SEUNG-TAEK LEE

Seung-taek Lee (b. 1932) is highly regarded as a leader of Korea’s avant-garde via his practice of “non-sculpture” that disrupts conventional artistic notions. His groundbreaking multidisciplinary practice utilizes traditional materials and folk objects and manifests itself in site-specific environmental land works, interventions, ephemeral performances, appropriated canvas works, sculptures, and photographs.

Much of Lee’s paintings, sculptures, and environmental interventions share a kinship with both American land art and Korean shamanic traditions and embraces chance and ephemerality in its attempts to form a collaborative partnership with natural phenomena such as fire, water, wind, and smoke.

Much of his work is rooted in folklore and has thus utilized traditional objects or natural materials such as tree branches, hanji paper, stones, rope and wire transformed in almost metaphysical ways. In this notion of “non-sculpture” or non-materialization or non-art, Lee’s practice has proven prescient given the current phenomenon appearing in much of the contemporary art discourse.

Lee used these non-materialistic and non-sculptural concepts as a manifestation of his rejection of existing ideas and orders, meaning that his work had no relation with any sculptural concept whose initial goal was plasticity resulting in his acknowledged place in Korean experimental art. Lee is not interested in what can make a work of art but in what cannot make one. He enjoys abnormality more than normality, what exists beyond common sense, and the freedom of non-art. For this reason, he has dealt with objects that are grotesque, unpleasant, ugly, and sexually provocative, regardless of their shapes or forms because they stimulate and invigorate the artist. This embracing of the alternative or the other through radically individual choices that Lee pursued with his practice is all the more remarkable given the complicated social and political context experienced in Korea during the 60s and 70s.

For Lee, the creation of the artwork is a reconstructive concept using various levels of cultural codes that are distinct from the creative concepts of modern art. The concept of ‘non-materialization’ is a key here, distinguishing his work and placing him firmly in the vanguard of contemporary art.

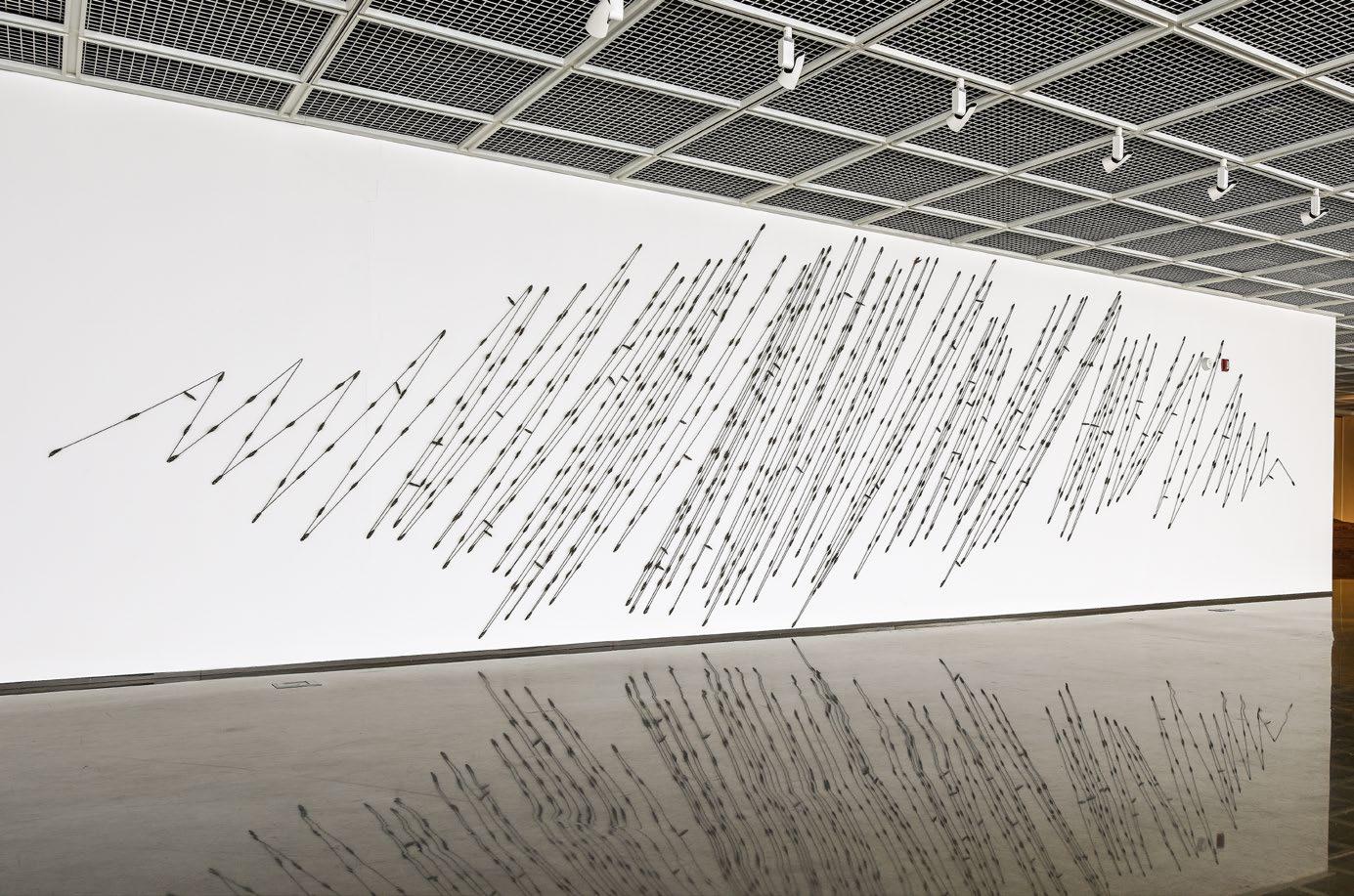

Installation view of Seung-taek Lee’s Non-Art : The Inversive Act, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, 2020

Installation view of Seung-taek Lee’s Non-Art : The Inversive Act, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, 2020

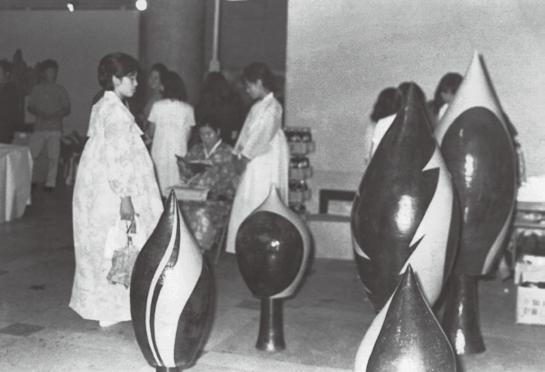

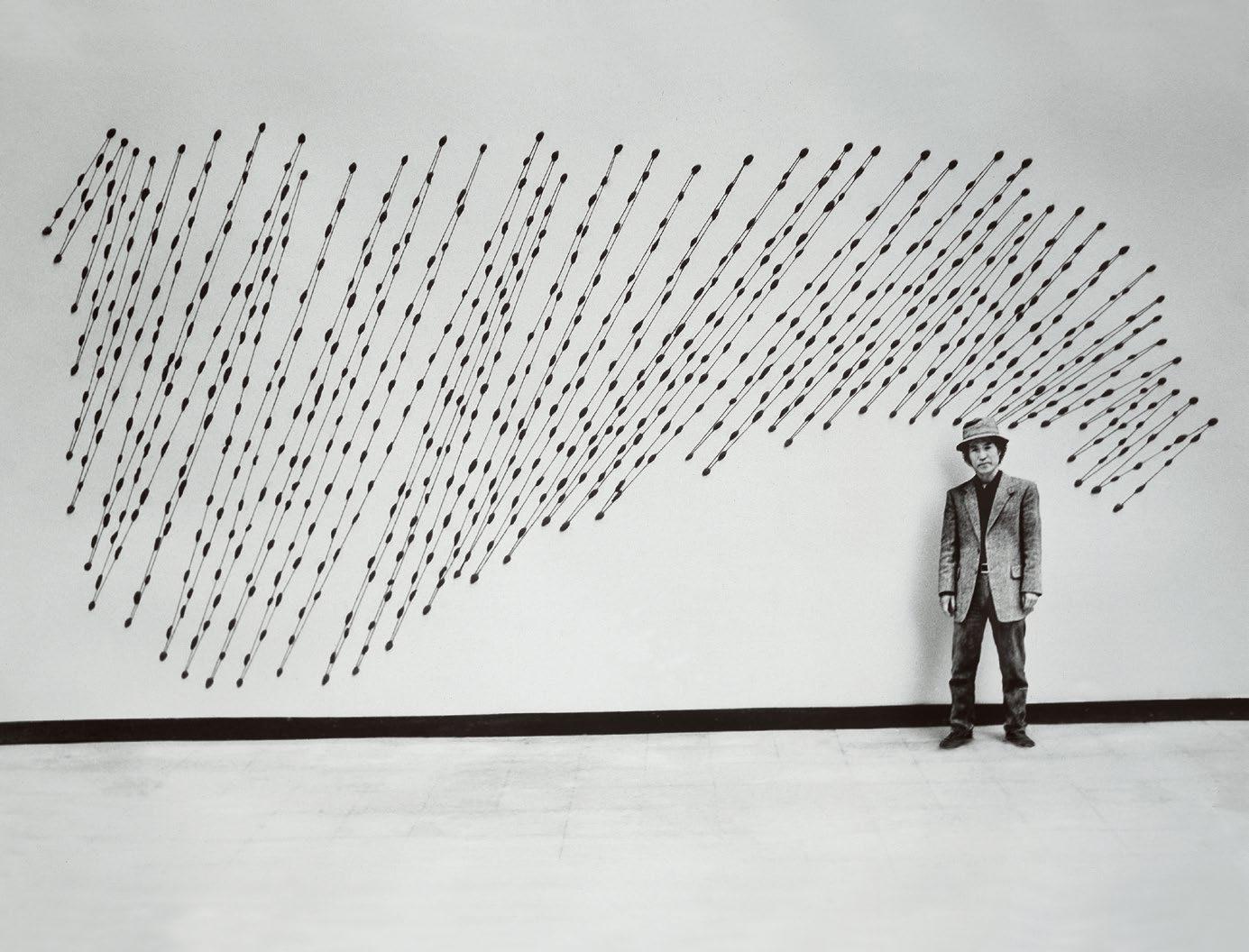

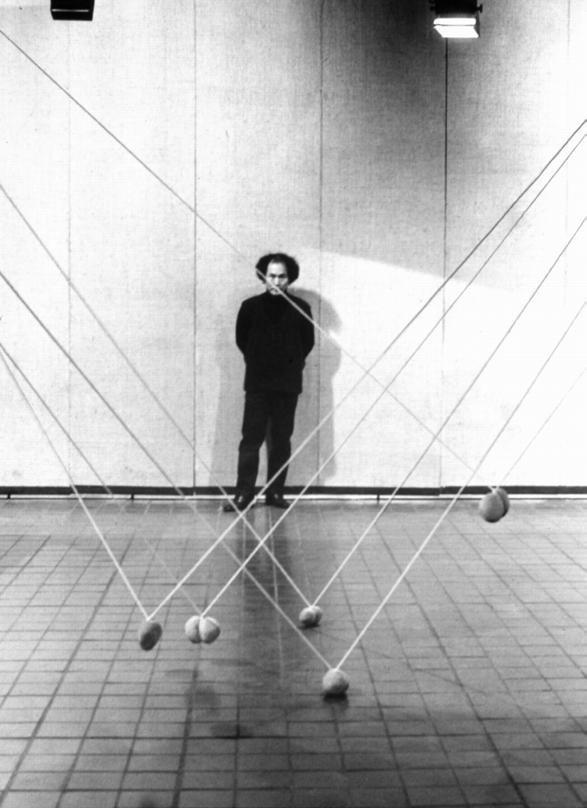

Installation view of Contemporary Sculpture Association, Central Information Center, Seoul, 1969

Installation view of Contemporary Artists Exhibition, Gyeongbokgung Palace Museum, Seoul, 1968

Installation view of the 2nd Original Form Association Exhibition, Central Information Center, Seoul, 1964

Installation view of Seung-taek Lee, White Cube, Mason's Yard, London, 2018

Installation view of Seung-taek Lee, White Cube, Mason's Yard, London, 2018

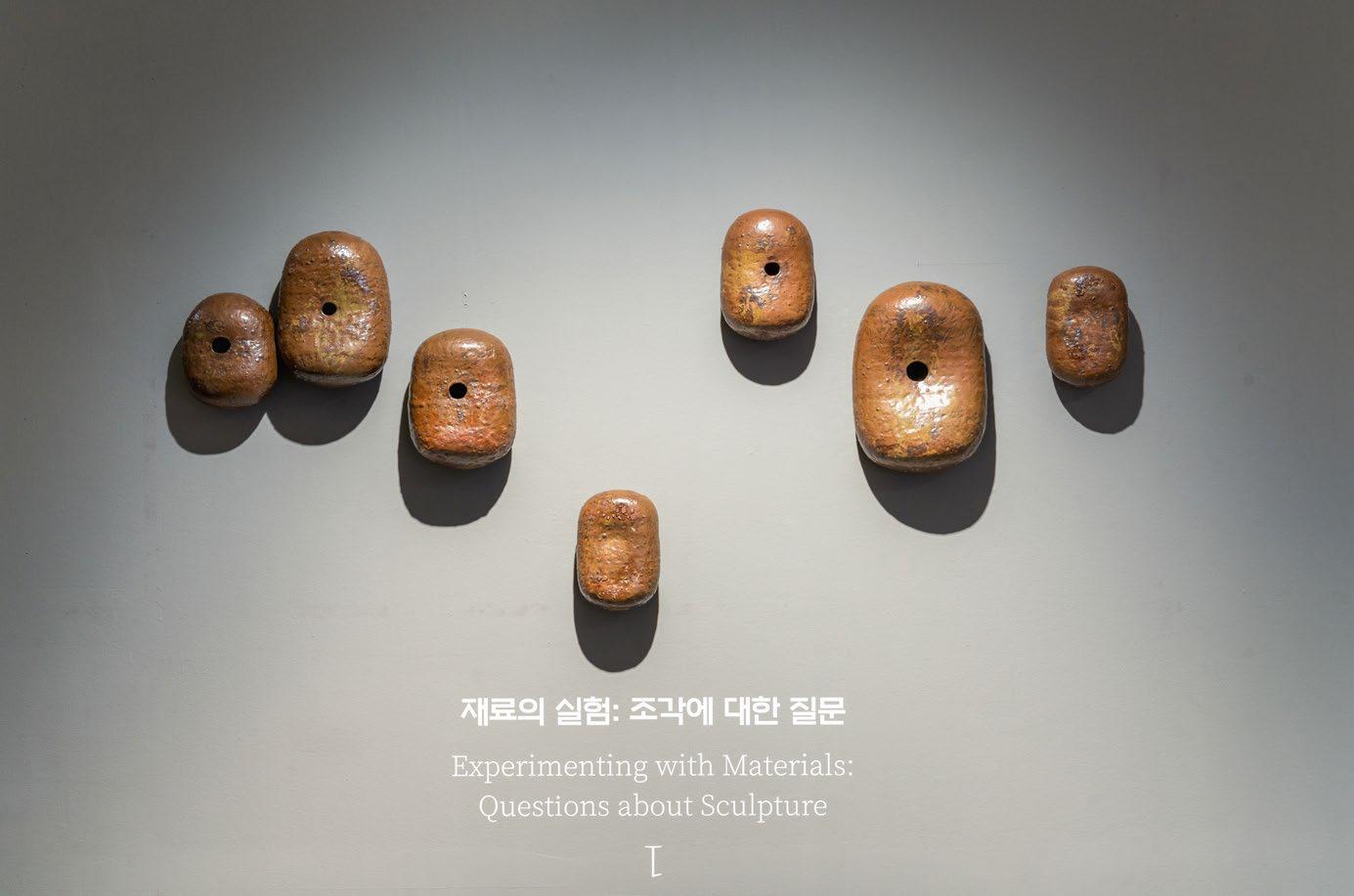

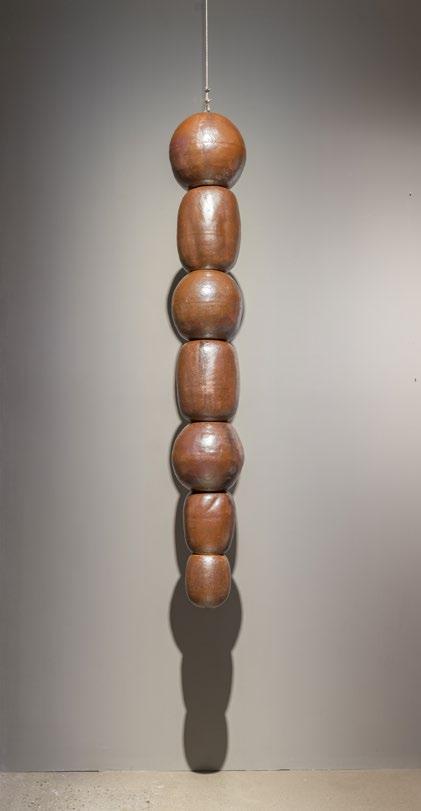

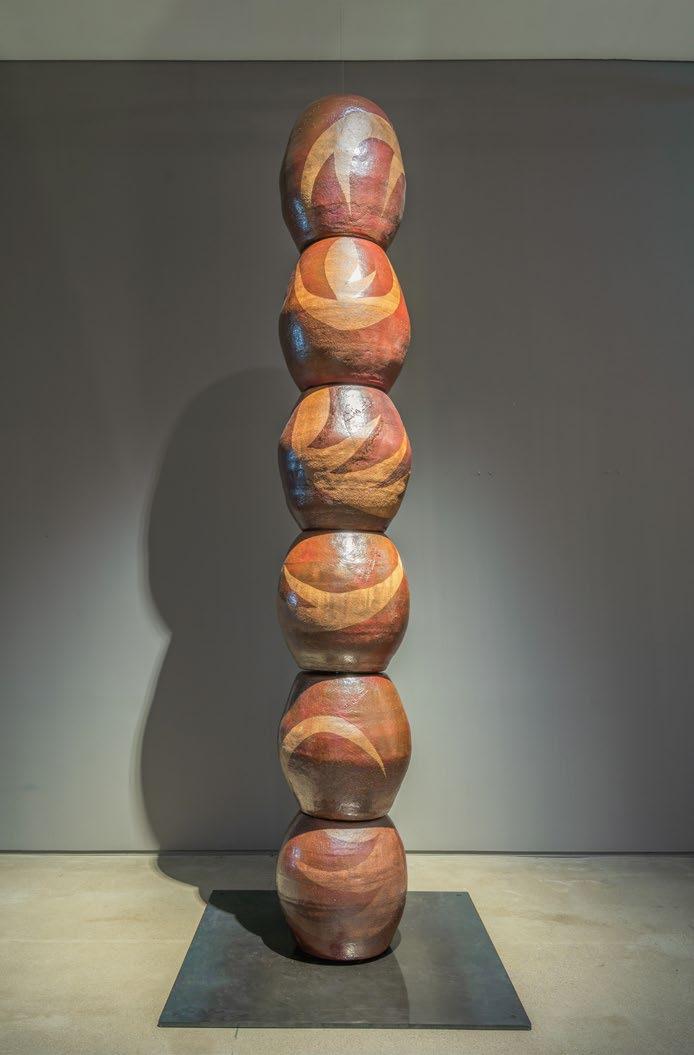

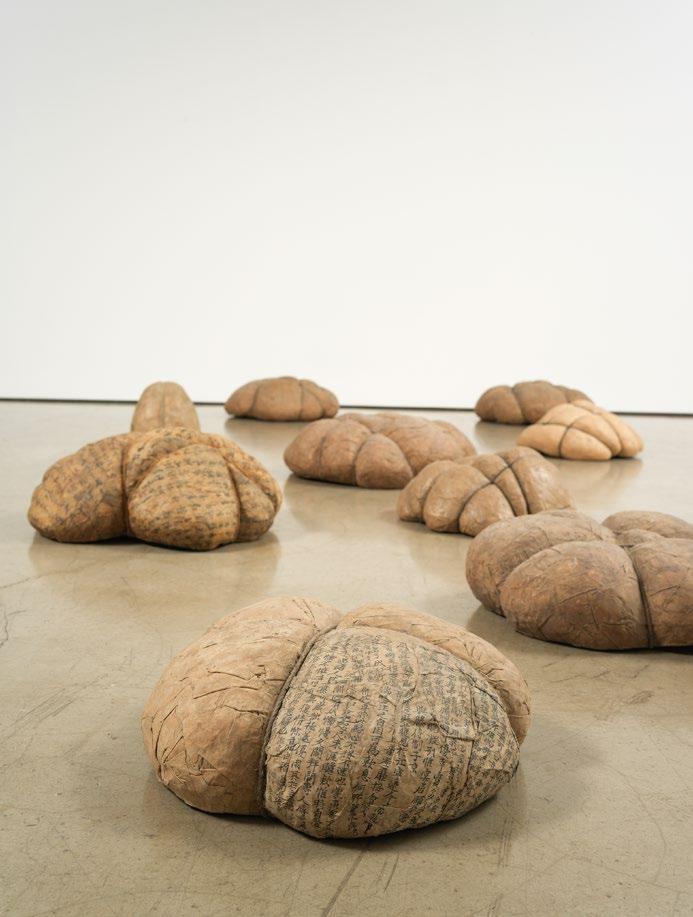

Untitled 1960/1980, Earthenware, Dimensions variable

Untitled 1962, Earthenware, Dimensions variable

Giacometti’s sculpture had a profound influence on my series of “immaterial” works. Sculpture is the art of using form to convey an artist’s idea, but Giacometti’s bodies appeared to be void of muscles. I wondered if even the bones could be removed from the sculptures. This led me to wonder deeply about the possibility of “formless” work, eventually immersing me in such “immaterial,” “formless” sculptures.

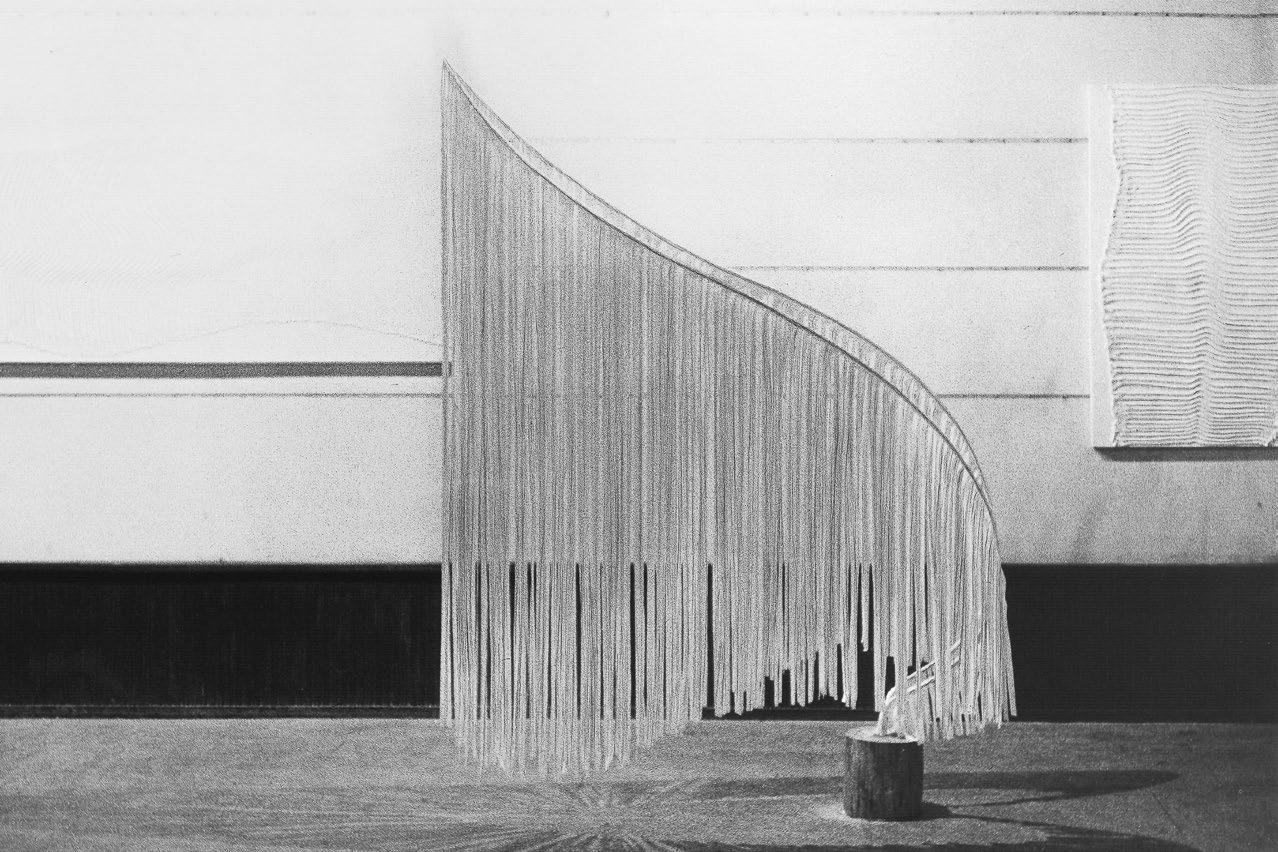

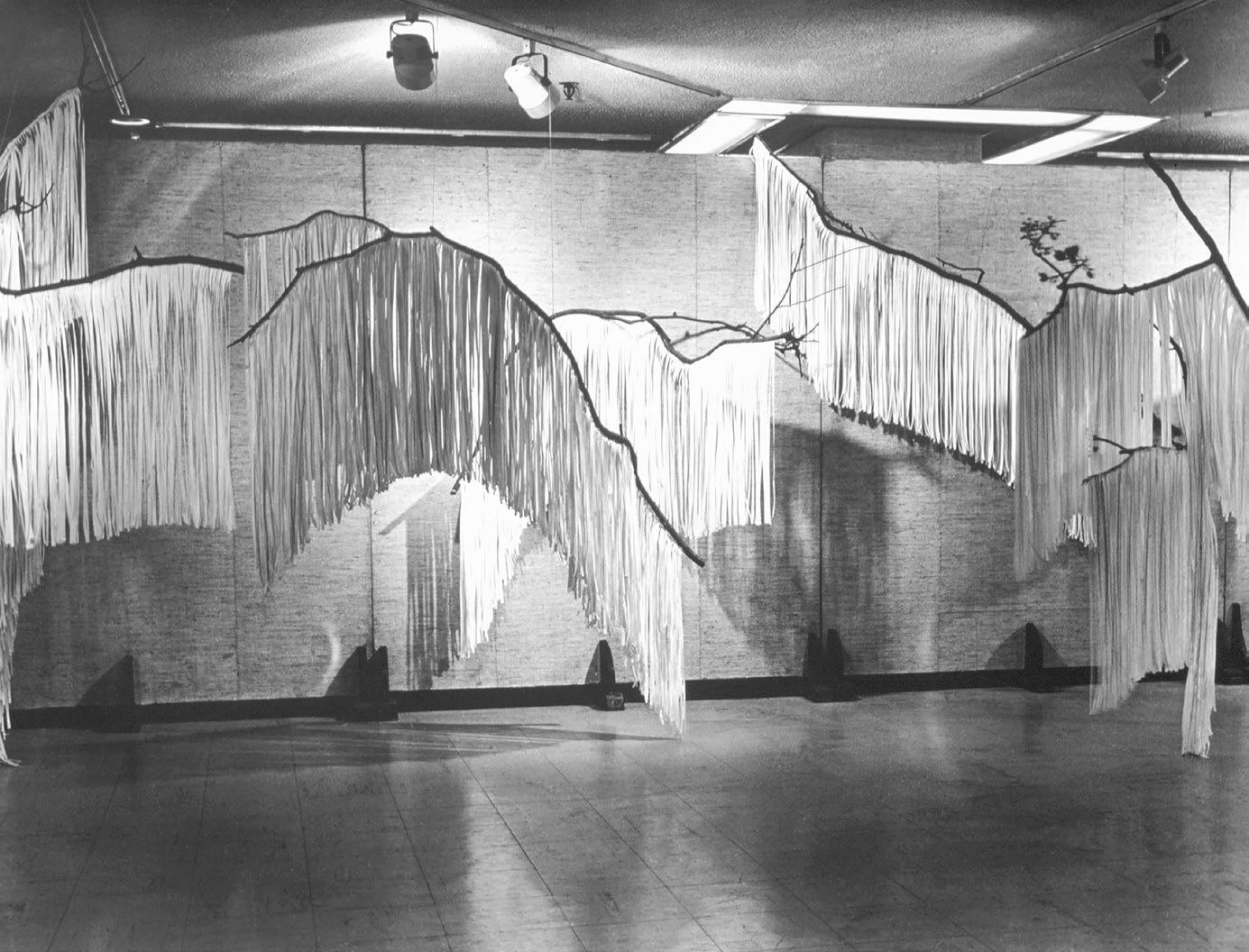

In retrospect, Smoking Sculpture and Wind were material works that nevertheless defied material fixity. My experimental endeavors continued as I tried to harness flexible, intangible natural phenomena by way of sculpture, explaining them with the concept of “non-sculpture.” As irony would have it, my experiments were destined to fail. The moment my performances succeeded in visualizing wind, that same moment would turn the work into a sculpture. In harnessing the wind, I would end up with a sculpture of the wind. Even so, out of my endless attempts and repeated failures to sculpt the wind came the creation of an original art phenomenon.

Sculpture 2019, Mixed media on mulberry Hanji paper, 202 × 142 cm Wind 1971, Cloth, rope, Dimensions variable

Excerpt from the interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist August 2020

Sculpture 2019, Mixed media on mulberry Hanji paper, 202 × 142 cm Wind 1971, Cloth, rope, Dimensions variable

Excerpt from the interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist August 2020

Wind

1970/2020, Cloth, rope, Dimensions variable

Installation view of Invitational Exhibition of Contemporary Korean Sculpture, National Central Information Center, Seoul, 1972

Installation view of Invitational Exhibition of Contemporary Korean Sculpture, National Central Information Center, Seoul, 1972

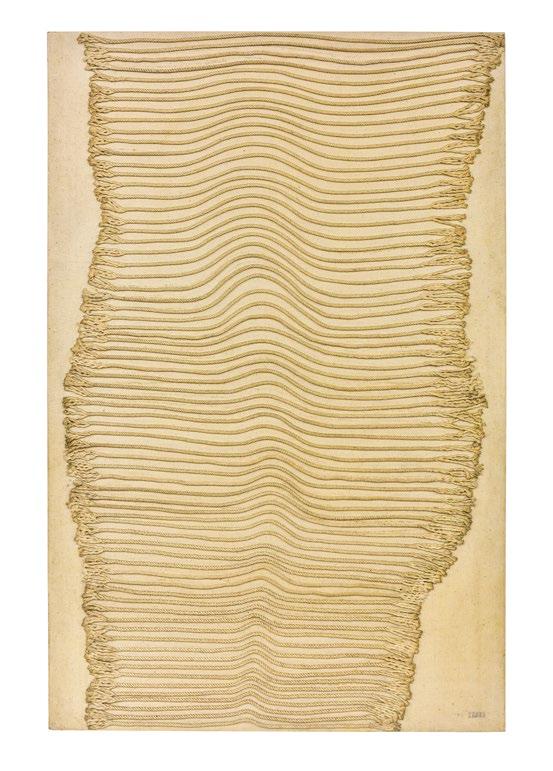

Untitled

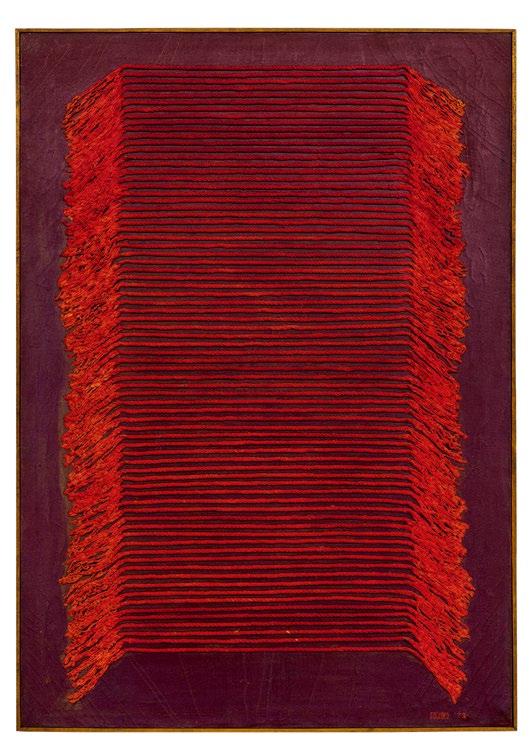

1972, Rope on canvas, 131 × 85.5 × 4.5(d) cm

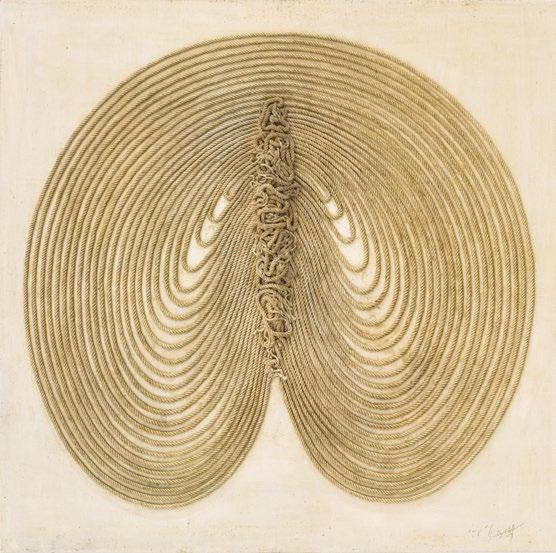

Untitled

1971, Rope on colored canvas, 110 × 110 cm

Installation view of Korean Contemporary Art Exhibition, Fine Art Center, The Korean Culture & Arts Foundation, Seoul, 1983

Installation view of Korean Contemporary Art Exhibition, Fine Art Center, The Korean Culture & Arts Foundation, Seoul, 1983

Installation view of Renegades in Resistance and Challenge, Daegu Museum of Art, Daegu, 2018

Installation view of Renegades in Resistance and Challenge, Daegu Museum of Art, Daegu, 2018

Installation view of Seung-taek Lee’s Non-Art : The Inversive Act, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, 2020

Installation view of Remember me, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, 2012

Installation view of Remember me, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, 2012

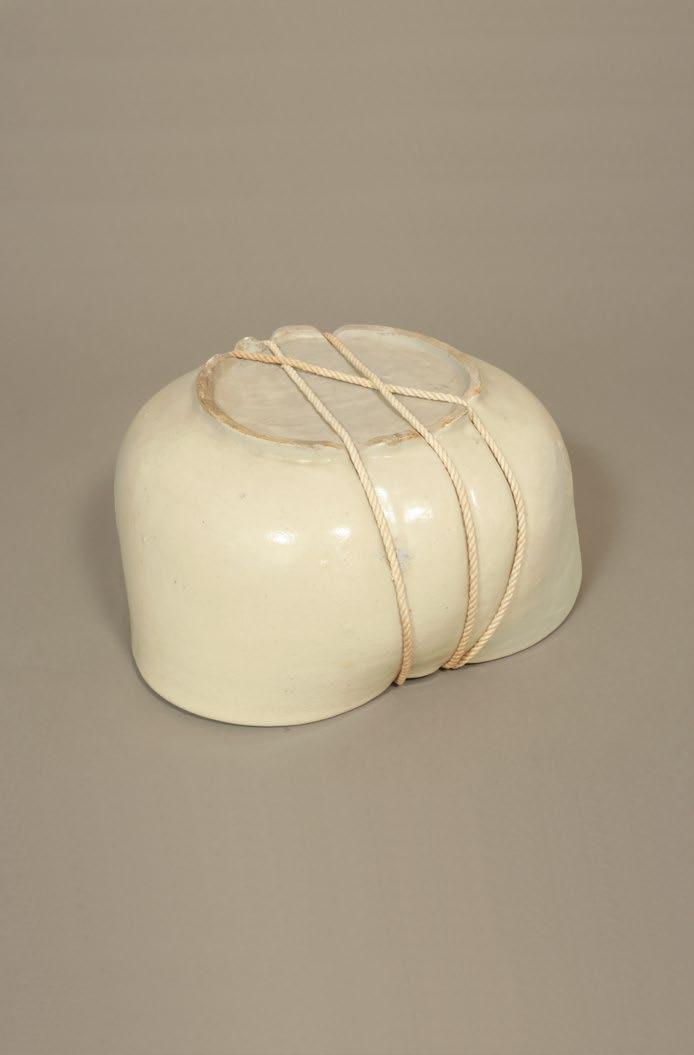

“Being a sculptor, string was a common material for me— something that was always lying around.

I was also captivated by the way string loosens itself when wound on a spool, revealing a certain energy in its materiality.

The elastic material made of cheap, cotton thread can bind anything, exerting a trace of physical force. Thinking this could be an original visual language of my own, I began binding everything.

Regardless of the objects and their materials— whether made of granite or hanji—I could bind everything with string.”

Installation view of Seung-taek Lee’s Non-Art : The Inversive Act, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, 2020

Installation view of Seung-taek Lee’s Non-Art : The Inversive Act, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, 2020

Excerpt from Brochure of 2nd Solo Exhibition Seung-taek Lee, Kwanhoon Gallery, Seoul, 1981

Excerpt from Brochure of 2nd Solo Exhibition Seung-taek Lee, Kwanhoon Gallery, Seoul, 1981

Lee Seung Taek’s “Korean” Non-art

Soojin (Art Historian)Lee Seung Taek states that his lifelong goal as an artist was “to pursue non-art, that is, to reject the fixed order and ideas of existing art.” Determined from the outset to create original art found nowhere else in the world, Lee searched relentlessly for “things unable to be art” and gave birth to his own style of “non-art.” Interestingly enough, Lee expressed this art theory of his with the term “non” rather than “anti.” This stems from the artist’s desire to pursue fundamental differences that go beyond mainstream versus non-mainstream divisions. In other words, Lee refused to acknowledge the art establishment and its authority, aiming instead to create “a different art” unlike any other form or style already in existence. Lee has mentioned that Korean tradition and folk motifs act as the most important examples for the origin of this “non-art.”

Lee often spoke about Korean contemporary art’s overly keen receptiveness to foreign art trends as well as his own effort to take a different path, searching for motifs in everyday life under the belief that “national motifs carry international appeal.” As a first-year student enrolled at Hongik University in 1955, Lee presented the sculptural work Tale (Great General of All Under Heaven, Female General Under Ground) based on Korean traditional totem poles (jangseung), and he has since created diverse works that reference folk and shamanistic motifs as seen in godret stones, glazed earthenware (oji), roof tiles, shrines to village deities, stone figures placed before tombs, and phallus stones. While Lee maintains that “Korean motifs” were merely one of the several methodological alternatives he chose for himself, he acknowledges that the modernization of tradition is still a valid way of establishing our

Cho

Cho

Installation view of Remember me, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, 2012 identity in the world, a method that allowed him to create unique works that differed from Western art. In confessing that “these [Korean motifs] made me the artist I am today,” Lee confirmed that, to him, individual identity was commensurate with national and state identity.

In Korean contemporary art history, the modernization and globalization of art and the investigation of traditional culture by Korean artists often took place at the same time; a number of artists besides Lee also aimed to meld Korean tradition with modern styles of art. In order to understand the uniqueness of Lee’s art, one must determine the nature of “Korean motifs” that he pursued all his life and examine how they

differ from the “Koreanness” sought out by other artists. How does Lee’s art stand apart from the “Koreanness” found in the numerous post-1960s works highlighting Korean motifs at the National Art Exhibition and non-mainstream exhibitions alike, the dansaekhwa movement that aspired to Korean modernism based on the Eastern spiritual world and its affinity to nature, or the Minjung Art movement that referenced basic culture to establish an artistic mode of sociopolitical resistance? Could it be what the art critic Park Yongsook once dreamed of—a primitive and raw Korean contemporary art, born from the culture’s most original, primordial forms? 1 Or is it a Korean version of modernist primitivism, which appropriates traditional motifs by removing

them from their cultural context? Are there any alternatives for viewing Lee’s “Korean” non-art without relying on these existing paradigms?

This paper aims to answer these questions by examining the artist’s own statements.

external imitation of antiques.

1. Reproducing “Uninventable” Korean Tradition

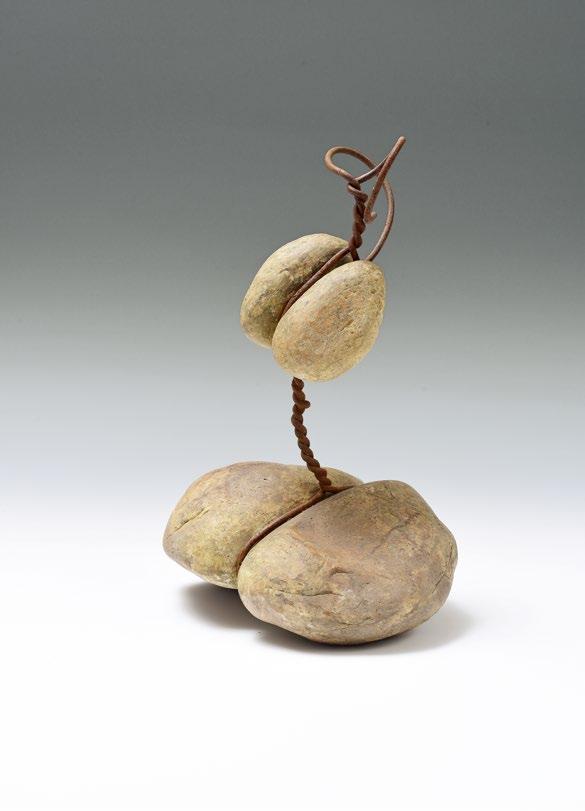

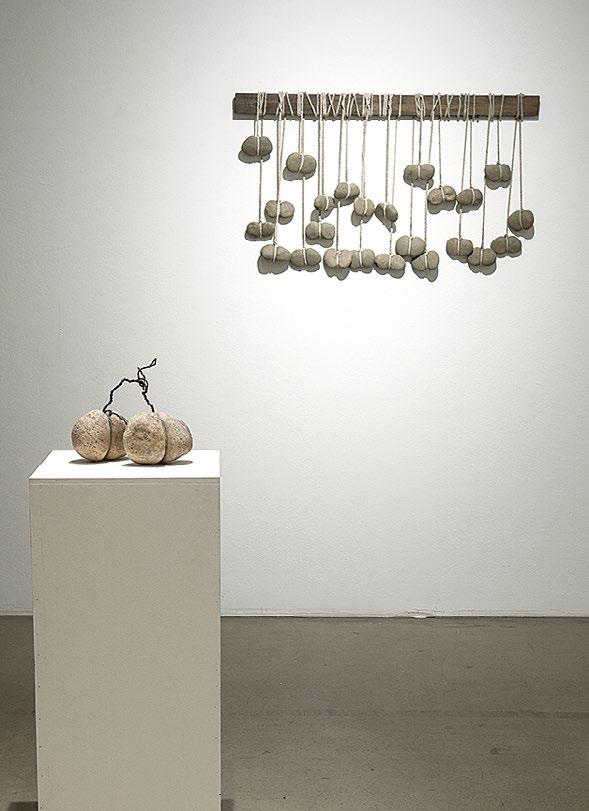

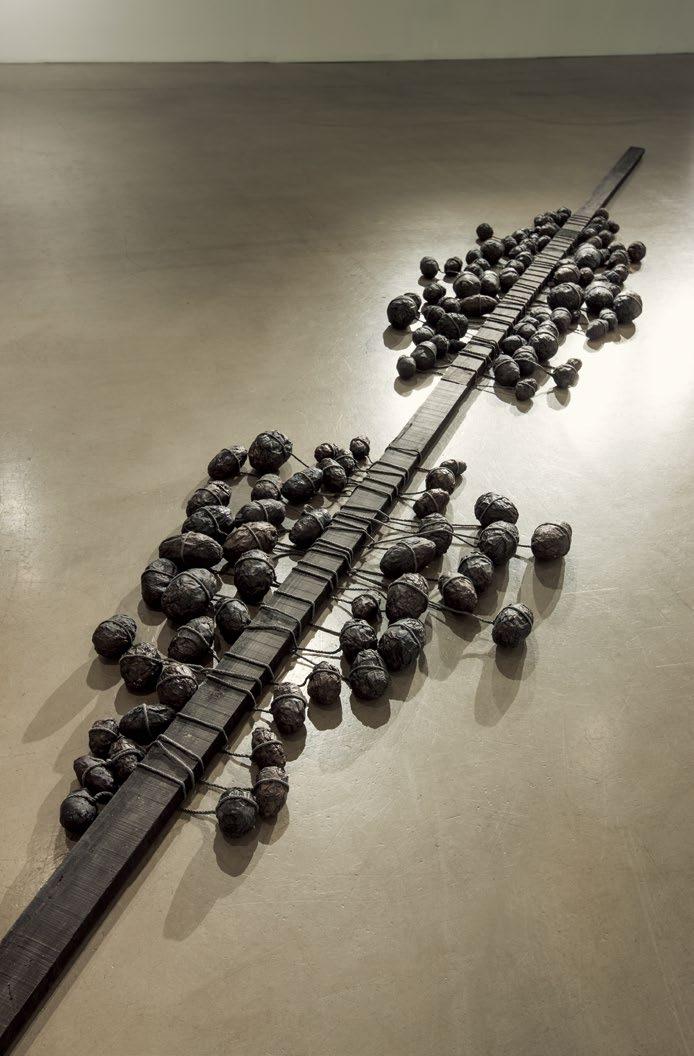

Godret Stone is now considered one of Lee’s representative works. Presented for the first time in the late 1950s, it has won acclaim for its avantgarde manner of creating the appearance of softness in solid objects, its revolutionary form as an installation displayed on the floor without plinths, and its pioneering method of “tying.” Lee’s motif of the godret stone is a small, grooved stone tied to a string, used by Koreans in the past to weigh down warp strings as they weaved straw shades or mats. After reproducing a portion of the traditional handloom device with several dozen godret stones hanging down, Lee gazed at the reproduction hung on his wall; this gave him the decisive idea that “tying any object or material makes the original item look new and different.” Observing traditional objects and therein finding the key to modernizing aesthetics and innovating art history was a process undertaken by several Korean artists of the time besides Lee. Nonetheless, Lee’s work took a decisively different path by drawing creative inspiration from replicas of folk art and

Based on the “authentic” antique of godret stones, Lee created “counterfeit” godret stones as artwork to incorporate Korean motifs into his creative world. This process began with the Tied Stone series featuring grooved stones tied with wire to resemble godret stones, eventually evolving into other related works featuring crumpled paper, textiles, wooden sticks, rope, and other materials. Folk traditions are a specific community’s way of life developed and accumulated over successive generations; folk artifacts are the reproduction of those traditions in the form of cultural artifacts. Whereas the godret stone as a folk artifact pertains to the cultural realm representing the daily life of past Koreans, the godret stone as Lee’s artwork enters the aesthetic realm by way of an artist living in the present age. Just as James Clifford has explained using the concept of an “artculture system,” traditional objects now traverse between the realm of folk-based cultural artifacts and the realm of creative artwork in various ways. The relationship between traditional, communal culture versus original, individual art becomes a more complex, sensitive issue when the traditional object, originating from a third-world society, is

Detail cut of Godret Stone

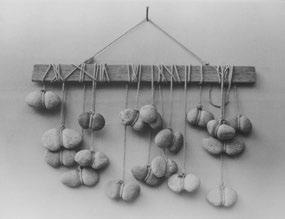

Godret Stone, c. 1957

Detail cut of Godret Stone

Godret Stone, c. 1957

deemed primitive in the West. 2

Even the most antiquated, authentic objects rarely become government-approved cultural assets when they have belonged to those in the social substratum. Even when collected and displayed in a museum, they are not awarded artistic value. Hence, most folk objects find their way to antique shops as common relics of the past; replicas might be sold as souvenirs for tourists as well. However, the folk or shamanistic objects selected or reproduced by Lee as Korean motifs—whether the sword in Tied Sword, the shamanistic shrines in the Wind and Stone Tower series, the roof tiles in The Land Wearing Roof Tiles, or the stone statues and Buddha statues in his Self Burning Performance—acquire the status of art, no longer abiding by the standard of value designated for cultural assets. Viewers observing Lee’s work are given the opportunity to compare the usage and value of traditional folk objects versus those of modern artworks, reflecting anew on the meaning of folk objects in Korea’s contemporary cultural arts.

“invented tradition.” The Park Chung-hee administration grounded its state ideology on the promotion of national culture, enacting the 1962 Cultural Property Protection Law and taking an avid interest in Korean cultural properties found in national culture and shamanistic rites. However, as the rapid modernization of Korean society in the 1970s widened the breach between traditional customs and Korean daily life, shamanism was even relegated to a symbol of premodern times. In the meantime, the government enacted policies for the discovery, conservation, and maintenance of high-value cultural properties such as handicrafts used in palaces.3 These cultural properties were not the kind of natural, dynamic products of culture created by Koreans of all classes across the country. Lee’s focus on folk and shamanistic objects as traditional Korean motifs not only testified to the fast-disappearing nature of the world in which they were made, but also served as an artistic endeavor to recollect a tradition distinct from the government-promoted “invented tradition.”

Within Lee’s artwork resembling an “uninventable” tradition, “tying” became the driving force converting cultural artifacts into unique works of art. According to Lee, the godret stones rendered into artwork were based on his method of tying solid rocks to make them look soft, but “tying” converted more than the apparent physical property of objects. As replicas of folk objects, Lee’s creations became true artworks only by the process of “tying.” “Tying” bestowed the title of “art” to his seemingly authentic yet counterfeit objects. Hence, it allowed the properties of folk and shamanistic objects from the past to gain new understanding within the Godret

Lee began experimenting with variations on Godret Stone in the post-1950s, an era when the Korean government engaged in the rapid establishment of what Eric Hobsbawm termed

Installation view of 3rd Solo Exhibition Seung-taek Lee, Kwanhoon Gallery, Seoul, 1982 Installation view of Hyundai 50, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, 2020

Stone and Tied White Porcelain, c. 1975

Installation view of 3rd Solo Exhibition Seung-taek Lee, Kwanhoon Gallery, Seoul, 1982 Installation view of Hyundai 50, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, 2020

Stone and Tied White Porcelain, c. 1975

aesthetic realm of contemporary art. In the work Non-Painting, which resembles a real antique book, the aged, brown paper covered with Lee’s handwritten Chinese characters becomes a work of art the moment it is tied with a straw cord and fitted with a frame. Even so, the title NonPainting aptly implies that the imported aesthetics of Western contemporary art cannot fully account for this work: it lies outside the bounds of modernist painting. Korean motifs thus allowed the artist to assert originality in his work.

2. Korean Motifs as “Already the Other”

While elaborating on his art world, Lee described

his methodology of “hypallage” as being inspired by Western avant-garde art, sharing similar expressive modes with collage and surrealist art. Just as these modes of art overcame the mannerisms of narrow-mindedness in art and launched innovative experiments in material and media, Lee thence derived the impetus to create works with objects that were bizarre, grotesque, and seemingly unable to be art. Themes such as “soft rock,” “stone hip,” and “hairy canvas” bring unrelated elements together or place certain objects in unexpected contexts. Encountering strangely unfamiliar, fantastical images in these works, the viewer experiences feelings of shock and awe that dismantle common notions of objects and art. Lee carried out his first work of

conceptual hypallage by converting a known object (a solid rock) into an unknown object (a soft rock) in Godret Stone. Based on a similarity in form, the soft rock led to the creation of another unknown object (a stone hip) in the work Hip, thus achieving a serial hypallage. The concatenation of new conceptual objects moved from “solid rock” to “soft rock,” then passed through “soft hip” before reaching “solid (stone) hip,” converting artwork resembling a traditional folk object into an artwork resembling a Korean body. After converting godret stones into a “hip,” Lee’s imagination carried on, converting the “stone hip” into a similarly shaped “hip-like antique book” titled Non-Painting, using the traditional folk motif of an antique book as a metaphor for a Korean body. The “hip-like book” in Non-Painting evolved into “sticks of books” in a work titled Paper featuring antique books tied together like sticks; it finally evolved into the “antique book frame” or “old painting” in Paper Installation featuring antique books tied to a canvas frame and displayed on the floor. This “old painting” is interchangeable with either the work Untitled made of a canvas frame wrapped

around in the kind of blue and red cloth often used by Koreans in the past, or the work Hairy Canvas consisting of two adjacent canvases each bearing a large clump of black, Korean hair. These examples demonstrate how such concepts as antique books as symbols of national spirit, the Korean body, and traditional paintings interact in this concatenative process of rendering “unknown (Korean) objects” into art.

Traditional Korean motifs in Lee’s art world shifted from one symbol to the next, changing in form while becoming unknown objects. The first version of Hairy Canvas, which featured the artist’s own hair, symbolized the increasingly ambiguous identity of Korean selves, including that of the artist. From a distance, the work appears to be an achromatic canvas stained with black paint, but when the viewer reaches closer and discovers the material for what it is, the raw physicality prompts shock and discomfort. The Korean as a modern, Westernized self thereby encounters a national subconscious that resists the conscious control of modern rationality, encountering a tradition that has already become a strangely unfamiliar, fantastical “Other.” The viewer also faces the disparity between presentday Koreans and Koreans of the past, realizing that the Other in Korean contemporary art might be found in Korean motifs of the past rather than Western motifs.

Although Koreanness has already become the Other in Lee’s work, it continues to seize our attention in provocative ways without vanishing. Like the work Wind presented indoors as an art gallery installation or the Land Wearing Roof Tiles installed outdoors

Installation view of 2nd Solo Exhibition Seung-taek Lee, Kwanhoon Gallery, Seoul, 1981

at the Olympic Park

Hip, 1972 and Tied White Porcelain, 1975

Hairy Canvas, 1990s, Hair on canvas, 73×116cm (each)

Installation view of 2nd Solo Exhibition Seung-taek Lee, Kwanhoon Gallery, Seoul, 1981

at the Olympic Park

Hip, 1972 and Tied White Porcelain, 1975

Hairy Canvas, 1990s, Hair on canvas, 73×116cm (each)

in Seoul, it acts as a whistleblower ringing the alarm whenever Korean contemporary art falls in danger of neglecting its inner reality in favor of virtualization. In a way, the unique endeavors veering from typically modernist sculptural methods—tying, binding, scattering, dripping,

and setting on fire—are creative acts functioning as the Other’s commentary on Western art and Korean contemporary art. Lee’s “self-burning” performance art, which sets carefully crafted artwork or cultural properties aflame as seen in Burning Canvases Floating on the River and Self Burning of a Stone Statue, rejects the celebration of tradition and art as objects of collective memory, turning them into objects of eternal loss. The Self Burning performance of Lee setting a self-portrait sculpture aflame outdoors serves as a key example of non-art, the speech act of the Other-as-artist that is not easily grasped in terms of conventional artistic meaning.

The Koreanness appearing in Lee’s art world as the Other extends even further. The concatenative hypallage that initially began with cultural products like folk objects gradually encompassed natural products nearby, which is to say they extended into natural environments. For instance, Paper Installation as an “antique book frame” shares its wooden material with Non-Sculpture, an outdoor installation of chopped branches and sticks wrapped with cloth; this led to yet another Non-Sculpture featuring nest-shaped bulges of textiles and object wrapped onto a living tree, which then led to Sky House, in which an artificial nest was juxtaposed against an actual magpie nest on a tall tree. During this process, Lee’s creative methodology entered a new phase of “privatization” whereby the artist intervened in natural environments or social situations affecting the Korean people. According to Lee, “privatization” entails selecting unique natural phenomena or mysterious structures and intervening only minimally to aestheticize them in an act of artistic creation. Over his lifetime,

Installation view of Contemporary Paper Art: Korea and Japan, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, 1982

Installation view of Earth, Life : the Expression of Earth in Korean Contemporary Art, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, 1997

Self Burning performance at Han river, 1989

Installation view of Contemporary Paper Art: Korea and Japan, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, 1982

Installation view of Earth, Life : the Expression of Earth in Korean Contemporary Art, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, 1997

Self Burning performance at Han river, 1989

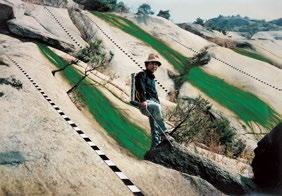

Lee “privatized” a wide range of subject matters, including mountains, fields, beaches, riversides, fishing villages, stone walls on Jeju Island, seaweed farms, military defense structures, massive shipyard machinery, earthenware factories, pencil factories, quarries, and waterfalls. Leaving photographic records of his encounters with such places, Lee turned them into art.

photographs to clarify the images. In Field and An Artist Planting Moss, images of black and white rods used for land surveying were collaged onto photographs of mountains, fields, and historic sites, turning familiar, everyday spaces into unfamiliar, artistic locations. While they varied in theme, these works of privatization shared a common feature: results of the artist’s performances were captured in photographs, many of which were modified like paintings in a post-processing stage. The results of Lee’s privatization came to be grouped as “photopictures,” which became a major category of his oeuvre.

Lee’s process of privatization involved bringing his focus and perspective on unique natural or artificial structures to create photographic works as seen in Solar Heat Painting, showing a warehouse roof with waterproof coating cracked by sunlight, and A Play of Tree Mouth, showing wooden boards piled in large circles to dry. The artist went on to create works such as Artificial Installation that introduced objects made of disparate material into mushroom or ginseng farms, along with works such as Moss Growing Artist, Drawing Falls, and Painting Water that required painting over cliffs, valleys, or sand beaches with a paint sprayer, capturing photographic images, and painting over the

According to Lee, his appearance in these photo pictures—which acts as a signature or trademark of sorts—was originally introduced to convey a sense of scale of the piece. Photos-pictures feature Lee engaging in creative acts upon intervening in an environment; they also feature him next to finished works, posing like a tourist visiting a scenic spot. The artist’s presence seemingly serves to verify the authenticity of the photo-picture, the veracity of Lee’s creative work carried out on site. In reality, due to the nature of Lee’s photo pictures as montaged images modified with drawings or paintings and, at times, incorporating artificial

Installation view of 11th Exhibition of Hongik Sculpture Association, Fine Art Center, The Korean Culture & Arts Foundation, Seoul, 1981

Play of Tree Mouth 1968

Green Campaign, Early 1990s

Installation view of 11th Exhibition of Hongik Sculpture Association, Fine Art Center, The Korean Culture & Arts Foundation, Seoul, 1981

Play of Tree Mouth 1968

Green Campaign, Early 1990s

props made to resemble landmarks, the artist’s presence serves to disrupt the viewer’s perception of the location and the objects placed therein. Modified with green paint applied on the image, the photo picture Green Campaign presents the artist apparently gathering the green water pouring out of a rock-carved Buddha, performing a kind of fake motion intended to make the image more believable. Through the artist’s performance, the idea of the Buddha carving as an extant cultural heritage, together with the site where it stands, breaks free of the modern era’s superficial, stereotypical image of tradition as well as the kind of scenic spectacle consumed by tourists.

Traditional cultural heritage sites are generally thought to be founded on temporal and spatial continuity with the past. However, given that many Korean traditions were invented anew and given new meaning to meet the era’s demands, present-day cultural heritage tends to be characterized by temporal and spatial discontinuity instead. Cultural heritage sites that currently exist as part of our environment function as points of intersection for different

1. Park Yongsuk, “New Year’s Special Roundtable: New Primitivism and the Originality of Korean Art,” Misulsegye 134 (December 1995): 73–81.

2. James Clifford, “On Collecting Art and Culture,” in ThePredicamentofCulture:Twentieth-CenturyEthnography,Literature, and Art (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988), 215–251.

3. Kim Mi Jung, “Folklore and Shamanic Motif at the 1960s Korean Modern Art Concerning on the Globalism and Localism of the Korean Modern Art,” JournalofKoreanModernandContemporaryArtHistory 16 (August 2006): 189–223.

spatiotemporal trajectories, always in the midst of formation and open to change. 4 The cultural heritage sites in Lee’s photo-pictures likewise contain both undecidability and uncertainty; there is no knowing where they are located, when they were photographed, or whether the artist actually intervened on-site. Disrupting the viewer’s faith in its continuity with the past, they prompt an encounter with actual Koreanness that cannot be subsumed under modern totality. Lee’s photo pictures exist as a site of “the local absolute” (un absolu local) dedicated solely to artistic meaning, presenting viewers with the spectacle of a different tradition—the Other lying outside the modern version of Korean tradition. As a way of guarding against essentialist attitudes toward tradition and keeping nationalistic fantasies at bay, Lee has spent a lifetime creating “Korean” non-art. The tradition found in Lee’s art refuses to exist as the Other that merely complements the West; it disrupts the essence of Westernness, acting as a weapon against its artistic stratagems. Lee’s “Korean” non-art lies outside modernity while also defying postmodern interpretation, thereby entering the realm of transmodernity. Untitled

4. Doreen Massey, ForSpace, trans. Park Gyeonghwan et al. (Seoul: Simsan Publishers, 2016), 13.

Installation view of Seung-taek Lee’s Non-Art : The Inversive Act, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, 2020

Installation view of Seung-taek Lee’s Non-Art : The Inversive Act, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, 2020

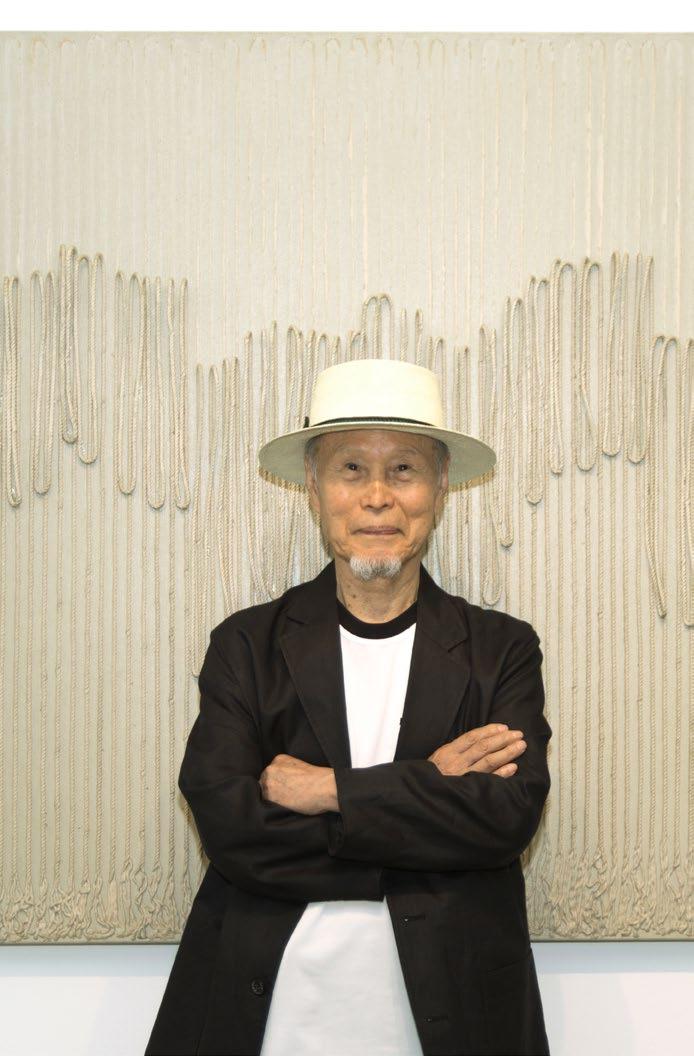

Born in 1932 in Gowon of Hamgyeongnam-do (currently a province in North Korea), Lee Seung Taek was recognized for his distinguished talent in art as of elementary school, and he was able to learn about Russian Constructivist and Realist artists in middle school and practiced realistic depiction. When the ROK-U.S. allied forces landed in his hometown during the Korean War, he volunteered for the ROK Army at the age of 18 and came to South Korea in 1950 and had the opportunities to engage in drawing and painting in the army. After the war, he made a living by painting portraits of American soldiers stationed in Seoul. In 1955, he enrolled in the department of sculpture at Hongik University. He joined the group called “Wonhyeonghoe (Original Form Association)” in 1964, and was invited to the 6th Biennale de Paris des Jeunes (1969) and AG 1970: Dynamics of Expansion and Reduction (1970). He exhibited Wind, a large-scale installation work, at the Korean Contemporary Sculpture Associations (1970), Tied White Porcelain at the inaugural Seoul Contemporary Art Festival (1975), and Tied Book at the Daegu Contemporary Art Festival (1976), and he continued to experiment with “tying” and “deconstruction” series utilizing various materials including daily objects and diverse forms through the 1970s and 1980s. Lee established with the concept of “non-sculpture” through his formative experiments around 1980 continuing the visualization of non-material (smoke, wind, fire, and water) including fire performance, Earth Play, and Green Movement series

In 2009, he received the Nam June Paik Art Center Art Award, and his world of work began to be reevaluated in earnest. Afterwards, he was invited to The 8th Gwangju Biennale (2010), Prague Biennale 6 (2013), Postwar: Art Between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945-1965 (Haus der Kunst, Munich, 2016), and Awakenings: Art in Society in Asia 1960s-1990s (The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, Japan; National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, Korea; National Gallery Singapore, Singapore, 2019). He held solo exhibitions including Gallery Hyundai in Seoul in 2014, Lévy Gorvy Gallery in New York in 2017, the White Cube Gallery in London in 2018, among many others, and held a retrospective exhibition Lee Seung Taek’s Non-Art: The Inversive Act at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea in 2020. His works are in the collections of major domestic art institutions as well as overseas institutions including Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, Tate Modern, London, M+, Hong Kong, and The Rachofsky Collection, Dallas.

After opening its doors as “Hyundai Hwarang” on April 4th, 1970 in Insadong, Seoul, Gallery Hyundai has been leading movements in the art world since boldly introducing contemporary art to what was at the time an old paintings and calligraphy-oriented gallery world. It was through Gallery Hyundai that Lee Jung Seob and Park Soo-Keun, now accepted as the “Korean people’s artists”, received spotlight. It also had been contributing to expanding the basis of Korean abstract art, organizing exhibitions with masters Kim Hwanki, Yoo Youngkuk, Yun Hyong-keun, Kim Tschang-Yeul, Park Seo-bo, Chung Sang-Hwa, Kim Guiline and Lee Ufan long before the Dansaekhwa boom.

Following the 1980’s, Gallery Hyundai adapted to developments in the international art world by opening exhibitions of international masters like Joan Miró, Marc Chagall, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Christo and JeanClaude Denat de Guillebon. From 1987, it would participate in Chicago Art Fair as the first Korean gallery to be included in an international art fair to introduce Korean art to global audiences. Including Nam June Paik’s performances and video art, many works by headliners of Korean experimental art such as Quac Insik, Seung-taek Lee, Park Hyunki, Lee Kang-So, Lee Kun-Yong were connected to wider audiences through Gallery Hyundai. To this day, it is always discovering and introducing emerging and mid-career artists like Minjung Kim, Moon Kyungwon, Jeon Joonho, Seulgi Lee, Yang Jung Uk, Kim Sung Yoon, Kang Seung Lee.

Art magazines Hwarang and Hyundai Misul, each first printed in 1973 and 1988, remain vivid documentations of their contemporary art scenes. In addition to two spaces Gallery Hyundai and Hyundai Hwarang in Samchung-ro, Seoul, it is also operating a showroom in Tribeca, New York.

www.galleryhyundai.com

1972-1973, Rope on colored canvas, 114×80.5 × 2.7(d)