Institute for Clinical Social Work

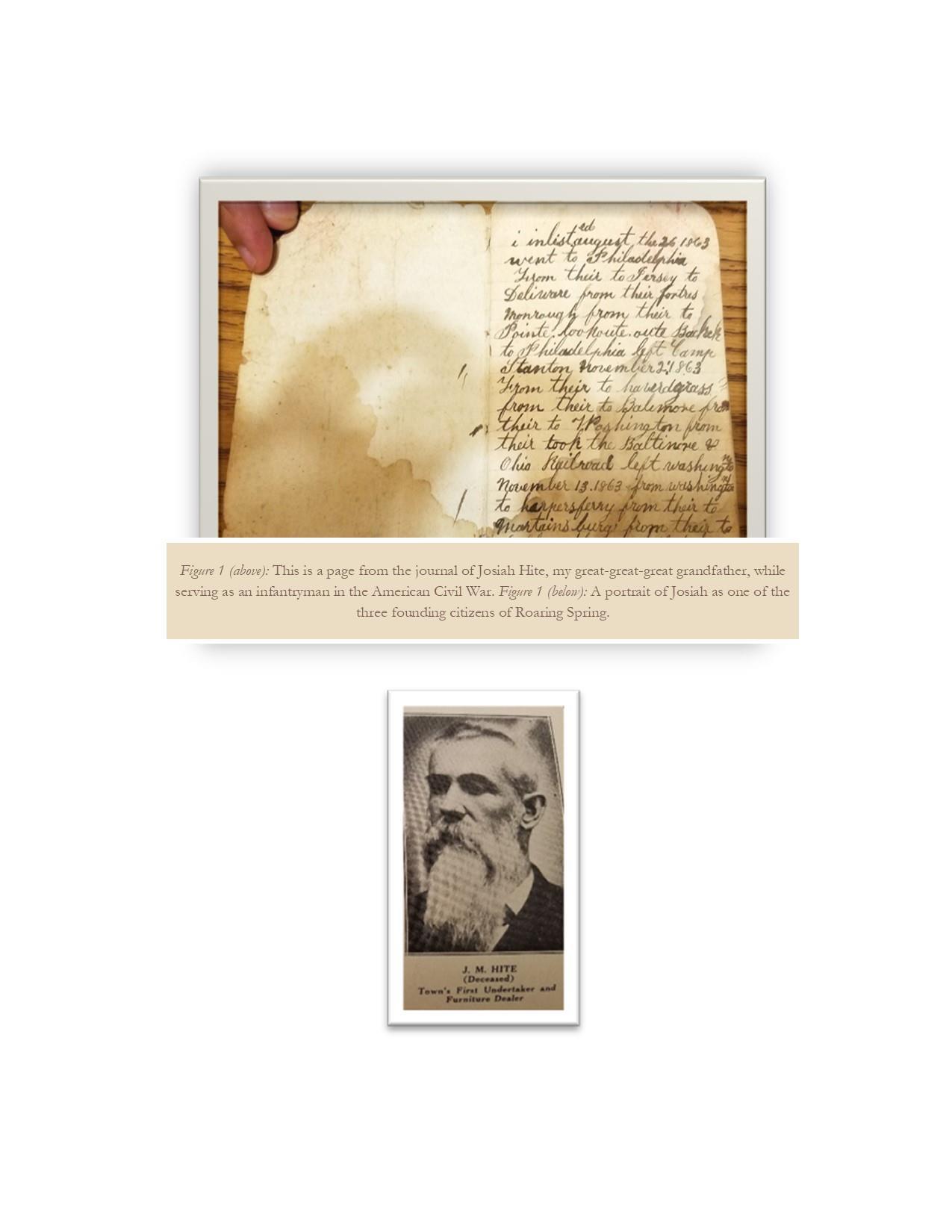

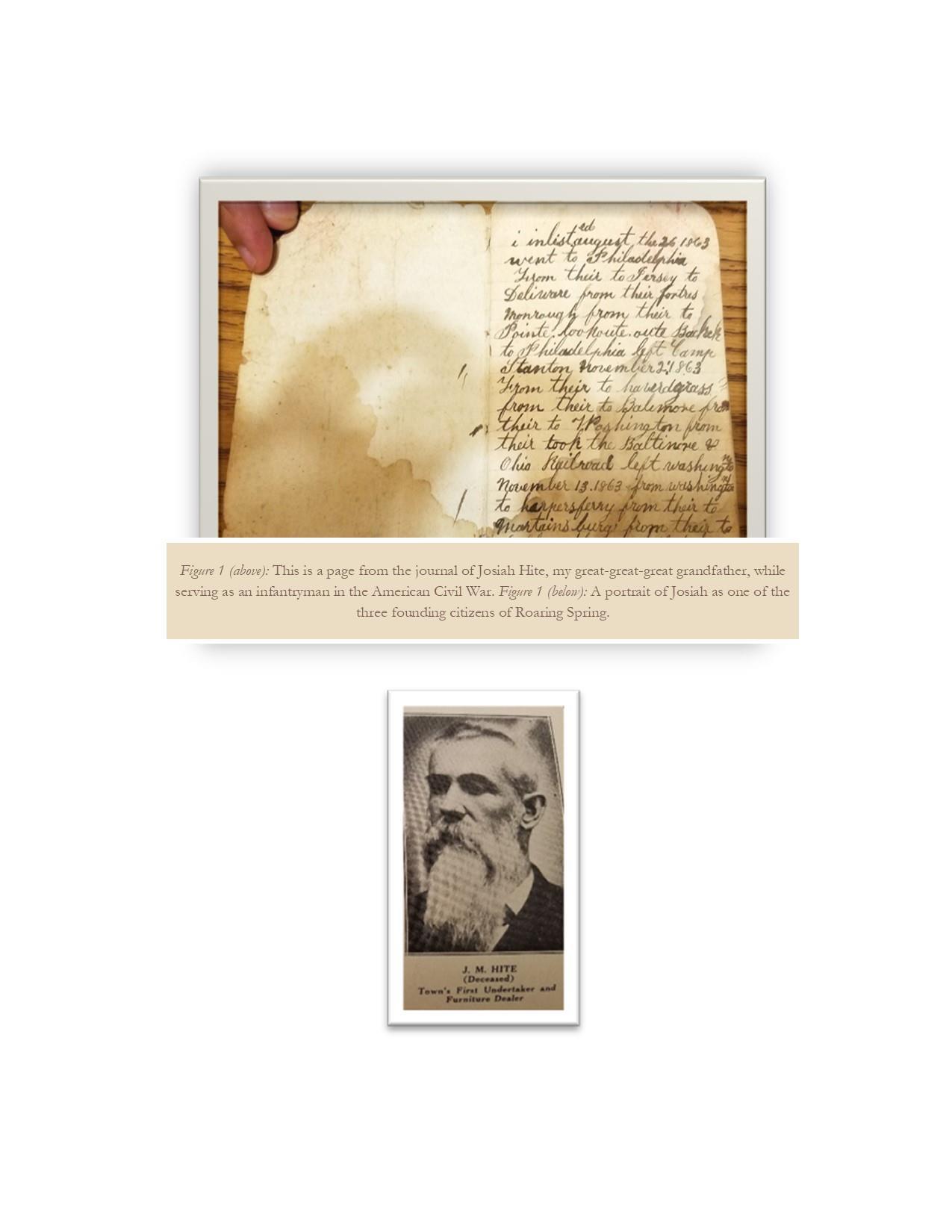

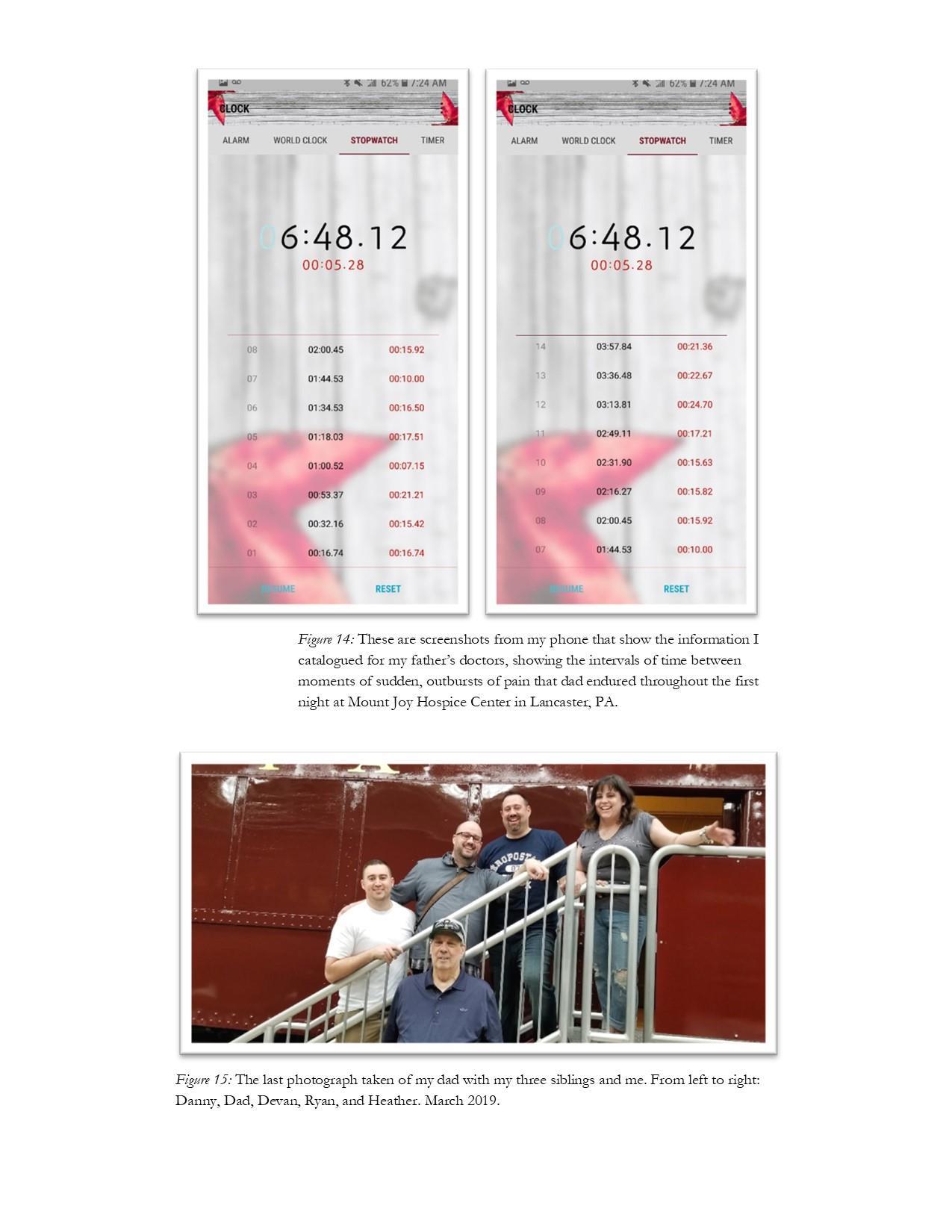

Mourning in Madness: An Autoethnographic Eulogy

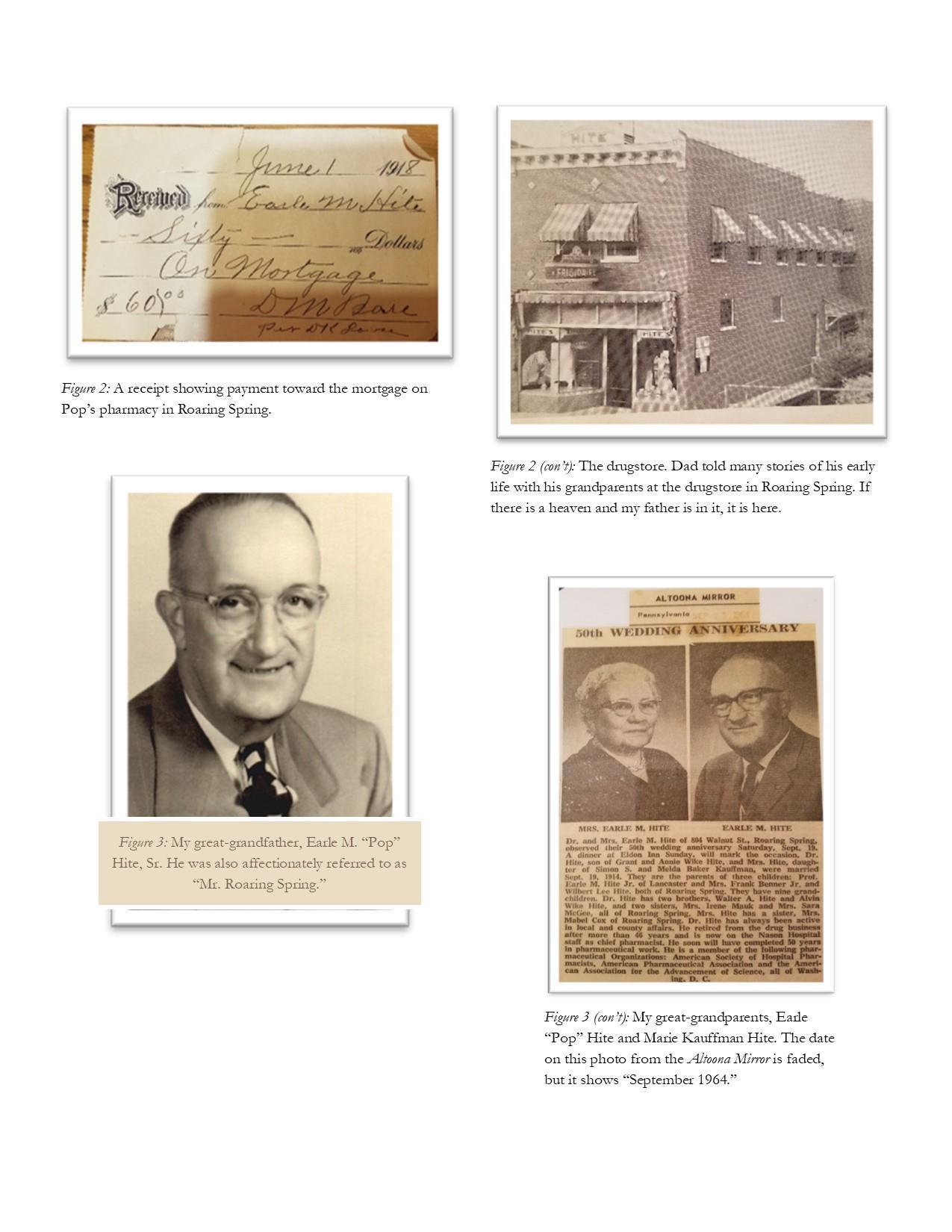

A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Institute for Clinical Social Work in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

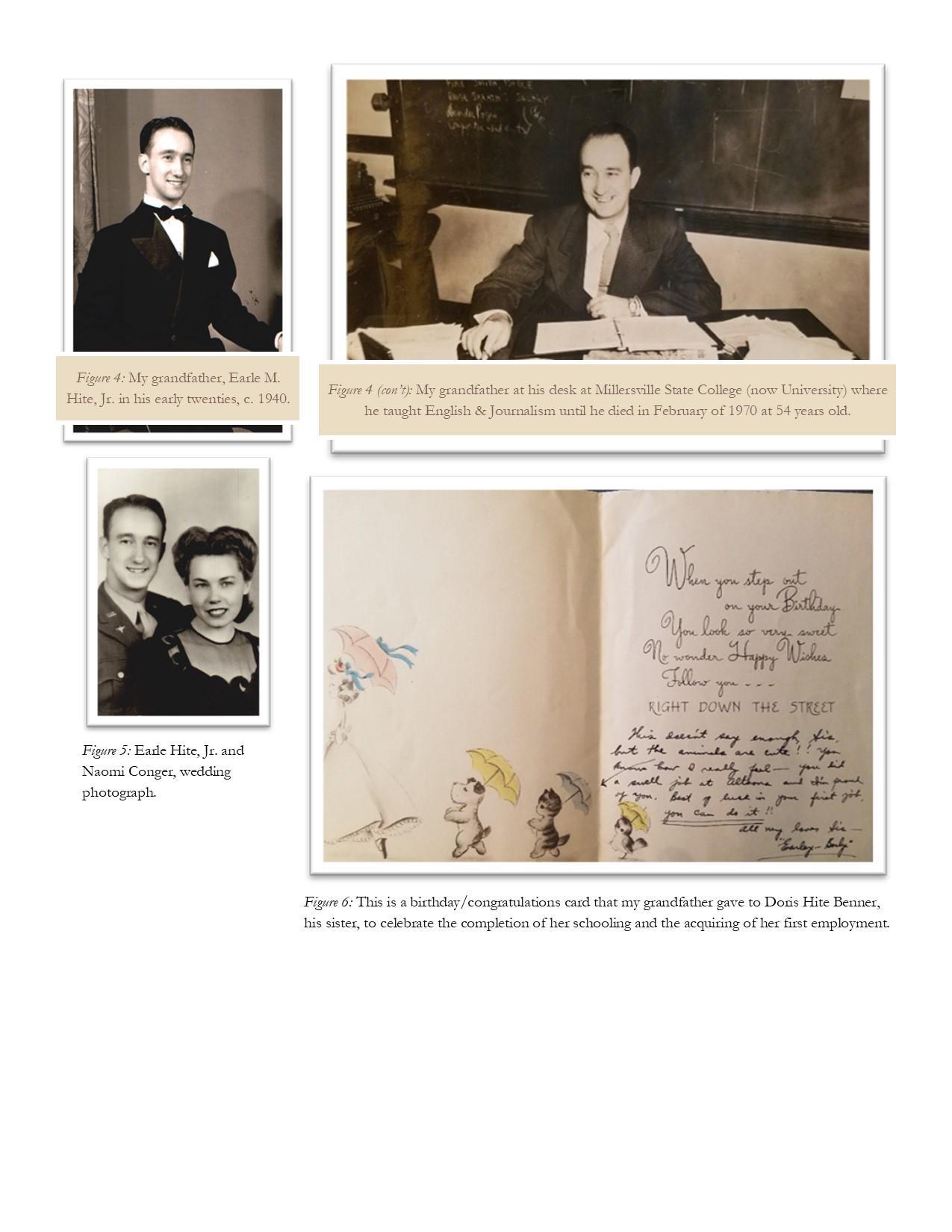

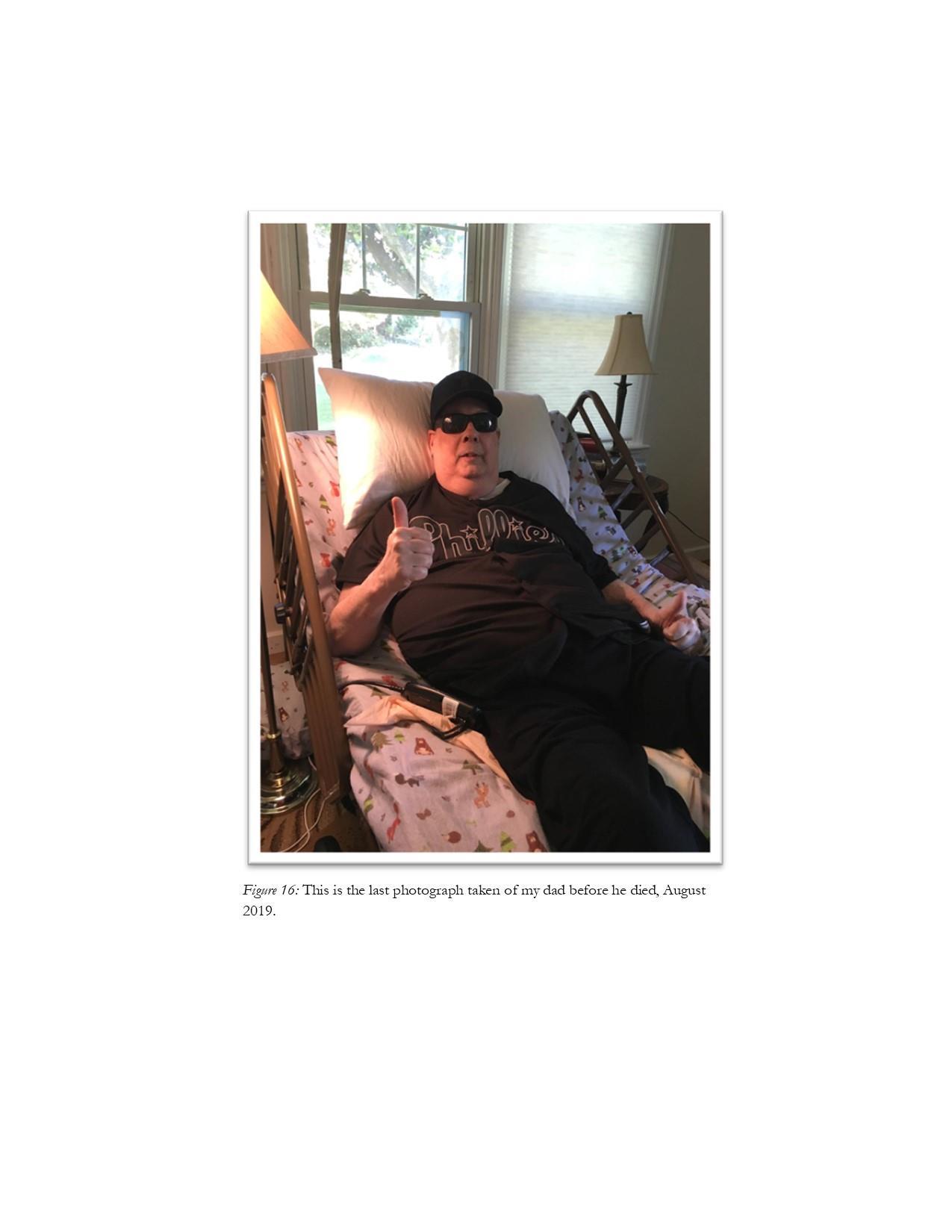

By Devan Hite Chicago, Illinois

2022

Abstract

This autoethnographic, interpretive self-analysis examines an adult son’s experience of a “complicated” type of anticipatory mourning that is stimulated by the impending death of his father with terminal cancer It provides a personal, autobiographical account of the author’s experience of the final year of his father’s life, followed by a thoroughgoing self-analysis of that year using psychoanalytic theory concerning the vicissitudes of object loss. In the narrative, the author is motivated by the ambition to make best use of the little time that he has left with his dying father to work to change the quality of the internal investment of their relationship. He does this by engaging his father in several, meaningful conversations regarding their life together, including attempts on his part to confront a past of emotionally- and sometimes physically-abusive behavior. Ultimately, the study reveals the ways in which the prospect of loss serves to amplify or intensify the negative, internalized ambivalences of their relationship (a phenomenon that the literature on the topic fails to consider or represent), which challenges the author’s capacity to effectively mourn both the anticipation of and the actual death of his father.

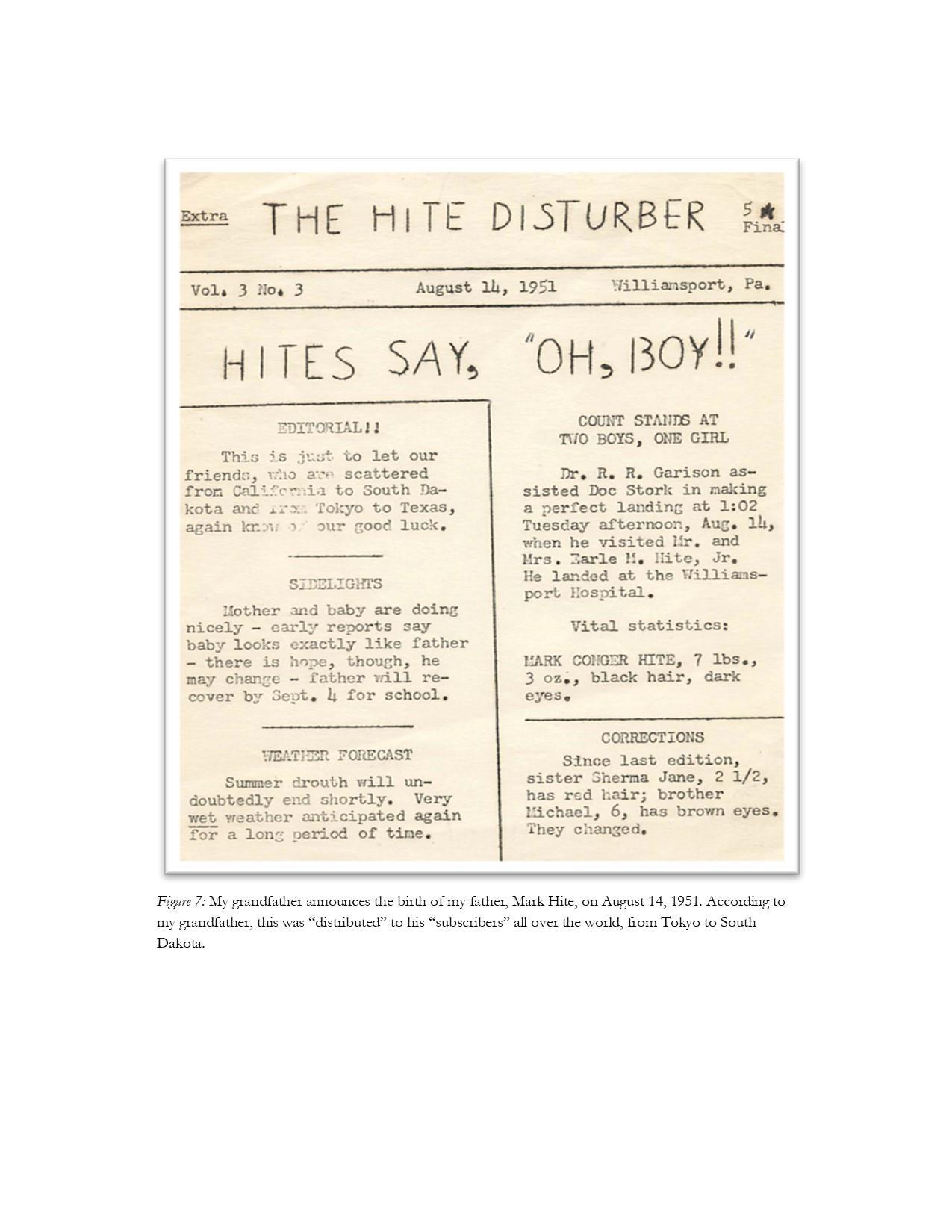

ii

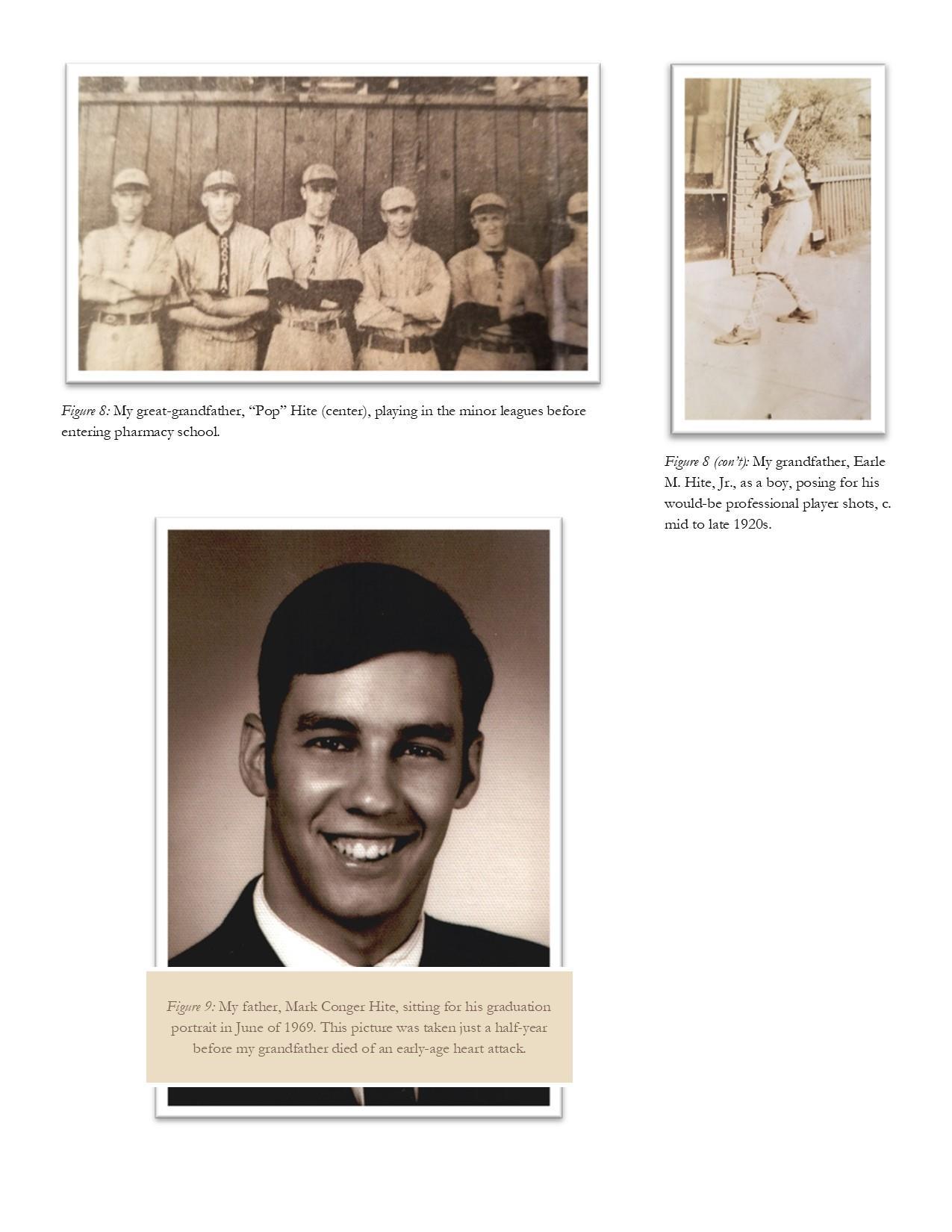

iv

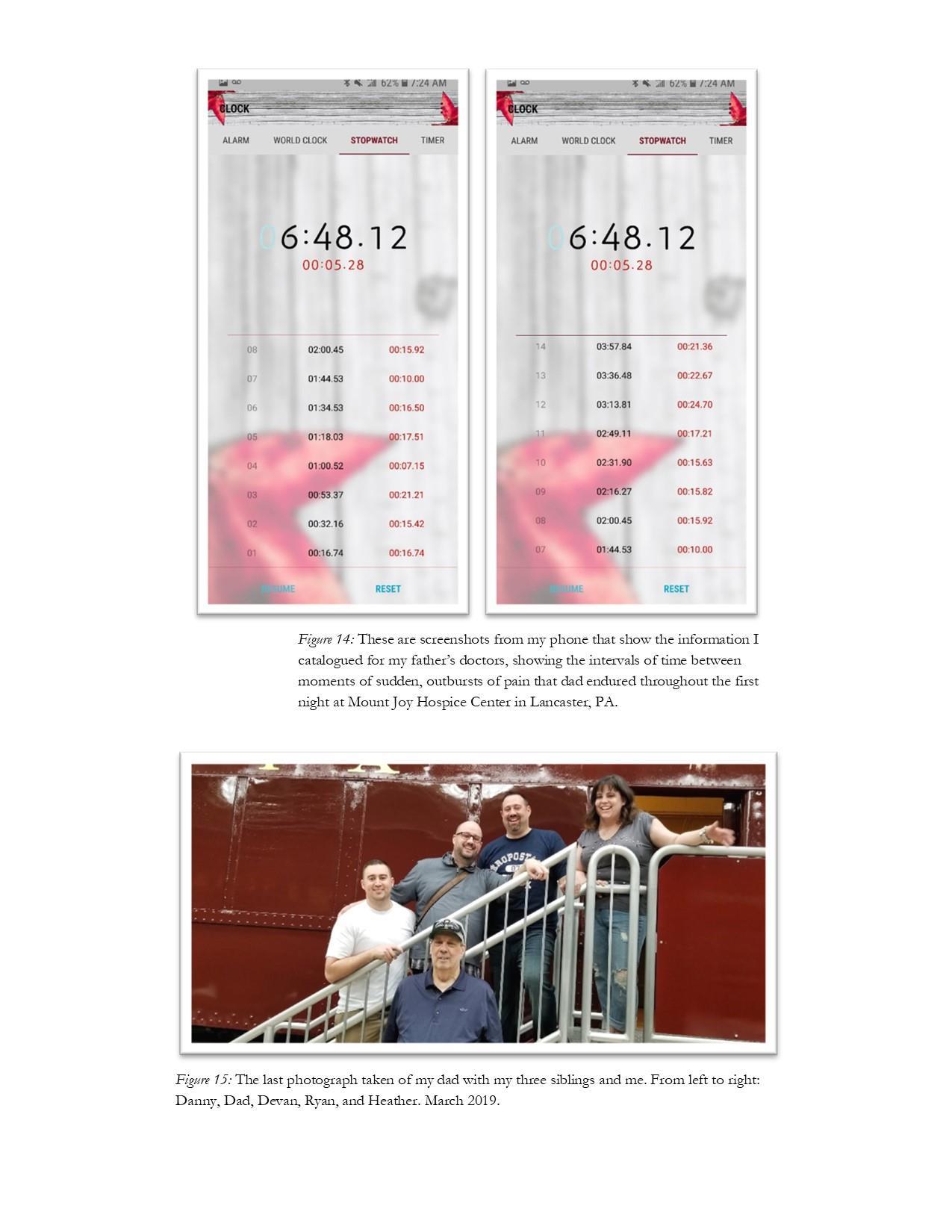

“When we tell our tales, we give away our souls.”

~ J. Hillman

Acknowledgments

Throughout the writing process of this dissertation, I have had my committee in mind as my primary audience, especially the chair of my committee, Jennifer Tolleson. Yet, doing so was not merely about completing program requirements; it was mainly about laboring to create a work for which I believed they would be proud. I allowed this to inspire me to ask deep, probing questions of myself and of my work – of the language I’d use, the thoughts and ideas I’d express, and so on. And I believe it has encouraged me to excel. So, it is for this reason that I extend my warmest gratitude to Jennifer and the rest of my committee for inspiring me to work to live up to my greater potential. I decided to become a psychotherapist because I wanted to help others do this, and I feel all the more capable or equipped of delivering on this as I’ve journeyed through and completed this process with Jennifer in mind.

DH

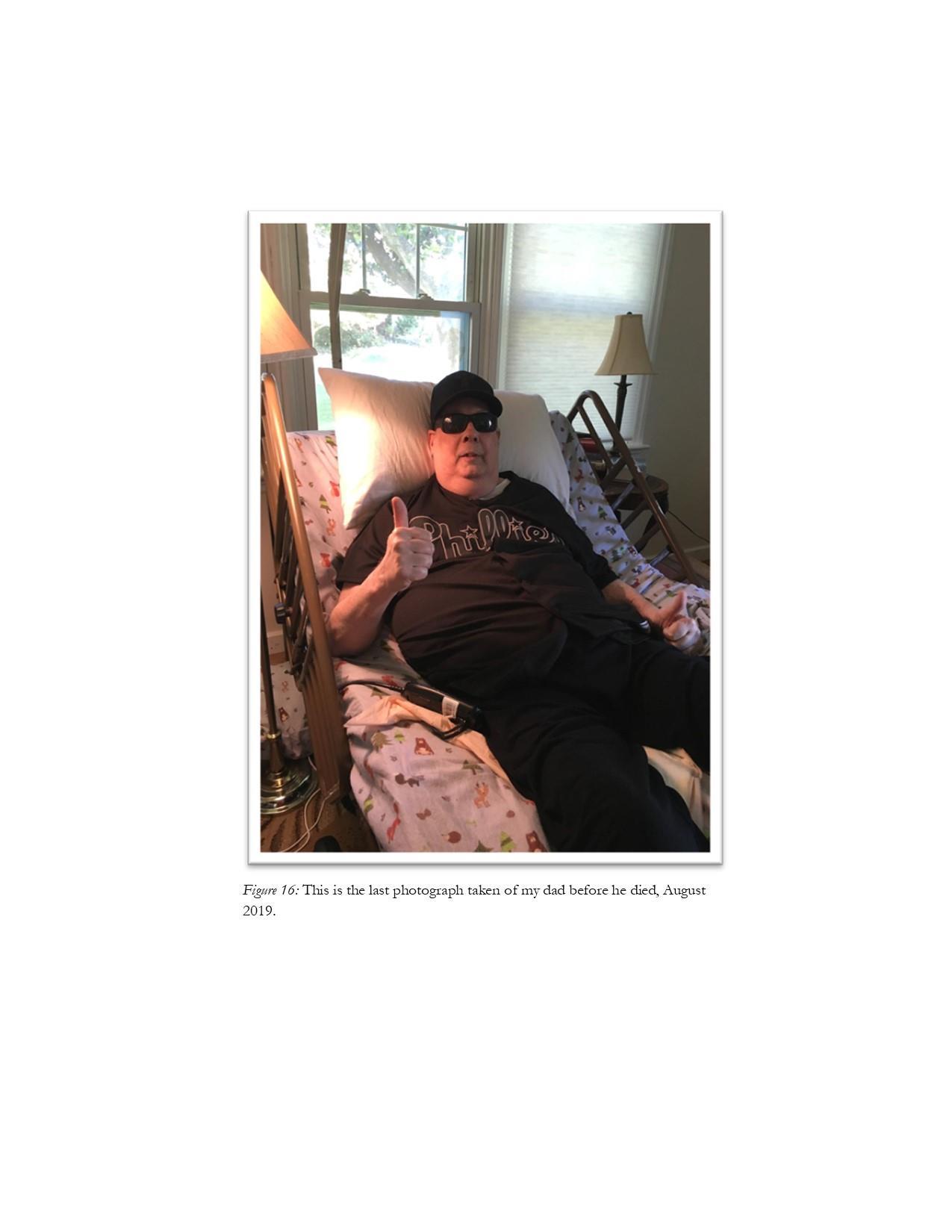

v

Table

vi

……………………………………………….…………………………

……………………………………………………………… v

………………………………………………………….

Questions

of Contents Page Abstract

ii Acknowledgements

Chronology of Significant Dates ix Chapter I. Introduction

1 Father, My Father The Beginning of the End The Purpose of this Study The Significance for Clinical Social Work Two General Problems Objectives Achieved Theoretical & Operational Definitions Foregrounding Hypothesis & Research

Epistemological Foundations Outline

Table of Contents – Continued

Chapter

Page II. Literature Review …………………………………………………… 35

Coddiwompling: A Prelude

Introduction to this Chapter How I Conducted this Literature Review

A Theoretical Overview of Anticipatory Mourning

Anticipatory Melancholia

A “Madness” in Mourning Relevant Autoethnographies

III. Research Methodology

Introduction Research Sample

……………………………………………… 78

On Methods of Data Collection

Research Design: Creating an Autoethnographic Story

Unusual Compositional Elements of the Story

The Process of Analysis & Interpretation

Doing Autoethnography Ethically

Regarding the Issue of the Study’s Trustworthiness

Limitations & Delimitations of the Study

Conclusion

vii

Chapter Page

IV. The Autoethnography 118

A Fatherland Museum

Good Dad/Bad Dad Moving Toward the Ill One the father You could not be Fait Accomplii Dearest Father Dad’s Cancer Miracle Reparation Primary Caretaking Epilogue: Life After Life

V. The Self-Analysis

343 Introduction The Intensification of Mourning Pining for Dad Conclusion VI. Concluding Remarks

Table of Contents – Continued

viii

Table of Contents – Continued

…………………………………………………….

………………………………………………... 423 Introduction Theoretical Conclusions & Actionable Recommendations

Appendices Page

A: A Fatherland Museum 434

B: Trump’s Tweet 444 References ………………………………………………………………. 446

ix

Chronology of Dates & Events Significant to the Autoethnography

July 22, 1979 I am born in Provo, Utah

Summer 1984 My parents divorce for the first time; my mother removes my siblings (Ryan and Heather) and me to Mesa, Arizona.

Summer 1987 My parents remarry each other in Mesa, Arizona.

May 2, 1988 My younger brother, Danny, is born.

October 2, 1988 My parents move our family to Pinetop-Lakeside, Arizona

Summer 1993 My parent divorce again; my father moves to Mesa, Arizona; my mother, siblings, and I remain in Pinetop-Lakeside, Arizona.

April 1994 My father is diagnosed with renal-cell carcinoma. His right kidney is removed, and he is told that he is cured.

Fall 1995 Heather and my father move to Cedar City, Utah.

February 1996 I move to Cedar City, Utah to live with my father and sister; my two brothers and my mother remain in Pinetop-Lakeside.

June 1996 Ryan departs to England to serve a Mormon mission; my mom and little brother, Danny, move to Cedar City, Utah and live across town from Dad, Heather, and me shortly thereafter.

May 1997 I graduate from Cedar High School.

September 1998 I suffer brain trauma from a car accident.

January 1999 I leave Utah to attend Berklee College of Music in Boston, Massachusetts.

December 1999 I begin serving a Mormon mission in Washington, D.C.

January 2002 I have returned from the mission and enroll in the spring semester at the University of Utah, studying classical languages and philosophy.

x

Fall 2003 My father and Danny move to Lancaster, Pennsylvania from Cedar City, Utah.

May 2006 I graduate from the University of Utah.

Fall 2006 I enroll at Yale University, and work to complete a master’s degree in philosophical theology and the philosophy of religion. I graduate June 2009.

January 2010 My mother moves to Lancaster, Pennsylvania to live with Heather.

Fall 2010 I move to Chicago, Illinois and enroll at Chicago Theological Seminary to begin a program in pastoral care and counseling.

Winter 2011 I learn that my brother, Ryan, is using methamphetamine and will begin his first in-patient treatment for it.

Fall 2011 I begin teaching courses in philosophy, religion, and ethics at Triton College in River Forest, Illinois.

May 2013 I graduate from Chicago Theological Seminary in pastoral care and counseling. I then begin practicing psychotherapy professionally at the Center for Religion and Psychotherapy of Chicago (CRPC).

July 2014 I meet Joel Sanchez.

I am promoted to direct the education program at CRPC. I discontinue teaching classes at Triton College.

September 2014 Ryan moves to Lancaster, Pennsylvania because treatments for meth addiction aren’t working well enough out west.

January 2015 I enroll at the Institute for Clinical Social Work (ICSW) in the middle of the 2014-15 academic year to begin a doctorate program in clinical social work.

July 2016 My father is diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. He begins chemotherapy treatment.

July 15, 2017 I begin a private practice at 8 South Michigan.

April 2018 My mother and sister move to Billings, Montana; Ryan moves home to Pinetop-Lakeside, Arizona.

September 2018 Intentional conversations with my father begin. This is also where the story of autoethnographic story of Chapter IV begins. Ongoing

xi

topics of conversation with Dad include our family history, his life, an exploration of his beliefs, and memories of our life together.

The tumors in my father’s lungs are also biopsied. His doctors learn that his renal-cell carcinoma has returned and grown into several tumors in his lungs. Prognosis does not look good. He begins immunotherapy treatment.

February 2019 We learn that my father’s immunotherapy treatment is not working.

April 6, 2019 A carcinoma tumor has eaten away my father’s left humerus bone just below the head of it and it breaks in half. My father enters hospice care.

June 2019 I spend Father’s Day with my dad in Lancaster, Pennsylvania with my three siblings: Ryan, Heather, and Danny.

July 22, 2019 My partner, Joel, my father, Heather, and I spend my 40th birthday together in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

August 31, 2019 My father dies at 1pm.

xii

Introduction

Father, My Father1

Father, my father, move past the mire, and grasp what can’t be spoken. The man who knows it, sees the boy’s desire, to find himself unbroken.

Father, my father, our time is short, and the want grows ever acute: For the boy to know his own import the man, himself, in you.

The Beginning of the End

The tumors in his lungs.

The journey from Chicago to Lancaster is an ambivalent one. Dad is in the hospital again, and I am on my way to provide support and care. I am unaware of it, but the procedure of making this trip will be one with which I become rather familiar.

Just a week before, in one of our regular conversations by phone or Facetime, Dad informed me that his oncologists were wrong about the nature of the tumors recently discovered in his lungs.

1 The poetry of this work is original unless otherwise indicated.

Chapter I

“We’re not sure what it means just yet, but I will have a biopsy next week.”

“Wait, Dad, I’m confused,” I respond. “I thought you had lymphoma. ”

“I do.”

“And that’s of the blood ”

“Yes, that’s right.”

“

So, how are there tumors. Does lymphoma do that?”

“They think it might be the renal carcinoma.”

I recall that renal is from the Latin term for the kidney, and I begin to put it together. Dad’s kidney cancer has returned, latching itself in his lungs like an unwanted parasite and complicating the lymphoma he’s been battling for several years now.

“I thought that when you had your kidney removed, they told you that that cancer was cured,” I say to him, somewhat flummoxed. “Are you saying it’s back?!”

I remember well the Saturday morning in 1994 that my father sat my siblings and me around the kitchen table of our modest, rural, cabin home in the White Mountains of Arizona. I was a few months away from my fifteenth birthday. My oldest brother, Ryan, was seventeen; Heather was just thirteen, and Danny a small boy nearly six. I doubt any of us really grasped what Dad was telling us, except that his doctors found a deadly tumor lodged in his kidney, and that the removal of it (the kidney, that is) would do the work to keep the carcinoma from spreading. It was also the first time I had heard concepts like “metastasize,” “carcinoma,” and even “deadly” in a personal sense. Nevertheless, Dad underwent the procedure, recovered from it, and that was supposed to be the end of it.

2

“So, what is it that went wrong?” I ask. “Help me out. I mean, a cure is a cure, right?”

In June of 2016, two months before his sixty-fifth birthday, Dad was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s, mantle-cell lymphoma. It is a terminal cancer of the blood that’s akin to leukemia, originating in the body’s lymphatic system. Dad began chemotherapy treatment shortly after this diagnosis and was given a three-to-five-year general prognosis regarding the time left in his life.

Over the next few years, his condition would oscillate through a series of shortlived improvements. His oncologists detected the tumors in his lungs as early as February of this year, but they didn’t put the pieces together until this past July while assessing for reasons for why Dad was coughing up blood. The experimental trials to treat his lymphoma appeared to be working, causing it to slip into remission by this time, which gave him hope that his life would be extended, perhaps indefinitely. But, he knew that the hemoptysis (pronounced hee-MOP-tuh-suhs) indicated a serious plummet in his physical health. A wrong turn.

As I disembark from the plane in Baltimore, I am accosted by the steamy mix of moisture and heat, swelling wantonly in the jet bridge that connects the aircraft to the terminal. It is a sunny Thursday at the end of summer September 6, 2018. As sweat accumulates under my arms and throughout my upper body and groin, I lament in secret the disdain I feel for inheriting so much of my father’s body.

I pick up a black, Toyota Corolla from Budget Rental and begin traversing the two-hour trip north into southeastern Pennsylvania. The drive stimulates a standard, stock

3

set of memories from voyaging this route in the past, as if on auto-trigger. Dad moved to Pennsylvania in 2003, after absconding from the home of his roots in a thirty-plus year hiatus. He never really belonged out west. Nothing made this clearer to me than the way his vocational life took off shortly after his prodigal return to Lancaster. Dad was home and he knew it.

The year he left Cedar City, I was entering my sophomore year at the University of Utah in Salt Lake. Visits to see him became fewer and far between. Nevertheless, my mind recalls, now, as I journey to his bedside, Dad’s heightened delight and joy (and consistent promptness) when greeting me at the airport after I would take the flight eastward to visit him. Life felt stable and dependable, even wholesome.

Our greetings were amiable, usually covering the weather, details of my experience of the flight, plans for the duration of time that I’ll spend with him, and so on. I’d look forward to the respite that Dad’s home provides. When we’d arrive in Lancaster, depending on the time of day, Dad would usually take me to Costco and his local supermarket as we’d plan our meals and snacks. These activities appeared to elevate his self-esteem, and I was only too glad to participate.

As I venture north on the beltway, now, I pass an exit that will take one either toward Towson, Maryland (and by extension, southeastern Pennsylvania) or south into downtown Baltimore. Snippets of another memory come to mind. My flight had arrived late at night, and Dad accidentally took the wrong exit at this pass, leading us toward downtown Baltimore instead of Towson. I recall how quickly he became anxious as he realized his mistake, and then furious at himself for making it. Dad has always been so nervous and afraid of big cities, I think to myself. Always had this anxiety of what bad

4

things can happen. It was common for me to experience him this way, a noteworthy aspect of our relationship together; anxious responses, for him, always seemed to convert into one in a limited set of standard options i.e., fury, rage, or anger. It was as if he were saying to himself, “Goddammit, Mark! You are fucking moron!” “You make foolish mistakes!” “You put your life in danger!” “How can you trust that you even know what you’re doing?!”

I grow uncomfortable with these thoughts. Dad and I are too much alike, I think to myself.

Puncture wounds.

When I arrive at the hospital later that morning, I don’t know what to expect. A nurse at one of the random stations directs me to the hall where I will find my father. As I near the area of his room, the echoes of a baseball game on television alert me that Dad is in close range

I enter his room and render a loving and encouraging greeting: “Hey Dad!” His face confesses that he is glad to see me safely arrived, but he is distracted as he struggles in conversation with a nurse, seeking a solution to the difficulty he had sleeping the night before and the post-biopsy pain he’s now feeling. At one point during the conversation, he pulls up his gown to reveal to the nurse several, fresh puncture wounds on the left side of his body, surrounded by scattered splotches of small purple, red, blue, and black dots discolored and bruised hair follicles that are now consumed with blood.

Standing about six-three, my father inherited a tall, beefy physique that was lean and athletic throughout most of his adolescence and early adulthood. He’s lost weight, now, and his skin looks thinner, bare, and more fragile. At the center of each wound is a

5

baleful, black dot, indicating where the oncologists have pierced his intercostal muscles to peer into his thorax with needles and scopes that would score small samples of the tumors installed in his lungs.

As part of my idealized hope to become a physician, I completed a demanding course in human anatomy my freshman year at the University of Utah. The course had a reputation for its tendency to weed out those not fit for medical school. It succeeded in this, but not before I was able to take advantage of learning from the anatomy lab. Now, as I observe the puncture marks on Dad’s body, I recall an impression I gleaned from examining the secondhand cadavers the way the facial tissue tightly wraps the intercostal muscles, creating a condensed and solid fixture between the ribs. I imagine the force required to penetrate them and I quietly wince to myself.

I make a request.

The nurse leaves us, and Dad and I have a moment alone. I ask him about how he’s feeling and, again, about ways that I can help. He doesn’t appear to be in much pain or discomfort, which is a relief to see. In fact, he appears to be enjoying the respite, but I think he is primarily relieved that I found my way to his bedside without incident, even though the activities of my life have been remarkably accident-free.

“Do you mind,” I ask, when the moment seems right, “if you and I take some time before I go to talk?”

“What about?” Dad asks.

I fear, for a brief moment, that my request may overwhelm my father; so, I quickly offer a tidy disclaimer. I respond, “I have some questions I want to ask you that come from the conversations I had with Doris last fall. Do you remember me doing that?”

6

“Sure, I do,” he replies. I think he might be relieved.

“She got me thinking about Pop and grandpa, and people like this from our family. I think you’d appreciate hearing what she had to say, and I would enjoy hearing about some of your own memories, too. What do you think?”

Dad agrees to this with some added enthusiasm, but he also appears to remain realistically cautious, given concerns he has about his recovery, or perhaps other matters. “But, I think for the most part,” he says, “I should be up for it.”

I take comfort in this. I begin to reason to myself that if Dad and I can address a few core topics that are on my mind that have been on my mind for some time now I’ll feel confident my time in Pennsylvania would be well-spent.

The Purpose of this Study

Lest a curse.

“See, the day is coming, burning like an oven … so that it will leave them neither root nor branch. … Lo, I will send you the prophet Elijah before the great and terrible day the LORD comes. He will turn the hearts of parents to their children and the hearts of the children to their parents, so that I will not come and strike the land with a curse” (New Revised Standard Version Bible, 2006, Malachi, 4:1-5)

A general statement regarding the purpose of this study.

The following work is an autoethnographic, interpretative self-analysis of my experience with anticipatory mourning throughout the final year of my father’s life, before he died of cancer. Herein, I consider two central phenomena: First, my personal experience of my father’s illness i.e., of witnessing the process and journeying with

7

him through diagnosis, treatment, palliative care, and death. Second, it is the analysis of how much my experience of anticipatory mourning influenced the relationship I had with my father and my own mental and emotional health.

The Significance for Clinical Social Work

“My self-analysis is the most important thing I have in hand, and promises to be of the greatest value to me, when it is finished” (Bonaparte, Freud, and Kris, 1954, p. 221; Letter 71 to Wilhelm Fliess).

“If we are willing to take an honest look at ourselves, it can help us in our own growth and maturity. No work is better suited for this than the dealing with very sick, old, or dying patients” (Kubler-Ross, 1969, p. 47).

Psychoanalysis and the loss of a father.

In the preface to the second edition of The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud (1900) wrote that a man’s loss of his father was the most important event of his life, to such an extent that he “felt unable to obliterate the traces of the experience” (p. xxvi). He repeated the sentiment in a letter to Ernest Jones in 1920, stating that his father’s death “revolutionized” his soul (Schur, 1972, p. 318). Mahl (1994) even argued that “Freud’s beginning his systematic self-analysis was, in part at least, a delayed reaction to his father’s death” (p. 34).

Broadly speaking, when Freud wrote that his self-analysis was the most important to him, he couldn’t realize how significant it would be for the future of the movement he created. In the conclusion to his book on this topic, Anzieu (1986) notes that Freud experienced a “creative surge” in 1895, and that, from that time through 1901 (i.e., during

8

the period of time that Freud was most engrossed in his self-analysis), he discovered and invented names for 116 clinical concepts of which he would later make considerable use to shape the burgeoning movement. Anzieu reports that Freud stored these concepts away; then, “over the twenty years that followed,” he “drew on this reserve to elaborate the whole of his theory of psychoanalysis” (p. 567). Freud’s self-analysis was “a quite exceptional event in that it coincided with the very discovery of psychoanalysis itself” (Anzieu, p. 568). The implicit message here appears to be about the understated positive and generative contribution that a self-analysis can lend to clinical theory and practice.

Two General Problems That This Study Seeks to Resolve

Mourning without grief?

In the periods of time before (and after) my father’s death, I didn’t feel grief not what would appear as conventional grief, I should say. I can only recall one or two moments when I felt something like it during the year in question for this study i.e., from August 2018 – 2019. To give an example, in Chapter IV, I write of a heartbreaking experience saying “goodbye” to Dad just before departing from our July visit with him. I didn’t know it at the time, but the incident occurred around a month before he would be gone. As Joel and I were leaving, Dad broke into tears. By this time, I had become accustomed, cognitively at any rate, to elevations in the frequency that Dad conveyed mental and emotional suffering, but this incident continues to stand out above the rest. Dad wept a torrential storm, you see, and my younger sister Heather, who was serving as his primary caretaker, mirrored to us, rightly, I think, that he was rapt with the sudden realization that this may be the last time he’d see us.

9

Since this episode occurred, I have toiled a bit to better understand it in terms of what it may indicate about my own grief in the anticipatory mourning process, given that my heart breaks with sadness and my eyes swell with tears whenever I recall it. Yet, this reaction is incongruent with the cumulative experience I had throughout that year, such that I have come to reason that the feelings that are evoked when I recall the episode in question resemble more of something like the experience of feeling deep, empathic sorrow for my dad, rather than a grief I might have been feeling over his impending death. It has seemed as if my grief were merely an installation of my dad’s, as enacted in this departing moment, as if to have my own feeling about his death, independent of his own, were impossible. I may be getting ahead of myself as we anticipate what’s to come, but nonetheless, as I have contemplated how the body of literature dealing with anticipatory mourning applies to my experience, I enter a state of (theoretical) crisis.

After the proposal phase of this project was completed, I began to rigorously examine the plethora of journal entries I had made throughout that year with Dad, about Dad, concerning my relationship with Dad, and so on, scouring it for evidence for what might indicate why I didn’t feel more of what would have looked like conventional grief. I compared my findings with psychoanalytic and attachment-based literature. This process was exceptionally stressful and decidedly painful, to some degree because I wondered if I had chosen the wrong topic of study, but, in most part, because it seemed to indicate that Dad meant little to nothing to me, which I knew couldn’t possibly be the case, given how much of a presence he has typically had in my life in my soul.

10

Did I actually mourn? I frequently grappled. After all, Therese Rando writes that anticipatory mourning is rare. 2

I then happened upon the seminal paper by Helene Deutsch (1937) titled “Absence of Grief,” where she resumes Freud’s argument that mourning is a process that does not always follow a normal course, adding that the degree of intensity imbued in that process is relative to the negative ambivalences in the relationship between the lost object and the one who lost it:

If the work of morning is excessive or delayed, one might expect to find that the binding force of the positive ties to the lost object had been very great. My experience corroborates Freud’s finding that the degree of persisting ambivalence is a more important factor than the intensity of the positive ties. In other words, the more rigorous the earlier attempts to overcome inimical impulses toward the now lost object, the greater will be the difficulties encountered in the retreat from that ultimately achieved position. (p. 12, emphasis mine) Might the absence of grief in the mourning process, pre- or postdeath, suggest or indicate the presence of a type of persisting ambivalence of a sort of relationship with the lost (or about-to-be lost) object that is characterized by a history of attempts to overcome inimical impulses that are directed at it?

Admittedly, Deutsch is contemplating the vicissitudes of grief under the rubric of Freud’s seminal assertions about mourning i.e., that it entails a decathexis from the

2 Theresa A. Rando is the conclusive authority on the topic of anticipatory grief and/or mourning, as I show in the following chapter. She argues with others that these phenomena are rare. See Rando, 2000, p. 6; see also Parkes & Weiss, 1983).

11

lost object. This point is central to the argument against the legitimacy of making theoretical comparisons between pre- and postdeath types of mourning that are extant throughout the conversation around anticipatory forms of it something that I explicate in greater detail in the following chapter. Researchers argue vehemently that anticipatory grief or mourning does not (and should not) include a decathexis from the dying loved one. Deutsch is asserting that the decathexis of grief will become far more complicated when “persisting” ambivalence is indicated in the relationship between the lost object and the one who mourns it.

As of the turn of the millennium, the study of this phenomenon “occupies the interesting position of being an arena of significant controversy,” that is, “one in which relatively minimal research exists” (Rando, 2000, p. 17). To drive this further, Miriam and Sidney Moss (2007) contend that even more scarce are investigations into the effect that anticipating the loss of a parent might have on their adult children. They attribute this tendency to multiple factors, most notably that these deaths are the most common.3 Academics “have tended to ignore the impact of the death of an elderly parent on an adult child,” because these deaths evoke “a less intense emotional response than the death of a child or a spouse” (p. 256). Furthermore, the authors also argue that “ageism” and what was termed by Kenneth Doka (1989) as “disenfranchised grief” provide insight into why researchers tend to neglect this topic (Doka, 1989; see also Moss et al., 2007, p. 257).

3 They write, “The death of a parent is the most common form of bereavement for adults in western societies” (p. 256). Furthermore, research tends to focus, they argue, on “the impact of deaths that are not normative,” e.g., death of a child or spouse (p. 256). This does not necessarily dissuade them, however. Given demographic changes, and the unique tie an adult child may have with their dying parent, the authors concede that multiple issues arise for adult children that are worthy of study.

12

Regardless, in this work, I show that although grief is often part of the larger phenomenon of anticipatory mourning, the research dealing with both has yet to investigate what the operations of predeath mourning might look like in the internal worlds of those involved in an intimate yet decidedly ambivalent relationship, especially between an adult child of a terminally-ill parent. There is, after all, not a single study of which I am aware that ties these factors together.

Epistemological concerns.

In a broader sense, this study also seeks to help address epistemological concerns about the dubious nature of the assumption in research that positivistic, quantitative research methods trump the sort I have conducted. Autoethnographic research tends to observe, uphold, and represent an extended response to criticisms that have been launched against nomothetic, deductive, positivistic, quantitative research enterprises that purport to prove a priori hypotheses and to explain, predict, and control generalizable phenomena. Although deductive and positivistic (etc.) methods might conjecture about human behaviors and practices, such a research method can “never [truly] predict what other people might think, say, or do” (Adams, Jones, & Ellis, 2015, p. 9). They cannot “establish singular, stable, or certain ‘truth’ claims about human relationships” (Adams et al., p. 9).

Adams, Jones, and Ellis (2015) refer to the leading problem that autoethnographic research intends to address, as a method, in terms of an epistemological “crisis of representation” (pp. 9, 11, 22, 83-84; Reed-Danahay, 2002, p. 423). This crisis asserts that researchers cannot separate themselves from their culturally-embedded experiences of carrying out the research itself. As “existence precedes essence,” in Sartre’s (2007)

13

famous slogan, there is no data before the researcher. To attempt to separate data from the researcher is not only impossible and renders incomplete results, but the effort otherwise tempts researchers to take advantage of vulnerable participants (Adams et al., p. 11).

Naturally, the observance of the crisis of representation and the philosophy that underscores it informs the ethics of conducting research projects that deal with the terminally-ill and dying. Adams et al. write, when contemplating the history of the qualitative movement, “Ethnographers who focused on the experience of anxiety, disability, illness, death, and dying recognized that they could not ignore the ways emotions infuse and are intertwined with physical experience and embodiment” (p. 11). Autoethnographies respond to these problems by emphasizing aspects of qualitative approaches that situate the researcher in the center of the study, having accepted, prima facie, the methodological quintessence of this enterprise. Thus, autoethnographic research works to think aesthetically, use language in unique and creative ways, provide thick descriptions of phenomena, and to focus on “meanings that can take readers into the heart of lived experience” (Bochner & Ellis, 2016, p. 34; Geertz, 1973).

This is, of course, what I have endeavored to do for this project.

Objectives Achieved

“The goal of autoethnographic projects is to embrace the vulnerability of asking and answering questions about experience so that we as researchers, as well as our participants and readers, might understand these experiences and the emotions they generate” (Adams et al., p. 39).

14

In the study that follows, I have endeavored to observe these principles as closely as possible. As I combed through the journals I created throughout that final year of Dad’s life, and as I have reflected earnestly on the implications of where I was at the time, how I felt, the moods that conversations with Dad generated as I contemplated the roles I played and the conflicts this raised for me as I attempted to penetrate and apprehend the relational dynamics between myself and other members of my family and, of course, as I contemplated the existential realities of dying and death in all of this, I labored, sometimes with great exertion, to recognize, comprehend, and accept what seemed to matter to me, what I seemed to care about, and most importantly, what it was that I felt I was blocking Ultimately (and broadly), I hope to have accomplished the following:

1. To identify major themes and noteworthy or outstanding events that occurred in my subjective experience of my father’s battle with terminal illness leading up to his death, primarily in the course of the final year of our time together (that is, from August of 2018 through the end of August 2019).

2. To organize those themes and events into a storyline.

3. To write a story and present it, here, as a work of “evocative” autoethnography (Bochner et al., 2016), constituting it as the whole of the data sample for this study.

4. To fashion and present an interpretive analysis of the story in the form of a psychoanalytic self-analysis.

15

Theoretical & Operational Definitions of Major Concepts

In the next chapter, I review the phenomenon of anticipatory mourning as it applies to this work, especially regarding the semantic evolution of the clinical focus on anticipatory mourning rather than (mere) grief. In the section below, I offer a short introduction to this, along with a simple yet relevant handful of other core concepts that have helped organize and guide my thinking about and constructing of the autoethnographic narrative of Chapter IV and the self-analysis of Chapter V. In other words, the concepts I define below are summarized in greater detail in the following literature review, coupled with a more extensive discussion of anticipatory mourning; furthermore, these concepts constitute the components of psychoanalysis that I use to probe my experience of this phenomenon in Chapters IV and V, which are chiefly influenced by the works of Freud and the British School of Object Relations. The major concepts in question are (a) “madness,” (b) both introjective and anaclitic depression, and (c) mania.

Anticipatory mourning in a nutshell.

Therese A. Rando (1986, 2000) develops an inclusive and comprehensive definition of anticipatory mourning, which I explain in greater detail in the pages that follow, and which guides my analysis throughout this work. Nevertheless, my straightforward definition of the phenomenon is as follows: Anticipatory mourning, simply defined, describes the mental and emotional experience of facing an eventual death, almost always due to terminal illness, be it one’s own death or that of someone close to one. Most of the current resources available that pertain to this phenomenon are

16

especially written for mental health professionals, families, clergy, or those otherwise in the helping professions, to accompany any one of the following three objectives:

1. To normalize confrontation with an impending loss.

2. To offer support and provide helpful clinical quips to those caring for the terminally-ill and dying again, often clinicians, mental health workers, and palliative caregivers.

3. To ease the transition from life to death for those who are terminally-ill and dying.

A pattern of madness.

Neville Symington died on December 3, 2019, just a few months after my father. Shortly before Dad died, I became interested in Symington’s life and work while listening to a podcast that featured him. Yet, I hadn’t discovered his final and perhaps most comprehensive work A Pattern of Madness (Symington, 2018) until I began working to better understand both the intensification of the ambivalences in my relationship with Dad and the lack of grief I felt in the pre- (and post-) death mourning process. “Madness,” Symington defines, “consists of a pattern of interlocking elements that distort perception, damage the self, and prevent emotional freedom” (p. 79). It is generated by the autistic disavowal of the “spontaneous gestures” (Winnicott, 1960, p. 145) of one’s emotional intuitions. It is akin to manic denial, paranoid-schizoid splitting, and the projective enterprise of emptying oneself of one’s negative feelings (Fromm, 2000).

In this work, I label myself “mad,” because I believe it captures well the frenzies of the internal operations of my psyche those which occurred during my final months

17

with Dad. As shown in the narrative, patterns of madness greatly limited my capacity to connect with my dying father in meaningful, potentially healing ways. This “madness” is indicated in any of the multifarious moments that I journeyed with him, yet declined to accept the deeper, non-cognitive realities of his mental, emotional, and physical suffering. As Dad declined, I understood the reality of what was occurring, and I accepted it, theoretically, more or less; yet, the primary mental and emotional experience, during that period of anticipatory mourning, appeared to yield regressive amplifications around the disturbing ambivalences that had always constituted my relationship with him. These were regressive contents against which I inadvertently applied, in “madness,” a rather committed set of manic defenses.

Mourning unto depression, mourning unto mania.

Sydney Blatt (2005) produced a comprehensive work, detailing the phenomena of two forms of depression i.e., a melancholic depression called “introjective” and an attachment-based form called “anaclitic.” Both types are indicated in my experience of mourning Dad, primarily the former (i.e., the “introjective” type). As I show hereafter, introjective depressive defenses, originally made rudimentary in even preoedipal configurations with my father, intensified factors that led to employing the complementary manic defenses against it, which blocked my acceptance of the realities of my father’s decline. The introjective type of depression is often referred to as a “selfcritical” type, that is “typified by punitive, harsh self-criticism; self-loathing; blame; guilt; … and intense involvement in activities” that are “designed to compensate for feelings of inferiority, worthlessness, and guilt” (p. 32).

18

The concept of introjective depression follows from Freud’s discussions of the processes entailed in object loss, both defensive and formative, from his seminal papers Ego and the Id (Freud, 1923) and Mourning and Melancholia (Freud, 1917). As I show, I did not begin mourning the losses of my father in August of 2018, nor in the summer of 2016, when I first learned of his terminal diagnosis. Dad has always (and rather consistently) been made an object of melancholia for me one which I have endeavored to properly mourn since the earliest years of my life.

Of the manic sort. On May 31, 2013, a little over a month after I received my first license to practice psychotherapy, my dad gifted me the book Psychoanalytic Diagnosis by Nancy McWilliams (2011). On the front cover page, he wrote: “Devan Hite, I thought you might like to have this especially from your dad. You will be a star in the profession You have made me very proud, as always, Love, Dad.”

Since then, I have found McWilliams’ contribution to the discourse on psychoanalytic assessment and treatment to be consistently and inordinately helpful, serving as a kind of bible I can consult in moments of clinical impasse, murky transferences and countertransferences, and, of course, this self-analysis. Furthermore, I have found her summary of hypomanic/cyclothymic personalities useful as I navigate the body of psychoanalytic literature to find a language that helps capture the essence of what was largely instituted in my history with Dad and what was elevated or heightened during the period of anticipatory mourning in question

McWilliams writes that “people with hypomanic personalities have a fundamentally depressive organization, counteracted by the defense of denial” (p. 256). She continues, “Hypomania is not a state that simply contrasts with depression; point for

19

point, it is a mirror image of it” (p. 257). Akhtar (1992) lists qualities and characteristics of hypomanic personalities from a psychoanalytic point of view, and a number of these are indicated i.e., I adopt them as an attempt to deal with Dad’s impending death. They include a neurotic-level, overt, false-self type of cheerfulness, a high/intense sociality, idealization of others, an “addiction” to work, flirtatiousness, articulateness, and covert guilt about aggression toward others, something that is especially poignant in moments with my father. (The expression of a licensed or “ruthless” form of aggression toward him was always unthinkable.) Furthermore, in moments that matter (i.e., otherwise appropriate moments), I show deficits in my capacity to empathize with or show love to my father. I lack a systematic approach in cognitive style and, at moments, I show an unfortunate corruptibility (p. 193). All of these attributes are indicated in the extended narrative of my experience with anticipatory mourning.

An important disclaimer.

McWilliams offers a useful proviso that also characterizes this experience, noting that “many individuals with characterological hypomania … have more mild versions than the personality disorder that Akhtar is describing,” in that, for one, they are “able to love and to behave with integrity” (p. 257).

The story shows that this is ultimately the case for me. It shows in me a pervasive use of hypomanic or cyclothymic operations that fit this diagnostic grouping, but not to the extent that a proper assessment might conclude, that I, the main character of the narrative, developed or feature a personality disorder as a result of undergoing this forceful experience with anticipatory mourning. For that matter, the same conclusion applies to the question of whether I meet DSM-V criteria for any of the various mood

20

disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). These will not be indicated in the story, necessarily. However, what shows straightaway in the narrative are the multifarious ways in which my depressive and manic defenses, constituted in large part in my historical relationship with Dad, become amplified as I face the realities of his impending death with the ambivalences of our relationship fully activated.

Conclusion.

That being said, perhaps the most prominent indication of this characterology in the narrative that follows is the rage I feel throughout that is meant to cover, deny, or block the sadness or grief that was also indicated in my encounter with mourning the forthcoming death of my father. McWilliams writes, “When negative affect appears in people with manic and hypomanic psychologies, it tends to manifest itself … as anger, sometimes in the form of episodes of sudden, uncontrolled rage” (p. 257). As I show, it is this aspect of my relationship with Dad for which I begin seeking a resolution as the story commences. We both use this defense, and our mutual employment of it has proven remarkably destructive for both of us, historically.

Gabbard (2014) defines mania, as well, of which I also make use in the pages that follow. He argues, citing Melanie Klein, that “the fundamental psychotherapeutic task,” when confronted with mania, “may be to facilitate the work of mourning” (p. 235). He says, “the threat of aggressive, persecutory feelings leads to the need for manic defenses to deny them” (p. 235). Thus, a work of mourning, I ultimately argue considered as either pre- or postdeath, anticipatory or otherwise is not merely a work of accessing, processing, and accepting the grief attending it, but also the active work to integrate splitoff aggression and fears of persecution that are necessarily inherent in it. Gabbard writes

21

that these defenses against grief, etc., work to issue one a temporary relief from pain, which I often welcomed, even when the emotional pain in question was “right” or reasonable to have, given the context of it, “but no chance,” he continues, “of ultimately resolving their depressive anxieties” (p. 235)

The motivation to confront these tendencies has become one of the principal factors for pursuing this effort and for working to produce a self-analysis of my experience with anticipatory mourning. It is borne from the motivation to better understand these tendencies and to take steps to “work through” (Klein, 1935) them properly. That being said, what are other, significant reasons that I have endeavored this study?

Foregrounding

Adams et al. (2015) argue that an autoethnography is itself a work of foregrounding. They introduce the fundamental nature of this concept by arguing unequivocally that autoethnographies, “as a method, mode of representation, and way of life,” require scientists and investigators “to foreground research and representational concerns throughout every step of the research and representational process” (p. 19). Thus, the following work on its own is a work that is focused on foregrounding my experience of the phenomenon in question.

That being stated, I want to make explicit what are likely the underlying reasons that I chose this topic and why I have pursued studying it. It has become, simply put, a core belief of mine that by working to make sense of my father’s existence, I can, perhaps, make better sense of my own The stimulation of this enterprise, underscored by this central belief, represents the most conspicuous way in which I traversed my personal

22

experience in the last year of Dad’s life. In other words, as I set out to better understand my father in the months before he died, the exercise served to help change the quality of the internal investment that I had (and have) with him (Hoffman, 1979).

The claws of the crab.4

The consequences of the seminal aphorism from Freud’s (1917) work Mourning and Melancholia cannot be overstated as I proceed: Thus, the shadow of the object fell upon the ego, and the latter could henceforth be judged by a special agency, as though it were an object, the forsaken object. In this way an object-loss was transformed into an egoloss and the conflict between the ego and the loved person into a cleavage between the critical activity of the ego and the ego as altered by identification. (p. 249, emphasis mine)

I believe, that is, that nothing in my life has produced more emotional and mental conflict and turmoil than the internalized, psychodynamic “cleavage between” Dad-introjects and my sense of self. This is the result of both action and inaction, direct participation in each other’s lives and the desolate lack of it. Both circumstances proved to be remarkably ambivalent. I wrote the following in my journal just before Dad’s health took another pivotal decline: 4 S. Mukherjee (2010) wrote, “It was in the time of Hippocrates, around 400 BC, that a word for cancer first appeared in the medical literature: karkinos, from the Greek word for ‘crab.’ The tumor, with its clutch of swollen blood vessels around it, reminded Hippocrates of a crab dug in the sand with its legs spread in a circle. The image was peculiar (few cancers truly resemble crabs), but also vivid. Later writers, both doctors and patients, added embellishments. For some, the hardened, matted surface of the tumor was reminiscent of the tough carapace of a crab’s body. Others felt a crab moving under the flesh of the disease spread stealthily throughout the body. For yet others, the sudden stab of pain produced by the disease was like being caught in the grip of a crab’s pincers” (p. 47).

23

January 13, 2019. Sunday afternoon. I don’t know my father. And, as a result, I feel that I am perpetually mourning a loss that I don’t want to mourn anymore. There’s a lot that I could say about how I, for a very long time, especially when I started to meditate more often, how when I would close my eyes and begin to do it, I would find that Sadness, capital S, seemed to always be lurking just under consciousness, just always right there outside the door. And I’ve wanted to understand it and eliminate it. I don’t think that he knew quite how much, but Dad has always been represented in terms of a potent, enduring, introjective dynamic of my inner world, the residue of which likely will remain for the rest of my life in some form or another. Historically, it has been remarkably melancholic. The nature of its existence is brawny and phantasmagoric enough for me to consider it preoedipally or preverbally constituted. When radioactive, it omits a type of intrapsychic fervor that is destabilizing unto “madness. ” It is the impetus for unpleasant and obtrusive cyclothymic mood swings that effect my relationships, my work, and the quality of my life. Of greatest value for this dissertation project (i.e., as one for a doctoral program in clinical social work) are concerns about how this madness affects my capacity to deliver effective treatments to the patients in my care. Blocking the implicit invitational cues of patients, that is, to settle into dark, negative feelings and moods so that we might further comprehend them, put words to them, find meaning in their existences, can at times be rather limited. Manic defenses that devalue such enterprises spring into action like a loyal pet warding off weighty cocktails of emotion encountered as if unwanted, opportunistic relatives. During that final year of Dad’s life, the ambivalent nature of our histories together was

24

intensified, as I show, and I failed to rise to the challenge that Dad’s dying moments inevitably offered me.

Shortly after Dad was diagnosed with his terminal illness, I became interested in studying our family’s history. Later, I would come to understand that this ambition was perhaps the most direct expression of the predeath mourning process I was undergoing, whereupon, rather than decathecting from Dad-introjects, which has been shown to be impossible, I was, as Irwin Hoffman (1979) reframes, working to “change the quality of the investment” that I had with my father i.e., working to change the introjective “Dad” cathexis rather than to decathect from it (p. 259). This distinction is crucial in the discourse of this topic of study, and I have worked to give it fair and honest attention in the following chapter. Regardless, it is right to note here that this desire again, an act of anticipatory mourning propelled me into the study of it without knowing I was doing it.

Paul Kalanithi wrote a short memoir about his experience of terminal illness, which he titled When Breath Becomes Air (Kalanithi, 2016). It is a work of anticipatory mourning, I believe, even though he never assigns it this term. Nevertheless, Kalanithi contemplates the meaning of his life as a neurosurgeon before and after his diagnosis of stage four lung cancer. He writes: As furiously as I had tried to resist it, I realized that cancer had changed the calculus. For the last several months, I had striven with every ounce to restore my life to its precancer trajectory, trying to deny cancer any purchase on my life. As desperately as I now wanted to feel triumphant, instead I felt the claws of the crab holding me back. The curse of cancer

25

created a strange and strained existence, challenging me to be neither blind to, nor bound by, death’s approach. Even when the cancer was in retreat, it cast long shadows. (p. 164-65)

He continues: But if I did not know what I wanted, I had learned something, something not found in Hippocrates, Maimonides, or Osler: the physician’s duty is not to stave off death or return patients to their old lives, but to take into our arms a patient and family whose lives have disintegrated and work until they can stand back up and face, and make sense of, their own existence. (p. 166)

It seems that death, especially the acts of facing the immediacy of death, forced my dad and me to attempt this. Whether we accomplished it or not, ultimately, is an important question, but I do not believe we were able to this very well. Examining that year contemplating what I felt, spoke, and did has helped me to begin, however, to work through the mysteries of my father’s personality better, and therefore, my own.

I have struggled to understand the role my father played in setting a foundation for my life before this ambition became a formal study, and, perhaps, before my father became terminally ill. That being said, the energy involved in this certainly increased during the period of time that concerns this study, to such an extent that it is clear to me that another core, motivating factor that underscored my need for conducting it is, plain and simple, the wish to be able to handle the losses of my life better, both great and small, as most of my life has dealt in struggling to accept and cope with loss on its own

26

terms. Furthermore, I believe that this type of work i.e., the work of properly owning one’s losses is foundational to human experience. It itself gives life meaning.

Hypothesis & Research Questions

I hope to have established by now that this work investigates the way that the ambivalences that constituted the relationship with my father were amplified during the final year of his life. I have argued that the following study reveals and investigates the manic defenses I employed against the negative intensifications of these ambivalences, along with the depressive/melancholic operations that appeared when these defenses were unsuccessful. I have asserted that it is a theoretical and clinical problem that the research regarding anticipatory mourning has failed to examine such dynamics, especially between adult children and their dying parents. This is likely due to the fact that studies on grief and mourning primarily focus on the sort that occurs between otherwise healthy relationships, leaving out what is in all probability the more-common-than-we-realize circumstance of mourning troubled ones, both before and after death. This is a point I have shown to have been introduced by Freud and Deutsch some hundred years ago when considering the lack of grief in postdeath mourning; yet, the studies of this sort have yet to be applied to its (more or less) complementary, that is, anticipatory mourning, process

Therefore, this dissertation is built upon the core hypothesis that it is not necessary that conventional grief be indicated in my experience undergoing anticipatory mourning for it to be labelled as such; but rather, the opposite is the case. That is, the absence of grief indicates an even elevated version of it a toiling with or a “madness” of mourning that is underscored by the internal dynamic consequences of this troubled relationship between my now dead father and me.

27

Therefore, this work addresses the following, central research questions:

1. How did my experience of anticipatory mourning affect me (personally) and the ambivalent relationship that I had with my father before he died?

2. What are some of the significant and noteworthy ways in which my life was disrupted and/or disordered by anticipatory mourning?

3. What impact might the reflexive conversations between my father and me have had on my experience of working through the ambivalences in our relationship, and, by extension, the lack of conventional grief as I journeyed through a unique encounter with anticipatory mourning?

4. How might my self-analysis of anticipatory mourning inform theory about the phenomenon, and how might this be useful to others, especially those in the helping professions?

The Epistemological Foundations of this Study

“It is essential to consider as a constant point of reference … the regular hiatus between what we fancy we know and what we really know, practical assent and simulated ignorance which allows us to live with ideas which, if we truly put them to the test, ought to upset our whole life” (Camus, 1955, p. 18).

General overview.

As a qualitative study, this dissertation project is located in the following, broader philosophical contexts. That is, it is a work that is “idiographic” in perspective; its language is “emic,” i.e., “unique to an individual, sociocultural context” (Ponterotto, 2005, p. 128). The study does not purport to offer generalizable predictions or outcomes.

28

Furthermore, inasmuch as the study holds the philosophical precept that argues “reality is constructed in the mind of the individual, rather than it being an external singular entity,” the project is a “constructivist-interpretivist” one (p. 129; Hansen, 2004).

Although this research observes principles of qualitative reflexivity i.e., there are moments when I report directly on my how my father responded to my thoughts about our experiences together and how they appeared to affect our relationship the study’s focus, as an autoethnographic one, is ultimately the interpretation I employ to describe my own experience in the embedded context of our lived experience traversing the strains of anticipatory mourning.

In the chapters that follow, I examine the “centrality of the interaction” between us (Ponterotto, 2005, p. 129; Schwandt, 2000), but my father is not the object of my investigation. Rather, it is my experience of losing him and how the events in this appear to invoke deeper relational themes between us as I experienced them personally as internal phenomena. Therefore, regarding this project, the reflexivity that is characteristic of constructivist projects concerns the “centrality of the interaction between [me] the investigator and [the phenomenon of anticipatory mourning] the object of investigation” (p. 129; Schwandt, 2000). The purpose has been to bring to the surface hidden depths of meaning through careful reflection.

Optimally, there are key moments in this work when these interpretations assist to spontaneously, and perhaps without even intending it, as Ponterotto (2005) argues, “disrupt and challenge the status quo,” advancing moments of “emancipation and transformation,” both for myself and those who might read it (p. 129; Adams et al., pp. 32-34). These are pivotal moments in the storyline when subjective yet “proactive values

29

are central to the task, purpose, and methods” of this research (p. 129). Thus, the work is also (secondarily) a “critical-ideological” one (p. 129). From the discussions I had with my father before his death, relevant themes to this paradigm concern issues of desire and sexuality, father-son roles and expectations, the iatrogenic effects of religious experience/the dominant political platforms of my upbringing, and ultimately, broadlyestablished ways of dealing with grief, loss, and mourning.

Although Ponterotto uses the terms “constructivism” and “interpretivism” synonymously to describe the epistemological foundation of qualitative inquiry, he does not push further to make the useful distinctions of interpretivist philosophies reviewed by Schwandt (p. 129; Schwandt, 2000). Schwandt’s (2000) overview breaks down interpretivist philosophies into four subclassifications (p. 191). These are “four ways of defining (theorizing) the notion of interpretive understanding (i.e., Verstehen)” (p. 191). The first three, Schwandt argues, “constitute the interpretive tradition,” while the fourth is philosophical hermeneutics, which is rightly set apart (p. 191). This work observes principles of philosophical hermeneutics, but how?

The “refining fires of interpretation.”

Porter and Robinson (2011) argue that Hans-Georg Gadamer’s name has become synonymous with “philosophical hermeneutics” (p. 74). This continental philosophy contends, in a nutshell, that “we are always taking something as something” (Gadamer, 1970, p. 87). It accepts on the onset that we cannot free ourselves from the influences of our history cannot set these aside (e.g., as in “bracketing” or, of course, epoché) to achieve some objective, interpretive truth (Schwandt, 2000, p. 194).

30

In their excellent and very useful summary of Gadamer’s philosophical hermeneutics, Porter et al. write, summarizing Gadamer:

Interpretation … is dependent upon our willingness (intention), the text (which we allow to interrogate us), and the structure of the experience itself (beyond our intention), in which we encounter the birth of new meaning and insight if we are willing to risk our preconceptions and expectations in the refining fires of interpretation. (pp. 87-88)

The authors continue: “Truth emerges only when our individual horizons and the horizons of the other (e.g., text, person, work of art) fuse, bringing different worlds together in surprising new ways” (p. 88). Gadamer’s philosophical hermeneutics provides an exceptional set of principles to apply for this study. For the remainder of this section, I want to briefly outline what they are and how.

Philosophical hermeneutics is both a critique of modernist epistemologies and a prescriptive solution to their tendency to alienate the researcher from experiences that would otherwise grant them access to more thorough and inclusive forms of truth. It is a critique against methodologically colonizing phenomena under examination via restrictive, “artificial boundaries” that formalize personal distance and “neutral objectivity” (Porter et al., p. 78). Porter et al. write: Gadamer wants to describe the concrete and universal nature of the hermeneutical problem that may only emerge when we are freed from the methodological and procedural assumptions that require us to control how we arrived at understanding, e.g., through experimentation, measurement, and theoretical principles. (p. 78)

31

Instead, understanding requires the researcher to surrender in much the same way that psychoanalysis often recommends a patient surrender to free-associative observation in session. To arrive at understanding is almost akin to encountering the unconscious, which is never static and always resistant to observational inflexibility and attempts to control. It is blocked by “any inquiry or investigation” that believes itself to be “without prejudice or bias” to its own “conditioned ways of understanding” (Porter et al., p. 85; Gadamer, 1960/2002).

Truth and understanding, for Gadamer, is also an event, but a tricky one. Each time we encounter the samsaric aspects of the hermeneutic circle, our dynamic and changing, conditioned and embedded locations inevitably influence how that encounter transpires. Rather than attempting to transcend these locations, as the objectivists are inured to do, the researcher should work to open themselves to what Gadamer calls a “fusion of horizons” (Gadamer, 1960). This fusion is neither an objective nor subjective enterprise. It is, rather, an “interplay of possibilities” that involves “real risk-taking” in dialectical and interpretive moments. It achieves a form of universality that “binds together language, tradition, and experience” (Porter et al., p. 86). Furthermore, this type of exchange may occur between a researcher and any form of “other,” e.g., another person, a text, or a work of art. All three are relevant to the inquiry in question. Porter et al. summarize that the fusion of horizons, as an alternative and more useful type of hermeneutical event, is “something that happens without our making or doing” (p. 86). They write, “We enter into the experience voluntarily and participate in it according to its own structure and rules rather than merely our own wishful desires” (p. 86).

32

How, then, do these principles apply to my inquiry? In the previous section, I stated that, ultimately, this study examines the interaction, as a reflexive dialectic, between me and the object of investigation, or, in this case, the phenomenon of anticipatory mourning. If I am to apply Gadamer’s philosophical hermeneutics to this study properly, then responses to my research questions, which concern the object of my inquiry, must actively consider what it is that I bring to those responses. I do this by remaining conscious of and making a serious attempt to observe the importance of opening myself to a fusion of horizons with others, texts, and the work of art that is the autoethnographic narrative of the fourth chapter.

In the third chapter, I explain in greater detail how I do this, step-by-step. I describe the difference between formal and informal types of data collection and presentation, and I justify the position that the autoethnographic narrative of Chapter IV serves as the only formal data sample for this study. I also explain my reasoning and logic for making full use of Chapter V to produce a self-analysis, including the steps I took to execute it. With this in mind, the text of the narrative, as a work of art, is ripe for the type of investigation that works to remain open to the dynamic fusion the refiner’s fire of philosophical hermeneutics.

Outline of the Dissertation

In this chapter, I have introduced this study. In Chapter II, I focus the literature review on works that are most directly relevant and useful to better comprehend both (a) the phenomenon of anticipatory mourning, and (b) the psychoanalytic ideas I used to conduct the self-analysis. In Chapter III, I explain in further detail the way I have applied the autoethnographic qualitative method to conduct this study, as well as the theoretical

33

justification for it. In Chapter IV, I present a narrative that is my best effort to capture and present, in story format, the experience that I had of the rather formidable and torrential anticipatory “mourning in madness.” Then, in Chapter V, I apply the literature reviewed in Chapter II to the story of Chapter IV, providing an interpretive self-analysis of the story, of my experience, using a psychoanalytic lens. Finally, in the closing Chapter, I conclude my remarks and summarize what I believe I have accomplished.

34

Chapter II

Literature Review

Coddiwompling: A Prelude

When Dad told me that he had been diagnosed with lymphoma, I can’t tell you that I remember what he said or how I felt when I heard it. I know it happened in June of 2016, and I know that I said and did everything that I was supposed to do and say: “Oh, my god!” “That’s terrible!” “What are we going to do about it?” “How can I help?” I behaved appropriately, completed my duties, and performed the tasks that were asked of me I don’t remember questioning whether or not I should. I was a “good” son, working to help my father achieve, ultimately, an “appropriate” death (Rando, 2000).

And yet…

This is a work about death and loss, but it is not going to reveal the standard narrative tropes around these themes because they don’t exist here. Since I began this project, I have taken in a good-sized plethora of books and papers on the topic, watched many films; I’ve contemplated the subject enough to know that my story may easily betray them. Stories about the dying process about anticipatory mourning normally feature main characters in terrible, formidable bouts of grief, sorrow, anger, sadness, hopelessness, and so on. They suffer, they scream, they bargain, they curse, they strive, they oscillate, and they love with amplified ardency, because they know that the death of

35

their loved one is inevitable and they abhor this. These are heart-breaking stories, and the many of them that come to mind have touched me deeply.5

Dad died on a Saturday afternoon at the end of August of 2019, just over three years from the day he received his terminal diagnosis. I was hustling my way back to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where he and my younger sister, Heather, were living (and dying). Waiting to board my flight, I was eating a chicken sandwich at the Chili’s just inside one of O’Hare’s bustling terminals. Heather left me a voicemail. I learned from it that Dad had died, and I felt relief. I felt guilt and sadness, too; but, I mainly felt relief. This relief my relief surprised me, because it was not the rueful sort (not merely, at any rate) that might reflect the kind of somber gratitude that one might feel when learning that someone one loves will no longer be suffering. Perhaps, it is more accurate to say that I felt release. The release I remember best is a release from the pressures of my father’s existence.

After his death, I continued to faithfully observe the primary duties Dad had given me to oversee preparations for his funeral and burial, and to close out his estate. And I do remember what I felt during this time: feelings of love, respect, appreciation, and gratitude for family and close friends who labored to support my father in the final days of his life and who came to our aid to help and encourage us in the process of following through with the standard, postdeath ceremonies that ritualized the end of Dad’s life.

5 For instance, the films Our Friend (Pruss et al., 2019), A Monster Calls (Atienza et al., 2016), Shadowlands (Attenborough et al., 1993), and My Life (Lowry et al., 1993) come to mind. Even the film Supernova (Goligher et al., 2020) is there, which is not about anticipatory mourning, in itself, but the death of a loved one’s mind from dementia. The book The Best of Us by Joyce Maynard (2018) also comes up, along with memoirs dealing with grief and bereavement after the death of a loved one, including A Grief Observed by C. S. Lewis (1989) and The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion (2005). I even recall Robert Stolorow’s (2005) formidable battle in Grief Chronicles

36

Yet, silently, through it all, I wished that I had loved my father enough to care more about his death beyond these features of it. I didn’t cry, you see. Most of the time, throughout the final year of his life especially, I felt angry I didn’t seem to care enough, though I behaved as if I did. I behaved like a good son: I honored him, sang to him, respected him. I helped clean him up and put him back in bed when he fell out of it. I engaged him in his psychotic fantasies the weeks before he died (because, what else are you going to do?). At his funeral and graveside, I esteemed his life and dedicated myself to learning from it. These were the behaviors he taught me to live up to, admire, and emulate, and they were the behaviors that put me into touch with the parts of his personality that I love. They were the behaviors I suppose I wanted him to see.

As I embark on the process of striving to understand my experience, I am “coddiwompling.” This is a British slang term to which a patient of mine recently introduced me. It is meant to describe the process of one travelling purposely toward a hitherto, unknown destination. Since I began this project, I have been engaged in the labor of seeking to better understand myself, and I don’t believe it will (or should) ever discontinue. Yet, as much as I have labored to find the right words, ideas, concepts, themes, or even arguments to describe what occurred throughout that year to find meaning in the thoughts, feelings, and events of it none appear to fit according to a very hefty set of hermeneutical standards that I have set for myself to adequately ensure the translatability of them. I think this ineffability is inherent in the nature of any type of work that involves the struggle to articulate one’s affair with mourning, before or after the loss of it has occurred. Nevertheless, what follows is, in a way, an invitation to join me in the effort of working it out.

37

Introduction to this Chapter

The review that follows is designed to operationalize the terms, concepts, and conditions that I will employ to provide an analysis of the narrative of Chapter IV Again, the goal is to present the concepts here and then apply them, in Chapter V, to relevant moments from the narrative of Chapter IV. In what follows, I begin by explaining how I conducted the review, generally. I then provide a theoretical overview of the discourse on anticipatory mourning, focusing on reasons why the term is used and on the essence of the phenomenon. After this, I devote a small handful of sections to summarizing psychoanalytic concepts regarding death anxiety and the manic-depressive defenses that characterize the complicated experience I had of grief and loss, as pertaining to this study. Finally, in the penultimate section, I review other, relevant autoethnographies, authored by sons who have lost their fathers.

How I Conducted this Literature Review

I gathered works from a handful of prototypical sources. They are (a) papers from online databases (e.g., PEP web), (b) books/anthologies from my own library, and (c) scanned chapters from books and/or papers from the Chicago Institute for Psychoanalysis and the Chicago Public Library. I made these documents PDF “readable” and uploaded them into the qualitative research tool Atlas.ti. This platform helped me organize and process my thinking.

I also searched for anthologies that provided introductory chapters summarizing relevant literature for this study to date. These have functioned nicely as helpful milestones to keep a pulse on the development of the discourse. I concentrated my search

38

on works that have been published within the last twenty years, but many seminal texts prior to this period of time were also identified and included. These involve works by authors who have written copiously on the topics in question or those who have critiqued them. They have been valuable in the process of teasing out core themes and trends in the discourse that help formulate my own thoughts, opinions, hypotheses, and conclusions.

A Theoretical Overview of Anticipatory Mourning

As I proceed, I want to stress the remarkable impact that the work of Therese A. Rando has had on the discourse of anticipatory grief and mourning. In a way, she has become an arbitrator, holding final word regarding the most important concepts in the most recent conversation around the topic This has helped to focus the discussion in question, but it has also shaped it to become a rather insular (perhaps, incestuous?) one. That being said, Rando’s contribution is unmatched in the history of the conversation that stipulates it is studying the phenomenon of anticipatory grief or mourning. Rando (1986, 2000) edited two anthologies that, respectively, sum it up to date. Perhaps most noteworthy are the comprehensive and thoroughgoing literature reviews that she delivers at the beginning of each anthology. I don’t believe anyone (including myself) could surpass them in terms of their value The great majority of what’s reviewed below belongs largely to the second and most up-to-date set of essays from her book Clinical Dimensions of Anticipatory Mourning: Theory and Practice in Working with the Dying, Their Loved Ones, and Their Caregivers (Rando, 2000). That being said, other overviews have been helpful, as well, including one provided by Charles A. Coor (2007) from the anthology Living with Grief: Before and After Death (pp. 5-20). Before launching into my own specific review of the literature, however, I want to make a

39

theoretical and clinical distinction between anticipatory grief and anticipatory mourning, showing how (and that) the latter term is preferred.

Erich Lindemann coins the phrase “anticipatory grief.” The study of anticipatory grief began in 1944 when the psychoanalyst and German-American psychiatrist Erich Lindemann coined the term in his classic work on acute grief (reprinted as Lindemann, 1994). He does not develop the concept much, but he observes the way that grief responses, typical to postdeath grief, were similar in persons who were “under the threat of death” (p. 200).6 He devotes a small section to introducing this concept at the end of his paper, noting that one can be so preoccupied with fantasies about adjustment issues after the death of a loved one that one undergoes all the phases of grief before that death transpires in a way that is in accord with how those phases were understood at the time i.e., before Elisabeth Kubler-Ross (1969) wrote her groundbreaking book On Death and Dying Anticipatory “grief” or “mourning”? By the year 2000, researchers and clinicians abandoned the phrase “anticipatory grief,” because of ongoing semantic or recurring problems with the definition. At the onset, Rando admits that both phrases have been used, historically, synonymously. This trend is something that I flagged in my dissertation proposal, where I noted that researchers were inclined to define the same phenomenon by different names, confusing the general study of it. It is not uncommon to see authors use alternative phrases to describe anticipatory mourning. For example, 6 Lindemann (1994/1944) refers to anticipatory grief as a condition of “genuine grief reactions in patients who had not experienced a bereavement but who had experienced separation … [which is] not due to death but is under the threat of death” (p. 147).

40

common interchangeable phrases include “anticipatory grief” and “anticipatory bereavement,” or even “death anxiety” (which, as early as 1893, Freud introduced as Todesangst, or “death-fear”) or “ambiguous loss.”

Charles and Donna Corr (2000) wrote a useful paper titled Anticipatory Mourning and Coping with Dying: Similarities, Differences, and Suggested Guidelines for Helpers.