8 minute read

Those Wandering Thugs of Art”: Nineteenth-century Itinerant Painters

Nineteenth-century Itinerant Painters

by JACQUELYN OAK Education Department, Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vermont

Itinerant Artist Scene, unknown artist. Northeastern United States, c.1845, watercolor, 11½ x 15 inches. Museum purchase.

American folk portraiture had yielded to changing tastes and new technology when Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. of Boston wrote about folk artists in the July 1861 issue of Atlantic Monthly: “Recollect those wandering Thugs of Art, whose murderous doings with the brush used frequently to involve whole families; who passed from one country tavern to another, eating and painting their way,—feeding a week upon the landlord, another week upon the landlady, and two or three days apiece upon the children, as the walls of those hospitable edifices too frequently testify even to the present day.”

Holmes’s criticism notwithstanding, hundreds of folk painters documented the faces of middle-class Americans, producing works of art that have been studied and appreciated for decades. Moving from place to place as demand dictated, these artists recorded thousands of likenesses of family, friends, neighbors, political allies, business acquaintances, and strangers. In so doing, they created one of the largest bodies of work in American art. In earlier centuries artists depicted wealthy businessmen, clergymen, distinguished magistrates, and other members of the powerful elite. Folk painters democratized painting by picturing rural merchants; country doctors and lawyers; ship captains; artisans; and newly prosperous families, thus documenting a new social order. By the 1820s, members of a new middle class sought portraits of themselves in record numbers. John Neal, one of America’s first art critics, wrote about the proliferation of folk portraits in 1829: “Already they are quite as necessary as the chief part of what goes to the embellishment of a house, and far more beautiful than most of the other furniture.... You have but to look at the multitude of portraits, wretched as they generally are.... You can hardly open the door of a best-room anywhere without ... being surprised by the picture of somebody plastered to the wall and staring at you with both eyes and a bunch of flowers.”

To meet the demand, coach, house, and sign painters as well as talented (and not-so-talented) amateurs attempted to capture a “correct likeness,” the term most often used by these artisan painters. Levels of formal training, if any, varied greatly. A scant few may have studied the work of well-known, academic painters in urban areas; some learned from other contemporaries; still others had access to instructional art books and manuals that were becoming available to the general populace. As a result, the quality of the artwork differed significantly.

Working methods differed from artist to artist. Some traveled from town to town, advertising their services

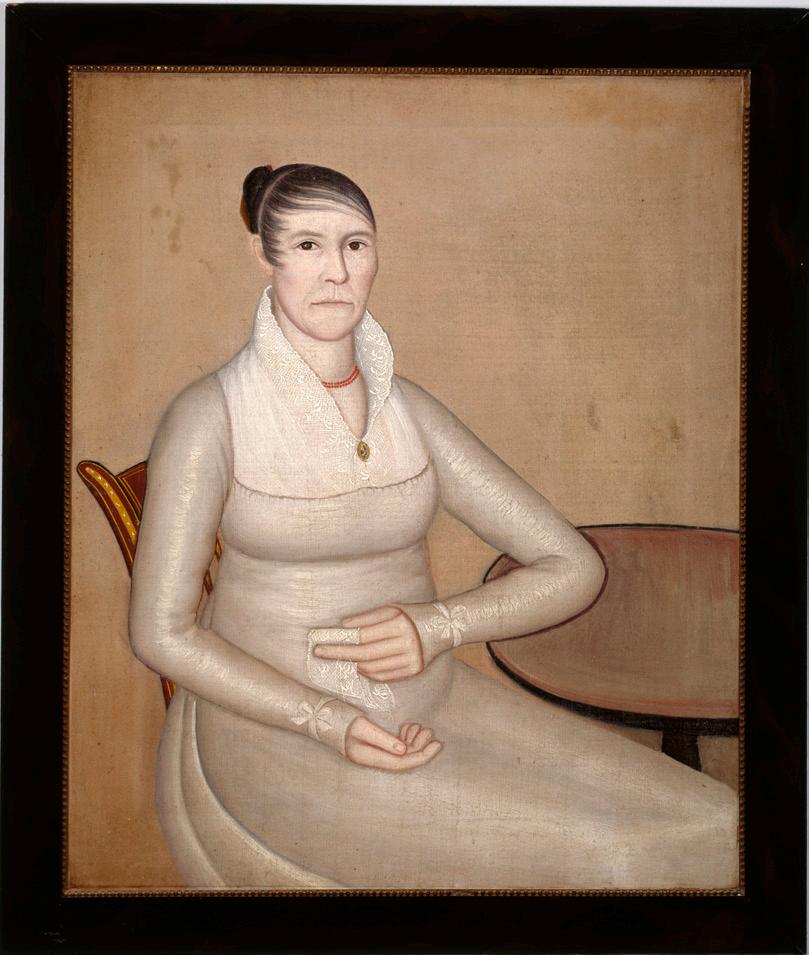

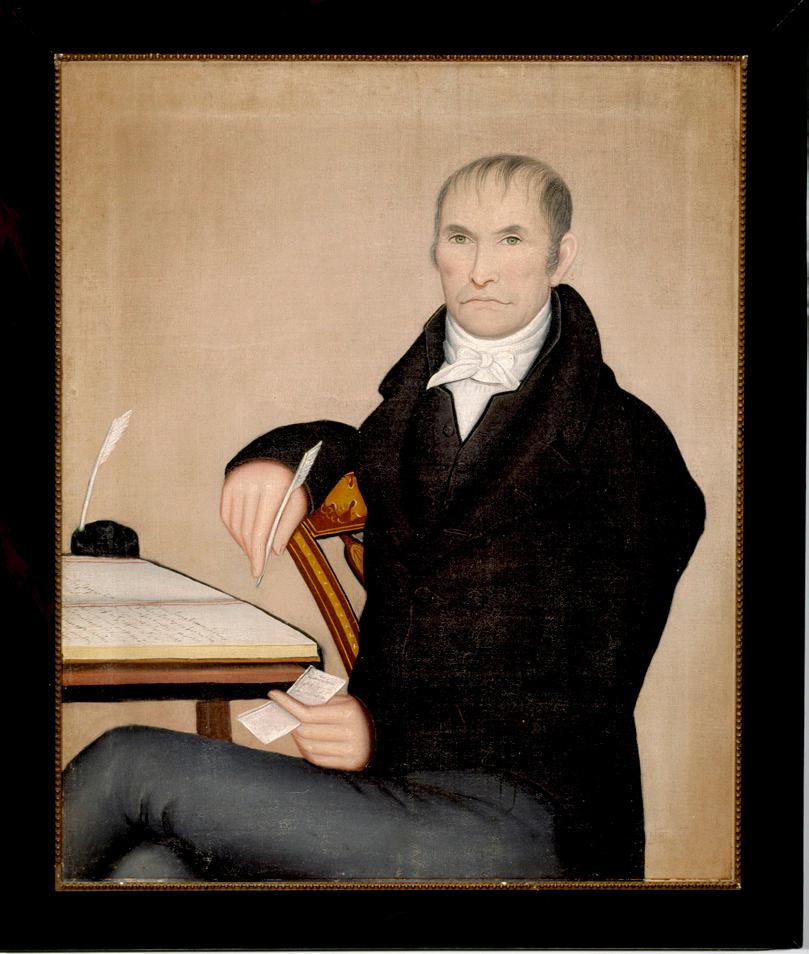

Sarah Bull Dorr and Colonel Joseph Dorr, attributed to Ammi Phillips. Probably Hoosick Falls, New York, 1814–1815, oil on canvas, 40 x 33 inches (both). Gift of Bertram K. and Nina Fletcher Little.

in taverns and stores for only a few weeks' time; others established a base and sought business in neighboring areas close to home. Most, but not all, practiced their trade in rural areas where there was less competition. Painting techniques and media varied among the artists, too. Those who had access to urban markets often used commercially prepared artist supplies. Others in more isolated, rural areas improvised with materials that could be purchased locally. It is no wonder that these conditions resulted in an enormously diverse group of paintings.

Historic New England’s recent acquisition of Itinerant Artist Scene, done by an anonymous artist, perfectly illustrates the working method of a traveling artist in the mid-nineteenth century. It also documents a “middling sort” of interior during this period. In a simply furnished kitchen, a boy sits somewhat patiently while an exceptionally well-dressed artist takes his likeness. The youngster casts a skeptical eye toward the painter as work progresses. Members of his family, shown in their best clothing, observe the scene. A cook, perhaps the grandmother, peels potatoes as she watches over the family. The furnishings of the kitchen—a drop-leaf table that serves as a work station, pewter plates, a ceramic bowl, and a “wag on the wall” clock—are typical of a middle-class, rural dwelling.

At the height of antique collecting in the twentieth century, no folk art collection was considered complete without a work by Ammi Phillips (1788–1865). One of the best-known and best-loved American folk artists, Phillips painted more than 900 likenesses in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New York, and Vermont from about 1811 until shortly before his death. Born in Colebrook, Connecticut, Phillips first worked in western Massachusetts and then around Albany, New York, during the first decades of the nineteenth century. There is no evidence to suggest whether he received any formal art instruction. His early efforts are those of an amateur but by the second decade of the 1800s his skills had improved significantly.

The Dorr portraits are part of a group of family portraits Phillips made in Hoosick Falls and Chatham, New York, about 1814–1815. Joseph Dorr and his wife, Sarah, were prominent residents of Hoosick Falls. As a successful businessman who owned several mills, Dorr also served as justice of the peace, county judge, and as a colonel in the militia during the War of 1812. Phillips successfully captured the couple’s personalities in these uncompromising likenesses. The paintings are typical of his early approach—sitters with awkward anatomical details depicted on pale backgrounds. Sarah is in the costume of a prosperous matron, wearing a finely embroidered dress, an amethyst pin, and coral necklace. She works on a piece of lace, her elbow on a round pedestal table. As suits his occupation as a businessman, Joseph is depicted next to a table that holds what appears to be his ledger book; in a pose Phillips typically used, the subject’s right hand rests on the back of a paint-decorated chair. His dark coat and vest contrast sharply with the pale background of the portrait.

The portrait of Edward Augustus Barrett shows a young boy similar to the lad pictured in Intinerant Artist Scene. Edward was the son of Charles Barrett Jr. of Historic New England’s Barrett House, in New Ipswich, New Hampshire. Edward’s portrait is attributed to Zedekiah Belknap (1781–1858), a Massachusetts native whose family moved to Vermont in the 1790s. Belknap studied divinity and theology at Dartmouth College, graduating in 1807. He reportedly preached only a few years before becoming a portrait artist. Working in the small towns and villages throughout Vermont, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts in a career that

spanned more than forty years, Belknap produced approximately 170 paintings.

Several characteristics Belknap frequently employed are evident in Edward's portrait—the use of a wood panel as a support; the awkward rendering of anatomy resulting in a rigid, stylized body; attention to facial features, often with heavy outlining in reddish brown; intricate detailing in costumes and accessories; and dark background. It is somewhat unusual for a male subject to be shown holding a bouquet of flowers, but several other examples by the artist exist.

Working in Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and his native Maine over a period of almost fifty years, William Matthew Prior (1806–1873) painted likenesses of more than 2,000 subjects, creating one of the largest and most recognizable groups of images in American folk art. His artistic training, if any, remains a mystery. For Prior, art was a business and he created likenesses to suit both his patrons' tastes and pocketbooks. He advertised extensively, indicating what customers could expect for a certain price—formal, polished portraits that resembled academic paintings, “flat likenesses without shade and shadow” for bargain prices, and “middling” efforts that combined elements of both. The sliding scale of charges proved successful throughout his long career.

Portrait of a Young Woman is typical of Prior’s economical offerings. These portraits are usually of a small size and the sitter's face and torso fill the frontal plane. Prior created this composition by using flat areas of bright colors; the face, neck, hands, and clothing are made by the use of repetitive shapes. Shading and contrasts are sometimes apparent, as they are here. Prior relied on a formula to execute likenesses quickly, sometimes in ninety minutes, and often copied costume details from likeness to likeness. In some instances, he made up accessories and props to embellish the image. Quickly applied brushstrokes, as seen on this sitter’s dress, suggest depth and enhance the decorative composition. The model is wearing fashionable, if middle-class, accessories of the time—a neckpiece attached by a brooch of Scottish agates, gold earrings, and a tortoiseshell comb. The artist clearly focused his attention on her youthful, attractive face, creating a pleasing image that undoubtedly suited his client.

Many of Prior’s portraits appear generic to contemporary eyes but often, as in this case, the artist captured the sitter’s personality. The painting has hung for years in Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House, a Historic New England property in Gloucester, Massachusetts. The original owner of the house, Henry Davis Sleeper, acquired the work in the early twentieth century. Sleeper may have been responding to a contemporary aesthetic that valued the simplicity of primitive paintings for their affinity to the work of modern artists.

The work of itinerant portrait painters offers a compelling glimpse into the lives of the provincial middle class of the nineteenth century. As French intellectual Alexis de Tocqueville observed when he visited America in the 1830s, “Democratic people may amuse themselves momentarily by looking at nature, but it is about themselves that they are really excited.”

Edward Augustus Barrett, attributed to Zedekiah Belknap. New Hampshire, 1815–1820, oil on wood, 26 x 21½ inches. Gift of Caroline Barr Wade.

Portrait of a Young Woman, attributed to William Matthew Prior. Pawtucket, Rhode Island, c. 1845, oil on academy board, 15d x 11d inches. Gift of Constance McCann Betts, Helena Woolworth Guest, and Frasier W. McCann.