ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL.

2

URBAN DESIGN STUDIO II

COLUMBIA GSAPP

A6820-1

INSTRUCTORS:

EMANUEL ADMASSU

NINA COOKE JOHN

CHAT TRAVIESO

JELISA BLUMBERG

REGINA TENG

A.L. HU

GALINA NOVIKOVA

FALL 2022

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY GSAPP Fall 2022

Urban Design Studio II

PROGRAM DIRECTOR

Kate Orff

ASSISTANT DIRECTOR

David Smiley

INSTRUCTORS

Emanuel Admassu, Coordinator

Nina Cooke John

Chat Travieso

Jelisa R. Blumberg

Regina V. Teng

A.L Hu

TEACHING ASSOCIATE

Galina Novikova

TEACHING ASSISTANTS

Donnal Baijnauth

Anagha Arunkumar

Verena Krappitz

FALL 2022

STUDIO PARTICIPANTS

Aashwita Yadav

Anagha Arunkumar

Anchalinad Anuwatnontaket

Ankita Sharma

Caroline Wineburg

Chongyang Ren

Deepa Gopalakrishnan

Devanshi Gajjar

Devanshi Pandya

Di Lê

Donnal Baijnauth

Hanfei Fu

Haoyu Hu

Haoyu Zhu

Heer Shah

Hongfeng Wang

Iza Khan

Jacqueline Liu

Jade Durand

Jiani Dai

John Grunewald

Maria Gabriela Flores

Marina Guimaraes

Mingrui Jiang

Naumika Hejib

Nupur Shah

Oréoluwa Gift Adegbola

Qiannan Guo

Reya Singhi

Rohin Sikka

Rubin Lian

Rutwik Karra

Ruxuan Zheng

Saloni Shah

Sanah Mengi

Sanya Verma

Simran Gupta

Siwei Tang

Tippi Huang

Verena Krappitz

Vir Shah

Wenjun Zhu

Xiutong Yu

Xu Cheng

Yan Huo

Yaoze Yu

Yashita Khanna

Yiwan Zhao

Yue Huang

Zicong Liu

ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL.

2

URBAN DESIGN STUDIO II

COLUMBIA GSAPP

A6820-1

INSTRUCTORS:

EMANUEL ADMASSU

NINA COOKE JOHN

CHAT TRAVIESO

JELISA BLUMBERG

REGINA TENG

A.L. HU

GALINA NOVIKOVA

ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

FALL 2022

07 04 03 09 02 01 13 12 05 10 06 11 08 FALL 2022 4

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION A Brief Introduction Studio Overview Reading List Itinerary and Site Visit PROJECTS 01 Peachtree Town Center 02 Mercedes Benz Stadium 03 Wellstar Atlanta Medical Center 04 Hulsey Yards 05 Peoplestown 06 Greenbriar Mall 07 Chattahoochee Brick Company 08 Blackhall Studios 09 Techwood Homes 10 Greenwood Cemetery 11 Forest Cove Apartments 12 Olympic Stadium 13 Downtown Parking COLLECTED SAMPLES CONCLUSION Guest Speakers Acknowledgments Epilogue I II III IV 06 - 35 36 - 141 142 - 195 196 - 201 5 ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

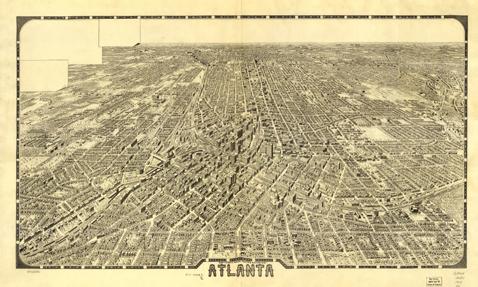

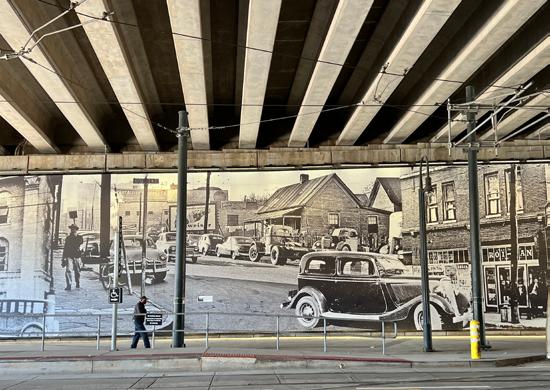

ATLANTA: A BRIEF INTRODUCTION

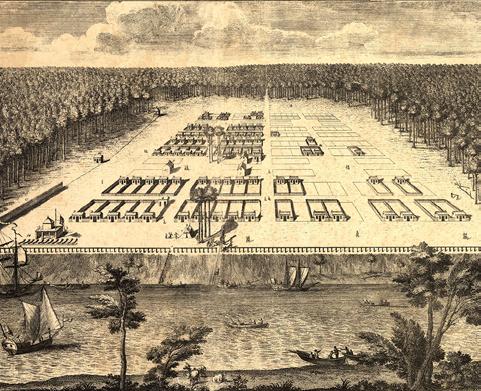

SPLIT: The Muscogee Creek people are the Indigenous stewards of the land and territory that is now known as Metro Atlanta. When Creek towns reached a population of approximately four hundred to six hundred people, they would split, with about half moving to a new, nearby site. These transient communities retained “mother-daughter” relationships between new and original towns/villages. These Indigenous spatial practices of mobility and stewardship based on mutual aid were subverted and replaced by a settler colonial logic: bifurcations fueled by covert and overt racial animus. Infrastructure built to facilitate the mobility of European settlers often doubled as a fort or embankment that limited the mobility of Black and Indigenous people. This contradiction has been maintained by the train lines that gave the city its current name and the contemporary highways that maintain these logics of negation and segregation.

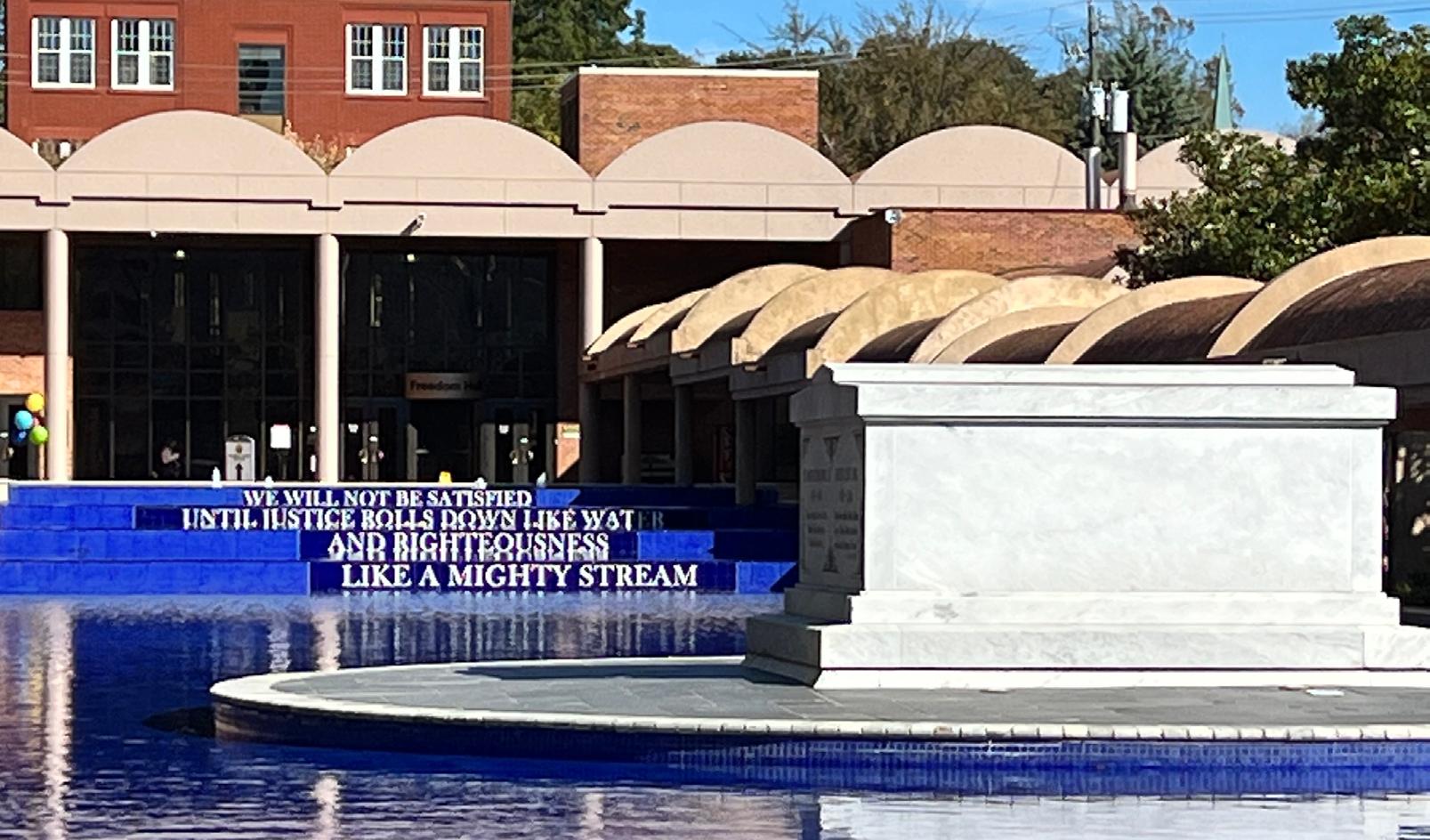

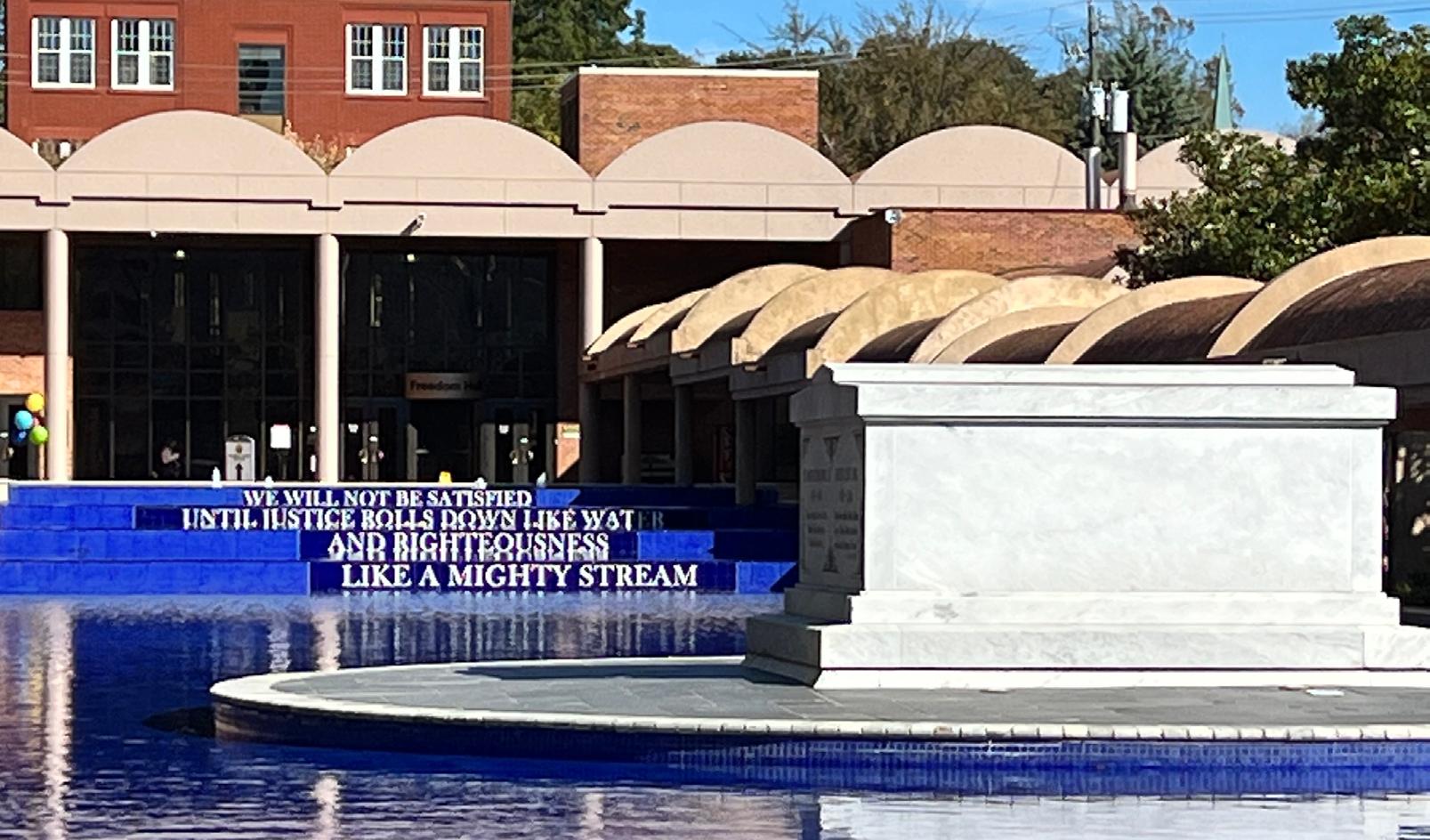

Self-determination: Throughout much of the twentieth century, Atlanta was the gravitational center for the struggle for Black liberation in America. The city was at the forefront of voting rights (a tradition that continues to this day with the work of Stacey

Abrams and others), as well as Black political and economic power. It is an educational haven for Black Americans with Atlanta University Center—a consortium of four pioneering and distinguished HBCUs that include Clark Atlanta University, Spelman College, and Morehouse College.

The city has the distinction of being the one-time home of a long list of key activists and organizers including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Coretta Scott King, Ralph Abernathy, Ella Baker, Bayard Rustin, Andrew Young Jr., John Lewis, Rev. C.T. Vivian, Dr. Roslyn Pope, and Constance Baker Motley, as well as the headquarters of the SCLC (Southern Christian Leadership Conference) and SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee). The tactics employed by these activists— sit-ins, kneel-ins, and lay-ins, picket lines and boycotts, barriers destroyed and bodies blocking traffic, church meetings and university organizing, Black residential expansion and school desegregation—also have been met with bitter opposition through arrests, police brutality, white supremacist violence, restrictive deeds, exclusionary zoning, segregation walls, voter suppression, and white flight.

Disposession: The codified dispossession of land, thinly veiled through the aspirational discourse of ‘Neighborhood Improvement’ or ‘New Urbanism’ has razed all of the public housing in Atlanta. This narrative relies on

6 FALL 2022

long-standing genealogies of spatial exclusion that span from redlining to predatory lending practices; eventually leading to the complete transfer of public housing over to the private sector in2008—Atlanta built the nation's first federal housing proj-ect in 1935. The ongoing displacement and dispossession facilitated by contemporary urban remediation projects like the BeltLine, rely on similar narratives of private ownership while providing no protection for poor and low-income tenants and homeowners (median rents are up 28% since 2000—3rd in evictions, nationally).

(Mis)education: By and large, Atlanta’s public schools segregate student populations based on race. The geographic outline of the school districts continues to be redrawn in order to sustain and/or intensify segregation.

The State’s unwillingness to educate Black children is augmented by limiting the physical mobility of low-income Black families—rejecting the expansion of the MARTA and other public transportation options—and entangling the quality of schools with the speculative real estate market (property value).

Instead of maintaining a consistent quality of public education, students who are born into working class Black and brown communities in Atlanta are forced to attend schools that are designed to maintain what Eddie Glaude

Jr. calls the “value gap.”

“Contemporary urban youth are exposed to police contact more frequently and at earlier ages than their predecessors. Schools— and for those who live in public housing, even homes—have begun to resemble correctional facilities. Metal detectors, surveillance cameras, and other mechanisms designed to monitor and control inhabitants are now standard equipment in American urban schools.” — Dr.

Carla Shedd

Enclaves: Atlanta’s film industry is one of the fastest growing economic sectors in the region. Film production companies are encouraging each county to maintain specific features, landmarks, and histories. The camera-ready communities program commodifies the differences between neighborhoods as a sales pitch for film producers. In addition, a growing number of production studios are being built in and around the city, including Tyler Perry Studios, Trilith Studios, and Studio City. These mini-cities have their own socio-spatial ecosystems. At the opposite end of the spectrum, these enclaves of affluence are contradicted with concentrated enclaves of poverty: higher costs and long commutes are intensifying hardships for low-income residents that are currently being displaced from the city and trapped in the suburbs due to inadequate public transportation.

7

ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

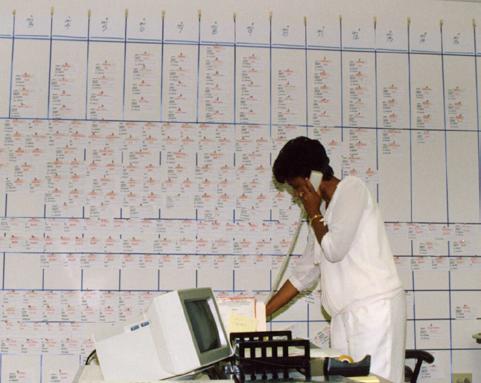

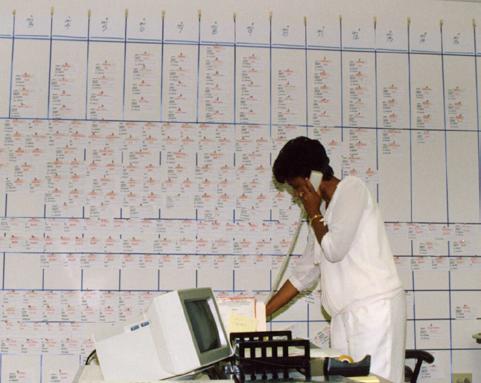

Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games (ACOG) Staff Member in Office With Dayto-Day Games Schedule Board | Unidentified photographer, Atlanta, 1996

“The imaginative functions of literature and culture, [...], can reveal and intervene in the colonial, racial, and gendered structure of the property system. Further, we might look to culture for ways of articulating notions of self and community that do not buy into the universalizing logics of possessive individualism and national belonging.”

– Grace Kyungwon Hong

– Grace Kyungwon Hong

STUDIO: A BRIEF INTRODUCTION

How can we disentangle urban design and architecture from property?1 How can we use this moment of environmental and institutional reckoning to disassemble the exploitative regimes of speculation and displacement that anchor the built environment? In other words, where do we go from here? This studio aims to identify temporal slippages and spatial practices that carve out moments of liberation from the limits of property. Studio participants will develop a collective intelligence, by gathering samples from various cultural and political geographies, to experiment with ways of seeing beyond the privatized enclosure in the metropolitan Atlanta region—the city and its sprawling suburbs.2 The aim is to design a region (with hopes of building a world) that is not tethered to individual land ownership, but instead, predicated on collective stewardship and care. This work will be done by recognizing ordinary spatial practices that operate against the hegemony of real estate. Through radical reinterpretations of historical and contemporary interventions where the everyday struggle begins to approach the surreal, we aim to liberate urban design from its historical commitment to borderization.3 We will celebrate undervalued spatial practices that actively dismantle the Cartesian frame of racial capitalism, as a gathering of performances committed to imaging a different world, because the status-quo is untenable. Atlanta After Property reframes the discipline of urban design by re imagining the city of Atlanta in solidarity with contemporary movements of Black liberation and mutuality; working against the ruthless policing, dispossession, and displacement of marginalized communities.

HHR, W.E.B. DU BOIS in his Atlanta University office, 1909

SITE (noun)A place, scene, or point of an occurrence or event.

8 FALL 2022

READING 01

READ: ARGUMENTS & DIAGRAMS

Team: Groups of four or three

Assigned: September 8th, 2022

Review: September 12th, 2022

The first assignment, Episode 01, will be accompanied by a series of readings. Each studio participant will read at least three texts from the list provided in the syllabus. Then, students will form groups of four to analyze and generate a short visual presentation on one of the readings. These readings—framing critical questions—will serve as foundations for our discourse on property, means of representation, and the urban conditions of Metro Atlanta.

How can we imagine a world after property?

Participants will examine ‘as found’ sites and spatial practices by everyday people that work against the alienating nature of private property.4 These samples will be added to the collective catalog of the studio. By drawing examples of communality that prioritize care over surveillance, we will imagine a world after property.

Is property a metonym for theft?

This studio will identify and define precise sites of privatization by selecting and transforming ‘as

found’ urban conditions that are emblematic of the contemporary regime of property. Participants will investigate the cultural, political, and spatial structures that continue to transform communal environments into securitized zones.

EPISODE 01

RESEARCH: SAMPLES & SITES

Team: Groups of two (or three) Assigned: September 8th, 2022 Review: September 22nd, 2022

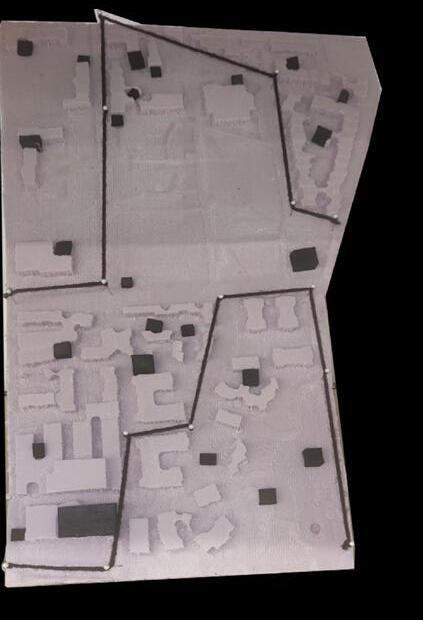

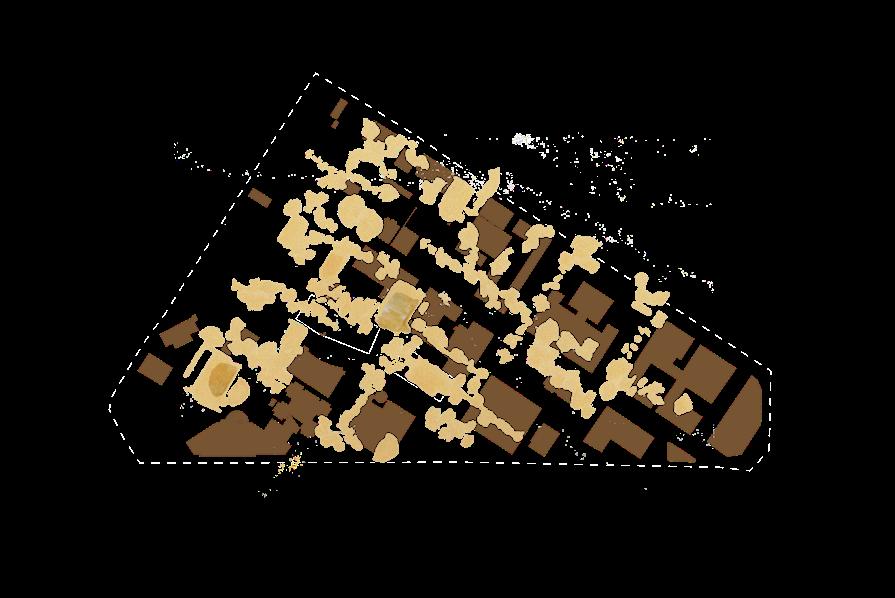

Participants will work in pairs to select critical images and invent analytical drawing techniques that identify, take account, and diagram specific ‘Samples’ and ‘Sites’. For the purposes of this studio, Samples are defined as existing spatial concepts and practices that defy the bounds of property. Inversely, Sites are defined as existing spatial conditions in metro Atlanta that are representative examples of the schema that defines the contemporary regime of property.

How can we use images to open new readings of history?

This studio aims to develop historical depth by navigating and mining images that have been used to document Atlanta’s transformations over time. This image research will offer another way of knowing the place before our visit to Atlanta.

“However, when Atlanta was named host of the 1996 Olympics in 1990, public housing demolition for temporary athlete housing (that would become permanent mixed-income communities) seemed like and ideal (public-private) solution for a public burden. Over two decades, approximately 7,000 public housing units were demolished, with less than 40% of all displacees eligible and willing to return to new public-private developments. Since 2007, the city has grappled with a foreclosure crisis that stands to remove even more working-class political interests from the city.”

— Akira Drake Rodriguez

The imperative to quantify and measure value created an ideological juggernaut that defined people and land as unproductive in relation to agricultural production, and deemed them to be waste and in need of improvement. The creation of an epistemological framework where people came to be valued as economic units set the ground for a fusing of ownership and subjectivity in a way that had devastating consequences for entire populations who did not cultivate their lands for the purpose of commercial trade and marketized exchange. These populations were by definition uncivilized and could be disposed of, cast out of the borders of political citizenship.”

— Brenna Bhandar

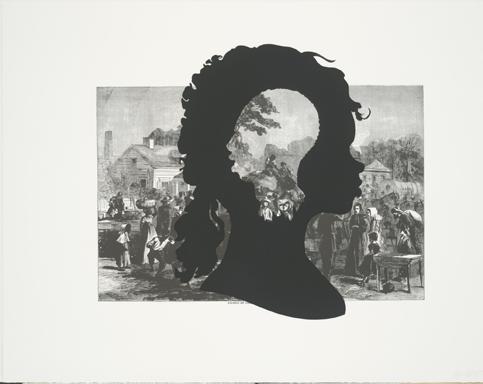

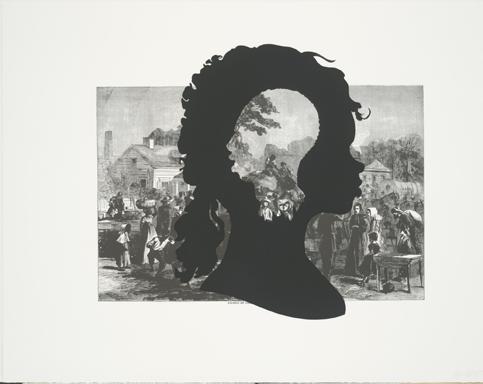

Kara Walker Exodus of Confederates from Atlanta from Harper's Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated). 2005

9 ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

“A practice is an unfinished or ongoing process. It designates a durational temporality that functions as a process of preparation. Practice is also fundamentally social in nature, as it forms a core role in the formation of subjectivity. More specifically, in this case, it is the social process of preparation required to enact new ways of inhabiting freedom.”

—Tina M. Campt

“The premise of the CLT relies on distinguishing the interest in the land itself from the interest in using the land. The land interest is held by a non-profit organization which holds the land ‘in trust’ for a particular community and its future residents, while the plot’s use interest is held by a leaseholder, who agrees to a long-term rental and resale agreement.”

— Gabriel Cuéllar and Athar Mufreh

How can we reclaim proximity?5

Participants will carefully examine how the logics of property produce spaces that overdetermine our physical interactions. The algorithmic abstraction of global capital and land speculation are continuing to produce homogenous cities; making them increasingly inaccessible zones for working class people. Therefore, unbuilding the cultural, political, and economic forces that delimit cities requires a critical engagement with the images used to do this work.

How can we resist removal?

Various, well-intentioned urban remediation projects like BeltLine Atlanta exponentially increase surrounding property value, contributing to the massive displacement of low-income communities. Understanding that the harm done to the environment is inextricably linked to the harm done to people, we will analyze how private developers continue to receive incentives and subsidies from tax dollars, leading to the ongoing abandonment of the civic realm, defunding public schools and public transportation.

EPISODE 02

TRANSLATE: SELECT & CATALOG Team: Groups of four (or three)

Assigned: Sept. 22nd, 2022

Review: Oct. 3rd, 2022

Two groups from Episode 01 will merge to form groups for Episode 02; inheriting four Samples and Sites from another group. The inherited Samples and Sites will be carefully sharpened—both conceptually and representationally. This will require further research and iteration on the arguments, images, and diagrams used to depict the samples and sites from Episode 01.

Consequently, each group will select and contribute two samples and one site to two catalogs: Collective Sample Catalog and Collective Site Catalog (the socio-spatial boundaries of each site will be defined by the group) in the metropolitan Atlanta region.

Is liberation achieved during, before or after property?

Each group will test various combinations through models and images—organizational, representational, and material—of the fragments in the collective catalog.6 The strategies gathered from these concepts will inform the dismantling of property.

Is property another word for prison?

The aim is to generate arguments and images that work against the ongoing borderization of the planet. We will establish

FX’s ATLANTA, Season 1

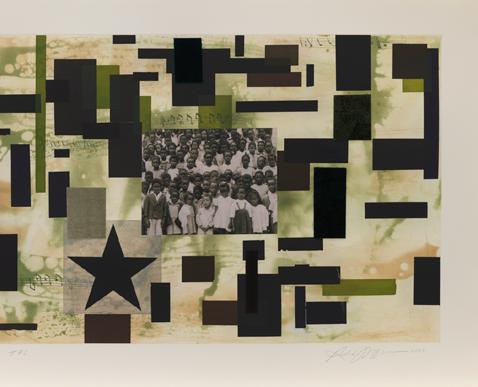

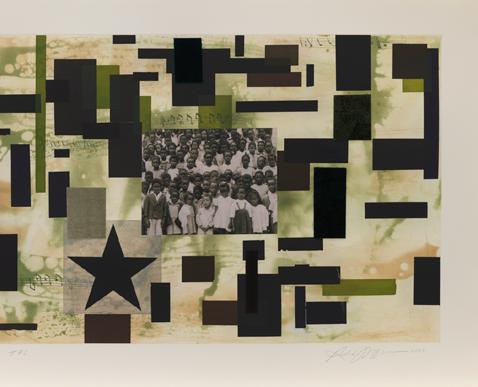

Radcliffe Bailey. In The Garden. 2003

10 FALL 2022

frameworks for mutual aid and communality that refuse the transformation of cities into homogenous zones of speculation.7

EPISODE 03

DESIGN:

ARGUMENTS & MODELS

Team: Groups of four (or three)

Assigned: Oct. 3rd, 2022

Review: Oct. 27th, 2022

Each group will select samples from the collective catalog. These samples will be used to redesign one of the sites in the collective catalog, prefiguring a world after property. The samples will be selected based on their potential to redress recursive dispossessions. What are the alternatives to the tyranny of permanence?

This studio will reintroduce people that were displaced from the city and liberate spaces that have been imprisoned by property.8

Is property foreclosing the promise of a livable planet?

Participants will sample from the collective catalog to establish frameworks for the production of alternative futures: free from alienation and dispossession.9

Mining key episodes from the historical evolution of the samples, we aim to fortify our commitment to the cultivation of a livable planet.10

EPISODE 04

RECONSTRUCT: ITERATE & STUDY

Team: Groups of four (or three)

Assigned: Nov. 7th, 2022

Review: Nov. 21st, 2022

The site will be reconstructed to reflect the various forms of cohabitation (human and morethan-human) that have been erased.11 This will be an iterative process, transforming the samples and sites of each project. The aim is to search for alternatives to speculative, predatory forms of land ownership, that undergird the built environment.12 It is an opportunity to imagine new ways of relating to our planet and to one another.13

EPISODE 05

PRESENT: DRAW & MODEL

Team: Groups of four (or three)

Assigned: Nov.19th, 2022

Review: Dec. 5th, 2022

The final presentation will be a non-linear accounting of the research and design decisions that generated your vision of Atlanta after property.14 The coherence and contradiction between your samples and sites will reveal transformative opportunities to redefine the limits of urban design.15

“Worldbuilding is utilized as a powerful feminist tool in Himid’s practice. The gallery space is transformed into a site where many of us audience members, curators, and artists alike—can congregate, converse and even time travel together as we move from one reality to the next by encountering each canvas.”

— Amrita Dhallu

“In this breathtaking moment, those who have been heir to most of the harm have been offering the most incisive critiques and the most potent antidotes, and they are often speaking a spatial language that inhabits the urban stage. Communities that rely on presence, proximity, and entanglement have special powers to provide some relief from or reparation for the environmental violence of dispossession, gentrification, policing, and climate catastrophes.”

— Keller Easterling

“While the legal transformation from slavery to freedom is most often narrated as the shift from status to contract, from property to subject, from slave to Negro, vagrancy statues make apparent the continuities and entanglements between a diverse range of unfree states—from slave to servant, from servant to vagrant, from domestic to prisoner, from idler to convict and felon.”

— Saidiya Hartman

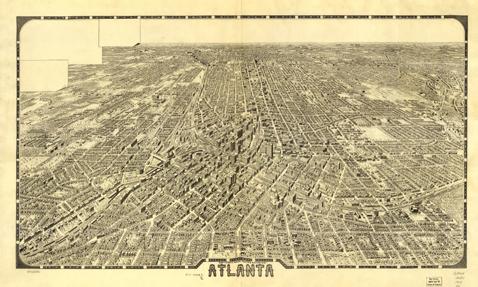

Foote and Davies Company, Atlanta, 1919

11 ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

W. E. B. Du Bois, “Chapter 5: Of the Wings of Atalanta,” The Souls of Black Folk;EssaysandSketches (Chicago: A. C. McClurg and Co., 1903).

Karen Pooley. “Segregations New Geography: The Atlanta Metro Region, Race, and the Declining Prospects of Upward Mobility,” in SouthernSpaces, April 15, 2015.

Ronald H. Bayor. “Chapter 3 - City Building and Racial Patterns,” in Race andtheShapingofTwentiethCentury Atlanta.Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

Dan Immergluck. RedHotCity:Housing,Race,andExclusioninTwenty-First-CenturyAtlanta. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2022.

Kevin M. Kruse. “Epilogue: The Legacies of White Flight,” in WhiteFlight:AtlantaandtheMakingofModernConservatism. Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2005, p. 259-266.

Krista A. Thompson. “Performing Visibility: Freaknic and the Spatial Politics of Sexuality, Race, and Class in Atlanta,” in TDR: The Drama Review 51:4 (T194) Winter 2007.

Akira Drake Rodriguez. “Introduction” and “Public Housing Developments as Political Opportunity Structures,” in DivergingSpaceofDeviants:ThePolitics ofAtlanta’sPublichHousing. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2021, p. 1-18 and 209-219.

NOTES

1. Grace Kyungwon Hong. “Property,” in KeywordsforAmerican Cultural Studies, edited by Bruce Burgett and Glenn Hendler. NYU Press, 2007, p. 180–83.

2. Akira Drake Rodriguez. ““What is Our City Doing for Us?”: Placing Collective Care into Atlanta’s Post-Public Housing Movements.” Antipode. Vol. 0 No. 0 2022.

3. Brenna Bhandar. “Lost property: The continuing violence of improvement.” Architectural Review. October 8 2020. https:// www.architectural-review.com/ essays/lost-property-the-continuing-violence-of-improvement.

4. Tina M. Campt. “Constellations of Freedom: Assembly, Reflection, and Repose,” in In Search of African American Space:RedressingRacism, edited by Jeffrey Hogrefe, Scott Ruff, Carrie Eastman, Ashley Simone. Lars Muller Publishers, September 29 2020, p. 12-17.

5. Gabriel Cuéllar, Athrah Mufreh. “Virtues of Proximity: The Coordinated Spatial Action of Community Land Trusts.” Footprint. May 31 2022. Vol. 15 No. 2, 2021, p.23-44, https://doi. org/10.7480/footprint.15.2.

6. Amrita Dhallu. “To Build Otherwise,” in Lubaina Himid, edited

by Michael Wellen. London: Tate Publishing, 2021, p. 40–61.

7. Keller Easterling. “Other Than “The City”.” Public Culture [forthcoming].

8. Saidiya Hartman. “The Anarchy of Colored Girls,” in WaywardLives,BeautifulExperiments:IntimateHistories ofSocialUpheavals. New York: WW. Norton & Company, 2019, p. 465-490.

9. Carla Shedd. “The Universal Carceral Apparatus,” in Unequal city:Race,schools,andperceptionsofinjustice. Russell Sage Foundation, 2015, p. 80–119.

10. Zadie Smith. “Toyin Ojih Odutola’s Visions of Power.” The New Yorker. August 10 2020. https://www.newyorker. com/magazine/2020/08/17/ toyin-ojih-odutolas-visions-of-power

11. Vanessa Watts. “Indigenous Place-Thought and Agency Amongst Humans and Non-humans (First Woman and Sky Woman Go on a European World Tour!).” Decolonization:Indigeneity,Education&Society. May 4 2013. Vol 2. No. 1, p. 20–34.

12. Mabel O. Wilson. “Mine Not Yours.” Dimensions of Citizenship, e-flux Architecture, July 4 2018. https://www.e-flux.com/ architecture/di-men

Latto, Photograph by Eric Hart Jr. for Rolling stone, 2022.

12 FALL 2022

sions-of-citizenship/178292/ mine-not-yours/

13. Sylvia Wynter. “1492: A New World View,” in Race,discourse, andtheoriginoftheAmericas:A new world view, edited by Hyatt, Vera Lawrence, Nettleford, Rex M. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1995.

14. K. Wayne Yang. “Sustainability as Plantation Logic, or, Who Plots an Architecture of Freedom?” Settler Colonial Present, e-flux architecture. October 16 2020. https://www.e-flux. com/architecture/the-settler-colonial-present/353587/ sustainability-as-plantationlog-ic-or-who-plots-an-architecture-of-freedom/

15. Rinaldo Walcott. “Abolition Now: From Prisons to Property,” in OnProperty:Policing,Prisons, and the Call for Abolition. Windsor, Ontario : Biblioasis, 2021.

“A recent investigative report released in February 2018 documented how discriminatory practices in bank lending have not disappeared, despite the fact that the Fair Housing Act of 1968 made many of them illegal. These patterns of discrimination have reemerged in loan allocations that have financed the gentrification of urban neighborhoods around the country.”

— Mabel O. Wilson12

“For it was to be in the context of this generalized challenge that Frantz Fanon would propose, against our present bicentric natural-instinctual and thereby arbitrary model of human behaviors, a new contestatory image of the human.”

— Sylvia Wynter13

“Wynter and McKittrick also imply other definitions of the world plot. A plan. A conspiracy. A drawing. An architecture.”

— K. Wayne Yang14

Two dope boys on a Cadillac: ANDRE 3000 AND BIG BOI in the early days. Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images.

“Ruth Wilson Gilmore has argued that abolition is not about, as so many have claimed, taking away anything; rather, it is concerned with the presence of being—of fully being: the self needs to be present to others beyond itself.”

— Rinaldo Walcott15

13 ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

FALL 2022

EPISODE 01 EPISODE 02 EPISODE

RESEARCH: SAMPLES & SITES

TRANSLATE: SELECT & CATALOG

DESIGN: ARGUMENTS

READING 01

1 — Read, analyze, and present a reading

EPISODE 02

7 — Select, edit, and contribute samples to the Collective Site Catalog

EPISODE 01

2 — Identify and diagram samples & site in groups of two (one group of three)

EPISODE 02

6 — Select, edit, and contribute samples to the Collective Sample Catalog

EPISODE 8 — Using a lottery choose from the

EPISODE 9 — Redesign using samples

EPISODE 02

5 — Inherit samples and sites from another group

EPISODE 02

4 — Transfer your combined samples and sites to another group

EPISODE 02

3 — Using a lottery system, merge with another group to form groups of four (one group of three)

Sample Sample Site 6

14

s

FALL 2022

ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

EPISODE 03 EPISODE 04 EPISODE 05

DESIGN: ARGUMENTS & MODELS

RECONSTRUCT: ITERATE & STUDY

PRESENT: DRAW & MODEL

EPISODE 03

lottery system, choose a site the catalog

EPISODE 03

Redesign this sites samples

READING 02 10 — Read, analyze, and present a reading

EPISODE 04 11 — Iterate and reconstruct the site

EPISODE 05

12 — Present your vision of Atlanta after property

7

15

FRAMING CRITICAL QUESTIONS ON READING LIST:

PROPERTY

Amrita Dhallu, “To Build Otherwise,” in Lubaina Himid, edited by Michael Wellen. London: Tate Publishing, 2021, p. 40–61.

Brenna Bhandar, “Lost property: The continuing violence of improvement.” Architectural Review. October 8 2020.

Carla Shedd, “The Universal Carceral Apparatus,” in Unequal city: Race, schools, and perceptions of injustice. Russell Sage Foundation, 2015, p. 80–119.

Gabriel Cuéllar, Athrah Mufreh, “Virtues of Proximity: The Coordinated Spatial Action of Community Land Trusts.” Footprint. May 31 2022. Vol. 15 No. 2, 2021, p.23-44.

Grace Kyungwon Hong, “Property,” in Keywords for American Cultural Studies, edited by Bruce Burgett and Glenn Hendler. NYU Press, 2007, p. 180–83.

K. Wayne Yang, “Sustainability as Plantation Logic, or, Who Plots an Architecture of Freedom?” Settler Colonial Present, e-flux architecture. October 16 2020.

Keller Easterling, “Other Than “The City”.” Public Culture [forthcoming]

Mabel O. Wilson, “Mine Not Yours.” Dimensions of Citizenship, e-flux Architecture, July 4 2018.

Rinaldo Walcott, “Abolition Now: From Prisons to Property,” in On Property

Saidiya Hartman, “The Anarchy of Colored Girls,” in Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheavals. New York: WW. Norton & Company, 2019, p. 465-490.

Sylvia Wynter, “1492: A New World View,” in Race, discourse, and the origin of the Americas: A new world view, edited by Hyatt, Vera Lawrence, Nettleford, Rex M. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1995.

Tina M. Campt, “Constellations of Freedom: Assembly, Reflection, and Repose,” in In Search of African American Space: Redressing Racism, edited by Jeffrey Hogrefe, Scott Ruff, Carrie Eastman, Ashley Simone. Lars Muller Publishers, September 29 2020, p. 12-17.

Vanessa Watts, “Indigenous Place-Thought and Agency Amongst Humans and Non-humans (First Woman and Sky Woman Go on a European World Tour!).” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society. May 4 2013. Vol 2. No. 1, p. 20–34.

Zadie Smith, “Toyin Ojih Odutola’s Visions of Power,” The New Yorker, August 10, 2020.

Mabel O. Wilson, “Mine Not Yours.”

Harwell Hamilton Harris, Weston Havens House, Berkeley, 1940. Photo: Maynard L. Parker. The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

Zadie Smith, “Toyin Ojih Odutola’s Visions of Power”

Mabel O. Wilson, “Mine Not Yours.”

Harwell Hamilton Harris, Weston Havens House, Berkeley, 1940. Photo: Maynard L. Parker. The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

Zadie Smith, “Toyin Ojih Odutola’s Visions of Power”

16 FALL 2022

Brenna Bhandar, “Lost Property,” 2020.

AFTER-PROPERTY FRAMING CRITICAL QUESTIONS ON

Arata Isozaki, “Erasing Architecture into the System,” in Re: CP, edited by Hans Ulrich Obrist (Basel, Switzerland: Birkhauser – Publishers for Architecture, 2003), pp. 25-47.

Browne, Simone, “Dark matters: On the surveillance of blackness.”

Catherine R. Squires, “Rethinking the Black Public Sphere: An Alternative Vocabulary for Multiple Public Spheres, Communication Theory,” Volume 12, Issue 4, 1 November 2002, Pages 446–468

Christina Diaz Moreno and Efren Garcia Grinda, “Everyday Delights,” (A conversation with Anne Lacaton & Jean Philippe Vassal) Nd “Lacaton & Vassal [Post-Media Horizon].” In El Croquis 177+178 (2015), 5 – 31.

Elleza Kelley, “No Man’s Land: The Architecture of Abolition,” in Imagination and theCarceral State, edited by Joshua Benne, Cabinet (8 December 2020)

Elleza Kelley, “Follow the Tree Flowers’”: Fugitive Mapping in Beloved,” in Antipode: A Radical Journal of Geography (2020)

Erica Avrami, “Toward Equitable Communities: Historic Preservation in Community Development: An Interview with Maria Rosario Jackson.” Preservation and Social Inclusion, Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, New York, NY, 2020, pp. 245–249.

Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, “Planning and Policy,” in The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study, (New York: Minor Compositions, 2013) pp. 70 –84.

Guy Debord, “The Decline and Fall of the Spectacle Commodity (1965),” Situationist International Archive, https://www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/si/decline.html

Harry Garuba, “Explorations in Animist Materialism: Notes on Reading/Writing African Literature, Culture, and Society,” in Public Culture Volume 15.2 (Duke University Press, 2003), 261 – 285.

June Meyer, “Instant Slum Clearance,” in Esquire. Vol. 63, no. 4, whole no. 377 (Apr.1965), pp. 108-111.

Mariame Kaba, “We Do This ‘Til We Free Us,” Haymarket Books, 2021.

Rinaldo Walcott, “The Black Aquatic,” liquid blackness, 2021, pp. 63–73.

Spade, Dean, “Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity during This Crisis (and the next).”

Sylvia Wynter, “Novel and History, Plot and Plantation,” in Savacou 5, (1972), pp. 95 – 101.

The Care Collective, “Caring Communities.” The Care Manifesto: The Politics of Interdependence

Beverly Buchanan, Marsh Ruins, Marshes of Glynn

Overlook Park, Brunswick, Georgia, 1981. Elleza Kelly, “No Man’s Land

June Meyer, “Instant Slum Clearance” Skyrise Harlem.

17 ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

ATLANTA

TRIP ITINERARY | OVERVIEW

DAY 01

Midtown Lunch & Walk

Civil Bikes Walking Tour

Beltline Walk to Ponce Street

Market

Studio Dinner

DAY 02

Artist Talk + Studio Visit

High Museum

LOCATIONS & MEETING AND POINTS

DAY 03

Panel Discussion Site Visit with The Guild Team Site Visits

DAY 04

Studio Breakfast + Debrief

GSAPP Departs

ATLANTA HILTON HOTEL

Atlanta Hilton Hotel, 255 Courtland St NE, Atlanta, GA 30303

HIGH MUSEUM

High Museum of Art, 1280 Peachtree St NE, Atlanta, GA 30309

CIVIL BIKES WALKING TOUR

King National Park - Amphitheater 450 Auburn Avenue NE, Atlanta, GA 30312

ARTIST STUDIO : YANIQUE NORMAN

Westview Studios, Suite 302, 1450 Ralph David Abernathy Blvd Atlanta, GA 30310

PANEL DISCUSSION

Haugabrooks, 364 Auburn Ave NE, Atlanta, GA 30312

THE GUILD - SITES

1st Project - 918 Dill Ave Sw, Atlanta, Ga

2nd Project - 1187 Ira Street Sw, Atlanta, Ga

18

FALL 2022

ARTIST STUDIO

HIGH MUSEUM

CIVIL BIKES

PONCE ST. MARKET

DOWNTOWN

PANEL DISCUSSION

KROG ST TUNNEL

SW ATLANTA

HILTON HOTEL

HIGH MUSEUM

CIVIL BIKES

PONCE ST. MARKET

DOWNTOWN

PANEL DISCUSSION

KROG ST TUNNEL

SW ATLANTA

HILTON HOTEL

ATLANTA:

Day 01 |Thursday, Oct. 20th, 2022

Midtown Lunch & Walk

Civil Bikes Walking Tour

Directions: Meet at King National Park - Amphitheater 450 Auburn Avenue NE, Atlanta, GA 30312 .

Ponce Street Market: Studio Dinner

John Wesley Dobbs Plaza, Fort St NE and Auburn Ave NE, Atlanta, GA 30312

Through his work as an architect and urban designer, Desmond questions what it truly means for a city such as Atlanta to ‘develop’. “A lot of the preservation and rebuilding efforts in Atlanta are driven by enterpreneurs in the Black community, and the Black Church.”

Nedra Deadwyler Founder, Civil Bikes Historian & Social Worker

“After being in gentrified cities from New York to Seattle, I realized that if we don’t talk about history and place, the very existence and inter-relatability of personal space and the public sphere, we are letting the same thing happen here in Atlanta.

So now we do everything from bike tours to advocacy centered mobility justice, among other issues.

One of the milestones we achieved was the conference ‘Untokening’ in 2012, a space for BIPOC and queer people, people experiencing disability and women to talk about being untokenized. A lot of planning erases us - we’re not even a part of the conversation.”

Rev Bryant, Antoine Graves 522 Auburn Ave NE, Atlanta,

“I don’t want to see Atlanta cessible city that won’t make new residents.”

Colin Delargy Graduate Student: Master Planning + Public Policy,

“Housing is definitely on the focus is on housing production, City, has over the last thirty cally cut its ability to do there are a lot of relationships built, fostered or continued financial actors, and more private sector.”

Desmond Johnson

Architect + Urban Designer

Brittany Williams Community Organizer

20 FALL 2022

Graves House, HDDC, Atlanta, GA 30312

Atlanta become an inacmake room for old and

Leslie Spencer

Atlanta-based Historian

Leslie’s work in uncovering and documenting the history of Atlanta is essential to understand how Black life has unfolded in the city - from birth to death, everyday domesticity, and the creation of Black wealth in times of deep racial divide and discrimination.

Master of City and Regional Policy, Georgia Tech

on the City’s agendaproduction, but the thirty years, systemithis. This means that relationships that need to be continued with developers, more stakeholders in the

21 ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

Thursday October 20, 2022

The Atlanta studio’s sojourn begins at the Martin Luther King Memorial. We begin to imagine what is thought to be the unimaginable, just as King did in this very spot.

A walking tour with Nedra of Civil Bikes traces the seam of the Old Fourth Ward and leads into the Beltline. Her stories of Black activism in segregated Atlanta offers a glimpse into the people that shaped this city.

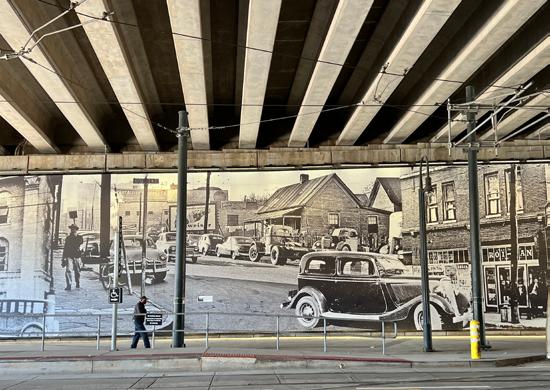

Juxtaposed with its present and future, we walked pass Atlanta’s historical schools, homes, and remnants of its industrial past.

The Beltline is lined with the same combination of old and new buildings. Some are repurposed, some are abandoned to the vagaries of time.

Newly constructed buildings look similar, with stacks of apartments and glass balconies wrapping around their exteriors, in stark contrast to the artfully weathered industrial aesthetic of the refurbished structures.

The Beltline offers no spaces of respite beyond the pressure of commerce or the exclusivity of luxury housing. As a result, everyone strides purposefully, constantly on the move.

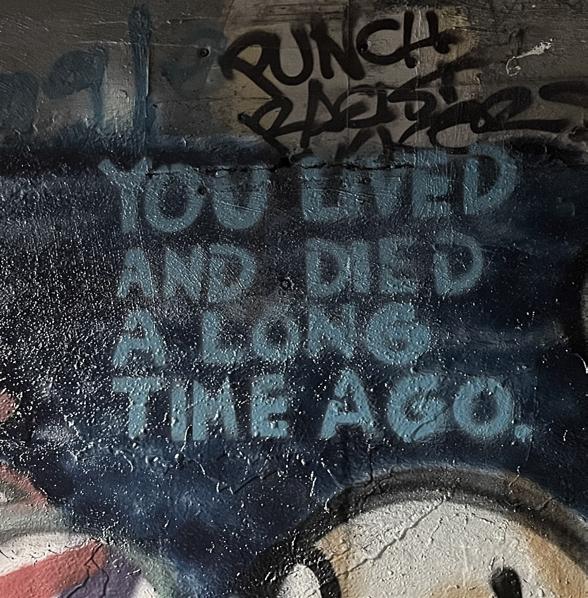

The Beltline displays its fair share of murals and graffiti. Curated art along the metal walls hide new construction, and tagging under the elevated transit corridors.

We met Colin in the shadow of

a high-rise under construction. His perspective on how the city is dealing with the housing crisis is almost drowned out by the din of the construction.

Colin’s words shed light on the necessity for strong partnerships between the city, private stakeholders in real estate, finance, insurance, as well as community organizations for Atlanta’s vision for inclusive housing.

Pondering our conversations with Nedra and Colin, we made our way back to the memorial for another set of enlightening discussions.

22 FALL 2022

We weave our way back through the Old Fourth Ward, tracing paths of Black activists from the decades past - Auburn Avenue, Wheat Street, Jesse Hill Drive, Edgewood Avenue to name a few.

After speaking with Brittany, Desmond and Leslie, we learned about the evolving history of Black Atlanta, the lives of people past, and the ongoing effort to document and represent. Leslie, a walking encyclopedia of names, stories, and dates shared proof of how these histories continue to live on.

The I-75 is a visible marker of a community intentionally divided. The historic YMCA building, and the tree growing within the abandoned Walden Building are a reflection of the social programming that should have thrived under the City’s watch.

We carry these fragments back with us to the Ponce City Market, yet another manifestation of the industrial aesthetic serving as a marker of new developments, a marker of gentrification. Day 1 in Atlanta is a study in contrast.

23 ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

ATLANTA:

DAY 02: Friday, Oct. 21st, 2022

Artist Studio: Yanique Norman

Westview Studios, Suite 302, 1450 Ralph David Abernathy Blvd Atlanta, GA

High Museum of Art:

High Museum of Art, 1280 Peachtree St NE, Atlanta, GA 30309

Panel Discussion

Haugabrooks, 364 Auburn Ave NE, Atlanta, GA 30312

Panelists: Yanique Norman, Dani Brockington, Jasmine Bernet, Sarah Al-Khayyal, Charmaine Minniefield, and LeJuano Varnell

Lauren oversees the African which includes masks and beadwork, metalwork, and As a scholar and curator, she African political and economic through the lens of cultural ining the spatial history of tistic practices within the the Atlantic.

Panel Discussion

The diverse set of panelists share their insight on what Blackness means, reflecting on new ways of thinking and living to shift towards a new found spatial agency.

The conversation delves deep into existing power structures, and raises questions about the possibilities of resisting the regime of neoliberal capitalism from within, by co-opting the tools of the same short-sighted regime. Further dialogue on each site prompts the students to reframe perspectives on Atlanta After Property.

Lauren Tate Baeza Fred and Rita Richman Curator High Museum

Lauren Tate Baeza Fred and Rita Richman Curator High Museum

24 FALL 2022

Yanique Norman

Atlanta-based Artist

“Black fungibility is an alternate ideological dream model” that tethers Black experience with scientific and technological actions of organic transmutation, multiplicity, reproduction, and shapeshifting through installation, sound, video, sculpture, and drawings.”

Curator of African Art, African art collection and sculpture, textiles, and ceramics. she has researched economic phenomena cultural geography, examof food culture and arcontinent and across

25

ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

Friday, Oct 21, 2022

The day starts with an inspiring performative piece on Black Fungibility by artist Yanique Norman. Once a church, her studio space now exhibits different forms of ethereality through the continuous production of radical forms of art.

Yanique takes the students through her process and experiences working with various media. At the center of her work, she questions and reframes what it means to be a Black woman in the American south, particularly

in Atlanta.

Our visit with Yanique is followed by a tour of the High Museum where her work is on display.

The Museum houses works of Atlantan artists who push the boundaries of representation both in terms of what is shown, and how it is shown.

Profound stories lie behind the creation of each piece at the Museum. The curation of each collection a careful, measured composition.

Of particular interest to us is the African Art collection. Curated by Lauren Tate Baeza. It hosts historic ritual objects and stunning sculptural pieces from the African continent, as well as modern artists’ works.

El Anatsui’s Taago entrances us all at once. It’s rigid and malleable, meticulous yet whimsical,

holding deep knowledge in its luminous folds.

Lauren explains some of the intricacies of what it means to curate African Art for the High Museum, and how she plans to steer this narrative going forward.

26 FALL 2022

The Haugabrooks Funeral Home was established in 1929, by Geneva Haugabrooks. It quickly became one of Atlanta’s most successful Black-woman owned businesses, and significantly contributes to Black life in the city by supporting business ventures, Black rights groups and many other philanthropic initiatives.

Today, it is a commercial meeting space and gallery. The panel discussion happens in this hallowed space on Auburn Avenue.

The panel is composed of experts from a diverse array of fields including the performing and visual arts, social activism, urban planning, architecture, and policy

making. Together, they weave a powerful image of Atlanta’s present reality and how we can move towards a radically reimagined city.

Drawing from historic practices of resistance and resilience, they speak of an abolitionist, anti-displacement future based on systemic reparations and progressive tactics to achieve a sustainable, long-term ‘commons.’

They leave us with thoughts of what it means to create restorative systems instead of punitive ones, and the deep significance of working from a sustainable and holistic perspective rooted in mutual trust, instead of a short-term, top-down, solution-based approach.

27 ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

ATLANTA: DAY 03: Saturday, Oct. 22nd, 2022

Site Visit with The Guild

MARTA to site is 28 minutes

1st Project - 918 Dill Ave Sw, Atlanta, Ga, 30310

2nd Project - 1187 Ira Street Sw, Atlanta, Ga, 30310

Team Site Visits

The Guild - Site Visit

Antarkish Tandon

“The idea with each of our projects is that the neighborhood, the stewardhip trust and residents gradually build ownership, and the local economy is strengthened in a stable and sustainable manner.’

A pleasant walk from the Oakland MARTA Station takes us through residential neighborhoods composed largely of single-family homes. Antariksh from The Guild greets us at the first site, a corner building that was once a grocery store. He shares with us the organization’s vision for more equitable and communal forms of ownership, while also pointing out the trials of working towards such a model from within a capitalistic framework.

Devising methods and tools to subvert the regime using the mechanisms of capitalism feels like a an exciting but arduous task. Antariksh fields question after question as we converse our way to a better understanding of this vision of an After-Property. A longtime local resident joins us and is invited to The Guild’s next gathering to learn more about what they can do for his community.

28 FALL 2022

29 ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

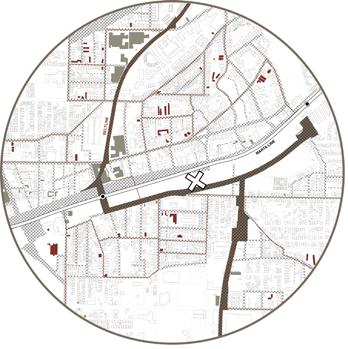

ATLANTA: Day 03 |Team Site

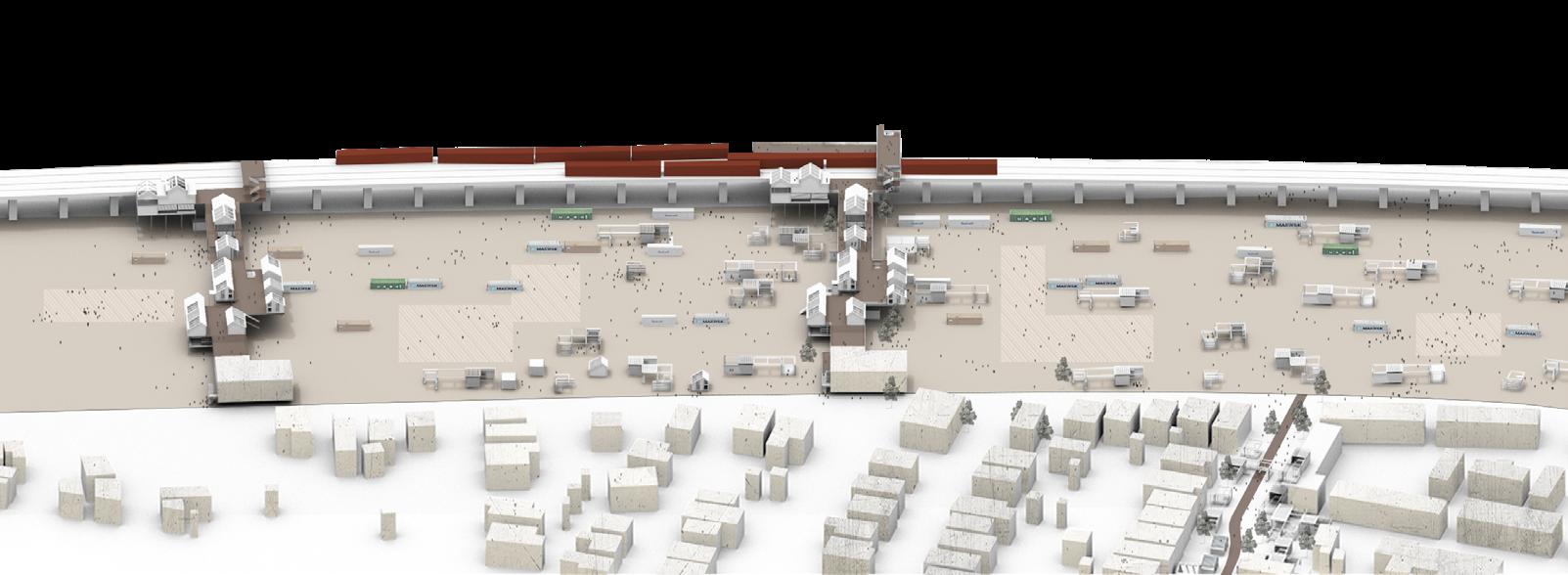

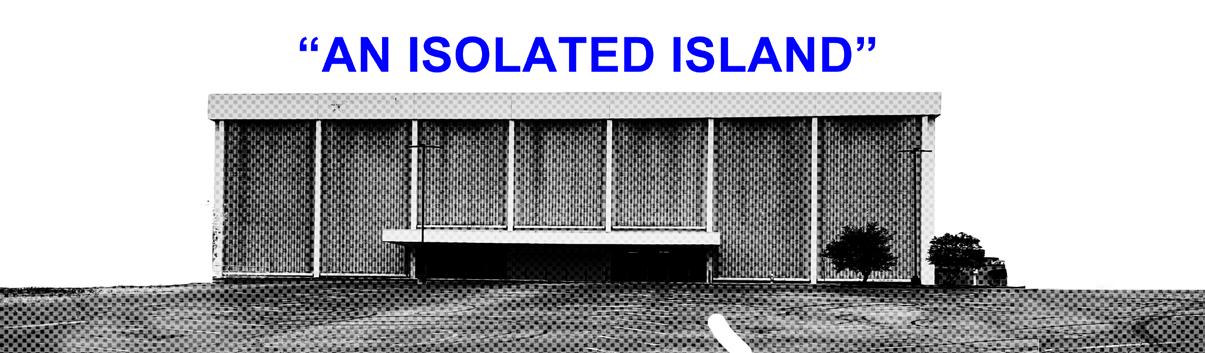

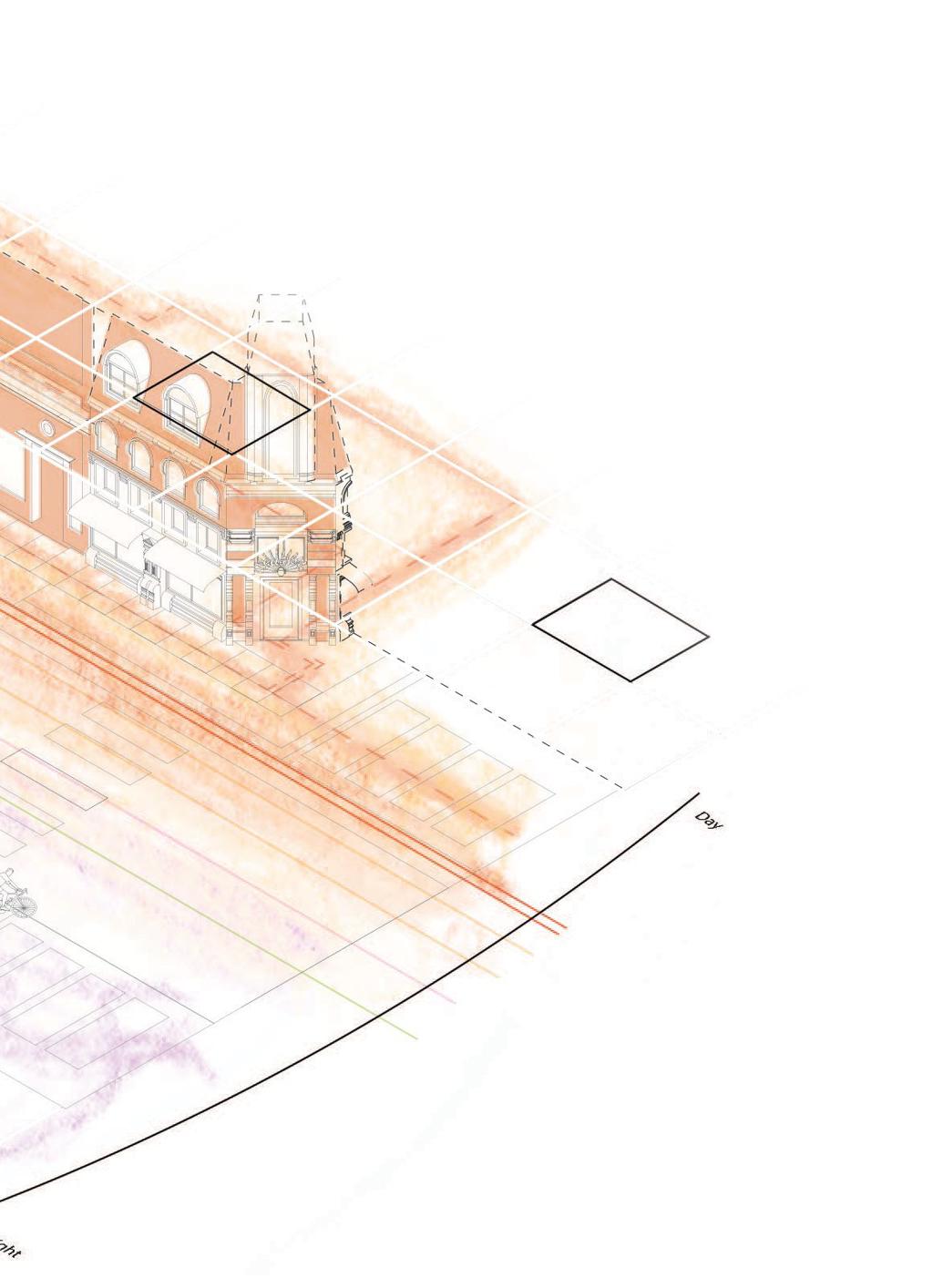

The Peachtree Downtown Center epitomises John Portman’s vision for the city of Atlanta. It is a textbook example of interior urbanism, which separates the district from the rest of the city.

The closure of multiple locations of the Wellstar Health Center is a symptom of Atlanta’s apathy towards holistic and inclusive healthcare, which should be a universal human right.

The Mercedes Benz Stadium is among Atlanta’s most prominent efforts to rebrand the city as a modern destination for sports and a cosmopolitan consumer culture.

Located at the junction of several contending forces of capital, Hulsey Yard is a vast concrete void separating historically intertwined neighborhoods and communities.

02 | Mercedes Benz Stadium 04 | Hulsey Yards 03 |Wellstar Health Center 01 | Peachtree Town Center 30 FALL 2022

Visits:

Peoplestown is where the forces of capital have long taken advantage of poor planning and the ravages of nature, to seize homes and property from the hands of those who can least afford it.

Built upon bonded, inhumane labor, the Chattahoochee Brick Company has witnessed deep injustice meted out upon the enslaved, the incarcerated, and the land itself.

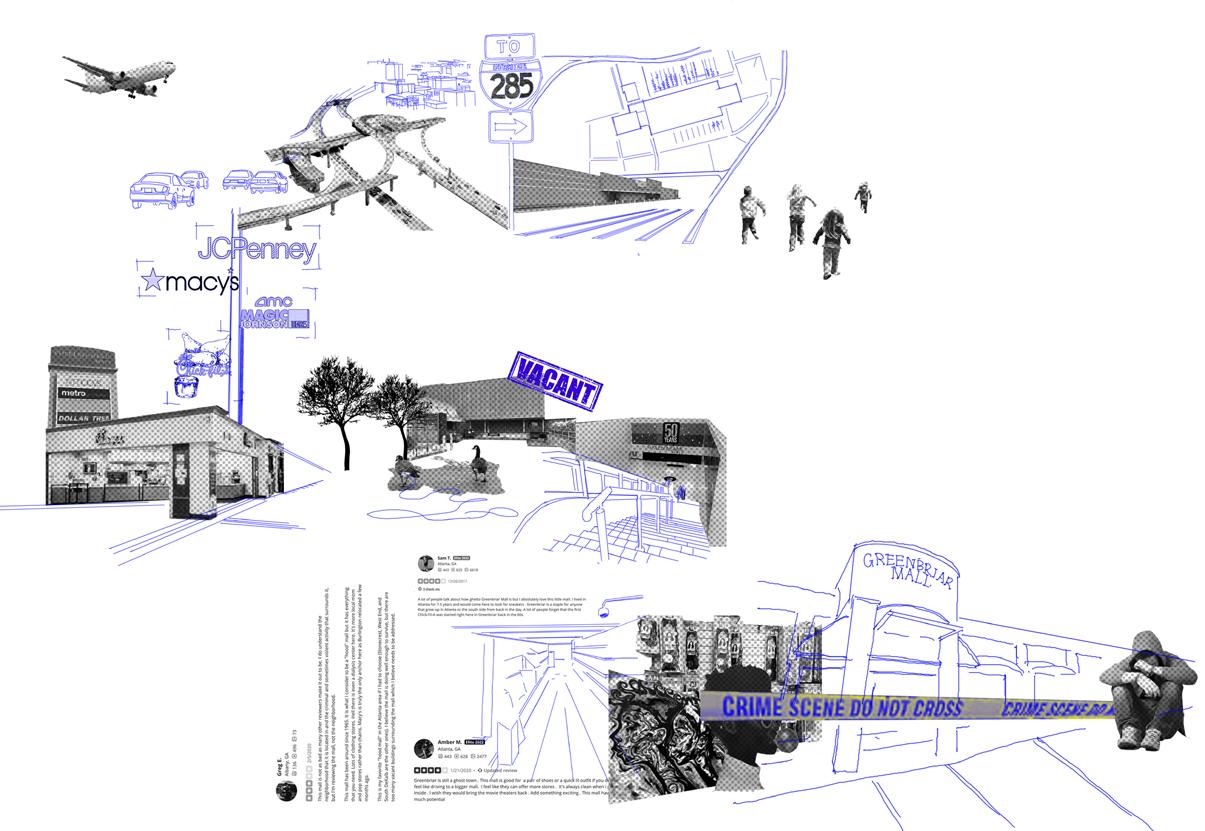

A mall that has long centered community, from its heyday to the present, where it has transcended its role as a shopping destination to become an icon of Black culture in Atlanta.

With the commodification of cultural production in Atlanta, the ‘City in the Forest’ is set to swallow the very forest it is set in a bid to further the city’s brand as a showbiz destination.

06 | Greenbriar Mall 08 | Blackhall Studios 05 | Peoplestown 07 | Chattahoochee Brick Company 31 ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

ATLANTA:

Day 03 |Team Site Visits:

09 | Techwood Homes

The city’s short lived commitment to public housing programming is clearly seen at the Techwood Homes complex, the site of many a broken promise and failed mandate.

11 | Forest Cove Apartments

Abutting one of the city’s numerous carceral complexes, Forest Cove Apartments has a complicated history entangled in policing, incarceration and layered forms of surveillance.

10 | Greenwood Cemetery

Segregation, property and commodity exist beyond even death. The Greenwood Cemetery is a stark reminder of the fact that we live and die within vicious cycles of property.

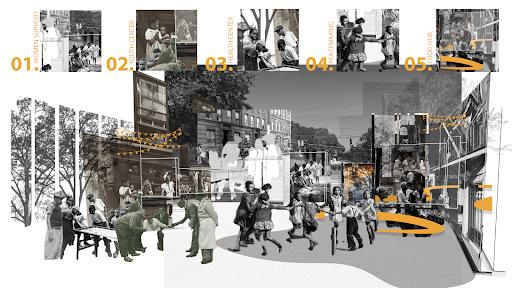

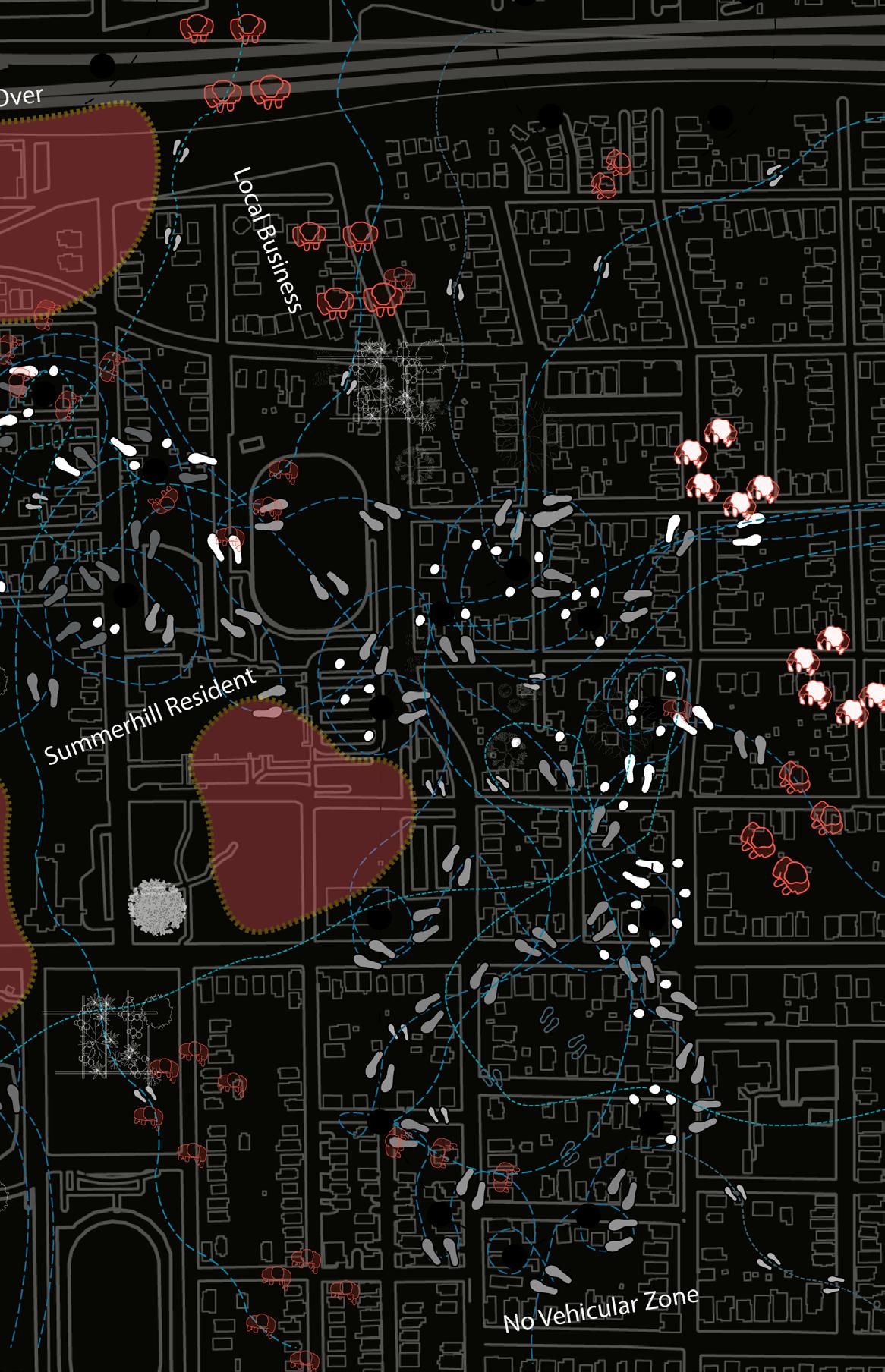

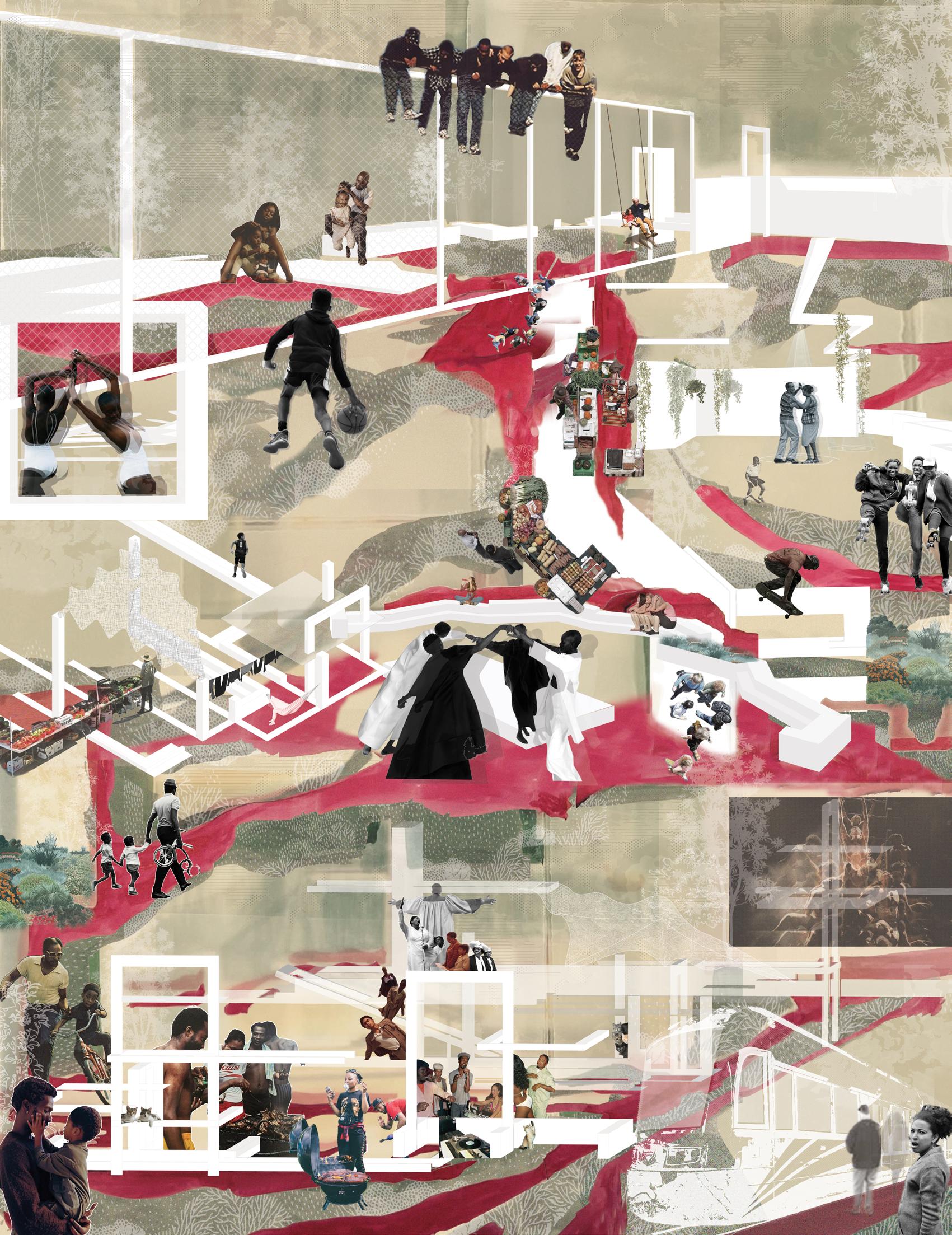

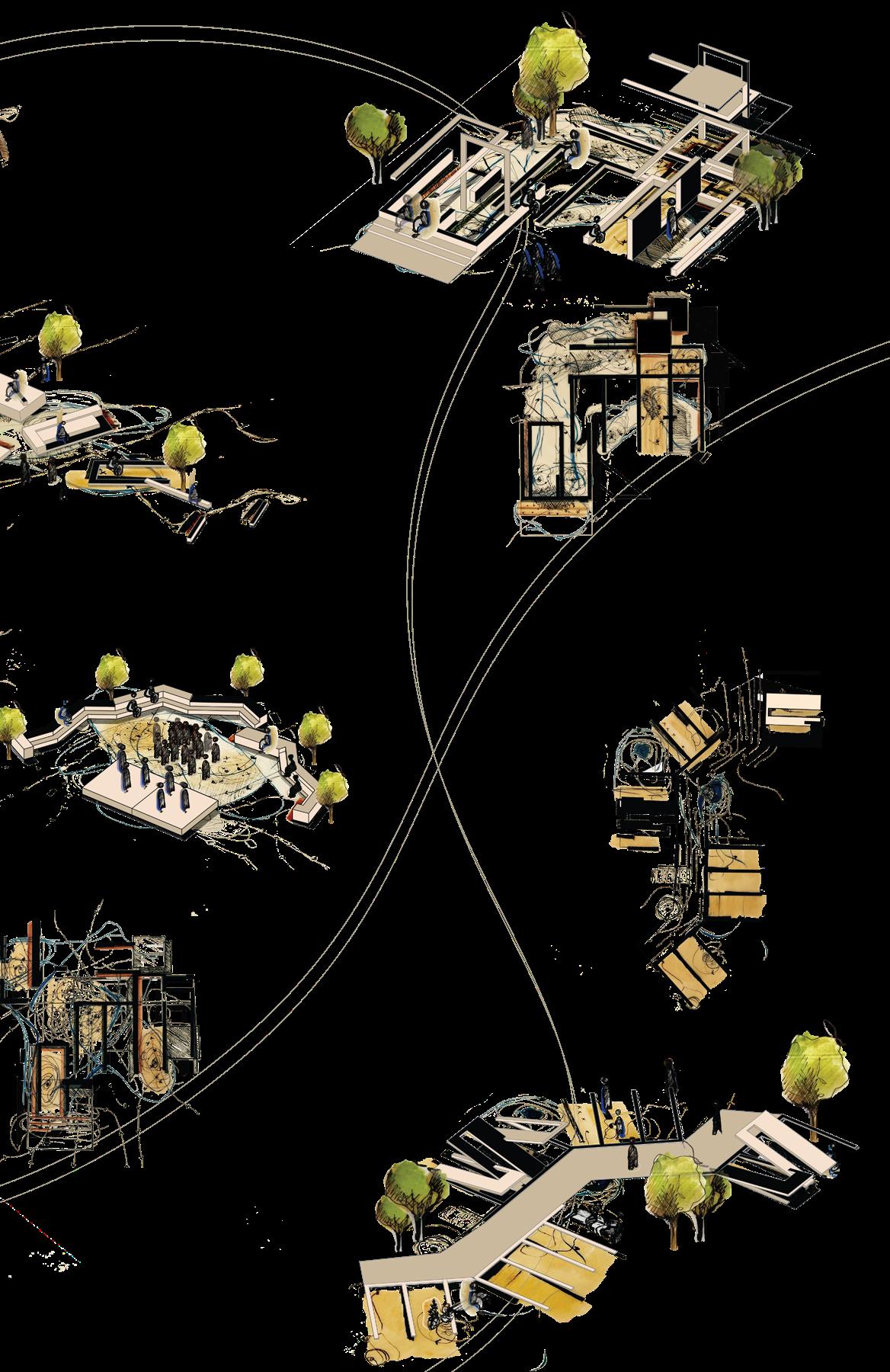

12 | Olympic Stadium, Summerhill

The Olymic Stadium reveals Atlanta’s desire to brand itself a destination for some of the most prominent events in human history at the cost of its own people’s lives and livelihoods.

32 FALL 2022

13 | Downtown Parking

The multiple concrete islands of parking lots and buildings in Downtown Atlanta exhibit one of the most elemental tenets of the property regime where possession is prioritized over people.

33 ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

How can we disentangle urban design and architecture from property?1

How can we use this moment of environmental and institutional reckoning to disassemble the exploitative regimes of speculation and displacement that anchor the built environment?

In other words, where do we go from here?

Our next step is to design a region (with hopes of building a world) that is not tethered to

individual land ownership, but instead, predicated on collective stewardship and care. This work will be done by recognizing ordinary spatial practices that operate against the hegemony of real estate. Through radical reinterpretations of historical and contemporary interventions where the everyday struggle begins to approach the surreal, we aim to liberate urban design from its historical commitment to borderization.3

We will celebrate undervalued spatial practices that actively dismantle the Cartesian frame of racial capitalism, as a gathering of performances committed to imaging a different world, because the status-quo is untenable.

34 FALL 2022

ATLANTA:

DAY 04: Sunday, Oct. 23rd, 2022

ITINERARY:

Studio Breakfast + Debrief

GSAPP Departs

The High - Field Trip!

35

ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

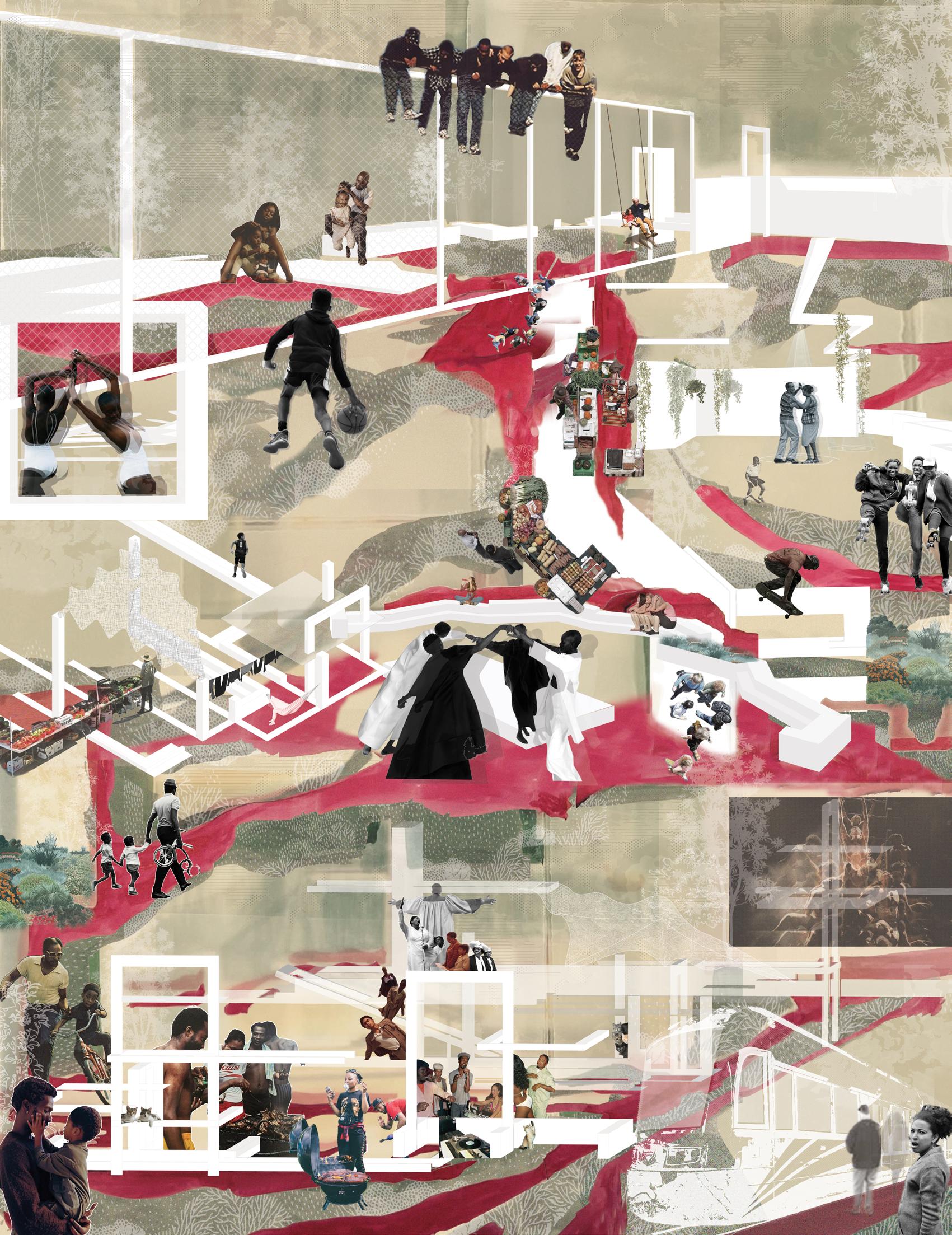

PROJECTS

The final project is an accounting of the research and design decisions that generated each team’s vision of Atlanta after property. The aim is to design a region (with hopes of building a world) that is not tethered to individual land ownership, but instead, predicated on collective stewardship and care. This work is done by recognizing ordinary spatial practices that operate against the hegemony of real estate. Through radical reinterpretations of historical and contemporary interventions where the everyday struggle begins to approach the surreal, we aim to liberate urban design from its historical commitment to borderization.

Atlanta After Property re-frames the discipline of urban design by re-imagining the city of Atlanta in solidarity with contemporary movements of Black liberation and mutuality; working against the ruthless policing, dispossession, and displacement of marginalized communities.

36 FALL 2022

01 Peachtree Town Center 02 Mercedes Benz Stadium 03 Wellstar Atlanta Medical Center 04 Hulsey Yards 05 Peoplestown 06 Greenbriar Mall 07 Chattahoochee Brick Company 08 Blackhall Studios 09 Techwood Homes 10 Greenwood Cemetery 11 Forest Cove Apartments 12 Olympic Stadium 13 Downtown Parking 37 ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

1. To develop an enclave of resistance beyond privatized enclosure working towards mutual aid.

2. To render visible the invisible social ecosystems, peoples and patterns of a place.

3. To dissolve objectivity in favor of dynamic, fluid and a multi-perspective way of seeing.

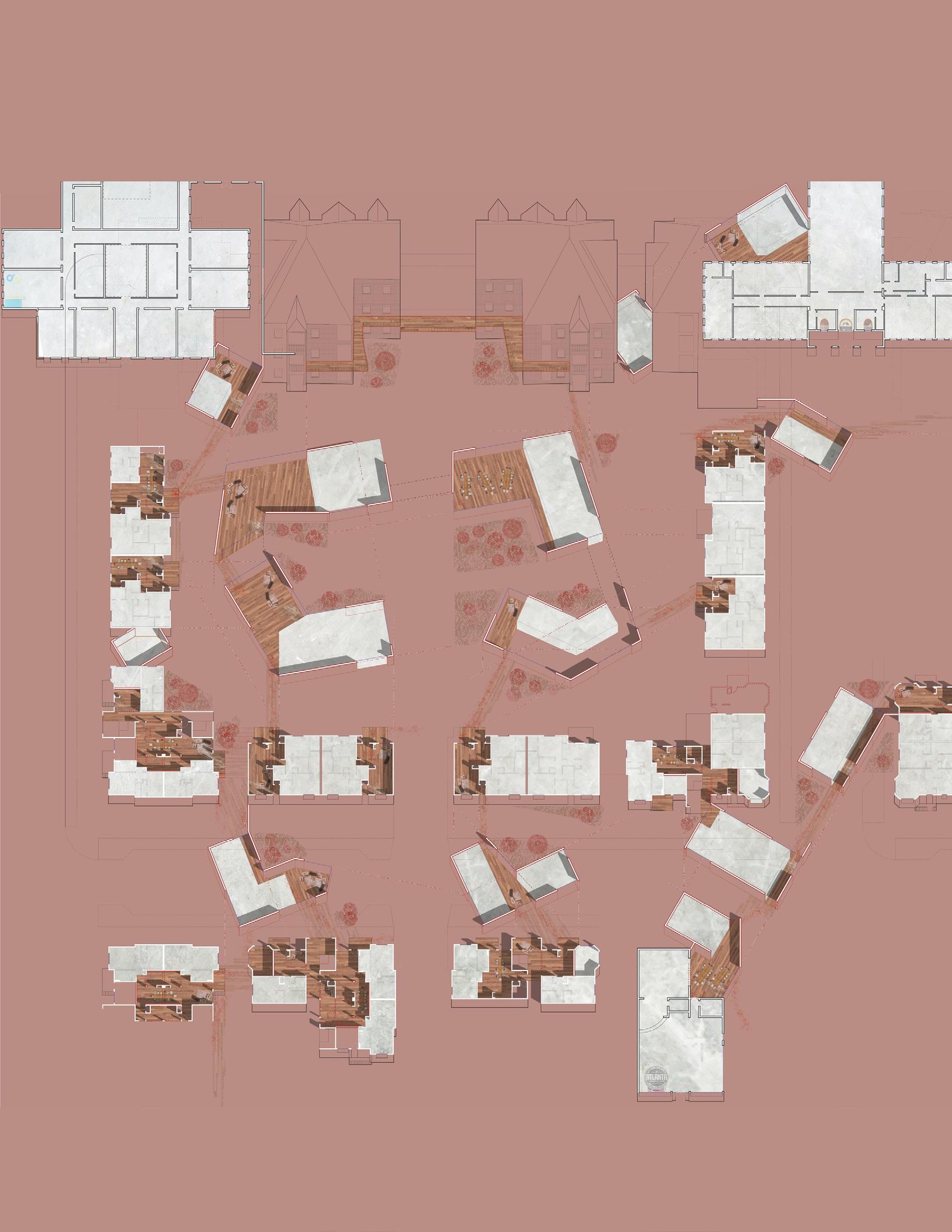

RE-WILDING DOWNTOWN PEACHTREE

PEACHTREE TOWN CENTER

TIPPI

YAOZE YU

MARÍA GABRIELA FLORES

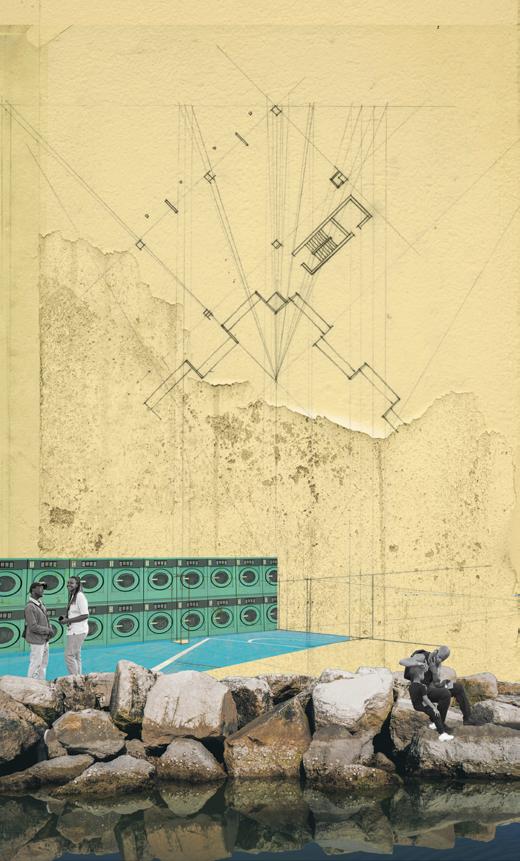

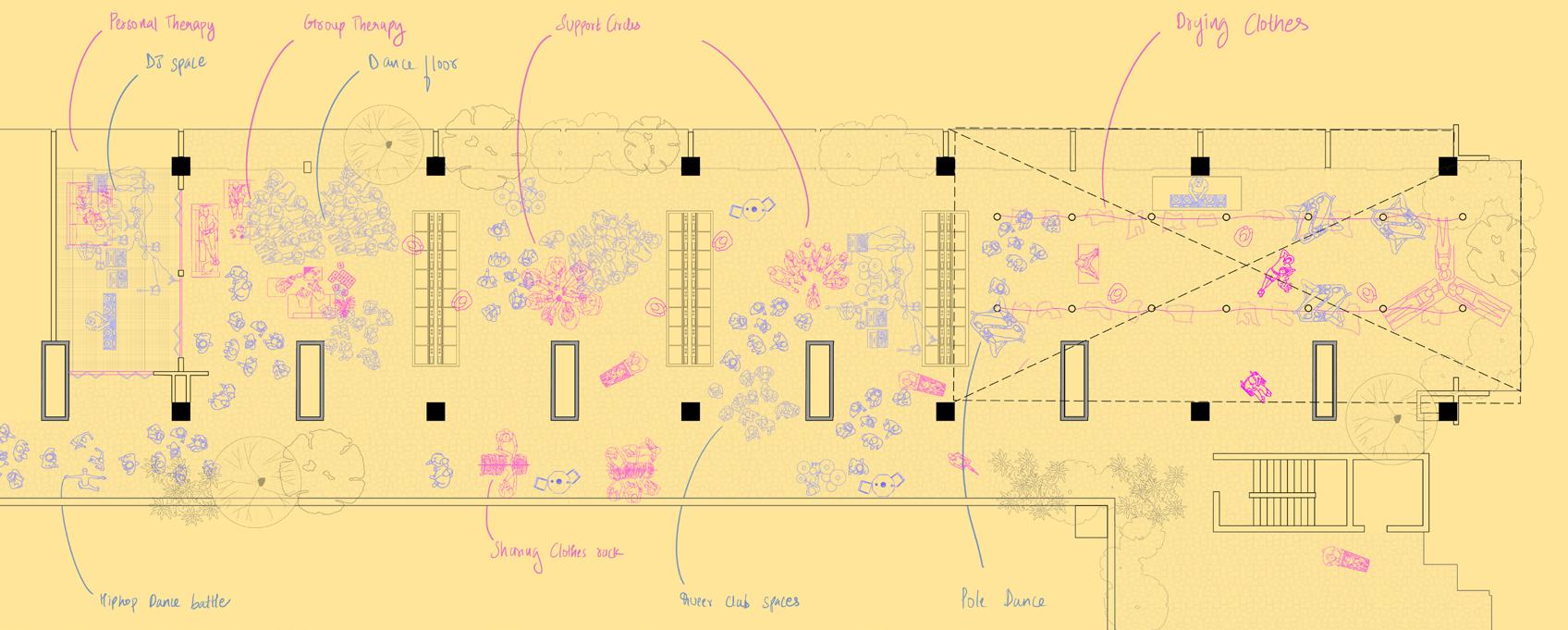

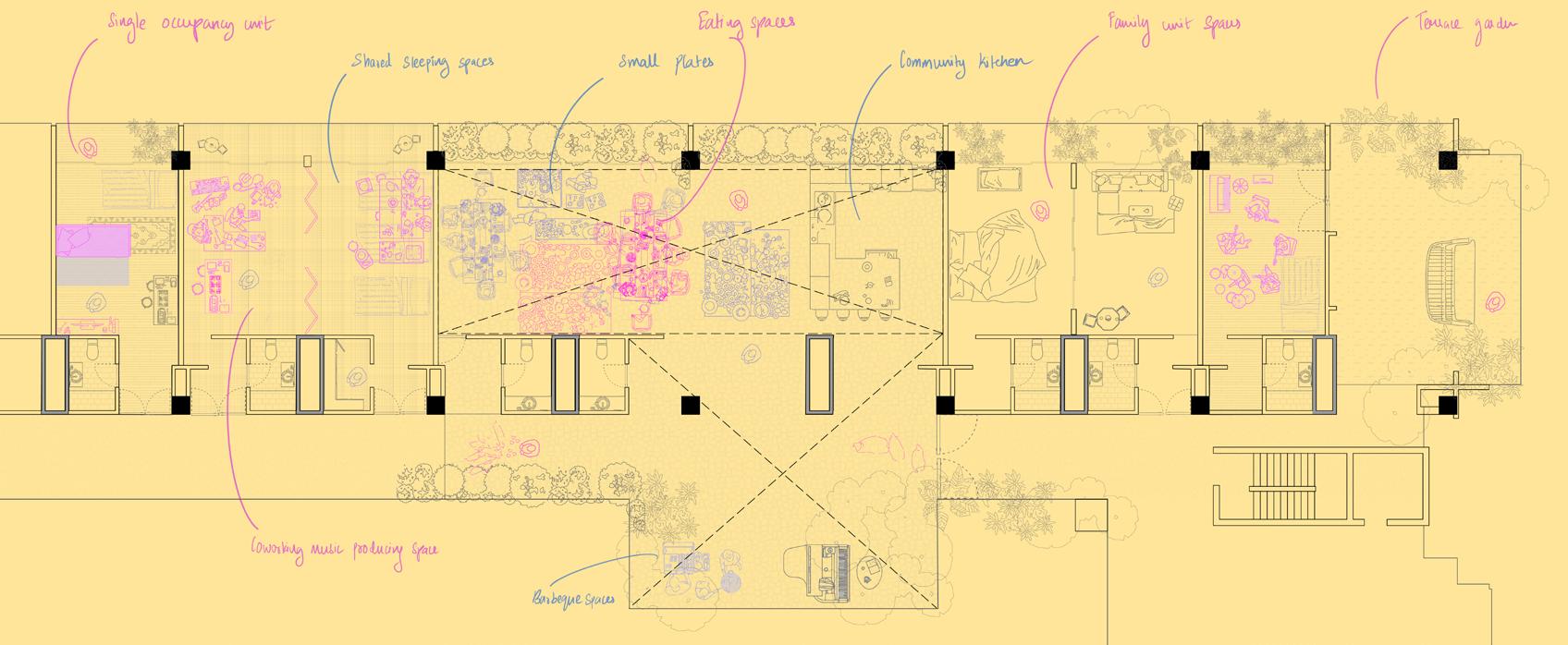

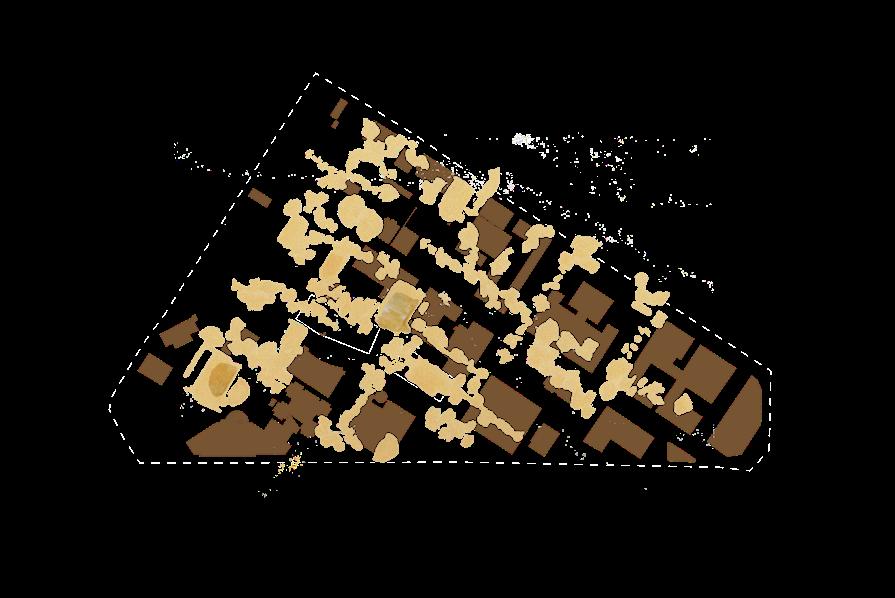

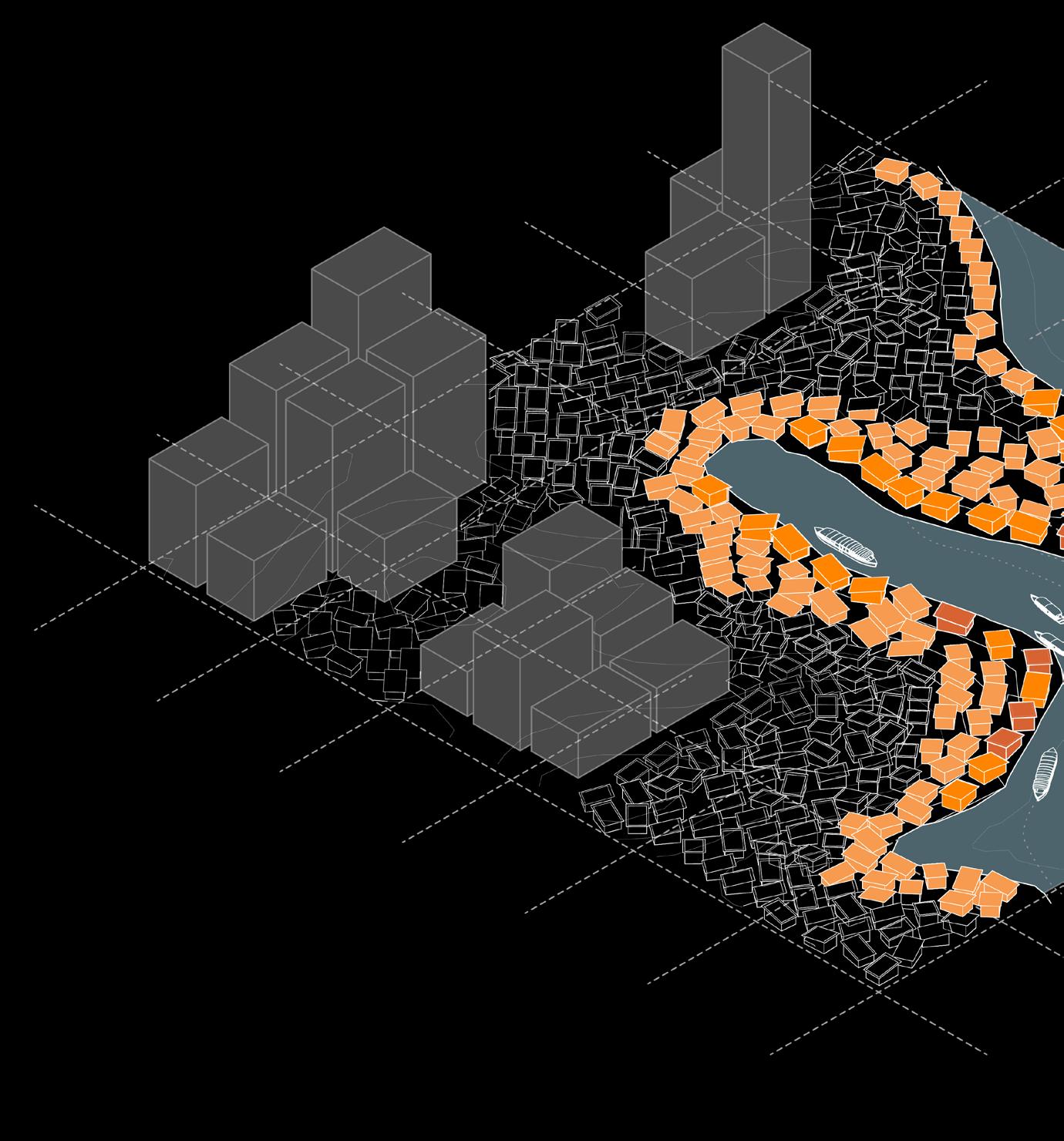

The Downtown Peachtree district sits at the heart of Downtown Atlanta. The large-scale division and dispossession of land alongside typologies of skyscrapers with internal atriums, encapsulate the pervasive forms of property. The legacy of neoliberalism has left future generations with areas such as Downtown Peachtree, which are emblematic of this regime of property, and manifest the relationship between architecture and politics, both involving architecture’s role in the economy, as well as its role as a cultural object.

In its current expression, interior urbanism leaves the city outside. Artificial ecologies are imagined, underserved people are marginalized, and everyday living experiences are suppressed. Individual comfort predominates over collective care.

We envision a future for the interior urbanism of atrium spaces that supplants the oppressive Cartesian regime of property. We reject the current, exclusive, and proprietary building owner and embrace long-term tenure of the land by welcoming the system-

ically overlooked and dispossessed. The unhoused, the housing-insecure, the sex worker, and the student come together in spaces of collective care to re-imagine spaces of transgression, ecology and the senses.

Critical of the current trope of sustainability, we embrace a multi-temporal understanding of spatial relations in order to develop an enclave of resistance beyond privatized enclosure working towards mutual aid. Our aim is to render visible the invisible social ecosystems, peoples and patterns of a place. We position ourselves as the ‘anti-developer’ developers!

Behind the Facade Queering of the City

Non-extraction Sonoran Desert Foraging

HEER SHAH

HUANG

Behind the Facade Queering of the City

Non-extraction Sonoran Desert Foraging

HEER SHAH

HUANG

38 FALL 2022

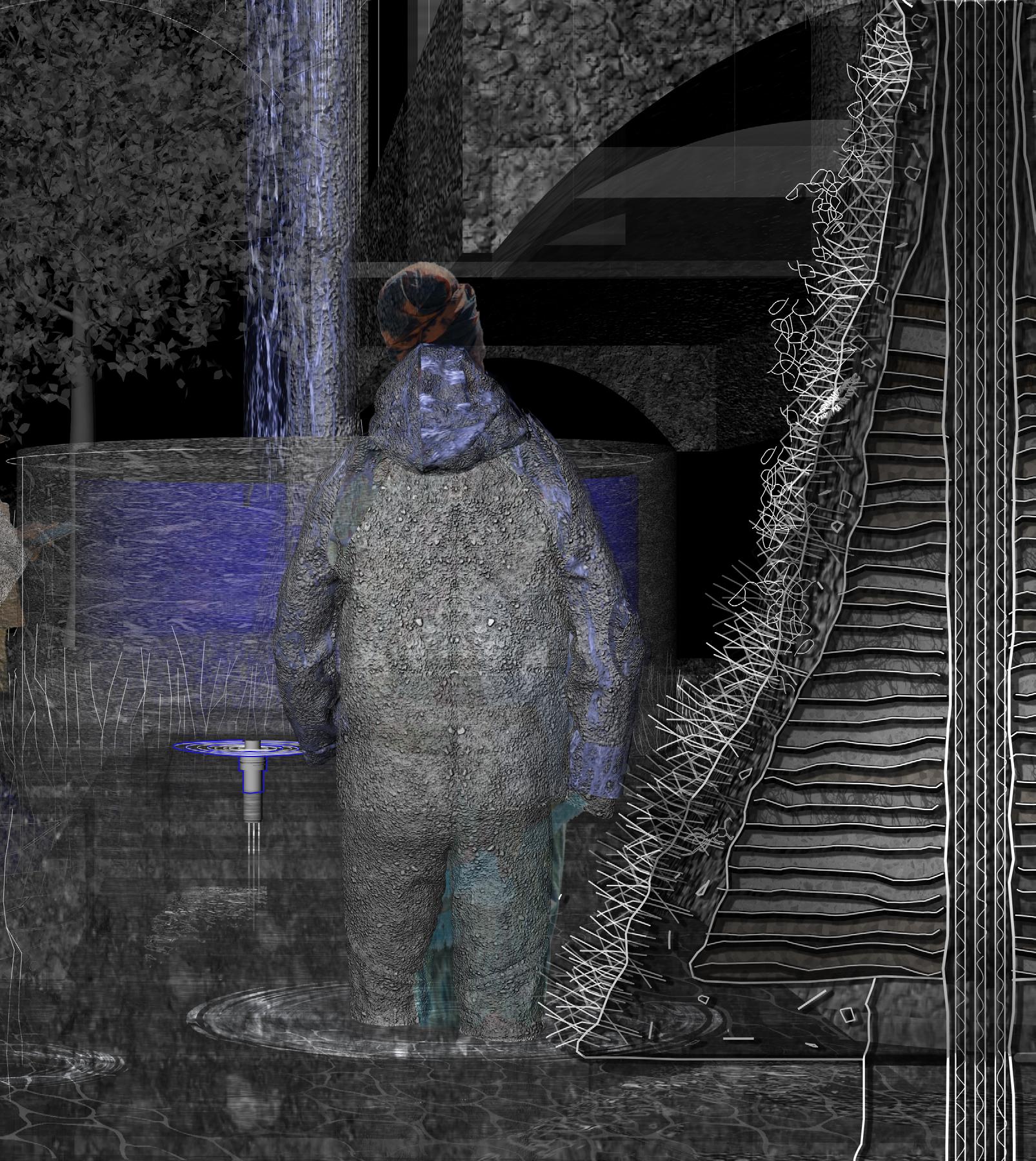

This building can be explored more deeply in terms of carbon output and temperature. The building will start to have a mixture of textures as the users begin occupying the space.

Provocation can be explored in a deeper way between the interior and exterior of the building. We shut off the air conditioning system of the building and start to create comfort across the building by introducing water, vegetation, ceiling fans etc.

In a world after property, we embrace comfort, the existing, the temporal use of activities and let the happenstance of the city into Portman’s top down built environment.

[1] Collaged vision of ecology in Portman’s building

[2] Conceptual scene at night in Portman’s building

[3] Vision of collective care in Portman’s building

[4] Elements occupying Portman’s building

[1] [3] [2] [4] 40 FALL 2022

6F

12F

18F

Plan

Plan

Plan

FALL 2022 Scenarios

42

of Atrium in Portman’s Building

To break up Portman’s current enclosure, we have adopted the concept of foraging. We observe the natural existing conditions and like the foragers find possibility even in the smallest of the things. We identify these elements from across Atlanta. These elements will be used in hotel buildings and exterior street spaces to form new social ecosystems.

We envision the after property of the hotel district through turning off the air conditioner and making it open to the city. For the atrium, we intervened with the ramp and vegetation. The ramp can clearly guide the sequence of public spaces, and the vegetation can make it a natural place with high living-quality.

ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2 43

Conceptual model of simulated atrium intervention.

Temporal Shifts

Wuhan Night Market

Proprietorship will be annexed by partnership.

We are against the dispossession of property and land speculation caused by mass media and the commodity-economy spectacle.

We propose new forms of communal living and ownership through authentic means of production and micro-industries native to Atlanta to encourage active relationships.

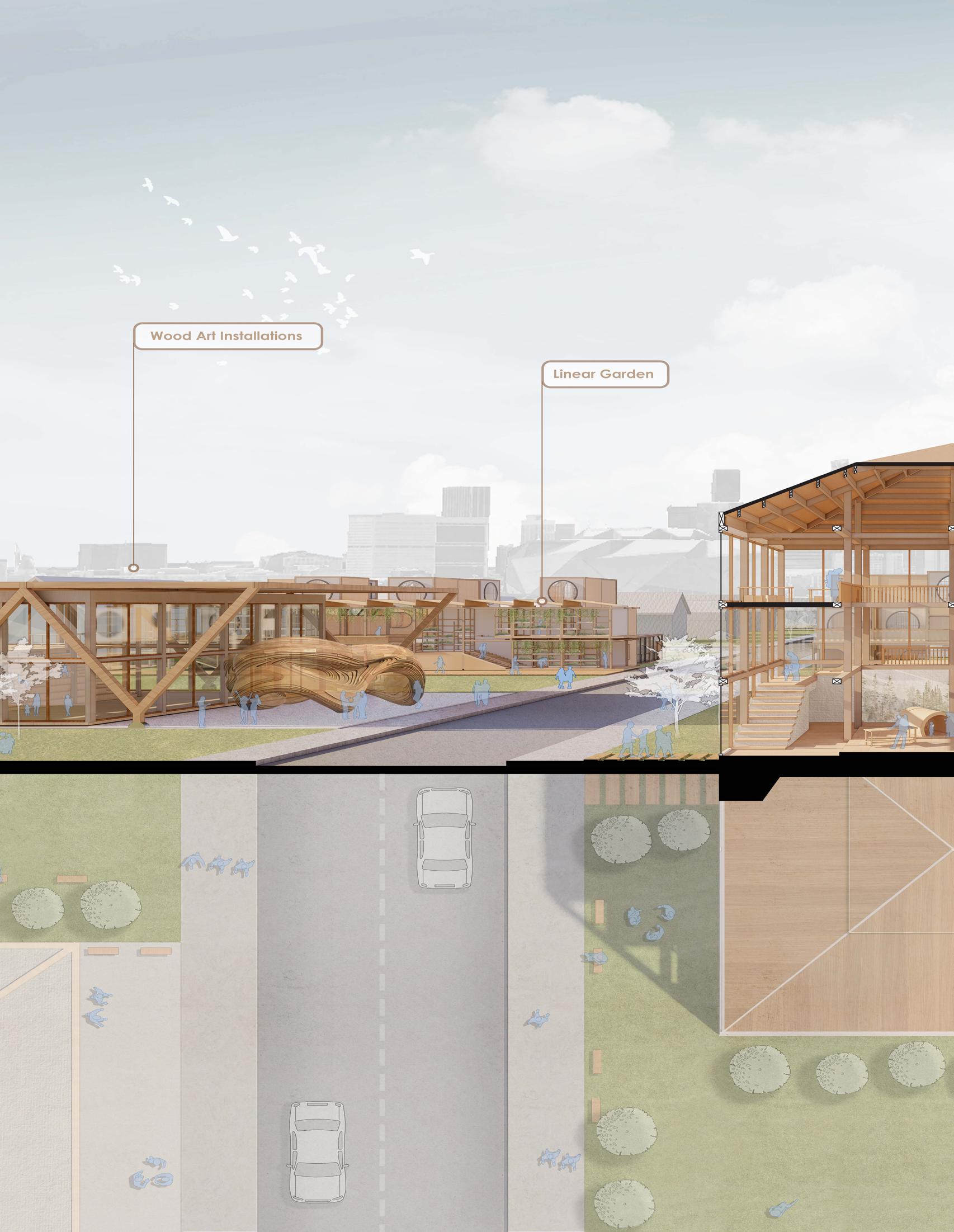

WOOD SPECTACLE

MERCEDES BENZ STADIUM

CHONGYANG REN

RUXUAN ZHENG

JIANI DAI JACQUELINE LIU

We believe that in current society, property is a framework for social, economic, and political rights that are the critical drivers of intergenerational wealth. It is a form of power. Each individual’s social identity is defined by this power hierarchy through ownership in the possession of time and space.

Since the 1960s, sports have caused a new way of land speculation in Atlanta. Atlanta’s political and economic elite have used sports to boost Atlanta’s national/international reputation as a major and modern city, which would help drive the city’s prospects for business and economic growth. Much of Atlanta’s history and culture was sacrificed in the name of the “Sports Spectacle”.

Specifically in downtown, the Mercedes Benz Stadium as a sports spectacle is assimilating surrounding neighborhoods and excluding residents of low

income neighborhoods. Our outlook for a world after property is that property shouldn’t be a vehicle for individualism that translates into an investment vehicle and wealth-generating commodity. Space is not a zero-sum game where one person’s loss is another’s gain, nor is it a resource that only one person must use simultaneously.

“The spectacle is the part of society that gathers all gaze and all focus of consciousness. It is, in fact, fragmented and conveys deceit and false consciousness. ”

——Guy Debord

Reclaiming Fragments Hehuatang, Nanjing

FALL 2022 46

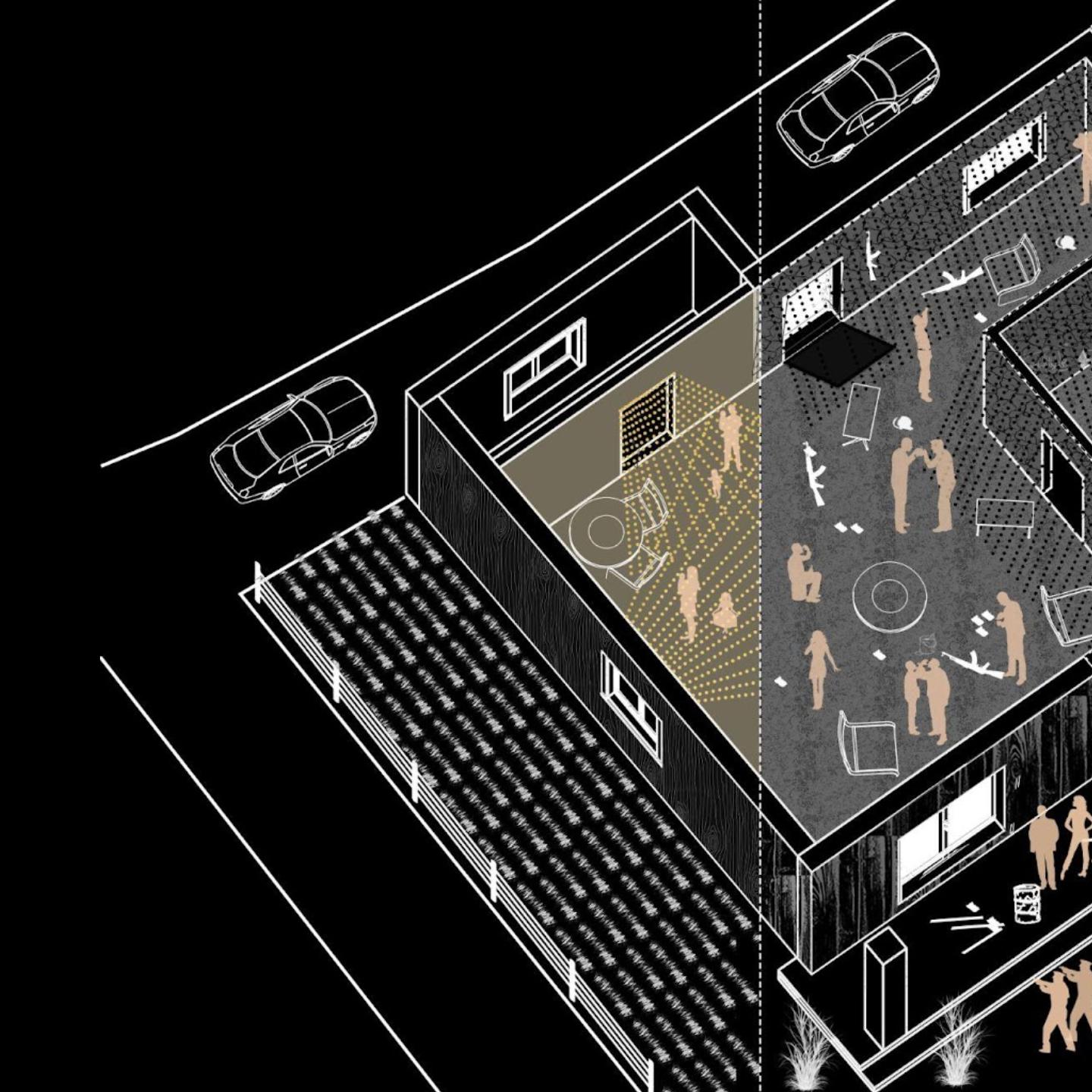

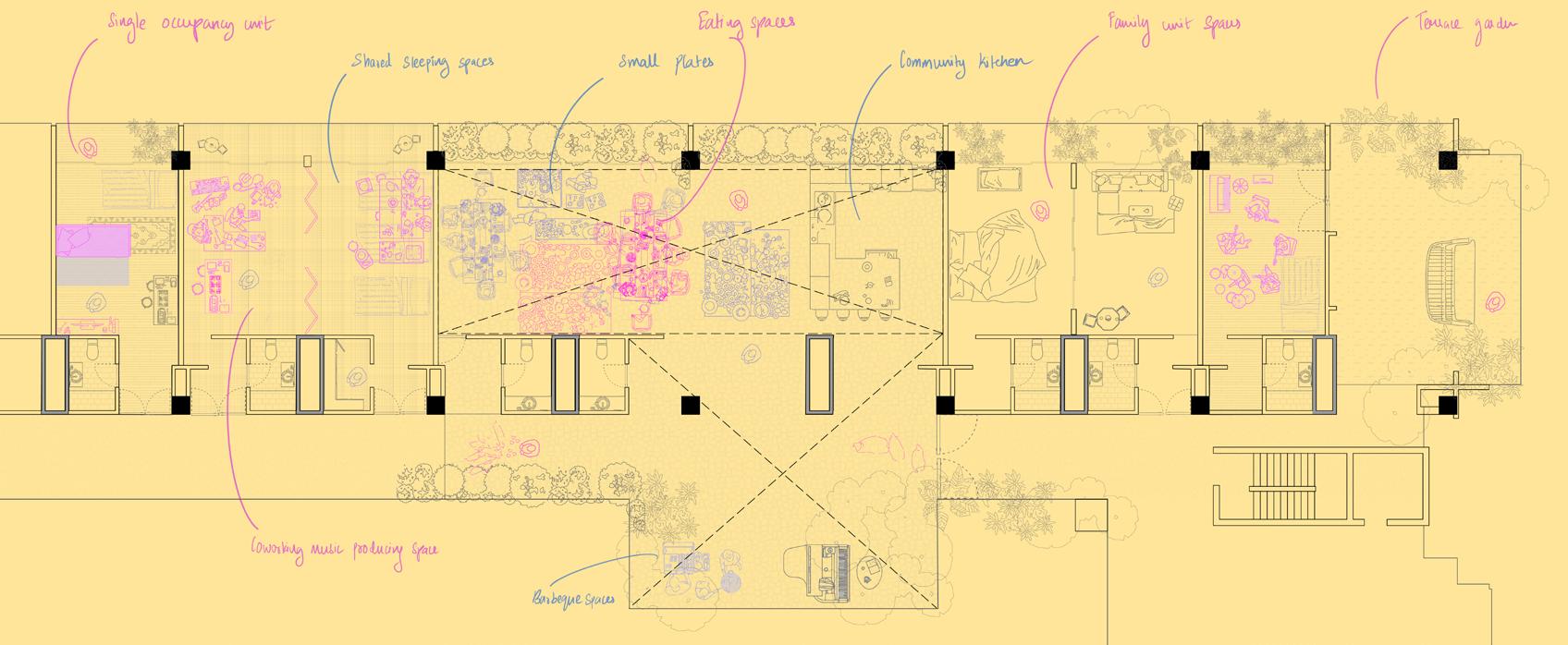

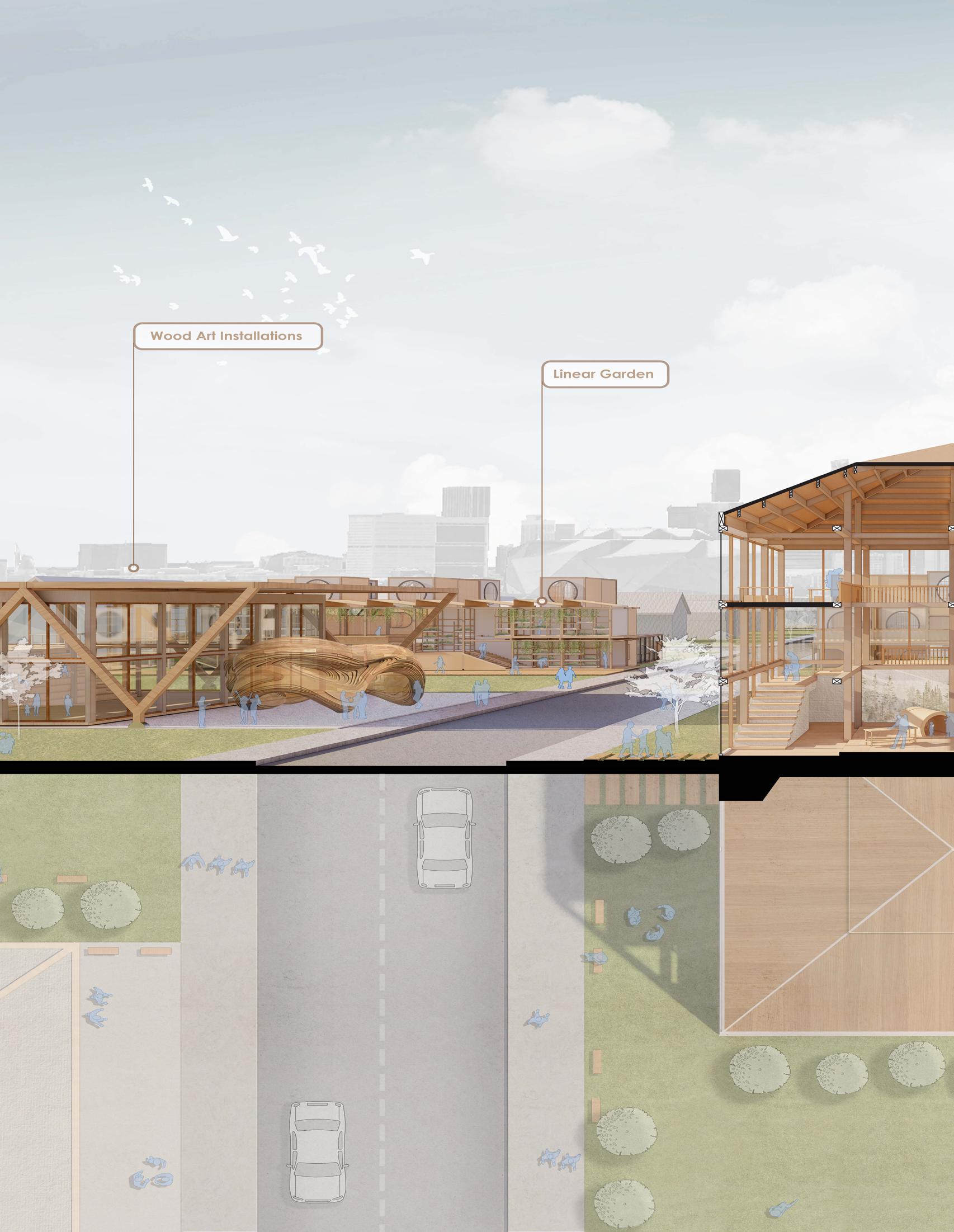

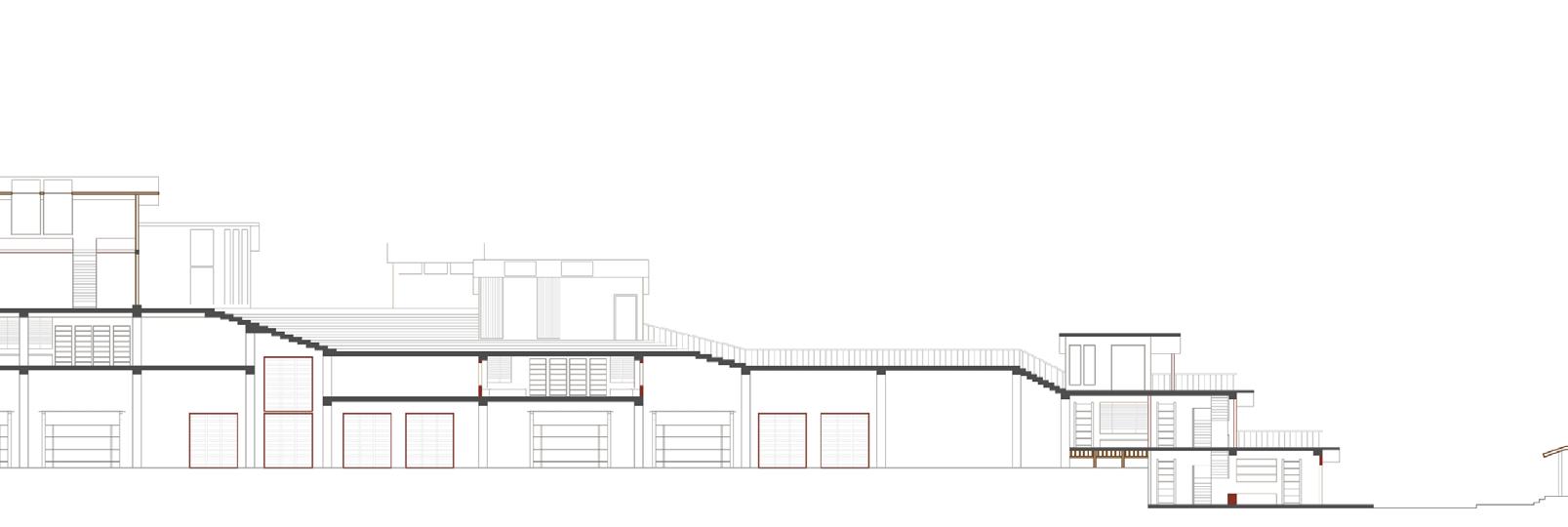

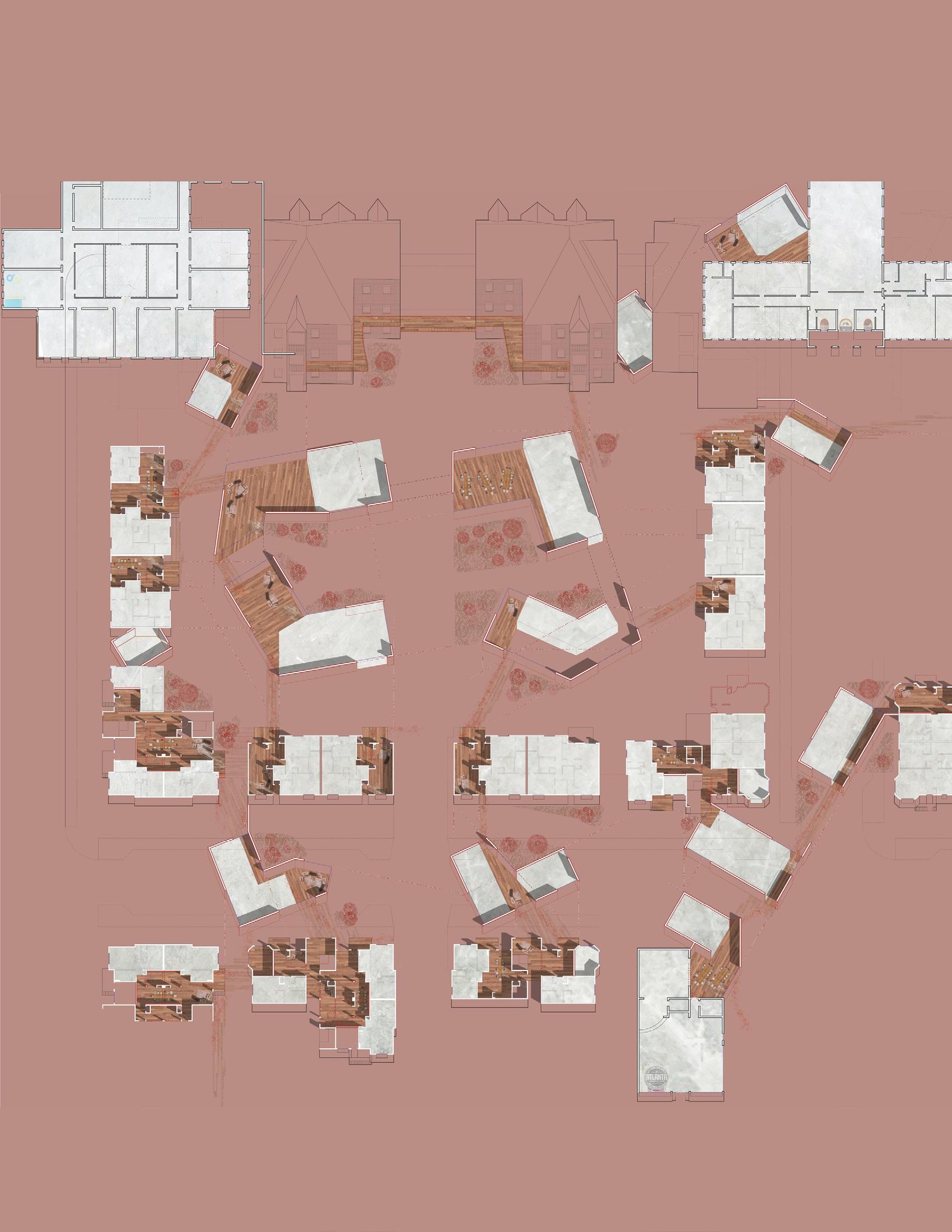

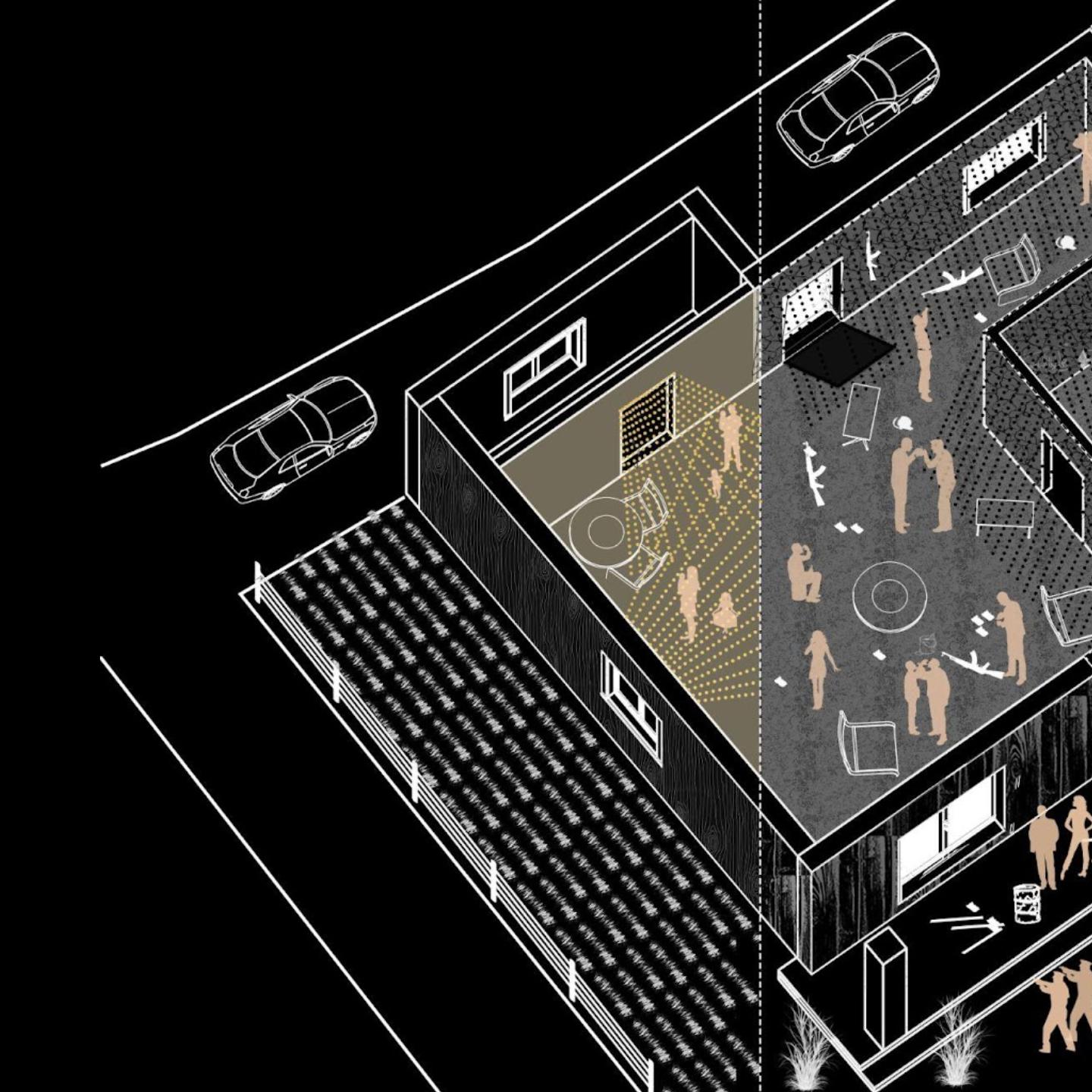

The living space begins with a base module of 12 feet by 12 feet with wooden panels attached to a wooden structure, providing suggestive ways for the living module assembly, whose spatial arrangements and combinations are based on familial structures and their needs.

With the wood shops acting as nodes with continuous circulation within the neighborhood along with the linear shared porches, the Wood City neighborhood is transformed into a skill-share community around themes of wood learning, training, and self-built housing. After assembling the collective living complex, the residents can live and learn together.

48 FALL 2022

49 ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

52 FALL 2022

A welcoming area for different groups of people, combining life, leisure, and wood production. Assembling each collective living complex together, the front porch acts as a linear continuation of the shared space, reinforcing the connection between residents through circulation and wooden functional areas.

53 ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

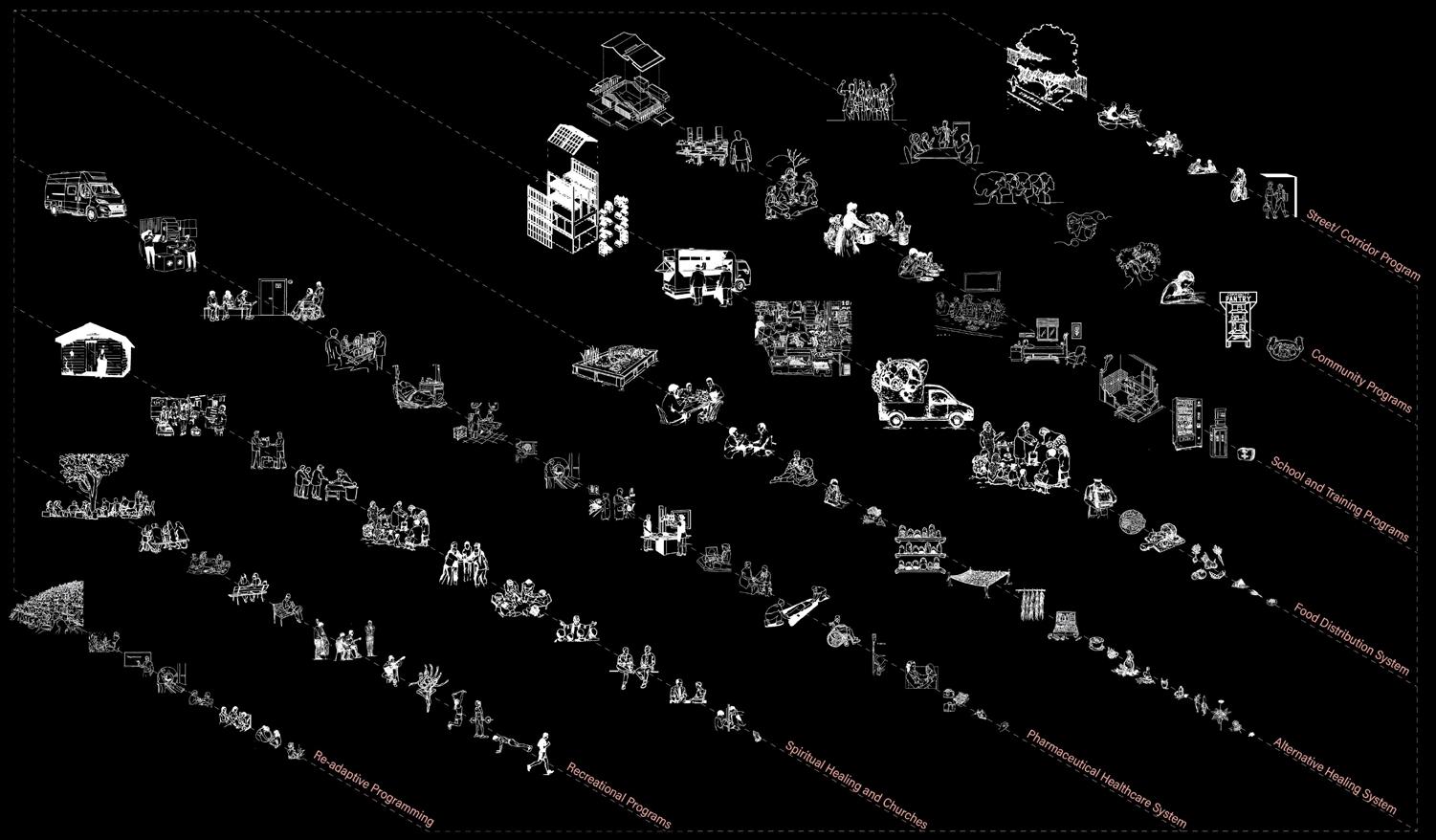

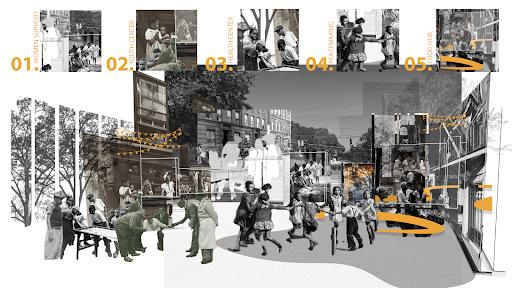

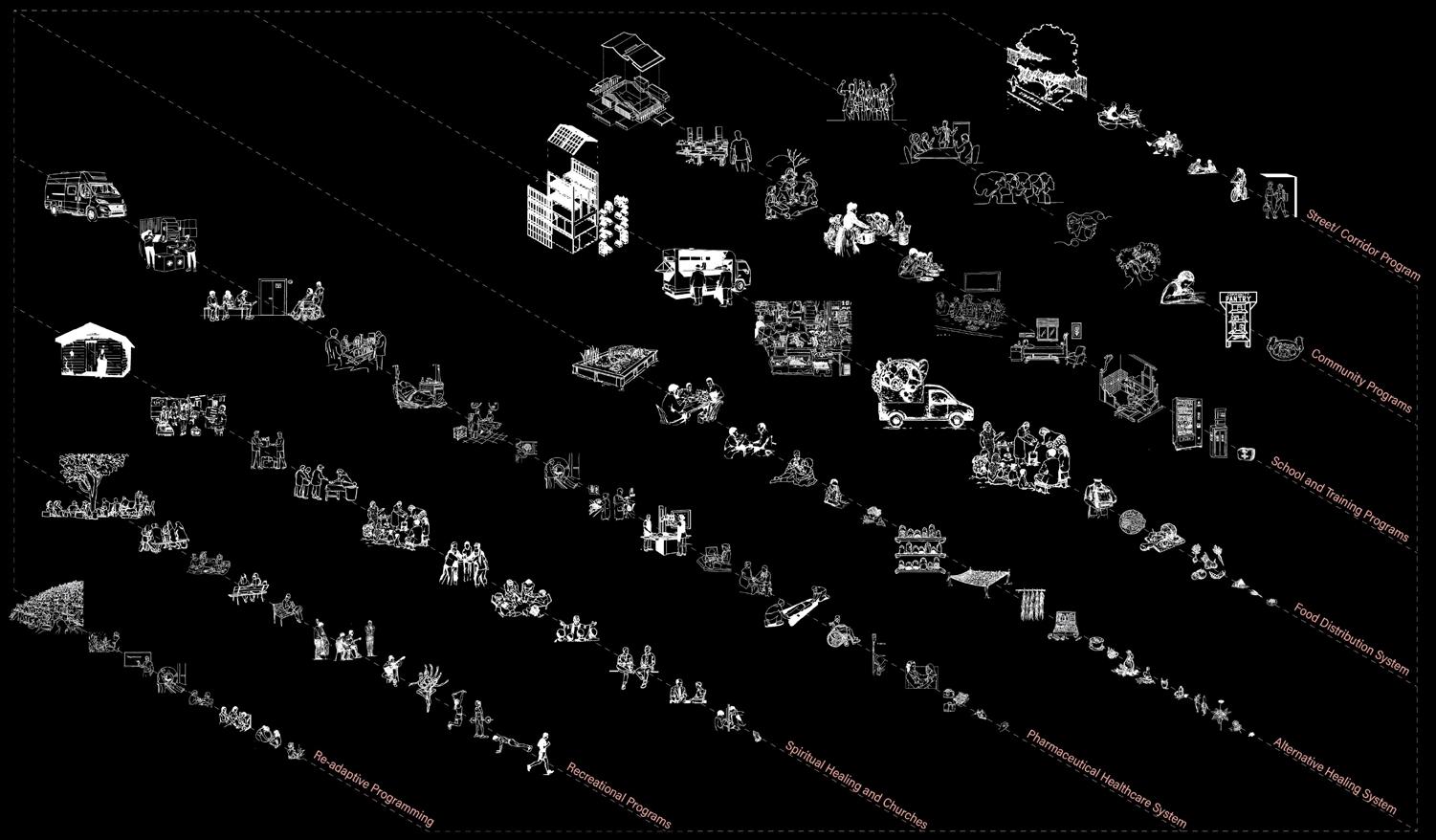

Decentralizing health care occurs by strengthening ties within the community, and putting people in power. Widening the focus not only from equitable treatment across a variety of income-groups, but also promoting interaction, engagement and a healthier lifestyle.

It is by the community, for the community and acts as a visceral layer amongst them.”

The diagram on the right explores a decentralized healthcare system that is rooted around you within existing paradigms of churches, schools, food centers, community programs etc.

HEALTHCARE AFTER PROPERTY

WELLSTAR ATLANTA MEDICAL CENTER

Within the bounds of one’s home, health is a value system. It is in the soup brewed with herbal garnishes, a hot cup of tea with ancestral decoctions (Kaadha) and the raised calls of a loved one when you walk out the door on a windy night, without a scarf.

It is within this care of social communities and the knowledge that generations of ancestors above us partake in, where such a value system exists. But somehow, when this system broadens to the scale of a city, it is devoid of dialogue and tangibility.

Homes become hospitals, people become patients, treatments are limited to syringes, tests or pills and all exchanges are about “Registration,” “Insurance,” and the inevitable, “The doctor will see you soon.”

You move around from department to department, while a series of medical professionals

follow a routine - Blood pressure - Heart beat - Temperature. Inquiries to the sound of “So what brings you in today?” The very same question you will hear repeatedly for the next 24 hours as you wait long hours navigating through the organizational hierarchy that healthcare is today.

The institutional system of treatment restricts basic communal access and a programmatic approach to physical and mental well-being. It puts pressure on one central node, linearly within property, while manifesting the bias of the society it exists in. With a history of every urban system that is privy to segregation, ‘Healthcare within Property’ selectively caters to only a specific population, the rich. And Atlanta is no such exception.

Temporality

Manek Chowk, India

Intimacy

Salmon Toor’s Back Lawn

AASHWITA YADAV ROHIN SIKKA SIMRAN GUPTA NUPUR SHAH

54 FALL 2022

56

[1] [2] 57 ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

58 FALL 2022

[3]

The entire network was split into typologies that were generic to Atlanta. Single-family homes, Apartment complexes, Supermarkets, Churches and Schools. To these we added our lens of care, where residents could engage in healthy eating habits, recreationally express themselves and as a community support the vulnerable.

The other two typologies were built into the fabric, reclaiming dilapidated or vacant buildings as healthcare centers or an urban farm [1] [2] [3]

Recasting the Image of Care: Taxonomy Chart of a Care Network

Acknowledging intimacy in Urban Scale Healthcare

The neighborhood layout of the healthcare network, as seen with transportation and various scales of intervention.

59 ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

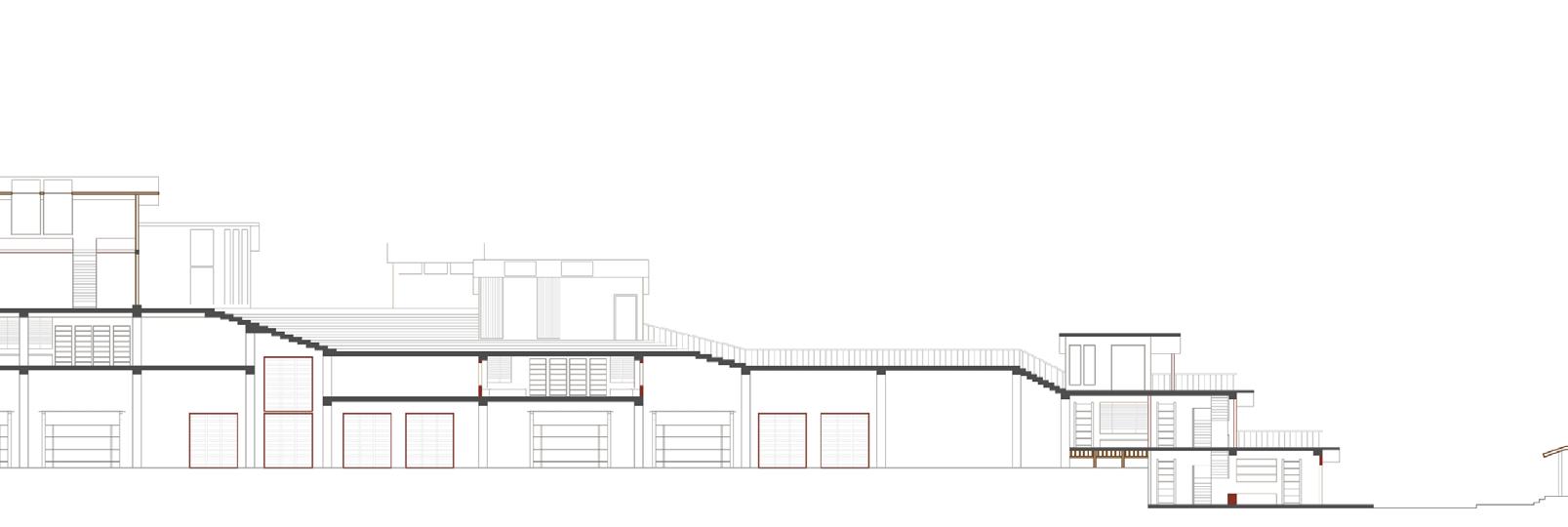

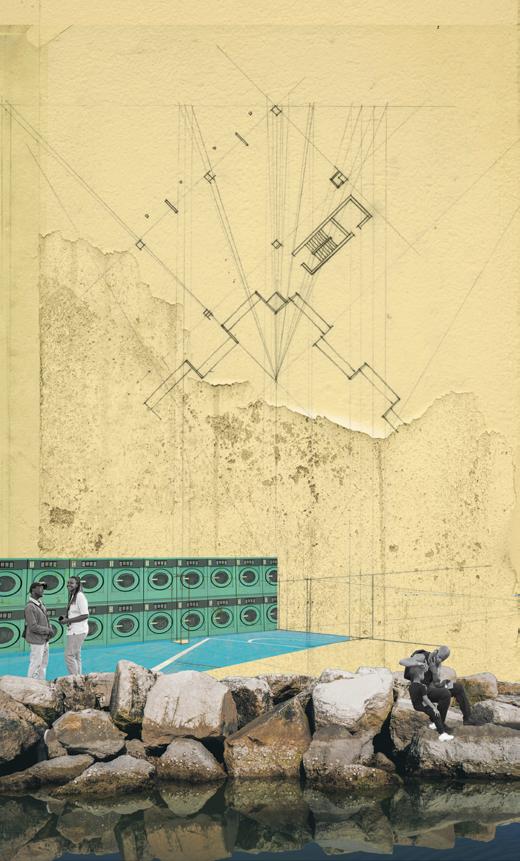

After property strips all notions of value from speculation, hoarding and exclusionary forces. It is based on community, collaboration and every human being’s inviolable right to shared knowledge, resources and opportunities. This world is realized through the very tools that the regime of property shaped for itself.

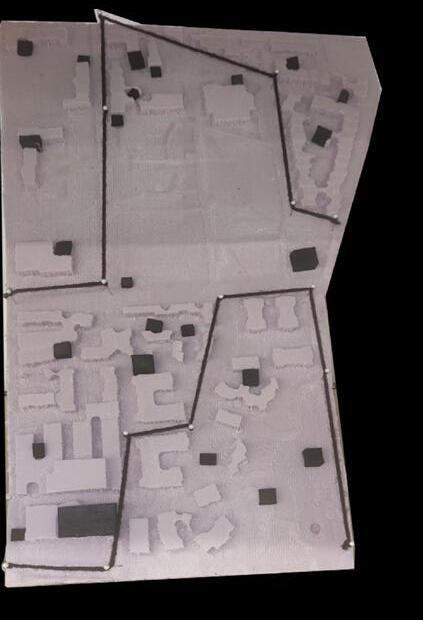

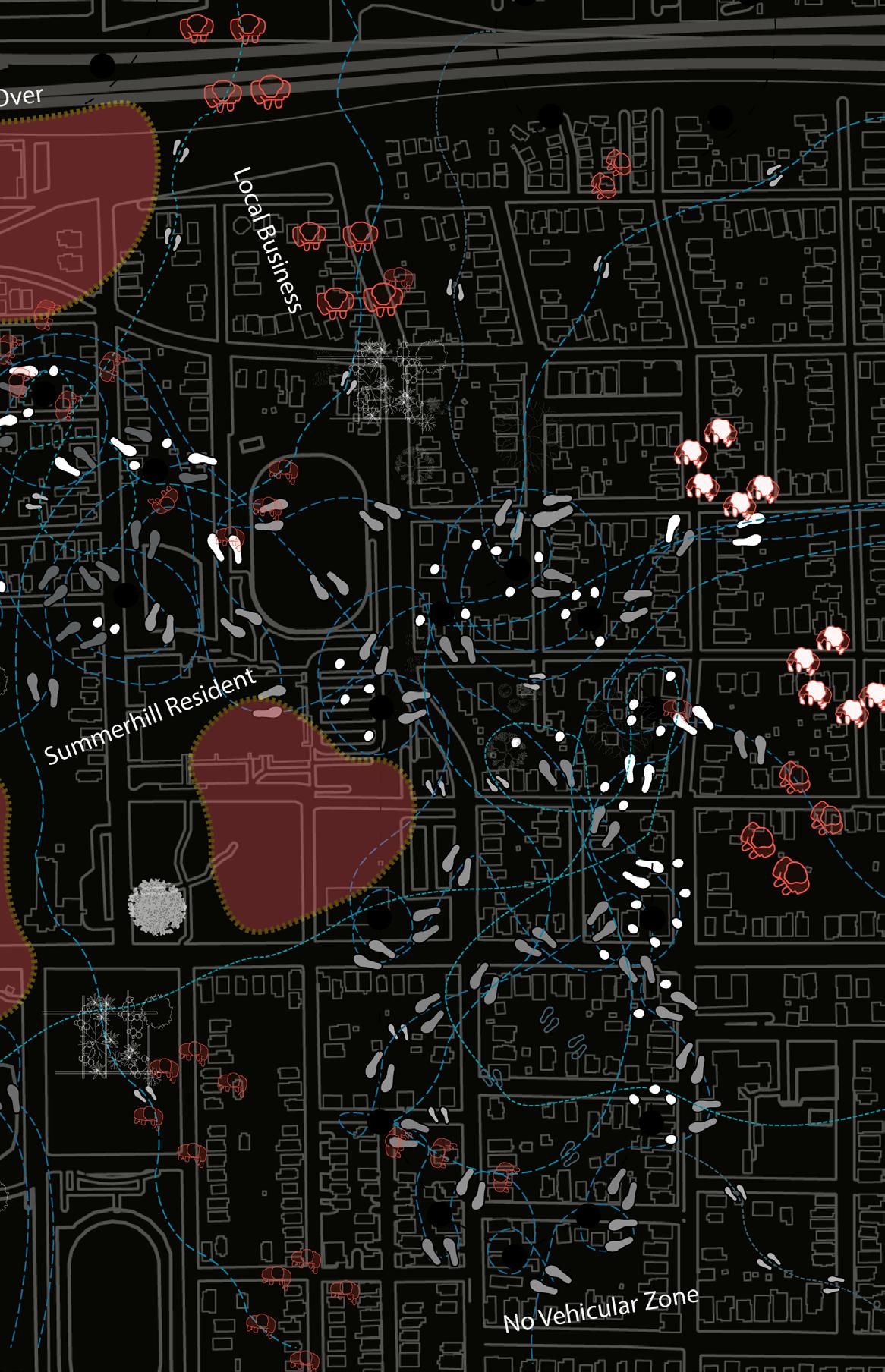

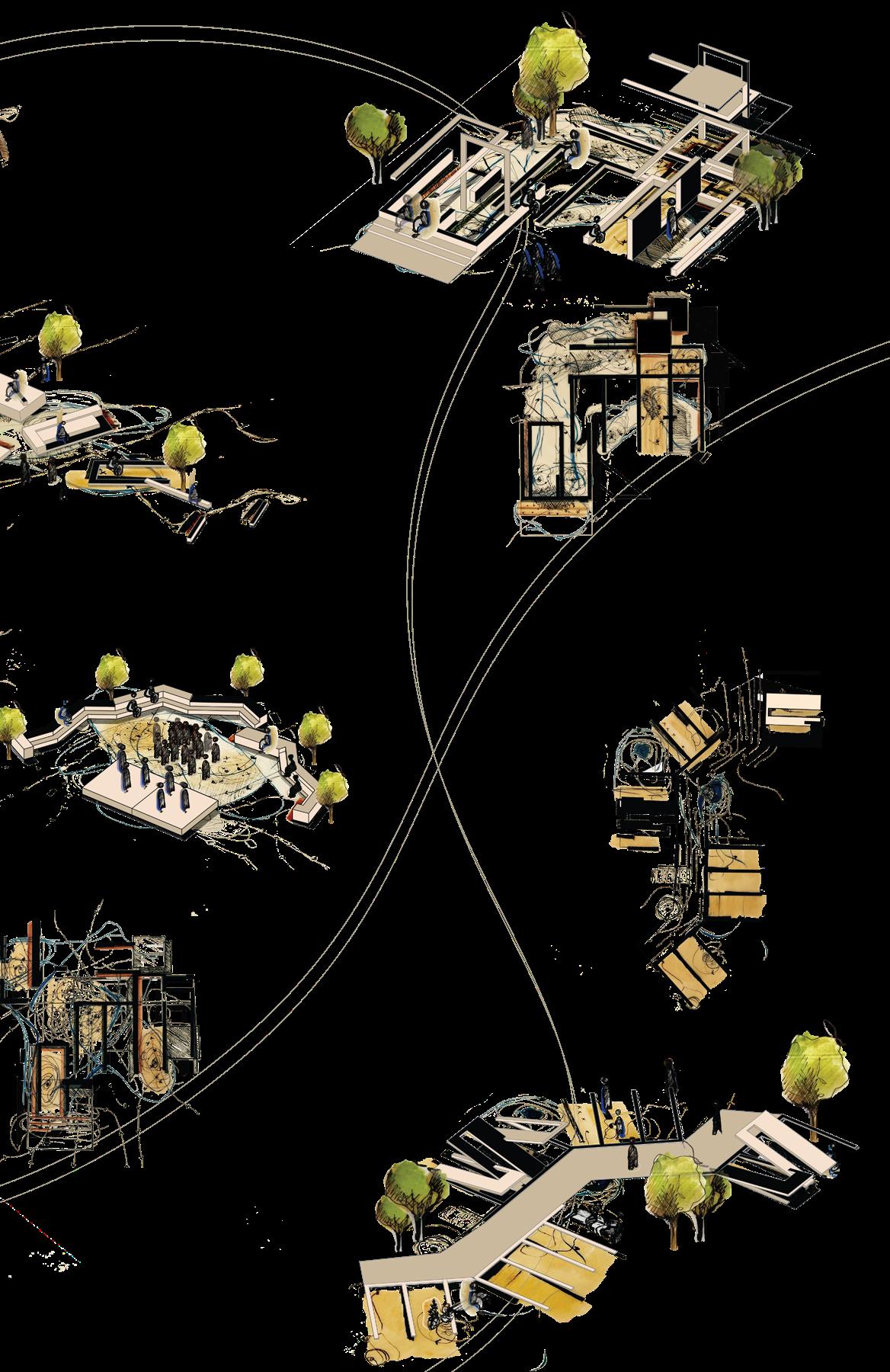

DE/NETWORK

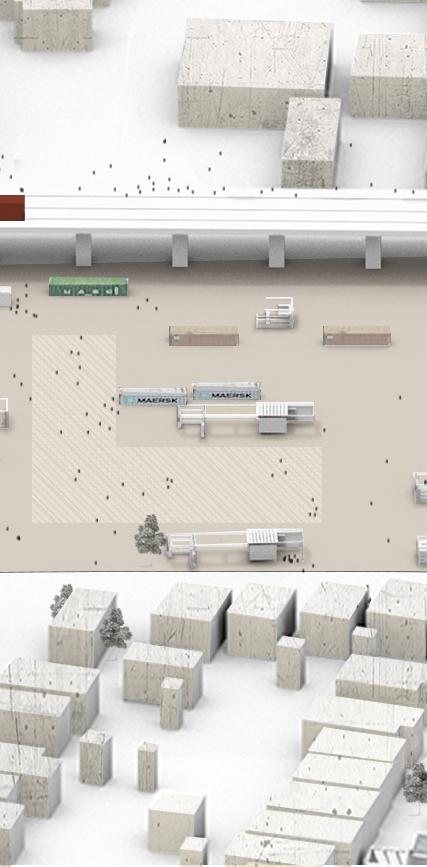

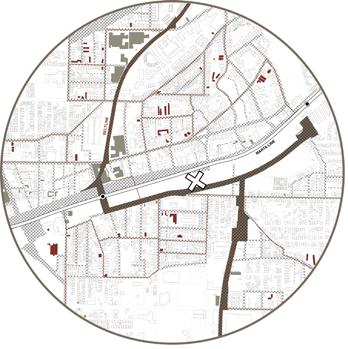

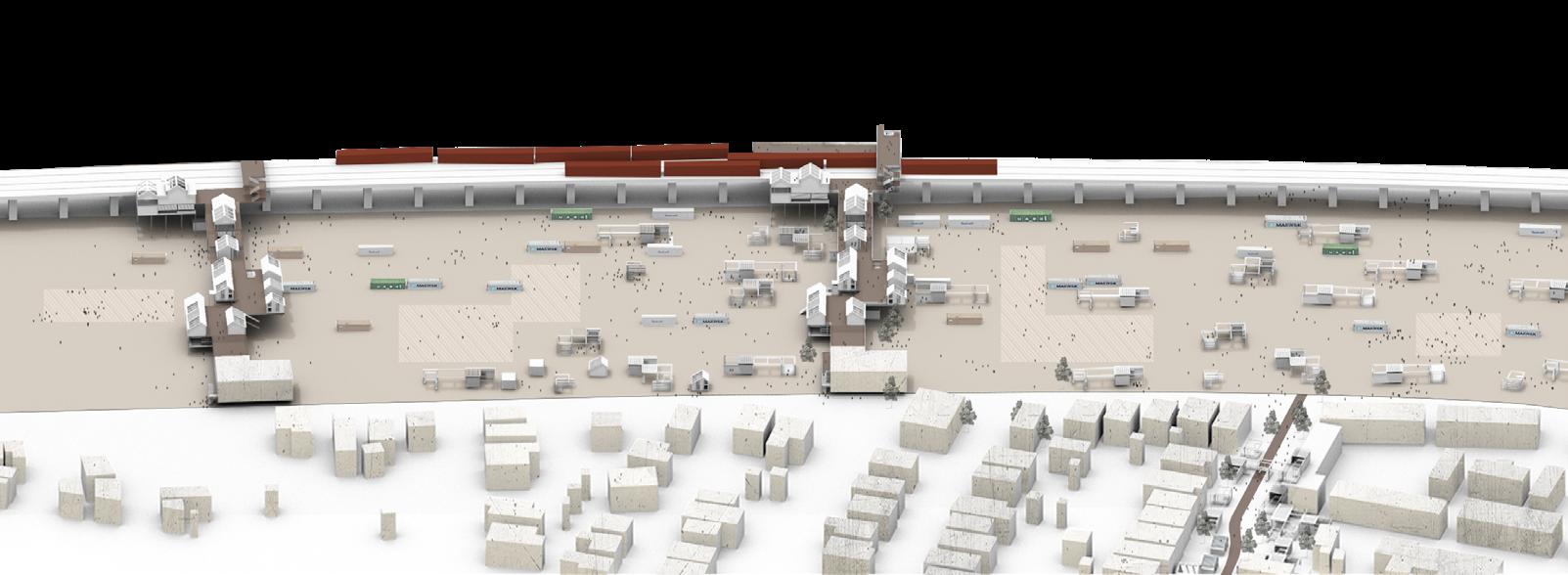

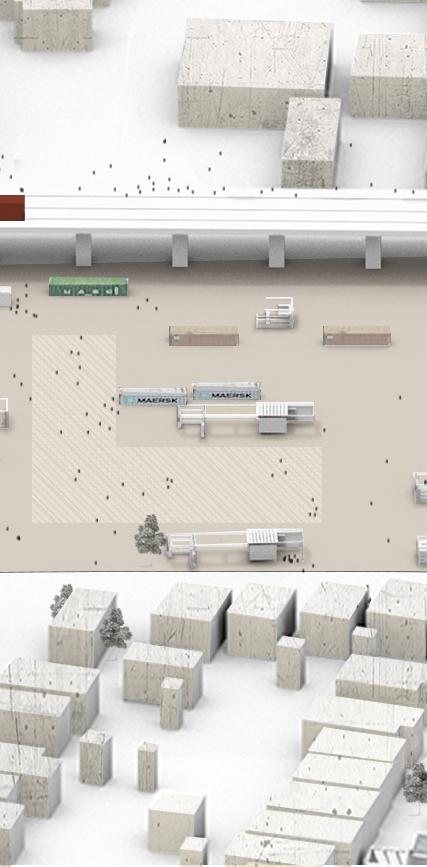

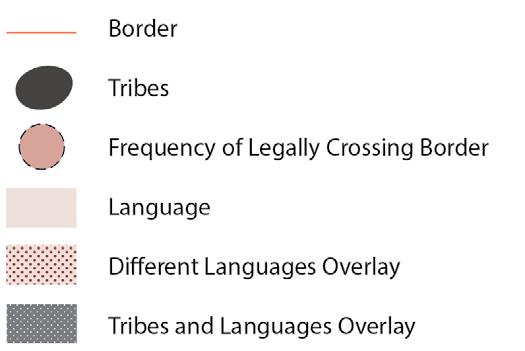

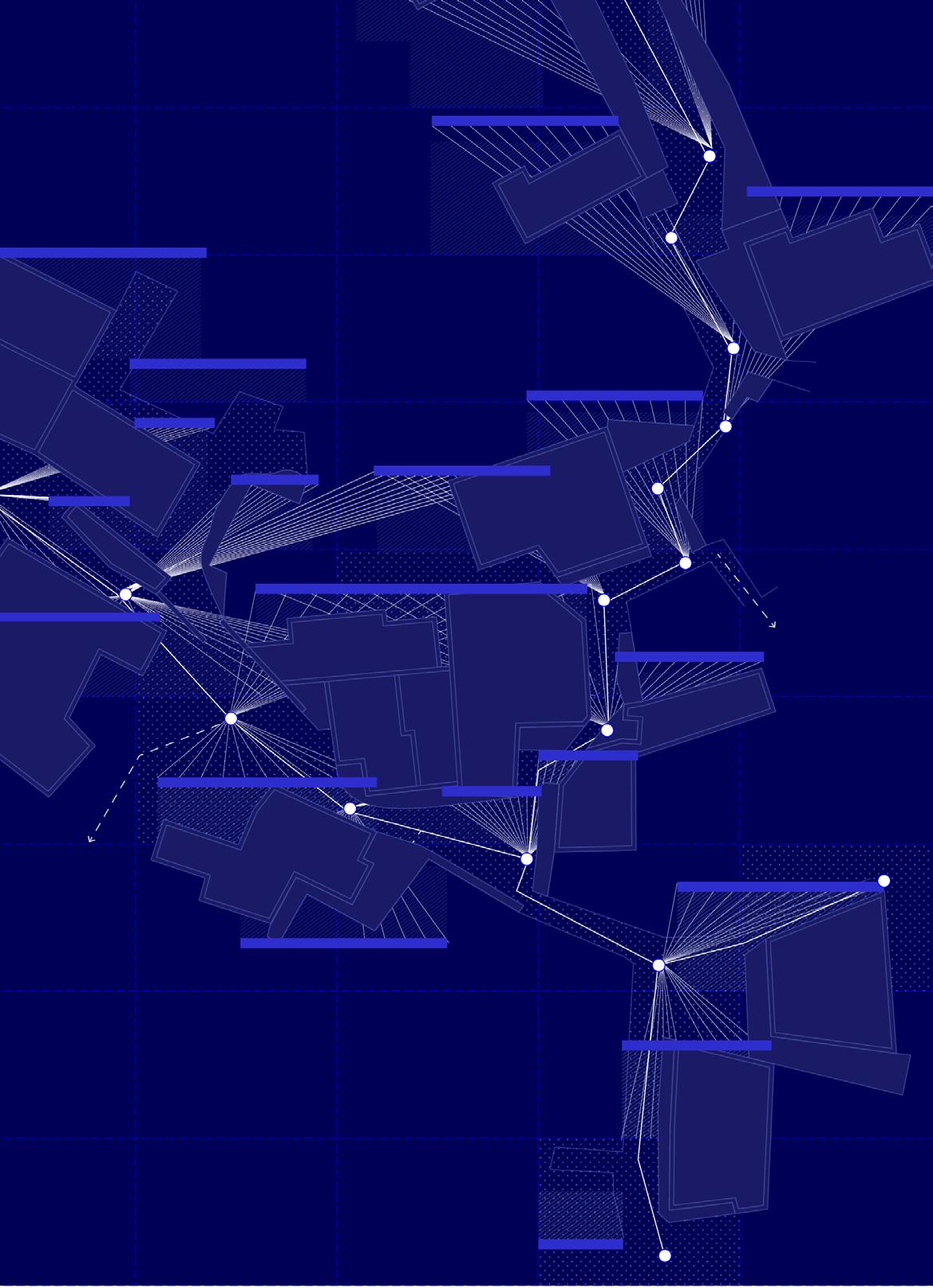

HULSEY YARD

DONNAL BAIJNAUTH

XU (CHELSIE) CHENG

HAOYU HU

The regime of property upholds possession, exclusion and control as markers of value. It reinforces these notions through the cyclic creation of borders and institutionalized barriers to the most fundamental human rights, housing, education, food and opportunity. The MARTA and later the Beltline envisioned a unified city, with everyone having access to housing, and every resource that this city has to offer. The realized mass transit network of metro Atlanta is a far cry from what was promised. The MARTA lines simply highlight the divides of race and economy, while the Beltline ousts those most vulnerable to gentrification.

Hulsey Yard lies at the junction of these two elements. Bordered by some of the most exclusive and fastest gentrifying neighborhoods in the city, the Yard is a vast void owned and operated by railroad giant CSX. There are several contesting

forms of property at play here. There are armies of cookie cutter homes and formulaic mixed use developments along the scar of the Beltline surround the heavily borderized and closed off yard. The city works to keep low-income, unhoused and historically marginalized people out of sight, with society’s amnesiac nature enabling authorities to perpetrate cycles of violence.

How do we begin to address this failure on the city’s part? We look at notions of value to envision Atlanta beyond borders. We question the legitimacy of these systems of value that thrive on exclusion and discomfort. We base our vision on a social value system that puts human needs above all else. We encourage people to take what they need, without hesitation, and share what they can, freely and joyfully. We thus revalue human systems by devaluing the forces of capital.

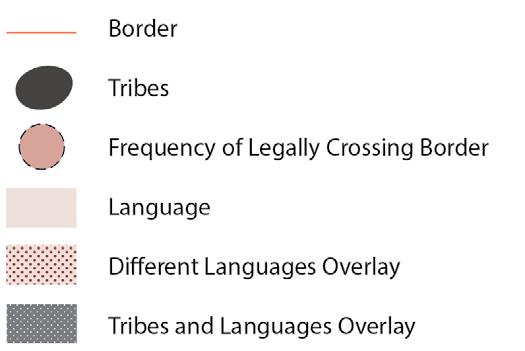

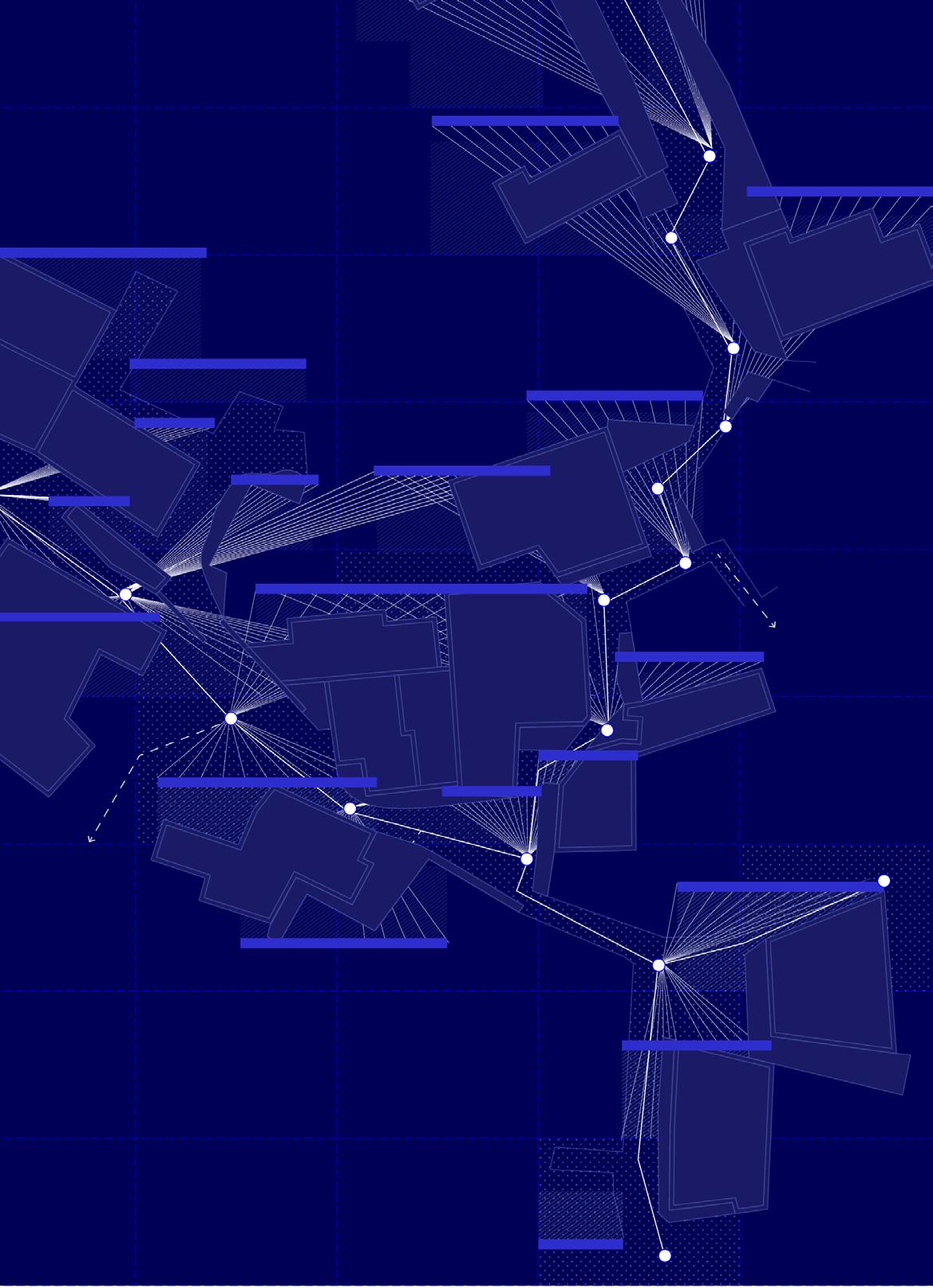

Intangible Crossing Mexico-US Border

Outdoor Living Rooms Dharavi

ANAGHA ARUNKUMAR

Intangible Crossing Mexico-US Border

Outdoor Living Rooms Dharavi

ANAGHA ARUNKUMAR

62

2022

FALL

[1] 64 FALL 2022

65 ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

[2] 66 FALL 2022

[3] [4] 67 ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

Vacancy to Shelter: Beltline

Vacancy to Shelter: MARTA

68 FALL 2022

The regime of property upholds possession, exclusion and control as markers of value. It reinforces these notions through the cyclic creation of barriers to the most fundamental human rights: home, education, food and opportunity.

In our project, we provide access to resources that enable people to learn, develop their skills through independent study or exploration, and engage in forms of unconventional collective learning and training.

Exposing Forces of Capital and Connecting Neighborhoods

Typologies: Sections and Perspectives Structures for the unhoused.

Perspective View, Making and Market

Perspective View, Gathering and Leisure

69 ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

[1] [2] [3] [4]

Republic of Rose Island Adriatic Sea, 1968

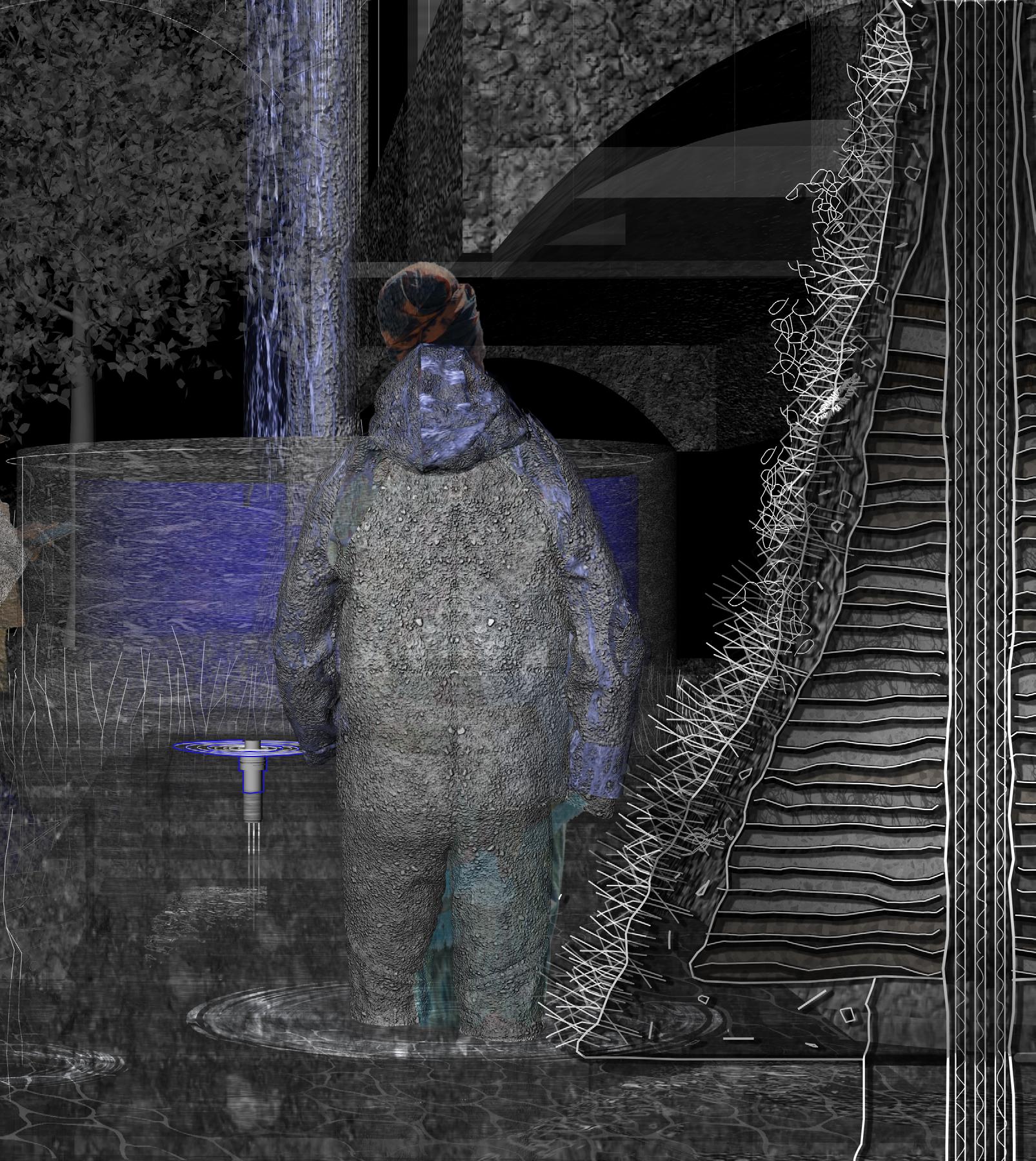

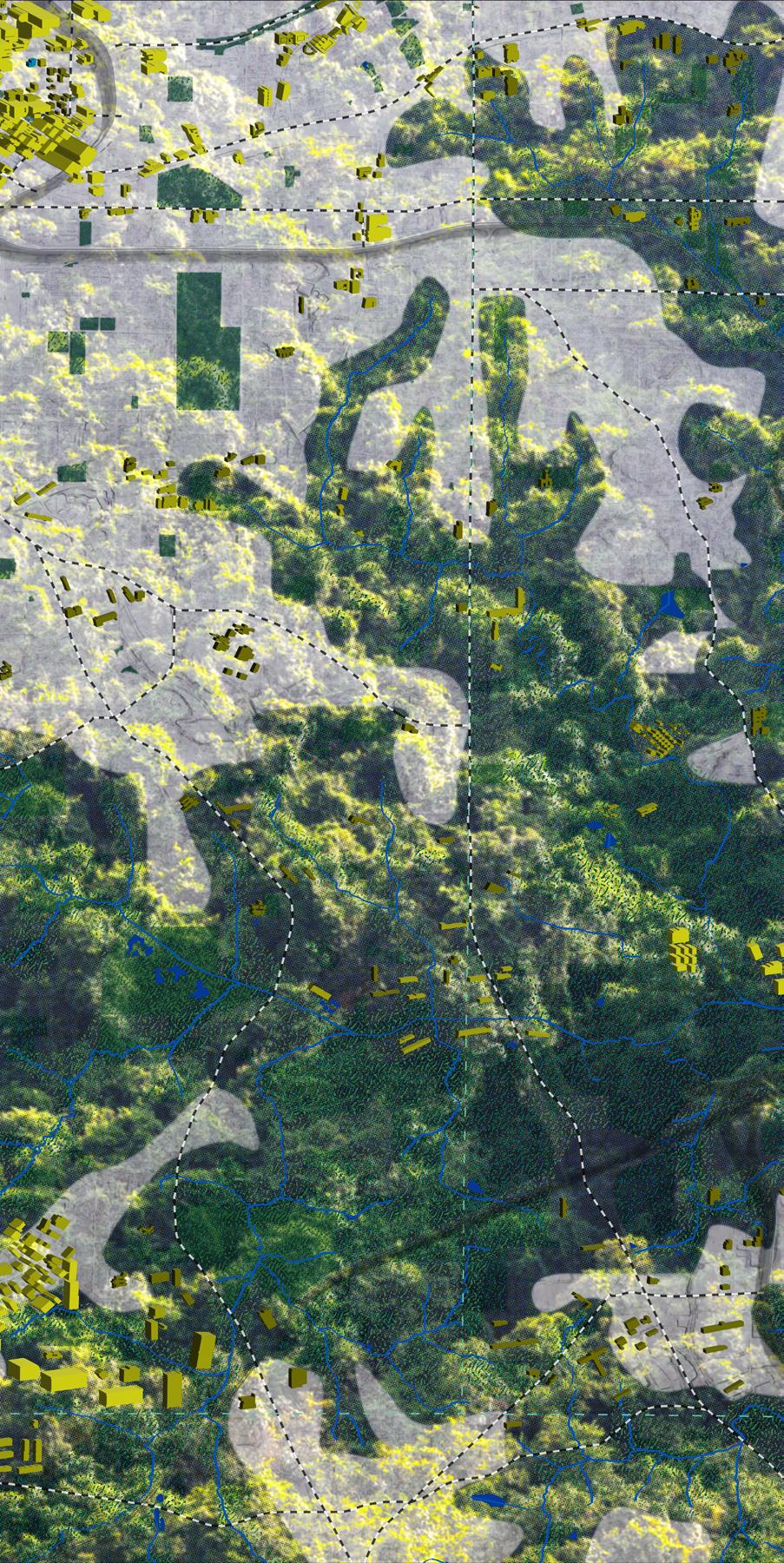

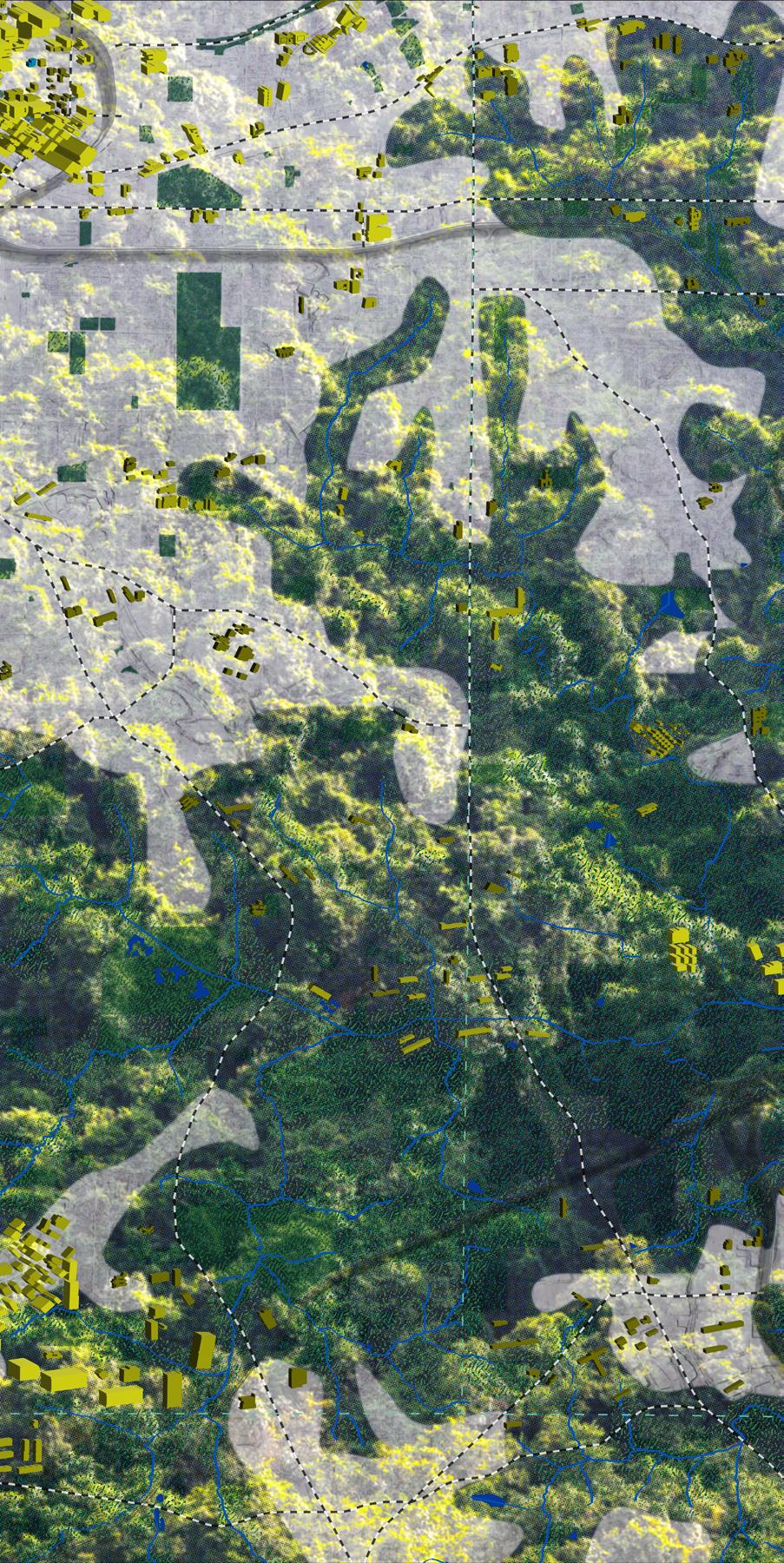

In a world after property, water is as an agent to liberate spaces and encourage a network of vegetation and non-human logics. Tracing roots is an appreciation of aqueous beginnings. It exposes the temporality, uncertainty and complexity of the places we inhabit. It is both a fragment and manifest to create a co-constitutive relationship with water.

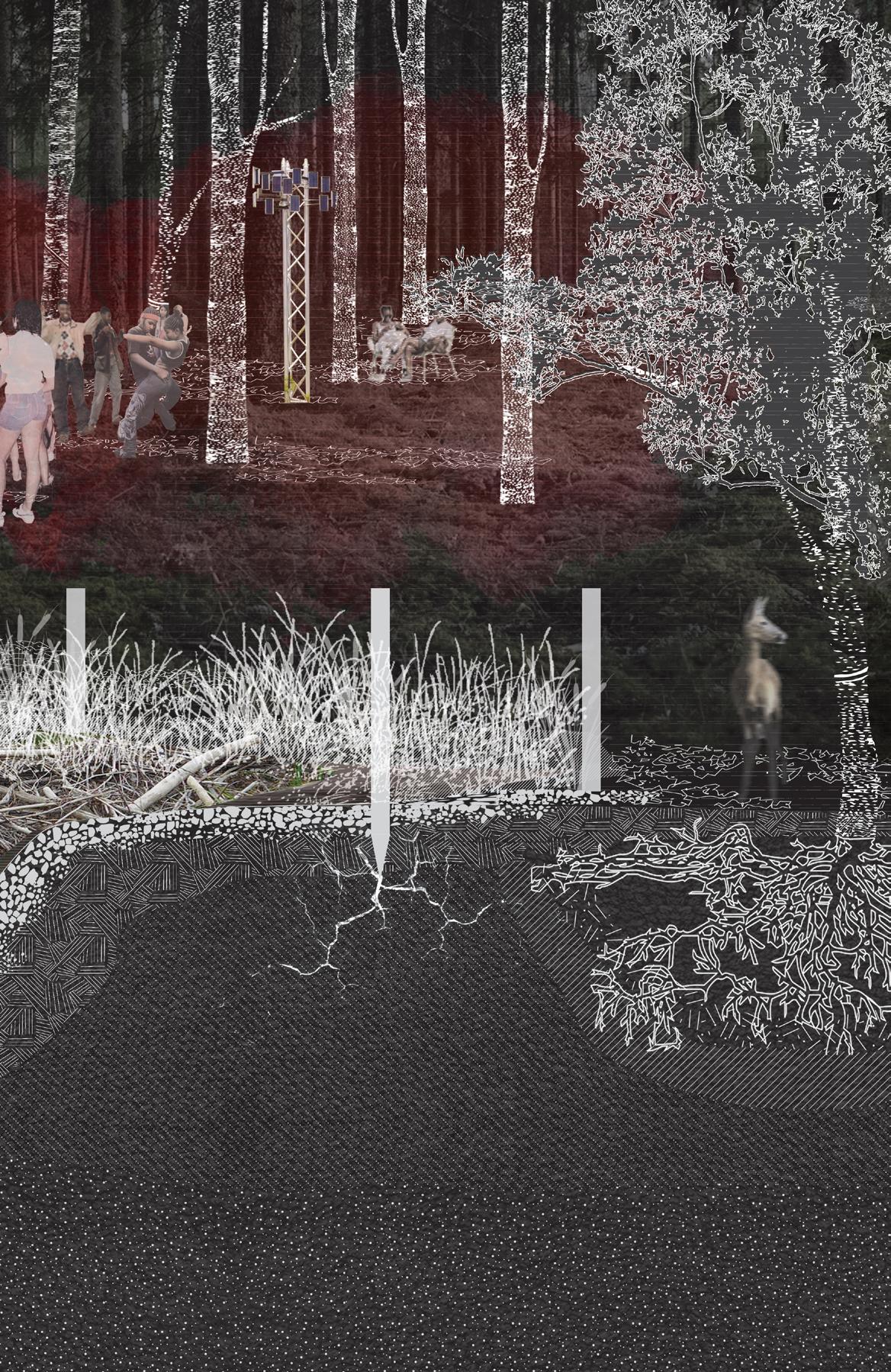

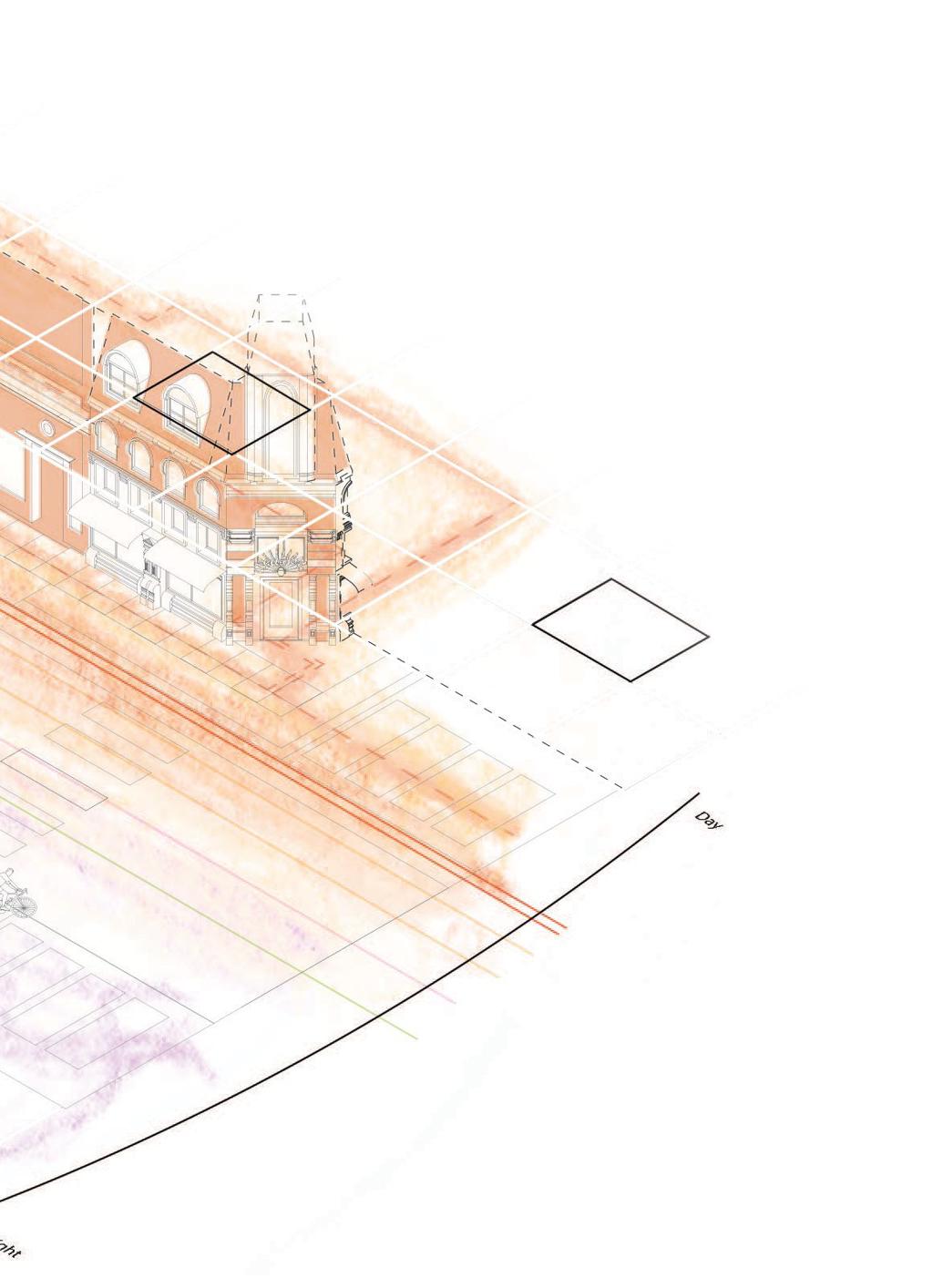

TRACING ROOTS

PEOPLESTOWN

YASHITA KHANNA VERENA KRAPPITZ

Water holds the past and present. Deciphering it´s layers, it mirrors decisions and the way land is acquired. The way current practices respond to water is defensive and results in impervious soils that redirect water somewhere else, destroying resilient networks and causing harm to the ones most vulnerable. These floods are consequences of a white governed property regime that has worked steadily towards the dispossession of people for the sake of western economy. It is undermining people’s intimate relationship to bodies of water; both natural and artificial.

Atlanta is a city of water, sourced from ranges of the Appalachian Mountains and occurring rainfall. It sits on the mountain ridge of two watersheds. The land lies on a thick granite foundation, holding rich groundwater reservoirs. Yet Atlanta´s soil contains a lot of hard clay, which makes the infiltration of water

difficult. Instead, the water tends to quickly run off to lower grounds.

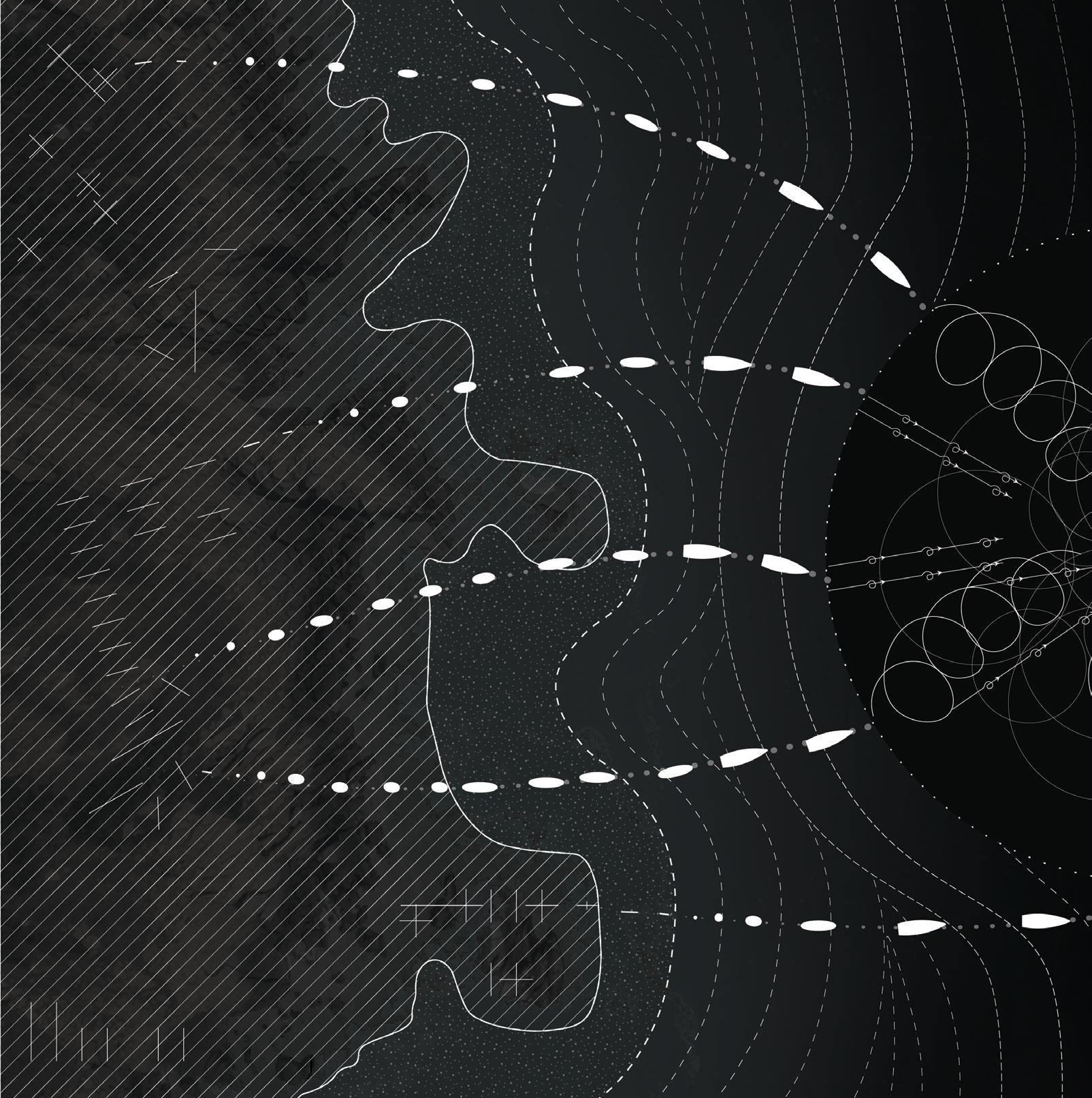

“Tracing roots”acknowledges the presence of water and re-imagines new conditions along sealed grounds in the watershed. Water is multiscalar and immeasurable and as such destabilizes conventional planning practices.

The diagram on the left shows a series of sections through the Intrenchment Creek Watershed in Atlanta. The existing built environment is marked in white. Water erodes property lines in the sealed soils, marked in gray.

The water flow is decentralized, through the increased permeability of vegetation, which creates water sensitive typologies for future generations. Over time, more water is able to be absorbed in place, relieving both low lying areas as well as existing gray infrastructure.

NAUMIKA HEJIB

DEVANSHI GAJJAR

Open Grazing in Ado Awaye White Oak Pastures Farm Stay USA, 2022

NAUMIKA HEJIB

DEVANSHI GAJJAR

Open Grazing in Ado Awaye White Oak Pastures Farm Stay USA, 2022

70 FALL 2022

[1] 72 FALL 2022

[1] [2] [3] ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

Cracks in asphalt are evidence that the land is already pushing back. We take advantage of asphalts characteristic to crack. In a world after property these seeds grow into full grown orchards where people collectively care for land and water. In a communal effort the structure evolves. Simultaneous field operations happen over time building a foundation for community growth in a co-constitutive relationship with water.

Generations preserving a foundation of precious root networks

Spaces

of communal care and living

[2]

[3]

An appreciation of aqueous beginnings 73

The collective care of water builds a new foundation. In additon, the rebar is anchored into the bedrock surrounded by a continuously hardening mycelium layer, which supports the topsoil. Additional support comes from several layers of rammed earth which have different absorbency levels. They incubate the grounds and are constantly rebuilt and reshaped. Over time, these foundations evolve into domestic spaces. They are home to multiple forms of creating, sharing, caring and living where water is embraced as a communal value to collect, nourish, filter and recharge.

74 FALL 2022

75 ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

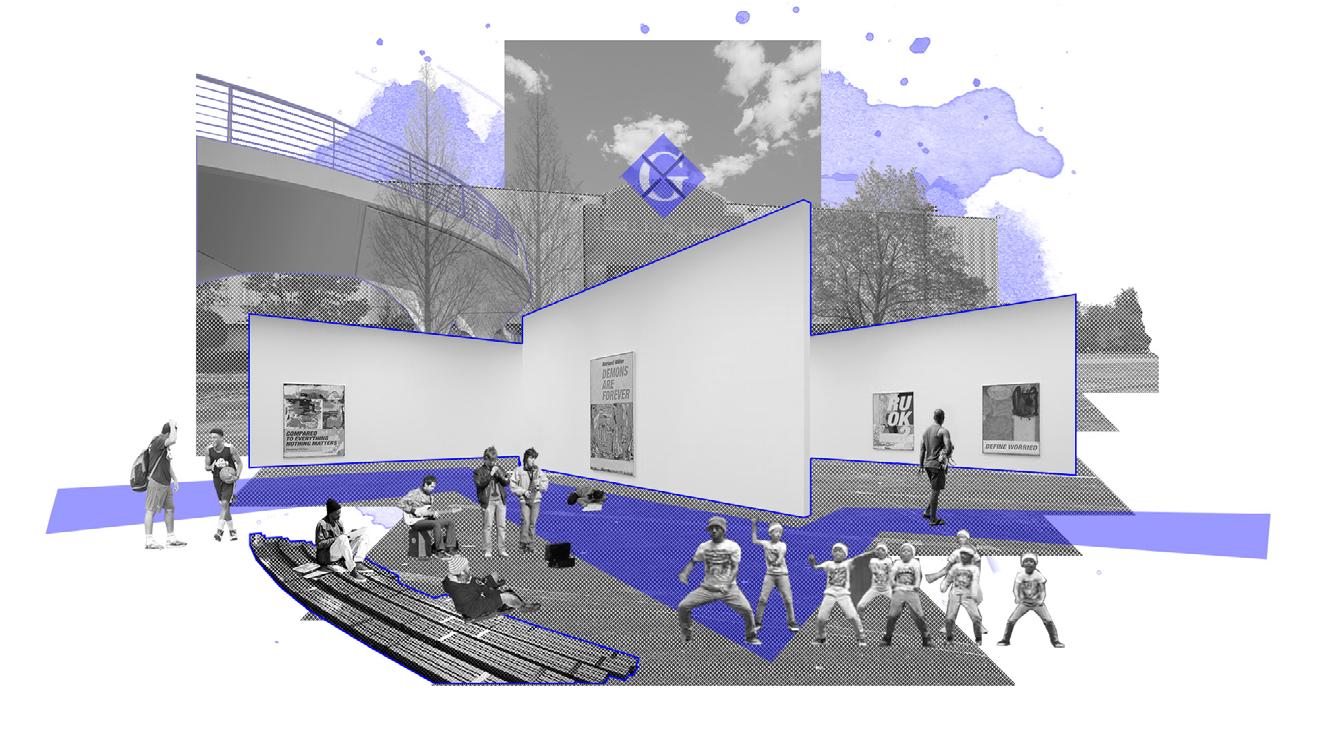

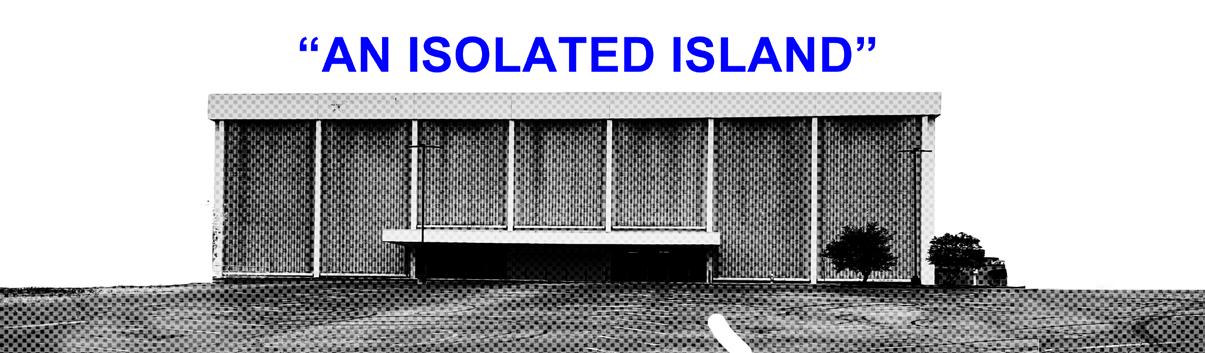

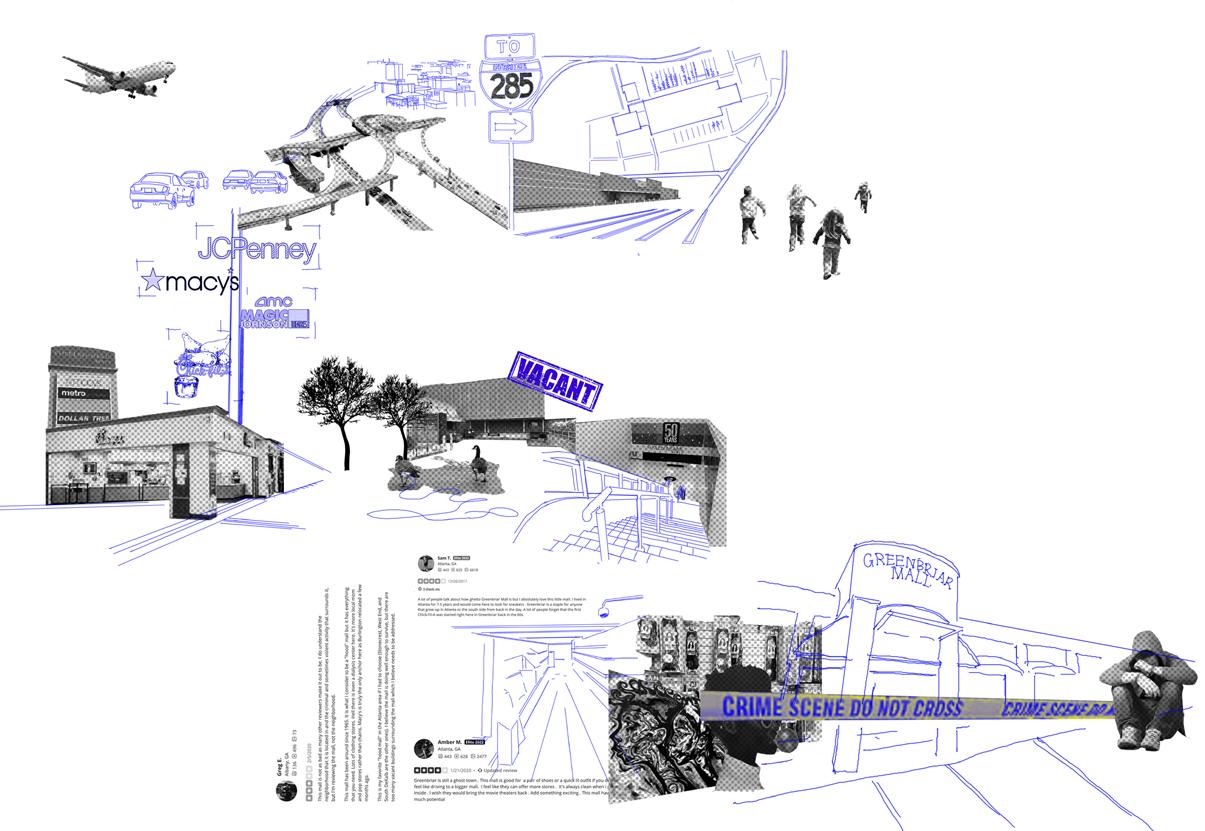

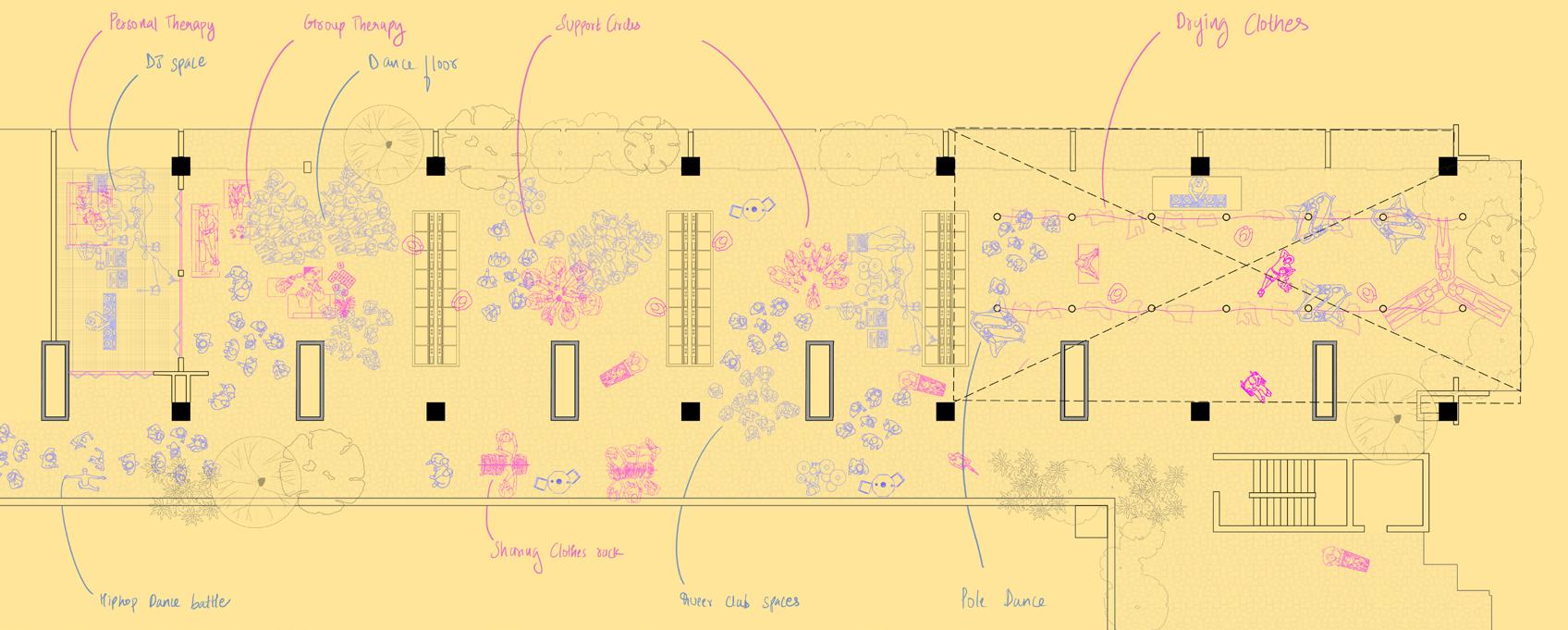

Property is reflected through capital-driven shopping Malls, that for a time, can bring the illusion of improvement to a community. A short lived boom, used and controlled by capital, and disappearing with its decline, during which any activity in its space that disturbs the interests of capital is repulsed. Its presence occupies a premium space that could have been used for more beneficial community care and development.

GREENBRIAR PALACE

GREENBRIAR MALL

WENJUN ZHU

HAOYU ZHU

HONGFENG WANG QIANNAN GUO

The suburban shopping mall is “property” built for the consumption and lifestyle of the American middle class. The design philosophy and operation of the shopping mall was created to maximize profits and economic benefits in the shortest amount of time. However, with changes in peoples’ lifestyles and the emergence of online shopping in the twenty first century, the traditional shopping mall has gone into decline.

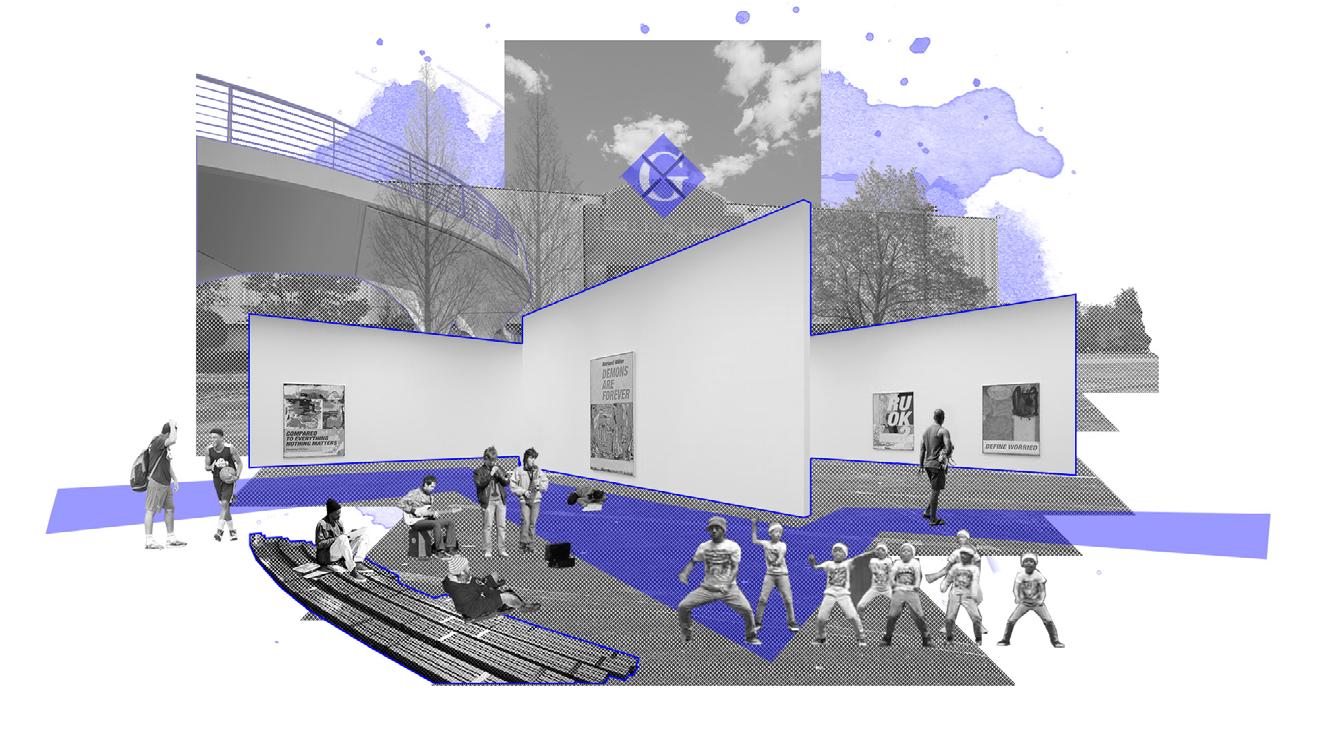

Although malls are dying commercial spaces, they are currently being used to attract people who were once overlooked or even rejected by them. Those who did not have the ability to spend but were active in every corner of shopping mall spaces: teenagers and youths. Shopping malls are one of the few safe recreational spaces in suburban communities for youth, who typically live far from thriving urban centers.

Unfortunately, most shopping malls over the last century still believe that the activities of young people in the mall are reducing the revenue that the mall can generate. They are unable to provide spending that is proportional to the time they spend shopping. Much of the youth has been driven away from the malls. We question whether this approach of breaking up kid’s groups and restricting where they can go is justified?

Instead, we claim that all malls in the US should encourage and support the social learning and leisure activities of the youth, especially for communities that lack safe public spaces for youth activities.

By infusing new and dynamic programs, dead malls have been transformed into places for young people to learn, play, and socialize. The traditional sense of a mall built for capital interests will be transformed into a youth paradise.

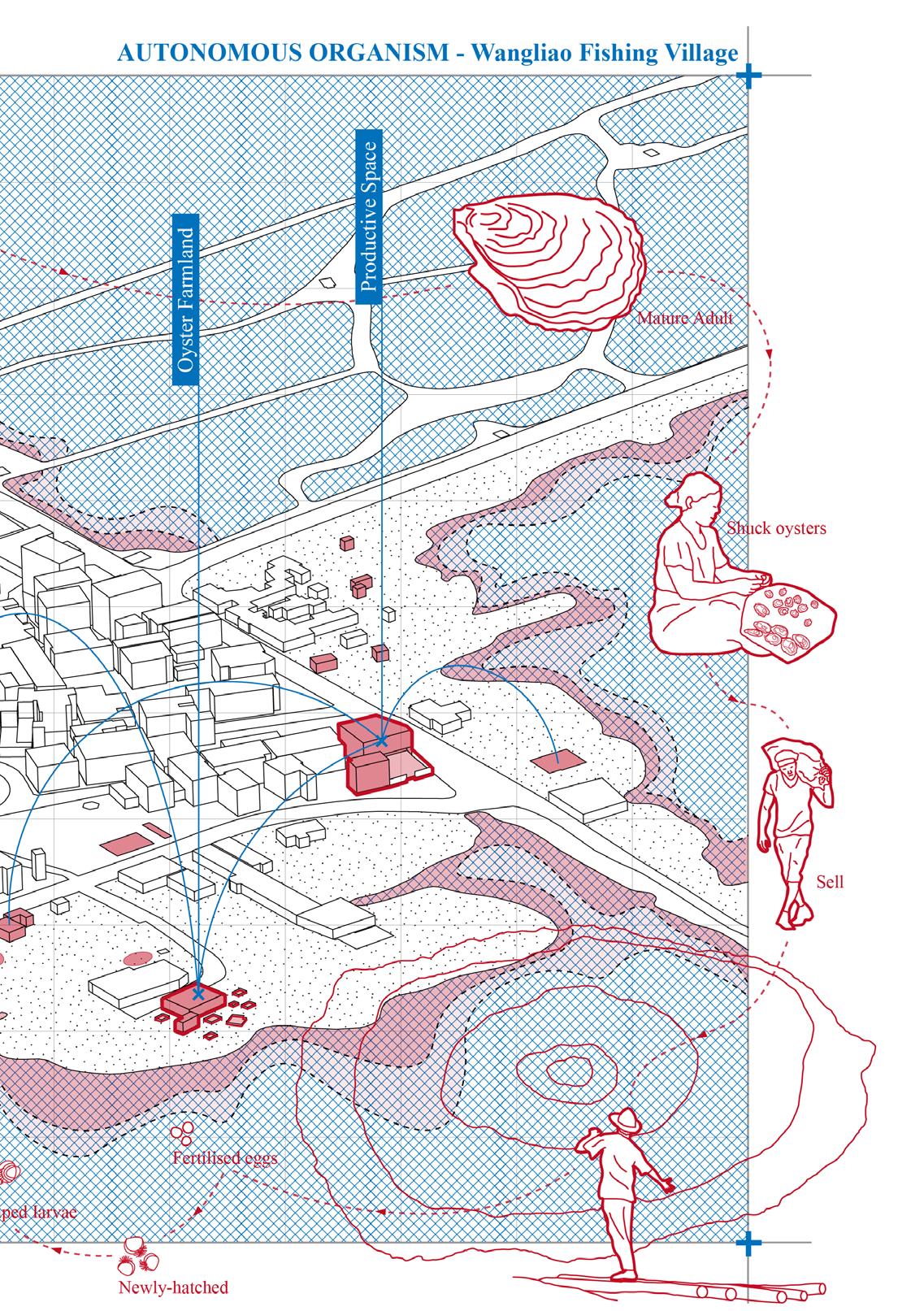

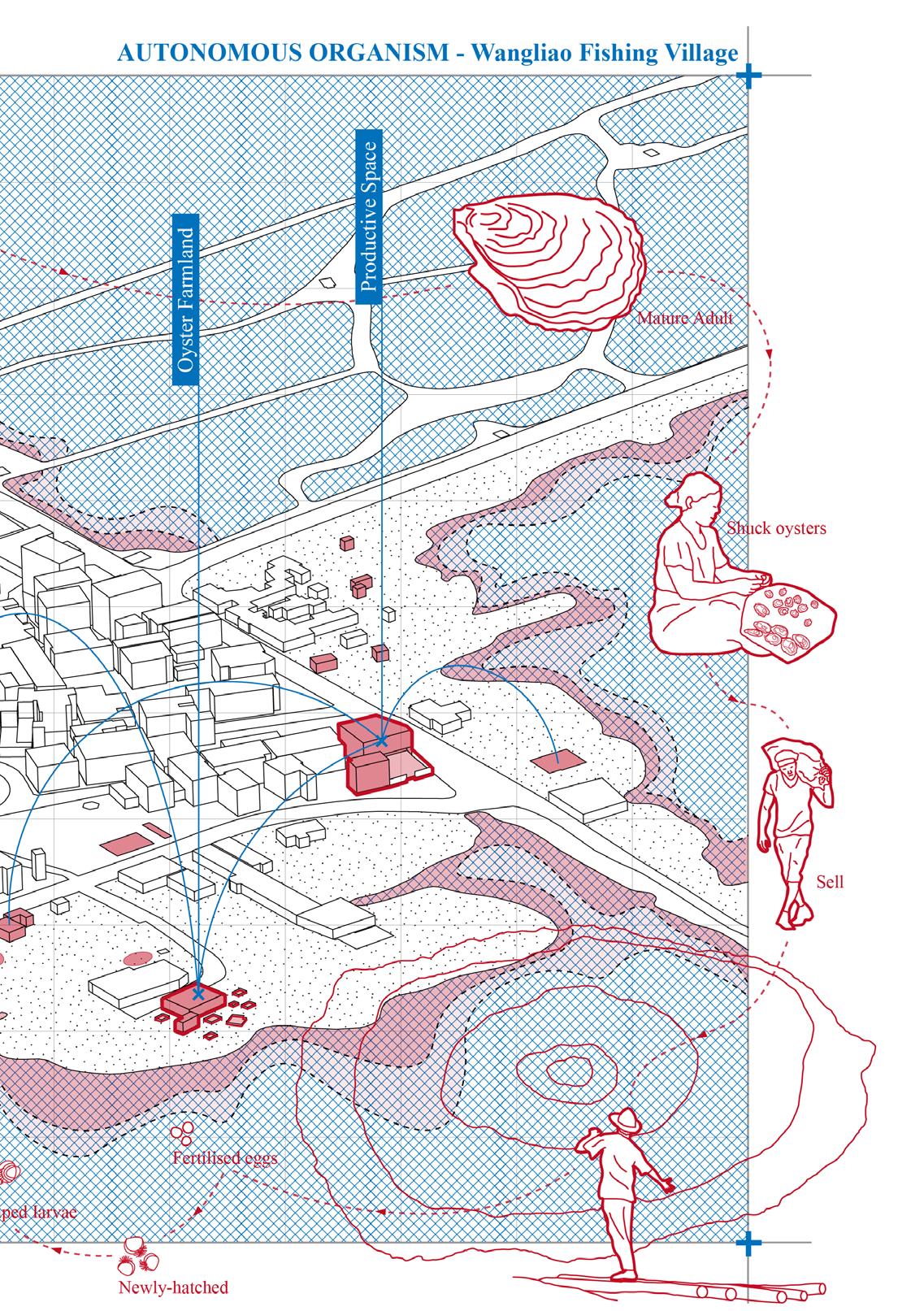

Wangliao Fishing Village Chiayi, Taiwan

Shanty Town Suzhou River

78 FALL 2022

Far from downtown, Greenbriar is a community that is full of vacant space but lacks safe recreational spaces. Greenbriar Mall could be a space that serves this function. However, with white flight and the loss of a large population with the capacity to consume, capital abandoned Greenbriar mall and the once thriving mall has seen a decline.

In addition, Greenbriar mall’s extremely large parking lots, I-shaped interior circulation, and inward-facing storefronts suggests to all that it is an exclusive, car-oriented consumption space.

Furthermore, because of the lack of educational resources and safe spaces for youth, the youth in the Greenbriar community are more likely to be misled and even in danger than other youth in wealthy communities.

Although, Greenbriar mall was considered hopeless, the youth of the community slowly began to occupy the vacant spaces with performance and school activity spaces. With their return, Greenbriar Mall plays a central role for the youth while still maintaining it’s identity as a “Hood Mall.” It has since inspired our new vision for Greenbriar mall as a place for youth social activity.

80 FALL 2022

81 ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

82 FALL 2022

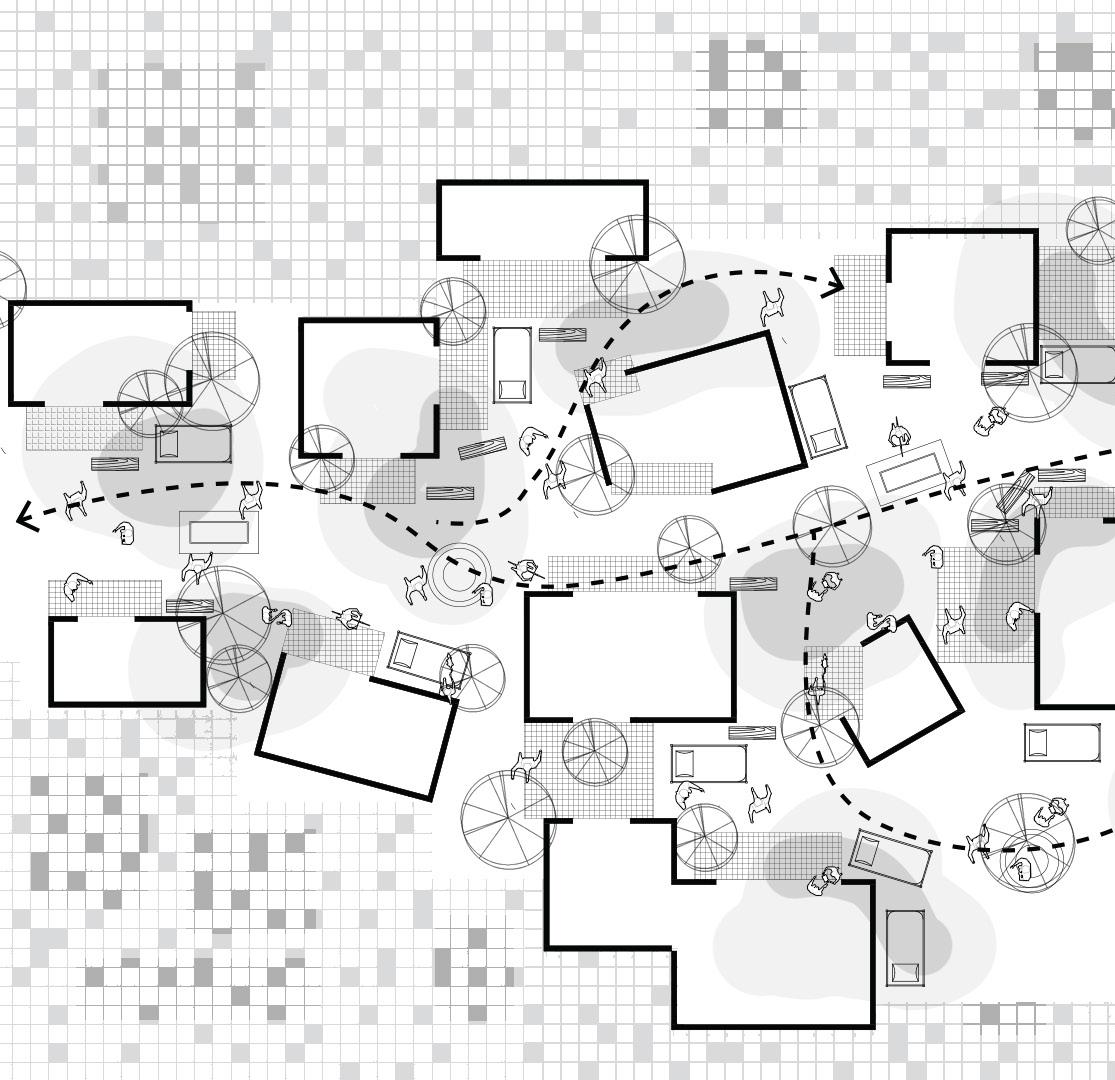

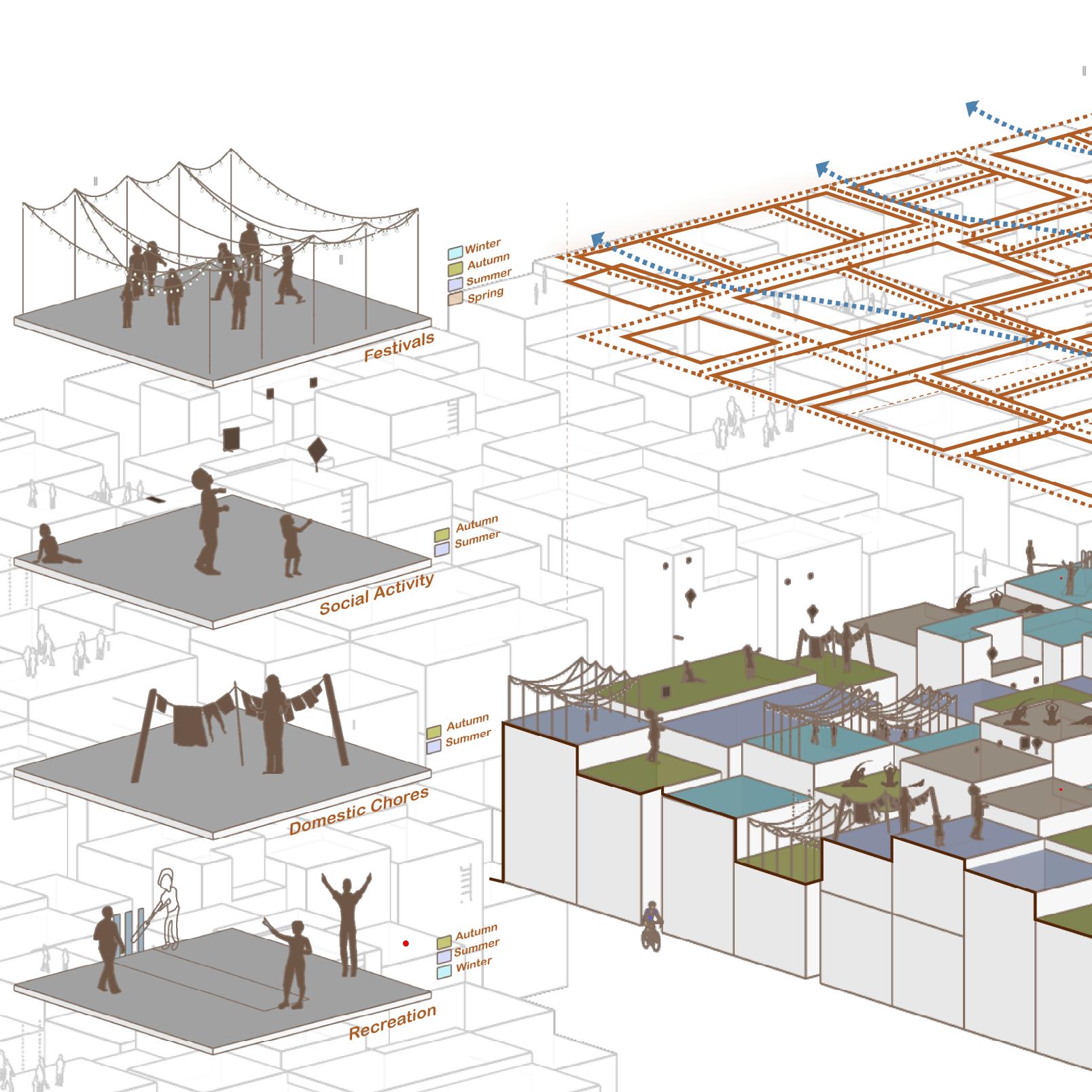

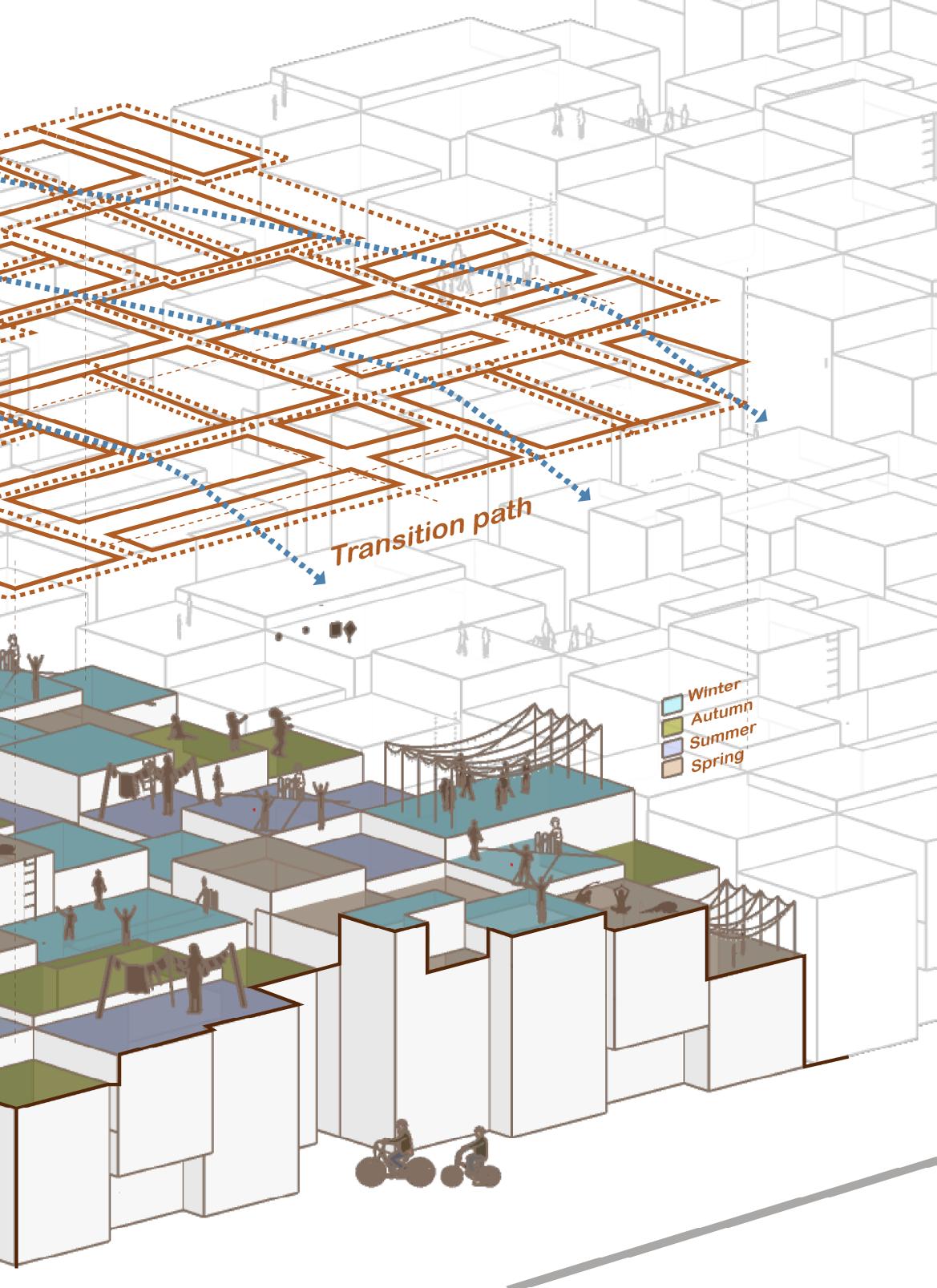

Our project embraces the idea that the youth’s opportunity to learn and communicate should not be tied to the confines of a classroom. Having this opportunity to learn outside of the traditional, social framework, allows for the integration of youth programs while at the same time, encourages existing social and cultural activities and the relationships between the mall and the community to thrive.

We propose a Greenbriar Palace as a multi-functional structure to accommodate youth activities attached to the existing mall structure.

The Greenbriar Palace connects the mall to it’s context. Connecting the nearby charter school and beyond, towards Atlanta’s greater communities and neighborhoods. Instead of walking through a large, boring parking lot, full of safety concerns, the youth can make their way through a dynamic space to enter the mall and school, especially for the youth who don’t own a car. By improving the mall’s walkability and accessibility, the original exterior space is transformed to feel much more secure.

Greenbriar Palace will also slightly change the flow and appearance of the mall. The I-circulation, which was originally designed for quick consumption and customer movement, is interrupted by Greenbriar Palace by enclosed gathering spaces. In addition, inward-facing store fronts are changed to more outward-facing storefronts with a glass covered façade.

83 ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

84 FALL 2022

[1] [2] [3] [4] ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

Our main take-away is that no matter how hopeless the capitalist regime perceives this “ dead” mall to be, Greenbriar Mall will continue to maintain its identity as a “Hood Mall” by the community. Its value is not based on how much economic profit it can produce, but the ways it provides the community and the youth a sense of identity and place, connections which property cannot take away.

Current I-Shape Circulation

Proposed Multi-Gather Spaces Circulation

Current Enclosed Inwardfacing Unit Front

[1] [2] [3] [4]

Proposed Open Outwardfacing Unit front 85

“This is a monumental step in transferring land ownership with a history of pain and injustice and placing it in the hands of the people of Atlanta.”

In the world after property, the notions of ownership and hierarchy are no longer present. After property is where shared memories recreate tangible and intangible forms of the ongoing future and is no longer a static entity.

MAKING AS HEALING

CHATTAHOOCHEE BRICK COMPANY

ANCHALINAD ANUWATNONTAKET

HANFEI FU

MINGRUI JIANG

XIUTONG YU

After the Civil War, Black Southerners were no longer enslaved, but they were not yet free. The Sheriff sold free Black people to corporations and coal mines. For 80 years, thousands of Black people were forced to labor against their will across the country. Atlanta, in the state of Georgia, had a long dark history from 1868-1942.

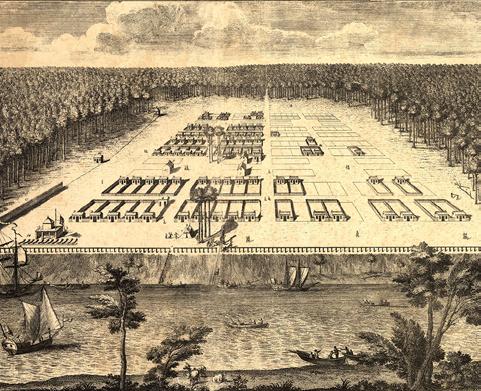

The Chattahoochee Brick Company used convict labor to produce bricks for the city, including Techwood Homes, Greenwood Cemetery, and Georgia State University. Its bricks were distributed to build the sidewalks, streets, and homes in Atlanta and across the United States. For decades, prisoners were forced to do unpaid labor at this brickyard. Through many years of struggling with property, the site finally belongs to the city of Atlanta. It is now time to recollect the lost memories and piece the stories together. Using remembrance as resistance,

we plan to use memorializing activities to excavate and discover the underground and on-ground memories. People will engage with the earth, remediate the land, and recreate new memories together. Through ‘Making as Healing,’ we remediate the spiritual and physical harm done to humans and the earth through material practices.

Our strategies of healing are inspired by the characteristics of the site. We are using raw materials and nature to heal social and ecological traumas: contamination, degradation, flooding, and the legacy of slavery. People have the opportunity to make and create with their hands, to engage in the practice of healing over time. With multiple fabricated realities, this after-property world will be seen as transcribing history and memory based on the cultural understanding of materials, plants, and spaces.

Koliwadas The Extension of Jugaad

Candle Vigils Remembrance as Resistance

Koliwadas The Extension of Jugaad

Candle Vigils Remembrance as Resistance

86 FALL 2022

[3] 88 FALL 2022

Touching and feeling from the cold concrete, to soft clay and soil, then to the florid brick, dynamic water creates immersive atmospheres for making activities.

Directly or indirectly, visitors use all the materials produced from these processes, build new architectures, and make handicrafts to heal traumas existing on-site and in their memory.

[3] Rediscovery of the underground and on-ground memories.

[1] A dilapidated brick wall on site.

[3] Rediscovery of the underground and on-ground memories.

[1] A dilapidated brick wall on site.

89 ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

[2] Vicissitudes textures reflecting a scarred and heavy history

[4] [5] 90 FALL 2022

The earth will keep growing and developing with nature and human power. With its multiple fabricated realities, the site will be seen as the transcription of history and memory based on the cultural understanding of materials, plants, and spaces. During those performances, the land’s traumas are removed and transformed into something new and beautiful.

Crafting and Creation

Performance-Extracting and Meditation

Engaging with the earth

Plan and Section Changing with Time

[6] [7]

91 ATLANTA AFTER PROPERTY VOL. 2

[4] [5] [6] [7]

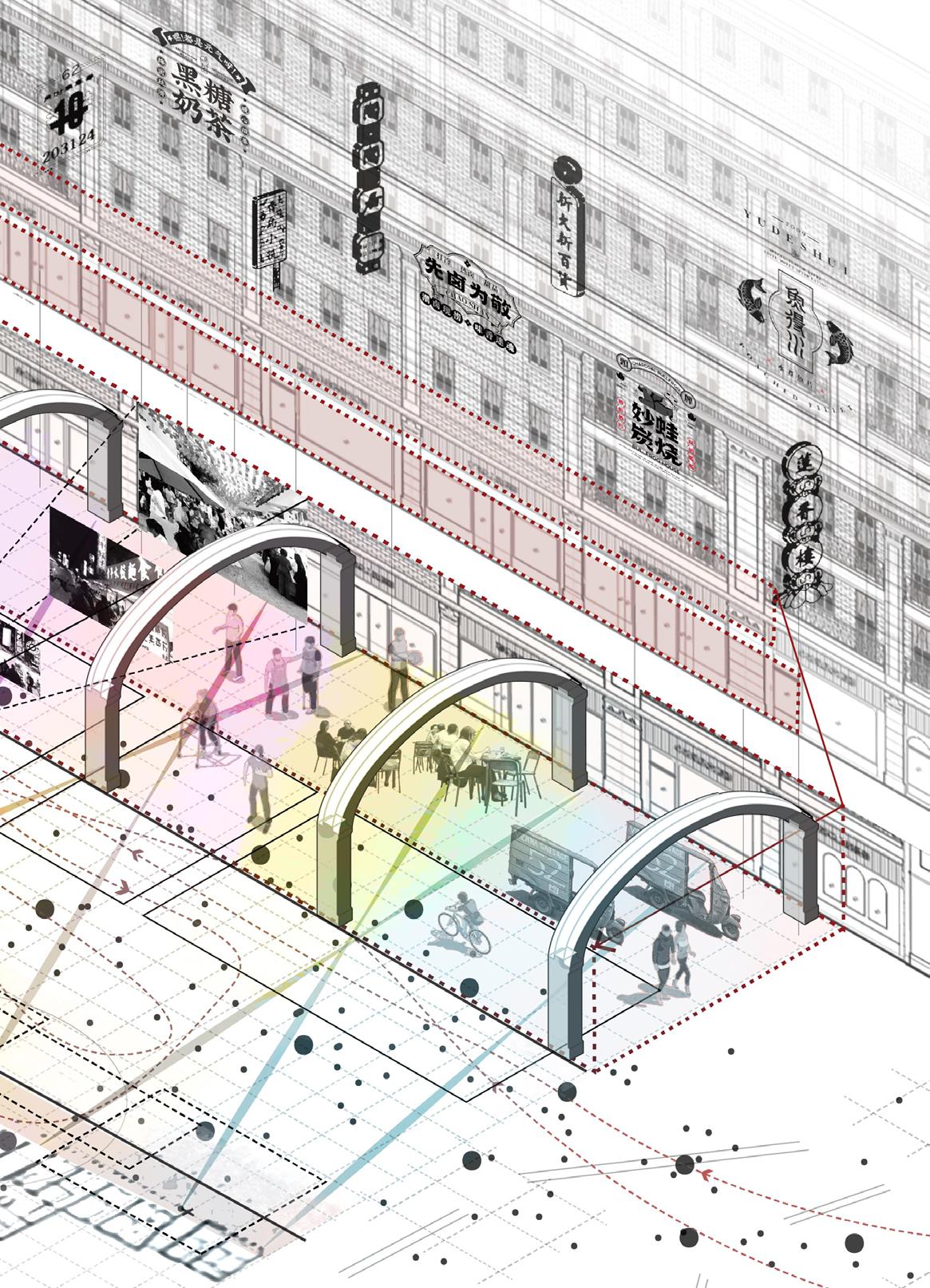

Color, Space, and Time

Jodhpur Brahmahpuri

Alex Reynolds, 2021.

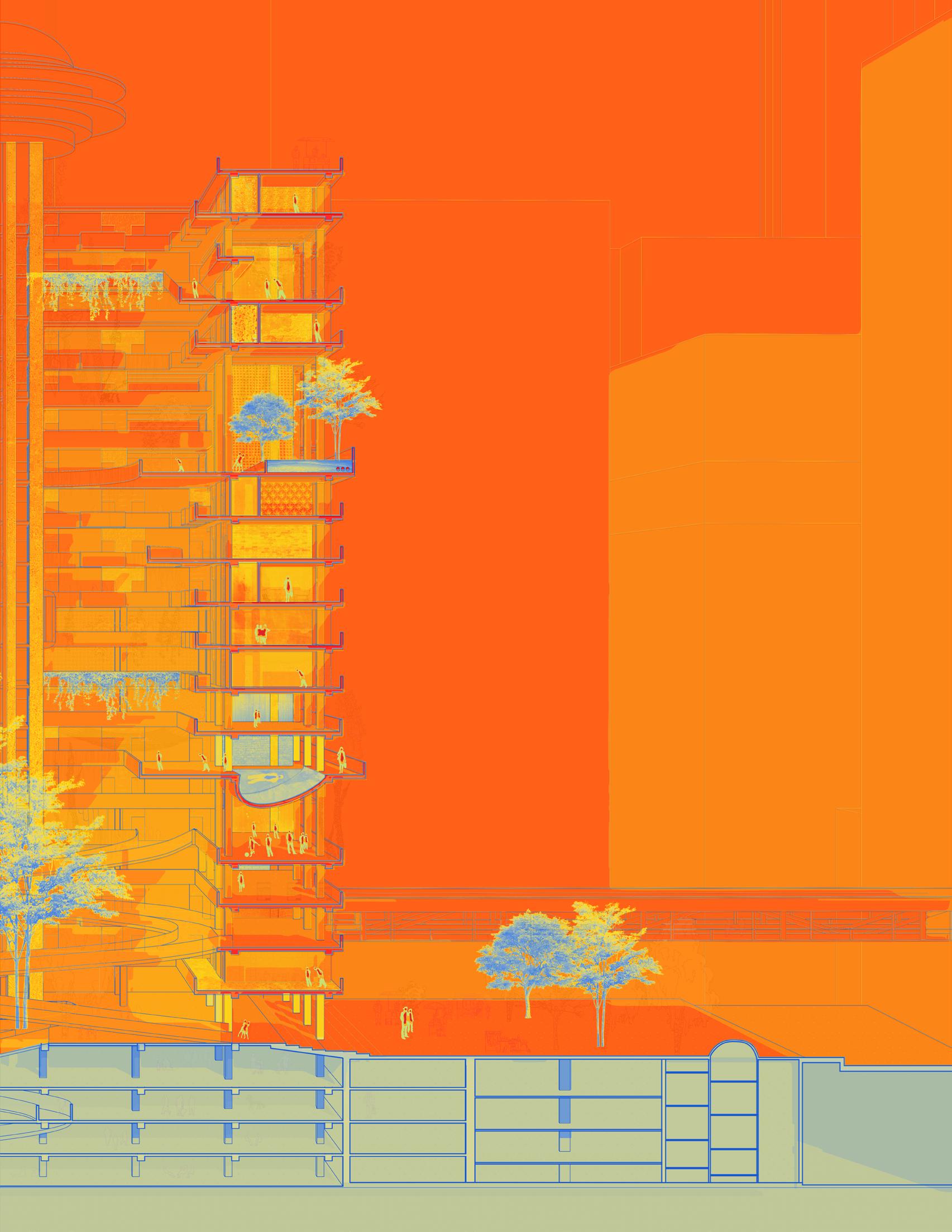

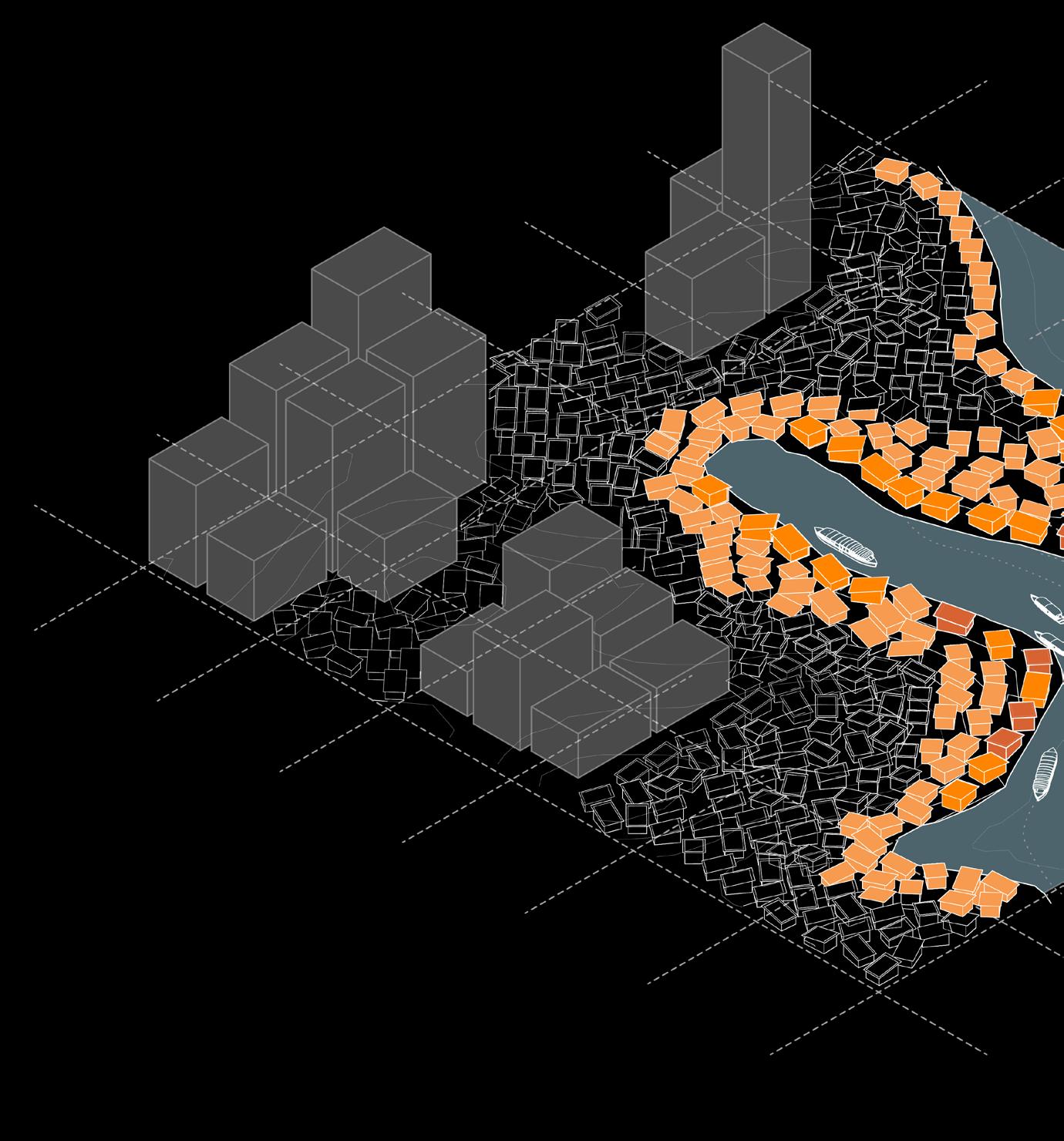

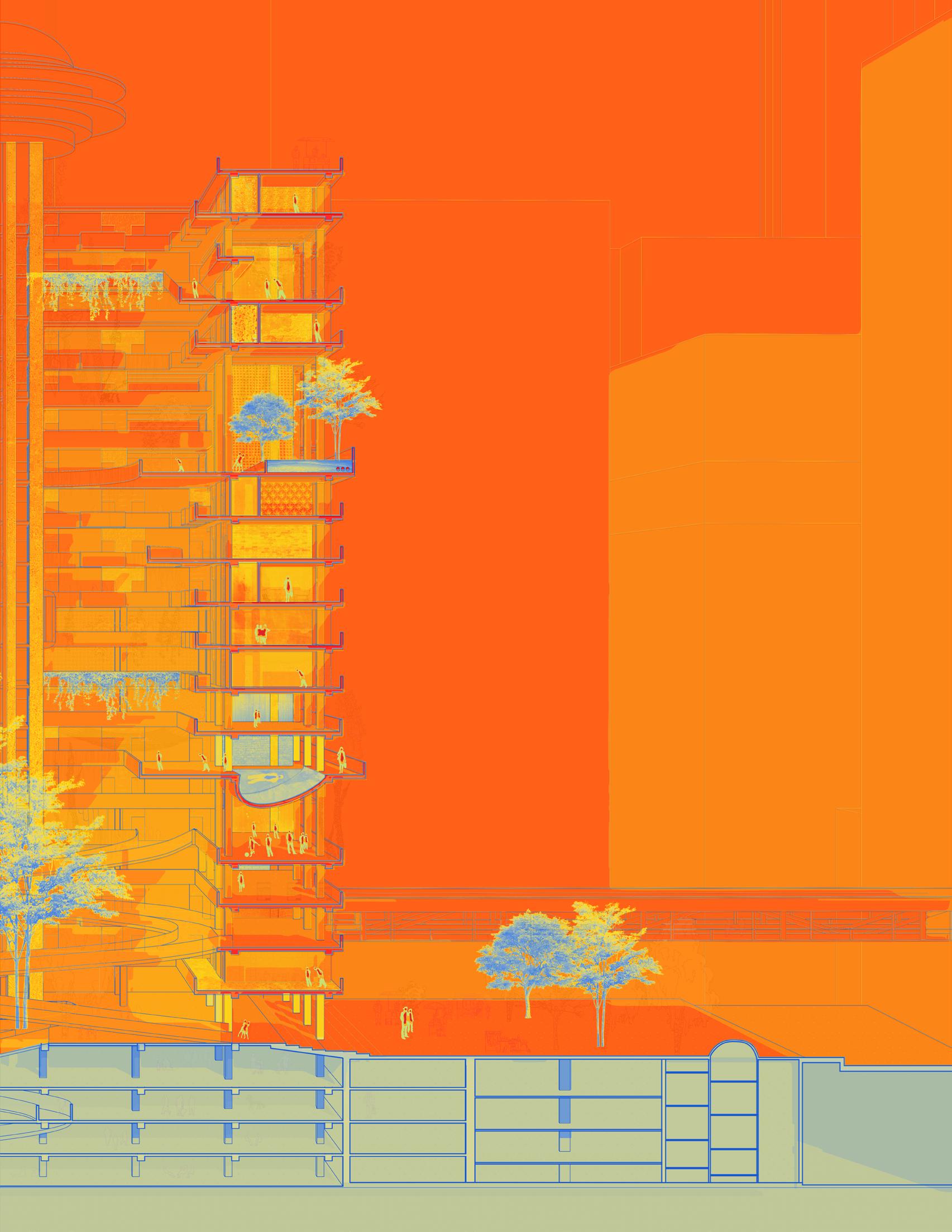

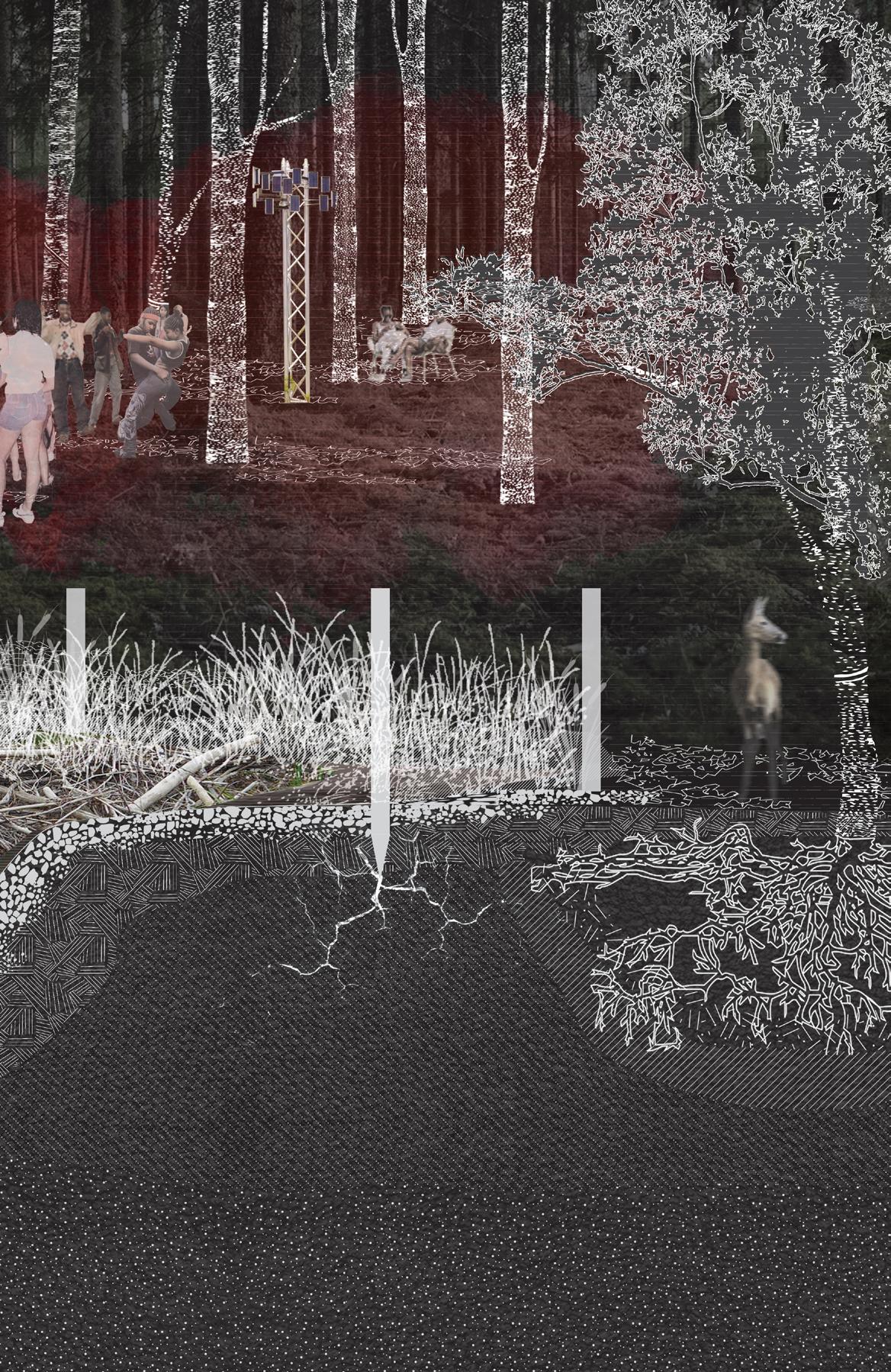

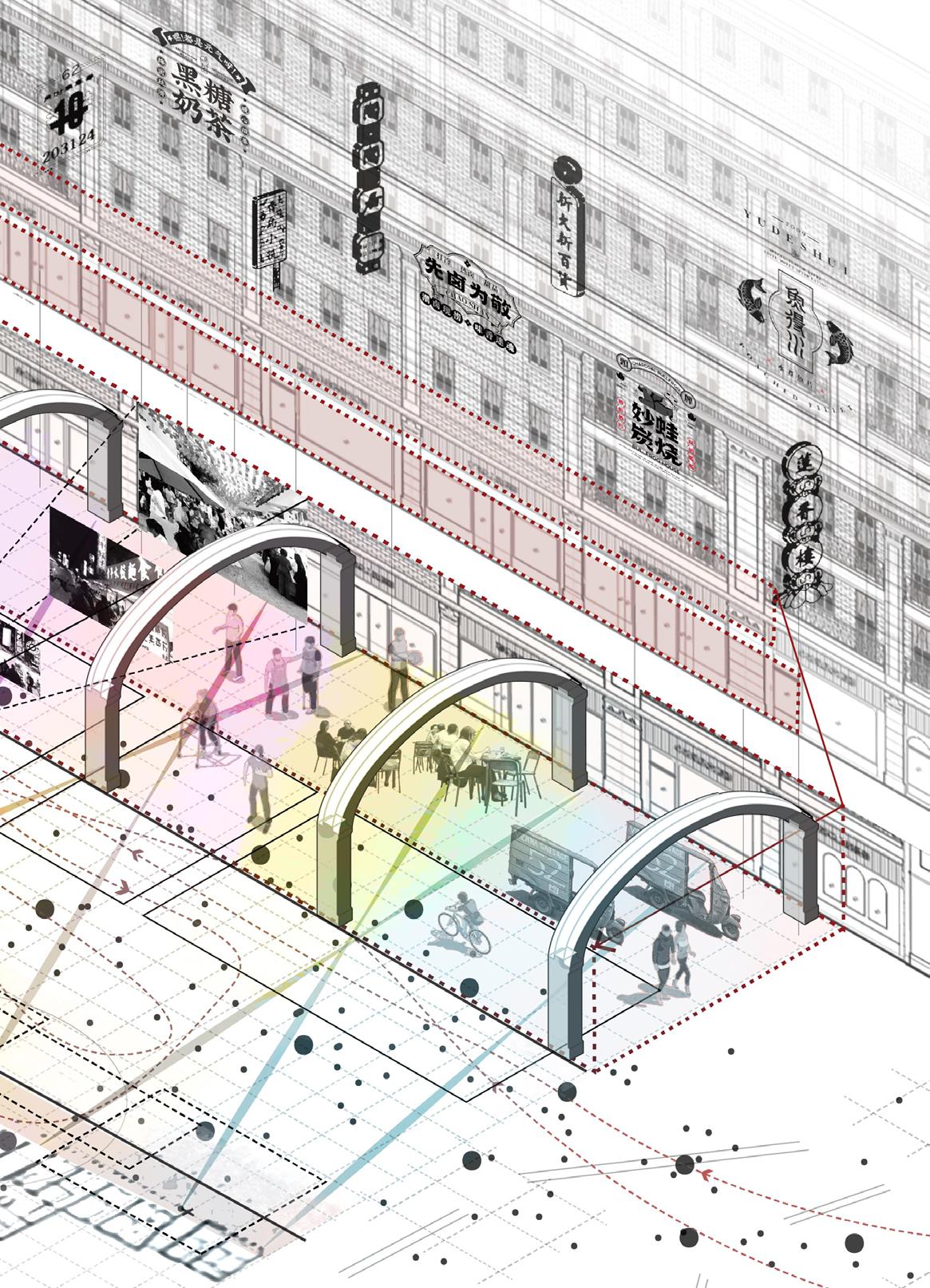

After-property envisions a society based on kinship amongst human and nonhuman actors to produce spaces for autonomy, connection, and expression. The forest, reimagined as the wild, becomes a place for the curation of life and production of culture: an expansive, immeasurable condition, and a process that transforms itself into an active agent within the city.

Vision of music production after property

Vision of wetland neighborhood after property

CITY OF THE FOREST

BLACKHALL STUDIO

Property is a social, spatial tool enacted to fortify the regime’s continuum of power and control. Through acts of domestication, preservation, and measurement, land and its inhabitants have been valued as resources to exploit and tame. Spaces deemed “natural” are not pristine landscapes but highly regulated environments that continue to reinscribe the systemic cycles of exclusion, erasure, and precarity.

Atlanta has been rendered as a placeless backdrop by the film industry and a tactical testing ground by the Atlanta Police Foundation. Through the extraction of public resources, flattening of history and culture, and the degradation of the forest and wetland ecologies, the South River Forest has been a site of ongoing trauma since its commodification as property.

Blackhall Studio’s vision for the future of the South River Forest proposes sound stage