8 minute read

x Book Club

The Medicinal Forest Handbook (Stobart, Anne; Permanent Publications, 2020) Reviewer: Marianne Hughes

A few of us are aiming to develop a small medicinal forest garden in a corner of Figgate Park, Edinburgh and this book has been a good companion. It’s written by a medical herbalist who set up Holt Wood Herbs in Devon, in 2005. An informative and practical handbook, it includes stories of forest and medicinal herb gardens across the UK— including Poyntzfield Herb Nursery in the Black Isle.

Advertisement

The book is divided into two parts. In Part 1 the author details how to approach designing, establishing and maintaining a forest garden. She includes tables (which sound boring, but in fact are a useful way to present a considerable amount of information) outlining soil preferences, height of growth, sun/shade/spacing, and medicinal actions. In addition to a section on how to propagate from seeds or cuttings, and how to save/store your own seeds, the author devotes a chapter to sustainable harvesting. She even gives examples of how the levels of active constituents differ according to the season, reinforcing what all herbologists know (from experience)— that labelling is very important! There are many books that can be used for practical guidance in herbal preparations, so this one may not be your go-to favourite. However, it does provide a number of recipes which explain tinctures, syrups, oxymels, fruit leathers, glycerites, capsules, hydrosols, poultices, infusions, incense sticks and balms/ointments; in this way it is comprehensive. For the reader who is interested in commercial opportunities, the author concludes Part 1 with ‘Scaling up the Harvest’, which covers all areas relevant to a business venture. In Part 2 is a directory of forty trees and shrubs. For each, Stobart includes: description of habitat; cultivation/hardiness/harvesting; pests and diseases; and seed propagation. The therapeutic uses section outlines traditional uses, medicinal actions and uses, clinical applications and research, sample preparations and dosage, plus key constituents and safety. This section is well laid out, accessible (plenty of photographs) and informative. We learn the benefits of companion planting, for example that pairing Cherry trees (Prunus spp.) with Lemon Balm (Melissa officinalis) provides the shade that increases the oil content of the Lemon Balm. The information on hardiness— always useful to know —is backed up with climate maps for Europe and the USA. The author comments on the shortage of organically certified seed and locally grown nursery stock, and provides an appendix of resources.

As the climate emergency develops, bringing more extreme weather, planting diversity in trees, shrubs and herbs —with differing sizes, structures and layers —helps to provide resilience for the land on which we all rely. I recommend this book is a useful resource for small, and large-scale enterprises.

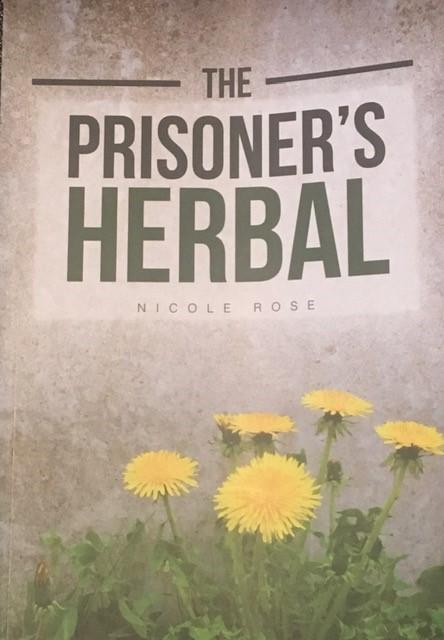

The Prisoner’s Herbal (Nicole Rose, Active Distribution, 2019) Reviewer: Edie Turner

Nicole Rose, an anarchist organiser and animal rights campaigner, was inspired to write this book whilst serving a 3.5-year prison sentence. As a consequence, it intertwines social justice and herbalism with a refreshing directness and practicality.

Created to support incarcerated women reclaim their health in the face of the medical neglect and lack of nutrition endemic in women’s prisons in the UK, it focusses on introducing the reader to plants that like to grow between the cracks in concrete, in scrublands and tarmac yards, as well some that might grow in the prison garden. The book also includes a section on ‘canteen remedies’; using spices, vegetables, and other widely-available ingredients. Conveniently, the lenses through which Rose writes also mean that The Prisoner’s Herbal is ideal for anyone who wants to forage, but is limited to an urban landscape. Whereas many herbological guides and foraging books use complicated terminology, steeped in a patriarchal history, Rose presents a manifesto for herbology in our time: a reclamation of health as resistance for communities marginalised by our current system.

In presenting each plant’s profile she gives a clear illustration to aid identification, alongside methods of preparation that don’t require any special equipment, nor any time spent decocting and making tinctures. I read the book whilst a long-term volunteer in the refugee camps at Calais, and I was able to recreate Rose’s suggestions with just the plants I could find on my 10 minute walks of the caravan park, using equipment available in my tiny shared caravan. And, for those reading from prison, there are tips on how to dry your foraged goods in books, where to hide produce in your cell, and how not to draw attention to yourself as you start to spend all your time with plants.

As much as it is informative and can be used as a practical guide, for me the most striking feature of The Prisoner’s Herbal is its ideology: it reminded me of the importance of the role of herbology in the fight for global and climate justice. Reclaiming this knowledge is resistance. It is a part of reclaiming our autonomy; of caring for our communities; of connecting with our planet, our folklore, our history. When we uncover this knowledge, we remember ourselves as a part of the web of the world around us. And when we reclaim it in this way— as direct action against a system of neglect and oppression —we act as a part of that web, too.

Why Willows Weep (The Woodland Trust, Indie Books, 2011) Reviewer: Kyra Pollitt

A recent online folk fiction writing course led me to this anthology, so I was expecting the nineteen authors gathered in these pages to have rewritten versions of tales familiar to Dr. Ella Leith (Foraging through Folklore) and Amanda Edmiston (Botanica Fabula). Not so. The subheading of this volume— ‘Contemporary Tales from the Woods’ —is the key. That’s not to say there aren’t traditional tropes here, as the satisfyingly rounded ending of James Robertson’s tale testifies: To this day the aspen’s leaves are sometimes known as ‘old wives’ tongues’, a name that springs, perhaps, from a tale such as this.

Yet other writers embrace the contemporary in myriad, bold ways. Tracy Chevalier’s story of the Birch, in which the young female character is too intelligent for her dim-witted suitors, begins: Birch trees did not always have silver bark. There was a time when their trunks were the grey-brown of most other trees. It was sex that changed things. It always does. And, indeed, sex is a theme echoed in other contributions. Phillipa Gregory’s encounter with Holly is positively, and therapeutically, sensual: He is King Holly and he slides up the sash window of my bedroom and steps over the sill, sure of his welcome. He lies with me and I cannot resist him, his mouth scratches my lips; and my naked body, white as the moon, is burnished red as a holly berry under the prickle of his touch… Rachel Billington takes a broader view: The wild cherry tree is a hermaphrodite, both male and female, and more than a little poisonous. This didn’t stop the cuckoo falling in love with him (and her).

Thus, although a light and entertaining volume, this is mostly a story book for adults. But not all these tales pivot on sexuality. Catherine O’Flynn, for example, gives a darkly hilarious account of innocent miscommunication between trees and humans: the limes trees decided to extend the initiative to all the cars in the road. They loved to see the people wave their fists in gratitude, to hear them phone the local authority and tell them all about the incredible sap. The people spent more time out on the street now, harvesting the glue from their cars with sponges and buckets, avoiding one another’s eyes and staring instead with great intensity at the trees around them.

The editor— Tracy Chevalier again —has gathered new tales on nineteen of the UK’s native trees; Ash, Aspen, Beech, Birch, Blackthorn, Cherry, Chestnut, Crab Apple, Elm, Hawthorn, Holly, Lime, Maple, Oak, Rowan, Scots Pine, Sycamore, Willow, and Yew. The contributions are the perfect length for a wee bedtime story, to fuel a night’s dreaming; as Kate Mosse’s tale notes: If you listen carefully, you will hear the trees speak all the words they have captured in the seams of their leaves…

The tales are inventive, the voices various, and the writing often gorgeous. Here’s the opening to Ali Smith’s, for example: Every question holds its answer, like every answer holds its question, bound so close that they travel together like the wings on either side of a seed.

Like the two wings, each story is prefaced by an enigmatic and colourful illustration from Leanne Shapton, the ‘twentieth contributor’. But you can make a contribution, too— every purchase allows The Woodland Trust to plant ‘at least one native tree’. This book comes highly recommended as a stocking filler for the nature-loving romantics on your Christmas list. Are you reading something you would recommend to others? We’re always interested in reviews of books to share with fellow herbal folk. Please simply send us a review, or get in touch: herbologynews@gmail.com

Do you have a book you’d like to submit for potential review? Post to: The Editor Herbology News Glen House, 3 Reinigeadal, Isle of Harris. HS3 3BD

ADVERTISE HERE

We’d like to offer a space to advertise products and paid events and for a ridiculously small fee. The funds raised would help us upgrade to a cleaner version of this platform without the imposed side adverts, and with additional useful features.

If you have an event, a product, or a service you’d like to advertise, get in touch. We can embed a link to take our readers directly to your website, Etsy shop, or platform of your choice.