7 minute read

Men in Black

IN

BLACK

by LAURA E. JOHNSON Curator

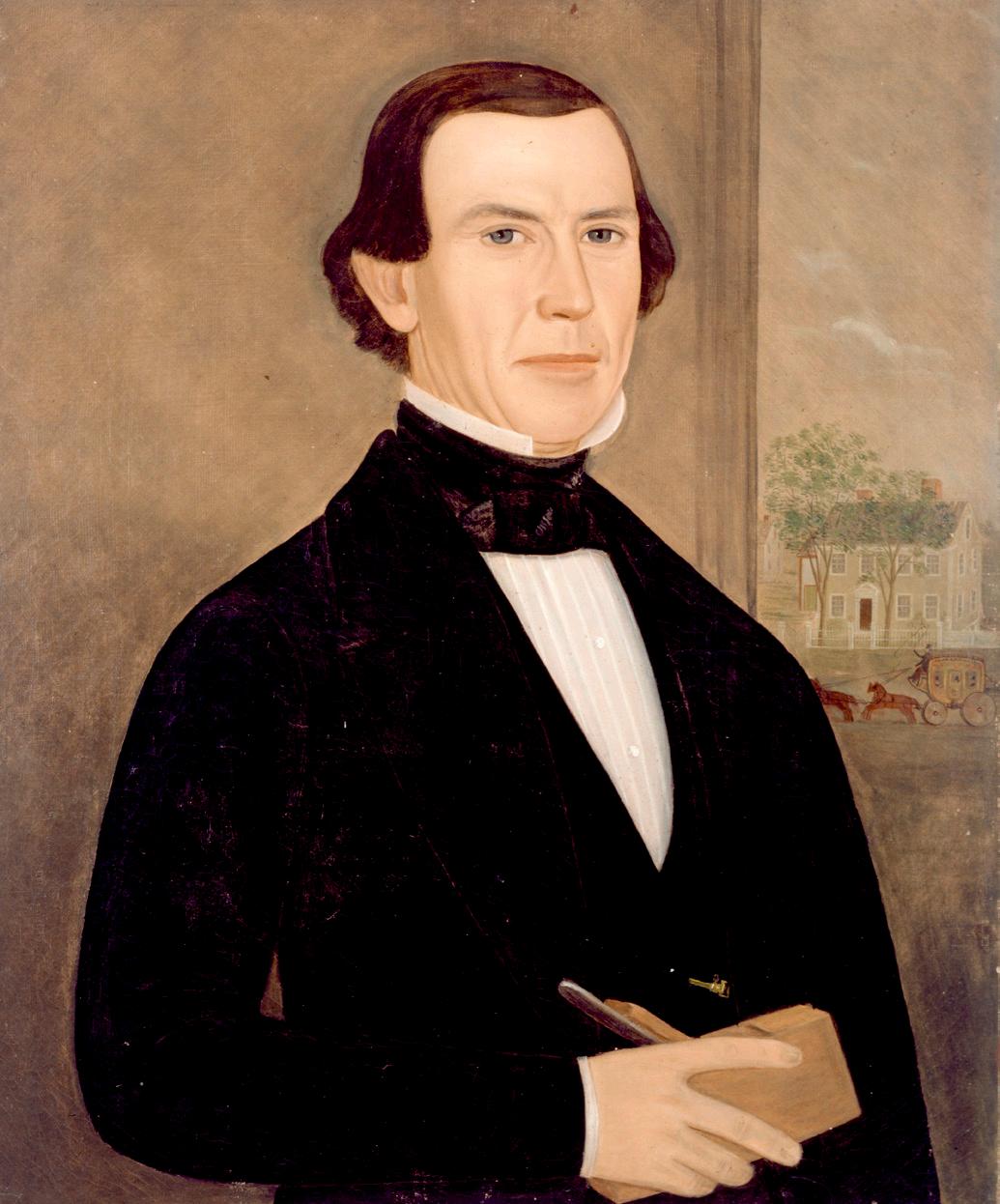

Portrait of an Upholster, Franciscus Cuypers. Boston, 1852, oil on canvas, 46 x 41½ inches. Museum purchase.

Fashion history tends to favor one end of the gender spectrum. Masculine clothing has traditionally received little attention from scholars, perhaps because so many men appear in variations on the same theme: a dark threepiece suit. It’s hard to get excited about a wool two-button coat when scholars can tackle divisive subjects such as high heels and corsets. Gender is performative. Clothing plays a key role in staging that action, but offers far more than a social mask to those who engage it. Rather than considering the four portraits discussed here as standard depictions of power and authority—the stereotypical man in a black suit—they can give the viewer interesting details about social constructions of identity.

Depicted nailing an elaborate covering on a carved chair, the unknown upholsterer painted by Dutch-born artist Franciscus Cuypers (1820–1866) meets the viewer’s gaze casually and comfortably. He is posed informally, cradling the chair in his knees with hammer in hand, wearing a spotless white shirt and a swath of apron around his waist. His shirt is typical of the early 1850s, with a hidden button placket down the center front flanked by pleats. His pants are good black wool, draped at the knees from wear but not threadbare or patched. His black, asymmetrically knotted necktie is fastened in the latest fashion. A black necktie was a somber choice in the early 1850s, when men often mixed plaids, stripes, and dots in eye-searing combinations; he most likely purchased his clothing ready-made from one of the many warehouses in Boston. Ready-made clothing, available to some as early as the eighteenth century, was one of the fastest-growing businesses in

mid-nineteenth-century America.

The upholsterer’s choices—or Cuypers’s, as the viewer cannot be certain—point to a craftsman preserving both his livelihood and his refined appearance. The informal setting, with tools tucked into a leather strap tacked to the wall as the only detail, confers a documentary gloss to this precisely constructed image. This portrait is often highlighted as one of the few depictions of a craftsman at work, but a careful analysis of his dress points to a more formal depiction than previously thought. Cuypers’s upholsterer illustrates the care with which portraiture allowed clients to craft their own visual identity.

The upholsterer makes an excellent comparison with the portrait of an unknown Cape Ann, Massachusetts, builder that Alfred J. Wiggin (1823–1883) completed four years earlier. Both subjects are highly skilled craftsmen who chose to be portrayed holding the tools of their trade, dressed in immaculate shirts and black neckerchiefs, but there the similarity ends. Wiggin depicts the Cape Ann builder as a formal, conservative craftsman. His coat, vest, and pants are all of dark wool, ready-made but good quality. He wears a black silk stock and tie, knotted in the more conservative style for the late 1840s, with his collar points cradling his chin. His pleated shirt closes down the front with pearl studs. In a nod to both fashionability and affluence, a gold watch key—used to wind the pocket watch he most likely has tucked into a vest pocket—hangs from a ribbon around his neck. Through the window one glimpses a carriage passing in front of a house, which the sitter presumably built, with a classically inspired doorframe and an elaborate white fence surrounding the yard. This conventional portrait formulation contrasts starkly with Cuypers’s informal and inviting depiction, one reinforced by the sitter’s clothing.

The men’s three-piece suit, standard business attire even today, was introduced in 1666 by England’s Charles II a few years after his reinstatement to the throne following a nine-year exile in France. His dress attempted to return political stability to the kingdom by visually reinforcing his support for domestically produced woolens. His fashionable patronage of English suits did not last long. Within a few years Charles resumed more elaborate sartorial choices, many derived from French fashion.

Men could, if they chose, be peacocks in the eighteenth century. Masculine attire embraced silks, embroidery, and powdered hair. While American men typically did not dress in extreme French styles, many cut fine figures in silk, linen, and velvet. It was not until the end of the eighteenth century, with a series of social and political upheavals around the Atlantic World, that fashion embraced what remains today the standard masculine silhouette: long pantaloons cut close to the leg, vest, and coat all cut from the same (or similar cloth), worn with a collared shirt. Many fashion historians trace the popularity of this style to notable dandy Beau Brummell, whose friendship with the Prince of Wales and constant presence in London society popularized his particular—minimal—approach to masculine dress. Brummell actively rejected the elaborate costume of court society, arguing for a wardrobe similar to that worn by English gentry while in the country. Brummell was fastidious about his appearance, reportedly spending more than an hour arranging his cravat, but he cut a vigorous line in his ensembles.

The American man who wished to appear both genteel and stylish—for Brummell had helped to make personal style a desirable attribute for men—chose a mixture of these elements for his dress. One garment had a decidedly different origin. The banyan, a loose robe with long sleeves, was worn open over a shirt and vest. Typically donned at home and in lieu of a coat, banyans entered European fashion at the end of the seventeenth century by way of trade with India. Men such as Boston Mayor Harrison Gray Otis, chose to have

themselves portrayed in banyans to signify their social status. Otis wears a banyan made from dark wool or silk and lined with fur in his 1809 portrait by Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828). Depicted at the height of his political career, Otis appears comfortably reclined, as if Stuart had gently interrupted his work to ask a question. Otis wears his expensive banyan over a white shirt, stock, and knotted cravat. His shirt frills are crimped and fluffed beneath a white waistcoat. A hint of crimson damask upholstery on the carved chair Otis has pulled up to his desk confirms both wealth and refinement.

The rise of ready-made clothing emporiums in the 1830s and 1840s offered a wide range of suits to a new class of city-dwelling young men. Clerks in banks, stores, and offices needed affordable yet genteel clothing that communicated their reliability and honesty to employers. This rise of what would become a nearly generic signifier for the middle-class working man paralleled an entirely different form of male fashionability: the dandy. Dandies (men who dressed to fashionable extreme) always formed a crucial part of the social scene but few American men chose to have themselves portrayed as such. Not many could afford the tailors and expensive textiles required to maintain that lifestyle. By 1906, when Wallace

Bryant (1870-1953) painted Henry

Davis Sleeper, men’s personal expression could take a wide range of approaches. While his career as one of the first

American interior decorators had yet to take shape, Sleeper was clearly crafting his personal style. Like Otis, Sleeper appears interrupted in study, his thumb tucked into a book. Other decorative elements remind the viewer of his interests: an antique chair, books, and framed artwork behind him reinforce his scholarly, refined nature. Sleeper’s clothing confirms it: a striking red tie stands out against his dark suit, echoed in the oxblood vase on the table and the damaskupholstered chair in which he poses. The only other hint of personal flair is his pocket square. The effort it took to look casually disarranged was perfected by Brummell and unfurled by fashionable men over the following century.

While it might seem extreme to focus on details such as pocket squares, it is by examining how these trends changed over time that we can better understand how men created and refined their personal presentations against the backdrop of American social, political, and economic change. Quoting nineteenth-century French writer Stendhal, fashion historian John Harvey once asserted, “Dress, like painting, consists of values made visible.” Fashion is not frivolous or superficial. It lies at the heart of how we craft our individual and collective selves. Portraits are insight made manifest.

top Harrison Gray Otis, Gilbert Stuart. Boston, 1809, oil on panel, 43 x 35. Museum purchase. below Henry Davis Sleeper, Wallace Bryant. Boston, 1906, oil on canvas, 60s x 66¼ inches. Gift of Steven Sleeper.