historic NEw england

DESTINATION PROVIDENCE:

The Historic New England Summit

CLIMATE ACTION and Preservation

CELEBRATING COMMUNITY

Cultural Placekeeping

DESTINATION PROVIDENCE:

The Historic New England Summit

CLIMATE ACTION and Preservation

CELEBRATING COMMUNITY

Cultural Placekeeping

Progress can be measured in an endless number of ways and increments. Sometimes significant momentum is immediately felt and noticed, but more often than not, change is seen most vividly when we examine the culmination of days, weeks, months, or even years of dedication and commitment to a particular goal. Reflection shows us how much has been learned and achieved – and how much work there is still to do.

Here at Historic New England, we are keenly aware of the power that time and intentionality can have on the ways history is recorded, shared, and experienced, which in turn, influences new goals we set for the future. And evident in this issue is our passionate commitment to making positive strides forward across all areas of the organization. From steps being taken to adapt to and mitigate the effects of climate change at our properties, to continuing to recover and share the stories of all those who lived across the region, to strategically diversifying our collection, and ambitiously expanding the reach and scope of the second annual Historic New England Summit in Providence, Rhode Island, there is much to be hopeful about for the future with many exciting opportunities for growth and collaboration on the horizon.

One major milestone was the announcement this June of Historic New England’s launch of a transformational redevelopment initiative in Haverhill, Massachusetts. We are reimagining more than three acres of historic buildings and vacant property in the heart of downtown Haverhill to create a cultural destination and dynamic mixed-use district anchored by the new Historic New England Center for Preservation and Collections. The goal of this new cultural district is multifaceted. Through creative exhibitions, innovative storytelling, state-of-the-art technology, and more, the Haverhill Center will reimagine how people experience history through our unrivaled collections and archives. By bringing new visitors to the area, this initiative aims to strengthen local and regional businesses, arts, environmental, and social institutions, and bolster revenue to the area. This bold undertaking is an ambitious step forward in fulfilling a major goal outlined in The New England Plan, Historic New England’s strategic agenda. All of us are excited and honored to be playing a role in bringing this initiative to life – one step, one story, and one experience at a time.

Each time we learn something new, bear witness to a voice not previously heard, or set our sights on a new goal, we move the needle of progress forward. There is much work still to be done and we are just getting started. I invite you to join us on this journey as we embark on this vibrant new chapter in Historic New England’s story. And I look forward to seeing you at our 2023 Summit on November 2 and 3 – turn to page one for inspiration!

With gratitude,

Deborah Allinson Chair, Board of Trustees

Deborah Allinson Chair, Board of Trustees

HISTORIC NEW ENGLAND magazine is a benefit of membership. To become a member, visit HistoricNewEngland.org or call 617-994-5910. Comments? Email Info@HistoricNewEngland.org. Historic New England is funded in part by the Massachusetts Cultural Council.

President and CEO: Vin Cipolla Executive Editor: Diane Viera Editorial Review Team: Alissa Butler, Study Center Manager; Lorna Condon, Senior Curator of Library and Archives; Erica Lome, Curator Design: Julie Kelly Design

Dylan Peacock is a resident of Providence. He and Miki Kicic received a 2016 Rhody Award from Preserve Rhode Island and the Rhode Island Historical Preservation & Heritage Commission for the restoration of their 1911 Shingle Style home, the Cook-Cohen house. Peacock is a lifelong Rhode Islander and has been with Historic New England since 2016.

Providence is the host city for the Historic New England Summit November 2 and 3 at The VETS, which is exciting. In addition to being a great travel destination for attendees, the city is a microcosm reflective of the experiences facing countless communities throughout New England and beyond. This makes Providence an ideal place to discuss our collective roles in creating livable and resilient communities. Providence’s human-scaled buildings and human-scaled issues have allowed the city to consider creative and innovative solutions to problems felt in both large cities and within many small urban anchors.

A lot can be learned from Providence’s ability to cultivate and leverage arts and culture in ways that positively influence community sustainability and the preservation of threatened or underutilized buildings. Organizations with national acclaim, like local nonprofit AS220 (an artist-run organization that offers opportunities to live, work, exhibit, and/or perform in its facilities), have played a pivotal role in creative placemaking in downtown Providence through the rehabilitation of numerous historic commercial structures. AS220’s portfolio of buildings provides artistic opportunities and programming for local youth, affordable live-work space for artists, as well as performance, gallery, and retail spaces that enliven the streetscape and bring new life to the downtown in these formerly underutilized historic structures.

Huge strides continue to be made in ensuring access to arts and culture for diverse communities in Providence. The city is home to world-class institutions of higher education along with an ambitious public library system that is creating new opportunities for

page 1 Interior of the Providence Public Library. below Fox Point Hurricane Barrier, Providence, a longstanding part of the solution to climate change induced storms. Left Abandoned warehouse, Olneyville, Rhode Island. The building represents the considerable sustainable reuse potential that still exists across the city.

engagement. That same need for access exists in public education, where there are deep struggles with equitable access to quality education. The experiences of Providence’s academic institutions with helping to engage and support the local arts community set an example of what is possible when education, arts, and culture all work together.

Providence also proves the value of preservation throughout its architecturally and culturally diverse residential neighborhoods. Preservation solutions deployed in the 1980s are still supporting quality of life and affordable housing as these needs continue to grow. Innovative and leading groups like the Providence Revolving Fund (an offshoot of Providence Preservation Society), Stop Wasting Abandoned Property (SWAP), and the former Elmwood Foundation (since subsumed into One Neighborhood Builders) have spent decades saving distressed and abandoned historic properties through preservation and conversion to affordable housing for rent or sale.

The Providence Revolving Fund also is a national leader in providing nontraditional lending to homeowners to make sensitive repairs to their historic properties, coupled with technical expertise, allowing homeowners an affordable means of preserving their homes. The marriage of these two important goals has resulted in unique, high-quality housing that remains an incredible asset contributing to community stability, livability, and sense of place.

While taking action today, the city also is addressing future challenges, particularly as a coastal city considering the reality of rising sea levels, while being mindful of remaining scars from the past –especially related to historical inequities stemming from twentieth-century divestment and urban renewal, resulting in more traffic, fewer trees, higher pollution, and worsening health outcomes in frontline communities. This is a story familiar to urban centers across the nation. In 2019 Providence released its Climate Justice Plan, which centers environmental justice and equity in the transition from fossil fuels to creating healthier and more resilient communities.

Providence’s many incredible assets – its historic housing stock, local main streets and shopping districts, vibrant arts and cultural institutions, and highly regarded restaurant and food scene – mostly exist in and around historic places and streetscapes that give the city its distinctive sense of place. It is the perfect place for the 2023 Historic New England Summit to convene leading voices in conversations about the multi-disciplinary and collaborative ways in which historic preservation can be leveraged to continue creating quality, sustainable, and resilient communities. For more information visit Summit. HistoricNewEngland.org.

I’ve been photographing urban settings in New England for more than forty years. Early on in my career I was drawn to the decaying and abandoned factories and vernacular architecture that had fascinated me since childhood. I sensed something of a once vibrant past that was disappearing. I was – and still am – drawn to that sense of loss; to the echo of the past that resonates all around me. As a photographer, I make each photograph as an individual work of art. But I have for some time been working in a larger context. Photographing urban areas and various types of vernacular architecture (e.g., diners and roadside structures, old movie theaters, mom-and-pop restaurants and businesses), I also see my work as a form of historical documentation: a record of what is passing from our architectural heritage before it completely disappears.

For more than a decade, Historic New England has been collecting my photography of New England and also featuring it in its publications, both printed and online. My work aligns perfectly with Historic New England’s mission of preservation and its appreciation of photography as an art form as well as a method of documenting the past and present. – John D. Woolf

Photography is — and has always been — a major collecting area for Historic New England. By 1912, only two years after the organization’s founding, photography had already been identified as a “specialty” of the collection. At first the focus was on images of noteworthy houses but soon expanded to include contemporary views of all kinds related to New England and its people. The first twenty issues of our Bulletin, dating from 1910 to 1919, are filled with comments about the importance of photographs as documents and detailed descriptions of photographic acquisitions, from single images to large collections.

Today, Historic New England’s photography collection includes more than 600,000 images, ranging from daguerreian portraits from the 1840s to images of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter Movement, and is used by thousands of people each year. We are tremendously grateful to John Woolf for significantly expanding the collection through his gifts of his beautiful and compelling photographs.

Our work could not continue without the support of individuals and institutions who share our commitment and invest in our efforts to preserve and share these visual documents. Historic New England recently received a $250,000 grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services to digitize 125,000 glass-plate and film negatives, allowing us to provide online access to this exceptional collection and ensure its long-term preservation. Dating from the 1880s to the 2000s, these negatives document the people of New England and its built and natural environments, and tell the fuller, more inclusive stories of the region. –Senior Curator of Library and Archives Lorna Condon

Plastic sheeting isn’t generally considered an environmentally friendly material, but in the case of the 2011 weatherization project at the Lyman Estate in Waltham, Massachusetts, it was vital. Using that all-important plastic sheeting, fans, and utility data, we were able to pinpoint where heat and energy loss was occurring in the estate buildings. Utilizing this new information, we sealed up drafts and repaired faulty duct work resulting in a fifty percent reduction in energy usage

the following year, and increased protection for our buildings and the collections they house.

Looking back, we recognize that this project was more than just a step toward better preservation and cost reduction, it marked the beginning of Historic New England’s climate journey and the realization that climate adaptation and mitigation are essential parts of historic preservation.

Since the completion of the Lyman Estate project, Historic New England has continued to do work

to reduce our energy use and make our properties more resilient to environmental change. Over the past decade we have completed several gutter and site drainage projects to improve capacity to manage flooding and increased rainfall. In 2013 we completed a baseline energy assessment of all Historic New England properties. In 2021 we participated in Culture Over Carbon, a project working to create more accurate emission benchmarks for cultural institutions. While all these projects have had a positive impact on the organization, what was missing were clear climate action goals and an overall plan to achieve them.

In 2022 two events moved Historic New England significantly closer to clarifying our goals and creating such a plan. The first was when one of our properties, Otis House in Boston, met the requirements for emissions reporting under the city’s Building Emissions Reduction and Disclosure Ordinance. Realizing that we wanted to take this work beyond just one building, Historic New England joined the 2022-23 cultural cohort of the Boston Green Ribbon Commission’s collaborative climate action planning process.

Later that same year Historic New England secured a grant from the 1772 Foundation that provided funding for a two-year sustainability coordinator position and the hiring of a consultant to help guide and support the organization in creating a comprehensive climate action plan for one of our more complex sites, Casey Farm, in Saunderstown, Rhode Island, to be used as a model for climate planning across the organization. Earlier this year, Joie Grandbois (co-author of this article) joined our team as sustainability coordinator and we contracted with the Massachusetts-based consulting firm GreenerU.

Historic New England’s climate planning focuses on three areas of action: mitigation, resilience, and justice.

Climate mitigation means identifying the ways in which we contribute to climate change and taking actions to reduce our impacts. We have set the goal of reaching net zero emissions by 2050. The first step in

mitigation planning is knowing where we are starting from. This fall we will have completed an updated baseline energy assessment of all Historic New England buildings including an in-depth energy audit of Casey Farm. We are also looking at our landscapes to assess the carbon sequestration potential of the forested lands at Casey Farm and other Historic New England properties.

Climate resilience focuses on assessing the climate change impacts our properties will face and taking steps that will enable them to withstand these changes. Many of our properties are in areas that will be impacted by sea level rise and increased storm activity as well as drought and increased fire risk. Our resilience work includes integrating climate change risks into our emergency preparedness planning for our historic buildings and properties and, based on the work at Casey Farm, creating site-specific resilience plans across the organization.

Climate justice is recognizing that climate change will have greater impacts on certain communities and taking steps to ensure our actions are equitable and don’t cause further harm. This includes actions such as telling the full story of our landscapes, increasing the accessibility of our properties, and participating in community-focused climate planning. As part of

the Casey Farm climate change work a programming assessment will help identify how we can better integrate climate change into our education and outreach efforts.

While this sounds like a lot of work, and it will be, it is important to recognize we are not starting from scratch. Our 2021 review of energy data for Culture Over Carbon indicated that several buildings are already meeting future benchmarks for energy reduction. Our organization has a history of sharing our preservation and energy efficiency best practices for historic buildings and we will continue to do so with our climate resilience work. Internally we formed the climate action staff advisory group with representatives from each Historic New England team to help integrate climate action planning into our daily operations.

Historic New England has been a leader in historic preservation for more than a century. During this time our approach to preservation has never been static, but has adapted and changed as new information, risks, or techniques developed. Climate change planning has become an essential part of the preservation of historic buildings and landscapes and Historic New England enthusiastically continues our commitment to being a leader in preserving the past while creating a more just and resilient future.

In the words of Eeyore, the beloved if slightly gloomy Winnie-thePooh character, “The nicest thing about the rain is that it always stops. Eventually.” While we need the rain to support our gardens, landscapes, farm animals, wildlife, and more, water isn’t particularly helpful for historic buildings. While the rain does “eventually” stop we know from studying the climate that we are experiencing weather events with higher volumes of rain falling at a single time. Too much rain can overwhelm a property’s gutters and drainage systems leading to constant exposure to moisture and ultimately major deterioration of the building materials.

At Watson Farm in Jamestown, Rhode Island, we are working on a multi-year project to implement a comprehensive storm water management plan for the structures and landscape around the historic farmyard. We started with the replacement of the farmhouse roof and upsized the gutters and the downspouts to carry more rainwater. In 2022 we completed drainage improvements to help carry the water away from the buildings and we are now poised to replace the roof on the historic barn and upsize the gutters on it as well. Many thanks to the van Beuren Charitable Foundation for their support of the drainage work and the Rhode Island Historical Preservation & Heritage Commission as well as Preserve RI for their support of the work on the historic barn.

JerriAnne Boggis is executive director and Barbara M. Ward is senior grantwriter and program developer at the Black Heritage Trail of New Hampshire.

Portsmouth, New Hampshire, on the surface, is a typical picturesque New England seaport bustling with tourists. Eighteenth-century wood frame houses huddle together in the South End and nineteenth-century brick waterfront warehouses now converted into restaurants and shops line the waterfront.

The history told at most places in the city is the history of merchants and mansions.

But there is much more to learn about the city’s past. As you stroll along the waterfront, you begin to see the bronze markers of the Black Heritage Trail. From the story of the first documented enslaved African in the region – a man sold to “Mr. Williams of Piscataquak” in 1645 – to the story of the desegregation of the former Rockingham Hotel in 1964, these markers share history that is too often forgotten.

As Portsmouth takes note of its 400th year as a colonial town, we acknowledge that the town was established on a site previously occupied by Indigenous peoples and fishermen from the Atlantic diaspora. And we take stock of what life here has been like for the descendants of African peoples who were unwillingly transported from their homeland and enslaved here, as well as for peoples of African descent who continue to come here from all over the world.

The best place to begin this introduction to Portsmouth’s Black history is the African Burying Ground memorial site on Chestnut Street between State and Court streets. In 2003 during routine road repairs thirteen coffins were unearthed in the area recorded by early Portsmouth historians as the site of the “Negro Burying Ground.” In use from 1705 until about 1810, the precise location was obscured, paved over, and forgotten by the early twentieth century.

The Burying Ground was one of the first sites identified by Valerie Cunningham when she founded the Portsmouth Black Heritage Trail in 1994. The trail soon stretched throughout the city. Cunningham’s initial pamphlet expanded into a book, Black Portsmouth: Three Centuries of African American Heritage, written by Cunningham with the assistance of Mark Sammons.

Even as the plaques began to be a familiar site in Portsmouth, it was not until the unearthing of coffins at the corner of Court and Chestnut streets that the whole city became involved in honoring this history. What had been theoretical became real as the shovels hit the coffins and residents realized what lay beneath a quiet street. Ground-penetrating radar was used to map the location of additional coffins. Archaeologists estimate that at least 200 grave sites exist and are now protected beneath the street.

Designed by sculptor Jerome Meadows, the African Burying Ground Memorial visibly tells the story of New Hampshire's involvement with enslavement. One element of the memorial, the Entry Piece on State Street, consists of two figures with a wall of granite separating them, their hands reaching out and nearly touching. The woman represents Mother Africa while the man represents the first enslaved man brought to Portsmouth in 1645. They reach out to one another but remain forever separated.

At the base of the park, at the point where the remains were found in 2003, is the Burial Vault surrounded by eight Community Figures representing the people who honor those buried here. The railing behind them is decorated with tiles incorporating African symbols, created by Portsmouth Middle School students under Meadows’s direction.

Connecting these is the Petition Line of pink granite, inscribed with words from the 1779 Petition of Freedom. To date, this is the only known eighteenthcentury document that directly records the voices of Portsmouth’s enslaved people. In November 1779, twenty men who described themselves as “Natives of Africa now forcibly detained in Slavery in the State of New Hampshire” signed this petition calling for

the restoration of their freedom. Most are identified by the first names given to them by the merchants, craftsmen, and gentlemen who enslaved them, and all are identified with the surnames of leading families of the colony, Loyalists and Patriots alike. Most of these enslaved men performed multiple functions within their households, acting simultaneously as body servants, butlers, footmen, artisans, and laborers. Only ten were living as free men at the time of their deaths. Four were enslaved in houses that are now open to the public as museums – Winsor Moffatt and Prince Whipple in the Moffatt-Ladd House, and Peter and Cato Warner in the Warner House.

The elected head of the Black Community of Portsmouth, known as the King of the Negro Court, Nero Brewster, appears first in the list, followed by his fellow officers. One signer, Prince Whipple, although only nineteen or twenty years old in 1779, had broad experience with the Revolution and Revolutionary rhetoric. Prince Whipple traveled to Philadelphia with William Whipple when William was one of the New Hampshire delegates to the Continental Congress from 1775 to 1779 and served alongside him in the New Hampshire militia at the Battle of Saratoga and during the Rhode Island campaign. Prince Whipple heard the signers’ debates and informal discussions. His familiarity with Enlightenment ideas suggests that he may have been the principal author of the Petition

of Freedom. But he and his fellow petitioners may also have drawn upon African tradition when they asserted that “the equal Dignity of human Nature” made them free in the eyes of God. They also pledged – at a time when new recruits for the Patriot forces were greatly needed – to, if freed, “exert” themselves in the Revolutionary cause. It is through the Petition, and its arguments against all the common apologies for slavery that circulated at that time, that we learn about the experiences of these enslaved men and feel the courage of their passion for freedom.

Prince Whipple and Winsor Moffatt were enslaved in the household of William Whipple and his wife, Katharine Moffatt Whipple, and Katharine’s elderly father, John Moffatt. Both William Whipple and John Moffatt had engaged in the slave trade in the 1750s

and early 1760s. Prince and Winsor may have been kidnapped from their homes and forcibly transported to New Hampshire aboard one of the ships owned by the Moffats or Whipples. They may have been assigned to the men who owned the ships or sold at public auction.

The sites related to this story are many – the Moffatt-Ladd House where two of the petitioners, Prince Whipple and Winsor Moffatt, lived, and the Warner House, where Peter and Cato Warner lived, the North Church where these men sat in the gallery and listened to church services every week. The wharves where slave ships docked and the taverns where captains, such as Nathaniel Tuckerman, and shipowners like John Moffatt and William Whipple auctioned their human cargo, are also part of the Black Heritage Trail.

Other Black Heritage Trail markers honor those who persevered in the fight for freedom by helping others to find refuge here, including free Black residents Pomp and Candace Spring. It was probably the Springs who housed Ona Marie Judge when she first arrived in Portsmouth having escaped from her enslavement in the household of George and Martha Washington. John and Phillis Jacks (Phillis was also enslaved in what is now the Warner House) gave Ona Judge a home in Greenland, New Hampshire, after Siras Bruce (also known as Cyrus or Sirus Bruce), a free Black servant in the home of Governor John Langdon, warned her that the president’s nephew was planning to capture her and take her to Mount Vernon.

The trail’s walking tours (guided, self-guided, and recorded, and available at www.blackheritagetrailnh. org) also include other sites such as the location of the African Ladies’ Charitable School on High Street, where Dinah and Rebecca Whipple taught from about 1790 to 1820, and Historic New England’s Langdon House on Pleasant Street. More modern sites are included as well – places where segregation gave way to integration in the 1960s, the Pearl Street Church where the Reverend Martin Luther King preached as a young student, the South Meetinghouse where Emancipation Day celebrations were held for many years, and the beauty shop owned by Rosary Broxay

Cooper who opened her business to serve the city’s Black community in the late 1940s.

Portsmouth is where the story begins, but it does not end on the Seacoast. In 2016, the Portsmouth Black Heritage Trail expanded statewide, becoming the Black Heritage Trail of New Hampshire. Many more sites are coming to light through the work of researchers from throughout the state. The Black Heritage Trail of New Hampshire now includes sites

in Andover, Derry, Dover, Hancock, Jaffrey, Milford, Nashua, Warner, and Windham, New Hampshire, and Kittery, Maine, with six additional markers already planned for 2024 and 2025. Our work is not only an opportunity to tell this history, but also an opportunity to celebrate Black life and culture through public programs.

Erika Slocumb was Historic New England’s 2023 Recovering New England's Voices research scholar. Her research focused on the lives and experiences of free Black and enslaved people of color who lived and worked at our sites. Each year we ask the outgoing research scholars to reflect on their experiences doing this work and share some of the stories they recovered.

As a historian, I am a storyteller. My practice is rooted in Black and Indigenous traditions of recovering and sharing history that values community narratives and oral storytelling. As a researcher, I use these narratives to discern where I need to look to uncover the breadth of any history. This year, as I embarked on the position of research scholar of African American history at Historic New England, I turned first to community narratives— the stories that are currently being told—and then to past scholars to develop my own interpretation of Black experience across New England.

My approach has centered on the reliance of those who have done this work before me, both scholars at Historic New England as well as community scholars. Over the past year I have been to six different archives and read numerous papers and books

scouring for a name, a mention of a family, or to just learn more about the events that took place in Lincoln and Salem, Massachusetts, and Portsmouth, New Hampshire. I have been working to unravel the tangled histories of Black communities in New England, working toward the goal of recovering voices that have been obscured by dominant narratives. The following are stories that I have found to be the most interesting and fulfilling from my work this year. While there has been more work uncovered I am delighted to share these snippets of the history of Black experience in and around Historic New England’s sites.

One of the first stories that I learned about was that of a Black man named Watson Tyler. His is a name known to many people who have toured the Codman Estate in Lincoln. He labored at the estate for more than forty years and was followed by at least three generations. His family is still part of the Lincoln community today. As I walked through the Italian Garden that he constructed and listened to the stories of enslaved people who had worked on the property before him, I envisioned what his life might have been like. Watson was born and raised in Nova Scotia, Canada. He lived his life, like his father, as an agriculturalist. Throughout the 1870s, members of the Tyler family began emigrating to Massachusetts from Nova Scotia. According to his mother, Hannah Tyler, his maternal grandfather was from New York and had been relocated to Canada sometime after the Revolutionary War. Watson eventually settled in Lincoln with his

wife, Annie, and their children. To piece together the history of Watson and his family, I utilized birth records, death records, census records and other town records, and newspaper accounts, as well as the research of other scholars. I was able to compile a somewhat comprehensive narrative of the life of Watson Tyler and his descendants. This research allowed me to think about Watson’s labor and contributions to the Codman Estate and more broadly to the town of Lincoln to expand on the fullness of his life.

I was drawn next to Salem, originally by the history of Negro Election Day, a celebration of free and enslaved Black people who voted for their Black “kings or governors.” These men were advocates of Black politics, both within the Black community and among the white community. By 1754 the Census of Salem listed 3,462 inhabitants of Salem, 123 (3.5%) of those individuals were Black. The population of Black families in Salem continued to grow and in 1790, Salem officials discovered that the majority of property was “in the hands of persons not Town born and who lacked permission to live within its limits.” These people were specifically Black folks, other people of color, and poor white folks. A “Warning to Depart” was issued to about 400 individuals and families. The first list of 103 Black individuals was given in December 1790, and they were warned to depart within twenty days of receiving the notice if they were not “lawful” inhabitants of the town. Many families did not in fact leave and a number of them settled in two neighborhoods, the area around Salem Neck and the Mill Pond area.

On April 20, 1816, Reverend William Bentley visited High Street at Pickering Hill burying ground and Mill Pond vulgarly called “Roast Meat Hill.” I was not able to determine why the neighborhood was named “Roast Meat Hill,” though it may have been related to the tannery and the smell of burning cattle hide. Reverend Bentley described the area: “properly our Black town…it was a mere pasture when I first came to Salem. There is now a twine factory about one hundred huts and houses for Blacks from the most decent to the most humble appearance.” This area was home to many Black families for up to fifty years after Reverend Bentley made his comments, even into the 1870s. The poor conditions in the neighborhood and the low rent

around Mill Pond made the area attractive to poor Black families and recent immigrants. Upon visiting the Phillips Library, in Rowley, Massachusetts, I was able to discern that Benjamin Cox, the owner of Gedney House (now owned by Historic New England), had owned a tenement house in the Mill Pond neigborhood on the Salem Turnpike—Cox simply called this the “Turnpike House.” In this home, Cox rented rooms to a number of Black Salemites and, in one case, a white man by the name of George Morgan lived in the “negro house.”

With little to draw Black people to Salem, the population shrunk further. There were no jobs for Black people and by 1910 fewer than 150 remained. The Great Salem Fire of 1914 destroyed the Mill Pond neighborhood. After this, many Black families dispersed to other parts of the city or left completely. And by the 1920s many had chosen to move to larger cities where economic opportunities were better. By the twentieth century, the demographics of the neighborhood had begun to shift to a largely Italian immigrant community and the area surrounding Gedney House and Cox Cottage became known as the Endicott neighborhood.

Isabelle Grimes—often spelled Grimm—was born in Richmond, Virginia, and was enslaved. She came to New Hampshire at the age of twelve by way of the Underground Railroad, according to family narratives. She was promised an education, but instead was made to wash clothes for local white families and sleep in barns until she was able to acquire a small shack for herself when she was about fourteen years old. In New Hampshire she met her husband, Jacob Tilley, who had run away from slavery to the North. Isabelle and Jacob married and had three daughters and two sons. They lived in the Old Jackson Hill House in Portsmouth until Isabelle's death in 1937. Though there are not many records of her life in archives, the family has passed down the story of Isabelle through oral stories and family papers. This year, I had the pleasure of speaking with the great-granddaughter of Mrs. Isabelle Tilley. When I sat down with her, she shared with me a letter that Isabelle had written to her granddaughter over ninety years ago from her home in Portsmouth about the arrival of her new great grandson, Floyd. She

wrote, “He is the dearless [sic] I had ever saw and the people do too,” adding that she wished that she had been well enough to go to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to help with his birth. Her letter (pictured above) was posted from 63 Jackson Hill Street in Portsmouth. Isabelle died a little while after Floyd was born. Through the interview I was able to learn that some of the information that Historic New England had about Isabelle was not complete and in some cases was inaccurate.

Mrs. Tilley’s story is passed to Historic New England through oral histories, and some of it through family archival documentation. Oral storytelling has long been the way that Black and Indigenous histories are passed from generation to generation. This project enabled me to work with family and community to unearth the story of a matriarch who was revered and respected in Portsmouth. I believe that Mrs. Tilley’s story and those of Watson Tyler and the Black community in places like Salem will continue to grow the more we commit ourselves to reaching out to archives, community members, and local scholars.

What I have learned from my research is that our work does not exist in a silo. This research must be a collective effort across repositories of historical collections. Through Recovering New England’s Voices, I have connected with scholars and community advocates who are working diligently to preserve the history of Black New Englanders. These individuals untangle narratives so they are clear and accessible to future generations and historians.

When Charles Bowie arrived in Boston in the early 1880s, he came with high expectations for his future. He had left his parents and siblings in Maryland and traveled alone to New England seeking domestic work. His family had likely been enslaved by the prominent Bowie family which included Maryland’s thirty-fourth governor, Odin Bowie. The Bowies enslaved large numbers of people at their Bellefield, Fairview, and Mattaponi plantations in Prince George’s County between 1810 and 1865. Charles was raised at or near one of these properties.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, plantation owners in northern Maryland gradually abandoned tobacco farming and replaced it with corn and cereals. This diversification of agriculture meant that the needs of plantations changed, resulting in a varied workforce. Maryland’s enslavers sometimes manumitted people and hired them seasonally rather than paying for their care year-round and by the time Charles Bowie was born in 1860, plantation work was often done by paid Black and white workers alongside those who were enslaved. After the Civil War, many Black Marylanders looked beyond plantations to more specialized work. Black-led communities and schools were established in the early, hopeful days of Reconstruction. This was the environment in which Charles Bowie grew up, and the one he left when he came north to create a life in Boston.

By 1882 Charles was working at Boston’s Hotel Berwick, seemingly for a successful young theater stage reader named Gertrude Griswold. He was not there for long, however, and by 1885 he had found employment as an “inside man” at the home of a successful clothier named Charles N. Carter in the city’s Back Bay. (The term “inside man” implied a variety of tasks within one position, from janitorial to butlering.) Bowie worked in this capacity in several

nearby houses over the next few years, including the large Beacon Street home of hemp merchant Richard Harding Weld. It was from this address in 1888 that Bowie published an advertisement in the Boston Evening Transcript seeking his next position which read, “Situation wanted by a young colored man as first-class inside man in private family: best of city references; will go to the country. Apply for two days at 110 Dartmouth.” This advertisement may have been answered by wealthy widow Mary Hemenway, because shortly afterward Charles began working at her home on Beacon Hill where he would remain through her death in 1894. After Mary’s death, Charles stayed on at the Mount Vernon Street house and oversaw the staff while taking direction from her son-in-law, W.E.C. Eustis, who sent his instructions via correspondence from his home in Milton, Massachusetts.

Charles’s professional ascent was impressive, but his ambitions extended beyond domestic work. In the mid-1890s he and a group of his peers began to explore Black political work in Boston, forming the Black Democratic Ward 9 Club (later the Ward 11 Club) in 1895. The sixteen founding members worked quickly to establish a presence in Boston and July of that year saw several announcements of their activities in local newspapers, including one in The Boston Globe stating that their objective would be “to perpetuate Democratic principles and to support Democratic nominees in state and municipal affairs,” and noting that “the members express themselves as being determined to do honest work for the advancement of the party, and have pledged themselves to do all in their power to elect Democratic nominees.”

Over the next five years the club pushed back against Black political suppression, working to place their members in elected positions in Boston with limited success as the promise of Reconstruction

faded into the Jim Crow era. Charles was nominated for the Massachusetts Common Council in 1896, although he didn’t win. His pace didn’t slow, however, and in 1898 he was married to Swedish immigrant Pauline Eggemann by Reverend George C. Lorimer of Boston’s Tremont Temple. The couple's interracial marriage was uncommon in 1890s Boston. However, Tremont Temple had one of the city’s oldest and largest integrated congregations and had long been a center for social activism, beginning with its early ties to the Underground Railroad and continuing as it hosted important abolitionist and suffragist speakers throughout the nineteenth century.

Although the Ward 9 Club seems to have disappeared by 1900, Charles and Pauline stayed in Massachusetts. By 1904 the couple had come to work for the Eustis family at their estate in Milton, where Pauline was a seamstress and Charles oversaw a large staff as butler. As majordomo of the house, Charles worked closely with W.E.C. Eustis to manage the dayto-day needs of the family and those who worked for them. His daily duties would have included arranging schedules and directing staff, monitoring and ordering supplies, serving the family in the house, and organizing the logistics of their frequent travel. While working in Milton the Bowies also purchased property of their own in nearby Dorchester, where they lived near several friends who had also worked for Mary Hemenway in the 1890s. Although Charles remained in the employ of the Eustis family until his death in 1928, his story reached far beyond the Eustis Estate. As a founding member of the Ward 9 Club, his work challenging establishment politics in nineteenth-century Boston helped to write an early and unique chapter in the history of Black activism in New England.

The Chinatown Community Land Trust has unwittingly become a new voice in the preservation arena. We work for community control of land, development without displacement, shared neighborhood spaces, and collective governance. But as we seek to strengthen the future of Chinatown, we must answer the question of what makes Chinatown Chinatown?

We are weaving together many strands of activism–historic and affordable housing preservation, policy and zoning reform, an approach to socially engaged art that we

Lydia Lowe is the executive director of the Chinatown Community Land Trust and the mother of two daughters who are sixth generation Chinese Americans. Daphne Xu is an artist/ filmmaker and cultural placekeeping consultant leading the Immigrant History Trail project.

call cultural placekeeping, and Chinatown’s designation as both a cultural and historic district.

Despite perceptions of the Chinese as newcomers, Boston Chinatown has more than 150 years of history with roots as a safe haven for immigrant laborers fleeing eastward in response to racial violence and exclusionary laws. Chinatown was built on the tidal flats reclaimed by the South Cove Company in the 1830s and next to a railyard that brought in new industries and immigrant workers from Ireland, Europe, and the Middle East. Today, this once undesirable neighborhood commands some of the hottest real estate values in Massachusetts with gentrification threatening Chinatown’s future.

At the Chinatown Community Land Trust, we don’t think of ourselves as historic preservationists so much as we consider ourselves activists who are trying to protect our community from urban renewal, highway construction, institutional expansion, or luxury development. We increasingly find ourselves allied with the preservation community as we define what we are trying to preserve.

We previously thought of historic preservation as a focus on landmark architecture and beautiful old buildings. Chinatown’s old buildings are mostly unglamorous, tenement-style row houses built for laborers and their families. Yet if you walk down the remaining row house streets you will feel there is something that we don’t want to lose.

If you go to Chinatown in Washington, DC, you encounter an ornate Chinese gate and franchise businesses boasting both English and Chinese names. What you won’t see are very many Chinese people and small businesses. This begs the question: Do Chinese cultural symbols—pagoda-style roofs, lanterns, stone lions—make a Chinatown? Community activists in Boston Chinatown are preserving the historic character of our community historic buildings, legacy businesses, small streetscapes, and some cultural icons. But it is so much more.

Preservation of historic character begins with defining that character. When we look at the history of Chinatown and the South Cove neighborhood, its culture and character stem from its role as a neighborhood for immigrant, working-class families

since the 1830s. This neighborhood was home to successive waves of Irish, Eastern European, Syrian, and Chinese immigrant laborers.

We cannot preserve this character without preserving the stories and maintaining the ongoing presence of the immigrants and small business entrepreneurs. That is why we work to preserve the Greek Revival and Federal Style brick buildings as permanently affordable homes for modest-income families and legacy mom-and-pop businesses. Equally important is the development of new affordable housing.

Within Chinatown’s small-scale streets, row houses on Oxford Place and Johnny Court are reminders of the past and spaces for growing a new sense of community and stewardship. The annual Chinatown Block Party is a celebration for Chinatown residents to become reacquainted, unlike the festivals focused on attracting visitors to Chinatown’s commercial streets.

In Chinatown, community organizations use the term “placekeeping” instead of “placemaking.” While placemaking often supports gentrification, our intention is to counter development pressures. We facilitate cultural programming, community-led urban design, and planning interventions to maintain Chinatown’s cultural identity and role as a workingclass immigrant hub. Cultural placekeeping creates opportunities to appreciate and promote conversations about Chinatown’s immigrant, working-class history and future. Past and current residents, small business owners, and those who work in Chinatown can all take part in shaping narratives and see themselves represented in the story.

We have engaged local artists, designers, researchers, writers, and historians to collaborate on projects such as the Immigrant History Trail. We hope to activate Chinatown’s many existing archives to engage various publics in person and online. Preserving Chinatown’s character will take the weaving together of many strategies. Binding it all is the community organizing necessary to grow each strand, and the people for whom Chinatown is home, livelihood, and identity. We hope that the strength of binding these interwoven strategies together will pull us into the future.

by MARTA V. MARTÍNEZ

by MARTA V. MARTÍNEZ

Marta V. Martínez, PhD, is the founder and current executive director of Rhode Island Latino Arts (RILA), where she has led the organization since 1988. In 1991, she also founded Nuestras Raíces: The Latino Oral History Project of Rhode Island, and the collection of oral histories has become the main focus of her work at RILA. In 2014, she published Latino History in Rhode Island: Nuestras Raíces (History Press).

There’s a place called Broad Street in South Providence, Rhode Island, where, as you walk, you will see stores selling plátanos and yuca; where you can smell the delicious aroma of freshly made tostónes, arroz con gandúlas, and pollo frito. On any given evening, you’ll see residents lined up at the many Chimi trucks parked along this busy street, and you can spot the handlettered signs and hear orders for this Dominican specialty in the Spanish language.

More than fifty years ago, Broad Street looked and sounded very different. Hy’s Deli sold bagels and lox for fifteen cents, Collier's Bakery made soda bread each morning, and most of the residents were Irish or Jewish. It was during this time, however, when families

began moving south to the suburbs. Postwar prosperity and the relative cheapness of automobiles made the tightly packed houses and three-deckers around Broad Street less inviting than a ranch house in neighboring and more affluent cities.

Soon, in the time-honored American way, new immigrants moved in.

Many of these newcomers were Latin Americans and although their Rhode Island numbers were almost non-existent before the early 1960s, in 2023 more than thirty-nine percent of the state's workforce is Latino, twenty-four percent are Providence residents, and more than half of Latino children still live in a home where English is not the first language.

If we had to find one person who we can say

is responsible for the growing Latino influence in Rhode Island, it would have to be Josefina “Doña Fefa” Rosario who, even after her death in 2018, is loved, respected, and celebrated as the "Mother of the Hispanic Community." Through her efforts, Dominicans are now the largest group of Latinos in the state, but in 1959 when she arrived, she was convinced that she was the first such person. By 1962, after driving to New York and back to purchase her favorite foods, Doña Fefa opened a bodega (market), known as Fefa's Market, where she sold the foods she missed from her home country, including plátanos, yucca, café, and cilantro. She stocked Dominican newspapers and gave the newcomers advice on where to find a job, how to get a driver's license, and made sure they registered their children for school. She was a one-woman welcoming committee, and her bodega provided familiar comforts in a new and strange world.

Doña Fefa’s story and the site where her bodega stood were a little-known part of Rhode Island’s history until 1991 when, as a way to preserve this history, I began collecting oral histories and documenting all that I learned. As a result, Rhode Island Latino Arts (RILA), the organization which I founded, has become the first and only community-based organization that holds the state’s only comprehensive collection of Latino history.

Fefa’s story was also the inspiration for the continuation of oral history work in the Blackstone Valley and specifically in Central Falls, Rhode Island, a small city one-square-mile in size. Central Falls has a rich industrial history and, as I discovered, is where the first Colombians who arrived in Rhode Island to work in the textile mills settled.

Through the collection of oral histories, RILA has given a voice to a history that has been overlooked by local historians and that before 1990 no one was collecting and documenting on a consistent basis. Through collective organizing and outreach, these stories are now accessible to the general public and we continue to work creatively to include digital storytelling through a website called Nuestras Raíces (www.nuestrasraicesri.net), which includes a platform for community members to document their own histories by sharing stories and/or photographs online.

Through place-based arts programming like a traveling art installation called Café Recuerdos, living history Barrio Tours, public art, and hosting

performances on the site of Fefa’s Market, we educate others about Latino history.

I’m also pleased to have launched a program that trains emerging Latinx oral historians who will collect and share their own stories while growing the collection. Through this program we pair elders and young people to ensure that today’s and future generations of Latinx people don’t forget who they are and where they came from.

Historic New England’s Herbert and Louise Whitney Fund Community Preservation Grants help support smaller preservation organizations tell truer, diverse, and representative stories across New England by funding projects that range from building restoration and archival digitization to research and publication, podcasts, and more. Historical memory of towns is often safeguarded by community organizations that are staffed by a small number of professionals and/or tireless volunteers. These organizations have no dedicated grant writers and are frequently out competed by larger institutions that have more capacity for grant seeking. However, their work is no less important and has a great impact on their communities. Grassroots work is the lifeblood of the preservation movement and without it much of our cultural memory would be lost. Historic New England acknowledges the dedication and perseverance of such organizations and annually awards six grants to one organization from each New England state to help them continue their work. We celebrate these communitybased efforts by sharing the following overviews of projects by four recent Community Preservation Grant recipients to help tell their communities’ diverse stories and celebrate their vibrant futures. – Elizabeth Paliga, Preservation Services Manager, Northern New England

Norwich, Connecticut

The Historic New England Community Preservation Grant was used to hire an intern to research Haitian connections to the c. 1750 Diah Manning House, listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Named for its most famous owner who served as a drummer and personal bodyguard to George Washington in the Revolutionary War, the Diah Manning House also played host to a future president of Haiti during the Haitian Revolution.

Young Jean-Pierre Boyer stayed with the Mannings as a prisoner and refugee from 1800 to 1801 and served as President of the Republic of Haiti for twenty-five years.

Later in his career he sent $400 to the widow of Diah Manning in fond memory and with thanks for his time with them. The Norwich Historical Society worked with the diversity director at the Norwich Free Academy and the Norwich NAACP to find a student to help research Jean-Pierre Boyer and his time in Connecticut. Tenthgrader Ashnaelle BiJoux, who is of Haitian descent, was hired to perform the research and write a short article on the subject.

Ms. BiJoux’s research will help improve public awareness of the site and its diverse history. The Norwich Historical Society frequently gives guided walking tours of the neighborhood, and this project will be integrated into those tours to explore Norwich’s historical Haitian connections and be more representative of its richly diverse modern population. - Regan Miner, Executive Director, Norwich Historical Society

People may think that Greenfield, New Hampshire, is a quiet, country town where nothing happens, but they are mistaken. The Greenfield Historical Society, with help from Historic New England’s Community Preservation Grant and NHGives, published a new book, In the Shadow of Crotched Mountain, Revealing Greenfield’s Colorful Characters, Past & Present, that includes research from newspapers, archival documents, and interviews.

The book was entirely researched, written, and self-published by the society’s directors. It tells stories of some of Greenfield’s most notable and renowned characters, such as the daredevil pioneer aviator who landed his biplane on the White House lawn, the inventor of the Narrow Gauge Railroad, the famous horticulturalist who cultivated the country’s first high bush blueberries from wild berries on Crotched Mountain, and the inventor of the Tommygun - “The gun that made the Twenties roar.” The book tells of the ghost of a grieving mother howling in the night; pumpkins, VW Beetles, and pianos flying through the

air; a gruesome 1881 murder/suicide; and the discovery of a 309-pound gold nugget. Mixed in are endearing and humorous recollections of Greenfield’s “ordinary people,” told by friends and family members. This book has caused quite the buzz with some locals ordering multiple copies to share, and even out-of-staters are chiming in with family stories. It has put a skip back into the steps of those who love Greenfield and has given the true flavor of this not-so-quiet, little, country town. -

Amy Lowell, Treasurer, Greenfield Historical SocietyThe Winsor Blacksmith Shop was built c. 1870 by Ira Winsor in Foster, Rhode Island, and remained in the Winsor-Hayfield family until 1992. In 1993 it was donated to the Foster Preservation Society with the stipulation it be removed from the property and relocated. The following year, the shop was moved to its current location on Howard Hill Road adjacent to the 1796 Town House.

The shop is unique in that it has an ox sling. Oxen, unlike horses, cannot stand on three legs, so the blacksmith required a sling to support the animal while affixing shoes to its hooves. The blacksmith did more than shoe oxen and horses, he made or repaired wagon springs, door latches, tools, hinges, andirons, harnesses, farm hardware, household utensils, pots, pans, and more. The Foster Preservation Society has made a sincere effort to restore the shop and to preserve the many artifacts therein.

Historic New England’s Community Preservation Grant, in addition to funding from the Rhode Island Historical Preservation & Heritage Commission and private donors, helped the Foster Preservation Society raise the funds to obtain a one-third matching grant from the State of Rhode Island Senate Grant. This allowed the society to preserve the Winsor Blacksmith Shop by installing a new fire hydrant and hand-hewn red

cedar roof, and the south side of the building has a new sill and shingles. The restoration is not complete, with window repair, door hinges, and staining left to do, but for the immediate future the structure is safe thanks to this work. - Ada Farrell, Director, Grants & Acquisitions, Foster Preservation Society

Vermont’s Lost Mural, painted by Lithuanian artist Ben Zion Black in 1910, is recognized internationally as a rare survivor of the artistic style that once proliferated in the thousands of painted wooden synagogues across Eastern Europe. In 1986, the 155-square-foot triptych treasure was hidden by a false wall when the mural’s former home, Chai Adam Synagogue, was converted into an apartment building. In 2010, with the encouragement of notable scholars, a campaign was mounted to rescue and preserve the mural. By 2015, following an extraordinary collaborative effort by experts in architecture, conservation, construction, engineering, and rigging, the fragile mural, encased in a protective steel frame weighing 7,500 pounds, was relocated to its new permanent home at Ohavi Zedek Synagogue less than a mile away from its original site.

With support from arts, humanities, and preservation foundations, including Historic New England’s Community Preservation Grant, the Lost Mural was fully cleaned in 2021, revealing the artwork’s original vibrant colors that had been obscured by decades of accumulated charcoal dust, grime, and coats of varnish. In 2022, final infill and careful repainting thoroughly restored the artist’s original vision.

Black’s artistic time portal depicts his threedimensional representation of the Biblical Tent of the Tabernacle. One can now experience walking through the marble columns from the outer courtyard complex and into the inner space, the Holy of Holies, containing the Ten Commandments. Welcoming all peoples within the Tent of the Lost Mural is the central message of the educational programming now actively being shared with school and community groups by the Lost Mural Project. - Aaron Goldberg, Co-Founder & President, Lost Mural Project

Tom

J.Hillard is a professor in the English Literature Department at Boise State University and he has published widely on early American and Gothic literature. He is currently working on several textual editing and book history projects related to Gothic literature in early US history –including Sally Wood – with the aim of making many such “lost” texts once again available to readers.

On the banks of the York River in Maine, overlooking the wharves where the river spills into York Harbor, stands stately Sayward-Wheeler House, one of the most remarkably preserved New England homes of the Revolutionary War era. Built c. 1718, it is best known as the residence of Judge Jonathan Sayward—among the wealthiest merchants of eighteenth-century Maine and an influential and sometimes polarizing political figure during the

Revolution. Like his house, Sayward’s life and legacy loom large in Maine lore. What is less known amid this storied building’s three-century history, however, is that Sayward-Wheeler House was also the birthplace of an extraordinary figure in early American literary history: Sally Sayward Wood.

Sally Wood—or “Madam Wood,” as she is sometimes known to locals—was among the most prolific novelists in the first decades of the nineteenth century, yet she remains unknown to most modern

readers because her fiction has languished, largely out of print, for more than 200 years. In her own day Wood was a pioneering author, publishing four novels in quick succession between 1800 and 1804: Julia and the Illuminated Baron (1800), Dorval; or the Speculator (1801), Amelia; or, the Influence of Virtue (1802), and Ferdinand and Elmira: A Russian Story (1804). Such a feat of literary production was exceeded at the time by only one other American-born author, Wood's Philadelphia contemporary Charles Brockden Brown (the so-called “father” of the American Gothic novel), and it was a feat that wouldn’t be replicated by any American author until the 1820s, when in the aftermath of the War of 1812 American literature soared to new heights. The other superstar of the period was Susanna Rowson, an English author who transplanted to America, and whose 1791 Charlotte Temple was the best-selling novel in the US well into the nineteenth century.

Both Brown and Rowson have far eclipsed Sally Wood in twentieth- and twenty-first-century reputation and readership, yet Wood’s story is a singular one that needs to be told. When her first novel, Julia, was published in June 1800, Wood became Maine’s first novelist (when Maine was still a district of Massachusetts). Moreover, because her novels—especially Julia and Dorval—draw heavily on the Gothic fiction that was then wildly in vogue in England (and eagerly imported by American readers), Sally Wood is the United States’ first woman Gothic novelist.

Wood’s novels follow the narrative patterns developed by her 1790s British Gothic predecessor Ann Radcliffe: frightening stories of danger and moral transgression faced by a virtuous young heroine, wherein the threats are ultimately overcome, and complications brought to safe closure. Along the way, readers experience vicariously the terror and violence of the stories’ villains, as well as hints of the supernatural amid foreboding, isolated settings. Historians of Gothic fiction often separate its lineage

into two major strands: the “horror” Gothic on one hand, as exemplified by Matthew Lewis’s scandalous, no-holds-barred The Monk (1796), and the “terror” Gothic on the other, made famous by Radcliffe in such works as The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) and The Italian (1797). Sally Wood’s Julia, set mainly in France, showcases the fear and paranoia produced by the recent French Revolution, and it is arguably the best and most faithful adaptation of the Radcliffean style of “terror” Gothic in early American literary history.

Wood’s path to becoming an author was an improbable one. Born Sarah Sayward Barrell on October 1, 1759, Sally (as she went by all her life) was the first grandchild of Jonathan Sayward, and the daughter of Nathaniel and Sarah (Sayward) Barrell. Sally grew up mainly in York, splitting time between her parents’ home, known as Barrell Grove, and her grandfather's mansion. Despite the tumult of the American Revolution, whose disruptions to the international shipping industry upended many aspects of her family’s daily lives, teenage Sally found love, and in 1778 she married Richard Keating, a young maritime clerk who worked for her grandfather. Five years later, as the long, worrisome war was finally coming

to a close, tragedy struck when Richard unexpectedly died from a fever. Thus, in the summer of 1783, Sally suddenly found herself a twenty-three-year-old widowed mother of two, with a third child on the way.

Few documentary details exist regarding Sally’s life in the decade following Richard’s death, so we can only speculate about her interior, imaginative world. We do know she remained in York, living near her grandfather, and it is during this time that Sally turned her eye toward literary ambitions. Extant correspondence shows Sally and her parents having a deep interest in reading and novels in the 1790s, and for her to be able to produce her novels at the pace that she did, she almost certainly had to have been fine-tuning her writing for some time. While only one manuscript poem from the period survives, about the death of a friend’s son, it is possible Sally may have published essays, tales, or poems anonymously in regional newspapers or periodicals. If true, no concrete evidence has yet been found.

Whatever her path to authorship, when Wood published Julia in 1800 she was entering uncharted territory. By then only a few dozen novels by American authors had appeared, almost all in the publishing centers of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia; and for Wood, in the comparatively isolated York, there was no literary infrastructure to speak of. In fact, to publish Julia, Wood sought out nearby Portsmouth, New Hampshire, printer Charles Peirce, who ran the United States Oracle newspaper and operated a bookshop out of his Daniel Street office. Julia was Peirce’s first foray into producing a full-length novel, and it was only the second American novel published in New Hampshire

(the first was Royall Tyler’s The Algerine Captive, printed in Walpole in 1797). At the time, publishing a novel was no small task and it was a risky venture for a printer to take on an unknown American author.

In bringing her fiction to the public, Wood herself also faced real social danger. While novels were widely consumed on either side of the Atlantic—and the Gothic novel particularly popular—both English and American society at large were still unsure what to make of this literary form. For the novel was still a relatively recent invention and, as is often the case with new things, it faced a strong, conservative backlash. The tenor of this backlash is perhaps best seen in a hyperbolic, oft-reprinted magazine piece of the era titled “Novel Reading, A Cause of Female Depravity.” Wood published her four novels despite an enormous social pressure that questioned, and even outright condemned, novel reading itself.

Sally was keenly aware of such critiques, and in the preface to Julia we see her masterfully navigate this rhetorical minefield. She writes about “a duty to apologize, with her very humble talents, for thus appearing in public,” and an awareness “that writers of Romance are not highly estimated.” And because “custom and nature . . . have affixed the duties of woman to very confined and very limited bounds,” she continues, “she does not hesitate to declare, that not one social, or one domestic duty, have ever been sacrificed or postponed by her pen.” There is a striking modesty (whether real or feigned) in this apology for putting herself before the public, as well as a memorable assertion that in taking up the pen, she hasn’t neglected any of her womanly or motherly duties. Wood clearly anticipated the criticism she might face in sending her fiction out in the world—yet she was prepared to take it on anyway.

Julia was a resounding success. It circulated widely in bookstores and libraries in the northern states, was marketed alongside the most famous novels of its day, and went through two editions in England. There was even a French translation in 1804. Sally rode this success with three subsequent books. Just after

the final one, Ferdinand and Elmira, was published, however, her novel-writing career effectively came to an end when she married her second husband, Abiel Wood, and the couple moved to his home in Wiscasset, Maine. Wood (as her married name was now) stopped publishing fiction, but her considerable energies found other outlets. Most notably, in 1805 she helped found the Female Charitable Society of Wiscasset, one of the earliest women’s organizations of its type. Thus, in life, Wood embodied the same generosity and virtuous spirit that characterizes so many of her stories’ heroines.

After Wood was widowed a second time in 1811, she relocated to live near or with her children and grandchildren, moving between Portland, Maine, New York City, and ultimately Kennebunk, Maine, where she died in 1855 at age ninety-five. In the final third of her long life, Wood tried her hand at publishing fiction only one more time, with two novellas collected as Tales of the Night (1827). The literary scene in America had changed considerably in the two decades since

her previous books and for whatever reasons, Wood never published any more fiction (though a fair copy manuscript of an unpublished novella, War, the Parent of Domestic Calamity, is held by the Maine Historical Society). Even so, for all her life she remained a storyteller: over sixty extant manuscript letters to family and friends attest to Wood’s penchant and talent for telling tales and recounting family lore.

Such a legacy of storytelling as Wood’s is indicative of the larger history of New England, whose very fabric is woven with innumerable stories and legends. And in the region’s literary history, writers of Gothic tales seem always to have occupied a special place— whether it’s Stephen King of Bangor, Maine, Shirley Jackson of Bennington, Vermont, H.P. Lovecraft of Providence, Rhode Island, or Nathaniel Hawthorne of Salem, Massachusetts. When reflecting on this rich legacy today, we would do well not to forget that long before there were any of those now-famous others, there was Maine’s pioneering Gothic novelist, Sally Sayward Wood.

As our major fundraising event of the year, we hope you will consider Save the Date

Saturday, March 16, 2024

6:00 PM

For more than forty years, William Rawn Associates, Architects, has designed influential and groundbreaking buildings across Boston, New England, and the United States. Civic centers, cultural institutions, college and university buildings, spiritual buildings, and transformative renovations are among the firm’s projects, which have been honored with numerous awards for design excellence.

Earlier this year, William Rawn, Douglas Johnston, Clifford Gayley, and the firm itself decided to donate the firm’s archives to Historic New England. We are thrilled with their decision and enormously grateful to Bill, Doug, Cliff, and the firm for their generosity. Historic New England is honored to be the long-term stewards of this extraordinary collection of materials documenting the ongoing design process and intellectual contributions of William Rawn Associates (WRA) to the field of architecture. We are greatly excited by the breadth of insight this gift provides and look forward to adding additional records as the firm continues to grow the scale and complexity of its work for decades to come.

The acquisition of the archives of WRA significantly expands and enhances our collection of architectural records dating from the seventeenth century to the present and allows us to provide an even richer history of the region’s architecture to the public.

WRA designs buildings and places that embody American democracy through their accessibility and openness to all. Their buildings represent an architecture built on the values of civic engagement and equal opportunity that is concerned with creating timeless, beautiful, and welcoming places where individuals of diverse backgrounds can come together to find “Common Ground” and exchange ideas and experiences that promote social interaction, cultural accessibility, and diversity.

Central to WRA’s continuing success is its commitment to creating and celebrating places that are engaging and inviting to everyone. Through a process of discovery known as “Patterns of Place,” designers immerse themselves and learn about the particularities of what makes a specific campus or city place memorable and authentic. This immersion occurs long before a building shape takes form. As

founder Bill Rawn often describes, “Architecture is, without question, a public art…Architecture should not be self-centered or self-absorbed. Rather, it carries with it the responsibility of creating, responding to, and strengthening a sense of community. The principal concern of the architect, then, is how buildings relate to the public—its most important audience.”

In its early years, WRA’s projects included innovative affordable housing complexes around Boston. These projects instilled fundamental principles of community engagement, design excellence, and budget rigor in the firm that continue to permeate its design process today. In the late 1980s, Bill was joined by designers Doug Johnston and Cliff Gayley, which began a team that has worked together to develop and

Top Central Branch Transformation, Boston Public Library (completed 2016). Photograph by Bruce T. Martin. WRA renovated the Johnson building of the Central Branch to become a more welcoming space that is a place for lifelong learning and exploration. Bottom Cambridge Public Library, City of Cambridge, Massachusetts (completed 2009). Robert Benson Photography. This project included the preservation of the original library and a major new building featuring the first double-skin curtain wall of its type in the US, which allows for complete transparency while protecting from excess heat gain, loss, and glare. Ann Beha Architects was the associate architect for the project.

grow the firm for more than thirty years.

WRA’s breakthrough project came in the mid1990s when the firm was hired by the Boston Symphony Orchestra to design the new Seiji Ozawa Concert Hall at its Tanglewood campus in Lenox, Massachusetts. Upon completion in 1994, Seiji Ozawa Hall achieved significant recognition from music and architecture critics alike.

As evidenced by more than seventy-five projects at fifty liberal arts colleges and major research universities, higher education work is central to WRA’s identity. From its early masterplan projects at the University of Virginia, the firm continues to celebrate connections between campus and city that foster the democratic free flow of physical,

cultural, and economic forces. WRA’s designs also seek to integrate residential, academic, and student life buildings on campus with appropriate open space to form a unified community rather than specialized precincts. This approach has informed projects at many universities and colleges, including Duke, Stanford, Yale, Northeastern, Williams, Amherst, Swarthmore, and Harvard Business School among others.

Concert halls, performing arts venues, and convening halls continue to comprise a major part of WRA’s work through their commitment to creating places that are accessible and democratic. In each project, the firm works to promote intimate connections between audience and performer, as well as between fellow audience members. Some of the firm’s most significant projects include concert halls and performing arts centers at Strathmore, Tanglewood, Duke, Williams, Bowdoin College, and Pennsylvania State University.

Historically and currently, ninety-five percent of WRA’s projects have been for non-profit or public institutions. Projects range from affordable housing, federal courthouses, and libraries to public K-12 schools, universities, hospitals, and even spiritual buildings, including projects at Cambridge Public Library, Boston Public Library, courthouses in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and Toledo, Ohio, and civic buildings in many other cities and towns across the US.

The firm’s national recognition includes sixteen Honor Awards for Architecture, Urban Design, and Interiors from the American Institute of Architects; three Harleston Parker Medals for “Most Beautiful Building in Metro Boston” from the Boston Society of Architecture; a #1 Firm in the Nation ranking from ARCHITECT Magazine in 2009 (including seven Top Ten rankings from 2009-19); and more than 250 additional national, state, and local design awards.

The collection now housed at Historic New England includes comprehensive project files for nine signature projects, plus summary files for nearly twenty other influential projects from the region, and a dozen projects outside New England. The collection also contains lecture notes, sketchbooks, presentation slides, and published essays by the firm’s leadership.

Historic New England’s landscapes are filled with stories that are now at your fingertips for five of our most popular outdoor sites:

w The Codman Estate in Lincoln, Massachusetts

w Cogswell’s Grant in Essex, Massachusetts

w Hamilton House in South Berwick, Maine

w The Lyman Estate in Waltham, Massachusetts

w Watson Farm in Jamestown, Rhode Island

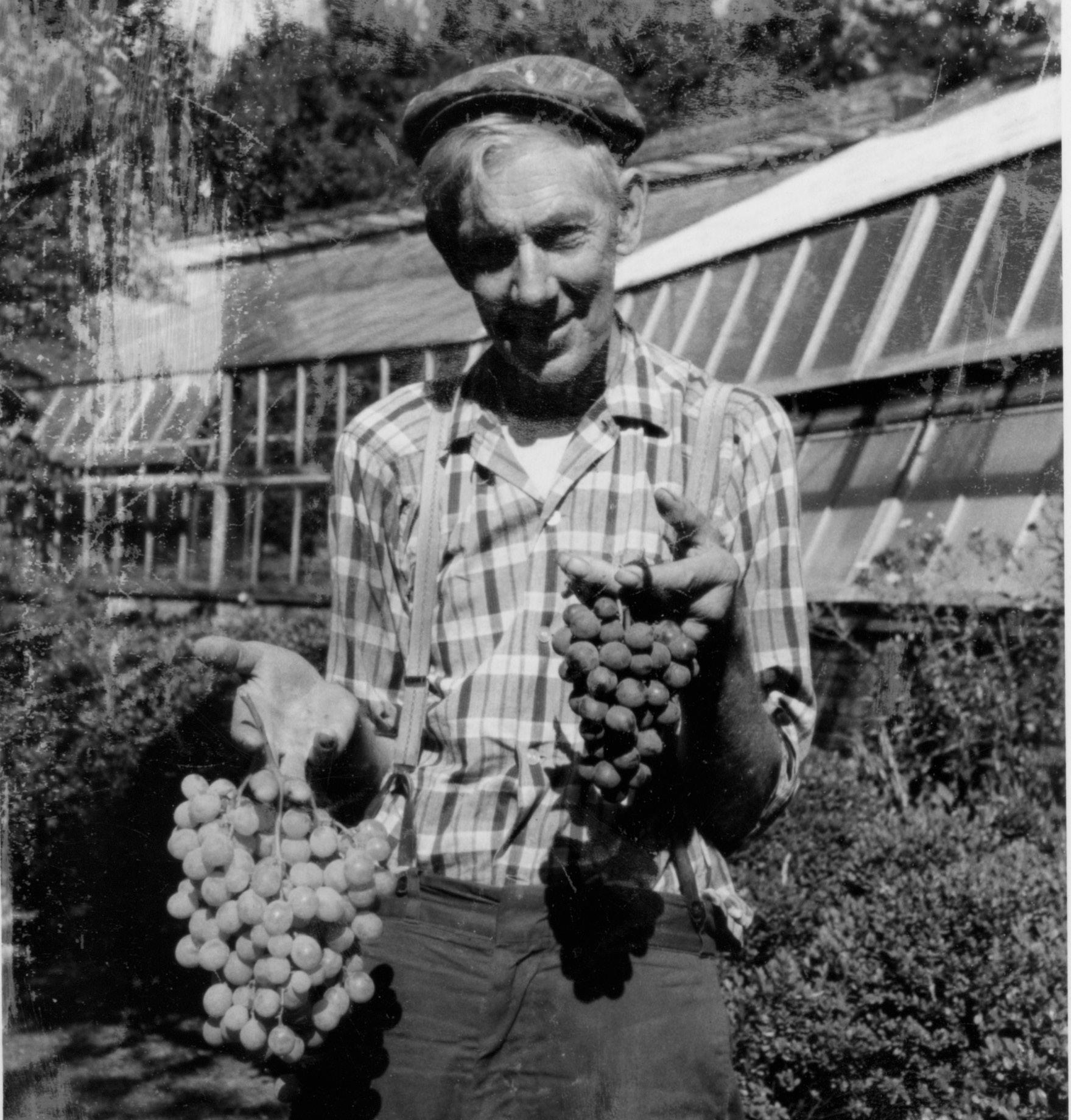

Whether you’re taking a self-guided tour while visiting or exploring from afar via our website, you’ll discover historic features such as the Codman Estate Italian Garden or the Lyman Estate peach wall and learn about their histories and origins. You’ll also find the stories of those who lived and worked on the land. At Hamilton House we tell the story of the Wabanaki, or "People of the Dawn," who called their home Quamphegan. At the Lyman Estate you'll meet Fritz Nelson (pictured at right holding grapes in front of the Lyman Estate greenhouses), son of Swedish immigrants, who worked on the estate as a gardener for more than fifty years.

Most Historic New England landscapes are open daily dawn to dusk and we welcome visitors for a leisurely stroll with friends, a dog walk, quiet contemplation, or to discover the wealth of stories the land has to tell.

To access your digital landscape tour, and all of our other digital tours, visit historicnewengland.org/ digital-visitor-experience/ or come explore on site where your outdoor experience is just a QR code away!

Fine art photographer, educator, and activist Archy LaSalle first came to Boston’s South End in the mid 1960s: