LEE KUN-YONG

Lee Kun-Yong is considered a master of Korean experimental art. Beginning his artistic career in earnest during the late 1960s, he was at the very forefront of experimental, avant-garde trends serving as a key member of the A.G. (Korean Avant-Garde Association) and helping to found the academic society S.T. (Space and Time Group). Adopting a unique methodology that he referred to as “logic,” he attempted an artistic interpretation of and communion with the chaotic South Korean political and social situation at the time, all while constantly posing the question, “What is the essence of art?”

Representing Korea at the 1973 Biennale de Paris, Lee traveled all around central Paris to produce Corporal Term, a work for which he transported trees from the nature into the gallery – roots, soil, and all. As he returned to Korea, he became increasingly convinced that he should attempt a form of performance art in which he used the body as an artistic medium. He had also been deeply struck by some of the fresh painting work he had encountered at the Biennale, produced by artists who were experimenting in new ways with fundamental material elements of painting such as the canvas frame and paints. Interpreting painting as a kind of “illusion,” he went on to produce the series Cloth (1974–75), for which he made wrinkles in fabric, splashed paint on it to leave marks from the wrinkles, and then stretched the fabric out again, thus revealing painting itself as an illusion. He also presented his Event-Logical series, which showed the actions of the body in deliberate and logical ways, as in works such as Indoor Measurement, Same Area, and Logic of Place. His later Bodyscape work is a continuation of Corporal Term and Event-Logical in the sense that it employs the artist’s own body as a medium encountering the world, positing the act of drawing as an incident that arises through necessary and logical actions by a constrained body, rather than as the expression of emotion or feeling.

His avant-garde spirit was not restricted to any one media, but carried on an ongoing connection with its times: the series of logical, conceptual performances he presented in the mid-1970s under the theme and title Event-Logical; his installationsculptures during the 1980s, in which he subtly varied the characteristic of objects by imposing his presence on natural materials such as wood and stone; his theatrical performances of the 1990s, which took place against a backdrop of personal, cultural, and historical narratives; his large postmodern paintings combining figurative and abstract elements on a single canvas; his installation art, which metaphorically expressed contemporary life by means of everyday personal objects; and the Bodyscape series.

Logic of Hands 1975, C-print

Five Steps

1975, Gelatin silver print, 28.3 × 28.3 cm (each)

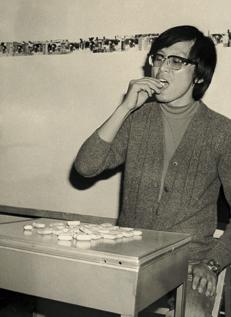

The Biscuit Eating Performance, 1977

The Biscuit Eating performed at The 4th ST Exhibition in 1975

The Biscuit Eating Performance, 1977

The Biscuit Eating performed at The 4th ST Exhibition in 1975

Logic of Place

Gelatin silver print, ⅰ)48 × 59 cm; ⅱ)48.5 × 59 cm; ⅲ)47.5 × 59 cm; ⅳ)48.5 × 59 cm

Logic of Place

Performed at Event-Logical at Gallery Hyundai in 2016

Logic of Place Performance, 1976/2001,

In a spoiled space of life, where system and authority have monopolized and nullified the public capacity to generate discourse, the only way for me to express, mark myself, or to make an imprint of myself was to overturn the mechanism of control. I began to do this in 1976, through The Methods of Drawing.

Lee Kun-Yong

Lee Kun-Yong

Installation view of Event-Logical at Gallery Hyundai, 2016

Installation view of Event-Logical at Gallery Hyundai, 2016

Usually, a painter paints something on the two-dimensional surface that he or she is facing. In my case I place the panel in front of my body and draw lines as far as my body allows without being able to see the pictorial surface. So it is not that I draw something on the two-dimensional surface while seeing it with my eyes, as my conscious instructs me. Rather, it is to represent the process through which my body perceives the twodimensional surface, via the lines drawn by the movements of my arm.

Lee Kun-Yong

Lee Kun-Yong

The Method of Drawing 85-0-3 (Male)

1985, Oil on canvas, 228 × 181 cm

The Method of Drawing 85-0-5 (Female)

1985, Oil on canvas, 226 × 180.5 cm

The Method of Drawing 76-5

The Method of Drawing 76-6 1976 Documentation of Bodyscape 76-6-2021

Installation view of Bodyscape at Gallery Hyundai, 2021

Installation view of Bodyscape at Gallery Hyundai, 2021

The Method of Drawing 76-7

Documentation of Bodyscape 76-7-2021

Installation view of Bodyscape at Gallery Hyundai, 2021

Installation view of Bodyscape at Gallery Hyundai, 2021

Documentation of Bodyscape 76-8-2021

The Logic of Topos and the Corporeal Subject in the Paintings of Lee Kun-Yong

Kim Bok-young art critic / professor, Hongik University / Ph.D (philosophy), scholar of aesthetics and art studies

Lee Kun-Yong has created paintings through his own sui generis approach, breaking with the time-honored conventions of painting by varying the physical conditions of creation: painting with the canvas behind him, for example, or fixing his wrists and elbows in place with wooden sticks. He has been practicing this method for half a century now. In straightforward terms, his experiments have been an attempt to ask and answer a question: How might he paint the world as it is, forgoing the idealist forms and abstractions permitted by the history of painting and eschewing painting that is rooted in sensuous illusion? It is for this reason that he has concerned himself with corporeal conditions and primitive topoi.

On the surface, little differentiates this approach from that of Western modernist painting and the rise of an approach “beyond illusion and idealism.” As the title of this essay suggests, however, the attempt at a meeting or correspondence between place and body must be seen as his own unique conception. This new idea is a matter of opening up new horizons in painting: removing the gap between the world and us so that we can be one, without any distortion of the world as it is.

Lee’s great ambition is to use painting as a way of realizing this anticipation and hope just as any sage would. To this end, he has adhered to the view that no illusions, no idealist fictions of any kind, should be supposed. His incorporation of primordial topos in painting, and his emphasis on “corporeality” and rejection of the “cogito” as a painter, have been part of this. It would be

Artist Note 1974-1977s.

Since 1974, Lee Kun-Yong has visualized the Bodyscape series performances in a form of story board.

by no means out of line to suggest that his logic of topos and corporeal subject hood are things that he has developed independently, reflecting an awakening that took place amid the historical shift from modern to postmodern. Here, the artist describes the motivation behind his choice:

In truth, it may be that I have come to dream of a primitive tribal society while living in a vast and mechanical society. As I perceive the artistic sensitivity in the primitive tribe’s way of thinking and meanings of life, I try to bind myself with the world and situate myself

within a larger world so that I am closer to the moment at which all language begins. (Kim Bok-young, Eye and Spirit, Hangil Art, 2007, pp. 57–58, 143, and particularly 431–438)

In the self-penned introduction to his fourth solo exhibition, Lee uses various words to express his motivations: “the relationship between body and place,” “that which exists between one object and another,” “original state,” and “moment of beginning.” They may be summed up in two main senses, however: one is his attempt

Installation view of 15th Bienal de São Paulo, 1979

Installation view of 15th Bienal de São Paulo, 1979

at unification of nameable places through the layering of “here” and “there” as a way of situating himself within a “larger world,” while the other is his use of the body to posit a “medial term” connecting the world to himself.

The “here” that he speaks of cannot be specified; his “there” does not exist as independent place. It refers to the unspecified topoi brought about by the body in accordance with time and space. Therefore, “place” for him has been less a subject of perception than an existential element in a broader sense, which has been necessary to “make the world of the world.” In that sense, Lee’s topos has been a “primordial topos,” considering that it is not defined.

Similarly, Lee’s own corporeality has not been that of a definable individual, an agent of perception, or the “idealist subjectivity” conceived by Western modernity. Rather, it has signified the “quantity” of the body, as in the reference to his own body measuring “1.70 meters in height” and “60 kilograms in weight” (“Self-penned Introduction,” 1983). Because of that, his corporeality has not been any kind of idealist product – certainly not the “Cartesian subjectivity” to which the West subscribed. Rather than a subject, his corporeality has referred to a sum total of neurons in our nervous system, which covers the sum of topoi in the world.

So the “bodyscapes” that Lee paints have effectively been assemblages of the world’s topoi and networks connecting neurons within the body. In this way, his painting has been a matter

Snail’s Gallop performed at The 7th ST Exhibition in 1980

Snail’s Gallop performed at The 7th ST Exhibition in 1980

of knocking at the original states connecting object to object – at the “instantaneous moment of the beginning of the world” portrayed by his lines. In a word, he has experimented with the possibility of making his own body one with the moment of the world’s beginning. For him, painting is thus about revealing the “natural” in the most plainspoken ways, as has been done in the Korean painting tradition. Like his forebears who alluded to “neither embellishing nor creating” (such as Ko Yu-seop (1905-1944) and Kim Won-yong (1896-1976)), he has sought to show how nature engenders laws of happenstance, and how that in turns ultimately gives rise to inevitability. Accordingly, his painting work has been another name for the relatum in which the world’s topoi are transposed with lines drawn by the body, and the lines drawn by the body assemble the topoi. Within these things, the world of objects churns, accompanied by various signs manifested by our bodies. The meaning of Lee’s painting has been about achieving this by connecting those two things – the world and the body – from their apex. This encompasses three main scenarios:

of the board with the limited reach of his arms

These three approaches have been techniques and methods of practice in which he has used primitive topos and corporeality in his painting to emanate, gather, and weave together. In 1979, he signaled the new possibilities of painting that he espoused when he was awarded the grand prize in an international drawing exhibition in Lisbon. If we also consider the “Snail’s Gallop” that he subsequently adopted on the ground and floors, these represent a robust catalogue of his avenues of exploration to date. Lee himself said, “By drawing repeatedly, making use of the correspondence between the acts of seeing and drawing, I arrive at a state of density, and as all of the things drawn are connected, the full picture emerges, from the initially haphazard and jumbled to systematic lines.” (Kim Bok-young, Studies of Contemporary Art: Late Tradition in the West and the Structure of Korean Contemporary Art, Jeongeum Munhwa, 1985, p. 299)

1. Placing the arbitrary board surface behind his body and drawing lines as much as his arms will permit, as though measuring the body from top to bottom and from left to right

2. Placing a board roughly his own height close in front of him, reaching his arms over it, and drawing lines as much as the board will allow him to, without being able to see them

3. Placing a cast on his arm or spreading his legs to fix his upper body in place and drawing in circular movements outward from the center

Here, we find ourselves faced with an obvious question: What meaning can these things hold – the lines that surround the world’s topoi, produced by the artist’s corporeal actions, and the paintings produced as assemblages of them? As mentioned before, his lines are meant to unite the world and the body. In that regard, his “line” is a name given to a mysterious state that is initiated by the body. Indeed, he declared that no matter what methodological means are called upon – whether it is language or action – the results may be called “art.”

Snail’s Gallop performed at the KunstCentret Silkeborg Bad, Denmark, 2005To reiterate, this is why his lines refuse definition by conventional language. The most fundamental thing is the flat repudiation of “expression of ideals” and “expression of emotions.” The lines that he speaks of are not subjective ideas or the objectification of emotion. The foremost essence of his lines is an “encounter” brought about as the body comes together with the existing world. Here, the line is a major event, signifying the “reciprocal crossing” of primitive topos and corporeality. The lines may be seen as “signs” representing this: they are reciprocal and yet they live in the same state. Since the world and body coexist by necessity within this process, Lee’s lines are not “things” or “objects,” but a medium in which all things must exist in interrelationship.

Because of this past, we can be sure that the line paintings produced by Lee Kun-Yong represent a different path from the “linear paintings” that we might encounter in history. Indeed, his paintings should rightly be placed on page one of a new precedent. This is entirely the result of the artist enlisting the body while rejecting the conventional “subject.”

Maurice Merleau-Ponty remarks as early as 1945 in his book Phénoménologie de la perception:

The body is not one object among many, but our means of belonging to our world, and facing our tasks. The body’s spatiality is not geometrical, but a spatiality of situation, an orientation towards a possible world. Expressiveness is not analyzable into simple units. The perceptual object

is never finally constituted, but is always spatially and temporally, a compound of perspectives opens to further exploration. Certainty is never achieved. We are always in process of self-constitution. We bring to the perceptual and behavioral field a field which is our own history, and we express ourselves through their union. We choose our world and our world chooses us. (Colin Smith, Phenomenology of Perception, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1962 [annotation])

A leading figure in late phenomenology, the philosopher Merleau-Ponty holds historic significance for his dismissal of the validity of Descartes’s “cogito,” which had espoused human subjectivity over two centuries earlier, and his invocation of the subject hood of corporeality once again as an intermediate realm between the body and thought. By means of the body, he dismissed the principle of representation that had been foundational for the past unitary “thinking subject,” heralding the “end of representational painting” as a symbol of pre-modernism.

In that regard, Lee Kun-Yong’s corporeal paintings are poised for reexamination. What I will say, however, is that while this may be true in a general sense, it is ultimately not so – for the lines in his corporeal paintings are not the visual ones we know, nor are they contour lines representing the perception of a specific object. Rather, they are lines that show the convergence of the world’s topoi and corporeality; they are primordial lines that cannot be labeled in terms of any known objects or events. They are not the

Untitled 86-1

1986, Paulownia tree, 48.5 × 75 × 62.5 cm

Untitled 83-2 Ginko tree, 22 × 22.5 × 127 cm

Relation Term-72

1972, Wooden boxes, stones Dimensionsvariable

Drawing for Cloth, 1975

Drawing for Cloth, 1975

dazzling “bodily lines” that evoke such wonder in the movements produced by a figure skater on the ice. The lines in Lee’s corporeal art are not oriented toward emotional beauty based on specific rules whereas in the lines of the skater there is a lack of perception of a connection between the body and spatial understanding of the world. The totality that it depicts is merely an elegant performance of a physical movement that embroiders the two to three dimensions of the ice. The cognitive implications of topos and body are rigorously excluded. Lee Kun-Yong’s corporeal paintings rather begin from this “zero sum” where emotion ends.

We find many other implications in MerleauPonty’s reference to the “autofigurative spectacle” of painting in his later book L’oeil et l’esprit (1969). Yet there is something he leaves out, both there and in Phénoménologie de la perception: consideration of “placeness,” the objective aspects of the world. Such consideration is utterly absent. To make up for this, he should have posited how there might be a separate “stateness” and possible world that is established through crossing-over between the world’s primitive topos and the body. Yet he is silent on this point. The reason is that he wished to hold on to the idealist horizon for perceiving the world that had been sustained since the Renaissance – and in particular the “world of Vorstellung [representation]” that had followed together with this. Merleau-Ponty’s consistent silence amounts to a missed opportunity. Perhaps he did not want to break with the long Western training of believing that the perceptual field of representation and the conditions of the

representational world were not arbitrary, but could be permitted only – for example – through the availability of the necessary conditions to “map from A to B.” I suspect that rather than breaking it, he wished to sustain it.

To resolve this problem, Lee Kun-Yong has been bolder than anyone not only about accepting the naturalist ideas expressed by the painter Jeong Seon (1676-1759) and traditional Korean pungsujiri (a theory of wind and water earthly principles analogous to Chinese feng shui), but also opening representation to nonrepresentation (Unvorstellung) as the quantum era allows. He has viewed the primitive topos – a condition for “making the world of the world” – as something that must be achieved ahead of the body’s field. Accordingly, he saw the body and topos as capable of interoperating without difficulty. Conversely, he saw that this was the only way to enable a horizon of sharing between the world’s primitive topos and the body.

It is fortunate indeed that the quantum scienceinstructed physiological psychology world did not discover this until 1977, a full generation after Merleau-Ponty’s publication of Phénoménologie de la perception. It can be found throughout the ideas of contemporary quantum scientists such as David Bohm and neurophysiologists such as Karl Pribram. They saw that for beings filled with the quanta of the “world” to be transposed with the virtual potential created by our visual cortex, the virtual potential of the quantum field within our bodies must be operating as much

as the world’s (Karl Pribram, 1977). According to this discovery, the relationship between the world and our perception is not possible through the unilateral map; it is fully dependent on how the “holographic bank” extracts a hologram as it operates in our bodies. This new discovery in the quantum era could be seen as a necessary

precondition brought about by the meeting between the body and the world’s primitive topoi. It is not possible with the representation (Vorstellung) of the past; it must be substituted with nonrepresentation (Unvorstellung).

For this to happen, a holon field must be

Relation Term Performance, 1983possible between the field of the aforementioned placeness of the world and the field of the body. This means that the relationship between “every” (holos), which encompasses all of these things, and any “one” (on) among them must be qualitatively symmetrical. In this way, hyperstates are permitted by the field of condition between the corporeal field and the sum total of places that make the world of the world.

The “hyper-state” here refers to a hyperlevel that is formed between the sum total of primitive topoi and the perceptual field of the body. “Holography” means a holographizing of the world through the operation of both whole (hol) and one (on). This is why we perceive the world as “the world” the instant we see it. For example, when Lee Kun-Yong refers to placing an arbitrary board behind himself as a surface and drawing lines up and down or side to side as his arms permit, this is possible based on a holography permitted by the holonal field in which the sum total of topoi and the artist’s own body interoperate. It is based on the detection of a hyper-state between the former and the later. Lee mentioned this in his recent “Artist’s Notes” (2021):

The lines in my canvas entered there from outside; they were not formed or constituted within. So my action in drawing lines on the two-dimensional image or leaving arbitrary traces is a matter of the physical action of my medium – be it pencil, paint, or other – entering the canvas in a certain state and being drawn, mixing together, or flowing down, so that it is discovered as

a phenomenon that arises to the extent it interoperated with the canvas.

Referring to his own lines here, he says that they “entered from outside” rather than being “formed or constituted” within the canvas. This could be seen as indicating that the manifestation of a hyper-state is possible as the information before and after is introduced from outside of the hyperstate by means of the artist’s body. In this way, his “corporeal painting” approach is qualitatively distinguished from the conventional drawing approach of composing unilaterally within the canvas.

The key thing here is the way in which the sum total of topoi that make the world of the world operate by means of the neural field that is formed in the field of our body. A more detailed understanding of this will become clearer as quantum science develops in the 21st century. But the fact that Lee Kun-Yong has already anticipated this and shared its harbingers through acts of art is significant in the sense that he has methodologically deconstructed the representational horizon that has been sustained since the Italian Renaissance and has foreseen the horizon of nonrepresentation – Korea’s unique holonal (every-one) horizon of nonrepresentation. That may be the greatest highlight that his corporeal painting presents to us.

Installation view of Corporal Term at The 8th Paris Biennale in 1973

Installation view of Corporal Term at The 8th Paris Biennale in 1973

Lee Kun-Yong was born in 1942 in Sariwon, Hwanghaedo Province (in present day North Korea). He developed an early interest in literature, religion, philosophy, and the humanities as he pored over the books in his minister father’s library, which included over 10,000 volumes. His first encounter with modern philosophy came through a course on logic while he was a student at Paichai High School. Through this, he came to learn about existentialism, phenomenology, and linguistic analysis. In particular, he discovered many aspects of the phenomenology of Maurice Merleau-Ponty that resonated with him.

He discovered the importance of logic and linguistics as he became especially preoccupied with two of the propositions that appeared in Ludwig Wittgenstein’s early work Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus: “The world is everything that is the case” and “The world is the totality of facts, not of things.” Graduating from the Hongik University College of Art, he became involved in avant-garde art activities: he organized the S.T. (Space and Time Group) in 1969, translating and discussing writings about contemporary art and holding open seminars, and he was an active member of the A.G. (Korean Avant-Garde Association). During the early 1970s, he produced three-dimensional installation work, most notably through his Corporal Term series. He also staged various historic and original performances, beginning with Indoor Measurement and Same Area in 1975 and continuing on to such works as Snail’s Gallop and Logic of Place. Since 1976, he has produced ongoing work in the “body drawing” series known as Bodyscape.

Lee Kun-Yong has held solo exhibitions at various major art institutions in Korea and overseas, including Pace Hong Kong (2022), Gallery Hyundai (2016, 2021), the Busan Museum of Art (2019), Pace Beijing (2018), the 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art (2018), and the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (2014). He has also taken part in various feature exhibitions in Korea and other countries, including Corpus Gestus Vox (Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, Ansan, Korea, 2021); Awakenings: Art and Society in Asia 1960s 1990s (National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, Korea; National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, Japan; National Gallery Singapore, Singapore, 2019); Renegades in Resistance and Challenge (Daegu Art Museum, Daegu, Korea, 2018); the 2016 Busan Biennale; the 1979 Bienal de São Paulo; and the 1973 Biennale de Paris. His works are included in the collections of numerous Korean art institutions, including National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, the Busan Museum of Art, and Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art in Korea, as well as many outstanding international institutions such as the Rachofsky Collection in the US and the Tate Modern in London.

After opening its doors as “Hyundai Hwarang” on April 4th, 1970 in Insadong, Seoul, Gallery Hyundai has been leading movements in the art world since boldly introducing contemporary art to what was at the time an old paintings and calligraphy-oriented gallery world. It was through Gallery Hyundai that Lee Jung Seob and Park Soo-Keun, now accepted as the “Korean people’s artists”, received spotlight. It also had been contributing to expanding the basis of Korean abstract art, organizing exhibitions with masters Kim Hwanki, Yoo Youngkuk, Yun Hyong-keun, Kim Tschang-Yeul, Park Seo-bo, Chung Sang-Hwa, Kim Guiline and Lee Ufan long before the Dansaekhwa boom.

Following the 1980’s, Gallery Hyundai adapted to developments in the international art world by opening exhibitions of international masters like Joan Miró, Marc Chagall, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Christo and Jean-Claude Denat de Guillebon. From 1987, it would participate in Chicago Art Fair as the first Korean gallery to be included in an international art fair to introduce Korean art to global audiences. Including Nam June Paik’s performances and video art, many works by headliners of Korean experimental art such as Quac Insik, Seung-taek Lee, Park Hyunki, Lee Kang-So, Lee Kun-Yong were connected to wider audiences through Gallery Hyundai. To this day, it is always discovering and introducing emerging and mid-career artists like Minjung Kim, Moon Kyungwon, Jeon Joonho, Seulgi Lee, Yang Jung Uk, Kim Sung Yoon, Kang Seung Lee.

Art magazines Hwarang and Hyundai Misul, each first printed in 1973 and 1988, remain vivid documentations of their contemporary art scenes. In addition to two spaces Gallery Hyundai and Hyundai Hwarang in Samchungro, Seoul, it is also operating a showroom in Tribeca, New York.