16 minute read

Contributors 5

i Editorial Artist of the Month

Advertisement

ii Herb of the Month Of Weeds & Weans Notes from the Brew Room

iii Our Man in the Field…. Kyra Pollitt Kenris MacLeod

Marianne Hughes, Hazel Brady Joseph Nolan Ann King

Dave Hughes meets Dee Atkinson

iv Nature Therapy Anthroposophical Views

v Jazz Ecology The Chemistry Column

vi Garden Gems

vii Plantstuffs Nathalie Moriarty Dora Wagner

Ramsey Affifi Dr. Michelle Armstrong

Ruth Crighton-Ward

Elizabeth Oliver

viii Plants and Places Foraging Through Folklore

ix Botanica Fabula StAnza Presents…

x Book Club: LearnGaelic Ella Leith

Amanda Edmiston Anna Crowe

Marianne Hughes reviews The Medicinal Forest Garden Handbook by Anne Stobart (Permanent Publications, 2020) Edie Turner reviews The Prisoner’s Herbal by Nicole Rose (Active Distribution, 2019) Kyra Pollitt reviews Why Willows Weep by The Woodland Trust (Indie Books, 2011)

xi The Herbologist’s Diary

xii Contributors Looking Forward 4 7

10 11 13

16

20 21

24 26

29

32

35 36

39 41

43

49

50 54

Sharp Kyra Pollitt

Welcome to the Sharp issue. Sharp can mean many things; the sharpness of the needle so deftly handled by Kenris MacLeod (our Artist of the Month), a thorn sharply turning the narrative in a fairy-tale (Foraging through Folklore), the sharp thinking of a good friend (Jazz Ecology), the sharp scent of a memory (Plantstuffs), the sharper end of childhood (Of Weeds & Weans). Here at Herbology News HQ, sharp has manifest in both good and less good ways over the course of the past month.

Firstly, we have been delighted at the response to our September issue. The new platform and expanded content have brought a sharp increase in readership. We welcome each and every one and hope you will find both interest and joy in these pages. We hope, also, that you will help us to continue this growth by sharing the link with friends, family and colleagues and encouraging them to subscribe. You can also now follow us on Instagram @Herbology_News, and we’d be delighted if you would connect, comment and share there, too.

Less comforting, the sharp increase in coronavirus Covid-19 cases as the world experiences the second wave of the pandemic has made itself felt even here. Some of our regular columnists are absent this month. Khadija Meghrawi, our Messy Medic, was poised to bring her inimitable take to an explanation of the functions of blood. Instead, like many brave young medics, she is working extra shifts on the hospital wards. Our thoughts are very much with her, and we look forward to welcoming her safely back in our next issue.

Khadija’s extreme dedication is a reminder that everyone on Herbology News gives their time voluntarily; each making their contribution in addition to their daily family and work commitments and, sadly, whilst also managing bereavement. I salute and thank every one.

Over at the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh, there are still restrictions on volunteers so, besides frustration, there remains little to report from the Globe Physic Garden. And yet, beyond the stasis, the pandemic inevitably also brings change and renewal. We wish Sutherland Forsyth all the very best in his new direction and look forward to new connections with the Physic Garden at the Palace of Holyroodhouse.

Our quarterly column on Plant Medicine & Social Justice will be back in December but, in the meantime, you can keep your focus sharp with Edie Turner’s Book Club review. And we are thrilled to welcome two new columnists to the Herbology News family. Nathalie Moriarty brings a soothing balm for the soul in Nature Therapy, whilst Dora Wagner promises to introduce us to a world of Anthroposophical Views. As ever, if you have something to add to these pages, we’d really like to hear from you.

We are delighted that Catherine Conway-Payne has accepted the role of Executive Editor, and we also welcome Marianne Hughes in her new capacity as Treasurer. Marianne is busy opening a bank account so that, in our next issue, we can begin to sell tickets for our Grand Winter Raffle. Please keep your wonderful offers of prizes coming in— just contact herbologynews@gmail.com. We also encourage you to consider advertising with us. All the money raised will go to upgrading our digital publishing platform, making your reading experience smoother, more efficient and more pleasant. Issuu, the digital publisher, have very kindly offered us a 30% discount on our first year’s subscription. The rest is up to you.

Executive Editor Catherine Conway-Payne Editor Kyra Pollitt Artistic Director Maddy Mould Illustrators Maddy Mould Hazel Brady Treasurer Marianne Hughes

Herbology News has grown from the Herbology courses taught at the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh, under the careful eye of Catherine Conway-Payne.

A suite of Herbology course options are available, as part of the broad range of education courses offered by RBGE.

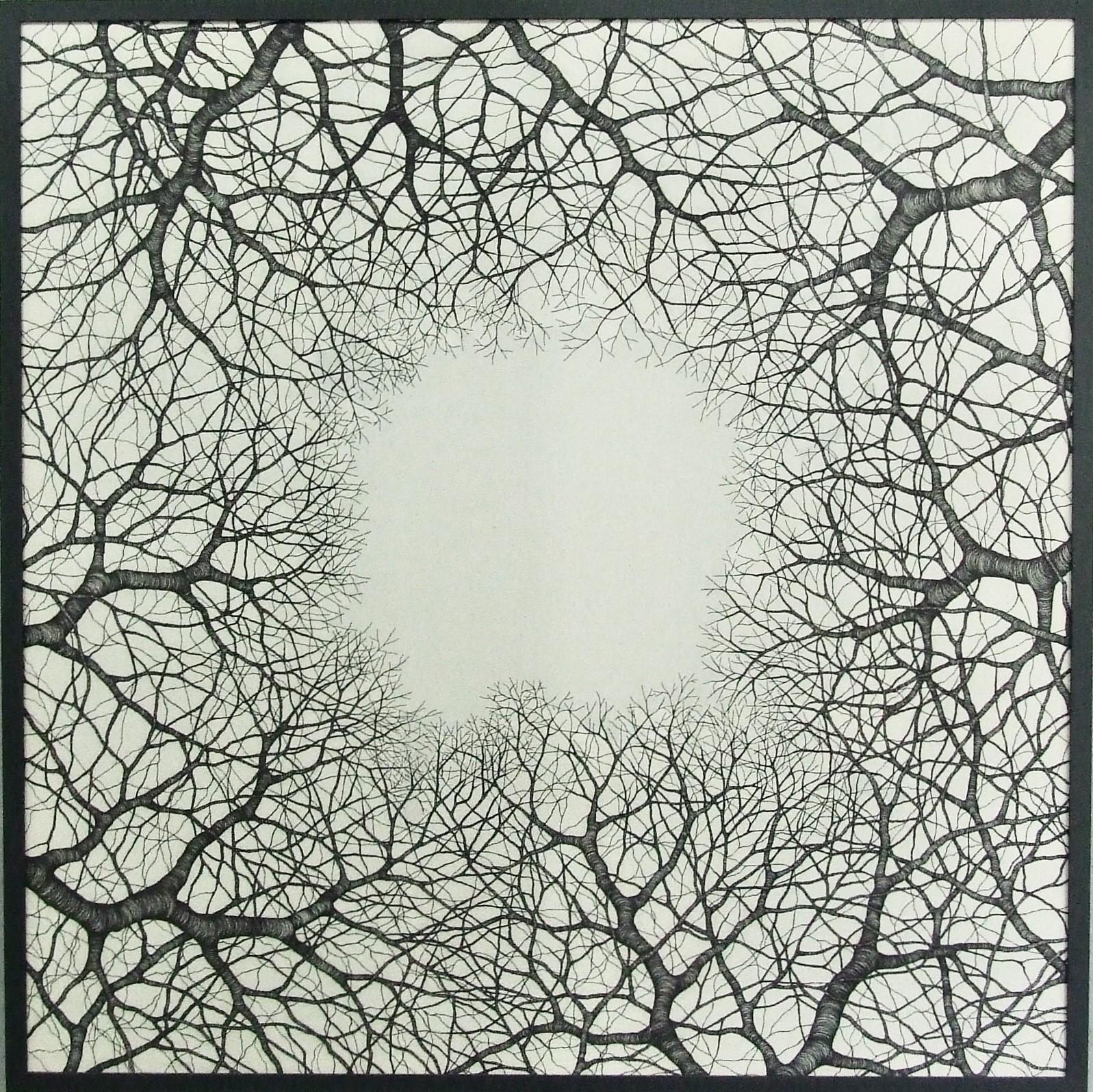

Kenris MacLeod www.kenrismacleod.com

Kenris MacLeod is a textile artist who lives and works in Edinburgh. For fifteen years she worked as a BBC radio producer, before swapping sound for vision to study at Edinburgh College of Art in 2008. Now she uses the medium of freehand machine embroidery to describe the textures and complexity of the natural world— specifically trees. Ostensibly fitting the tradition of ‘textile art’, Kenris’s work is probably more akin to drawing and painting— it’s just that she uses thread. In fact, Kenris says, she was thoroughly put off sewing at primary school and it wasn’t until she was required to take a Stitched Textiles module as part of her BA Degree that she realised how versatile a sewing machine could be: Put your feed dogs down, attach an embroidery foot and the rest is up to you. It quickly became apparent to Kenris that freemotion machine embroidery was the medium she’d been searching for; that thread could create tonal complexity, texture and depth, and give her a language through which she could explore her love of trees. She has since become: totally and irretrievably absorbed by the forest as well as being covered in bits of thread. Her childhood love of trees has proved long-held, and her obsession shows no sign of abating. Kenris lives near the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh and spends hours up close with their wonderful collection of trees. As she asserts: if trees were sculptures, we would look up in awe and disbelief that something so epic and beautiful could exist. But all over the world we, at best, take them for granted and, at worst, indiscriminately destroy them, instead of cherishing and protecting them. Trees are our giant protectors, they are beings that defend us, hold the earth together. Kenris’s work is an investigation of her relationship with this notion; how we depend on them, how we are often merciless in their destruction. Their presence dwarfs us. We are like insects, endlessly busy, leading manic, futile lives. We come and go. Those trees we choose to protect, or ignore, live on— silent, dignified. The horror of human treatment of trees fires Kenris’s practice. The philosopher, Martin Buber, suggests if we refer to the world in terms of ‘I and Thou’ rather than ‘I and It’ we suddenly apprehend new beings. Thus, trees become considered unique individuals, each one ‘you’ rather than ‘it’, and they become known to us in an entirely different way. It is the sense of living alongside a race of ‘others’, who we can never fully comprehend, that Kenris wishes to convey in all her work. In particular, You asks us to enter into their realm and allow ourselves to be enveloped and absorbed. We become a sapling in the forest, surrounded by a family.

Kenris’s pieces demand close proximity. She sews only centimetres from each work, as if examining the texture of bark by touch, and is only able to see what she has achieved by stepping back. Each work is composed of tiny stitches, creating her representations of these beings cell by cell. It is a form of reverence, of tree worship. The machine is noisy, she barely hears the world beyond, her eyes focused on the tiny points where the thread appears and disappears. Creating these giants from such microscopic marks is a way of honouring their majesty— Kenris’s attempt to come to terms with what they are, whether they are conscious of us —and our responsibilities to them and the natural world.

Kenris is currently accepting commissions but does have a waiting list. We are grateful to Kenris for permission to include the following images:

Cover Image and insert (page 38) The Blameless Trees Thread and ink on calico, 36cm x 24cm, 2020

Page 9 When We Slept in Trees Thread on calico,142x142cm, 2017

Page 15 By Helford River Thread on calico, 70cm x 37cm, 2019

Page 23 The artist at work, wrapped in ‘You’

Page 28 Muriel's Wood Thread and ink on calico, 36cm x 24cm, 2020

Page 31 A Dream of Wings Thread and ink on calico, 25cm x 25cm, 2020

Page 34 Invincible Summer Thread and ink on calico, 41cm x 37cm, 2020

Page 42 The artist and ‘You’ SSA exhibition Time Spent Among Trees, Meffan Gallery, Forfar, 2019

Sea Buckthorn (Elaeagnus rhamnoides, previously Hippophae rhamnoides) Marianne Hughes, with illustration by Hazel Brady

For those of us who have been Herbology students at the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh, the wonders of Sea Buckthorn are memorable. Perhaps it was the thick gardening gloves and secateurs required to forage along East Lothian’s coast, perhaps the tart taste of one small berry, or perhaps learning that one berry held the equivalent Vitamin C of six oranges.

Sea Buckthorn was probably introduced to the East Lothian coast to stabilise the sand dunes. It has extensive roots which seek out water, making it drought resistant and an ideal plant for that environment. It is invasive, so there can be a conflict of interest between foragers and conservationists who favour a more mixed and biodiverse planting. While Kenicer (2018) notes the absence of Sea Buckthorn in Lightfoot’s Flora Scotia (1777), in the present day it is a useful medicinal plant.

There are very few fruit-producing plants that thrive in sandy soil, in salt-laden air, so it’ s interesting that Sea Buckthorn forms a symbiotic relationship with a fungus from the genus Frankia, which occupy specialised oxygen-excluding nodules in the roots. The Frankia fix nitrogen from the air directly to the Sea Buckthorn, conferring the shrub with a major advantage and improving soil fertility for the benefit of other plants. Medicinally, Sea Buckthorn berries not only have exceptionally high levels of Vitamin C, they are unusual in containing Palmitoleic acid— a valuable omega-7 monounsaturated fatty-acid. This fatty acid is present in breast milk and it helps suppress the production of new fat molecules, especially those that damage tissue and raise cardiovascular risk. Thus, Sea Buckthorn has some anti-obesity action.

Its other medicinal actions are antioxidant, antianaemic and anti-inflammatory, hence its reported use in wound healing. As anyone who has collected Sea Buckthorn knows, freezing ensures the oil in the berries is preserved and the berries can be removed without a squishy mess. There is a considerable amount of leaf and twig to be managed while preparing the berries for freezing, and these parts are often discarded. As recent Polish research into Sea Buckthorn leaf and twig extracts has noted, however, these parts also have important radioprotective, anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties (Skalski et al 2019). Indeed, Sea Buckthorn has been used in Russia to treat the effects of radiation.

References Kenicer, G. (2018) Scottish Plant Lore: An Illustrated Flora, Royal Botanical Gardens Edinburgh: Edinburgh Skalski, B.; Kontek, B.; Lis, B.; Olas, B.; Grabarczyk,L.; Stochmal, A. & Żuchowski, J. (2019) ‘Biological Properties of Elaeagnus rhamnoides (L.) A. Nelson twig and leaf extracts’, in BioMed Central’s Complementary Medicine and Therapies, 19:148 (accessed 16.9.20) Stobart, A. (2020) The Medicinal Forest Garden Handbook: Growing, Harvesting and Using Healing Trees and Shrubs in a Temperate Climate, Permanent Publications: Hampshire

Scrapes & Scratches Joseph Nolan

Children and sharp things inevitably meet; pins, tacks, pavement, wooden fences, thorns, errant bike cables, etc. No matter what you do, eventually there will be tears. There are several types of injuries that result when sharps and children mix and, provided they are minor, these garden variety hurts are easily managed with herbs at home. Scrapes & Scratches Child + Concrete. These injuries are not deep and do not bleed much, but they can be painful, weep a bit, and are prone to inflammation and itch, especially when healing. Grazes and scratches are also often dirty— the result of falling on gritty roads or afoul of the cat. Mostly, they just need to be cleaned, disinfected, and lightly dressed to keep them clean and comfortable for a few days. Cuts Child + Glass. In the main, cuts are treated much like scrapes and scratches, but they are deeper, can be ragged and difficult to keep closed on areas that move, and may bleed more. When cleaning, be sure to check for dirt, shards of glass, or other debris, and disinfect carefully. Cuts need dressing to keep them clean and closed and as comfortable as possible. Bites & Stings Child + Buzz Buzz. Between the ages of 1 and 12, I was bitten or stung by an uncountable number of invertebrates; mosquitos, gnats, spiders, bees, yellow jackets (aka wasps), fleas, ants, ticks, Portuguese Men-o-War, and many other beasties. Mostly, they itch. Some of them produce an awful electric shock feeling that can last for hours. Assuming there is no serious allergic reaction, bites need de-itching and stings need neutralizing. Beware of sores and infection from scratching. Splinters & Punctures Child + Wood. Splinters are particularly unpleasant; draw them rather than digging them out. Having endured many, many splinter digging sessions as a child, I am confident in saying that drawing is vastly superior to going at it with a needle and tweezers. Sometimes there is no splinter, just a puncture wound from a thorn or a pin. Treat these as though there were debris inside, because you never know. If the sharp item is rusty or dirty, consult a medic.

So, what does a herbalist to do when wee ones and sharps collide? Here are some herbal remedies for workaday wounds:

Cleaning & Disinfecting While ye olde soap and hot water is the gold standard for cleaning a wound, in the field you have to get creative. If washing is not possible, think anti-infective herbs. I carry a small bottle of Commiphora molmol (Myrrh) tincture in my bag. Myrrh, being resinous, is a high alcohol tincture and it burns like the dickens, but for dirty likely-toget-infected wounds, you can’t beat it. The tincture is anti-infective, and the sticky resin helps glue a cut together and encourages healing. You can reapply the myrrh as often as needed until the injury is healing well. On older children, you can use a little Tea Tree essential oil for its strong antiinfective qualities. And, despite the powerful smell, the oil doesn’t hurt when applied. Alternatively, you can pick some Achillea millefolium (Yarrow, Knight’s Millfoil), slap it on the wound, apply a dressing, and carry on. Yarrow has a strong, clean, medicinal smell, prevents infection, stops bleeding, reduces inflammation, and eases pain. Because it regulates blood flow, Achillea stops bleeding while encouraging local circulation, which promotes healing. And it is ubiquitous.

Dressing Plasters are great, if you have them. If you get caught without one, look around for some Plantago lanceolata or P. major (Plantain, Wide Weed). Roll a few leaves between your hands until they get juicy, and bind them on with an intact leaf. Plantain glues a wound closed, encourages healing, and discourages infection. Use with Yarrow, especially for bleeding or weepy wounds. If the hurt is itchy, Plantain cools and calms the inflammation. Failing Plantain, you can use Rumex obtusifolius (Broad Leaf Dock), R. crispus (Curly Dock), or another Dock species instead. Not as effective, but the tannins will help a wound close up and heal and draw out debris. Dock leaves also make good outside dressings for Plantain or other poultices, and the thinnish stems of the young leaves mean you can wrap and then tie them securely.

Drawing Preparations draw because they contract and squeeze, absorbing moisture from a wound. So, you apply a wet thing, let it dry and tighten, and it pulls out the offending item— be it stinger, splinter, gravel, or a minor infection. Such preparations are exceedingly useful and drawing can wait a few hours until you get home. Plantain is effective at drawing splinters or dirt, and likewise the Deadnettles Lamium album, L. pupuruem, and L. galeobdolon (White Deadnettle, Red Deadnettle, and Archangel), which Culpeper recommends for “things gotten into the flesh.” Roll a good quantity of the leaves between your hands until juicy, apply to the wound, dress with gauze or a breathable bandage so the poultice can dry, and leave overnight. The offending thing should be out in the morning. If the first application does not remove the item, apply a new poultice. Sometimes, though, you need to act quickly. With stings in particular, the offending object— like a bee’s stinger —may be left in the skin. Remove it as quickly as possible, flicking the stinger out with a fingernail rather than pulling with tweezers, which could empty the venom sac into the wound. Proper removal can go a long way towards mitigating a sting. For pulling out venom and debris, drawing is effective, and a Plantain or Symphytum officinale (Comfrey) leaf poultice calms inflammation, soothing itch and swelling. Hypericum perforatum (St. John’s Wort), used either as a fresh plant poultice or in extract form, relieves inflammation and that dreadful electric shock sensation. When neutralizing, use vinegar on wasp or yellow jacket stings, and baking soda paste on bee stings. For ticks, consult the NHS or CDC official page. There are many nasty tick-borne infections, including but not limited to Lyme, and proper removal reduces the risk. Remember to check the kind of tick, because not all ticks carry disease.

While Plantain, Deadnettle, and Comfrey leaf poultices are great, you can also use many things you already have. The best medicine is what you have to hand. Here are my store cupboard tips for making a drawing poultice to combat those “things gotten into the flesh”:

Take powder of Ulmus fulva (Slippery Elm), Althea officinalis Radix (Marshmallow Root), or cosmetic clay (like Bentonite) and make into a paste. Things you can use in place of the medicinal powder include oatmeal, any flour, and moistened bread. Anything that will dry and pull, even a chamomile teabag, will be useful for its drawing action. To make the powder into a paste, water is fine, but you can also use Myrrh or Calendula officinalis (Marigold) tincture (25%, 45%, and 90% all work well), or a herbal infusion like Calendula for the liquid. Dab a generous amount of the paste onto the wound so it is well covered. Dress to keep it in place, but keep the bandage light and breathable so the poultice can dry out. Leave overnight, and check in the morning. Renew if required.

Lastly, one must use sense. If an injury is more than minor, seek professional medical attention. Happy Herbing!