9 minute read

Dave Hughes meets Dee Atkinson

David Hughes meets Dee Atkinson

You seek ‘The Good Life’ but can you deal with trailing dirt across the carpets? Living off the land requires commitment, a firm constitution, a can-do attitude, and the kind of single-minded approach often described as pig-headed (though I rather prefer the expression ‘dogged’). The health and wellbeing benefits of the lifestyle are massive, but let us not kid ourselves— full time survivalist gardening is no small undertaking and success very much hinges on having both wellies planted firmly in the soil. Unreliable meteorology can be a fraught affair, and incorrect usage of a variety of animal poops may present all sorts of barriers to success. Nonetheless, the peoples of Britain have been dealing with these matters since the end of the last Ice Age. So, could you go back to the land?

Advertisement

Obviously, mine is not the only mind that has lately wandered to fancies of self-sufficiency; cutting loose, foregoing the trappings of urban life, shifting to a croft in the countryside, escaping the tiresome supermarket shop. It sounds dramatic, possibly overly so, but if you zoom out and examine our current times through the lens of history you will see that shifts in food security often usher in societal shifts toward agrarianism. When the structures that provide our basic needs begin to fail, we have a tendency to take matters into our own hands, to provide for our immediate communities. The pockets of urbanized farmland still seen around Rome are the result of the citizenry taking food security into their own hands when the trousers of the Roman Empire’s trade mechanisms slowly began to fall down. But we don't have to reach that far into history to see ‘back to the land’ movements trending upward. The global depression of the 1930’s triggered the first iteration of the 20th century. In the United States, the unsustainable farming practices that led to the bitter ‘Dust Bowl’ era, described by the likes of John Steinbeck, forced families and communities to fend for themselves. This ushered in a period of modern homesteading and community-building, and model societies offering fellowship of labour. These were especially popular amongst young people, who sought security and community spirit. Back to the land movements can also be civic affairs; in Britain such activity was encouraged by the government, both during and after the Second World War— you’ll be familiar with ‘Digging for Victory’ . This kind of self-reliance proved vital to a population experiencing a rationing of goods that continued into the 1950’s. As the century rolled on, the lifestyle continued to attract followers and enjoyed its moment of getting a little freaky in the 1960’s, when it began to run in parallel with the counter-cultural revolution. In the Californian hills around San Jose, Joan Baez established a community she dubbed ‘Struggle Mountain’, which remains community-owned to this day. At its peak, the US census recorded around 10 million people actively involved in the wider movement. Closer to home, Donovan and his entourage formed a short-lived commune at Stein, on Skye's Waternish peninsula, soon realising that if you want to live off the land, you actually have to grow some food.

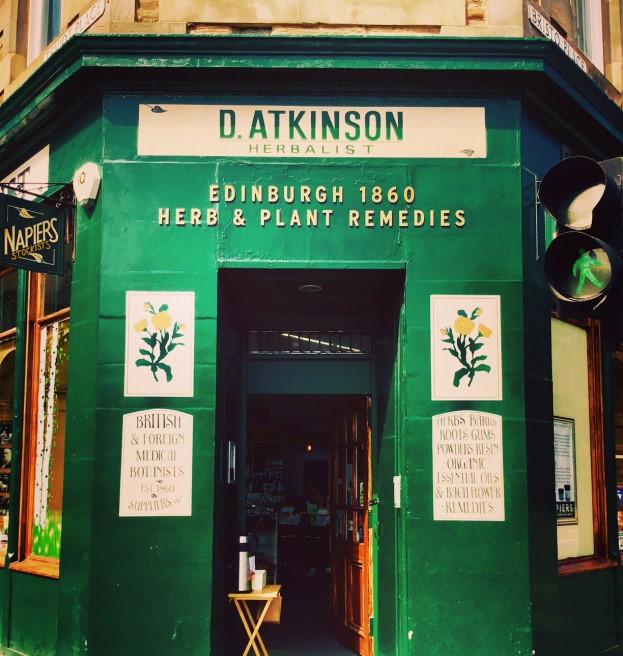

I was delighted to discover that Bristo Square’ s own high hiedyin of herbology— Dee Atkinson of Atkinson’s Herbalist, Clinic & Dispensary —grew up with more successful ‘back to the land’ parents. The movement obviously had its influence; her story is populated with a familiar cast of fascinating, strong-willed characters, with strong vision and an equally strong sense of community:

John Seymour— author of The Complete Book of Self-Sufficiency -—my parents knew him and were enthused by his writing. They were ageing hippies, I suppose, and moved us to Wales from Ardnamurchan for the late 60’s and early 70’s, to a farmhouse stuck on the edge of a hillside down half a mile of track— no

bathroom! —and took on twelve acres of land to start an organic farm...with absolutely no knowledge of farming! The first year they cut the hay using a hand scythe and we just learned as we went along; milking Jersey cows by hand; making butter; making bread; fattening up the pig and killing it and swapping the parts of it for things we needed. Dee’s own herbal practice is clearly rooted in her experience as a back-to-the-lander, with her curiosity for creating things nurtured by her selfsufficient upbringing, surrounded by nature: My mother used to make cough syrups, and I would see this happening and get involved. And I remember a particularly fantastic year— they made homemade wine. Over 100 gallons, made of dandelions and hedgerow plants.

This influence almost seems a footnote when you consider the herbal practice that Dee Atkinson has gone on to build. For those unaware, Dee began operating out of Edinburgh institution Napiers the Herbalists in 1988, acquiring the business entirely in 1990 when presented with the opportunity to take on the lease at Bristo Square. The original business had been established in 1860 by Duncan Napier, one of the founders of the Institute of Medical Herbalists. Yet, down the generations, it had begun to move away from its raison d’être as a traditional herbal practice: It was being run as a health food shop and no one had touched the medicines or the formulas for years. These medicines and formulas, devised by Duncan Napier, are an archival treasure to which Dee Atkinson holds the key: It was like opening Pandora’s box! All the formulas and recipes were still there, it was incredible. I researched them and rewrote them from the old-fashioned drams and fluid ounces.

The closely-guarded recipes of these illusivelylabelled proprietary blends— like the legendary pick-me-up Composition Essence, or the Nerve Debility Tonic —often contained over 30 herbal elements, each playing an important part. The process of rediscovering and reworking the Duncan Napier archive was of such a scale it became a family affair:

My dad helped with it. He was in heaven— going backward in time, as it were. My mum came and sat on the reception desk and answered the telephone while counting pills and bottling essential oils. With new life breathed into the archival formulas and cures, Dee’s attention returned to Bristo Square, now rebranded as Atkinson’ s. My whole thing is about rebuilding the business; making herbal medicine viable and getting it back on the high street, where it should be, as the people’s medicine.

Thankfully for us, Dee is also at the heart of building the next generation of herbal practitioners in Scotland, keeping a keen eye on those whose talents she can help develop through apprenticeships or mentoring. Making careers for people, as she puts it, in its turn pushes the benefits of herbal medicine farther into the wider community. Just as the community that once surrounded Dee also nurtured other highly respected herbalists; David Hoffman, and Chancel Cabrera— Dee’s sister —have each gone on to become two of the most highly respected herbal practitioners in North America. As Dee tells it: Self-reliance, an interest in nature, and making our own way in the world was a huge influence, and we both just fell in love with the plants that surrounded us…

So, could I do it? Have I the skills? Could I go back to the land? When I used to work the Phantassie Organics fruit and vegetable stall, Patricia Stevens used to tell me: You just have to go for it. Learn on the hoof… Failure is just not an option. I have a feeling Dee Atkinson might say the same.

www.deeatkinson.net IG: @datkinsonherbalist Twitter: @deetheherbalist FB: D. Atkinson Herbalist

Endings and Beginnings Nathalie Moriarty

A small gust of wind moves through the stand of Beech trees and a glitter of yellow, orange and brown gently falls to the ground. Another light breeze and some sparkling leaves seem to defy gravity, moving gently upwards and into the canopy of a much larger Sycamore. As I set my foot on the autumnal carpet, the leaves crunch and I feel such joy and delight, even with the cold air snapping at my cheeks. My gaze is drawn to the leaves on the ground; I see crystals of ice formed along their veins, each leaf a differently coloured canvas. Amongst the Beech and Sycamore leaves, I see the spiky seed capsules, and thousands of tiny helicopters.

As a child Sycamore keys fascinated me. My dad, who was a tall guy, would drop them from a height and I would delight in trying to catch all the little helicopters that whirled around me. Autumn was undoubtedly my favourite season. Pushing through leaf drifts as high as my waist and hearing the thousands of soft rustles the dry leaves made against each other. When a gust of wind ripped through the forest, I could hear the crowns groaning as they bent forwards and backwards together, resisting its force and, inevitably, after the wind passed, a whole array of colours would come dancing through the sky. I would be waiting for them, trying to calculate the infinite impossibilities of where the leaves might make contact with the ground. Trying to be there first, I’d jump up and catch them before they fell; moving my body quickly and concentrating intensely. It was my favourite game of the season and an activity that would fit well into an autumnal Forest Bathing session for the more active among us.

Forest Bathing is about immersing all our senses in the natural environment. It helps slow our minds and focus on the present. It also adapts well to different outdoor activities, and to different ages or abilities. The key to the activity is that it should enable you to notice details in the natural environment around you. You should be surrounded by trees, although it is not entirely necessary that these trees are in a forest. Studies on tree phytoncides have shown that those which have the greatest effect on our immune system are released by coniferous trees, particularly during warm summer days. Whilst this immune response to phytoncides may be much reduced on cold days, there are still benefits in paying attention to the patterns in nature, and to slowing down for meditative activities. Taylor (2016) has shown that viewing the fractal patterns in nature can reduce our stress levels by up to 60%. Furthermore, practising mindfulness in forest environments can improve our levels of calm and help us cope with symptoms of stress and anxiety (Li, 2018).