MINJUNG KIM

For the last three decades, Minjung Kim has been presenting works that ingeniously combine East Asian traditions of ink-on-paper painting with the compositional language of Western abstract art.

Minjung Kim’s artworks always embark from Korean hanji paper. Korean paper does not remain merely at the background of what is being depicted - for the artist, it functions as both shades of color and the subject of painting in itself, a stage for mediation and training. In the process of investigating lines as the basis of East Asian painting, she would start to burn Korean paper, seduced by lines of a different sense: those created from the “collaboration” of paper and fire. The destructive act of burning and obliterating the most delicate human invention, paper, with candle or incense light led to revelations on the power of nature and the sense of self-restraint.

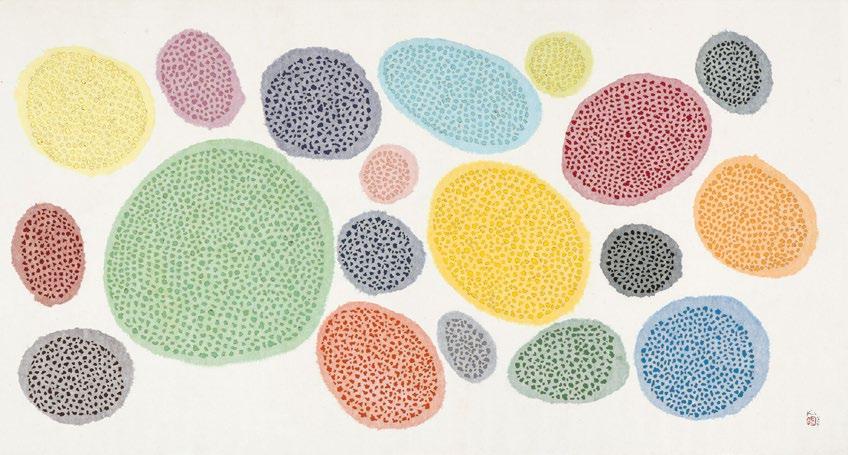

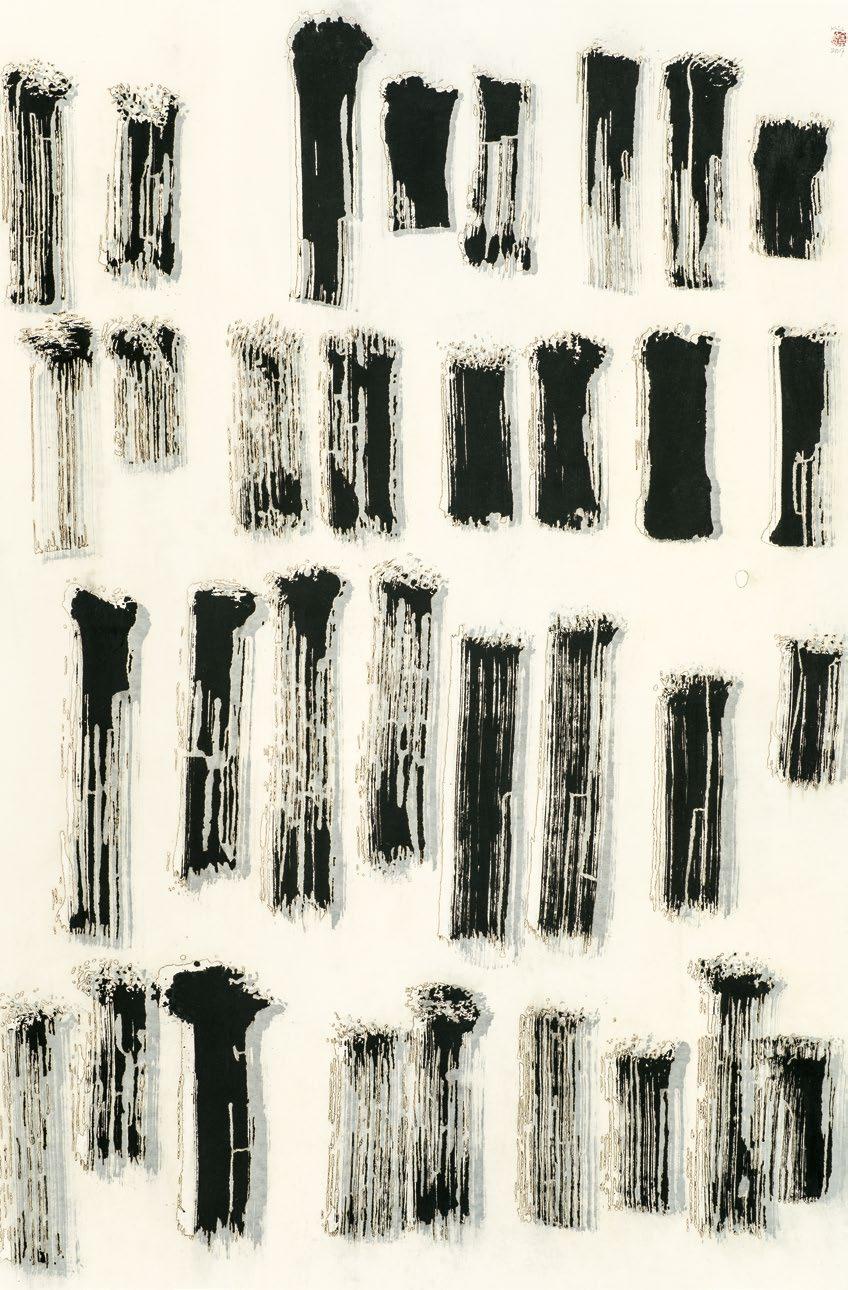

Kim completes her work through meticulous handiwork and concentration on Korean paper, like a master craftsperson. She uses straw cutters or fire to create ovals or strips of colorful Korean hanji paper pieces, which are then placed upon a background of Korean paper - countless variations of shade, form, and texture create a sense of suspension in space and unresolved aesthetic tension. Threedimensional effects at the fine seams between thin paper pieces evoke the diligent movements of the artist’s hands and their inherent tactility. The creative process is in itself a ritual journey from chaos to order, static to movement, impulse to restraint.

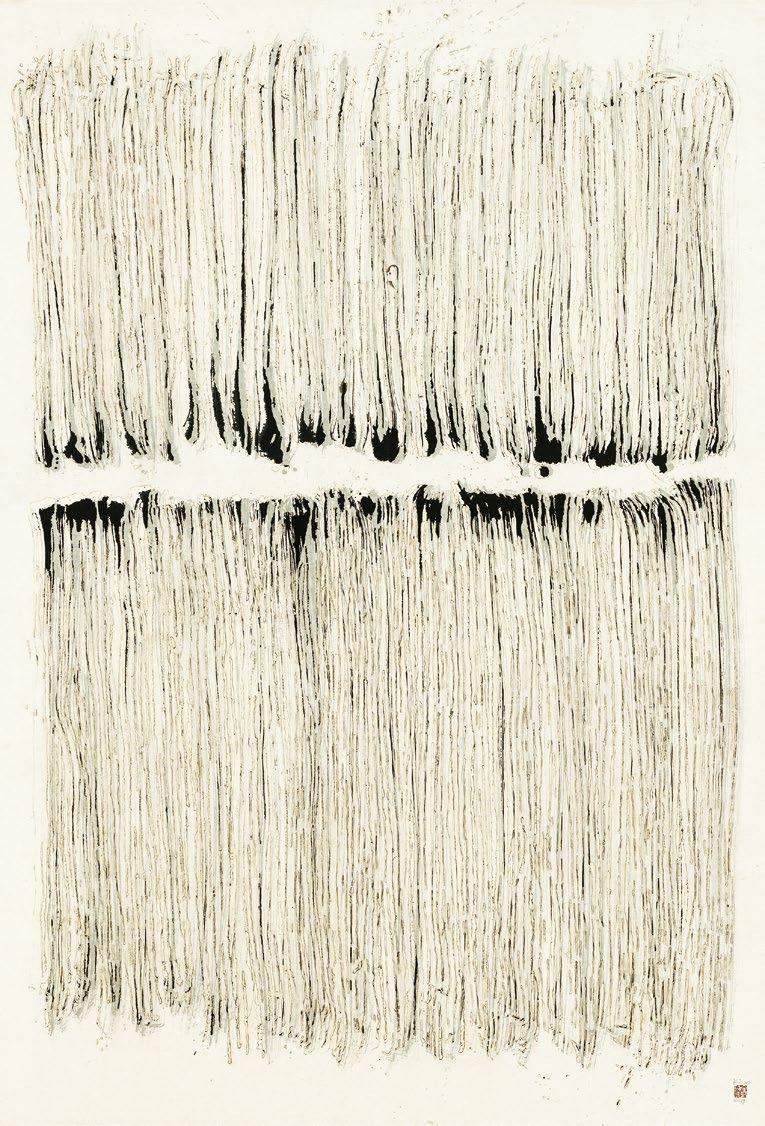

Timeless

2019, Mixed media on mulberry Hanji paper, 143.5 × 194 cm (detail)

Installation view of Oneness, 2017, Hermès Foundation, Singapore

Installation view of Oneness, 2017, Hermès Foundation, Singapore

Time is not existing.

We extract time through phenomena of mutation – biological process.

I paint mountains and I cut and burn to make a cage of tide and I glue them.

Trace of existence of mountain becomes the sounds of the millennial tide.

Horizon of ink colored stripes gives me a sense of timeless.

Minjung KimThe Water

2020, Mixed media on mulberry Hanji paper, 200 × 140 cm

Sculpture

2019, Mixed media on mulberry Hanji paper, 137.5 × 166.5 cm

Sculpture

2019, Mixed media on mulberry Hanji paper, 202 × 142 cm

Installation view of Minjung Kim, 2020, Hill Art Foundation, New York, USA

Installation view of Minjung Kim, 2020, Hill Art Foundation, New York, USA

Installation view of Minjung Kim, 2019, Langen Foundation, Neuss, Germany

Installation view of Minjung Kim, 2019, Langen Foundation, Neuss, Germany

Breath,

Breathing means to me inserting an instantaneous trace of my life in the great flow of the Tao.

I hold my breath when I draw with a brush.

I breathe out when I complete the draws.

Minjung Kim

Phasing

2019, Mixed media on mulberry Hanji paper, 205 × 140 cm

Installation view of Cendre & Lumière, 2017, Musée des Arts asiatiques, Nice, France

Installation view of Cendre & Lumière, 2017, Musée des Arts asiatiques, Nice, France

Pieno di Vuoto

2020, Mixed media on mulberry Hanji paper, 145 × 200 cm

Pieno di Vuoto

2020, Mixed media on mulberry Hanji paper, 140 × 105 cm

Pieno di Vuoto

2020, Mixed media on mulberry Hanji paper, 145 × 200 cm

Pieno di Vuoto

2020, Mixed media on mulberry Hanji paper, 140 × 105 cm

Minjung Kim, overlapping Korean Paper in Water and Fire Kwon Young-Jin | PhD. Art History

The Return of Minjung Kim

At her solo exhibition Traces held in 2015 at Seoul’s OCI Museum, Minjung Kim presented her works to the Korean audience for the first time since leaving for Milan in 1991. Twenty-four years had passed since her first solo eaxhibition at Baiksong Gallery in Seoul and Injae Museum in Gwangju followed by her decision to study abroad at Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera. Kim’s return saw the introduction of two dimensional works of Korean paper that seem quite familiar to us exuding sentimental expressions in ink, color, and collages of reconstituted pieces of Korean hanji paper. The two strands of her presented workone whose gradations of splashed ink recall the ambience of traditional ink wash landscapes, and the other consisting of cut Korean paper blackened with incense and reconstituted as collage into uniform patterns – seemed unremarkable at first glance to the attuned Korean viewer. Yet, the sudden emergence of these works in fully realized form without tangible context or explanation was intriguing.

The process of Kim’s work, with its repetitive handwork utilizing hanji paper as its main material, was enough to place Kim within the Dansaekhwa boom of the 2010s that had just started rearing its head. However, brush-drawn lines and inherent sentimentality were much more prominent in Kim’s works pointing more towards the influence of traditional East Asian

or Korean painting. We can also observe her bold use of primary colored hanji paper that goes beyond greyscale monotone, as well as the geometric abstraction of burned paper pieces and subtle Op-Art effects that take her work beyond the edges of Dansaekhwa. Moreover, the quarter century gap makes it hard to place the artist within the group of original Dansaekhwa artists born in the 1930s or the second generation Dansaekhwa born in the 1960s. Though being born in 1962 makes her a contemporary of second wave Dansaekhwa artists, she had no contact with any Dansaekhwa artists since her move to Europe in 1991. Instead, she remained active in major European cities (Milan as the base) moving to Geneva, Turin, Rome, Venice, Copenhagen, Antwerp, Hamburg, London among others. The physical distance and the time and space prior to her return in 2015 further adds to the difficulty of referring to her hanji paper works as Dansaekhwa.

painting styles. With support from her mother who recognized her daughter’s talents, Kim received painting lessons from the watercolor painter Kang Yeongyun (1941-) and eventually enrolled in the department of Oriental Painting at Hongik University where she participated in various group and organizational exhibitions.

Gwangju, Seoul, Milan, and Again Back to Seoul

Born in Gwangju in 1962, Minjung Kim was determined to become a painter from an early age having grown up in a household familiar with Korean painting traditions including calligraphy, literati painting, and flower bird

During her formal studies, Kim was fascinated by East Asian color paintings by the likes of Chun Kyungja(1924-2015) and Lee Sookja(1942-) as well as the Renaissance paintings from Italy and Flanders introduced in Western Art History lectures. Korean art in the 1970-80s saw conflict between monochrome abstract paintings driving a “Koreanized” Modernism and the countering Minjung Art movement that emphasized sociopolitical participation. Both movements were spearheaded by male painters and particularly those who majored in Western painting. East Asian color painting was deemed the “appropriate” medium for female artists majoring in Oriental art. After modernization, Korean art had been fraught with the dichotomy of Eastern and Western painting representing the conflicting tasks of inheriting Korean traditions and venturing into Westernized contemporary art. In addition to this division between Eastern painting (as tradition) and Western painting (as contemporary), gender dynamics dominated Korean art providing female artists within

The Street

2007, Mixed media on mulberry Hanji paper, 129 × 193 cm (detail)

Predestination

2013, Mixed media on mulberry Hanji paper, 74 × 115 cm

higher education only a limited range of opporessed activity.

Faced with such a structure, Kim made a pivotal decision to move to Europe in 1991. Her decision to attend Milan’s Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera provided the opportunity to witness the canon of Western painting with its vast collection of renown paintings from the Middle Ages up to the modern and contemporary (but with a focus on the Northern Italian Renaissance). Kim finally enjoyed complete freedom from the restrictions of Korean traditions that strictly delineated genres and her identity as a woman. While

the early years in Milan were by no means easy, this time allowed her to take a fresh look at the paper, ink, and brush of East Asian painting she had taken for granted. While the Pinacoteca di Brera is most famous for works that form the backbone of Europe’s painting history, its academy functioned as a hub of a radically free, post-painterly contemporary art that encouraged creative license and conceptualization. Notwithstanding the prevailing atmosphere at the academy, the collection of Pinacoteca di Brera provided her the impulse to reassess the heritage of East Asian painting.

If the paintings at Brera demonstrated all the narratives and illusions that can be conjured by oil paint upon panel and canvas, the paper, ink, powder color, and brush used in East Asian painting reflected the traces of the artist’s act of painting marked by the sensitivity of the watersoluble pigment absorbing onto the paper. This allowed for chance and improvisation as the artist cannot completely control the effect of the paint upon paper. This would become a point through which Abstract Expressionism was absorbed into the East Asian based extant traditions. It was here in Milan during the 1990s where Kim transitioned from East Asian color painting to more abstract paintings in ink and color. Upon her graduation from the academy, Kim started to present her works where her abstract brushstrokes of ink and color on hanji paper were well received.

The relation and significance of hanji paper for the artist and its significance and full potential became fully realized in Milan. Which is ironic given its position as a stronghold of Western painting. Monochrome painting in 1970s Korea was the result of the Korean PostWar generation artists viewing abstraction as synonymous to contemporary art striving to escape the limitations of modern art as the imperative of their time. For these artists, to realize Korean contemporary art in the form of abstraction was their manner of confirming that Korean art could indeed keep up with

international currents and be presented in the overseas context. This collective movement in the name of the nation and its people, the age and history of abstract art in 1960-70s Korea, was essentially a master narrative of male artists. In contrast, Kim’s ink abstractions embarked from recollecting her own life with the familiar paper, brush, and ink, seen through fresh eyes and expanding the potential of the medium within the context of contemporary art that saw no division between Western and East Asian art. While to conjure abstraction as an identity seen from the outside is a common theme shared between the Korean monochrome painters and Kim, the motivations are opposing. The almost exclusively male painters in 1970s monochrome developed abstraction in anticipation of expanding their practice abroad while Kim enters the stronghold of Western painting two decades later to look back at her own determination to become an artist and her reconceptualization of the abstract of ink upon hanji paper.

Korean Paper Collages: An Experiment in Fire, not Ink and brush

Minjung Kim’s work could be called rediscovery of the medium of paper as opposed to oil canvas. We know of the challenges

Alveare

2014, Mixed media on mulberry Hanji paper, 76 × 139.5 cm

against the illusionism of Western painting led to experiments from numerous artists, starting from Cubist collages, to expose the raw surface. It doesn’t seem like mere coincidence that Lucio Fontana’s(1899-1968) renown Spatialism was born in Milan. After fully settling into life in Italy (in and around 2000), Kim would take further steps in experimenting with hanji paper including cutting up and burning the material.

While Lucio Fontana sliced a tightly pulled canvas with his sharp-edged knife to announce the death of traditional oil painting, Kim escapes the traditions of Korean or East Asian painting by cutting hanji paper in thin strips and blackening the edges with incense. Kim’s ink abstractions in the 1990s illustrated the process of gradually departing from the typical subjects of traditional ink wash and powder color painting, while still maintaining the medium of paper, brush, ink and coloring technique. Korean paper collages in the 2000s, discards the support of East Asian painting entirely. Hanji paper, a symbolic ground for East Asian philosophy, is cut and burnt, its materiality and nature as medium reaffirmed as the artist interacts with it by hand.

Interestingly, Kim’s hanji paper collages

Dobae 2018, Mixed media on mulberry Hanji paper, 98 × 141.5 cmare not satisfied with resisting tradition. The reinterpretation of cutting and burning edges into a new composition includes a unique process of transmutation where the materiality of hanji paper is revealed to the naked eye yet is reborn in an entirely new context. The cutting and burning is indeed a radical negation of East Asian painting (as characterized by the contemplating sage) - but the attention to detail in cutting each piece and regrouping them in premeditated geometric compositions or more organic patterns also realizes many possibilities for the paper’s usage. Hanji paper that once housed the lofty spiritual worlds of literati, mostly of men, is cut apart and blackened in the hands of Kim, a female artist. Rather than dashing off the strokes of the brush, Kim’s meditation and practice unfold in the long, arduous handiwork of quietly cutting paper pieces in the hold of her breathe, burning them just enough to maintain their original shape, and then stringing them one by one and tailoring them into a new surface.

If earlier ink abstractions translate the essence of ink into a particular material form, Korean paper collages replace the essence of singular brushstrokes with the acts of cutting and burning. In this way, the brush is resisted in favor of fire. Kim’s arrangement of burnt paper pieces in regular pattern compositions allow for geometric spatiality resulting in color-field

paintings of primary colors, spirals of a nautilus clam, or the minuscule folds of a mushroom cap. The reconfiguration of small, thin hanji paper pieces resembles the rebirth ceremony of Isis, who gathered and pieced together the dead body of her partner Osiris scattered all over the universe. It is at the same time the complete deconstruction and a novel reincarnation of traditional East Asian painting upon paper. Minjung Kim’s collages can divulge the materiality of hanji paper while also becoming bright colored geometric compositions, even Op-art that confuses one’s visual perception. Mundane, repetitive handiwork reaps its reward in front of the collage that is transformed into such forms. The heartfelt joy in mind and body at the end of the laborious process of gathering and reconstituting is what renders Kim’s cutting and burning a process of training and meditation. The artist herself also cites Taoist training and meditation, but these are embodied experiences that permeate her body and occupy her mind in the rhythm of paint and ink soaking through paper and fire burning through paper.

This all being said, Kim remains loyal to the material of paper, brush, and ink that represents the self-identity of East Asian or Korean painting. After the stages of cutting, burning, and piecing together, these materials are wholly absorbed as that constituting the universalized surface of painting. Since

Phasing

2017, Mixed media on mulberry Hanji paper, 205 × 145 cm

the audience can follow the time and effort interacting with the materials, they also are offered the joy and ecstasy facing the hanji paper collages the same way the artist does after an arduous creative process. This sympathy does not require explanations on the distinction between genres of painting, Korean identity, or philosophies of East Asian painting.

with the burnt holes above, holes that reveal the original dots and lines below. Because the two layers are slightly out of sync, they echo back and forth like a reverberation with the ink lines and burnt traces simultaneously revealing and concealing each other.

The Contemporary in Tradition, Tradition in the Contemporary

Minjung Kim’s material experimentations achieve synthesis in her Phasing series that overlaps pictures of water and fire upon hanji paper. Hanji paper collages, as mentioned above, cut and burnt material qualities of paper, ink, and brush dismantle the traditions of Korean or East Asian painting. However, that does not mean Kim has relinquished ink wash painting. The Phasing series from the 2010s has Kim laying dots and lines upon hanji paper towards a conventional ink wash abstraction, then overlapping another layer of paper on top to puncture where it aligns with the underlying dots and lines. The lower layer demonstrates spontaneous brushstrokes, and the upper layer utilizes the semi-transparency of hanji paper to pencil-trace the lines and dots below with the ensuing traced forms burnt with incense. In this way, the lower dots and lines are replaced

The lower layer of ink wash painting is the East Asian or Korean painting Kim trained in Korea; the burnt and punctured upper layer is the material support of contemporary painting that the artist articulated in Milan. By combining the two layers for one painting, tradition pervades the present and the present penetrates tradition, the two opposing pictures mirror each other in contradiction and coexistence. As if overlapping an earlier and later part of her life, Kim returned to Korea after completing this Phasing series - as if to say that her loyalty to ink wash traditions is as much Minjung Kim as her compulsion to pierce and deconstruct them.

The Spring of 2021 marks three decades since leaving Korea and the works Minjung Kim has chosen to present in her solo exhibition at Gallery Hyundai is the Timeless series begun in 2019. Gradations of austere ink tones expand to all edges of the canvas in thin horizontal strips. What existed as visual metastases of color at the stage of ink wash abstraction has transformed into gradual changes in tone upon thin hanji paper strips within the tactile

body. The uncomplicated composition based on horizontals, metamorphosed through Kim’s burning of edges, comes to emanate organic waves like the tranquil rise and fall of the night sea. Not lacking in poetic temperament, the restrained greyscale, the thin, delicate texture of hanji paper, and the traces of fire lapping at the corners form the simplicity and lucidity of the Timeless series. Kim’s material experiments riffing with the limited ingredients of paper, brush, and ink, are still well in progress and we can undoubtedly expect her to constantly grow towards an ultimate result.

Asian painting.

The time and effort Kim invested in reflecting the significance of painting to her own self in front of the Renaissance paintings she had so admired, for diligently reworking materials and media familiar to her, and so honoring hanji paper with mind and body, were all supported and appreciated first by European audiences.

What makes this exhibition in Seoul so profound, after her ongoing journey, is the opportunity for reflecting on what is taken for granted. Presented works are familiar as much as they are ingenious and as new as they are aged. We revel in the artist’s works because of the things we know that are bypassed due to the breathless pace of Korean’s modernization and the corresponding compressed development of modern Korean art are precisely what Kim lays out in front of us in the form of works she has built up almost half of her lifetime. Perhaps we feel the sense of relief at finally recouping the time and space we had hurriedly blown through. It appears that we also needed these past thirty or fifty years, the time Kim has spent to overcome the boundary between East Asian and Western painting through her practice that provides new breath into Korean and East

Major critiques of 1970s monochrome painting includes the argument that it derived from a tradition and aesthetic familiar to Korean people, and that the sympathy of one person to another led to a collective flourishing of the genre. However, this one-person-toanother model of collective identity leading to a collective flourishing and the success of this defining identity barely mentions the existence of female artists. In the Dansaekhwa boom that almost entirely revolved around the male, the belated rise of Kim as an artist can be explained only when we zoom in on the individual over collective, artisan over literati, female over male, the everyday over the Avantgarde, and practice over transcendence. Rather than assessing how much Kim inherits the patrilineal history of Dansaekhwa, we should enjoy Kim’s hanji paper experiments that acquired heart-to-heart sympathy abroad and take passage in a detour in contemporary art that Kim selflessly draws.

Born in Gwangju, South Korea in 1962, Minjung Kim studied calligraphy and watercolor from a young age and went on to major in Oriental Painting at the undergraduate and graduate schools at Hongik University. She studied abroad in Milan’s Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera. During studies in Europe, she was deeply inspired by artists like Constantin Brâncusi, Carl Andre, and Brice Marden.

In the past two decades, she has presented works in Italy, Switzerland, China, the UK, the U.S, and Israel. Solo exhibitions at renown galleries and museums around the world include Marco (Museo d’Arte Contemporanea Roma), Rome (2012); Hermès Foundation, Singapore (2017); White Cube, London (2018); Langen Foundation, Neuss, Germany (2019), and Hill Art Foundation, New York (2020). She was introduced to Korea through Traces (2015) at OCI Museum of Art, Seoul, solo exhibition Paper, Ink and Fire: After the Process (2017), at Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, and the international invite Making the Void, Filling the Void (2018) at Gwangju Museum of Art, Gwangju. The Light, The Shade, The Depth at Palazzo Caboto in Venice, curated by JeanChristophe Ammann, received particularly positive reviews worldwide. Minjung Kim also participated in Gwangju Biennale in 2004 and 2018. Her works are part of collections at major institutions such as Fondazione Palazzo Bricherasio in Turin, Italy; The Museum Sbygningen in Copenhagen, Denmark; and the British Museum. She is currently active based in France and the U.S.

www.minjung-kim.com

After opening its doors as “Hyundai Hwarang” on April 4th, 1970 in Insadong, Seoul, Gallery Hyundai has been leading movements in the art world since boldly introducing contemporary art to what was at the time an old paintings and calligraphy-oriented gallery world. It was through Gallery Hyundai that Lee Jung Seob and Park Soo-Keun, now accepted as the “Korean people’s artists”, received spotlight. It also had been contributing to expanding the basis of Korean abstract art, organizing exhibitions with masters Kim Hwanki, Yoo Youngkuk, Yun Hyong-keun, Kim Tschang-Yeul, Park Seo-bo, Chung Sang-Hwa, Kim Guiline and Lee Ufan long before the Dansaekhwa boom.

Following the 1980’s, Gallery Hyundai adapted to developments in the international art world by opening exhibitions of international masters like Joan Miró, Marc Chagall, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Christo and JeanClaude Denat de Guillebon. From 1987, it would participate in Chicago Art Fair as the first Korean gallery to be included in an international art fair to introduce Korean art to global audiences. Including Nam June Paik’s performances and video art, many works by headliners of Korean experimental art such as Quac Insik, Seung-taek Lee, Park Hyunki, Lee Kang-So, Lee Kun-Yong were connected to wider audiences through Gallery Hyundai. To this day, it is always discovering and introducing emerging and mid-career artists like Minjung Kim, Moon Kyungwon, Jeon Joonho, Seulgi Lee, Yang Jung Uk, Kim Sung Yoon, Kang Seung Lee.

Art magazines Hwarang and Hyundai Misul, each first printed in 1973 and 1988, remain vivid documentations of their contemporary art scenes. In addition to two spaces Gallery Hyundai and Hyundai Hwarang in Samchung-ro, Seoul, it is also operating a showroom in Tribeca, New York.

www.galleryhyundai.com

2011, Mixed media on mulberry Hanji paper, 110 × 248 cm (detail)