STAFF INDUCTION HANDBOOK

2023-2024

2023-2024

FOREWORD

The Hampton Extended Learning Programme (or HELP for short) is a programme of extended learning open to pupils in the Second Year and above.

Now in its fourteenth year, HELP provides an opportunity for Hamptonians to extend their learning in an academic area of their choice.

There are four levels of HELP:

• Level 1 – Second Year

• Level 2 – Third Year

• Level 3 – Fourth/Fifth Year

• Level 4 – Sixth Form

Hamptonians have an exceptionally wide range of interests, and HELP aims to foster a love of learning for learning’s sake, where pupils can pursue these passions free of curriculum and examination constraints. A pupil completing a HELP project pairs with a teacher supervisor who guides them through the process, providing useful mentoring throughout the research and project-writing phases. This gives Hamptonians an invaluable opportunity to develop research, communication, and organisational skills. The only pre-requisite for completing a HELP project is that the topic must be genuinely outside the curriculum.

I thank Mark Cobb, the School’s Reprographics Technician, for designing and compiling this collection of prize-winning Level 3 and 4 projects from the academic year 2023-24. They represent just a small fraction of the scores of projects Hamptonians submit each year. I also thank the dozens of teachers who, each year, devote their time in supervising their HELP mentees. My final thanks go to all the pupils who see a HELP project through from start to finish; they never cease to amaze their teachers with the level of detail and passion that shines through in their projects. I hope that you enjoy reading these highly impressive pieces of work.

Dr J Flanagan Assistant Head and HELP CoordinatorTO WHAT EXTENT WAS AUSTRIAN FOREIGN POLICY IN THE 19TH CENTURY A SUCCESS?

BY PIERS MARCHANT(Upper Sixth, HELP Level 4, Supervisor: Mr O Roberts)

To what extent was Austrian foreign policy in the 19th century a success?

By Piers Marchant

By Piers Marchant

“It’s obvious that one day it will all collapse. It can’t last forever. Try to pump glory into a pig and it will burst in the end.”

Jaroslav Hašek, The Good Soldier Švejk

“The age doesn’t want us any more! This age wants to establish autonomous nation states! People have stopped believing in God. Nationalism is the new religion.”

Joseph Roth, The Radetzky March

Introduction

Over the course of 99 years, from the end of the Napoleonic Wars to the beginning of the First World War, the European continent experienced a period of peace previously unknown in its history. International relations entered a new era in which pragmatism, rationalism and material superiority began to trump the antiquated notions of prestige, precedence, and absolutism. The Habsburg Monarchy was situated in the centre of Europe and in the centre of the diplomatic scene. The lands owned by this dynasty had evolved from a collection of distant duchies and kingdoms combined through the familial ties of their rulers in the Middle Ages, into a vast contiguous empire spanning most of central Europe, second in size only to Russia by the end of the Napoleonic wars.

Despite its embarrassment by Napoleon, Austria came out of the wars in a stronger position than before. Indeed, it could be argued that Austria occupied a stronger position than it had occupied for centuries. This is thanks to the successes of the Congress of Vienna, which kept Austria out of any major conflict for 99 years and established an

early system of collective security through Metternich’s balance-of-power vision of Europe. Austria emerged as the dominant power in Central Europe, Italy and Germany, and through a complicated network of alliances managed to keep the Russians submissive, which is by no means an easy feat. Even during its most difficult test in the revolutions of 1848, the Austrian Empire emerged from the crisis remarkably stable and continued its position of dominance in European affairs.

However, this diverse, multicultural empire would quickly be confronted by the forces of the 19th century which came to threaten its very existence. Liberalism, the revolutionary movement and, above all, nationalism rose in popularity throughout the century and challenged the principles underpinning the age-old monarchy. Across the empire, from Lviv to Trieste, national minorities began calling for self-determination and independence. While Germany and Russia had embraced nationalism, Britain liberalism, and France both nationalism and liberalism, Austria was left as the odd-oneout in the great power system that it had helped create. Indeed, after the 1850s Austrian diplomacy, still based on antiquated Metternichian notions, began to look more and more out of date and led to far fewer successes than it once had.

It is important to note that the Habsburg Empire lay at an interstitial point in European geography – that is, it was located between other large power centres. This meant that more than any other power, it was likely to be challenged by a war on two fronts, a strategic challenge which very few countries have historically been able to handle. A country like France, whose “hexagone” was protected on three sides by open water and on another two by mountains, was only required to commit extensive defence to a relatively small area, making it difficult to invade. The Habsburg Monarchy had no such luck, relying solely on the Carpathian Mountains for natural protection against an eastern invader, and with practically no natural defences against an attack from north or south. And while the Carpathians are by no means a small barrier, they do not pose quite the same difficulties as the Alps or the Pyrenees, thus further compounding the problems facing the empire

So overall, can the foreign policy of the Austrian Empire in the 19th century be called a success? To answer this, we must establish what is meant by the term ‘success’. Throughout the century, success for Austria meant the maintenance of Austria’s position as a great power in Europe as a whole, meaning that revolutionary, liberal and nationalist forces would have to be subdued. Success also meant that other great powers e.g., Russia, France, Prussia, did not eclipse Austria in its position at the centre of European affairs.

The story of this empire is therefore one of managed decline and mixed results. We cannot dismiss just how successful Habsburg policy between 1815 and 1853 was, with the effects of the Congress of Vienna not only shaping Austria’s role in the 19th century, but also changing the role of diplomacy in international relations in a revolutionary manner. In addition, a combination of defensive grand strategy and a generally creative foreign policy meant that Habsburg diplomats could maintain Austria’s status as a great power However, as the century wore on, in every diplomatic engagement involving Austria, it began to slip from its ivory tower, and increasingly found itself making

concessions to surrounding powers. Overall, Austrian foreign policy therefore gives us a mixed legacy, a combination of successes and failures.

The Congress of Vienna

From Napoleon’s first surrender at the end of May 1814 to his exile to St Helena after the Battle of Waterloo in July 1815, delegations from all the great powers of Europe (and many minor ones too) met in Vienna to create a new continental system based on the establishment of a balance of power between the various nations intending to avoid war at all costs and uphold the status quo. The congress was chaired by Klemens von Metternich, the Habsburg foreign minister, who would go on to be one of the most consequential men of the 19th century, not just for Austria but for Europe as a whole. Metternich was not Austrian by birth but rather a member of a cosmopolitan Rhenish diplomatic family. Having served in a variety of ambassadorial roles during the Napoleonic Wars, he emerged as the Habsburg foreign minister in 1809. Metternich’s style was reminiscent of the sober rationalism of the enlightenment; he avoided entertaining abstract theories or overtly dogmatic solutions to problems he faced, instead advocating for pragmatic solutions which would ensure stability for all parties involved. Hence, the balance of power system.

At the onset of the congress, it was not certain as to whether such a wide-ranging meeting could achieve its goals, but Metternich succeeded with consummate diplomatic skill in bringing together all the apparently conflicting interests of the victorious powers Metternich’s principles with which he guided the conference were “legitimacy, restoration of the pre-revolutionary status quo, adequate compensation if necessary, and balance of power between the great European states as imperative.” 1

The concept of legitimacy acted primarily as insurance against the potential success of any revolution that may arise in the future and was particularly beneficial to the Austrians. A regime such as the French First Republic was to the other great powers inherently illegitimate, as it had come to power by overthrowing the long-established Capetian monarchy, and did not claim any divine right, operating under revolutionary principles which were anathema to the ruling powers. The Habsburgs, on the other hand, could be considered the great power with the highest legitimacy. They had been emperors of the Holy Roman Empire almost uninterrupted since 1452, and one of only two states with an imperial title, the other being Russia. By asking the delegates at Vienna to uphold legitimate rulers, Metternich was essentially asking for stability, both internal and external, to be the prerequisite for the new European constitution. Europe, ravaged by two decades of war, could hardly refuse.

The most physical manifestation of the legitimacy doctrine came in the form of the Holy Alliance between Austria, Prussia and Russia. A key theme of Austrian diplomacy in this period is the creation of common European causes to distract from Austrian internal or military weakness. Prussia and Russia posed the two biggest threats to Austria, with Prussia having a history of rivalry, particularly under King Frederick the Great, and with the interests of Russia and Austria increasingly clashing over spheres of influence in the 1

Balkans. Metternich’s diplomatic skill allowed him to convince these two powerhouses that the spectre of revolution posed too great of a threat for them to be divided The Holy Alliance was therefore committed to intervention should a European country fall to revolution, “but it also obliged them to act only in concert, in effect giving Austria a theoretical veto over the adventures of its smothering Russian ally” 2 This is the first instance of the creation of a complicated series of alliances that would work in Austria’s favour in the 100 years that followed.

“Restoring the pre-revolutionary status quo” simply meant undoing the damage that the French Republic and later Napoleon had done to Europe. The Ancien Régime was restored in France, with its borders cut down to the size at which they exist today. Napoleonic client kings in the Netherlands, Italy and Spain were deposed and the independence of Switzerland was restored. In this way a conservative, reactionary order was established over Europe, intending to cause further strain on the revolutionary movement to the point of such a rebellion being considered impossible.

The principle of compensation was spearheaded by Metternich to be the primary way to resolve disputes between nations in the new European order, and he demonstrated this with many territorial changes imposed on Austria itself. Austria gave up the territories they had held in the low countries, first inherited from the Burgundian Succession in 1482, as well as a variety of exclaves known as Further Austria (largely just a collection of towns in and around what is now southern Germany). Not only were these territories difficult to manage, being separate from the metropole, but they were also prone to rebellion. By giving them up, the Habsburgs could free themselves from lands that were more trouble than they were worth, and also begin to foster improved relations with the southern German states, perhaps establishing a leadership role with which they could rival Prussia. 3 It also helped further remove the possibility arising of a direct conflict between Austria and France, particularly in the French-speaking Walloon parts of the Austrian Netherlands.

Nonetheless, in the spirit of the conference Austria demanded compensation to maintain the balance of power. This came in the form of northern Italy as Austria took control of Lombardy and Venetia. This would turn out to be one of the most controversial and fateful decisions of the Congress. The Austrian encroachment into Italy coincided with the rise of nationalism in the area. The Kingdom of Sardinia would embrace this ideology (which we will expand upon later) and by the 1850s would pose a serious threat to the Austrian presence in the region, eventually conquering the two provinces. Austrian foreign policy was realigned to centre on the Italian question for more than 40 years after the Congress of Vienna; even in 1866, it was the Italian entry into the war that can be blamed for Austria’s loss to Prussia “The Italian ‘mission’ was to be Austria’s justification in the eyes of Europe 4” While the intrusion of the Habsburgs into Italian affairs certainly gave them more influence, it ultimately proved to be more trouble than it was worth and was perhaps Metternich’s largest blunder at the Congress. He considered

2 “Diplomacy” Henry Kissinger p. 83

3 Kann p. 230

4 “The Habsburg Monarchy 1809-1918” A.J.P. Taylor p. 40

Italy simply to be a geographic concept and was blind to the forces of nationalism that would come to envelop the region.

Another aim in the acquisition of Lombardy and Venetia was to serve as a buffer zone to protect Austria against threats from the West, namely France. The quest to secure these buffer zones was one of the most vital aims for Metternich, due to Austria’s inherent geopolitical weaknesses in its location in Europe, and its military inferiority compared to the disciplined Prussians and the innumerable Russians. He knew that direct contact with other great powers was more likely to lead to war, as it had done most notably in the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763). Actions such as the establishment of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands (to remove itself from France and create a buffer between France and Prussia) therefore make a lot of sense both for the maintenance of Austrian sovereignty and by extension a European balance of power. Other examples include the maintenance of Saxon sovereignty to preserve the buffer between Austria and Prussia, the creation of the autonomous Congress Poland to act as a buffer between all three Eastern powers, and the growing independence of Wallachia and Moldavia, to dissuade Russia from growing its influence in the Balkans. So, while Austrian encroachment into Italy and Germany did bring its fair share of problems, on the other hand, it also kept the challenges to Austrian power on the periphery of the empire, thus keeping the main body more secure for a longer time. 5

The most intricate display of the fashioning of the balance of power was the establishment of the German Confederation. The German question was long-established in European discourse, emerging during the proto-nationalistic Reformation, and this perennial problem arose again in Vienna.

German weakness was in many ways responsible for the success of Napoleon’s conquests. The almost non-existent Holy Roman Empire provided no resistance to the French and Napoleon quickly overran the hundreds of margraviates, principalities and archbishoprics in western and central Germany. A divided Germany tempted its neighbours into expansionism, making it impossible to maintain a balance of power. On the other hand, the prospect of a united Germany terrified all other European states, as they could not imagine being able to stand up against the united resources of a German nation. In the words of Kissinger, “historically, Germany has been either too weak or too strong for the peace of Europe.” 6

Recognizing this, the plenipotentiaries at Vienna crafted the German Confederation. In many ways a more centralised (although still disparate) version of the Holy Roman Empire, the Confederation was composed of only 39 members as opposed to the several hundred of the Holy Roman Empire Led by Austria and Prussia, the main purpose of the Confederation was to serve as a mutual defence bloc to defend Germany from French aggression. By balancing Prussia’s military strength and tradition with Austria’s legitimacy and prestige, it was remarkably successful in achieving this aim. The Confederation also served as a “legitimist” preservation of the rights of its ancestral princes and as a stopgap to further ambitions of German unification; while it lasted it

5

achieved both of these aims too. By forestalling German centralisation, Metternich secured a relatively peaceful Europe, standing for unity rather than union and preventing the premature rise of Prussian hegemony, thereby extending the relevance of the Habsburgs further into the 19th century. 7

Despite their collaboration during the Napoleonic wars and in the Holy Alliance, the beginning of the Austro-Prussian rivalry can be seen in the German Confederation. The Confederation had significant influence over its smaller member states, as it had the right to intervene in domestic crises, and it was a fixed bloc from which secession was ruled illegal Middle Germany essentially became a stomping ground for Austria and Prussia to exert their influence, initiating a German “great game.” Austria was also given the politically meaningless but nonetheless prestigious title of “permanent president” of the Confederation, which further increased the rivalry as Prussia did not want to be seen as secondary. This burgeoning rivalry would increase over the course of the century before coming to a head in 1866.

The German Confederation served as an unusual combination of pragmatism, reactionism and yet also progressivism, rejecting the orthodox nuances of the Holy Roman Empire in favour of a simpler system that ultimately became a conduit of Austrian power 8

The Congress of Vienna marks a stark turning point in the history of diplomacy, as the leaders of Europe “softened the brutal reliance on power by seeking to moderate international conduct by legal and moral bounds.” 9 Metternich designed an early system of collective security (which just so happened to particularly favour Austria.) This served as the genesis for the rules-based system we know today.

Regarding the Congress’ aims, it was largely successful in its overall goal in making a peaceful Europe. Between 1815 and 1914 there were only four short wars between major powers whereas between 1700 and 1790 there had been sixteen 10, a testament to the stability that a balance of power system can bring. The Congress of Vienna gave European statesmen the opportunity to choose peace, should peace be their aim While the Congress system began to break down by the 1850s and 60s, its overall influence on both 19th century politics and on diplomatic theory as a whole is vast.

Metternich fashioned his aims throughout the Congress as Europe-wide aims, but in reality, he was acting on behalf of the Austrians, with stability, legitimism and the status quo which would favour the Habsburgs more than anyone else With the many challenges that the Habsburgs would face in 1848, 1853, 1859, 1866 and beyond, it was Metternich’s skill in fashioning a system favourable to the Habsburgs that kept their empire alive.

7 Kann p. 232

8 Ibid p. 234

9 Kissinger p. 22

10 “The Habsburgs: The Rise and Fall of a World Power” Martyn Rady p. 241

A note on nationalism

The spread of nationalism took hold in the early 19th century as the idea of a unified culture of peoples tied to a state could begin to be spread through the expansion and centralisation of education as well as through the emergence of mass media. The phenomenon became particularly pronounced in divided polities, most notably Italy and Germany, as the peoples there, already considering themselves to be of the same “national culture”, could campaign for the establishment of nation states along the lines of France or Russia in which a predominant national group were in control of the state and the reins of power. In addition, the influence that Napoleon had left on these regions, both of which he had dominated for 15 years, left behind rationalist administrations and the proto-nationalist ideas of the French Revolution which would go on to animate the people into culturing a nationalist feeling 11 Nationalism would prove to be the greatest threat to Austria and would cause its destruction a century later. The Habsburg Empire could not inaccurately be called the “enemy of nations”, as Czech, Hungarian, Serbian, Romanian, Italian and many other nationalists among ethnic groups longed to establish independent nation states. Even the German nationalists despised the empire, believing the German speaking parts should be part of a unified Germany, not the custodian of an antiquated, multiethnic superstate. Other powers like Prussia and Russia had sizeable minority groups, but at least over half of the population spoke the tongue of the ruling class. In Austria, less than a quarter of the inhabitants spoke German as their main language in 1910. The rise of nationalism would be Austria’s perennial and greatest enemy up until the end, and it would mount its first significant challenge in the fateful year of 1848

1848: the brink of destruction

Metternich’s fashioning of a Europe averted to revolution manifested itself in the cultural and artistic movement of the Biedermeier period. The stability brought about by the Congress of Vienna led to economic growth and the expansion of the middle classes throughout Europe and therefore the creation of a socially conservative bourgeois culture focused on the idealisation of family life, the countryside and sensibility, with an overall sense of calm sweeping through the empire Indeed, there were no wars between great powers which could disturb this tranquillity and the congress system held firm, with subsequent congresses being held at Aix-la-Chappelle in 1818, Troppau in 1820, Laibach in 1821 and Verona in 1822. 12

However, beneath the surface, burgeoning political movements such as liberalism and nationalism grew in number, as did the urban working classes who were more desiring of social change than the conservative bourgeoisie. Liberalism in the Austrian Empire did not differ wildly from the mainstream seen in Britain and France – ideas such as freedom of speech and the press, political representation, and the rights of the citizen as an individual were universal – but the regime onto which it attempted to impose itself was

11 Mitchell p. 229

12 “Danubia” Simon Winder p. 319

markedly more authoritarian than its Western European counterparts. 13 Censorship was widespread in the empire, with overzealous bureaucrats prohibiting anything which could be considered even remotely seditious or uncouth, meaning liberal ideas could not spread as effectively, and the lack of elected government meant there would be no “revolution from above ”, as Metternich’s conservatism was unlikely to change. This left only one option for Austria’s liberals – a revolution from below.

It is important, however, not to overstate the ideological causes of the 1848 revolutions. Underwhelming harvests in the 1840s and the spread of the Industrial Revolution caused widespread economic and political unrest as quality of life for the rural peasants and urban working class began to dip, further contributing to the spectre of revolt. 14

For context, the tumultuous overthrowal of Louis Phillippe I in Paris spurred on revolutionary movements in the Habsburg Empire. In Vienna, Metternich, now unpopular both within court and in the overall empire, was forced to resign. Full executive power now lay with the monarch for the first time since Metternich’s rise. Unfortunately, that monarch was Ferdinand I, who, while amiable, suffered from severe epilepsy and a variety of mental conditions, perhaps the legacy of the infamous incestuousness of the earlier Habsburgs. Ferdinand was easily influenced and agreed to all proposals of the liberal coffeehouse masses and German nationalists, likely overwhelmed by the upheaval Metternich was thus succeeded by a series of five liberal noblemen in the space of eight months, demonstrating just how unstable the central government was at this time.

Although Vienna had been saved from a greater bloodshed, the rest of the empire had practically ceased to exist under the control of the Habsburgs. In this manner, the interactions between the rulers in Vienna and the revolting governments in Bohemia, Hungary and Italy can be seen as foreign policy and is therefore particularly relevant to the main question of this essay. It was through the admittedly brutal interventions of three generals that the empire regained its strength after 1848, coming from the brink of collapse to achieving the status of a great power once more.

The Bohemian revolt

In the aftermath of the Viennese revolution, the subnational entities within the empire almost immediately rose in revolt, inspired by the achievements of the nationalists in Vienna. Prague was, by most metrics, the second most important city in the empire, and the Bohemian crownlands had been under Habsburg control since the 16th century. Nonetheless, Czech national feeling, following a renaissance of national consciousness 15 , was at an all-time high in 1848, and nationalists were keen to follow the Hungarian example (which we will discuss later) and develop at the minimum, an autonomous liberal nation-state.

Bohemia was, much like the overall empire, ethnically divided. The Czech majority inhabited the interior of the region and began to exert more influence with the onset of Czech nationalism but was still largely controlled by the significant German minority

13 Rady p. 245

14 https://www.thecollector.com/revolutions-of-1848-anti-monarchism-europe/

15 Taylor p.66

living in the Sudetenland. While these tensions would come to a head most famously and disastrously in 1938, ninety years earlier an apprehensiveness was already brewing.

František Palacký is today remembered as the father of the Czech nation. He led the Czech national revival, and in 1848 he rejected the overtures from the revolutionary liberal German government in Frankfurt to incorporate Bohemia into a new German nation state, instead opening the first pan-Slavic congress on 2nd June in Prague.

Incorporating the Czechs, Slovaks, Slovenes, Croats and Poles of the empire, the broad aim of the meeting was to rally for increased political autonomy and respect for the Slavic peoples within the Empire, a movement known as Austroslavism that would go on to form the basis of the federalist movement that would emerge at the beginning of the 20th century. However, it was plagued from the beginning by disagreement between the Slavic groups and was ultimately vague and unconvincing in its messaging, as delegates were divided on the extent of their loyalty towards the Habsburg emperor, and this congress ultimately failed to project any power beyond Prague’s walls. 16

However, within the city, the political excitement of the revolution spurred the young radicals to violence, culminating in the Whitsuntide riots of 12th June, pitting Slav against German within the city.

It is here that we must introduce another aspect of the Habsburg longevity: military tradition. While not necessarily renowned in Europe, often being overshadowed by countries like Prussia and France, the Habsburg army had nonetheless produced its fair share of large personalities who could command forces both on the battlefield, and within the tricky political manoeuvrings of the Hofburg 17. One such of these men was General Windischgrätz, the veteran military commander of Bohemia, a German Bohemian and an arch-conservative. During the congress, Windischgrätz had deployed his army close to Prague, ostensibly to keep order, although in reality provoking the nationalists into open revolt. Once the riots commenced, which resulted in the death of his wife, he began a bombardment of the city, with his troops battling their way through the old town until all opposition was crushed on 17th June. The general subsequently abolished all governmental framework in Bohemia, closed the congress and declared martial law, making the country his own personal fiefdom, albeit one that was fiercely loyal to Vienna. 18

This heavy-handed approach is representative of the Imperial army’s lack of aversion to violence and direct military action and would compensate for the impotence of the government in Vienna, even going as far as being responsible for the Empire’s continued existence after the revolution. While the influence of figures such as Windischgrätz came with drawbacks, such as the now permanent lack of desire for constitutional reform within the court, it is undeniable that without him and the other generals who dealt with Italy and Hungary, there would have likely not been an empire at all after 1848.

16 Taylor p.69

17 The Austrian court

18 Rady p. 247-248

The First Italian War of Independence

The second of the three generals responsible for reestablishing Austrian power in 1848 is perhaps the best known of any Austrian military figure – Joseph Radetzky. Of course, he is well known in popular culture not because of any particularly outstanding military victories but because of the celebratory Radetzky March, composed by Johann Strauss in celebration of the old general’s victory at the Battle of Custoza in July 1848, and now part of the established classical music canon.

Nonetheless, the general, born in 1766 and 81 years old by the time of the revolutions, was undoubtedly a shrewd commander and one of Austria’s greatest generals, singlehandedly maintaining a Habsburg presence in Italy.

Much like in Bohemia and Hungary, the Italian revolutionaries were heavily inspired by the success of the revolutionaries in France (although the first successful revolt had actually been in Sicily in January). Rebellions in Milan and Venice forced the Austrian commander in Italy, Radetzky, to retreat and the Italian kingdom of Sardinia declared war soon after, taking up the nationalist mantle.

The Austrian position was all but lost save for one timely aspect of Austrian grand strategy, reliance on fortifications.

The Austrian Empire was always defensively focused; it had acquired its vast array of lands almost exclusively by diplomacy and marriage rather than warfare and whenever it had to go to war it was rarely the aggressor, therefore its fortifications were particularly important. Aaron Wess Mitchell notes that “the fact that Austria faced foes on every side as well as potentially internally while possessing a relatively weak army gave forts greater utility than most states.” 19

Because of their importance in Austrian defence, Austrian military commanders wrote extensively about the use of forts in military strategy. Radetzky wrote that “the purpose of fortifications is to make a defence of the few against an attack by the many possible.” 20

The First Italian War of Independence would prove to be a textbook example of this maxim succeeding.

Perhaps the best illustration of the role forts played in this period in advancing Habsburg political and strategic goals can be seen in the famous quadrilateral fortresses of Italy.

The four fortress towns of Peschiera, Verona, Mantua and Legnano (“the quadrilateral”) had been the primary outlet of Austrian power in Italy since the 18th century and had even posed problems for Napoleon in 1796. These state-of-the-art forts were designed to “keep the French out and the nationalists down” and in 1848 they were hugely successful in the latter 21

It is worth remembering that the Italian nationalists were the only imperial minority completely set on secession from the empire. The independence of the Kingdom of Sardinia, which had embraced the nationalist cause, meant nationalists within the

19 Mitchell p. 241

20

21

Ibid p. 242

Ibid p. 246-247

empire could vocally call upon an outside power to liberate them, knowing that Sardinia would have no reservations.

With this in mind, it is clear the Italians posed a serious threat to both the general Habsburg position in Italy, and also the concern that if they succeeded, copycat revolutions might break out in the not-already-revolting parts of the empire. It was therefore vital that Austria maintained its position in Italy and put the nationalists down.

One of Austria’s general strategies in dealing with the 1848 insurgents was to separate the rebels and deal with the weakest first before moving onto the stronger foes. The stronger forces in Italy and Hungary would be preoccupied with sieging the strong internal fortresses, buying time for the army to deal with the Czechs and other more minor rebels before being freed up to combat the main threats. This strategy was by and large a success and was the main strategic reason Austria survived the revolutionary wave. 22 The success of this strategy can be clearly seen in Italy. After the revolts in Milan and Venice, Radetzky retreated to the safety of the quadrilateral, giving his army the chance to regroup and recover before counterattacking to take back control of Lombardy-Venetia. The Italian armies had no chance of taking control of all four forts, which were well equipped with up-to-date weaponry, as they were not backed by a foreign power such as France, although they did take control of Peschiera. Once Radetzky counterattacked at the Battle of Custoza on July 24th, he was able to defeat a numerically superior Italian army, showing the strength of the quadrilateral in maintaining Habsburg presence in Italy. Indeed, Austria would only be pushed back from Italy in 1866 due to diplomatic failure, not due to military defeat.

With the Italian forces crushed, Radetzky and Windischgrätz could turn East and South respectively to help deal with the largest threat of all, the Hungarians.

A Hungarian Rhapsody

As part of the widespread instability in the wake of the revolt in Vienna, Hungarian liberal and nationalist revolutionaries, who had conducted an uprising in Pest were granted a constitution by Ferdinand in April 1848. These “April laws” established a separate Hungarian government responsible for the entire administration of the Kingdom of Hungary including financial and foreign policy. Whilst the emperor and his advisors hopelessly insisted on an inseparable bond between Austria and Hungary, this existed in name only, and by April Hungary was de facto an independent nation, exercising its independence by refusing to assist Austria in pushing back the Italians. Half of the empire had disintegrated on the emperor’s pen stroke.

However, for the same reason that Hungary had risen up in the first place, nationalism was also an inherent weakness in the burgeoning state. In 1848, Hungary administered far more land than they do today, which meant significant Slovak, Serb, Romanian and German minorities came under the administration of the Hungarian nationalists. None of these ethnic groups preferred the openly nationalist Hungarian government to the blatantly multiethnic Austrian Empire, and many had nationalist movements of their own which then came into conflict with the irredentist Hungarians, thus weakening the 22 Mitchell

internal position of the revolutionaries from the offset with a second, racial war against the Serbs, Romanians etc. ensuing at the same time as the war to maintain their independence. 23 This nationalist infighting only served to strengthen the Habsburg army, in reality the only consistent governing force in this period. 24

Nonetheless, with the immediacy of the revolts in Bohemia and Italy, the Habsburg generals were resigned to relying on the fortresses in Hungary to buy time. To the credit of the fortification system this worked, with the fortress at Arad holding out for 270 days and the one in Timişoara for 59 days, furthering Habsburg strength. 25

It is here that we must introduce the third of the three generals mentioned earlier, that being Josip Jelačić As the Ban 26of Croatia he had witnessed an increasingly nationalist Hungarian administration begin to assert itself by enforcing the establishment of the Hungarian language as the official language of the kingdom and became increasingly devoted to Croat nationalism and the preservation of Croat culture. Despite this, he was a loyal Habsburg citizen, high up in the chain of command. This may seem unusual due to his nationalist leanings, but it is worth noting that he did not wish for autonomy from the entire Empire but merely autonomy from Hungary, content to be under the rule of the Habsburgs as an equal to the Hungarians. This type of nationalism was far more palatable to the Habsburg authorities, as it contributed to the image they were trying to build of the empire as a pan-European state, and they encouraged it through methods such as the promotion of Jelačić.

The first sign of conflict between the Habsburg army and the Hungarian state came in September of 1848 and it was over the issue of Croatia. The new Hungarian Diet 27 had abolished the region’s already marginal autonomy and subsumed it into the Hungarian lands while at the same time the administrators in Vienna and the Croatian Diet itself still believed in its existence. The restoration of Jelačić to his office on September 4 “was an open declaration of war with Hungary” 28, and he began his invasion a week later. It is here that the facets of Habsburg grand strategy: a strong military tradition, wellequipped fortifications, and a “divide-and-conquer” mindset, converge, resulting in the total destruction of the Hungarian revolutionaries. Windischgrätz and Radetzky met up with Jelačić’s army, which had been routed by the Hungarians, outside of Vienna. The imperial capital had been in a state of upheaval since Metternich’s overthrowal, and the student revolutionaries, sympathising with the Hungarians, began a full-scale uprising against the generals on 26 October, invading the war ministry and lynching the Minister for War, Count Latour. This provided the generals all the incentive they needed to regain control, with Windischgrätz subjecting the city to his tried and tested tactic of artillery barrage. By 30 October, all resistance had been crushed, and the generals were again in control of Vienna. It is here that Windischgrätz’s conservatism comes into play, as he abhorred Ferdinand’s liberal streak. The triumvirate agreed, with the cooperation

25

26

of the new minister-president Felix zu Schwarzenberg and Archduchess Sophie, to force Ferdinand to abdicate in favour of his 18-year-old nephew Franz Joseph. This momentous decision would decide the fate of the Habsburg empire, as Franz Joseph would go on to rule for nearly 68 years, a rule characterised by reactionism, resisting constitutionalism and much needed internal reforms to hold back the tide of nationalism. 29

The final blow to the Hungarian revolution was the sound of 200000 Russian troops marching across the border in early 1849. Franz Joseph had called upon the Holy Alliance and Tsar Nicholas, somewhat bizarrely unaffected by the revolutionary wave, answered, agreeing to help put down the revolution. 30

The Hungarian armies had their fair share of victories against the Habsburg army in late 1848 and early 1849, but none were decisive, and the Russian intervention meant that by August, the Hungarian army officially surrendered at the town of Világos (now Şiria), thus ending the revolutions of 1848.

Reflections on the brink of destruction

On the surface, the revolutions of 1848 look like a failure of the Metternich system. After all, one of the key aims of the Congress of Vienna was to fashion a system which would systematically put down any revolution and yet in 1848 the governments of France, Austria, Hungary, Denmark and several German and Italian states were rocked by the revolutionary waves and in some instances completely replaced. It could be argued that Metternich’s favouring of legitimacy and conservatism had completely fallen apart.

However, despite the tempestuousness and bloodshed of the years 1848-1849, were there any substantial liberal or nationalist gains? In the case of the Habsburg Empire, it is hard to argue that there were. The revolutionary governments in Vienna established between March and November had been unabashed failures, and the sympathetic Ferdinand had been replaced by the conservative Franz Joseph. By the middle of 1849, Austria projected the Metternichian ideals of legitimacy and the status quo more strongly than it had done since Ferdinand first took the throne in 1835.

And to what extent had the balance of power in Europe been disturbed? Despite the upheaval there were remarkably few border changes in 1848. France had undergone a significant revolution, but the foreign policy of the Second French Republic did not resemble the expansionist ideological fervour of the First Republic of the 1790s. The attempt to unify the German states had been thwarted largely because of infighting about what a German Empire would look like. Italy was still fractured as Sardinia’s bolt for national leadership had been defeated by Radetzky. Meanwhile Austria, despite being fractured and practically dissolved for a year and a half, had regained its rebelling territories and its previous position of power. It cannot be argued that the balance-ofpower system had fallen apart.

So, while 1848 was undoubtedly a challenge to the Metternich system it was not fatal to it. Indeed, the greatest measure of Metternich’s legacy can be seen in what did not

29 Rady p. 252-253

30 Mitchell p.253

happen during this period. None of Metternich’s fears (renewed conflict with France, the overrunning of Europe by revolutionary forces, the accession of Prussia to a predominant position in Germany) came to pass. The only fear that could be said to have been realised was the incursion of Russia into Austrian territory, but this was at the behest of the Austrian Emperor and under the Metternichian guise of the Holy Alliance. Russia could not claim a position of overwhelming superiority here as in the mind of Franz Joseph, Russia was simply doing Austria a service in the name of cooperation. 31

Austria would survive the next 70 years as a great power, with 1848 being its most frightening test up until 1914, but the second half of the century would nonetheless see Austria’s decline and eventual eclipse in the European arena

The perils of neutrality

The position of the Austrian Empire in the Crimean war remains one of the most interesting tales of neutrality from the 19th century. Torn between self-interest and loyalty, Vienna opted for an uncomfortable compromise that, whilst not totally inept, helped set the stage for the great disasters over the following decade.

The “Eastern Question” developed in European diplomatic discourse in the 19th century to deal with the status of the ailing Ottoman Empire, stagnant since the middle of the 18th century. “The sick man of Europe” could no longer effectively fight for itself and its fate was due to be decided by the surrogates of the great power system.

Russia was the great power who could potentially benefit most from the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, as the Ottomans still had control of most of the Balkans, from Bosnia to Thrace. Russia had already gone to war with the Ottomans in 1828, ostensibly to support the Greeks in their war of independence, but in the process gaining control of the Danube delta and pushing the Turks out of the Sea of Azov, and the Caucasus. Now in 1853 Russian strategy hinged on total dominance of the Balkans, even the potential occupation of Istanbul, hoping to open up the strategic chokepoint of the Dardanelles so that Russia could finally have access to a warm water port with direct access to the main trade routes in the Mediterranean

It is already possible to see the significant problems Austria faced during this crisis. Had it been the 18th century, Russia would have likely invaded the Ottoman Empire under the justification of Raison d’État and no one would intervene (as no country would feasibly ally the Ottomans). However, under Metternich’s system (who was still alive at this point, having returned to Vienna in 1849), this justification would not suffice, as it would cause an untenable destabilisation of the balance-of-power, making Russia far too powerful for such a system. This was in the minds of Great Britain, France and Sardinia when they decided on intervention in the conflict. This was also on Austria’s mind, but it was a significantly harder situation to manage due to the Holy Alliance. When Russia helped Austria put down the Hungarians in 1849, the Habsburgs were considered in debt to the Romanovs and during the Crimean Crisis, Tsar Nicholas I expected unconditional Austrian support.

31 Ibid p. 255

Looking back at the Congress of Vienna and the buffer zones created to bolster the Austrian position in Europe, we can see these areas coming increasingly under threat as the 19th century wore on. Congress Poland, originally designed as a highly autonomous organ of the Russian Empire, had lost its autonomy after an uprising in 1830, and in 1853, in the lead-up to the Crimean war, Russia occupied the Danubian principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia, which make up part of modern-day Romania. This created numerous problems for Austria. On the one hand it effectively doubled the already overstretched border zone between Austria and Russia, and it gave Russia control over the mouth of the Danube River, vital for Austrian trade and unity. In addition, by the middle of the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire was effectively a buffer state for Austria too, as it stopped independent nationalist states such as Serbia or Bulgaria from being established which would inevitably be formed under the Russian pan-Slavic influence 32 The Austrian policy was therefore to avoid war and avoid siding with anyone at all costs. Fighting against the Russians would mean the main theatre of war would move to the Austrian province of Galicia, undoubtedly the worst-case scenario, but fighting alongside with the Russians would mean alienating the Western powers and fighting for Russian dominance in the Balkans. Peace was the only strategy that left Austria stable.

Despite Austrian attempts at mediation, relations quickly broke down and by October 1853 war had been declared. Austria continued to negotiate with the Russians, suggesting that a limited war with no change of territory would be sufficient for Austrian neutrality but Nicholas would not sacrifice his aims. Thus, the Austrians looked West, and diplomatically supported the French and British for the remainder of the war, in the meantime occupying the Danubian principalities once Russia withdrew in 1854. However, Austria’s prevarication and lack of commitment to a war which would almost certainly have bankrupted it meant that the West did not see Austria as anything more than an unreliable, oppressive and antiquated regime. Thus, the Austrians were friendless at the Congress of Paris in 1856, which concluded the war

The position of not taking a side thereby making everyone dislike you is a classic political blunder but in the case of Austria in the Crimean War it is even today difficult to decisively advocate for Austria having taken either side. A. J. P. Taylor saw alignment with the West as the only sensible option, since geopolitically speaking it would have neutered Russia’s advance into the Austrian sphere of influence in the Balkans and given Austria a stable foundation for a realignment with the Western powers, who were in the midst of the Industrial Revolution and an economic boom. While a war in Galicia was not in Austria’s best interests, if it was fought in 1853 it would have been in far more favourable circumstances than it was eventually fought in 1914. 33 However, such a course would invariably have resulted in a need for liberalisation in the Habsburg Empire, and the unwavering Western support for Italian unification would have meant Austria giving up Lombardy and Venetia, two of the Empire’s richest provinces. In addition, liberalisation was simply anathema to the young Franz Joseph, adamant on remaining as an autocrat.

32 Mitchell p.269

33 Taylor p. 91-92

On the other hand, the argument for alignment with Russia is even more preposterous Although Russia was prepared to divide the Balkans into direct Austrian and Russian spheres of influence, this would not have been particularly useful to Austria as with its already tenuous multi-ethnic nature, further expansion would hardly have helped. The status quo with the Ottoman buffer was a more stable situation. In addition, the gains Russia would have made would have meant Austria’s ultimate eclipse in the region and it is difficult to see an alliance between the two lasting more than a few years. While Austria and Russia could be friends everywhere else, in the East, they were enemies. In addition, Austria would have alienated itself from the other great powers even more than it did in its canonical course of action.

So, while Austria sat friendless at the Congress of Paris, there was nonetheless a silver lining for the Habsburgs. Firstly, the fact that the outcome of the war was being decided at a Vienna-esque conference is surely an indication of the lasting legacy of the Metternich system, as all the outstanding issues surrounding the conflict were resolved in a single congress and a single treaty. There would be no other war involving more than two great powers until 1914 However, as a whole, the experience of the Crimean War had fundamentally shifted European diplomacy for the first time since the Congress of Vienna, as the shared values created by Metternich in 1815 began to be replaced by the power politics that would culminate in the First World War.

This would prove to be catastrophic for Austria, who because of the Crimean War had to sacrifice the self-restraining Holy Alliance, liberating Russia and Prussia to pursue their own undiluted national interests. The principle of legitimacy, which had guided Europe for 40 years, was being challenged by upstart leaders like Napoleon III and Bismarck and the concept of the unity of conservative interests had thereby disintegrated. Henceforth diplomacy would rely more on naked power than on shared values. 34

But for now, Austria was stable and had not sacrificed its positions in Italy, Germany or the Balkans, nor had any of its buffer states been compromised. Perhaps that was enough.

The Second Italian War of Independence

Despite its castigation in 1848, Italian nationalist ambitions for unification were not hampered. 11 years later, the Kingdom of Sardinia would take its second shot against the Habsburg Empire, this time with far more success.

The Austrian position in Italy while intended as both compensation and a secure buffer zone for Austria at the Congress of Vienna, had actually placed the empire in the position of administering a security liability and source of conflict rather than “an intermediary body to act as a shock absorber in Great Power politics.” 35 While Lombardy and Venetia were undoubtedly some of the richest provinces of the empire, by the 1850s, Austria was collecting a quarter of the empire’s tax revenue from the Italian

34 Kissinger, p. 94

35 Mitchell, p. 262

lands alone 36 , they were consistently the most under-threat areas of the empire and the people there were completely resigned to refusing accommodation with Austria.

In addition, the aim of the territories to act as a buffer became less convincing as the century progressed, as it became clear that France would no longer pose a similar threat to during Napoleon’s rule. This meant that the Italian population, who had previously been more afraid of France due to centuries of French incursions, now became more wary of Austria, further adding to the issues in the region. 37

Thus the events in 1859 represented the first of the two-part Austrian defeat in Italy Diplomatically isolated, there was nothing to dissuade the French emperor Napoleon III, a virulent supporter of Italian unification since his youth, to urge the Sardinians into mobilisation. Austria actually initiated the war by sending an ultimatum (just as they would do with even more disastrous results 55 years later) demanding that Sardinia disengage, which was promptly ignored. Unfortunately for Austria, which economically lagged far behind the industrialising French, there was practically no hope for the Habsburg army aside from the prospect of a quick circuitous victory, much as Radetzky had achieved in similar circumstances in 1848. However, a quick look at military spending in this period shows the Austrian inferiority, as combined French-Italian spending was 2.5 times more than Austrian 38As a result, the war lasted only a little more than 2 months, with the only major battle being the Battle of Solferino In the Armistice of Villafranca Austria was forced to cede Lombardy, although they obstinately refused to hand it to Sardinia, instead ceding to France who subsequently handed it to the Italians two days later. Sardinia also gained control over the duchies of Tuscany, Parma and Modena which had previously been under Habsburg domination.

The novel The Radetzky March, written in 1932 by the Jewish-Austrian author Joseph Roth, is an allegory for the decline and fall of the Austrian Empire, as it follows three generations of the Austrian bourgeoisie. It is telling that the novel begins in 1859 at the Battle of Solferino, indicating the belief that this was the beginning of Austria’s decisive and ultimate fall.

The Brothers War

Austria’s relations with Prussia in the 19th century arguably went through the largest variation of any of Austria’s foreign relations. Emerging from a particularly violent rivalry in the 18th century, the two states were forced into an uneasy alliance because of Napoleon’s threat. However, as we have seen, at the Congress of Vienna, Metternich sought to curb Prussia’s rise to the top. While Prussia did receive much of the economically bounteous Rhineland, this was separated from the main body of the state and the kingdom as a whole was confined within the German Confederation which was expressly designed to promote German unity (against foreign aggressors) but forestall German union. In these aims it was largely successful.

36

37 Mitchell, p. 263

38 Mitchell, p. 281

Prussia and Austria were also aligned under the auspices of the Holy Alliance, which among other things was designed to inhibit Prussia’s ambitions through the Austrian promotion of collective security. However, by the 1860s this alliance had broken down, and it is at this point that Otto von Bismarck enters the scene.

Bismarck first came to a national prominence as Minister President of Prussia in 1862, having spent the last 14 years as a conservative opponent to the German liberal strain that rose up in revolution in 1848. Despite his conservatism, he was a revolutionary on the diplomatic scene, being an avowed opponent of the Metternich system which he (rightly) interpreted as hindering Prussia from pursuing its national mission of unifying all Germans. Bismarck developed the theory of Realpolitik, essentially a return to the power politics of the 18th century relying solely on the consideration of national interest in international conduct. Since that point, international relations theory developed into two major schools of thought: the liberal school (somewhat ironically developed from Metternich’s system), and the realist school (developed from the theories of Raison d’État and subsequently Realpolitik 39

It is therefore easy to see how the Austro-Prussian rivalry developed over time. Bismarck is quoted as saying “Germany is too small for the two of us … Austria is the only state against which we can make a permanent gain” 40 (i.e. control of Germany as a whole.) Within five years of his appointment as minister-president, he severed Austria from its historical position in Germany, sending the empire to a second-rate position in Europe.

The Austro-Prussian war was undoubtedly the most tragic event of the 19th century for the Habsburg Empire and spelled its downfall as a nation. After just eight short weeks Prussia defeated the Austrian-led faction of the German Confederation, with the key moment being the Battle of Königgrätz in July 1866. In addition, Bismarck demonstrated his commitment to Realpolitik by allying with the Italians, who shared Prussia’s national interest in wanting to take something from Austria. At the Treaty of Vienna, the province of Venetia was ceded to Italy and Austria’s “Italian mission” was fundamentally destroyed.

Bismarck conceded a liberal peace to Austria, largely because he did not want to ensure permanent Austrian hostility and drive them to rapprochement with France or Russia. Nonetheless this included Austria’s total exclusion from German affairs and the dissolution of the German Confederation, which had always been a tool for Austrian power. Despite his leniency, Bismarck had destroyed Austria’s “German mission” too, leaving the empire in a state of stasis and decline.

In less than twenty years, Franz Joseph and his advisors had lost Lombardy, Venice and the German Confederation. The Austrian Empire had shrunk back into Central Europe and would largely stay there until its demise in 1918. The Metternich system had been replaced and by extension any conduit for Austrian power. 41

39 Kissinger p. 121-122

40 Ibid p. 133

41 Rady p.263

Conclusion

After its humiliation to Prussia in 1866, Austria would also have an internal Hungarian crisis to deal with a year later. Seizing upon a moment of Austrian weakness, Hungarian officials declared a tax strike and there were rumours of insurrection. The Habsburg rulers had no choice but to yield to a compromise. The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 separated the Kingdom of Hungary from the Austrian Empire, with the only enforced cooperation between the two states being in the realms of diplomacy and defence. While the two halves were still considered “inseparable and indivisible”, in most respects they were independent of each other, including everything from separate coronations of the emperor to athletes at the Olympic Games competing separately. The simple majesty of the Austrian Empire was gone; it was now known as the awkwardly named Austro-Hungarian empire. 42 This entity would drudge on for another 51 years, most of them with Franz Joseph at the helm. While the empire would maintain a prominent role in European diplomacy, even gaining territory through the acquisition of Bosnia in 1878, it would never regain the dominant role it held in the first half of the century and would ultimately succumb to the brutality of nationalism and Realpolitik in the First World War.

How then can we assess the success of the foreign policy of the Austrian Empire in the 19th century? Let us start by looking favourably. The Congress of Vienna was an unbridled success for the Habsburg Empire and created the mechanisms which were to secure a primary position for Austria among the great powers of Europe in the 19th century. Metternich designed a system based on alliance networks, collective ideals and security all to Austria’s benefit. Not only did this system arguably make the 19th century the most peaceful century (at least for Europe) in recorded history, its influence on the practice of diplomacy can still be felt today, as collective security is today remarkably significant, with organisations like NATO purposefully dedicated to it. In addition, other Austrian practices such as its defensive policies, and their attempts to subjugate nationalists certainly allowed it to extend its lifespan into the 20th century.

However, the middle of the 19th century presented some undeniably catastrophic failures in Austrian diplomacy The most severe failure was its isolation among the great powers, largely created by the Crimean war. With the support of Russia or Prussia, the 1859 crisis could have looked very different, and the support of Russia, or even Great Britain (usually aloof from European affairs, but not resolutely against being involved) could have averted the disaster in 1866, resulting in the maintenance of Austria’s position in Europe. It is this inflexibility in diplomacy that can be blamed most for the loss of Austria’s primary position in Europe. In the end, it was forced out of Italy, lost its position in Germany to Prussia, and even had to concede internally to Hungarian pressure, making the Austro-Hungarian empire a shell of its former self. 43

The Austrian empire is so fascinating because of its ability to respond to its enemies despite all odds (we see this in 1848) and despite constantly seeming on the verge of collapse, to always pull through. Indeed, it is somewhat surprising that the final end of

42 Rady p. 266

43 Mitchell p. 302-303

the Empire in 1918 was because of a long and managed decline rather than a swift overthrowal such as what could have occurred in 1848 or in 1866 had Bismarck wished for it. The Habsburg Empire was a bizarre aberration of a world power: a monarchy of a made-up Empire, a multicultural powerhouse whose strengths were also its greatest weaknesses, a state that lost war after war but somehow managed to resurface each time. Even its decline in the 1800s was postponed to the second half of the century. If we return to the concept of an interstitial power posited in the introduction, it is difficult to see in many cases how Habsburg conduct in the 19th century could have been improved. The Austrian dissolution seemed a foregone conclusion in 1812, 1848, 1859 and 1866, but it survived each of these crises until its final fall in 1918. Perhaps this is its greatest success.

(Final word count 9601 words)

Bibliography:

• Wess Mitchell, Aaron The Grand Strategy of the Habsburg Empire Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018

• Rady, Martyn. The Habsburgs: The Rise and Fall of a World Power. London: Penguin Random House, 2020

• Kissinger, Henry. Diplomacy. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994

• Winder, Simon. Danubia: A Personal History of Habsburg Europe. London: Picador, 2013

• Taylor, Alan John Percivale. The Habsburg Monarchy 1809-1918. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1948

• Kann, Robert Adolf. A History of the Habsburg Empire, 1526-1918. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1980

AN EXPLORATION INTO CONCEPTS

AND APPLICATIONS OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE (AI)

BY AVI BHATT(Fifth Year, HELP Level 3, Supervisor: Mrs T Scorer)

An Explora�on into Concepts and Applica�ons of Ar�ficial Intelligence (AI)

By Avi BhatLevel 3 HELP Project

Supervisor: Mrs. Scorer

1.1 Introduc�on

Ar�ficial Intelligence (AI) is a term for any computer system given human-like intelligence. It is currently shaping the future of computer science and almost every aspect of our lives, anywhere from in finance to engineering to health to crea�ve wri�ng.

This project aims to give the reader a comprehensive understanding of what will almost certainly play a significant role in their lives, regardless of who they are and whether they realise it or not.

Some vital AI terminology:

Machine Learning (ML) – A subset of AI in which computers learn from experiences without explicit human instruc�on. This involves looking at data, recognising pa�erns, and applying pa�erns to predict new data.

Deep Learning – A subset of ML where learning is completed by algorithms called neural networks, that mimic the human brain.

Model – The algorithm that is responsible for how the computer learns. There are several different types of models, and they all have different applica�ons where they give different levels of success; they can be simple or complex.

1.2 Some Applica�ons of AI

All forms of AI can be split into three parts:

Weak AI (aka Ar�ficial Narrow Intelligence) – Ar�ficial Intelligence that enables a computer to carry out a specific task. This accounts for all AI applica�ons that exist now, including but not limited to:

- Trend Forecas�ng, that can be used to predict anything from investment pa�erns to success of new medicine to future effects of climate change.

- Recommenda�on Algorithms that are used in almost every service-offering online pla�orm, including Google Search, YouTube, Amazon, Ne�lix, Instagram, Facebook, Spo�fy…the list goes on.

- Automa�ng Tasks e.g., recognising when sales for an online store are low, and then pu�ng appropriate items on sale

- Op�misa�on algorithms that look for the most efficient solu�ons to problems, such as the best business strategy or the best city design to reduce traffic.

- Genera�ve AI that can create mediums such as text (literature), images (artwork), and sound (music).

- Cybersecurity using AI to protect computers and users, to recognise characteris�cs of malware/ scam emails so following necessary ac�ons can occur.

- Informa�on Retrieval (IR) Systems that organise, store, retrieve and evaluate informa�on in a computer and require AI at each step – this includes search engines.

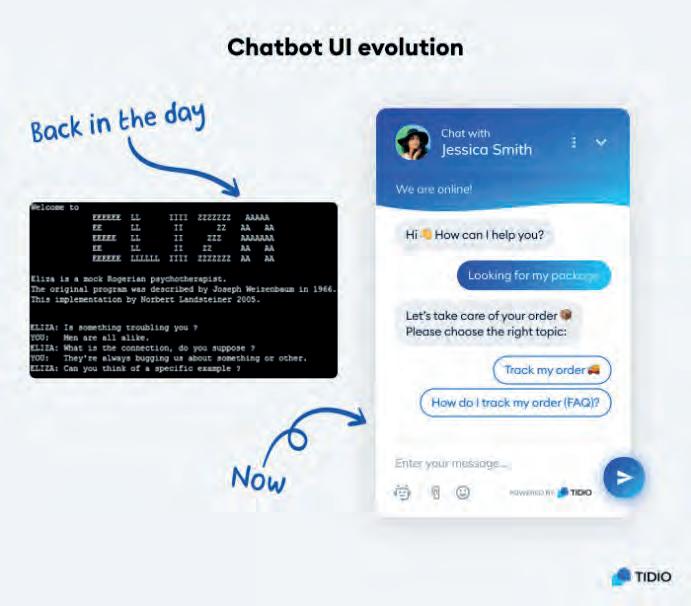

- Chatbots that allow users to navigate websites through standard English dialogue.

- Voice Assistants that are trained to carry out ac�ons verbally, such as Alexa, Siri, Bixby, Google Home, Cortana, etc…

- Game Development from crea�ng constantly different levels to making complex game bots that mimic a real human player.

- Image Recogni�on, used for conver�ng handwri�ng to computer text, and comple�ng facial recogni�on whilst accessing smartphones and laptops.

- Cruise Control and Autopilot features in several road vehicles.

- Natural Language Processing (NLP) – AI that involves computers interpre�ng human language, used in chatbots, voice assistants, translators, spellcheckers.

Above shows some men�oned AI uses, as follows (listed le� to right, top to bo�om): chatbots, chess bots, city planning, cybersecurity, Spo�fy, generated art, Amazon Alexa, Instagram

Ar�ficial General Intelligence (AGI) – Ar�ficial Intelligence that results in computers having general human-like thinking, across any field. This has not been achieved yet, but two examples are not far off:

- IBM Watson is a ques�on answering computer system, that a�empts to answer ques�ons posed in English across any topic.

- ChatGPT is also a ques�on answering computer system, but can generate content and has generally greater understanding accuracy than IBM Watson.

Ar�ficial Super Intelligence – AI that means computer systems/ machines have greater than human intelligence. This certainly does not exist yet, and has been idolised by science fic�on as a means for ‘the end of the human race’ through some unstoppable evil machine. Whilst mainly unreasonable, concerns are rooted in the vast future poten�al of AI.

1.3 The Simple Process

All Ar�ficial Intelligence applica�ons are slightly different, yet they require the same basic process as follows:

1. Training from the data. Models in AI learn by viewing ‘training’ data and recognising the paterns in it. The model remembers the paterns it has viewed.

2. Tes�ng the data. The model is then shown new pieces of unseen ‘tes�ng’ data, which are close matches to the training data By applying the paterns it previously analysed to the new data, it can make a predic�on for what to do with the new data.

3. Humans improving the model based on how accurate the model’s predic�ons were.

For example, a chatbot is being designed so that it can help visitors to a website’s homepage. The model that the chatbot uses must first be trained. Therefore, the model is shown examples of frequently asked ques�ons, and the correct response:

NB: This would be several entries long.

And a�er recognising the paterns in the training data it can then be tested to see if it learned the paterns correctly:

The model must use the paterns it learnt to predict what the outcomes of the tes�ng data are. It makes its predic�ons before the answers to the tes�ng data are revealed:

The accuracy of the model’s results can then be calculated, and the model improved to get beter results.

Addi�onal points:

• The original data is normally found as one part. It is then split into training and tes�ng data, where the model sees all the training data but only the tes�ng data inputs. Programmers control this split, normally le�ng 70% of the data go for training and 30% for tes�ng.

• Some�mes, the data can be split into three categories, with an extra valida�on data category. This is like tes�ng data, but the accuracy of the model is only noted by the computer, so it can ‘learn from its mistakes’. Valida�on data is not used to evaluate the model by humans; it is just another way of the model learning.

• Above, supervised training was carried out, where the model was shown some correct input and output data with assigned labels. Different models can be used for unsupervised training, where the model is not told about exis�ng data rela�onships.

Models are fundamental to AI and knowing when to use which one(s) is important.

Image source: htps://editor.analy�csvidhya.com/uploads/375512.jpg

2.1 Introduc�on

Linear regression is a ML model. It is widely used in explaining why things occurred, predic�ng future values, and deciding which future approaches are best for different situa�ons. Understanding it also reveals many fundamental concepts within more complex models. Before reading this, it is important to know how equa�ons of straight lines are represented (y=mx+c).

Linear regression operates using a line of best fit, that aligns to exis�ng data represented on a graph, before being used to predict unknown values. This approach is some�mes carried out manually in sciences (see below), but a computer has no error in best fi�ng a line to match data and can return predicted values faster.

2.2 How to fit a line to data

Once the computer has received tes�ng data, it must find the line that best represents this data, in a decisive way (unlike the subjec�ve manual method). This is done using a cost func�on; the func�on returns the op�mum gradient and y-intercept for the best fit line. The ‘Mean Squared Error ’ (MSE) cost func�on is widely used for this:

• Errors (aka residuals) of data are the distances between points and their predicted values:

• The MSE func�on takes the error for a data point, squares it (to make sure there are no nega�ve errors), and repeats for all data points.

• It then divides this sum by the number of data points, leaving the average squared error for the data.

Mathema�cally, the MSE func�on can be shown as:

Error (actual – predicted)

Mean

Squared

Minimising this value will mean that on average, the squared error for each data point is smaller, and therefore the error produced by the en�re line is smaller. So, various posi�ons of the best fit line are tried, and the one that produces the smallest MSE is the true line of best fit:

2.3a Evalua�ng the model – RMSE and RSE

The simplest way of evalua�ng how well the model (complete with its true best fit line) would work is to find the square root of the MSE func�on for its line. Intui�vely, this is called the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE).

However, it has limita�ons because different datasets have different units:

Clearly, a normalised measurement is needed, that is consistent with mul�ple units. This is achieved by adap�ng RMSE slightly to accommodate degrees of freedom:

NB: Residual Sum of Squares (RSS) is the sum of squared errors.

2.3b Evalua�ng the model – R2

R2 is another normalised evalua�on metric. It is derived from R, a correla�on metric, where R=1 is the maximum posi�ve correla�on, R=-1 is the maximum nega�ve correla�on, and R=0 is no correla�on. However, R is not intui�ve:

For R:

For R2 however:

If R = 0.1 it is unclear that this is four �mes worse that R = 0.2

(This is because R = 0.1 has R2 = 0.01, and R = 0.2 has R2 = 0.04)

If R2 = 0.01, this is four �mes worse than R2 = 0.04 (More intui�ve)

So how is R2 calculated?

• Varia�on around the mean of a dataset is the largest possible varia�on. Varia�on around the line is hopefully much smaller:

• So, to find how well the line of best fit aligns to the data as a percentage, the following formula is used:

• By factorising out the var(mean), the formula can also be shown as follows:

2.4 What linear evalua�on metrics show

A high R2 value shows that data points and the line of best fit align very well, and that the linear rela�onship is very strong. When plo�ng how hours of sleep impacts height, for example, if R2 =1, hours of sleep impacts 100% of the data varia�on (i.e., it is the only factor determining height). The line of best fit goes through all the data points because no other factor apart from hours of sleep impacts height:

On the other hand, if values of R2 are low, it indicates that the independent variables do not accurately explain the dependent variable. Maybe there are other variables that determine height which were not included, or hours of sleep is irrelevant towards sleep.

Hence, a low R2 value indicates that the AI model will not work very well, because the training data does not contain proper variables that affect outcomes.

For example, �me spent watching paint dry and height have no correla�on. If I asked a computer to tell me a person’s height based on the �me they spent watching paint dry, it will perform poorly. Beter training data must be found with relevant variables affec�ng height.

More about evalua�on metrics

Other methods of assessing a model include t-tests, f-tests, p-values, chi squared tests, ANOVA, etc.

These work in different scenarios depending on e.g., which variables are categoric or con�nuous, and all convey some hypothesis (is the straight line significant, is data explained by the dependent variables, etc.)

2.5 When to use linear regression

As previously men�oned, different models are used in different scenarios. Linear regression should be used only if:

• There is a linear relationship between the dependent and independent variable(s) – which is determined using the evalua�on metrics previously discussed

• Errors (aka residuals) should be random and not have contain any paterns. If there is no rela�onship between errors this is called autocorrelation:

• There is a normal distribution of errors (there are not any anomalies):

Image source: htps://editor.analy�csvidhya.com/uploads/85436Screenshot_3.jpg

• Error terms have equal variance around the line of best fit (homoscedasticity not heteroscedas�city):

2.6a Using linear regression in Python – Basketball Players

The aim of this project is to give the reader a comprehensive overview of how to use AI for themselves. This is through choosing which model is appropriate and then implemen�ng it. I will atempt this first with predic�ng weight of basketball players based on their height.

Link to source code: htps://colab.research.google.com/drive/1DDRA2IH8XI9_huNCtHpFtzB-HZ2NbpCv?usp=sharing

Note: To view the code through the above link, uploading the data manually is required.

Navigate to the menu on the right and click the buton in red (see right).

Upload this data file: players_stats_by_se ason_full_details.csv

Impor�ng Data and Libraries, Cleaning the Data

Visualising the Data

The line has R2 = 0.668 which is quite poor (hovering over the graph in the editor tells me this):

This produces R2 = 0.659 which is even worse! There is also some heteroscedas�city in the data. Hence, using skills from before, I concluded that this was a poor dataset for using linear regression

2.6b

Using linear regression in Python – Test Scores

I made my own dataset in Excel, to predict test scores based on hours revised. This should hopefully be more suitable for linear regression.

Link to source code: htps://colab.research.google.com/drive/1tHTHXdGe7GlGELcIwTlfOmx0dG7eyXTR?usp=sharing

Data (can be uploaded like before):

Impor�ng and Visualising Data

(R2 = 0.924 and there is no heteroscedas�city, good enough for linear regression)

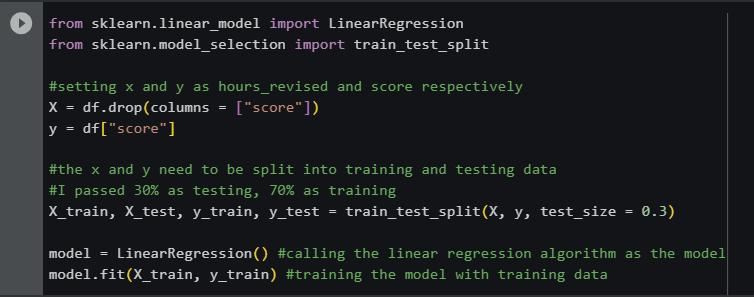

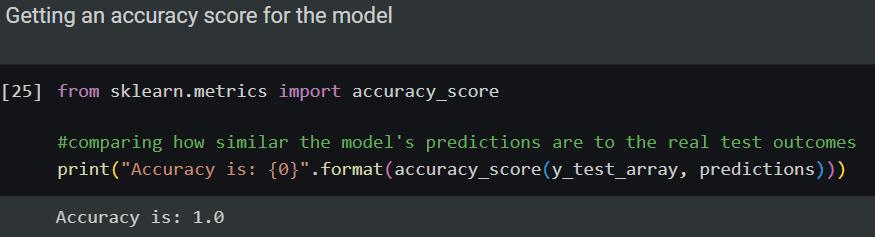

Spli�ng data into training and tes�ng sets, before training the model with training data:

Predic�ng Values with the Trained Model

Having seen that the computer performed well, I made the following user interac�on:

2.7a Considera�ons when using mul�ple variables (Mul�ple Linear Regression)

When using more and more dependent variables, some addi�onal factors must be considered before implemen�ng a linear model:

• Overfitting – adding too many variables means that the model memorises the exact training data too well and loses the ability to predict unknown situa�ons. This introduces high variance (discussed more later).

• Variables must be relevant – too many irrelevant variables can confuse the model.

• No multicollinearity – all variables should be for dis�nct quan��es. If too many correspond to the same thing, e.g., 5 are about height, the model again gets confused.

2.7b Mul�ple Linear Regression in Python – Life Expectancy

I now used mul�ple variables to predict the life expectancy of different countries

Link to source code: htps://colab.research.google.com/drive/19oy82sVq8M6jEuxkZs0Rx2ldGC9gZh4a?usp=sharing

Data:

Impor�ng and Cleaning Data

• The data is too large because each country has mul�ple years of data

• Also, some columns are not numerical, so cannot be used to train linear regression models

• I will filter extra rows/columns out

Implemen�ng Linear Regression

The model performs decently, and can now predict life expectancy of a country, given 5 variables

3.1 Introduc�on