Anita Berrizbeitia / Marc Armengaud / Matthias Armengaud

Anita Berrizbeitia / Marc Armengaud / Matthias Armengaud

Anita Berrizbeitia / Marc Armengaud / Matthias Armengaud

Fallowscapes: Territorial Reconfiguration Strategies for Arles

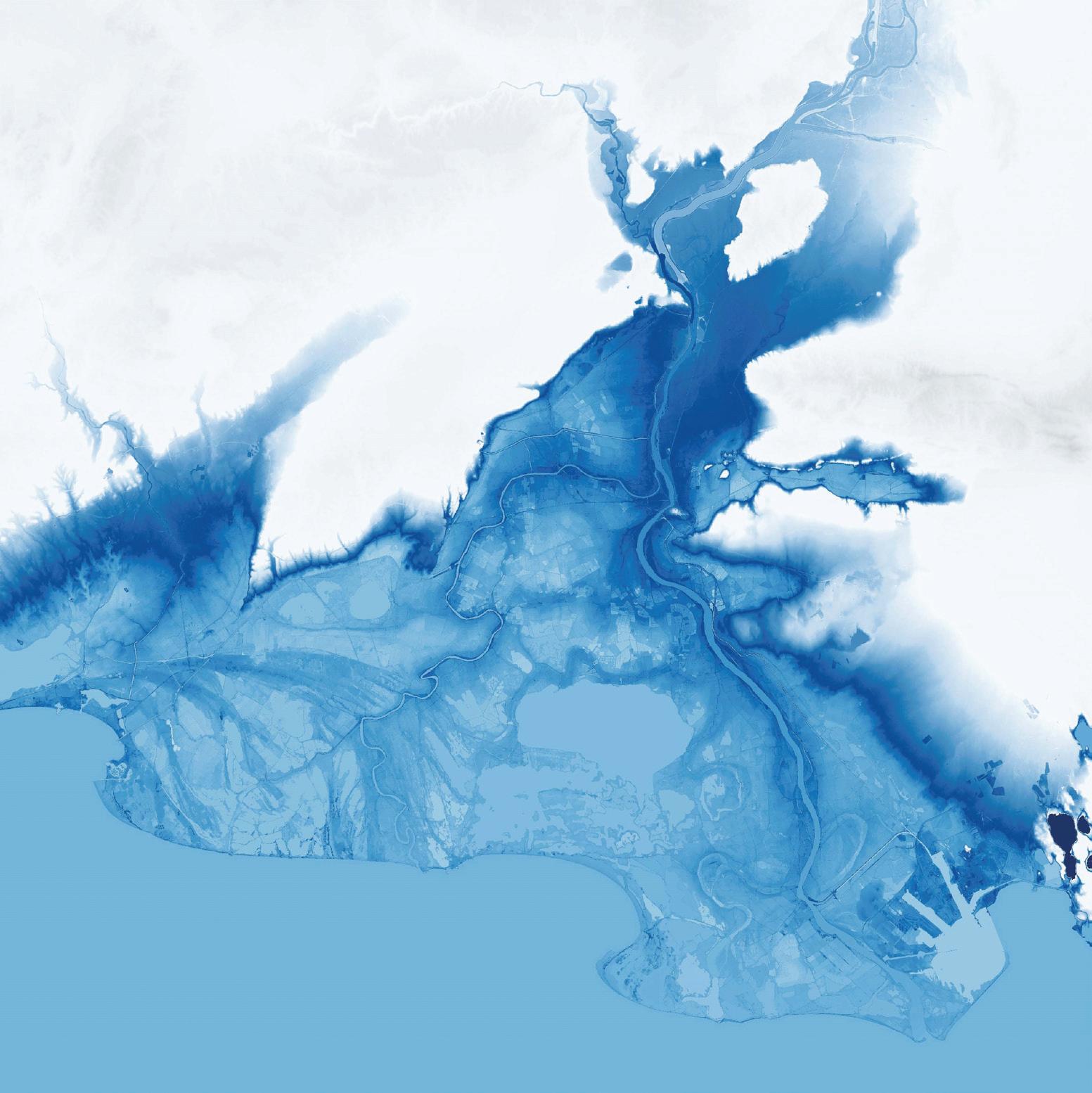

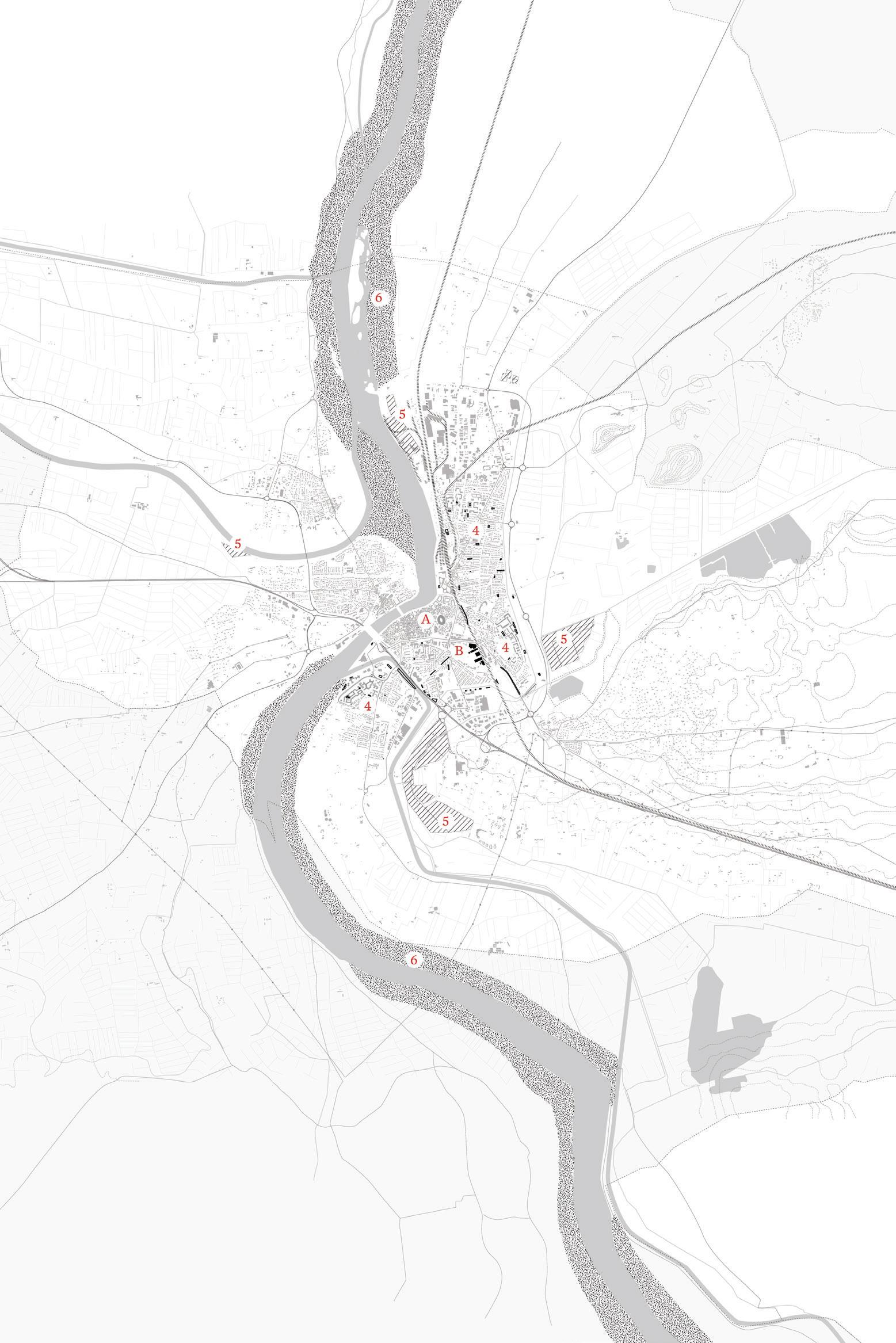

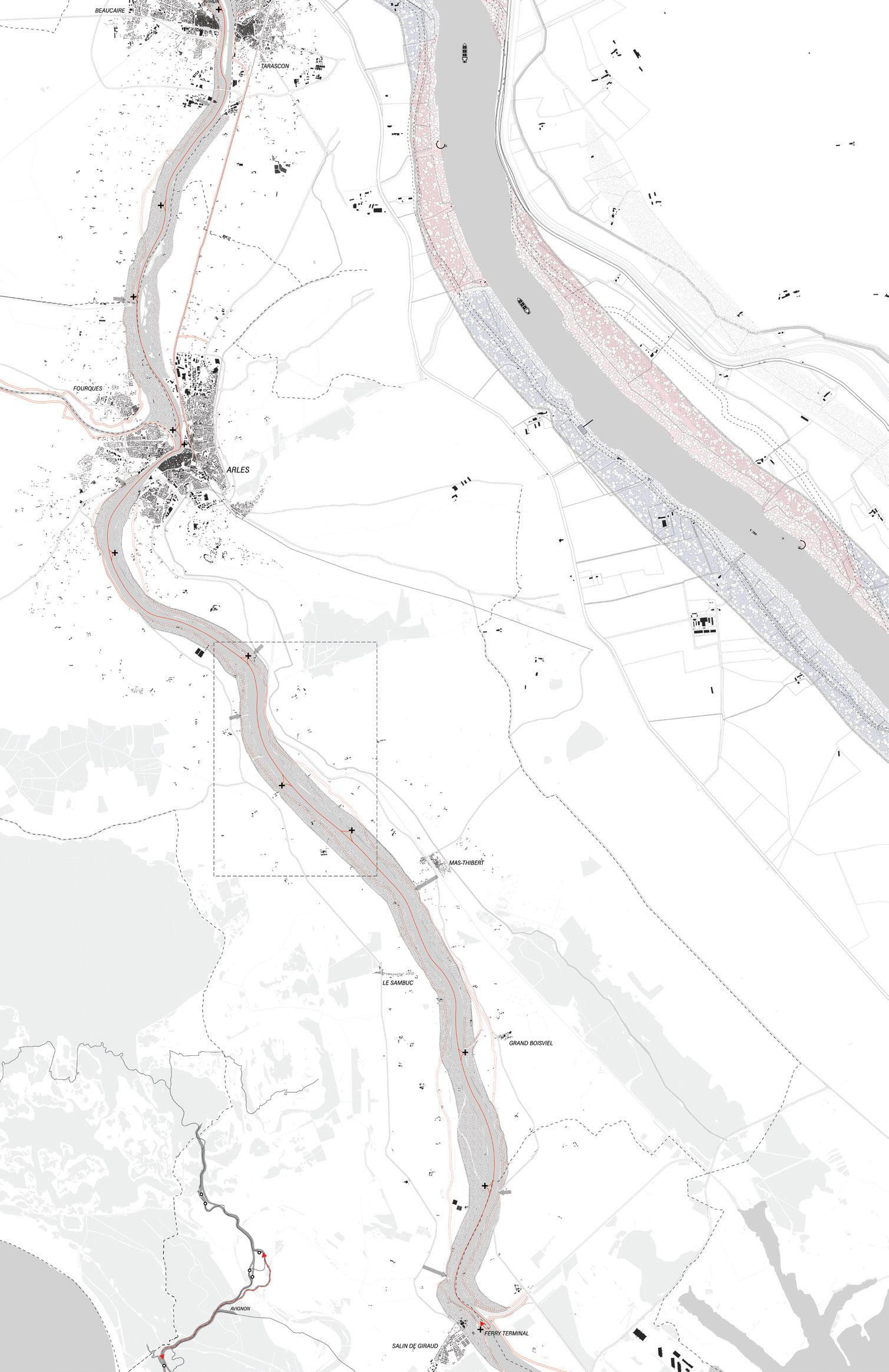

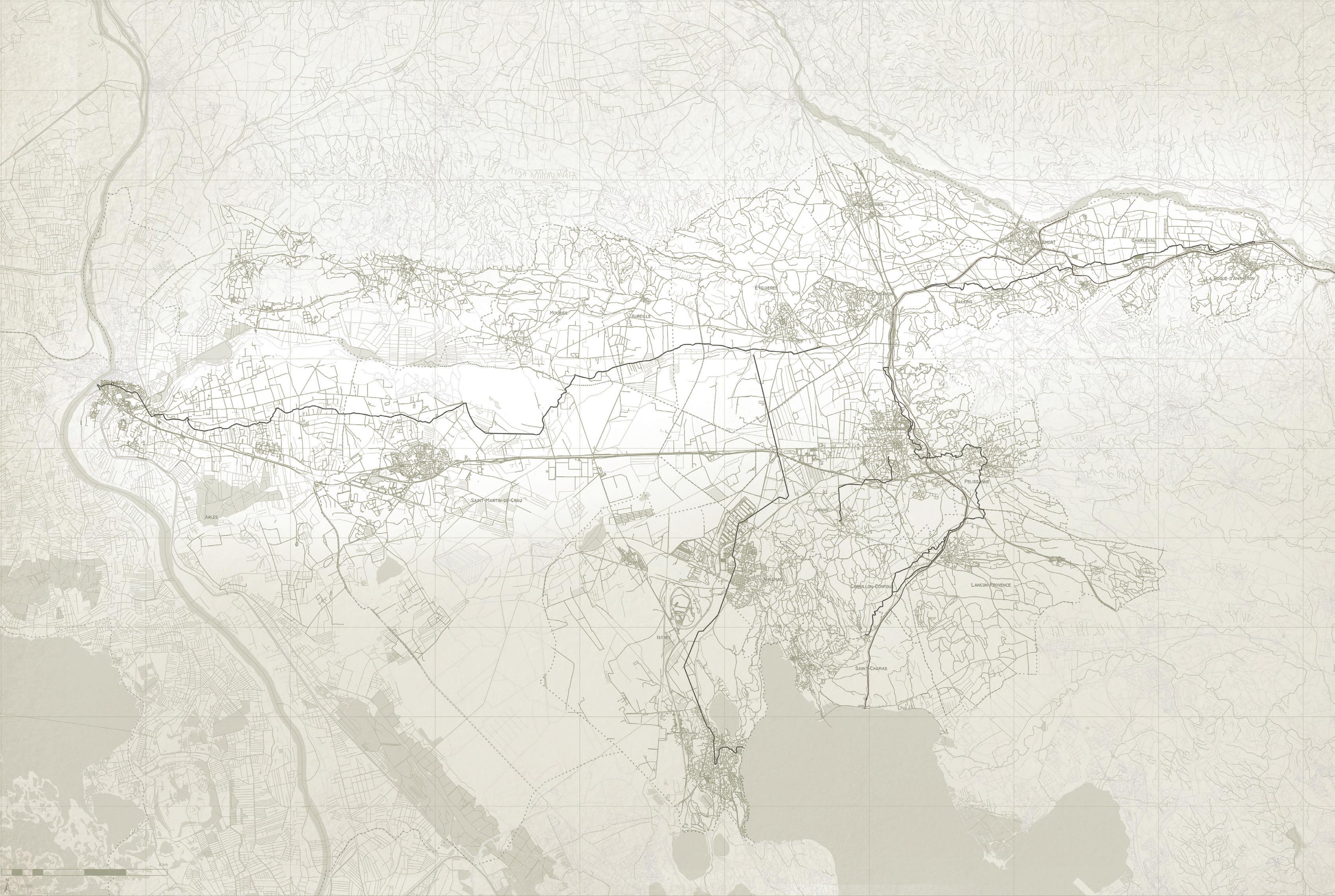

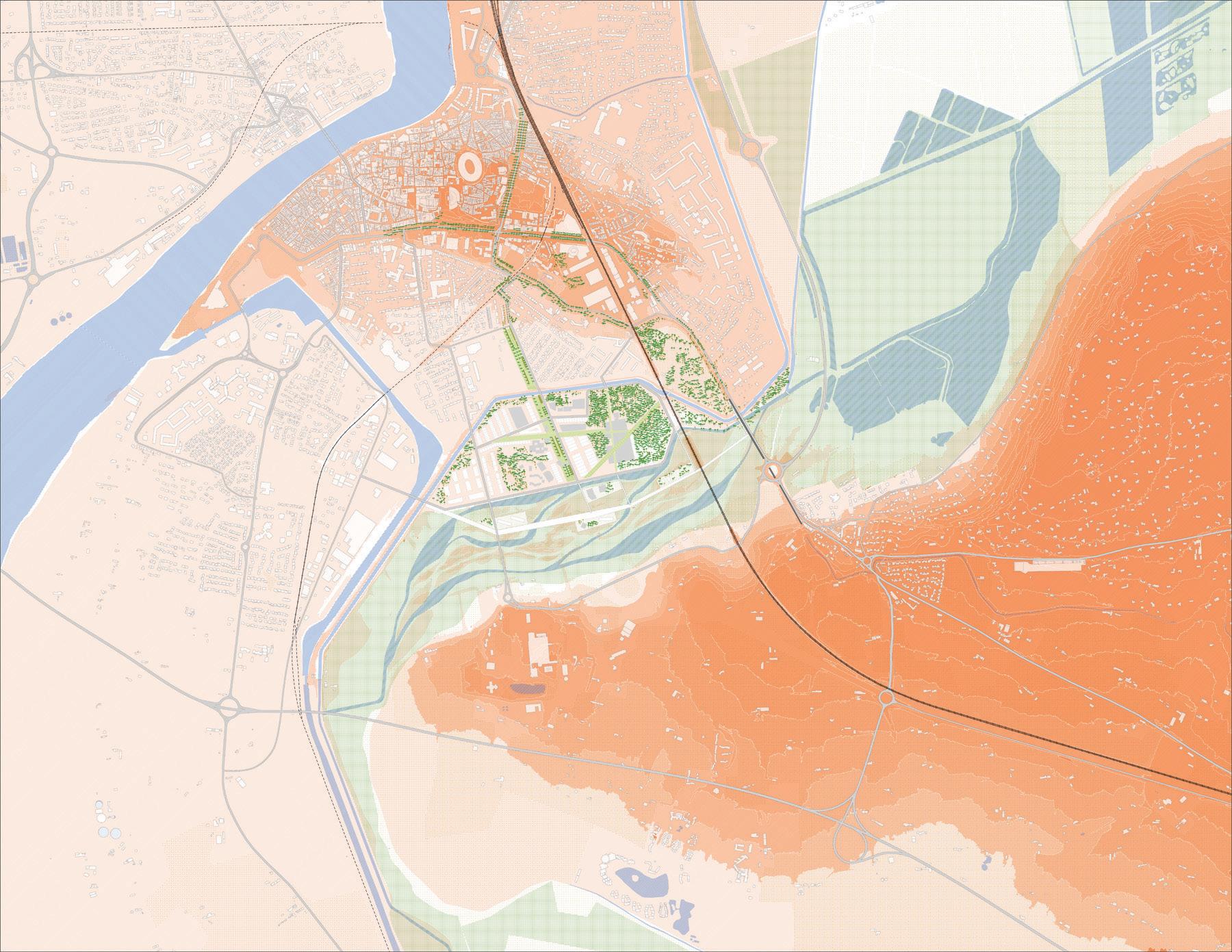

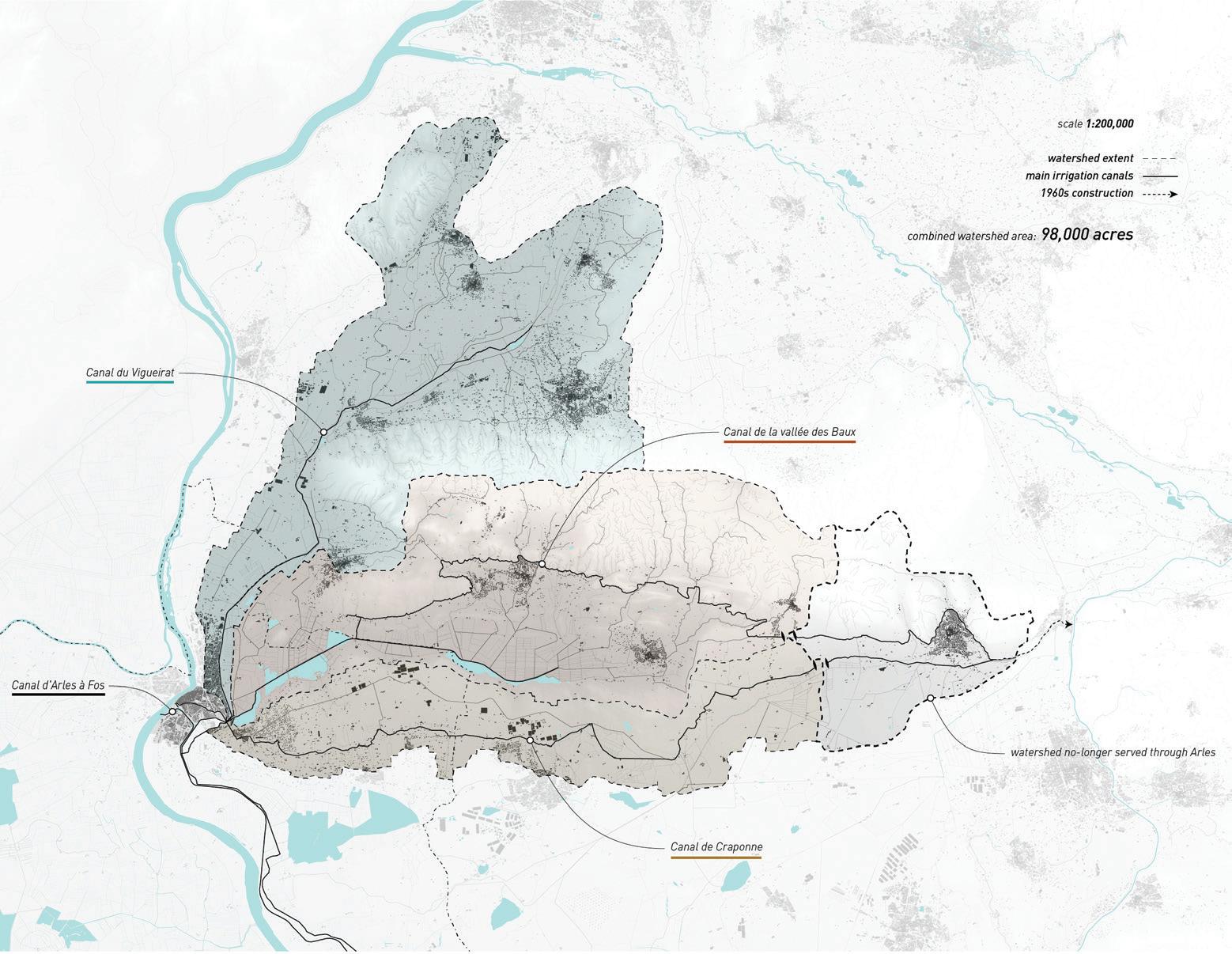

On a promontory on the left bank of the lower Rhône River, just before it reaches the Mediterranean Sea, the city of Arles presides over vast plains that, until fairly recently, were characterized as wastelands destined to remain permanently uncultivated. Once a thriving Roman outpost, built almost entirely from limestone quarried nearby, the city retains its original configuration. However, high unemployment for the past several decades calls for a renewed destiny beyond its high-end cultural and historical profile. By contrast, modernity radically changed the city’s hinterland, separating—in the Camargue Delta—salt from fresh water, and from sea, and redistributing fresh water from Alpine rivers into a filigree of canals that turned the arid Crau plain into a productive landscape. In the seams that formed between waterways, orchards, rice fields, quarries, logistics sites, infrastructures, and drainage ways, a fallowscape lies in a weird state of neglect. This studio reconsiders the interactions between systems and landscapes according to different scales, limits, time, and material, advocating for territorial reconfiguration strategies that investigate the existing and the potential, in order to face dramatic ecological threats and an enduring social crisis.

Studio Instructors

Anita Berrizbeitia, Marc Armengaud, Matthias Armengaud

Teaching Fellow Santiago Mota

Students

Shira Grosman, Camila Huber, Jonathon Koewler, Andy Lee, Jason Liu, Koby Moreno, Roberto Ransom, Eleanor Rochman, Andreea Vasile Hoxha, Yifan Wang, Zhaodi Wang, Xinyi Zhou

Mid-Term Review Critics

Maja Hoffmann, Vassilis Oikonomopoulos, Jan Boelen, Ingrid Taillandier, Sarah M. Whiting

Final Review Critics

Katarzyna Balug, Julie Bargmann, Mustapha Bouhayati, Felipe Correa, Edward Eigen, Robert Gerard Pietrusko, Alessandra Ponte, Jean-Pierre Pranlas-Descours, Brent Ryan

M.

10 Arles’s Invisible Landscapes

Anna Positano

32 Arles Unbound

Anita Berrizbeitia

40 Arles in the Crossfire of Territorial Dimensions and Dissension

Marc Armengaud and Matthias Armengaud Projects: 12 Sites

48 Portrait of Arles

54 Recycling and Depolluting

58 Hedgerow Funds: Investing in the Cultural Value of Fallow Lands

Koby Moreno

62 Co-Mingled: A New Waste Economy for Arles

Andy Lee

66 Productive Fallowscapes: Shifting the Politics of Water in Arles and its Larger Territory

Andreea Vasile Hoxha 70 Vulnerability

74 Street Arles Initiative: Transforming Arles through Street Football Pitches

Jason Liu

78 Department of Fallow Land: Institutional Presence of Fallow in Arles

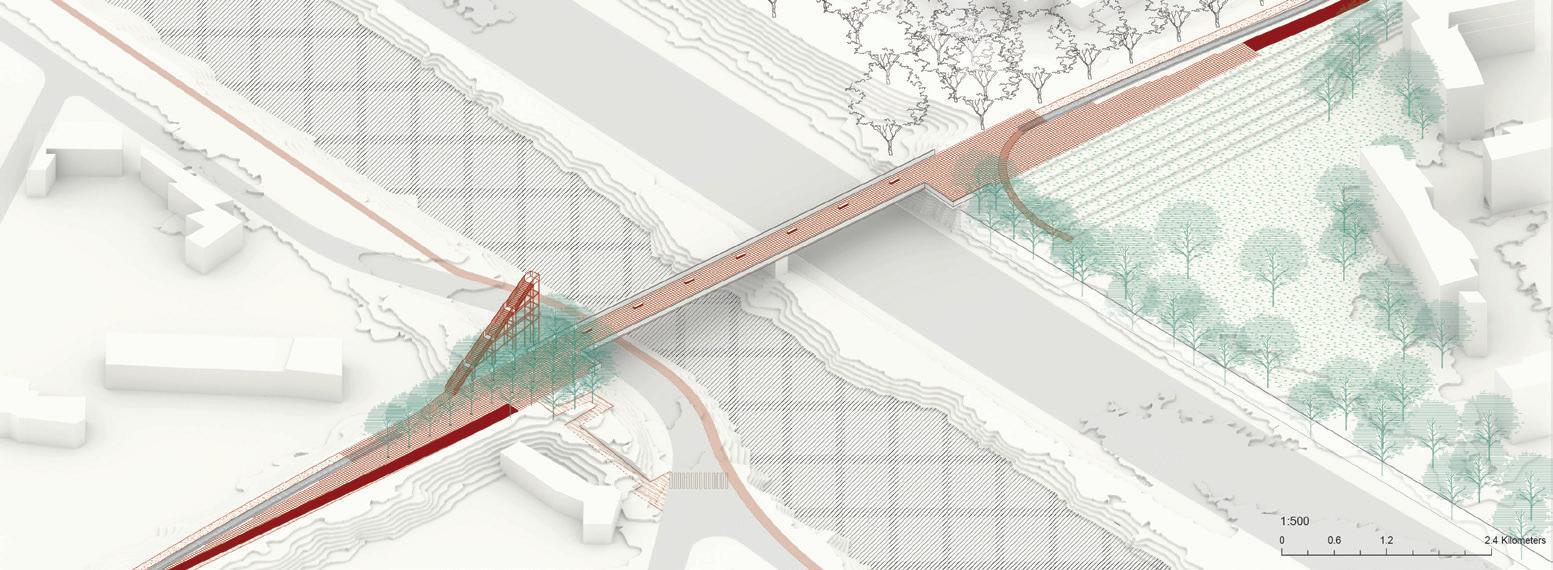

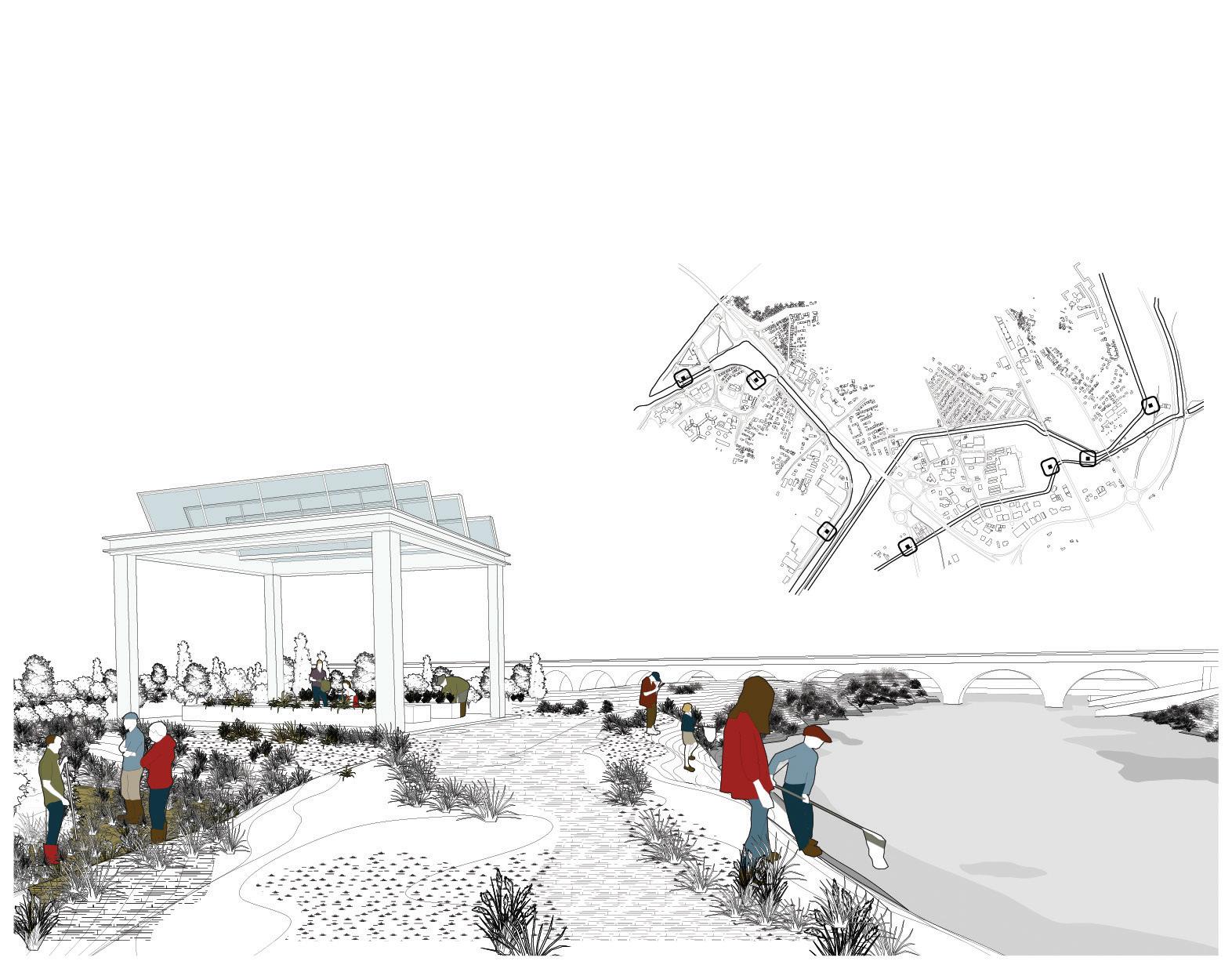

Camila Huber 82 Back to the Banks: Coproducing a New Edge on the Rhône

Shira Grosman

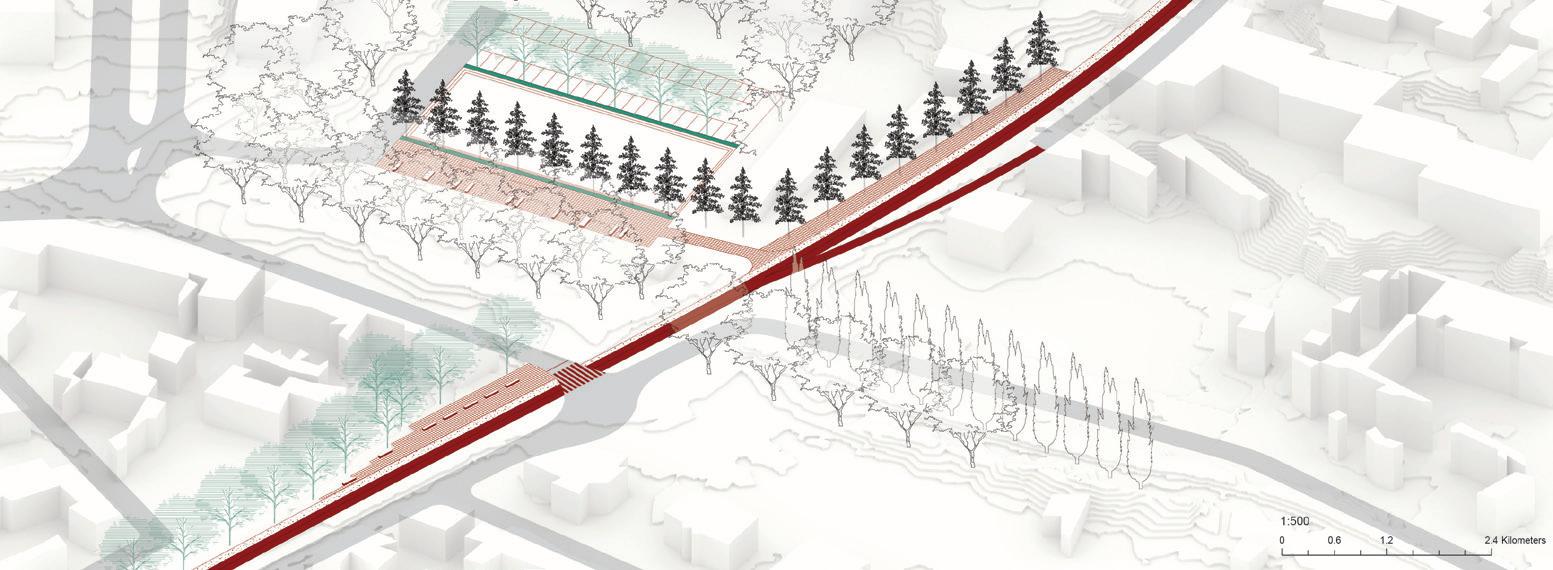

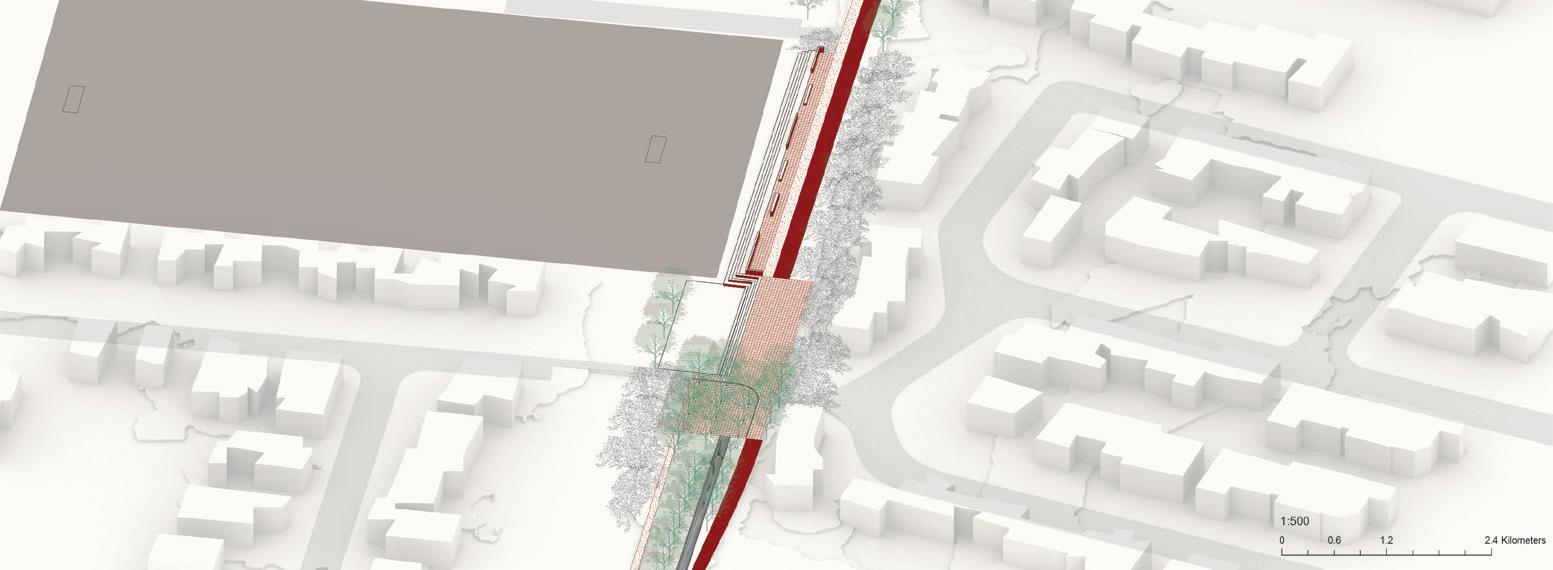

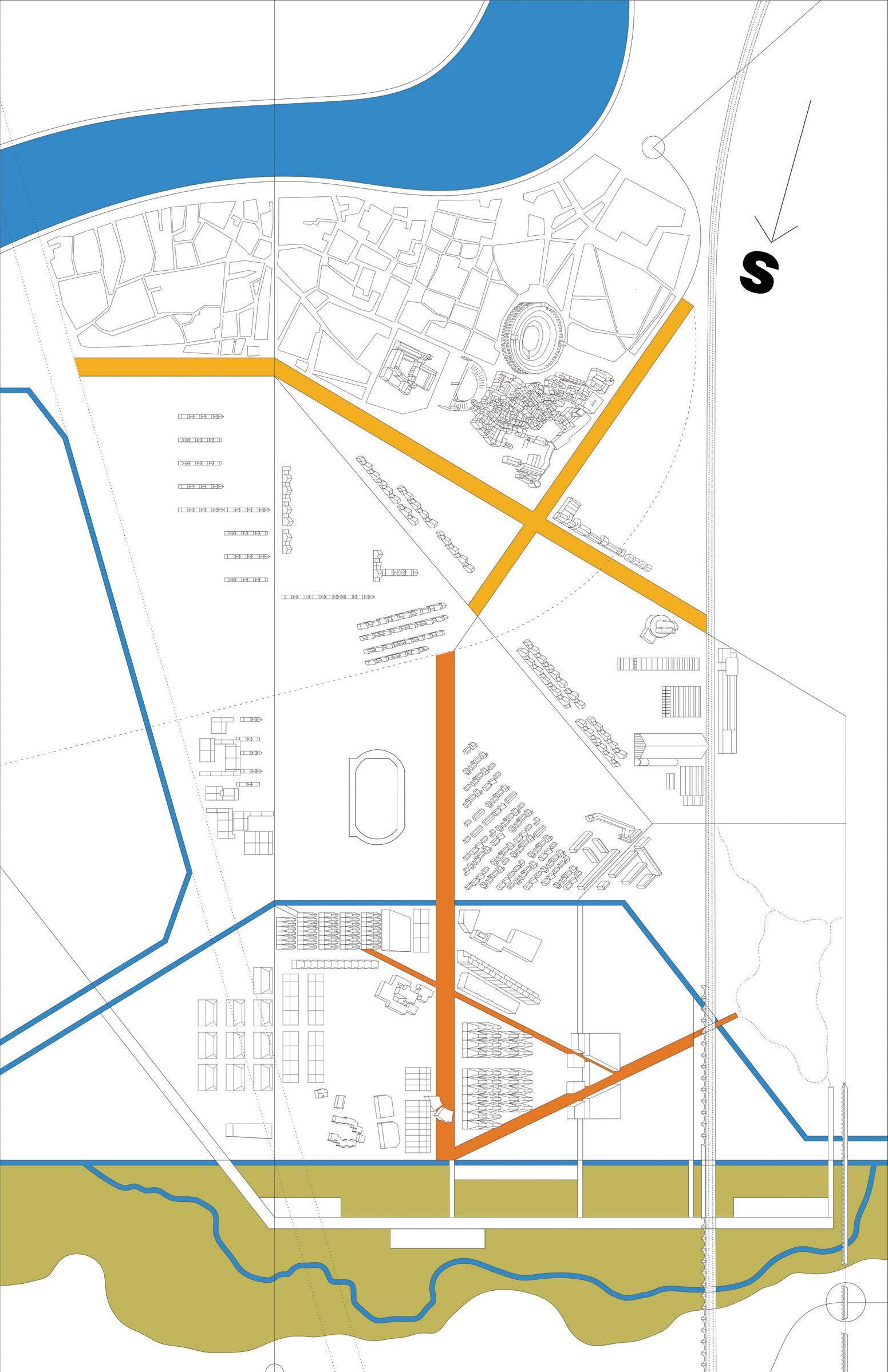

Bike City: Fallow Infrastructure as Infrastructural Fallowscapes

Xinyi Zhou

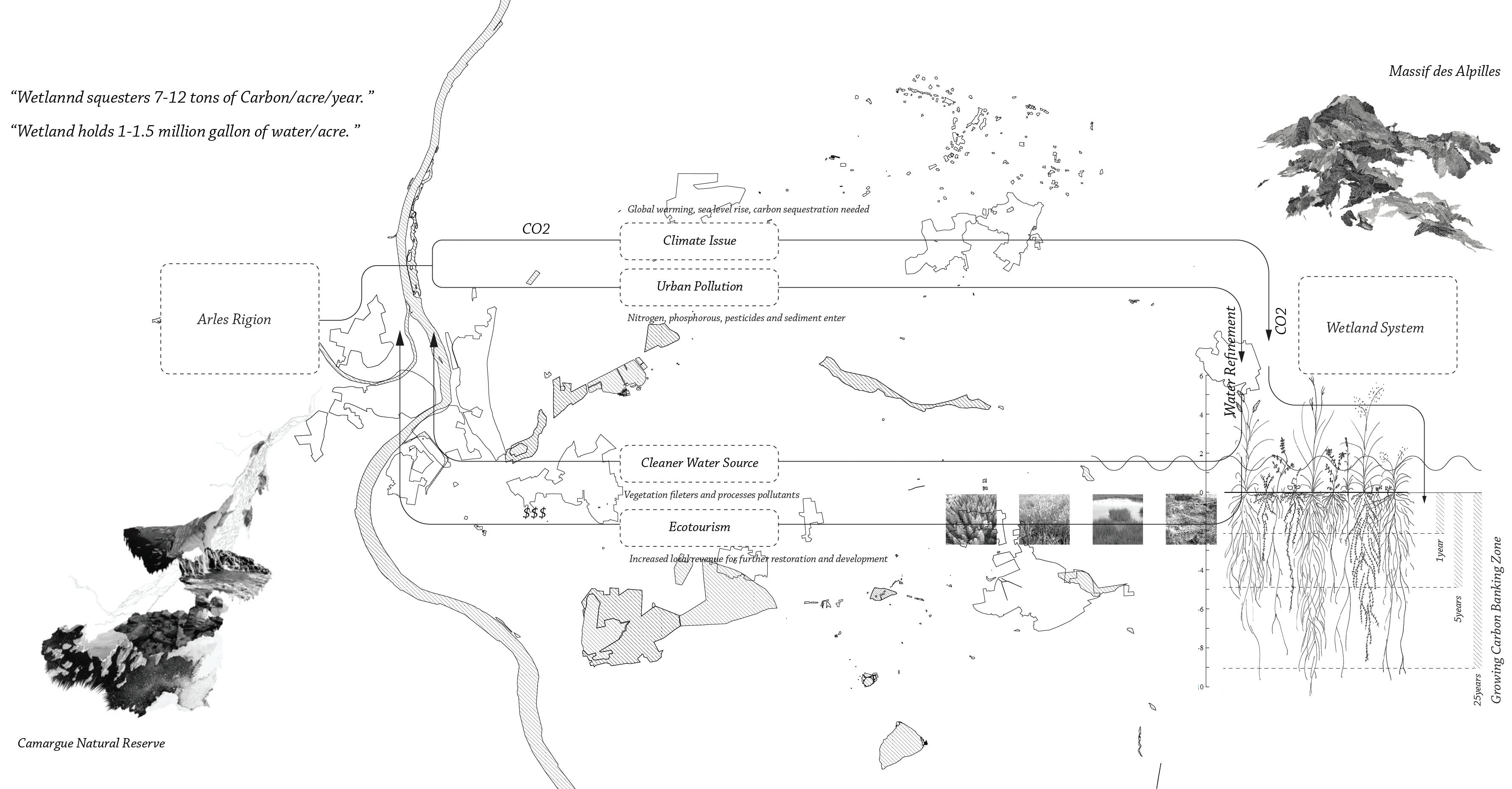

(Re)Fallow: Reviving a Wetland System in the Arles Area

Zhaodi Wang

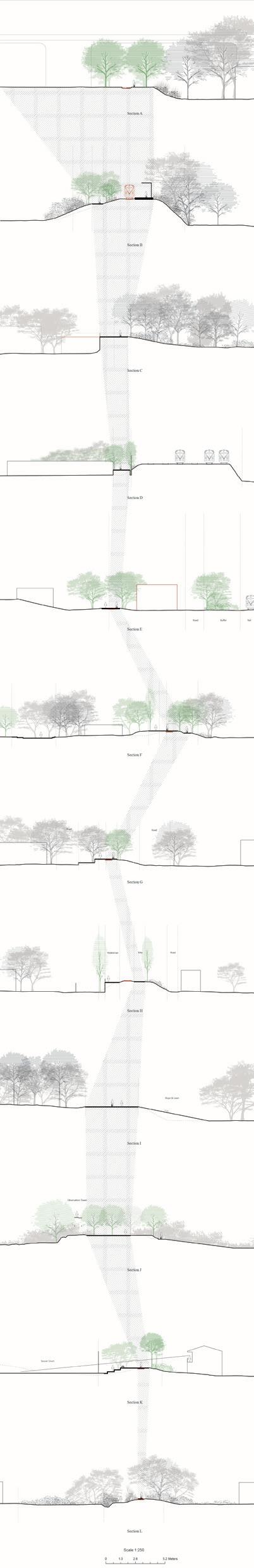

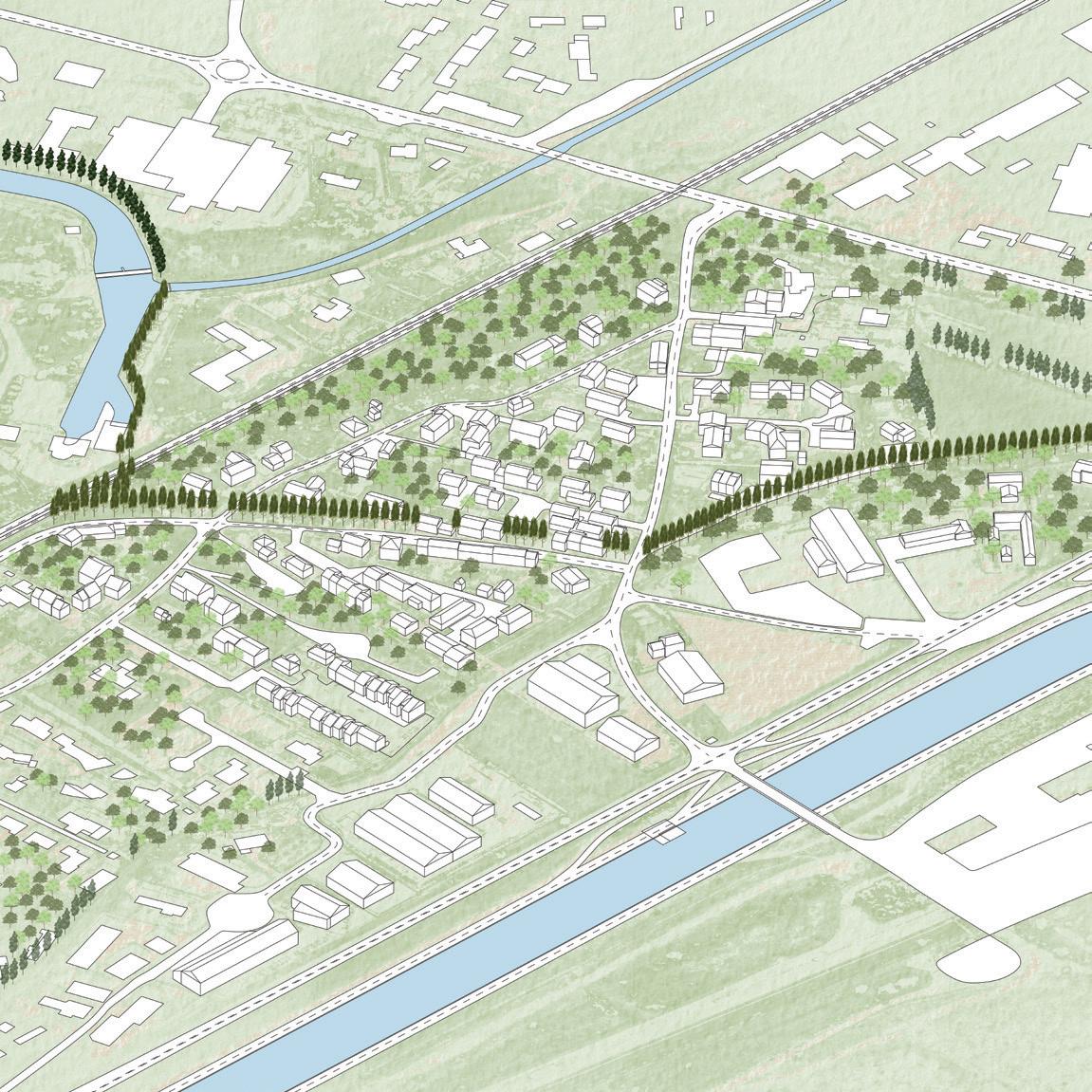

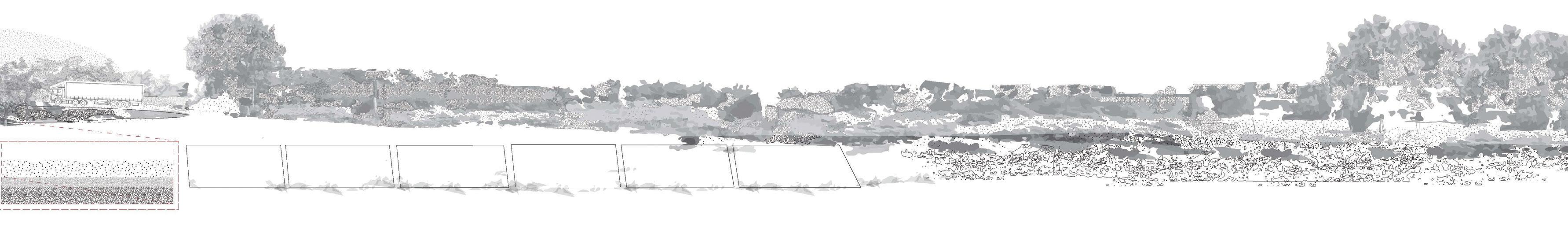

Fertile Fallow: A Line of Trees Along the Canal de Craponne Eleanor Rochman

the Motorway

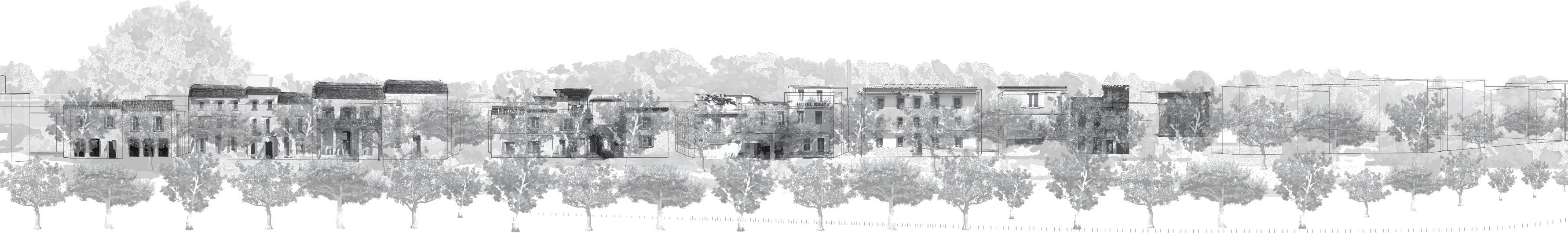

Prospect South: Opportunities in Connectivity

Yifan Wang

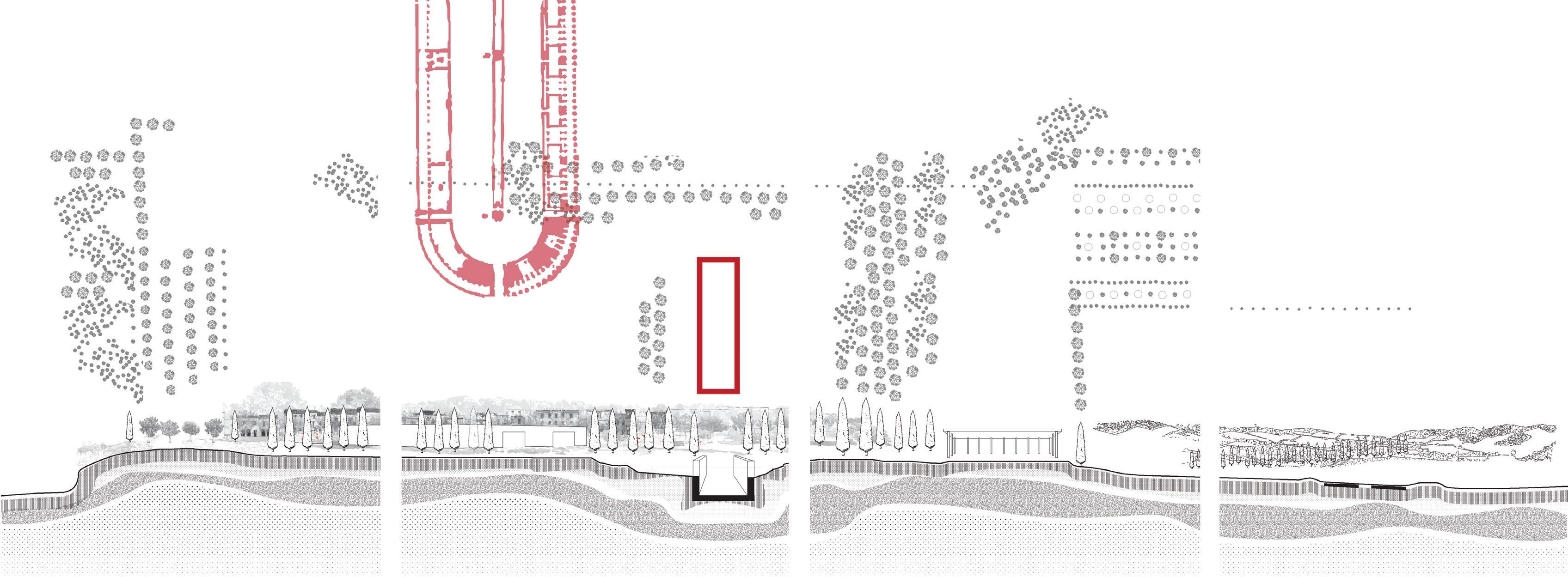

Engagé: The Spectacle of Reconnection

Roberto Ransom

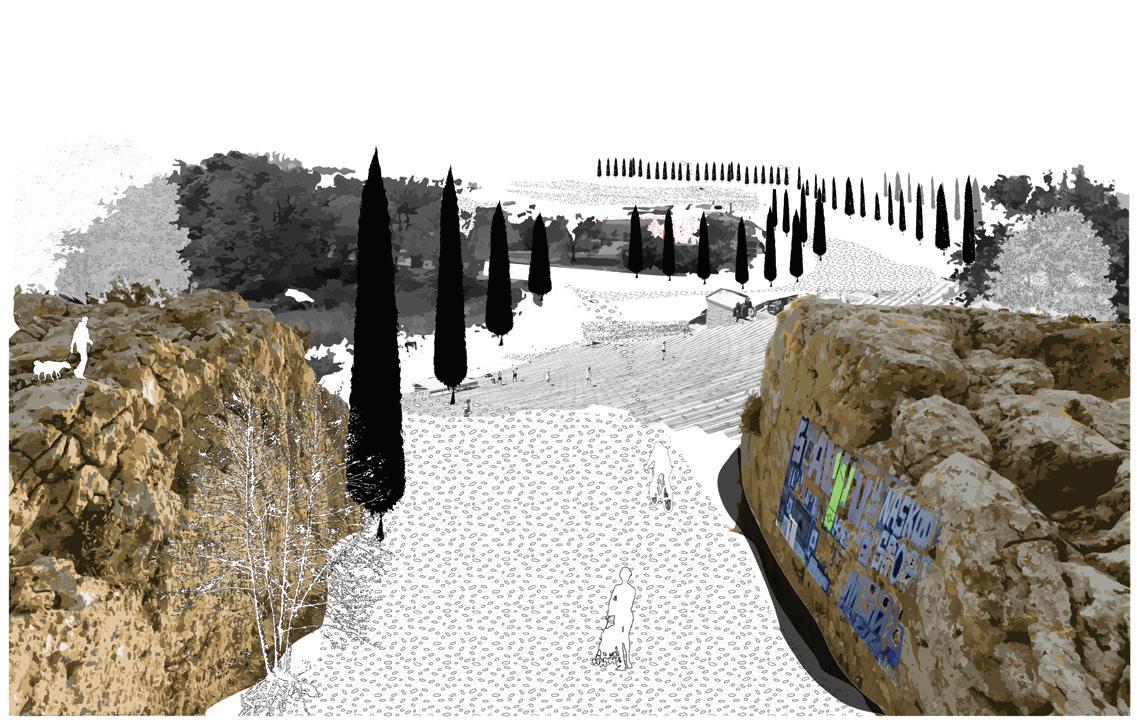

Back of House: Curating Fallow Along the Canals

Jonathon Koewler

Network City

In her recently published book Wintering, 1 memoirist Katherine May writes of times in life when one is “cut off from the world,” whether through illness, losing a job, losing a family member, or even through happier occasions, like a cross-country move or the birth of a child. These are moments that she describes as transitions, or “temporarily fall[ing] between two lives,” or, further, as “a fallow period in life . . .”

I had previously only considered “fallow” to be tied to physical, agricultural sites—the practice whereby a field is left fallow for a season to coax it back into an arable state. But May’s use of the term led me to recognize fallow sites, like the ones that this studio took on in Arles, as being sandwiched between two lives: between temporal lives (sites that had a history, once, that has been rendered obsolete, like the Canal de Craponne), or as being between productive lives (sites like the Port of Arles, a largely empty site between active road, river, canal, and train networks), or between fecund lives (sites like the water infrastructure that is now polluted but could be purified). The propositions in this Studio Report neither romanticize these sites as relics of the past, nor do they valorize their current derelict state; instead, each project suggests the next life that each of these identified sites of between might take.

Here in Cambridge, “fallow” is hardly the first word that comes to mind when thinking of Arles, which evokes instead Vincent van Gogh, sunflowers, Roman ruins, and the sunshine of Provence. As the “Fallowscapes” studio quickly discovered on site, however, the fallow exists everywhere in the world—the proposals contained in this Report unravel the fallow by brilliantly, if perhaps counterintuitively, tying it tightly to larger scales and systems: infrastructure, politics, economics, and culture. Rendering

Sarah M. Whiting

the fallow systemic is a strategy that can apply as much to Akron as it does to Arles, or to Chengdu as much as it might to Cambridge.

Wintering. We’d be hard pressed to find a more apt description for this past year, 2020–2021, when the entire world found itself in a collective, if individually isolated wintering state, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. We never could have anticipated the prescient timeliness of this studio, but the inspiring work contained here suggests that this year, like the fallow-scapes of Arles, is best understood as a moment between two lives. And moving beyond that between requires similarly situating this year with precision: placing it within larger scales and systems—recognizing, articulating, and affecting shared structures, connections, opportunities, and possibilities. Thank you to Anita, Marc, Matthias, and all of the students for rendering the fallow so productive.

1 Katherine May, Wintering: The Power of Rest and Retreat in Difficult Times (New York: Riverhead Books, 2020).

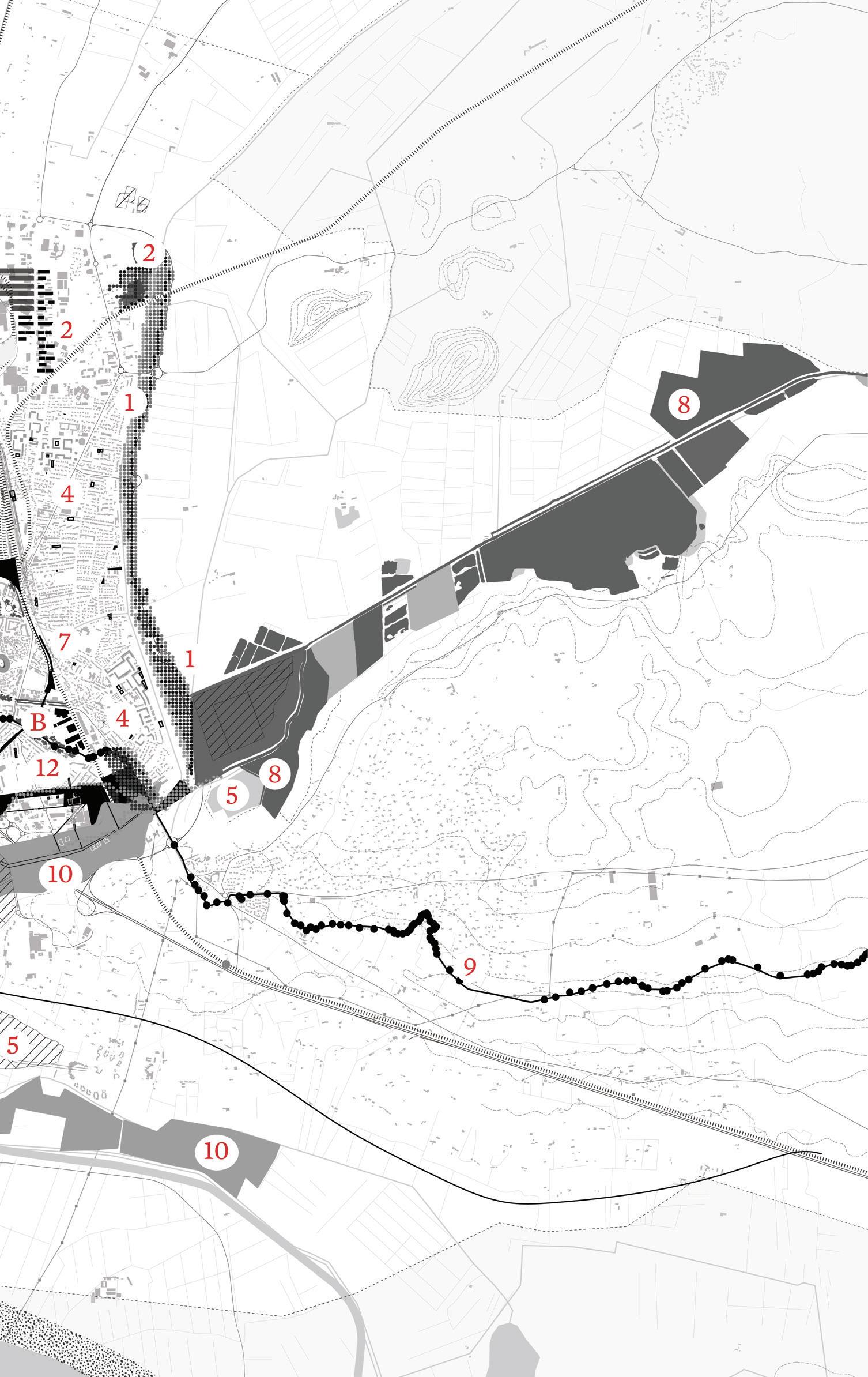

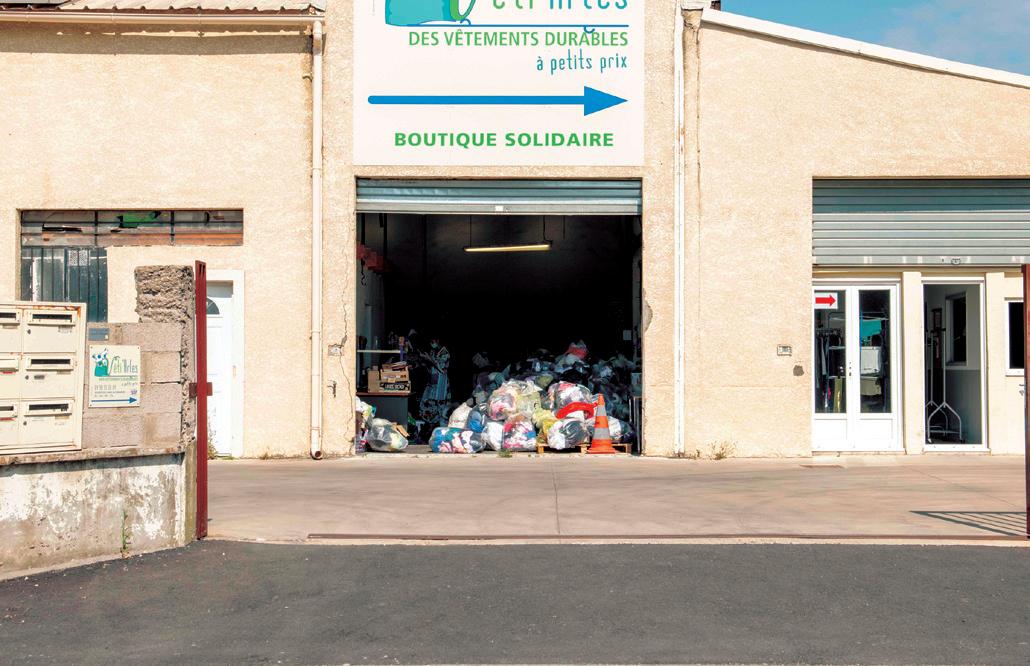

The photographs that appear on the following pages document a selection of the fallow landscapes of Arles: networks of underutilized or abandoned infrastructure, land, and resources that are as much a part of the city’s history as its celebrated architectural monuments. Many of these sites are addressed by student projects throughout the publication. The geographical coordinates indicated for each site are intended as an invitation for the reader to visit them.

Between Canal du Vigueirat and Canal de navigation d’Arles à Bouc. 43.65774917648108, 4.621849272286146.

Canal du Vigueirat. 43.667118607308915, 4.630936987102593.

Nouveau pont d’Arles. 43.674963173522606, 4.619325394683874.

Between Canal du Vigueirat and Canal de navigation d’Arles à Bouc. 43.658530426587674, 4.622100592979152.

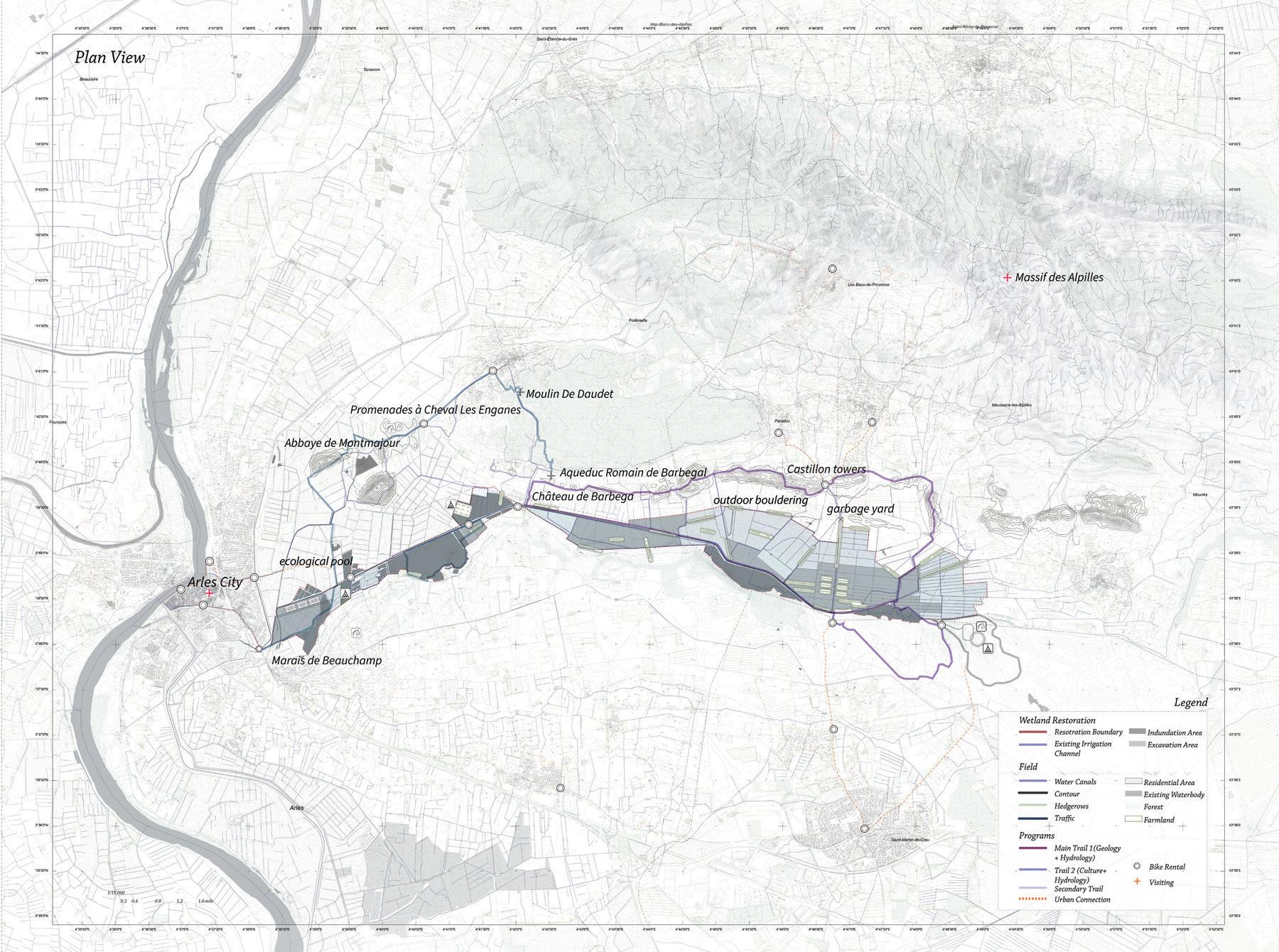

Fallowscapes: Territorial Reconfiguration Strategies for Arles documents the second in a series of three design studios that reimagine the city of Arles, France, and its region. While last year’s studio focused on regenerating the depleted soils in Arles’s agricultural landscape, this year’s studio explored the concept of fallow lands and their capacity to redefine the relationship between the city and other “actors” in the area—infrastructure, open space, industry, and economy—with the intention of exploring new relationships between the city and its neighboring towns, the city and its hinterland, and, ultimately, the city itself.

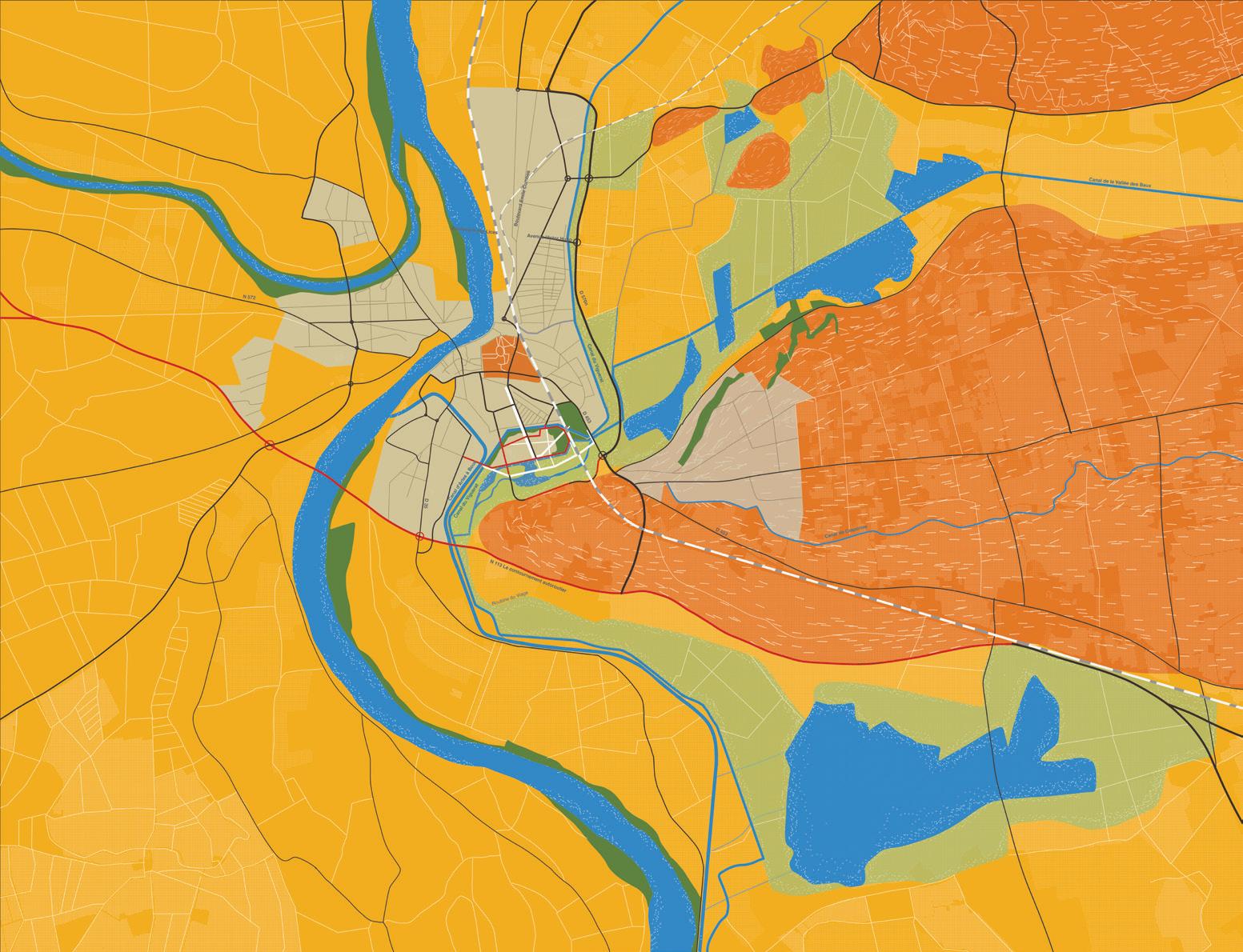

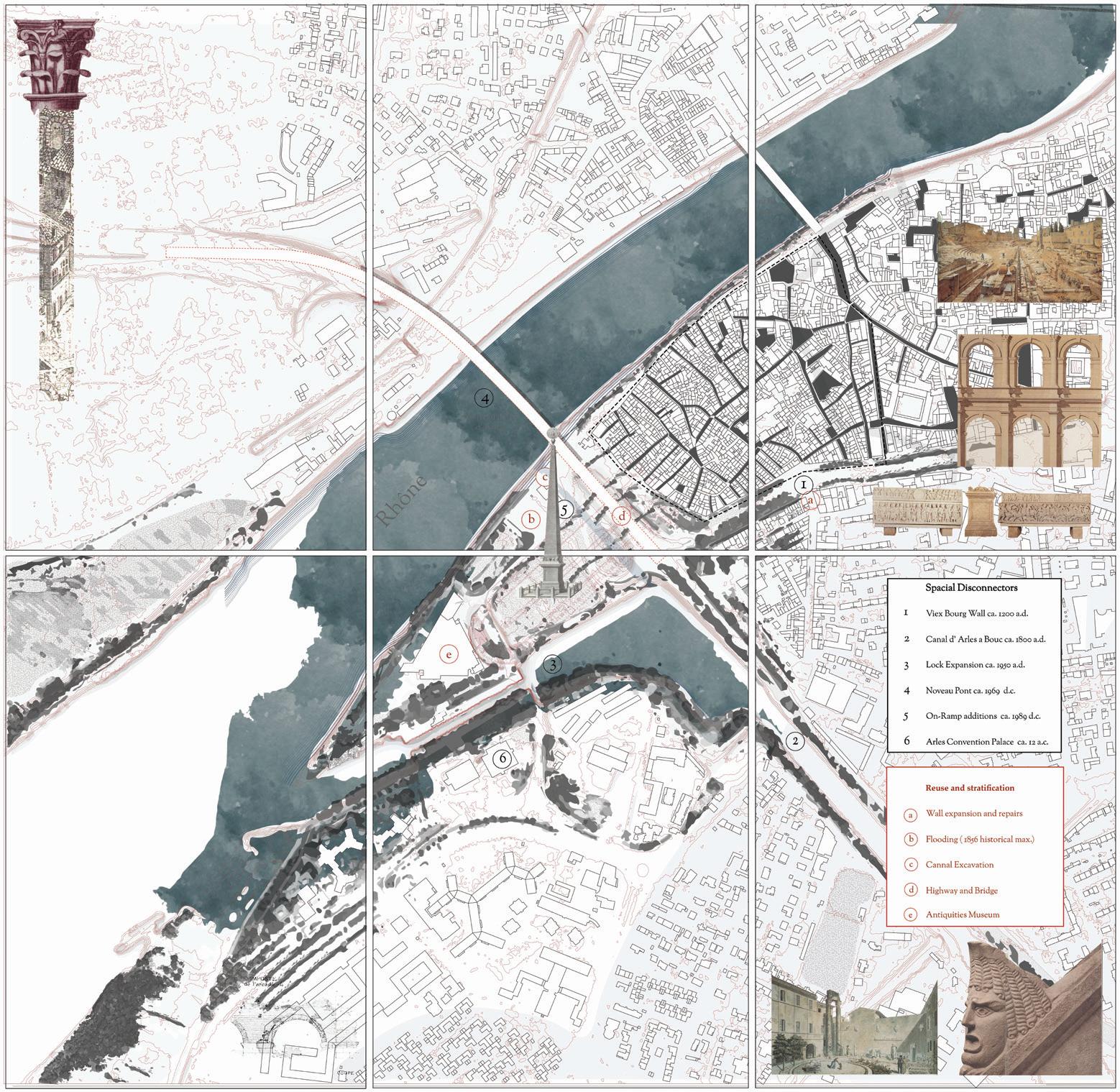

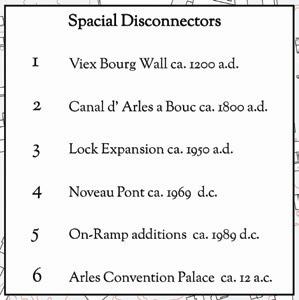

On first impression, Arles’s fallow lands are not immediately apparent; the city appears stable and “completed.” Its dense medieval core punctuated by Roman civic architecture, Romanesque monasteries and churches, and the scenic landscapes that surround it give the impression that the identity of the city is as fixed today as it was centuries ago. Yet Arles’s stable image belies another reality, one of networks of aging and underutilized irrigation canals, abandoned rail lines, remnants of industrial production, and high unemployment. In addition to these signs of decay are the looming impacts of climate change on this region that is characterized by both the presence of a great deal of water, with risk of significant and frequent flooding on one hand, and arid conditions, with the tendency of desertification, on the other.

The studio asked a fundamental question about the role of fallow lands in contemporary urban contexts: What are the various processes that have led to the emergence of fragments and systems of fallow land, infrastructure, and buildings? Is it possible to “unbound” Arles—to envision a different, more diverse and adaptive future if we were to open these underutilized

spaces, infrastructures, resources, and materials to other possibilities, modes of occupation, new forms of connectivity, and an expanded identity for the city? Can fallow lands address present-day challenges that the city is not able to address through conventional means? What do fallow lands add to the experience of a city, for whom, and how is this made available?

Pedagogy: Repositioning the Category of Fallow

Fallow, in its agricultural sense, is land taken out of production, its soil left to recover its nutrients before it is put to work again to begin a new productive cycle. The term is also applied to urban lots that are abandoned, typically in response to periods of economic downturn, private and public disinvestment, and environmental factors such as flooding and pollution. Whether agricultural or urbanized lands, fallow generally implies a productive potential that, though dormant, accrues value that will bear profits in due time. While this cyclical view of urban economies explains in broad terms how cities as sites for the accumulation of capital evolve over time, the studio sought to criticize the idea that the fallow must always be understood as having an inherent and latent value that is to be realized through urban growth and development. Instead, the studio hypothesized that the strategic design of fallow lands can expand received notions of the urban by addressing issues in a manner that is outside utilitarian (capitalistic) conceptions of urban space, such as issues of social and environmental equity, fragmentation, alternative modes of settlement, new and dormant regional economies, and unexplored forms of tourism. During the past four decades, many cities around the world have grappled with the chal-

lenges posed by the presence of fallow lands, including derelict infrastructures. Without clear prospects for economic recovery, four basic approaches have characterized most interventions in abandoned urban resources. The first is the understanding of fallow lands as “voids” in the city. Such a conception presumes that cities are made only of buildings, and that voids are therefore gaps, empty and thus undesirable spaces in the architectural fabric of the city. The adaptive approach, in which post-industrial remnants on the site are incorporated into new uses, such as public parks, restaurants, housing, and others, resists the tabula rasa of modernism and works from the ground up, accepting and incorporating what is on site, and adapting past

programs to present needs. The “urban wilds” framework, most notably applied in Berlin and Boston, is also known as the “do nothing” approach, and it works with the understanding that vegetation will eventually take over sites that lack budget and maintenance, eventually evolving from fields to forests. Finally, urban agriculture, perhaps the oldest response to abandoned urban land, most famously practiced in Rome’s desabitato, in Lisbon’s hortas, and in Detroit, invites communities to care for these parcels by cultivating them as their own vegetable plots. Ultimately, these are understood to be provisional measures, and in many cases the sites revert back to development. Their exchange value is latent in the proposals to address their condition as fallow.

However, fallow urban lands are not only discrete parcels, they are also embedded in larger urban and ecological systems. This property of landscapes—how they operate at multiple scales—was the guiding framework for the stu-

dio. To reconfigure is to rearrange “the parts or elements [of a system] in a different form, figure, or combination” such that the system can be activated to do more. As agents in the territorial reconfiguration of Arles, the studio introduced the idea of “fallowscapes” as urbanized fallow lands at the scale of the landscape, with the capacity to operate as structuring elements in the larger territory. In addition to multi-scalar properties, the studio explored the convergence of complementary potentials in fallowscapes, such as the permanence of the impermanent, of materiality as a function of the transient, of degrees of flexibility as a condition embedded in design, and of the aggregate effects of a system of fallow lands when they offer places of possibilities rather than fixed programs. To be clear, doing nothing was not an option, because such a position would cancel the possibility of thinking differently about the city and, equally important, about new approaches to design and planning. Instead we pursued the question of how to avoid instrumentalizing fallow lands for economic gain only. Is this even possible? And what would design look like if we were to avoid instrumentalizing landscape?

Arles, the largest commune of France, encompasses an area of 759 square kilometers (293 square miles), and includes part of the Camargue Delta as well as a portion of the stony plains of the Crau. The city of Arles is located near the northern boundary of the commune, on the left bank of the Rhône River, about 42 kilometers upstream from its mouth in the Camargue. Founded as a Roman outpost at the intersection of the Via Aurelia and the Rhône, and easily accessible to the Roman port at Marseille-Fos, Arles was part of a network of settlements—Salon, Nîmes, Avignon, and Tarascon—perched on hills that punctuate the otherwise flat topography of the surrounding landscape. As previously mentioned, Arles is renowned for its Roman coliseum, amphitheater, and burial ground—the Alyscamps—as well as its Romanesque monasteries, several of which are UNESCO World Heritage sites. Equally well known is its surrounding landscape of orchards, vineyards, and sunflower fields, so famously represented by Vincent van Gogh and other impressionist painters. Less well known—without any urbanistic or architectural pedigree—but much larger in area is the 20th-century expansion of the city: loosely aggregated car-dependent forms of

urbanism, including industrial production, midrise housing projects, suburban single-family developments, and shopping malls.

The agricultural landscape of the commune, a major regional producer and Paris’s primary source of vegetables, fruits, and herbs, was characterized since antiquity as a wasteland, either too wet or too stony for agriculture, and destined to be permanently uncultivated. Against these predictions, over the past four centuries the Camargue and other major wetlands have been drained for pastures and other crops, and the formerly arid plains between the Durance and the Rhône were colonized by an extensive network of irrigation canals. In the seams between these different forms of settlement and infrastructural interventions, a series of fallow lands has emerged, evidence that the history of the landscape of this region is one of major environmental transformation, where natural forces and systems have been redirected for human use.

Because most if not all lands are privately owned, there is not a strong system of publicly accessible landscapes beyond the scattering of small plazas in the historic center, football fields in the more recently built neighborhoods, the Boulevard des Lices with its ample sidewalks, storefronts, and restaurants—also the site of the main regional fresh-air market—and one small public park. The Rhône is not easily accessible except in very few places, mostly because the river is girdled by a system of monumental dikes and levees along its banks.

A major economic driver is tourism, especially during the summer, when the population of the commune swells from 55,000 to 600,000. The city itself hosts two major cultural events, the Rencontres d’Arles, an international festival of photography, and LUMA Days, a forum of arts and culture, both of which draw many visitors. Migrant workers largely from North Africa comprise an important part of the agricultural labor force, and 8 percent of the commune population is foreign born. However, there is persistent unemployment, especially in immigrant youth, who have few prospects for economic and social advancement.

The students chose sites throughout the territory of the commune, and the projects show a wide range of locations, scales, and material conditions. They were asked to develop interdisciplinary design techniques that engage a range of frameworks from related design disciplines (landscape architecture, architecture, urban

planning, urban design, conceptual art, forestry, agriculture) to fully explore the potential of underutilized land and resources. Three questions are common to all projects presented here: the question of time, or how to slow down decision making to keep options open—as strategic reserves—given uncertain economic, social, and climate futures; the question of the appropriate scale of analysis and intervention; and the question of governance, which considered new institutions that would sponsor new categories of landscapes.

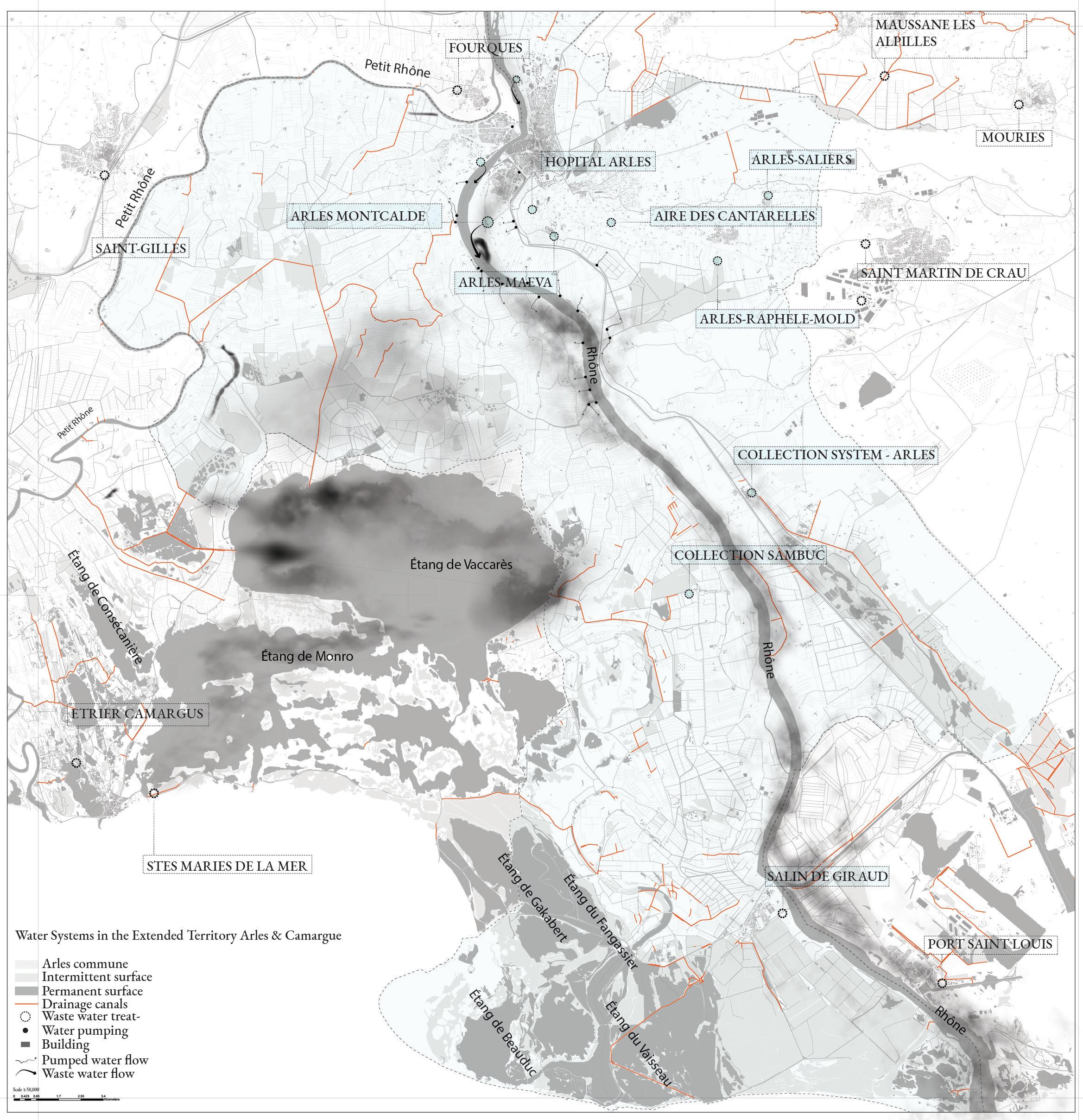

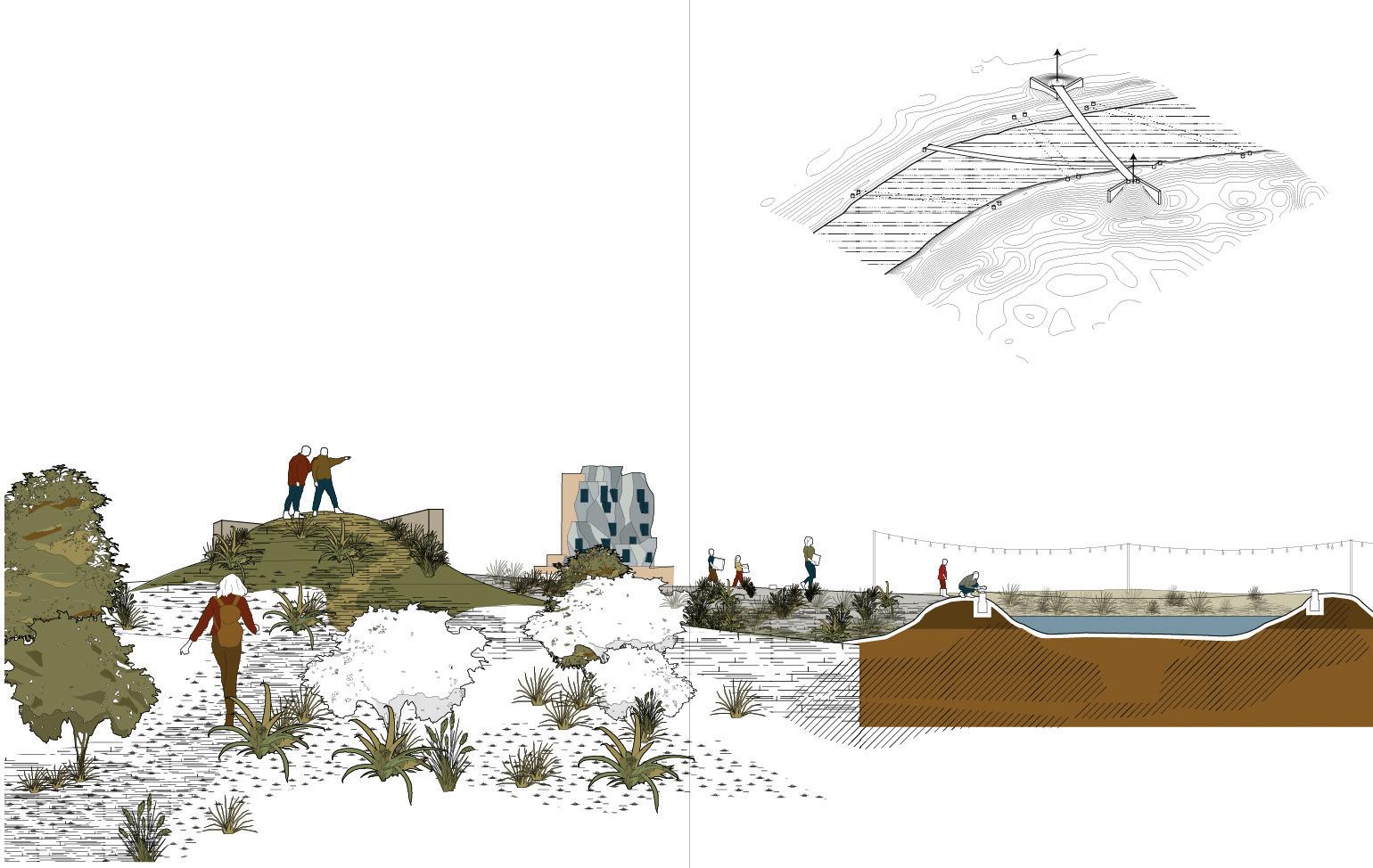

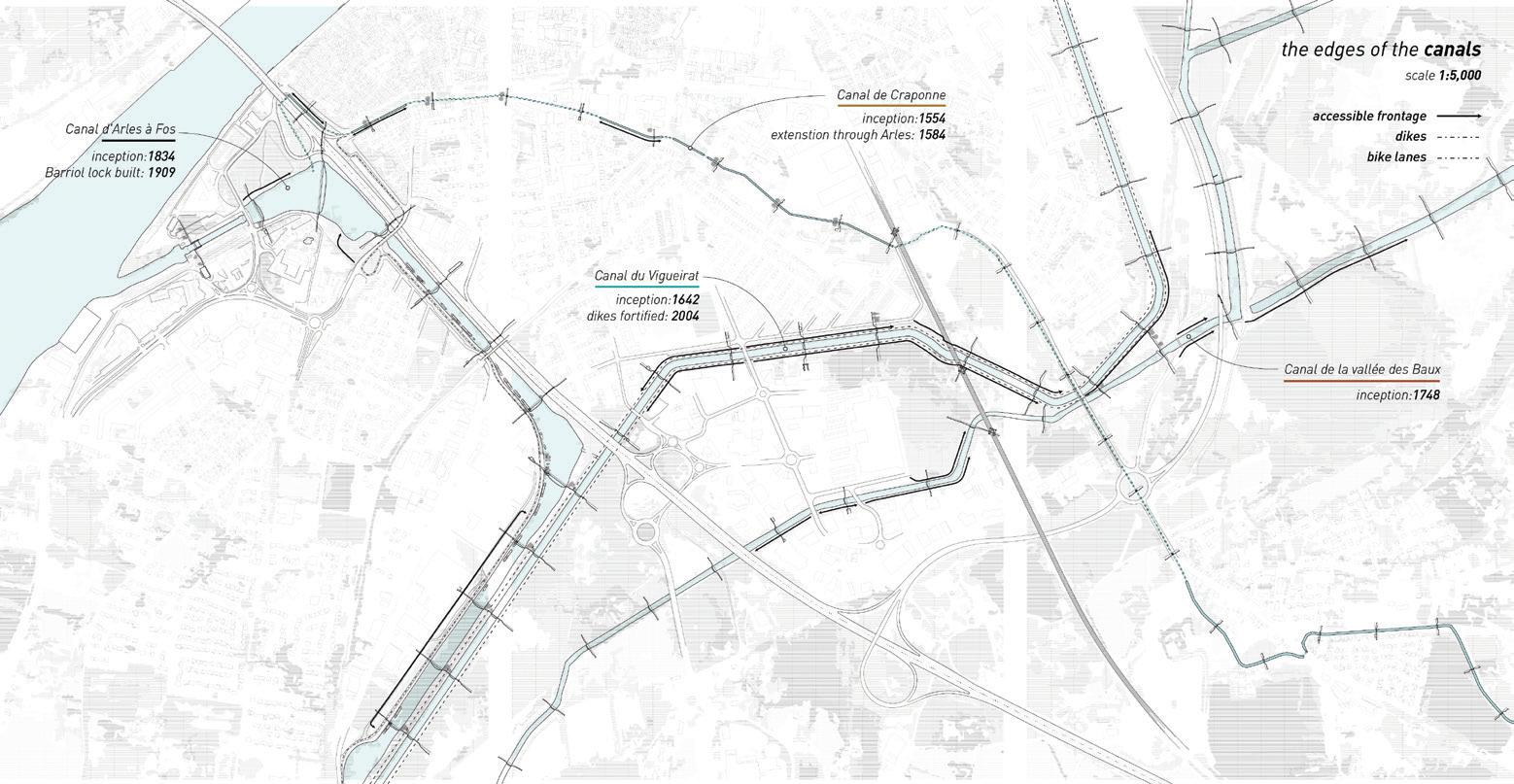

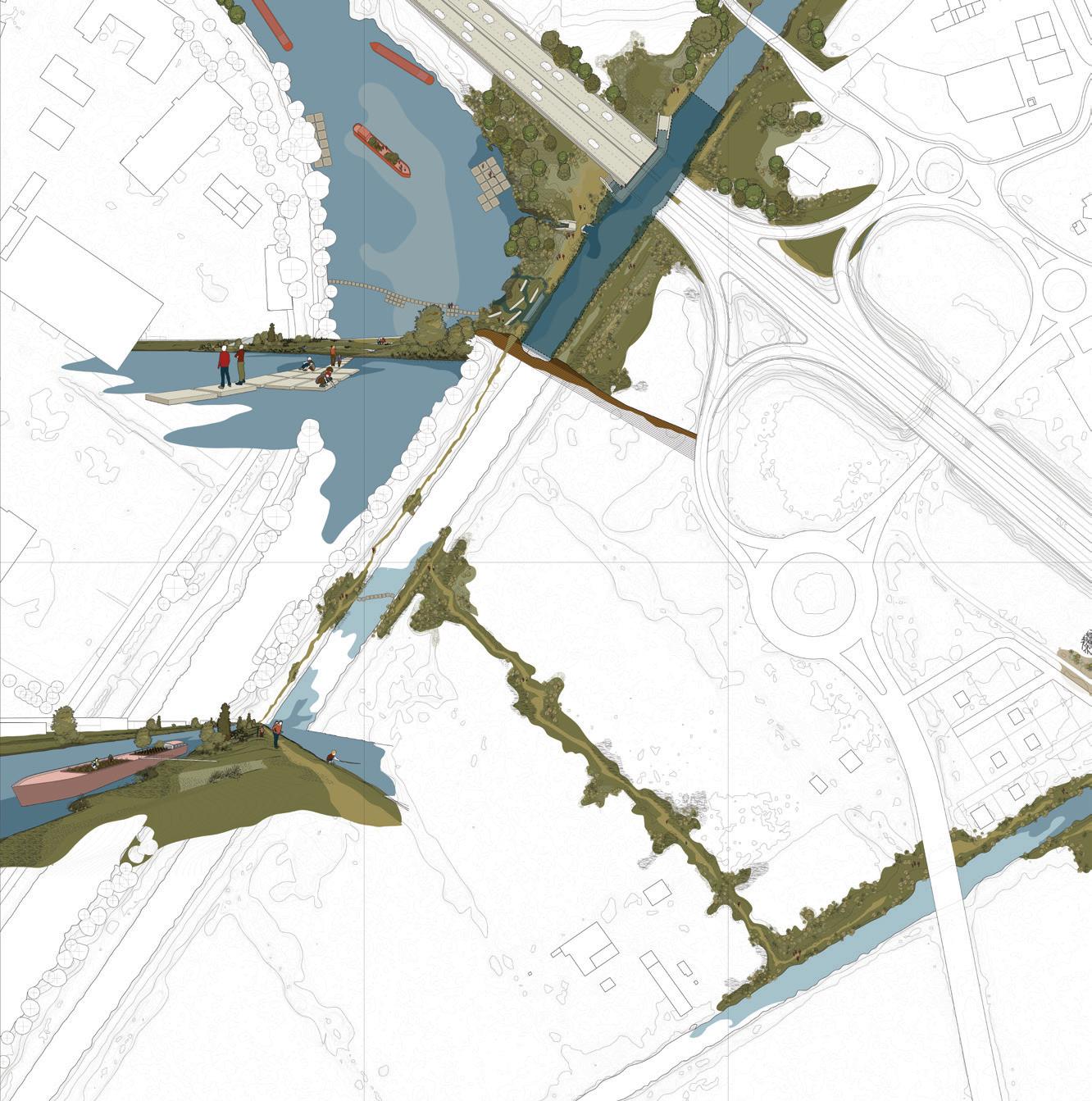

Water and water infrastructure, perhaps unsurprisingly, figure prominently in many of the projects. Andreea Vasile Hoxha worked with treated water as a fallow condition as the commune releases it into the polluted Rhône, wasting a potentially valuable resource. She proposed instead a new infrastructure that will convey the cleansed water to the Camargue, for the regeneration of wetland ecosystems. Jonathon Koewler examined the series of irrigation and flood-control canals in the southern part of the city and their potential to trigger new forms of recreation and cultural events. Eleanor Rochman traced the entire length of the Canal de Craponne, from the Durance to the Rhône, and explored a new identity for this 65-kilometer (40-mile), 400-year-old irrigation infrastructure. Andy Lee studied how a new regional network of waste recycling based at the fallow port north of the city could potentially spawn a new economy for the city. Zhaodi Wang and Yifan Wang re-fallowed already drained land by reclaiming lost wetlands from agricultural fields and development. With a similar eye toward turning back time, Roberto Ransom explored unearthing Roman ruins as a strategy to knit back together a fragmented part of the city. Jason Liu and Camila Huber addressed the needs of underserved communities through the provisional occupation of fallow lands or underutilized urban streets and spaces. Shira Grosman researched the flood-prevention dikes along the Rhône and proposed a system of adaptive levees that enable the continuation of agricultural production while at the same time introducing the idea of a publicly accessible shore along the banks of the river. Koby Moreno proposed a system of conservation lands in remnant and contaminated strips of land along the margins of highways. Lastly, Xinyi Zhou reclaimed an abandoned railway as a bike path that connects isolated neighborhoods to each other and to areas and programs in the city that would not be possible to connect otherwise, including the extension of a recreational way to the sea.

Nothing exists in isolation, and yet the interconnectedness of things across scales of time and space, and between places, regions, and territories is seldom readily apparent. To work with territorial systems entails knowing each one individually and in relationship to others. Thus each of the projects addresses, through their specific sites, broader issues that the commune is facing. To highlight these broader issues, the proposals are grouped into four topics that together describe possible fields of action, each aimed at reconfiguring the city in relation to its landscape.

“Recycling and Depolluting” refers to projects that address the management of waste, water, and contaminated soil; “Vulnerability” addresses marginalized communities but also increased susceptibility to weather events such as flooding; “Landscape Networks” extend across the territory to integrate and restore lost connectivity; and “After the Motorway” explores the opportunities to reconfigure neighborhoods that were severed from the city after the construction of the N113 highway between 1990 and 1996. The projects work retrospectively to unveil connections and forgotten histories, and prospectively, describing the next stage in the potential evolution of the city.

Design is fundamentally an optimistic endeavor. It liberates us from old patterns of thinking and allows us to search for alternative, and better, approaches. Individually and as a group, the projects offer a fresh understanding of Arles and its larger territory. If we began the semester by thinking of Arles as a city of ancient monuments, we ended knowing it through its material flows and histories, its tendrils of land and water, its many cycles and scales of human occupation and social relations, its politics and institutions, and how fallowscapes could engage these multiple spheres and transform them to inclusive, sustainable, and just landscapes. Far from inert and complete, Arles is full of possibilities.

1 Teresa Gali-Izard, Regenerative Empathy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Graduate School of Design, May 2019).

2 Alvaro Sevilla Buitrago, “Antinomies of Space-Time Value: Fallowness, Planning, Speculation,” New Geographies 10: Commons, edited by Michael Chieffalo and Julia Smachylo (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Graduate School of Design, 2019).

3 Marc Bloch, French Rural History: An Essay on its Basic Characteristics (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1970).

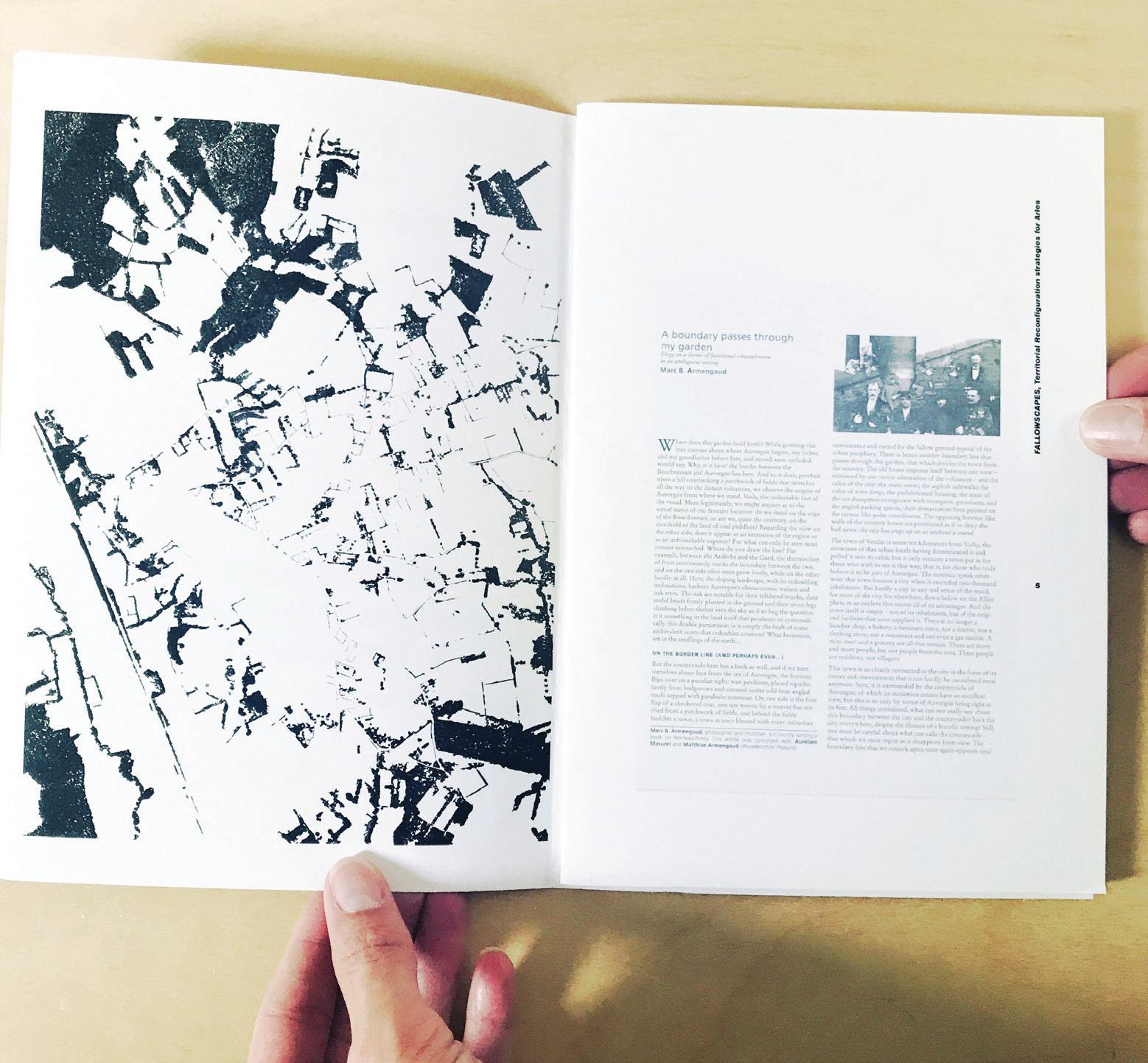

Following spread: It was on the initiative of Louis XV, impressed by the cartographic work carried out in Flanders, that the first geometric map of the Kingdom of France was produced. César François Cassini de Thury, known as Cassini III, son of Jacques, is charged to carry out this work at the scale “of a line for one hundred toises,” that is to say 1/86400th. The map is based on the geodetic network that Jean-Dominique Cassini and his son Jacques had just established (from 1683 to 1744). The surveys began in 1753 with César François Cassini de Thury; its realization took more than fifty years.

Marc Armengaud and Matthias Armengaud

They say we need to come down from our high horses and indulge in some critical introspection because everything is different now. Indeed, while most of the attention and funding over the past 20 years have gone into hyper-metropolitanization strategies across Europe—and in France in particular—a series of crises radically challenges the efficiency of these planning and design tools. We are summoned to face multiple environmental and lifestyle crises, and the subtext is very clear: We the architects must undo what we have been reproducing at scale—the sinful 20th-century modernist ethos of productivity, mass consumption, high-speed transportation, strict zoning, and nature-turned-into-infrastructure. But

sprung up as a leaderless grassroots uprising via social media, without help from unions or political parties. At first, the Yellow Vests enjoyed national sympathy for their peaceful provincial blockades of roundabouts. The movement of the all-white yet invisible citizens took center stage for the first time: elderly people fought for their grandchildren alongside teenagers who joined their parents to refuse an overlooked existence far from the glow of metropolitan life. These roundabouts, found in the middle of “nowhere,” are the spatial totems of idiotic, top–down policies that scar the entire country’s landscape. But life took root around them with the blockades, and the French media relished with the anecdotes. Although protests con-

to which tune should we sing now? “Where Have the Birds Gone and the Six-Legged too, and What About Snowy Christmas and our Children’s Lungs?”

As one could expect, there is momentum for Green politics, as proven by the mobilization of the youth and recent elections across Europe. But there are also counter-insurgencies, such as the year-long protest of the French Gilets Jaunes (Yellow Vests). The unexpected movement

sisted of heterogeneous voices, they joined an undoubtedly populist choir: “Give Us Back the Cheap Diesel Gas, Abolish Lower Speed Limits, Cut Down Taxes on Cigarettes and Alcohol, and Raise Our Pensions to Adjust to the Real Costs of Living Out Here.” Sympathy soon faded with the systematic show of violence in the fashionable shopping districts of Paris and many other cities, every Saturday. Behind the legitimacy of refusing to be victims of a transitioning economy, the loud denial of climate change and public health imperatives, systematic blasting of elites,

and refusal to share the burden of social welfare as well as EU commitments, has drawn a red line. Yellow Vests gave voice to the “Invisible France,” one of remote suburbs and forgotten “rur-banized” countryside. In spatial terms, this represents at least two-thirds of the national territory, where planners, architects, and landscape designers mostly never set foot because there is not enough business for them in those empty parts. Landscapes without projects?

Arles’s territory is emblematic of such tensions, with the geographic area of a major metropolis that is only populated with 50,000 inhabitants, in a regional area that has more than 3 million in the winter, and far more in the summer. The town could hardly be defined as “urban,” although Marseille and Montpellier are less than an hour away. The Rhône Delta region, which is most of Arles’s vast natural and agricultural territory, is under deadly threat from rising sea levels, while a combination of escalating temperatures, droughts, and floods are increasingly affecting crops. Since Roman times, between the southern valleys of the Alps and the Rhône Delta, nature has been engineered by an incredibly sophisticated irrigation system, which is now in peril. The entire river’s adjacent industrial activities, from Marseille going upstream to Lake Geneva, urgently need to be reassessed before this infrastructure is irreversibly damaged. Blessed as it is by the sun and its historic glory, Arles must find a viable path forward, as it has been unplugged from the European high-speed train network and thus relegated to a second or third tier city. The city was once a major logistical and maintenance hub for the railways, but modernization provided a convenient excuse for shutting down the operations of an unruly union stronghold. The massive shrinkage of rail traffic was a blow to local industries, which in turn affected the harbor’s operations. While a successful shift toward international cultural tourism is already well underway, those who were hit by the dissolution of the industries remain ashore, many of whom are second or third generation immigrants. None of them own coveted assets such as apartments de caractère in the historic center, or old ranches de charme in the landscapes of Provence or the Camargue, each increasingly rented out short-term as highly profitable vacation properties. Tensions between the different social groups (age, origin, income, lifestyle) are rising. Yet, Arles has had its own political

microclimate resisting the sirens of populism, in a region where the openly racist far right is hitting bingo scores election after election.

If you came to Arles and the Camargue, you wouldn’t see any of these problems unless they were pointed out. As with most landscapes in Provence, there remains a feeling of eternity and elegance that overcomes such petty circumstances. As a summer destination for wealthy Parisians and European tourists, Arles probably suffers from its own sex appeal, which doesn’t help give credit to its struggles. What could go wrong in such a beautiful place, whether town or country? But if you scratch the postcard’s glow, the colorful local mythologies of romantic ruins, Van Gogh, the bullfighters in shiny outfits, and the gypsy women dancing, it turns grey: what emerges is the reality of high unemployment rates, rising income disparities, an aging population, shrinking opportunities for young farmers. . . . Farmers used to be “the real McCoys”: fruit growers, rice producers, and of course cattle ranchers. Black bulls and white horses grazed in the Delta under the surveillance of a local brand of cowboys, the Guardians. But for how long? In the eyes of contemporary agriculture standards, their small properties hardly reach sufficient productivity, while being simultaneously criticized for negatively impacting the natural environment surrounding their fields. Once in a commanding position, farmers will be gradually forced out from the Delta by river floods and rising sea levels, just like the fishermen were already, after the central lake that provided fish for thousands of years was saturated by sea water infiltration. Salt production, another venerable industry by the shore, has faced closing operations because of a global price collapse.

Under pressure from both economical and ecological crisis, it seems that Arles is at a turning point: it cannot solely rely on its past splendors and Contemporary Art Foundations to face the many challenges of its present and future. But what is the right path? And should there be just one? Each of the above problems is linked intricately across different scales, timelines, and modes of governance that require the planning resources of a metropolis, except Arles is just a town by the delta. A new spatial framework is necessary for this contemporary territory, one that is removed from the obsession of high density but still acknowledges significant infrastructural, environmental, and economic mutations. While our attention has been focused on hyper-density, it is necessary to investigate the hinterlands of such concentrations and question the need for other types of spatial strat-

egies and designs. Indeed, more and more local initiatives at the smallest scale tend to bypass the heavy institutional programs. Acting here with such knowledge, designers and planners might impact a much wider set of territories than just the one at hand. Considering that the scale of Arles calls for an exercise of “territorial reconfiguration,”1 we can look at the existing territory as a “found object” constituted by layers that can be redirected and made to interact with each other—layers that we can learn to unfold, confront, and use to imagine other possible scenarios.

While Arles might look like its old self, ongoing mutations transform its very shape. Arles’s territory is populated with ghosts, missing parts, new leads, and paradoxical appearances. One could even say that most of its potential is actually hidden, invisible, or at least unseen: areas exposed to increasing flood risk, archaeological treasures waiting to be dug out, former industrial and logistics sites crippled by pollution, waterways that have been deprived of their former infrastructural roles, decommissioned railways across town and country, a train station and a harbor devoid of traffic, a shopping mall in decay, frozen land for a potential highway bypass, and many more unused pieces in the puzzle across patches of wetlands, around and between infrastructures and zoned areas. In studying this situation, one particular notion seems an obvious tool for reimagining Arles and its surrounding landscapes: la jachère (fallow land). This is more than just an inspiring metaphor; it is an operational tool for territorial reconfiguration strategies.

Fallow land is an alternative practice of the soil and a tool for land management inherited from ancient agricultural techniques. Keeping some land in a state of fallow is part of a phased crop rotation, but it is also a particular temporality that resists measurement by productivity and immediate profit: it is by nature a strategic asset and a vision of the future. Yet fallow land is not the absence of cultivation—and therefore of economy—because frequently something is still planted, or else is growing by itself, such as native flowers. Fallow plants are critical as they contribute to the reoxygenation and remineralization of the soil and can also be harvested and made “productive” in economic terms. If they can be monetized within the full cycle of crops, such plants can be most valuable.

In the current context, the act of keeping land fallow is also a legal matter in many coun-

tries. In France the law asks every farmer to keep 10 percent of his land fallow to enable regeneration of the soil, and thereby sustain an average quality of the crop. Interestingly, this percentage is roughly approximate to the “unused” land in most cities. In the Swiss city of Neufchâtel, this is even a municipal regulation: 7 percent of the city’s land must remain fallow, which is telling for a European country that never suffered the modern destruction of war and therefore has had a relatively fixed structure of land use.

In terms of a strategic approach, fallow land can be seen as a framework for experimenting, a reserve for the next “move,” or a prospective resource. And making projects with fallow land doesn’t mean filling up the emptiness once it has been unveiled, but rather redistributing invisible qualities by setting them in motion to generate new interactions. Restart from the margins. Existing arrangements that are currently in a state of blur and suspension, where activities are informal, impossible, or unknown, are actually major assets for territorial reconfiguration strategies. Fallowscapes is not simply a new label for the old fascination of industrial wastelands—if only because brownfields have, for the most part, fed the blind greed of investors who will force any program onto an empty lot under the tag of “development,” even though said programs quickly become obsolescent, even before completion. What if, on the contrary, fallow land was seen as a critical necessity in order to free up other areas now in full use? A balance factor. Fallow lands become additional chessboard boxes—not as new space to invade, but rather as enablers of new ways to play and new moves to extend the game. They are not readyfor-use land, but another kind of configuration that provides temporal depth and flexibility.

Fallow land escapes standardized zoning not only in space but also in time. Nighttime2 is the fallow state of the day, accommodating contradictions, variations, and informality. Time planning has demonstrated since the 1970s that it could soften stiff planning. This was until the “temporary” came to be seen as a measure of space’s value: its flexibility. For instance, one could almost flip upside down a classic definition of infrastructure as the spatial framework of order. Instead, infrastructures could go on to generate surrounding landscapes as a type of collateral reality, a precious blur or “state of fallowness” that can be revealed and activated in favor of renewed priorities. Likewise, some informal daytime situations are just like fragments of nighttime displaced into social normality. Therefore, pointing to the share of fallow land

is to look at the territory and to draw it in a different way, with a new depth that enables transitions and transactions. Making projects from fallowscapes is different as they cannot be made into idealized superproductions, neatly presented on a tray like an iced cake. Projectmaking becomes the complex effort of weaving a system of interactions (past, present, future) that can be measured by its ability to generate relevant impacts on the territory, while maintaining a constant margin for adaptation. As crises multiply into uncertainty, strategies must embrace a framework of instability. This is perhaps where a formal link to the culture of architecture as “masterpiece” is let go, because there cannot be a masterplan for fallowscapes, only layers

What about fallowscapes planning? This would mean operating the territory not from a static position but from a regime of difference, thresholds, and variations. You could describe it as an heteronomía of the territory—articulating the slow and the fast, the antiquity with the futuristic, the intense and the invisible, and the actual and the possible into specific systems, networks, arrangements, and gardens. Differentiation is a key part of this approach because fallowness is not proper to a site but is situated between sites and movements. A site that is not activated in a standardized productive way at any moment is considered fallow, and fallowness is a condition for reinstating dialogue between territorial systems and landscapes.

of scenarios that may or may not happen, that you must be ready to play (just like a DJ) if it becomes necessary to mix within the overall strategy to activate a specific dimension.

To challenge the conventional idea of the “final project,” we have proposed the format of a Libretto, which brings together a score, lyrics, and directing indications, sometimes even including set-design sketches. Because the

territorial reconfiguration approach is by nature a transversal exploration of the existing, it brings together tools and cultures that tend to be dealt with in silos, just as the opera appeared as a new art form prophesizing modern media. In retrospect, the opera emerged as a combination of formerly well-defined arts, which created something radically new once brought together. This seems appropriate for a territory like Arles. It is a place that deserves to be sung, danced, told, played, staged: stories and chants for the Delta. Not all scenes need to be performed, you might change the importance of a character, and there is always a possibility to dust up the dancing or the orchestration. Each performance is a specific montage, an agency of circumstances, a tailored to measure variation. Our interest in the opera format also relates to the way it plays with time in a dramatic way: unfolding, distending, and using shortcuts and reminders. It works with these layers of time, and has no problem juggling multiple dimensions with a plurality of rhythms. The Delta’s landscapes appear already prescient of our contemporary wish to find ways of combining different powers of time and transformation. The weak beats redefine the strong beats, and a multi-site conversation arises. This is perhaps the real value of the experiment conducted with the students in this studio. As much as each proposal is highly stimulating and carried through with great care and talent, we find even more value in the combination of the 12 proposals. Not necessarily as a collective proposal with 12 chapters that pretend to cover everything, but more like a set of narratives that can be coordinated in twos or threes, activated together as a phasing approach. Each project is rooted in detailed diagnostics which can become common ground for coordinating several strategies. For instance, projects that point out the potential for reactivating wetlands, or those that identify a state of pollution that should be a priority, or those that reconsider what waste and water infrastructures might sustain while facing the climate crisis, or those who push forward a slower approach to logistics between town and country…These intervention proposals are possible in more than one place, in more than one instance, and more than one way. As such, the studio’s results can be seen as a territorial clock, because fallowscapes provide opportunities for new cycles that will reload places, systems, and movements. In future developments related to these present explorations, we very much hope that the focus goes into the fine tuning of this built-to-measure instrument, with multiple keys to play as chords and melodies.

1 AWP is an office for territorial reconfiguration.

2 See: Nightscapes (Gustavo Gili, 2009) and Paris la nuit, Chroniques nocturnes (Pavillon de l’Arsenal, 2013), by AWP.

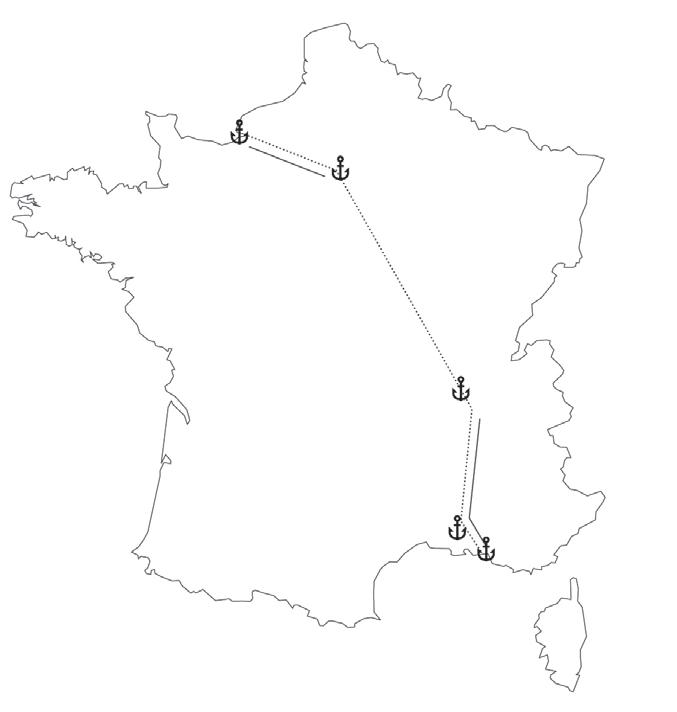

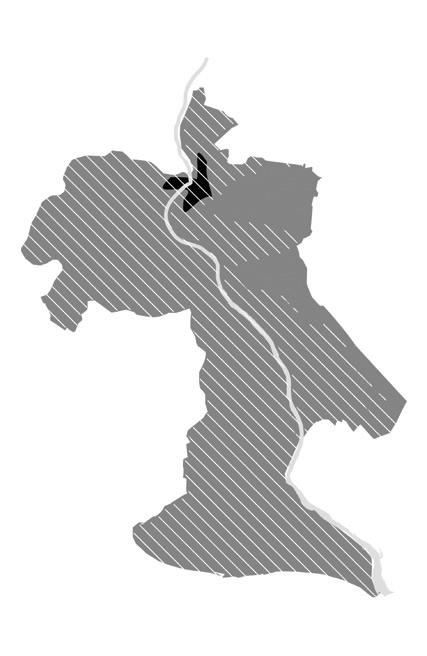

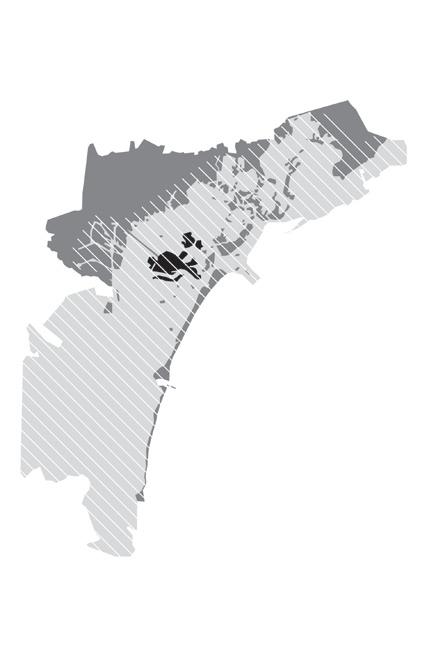

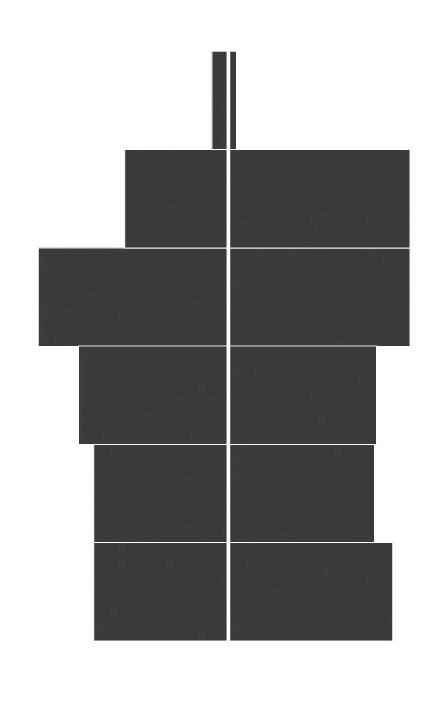

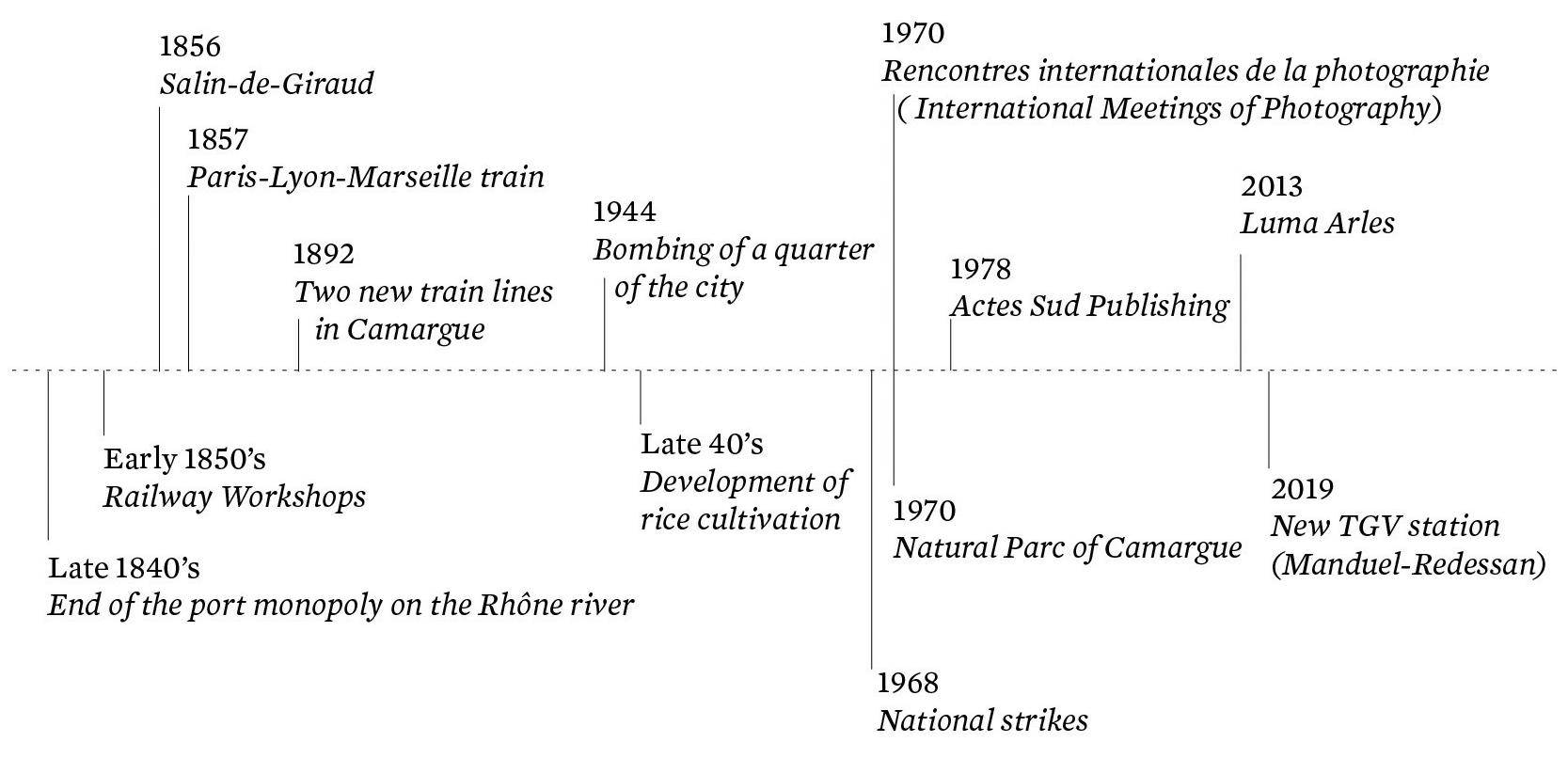

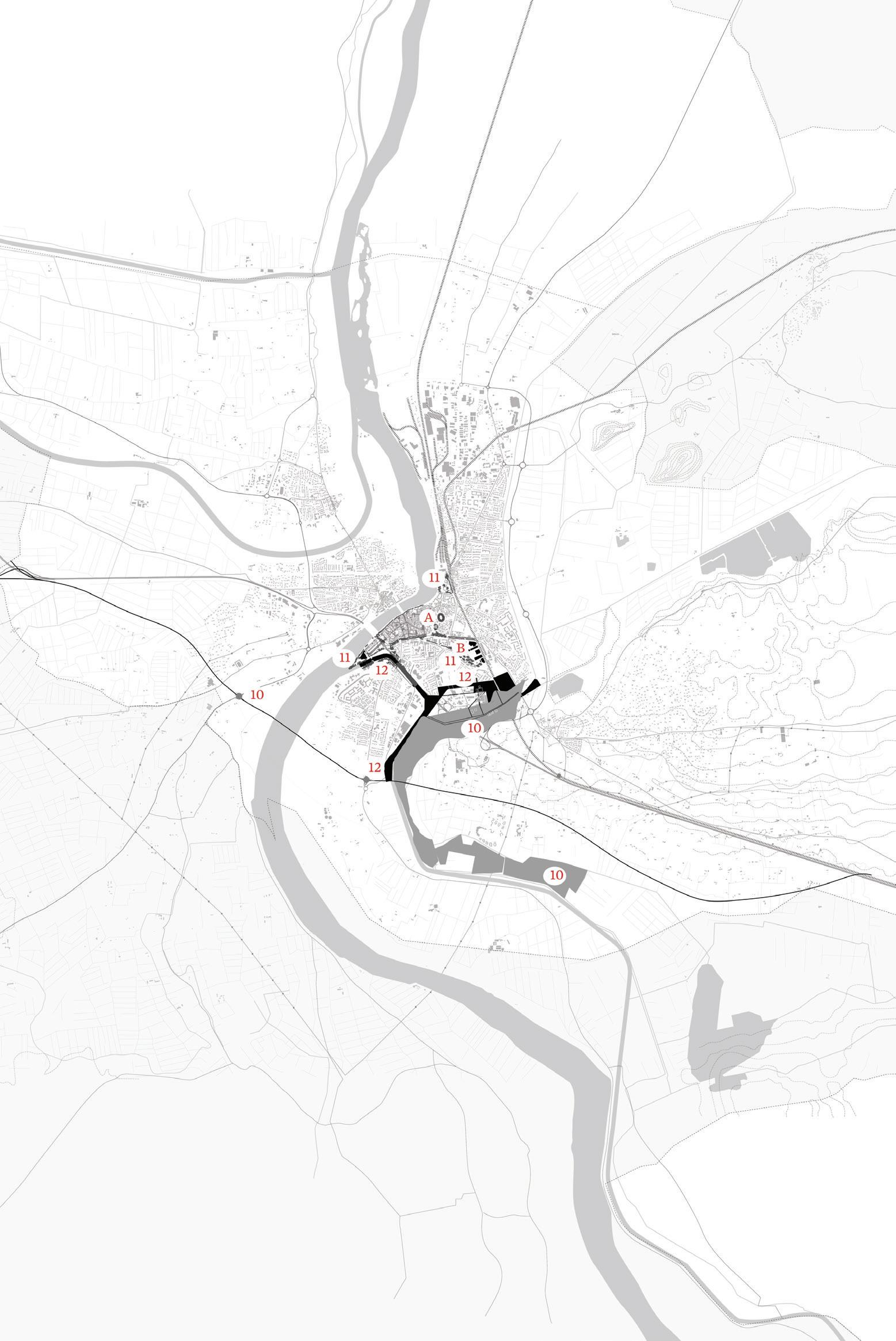

PLM (Paris-Lyon-Marseille) train line connection. Mediterranean arc: highway and TGV connection.

759 km2

69 inhabitants/km2

carbon footprint: 0.84

MteqCO2 /year

grey: 3% – hatch: 85%

105 km2

20,755 inhabitants/km2

carbon footprint: 12.2

MteqCO2 /year

grey: 1% – hatch: 0%

415 km2

632 inhabitants/km2

carbon footprint: 3.1

MteqCO2 /year grey: 60% – hatch: 70%

283 km2

1,768 inhabitants/km2

carbon footprint: 5.84

MteqCO2 /year grey: 15% – hatch: 5%

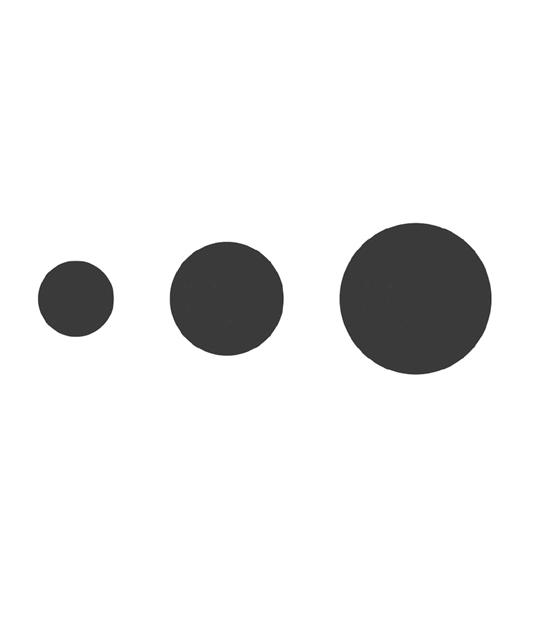

•* 170,000 annual residents in Pays d’Arles

•** 264,000 in the summer (June–September)

•*** 344,000 during special events (Férias, International Festival of Photography, SaintesMaries-de-la-Mer pilgrimages)

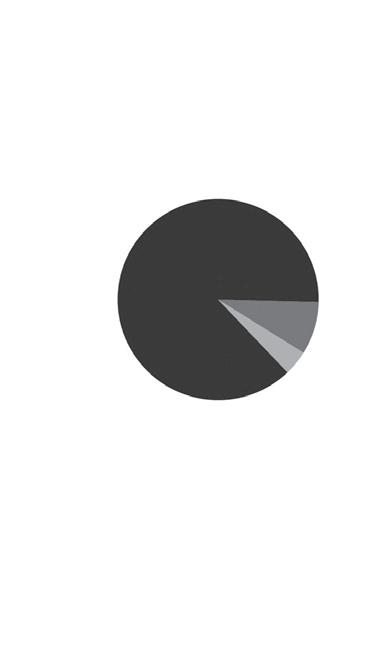

• Tourism: 13% of the GDP

secondary residence vacant

• Flat price/m2

June 2020: EUR 2,330

March 2019: EUR 1,930 + 20.7% in 10 months

• Population leans older

• 19,087 employees (5th hub in the Department)

79% in services

• Jobless rate: 11%

• Poverty rate: 23%

220 linear kilometers of dikes

TRI: high flood risk territory

Horizontal hatch: TRI perimeter (100% of Arles territory)

Heavy black lines: non-submersible dyke

Thin black lines: millennial dyke

Heavy grey line: closed protection dyke

Thin grey line: sea dyke

Circles: significant landscape views

• Wastewater: 36 water treatment plants

• Theoric treatment capacity: 242,910 equivalent inhabitants

• Canals: More than 1000 linear kilometers

• Sport: 1 in 4 inhabitants of Arles (13,000 people) participate in sports; 74 sporting clubs or associations; 165 sporting equipment (national average: 91)

Climate: Last big flood: 2003

300 sunny days/years

Mistral (wind) violent autumnal storms

Crosses: flood markers

Grey shades: submersible areas (85% of Arles’s territory)

Horizontal hatch: natural regional parks (60% of Arles territory)

Vertical hatch: listed landscapes

White arrow lines: sea level +1m (2100)

Submersible areas, floods, and landscape in Arles.

• Rubbish collected, regardless of type: 189,210 tons/year (1,421 kg/inhabitant/year)

• Rubbish management: 16 dumps, 2 composting platforms, 2 waste recycling centers, 4 transfer centers for household waste

Hedgerow Funds: Investing in the Cultural Value of Fallow Lands

Co-Mingled: A New Waste Economy for Arles

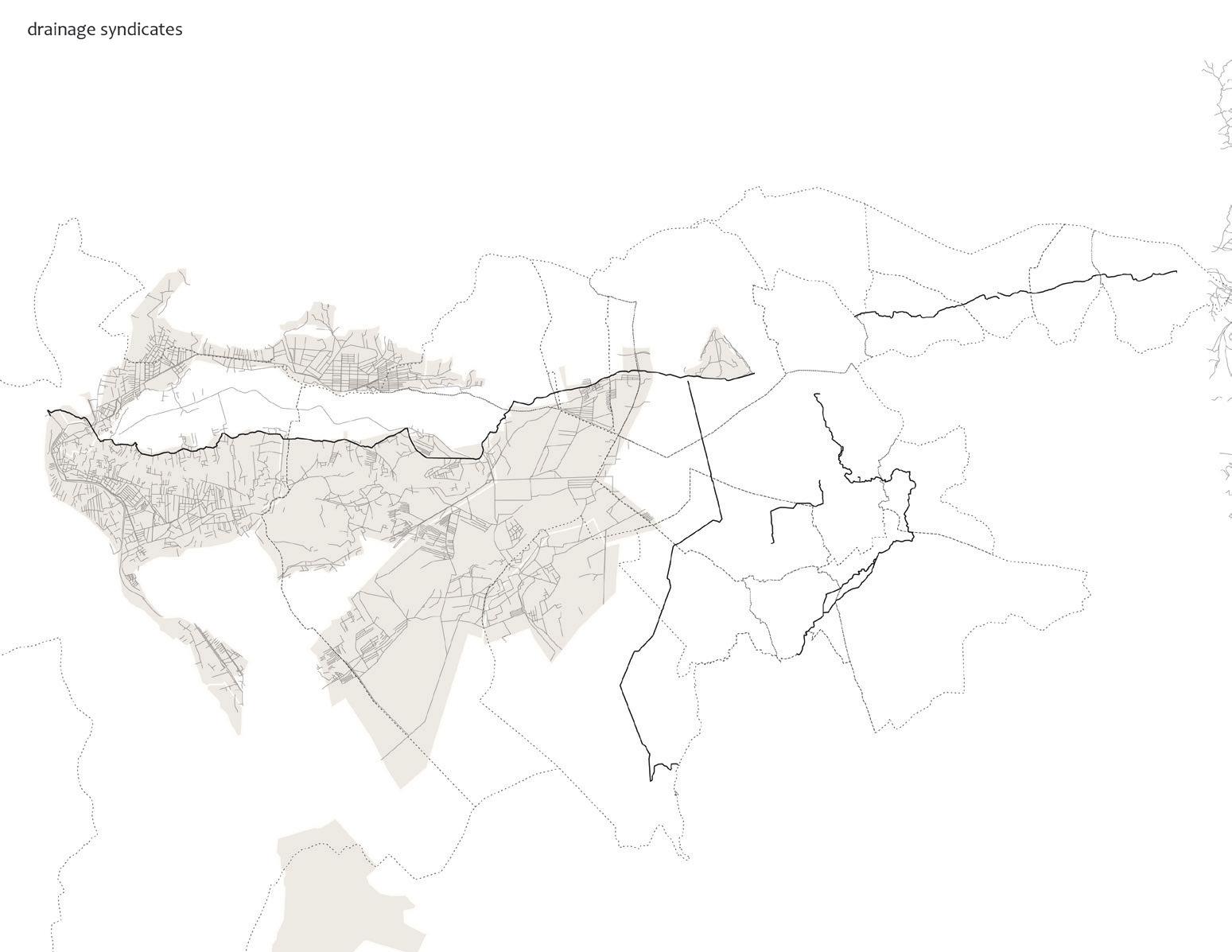

Productive Fallowscapes: Shifting the Politics of Water in Arles and its Larger Territory

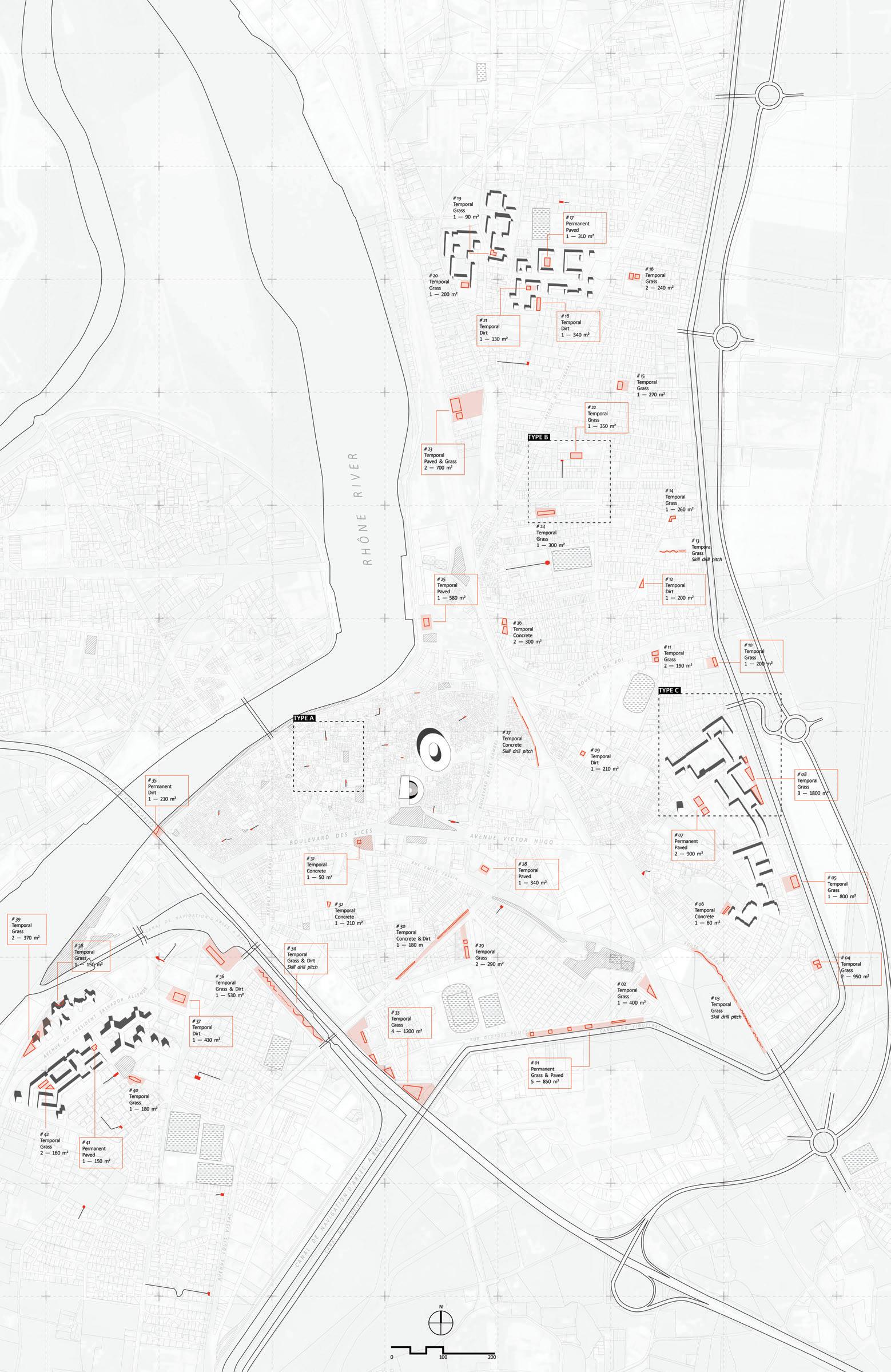

Street Arles Initiative: Transforming Arles through Street Football Pitches

Department of Fallow Land: Institutional Presence of Fallow in Arles

Back to the Banks: Coproducing a New Edge on the Rhône

Bike City: Fallow Infrastructure as Infrastructural Fallowscapes

(Re)Fallow: Reviving a Wetland System in the Arles Area

Fertile Fallow: A Line of Trees Along the Canal de Craponne

Prospect South: Opportunities in Connectivity

Engagé: The Spectacle of Reconnection

Back of House: Curating Fallow along the Canals

It is often said that most cities waste their waste, and Arles is no exception. The projects in this section put idle resources to work and turn them into active agents of territorial reconfiguration. The agency of each resource—an abandoned port, domestic waste, treated wastewater, toxic soil—is not inherent to the resource itself, but rather to the new uses and institutional contexts they are given. Fallowscapes work “outwardly”: they are not “things in themselves,” but rather a domino effect of relations, and a new realm of possibilities for the future of the city.

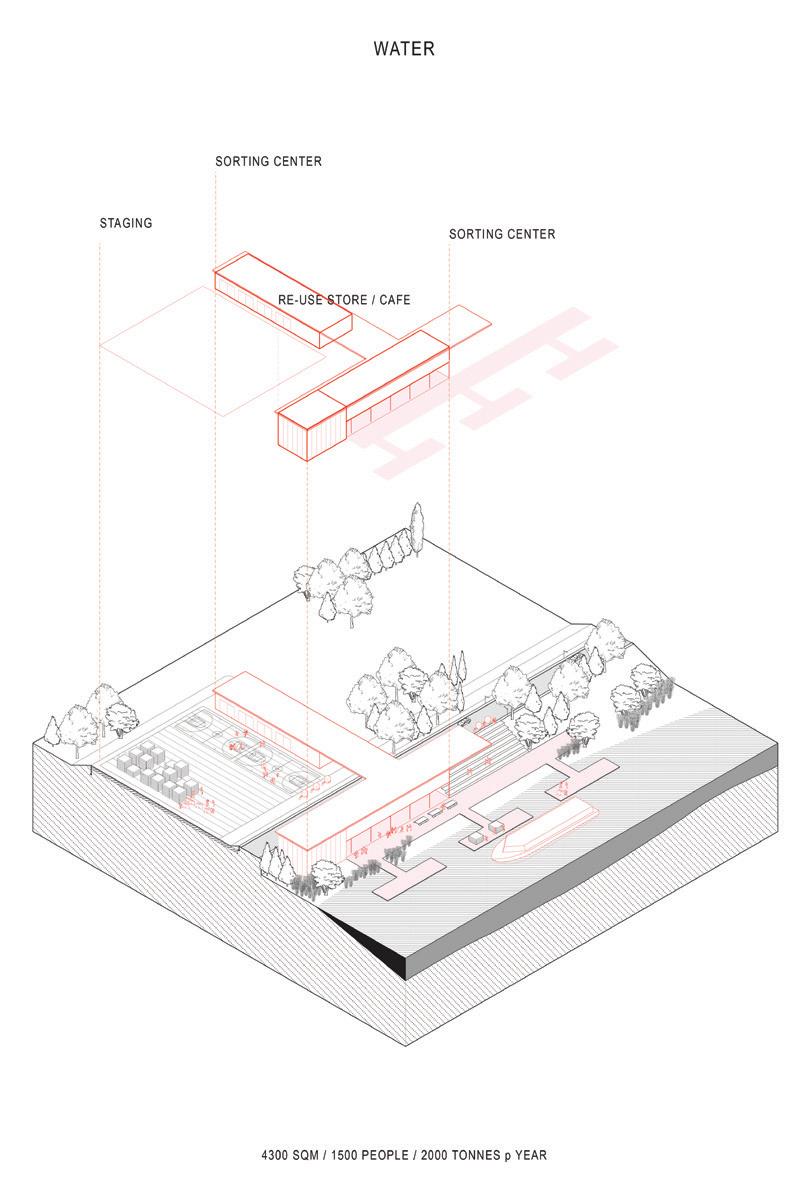

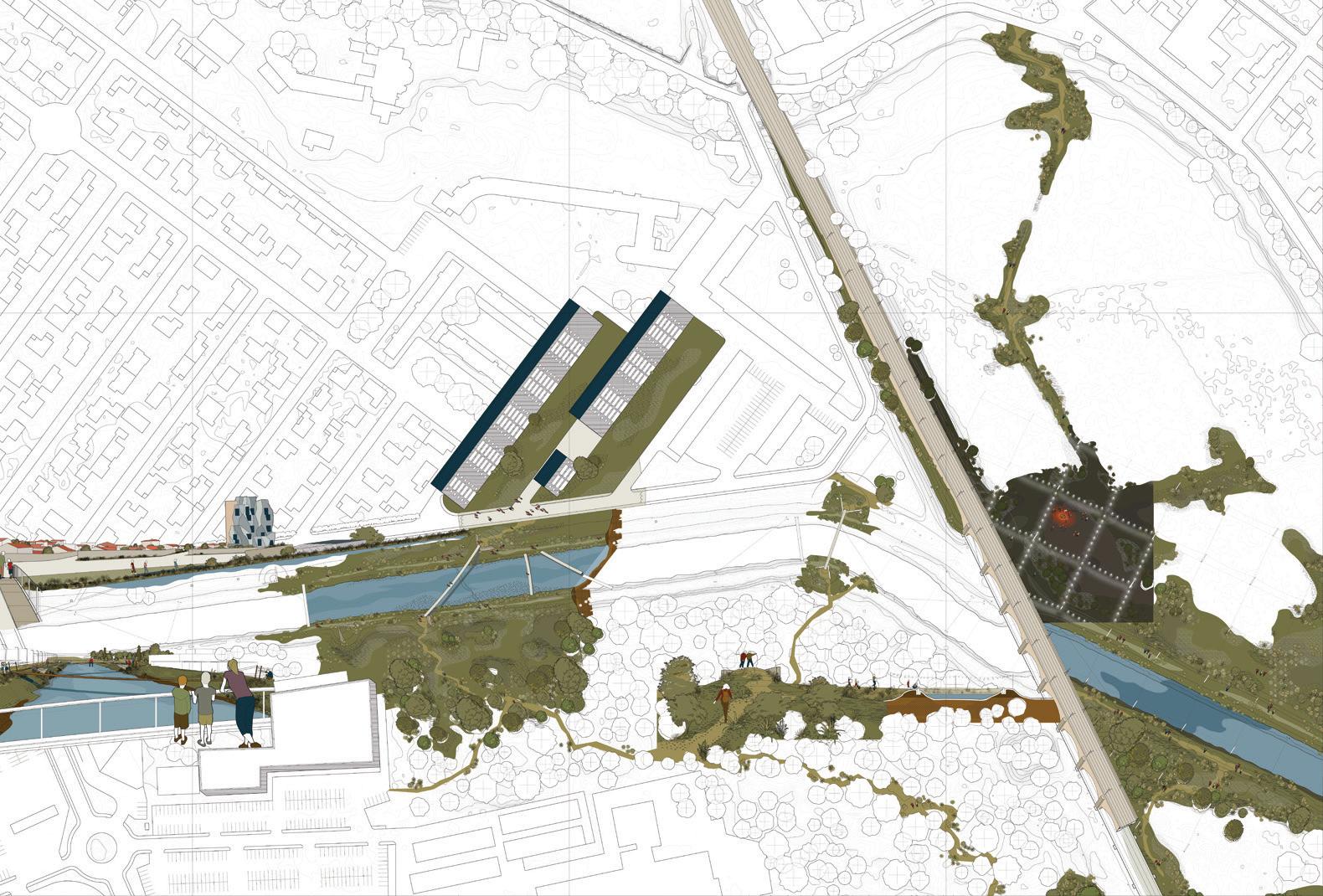

For example, Andy Lee saw an opportunity in the convergence of four conditions: the presence of a semi-abandoned fluvial port in north Arles; the impending relocation of the functions of the current port at Marseille-Fos due to rising sea levels; a robust network of navigation canals, rails, and roads; and the fact that domestic waste processing in France is largely in the hands of an international conglomerate. His project, “Co-Mingled: A New Waste Economy for Arles,” explores the synergies between these conditions and proposes a new decentralized waste economy for Arles with its main base of operations at the point of convergence of all these infrastructures at the fluvial port.

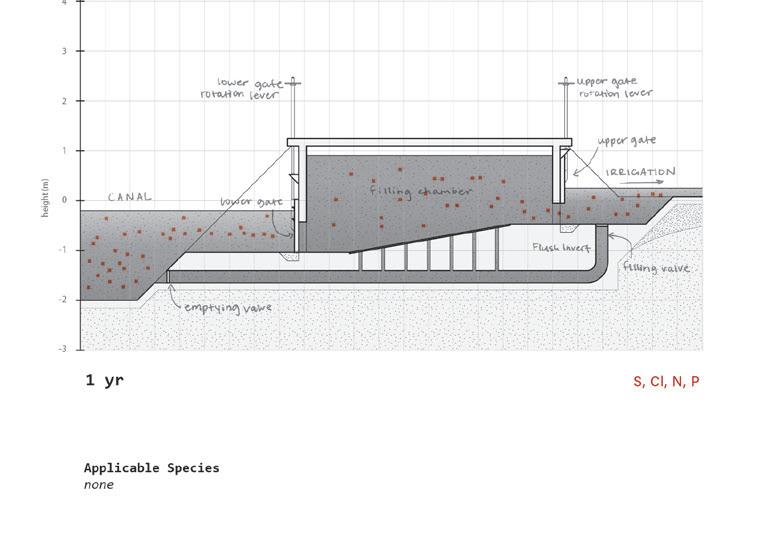

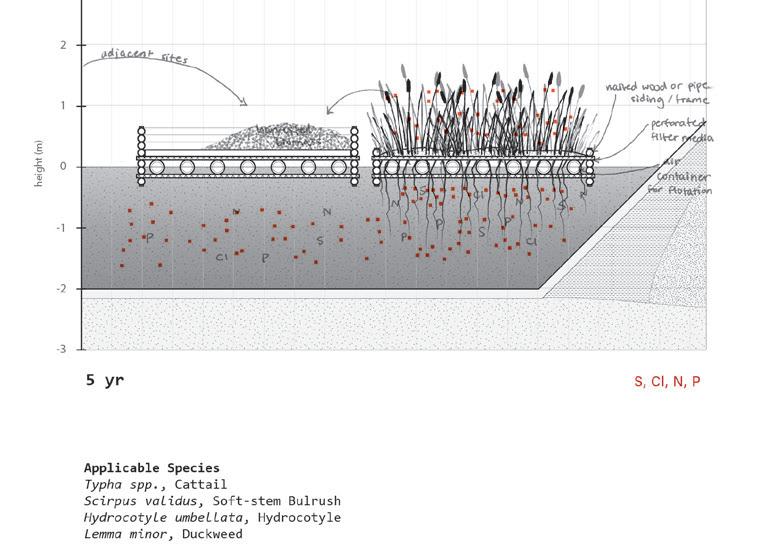

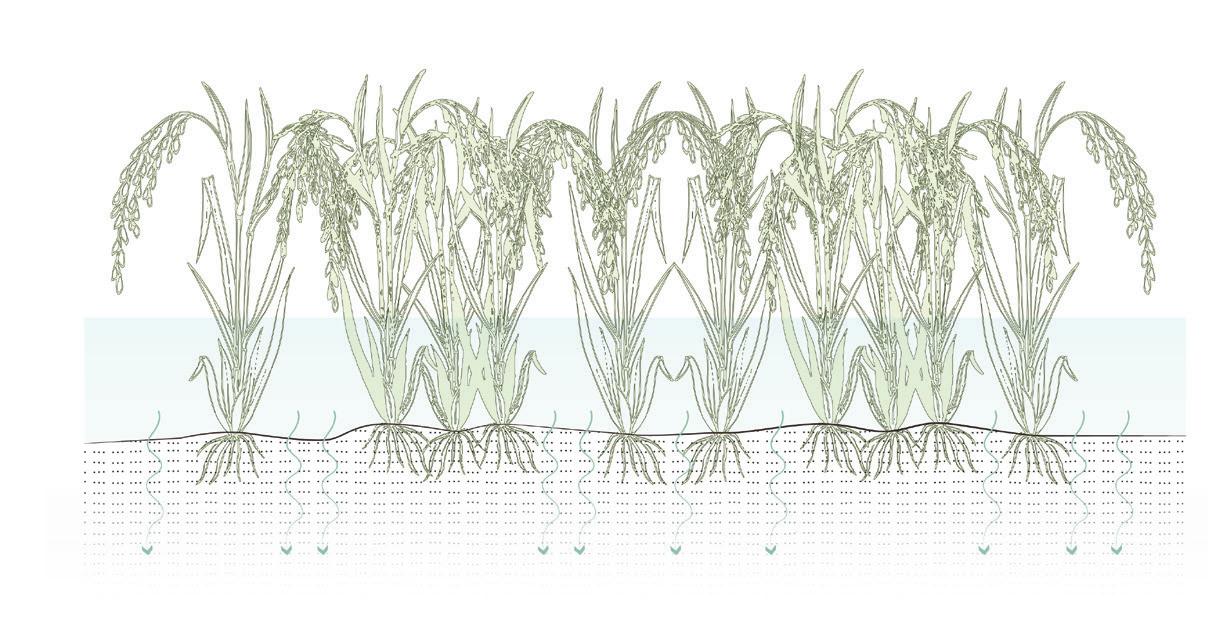

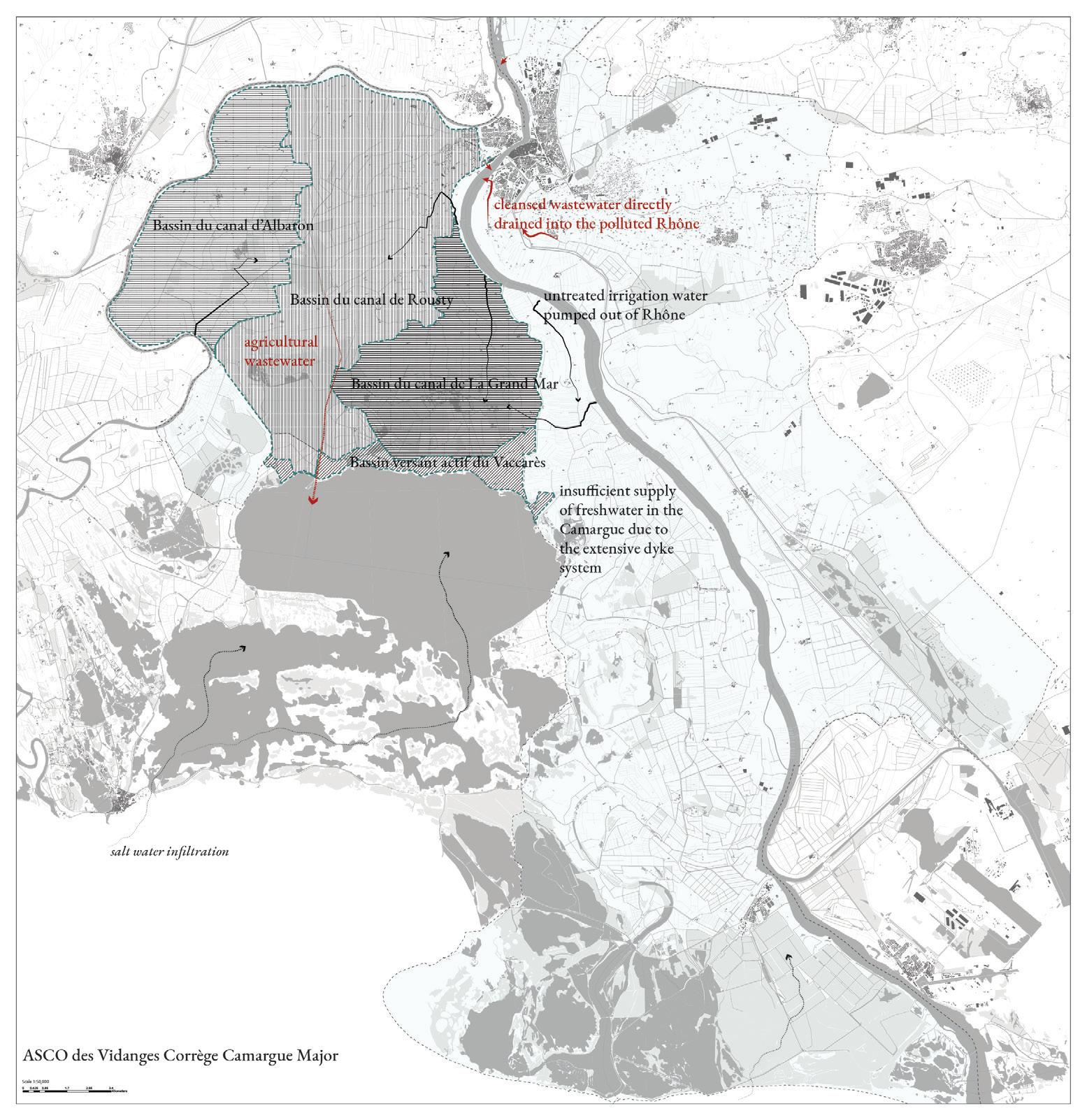

Arles discards its treated water by releasing it into the Rhône, where it mixes with the river’s polluted waters. Further downstream, these waters enter the agricultural fields of the Camargue in a contaminated state. New economies can be generated from waste, but equally important are alliances around a newfound resource. While most cities would recycle their water back into the city for a variety of uses, Andreea Vasile Hoxha proposes an infrastructure of new in-ground and elevated canals and marshes that will direct the cleansed water to the Camargue. There, it will offset the effects of

saltwater infiltration and potentially open new dialogues between Arles and its hinterland.

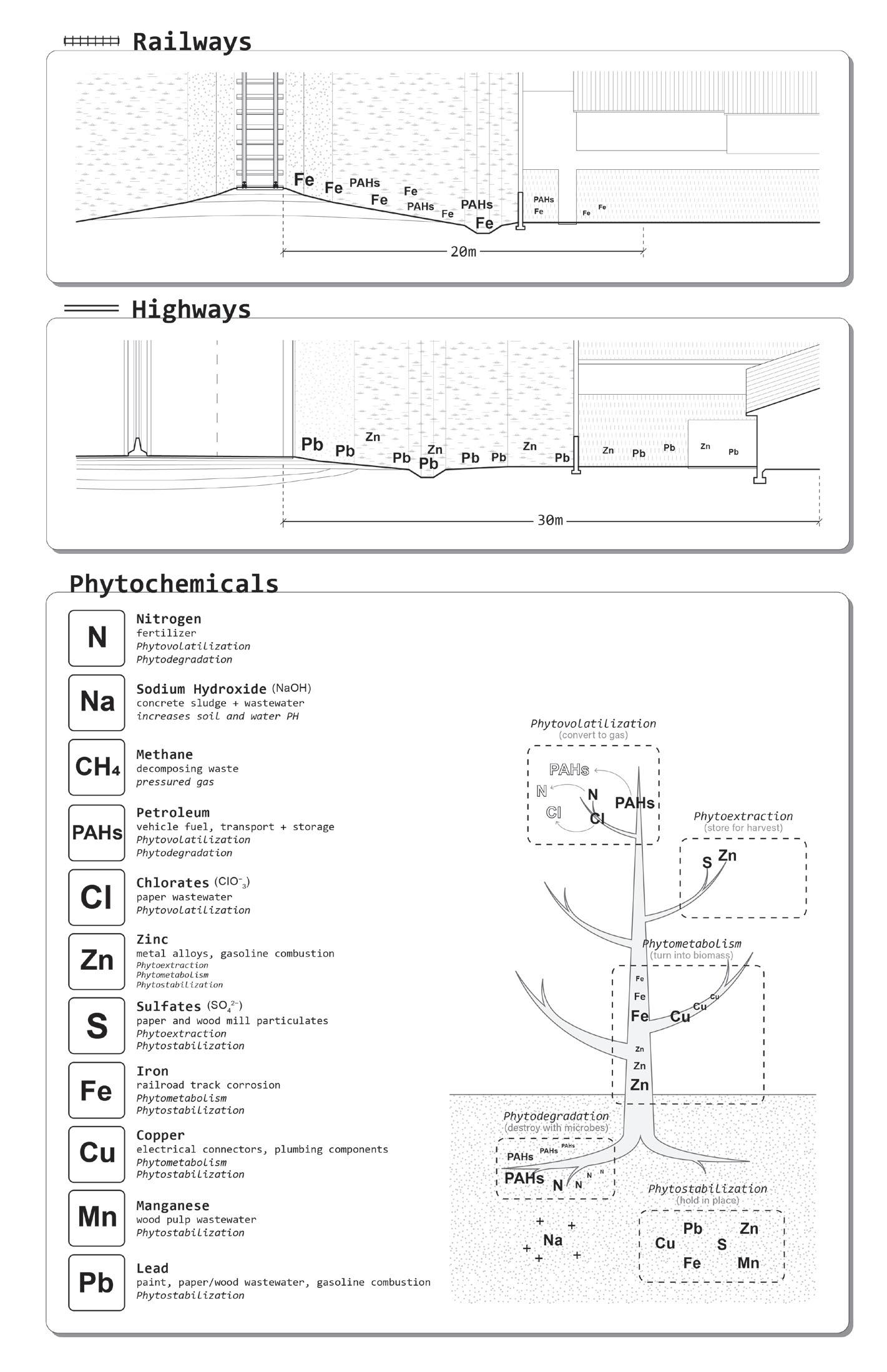

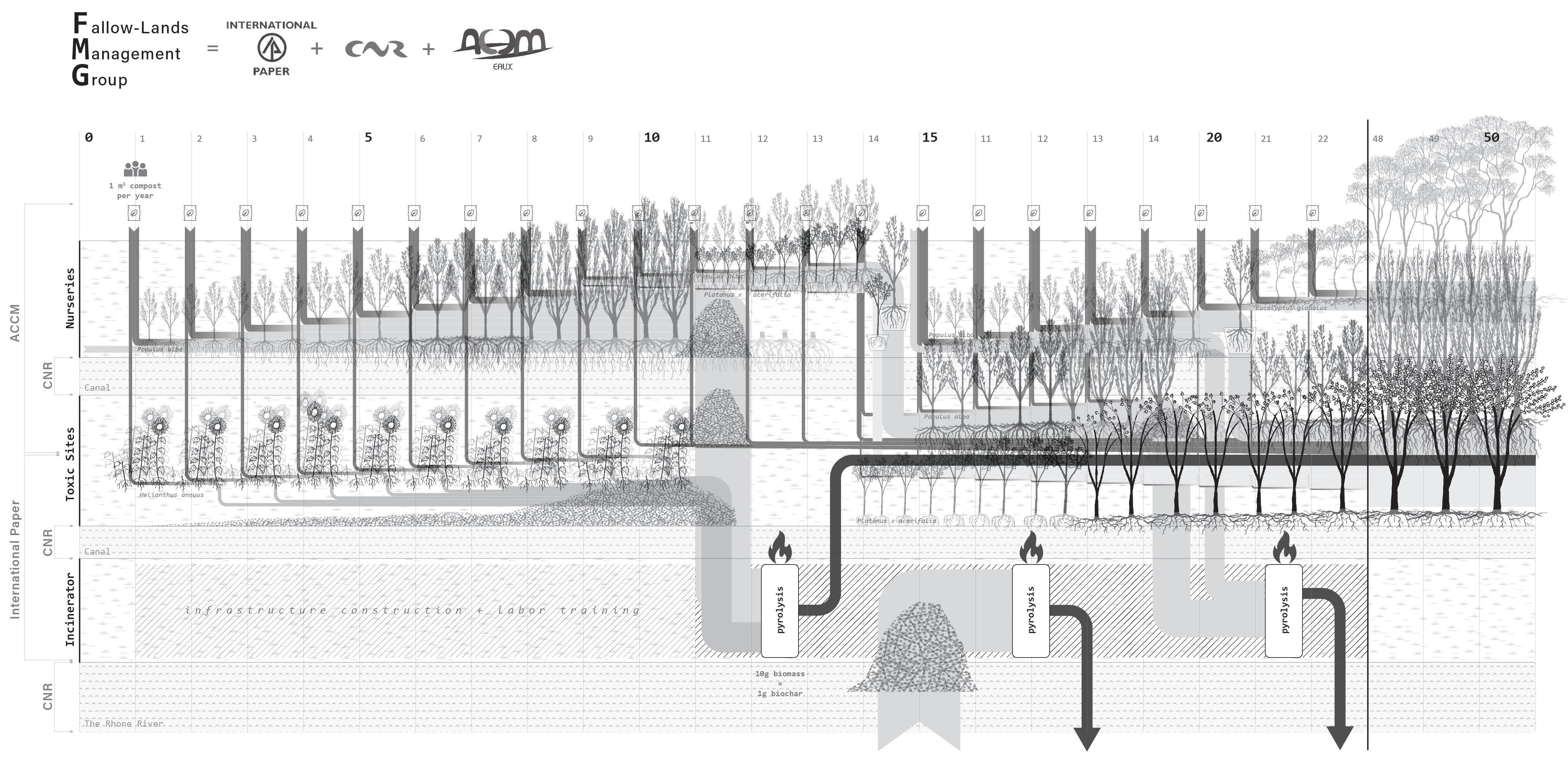

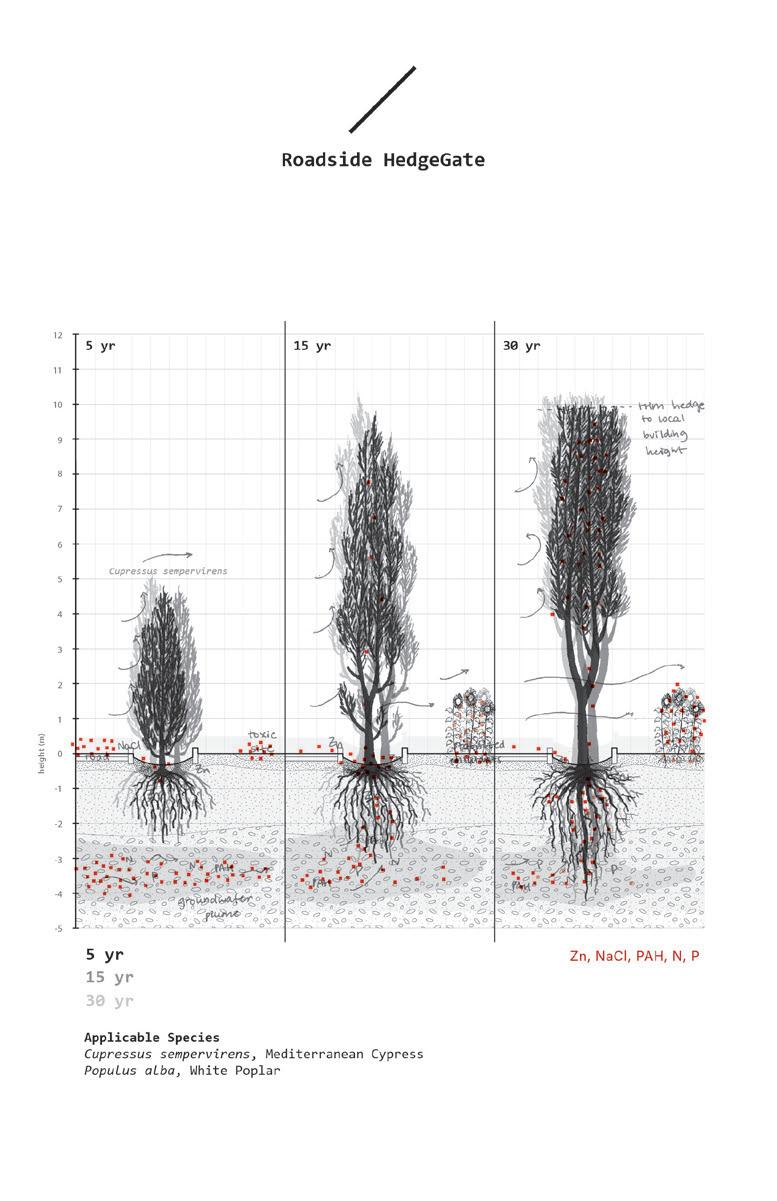

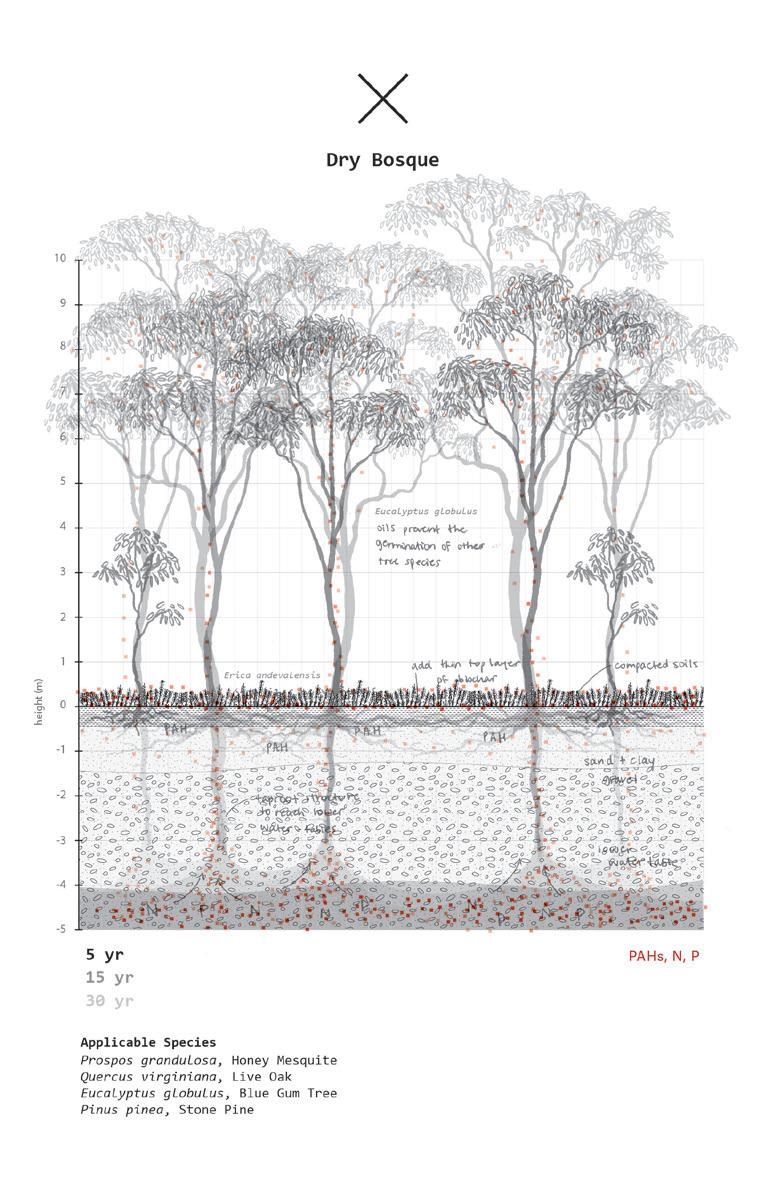

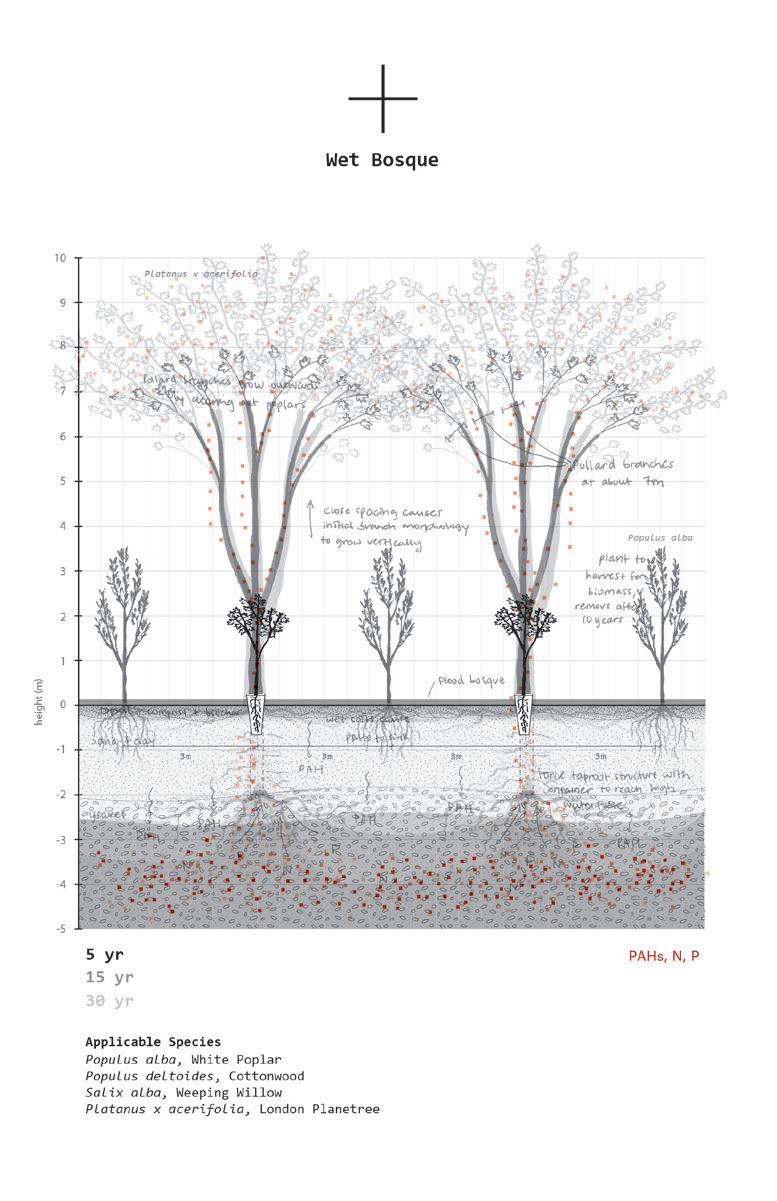

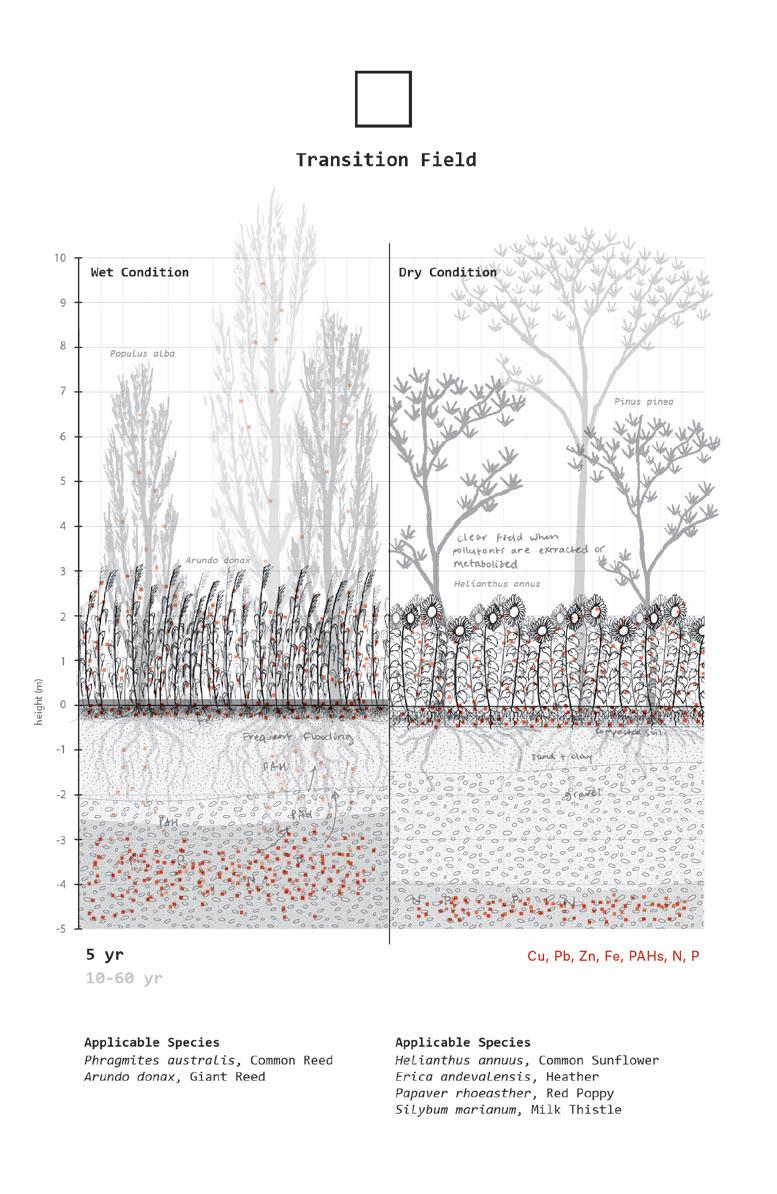

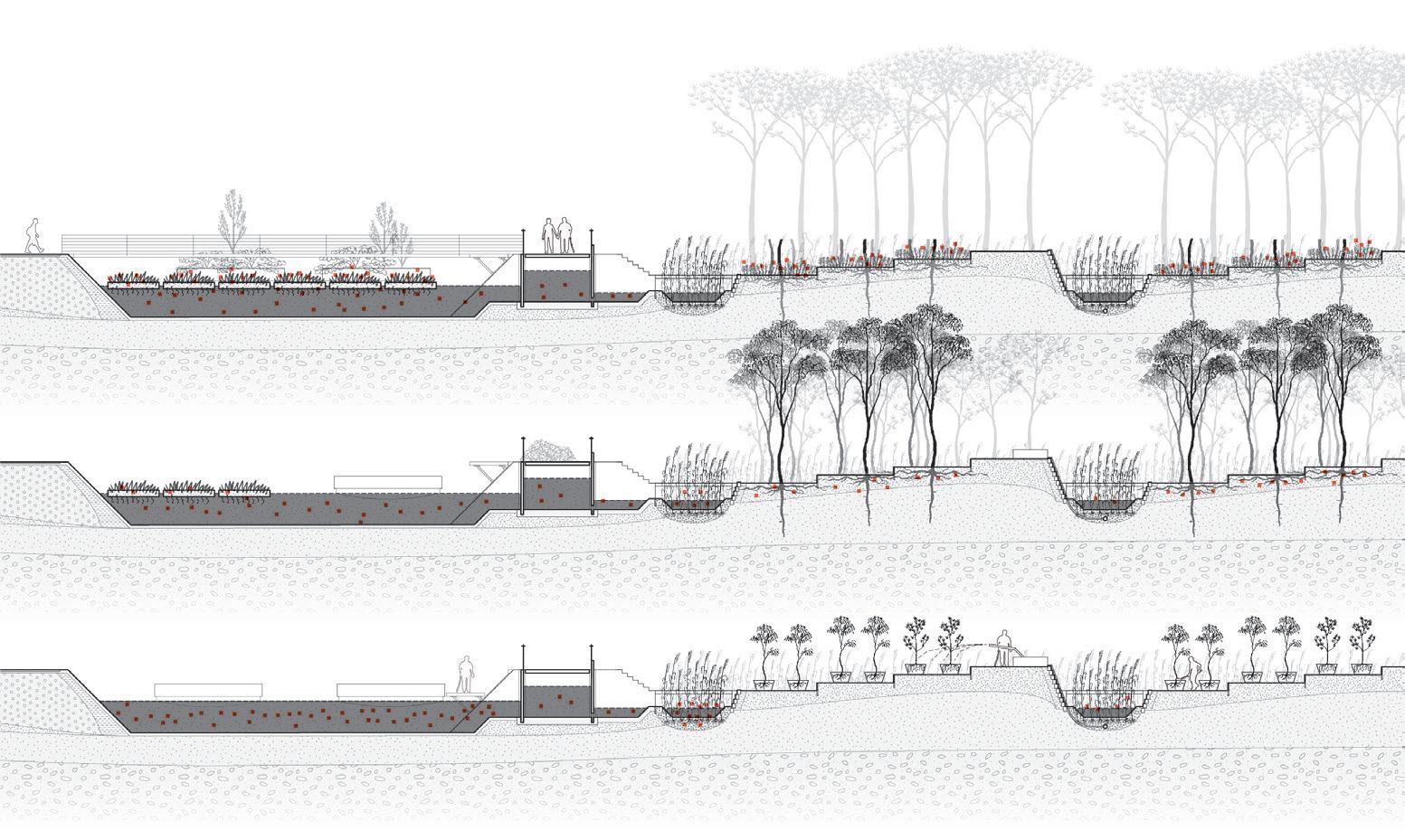

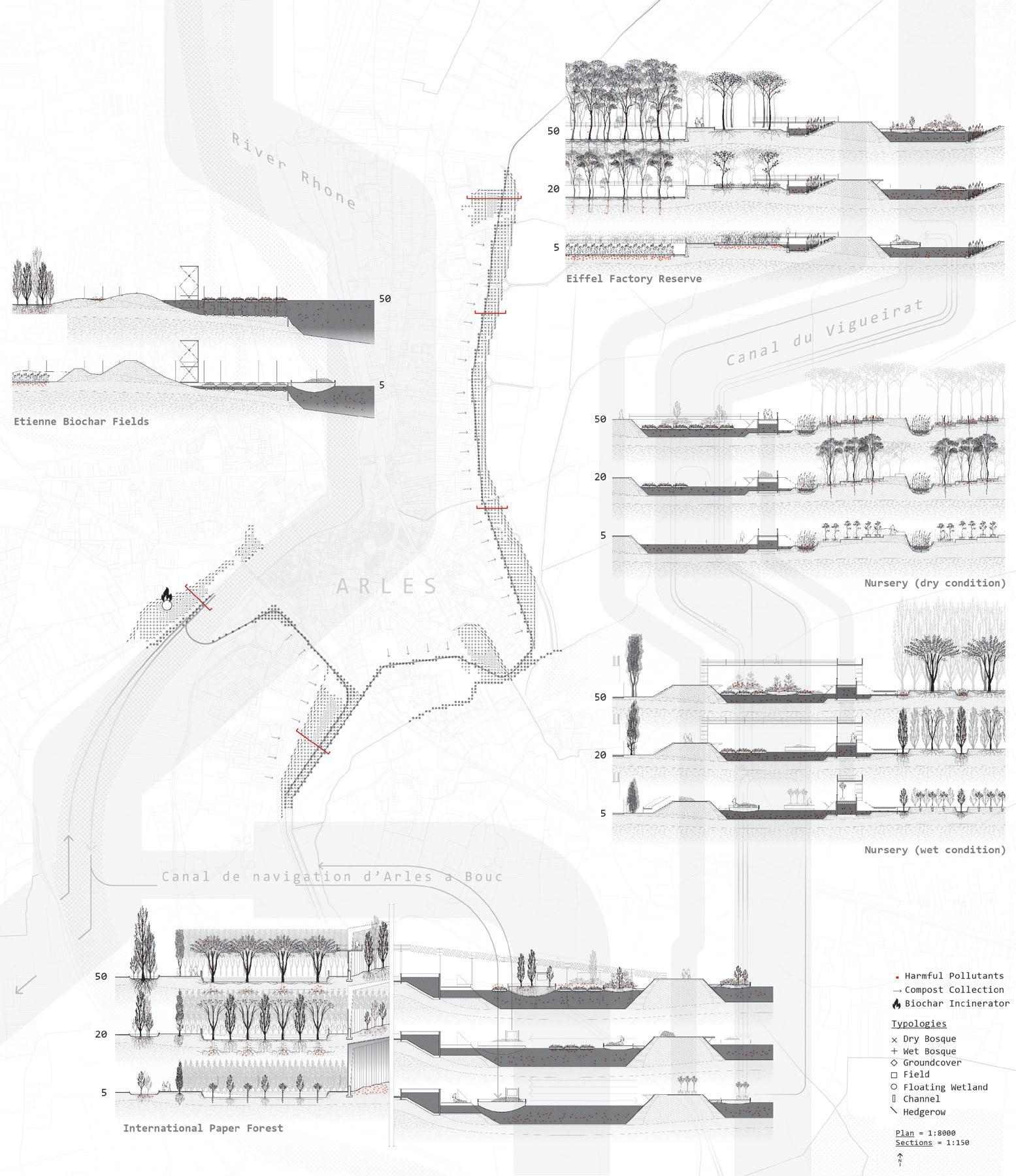

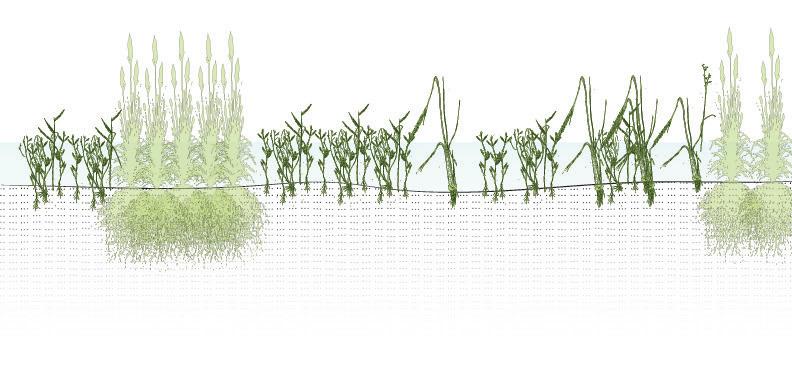

Contaminated soils are ubiquitous in Arles, especially along highway embankments and rights of way, and in the canals, parking lots, and industrial and post-industrial sites. Koby Moreno’s “Hedgerow Funds: Investing in the Cultural Value of Fallow Lands” is a call to invest in the care and cultivation of Arles’s soil. The proposal calls for the extensive phytoremediation of all these lands through a continuous system of hedged gardens, bosques, thickets, and flower plantations that recall the vernacular French landscape. Because phytoremediation is a process that entails long periods of time, he proposes slow recovery as a way of stalling any rush decisions about land, in favor of an appreciation for the cultural value already embedded in these places. Further, the project argues that the pairing of phytoremediation technology with conservation practices will not only prevent further land degradation but will provide Arles with a new network of recreational spaces that recognizes the historical significance of fallow land.

Both the port and water projects demonstrate how thinking of the fallow as a resource can potentially recenter Arles in the region, given the new mandates for reduction of waste, the desire for new regional and circular economies, and how these have the potential to reconfigure a new set of systems and processes for a more sustainable future. All three projects are fundamentally an appeal for an ethos of care and maintenance that needs to be embedded in how we consume and how we use and reuse as a counter to a long history of practices of producing and of wasting waste.

Koby Moreno

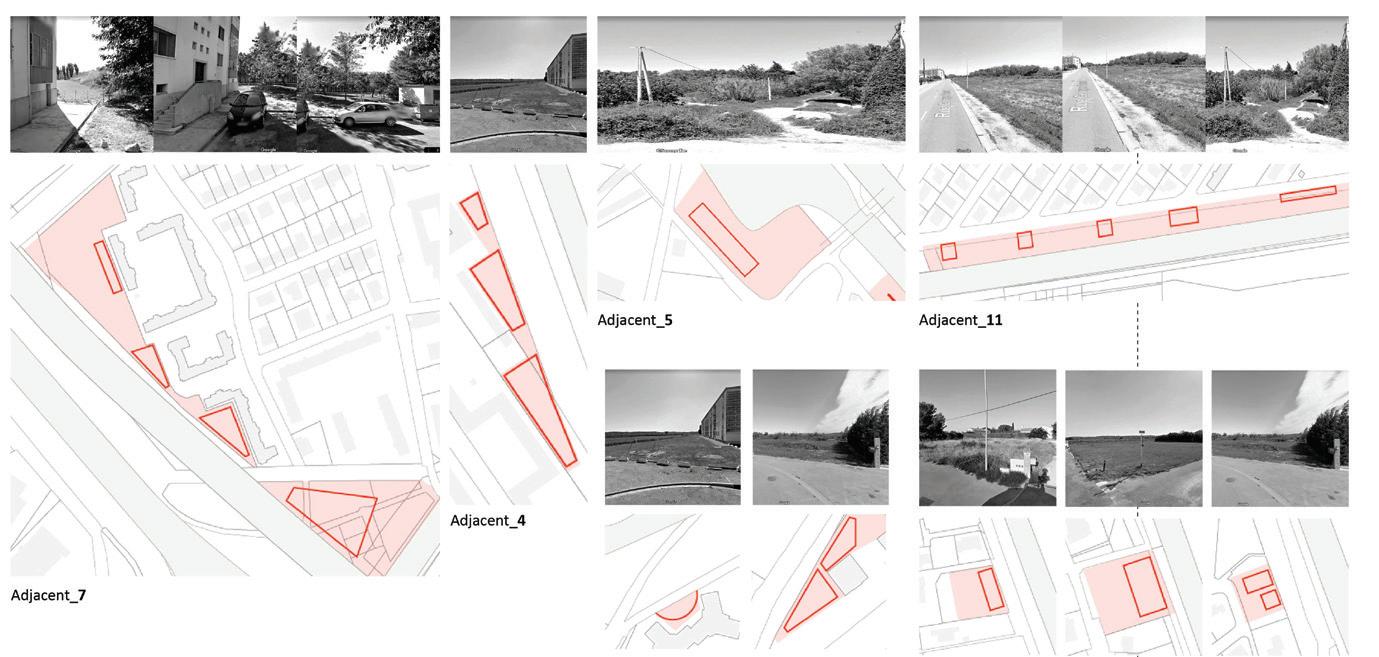

Fallow spaces exist along the margins of Arles’s urban boundary, hidden behind walls, dikes, and thickets and ranging in size from post-industrial sites to infrastructure rights of way. Their unseen beauty lies in their ability to layer time, freeze history, and show the succession of nature. While often mislabeled as abandoned or nonfunctional, these landscapes are in fact rich cultural assets whose development should preserve their character, reintegrate them into the urban experience of Arles, and gradually transform them over long periods of time.

The locations of many of these parcels make them prime real estate for commercial development, but their former land use makes them unsafe spaces for humans to inhabit. Agricultural pesticides and macronutrients, wood pulp and paper refining, rail and road transportation, warehouse storage, and landfilling have significantly altered the chemical composition of urban soils and waterbodies. French policy additionally prohibits public access to these spaces until contaminants are removed or stabilized.

A possible management strategy for these sites lies in phytoremediation, a process of cleaning polluted soil and waterbodies with plants. By coordinating hearty plant species with the right chemical composition present in the soil, these plants can degrade toxic chemicals with their roots, stabilize them in the soil, redistribute them into the plant’s biomass, or volatilize them into a gaseous form. As a newly utilized technology, phytoremediation is inherently slow and unpredictable. Depending on the plant species, pollutant type, and pollution concentration, this process could take five to fifty or more years.

Embracing the slow and unpredictable nature of phytoremediation, this project imagines an urban forestry initiative combined with planting design strategies that both process tox-

ins and recall locally familiar landscape forms. As agricultural and industrial waste continually flow through Arles’s soils, these critical green infrastructures work to preserve these sites’ historic and cultural importance, open public access, and increase awareness about larger issues of land management.

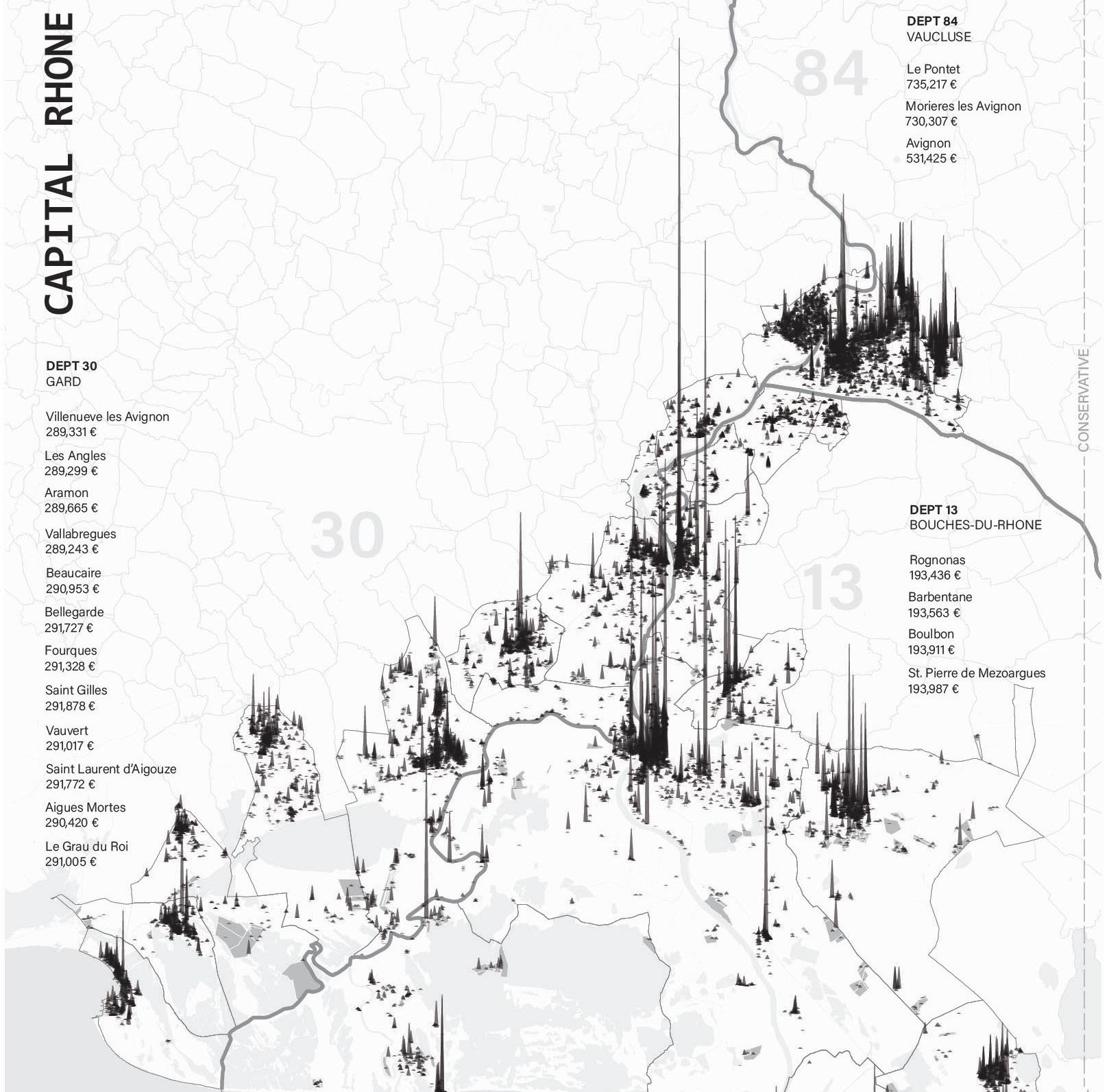

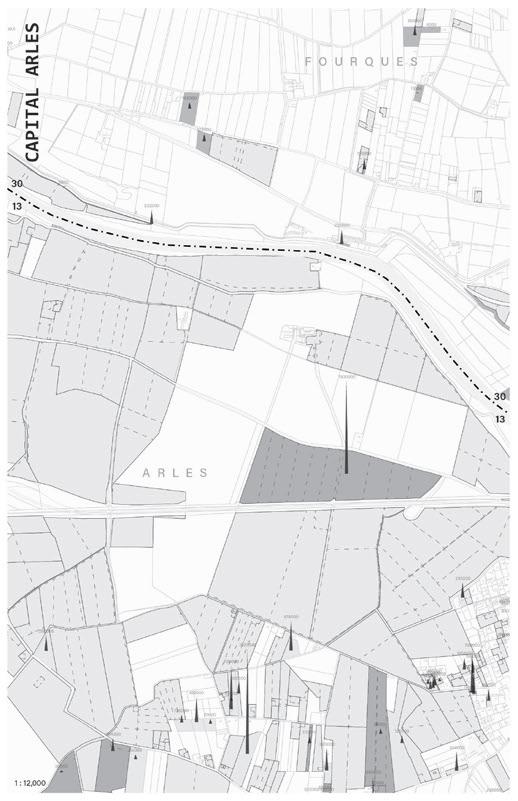

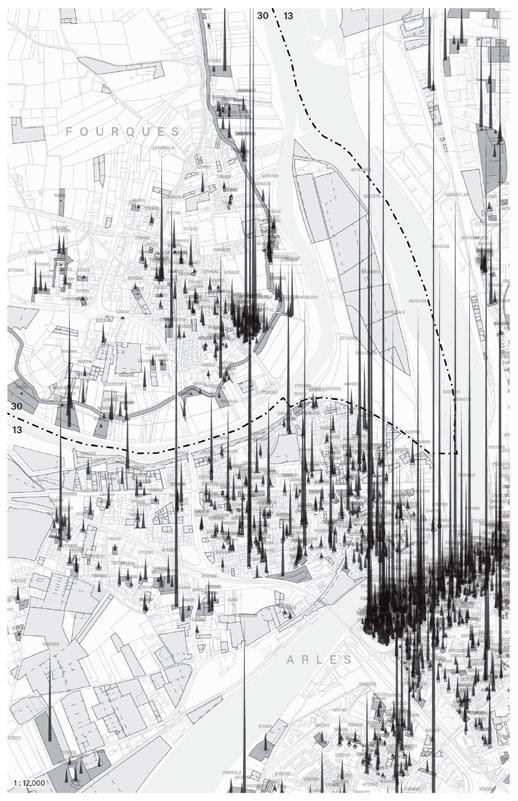

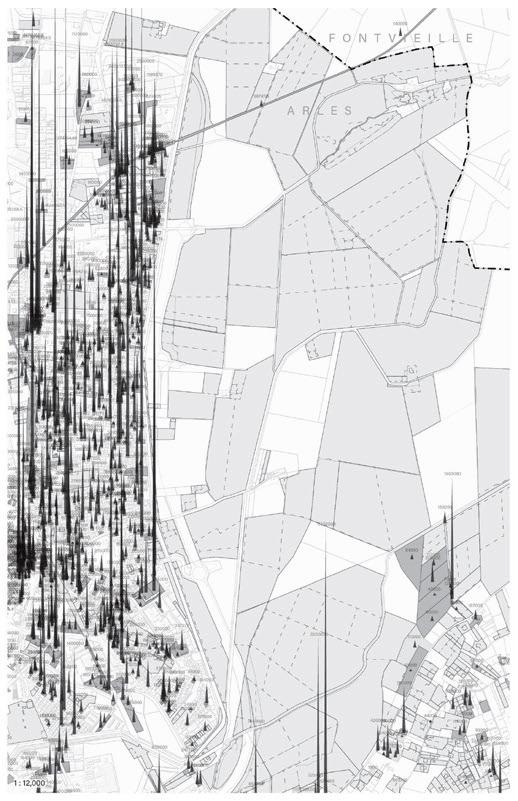

These maps use property transaction data from the Rhône River Delta from the past five years to illustrate economic activity and real estate pressure in Arles’s city center.

Planting designs that combine phytoremediation technologies with planting typologies of the French vernacular language.

50-year phasing strategy.

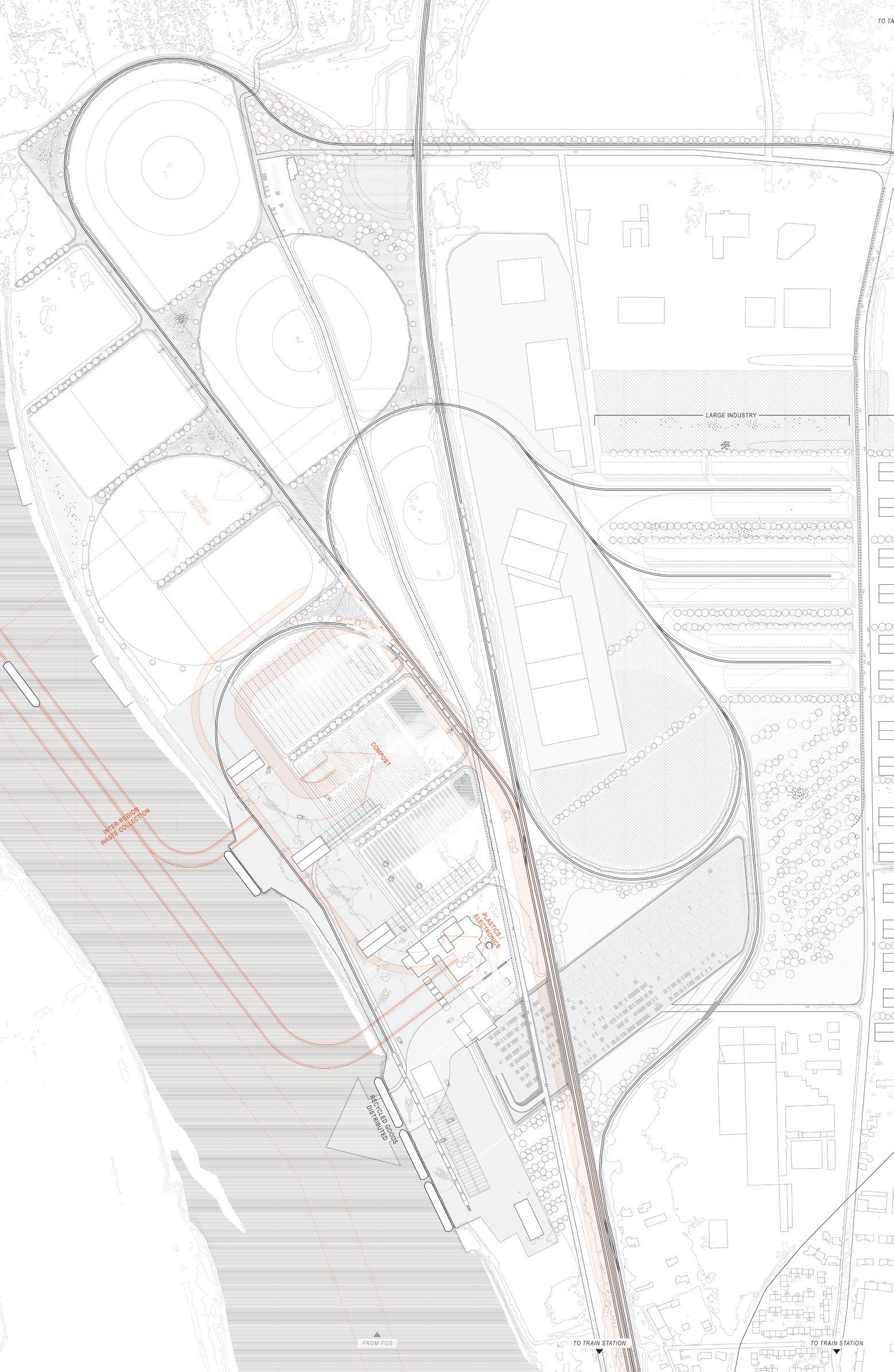

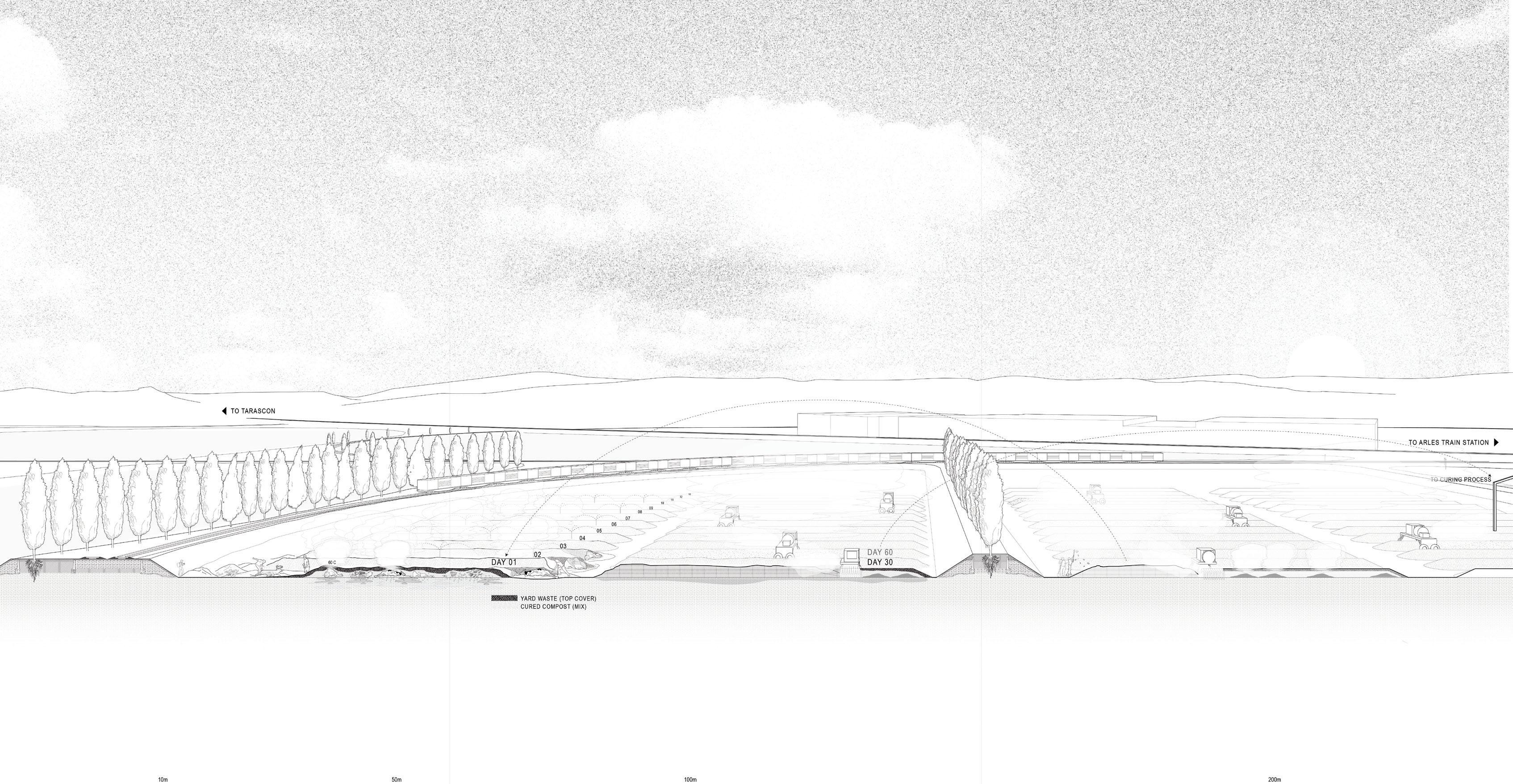

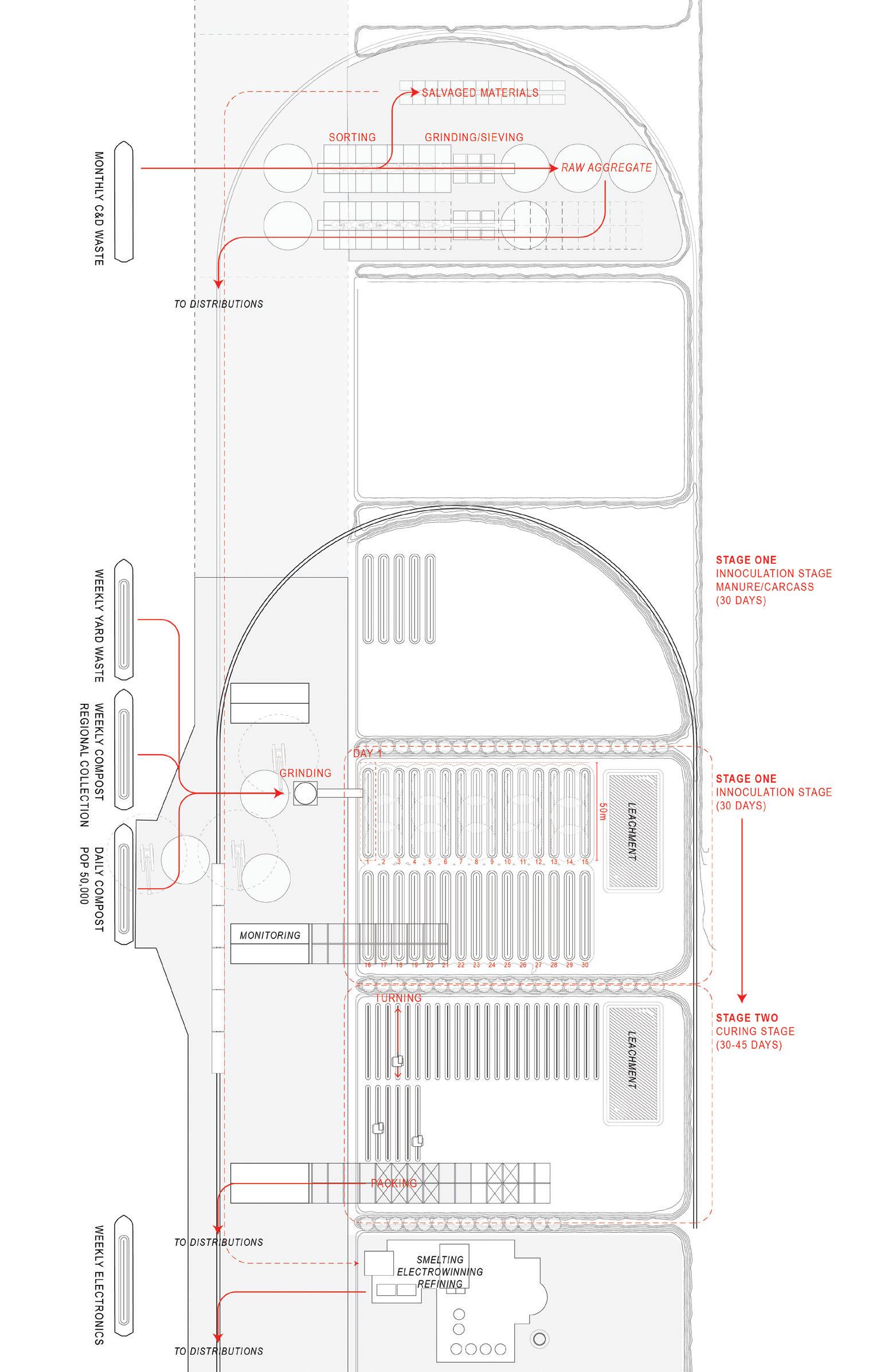

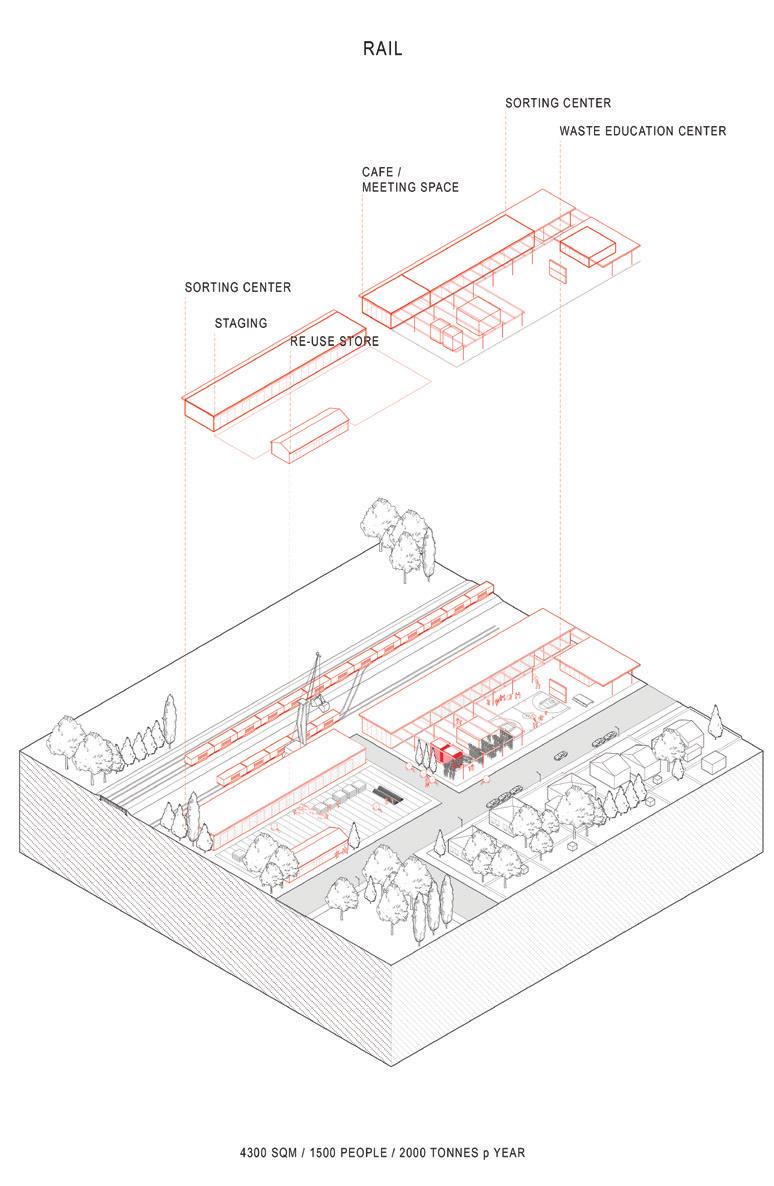

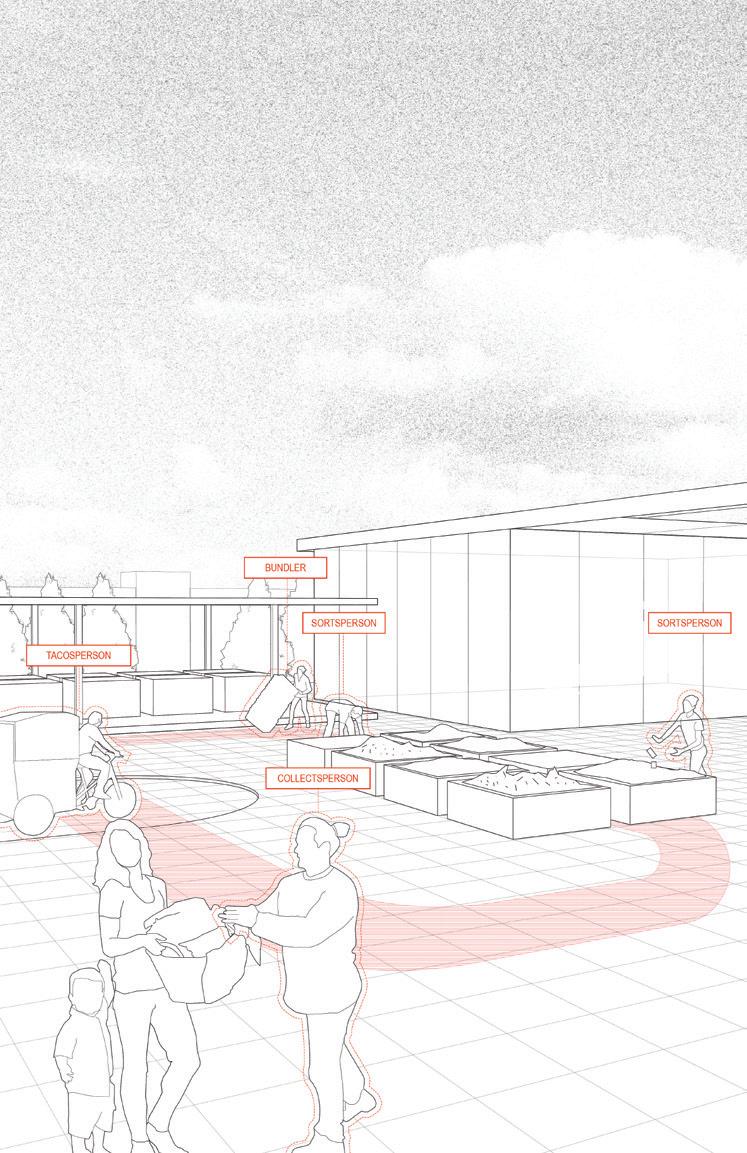

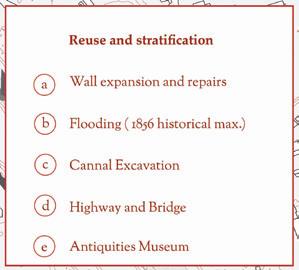

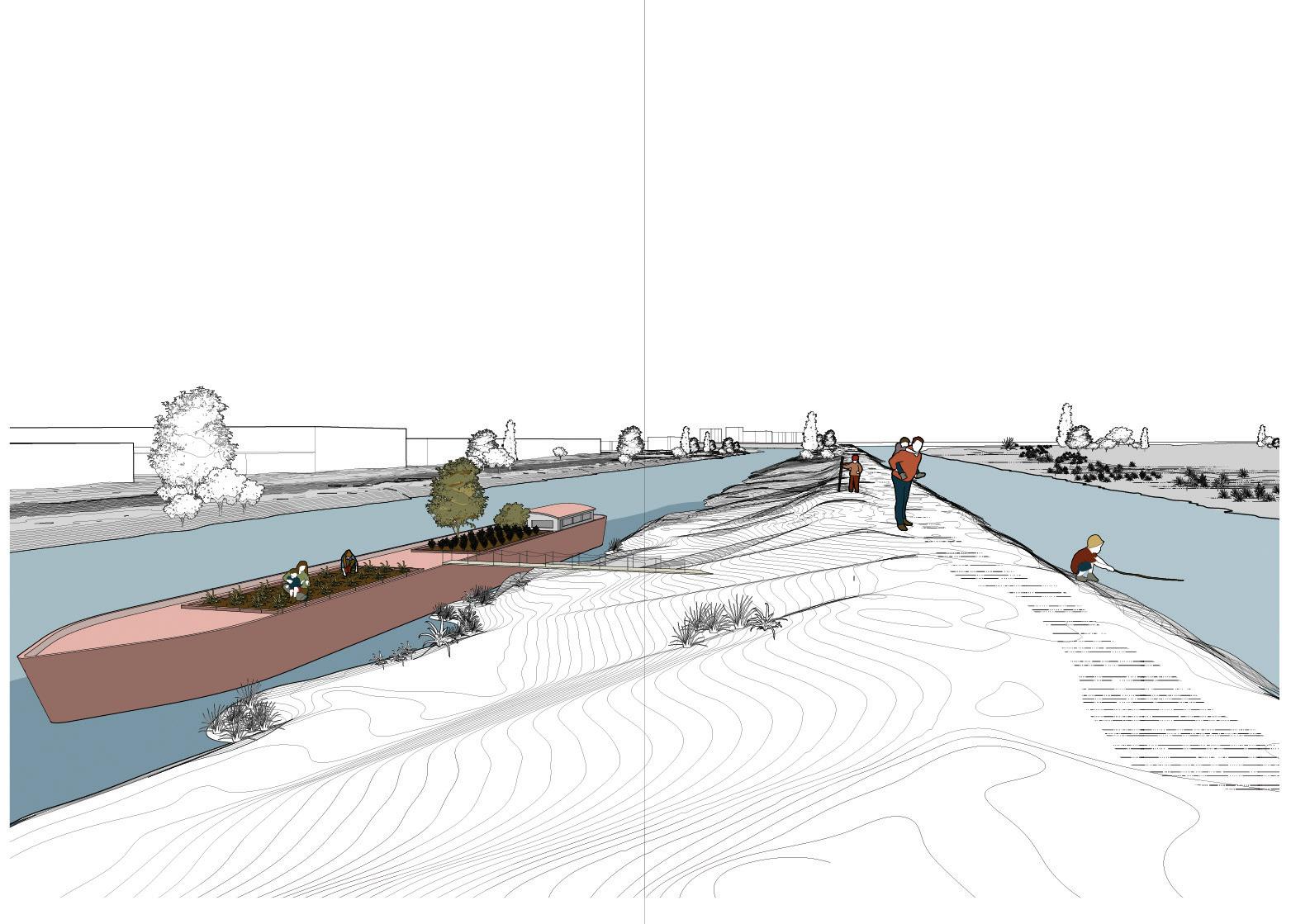

“Co-Mingled” proposes a new port facility at the Port of Arles, a semi-fallow landscape just north of the city center. The site is located at the margins of a major industrial corridor yet connected through four distributional networks—river, canal, rail, and road—that originate from the Marseille-Fos Port, one of the largest ports in the Mediterranean. The proposal generates a new type of port through the continuous re-fallowing of the landscape in the form of a new, collectivized waste economy. This proposal anticipates the future relocation of distributional services from the MarseilleFos Port to Arles, and is predicated upon two scenarios: (1) The conclusion of the 70-year concession between France and the Compagnie National du Rhône, which manages the port and other infrastructure along the Rhône River. There is a high likelihood this concession will not be renewed in 2022, and (2) The projected sea level rise of 6 meters for the Marseille-Fos Port, leaving Arles as the southernmost port on the Rhône.

Despite its long history as a port city since Roman times, Arles’s port currently sits largely empty. Two main materials are stored and processed there—cement aggregate and recycled goods—placing the port at the two ends of the production cycle, far upstream or far downstream. Sea level rise and the end of the concession constitute an opportunity for Arles to center a new cyclical waste economy on the Port, operated by a cooperative, employee-owned system.

Existing road and train networks, mostly built on berms, are reconfigured to lay the groundwork for the new waste economy and the eventual relocation of Fos logistics to the site. Inscribed onto this framework is the collective ownership of the port, in which the fallow areas between the berms can be operationalized and

Andy Lee

de-operationalized according to the ebbs and flows of waste and materials that come through the port.

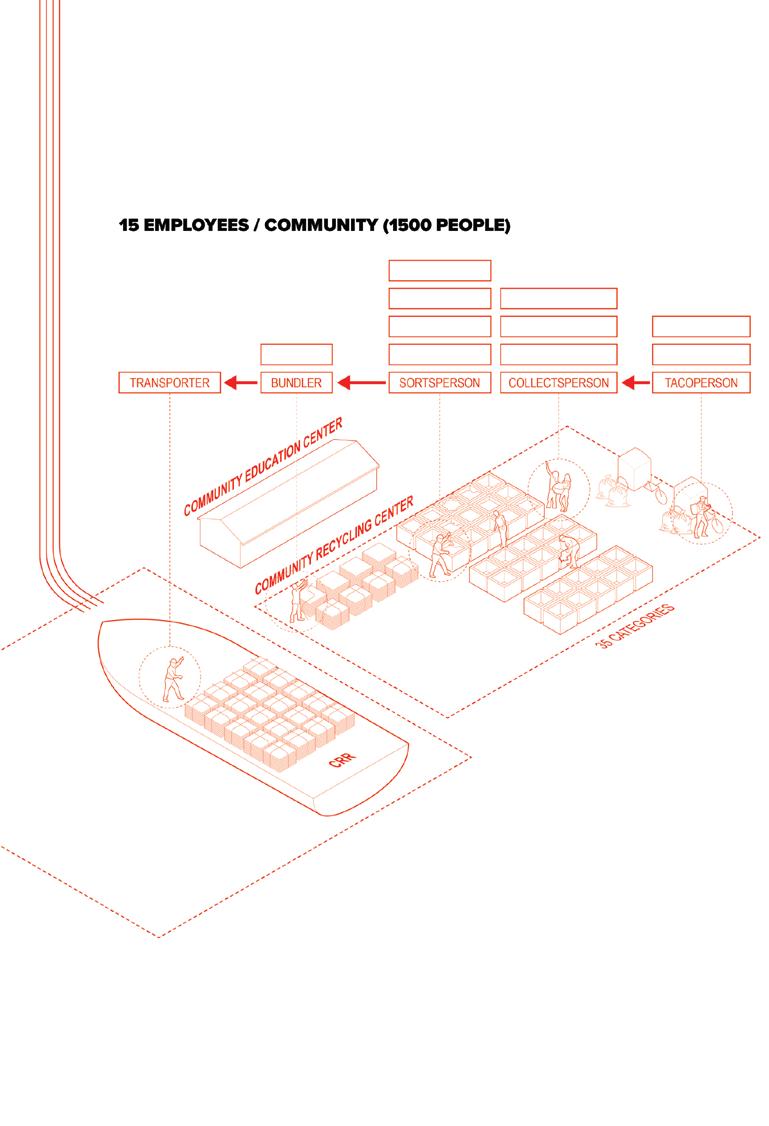

The various waste sorting functions are decentralized and dispersed in participating towns and villages, forming a regional network of community sorting centers. These will, in turn, form new local nodes for community engagement around waste. New categories of sorting and new waste-based vocations generate local employment opportunities, allowing capital generated from waste otherwise exported to companies or faraway places to stay within Arles, compensating residents for their waste stewardship.

As the new regional hub for waste stewardship, the new Port of Arles provides a physical and institutional structure for the collective management of waste, expressed through a framework of distributional infrastructure inscribed onto the site.

Collective waste system: Various waste sorting functions are dispersed into a network of community sorting centers that form new nodes for community engagement around waste. New categories of sorting and new waste-based vocations generate community centers, allowing capital generated from waste otherwise exported to companies or faraway places to stay within Arles.

Connected through four distributional networks, the existing road and train networks form berms through which the port is deconstructed and organized. Different parts of the berms are used as public promenades and parks, allowing the community to experience the port.

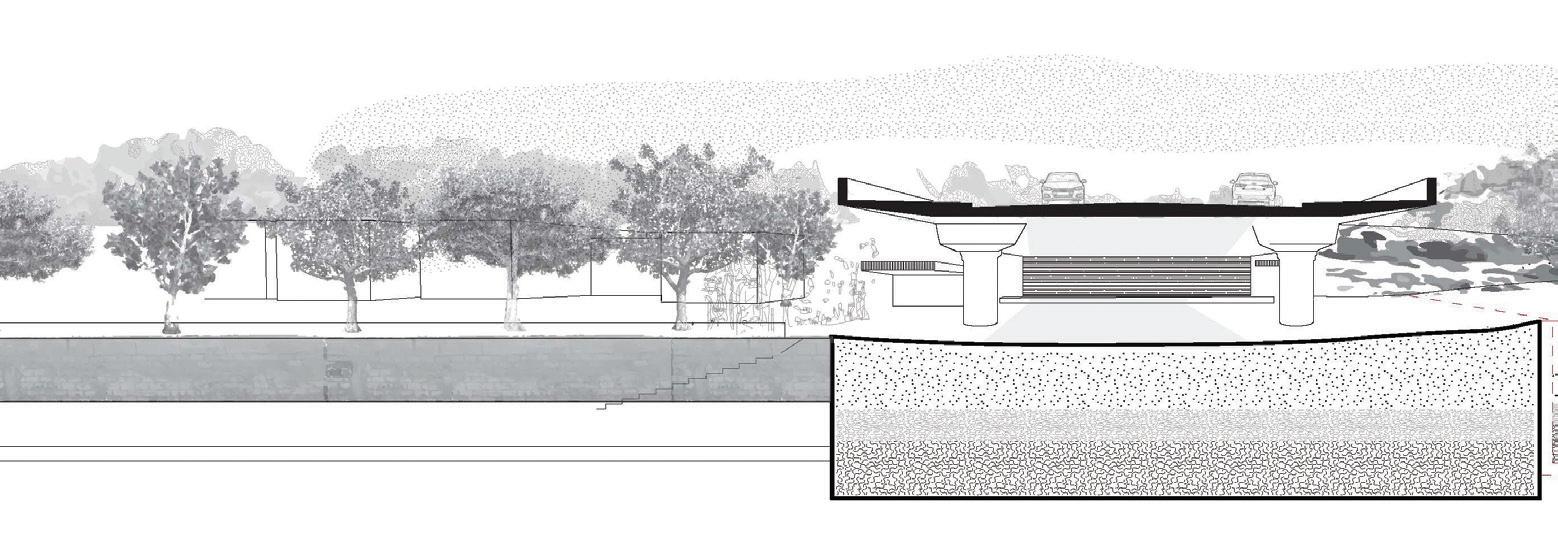

Cross section showing the areas that receive and process waste delineated by a system of hedgerows. Compost will be sorted and processed based on its provenance. Noise and smells are contained within the system of berms and hedgerows planted along them.

Waste and other materials organized in linear berms flow through areas demarcated by hedgerows in the former port.

New community sorting centers form new nodes of community engagement around waste. They are located along the four main distributional networks that organize the port itself, allowing waste that cannot be recycled to reach the port with ease.

When not in use, the areas are simply voids: monumental landscapes, almost 300 meters in diameter, laying fallow. The effects of the surrounding environments in the Camargue and the Crau can be felt here.

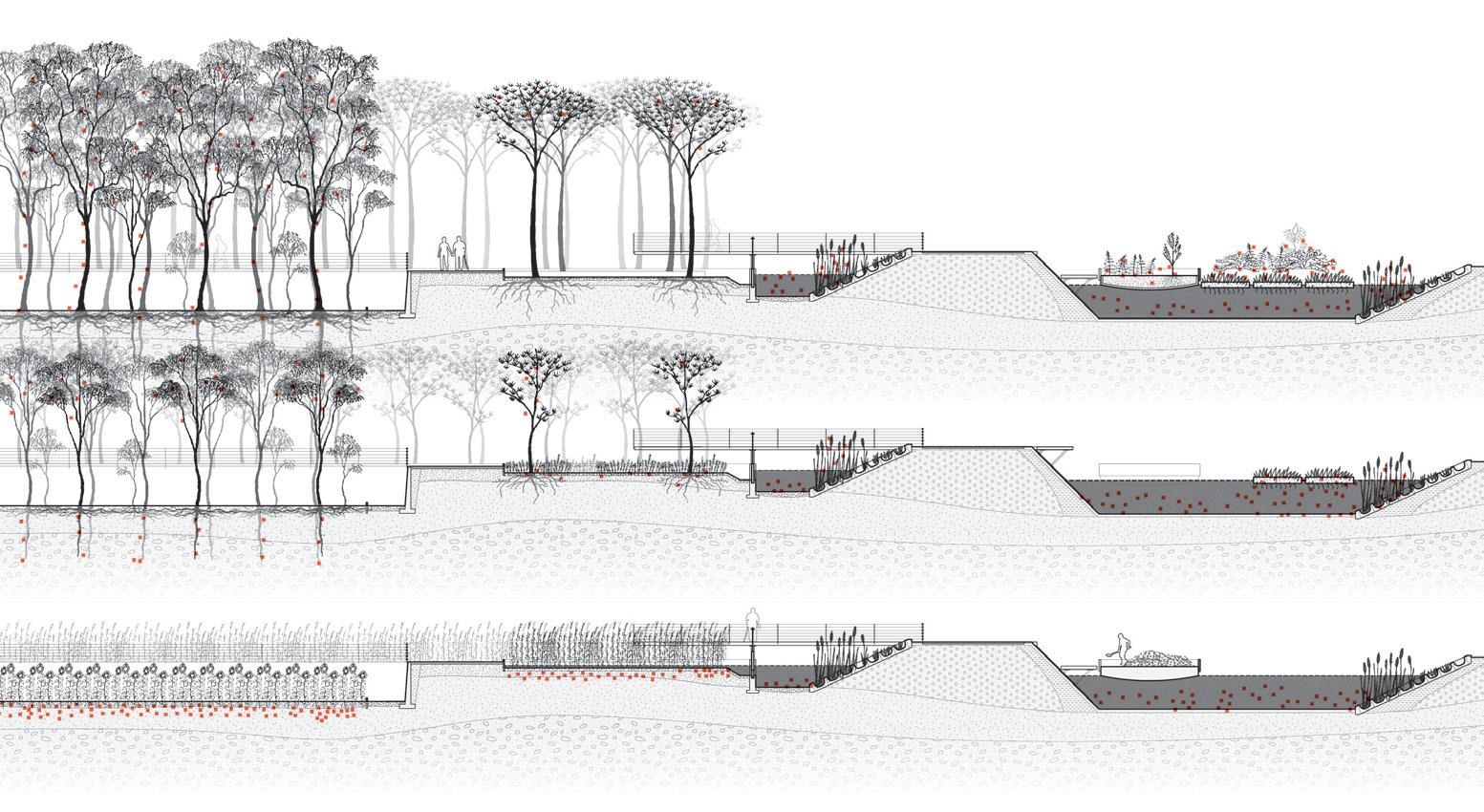

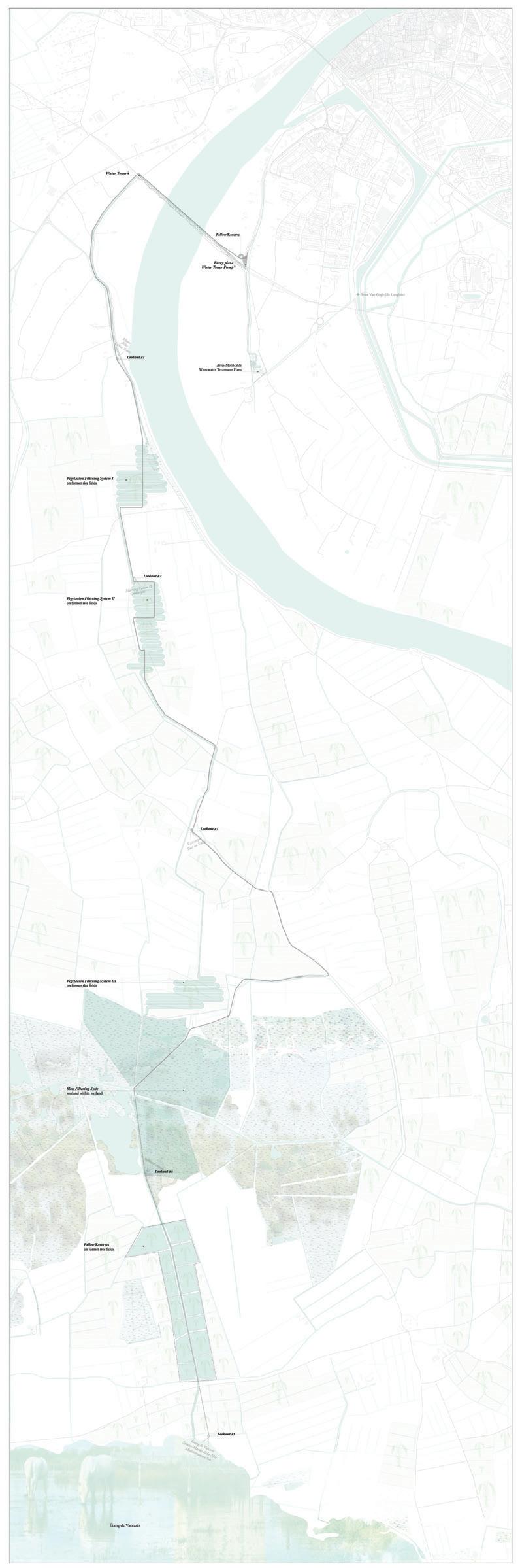

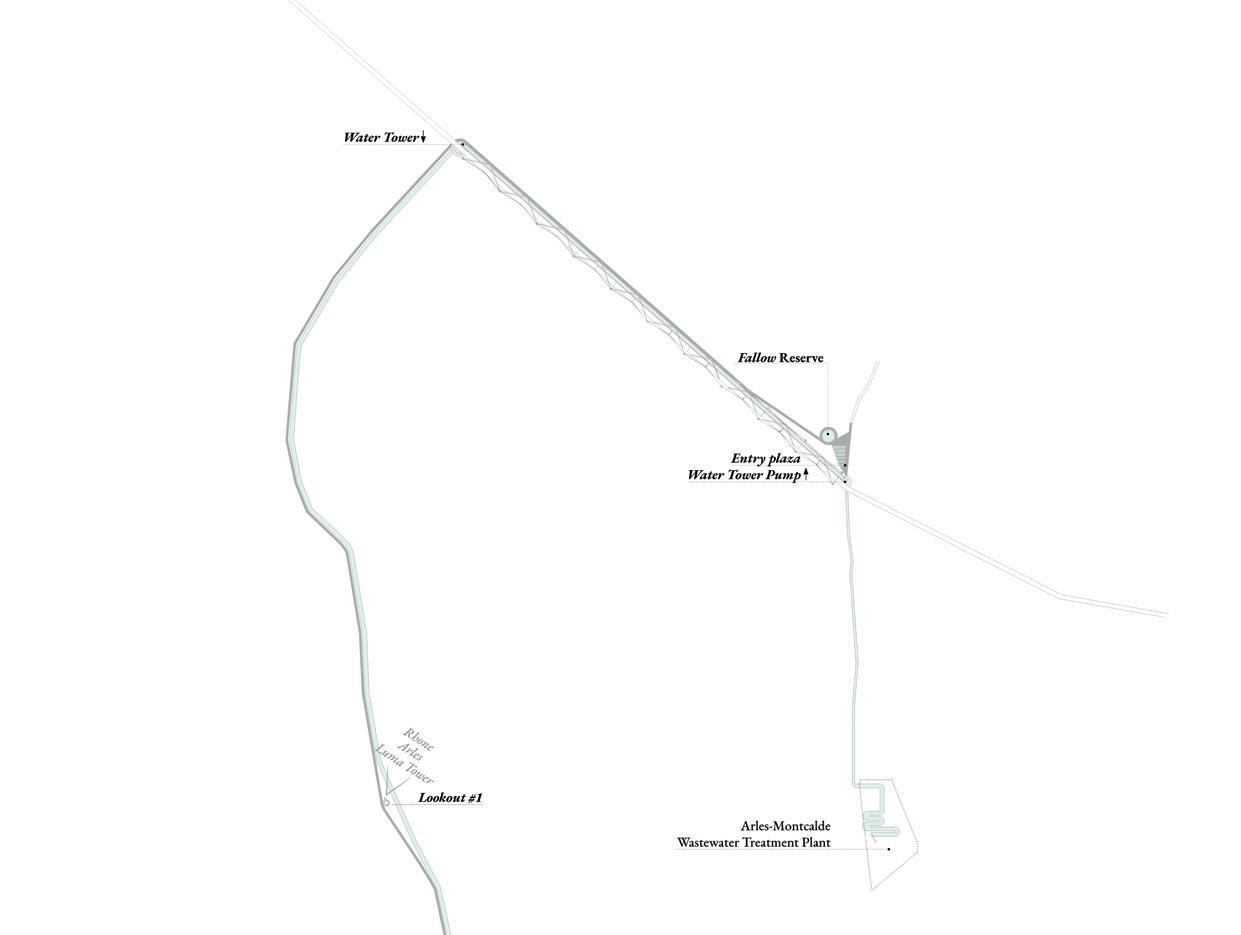

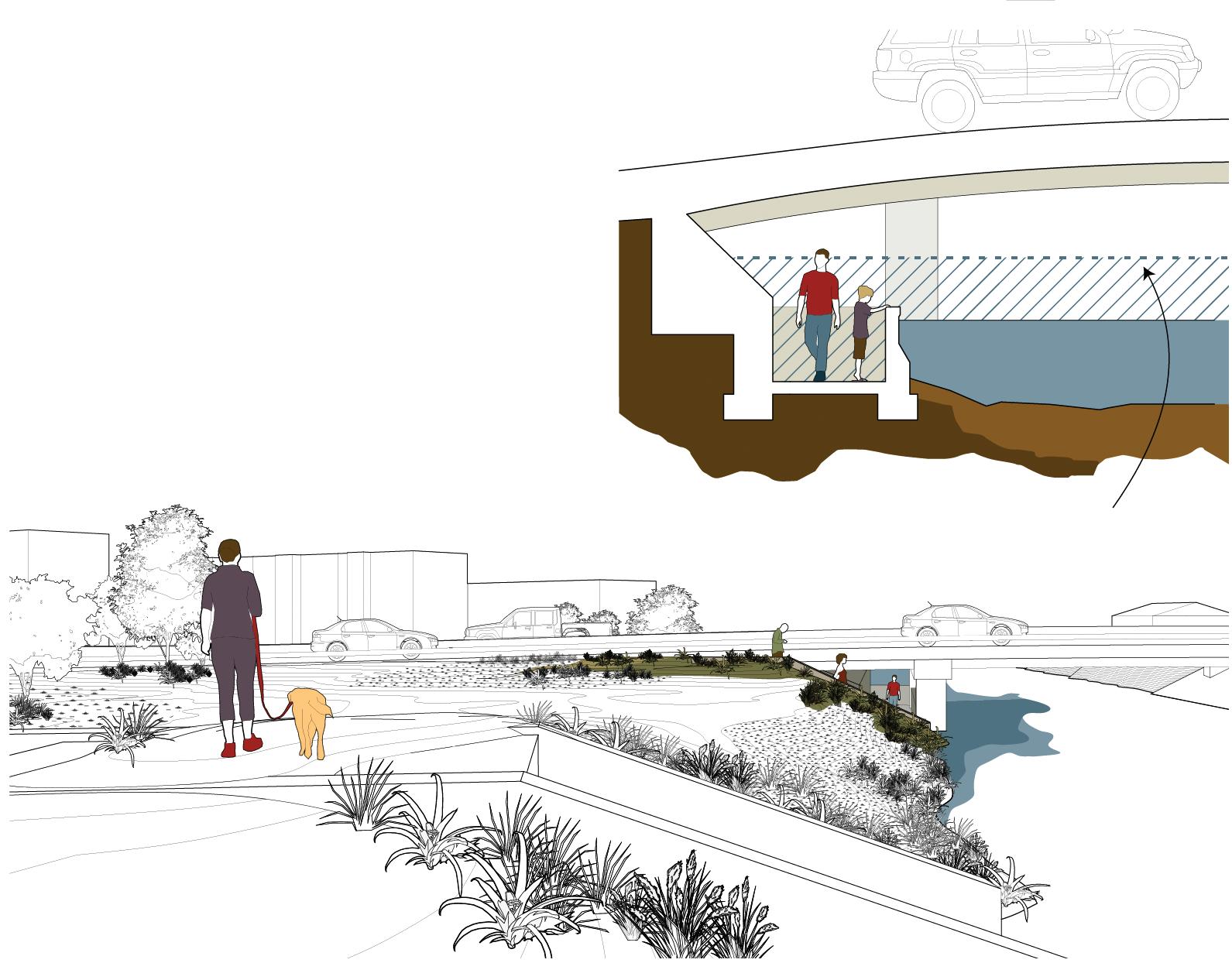

The landscape of Arles is a complex territory, fragmented by land use and ownership, and where an intricate web of irrigation and drainage canals reveal water as a key resource that is not exempt from a long history of political contestations.

Facing a rising ecological crisis with repercussions for its population and extended ecosystems, this project contemplates whether Arles could find a catalyst for change in reconsidering its water infrastructures at the territorial scale.

Currently, the city possesses a valuable resource that is misused: purified wastewater is discarded into the polluted Rhône. However, this cleansed water has the potential for addressing some of the most pressing issues the territory is facing: polluting agricultural practices, unbalanced salinity infiltration, and decay in the overall health of Camargue’s ecosystem. In this context, purified water could become a key player in the unspoken political realities of Arles and the Camargue.

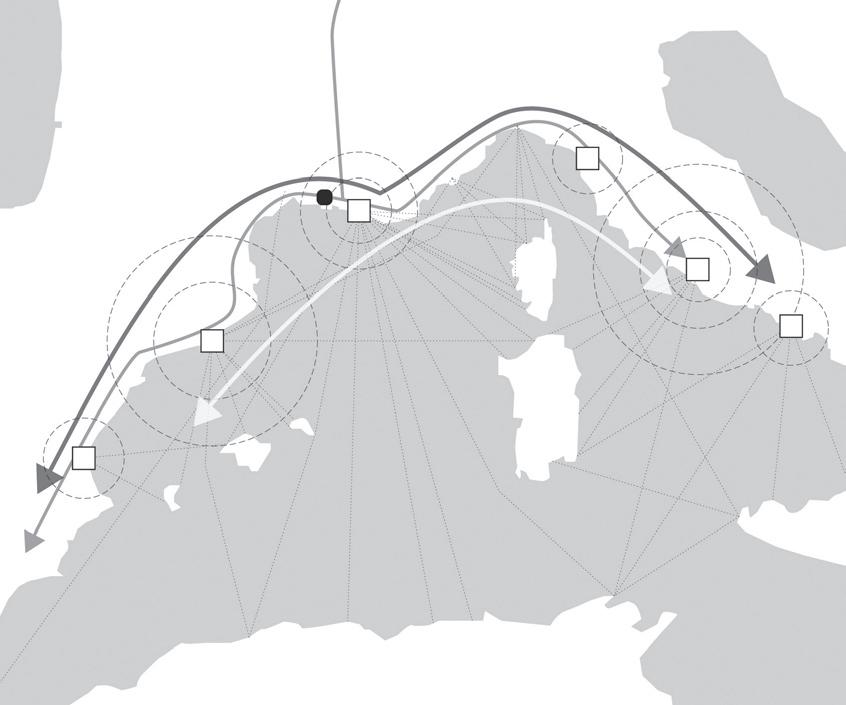

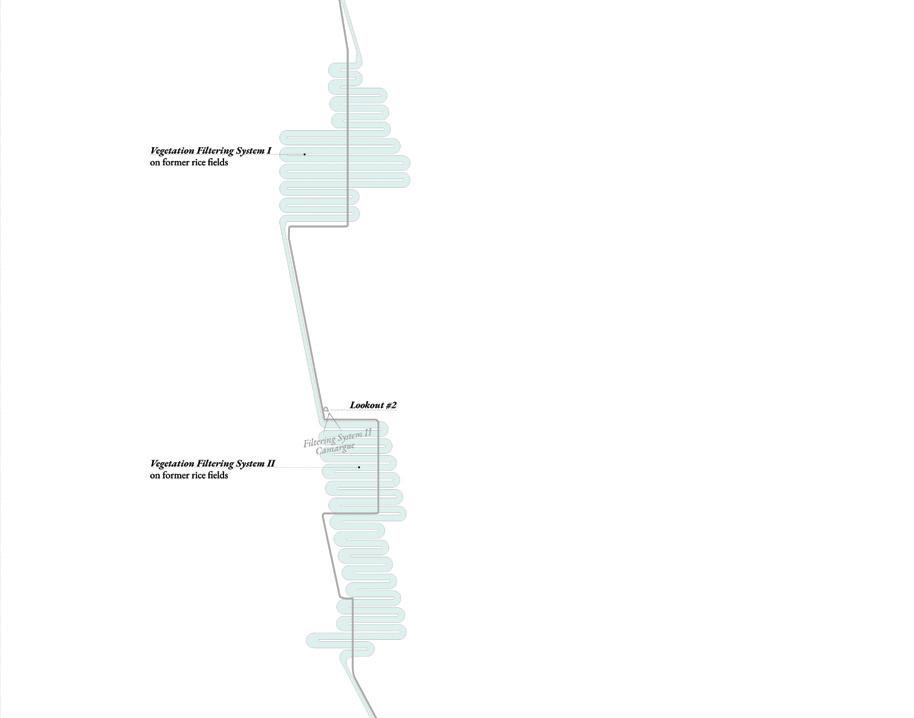

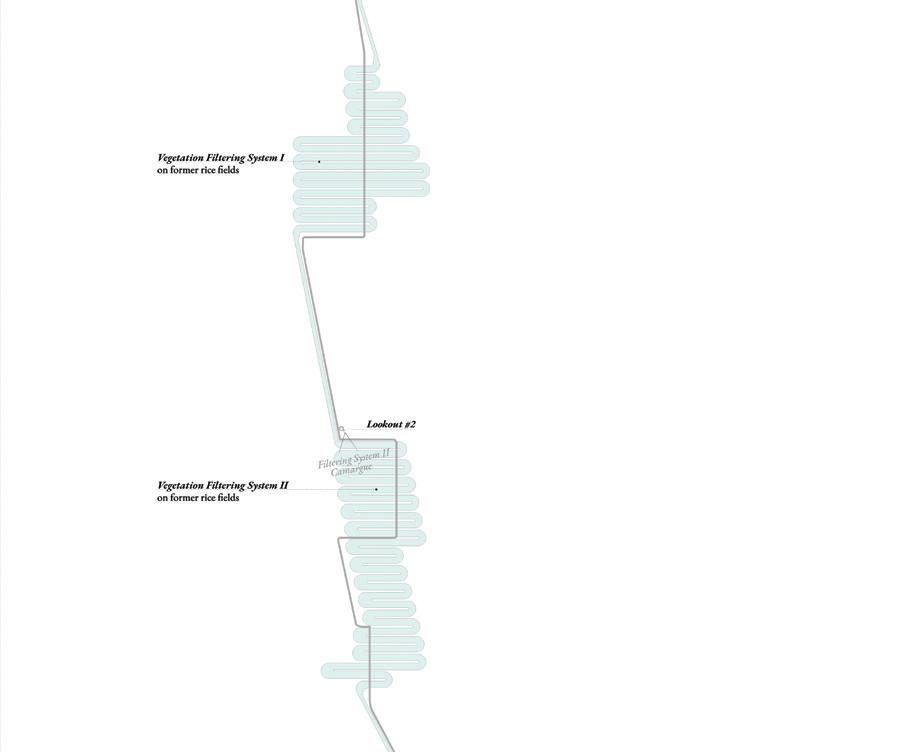

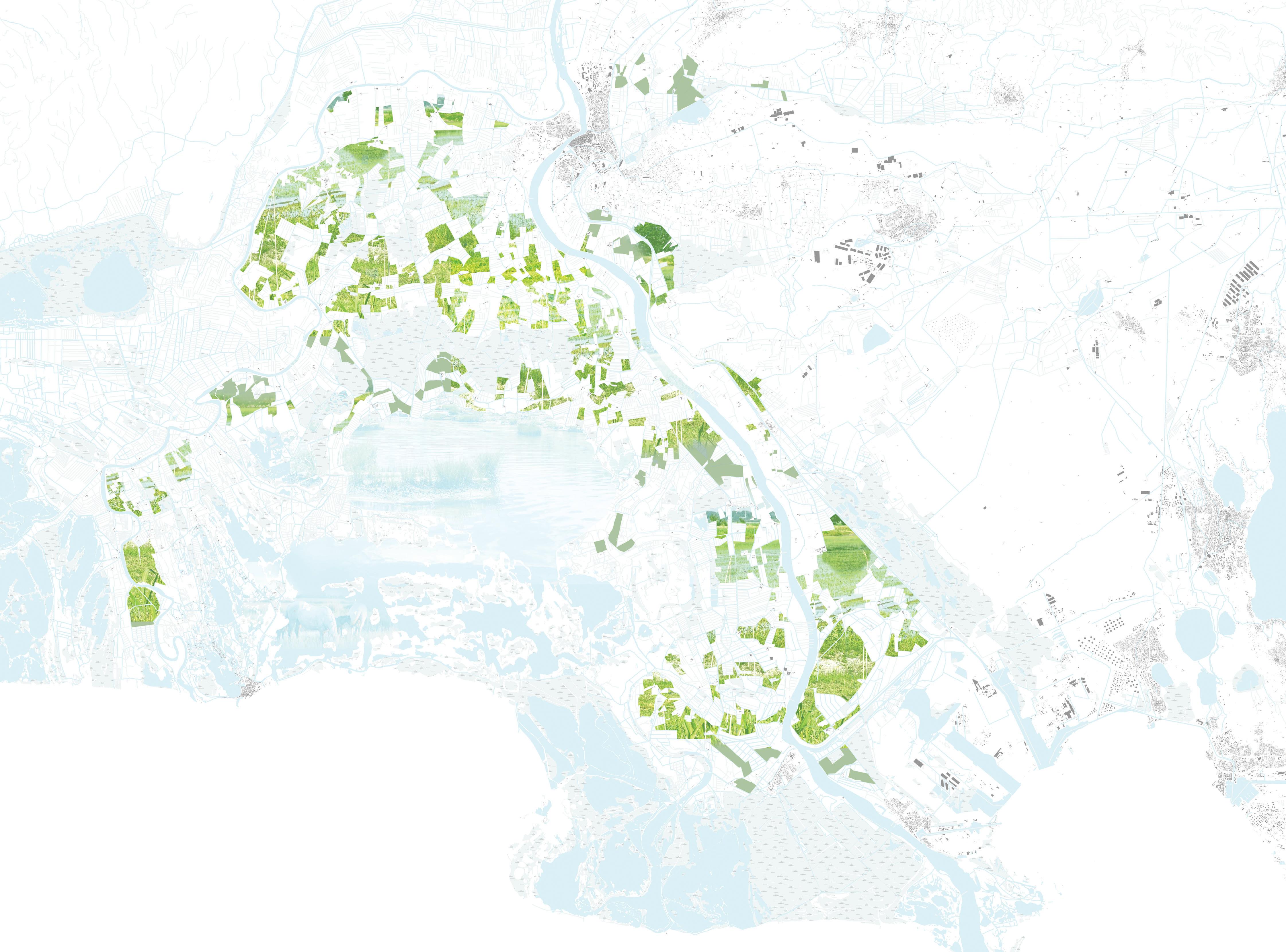

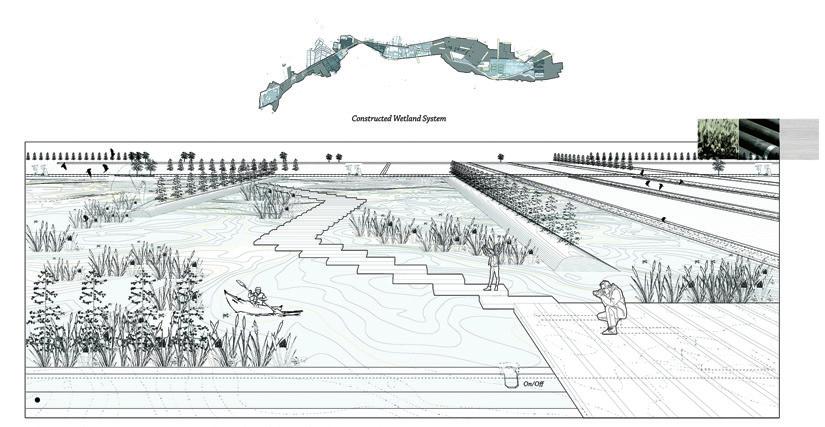

“Productive Fallowscapes” proposes a new infrastructure that will convey cleansed wastewater from the city of Arles to the Camargue through a system of waterways and rice fields repurposed as wetlands, further filtering the water to stage IV (per French standards). The water will be used for agricultural production and to balance the salinity in the delta, in particular high salinity levels at Étang de Vaccarès. The proposed system could initiate a rebalance of water politics from antagonism to collaboration: the City of Arles would offer a valuable resource to the landowners in the Camargue in exchange for their support in sharing current economic burdens.

Andreea Vasile Hoxha

Wastewater filtering system: from Arles to the Camargue. A catalog of the existing wastewater treatment system’s capacity, commissioning, input loads, and focus.

it reenters the hydrological system. In doing so, it will establish a new relationship of collaboration between the

Agricultural lands in the Camargue are highlighted in relation to the water bodies and water infrastructure that enable their productivity.

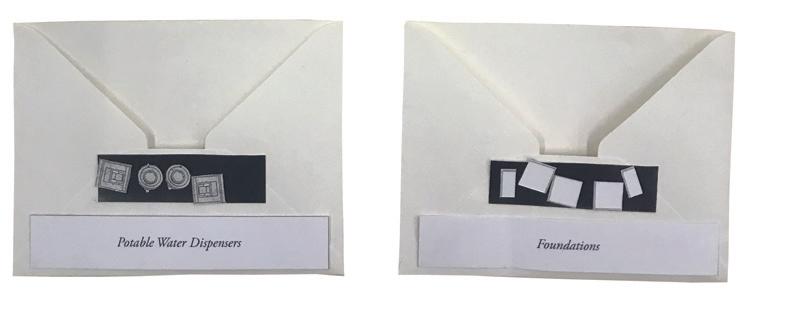

Water systems at the territorial scale, highlighting capacity, significant historical moments in the region’s water infrastructure, and important actors.

How can Arles become a more inclusive city—one that welcomes those who are most exposed to displacement, marginalization, or who are at risk of losing their livelihoods due to environmental change? In this section, fallowscapes appear as sites of ingenuity, innovation, and possible solutions to the challenge of integrating those on the fringe of society.

But the introduction of new categories of urban space requires that an institutional framework for their long-term survival also be created. These can be located in governmental institutions with budget and authority for decision making, NGOs, or private, not-for-profit organizations, who foresee the funding and well-being of those places that serve vulnerable populations. The students have considered governance as a design variable: unless it exists, these projects would not be feasible.

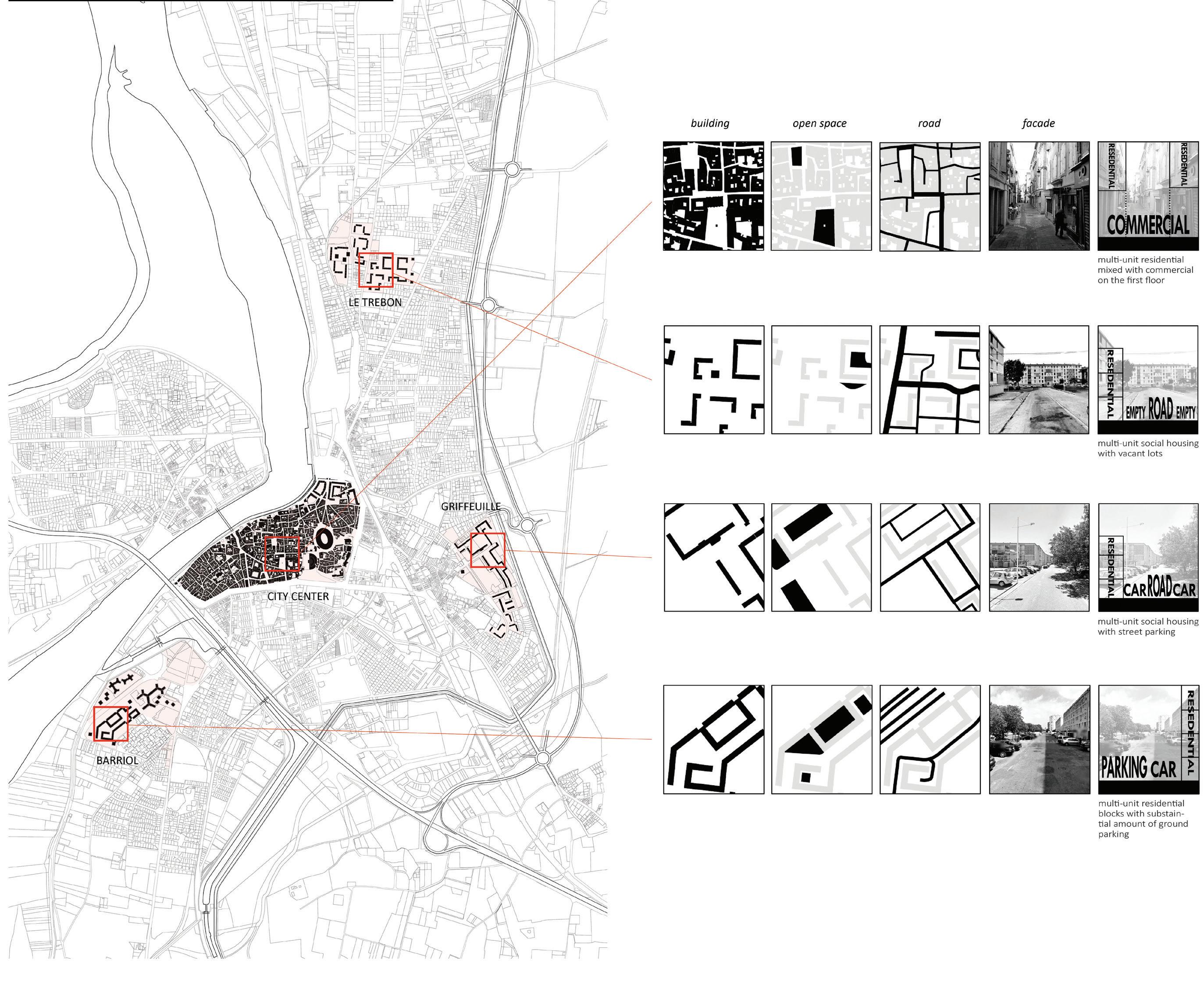

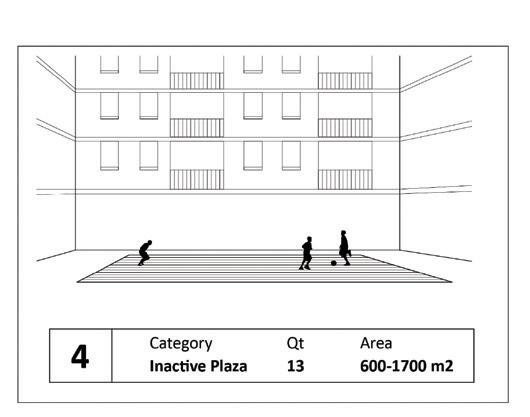

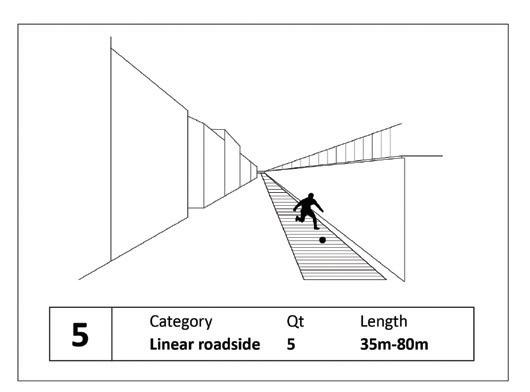

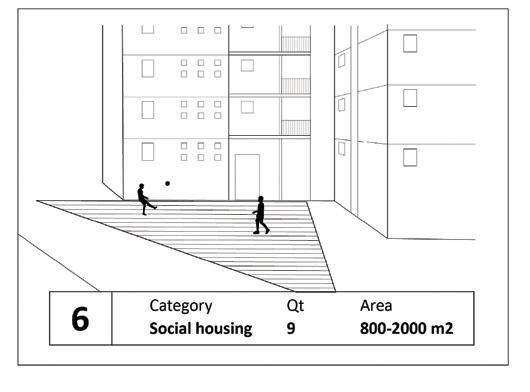

Arles has an immigrant population that lives mostly in neighborhoods built during the mid-20th century around its historic core: Barriol, Griffeuille, and Le Trébon. These social housing projects, with their large parking lots, unwelcoming streets, and nearby highways that separate them from the rest of the city, further marginalize these communities. Inequality is reflected in the social and geographical distribution of groups of people and in the quality of their social landscapes and spaces.

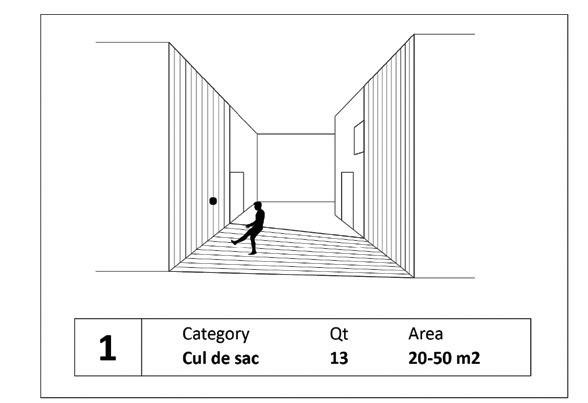

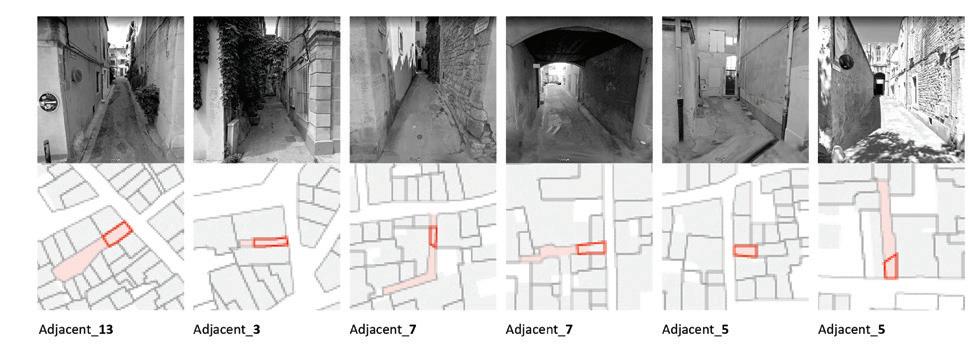

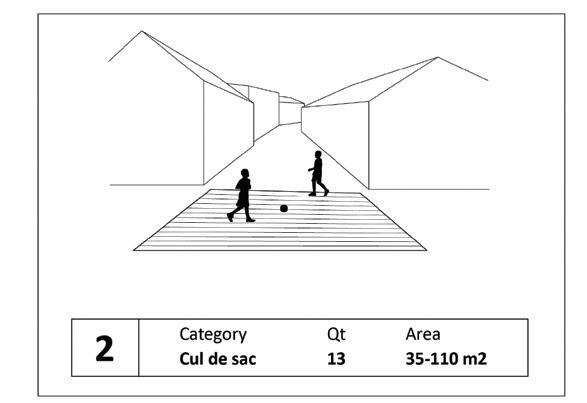

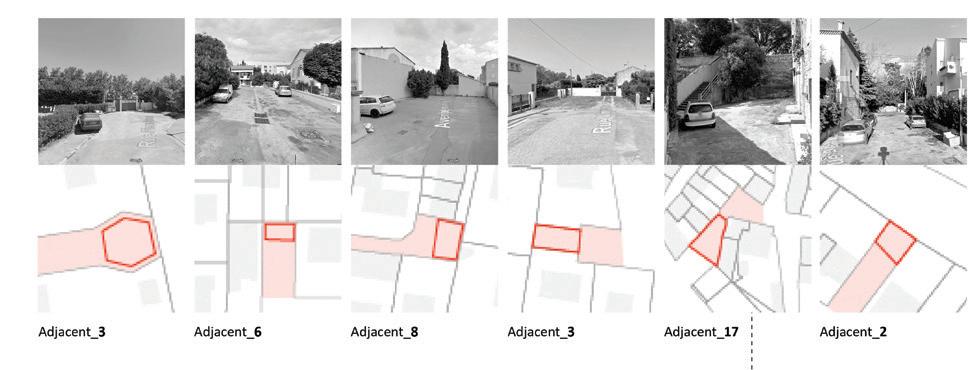

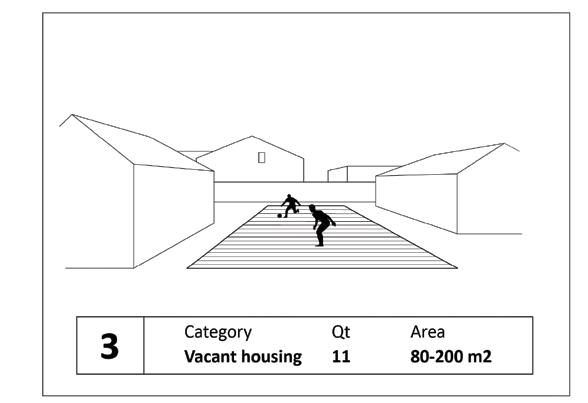

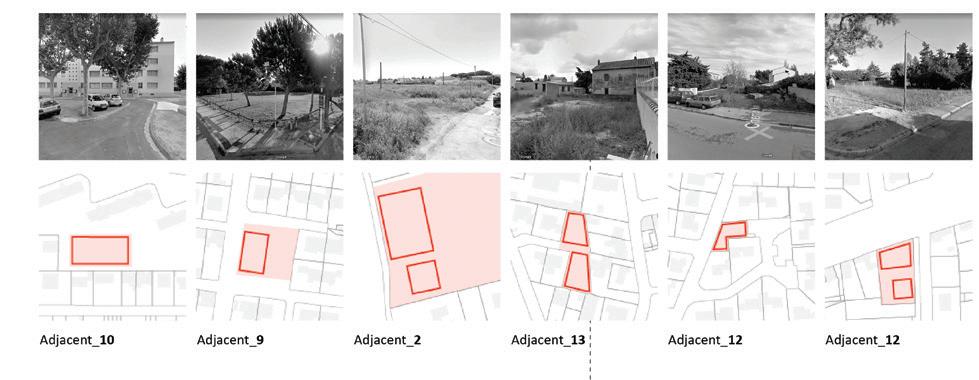

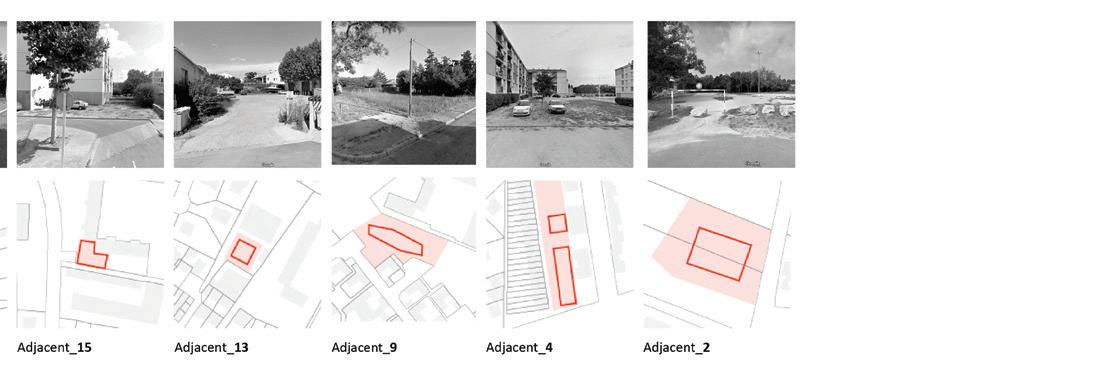

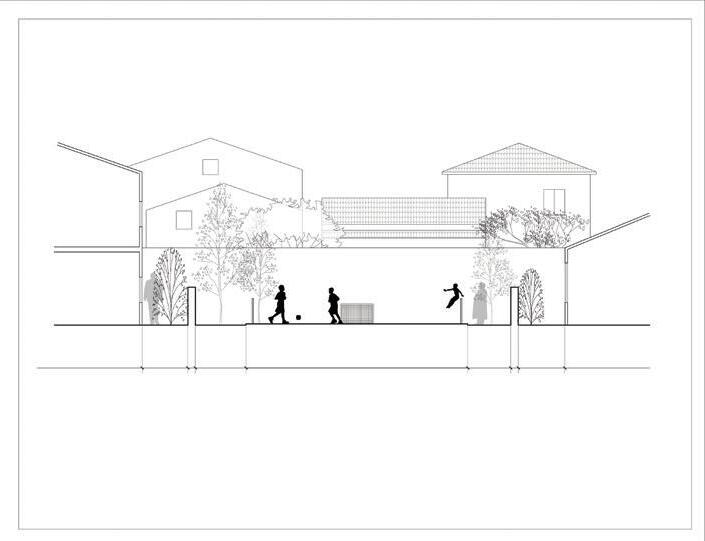

Football is a beloved sport with a long history in Arles, which has its own team: AC Arles-Avignon. However, although Arles is well supplied with regulation-sized playing fields, it does not have any spaces for informal play. Jason Liu’s “Street Arles Initiative: Transforming Arles through Street Football Pitches” explores how a distributed system of spaces can simultaneously revitalize street life in the districts, while at the same time provide opportunities for social life

through play. After a detailed analysis of each street and an inventory of all possible spaces cataloged by size, the pitches were carefully located in fallow lots and underutilized streets. With minimal materials—paint, fencing, lighting—the fallow activates a project of inclusion by celebrating this broad-based interest in the fabric of the neighborhoods. Institutionally, this proposal would be supported by locally organized community associations and endorsed by the city.

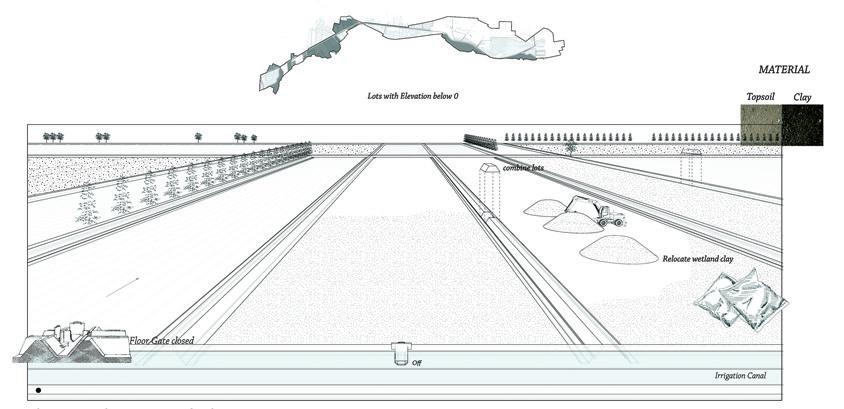

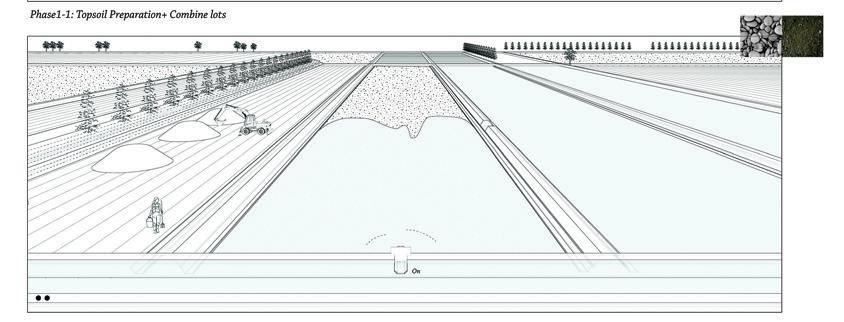

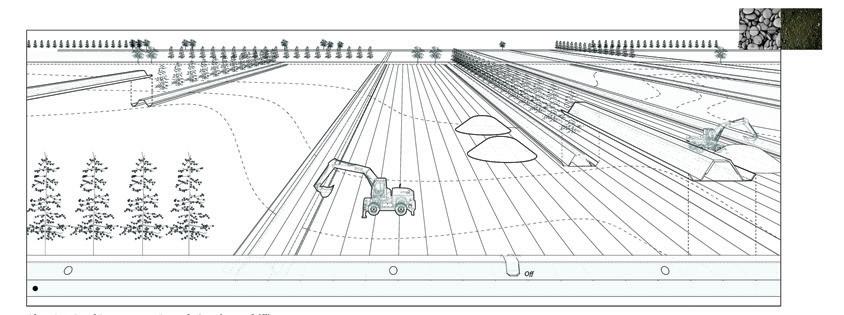

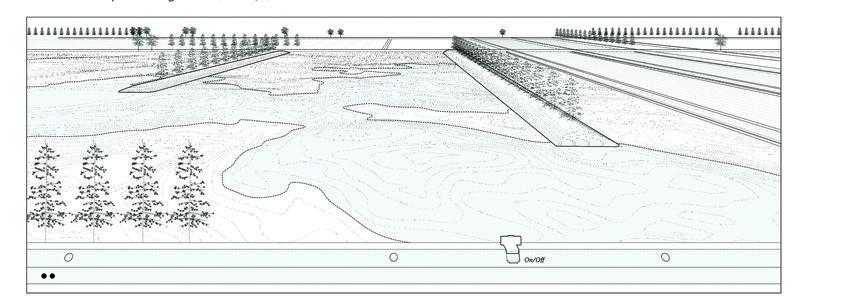

Camila Huber explores the threshold between fallow and productive in the service of accommodating the Romani population that temporarily settles in locations throughout Arles. Sites with wet soils and plenty of vegetation for privacy are usually both fallow and the preferred locations. She proposes a “Department of Fallow” to oversee the lands to be inhabited temporarily by Romani travelers. A system of cultivated lots goes into a fallow state to welcome the Romani. Both the occupied (fallow) and the productive lots are rotated in an orchestrated and dynamic relationship to allow for fluctuations in the numbers and needs of the group.

Finally, although Arles has been much transformed by extensive drainage infrastructure, the agricultural lands adjacent to the Rhône remain at risk of major flooding. The impressive and massive system of continuous dikes along the river’s banks continue to rise, further severing the connection between the city and the river. Shira Grosman proposes an alternative that, when combined with other forms of agriculture and land management, reenvisions the river and its shores as a hybrid landscape of fallow, managed, and agricultural landscapes each with its own socio-temporal scale, a landscape of transition where the forces of nature are invited to coproduce a publicly accessible landscape while protecting the livelihoods of those that live from this land.

Street adjacent to Route de la Mer in Salin-de-Giraud.

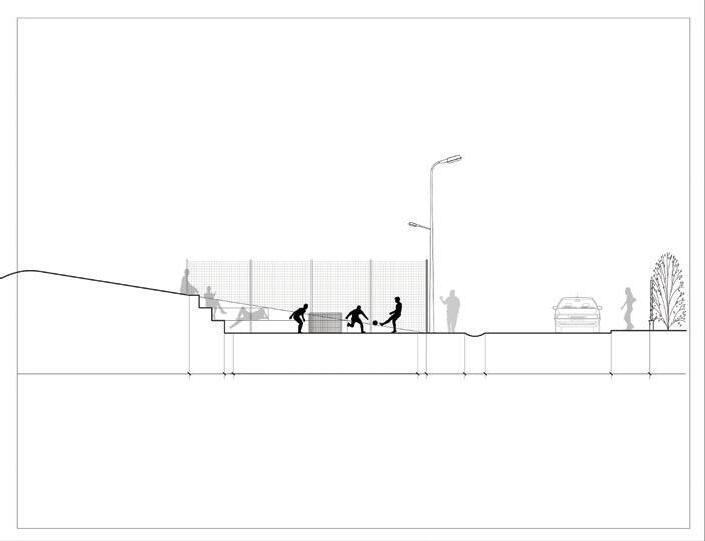

The social housing neighborhoods of Arles— Barriol, Griffeuille, and Le Trébon—were severed from the city center after the construction of the highway and canals, leaving these communities underserved and marginalized. In addition, as is usually the case with the large apartment block and largely car-dependent housing typology, people living in these places face the reality of too little activity on the street, and too many cars all around. The youth in this largely immigrant community are crippled by unemployment without a clear way out of their predicament.

There is no “silver bullet” to this multi-faceted problem, but there is potential in seeking some answers in the dynamic between the French suburb (the banlieue) and football, specifically the role of street-play. But the ambition has to be tailored to fit in Arles’s ground conditions: extremely limited public space in the tourism-intensive historic core, on one hand, while there is an enormous amount of underutilized land concentrated in the outlying neighborhoods where few would visit, on the other.

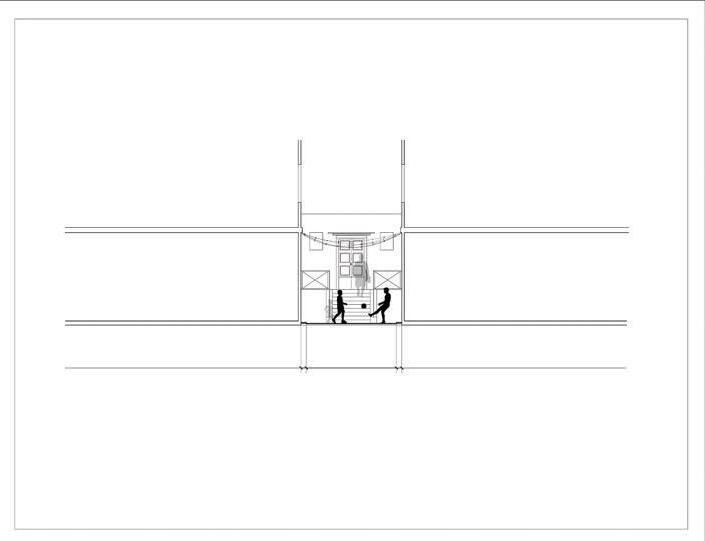

This project scavenges those undesired and underutilized pieces of land—empty lots, dead ends, low traffic streets—and transforms them into street football pitches, thereby promoting a beloved sport as a strategy for social intervention. The unique form of street football is intended to encourage creativity and self-expression. Formed by minor design interventions such as paint and lighting, the street pitches address the dilemma between total land inactivity in long-term land uses (e.g., parking lots) while leaving possibilities open for future, yet unknown transformations in the city.

This proposal also envisions an annual city-wide street football tournament that aims to unite the different communities in Arles while

Jason Liu

breaking down social/cultural barriers through the shared passion for sports. However, the true spirit of the proposal is to reclaim the role of the street in everyday life, as a social space that supports the advancement of citizens, bustling with activities of integration and exchange that are currently being negated by vehicle-dominated roads and gigantic parking lots.

Camila Huber

The presence of the nomadic Romani population in the South of France provides an opportunity to question the definition of fallow land, as these communities tend to settle for varying periods of time in sites considered abandoned.

Romani groups seek to inhabit sites that fulfill their desire to be hidden, but that are at the same time close to road infrastructure. Although the particular characteristics of each occupied site may differ, in general they share the following conditions: empty lots in the periphery without close neighbors, with little or no services such as water or sewer and no paved roads, and with mature vegetation that protects their privacy. Such features qualify spaces as ideal for the Romani to settle and, at the same time, define a state of fallow land to most city authorities.

According to the European Social Charter, cities are obligated to provide stopping sites for the Romani and improve those in current use with access to basic services such as water, electricity, and sewer. Nonetheless, throughout the years, the French government has chosen, instead, to develop housing projects to accommodate the Romani population. Such solution, generally, goes against the nomadic culture of these communities, as they receive housing with the expectation of permanent residency.

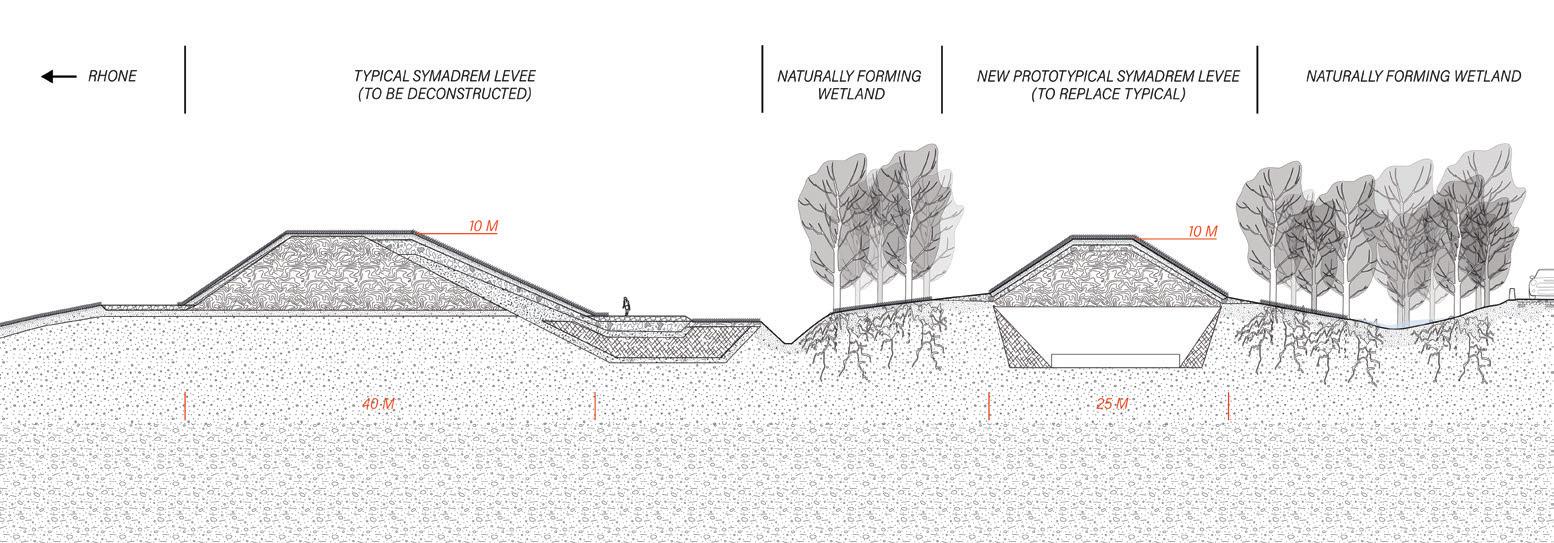

In order to better accommodate the cultural practices of the Romani community, I propose the establishment of a “Department of Fallow Land” in the city of Arles. This municipal agency will be in charge of orchestrating the cyclical programming of pre-selected fallow lands, for periods of ten years, to accommodate temporary uses in these sites. The commissioned land serves the purpose of distributing services outside the center of the city, making it more accessible to the population that lives on the periphery.

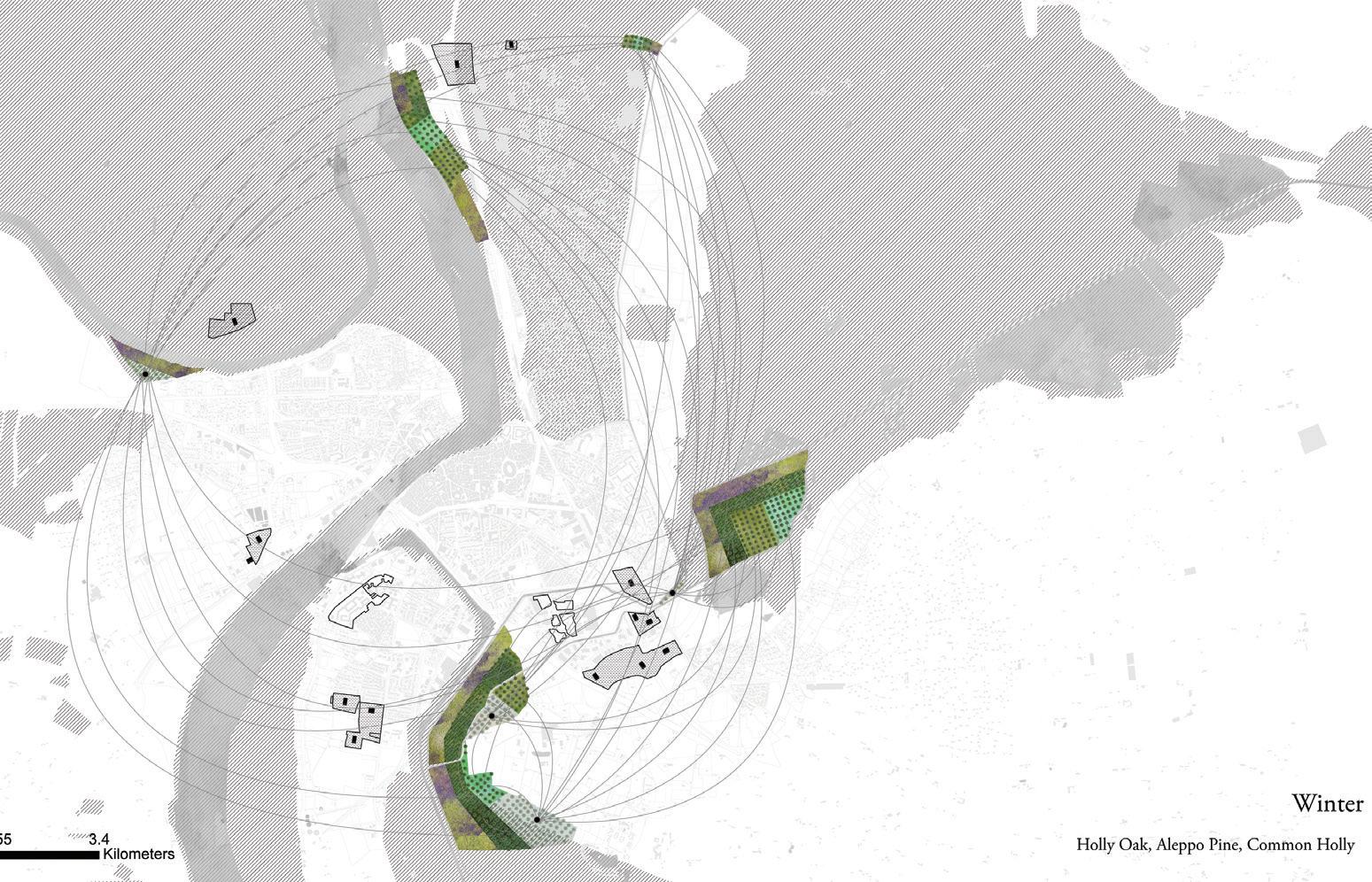

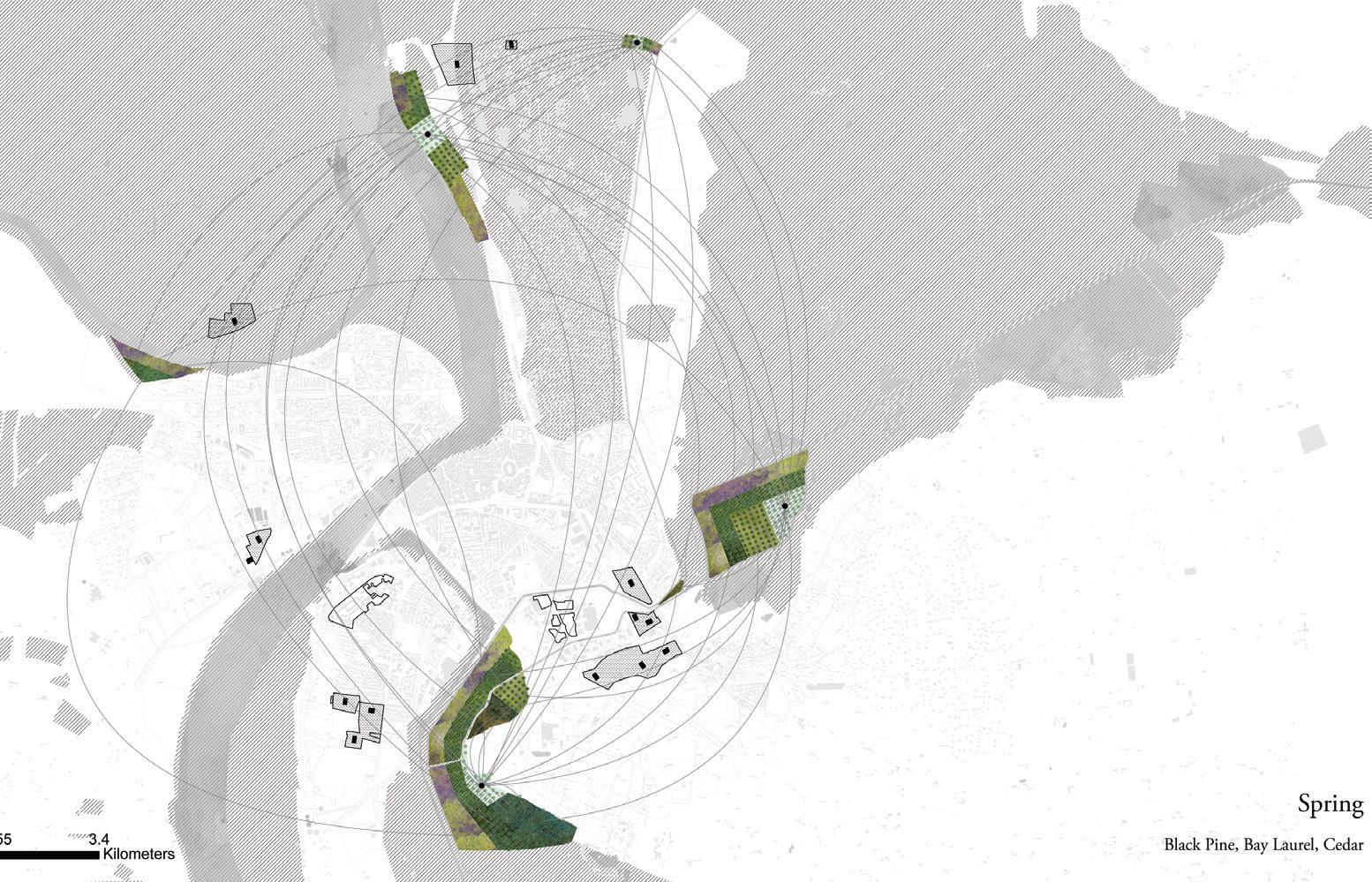

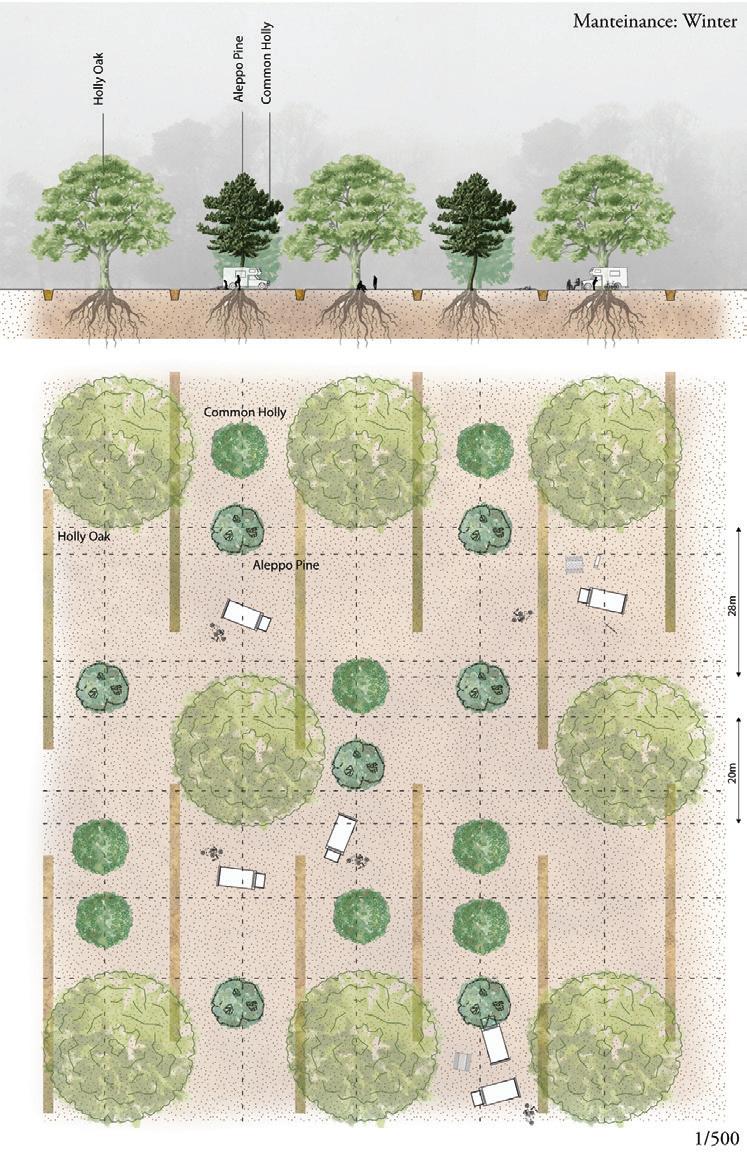

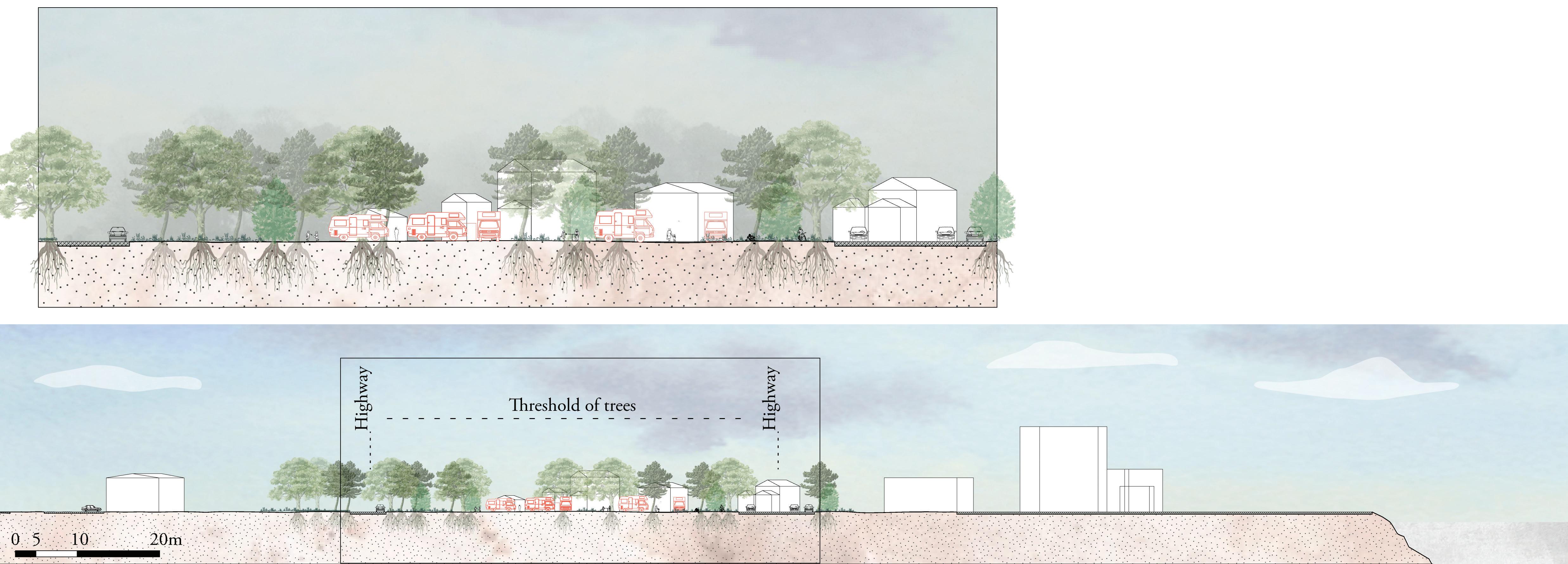

In this proposal, the programmatic needs of the Romani have been paired with a system of urban forestry that also requires management and rotation. The forested sites will shelter the Romani, providing enclosed and camouflaged environments appreciated by them. In turn, the required maintenance and management regimes of the forest will support the community’s nomadic culture: When the trees need to be pruned or harvested, the Romani will relocate to another site as they tend to have very little interaction with strangers outside their community. The department values and recognizes the preferred environment of the Romani population and creates an economy that ensures the presence of fallow land in the city and benefits Arles in its totality, generating revenue from wood products and expanding the availability of green spaces for the city.

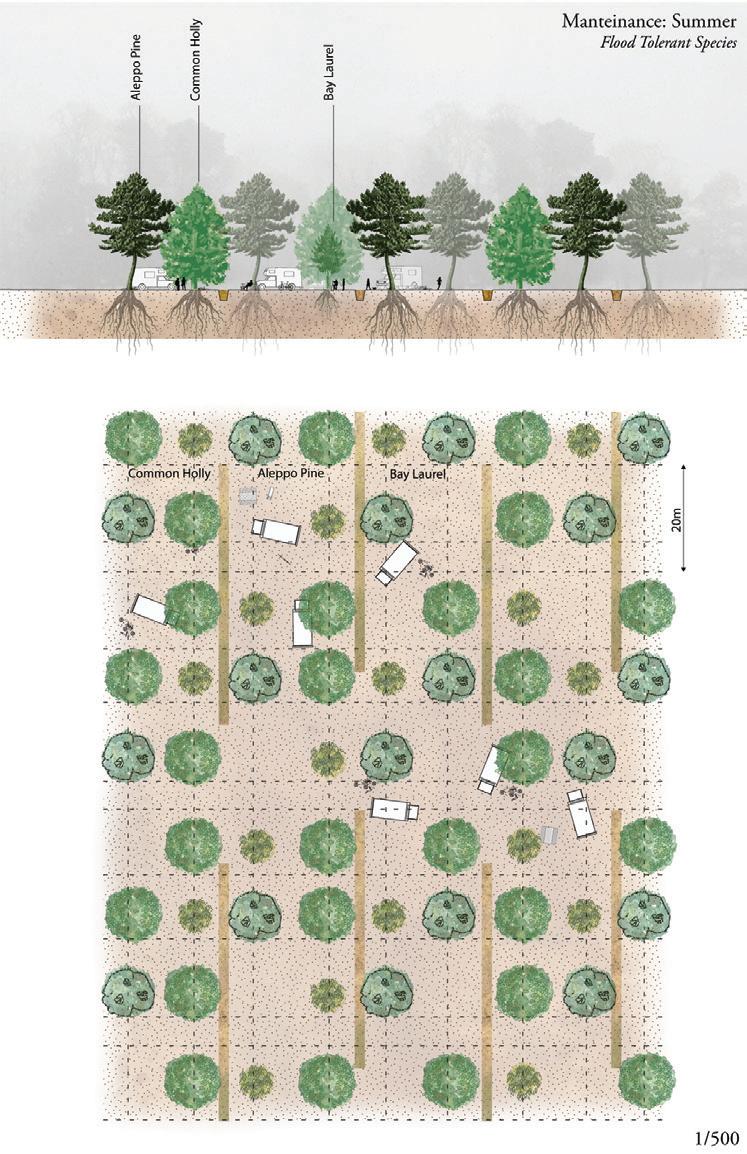

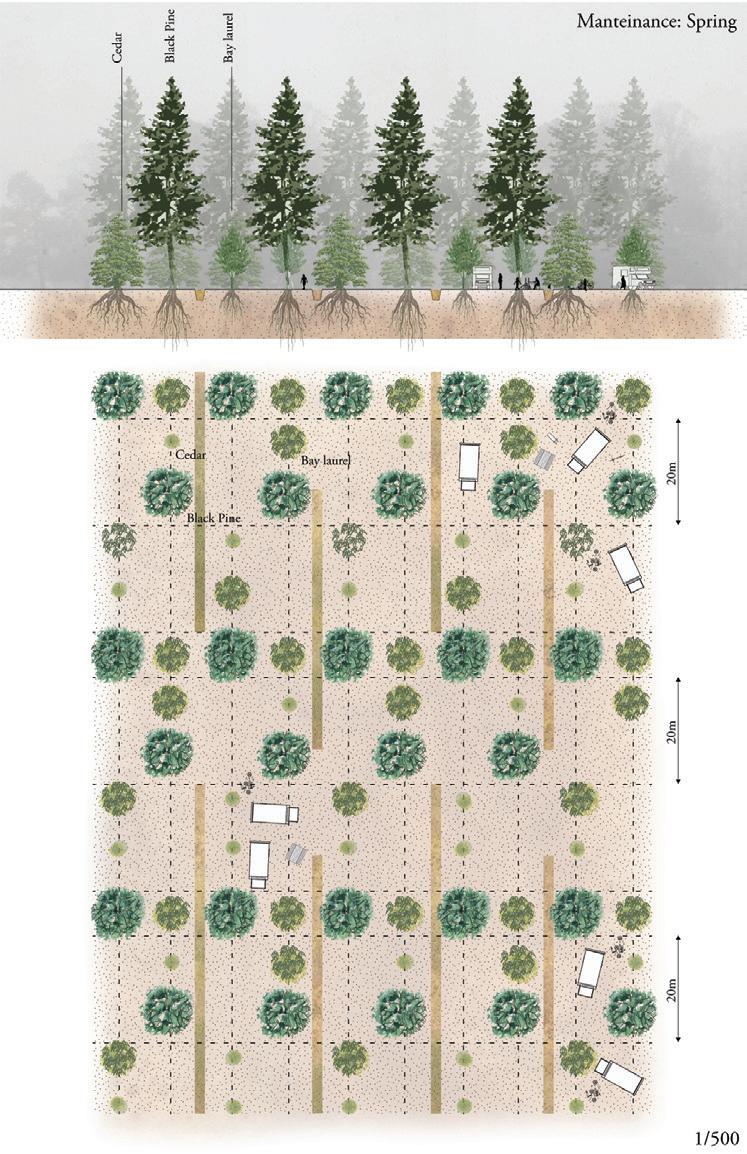

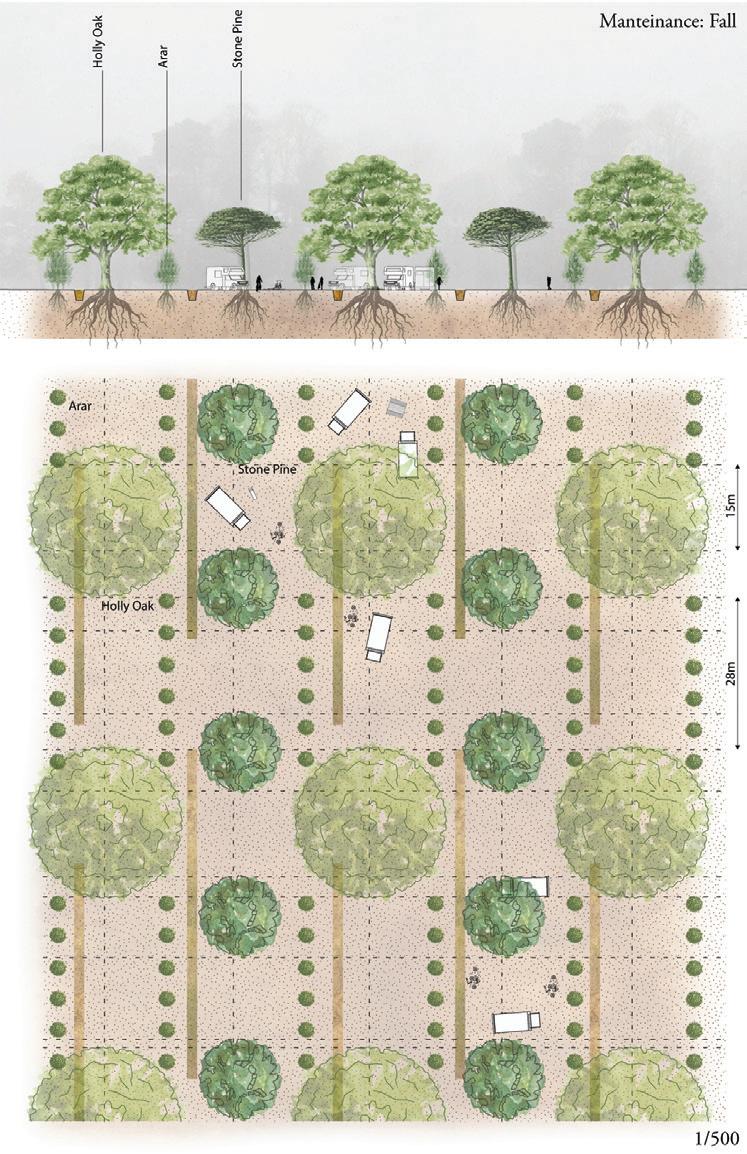

Forestry species rotation is seen in its seasonal variation. The trees create different spaces for gathering and recreation in different seasons.

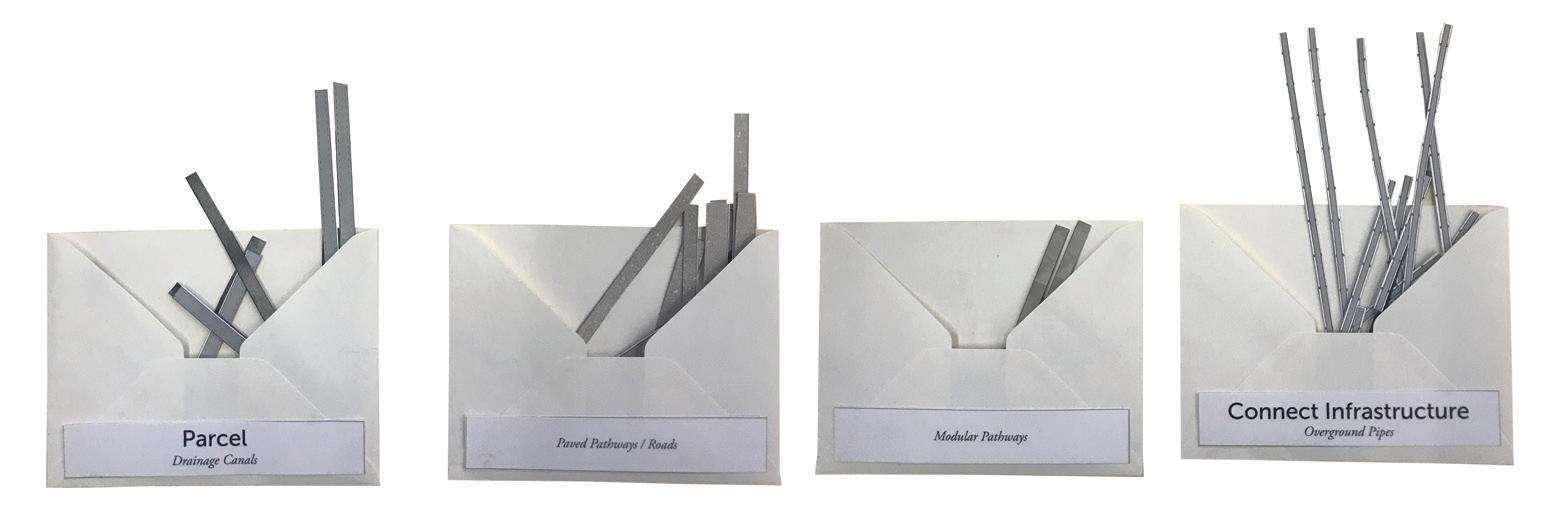

The envelopes contain a toolkit for the Department of Fallow Land, a fictionalized overseeing body for fallow land in Arles. Toolkit parts include cedar, black pine, holly, oak, and bay laurel, and are applied to the unoccupied site, illustrating one of many possible configurations.

The envelopes contain more elements of the toolkit for the “Department of Fallow Land,” including drainage canals, overground pipes, vegetation, and foundations, among others. The toolkit is applied to a small part of one of the sites.

Shira Grosman

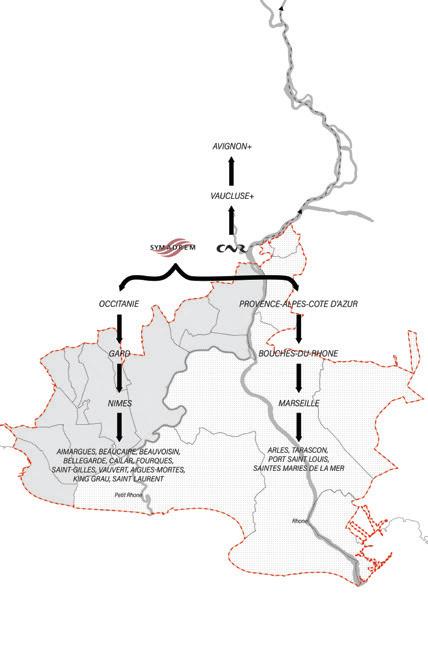

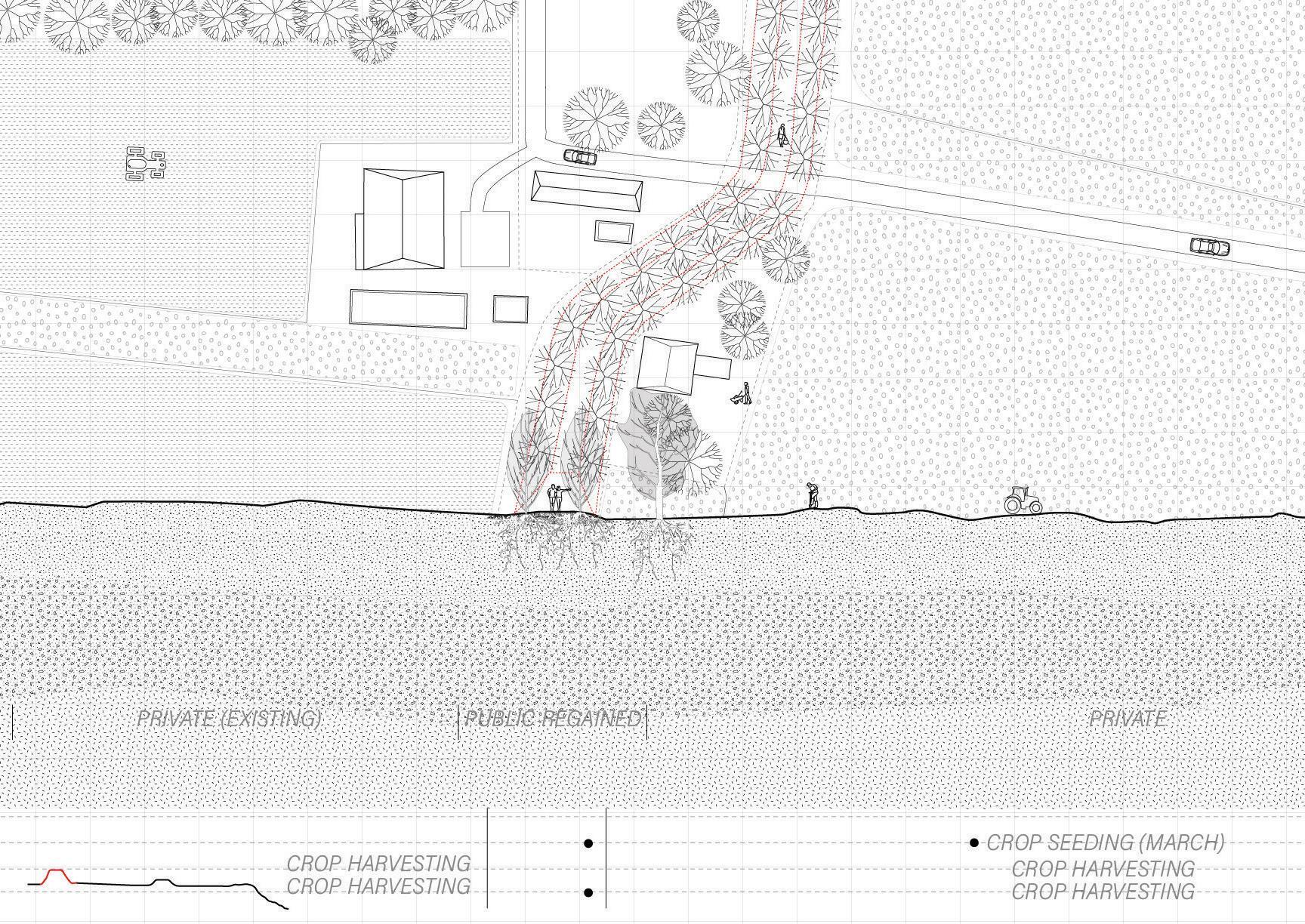

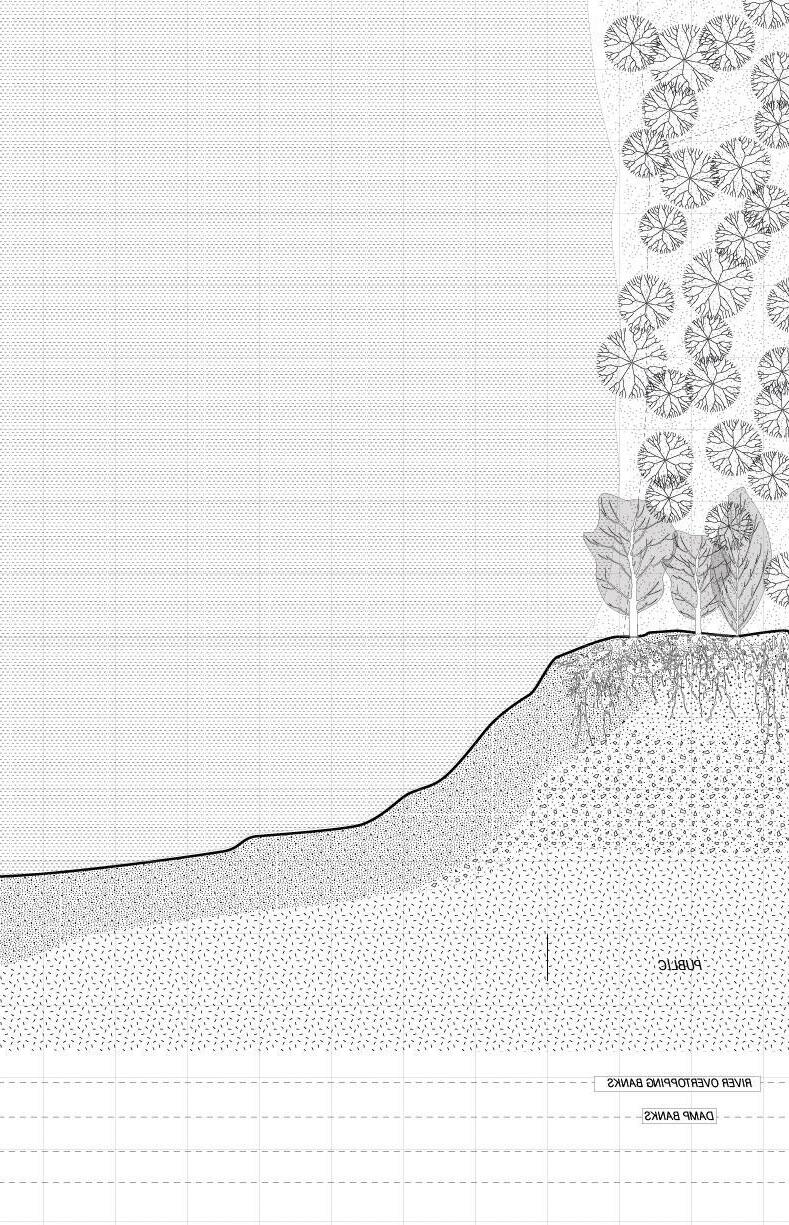

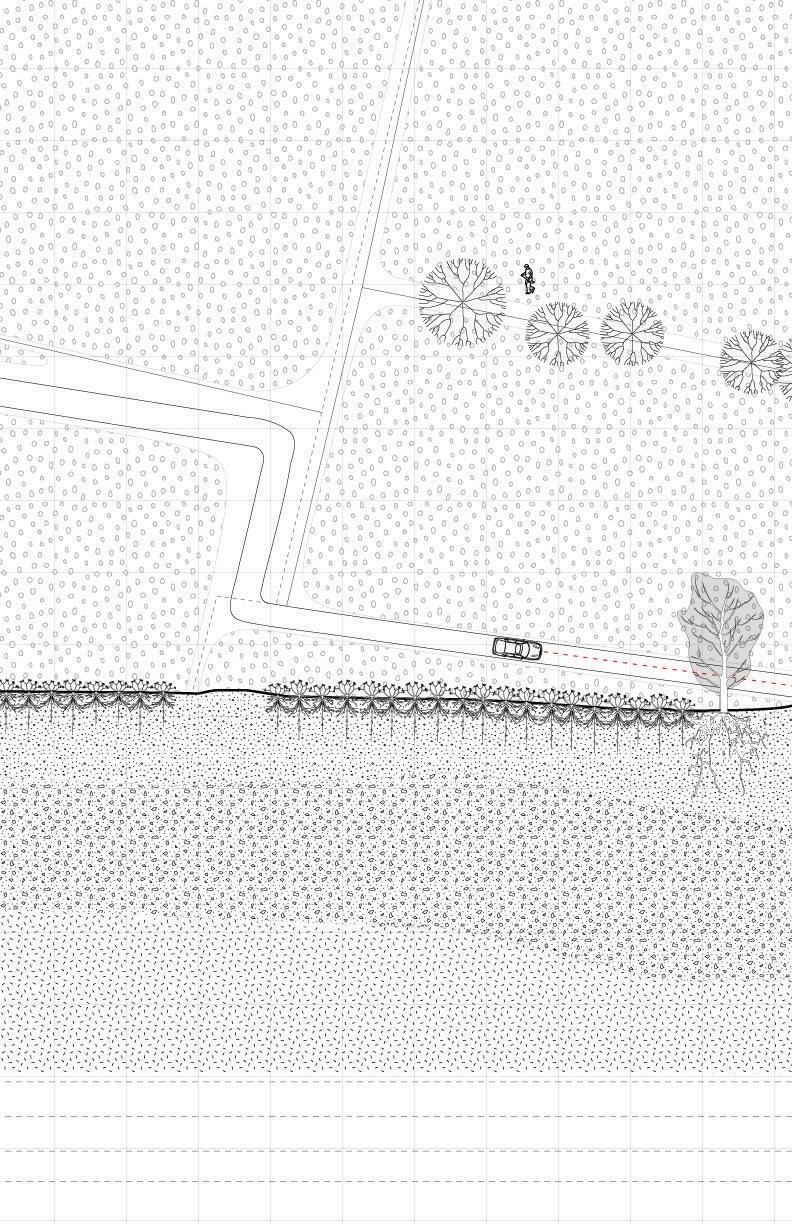

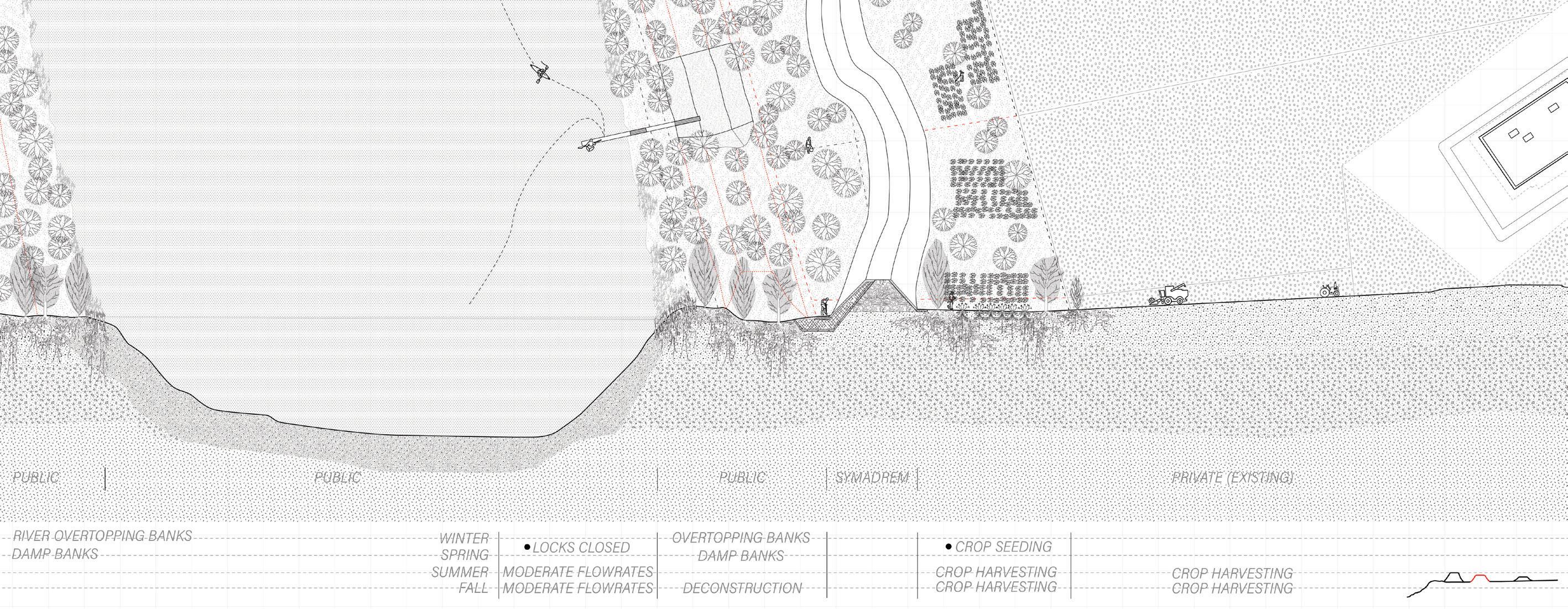

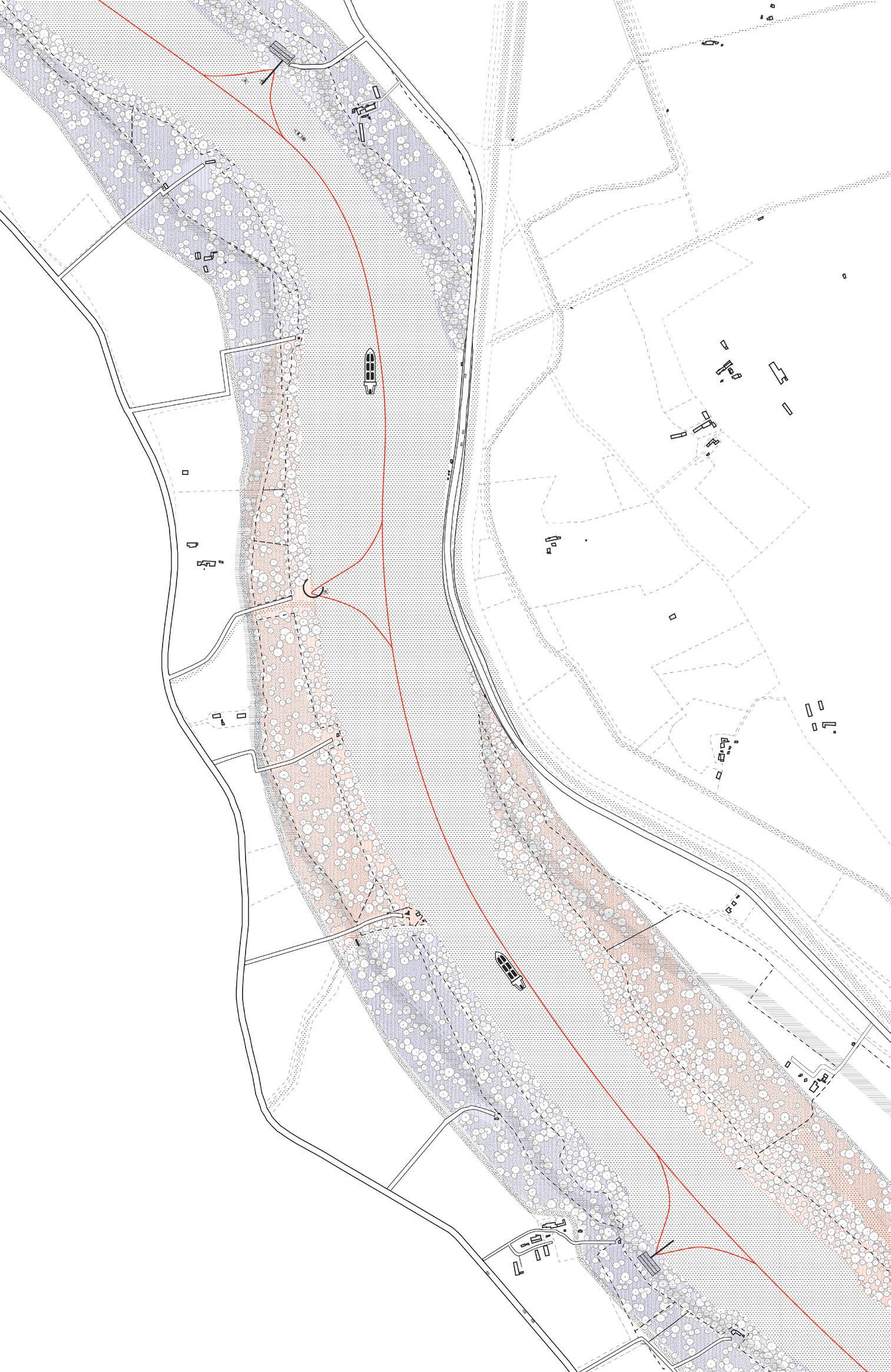

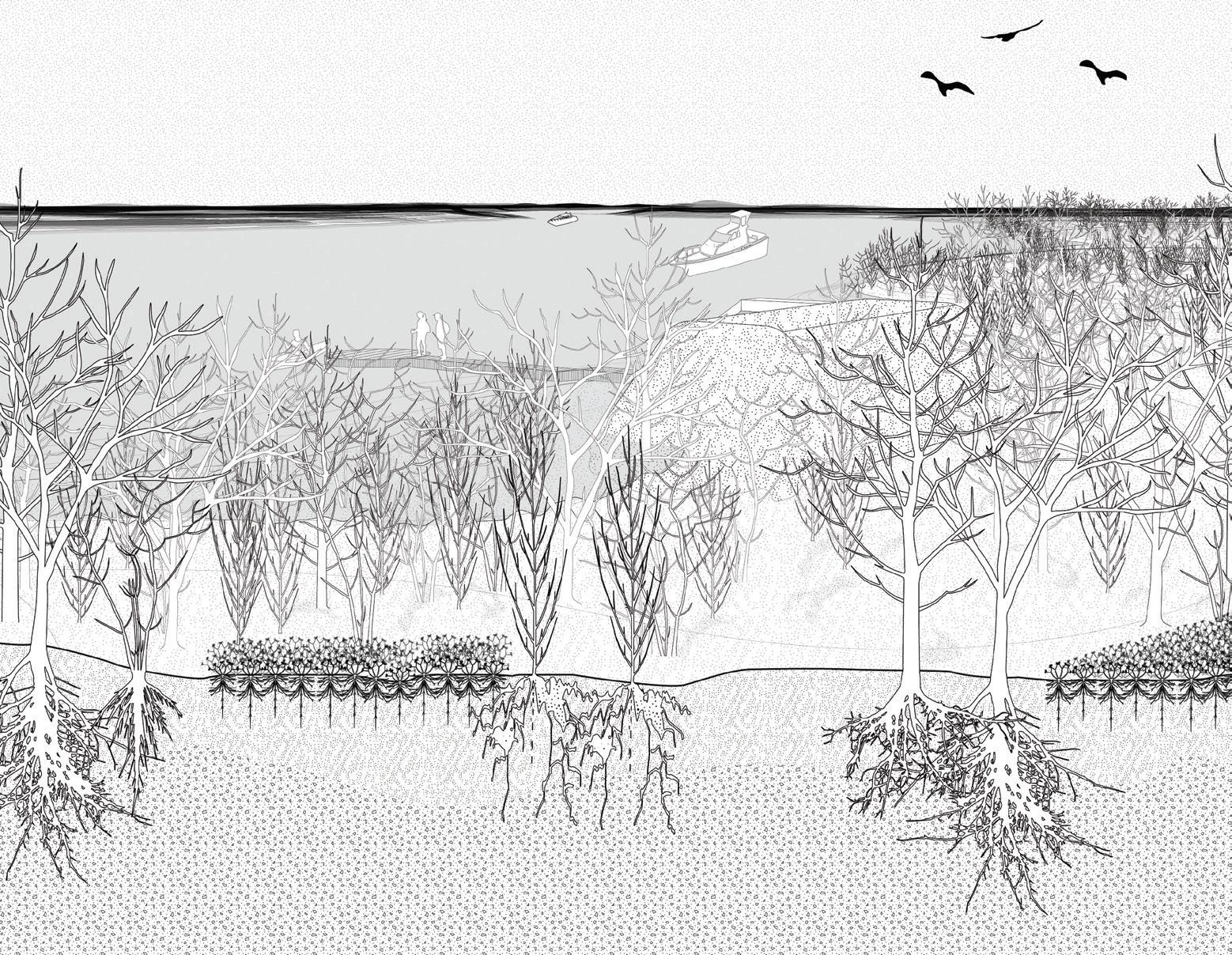

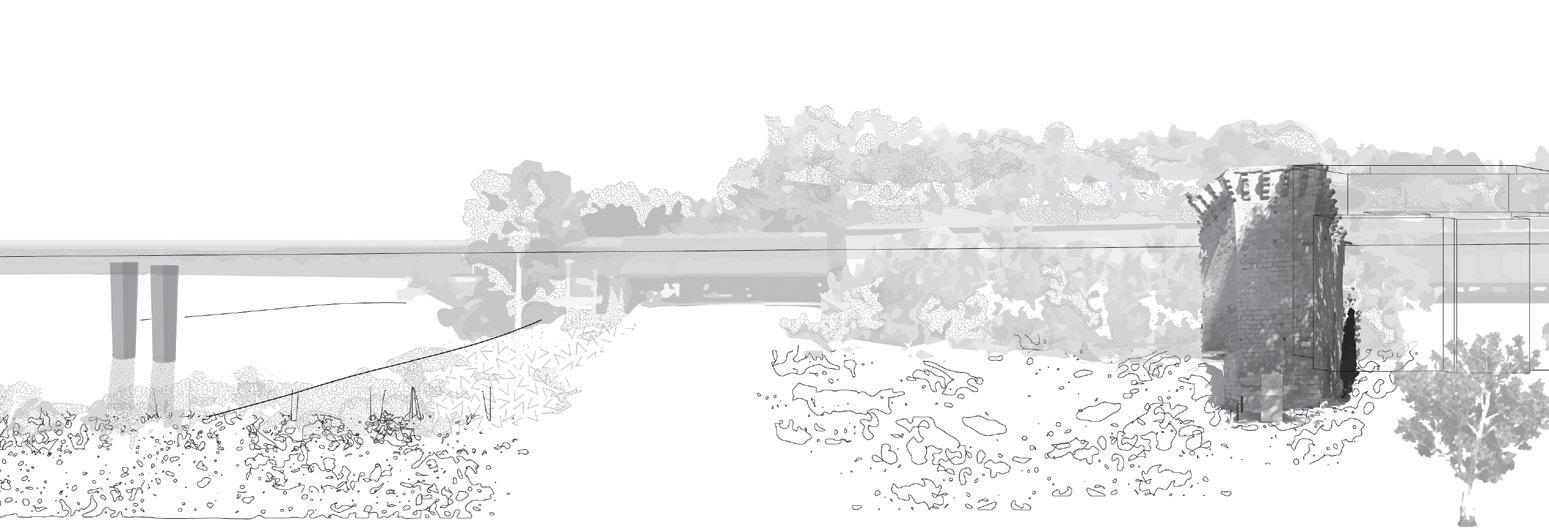

This project reimagines the banks of the Rhône, which are currently inaccessible due to both private land ownership and extreme flood protection measures in the form of large dikes. New projections of sea level rise increase the risk of floods, perpetuating a cycle whereby SYMADREM (an abbreviation for Syndicat Mixte Interrégional d’Aménagement des Digues du Delta du Rhône et de la Mer—an organization responsible for the management of the southern portion of the Rhône, including flood prevention) reconstructs taller dikes each time a new projection for greater floods is confirmed. This project explores alternatives to the service SYMADREM provides the region as the gatekeepers of the Rhône, through embedding processes of agriculture and multiple ownership into the methodology of flood protection.

The proposed deconstruction of the hard line of dikes along the Rhône, is informed by existing private property ownership along the banks and agricultural production. Through a process of sequential repositioning of the dike away from the bank, the river edge is expanded, and a wetland is formed and forested around a new, smaller berm. Coproduction appears through two processes in this newly thickened bank: the new low berm is embedded within the wetland to serve as flood protection, stabilizing the soil along the bank and preventing an expanded flood zone. Agricultural plots are knitted within the forested zone to support the wetland system and allow farm owners to maintain agricultural production in a new way.

This thickened bank incorporates landowners as agents with SYMADREM in the flood protection system. The transition inland of dike to berm includes a shift of the property line, limiting the edge of agriculture production and creating a publicly accessible band along the riv-

er’s edge. These new public embankments allow for both river and inland access, connecting specific points along the Rhône through a series of docks, providing a riverine route running south of the Écluse de Vallabrègues dam from Beaucaire to Salin-de-Giraud.

The processes of constructing the expanded bank occur in phases, shifting portions of the dike in tandem with the construction of a forested wetland. As these phases are completed, new bands of public space become accessible through the construction of landing sites. This thickened edge creates a new figure for the Rhône, and greatly expands river access to the public.

N.B.: Much has changed with SYMADREM’s organizational structure and dike upgrading work since this project was completed in December 2019.

Top: The riverbanks of the Rhône are diked through a variety of structures, and the land adjacent zoned according to its risk due to floods, dike breaches, and sea level rise. This system is managed by a complex organizational structure including SYMADREM and CNR.

Bottom: Typical section of SYMADREM’s newest flood protection system, which is slowly being implemented along the Rhône in Arles.

These composites show the multiphase transformation of two conditions along the Rhône. The first phase of construction involves lowering the dike, establishing a wetland forest, and protecting agriculture. This construction is in tandem with a conversion of the Rhône bank to public property.

The

of

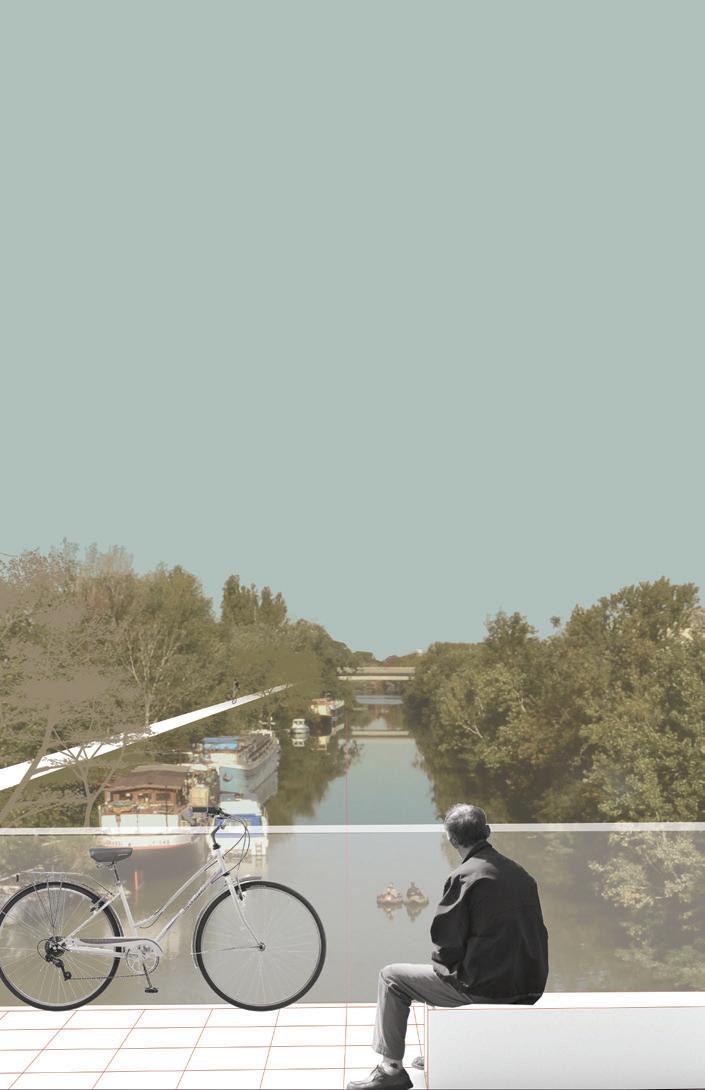

In a segment of the Rhône south of the Arles city center, the riverbanks are shown in their fully developed state. The docks are accessible from the roadways and the river, encouraging an afternoon spent meandering down the river.

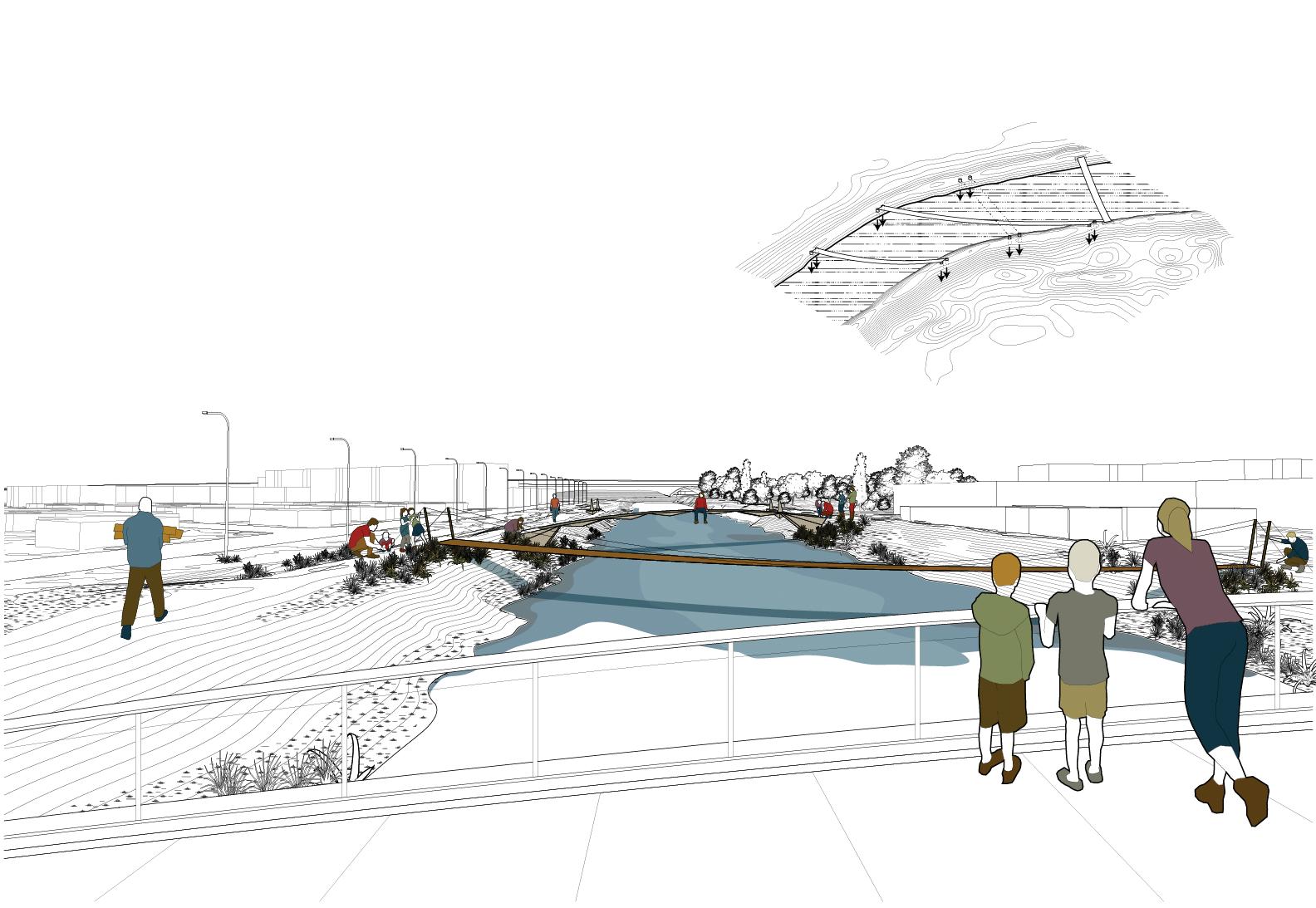

The projects in this chapter invite us to reconsider the deep temporality embedded in fallow networks at the urban and regional scales. An abandoned railway, a defunct wetland, and an inactive water supply system reveal histories of large-scale interventions on the land, yet today they are largely invisible. What is remarkable about these projects is not only that they give a new use to a fallow infrastructure, but how they work to reconnect the city to its territory, making new sense out of dormant and isolated fragments. Reframing and reconstituting these networks in contemporary terms addresses current needs for recreational space, gives recognition to the lesser-known histories and identities of the city and the commune, and values their potential to provide ecosystem services. Each project brings them to the surface in different degrees, allowing a dimension of their fallow condition to stay alive.

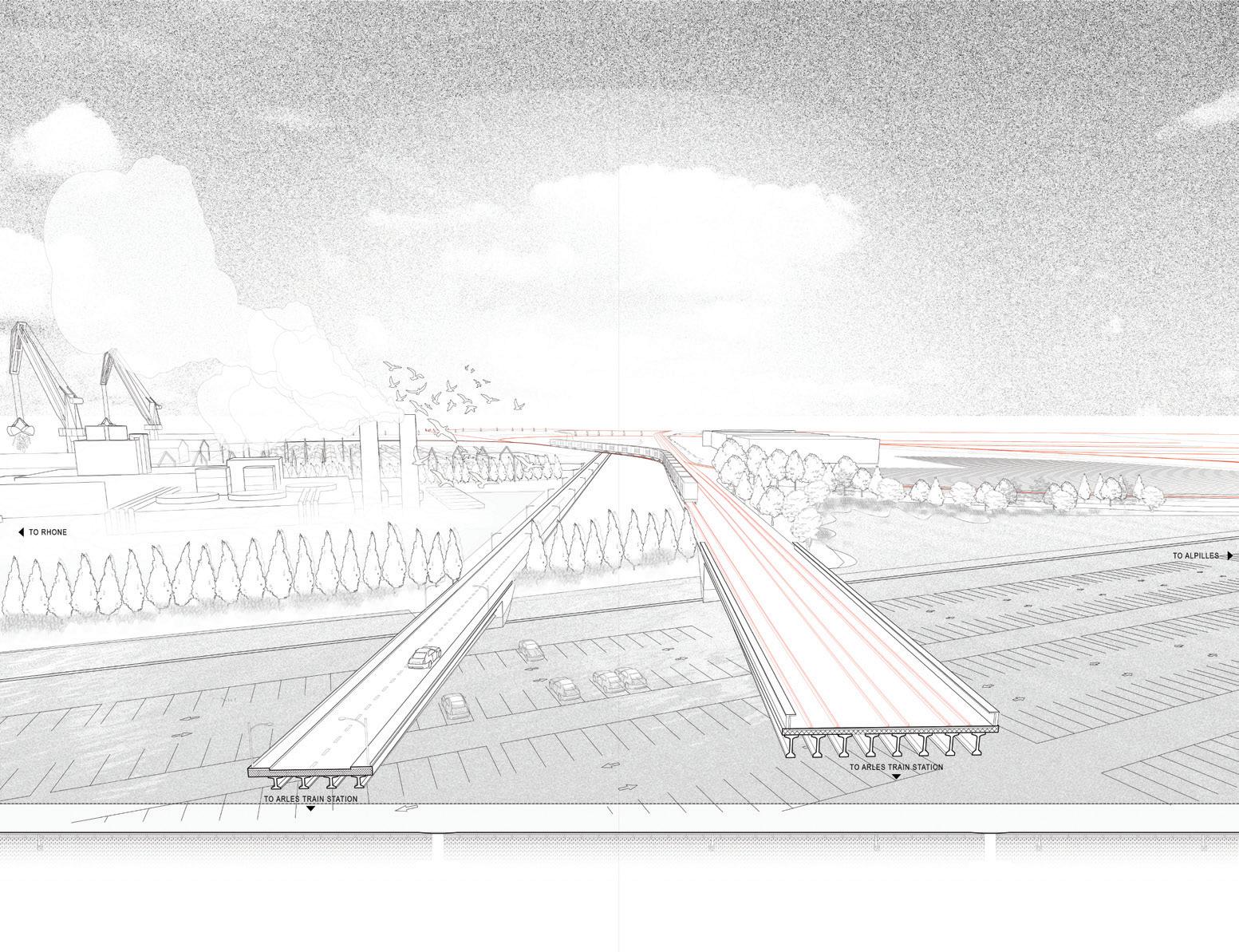

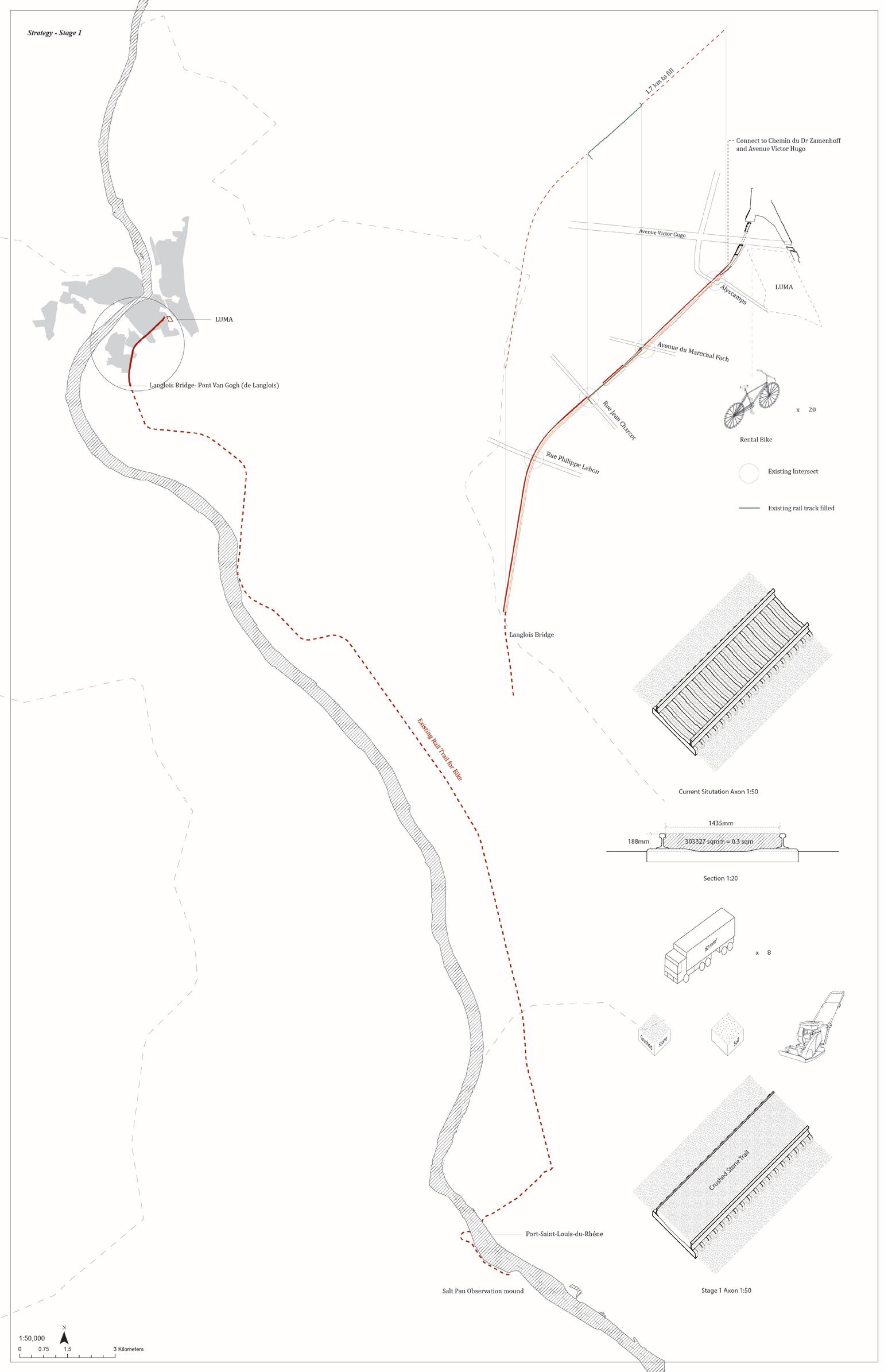

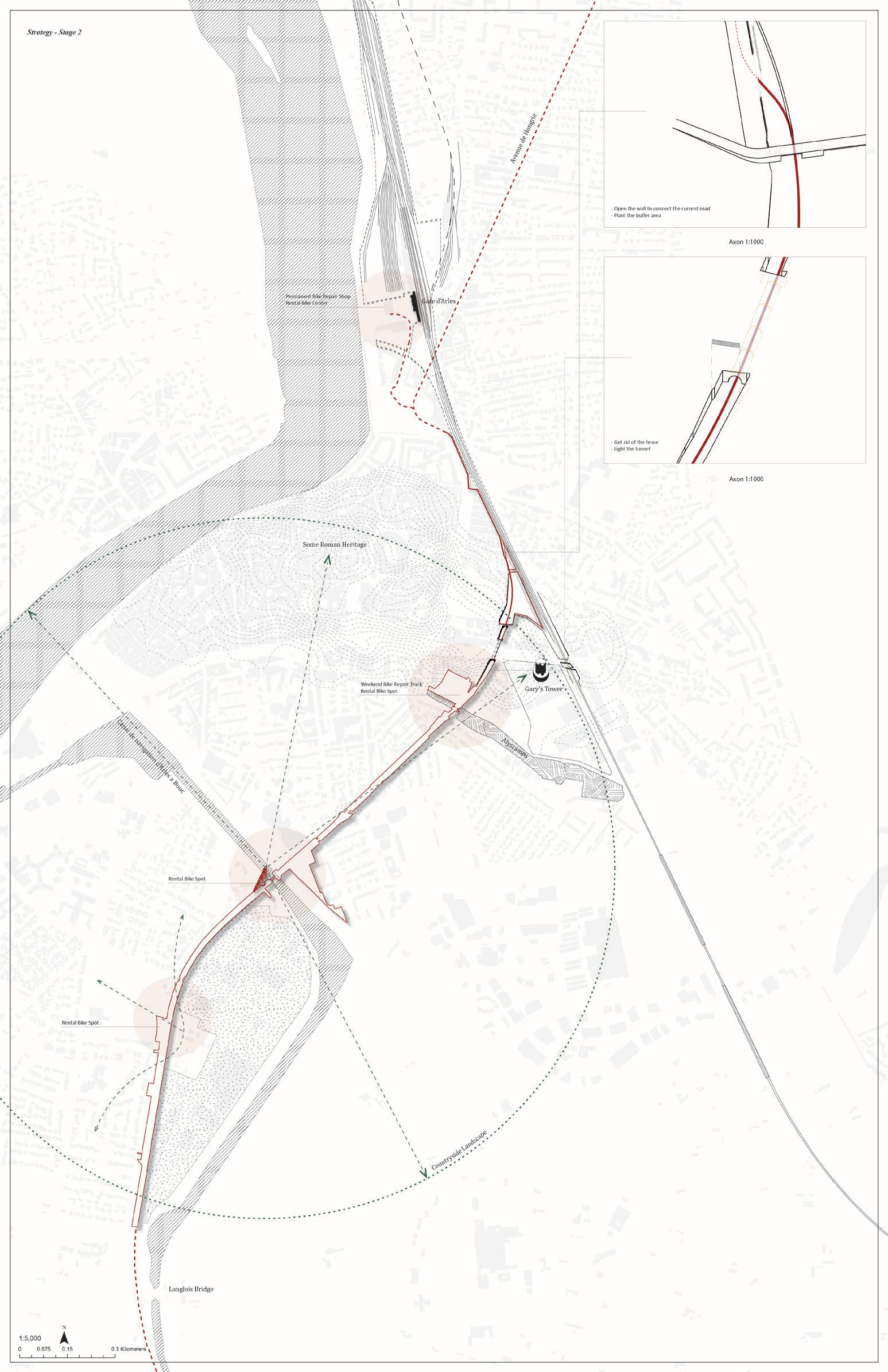

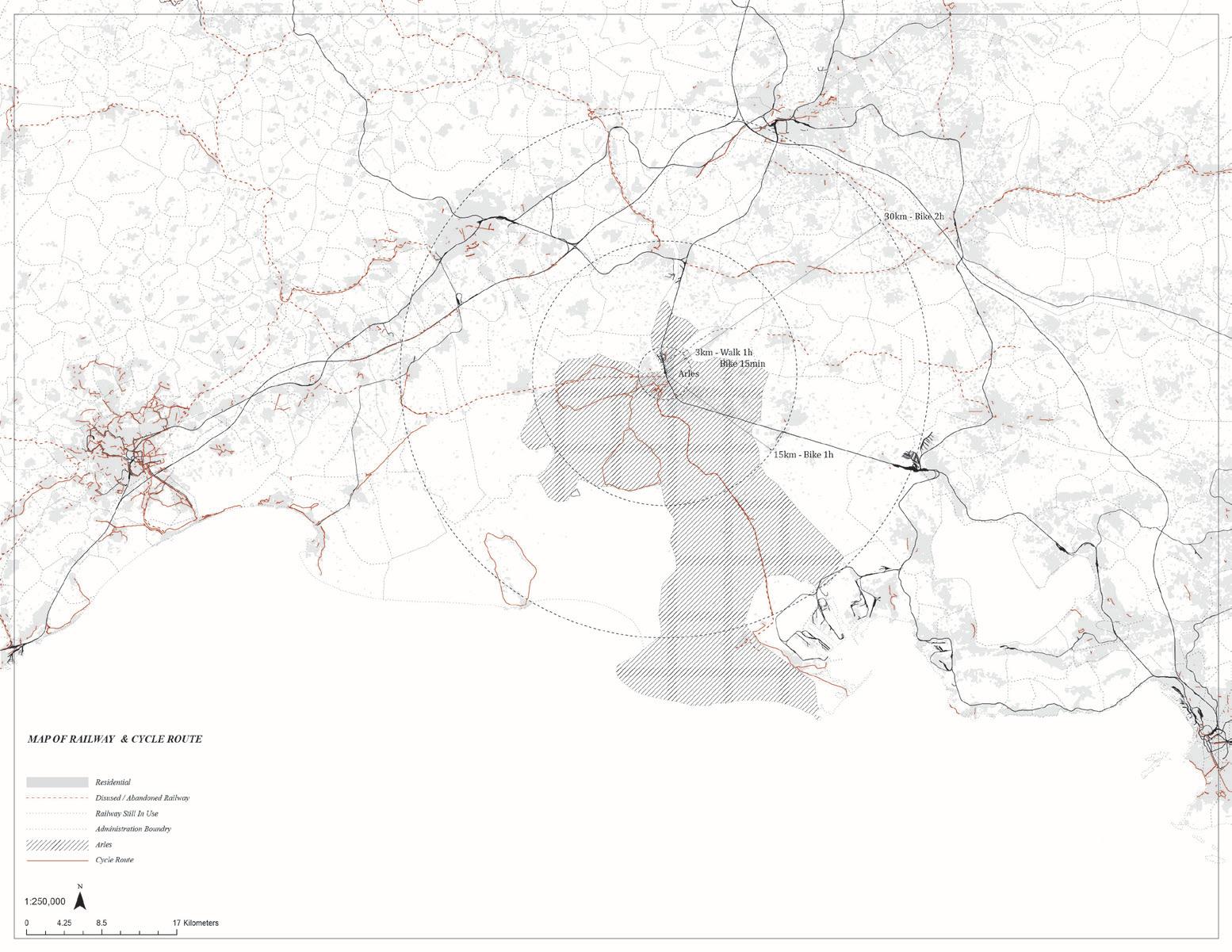

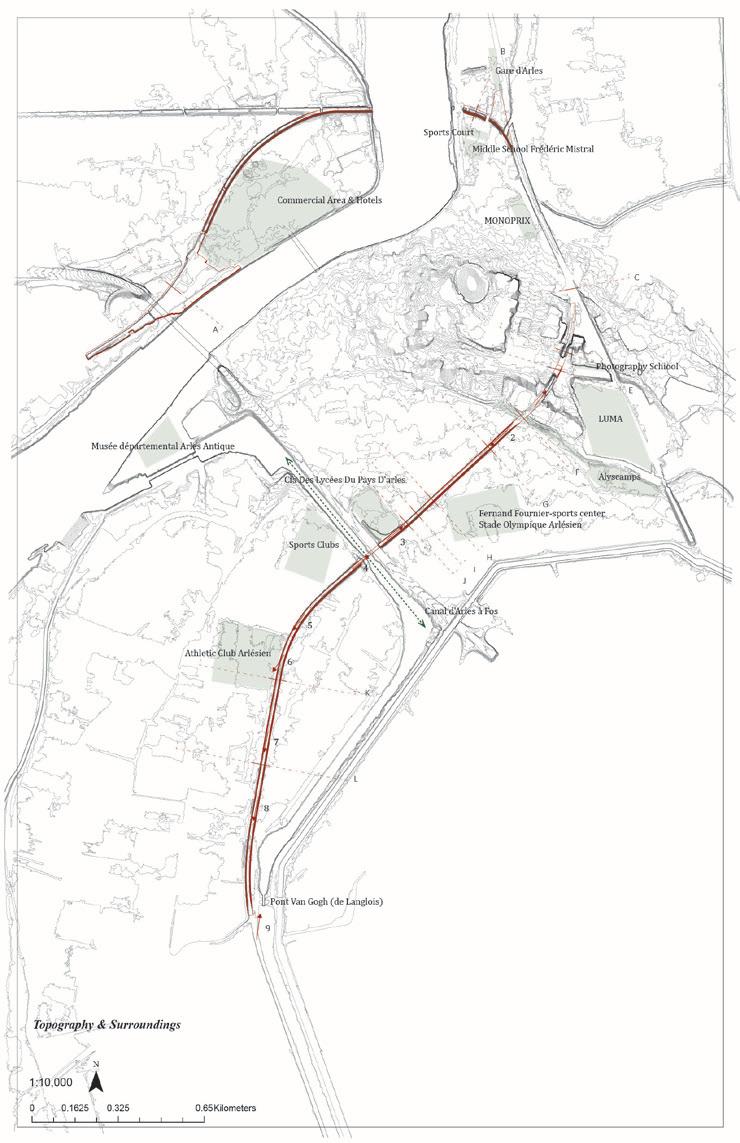

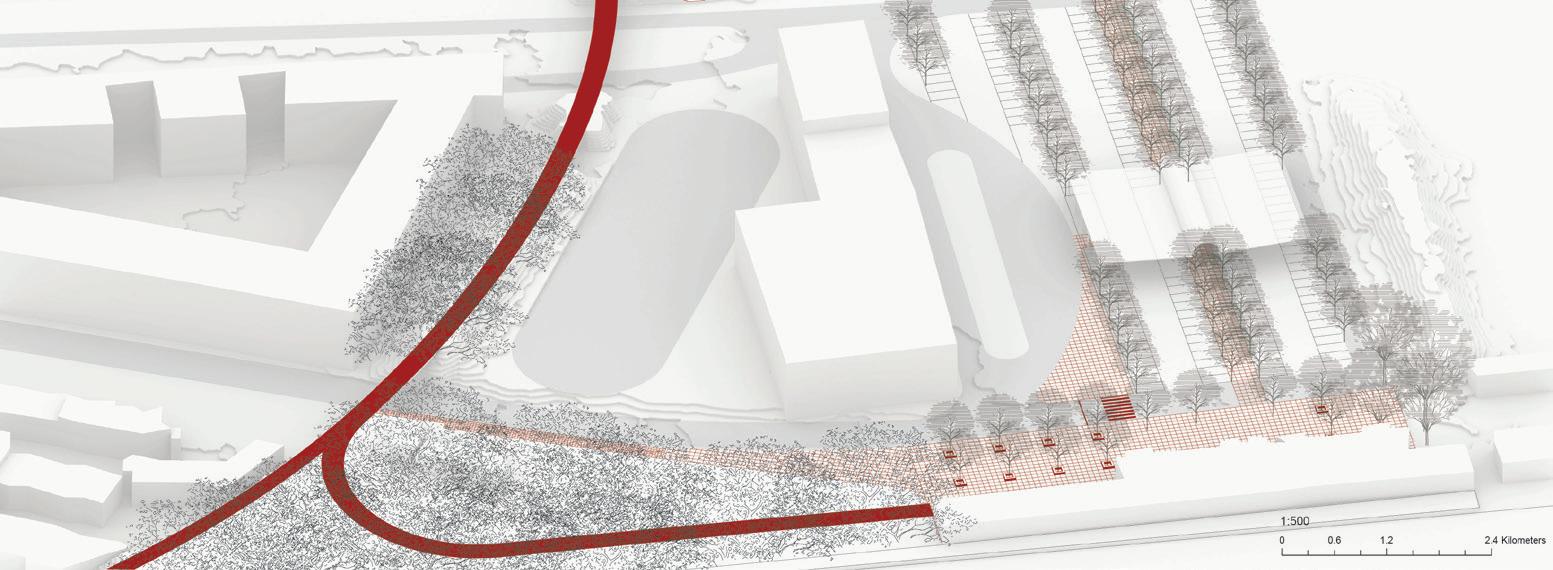

Xinyi Zhou reclaims an abandoned railway and converts it into an urban bike trail that makes a loop within Arles, connecting areas to other parts and programs in the city that are out of reach and impossible to connect with traditional means of transportation. At the same time, this trail links to roadways and other trails, spawning a system that reaches 30 kilometers (18 miles) outside the city in all directions, from the Alpilles to the northeast to the port to the south and the Camargue to the southwest. At the scale of the city, the trail generates much-needed neighborhood-scale social spaces, especially in the underserved neighborhoods in southern Arles.

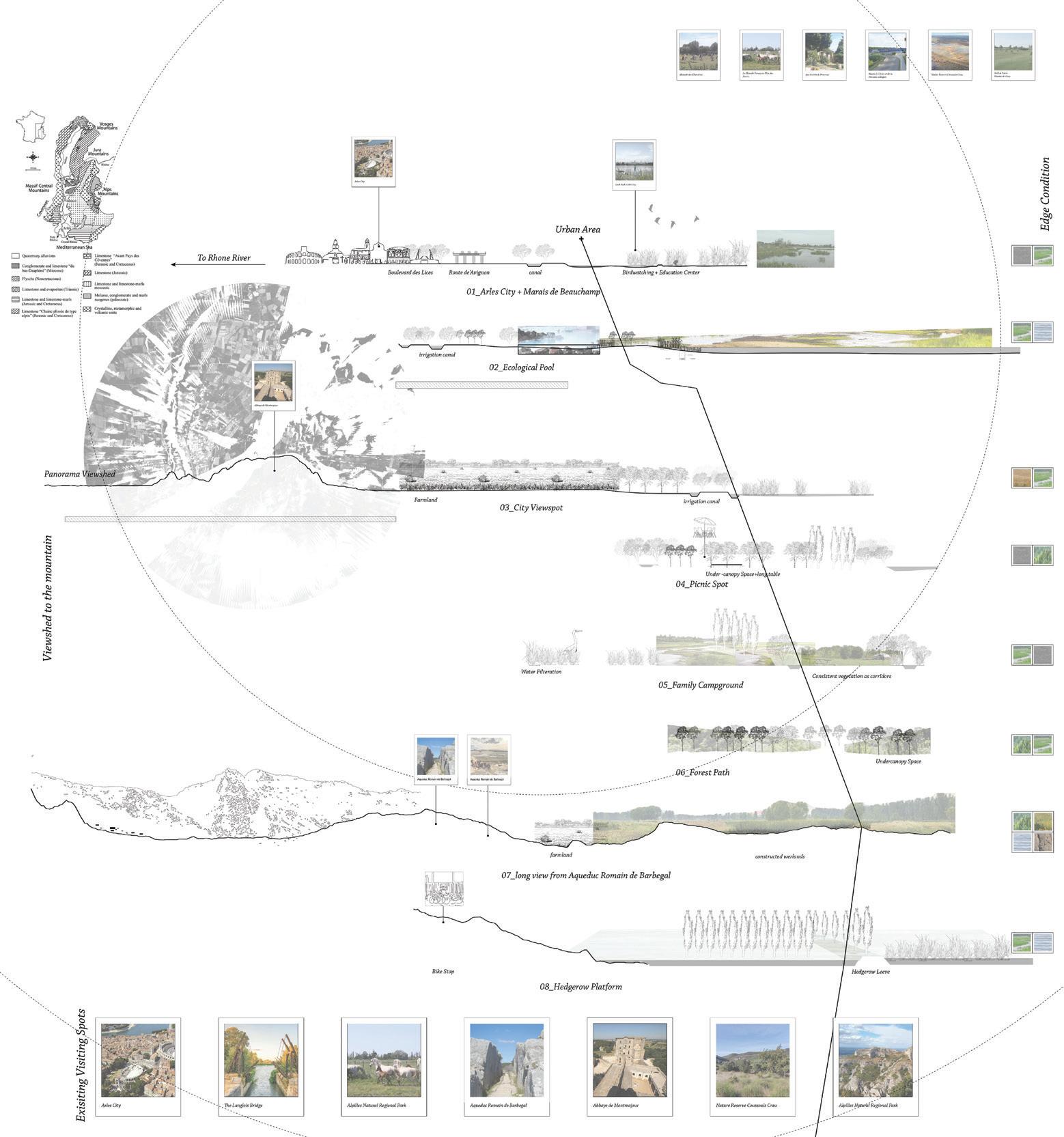

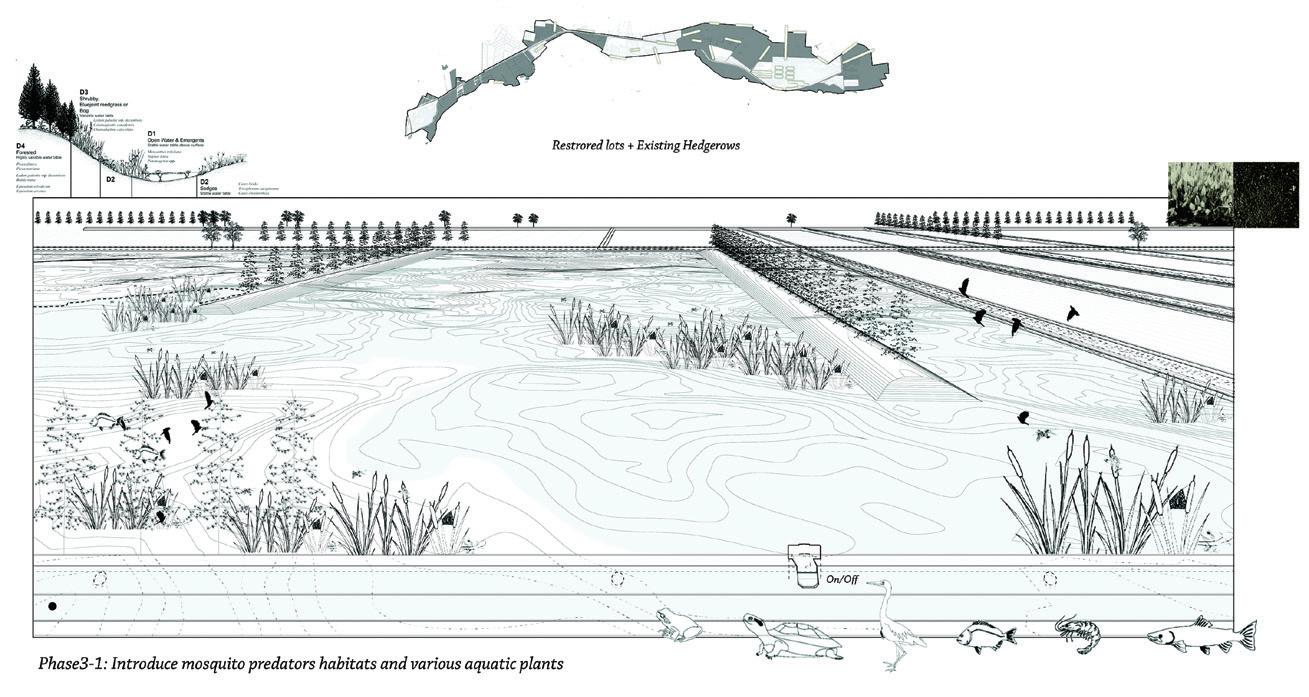

Considered wastelands until recently, Arles’s extensive system of marshes was drained and transformed into productive agricultural landscapes. Knowing the great environmental costs of such transformations, Zhaodi Wang

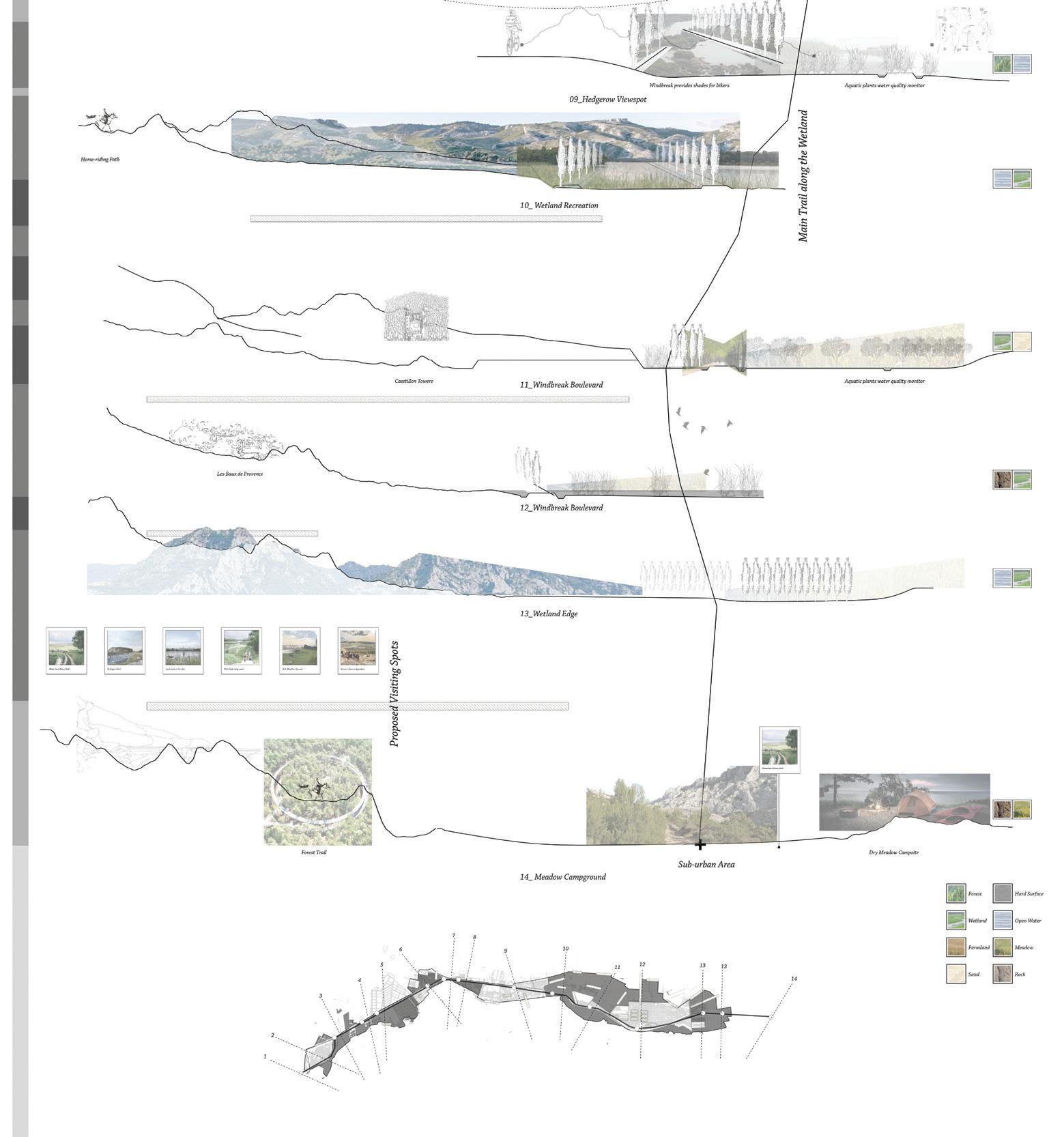

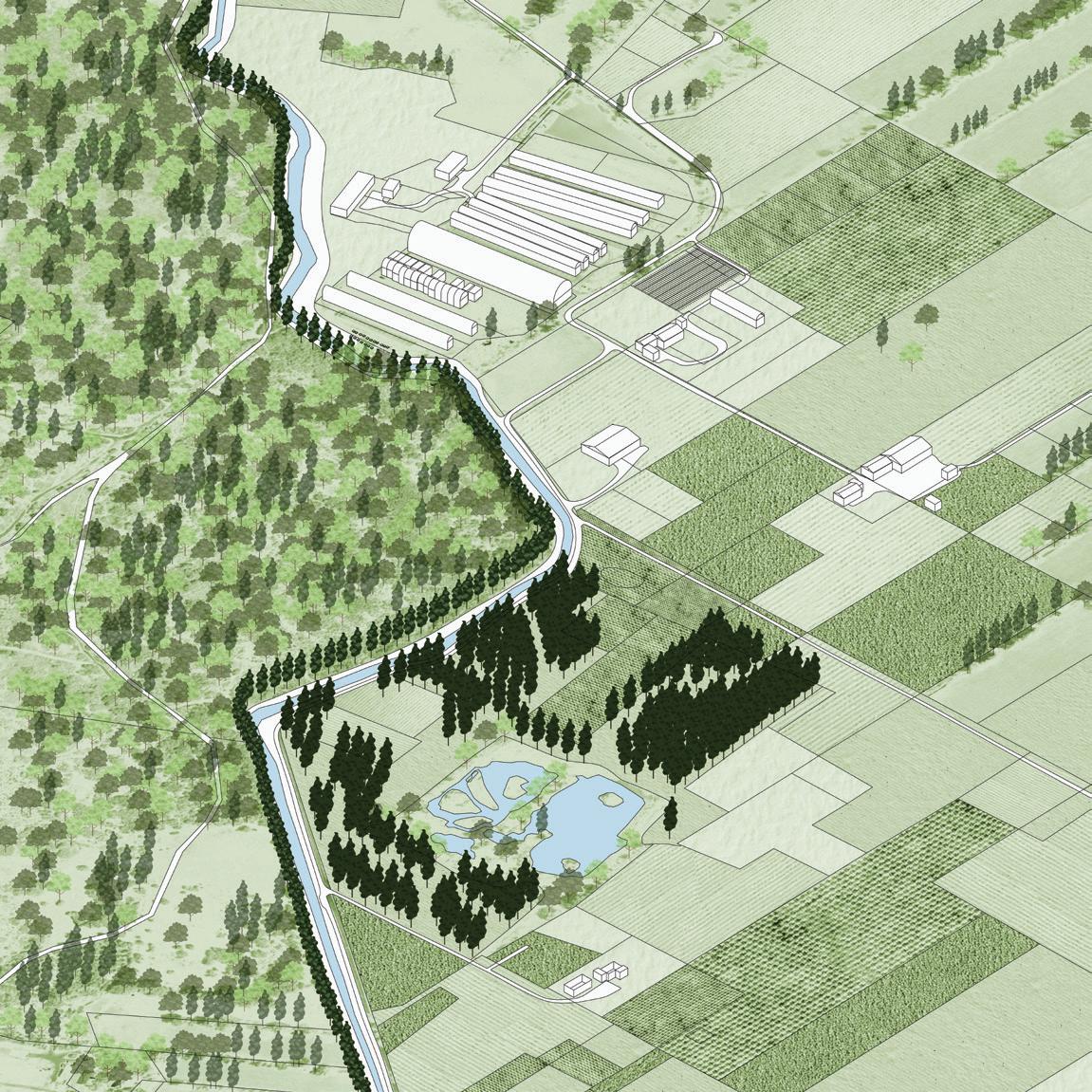

proposes to revert the fields in the valley of Les Baux back to a working wetland. However, acknowledging the importance of the cultural landscape of windbreaks and fields that have articulated this landscape, she explores the intersection between fallow, restoration, and conservation by “curating” agricultural retreat, utilizing the irrigation and drainage infrastructure to rebuild the wetland while maintaining the traces of its more recent past.

After meticulous research, Eleanor Rochman recovered the Canal de Craponne, piecing together the visible and invisible sections of the 124-kilometer-long (77-mile) irrigation canal that joins the Durance to the Rhône, irrigating thousands of hectares of agricultural land in the 19 communes along its route. In the process, she also uncovered the elaborate governance system that regulates the distribution of the waters of the canal. The simplicity of her project, a singular line of trees that makes visible the trajectory of the canal, belies its political complexity: planting and maintaining this line of trees would entail negotiation between many stakeholders over the longue durée.

as Infrastructural Fallowscapes

Xinyi Zhou

Cities continuously build infrastructures of mobility, water supply, waste management, communication, and energy, to name just a few. Many of these are continuously updated while others are simply abandoned with the introduction of new and more efficient technologies, and shifts in cultural sensibilities.

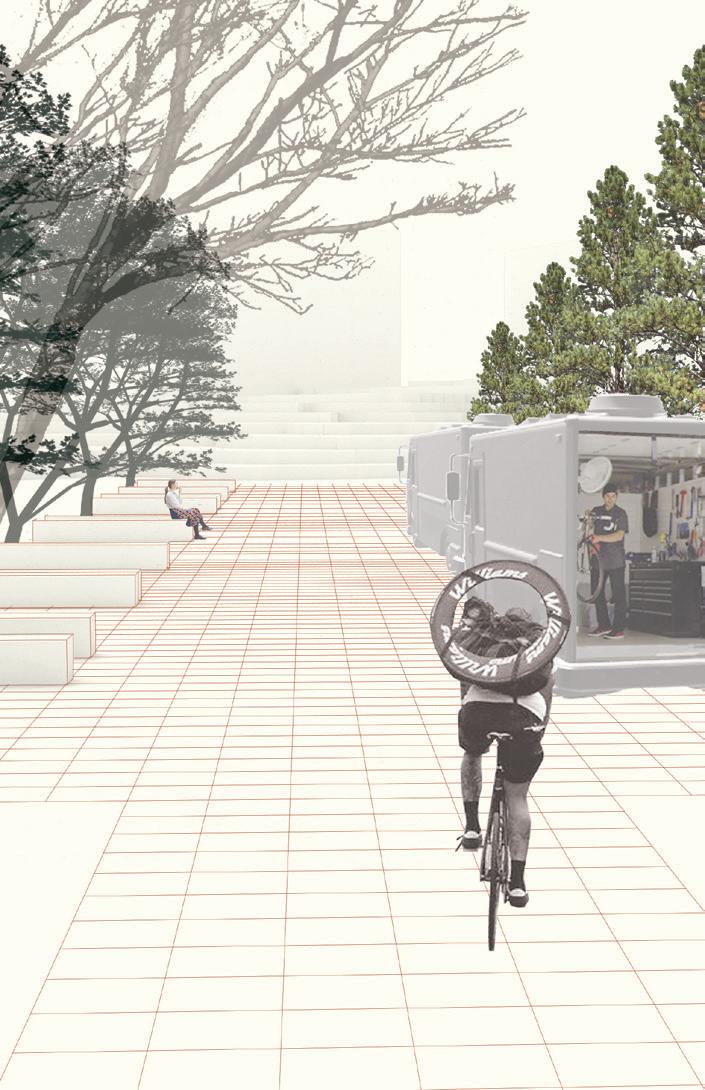

“Bike City” works with abandoned infrastructures of mobility that generate a significant amount of fallow land in Arles. I argue that these abandoned corridors have the potential to reorganize and revitalize relationships between the different parts of the city.

Railway corridors are, more often than not, obstacles in the otherwise continuous surface of the city, generating dead-end streets, discontinuity in the community, and barriers to accessibility. But on the positive side, these rail infrastructures are continuous, flat, and smooth, and traverse through different neighborhoods, industrial areas, cultural centers, and historical sites, as well as larger programs in the periphery like shopping centers and sports venues.

This proposal seeks to reclaim an existing rail track that originates in southern Arles and transform it into a dedicated bicycle route that will form a circuit inside Arles—connecting both sides of the river—and extend to the port at Fos-sur-Mer. The new bicycle circuit pieces together fragments of abandoned rail tracks, existing roads, and bridges to from a continuous, multi-kilometer route.

A close examination of the rail in relationship to its immediate surroundings reveals new potential for connectivity and public space in the city. Presently, the tracks run at different elevations—sometimes above street level and sometimes below—generating leftover spaces in the transitions between grades, which suggests a new range of qualities for the city. For instance,

the disconnect from the street level protects potential activities from vehicular traffic.

Introducing an uninterrupted bicycle route, on one hand, is to make full use of the current situation and to address urban fragmentation. It also provides a new vision for a city that, outside the historic core, is totally dependent on car culture. More importantly, the new bicycle route is a major integrative element, a singular instance of continuity that makes visible Arles’s multiple qualities, histories, and communities.

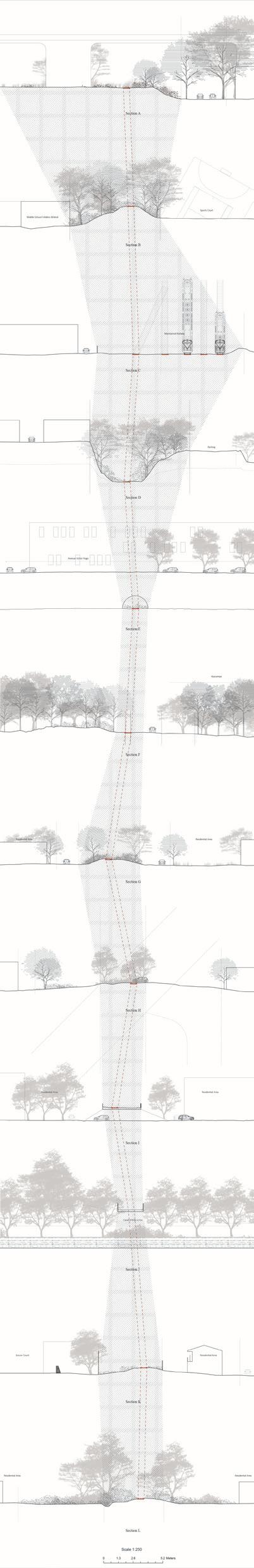

Plan of the extent of bike path in Arles following existing rail infrastructure.

of existing connections to the project’s future bike corridor, including material transitions.

Strategies to revitalize the abandoned rail line include adding lighting, highlighting viewsheds, and providing sites for bike rentals.

Zhaodi Wang

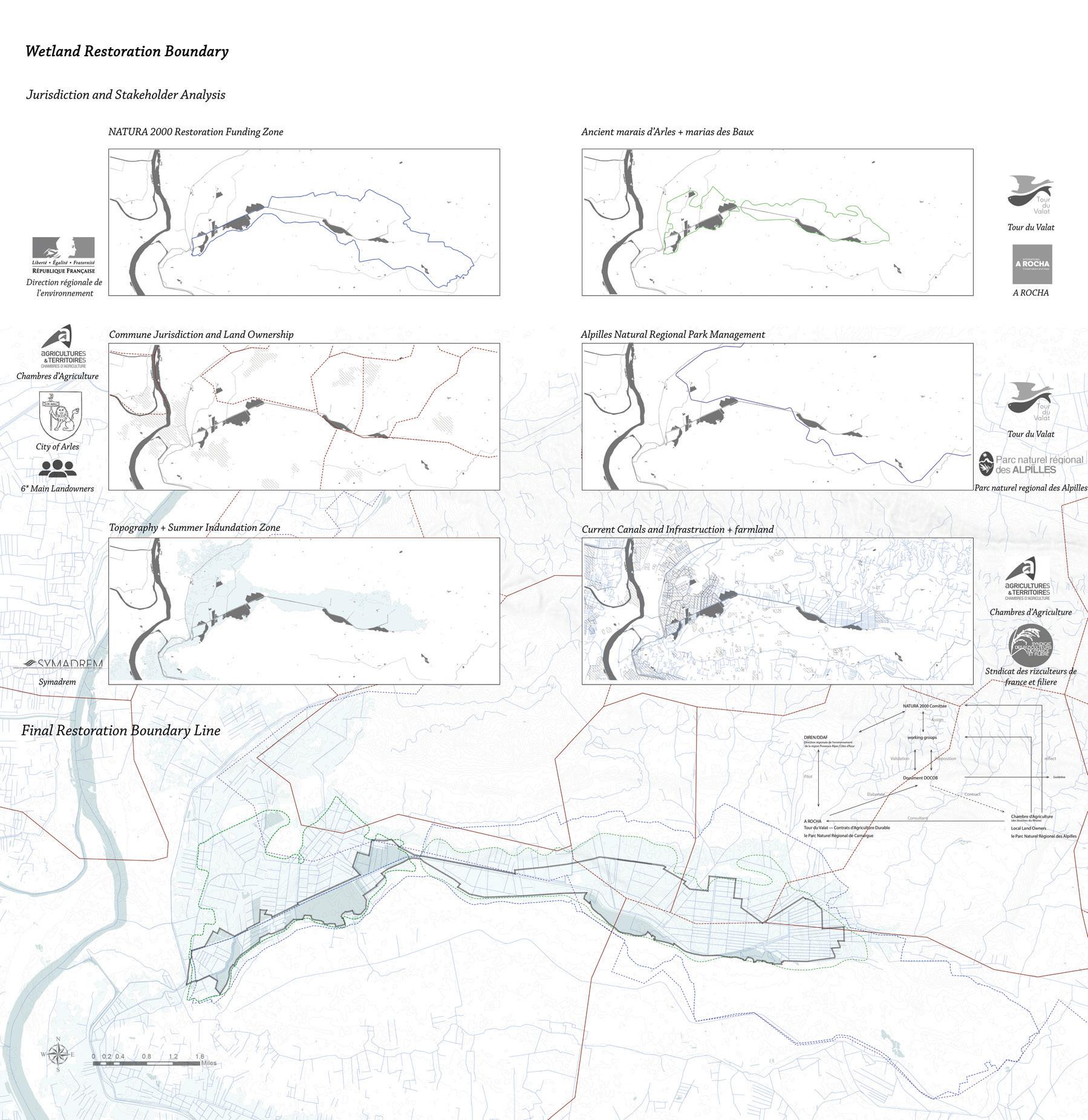

The project proposes to restore a series of wetlands in the lowlands of the Vallée des Baux, and to reconnect them with the surrounding landscape as a new ecotourism framework, strengthening and diversifying the tourism economy from the city center to a larger territory. Wetlands were a major ecosystem in ancient Arles. Before the 19th century, they formed a nearly continuous system between the Alpilles mountains and the Camargue Delta. However, they were gradually drained and replaced with farmland, and today only a few disconnected fragments remain, with little ecological value. At the same time, the agricultural production currently in place is not sustainable, requiring continual draining and extensive irrigation, and it is an agent of pollution from the use of fertilizers.

Why restore the wetlands? In the context of the current climate crisis, wetlands are understood as productive ecosystems for resisting local and global warming, as potential carbon sinks at the regional and local scale, and as habitats that support biodiversity, especially of species that adapt to changing conditions. Urbanistically, the region is characterized by widely dispersed towns and historical sites, with no connectivity between them. In this project the wetlands are introduced for both their ecological and urbanistic potential, as they will form a matrix for connectivity between the towns and between a system of recreational and ecological landscapes, and support the development of new forms of healthy tourism. Methodologically, the reconstruction of the wetland is not entirely technical, but recognizes the historical value of the cultural landscape, specifically the system of hedgerows—windbreaks to weaken and divert the Mistral—that articulate the agricultural

fields. These would be carefully protected and replanned, aiming to provide habitats for biodiversity (especially mosquito predators) and better enhance the view to the Alpilles mountains. Likewise, the existing drainage and irrigation systems will be selectively removed to support the restoration of the wetland. Together, the restored wetland, the preserved hedgerows, and remnant irrigation and drainage systems will form a palimpsest that marks the history of this landscape.

Meanwhile, the ecotourism framework would be established with the construction of cycling and horse riding trails, and additional recreational areas. Such networks would both improve the travel experience of tourists as well as provide new accessibility for the residents of surrounding towns.

In the map, recreational trails weave through various wetland ecological areas and reconstructed hedgerows. Views present activity, both human and nonhuman, within the wetland network.

Wetland sequesters 7–12 tons of carbon/acre/year.

Wetland holds 1–1.5 million gallons of water/acre.

The expanded wetland provides ecosystem services to the Arles region, including addressing pollution and purification, and provides an additional tourism destination in the region.

Extents of the wetland restoration project are visible in relation to the historic center of Arles. The boundary is derived through a redrawing and manipulation of existing stakeholder areas of interest.

Planned visiting routes show the spatial experience of restored mountain views along the journey, and perspectives detail wetland pools with ecological activity.

Eleanor Rochman

In some cases, fallowness should be left to its own devices; it should be used by the designer to reveal socio-cultural values of certain environments and spaces at specific moments in history.