SAMSAM SEULGI LEE 삼삼 이슬기

SAMSAM

SEULGI LEE

독립큐레이터

여행을 통해 조우했던 여러 도시와 마을의 체류와 접촉의 경험으로부터 촉발된

것이기도 하다. 지난 수년간 모로코의 페즈(Fes), 멕시코의 산타마리아 익스카틀란(Santa María

Ixcatlán), 이탈리아 로마(Rome), 프랑스 푸아투(Poitou)와 브르타뉴(Bretagne) 지역, 한국의 통

영과 인천, 일본 교토(Kyoto) 등을 방문하면서 그 지역과 공동체 내부에 존재하는 문화 중 특히 민

예품, 수공예 기술, 민요, 언어들 안에서 발견되는 버내큘러(vernacular), 즉 방언화된 상태와 양

상, 지식을 살피고 그로부터 영감을 받은 작업들을 전개해 왔다. 또한 성애(性愛)에 대한 인류학적

원형들에 대한 자신의 관심에 상상력, 색과 선의 유희가 가득한 조형적 실험을 보여준다.

이번 전시의 제목인 《삼삼》은 직조 체계를 작은 모형으로 만들고 긋기 단청으로 칠하여 만든 가로

세로 11×11cm의 스터디 모형들의 제목이다. 얇은 격자선 구조가 전시장의 모든 공간에 서양음

악에서 말하는 바소 오스티나토(basso ostinato) 즉, ‘고집스러운 베이스’로서 서로 다른 스케일을

취하며 반복된다. 작가는 그리드 구조를 단청의 색으로 변주하는 방식으로 작은 모형과 큰 구조를 통해 다양하게 실험한다.

조선 시대 절, 궁궐, 관청이나 큰 기와집 문 위를 정면으로

판자를 이용하여 장인과의 협업으로 제작한다. 현판에

출입구나 현판 주변의 동적 상태들을 의성어로 만들고 서예체의 횡서(가로쓰기)와 종서(세로쓰기) 방식으로 다소 장난스럽게 마치 캘리그래피처럼

진 현판에 줄줄 흐르는 빗물의 의성어적 표현인

라 할 수 있다. 예를 들어 〈U : 미주알고주알〉에서 미주알은 항문을 이루는 창자의 끝부분을 일컫

는 것으로 장기나 성기 끝까지 파고들 정도로 사안을 캐고 말한다는 뜻을 담고 있으며, ‘트집 잡다’

의 트집이 갓 챙을 인두질하는 작업을 일컫는 뜻으로 트집 작업으로 돈을 뜯던 조선시대 갓 장인

들의 행위에서 유래하고 있으며, ‘부아가 난다’라는 말은 허파가 부푸는 것을 뜻한다. 이러한 말의

기원에 대한 관심이나 속담의 풍자성에 대한 관심으로부터 극도로 사적인 공간인 이불은 문화 인

류학적 흔적들의 사랑스럽고 위트 있는 공동체적 저장소로 변모한다.

이슬기 작가는 격자, 사각, 직선, 원형, 난형, 곡선 등의 가장 기본이 되는 조형적 요소나 단위들을

자주 반복해 사용한다.

"AFFABLE

AND CONVIVIAL, INNOCUOUS YET LASCIVIOUS": NOTES ON SEULGI LEE'S SAMSAM

Hyunjin Kim Independent curator

즐거운 기술로 끊임없이 호출된다. 그리하여 오늘

같다.

Seulgi Lee’s works have evolved into a joyful form full of wit, incorporating traditions and artisan techniques from folk art which she has encountered over many years of pursuing her anthropological interest. For more than two decades, Lee has been traveling to different cities and villages that range from Rome (Italy), Kyoto (Japan), Fes (Morocco), Santa María Ixcatlán (Mexico), and Poitou and Brittany (France) to Tongyeong and Incheon (South Korea), among others. Such travels have become a constant in both her personal life and creative practice. As she observed the cultures of regions and communities she encountered with emphasis on folk art, traditional craftmanship, folk songs, and languages, she found within them vernacular knowledges and human conditions which came to serve as triggers for developing works. In addition, Lee’s formal experiments demonstrate a combination of her interest in recurring motifs in anthropological objects, often sexually connotated with a unique imagination and playful colors, shapes and lines.

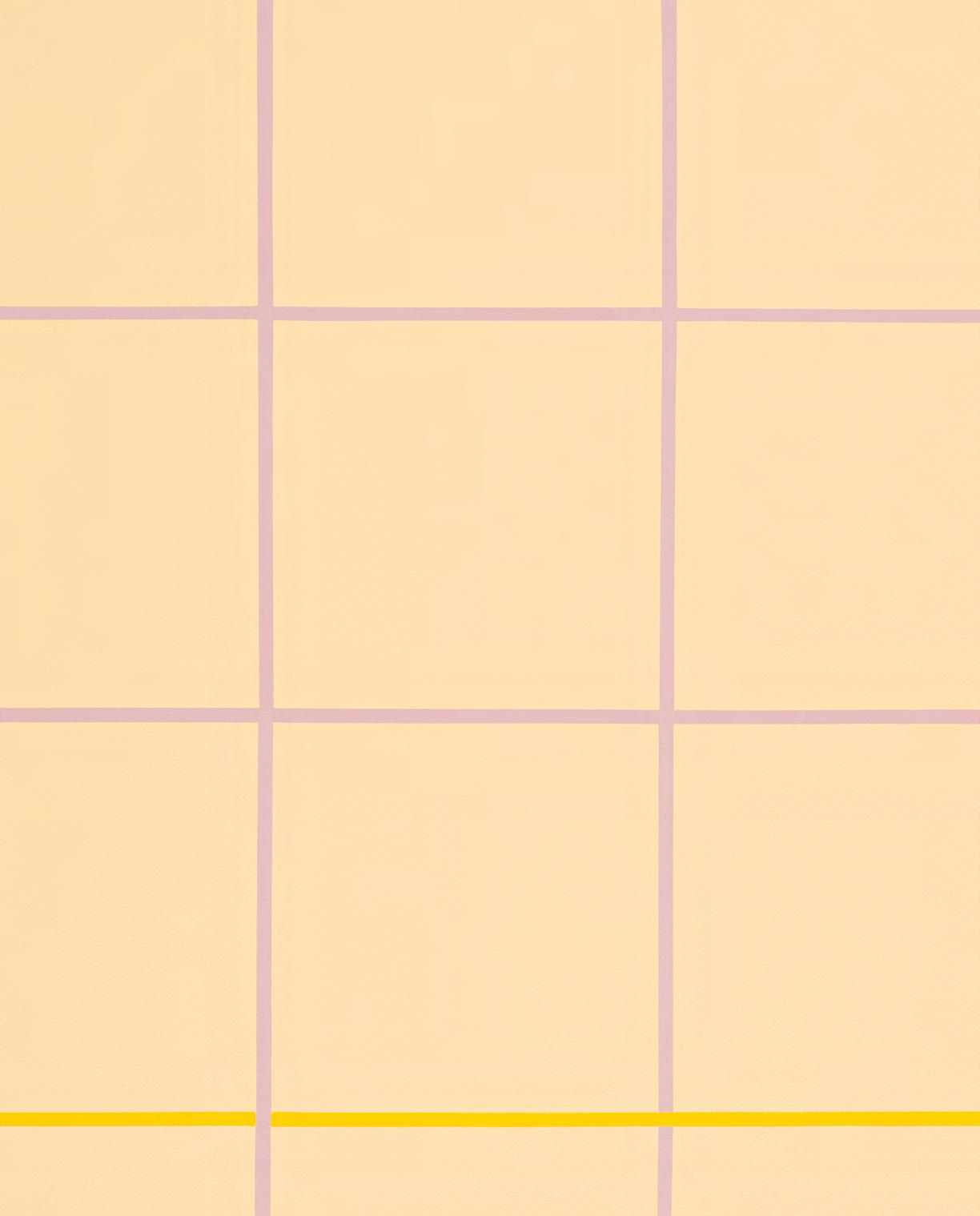

The exhibition title, SAMSAM, refers to the name she gave to the 11 x 11 cm models for study that represent a system of weaving, colored in the style of geutgidancheong—with dancheong denoting traditional Korean decorative coloring for

mostly temple and palace architectures, geutgi-dancheong refers to one style of dancheong consisting exclusively of straight lines. The grid-like form, which serves as a bass ostinato (“obstinate base”) throughout the entire exhibition, is present all over the exhibition space not only in different combinations of dancheong pigments but also in different scales—ranging from palm-size miniature to lifesize. Taken as a representation of the modern matrix that grows ever more precise with the overaccumulation of data, it is plausible to see a grid structure in general as signifying mechanisms of modern rationality which confines nature. However, for Lee, the grid has been, in the past couple of years, a signifier of the warp and weft of ramie fabric (mosi in Korean) or the traditional latticework for wooden doors known as munsal, literally meaning “door rails,” in which people in East Asia will likely see the shape of Chinese character chŏng (井) that stands for water well. It is also a structure predicated on emptiness, whereby hollow and porous spaces, marked by lines that do not delineate the inside from the outside, let things in and through. Grid forms that derive from different cultures, thoughts, and cosmologies become fully integrated in Lee’s formal vocabulary and merge into a single corpus, serving as a major motif in Lee’s practice where the geometric forms operate as a vessel for tradition. In this exhibition, Lee’s Ramie Dancheong Mural (2024) is spread across three stories—from the basement to the second floor of Gallery Hyundai's new building. The tripartite grid pattern painted in dancheong turns out to be a giant egg-like form divided and allotted to three separate spaces. When the lighting hits the background painted in apricot, the viewer feels as if they are enveloped by the sunset.

Installed between the staircase to the basement and the adjacent wall is a segment of Slow Water (2021), originally a large circular latticework that hangs from the ceiling, built in the style of munsal and painted in dancheong. Inspired by the frescoes at Villa de Livia during her stay in Italy, Lee recreates their phantasmagoric and illusive effect in the site-specific context of the Incheon Art Platform (IAP), which has been built on reclaimed land, once part of the shore that met waves. Lee invites the viewer to imagine being underneath the surface of water dappled by sunlight prior to the land reclamation—not only do the colors change constantly from different angles but the viewer also feels as if they are standing underneath the sea with the sunlight sipping through the grid above. The subtle yet notable choice here is the design of the grid: the orthogonal lattice, known as jikgyo (直交) in munsal structure, where the term

literally means “straight intercourse” and is therefore ripe with connotations of sexual union between men and women. In fact, depending on the shape of the munsal, the door can also reveal the gender of the room's owner. As the sides of thin wooden bars constituting the lattice are colored with entrancing dancheong pigments that have been refashioned with a modernist touch by the artist, the sexual connotations are further reinforced by the fact that the five colors of dancheong derive from the concepts of yinyang and wuxing in East Asian cosmology that pertain not only to the laws of nature but also to the ancient views on reproduction. Like a prism refracting light, Slow Water emanates mesmerizing colors that offer a sense of tranquility to the viewer, which seems at first glance devoid of any sexual connotation. However, the polysemic play on the Chinese character saek (色, “color”) that has both sexual and chromatic connotations is unmistakable in the unfolding of dancheong colors’ full potential in munsal, evoking the microcosmic space of harmony and humanity in the ancient worldview.

***

Around the mural in each floor hang large, heavy slates at different heights. Inspired by plaques that were placed above gates of temples, palaces, offices or large mansions during the Joseon Dynasty, these large panels are made from red pine in collaboration with a plaque artisan. Observing that such traditional plaques are usually fixed to a wall or directly above a gate and engraved with words or images, Lee creates reliefs of onomatopoeias or ideophones associated with the movement of doors or walls, oriented either horizontally or vertically on her wooden panels. However, Lee’s evoke the playfulness of highly individualized handwriting or calligraphy, whereas textual inscriptions on traditional plaques impart the solemnity of the place. In this series, Lee renders the following onomatopoeias into pictographs: K'ungk'ung and sŭrŭrŭk are onomatopoeias in Korean for door slamming (“bam!”) or sliding (“shrrrk”), ch'ulch'ul evokes rain dripping on a door or plaque hanging at a slant, and pusisi refers to the rustle of fabric or hair whose jocularity contrasts with the awe-inspiring presence of plaques. In the handwritten fashion of comic strips, each letter is designed to capture the sound, amplitude, and movement of the word, thus serving as both image and word. Painted over the relief is yet another set of texts that form rhythmic couplets with onomatopoeias mentioned above—k’ung-duk, sŭrŭrŭk-shi, ch'ulch'ul-ssua, pusisi-h—, usually a single letter or character in a highly

stylized typeface rendered dancheong white. Plaques often indicate liminal space and delineate the inside from the outside, as they are usually hung and presented above a door or a gate. Whereas plaques are traditionally meant to be read or seen from the outside, Lee's wooden monuments hang in an interior space. Their past role in defining interiority and exteriority is replaced by the onomatopoeias in graphic types that embody the motion of door and the state of a threshold, mediating and connecting two different worlds.

While Lee closely examines the origins of the artifacts that serve as motifs for her work and incorporates them in a way that retains relevance to their original tradition or cultural context, Lee’s work is by no means bound by an orthodox attitude toward tradition. Plaques are exemplified by the overbearing weight and thickness of the wooden material, on which letters are written in bold and unrestrained calligraphy, as they are meant to command authority and legitimacy. Lee breaks with this tradition and instead employs a play on forms and contemporary sensibilities through onomatopoeias rendered in cartoon-like pictography. The virtue of her practice lies in her invitation of traditional crafts to the playground of forms that characterize contemporary visual arts as well as seamless incorporation of knowledge or experience of tangible and intangible cultural heritages, thereby delightfully recognizing the scope, the value and flexibility of traditional crafts and the associated techniques.

Most artisan traditions today, recognized as local cultural heritages, are characterized as much by locality and claims to authenticity as they are by adaptability and modifiability—a testament to how they have survived the ups and downs of modernity, namely the process of acculturation by sociocultural and temporal entanglement. In her collaboration with artisans, Lee witnesses their pride, stubbornness, details and idiosyncrasies of their techniques, and the circumstances that seem untenable to the survival and viability of their practice. Most of the time, the artisans with whom Lee collaborates are uncompromising in their attitude, which makes their collaboration a string of moments of tension and compromise. As partially witnessed by myself, however, the moments of potential conflict in Lee’s collaboration with dancheong and munsal artisans quickly develop into something that resembles ethnographic fieldwork, where Lee closely listens to them and tries to understand the reality of their livelihood and practice. Instead

of jumping to conclusions about their vernacular “temporal-states,” Lee, like a field researcher engaged in an oral interview, invites the artisans, patiently and diligently listens to what they have to say, and sets the wheel of imagination in motion. While they may complain or gripe at the artist for bringing proposals hitherto unheard of in their tradition, their undertakings are marked by sincerity, a testament to not only their great problem-solving skills but also their willingness to take on a new challenge. Instead of subscribing to the rhetoric of so-called integration of tradition and the modern predicated on the clichés involving traditional East Asian aesthetics, Lee strives to achieve the union between a pure sense of joy, wit and humor, and minimal and unpretentious forms. In the end, the artist succeeds in demonstrating the efficacy, flexibility, and viability of traditional craftsmanship—something which orthodox attitudes toward tradition often fail at.

***

One other major feature in Lee's work is her interest in representations of sexuality in the folk art traditions. In fact, Lee has explored various artifacts associated with fertility and childbirth and the folk songs—especially those sung by women—that are, either explicitly or implicitly, ripe with women’s erotic fantasies. She has also created a series of works inspired by such an exploration. Take, for example, the BAGATELLE series (2020), which appropriates and reconstructs a billiard-like table game of the same name. In French, the word bagatelle denotes a number of things: something too insignificant to be worth much consideration, a short piece of music usually of a light, mellow character, or sex. Lee closely examines the etymology and semantic changes in the usage of the word, where the term is more readily used as a sexual slang nowadays as the table game fell out of popularity. To her, the bagatellederived work serves as an intermediary site of sexual play where connotations of sex and the female body are implied by the relationship between nails and holes within the U-shaped object.

While Lee was investigating bawdy folk songs sung by women in France, she chanced upon cave paintings and Gargantua and Pantagruel, a Renaissance-era novelization of oral folk tales by Francois Rabelais, which inspired her KUNDARI series. Lee began her work with a somewhat wild imagination: What if Gargantua, a cheerful, free-spirited, and itinerant giant driven by innocuous curiosity—the

very terms that have also been used to describe Lee's oeuvre—was a woman? In KUNDARI, this idea blends in with exaggerated representations of the female body or genitals in artifacts associated with fertility and childbirth, such as Sheela Na Gigs or the Venus of Willendorf. The word kundari comes from a Korean term kubŭn tari, meaning “bent knees,” a neologism that Lee has coined for a human figure squatting down to remove a thorn under the foot that she had found in a modillion of a Romanesque church. It is also a slight nod to Kuṇḍalinī, one of the Hinduist concepts for a divine feminine energy visualized as a snake coiled under the human spine. The artist then renders the term a simplified pictographic structure, freely experimenting with its graphic elements (the referent) by adopting anthropomorphic letter forms or symbols of animals such as frogs and spiders—these processes of formal reconstitution culminate in linear and round metal casts in bright, playful colors.

Blanket Project U is the result of Lee’s long-term collaboration with a nubi (Korean traditional quilt) artisan in Tongyeong, South Korea. This series of two-dimensional works finds its motif in figures of speech such as Korean proverbs or vernacular expressions and their origins—indicated in the title of each work—in the form of simple graphics, where Lee demonstrates a uniquely humorous aesthetic in her playful approach to color and textures of the quilt. Every work in the series is made of pearl-like reflective silk from Jinju, South Korea, and each patch is meticulously stitched in different orientations depending on the meaning of the proverb or figure of speech, which calls for a highly nuanced reading. The “U” rendered in pink seems to symbolize sexual union that might happen under the blanket, as it resembles both the shape of the uterus and upside-down phallus. However, Lee finds the shape of a bowl in the letter “U,” which she compares to a blanket that contains and protects people wrapped in it. The composition of forms and colors that unfold on the blanket are abstracted visuals standing in for figures of speech that serve as vehicles of vernacular thinking specific to a particular society or community. The Korean idiom mijualgojual, meaning “to the last detail,” derives from the word mijual, which stands for rectum—giving off an impression of someone willing to go as far as to the end of someone's insides. The expression t’ŭjipchapta, “finding faults with something or someone,” derives from t’ŭjip, the finishing touch on the brim of a traditional Korean hat for men, which was not an insignificant source of income for tailors during the Joseon Dynasty. Similarly, the literal meaning of puaga nanda, which is used in

situations of extreme annoyance or anger, is “swollen lungs.” Lee’s interests in the satirical aspect of idioms and their etymology turns the private and intimate space of a blanket into a witty and alluring communal storage of cultural anthropological traces.

Lee’s oeuvre is characterized by the repetitive use of basic forms or units of form: grid, rectangle, straight line, circle, oval, curve, etc. As forms like a perfect circle or perfectly straight line do not exist in nature, it is not difficult to draw a link between their artificiality and their significance as the origin and archetypical form of modern rationalism. For Lee, however, they recur as rather neutral motifs. Like a child full of mischief who puts on an expressionless face, Lee’s basic forms communicate not only a sense of humor, satire, and wit but also the spirit of the communality and sharing, all of which originate from her engagements with specific artifacts, histories, and traditions driven by an insatiable anthropological curiosity. With insights into the vernacular and the specificity of local heritage as well as universally recurring motifs in anthropological objects, Lee’s work frequently traverses the threshold of playfulness with a sense of humor that is at once lascivious and innocuous, and imaginative power driven by a chain of associations between shapes and origins of objects. For the artist, traditional craftsmanship is not alienated from or at odds with contemporary visuality. Instead, Lee emphasizes the adaptability and openness of traditions, which allows them to ceaselessly return as friendly, convivial, and fun practices. In this sense, Seulgi Lee’s practice amounts to a self-driven act of remembrance, a door that slides open between the past and the present towards a community of humor.

BIANE Hanging Board Project

2024

Douglas pine, Korean traditional painting Dancheong

88 × 69 × 4 cm

Boushishi

2024

Douglas pine, Korean traditional painting Dancheong

240 × 161 × 4 cm

Tchoul Tchoul BIANE Hanging Board Project

Seureureuk BIANE Hanging Board Project

2024

Douglas pine, Korean traditional painting Dancheong

200 × 300 × 4 cm

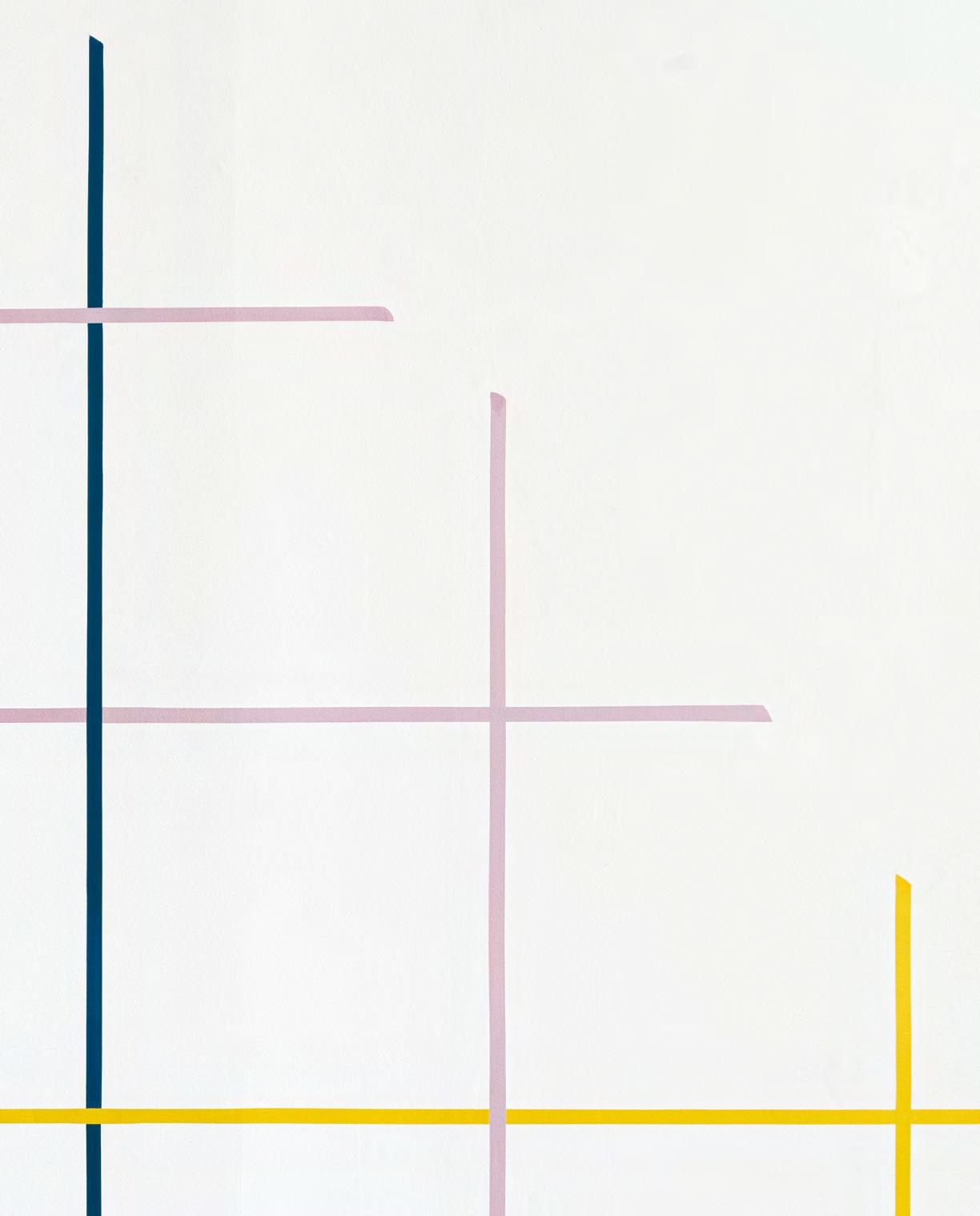

Installation view of SAMSAM, 2024

Second floor of Gallery Hyundai, Seoul

Red

Moonsal including a musical note in reference to Dong Dong Dari from the 12th Century 212 × 77.5 × 7.5 cm

pine, wooden trellis

× 2pcs

Installation view of SAMSAM, 2024

Second floor of Gallery Hyundai, Seoul

Dancheong on the wooden trellis Moonsal Ø 1,100 cm adapted for the basement of Gallery Hyundai

Installation view of SLOW WATER, Incheon Art Platform, Incheon, 2021

Photo by Cholki Hong

Installation view of SLOW WATER, Incheon Art Platform, Incheon, 2021

Photo by Cholki Hong

Installation view of SLOW WATER, Incheon Art Platform, Incheon, 2021

Photo by Seulgi Lee

Installation view of SAMSAM, 2024

Second floor of Gallery Hyundai, Seoul

2024

Korean traditional painting Dancheong with Geuk-ki technic, collaboration with Dancheong artisans

1,200 cm large wall with 12 mm width lines over 3 floors

Ramie Dancheong Mural

작가 전시에 사용된 안료

안료란 물, 기름, 알코올 등의 용매에

등의

세계적으로 회화뿐만 아니라 건축물, 공예

품, 조각 등의 채색에 널리 이용되어 왔다. 고대의 안료 중에서 가장 먼저 사용된 것은 천연 암석

과 황토, 적토 등의 흙을 가루로 만들어 사용한 것으로 볼 수 있다. 전통안료란 이러한 고대부터

사용해 온 천연안료를 말하며, 천연광물이나 토성안료를 분쇄 수비한 무기안료가 대부분으로 착색

력은 약하나 아름다운 빛깔과 변색되지 않는 특성이 있다.

한국의 전통안료의 사용은 고대에서부터 삼국시대 고분벽화, 조선시대 단청과 불화 등에서 널리

사용되었음을 알 수 있다. 그러나 조선말, 일제강점기를 거치면서 화학안료 유입이 본격화되었고,

전통안료의 사용이 점차 사양실로 접어들었다. 천연 암석, 흙 등이 원료가 되는 전통안료는 그 수 요가 적고 값이 매우 비싸기 때문에 현재의 안료는 인공 화학제품이 대부분이며, 특히

계열 당주홍, 번주홍, 왜주홍, 주토, 황단, 편연지, 석간주, 장단, 주홍 청색 계열 청화, 대청, 이청, 삼청, 양청, 군청 황색 계열 석자황, 석웅황, 동황, 석황

녹색 계열 당하엽, 하엽, 뇌록, 삼록, 석록, 양록 백색 계열 진분, 정분 흑색 계열 송연, 진묵, 당묵, 청화먹 기타 재료 아교, 교말, 법유, 명유 <표1> 조선시대 의궤에 나타나는 단청안료

지 않는다. 그 대체품인 저가이면서도 다양한 색감과 사용이

있는 화학안료는 크게 유기 안료와 무기 안료로 구분되며, 안료의 원색은 장단, 주홍, 양청, 황, 하엽, 석간주, 지당, 먹 등이며, 혼색을 통해 육색, 삼청, 다자, 뇌록, 양록 등을 만들어 대 략 20여가지 색을 사용한다. 국립문화유산연구원의 실험을 거쳐 국가유산청에 의해 지정된 단청 안료의 종류는 <표 2>와 같다.

2) 단청의 채색기법 단청의 쓰이는 색은 색의 명도단계를 2~3단계로

명도에 따라 백색과 흑색 사이에서 초빛, 2빛, 3빛의 순서로

구성을 살펴보면, 모로단청에서는 2빛 단계를,

색상 사 용 안 료 성분

녹 Cyanin green 유기

장단 Read Red(Pb3O4) 무기

황 Chrome yellow(PbCrO4) 유기

주홍 Toluidine Red(Hgs) 유기

먹 Permanent Black(Carbon Black) 유기

백색(지당) Titaniume Dioxide R760(TiO2) 무기

황토 Iron Oxide Yellow(Fe2O3) 무기

양록 Emerald Green(Cu(C2H3O2)2ㆍ3Cu(AsO2)3) 무기

석간주 Iron Oxide Red(Fe2O3) 무기

하엽 Chromium Oxide Green(Cr 2O3) 무기

양청 Cobalt blue, Ultramarine(3NaAlㆍSiO4ㆍNa2S2) 무기

교착제 아교, Acryl Emulsion

기타 재료 호분 (CaCO3), 들기름

<표 2> 현대 단청안료 (화학안료)

용하는 것이 보통이다. 그러나 고려시대의 사찰 봉정사 극락전에서는 부분적으로 최대 4빛까지 사

용한 예가 보인다. 금단청 양식에서만 적용되는 3빛 단계인 경우 초빛, 2빛, 3빛의 순서로 채색하 고, 초빛 앞에는 분선으로, 3빛 뒤에는 먹선으로 마감한다. 따라서 3빛으로 할 경우 실제 명도는 5 단계로 구분된다.

단청에서 문양의 입체감을 표현하는 방법으로 초빛, 2빛, 3빛의 빛 체계를 ‘우림법’이라 하며, 우림 법은 점층적인 명도 차에 의한 계열색을 인접하게 배열하는 도채 방법이다. 우림법은 단청의 대표

색들은 안료의 입자가 곱고 착색력이 뛰어나 긋기하기에

색들은 긋기나 선묘시 그 선의 디테일이 떨어질

PIGMENTS USED IN THE WORKS OF SEULGI LEE’S EXHIBITION

Kwang-kwan Joo

Seoul Intangible Cultural Heritage Dancheong Artisan Certified Trainee

Cultural Heritage Repair Engineer No. 886

Ph.D. in Cultural Heritage Science, Chungbuk National University

M.A in Art History, Dongguk University

1. Definition of Pigment

Pigments are inorganic or organic compounds of fine particles that are not soluble in solvents such as water, oil, and alcohol. Their stronger coloring and hiding power compared to dyes have rendered pigments the most basic materials for paintings, dancheong, and murals. From cave paintings such as Lascaux and Altamira of the Paleolithic period, pigments have been widely used not only for paintings but also for coloring buildings, craft works, and sculptures around the world. Among the pigments in ancient times, the very first instances were made from powdered natural rocks and earth such as loess and red soil. Traditional pigments refer to such natural pigments that have been used since ancient times. Most of them are inorganic pigments that have been crushed and refined from natural minerals or soil. Although their coloring strength is low, traditional pigments are characterized by beautiful colors and resistance to discoloration.

Traditional Korean pigments have been widely used since ancient times, from tomb murals of the Three Kingdoms period to dancheong and Buddhist paintings of the Joseon period. However, due to the introduction of chemical pigments at the end of

the Joseon Dynasty and throughout the Japanese Occupation of Korea, the use of traditional pigments gradually declined. As traditional pigments made from natural rocks and soil are in low demand yet very expensive, most pigments used today are artificial chemicals. In particular, chemical pigments have long dominated dancheong on buildings for their low cost and convenience.

2. Dancheong Pigments and Coloring Techniques

Dancheong refers to the act of coloring walls or other parts of a building using various pigments. Since ancient times, dancheong has been widely applied to wooden buildings, tomb murals, paintings, crafts, and lacquerware. In particular, dancheong in wooden buildings was essential to both extending the lifespan of structures and imparting a sense of magnificence, depending on the building’s purpose. The color of dancheong is based on the five cardinal colors of blue, red, white, yellow, and black, which are applied using the urimbeop technique with three levels of brightness called chobit, 2 bit, and 3 bit

1)

Types of Dancheong Pigments

The pigment used in dancheong is a colorant consisting of inorganic or organic compounds and takes the form of colorful fine particles that are insoluble. When mixed with an adhesive and painted on the base surface of a building structure, a film forms on the surface, emanating uniquely vibrant colors. Before the Japanese Occupation and introduction of chemical pigments, inorganic mineral pigments (jinchae, dangchae, and amchae) and Bunchae (also called ichae) were used, and most of them were imported from China. <Table 1> lists the types of dancheong pigments recorded on various uigwe (royal protocols) from the 17th century to the early 20th century.

However, since these natural inorganic pigments are produced in small quantities and are expensive, they are rarely used in dancheong today. Instead, chemical pigments are preferred for their low cost, convenience in use, and variety of colors. Chemical pigments currently used are largely divided into organic and inorganic pigments, and their primary colors are Jangdan, Juhong, Yangcheong, Hwang,

Color Series Pigment Used

Red Dangjuhong, Beonjuhong, Waejuhong, Juto, Hwangdan, Pyeonyeonji, Seokganju, Jangdan, Juhong

Blue Cheonghwa, Daecheong, Icheong, Samcheong, Yangcheong, Guncheong

Yellow Seokjahwang, Seokunghwang, Donghwang, Seokhwang

Green Danghayeop, Hayeop, Noilok, Samrok, Seokrok, Yangrok

White Jinbun, Jeongbun

Black Songyeon, Jinmuk, Dangmuk, Cheonghwameok

others Glue, Kyomal, Beopyu, Myungyu

<Table 1> Dancheong Pigment Recorded in Uigwe in the Joseon Dynasty

Color Pigment used Ingredient

Rok Cyanin green organic

Jangdan Read Red (Pb3O4) inorganic

Hwang Chrome yellow (PbCrO4) organic

Juhong Toluidine Red (Hgs) organic

Meok Permanent Black (Carbon Black) organic

White (Jidang) Titaniume Dioxide R760 (TiO2) inorganic

Hwangto Iron Oxide Yellow (Fe2O3) inorganic

Yangrok Emerald Green (Cu(C2H3O2)2 · 3Cu (AsO2)3) inorganic

Seokganju Iron Oxide Red (Fe2O3) inorganic

Hayeop Chromium Oxide Green (Cr 2O3) inorganic

Yangcheong Cobalt blue, Ultramarine (3NaAl · SiO4 · Na2S2) inorganic

Gyochakjae Glue, Acryl Emulsion

others Hubun (CaCO3), Perilla oil

<Table 2> Contemporary Dancheong Pigments (Chemical Pigments)

Hayeop, Seokganju, Jidang, Meok, etc. Mixing the primary colors produces about 20 transitional colors including yuksaek, samcheong, daja, noirok, and yangrok. <Table 2> lists the types of dancheong pigments designated by the Korea Heritage Service through trials at the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage.

2) Dancheong Coloring Technique

Dancheong colors are divided into two to three brightness levels, each referred to as “bit.” These bit levels are arranged by brightness in the order of chobit, 2 bit (yibit), 3 bit (sambit) and so on between white and black, with the maximum of 4 bit

Examining the tiered utilization of bit, 2 bit is usually applied to Moro Dancheong and 3 bit to Geum Dancheong. However, there exist cases of using up to 4 bit, for example on parts of Geuknakjeon in Bongjeongsa Temple built during the Goryeo Dynasty. For the three levels of bit which is applied only in the Geum Dancheong style, the colors are coated in the order of 1 bit, 2 bit, and 3 bit. White lines (bunseon) are drawn before coloring 3 bit, and black lines (meokseon) are drawn afterwards as a finishing touch. Therefore, when using three levels of bit, the actual level of brightness is divided into five levels.

As a method of conveying the three-dimensionality of patterns in dancheong, the shading system of urimbeop juxtaposes chobit, 2 bit, and 3 bit Urimbeop is a coloring method that arranges colors of the same shade family by gradual differences in brightness. A representative color system of dancheong, urimbeop forms the basis of the standardized form of dancheong. In the dancheong field, the

division Red Yellow Green Blue

1 bit Jangdan Yuksaek Juhong Yukseak Jangdan Seok ganju Hwang Samrok Yangrok Hayeop Bunsam cheong Sam cheong

2 bit Jangdan Juhong Juhong Daja Jangdan Yangrok Hayeop Yang cheong Sam cheong Yang cheong

3 bit Juhong Daja Daja Meok Juhong Hayeop Yang cheong Meok Yang cheong Meok

<Table 3> Levels of Color Arrangement by Bit in the Joseon Dynasty

execution of urimbeop is referred to as “placing bit (bit neot-gi),” as in chobit neotgi, 2 bit neot-gi, and 3 bit neot-gi, respectively. Also, when applying the urimbeop method, the overall color description of a particular pattern is based on its chobit color. For example, a lotus flower pattern (yeonhwa) that uses up to 3 bit of jangdan color is called Jangdan Yeonhwa, and a spiral vine pattern (golpaengi) that consists of up to 2 bit of yangrok is called Yangrok Golpaengi. Coloring proceeds in the order of chobit followed by 2 bit and 3 bit, with no empty space between each planes of bit. Thus, one colors tightly so that there is no gap between chobit and 2 bit or between 2 bit and 3 bit

3. The Pigment and Dancheong Techniques Used in SHADOW and Munsal (Wooden Frames) for the Exhibition, SLOW WATER

The pigments used in Seulgi Lee's exhibition SLOW WATER held at Incheon Art Platform (IAP) were produced from modern chemical pigments mainly used in today’s dancheong. However, different adhesives were used depending on the base material—an acrylic emulsion was used for SHADOW, while for the munsal (wooden lattice frames that cover doors in Korea) of SLOW WATER, glue was mixed with pigment. Acrylic emulsion, a synthetic resin adhesive with excellent adhesion and waterproof performance, was an apt material for works on exterior walls exposed to UV rays, rain, and wind. Afterwards, low-concentration vinyl acetate-based resin was applied on top to improve the lifespan of dancheong pigments. On the other hand, as the munsal of SLOW WATER was made from wood and displayed indoors, glue made from the inner skin of cattle was used at a concentration of 5% to 7%.

The dancheong pigments used for the exhibition were commercial dancheong pigments commonly used nowadays, but were mixed in a manner distinct from the aforementioned traditional dancheong color scheme. Namely, the artist utilized intermediate colors with saturation and brightness more various than the color and bit system used in dancheong, so that she may better realize the palette she envisioned.

The line elements in this work were applied using techniques such as meokbun-

geutgi (black ink drawing) and saek-geutki (color drawing), which are commonly used in dancheong. However, if dancheong uses a limited number of colors for drawing lines, various colors were used to for lines in Seulgi Lee’s work. In dancheong, three colors are mainly used for line drawing: black, white, and vermilion. These colors are made of fine pigment and have excellent coloring power, which makes them apt for drawing lines. Heavier colors that are mostly used for chobit are less convenient for delineation as details of fine lines are inevitably lost. In order to realize neat lines, the artist departed from the conventional dancheong method, mixing various colors with titanium dioxide (jidang) as a base instead of using an extender pigment (hobun or baekto), which enables an excellent expression of details.

* This is the re-edited version of an essay originally written for Seulgi Lee's 2021 solo exhibition at Incheon Art Platform (IAP).

Installation view of SAMSAM, 2024 Basement floor of Gallery Hyundai, Seoul

Kkoung Kkoung BIANE Hanging Board Project

2024

Red pine, Korean traditional painting Dancheong

88 × 69 × 4 cm

drawings for BIANE Hanging Board Project

U:

U: Take Teu-jip (Make Round the Visor of the Korean Top Hat) = To Nitpick 2024, Korean silk, collaboration with Nubi artisan of Tongyeong, 195 × 155 × 1 cm

U: 부아가 나다

U: To Have a Swollen Lung = To Get Angry

2024, Korean silk, collaboration with Nubi artisan of Tongyeong, 195 × 155 × 1 cm

Installation view of SAMSAM, 2024 Basement floor of Gallery Hyundai, Seoul

U: The Shoes Have Ears = Things don't Go Together

2024

Korean silk, collaboration with Nubi artisan of Tongyeong

195 × 155 × 1 cm

U: The Shoes Have Ears = Things don't Go Together

U: To Have a Big Liver = To Be Brave

2024

Korean silk, collaboration with Nubi artisan of Tongyeong

195 × 155 × 1 cm

간이 크다

U: To Have a Big Liver = To Be Brave

2024

Mixed media on paper

30 × 21 cm

U:

U:

U: (To know until the) Asshole at the End of Intestines = To Know in Detail 2024, Korean silk, collaboration with Nubi artisan of Tongyeong, 195 × 155 × 1 cm

U: The Sparrow (Sinosuthora Webbiana) Has Its Legs Spread as It Follows the Stork 2024, Korean silk, collaboration with Nubi artisan of Tongyeong, 195 × 155 × 1 cm

U:

2

U: (To know until the) Asshole at the End of Intestines = To Know in Detail 2 2024, Korean silk, collaboration with Nubi artisan of Tongyeong, 195 × 155 × 1 cm

U: 김칫국부터 마신다

U: Drink the Kimchi Soup = To Hope for Something to Be Given 2024, Korean silk, collaboration with Nubi artisan of Tongyeong, 195 × 155 × 1 cm

2021–2024

Urethane coating on stainless steel

180 × 200 × 100 cm

Production supported by Incheon Art Platform

쿤다리

II KUNDARI Spider II

Installation view of SAMSAM, 2024

Ground floor of Gallery Hyundai, Seoul

2021–2024

Urethane coating on stainless steel

220 × 220 × 120 cm

Production supported by Incheon Art Platform

KUNDARI Frog

Saint-Aubin de Baubigné, France

2021–2024

Urethane coating on stainless steel

25 × 25 × 55 cm

Production supported by Incheon Art Platform

2021–2024

Urethane coating on stainless steel

50 × 35 × 35 cm

Production supported by Incheon Art Platform

BAGATELLE 1

2020 Oak, nail, ball

120 × 60 × 6 cm

Production supported by National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA) and SBS Foundation

BAGATELLE 2

2020, Oak, nail, ball, 120 × 60 × 6 cm

Production supported by National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA) and SBS Foundation

바가텔 3

BAGATELLE 3

2020, Oak, nail, ball, 120 × 60 × 6 cm

Production supported by National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA) and SBS Foundation

Installation view of SAMSAM, 2024

Ground floor of Gallery Hyundai, Seoul

K (계란코)

K (Egg Nose)

2024

Paper mache 27 × 26 × 17 cm

Installation view of SAMSAM, 2024

Basement floor of Gallery Hyundai, Seoul

트람

Color on wood 11 × 11 × 2 cm

Installation view of SAMSAM, 2024 Second floor of Gallery Hyundai, Seoul

Color on wood

15 × 15 × 3.5 cm

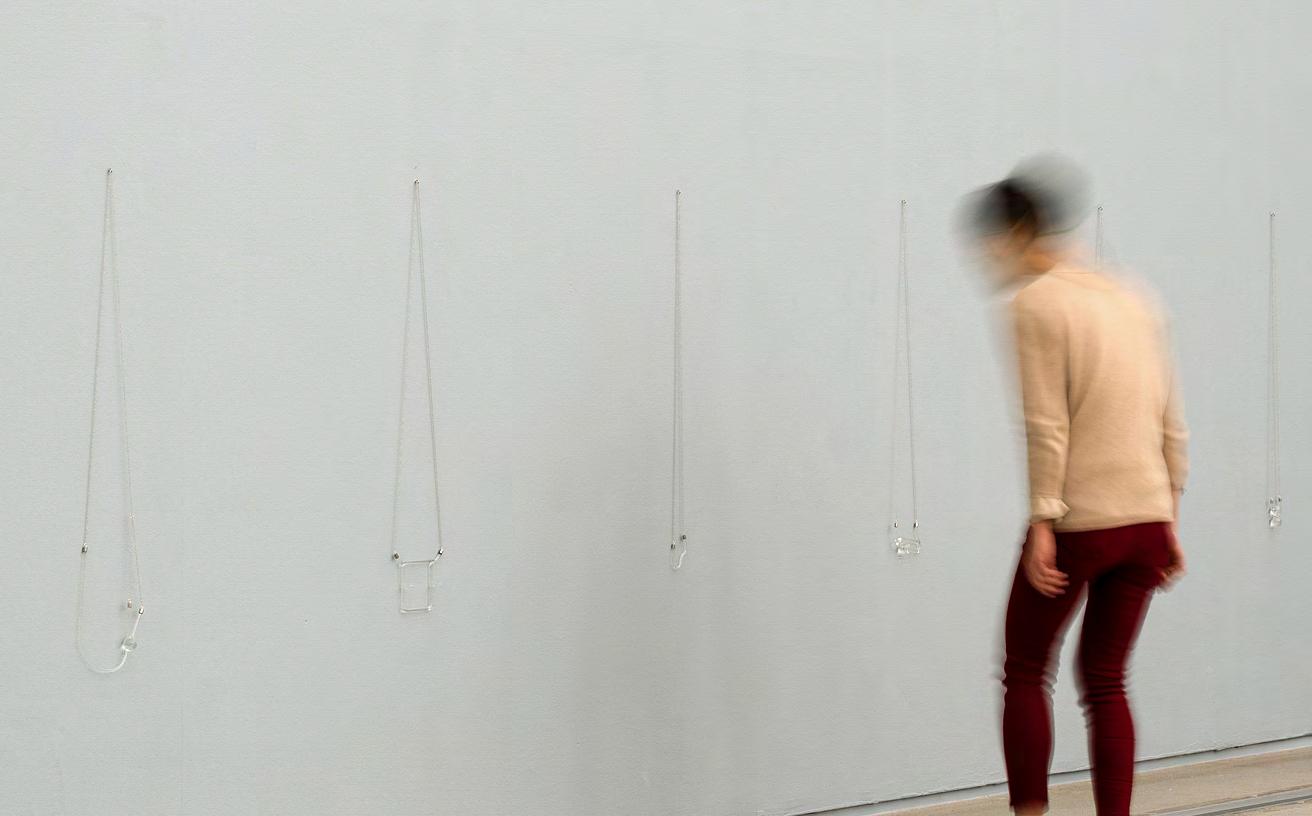

Han River and glass

Ø 5, 4, 6 cm

기원과 기슭을

흐르는 물

우리가 기억하는 경험과 감각 사이를 미끄러지며

1990년대 초 파리로 이주 후 유럽과 한국을 오가며 활동해 오고 있는 이

1. 요한 볼프강 폰 괴테, 『괴테의 이탈리아 기행』, 박영구 옮김, 도서출판 푸른숲, 1998 14.

2 김현진, 오혜미, 이슬기 《느린 물》 리플릿 전시 소개 글 참조 3. 김광억 외, 『처음 만나는 문화인류학』, 한국문화인류학 (엮은이), 일조각, 2003, 19 <왜 문화인가>라는 글에서 문화인류 학자 한경구는 “우리도 때때로 기억을 더듬을 때 그러한 경우가 있지만, 이들의 기억 속에서

동된다.

기원과 기슭을 흐르는 물

《느린 물》 전시는 지표면 아래 여러 갈래로 흐르는 물처럼 인천아트플랫폼의 내부와 외부에 흩

어진 공간들을 유기적으로 연결한다. 본 전시장과는 분리된 윈도우 갤러리에 설치된 〈밤 그림자 (SHADOW)〉는 장소가 머금은 온도와 빛 그리고 시간성이 격자무늬 단청과 풍부한 색감의 기하 학적 조형으로 하나의 ‘풍경’을 만든다. 윈도우

폰 괴테, 『괴테의 이탈리아 기행』, 박영구 옮김, 도서출판 푸른숲, 1998

• 김현진, 오혜미, 이슬기 《느린 물》 리플릿

• 김광억 외 지음, 『처음 만나는 문화인류학』, 한국문화인류학회(엮은이), 일조각, 2003

• 이영자 편집 기획, 손현숙 논고 사진, 『오색 빛깔 단청』, 연두와 파랑, 2010

• 한스 울리히 오브리스트, 아사드 라자, 『한스 울리히 오브리스트의 큐레이터 되기(Ways of Curating)』, 양지윤 옮김, 아트북 프레스, 2018

• 박환영, 『속담과 수수께끼로 문화 읽기』, 새문사, 2014

• 곽은희, 『현대 속담』, 커뮤니케이션북스, 2015

• 서영숙, 『금지된 욕망을 노래하다(어머니들의 숨겨진 이야기 노래)』, 박이정, 2017

지위를 부여받아 직접적인 경험을 통해 연구현 장의 문화에 대한 이해를 높이고 인간 삶의 다면적 영역에 접근한다. 이 과정에서 필연적으로 수

반되는 통찰력과 유연함은 이슬기의 작업 전반에서 드러나는 개방적 태도와 맞닿는다. 이슬기의

작업은 공예가들을 포함한 폭 넓은 분야의 전문가와의 협업을 기반으로 이뤄지는데, 특히 작가는

이들과의 관계에 있어 예술가와 장인, 순수미술과 그 외 장르라는 구별을 넘어선 수평적 협업을 이

어간다. 이슬기는 ‘한 가지 일을 너무 좋아해서 몰입하는 아마추어적인 태도’를 경외의 눈으로 바

라보고, 어떠한 우위를 점하지 않은 채 함께 노동요를 부르는 ‘그들 중 한 사람’으로 존재하고자 하

는 예술가적 면모와 미학적 실천을 보여준다.11

물의 깊은 심연에서 수면 너머의 세계를 연결하는 〈느린 물〉은 선형적인 시간의 흐름을 벗어난 여

관통한다. 이슬기 작업 속에서 ‘물’은 태초, 생명의 기원에서 출발하여 지금, 우리가 발 을 딛고 있는 현재라는

유속으로 흐른다.

존재와 망각의 사이를 고유한 방

Installation view of Korean Artist Prize 2020

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA), Seoul, 2020

Photo by Cheolki Hong

Installation view of Korean Artist Prize 2020

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA), Seoul, 2020

Photo by Cheolki Hong

WATER FLOWING BETWEEN ORIGIN AND SHORE

Okkum Yang

Chief Curator

Head of Exhibition and Education Division, Seoul Museum of Art

The land continues to rise until you come to Tirschenreuth, and the waters flow against you, to fall into the Egra and the Elbe. From Tirschenreuth, it descends southwards, and the stream run towards the Danube. I can form a pretty rapid idea of a country as soon as I know by examination which way even the least brook runs, and can determine the river to whose basin it belongs. By this means, even in those districts which it is impossible to take a survey of, one can, in thought, form a connection between lines of mountains and valleys.1

From September of 1786, Goethe wrote Goethe's Travels in Italy, which contains his deep reflections and contemplations during his stay in Italy for a year and nine months. Traveling all over Italy, a place he had long admired, Goethe depicted in his travelogue not only the Roman art he was infatuated with, but also the topography, weather, and native plants of the country’s various regions. From there he retraced rivers to their origins, conceptualizing the places he had visited. Fast forward to the

1. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Goethe's Travels in Italy, trans. Yeonggu Park (Paju: Prunsoop, 1998), 14.

present, Seulgi Lee’s recent work SLOW WATER was inspired by the oldest ancient indoor fresco mural of Villa de Livia, which she visited during her stay in Rome, Italy from March to August 2021. One finds subtle, serendipitous intersections between Goethe's physical and spiritual wandering through pulses of history and culture with the entire Italian peninsula as a museum, and the trajectory of Lee’s work that brings to the present prototypes of human culture that once existed but are currently in decline, mediated by the location of Italy.

SLOW WATER

Images of nature and human civilization often appear to us like a thin membrane called “the present,” which forgets the layers of eternal time accumulated under the earth. The “water” flowing on the surface of and within the thin membrane has served as the source of life from the beginning of the Earth to the present, passing through the strata of time. The title of Seulgi Lee’s 2022 exhibition at Incheon Art Platform (hereafter IAP), SLOW WATER, encapsulates her body of work which “summons the experience of water and the history of old space.” 2 As an anthropologist once said, for prehistoric tribes who lived before the arrival of civilization, time is remembered as a place or a space3 —time slides between and blurs the boundaries between experiences and sensations in our memory, just like water.

Born in Seoul, Seulgi Lee moved to Paris in the early 1990s and has since been actively working between Europe and Korea. Water is a familiar material that is being continuously utilized within her work. For her solo exhibition Informal Economy (2004) at Ssamzie Space, Lee purified the water she collected on the rooftop of the building for approximately three months and made it spring up from a fountain installed inside the exhibition space, inviting the audience to drink it in Natural Rain Drink. As seen in Gobelet (2008) where water comes out from a straw stuck in a disposable paper cup

2. See the introduction to Seulgi Lee’s SLOW WATER exhibition leaflet by Hyunjin Kim and Hyemi Oh.

3. Kim Kwang-eok et al., Cheo-eum man-na-neun mun-hwa-in-lyu-hag [Cultural Anthropology], ed. Korean Society for Cultural Anthropology (Seoul: ilchokak, 2003), 19. In the chapter “Why Culture,” cultural anthropologist Kyung-Koo Han states: “As we also sometimes do when retracing our memories, they [prehistoric tribes] remember time by translating it into a place or space. All events are remembered not as they happened ‘when’ but ‘where.’ This is radically different from the temporal framework of our industrial society.”

like a fountain, or Le Mauge, a public art project in 2015, water often appears to be gushing or flowing, reflecting the artist’s view that water is the source of movement and the beginning of life. Presented in the 2020 Korea Artist Prize exhibition, Différence entre Fleuve et Rivière began when she requested her friends in Europe and the US to send collected water from the downstream of the river near their homes or where the river meets the sea, in response to a situation where movement and collaboration were impossible due to a transnational crisis. In the midst of the global pandemic, the artist attempted to connect with others by placing water—which contains microorganisms that coexist within different environments of those who collected the water—in glass vessels and installing them on the wall of the exhibition space. SLOW WATER, then, can be seen in organic connection to previous works through which it transforms and expands.

Stepping into the gallery showcasing SLOW WATER through the low curved structure marking the entrance of an old red brick building of the IAP, the visitor intuitively feels that they have entered a different dimension where Earth’s gravity works in an unfamiliar way. In traditional Korean architecture, munsal (wooden lattice frames that cover doors in Korea) is usually installed vertically as an important part of a door or window structure that divides internal and external spaces, functioning as an entrance and exit and enabling the influx and control of light and air. However, SLOW WATER's munsal are installed horizontally in the exhibition space’s high ceiling to divide the space above and below rather than left and right, and to direct our gaze upward. The combination of minimal forms and structures with bold colors observed throughout Seulgi Lee’s oeuvre manifests in SLOW WATER as the coexistence of wooden munsal with dancheong. For this exhibition, the artist closely collaborated with traditional munsal carpenters and dancheong artisans to study the structure and characteristics of traditional Korean munsal as well as its usage of colors and traditional significance. Then, she carried out repeated experiments to realize works that meet the architectural conditions of the IAP. Particularly notable is the way such a firm, geometric structure seamlessly conveys the multisensorial experience of being at the depths of water, a formless and fluid substance. The unique dancheong palette painted on the lattice hanging in the exhibition space morphs into various appearances depending on the movement, angle, and position of the viewer, like a wave that can move fast or slow at each moment. In dancheong, artisans mainly use the five cardinal colors of yellow, blue, white, red, and black to

make intermediate colors only when needed. In comparison, Seulgi Lee utilizes a variety of intermediate colors to convey the intensity and direction of light, shadow, and the impression of a munsal’s reflection on water, imbuing her work with a more modern and three-dimensional look.4

Based on a record that suggests that there was a pond in the center of the room of frescoes in the Villa di Livia which she encountered during her aforementioned stay in Rome, Seulgi Lee imagined a beautiful landscape and its reflection on water based on the fresco that survives since approximately the 3rd Century. The landscape, a verdant garden surrounded by a low fence brimming with various species of flowers, birds, fruits, and trees, had not lost the vivid colors of illusions and fantasies despite centuries of erosion. Additionally, noting the physical space of the frescoed villa has the quality of both above and below ground levels, and has a unique aura where interior and exterior coexist, the artist explored the etymology of the word “grotesque” and reinterpreted it from a fresh perspective. SLOW WATER is therefore a location created by combining the concept of the grotesque as a strange intermingling of heterogenous elements with the memory of water flowing in the vicinity of the IAP. This “memory” designates not just a rumination about the past, but rather a “dynamic process that constantly transforms what is uncovered from the depths.” 5 Here, we are encouraged to convert sensibilities of water without the aid of cutting-edge devices or technical spectacles, to imagine a different world beyond the surface of water beneath the deep abyss.

Blanket as Shamanistic Sculpture

“Proverbs and riddles are the most concise and highly abbreviated compression

4. Dancheong artisan Soo-yeon Kim who participated in the affiliated program of artist’s talk for 2021 IAP Special Exhibition Seulgi Lee’s SLOW WATER (September 24, 2021) stated: “The production of this work was a very unusual experience because it expresses water not in a monochromatic manner, but by combining dancheong with a three-dimensional contemporary form."

5. Hans Ulrich Obrist, WAYS OF CURATING, trans. Ji-yoon Yang (Seoul: Art Book Press, 2018), 65. Hans Ulrich Obrist stated that “memory is not just a record of the past, but a dynamic process that always changes what is revealed from the depths.”

of traditional culture.” 6 In addition, a proverb is a “secular story belonging to the public” which has been passed down from mouth to mouth through generations in the community. The linguistic characteristic and structural framework of proverbs can often be found in symmetrical rhythm, which functions as the concretization of lessons and symbols through metaphorical images and literary figures of speech.7 In modern times, proverbs showcase the values of a new era by adding play on words or other playful elements to the didactic meaning of their traditional forms. Seulgi Lee has continuously worked to revive pieces of human culture that are gradually disappearing by collecting fragments of time and retracing the history of the formation and continuation of each community. One of her best-known projects, Blanket Project U, visualizes on the traditional quilted nubi blanket Korean proverbs that have permeated the lives of various language communities. The artist penetrates the linguistic structure and literary characteristics of proverbs and reinterprets the metaphors and connotations condensed by this long-standing oral literature through minimalist aesthetics and humor, which emerge cheerfully and lucidly in the blanket as a ubiquitous object.

Placed on a low pedestal in this exhibition, the “U” of Blanket Project : U derives from the observation that the letter takes the shape of a bowl, and can also be interpreted as a vessel that holds a person. The geometric forms, compositions, and intense colors placed in a rectangular screen hand stitched by quilt craftsmen seem to inherit the lineage of Geometric abstraction at first glance. However, titles that are directly associated with proverbs such as The thief takes a whip, Drunk like a Whale, The butterfly dream, The rat pretends to be dead, and Cat washing its face provide a key for plain and intuitive access to the elusive side of images, penetrating the formal devices of Color-field abstraction that combines vivid five cardinal colors with master artisans’ craftsmanship. A blanket is a mundane yet special object that humans cherish from birth to death. The world of dreams you drift off to under a blanket enables an infinite array of possibilities beyond the limits of the real world. The practice of magic, including chanting spells or performing magic to prevent misfortune or bad luck, leads us to different interpretations and imaginations of

7. Hwan Young Park, Sog-dam-gwa su-su-kke-kki-lo mun-hwa ilg-gi [Reading Culture with Proverbs and Mysteries] (Seoul: Saemunsa, 2014), 39.

7. Eun-hee Kwak, Hyeon-dae sog-dam [Modern Proverbs] (Seoul: Communication Books, 2015), 3.

the proverbs encoded in the patterns of the blankets, and even harkens primordial sensibilities. The artist describes this effect as “a shamanistic sculpture that influences dreams and is in fact the boundary between dreams and reality”—placed on the pedestal, blankets are granted a new life as a work of art in place of losing its function as an everyday item.

Indifferent and Lewd Songs Sung by Women

Seulgi Lee's ceaseless formal experiments based on oral folk songs and indigenous languages form an important thread in her oeuvre as they are translated into various media and genres such as sound, video, and performance. In particular, the exploration of oral literature, which originated from the earliest form of language that sprouted from various cultural “nutrients” from the community and passed down from mouth to mouth, demonstrates the artist's interesting approach to invisible human cultures.

Produced in 2019, Women's Island is a video work that borrowed obscene folk songs sung by women in the Penvénan region of Brittany, where the indigenous language remains best preserved in France. The song in this video, shot against the backdrop of “Woman's Island,”—which is also the name of an existing small island—was created by adding lyrics composed from the artist's experience to the rhyme of folk songs of this old town. The intersection between indifferent and sorrow melodies sung by young women and the lyrical seaside landscape during a breezy sunset adds depth to the mise-en-scène of the video. Out of a larger group of traditional work songs, oral folk songs, or “raunchy folk songs or lewd songs” as the artist calls them, mainly refer to those sung by women that boldly and directly express sexual intimacy and taboos. In many cases, work songs contain some level of hope to escape the strain of hard work. This includes Korean traditional work songs sung by women of old while turning a spinning wheel, picking cotton seeds, or doing laundry. They functioned to enhance the efficiency of work or expressed a desire for wellbeing and abundance, often reflecting individual personalities such as play on words and playful singing8. The reason Seulgi Lee was mesmerized by work songs out of the myriad kinds of traditional folk songs lies in her long interest in communities.

9. “Work Song,” Encyclopedia of Korean Folk Culture, https://folkency.nfm.go.kr/kr/topic/detail/670

There are 160-or-so large and small islands off the coast of Incheon, Korea. Geographically adjacent to the mouth of the Han River, people in this area built their lives claiming the rough sea as their home, leading to countless sea songs and boat songs that were sung during tiresome work on boats and tidal mud flats. Sound work Lament for NANANI GONG-AL, presented at the IAP in 2022, was created by contemporary musician Park Min-hee based on the fishermen's boat song “Nanani Taryeong” and “Gong-al Taryeong” and utilized the melodies of “Akita Ondo” from Japan in addition to lyrics from “Gong-al Taryeong.” A “gong-al” refers the part of a woman's genitals that arouses sexual desire and pleasure. As directly apparent in the title, this song features candid descriptions and fierce expressions of the genitals, merged with the hummed melody and voices that are unembarrassed as if careless, evoking a strange contrast between the enchanting melody and the explicit lyrics. Traditional folk songs sung by women are conventionally known to express sorrow and joy, hope, and resentment from their oppressed life, but there exist a surprising number of songs that go beyond our imagination in their function as an expression of desires that were not normatively permitted, and as acts of disruption and liberation from social norms.9 Similarly, Seulgi Lee’s Lament for NANANI GONGAL not only expresses sexual desires that were not permitted for women in the past but highlights the archetypal role of the image of genitalia, which were early cultural symbols fertility, reproduction, and production. In fact, the folk worship of genitalia10 has a long history of imbuing spiritual meaning to objects that resemble male and female genitalia, documented in the form of artifacts symbolizing masculinity such as petroglyphs, phallic stones, and clay dolls from Korea’s Silla period, and on the other hand, menhir or topographical features that resemble women's bodies such as host rocks and gong-al (genital) rocks with related myths. The practice has generated a wider range of forms and meanings, expanding from its original reference to reproduction, fertility, and the sanctity of creation, to the richness of life,

9. Young-sook Seo, Geum-ji-doen yog-mang-eul no-lae-ha-da [Singing Forbidden Desires (Songs of Mother's Hidden Stories)] (Hanam: Pagijong Press, 2017). In the preface, the author states:“These songs contain bold and daring stories that would be hard for us to imagine even in modern times. Through narratives in songs, he mothers sung of desires that they could not dare express in reality […] The desire to escape from the countless norms and ideologies imposed on women […] It was forbidden for women to reveal these desires, or even to sing these songs out loud.”

10. “Genital Worship,” Encyclopedia of Korean Folk Culture, https://terms.naver.com/entry.naver?docId=575461&cid=46655&categoryId=46655

hope, and fortune. In Korean folk traditions, it also merged with the belief in feng shui. Installed both inside and outside of IAP, Seulgi Lee’s series KUNDARI takes as its motif an original indigenous depiction of the body of an ancient woman, infusing a new approach to femininity as it appears in the various ancient folk and indigenous cultures. Here, styles of depicting the female body or genitalia shared by ancient cultures in both the East and West have been reinterpreted as simple symbols and diagrams.

Tracing the trajectory of Seulgi Lee’s practice, we see its beginning in the shift of perspective between “objects and I (the artist or human),” that is, a process where “the object becomes the subject and the artist becomes the object” in the words of the artist. Objects such as dokkebi (goblins), masks, blankets, and baskets as well as obscene and erotic oral folk songs that appear in Lee’s various performances, installations, and three-dimensional works evoke a magical and primitive sensibility and ancient primitive beliefs. They can be seen in relation to animism, a word derived from the Latin word anima, meaning life or spirit.11 Animism, which refers to the primordial belief that there is no distinction between nature and culture, and that the soul is imbued in all things that exist in the world, comes to work as a new “anima” as it merges with expanding, modulating concepts of contemporary art.

Water Flowing Between Origin and Shore

The exhibition SLOW WATER organically connects the spaces scattered inside and outside of the IAP, like branching streams that flow under the earth’s surface. Installed in a window gallery separate from the main exhibition hall, SHADOW creates a kind of landscape consisting of dancheong lattices and rich colors of geometric forms alongside the space’s own temperature, light, and temporality. The installation placed around the periphery of the window gallery utilized the dyeing technique unique to Ganghwa’s Sochang region and presents the result of collaborative production with the local community, an Incheon-based dyeing studio. Seulgi Lee’s work first and foremost highlights the coexistence of visual and tactile

11. Regarding this section, I referred to the comments presented by art director Hyunjin Kim in the previous Artist Talk (2021.9.24.) in conjunction with Animism (an exhibition organized by Anselm Franke in collaboration with director Hyunjin Kim) presented at Ilmin Museum of Art (2013-2014).

sensations. This is because her work amplifies tactile images along with the visual work of transposing intangible culture with tangible work through a mixture of fine arts and crafts, abstraction and representation, and tradition and contemporary. The artist's method of collecting and reinterpreting indigenous cultures and invisible heritages based on her artistic curiosity and intuition is reminiscent of the kind of anthropological field research conducted by cultural anthropologists as “participant observers.” 12 Participant observers enter the group of subjects they want to observe wherein they are given the status of a member of the community, which then allows them to improve their understanding of the culture of the site through direct experience and to approach the multifaceted aspects of human life. The insight and flexibility that inevitably accompanies this process is in line with the open attitude we witness from Seulgi Lee’s practice overall. Another characteristic of Seulgi Lee’s methodology is that she continues to collaborate horizontally with experts in a wide range of fields, including craft artisans. In particular, the artist seeks to transcend the division between artists and artisans, between fine art and other genres. Seulgi Lee deeply admires “the amateur attitude of being immersed in something out of genuine love” 13 and demonstrates the artistic virtue and praxis equivalent to singing work songs without claiming superiority over others, to singing with others simply as “one of them.”

Connecting the deep abyss of water to the world beyond the surface, SLOW WATER penetrates multiple layers beyond the linear flow of time. In the work of Seulgi Lee, water flows from the primordial beginning, the origin of life, into now, a crevice in the shore that is our present. In the process, it flows between past and present, reality and fiction, existence and oblivion, all in its own manner and speed.

12. Kim Kwang-eok et al., Cheo-eum man-na-neun mun-hwa-in-lyu-hag [Cultural Anthropology], ed. Korean Society for Cultural Anthropology (Seoul: ilchokak, 2003), 41. In “Hyeon-jang-eu-lo ga-ja [Let's Go to the Scene],” Hong Suk Joon states: “Participatory observation is a state of mind rather than a specific behavioral program or investigation technique, and a framework for life on site. Therefore, insight, curiosity, and empathy towards others makes an ideal observer for participatory observation.” Seulgi Lee’s approach and methodology in producing her works are reminiscent of this “ideal observer for participatory observation.”

13. Refer to the Artist’s Talk mentioned above (Sep 24. 2021)

Bibliography

• “Genital Worship.” Encyclopedia of Korean Folk Culture. https://terms.naver.com/entry.naver?docId=575461&cid=46655&categoryId=46655

• Von Goethe, Johann Wolfgang. Goethe's Travels in Italy. Translated by Park Yeonggu, Paju: Prunsoop, 1998.

• Kim, Hyunjin and Oh, Hyemi. Seulgi Lee's SLOW WATER [leaflet]. Incheon: Incheon Art Platform (IAC), 2022.

• Korean Society for Cultural Anthropology ed. Cheo-eum man-na-neun mun-hwa-in-lyu-hag [Cultural Anthropology], Seoul: ilchokak, 2003.

• Lee, Young-ja and Son, Hyun-sook. O-saeg bich-kkal dan-cheong [Colorful Dancheong]. Seoul: Yeonduwaparang, 2010.

• Obrist, Hans Ulrich. WAYS OF CURATING. Translated by Yang Ji-yoon. Seoul: Art Book Press, 2018.

• Park, Hwan Young. Sog-dam-gwa su-su-kke-kki-lo mun-hwa ilg-gi [Reading Culture with Proverbs and Mysteries]. Seoul: Saemunsa, 2014.

• Kim, Kwang-eok et al. Cheo-eum man-na-neun mun-hwa-in-lyu-hag [Cultural Anthropology], ed. Korean Society for Cultural Anthropology. Seoul: ilchokak, 2003.

• Kwak, Eun-hee. Hyeon-dae sog-dam [Modern Proverbs]. Seoul: Communication Books, 2015.

• Seo, Young-sook. Geum-ji-doen yog-mang-eul no-lae-ha-da [Singing Forbidden Desires (Songs of Mother's Hidden Stories)]. Hanam: Pagijong Press, 2017.

• “Work Song.” Encyclopedia of Korean Folk Culture. https://folkency.nfm.go.kr/kr/topic/ detail/670

* This is the re-edited version of an essay originally written for Seulgi Lee's 2021 solo exhibition at Incheon Art Platform (IAP).

쿵쿵·덕

Kkoung Kkoung · DEUK

U : The Shoes Have Ears = Things don't Go Together

스스륵·쉬

Seuleuleuk · SHII

출출·쏴

Tchoul Tchoul · SSWA

부시시·ㅎ

Boushishi · R

모시단청

Ramie Dancheong Mural 느린

SLOW WATER - Dancheong on wooden trellis Moonsal

U : 간이 크다

U : To Have a Big Liver = To Be Brave

U : 미주알고주알

U : (To know until the) Asshole at the End of Intestines = To Know in Detail U : 미주알고주알 2

U : (To know until the) Asshole at the End of Intestines = To Know in Detail 2

U : The Sparrow (Sinosuthora Webbiana) Has Its Legs Spread as It Follows the Stork

U : 트집잡다

U : Take Teu-jip (Make Round the Visor of the Korean Top Hat) = To Nitpick

U : 부아가 나다

U : To Have a Swollen Lung = To Get Angry

TRAME SAMSAM

U : 김칫국부터 마신다

U : Drink the Kimchi Soup = To Hope for Something to Be Given

이슬기

DNSAP Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Paris, Paris

단청, 문살, 멕시코 오아 하카(Oaxaca)지방의 바구니, 모로코 리프(al-Rif )지방의 토기 장인들 과의 협업 등을 통해 작품을

제작하는 방식을 채택하여, 언어와 문화를 지속시키는 하나의 방법이자 그 과정을 작업의 일부로 편입시킨다.

1992년 이슬기는 만 19세의 나이로 프랑스 생활을 시작했다. 학생들이 모여서 토론하고 협업하며

작업 초기 퍼포먼스 작업에 집중했다. 작가는

당시 사회의 정치적 상황을 교차 시켜 작품에 활용하기도 하며, ‘아시아 여성’이라는 본인의 아바타

를 퍼포먼스에 적극적으로 활용하여 사람들의 반응과 함께 문화적 차이를 작품의 일부로 편입시켰

다. 2010년 이후, 작가는 구술문화에 대한 흥미를 작품에 적극적으로 반영해오고 있다. 작가의 대

표적인 연작이 된 〈이불프로젝트 : U〉는 2014년부터 진행해 온 한국 속담의 내용을 추상화 하여

기하학적인 색면으로 이불 위에 펼친 작업이다. 이러한 작업을 바탕으로 이슬기는 다양한 브랜드들

과 협업을 진행했다. 2017년에는 패션 브랜드 에르메스(Hermès)와 함께 캐시미어 플래드 리미티

드 에디션 콜라보레이션 프로젝트를 진행하였는데, 〈이불프로젝트 : U〉에서 사용했던 방식인 한국

속담을 차용해 기하학적 형상과 선으로 묘사하되, 진주명주가 아닌 어두운 톤의 캐시미어를 이용

또 한 번 알리게 되었다. 더해서, 2019년에는 가구

무너트리기 도 한다.

이슬기 작가는 갤러리현대(서울, 2024, 2018), 게이지반(가나자와, 2023), 갤러리 주스 앙트르프리

즈(파리, 2022, 2017), 맨데스 우드 DM(브뤼셀, 2022), 인천아트플랫폼(인천, 2021), 카사 다 세 르카(알마다, 2020), 라 크리에 아트센터(렌, 2019), 라파트망 22(라바트, 2019), 라 샤펠 잔다르크 아트센터(투아르, 2019) 등에서 개인전을 개최하였다. 2020년 국립현대미술관과 SBS 문화재단 이 주관하는 《올해의 작가상 2020》 최종 수상자로 선정되었으며, 카디스트 문화재단(샌프란시스 코, 2022), 쿤스트할오르후스와 아트선재센터(오르후스, 서울, 2022), 제12회 부산비엔날레(부산, 2020), 수원시립미술관(수원, 2020), 우란문화재단(서울, 2019), 국립아시아문화전당(광주, 2017), 제10회 광주비엔날레(광주, 2014), CRAC 알자스(알트키르슈, 2017), 장식 미술 박물관(파리, 2015), 파리 라 트리엔날레(파리, 2012), 이벤토 보르도 비엔날레(보르도, 2009) 등의 기관에서 개 최된 단체전에 초대되었다. 주요 소장처로는 멜버른

파리 프 랑스지역자치단체 현대 미술컬렉션 프락(FRAC), 파리

SEULGI LEE

Born in Seoul in 1972, Seulgi Lee graduated with a DNSAP (Diplôme national supérieur d'arts plastiques) from Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Paris and has since been working in Paris, France. Embarking from anthropological interests, she connects references from various cultures and traditions around the world to her own unique practice. Lee’s sculptures and installations, with pronounced plasticity, have often channeled her investigation of everyday objects, language, and fundamental forms of nature. Moreover, the artist produces work through collaboration with master artisans from all around the world, incorporating the preservation of languages and cultures as a process and methodology. Her collaborators include Dancheong (traditional coloring on wooden buildings and artifacts in Korea) and Munsal (wooden lattice frames that cover doors in Korea) artisans, master nubi (Korean traditional quilt) artisans from Tongyeong, Korea, traditional basket weavers from Mexico, and traditional ceramic makers from al-Rif, Morocco.

It was in 1992 that Seulgi Lee started her life in France at the age of 19. Intrigued by the discussions and collaborations among students in the process of organizing new projects, she focused on performance works in the early part of her career. Highlighting intersections with sociopolitical situations of the time, Lee’s performances actively utilized her avatar as an Asian woman to integrate cultural differences and audience’s reactions to them as part of the work. In 2010, the artist began seriously incorporating her interest in oral cultures into her practice. Blanket Project U, which started in 2014 and has since become Lee’s signature piece, translated Korean proverbs in abstract, geometric color fields on the surface of blankets. Based on similar projects, Seulgi Lee has collaborated with multiple brands such as the cashmere plaid limited edition collaboration project with Hermès in 2017. The collaboration retained her reference to Korean proverbs as well as geometric forms and lines, but replaced Korean silk blankets with darker colored cashmere to embody the brand’s visual identity. In 2019, Seulgi Lee collaborated with IKEA for the 5th IKEA Art Event.

BIANE Hanging Board Project is Seulgi Lee’s new work that debuted at this exhibition— a humorous visualization of the link between the meaning and appearance of words through designs of onomatopoeic or mimetic words engraved on wooden plaques. Having spent more than three decades of her life abroad, language has always been alien for Lee but supplies new inspirations as a condensation of culture and soil for the imagination. In addition, it serves as a tool for her dedication to connecting folk culture with the present, while creating a sense of cohesion in the community.

As such, Seulgi Lee summons folk elements through the eclectic use of materials, whilst consistently upholding a material formal language which reflects a sense of contemporaneity. Through a uniquely humorous perspective, she constructs geometric patterns, vibrant colors, and primordial yet humorous forms to transform everyday objects into works of art. Furthermore, her use of the lexicon of crafts dismantles the boundaries between sculpture, popular design, and craft aesthetics.

She has held solo exhibitions at Keijiban, Kanazawa (2023), Galerie Jousse Entreprise, Paris (2022, 2017); Mendes Wood DM, Brussels (2022); Incheon Art Platform, Incheon (2021); La Casa da Cerca Art Centre, Almada (2020); La Criée centre d’art contemporain, Rennes (2019); L’Appartement22, Rabat (2019); Centre d’art La Chapelle Jeanne d’Arc, Thouars (2019); and Gallery Hyundai, Seoul (2024, 2018). Lee was selected as the final winner of the Korea Artist Prize 2020, organized by the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA) and SBS Foundation. Lee participated in major biennales such as the 12th Busan Biennale, Busan (2020); the 10th Gwangju Biennale, Gwangju (2014); La Triennale, Paris (2012); and the La Biennale Evento, Bordeaux (2009). She has also been invited to group exhibitions at institutions like Kadist Foundation, San Francisco (2022), Kunsthal Aarhus and Art Sonje Center, Aarhus and Seoul (2022); Alternative Space LOOP, Seoul (2021); Suwon Museum of Art, Suwon (2022); Wooran Foundation, Seoul (2019); National Asian Culture Center, Gwangju (2017); Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris (2015); Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna (2007); CRAC Alsace, Altkirch (2017); and Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2001). Her works are included in collections of renowned institutions including the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul; Suwon Museum of Art, Suwon; FRAC IDF Fonds Régional d’Art Contemporain Île-de-France Le Plateau, Paris; The Centre national des arts plastiques (CNAP), Paris; and Musée Cernuschi, Paris. Moreover, Lee has been invited to the 17th Lyon Biennale, Lyon in September

2024. Her next solo exhibition will be held at the IKON Gallery in Birmingham in 2025.

THANKS TO

누비 | 조성연

단청 | 김수연, 최태성, 배강선,

이은영, 주광관

문살 | 강성철

현판 | 김형철, 한정화

바가텔 | 김재경

별길 | 이준식

쿤다리 | 정성원, 정연태

한강 | 김종진

설치 | 신호철, 남민우, 이창현, 이건희, 이용운, 양숭식

시몽 부드뱅, 한지윤, 한승재, 노우영, 김포그니, 최희정, 노현균, 양용호, 한승우,

최상일, 정소영, 이운호, 권오준, 닐 벡스, 베르나르 모프레, 파스칼 떼오돌리, 스테판

리보알, 필립 쥬스, 소피 까쁠랑, 페드루

멘드스, 멜라니 포콕, 아델프러 몰, 마사코

코테라, 미와 코이즈미, 아야미 미야코시, 도형태, 김민수, 이지현, 김성은, 장희정, 정경미, 윤혜영, 황유경, 연소라, 김현진, 양옥금, 권윤숙, 이영민, 삼삼는 소리

SAMSAM

SEULGI LEE

This catalogue is published on the occasion of the exhibition which took place from June 27 to August 4, 2024 at Gallery Hyundai, Seoul

Organized by Yookyung Hwang, Sora Yeon

Texts by Hyunjin Kim, Okkum Yang, Kwang-kwan Joo

Designed by Kwon Yunsuk

Photographed by Youngmin Lee

Installation team Hocheol Shin, MinWoo Nam, ChangHyun Lee, GeonHee Lee

Coordinated by Jihyun Lee

Translated by Han Gil Jang, Haena Chu, Okkum Yang

Works ⓒ Seulgi Lee

Seulgi Lee © Adagp Paris 2024

Catalogue ⓒ 2024 Gallery Hyundai

Nubi Sungyoun Cho

Korean traditional painting Dancheong

Su Yeon Kim, Taeseong Choi, Gangseon Bae, Eunyeong Lee, Kwang-kwan Joo

BIANE Hanging Board | Kimhyungchul, Han Jeong Hwa Moonsal Seongcheol Kang

BAGATELLE Jaegyeong Kim

STARLINK Junsik Lee

KUNDARI Seongwon Jeong, Yeontae Jeong

Han River Jongjin Kim

Installation Hocheol Shin, MinWoo Nam, ChangHyun Lee, GeonHee Lee, Yong Woon Lee, Sung Sik Yang

Simon Boudvin, Ji-Yoon Han, Seungjae Han, Uyeong Noh, Pognee Kim, Hee-Jung Choi, Hyeongyun Noh, Yong Ho Yang, Seung Woo Han, Sang-il Choi, Soyoung Chung, Uno Lee, Edward Kwon, Neal Beggs, Bernard Mauffret, Pascale Theodoly, Stephane Rivoal, Philippe Jousse, Sophie Kaplan, Pedro Mendes, Melanie Pocock, Adèle Fremolle, Masako Kotera, Miwa Koizumi, Ayami Miyakoshi, HyungTeh Do, Minsoo Kim, Jihyun Lee, Sung-eun Kim, HeeJeong Chang, Kyungmi Jung, HyeYoung Yoon, Yookyung Hwang, Sora Yeon, Hyunjin Kim, Okkum Yang, Kwon Yunsuk, Youngmin Lee, Sound of boiling hemp (samsamneun sori)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise, without prior written permission of the copyright owners.

www.seulgilee.org

03062 서울시 종로구 삼청로 14 14, Samcheong-ro, Jongno-gu, Seoul, 03062, Korea T +82 2 2287 3500 www.galleryhyundai.com