7 minute read

Framing Conventions Hold Artists’ Intentions

by LISA MEHLIN Painting conservator and owner of Mehlin Conservation

When we look at a painting, the structure of the work is the scaffolding behind the stage. The artist usually does not want us to be aware of it. Most paintings are a complicated effort to fool the eye into seeing something that is not there. Paintings are executed on a two-dimensional surface, but attempt to make viewers believe they are seeing something three-dimensional, like a landscape, or a portrait. But when we understand this complex relationship between the very real ingredients in a painting and the illusory result, we start to truly appreciate the complexity and subtlety of the artistic effort involved.

Oil paint started gaining popularity in northern Europe in the fifteenth century. Paintings were initially executed on wooden panels, but by the beginning of the Renaissance in Italy, artists started painting on woven hemp cloth, which was also used for sailcloth in Venice and thus readily available. This cloth, when stretched, survived the heat and humidity of southern Europe far better than wooden panels, which warped and cracked. This technology also enabled artists to paint much larger works than previously possible. As painting on canvas moved north into France and the Netherlands, hemp was replaced by linen, which was available locally and much more durable. To this day, Belgian linen is considered one of the best materials for painting canvases.

This woven cloth was stretched onto a stretcher—which usually could be expanded at the corners—and secured with "keys" in the corners, allowing for tensioning of each side

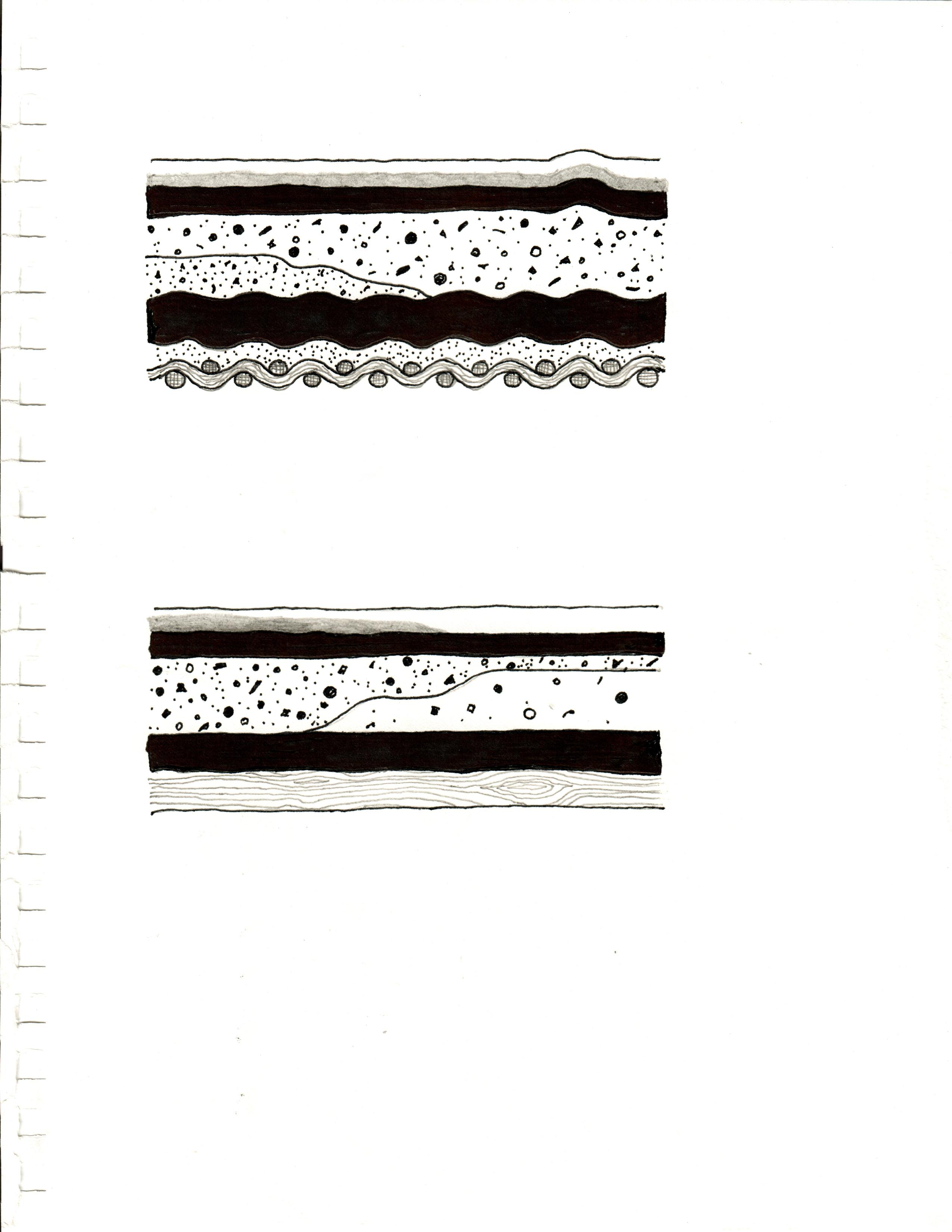

page 26 Detail of a painting in a private collection showing the results of a failing ground layer. The unprimed canvas can be seen where the paint has flaked off. right Drawings show cross sections of the layers of a typical panel painting and a painting on canvas. Drawings by Bruce Blanchard.

independently. This enabled the artist to tighten the canvas like a drum and to adjust it over time as the canvas expanded or contracted due to changes in humidity.

Because this cloth was absorbent, it was important to "size" the canvas, usually with a dilute rabbit skin or hide glue, which was applied warm after stretching, then allowed to dry. Next, a ground layer, usually calcium carbonate and dilute animal glue, would be applied over the sized canvas in order to prepare a foundation for painting. Ground layers form the central layer of the painting, and many issues with painting condition can be traced to failures in this layer. It is vital that the ground layer adheres properly to the underlying canvas and that the subsequent layers of oil paint adhere properly to the ground.

After this, the paint was applied. Traditional oil paint is composed of ground pigments often derived from naturally occurring minerals like siennas and ochres, called earth pigments, but also semiprecious stones like lapis lazuli, which makes ultramarine blue. These would be ground into linseed or walnut oil and applied to the canvas in layers. These layers would then have glazes applied over them, which used added medium or varnish and thin layers of pigments to build up a sense of depth and atmosphere.

After the painting was finished and allowed to dry, it would be varnished. The varnish was usually made from a natural resin like dammar or copal, which was dissolved in turpentine and applied evenly to the surface of the painting. This varnish would saturate the colors of the painting and protect it as well.

When looking at paintings, we can tell something about the techniques used by the artist to make us think we are looking into a threedimensional scene. Do architectural elements in the painting recede into the background? Is there a vanishing point (the area where parallel lines seem to meet on the horizon line)? Are the colors applied to make things appear round, with no perceptible edges? Is there a light source, and if so, from where? Does the painting appear to have been built up in layers of glazes, giving it atmosphere and depth?

We can also see if a painting has condition issues that are making the structural elements more evident than they were intended to be. If a painting is distorted, or has tears, paint loss, or damage, its illusory effect is lost. If it has paint loss, and the area underneath the loss shows white or gray, the flaking is probably being caused by a lack of adhesion between the paint and the ground layer, because the ground layer is still visible. This is usually because the ground is composed of something that the oil paint is incompatible with. For example, during the Victorian period, artists were experimenting with new materials and often prepared their ground layers with wheat starch instead of animal glue. These starch layers, after many decades, start to turn powdery and disintegrate. They also absorb water, which can make the layer swell and can actually start to push the paint layers away. Paintings with starch grounds can have catastrophic paint failures, even looking like popcorn on the surface.

Even regular grounds can be problematic, often because they were made by hand and the recipes differed so much. Many issues with ground layers have to do with the proportion of animal glue to calcium carbonate. Severe lifting and cracking can be caused by a ground layer made with too much animal glue. Likewise, too little glue can cause the ground layer to become powdery and fail. Many contemporary oil painters use prestretched commercial canvases with an acrylic ground layer instead

CANVAS PAINT LAYERS

GROUND SIZE

CANVAS

VARNISH GLAZE

PAINT LAYERS

GROUND

VARNISH OR GESSO

GLAZE } PAINT LAYERS PANEL

GROUND

OR GESSO

PANEL

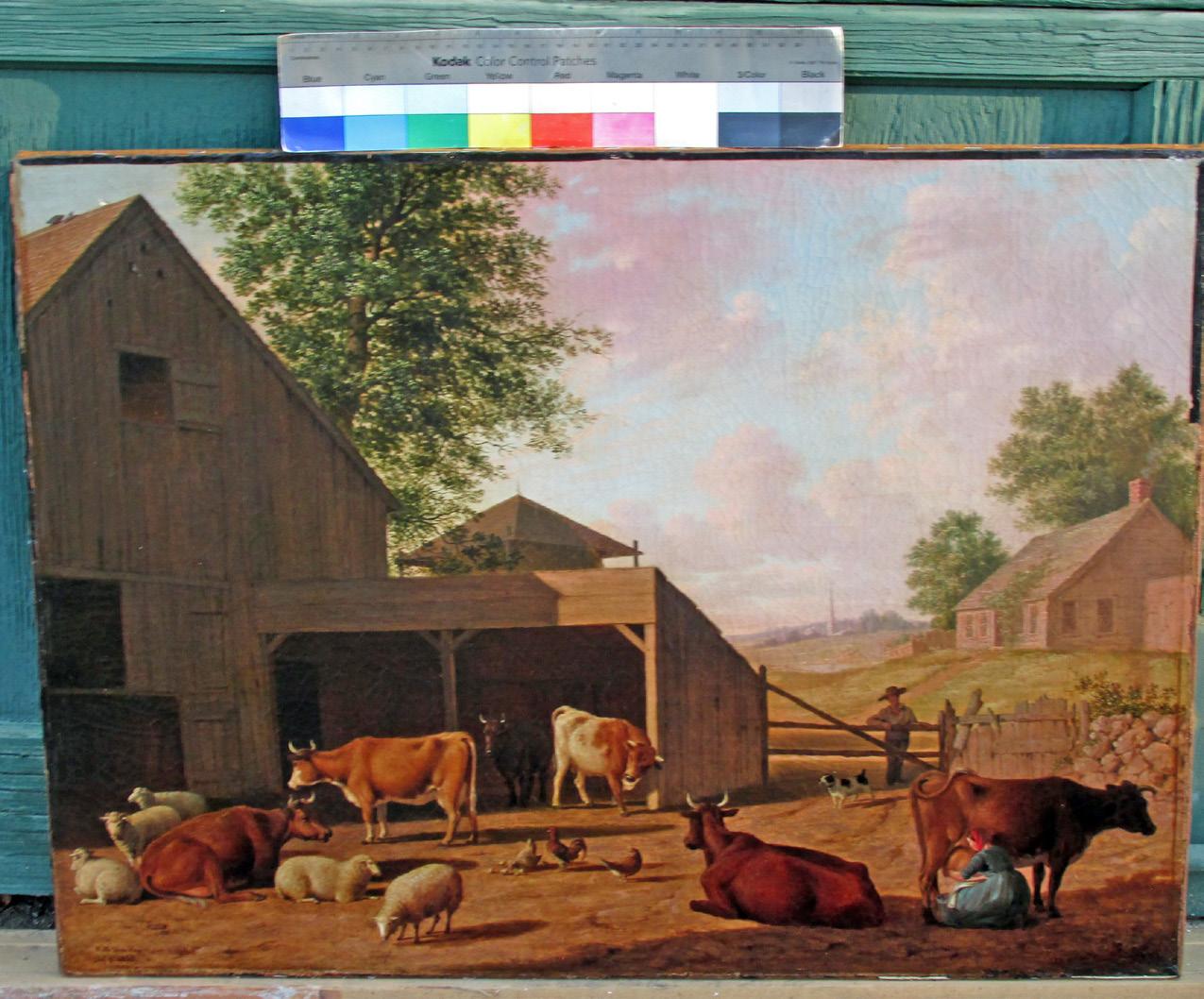

Barnyard Scene, Sunset, Thomas Hewes Hinckley (1813–1896) [Dorchester, Massachusetts, 1848. Bequest of Dorothy S. F. M. Codman] before treatment in raking light, showing the “cupped” surface and raised edges of the cupped paint. On the right is the painting in normal light after lining, showing the effect of reduced surface deformations, making it easier to “read” the image.

of oil. These two types of paint are incompatible and can cause major issues, even in new paintings.

Because canvases are stretched, and thus are under tension, the paint layers above the canvas are under tension as well and tend to crack over time in response to mechanical stresses. Typically paintings will crack more at the corners, because this is where the stresses are most pronounced. This is called "craquelure" and is a normal part of the aging of the painting. But when this cracking becomes extremely severe, either due to a very heavy paint layer, a canvas that is too thin, or of poor quality, the painting can become “cupped”—where the paint forms large concave patches across the surface. This is often accompanied by loss of paint at the intersections of the planes, where small triangles of paint start to detach. If one were to look at the back of a painting in this condition, one would see that it exhibits “quilting”—showing an uneven surface like a quilt that corresponds to the cupped areas on the front.

When a painting is exhibiting extreme cupping, with quilting on the back and paint loss on the front, one traditional method to address it has been to line the painting to a new fabric support. This may seem counterintuitive—why would a new backing fabric help the issues with the paint on the front? The reason is that the real cause of the failure is an inadequate support fabric and accompanying problems with the ground layer. Attaching a new foundation fabric with an adhesive that impregnates this ground layer, all while under suction and heat to flatten the cupping on the front, successfully addresses the problem.

Lining paintings is a controversial subject, and there has been severe backlash to an extreme campaign of lining paintings that happened in the 1960s and 1970s, resulting in many paintings becoming flattened and losing all impasto (texture) and surface character. These linings were often undertaken using a form of wax resin under heat and pressure, which impregnated not only the canvas and ground layers but also the paint, darkening it permanently. Wax linings are extremely difficult to remove. Nowadays, linings are only undertaken as a last resort and done with reversible materials and significantly less pressure and heat, so the impasto on the surface is retained.

Artwork can seem fragile when considering painting structure and potential failures of structure. However, most condition issues with paintings have to do with the use of incompatible materials or inadequate quality of the component parts, not to mention the vagaries of poor storage or accidents. These elements are not what the artist intended us to focus on, but rather what they hoped we would not see. However, looking more deeply into paintings, we can see the scaffolding behind the stage and learn to appreciate its structure. That understanding can actually enhance what we see.