FOR ART’S SAKE

Protecting our public art heritage

WILD PLACES

Remembering

Katherine Mansfield

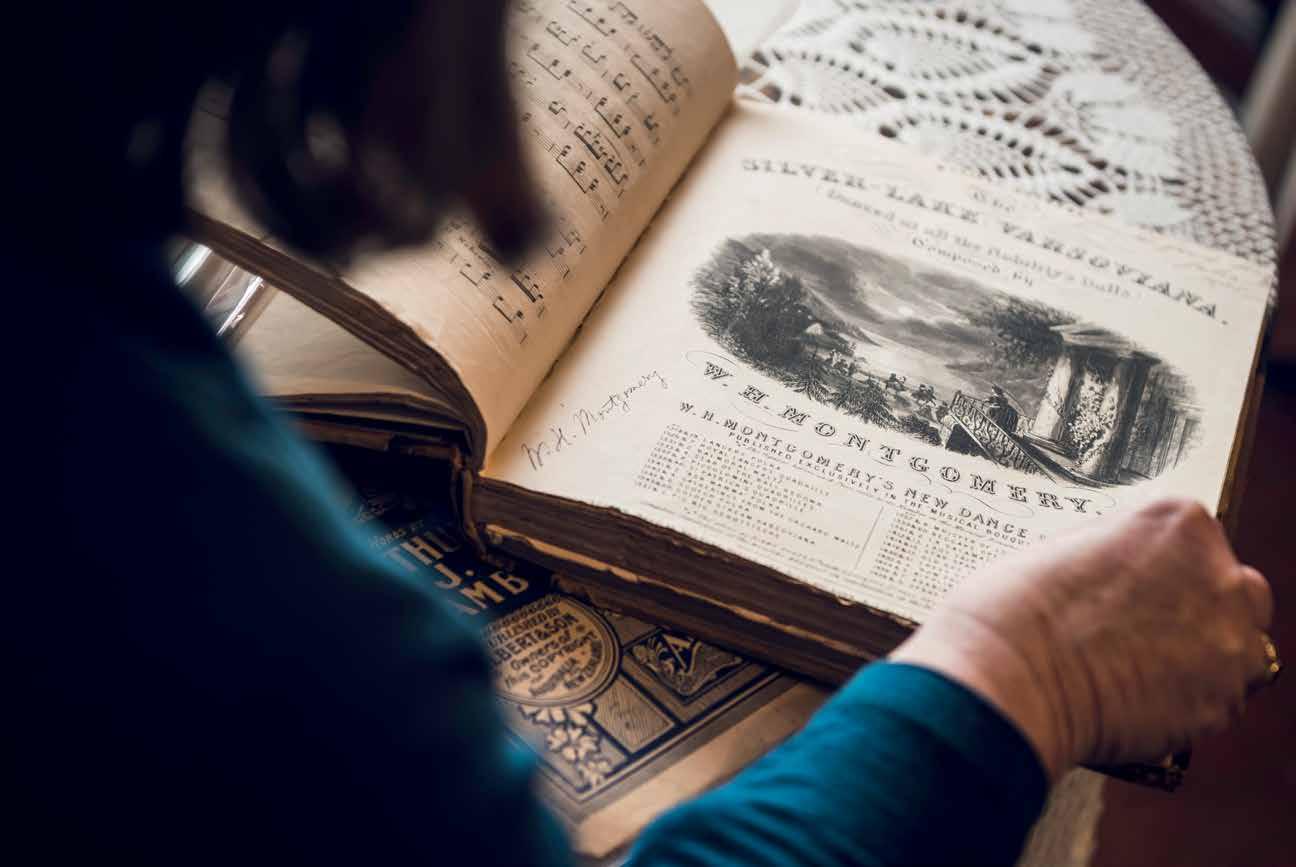

KEEPING SCORE

Heritage sheet music

SURVEY THE SCENE

Mucking in at

Invercargill’s Lennel

Heritage New Zealand

Kōanga / Spring 2023

Features

12 The journey home

The career of archaeologist Amber Aranui has been defined by her work in the repatriation of ancestral remains to their people

16 A creative legacy

One hundred years after her passing, Katherine Mansfield’s birthplace remains a place of inspiration

22 Sounds familiar

Sheet music belonging to the former inhabitants of historic homes sheds light on their lives – and the musical tastes of the times

30 Fulfilling aspirations

Thanks to the commitment of tangata whenua and tangata Tiriti, the stories of one of the nation’s most significant historic places are starting to be told

34 A women’s place

Dedicated to women who fought for the right to vote, an Auckland historic place is a reminder of the ongoing fight for women’s voices to be heard

38 Going public

The public artworks of some of New Zealand’s most significant 20th-century artists are being documented and saved thanks to a new project

42 Mucking in

For one young family, restoring an historic place in Invercargill has meant getting their hands dirty

Explore the list

8 Community embrace

While the school at which fallen soldiers once studied as children has gone, a memorial to their sacrifices has been embraced by a new community

10 Looking lively

A landmark house in Wellington’s Thorndon has had three distinct phases in its life – and is now set for another

Journeys into the past

48 The people’s palace

Innovative social housing projects in Vienna now attract international tourists – could they one day do the same here?

54

Members’ Hub

An exclusive online experience

Introducing our all-new digital hub, at your fingertips and designed just for you.

Accessing the membership area is effortless. Simply grab a smartphone, tablet, or similar device, and scan the QR code on the back of your membership card to unlock your content.

Awaiting your exploration is an exciting range of benefits and discounts, and digital copies of the latest Heritage New Zealand magazine and Members Club enewsletter.

But that’s not all – we won’t stop there. Over time, we will add news, events, and other features to continue to provide you with the very best experience as a member and stay up to date on the latest heritage news.

Your voice matters! Use the contact section to share your thoughts, ideas, and feedback direct from the Hub.

Visit your Members’ Hub today and unlock a world of heritage news, tailored exclusively for you.

Ngā mihi | Thank you!

We are very grateful to those supporters who have recently made donations. Whilst some are kindly acknowledged below, many more have chosen to give anonymously.

Mr Paul Wilson and Ms Catriona McBride

Mary Brennan and Peter Morgan

Mrs Gaye Morton

Mr Peter and Mrs Trish Woodcock

Ms Sheryl Frew

Mr Andy and Mrs Sarah Bloomer

Faye Fleming In Memory of Neil Fleming

Mr Mark and Mrs Laurel Watson

Mrs Jennifer and Mr Peter Andrews

Mrs Gillian Clarke

Mr Philip and Mrs Anne Herbert

Mrs Frances Bird

Mr Kelvin and Mrs Sue Allen

Mrs Ellen Stewart

In Memory of Frances M Powell

Mr Bruce and Mrs Barbara Lockett

Mrs Margaret and Mr Nigel McConnochie

Heritage New Zealand

Issue 170 Kōanga • Spring 2023

ISSN 1175-9615 (Print)

ISSN 2253-5330 (Online)

Cover image:

Public art heritage: Ralph Hōtere and Mary McFarlane, ‘Rūamoko’ (1998), cnr Lambton Quay and Stout Street. Image by Mike Heydon

Editor

Caitlin Sykes, Sugar Bag Publishing

Sub-editor

Trish Heketa, Sugar Bag Publishing

Art director

Amanda Trayes, Sugar Bag Publishing

Publisher

Heritage New Zealand magazine is published quarterly by Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga. The magazine had a circulation of 7460 as at 30 June 2023.

The views expressed in the articles are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga.

Advertising

For advertising enquiries, please contact the Manager Publishing.

Phone: (04) 470 8054

Email: information@heritage.org.nz

Subscriptions/Membership

Heritage New Zealand magazine is sent to all members of Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga. Call 0800 802 010 to find out more.

Tell us your views

At Heritage New Zealand magazine we enjoy feedback about any of the articles in this issue or heritage-related matters.

Email: The Editor at heritagenz@gmail.com

Post: The Editor, c/- Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, PO Box 2629, Wellington 6140

Feature articles: Note that articles are usually commissioned, so please contact the Editor for guidance regarding a story proposal before proceeding. All manuscripts accepted for publication in Heritage New Zealand magazine are subject to editing at the discretion of the Editor and Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga.

Online: Subscription and advertising details can be found under the Resources section on the Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga website heritage.org.nz

New life

Spring – a time to unfurl from winter hibernation. At our house that means the deck gets spruced up and the barbecue is scrubbed in preparation for blowing some dust off the social calendar. And I start a daily watch for the first bright-green leaves that burst from the giant oaks that stand in the park next door.

I love spring. But it’s not just the warmer and longer days that I look forward to, it’s those signs of new life that seem to bring with them a sense of optimism and opportunity.

In that spirit, we’ve introduced a couple of changes to this Spring issue. The first, appropriately, is a gardenfocused feature at the beginning of the magazine. We often receive feedback that our readers are interested in gardening and visiting gardens, and we wanted to recognise this by shining a light on a garden associated with an historic place in each issue.

As it happened, we had already planned two stories with a strong garden focus, so we were spoiled for choice in terms of imagery. In the end we went for a scene captured by award-winning photographer Rob Suisted in the garden of Katherine Mansfield’s birthplace, a Category 1 historic place in Wellington. This year marks the centenary of Katherine’s death, and 35 years since Katherine Mansfield House and Garden – the museum housed in her birthplace –opened its doors to the public.

As the museum’s Director, Cherie Jabsobson, notes in our story on page 16, Katherine loved plants and flowers, often mentioning them in her writing. The museum’s garden has been populated with plants available in her lifetime, including French heritage roses, in recognition of her time in France, where she is buried.

Gardening is also a focus in our story on Lennel. Since Will Finlayson and

Laura Thompson took ownership of the Category 1 historic place in Invercargill in late 2021, they’ve been getting stuck in to the property’s 1.2-hectare section. The couple was awarded $13,000 from the National Heritage Preservation Incentive Fund last year to help them research the original garden plantings, develop a masterplan to conserve and manage surviving garden elements, and manage the garden’s protected trees and shrubs. You can learn more about their journey so far on page 42.

The second change we’ve introduced in this issue isn’t strictly new; it’s more of a refresh. We’ve always loved highlighting people’s special relationships with historic places in our ‘My Favourite Building’ story. But in order to show the diversity of Kiwis’ connections to historic places we’re now inviting household names – from well-known musicians to actors and sporting heroes – to share their stories of historic places that hold meaning for them.

First up is Delaney Davidson (page 54). Perhaps best known as a musician who has collaborated with everyone from Marlon Williams to Tami Neilson and Troy Kingi, he’s also an accomplished visual artist. Delaney recently undertook an artist’s residency at Stoddart Cottage – a Category 1 historic place at Diamond Harbour on Banks Peninsula, which was the birthplace of Margaret Stoddart, one of New Zealand’s foremost 19th-century painters. He shares how Margaret became more of a “real person” to him through the experience “instead of some distant person from the past whose name is associated with an old house” – highlighting, I think, the power of historic places to inspire something new in us all.

Ngā mihi nui Caitlin

Heritage New Zealand magazine is printed with mineral oil-free, soy-based vegetable inks on Impress paper. This paper is Forestry Stewardship Council® (FSC®) certified, manufactured from pulp from responsible sources under the ISO 14001 Environmental Management System. Please recycle.

ROOM OF ONE’S OWN

As a young man in the early 1970s, Dr Ross Ferguson had the run of one of Auckland’s great houses.

Ross had recently returned from overseas when he was approached by his boss at the then DSIR, who in turn had been approached by heritage architect John Stacpoole with a unique opportunity: would Ross be open to staying at neighbouring Alberton to provide live-in security while the Category 1 mansion in Mt Albert was being restored?

John Stacpoole oversaw a major restoration of Alberton, built by the Kerr Taylor family, after it had been bequeathed in 1970 to Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga (then the New Zealand Historic Places Trust) by the last of the Kerr Taylors’ 10 children. The work began in 1972 and Alberton’s doors were subsequently opened to the public in December 1973.

Ross, an expert on kiwifruit who still works at the neighbouring research facility these days known as Plant & Food Research, recalls many memorable incidents while living in the house. These included watching a Hitchcock movie under the ballroom’s dim lights on a stormy night as branches scratched at the windows, and a rat that would poke its head out of a hole in the wall during dinner parties.

While living at Alberton, Ross also helped with the restoration project during weekends, learning much from the heritage professionals involved.

“When I eventually got a house of my own, 10 minutes’ walk away, it was a 100-year-old house and I started collecting more antique furniture and paintings and so on. John was an inspiration.”

MEMBER AND SUPPORTER UPDATE…

Frances (Fran) Powell (nee Hansen) was a member of Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga for almost 30 years. Here, one of her daughters, Sandra Page, shares recollections of her mum’s love of heritage and what motivated her to leave a bequest to the organisation on her passing last year. As told to Caitlin Sykes.

“I’d just come back and hadn’t arranged accommodation, so I moved in. They wanted someone to live in the house more to keep vandals at bay; someone to keep the lights on,” recalls Ross. He lived in the house for around two years – on his own for most of the first year until a DSIR colleague moved in for the remainder of the duration of the work.

“You could have a dinner party for 12 or 14 people quite comfortably. If you had a party in the ballroom you’d need 50 or 60 to make the place feel lived in,” says Ross. “The real crunch came when I moved out of Alberton and started looking for a flat around Mt Albert; everything looked very poky.”

Ross will speak at an event for invited guests on 8 December celebrating 50 years of Alberton being open to the public. It will also include a musical performance of Cathie Harrop’s ‘Yours Affectionately’ about the Kerr Taylor women.

Alberton was constructed in 1863-64, so this year and next will also mark 160 years since the house was built.

To celebrate this anniversary, a variety of events that will stretch from this year and through 2024 will be held. They will include a St Valentine’s event, where those married at Alberton will be invited and encouraged to attend wearing their bridal outfits; scone and tea services marking occasions such as Mother’s and Suffrage Days; and Alberton’s Vintage Market Day.

To keep up to date with the details, visit alberton.co.nz

Mum was a fourth-generation local who lived her entire life here in Arrowtown. She absolutely loved Arrowtown and the Wakatipu district and was very connected to the history of its people and buildings –like Reidhaven, Dudley’s Cottage, the BNZ building and the Chinese settlement. The house once owned by Mum’s grandmother in Arrowtown has heritage recognition and Mum was very proud to have Hansen Reserve named in honour and memory of her late father, George Hansen. She was also a big supporter of the Lakes District Museum. It was her grandmother who first came here from the Orkney Islands at age 17, so Mum knew all the family connections to different places. For example, Mum talked about how her own mum and sisters had had to walk from where they lived at Arrow Junction to Crown Terrace to go to school. Believe me, that’s some feat – six miles [9.6 kilometres], including crossing the river and climbing up to the Crown Terrace – and they did that summer and winter. At one of the bends on their route, they planted a small garden, which they tended on their way home from school. Not that long ago, daffodils still bloomed on this site – maybe they still do today.

Mum had a huge book collection, including some beautiful books on heritage buildings. She loved to share her books and knowledge and was proud that one of her grandsons studied heritage architecture at Victoria University of Wellington.

Because of Mum’s passion for the district and her love of heritage, it was important for her to acknowledge the work carried out by Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga and help it to continue preserving the heritage of New Zealand.

Brendon Veale Manager Supporter Development 0800 HERITAGE (0800 802 010) bveale@heritage.org.nzBEHIND THE STORY... writer Anna Dunlop

For this issue you write about the (former) High Street School War Memorial and Gates in Dunedin and The Moorings in Wellington. What’s something you were interested to learn from these assignments?

I was fascinated by The Moorings’ incredible ballroom/games room –not just by its nautical design (I love the underwater frieze of mermaids and seaweed) but also by the social life that the room has seen in its lifetime. It hosted parties, concerts, weddings, plays, community meetings and society events during times of important political and social movement. So much history must have been made in that one room.

Your images have also featured in Heritage New Zealand magazine. What role does photography play in your life and work?

I enjoy wildlife and landscape photography and have recently been experimenting with macro photography. I like trying to find that certain composition, angle or light that makes an image exceptional. Photography also encourages me to look for the beauty in everything, no matter how mundane it may seem.

What’s a favourite heritage place for you?

I live in Central Otago and my favourite place is Oliver’s, housed in a Category 1 historic place in Clyde. It used to be Benjamin Naylor’s general store – he was a significant local figure and property

Places we visit

owner during the gold rush of the 1860s and ’70s – and the eight schist buildings now house a lodge, restaurant, café, deli, bar and brewery. A lot of original details have been retained, including the shop counter from the old store, which is now the bar. I love the cosiness of its pitched gabled roof and open fire in winter and being able to sit under the tranquil fruit trees in its orchard courtyard during Central Otago’s hot summers.

HERITAGE NEW ZEALAND POUHERE TAONGA DIRECTORY

National Office

PO Box 2629, Wellington 6140

Antrim House

63 Boulcott Street

Wellington 6011

(04) 472 4341

information@heritage.org.nz

Go to heritage.org.nz for details of offices and historic places around New Zealand that are cared for by Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga.

SOCIAL HERITAGE… with Paul Veart, Web and Digital Advisor, Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga

It’s not often that cabbages inspire a social movement, but that’s (more or less) what happened in Wellington almost 50 years ago.

The cabbages in question first appeared on the corner of Willis and Manners Streets in the summer of 1978. There were 180 of them, planted to spell out the word ‘CABBAGE’. For six months the vegetables flourished in their urban home before finally being harvested.

But their influence didn’t stop there. For many, their appearance marked the beginning of what Rosslyn Noonan, former Chief Commissioner of the New Zealand Human Rights Commission, has called “a special Wellington spirit” and an attempt to make the capital a more liveable, human –and charmingly weird – place.

Duly inspired, Wellington City Council harnessed this newfound energy by employing musicians and performing artists to hold events in the capital’s parks. The first iteration was such a success that it was expanded into an annual series under the banner ‘Summer City’.

If you’ve ever lived in Wellington, there’s a good chance you’ve attended a Summer City performance – you may even have been involved with one. While the Wellington Botanic Garden Soundshell is the hub, performances have taken place throughout the city, including in Cuba Mall, Willis Street, Wellington Zoo and many suburban locations. In the past few years, Wellington City Archives has been uploading photos of Summer City events taken in the 1980s and ’90s. As well as highlighting Wellingtonians’ ever-changing fashions, the collection shows the importance of public spaces for the capital’s transformation into an inspiring place to live.

We recently featured some of the photos on our Facebook page – and it wasn’t easy to choose our favourites. It’s worth visiting the Archives Online website to have a look yourself. Find out more at archivesonline.wcc.govt.nz

Ngā Taonga i tēnei marama, Heritage this month – subscribe now

Keep up to date with heritage happenings with our free e-newsletter Ngā Taonga i tēnei marama, Heritage this month. Visit heritage.org.nz to subscribe

Wild places

Katherine Mansfield loved gardens, and often wrote about plants, so it seems fitting that a bust of the groundbreaking writer sits under a magnolia tree in the back garden of her birthplace.

The bust – by artist Anthony Stones, who created sculptures of many New Zealand literary giants – serves as a memorial to Oroya Day, the founding president of the Katherine Mansfield Birthplace Society, and her husband Melvin Day, who was also a key early supporter of the society. Established to buy the house in 1987, the society subsequently restored the Category 1 historic place before opening it to the public the following year.

Katherine died in France in 1923, aged just 34. You can read more about what’s been happening at her birthplace to mark this centenary, and the 35 years since Katherine Mansfield House and Garden opened to the public, from page 16.

“And you walked there – you planted hope. And now I cannot imagine myself without it.”

WORDS: ANNA DUNLOP / IMAGERY: MIKE HEYDON

embrace

of modern living that is likely to become more common in the decades to come.

The memorial, a Category 2 historic place, was built in 1926 to honour the primary school’s former pupils and teachers who had died in World War I. The arch was constructed by monumental mason HS Bingham & Co, while the wrought-iron gates and the fence that surrounded the school site were built by notable ironfounder J & W Faulkner & Sons.

On the corner of Dunedin’s High and Alva Streets, old meets new in a striking way: the city’s High Street School War Memorial and Gates, an important symbol of New Zealand’s history, stands proudly in front of the Toiora High Street Cohousing Project – Dunedin’s first cohousing scheme and an innovative style

The arch uprights feature two leaded marble tablets inscribed with 56 names (Otago and Southland lost many young men involved in front-line fighting at Gallipoli, Messines and Passchendaele). An inscription on the arch itself reads ‘The Empire’s Call 1914–1918’.

According to Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga listing information, the memorial was erected as an emblem of loss, sacrifice and nationhood, and its historical significance lies in it being “both uniquely local and an intrinsic part of a national story”.

While the school at which fallen soldiers once studied as children has gone, a memorial to their sacrifices lives on

Community

It is unique in its use of Oamaru stone thought to have been salvaged from deconstructed New Zealand and South Seas International Exhibition buildings, local because it was commissioned by local individuals and specifically honours those connected to High Street School, and part of a national collective of more than 500 public memorials to soldiers of the Great War.

The location of the memorial is also significant: it replaced the school’s main gates, making it accessible to grieving relatives and the public and also providing a daily reminder to pupils of the sacrifices of former students. Many of the children who passed under the memorial arch would later lose their lives in World War II; in 1950 a third marble tablet was added to honour them.

High Street School closed in 2011, but in 2013 a heritage covenant was placed on the war memorial, as well as the school’s gates and parts of its fence, to ensure their preservation. When the site was chosen as the location for Toiora, Tim Ross, Director

of architectural practice Architype, was aware of its significance to the community.

“We saw the memorial arch, gates and fence as immensely important and something that provided a sense of heritage and history to the site,” he says.

The Toiora project, which officially opened in 2021, consists of 21 energy-efficient passive townhouses (the first in New Zealand), along with a range of shared facilities – some of which are housed in a converted High Street School building – including living and dining spaces, guest rooms, meeting rooms, workshops, a laundry, a sauna and green spaces.

Tim, who co-founded the project and lives in one of the townhouses he designed, says the cohousing community put a huge amount of work into restoring the memorial, while also carefully modifying the fence and adding new gates to allow people to access their homes.

“I worked closely with local metalworker Frank Scurr, who had extensive knowledge of the different types of steel and cast-iron and how to work with them. Through him, I got an excellent idea of the history of the fence and how it was made.”

The school gates and fence panels were sent offsite to be sandblasted (to remove the peeling lead paint) and repainted with epoxy enamel before being reinstated by the cohousing group.

“The residents at Toiora worked very hard to get the fence finished.”

Toiora also engaged Dunedin stonemason Marcus Wainwright to clean the arch and treat it for mould, and replace some of the lead lettering that had been damaged or lost over time.

Sarah Gallagher, Area Manager Otago Southland for Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, says that despite the loss of the primary school, the new cohousing development is a welcome addition to the neighbourhood.

“We have retained an important record of the school site through restoring the decorative fencing and war memorial, which are very significant to the wider community. At the same time, this new community is growing up within that space and providing a multigenerational facility. People had to buy in to the cohousing concept, so they invested in developing and being part of this new way of living, while being reminded of the school’s ties to the past.”

Due to the design of the project, the memorial gates no longer serve as the main entrance to the site, but the cohousing group came together to ensure they were repurposed in a meaningful way.

“We’ve created a peace garden directly behind the war memorial and adjacent fence, and once it has grown it will frame the structure beautifully,” says Tim.

“It’s a common space that everyone in the Toiora community can enjoy, and it also gives the gates and memorial arch a continued sense of purpose.”

heritage.org.nz/list-details/9645/ HighStreetSchool(Former)WarMemorialGates

Looking lively

as Sydney) Swan, one of Wellington’s most notable architects, who built it in 1905 as a home for himself, his wife and their four children.

It was constructed as a two-storey house, but John made various additions over the years, including a third storey to act as an architectural studio in 1906, a spectacular double-height billiard room in 1926, and a conservatory in 1930.

The interior features beautiful timberwork, plush dados, tiled fireplaces and stencilled paper frieze cornices. The materials were the best of their types for the time and paint a picture of the life of a wealthy Wellington family in the early 1900s. They are also indicative of the taste of one of the leading architects of the period.

It was full circle for conservation architect and recently retired Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Board member Chris Cochran when he received a commission to write a conservation plan for The Moorings, a Category 1 historic place on Glenbervie Terrace in Thorndon, Wellington.

“I’m actually a small part of the history of the building,” he says.

Chris is referring to the summer of 1964 when he and a group of 15 fellow students from Victoria University of Wellington painted the house for the new owners – Martin (Johnny) and Betty Leniston – in return for free board and the use of their 17-seater Chevrolet bus (family transport for the Lenistons, who had 11, soon to be 12, children).

“We had some incredible summer holidays in that bus,” Chris recalls. “Since then I’ve always had a fondness for The Moorings, and getting the commission was a lovely coincidence.”

The large nine-bedroom Edwardian house, which dominates the skyline of the area, has been owned by the Leniston family for more than 60 years. It first belonged to John Sidney (also sometimes seen

John had a passion for the sea that was apparent not only in the name of the house but also in its design: nautical flourishes in the architecture (including an underwater frieze of mermaids and seaweed); a flagpole posted on the balcony outside the master bedroom, which John would use to signal ships in the harbour; and porthole windows and a ship’s wheel in the billiard room.

At the time of his death John possessed a collection of around 700 nautical images – photographs, paintings and lithographs (one of the largest collections in the world) – that were hung around the house. Most of the collection has since been dispersed, although a few items are still on display in the house today.

While The Moorings is important from an architectural perspective, Chris says that it’s the social life of the place that is particularly significant.

“It’s had three distinct phases and they are all interesting: first as the residence of the Swan family, then as a boarding house of varying fortunes, and then as the family home of the Lenistons.”

The Swans left The Moorings in 1936 and the boarding house it became for the next 30 years was typical of those in the 1940s and ’50s. John’s

A landmark house in Wellington’s Thorndon has had three distinct phases in its life – and it’s now set for anotherWORDS: ANNA DUNLOP

architectural studio was divided into four rooms, and it’s thought that up to 20 people lived in the building, sharing just one kitchen and bathroom.

During World War II several US officers were billeted in The Moorings; they left behind a grenade, which was found by one of the Leniston boys in the late 1960s when he ran over it with a lawn mower. Thankfully it didn’t explode, and it was subsequently taken away and disposed of by police.

Throughout its three decades as a boarding house, the building was badly neglected and fell into a state of disrepair; this was in keeping with the Thorndon neighbourhood, which had become very rundown (partly due to the threat of the proposed urban motorway) and was seen as ripe for redevelopment.

In fact, the Leniston family had only been living in The Moorings for six months when the Ministry of Works began demolishing nearby houses to make space for an off-ramp for the motorway. For a time, The Moorings was under threat, but Johnny Leniston resisted attempts by the Ministry to buy the house for demolition – something for which Chris is thankful.

“The Moorings is hugely important within the Thorndon conservation area. If it had been demolished we would have lost the single most significant building in the neighbourhood,” he says.

The Lenistons’ eldest daughter Margaret was 11 years old when her family moved into The Moorings in 1965, and says that from the beginning the house was full of life.

“My parents had this philosophy of having an open home,” she says, adding that on occasion they would welcome in members of the community who had nowhere else to go.

“The house has also seen the most amazing parties, events, fringe festivals and concerts. My mother once had to bribe me with a pair of coloured stockings to go to a school ball because I just didn’t want to leave the house; it provided this unique social environment.”

Tim Leniston agrees. As the youngest of the 12 siblings, he was born while the family was living at The Moorings. He says it was a special place in which to grow up.

“The 1970s was an optimistic time – there was a lot of social movement and a lot of change,” he says.

“I remember political discussions, talk about feminism and the beginnings of ecological politics, and plenty of debate. It was an extremely wideranging childhood in which I was exposed to many more influences than I would have had growing up in a nuclear family household.”

John Swan’s billiard room – known by the Lenistons as the ballroom or games room – played host to these famous parties and events, including meetings of the Thorndon Society and other community groups. It is one of Chris’s favourite features.

“It’s one of the most remarkable domestic spaces in Wellington and has been well used by so many people over such a long time,” he says.

Another standout feature for him is the timberwork.

“The timber finishing is very high-quality work of the period [early 1900s] and is still unpainted and in its original state. There are heart native timbers and burr timber panelling – they are beautiful.”

Tim, who currently lives in the house with his brother Patrick, their families, some distant relatives and several others, says that since The Moorings has been in the Leniston family it has functioned as a mix of family home and flatshare, and this communal living style has worked well. However, the family has recently decided to put the house on the market.

“It’s time to let the house have another phase,” he says. “I’d like to see it preserved well so it has another 100 years of life.”

As for Margaret, she only wants one thing: “I just want to see it loved.”

heritage.org.nz/list-details/1437/TheMoorings

Thehomejourney

WORDS: JACQUI GIBSON / IMAGERY: ROB SUISTED

The career of archaeologist Amber Aranui has been defined by her work in the repatriation of ancestral remains to their people

Dr Amber Aranui admits she often felt anger in her early days of working as a repatriation researcher for Te Papa Tongarewa Museum of New Zealand. “I’m an emotional person,” she explains, laughing now as we sit across from each other in a quiet meeting room. “And what I read in the archives in those first few years often made me really angry.”

Amber, who is of Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāti Tūwharetoa and Pākehā descent, joined through the Te Papa Karanga Aotearoa Repatriation Programme as a researcher in 2008. The role followed a bachelor’s degree in anthropology and religious studies, a master’s in archaeology and a couple of years of hands-on field work and report writing for the Department of Conservation Te Papa Atawhai and OPUS International Consultants.

From day one, she loved working at New Zealand’s national museum in Wellington. Hours were spent trying to find and bring home kōiwi tupuna and toi moko tightly held in overseas museums, private collections and institutions.

“I first encountered kōiwi as a master’s student working under the supervision of Professor Geoffrey Irwin – the father of maritime navigational archaeological theory –in the Eastern Bay of Plenty,” says Amber, who grew up in Wellington’s Hutt Valley.

“Excavations of a wetland site known as Kōhika gave me the chance to study fibre materials used by Māori back in the 1700s, as well as two ancestors reburied there in

the years following a massive flood event and abandonment of the village. It was an incredible experience. Working with iwi and learning the tikanga and protocols involved in interacting with the remains of their tūpuna felt very meaningful.”

But in her new role she was shocked to encounter blatant disrespect for ancestral remains and the indigenous communities they represented.

“It was right there in black and white in so much of the archival material I read through.”

Letters penned by Frederick Meinertzhagen, for example, showed that the Hawke’s Bay farmer had deliberately gone behind the backs of local Waimarama iwi to steal kōiwi for the British Museum following his emigration to New Zealand in 1866. Kōiwi were eventually returned to Waimarama in 2013 through the Te Papa repatriation programme.

A separate letter from the 1890s, written by the then director of the Australian Museum, lamented the end of Aboriginal hunting for the purpose of supplying human specimens to institutions such as New Zealand’s Colonial Museum.

“The things I read disgusted me,” recalls Amber. “I just couldn’t believe it. I felt like the average person had no idea what had gone on in our museums and public institutions. Eventually, I realised I couldn’t change the past. I could only help make things right by bringing kōiwi home and sending them back to their people.”

Amber says the archival material gave her grim insights into why thousands of Māori remains came to be traded, stolen and dispersed around the globe, particularly during the late 19th century.

“Darwinism was at its peak. Natural history hobbyists like Meinertzhagen and institutions like museums were excited to get their hands on the body parts of indigenous people for their collections, and oftentimes didn’t question how those human remains had come into their possession.

“The goal was to collect and study them to prove Darwin’s theory of human evolution, in which Europeans considered themselves the most evolved species and believed all others were savages.”

Centuries later, the justification for holding on to ancestral remains continues to favour Western ideas over indigenous ones in some places, says Amber.

The domestic repatriation of more than 66 Rangitāne o Wairau ancestors from Canterbury Museum and Te Papa to Wairau Bar in 2016 is a case in point.

“Yes, those remains were essentially the holy grail of New Zealand archaeology; evidence of our first people. But I think it took three or four generations of fighting by the same family to get those ancestors returned and reburied.

“Their request was finally honoured as part of their Treaty settlement. Even so, Canterbury Museum still chose to defend its right to dig up those remains for future scientific study. At Te Papa, we said we want no such right; they’re 100 percent yours.”

Amber, now a Curator Mātauranga Māori at Te Papa, says the 13 years she spent in the repatriation team have come to define her career. In 2013, while in the team, she joined the Australian National University’s Return, Reconcile, Renew project to network with other repatriation experts around the world and co-author academic texts on repatriation.

Project members hope to launch an international research centre aimed at further helping indigenous communities to repatriate ancestral remains.

“I realised I couldn’t change the past. I could only help make things right by bringing kōiwi home and sending them back to their people”

It’s an exciting milestone, says Amber, who continues to be involved in the project and frequently lectures about New Zealand’s repatriation work at home and overseas.

In 2014 Amber worked alongside Makere Rika-Heke, Director Kaiwhakahaere Tautiaki Wāhi Taonga at Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga , and Gerard O’Regan, Tūhura Otago Museum’s Curator Māori and Pouhere Kaupapa Māori, to set up the New Zealand Archaeology Association’s Kaihura Māori Advisory Group, to focus, in part, on strengthening the profession’s understanding of repatriation.

Te Ara Taonga, an inter-agency group that includes Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga and was set up to help iwi access taonga held by government agencies, followed.

In 2018 Amber completed a PhD in Māori Studies at Te Herenga Waka–Victoria University of Wellington, publishing a thesis on the repatriation of Māori and Moriori remains and the ethical issues associated with the scientific study and treatment of the dead.

As a board member of Museums Aotearoa for the past two years, she has helped to develop a repatriation policy for New Zealand museums and set up the New Zealand Repatriation Research Network for museum staff working in repatriation research.

In February Amber was called on to help to recover and rebury kōiwi washed out of an urupā in Omahu by Cyclone Gabrielle. Makere Rika-Heke was also there.

“Amber’s made a huge contribution to the repatriation field in New Zealand and internationally,” says Makere.

“In a hands-on way – like we saw in Hawke’s Bay recently – and, just as importantly, she’s challenged the archaeology, heritage and museology communities to consider the ethics of storing and managing kōiwi more deeply than we have before. She’s brought the voice of iwi to the fore and, in doing so, is helping many of us to confront the past.”

Amber says she had no idea what she wanted to do as a kid growing up or even during her first few years at university as a young mum of two. It was the Māori Studies paper by Professor Peter Adds called ‘The Peopling of Polynesia’ that set her on the path to archaeology.

“I realised archaeology would help me learn about myself and the history of Aotearoa through my own eyes.”

Right now, she’s putting her knowledge and skills to use by helping her aunty, Rose Mohi, to track down ancestral taonga and bring them home to Heretaunga. For decades Rose has searched the world for more than 60 carved wharenui panels commissioned by her great-grandfather, the late Ngāti Kahungunu rangatira and politician Karaitiana Takamoana.

“We think we’ve found them all,” says Amber. “So we’re now in the final stages of writing up reports and making our case to the 15 or so museums in New Zealand and overseas that have them in their care.”

There are museums that will be open to returning the taonga, believes Amber, while others will likely say no.

“What I’ve learned in this game is that things take time; no doesn’t mean no. It just means not right now.”

To hear more from Amber, listen to episode four of the Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga podcast Aotearoa Unearthed.

kōiwi tupuna: ancestral remains rangatira: chief

taonga: treasures

tikanga: cultural protocol

toi moko: preserved tattooed heads

tūpuna: ancestors

urupā: cemetery

wharenui: meeting house

WORDS: SARAH CATHERALL / IMAGERY: ROB SUISTED

One hundred years after the passing of Katherine Mansfield, her birthplace remains a place of pilgrimage and inspiration for admirers of the influential author

A CREATIVE LEGACY

Entering the home in which Katherine Mansfield, New Zealand’s most internationally renowned writer, was born and spent her first four years is like stepping back into the late 19th century. Her parents, Harold and Annie Beauchamp, were a fashionable, middle-class colonial couple who followed the design movements of the time and would have decorated their first house accordingly.

For 35 years, Katherine Mansfield House and Garden has welcomed visitors and served as a memorial to the writer. In 2019 the house – a Category 1 historic place – was closed for maintenance work and an extensive interior refresh. This work helped to ensure its future preservation and better convey a sense of what it was like when Katherine and her family lived there.

This is a big year for the Katherine Mansfield Birthplace Society – the charity that runs the house museum – and for Katherine Mansfield fans around the globe as they celebrate 100 years of her creative legacy and commemorate the centenary of her death.

On her birthday, 14 October, entry to her birthplace will be free and the house shop will sell the Katherine Mansfield NZ Post centenary stamps the Society helped to create in recognition of her work, her life and her legacy. Each stamp includes a quote, a photo of Katherine and a watermarked item of significance in her life. The centenary is likely to bring in even more visitors keen to see the house in which the writer was born. In Avon, France, a global conference organised by the international Katherine Mansfield Society will be held on the day before her birthday.

Katherine Mansfield House and Garden Director Cherie Jacobson is a huge admirer of the writer’s work, particularly the way she wrote about characters who were generally overlooked at the time, such as women and children.

“The centenary of Katherine Mansfield’s death is an important opportunity to recognise and celebrate her creative legacy. One hundred years on, her works are still in print – they’ve been translated into more than 25 languages – and her life and writing continue to inspire people in all sorts of ways.

“In my role I get to see that every day – in visitors to the house who tell me how strongly they’ve connected with Katherine’s letters and journals, and in writers, musicians, artists and choreographers who have created new work inspired by her. It’s a pretty extraordinary legacy that shows no sign of fading.’’

Katherine was born in the house on Tinakori Road, Wellington, in 1888 and lived there with her parents and older sisters Vera and Charlotte, and her younger sisters Gwen (who died in the house aged three months) and Jeanne, along with her maternal grandmother and two aunts.

It is easy to imagine Katherine playing with wooden toys in the children’s upstairs nursery, and running up and down the original staircase with the bamboo-shaped balusters, or sitting quietly in the apple-green drawing room while her parents entertained visitors.

In 2019 colonial furniture expert Dr William Cottrell was commissioned to source furniture and objects that were in vogue in the late 19th century, so the house also offers a glimpse of what life would have been like for a middle-class colonial family at the time.

“The centenary of Katherine Mansfield’s death is an important opportunity to recognise and celebrate her creative legacy … her life and writing continue to inspire people in all sorts of ways”

For the Beauchamps, the Italianate totara weatherboard villa house was their first step on the social ladder. Harold was a clerk at a general merchant store at the time, and they would later move to three larger houses around Wellington when he became a partner in the firm and later the Chair of the Bank of New Zealand.

There are no known photos of the house’s interior during the Beauchamps’ time there, so Cherie describes the house as “an educated imagining’’. The family wanted to present themselves as fashionable, modern and confident about the future and are likely to have expressed these ideals in their home.

They moved into a larger home in Karori when Katherine was four and the Tinakori Road house was leased to other families. (Plunket founder Truby King and his wife lived in the house when they first moved to Wellington.) In the 1940s the house was converted into two flats, and that was how it was when it came up for sale in 1987 and a group of passionate Wellingtonians set out to buy and renovate it, then run it as a house museum.

Led by art historian Oroya Day, then a Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Board member, they formed the Katherine Mansfield Birthplace Society

to buy, preserve and restore the house. Oroya and her husband, artist Melvin Day, raised a mortgage to get the project off the ground, and obtained further grants from the then Department of Tourism and Publicity, the Stout Trust and others.

When the house was bought by the Society in 1987, Cherie says, they undertook a major renovation. It was returned to its original layout, and plasterboard was removed from the walls and ceilings to expose the original rimu. Five archaeological investigations found fragments of china and glassware.

Behind the skirting boards, fragments of original wallpaper, different in each room, were revealed, and Wellington artist Rachel Macfarlane designed reproduction wallpaper based on those designs. The Society put out a call for people to help furnish the house and it was opened to the public in 1988, on the anniversary of Katherine’s birth.

In its 2019 refresh, William overhauled the colour scheme, lighting and furniture. Part of his mission was to shake off the idea that Victorian homes were dark and dull. He points out that homes of that era were often alive with colour, with bright furnishings, wallpaper and paintwork, right through to objects scattered throughout.

2. Objects on display in the scullery include a reproduction of Mrs. Maclurcan’s CookeryBook, a popular 19th-century publication, with recipes such as ‘Stewed Sheep’s Head and Brain Sauce’.

3. The house number in Tinakori Road changed from 11 to 25 in the early 1900s.

Houses of that time are generally remembered in black-and-white photographs, so historians must rely on archaeological investigations and their imaginations. In the formal rooms, William arranged for the repainting in authentic heritage colours of all the stripped doors, skirtings, fireplaces and tongueand-groove and bead wall linings.

Each room was themed to emphasise individual character. The drawing room was painted a feminine apple-green, while the underlit dining room was painted a cobalt-blue to add dramatic colour and complement its heavy, dark furniture.

The door mouldings and panels are shown in three contrasting colours, typical of 19th-century paint themes, to create a sense of unity between rooms and further introduce character.

“Victorians liked colour as much as we do,” says William, “and there would have been a mix of painted and varnished wood at the time.’’

William also sourced furniture and objects to showcase the era and design movements of the time. Where possible, he found and bought New Zealandmade furniture.

By the late 1800s, many New Zealand homes had pianos and music rang out as families entertained themselves and their guests. Katherine and her sisters all had music lessons – Katherine played the cello and wanted to play professionally – and the Beauchamp family were praised in the society pages of local journals.

Cherie explains that the back rooms of the house – the kitchen, servery and scullery – were the engine rooms, in which food was prepared and clothes were washed. The Beauchamps were lucky enough to have a servant.

The original kitchen bench and the coal range remain, while pots and pans hanging on a rack hail from the era, and crockery resembles that found during the archaeological investigations. The investigations also provided clues to what the Beauchamp family ate: roasts of mutton, soups made from beef bones, and the occasional meal of rock oysters. Meat dishes were served with spicy sauces. Puddings (sometimes two) were important parts of a dinner, along with a cheese dish. Adults drank tea, beer, wine and spirits in moderate quantities.

Katherine loved plants and flowers, often mentioning them in her writing. In 1988 the Society began planting the garden with plants available in her lifetime, including French heritage roses – a nod to her time in France, where she is buried, says Cherie.

Native shrubs and trees flourish in the back garden, while each autumn a medlar tree produces fruit that a volunteer turns into a delicious jelly sold in the small shop. Volunteers also grow seedlings that are sold at annual fundraising garden sales.

It’s the site’s tranquility and calm and its sense of walking back in time that have inspired Cadence Chung since she first visited the house in her early teens. The 19-year-old Victoria University of

Wellington music student won Katherine Mansfield House and Garden’s annual secondary school short story competition in 2021, and on the anniversary of Katherine’s death this year she read a poem at an event at Katherine Mansfield Memorial Park in Thorndon.

“I enjoy history and historical houses. I first visited the house when I was about 13, when I started loving her work, and was amazed by its rich history and the way it was presented around her life,’’ says Cadence.

“I’m a big fan of Katherine Mansfield. Her work is so modern, and I relate to her as a writer, a musician and a woman.’’

Centenary events

2023 marks 100 years since the death of Katherine Mansfield from tuberculosis in France. A website (km23.co.nz) has been created to promote the range of events being held around the country throughout the year, as well as ideas for DIY activities, such as whipping up an orange soufflé from a recipe Katherine herself copied in a notebook and hosting a dress-up party in honour of the fashion-loving writer. n

1. Volunteer Ruth Page plays at Alberton underneath a portrait of Sophia Kerr Taylor (1847-1930), who played the same piano 100 years earlier.

1. Volunteer Ruth Page plays at Alberton underneath a portrait of Sophia Kerr Taylor (1847-1930), who played the same piano 100 years earlier.

WORDS: GARETH SHUTE / IMAGERY: MIKE HEYDON

SOUNDS FAMILIAR

Sheet music belonging to the former inhabitants of historic homes sheds light on their lives – and the musical tastes of the times

Pianos take pride of place in many historic homes, embodying a time when former residents would gather around them to sing, or watch the best pianist in the house perform.

In larger homes there could even be more than one; Auckland’s Alberton, for example, has one in its ballroom and another in the drawing room (although the instrument in the latter is not playable).

But it is the sheet music these residents owned that perhaps provides more of an insight into the role that music played in their lives. These tunes, after all, can still be played, and their scores offer clues to how they were obtained and used.

Many properties cared for by Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga have their own collections of sheet music, including the three historic Auckland homes of Alberton, Highwic and Ewelme.

Dr Elizabeth Nichol, who catalogued the collections at the three properties – having

written her PhD on New Zealand sheet music from 1850 to 1913 and drawing on knowledge from her years as a librarian –saw many reminders of the central role that pianos played in the lives of early European immigrants, such as the Lush family, who lived at Ewelme.

“There is a comment in [Revd] Vicesimus Lush’s diary in 1852, saying how excited he was that the piano had arrived and would soon be in their house,” she says.

“You can also see that music was important for the Kerr Taylors, who lived at Alberton, because they had sheet music that they had brought with them from England, which is clear from the dates or places of purchase printed on the volumes.”

In those days the only way to listen to music at home was when it was performed, so pianos played the role of the modern stereo. The central city felt more distant in an era when most people travelled by foot, so local halls held regular events that drew on the talents of those in the neighbourhood. It was only by practising with sheet music

at home that budding musicians could become involved, Elizabeth explains.

“There were lots of benefit concerts and concerts organised by amateur clubs and associations, and the Kerr Taylor daughters performed in some of those. There are also vocal scores in the [Kerr Taylor] collection from when the girls sang in the local St Luke’s choir and the Auckland Diocesan Choral Association festivals.

“The Lush’s piano in their home at Ewelme was also used by members of the family who played the organ at the church. This is reflected in pieces of church music and music for the harmonium.”

The Ewelme collection also contains some violin music, as Revd Lush’s granddaughter studied it in London, returning to teach it in the 1920s and ’30s. Sheet music was largely imported from overseas, although local publishers, such as the Dunedin firm Beggs, began producing works from the 1860s.

In the Highwic collection, there are two locally printed copies of ‘Long It Is, Love,

Since We Parted’ by Australian composer and performer David Cope, which was released to coincide with his 1870-80s tours (they are the only copies of this edition known to exist, according to Elizabeth). The Ewelme collection holds the earliest New Zealand-printed piece (1862) that Elizabeth could find: ‘Fairy Bells: Polka Mazurka’ was clearly a personal copy since it had ‘BH [Blanche Hawkins] Lush’ written in pencil at the top.

Some scores in the Alberton collection were torn from magazines, such as The Lady’s Companion and The New Zealand Graphic and Ladies’ Journal , and from newspapers (usually from the ‘Ladies’ pages). Elizabeth found that she could tell which songs the families liked the most because the pages had been repaired (with brown paper tape, for example) or still showed fingermarks on the corners.

In order to keep their collections in good shape, families sometimes arranged for bookbinders to combine loose sheets into single, bound volumes.

There are few New Zealand compositions in the sheet music collections in the three houses, but they provide some fascinating links to the wider history of local music; for example, there are some early pieces by internationally successful New ZealandAustralian composer Alfred Hill.

In other cases, more tangential threads tying the past to the present can be found. There is a composition (‘The Countess Waltz’) by child prodigy pianist Clarice Brabazon, which was published in The New Zealand Graphic in 1903. Clarice later married renowned singer Horace Stebbing, who was the uncle of Eldred Stebbing –the founder of Stebbing Recording Studio, which is still operating on Auckland’s Jervois Road.

Local compositions were often written for specific purposes, Elizabeth explains.

“A piece might be written for a particular occasion, so a publisher could put it in the shop window and hope to sell a few in that short period of time, for example if the Governor-General was visiting, or as a way to support our troops fighting in the Boer War.”

Compositions might also be written to raise the profile of the composers, such as when music retailer and teacher WH Webbe wrote a piece named after his daughter Madoleine (also a teacher at his music school). A copy of this piece is still at Alberton.

The existence of these collections begs the question: could this same music be played once more in these historic homes? The locations have certainly been used by musicians in more recent times. Highwic’s interior has been used for music videos such as Troy Kingi’s ‘First Take Strut’, and its grounds have hosted a garden party featuring a harpist, cellist and roving carol singer.

There has even been a performance by string quartet The Whistledowns, featuring a selection of modern songs rewritten in an historical style from the TV show Bridgerton Alberton has seen similar small ensembles play, and has also hosted music video shoots, such as for ‘You’ by Hollie Smith, featuring the NZSO.

The question also played a part in a recent internship undertaken at Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, which investigated how the sheet music might be used to plan a concert. Tessa Dalgety-Evans, then a University of Otago student (and now working as a learning facilitator at the National Library of New Zealand Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa), undertook the research, with her background as a musician (cellist) also helping.

“The music I was seeing at Alberton was classical and popular salon music from the early 1900s or even late 1800s,” says Tessa.

“For example, there was ‘Ta-ra-ra-Boomde-ay’, which was used in the kids’ TV show Barney in the early 2000s but harks back to that salon era. It would be great to do a new arrangement of a piece like that, or even some of the very early jazz in the collections, which could possibly allow improvisation.”

Tessa acknowledges that some of the light romantic songs popular in the 1800s might sound treacly to modern ears. However, she made a playlist of those recordings she could find, and she believes a good arranger could update them for a modern audience. She also began transcribing sheet music in the collection onto digital software (MuseScore) to make it more accessible.

Tessa did find a small number of songs that would now be inappropriate to play. For example, some are written in a mock-AfricanAmerican vernacular that would be culturally offensive to modern listeners.

Nonetheless, she believes there is plenty of worthwhile material to underpin a

stripped-back performance in the style of NPR Music’s ‘Tiny Desk Concerts’. This suggestion is echoed by Elizabeth, who has heard of ‘living museums’ where performers were hired to play in historic homes, even if just practising a piece as the original inhabitants would have done. (She notes, however, that the concept sometimes confused visitors, who were reluctant to enter and disturb the musicians.) Elizabeth agrees that the collections hold some hidden gems that could be brought back to life if treated in the right way.

“It is really hard to get in the right headspace to listen to some of this light music from 150 years ago. It is a pity they’re all tarred with the same brush. Some of them don’t show much originality or musical skill; however, others are quite lovely, and it is a bit sad that those ones are lost to modern listeners.”

To hear more from Elizabeth, view our video story here: youtube.com/ HeritageNewZealand PouhereTaonga

WORDS AND IMAGERY: SHELLIE EVANS

High art

The Waimate silos, completed in 1921, stand 36 metres tall and can hold nearly 3000 tonnes of grain. The four silos are still in use, despite little local demand now for grain storage.

Transport Waimate boss Barry Sadler came up with ‘The Silo Project’ idea, commissioning Waimate artist Bill Scott to paint local heroes onto the silos in 2018.

Seen here is Eric Batchelor (born in Waimate in 1920), who was twice awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal –the only New Zealand soldier in World War II to achieve this. He died in 2010 and was buried in the local cemetery with full military honours, including a 21-gun salute.

Also pictured is Dr Margaret Cruickshank, who in 1897 was the second New Zealand woman to graduate as a medical doctor (from the University of Otago) and the first to become a registered doctor. She spent most of her career in Waimate, where she was the only doctor during the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, to which she herself ultimately succumbed.

Pictured on the silos’ other sides are former Prime Minister Norman Kirk walking hand-in-hand with Moana Priest at a Waitangi Day celebration, and the figures of two well-respected local men: Michael Studholme and Ngāi Tahu leader Te Huruhuru.

Technical data

• Camera: Nikon D7500

• Lens: 18mm • Aperture: f/10

• ISO: 200 • Exposure: 1/250

Fulfilling aspirations

Takapūneke is one of the nation’s most significant historic places. Thanks to the combined commitment for almost half a century of many people – both tangata whenua and tangata Tiriti – its stories are starting to be told

Pou-tū-te-Raki-o-Te-Maiharanui commands a spectacular view across Akaroa Harbour. The striking pou takes in features of the cultural landscape such as Tūhiraki, the famed kō of Rākaihautū on the ridgeline to the west, and the distinctive, teardrop-shaped Ōnawe Pā peninsula to the north.

Standing more than eight metres tall, it was carved by Ngāi Tahu tohunga whakairo Fayne Robinson and rises from the centre of a takarangi pathway that draws visitors inward, in ever-decreasing circles. The curvilinear route is punctuated with tohu etched into the ground that invite you to pause and reflect. Harakeke. Rope. A musket. A map. A quill. Each tohu alludes to a specific story associated with Takapūneke, ‘the Waitangi of Te Waipounamu’.

Takapūneke sits quietly in the landscape, but in the 1820s this small, sheltered bay just south of the present-day Akaroa township was home to a bustling kāinga from which Ngāi Tahu upoko ariki Te Maiharanui conducted a lucrative trade in harakeke.

This enterprise and Ngāi Tahu life in the bay ended abruptly and devastatingly in November 1830, when a Ngāti Toa war party led by Te Rauparaha was secreted into the harbour beneath the decks of the British mercantile brig Elizabeth, captained by John Stewart.

Lured aboard under the guise of trade, Te Maiharanui was captured and killed in revenge for Ngāti Toa losses at Kaiapoi pā two years earlier. The war party razed the kāinga and brutally killed or enslaved many Ngāi Tahu people, thus rendering the bay tapu.

The Ngāi Tahu survivors retreated and eventually re-established themselves elsewhere, including at Ōnuku, the next bay to the south. Within a few years, the site of the onceflourishing trading kāinga was taken over by colonial settlers for farming.

The business arrangement struck between Captain Stewart and Te Rauparaha, and the toll it inflicted on Ngāi Tahu, has been documented as one of the most infamous events in Aotearoa New Zealand history. It was also an important impetus for the formal British intervention in New Zealand that followed.

As a direct result of British concern about the complicity of a British sea captain in the Takapūneke massacre, James Busby was sent to the Bay of Islands as British Resident in 1833, and by 1839 Britain had decided to annex New Zealand. Te Tiriti o Waitangi was signed the following year at locations around the country, including at Ōnuku, where Ngāi Tahu rangatira Iwikau and Tikao signed on 30 May 1840.

Three months later a symbolic flag-raising and court sitting took place at Takapūneke on the northern point overlooking the Tāhunatōrea reef. This event, intended to subdue French intentions to lay claim to Akaroa, was the first

effective demonstration of British sovereignty in Te Waipounamu. Captain Stanley of the British sloop Britomart hoisted the flag and delivered a speech that was translated into te reo Māori for the assembled Ngāi Tahu community by James Robinson-Clough, a ‘Pākeha Māori’ and partner of Puai from Akaroa. This was the culmination of a decade-long chain of events connecting Takapūneke to te Tiriti.

The flag-raising site was later named Green’s Point after the first Pākeha who managed a farm there. A monument was erected on the point in 1898 to mark the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria’s reign and to proclaim the significance of the site in the history of the assertion of British sovereignty over Aotearoa New Zealand. George Robinson (the son of James Robinson-Clough and Puai) cut a fine figure, wearing a kahu huruhuru and riding a magnificent white horse, as he led a procession of 1000 people from the jetty at Akaroa to the monument for its unveiling. There, cloaked in the Union Jack, the freshly engraved stone obelisk was described in the Lyttelton Times in 1898 as “a striking symbol of British sovereignty”.

A generation later, George’s son Tom Robinson played the role of his grandfather in a re-enactment of the original flag-raising during the official National South Island Centennial Commemorations at Akaroa in 1940. Ngāi Tahu took the opportunity during the formal speech-making to urge the Crown to uphold its Treaty obligations.

When Pou-tū-te-Raki-o-Te-Maiharanui was unveiled at dawn on a crystal-clear Matariki morning in June last year, it presented a bold counterpoint to the now somewhat diminished ‘Britomart Monument’ down the hill. Twenty years had passed since Takapūneke had been listed by Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga as a wāhi tapu area – the first site in mainland

Te Waipounamu to be afforded this status. At the time of its 2002 listing, nothing tangible in the bay’s rural aspect conveyed any sense of the site’s history or cultural significance to the Ngāi Tahu hapū of Ngāi Tārewa and Ngāti Irakehu, who are represented by Ōnuku Rūnanga. The stories of Takapūneke were still buried deep in the whenua. Dedicated efforts to protect and preserve Takapūneke had been underway for almost a decade, but another 19 years would pass before the last parcel of land was granted historic reserve status.

Today the entire bay is owned by Christchurch City Council and a large proportion of that is managed as a historic reserve by the Takapūneke Reserve CoGovernance Group, which comprises equal numbers of Ōnuku Rūnanga and council representatives, and an independent chair. It’s an outcome that’s testament to the advocacy and commitment of many people, both tangata whenua and tangata Tiriti, working together for almost half a century.

Ōnuku whānau carried the mamae of the atrocities that occurred at Takapūneke in relative silence for generations. They had no say in what occurred on private land that they no longer owned. Ngāi Tahu children were told not to go there because it was an urupā.

Writer Helen Brown shares her connections to Takapūneke

I first learned the story of Takapūneke in 2004 when I interviewed Waitai Tikao for Christchurch City Libraries’ place-based Ngāi Tahu histories project, Tī Kouka Whenua. It was one of my first forays into oral history, and the poignancy of the story had an unforgettable impact. So too did Waitai’s quiet determination that Takapūneke would be protected for future generations. Audio clips from that interview can still be accessed online.

In 2009, as Pouārahi for Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, I presented evidence at a Christchurch City Council hearing in support of a proposal to classify the Green’s Point land at Takapūneke as an historic reserve. The following year I worked closely with Ōnuku Rūnanga and the Akaroa Civic Trust on an award-winning exhibition Ngā Roimata o Takapūneke at the Akaroa Museum, which coincided with the formal blessing and acknowledgement of Takapūneke as an historic reserve.

I was a member of the steering group and a co-author of the Takapūneke Conservation Report 2012, which continues to guide and inform activities at Takapūneke, including the development of the Takapūneke Reserve Management Plan 2018. It has been a privilege to work with and for my Ngāi Tahu relations on the protection of Takapūneke over the past two decades.

“We are equal partners who bring different strengths to the table, and we also agree that the mana whenua values and storytelling take precedence”

In the 1960s and ’70s insult was added to injury when the local council purchased land in the bay to establish first a sewage treatment plant and then a rubbish dump. Damage to archaeological sites and the threat of subdivision in the 1990s further added to the mamae but also provoked Ōnuku whānau and their supporters, including the Akaroa Civic Trust, to act.

Victoria Andrews first learned about Takapūneke in 1997. A new New Zealander, she had relocated permanently from Santa Fe, New Mexico, to Akaroa in 1995. As a museum professional who had worked with multicultural and indigenous communities, she had a low tolerance for inequality and inequity.

“One day I was out at the Britomart Monument and I looked at the land that was going to be subdivided and I just thought, ‘That’s not right. It’s morally and ethically unacceptable; it’s a cemetery and it shouldn’t be built on’. That’s when the Akaroa Civic Trust decided to oppose the subdivision point blank.”

Over the ensuing years, Victoria and others in the trust worked alongside Ōnuku kaumātua, Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga staff, historians, community members, councillors and MPs to campaign for the protection of Takapūneke. Among the influential supporters were historians Harry Evison, John Wilson and Dame Anne Salmond, Prime Minister Helen Clark, MPs Dame Tariana Turia, Chris Carter, Ruth Dyson and Rod Donald, and Mayor Bob Parker. Eventually, in 2009, the large land parcel that had been destined for subdivision was integrated with the historic reserve, paving the way for the mana and mauri of Takapūneke to be restored.

Rik Tainui, Chair of Ōnuku Rūnanga, describes himself as a “Johnny come lately” to the Takapūneke kaupapa, but he has played a crucial role in recent years in negotiations with the council, funders and the local community. (In 2022 the rūnanga received a civic award for its contribution to the community through its work on Takapūneke.)

For Rik, the completion of Pou-tū-te-Raki-oTe-Maiharanui is the realisation of the vision of his late brother Pere Tainui and the broader aspirations of Ōnuku kaumātua, including the late Waitai Tikao and the late Revd Maurice Gray.

“My brother Pere and others made us all conscious of what could be possible at Takapūneke. It was my job to help secure the resources to make it happen.”

hapū: sub-tribe

kahu huruhuru: feather cloak

kāinga: village

kaumātua: elders

kaupapa: project, initiative or principle

kō: digging stick

mamae: pain, injury

mana: authority, power, prestige

mana whenua: those with tribal authority over land or territory

manuhiri: visitors

mauri: vital essence, life force

pou: post, pillar, support pou whenua: post markers of ownership

rangatira: chiefs

rūnanga: tribal council takarangi: intersecting doublespiral pattern, signifying creation tangata tiriti: non-Māori, person/people of te Tiriti/the Treaty tangata whenua: descendant of indigenous person/ people of the area; local Māori descendant tapu: sacred spiritual restrictions tohu: symbols tohunga whakairo: master carver upoko ariki: the head spiritual and temporal chief (ariki) of the iwi

urupā: cemetery, burial ground

waharoa: main entranceway to a pā wāhi tapu: site of sacred significance whenua: land

Pou-tū-te-Raki-o-Te-Maiharanui is the first stage in an ambitious development that will see multiple pou whenua, takarangi, waharoa, palisade fencing, seating, planting and interpretations installed across the Takapūneke site in the next six years. Rik emphasises the importance of sticking to this timeframe; he wants to see it completed in his lifetime.

The Takapūneke Reserve Co-Governance Group is overseeing the work. Chaired by Banks Peninsula stalwart and community leader Pam Richardson, the group is invested in attaining the best outcomes for Takapūneke and Ōnuku whānau. Russel Wedge has represented the council on the group since its inception in 2013.

“Our role as council staff is to ensure we meet the council’s regulatory obligations to the Minister of Conservation, the Reserves Act [1977] and the District Plan and to acknowledge that the land and the values associated with it are significant to mana whenua. We are equal partners who bring different strengths to the table, and we also agree that the mana whenua values and storytelling take precedence in the development of the reserve.”

Landscape architect and Ōnuku whānau member Debbie Tikao agrees that the group has worked in the true spirit of te Tiriti partnership. When the Reserve Management Plan was being prepared, she says, “We held the pen, writing several of the sections and helping to craft a lot of the objectives and policies. It was a great co-design, co-authoring process”.

Debbie also acknowledges the significant role played by the ‘Uncles’ (Waitai, Pere and Maurice) in developing an overarching vision for Takapūneke.

“They wanted the story of Takapūneke to be told, and for Takapūneke to become a place of wānanga/learning.”

The co-governance group is poised to begin work on an application to the Minister of Conservation to achieve the longstanding goal of elevating Takapūneke to National Reserve status under the Reserves Act.

It was an ambition that was first voiced by historian and friend of Ngāi Tahu the late Harry Evison in a speech he delivered at the foot of the Britomart Monument in 2001.

“We’re fulfilling the aspirations of our people who championed Takapūneke before us,” says Rik. “We just need to ensure we reach for new aspirations that we in turn can pass on, so we can continue to increase our footprint.”

A WOMEN’S

“I’ve been a fighter for justice my whole life,” begins a conversation with artist Jan Morrison. “There were massive issues, particularly in the ’70s and ’80s –human rights, women’s rights, save the planet – so from my late teenage years I was on marches, wearing the t-shirts, drawing illustrations for Greenpeace.”

So in the early 1990s, when she heard a call for proposals for projects celebrating the centenary of New Zealand women winning the fight for the vote, it was natural for her to put in a bid.

“I couldn’t pass it up. It was just so exciting. I really, really wanted to get it, but I never thought for a minute I would. And they accepted my proposal.”

The proposal was for a tile mural, which today sits between central Auckland’s High and Kitchener Streets. It depicts people and imagery associated with the suffrage campaigns that ultimately led, on 19 September 1893, to New Zealand becoming

the first self-governing country in which all women had the right to vote in parliamentary elections.

The artwork was unveiled in the space known as Khartoum Place on 20 September 1993, with the lower part of the space renamed in 2016 as Te Hā o Hine Place (a name gifted by Ngāti Whātua that can be interpreted to mean ‘pay heed to the dignity of women’). And almost 30 years on, the Auckland Women’s Suffrage Memorial was last year recognised as a Category 1 historic place.

Funded by the Suffrage Centennial Year Trust and Auckland City Council, the mural was created collaboratively by Jan and artist Claudia Pond Eyley specifically for its site, where it travels across several façades of a fountain and a stairway that runs between the two streets.

While Jan didn’t know Claudia personally at the time, she was familiar with her work as a prominent feminist artist and,

Dedicated to women who fought for the right to vote, an Auckland historic place is a reminder of the ongoing fight for women’s voices to be heardWORDS: CAITLIN SYKES / IMAGERY: MARCEL TROMP

sensing their artistic styles were also compatible, asked her to join the project. “I admired her enormously,” says Jan.

For her part, Claudia recalls being excited by the project and its large scale. Adding to the excitement was a personal connection to Amey Daldy, one of the suffragists ultimately depicted in the artwork. President of the Auckland Women’s Franchise League in 1893 (and later of the National Council of Women of New Zealand), Amey was a leading figure in the local and national suffrage campaigns. She was the second wife of William Daldy, who was the business partner of Claudia’s great-great-grandfather.

And there is a further family connection in another panel of the mural, Claudia says. It features a group of women on

bicycles – a crucial mode of transport for campaigners as they gathered signatures to petition parliament – who bear the faces of Claudia’s great-grandmother and her friends and cousins. A central aspect to the mural is its depiction of the ‘monster petition’ that suffragist Kate Sheppard famously pasted together and rolled around a broom handle before it was submitted to the House of Representatives in 1893. The mural also prominently depicts the iconic white camellias that suffragists presented to their supporters, and elements such as the now-extinct huia representing the past, and woven harakeke representing the weaving together of Māori and Pākehā cultures.

Comprising 2000 tiles, the mural was under construction right up until its unveiling by then Governor-General Dame Catherine Tizard (further panels were later added).

As Claudia noted in her diary on the day: “The New Zealand Air Force hung a huge cargo parachute across Khartoum Place and was organised with knots to drop upon the cutting of the ceremonial ribbon. The city council sent along the water fountain keeper to fill and set the fountains in motion while I rushed around wiping off the marker pen numbers on the tiles.”

Her entry went on to detail how, following an address at the Auckland Town Hall by then president of Ireland Mary Robinson, a Navy band led a procession of 300 women, many in period dress, down Queen Street to the site of the mural. There was a pōwhiri and speeches, and after the mural was revealed “the crowd cheered, everyone hugged and kissed”.

The celebrations, however, did not last and in a case of life imitating art, the mural’s own history has been characterised by fight.

As noted in its Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga listing report, the memorial has come under threat due to redevelopment a number of times since 2005, with the National Council of Women of New Zealand (NCWNZ) and other prominent campaigners leading a decade-long fight to save it. Their cause received significant public support and ultimately led to the site being given the highest available protection in the Auckland Unitary Plan in 2015.