SHIN SUNG HY

SHIN SUNG HY (1948―2009)

Shin Sung Hy (1948 – 2009) is regarded as one of the most original artists not associated with any particular trend in contemporary Korean art history. The forty-odd years that define Shin Sung Hy’s creative practice almost seem like a compendium of contemporary art history itself.1 Shin’s stylistic forms of painting range from hyperrealism to minimalism, experimenting with the materiality of picture planes and collages, exploring two-dimensional structures and spatiality in painting, and engaging with space in unconventional ways. These interests encompass not only the main motifs in the history of contemporary painting but also the currents of our time. What is certain is that, amidst the variety of expressive methods, he never relinquished the core of his artistic integrity.

Shin was a seeker who transcended the bounds of the canvas as an absolute space in painting and explored the integration of the two- and three-dimensional. After gaining attention at major competitions such as the Korean Art Grand Award Exhibition—where he received special honors for his 1971 surrealistic trilogy Empty Heart—he presented his series of Toile de Jute paintings in 1974. These paintings featured realistic renderings of shadows and fraying strands on coarsely textured burlap sacks. With this work, he explored the relationships between representation and abstraction, object and painting, and truth and fiction. This marked the genesis of a new kind of painting that appears to share commonality with the monochrome painting that was prevalent in the 1970s Korean art scene, but remained distinct from the abstract paintings that emphasized spirituality. By painting hyperrealistic burlap on actual burlap, Shin achieved a coexistence of the real and the imaginary on the same canvas.

After moving to Paris in 1980, Shin Sung Hy spent the next thirty years serving as a

Parisian home base for various figures from the Korean art world. As an artist, his work was unprecedented, exploring the possibilities of three-dimensional painting on a flat plane from a position closely aligned with Dansaekhwa and Supports/Surfaces, the major artistic movements of Korea and France at the time, respectively. Shin dedicated his career to overcoming the limitations of the flat canvas, the most absolute of painterly spaces, seeking to integrate the two- and three-dimensional realms. He continued his experimental path toward the “essence of painting,” responding to the diverse aesthetic stimuli of the city. Shin explored the three-dimensional reality of abstract paintings through explosive color combinations. Rejecting the realm of the illusory, he experimented with introducing physical volume and spatial sense to the flat plane of the canvas. By tearing up thick cardboard to create collages or utilizing the pliability of paper by cutting and ripping it into pieces, he created paradoxical works that were two- and three-dimensional at the same time.

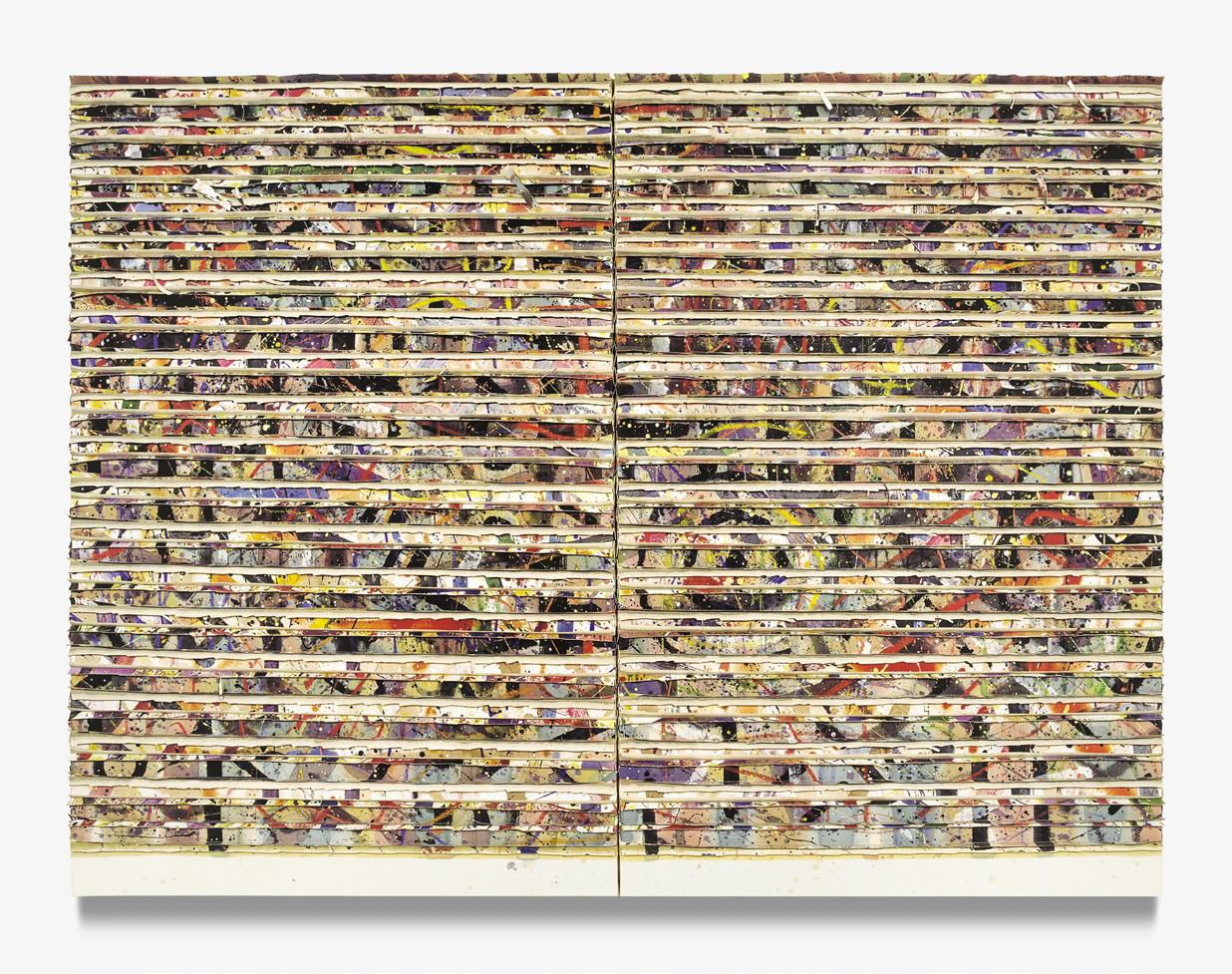

Shin continued to expand his artistic vision with works like Spaces of Structure, the “collaged paperwork” collage (1983– 1992), a series of cardboard collages characterized by bold, vibrant color, and his “sewn-canvas” couturage (1993– 1997) series, which involves cutting painted canvases into uniform strips and stitching them together. Shin continued to build his practice by developing various methodologies to create unconventional works in which the painting incorporated three dimensions rather than settling for the visual illusion of the elaborately rendered image. Next came the birth of his “knotted-canvas” nouage (1997–2009) series, which integrated surface and volume by gathering strips of colored canvas and tying them to a frame or other support structures. The artist meticulously sliced the vibrantly painted canvases only to stitch them together with a sewing machine or weave and knot them into a weft and warp formation, constructing a three-dimensional canvas “body.”

These cut strips of canvas covered the front and back of the work like a sculpture, creating a three-dimensional painting that generated shadows within and beyond the canvas.

Throughout his 40-year-long career, Shin Sung Hy remained dedicated to the canvas,

consistently exploring the continuous space of color resonating in both vertical and horizontal dimensions. His woven pictorial space, constructed through stitching and weaving, marks a significant step forward from the painterly heritage of 20th-century artists at large. Shin’s paintings are both deeply Korean and boldly Western. Colors extend into space, while the skeletal structure constructed by stitching and weaving provides a firm foundation for the coexistence. This coexistence is regarded as the most original aesthetic of Shin’s artistic language by the art historian Jeon Young-baek. Cultural elements serve as the basis of the artwork, and the more masterful the pieces become, the more subtly they assume their own cultural identity. After spending nearly thirty years―the majority of his life―in Europe, Shin pioneered a unique oeuvre by skillfully mixing Korean influences with Western aesthetics.

Born in Ansan, Korea, in 1948, Shin Sung Hy earned a BFA in Western Painting from Hongik University, Seoul, Korea. In 1980, Shin moved to Paris, France, and continued his artistic career for thirty years. His works are in the permanent collection of national and international institutions, including UNESCO, Paris, France; National Foundation for Contemporary Art (FNAC), Paris, France; National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, Korea; the Busan Museum of Art, Busan, Korea; Whanki Museum, Seoul, Korea; Ho-Am Art Museum, Yongin, Korea; Daegu Art Museum, Daegu, Korea; Daejeon Museum of Art, Daejeon, Korea; Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, Ansan, Korea; OCI Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea; Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea; and SOMA Museum, Seoul, Korea. The artist has been the recipient of the Special Award at the 2nd Korean Art Grand-Prix Exhibition (1971), the Special Award at the 18th Korean National Art Exhibition (1969), and the Grand Prize at the Korean Young Artists Prize (1968). The artist remained active until he died in 2009. Shin’s recent retrospective was organized by Kim Tschang-Yeul Art Museum in Jeju, Korea in 2022.

1. Shin Sung Hy had exhibitions at Leonard Hutton Galleries, New York; Gallery Proarta, Zurich and Gallery Baudoin Lebon, Paris.

He cuts the base of the canvas into long strips horizontally, parallel to each other, each about 5 cm thick, and folds the seams outward. These seams, protruding like scales over the canvas and forming the skin of the painting, represent a solution in terms of continuity when viewed in terms of color tones. Here, the painting looks like it’s decorated with “a dress of light” or “a palette of Impressionist colors,” dotted all over. I must confess, I feel a great thrill of desire to touch the trembling edges of the canvas with my hands. It’s an exciting festival for both the eyes and the hands. Our eyes follow the movement of the colors and their steady wavelengths.

A great innovation! The pieces of colored canvas create a technique similar to that of the Impressionists from an objective point of view, where the finely cut textures are almost pointillist, evoking a tremor, and becoming the physical support for visual resonance. I find immense pleasure in seeing and touching this fluttering canvas, which enables the richest and warmest visual color mix, as if made entirely of sunlight.

Shin Sung Hy’s “Solution de Continuité” depicts his technique in handling color and his visually insightful, nurtured talent to enchant. In our era of artistic crisis, this represents a highly symbolic gesture of belief and hope, a message from Shin Sung Hy and his artworks, The Daughters of the Sun.

- Pierre Restany, art critic, 1994

A Solution to Continuity | Solution de Continuité

1996

Acrylic and oil on canvas

200 × 8 cm each

A Solution to Continuity | Solution de Continuité

1996

Acrylic on canvas

200 × 14 cm each

Interlace | Entrelacs

1998

Acrylic on canvas

60 × 73 cm

Interlace | Entrelacs

1997

Acrylic on canvas

73 × 60 cm

Interlace | Entrelacs

1998

Acrylic on canvas

60 × 73 cm

Interlace | Entrelacs

1997

Acrylic on canvas

73 × 60 cm

1998

73 × 91 cm

Interlace | Entrelacs

Acrylic and oil on canvas

Interlace | Entrelacs

Acrylic and oil on canvas

1999

My canvases are painted to be torn apart; in a sense, this act of tearing questions contemporary art, while the act of folding and knotting them serves as my response. I renounce the flat surface for that of three-dimensional space, believing that we must let go of ourselves to be reborn. Therefore, painting initially serves as a reminder to myself of what I must be forsaken. The separated pieces of my canvases act as a witness to my knowledge and expression.

My hands then summon this witness and, with them, construct a new and spontaneous fabric in a volume where air is free to circulate. Being bound together incites the fusion of the elements. This method provides a visual and logical means of synthesizing a contrast between self and others, material and spirit, or affirmation and negation. I was brought into this era to work with surfaces that honor the flatness, volume, and space, creating works that, through synthesis, validate the interplay of colors, lines, sides, and three-dimensional figures in space.

- Artist’s note, 2001

1999

120 × 120 cm

1999

Acrylic and oil on canvas

100 × 100 cm

Microcosmos | Microcosme

Microcosmos | Microcosme

Towards a Space | Vers un Espace

1999

Acrylic and oil on canvas

100 × 100 cm

We were born from the two-dimensional space, aspiring to become three-dimensional beings. The desire of the two-dimensional was to expand and rise in the vast, open space. However, only the hands of the artist could help us break out of the shell and enable us to stand tall in the new dimension. What lies flat is akin to being dead. So we were folded and overlapped, torn and tied together, to rise in the three-dimensional world. Deconstruction and construction, chaos and order, compression and tension, pulling apart and bounding together…

These experiments transformed the two-dimensional into the three-dimensional, opening the doors wide enough for the wind to pass through. The energy and blood of colors flowed, merging pieces of images visually and bringing them together as an organic body that serves as a vessel for art.

We gained freedom from the two-dimensional limitations, and we finally were allowed to breathe. The surface became the matière and the elements of the painting became the volume and form.

Now, let us cast shadows as all creatures and beings do. Let us stand in the light donning paintings that are not illusions but realities that exist in tangible space.

Shin Sung Hy, the artist has granted us existence and affirmed our significance in the land of art.

- Door on Flat Surface, Shin Sung Hy, 2005

Acrylic and oil on canvas

220 × 150 × 120 cm

2001

Interlace | Entrelacs

Acrylic on canvas

Interlace | Entrelacs

Acrylic on canvas

Interlace | Entrelacs 2006 Acrylic on canvas 60 × 60 cm

Interlace | Entrelacs 2006 Acrylic on canvas 60 × 60 cm

SHIN SUNG HY, TRANSCENDING PAINTING THROUGH PAINTING

Kim Hong-hee

Chairperson of Nam June Paik Cultural Foundation / Former Director of Seoul Museum of Art

1. Prologue

Shin Sung Hy is a painter who marked our own era with his art of painterly maximalism saturated with various colors and rich texture. Nouage (weaved painting or painting of knots), a trademark of Shin’s art and the ultimate expression of his painterly maximalism, signaled a new concept of painting that transcends painting through painting. Namely, nouage was born as a result of his fervent interrogation of painting through life-long experimentations and struggles.

When he graduated from the Department of Painting at Hongik University in 1971 and was just starting his career, Shin quickly proved himself a talented young artist who received acclaimed prizes at Kookjeon and Mijeon, grand art exhibitions in Korea, with his Surrealist and Expressivist figurative paintings. Since the mid-1970s, Shin earnestly searched for his own distinctive style while also responding to movements of the time, as demonstrated by his hyperreal monochrome series, Peinture, a painting of jute on real jute. The formal starting with these jute paintings would come to fruition through hardships that followed his

immigration to France in 1980. After collage series Peinture from 1983 to 1992, consisting of pre-painted cardboards which were torn and then attached to acrylic board, and the Solution de Continuité series from 1993 to 1996 in which pre-painted canvases are cut into pieces then re-sewn, Shin arrived at the innovative style of nouage.

Distinct from his earlier series in which colored canvas strips are sewn together, Shin’s nouage series including Entrelacs, Vers un Espace, and Peinture Spatiale featured a fresh and intriguing methodology of weaving colored canvas strips onto the canvas frame, which garnered much attention from the Paris art scene. Truly, nouage was the most valuable gift that he received from the city of Paris. For a solitary artist away from the Korean art world, Paris provided a chance to independently pursue formal experiments, which is what eventually brought him to international recognition. Until he passed away in October 2009, Shin continued to deepen his experimentations in nouage while working between Paris and Seoul, and held numerous solo exhibitions in Korea, France, Switzerland, Japan, and New York, thus establishing a reputation as the colorist painter from Korea who invented nouage.

The radical transition from jute monochrome paintings of the 1970s to colorful nouage paintings of the late 1990s corresponded to the stylistic shifts in contemporary painting from modernism to postmodernism, and from monochrome minimalist painting to maximal post-minimalist painting. However, it also reflected a kind of resolution concerning painting emerging from Shin’s own ceaseless inquiry into the nature of painting. The trajectory of Shin’s art, from jute painting, collage, sewn-canvas (couturage), and finally to nouage, is marked by the artist’s inquiry, doubts, and searches for an answer regarding the essence of painting itself, including issues such as the flatness of the canvas, the materiality of pigments, and the limitation of the canvas frame. In other words, Shin’s post-minimalist motivation to break away from the modernist devotion to the intrinsic quality of painting itself — and especially from its most radical expression, monochrome minimalist painting — provided the foundation for the creative and innovative strategy of nouage.

Innovation of Nouage

From Painting to Weaving

As foregrounded in the previous section, nouage is the culmination of Shin Sung Hy’s creativity that brought his post-minimalist aspirations to full bloom through maximalist aesthetics. Beyond being the artist’s personal achievement, nouage carries an art historical value due to its timeliness that exemplifies post-minimalist painting that followed monochrome minimalist painting, and more precisely, within the context of the pictorial innovation of replacing painting with weaving.

Nouage, a French word with the lexical meaning of “weaving” or “connecting,” primarily stands for the method of weaving or knotting in Shin’s work. Furthermore, it can be compared to “collage,” a now-canonical term in art history, in both terms’ implication of anti-painting which resists painting or representing. Just as the term “collage,” which originally indicated a methodology of attaching real objects or fragments of objects on the surface provided foundation for a new anti-aesthetic concept of “from representation to presentation,” the meaning of nouage gains efficacy as a new style and aesthetic concept when it is expanded from a methodology of weaving to a signification of anti-painting. This anti-pictorial feature of nouage is based on a kind of deconstructivist method of cutting the canvas in many pieces and weaving them together to reconstruct a new plane, instead of painting upon canvas. First, Shin draws dots, lines, and patches on an empty canvas, in poetic, abstract expressionist strokes using pointillist or dripping methods. Then, this “prepared canvas” that displays the artist’s spontaneous brushstrokes is cut into thin colored strips of one to two centimeters width. Initially, Shin attempted nouage by tying these color strips to a wooden branch then letting them naturally hang down from it. However, this method was soon developed into a style of colored nets where Shin weaved strips in multiple directions using the canvas frame as a support, filling up the once-empty

background with interlocking warps and wefts, and painted once more on this surface.

Deeply absorbed by the effect of knots and gaps in between harmonizing to form a striking tactility, and even light and dark contrasts as one or two more weaves were layered on top, Shin would delve further into the process and sculptural effect of nouage.

This mode of nouage that Shin started experimenting with around 1997 rewarded him with an amazing aesthetic discovery and the thrill of creation as if compensating for the pain of cutting and ripping canvases that he himself had painted. The weaved canvas of knots and holes departs from the flat surface to become a three-dimensional relief, and the canvas as conventional background for painting transforms into a work of art in itself. Namely, as the linear color strips compose a surface and the surface becomes a textured relief where lines, planes and solids coexist, nouage, a pictorial sculpture or a sculptural painting, disrupts the identity of single genres. Shin Sung Hy’s post-pictorial nouage that destroys the flatness of painting and endows a three-dimensional texture to the surface results in a pictorial revolution that is comparative to that of collage.

Sculptural Painting / Pictorial Sculpture

The true significance of nouage originates in its indeterminate and ambivalent existence in terms of dimensionality and genre. Shin’s nouage, whether the whole canvas is filled with net structures or only decorated on upper, middle parts or around the edge, gains a nonrepresentational and self-referential nature of an object distinct from a traditional painting. In an attempt to emphasize this quality as object, the artist moderated the square shape and linearity of a canvas painting by rounding the square frame (Peinture Spatiale, 2002) or by arranging the color strips to just outside the frame (Painture Spatiale, 2000). This non-pictorial object-ness is further stressed in modified canvas shapes such as reverse triangle (Entrelacs, 1998) or circle (Microcosme, 1999). Some other works where color strips are weaved in three overlapping layers almost present themselves as a three-dimensional structure. In fact, Shin produced an actual three-dimensional structure: Peinture Spatiale

from 2000 is a pictorial sculpture and a sculptural painting as the title suggests. In this work, Shin dismantled a canvas frame and reassembled it into a horizontal/vertical support, wrapping it with wires to create a birdcage-like spatial structure. Here, in addition to deconstruction of canvas, the artist attempted recreation through the deconstruction of the frame.

The coordination of textural surface and dazzling colors in the weaved color strips of Shin’s nouage invokes sculptural maximalism. This effect is further enhanced through irregular weaving patterns, that is, a rich, unbridled composition imprinted with the artist’s own hands. Indeed, the sculptural richness in Shin’s nouage arises from the playfulness of the artist’s hand movements, of pulling and tying strips with both hands. As if playing a harp or gayageum (a twelve-stringed Korean harp), he pulls and pushes color strips with one hand, and ties and hangs them with the other, traversing between warp and weft, hole-by-hole, and layer-by-layer.

As a painter’s material imagination is triggered from the moment their brush-holding hands encounter paint and canvas, from the moment Shin Sung Hy’s hands hold color strips, his intuitive decision creates random yet controlled weavings. Shin once stated: “I can control every single detail happening on the canvas. My hands in the empty space decide every single knot.” The artist controls the concentration and dissipation of energy with his fingers, creating a strained surface tension in structure, and a chaos of color strips as formally complex as a labyrinth.

New Spatialism

For Shin, color strips are not a mere material but a creative medium. He builds up another kind of canvas with strips cut from a canvas — a weaved canvas with numerous holes recreates a post-dimensional scene that simultaneously exists as line, surface, and relief. In his work, color strips are a medium of artistic rebirth that brings forth reconstruction after

demolition and recreation after deconstruction. Shin’s nouage revived with color strips came into its artistic existence through countless knots made of color strips and empty holes between strips, beyond the boundaries of background or surface. The maximalism of colors and textures that characterize nouage is also a maximalism of holes and knots.

In Shin’s nouage, constructed from the intersection between protruding knots and receding holes, tight knots and empty holes, and the immaterial and untouchable element of holes are as formally important as the material and touchable. These holes, for the artist, provide a productive space where the flat and superficial surface of a painting is breached and a new spatial aesthetic is established. Similarly, Lucio Fontana contended that spatialism, “spazialismo,” transcends the limit of the two-dimensional surface of a painting by perforating or incising the canvas. However, Shin’s approach to spatialism differs from that of Fontana — while Fontana’s work exists as traces of attacking or destroying the canvas, Shin’s work should be understood in the context of recreation to produce empty holes with the strips taken from an already destroyed canvas. Shin asserts a different mode of spazialismo through his webbed nouage, which provides gaps or space to replace the canvas. As titles of his series such as Vers un Espace and Peinture Spatiale suggest, to create space is the ultimate aesthetic achievement that the artist pursues.

In Vers un Espace of 1998, a large gaping hole is formed in the middle of the netted canvas, as if tiny holes are gathered to form this larger hole. In Vers un Espace produced in the same year, an empty round space like the sun or the cosmos fills the entire canvas. In Entrelacs made in 1996, a nouage web shapes a circular ring at the center of the canvas. Finally, in Microcosm and Espace Vital of 1999, Shin constructed a round canvas rimmed with nouage rings as if visually implying an evolutionary process of tiny holes of nets resembling cells expanding into the circular cosmic space. His Microcosm is the miniature of a macrocosm that is also in itself a macrocosm evolved from small holes of the web.

Created from Shin’s nouage is an invisible and immaterial space, a vacant hole. While a hole is usually a representation of a gap, an aperture, a vacancy or a void, for Shin Sung Hy, it is inscribed as respiration, breath, comma, or temporary pause that makes room for creation. Shin endows vitality to nouage, breathing life into the holes and gaps between layers through which air and light permeate. Shin’s nouage is a web of life, a neural net that connects his body to soul and hands to his work, and a communication network that links the self and the other, work and audience, people and people. Thus, as the title Espace Vital implies, Shin’s hole or space is not a lack but abundance, not the periphery but the center, not the end but the beginning, and not death but life.

3. Jute Painting: Painting Jute on Jute

Shin Sung Hy’s earlier jute paintings produced between 1974 and 1982 are noteworthy in that colors, styles, and concepts used then stand on the extreme opposite to his nouage. The artist hyperrealistically delineated every single strand of jute cloth, and sometimes even its unraveled strings, on the surface of real jute, which was often used as a substitute for the canvas at the time. As its title Peinture suggests, this series exemplified the essence of painting. To illustrate the precise shape of jute as well as its shade effect and texture, the artist applied at least three layers of brushstrokes for each strand. Unlike bold abstract expressionist paintings created by rough, spontaneous strokes or the mechanical design of geometric abstract paintings, these jute paintings, created by repetitive brushstrokes evocative of the manual labor of a weaver, require a highly technical skill in painting. Shin’s jute painting is the result of the artist’s meticulous dexterity that also enabled nouage.

The Peinture series, nevertheless, already hints at the artist’s fundamental question on what painting is and a resistance against painting, offering foci for critical discourse. In his jute paintings, the artist merges canvas and figures, background and images into one by painting

jute on top of jute, but also reaffirms the fact that painting is an illusion and deception by contrasting the real with the fictional. Contrast between the real and fictional is established by leaving portions at the middle or edges of the canvas unpainted or in empty stretches of linear or diagonal shape. Through such lacunae, the artist refuses the ontology of painting and challenges the history of painting.

The history of painting has evolved with the invention of pictorial techniques that represent spatial depth and three-dimensionality upon a flat surface, such as one-point perspective, linear perspective, and foreshortening. However, representational art or illusionist art that imitated the appearance of the external world and objects by means of these techniques had lost its dominance to abstract art with the advent of the modernist aesthetics in the late 19th century, which emphasized the autonomy and formality of art. Since the 20th century, numerous modernist painters have created flat and surface-oriented minimalist abstract paintings in which the flatness of the canvas and the materiality of the paint are accentuated.

Keeping pace with this tendency, Korean art circles of the 1970s gave birth to monochrome painting, a Korean interpretation on minimalist painting.

In this environment, Shin conversed with the trend of the time with his jute painting while also trying to establish his unique perspective on painting. The contemporaneity of Shin’s jute painting stems from the abstractness of jute patterns that repeat strand-by-strand, and their earth-toned palette. Ultimately, Shin’s jute painting is a representation of jute on one hand, and an all-over monochrome abstract painting in brown tone on the other, in which abstractness is further emphasized through subtle texture and even surface. While the artist reflected his contemporary artistic current dominated by abstract painting with his abstract hyperrealistic paintings, he established a unique aesthetic of ambivalence that dismantles the border between figuration and abstraction, and representation and presentation.

Yet, a more critical core of Shin’s jute painting lies in his pictorial strategy of painting jute

occurs — a minimalist jute painting becomes a maximalist collage.

4. Cardboard Collage and Sewn Canvas: Between Jute Painting and Nouage

During the transitional period from jute painting to nouage, Shin Sung Hy started to produce cardboard collage and sewn canvas works. The former is a series made with torn-off cardboard pieces attached on canvas with a collage technique, and the latter series is made of long pieces cut from a canvas then sewn together by a sewing machine. These series can be regarded as the precursor of Shin’s nouage in the context that they reveal the process of deconstruction and recreation.

From Minimalist Jute Painting to Maximalist Collage

Shin’s cardboard collage series that started around 1983 are entitled Peinture, the same title as his jute paintings. However, their underlying concept is completely different from jute painting — the artist painted color dots and patches on a cardboard or an anti-oxidized board, then tore off, crumbled or folded them with hands, and finally collaged the pieces onto an acrylic board. Unlike the conventional collage where pieces are attached on parts of a painting, Shin created a new all-over surface fully covered with cardboard pieces, which is then repainted. Through these multiple layers of texture and colors, a dramatic transition

From the collage work, the artist seemed to be concerned more about how to paint rather than what to paint. Through this “how,” Shin forsook the representation of objects that he still maintained in jute paintings, and instead entered the realm of abstraction. At the same time, he revived colors as a key formal element, which were subdued in his jute paintings, and disrupted flatness by creating three-dimensional textures with non-pictorial acts of cutting and attaching. As colors, texture, and their rich materiality — which his monochrome jute paintings forego — emerge as a presentation replacing representation, the primary meaning of collage was reaffirmed.

Arriving in 1985, Shin even discarded the support of acrylic board and started compositions made solely of cardboard pieces. The formal logic of anti-painting one observes in nouage was foreshadowed already in this series, as torn-off cardboard pieces construct a new board, thus aligning the support of a painting with the painting itself. As pieces of torn-off colored cardboard are reconstructed in collage, holes that appear randomly on the canvas create an uneven surface. Then, as in nouage, this work affirms its own identity as a painting in relief or a three-dimensional object. As exemplified Peinture of 1985 and 1988, the objectquality is expressed in its extreme through the uneven edges of the canvas made of crosssections of cut off cardboard. The object-quality of Shin’s work is further emphasized as the squareness of canvas mutates into irregular forms: the canvas of 1992’s Peinture is transformed into an oval roughly torn in half, leaving a jagged edge at the bottom, and that of 1989’s Peinture is the shape of a T-shirt.

Shin’s cardboard collage obtained a free formal construction, an open composition, distinct from jute painting but which would soon be displayed in his nouage, through the creative play generated from the movement of hands: tearing and attaching rather than painting with a brush, and especially from the encounter between the organic material of paper on real jute, or, painting a flat object on a flat surface. As American Neo-Dadaist Jasper Johns painted flat objects such as the Stars and the Stripes, targets and numbers, on flat canvases, Shin tried to overcome the pictorial dilemma of representing a three-dimensional object on a flat canvas by painting brown jute on real brown jute. In this context, Shin’s pictorial rebellion manifesting in his jute painting followed by the innovation of nouage works can be understood as an extension to the questions and resolutions on painting explored by Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso, the pioneers of collage, Marcel Duchamp who extended collage into the realm of the Readymade, and Jasper Johns who inherited the Dadaism of Duchamp.

and the artist’s hands. The artist’s feature as a colorist, which was suppressed in his earlier jute painting but later came into bloom in nouage, can be discerned in Shin’s collages that exude formal maximalism through the materiality and immediacy of paper and paints. In the progressive cultural environment of Paris, which was quite different from Korea’s Confucianist cultural tradition and its controlled and restrained aesthetic sensibility of the “people of white clothing,” the artist was able to express without reservation of his inner desire for richness and diversity of colors and forms. This was a revival of the liberatory expressionist urge that had been oppressed and hidden in the atmosphere of the Korean art scene in the 1970s where color was disparaged as a cheap, juvenile element.

Return to the Canvas with Sewing

During the period when Shin was making cardboard collage works, he produced another series of canvas collage using the same method. Canvas is the ultimate medium in his artistic experiment — as his desire to refuse and depart easel painting became stronger, more persistently did he cling to the canvas as the ultimate medium of his formal experiments. As Shin distanced himself from painting while adhering to the title Peinture, he returned to canvas through cutting the canvas in pieces then sewing them together.

The artist’s deep attachment to canvas strongly manifested in the sewn canvas made in 1993. As he did in his collage or nouage, he first painted color dots and patches on a canvas, and then cut it into pieces of a five-centimeter width each, finally stitching them together with a sewing machine. Seams are exposed and edges are coarsely cut with a knife to highlight contrasts between lights and shadows. Through this process, Shin’s sewn canvas attains a relief-like three-dimensionality similar to his previous collage and nouage pieces. As the title Solution de Continuité alludes, this new method of sewing finesses and completes Shin’s post-pictorial endeavors that began with his collage.

The sewn canvas with its three-dimensional plane and tactile surface shares a formal

characteristics with the cardboard collage. But, in contrast to the random arrangement of cardboard collage torn off and attached all by hands, the systematic composition of sewn pieces in straight lines displays a calm and tidy regularity. In terms of color, unpainted parts of seams that protrude to the front add a toned-down soberness to the overall appearance of the work. Later in nouage, the linear composition of sewn canvas was gradually transformed into a free organic composition and its colors became brighter and richer. Given this progression, Shin’s earlier cardboard collage, and not the sewn canvases in this later period, can be seen as the prototype of his nouage in color and composition. Still, the sewn canvas becomes the precedent of nouage in that a new plane is created from cut-up canvas pieces.

The distinctive difference between a collage and sewn work can be found in their production processes. While the former is dependent on the artist’s intuitive decision and the playful movement of his hands, the latter demands multiple steps of creation including painting a canvas, cutting the canvas, stretching and sewing together the pieces, trimming the seams, erecting the frame, and corresponding collective collaboration at each step of the process. In fact, a collaborative system that resembles a “factory” exists in his family. A four-person handicraft factory made up of his wife who graduated from a fine arts university, his architect son, and fashion designer daughter, was a key support for Shin’s art.

Through discussions and conversations among the family, the artist’s creative inspiration was concretized, and the methodology of creation was established. Sewing, which was traditionally devalued as a mere housework or women’s labor, has been applied or used as a new production method by many contemporary male and female artists. Particularly in the case of Shin, sewing was elevated even as a mechanism for reconstruction or motif for creation by means of his family’s professionalism and skills in different genres, which subsequently resulted in a new form of art, the sewn canvas.

Shin Sung Hy’s oeuvre, a passage from collage to nouage through sewing, can be epitomized by painting that transcends painting. This was realized by the unconventional creative acts of tearing and attaching, cutting and sewing, and weaving by hand. However, the artist never gave up painting. He painted color dots and patches on a cardboard or canvas before tearing them, and repainted on collages, sewn canvases or weaved surface of nouage. The working process of Shin’s art began from a paintbrush and ended with a paintbrush.

The artist’s attachment to the brush is clearly stated in his drawing series Brush made during 1999–2000, Brush and Clock in 2000, and a small sculpture From Painting (2003) that employed an actual brush of the artist as a Readymade. In addition to brushes, other implements such as cutters, scissors, rulers, palettes, glasses, and a magnifying glass he used while working, and everyday objects like a mirror and a clock and even children’s toys were painted or attached on the canvas. Shin occasionally made small sculptures with these objects in which these objects are placed inside a hole cut from a thick board made of many layers of corrugated cardboards. In an artist’s note, Shin wrote about his object pieces that he views as “homes” for thankful tools that are “dedicated to working for him” and other everyday objects that he was equally fond of, and wished that they would “live well beyond his own life.” This is an expression of the artist’s warm-hearted sentiments as an individual in contrast to the serious and decisive mindset as an artist.

Everyday objects employed in Shin’s object pieces and small sculptures become motifs of narratives or symbols that represent the artist’s worldview on life or art. A mirror, for example, was one of the artist’s favorite readymades. In Self-portrait (2004), the artist attached a mirror at the center on the net of bent and intertwined wires. Based on the reflective nature of a mirror, this work conveys a message of participation and

communication, that whoever looks into the mirror is the protagonist of this self-portrait — therefore, audiences are the real owners of this work, Self-Portrait. Imbued with Shin’s affection and consideration for audiences, the mirror in this work functions as a cord that connects the work and the spectator.

The creative act of attaching, sewing, and weaving is also a mechanism for conjunction and a cord that links art and life, artworks and livelihood, artworks and audience, and self and neighbors. Sewing in the series of Solution de Continuité aim not to complete but to connect, finally arriving at nouage, in which even the audiences are weaved together in the net of color strips. Quoting the artist’s own words, nouage can be compared to a “fisher’s net” that catches everything: “tuna, mackerel, salmon, flatfish, and more.” In embracing everything, nouage also resembles bojagi, a flexible and receptive wrapping cloth traditionally used in Korea. Prior to its meaning as an artwork, Shin’s nouage is a “visual language that integrates dialectic oppositions between you and I, material and spirit, affirmation and negation,” which expresses the artist’s personal ethos and raison d’etre: his wish for communal unity. Therefore, Shin Sung Hy exists as long as his nouage does. This is why he is still with us and will continue to be with us.

SHIN SUNG HY

b. 1948, Ansan, Korea

d. 2009, Paris, France

EDUCATION

1971 BFA Hongik University, Seoul, Korea

SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2022 Ecole de Paris: SHIN SUNG HY, Kim Tschang-Yeul Art Museum, Jeju, Korea

Espace Pictural, Gallery Hyundai Dugahun, Seoul, Korea

2019 Solution de Continuité, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, Korea

2016 The Surface and Behind, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, Korea

Before Nouage, Space K, Daegu, Korea

De La Figuration Textile Aux Nouages Paris de 1980 a’2009, Baudoin Lebon, Paris, France

2015 Shin Sung Hy, Danwon Art Museum, Ansan, Korea

2014 Space of Nouage, Light of Life Church, Gapyung, Korea

2013 Shin Sung Hy, Galerie Proarta, Zurich, Switzerland

Shin Sung Hy, Maison de Elsa Aragon, Yvelines, France

Shin Sung Hy, GalleryDate, Busan, Korea

2012 Shin Sung Hy, Shinsegae Art Wall Gallery, Seoul and Busan, Korea

Shin Sung Hy, Yvelines Art Center, Yvelines, France

2011 Shin Sung Hy, Atelier 705, Seoul, Korea

2010 Shin Sung Hy, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, Korea

Shin Sung Hy, Centum City Shinsegae Gallery, Busan, Korea

Shin Sung Hy, Gallery Baudoin Lebon, Paris, France

1999 Shin Sung Hy, Andrew Shire Gallery, Los Angeles, USA

1998 Shin Sung Hy, Gallery Convergence, Nantes, France

1997 Shin Sung Hy, Baudoin Lebon, Paris, France

1995 Shin Sung Hy, Shinsegae Gallery, Seoul, Korea

1994 Shin Sung Hy, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, Korea

1993 Shin Sung Hy, Sigma Gallery, New York, USA

1992 Shin Sung Hy, Kongkan Gallery, Busan, Korea

1988 Shin Sung Hy, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, Korea

Shin Sung Hy, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Korea (MMCA), Gwacheon, Korea

1985 Shin Sung Hy, Gallery Dongsanbang, Seoul, Korea

1983 Shin Sung Hy, Gallery Municipale d’Elancourt, d’Eancourt, France

1982 Shin Sung Hy, Gallery Samii, Los Angeles, USA

1976 Shin Sung Hy, Gallery Seoul, Seoul, Korea

SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2022 Whose Story Is This, Museum of Contemporary Art Busan, Busan, Korea

2020 HYUNDAI 50 Part I, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, Korea

100 Collective Signatures of Daegu Art Museum, Daegu Art Museum, Daegu, Korea

2018 Chung Sang-hwa, Shin Sung-hy, Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, USA

2015 Rhapsody in Ansan, Danwon Art Museum, Ansan, Korea

Primus Sensus, Pont des Arts, Seoul, Korea

Again 1970’ Daegu, S-space, Seoul, Korea

Expressions and Gestures, Seoul Olympic Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

2014 Wall, Collective Highlight, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, Korea

2011 Art Elysees, Baudoin Lebon, Paris, France

2010 Power of Gyeonggi-do, Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, Ansan, Korea

2009 Re-discovery, Seoul Olympic Museum of Art, Seoul Correspondances de l’âme, OECD, Paris, France

Vide & Plenitude, Espace Commines, Paris, France

2007 Poetry in Motion, Galerie Beyeler, Basel, Switzerland

2006 Friendship Named Painting, Galerie Jean Fournier, Paris, France

2003 Age of Philosophy and Esthetics, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Korea (MMCA), Gwacheon, Korea

2002 Sight and Language, Elancourt, France

Collective Exhibition, Busan Museum of Modern Art, Busan, Korea

Football through Art, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, Korea

The Korean Culture Viewed by Light and Color, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul

Korean Contemporary Art, Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art, ATC Museum, Iwate Museum, Japan

2001 Tradition and Innovation I, Korean Cultural Center, Berlin, Germany

2000 30th Anniversary, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, Korea

1999 Habanos 2000, International Exhibition, Barcelona, Spain; Paris, France

Reflection of Korea: 12 Contemporary Artists, Korean Embassy, Paris, France

1998 80 Artists Around the World, Enrico Navarra Gallery, Paris, France

1995 Seoul-Paris, Convent des Cordeliers, Paris, France

1994 Whanki and the Young Artists, Whanki Museum Seoul, Korea

‘94 Korea Art Light and Color, Hoam Gallery, Seoul, Korea

1992 Korean Contemporary Painting, Nichido Museum, Ibaraki, Japan

1991 Meet the International Art and Music, Riadem Art Festival, Montigny, France

Inauguration Exhibition, Wooyang Museum of Contemporary Art, Gyeongju, Korea

1990 Whanki Foundation, Gallery Dintenfas, New York, USA

1988 Olympiad of Art: International Contemporary Painting, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Korea (MMCA), Gwacheon, Korea

Modernism in Korean Contemporary Art Scene: 1970-1979, Hyundai Department

Store Gallery, Seoul, Korea

Inaugural Exhibition of Total Museum, Total Museum of Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

1987 UNESCO 40 Years Anniversary Exhibition, Walker Hill Art Center, Seoul; Travelled to France, Russia, Thailand

Inauguration Exhibition of Gallery Hyundai Second Space, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, Korea

1986 Seoul-Paris, National Center of Visual Arts, Paris, France

Korean Art Today, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art,

Gwacheon, Korea

1984 Sight and Language, Westbeth Artists Community Gallery, New York, USA

1983 The 39th Salon de Mai, Espace Pierre Cardin, Paris, France

Korean Contemporary Arts of the 70s Exhibition, Travelled to Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, Tokyo; Tochigi

Prefectural Museum of Fine Arts, Tochigi; Fukuoka City Museum, Fukuoka, Japan

1982 60 Korean Artists Working Abroad, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

The 23nd Salon des Grands et Jeunes d’Aujourd’hui, Grand Palais Museum, Paris, France

3 Painter Exhibition, Myungdong Gallery, Seoul, Korea

1981 The 22nd Salon des Grands et Jeunes d’Aujourd’hui, Grand Palais Museum, Paris, France

1980 The 21st Salon des Grands et Jeunes d’Aujourd’hui, Grand Palais Museum, Paris, France

Kim Whanki and Young Artists, Whanki Foundation, Paris, France

1978 Exhibition of the Asia Modern Arts, Tokyo, Japan

Korea: The Trend for the Past 20 Years of Contemporary Arts, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

The 6th Independents, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

1977 The 3rd Ecole de Seoul, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

The 3rd Seoul Contemporary Art Festival, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

Contemporary Art Festival, Taipei, Taiwan

The 4th India Triennale, New Delhi, India

1976 Exhibition of the Asia Modern Arts, Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan

The 2nd Ecole de Seoul, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

The 3rd Group-X Exhibition, Seoul, Korea

The 2nd Seoul Contemporary Art Festival, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

The 4th Independents, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

1975 The 13th Sao Paulo Biennale, Sao Paulo, Brazil

The 1st Seoul Contemporary Art Festival, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

The 3rd Independents, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

The 2nd Group-X Exhibition, Seoul, Korea

1974 The 1st Seoul Biennale, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

The 1st Daegu Contemporary Art Festival, Daegu, Korea

1973 Exhibition of the 20th Age Modern Artist’s Association, Seoul, Korea

The 2nd Independents, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

1972 The 1st Independents, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

1971 The 2nd Korean Art Grand-Prix Exhibition, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

Group-X Founding Exhibition, Seoul, Korea

1970 The 19th Korean National Art Exhibition, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

1969 The 18th Korean National Art Exhibition, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

GRANTS AND RESIDENCIES

1971 The 2nd Korean Art Grand-Prix Exhibition, Special Award

1969 The 18th Korean National Art Exhibition, Special Award

1968 The Korean Young Artists Prize, Grand Prize

SELECTED COLLECTIONS

Busan Museum of Modern Art, Busan, Korea

Daegu Art Museum, Daegu, Korea

Daejeon Museum of Art, Daejeon, Korea

Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, Ansan, Korea

Hanlim Museum, Daejeon, Korea

Ho-Am Art Museum, Yongin, Korea

Kumho Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

Museum SAN, Wonju, Korea

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, Korea

OCI Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

SOMA Museum, Seoul, Korea

Whanki Museum, Seoul, Korea

Wooyang Museum of Contemporary Art, Gyeongju, Korea

Moulin Art Center, Moulin, France

National Foundation for Contemporary Art (FNAC), Paris, France

UNESCO, Paris, France

Seoul

8 Samcheong-ro & 14 Samcheong-ro

Jongno-gu, Seoul, 03062, Korea

+82 2 2287 3500

mail@galleryhyundai.com

New York

500 Greenwich St., #202

New York, NY 10013, USA

newyork@galleryhyundai.com

By appointment only