Heritage Hispanic Heritage

Local bakery modernizes traditional recipes

By Megan WehringKeeping traditions alive is the heart and soul of Abuelita’s Bakery Spot in Kyle.

Brother and sister Hector and Vanessa Rodriguez started their business originally out of their home in December 2020, and later in September 2021, they moved to a food truck establishment. But after learning that they needed to expand the ven ture even further, they moved into their current brick-and-mortar location in June.

“We waited eight months in order for that build ing to get built,” Vanessa Rodriguez said. “During

the eight months, we were in the food truck – we gained a lot of respect and support from the com munity. They showed us a lot of love.”

The business idea started when Hector posted on social media about the traditional bunuelos, a sweet dessert that their abuelita would make throughout December and around the holidays. Hector then developed the idea to modernize the dessert into small treats and he received exponen tially positive feedback.

“If you’ve ever gone to our building, [you know] it is not a traditional bakery at all,” Vanessa Rodri guez said. “We grew up in South Texas in the McAl

len area, and for anybody that has ever lived there, they know that our bakery is not traditional as [the bakeries were] where we grew up. We understand that.”

Aside from the bunuelos, the Rodriguez family has continued to take traditional recipes and put modern twists on them – this includes their empanadas and mini conchas. “People here [in Kyle] have never seen a mini concha because they are so used to traditional conchas,” Vanessa Rodriguez explained. “Even my abuelita, when my brother and I showed her the mini conchas, she said ‘I wish I could have eaten this back in the day because it is less bread and less sugar.’ A lot of the customers say, ‘This is amazing. I was never able to go to a regular panaderia (bakery) because the traditional conchas were huge but the minis really minimize the sugar for me.’”

Vanessa Rodriguez concluded that her family just wants to bring a little piece of home to the bakery.

“We want to show people here who are not used to Hispanic household food that this is what we eat in our household and to show them a little part of us,” Vanessa Rodriguez said. “I think it’s really cool that people get to know us and that we get to know them.”

“We want to show people here who are not used to Hispanic household food that this is what we eat in our household and to show them a little part of us,”

Vanessa Rodriguez

the Publisher’s Desk:

I just love this edition of the Echo.

When our team first discussed the theme for this, we were excited about focusing on members of our community as part of celebrating National Hispanic Heritage Month, which is celebrated from Sept. 15 to Oct. 15 each year. The observation started in 1968 as Hispanic Heritage Week under President Lyndon Johnson, but later was expanded to a full month by President Ronald Reagan in 1988.

As we delved into the articles in this edition, we found such great stories of tradition, passion and culture and the final product was much better than I could have ever envisioned.

From the stories, to family recipes, to layout, we think this is one of our best yet. As you thumb though this magazine, I hope you enjoy reading it as much as we enjoyed putting it together.

provecho!

What

According to the CDC, more than half of Hispanic or Latino adults are expected to develop type 2 diabetes in their lifetime. Uncontrolled diabetes can lead to poor blood flow or circulation throughout your body, a condition known as Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD).

Early warning signs of PAD include legs or feet that are cold or have noticeable hair loss and slow-growing toe nails. See your physician if you have progressing symptoms including cramping in your legs or buttocks when walking, and numbness or weakness in your legs or feet with or with out discoloration or ulcers.

CTVS, which just opened in Kyle earlier this year, is Central Texas’ leading provider of cardiothoracic and vascular surgi cal care for more than 60 years. For more information, visit ctvstexas.com or call 512-459-8753.

CENTRO CULTURAL

celebrates and embraces Hispanic culture

By Brittany AndersonBeing able to not only embrace your own culture but have it be recog nized, appreciated and celebrated is incredibly important, and one local organization aims to do just that through every facet of their outreach.

Nonprofit San Marcos-based organization Centro Cultural Hispano de San Marcos has been a fixture in the community for over a decade, since it opened in September 2010.

Located in the heart of one of the first Mexican-American “barrios,” or neighborhoods, of San Marcos, Centro consists of four components: an art gallery, a library, a museum, and various educational and culturally-en riching programs.

Centro’s programming includes curriculum in visual arts, theater, dance, literature, music, multimedia and culinary arts. From Ballet Folklórico and Mariachi classes to art classes and piano lessons, the goal is for youth to celebrate, learn about and have a better understanding of the culture and country of which they are from.

“Awareness brings more of an acceptance and recognition of what these countries bring to us,” Dr. Gloria Martinez of Centro said. “The sooner chil dren can be exposed to that, to other countries’ cultures and understand they’re not trying to harm you. … Every country has its beauty.”

Centro strives to provide a space for the community to learn about and share their Hispanic Heritage with others, notably through their many events.

After collaborating with Lucy Gonzalez, who serves as the out reach and recruitment specialist at Community Action, Inc. of Central Texas, Centro planned and held its inaugural Hispanic Heritage Exhibition Walk on Sept. 17.

The event was the first for the community, intended to rec ognize people that come from “all of the countries” and bring attention to the “vibrant Latin American countries and bring awareness of the diversity of Hispanic Heritage to the local community.”

“In our community, everyone automatically thinks you’re Mex

ican, but you might be Peruvian, Colombian, Salvadoran — we have tons of people from all over,” Martinez said. “We need to recognize and appreciate all that they have done within our community.”

The flags of 21 Latin American countries, from Argentina to Mexico to Venezuela, were dis played at Centro. Then, following a half-mile walk to the Histor ic Hays County Courthouse, community members gathered for music, food, market vendors, family-friendly activities, words from various community lead ers, and Folklórico and Mariachi performances, celebrating the kick-off of Hispanic Heritage Month.

On top of bringing awareness to Centro and their mission, all of the proceeds from the walk will go towards granting local students with scholarships.

Gonzalez’s personal experi ences helped shape this event, saying that she lived abroad in Mexico for about eight years

and found people there to be very warm and welcoming — something that might be lacking stateside.

“What I feel here in the U.S. is we’re not very warm and welcoming to immigrants from other countries. [It’s] ‘I have to fit in’ instead of ‘I belong,’” Gonza lez said.

“Or that I have to watch from the outside,” Martinez added.

“With something like this [ex hibition walk], it’s, ‘I am a part of this community; I see my flag represented; I see my people here to celebrate,’” Gonzalez said.

With such a prominent and important Hispanic population in Hays County, Centro will con tinue the mission it has served for years: being a beacon for the preservation, development, promotion and celebration of Hispanic arts, culture, heritage and values.

Be sure to keep an eye out for 2023’s Cultural Exhibition Walk, and visit Centro at 211 Lee St. in San Marcos.

“The preservation of one’s own culture does not require contempt or disrespect for other cultures.” – Cesar Chavez

PASSION for education inspires local executive coach

my community,” Lopez said.

“[It’s] why I have such a passion for education. It’s not where

I thought I was going to be, I really thought I was going to become an attorney. I fell into higher education, and I loved it. I think mom probably knew that from the beginning, but I wasn’t willing to listen when I was in college. But once I got into higher education, I loved it.”

Growing up in a Hispanic household, Lopez was able to witness multigenerational and diverse relationships.

It was always so much fun to be with all of the older ladies in the family, hearing them talk, laugh and tell stories that we were all going to sit down together and share in the meal. I remember those memories very vividly.”

She also shared one special memory that she still holds near and dear to her heart.

By Megan WehringWatching both of her par ents become academic leaders eventually inspired Michelle Lopez to enter the higher education field – and later become an executive coach.

Lopez is the president and owner of Next Gen Latinos, LLC, which works to deliver cut ting-edge collaboration for indi viduals and teams. This includes strategic planning workshops and retreats, team building, lead ership development, coaching for individuals and groups, personal and professional development, and speaking.

“I started it, really thinking ini tially with all of my experience in higher education (over 20 years), that I would focus a lot on help ing universities and consulting with them on issues of Latino stu dent retention or Latino student programming,” Lopez said.

Lopez credits her parents for instilling into her the importance of contributing to local commu nities.

Before they retired, Lopez’s parents were both educators and administrators in public schools. They both established firsts in

Michelle Lopez“I think being a Hispanic busi ness owner has really been a nice way to [develop] a connection with a lot of different commu nities,” Lopez said. “There are a lot of great memories of family gatherings. My mom’s sisters, grandmothers and I would all be in my grandmother’s kitchen – everyone would have our own station to [help] make tamales.

“One day, I had gone to a friend of mine’s home and her mother had made pozole and I loved it,” Lopez said. “So, my grandmother learned how to make pozole – she knew how to make Menudo and all of that but [pozole] wasn’t something that was served in the part of Mexico where she grew up. She learned how to make pozole for me and that was so special. She would make it every once in a while for me.”

For more information about Lopez and her business, visit nextgenlatinos.com.

a Fort Worth school district: Lo pez’s mom was the first bilingual education specialist, and the couple were the first husband and wife to be principals in the district back in the ’80s. They were both Mexican-American individuals.

“Because they were such great role models for me, that’s why I give back and why I support

“One day, I had gone to a friend of mine’s home and her mother had made po zole and I loved it,” – Michelle Lopez

Maravillas:

Keeping the culture alive

By Amira Van LeeuwenCynthia Martinez communicates with artisans across the border to supply her small business, Maravil las, located at 11525 Menchaca Rd #104 in Austin, with unique, handmade Mexican products. Martinez purchases bags, textiles, hats and clothing from artisans in several states in Mex ico: Chihuahua, Puebla, Quereta ro, Wahaka, Guanajuato, Chipasa and Jalisco. She purchases cloth ing items and ornaments from Puebla and Chipasa, and most of her dolls come from Queretaro. Martinez also buys many skulls from Guanajuato.

But sometimes, it takes her days or even weeks to research the items she wants.

Contributed

When considering what kinds of products to fill her shop, Marti nez looks at color and quality.

“I am drawn to what’s unique,”

Martinez said.

Much of Maravillas’ customer base is from Kyle, Buda, San An tonio, Round Rock, Edinburg and other parts of the Valley.

Martinez feels like the items she sells draw out memories and gives people a space to appreci ate their culture.

“I feel like we’re keeping the culture alive. We’re keeping that pride, those memories — we’re reigniting those memories for a lot of people when they see our stuff. It reminds them of how wonderful even the smallest little thing can trigger those beautiful memories,” Martinez said.

“Every person who comes to my booth will be like, ‘Oh my God, my mom used to have that.’ I have kids going, ‘I just ate that today,’” Martinez said, referring to her pan dulce keychains. “I swear, everyone has some type of connection to what I have.”

When working with the

artisans, Martinez emphasizes the importance of honesty and keeping your word.

Martinez remembers there was once an artist who, after immediately getting paid, came up with a story as to why she couldn’t give Martinez her prod uct. At the time, Martinez was in disbelief.

“It was a good amount of mon ey,” Martinez said. “I remember feeling like, ‘I don’t know if I wanna do this. This is risky.’”

Martinez said she told one of the artists she worked with the second time that she would order from her but asked if the artist could send Martinez a photo of the product she was ordering to ensure she had it.

She asked Martinez if every thing was okay, and Martinez was honest and told her that she had been stiffed and was trying to be careful. The artisan said, “You know, I hope you know that

[there are] so many good artists, we are honest and truthful and I’m sorry that you had to deal with one that wasn’t.” After this response, Martinez realized that it goes both ways.

“They’ve made products before and waited on the money, and no one ever sent anything. And here they are, they spent this money, and they don’t have extra money to be wasting,” Martinez said.

Now, Martinez talks to the artisans and tries to purchase items from people that were recommended in the small vendor com munities. She says many of the artisans she works with have now become friends; they text and send photos to each other, wish her well in her sales and even follow her on Face book and Instagram. She also likes to send the artists photos of her setup and pictures of their products on her Instagram.

Martinez said she never asks for a product if she’s unsure that she wants it.

“When I tell someone ‘I want this’ and ‘This is how many I want,’ that’s what I’m getting. I don’t back out,” Martinez said.

Three challenges Martinez faces as a small Hispanic business are: pushback at vendor events, limited inventory space, and people attempting to negotiate prices.

“If you say you sell Mexican items, a lot of people think, ‘Oh, you’re just like all of them.’ No, we don’t need that; we don’t want that here,” Martinez said.

Martinez also says she gets pushback at some vendor events because the items must be handmade.

“I have to explain; literally everything I sell is handmade. There’s nothing ma chine-made,” Martinez said.

Additionally, Martinez doesn’t have a lot of

space to order large quantities of items. She also gets pushback from people who accuse her of taking from the artisans or individu als who want items at a cheaper price.

“Small businesses get compared to the large corporations too much,” Martinez said. “I’m not fiesta. Nobody questions H-E-B. Nobody says, ‘Hey can you give me a better price? Because that’s too much’ or ‘If I buy five, will you give me a discount?’”

In the future, Martinez would like to sell women’s clothing, silver jewelry and custom papel picada.

“Every person who comes to my booth will be like, ‘Oh my God, my mom used to have that.’ I have kids going, ‘I just ate that today,’” – Cynthia Martinez

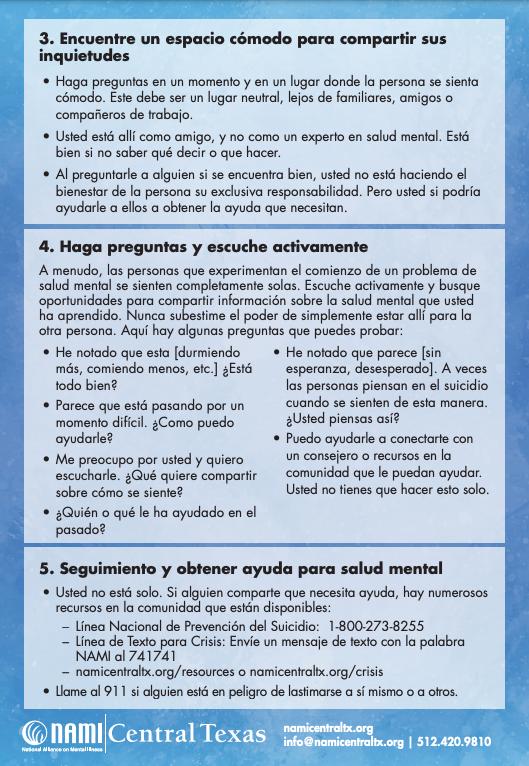

Navigating the mental health system as a Spanish speaker

By Brittany AndersonNavigating the mental health sys tem can be tough for anyone — but for those who don’t speak English, it can be even more challenging.

There are many disparities within the system that prevent individuals from having proper access to care. Texas also doesn’t have the best track record of mental health support and accessibility, but fortunately, there are resources that are addressing this issue and making it easier for Spanish speakers in particular to find the help that they need.

NAMI (National Alliance on Mental Illness) is a 501(c)3 nonprofit organi zation, and its Central Texas branch serves Hays, Caldwell, Bastrop, Travis, Williamson, and Burnet counties. Through a variety of education and support programs, NAMI works to provide a system that breaks down barriers to address mental illness.

According to NAMI, more than half of Hispanic young adults ages 18 to 25 with a serious mental illness may not receive treatment. Only 35.1% of His panic/Latinx adults with mental illness receive treatment each year compared to the U.S. average of 46.2%.

Language is one of these barriers. Being able to communicate with healthcare providers and relay mental health struggles is crucial.

Dulce Gruwell, peer program coor dinator for NAMI Central Texas, helps coordinate programs for adults living with mental health conditions, from peer/family support groups and re covery education to classes that teach coping skills and more. She also leads the effort in ensuring these programs are offered in Spanish.

“I’m very passionate about bringing our programs in Spanish. It’s kind of self-care, because I can do what I’m passionate about,” Gruwell said. “It’s not just providing peer support in Spanish, it’s being able to provide

a presentation in our own voice, [be cause] we don’t talk about it.”

Gruwell said that in general, there is “not a lot of mental health peer sup port in Central Texas,” but the stigma surrounding mental health is another huge barrier within the Hispanic/Lat inx community.

People are sometimes simply em barrassed to admit they have a mental health condition and fear bringing shame to themselves or their families. For many, doing so is “taboo,” but this only leads to a longer laundry list of problems including not seeking treat ment, especially if they are unsure of where to start.

According to NAMI, there are several other mental health systemic barriers that can hinder the Hispanic/ Latinx community:

• Poverty or lack of health insur ance coverage. NAMI resources state that 17% of Hispanic/Latinx people in the U.S. live in poverty, and in 2019, 20% of non-elderly Hispanic people had no form of health insurance, fac ing an already limited pool of provid ers due to language barriers. Gruwell noted that NAMI is free and does not ask about insurance.

• Legal status. Fear of deportation can prevent immigrants from speak ing up and seeking help.

• Cultural differences. These can cause mental health providers to mis understand or misdiagnose Hispanic/ Latinx patients if they lack under standing of how their patient’s culture influences their interpretation of what they are feeling.

• Acculturation. Assimilating into the predominant culture can play a role in mental health and access to care, and the process can be stress ful for Hispanic/Latinx communities

Navegar por el sistema de salud mental como hispanohablante

Por Brittany AndersonNavegar por el sistema de salud mental puede ser difícil para cualqui era, pero para aquellos que no hablan inglés puede ser aún más difícil.

Hay muchas disparidades dentro del sistema que impiden que las perso nas tengan un acceso adecuado a la atención. Texas tampoco tiene el mejor historial de apoyo y accesibilidad a la salud mental, pero afortunadamente, hay recursos que están abordando este problema y facilitando que los hispano hablantes en particular encuentren la ayuda que necesitan.

NAMI (National Alliance on Mental Illness) es una organización sin ánimo de lucro 501(c)3, y su sucursal en el centro de Texas sirve a los condados de Hays, Caldwell, Bastrop, Travis, Williamson y Burnet. A través de una variedad de programas de educación y apoyo, NAMI trabaja para proporcio nar un sistema que rompa las barreras para hacer frente a las enfermedades mentales.

Según NAMI, más de la mitad de los adultos jóvenes hispanos de 18 a 25 años con una enfermedad mental grave no reciben tratamiento. Sólo el 35,1% de los adultos hispanos/latinos con enfermedades mentales reciben tratamiento cada año, en comparación con la media de Estados Unidos, que es del 46,2%.

El idioma es una de estas barreras. Ser capaz de comunicarse con los prov eedores de atención médica y trans mitir los problemas de salud mental es crucial.

Dulce Gruwell, Coordinadora del Programa de Pares de NAMI Central Texas, ayuda a coordinar los pro gramas para adultos que viven con condiciones de salud mental, desde grupos de apoyo de pares/familiares y educación para la recuperación hasta clases que enseñan habilidades para enfrentar problemas y más. También lidera el esfuerzo para asegurar que es

tos programas se ofrezcan en español.

“Me apasiona llevar nuestros pro gramas en español. Es una especie de autocuidado, porque puedo hacer lo que me apasiona”, dijo Gruwell. “No es sólo proporcionar apoyo a los com pañeros en español, es poder ofrecer una presentación en nuestra propia voz, [porque] no hablamos de ello”.

Gruwell dijo que, en general, “no hay mucho apoyo de pares de salud mental en el centro de Texas”, pero el estigma que rodea a la salud mental es otra gran barrera dentro de la comunidad hispana / latina.

La gente a veces simplemente se avergüenza de admitir que tiene una condición de salud mental y teme traer la vergüenza a sí mismos o a sus familias. Para muchos, hacerlo es “tabú”, pero esto sólo conduce a una lista más larga de problemas, incluyen do el no buscar tratamiento, especial mente si no están seguros de por dónde empezar.

Según NAMI, existen otras barreras sistémicas de salud mental que pueden obstaculizar a la comunidad hispana/ latina:

• Pobreza o falta de cobertura de seguro médico. Los recursos de NAMI afirman que el 17% de los hispanos/ latinos en Estados Unidos viven en la pobreza, y en 2019, el 20% de los hispanos no ancianos no tenían ningún tipo de seguro médico, enfrentándose a un grupo de proveedores ya limita do debido a las barreras lingüísticas. Gruwell señaló que NAMI es gratuito y no pregunta por el seguro.

• Situación legal. El miedo a la deportación puede impedir que los inmigrantes hablen y busquen ayuda.

• Diferencias culturales. Éstas pueden hacer que los proveedores de salud mental malinterpreten o

Hays Latinos United

works to erase racial disparities

By Megan WehringWitnessing communities of color face barriers throughout the COVID-19 pandemic inspired Michelle Cohen to do something to help.

Hays Latinos United, created in 2020, is a community orga nization formed as a direct response to the disparities of the Latino community and other people of color, which started with the onset of COVID-19. Latinos were asked to be at the front lines of the pandemic as essential workers and when the state opened up, they were asked to return to work with little protection for themselves and their families.

Cohen said that right at the beginning of the summer of 2020, she learned that communities of color were getting the most confirmed cases of COVID-19 at the national level. It left her with one question: What about in Hays County?

She wrote a letter to the county asking if it could release the de mographics because she believed it was important for the commu nity to understand how it was doing in relation to COVID-19. Eventually, they released the demographics.

“Latinos were leading in every category related to COVID: con firmed cases, the deaths, hospi talizations [and] positivity rates,” Cohen said. “They were the most impacted.”

The lack of organized efforts

to provide resources at the beginning of the pandemic drove Cohen to start her own.

“Food was beginning to be come a scarce resource. I started seeing stores charging $10 for a mask and I thought that a strug gling family is not going to buy a mask over food,” Cohen said. “What I started doing is buying my own masks and hanging out at the COVID-19 testing centers. I would stand there with a table [and] I would offer masks to anybody who walked by. With me and a few other community leaders, we did our own PPE drive once or twice a month. It was all self-funded with donated materials.”

Within the past two years, Hays Latinos United has become a source for anything ranging from COVID-19 resources, food, water, school supplies and getting its wellness partners to provide resource information in both English and Spanish.

“I’ve really started focusing on making sure that we provide bilingual information because we were fighting the misinformation this entire time and we still do,” Cohen said.

While the organization has come a long way since the beginning and has positively impacted the community, it still faces barriers including the lack of community infrastructure on the east side of the county.

“There are no libraries, com munity centers or buildings for us to access,” Cohen said. “I have to use little venues that may be

used for a quinceañera [or] birth day party like Gemstone Palace. They donate space for us for our vaccine events.”

Currently, Cohen’s main goal is to reach 50% full vaccination of the Hispanic population in Hays County.

“Right now, we are nowhere near that,” Cohen said. “We have over 94,000 that live in this coun ty and maybe 24,000 are actually fully vaccinated.”

To learn more about Hays Lati nos United, please visit https:// www.hayslatinosunited.org/.

who are also trying to navigate between cultures while possibly facing discrimination.

Martha Lujan is a mental health specialist and community health worker at the UT School of Nursing Social Resource Center in Del Valle and a NAMI volun teer. Her hands-on role allows her to also see these barriers and help the community work through them.

“It does take a level of healing process. You have to come to a place in your life where you can understand your own behavior,” Lujan said. “It’s a cycle. You want

SALUD MENTAL,

diagnostiquen erróneamente a los pacientes hispanos/latinos si no comprenden cómo la cultura de sus pacientes influye en su inter pretación de lo que sienten.

• Aculturación. La asimilación a la cultura predominante puede desempeñar un papel en la salud mental y el acceso a la atención, y el proceso puede ser estresante para las comunidades hispanas/ latinas que también están tratan do de navegar entre las culturas mientras posiblemente se enfren tan a la discriminación.

Martha Luján es especialista en salud mental y trabajadora de salud comunitaria en el Centro de Recursos Sociales de la Escuela de Enfermería de la UT en Del Valle y voluntaria de NAMI. Su papel práctico le permite ver también estas barreras y ayudar a la comunidad a superarlas.

“Hace falta un nivel de proceso de curación. Tienes que llegar a un lugar en tu vida donde puedas en tender tu propio comportamien to”, dijo Luján. “Es un ciclo. Quieres romper ese ciclo. Cuando buscas asesoramiento, terapia, grupos de apoyo, recursos, eso es parte de tu curación”.

El estigma de la salud mental dentro de la comunidad hispana/ latina no pasa desapercibido para Luján: “Nosotros no hacemos eso; no tenemos ansiedad; no toma

to break that cycle. When you seek counseling, therapy, support groups, resources, that is part of your healing.”

Mental health stigma within the Hispanic/Latinx community is especially not lost on Lujan:

“We don’t do that; we don’t have anxiety; we don’t take medica tion; you’re just bored, you need to go do something,” are common justifications, she said.

“I feel that my people have a lot of healing to do,” Lujan said. “We are trying to make sure these conversations in Spanish are normalized, that these feelings are normalized, that there’s a safe place for them to speak about.”

Lujan also acknowledged that

mos medicación; simplemente estás aburrido, necesitas ir a hacer algo”, son justificaciones comunes, dijo.

“Siento que mi gente tiene mucho que sanar”, dijo Luján. “Estamos tratando de asegurarnos de que estas conversaciones en español se normalicen, que estos sentimientos se normalicen, que haya un lugar seguro para que hablen”.

Luján también reconoció que las barreras, ya sea el estigma, el idioma, el dinero, el seguro, la documentación o incluso sólo el día a día en el trabajo, deben ser abordadas para que las personas puedan ser atendidas donde se encuentran con apoyo.

“Cuando se llega a ese punto y se sabe que es un espacio seguro, se ha pasado por el infierno y la espalda, se trata [de] el acceso”, dijo Luján. “Cuando llegan a ese punto y no tienen el acceso, eso es una barrera. Se rinden. ... Es una cuestión de supervivencia. Si no está ahí cuanto antes, perderás a esa persona”.

Aunque el sistema todavía tiene mucho trabajo por hacer, especialmente para la población hispana/latina, los miembros de la comunidad como Gruwell y Luján se han consolidado como parte de la solución comprometida con el acceso a la salud mental para todos.

“Cuando descubres algo tan tranquilo, descubres un lugar donde puedes ser tú mismo y hablar de ello, y quieres dar eso

barriers, whether it’s the stigma, language, money, insurance, documentation or even just day-to-day work life, need to be addressed so people can be met where they’re at with support.

“When you get to that point and you know it’s a safe space, you’ve gone through hell and back, it’s [about] access,” Lujan said. “When they get to that point and do not have the access, that’s a barrier. They give up. … It’s survival. If it’s not there asap, you will lose that person.”

Although the system still has a lot of work to do, especially for the Hispanic/Latinx popula tion, community members like Gruwell and Lujan have cement ed themselves as being part of

a la otra persona”, dijo Luján. “Me gustaría poder mostrarles lo que puede ser su viaje. ... Todos tenemos antecedentes y traumas diferentes. Estamos en diferentes niveles. Ser capaz de dar esper anza a la gente, eso es lo que me empuja. ... Sólo para sentir algo

the solution and are committed to providing mental health care access to all.

“When you discover something so peaceful, you discover a place where you can be yourself and talk about it, and you want to give that to the other person,” Lujan said. “I wish I could show them what their journey could be. … We all have different back grounds and traumas. We’re at different levels. Being able to give people hope, that’s what pushes me. … Just to feel some peace.”

For more information on how to get Spanish-language mental health support, visit www.nami centraltx.org/en-espanol. NAMI’s phone line also offers bilingual services at (512) 420-9810.

de paz”.

Para obtener más información sobre cómo obtener apoyo para la salud mental en español, visite www.namicentraltx.org/en-es panol. La línea telefónica de NAMI también ofrece servicios bilingües en el (512) 420-9810.

1 Year Digital & Print

Seniors

1 Year Digital Only

Seniors

$31.50/year

CONFIDENCE AND COMMUNITY LOCAL BARBERSHOP INSTILLS

By Brittany Anderson

By Brittany Anderson

A

good haircut can make or break your spirit — and it’s in this crucial moment where Chris Ortiz and Tony Arredondo shine best. Ortiz and Arredondo, cousins and Kyle natives, are the owners of Gentlemen’s Grooming 101, located at 225 S. Main Street in Kyle.

Ortiz started Gentlemen’s Grooming in 2013, rebranding what was formerly C&J Barbershop. Arredondo later joined the team in 2015, but the duo didn’t become official business partners until earlier this summer.

For Ortiz and Arredondo, their philosophy behind being barbers is simple: they like to make people feel better about themselves.

“I remember the first time I got inspired to be a bar ber was when I got a really nice haircut. I want to say I was about 13,” Ortiz said. “I remember how much confi dence it gave me as a kid, and that’s when I got infatuated with it. … That’s where the whole passion started for me. I know it sounds a little cheesy, but that’s the truth.”

Arredondo had similar aspirations from a young age but didn’t get his start in hair until a little bit later in life.

“I didn’t become a barber until I was 23,” Arre dondo said, noting that he was then a tow-truck driver and thought he would do that forever — until his mother-in-law asked what he truly wanted to be.

“I’ve always had an interest for hair ever since I was growing up,” Arredondo continued. “I grew up in the barber shop. I was always clean cut. I know sometimes my mom couldn’t afford hair cuts, but when [she] did, I cherished it.”

Like many small business owners, the journey hasn’t always been easy. The pair have faced struggles that go beyond what they experienced during the COVID pandemic.

“A lot of landowners will see a young Hispanic business owner, [and] sometimes they didn’t believe in us as much as we would’ve liked them to, and that was tough,” Ortiz said. “It’s not something that me and Tony hang our heads on and hold a grudge. It is what it is. We just have to

keep moving, keep the good fortune and positive vibes on our side.”

But for Ortiz and Arredondo, being Hispanic plays an integral role in how they are able to cultivate the atmosphere of their shop.

Ask any barber or hair stylist and they’ll most likely tell you they know everything about every one. From their client’s personal highs and lows to the latest news and local gossip, barbershops and salons have long been a place where people feel safe and welcomed, and Gentlemen’s Groom ing is no exception.

“One thing about Hispanic families and cul ture, it’s a real tight-knit type of family and community. … I feel like our shop has that,” Ortiz said. “I think that stems from coming from a Hispanic background. That’s something I’m grateful for, and I think that’s helped our business thrive a lot. When we have that type of environ ment, the clients feel that too.”

Outside the four walls of their shop, the Gentlemen’s Grooming team made it a point to bring this energy and get out into the community

as much as possible, brightening days and making friends wherever they go. For several years, the business has held two notable events: Cutz4Kidz, offering free haircuts for school-aged children that is coupled with a backpack/school supply drive, and their commemorative 9/11 free haircut event for first responders. They are also looking to collaborate with another barbershop to give free haircuts to unhoused individuals.

For them, doing this kind of work beyond their regular barbershop duties just makes sense — and the love and support they receive in return from the community isn’t lost on them either.

“We’re fortunate enough to have a business now, but it wasn’t always like that growing up. We definitely grew up with humble experiences, me and Tony both,” Ortiz said. “Being from the community, to me, I feel like it’s my duty to give back when I can. Everybody needs that at a point in their life.”

“Once you do give your first haircut, and you actually make people feel good, that’s the other turning point,” Arredondo added. “You’re more than just a barber.”

The Pink Penthouse:

The Pink Penthouse:

Back and better than ever

Photo credit: Amira Van Leeuwen

Feathered lamp from Home Goods.

By Amira Van Leeuwen

By Amira Van Leeuwen

Owner and creator Charlie Leanne Murphy was 12 years old when she saw American actress, model, and singer Jayne Mansfields’ pink shag bathroom and said, “I want a bedroom like this one day.”

The Pink Penthouse, formerly located in San Marcos, has moved its way up the I-35 Corridor to Kyle.

The Pink Penthouse has various photoshoot rates like $60 an hour with one photographer and one model. The half-day rate (3 hours) allows two models and one photographer for $330. A fullday rate (5 hours) allows two photographers and two models for $440. If a customer decides they want to bring additional models, it is an extra $100 per model.

Murphy and Chavez also offer makeup services for $150 per person. If a customer wants only hair or only makeup, the price is $75.

Due to unforeseen circumstances, Murphy and Pink Pent house Manager Lexi Chavez had to leave San Marcos along with all of their belongings. Chavez said a lot of things were chang ing, and they were changing fast.

“We had to sell everything, literally overnight,” Murphy said.

“I remember when we had to sell all of our stuff. It was crazy because people were coming in fast,” Chavez said. “In at least like one or two days, the studio was almost empty.”

But despite the sudden change, Murphy and Chavez adapted, and the Pink Penthouse was able to reopen its doors once again in August.

Murphy says she’s always felt like she’s had her own style.

Murphy says she spent about $50,000 overall on materials.

Photo credit: Amira Van Leeuwen

Murphy and Chavez sitting and smiling in front of their fireplace.

Photo credit:

Amira Van Leeuwen

The bathroom has a lot of small pieces from Hobby Lobby and Home Goods.

Many of the pieces in the Pink Penthouse are antiques that have been upcycled. When look ing for vintage pieces, Murphy likes to look on Facebook Marketplace and also has a couple of places in San Antonio where she likes to go and hunt. Other times, people will gift vintage items to the two because they want to see their pieces in the house.

For the pink shag, Murphy said she tried to get all of it locally, but due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it was difficult to find. Back in San Marcos, Murphy began shagging her walls in mid-October of 2021 and was not finished until around December or January.

Contrary to popular belief, the shag walls do not require much upkeep. Murphy said it’s mainly dusting, vacuuming and brushing.

“A lot of people think, ‘Oh she just vacuums the whole entire wall’ — I don’t do that. I don’t vacuum the whole wall. I’ll vacuum the cor ners and of course check for spiders – which sounds stupid, but everybody has spiders in their house,” Murphy said, adding that she vacuums her walls about once a month and also has a rake that she has for her ceiling to get rid of any staple lines.

“It’s so funny because it’s so normal for us to have shag walls, so everyone’s probably like ‘This is insane,’ but we’re just so used to it,” Chavez said. “People will love it, or they hate it.”

Murphy and Chavez said many people assume that it’s hot in the room and that there are bugs and dust, but they don’t have many problems with their pink shag walls.

Apart from the upkeep of the Pink Pent house, going on excursions for new vintage pieces and posting social media content, Mur phy also opened up about her struggles with mental health.

Murphy suffers from PTSD and short-term memory loss, which stems from childhood trauma and past partners. Personal matters prompted her to check into a mental facility in March where she stayed for about eight days.

Murphy said it was scary being there and she felt like once someone is in there, they lose their human dignity.

“It was just really depress ing to see how cold it was,” Murphy said.

Murphy also said she watched the kids unit walk through the women’s unit that she was in every day.

“They just looked so sad, and there wasn’t a lot of stuff, like activities for them, and there’s not a lot of

money in mental health at all, especially with the kids and women’s units,” Murphy said.

Murphy’s battle with mental health and her time in the hospital inspired her to think about making a clothing line for women and creating a fun space for kids.

In the future, Murphy and Chavez plan on hosting invite-only house parties and events with other small businesses. Murphy says she would love to get into filming music videos at the penthouse and dreams of having artists like Megan The Stallion, Doja Cat or City Girls at the penthouse.

Buñuelos

Recipes

Carne Guisada