Georgia MEDICAL COLLEGE OF

EDICINE M SCHOOL OF MEDICINE

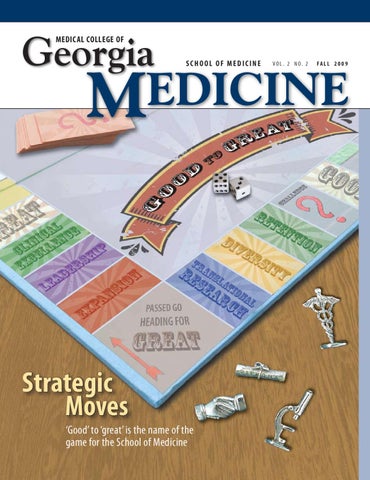

Strategic Moves ‘Good’ to ‘great’ is the name of the game for the School of Medicine

VO L . 2 N O. 2

FALL 2009

Georgia MEDICAL COLLEGE OF

EDICINE M SCHOOL OF MEDICINE

Strategic Moves ‘Good’ to ‘great’ is the name of the game for the School of Medicine

VO L . 2 N O. 2

FALL 2009