10 minute read

Introduction

INTRODUCTION

The relationship between death and architecture is one that predates to ancient times. Adolf Loos famously wrote “When we come across a mound in the wood, six feet long and three feet wide, raised in a pyramidal form by means of a spade, we become serious and something in us says: somebody lies buried here. This is architecture.”1 The grave engenders emotions of seriousness created by the construction of the mound, intentionally formed to mark a burial site, as it is the task of architecture to evoke emotions through the construction of a curated space. Adolf Loos was not alone in believing that architecture began with the burial site; historically, finding a place for the dead was as much a predecessor of town planning as designing burial sites was for architecture.

Advertisement

Presently, cities are entities with limited resources of land and this will only become more limited in the future. Thus, every city faces the dilemma of how to meet the demands of residents, corporations and future prospects with the limited funds and land they are in control of. An oversight that needs focus, is how to facilitate the land available to honour the dead? The way in which this question is resolved will represent the city and its residents.

In this dissertation I will research the lack of burial spaces in London. As cemetery experts have issued warnings over the impending burial crisis for decades that have largely been ignored. A study in 2013 by the BBC found that “Almost half of England’s cemeteries could run out of space within the next 20 years.”2. However, this crisis has already hit London as it is a city with finite availability of land in comparison to the rest of the UK. Many cemeteries within the boroughs of London have reached their capacity. Currently, the deceased are buried or cremated with the cremation rate in the UK being 78% as reported by the United Kingdom’s Cremation Society,3 surpassing traditional ground burials as the preferred method in Britain. This can be attributed to a shift in societal preferences on the freedom that is achieved through cremation in comparison to a burial that is bound to a location. Yet, London still prefers burials over cremation and this will be explored further in this dissertation.

To investigate social preferences for laying their loved ones to rest, the UK’s Funeral Guide website compared the costs of burials and cremations. The findings revealed that “The average cost of cremation in the U.K. is £823”, whereas “The average cost of burial in the U.K. is £1698.”4 Figure 1 Illustrates the regions in the UK and the average cost of cremation and burials. The results illustrate that London is amongst the cheapest regions for cremation and the most expensive in terms of burials in the UK.

(Heymann, 2011) Strange ways-Booth, 2013) (Progress of Cremation in the British Islands from 1885 to 2019, 2020) (UK Cremation & Burial Costs, 2020)

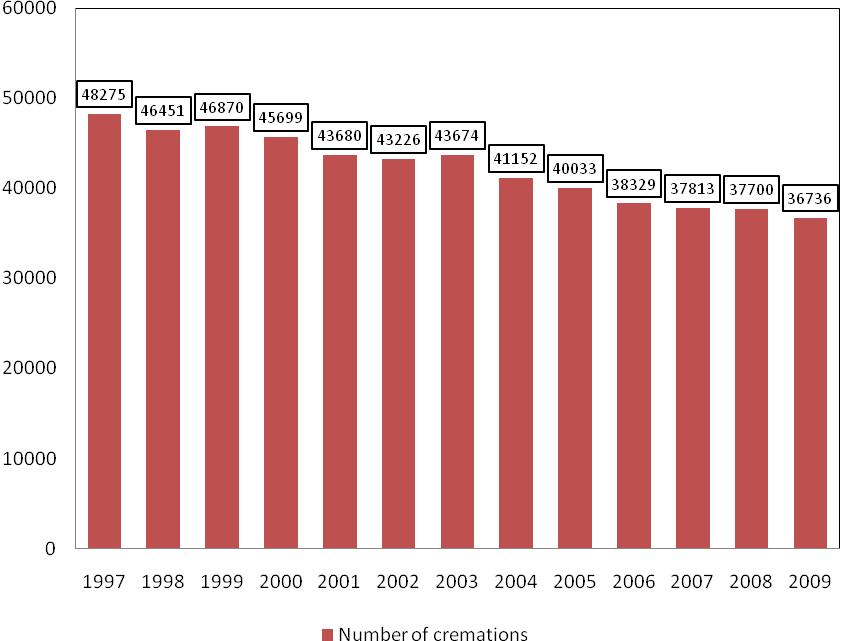

Figure 2.1: Decrease of cremations in London from 1997 to 2009 – “An Audit of London Burial Provision” 2011- Dr Julie Rugg and Nicholas Pleace

Figure 2.2: Stability of cremations in London from 2010 to 2019– Data collected from ‘The Cremation Society”- By Author

The figures incline drastically for burials within London, as the average cost is £4391, with the most expensive cemetery to be buried is at Highgate Cemetery costing £21975. Surprisingly, London is relatively cost sensitive for cremations, with the average cost being £755. “This is possibly because 63% of crematoriums in London are owned by local councils, rather than private providers.’’5 In addition, due the smaller footprint it has on the physical landscape of the city, local councils have a higher incentive for cremation opposed to burials to preserve the longevity of the cemeteries and to keep up the demands of the numbers of death, justifying it being a viable financial option for Londoners.

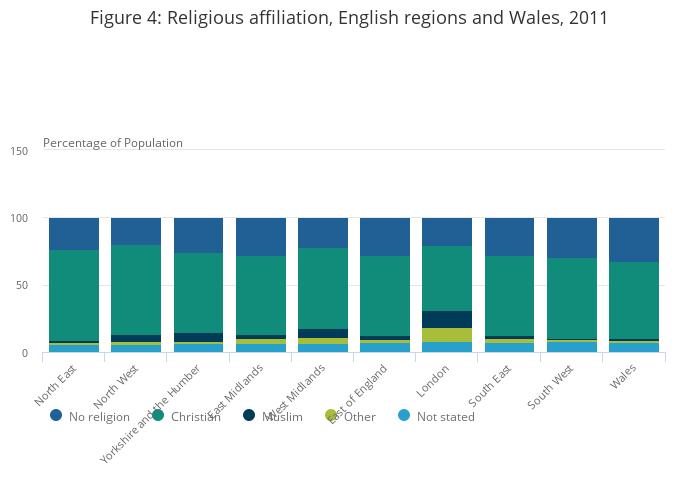

Despite a large number of Brits opting for cremations, the nation’s capital’s figures contradict these numbers, with more Londoners preferring burials. An extensive report by Dr Julie Rugg and Nicholas Pleace in 2011 titled “An Audit of London Burial Provision”, a report for the Greater London Authority, indicates that there is a reduced prevalence of cremations in London, Figure 2.1 and Figure 2.2. The graph illustrates a fall of 24% from 1997 to 2009 and it being stable from then on indicating “It may be the case that there was a growing preference amongst Londoners for burial.”6 The preference for burials may be explained by the vast conglomeration of different cultures and religions that exist in London compared to other areas of England. London is a city renowned for its cultural diversity and is often dubbed a “melting pot”. The Office of National Statistics (ONS) has provided information on the ethnicities across regions of England and Wales, Figure 3.1, and Figure 3.2, showing the religions across the same regions; results on the findings prove that no other region in the UK clusters a multiplicity of ethnic and religious backgrounds in a single location like London.

Figure 3.2: Areas of England and Wales by religion, Census 2011, ONS - Office of National Statistics

Figure 3.1: Areas of England and Wales by ethnicity, Census 2011, ONS - Office of National Statistics

Figure 4: London’s Population by Religious Affiliations 2019, ONS - Office of National Statistics

For many people in London, how their body is laid to rest is heavily influenced by their religion; according to the 2019 ‘Population by religious affiliations’ survey from the Office of National Statistics (ONS), Figure 4, London’s largest religious groups are comprised of Christianity, Islam, Hinduism and Judaism. Individuals who affiliate within these religious denominations follow different funerary rituals that dictate the method of laying their loved ones to rest.

The Londonist reports that in 2020, ‘The shifting ethnic landscape of London as these religious groups increased in number, has led to burial overtaking cremation in terms of popularity.’7 In this dissertation, I will study the ritualistic practices performed by the major religious groups in London; as a large percentage of the population isn’t religious, I will also study the funerary customs of a non-religious group called Humanist UK - comprised of people who are atheist and agnostic. The aim of this dissertation is to analyse which groups are open to sustainable solutions and how current customs could be adapted to create a more viable future for the city.

I am an architect who is interested in sustainability and the planning of cities, but I am also of Muslim faith who follows my religion’s method of honouring the dead. When London is planning on their chosen method of funerals for its future it must account for population growth, viral pandemics and a lack of burial space. As it is clear that ancient burial traditions cannot continue due to a lack of available land. The current dissertation argues that burial practices within religious groups would need to bend in favour for sustainable and pragmatic solutions to address issues facing London and cities across the world. In order to expand my knowledge of the topic, I have read extensive studies conducted in the field, particularly those by Dr. Julia Rugg on burial provisions in London. Rugg leads the University of York Cemetery Research Group. I will be referencing the pivotal research reports and articles that shed light on the burial crisis that currently faces the city.

I conducted an interview with Mohamed Omer, the regional lead of the National Burial Council. Like Dr. Julia Rugg, he is a chair member of the Ministry of Justice Burial and Cremation Advisory Group and a board member of Garden of Peace Cemetery. Similar to myself, Mohammed Omer is also a Muslim, a religion that holds value in traditional burial of the dead. Nevertheless, he is forthright on pragmatic solutions on the current issues involving the funerary industry.

James Stevens Curl’s book, ‘Death and Architecture’, presents a historical insight of the Victorian era solutions to London’s overcrowded churchyard burial grounds. It was a historic period that brought the current conditions of urban garden cemeteries to the city; also ushering reformation of burial practices and laws that are still in practice today.

Kensal Green Cemetery Forest Park Cemetery and Crematorium

Gardens of Peace - Five Oaks site Gardens of Peace - Elmbridge site

Through these readings I will explore the iconology and iconography of London’s cemeteries as the nineteenth century’s churchyards were facing a crisis that parallels the current issues in the funerary industry. I extrapolate pragmatic lessons from this era to question whether similar approaches can be made in current times. In order to analyse the current condition, I conducted primary research, surveying visits to case studies at cemeteries and crematoriums; these range from single faith groups to mixed faith groups. The burial and cremation grounds were representative of sites owned privately and others by local authorities. The case studies I visited were:

Kensal Green Cemetery – 1832 - Henry Edward

Kendall, (Public Municipal cemetery)

Forest Park Cemetery and Crematorium - SDA

Architects - 1995 (Private mixed-faith cemetery)

Garden of Peace – 2002- Austin-Smith: Lord

Architects, (Private Muslim cemetery)

Garden of Peace – 2015- Methodic Practice, (Private Muslim cemetery)

Old Bushey Cemetery – 1954 – Lewis, Solomon,

Kaye & Partners, (Private Jewish cemetery)

New Bushey Cemetery – 2017 – Waugh

Thistleton Architects, (Private Jewish cemetery) Figure 5 capitulate the case studies that would be discussed in the essay.

London is comprised of many religions that are polarising by nature. Traditional monotheistic religious groups from the Abrahamic faiths (Christian, Muslim and Judaism), polytheistic groups from he Sanskrit religions (Hinduism and Buddhism) and non-religious groups (Humanist comprising of Atheists and Agnostics). Each group has specific rituals regarding final disposition but have unifying elements within their practices. The nature of the topic branches out to interdisciplinary research of philosophy and religious teachings that form rituals for the rites of passage within differing groups. These would be referenced throughout as I examine how funerary practices could change. The current dissertation is divided into three parts: ‘The Ideal’ will investigate how the methods of final disposition are prescribed within the major denominations in London, noting the ritualistic rites of passage and where they take place. I will question whether these groups could adapt to or struggle with finding sustainable solutions within their funerary practices. ‘The Reality’ - this section will further investigate the contributing factors which have led to the current crisis in this sector. Finally, I will explore ‘The Future.’ This section consists of alternative choices for the funerary industry to fix the current crisis and provide a sustainable plan for the future. A sustainable attitude to death cannot be achieved without some religions becoming more flexible in their method of their funeral practices. These changes that I will be arguing for will range from conservative changes, such as alterations to legislation, whereas others would require more radical changes that embrace scientific developments in the funerary industry. As there is increasing demand placed on cities in terms of available land for both housing and corporations. Land is increasingly becoming a scarce commodity throughout the world, with major cities with high populations being at the forefront of the crisis. Thus, it is inevitable that a change in the funerary industry has to occur to accommodate this. Architecture, together with science, can find alternatives for the current crisis in reimagining the historical vernacular of cemeteries; in turn, changing the infrastructural planning of the city.