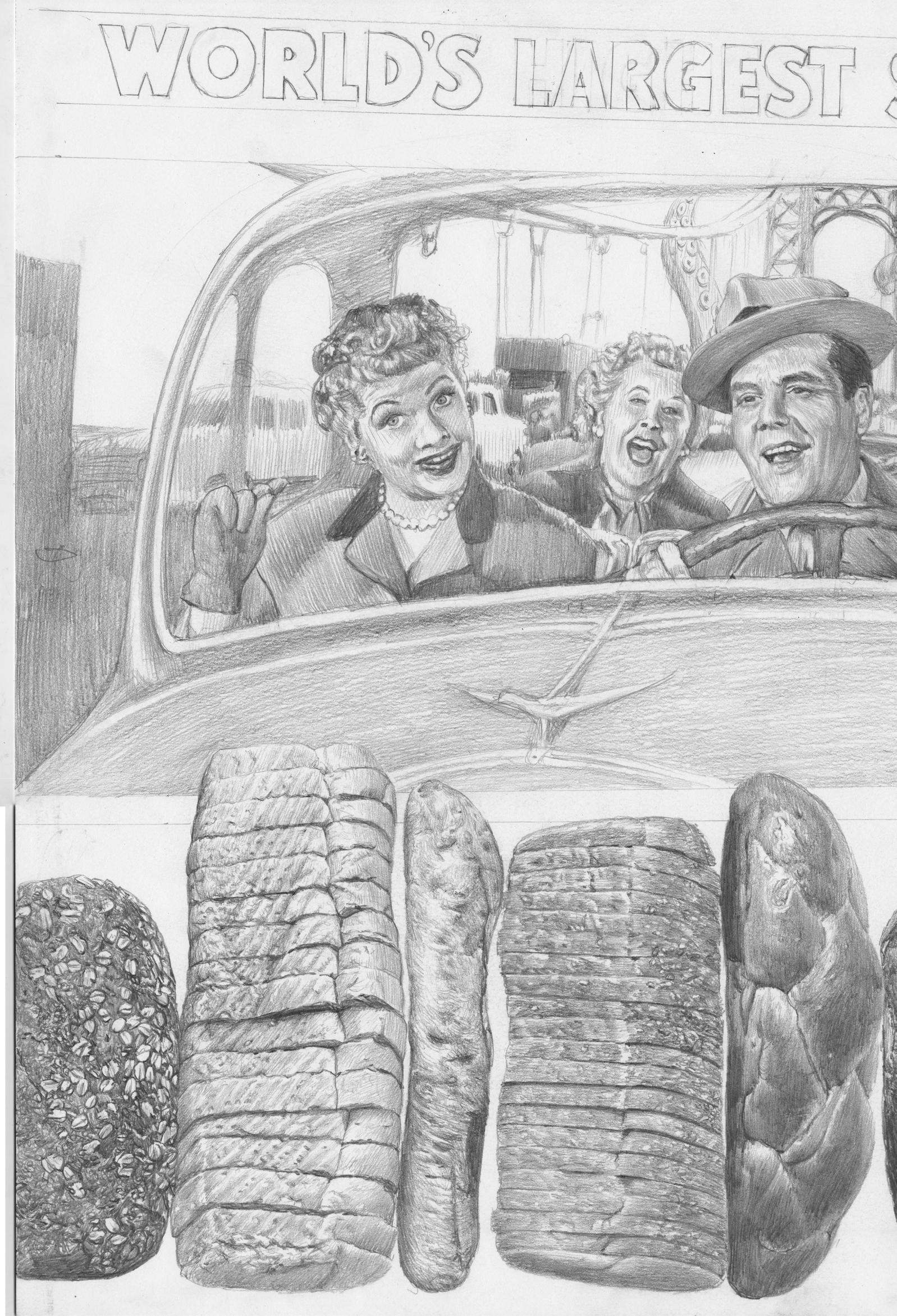

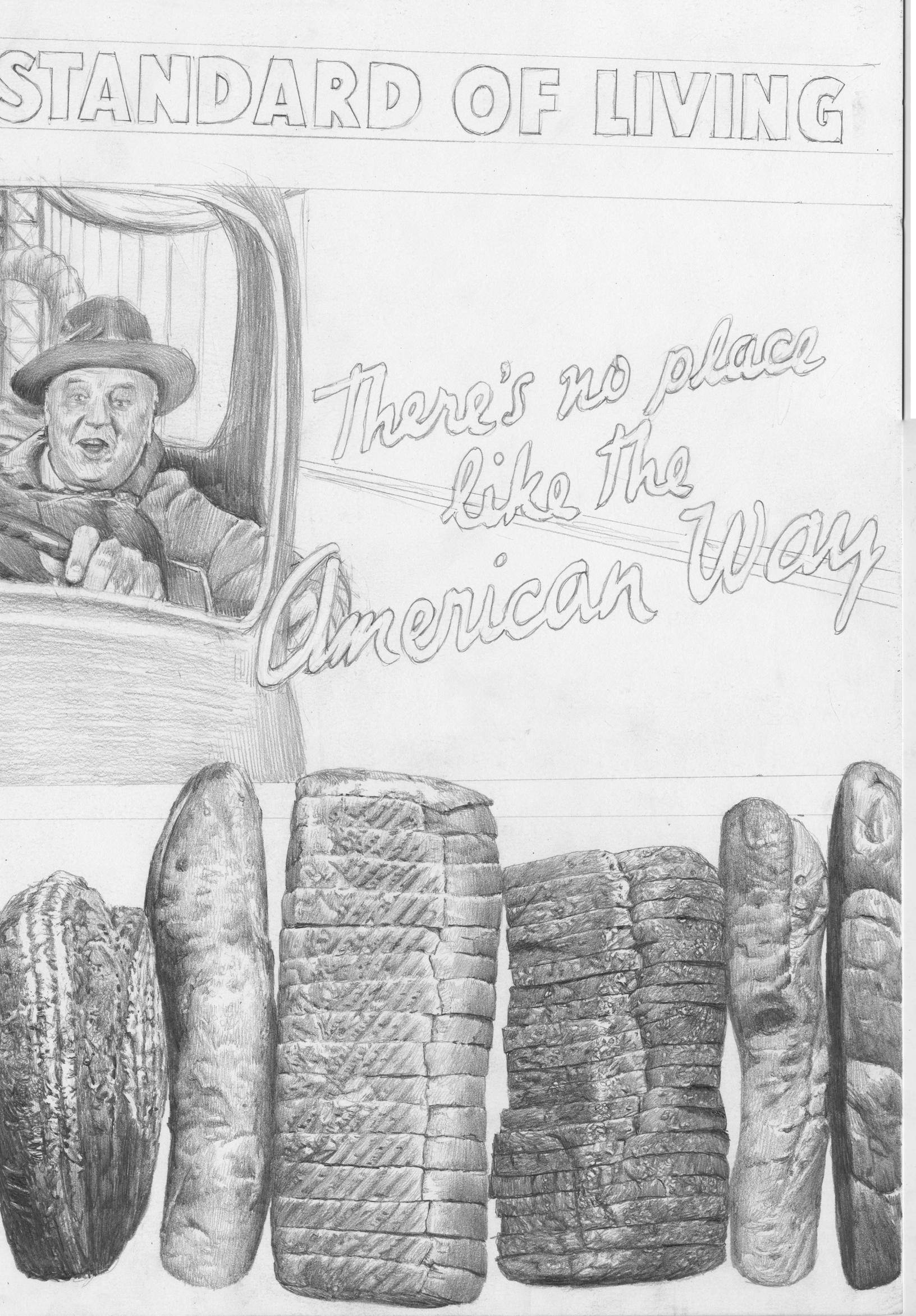

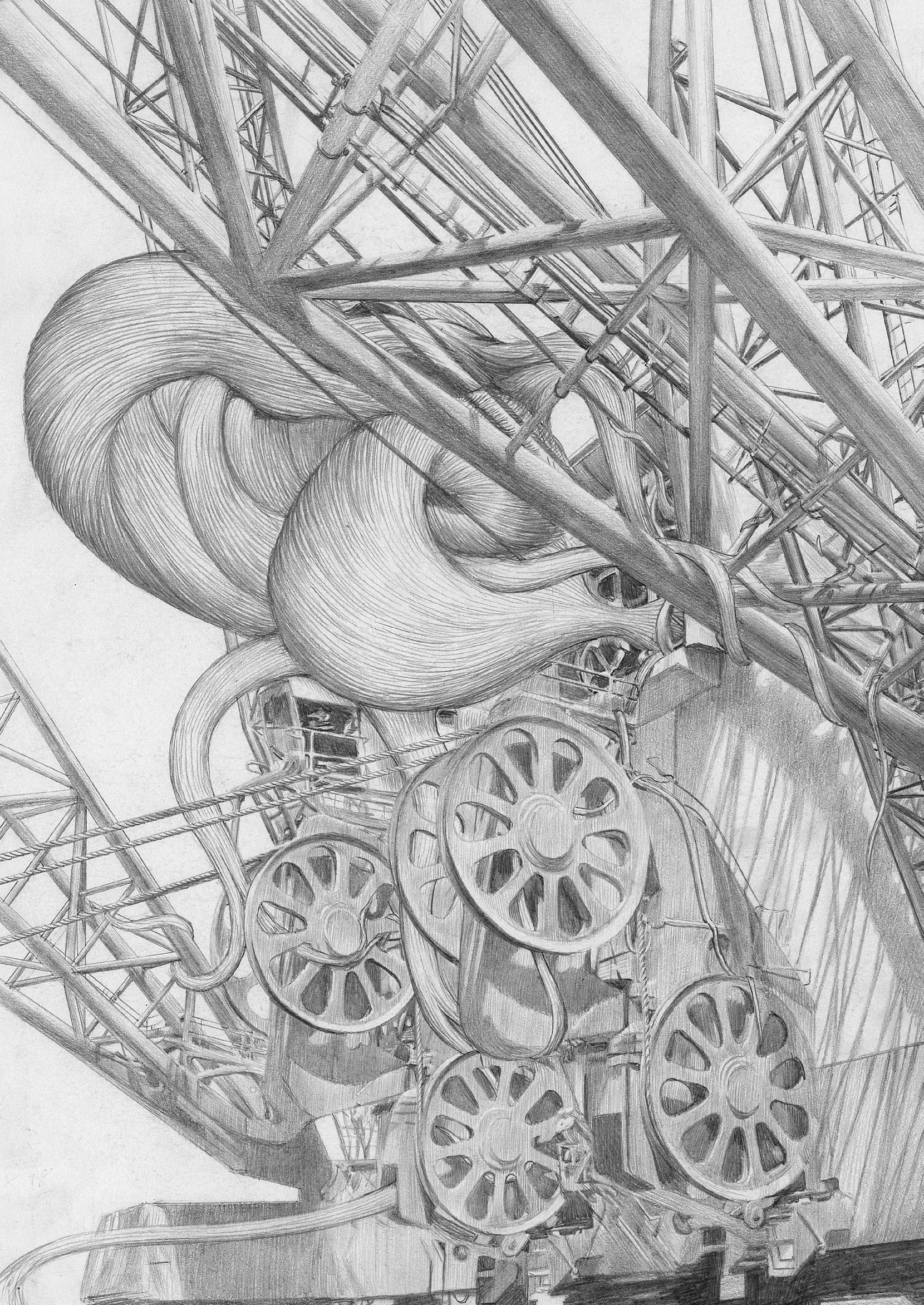

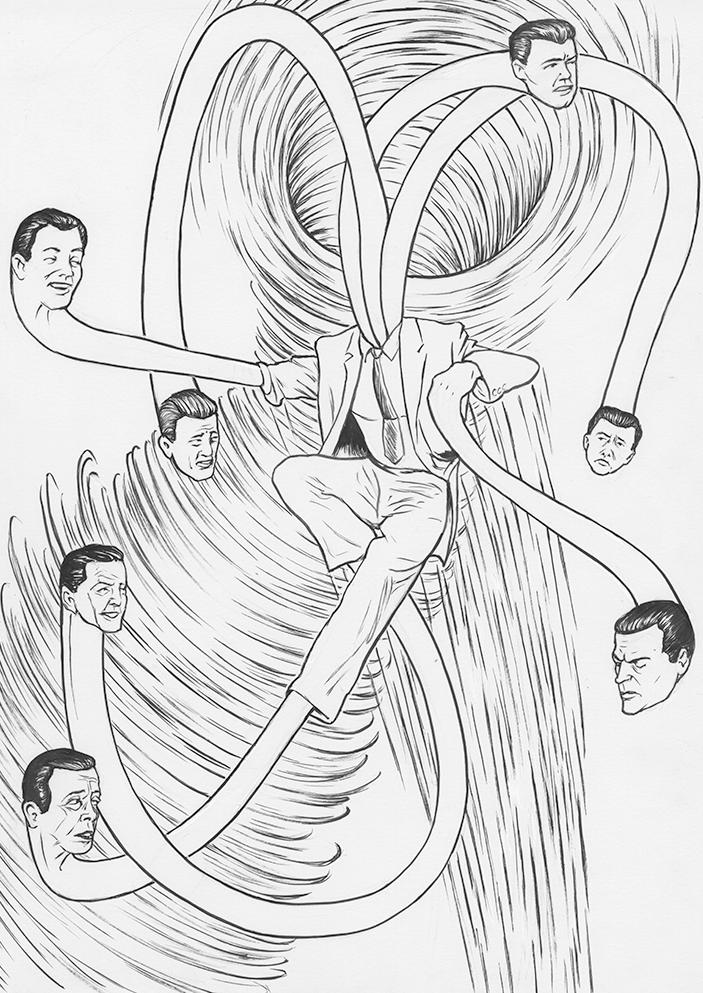

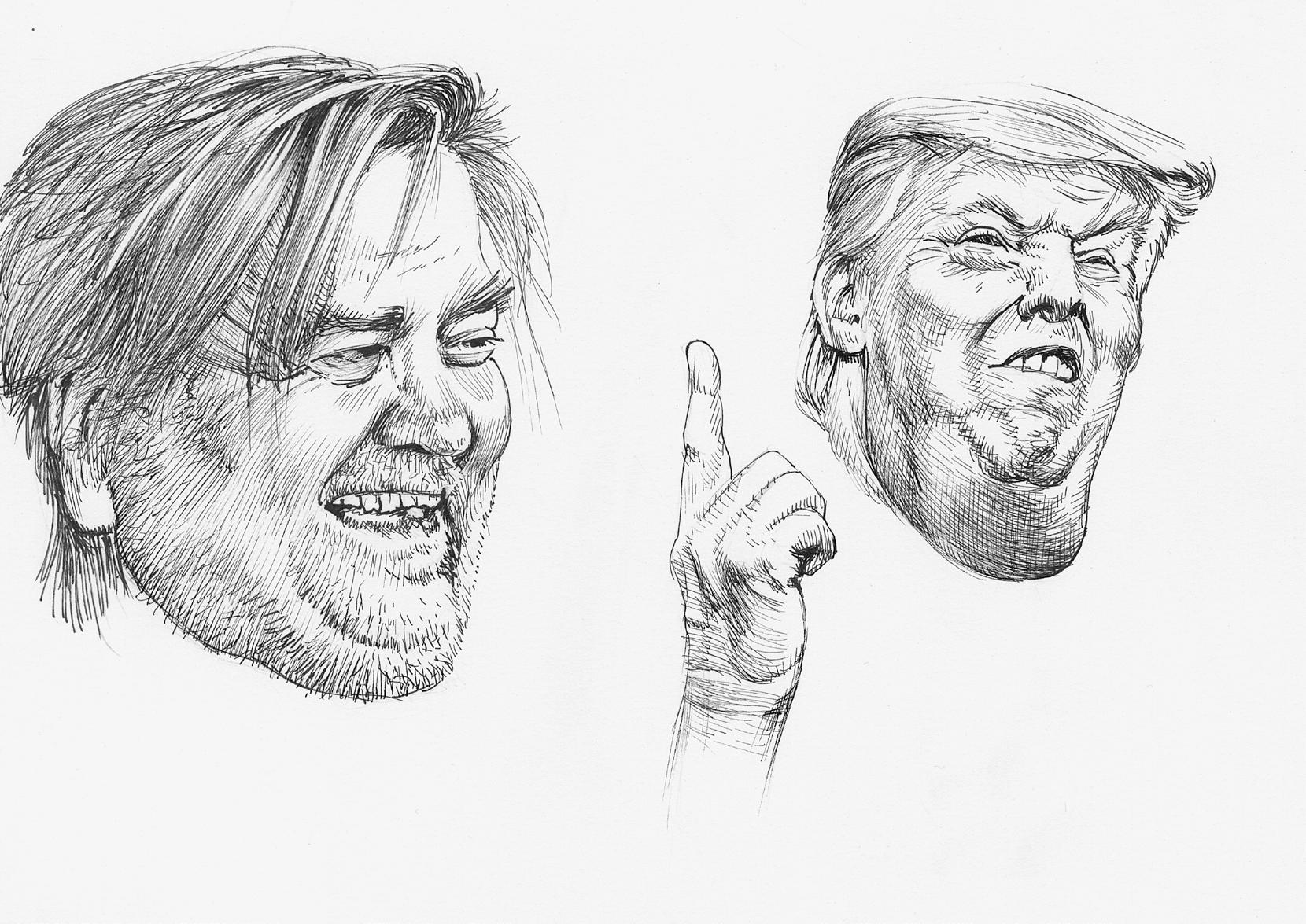

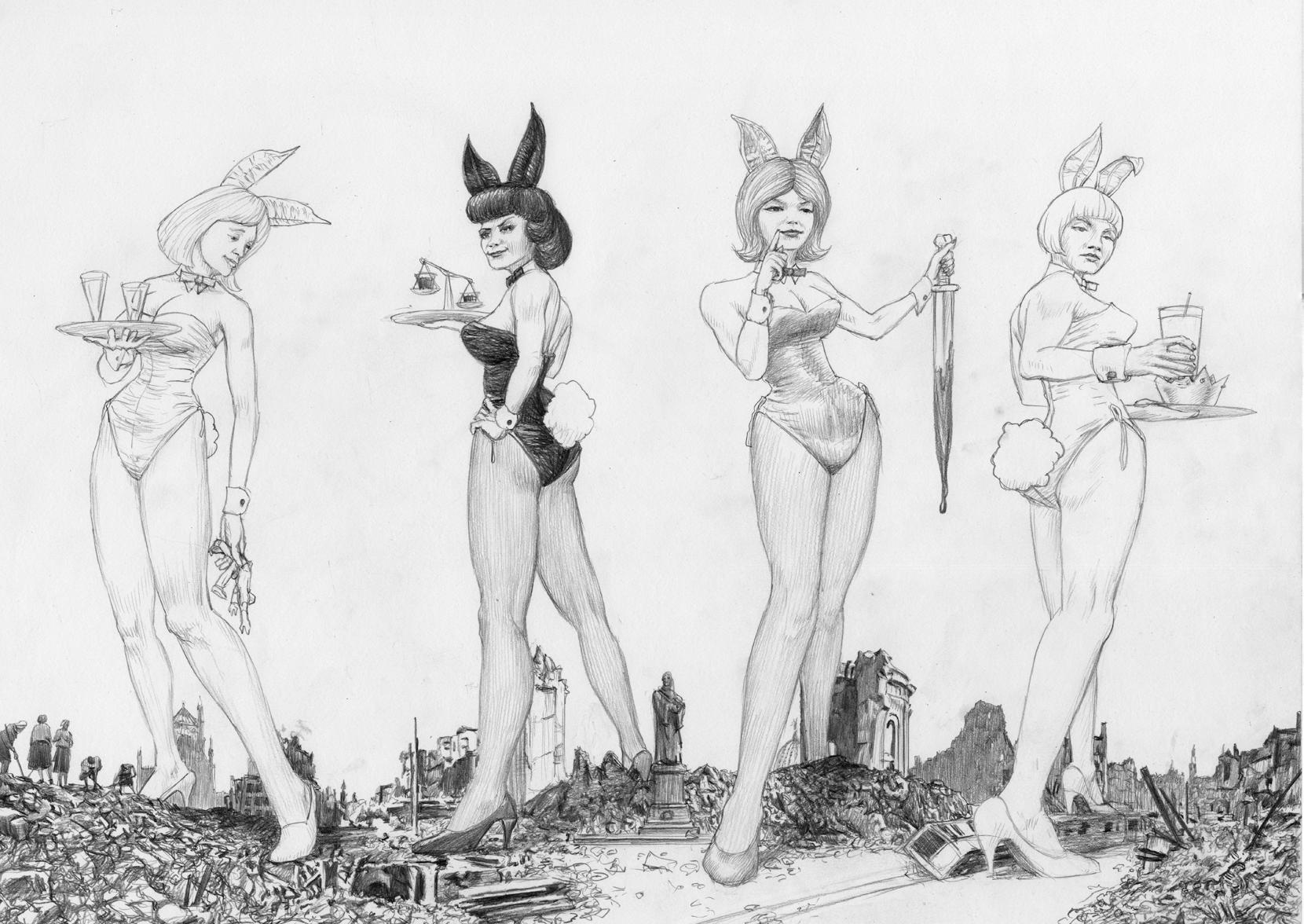

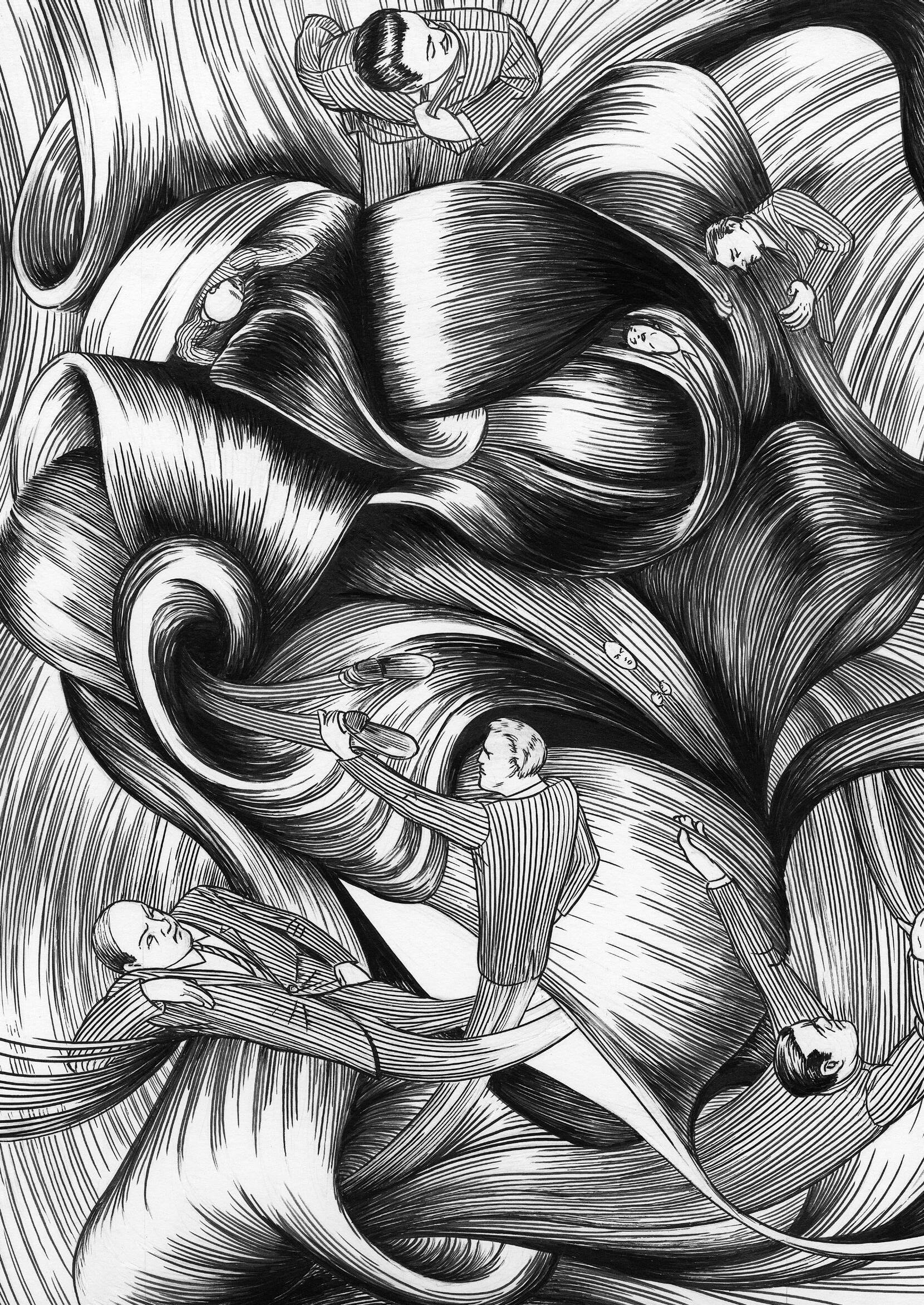

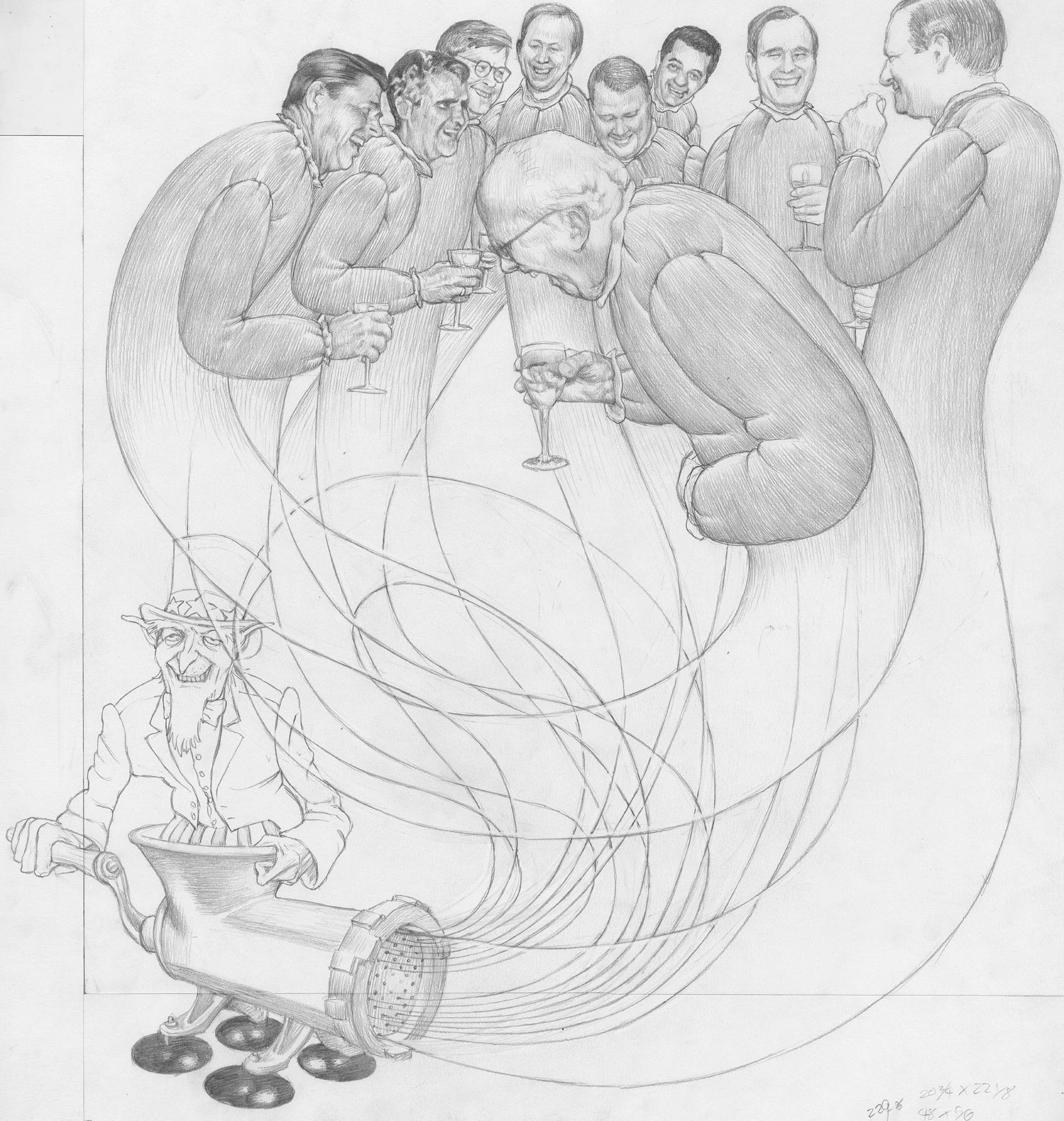

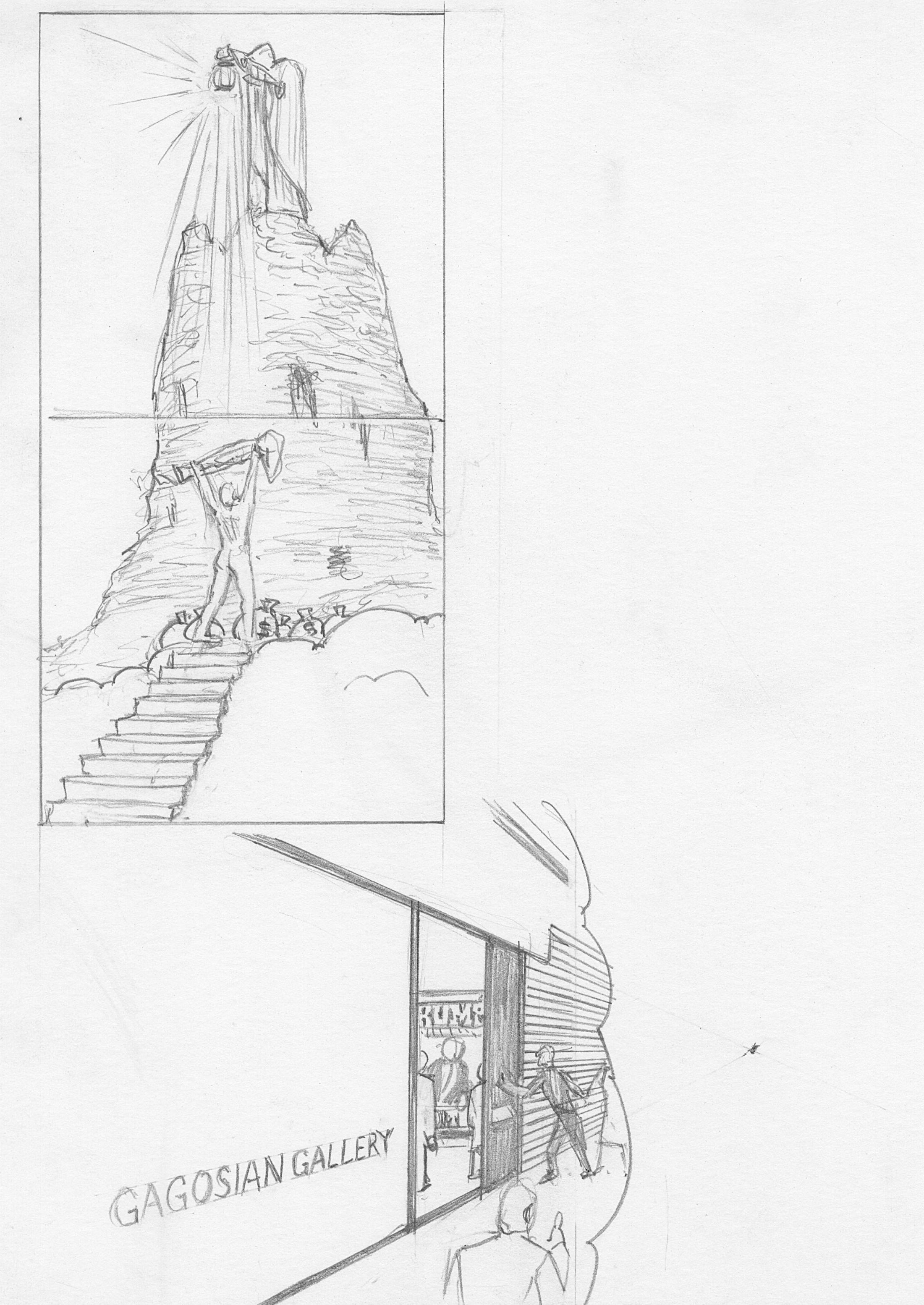

72 Jim Shaw: Thinking the Unthinkable

A zine by Jim Shaw produced on the occasion of the artist’s exhibition at Gagosian, Beverly Hills.

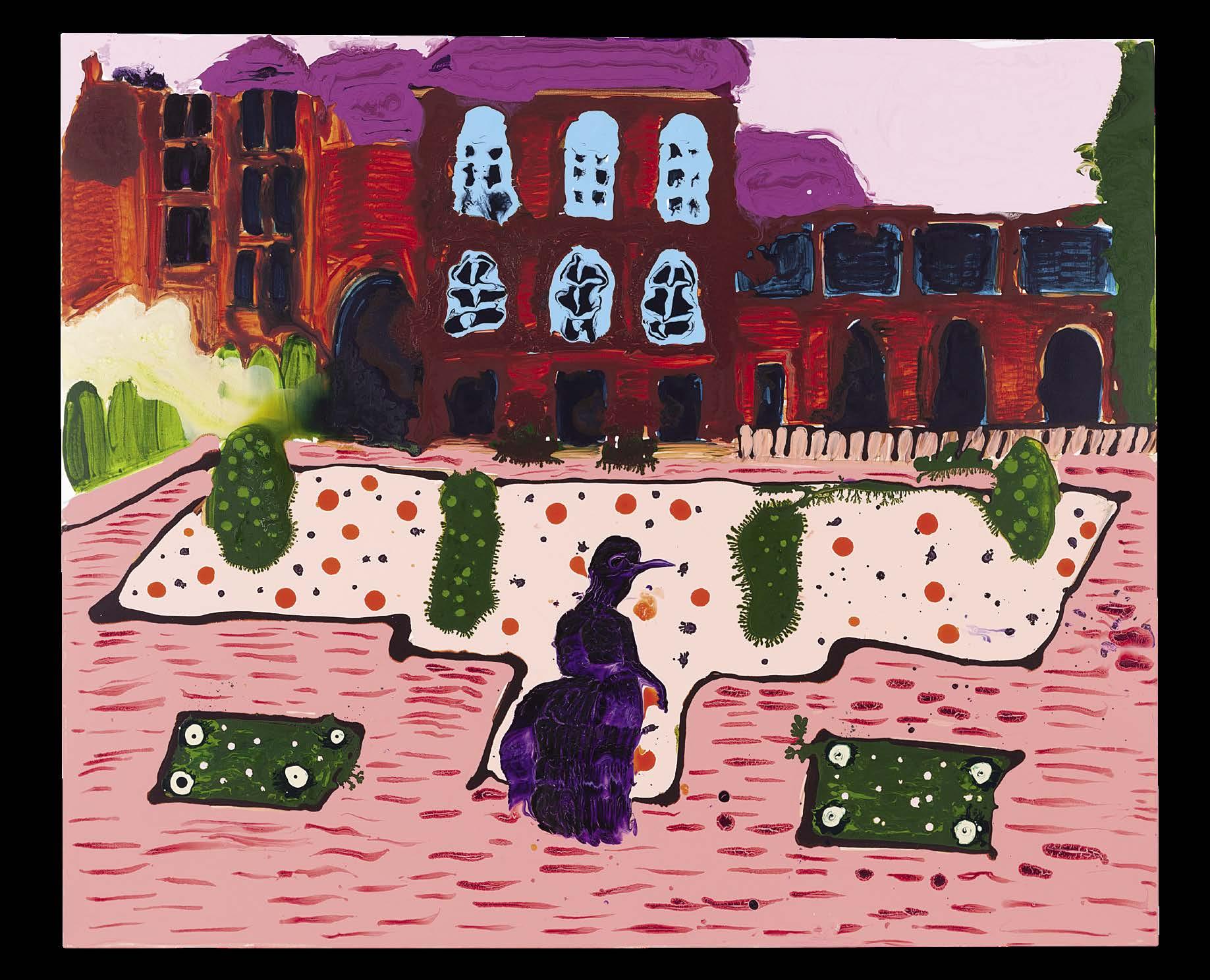

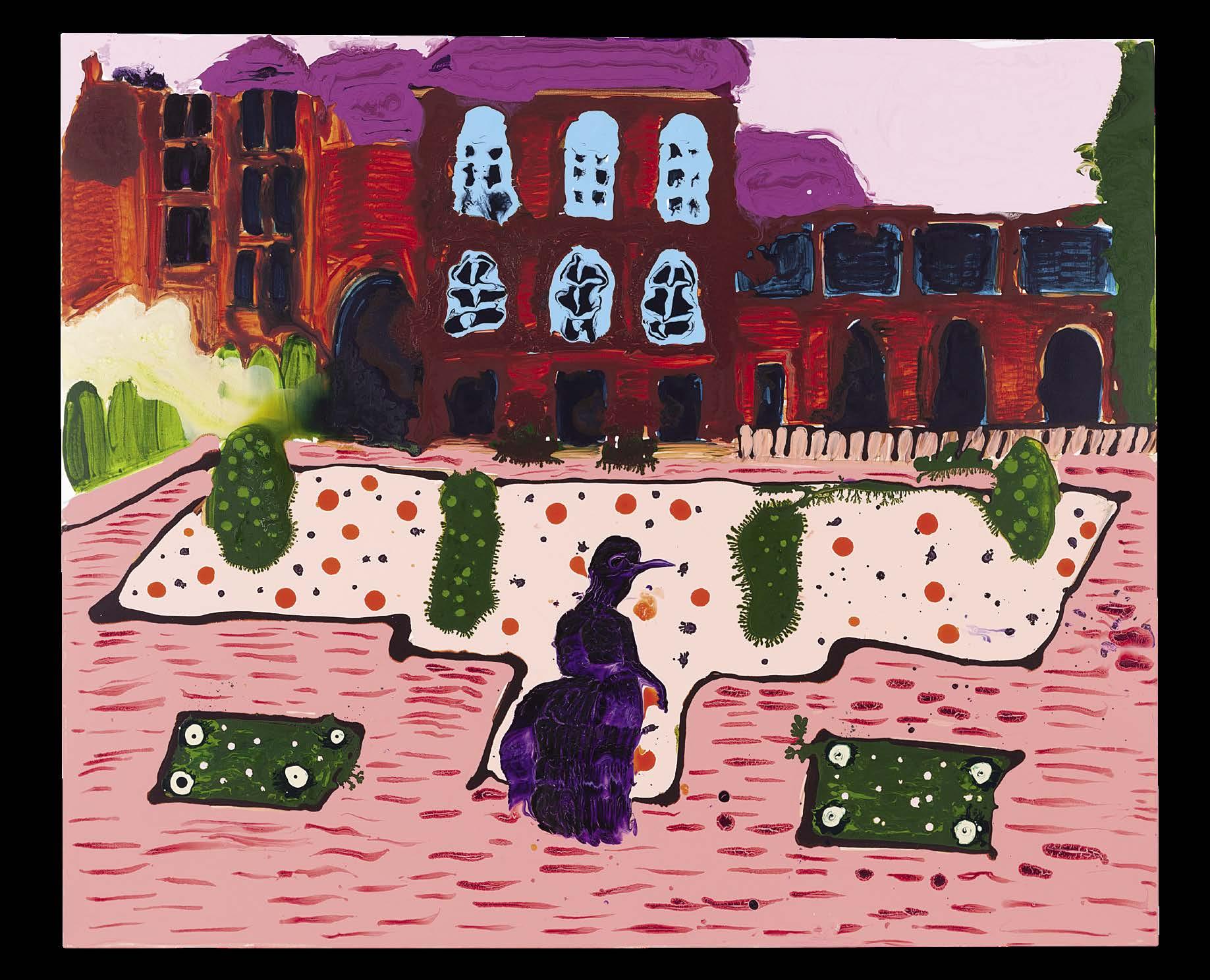

74 Picture Books

The fourth book published by Picture Books, an imprint organized by Emma Cline and Gagosian, is Lydia Millet’s novella Lyrebird . Accompanying the text is a painting by Genieve Figgis, inspired by the story’s lush setting. In celebration of this forthcoming publication, Figgis and Millet spoke to each other about the process, the role of humor in their work, and the genesis of their contributions.

80 Sally Mann and Benjamin Moser

During the 2022 edition of Paris Photo, Sally Mann and Benjamin Moser sat down for an intimate conversation as part of Gagosian’s Paris Salon series. The two discussed the power and responsibility tied up in their respective practices of photography and writing.

86 Building a Legacy: The Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art

For this installment of Building a Legacy, Lisa Turvey, editor of the catalogue raisonné of Ed Ruscha’s works on paper, met with Ben Gillespie, oral historian, and Jennifer Snyder, oral history archivist—both at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art—to discuss the institution’s Oral History Program.

90

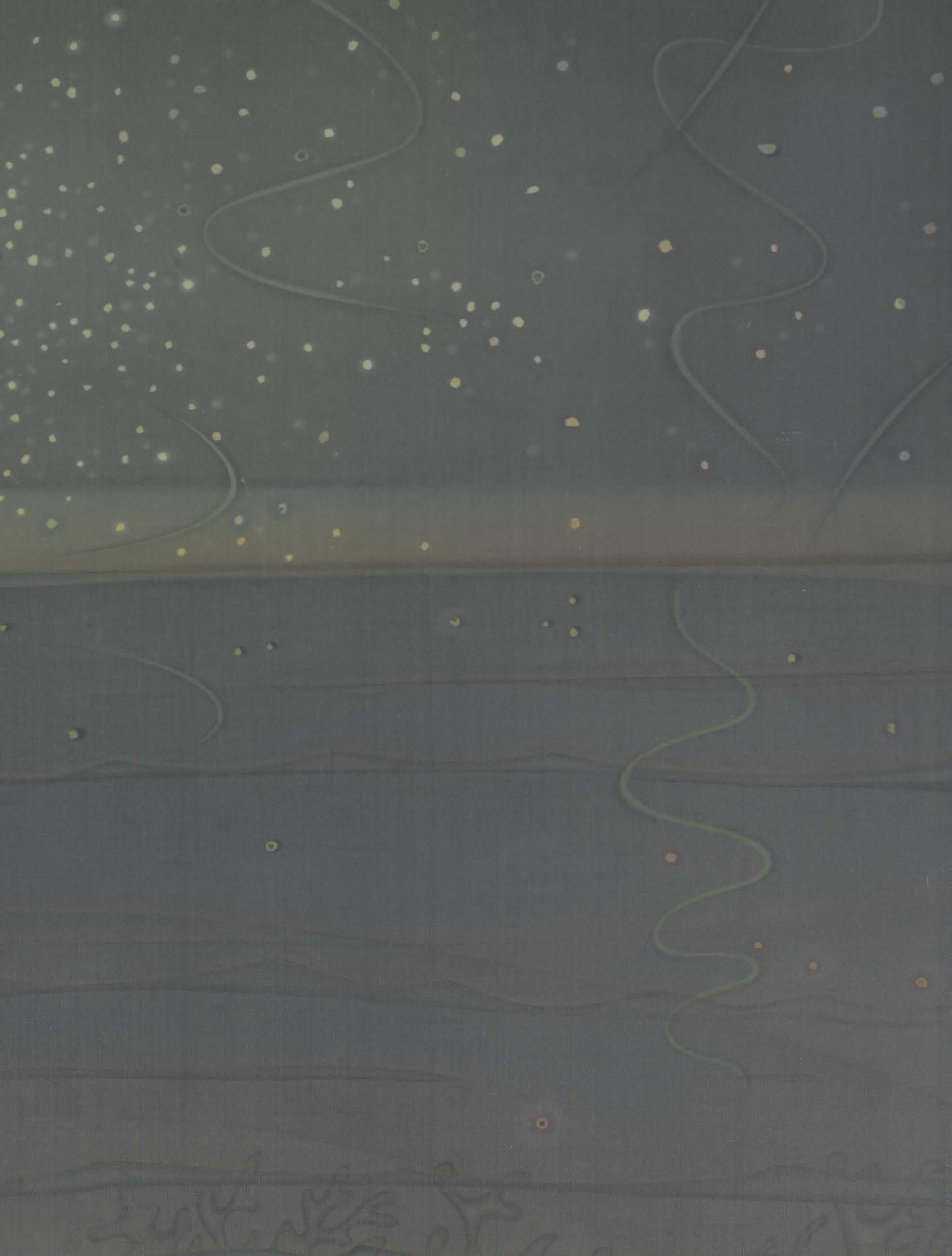

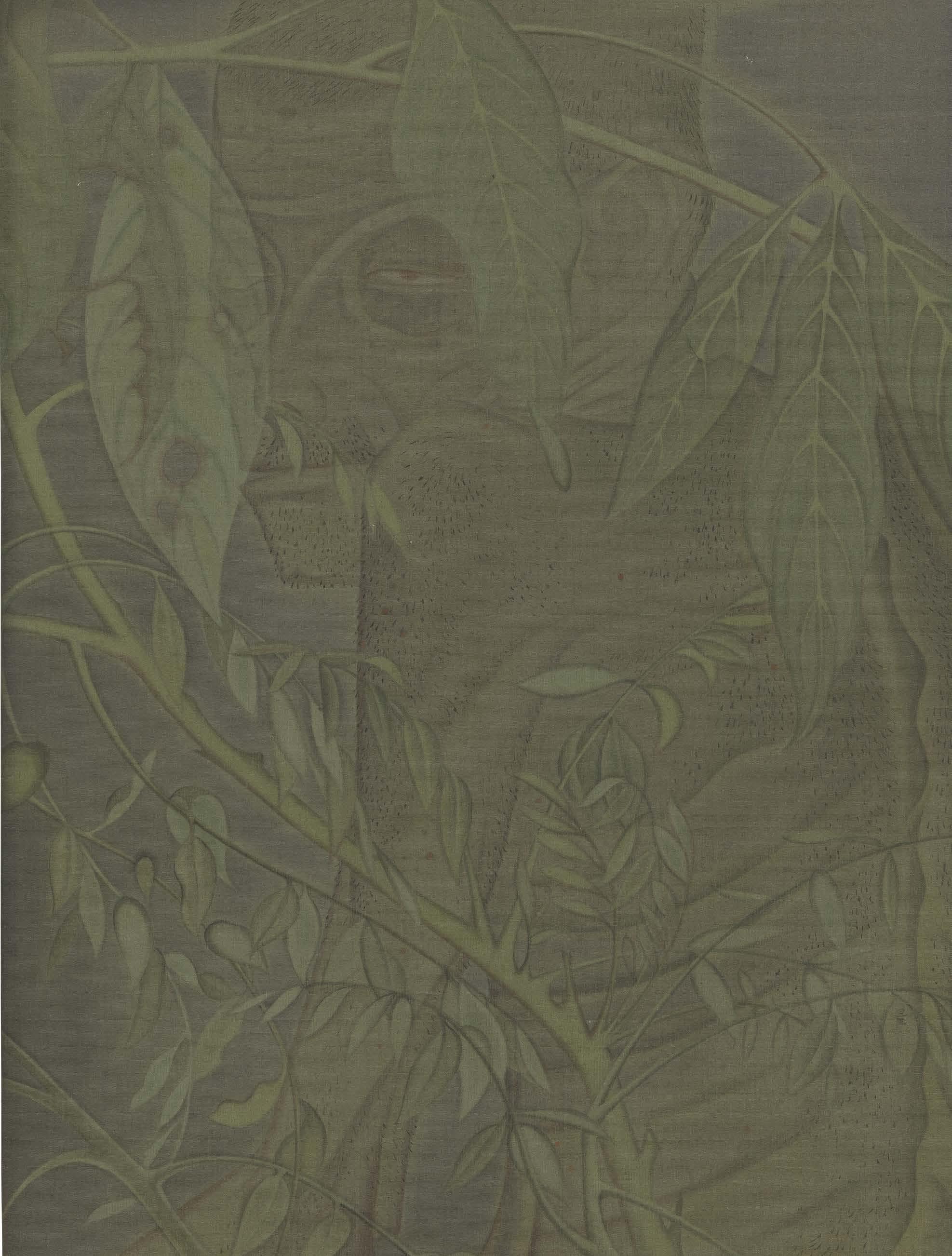

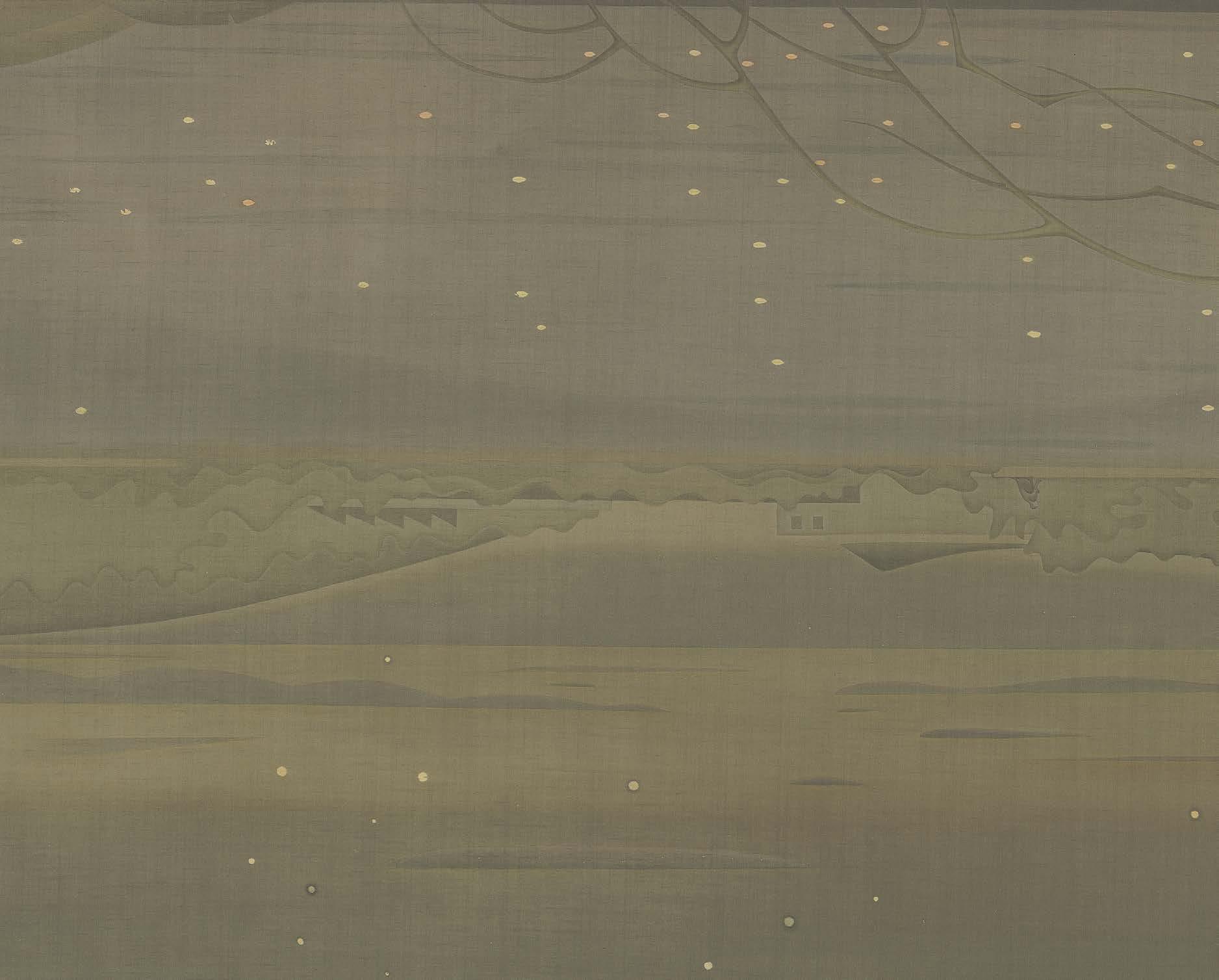

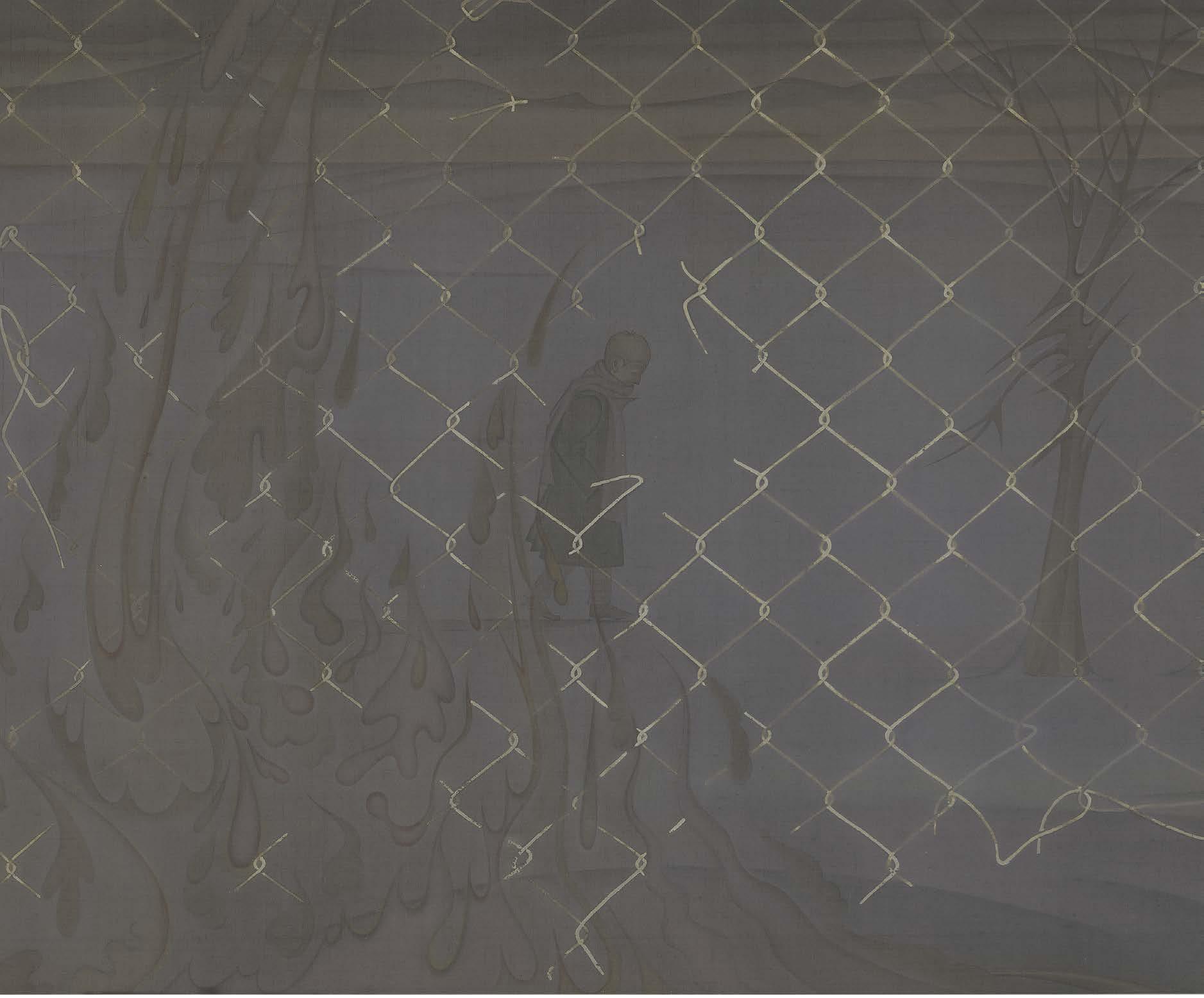

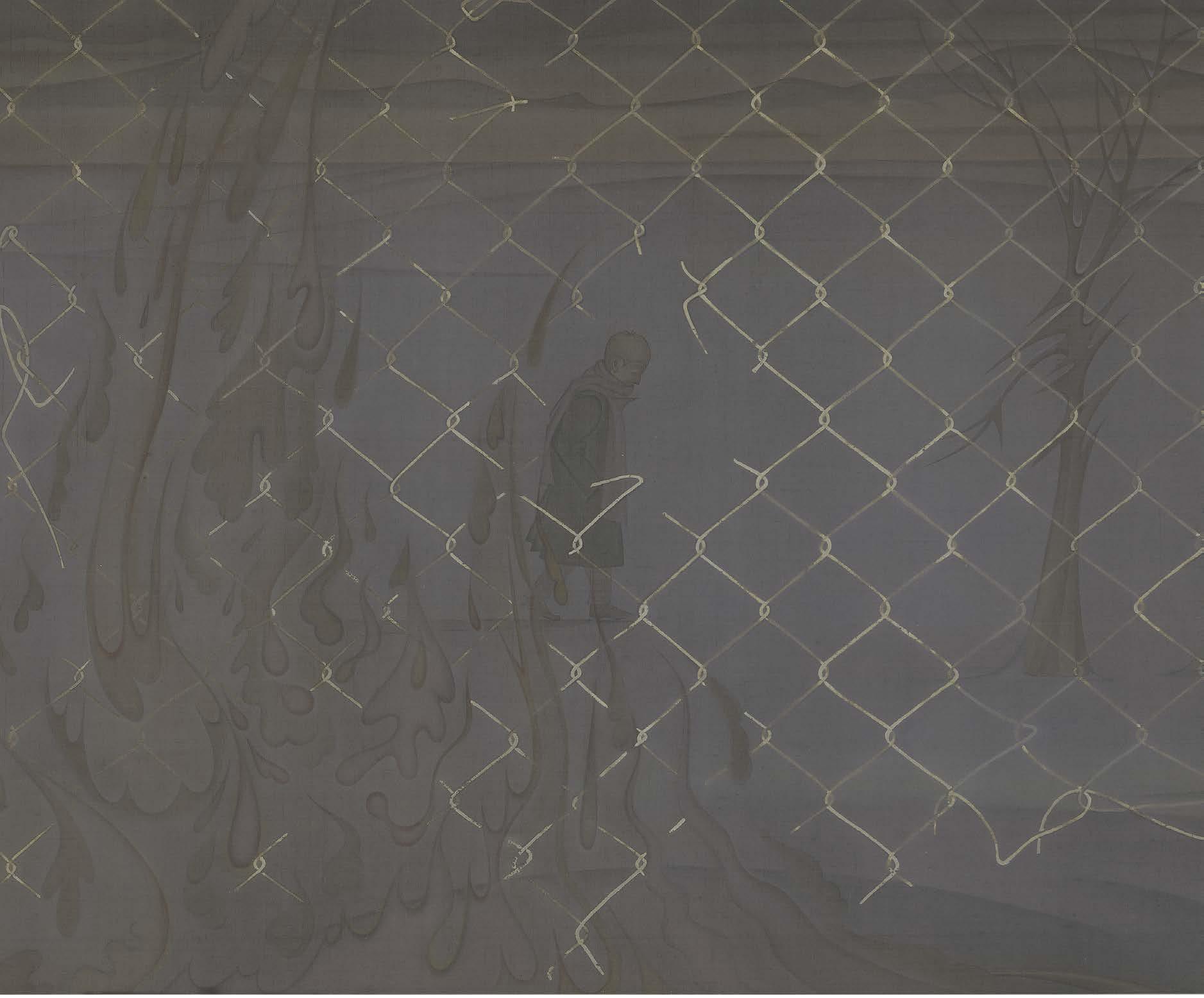

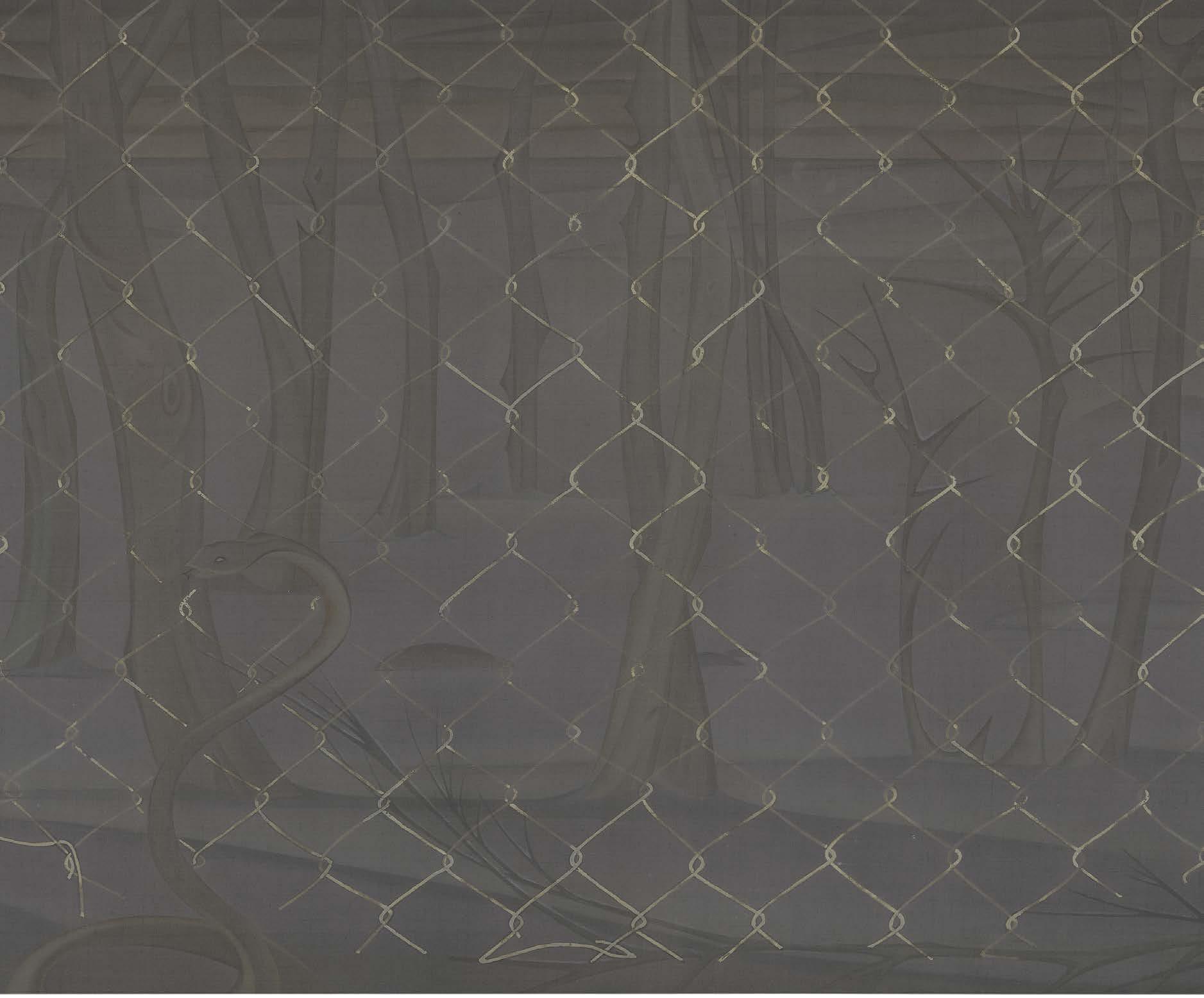

Hao Liang Emaciation Now: Paintings of My Contemporaries

Travis Diehl pens an essay on Hao Liang’s latest paintings.

100 A Vera Tatum Novel by Leonora McCrae by

The first installment of a short story by Percival Everett.

116

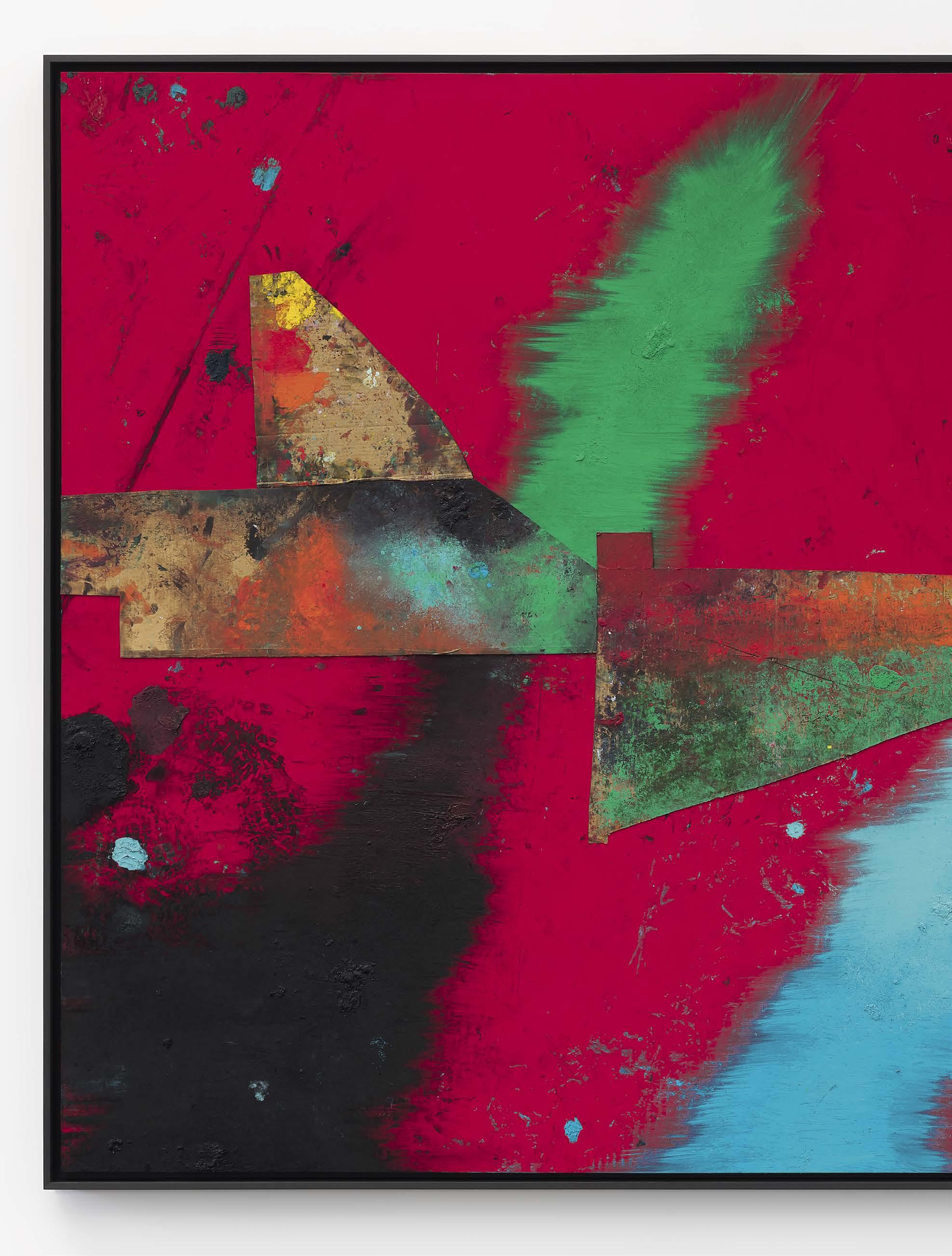

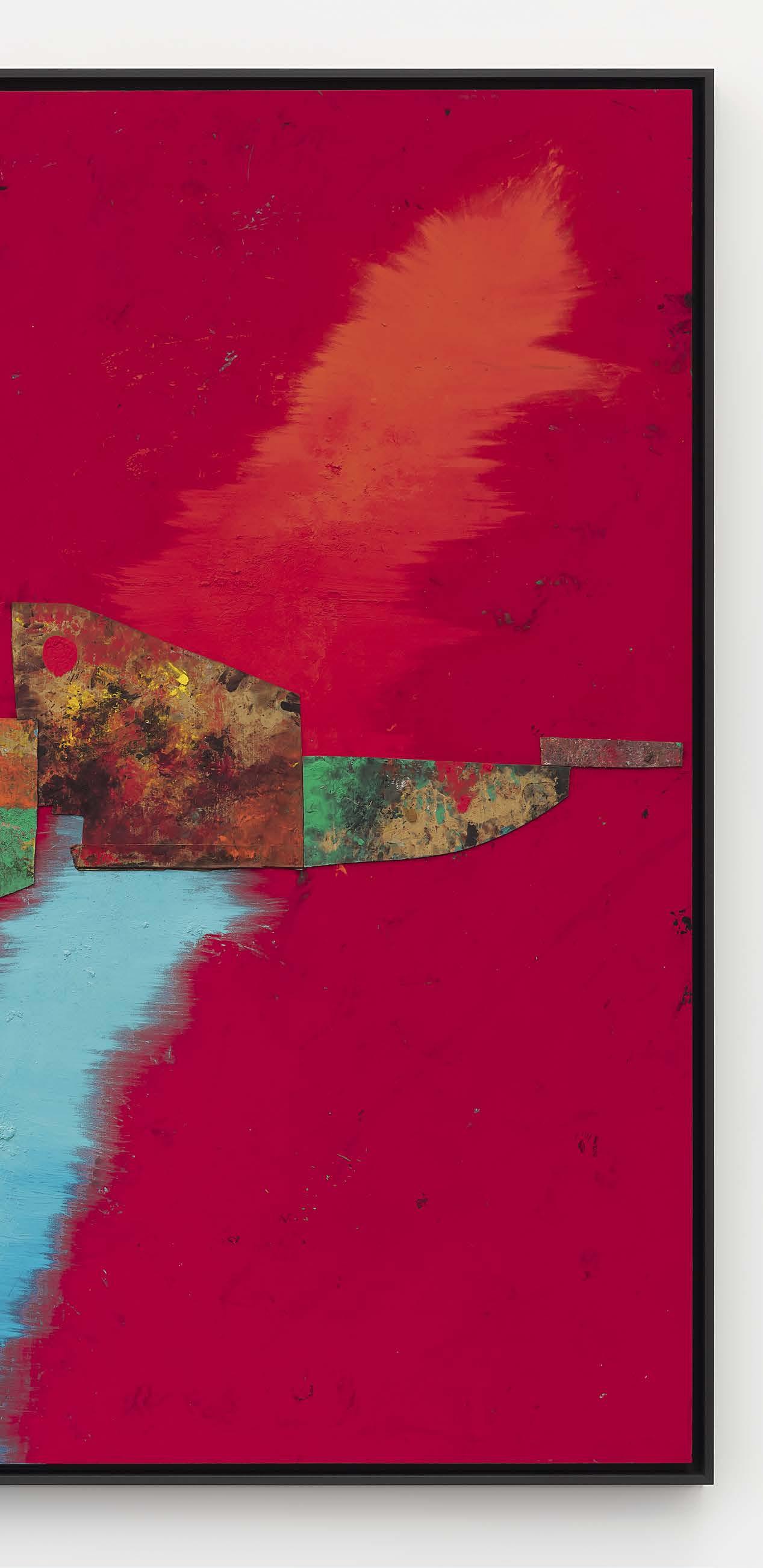

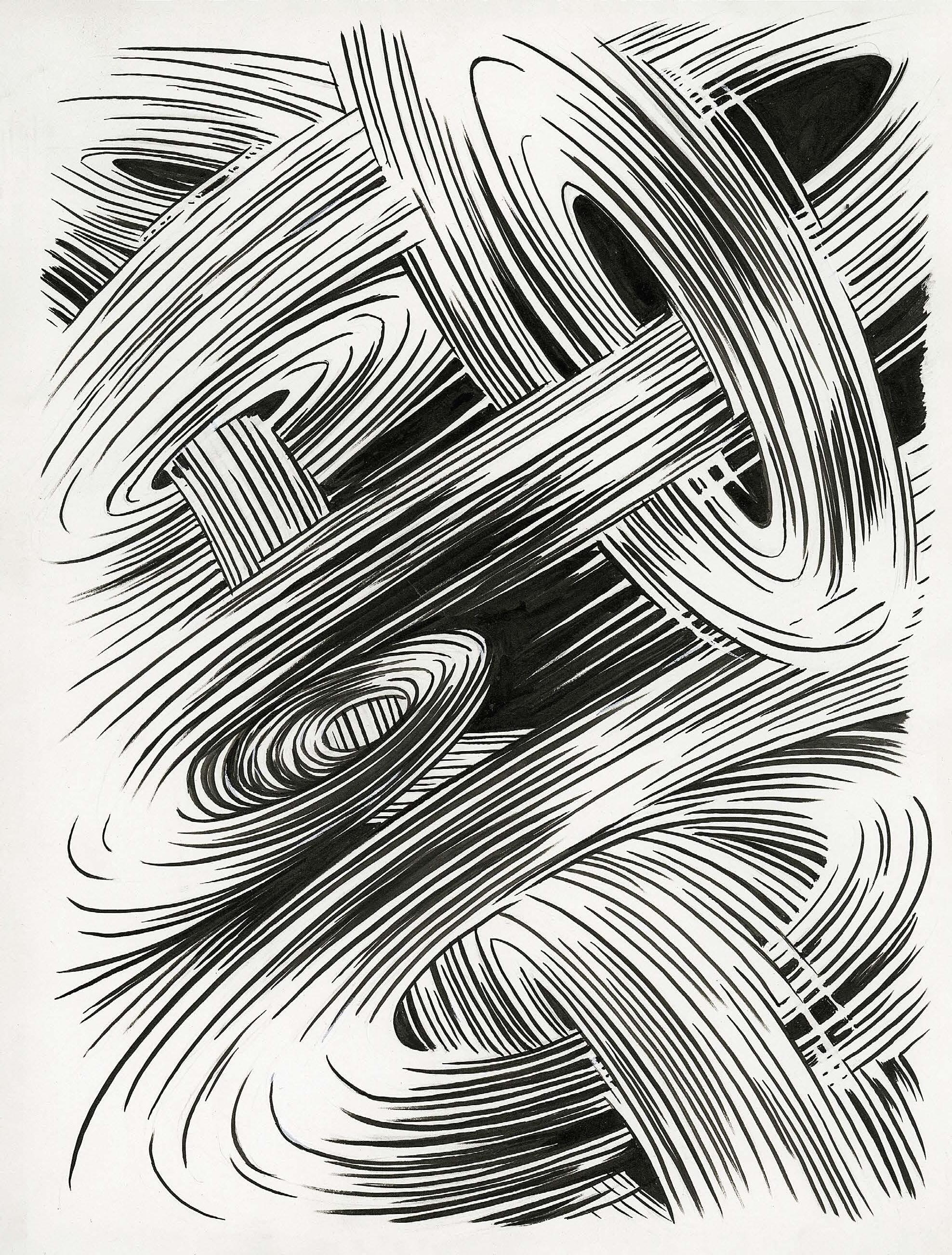

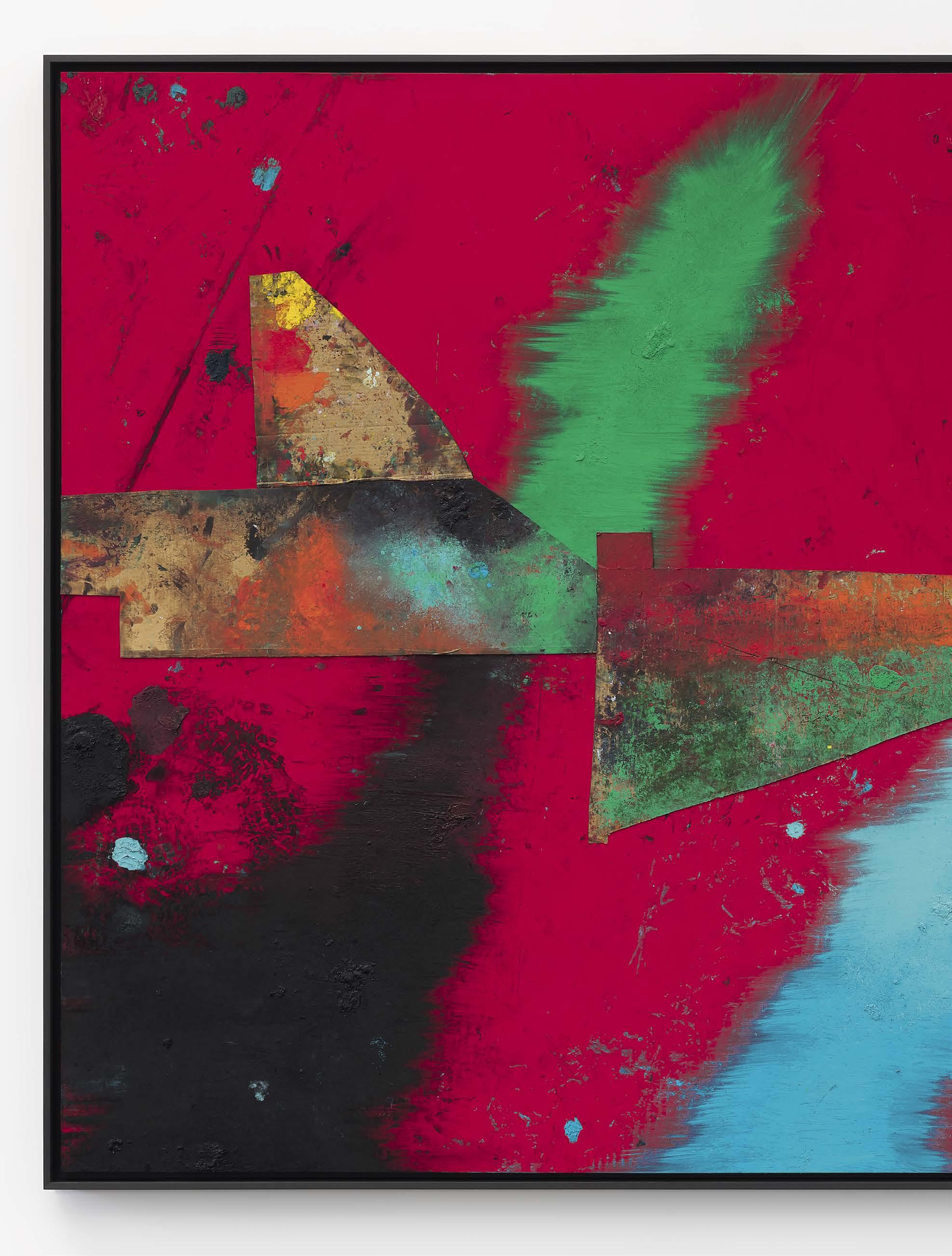

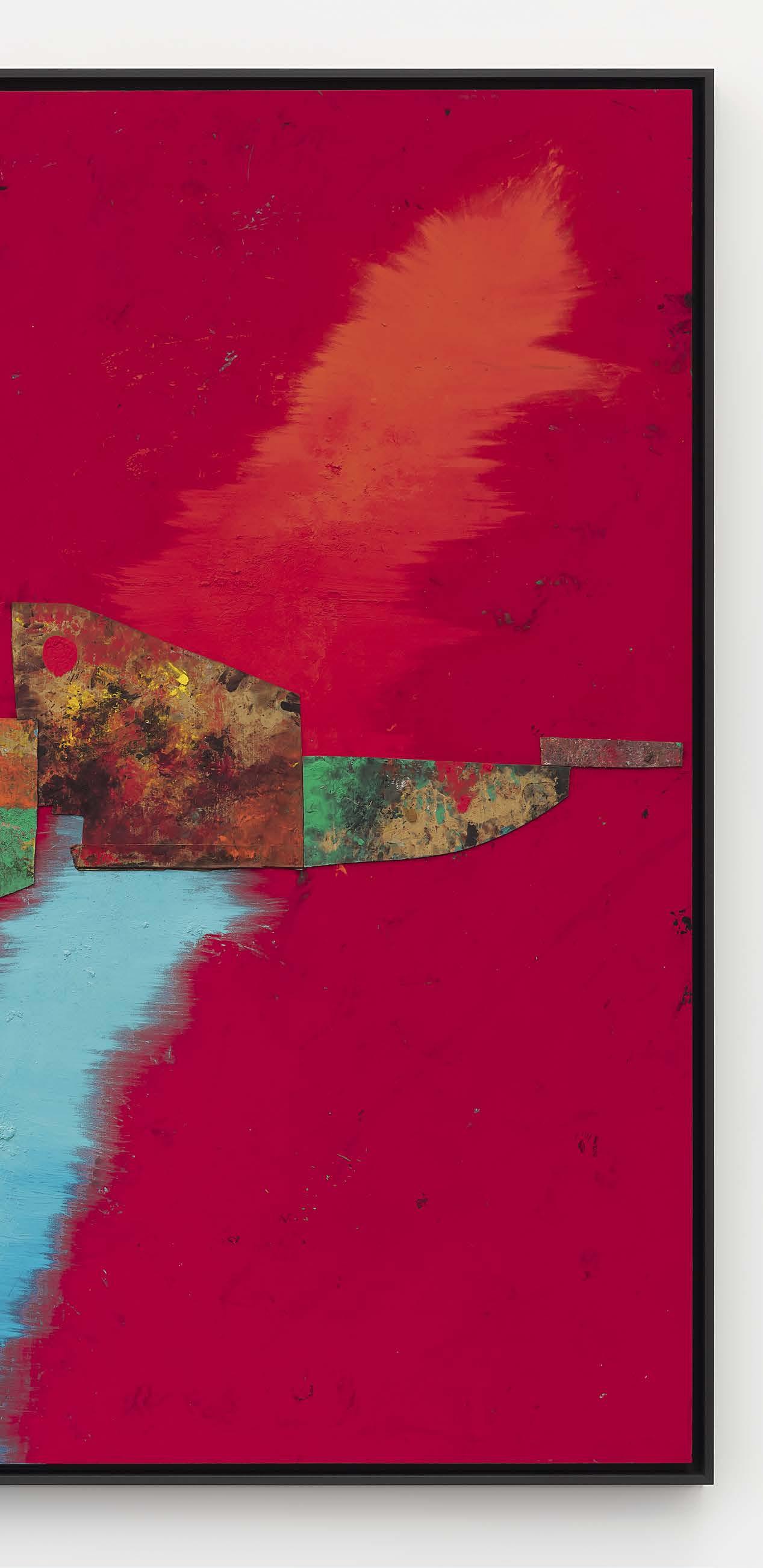

Sterling Ruby: The Frenetic Beat

Ester Coen meditates on the dynamism of Sterling Ruby’s recent projects, tracing parallels between these works and the histories of Futurism, Constructivism, and the avant-garde.

126 Marc Newson

A special section guest-edited by Marc Newson.

162 The Future of the Internet

In an effort to better understand the recent past, present, and future of the Internet, Fiona Alison Duncan joins professors Tiziana Terranova and Mindy Seu to discuss their practices and their latest publishing projects.

166 No Title

In an excerpt from his forthcoming monograph, Richard Wright pens a personal and philosophical text about painting.

176

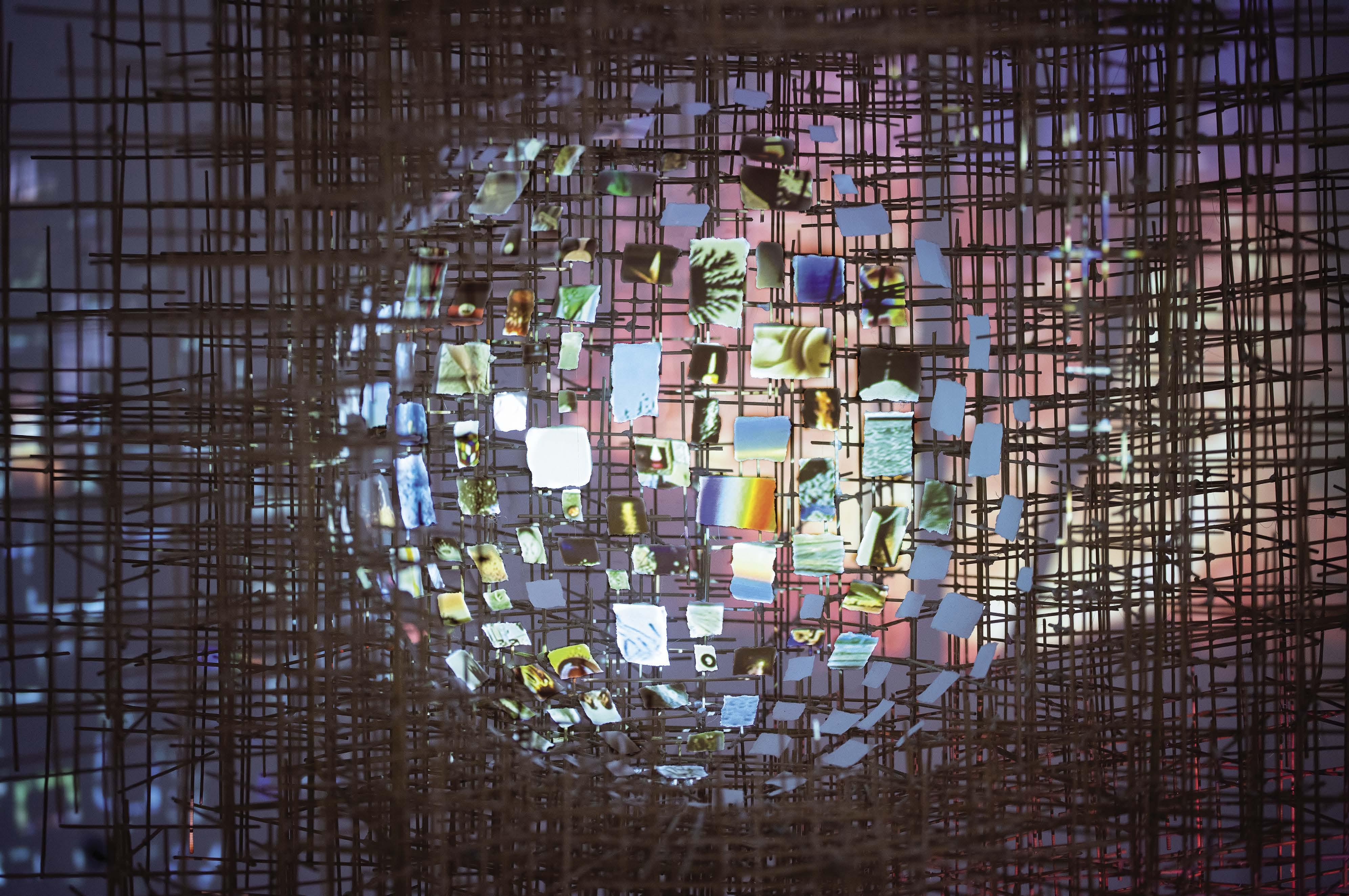

Red, White, Yellow, and Black: 1972–1973

In December 1972 and April 1973, Shigeko Kubota, Mary Lucier, Cecilia Sandoval, and Charlotte Warren conceived of “multimedia concerts” at The Kitchen, New York, under the name Red, White, Yellow, and Black Here, Lumi Tan, former senior curator at The Kitchen, and Lia Robinson, director of programs and research at the Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation, speak with the Quarterly ’s Wyatt Allgeier about the project.

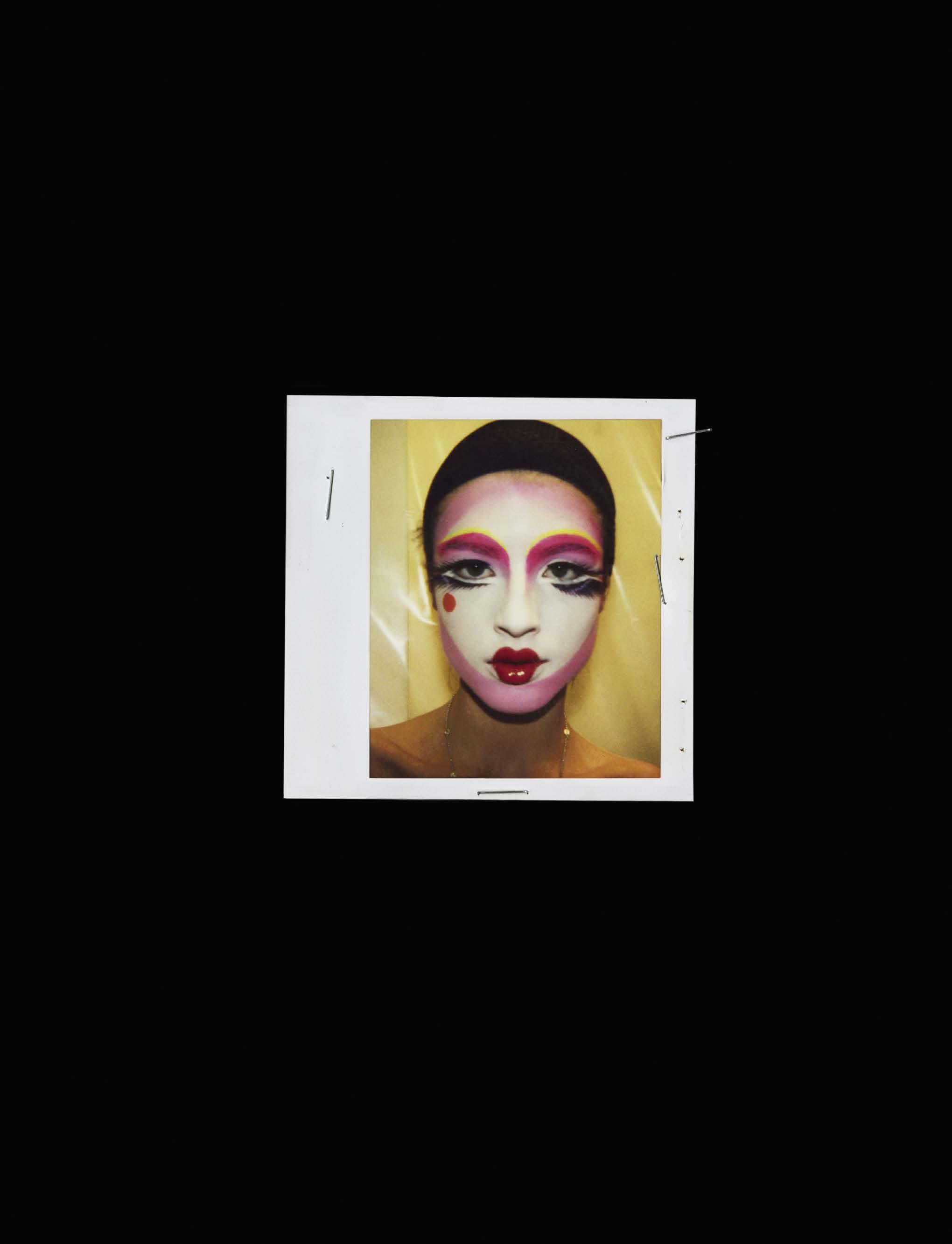

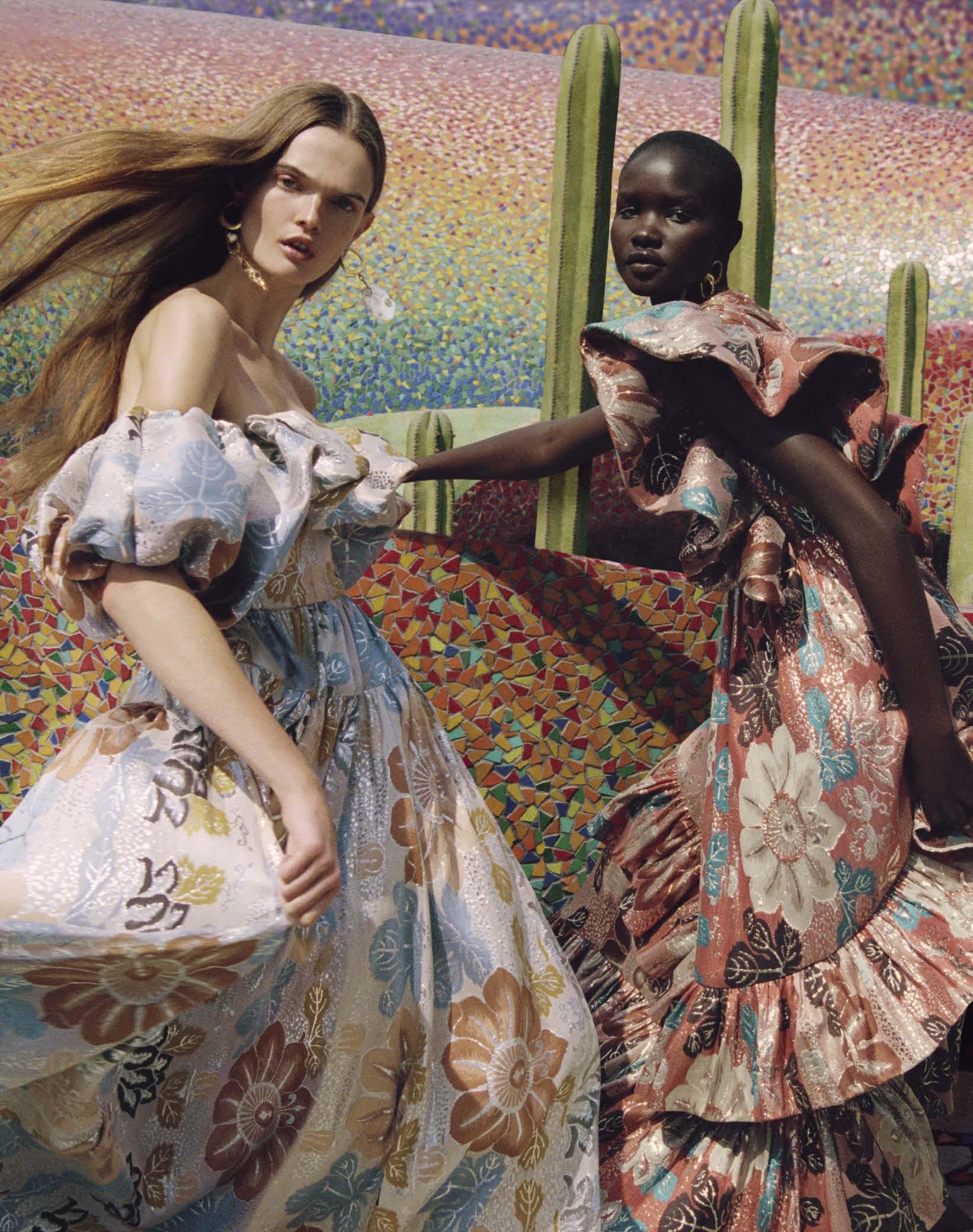

180 Fashion and Art, Part 13: Arianne Phillips

Derek Blasberg speaks with costume designer and stylist Arianne Phillips about her early friendship with Lenny Kravitz, the diverse set of artists and mediums that informs her work, and why she refuses to settle down into any codified vocation.

184

Screen Time: How Nadya Tolokonnikova and UnicornDAO Are Warming the Crypto Art World

Ashley Overbeek profiles

Pussy Riot member Nadya Tolokonnikova and the feminist collective UnicornDAO, highlighting their efforts to harness blockchain technology for art and activism.

190 Dan Colen

Curator and artist K.O. Nnamdie speaks with Dan Colen about his recent show in New York: Lover, Lover, Lover. Colen delves into the concept of “home” as it relates to his work, specifically the Mother and Woodworker series.

214

Game Changer: Ashley Bickerton

Michael Slenske pays tribute to the life and work of the artist Ashley Bickerton.

Front cover: Roe Ethridge, Two Kittens with Yarn Ball , 2017–22 (detail), dye sublimation print on Dibond, 40 × 60 inches (101.6 × 152.4 cm)

© Roe Ethridge

42

2023

TABLE OF CONTENTS SPRING

JE W ELRY

FINE

Spring Summer 2023

Photographe d by David Sims

Spring Summer 2023

Photographe d by David Sims

loewe.com

da vid yurman.com

CA BL E ED GE ™ COLL EC TI ON

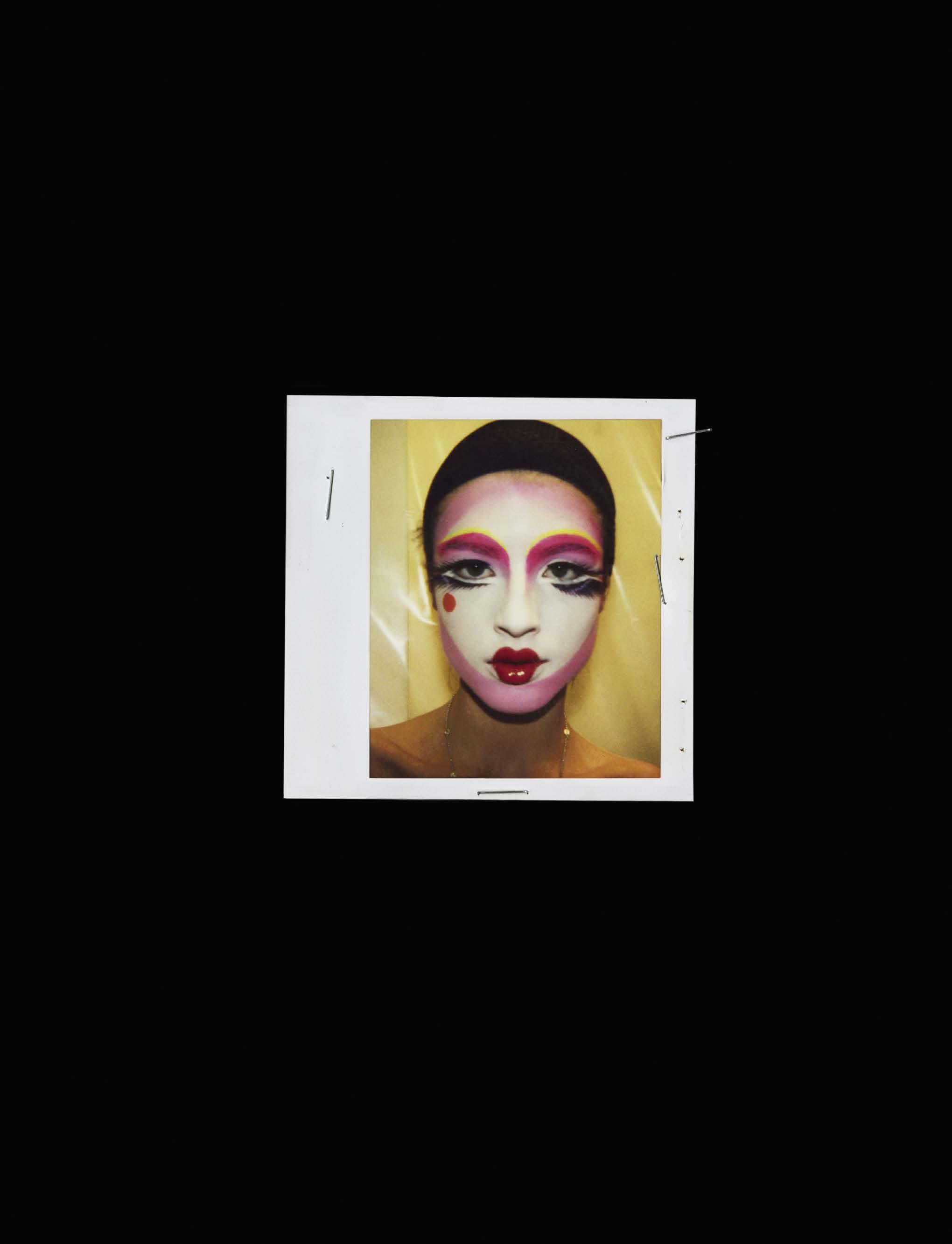

Daphne Guinness, photogra phed by Dylan

P erlot .

Daphne Guinness, photogra phed by Dylan

P erlot .

Editor-in-chief

Alison McDonald

Managing Editor

Wyatt Allgeier

Editor, Online and Print

Gillian Jakab

Text Editor

David Frankel

Executive Editor

Derek Blasberg

Digital and Video Production Assistant

Alanis Santiago-Rodriguez

Design Director

Paul Neale

Design

Alexander Ecob

Graphic Thought Facility

Website Wolfram Wiedner Studio

Gagosian Quarterly, Spring 2023

Cover Roe Ethridge

Founder Larry Gagosian

Published by Gagosian Media

Publisher

Jorge Garcia

Associate Publisher, Lifestyle

Priya Nat

For Advertising and Sponsorship Inquiries Advertising@gagosian.com

Distribution

David Renard

Distributed by Magazine Heaven

Distribution Manager

Alexandra Samaras

Prepress DL Imaging

Printed by Pureprint Group

Contributors

Wyatt Allgeier

Derek Blasberg

Michael Cary

Alison Castle

Emma Cline

Ester Coen

Dan Colen

Jeremy Deller

Travis Diehl

Fiona Alison Duncan

Percival Everett

Genieve Figgis

Ben Gillespie

Sally Mann

Adam McEwen

William Middleton

Lydia Millet

Benjamin Moser

Marc Newson

K.O. Nnamdie

Hans Ulrich Obrist

Ashley Overbeek

Arianne Phillips

Tiana Reid

Lia Robinson

Ruth Rogers

Mindy Seu

Jim Shaw

Michael Slenske

Jennifer Snyder

Lumi Tan

Tiziana Terranova

Lisa Turvey

Carlos Valladares

Joy Williams

Andrew Winer

Richard Wright

Thanks

Karrie Adamany

Richard Alwyn Fisher

Julia Arena

Amelia Atlas

Sonja Bartlett

Priya Bhatnagar

Cherry Saraswati Bickerton

Tyler Britt

Glenn Brown

Serena Cattaneo Adorno

Vittoria Ciaraldi

Inge Colsen

Roe Ethridge

Andrew Fabricant

Hannah Freedberg

Hallie Freer

Elisabeth Frood

Julien Garcia-Toudic

Brett Garde

Cy Gavin

Richard Geoffroy

Jonathan Germaine

Lauren Gioia

Darlina Goldak

Hao Liang

Camille Haus

Rayna Holmes

Delphine Huisinga

Melanie Jackson

Sarah Jones

Steven Klein

Jennifer Knox White

Kengo Kuma

Lauren Mahony

Christopher McCoy

Kelly McDaniel

Rob McKeever

Maxime Meignen

Olivia Mull

Kathy Paciello

Kay Pallister

Charles-Antoine Picart

Angelique Rosales Salgado

Sterling Ruby

Antwaun Sargent

Marguerite Shore

Isabel Shorney

Diallo Simon-Ponte

Jenny Smith

Micol Spinazzi

Chandler Sterling

Putri Tan

Harry Thorne

Nadya Tolokonnikova

Kara Vander Weg

Natalia Vargas

Timothée Viale

Misha Vladimirskiy

Lilias Wigan

Eva Wildes

Mimi Yiu

Alice Zhong

Blake Zidell

31

Quinn

Opposite page: Glenn Brown, Shipwreck, Custom of the Sea, 2022 (detail), oil on panel, 59 × 113 inches (150 × 287 cm) © Glenn Brown

CONTRIBUTORS

Alison Castle

Alison Castle (seen here with Marc Newson in a Ferrari 857 S at the 2022 1000 Miglia) is a writer, editor, and filmmaker. She holds a BA in philosophy from Columbia and an MA in photography and film from New York University. She has edited and written many books on photography, film, and design for Taschen.

Marc Newson

Marc Newson CBE is an industrial designer whose work spans a wide range of disciplines. Born in Sydney, Newson staged his first solo exhibition at the age of twenty-three and two years later created the now iconic Lockheed Lounge chair. He is the only designer represented by Gagosian and his designs are featured in the permanent collections of more than forty institutions worldwide.

Carlos Valladares

Carlos Valladares is a writer, critic, programmer, journalist, and video essayist from South Central Los Angeles, California. He studied film at Stanford and began his PhD in History of Art and Film and Media Studies at Yale University in the fall of 2019. He has written for the San Francisco Chronicle , Film Comment , and the Criterion Collection.

Ruth Rogers

Ruth Rogers is a chef and co-founder of the iconic London restaurant The River Café. Known for her elegant and seasonal Italian cuisine, she has been instrumental in shaping the UK’s modern culinary landscape. Along with her business partner Rose Gray, Rogers has been awarded multiple accolades and accolades, including a coveted Michelin star. She has also published several cookbooks, sharing her love of Italian food and cooking techniques with home chefs. Ruth Rogers continues to be a leading figure in the world of food and a champion of sustainable and seasonal ingredients. She is also the host of the podcast “Ruth’s Table.”

Andrew Winer

Andrew Winer is the author of the novels The Marriage Artist and The Color Midnight Made . He writes and lectures on art, philosophy, and literature. A recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in fiction, he is presently completing a novel and a book on the contemporary relevance of Friedrich Nietzsche’s central philosophical idea, the affirmation of life.

32

Photo: Jerry Schatzberg

Sally Mann

Sally Mann is an American photographer and writer. Her work is held in many notable collections, including the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Victoria & Albert Museum, London; and the Moderna Museet, Stockholm.

Mann’s Hold Still: A Memoir with Photographs (Little, Brown, 2015) was named a finalist for the 2015 National Book Awards and in 2016 won the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Nonfiction. She was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2022 and is a Prix Pictet laureate. Photo: Annie Leibovitz

Benjamin Moser

Benjamin Moser is a writer based in the Netherlands. He is the author of Why This World: A Biography of Clarice Lispector (2009) and of Sontag: Her Life and Work (2020), for which he won a Pulitzer Prize. His new book, The Upside-Down World: Meetings with the Dutch Masters , will be published in October.

Derek Blasberg

Derek Blasberg is a writer, fashion editor, and New York Times best-selling author. He has been with Gagosian since 2014 and is the executive editor of Gagosian Quarterly.

Jim Shaw

Jim Shaw has responded to American cultural history through painting, drawing, and sculpture since the 1970s, drawing on sources as wideranging as comic books, pulp novels, rock albums, protest posters, and amateur paintings. Often unfolding in extended narrative cycles, Shaw’s works juxtapose images of friends and family with depictions of world events, pop-cultural phenomena, and alternative realities, blending the personal, the commonplace, and the visionary. Photo: LeeAnn Nickels

Michael Slenske

Michael Slenske is a Los Angeles–based writer and independent curator who has organized exhibitions at Praz-Delavallade, the Landing, Wilding Cran Gallery, and Frieze LA. His work has been anthologized, included in many artists’ monographs, and appears regularly in W, Galerie , and Los Angeles Magazine Photo: Ry Rocklen

Mindy Seu

Mindy Seu is a New York–based designer and technologist, an assistant professor at Rutgers University’s Mason Gross School of the Arts, and critic at the Yale School of Art. Her expanded practice involves archival projects, techno-critical writing, performative lectures, design commissions, and close collaborations.

33

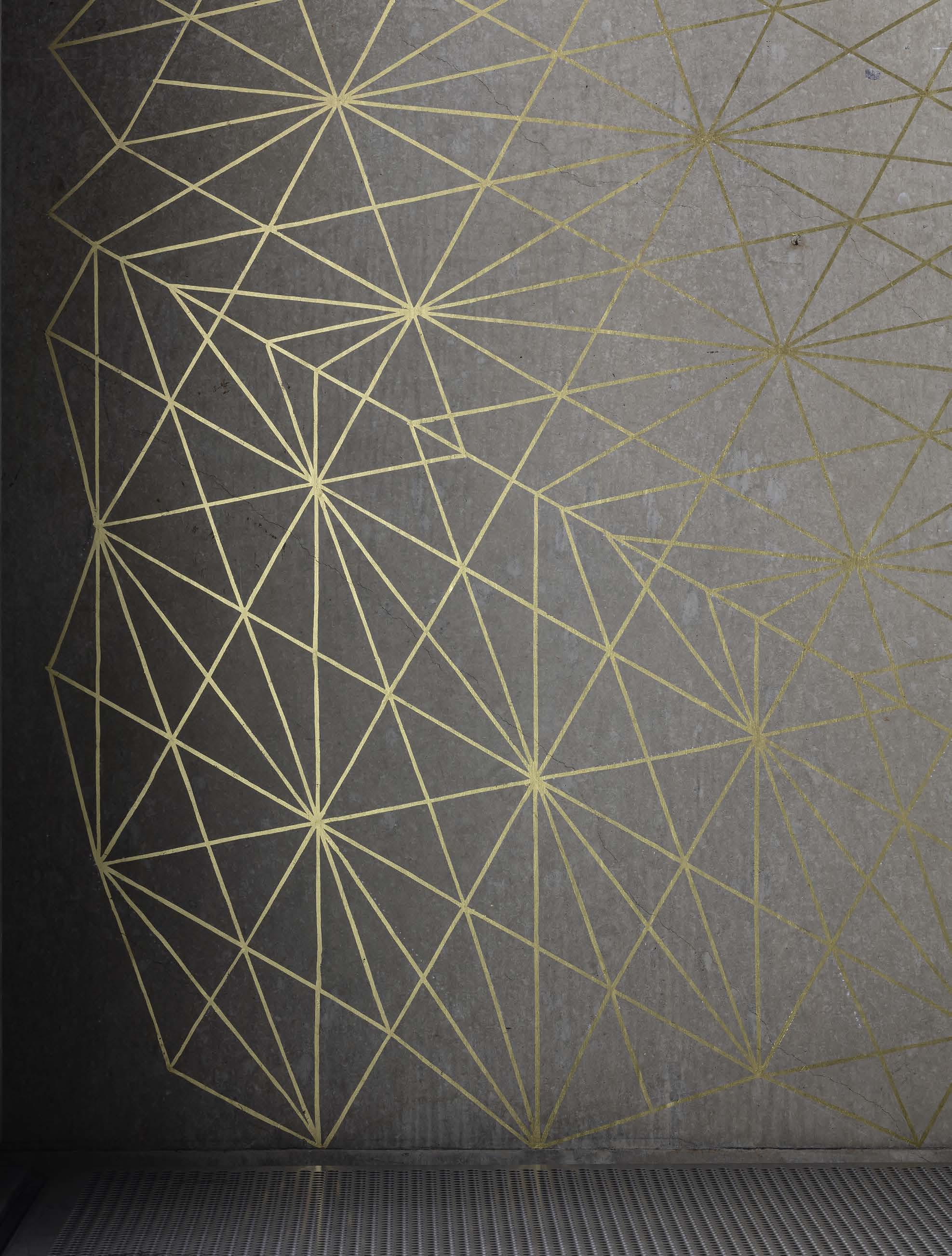

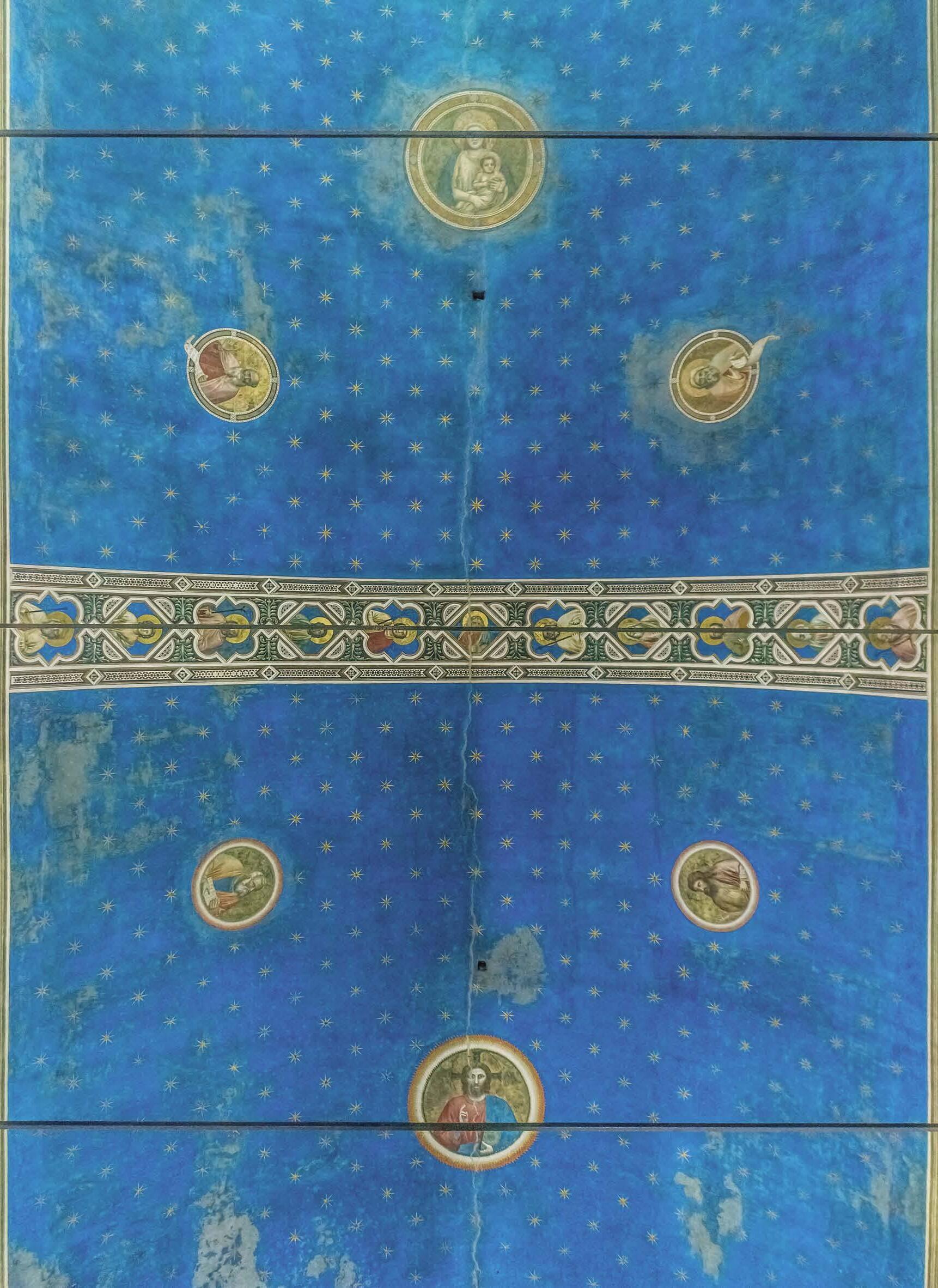

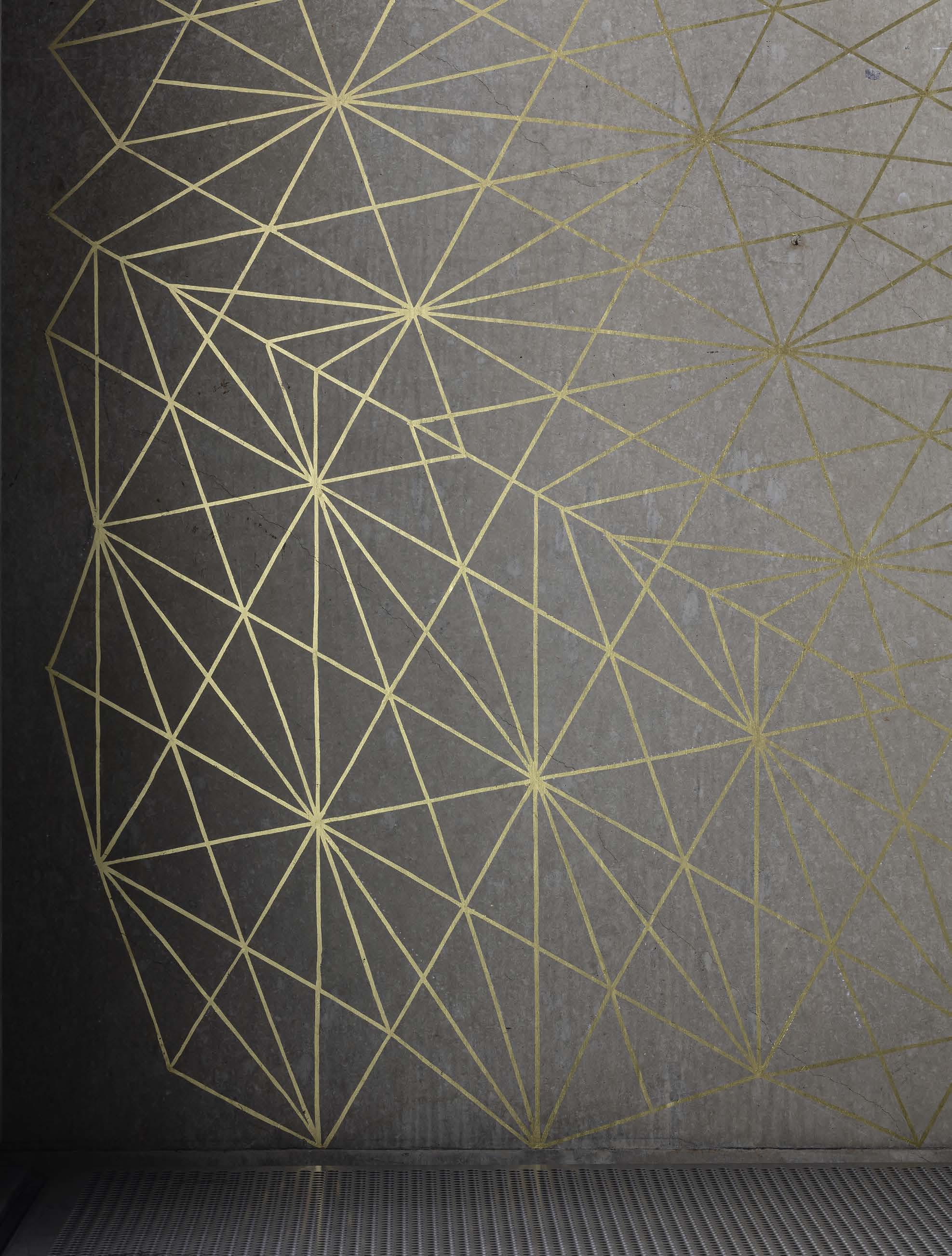

Richard Wright

Richard Wright is best-known for his painted and gilded works applied directly to walls and ceilings. His pieces, which are often transient, charge the spaces they inhabit with a range of forms, from baroque ornamentation to constructivist patterns. In recent years he has produced commissions for numerous public spaces and institutions, including the Tottenham Court Road Elizabeth-line station, London (2018), the Queen’s House, Greenwich, London (2016), and the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (2012). In addition to these site-specific works, Wright also creates watercolors, silk screens, and leaded-glass windows and skylights. In the spring of 2023, Gagosian will publish a major monograph documenting the last ten years of his work; in March, he will have an exhibition at Gagosian Davies Street, London. Photo: David Ersser

Percival Everett

Percival Everett is the author of twenty-two novels and four collections of stories. His novels include The Trees (2021), Telephone (2020), So Much Blue (2017), and Erasure (2001). He has received awards from the Guggenheim Foundation and Creative Capital. He lives in Los Angeles, where he is distinguished professor of English at the University of Southern California.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

Hans Ulrich Obrist is artistic director of the Serpentine Galleries, London. He was previously curator at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Since his first show, World Soup (The Kitchen Show), in St. Gallen, Switzerland, in 1991, he has curated more than 300 exhibitions. Photo: Tyler Mitchell

Ashley Overbeek

Ashley Overbeek is the director of strategic initiatives at Gagosian. She has been collecting NFTs since early 2019 and is a cohost on Wednesday Wonders, a weekly Twitter space where she interviews leading crypto artists.

Ester Coen

Ester Coen is an art historian and curator. She is an expert on Italian Futurism, the Metaphysical artists, and the international avant-gardes, and her research for her numerous essays and publications extends from the 1960s to the contemporary scene. She has curated many exhibitions, their subjects ranging from Giorgio de Chirico, Umberto Boccioni, Giacomo Balla, and Henri Matisse, to Richard Serra and Gary Hill.

Tiziana Terranova

Tiziana Terranova is an Italian theorist and activist who studies the effects of information technology on society and explores concepts such as digital labor and commons. Terranova has published the monograph Network Culture

34

Lydia Millet

Lydia Millet has written more than a dozen books, most recently the novel Dinosaurs (W. W. Norton, 2022). Her previous novel, A Children’s Bible , was a finalist for the National Book Award in fiction and one of the New York Times Book Review ’s “10 Best Books of 2020.” Other titles include the novels Sweet Lamb of Heaven (2017) and Mermaids in Paradise (2015). Millet has been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in fiction and various other honors, and works as a writer and editor at the Center for Biological Diversity, an organization dedicated to fighting climate change and species extinction. She lives outside Tucson, Arizona. Photo: Nola Millet

Genieve Figgis

Genieve Figgis is an artist who lives and works in County Wicklow, Ireland. She received her BA in Fine Art from the Gorey School of Art, Wexford, Ireland, in 2006; BA honors from the National College of Art and Design, Dublin, in 2007; and her MFA from the National College of Art and Design in 2012.

Travis Diehl

Travis Diehl is a critic, writer, and editor. Recent reviews and essays of his have appeared in the New York Times , Artforum , Art in America , x-tra , Frieze , the Financial Times , and Tank ; recent poems have appeared in Forever. Awards he has won include the Creative Capital Arts Writers Grant and the Rabkin Prize in Visual Art Journalism. He is Online Editor at x-tra

Jennifer Snyder

Jennifer Snyder is the oral history archivist at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, where she manages and cares for more than 2,500 interviews and their related assets. Snyder earned her MLS from the University of Maryland and enjoyed a career as a processing archivist before finding her way to oral history.

Lumi Tan

Lumi Tan is a curator and writer based in New York. She is currently the curatorial director of Luna Luna, a traveling art amusement park that originated in a 1987 project conceived by André Heller. She was previously senior curator at The Kitchen, New York, where she organized exhibitions and produced performances with artists including Kevin Beasley, Gretchen Bender, Abraham Cruzvillegas, E. Jane, Baseera Khan, Autumn Knight, Moor Mother, Sondra Perry, the Racial Imaginary Institute, Tina Satter, Kenneth Tam, and Anicka Yi. Tan has also held positions at the Fonds Régional d’Art Contemporain du Nord-Pas-de-Calais, France, the Zach Feuer Gallery, New York, and MoMA PS1, New York. Her writing has appeared in the New York Times, Artforum , Frieze , Mousse , Cura , and many exhibition catalogues. She was the recipient of the 2020 via Art Fund Curatorial Fellowship.

Lia Robinson

Lia Robinson is a curator specializing in global modern and contemporary art. She currently serves as director of programs and research at the Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation, which is committed to presenting and preserving the legacy of the video pioneer Shigeko Kubota (1937–2015) and to supporting research, experimentation, and broader access to artistic practices at the intersection of art and technology.

36

JUDE LAW & RAFF LAW

Joy Williams

Joy Williams is the author of five novels, most recently Harrow (2021); four collections of stories; and Ill Nature (2001), an essay collection that was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. Her many honors include the Rea Award for the Short Story and the Strauss Living Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. She was elected to the academy in 2008. She lives in Tucson, Arizona, and Laramie, Wyoming.

Ben Gillespie

Ben Gillespie works as an oral historian at the Archives of American Art, where he manages the oral history program and produces the podcast Articulated . His research attends to the ways in which we might recuperate, preserve, and amplify neglected artistic voices. He received his PhD from Johns Hopkins University.

Dan Colen

In works ranging from painting and sculpture to installation and performance, Dan Colen plays with familiar materials and cultural symbols to interrogate the relationship between meaning and object. He is the founder of Sky High Farm, a nonprofit committed to improving access to fresh, nutritious food for New Yorkers living in underserved communities. Photo: Eric Piasecki

K.O. Nnamdie

K.O. Nnamdie is a curator, writer, art advisor, and artist based in New York City. He is the director at anonymous gallery and runs Restaurant Projects, a curatorial project and research-driven art-advisory service founded in 2018 and based on Nnamdie’s interest in the intersection between hospitality and the arts. Photo: Thomas Polcaster

William Middleton

The Paris-based writer William Middleton is the author of Double Vision , a biography of the legendary art patrons and collectors Dominique and John de Menil, published in 2018 by Alfred A. Knopf. He has contributed to such publications as W, Vogue , Harper’s Bazaar, Architectural Digest , House & Garden , Departures , Town & Country, the New York Times , and T. Middleton’s next book is Paradise Now: The Extraordinary Life of Karl Lagerfeld , to be published by HarperCollins in February 2023.

Michael Cary

Michael Cary organizes exhibitions for Gagosian, including eight Picasso exhibitions in collaboration with John Richardson and members of the Picasso family. He joined Gagosian in 2008 after working for six years with the late Kynaston McShine, then chief curator at large at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Clive Smith

38

Photo: Jonno Rattman

Tiana Reid

Tiana Reid is an assistant professor in the Department of English at York University, Toronto. Her writing has been published in Aperture , Art in America , Artforum , Canadian Art , Frieze , the Nation , the New York Review of Books , the Paris Review, Vulture , and elsewhere.

Fiona Alison Duncan

Fiona Alison Duncan is a CanadianAmerican author and organizer and the founder of the social literary practice Hard to Read. Duncan’s debut novel, Exquisite Mariposa (Soft Skull Press), won a 2020 Lambda Award. She is currently developing a narrative biography and critical study of the transdisciplinary American artist Pippa Garner.

Adam McEwen

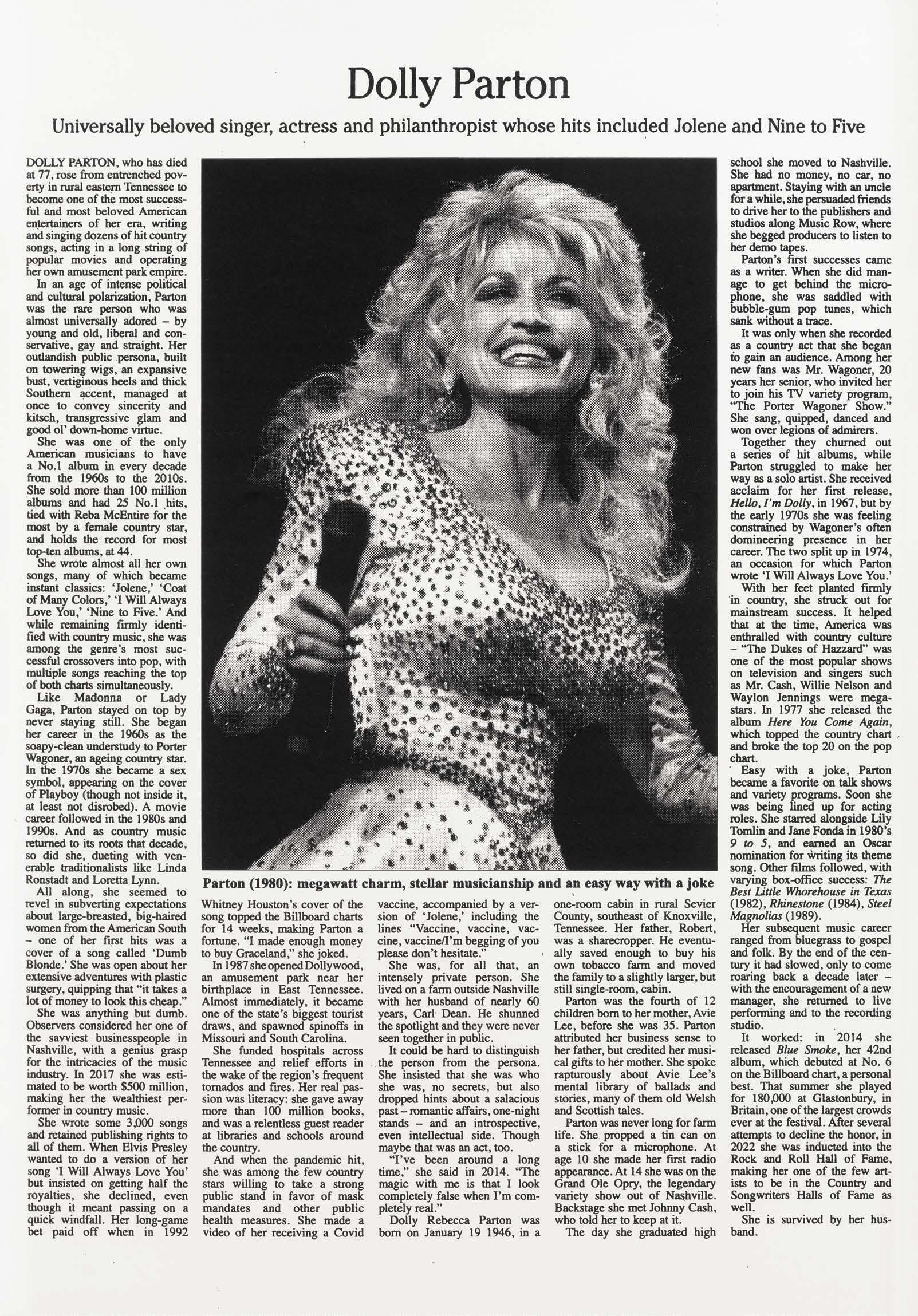

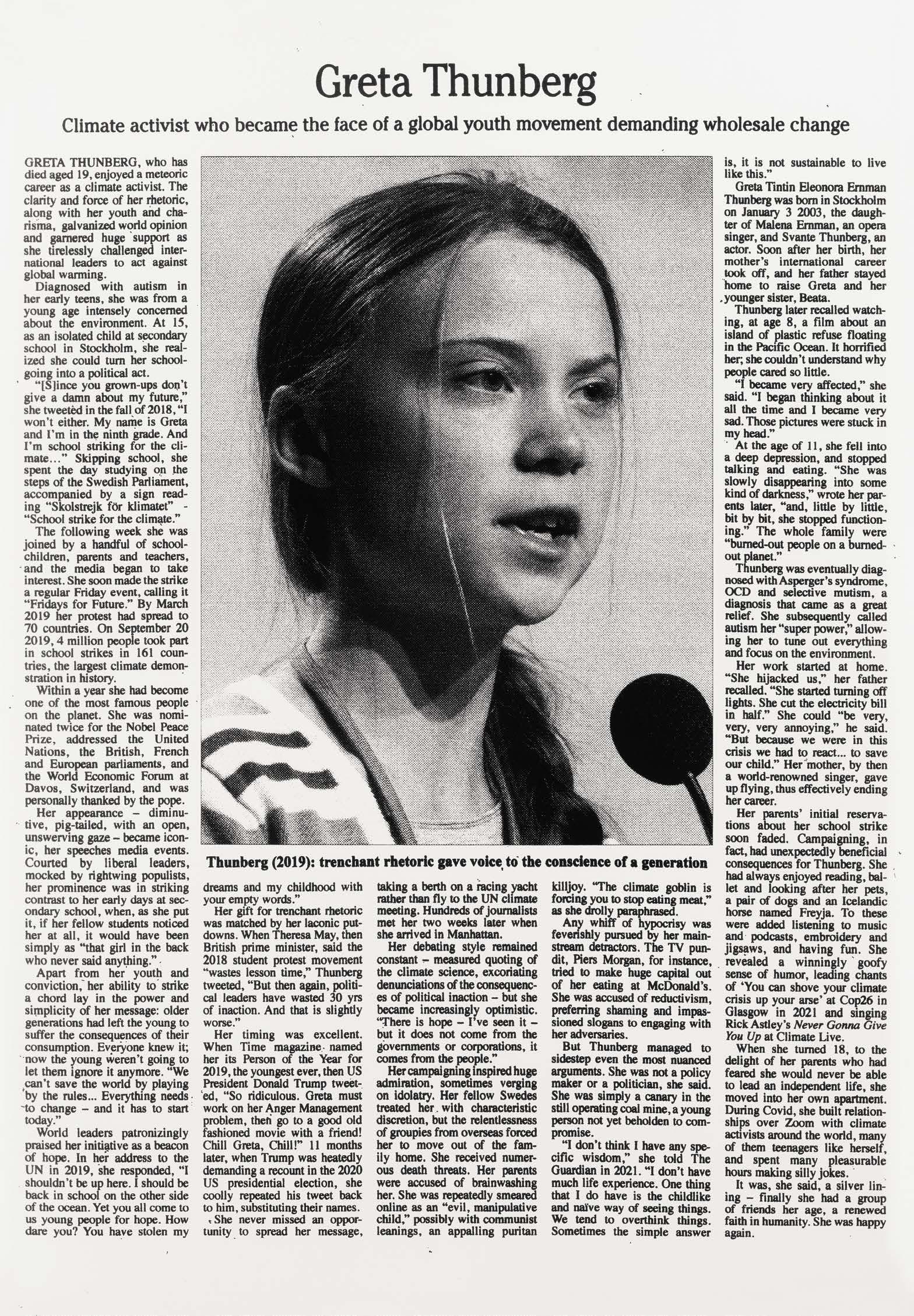

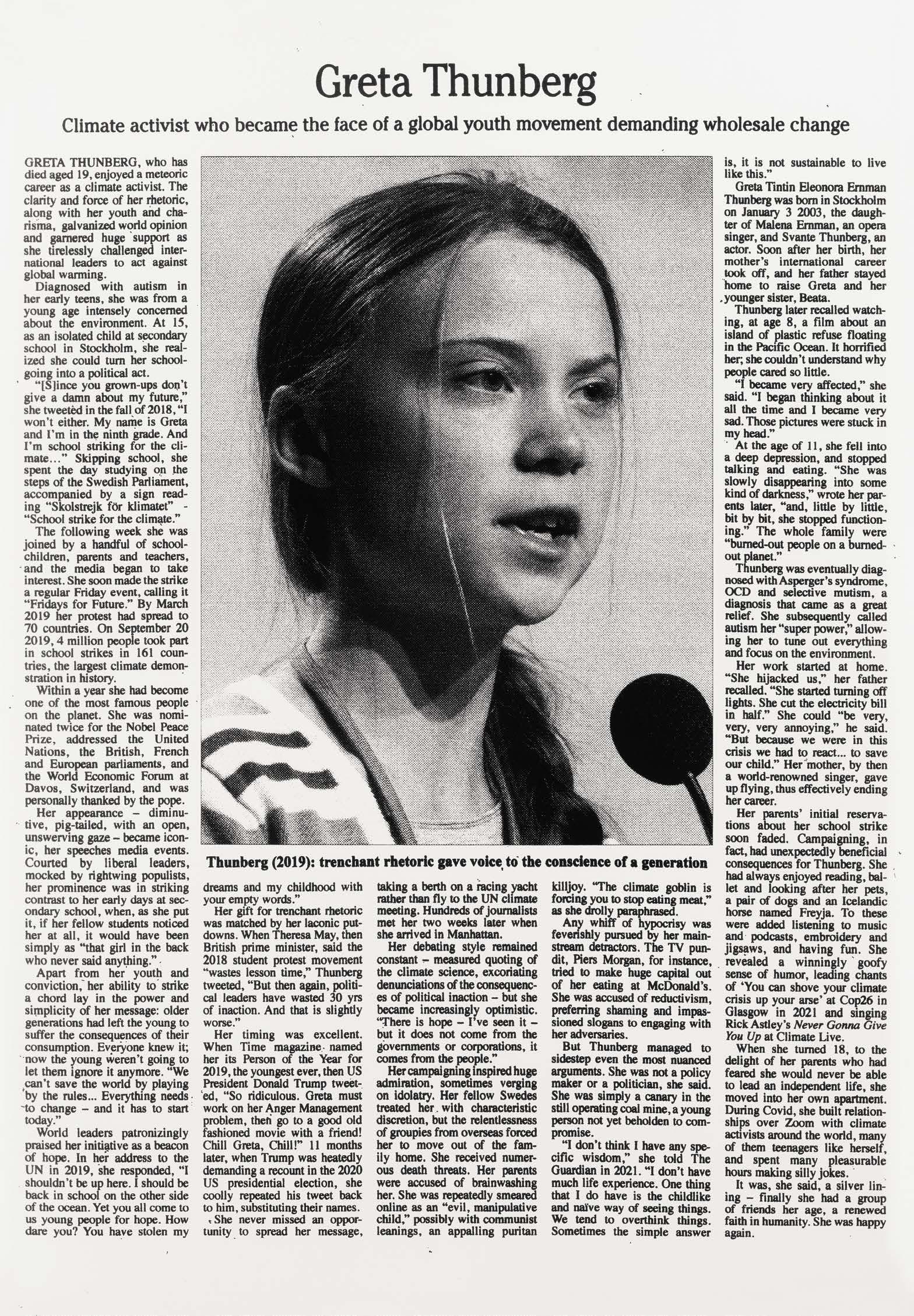

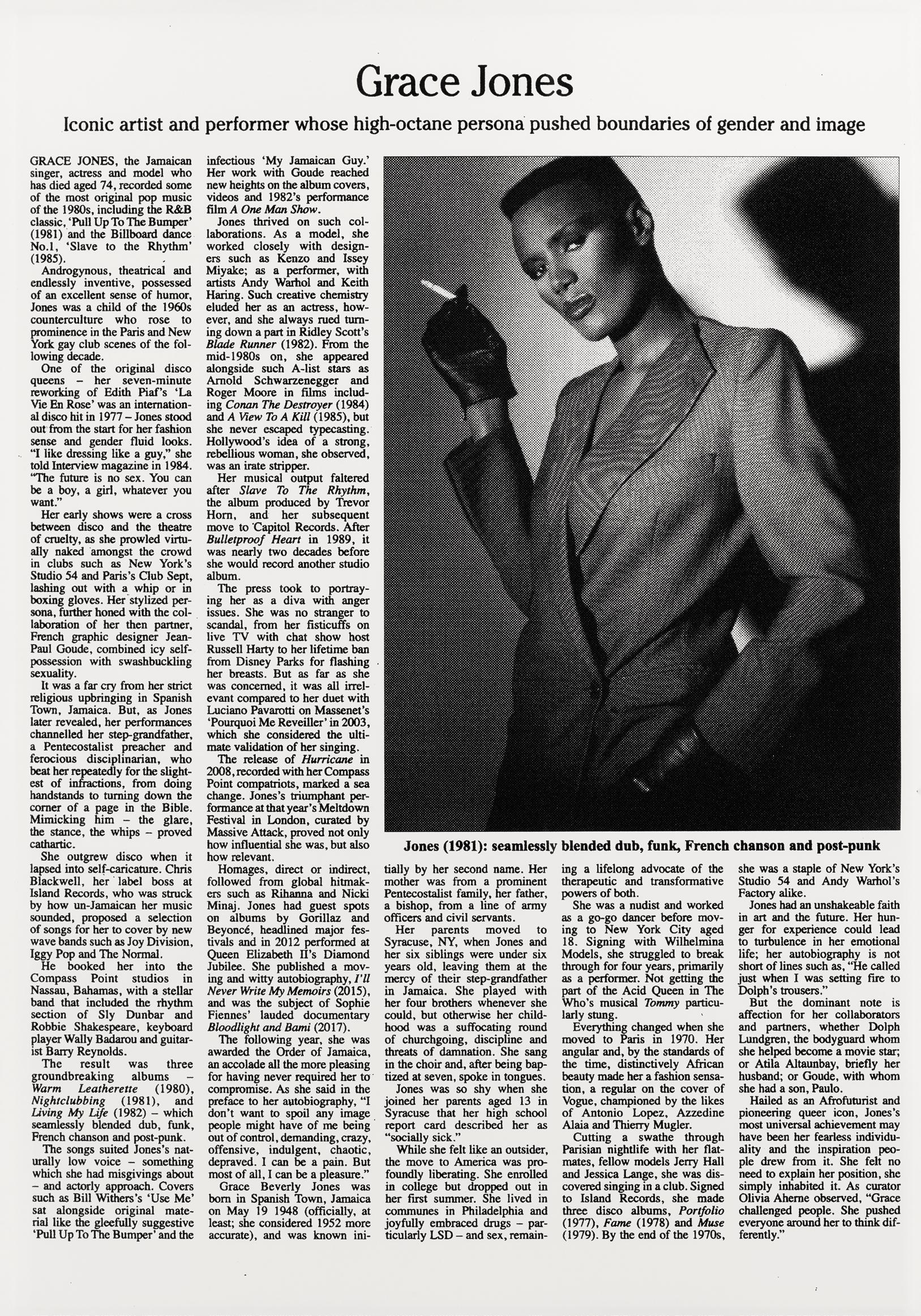

Adam McEwen was born in 1965 in London, England. He received his BA in 1987 from Christ Church, Oxford, and then received his BFA in 1991 from the California Institute of the Arts, Valencia. His multifarious practice includes obituaries of living subjects such as Bill Clinton, Greta Thunberg, and Grace Jones, alongside sculptures in various media and paintings on canvas and sponge. McEwen currently lives and works in New York City. Photo: Andisheh Avini

Lisa Turvey

Lisa Turvey is the editor of the catalogue raisonné of Ed Ruscha’s works on paper. Before joining Gagosian, in 2008, she was the managing editor of October. She has written for publications including Aperture , Artforum , Art Journal , and October

Jeremy Deller

Jeremy Deller studied art history at the Courtauld Institute. Deller won the Turner Prize in 2004 and represented Britain in the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013. He has been producing projects since the mid1990s, often in the public realm.

Wyatt Allgeier

Wyatt Allgeier is a writer and an editor for Gagosian Quarterly. He lives and works in New York City.

40

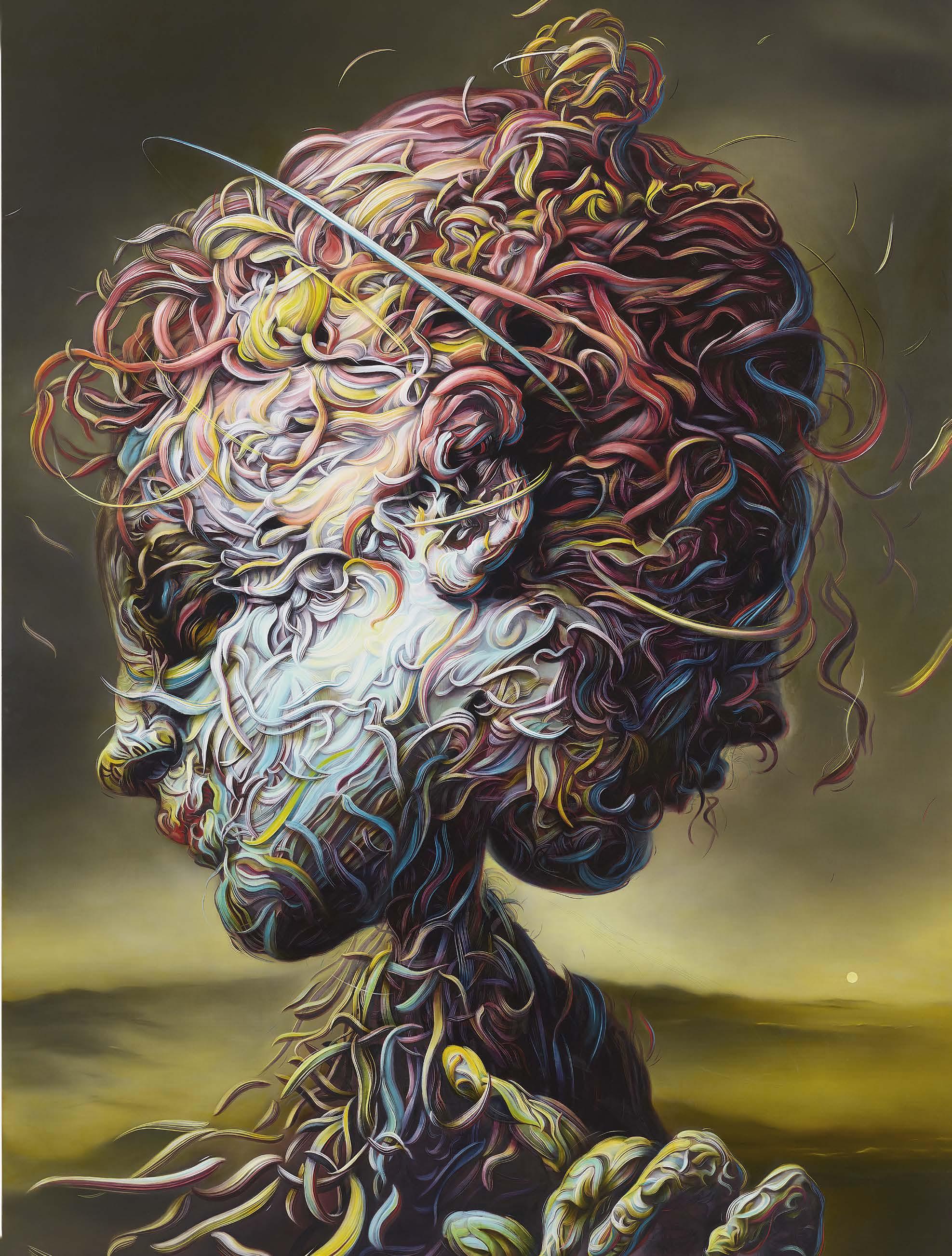

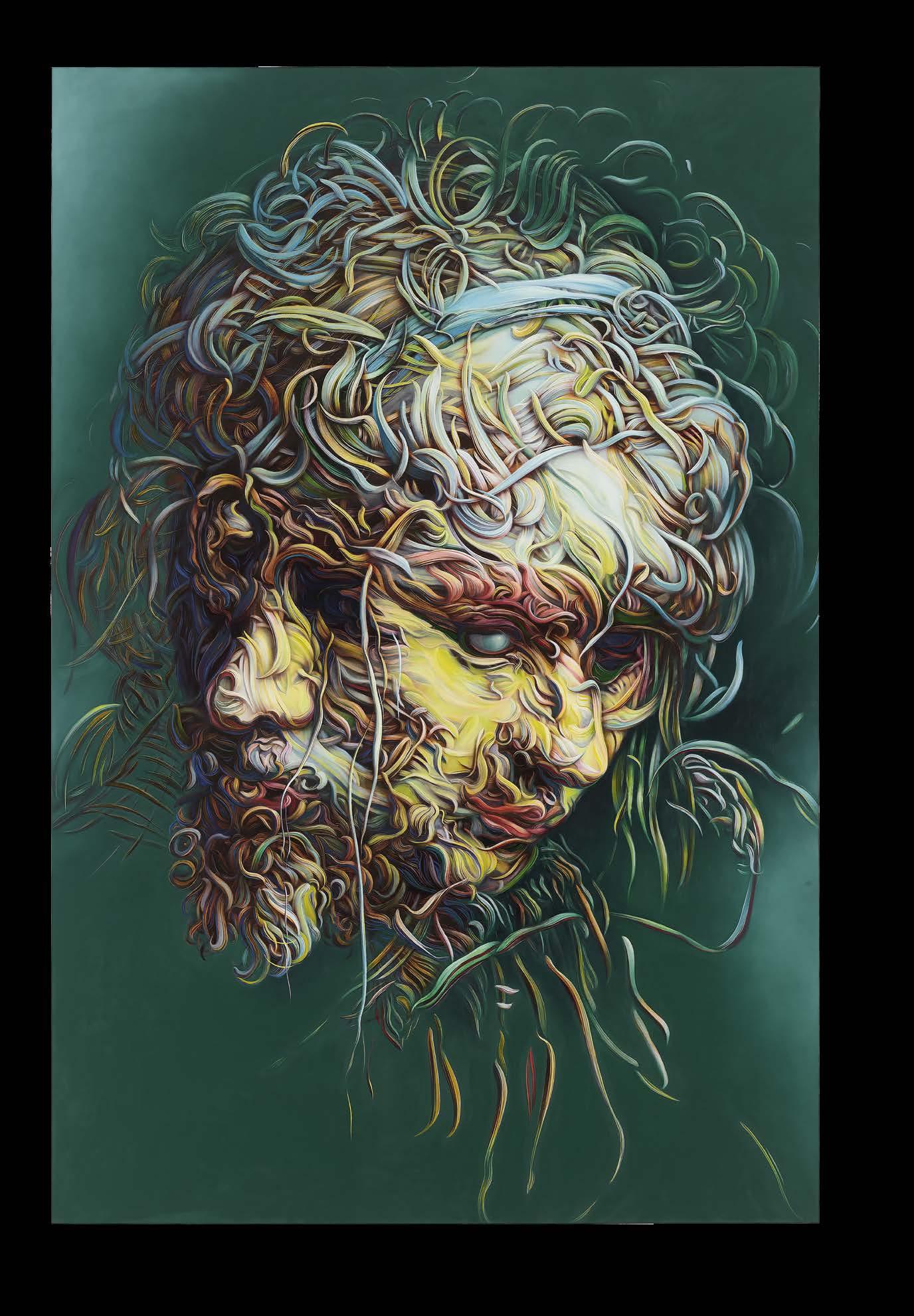

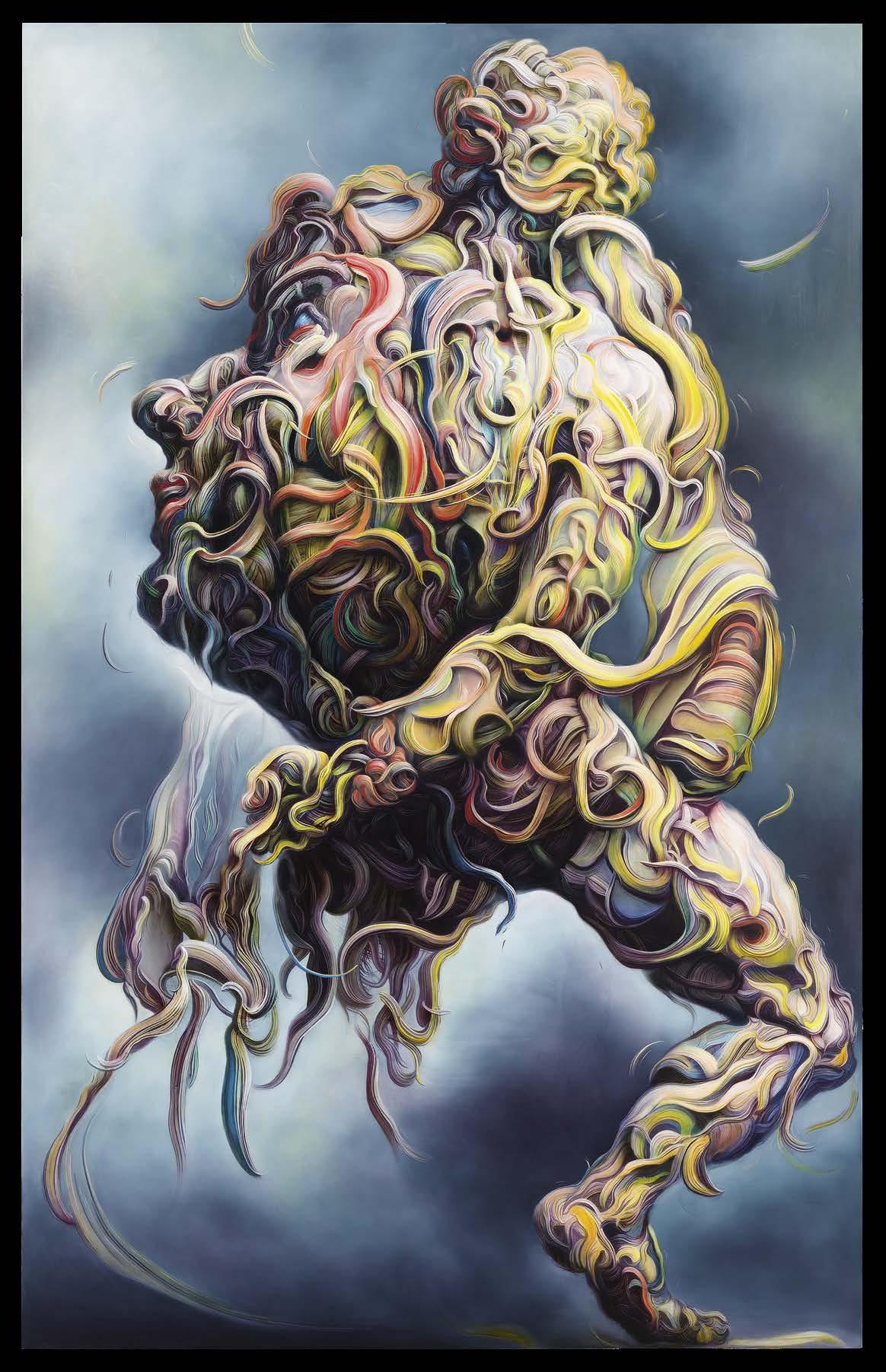

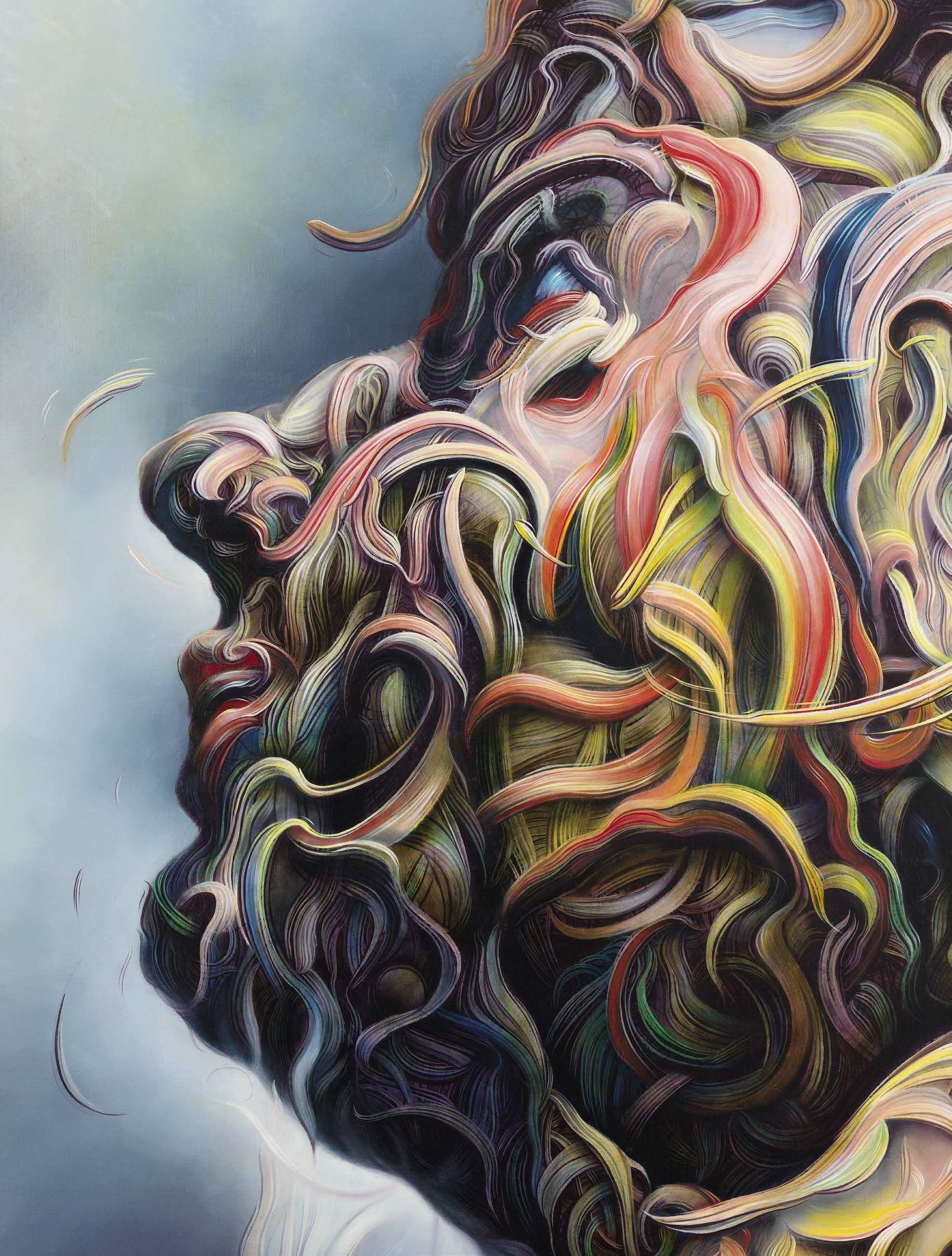

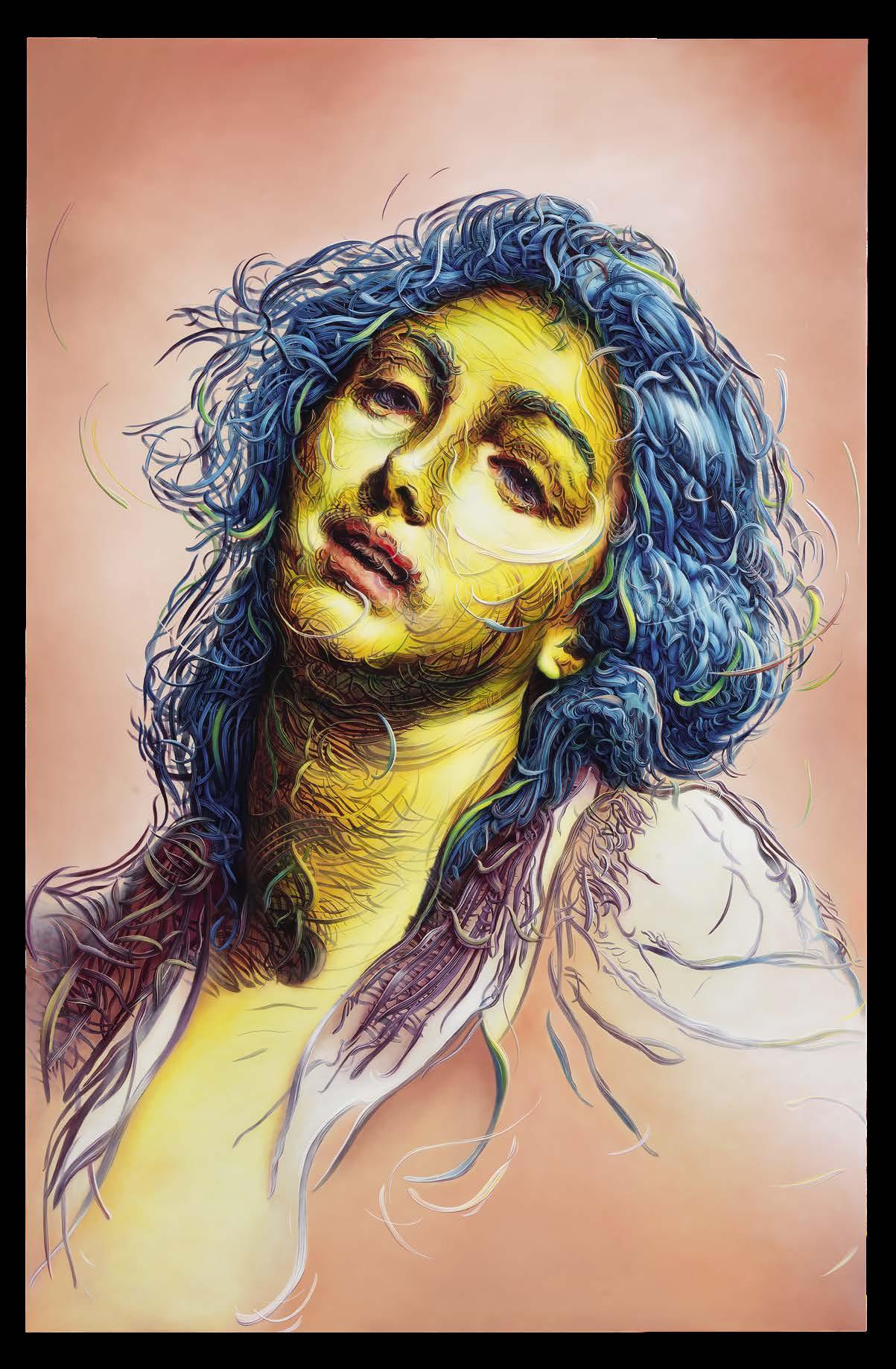

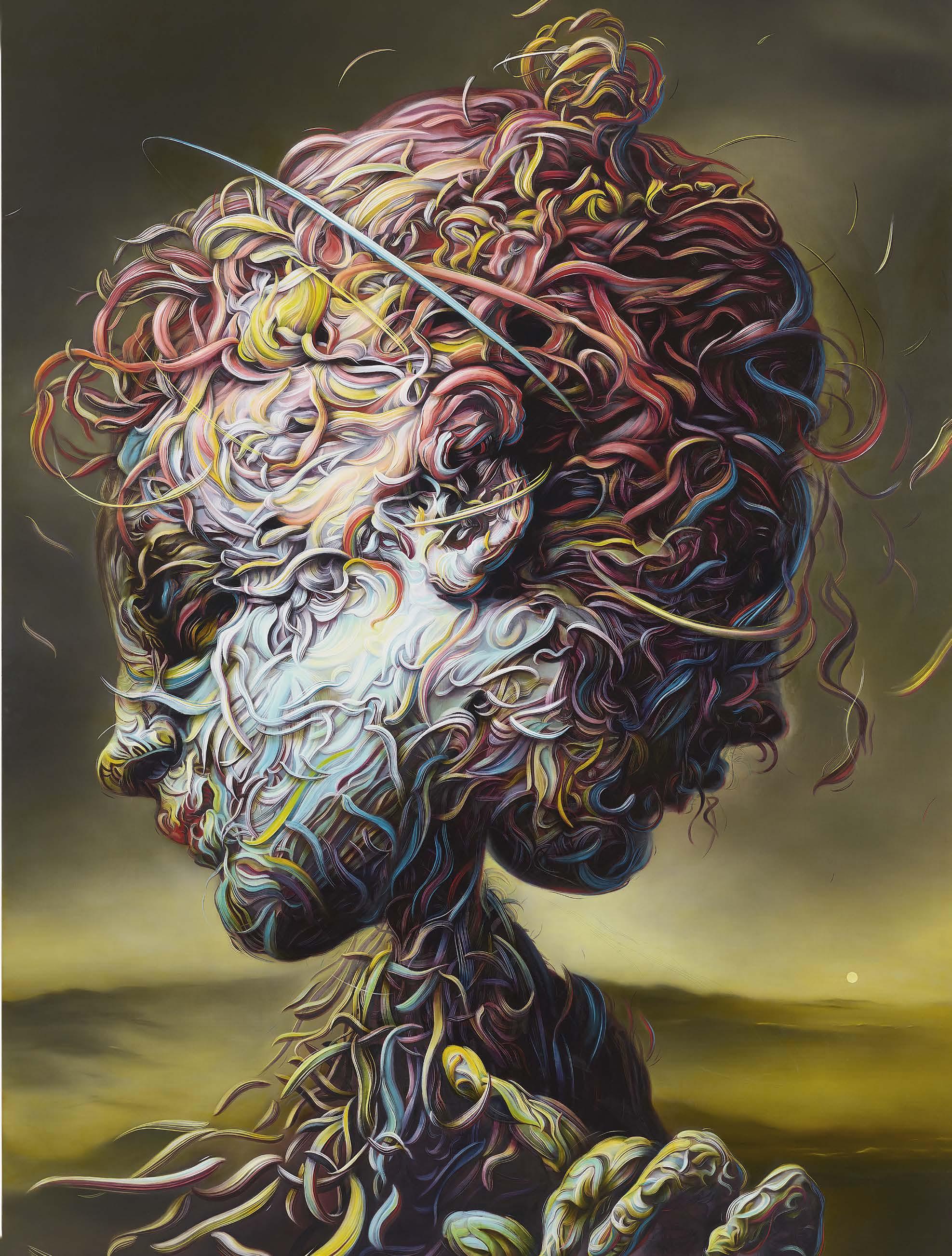

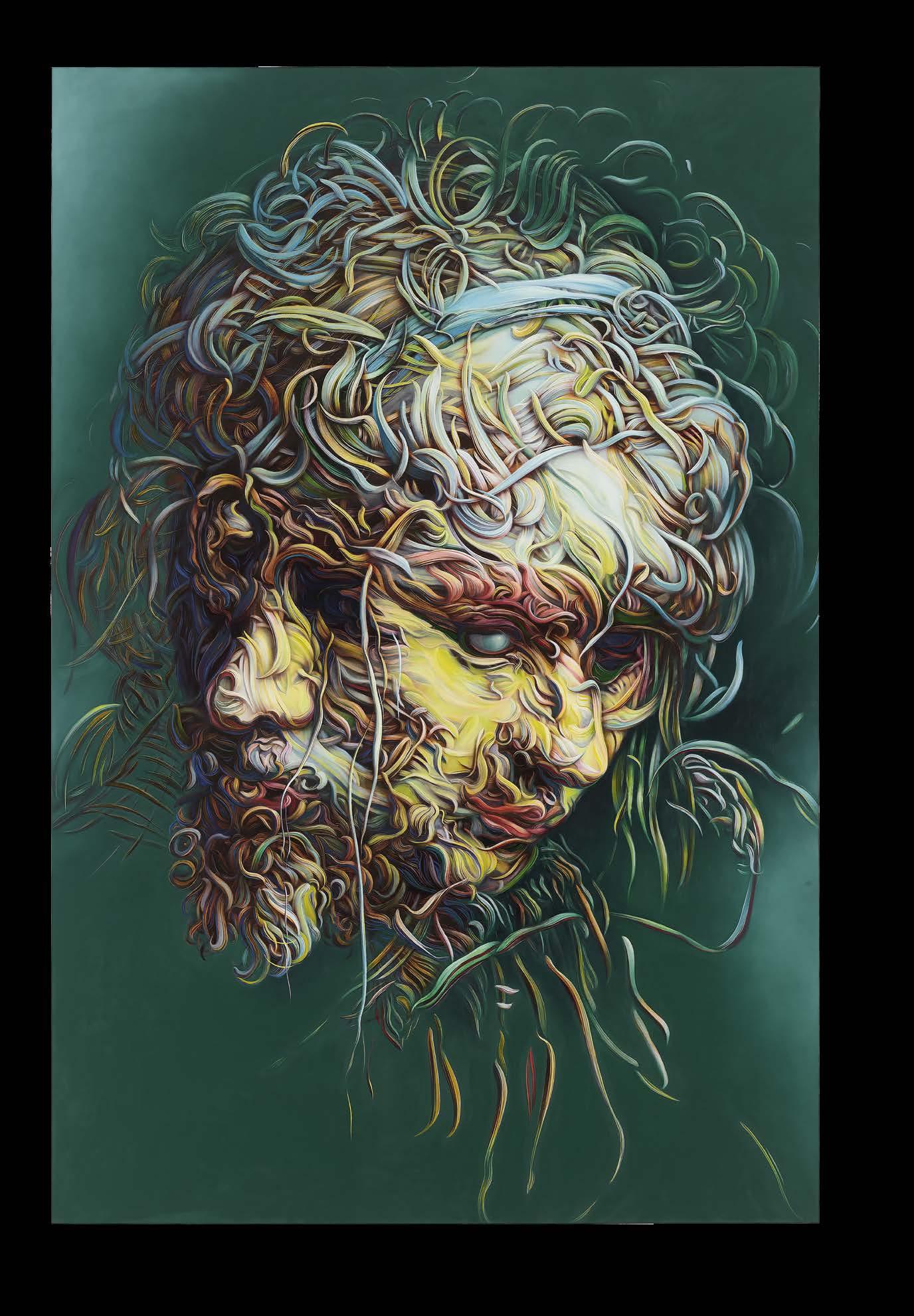

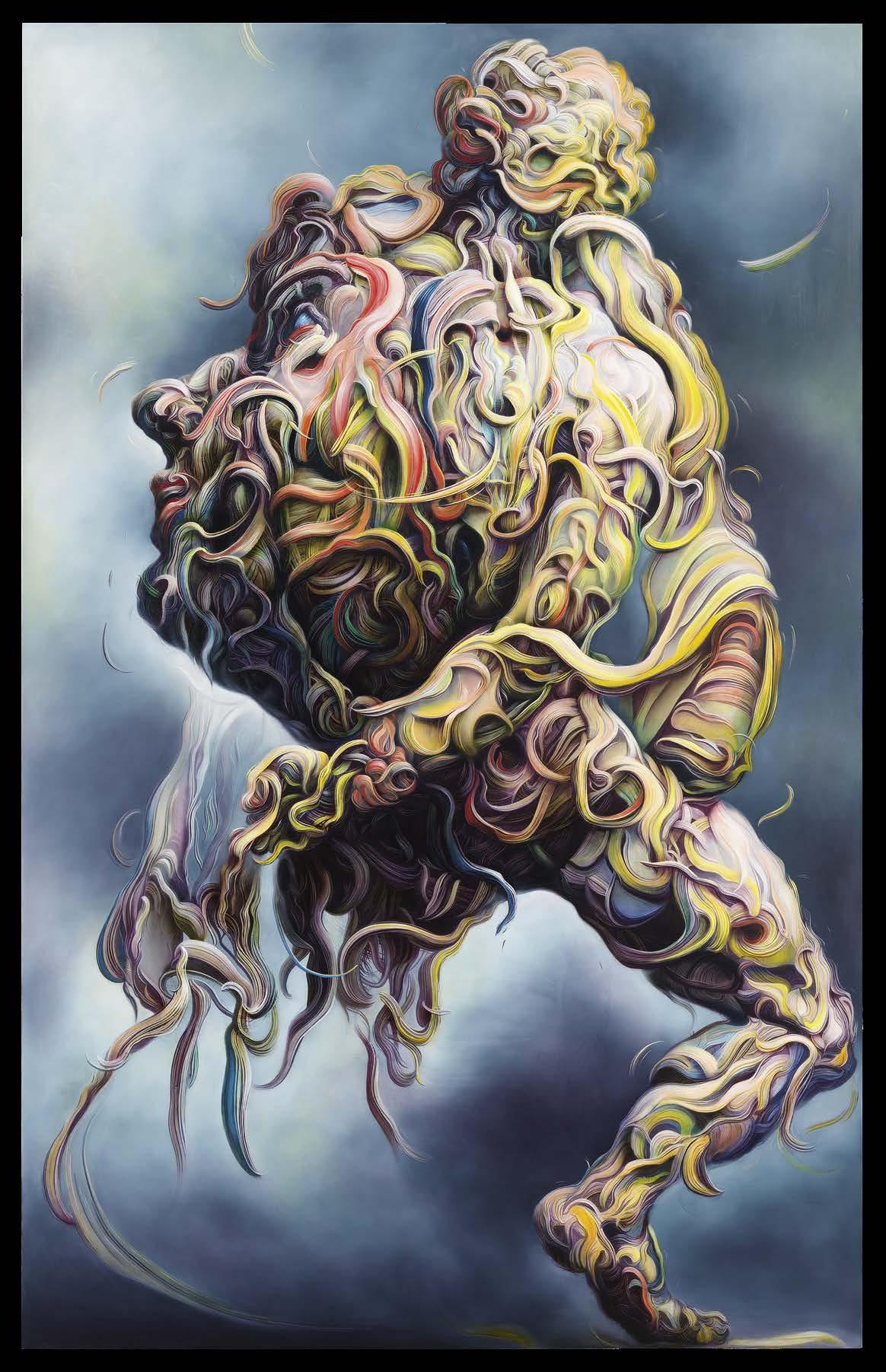

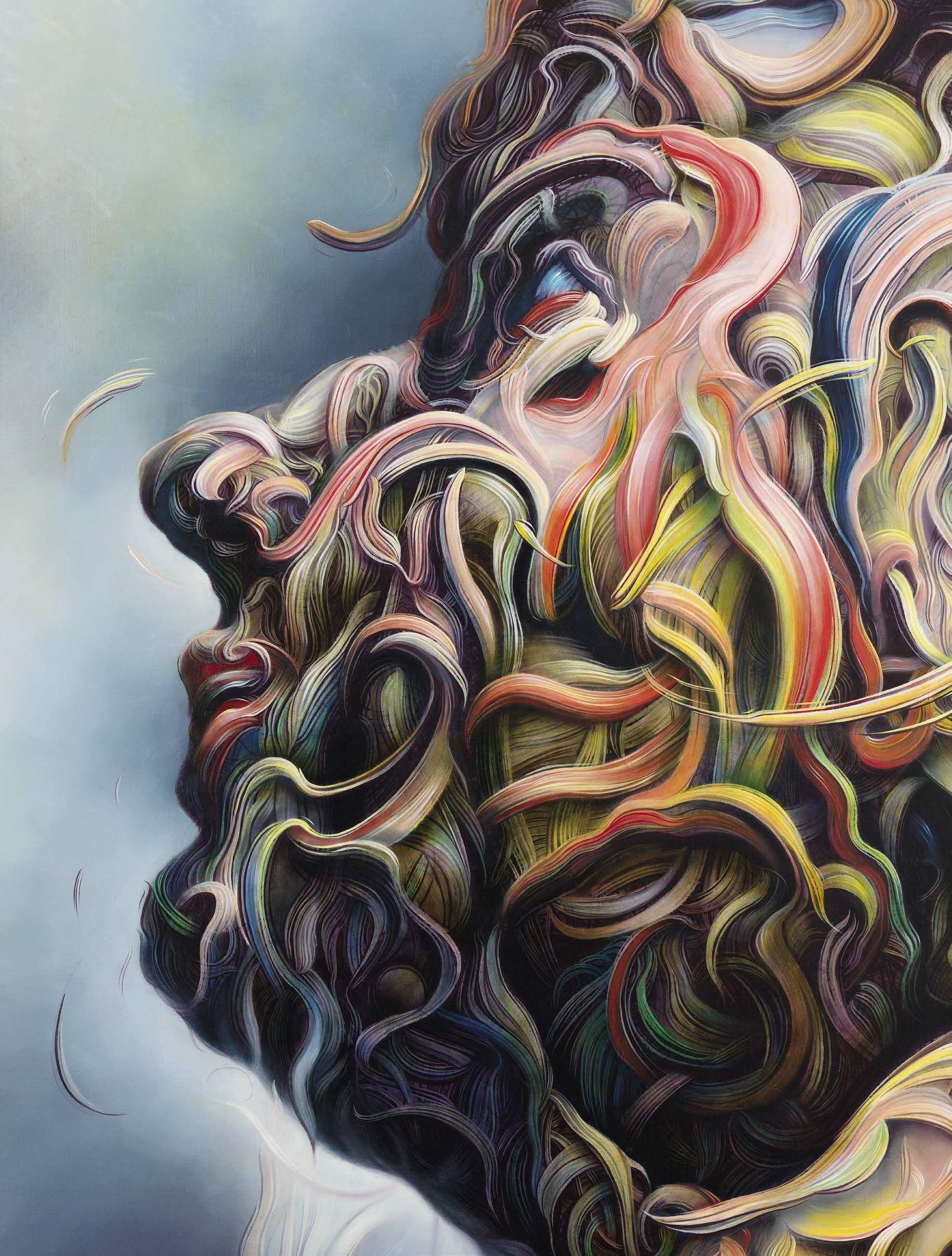

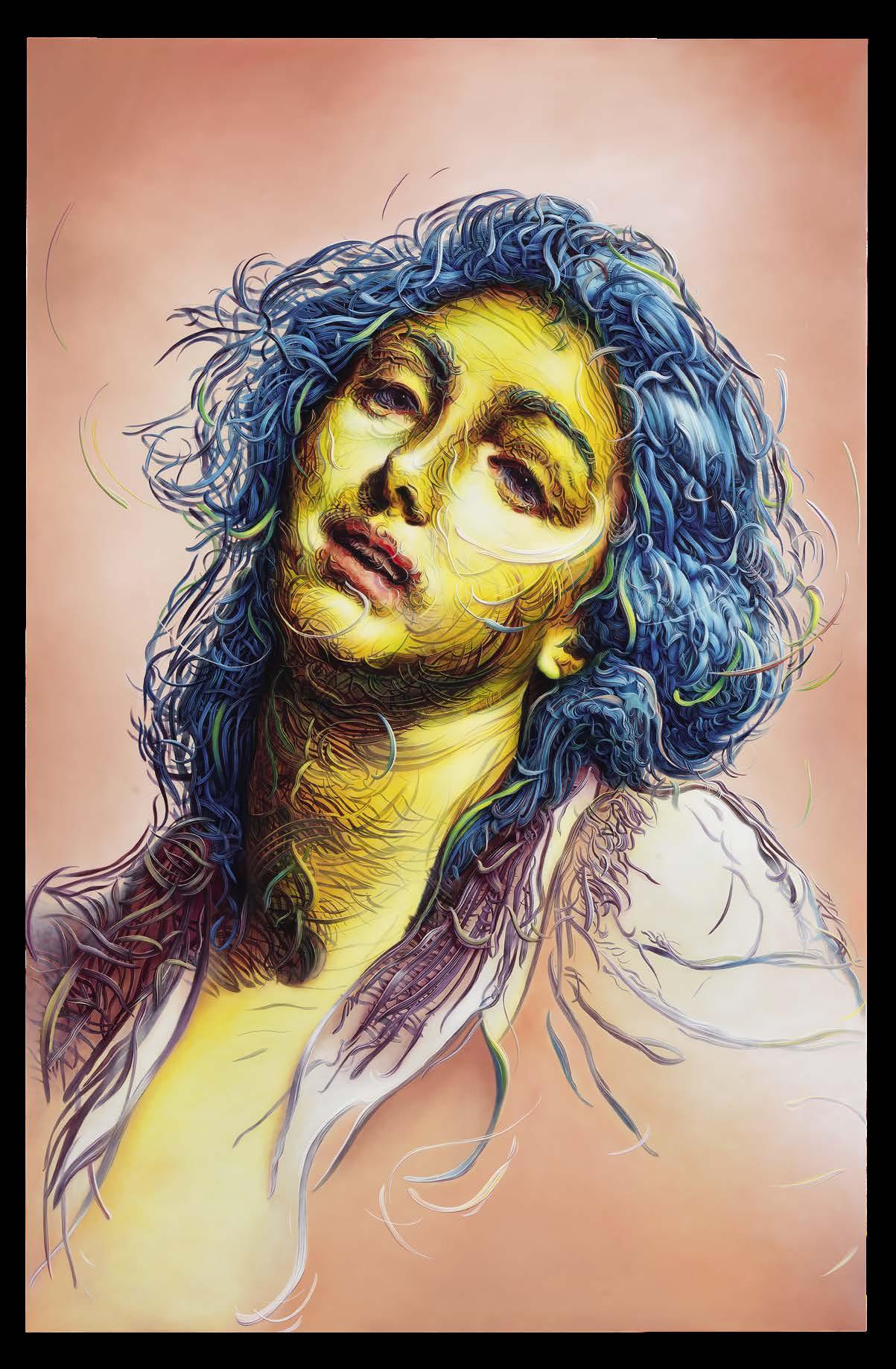

GLENN BROWN FROM THE INSIDE OUT

Novelist Andrew Winer reports on the formal, conceptual, historical, and philosophical perspectives embedded in Glenn Brown’s latest paintings and drawings. The two talked after the opening of the artist’s recent New York exhibition Glenn Brown: We’ll Keep On Dancing Till We Pay the Rent .

It’s late, Glenn Brown’s opening is over, and at last all sixty of our party—dealers, collectors, curators, gallery staff, friends, and various beautiful people—have snuggled into the tables that have been reserved at a hip new restaurant in Chelsea. To our relief, waters arrive, followed by wine and hors d’oeuvres— extraordinary Tuscan things we can’t wait to try—but then the artist gets to his feet with a curl of paper in his hand. He’s making a speech.

“The Over-Soul,” Brown explains, referring to the Emersonian concept that inspired one of his paintings, “concerns whether we have a soul or not.”

Everyone at my table reaches for their wineglass.

Any artist willing to regale a restaurant full of hungry art-world cognoscenti with a lesson on Ralph Waldo Emerson is after my own heart. But that will not be the only lesson. Standing there in his elegant three-piece suit as waiters push past, Brown shares that he was given the middle name “Emerson” by his late father, who had derived his sense of morality from the great American transcendentalist. It’s his father’s tie that Brown is wearing tonight, an homage to how much the man helped him with his paintings. Help that was apparently needed. “I’m fifty-six,” he continues, “and it feels like painting is this most awful mistress that you try and please, but she just punishes you. You keep struggling and fighting with it, you want this marriage to work. But we never actually get to make the painting we actually really set out to make. And my father used to look at the painting I was working on and tell me, ‘Within painting you cannot lie. You think you’ve gotten away with it, Glenn. But like Emerson tells us, honesty and integrity are the most important parts of being an artist.’”

What has Brown gotten away with?

“I’m pointedly lying. My paintings are completely dishonest.” I’m walking with him through the gallery the following morning and we’ve arrived at the painting that lent the show its title, We’ll Keep On Dancing Till We Pay the Rent , because he wants me to examine the color-drenched, twofaced head that graphically dominates the canvas, a sort of iconic modern-day Janus. “Look—it’s not real painting. It’s pretend painting. Pretend white light that comes from the left here, fake red light emanating from the right, yellow light coming down from there—I have imaginary lights lighting every single brushstroke, leaving some of them in shadow and some in light.” He points to one of the many large, overlapping, whipping brushstrokes

44

Previous spread: Glenn Brown, We’ll Keep On Dancing Till We Pay the Rent , 2022 (detail), oil on panel, 78 ¾ × 55 ½ inches (200 × 141 cm). Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd

Opposite: Glenn Brown, The Holy Bible, 2022 (detail), acrylic on panel, 78 × 48 5⁄8 inches (198 × 123.4 cm). Photo: Rob McKeever

This page: Glenn Brown, Doggerland , 2022, oil and acrylic on panel, 85 1 8 × 56 ¾ inches (216 × 144 cm). Photo: Rob McKeever

that, in aggregate, seem to thickly make up the head (some of them are also twirling and peeling and otherwise falling away from it). “There are umpteen lines there in any single brushstroke. I’m trying to trick the eye. Make the stroke look three-dimensional. But it’s all smooth.” Indeed, the strokes’ impasto look is simulated. What appears to be spontaneous, heavily applied brushwork is the result of a laborious, precise, lapidary process—and all of it is pressed beneath the glassy surface of the painting. “For many artists—look at Joan Mitchell—their work sits on the picture plane. Or Willem de Kooning. Frank Auerbach. My work exists on the other side of the picture plane. It’s illusion and the use of trompe l’oeil and perspective, which is not a modernist thing to do, generally. It’s artifice. It doesn’t tell you the truth of how it’s made.”

Nearly all good paintings enjoin us to contemplate how they were made. Brown’s do so swiftly and arrestingly. He’s a superb draftsman and an equally superb image-maker, and his show’s large heads and figures seem to punch out into the gallery with graphic, eye-catching boldness. Yet they don’t catch your eye with their eyes. By intention, none meets your gaze. “It’s rude to stare,” Brown tells me. “But these will never stare back at you, so it gives you permission to look.” What else is there to do but look, then—how is each painting made? For Brown, the answer is brushstrokes, brushstrokes, brushstrokes. But it isn’t simple.

In a way, every painter has to search for permission to paint. Something else Brown has gotten away with: making paintings at all. That may seem a funny thing to say, but the charge to self-justify is embedded in modern art’s subservience to the avant-gardist idea that it must constantly evolve, rejecting what came before (even as it indirectly furthers, sometimes, what has been). In the 1950s, the Abstract Expressionists fervently adopted this history-erasing ethos, which evolved into Pop indifference before being turned into something like dogma by Conceptualism and Minimalism. By the time Brown was an art student, several schools of artists had emerged with another attitude toward progress in art: the Pictures Generation, the Neo-Expressionists, the appropriation artists, and the Neo-Geo painters retained the idea that art must evolve, but they were interested in finding ways to work with art history—an interest that you might say was forced on them by an abiding sense that art had reached a point of exhaustion. What about it was exhausted, exactly? Certainly

45

the idea of authenticity and originality, the privileged status of a work of art. The image as a carrier of meaning and significance came into question. And in the case of painting, a related, older sort of exhaustion inhered: namely, a distrust—felt by Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg as early as the mid-1950s—of the expressive mark’s ability to convey meaning.

Yet the history of art has proven that exhaustion can lead to renewal and freedom. And the reduced status of the image, the brushstroke, and the work of art itself paradoxically made each of these not only serviceable but enticing as raw material to artists of the 1970s and ’80s, who were inclined to use them with a new knowingness. Driven by a sense of intellectual authority inherited from Conceptualism, such artists as David Salle, Sherrie Levine, and a whole host of their contemporaries claimed

a new freedom to fish out and use images from a grab bag history of art and culture. Then there were those oriented around the brushstroke. For the most part eschewing any conceptual justification, painters such as Georg Baselitz, Julian Schnabel, and Jean-Michel Basquiat wielded the expressive mark anew, often with a sort of devil-may-care abandon. Whatever justification they sought or claimed for all the demonstrative painterly license they were taking showed up as some mix of irony, self-consciousness, or cultural signification. A cooler approach was adopted by painters like Brice Marden and, in his abstract canvases, Gerhard Richter, who found various mediated means to produce strokes that were pleasing but drained of much of the emotiveness that attended the work of their Neo-Expressionist contemporaries. (Anselm Kiefer can be thought of as an amalgam of these

hot and cool approaches: his brushwork is manifestly loose and expressive, yet fettered by the grim task of grappling with some ugly German history.) Such were the currents into which the young Glenn Brown and his contemporaries first dipped their toes. But as roiling and vigorous as those postmodern seas were, even they, for Brown’s generation, gave off a slightly malodorous reek of exhaustion. It so happens that I’m Brown’s exact age, having matured in the late ’80s—after the party was over. But then the party was over for our generation before we ever knew what the art world was: if our parents in the ’60s and ’70s experienced the vertiginous feeling of living in a way no one seemed to have before, we experienced living in a hundred different ways that had just been lived. (I am suddenly reminded by this, and by Brown’s paintings, of waking up as a child to a house strewn with

46

sleeping hippies, wine bottles, smelly old food, dirty plates, half-smoked doobies, gothic-looking album covers, sci-fi novels, books on ecology and philosophy and cabin building, and a pot of spiced wine on the stove, still warm and fragrant, beneath a framed, counterfeit Salvador Dalí etching.) What were we to do, in our youth, but cherry-pick from the leftovers? Later, in the arena of cultural production occupied by artists (always more advanced than parents!), we had no choice but to cherry-pick from the leftovers of the leftovers. For painters, this often meant leaping backward over the postmodernists and over the history-annihilating Minimalists and Pop artists—sometimes to the Abstract Expressionists (as in the case of Cecily Brown) or even much farther back (as in the case of John Currin). Brown leapt, and continues to leap, back to all such places, taking his imagery mainly from the old

masters and his technique from Abstract Expressionism—with a twist.

That twist, an inward one, emerged from the fact that Brown, like other art students of his generation, took his justification less from Conceptualism than from French and German theorists. The influence of semiotics, poststructuralism, and deconstruction encouraged these fledgling artists to look not just at the language of a made thing but at the smallest components of that language. Brown, arguably, looked harder in this direction than most of his generation did, and it’s part of what led him, oddly enough, toward that old exhausted thing: the expressive brushstroke. But his love for the work of de Kooning and Rauschenberg in America, and of Auerbach, Lucian Freud, and Francis Bacon in his own country, also led him to the brushstroke—even if that love can’t quite be separated, in my opinion,

from Brown’s mischievous desire to go toward what is least fashionable.

What to do, though, with the brushstroke?

Rauschenberg, having gone about deconstructing and reconstructing Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s with a kind of insouciance, offered a clue. Brown certainly seemed to want to pay expressionism, among his other historical references, the compliment of repurposing and reconstruction— of homage rather than outright rejection. But so did the Neo-Expressionists in the ’80s; how was Brown to distinguish what he was doing from their efforts? Another, less obvious clue came from farther back, in one of those unfashionable precincts where dwelled artists such as Fragonard. “I’ve always been trying to save him from the guillotine,” Brown admits when I ask what the Rococo painter has meant to him, “because taste is continually

47

trying to string him up. But take his suite of paintings in the Frick: the subject matter is really rather downplayed, and if you look at them as abstract paintings, you get a sense that this is all a dream because of the way everything is painted. His gelatinous mark-making causes you to think that everything is made of the same material almost.” How could Brown deconstruct expressionism and realism at the same time? How could he make a kind of realist painting that feels as artificial as an Abstract Expressionist painting—that “makes you think that everything is made of the same material”? Brown’s solution, following the model of the poststructuralism he was reading, was to take his deconstructing down to the smallest possible unit of the language of painting. If artists throughout history had acknowledged the artificiality of painting in a thousand different ways, it was time to take the artificiality inside the stroke.

Brown must have galled more than one envious peer trying to figure out, as many were then, how to get away with de Kooning– or Auerbach-like brushwork without copying Richter. He had found a way to pay his own kind of homage. As with Richter, it was ironic homage, to be sure, but not cheapened. (Accusations of cleverness and trickery will ring hollow to anyone who really looks at what Brown achieves with his trompe l’oeil brushstrokes: they’re simply too adept, too bravura, too fun, not to be taken seriously.) To be successful, homage of this sort must first be directed just to the right or left of the thing to which homage is primarily being paid. Richter’s abstract paintings pay homage to photography, for example, on their way to paying respect to expressionism. So what about Brown? His paintings ultimately pay homage to expressionism as well, but before that, they defer to something that no longer exists, something that was lost when we “wised up” about painting in the ’60s and ’70s. I’m not referring to the mid-twentieth-century idea, questionable even then, of painting as an activity that, for the artist, is self-actualizing, self-fashioning, and self-expressive. I’m referring to that idea’s more defensible concomitant: that the extemporized brushstroke is a vessel or catalyst for feeling.

Still, Brown’s brushstrokes ought to make us feel. Is there not something poignant about his dedicating years of very fine painting to an idea that was for him and his contemporaries already debunked? And what about the haunting fact that he reproduces brushstrokes that never were? Or that he can spend many hours on a stroke that might have taken an expressionist a second? A lot of longing attaches to this enterprise. I’m deeply

48

Previous spread: Installation view, Glenn Brown: We’ll Keep On Dancing Till We Pay the Rent, Gagosian, 541 West 24th Street, New York, November 8–December 23, 2022.

Photo: Rob McKeever

This spread: Glenn Brown, The Over-Soul , 2022, oil on panel, 76 × 48 inches (193 × 122 cm).

Photo: Rob McKeever

moved by it; I hope other viewers are too. Brown’s strokes may be slowly crafted simulations that exert a subtle steeliness across the canvas, but such is our contemporary fate: that feeling, like the humans who carry it, must come through metal detectors in order to fly.

What is life? What are we doing here? Brown’s paintings, for all their incendiary, campy colors, for all their denial of art’s old heroism, still ask these philosophical, even spiritual questions. They, along with the three drawings in the show into which Brown also layered multiple images, have something to say about the complexity of being a person. And this is the final thing that Brown gets away with: being a storyteller. (Even though narrative painting made a comeback forty years ago after its banishment by abstraction and Minimalism, and despite having always had an audience, it continues to sit uneasily with more than a few critics and theorists, and indeed with a number of artists.) So what story is Brown telling? “I’m not trying to depict the world as it is,” he tells me as we stand before The Holy Bible , his sensational painting of a tree trunk that has the flatness of Pop and the somber blues and browns of Dutch landscape. I take in the tree’s burled bark and knobby, almost grotesque roots. “I’m trying to describe the world as it might be if it could express itself,” Brown goes on. “So hence the tree starts to describe what it might be to be a tree. And the human body tries to describe all the pains and agonies, the loves and sexual drive that’s within our bodies. And not just that: I’m trying to describe the world as it might be if we stopped dominating it. So this tree is a fully sentient being—literally has faces in it. When I paint trees, I paint them as if they are people. And I paint people as if they are trees. Everything becomes more exuberant. It’s very much against the classical idea of the perfect human.”

Brown is certainly telling that story, too—of the imperfect human. This is a good thing, though not because we will find reassurance there. Selfhood in our altered world is an anxious place, as this show makes obvious. In the final room of the gallery, we at last face The Over-Soul , in which an enormous female face merges with a smaller male figure against an indeterminate blue-and-white background. “I’d like my paintings to describe not what the human body looks like, but what the human body feels like,” Brown declares, echoing the Mannerist credo about distorting the parts of the body that are more important. “If you close your eyes and imagine what your body is, then that’s what I’m trying to depict here. So it’s the human body from the inside out. Your stomach, your intestines, your

musculature, your bones—they’re just as important as what happens to be on the outside.” Brown puts Surrealism at the service not of the unconscious, then, but of the body—at the service of a self that is multiple, androgynous, contingent. . . .

And psychologically cocooned. By preventing his figures’ eyes from meeting ours, Brown delivers portraits of subjective solitude caught in a moment (not in an instant: there’s too much movement, and anyway instants are the same thing as forever, where all portraits of people meeting our eyes live). In this sense Brown is a realist. Catch anyone in a moment and what you will get is the reality of their aloneness. Togetherness, like happiness, is banked on the fiction of the always incipient next moment: the thing that will be said, the love that will be expressed, the meeting that will occur, the physical contact that will be made. Take the next moment away for a moment, and, as at the moment of death, we are irremediably alone in the universe. Brown’s snaking, intertwining brushstrokes, fastened together by nothing more than the artist’s precise and subtle wrist action, seem to embody and enact, in this way, the reckoning mind: synapses grappling with absolute questions, always at risk of fragmenting into chaos. Here, Brown’s paintings prove that art can still do its old job of revelation, or, at a minimum, of offering apt metaphors for our tenuous present-day condition. To look at them is to see that truth, beauty, and other values that make life worth living turn out to be human made. It’s to see that our ultimate concerns, resistant to earnest representation, are constructed things, requiring the most advanced tools of leavening and artifice—irony, deflection, dissonance, and wit—to make a rare appearance. But Brown’s paradox extends even further: heartbreakingly, these figures are only representations—representations of other representations. They live nowhere but in paint. We have to look at dead things to know how to live. Brown is a realist because he catches us in the problem of being at all.

Not bad for a self-declared Marxist who, performerlike, accepts democracy’s leveling effects when it comes to his audience. His tastes may run to the more embarrassing jewels of art history, but once he has drawn his subjects on the canvas, they stop mattering, becoming for him little more than overlapping congeries of lines. Then he begins to paint, turning up the heat with imitations of slashing strokes and the acidic colors of our time, weaning old master charm and splendor into proper plebeian shape. Only the drawings, with the help of almost comically ornate frames, are easily

traceable to the old masters. For this reason I give them pride of place in my imaginary lobby installation of Glenn Browns at museums of old paintings the world over. If people could only be made to walk through a room of Browns before entering those venerable institutions, their hearts might be alleviated of fears of elitism, their eyes might be opened to what still matters in the old masterworks. In this sense Brown’s work is like a bridge left standing amid the devastation wreaked on high art and subtle sensibilities by war and entertainment and grim commercial prudence, to say nothing of populist resentment and radical egalitarianism. “I think it’s that balance between beauty and the bourgeois and the sort of underbelly and turgid shit,” Brown tells me as we pause before one last painting—of a ravishing woman’s face— that he has entitled Led Zeppelin II . “I was talking to John Currin with the couple who bought this and he said, ‘What’s that color you’re using on her face? It sort of looks like warm piss.’ I told him it is piss! It’s painted with Indian yellow, which is made with the urine of oxen that they’ve fed with mango leaves. So I’m asking for somebody to look at these as both beautiful, like a sort of delicatessen, and rather stinking and shitlike.”

I mention Milan Kundera’s notion, in his novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984), that kitsch is the fear of shit.

Brown looks surprised. “What does that mean?”

“Well,” I say, “that the saccharine clichés of kitsch represent a kind of running away from shit. A pretending that we don’t have plumbing pipes to take away our fecal waste.”

His eyes do a tour of his paintings around the gallery, and then he looks at me almost apologetically. “I mean—” he starts, and stops. Then, in a confiding tone: “All of the paintings here do look to me very kitsch .”

He catches me staring at the piss-yellow face in front of us.

“Like I say, my paintings are completely inauthentic,” he offers. “Any emotion you see in them isn’t necessarily emotion I feel.”

“But do you like to paint?” I ask.

“I like it more than anything else.” He chuckles, before turning serious. “Really—anything else.”

There’s a pause. We’re both winding down, tired from the late dinner last night and from a long, fruitful conversation today.

“People think you have so much talent,” he says with a faint tinge of regret. “They’re trying to read my work. It’s still the thing of the genius artist. Which I just don’t believe. I wasn’t born with any more talent than anybody else. I just learnt to do it.”

50

Opposite: Glenn Brown, Led Zeppelin II , 2022, oil and acrylic on panel, 84 7⁄8 × 55 inches (215.5 × 139.5 cm). Photo: Rob McKeever

Artwork © Glenn Brown

“So it’s a performance?”

“Life is a performance.”

“Was the speech you made at the restaurant a performance?”

He breaks into a smile. “You have to stand up and sing for your supper. Quite literally, in that case. It’s part of the role of being an artist. There’s the cliché of the isolated existentialist outsider artist. For about fifteen or sixteen years I sort of played that game, because I never allowed myself to be photographed. Then it just became impossible, because people would just come up and shoot me with their phones.”

“Was it because you wanted anonymity?”

He nods. “Because I didn’t want people to know who made the paintings. Because they’re not real gestures. They exist in this other world. And I wanted me to exist in this other world too, in people’s minds.”

“But maybe it was also an effort,” I suggest, “to be a little mysterious.”

A bashful look comes into his face. “It seemed like a good idea.”

“Nevertheless you came to your openings, I assume—you made appearances.”

“Mostly. Sometimes I actually didn’t turn up.” He gives me a nervous glance before averting his gaze. “I mean—I’d tell everybody. I’m polite.”

His almost dandyish contradiction is extremely winning. Still, after all his talk of insincerity, inauthenticity, and performance, I find myself reminding him of his emotional speech about his father and Emerson at the dinner: how honesty and integrity is the most important part of being an artist.

Now our eyes meet, for a moment.

“One of the last paintings he saw me make was Dirty Creamer,” he tells me, referring to the first painting you see upon entering the show. It portrays the comical character of a hearty bagpiper, he explains, based on a Flemish Baroque drawing known to represent the Dutch proverb that the young always follow the example of the old. I sense a bit of sentiment suddenly rising in Brown. “He really didn’t like that painting,” he continues, and we both laugh. “‘Why would anyone want that painting on the wall?’ my father said. ‘He looks like such an unpleasant and untrustworthy guy. You feel like you’d need to check your pockets when he walked into the room.’”

“Nice,” I offer.

And as if to correct me, he says of his not-sonice bagpiper, “I don’t want you to like him. I just wanted you to think that, somewhere in his soul, was a little element of goodness that might make him interesting.”

51

THE ART OF BIOGRAPHY PARADISE NOW: THE EXTRAORDINARY LIFE OF KARL LAGERFELD

William Middleton’s forthcoming biography of Karl Lagerfeld, Paradise Now, comes as a major follow-up to his lauded history of Dominique and John de Menil, Double Vision from 2018. Here, curator Michael Cary speaks with Middleton about the challenges, strategies, and revelations that went into telling the story of this larger-thanlife visionary in the world of fashion and the culture at large.

MICHAEL CARY You’ve written two Francocentric biographies: Double Vision , about the de Menil family, published in 2018, and Paradise Now, about Karl Lagerfeld, which will be released later this year. I can see, here on Zoom, that you’re in Paris as we speak. How did your Francophilia begin, if I can phrase it that way?

WILLIAM MIDDLETON Well, I’m from Kansas. I had a formative teacher in high school, my advanced-placement English teacher, and she was focused on French literature, so I was engaging in that canon from a young age. I think that’s the beginning of my fascination with France. And then, at the University of Kansas later on, I had a little map of Paris that I found at a travel agency; I kept it for many years and treasured it. My adoration was always from afar until I first went to France, for Christmas and New Year’s in 1989–90. I was living in New York but I immediately felt the need to live in Paris, so ten months later I moved there, remaining for a decade.

Then in 2000 I moved back to New York—and I love New York, I’ve lived there many times and I’ve always worked for New York magazines and New York book publishers. Wherever I am, I’m always connected to New York—but leaving Paris, I immediately felt that I had made a terrible mistake. In the end, it took me nineteen years to get back! But these things happen for a reason, and the silver lining was that coming back to America prompted the de Menil book. I moved back to work for Harper’s Bazaar and I went down to Houston to do a story on the city. Before I even headed there, I knew that I wanted to look into the de Menil family. In 1986, there had been a cover story in the New York Times Magazine on Dominique de Menil and her five children. It was called “The Medici of Modern Art.” I thought the family’s connection between France and Texas was intriguing, so I filed it away.

I went to Houston for the first time in the fall of 2000. Dominique de Menil had died a few years before and there was interest in a biography. I wrote a book proposal and had a contract with Alfred A. Knopf and the editor Shelley Wanger. For many years I’d been writing magazine-length features and I wanted to find a project that I could really sink my teeth into. In fact, in 1998 I did a big story for W on Yves Saint Laurent, for the house’s fortieth anniversary, and I had the possibility of writing a

biography on Saint Laurent. But I never fully moved forward on it because frankly I felt like there was so little there that was relevant to life today, to the life of people around me. It put a block on the project— one that, interestingly, I didn’t encounter with this new book on Lagerfeld. Karl has always felt relevant to me; he’s always been connected to what’s going on in the world.

MC So you saw Karl as a less rarified figure than Saint Laurent?

WM Absolutely. I met Karl in January of 1995, when I was working for W and Women’s Wear Daily. From there we had a good working relationship that developed into a genuine friendship. I was in no way his best friend or anything like that, but we had a friendly rapport and he was somebody I always admired because of his connection with the culture of his time. He knew everything that was going on in terms of cinema, architecture, music, art, everything. I remember thinking at the time, and I’ve revised my thinking a little on this since, “There may be others who are more important in terms of fashion but Karl is superimportant in terms of the culture.” Now that I’ve done all this research on his career in the ’50s and ’60s and ’70s, I’ve realized how important Karl was in terms of pure fashion, even before he got to Chanel. Everything he did during the last two decades of his life was incredibly significant in terms of fashion—what he did with H&M, what he did with Fendi, what he did in terms of fashion photography, what he did redefining the fashion-week spectacle.

MC You make the point several times, and Karl does himself throughout the book in quotes and anecdotes from friends, that he’s not interested in retrospective. It’s the present, it’s what’s happening now. Everything past is past, why bother with it? But there’s also this contradiction, because he’s obsessed with the eighteenth century and studies history voraciously.

WM I always felt like that was a little disingenuous of him to say that he was only focused on the present or the future. He had an amazing grasp of history and the development of aesthetics; it was just his own history that he didn’t want to focus on. There’s a moment in the book where his colleagues, including Amanda Harlech, are working on staging a museum retrospective in Germany, and he’s happy to work on it, he plays along, and then it comes time for the exhibition to open and they want him to attend and he gets furious. Where so many designers want that consecration, want people to be admiring their past work, he saw any focus on his past as funereal.

And this is where the title for book, Paradise Now, comes from. Karl sat for an incredible number of interviews throughout his life—these were critical resources in the creation of the book—and in 2014 he did a radio interview with this brilliant French journalist Augustin Trapenard. He’s a serious cultural journalist and he was pushing Karl on this whole idea of posterity, and Karl was like, “Posterity, you know, I don’t care. I just don’t care.” He’s like, “It won’t do anything for me. It’s today that counts. Paradise now.”

MC That attitude must have presented some obstacles for you as a biographer. While he was larger than life and participated in many public forums, giving interviews and so on, he didn’t leave the resources that are so often key in these projects. He doesn’t have heirs. He didn’t keep a diary. What are the implications of that? I’m thinking, as an initial example, about the decisions you had to make around depicting his relationship with his mother.

Previous spread, left: Karl Lagerfeld in 1937.

Photo: courtesy Gordian Turk

Previous spread, right: Roe Ethridge, Karl Lagerfeld with Neon , 2013 © Roe Ethridge

This page: Karl Lagerfeld at Maison Chloé, Paris, 1972. Photo: Sueddeutsche Zeitung

Photo/Alamy Stock Photo

Below: Karl Lagerfeld with Antonio Lopez, Eija Vehka Aho, Amina Warsuma, and Jacques de Bascher at La Coupole, Paris, 1972. Photo: Sueddeutsche Zeitung

Photo/Alamy Stock Photo

Opposite: Ines de la Fressange, reinterpreting the classic style of Gabrielle Chanel in Karl Lagerfeld’s January 1983 debut for Chanel, photographed by Dominique Issermann. Photo: © Chanel/ Photographer, Dominique Issermann/Ines de la Fressange/1983 Spring/ Summer Haute Couture Collection

Following spread: Karl Lagerfeld, 1978. Photo: Guy Marineau/WWD/Penske Media via Getty Images

54

While he certainly revered her, she’s surrounded by many mysteries, and after she moves to Paris to live with him, she’s almost like this spectral figure. When you speak to Karl’s friends, even if they saw her, they don’t know anything about her—she was simply a woman wandering through the house while they were having lunch. And then when she dies, it’s as if the door is closed and it’s never mentioned again. Keeping in line with his focus on the present, she was immediately relegated to the past. WM A lot of the quotes that I use from Karl about his mother came in later years. He talked about her a lot, but you’re right, she’s not easy to locate as a fully dimensional person. I had to approach her obliquely. Amanda Harlech recounts talking about Karl’s beloved cat Choupette, and she says, “Beautiful, withholding, pampered: it’s your mother.”

And he’s like, “Exactly!” With direct references to her from Karl, it’s tricky, because I think some of the comments he has her saying sound suspiciously close to his own voice. Is that because he’s like his mother, or is he spinning that for effect? So, in general, I had to approach that material with caution, instead focusing on real material evidence and recollections of more impartial observers.

Luckily, I discovered this incredible notebook

from 1954 at a Sotheby’s auction that proved revelatory in terms of understanding her. As I detail in the book, the notebook had all these press clippings and notes and drawings related to Karl’s winning the Woolmark Prize in 1954, which really jump-started his career. The auction records had this listed as a work by Karl, which I found odd, given that Karl wasn’t likely to hold onto something so retrospective. It stayed on my mind for a while, and then I was able to speak with two people who knew Karl very well, Caroline Lebar and Sébastien Jondeau. Sébastien immediately clarified, saying, “Oh, that was his mother who compiled and kept that.” Of course it was his mother’s! It’s her handwriting. It’s in German. He sends everything back to her in Germany and she puts the whole thing together. And I think that’s not only revealing of the facts of 1954, when Karl won that prize, but it’s also superrevealing about what she really thought about her son: this was someone who was very proud of her son. Karl always tried to give the impression that she wasn’t. He quotes her saying something like, “It’s good that you’re not very ambitious, since you just want to be a fashion designer,” right? The truth is much more interesting.

Piecing together the details of Karl’s life was a radically different project from the research for the de Menil book, because the de Menils had an incredible archivist impulse long before they founded their museum. They kept all their correspondence. In the family archives, Dominique de Menil had not only her letters from her family but she’d recovered her side of the correspondence as well. A biographer’s dream.

MC And Lagerfeld seems like it’s the absolute opposite, right?

WM Exactly. He did not keep information like that.

MC I’d love to speak about Jacques De Bascher, who plays such a key role in the first half of the book. Lagerfeld’s relationship with him was obviously an intense one, but there are a lot of lingering questions. In terms of writing about Karl’s sexuality, there is this duality of guardedness on one side and unapologetic flaunting on the other, especially for 1970s Paris. There are several points in the book where people insist that Bascher and Lagerfeld had no physical relationship and it feels a little bit like the lady doth protest too much [laughter ]. How did you navigate the queerness of Lagerfeld’s life?

WM You’re absolutely right to point it out as a contradiction, because on the one hand, Karl never hid his sexuality. He never pretended he was straight. But he also wasn’t militant. It’s a funny contradiction, and Karl himself said that he was a bit of a puritan. I don’t think it was an internalized homophobia, but there was `a puritanism at play, most definitely. And yet he loved looking at and taking pictures of naked men. I think it’s another of those instances of, How can you really know someone’s truth? The only thing that I can do as a writer is to say what I know, what I’ve discovered, say what other people have said, and then readers can make up their minds. With Karl, that opacity and complexity make for a more interesting subject.

MC You open one of the chapters with a quote where he says, “Essentially I am a Calvinist attracted to superficiality.”

WM Which again is not fully true, do you know what I mean? That he’s a Calvinist, yes, but attracted to superficiality—well, yes, but also incredibly deep. There are some statements that he makes that are interesting and not exactly true.

MC In both of your books, I notice that you consider details of how someone lives—the seemingly

55

superficial, the materiality of ordinary objects, the way furniture is arranged, how someone greets a visitor—as important as what that person does. With the de Menil book, you go into so much detail about the opening of the museum, like how the napkins are going to be folded. It’s a beautiful detail that tells us so much. Where does that sensibility come from for you? Is it that you come across these details and they fascinate you? Are you searching for them?

WM I look for them. Detail makes for a good biography. In any life, I’ve found, the littlest detail can be unfolded and opened in revealing ways. But more generally, I find that the most compelling writing conjures images. The reader must be able to experience this life visually, especially for a subject as image-obsessed as Karl was.

MC And Karl also creates an image of himself, especially at the end of his life. After he loses the weight, he becomes this avatar of himself. How did

you use this extensive visual record of him to work on the book?

WM There are so many images. I can’t tell you how hard it was to do the photo research for this book! There were so many amazing pictures of Karl that we couldn’t include them all. Even if we couldn’t include them in the book, reviewing as many photos and videos as I could was invaluable. There’s one video that I found in archives in Texas, from his trip to Houston in 1979, when he was greeted by the marching band and pompom girls. That whole moment—the limousine with the steer horns on the front, and the horn plays “The eyes of Texas are upon you”—it’s just bananas, right? Those materials make for some of my favorite moments in the books.

MC That kind of excess and spectacle is a motif in the book. I’m thinking about the fact that Karl spent $1.5 million a year sending flowers to people. Everything is fantasy on a scale that is unattainable, and yet somehow this man attained it. You do a

great job of developing that grandness in its exponential growth throughout his life, and I wanted to ask you how you thought he was able to maintain this level of achievement and productivity for so many decades.

WM As you probably know, a lot of creators never get into the position to be able to concentrate fully on their work, or to have the best kind of conditions for their work. Karl made sure that he always did. He would get up in the morning, he would get ready, his pads were there, his pencils were there, he just had to sit there and design. He came back from the house, everything was ready. Silvia Venturini Fendi said she thought one reason their relationship lasted so long was that the Fendi house gave him the means to do everything that he wanted to. But it was the same way at Chanel and at every house he worked with: he always had this extraordinary kind of support so that all he had to do was work.

MC What do you think prompted people to give him that support? Do you think it was something he demanded?

WM Well, I think he earned that—through the work he did and the success he had. If he hadn’t been successful he wouldn’t have continued to get that. But also, Karl was equally generous in return for all the support he received. He didn’t take it for granted. There’s a story, which didn’t make it into the book, told by Anita Briey, who worked with Karl at Chloé and then ran the Lagerfeld atelier. Karl had an annual lunch at his apartment for the Lagerfeld team. Each year, he would give them a little Chanel bag. And Anita Briey said to him, “You know, there’s someone here and she has received a bag—it’s so beautiful—but she’s a lady of a certain age, and it’s red, and maybe that’s a little too much, and do you think it might be possible to change?”

And he replied, “Oh, absolutely,” and he got one that was navy or black and he gave it to her and she started to give the other one back, and he was like, “Oh no, keep both of them.” That’s someone who knows how to treat people who work for him, how to get good work out of people. I think Karl was a good manager in that sense. The teams at the various houses who worked with him adored him. It’s fascinating because he has this image of being so harsh, but that’s not at all the impression that people in the atelier had. This was someone who loved his work and encouraged other people to do great work.

MC You quote Alain Wertheimer, one of the owners of Chanel, saying that Karl was very, very nice, he just didn’t want anyone to know it.

WM Absolutely.

MC In the interviews you conducted, you get the sense of intense love and loyalty from a lot of the people in his life.

WM I once told him, I’ve rarely seen anyone who has a public image that’s so harsh, but when you get to know them you see that the reality is much warmer and almost touching. And he said, “Well, it’s better that than the opposite, non ?” [Laughter ] I love the fact that he was aware that it was a performance, that he was an avatar, as you said. There is an anecdote from the photographer Jean-Baptiste Mondino: he was getting ready to take some photographs of Karl, and as Karl was heading to the hair and makeup room, he said, “Time to go freshen up the marionette.” That’s someone very conscious of the effect that they’re having.

MC He’s a marionette but he’s also pulling his own strings.

WM Absolutely.

56

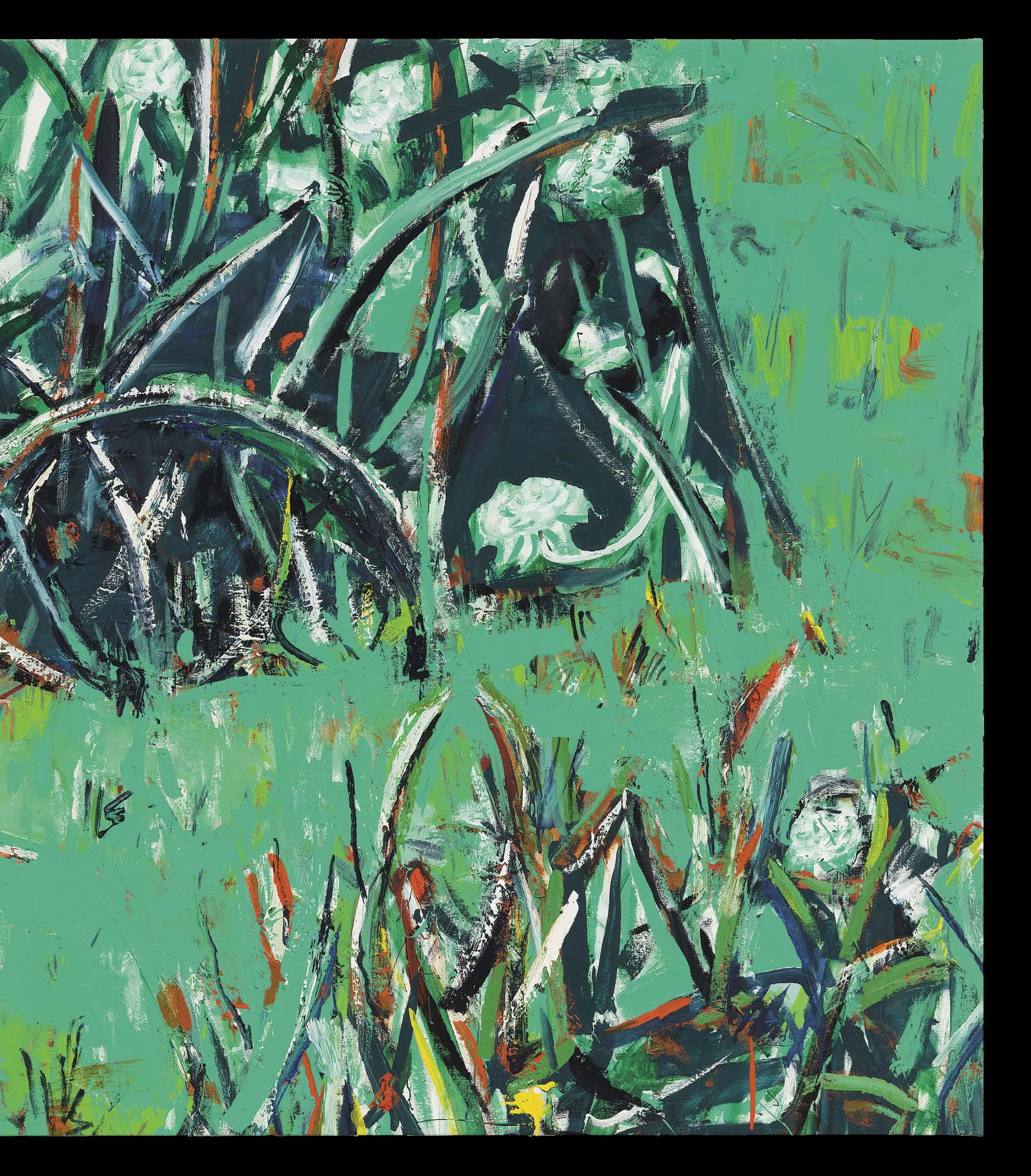

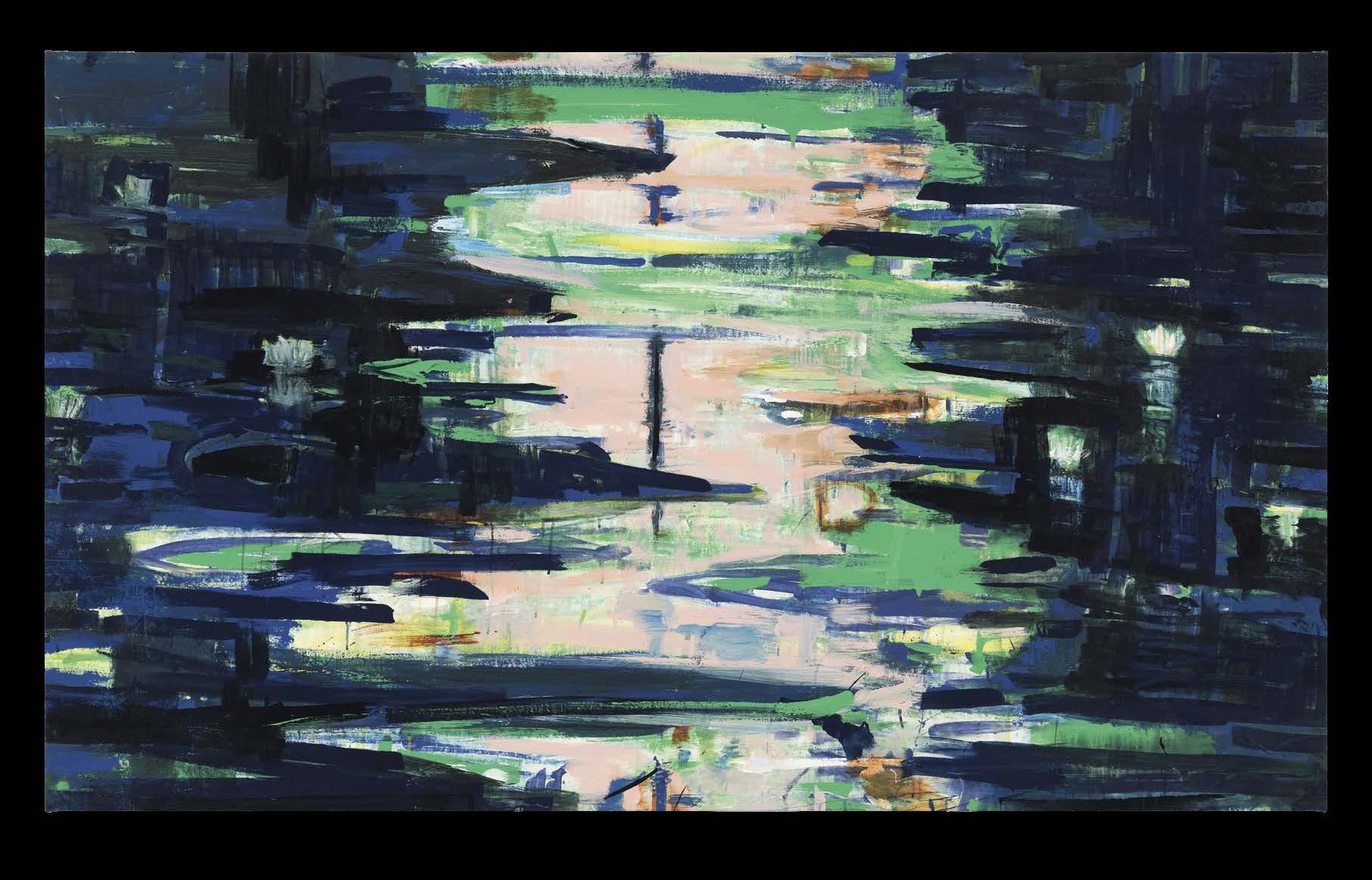

CY GAVIN: ON THE OTHER

SIDE OF THE LIMIT

Tiana Reid reports on her encounter with the artist Cy Gavin’s new paintings.

Previous spread:

This page:

Opposite:

Cy

In the neighborhood I moved into recently, real estate developers keep putting up signs demarcating their investment. This is the same neighborhood that my grandmother immigrated to from Jamaica in the 1970s, the same neighborhood where my parents first met in the 1980s, and the same neighborhood where I grew up in the 1990s.

Several of the infrastructure company’s warning signs read “ danger due to demolition.” But all over the fenced enclosure, “ demolition ” has been crossed out and replaced by words including “ profiteering,” “speculation,” “ lack of housing ,” and “capitalism .” In the midst of all that rewriting, an advertising poster for the future building has a tattooed white man modeling in a white T-shirt and khaki pants. Over that someone has written, “ diversity via fake working-class trousers.” I laugh, realizing I’m wearing my brown Carhartt jacket on the way to my office, and then I look down to change the song on my headphones and I keep walking.

It is all rather cute and rather funny, maybe even worthy of an Instagram story or two, but then, a few days later, the sidewalks don’t get shoveled

in front of the demolition site. I’m walking to the subway after an ice storm and the developers still haven’t salted their sidewalk either, and while I’m slipping and sliding, it is clear that the joke is in fact on me. Uh oh, property—a sick joke, mocking basic needs for housing as if it were some sort of private indulgence.

But before I cross a line, your little boundary, let me take a step back. I hesitate to push too much concept around here, too many narratives. I am here to discuss some new art by Cy Gavin. In Gavin’s telling, the work has him thinking about property lines, pathways, and boundaries. Just before a new exhibition, in conversation, he is often using that saying. He is always “thinking about” something, if my memory has it correctly.

At the same time, as the late critic Peter Schjeldahl wrote in 1993 in a review of a Gerhard Richter show (republished the following year in his book Columns & Catalogues), “Painting is art’s philosophical warehouse, stocked with visceral responses to Western culture’s every big idea.”

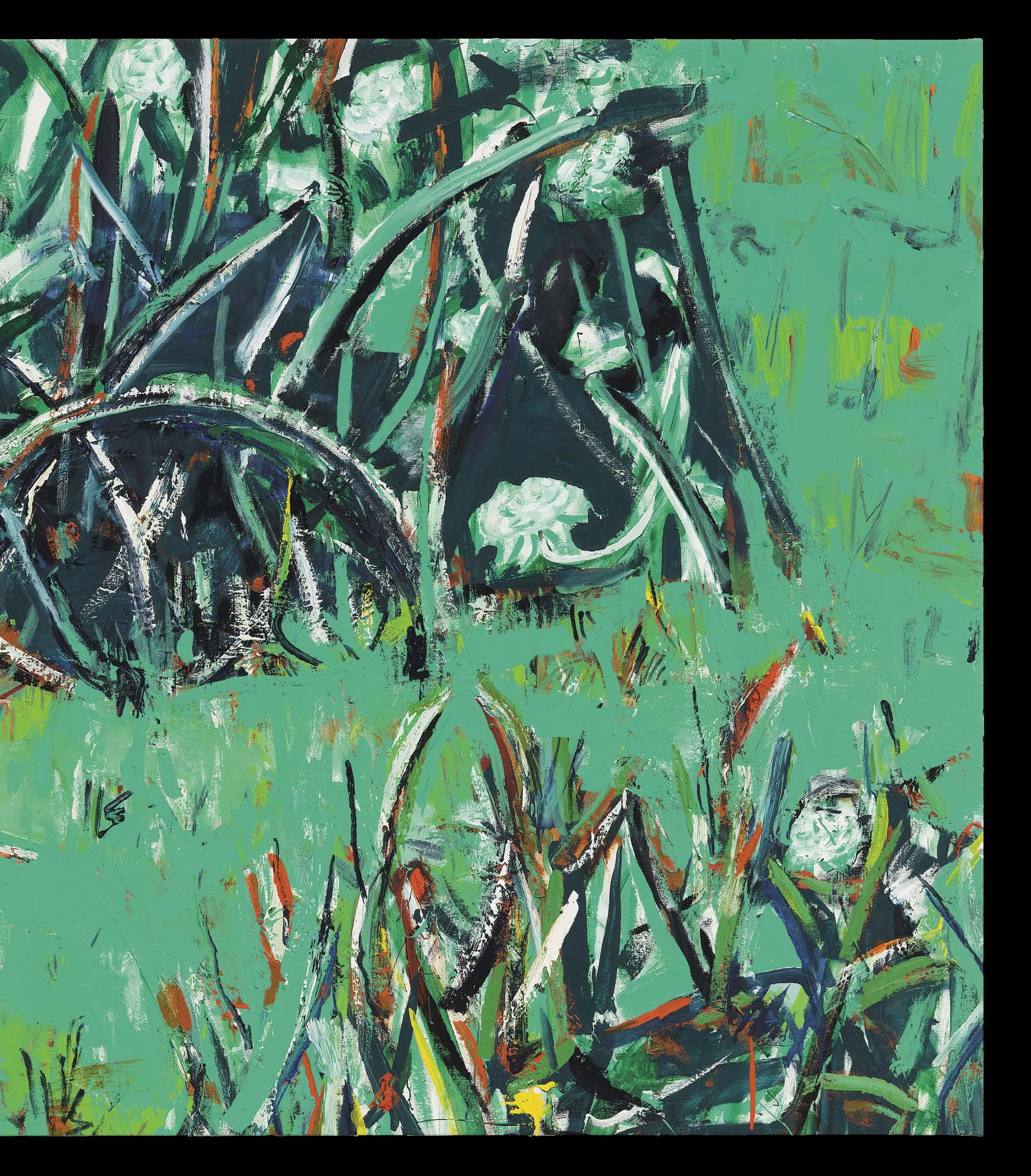

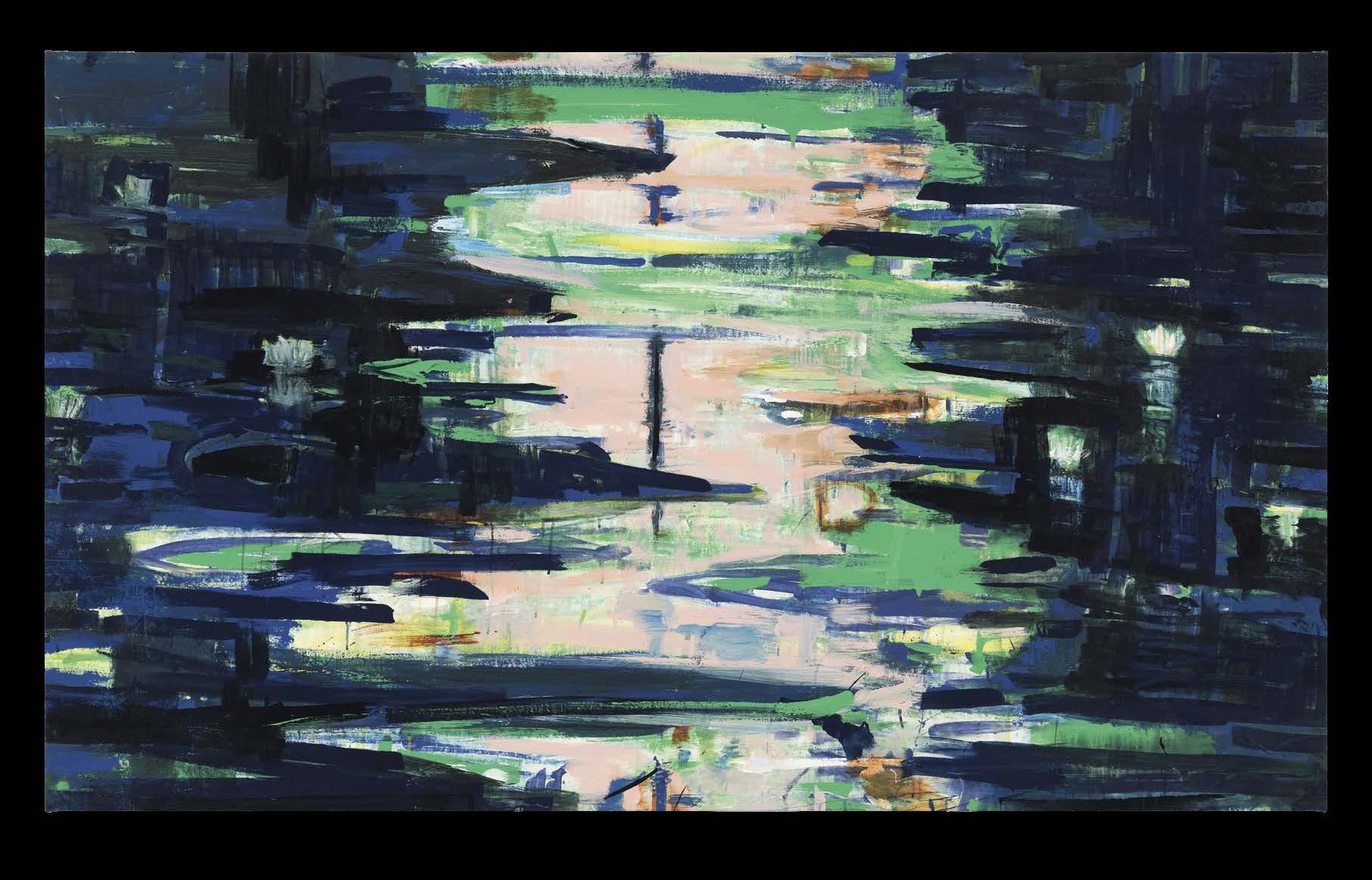

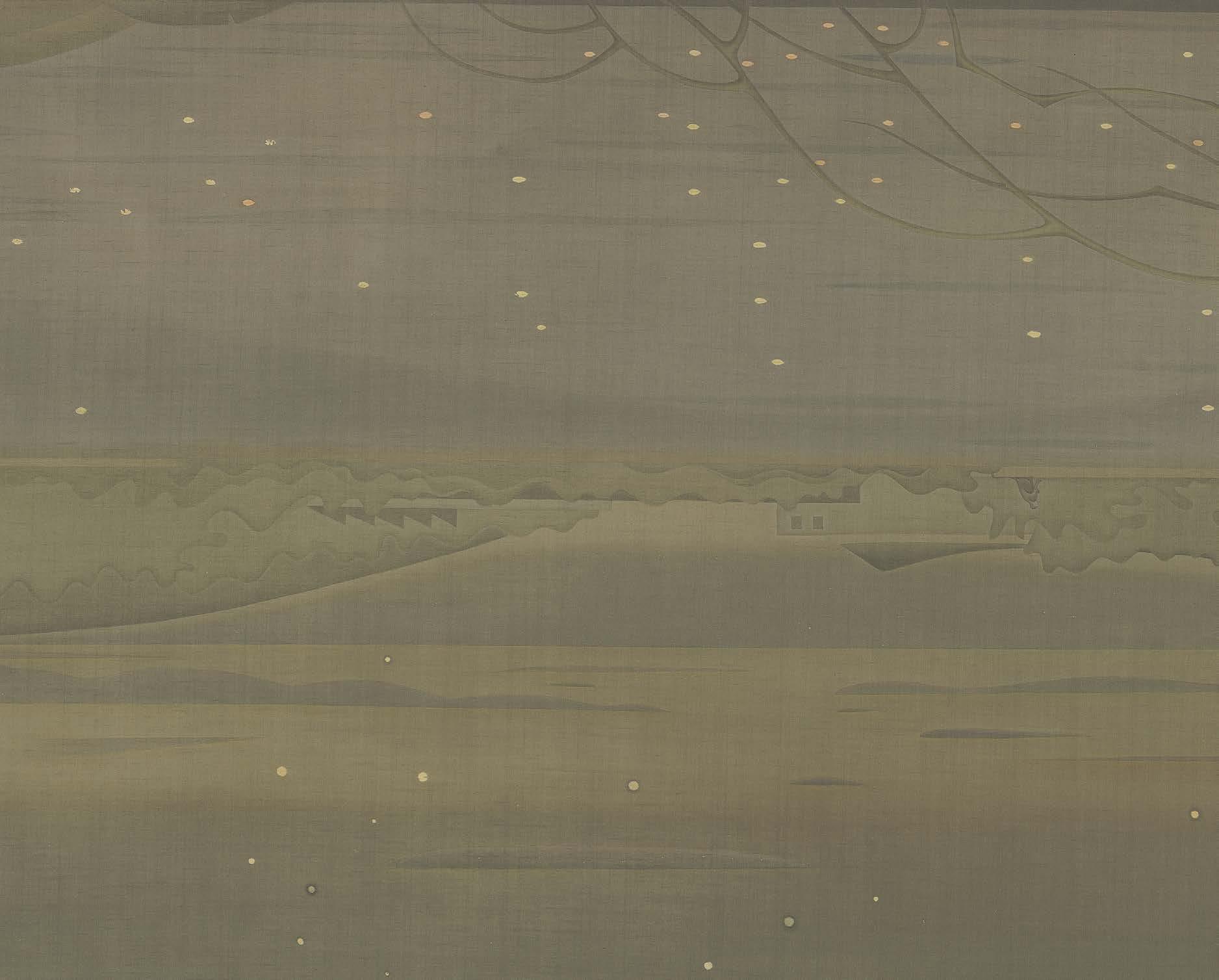

Painting stores the history of thought itself. Gavin’s richly colored paintings—bringing about illumination, shadows, movement, and lines in constant

flux—engage with the idea of painting itself. What does painting’s tortured availability yield? Gavin constitutes a world that seems to be growing, outlining, shifting, shrinking, changing, soaking, moving, selecting, swallowing, surrendering, allowing, forbidding, deepening, pronouncing, rising, historicizing, filling, contrasting. And so his sublime renderings (of waves, trees, paths, rivers, beaver dams, moons, stars) gesture to property as well as to the postindustrial contraaesthetics of boundaries more generally.

While the art world has an enduring preoccupation with figurative representations, postmodern, poststructuralist art-historical discourse has also embedded abstraction with possibility, transgression, and innovation. In critical discourse there has been some talk about abstraction in Gavin’s work. If this is true, it is perhaps only partly true. In the New Yorker, critic Johanna Fateman uses the phrase “semi-abstract,” writing, “In the past, Gavin has paired his panoramas of wild coasts with figures in mythic scenes drawn from the African diaspora and his personal history, but these semi-abstract expanses of craggy shadow are bereft of protagonists.” In 2021, the

60

Cy Gavin, Untitled (Paths in a meadow), 2022, acrylic and vinyl on canvas, 42 × 75 inches (106.7 × 190.5 cm)

Cy Gavin, Untitled (Grass growing on a weir), 2022, acrylic, vinyl, and pencil on canvas, 45 ½ × 77 ½ inches (115.6 × 196.8 cm)

Gavin, Untitled (Wave), 2022, acrylic and vinyl on canvas, 81 × 81 inches (205.7 × 205.7 cm)

writer Hilton Als likewise noted Gavin’s interest in landscape, confessing that “Gavin’s images helped me face the hour that I was living in then. I may spend time with the transcendentalists of yore, but acts of transcendence happen in the now. Gavin’s hour was the hour where I felt filled up, quenched, by his faith in art, which reinspired me to see there is faith in the moment of looking.” He continued, “Not too far from where those early transcendentalists set up camp, I saw what Gavin longs to make one feel: his cosmos of planets and colors that were bigger than you and me, and as big as the mind and eye makes them.”

I too feed off Gavin’s cross-wired sensorium, his historically fed and gravely pretty interpretations of settings too fleshly to be called merely “outside.” He moves across the self, the family, the community, the neighborhood, the city, the country, the earth. Gavin stays small, painting his own corner, yet he somehow still manages to address the concentricity of relation with a brutal honesty that has me baffled.

His newest paintings are unfussy recognitions of the artist’s vicinities in not-so-upstate New York. The geographic, social, and political contexts of his

wide-ranging engagements are varied. I also think of Gavin as a color theorist, though that sounds limiting. “I think that my colors can be strident, but I also think you can use strident things with subtlety. That’s what I’m trying to do,” Gavin told Alex Frank, in one of the Studio Museum in Harlem’s “Studio Visit” interviews, published in 2017. “It’s hyperbolic in the way of caricature, which can feel closer to the truth by being an exaggeration.” The effect of moonlight, for example, is conveyed in a rich palette of blues.

Taking in the artist’s latest work in person on a rainy and gray day in Long Island City, I got to see the depth and variety of Gavin’s brushstrokes, suggesting choral echoes, a frisson of impressionistic autonomy. In the middle of December, as the city gets duller, darker, blander, I see something of that hyperbole in what I, at first not knowing the work’s name, started referring to as the “pink painting.”

I don’t identify as a pink person but Gavin’s vision is almost aggressive, rising and falling with great violence. Relating to waves and drowning, this is not what in addiction-recovery circles they call a “pink cloud,” not a honeymoon phase. Pink is mired in a long and thorny gendered history; I’ve

never seen it used in such a way as to evoke a kind of terror that I can’t quite put my finger on. Spectacular fear, maybe. The uncertainty is exaggerated by Gavin’s decision to leave some of the canvas seemingly bare, leaving the viewer alone to think instinctively about what is beneath, and to inquire about painting in general.

To the contrary, a green piece is tight and dusky, melancholic yet somehow representing an opening. This indirect flare of light is both path-making and path-breaking. The painting offers a new drama of greenness, a pungency one can nearly smell. Gavin’s paintings of trees verge on orgiastic: branches and branches, rings and rings, myths and myths, secrets and shadows—multiples all engrossed in one. That tree there, though, is actually not as old as it looks; it is a young tree, he tells me.

But I cannot stray too far from the earth’s thick sedimentation of history. An example: one of Gavin’s newer 2022 pieces, carving out frantic cuts of yellows and oranges, ostensibly represents “crossroads/meadows.” I say “ostensibly” because his stylized reality is faithful not to whatever gets called fact but to the uneventfulness of danger,

61

the cumulative knots of social surrender. It feels like fire.

No doubt it is part self-will and the dominating transcendence of Gavin’s poetics—yes, I can and will call visual art poetry—that chains me to the unverifiable beauty of literature. A passage in the third volume of Mary Shelley’s well-known novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus , of 1818, strikes me as an apt description of the quietly powerful scenes that Gavin forges: “It was eight o’clock when we landed; we walked for a short time on the shore, enjoying the transitory light, and then retired to the inn and contemplated the lovely scene of waters, woods, and mountains, obscured in darkness, yet still displaying their black outlines.” This is the kind of elegiac blackness to which Gavin commits: textural, brief, thoughtful, and able to be seen. Or is it sensed?

Where Gavin lives a symbiotic, intertextual relationship to process, his studio world and life upstate embedding themselves in the artistic outcome, I see the stark lines of American society and politics to which he has drawn my attention. To think of boundaries, material and mental, as complex designations of human and plant life is also to

find new ways to relate to the desire to turn inward, to isolate, to be single and to believe so wholly in singularity. On the surface this essay does the work of setting, describing the surroundings, walking about. However, as property lines have made and maintained the capitalist world order, they’ve also reordered our minds. I mean that brutality can feel familiar and soft, full of libidinal/ economic structures that stagger individual and collective attachments to property relations and juridical sovereignties.

The task of living, which we can only do day by day or minute by minute, can never be fully sanctioned. How else can I explain it? Let me conclude with a quotation from Ludwig Wittgenstein’s book Philosophical Investigations , which was published in 1953, two years after the German philosopher’s death. “When I talk about language (words, sentences, etc.) I must speak the language of everyday,” Wittgenstein exclaims. “Is this language somehow too coarse and material for what we want to say? Then how is another one to be constructed? —And how strange we should be able to do anything at all with the one we have!”

In a broad sense, I am also thinking here of Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921; translated into English in 1922), and especially of how he posits the limits of language as a “limit of the world.” How to unravel the aesthetic records of those of us who encounter the disappointments of the “limit of the world”? and the word? That is to say, the terms of language circumscribe our imaginaries about the past, present, and future. But “what lies on the other side of the limit,” to quote Wittgenstein again, for Gavin is an artistic practice and a poetic labor that looks at visuality the way a writer might look at language.

Expressed in a different way, it felt more impossible than usual to write this essay, especially at first. Every mad moment rushed back to peacekeep itself, to tame the wonder emanating from Gavin’s project. With every word, I feel the deep well of interiority in Gavin’s stunning, inimitable, and dense landscapes, outer and inner swaying back and forth, then a stumble. The trip is almost like the way, upon being born, the boundary you were used to dissolves, and then there is a universal trauma, all of it, and all of a sudden. All of a sudden: time, tears, blood, the difficulty of now.

62

This spread: Cy Gavin, Untitled (Crossroads/meadow), 2022, acrylic and vinyl on canvas, 90 × 185 inches (228.6 × 469.9 cm)

Artwork © Cy Gavin