17 minute read

Chapter II Reality

CHAPTER II REALITY

The ideals of religious practices are not always a truthful representation of reality. Ordinarily, steps are taken prior to the rites of passage. In the United Kingdom, documents are required to obtain the body for the funeral. These documents are required by law to correctly register the death. Therefore, precede the religious customs of the rites of passage in the United Kingdom.

Advertisement

The ideals of death painted by faith customs only comes to realisation if one was fortunate in having particular circumstances favouring a quick release of the body. This is an example of how the realities of death do not always equate to the ideals. Whilst religious teachings primarily focused on the existential concerns for death, it neglects the reality and its physical impact to its surroundings.

This chapter will investigate the realities of cemeteries by looking into the particulars of the provisions currently available in London. I will do this by primarily referencing the research reports and interviews of Dr Julie Rugg. This will give an overview of the amount of space available whilst expressing the challenges that the funeral industry is dealing with this issue of land scarcity.

Having established in the previous chapter that particular religions, Islam and Judaism, are strictly bound to the traditional means of burial, it is likely that they face tough obstacles in continuing their funeral practices. In this chapter I will follow up on how these religious groups are keeping up with the demands whilst there is a shortage of space.

There is a big discrepancy where public cemeteries, owned by the local authorities, are becoming abandoned and privately owned cemeteries are highly active. To examine this phenomenon, I set out to visit cemeteries and crematoriums belonging to the private and public sector to note the contributing factors that led to this. It is clear that reformation of cemetery traditions is needed. However, London is not estranged to evolving its burial strategies, the Victorian era saw drastic changes to the planning of the city to provide burial space for the growing population. This era brought forth urban garden cemeteries that are still a part of the city’s infrastructure. I will reference James Stevens Curl’s book, ‘Death and Architecture’, to analyse this era and question whether we should be more like the Victorians and take radical measures to address this crisis?

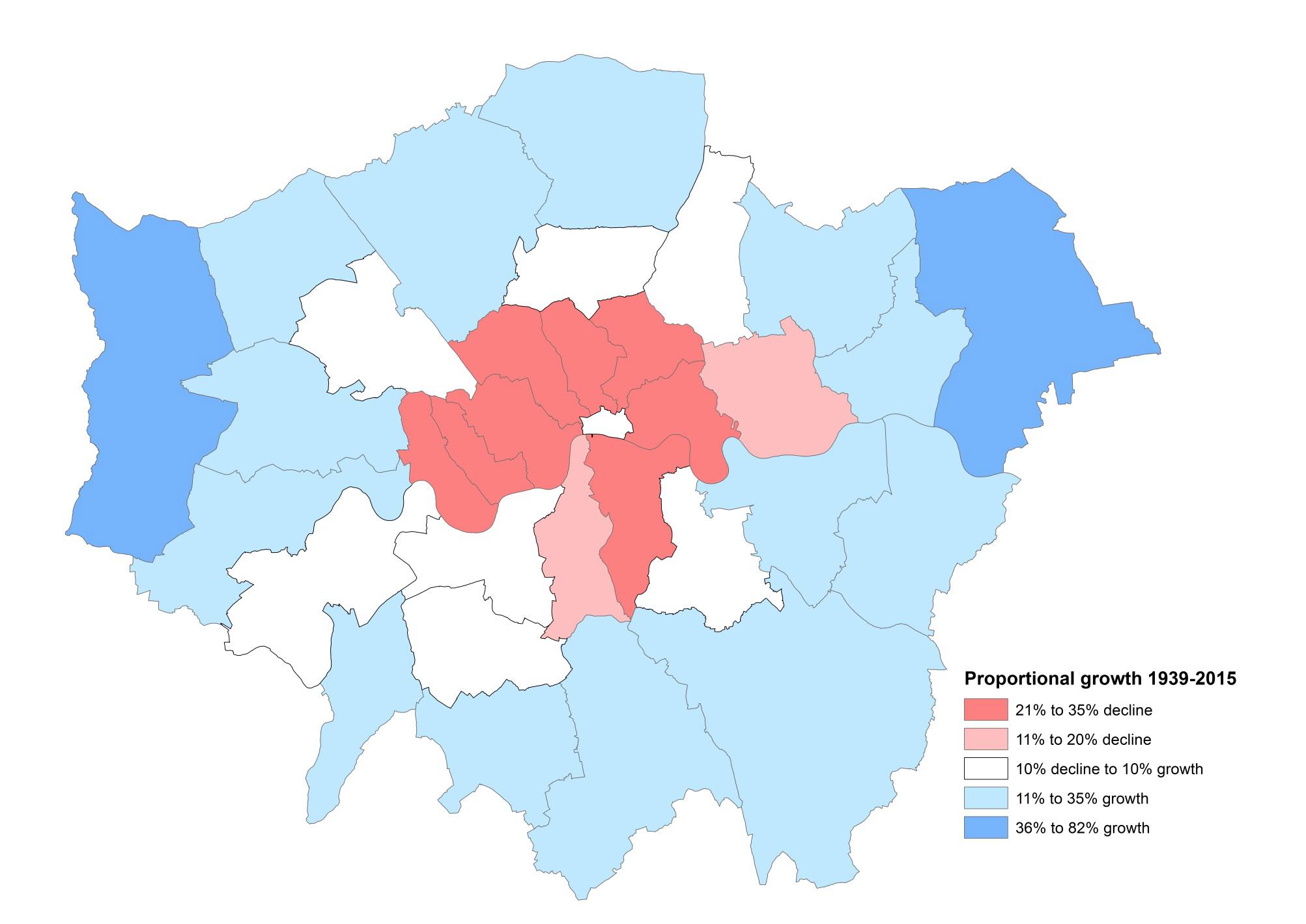

Figure 13: Population growth of London boroughs from 1939 to 2015 - Greater London Authority (GLA) Intelligence 2015

London’s capacity for burial space has been stretched for decades; the issue of the lack of burial space is ingrained into the fraudulent burial system. As in January 1997, research by Halcrow Fox on behalf of the London Planning Advisory Committee (LPAC), titled ‘Burial Space Needs in London’ estimated that inner London had nine years worth of land that could be used for burial. In outer London this land was unevenly distributed; six boroughs would run out of space before 2016, but some boroughs had sufficient burial space for the next hundred years.32 Although it is almost a quarter of a century since the report was issued to London authorities, the same need for space in cemeteries has remained. This is evidence that not enough change has been carried out in regards to burial spaces.

Since the mid-1990s additional land was released to supply burial space for Londoners. This is stated in a report titled ‘An Audit of London Burial Provision’, by Dr Julie Rugg and Nicholas Pleace in 2011. It reads: “supply has been for the most part underpinned by the creation of graves in areas of cemeteries where burials were not originally anticipated.”33 This strategy is clearly not sustainable as burial land is increasingly limited within London.

In this report the assessment of provisions for space in all boroughs in London found that a number of boroughs have no space for burials at all. Others are reliant on creating additional space within the cemetery or have a limited number of new graves, and some have sufficient space for the next twenty years or more. Compared to the 1997 research, burial provisions remain equally uneven across boroughs. Figure 12 illustrates the current capacity status of burials in the London boroughs. The illustration maps 22 out of 32 boroughs are either full or at critical capacity or are problematic, leaving 10 out of 32 boroughs with adequate or sustainable capacities for burials. Figure 12 illustrates the significant scarcity of burial lands across London. However, this crisis is made apparent when the data is compared to London’s population growth. In 2015 Greater London Authority (GLA) Intelligence analysed the population growth of London boroughs from 1939 to 2015, Figure 13. The findings suggest that large increases in population and urbanisation is occurring within the outer London boroughs, whilst population density in inner London is decreasing.34 The continuation of the same burial strategies in these outer boroughs would mean that further land needs to be exhausted, but Figure 12 clearly illustrates that this is not possible.

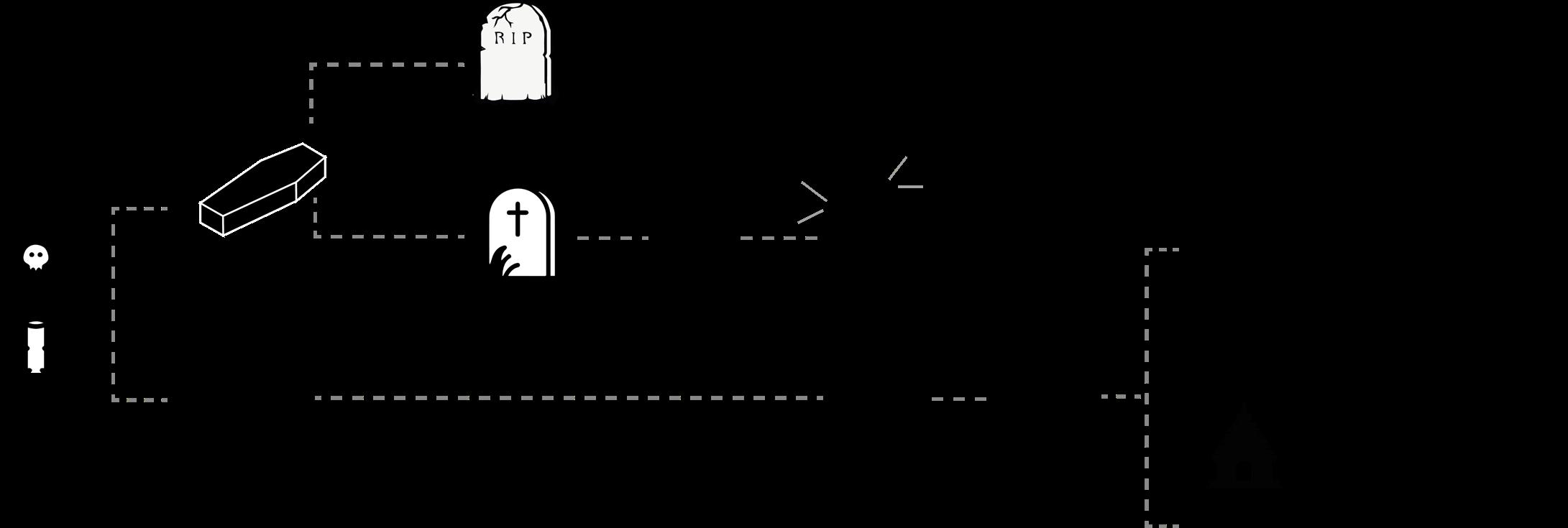

Figure 14: Contemporary methodology of burial and cremation in the UK. By Author

Despite the overwhelming evidence proving that new burials cannot be sustained, large groups of London’s population, including particular faith groups for whom burial is a religious requirement, do not wish to consider alternative means of disposal. To address these growing issues the London Authorities Act 2007 granted London Burial Authorities permits to reclaim and reuse graves. “Burial authorities in London may reclaim a grave and then use the remaining space in it, where the rights of interment have not been exercised for 75 years or more and notice has been published.”35 This has been an initiative of the burial experts for a number of years prior, to enable the continuing service of burials in London. Figure 14 shows the current options for disposal in London; however, no London borough has adopted these powers of grave reuse.

Furthermore, in the 1995 book “Reusing Old Graves”, written by Douglas J. Davies and Alastair Shaw, researchers exploring attitudes towards reusing graves asked people from different denominations about the nature of funerary arrangements for their deceased relatives36. The findings show that boroughs with larger populations of Jewish and Muslim people are likely to face increased pressures for burial space. In addition to requiring burials, these faiths tend to have one interment per grave and would not support the idea of reusing graves.37 Due to this resistance against grave re-use and an increase in demand for permanent graves, burial land has become highly valued within these religious demographics. Purchasing a common grave in a municipal cemetery, it gives you the exclusive right of burial for a maximum of 100 years, it is not a purchase of land. Once the exclusive rights are ended, graves can be reused. This has led to many Jewish and Muslim people not using common graves, as they forbid the reuse of graves due to their religious rites of passage. Thus, using privately owned cemeteries.

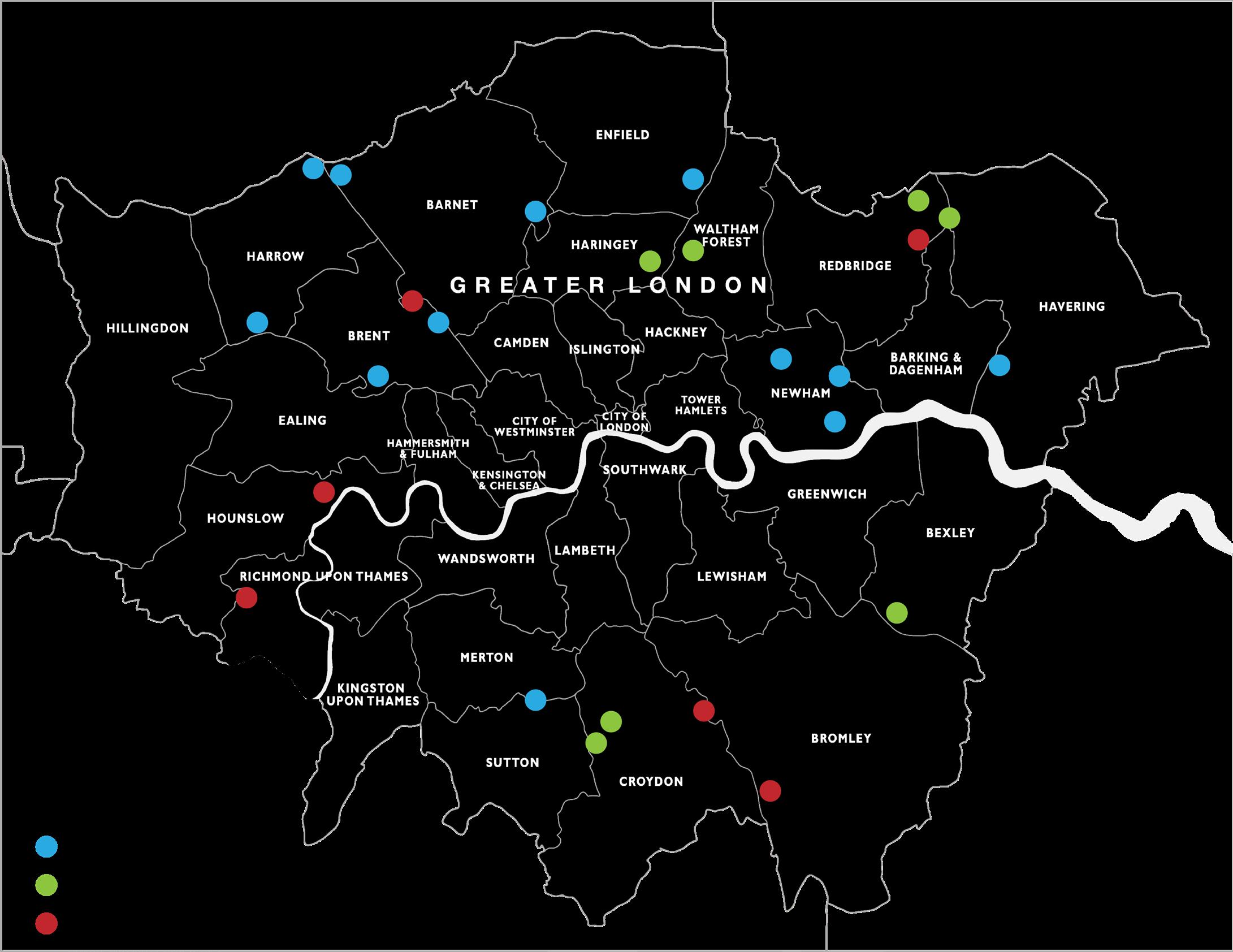

Figure 15: Private Cemeteries owned by Jewish and Muslim denominations and Private mix-faith cemeteries and crematoriums– by Author

Furthermore, the reluctance shown by councils of London boroughs in gaining grave re-use permits creates problems for others in different denominations who wish to be buried. This has led to measures where additional land was acquired by other faiths and organisations to accommodate the preferences for Londoners. Figure 15 maps the location of privately owned cemeteries by the Jewish and Muslim denominations. Additionally, the map points out the location of mix-faith private cemeteries and crematoriums. It reveals growth of private cemeteries at outer boroughs of London.

As noted above with Figure 12 and Figure 13, these measures by the private sector cannot continue for too long. In a 2015 interview with The Guardian, Dr Julie Rugg says “..of a not-too-distant future where vast, private cemeteries on the outskirts of cities accommodate graves rented out for short-term occupancy.”38 Due to the short supply of space, it would be inevitable for the private cemetery providers to resort to alternative measures, like grave reuse and exhumation, to keep up with the growing demands. To analyse the constraints faced in Muslim and Jewish cemeteries I visited a number of their sites. Including private cemeteries and crematoriums that serve all denominations. I also compared these findings with the following case studies: • Garden of Peace Cemetery – 2002 - 57 Elmbridge Road, Hainault, Ilford IG6 3SW (Muslim)

• Garden of Peace Cemetery – 2015- 1 Five Oaks Lane, Chigwell, IG7 4QP (Muslim) • Old Bushey Cemetery – 1954 – Little Bushey Ln, Bushey, WD23 3FP (Jewish) • New Bushey Cemetery – 2017 – Little Bushey Ln, Bushey, WD23 3FF (Jewish) • Forest Park Cemetery and Crematorium - 1995 – Forest Road, Hainault, IG6 3HP (mix-faith)

Figure 16.1:Garden of Peace Cemetery Elmbridge – 2002- Austin-Smith: Lord Architects – Pictures by Author - 13th September 2020

Figure 16.2: Garden of Peace Cemetery Five Oaks – 2015- Methodic Practice – Pictures by Author 13th September 2020

Figure 16.1: Garden of Peace Cemetery Elmbridge – 2002- Austin-Smith: Lord Architects – Pictures by Author - 13th September 2020

My findings support this prior research. Private cemeteries are moving further away from cities and this trend is likely to continue with land becoming more difficult to obtain and reserve for burial sites. Gardens of Peace Cemetery, founded in 2002 at Elmbridge Road, Hainault acquired a new site in 2015 at Five Oaks Lane, Chigwell, Figure 16.1 and Figure 16.2. The old Bushey Cemetery, founded in 1954, as a result of subsequently expanding to adjacent lands, led to establishing the New Bushey Cemetery in 2017 Figure 17.1 and Figure 17.2.

The stringent measures to maintain burial customs means that both single-faith and multi-faith cemeteries are not taking up additional strategies to tackle the issue and are more focused on acquiring more land. London is an expensive location for these companies to acquire land, yet both people and companies are prepared to pay a premium for these services, leading to the current crisis. For example, Forest Park Cemetery and Crematorium are seeing an increase of demand for spaces, Figure 18.

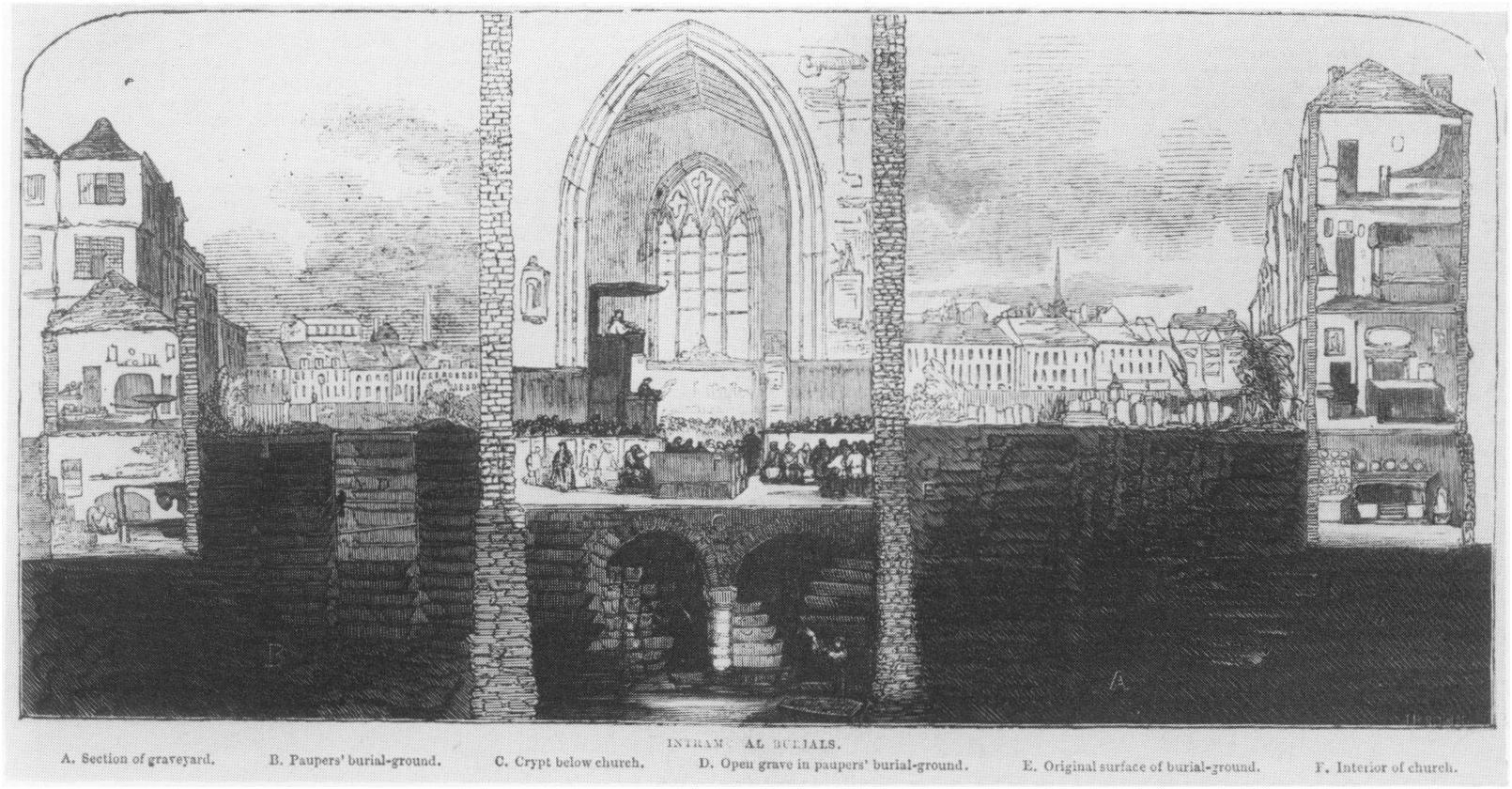

Figure 19: A Cross-Section of Churchyard during the Mid-Nineteenth Century - James J. Curl, Death and Architecture, Page 287

In James J. Curl’s Book, Death and Architecture, two chapters are dedicated to the development of cemeteries in Great Britain in the nineteenth century and the Garden Cemetery movement. As the mid-nineteenth century was at a point of change, there were growing concerns over hygiene and sanitary conditions of London’s burial grounds.

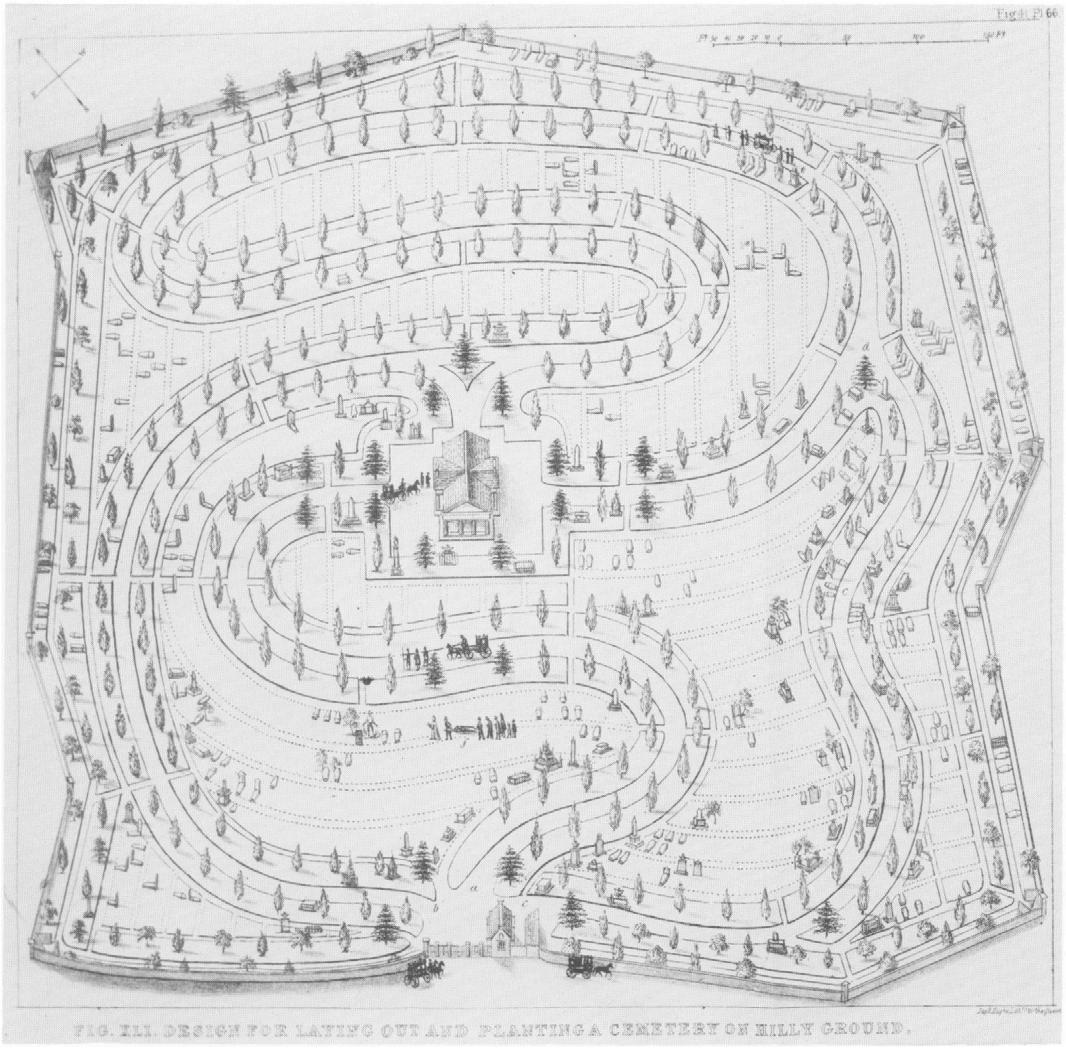

England was a country predominantly built on Christian values, where the rich were buried in churches. This then created a demand for the poor to also be buried within the church grounds. Christian cults encouraged this because they believed that martyrs and powerful people deserved this right, eventually leading to overcrowded churchyards. Famous writer, John Evelyn, quoted in James J. Curl’s Book, describes the condition of the churchyards being congested with dead bodies “one above the other, to the very top of the walls, and some above the walls’’39, the church itself appeared to be built upon graves. (Figure 19). Burial grounds in London were facing crisis. The need to alleviate overcrowded London’s parish burial grounds was of high concern when it was realized that the population of London “increased by a fifth in the 1820’s, and that the average number of new burials was two hundred per continued. John Claudius Loudon was an industrious influence on the British garden cemetery movement. The garden cemetery movement was a pioneering movement that became popular due to its provoking solutions to the overcrowded and unsanitary cemeteries in urban areas, the movement was the solution for the burial crisis of its time. In Loudon’s ‘Design for Laying Out and Planting a Cemetery on Hilly Ground’ (Figure 20), he applied green paths between burial plots to ease access to each grave and proposed orderly paths with trees planted around the perimeter. This allowed as much

acre,”40 - the horrendous conditions could not have light and air to get on the surface.

Figure 20: Loudon’s ‘Design for Laying Out and Planting a Cemetery on Hilly Ground’. - James J. Curl, Death and Architecture, Page 257

Figure 20: Map of London’s 1832-1841 cemeteries expansion outside the city of London with seven large cemeteries, nicknamed ‘the magnificent seven’ - By Author

The growing population and unsanitary conditions of burial grounds in London became a cause for concern. Organisations and notable figures called for the expansion of burial sites, stating that large cemeteries in the greater London area were the best mode of interment for the metropolis. Loudon wrote to the Morning Advertiser of 14th May 1830 to set out his ideas on the subject. He advocated several burial grounds, equidistant from each other, and at a constant radius from the centre of the metropolis41. In 1832-1847 authorities saw approval of these cemeteries, Figure 20, aiming to address the issues of its overcrowded churchyards. The cemeteries were highly celebrated, nicknamed ‘the magnificent seven’, thought to be the permanent burial grounds for the metropolis. The seven cemeteries consisted of Kensal Green Cemetery (1833), West Norwood Cemetery (1837), Highgate Cemetery (1839), Abney Park cemetery (1840), Brompton cemetery (1840), Nunhead cemetery (1840) and Tower Hamlets cemetery (1841). Kensal Green cemetery was the first of the seven cemeteries, opened in 1832, it is the largest and oldest public cemetery in London42. Henry Edward Kendall, architect, designed the cemetery grounds in the garden cemetery style, Figure 21. To those in the nineteenth century, the planning of the ‘magnificent seven’ provided “’The burial-places for the metropolis’, Loudon wrote, ‘ought to be made sufficiently large to serve at the same time as breathing-places.”43 There was a clear ambition to place large cemeteries outside of the inner city to adequately serve London at the time and future

generations.

Figure 21: Watercolour, showing a prospect of Kensal Green Cemetery, dating from 1832 - James J. Curl, Death and Architecture, Page 219

The objective to change the negative perception of the burial grounds away from the cramped churchyards to large-scale picturesque gardens was achieved. This is due to a strong incentive behind the movement in turning cemeteries into public gardens, “Loudon was confident that, if his ideas were implemented, all cemeteries would be as healthy as gardens or pleasure-grounds, and indeed would form the most interesting of all places for ‘contemplative recreation’44. When imagining the future, it was for Londoners to spend their recreational time in these cemeteries as public gardens.

James J. Curl agrees with this idea of turning cemeteries into public gardens in his book, stating that “Loudon was practical about cemeteries, for he wrote that ‘the greater the number of present cemeteries, the greater number of future public gardens.’ All cemeteries, once filled, should be gardens, but all gravestones and all architectural or sculptural monuments should be retained and kept in repair at public expense.”45 The foresight in considering the lifespan of cemeteries as a tenure that comes to an end and becoming public gardens comes at a cost in retaining all the graves. Kensal Green Cemetery 188 years later, once one of the Magnificent Seven, has been left to fend for itself with it being largely abandoned in 2020. Figure 22. The realisation of Loudon’s statement where all gravestones and sculptures are to be retained became a reality, but the subsidies are not coming out of the public’s expense. Cemeteries make earnings from burials, upon reaching grave capacity the income came to an end, resulting in the cemetery to be left stranded. Kensal Green Cemetery is not alone - the present condition of all municipal cemeteries across London are similar. This is all underpinned by one principal reasoning, Victorian law deemed all burials to be ‘in perpetuity’.

The idea of graves remaining untarnished was a direct response to churchyards cramming and reusing graves to maintain service, as seen in Figure 19. Dr Julie Rugg states in a 2016 journal, Respecting corpses: The ethics of grave re-use, “… the re-use of churchyard graves is long-established, legally permitted under Church law and was routinely performed.”46 Despite it being deemed lawful by religious teachings, people wanted to restrain away from it because of their unsanitary conditions.

There was a withdrawal from Churchyards, where burial spaces are consecrated areas owned by the Church of England and governed by ecclesiastic law, to unconsecrated burial grounds in municipal cemeteries, governed by local authorities. This brought legislative changes in a burial act in 1857 to unconsecrated burial spaces in municipal cemeteries where it became illegal to interfere with human remains. Hereby, the ideals of ‘perpetuity graves’ became popularised from this era onwards.

This is the largest reason why London’s provisions are still struggling to keep up with demands, “In the UK we are in an acute crisis, largely because of our burial law,”47 Dr Julie Rugg says at an interview with The Guardian Newspaper in 2015. The burial law referring to was ‘The Burial Act 1857’. Section 25 of the Burial Act 1857 states: “Bodies not to be removed from Burial Grounds, save under Faculty, without Licence of Secretary of State.”48 The act makes it a legal offence to remove buried human remains without a licence from the Secretary of State. However, London Burial Authorities provide permits for the reuse of graves, but no local authorities used these powers. This has left the burial industry burdened with the burial act enacted in the Victorian era still being enforced today.

In summary, London’s provisions are still struggling to keep up with demands for burials. Drastic measures of grave reuse can be exercised after the exclusive rights of interment has come to an end, which is usually 75 years depending on the local authority. However, the strategies in place are veiled behind complicated burial laws. There is an underlining incentive for local authorities to advocate cremations where laws are less complex, but they struggle in compromising with religious groups.

As there is a high population of Islamic and Jewish faiths in London - where burial is the only option and a preference for single interment per grave - it is difficult to implement the reuse strategy. Additionally, a preference to be buried next to someone of the same faith is facilitating growth of single faith cemeteries in the private sector.

Alongside limited space in municipal cemeteries, private cemetery providers are beginning to grow so they can serve all irrespective of denomination. Furthering complications with burial laws that are not complied equally by both private and public sectors. The main issue is that no clear actions have been devised to resolve a lack of available burial space and with current trends, the private sector will exhaust all available burial spaces in cities very soon. The notion of graves remaining in perpetuity, a staple of Islam and Judaism, cannot be achieved in major cities. Yet, where there are individuals who can afford such a service, the private sector can provide a service. Dr Julie Rugg says in her 2015 interview with the Guardian, “Location and long tenure could become the privilege of a wealthy urban elite, while those unable to meet the rates find their mortal remains separated from those of their families, or relocated to less desirable locations – for as long as someone can pay the rent.”49 Suggesting that cemetery land owners may be incentivise to provide an exclusive right of burial and charge additional fees for maintenance and services rather than the current burial system.

Drawing similarities to trends observed in the Victorian era which created change in response to unsanitary conditions that were present at the time. Including the establishment of the Magnificent Seven and new legislative laws, so that graves are in perpetuity for unconsecrated burial lands in municipal cemeteries which has led to the downfall of the entire system of burials and the abandonment of cemeteries across the public sector.

We have turned full circle - we cannot build large cemeteries outside the border of the city as was done in the 19th century; feasible access to land is under constant threat of running out.

Figure 23.1: Waterloo Necropolis Station – 1854