Institute for Clinical Social Work

EXPLORING THE FUNCTION OF TATTOOING IN DEVELOPMENT OF THE SELF: A CONCEPT

MAPPING STUDY

A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Institute for Clinical Social Work in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

By Jill Bajorek Chicago,

Illinois

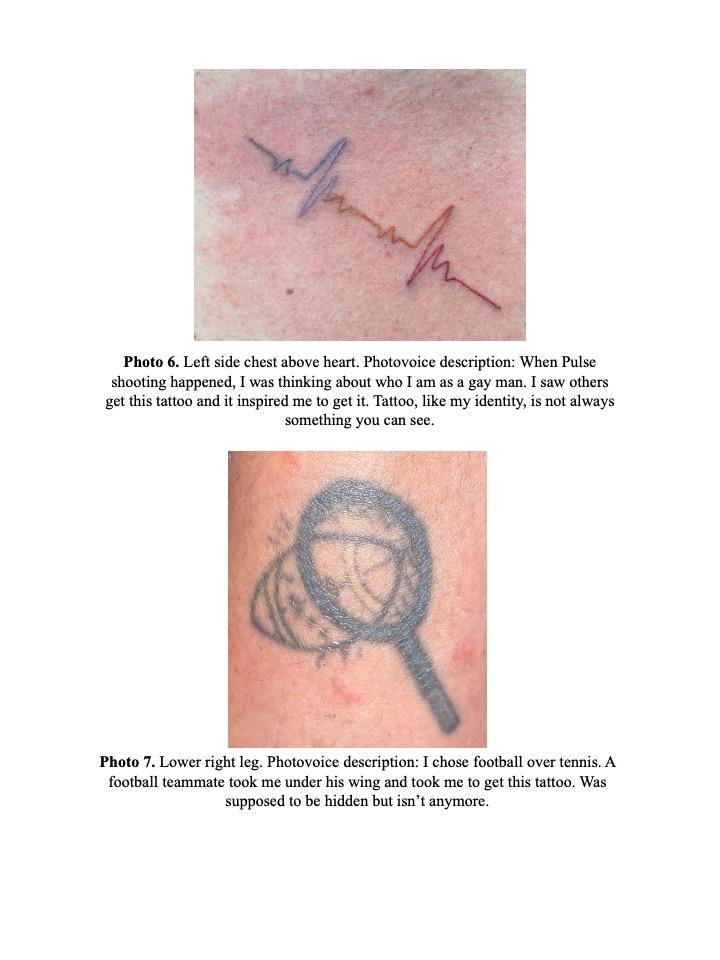

April 22, 2023

Abstract

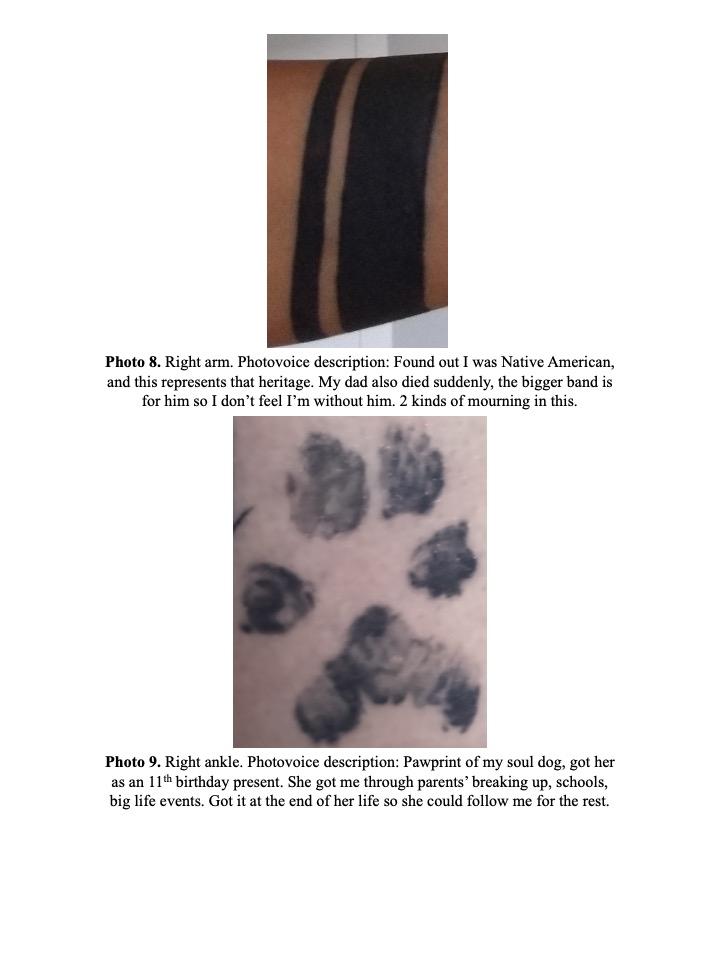

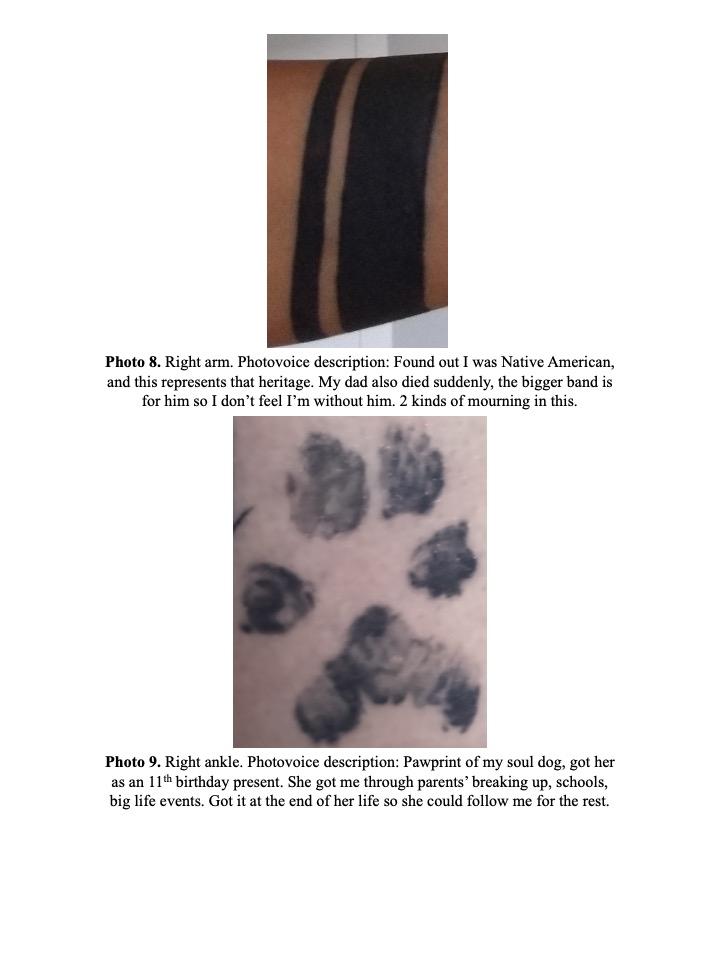

This research explored the meanings of tattoos to various participants and provides insight into the complex emotional processes that led them to obtain tattoos. This exploration was achieved through interviews with this researcher, where she asked participants questions about their tattoos and the specific meanings they associate with them. The questions centered on the theme of identity and yielded some quantitative demographic data and narrative qualitative data discussing the meanings behind their tattoos.

Concept mapping analysis was utilized in this study to better understand and make meaning out of the narrative qualitative data. This methodology allows for finding similarities and differences between data items and is a helpful tool for making sense of the narrative data participants provided. The photovoice method adds to this process as it allows participants to better comprehend the responses people gave.

In this study, 51 participants engaged in Phase I interviewing and provided quantitative and qualitative data, and 48 provided pictures of their tattoos as requested by this researcher. Subsequently, 11 people participated in Phase II and sorted tattoo pictures based on their meanings, generated and discussed a concept map, and discussed the findings with each other to better develop the meanings of the tattoos and the study as a whole.

The final map consisted of eight clusters decided by the participants that best represent the categories of meanings of tattoos in this study. The findings revealed unique reasons for getting tattoos while having a connecting factor of helping the recipients feel connected to their identities. This connection is crucial when thinking of the development of the self from a self psychology perspective. The findings highlight the complex nature of tattoos and tattooing and how deep meaning can be under the surface.

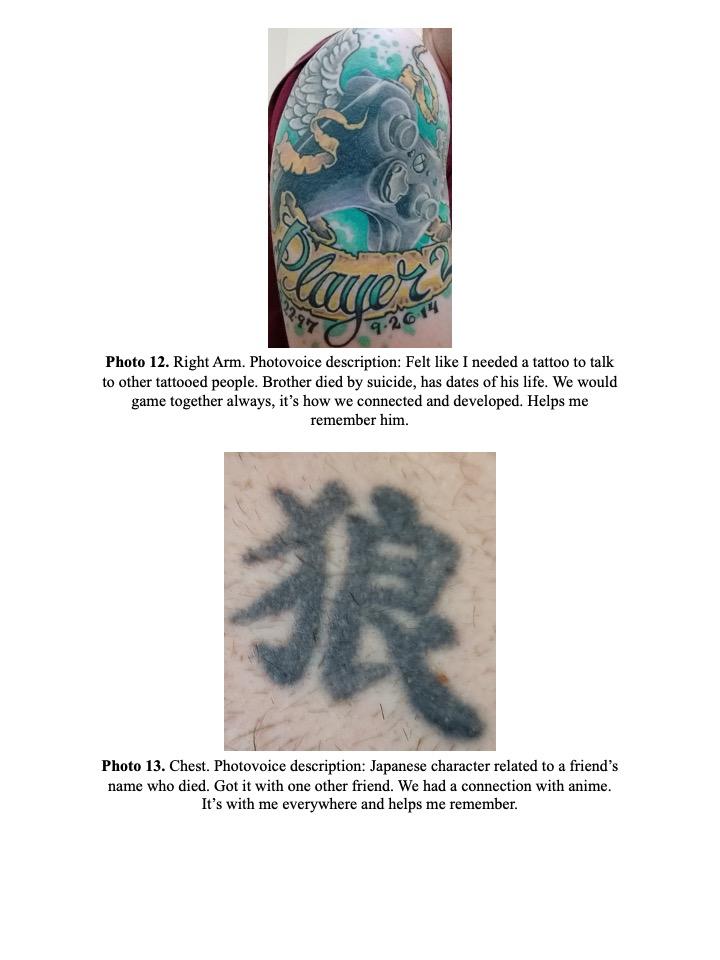

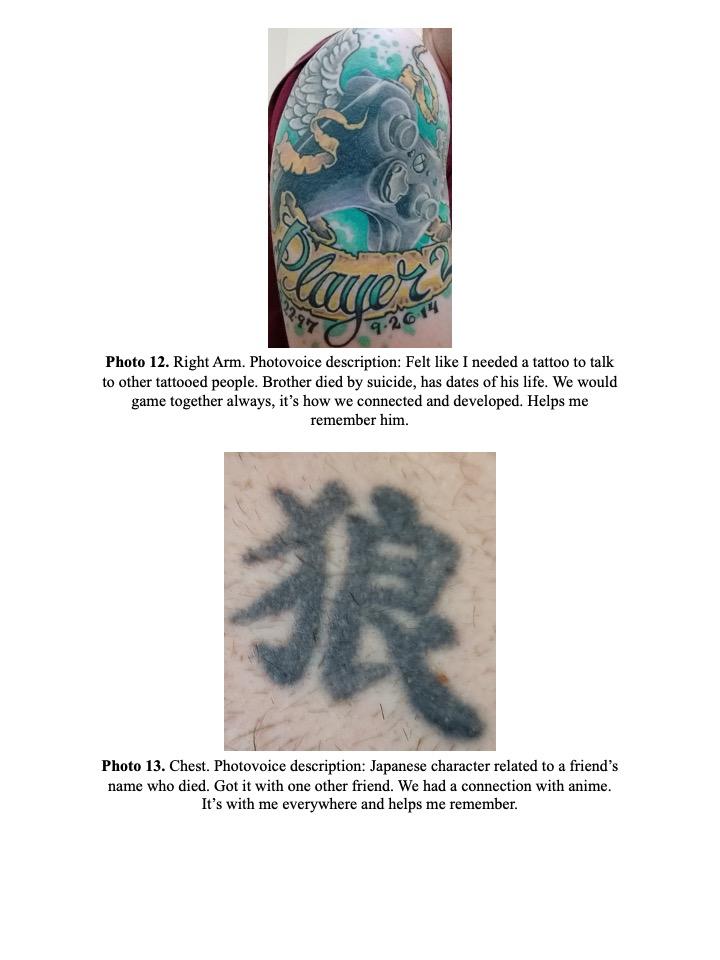

ii

Acknowledgements

I would like to sincerely thank my committee members, who have given me incredible guidance on this dissertation journey. Thank you to my chairperson, Dr. John Ridings, who guided and supported a unique topic that was also close to my heart. I appreciate the late-night feedback, which genuinely highlighted his dedication. Thank you also Dr. Jim Lampe, for helping me remember all the specific psychological terminology and for his consistent support and moments of comedic relief through my years at ICSW. His demeanor made learning much more enjoyable and easier to consume.

I'd like to also thank Dr. Greg Rizzolo for helping me develop a comprehensive understanding of theory that I find invaluable to who I am as a therapist, and Dr. Michael Casli who helped me work through an especially challenging case. I have worked with outstanding faculty members in the program and would not be as effective in my work without them all.

I am thrilled to extend a thank you to my parents, Tom and Louise Bajorek, who consistently remind me how proud of me they are and how genuinely excited they have been to hear every update along the way. Thank you to my partner Erik Sandberg who provided me support and comfort while listening and caring so wonderfully for my emotions through this journey. Thank you to all my wonderful friends for supporting me and allowing me to vent while providing me so many good memories. Lastly, thank you to my cats, who provided me the most comfort I could ever ask for.

iii

iv Table of Contents ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................................ ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF TABLES vii LIST OF FIGURES viii Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................1 A. Statement of purpose..........................................................................................1 B. Significance of the Study for Clinical Social Work...........................................1 C. Foregrounding 2 D. Theory ................................................................................................................3 E. Statement of the Problem and Specific Objectives to be Achieved 5 F. Research Questions 7 G. Theoretical and Operational Definitions of Major Concepts .............................8 H. Statement of Assumptions 8 I. Epistemological Foundation of the Project ........................................................9 J. Outline of the Dissertation 10 II. LITERATURE REVIEW AND THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK .....................11 A. Introduction ......................................................................................................11 B. Brief History of Tattooing in the United States ...............................................12 C. Societal Meaning and Culture 23 D. Symbolism .......................................................................................................25 E. Psychoanalytic Thought on Tattooing 30 F. Theoretical Framework 34 G. Tattoos as Narratives........................................................................................38 H. Intersubjectivity Theory 41 I. Categories of Tattoos .......................................................................................43 J. Summary 45 III. METHODS ............................................................................................................47 A. Introduction ......................................................................................................47 B. Rationale for Mixed Methods Design ..............................................................48 C. Rationale for Concept Mapping Methodology 50 D. Photovoice........................................................................................................56 E. Research Sample 61 F. Demographic Information 62 G. Research Design...............................................................................................62 H. Data Collection 63

v Table of Contents Continued I. Phase I: Tattoo Survey .....................................................................................64 J. Phase II: Data Analysis 65 K. Ethical Considerations .....................................................................................65 L. Issues of Trustworthiness .................................................................................67 M. Dependability 67 N. Limitations and Delimitations..........................................................................67 O. Role and Background of the Researcher 69 IV. RESULTS ..............................................................................................................72 A. Introduction to Results .....................................................................................72 B. Phase I: Survey Results ....................................................................................73 1. Sample Description 73 2. Participant Survey Interview Data .............................................................75 C. Phase II: Concept Mapping Results/Focus Group 84 1. Photovoice and Qualitative Data ...............................................................84 2. Sample Description ....................................................................................85 3. Demographics 86 4. Photo Sorting .............................................................................................90 5. Cluster Analysis 91 6. Group Interpretation...................................................................................95 D. Summary ..........................................................................................................98 V. INTERPRETATION OF FINDINGS ....................................................................99 A. Phase I: Quantitative Data Discussion 99 B. Phase II: Quantitative Data Discussion..........................................................102 C. Revisiting Research Questions 104 1. Research Question #1 ..............................................................................104 2. Research Question #2 ..............................................................................107 3. Research Question #3 ..............................................................................108 4. Research Question #4 ..............................................................................109 5. Research Question #5 110 6. Research Question #6 ..............................................................................111 7. Research Question #7 ..............................................................................112 D. Clusters ..........................................................................................................113 1. Self-Discovery .........................................................................................113 2. Pride 115 3. Journey .....................................................................................................116 4. Self-Acceptance 118 5. Heritage ....................................................................................................119 6. Connection 121 7. Familial Bonds 122 8. Homage ....................................................................................................124 E. Revisiting Assumptions 127 1. Assumption #1 .........................................................................................127

vi Table of Contents Continued 2. Assumption #2 .........................................................................................128 3. Assumption #3 129 4. Assumption #4 .........................................................................................129 F. Summary of Interpretation of Findings..........................................................131 1. Major Finding 1 131 2. Major Finding 2 .......................................................................................131 3. Major Finding 3 132 VI. IMPLICATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ..............................................134 A. Implications for Practice ................................................................................134 B. Recommendations for Future Research .........................................................135 C. Strengths and Limitations for the Study 136 D. Research Reflections ......................................................................................140 E. Conclusion 140 REFERENCES 142 APPENDICES .................................................................................................................................... 149 Appendix A 149 Appendix B 152 Appendix C ................................................................................................................155 Appendix D 163 Appendix E ................................................................................................................188 Appendix F.................................................................................................................190 Appendix G ................................................................................................................193 Appendix H ................................................................................................................195

vii List of Tables Table # Page 1. Steps in a Concept Mapping Process ...........................................................................53 2. Phase I: Participant Demographics ..............................................................................76 3. Phase I: Participant Tattoo Table 78 4. Phase I: Participant Experience of Tattoos ..................................................................80 5. Phase I: Participant Discussion of Identity Tattoo 83 6. Phase II: Participant Demographics .............................................................................87 7. Phase II: Participant Experience of Tattoo(s) 89

viii

Figures

# Page

List of

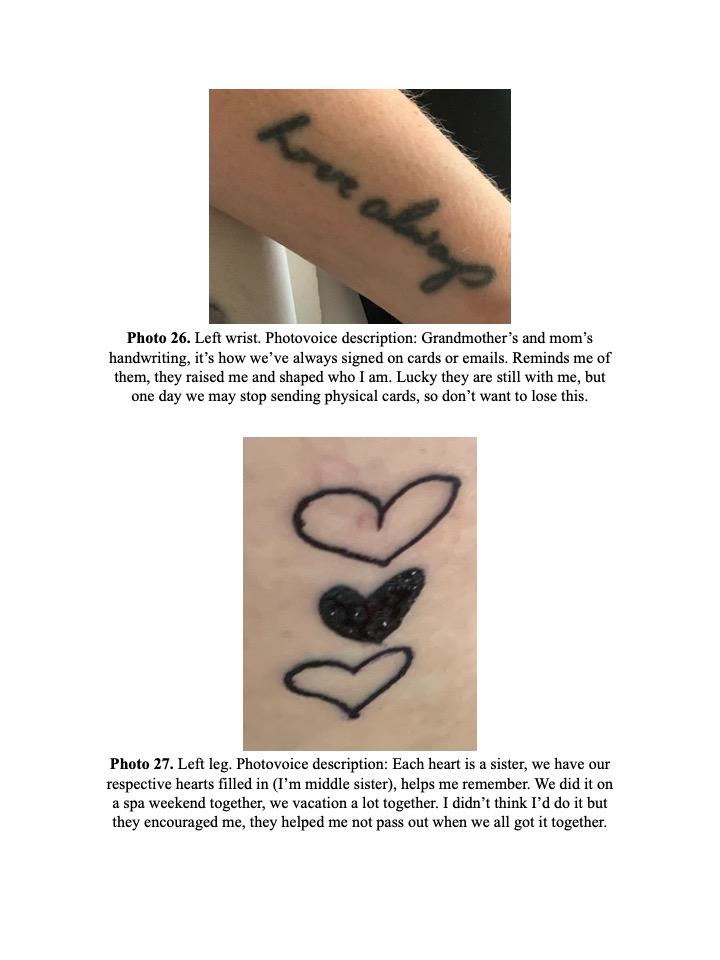

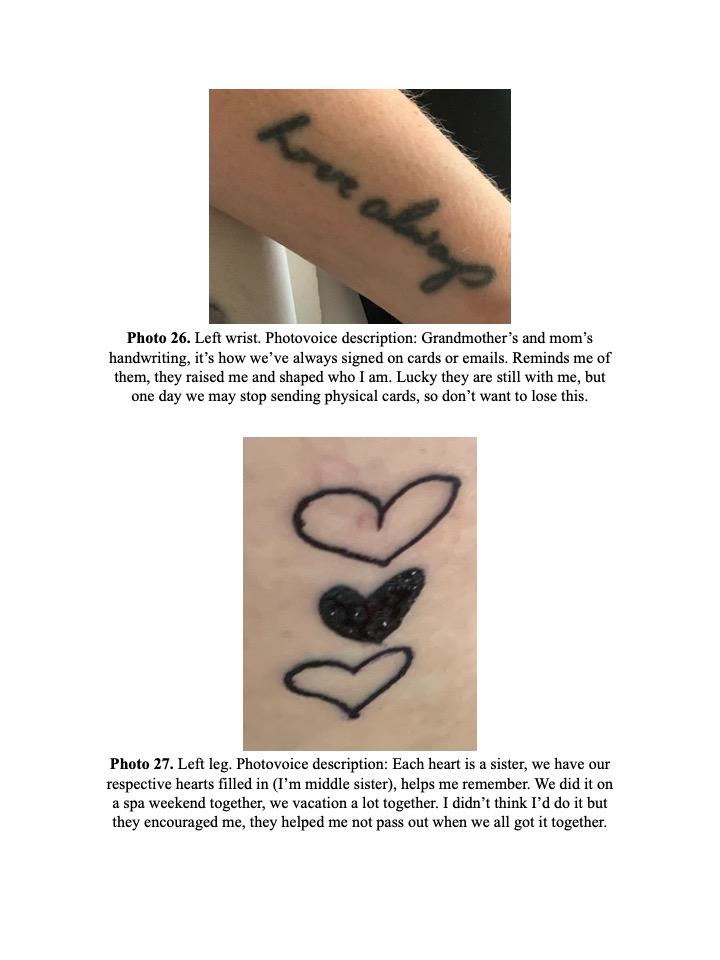

Figure

1. Point Map of Tattoo Meaning

Outcomes.....................................................................92

2. Eight Cluster Map of Tattoo Meaning Outcomes with Point Map

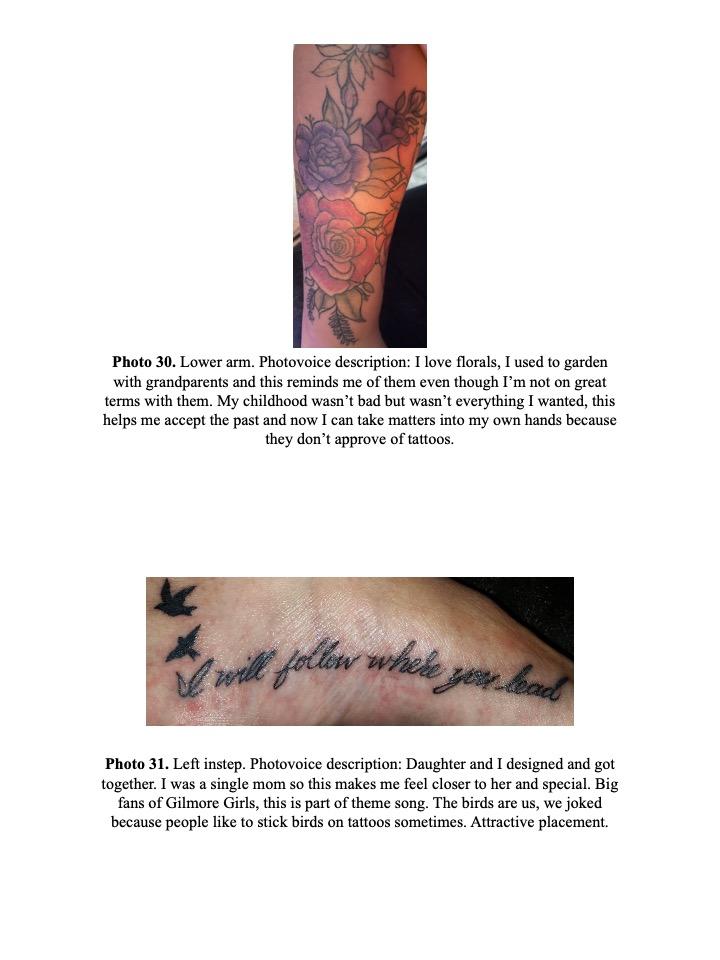

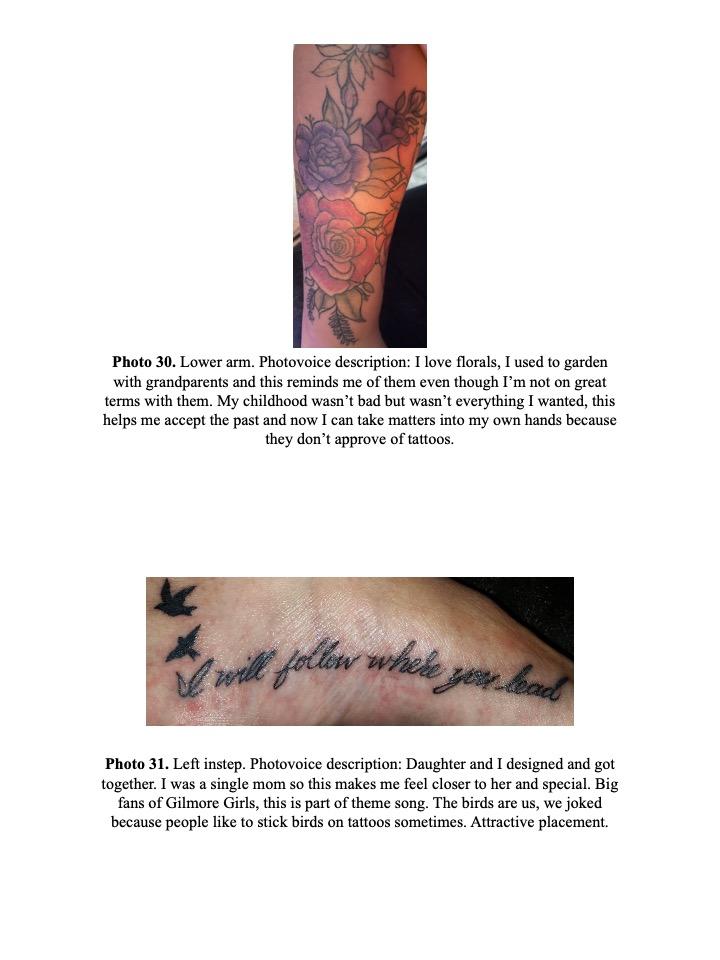

..............................93

Chapter I Introduction

A. Statement of Purpose

The primary purpose of this study was to investigate if and how people use tattoos to contribute to their sense of self. In order to understand the idea of developing a cohesive self through tattoos from a psychodynamic perspective, self psychology theories were utilized to explore the information found. Participants provided testimonies through an interview survey about why they chose to receive their tattoos, resulting in quantitative and qualitative data. Photovoice was utilized to generate descriptions of narrative responses from the interviews, and concept mapping was the method used to analyze data. This data was ultimately used to develop a conceptual map of the tattooing phenomenon. Self psychology was the best theoretical lens to use in order to study what functions the act of being tattooed serves for people as it allows for the exploration of conscious and unconscious processes in a way that looks at the formation of the self.

B. Significance of the Study for Clinical Social Work

This study contributes information to the base of knowledge in social work, specifically regarding the development of the sense of self. There are many reasons people choose to get tattoos. From the outside, tattooed people are often viewed as dangerous or reckless, which stems from several historical instances where tattooed people were associated with criminals. Over time tattoos have become more mainstream and accepted by various groups, though still sometimes seen as something distasteful. (Jones, 2000; Patterson, 2018). This stigma creates the importance of studying tattoos and understanding some of the individual and collective reasons

1

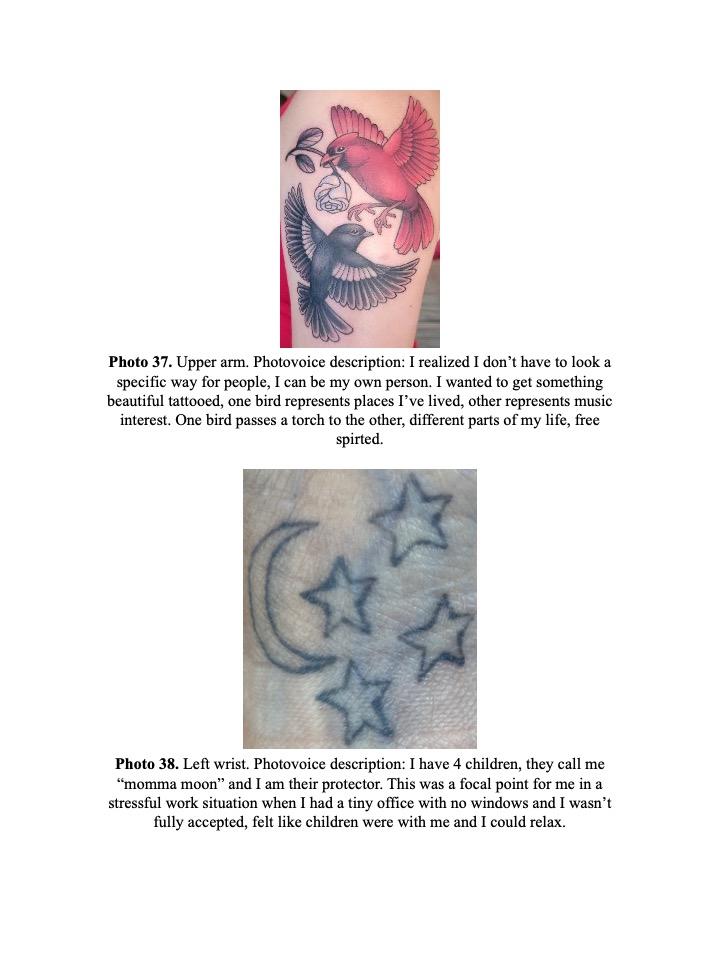

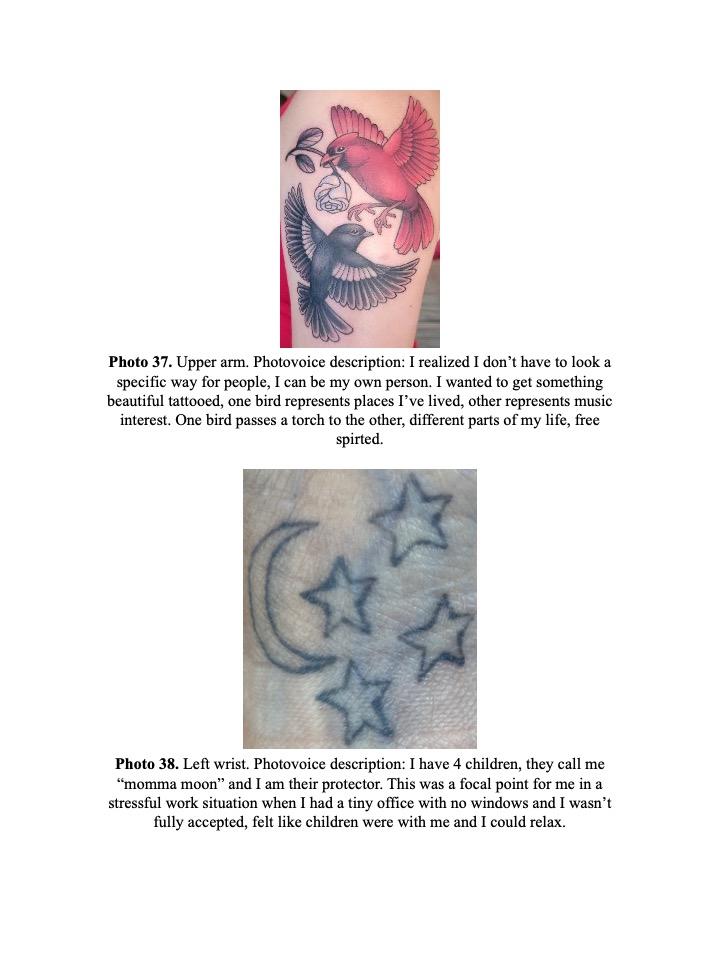

someone may choose to get a tattoo. Some tattooing decisions are not made quickly; much thought goes into the permanent image someone puts on their body. For many people, that decision includes thinking about the image itself, where they want to put it on their body, and a conscious understanding of the significance of both those choices (Bell, 1999). There might also be some consideration about the social implications of having a tattoo. This study explores the conscious and possible unconscious reasons people get tattoos and how that affects their identity. Exploring how people unconsciously develop their sense of self is something crucial in the field of social work. People utilize the selfoject functions based on other people or objects in their lives to form a cohesive self. This utilization of selfobject functions starts when someone is young, and the selfobjects functions are often provided by parents or caregivers. The self develops as the caregivers respond to the child and either affirm or reject the child's affect. Rejection would lead to a deficit the child may look to fulfill later in life. Learning what has and has not been affirmed for people provides insight into how their selves have been developed and what might be lacking (Banai, 2005; Kohut, 1977; Scorides and Stolorow, 1984). Through therapy, the therapist and client can investigate the client's potential deficits in an attempt to resolve something conflicting. Investigating specific ways selves develop can saturate the body of knowledge in social work. Discussing the presence of tattooing provides insight into a particular area of body modification and how that can provide a selfobject function and relate to self formation.

C. Foregrounding

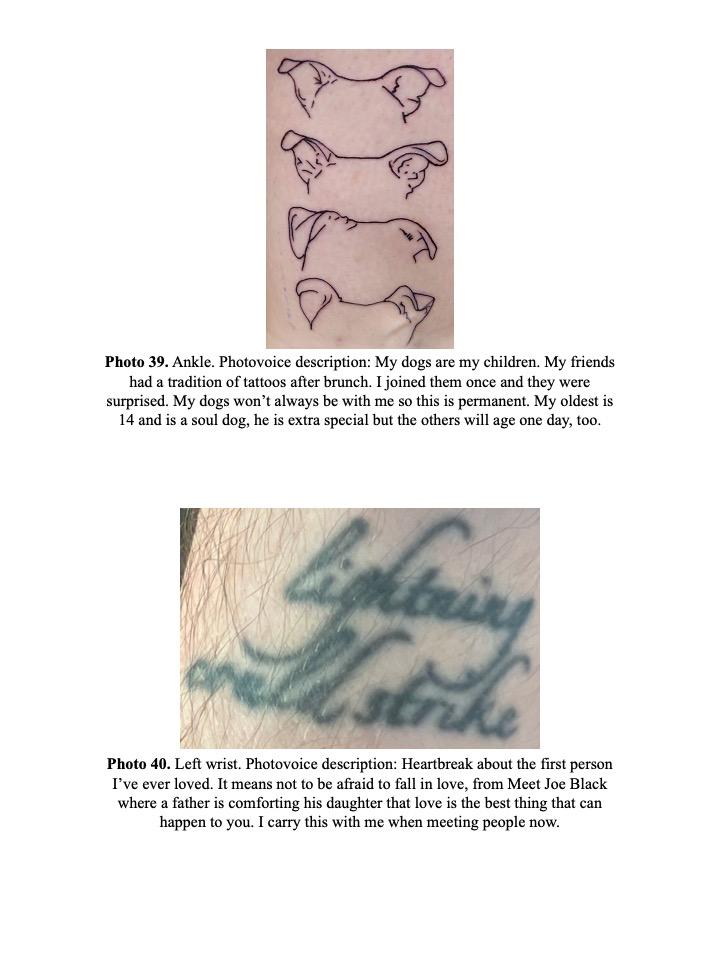

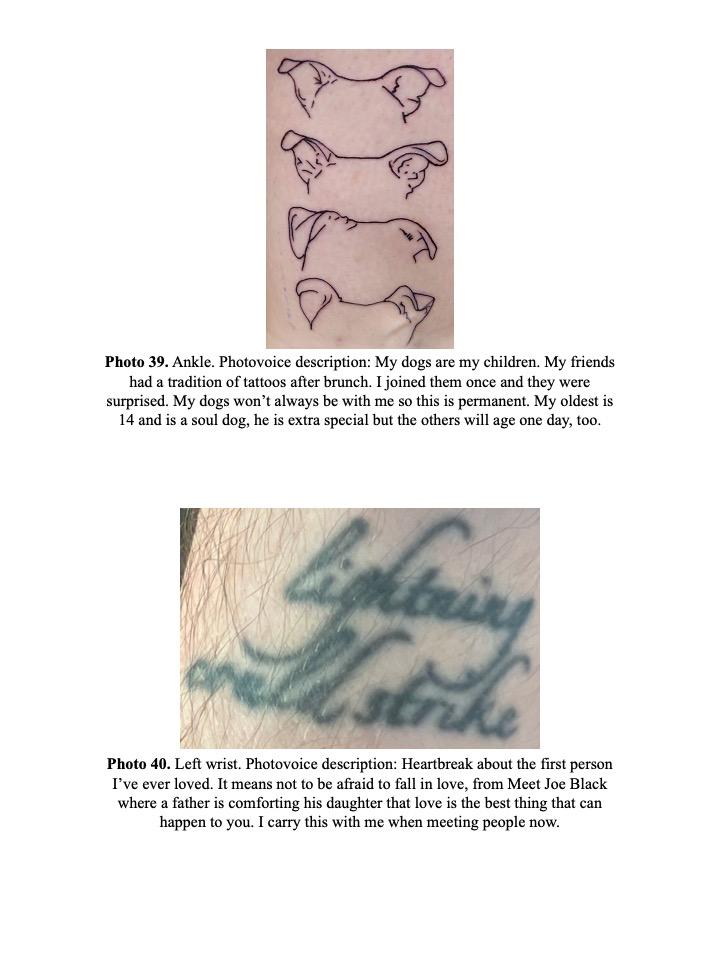

This topic is especially of interest to this researcher as she identifies as a member of the tattooed community. She has been tattooed 14 times, with a few pieces being large. There is companionship with others who have tattoos, and there seems to be an instant social bonding

2

opportunity between tattoo community members. It seems like they already have something in common and have an easier time starting a conversation. There are differences, however. People often ask why this researcher chose her tattoos. She typically responds that she wanted to look a certain way, suggesting intent related to aesthetic components compared to the singular meanings of the pieces. This aesthetic intent feels like its own meaning, however. Intentionally looking a certain way has meaning by defining how one presents to themselves or others. Other people have expressed less importance on aesthetics and more on the specific significance of their tattoos. Some explain that their tattoos hold a deep emotional meaning connected to someone they love or an experience they had or represent something they want to remember. Differences like those have interested this researcher for a while because they indicate a broad spectrum of reasons people choose to get tattoos. However, this researcher has not looked at that dynamic through a psychodynamic perspective until now. This study hoped to better understand what people hope to achieve by getting tattoos and how that helps them psychologically.

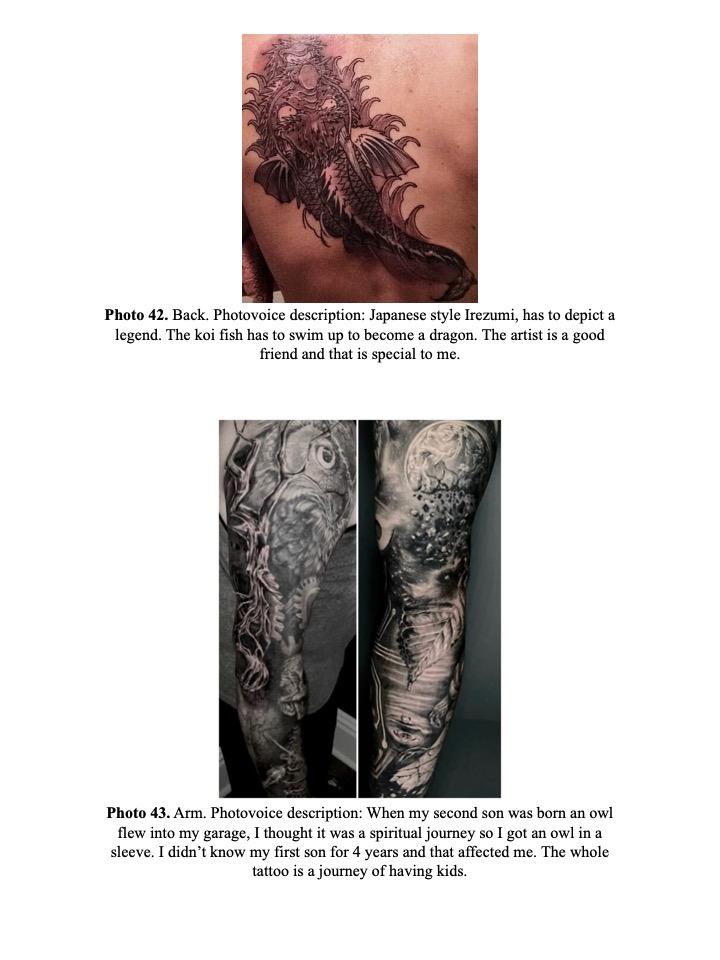

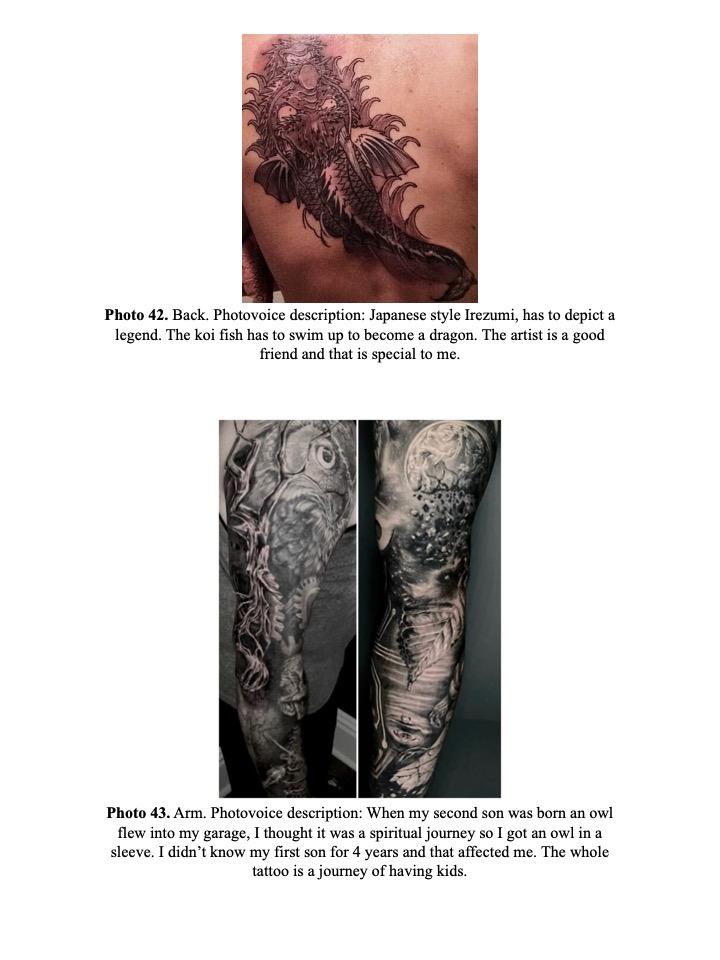

D. Theory

The theory used in this study to understand tattooing is self psychology. Heinz Kohut developed this theory, which has since been used to study the development of the self. According to Kohut (1977), the normal psychological development of the self consists of a bipolar split of two lines of narcissistic development. This development begins in childhood, and the child's caregiver provides a selfobject function that will be internalized. The split occurs for the infant when the caregiver does not adequately respond to all the child's needs. The child preserves the caregiver by splitting off the idealized parental imago. On this side, there is a need for the child to merge with the strong, competent, calming, and protective other. Ideally, the parent exhibits behaviors that provide calming reassurance functions, creating a feeling of safety. If this

3

successfully occurs, those needs are satisfied. The other pole is the grandiose self which requires preserving the perfect sense of self. Mirroring occurs, which affirms and validates competency. An example of mirroring is a mother smiling at her child when they accomplish something like walking. These moments start as primary need fulfillments and continue as the child grows. When the needs of these poles are not satisfied, a disorder can develop. Kohut (1977) explains that in a normal situation, the caregivers will satisfy most needs, but there will be a certain amount of frustrations when the child's needs are not perfectly met. These frustrations can be moments of anxiety that are not actually traumatic but imperfections in situations. He refers to these as "optimal frustrations." The child feels the frustrations of not having their needs immediately met and having to manage anxiety, and the caregiver's presence assists them in working through the frustrations. Ultimately, after experiencing many small moments of unresponsiveness, the child will retain self-esteem and be able to handle frustrations throughout life without the parent present because the soothing function of the parent has been internalized. The child will feel the safety alone they once felt with their caregivers in those frustration situations (Kohut, 1977).

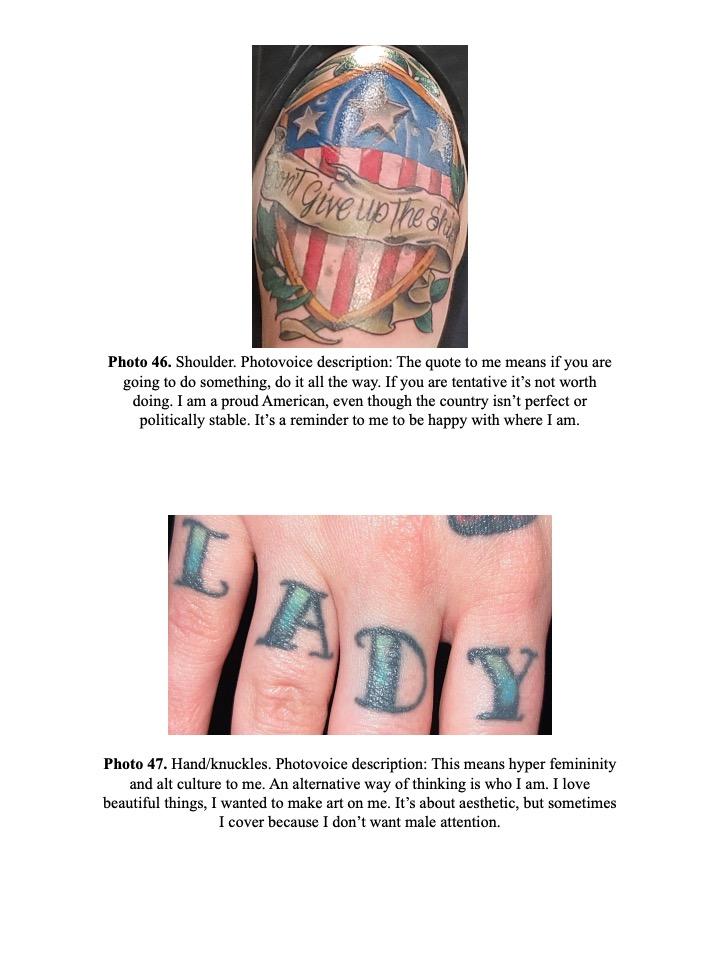

Sometimes these needs are not optimally met, and problems can arise. When the child cannot work through these frustrations due to them being excessive, they begin to seek fulfillment of these needs elsewhere. They seek selfobject functions through people in their lives and possibly in therapy. This seeking can persist through adulthood. In therapy, the therapist can explore the needs and possibly work towards the patients being able to learn to serve those needs for themselves healthily (Kohut, 1977). As applied to this study, the theory holds that people would get tattooed to help them better manage their frustrations and needs through meaningful

4

expression through this method of body modification. This frustration management could happen through tattoos serving affirming functions for the recipient.

E. Statement of the Problem and Specific Objectives to be Achieved

Recent studies show that 29% of Americans in 2015 had at least one tattoo, compared to 15-16% of the population in 2003 (Bridges, 2006; Shannon-Missel, 2018). This percentage is a significant portion of the population choosing to permanently alter their bodies. While it is unknown exactly when the art of tattooing began, there is data to suggest it dates back to ancient times, and meanings have changed throughout centuries and across cultures (Lineberry 2007). Through these changes, tattooing is becoming increasingly common in mainstream American culture and holds different meanings for groups and individuals (Patterson, 2018). Often these meanings are analyzed as surface-level understandings, such as group affiliation or culturally assumed meanings. Missing from that is the range of deeper psychological meanings that may not be talked about as often or even consciously known by the recipients. There is a dearth of research available on both tattoos and self-reported formation of the self. While many articles address those topics, few examples explore the direct connection between the two. The application of how tattooing helps a person develop a sense of self is still unclear and could be due to the highly individual aspect of tattooing. Broadening that research to include additional understanding aids in better understanding the functions that tattoos serve for people.

Some have speculated that being tattooed represents ownership over one's body. One feels a sense of control when one can permanently change their appearance. Tattooing can also serve as a connection between someone and something external (Eli, 2013a). It is also speculated that a tattoo can aid in the formation of one's self or identity (Bridges, 2006). This concept could

5

manifest as tattoos provide a way to separate one's psychological self from others and the environment. When one gets a unique tattoo, they will look different than other people, which is a desired outcome. Also suggested is the idea that a tattoo has both pain and pleasure associated with it, which together create a self that can experience both in other areas of life, too. An example of this concept could be a person who can experience optimal frustrations and better understand that there will always be disappointments in life. A strong sense of self will aid in tolerating those frustrations (Eli, 2013b). Unconsciously, a tattoo may allow someone to reenact something from childhood and internalize the ability to heal oneself (Karacaoglan, 2012).

A study by Gadd (1992) explored the intentions of tattooed soldiers in the United Kingdom. The soldiers answered questions to explore the reasons for their tattoos and any risks they experienced. The study mostly explored appearance, questioning how attractive the soldiers felt because of their tattoos. That study's researchers also explored how attractive the soldiers found women with tattoos. While most participants found themselves and women with tattoos attractive, they also questioned people without tattoos and found significantly lower ratings of finding tattooed people attractive. These findings indicate the presence of a collective tattoo culture, specifically with this group of soldiers. People with tattoos seem more likely to find them attractive on other people (Gadd, 1992).

Sands (1989) discusses the analysis of a specific person in therapy who chose to get tattoos to express exhibitionism due to having grandiose fantasies. This person got her entire body tattooed, which was likely viewed as unusual compared to mainstream acceptance. This patient did this because she was not adequately mirrored as a child, resulting in the need to express herself for validation. This lack of mirroring created a deficit in the formation of the self, resulting in her inability to independently formulate a grandiose self. In this case, discussing her

6

tattoos in a therapeutic setting ultimately revealed this deficit (Sandy, 1989). This case is an example of tattoos providing a function due to a problem of a need not being met. It is possible that the act of tattooing specifically led to resolving this deficit and was a favorable decision by the patient.

These studies and articles above explore the ideas of tattooing and some reasons behind those choices. What is still unclear is how this can be utilized from a direct therapeutic application with self psychology theories. Also, it is worth exploring whether tattooing is ever a method, consciously or unconsciously, that people use to access the feelings behind finding deficits of the self and serving functions.

This study will explore those ideas and potentially suggest the connection between tattoos and self formation. The results could be used in therapeutic settings to explore why people get tattooed and how that can develop into conversations about identity formation. This exploration could lead to a better understanding of the selfobject functions people seek.

F. Research Questions

1. Do tattoos help people develop a more cohesive sense of self?

2. What are the individual theoretical concepts that should be used to understand the drive to get tattooed?

3. What are the various conscious motives people identify for getting tattoos?

4. What are some observed or understood unconscious motives people may have for getting tattoos?

5. Does position on the body, specifically if the tattoo is hidden or visible to others, signify something either consciously or unconsciously?

7

6. Does the meaning of the tattoo change based on how an outsider sees it and assumes meaning, compared to the original intent of the recipient? Does that matter to the development of the self?

7. What similarities or connections, if any, are there between people’s reasons for getting tattoos?

G. Theoretical and Operational Definitions of Major Concepts

Self

“The self (viewed as a process or system that organizes subjective experience) is the essence of a person's psychological being and consists of sensations, feelings, thoughts, and attitudes toward oneself and the world” (Banai et al., 2005, p.225; Kohut, 1977).

Selfobject

“Significant others...experienced as non-autonomous components of the self.” These “play a vital role in the development of healthy narcissism” (Banai et al., 2005, p.227; Kohut, 1977).

Tattoo

“An indelible mark or figure fixed upon the body by insertion of pigment under the skin or by production of scars” ("Tattoo," n.d.).

H. Statement of Assumptions

Based on this researcher's experience as a therapist and a person with tattoos herself, the following four assumptions were made for this research study.

Assumption #1

Tattooing helps a person develop a sense of self.

8

Assumption #2

Tattooing is not associated with the development of collective identity.

Assumption #3

Tattooing is both associated with social identity and personal identity, which both contribute to the sense of self.

Assumption #4

Tattooing serves both a conscious and unconscious function for the recipient.

I. Epistemological Foundation of the Project

To best frame this research and assess the assumptions, the most appropriate research paradigm is social constructivism/interpretivism. In this epistemology section, knowledge is gained through studying cultural meanings assigned to concepts. Context is crucial, and no one reality exists within this worldview (Bloomberg & Volpe, 2012). This idea is essential for exploring tattoos because the meanings and symbols often found in tattoos are different throughout history and various cultures, all decided by the people in those situations. Additionally, tattoos have individual meanings and can still be viewed differently by others within a cultural context.

This study partially relied on personal narratives as data since the tattooed person can best discuss what their visual artwork represents to them. It was impossible to remove the researcher's subjectivity, so it was imperative that participants' reported tattoo meanings were accepted as truth (Bloomberg & Volpe, 2012). The open-ended interview questions asked of the subjects in this study allowed for meaningful dialogue in which the researcher could inquire about a broad picture of the participants' narratives. One symbol may hold meaning for someone with that tattoo, while the same symbol can mean something entirely different for another person

9

who has that same tattoo. Additionally, society may assume an interpretation of a symbol that matches or differs from the individual's meaning. These perspectives were all essential to consider for fully understanding participants' tattoos.

J. Outline of Dissertation

This dissertation is composed of six chapters. Chapter I initiates an overview of the study and associated goals. Chapter II provides a review of relevant literature and a discussion of the base framework used to best understand and interpret the data. Chapter III discusses the methodology used and details the importance of the procedures. Chapter IV presents the results of this study, including quantitative and qualitative data, and introduces some significant findings. Chapter V discusses all relevant and meaningful findings in this study. Lastly, Chapter VI looks at the different implications and recommendations on what to do with the findings of this study.

10

Chapter II

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

A. Introduction

This mixed methods study explores the psychological significance behind tattoos and tattooing. This researcher sought to obtain narratives from participants, from which different themes can be drawn and explored. The psychological meanings were explored in what the act of tattooing consciously and unconsciously means for the participants and the meanings of the images themselves.

This literature review collects information about tattoos and tattooing from a broad perspective. The information presented includes exploring the act of tattooing for an individual, what the tattooed image itself means to the person, what this means in society, how history has viewed tattoos over time, and what tattoo images mean in a more symbolic and global context.

The most relevant research to this study centers around psychoanalysis and psychology related explicitly to tattooed individuals since that is the lens with which the narratives of participants were studied. From a broader perspective, the meanings of tattoos in society are discussed since it is imperative to see participants as part of their own environments. In order to encompass a more comprehensive understanding of the topic, the history of tattooing is presented. Lastly, to best understand the tattooed images, this author explored the symbolism of images in art and what psychological meanings exist in that field.

Keywords that were used in searching for materials were: “tattoos," “tattooing," “tattoos identity," “tattoo AND identity," “psychology tattoos," “psychology body modification," “history tattoos," “tattoos meaning," “symbolism tattoos," “symbolism in art," “tattoo narratives," “tattoos

11

mainstream," and "art in psychoanalysis." These resources include peer-reviewed journals, dissertations, internet searches, articles and websites, books/ebooks, and data files. These were obtained by internet searches in Google, Google Scholar, PsychInfo, PEP (Psychoanalytic Electronic Publishing), www.amazon.com, and recommendations from faculty and peers. These were collected from the Fall of 2014 through the Winter of 2023. While this researcher did not limit the date range of materials overall, much of the information presented is from the more recent past. This era significantly impacts the main themes addressed in this study, including current societal implications. This research was limited to tattoos obtained voluntarily, and excluded tattoos received nonconsensually through imprisonment, genocide, or otherwise forced. Thus, this discussion of literature mainly reflects that material. Each section of this literature review provides a comprehensive synopsis of the information available on the topics.

B. Brief History of Tattooing in the United States

This researcher has grown up in a culture where getting tattoos and other body modifications are relatively common and often thought of as trendy. In fact, tattooing is the sixth fastest-growing retail business in the United States (Taylor, 2012). Large tattoos and tattooing certain areas of the body are still sometimes taboo, but for the most part, they are generally not seen as shocking in society. However, getting tattoos was not always as prevalent or accepted in the past. It is crucial to explore their origins and how the reasons and meanings for tattooing have changed throughout history.

Tattooing has been around for thousands of years. The name comes from the Polynesian word "ta," meaning to strike something, and "tatau" from Tahiti, which indicates marking something (Taylor, 2012). Pinpointing the exact time it began is debated, but multiple sources cite incidents from thousands of years ago. In 12,000 B.C., tribes would cut their skin and rub

12

ashes over the area during times of bereavement, resulting in permanent markings (Grumet 1983). This practice mirrors similar rituals of the present day since it seems significant to the grieving process. Puncture tattooing likely existed in 8,000 B.C. as archaeologists in some European countries found pigments and sharp objects to suggest they were used to penetrate the skin. Egyptian mummies from 4000-2000 B.C. display markings on their skin. African countries, China, and Japan have also noted instances of tattooing during a similar time period (Grumet 1983). Since then, tattoos have been noted at many historical points, and their significance has varied dramatically. This section will present and discuss some of those meanings over time.

One specific ancient example of a tattoo was on a frozen man found near Austria from 5,200 years ago. The way the markings were arranged on his body suggested they were performed for therapeutic reasons to assuage pain (Lineberry 2007). This example gives some insight into the meaning behind the tattoo. The image itself may not have been the main reason for its occurrence; the penetration of the skin could have served a healing purpose. Drawings on tombs representing the skin of the people inside were found from 3,000 B.C. in Japan. They seemed to have a spiritual meaning and give insight into the traits of the deceased person (Taylor, 2012). Hambly (1927) reviews multiple groups who engaged in body marking for religious reasons, suggesting the rites (tattooing) were ways to access non-human forces. People were tattooed in a ceremonious fashion that often corresponded with being a certain age. The Naga people get tattoos to be recognized in the spiritual world. These tattoos focus less on aesthetics and more on function. While wealthier people would wear jewelry that would identify them in the afterlife, poorer people would get tattoos (Hambly, 1927). Ancient Greeks would differentiate between classes with tattoos. A tattoo on someone would indicate a lack of civility, so enslaved people and criminals would be tattooed to be easily identified among others (Jones,

13

2000; Patterson, 2018). Romans would tattoo criminals for the same reasons, sometimes even tattooing the crime or punishment. These examples are thought to be why criminals voluntarily got tattoos later in history as an act of resistance by embracing the tattoo (Gustafson, 2000; Patterson, 2018).

Aboriginal cultures would utilize tattoos as rites of passage into adulthood and marriage. They were done by hand and connected to images in nature and would indicate to others their age or status (Bell, 1999). The Māori people in New Zealand also utilized tattoos to indicate the status of a person, getting decorative tattoos to suggest ranking among the tribes. Women would have smaller tattoos, and men would have more extensive and visible ones. Occasionally those tattoos would be used as signatures (Hambly, 1927; Sanders, 1988). In these examples, the tattoos have a meaning as a group since the people getting them are following a group custom. However, there is also an individual component as they are different enough to distinguish people from each other. The ritualistic aspect seems to suggest a connection to identity both within the community and the individual.

In Japanese history, tattoos were accepted for many centuries as the irezumi art form (Sanders, 1988). Japanese tattoos historically center around telling a story and expressing a broader theme. This concept differs from American tattoos, which tend to present more often as individual objects with less abstract themes (Bell, 1999). In the 5th century B.C., however, tattoos were used as a form of rebellion against the elite, who were allowed to wear kimonos. Tattooing was made illegal in 1870, so it became less common and less accepted (Taylor, 2012). Today they are rarely seen except on laborers and Yakuza groups as forms of expression, often with themes of inner conflict (Bell, 1999; Sanders, 1988; Taylor, 2012). These examples suggest the impact the culture and government have had regarding why people chose to get tattoos and how

14

they are perceived. As an art form, it was respected, but as an act of rebellion, it was seen as uncouth. Thus it spawned a vast dislike of tattooing, generally being associated with lower classes and criminals.

Tattoos began infiltrating Western cultures, and some literature suggests this effectively happened because Captain James Cook, a British explorer, began seeing tattoos in his travels to the South Pacific in the mid-18th century. The sailors would then get tattoos related to the various places they had been to commemorate their travels (Demello & Rubin, 2000; Lineberry, 2007; Patterson, 2018; Sanders, 1988; Taylor, 2012). Since some tattoos were of distasteful images, more polite societies in the U.S. and England did not favor them. This act suggests that something negative was assumed about the person based on what image they chose for their tattoo. An image on the skin resulted in dismissing someone entirely due to stereotypical assumptions. These negative assumptions continued in the mid-20th century when having a tattoo indicated some deviance about a person since many tattoos were done in unhygienic parlors or seedy areas. Even though going to high-class tattoo establishments did not exist, the recipients were still considered deviant based on going to unsavory venues. Even today, people can be viewed negatively for having a tattoo even though high-end, clean tattoo parlors exist and are more mainstream. The person is sometimes assumed to be part of a dangerous group or may seem untrustworthy and unreliable; tattooed people are even sometimes denied employment. There became a perceived social division between tattooed people and law-abiding, familyoriented people, assuming there could be little overlap (Patterson, 2018). There are some exceptions, however.

The U.S. has historically seen a connection between military service and tattoos in the name of honor. One example was from the 1960s when tattoos were viewed differently, and

15

during some wars, soldiers would respectfully get tattoos in solidarity with each other (Grumet, 1983; Sanders, 1988). The tattoos for the military and navy would indicate a proud life separation from mainstream society (Patterson, 2018). In the 1970s, popular bands embraced tattoos, which has continued with the music scene for decades. The 1980s saw an improvement in the quality and artistry of tattoos, allowing more incorporation into mainstream society and contribution to the economy (Patterson, 2018). In the 1990s, tattoos were seen as fashionable and became popular with athletes (Taylor, 2012). Today, contributing to the more accepting modern attitude, experienced artists often express their work through tattoos. Because tattoos are seen as art forms in these cases, they are more well-received. Sometimes museums feature them from an artistic perspective (Sanders, 1988).

It still seems that a tattooed person might be negatively perceived because of the external factors of the tattoo rather than for the person's inner qualities. This concept is intriguing, as many people today get tattoos to represent something individual and internal. Grumet (1983) even suggests that much tattoo research focuses on the more deviant and poorly executed tattoos and neglects information about well-done pieces. This information gives additional significance to this study as it focuses on the internal processes someone experiences when getting a tattoo that people often overlook when initially assessing someone.

Taylor (2012) suggests the circus industry helped with the acceptance of tattooing as fans would get tattoos to model those of the performers who made a good wage and were respected. The industry created a popularity for this body modification (Taylor, 2012). What motivated spectators to emulate what they saw in the sideshow entertainment pieces is still unclear. Perhaps the viewer wanted to identify with someone they respected or admired and hence followed similar actions.

16

Tattoos, even as they are more prevalent, are considered body modifications against typical beauty standards. Sanders (1988) discusses any changes to the body as interactions with culture and how some modifications are done in conjunction with the accepted beauty aesthetic. Women in China binding their feet to create the illusion of having smaller feet aided them in achieving beauty and therefore being more likely to find marriage. Plastic surgeries and exercise to conform to beauty standards are body modifications that society accepts in the U.S. and are sometimes proudly publicized. However, the corset in history was an example of a body shape change that was a resistance to the cultural norm. As the corset made women appear skinnier, it was believed they would be less able to bear children, and therefore the look was not favored (Sanders, 1988). Now, this culture tends to favor a slimmer figure. This example suggests that changing appearance as a form of protest is not exclusive to tattoos. However, the perception of the end image (i.e., appearing skinnier) can change over time from being less desirable to attractive from a general societal perspective. This concept mirrors the changes in how tattoos are perceived differently over time.

The types of body modifications are growing beyond the act of tattooing. One modification is scarification which is intentionally cutting or burning the skin to leave scar marks for aesthetic purposes. Initially, the Māori people partook in scarification on their faces to display identity and fierce attitudes. Like tattooing, this has also become more mainstream in Western culture. Scarification was first seen in the U.S. in San Francisco in the 1980s with gay and lesbian cultures (Guynup, 2004). Guynup (2004) also considers that scarification may be a more daring means of expression as tattooing may be more mainstream and accepted. This type of body modification is often popular among darker-skinned people when a tattoo would be less

17

visible (Sanders, 1988). Therefore, body modification is becoming more common as an attempt to stand out for people who are not just lighter-skinned.

The perception of tattoos' roles and presence can depend on the cultural and societal context. In the past, tattoos were often connected to a certain kind of cultural expression, whereas now, tattoos are becoming more commonplace. One example of this is explored by Bell (1999), who discusses gender differences. He suggests that tattoos are a liberation from societal beauty standards for women in general. When women get tattoos, they tend to be softer images like flowers. There are also differences in the quality of tattoos; well-done tattoos by artists would be more respected than prison tattoos, for example. He suggests a societal fear of permanence that can present in a non-tattooed person acting judgmental towards someone with a tattoo. Sanders (1988) discusses how often stability is inferred from a person's image. Someone risks being defined as unstable or inferior when permanently altering their body. This inference could be based on assumptions, whether or not they are correct. Alternatively, the person with tattoos can be seen as someone who has the strength to tolerate those judgmental stares and assumptions (Bell, 1999). The perception of the person likely starts with how the viewer perceives the act of intentionally looking different.

Many people understand tattooing as a way to divide oneself from society; it can be seen as antisocial. For example, certain gangs get tattoos to differentiate themselves. Additionally, since tattoos are still not a norm, frequently marginalized groups embrace their identities through tattoos. This act implies a meaning of resistance for some and pride in doing so (Bell, 1999; Grumet, 1983). Pritchard (2000) and Sanders (1988) note how tattoos can function to separate someone from cultural norms while linking someone to certain parts of society. So, while someone may be using tattoos to separate themselves from larger societal groups, they are

18

simultaneously permanently tying themselves to smaller subgroups or cultures. This divergence itself is a kind of identification with a group. There is a perceived strength and emotional closeness in resisting something together with others or even having a common enemy and joining in solidarity.

When people get tattoos to align with a specific group, it is often an attempt to feel included. Soldiers would get tattoos together to boost connectedness and morale in wars. Family members might get similar tattoos as each other to all feel connected. (Bell 1999; Grumet, 1983). Some people will get them to mark progress and feel connected to others who have been through similar challenging life events, such as people who have been suicidal, had related psychological issues, experienced trauma, or dealt with addiction. (Grumet, 1983). The act of doing this with others seems to solidify closeness. One could argue that family members or groups experiencing hardship together already feel close without getting the tattoo. However, because tattooing is often seen in these situations, there must be something more solidifying about it on an emotional level. For this reason, discussing this phenomenon with people who choose to get tattoos could give insight into this process.

Adolescents often feel isolated as they learn about their identity, and getting tattoos can remind them of how they begin to define themselves (Grumet, 1983). The prevalence of tattooed people has even increased dramatically since 1990, when the percentage was 3% of the population (Armstrong & Fell, 2000; Dickson, Dukes, Smith, & Strapko, 2015). In 2016, The Harris Poll showed that 53% of people ages 18-35 had tattoos, signifying increased popularity with younger age groups (Dickson, Dukes, Smith, & Strapko, 2015; Shannon-Missal, L. 2016). Could this rise be related to identity development if younger groups are getting tattooed more?

19

Some suggest this can be a way to define body autonomy and mark developmental milestones, similar to how some tribes would do (Karacaoglan, 2012).

Getting a tattoo shows ownership and choice over one's body, allowing one to feel a greater sense of control. The body is the external physical manifestation of the self and needs to be adequately cared for. Many agree that it is inherently connected to identity, and therefore if someone makes changes to theirs, a new or changed identity is projected outwardly. How the physical body connects to identity is debated, but many recognize it as one of the ways people perceive others and their own identities (Alcina, 2009). When people observe someone's physical presence, they can recall and hold space for the person's existence in their mind. This concept suggests uniqueness that already exists when perceiving someone; with or without tattoos, each body reflects different identities. If it is acceptable for people to have different facial structures, why is it harder to accept the presence or absence of skin markings? A combination of born physical looks combined with chosen ones such as clothing, body modifications, and other physical changes all create an image for each person that is different from others and therefore meaningful and representative of the self (Alcina, 2009; Butler, 1990).

Tattoos about permanent status changes, like adolescent development, metaphorically coincide with the idea that tattoos are permanent. Sanders (1988) compares this idea to impermanent ways to alter the appearance (like costumes) as less connected to life changes. Therefore, getting a permanent tattoo about a stage in their life could show the recipient understands the significance of passing that point and are proud of it. Getting the tattoo means the person does not want to forget about it. Armstrong et al. (2002) found that the college-age students interviewed perceived tattoos as a part of their identity, and that act aided them in feeling more identified with others their age. That act allowed them to assume support from

20

others when they could connect with them because of having tattoos. This emphasis on support seems to differentiate permanently marking developmental milestones with others from simply going through adolescence together. When someone intentionally gets a tattoo about a shared experience, it shows some acknowledgment of the event. It could aid in that perception of support between people, which helps them accept the journey (Sanders, 1988).

Alcina (2009) suggests a connection between tattoos forming an identity and someone having a consistent narrative of their self. Tolpin (1971) also discusses a cohesive self connecting to an inner narrative. While much of someone's identity comes from an unconscious place, someone's conscious awareness of the self also plays a role, and an internal narrative encompasses both. This researcher's intent in this study was to understand if people who have tattoos consciously and unconsciously utilize tattoos and tattooing in the formation of their identities.

Kertzman, Kagan, Hegedish, Lapidus, & Weizman (2019) performed a study with 120 women in order to better understand the connection between tattooing and self-esteem. Since tattooing is a form of body modification, they wondered if people who chose to get them lacked satisfaction with their bodies on a more general level. They also wondered if those with tattoos saw themselves as individual and creative, which could suggest a higher level of self-esteem. Overall, they found that the tattooed participants showed lower levels of self-esteem than the non-tattooed participants. However, tattooed participants showed higher levels of body satisfaction based on feeling more connected to their ideal selves. Those participants seemed to achieve higher self-esteem once their tattoo was completed and therefore felt closer to their ideal body image. Those participants saw themselves as unique and felt favorable about that. This feeling likely resulted from participants making an active decision to change their bodies based

21

on how they wanted to look. They also found a stronger correlation between body image and self-esteem with tattooed participants, which supports this researcher's interest in studying the importance of tattoos in developing the self (Kertzman et al., 2019).

What about tattoos for the sake of tattoos? Purely aesthetic preference and expression is itself a culture, and tattoos have created a subgroup. The presence of tattoos has fostered a sense of camaraderie among individuals who share this form of self-expression, surpassing their initial symbolic meanings while simultaneously coalescing with them. Not much research addresses this or considers people with tattoos their own culture, but Bell (1999) sees a difference between "people who have tattoos," which refers to people with a few, possibly hidden ones, and "tattooed people" who tend to have more bold and prominent images. The latter example is a group subscribing to the culture with the word "tattooed," modifying them as a person. In contrast, the former example is simply a person who added some images to their body and probably would not want to be considered a "tattooed person" due to negative perception from society. She considers the tattooed people part of a subculture that can withstand judgment and embrace marginalization. Armstrong et al.'s (2002) research of tattoos among college students concludes that tattoos are less seen as deviant behavior among people in that demographic and more seen as body art. While not everyone accepts the image of a tattooed person as "normal," it is more accepted now than in the past, even by people who do not have tattoos (Armstrong, 2002).

In summary, tattooing goes back centuries without one specific, easily recognized origin date. The act signified different meanings over time. Tribes utilized tattooing to signify milestones and rankings among each other. This act helped them quickly identify specificities in each other. In more contemporary Western culture, it became more commonplace with

22

subgroups as a way to both stand out from the crowd and assimilate with the other people in their respective groups. Apart from the specific groups of people with tattoos that signal their affiliation, many people get tattoos for highly individual reasons as a deeply personal choice and do not wish to express connections with others. The meaning behind this choice is internal and therefore connects with their self identification. This study explores those reasons and attempts to understand any internalized meanings for people who get tattoos.

C. Societal Meaning and Culture

Because of the increase in tattooing, societal norms are changing; tattoo-seeking individuals are not necessarily seen as marginalized, nor do they have to have a particular group affiliation. The increase in tattooing (Taylor, 2012) perpetuates the newly emerging flexibility and variance in the reasons people identify why they get tattooed. Furthermore, this progression has developed the possibility of people getting tattoos for essentially any reason (or lack thereof) they choose with greater acceptance by society.

In today's culture, tattooing typically has a specific meaning. Karacaoglan (2012) and Grumet (1983) see this as a means of expression that is more tangible than words that can help certain people who may be socially shy express their deeper feelings without engaging in conversation. It is also possible to glean how someone feels about their own tattoo when they speak about it, depending on how they describe it and what body language they use (Grumet, 1983; Kertzman et al., 2019). The images represent something about the person. Hambly (1927) sees connections in today's culture with developmental changes like puberty and adolescence, love, status, mourning, and connections to some groups. Bell (1999) suggests that the meaning of a tattoo can even change over time, and the person who got it can go through different phases of interpretation of the image.

23

From personal experience, this researcher has heard many people say they got a tattoo to commemorate a deceased loved one or to remember a significant life event like traveling somewhere or achieving a goal. These suggest personal meanings where permanence is of some significance. Bell (1999) discusses a type of person who might get a small tattoo or cover one with clothing, intending the tattoo to represent something important about themselves. They may keep it secret or tell a select few people about it, but the intention of getting the tattoo is less about aesthetics and more about what it means to them. Bell also notes that in her experience, not every tattoo has to mean something specific to the image portrayed, especially to people with many visible tattoos. She suggests the act of tattooing can have meaning, as she described with wanting to be part of a tattoo subculture.

Karacaoglan (2012) also discusses the secrecy behind some tattoos and connects this meaning to psychological processes. He understands tattoos can be hidden, but the fact that they are visible suggests a need to express something. Suppose someone needs to make an image permanent. In that case, they might view it frequently for "prohibited identification," described as looking at the image to assimilate to it again (Karacaoglan, 2012). In doing this act, someone might put a tattoo in a spot where they and possibly others can see it. Similarly, someone might choose a tattoo to commemorate a deceased loved one, for example, to process their feelings about that loss. The person can look at their tattoo at any time and be able to remember and feel connected to the person lost, which would imply it assists in the mourning process. It also implies that grief might be more difficult for that person without an ever-present image.

Karacaoglan (2012) relates this to identity formation, as someone looks at objects and identifies with them. This idea suggests a psychological and possibly unconscious component to forming the self through the process of tattooing.

24

Seemingly a paradox, tattoos indicate both the plasticity and permanence of the body. People hold the control to get tattoos and change what is on their skin. Once someone decides to get a tattoo, they accept its permanence. People can change themselves to an extent (Patterson, 2018). This concept indicates a level of risk someone is willing to endure when getting a tattoo. The recipient must be sure they will like the tattoo for the rest of their lives, or at least understand the permanence of it. Tattoo removal is an option, but it is unlikely that someone would get a tattoo with removal as a future plan. By committing to a tattoo, the person accepts the permanence; therefore, most tattooed people would not likely engage in a brief fad. Alternatively, they could get a tattoo of something trendy, understanding the risk of that trend passing (Patterson, 2018). These ideas highlight the different considerations people make when deciding to get a tattoo.

Freud (1917) suggests there is meaning in holding onto objects to assimilate to them. When people possess something that helps them remember, they can feel connected and relate to whatever the object represents. This concept can apply to those people or memories the tattooed person has lost. When people get tattoos to commemorate a lost loved one, they may be trying to hold onto that person as a means of grieving and not seeing them as truly gone. For them, this eases intense feelings of grief into something more tolerable. They integrate the lost person within themselves to move through the grieving process, hold that person, and better assuage the pain of grief (Freud, 1917). Tattoos can be used to connect someone to whom or what they have lost as it better helps them remember someone or something, which can aid in that holding function.

D. Symbolism

25

Since tattoos are a form of visual art, it is essential to consider the possible meanings of symbols. There could be some conscious or unconscious meaning behind the actual images people choose to have tattooed on them. Why choose one image over another? When thinking of symbols, metaphors also come to mind. People sometimes choose tattoos that are not an exact depiction of what they say it means, suggesting there could be some meaning coming from a less conscious place. Understanding symbols can aid in interpreting the choices people make.

Humans and primates use symbols, and psychoanalytic symbolism is exclusive to humans (Blum, 1978). Art and psychoanalysis have always been connected. Slochower (1965) discusses the importance of symbolism for communication between people. Symbolism provides a way to better understand each other which relates to psychoanalysis; both symbolism and psychoanalysis allow for exploring subconscious states through indirect means (for example, words or pictures). These means create a way to express the self to more effectively connect and relate to others (Bernstein, 1982; Burchard, 1958; Slochower, 1965). Many have connected the use of symbols to the development of cultures and humanity as a whole, suggesting they affect how people think and perceive things (Burchard, 1958; Slochower, 1965). Slochower (1965) notes Freud's stance that the mind functions in symbols, such as representations and language, and they can often be seen in dreams.

Symbols can be used to make someone's thoughts more understandable and relatable. This concept is essential when thinking about tattoos because while they mean something specific to the recipient, if the intent is to convey a message to someone else, there has to be a way for the other person to understand the image. Freud suggests (Slochower, 1965, p. 122) that the artist opens the meaning of an image to those who cannot create it themselves; they take it from thought and make it something comprehensible to others. Thus, the tattoo artist serves that

26

purpose since the recipient needs their expertise to implement the design. Abstract painting and sculpture themes are often less clear without direct or obvious meaning. Instead, those are depictions of the artist's experience creating it which is often ambiguous (Blum, 1978; Burchard, 1958). Perhaps art is more relatable if people can find their own way to connect with it, seeing something that resonates with them. This idea suggests the potential that someone will interpret it differently than the artist intended, which makes sense since the symbol is something displaced from the initial idea to something more abstract (Blum, 1978).

Symbols are representative, and the intended meaning is often more profound than the external expression. These deeper meanings can even connect to psychological concepts that might otherwise feel crude or vulgar. The symbolic image or word is conscious, such as a flower, and the underlying meaning could be unconscious, such as a vagina. In this way, the symbol is a disguise that can be processed through psychoanalysis (Blum, 1978). Slochower (1965) cites Jones (1916), who suggests that symbolism is what is repressed from consciousness. Blum (1978) suggests that what is not repressed will not manifest in a symbol. That symbol, which represents the repressed idea, can be expressed then. The symbol has its own separate meaning that is more worldly, with which others can identify. This idea reinforces the connection of symbols to the unconscious; utilizing symbols can allow someone to express something they might otherwise repress since they can be disguised as something else and are, therefore, easier to express (Slochower 1965). When someone engages in this type of repression, there is internal conflict. Using symbols would aid in alleviating and resolving that conflict as they are a means to access the repressed ideas. With this idea in mind, it seems getting tattoos can aid in conflict resolution, as one may get a tattoo in an attempt to resolve an unconscious internal conflict.

27

Esman (2011) explicitly discusses using imagery in art as a function of psychological drives by highlighting the use and frequency of erotic imagery in art. It is again related to psychoanalysis as the artist's feelings emerge through the expression of these symbols. This concept is seen in the works of Salvador Dali, as sexual expression is seen frequently in his works. He developed a negative association with sex after his brother died of a sexually transmitted disease, and his father instilled fear when educating him about sexuality. His expression of sex in his art suggests that his childhood remained relevant to him throughout his adulthood, which is often seen in psychoanalysis. While expressing those fears in his works, some of his images are more clearly associated with sex, while others are more abstract. In the abstract images, the viewer is allowed to draw their own, possibly different, interpretations from looking at the same image (Martínez-Herrera, 2003). The viewers' subconscious minds connect to the painting and, therefore, Dali. Viewers likely form interpretations as a combination of their and Dali's ideas (Burchard, 1958; Martínez-Herrera, 200).

When a symbol's meaning is unclear or abstract, the symbol can serve a defensive function, like displacement or repression, for the artist. This defense could mean the artist has a reason for being unclear, possibly indicating something about their relationship with the object or idea being represented (Blum, 1978). This notion highlights the connectedness between visual art and the use of words during psychoanalysis, both sometimes being an indirect path to understanding what is unconsciously trying to be expressed.

While abstract symbols allow for more extensive interpretation, some symbols have become more common and generally accepted to represent something specific, such as objects looking phallic that can relate to the penis. Sometimes words bring up the same unconscious meanings across languages, and this is often seen with genitalia. The underlying ideas and drives

28

are often connected to the ego, infantile instincts, and body. (Blum, 1978). This concept is imperative to explore when people get tattoos because it could indicate how much the tattooed person wants the viewer to understand about the design and them. If the design is more abstract, does that mean the viewer has more freedom to interpret what they see? If it is a commonly known image, does the tattooed person want to convey a specific message that does not involve as much of the viewer's own thoughts?

Language is a common symbol people use to express thoughts. Spoken words do not have any inherent connections to what they describe, except if the word is onomatopoeic, where the sound is associated with the object or action (Blum, 1978). Humanity created words in order to have symbols and relatable ways to communicate about objects and thoughts. Because of this, people use symbols to define and better understand themselves (Blum, 1978). Freud was interested in language since it was a secondary function of verbalization after thinking. Language can be verbal or non-verbal, but it gets someone to think outside their own thought process (Blum, 1978). Tattoos can be used to communicate something non-verbally to someone else.

Kertzman et al. (2019) highlight the extensive way that tattoos communicate one's unique feelings using the body as a platform.

Piaget (1951) highlights the importance of symbolic play in infants. The infant learns through what they perceive, and most objects have no inherent meaning yet. The child initiates cues based on their needs and ultimately learns via imitation of other cues and language through others around them. The child can eventually accept those symbolic means of communication as their own without having to mirror them. Lacan (1966) discusses the idea of a mirror image as a separate self that a child can project themselves onto to better understand their self. It seems that being able to visually perceive the self at a slight distance provides some aid to the child in

29

simultaneously dissociating and relating. In these examples of development through symbols, the level of dissociation that occurs since the expression or image is separate from the self aids in the development of identity.

Tattoos can be seen as transitional objects. Similar to an infant using symbols to represent the mother, for example, when differentiating themselves, tattoos can be used as a symbol to represent something else. It creates a bridge between the two (Blum, 1978; Karacaoglan, 2012). The classic transitional object example of a security blanket does not inherently relate to the mother as they share no outward characteristics. However, the infant unconsciously utilizes it to represent the mother. Eventually, the blanket becomes not the mother, which indicates a resolution of the differentiation. Tattoos may sometimes look like what they represent and sometimes not, but ultimately the unconscious meanings are not fully depicted through the visible ink. The psychodynamic implications of tattoos as transitional objects will be discussed further in the next section.

Looking at tattoos as symbols, it is clear there are similarities with the artistic world. Tattoos fit with many other art styles by connecting people through familiar images and ideas while allowing for individual interpretation by the viewer and the holder of the art. The connection between science and art allows science to observe, understand, make connections, and make predictions about art (Bernstein, 1982). This idea is the reason for this dissertation, to understand the various meanings behind tattoos from different artistic and psychological perspectives in the hopes of better understanding the mind within the environment. A psychodynamic understanding of tattoos will be discussed next.

E. Psychoanalytic Thought on Tattooing

30

Some research supports the idea that tattoos represent conscious and unconscious psychological meaning. Patterson (2018) suggests tattoos depict the narratives the person intends but also allow others to formulate a story about the recipient that may have nothing to do with their original intentions. Karacaoglan (2012) suggests that tattoos signify stability in the chosen image for the person who possesses it. The tattoo sometimes aids a person in achieving stability in conflictual situations. In the example of someone who got a tattoo to commemorate achieving something, say an educational degree, they may have particularly struggled with the process. The initial conflict, i.e., completing school, threatened the person's stability. Getting the tattoo on them after graduating solidifies the achievement as representing success.

Grumet (1983) believes the tattooed person is attempting to define boundaries of the body which could be related to childhood fantasies. He does not explicitly elaborate on this, but he seems to suggest that getting a tattoo mimics the development of the ego when someone is seeking a sense of belonging and adequacy. The tattoo, representing an alliance with a group or a way to commemorate a milestone, acts as proof and a declaration of that identification.

Karacaoglan (2012) further develops this idea, discussing infants knowing the skin to contain the body and personality. It plays a role in separation as the infant sees the skin as a part of them that contains them, but what separates them from external space. Karacaoglan (2012) cites Ogden (1985) when speaking of infants seeing the skin as an object, and while most objects are external, the skin is still part of the person when seen as a separate object; the skin is both part of, and separate from, the infant. This awareness would also help someone define their identity by seeing the skin acting as a boundary, strengthening the ego in the development of the self (Armstrong et al., 2002; Bell, 1999; Grumet, 1983). As the skin acts as a boundary between the internal and external world, the tattooing process would imply a function of connecting the external to the

31

internal. The skin becomes permeable with the meaning of what is being tattooed. This process impacts the ego as the meaning is internalized from something that began as external.

Karacaoglan (2012) discusses the ability of tattoos to be transitional objects. Ogden (1985) describes these objects in the following way: The transitional object is a symbol for this separateness in unity, unity in separateness. The transitional object is at the same time the infant (the omnipotently created extension of himself) and not the infant (an object he has discovered that is outside of his omnipotent control). (p.132).

These physical objects can be utilized symbolically for an object an infant is separating from at age-appropriate times. The child eventually realizes they do not have control over their caregiver and separates. The transitional object helps the infant in understanding and experiencing the caregiver (or other object) as separate, thus with less anxiety than without something they can hold during the transition, while they develop that sense of connectedness (Ogden, 1985; Winnicott, 1953). Karacaoglan (2012) discusses how a tattoo recipient could have difficulties maintaining the difference between the tattoo and what is represented, or what Winnicott (1953) refers to as potential space. This struggle is due to the tattoo's permanence and the recipient's need to not relinquish the symbol. A tattoo can only partly be a transitional object since it is permanently affixed to the skin, and true transitional objects are separate. The tattoo becomes an object someone never has to give up. The experience of having the tattoo is maintaining the fantasy of holding the object from which the person must separate. For example, a person struggling with grief may utilize a tattoo as a coping mechanism to try to gain stability and hold onto something or someone they have lost.

32

As previously mentioned, Freud (1917) discusses the psychological importance of holding on to an object through the process of grieving. In the case of melancholia, someone falls into a pathological grieving that becomes more problematic than normal mourning in a conscious state. The object lost can be someone deceased or lost in another way, such as a breakup. The impact of the loss occurs on an unconscious level and diminishes the person's self-worth. Freud concludes that the loss causes the person to unconsciously feel pain about the object. They then feel pain about their self in an effort to identify with that object. That painful feeling that would otherwise be directed toward the object is now directed within since the object is no longer present. Thus, the person internalizes the object into the ego. This internalization occurs because the loss is too difficult to tolerate. The person cannot replace the object with a new one and instead has to take it on (Freud 1917). This concept relates to tattooing to commemorate a deceased loved one if the person struggles with the grieving process and wants to get a tattoo to feel the deceased as a part of them. It could suggest that the grieving process of a lost loved one could not be accomplished with external objects, and the person had to take action to permanently affix the lost one to them. Perhaps this aids in the unconscious transfer of the object to their ego, and perhaps it is not quite as extreme as melancholia if it is believed the skin is both part of the person and a permeable boundary to external objects.

The body healing from a tattoo can also be a transitional object as the pain reinforces physical presence and solidifies existence. If someone were to struggle with identity formation, they could benefit from the pain of the tattoo as a reminder of their own presence. It reminds people of their consciousness and allows them to feel connected to themselves (Patterson, 2018). Additionally, needing care requires the presence of a caregiver in some form, which would also validate someone's existence (Karacaoglan, 2012; McDougall, 1989). In the case of a tattoo, the

33

healing care typically comes from the self. This idea further emphasizes that the act of tattooing, and not just the images portrayed, has a purpose (Bell, 1999). Oksanen and Turtiainen (2005) found that people report the pain helping them access previous feelings, especially when those feelings are emotionally painful. When someone gets a tattoo, it breaks the skin and the skin has to heal itself. Karacaoglan (2012) suggests that rupture provides the person an opportunity to take care of themselves. The person has to soothe their skin which could allow them to engage in necessary self-care. This need for a tattoo could also be connected to a rupture from childhood, and by getting a tattoo, the person is attempting to reenact and resolve a situation. When someone has an opportunity to take care of their body, it can be a reaffirmation of their abilities. Suppose one felt conflict when a parent neglected caregiving, requiring them to take on that task themselves. In that case, they may recreate that feeling and initiate a chance to invoke soothing self-care that applies to that past rupture.

F. Theoretical Framework

Self psychology provides a theoretical lens that lends itself to interpreting the findings of this study. Through this lens, one can understand that tattoos provide the recipient a selfobject function. When one internalizes the function of a selfobject, that function becomes part of the self. Ultimately, this process helps develop the self and, more specifically, a cohesive self (Kohut, 1977; Scorides and Stolorow, 1984). As outlined throughout this literature review, a survey of research has defined an association between tattoos and persons or ideas that indicate they assist in internalizing that function. The tattoo becomes a visual representation and reminder of the function the image represents. If someone consciously chooses a tattoo that reminds them of someone who represents strength, for example, the tattoo serves as a visual reminder of the

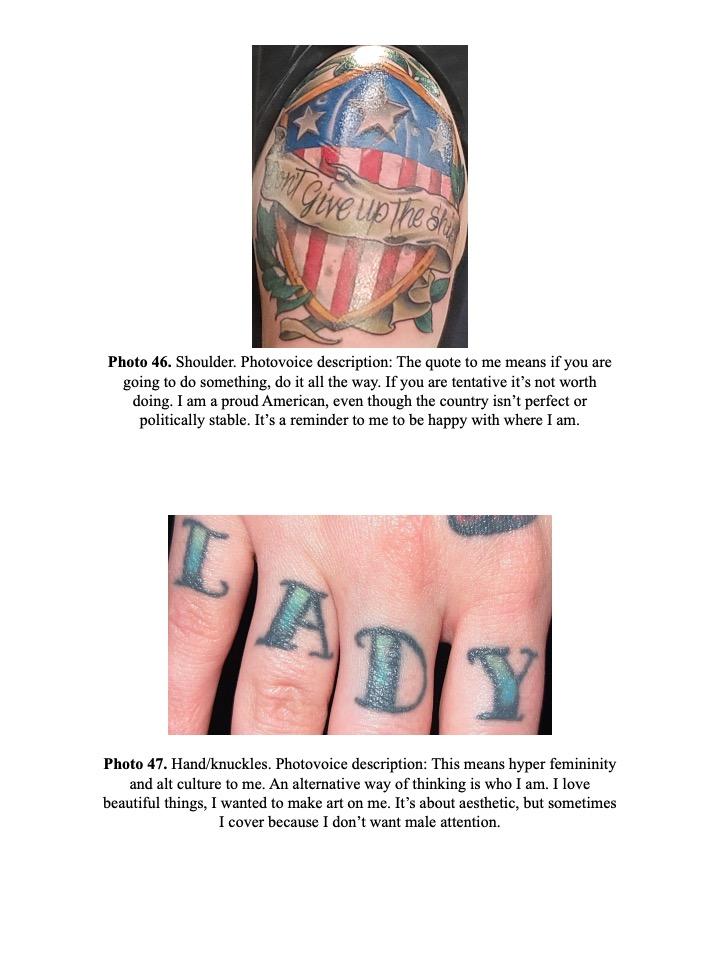

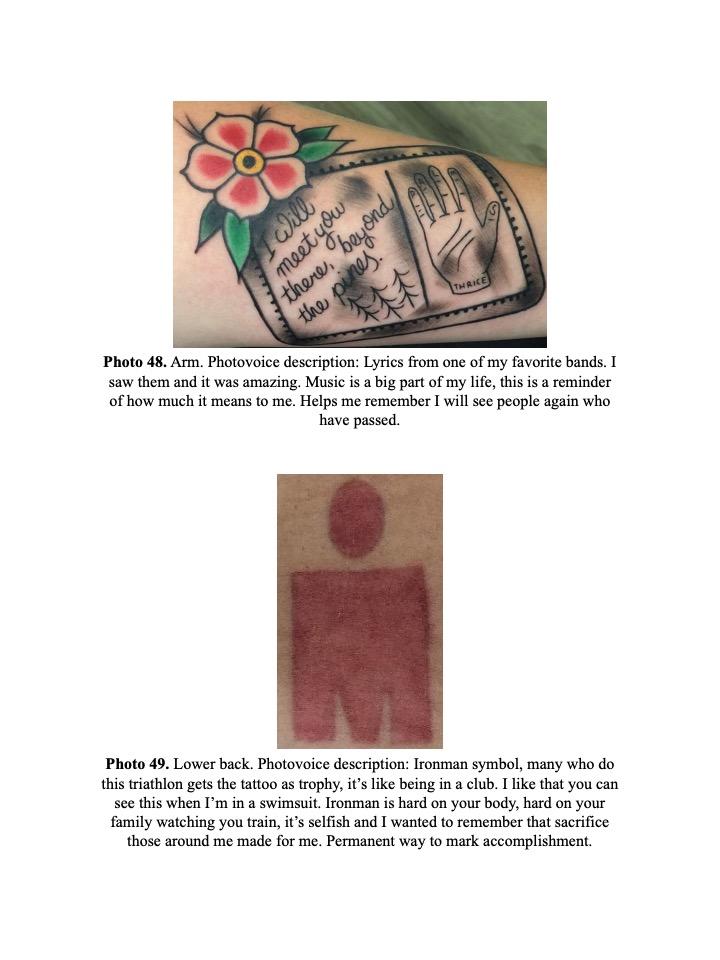

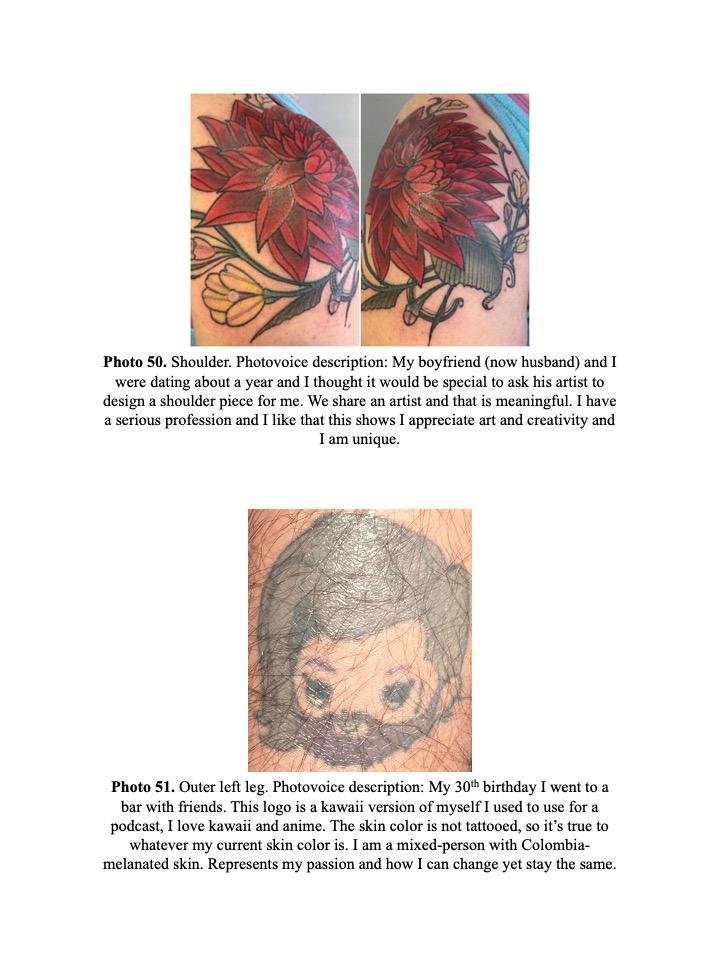

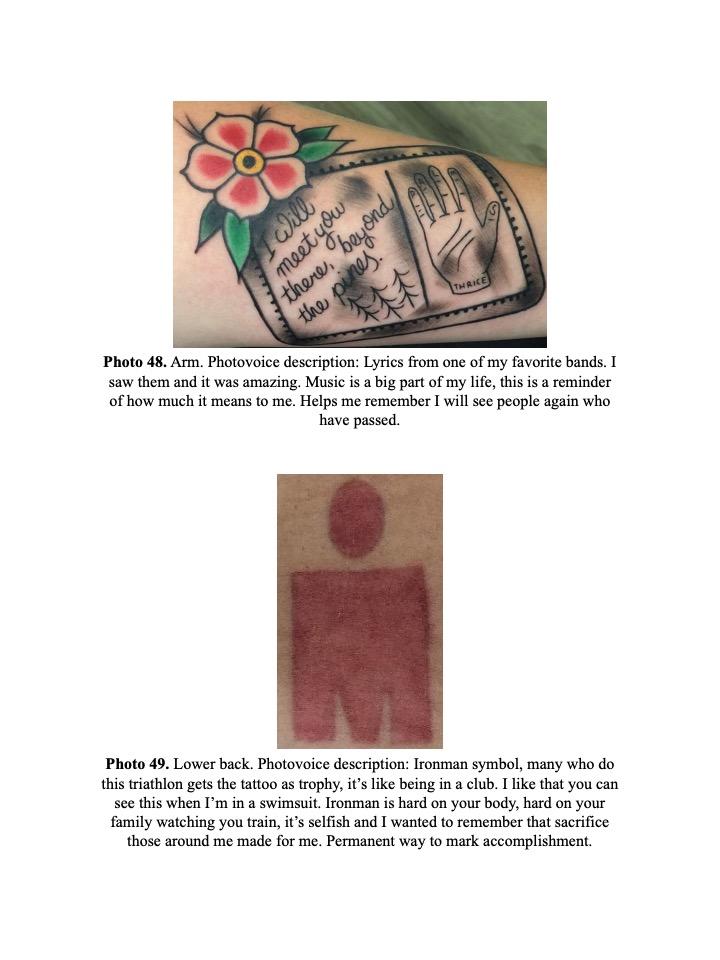

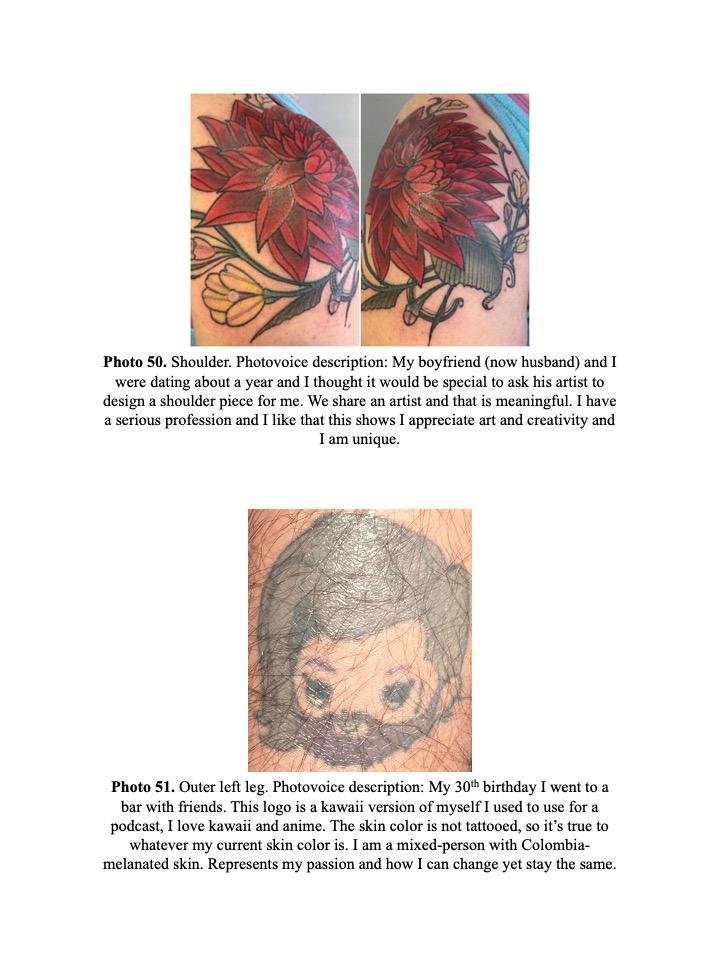

34