Peek inside our classrooms

When you think of interdisciplinary projects, natural pairings come to mind: math and science, history and literature, social science and religion. What about math and religion?

In the mind of Math Department Chair Kati Hylden Krueger ’99, this unlikely pairing is a perfect fit.

As the end of the school year approached, Kati was searching for a new way to help her students master and apply—not just memorize—the concepts they were learning in her Honors Pre-Calculus class. “Our math department really embraces the idea that competency with math is essential preparation for being a leader in the 21st century,” she shared. “That means we fight to make sure our students understand what they are doing when they solve a problem and that they are constantly being asked to solve problems not by simply repeating an algorithmic process, but by wrestling with the core of a concept and applying it in creative problem solving.”

During a run, she had an epiphany: she would challenge the girls to apply their pre-calculus skills to their Religion III Praxis Projects, developing researchbased solutions to social injustices. While working on their Praxis projects, students had already identified ways to educate their peers about social justice issues and advocate for change; now there would be an opportunity to build on that work.

Livi Hally ’18 partnered with classmate Michaela Kirvan ’18 to address the Syrian refugee crisis. When examining the problem, they were struck by the concept of a “lost

generation”—Syrian youth in refugee camps who are not receiving an education because of the dire need to focus on survival; and thus will not be prepared to take on the mantle of leading the country when they come of age. The girls realized that getting the refugees out of the camps is not enough. Livi noted that humanitarians need to “give them a way to improve their lives now so that what is being done to them

doesn’t impact what they are able to do with their lives, that the refugee crisis doesn’t define them.”

The pair used pre-calculus functions to analyze the problem, including a quintic regression of the number of refugees and people of concern over the past few decades. They then explored how to improve living conditions in refugee camps by increasing federal funding to create

It was inspiring to see what our students came up with when they took a problem they were already passionate about and were challenged to identify solutions. You could tell how empowered they became to analyze and propose concrete opportunities that would have a direct impact on improving the lives of other human beings.

MATH TEACHER KATI HYLDEN KRUEGER ’99

In Religion III, juniors study Catholic social teaching, which has two branches, service and justice. Starting as freshmen, students engage in Christian service and become well-versed in volunteer work, but it’s not until junior year that the Praxis Project introduces them to the justice component.

Praxis is a process of realization and action, often related to wellbeing and righteousness. For Visitation’s Praxis Project, students work in small groups to research, evaluate, and act to combat a social injustice. Praxis projects have focused on the environment, human trafficking, immigration, sexual assault, and racial injustice.

x f(x)

Problem Analysis

Over-use of Potential of algae farms to

g(x)

g(f(x))

Pre-Calculus Based Solution Impact

Parametric function to describe Build algae farms fossil fuel produce biofuel model and scale of a farm and to produce biofuel its production, relative to to slow dependence environmental factors for on fossil fuels its location

Foster care Data analysis shows foster care Using social media-based More children getting the care ‘graduates’ have a much higher technology to triangulate info and support they need to be percentage of people likely to be about children, as inputed from thriving adults incarcerated, homeless, or suffer police officers, social workers, from depression than the teachers, and foster parents to average population enable large data to find better indicators of children more likely to have challenges

Food waste Series analysis of food waste in Parametric functions to More excess food gets eaten, tons of pounds over the past decade describe mapping of local food reducing waste and allowing suppliers for left-overs more people in need to get the food produce (after grocers take the prettiest food) system

proper sewage systems and make clean water more attainable.

Their classmates similarly analyzed other timely social justice issues, including child labor, over-use of fossil fuels, the foster care system, and food waste.

Livi and Michaela were inspired and empowered by the project; Livi observed, “You don’t think that as a junior in high school you could have any ideas that would impact the world, but we were able to come together and come up with a solution.” Michaela added, “When we talk about the refugee crisis in the U.S., the talk is mostly about policy, but this was a real way to talk about tangible solutions.”

Michaela was so energized by their work that she is considering studying engineering in college: “There is a group

called Engineers for Change that uses engineering projects to solve social injustices; designing for a purpose really speaks to my background of Catholic social teaching and Salesian values— I want to improve the common good.”

Kati’s students saw the project as a prime example of how Visitation teachers bring learning to life by offering students hands-on opportunities to put their newly acquired knowledge and skills into action. Beyond cementing their understanding of pre-calculus, the project gave them a sense of purpose.

As Michaela noted, “Everyone always asks, ’What do you want to do?’ not ’why?’ This gets at the why …. This has given us a purpose.”

Read more about women with a purpose on page 23.

What makes an effective argument?

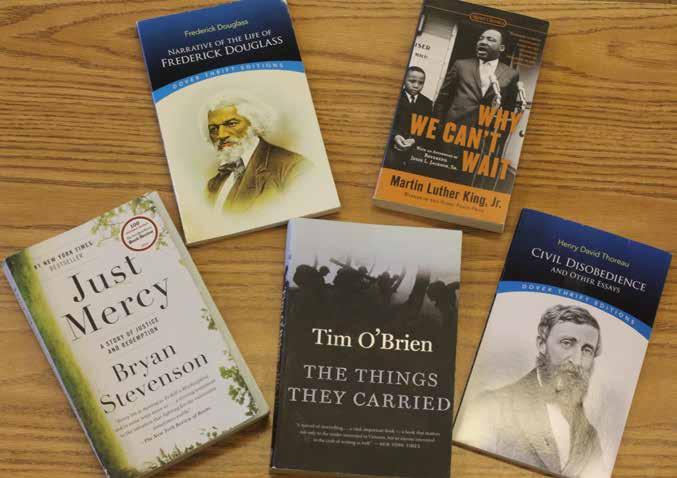

This is the central question explored by students in AP English Language and Literature, taught by Peggy Judge Hamilton ‘85. They delve into the study of rhetoric to learn what creates effective arguments and then employ those strategies in their own writing. The curriculum issued by the College Board focuses on non-fiction, but Peggy has put her own stamp on the class to ensure it is quintessentially Visitation (all junior English students study American literature) and that the girls walk away with a deeper understanding of the conflicts that have shaped our nation.

When she started teaching this class, Peggy saw the opportunity to go beyond the College Board’s narrow curriculum and broaden the educational impact of the class. She introduced a research paper on the Vietnam War after students read Tim O’Brien’s stirring fiction account of the war, The Things They Carried. The project helped girls explore a historical event through fiction. Later, Native Son, Richard Wright’s classic novel on race, poverty, and hopelessness in 1930s Chicago, was added as an option, prompting students to explore racism.

After the school’s release of our report on The History of Enslaved People at Georgetown Visitation last year, Peggy, who is also a Diversity Co-Coordinator along with Raynetta Jackson-Clay, saw the opportunity to deepen students’ understanding of race in America through a focused series of fiction and non-fiction works.

This year, in addition to The Things They Carried, students read Just Mercy, a non-fiction account of lawyer and author Bryan Stevenson’s work to exonerate a convicted murderer who professed his innocence. The work explores the themes of justice and mercy and the role race plays in our modern court system. They also read Henry David Thoreau’s Civil Disobedience, in which he asserts the individual’s mandate to actively work against injustice perpetrated by the government; Martin Luther King Jr.’s

Letter from Birmingham Jail, a defense of non-violent resistance to unjust laws; and Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, the memoir of former slave turned abolitionist leader. In addition, the young women in Peggy’s class watched the documentary 13th, which looks at the criminalization of African Americans. The title refers to the Constitution’s Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery except as punishment for crime.

This new syllabus prompted girls to

The girls are really making connections. The blend of fiction and non-fiction offers them so much more to delve into. The overlap among the worlds prompts rich discussion and deep thought.

delve into a diverse range of topics at the intersection of race and justice, from the war on drugs to bail to Black athlete activism to slaveholding and Christianity.

As Peggy notes, “The girls are really making connections. The blend of fiction and non-fiction offers them so much more to delve into. The overlap among the worlds prompts rich discussion and deep thought.” This fall study segues seamlessly into the rest of the year’s curriculum, which explores the tension between individual and society, self-reliance and conformity through such classic American novels as The Great Gatsby, Catcher in the Rye,

The Scarlet Letter, and Huck Finn. It also complements what the girls are learning in other classes, like AP U.S. History, taught by Patrick Kelleher, and Religion III.

Junior Bridget Newell shared, “What I love about junior year is that AP Lang, religion, and AP U.S. History come together and look at the same topics from different angles, especially diversity. We read the Martin Luther King letter in religion and AP Lang, but from different angles. In AP Lang, we looked at the rhetoric he used and then we learned the history behind why he was there. In religion, we learn Catholic

social justice teaching, so there we applied what King was saying and how the times were violating Catholic teaching. [When we] … look at the structure, the values, and the history, it becomes a more full topic.”

Her classmate Mae Schwab added that in these classes, “We’re focused on justice, on issues we can do something about, things we can apply to the world. We learn what we can do now. That makes it more interesting.” Her examination of the criminal justice system—she wrote her AP Lang research paper on how bail impacts the poor—has sparked her interest in studying law.

BY DR. LUKE O’CONNELL, RELIGION FACULTY

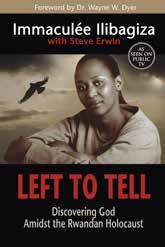

For almost a decade, Visitation students have been invited to read Immaculée Ilibagiza’s Left to Tell as part of the sophomore religion curriculum. This is typically done as a Lenten retreat of sorts. In the third trimester, the instruction on Church history and Ecclesiology pauses to introduce the reality of the depth of faith in the life of this remarkable woman as students prepare for Easter.

Immaculée was born and raised in Rwanda, a populous, landlocked country in central Africa. In 1990, the nation was torn apart by civil war.In 1994, her family was murdered during the three-month genocide that killed nearly one million Rwandans.

Miraculously, Immaculée survived. Along with seven other women, she took refuge in the confines of the bathroom of a local pastor for 91 days during the massacre. While there, she began praying the rosary; it was Immaculée’s faith that saw her through those unspeakably horrific days and nights and, ultimately, enabled her to forgive her family’s killers. Left To Tell: Discovering God Amidst the Rwandan Holocaust is her inspiring memoir about this experience.

In the classroom, the focus on Immaculée departs from typical seminar-style instruction and builds around the connection of the lived experience of Immaculée in the text and the timeless mysteries of the rosary. First, introductory lessons are given explaining the historical context in which the violence in Rwanda arose in the mid-90s and the conditions that preceded the outbreak of violence. Next, students “meet” Immaculée through one of the multitude of interviews available online. Finally, students write daily reflections as they read the 24 chapters of her book.

Bree Bonner ’22 welcomed this new perspective on faith studies at Visitation, “I really loved reading the book; usually, we don’t read too many books like this in religion class, we read more of a textbook. Immaculée’s experience inspires you to not take things for granted; a lot of us have tendencies to complain about first world problems, but this really helps put things in perspective. I was inspired by the way she carried herself, the way she looked to God throughout her journey, even in tough situations. She would always say that, ‘God has my back.’ Others would give up or feel hopeless, but she never did.”

Three years ago, Dr. O’Connell’s students suggested that the school invite Immaculée to campus. After years of planning, she was scheduled to come this spring. We are blessed that she was able to reschedule and will now be joining the Visitation community in the Nolan Center this fall to lead a discussion on the power of prayer and unconditional love and how they have helped her survive and recover from unimaginable terror. We hope you will join us; watch your email this summer for an invitation and link to RSVP.

By the close of the unit, students have been invited to understand mystical experiences like those of Immaculée through a contemporary lens. Connections to powerful figures of faith like Mary as disciple and Mother of God; martyrs like Perpetua and Felicity; and advocates for victims of injustice and the marginalized, such as Clare of Assisi are connected to a woman who lives and breathes in the world of our students. In this way, she has figured powerfully into the curriculum and imagination of students at the sophomore level.

As Caroline McMahon ’22 shared, “I found it hard to relate to her struggles at first. [But,] her journey of faith showed me the connection God brings to those who are in opposite parts of the world facing opposite struggles. I found

her complete trust in God astonishingly inspiring. I often find myself trusting God, but in a way where He is not my only source of security, but Immaculée puts everything on the line time and time again based solely off of what she believes God is telling her to do. This blind faith she practiced is something I continue to try and implement into my

life since reading Immaculée‘s story.” Beginning next year, we will move our encounter with Immaculée to the sacraments and social teaching course during junior year. In this way, we hope to more deeply engage the questions of justice surrounding her witness and invite students into the text near when the junior class experiences the

Immaculée is a stunning example of a modern saint. Her capacity for forgiveness exemplifies spiritual strength and faith, and her writing offered us a window into the soul of a person who was able to accept the challenges and grief in life through turning to God for comfort and help. Throughout reading Left to Tell, I found myself looking to Immaculée’s experiences as an inspiring and poignant reminder that great faith grows from dedication to the cultivation of Little Virtues.

EVELYN WADDICK ’21

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. We see this as faithful to the legacy of Immaculée in the curriculum, and better amplifying the lessons of Left to Tell for future Visi students.

In the spring of 2020, the history and social sciences team at Visitation launched a new initiative in their Global Patterns class to bridge the study of ancient civilizations with an understanding of current day geopolitical challenges. The idea is to ignite students’ interest with a question and then work backwards through history to untangle the roots of the answer.

What better challenge to tackle this fall than the election and citizenship in America! The natural ties to ancient Rome and Greece offered a jumping-off point for students to explore questions of what it means to be a citizen: who is a citizen? What rights come with that privilege? What responsibilities? First year Global Patterns students particularly explored how rights and responsibilities have been decided along race and gender lines across societies and over time.

In re-imagining the course, they drew on the talents and passions of the entire social sciences team—Daniel Petri is a specialist in government and political science; Carolyn Fay brings deep expertise in psychology; and department chair Jane Hannon has a straight historical focus. Together with colleague Andrew Brown, who joined the team this fall, they are able to integrate concepts, approaches, and questions from across the social sciences spectrum to bring material to life.

After exploring the ancient roots, students moved forward in time to the founding of the United States, examining the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, then delving into the birth of the census, the civil rights movement, and the 14th

The fun—and challenging— part of a class like this, when you base things in current events, is that it is dynamic and you never know how things will turn out!

DEPARTMENT CHAIR JANE HANNON

amendment. This historical framework helped students explore how Americans have debated the merits of a strong vs. a weak national government over time, how the Electoral College works and why it is controversial, how voting have rights expanded over time, and what limitations or obstacles still remain.

Freshman Sophia Brinkman observed, “When we were looking at the Athenian government, there were similarities and connections to how our citizenship and our democracy works. I was surprised to learn that although the idea in Athens was good, they lacked in inclusivity and involving all citizens and not just men who own property. We see this in our history as we gradually included more and more people when we spoke about ‘citizens.’”

having the right to vote: “Women are too emotional” or “It will eliminate gender roles in society.” Students were amazed to find that many arguments still made today about women in society and politics were also in this more than 100-year-old document.

Understanding our nation’s history provided them with valuable intellectual context for the national discussions surrounding the election. As part of their coursework, students watched election debates and made electoral college predictions. Brown noted, “Our students had a lot to say after the first presidential debate! ”

Fay added, “The election was such a big news story this year—they liked understanding it on a level where they could be knowledgeable about the issues and have informed points of view, particularly around the electoral college. Many students said they hadn’t ever really watched the debates or paid attention before. They liked feeling like they had intelligent things to say about what was happening in our nation.”

When discussing the 19th Amendment, students read a piece from suffragist Alice Stone Blackwell that responded to arguments people were making at the time against women

Other assignment highlights included conducting interviews with family members regarding their political participation, looking at historical and current political ads to see which worked and which were most effective, learning about polling and watching the polls, and joining an election night watch party hosted by Petri. Sophia shared, “My favorite assignment was when we were given sample questions that were actually

on the naturalization test. It showed me truly how difficult it was to prepare for these kinds of tests.”

Given how heated this year’s election was, fostering civil discourse was an important part of the class. As teacher Petri noted, “Getting students to talk about politics in an objective way is always a challenge, but students did a good job of approaching the material in a non-partisan manner and our

discussions were always inclusive and respectful.”

Fay added, “I was impressed with my students—they had strong opinions, but they understood the line between it being your opinion and being respectful of others viewpoints. I heard a lot of, ‘I understand this part of your view, but this is how I see things.’ I don’t feel I need to steer away from these topics. I felt the discussions we had were really good.”

Petri concluded, “Talking about the role and responsibilities of citizenship is a good way to get students talking about participation in American politics. I hope my students will become active and engaged citizens who appreciate and embrace the complex political world that we live in.” Added Brown, “To me, the real benefit is that so many of my students are excited to vote in the next presidential election.”

More than thirty students dropped in throughout the evening on November 3 for AP Government teacher Daniel Petri’s Election Night Watch Party. Petri invited students to analyze the media’s coverage of the election, including potential biases and how states were called, important races to keep an eye on, and the context around the presidential election itself, including what would influence the long wait for results. The evening began in prayer with Fr. Patrick Kifolo, OSFS, Campus Minister. Principal Mary Kate Blaine, who has taught government, economics, and U.S. history over her education career, was also on hand to answer students’ questions. Annie Paxton ’21 joined in on the live stream with Petri. “I learned a lot about the election process while watching the Watch Party,” she said. “It was helpful to have Mr. Petri, who is so knowledgeable, keep us up to date on election developments while also answering any and all questions we had. I appreciated that we were able to learn about the Senate races as well as the presidential election, because I hadn’t been focusing on those as much.”

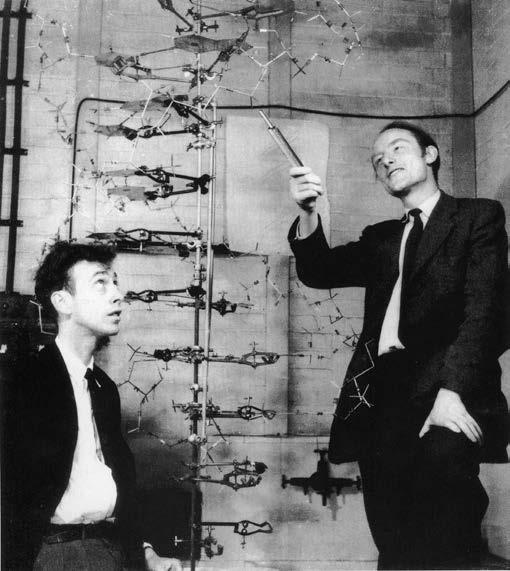

In decades past, learning about DNA involved looking at a model, much like the one in the iconic photo of scientists James Watson and Francis Crick, who first accurately described DNA’s double-helical structure.

Today’s students have far more high-tech learning tools at their disposal—tools that enable them to dig deeper into the mysteries of our biology, our individuality, and our shared humanity.

After spending the first part of the year learning about the characteristics of life and its building blocks, how cells work, and how we get energy, students in Dr. Mark Pennybacker’s biology class begin to delve into genetics, exploring how traits are inherited and how the genetic code works.

Using the same basic technology that is used to test for Covid, students are able to take samples of their own DNA by swabbing the inside of their cheeks. Once students have collected these samples and used primers to make copies of a short sequence of their DNA, those are sent to a lab for mitochondrial sequencing. Nina Lose ’23 shared more about the process: “We [sipped] salt water and

washed it around in our mouth [to isolate cheek cells], spun [the sample] in a vial, and sent it to a lab, where they did a PCR test.”

Once students receive the results back, they are able to compare their DNA sequence with that of other students and, through an online database, with people from other countries, other animals, crustaceans, primates, birds, and fish. They can see how many differences there are among humans and between humans and other species. This hands-on experiment helps them better understand the molecular clock (see side bar).

The comparative data in the lab confirms what they have learned in class: all modern humans have the same average number of mutations. By then comparing their DNA with that of other students, they can see if there are factors that impact how closely related two sequences are. After comparing sequences with

Just like your team—Gold or White— all mitochondrial material is inherited from your mother.

DR. MARK PENNYBACKER

Each of our cells has hundreds or thousands of mitochondria, which generate the cell’s energy. Each mitochondrion has several copies of the organism’s genome (the complete set of genes present in its DNA1). This makes mitochondrial DNA the easiest type of human DNA to amplify by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)2.

Racism occurs because a person ignores the fundamental truth that, because all humans share a common origin, they are all brothers and sisters, all equally made in the image of God.

U.S.

According to the molecular clock hypothesis, DNA and protein sequences evolve at a rate that is relatively constant over time and among different organisms.3 Using this knowledge, scientists can determine both how closely related two species are as well as how long ago they diverged, allowing them to paint a more detailed picture of evolution. Students in Dr. Pennybacker’s class use this model to determine how closely related they are to “Otzi the Iceman,” a glacier mummy from the Copper Age that was preserved in ice for more than 5,300 years.

classmates, Sophia Jeffress ’23 raised her hand: “I learned that there’s no scientific difference between races.”

She’s right, asserts Dr. Pennybacker: “If you compare a White person and a Black person, there are no more differences than if you compare two White people or two Black people. Scientific evidence shows no race is significantly different from another; it validates the viewpoint that everyone is created equal and is unique.”

In this year’s lab, students immediately grasped the import of their observations. Sophia said, “It proves that a lot racial biases that people have

because they believe they are biologically superior are false. There isn’t a scientific basis between races on a genetic level.”

Classmate Nina agreed, “Racism in our world is just based on the color of someone’s skin; science shows we’re way more similar than we think… [R]egardless of race, we all share most of our DNA.”

As religion and science are pitted against each other in popular media, these student insights from Dr. Pennybacker’s class make clear that not only are faith and science compatible, but they complement and strengthen one another when harnessed to advance the common good.

1 “Genome.” Oxford Languages. https://www.google. com/search?q=genome&rlz=1C1CHBF_ en&oq=genome&aqs=chrome.0.69i59j0i433i512l2 j0i131i433i512j0i433i512l2j0i131i433i512j46i199i 433i465i512j0i3j0i512.723j0j15&sourceid=chrome &ie=UTF-8&safe=active&ssui=on. March 18, 2022.

2 “Mitochondrial Control Region.” Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory DNA Learning Center. http://www. geneticorigins.org/mito/mitoframeset.htm March 18, 2022.

3 Ho, Simon. “The Molecular Clock and Estimating Species Divergence.” www.nature.com, Nature Education, https://www.nature.com/scitable/ topicpage/the-molecular-clock-and-estimatingspecies-divergence-41971/. March 18, 2022.

Teaching second semester seniors in high school is a daunting challenge. How do you engage students meaningfully in their studies when the promise of warm weather and the excitement of a new beginning lay tantalizingly close just outside the door of your classroom?

The answer in Stella Schindler’s Honors English IV class is a combination of compelling, relevant material and a thought-provoking, interactive final project.

Ms. Schindler ends senior honors English with a unit on dystopian literature: “It is a way to connect with the world the students live in and their personal lives. They leave here [understanding how] literature is relevant in the universal sense, but also in the immediate here and now of their particular situations and of the world.”

In the unit, students read 1984, Brave New World, Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave”. In recent years, they have also watched the movies The Truman Show and The Social Dilemma. In addition, students read a dozen supplemental articles that help them discover the connections between dystopian literature and the modern world. The dystopian unit is the culmination of a year spent exploring themes first established with one of their summer reading books: Viktor Frankel’s Man’s Search for Meaning

As a capstone project, each senior writes a TED Talk—a popular format of brief speech on a compelling topic. Each

10–12 minute talk must be centered on a thesis answering the question: “What can we learn about the meaning of our lives from the works we have read and viewed this year?”

For her TED Talk, Sofia Tejada ’22 asked, “How do ordinary people become perpetrators of genocide?” During the course of her speech, she identified three key factors: authority, anonymity, and propaganda and then wove together insights from the materials she read in class and information about research like the 1971 Stanford Prison Experiment.

Neso Mere ’22 explored the question, “What is truth?” positing that we can never know the truth because of human fallibility. She explored how the uncertainty in life caused by humans’ tendency to lie is further exacerbated by technology today, which has the power to distort reality.

Of the project, she observed, “The approach to this presentation was essentially open-ended; you could choose a more scientific approach, a philosophical approach, or a mixture of both, which is what I personally chose to do. Students … enhance their public-speaking skills through an

Camille Hodgkins ’22

enriching and exciting presentation, practice lateral thinking, and [build] skills that they will use for a lifetime.”

The breadth and depth of the students’ probing is impressive. Students have considered such topics as the intersection of polarization, technology, and democracy; art censorship; the problem of individualism; how propaganda works; the problem with perfection; celebrity worship; and “why we can’t put our phones down.”

(See sidebar for additional list of titles.)

Truth Behind Conspiracy

“To See Takes Time”: How Art and Beauty Are an Essential Part of Our Being

A.I. and Machine Learning

Why Are We Unhappy in the Digital Age?

Technology is Quietly Controlling Us

Vilifying Mental Illness

The Role of Music in Our Lives Are iPad Kids More Than a Trending Meme?

Electricity of Human Connection

How Do Modern Day Technologies Affect Our Psychology?

Does Freedom Of Speech Give Us The Right To Offend?

Beyond challenging students to make connections across the diverse body of literature they’ve read for class, Ms. Schindler also empowers students to incorporate ideas from their other classes. Ellie Campbell ’22 noted that she “loved having the opportunity to connect ideas across classes and … [engage] questions…in a way that interested me.” For her project, Ellie focused on the importance of feeling small. She theorized that diminishing your emphasis on yourself—such as by spending time in the expanse of nature—you become more altruistic and increase your capacity to love. Reflecting on the experience, Ellie said, “The projects showed how there are direct connections between what we learn in school and finding one’s meaning in life. It showed me that my Visitation education will continue to help me figure out who I am and my path for the future.”

The project doesn’t just keep second semester seniors engaged, it also prepares them for connecting themes and ideas across classes and disciplines in college. Lily Nicholson ’22 wrote Ms. Schindler this fall to say that she had heard a quote in her “Exploring

Existential Thought” class that she would have loved to weave into her TED Talk. She said, “I loved this project because it allowed me to choose a theme from the year that I found interesting. I … think about my project all of the time, and it provided me a way to sum up some of my favorite takeaways from the year. … [T]his thematic look at literature both stimulated a college class and taught me how to learn from the literature I read and use it to better myself.”

Her classmate Citiana Belayneh reflected, “I can truly say that the TED Talks … allowed me to reflect on society and the world around me. … Not only was I able to learn more about my topic, but also by listening to my classmates present their topics, I learned to open my eyes to different perspectives. Even now in college, I’m able to have honest conversations on a wide range of topics and beliefs because of how exposed I was in English class to key concepts. … [Now, I watch TED Talks, read articles and books, and have discussions that expand my knowledge of the world around me, deepen my passions, and inspire me to make lasting changes.”

The challenge of reading and understanding dense scientific text has grown in recent years, thanks to changes in how individuals consume media and process it. The shift to digital media has prompted a greater tendency to skim text rapidly to glean the gist, rather than to thoughtfully engage with the material; quite simply, students today have less practice with deep reading and need to build a toolkit of ways to engage with material so they fully understand it.1

In Dr. Nancy Cowdin’s neuroscience class, the answer is art.

As an undergraduate pursuing a BA in French and a BS in education, Dr. Cowdin often drew in class as a way to stay focused. She found this strategy even more effective while pursuing advanced degrees, helping her organize and visualize complex material.

“I… realized as I was doing it that there was something else going on; I was able to retrieve information that was represented in my drawings in a much better way.”

After becoming a teacher, Dr. Cowdin wove drawing into her science classes as a tool to help students better understand and retain the information they were learning. She finds the

“ Students are challenged by content-heavy, dense subjects like science. When they are reading, there is a lot of noise. We have to help them find the true signal amidst all that noise.”

DR. NANCY COWDIN

technique very useful when teaching life sciences, particularly learning processes and structures.

“Drawing forces students to pull out information and create a new construction from their knowledge base that they may not otherwise do. It helps them to understand, process, and make connections which endure in memory systems far longer.…By creating your own picture representations using color, you derive and develop your own meaning from the concepts and are able to visualize it later.…This often leads to that ‘eureka’ moment when a student ’knows that she knows’ the material!” Dr. Cowdin shared.

Asking students to create handdrawn sketch notes after lectures

DR. COWDIN’S TIPS FOR DEEP READING

1 Slow down your reading. Take your time and go through less text but more thoroughly.

2 Disrupt a pattern of skipping around. If you are reading online, try limiting the amount of text visible in the window or enlarging the text to reduce the tendency to jump ahead.

3 Breakdown and/or pull-out difficult vocabulary and extract your own meaning from it.

4 Illustrate new terms using your own colorful graphics.

5 Practice searching and finding key ideas. Then, organize these ideas and create an illustrated concept map showing relationships.

1 Wolf, Maryanne. Reader, Come Home: The Reading Brain in a Digital World. Harper, August 7, 2018.

facilitates attention to detail and retention. Her students agree. “Using drawings in neuroscience helps me to visualize a complicated subject that we cannot directly see with our eyes, like a neuron firing a signal. Drawing in class helps to keep me engaged and better understand the material,” shared Gigi McLaughlin ’24

Her classmate Alex Maloney concurs, “I am definitely a visual learner—being able to see what I’ve drawn in my sketchbook when I go back to review is helpful along with the muscle memory.” The process of creating the drawings requires that students consult multiple sources and integrate that information. “You have to go and find the content you’re going to draw in your sketchbook, you have to look at multiple photos, think about how to do it, label it, look at Dr. Cowdin’s notes,” Alex shared.

Recent research supports Dr. Cowdin’s innovative approach. A study published in Current Directions in Psychological Science2 in 2018 confirmed Dr. Cowdin’s observations. In “The Surprisingly Powerful Influence of Drawing on Memory,” a team of researchers demonstrated that drawing is a powerful mnemonic device that can improve memory.

While the research and results are powerful testimonials to the impact of drawing as a teaching tool, drawing also brings joy to Dr. Cowdin’s classroom. “I started doing this because I wanted my students to love learning,” she said. If her students’ academic and professional paths after Visitation are a gauge, she’s succeeding. Several of her students have actually gone on to study neuroscience in college and many have pursued medical degrees. Both Alex and

Student illustrations

Gigi hope to study psychology in college and are confident that their neuroscience studies here will help them in the future.

Dr. Cowdin has authored a book called Teaching Neuroscience, A Field Guide For Teachers, that will be published in the fall of 2024. Kudos, Dr. Cowdin!

2 Fernandes, M. A., Wammes, J. D., & Meade, M. E. (2018). The Surprisingly Powerful Influence of Drawing on Memory. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(5), 302-308. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721418755385