Biospheric Urbanism: Changing Climates

Studio Instructor

Bas Smets

Teaching Assistant

Austin Sun

Students

Jiyoung Baek, Li Jin, Tristan Kamata, Julia Li, Angelica Oteiza, Chanwoo Park, Austin Sun, Parama Suteja, Jessie Xiang, Weiran Yin, Sunjae Yu, Zheming Zhang

Final Review Critics

David Barry, Tatiana Bilbao, Simon Demeuse, Craig Douglas, Beatrice Galilee, Daniel Kiehlmann, Jungyoon Kim, Marten Van Acker

In his legendary 1906 novel The Jungle, the journalist Upton Sinclair characterized degraded urban living conditions, alienation, and hopelessness in the city as breeding a nearly uninhabitable urban purgatory—the “asphalt jungle.” The book systematically exposed American capitalism’s exploitation of workers in the Chicago meatpacking industry along with an attendant lack of urban services and social support nets. The writer Ryan McClure identifies the “jungle” analogy in Sinclair as portraying a lawless, social Darwinist, dehumanizing place (2024).

The metaphor persisted. Director John Huston released his urban crime film The Asphalt Jungle in 1950, and its success led to a television series of the same name airing in 1961. In 1967, the canny San Francisco social commentator Herb Caen famously described the contemporary city as ‘a crazy concrete jungle whose people at the end of each day somehow make a small step ahead against terrible odds.’

The Jamaican reggae virtuoso Bob Marley revised the metaphor in his hit song “Concrete Jungle” in

Gary R. Hilderbrand

1972, quoting the zoologist Desmond Morris: “The city is not a concrete jungle; it is a human zoo.”

Even more than Chicago, San Francisco, or Kingston, Manhattan came to embody the trope of the ‘concrete jungle.’

The 19th century urban reform projects of the Central Park and Prospect Park, by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, had proven that an adapted and wholly constructed “nature” could render the city more livable for humans and nonhuman species. But New York’s and Brooklyn’s parks were patches, to use a contemporary ecology term, in a matrix of dense, hardened development.

During the 20th century, especially in the early decades and then again towards the turn of the 20th century, the planting and maturation of street trees brought relief to the urban grid in parts of the city and served to connect the many of parks and squares with shady corridors. And in post-war housing developments in New York, the prevailing model for exploded modernist building organizations led to internal residential

voids—playgrounds and gardens—that in some cases were designed to humanize otherwise stark environments for working class city dwellers.

Beyond the cause for beautification or recreation, in the early 2000s, scientists and engineers in urban forestry agencies began making far more potent arguments for trees in the city: cooling from shade, oxygen production, storm water management, pollutant uptake, habitat benefits and biodiversity, and carbon sequestration. Tree planting campaigns with ambitious goals became common in cities across the US—in New York, it was the promise of a million trees (mostly small ones) in a few short years. Big city mayors like New York’s Michael Bloomberg believed these programs were popular with voters.

Alas—enter the climate crisis. The concrete jungle needs to be urgently adapted if we are going to survive.

Given the extremities of the climate emergency, there are now few deniers; rejection of climate change persists in remote and familiar corners purely for political posturing, without any basis in science or, frankly, even self-awareness. Our cities are palpably, undeniably hotter. And getting hotter every year.

Professor Bas Smets brings to the Graduate School of Design a deep and urgent passion for altering microclimates in cities. He’s worried—and rightly so. But the work in his design studios, like that of his firm, attests to an optimism about what his medium can do: Landscape architecture can help. Smets sees the city as an “imbrication of climate conditions” and he’s committed to reversing worrisome trends and measuring the potential impacts of design action at the local scale. He also understands that our students are somewhat radicalized around climate and justice—it’s widely known that those who are most affected in cities tend to be the less well-served populations.

Smets has committed to five years of developing, with students from all of the disciplines at GSD, design innovations rooted in and supported by climate science. These include tools for mitigating climate risk and detailed strategies for adapting the physical and spatial organization of public realm space towards greater human comfort and increased biodiversity, among other like aims.

Biospheric Urbanism: Changing Climates, Case Study I, New York City is the pathbreaking first installment in the series. It documents the student work of Fall ’22 in three acts, which will be repeated in five cities worldwide over the coming years: “Mapping of Urban Climates,” “Analysis of the Chosen Site,” and “Project for a Microclimate.” Utilizing proprietary calculating software and consulting provided by the climate science and engineering firm Transsolar, students moved beyond instincts and speculations to precisely measurable impacts in their design proposals. I’m especially grateful to Transsolar for their partnership in this five-year research and design endeavor. And we are most fortunate to have the generosity of Maja Hoffmann and the LUMA Foundation as partners in this important, groundbreaking work.

The Department of Landscape Architecture at Harvard remains a committed testing ground for innovation on climate and justice—these are the existential issues of our time, worldwide, and they stand at the heart of what we do throughout our curriculum and faculty research. I’m ever appreciative of Bas Smets’ determination and his unique pedagogy on these fronts. We hope you enjoy this very promising work by our students. Through all our work, we are building a generation of climate warriors. And we are sending them out into the world to act on their passions with determination and drive. The world needs to change; we are ready to do it.

The climate crisis raises the urgent question of how to make our built environment more resilient to the challenging atmospheric changes, including heat islands, rising temperatures, intensified rainfall, and prolonged droughts. Landscape architecture has a long history of using growth and transformation as its agents to better inhabit this planet. This unprecedented crisis presents both an opportunity and equal responsibility for landscape architecture to radically rethink its field.

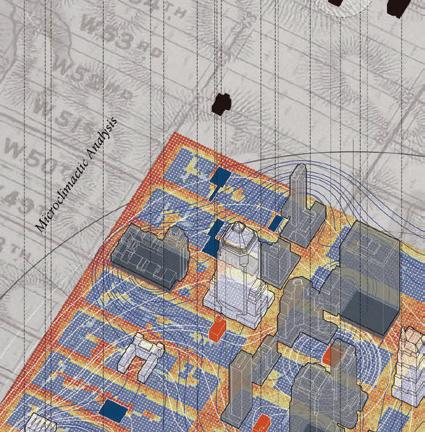

A city can be understood as an imbrication of a myriad of microclimates. Buildings alter wind patterns and sunlight exposure, while streetscapes affect soil permeability, runoff, and solar radiation.

For every man-made microclimate, a comparable natural condition can be identified. The study of their living organisms informs how to introduce vegetation and living agents into artificial environments with a similar climate. Using the principles of nature, cities can be transformed into

complex urban ecologies.

Biospheric Urbanism

Biospheric Urbanism is the study of the built environment as the interface between meteorology and geology. It seeks to transform the critical zone between the above and the below, to better adapt to uncertain changes in climate while optimizing the use of underground capacities.

The Option Studio will focus on New York City as its primary subject of study, structured in three acts. The main learning objective is to use science-based research to develop solution-based design.

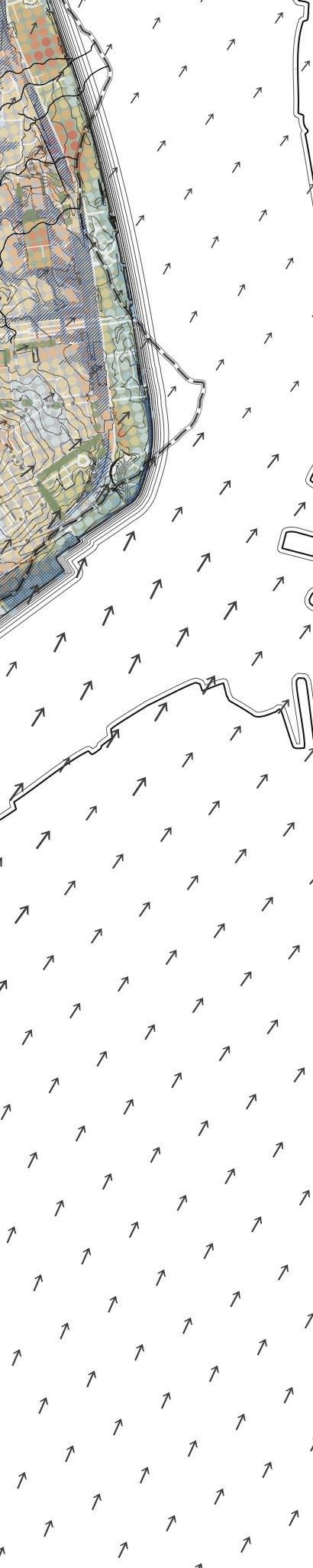

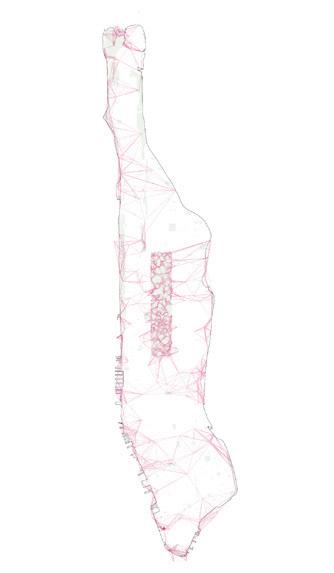

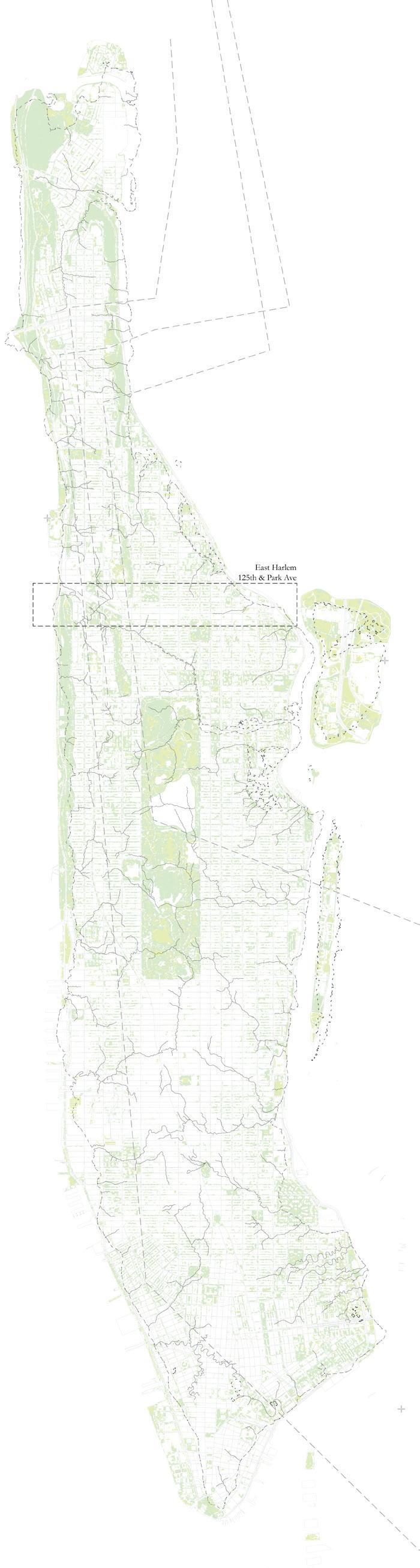

The first act is to map the existing microclimates of the city using all available data. Students will explore the city through historical maps, satellite imagery, flooding maps, and geological surveys, among others. The goal is to create a new map that reveals the various climatic conditions. This climatic cartography will assist the students in identifying the most crucial areas where they believe an intervention would be most beneficial.

The second act involves a comprehensive understanding of the climatic conditions in the selected area. An analysis will be conducted of the existing physical conditions, with a particular emphasis on the underground and its geology. The objective is to explore the potential for rainwater storage and to create continuous volumes of plant medium to integrate vegetation into the urban fabric. The result of the second act will be a mapping of the potential areas for intervention.

The third act transforms the selected area into an urban ecology, effectively altering its microclimate. This will be accomplished through collaboration with other fields such as pedology, hydrology, and ecology. The goal is to elaborate a pragmatic proposal that grounded in a strong vision for the future.

Jiyoung Baek

Manhattan Porticoes

Chanwoo Park Park, Shift, Adapt

Austin Sun

Jessie Xiang

Harlem River Park

Weiran Yin

Turtle Bay Raingarden Oasis

Zheming Zhang

Keep Cool and Enjoy Summer

Sunjae Yu A Bird’s Eye View of Manhattan

Julia Li

Public Space for Public Health

Parama Suteja

Resurfacing Mannahatta

Tristan Kamata

Grey to Green

Angelica Oteiza

Negotiating Resiliency

Li Jin

Subway Dry-Land

Jiyoung Baek

There are more than 4,000 sidewalk sheds in Manhattan, and their total linear length is 13 times that of Manhattan Island. Many people consider sidewalk sheds to be an eyesore that detracts from the streetscape, one that creates a claustrophobic atmosphere and diminishes the appeal of storefronts. However, these structures are essential for protecting pedestrians from falling façades, a hazard that continues to this day. If we must accept these structures, we can also enhance them for our benefit. ‘Manhattan Porticoes’ leverages the prevalence of sidewalk sheds to establish a new series of microclimates throughout Manhattan. By incorporating plantings and a water retention layer into these sidewalk sheds, we can lower the ambient temperatures, enhance air quality, and foster a more diverse urban ecosystem. This straightforward concept can be easily replicated. The porticoes of Manhattan will generate innovative urban microclimates that could significantly impact the city when implemented.

assembly parts

Sidewalk Sheds Typologies

Asssembly Parts

Sample Sites and

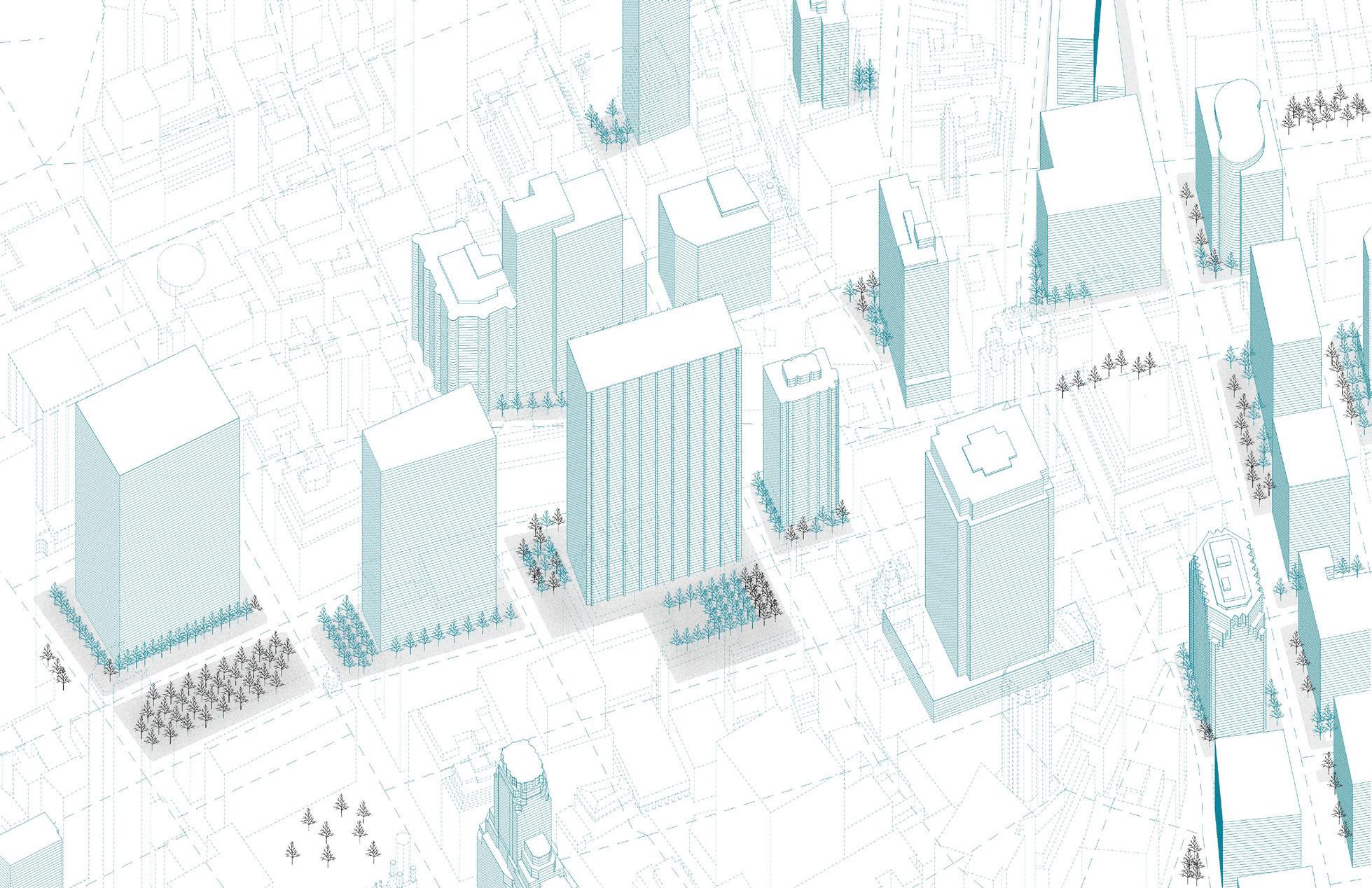

The goal of this project is to repurpose over 1,000 parking structures on Manhattan Island as green infrastructure. Major cities worldwide are embracing the transition toward a carfree future, and New York City has recently taken its first step by implementing congestion pricing in Manhattan. This development encourages us to reconsider the potential of remnants of a once car-centric infrastructure. Operating under the studio name Biospheric Urbanism, this project examines the microclimatic conditions created by extreme urban density and aims to establish a framework for transforming parking structures to enhance urban resilience. The project categorizes parking structures into three distinct typologies, enabling tailored design solutions. These solutions include converting open-air parking lots into inviting pocket parks, repurposing enclosed car parking garages into flourishing botanical gardens, and transforming underground parking spaces into environments for cultivating mushrooms.

Mapping Manhattan: The Hyper-Urban Lanscape

Typological Design Approach

Privately owned Publics Spaces, or PoPs, is a legal term used to describe public spaces that are owned and developed by private property owners. Popularized in New York City as a way to incentivize developers in the 1960s, today, there are over 500 PoPs in Manhattan. During this period, the Global Historical Climatology Network has recorded rising temperatures in the New York area. Manhattan-wide initiatives to combat climate change include MillionTreesNYC, NYC Cool Roofs, and the Climate Leadership and Protection Act. This project is situated at the intersection of New York City’s climate initiatives and regulations surrounding PoPs. A new Climate Zoning Amendment will require retrofitting existing PoPs to lower the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI), or perceived temperature, through an urban ecology transformation. A climatic update to PoPs can create a new network of thermally comfortable public spaces throughout Manhattan.

Climate analysis, UCS existin and UCS project

The “Harlem River Park” project aims to transform urban heat spots into cooling marshlands, meadows, and perennial grasses to mitigate the urban heat island effect in East Harlem. As climate change leads to rising temperatures and an extended growing season in New York City, the need for sustainable urban design has become critical. East Harlem, a neighborhood marked by impermeable surfaces and high population density, is particularly vulnerable to heat. Currently, the park is dominated by turf fields and impermeable surfaces, which exacerbate heat stress. The innovative design incorporates a cut-and-fill strategy, utilizing excavated material to create a berm that shields against highway noise while forming marshlands for water retention and biodiversity. The planned gradient of plant life in the marshland, ranging from water lilies to bulrushes, is designed to enhance ecological resilience, providing essential functions such as water filtration, carbon sequestration, and habitat creation.

Proposed Design, plan

Above: Proposed Design, detail sections

Below: Proposed Design, section

Weiran Yin

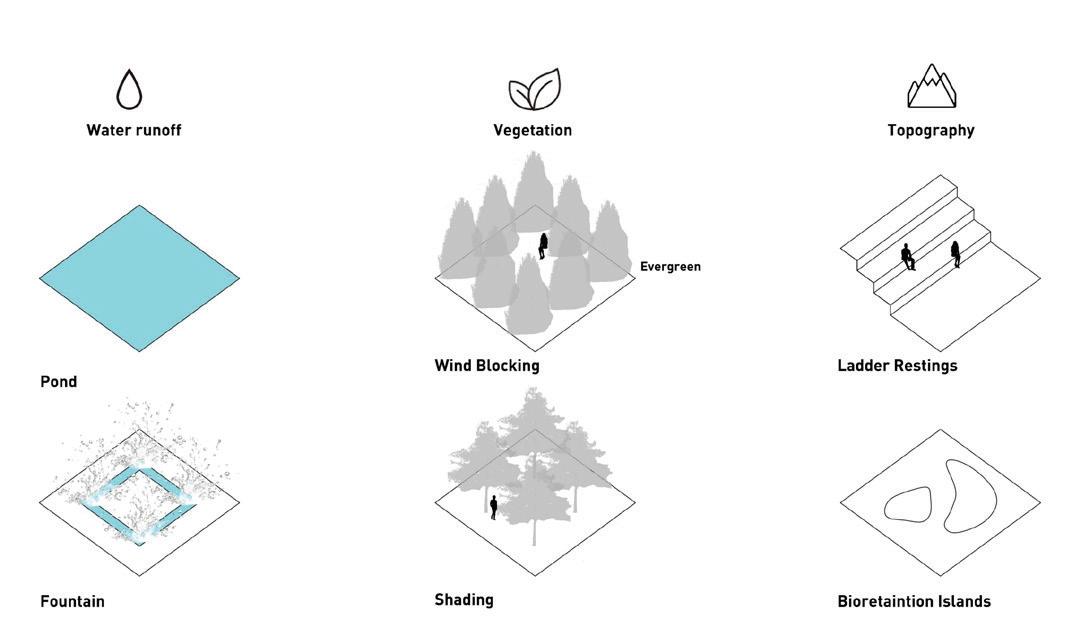

The project proposes a solution to mitigate the impact of combined sewer system overflows (CSOs) in New York City by creating rain gardens that reduce and purify stormwater volume. New York’s extensive waterways are vital yet vulnerable to pollution from CSOs, which occur when the sewer system is overwhelmed by stormwater, resulting in the discharge of untreated sewage. This project identifies vacant lots near sewer lines and water bodies as potential sites for stormwater management. Focusing on a 6.5-acre site in Turtle Bay, the project aims to reintegrate the area’s historical natural landscape and ecological functions. The design employs the Manhattan grid to organize a series of ponds and bioretention areas, complemented by boardwalks that facilitate public interaction with the purified water environment. Selected vegetation in these areas is intended to remove pollutants while simultaneously enhancing the aesthetic and recreational value of the urban landscape.

Scheme proposal element for the design

Proposal Design

Zheming Zhang

In response to the urban heat island effect, this project aims to cool New York’s microclimates by modifying surface and perceived temperatures. East Harlem has been identified as a focal point due to its vulnerability to heat, which is exacerbated by expansive, tree-scarce areas.

The initiative proposes transforming parking lots and vacant spaces into shaded, wind-friendly areas, which are essential for summer relief. By planting linear tree formations, the design facilitates the passage of breezes during hot months while providing wind protection in winter. These interventions seek to create inviting community spaces, featuring vegetation that supports water management and social functions, thereby enhancing the local microclimate for improved comfort and environmental quality. This approach offers a scalable model for urban cooling, with the potential to revolutionize summers in Manhattan, one block at a time.

Typical Section of Existing Typologies Proposed Transformation, scheme

Proposed Transformation, isonometric view

Proposed Transformation, plan and section

Sunjae Yu

This project aims to create a network of livable rooftop gardens in Manhattan to protect and promote urban bird populations. Aves in cities confront constant dangers due to unfriendly surroundings and end up crashing into buildings. Modifying their trajectories by providing consecutive roof gardens will not only protect the birds from those threats but also contribute to the entire ecosystem by offering habitats for a variety of bird species in urban areas. Those green roofs will also work for the microclimate in various ways: they reduce the surface temperature to moderate the heat island effect, capture water, block wind in the winter, provide shade in the summer, and help maintain clean air. By transforming unused rooftops into thriving gardens, we can create a more sustainable, bird-friendly urban environment that benefits both humans and wildlife, resulting in preserving and protecting birds, nature, and the planet.

northern

common

terrestrial birds sea birds

terrestrial birds

northern

blue

Julia Li

This project focuses on the microclimate of pollution and hazardous health conditions caused by the elevated railway that continues to run along Park Avenue, through East Harlem. The core of the project uses landscape strategies and typologies to address public health concerns of East Harlem, brought about by noise and air pollution. To reutilize the stretch of elevated railway, redirecting the car lane under the railway’s steel frame increases available sidewalk space that can be transformed into occupiable green space for the local community. The park utilizes landform typologies and planting archetypes as methods to decrease the impact of noise and air pollution for the surrounding community, while also working within the spatial organization of the incorporated lots. Once combined, a linear park that runs along both sides of the railway is formed. This park is an addition to the East Harlem community to contribute to better public health for the neighborhood and its residents.

Parama Suteja

The name Manhattan originated from the word “Mannahatta”, which can be traced back to the Indigenous American’s Lenape language, meaning “island of many hills.”

This project aims to resurface Mannahatta, transforming the current Manhattan to its natural landscape and harnessing the city’s power to thrive in harmony. Urbanization has resulted in ecological disruption, leading to issues like flooding and the urban heat island effect. The proposal suggests creating a “third landscape” on rooftops, utilizing abandoned and inaccessible spaces throughout the city. These rooftops would be transformed into natural habitats with native plants, promoting biodiversity. The project envisions a revitalized Manhattan skyline that seamlessly blends nature with the built environment. Ultimately, this undertaking aspires to cultivate a more ecologically balanced and biodiverse urban environment that not only supports native wildlife but also enhances the overall quality of life for its residents.

Buildings and Hills Relationships

Resurfacing Mannahatta - Buildings and Hills Relationships

Vegetations and Buildings Relationships

Vegetations and Buildings Relationships

Transformation of Third Landscape from 2023-2050

Tristan Kamata

Canal Street, a vibrant thoroughfare that stretches from the East River to the Hudson River in Manhattan, faces a significant threat from future stormwater flooding. Recognizing the urgent need to address these vulnerabilities, the project reimagines the traditional streetscape by implementing a series of stormwater mitigation modules. The proposal introduces a collection of simple yet distinctive green infrastructure elements that serve a dual purpose: they effectively slow, spread, and absorb stormwater in an area historically plagued by impermeable surfaces, while also revitalizing the neighborhood. By integrating these green infrastructure components, the once utilitarian thoroughfare will transform into a welcoming and vibrant space, inviting both locals and visitors to engage amidst a backdrop of lush greenery. This approach not only addresses immediate stormwater management needs but also enhances the overall quality of life for the community.

Angelica Oteiza

Manhattan island serves as a prime example of the Anthropocene, illustrating humanity’s impact on a geological scale. The island is entirely occupied by human-built systems, both above and below ground, which dominate what was once a tidal marsh island. Today, it faces the threat of increasingly severe and unpredictable climatic events. Its anthropocentric design heightens the potential hazards to which the island is vulnerable, as existing conditions contribute passively to environmental devastation. My proposal views adaptation as an opportunity to engage in broader discussions about public space and resilience. By acknowledging the transformative power of water in shaping spaces and the principles of environmental justice, I propose ‘hybrid streets’, the negotiation between natural and human flows. The project begins with the density and land use codes of Harlem’s block’s and seeks to reclaim the streetscape to support three key principles: space for biodiversity, space for resilience, and space for urban use.

Built Space, Understanding the Anthropocentric Footprint of Manhattan

Typology

Environmental Performance

Typology

Environmental Performance

Typology 04: Environmental Performance

Typology

Environmental Performance

Typologies: Environmental Performance

Typology 01: Base Section

A negotiation between Human and Natural Space in Manhattan

In recent years, New York City’s subway system has experienced severe flooding during storms, as the drainage system is unable to effectively manage and store stormwater. To address this issue, I have selected the Canal Street subway station as the site of my investigation. My proposal consists of three parts. 1. Repurposing ventilation openings as water storage to substantially reduce the amount of water flowing directly into the station. 2. Installing a heat harvesting plant on the station’s abandoned tracks that connect to the Manhattan Bridge; this facility can capture exhaust heat and contribute to Manhattan’s steam system while simultaneously cooling the platforms. 3. Expanding sidewalks with sloped permeable materials, tree planting, and introducing narrow runnels to improve the street environment and drainage. During heavy rainfall, water can be directed into storage or sub-drainpipes; on dry days, it can be used to irrigate trees, thereby alleviating strain on the sewer system.

Design Proposal, plan

Design Proposal, isometric section

Bas Smets has a background in landscape architecture, civil engineering and architecture. He founded his firm in Brussels in 2007 and has since completed more than 50 projects in more than 12 countries with his team of 25 architects and landscape architects. These projects vary in scale from territorial visions to infrastructural landscapes, from large parks to private gardens, from city centres to film sets. His realised projects include the Parc des Ateliers in Arles, the park of Thurn & Taxis in Brussels, the public space around the Trinity Tower in Paris La Défense, the Sunken Garden and Mandrake Hotel in London, and the Himara Waterfront in Albania. In 2022 he won the international competition for public space around the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, France.

Jacopo Fochi

Jacopo Fochi is an architect and project leader at Bureau Bas Smets.Since 2017 he’s been responsible for international projects in Europe and North America.He also leads the BBS team on cartography and computational techniques. His research is focused on the dynamic character of landscape, using a generative approach to reveal the hidden characteristics of territory and simulate its transformation processes.

Wolfgang Kessling

Wolfgang Kessling is the Director of climate engineering company Transsolar, which aims to build structures that provide the highest possible comfort levels with the lowest possible impact on the environment. He focuses on low energy/high comfort concepts for hot and humid climates. He has been a project manager for the Experimental Cloud in Frankfurt, Germany and the Gehry building for Novartis in Basel, Switzerland. In Asia he has worked on the innovative cooling concept of the Suvarnabhumi International Airport in Bangkok, Thailand and the first Zero Energy Office in Malaysia.

Daniel Kiehlmann

Daniel is an expert for integral design on all kinds of innovative buildings focusing on energy efficient design and sustainability. He has developed special knowledge in complex building and system analysis and leads high profile projects of different scale ranging from buildings to masterplans. He has been involved in projects throughout Europe, North America, the Middle East and Asia.

Biospheric Urbanism: Changing Climates

Instructor

Bas Smets

Instructor Assistant

Jacopo Fochi

Report Editor

Briana King

Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture

Sarah Whiting Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture

Gary R. Hilderbrand

With the generous support of the John Portman Foundation.

Copyright © 2024 President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without prior written permission from the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Text and images © 2024 by their authors.

The editors have attempted to acknowledge all sources of images used and apologize for any errors or omissions.

Harvard University

Graduate School of Design

48 Quincy Street Cambridge, MA 02138

gsd.harvard.edu

Studio Report Spring 2023

Harvard GSD

John Portman Design Critic in Landscape Architecture

Jiyoung Baek, Li Jin, Tristan Kamata, Julia Li, Angelica Oteiza, Chanwoo Park, Austin Sun, Parama Suteja, Jessie Xiang, Weiran Yin, Sunjae Yu, Zheming Zhang