與眾共舞 DANCING WITH THE AUDIENCE

人人都有欣賞藝術的權利。把舞蹈畫面轉化為說話和描述, 讓不同能力和需要的朋友能一同享受舞蹈的美麗,反映發展 口述影像的重要性;不同持份者的參與,為潛在觀眾探討更 多發展的可能。至於疫後如何應對新的觀眾推廣策略,照顧 不同層面的需要,趕上社會的變化,台灣兩廳院的分享值得 參考。觀眾無處不在,讓我們以不同方式找到彼此。

Everyone has the right to enjoy the arts. When the visual medium of dance is translated into speech and description, it allows people with different abilities and needs to enjoy the beauty of dance. This shows the importance of developing audio description for dance, as enabling a wider range of people to participate reveals more possibilities for developing potential new audiences. The post-pandemic era calls for new audience development strategies that respond to the needs of different segments of the community as well as changes in our society. The insights on audience building from the National Theater & Concert Hall in Taiwan are illuminating in this regard. The audience is all around us. May we meet one another in different ways.

講好一場舞蹈:探討香港口述影像發展

WHAT MAKES GOOD AUDIO DESCRIPTION FOR DANCE:

EXPLORING THE DEVELOPMENT OF AUDIO DESCRIPTION IN HONG KONG

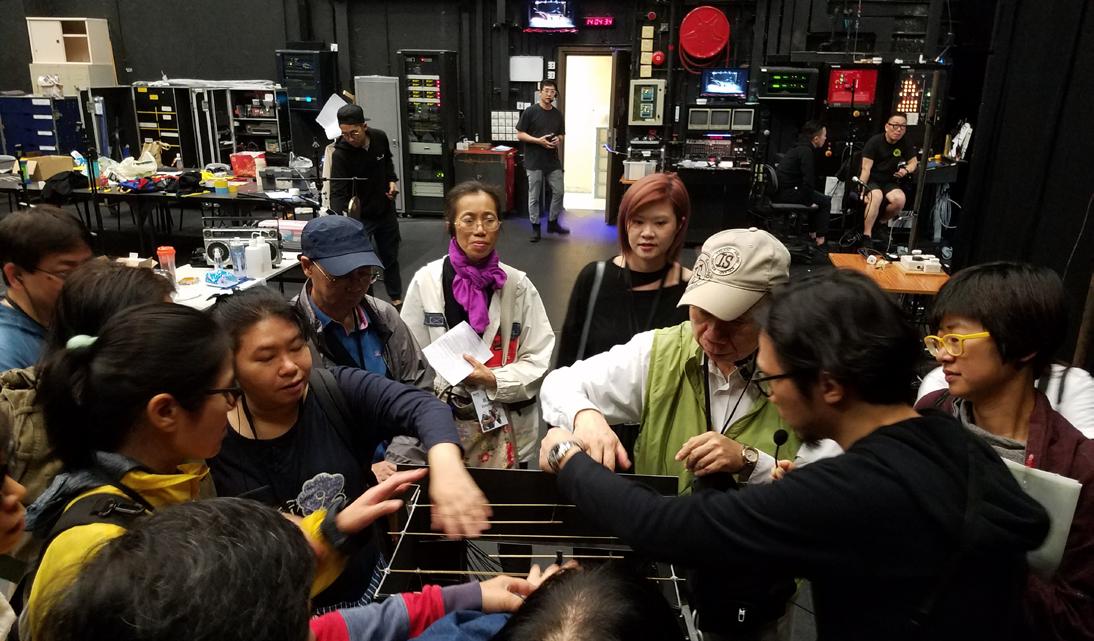

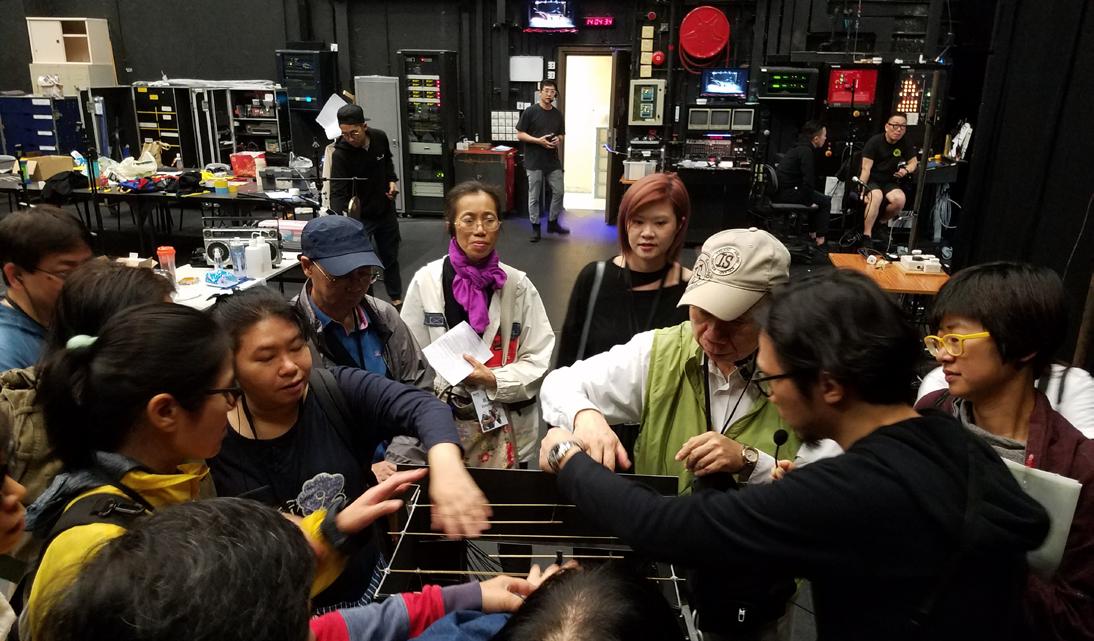

城市當代舞蹈團安排的演前導賞工作坊,讓參與者透過觸摸舞台設計的模型(觸感),了解表演空間的設計

當舞蹈欣賞對大部分觀眾來說是自然而然的事,如何令藝 術真正邀請不同能力和身體狀況的觀眾共同欣賞和參與,

是這個社會要一起關心的事。隨著本地不同組織如香港展 能藝術會、香港盲人輔導會等近十多年推動口述影像發展 的成果,透過政策倡議、爭取資源、持續培訓、教育推廣 等各方面,加強大眾對之的認識,特別是製作人、藝術家 和藝團的關注。多年從事口述影像服務與藝術策劃的顏素 茵( DD )本期訪問接受。她曾在發表於 2021 年 8 月《舞蹈手

札》第 23 ( 4 )期的文章〈不敢評論的困惑——《我的無限舞

台》口述影像舞蹈錄像〉內坦言:「在香港講平權是漫漫

長路,藝術通達服務是體現平權之舉,畢竟仍是要加以宣 傳的事,此舉起碼讓有需要口述影像的觀眾留意得到,如

有噱頭效果並非壞事。」

While dance appreciation comes naturally to most of the audience, there is increasing concern in society as to how the arts can genuinely welcome audiences of all abilities to appreciate and participate in arts events. Over the past decade or so, public awareness and in particular that of producers, artists and arts groups of this issue has been strengthened due to the efforts of various local organisations such as Arts with the Disabled Association Hong Kong (ADAHK), and the Hong Kong Society for the Blind (HKSB) in facilitating the development of audio description (AD) for visually impaired audiences through policy initiatives, striving for resources, continuous training, education and promotion, etc.

6 7 FOCUS 一 二 三月•Jan / Feb / Mar 2023

焦點 FOCUS

文:陳國慧

Text: Bernice Chan

Translator: Eva Kan

(照片由香港展能藝術會提供

Pre-performance workshop arranged by City Contemporary Dance Company, where participants could know the design of the stage space by touching the set design model (tactile)

Photo provided by ADAHK)

如以 2011 年香港展能藝術會獲賽馬會慈善信託基金的支持 下進行的「藝術通達計劃」為一個參考起點,這十年間從 有機會被視為噱頭,到業界與大眾都意識到藝術平權的重 要性,「漫漫長路」有很多朋友同行,即使知道還有一段 路要走。藝術通達計劃網頁列出 2011 年後由計劃提供口述 影像的舞蹈製作,早期主要是香港芭蕾舞團的公開綵排, 後來陸續有不同大小舞團作品參與。 DD在 2020年 9月透過西 九表演藝術教育創研計劃支持項目進行「香港通達劇場調 查計劃:跨越視覺障礙」並發表了研究報告,其中有關統

計,可見演藝口述影像的發展空間:「在 2011 年至 2019 年 期間,本地劇場為視障觀眾提供的口述影像服務場次總計

只有約 260 場,平均每年只有 28.9 場,與每年表演藝術節目 逾 6,000 場作比較,未及 1% 。」(頁 8),當中舞蹈作品佔不 足 15齣。

香港展能藝術會藝術通達計劃經理陳嘉賢表示,戲劇作品 相對受歡迎,有情節和故事脈絡的確是原因,舞蹈作品的 呈現有時難免抽象,因此初期選述的舞蹈作品都會是大家 較熟悉的故事和舞碼。身為 2008 年本地首批獲培訓的口述

影像員, DD 則娓娓道來當透過口述影像來呈現舞蹈這表演 形式時,在本質上最大的挑戰。她首先肯定的是縱然演藝 類型不同,但口述原則是相同的,就是「把(在表演空間 內)見到的說出來,並非詮釋,要以精準客觀的文字去描 述,令聽的人能有清晰的想像。」

然而最困難的,是如何追求口述影像和舞蹈動作同步,還 有對節奏的把握,「當動作已經完成,口述亦不能太慢」。

DD 笑言獨舞還可以「死跟」,但如果是群舞或編舞選擇整 個舞台空間都有活動發生,口述影像員就難以完全描述清 楚全貌。 DD 會反思如果自己是觀眾,其實在這樣的情況

下都要選擇的,因此她會替用家( user)去進行選擇,而在 這時就會思考,到底編舞希望觀眾見到的呈現會是甚麼:

「如果編舞是要表達紛亂的景象,就不要只集中描述單一

舞者的動態。」當我們經常在演後討論,聽到觀眾像追求 正確答案般問編舞其意圖時,編舞可能會想保留最大的想 像空間;然而當為舞蹈作品進行口述影像時,編舞意圖表 達的訊息和氛圍就顯得相當重要,能夠為口述影像員提供 最恰當的資訊讓他們能實踐口述原則。

舞蹈作品經常會介入即興元素, DD 說這些就要依靠口述影 像員多看、多思考和多揣摩:「舞台上有獨舞、群舞同時 發生,口述影像員要選擇焦點,或有不同考慮,但這些考

慮必須要和編舞想法貼近,並且要判斷描述的內容所需時 間。這不是隨便來的,否則對聽者造成干擾,對編舞亦不 公平。」

事實上,要順利讓舞蹈作品進行口述影像,主辦者和編舞 的共識是重要的,口述影像員要了解編舞的創作背景、使

用的身體語彙的特色等,最理想是能與編舞直接溝通,如

最近「自由舞 2023 」《女俠傳奇》的編舞,因其本身做口

述影像研究,所以 DD 很早就能與她溝通。至於藝團本身是 否意識口述影像的價值也是一環,她曾經參與過最豐富配

套的,是 2016 年天堂鳥劇團來港演出《米蘭達與卡里班:

惡魔審判日》,她與隨團口述影像員有機合作,演員甚至 錄音自我介紹,聽者在演出前已經認知角色的聲音了。

還有的是,編舞是否認知和相信口述影像, DD 說:「我理 解編舞會擔心,我們如何用文字來呈現原是跳出來的作品 ──的確在形式上是轉換了──肢體的表達加上劇場效果 如何被語言再現,這件事是複雜的,他們會覺得作品因此 變得平板沒趣,即使編舞開綠燈,但聽者是否明白和接收 到又是另一問題。」以文字再現舞蹈的複雜性,對舞評人 來說應該絕不陌生,甚至是書寫入門的必修課,看來有心 的舞評人可能別具條件參與口述影像呢。

然而,清楚表達、精準到位這些原則還是要把握,口述影 像員的文字功力未必有很大的創造性,反而是實用性較重 要。不過,舞蹈終究會較多抽象的呈現,對先天失明者來 說會不容易理解,如避用「飄」,或DD舉例芭蕾舞有很 多抬起或舉起的動作,「如直說男舞者托起女舞者──這 樣甚麼美感也沒有了,改用抱、舉或輕托這些字眼會較 好」。但保持用字淺白,同一用字盡量不要重複太多次, 否則聽者的想像也會沒變化:「要多思考靈活地用字,想 像聽者如何透過你的描述想像到豐富的畫面。」

DD 說大部分舞蹈的口述影像是要備稿的,因一旦抓不住那 瞬間數秒便會影響節奏:「(粵語)一秒約 3.5至 4個字,一旦

“There is a long way to go when speaking of equal rights in Hong Kong. Arts accessibility services embody equal rights and continue to need more promotion, through which we hope at least to attract the attention of audiences who need AD. Even if it’s perceived as a gimmick, that may not be a bad thing.” Dorothy Ngan So-yan, an experienced audio describer and arts administrator interviewed for this Focus piece, says frankly in the article “The Perplexity of Not Daring to Comment — My Unlimited Stage [Dance Video with Audio Description]” published in dance journal/hk 23-4 Issue in August 2021.

If we take ADAHK’s Arts Accessibility Scheme, supported by the Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust in 2011 as a starting point, equal access to the arts over the past ten years has progressed from being regarded as a ‘gimmick’ to being recognised as important by the arts sector and the public. There are a lot of companions on the ”long way”, even though we know there is still some distance to go. The Arts Accessibility Scheme website lists dance productions which have provided AD services under the Scheme since 2011. In the early period these were mainly Hong Kong Ballet’s open rehearsals, later on more dance groups and productions on different scales have gradually joined in.

Ngan conducted a study entitled “Research on Accessible Theatre in Hong Kong – Overcoming Visual Barriers” and

published a report in September 2020 with the support of West Kowloon Young Fellows Scheme (Performing Arts). The statistics shown in the report revealed room for development for providing AD services in performing arts:

“Between 2011 and 2019, the total number of local theatre performances which provided AD services for visually impaired audiences was only around 260, with an average of 28.9 performances each year. Compared to the total number of over 6,000 performances each year, this came to less than 1%.” (Page 8) and out of these less than 15 were dance productions.

The Arts Accessibility Scheme Manager of ADAHK, Chan Ka-yin, says that drama performances are more popular, as they have storylines, while the nature of dance works is inevitably often abstract. As a result, early on dance productions equipped with AD were narrative works or those that people are more familiar with. As one of the first batch of local audio describers who received training in 2008, Ngan explains what are the biggest challenges of using AD to describe dance. She first notes that even though there are different performing arts forms, the principle of AD is the same, that is “say what you see [in the performance space], not interpreting it but describing it in precise and objective words, giving clear information for the audience to use their imagination”.

8 9 焦 點 FOCUS 一 二 三月•Jan / Feb / Mar 2023

香港芭蕾舞團安排演前工作坊,在導師帶領下,參與者自己舞動身體,了解作品內的主要動作 Pre-performance workshop arranged by Hong Kong Ballet, where participants moved their bodies to understand the main movements of the work under the guidance of the instructor(照片由香港展能藝術會提供 Photo provided by ADAHK)

However, the most difficult thing is how to synchronise AD with dance steps, and also the grasp of rhythm, “when the movement is completed, the AD cannot lag behind”. Ngan says jokingly that AD can still ‘closely follow’ a solo dance, but if it is a group dance, or the choreographer chooses to fill the whole stage with movement, it is difficult for the audio describer to convey the full picture. Ngan reflects that if she was in the audience, she would also have to make choices of what to look at in this situation, and therefore she would help the AD user to choose. When doing this, she thinks about what the choreographer would like the audience to see: “If the choreographer would like to display a chaotic scene, the AD should not be focused on an individual’s movement.” During meet-the-artist sessions, we often hear audiences ask about the choreographer’s intention, as if hoping to receive the ‘right’ answers, while the choreographer may want to leave room for audiences to use their imagination as much as possible. However, when applying AD to a dance work, the message and vibe that the choreographer intends to portray become crucial in order to provide the most suitable information for the audio describer to practise the principle of AD.

Improvisation is common in dance works, and Ngan says audio describers frequently need to watch, think, and surmise: “Solos and group numbers can take place at the same time on stage, and the audio describer has to decide what to focus on, or, when taking different things into consideration, those considerations must be close to the choreographer’s thoughts, plus the describer also needs to determine the timing of the description. These are not casual decisions, otherwise it will be unsettling for the audience as well as unfair to the choreographer.”

In fact, consensus with the choreographer is important to create effective AD for a dance work, as the audio describer

needs to have information such as the background of the work and the movement style of the choreography. Direct communication with the choreographer is ideal. For example, the choreographer of Freespace Dance 2023: She Legend does AD research herself, so Ngan was able to communicate with her at a very early stage. It also matters whether the arts group itself is aware of the value of AD. The performance with the most comprehensive ancillary services that Ngan has participated in is Birds of Paradise Theatre Company’s Miranda and Caliban: The Making of a Monster, an overseas production staged in Hong Kong in 2016. She worked organically with the audio describer who was accompanying the company. The actors even made recordings introducing themselves, so that the audience could learn to recognise the voices of the characters before the performance.

Another question is whether choreographers understand and believe in AD. Ngan says, “I understand that choreographers would worry how we use words to present a dance work—the form is undeniably changed— reproducing body movement together with theatrical effects in language is complicated. They think the work may become dull and uninteresting. Even if the choreographer gives the green light, another problem is whether the audience could understand and perceive it.”

Nonetheless, audio describers still need to grasp the fundamental principles of AD—being clear and precise. They may not use too much creativity in their language, as practicality is more important. Dance, however, has more relatively abstract forms, which are not easy to understand for people who are born blind. For example, the word ‘float’ should be avoided. Ngan also notes that in ballet, where there are many lifts,“If we say the male dancer lifts up the female dancer—the beauty is lost. It would be better if we

11 FOCUS 一 二 三月•Jan / Feb / Mar 2023

顏素茵在控制室為劇場演出提供現場口述影像服務

Dorothy Ngan providing live audio description service for a theatrical performance in the control room (照片由顏素茵提供 Photo provided by Dorothy Ngan)

失神落差了幾秒有可能窒礙聽者接收,以舞蹈來說,一分

鐘不間斷的動態表演,要用一小時寫首稿,往後不斷修改 完善。」至於如何講出節奏感,她說要懂得計算拍子,與 音樂配合,或可以四字、五字或七字發展句子:「當然口 述影像員本身要投入,當表演者慢慢移動,你的語氣也要 配合。」能找到這種「共感」對口述影像來說相當重要。

對聽者來說這種「共感」又如何找到?近年舞蹈口述影像 也有不同程度的發展值得進一步開拓。陳嘉賢表示自五、 六年前,他們參考了海外舞團的做法,為視障朋友舉辦演 前工作坊,讓他們透過舞動身體了解作品內重要的動作和 所用的力量,或讓他們觸摸戲服,感覺物料的輕重,更多 元地了解該舞蹈作品的構成; 2021 年為進行香港舞蹈團製 作《媽祖》口述影像影片,甚至安排在放映會前參觀香港

仔天后廟,這樣的配搭在不同持份者的努力下,令舞蹈的 美麗體現在不同社群裡。

回想初期先從香港演藝學院舞蹈學院的畢業展開始,與學 生探索與舞作相關的觸感工作坊,陳嘉賢表示從學院開始 是希望透過讓學生了解舞蹈如何透過不同方式呈現,以致

更多觀眾能共享,播下這些理念的種子,對未來不論是口 述影像或是其他通達方式的發展是大有幫助。

另一發展進路是培養口述影像員。 DD 表示當年在香港受訓 時,在有限節數內蜻蜓點水地認識口述影像在所有藝術範 疇的應用,但近年主辦者考慮不同範疇在口述策略與進路 上的差異,就有意識地分開視覺藝術、表演藝術等由不同 的專家提供訓練,同時口述影像員亦自動分了組,專注進 行較熟悉或擅長的藝術範疇。這樣的發展既保持口述的質 素,同時讓口述影像員更聚焦去累積經驗,長遠來說對聽 者來說是有效益的。

DD 表示訓練必須包含實習,而香港的口述影像課程近年亦

開始規範化與系統化,相對於早年較寬鬆的做法,儘管已 受訓但學員水平難免較參差,而他們是否有「時間、熱誠 和能力投入服務」是很大疑問。因此訓練的規範化與系統 化,長遠令學員可持續投入服務的條件提高。DD舉例盲人

輔導會專門舉辦電影口述影像課程,最近的一年制課程就 很完善,包括在錄音室錄音、訓練聲線,還有實習和導師 跟進;香港展能藝術會亦是先行者,結合海外導師的授課 與本地導師的後續跟進,畢竟懂粵語的導師才能較準確地 了解本地語彙和語言節奏。

事實上除了與編舞溝通、備稿和看綵排外,一個演出多數 只由一位口述影像員負責,換人意味聲音的轉變,聽者要 重新適應,並不理想。因此口述影像員的付出真的不少, 而參與口述影像的工作也是一種承擔。當然這種承擔要 讓業界來分擔不同角色。隨著業界意識藝術通達的重要 性,DD覺得藝團的行政人員和製作人,可以多了解本地 不同能力與需要的觀眾的分佈和構成,主動接觸不同組織 探索更多潛在的觀眾,以制定恰當的推廣策略與配套,讓 所有人能平等地享受藝術。這願景需要不同持份者繼續澆 花,讓藝術的香氣恆久散發。

參考資料 「香港通達劇場調查計劃:跨越視覺障礙」研究報告: https://www.westkowloon.hk/tc/youngfellows-2019-awardedfellows

use expressions like ‘carry (her) in his arms’, ‘raise’ or ‘lift lightly’ ”. You must remember to use plain language and try not to repeat the same word too many times, or the audience's imagination will not be inspired: “You need to think more about using a variety of words, to imagine how you can convey a rich picture to the audience through your description.”

Ngan says that for most audio described dance works, a script is prepared, because once a few seconds are missed, that will affect the rhythm: “It is around 3.5 to 4 words per second (in Cantonese), if one misses a few seconds, that might affect the reception by the audience. For dance, writing the first draft of a one-minute performance with non-stop movement takes an hour, followed by continuous amendments and refinements.” As for finding ways to deliver the sense of rhythm, she says one needs to know how to count the beats and speak in time with the music, or articulate a sentence in four, five, or seven words: “Of course the audio describers have to be engaged themselves. When the performer moves slowly, you need to match that.” It is really important to find this ‘shared sense’ when doing AD.

As for the audience, how can they find this ‘shared sense’?

In recent years, AD for dance has undergone a number of different developments worthy of being taken further. Chan mentions that five to six years ago, they started to take reference from overseas dance groups and hold pre-

performance workshops for visually impaired audiences, where participants could move their bodies to understand the main steps and the energy required in the dance piece, or touch the costumes to feel the weight of the fabrics, thus giving them a fuller understanding of the composition of the work. In 2021, for the production of the AD for Hong Kong Dance Company’s Mazu the Sea Goddess, a visit was arranged to Tin Hau Temple in Aberdeen before the screening, in which the efforts of different stakeholders brought the beauty of dance to life for different communities.

Chan recalls that early on they started with a graduation exhibition at the School of Dance of the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts, exploring touch workshops related to dance with the students. Chan says they started with the Academy with the aim of planting seeds for the future by letting students learn how dance can be presented in different ways and shared by more audiences, so as to benefit the development of AD or other accessibility services in the future.

Another area of development is the training of audio describers. Ngan says when she received training in Hong Kong in the early days, she briefly learned the application of AD for all art forms through limited sessions, while in recent years, considering the differences in AD strategy and development for different art forms, organisers have consciously separated visual art and performing arts and

12 13 焦 點 FOCUS 一 二 三月•Jan / Feb / Mar 2023

作者

國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)總經理,策劃超過五十個本地和國

陳國慧

際藝評項目。

陳國慧與顏素茵就香港口述影像的發展進行對談 Bernice Chan in conversation with Dorothy Ngan about the development of audio description in Hong Kong (照片由國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)提供 Photo provided by International Association of Theatre Critics (Hong Kong))

在香港舞蹈團演出前的導賞工作坊,參與者透過觸摸表演服飾,探索不同質感在舞台上的呈現,有助了解作品內容

Bacchus 會先要他們思考舞者跑過舞台時空間構成的變化,

和舞者與舞者之間的能量,這些都會產生出設計的創意。

assigned different experts to provide training. Also, audio describers are split into groups to focus on the art forms they are more familiar with or more skilled at. This kind of development maintains the quality of AD, as well as allowing audio describers to focus on accumulating experience, which will benefit audiences in the long term.

Ngan says training must include practice, and the AD courses in Hong Kong have become more standardised and systematic in recent years, compared to the less rigorous methods in the early days. Even if the students are trained, the quality of their work inevitably varies, and whether they have sufficient “time, passion and capability to commit to the service” is always a big question. Therefore, making the training more standardised and systematic in the long run can improve sustainable service delivery. Ngan gives the example of the “Audio Description Training Programme of Film” organised by HKSB, saying that its recent elementary and advanced courses are more comprehensive than the previous ones, as they include professional recording training and vocal training, as well as internships and mentorship; ADAHK is also a pioneer, combining teaching by overseas tutors with follow-up by local ones, as tutors who speak Cantonese have a more accurate understanding of the vocabulary and rhythm of the language.

後疫情時代的超前部署 PLANNINGFORTHEFUTUREINTHEPOST-COVIDERA

NATIONAL THEATER AND CONCERT HALL : CONNECTING WITH AUDIENCES THROUGH ART PROMOTION

國家兩廳院於1987年落成,為台灣表演藝術劇場指標性場 館,兼容台灣內外大型製作與實驗性展演。在節目策劃之

外,藝術推廣與會員經營等公共溝通也是兩廳院的重點工 作,此兩項目長年的經營,也在疫情期間為兩廳院維持穩定 的觀眾能量。

Bacchus 以曾經參與過的一個蒙古舞蹈作品為例,當時他

In fact, in addition to communicating with the choreographer,

一直不明白為何要用輕質布料,而且服裝要做得鬆身,這 與印象中的大漠服飾好像有差;但原來當舞者在舞台上躍 動,空氣流動令布料鼓起來,就恍如人在草原上騎馬的奔 騰之感:「這不完全是寫實的,而是浪漫化了的動作和意 象。」這鮮活的例子也呼應了 Bacchus認為,舞蹈服裝設計 者其實更重要的角色,是一位協進者( facilitator):「設計 師有時會很想讓大家見到設計本身,設計是我的,表演是 舞者的,編排是編舞的,但這樣的割裂對作品來說不是好 事,我們應該要協調呈現作品的整體性(totality)。」

preparing the script and watching rehearsals, an individual audio describer is responsible for the whole of each performance, as switching audio describer would mean obliging the audience to adapt to a new voice, which is not ideal. Therefore, being an audio describer means putting in a lot of effort and participating in AD services requires a serious commitment. Of course the commitment to AD needs to be shared by different players in the industry. With the rising awareness of the importance of arts accessibility, Ngan thinks that arts groups should seek to learn more about the distribution and composition of local audiences with different abilities and needs. They can then reach out to various organisations to explore building potential audiences and formulate targeted promotion strategies and support services, so that everyone can enjoy the arts equally. This vision of accessibility is a flower that needs to be watered continually by different stakeholders, so that the fragrance of the arts does not fade.

Reference Research report on “Research on Accessible Theatre in Hong Kong – Overcoming Visual Barriers”: https://www.westkowloon.hk/tc/youngfellows-2019-awardedfellows

目前兩廳院下設八個部門,分別負責節目企劃、演出技術、 業務發展、公共溝通等業務。其中公共溝通部涵蓋公關、行 銷、會員與藝術推廣等四個組別,是廳院對外溝通的主要部 門,不僅面對買票觀眾,也會面對進到場館的民眾,涵蓋 面相廣泛。公關組主責議題、媒體與品牌操作;行銷組則是 專營節目銷售。會員組對應到經營兩廳的核心觀眾,以會員

Completed in 1987, the National Theater and Concert Hall (NTCH) is the key venue for performing arts in Taiwan, staging large-scale productions and experimental work from both Taiwan and overseas. In addition to programme planning, the NTCH gives high priority to art promotion and membership management, something which helped to keep audience numbers stable during the pandemic.

The NTCH has eight departments. Among them are Programming & International Development, Technical Management, Business Development and Communications. The Communications Department covers four areas: public relations, marketing, membership and outreach,

14 15 焦 點 FOCUS

Writer Bernice Chan Bernice Chan is the General Manager of the International Association of Theatre Critics (Hong Kong). She has curated over 50 local and international projects about performing arts criticism.

嚐劇場《韓德爾先生,您好!》親子說故事(

(照片由國家兩廳院提供

一 二 三月•Jan / Feb / Mar 2023

國家兩廳院:以藝術推廣建立與觀眾的連結

文:黃馨儀 Text: Huang Shin-yi Translator: Laura Chan

2022)Bon Appétit Theatre's Hello, Mr. Handel! Story Time for Kids (2022)

Photo provided by the National Theater and Concert Hall)

At the pre-performance workshop of Hong Kong Dance Company, participants touched the costumes and explored the appearance of different textures on stage, which was helpful in their understanding of the content of the dance work(照片由香港展能藝術會提供 Photo provided by ADAHK)

制直接和會員產生互動。藝術推廣組主要透過教育推廣的方 式,進行觀眾開發,試圖去跟最多的觀眾接觸,讓更多人可 以接觸表演藝術。

除了觀眾觸及,兩廳院也是希望逐步推進、進行觀眾養成。 現任公關組組長,並曾為藝術推廣組組長的蔡宛凌表示公共 溝通部的工作是層層的銜接和洗選,維持不同的群眾黏著需 求:「有些人參加完活動可能對節目產生興趣,進而成為節 目觀眾;有些則不一定想看節目,但會透過參與周邊活動、 使用圖書館等,與場館保持某種程度的關係,而某些人或許 會成為忠實會員。」

蔡宛凌於2015年進入兩廳院任職,進入較新成立的教育推廣 部活動組。而後經過幾次組織改制,2020年藝術推廣業務與 表演藝術圖書館業務結合,成立藝術推廣組,希望能連結圖 書館資源,成為民眾認識表演藝術的渠道,更專注於分眾推 廣與圖書館經營。

對宛凌而言,分眾推廣目的不在分別民眾:「我們知道每個 年齡層或族群,習慣接觸藝術的方式或是內容多少有所不 同,因此針對該年齡層或族群,希望找到最合適的方式跟他 們溝通。尤其對沒有接觸過表演藝術的民眾,要怎樣進到表 演藝術的世界裡面?」

目前藝術推廣的對象上分為親子、學生、樂齡三大族群,同 時也回應台灣文化部所推行的文化平權理念。兩廳院從疫情 前就開始工作文化平權與共融概念,不管是節目類型或是場 館設施,都一直在創造能使不同族群進到廳院的方式。最近

更以成為永續共融場館為目標,思考怎樣可以讓藝術文化場 館能更好、更持續地發展下去。在過去的實踐累積之下,疫 情反倒成為一個學習的機會,讓兩廳院更能有彈性去關注社 會變化與脈動,也迅速因應疫情做調整。

2020年初,台灣開始受到新冠肺炎影響,並於2021年5月開 始近三個月的封城,在2022年開始與疫情共處,進入後疫 情時期。面對疫情對於表演藝術界的衝擊,兩廳院亦首當其 衝,然而卻也因為多年的會員經營與藝術推廣累積,雖然增 加推票難度,但初步來看,並沒有直接造成觀眾樣貌的大幅 變化。

談及疫情的影響,蔡宛凌覺得還可再持續觀察,以蒐集更多 數據。即使疫情對產業衝擊很大,但台灣現在也才進入疫情 後的第一年,無法具體看出後續變化。台灣現階段的許多討 論都仍對應著疫情前的狀態在進行,但到底我們可不可以回 到疫情前?蔡宛凌引用總監劉怡汝的話:「世界的劇場已 經不一樣,經歷過疫情、戰爭、種族與性別覺醒的種種運動

之後,身為劇場一分子的大家都知道,我們再也沒有『疫情 前』的劇場可以回去了;或者,可以更精確地這麼說:我們 不打算『回去』了。我們回不去是因為心變大,看世界也不

一樣了。邀請大家跟我們一起看世界,跟我們迎接下一個更 美好的世界!」

and is the NTCH’s main channel of external liaison. The Public Relations Section handles public affairs, media and branding, while the Marketing Section handles programme sales. The Membership Management Section interacts with audiences through membership schemes, while the ArtReach Section seeks to develop new audiences through education and outreach, and to expose as many people as possible to the performing arts.

Thus, in addition to connecting with existing audiences, the NTCH aims to gradually nurture new audiences. Tsai Wanling, Director of Public Relations and former Director of ArtReach, says that the Communications Department uses a variety of elements to serve the needs and encourage the loyalty of different audience groups. “Some might become interested in our programmes after attending an event, some are not interested in performances and would rather maintain a bond with the venue through going to other events and visiting the library, while others become loyal members.”

Tsai started her career at NTCH in 2015, when she became part of the newly-established Education and Events Section. After several restructurings, in 2020 the art promotion team merged with the library of performing arts to form the ArtReach Section, using the library as a means of outreach and focusing on segment promotion and library development.

To Tsai, segmentation does not mean differentiating between sections of the public. “Different age or cultural groups have different approaches in terms of interacting with art, and therefore we want to find the most suitable way to communicate with each of them. How can we best help people to discover the world of performing arts, especially those who have never experienced it?”

Currently the target audience can be divided into three groups: parents and children, students and senior citizens, which also matches the Taiwan Cultural Department’s emphasis on cultural equality. Before the pandemic the NTCH had already started to work on cultural equality and

16 17 焦 點 FOCUS

一 二 三月•Jan / Feb / Mar 2023

兩廳院《感覺超能力親子音樂課》Parent-child music lessons(照片由國家兩廳院提供 Photo provided by the National Theater and Concert Hall)

而在藝術推廣的現場也是如此,細數這幾年的實踐經驗,藝 術推廣對於蔡宛凌而言不僅有觀眾觸及的目的,更是建構觀 眾與表演藝術關係的重要方式:「假設我們觸及到的是第一

次接觸表演藝術的觀眾,那我們在做的這件事情就會是他們 接觸的印象。他們怎麼認識這件事情、從哪一條路徑進來, 會影響這些人怎麼跟表演藝術維持關係。」

因此,藝術推廣組的活動設計著重在後續影響的發酵,並依 據實踐的觀察,每兩年調整一次策略方向。以樂齡族群來

說,起初以工作坊為主要方式,讓大家來認識朋友與學習。

後來則希望打破既定參與的群體、讓其他社區的長者也能參 與,所以有了OUTREACH計畫,開始走出兩廳院辦理活動。

之後又因為發現長者對青年世代的好奇,有溝通交流的想 法,2020年起有了青銀有約與青銀共創的設計,讓長者與青 年能藉由劇場活動深刻討論議題。

保持開放、回應社會,作為台灣代表場館的兩廳院,將以此 態度,持續作為創作者與民眾的橋樑、推廣藝術、觸及群 眾,穩健面對後疫情時代的來臨。

inclusivity, and made efforts to ensure different groups were able to enjoy its programmes and facilities. Recently, they have been working on the goal of becoming a more sustainable and inclusive venue moving forward. The pandemic became a learning opportunity, making the departments more flexible in observing and responding to social trends and community needs and making adjustments quickly .

Taiwan has been affected by COVID-19 since early 2020 and had a 3-month-lockdown in spring 2021, finally entering the post-pandemic period in 2022. Although the NTCH felt the impact of the pandemic, due to its robust membership base and many years of art promotion, despite initial challenges in terms of ticket sales, its audience landscape was largely unaffected.

the real effect of the pandemic on the industry can be determined, as Taiwan has just entered its first post-COVID year and it is not yet possible to get a clear picture. Many ongoing discussions in Taiwan are still based on prepandemic experiences, but is it possible to go back in time?

Tsai quotes NTCH’s artistic director Liu Yi-ru, “The world’s theatres are no longer the same after all the upheavals brought about by the pandemic, war, and ethnic and gender awakening movements. As part of the industry we all know that there is no longer a “pre-pandemic” theatre for us to go back to, and we are not going back anyway. Our hearts have grown bigger and our horizons broader and we see the world differently. We invite everyone to see the world with us and welcome a better world together.”

作者 黃馨儀 德國羅斯托克音樂與戲劇學院,戲劇教育碩士;國立臺灣大學中國 文學系學士。現為應用劇場工作者與評論人。 2015 年回台後,持 續以戲劇作為媒介,接觸群眾、開啟對話,探索自身與周邊議題。

Tsai feels that more data will have to be gathered before

The same thinking applies to art promotion. Reflecting on the experiences of the past few years, Tsai feels that the goal of art promotion is not only to boost audience

18 19 焦 點 FOCUS 一 二 三月•Jan / Feb / Mar 2023

表演藝術圖書館 NTCH Performing Arts Library / 攝 Photo : 丰宇影像 YUCHEN CHAO Photography (照片由國家兩廳院提供 Photo provided by the National Theater and Concert Hall)

「廳院學計畫」在新北市林口國民中學的當代音樂課

numbers, but also to build the public’s relationship with the performing arts. “What we do affects the first impression of the performing arts for those who are new to them, and in turn their future relationship with the performing arts.”

With this in mind, the ArtReach Section designs its events with a focus on making a long lasting impact on the audience, and adjusts its strategies every two years based on what it observes. For example, workshops set up for elderly people were originally intended for them to meet their friends and learn about the arts. Later, participation was expanded to include elderly people from other communities in order to broaden the mix of participants. This developed into the OUTREACH programme. Eventually it became apparent that the elderly were curious about the younger generation and wanted to have contact with them. As a result, starting in 2020 Intergenerational projects were designed for elderly

決戰 2024巴黎奧運——

香港霹靂舞代表隊遠征 出戰奧運資格賽

受訪:B-Boy MC Fat Joe、B-Boy SoulGreen 訪問及文字整理:《舞蹈手札》編輯部蔡曜鴻

and young people to have in-depth discussions through participating in theatre activities together.

As Taiwan’s iconic venue, NTCH continues to be open and responsive to society. It acts as a bridge between creators and the public, promotes art and connects with audiences while moving forward in the post-pandemic era.

2020年國際奧委會宣佈霹靂舞(Breaking)成為 2024年巴黎奧

運會的新項目,屆時一眾舞迷將一同見證霹靂舞於奧運會首 次亮相的歷史時刻。為了解更多霹靂舞文化以及霹靂舞賽事 的資訊,《舞蹈手札》編輯部有幸邀請到香港霹靂舞界傳奇

人物,同時身兼香港體育舞蹈總會霹靂舞臨時委員會成員

的B-Boy MC Fat Joe,以及香港霹靂舞代表隊成員之一——

B-Boy SoulGreen,分享經歷與感受,宣揚霹靂舞文化。

蔡:國際奧委會於 2020年宣佈新增霹靂舞為 2024年巴黎奧運 會的新項目。此舉無疑引起社會大眾關注,令香港霹靂舞文 化更上一層樓。作為香港霹靂舞界的前輩,能否介紹一下霹

靂舞的元素、特色,以及有別於其他舞蹈的地方嗎?

Joe :首先,感謝《舞蹈手札》的邀請進行訪問。霹靂

舞的特色在於舞蹈系統的構成,包括站立式的舞步

TopRock ,亦有講求排腿動作的 Footwork ,還有涉及靜

止動作的 Freeze 。除了基本的元素外,還有一些高難度的

轉動元素如 Powermove,包括了 Windmill、 Flare等動作,就

像體操的湯馬斯迴旋(Thomas Flare)。霹靂舞在練習及交流

上有不少獨特之處,舞者之間會進行一種名為 Cypher 的交 流,在音樂播放期間,不同舞者會圍成一個圓圈,各自演練 自己的舞步。 Cypher不單會出現於練習上,亦會出現在比賽 之中。這些都是霹靂舞者較為獨特的交流方式。

蔡:香港的霹靂舞代表隊目前由哪些/哪個單位負責以及提 供支援?

Joe:香港霹靂舞代表隊目前由香港體育舞蹈總會以及其轄 下的霹靂舞臨時委員會負責統籌霹靂舞代表隊賽事,並提供 各方面的支援。

蔡 :去年香港體育舞蹈總會一共舉辦四輪霹靂舞選拔積分 賽,並選拔出6男6女作為香港代表隊成員,將參戰 2 月於日 本九州舉行的Breaking For Gold World Series賽事。眼見一 連串國際賽事逐漸逼近,訓練的方式以及隊員的心態上會有 所調整嗎?負責單位會如何支援選手?

Joe :每一次國際霹靂舞賽事均有不同的提名以及提名名

20 21 焦 點

NTCH Open School

一 二 三月•Jan / Feb / Mar 2023

programme in New Taipei Municipal Linkou

Junior High School / 攝 Photo 周嘉慧(由國家兩廳院提供 Photo provided by the National Theater and Concert Hall)

OBSERVATION

B-Boy SoulGreen(照片由SoulGreen提供)

Writer Huang Shin-yi Huang Shin-yi graduated with a Master of Theatre Education from Rostock University of Music and Theatre in Germany and a Bachelor of Chinese Literature from National Taiwan University. She is now an applied theatre worker and commentator. Since her return to Taiwan in 2015, she has continued to use drama as a medium to reach the public, initiate dialogue, and explore herself and social issues.

額,這次將由 3 男 3 女霹靂舞代表隊成員出戰 2 月的賽事。這 次的訓練方式有別於以往,我們賽前先於日本進行集訓,增 加高強度訓練,讓代表隊成員盡早適應比賽節奏。

我們希望將來能引入不同的訓練模式,甚至到訪不同國家參 與訓練營,所以現時不斷為選手爭取更多資源,尋找合適的 贊助商資助旅費及提供各式各樣的援助,幫助代表隊成員出 國比賽。

蔡:可否簡單講述一下霹靂舞比賽的評分準則?

Joe:現時國際霹靂舞比賽中常見的評分準則是 Trivium ,香 港本地比賽則使用 OMEGA的評分系統,類似於Trivium,透

過身(Body)、心(Mind)、靈(Soul)三個範疇作評分準則。

詳細準則可於世界運動舞蹈總會細閱。

蔡:香港的霹靂舞起步早於台灣、日本,但基於社會文化問

題,加上近年不少經濟和社會活動受疫情影響,某程度上限

制了香港的霹靂舞發展。你如何看待霹靂舞成為奧運項目?

你認為香港的霹靂舞運動員能夠追趕,甚至超越世界級的霹

靂舞運動員嗎?

Joe :事實上,香港的霹靂舞起步較日本慢。早於八十年

代,亞洲地區先從日本興起霹靂舞風潮,然後到台灣、 香港。本地一直存在不少霹靂舞者,令霹靂舞文化得以萌

芽, 2000年代初本地各大網上論壇均有提及霹靂舞晉身成為

奧運項目的可能性。二十多年後,霹靂舞終於成為正式的奧

運項目,證明世界各地霹靂舞者的努力得到認可,令大眾更 容易接受霹靂舞文化。霹靂舞技巧不外乎於練習,但在創意

上,香港霹靂舞運動員更勝一籌,生活於資訊發達的城市令

他們能有系統地將自身的創意發揮得淋漓盡致,呈現不同的 想法。因此我相信香港霹靂舞運動員水平能夠超越世界級霹 靂舞運動員。

蔡:霹靂舞源於街頭,強調自由奔放。但香港一直以經濟利 益掛帥,不少街頭文化難以立足於大廈聳立的鋼筋森林之

中。在推廣香港霹靂舞文化的路上,你們遇到的最大障礙是 甚麼?

接觸到霹靂舞,或者是近年的 K-pop,亦有很多帶 Hiphop元 素的音樂能夠打入主流文化市場。但文化產物原本就容易被

人遺忘,畢竟香港是商業社會,因此長時間的堅持,將會是 霹靂舞文化發展不可或缺的因素。只要在發展路上仍然堅持 發掘更多可能性,相信不會有太大障礙。

蔡 :你曾經到訪不少國家出席 B-Boy 活動,當中最深刻、最

具有 B-boy特色的國家是哪一個?你認為香港跟外地的 B-boy 文化有著怎樣的差異?

Joe:很多不同國家均有大型而歷史悠久的霹靂舞活動,例

如韓國 R16 國際街舞大賽,由韓國旅遊發展局鼎力支持, 系統比較完整。此外亦有荷蘭海爾倫國際嘻哈舞蹈節 The NotoriousIBE ,由舞蹈節與當地市政府合辦,由市政府提 供大量空間作比賽之用,猶如霹靂舞的主題樂園。內地的

Keep On Dancing(KOD)同樣是非常宏大的賽事,能容納

超過一千人參與,涉及不同的舞種演出,包括霹靂舞和鎖舞

(Locking)等等,不少舞者慕名而來。香港雖作為文化共融 的社區,但一直缺乏長期推動霹靂舞文化發展的項目,希望 日後能看見本地舉辦此類大型舞蹈活動。

蔡:最後,有不少對霹靂舞有興趣人士以及喜好者均渴望成 為霹靂舞運動員。可否向他們,或即將出戰的霹靂舞運動員 分享心得,給予他們相關建議?

Joe:不論初學者、熱衷霹靂舞人士、資深舞者等等,長時 間的堅持最為重要, Hiphop 文化中有一項宗旨「 alwaysa student」,意指永遠保持一顆學習的心,對自身以及日常練 習絕對有幫助。另外,必須時刻認清自己的目標,選擇一些 可持續的方式學習霹靂舞,用一個詞語概括——努力!

蔡:可否簡單描述一下你投身霹靂舞的年資以及經歷嗎?

SoulGreen :我從 2007 年開始投身霹靂舞,已經十五年有

多。當時資訊並不流通,只能到公園看舞者表演,藉此認識

街舞。這也是香港的 B-boy 文化。霹靂舞改變了我的生活,

小時候抱著玩樂的態度接觸街舞。但很快我就從霹靂舞中找

到不少成功感,到後來一個星期練習四至五天,不眠不休地 跳舞,心態轉變很大。疫情前,我在香港的成績已不俗,偶

爾會到外國參加比賽,漸漸得到更多認可,亦見識到不同國 家的街舞文化。尤其是當有外國舞者欣賞自己的演出,會令 我加倍努力。

蔡:讓你接觸霹靂舞的契機是甚麼?有甚麼令你一直堅持身 為霹靂舞者?

SoulGreen:當時受到熱愛舞蹈的哥哥感染,加上街頭有不

Joe:在推廣香港霹靂舞文化的路上曾出現過幾次霹靂舞熱 潮,例如2000年初Hiphop音樂風潮席捲香港,令不少年輕人

蔡 :成為代表隊的過程絕不容易, SoulGreen 對即將首次參 與國際級別霹靂舞賽事的感覺如何?有信心能夠在奧運資格

賽上旗開得勝嗎?

SoulGreen :作為近兩屆霹靂舞代表隊隊員,感覺相當奇

幻。以往認識霹靂舞或街舞都是源於街頭。當我意識到原來 街舞也能夠登上國際舞台,我深切地感受到整個世界的改

變。我們有信心取勝,但畢竟是首屆奧運資格賽,加上香港

的霹靂舞水平與外國有一定的差距,因此會盡力做到最好,

不會過分在意賽果。

OBSERVATION 23 觀 察 22

一 二 三月•Jan / Feb / Mar 2023

B-Boy Joe(照片由Joe提供)

香港霹靂舞代表隊赴日本集訓、比賽(照片由Joe提供)

少舞者演出,學校亦有興趣班作為學習途徑。嚴格來說, 我並不算是一直「堅持」成為霹靂舞者。我一直享受作為

B-boy 的生活,沉醉於霹靂舞為我帶來的衝擊,不論高低起 跌,都是我身為舞者的里程碑。現時我享受霹靂舞帶來的一 切,我深信每個人都會想辦法維繫興趣與生活,做自己喜愛 的事。

蔡:這次奧運是首屆有霹靂舞在內的體育盛事。作為霹靂舞 運動員,你心目中香港風格的霹靂舞相比起其他地區有甚麼 過人之處?

SoulGreen:正如剛才提及,雖然香港的霹靂舞水平與外國 有差距,但霹靂舞並非只講求技巧。香港本身有著各式各 樣的文化, B-boy 的出身以及接觸 B-boy 文化的方式亦截然 不同,造就出香港風格霹靂舞的獨特風格。在亞洲,日本的 霹靂舞水平位列世界前茅,擁有一套完整的 B-boy 系統供大 眾學習,但亦因為系統過分完善,令霹靂舞者的演出大同小

異。相反,香港的霹靂舞者憑藉各自的方式學習霹靂舞,每 個人的演出獨一無二,只為演繹出自己的風格。這一點與美 國霹靂舞文化相似。

蔡:作為霹靂舞運動員,如何看待此項目成為奧運項目?如

何從舞者身分,過渡至運動員身分?兩者有甚麼不一樣的

地方?

SoulGreen:很多人並不看好霹靂舞成為運動項目,他們只 視其為藝術。我認為霹靂舞不止是藝術,同樣也是運動。霹

靂舞成為奧運項目能令更多人認識霹靂舞,使其發展得更蓬

勃。舞者分兩種,一種是純粹玩樂,享受舞蹈樂趣,另一種 則是以比賽為目標。我屬於後者,一直以舞者身分參與不少 比賽,為此不斷反覆練習,與運動員一樣。因此從舞者身分 過渡至運動員身分沒有太大差異。唯一的分別在於奧運比賽 有著明確獨特的評分系統,需要針對評分準則而作訓練。

蔡:除了技巧外,要如何準備心理素質應對國際賽事?在霹 靂舞比賽中,特別要保持哪些心理素質?或者是其他備戰的 因素?

SoulGreen:這個問題相當好。我認為參與國際賽事最大的 難關便是心理質素。以往比賽的壓力源於對自身的表現感 到不滿。但參與國際賽事所代表的是香港,背後所肩負的 責任、使命感令自身壓力倍增。在霹靂舞比賽中需要盡量放 鬆,日常亦要多加操練,愈熟悉每一個動作,信心便會愈 大,尤其是舞蹈動作原本就會留下身體記憶,有助減少壓 力。奧運賽事的模式講求體能,回合較多而且休息較短,因

此現時備戰需多加訓練體能,身體質素的鍛鍊不可馬虎。

蔡:最後,作為現役霹靂舞者,你認為社會或政府可以如何

支持並推廣霹靂舞文化?

SoulGreen:希望大家接納霹靂舞,不要因為偏見而對霹靂 舞留下刻板印象。另外希望政府在經濟上提供更多援助,作 為全職運動員沒有任何收入,有部分運動員為了專心備戰奧 運賽事而放下工作,卻得不到政府的援助支持,過程煎熬。

作為運動員,希望得到足夠的支持,不論收入、贊助、場地 提供、醫療上,這些都絕對能夠成為我們的動力。

照片由Worldwide Dancer Project 提供 觀 察 24 25 舞動潛能

與盧綽蘅對話II:受傷與徬徨之間 文字整理:余曉彤 COLUMN 一 二 三月•Jan / Feb / Mar 2023

OPTIMIZING DANCERS' PERFORMANCE

余 :當年我在內地接受專業芭蕾舞訓練期間,身體條件 好、能吃苦的強者才能繼續發展,容易受傷、意志力薄的 弱者自然被行業淘汰。近年全球舞蹈業界對預防傷患和健

康習舞的興趣和關注有所增長,與以往的環境相比有很大 的進步。當然即使我們盡力確保習舞的環境合適,科學地 計劃循序漸進的訓練,也不能100%避免傷患。你可否和

我們分享,當運動員或舞者因傷患陷入低潮、被情緒困擾 時,你會給予甚麼幫助和建議?

盧 :文獻嘗試用不同的傷患類型( injurymodels)來解釋受 傷後情感經歷的種種變化。包括當舞者受傷經歷較少時, 開頭可能無法接受,甚至否定曾發生過受傷這件事;隨後 的情緒可能是比較煩躁、生氣、憤怒,覺得「何必當初 呢」、「早知比賽當日提前做多點拉筋,就不會這樣受 傷啦」等思前想後的念頭;然後到康復進展良好時,才接 受經歷過受傷的事實。坊間上各個心理學派,對受傷後經

歷不同的心理變化有不同的看法,以上便是其中的一個例 子。當然文獻和學派都是用作參考,因為真實個案都各有 不同,我個人不會太過依賴,最主要看當刻運動員或舞者

正在經歷哪個階段,面對情感上怎樣的變化,從而對症 下藥。

余 :一般討論傷患時,只會聯想到運動量過大或者急性扭 傷等肢體上的因素。有研究則表示,壓力與傷患是有相關

性的,當一個人處於高壓力下或者過勞( burnout )時,受 傷的機率亦會有所遞增。在你的經驗裡,這些說法是否常 見呢?

盧 :壓力有可能是最開初的其中一個元素。可能是家中發

生了事情,或者學校有很多功課,當需要顧及的事情較多 或煩惱較多時,人就比較難集中,做動作時可能會產生較

多的錯誤、睡眠質量下降、精神不足等,全部都直接影 響注意力和判斷。平時可以觀察整個舞台,但當疲累、緊 張、壓力大、難以集中時,視野會變窄。這樣就較難顧及

一個大的範圍,導致出現錯誤的次數增加,受傷的機率也 增大。其中一個傷患模型被稱為壓力傷患模型(stressinjury model),形容的正是這種情況。

余:請問如何能夠避免這種情況發生呢?

盧 :可以通過心理技能訓練( psychologicalskills),教你 集中注意力。譬如要踏上舞台,你能否將生活上煩惱、壓 力大的事情忘卻,或暫擱一旁呢?曾經有運動員和我分享 他的例子,生活的事情和思緒常常令他感到混亂,但當

上到球場時,他就會將日常的擔憂放到一個想像的垃圾桶 內——這個大垃圾桶是綠色的,就在球場的線外。這有助 他將注意力完全轉移到球場賽事上。或可以在準備上場表 演前,把煩惱的問題在腦海寫到一張紙上,然後大力地丟 進垃圾桶。利用以上這些意象工具(imagery tools),去嘗試 幫助自己。

余 :這些練習雖然不能直接幫你解決壓力,但能協助你在 關鍵時刻集中注意力,不任由壓力影響表現。另外我想請

教,當舞者不幸受傷而無法完全參與課堂,只能坐在旁邊

觀看,你建議如何能令他/她繼續成為課堂的一分子呢?

盧 :這個問題超級好。受傷後未能融入課堂、與同伴一起 舞動,那種很孤單、被遺忘的感覺,是身為舞者常會擔 憂的其中一個問題。我建議老師可以佈置任務給受傷的 舞者,譬如他腳傷了,只能坐著看課,老師可以邀請他幫

忙,哪怕是很簡單的事情例如點名,讓他覺得自己仍然有 參與課堂;或者邀請他變身為教學助手,幫忙檢查同學

們是否完成動作的要求,又可以負責解釋一個動作等這類 型的小任務。如果老師未能抽身去關注受傷舞者和佈置任 務,舞者自己亦可以主動複習舞步,在課堂整個過程中擔

當或者扮演其他的身份或角色。

余 :假如面對一些需要長時間才能康復的嚴重傷患,康復 後舞者害怕再次做與受傷當時相似的動作,又應如何幫助

他克服恐懼和陰影呢?

盧 :整體來說恐懼源於不確定性。因為有未來、未知的事

情,令我產生不安的感覺,便導致恐懼。害怕做同樣動作 會再次受傷,是因為我們不確定是否能正確地處理,例如 落地的姿勢是否有把握等。所以當重新練習技巧時,我們

需要營造更高的確定性,每一步都熟悉至變為常規。老師 亦需恰當地反饋,做得好的地方就即時指出,讓舞者重新 建立自信,而不能只指出錯處。

余 :這樣他們便能在老師的輔助下,重新培養對自己做這 個動作的信心。

盧 :正確。若舞者有同步進行物理治療,可請物理治療師 分享康復進度,這些資訊能幫助舞者增加對未來時間的安 排和計劃的確定性。舞者亦可以嘗試在康復期間訂立短期

的小目標,以一星期為限期,這可包括心理和生理上想做

到的事情。譬如這星期我想照顧自己的情緒,而下星期我

想慢慢嘗試增加雙腳走路的時間,感受著地的知覺。這樣

一步一步地主動讓自己看見進展,重建自信。

作者 盧綽蘅 香港運動及表現心理學家,分別於香港大學和美國波士頓大學取得 社會科學學士(心理學)及運動心理學碩士學位。她的主要興趣為表 現優化、學生運動員身份認同的顯著性、動機、心理抗逆力和教練 心理學。

專 欄 26 27 COLUMN

一 二 三月•Jan / Feb / Mar 2023

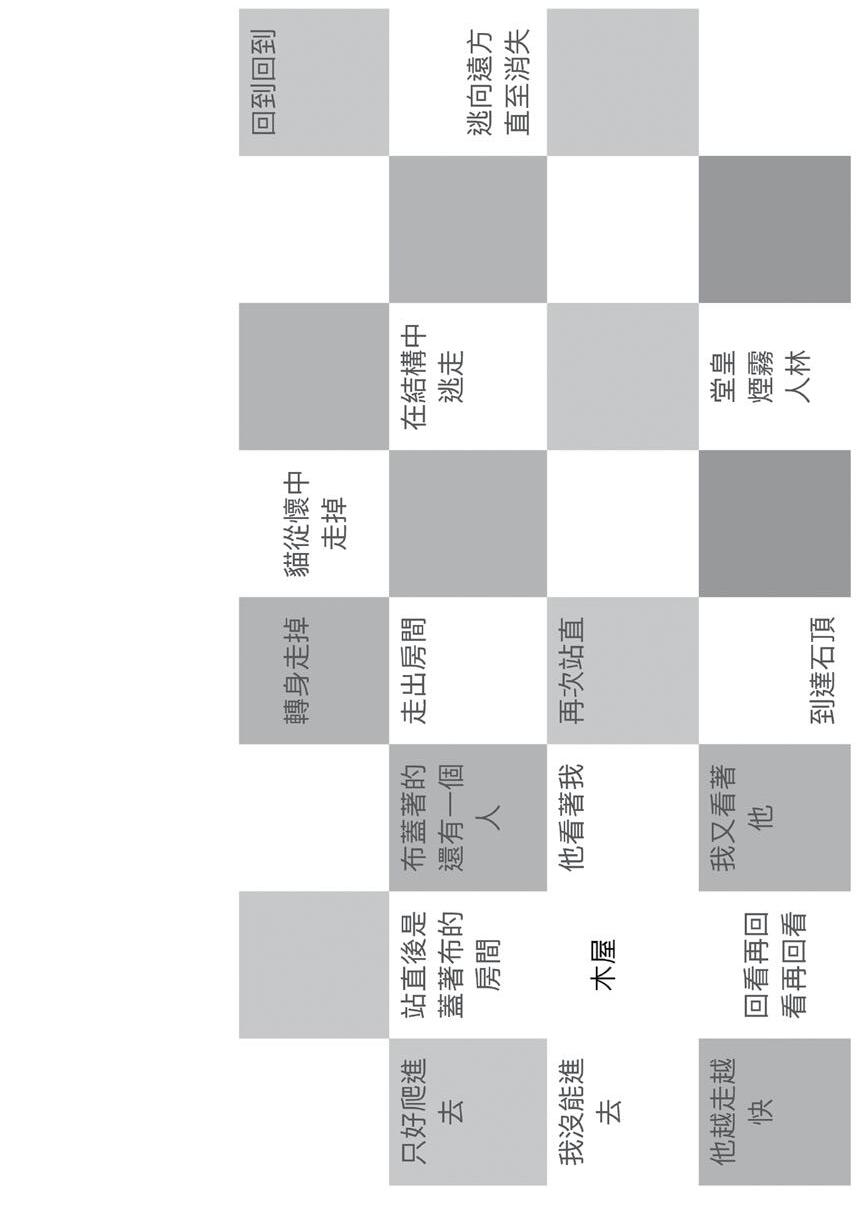

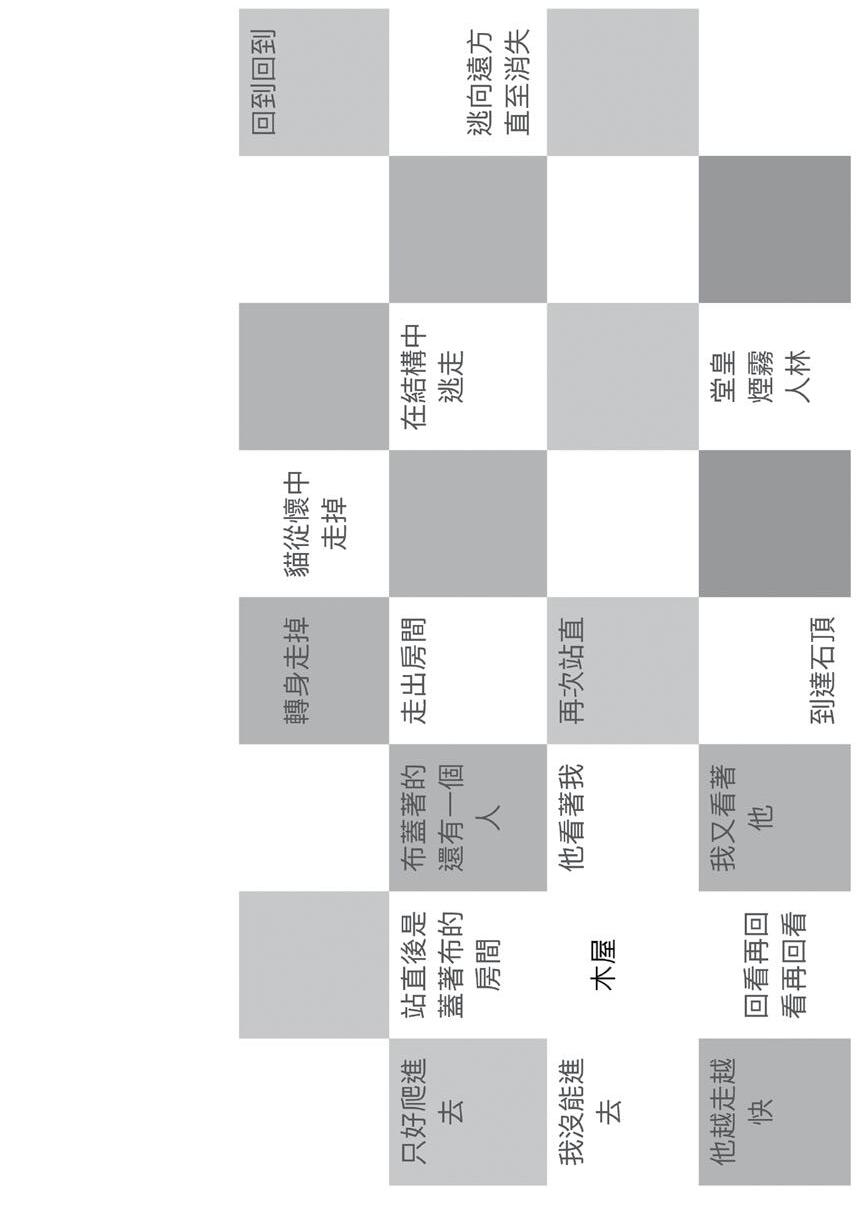

COLUMN 專 欄 28 29 編劇/導演 Directed/Written : Maya Deren 主演 Starring : Maya Deren, Alexander Hammid, John Cage, Parker Tyler 電影製作 Cinematography : Hella Hammid ( 即 Hella Heyman), Alexander Hammid 字/舞 CHOREO-WORD-GRAPHY 《在陸上》( 1944 ) "At Land" (1944) 文:徐奕婕 Text: : Ivy Tsui 瀏覽網頁版本 一 二 三月•Jan / Feb / Mar 2023 作者 徐奕婕 跳舞人, 2019 年開始以即興文字方式回應舞蹈作品,思考舞評以外的紀錄和回應的可能性,好奇由舞 蹈身體延伸的文字與觀看經驗之間多次創作的來回推進關係。 「字/舞」始於 2021 年,由 2022 年起聚焦流動影像 Moving Image ,思考文字及影像如何成為身體的 延伸,穿梭虛擬和真實的世界。

環亞舞略 DANCE CURATING IN ASIA

TOKYO REAL UNDERGROUND: BUTOH AND THE CITY TODAY

環亞舞略 DANCE CURATING IN ASIA

TOKYO REAL UNDERGROUND:

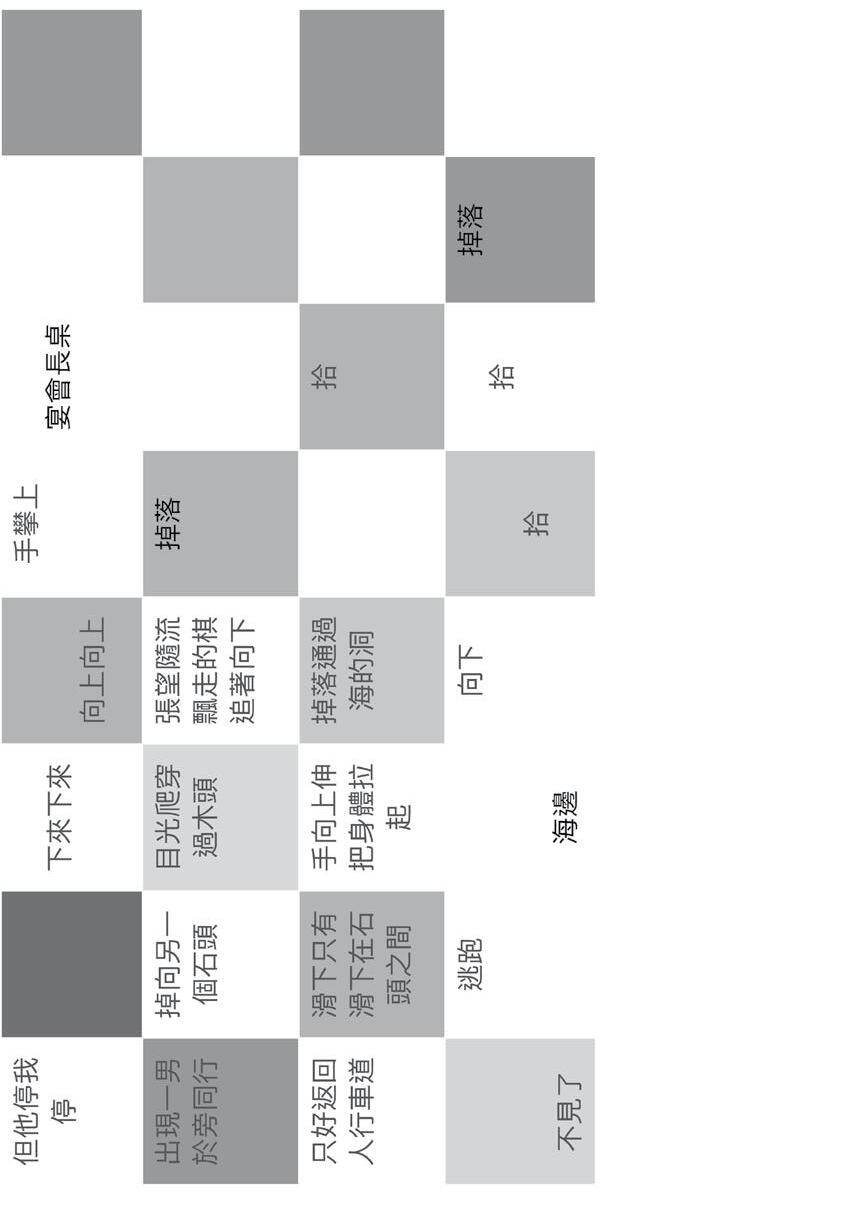

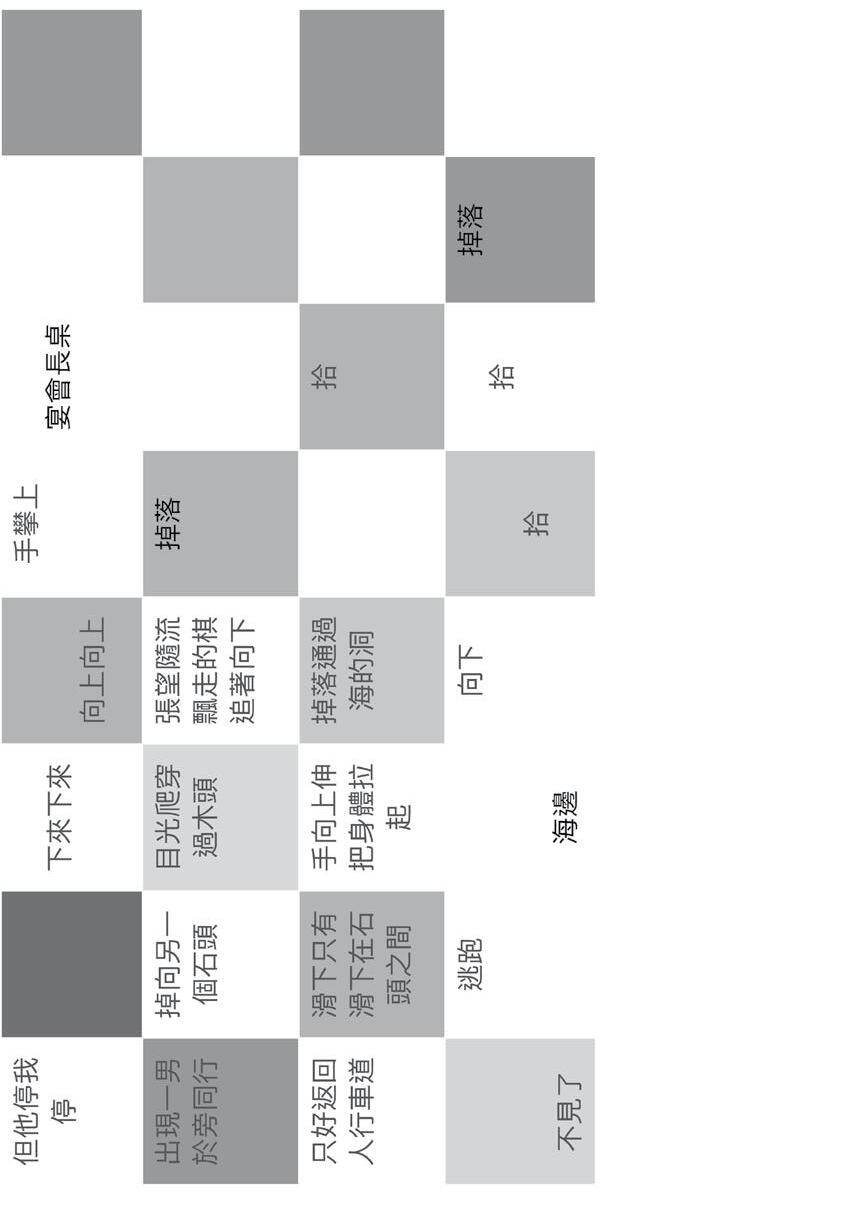

From April to August 2021, the TOKYO REAL UNDERGROUND (TRU) festival took place online. It was part of the “Tokyo Tokyo FESTIVAL” cultural programme, launched in conjunction with the Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games. TRU was selected from 2,436 submissions by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government and Arts Council Tokyo (Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture) to be presented as one of 13 projects collectively highlighted as the “Tokyo Tokyo FESTIVAL Special 13”

The curation team for TRU included producer Toshio Mizohata (Representative Director of NPO Dance Archive Network), artistic director Takao Kawaguchi (performer), and two curators: myself, naoto iina (film maker and Director of DANCE AND MEDIA JAPAN) and Dai Matsuoka (butoh dancer and Director of LAND FES). The overall vision for TRU was put together by these four members. Originally scheduled

to be held in 2020, the festival was postponed in response to COVID-19 and some of the content was changed.

TRU was planned and produced by the non-profit organisation Dance Archive Network, whose parent organisation is the Kazuo Ohno Dance Studio. Involved in many archival projects, the organisation specialises in “butoh and archives”. However, one of the biggest challenges it has faced is how to present butoh in a contemporary manner. While it is easy to imagine an archive as a repository of information about the past, it was harder to know how we could present butoh as a continuing art form.

In the winter of 2018, Mizohata proposed the theme “butoh and Tokyo’s underground spaces”. What form of dance from Japan would appeal to a worldwide audience ahead of the Olympic and Paralympic Games? Butoh, of course.

2021年4月〜8月、オンライン舞踏フェスティバルTokyo Real Underground(以下TRU)が実施された。オリンピッ

ク・パラリンピックの東京開催を踏まえ、文化イベントとし

て「Tokyo Tokyo FESTIVAL」が立ち上がった。東京都及び 公益財団法人東京都歴史文化財団アーツカウンシル東京

が実施し、国内外から応募のあった2,436件から選定した

13の企画を「Tokyo Tokyo FESTIVALスペシャル13」と総称

し、TRUはその中のひとつである。

TRUのキュレーションチームは、プロデューサー溝端俊夫 (NPO法人ダンスアーカイヴ構想理事長)、アーティスティ

ックディレクター川口隆夫(パフォーマー)、キュレーター飯

名尚人(映像作家、DANCE AND MEDIA JAPAN主宰)、松 岡 大(舞踏家、LAND FES主宰)。この4名でミーティングを 重ね、フェスティバルの全体像を組み上げた。2020年に開 催する予定だったが、コロナの影響で延期され内容も変更 された。

TRUの企画・運営はNPO法人ダンスアーカイヴ構想で、そ の母体は大野一雄舞踏研究所である。これまでも舞踏に関

するアーカイヴ事業を多く手掛けてきたため、「舞踏とアー

代的手法の中で発表していくかには大きな課題があった。

2018年冬、溝端氏の提案で「舞踏と東京の地下空間」とい うテーマが掲げられた。オリンピック・パラリンピックを前 に、日本から世界にアピールできるダンスは何か。それは 舞踏に他ならない。1961年、写真家ウィリアム・クラインが 東京にきて、銀座・新橋の街を背景に、土方巽、大野一雄、 大野慶人を撮影した写真シリーズ「ダンスハプニング」。そ の数点がクラインの写真集「TOKYO」(1964年発表)に掲 載されている。この写真は、三人の舞踏家を撮影しただけ でなく、1961年の東京の風景と、この撮影を見学する人々 の姿が克明に記録されている。まさに「舞踏と都市」のア ーカイヴであった。この一連の舞踏・都市・写真のセッショ ンは、銀座四丁目駅の地下改札口のショットで終わってい る。1964年の東京オリンピックを控えた東京を舞台に、クラ インは三人の舞踏家を撮影した。そこで、我々は2020年の 東京オリンピックの真っ只中で、舞踏・都市・マルチメディア でセッションしようとしたのだった。

東京には無数の地下空間が存在している。幾層にもわたっ て地下鉄が走り、地下街、地下駐車場は至る所にある。現在 では封印され幻の地下街というのも存在する。目には見え

ないが確かにそこに存在する空間と、日本における舞踏の あり方が重なった。光の届かない暗黒の地下で踊る身体が あり、今そこを掘り起こして光を当ててみる、という意味もあ った。

舞踏は、60年代-70年代に「アングラ」と称された。つまりア ンダーグラウンドのことである。そこでメイン会場を地下空 間に限定して実施することにし、東京の地下空間のリサー

專 欄 30 31 COLUMN

現在進行形の舞踏、そして都市

一 二 三月•Jan / Feb / Mar 2023

Online Talk: Butoh Exhibition Dance (Photo Provided by naoto iina)

カイヴ」は専門である。しかしながら、舞踏をどのように現

アーカイブとして過去の情報を保管していく作業には想像 がついたが、舞踏を現在進行形のアートとして発信してい くために何ができるかを考えなければならなかった。

Text: naoto iina Translator: Mai Burns Text: naoto iina

In 1961, photographer William Klein came to Tokyo and shot Dance Happening, a series of photographs featuring Tatsumi Hijikata, Kazuo Ohno and Yoshito Ohno on the streets of Ginza and Shimbashi. A few of these pictures appeared in Klein’s TOKYO (published in 1964). These photographs not only capture the three butoh dancers, they also clearly record the landscape and people of Tokyo in 1961. They are a quintessential example of how to archive “butoh and the city”. This spontaneous butoh/ city/photography session ended with an image taken at the underground ticket barrier of Ginza Station’s 4-Chome exit. In a Tokyo anticipating the Olympic Games of 1964, Klein chose to capture three butoh dancers. It was for this reason we chose to hold a multimedia event featuring butoh and the city in the context of the Tokyo 2020 Olympics.

There are numerous underground spaces in Tokyo. Subway trains run through several layers of ground, and there are underground malls and car parks all over the place. There are even some underground malls that are now disused and

have been sealed off; phantom spaces that cannot be seen, yet certainly exist. There was an opportunity here for these invisible yet enduring spaces to overlap with the butoh of Japan. We would find the bodies of dancers in the pitchdark underground, and shine a light on the darkness.

In the 1960s and 70s, butoh was defined as part of the “angura” movement, a word which comes from the Japanese pronunciation of “underground”. This was the basis for our decision that the main venues for this project would be underground, and we began researching underground spaces around Tokyo. In the end the Former Hakubutsukan-Dobutsuen Station in Ueno became our main venue. Although now closed, the old underground station is an incredibly valuable site and has a long history. Even though we were given permission to use the building, there were many restrictions in place, and we had to proceed with our work in a carefully planned and strategic manner.

Butoh is not very well recognised in Japan, where it is

チが始まった。最終的には、上野の旧博物館動物園駅がメ イン会場となった。現在は閉鎖されている地下の駅である が、建物は歴史的建造物として価値の高いものである。場

所は見つかっても、歴史的建造物には使用規制も多く、計 画的・戦略的に進行する必要があった。

日本国内の舞踏の認知度は一般的には低く、裸体に白塗 り、不気味な動きをする、という程度では知られているが、 その歴史はあまり知られていない。そして海外から見られ

ている舞踏と、日本国内で見られている舞踏とは、どこか違 いがある。そこで、あえて海外からの視点で舞踏を捉えてみ

ることになった。2010年代は、世界的にも舞踏をモチーフ

にしたコンセプチュアルパフォーマンスが多く生まれた。舞 踏作品を作るのではなく、舞踏がコンセプトになっている

アート作品である。そういった作品を日本で上演し、舞踏が 彼らによってどのように解釈され、また発展しているかを検

証しようとしたのである。舞踏を現在進行形のアートとして

見たかったのと、我々日本人が外からどんな風に見られて いるかを知りたかったからである。舞踏の精神、エッセンス が組み込まれたアート作品に我々日本人が触れることで、 舞踏の新しい風が日本国内に吹くように思えた。2020年に 実施予定だったのは、「現代:舞踏をモチーフにしたコンセ プチュアルパフォーマンスの招聘(海外アーティスト)」「伝 播:海外に拠点を置く舞踏家たちの日本公演」「歴史:舞踏 に関するアーカイヴ展示」の3本軸である。あえて日本拠点 の舞踏家のライブパフォーマンスを入れない舞踏フェステ ィバルは挑戦的なことでもあった。

2020年、コロナでフェスティバルが延期となり、2021年も公 演再開の見通しが立たないため、「オンライン配信によるフ ェスティバルの実施」という判断が主催者から下された。企 画が大幅に見直され、我々は映像作品をメインにしたフェ スティバルを目指すことになり「映像アーカイヴ」というキ ーワードが強化された。キュレーターの私は映像作家であ

32 33 專 欄 COLUMN 一 二 三月•Jan / Feb / Mar 2023

Former Hakubutsukan Dobutsuen station / Photo: Tatsuhiko Nakagawa (Photo Provided by Naoto Iina)

THREE naoto iina + Takao Kawaguchi + Mikiko Kawamura + Dai Matsuoka (Photo Provided by naoto lina)

generally known only as an art form that involves nudity, white body paint and eerie movements. Knowledge of its history is not widespread. There are also some differences between how butoh is seen abroad, and how it is viewed in Japan. We therefore decided to take on the challenge of looking at butoh from an outside perspective. The 2010s saw a worldwide rise in conceptual performances that have been inspired by butoh. These works aim not to create a “butoh performance”, but to use butoh as a concept. Our plan was to present such pieces in Japan, and examine how the artists concerned were interpreting and developing butoh. We wanted to present butoh as an ongoing art form and see how the Japanese were perceived by those outside the country. By exposing Japanese people to such works that still contain the spirit and essence of butoh, we hoped to see a new form of butoh blossom in Japan.

The three main themes we had planned for 2020 were:

“Contemporary: Invitation to international artists to present conceptual performances that use butoh as inspiration”, “Propagation: Performances in Japan by butoh dancers who are now based abroad” and “History: A butoh archive exhibition”. The challenge was to try and hold a butoh festival that did not include any live performances by butoh dancers based in Japan.

In 2020, when the festival was postponed due to COVID-19 and it became clear that there was no prospect of resuming live performances in 2021, we took the decision to implement the festival through online distribution. The

programme had to be drastically revised, and as our aim shifted to creating a festival based around video works, we emphasised the key words “video archive”. This switch to a film-based festival was relatively smooth, as both curators had a strong background in video technology; I had my own experience as a film maker and as an organiser of the online International Dance Film Festival, while Matsuoka was actively involved in an online live-stream dance festival called LAND FES. For TRU, we decided not to live-stream staged performances, but to create video works based on a collaboration between film makers and butoh dancers.

Responsibility for implementing each of the three themes of the festival was divided between us as follows, according to our respective areas of expertise:

• Takao Kawaguchi was in charge of setting up a programme of video works created in collaboration between butoh dancers and film makers.

• naoto iina took the lead on Butoh: New Archive Exhibition, an augmented reality exhibition of William Klein’s photographs, butoh holograms and an online butoh timeline.

• Dai Matsuoka organised an online discussion between Japanese butoh dancers now based around the world, directed distribution of the video works and ran a series of online talks.

• Toshio Mizohata was responsible for the general production of the entire festival, as well as an onsite William Klein photography exhibition.

松岡 大はLAND FESというオンラインのダンスライブ配信 を積極的に実施しており、どちらも映像技術に強かったた

め、フェスティバルの映像化への移行はスムーズであった。

映像化の際、舞台記録のライブ配信は行わず、映像作品と して見ることができるように映像作家と舞踏家のコラボレ ーションを仕掛けることになった。

当初の企画3本軸は、以下のように変更した。それぞれの 専門領域を生かした企画分担がされた。

• 川口隆夫担当:舞踏家と映像作家のコラボレーションに よる映像作品の制作

• 飯名尚人担当:舞踏ニューアーカイヴ展、ウィリアム・ク ライン写真AR、舞踏ホログラム、オンライン舞踏年表

• 松岡大担当:海外拠点の舞踏家とのオンラインディスカ ッション、映像配信のディレクション、オンライントークイ ベント

• 溝端俊夫担当:総合プロデュース、ウィリアム・クライン 写真展

34 35 專 欄 COLUMN 一 二 三月•Jan / Feb / Mar 2023

Paradise Underground – Kim Itoh and Tokyo Reiwa Underground Dancers (Photo Provided by naoto lina)

り、国際ダンス映画祭のオンライン開催をしていたことと、

Online Timeline Butoh Incidents / Photo: Tatsuhiko Nakagawa (Photo Provided by naoto lina)

The greatest advantage of switching to an online festival was the number of viewers we were able to attract. Unfortunately, butoh tends not to garner a large audience in Japan. However, by making our festival accessible online, we were able to reach both a greater number of viewers and a wider international audience than we would have if we had held the festival on stage in small theatres.

It then also became necessary for us to give people a better understanding of butoh. We wanted to create a new audience who would be interested in coming to see live butoh performances once the COVID-19 situation settled down. For the duration of the festival we asked people to register for free to access the films, and 3,264 people signed up. Considering the usual demand for butoh, this was an incredibly large number of viewers. We also presented talks with English subtitles to cater to an international audience.

Looking over butoh’s history, it is clear that butoh’s popularity around the world is largely due to the photographs and words that have been left behind. Our imagination can be expanded with the aid of images and words; I see it as butoh being installed into the bodies of individuals. There is also a lot of video documentation; in fact, butoh has had a lot of

exposure on film over the years. Video documentation of the performing arts has no doubt increased considerably since 2020 with the outbreak of COVID-19. The next challenge will be how to preserve this archive of films and make them available to the public, as well as how to connect them with other art forms. Since TRU was created in the form of a series of video pieces, we are now able to continue to expand our audience by, for example, submitting those pieces to international film festivals. In 2022 we also published a catalogue of the festival titled T.R.U. 2020-2021 Part Illusion: Tokyo Underground. In Japan the archiving of festivals is a challenge that has not yet been undertaken, but there are still many methods we can continue to experiment with in order to archive the performing arts.

TOKYO REAL UNDERGROUND website

http://www.tokyorealunderground.net/english

し、海外の視聴者も獲得できる。そしてとにかくまず舞踏を 知ってもらう必要があった。コロナが収束したら、劇場で生

の舞踏を観てもらえればよいと考えた。フェステバル期間 中は無料登録で映像配信が見られ、3264名の申し込みが あった。舞踏のマーケットを考えればかなり多くの視聴であ

る。トークイベントの配信も、英語字幕を入れるなどして海 外の視聴者に向けてのサービスも行った。

映像アーカイヴをどのように公開しながら残し、他のアート と繋げていけるかが次の課題になるだろう。TRUでは、映像 作品として舞踏を残したので、各国のダンス映画祭などへ 参加するなど継続的なコンテンツ発信が実現している。ま た、カタログとして書籍「T.R.U.2020-2021 半分まぼろし東 京アンダーグラウンド 」も出版した。日本ではまだフェステ

ィバルのアーカイブ化まで手が回っていないが、舞台芸術 をアーカイヴするための様々な手法は今後も実験していく 必要があるだろう。

Writer naoto iina

Videographer, director and producer. iina is the founder of Dance and Media Japan and International Dance Film Festival. Iina has been working on cross-genre works with video, dance and text. He is in charge of direction, composition, filming and editing of the online Butoh program "Re-Butoooh" (NPO Dance Archive Network).

舞踏の歴史を見返すと、舞踏が世界に伝播したのは、写真 と言葉が残されていったことは大きいだろう。写真と言葉 によってイマジネーションが膨らんで、各々の身体に舞踏 がインストールされたように思う。記録映像も多く残され ており、舞踏は映像メディアとの接点が多かったともいえ る。2020年のコロナ発生以降、舞台芸術の映像記録のアー カイヴはだいぶ増えたのではないだろうか。こうして残った

36 37 專 欄 COLUMN 一 二 三月•Jan / Feb / Mar 2023

Former Hakubutsukan Dobutsuen station / Photo: Tatsuhiko Nakagawa (Photo Provided by naoto lina)

オンライン映像配信フェスティバルにしたことで、大きなメ リットは集客である。残念ながら日本国内で舞踏の観客は 少ない。小劇場でのフェスティバルを組むより、映像配信

をしてより多くの観客に舞踏に触れてもらうメリットがある

Tokyo Real Underground WEB http://www.tokyorealunderground.net/

淺談舞蹈攝影—— 以攝影推廣舞蹈藝術

文:《舞蹈手札》編輯部

《舞蹈手札》最新一期的封面,以嶄新風格示人,在疫後的 日子,開展煥然一新的面貌。 25-1 期封面的舞者是兩位知名

街舞舞者小四老師(KayChan)以及 LuenMo 。我們有幸邀 請到 WorldwideDancerProject 創辦人李偉良(阿良)為接下

來一連四期拍攝封面照,以有趣生動的舞蹈攝影,讓讀者陶

醉於各種舞蹈風格之中。舞蹈攝影需以靜態方式展現出舞者 舉手投足間的姿態魅力,將場景、舞者、自身的構思融為一 體,描繪出栩栩如生的動態感。擁有六年豐富舞蹈攝影經驗

的阿良,分享了一些有關舞蹈攝影的經歷以及看法,並希望 透過舞蹈攝影推廣舞蹈藝術,為亞洲舞蹈攝影帶來一番新 景象。

舞蹈攝影與一般攝影的差異

舞蹈攝影的精髓在於對舞蹈的觸覺,攝影師需掌握不同的 舞蹈風格及特色,並具備基礎的舞蹈知識。阿良表示,舞 者舞動時每一刻的動作、節奏、位置、速度,都是拍攝的 關鍵,需要預測舞者下一秒的動作,才能夠捕捉一瞬即逝 的姿態。不同舞種的拍攝手法也不盡相同,需要不斷學習 以增加拍攝成功率。

宣揚舞蹈藝術

以往亞洲地區的舞蹈攝影並非主流拍攝題材,但如果舞蹈 攝影能進一步推廣舞蹈藝術,將帶來更大的發展空間。相 比世界各地,亞洲地區比較少以舞蹈攝影宣揚舞蹈藝術。

阿良為此成立 Worldwide Dancer Project,除拍攝芭蕾舞、 當代舞及中國舞外,亦有不同舞種的作品在內,與大大小 小的舞團合作,包括香港芭蕾舞團、城市當代舞蹈團、香

港舞蹈團、 Studiodanz及上海芭蕾舞團等,希望舞蹈攝影的

風潮席捲亞洲,以作品詮釋何謂舞蹈攝影。

創造嶄新風格

亞洲舞蹈攝影仍有不少發展空間,阿良希望未來拍攝出更 多跨舞種的照片,例如芭蕾舞、中國舞、當代舞同時呈現 於獨立照片之中。此外,主流舞蹈以外的舞種同樣是《舞 蹈手札》接下來四期的重點拍攝方向,例如社交舞、鋼管 舞等等近年曝光率較少的舞種,希望藉此連結不同的舞 者,將亞洲舞蹈藝術發揚光大。

由本期開始,《舞蹈手札》的評論文章將會移師至 dancejournal/hk 《舞蹈手札》網頁 ( www.dancejournalhk.com),並同步刊登於國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)網頁。 請掃描文章簡介旁邊的二維碼以細閱文章。如欲閱覽更多精彩文章,請至《舞蹈手札》網 頁,亦可留意於本刊社交平台之發佈。

[中]《異舞.迴聲》——看不出傳統 以外的編碼與重啟新譯

文:格子

//筆者曾經跟一些中國舞訓練背景的舞者和 編舞家交談,大家都致力推廣傳統的中國舞文 化,糅合創新的元素和自家風格展示於觀眾

前,希望當代中國舞受到更多觀眾關注。 LaP en V優之舞藝術總監兼《異舞.迴聲》編舞莊陳 波在場刊簡介:「舞蹈會否像編碼一樣,有既

定程式?讓我們重啟舞碼之匙,探索不同維度 的虛與實,透析肢體語言以外的紋理……」既 然如此,我的著眼處會是作品中的「傳統、編 碼、重啟、虛實、肢體」和以外的 東西,到底想向觀眾呈現甚麼觀感 與訊息。//

[中] 戲曲人物在當代舞蹈中的角色 轉化——小龍鳳舞蹈劇場《夜奔》

文:Yumi Leung //小龍鳳舞蹈劇場十周年製作《夜奔》,邀請 了三位概念編舞周佩韻、馬師雅和黃家駒,與 創作舞者李婷炘和許俊傑一同想像,將《水滸 傳》中的林沖夜奔改編成當代舞,

從不變的文字中找尋流動的角色與 身份。//

[中] 一對探索的心在獨舞

文:葉智仁

//觀賞《一個人共舞》的六段獨舞組合演出,

雖然感官上屬於藝術創作結果的視聽接收,但 深層的樂趣,對筆者來說,來自一連串思維層 面燃起的聯想。我感受到參與創作 者對當代舞蹈的「可能性」這三個 字,持續拷問的熱情。//

[中] 畫廊中的身體:《站在三角尖 頂上看瞬間的我》

文:Maze Chan //離開傳統舞台的演出,總教人期待作品如何利 用不一樣的空間,又或是作品和空間的對話。

《站在三角尖頂上看瞬間的我》在香港藝術中 心包氏畫廊演出三支舞作,演出由最低層開 始,隨著第一舞作完結再往上走, 最後在頂層作結,回應主題的「站 在三角尖頂上」。//

[中] 後疫情時代的舞蹈人生── 看《心渡哲奏》有感

文:程天朗 //如果沒有那場肆虐了三年的瘟疫和政府的嚴 厲防疫政策,《心渡哲奏》不會以這種方式呈 現。儘管真正踏台的只有三位資深 編舞兼舞者,但其實是兩對夫妻檔 的演出。//

[中] 看盤彦燊的《鳴》

文:聞一浩

//盤彦燊是香港少數關注及鑽研亞洲哲學及道家 理論以發展其舞蹈理念及創作的編舞。以往多 自編自跳,這次由西九文化區自由空間委約創 作的《鳴》則是首次看到他只編不跳,純由四 位舞者演繹的作品。不過,舞作仍 可看到盤彦燊繼續探索身體呼吸與 舞蹈動作之間的連繫。//

《舞蹈手札》dance journal/hk Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/dancejournalhk/

攝: Lee Wai Leung @ Worldwide Dancer Project 專 欄 38 39

一 二 三月•Jan / Feb / Mar 2023

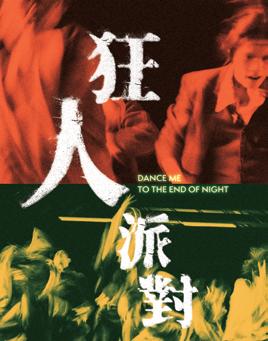

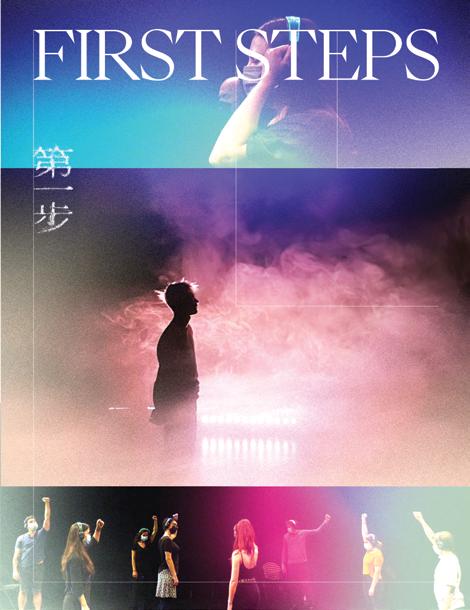

10-12/3 @20:00 | 11-12/3 @15:00

First Steps

香港藝術節 2023 Hong Kong Arts Festival2023

導演: 伯姆@食蟻獸沉浸式藝術工作室

Director: Böme@Tamanoir Immersive Studio

劇場構作及劇本改編:鄭得恩

Dramaturge and Translator: Enoch Cheng

香港藝術家與法國創新媒體工作室共同創作

A collaboration of Hong Kong artists and an innovative studio from France

西九文化區自由空間大盒

The Box, Freespace, WKCD

16-17/3 @20:15

18/3 @16:00

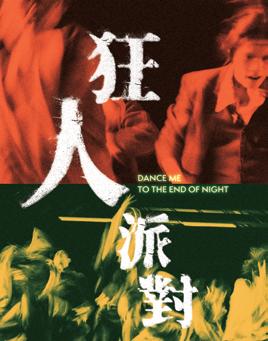

《狂人派對》

Dance Me to the End of Night

香港藝術節 2023

Hong Kong Arts Festival 2023

編舞:毛維 Choreographer: Mao Wei

香港文化中心劇場 Studio Theatre, Hong Kong

Cultural Centre

17-18/3 @19:30 19/3 @14:30

舞蹈歌劇《兩生花》

Dance-Opera–Love Streams

香港藝術節 2023 Hong Kong Arts Festival 2023

導演及編舞:楊雲濤

(香港舞蹈團藝術總監) Director and Choreographer: Yang Yuntao (Artistic Director of the Hong Kong Dance Company)

香港演藝學院歌劇院 Lyric Theatre, HKAPA

24-26/3 @19:30

25-26/3 @14:30 《香奈兒:潮流教主 傳奇一生》

Coco Chanel: the Life of a Fashion Icon

香港芭蕾舞團

Hong Kong Ballet

編舞:奧喬亞

Choreographer: Annabelle Lopez Ochoa

香港演藝學院歌劇院 Lyric Theatre, HKAPA

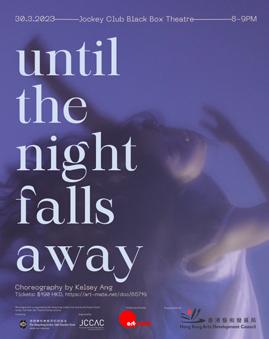

30/3 @20:00

《直到夜幕降臨》

Until the Night Falls Away

編舞 Choreographer: Kelsey Ang

賽馬會黑盒劇場 Jockey Club Black Box Theatre

2-4/6 @19:30 3-4/6 @14:30

《舞姬》La Bayadère

香港芭蕾舞團 Hong Kong Ballet

編舞:馬拉科夫(根據佩蒂巴版本改編)

Choreographer: Vladimir Malakhov (after Marius Petipa)

香港文化中心大劇院 Grand Theatre, Hong Kong Cultural Centre

12-13/5 @19:45 | 13-14/5 @15:00

舞蹈劇場《如影》Dance Theatre: “Womanhood”

香港舞蹈團 Hong Kong Dance Company

編舞:謝茵 Choreographer: Xie Yin

香港文化中心劇場 Studio Theatre, Hong Kong Cultural Centre

41

40

DANCE

舞蹈節目表

LISTING

《第一步》

一 二 三月•Jan / Feb / Mar 2023

24 th