13 minute read

Chapter III Future

CHAPTER III FUTURE

In this chapter I will investigate solutions for the future of London. I will first investigate the dire situation London is in, and then argue that we need to follow Victorian . I will be analysing a wide range of solutions from moderate methods, like advocating for legislative changes, to extreme approaches, like alternative means of disposal. I focus on practical proposals that aim at reducing land uptake due to burials.

Advertisement

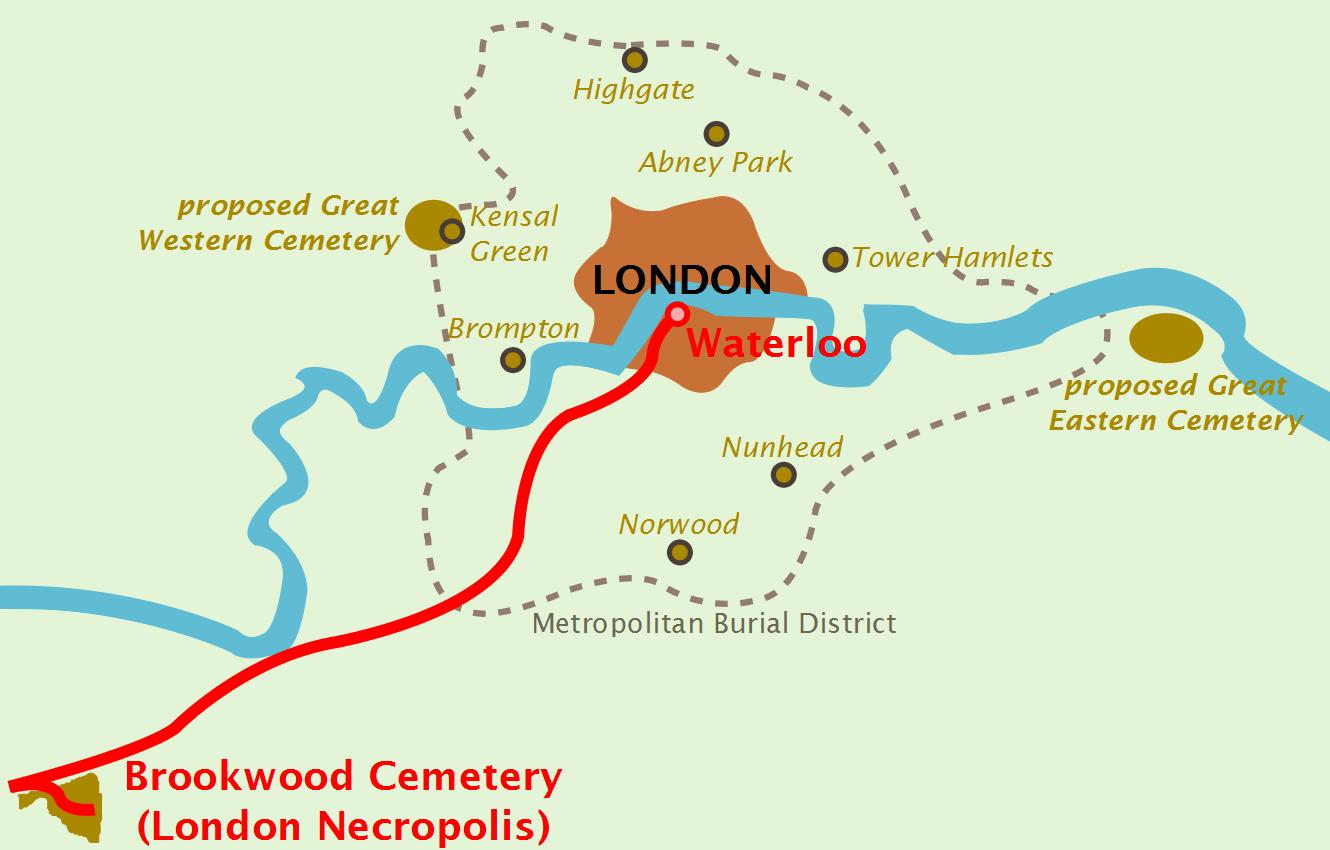

Modern architecture has not been able to resolve the complications discussed. I fear that death is not a conversation that religious groups which prefer burial are willing to engage in; thus resulting in a crisis similar to that of the Victorian era. It was only until “the disgusting conditions of churchyards”50 became unbearable, that in the nineteenth century “remarkable change”51 was seen. During this period of desperation London saw advancements in medicine, industrial innovations and changes to perceptions of depositioning - all of which aided in the realisation of provocative solutions that London holds dear today. to Bookwood Cemetery - 1854 In addition to the ‘Magnificent Seven’, the city saw the development of the Necropolis Railway in 1854, with a designated station at London Waterloo, Figure 23.1. The Necropolis Railway aimed to rapidly take mourners from London to Brookwood Cemetery in Surrey, nicknamed London Necropolis, Figure 23.2. It was the largest cemetery in the world that was planned to be big enough to accommodate all burials for centuries.

The Victorian era also conceived the establishment of Woking Crematorium; the first crematorium in the United Kingdom, Figure 24. The crematorium was founded by Sir Henry Thompson who also founded the Cremation Society of England in 1874. He advocated for cremation as a precaution against

Figure 23.2: Map of London Necropolis Railway Line the spread of diseases among the population. Figure 24:The cremator at Woking Crematorium in the 1870s, before the chapel and buildings were constructed

Figure 1.2 London’s population 1971 - 2036

10,500,000

10,000,000

9,500,000

9,000,000

8,500,000

8,000,000

7,500,000

7,000,000

6,500,000 1971 1976 1981 1986 1991 1996 2001

ONS mid-year estimates

GLA estimates

2006 2011 2016 2021 2026 2031 2036

Source: O ce for National Statistics mid-year estimates to 2001, GLA estimates 2002 to 2036

Figure 25: London’s Population is projected to increase - GLA Intelligence, 2015

All these approaches took onboard modern developments of innovation in their solutions. The Necropolis Railway embraced London’s underground trains that were new at the time and Woking Crematorium was the first modern crematorium in the country. The extreme conditions of churchyards saw equally extreme pragmatic approaches to resolve this issue. London now needs to see a period of reform, as the city is rapidly heading towards seeing realities where compromises cannot be made.

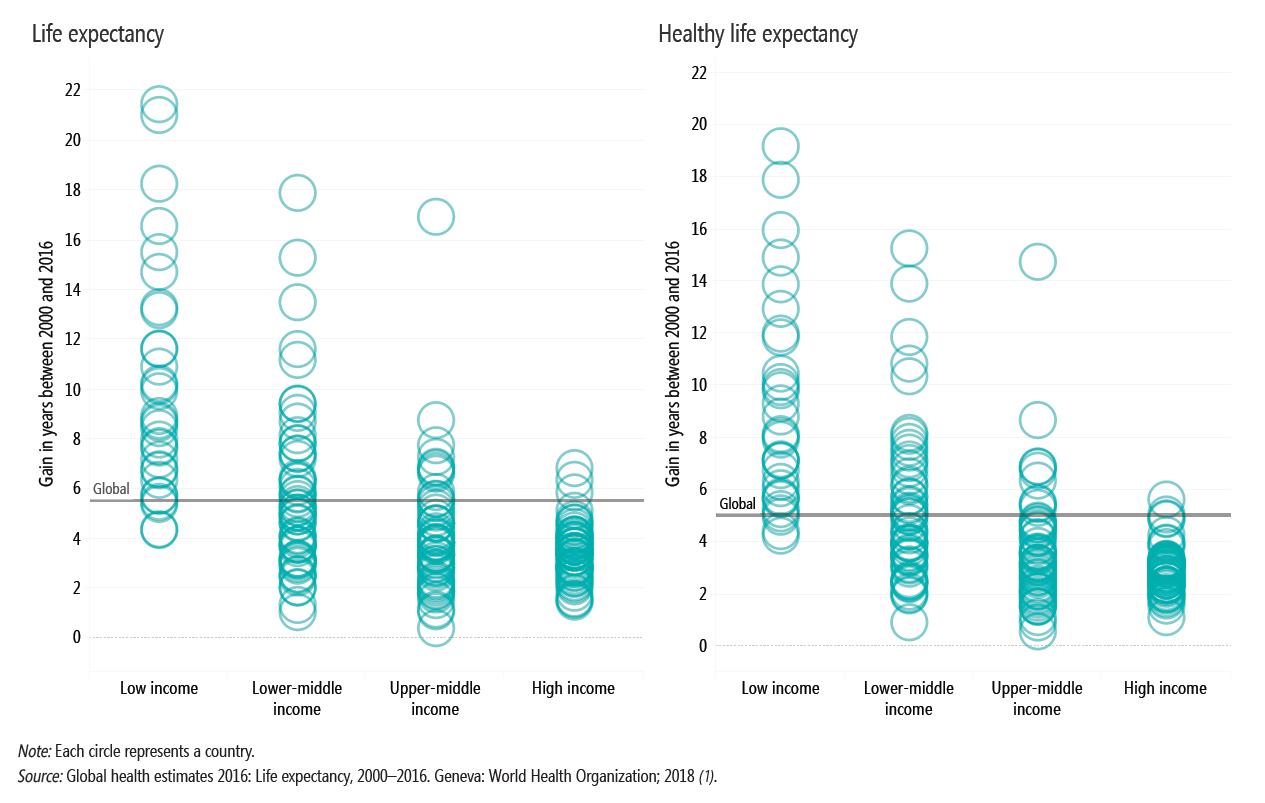

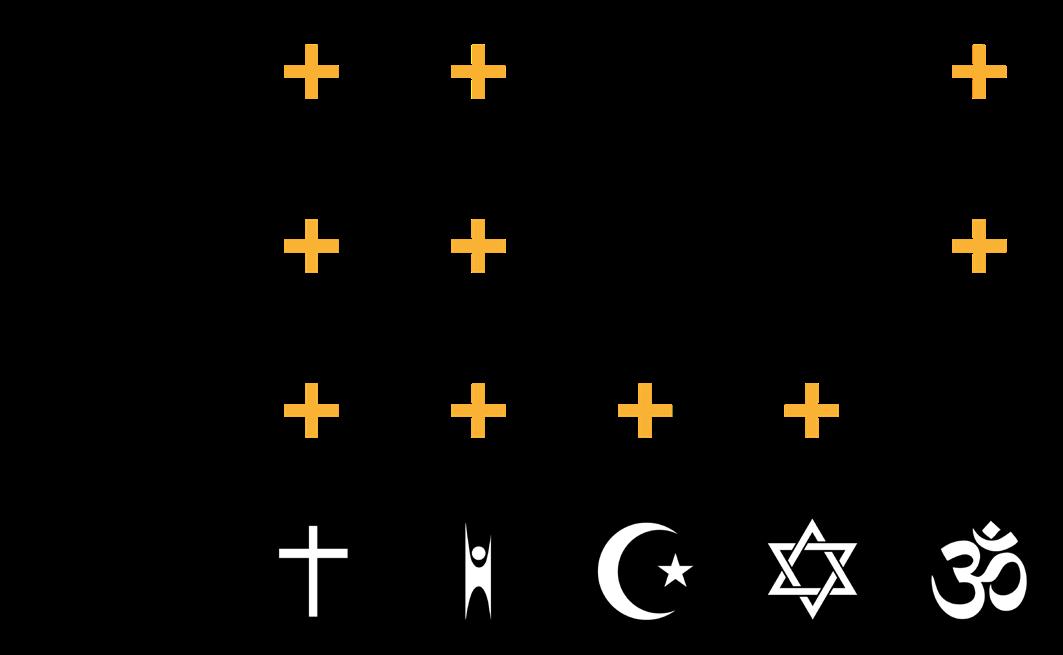

The increase of London’s population during the Victorian era was a major factor contributing to the evolution of burial customs. Similarly, over the past decades, there have been a steady incline of population growth in London, largely due to influxes of migration from other regions and immigration - a trend that is likely to continue. Figure 25 illustrates the expected growth according to the Greater London Authority (GLA) Intelligence in 2015. In addition, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO), “Life expectancy and healthy life expectancy (HALE) have both increased by over 8% globally between 2000 and 2016,”52 a figure given across all developed nations, Figure 26. There will be a greater need for provisions in the funeral industry in the future. expectancy between 2000 and 2016, by country income group, WHO statistics 2020 P. 02 The issues surrounding this matter dangerously overlap with funerary traditions of the major religions. Religious traditions are sacred and should be cherished, but the overwhelming truth is that religious traditions must adapt and establish alternative methods of disposal to address these issues. Religious traditions are formed based on the vastly different climate and environment conditions during the ancient times of its conception. Figure 27 shows a table of the preferred methods of dispositions for London denominations, noting the

Figure 26: Gains in life expectancy and healthy life likeness of adopting alternative measures. Figure 27: Preferences of depositioning the deceased – by Author

Figure 28: Mohammed Omar - National Burial Council and a board member of the Ministry of Justice Burial and Cremation Advisory Group and Board Member of the Gardens of Peace Cemetery

As mentioned in the first chapter, the Abrahamic religious groups’ opinions on cremation sets a precedent for the views on alternative means of burials. Christians, Muslims and Jewish people share commonalities with the reasoning why they prefer burials. However, Christians have reformed to accept cremation and are likely to adapt to other means. Humanists do not have a preference for any particular method and accept all methods. Hindus have a preference for cremation but are overall likely to adapt to approaches that include heating the body. Jewish and Muslims have strong preferences for burial and will be facing tougher future realities.

As the Jewish and Muslim denominations are constantly at the burning end of this dissertation, I interviewed Mohamed Omar, a board member of the Gardens of Peace Cemetery (visited above), and believer of the Muslim faith. Mohamed Omar is also a chair member of the National Burial Council and a board member of the Ministry of Justice Burial and Cremation Advisory Group, Figure 28, The questions - asked for those within the faith and for private cemetery providers - primarily focus on provisions for land, interment regulations and future sustainability practices. Some responses regarding future practices may be extended to those of the Jewish faith, as they share similar beliefs.

I understand that this solution would be difficult to implement; whenever societal views are challenged, there tends to be major resistance. A moderate approach that may be more accepted in society that I advocate for is legislative change. Permits for grave reuse must be obtained by municipal cemeteries but currently no boroughs have requested to use these powers. However, the ideals of perpetuity graves in religious traditions juxtaposes with grave re-use, particularly in Islam and Judaism. I questioned Mohammed Omar if burial practices in these religious groups can be changed to permit the reuse of graves. Mohammed Omar answers: “I cannot speak on behalf of other faiths like Judaism, but we share core values on the traditional means of burial.”

“In an Islamic perspective, there is a dispensation where you can bury one person at different depths in the same burial plot if there is a shortage of land, not many people know this. In Islam, you can also bury at the same depth with the condition that the body is fully decomposed.

The government does not allow to bury at the same depth for a minimum of 75 years, that’s the law of the land. We, in the Ministry of Justice Burial and Cremation Advisory Group, have been fighting for the past few years to reduce that to 50 years. There is a strong incentive for us to do that, so the land is used quicker.”53

where the religious law allows for reuse of graves in situations of land scarcity, so it is permitted. He and I both agreed that there should be greater awareness of grave reuse in the religion. During the interview, desperation was a prevalent theme in our discussion - the period for reformation in this legislation needs to happen now. He proposes that the period for the exclusive right of burial should be reduced from 75 to 50 years in order to increase the yield of the land.

The provisions of Gardens of Peace Cemetery do not allocate enough space for a single interment of all Muslims in London. They currently provide an interment period of 50 years, after which provisions for grave reuse and cramming will begin. I questioned him further on the unsustainable vernacular of cemeteries, and in a situation where current conditions stay the same, what are the green alternatives in single faith cemeteries? He answers:

“In terms of architecture the way cemeteries should go forward, they should design to be more appealing, so when people go there, you feel calm. That is the reason the ambiance and landscape is important. It goes towards this concept of in Islam, we believe in respecting the environment, so we should advocate for natural burials. Natural burials are what we consider to be the type of burials that would align with the Islamic and Abrahamic teachings.

The shift as we move forward should be for Woodland burials, which is something Islam would strongly encourage. In Islam we believe in respecting every living being because it has been created to worship the almighty God, so that we believe that every tree, while its still alive, glorifies God.”54 He predicts, if the continuation of current strategies remains, the future cemeteries for those in the Abrahamic faiths would be natural woodland burials, an approach that can be embraced by all. A woodland burial involves a corpse, or ashes, being laid to ground in a biodegradable shroud or casket. It allows the body to be decomposed to become fertilisers for trees. This is a method that has existed in the UK since 1993.55

I am not arguing in favour for cremation, as cremation also leaves a negative footprint on the environment. However, I concede that crematoriums’ requirements for land usage are significantly lower than cemeteries’. Cemetery providers and authorities should learn from this convention and provide accessible solutions that are pragmatic.

The extreme approach is to establish alternative means to replace burials and cremation that reduces the carbon footprint of corpse disposal. Alkaline Hydrolysis, alternatively known as green cremation or recomposition, is a method of compositing human remains. Although the two approaches for the future of London’s dead are radical, I insist that these solutions are pragmatic and are actual methods that can easily be

implemented.

ALKALINE HYDROLYSIS

Religious Denomination: Christians, Humanist and Hindus.

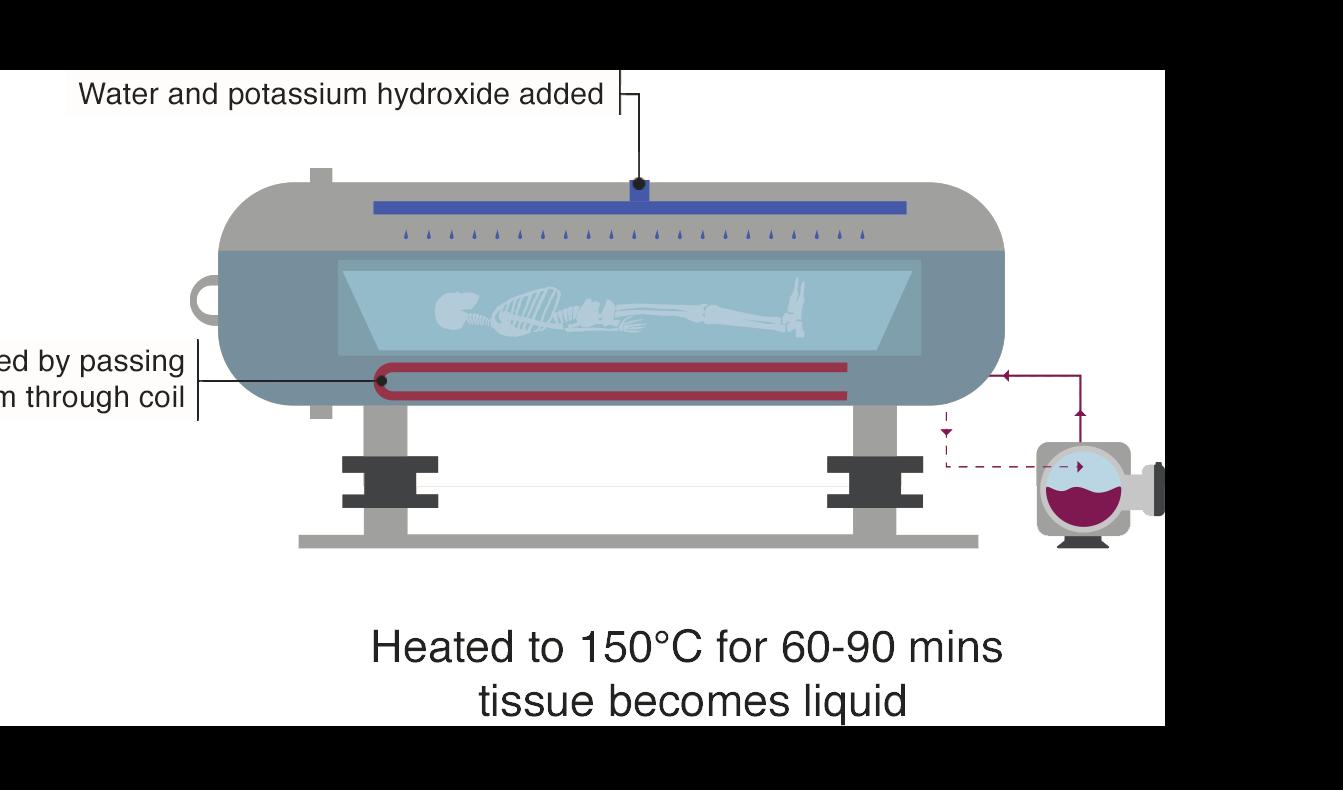

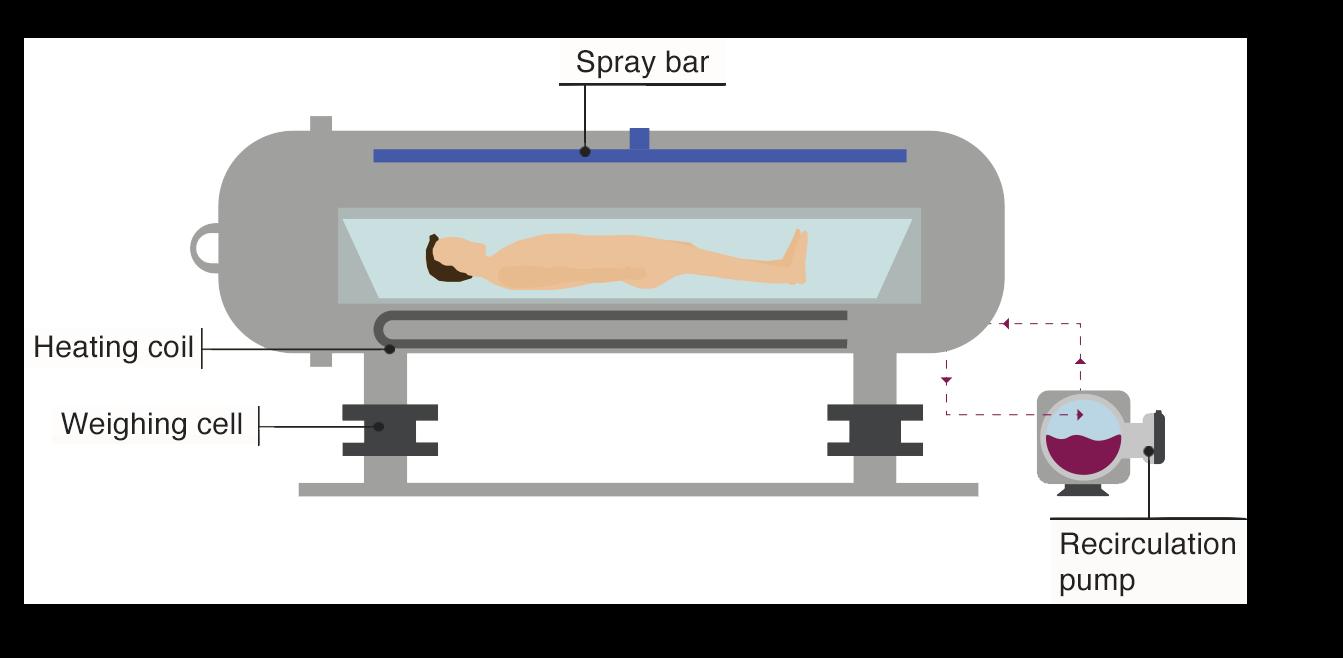

Alkaline hydrolysis is environmentally friendly to conventional cremation, it is the Green option. A body can be shrouded or be placed in a coffin made from biodegradable materials and then carefully positioned into the chamber. The alkaline solution is heated to 152C (306F), but because the digester is pressurised it does not boil. Figure 29, captures the Alkaline Hydrolysis machine.

The alkaline hydrolysis machine takes 2-3 hours. The dissolved tissue is a waste by-product and is disposed of, leaving the bones behind. These are put through a machine called a cremulator, which pulverises them into a powder just like ashes. The remains can be collected and placed into an urn and returned to the family.56 Figure 30 illustrates the process in a diagram.

The Alkaline hydrolysis machine is a rectangular steel box manufactured in the UK by a company called Resomation Ltd. Although manufactured in the UK it is not passed law to regulate it as a viable means of disposal. However, it has been legal in the USA since 2007.

Figure 30: Alkaline Hydrolysis Process Diagram - BBC

COMPOST - RECOMPOSE

Religious Denomination: Christians, Humanist, Muslims, Jews and Hindus.

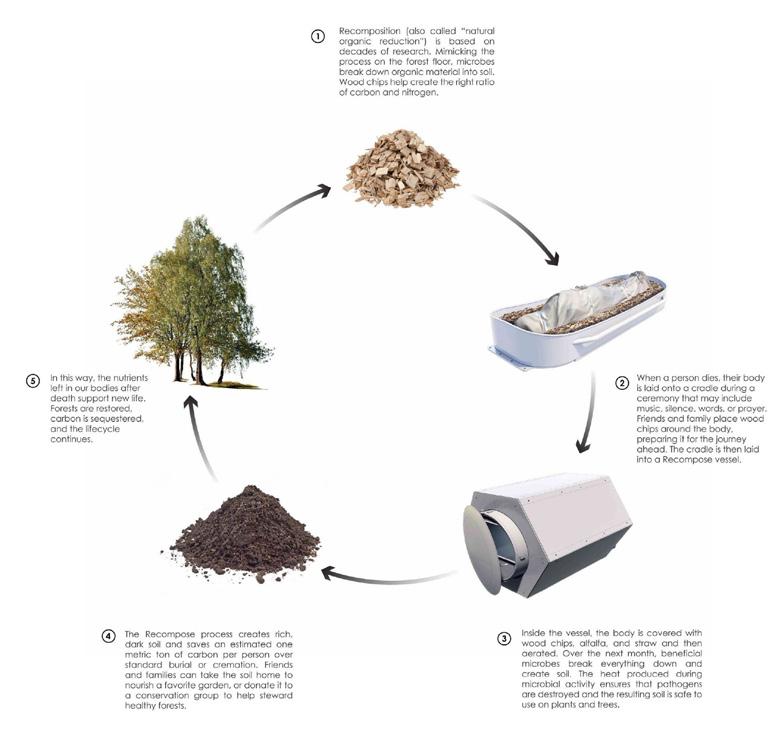

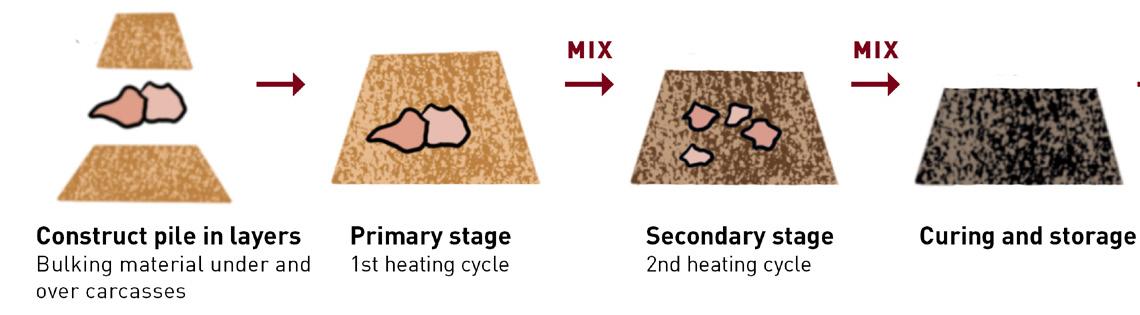

Recompose is a corporation that uses a method of composting human remains into soil. This process replicates a system that farmers in agricultural institutions have been practicing for decades, called livestock mortality composting, Figure 31. Mortality compositing is when an animal, high in nitrogen, is covered with compositing material that is high in carbon. It is an aerobic process, only requiring oxygen and moisture. After nine-months, all that remains is a nutrient-rich compost. The flesh and bones are decomposed entirely. 57

The process is powered by Natural Organic Reduction (NOR), these are microbes that occur naturally in bodies once dead. After wrapping a deceased in a shroud, the body is laid in a cradle surrounded by wood chips, alfalfa, and straw. The cradle is placed into a Recompose vessel and covered with more plant material which remains in the vessel for 30 days. This begins the gentle transformation from human to soil, Microbes break everything down on the molecular level, resulting in the formation of a nutrient-dense soil.

Each body creates 97 cubic metre of soil amendment, which is removed from the vessel and allowed to cure. Once completed, the remains can be used to enrich conservation land, forests, or gardens.58 Figure 32 , illustrates the process in a diagram. Figure 33, Inside a vessel contains the decomposition system where bodies and woodchips undergo accelerated natural decomposition, or composting, and transformed into soil.

Recompose is a start-up corporation founded in 2017, at Seattle, USA. Due to worldwide attraction and public endorsement, it got signed into law 2019 in Washington D.C. being recognised as an official method of disposal.

Figure 32: Recompose Process diagram. - Olson Kundig Architects

Figure 31: Livestock Mortality Composting diagram – University of Minnesota

Both the extreme and moderate approaches are sustainable means for the internment of Londoners. I would argue all of the above methods of depositioning and legislative changes should be put forward into practice, it would ensure more sustainable options in contrast to the destructive methods currently in use.

The moderate method of making the reuse of graves mandatory across all municipal cemeteries and to reduce the exclusive rights of burial licence from 75 years to 50 years. The combination of these two methods would reactivate dead public cemeteries. The existing provisions of cemeteries in London does provide enough space for burials in perpetuity if grave use is correctly implemented, there is no need for additional burial spaces. Dr Julie Rugg mentions in a 2015 interview with the Guardian news, “We have cemeteries of over 100 acres in London, but the way we use the space is not sustainable.”59Cemetery professionals across the board would advocate for these provisions. This would alleviate demands in the private sector and would see a rebirth of the Victorian garden cemeteries in London. The extreme methods of Alkaline Hydrolysis and Recompose are alternative facilities that embrace the advancement science in our burial methods. Just like cremation and crematorium these two methods follow the same vernacular. A 2017 BBC article titled ‘Dissolving the Dead’ collected research data to illustrate the environmental and cost benefits to Alkaline Hydrolysis as opposed to traditional methods of depositioning, in all accounts it outranks burials and cremation, Figure 34. Recompositing is a method that builds upon the same notion of natural woodland burials. The method mimics the process that happens in livestock farming, it happens in nature naturally over the span of months but with Recompose it happens under controlled settings to accelerate the rate of decomposition. The greatest advantage about this method is that it provides a sustainable method to those in the Abrahamic faith who would otherwise

oppose all other alternatives. Figure 34: Bar chart shows it being the cost sensitive option and the disposal method that is the most environmentally friendly – BBC