Where Great Music Comes to Play Major support provided by: TM Creative Connections JUNE 8 - 22, 2024

31 S t Sea S o N

Sound Medicine by Sabrina Nelson

Welcome to the 2024 Great Lakes Chamber Music Festival!

Collaboration is the essence of chamber music and has been at the center of my musical life since I was a child, reading sonatas and four-hands music with my parents and brother at our home in Wales. In this year’s Festival, which we have called “Creative Connections,” I wanted to explore the myriad of different ways in which musicians collaborate, influence and inspire each other.

In a festival which spans works from Bach to the present day, we will hear how composers and performers have reached across generations and even centuries to fuel and enrich their creativity. For this festival, my tenth as Artistic Director, I have been influenced more than ever by suggestions from our extraordinary roster of artists. Every one of these outstanding musicians has contributed personally to the programming you will experience throughout the Festival. I am deeply grateful for the way their inventive and sometimes unexpected ideas have made these concerts into such a rich and diverse mix of genres, challenging me to create a menu of music that is perhaps bolder and more contrasting than ever before.

I can truly say that being connected with the Great Lakes Chamber Music Festival for the last 10 years has been a life-changing experience. It continues to be my privilege and joy to bring great music to you.

OUR MISSION

The Great Lakes Chamber Music Festival celebrates and advances its art form through extraordinary performance, collaboration and education, inspiring diverse audiences to share in the intimate dialogue that is unique to chamber music.

3 TABLE OF CONTENTS

WELCOME

Welcome ............................................................................ 3 Festival Leadership 4 2024 Sponsors | About the Cover ................................... 5 Saturday, June 8, 2024 ..................................................... 6 Sunday, June 9, 2024 ........................................................ 8 Tuesday, June 11, 2024 ................................................... 10 Wednesday, June 12, 2024 12 Thursday, June 13, 2024 .................................................. 14 Friday, June 14, 2024 ....................................................... 16 Saturday, June 15, 2024 ................................................. 19 Sunday, June 16, 2024 .................................................... 22 Tuesday, June 18, 2024 ................................................... 22 Wednesday, June 19, 2024 ............................................ 24 Thursday, June 20, 2024 .................................................. 24 Friday, June 21, 2024 ....................................................... 27 Saturday, June 22, 2024 ................................................. 36 Community Engagement | Artistic Encounters ........... 38 Festival Artists .................................................................. 40 Shouse Institute ................................................................ 50 Living Composers ............................................................ 52 Ways to Give .................................................................... 54 Ticket Sales | FAQ ........................................................... 55 Reserve Funds .................................................................. 56 Sponsors & Donors 57

FESTIVAL LEADERSHIP

ARTISTIC DIRECTOR

Paul Watkins

ARTISTIC DIRECTOR EMERITUS

James Tocco

SHOUSE INSTITUTE DIRECTOR

Philip Setzer

CHAIRS

Virginia & Michael Geheb, Board Chairs

Marguerite Munson Lentz

Janelle McCammon & Raymond Rosenfeld

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Kathleen Block

Nicole Braddock

Cathleen Corken

Christine Goerke

Robert D. Heuer

Judith Greenstone Miller

Gail & Ira Mondry

Bridget & Michael Morin

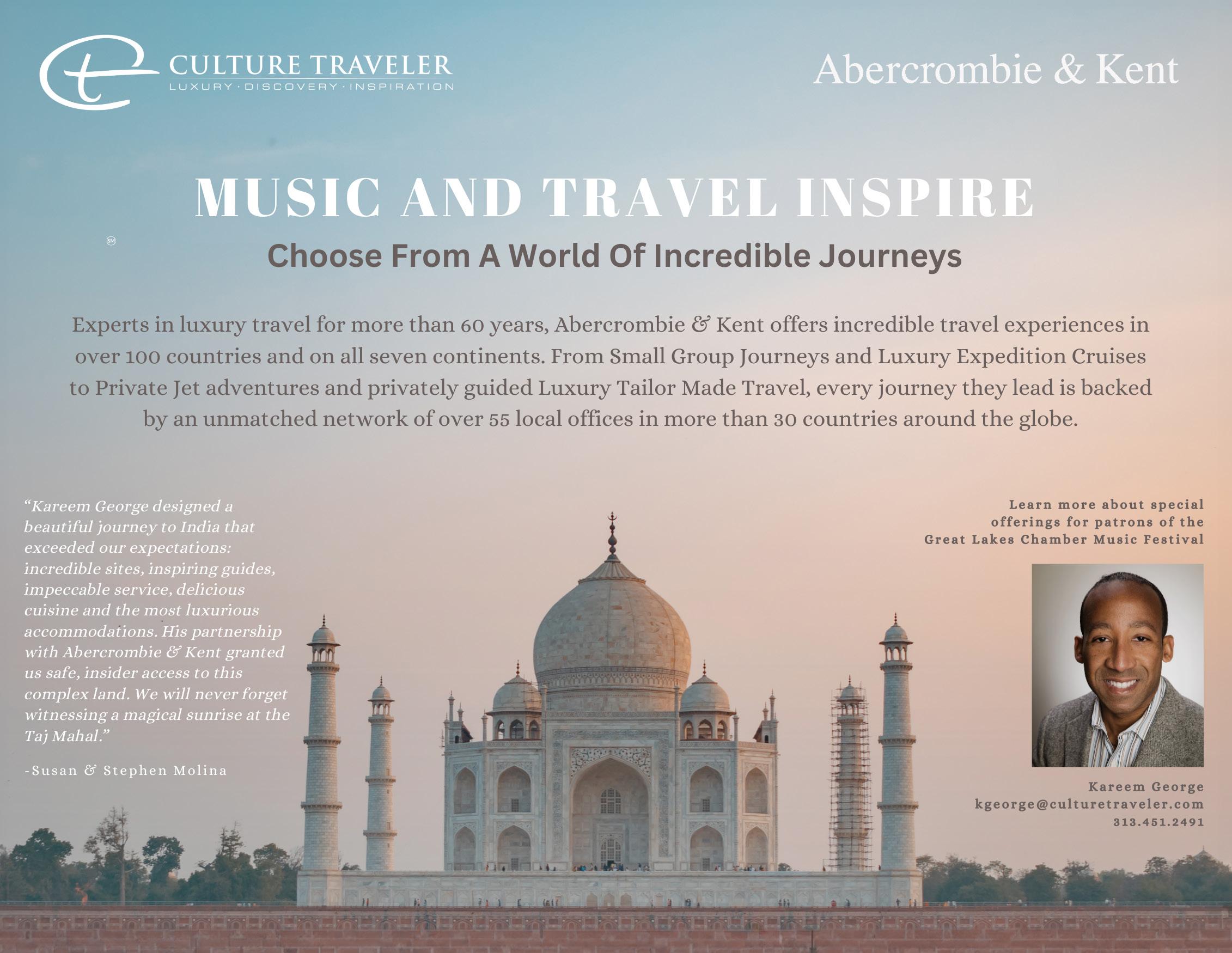

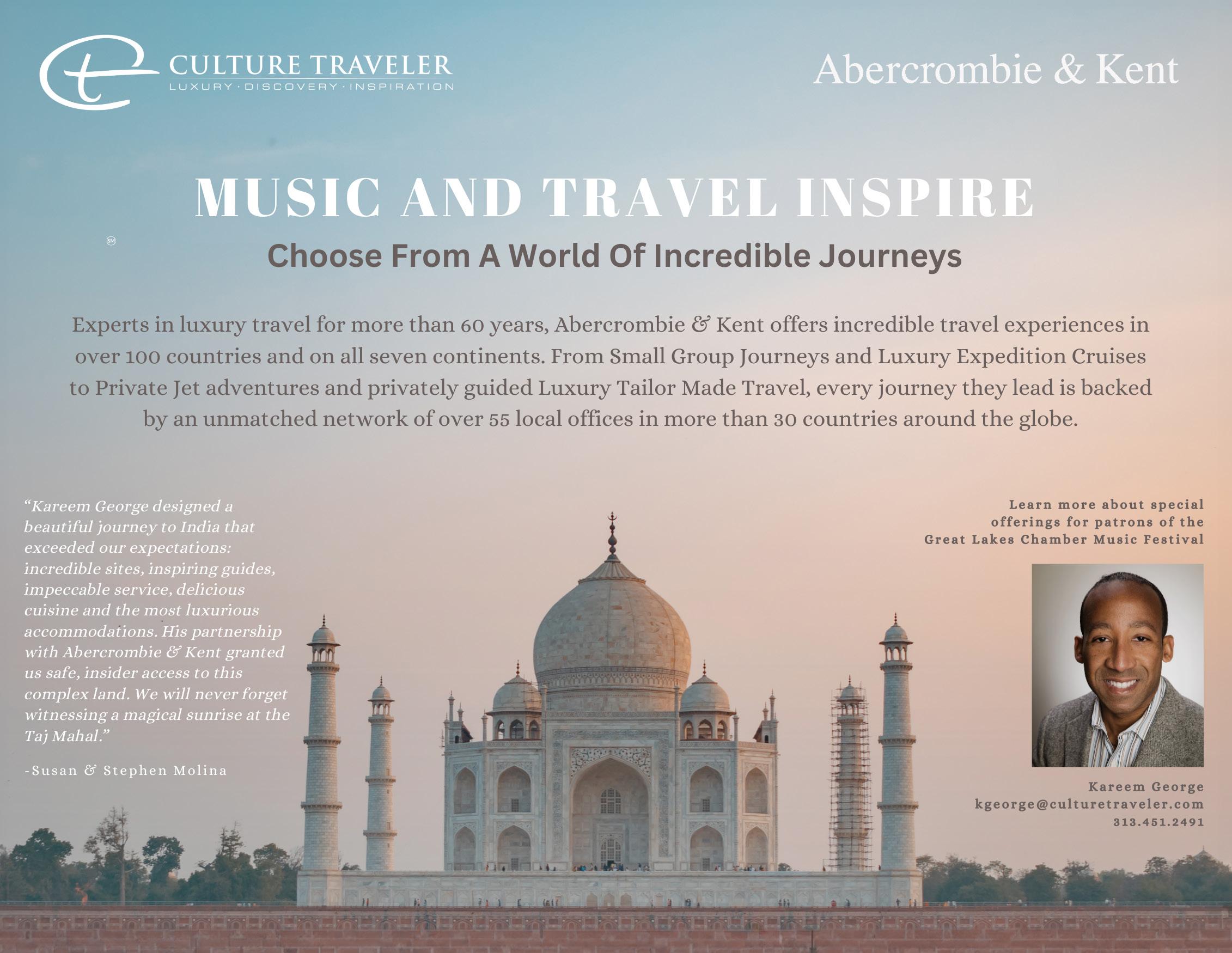

Frederick Morsches & Kareem George

Sandra & Claude Reitelman

Randolph Schein

Lauren Smith

Jill & Steven Stone

Rev. Msgr. Anthony Tocco

Michael Turala

Gwen & S. Evan Weiner

EX-OFFICIO MEMBERS

Fr. Mark Brauer

Mitchell Garcia

Cantor Rachel Gottlieb Kalmowitz

Rabbi Mark Miller

Maury Okun

TRUSTEE ADVISORY COMMITTEE

Cecilia Benner

Linda & Maurice Binkow

Cindy & Harold Daitch

Lillian Dean

Nathalie Doucet

Afa Dworkin

Adrienne & Herschel Fink

Jackie Paige-Fischer & David Fischer

Barbara & Paul Goodman

Barbara Heller

Fay B. Herman

William Hulsker & Aris Urbanes

Rayna Kogan

Yuki Mack

Martha Pleiss

Kristin Ross

Franziska Schoenfeld

Marc A. Schwartz

Josette Silver

Isabel & Lawrence Smith

Kimberley & Victor Talia

James Tocco

Beverly & Barry Williams

STAFF

Administration

Maury Okun, President & CEO

Jennifer Laredo Watkins, Director of Artistic Planning

Community Engagement

Jainelle Robinson, PR/Community Engagement Officer

Development

Jocelyn Conselva, Director of Development

Gramm Drennen, Patron Engagement Associate

Priya Mohan, Grants & Communications Manager

Allison Prost, Development Associate

Marketing

Bridget Favre, Director of Marketing

Layla Blahnik-Thoune, Multimedia Marketing Associate

Lauren Cichocki, Marketing Associate

Sabrina Rosneck, Marketing Associate

Logan Gossiaux, Arts Administration Intern

Finance

Triet Huynh, Controller

Phuong Huynh, Finance Assistant

Operations

Chloe Tooson, Artistic Operations Manager

Lane Warren, Arts Administration Associate

Madi LaJoice, Production & Artistic Operations Intern

FOUNDING MEMBERS

Wendy & Howard Allenberg

Kathleen & Joseph Antonini

Toni & Corrado Bartoli

Margaret & William Beauregard

Nancy & Lee Browning

Nancy & Christopher Chaput

Julie & Peter Cummings

Aviva & Dean Friedman

Patricia & Robert Galacz

Rose & Joseph Genovesi

Elizabeth & James Graham

Susan & Graham Hartrick

Linda & Arnold Jacob

Rosemary Joliat

Penni & Larry LaBute

Emma & Michael Minasian

Beverly & Thomas Moore

Dolores & Michael Mutchler

Nancy & James Olin

Helen & Leo Peterson

Marianne & Alan Schwartz

Leslie Slatkin

Sandra & William Slowey

Wilda Tiffany

Rev. Msgr. Anthony Tocco

Debbie & John Tocco

Georgia & Gerald Valente

Thelma & Ganesh Vattyham

Nancy & Robert Vlasic

Gwen & S. Evan Weiner

Barbara & Gary Welsh

SPECIAL THANKS TO

Lynne Dorando Hans, Graphic Design

Ty Bouque, Program Notes

4

THANK YOU TO OUR SPONSORS AND FUNDERS OF THE 2024 GREAT LAKES CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL

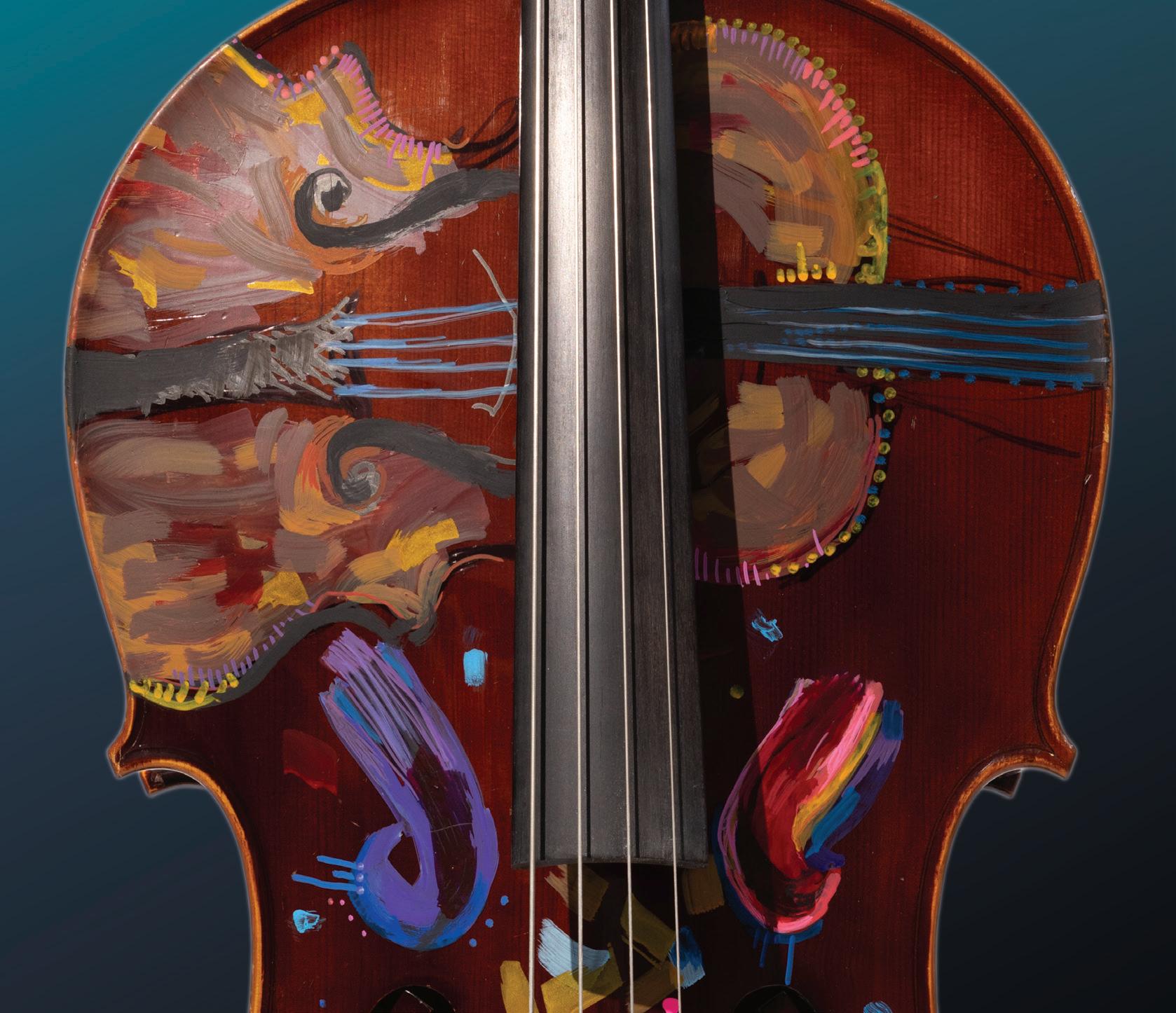

SABRINA NELSON: SOUND MEDICINE

Artist Statement: Creative Connections

Sabrina Nelson's Sound Medicine delves into the profound connection between spirit, motion, and intimacy within the realm of healing. Influenced by Yoruba Religion, alongside Eastern and African philosophies, her multidimensional approach transcends traditional boundaries, encompassing painting, sculpture, objects, performance, and installations.

With over 35 years of professional experience and a dedication to education, Sabrina aims to inspire and empower others through her art. As a studio art teacher at the Detroit Institute of Arts and a staff member at the College for Creative Studies, she instills in her students the belief that art is not only a creative outlet but also a tool for healing and transformation.

Through Sound Medicine, viewers are invited to contemplate the innate power within themselves and their communities to heal. Each stroke of the brush, or stroke of the bow, serves as a reminder of the abundant connections available to us for healing—resources found within ourselves, each other, and the natural world.

TY BOUQUE: PROGRAM NOTES

Ty Bouque writes about opera: its slippery histories, its sensual bodies, and the work of mourning for a dead genre. Writing can be found in VAN Magazine, TEMPO, Opera News, in the liners of Huddersfield Contemporary Records, in a forthcoming book from Lyrebird Press, and, less formally, on Substack.

Elsewhere, Ty sings as one-fourth of the new music quartet Loadbang, as well as in various solo, ensemble, and opera configurations around the world. www.tybouque.com

5 2024 SPONSORS & FUNDERS

ABOUT THE COVER TM

Wilda C. Tiffany Trust

Burton A. Zipser & Sandra D. Zipser Foundation

Mary Thompson Foundation

Maxine & Stuart Frankel Foundation

Lula Wilson Trust

Phillip & Elizabeth Filmer Memorial Charitable Trust

SATURDAY, JUNE 8 | 7:30 PM

FESTIVAL IN RESIDENCE: ANN ARBOR

Kerrytown Concert House

Sponsored by Pearl Planning

LINDA LEE, piano*

MINKYUNG LEE, violin*

TAI MURRAY, violin

MATTHEW MCDOWELL, viola*

JENNY BAHK, cello*

PAUL WATKINS, cello

PROGRAM

*Member of the Amnis Piano Quartet

Han Lash Sonata for Violin and Piano (b. 1981) Movement I Murray, L. Lee

Anton Arensky String Quartet No. 2 in A minor, Op. 35 (1861-1905)

Moderato

Variations on a theme of Tchaikovsky. Moderato

Finale: Andante sostenuto - Allegro moderato

M. Lee, McDowell, Bahk, Watkins INTERMISSION

Robert Schumann Piano Quintet in E-flat major, Op. 44 (1810-56) Allegro brillante

In modo d’una Marcia. Un poco largamente

Scherzo: Molto vivace

Allegro ma non troppo Murray, Amnis Piano Quartet

PROGRAM NOTES

Tonight’s program is something of a prologue, a spell for the coming. Inaugurating the overarching theme of our 2024 festival, all three works tonight owe huge debts to their historical connections: they are bound—by codes of articulation, means of construction, and aesthetic inheritances—to a past whose models and methods guide them into new territory. Classical music is first and foremost a thinking art: it critiques, corrects, confirms, and cohabitates with the body of work that takes its name, casting itself always in orientation to the ideals of its past and present. When we hear any one iteration, we are at the same time attending to the process by which an artist orients their selfhood in relation to the baggage of history. So in the

spirit of the two weeks before us, I thought we might turn over four of the major areas of inquiry that govern the festival’s programming—genre, form, source, and sociality—to better understand (a kind of invocation) how classical music thinks about itself.

[Genre]

We have before us three staples of canonic genre: the sonata, the quartet, and the quintet. But reality is never that simple. One is an archaism, one a subversion, and the other an act of invention, though they all parade as self-evident. Which is to say that “genre” is never a given; it’s what you do with your medium that counts.

To call a work “Sonata for Violin and Piano” in the 21st century is an intentional and risky take-up of the mantle. But Han Lash knows the consequences full well. Our 2024 composer-in-residence has always written music as a way of grappling with classical music’s past, and tonight’s sonata is no exception. Borrowing wholesale from a long legacy of instrument and piano duos, the work mobilizes an outdated genre as a means for thinking about how filling these old containers with new language reveals the strange behaviors of both.

Arensky pulls the subversive move of scoring the string quartet not, as is commonly the case, with double violins, but with double cellos instead. The nod is to Schubert’s “Cello quintet,” so-called for the same reason, but the result—a warm and heavy blanket of sound—is a means to end: a work of mourning is better weighted in the low register.

And Schumann, too, deploys an odd (for its time) orchestration. Before his quintet (finished in 1842, his self-professed “Year of Chamber Music”) the standard scoring was piano, violin, viola, cello, and bass. Schumann, however, who had spent the better part of the year writing three string quartets, simply opted to keep that format going. Marrying piano with the quartet proved endlessly effective: the large body of repertoire for the latter set up more contrasting possibilities of social interplay, while the tip to higher registers permitted greater nuance and variation in melodic expression, ushering in a medium custom-built for the priorities of Romanticism. Genre is only ever generic, and the best works know how to upend those conventions in search of fresh solutions to the problem of articulating something specific through the general.

[Form]

We’ll talk about form a lot over the next two weeks. When we do, it will almost always be in reference to music’s structuring of experience in time: how details at the local level—notes, rhythms, melodies, harmonies—play out in contingency with global or architectural organization—sections, passages, or movements. What we’ll find—and this is especially true tonight—is that no work ever articulates a “perfect” formal model: there is no Urtext or diagram-work for a sonata or a theme-andvariations. Forms, even the most established of them, are just ideas of relation whose rules and regulations have to be recast with each new work to accommodate the idiosyncratic needs of the material.

Take the final movement of tonight’s Schumann Quintet. It is, by all accounts, a sonata form, a historical model in which two disparate themes enter into a process of forced reconciliation. But Schumann—who, across his corpus, struggled hard with ensemble sonata forms—pulls some lengthy tricks to make it work. Despite an

6 WEEK ONE | JUNE 8

ostensibly E-flat major centrality, it will take him almost 175 bars and three—rather than two—themes to get there. Having found the center at last, the music mounts a breathtaking coup d’état and throws in an extra fourth theme, right at the end. It is only having passed through the extreme limits of material that the music arrives at its final fugue where, after traveling as far away from home as one can get, the first theme returns in blazing glory to the key where it belongs. It is a deeply unconventional sonata that breaks almost every “rule” of the game; but it is those breakages and how they’re handled that make it so recognizably Schumann.

Form is a slippery subject, one we’ll continue to pick at as the weeks go on. Here it is enough to say that form is never cut and dry. It is the space in which composers find personal solutions for the problem of articulating music in changing contexts across large swaths of time: there is always active play involved in that discovery.

[Source]

The danger of putting this much classical music in the same, confined space is that it reveals how many of these works owe ideas to their historical companions. Arensky’s second quartet, for instance, is saturated by a second, more famous composer. Belonging to a long Russian tradition of tribute pieces written on the death of a colleague, the Arensky is, both in material as well as bent, an homage to his friend Tchaikovsky. Not only does the central movement lift directly from Tchaikovsky’s song “Legend,” it also follows Tchaikovsky’s own model of homage: the older composer’s Piano Trio, also in A major, was written in memory of Nikolai Rubinstein. Later, melodies from the Russian Orthodox Mass will weave their way into the texture which, while invoking the two men’s national heritage, also draws a clear lineage with Beethoven: his “Razumovsky” quartets do the same. This is a work bound upon reference and citation, a private letter of mourning and communion.

And though less locally specific, both Lash and Schumann keep constant eyes to prior models. Schumann’s formal ideas owe considerable debt to the string quartets of Beethoven (specifically the ninth, from the same Opus 59 set that Arensky so admired). So considerable are the shared ideas that the Schumann scholar Donald Tovey went so far as to say the scherzo “might almost have come [directly] from Beethoven.” And the funeral march in the quintet’s second movement—one of the work’s most famous and arresting passages—is an explicit citation of Schubert’s Piano Trio No. 2, which used the same device (in the same key no less) fifteen years before. Lash, meanwhile, sources the very language of the genre. Endless series of chromatic suspensions, expressive leaps, and fleeting but recognizable harmonies are, like found artifacts in an archeological dig, mobilized to study how the grammar of our past is implicated in the sensibility of our present. The “source” for the sonata is the thinking syntax of Western classical music itself.

[Sociality]

Finally, however briefly, it’s worth remembering that music never takes place in a vacuum. Written by people for people, the ethical codes of care and intentionality that govern any social interaction are at play here as well. In the writing of music for performance, what is first being considered is not ideas or instruments but feeling, thinking bodies (often the original bodies were beloved; Schumann’s piano part was written for his wife, Clara). In each of the pieces tonight, we’ll hear music concerned first and foremost with protecting the avenues of emotional, physical, and intellectual exchange along which colleagues become friends and friends become family: and that is what chamber music is really about, in the end. © Ty Bouque 2024

The Levy Group of Companies celebrates the Chamber’s mission of bringing together the world’s most celebrated artists to deliver extraordinary musical performances and experiences for all.

Thank you for your commitment to an inclusive and welcoming culture where differences are valued so that the community may experience these outstanding artists performing chamber music at its best!

WEEK ONE | JUNE 8

SUNDAY, JUNE 9 | 5 PM

OPENING NIGHT: THE CREATIVE ESSENCE

Seligman Performing Arts Center

Sponsored by Aviva & Dean Friedman

LEILA JOSEFOWICZ, violin

PAUL WATKINS, conductor

DETROIT CHAMBER WINDS & STRINGS

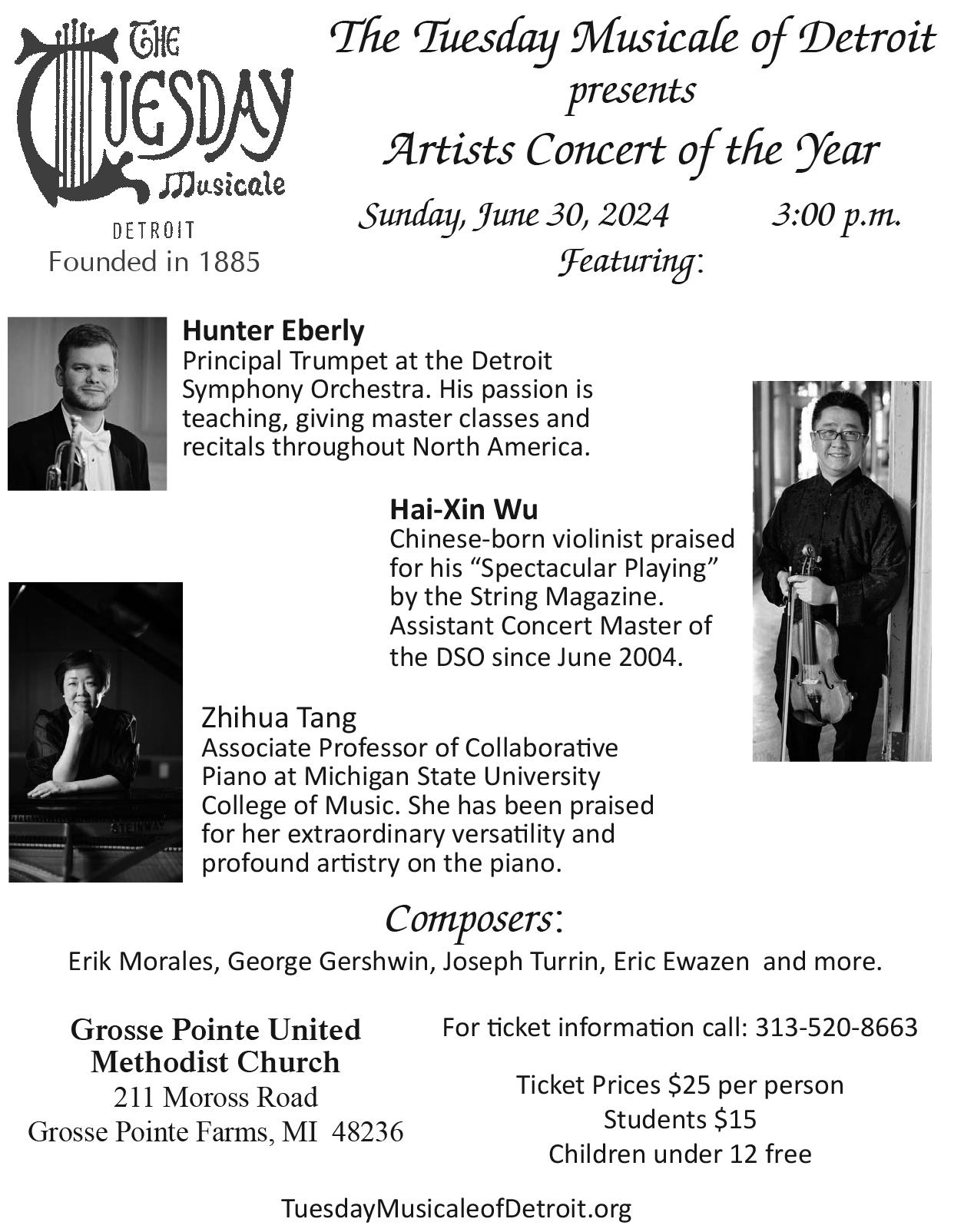

HAI XIN WU, violin

MINGZHAO ZHUO, violin

MATT ALBERT, viola

DAVID LEDOUX, cello

KEVIN BROWN, bass

NANCY STAGNITTA, flute

MERIDETH HITE ESTEVEZ, oboe

PROGRAM

SANDY JACKSON, clarinet

JACK WALTERS, clarinet

CORNELIA SOMMER, bassoon

KRISTI CRAGO, horn

JOHANNA YARBROUGH, horn

ROBERT WHITE, trumpet

Richard Wagner Siegfried Idyll, WWV 103 (1813-83) Detroit Chamber Winds & Strings, Watkins

Benjamin Britten Sinfonietta, Op. 1 (1913-76) Poco presto ed agitato

Variations

Tarantella

Detroit Chamber Winds & Strings, Watkins INTERMISSION

Béla Bartók Violin Concerto No. 2, BB 117, Sz.112 (1881-1945) Allegro non troppo

Andante tranquillo

Allegro molto

Josefowicz, Detroit Chamber Winds & Strings, Watkins

OPENING NIGHT DINNER

Join the artists after the performance for our Opening Night Dinner, kicking off the 2024 Festival. Catered by Plum Market.

Call 248-559-2097 for more information.

Donation to attend is $100 per person.

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE PROGRAM

It is a festival of doors. Windows too. Not to mention all manner of crevices, vents and cracks, joints, seams, sutures, little ducts and drafty tunnels down which music whispers to itself across the centuries.

Creative Connections: connect, from the assimilated Latin com+nectare, literally to bind together. If the task of the composer is to erect a world from sound, ours is to find the portals that hinge between their realms.

So: let’s crack the doors a bit, and see just what slips through. © Ty Bouque 2024

PROGRAM NOTES

We begin on a staircase. It is Christmas morning, 1870, and Cosima Wagner wakes at 7:00 AM to music. Confined by the narrow red-carpet stairway that wound through the center of the little villa in Tribschen, 15 musicians had tiptoed in at sunrise to surprise Wagner’s soon-to-be-legal wife with a musical tribute on her birthday. For a man better recognized by his egomania, it is a rare gesture of selflessness, and Cosima’s diary records something of her rapture:

When I woke up I heard a sound, it grew ever louder, I could no longer imagine myself in a dream, music was sounding, and what music! […] I was in tears, but so, too, was the whole household; R. had set up his orchestra on the stairs and thus consecrated our Tribschen forever!

The Siegfried Idyll is thus a love letter first, a private communion between two souls that was never meant to be heard by others (it was only sold off when the couple hit financial straits in 1877; even acts of love can be given a price if necessary).

The piece stands as a document to what Wagner called the happiest year of his existence: “he [has] unconsciously woven our whole life into it,” Cosima fawned. And though much of the music was later repurposed for the final duet of his opera Siegfried—prompting the title change from Tribschen Idyll to Siegfried Idyll—the music retained its intimate significance for the pair: Siegfried was also the name given to their only son, born in June of that same happy year, whose arrival is preserved in the music’s central swells.

Performance Sponsors

Bartók Violin Concerto | Linda & Maurice Binkow

But it is also a document to perceived inadequacy. The symphonic form weighed heavily on Richard Wagner. His intense veneration of Beethoven meant he prized the symphony above all, and his inability to produce one of personal satisfaction was a constant source of anxiety. Even on his deathbed, he clung to the dream

8 WEEK ONE | JUNE 9

of someday crafting a symphony where all themes would flow together in a long unbroken phrase. He never did write that work. And so the foreshortened Idyll is as close as we have to a Wagner symphony: it testifies to a vision of music much broader than it contains, like a small sliver of an imagined landscape that stretches beyond its borders into infinity.

Like Wagner, Benjamin Britten endured a fraught and often volatile relationship with symphonic form. We are in 1932 now, change is heavy in the air: Arnold Schoenberg has gone public with his method of organizing twelve-tone music, and it sends shockwaves through music students around the globe. At a time when the dominant fashion in England is still pastoral grandeur, Britten, an 18-year-old student at the Royal College of Music, becomes fixated on an Austrian’s quest for total formal unity. The Sinfonietta, completed in just three short weeks over the summer of 1932, is his private form of rebellion. “It was a struggle away from everything Vaughan Williams seemed to stand for,” Britten later admitted, and by Vaughan Williams, he meant that distinctly English incarnation of the Germanic symphonic model: fast movement here, slow movement here, insert, copy, paste. Britten, even at that early stage, was always a structuralist at heart; the inherited architecture of the classical symphony was only getting in his way.

An Opus One, however, is a volatile and loaded thing, and Britten’s Sinfonietta is no exception. That it has survived this long is not so much a measure of its achievement as its ideal: it is the first work where we can see the adult Britten stretching his legs. Taking Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony as a model—he also borrows its instrumentation, minus doublings—the work is a twenty-minute attempt at a musical form which arises solely from the organic metabolism of its materials (which is to say: without the delineated boundaries of the standard partite symphony; each of the three movements elides with the next). In this regard, it fails. What begins as distinctly Viennese, with all these little cells of material sprawling across the canvas, arrives in the final movement at the sort of recapitulating dance we’ve come to expect of Britten.

And yet the pair of brazen fifths that close the Sinfonietta still manage to feel so fully satisfying perhaps not because they’re musically earned—the form is tenuous, uncontrolled—but because they’re the symbolic result of Britten sloughing off his borrowed clothes. The work’s great joy today is hearing the adult Benjamin Britten peeking out between the sometimes-clumsy folds. Peter Grimes’ tolling steeple, Screw’s terse austerity, the Requiem’s brooding majesty flash in an instant before our eyes. The Sinfonietta, like Wagner’s Idyll, is a dream of music yet unwritten, echoes of the promise of what’s to come.

And Béla Bartók, too, found himself at odds with a borrowed form. Flash forward five more years to 1937, and the Hungarian maverick is just unpacking his bags from a research trip to Turkey when his fellow countryman Zoltán Székely—a violinist and composer in his own right—is announced as the concertmaster-to-be of Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw Orchestra. To mark his proper debut, Székely wants a new concerto; Bartók, twenty years his senior and an early advocate, is the obvious choice.

When asked for a concerto, Bartók immediately suggests an austere work of modernist invention: like Wagner and Britten, his dream is a test of movement-less variation, one grand unbroken string spinning a single idea to infinity. To which Székely says: no. He wants a classic, something to join the repertory, a three-movement showpiece to rival the best of them. And Bartók, acknowledging the concerto was for Székeley and not for himself, concedes—but not without a few tricks up his sleeve.

The work, true to promise, is dutifully divided into fast-slow-fast, but at every turn remains overloaded with the variation-structures of its original dream. The first movement rhapsodizes its central theme to nauseating limits, pushing and pulling the gravity around it into a kaleidoscope of temporal friction. The same theme is then picked up in the final movement, which weaves from it a tapestry of dizzying permutations. (Here, as in the Britten, Schoenberg’s influence rears its head: though resistant to serial purity, twelve-tone melodies abound.) And then the middle movement is what Bartók had desired all along: a set of six variations on a lonely, simple theme whose plaintive urgency is the product of nothing less than rigor. The work unifies itself by the idea of endless difference—even with the movement breaks left in.

All three works tonight nestle somewhere in the thresholds between inherited model and personal dream, social container and artistic conception, practical limitation and utopian ideal. They speak to a not-quite-yetness, a state of becoming whose incompleteness is, paradoxically, what makes them feel so full. This reaching out is what we might call their essence: from Latin esse, “to be,” the very thing that the thing is. Blanchot, writing in The Space of Literature, admits that “the work—the work of art, the literary work—is neither finished or unfinished: it is.” Tonight, the Creative Essence will be revealed in the gap between imagination and achievement, because there is no such thing as musical perfection: only the endless work of reaching towards the impossible. © Ty Bouque 2024

WEEK ONE

JUNE

|

9

TUESDAY, JUNE 11 | 7 PM

CONVERSATIONS ACROSS CENTURIES

Temple Beth El

Sponsored by Plante Moran

ANDREW LITTON, piano

LEILA JOSEFOWICZ, violin

TAI MURRAY, violin

PHILIP SETZER, violin

YVONNE LAM, viola

KATHARINA KANG LITTON, viola

PETER WILEY, cello

ALEXANDER KINMONTH, oboe

PROGRAM

Marc Neikrug Oboe Quartet in Ten Parts (2022) (b. 1946) Kinmonth, Murray, Lam, Wiley

Commissioned by Great Lakes Chamber Music Festival, Chamber Music Northwest and Music from Angel Fire

PROGRAM NOTES

It’s often said that chamber music is the medium closest to the dinner table. In small settings, we say that instruments talk, they speak to one another like family: as in we can talk about anything and pick up where we left off and finishing each other’s sentences, but also sometimes talking over one another or agreeing to disagree or pushing buttons. So it’s no accident that chamber music has historically been music for the living room. Salons and foyer recitals were spaces of intimate exchange where music served as a kind of audible extension of lifelong companionships: think of young Wolfgang and Nannerl Mozart playing trios with their father Leopold, or Clara and Robert Schumann, reading duets together. The music written to fill the chamber—in its archaic form, that word means the privacy of a bedroom—is first a testament to the invisible web of memories, personalities, and relationships tying together the people who are playing it. We, the audience, are like voyeurs, eavesdropping on a private chat between loved ones. (The root of the word converse means the familial, after all.)

Tonight, we’ll hear that, though the vocabulary and content of those “chamber conversations” has changed over the centuries, the bedrock of care that defines any surrogate family—the tenderness of parental figures, the jocular gentility underwriting sibling rivalry, the love that makes transparency and exchange possible—is what unifies the genre across time. To make music together remains among the most vulnerable of shared activities, and the best chamber music creates space for individuals to enter into dynamics of compassion and trust, whereby families—with all their frustration, pain, and joy—are knit in real time.

INTERMISSION

Johannes Brahms Piano Quintet in F minor, Op. 34 (1833-97) Allegro non troppo Andante, un poco Adagio Scherzo: Allegro

Finale: Poco sostenuto – Allegro non troppo

A. Litton, Setzer, Josefowicz, K. Litton, Wiley

Performance Sponsors

Neikrug Oboe Quartet | The Maxine & Stuart Frankel Foundation

Marc Neikrug is no stranger to the familial in music. The child of two distinguished cellists, he spent his earliest years listening to his mother compose at the piano, and there was a constant rotating door of musicians in his family’s New York apartment. His later career—he’s best known as Pinchas Zukerman’s pianist of preference—was dominated by the give-and-take of duo recitals, and his compositional sensibilities come predisposed to how musicians locate themselves in social relation to one another. He is, almost by birth, a musician’s musician: his music thinks first about that sociality.

Tonight’s oboe quartet works like ten versions of the same conversation among family. Think of it like a hanging mobile, variations on the same general shape all suspended in close proximity. Each part takes roughly the same structure: the wedge, or <>. They start from a single point (usually a sole note or a sparse chord), spiral outward in both chromatic directions until achieving maximum density, then cleave a path through the bramble back towards a solitary exit. Within that wedge, however, the roles played by individual instruments can vary drastically. Who starts, who accords, who resists, who, having heard the first note, sets off a “conversational tangent” that sends the music wheeling on its trajectory of expansion—these roles shift with every iteration. The wedge is a kind of common ground on which the internal dynamics of conversational space are subject to constant renegotiation, and by the end, the four have exhausted every possible pathway that the shape can take. But that exhaustion never sours into resentment: on the contrary, the four grow closer and more comfortable with every variation. Effortless conversation, as anyone can tell you, takes practice.

And if we zoom out a bit, the quartet as a whole forms a similar cross-movement diamond, announced by a return of the opening material in the eleventh hour of its final movement. Except the knotty byways we’ve taken to get there have

10 WEEK ONE | JUNE 11

fundamentally changed the group along the way. The lonely oboe note on which the work sets out is conspicuously absent from the final chord, which instead comprises its three closest neighbors. We can “hear” the perfect closure of the circle only in its failure to arrive, a ghostly kind of echo: the ensemble, though the same as it was when it began, is different for having traveled this far together. And is conversation with loved ones not like that too? After a certain period, one no longer needs the promise of clean resolution, of every thread tied neatly; coexistence is synonymous with change, and transformation is not only permissible here but healthy: “I love you enough to change alongside you.”

Brahms’ Piano Quintet, meanwhile, is a kind of mixed family, a second marriage maybe, a group of people who know what they want only after having had time to go out into the world to explore other less-satisfying options. The work began life as a string quartet, finished in 1862 and later destroyed by its composer (Brahms was in the habit of doing this, to the endless frustration of musicologists). Then it became a piano duo sonata, published as Opus 34b and premiered by Brahms himself alongside Karl Tausig. It was only after these two separate versions had come and gone did Brahms opt to bring the two together, following the formula laid out by Robert Schumann’s Quintet twenty years earlier, and the result has been the genre’s enduring masterpiece.

The beauty of this mixed family is how audible traces of their individual pasts are brought to the table not as points of unspoken conflict but valued viewpoints. The piano part slips in and out of its Opus 34b virtuosity, never as a means of dominating the conversation but without abandoning itself totally to secondary accompaniment. The strings move as a unit, they talk like a well-oiled machine with a century of discursive practice, but never at the exclusion of the newcomer. The instruments speak in the dialect of their previous existence, but still listen wholly to what the other has to say: it’s a coupling of individuals who’ve been single for a while and now know what they want to build together.

The key to this in musical terms can be spotted in all the linkages. Brahms—and we’ll see this more clearly in the week to come as we explore his late clarinet works—has a tendency to overlay his ideas like tectonic plates, one sliding seamlessly beneath the rim of the other. The result is that tension doesn’t built to hard, structural apexes or ultimatums but is instead continually stretched and released at the moment of its appearance, like an exercise in patience and trust. For all its musical tension, the Quintet is dominated by a sense that difference is not cause for oppositional rupture but (this is the mixed family part) actually why they speak together so fluidly. Five individuals with varying histories are rarely going to agree, but love knows how to piggy-back, echo, juxtapose, or amplify without needing to prove anyone wrong. Dissonance—especially in the famous chromatic staircase of the final movement—is bargained as the ground and not the earthquake.

In both works tonight, the shared DNA is the ethics of compassion that give chamber music its discursive magic. Instruments here leave space enough to always attend to one another and their needs while maintaining independence in the conversational network, as only the best families—chosen or otherwise—know how. © Ty Bouque 2024

11 WEEK ONE | JUNE 11

WEDNESDAY, JUNE 12 | 7 PM

FESTIVAL IN RESIDENCE: WINDSOR

The Capitol Theatre, Windsor

Sponsored by the Morris & Beverly Baker Foundation

SHAI WOSNER, piano

HESPER QUARTET, Shouse ensemble

PROGRAM

Franz Schubert String Quartet No. 14 in D minor, D. 810, (1797-1828) “Death and the Maiden”

Allegro

Andante con moto

Scherzo: Allegro molto

Presto

Hesper Quartet

INTERMISSION

Edward Elgar Piano Quintet in A minor, Op. 84 (1857-1934)

Moderato - Allegro

Adagio

Andante - Allegro

Wosner, Hesper Quartet

PROGRAM NOTES

Schubert first set Matthias Claudius’ short poem Der Tod und das Mädschen (“Death and the Maiden”) in 1817, in a version for voice and piano. Seven years later—having contracted terminal syphilis in the interim and facing for the first time his own mortality—the 27-year-old pilfered his piano part for a new string quartet, transforming the razor-thin tension of that earlier gallows march into the second of four movements. As the name suggests, his new quartet grapples with the delirious melancholy that accompanies the promise of death. It throws itself headlong towards the specter of bodily destruction, but for all the death-related music in the classical canon, Schubert’s stands out by refusing to be sad. It is a weighty quartet, certainly, and at times almost unbearably terse, but never unremittingly depressive. Death and the Maiden is, first and foremost, strange.

What is often chalked up to syphilitic madness in Schubert’s late work—its extremity, its violent tenor, the almost sadistic levels of play and invention that characterize its transformation of materials, and his frequent disregard for symmetry and regulation— is, I think, better contextualized by a puzzling moment in the Claudius text that nearly stops the poem in its tracks. Take a look at what Death calls the Maiden when he first speaks to her:

The Maiden:

Pass me by! Oh, pass me by! Go, fierce man of bones! I am still young! Go, rather, And do not touch me. And do not touch me.

Death:

Give me your hand, you beautiful and tender form! [Gebild] I am a friend, and come not to punish. Be of good cheer! I am not fierce, Softly shall you sleep in my arms!

Strange, no? Of all the names Death might give to a young woman, he calls her form: “you beautiful and tender form.” The sudden shift to figural abstraction, in a conversation of intimacy and assurance no less, is both troubling and irresistible. It seems to suggest that innocent beauty becomes something Other when proximal to Death. Something formal happens when the threat of extinguishment reaches a steady hand towards that which is not yet corrupted by the world. Tonight’s program asks that question: What becomes of Beauty when Death meets it?

The Romantic ideal of beauty—one to which Schubert absolutely ascribed—is celestial purity assembled through truth: “Truth is beauty, beauty truth,” Keats was writing at the same time. Schubert, meanwhile, is attempting to write a “beautiful truth” of what is first and foremost impure: death by infection, physical corruption, terminability, corporeal ruin. But, still bound by the aesthetic obligations of nineteenth-century Romanticism, he cannot kill beauty, at least not yet. Death the Destroyer—if it wants to be received as truth (as it certainly was for Schubert)—must paradoxically become beauty, must take beauty as a shape for itself, must make beauty a form to be filled.

So Death—that which does harm to living forms—turns around to find harm done to it by Beauty. Death is forced to twist itself into elastic and bulbous knots in an effort

12 WEEK ONE | JUNE 12

to maintain proper aesthetic codes: it cannot adequately articulate the brutality of the thing it wants to say. At the same time, the presence of something so unwieldy as Death in a system of highly controlled articulation warps the Beautiful into something dented, fraught, screaming while it smiles.This interior tension between violence— what is being said—and purity—how it is being said—lends Death and the Maiden its defining balletic grotesquerie: Beauty is indeed the form that Death must take, and both become so strange for that cooperation.

The French novelist Hervé Guibert, writing The Compassion Protocol on the brink of his own death from illness (AIDS) in 1993, described something of the same alienating flight into polarity: “I have the feeling I’ve created a work both barbarous and delicate.” Even as Schubert’s final movement whirls ever faster towards its climax, the brutality of terminal acceleration never outpaces the sheer eloquence of its form. It stays this side of madness but only barely, lending the work a twisted and surreal viscerality, at once cruel and cruelly gorgeous.

In Elgar’s Piano Quintet, however, that same notion of conflating death with beauty can be glimpsed not in the music itself but rather by locating the work in aesthetic history writ large. It is 1918. Music is in the midst of its most serious social upheaval in a century, but Edward Elgar, aged patriarch in the English musical landscape, is nowhere to be found. He has fled progressive London for the seclusion of a little hamlet called Fittleworth in West Sussex, a village of just 900 with a church, a school, and a single pub. Away from the city, he completes the final four works of his major output: the Violin Sonata, the String Quartet in E, the Cello Concerto, and the Piano Quintet.

From our vantage point in time, this late work is Elgar in marked retreat. Cast in an unapologetically sentimental vocabulary at a time when the dawning consensus among musical elite was that tonality’s universality and comfort had become untenable, it is an old guard retrenchment that aligns its creator firmly with the past. Of these four major works, however, the Piano Quintet is conspicuous for not totally beginning there. The long first movement warps and bends with uncanny fluidity, juxtaposing eerie, almost modernist sparsity with high-output vigor and dance. (His wife Alice would suggest in her letters that the thicket of barren, scraggly trees near their cottage was the primary inspiration for the movement’s sinuousness.) Teetering between nostalgia and nervousness, we open on an internal battle whose victor is not immediately clear: we can hear Elgar almost think about a more unsettled future.

But by the end of the first, and with each successive movement—the second is a wistful pastoral; the third, a long wind-up to exuberance—the from the promise of any change. The final cadence, jubilant and measured, is the long-awaited sigh of a recusal: Elgar will go no further, and ends by affirming the same values his music has always upheld. And so the Quintet like it floats outside of time. It has a kind of anachronistic estrangement, insisting on a guarantee of beauty that, deep down, it knows is only temporary. This is perhaps what makes the work rather emotional now: its naïveté bespeaks a deep desire for a world no longer possible. It grieves what will inevitably be lost by holding fast to it until the last possible second.

Though tonight’s concert will proceed chronologically, the pair feel curiously out of order. Schubert, seeing death on the horizon, throws himself towards it; Elgar, seeing the same, recoils. For the century dividing them, Death and the Maiden more prophetic of the pair, heraldic in its uncompromising vision of beautiful horror. © Ty Bouque 2024

WEDNESDAY, JUNE 12 | 7:30 PM

TASTING NOTES: FLAVORS OF EUROPE

Mongers’ Provisions - Berkley

Sponsored by Joy & Allan Nachman and Linda Goodman in memory of Dolores Curiel

LEILA JOSEFOWICZ, violin

PAUL WATKINS, cello

PROGRAM

Huw Watkins Sonata for Solo Cello (2022) (b. 1976) Watkins

Matthias Pintscher La Linea Evocativa (2020)

WEEK ONE | JUNE 12

Call 248.560.9200

THURSDAY, JUNE 13 | 7 PM

CROSSING BORDERS

Kirk in the Hills

Sponsored by Marguerite Munson Lentz & David Lentz

ANDREW LITTON, piano

ALVIN WADDLES, piano

KATHARINA KANG LITTON, viola

PAUL WATKINS, cello

MARION HAYDEN, bass

DAVID TAYLOR, drums

TRIO GAIA, Shouse ensemble

PROGRAM

Joseph Haydn Piano Trio in A major, Hob.XV: 18 (1732-1809) Allegro moderato

Andante

Allegro

Trio Gaia

Johannes Brahms Viola Sonata in E-flat major, Op. 120, No. 2 (1833-97) Allegro amabile

Allegro appassionato

Andante con moto — Allegro

K. Litton, A. Litton

INTERMISSION

Claude Bolling Suite for Cello and Jazz Piano Trio (1930-2020) Baroque in Rhythm

Concertante

Galop

Ballade

Romantique

Cello Fan

Watkins, Waddles, Hayden, Taylor

PROGRAM NOTES

In keeping with our festival theme of “that which connects,” doors are exactly what we’re thinking through tonight. The operative word is borders: What does it mean for music to cast itself towards thresholds, limits, demarcations, lines in the sand, any divide separating this from that or there from here? Each work on this program locates a perceived hard boundary—national lines, physical thresholds, intellectual limits, generic divisions—and makes it thin, slippery and permeable like bubble-film. These pieces are snapshots of transition states in a chemical reaction: we meet them in the halfway place.

Franz Joseph Haydn’s move to London in 1791 was a long time coming. Beginning in the early 1780’s, the boy-soprano-turned-composer found a rabid fanbase in urban England, but his financial contract to Hungary’s Prince Nikolaus I prevented him from reaping the social fruits of that celebrity. It was only Nikolaus’ death in 1790, coupled with a standing (not to mention well-padded) invitation from the impresario Johann Peter Salomon, that permitted him to finally make the trek. On New Year’s Day of 1791, Haydn crossed the English Channel from Calais to Dover; it was the first time the 58-year-old had ever seen the ocean.

At this point in the 18th century, London was a cosmopolitan hot spot. Bolstered by Parisians fleeing the Revolution, the perfect storm of talent, population, and cultural investment in new music generated the most robust professional music scene in Europe: London was drowning in virtuosos, and there was a substantial and appreciative audience. Haydn suddenly found himself honorary composer-inresidence of a city eager to push the physical limitations of their instruments, and his music had to adapt to match the moment.

Though written shortly after his return to Hungary in 1793, the Piano Trio in A Major bears all the evidence of the professional changes undergone in those first two London years. The plot-twist callback to development material at the close of the first movement, the extreme filigree of ornamental detail that decorates the melodies of the second, and the deployment of sudden dynamic shifts (facilitated by the introduction of the pianoforte into European musical life only a few years earlier) for drama in the third all demonstrate a composer whose ideas of performer limitations have recently undergone drastic extension. As far as the listener goes, he is still pleasing his new patron, Prince Anton: the dedication to the Princess makes that much obvious, and the work does nothing to break the mold for the listener. But the borders of technical dexterity and imagination to which Haydn’s early work was beholden have now fallen away, and he is offering both trust and physical challenge to his players and blurring another line—between chamber music and concerto—along the way.

Johannes Brahms’ threshold is the most vulnerable and poetic of the night. Premiered in a private performance with the composer at the piano in September of 1894, the Opus 120 was his very last instrumental work, and only two more vocal works precede his death in the spring of 1897. A lifetime of labor at the chamber medium ends here: this is, in many ways, the death of Brahms as we’ve come to know him.

The circumstances of commission are equally remarkable. In 1891, Brahms announced himself publicly retired, feeling he had no more to say in music. It took the playing of clarinet virtuoso Richard Mühlfeld to drag the melancholic master out of his slump and convince him to take the pen back up. The last eleven opuses are dominated by the instrument, and in their few years of shared work, Brahms wrote for Mühlfeld some of the instrument’s most beloved music. (His Clarinet Quintet from the same period can be heard in our concert on June 18th.)

14 WEEK ONE | JUNE 13

These last two sonatas are unlike anything else in music. Brahms is no longer the effusive Romantic he was in his youth; this is late-life writing, devastatingly reserved, that knows how much can be done with how little. The structural relationships between melody and form are the most slippery and idiosyncratic of his career: no hard borders, no sudden changes, all passing as water over rocks. Here, in all these places where musical ideas exit one state towards another, we can hear the poeticism of death’s threshold. There is no sense of failure or of loss in this music, but rather of quietude, of being at peace with final change. The sonatas have the eloquence of a last will and testament, written in steady hand before the final doorway.

In tonight’s performance, the Opus 120 also calls our attention to translation, itself an act of border-crossing that leaves traces of both hemispheres on the object. Brahms himself, shortly after the premiere, arranged the pair of sonatas for viola at Joachim’s behest (and not totally willingly: letters reveal his initial hesitation to do so). A clarinet sonata transformed into a viola sonata is no simple feat. Idiosyncratic instrumental writing requires accounting for the limitations of mechanism: the demands of breath, for instance, differentiate the clarinet from a viola, as do its keys, which make notechanges far easier across extended range. Where the clarinet slithers, liquid and elusive, the viola must start each phrase with a bow-stroke, lending the transcriptions a more rarified and often far more metric quality than the original. But the warmth and woody resonance of that low C string adds a quivering vibration almost like tears, and though the musical material breathes with the capacity of lungs, it here speaks with the infinite delicacy of the hand.

Tonight we’ll hear a viola that still remembers, far in the distance, the clarinet that it once was. A border was crossed, but softly, tenderly, and not without carrying something of the original over with it.

As for Claude Bolling, the borderline is right there in the title: Suite for Cello and Jazz Trio. Bolling, trained first as a jazz pianist and later as a film composer, made his international name in 1975 with a parallel formula, the Suite for Flute and Jazz Piano, written for and recorded alongside Jean-Pierre Rampal. The Columbia record skyrocketed Bolling to a household name and spent ten years on the Billboard Classical Top 40, earning the duo a Grammy nomination along the way and Bolling a whole slew of commissions for blue-chip stars. Tonight’s work, completed in 1984, was written for Yo-Yo Ma.

When anything is crossing over—like we saw in Brahms’ clarinet-to-viola transformation—it’s important to think about fidelity. (It’s no accident that the first album cover for Bolling’s suite featured a cartoon flute and piano smoking sideby-side in bed; the exchange of identity is a fundamentally sensual and intimate act. One is giving of one’s body to the other.) What has made Bolling so popular to listeners on both sides of the exchange is that nothing is misused or appropriated: the suites have the uncanny ability to not just simulate jazz but actualize it without compromising the structural integrity of classical chamber music. It is that rare kind of hybrid in which two presences are not halved, and therefore less, by sharing space, but rather more authentically themselves for their proximity to the Other.

Tonight, in different ways, all three works trace out a liminality of imagination. They situate themselves willingly at borderlines, imagining hybridity, extension, and threshold as the very foundations of their truth. What binds this program is a willingness to think beyond a social delineation towards something utopian, something unknown and invisible in the between. © Ty Bouque 2024

15 WEEK ONE | JUNE 13

FRIDAY, JUNE 14 | 11 AM

YOUTHFUL INSPIRATIONS

Kirk in the Hills

Sponsored by JPMorgan Chase

PHILIP SETZER, violin

KATHARINA KANG LITTON, viola

DILLON SCOTT, viola

PETER WILEY, cello

AMNIS PIANO QUARTET, Shouse ensemble

PROGRAM

Frank Bridge Lament for Two Violas (1879-1941) Litton, Scott

PROGRAM NOTES

This morning marks the first of a pair of programs—tonight is the second—devoted to an excavation of childhood and its memories. Under inquiry here is reflection: at the moment when we, as fully grown adults, turn critically towards our upbringing, do the memories themselves change? What is revealed and what stays hidden? And how does hindsight interrogation help us to better clarify our mature senses of self?

Frequently in music, when we talk about childhood attractions, we default to the loaded language of influence or inspiration. What we often mean by doing so is an imported genetic likeness: we say that Mozart was inspired by Bach as a means of understanding how Mozart’s music inherits—bloodline-style—compositional sensibilities begun before his birth. But, leaping an etymologic step backwards to inspirare, a word originally signifying “the breath of truth given to humanity by a deity,” we would be better suited to think about what Mozart never dared to call his own. Our American sense of casual inspiration falls flat here: Mozart does not just like or pick up a few tricks from or mimic J.S. Bach. He treats it like doctrine, like truth.

J. S. Bach Selection from Six Preludes and Fugues, K.404a (1685-1750)

No. 4 in F major: Prelude (after J.S. Bach BWV 527)

W. A. Mozart & Fugue (after J.S. Bach BWV 1080) (1756-91)

No. 5 in E-flat major: Prelude & Fugue (after J.S. Bach 526)

No. 6 in A-flat major: Prelude - Adagio (W.A. Mozart) & Fugue (after J.S. Bach BWV 882)

Setzer, Litton, Wiley

William Walton Piano Quartet in D minor (1902-83) Allegramente

Allegro scherzando

Andante tranquillo

Allegro molto

Amnis Piano Quartet

Concert to be followed by a Lunch & Learn with oboist and author Merideth Hite Estevez.

The Bach transcriptions—originally keyboard fugues in The Well-Tempered Clavier were made as compositional exercises for parlor gatherings in Vienna, and Mozart even wrote a few Bach-style Preludes to accompany their performance. But Mozart, playful rebel Mozart, does not pull his usual tricks here. He is a studious and detailed observer, attendant to Bach’s decisions in registration and affect with a fidelity and a reverence that he shows to almost nothing else. This is 1782; he is 26, none of his world-shifting operas have been written yet, and, though he’s already internationally famous for an instantly recognizable voice, he clearly still believes he has things to learn from a music he knew almost from birth. In the F Major No. 3, which will be played last in today’s series, we’ll hear a slow Prelude that, though entirely by Mozart, risks absolutely no games: it strives, in every way, to make its namesake proud. All the fugues that crop up in Mozart’s music after this—the end of the Jupiter symphony, most famously—border on a transcendent spirituality which is actually not all that common in Mozart’s largely humanistic output, because the weight of reverence he feels each time that titan is even peripherally invoked is impossible to shoulder. He cannot bring himself to play around with Bach: there is always a distance of god-like childhood idolatry keeping him in line.

But for someone like Frank Bridge, adolescent musical studies come with their own baggage. Bridge floats as a kind of island-figure in British musical history. Situated somewhere between the waves of French impressionism and late German romanticism, the establishment of the English pastoral, and the onslaught of Viennese modernity, he often gets the short end of the stick for not falling evenly into any one school of thought. Apropos the dangers of influence, Bridge is perhaps best known as the private teacher of Benjamin Britten; we know Bridge best for what he influenced, and not the other way around. This is especially hampered by an uncompromising austerity and reserve in Bridge’s work that is, on the whole, deeply adult. It is music borne by an intensely plaintive melancholy that can only be acquired with time, a music of age, of maturity, of sense; he is, at least in work, old long before his time.

And so it would be easy to chalk up the throaty keening of the Lament for Two Violas as just the default tenor for a perennially pensive man. But doing so would overlook the very fragile relationship to its creator’s childhood that underpins its mourning. Bridge was taught violin—rigorously, “with an iron fist” he would later say—by his own father. That Bridge enjoyed a successful career as a chamber musician on both violin and viola alongside his composing was due in no small part to the domineering force of his first music teacher, who taught him to hold a fingerboard before he knew how to write. The sound of twin string instruments echoing through time and space is thus

16 WEEK ONE | JUNE 14

a core childhood memory for Bridge, though not an altogether happy one. There is, one imagines, considerable tension in that recollection, both a wistfulness and a resentment. The poignancy of the Lament—admired as one of Bridge’s most direct and devastating works—is in no small part the product of complicated nostalgia for a painful but still sentimental memory. What we hear is Bridge forging an even-ground relationship between the two identical strings that repairs, in some small way, one that did not exist for his childhood self.

Walton’s Piano Quartet is an especially acute iteration of this late-stage selfreflection. The earliest drafts of the quartet date from 1918: Walton was just sixteen at the time, a freshman at Oxford who was only just beginning to find his social circle. Most composers would dismiss anything produced in these early untrained years as mere juvenilia, but Walton clung to the quartet with a certain sense of pride, so much so that he substantially revised it twice in his later life —once, just shy of his 53rd birthday, and again, just shy of his 74th. But for all this editing after the fact, William Walton never succumbs to intentional self-censorship like the image-obsessed Stravinsky. On the contrary, his adult revisions of the quartet are the opposite of maturations; in every subsequent update, the sense of brazen audacity only crystalizes further. It sounds bizarre, but what he’s doing is sharpening in retrospect his own sense of adolescence.

Which is why—after fifty years of updates—the work is still a little brash: it is meant to be, as a document of the musical imagination of a teenager who knows too much about music for his own good. The ghosts of Ravel and Elgar make appearances so unabashed that their presence verges on camp, but that cheeky transparency is precisely what makes the work so maddeningly ingenious. This is already the William Walton of Façade, of comic theater that does not take itself seriously. The quartet accordingly never plays at profundity; it adores its idols with excess vigor, it pays no mind to social moderation, it is brash and bold, overly excitable, and all the more lovable for it.

Later in life, Walton chided the quartet as the product of a “drooling baby,” but he doesn’t give himself enough credit. The quartet is a rebellious teenager through and through, a time he would later look back on with a wistful sense of pride. The revisions betray an eagerness not only to never spoil its naïve energy with the cynical judgements of age, but to regain, just a little, that reckless sense of youth.

© Ty Bouque 2024

FRIDAY, JUNE 14 | 7 PM

FESTIVAL IN RESIDENCE: DIA

Detroit Institute of Arts Rivera Court

Sponsored by Barbara Heller

ANDREW LITTON, piano

SHAI WOSNER, piano

CHERYL LOSEY FEDER, harp

AMNIS PIANO QUARTET, Shouse ensemble

PROGRAM

Frank Bridge Phantasy for Piano Quartet, H. 94 (1879-1941) Andante con moto

Allegro vivace

Andante con moto

Amnis Piano Quartet

Han Lash Stalk (b. 1981) Losey Feder

Dave Brubeck Points on Jazz (1920-2012) Prelude Scherzo

Blues

Fugue Rag

Chorale Waltz

A La Turk

Wosner, Litton

Event is free with museum admission. Visit dia.org or call 313-833-7900 for more information.

Performance Sponsor

Lash Stalk | Martha Pleiss

17 WEEK ONE | JUNE 14

Amnis Piano Quartet

FRIDAY, JUNE 14 | 7:30 PM

FESTIVAL IN RESIDENCE: ANN ARBOR

Kerrytown Concert House

YVONNE LAM, viola

TRIO GAIA, Shouse ensemble

THE DOLPHINS QUARTET, Shouse ensemble

PROGRAM

Joan Tower White Granite (2010) (b. 1938) Lam, Trio Gaia

The Dolphins Quartet The Dolphin Miniatures Open Waters

Blueberry Soda

Rainy Sunday The Infestid Garden Under the Light of the Stars

The Sinking Sandal Old Farmer John

The Dolphins Quartet

INTERMISSION

Antonín Dvor˘ák Piano Trio No. 4 in E minor, Op. 90, B. 166, “Dumky” (1841-1904) Lento maestoso — Allegro vivace — Lento maestoso — Allegro molto

Poco adagio — Vivace non troppo — Poco adagio — Vivace

Andante — Vivace non troppo — Andante

Andante moderato (quasi tempo di marcia) — Allegretto scherzando — Allegro — Moderato

Allegro

Lento maestoso — Vivace

Trio Gaia

PROGRAM NOTES

Tonight’s program unifies around the formative: what, at a crucial moment in time, impresses on our sense of self with such force that who we are is forever cast by the memory of its intensity. These are rarely the big moments in life; often what is formative is small in scale, a smell, a texture, some brief and passing interaction with the world when we are young that has a disproportionate influence on how we understand ourselves. The work of the artist is, in many ways, a constant labor of impossible return to that primary state of full-bodied sensation; the formative, the “original memory” of being-human in the world, is what art attempts to give back to us for a moment.

Understanding the music of Joan Tower, for example, requires knowing the timid nineyear-old she once was. A small child, uprooted from the quiet of New Rochelle and relocated to Bolivia at the height of its national revolution, finds in her father’s new workplace a sonic and geologic culture that upends everything she understands. Tower cites her love of rhythm and of color in the sweaty memory of an equatorial nation in revolt, but her geologic predilection dates from these years as well. Tower’s father, a mineralogist working in extraction mines in South America, instilled in her an early expertise for thinking about the materiality of the Earth. Rock is a substance of power and endurance, but also constant change, subject to pressure and to heat; it is utilitarian, the bedrock of housing and the thing on which nations are built; it is also a symbol, a metaphor of birth and of belonging to the ground, flush with mythic properties for healing, protection, and strength.

Tower’s White Granite belongs to a collection of pieces—Black Topaz (1976) and Silver Ladders (1986) the most famous among them—whose musical language draws on these many physical and metaphoric qualities of their titular minerals. Granite, so named for its grain, belongs to a class of rock called phanerite whose distinguishing quality is the coarse visibility of its comprising crystals: there are no pure surfaces or smooth edges in granite, only endless, glittering variation sprawled out in all directions. Tower’s music follows suit: every large gesture is scattered with small breakages, streaks of charcoal, ash, beige and ivory knit across the surface, veins of snowy variegation that never perfectly repeat. It is the idea or image of “white granite” as translated into sound.

Tower’s mineral works are thus not documents of lithography—we do not hear fractional crystallization or the cooling of magma taking place—so much as poetic cross-sections of their object, loving inspections of the stone in question. White Granite turns the slab over in one hand, zooms close into its crystal composites, pulls it out to inspect its roughshod edges, traces a dusty finger on the ridge of its fracture, tastes the earthen richness of its chalky powder, feels the weight of centuries in this small piece of a planet. That early childhood insight, instilled by her father, that even the most solid and imposing masses in our world are divisible into the tiniest particulate crystal, has guided Tower’s work for nearly six decades. In White Granite, it’s easy to imagine the thrilled fascination of a nine-year-old seated by her father’s side, captivated by these fragments of stone in her small hands, by their weight, their texture, and the way they refract the beating South American sun.

The Dolphin Miniatures are, not dissimilarly, all fleeting attempts at capturing the incandescent knowledge of substances that, early in life, sketch out our thresholds of pleasure and sublimity. Each of the movements, written in turn by members of the quartet, maps the physical properties of a formative childhood moment into the realm of sound. The fizz of a first sparkling drink; the planar vastness of the first sight of

18 WEEK ONE | JUNE 14

the ocean; the sound of rain on a childhood roof; the half-memory of a pre-school song: these are small moments, perhaps, but the kind so rich in sensory overload at the start of our existence that they never quite lose their luster, no matter how far away from them we get. The seven miniatures tonight thus testify to a kind of group ethos: each time these four individuals play music at all, they revisit in some way these core, early memories.

With Antonin Dvořák, what is formative is much harder to distinguish on the basis of material. Dvořák operates with a kind of blunt omnivorousness; he borrows, bargains, lifts and loves music from all corners of the world with a kind of indiscriminate fascination. He is curious, a collector: American spirituals, Moravian folk dances, German opera, English choral music—it can all get translated into his sound world without so much the batting of an eye.

But there is a kind of core sensibility that guides the how along which these musical objects arrive in his vocabulary. Dvořák gravitates towards emotional extremes that are inextricable from their sense of place. His music wagers a kind of double motion, reaching upwards towards the limit-states of human sensation—grief, ecstasy, rage, pride, lust—while keeping one foot firmly planted in the soil of their upbringing. Raised in the foothills of Bohemia where music was in turn financial survival, social modality, and cultural identity, the intensity of his music can’t be separated from its where: what is formative is thus an idea of place that gives rise to energy in music, emotion as interlocked with landscape.

In the fourth Piano Trio, Dvořák abandons classical forms and instead borrows from the folk music of his native Eastern Europe. Each of the six sections is a discrete “dumka,” a Ukrainian epic lament song traditionally delivered by itinerant bards with nothing but a small bandora for accompaniment. Though the means were often minimal and painfully local, these songs were immense things, testimonies to the generational memories of captive people and their struggles. The “dumka”—the word literally means “rhapsodic thought,” thought letting itself be drawn out beyond a natural limit—is the perfect kind of keyword for thinking about Dvořák and his music. Each of the sections trace huge emotional arcs without ever leaving the key in which they start. They are stabilized by place, both geographical and musical, capable of extremity because of their foundation. Dvořák, a Czech who traveled as far as Iowa before returning home, knew this about the formative: like those traveling bards with their songs and their bandoras, we carry our roots with us through the years. © Ty Bouque 2024

SATURDAY, JUNE 15 | 11 AM

CHILDREN'S CONCERT: ACCENT PONTIAC BUCKET BAND

Bloomfield Township Public Library

Sponsored by Gwen & S. Evan Weiner

PROGRAM

Join Accent Pontiac for a children’s music workshop. Their instruction includes percussion lessons using drumsticks and buckets. These “bucket bands” learn rhythmic skills and percussion techniques. More importantly, participants experience what it is like to be part of an ensemble, sharing responsibility and pride with each other.

Admission is free; all ages are welcome.

WEEK ONE | JUNE

14-15

SATURDAY, JUNE 15 | 7 PM

CREATIVE CONNECTIONS

Seligman Performing Arts Center

Sponsored by Josette Silver

HAN LASH, piano

ANDREW LITTON, piano

SHAI WOSNER, piano

TAI MURRAY, violin

PHILIP SETZER, violin

PROGRAM

KATHARINA KANG LITTON, viola

PETER WILEY, cello

KEVIN BROWN, bass

THE DOLPHINS QUARTET, Shouse ensemble

HESPER QUARTET, Shouse ensemble

Han Lash Excerpts from A Journey Through the Underworld: (b. 1981) Counterpoint

Lash

Franz Schubert

Impromptu in G-flat major, D. 899 (1797-1828) Wosner

George Gershwin Impromptu in Two Keys (1898-1937) Wosner

Rhapsody in Blue A. Litton, Wosner

INTERMISSION

Maurice Ravel String Quartet in F major (1875-1937) Allegro moderato - Très doux

Assez vif - Très rythmé

Très lent

Vif et agité

Hesper Quartet

Olli Mustonen Nonetto II (2000) (b. 1967) Inquieto

Allegro impetuoso

Adagio

Vivacissimo

Murray, Setzer, K. Litton, Wiley, Brown, The Dolphins Quartet

PROGRAM NOTES

It is our titular night, the heart of the festival theme, and so tonight, we’re going to think about connections. Each piece on this program animates economies of twoness: systems of bartering, bargaining, trade and transfer, exchange and interception that occur when a pair of opposing objects are forced to negotiate cohabitation in the same musical space. There is, in each of these works, some thing—a melody, a sound, a reference, a genre, a general musical object—dropped in too-close proximity to its Other, its problematizing opposite. Reconciliation has to be arrived at, whether by force, by love, by destruction or by contortion, but reconciliation nonetheless because the two can never last as one and one: we need to find a plus somewhere to finish the equation. And so we’ll see across the program that the additive composite of being two is always arbitrated according to what can be given and what can be taken in return.

[Pair 1: composer+composition]:

We begin with Han Lash’s Excerpts from A Journey Through the Underworld: Counterpoint—like so much of their music—finds their independent musical sensibility by transforming or transcribing existing historical objects: what we might think of as “the music of Han Lash” almost always emerges in the cracks of a dialogue with other, older melodies and models. In this case, the denuded scaffolds of the old forms becomes a blank drawing board, against which the ornamentations (arpeggios, glissandos, shimmers and flickers) come material for Lash’s articulation of musical selfhood. What at first sounds like the discovery of long-forgotten melodies— the glimpses of the past that float in and out of perceptibility—is actually the inverse: the composer discovering themself by organizing what slips through history’s newly opened crevices.

[Pair 2: melody+accompaniment]:

The slippery relations between arpeggio and melody lead us neatly into Schubert (a composer who, incidentally, has been a life-long love of Lash’s). The G-flat major Impromptu belongs as the third in a set of four improvisations that, true to their name, are governed by an overwhelming sense of “pulling it out of thin air.” A long, traipsing melody in the upper fingers of the right hand unfurls itself over a slow bass line, while between the two, a rocking arpeggio fills in the chasms between notes. But this accompaniment doesn’t stay subservient for long. Forced by the impossible slowness of the melody to fill more and more of the texture, the arpeggio gradually begins to reach out and take control, pushing and pulling the melody along with it like an independent force. This assertion of character arrives, right at the end, at an astonishing feat of rebellion: the accompaniment strays so far from the melodic center that Schubert is forced briefly (it lasts a bar and a half) to change keys to accommodate the digression. Accompaniment has overstepped the melody. And while the two quickly return home, that assertion of the accompaniment’s autonomy keeps them both as active and equal characters right through to the final note.

[Pair 3: key+key]:

Next, we’ll break key signatures entirely. The “two keys” in the title of George Gershwin’s own short Impromptu refer to the irreconcilable harmony separating the hands: the right-hand melody lives in a key one half-step lower than the left-

20

ONE | JUNE

WEEK

15

hand bass. Each phrase is thus an experiment into routes of realignment for a form that always starts in adjacency. What Gershwin gradually realizes is that, in parallel systems, all it takes is a single point of overlap for the whole thing to collapse into unity. Here, the fluid absorption of dissonance on which so much of jazz is predicated works in Gershwin’s favor: the “blue note” (what jazz musicians call a particular moment of dissonance) in one key can become a green light for another.

[Pair 4: genre+genre]:

And ending the first half is a work whose twoness is synonymous with the nation that brought it forth. Rhapsody in Blue, Gershwin’s eternal marriage of American jazz and classical music, turns 100 this year, offering a fresh chance to reevaluate that genetic exchange. After so many years in the public eye—the Fantasia cartoon cemented its American ubiquity—it’s hard to remember how audacious and risky that work was when it was written. Gershwin attempts a reconciliation between what was then considered “high” and “low” art. He achieves a blend so effortless and thrilling because he locates, in the values of the Roaring Twenties, a common ground on which the pair could absolutely agree: excess, glitter, virtuosity, brashness, and a certain love for drama are traits that jazz and classical music share in spades.

[Pair 5&6: rhythm+rhythm and technique+technique]:

Like Rhapsody, the Ravel String Quartet in F, one of the most recognizable instances of French fin de siècle music in the repertoire, hardly needs an introduction. But it is the second movement—marked “rather lively and very rhythmical”—that has garnered the most attention in the years since its composition. Ravel’s musical wager is simple: two pairs of opposite objects placed in constant juxtaposition. Between the melody and the accompaniment is an ongoing argument over whether dividing six is easier as 2+2+2 or 3+3. That debate gets personal as two playing techniques— pizzicato (the plucking of the string) and ordinary bowing—begin to overlap, and what is gradually revealed is that opposition and temporary disjunction form the very ground on which the quartet stands. As with Gershwin and with Schubert, the roles of accompaniment and melody are never so clear as we’d like them to be.

[Pair 7: then+now]:

Finally, Olli Mustonen’s Nonetto II brings all these strands of our diverse and exhilarating program into a tidy final flourish. Mustonen, like Lash, is a composer of our time with one foot firmly grounded in the language of the past; we are bookended by compositional outlooks which see the act of writing music as a fundamentally historicist behavior. The Nonet, like Tchaikovsky’s Souvenir de Florence or the Mendelssohn Octet, is an old-style showpiece for string players, a chance to play together in consort, to feel the thill of virtuosity among a group of peers. But its two-ness—as is ours at this festival—is the split of now and then: nostalgia for the forms and the melodies of a long-since-bygone time, finding new meaning in the imaginations and freedoms of our own age. (And is there a better hope for classical music than that?) © Ty Bouque 2024

We bring the concert experience into your home...

david michael audio

4341 Delemere Court

Royal Oak, Michigan 48073

248.843.7632 www.davidmichaelaudio.com

Featuring Accuphase, Aurender, Ayre Acoustics, Boulder, Chord Electronics, Devore Fidelity, Dohmann, Estelon, Harbeth, Heed, Innuos, Kabala Sosna, Leben, Line Magnetic, Magico, Metronome, MSB Technology, Nagra, Riviera Audio Labs, Spendor, Sugden, Totem Acoustic, Vimberg and many others…

21 WEEK ONE | JUNE 15

WEEK TWO | JUNE 16-18

SUNDAY, JUNE 16 | 2 PM

PRIDE AT THE DIA

Detroit Institute of Arts Rivera Court

Sponsored by Henry Grix & Howard Israel

THE DOLPHINS QUARTET, Shouse ensemble

HESPER QUARTET, Shouse ensemble

PROGRAM

Em Singleton glint, gleam, glow (WORLD PREMIERE) (b. 2002) Hesper String Quartet

Han Lash String Quartet No. 2 (2022) (b. 1981) The Dolphins Quartet

INTERMISSION

George Enescu String Octet in C major, Op. 7 (1881-1955) Très modéré

Très fougueux

Lentement

Mouvement de Valse bien rythmée

Hesper Quartet, The Dolphins Quartet

TUESDAY, JUNE 18 | 7 PM

WRITTEN FOR THE STARS

St. Hugo of the Hills

Sponsored by Virginia & Michael Geheb

ALESSIO BAX, piano

SHAI WOSNER, piano

ROBYN BOLLINGER, violin

TESSA LARK, violin

PROGRAM

HSIN-YUN HUANG, viola

PAUL WATKINS, cello

MICHAEL COLLINS, clarinet

Ludwig van Beethoven Sonata for Piano and Cello No. 2 in G minor, (1770-1827) Op. 5, No. 2

Adagio sostenuto e espressivo

Allegro molto più tosto presto

Rondo. Allegro

Bax, Watkins

Béla Bartók Contrasts, BB 116, Sz. 111 (1881-1945) Verbunkos (Recruiting Dance)

Pihenö (Relaxation)

Sebes (Fast Dance)

Wosner, Lark, Collins

INTERMISSION

Johannes Brahms Clarinet Quintet in B minor, Op. 115 (1833-97) Allegro Adagio

Andantino

Con moto

Collins, Bollinger, Lark, Huang, Watkins

Performance Sponsors

Beethoven Sonata No. 2 | Franziska Schoenfeld

Presenting Sponsor of Beethoven Complete Cello Sonatas | David Nathanson

PROGRAM NOTES