historic NEw england

REFLECTIONS ON A RELATIONSHIP

Sarah Orne Jewett and Annie Adams Fields

ANNUAL REPORT

Fiscal Year 2018

REFLECTIONS ON A RELATIONSHIP

Sarah Orne Jewett and Annie Adams Fields

ANNUAL REPORT

Fiscal Year 2018

It is all about the stories.

As we look back on the 108-year history of Historic New England, the largest shift we see is from the early goal of saving historic buildings and artifacts to efforts to widely share those resources. Today, our primary focus is on engaging people with the past as it is represented by Historic New England’s buildings, landscapes, and collections. The key to our success is the stories. I often say that engaging people with history starts with hearing their own stories. What is important to them? What personal experiences have they had thus far in life, all of which are indeed now history? From such stories we can make connections to the people who lived in our historic properties, and the folks who used the things that Historic New England collects.

When starting with individuals, the stories will be incredibly diverse, every one distinctive. We see this throughout the stories told in this fall’s issue. From World War I government-constructed housing for shipyard and arsenal workers, to holiday traditions, to the fascinating personal life of writer Sarah Orne Jewett of South Berwick, Maine, and the presence of a formerly enslaved man whom Governor John Langdon employed as head steward of his Portsmouth, New Hampshire, household, the stories bring us glimpses of the great range of experiences found in New England’s past and encourage us to think about our own stories. While each of our tales is unique, they all are the continuation of the shared New England experience.

Carl R. Nold President and CEOHISTORIC NEW ENGLAND magazine is a benefit of membership. To become a member, visit HistoricNewEngland.org or call 617-994-5910. Comments? Email Info@HistoricNewEngland.org. Historic New England is funded in part by the Massachusetts Cultural Council.

Executive Editor: Diane Viera Editor: Dorothy A. Clark Editorial Review Team: Nancy Carlisle, Senior Curator of Collections; Lorna Condon, Senior Curator of Library and Archives; Sally Zimmerman, Senior Preservation Services Manager Design: Three Bean Press

JerriAnne Boggis, executive director of Black Heritage Trail of New Hampshire, contributed to this article.

Cyrus Bruce was a prominent figure in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, more than 200 years ago in his capacity as the governor’s majordomo. Few hard facts are known about his life, as is the case with many early African Americans, so he comes to us by way of oral tradition and a discursive sketch written in the nineteenth century.

Yet artist Richard Haynes has gotten to know Cyrus Bruce in a way that no one in the present day has.

He has given Bruce, the emancipated chief steward of Governor John Langdon’s household, a permanent visual presence that is now a part of history. Haynes spent the summer as Historic New England’s artist-in-residence at Governor John Langdon House, during which he created a pictorial representation of Bruce. “He’s a man full of pride, confident in who he is,” Haynes said, sharing his interpretation of Bruce. “He is not downtrodden. He is a man who is happy with who he is.”

Haynes, a resident of Portsmouth, was the third artist-in-residence at Langdon House. This program affords artists the opportunity to create works based on an aspect of the history of the 1784 Georgian mansion or the people who lived there. The artists also lead public workshops and hold open studio hours during which anyone can drop in and discuss the work in progress. Haynes’s residency began with the opening of an exhibition of his drawings, which Historic New

England presented in partnership with the Black Heritage Trail of New Hampshire. A Life in Color: Two Cultural Makers, Centuries Apart, which ran through early fall, displayed Haynes’s bold, colorful work, and with its emphasis on freedom, united Haynes and Bruce culturally over the centuries. Both men exemplify makers and keepers of culture. They traveled long distances for the freedom of self-expression and self-determination. Theirs are stories of personal transformation. Bruce was once enslaved; who his owner was is not known. After he was freed from bondage he became a paid servant of the governor. With his eye-catching mode of dress, Bruce was highly recognizable around the city. Portsmouth Journal editor Charles W. Brewster wrote about Bruce in an installment of his “Rambles” column titled “Slaves in Portsmouth” (1856): “There could scarcely be found in Portsmouth, not excepting the Governor himself, one who dressed more elegantly or exhibited a more gentlemanly appearance. His heavy gold chain and seals, his fine black or blue broadcloth

page 2 Richard Haynes’s completed portrait of Cyrus Bruce. page 3 Haynes shares his views on creating art and the method he uses during open studio hours in the South Lodge at Governor John Langdon House. A visitor studies panels displaying some of Haynes’s preparatory artwork. Photographs by Nicolas Hyacinthe.

coat and small clothes, his silk stockings and silverbuckled shoes, his ruffles and carefully plaited linen, are well remembered by many.”

That description of elegant dress and refined bearing could easily refer to the often bow-tie-attired Haynes, a man of engaging distinction. In addition to being an artist, Haynes is a photographer, lecturer, professor, mentor, and a strong advocate for social justice. He is associate director of admissions for diversity at the University of New Hampshire.

Born in the segregated Deep South city of Charleston, South Carolina, Haynes, his three siblings, and their parents were among the more than six million blacks of the Great Migration (approximately 1914-1972) who tried to escape racial oppression by moving to the West, Midwest, and North. Haynes’s parents sought to make a better life for the family in America’s black mecca, Harlem in New York City, moving there in 1958. Unfortunately, it was not the fresh start the family had imagined. Afflicted by drug addiction and desperation, the urban environment was a tough place; eight-yearold Richard was frequently beaten up because of his Southern drawl. However, Harlem was the place where he also saw the dignity of black folks as they struggled to honor their cultural identity and maintain self-determination to provide for their families. These images of strength and dignity would greatly influence his work.

Haynes’s work—part memory, part nostalgia, and part hope—tells a story that is both instantly familiar yet refreshingly novel. There is a dynamism in his drawings that is revealed gradually and gains a graceful momentum during the viewing experience. His artistry, reminiscent of the flat, bold shapes and colors that Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000)—one of the most noted black American painters of the twentieth century—used, is a celebration of African American life and a reimaging of blackness and natural beauty. Historically, African American portraiture by white artists has been largely derogatory. A plethora of nineteenth-century images that stereotyped and caricatured physical features of blacks remains part of American iconography today. Haynes populates his drawings with faceless people, not to render them anonymous or suggest that they have no identity, but to allow them to deliver a universal message: “This could be anybody.”

For his A Life In Color: Two Cultural Makers, Centuries Apart exhibition, Haynes reprocessed a familiar topic that is steeped in controversy. Ten of the drawings depict vibrant quilt patterns inspired by the book Hidden in Plain View: A Secret Story of Quilts and the Underground Railroad by Jacqueline Tobin and Raymond G. Dobard. The drawings served as the foundation for the story the exhibition told of the complex, ingenious, and necessarily covert ways— including, supposedly, the use of coded quilts—in which enslaved men, women, and children navigated their escapes from the South via the Underground Railroad. To some commentators, the book presents another challenge to the abolitionist “white savior” trope that has long been prevalent in antislavery literature and scholarship. The book also has detractors who have criticized the authors’ research as well as their qualifications to write about the topic. For Haynes, the drawings that the book inspired him to create offer viewers the opportunity to reshape the way they have imagined or experienced black art in America.

The capstone of Haynes’s residency is the portrait of Bruce, which the artist executed in his signature medium, Caran d'Ache oil wax crayons on watercolor paper. The first step in his creative process is to make photographs: “I started by photographing myself as Cyrus Bruce.”

Haynes’s photographs provide the basis for making simple sketches and later, the small-scale artist’s studies he uses as guides in developing his final rendition of a work. As part of his research for the Bruce portrait, Haynes visited Historic New England’s Haverhill Regional Office to look at period textiles to get a sense of the fabrics and styles that Bruce might have worn. “I was trying to be as real as possible to the historical aspect,” he said.

The finished portrait, approximately twenty-three inches by thirty inches in size, depicts a welcoming personage dressed in lively colors holding the front door handle at Langdon House. “He wears his outfit with dignity,” Haynes said. The portrait will remain with Historic New England.

Haynes hopes to use his work to keep black culture vibrant and alive. He strongly believes that the only way to invigorate culture is to create culture. “Artists are culture keepers and culture makers,” he said, recalling the prehistoric artists who documented their experiences on cave walls. “An artist has to seek deep

beneath the surface to find the importance of art,” he said. “That’s what art is to me. …That’s how you change the world.”

Historic New England’s 2018 artist-in-residence program at Governor John Langdon House was funded in part by the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation from the Krasker Fund for the Arts and Humanities and the Tyco International Fund for Art Builds Community.

The non-profit Black Heritage Trail of New Hampshire was established in August 2016 with a mission to promote awareness and appreciation of African American history and culture in New Hampshire. Visit black heritagetrailnh.org.

t the very core of what we do, historians offer interpretations of the past. Even as we strive to remain objective in these interpretations we must be ever conscious of contemporary issues, our own biases, and our relationship to the materials we are working with. We constantly seek to arrive at an ever-richer understanding of those we write about—to narrate our subjects' lives with their

own words when possible; to highlight the significance of their lives, their relationships, and their work; and to bring to light new primary and secondary evidence. Despite our aspirations toward objectivity, the past can still feel very subjective, and at times, very personal. That feeling is not always a bad thing; indeed, historical empathy is an important part of seeking a greater understanding of the past.

In reading letters and diaries,

by LIBBY BISCHOF Professor of History University of Southern Mainehistorians encounter intimate details of relationships alongside the banalities and trivialities of daily life. We hone in on an image, a word, a phrase, a reference, and ponder what it might mean, what it reveals about our subject, what it can tell us about her life. Thus we find at the center of our historical interpretation the often messy process of reinterpretation—of the work of our subjects, the work of other historians and scholars, and even of our

own work. The past then is never really settled; it is in a constant state of reinterpretation.

The past felt very present to me when I recently returned to the house where Sarah Orne Jewett (1849-1909) lived in South Berwick, Maine. (Historic New England acquired this 1774 house and the adjacent 1854 Jewett family residence in 1931 and operates the site as Sarah Orne Jewett House Museum and Visitor Center.) When asked by Historic New England to pen an article on the relationship between Jewett and Annie Adams Fields (1834-1915), a relationship I have interpreted and reinterpreted on and off for over a decade, I did what any good photo historian does: I started with images.

While many of the literary scholars who have written about Jewett

and Fields have rightly concentrated on the pair’s published and unpublished writings, correspondence, and diaries, I chose to explore the visual record of their relationship— specifically through a close reading of photographs and objects in Jewett’s bedroom. These photographs hint at the intimacy of their relationship, as well as the important role each woman played in the life of the other. The images also reveal the tensions between public and private spaces in the nineteenth century and invite a reinterpretation of Jewett’s home as a space peopled by women, as a central site of friendship, love, and mentorship.

In 1870, Sarah Orne Jewett, a twenty-one-year-old author from South Berwick, met thirty-six-yearold Annie Adams Fields, wife of publisher James T. Fields, who fa-

mously edited The Atlantic Monthly literary magazine. The Fieldses had a summer home in Manchesterby-the-Sea on the North Shore of Massachusetts and Jewett spent time visiting the couple in the summer of 1870; James had published some of Jewett’s early stories in The Atlantic

Over many subsequent summers, the women established a friendship, and then, according to Jewett’s biographer, Sarah Sherman, “sometime in the winter of 1881, in the wake of James Fields’s death, Annie Fields and Sarah Jewett fell in love.” Judith Roman, Fields’s biographer, concurs, noting, “Annie and Sarah’s relationship was more reciprocal than Annie’s marriage had been; in it, Annie received as well as gave the kind of emotional support which she had given James.” Roman con-

page 4 Sarah Orne Jewett photographed reading a book, date unknown. Southworth and Hawes daguerreotype portrait of Annie Adams Fields, 1861. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of I. N. Phelps Stokes, Edward S. Hawes, Alice Mary Hawes, and Marion Augusta Hawes, 1937. below Photograph of Jewett’s bedroom taken before 1931. Sarah Orne Jewett Compositions and Other Papers, 1847-1909 (MS Am 1743.26 [16]), Houghton Library, Harvard University.

tinues, remarking that the second half of Fields’s life actually was what editor and author Mark Antony De Wolfe Howe, who knew them personally, called “a union—there is no truer word for it.”

Annie Fields has too often been pigeonholed as only a literary hostess (though she was, certainly, a famous one); she was also a writer, a club woman, and eventually, founder of Associated Charities of Boston. She was also the most important presence in Jewett’s life from the 1880s until Jewett’s death of a stroke in 1909.

A relationship with Fields provided Jewett access to the leading literary lights of Boston’s Golden Age, with a metropolitan home base outside of her beloved coastal Maine, and the deep and

abiding female companionship she sought and cultivated throughout her life. A relationship with Jewett provided Fields with a model of a successful woman writer, a partner who respected her influence and her talents, and a companion who provided love and support during a time of profound loss. Their relationship, as many have argued, was deeply reciprocal, and complex. It was also transformative for both. With Fields, Jewett was able to travel abroad for the first time; they went to Europe in 1882 and took many subsequent trips to Italy, Greece, England, and France among other destinations over the course of the next two decades.

Beginning in 1881-82 and lasting until the injuries Jewett suffered

These images made c. 1900 and in 2009 show that little had changed in Jewett’s room.

in a 1902 carriage accident, the two women lived together for most of the year at Fields’s home at 148 Charles Street in Boston. Notably, Fields often referred to the Charles Street residence as “our home” in letters to Jewett and others in their circle. Jewett would spend the autumn and winter there, returning to South Berwick in the late spring and staying there through early summer. Fields would briefly visit her in Maine and then go open the summer house in Manchester-bythe-Sea; Jewett would join her later in the season. After the accident, although Jewett recovered some of her strength, she spent far more time in South Berwick, wintering in Boston only occasionally until suffering a stroke in January 1909.

In what is probably the most

published photograph of the two women together, Jewett and Fields can be seen in the library of 148 Charles Street—Jewett by the window, Fields closer to the door—reading in companionable silence (above). This picture, while it reveals a wellappointed Victorian library where such literary celebrities as Charles Dickens and Nathaniel Hawthorne were entertained, is not an intimate one. It does not display the closeness of the two women nor their abiding love for one another. Indeed, the figures play an almost secondary role to the innumerable books, paintings, heavy furniture, long drapes, and grand piano in the foreground.

In a multitude of ways, the photograph reflects the propriety and decorum of the era in which it was

produced. It stands in stark contrast to the loving and affectionate letters—filled with pet nicknames (Jewett was “Pinny,” Fields was “Fuff”), signs of physical affection, and true companionship—that Jewett and Fields sent to one another. Their relationship was far more intimate than the Charles Street portrait suggests.

While the close and loving friendship Fields and Jewett shared at times stretches the confines of the ways we tend to categorize and define twenty-first-century relationships, it is typically categorized by the nineteenth-century term “Boston marriage.” By all accounts, the label was used at the turn of the twentieth century (first by Henry James) to describe the association between two un-

married women living together in a long-term, committed relationship; it could certainly mean a lesbian relationship, though that was not always the case. In the late 1800s and into the first years of the 1900s, Boston marriages were most often found among middle-class, educated, financially independent white women. These unions were considered quite socially acceptable. One reason for their respectability was the widely held Victorian-era assumption about women as asexual and passionless.

To truly understand the depths of the Jewett-Fields relationship, we must shed our twenty-first-century sensibilities and beliefs and enter into what Josephine Donovan, another Jewett biographer, called in a 1979 article “a lost world

of female behavior,” a world where, as historian Carroll Smith-Rosenberg reminds us in a 1975 journal article, “such deeply felt, same-sex friendships were casually accepted in American society,” particularly in New England and especially so in Boston.

Although Fields was Jewett’s senior by fifteen years and sometimes took on a mothering or mentoring role, it is clear from their correspondence that the pair frequently interchanged the roles of caregiver and mentor. They encouraged one another’s work, widened each other’s horizons, and respected each other’s literary ambitions. The relationship also allowed the two women a great deal of independence in terms of pursuing separate interests—Jewett’s increasing prominence as a writer and Fields’s growing concern with charity, urban reform, and social work—than would ever have been possible in a heterosexual Victorian marriage, no matter how sympathetic one’s male partner might have been. Frequent glimpses into the loving intimacy of their relationship can readily be found in their published and unpublished correspondence and in their written work. If one looks closely, it can also be found in photographs.

Historic New England has many photographs of Sarah Orne Jewett House, including images from 1931 that document each room. These photographs play a central role in the current interpretation of the house museum

for visitors. Among them are various views of Jewett’s bedroom. By studying her quarters, both in terms of the photographs and while actually standing in the room, we can see that she shared this space with Fields, virtually if not physically. The space is organized around Fields’s visage; everywhere one turns she is present. During their three decades together, Jewett and Fields were so much a fixture in one another’s lives that when they had to be apart, photographs, letters, and objects stood in as necessary talismans of love and friendship.

Clearly depicted in photographs of the house in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Jewett’s bedroom fireplace and mantel were typical of a Victorian-era woman of her class and stature (see page 6).

Above the fireplace, books (including many volumes written by one of her favorite authors, Sir Walter Scott), antiques, candles, ceramics, riding crops, handicrafts, a crepe paper and wood owl (representing one of the nicknames Jewett’s friends called her—“Owl” or “Owlet”), and bric-a-brac commingle with photographs, embroidered samplers, and statuettes. There can be no doubt, however, that the central focus of the fireplace, mantel, and the wall is a rather large framed photographic portrait of Fields. In this photograph Fields, in profile, hair swept-up, is forever young. This image is a later-printed variation of a daguerreotype made by the Boston photographic firm of Southworth and Hawes when Fields was

just twenty years old and had recently married the widowed James T. Fields, who was fourteen years her senior.

There are many famous portraits of Annie Fields, photographs as well as paintings, but none showcases her youthful beauty to the extent that the daguerreotype does. Taken nearly two decades before they met, it is significant that this image of Fields was so central to Jewett. This photograph would denote to Jewett, and to anyone who viewed it, that the two women had been in each other’s lives decades longer than they actually had. We do not know how Jewett came into possession of this photograph—if Fields gave it to her, or if Jewett asked for it. I can also imagine that Fields was fond of this portrait and may have wanted Jewett to have the very best image of her in her possession. (There is another, much smaller version of this Fields portrait in Jewett House. It rests in a small wooden and glass case displayed outside Jewett’s bedroom.)

The way Jewett arranged her bedroom and her mantelpiece assured that, upon waking and looking straight across the room, Fields’s portrait would be in her line of sight. A small mirror angled over Jewett’s bed also reflects the portrait (see cover photograph). Jewett could look everywhere around the room and sense her companion’s gaze despite her absence—an absence Jewett felt very profoundly when they were apart.

Jewett constantly surrounded herself with ephemera from her friends, her travels, her writing career, and her passions. This is true throughout all the rooms in the house, as well as the way in which

By studying her quarters … we can see that Jewett shared this space with Fields, virtually if not physically. The space is organized around Fields’s visage; everywhere one turns she is present.

Jewett arranged materials on her writing desk, located right outside her bedroom on the second-floor landing where she could look out the front window onto the street.

One need only glance at the photograph of a middle-aged Jewett writing at her desk to know and understand how she curated spaces for herself wherever she took up residence; her bedroom and her desk were her most personal spaces. While photographs and items representing friends and close relatives were important to Jewett, she believed, however, that pictures were poor stand-ins for the presence of those she loved. She missed hearing the voices of her loved ones as much as she missed seeing their faces; photographs were an inferior but necessary substitute. In a letter dated January 1900 to her friend Dorothy Ward, Jewett wrote: “But one must look at it often in these conditions, and finally gather a good bit of companionship out of a photograph, it being all that one can get! If somebody would only invent a little speaking-attachment to such pictures, a nicer sort of phonograph,—it would really be very nice.”

Bedrooms are intimate spaces. Jewett’s bedroom, visitors to her house are told, looks almost as it did when she passed away more than a century ago. Extant photographs support this interpretation. Jewett occupied her bedroom from 1887, when she moved into the house, until 1909, when she died. In the Victorian era the homes of the middle and upper classes were strictly gen-

dered, marked as separate spheres of influence for men and women, as well as divided into public and private spaces. Second-floor spaces, like Jewett’s bedroom, would not have been seen by most visitors, who would have been confined to the public spaces on the first floor, such as the library or the parlor.

Today, visitors to Jewett House have much more access to the intimate spaces than a nineteenth-century visitor ever would have had. We must be conscious, then, of what this access, this intimacy, would have meant at the turn of the twentieth century. In an era when everything was covered, corseted, overstuffed, and overdone, the bedroom offered a respite. One could let down one’s proverbial hair and be oneself. One could decorate the space in accordance with personal preferences rather than adhering to the dictates of social convention. An individual could store and display items of particular significance without worrying about who might see them, or how such items might be interpreted.

Jewett’s bedroom, and the photographs and objects contained within, reveal what the author treasured most and that included her thirty-year relationship with Annie Adams Fields.

If you have not visited Jewett House in a few years, I invite you to engage in Historic New England’s newly reinterpreted tour and to immerse yourself in the central female relationships that are so important to understanding Sarah Orne Jewett’s life and work.

“One’s house,” Sarah Orne Jewett told an interviewer in 1895, “is almost like one’s body when it is so much a part of life.” Jewett’s 1774 home in South Berwick, Maine, was indeed a constant throughout her life and its interior lends insight to her life as an artist, as well as her interest in preservation. The writer’s home and family residence next door, which now comprise Historic New England’s Sarah Orne Jewett House Museum and Visitor Center, is the perfect venue for the exhibition Hand-Hooked Rugs: New Works by Members of Seacoast Ruggers

On view through January 5, 2019, Hand-Hooked Rugs is a display of new works by members of the Seacoast Ruggers, a group of approximately twenty-five hobbyist rug hookers of all levels. “We want the public to realize we consider rug hooking an art form, more than a craft. It is ‘painting with wool.’ We choose the colors, dye wool to get specific colors, and in

many cases design and draw our own patterns,” said group member Patricia Laska. “We hope to attract others to enjoy the fun of rug hooking, the way we do.”

The Seacoast Ruggers’s collaborative approach to their artistic hobby is similar to the type of network in which Jewett created; she belonged to a community of artists and writers who supported and nurtured each other’s work. With its roots in York, Maine, the decades-old group includes participants from across the Southern Maine Coast and New Hampshire Seacoast regions. Members exhibit their rugs annually with showings in a number of area venues.

Jewett and two friends, Emily Tyson and her stepdaughter, Elise, owners of Hamilton House (c. 1785) in South Berwick (Jewett encouraged them to buy the nearby Georgian mansion, which is now owned by Historic New England as well), collected hand-

crafted hooked rugs for their homes. Today, hooked rugs are among the furnishings of both properties. To highlight that, Seacoast Ruggers created a reproduction of a late-nineteenth-century hooked rug at Hamilton House for the exhibition. It depicts a two-mast, full-sail British ship flying the Union Jack and the banner “Moss Rose.” Five swallows are also depicted on the rug. The swallow image is sometimes used in art to convey a variety of meanings, such as the sighting of land and thus the end of a seafaring journey. At the close of the exhibition, the reproduction rug will remain with Historic New England.

Once considered a craft of the impoverished—scraps of fabric pulled through stiff backings such as burlap could be used to create floor coverings for those unable to afford machine-made carpets—in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, hand-hooked rugs were collected by homeowners as a staple of Colonial Revival interior decoration. In Hamilton House Furnishings Report, Richard Nylander, Historic New England’s curator emeritus, points out that handhooked rugs (as well as Currier and Ives prints and Sandwich glass) were “‘musts’ for the early 20th century collector.”

Hand-Hooked Rugs enriches the visitors’ experiences at Sarah Orne Jewett House Museum and Visitor Center and promotes a regional art form that continues to inspire many artists.

Since the mid-1990s

Casey Farm in Saunderstown, Rhode Island, has had a reputation for growing an abundance of fresh, certified-organic fruits, berries, vegetables, herbs, and flowers. Some 150 member families supplement their diets annually through our Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) program. We also sell to nearby restaurants as well as to locals and tourists at the Coastal Growers’ Farmers’ Market, hosted at Casey Farm from May through October.

As the local food movement expands, small farms are looking for ways to broaden their operations to stay viable and Casey Farm is no exception. With demand for locally produced food increasing and market trends shifting, we are looking at how to extend our reach into the community. We work constantly to become a more sustainable farming operation.

One way we are expanding vegetable production at Casey Farm is with the installation of a high tunnel. Also known as hoop houses or unheated greenhouses, these structures allow growers to extend the

crop season later into the fall and, in some cases, through the winter, as well as produce high-value crops like tomatoes much earlier than when they are grown in the field.

We constructed our Northern Star high tunnel (the dimensions are twenty-five feet by ninety-six feet) last spring. It consists of large metal arches or hoops covered with a plastic film that allows sunlight through to the ground, warming the soil and allowing for higher temperatures than those occurring naturally outside. Seeds or seedlings are sown directly into the ground, with some crops mulched over for added protection and water retention. Often, smaller plastic-covered tunnels are used as another layer of insulation.

Plants slow their growth as the days get shorter in the fall and stop growing, go dormant, or die amid cold temperatures. A high tunnel doesn’t help to extend the length of the day but it does help to increase temperatures in this microclimate so that mature, healthy plants will survive the changing seasons.

Produce from plants nurtured in a high tunnel can be harvested for a longer period of time than field crops. This type of vegetable

and fruit production has grown in popularity among small farmers who are trying to meet local demands and compete with the large industrial farms that dominate the U.S. food system.

Now that we have a high tunnel at Casey Farm, we plan to offer an autumn CSA share, as well as possibly join a winter farmers’ market or two to generate revenue yearround. This fall, we plan to offer a trial share to a small number of CSA members on a first-come basis and to extend our restaurant sales into the winter months.

With greater access to information, consumers are becoming more aware of the impact their financial choices make on our economy, environment, and inevitably our health. Shopping locally is more important for the health of our planet. Studies have shown that foods grown and purchased locally contain more nutrients than foods shipped long distances. Consider your own spending power and support local agriculture by joining a CSA and shopping at farmers’ markets.

And don’t forget to bring reusable bags.

by LORNA CONDON Senior Curator of Library and Archives

by LORNA CONDON Senior Curator of Library and Archives

Arecent gift from Stephen L. Fletcher to Historic New England of a set of photographs helps illustrate the story of a little-known World War I initiative: the U.S. government’s construction of well-planned and welldesigned communities around the country to house workers hired for jobs in arsenals and shipyards.

The images—twenty panoramic and twenty standard photographs— depict a construction site in Quincy, Massachusetts, where, from October

1918 to March 1919, the United States Housing Corporation (USHC) erected more than 250 homes, a number of which still exist.

The First World War created the need for expanded production in shipyards and arsenals across the country. As more and more workers were hired at these facilities to meet wartime demands, severe housing shortages and public health issues arose in the home communities. To address the problem, Congress appropriated $1 million in July 1918 “for the purpose of provid-

ing housing, local transportation, and other community facilities for such industrial workers as are engaged in arsenals and navy yards of the United States and industries connected with and essential to the national defense, and their families.”

The oversight of this massive, nationwide project, which included land acquisition and construction, was assigned to the USHC, an agency established in 1918 under the purview of the Department of Labor’s Bureau of Industrial Housing and

Transportation. The funding was allocated to more than eighty-three sites in twenty-six states. Quincy, with its Fore River Shipyard, a subsidiary of Bethlehem Steel Company, was one of these.

The USHC secured three tracts of land for houses in Quincy— Arnold Street, River Street, and the Baker Yacht Basin—and hired local professionals to undertake the work.

James E. McLaughlin of Boston was chosen as architect of the project and noted landscape architect Herbert J.

Kellaway, also of Boston, was named town planner.

McLaughlin and Kellaway were notable in their fields. McLaughlin had designed Fenway Park (1912) and the Commonwealth Armory (191415) in Boston, among many other commissions. Kellaway had worked for fourteen years with Frederick Law Olmsted and the Olmsted firm. He had developed landscape plans for a wide range of municipalities, institutions, and private clients and wrote books about landscape architecture.

McLaughlin and Kellaway wrote about the Quincy housing project in the January 1919 issue of The Architectural Review: “A total of 256 buildings is being built…There are ninety single houses…57 semi-detached houses… and 109 two-family flats, accommodating in all 422 families or about 2,120 persons. …While a very few types of plans have been used yet a great variety of appearance has been obtained by the use of varying types of roofs, porches, and other external features, such as clapboards here and shingles

there with some few brick houses. …

Simplicity of line and decoration has been the keynote of the designs and they have been modeled…after those fascinating relics of the Old Colony. …Nor will the similarity end with mere external appearance, for every effort will be made to make these new houses as sound and enduring as their venerable prototypes.”

Construction began in the fall of 1918 and, according to McLaughlin and Kellaway, “was carried on with a degree of speed that would have been thought impossible in pre-war days.” (Workers

were required to spend ten hours per day, six days per week on the job.)

Given the enormous scope of the undertaking and the urgency with which these funds had to be expended and the dwellings erected, the USHC implemented a system of checks and balances to document work and ensure that local projects were on budget and on schedule. Photographic documentation was a part of the process. Architectural photographer Paul J. Weber of the Dorchester section of Boston was hired to record the Quincy site.

Weber was well known. One of his business cards in Historic New England’s archival collection advertises that he did “Landscape and Architectural Work” and “Panoramic Views.” Weber worked extensively for Harvard University and other educational institutions; for architects and landscape architects such as Eleanor Raymond, William T. Aldrich, and Fletcher Steele; and his images were published in Architectural Forum and House Beautiful, among other magazines.

He also recorded Historic New England’s Abraham Browne House

(c. 1698) in Watertown, Massachusetts; Cooper-Frost-Austin House (c. 1681) in Cambridge, Massachusetts; and Hamilton House (c. 1785) in South Berwick, Maine. (In addition to these photographs, the Library and Archives holds numerous other examples of Weber’s work.)

Weber began recording the work at the three Quincy sites in October 1918 and continued at least through March 1919. As part of the administrative oversight, the Casper

Ranger Construction Company, the project builder, collected the images from Weber and mailed them to A. M. Ganson, the USHC’s traveling supervisor, who lived in Petersham, Massachusetts, for review. We know this because the Weber photographs came to Historic New England in the original mailing package.

Following the war the USHC offered the houses for sale to the public. Now, after 100 years, the three Quincy neighborhoods still exist, a testament

to the vision of the designers and to the work of the many unnamed individuals, skilled and unskilled, who built these communities in support of the war effort, which are recorded for posterity in Weber’s photographs.

To see additional photographs and learn more about the United States Housing Corporation development at Quincy, visit Workers’ Paradise: The Forgotten Communities of World War I at web.mit.edu/ebj/www/ ww1/ww1a.html.

Panoramic photographs of the construction of the Arnold Street site in Quincy, Massachusetts, taken in October and November 1918 (pages 12-13) convey the rapid speed with which the United States Housing Corporations’s World War I housing project progressed, as do the images of the Baker Basin taken in October 1918 and March 1919 (above and below).

by JOSEPH M. BAGLEY City Archaeologist of Boston

by JOSEPH M. BAGLEY City Archaeologist of Boston

“Trendy” does not seem to be a word one would associate with archaeology, but among the latest trends in the field are public archaeology and community archaeology. Each has a slightly different connotation, but the point is for professional archaeologists to worry less about what other archaeologists want to know. Instead, the focus is more on determining how the history and stories found in the ground are relevant to the community associated with a site. It is equally important to directly involve community members in the planning, digging, and interpretation of a site.

Boston’s City Archaeology Program (BCAP) came about in the early 1980s as a direct response to the

massive archaeological surveys conducted downtown and in Boston Harbor in conjunction with the proposed tunneling for the Big Dig highway rerouting project (officially called the Central Artery/Tunnel Project). Most of these digs were done by private companies, but the outreach and curation of artifacts were done by the city archaeologist. The role of the city archaeologist has varied with each person who has held the title, but the emphasis has always been on public education.

In 2011 when I became the fourth city archaeologist in the program’s history, I started emphasizing the need to do more excavations and get Bostonians not only interested in the stories that the stuff reveals, but

also participating in the process of planning, digging, and analyzing the sites and artifacts. Being the sole staff member of BCAP, it didn’t hurt that anything beyond what I was able to do by myself was going to require the participation of the public. By default, BCAP became a “trendy” community archaeology program.

In 2012, BCAP had the opportunity to survey the Training Field, a park in the Charlestown section of the city. The Charlestown Preservation Society called for an archaeological survey ahead of a full park renovation, and all aspects of planning for the dig were shared with the Charlestown community by the preservation society. As a result, about half of

our crew members were part of the Charlestown community, most of whom had never done archaeology. Making up the rest of the team were student and professional archaeologists volunteering on weekends.

We saw an instant success story. Besides having more than one person on site to dig the holes, Charlestown residents were directly

page 16 Public Archaeology Laboratory Inc., a cultural resource management services firm based in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, conducted a survey in 1985 at City Square in the Charlestown section of Boston as part of the Central Artery/Tunnel Project, also called the Big Dig. below, left Charlestown residents, site visitors, and volunteer archaeologists at Training Field park in Charlestown. right Volunteers and visitors participate in excavations at Malcolm X House on Dale Street in Roxbury in 2016. The house, where Muslim minister and civil rights activist Malcolm X lived with his sister during his youth, was built in 1872 on a country estate that was subdivided. Photographs courtesy of Joseph M. Bagley.

involved with the physical process of improving their much-loved park. They were able to take ownership of their history by being the individuals who found the artifacts, and, because there were no barriers, the public had access to the BCAP dig. Community participants asked questions, helped to screen for artifacts, and immediately held discoveries in their hands.

Since then, BCAP has conducted numerous field projects, mostly on non-profit-owned properties, with several stipulations: we allow the public to dig, everything found is shared publicly, there is no time frame to adhere to for finishing, and anyone is allowed to come by and ask questions about what is happening. This model has become BCAP’s standard operating procedure out of necessity, but over the past few years, more government and non-profit archaeological groups and historical organizations are following BCAP’s successful lead and are beginning to make their own digs more accessible. They post live-from-the-field social media updates and promote their digs so the public can watch or participate. Most important, these efforts are designed so that the public does not feel excluded from the ar-

Today, hundreds of Bostonians are part of BCAP’s field and lab volunteer signup process; the slots fill within hours of being announced. With the elimination of barriers there is unprecedented support from community members to be involved in the discovery of their history and the stories of their neighbors gone by.

Looking ahead to future digs, the city archaeology program seeks even more community engagement with the development of a dig where neighbors contribute to the research on the history of our project area and identify interesting historical narratives that the archaeology can contribute to. Most important to BCAP is making sure that community members define what they want to know about a site’s history and what stories they want to hear from the artifacts—and then have them find the stories in the ground themselves. Community archaeology, especially in urban areas like Boston, is growing throughout the United States, and I am proud to be an innovator and groundbreaker (literally) in its development.

Before embarking on an infrastructure project this year at the Codman Estate (c. 1740) in Lincoln, Massachusetts, Historic New England sought the expertise of Public Archaeology Laboratory Inc. of Pawtucket, Rhode Island. Also known as PAL, this cultural resource management services firm conducted an extensive archaeological survey in Boston for the Big Dig, officially known as the Central Artery/Tunnel Project and has done assessments at other Historic New England properties.

Last May, PAL specialists reviewed the areas of impact for the Codman Estate infrastructure project to make sure that nothing significant that might lay underground would be affected. The archaeologists found odds and ends typical of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century habitation. These included fragments of nails: handwrought, cut (fashioned individually using a cutting or stamping machine and a handmade head), and machine cut (both head and shaft produced by machine); coal; brick chips; a variety of dishware shards (or sherds, the spelling that archaeologists use)—redware stoneware, creamware, Chinese export porcelain, yellow ware, white ware, and pearlware; bottles; broken window glass; bone bits; and a piece of a smoking pipe stem.

A particularly important discovery was made when the archaeologists compared soil profiles from different areas of the estate: they established that the terraces upon which the residence was constructed were built for the house. It had long been surmised that the terraces and the house were built at the same time but there was no documentation to prove it. This archaeological work validated that opinion.

A History of Boston in 50 Artifacts was of Historic New England’s 2017 Honor Book award recipients. In it, he presents items retrieved from the ground that tell stories about the daily human occupancy of the city in five periods from 12,000 BP (Before Present) to 1983. These fifty artifacts form a timeline that marks the course of change and development in Boston. The following are among our favorites:

Barbed bone fish spear, 2000-1500 BP, found on Spectacle Island in Boston Harbor during archaeological studies conducted during the Big Dig highway project.

Chamber pot, 1660-1715, from the outhouse at the North End residence of Katherine Nanny Naylor, discovered by Boston Uni versity archaeologists in 1994. This site pro duced a rich collection of artifacts, including the eggs of disease-causing intestinal parasites (along with evidence of remedies), a bowling ball, china shards, a child’s shoe, a thimble and pins, and a scrap of lace.

3. Bar shot from the Battle of Bunker Hill, June 17, 1775, unearthed in Charlestown’s City Square. A bar shot is two cannonballs connected by an iron bar, designed to spin when fired.

4. Lipstick, c. 1940-1950, found in 2013 at the site of Clough House (c. 1715) in the North End where it no doubt was inadvertently dropped.

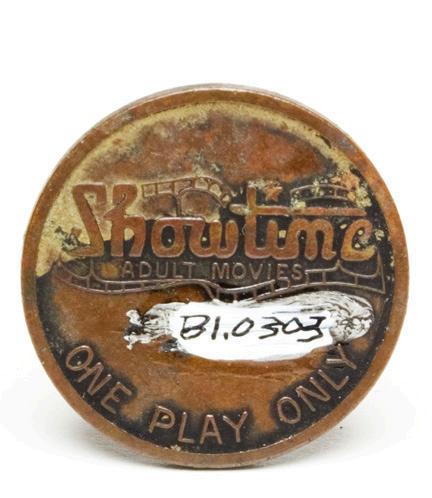

5. Peep-show token, c. 1960-1984, for a theater in the former red-light district known as the Combat Zone, found at the 1987 Boston Common archaeological survey.

The parcel of land in Newbury, Massachusetts, known as Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm was established in a land grant to John Spencer in 1635. It has been in continuous use ever since, yielding a rich mix of material, documentary, architectural, ecological, and archaeological history. Historic New England draws on all those fields for our Newbury area school and youth programs, which serve more than 8,000 young people annually on the farm and in their classrooms.

One of the longest running and most popular school programs at Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm is Dirt Detectives. Students become archaeologists as they excavate a mock pit using actual tools of the trade and then process the reproduction artifacts they find in a field lab. Inside the museum, they explore the structure’s archaeology via trap doors. They analyze the objects they find in order to learn what daily life was like at the farm.

Dirt Detectives was established after a 1990 dig at the farm headed by archaeologist Mary C. Beaudry and a team of graduate students from Boston University. Their work led to discoveries that we use to enrich our presentation of Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm history.

Each class that participates in the program recreates the process the archaeologists used. Students begin at the pit, a three-meter square that is stocked with reproduction artifacts. They learn how to use trowels and brushes to carefully remove dirt one layer at a time, as well as how to chart their findings on a collection sheet. As they remove the soil, they collect it in a bucket to be sifted later to make sure they have discovered every last button, bone, and pottery shard. In the processing station, they encounter a tableful of mixed up shards from plates, bowls, and serving platters that they must match and tape together, a process known as cross-mending.

When students begin the indoor component of the program at the 1690 farmhouse, they see items on display that the archaeologists have recovered. Among the activities we engage them in is a discussion of stratigraphy, the study of rock and soil layers (older items are generally found in the deeper layers). The youngsters also get to examine items found under a trap door in the kitchen. Finally, they analyze a set of unfamiliar artifacts—looking at the materials each is made of, the shape, markings, moving parts, places that show wear—to try to determine what each object was used for.

At the conclusion of Dirt Detectives, students have a greater understanding of the general work of an archaeologist and a deeper knowledge about the history of Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm.

Historic New England’s school and youth programs employ innovative ways in which to use historical resources to enhance student learning. The programs are multidisciplinary and accommodate a variety of styles of learning. The offerings include after-school sessions, camps, and field trips for preschool through middle school. For more information, visit www.historicnew england.org/school-youth/for-schools-and-afterschoolprograms.

Can three-deckers, those ubiquitous, three-story multifamily houses that are a hallmark of New England’s architecture, serve the purpose they once did: provide an affordable option for renters and a gateway to homeownership for an urban workforce?

This was a key question among many issues discussed this past spring at Preserving Affordability, Affording Preservation—Prospects for Historic Multifamily Housing, a conference Historic New England convened in April. The event was held in the Dorchester section of Boston—just one of the areas of the city where these highly recognizable houses were built. The landmark All Saints’ Episcopal Church, one of the properties in Historic New England’s Preservation Easement Program, hosted the conference, which assembled a distinguished group of planners, preservationists, scholars, and housing advocates for a daylong session looking at the past, present, and future of New England’s three-deckers.

Participants included Lydia Edwards, a Boston City Council member; Chrystal Kornegay, executive director of MassHousing, an independent, quasi-public agency that provides financing for affordable housing; and Northeastern University’s Stearns Trustee Professor of Political Economy Barry Bluestone.

Panelists raised a range of questions about three-deckers, such as who built and lived in them and

why construction of this house form ceased. They noted the economic pressures on existing three-deckers posed by “flipping” in the real estate market and condominium conversion, as well as the desirability of developing innovative housing forms, such as microunit shared amenity projects, to meet new demographic needs.

Historic New England’s aim in spearheading such conferences is to pose questions that will provoke thinking about preservation challenges in the twenty-first century. Earlier conferences looked at historic cities as sources of dynamism and prosperity and at diversifying the scope of cultural history. Historic New England drew on its legacy of advocacy to consider the three-decker’s place and potential in today’s difficult housing situation.

Sally Zimmerman, Senior Preservation Services Manager

Historic New England is among the first recipients of the City of Boston’s Community Preservation Act (CPA) funds, receiving $43,552 for an exterior preservation project at Otis House on Cambridge Street in the West End neighborhood. The Otis House project was one of thirty-five that the city’s Community Preservation Committee selected for its pilot round of funding.

CPA, an initiative of the Massa-

chusetts Legislature, levies a property tax-based surcharge in municipalities that approve the initiative through local referenda. Boston voters approved the measure in 2016, authorizing a surcharge of 1 percent to raise revenue to fund affordable housing, historic preservation, open space, and public recreation.

The Otis House preservation project focuses on the facade of the 1796 building and calls for repairs to wooden elements such as door and window trim and the cornice, as well as window conservation. Work begins in spring 2019.

Other Boston organizations contributing to the project are the George B. Henderson Foundation with a grant of $40,000; and the Beacon Hill Garden Club, whose $1,500 donation will go toward landscaping.

Dorothy A. Clark, Editor

n 2016 the curator at Saugus Iron Works National Historic Site in Saugus, Massachusetts, discovered a box of century-old plans that had been purchased decades earlier but had not been fully catalogued. The plans shed new light on the work of Henry Charles Dean, an architect who had a brief but important career. Dean, who died in 1919 at the age of thirty-three, was at the heart of the early debate in New England over the goals and practices of historic preservation, but his contributions were overshadowed by two prominent collaborators, who were a generation older: Wallace Nutting (18611941) and William Sumner Appleton (1874-1947).

For the entrepreneur Nutting, who headed a Colonial Revival tourism venture, Dean restored five houses in New England. For the preservationist Appleton, who founded Historic New England (as the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities—SPNEA) in 1910, Dean worked on three of the organization’s earliest properties, including Harrison Gray Otis House (1796) on Cambridge Street in Boston. As we approach the centennial of Dean’s untimely death, we can learn a lot from this architect whose work influenced modern preservation practices.

Born in Canaan, Connecticut, Dean (who went by Harry) attended Yale University and studied architecture at Columbia University, then worked as a draftsman for the preeminent Boston architect Ralph Adams Cram. Dean was an ambitious student of historic houses, photographing and studying them around New England, documenting them with measured drawings, and building a large ref-

erence library on colonial architecture. Dean believed that the earliest American architecture “must be sacredly preserved.” He collaborated with several antiquarians, producing drawings of colonial houses with a close friend, Rev. Donald Millar, and designing memorial tablets honoring Revolutionary War hero Nathan Hale for historian George Dudley Seymour of Connecticut.

Dean’s work for Nutting is sometimes overlooked. Nutting, a Harvard-educated antiquarian, artist, and capitalist, was also a Congregational minister who left the church at age forty-three after a nervous breakdown. During long bicycle rides in the countryside that he took for his health, Nutting made photographs of old houses. He started selling hand-colored prints and opened a studio, building a wide commercial audience through shrewd marketing. Nutting turned Colonial Revival nostalgia into a business, employing 200 colorists and selling ten million prints. He collected furniture as props and eventually began producing high-quality reproductions. He lectured and published widely.

In 1915 Nutting embarked on his most ambitious project to monetize Colonial Revival fervor. Connecting the established popularity of restored houses with the emerging interest in automobile tourism, he bought five historic houses in New England and inaugurated “The Wallace Nutting Chain of Colonial Picture Houses.” Nutting hired Harry Dean to restore the houses. The houses, which charged an admission fee, became sets for staging and exhibiting Nutting’s photographs, workshops for crafting colonial furniture reproductions, and gift shops for selling both. The entrepreneur’s profit motive shocked New England

preservationists, who thought of the houses as antiquarian relics or patriotic shrines.

The oldest link in the Nutting chain was the Iron Works House in Saugus. Long celebrated for its age—c. 1689—and supposed connections to the adjacent ironworks site, the house came up for sale in 1912. Appleton and Nutting were in competition to secure the property. On January 30, 1915, Appleton toured the Iron Works House with Nutting and Dean; Nutting bought it the following March. After Dean restored it, Nutting romantically branded it as Broadhearth.

Perhaps the most striking change Dean made to the much-modified Iron Works House was the removal of the projecting front porch and the addition of a trio of dramatic front gables. Dean had first visited the property in 1908 and made measured drawings of the exterior; those drawings suggest that he had envisioned the front wall gables years before his restoration commenced.

The emphatic gables were criticized. After seeing the house in 1921, fellow restoration architect Joseph Everett Chandler, known for his conjectural restorations of Paul Revere House in Boston and the House of Seven Gables in Salem, Massachusetts, wrote in his diary that Broadhearth was “an overdone exterior whatever the intention may be.”

But Dean justified his work at the Iron Works House in a 1917 talk. “The scarcity of the work of the seventeenth century makes the sacrifice of the later work (unless it is unique, or otherwise exceptional) necessary and imperative,” he said. “When the time came to repair the injuries of many generations—it was quickly seen that the chief interest

and glory of the place was its great age, and the old chimney [and] skeleton of the first building.”

Appleton, though he grew increasingly distrustful of Nutting’s brand of renovations, admired Dean’s abilities, and Dean had long been a supporter of Appleton, donating photographs, architectural fragments, and measured drawings to Historic New England’s collections.

above Left, Dean added hints of the massive gables he would add to the Iron Works House in this measured drawing he made in 1908. On the right is his 1915 restoration drawing of the facade. Images courtesy of the National Park Service. left This photograph of the structure was taken c. 1900 by Sullivan Holman. It had housed a number of occupants over the decades. below Dean made this photograph of the transformation of the house in 1915. In the foreground are timbers for the porch framing.

In a tribute to Dean, Appleton remembered taking “many trips with him, for the purpose of inspecting quaint towns or old houses, and during them had ample opportunity to observe his extraordinary fondness for old colonial work.”

Appleton noted how carefully Dean documented historic buildings. “In this work he always had his camera with him and took hundreds of snap shots of an astonishing variety of buildings, and of these photographs many are [now] in the Society’s collections,” Appleton said. “The particular feature in a house that most interested [Dean] was the plan, and he never inspected one carefully without being able, on leaving it, to give each floor plan as well as sketches showing the various elevations, and often even the cross sections.”

By 1916, Dean was documenting and making “repairs”— Appleton’s term for the removal of newer materials that had been added to historic properties—to Historic New England’s first property, Swett-Ilsley House (1670) in Newbury, Massachusetts. For Boardman House (1692), also in Saugus, though, Appleton conferred with several architects before Dean, his “consulting architect,” began restoration work. Appleton conceded that “owing to later alterations in the back of the chimney many questions arose as to the proper lines of restoration, and in solving these Harry Dean’s advice was of great value.” But Appleton became increasingly conservative

The earliest American architecture “must be sacredly preserved,” Dean said.

in his work; when he next undertook a restoration, the c. 1698 Abraham Browne House in Watertown, Massachusetts, Appleton consulted his architects but supervised the work on his own.

Still, given the challenge in 1916 of quickly restoring the Charles Bulfinch-designed first Harrison Gray Otis House as a museum and the headquarters for his preservation organization, Appleton again turned to Dean. He wrote that Dean “was in full charge of this work and must be given credit for the excellence with which it was done.”

After Dean enlisted in the Army, Appleton completed the work with Boston architect Herbert Browne.

Dean signed up for military service about a year and a half after the United States entered the World War. His draft registration card, dated September 1918, lists him as being thirty-three, single, and living in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He was working for architect William H. Cox, who had offices in the Boston Stock Exchange Building. Cox was then designing a Colonial Revival company town at Danielson, Connecticut, for a textile mill.

The war ended just two months after Dean enlisted, on November 11. Tragically, Dean’s promising career as an architect ended in January 1919, when he died after contracting the flu. More deadly even than the war, the influenza pandemic killed an estimated 675,000 Americans in 1918 and 1919 and more than fifty million people worldwide. The flu was particularly deadly among people in the prime of their lives: college students, couples, and soldiers. Dean died of influenza-related pneumo-

nia at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland, where he was stationed in the Army’s Architectural Division.

Dean’s family gave Historic New England his glassware collection, sketchbooks, and measured plans for twenty-two historic houses. Appleton selected some books from Dean’s library; the rest were given to the University of Virginia. In its 1922 catalogue, the university boasted that the School of Fine Arts was especially equipped for research into colonial architecture: “In this field the library is of exceptional strength, including the private library of the late Henry Charles Dean, one of the leading students on the subject.” Dean’s library supported the leading American architectural historian of the early 1920s, Fiske Kimball, who headed the university’s newly established art and architecture department.

Unfortunately, America’s entry into the First World War and gas rationing also doomed Nutting’s project; by 1919, he had emptied his chain of houses of their contents and began selling the historic sites. The Iron Works House was eventually saved by the First Iron Works Association, and fifty years after Dean’s death it became part of Saugus Iron Works National Historic Site.

The National Park Service had purchased the box of rolled drawings to secure Dean’s Iron Works House designs. The newly revealed work includes his student drawings from Columbia University and his brightly colored designs for “super frontals,” or altar vestments, for Grace Church in Providence, Rhode Island, which he completed while working for Cram, Goodhue,

and Ferguson. A blueprint details a tall clock Dean owned, built by Preserved Clapp, a colonial-era Massachusetts craftsman. Amid interior work for the house of Charles P. Kling in Augusta, Maine, is a 1916

Undated photograph of Henry Charles Dean.

drawing for a “Gothick” house Dean designed for himself.

Dean remains an obscure figure in architectural and preservation history, though, as Appleton noted, his memory would “live in the services he rendered” to Historic New England. Dean was probably most proud of his restorations, as he declared, “The appearance of the house does now suggest quite forcibly the charm and strikingly picturesque mass of the original Iron Works House in the Wilderness.” Partly due to Dean’s scholarship and documentation, though, modern preservation practice increasingly moved from this romantic vision to Appleton’s efforts to maintain the changes rendered to a structure over time as part of its historical record.

It’s time to start thinking about your holiday cards, whether they be for Hanukkah, Kwanzaa, Christmas, or other seasonal celebrations. Will you send e-cards, buy boxed sets, order photograph cards, or send any at all? With about ten billion cards sent out in the United States each year, the Christmas greeting is still immensely popular.

The early history of the Christmas card is well known. Sir Henry Cole commissioned his friend, the artist John Callcott Horsley, to design the first card and had it printed in London in 1843. It featured a raucous crowd bordered on either side by scenes of charity. In America, the two earliest

above The Ciroli family’s c. 1975 Christmas card featured a studio photograph of father Mario (back row, second from right), mother Mary (seated in front of her husband) and their three daughters, sons-in-law, and five grandchildren. Courtesy of Kenneth C. Turino. left Cultural historian Lura Woodside Watkins and her husband, Charles, a museum professional, used a photograph of their historic home, the c. 1750 Captain Andrew Fuller House in Middleton, Massachusetts, for their 1954 holiday card. The property has been protected since 2015 by Historic New England’s Preservation Easement Program.

known cards show a family gathering flanked by food and drink with a holly garland nestling smaller domestic images draped across the top of the tableau. The c.1850 cards vary slightly, one of them designed for consumers and the other for commercial use; the latter advertises “Pease's Great Variety Store In The Temple Of Fancy,” a department store in Albany, New York, on the garland.

It took several decades for the Christmas card to become an integral part of the holiday celebration. Boston printer and publisher Louis Prang is credited with popularizing the yuletide greeting card in America. Prang used the chromolithography method of making multicolor prints starting in 1875.

Less well known is the history of the photograph Christmas card, an image printed on postcard stock. In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, black and white photo-

above Lydia Vagts adapted Jan van Eyck’s 1434 painting, Arnolfini Portrait, for the holiday card her family used in 2002. right This happy youngster is the author of this article c. 1960 at his family home in Stoneham, Massachusetts. Photograph by Ciroli Studios, Boston, courtesy of Kenneth C. Turino. Architect and interior decorator Ogden Codman Jr. (1863-1951) chose a photograph of Chateau de Corbeil-Cerf in northern France to decorate his 1912 Christmas card. Bill Finch and Carol Rose used a picture of their cats, Captain Oliver and Samantha the Panther, for their 2007 holiday card. The Library and Archives holds a collection of Finch and Rose cards, all depicting the family felines at holiday time.

graphs were occasionally sent through the mail as cards. Often, these took the form of a portrait affixed to a designated spot on a preprinted or a simple handmade card. Kodak introduced the No. 3A Folding Pocket Kodak, designed for postcard-size film in 1903. This camera permitted anyone to take photographs and have the pictures printed on postcards.

In 1907 Kodak created a service called “real photo postcards,” enabling consumers to make postcards from any photographs they took, regardless of the type of camera or film size. Holiday scenes were just one of many types of events and activities people chose to capture to make “real photos.”

The popularity of photo Christmas cards grew steadily in the early decades of the 1900s and really caught on after World War II, and were mailed either as postcards or in envelopes. Also,

this was when it became common for photo Christmas cards to feature a family portrait or that of a child or children. They might also show a house, fireplace, or advertise a business. Some were formal, some humorous. Cards were usually printed with the phrases “Merry Christmas,” “Season’s Greetings,” or some variant of a holiday salutation and contained stylized designs that used holly, houses, or musical notes from a Christmas carol.

By the 1960s, with improvements in printing processes, color photo Christmas cards were dominating the market. Christmas cards often reflected a nostalgic past but just as often they reflected the period in which they were manufactured. Cards from the 1950s and later mirrored current design trends, including the use of more modern typefaces. As with the early photo cards, people’s mode of dress reflected the period. Quite often, these

photographs were not season-specific, and they weren’t marketed as such. For example, Eastman Kodak took out full-page advertisements for photo Christmas cards in popular magazines of the day such as Life, which read: “It could be a snapshot you took over the Fourth. Or one of the whole family on vacation. Or just the baby alone. The important thing is that it’ll make an unusual—and unusually appealing— Christmas card. But don’t wait until it’s too late. Or you may have to settle for an ordinary card.”

No one wants to settle for an ordinary card. It is the uniqueness of these photo Christmas cards that continues to appeal to people. Even with the advent of e-cards and the prevalence of social media, the act of signing a card bearing an image that has strong meaning to the sender (and, one hopes, the receiver), makes it more personal. Happy Holidays.

Fiscal Year 2018 (April 1, 2017-March 31, 2018)

As a preservation and cultural heritage organization, our properties and collections reflect the past. To advance our mission and accomplish our goals, however, Historic New England strives to be a forward-looking leader among museums around the world. With all of your help, we think we achieved that objective in Fiscal Year 2018.

We entered the period with a generous and devoted base of members, volunteers, and donors who helped us make robust strides throughout the year. Our volunteers dedicated a total of 10,179 hours to Historic New England’s operations. Strong endowment growth reflected outstanding commitment by donors. Attendance at our museum properties achieved a record high with 214,650 visitors, representing 3 percent growth from the previous year. Membership registered a record increase to 8,715 households, up 5 percent; we gained 2,078 new memberships, exceeding the previous year’s count by 464.

Our Eustis Estate Museum and Study Center in Milton, Massachusetts, was a big contributor to these successes. Opened to the public in May 2017, the Eustis Estate is a major achievement for Historic New England, affording us an opportunity to present a twenty-first-century model for engaging visitors with historic houses. Creative use of technology provides user-selected access to deep information about the site. The setting encourages people to feel at home in the museum. We curated popular exhibitions in the Eustis Estate galleries, some drawn from Historic New England’s collections—such as the Mementos jewelry exhibition—and some arranged through partnerships with other organizations.

We cannot rely on our properties and collections alone to reach a broad public. Partnering with community organizations is an important part of our activities. Among the fruits of such efforts are two series—the photographic and oral history exhibition We Are Haverhill: about the Massachusetts city; and our latest documentary

Rooted: Cultivating Community in the Vermont Grange Engaging Students of Color through Internships. This program attracts people of color to work at the organization to better reflect the diverse communities we serve

Attaining reaccreditation from the American Alliance of Museums reaffirmed what a highly relevant institution Historic New England continues to be. Accreditation, considered the gold standard of museum excellence, recognizes commitment to excellence and continuous institutional improvement. Historic

We continue to strive to work with all of you to implement a forward-looking mission and vision to serve and benefit the diverse New England public. Thank you for helping with our efforts!

Carl R. Nold President and CEO ABOVE David A. Martland and Carl R. Nold. COVER The small parlor at the Eustis Estate Museum and Study Center, Milton, Massachusetts.David A. Martland

Chair

David L. Feigenbaum

Vice Chair

Sylvia Q. Simmons

Vice Chair

Sandra Ourusoff Massey Chair

Deborah L. Allinson

Nancy J. Barnard

Ronald P. Bourgeault

Jeremiah E. de Rham

Joan M. Berndt

Co-chair

Robert P. Emlen

Co-chair

George Ballantyne

Frederick D. Ballou

Lynne Z. Bassett

Russell Bastedo

Ralph C. Bloom

Randolph D. Brock

Harold J. Carroll

Michael R. Carter

David W. Chase

Richard W. Cheek

Martha Fuller Clark

Karen Clarke

Barbara A. Cleary

Frances H. Colburn

Gregory L. Colling

Julia D. Cox

Trudy Coxe

Elizabeth Hope Cushing

Elizabeth K. Deane

William H. Dunlap

Jared I. Edwards

Harron Ellenson

Eugene Gaddis

Diane R. Garfield

Marcy Gefter

Lucretia Hoover Giese

Debra W. Glabeau

Martha D. Hamilton

Eric Hertfelder

Bruce A. Irving

Edward C. Johnson 3d

Elizabeth B. Johnson

Joseph S. Junkin

Mark R. Kiefer

Anne F. Kilguss

Matthew Kirchman

Nancy Lamb

Joan M. Berndt

Clerk

Randy J. Parker

Treasurer

Carl R. Nold

President and CEO

Edward C. Fleck

William F. Gemmill

Leslie W. Hammond

Stephen W. Harby

Eric P. Hayes

William C.S. Hicks

James Horan

Paula Laverty

Arleyn A. Levee

Anita C. Lincoln

John B. Little

Charles R. Longsworth

Janina A. Longtine

Peter S. Lynch

Peter E. Madsen

Elizabeth Hart Malloy

Johanna McBrien

Paul F. McDonough

William L. McQueen

Julianne Mehegan

Maureen I. Meister

Pauline C. Metcalf

Thomas S. Michie

Keith N. Morgan

William Morgan

Henry Moss

Cammie Henderson Murphy

Stephen E. Murphy

Ann Nevius

Richard H. Oedel

Janet Offensend

James F. O’Gorman

Mary C. O’Neil

Robert I. Owens

Elizabeth Seward Padjen

Anthony D. Pell

Samuel D. Perry

Patrick Pinnell

Marion E. Pressley

Sally W. Rand†

Gail Ravgiala

Courtney Richardson

Kennedy P. Richardson

Marita Rivero

Timothy Rohan

Carolyn Parsons Roy

Virginia Rundell

Gretchen G. Schuler

Kristin L. Servison

Jacob D. Albert

Jeffrey P. Beale

Jon-Paul Couture

George F. Fiske, Jr.

James F. Hunnewell, Jr.

Christopher Karpinsky

Sidney Kenyon

Gregory D. Lombardi

Kathrine Williams Kane

Lydia F. Kimball

Elizabeth Leatherman

A. Richard Moore, Jr.

Paul Moran

Stephen Mormoris

John Peixinho

Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr.

Joseph Peter Spang III

Andrew Spindler-Roesle

Dennis E. Stark

Charles M. Sullivan

Jonathan Trace

Paige Insley Trace

John W. Tyler

William B. Tyler

Theodore W. Vasiliou

Gerald W. R. Ward

David Watters

Alexander Webb III

Roger S. Webb

Sandra Ourusoff Massey

F. Warren McFarlan

Elizabeth H. Owens

Julie A. Porter

Roger T. Servison

Angie Simonds

Nancy B. Tooke

Stephen H. White

Susan Rogers

Susan P. Sloan

Anne S. Upton

William P. Veillette

Elisabeth Garrett Widmer

Kemble D. Widmer II

Richard F. Wien

Susie Wilkening

Robert W. Wilkins

Richard H. Willis

Robert O. Wilson

Linda W. Wiseman

Gary Wolf

Ellen M. Wyman

Charles A. Ziering, Jr.

Margaret W. Ziering

† = Deceased

April 1, 2017 – March 31, 2018

The names listed on the following pages recognize those who, through their generous and thoughtful gifts, have strengthened Historic New England this past fiscal year. To each of them, we extend our most sincere appreciation. In addition, we would like to thank those who supported us at every level, including 8,715 members.

Over $1,000,000

Anonymous

Vingo III Trust and Catherine Coolidge Lastavica, David W. Fitts and Peter Mulholland, Trustees

$100,000–$999,999

Mr. Leslie P. Brodacki

Ogden Codman Trust

Nancy Foss Heath and Richard B. Heath Educational, Cultural and Environmental Foundation

The Thomas Jefferson Memorial Center

Massachusetts Historical Commission

Mary L. McKenny Fund of the Toledo Community Foundation

New Hampshire Land and Community Heritage Investment Program

Estate of Ms. Pauline Perry

The Harold Whitworth Pierce Charitable Trust

City of Waltham Community Preservation Committee

Estate of William G. Waters

$50,000–$99,999

Anonymous (2)

Estate of Thomas C. Casey

Mr. Nicholas C. Edsall

Institute of Museum and Library Services

Catherine Coolidge Lastavica

Teresa and David Martland*

Mass Cultural Council

National Historical Publications and Records Commission

Ms. Helen Norton

Rhode Island Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission

Mr. and Mrs. Roger T. Servison*

$25,000–$49,999