9 minute read

Artful Women

by NANCY CARLISLE Senior Curator of Collections

While researching the paintings in Artful Stories, co-curator Peter Trippi and I learned about a range of extraordinary New England women. Some were the subjects of portraits while others were artists, collectors, or patrons. Here are a few of their stories.

ARTISTS

ELIZABETH ADAMS (1825–1898)

Copying the work of other artists is a time-honored way for painters to improve their own technique. Alas, most copies are painted over or destroyed. Few are framed, and even fewer make their way into museum collections. This one is an exception and the story

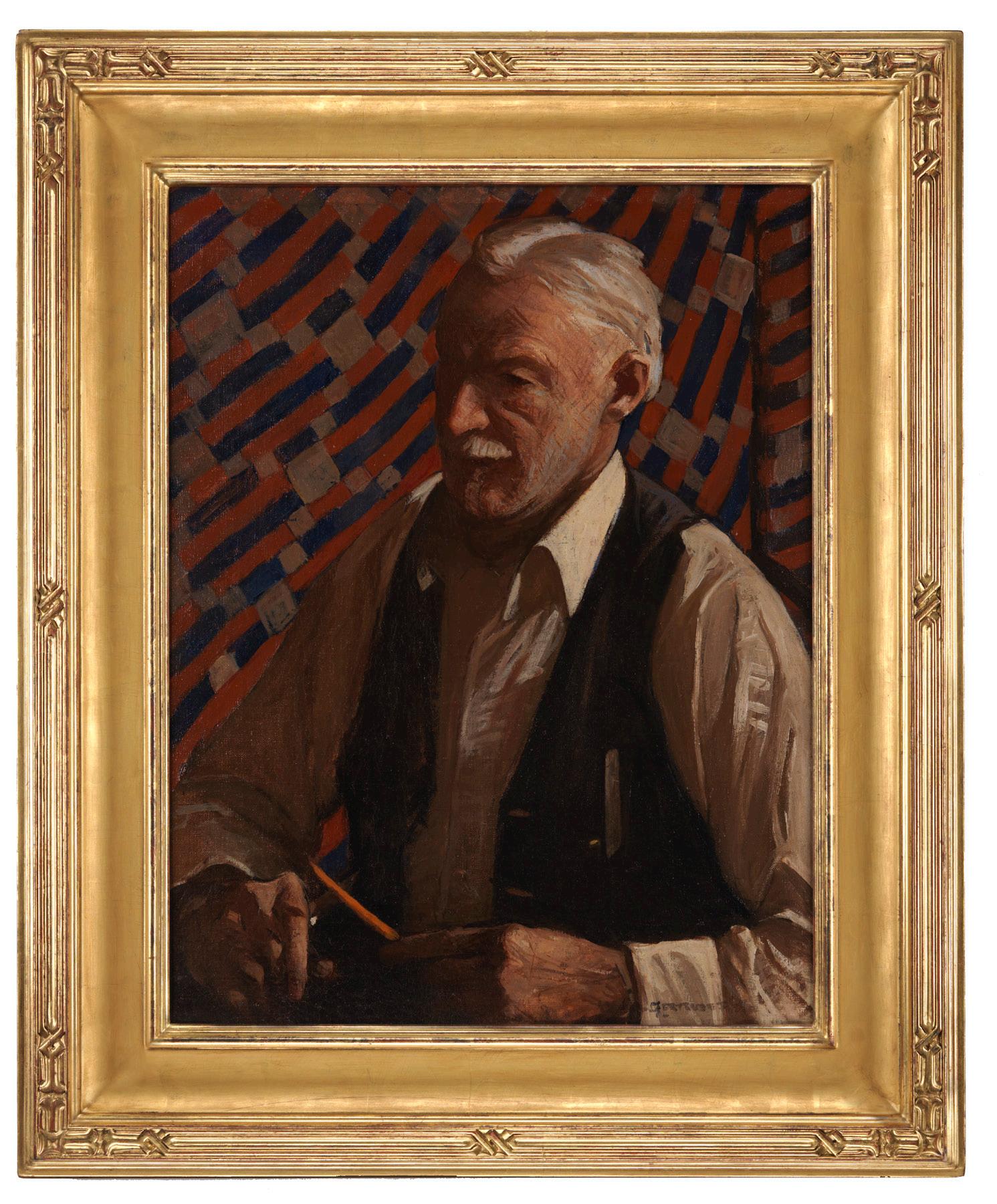

page 2 Copy of Self-portrait of Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Elizabeth Adams. Florence, 1865–1874, oil on canvas, 52½ x 46 inches. Gift of the artist’s nephew, Boylston Adams Beal. right Man Whittling, Gertrude Fiske. Massachusetts or Maine, c. 1935, oil on canvas, 36 x 29 inches. Museum purchase.

behind it is profound.

The copyist was Elizabeth (Lissie) Adams, a member of a distinguished Boston family whose parents believed that their daughters had as much right to an education as did their son. They sent Elizabeth to a school for girls founded by the eminent educator George Barrell Emerson. A former tutor in mathematics and philosophy at Harvard College, Emerson empowered his students to believe that women should cultivate their talents. For Adams, that meant becoming an artist.

In mid-nineteenth-century Boston there were no clear avenues for women who wanted to train as artists. While successful male artists took on male students, few took on females until William Morris Hunt began classes for women in the late 1860s. So when Adams’s sister Annie and her husband, James T. Fields, went to Europe on their honeymoon in 1859, Lissie went with them. When the Fieldses returned home, she stayed behind.

Adams spent eleven years in Europe, mostly in Paris and Florence. In France, she joined the classes of painter Charles Joshua Chaplin, who was among the few who took on aspiring women. Like most female students, Adams no doubt paid twice what male students did and received half the attention. In Florence she could learn from the masters by copying their work. The Vasari Corridor of the Uffizi Gallery, newly opened to the public in 1865, contained paintings by masters such as Filippo Lippi, Rembrandt, Velázquez, and Delacroix. Among them was the self-portrait of Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun. Here, Adams could learn by copying the work of a female master. Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842) was a successful French court painter whom Marie Antoinette favored. Adams’s career never reached the heights of Vigée Le Brun’s, but the quality of her work was acknowledged in 1885 when a painting she submitted to the annual Paris Salon was accepted.

By that time Adams had returned to the United States, and she and her life partner, Frances Burnap, had set up a home and studio in Baltimore where Adams taught classes and continued to paint. Their home and their summer property in Watch Hill, Rhode Island, were, according to Adams’s biographer, places where like-minded friends gathered for lively conversations about art and literature. Adams died in Watch Hill in 1898. Her painting survives as a record of her affinity and respect for her artistic role model.

GERTRUDE FISKE (1879–1961)

By the time Gertrude Fiske studied painting in the early twentieth century, hundreds of women in New England had had professional training. Like Elizabeth Adams, Fiske grew up in a well-to-do family in Boston. After graduating from a private girl’s school in the city she

spent a few years pursuing various sports and won the Amateur Golf Championship of Massachusetts in 1901. It wasn’t until 1904, when she was twenty-five, that she enrolled in the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston [the Museum School], studying with Edmund C. Tarbell, Frank Benson, and Philip Hale. In 1909 she began working with Charles Woodbury at his Ogunquit Summer School in Maine. Woodbury’s style was distinctly different from the one taught at the Museum School—less rigorous and more fluid. By integrating the two styles, Fiske developed her own.

By 1916 she was a rising star. In the February 13 edition of the Boston Sunday Herald, art critic Frederick W. Coburn extolled, “Largeness and serenity of vision mark the work of this painter, only a few years out of the art school and already hailed as a probable celebrity.” In addition to Boston, Fiske exhibited her paintings in Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., Chicago, and Detroit. She won a silver medal at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco in 1915. She was admitted as an associate member of the National Academy of Design in 1921 and became a full member in 1930.

While Fiske had success with landscapes and portraiture, it is her figurative work for which she may be best known. In the 1910s and early 1920s she painted the beautiful young women popular in the Boston School, a style of painting that had emerged by the beginning of the twentieth century. Practiced by Tarbell, Benson, and William McGregor Paxton, among others, it was characterized by exquisite craftsmanship and a love of beauty. But by the late 1920s and 1930s she had moved on to models who were older, often New England archetypes—carpenters, soldiers, grandmothers. Fiske’s insightful character studies of older models in the 1930s were unusual at the time and her paintings of men were a departure from the Boston School tradition of portraying attractive women in beautiful settings.

An undated label on the back of Man Whittling from the National Academy of Design provides evidence that the painting was a successful submission. It is typical of Fiske’s best figurative work. The subject is brightly lit and sharply contoured; his lined face and darkly veined arthritic hands suggest years of physical labor.

PATRON

ANNA PERKINS PINGREE PEABODY (1839–1911)

The marriage of Anna Perkins Pingree to Joseph Peabody in 1866 was an alliance of two of the wealthiest families of Salem, Massachusetts. Anna’s father, David Pingree, was a merchant prince and lumberman who owned vast tracts of land in New Hampshire and Maine. Anna grew up on Essex Street in the brick mansion designed by Samuel McIntire, now known as the Gardner-Pingree House. Joseph’s grandfather, also named Joseph, was a China trader and, until his death in 1844, the wealthiest ship owner in Salem.

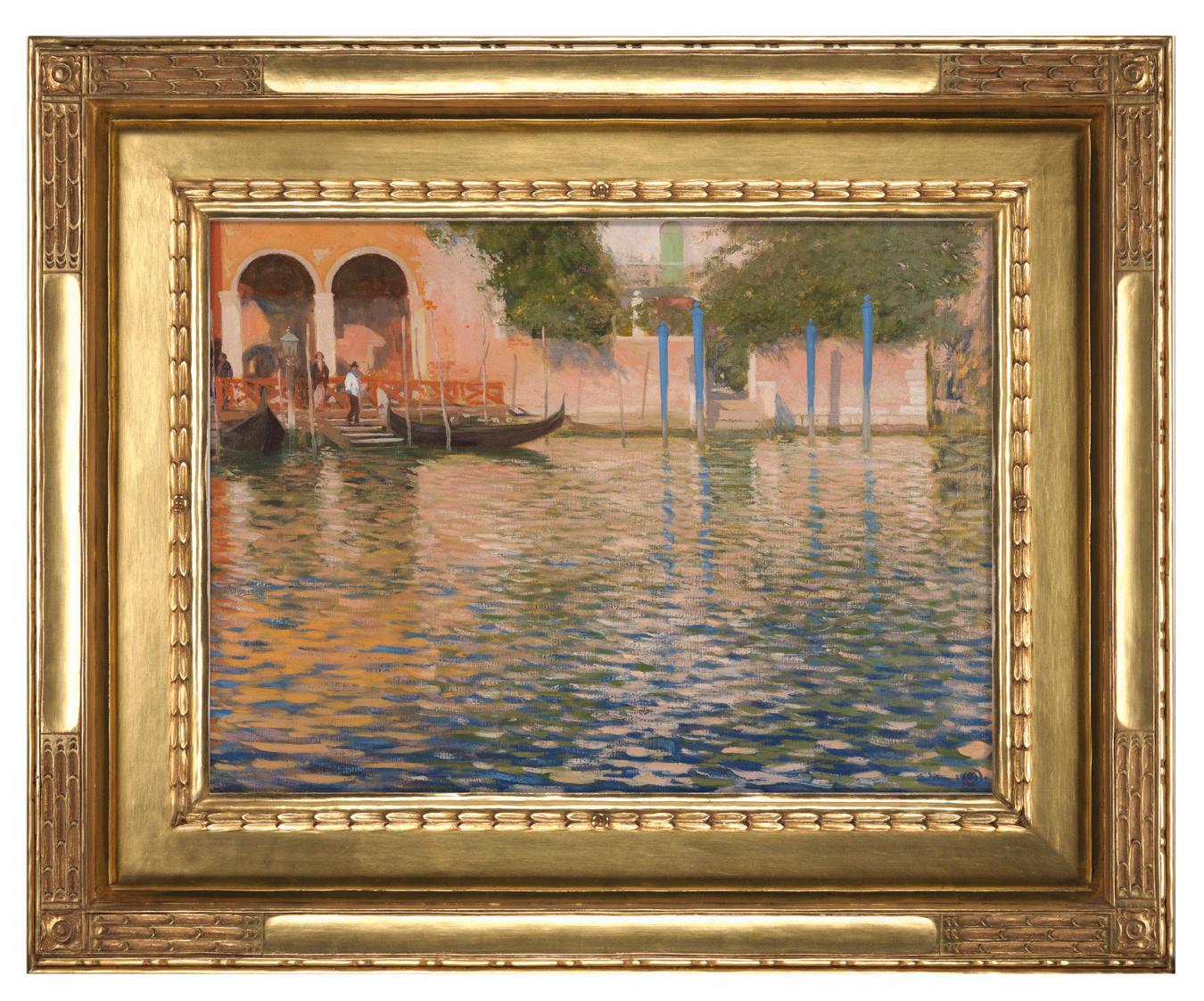

It is not clear how quickly the marriage deteriorated. In 1877 the couple purchased a mansion in Anna’s name on Commonwealth Avenue in Boston’s Back Bay; by the late 1880s they had separated. Anna was still living in the Commonwealth Avenue townhouse at the time of her death in 1911. A complete inventory survives and tells something of her interests—French and American furniture, Persian rugs, bronze objets de vertu, extensive silver services, rich textiles at the windows, on the walls, on the pianos. In many ways this house reflected the tastes of a number of families with Anna Peabody’s upbringing and resources. But it is her collection of paintings that sets her apart from most of her contemporaries. One hundred sixteen works of art represent 20 percent of the value of her furnishings. While more than half the artworks are not identified—listed as “12 assorted pictures,” for instance—of those that are, the majority were painted by Boston-trained artists who were still Venice, Hermann Dudley Murphy. Venice, c. 1908, oil on canvas, 31½ x 38 d inches. Gift of the Stephen Phillips Memorial Charitable Trust for Historic Preservation.

living when Peabody purchased their work. These artists were working in a new style that was clearly influenced by the French impressionists.

Among her favorite painters was Hermann Dudley Murphy (1867–1945). Peabody owned between half a dozen and a dozen paintings by Murphy, who trained at the Museum School and the Académie Julian in Paris. He was strongly influenced by James Whistler (1834–1903), not only in his style of painting but also in recognizing the importance of the picture frame. Around 1899, Murphy began designing frames and before long, fellow artist Charles Prendergast (1863–1948), woodcarver Walfred Thulin (1878–1949), and Murphy established the Carrig-Rohane frame shop. The example that holds Murphy’s painting of Venice is typical of the shop’s work and marks a sea change from the applied flowers and leafage that covered earlier frames.

Around 1895, Peabody commissioned the construction of a summer cottage in Bar Harbor, Maine. By 1906 she had a second summer home built in Ipswich, Massachusetts, a huge mansion called Floriana. No doubt both houses provided the wall space she needed to continue showcasing the work of her favorite artists.

SUBJECT

CLEMENTINA BEACH (1774–1855)

Clementina Beach emigrated with her family from England to Gloucester, Massachusetts, around 1793. Renowned diarist William Bentley of Salem met Beach in 1799 and described her as “a young lady of accomplishments.” Judith Foster Saunders also lived in Gloucester, separated from her husband and teaching needlework to young girls. In 1803 the two women moved to Dorchester and opened a school. Mrs. Saunders & Miss Beach’s Academy on Meeting House Hill thrived for more than thirty years. In 1804 there were thirty-six boarders and twenty day scholars ranging in age from six to eighteen. A former student, Sarah Chauncey Cutts of Kittery, Maine, described her classes:

“Beside the Latin and English classics and mathematics . . . in the course were music, penmanship, painting in water colors, map-drawing, done with pens—waxwork—and fine needlework in the shape of lace and silk embroidery—specimens of all, excepting the music, are in existence. Every nice point of etiquette was practically taught as only genuine ladies could teach, and underlying all— moral training—and a deep reverence for everything sacred—without affectation, or bigotry.” The students were the children of New England’s elite families who sent their girls to school to learn the refinement expected of the future wives of the region’s educated and successful men.”

One student in the early years was Beach’s younger cousin Mary, whose needlework survives in its original frame in Historic New England’s collection. While Mary completed the needlework, Beach most likely painted the faces and sky on this and other needlework produced at the school. According to several sources, including Lawrence Park, the early twentieth-century authority on Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828), Beach studied under the portraitist.

Stuart’s portrait of Beach was completed about twenty years after the founding of Mrs. Saunders & Miss Beach’s Academy. Beach was approaching fifty years of age. She is shown as she was described by one of her students—“a woman of much beauty and dignity.” We don’t know who commissioned the portrait. Was it grateful parents, or was it Beach herself? In either case, the work is a rare example of an early portrait of a woman painted not because of her family’s prominence but because of what she had achieved.

Clementina Beach, Gilbert Stuart. Boston, 1820–1825, oil on canvas, 35½ x 30¾ inches. Museum purchase.