Surrounded by Idaho’s mountain beauty, our soak experience is more than just a hot springs. Pool-side beverage service, private pools and hotel accommodations, all in a facility that invites relaxation.

With over 30 years of experience, Donna Stackhouse's designs and talent span cartoons, fashion illustrations, technical drawings, silk screen designs, book illustrations and movie animations. Donna custom-designed this month's IdaHome Holiday cover as a vintage tribute to Idaho winter recreation. Find out more at www.dstackillustration.com

Mike McKenna is an award-winning author and journalist from Hailey. Mike’s writing has appeared widely, from Forbes, People, and Trout to numerous regional newspapers. He has served as the editor of The Sheet and Sun Valley Magazine and is the author of two prizewinning guidebooks, including Angling Around Sun Valley

Pamela Kleibrink Thompson is an internationally-acclaimed recruiter, career coach and animation veteran. She's been published in more than 124 different publications and is also writing children's picture books. As a career coach, she works with creative people to help them pursue their passions.

Cherie Buckner-Webb is a former Idaho State Senator, executive coach, speaker, business consultant, strategist, and fifth-generation Idahoan. In addition to her work in corporate and nonprofit environments, she assists institutions of higher education in the development of diversity curriculum and training and sits on a variety of local and national boards.

Arianna Creteau is a freelance writer based in Northern Idaho. A dessert enthusiast, avid hiker and amateur runner, Arianna spends her weekdays working a desk job and weekends chasing adventure. Her previous work has been published in Boise Weekly

April Neale is an entertainment features writer and has read her work on NPR and Spoken Interludes and writes for various industry trades and entertainment websites. Neale is a member of the Critics Choice Association, Alliance of Women Film Journalists, Hollywood Critics Association, Television Critics Association, and other professional entertainment organizations.

Micah Drew is a writer currently based in northwest Montana. A multiple Montana Newspaper Association award-winning journalist covering politics, sports, and the outdoors, he has written for Edible Idaho, Boise Weekly, and High Country News . When not in the newsroom, he can be found trail running throughout the West.

April Thomas Whitney’s career path has taken her on many professional adventures. After spending a decade as an awardwinning journalist and newsroom manager in Portland, OR, she spent 17 years managing communications at Brundage Mountain before striking out on her current adventure as a freelance journalist, copywriter, and PR contractor.

Heather Hamilton-Post is a writer and editor in Caldwell. She holds degrees in both agriculture and creative writing and is herself surprised by that. When she’s not writing, catch her at a sociallydistanced baseball game with her husband and young sons. Find her work across the web and buried in the lit journals you didn’t know you had.

When people ask me what I do for a living, I tell them I’m a storyteller. In my opinion, this is the second most elemental human job, right behind being a parent. At this point in history, we are all equally hunters and gatherers, albeit competing for organic beef at Whole Foods and searching for what’s trending on TikTok. But imagine our early predecessors in caves. Sitting around the fire, after the mastodon was digested and the kids were asleep in its dirty fur, storytellers were the televisions and iPhones of yesteryear. Plato even wrote an allegory about this. Our job was, and still is, to offer information that matters to the audience. And some of us believe what matters most in the telling is truth. That’s why I started IdaHome Magazine four years ago. I suspect it also explains why our online readership has grown to more than 100,000 per issue. Of course, it helps that 20,000 copies are distributed for free—the photos beautiful, the topics relevant, and the people herein are interesting. Most important—the stories are true. Still, you the reader have the choice not to read IdaHome. Therefore, we— the writers, designers, and photographers who create these pages—are grateful that you choose to spend time with us. You honor us with your attention.

As a storyteller, I’m also a documentary filmmaker, and for my second film, I somehow was invited to work with the Dalai Lama. I spent months feeling unworthy with the fabled National Geographic photographer, Steve McCurry, following and filming His Holiness around East Asia. I even slept in his mother’s home in Dharamshala, India, where he resides since being exiled from Tibet by the Chinese. You’d think I’d be enlightened by now. Instead, I’m just trying to figure out the simple answer he gave me to the complicated question we are all struggling to answer about humanity. “Why can’t we all just get along?” His answer: “Compassion is black and white.” Oh.

Since 'tis the season of compassion (and bah-humbug), our final issue of 2022 revolves around the holidays. Arianna Creteau delves into the ethical and environmental dilemma of buying a real or artificial Christmas tree. April Neale interviews John Ondrasik, the lead singer of Five for Fighting, an activist using his voice to support Ukraine here in Boise and beyond. The fascinating history of Brundage Mountain in McCall is told by April Whitney. We travel to Twin Falls to learn how Riverence, the largest sustainable producer of fresh trout in the United States, is preserving the pristine waters of the Idaho aquifer. There’s also plenty of good old-fashioned holiday events and pretty pictures to inspire you to put down IdaHome Magazine and enjoy the festivities.

BTW- I forgot to tell you that we’re starting a NEW magazine! IdaHome FLAVOR , the premiere guide to Treasure Valley restaurants, breweries, and wineries—with lovely photos, celebrity chef interviews, and incredible FOOD—arrives this month! Find it online at www.idahomeflavor.com and throughout the Treasure Valley, McCall, and Sun Valley. FLAVOR is all about good taste and raising a glass to 2023!

There’s nothing quite like the first run on a powder day at Brundage Mountain. Whether you woke up to take the quick eight-mile drive from McCall or journeyed up from the Treasure Valley, once you’ve parked your car, geared up, and loaded the lift, your mind’s singular focus can’t help but turn to that first, glorious line that you’ll trace through an untracked field of powder.

Now, imagine…instead of reaching the top of the lift and pointing your tips toward your favorite pow day run, you get to the unload ramp and “Pack the snow!” “Pack the snow!” comes bellowing at you from a uniformed employee standing guard at the top.

That’s what powder days were like in the Winter of 1961-62, the first year Brundage Mountain was open. While the bootstrap ping ski area went from an idea to an operation—with a chairlift

and lodge—in a remarkable two-year timespan, the budding ski area did not have any grooming equipment that first season.

Phil and Jan Van Schuyler skied at Brundage in the early 1960s, and they shared this memory with daughter Bea Clark. “They would ride up the chairlift, and ski instructor Herb Hyna would be standing on top. As they got off the lift, Hyna would bellow out, ‘Pack the snow!’ and they would have to side-slip down the mountain to help pack the run. One day, J.R. Simplot rode the chair after my parents, and Hyna was waiting for them on top. Herb yelled out his order to ‘Pack the slope!’ and J.R. and my parents dutifully packed the run.”

This is just one of the incredible memories that author Eve Chandler recounts in her 2012 history book, Brundage Moun tain, The Best Snow in Idaho. Idaho potato mogul J.R. Simplot was one of three founders of the resort who exemplified the pioneering spirit that helped make Brundage what it is today.

The townspeople of McCall had a passion for skiing and ski jumping dating back to the early 1900s. The Little Ski Hill had been satisfying most of the town’s alpine needs since 1937, but after a meager snow year in 1959 when Little Ski Hill was able to open for only three weeks, local mill owner Warren Brown and Norwegian ski champion Corey Engen decided it was time to go bigger and higher.

They asked Simplot to join the pursuit and began scop ing out several steeper, taller mountains near McCall, giving careful consideration to where the snow fell deepest and most consistently. They chose the west-facing slopes of Brundage Mountain and within two short years developed a master plan,

arranged financing, built a ski lodge, installed a chairlift, and cleared two runs that were called North and South (Modern day Main Street and Alpine).

“It’s pretty amazing that they put up that Triad Lodge in one summer,” said Chandler. “They started as soon as the snow melted and got it open by Thanksgiving Day. The thing that people never think about is the infrastructure like sewer, water and electricity. To get those three things in—in two years’ time—is phenomenal.”

The effort paid off. The ski area opened on Thanksgiving Day of 1961 with a 28-inch base on top of the mountain. By the end of the holiday weekend, a series of storms dumped a couple more FEET of snow, raising the snow depth to 48 inches. Ski ers were encouraged to purchase a season pass: $50 for adults, $25 for junior skiers.

A first season postcard by professional photographer Walt Rubey shows the Triad Lodge, designed by Warren Brown’s son, Frank, and built in a single summer.

L to R: Johnny Boydstun loads two skiers on the chairlift during Brundage Mountain’s first season, with general manager Corey Engen looking on from the right.

JERRY CORNILLES PHOTO

A first season postcard by professional photographer Walt Rubey shows the Triad Lodge, designed by Warren Brown’s son, Frank, and built in a single summer.

L to R: Johnny Boydstun loads two skiers on the chairlift during Brundage Mountain’s first season, with general manager Corey Engen looking on from the right.

JERRY CORNILLES PHOTO

“McCall has always been the kind of community where, if they wanted something, they just went out and did it. And not just Corey and Warren and JR, the people of McCall are a little tougher than everyone else,” said Chandler. “McCall is located in a mountainous environment that is rugged in the winter. There are terrible storms. But you can’t just not feed the cattle and not go to school, and there’s always been a lot of pride in being a mountain community that perseveres and really relishes in the fun they can have in the wintertime.”

PHOTO BY GARY PETERSON PHOTOGRAPHYOver the years, that pioneering spirit and passion for fun served the small resort well. It grew from a two-run ski area with no grooming equipment to a 1,920-acre resort with 70 runs and a reputation for perfectly-pressed corduroy. (Now provided entirely without the labor of the paying guests, to be clear). And of course, the powder.

“Brundage has just always had these epic dumps of snow. And that’s why people come to Brundage. They remember that epic powder day…they’re coming back for more,” said Chandler.

Chandler believes the ease of skiing at Brundage is what makes it so special. Skiers and snowboarders can go from their cabin or hotel and be on the mountain in 20 minutes. It’s easy to park, and mountain ambassadors help you unload skis and answer questions.

“I do think that people feel like they’re on vacation if they come from out of town, they feel like they’re out of their ev eryday routine, and I also think that Brundage is easy for a lot of people to ski,” said Chandler. “It’s not intimidating. If you really want to ski more challenging things, you can go off trail, you can ski Hidden Valley, but the intermediate to advanced

terrain is very easy for most people to ski. They feel comfortable. And I also think they feel welcome.”

And that’s exactly the vibe that the new owner ship group aspires to protect while they modernize the mountain infrastructure and expand to keep up with the growing skier population that’s discovered Brundage Mountain’s charms.

In 2006, The J.R. Simplot Company sold its interest in Brundage Mountain to co-owners, Judd and Diane Brown DeBoer (Warren’s daughter). After Judd passed away in 2020, longtime board member Bob Looper pulled together a group of Idaho-based families—who already had a deep passion for Brund age Mountain—to invest in the resort.

Looper says the exciting thing about the own ership group’s ten-year plan is that it’s completely home grown. There are no remote corporate mandates dictating how to move forward.

“We are really focused on enhancing the skiing and snow boarding experience in the winter and the outdoor activities in the summer,” said Looper. “We’re making the facilities more comfortable and more functional to make it easier to enjoy what the mountain naturally has to offer.”

Those plans are already in action. This summer, Brundage built a new ski and bike patrol building at the base area and upgraded underground infrastructure to make way for a new 20,000 square foot day lodge. Construction on that facility will begin as soon as the snow melts in the spring of 2023. The Cen tennial triple chair will be upgraded to a high-speed quad in summer of 2023 to give the mountain two high-speed quads on the front side. On site lodging, additional lift upgrades, snow making, and terrain expansions are also in the ten-year plan.

According to Looper, “We take our responsibility to the mountain and to the community very seriously and we think our guests are going to love seeing Brundage grow into the future.”

There’s an old saying in Sun Valley that you sometimes hear on snowy winter days, and it goes: “We’re living in a snow globe.”

The slopes and Austrian-inspired village at Sun Valley, as well as the quaint mountain towns of Ketchum, Hailey, and Bellevue that line the Wood River Valley can be downright dreamy during the holiday season. Not only are the towns all gussied up in lights and decorations, but there are all kinds of festive ways to have fun for folks of every age and abili ty—indoors and out.

Few know and love the holidays in Sun Valley more than Hailey’s beloved Mayor, Martha “Beaver” Burke.

“What I love most about the holiday season here are the wonderful smells of wood smoke from fireplaces and the scent of fresh cut Christmas trees. The sounds of groups like the high school choir, Colla Voce, singing and the crunch of fresh snow under your feet as you walk. The lights that line the trees along Main Street and the beautifully decorated shops and stores. The mountain skyline in the winter and, of course, the stars at night,” Burke said. “It becomes a fairyland around here. It looks like we’re living in one of those decorative villages people put under their Christmas trees.”

Sun Valley celebrated its first Christ mas in 1936 and most of the resort still looks the same as it did that star-stud ded first holiday. But you don’t have to be as famous as Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert once were to enjoy the same stunning spots to eat, drink, and be merry. From the slopes to the hot tubs to all the tasty places to dine and drink, or shop and play, it’s tough to top the holiday season in Sun Valley.

The holiday festivities kick off with tree lightings and appearances by Santa in Hailey, Ketchum, and Sun Valley as December storms in. The famous Torch Light Parade rings in Christmas Eve, as

skiers alight the slopes of Dollar Moun tain and offer a guiding light for Santa to find this little slice of wintry heaven.

The lights that line Main Street in Hai ley were the guiding lights for current Sun Valley Mayor Peter Hendricks for years, back when he and his family would make the trek from California to the Wood Riv

er Valley each winter for the holidays.

“We’d get so excited when we’d see them. They were our welcome to Sun Valley,” Hendricks said about a tradition that began in the 1980s, nearly 30 years before he would move to Sun Valley full time and eventually be elected as mayor of the small town (population 1,814).

BY CAROL WALLER“It becomes a fairyland around here. It looks like we’re living in one of those decorative villages people put under their Christmas trees.”PHOTO PHOTO BY CAROL WALLER Hailey’s Main Street lights up with down-home holiday spirit and plenty of local revelry.

“Part of the charm of the place is that you had to go out of the way to get here,” Hendricks fondly recalled, “But when you got here, boy it was worth it. This is a really cool, a really special place.”

Besides all the traditional holiday fun, there are a lot of unique ways to enjoy the season in Sun Valley. Of course, there’s plenty of skiing—Sun Valley is America’s original ski resort and was named “Best in the Country” by the Ski Magazine Readers Poll for the third con secutive year. Sun Valley was also once again selected to host the U.S. Alpine Nationals in April.

Baldy, as locals call Sun Valley’s largest ski hill, offers over 2,000 acres and 3,400 vertical feet of skiing. Meanwhile, Dollar

Mountain is a great place for beginners as well as fans of parks and pipes. There are also over 40 kilometers of groomed Nordic ski trails that offer snowshoeing, fat tire mountain biking, and idyllic winter walking.

There are lots of sledding options, too. The sledding hill in Sun Valley is very popular as are spots to the north of town at Baker Creek and in the hillsides of Hailey.

Playing hard during the day is part of the Sun Valley tradition, but so is partying hard afterwards. Après options abound as well, from classic ski town bars like the “the Pio” or “the Pioneer Saloon,” Grumpy’s, and the Casino to more mod ern hot spots like Enoteca, The Covey,

While all the fun things to do and gorgeous mountain views in the winter make Sun Valley a sweet spot, it’s the community that really makes the place special.

“The natural beauty of this place is really inspiring, but it’s the attitude of the people here. They’re friendly, welcoming. They really put a smile on your face,” Hendricks said. “People here have an attitude of being fun, hopeful, positive, optimistic. It makes this an upbeat place.”

Sun Valley is especially upbeat during the holiday season when the snow is falling, the lights are glimmering, and you feel all snuggled up deep in the heart of the mountains of Idaho.

As Mayor Burke said, “It really is a snow globe come to life.”

“The natural beauty of this place is really inspiring, but it’s the attitude of the people here. They’re friendly, welcoming.”PHOTO BY CAROL WALLER PHOTO BY CAROL WALLER PHOTO BY CAROL WALLER

BY JAXPAXPHOTOGRAPHY.COM

Winter Garden aGlow

BY JAXPAXPHOTOGRAPHY.COM

Winter Garden aGlow

It’s that jolly time of the year, and there are plenty of Treasure Valley holiday events to make you smile or scowl, depending on your tolerance for hot cocoa and cold temperatures.

Now in its 26th year, the annual Winter Garden aGlow, presented by Idaho Central Credit Union, is a holiday tradition that many residents treasure. A dazzling display of more than 600,000 twinkling lights illuminate the Idaho Botanical Garden, and even Santa makes appearances. Children can write a letter to Santa, and unlike your rich aunt when you ask her for money, Santa always writes back!

Carolers serenade visitors with tales of three wise kings, angels, and Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. If your nose is turning red, head to the Stocking Stuffer Station for free hot drinks and cookies. One night only, December 18th, there’s “Pride in the Garden” with gay and lesbian choruses, a drag Santa, and speciality drinks for grown-ups—sure to be rainbow of fun!

Winter Garden aGlow is a community-based event with partners and supporters coming together to make a truly magical experience. “Each year, I visit the garden with my aunts and cousins and their children, so it has become my tradition too,” said Erin Ander son, Executive Director. “I love seeing the sparkle and delight in the little ones’ eyes…and that same sparkle in the grandparents who have been coming for years. When you come to Winter Garden aGlow, you are investing in the garden, keeping our gates open, and the plants flourishing, but mostly you are investing in our community.”

Scentsy’s holiday light display starts November 11th, with lights blanketing more than 450 trees. Pathways meander more than 40 miles through the Meridian campus. A 250 foot-long lighted tunnel delights all ages.

Whether you sing with Bing or Sinatra or Mariah Carey, be sure to bundle up against the cold to enjoy an uncountable number of lights along Indian Creek in Caldwell from November 19th to January 9th. Visit with Santa and glide into winter on the nation’s sev enth ice skating ribbon and ice rink—an ice pathway that winds around the plaza and culminates in a rink.

On December 3rd, be bedazzled by the 19th annual Treasure Valley Night Light Parade in Caldwell. This year’s theme is Christmas at the Movies. It’s a wonder ful life in Caldwell at the Winter Wonderland. “Win ter Wonderland and all of the events in downtown Caldwell are part of what makes our city unique,” said Mayor Jarom Wagoner. “People come from all over to see the light display along Indian Creek and we are proud to host such a great family event. It is truly one of my favorite things about living in Caldwell.”

Top: Visit Winter Garden aGlow at the Idaho Botanical Gardens November 24-December 31, 6-9:30 pm. Center: Scentsy’s Tunnel of Lights starts sparkling with 40 miles of pathways at the Meridian offices on November 11. Bottom: A glittering universe of lights illuminates Indian Creek in Caldwell November 19-January 9. COURTESY OF IDAHO BOTANICAL GARDEN PHOTO COURTESY OF KEARNEY THOMPSONToys for Tots was founded by Major Bill Hendricks, United States Marine Corps Reserves, in 1947. The idea originated with his wife, Diane Hendricks, who handcrafted a doll and asked her husband to deliver it to an organization so it could be given to a needy child at Christmas. When the couple discovered no such organization existed, Diane suggested that her husband start one. That first year, 5,000 toys were collected and distributed in Los Angeles. The following year, Toys for Tots expanded into a nationwide community action project when the United States Marine Corps adopted the program. Walt Disney designed the Toys for Tots train logo and created the first national Toys for Tots poster. In 2021, Toys for Tots distributed over 22.4 mil lion toys to nearly 8.8 million less fortunate children.

“Having the opportunity to help and serve families that are struggling during the holiday season is a bless ing,” said community volunteer Nicole Zuber. “Per sonally, I come from a family that had very little, and I remember from a very young age, we had people in our lives who helped us. Receiving things from programs like Toys for Tots made a huge difference in my child hood. I truly believe it is our duty to pay it forward.”

Sponsored by the Kuna Chamber of Commerce, the Down Home Country Christmas attracts about 2,000 to 3,000 people, including Santa. “Down Home Coun try Christmas is a great community event for Kuna,” said Jodie Harrington, Vice President of the Kuna Chamber of Commerce. The evening culminates with lighting Caldwell’s Christmas tree with the mayor.

Sara Goodpasture, Executive Director of the Kuna Chamber of Commerce, agreed. “We love the commu nity togetherness it brings in the spirit of Christmas,” she said. “We have been hosting the parade for several years…people from all over the Treasure Valley come to our small wonderful town of Kuna to celebrate the holidays and festivities.”

A village of shopkeepers and animals including sheep, a donkey, a horse, Samson the camel, and shepherds bring the story of the birth of Jesus to life in Eagle at the Seventh-Day Adventist church. “Taxes” of non-perishable food are collected for the Treasure Valley Mobile Food Pantry.

Hanukkah or Chanukah, also known as the “festival of lights,” celebrates a military victory and the rededication of the Holy Temple and means “dedication.” A small band of faithful Jews, led by Judah the Maccabee, defeated one of the mightiest armies on earth which had forbidden the practice of the Jewish religion, reclaimed the Holy Temple in Jerusalem and rededicated it to the service of God. After the battle, only one vial of pure olive oil remained in the Temple in Jerusalem to kindle the menorah, but the menorah miraculously burned

Top: A Toys for Tots donation center is located at Sportsman’s Warehouse, 3797 E Fairview Ave, Meridian: November 26 to December 6. Toys For Tots Boise - Marine Toys for Tots. Bottom: Kuna’s Down Home Country Christmas happens December 10 with a theme of Candy Cane Christmas and a Santa Parade.for eight nights. That’s now how long Hanukkah lasts—December 18th to 26th in 2022.

Beth Harbison is the Director of Lifelong Learning and the Jewish Community School of the Congrega tion Ahavath Beth Israel. “Chanukah is a celebration of freedom and the right to practice our religion. We cook a million different things with oil such as latkes (potato pancakes) and sufganiot (little round donuts) and our houses reek of oil long after the holiday is over,” she said. “Chanukah is primarily celebrated at home where we put a Chanukiah in our window. Chanukiah is the more accurate/preferable title for the nine-branched candelabra. Many Jews and non-Jews alike call it a menorah, but a menorah is actually a seven-branched candelabra and a symbol of the State of Israel.”

Kwanzaa is an African American and pan-African holiday which celebrates community, culture, and fam ily. Created in 1966 by Professor of Africana Studies Dr. Maulana Karenga, the seven-day cultural festival begins December 26th and ends January 1st. Celebra tions include feasts, music, dance, poetry, narratives, and a day dedicated to reflection and recommitment to the seven principles–unity, self determination, collec tive work and responsibility, cooperative economics, purpose, creativity, and faith. Celebrate on December 29th at NNU in Nampa with a banquet and program.

Start 2023 with a shiver at the 20th Annual Geb ert-Arbaugh Polar Bear Challenge. Hundreds of hardy Idahoans will plunge into freezing Lucky Peak Reservoir to raise money to benefit local children with critical illnesses through Make-A-Wish Idaho. The fundraiser starts at 11 a.m. on January 1st and will include a costume and mustache contest. Registration begins at 10 a.m. The annual challenge was named after the late Gary Arbaugh and Larry Gebert who brought the Polar Bear Challenge to the Treasure Valley 20 years ago.

“This is a crazy, fun event and a great way to start the new year,” said Make-A-Wish Idaho Director of Development Helene Peterson. “Make-A-Wish Idaho deeply appreciates all the Polar Bears who will come and plunge with us this year.”

In mid-January, festivities continue with the Peking Acrobats performing daring maneuvers and lyrical feats at the Morrison Center. “We are thrilled to share these incredible artists and programs with the Trea sure Valley,” said Laura Kendall, Executive Director of the Morrison Center. “We are a vibrant, growing city, and we aim to bring programming that reflects a wide range of excellent touring companies that you would see in major metropolitan cities.”

From the IdaHome family to yours–Happy Holidays! We hope these diverse holiday events warm your heart and bring a smile to your face. We’ll see you in 2023!

Top: Celebrate Kwanzaa, December 29 at NNU in Nampa with a banquet and festive program. Center: Take the plunge at the Polar Bear Challenge and Make-a-Wish fundraiser January 1, 2023.

BY HEATHER HAMILTON-POST

BY HEATHER HAMILTON-POST

Leigh Evans empties a small jar of marbles onto the table, rolling each one between her fingers as she gazes through the wall of windows that overlooks a scenic Idaho landscape. Gathered from the dirt outside her schoolhouse-turnedhome, the marbles are among the only things she’s found in the years—seven of them—since owning the property with her husband Allen.

The Huston School, located on Homedale Road at the entrance to the Sunnyslope Wine Trail, was used as a schoolhouse from 1918 until 1973, when

it was converted to apartments. When the apartments caught fire in 1991, the building was emptied, left to Idaho’s often volatile weather and whomever happened upon it. Although the building had several owners, it remained vacant until Leigh and Allen purchased it with plans to renovate in 2015. In addition to the interior work, the Evans family has put in over 400 hours moving dirt and digging trenches, joking that, previously, they’d been renovating, yes, but also, raising goatheads.

Because much of the schoolhouse had to be entirely reimaged to make it work as a home, the couple says they’ve done their

best to preserve the outside, particularly in the front. And, even where they’ve changed things entirely, Allen and Leigh have done so with a dedication to the communities that raised them. “We feel so blessed to be given the responsibility of this building that was the center of the community for so many years. And we’ve been able to welcome people back,” Allen said.

It’s a responsibility they don’t take lightly. Before construction began, they had an engineering firm tell them to just tear it down. “And we didn’t like that,” Allen said. “So we found another firm.”

Slowly, and with moments of sheer panic,

Leigh said they began the work, literally chipping away at it with the help of family and friends. “It’s determination, and joy, and hard work, coming home exhausted and dirty and tired. And it is so cool to live in—so lovely and welcoming,” she said.

In the kitchen sits a walnut-topped island that Allen explains came from his grandmother, who homesteaded nearby. “They had this walnut orchard, and when they tore it down, my dad kept the wood. It sat in storage for 40 years, so when we moved in, we turned it into this top,” he said. There’s also a slab of butcherblock

up one day. Each element connects the past and present in a house that is truly a reflection of the community that built it.

Throughout the home, there are reminders that it was indeed a school house—original brick, evidence of a stage, lunch counter, and cold storage. People stop by often to drop things off too. There are paintings, report cards, and photographs that have shown up, which help to piece together what the school might have looked like inside. Because living in a schoolhouse offers an excess

Leigh and Allen, who grew up in Idaho, said that they both come from families that opened their homes and dinner tables to others. Since moving into the schoolhouse, they’ve hosted a daughter’s wedding, a variety of families down on their luck, and a host of com munity members and neighbors anxious to see their work, which continues— Leigh and Allen have a lot of projects on the list, including a pantry sink, adding an original beam to the kitchen, a lift, and a secret door connecting the primary bedroom and the library. But

that Leigh incorporated, which they’ve owned for nearly their entire marriage, and an expansive table made from the school’s open floor joists and built by Allen’s high school friend.

Behind the school sits the swingset and slide that Allen’s family owned in Middleton when he was growing up, a seed cabinet, and a card catalog from a school where Allen taught. There are shutters they’ve built, family paint ings, Leigh’s handmade curtains with accents from a friend’s grandmother’s button collection, and a friendly cat named Raggedy Ann that just showed

of square footage, Leigh and Allen say they’ve been able to leave things, like the entrance, as they likely were when the school was running.

One of the couple’s daughters lives with them, as well as Keith Farris, Leigh’s father, who frequently inter acts with the myriad of folks who stop by—recently, a pair of elderly sisters who were students at the school. Farris, who moved back to Idaho fairly recently, is happy to be back around what he called “that Idaho helpful ness,” and said the schoolhouse is a wonderful place to live.

they’ve also talked about an eventual afterschool arts program, a natural fit for two former teachers living in a schoolhouse with two art studios and a gorgeous outdoor courtyard.

“It isn’t really surprising that God let us to a big house when we were trying to downsize,” Allen laughed. “We’ve been able to provide a great place for Dad and our daughter and community picnics.”

To see what the schoolhouse looked like when the Evans family began their work, check out the Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star by 92Keys music video on YouTube!

Delight in single-level living in this high quality home situated in coveted NE Boise. A chic and inviting entry opens to beautiful 4” wide white oak floors, high coffered ceilings, and a limestone fireplace framed by floor-to-ceiling windows. Experience relaxed elegance in the intimate formal dining room, or serious cooking in the Chef’s kitchen, which enjoys custom European walnut cabinetry, 5-burner cooktop, double ovens, vegetable prep sink, stove pot filler, and corner nook for informal meals. Four spacious bedrooms each have direct access to a full bath, including two primary suites! Private lower-level space with a full bath serves as a great guest quarters, expansive office, and/or music room! Relish in year-round outdoor living on a private covered patio surrounded by lush landscape and mature trees. Don’t miss the large flat yard beyond the boulders & trees. This well-designed, well-built home appreciates close proximity to trails, the river & greenbelt, and downtown!

Move over, potato! Idaho’s significant role in responsible land-based aquaculture conservation is flourishing thanks to Riv erence, a privately-held company, making waves in sustainable trout farming in Twin Falls. Chalk it up to a freakish geological set of circumstances from over 17,000 years ago; the Gem State might aptly be renamed “The Water State” despite no ocean beach es. Aquaculture is ready for its close-up, Mr. DeMille, and Idaho is where this Holly wood magic happens, thanks in significant part to Riverence Provisions and Riverence Farms’ thoughtful CEO Rob Young and co-owner/producer David E. Kelley.

The other star in this big fish story is the vast reservoir of crystal clear spring water that exists, compressed over time in the enormous basalt basin of ancient beds that hug the winding Snake River and the jagged Sawtooths. The great geo logical abundance of Idaho’s aquifer and some existing land-based aquaculture businesses were combined by Riverence with a keen focus on genetics, superior fish as food, and a desire to decrease carbon emissions compared to other food sources like cattle. The company’s unique dedication to serving the envi ronment and native habitat governed by science, ethics, and fish health have made

Riverence—a wordplay on river and rev erence—the kingfisher of Idaho trout.

Riverence is an egg-to-table purveyor of hormone-free, ethically-raised rain bow and steelhead trout (a cousin to Ida ho’s other big fish, salmon). Their prod uct has made a big splash with top chefs at fine restaurants, selling the whitefleshed variety and the heritage fish with a reddish-hue to their flesh. The red flesh of trout is accomplished by feeding them naturally-derived carotenoids, the same algae food source that give flamingos their pink color. Pink flesh, however, is not considered desirable; deep red is the most desirable and tasty.

Riverence swims upstream, counter to the corporate Big Agra mindset, and creates a stunningly delicious end product. Their method minimizes environmental pollution and threats like depletion of the wild fish stocks from overfishing, rising water temperatures, loss of habitat, and toxicity in the oceans. Riverence’s approach incorporates careful genetic selection and a proprietary feed made in the USA that not only boosts the fish’s health and Omega-3 levels but also takes enormous pressure off fish in the wild. Riverence even composts and recycles the fish’s waste and gives it free to farmers.

And even with high-profile chefs like Andrew Zimmern, who is on record tout ing the excellence of Riverence trout, there is a stigma when “farmed fish” is men tioned. But Riverence in the Magic Valley is a marvel of dramatic terrain carved by the Snake River Canyon, boasting the Blue Lakes aquifer and Crystal Springs, which has pristine potable water pouring out of the Idaho ground. You can even see the spot where Evel Knievel attempted to jump the canyon!

But seeing Riverence at work raising healthy fish is as stunning as the topog raphy.

One woman carefully watches over and hand-feeds the fish at one of the hatcheries from the egg to the small fry stage, kept carefully in a facility replete with descend ing spring-fed water courses. It’s a literal trout nursery, with 400,000 fish being produced per month.

Idaho’s continuous clean water sources provide the environment the “troutlets” or “fry” need to flourish. The Thousand Springs Scenic Byway and surrounding towns like Buhl explode with drinkable at-the-source 58-degree water, with the Riverence farms situated close by so that gravity pulls that consistent flow down the contained raceways where the fish are grown to maturity. Their runs are thor oughly cleaned weekly and fish waste is vacuumed up, composted, and sent free of charge to farmers nearby. As a result, na ture remains unsullied, the wild fish stock can replenish naturally, and people will dine on tasty, clean trout with enormous heart and brain-boosting nutrients.

Of late, Riverence Provisions and Riv erence Farms—the United States’ largest trout producers—have achieved certifica tion from the Aquaculture Stewardship Council. Not an easy feat, ASC’s sea green label can only appear on seafood from

farms independently assessed and certified as environmentally and socially responsible. It takes a long time to achieve this strict certification. Still, Todd English, Vice President of sustainability at Riverence Provisions, shared the company ethos, which has taken them to this certification on a walking tour with our IdaHome team at their facilities in the Magic Valley.

He noted the secret to their success. “It’s Idaho’s water. That’s why we’re here. We borrow the water and efficiently raise healthy fish and remove most of the waste from that water through settling ponds that allow uneaten food or fecal matter to drop to the bottom. The water returns clear to the rivers. Other nutrients are absorbed by native plants and become cover and food for waterfowl. We provide a lot of habitat for wildlife.”

Noting Idaho’s good fortune for plenti ful water, English added, “There are only a few places on the planet where this type of geology exists, the access to an aquifer. I believe it is just Iran, Turkey, and Idaho. People’s perception of aquaculture is that fish swim in dirty, muddy ponds. But our fish are in crystal clear water at a consis tent 58 degrees. You can see the bottom of a 50-foot-deep river here. And that’s

why Riverence trout taste so good. The technologies we employ create a better strain of fish without genetic engineering, just careful genetic selection. The feed can have a considerable impact. So we revamped the feed here in Idaho for these trout from North American-certified sources. We minimize our use of fish meal and fish oil, which is one of the signifi cant challenges with aquaculture. Back in the eighties, the fish feed would contain upwards of 70, 80% fish meal and fish oil caught from Peru or the Gulf of Mexico. But those days are over. We’re below 10% fish meal and fish oil from wild forage fisheries. And so the reason that we want to reduce that is because of the impacts on the ocean. But fish need that fish meal and fish oil. So we’re using fish meal and oil derived from the processing wastes of wild fisheries in our feed—trimmings in Alaska or haddock fisheries on the East Coast— heads, racks, and frames are ground into

a fish meal and fish oil for aquaculture. Another is soldier fly larvae as a replace ment for fish meal. There’s also a company called Veramaris that ferments the algae that creates a fish oil replacement rich in Omega-3s. We use some of that in our fish feed, allowing us to use less fish oil. So fewer resources, less need, and making sure that what we do keeps the impact on the fish and the environment very low.”

English is optimistic about Riverence’s low-impact footprint and the public’s desire for more healthy, tasty fish as wild species are on the wane and environmen tal concerns rightly on the rise. “We take the pressure off the wild stock and allow people to not go without a fantastic tasting fish. Currently, Riverence produces about 20 million pounds a year, and we want to grow that in the future.”

For more information, visit riverence.com and follow Riverence on Twitter and Insta gram at @RiverenceUSA

Four and a half decades after its discovery, the Borah Glacier was officially recognized, named, and put on maps. Now researchers and glacier enthusiasts are curious if it’s really a glacier, and whether Idaho’s mountains are hiding any more.

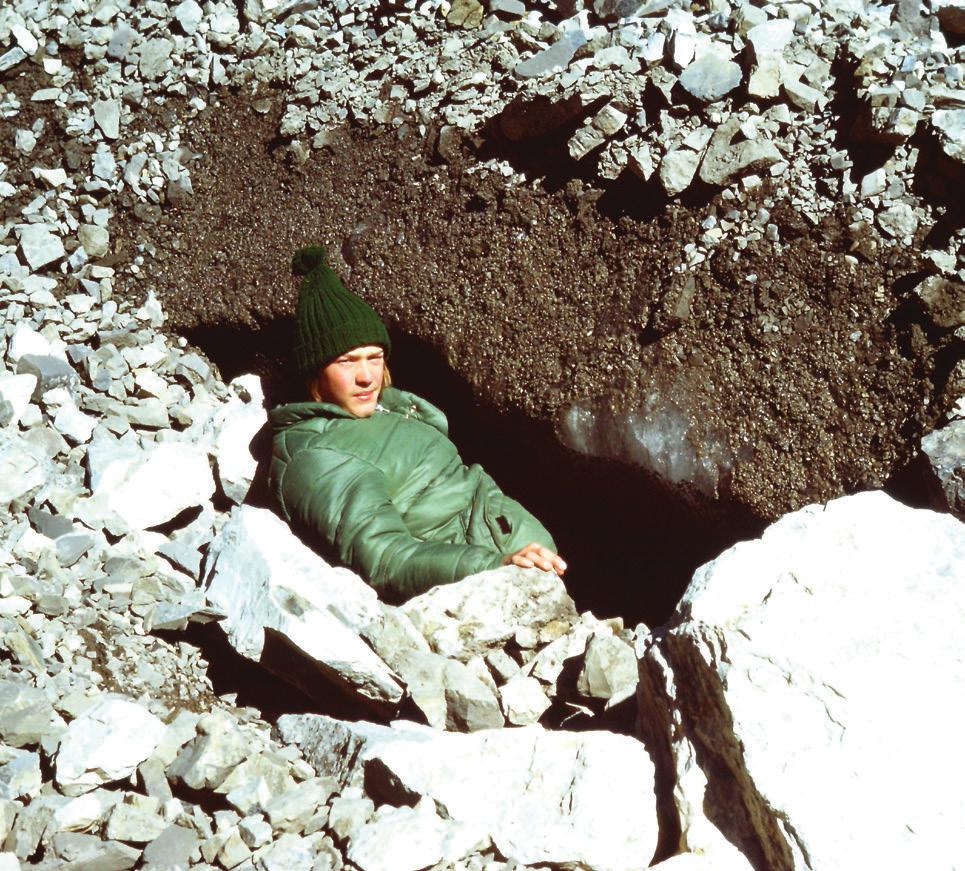

BY MICAH DREWDown from the north side of Idaho’s tallest mountain lies an unassuming pile of rubble.

Nestled against the north-facing cirque of Mount Borah, a perennially-present snow field angles downhill into a stretch of boulders and rocks that stretches nearly 2,000 feet downslope to a moraine, a pile of rocks pushed into place by an ancient glacier.

This patch of snow, and more specifically, the seemingly run-ofthe-mill rock pile are covering up Idaho’s most unique geological feature, officially recognized by the U.S. Geological Survey in 2021 as the state’s only glacier.

In the 1970s, a geology student at Boise State University needed a project for Monte Wilson’s geomorphology class. The student, Bruce Otto, was an avid backpacker and decided to do some field work in the Lost River Range to study snowfields on Mount Borah.

“I had a lot of undergraduate naivety,” Otto said. “I was just going to measure this snowfield and see how much it would need to grow in order to be considered a glacier.”

In 1974, Otto and his father hiked into the cirque, headed for the snow field, and began surveying the site. While walking along the lateral moraine that formed the side of the cirque, Otto stum bled across some crevasses that were “so deep they were black.”

Under the top two or three feet of rock was sheer ice. The entire basin was covering up a mass of ice so thick that it was able to move and flow of its own accord. Otto had discovered the first glacier in Idaho. “Monte was flabbergasted,” Otto said.

That fall, Otto, Wilson, and several students returned to the glacier. They went spelunking in the vast crevasse at the head of the glacier, called a bergschrund, and conducted seismic testing to determine the depth of the ice. The readings showed that the glacial ice, hidden from view by a boulder field, was 210 feet thick in the middle. It stretched 300 meters across and nearly 400 meters in length. Otto estimated the glacier was at its peak in the mid-1800s before the climate began warming.

For the next decade, Otto and Wilson returned to the glacier almost every year, monitoring precipitation in the cirque and taking regular measurements, until 1985 when the monitoring gauge was taken out by an avalanche. They made one attempt to get it registered and named, but didn’t make it through the bureaucratic process.

“We knew there were potential places for more of them, but we never did any other searching for glaciers,” Otto said. He soon moved from Idaho and went about a career in mineral exploration.

In 2008, an article in the Idaho Statesman quoted a Boise State geology professor saying that the glacier was gone and nothing remained on Mount Borah but patches of snow.

The idea of a glacier conjures up enormous rivers of ice, slowly flowing downhill, breaking off icebergs into coastal waters or inland alpine lakes. While those glaciers fit the storybook idea, the definition encompasses a range of hydrogeological features on a much smaller scale.

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) defines a glacier as a “a large, perennial accumulation of crystalline ice, snow, rock, sediment, and often liquid water that originates on land and moves down slope under the influence of its own weight and gravity.”

Glacial researchers classify the features based on their location, nearby landforms, size and internal structure, including debris content. In a traditional classification system, smaller alpine glaciers can be considered “uncovered,” a traditionally white glacier with clearly visible ice; a debris-covered glacier, where the surface is covered by rocks and mud of varying thickness and coverage; and rock glaciers, where the internal structure is a mixture of rock and ice.

Glenn Thackray, a geosciences professor at Idaho State University who studies the history of glaciers, said it’s easy to get mixed up between true glaciers, rock glaciers, and perennial snow fields.

“We have a lot of rock glaciers in Idaho, masses of bro ken-up rock in steep mountain areas that have some ice in them and seem to flow like glaciers,” Thackray said. “Perennial snow fields, which we have quite a few in Idaho, can melt and refreeze throughout the year and mimic glaciers, but aren’t tru ly moving in the same way. True glaciers act, look, and function like a glacier.”

It’s the latter that is so rare in this state. According to Thack ray, the most distinguishing features of a true glacier are the presence of glacial ice, which is metamorphosed snow compact ed together in clear-to-blue-looking ice crystals and the flow of the glacier, where the ice deforms itself internally, as opposed to just following the flow of gravity.

Climate and geography constitute the main reasons Idaho is not a glacier haven. While many neighboring states—Montana, Wyoming, Washington, and Oregon—are home to multiple gla ciers, central Idaho’s dry climate and lower elevations limit the annual snowfall critical to maintaining glaciers year after year.

“When we say there’s probably no glaciers in Idaho, we’re really thinking of that idealized glacier notion,” Thackray said. “But rock glaciers, there’s dozens of those throughout the mountain ranges. We just don’t hear much about them because they just look like a pile of rubble, and we have lots of rubble in Idaho’s mountains.”

Self-identified glacier hunter Collin Sloan got hooked on ice in the early 2000s, after hearing reports that the ancient ones in Glacier National Park were vanishing. Unable to make it to Montana to see them in person, the Boise resident turned to Google Earth to see how the glaciers had changed over the years through historical satellite photos.

“It’s such a cool landform,” Sloan said. “To have an amount of ice of that size where it’s moving and shaping the mountain, it’s like a living creature on the side of the mountain. It’s not just a snowfield sitting there.”

When he read in the Idaho Statesman that Idaho’s only glacier was gone, he wondered whether the disappearance was confirmed, saying he felt “offended people were bad-mouthing” Idaho’s only glacier, seemingly without hard evidence. After reading through Otto’s studies, Sloan reached out to climbers and researchers who frequented the area and might offer infor mation about the glacier’s presence.

He searched the three-dimensional satellite maps of Idaho, spending hours scrolling through archival Google Earth images of Mount Borah. He compared each year’s photos, looking for changes in specific rock locations that might indicate movement, depressions that might be crevasses, and how the snowfield’s size changed with each winter. The longer he spent looking at the images, the more he became convinced that there was more to the rubble field than rocks and rumor.

Finally, he decided to see for himself. With his father and three brothers, he set out to rediscover Otto’s glacier in 2015.

“I have a bit of glacial fever when I get going,” Sloan said. “I’m not a big mountaineer, really a desk jockey mountaineer, but I wanted to stand there and see what was actually going on.”

Sloan said that when he reached the cirque below Borah, it just looked like a pile of gravel.

“I was walking down a little slope and suddenly through the grav el, I saw ice,” Sloan said. “It was just perfectly crystal clear ice and I was still almost 1,000 feet from exposed snow. It was awesome that my hunch was confirmed.”

For a glacier to be recognized and listed on a map, the Idaho De partment of Water Resources requires the Forest Service to conduct a survey and map the glacier. Just two weeks after Sloan’s visit, Josh ua Keeley, with the Salmon-Challis National Forest, checked it out.

In his published report, Keeley wrote that the feature appeared to be relatively unchanged from Otto’s initial surveys, concluding that “the ice mass is indeed a glacier that continues to move under its own weight.” Measurements estimated that the glacier covered roughly 25 acres and crevasses in the ice reached more than 40 feet deep. Keeley also estimated the glacier showed between 50 and 200 centimeters of movement per year.

Keeley was a former student at ISU, and when Professor Thackray read the glacial report, the news inspired mixed feelings.

“I was excited about it, but still have enough questions that I’m not quite sure about it,” Thackray said. “I’m suspicious it may be a persistent snowfield or maybe it’s covering a rock glacier under the snow, but then again, the survey and research was done well and their conclusion that it’s a glacier is very rational.”

With the Forest Service officially concluding that the Otto Gla cier was, in fact, a glacier, Sloan set about getting it officially named and recognized. He submitted paperwork to the U.S. Board of Geographic Names (BGN), the federal entity in charge of naming geological features. Due to BGN rules, features cannot be named after living people, so the Otto Glacier was a no-go. Instead, Sloan opted to use the most prominent feature in the area, and the Borah Glacier received its official name in February 2021.

“My glacier is a little bit thinner now,” Otto said from his Boise home. “But it felt really good to have it recognized as still being there.”

Otto, who is in his late 60s and recently had two hip re placements, doesn’t think he’ll ever make it back to his glacier. Still, he continues to cheer on the efforts of Sloan and readily offers up information.

As for the skeptical scientists, Thackray plans to take some students to the Borah Glacier next year to do some onsite data collection, with possible trips to Sloan’s other projects as well.

“While I’m scientifically skeptical about some of the features that are being identified as glaciers, I think it’s great [there are] people who want to go out and search for these things,” Thackray said. “We don’t know where everything is for sure, especially in a state like Idaho. There could be some hidden glaciers out there—no question there could be some others.”

“I’d be excited if we really found we have a glacier or two in Idaho,” Thackray added. “Studying glaciers in a place that doesn’t have glaciers isn’t very fun.”

Sloan is continuing his pursuit of other possible glaciers in Idaho.

“I consider this to be Bruce’s glacier,” Sloan said. “He dis covered it, I just helped it get named. I want to find my own now. And along the way if I could inspire more people to go find more ice, that would be cool.”

He says he’s identified one in the Sawtooth Mountains above Redfish Lake and another in the Pioneer Mountains and has made expeditions to both, with plans to return next summer for more comprehensive surveys.

“That guy’s tenacious,” Otto said. “He’ll find others if they exist, but I don’t think there’s that many left around.”

Five for Fighting singer-songwriter John Ondrasik has an affinity for Boise. The Boise Chamber of Commerce appre ciates his business connections to the City of Trees as well as his penchant for illumi nating extraordinary people and troubling times in his hit music. On a recent trip to Boise for a sold-out performance at the Chamber’s Annual Gala, Ondrasik said, “I have a weird dichotomy with Boise be cause I am a singer—songwriter and [my family] business since the 1940s is based in California and called Precision Wire Products. I’ve worked there my whole life. Our claim to fame is we make the best

shopping cart in the world, and Albert sons is one of our customers.” Because of the pandemic, Ondrasik noted that three years have passed since he returned to Boise. “Previously, I performed at the Egyptian Theater, at outdoor concerts, and was meeting with Albertsons. I love the town. I always run the [Boise] river. Now, I am trying to get my son to go to Boise State!”

Ondrasik’s children, Olivia and John, are two of his biggest muses and have titled a few of his songs. Being present for them reinforced what Ondrasik believed was the key for leaders and people of all backgrounds to discover–the power of

listening. Listening is what inspired his latest hit song, “Can One Man Save The World?” Inspired by Ukrainian Presi dent Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Ondrasik performed this hit at the Chamber Gala, which helped the event raise $20,000 for Red Cross Ukrainian relief.

“One thing I talk about a lot is just listening. It’s a critical skill, not just for songwriters, but for all leaders; to listen to the people around you and empower them,” he said. “Some of my best songs come from just listening, not just to my kids and what they say, but walking down the street, watching something on TV, or just being open to ideas. So often I’ll hear

a phrase or something, and I’ll be like, ‘Oh, that there’s a song there or a song title.’” Creativity, however, can also attract controversy. Ondrasik’s song, “Blood On My Hands,” was removed by YouTube.

“I’d written a song a little over a year ago about the Afghan withdrawal. I’ve never been somebody who talks about politics or writes political songs. I find celebrities who get on their soapbox annoying. So the Afghan song was born out of being upset about the withdrawal because, like many veteran friends I have, we were angry that we abandoned allies,” he said.

“A lot of work was just left, and I was outraged. So I wrote that song. And when

I wrote it, everybody said, ‘You can’t put that out.’ But I put it out. And there was a powerful reaction from the veteran community and others who were also angry about the withdrawal. And then it became this worldwide story. But I found myself on the front lines of some of these geopolitical issues. And I swore I’ll never do it again. Because that’s not me.”

Yet, as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine devolved into chaos and death, Ondrasik wondered how the stakes would go down. “In the initial days of the war, General Mark Milley said it would be over in three days and Russia was going to win,” he said. “And then, there was this little Zelenskyy guy, and I didn’t know anything about him. He was a comedian. What’s that all about?

“If I took anything from Ukraine, I had a sense of what they’ve been living under for these nine months. Even when you’re not on the front. But I was very grateful that they wanted me to come and that we did this and tried to shine the light on their cause.”John Ondrasik with the Ukrainian Orchestra at Antonov Airport – Kyiv, Ukraine PHOTO COURTESY HOLLWOOD HEARD PHOTO COURTESY OF PRO IMAGE EVENT PHOTOGRAPHY

And then I found out when Russia invaded, we [the USA] offered him a plane ticket. And he said, ‘No, I’m going to stay. My wife and my children are going to stay,’ knowing the Russians would likely kill him within days. And I thought, who does that in this day and age? This little David-to-the-Goliath just profoundly moved me.”

“My passion has always been for our troops who provide our freedom, which has always mattered to me as a song writer… and so when I saw that, I was so inspired.” Ondrasik was moved to action. “The Russians had hired assas sins to kill him. And Zelenskyy said, ‘I may not be here tomorrow, but this fight needs to go on.’ So I wrote, ‘Can One Man Save The World?’ quickly, just

BY KAREN DAY

BY KAREN DAY

like the Afghan song. And put it out the next day becauase I didn’t think he’d be alive two or three days later. I had no idea I’d be making a video five months later in Kyiv.”

Performing in a war zone with people in harm’s way changed his entire perspective. “It was scary. We’d been at the airport and saw body parts lying around, and we toured places

where the atrocities happened. You’re overwhelmed, you’re sad, but you’re inspired. Not just soldiers, but the musicians who say, ‘the more horrible things Putin does to us, the more we stand up to fight him.’ Everybody I met had someone on the front lines, or they had lost someone. Our translator hadn’t heard from her brother for 11 days,” he said. “All these stories were emotional.

You are scared. You don’t sleep. But, I got to leave in a few days. When I crossed that border back into Poland, I thought about all those people who had to stay there and endure the weight of uncertainty. The mental stress of that. If I took anything from Ukraine, I had a sense of what they’ve been living under for these nine months. Even when you’re not on the front. But I was very grateful that they wanted me to come and that we did this and tried to shine the light on their cause.”

The lack of creatives also penning songs and singing about the injustices leveled at Ukraine weighs heavily on Ondrasik, who wished that President Zelenskyy’s bravery also moved higher profile singer-songwriters to action.

“We take this freedom for granted in a world where it’s under attack every where. That’s one reason why I do it. I wish it were Bono, Springsteen, Lady Gaga, or Ariana Grande—people with more stature than me—but all I can do is what I can do,” he said. “These Ukrainian people and their fortitude, knowing they’re going to die, but stand ing up for their country and freedom. I wish there were a thousand songs, and frankly, there should have been. But it certainly took me on an adventure I could never have imagined.”

It’s that time of year again for dragging an iconic, giant holiday dispenser of fresh pine scent into your living room. Despite rising prices and the implications of environmental guilt, Treasure Valley buyers are predictably readying to flock to Christmas tree lots be fore their Thanksgiving dinner has been digested. But beyond the Nativity, what’s the reality behind the jolly tree business? And of course, let us admit to considering conversion to the convenience of the “unreal” tree.

“Farmers sell ten years’ worth of work and investment in basically two weeks. It’s a unique business,” said Tim O’Conner, Executive Director of the National Christmas Tree Association. “When you buy a real tree, even the largest growers in the industry are family farms.”

There are two types of Christmas tree growers: wholesale grow ers and choose-and-cut growers. Wholesale tree growers grow, cut, load, and sell trees to big chains, charitable groups, and corner lots. Choose-and-cut farms are where consumers cut and bring home their own trees. Idaho is not a major Christmas tree state—most trees you’ll find in the Treasure Valley are sourced from surround ing states like Washington and Oregon. Oregon just so happens to be the largest Christmas tree grower in the United States. Approximately 25-30 million trees are sold every year.

A Christmas tree’s life begins as a seed from a pinecone. Nurseries plant and grow the seeds for three to five years. Tree farms then purchase the seedlings and typically plant them in early spring. Farmers will then manage and maintain the trees for six to ten years. Once a tree is harvested, they last for about one month, usually in our living rooms. Despite viral internet advice, trees don’t need any fancy potions to stay healthy—they thrive with just water.

Every year, many a tattered cardboard box is pulled from the garage with a ready-to-set-up artificial tree. Their converts cite cost-effectiveness, sustainable reuse, and no dead needles to clog your vacu um. A perfumed candle offers removable fresh pine scent.

The retail motherload of millennial artificial trees is Balsam Hill, a flagship brand under Balsam Brands. Balsam Brands is based right here in Boise, as well as Redwood City, Dublin, the Philippines, and Windsor, Canada. CEO Mac Harman founded Balsam Hill, inspired by a relative with tree allergies. As the “lead tree designer,” Harman analyzes trees all the way to their needle tips, creating extremely realistic Christmas trees. Artificial trees are used in the entertainment industry, retail settings, residential buildings, offices, and more. Perfection is purchasable without the cold nipping your nose.

Despite the differences between real and artificial, Balsam Brands says there is no such thing as a bad Christmas tree—tradition is what it’s all about. In some cases, they’ve heard of families passing down their artificial tree like an heirloom from one member to another—and with the cost of realism running from $800 to more than $2,000, extended use makes financial sense. And did you know maintaining an artificial tree lengthens its display life? With a lifespan of six to ten years, artificial trees may not last until your kids go to college, but the true environmen tal impacts are often overshadowed.

O’Conner claims that the benefits of buying “real” far outweigh the artifi cial. “By choosing to buy a real tree….you’re keeping your money flowing in local communities, where the money buys goods and services locally, rather than sending it to a factory in China or some corporate headquarters,” he said. “There’s just no comparing environmental footprints to where a fake tree comes even remotely close to being better.”

Above: A familiar tradition of the Hopkins Christmas tree lot in Nampa. Below: The Risch family is in the Christmas tree business all year long. PHOTO COURTESY OF BRETT HOPKINSWhen comparing natural and artificial trees, it’s important to understand their carbon footprint. A carbon footprint is the amount of carbon dioxide and other carbon compounds emitted due to the consumption of fossil fuels. While it grows, a tree absorbs carbon diox ide and other gasses and then releases much-needed oxygen. Trees lower surface temperatures, provide natural habitats for wildlife, and filter water. Transportation of trees is typically to local customers, reducing their carbon footprint compared to artificial trees that are shipped and manufactured from overseas.

Few trees are cut directly from the woods. A majority are grown and replanted intentionally by farmers. According to the National Christmas Tree Association, there are approximately 350 million Christmas trees from Christmas tree farms right now.

At the end of the holiday season, many cities have tree recycling programs. Boise, Eagle, Nampa, Star, and Meridian, to name a few, participate in city Christ mas tree recycling programs. Trees can be composted or turned into mulch and wood chips. 97% of households in Boise participate in the city’s compost program and are eligible for two yards of finished and free compost per year.

During the low-demand years, trees that were of ultimately of no value ended up being sold for pulp or to other sec ondary markets. Jordan’s Garden Center

and Seasonal Market donate unsold trees at the end of the season to Zoo Boise for animal enrichment. Almost all the animals at the zoo, from the smallest of birds to the mighty lion, benefit from Christmas trees.

During the late 1990s and early 2000s, an excess of wholesale trees fueled low demand. increased competition, and price wars among sellers ensued, followed by the 2008 recession.

Managing trees is a costly endeavor, so economic factors meant fewer trees were planted. Fast forward to today—supply is tight and demand is high—and Christmas tree lots from the Treasure Valley to New York City are selling out every year.

Started in 1942, Hopkins Evergreens in Nampa is one of the oldest family-owned Christmas tree businesses in Idaho. Brett Hopkins, the Operations Manager at Hop kins Evergreens, says it’s now difficult for start-up businesses to find inventory.

“Back when my dad started, they used to grow, cut, and ship the trees down here. That was over 30 years ago when he start ed growing trees in Oregon. Then he got connected with a grower up there, and has been using him instead ever since,” said Hopkins. He grew up around the family business and has seen the industry change over time.

Costs of trees have steadily risen each year due to demand, weather, inflation, fuel, and labor. Average trees cost around $50 to $100. A heat wave in the Pacific North

west in the summer of 2021 substantially impacted Christmas trees. Ideal growing conditions require long cool summers and enough moisture. Many farms found their crops to be damaged, affecting years’ worth of work and future sales.

Trends also play a role in what types of trees are in demand. Instead of fuller trees like pine trees, Jordan Risch, the owner of Jordan’s Garden Center and Seasonal Market, said more people are looking for what he calls “Pinterest trees,” or trees with fewer branches and an open concept. Risch says selling a tree that’s “not perfect” actually gives customers the opportunity to buy more affordable trees.

At Hopkins Evergreens, during COVID, new customers made the switch from artificial to real trees because they had more time at home and wanted a more tradi tional Christmas experience. “The cost of a Christmas tree is going up a little bit. I can’t blame people for wanting to buy an arti ficial tree that they can just slap together,” said Hopkins. “I may be biased from how I grew up, but a fake Christmas tree feels like a fake Christmas.”

Real or artificial? The Christmas tree discourse appears to be as divided as our country’s politics. As the holidays approach, however, does it really matter if you choose to gather around a tree that resembles a revolving disco ball, a Pinterest picture, or a weed from the Grinch’s garden? After all, a tradition is what you make it.

Left: A seven-foot Christmas tree takes 8-12 years to mature. Right: Artificial Christmas trees are the specialty of Boise-based Balsam Brands, a leader in the industry. PHOTO COURTESY OF THE NATIONAL CHRISTMAS TREE ASSOCIATION

As the holidays approach, my elders are all around me. Though they have passed on, they seem to show up in a big way this time of year. Their words, wit, and wisdom wash over me. I marvel at the strength of the women who made a way out of no way and left a firm foun dation for me. My grandmother, Pearl Emeline Johnson, was the most elegant woman. A strong woman of faith, not given to gratuitous conversation, Nanny demonstrated grace and much gratitude in every aspect of her life. Her first words in the morning and the last at night were prayers of thanks. When my brother and I spent the night with her, she prayed with us at night and woke us up to do the same in the morning.

That amazing woman worked hard: stoked three stoves to heat her home, raised rabbits and chickens, and main

tained a huge vegetable garden and a beautifully landscaped front yard. She did laundry in an old wringer washing machine, used bluing to ensure the whites were just right, and took great pride in ironing. She was an artist at “puttin’ up” (canning) beautiful fruits and vegetables. She was an active member of St. Paul Baptist Church, serving as Mother of the Church, and she ran a boarding house in her home! No com plaints, just gratitude.

My grandparents raised eight chil dren in a segregated Arkansas. Idaho provided opportunities unimaginable in Van Buren. Nanny made few references directly about the trials and tribula tions of living in an environment that offered little or no respect, economic or educational opportunity for her family. But she shared regularly how much she appreciated being in Idaho. She could be heard saying “thank you Lord” on the daily after settling in Boise. And she demonstrated her gratitude by the way she lived. No matter what was going on, she expressed gratefulness and was purposeful in sharing the same to generations of Johnsons and her community. She wanted all to know and appreciate how far the family had come. She shared all she had generously to any she could help.

Pearl was quietly powerful and shared so many concise “pearls of wisdom.” As I grew up, I came to realize that

BY CHERIE BUCKNER-WEBBthe source of her strength was embedded in her history, her faith, and her human ity. Her legacy included lifelong demon strations of gratitude. She encouraged us to demonstrate genuine gratitude and appreciation and never to forget from “whence we came.”

She believed that gratitude:

• is healing

• makes you feel alive

• breaks down barriers

• improves relationships

• is good for your mind, body, and spirit

• increases generosity and sharing

She taught me not to be concerned about what others do, but rather to concentrate on our “charge to keep” (the right thing to do).

She cautioned that some folks have to go through something in order to get to a place of gratitude. My grandmother had a mantra that I remember still today: Thank you Father:

• for awakening this morning clothed in my right mind

• for the use of my limbs

• for life, health, and strength

• for the blood running warm in my veins

• that my bed was not my cooling board

• for another day’s journey

I am so grateful for my grandmother.