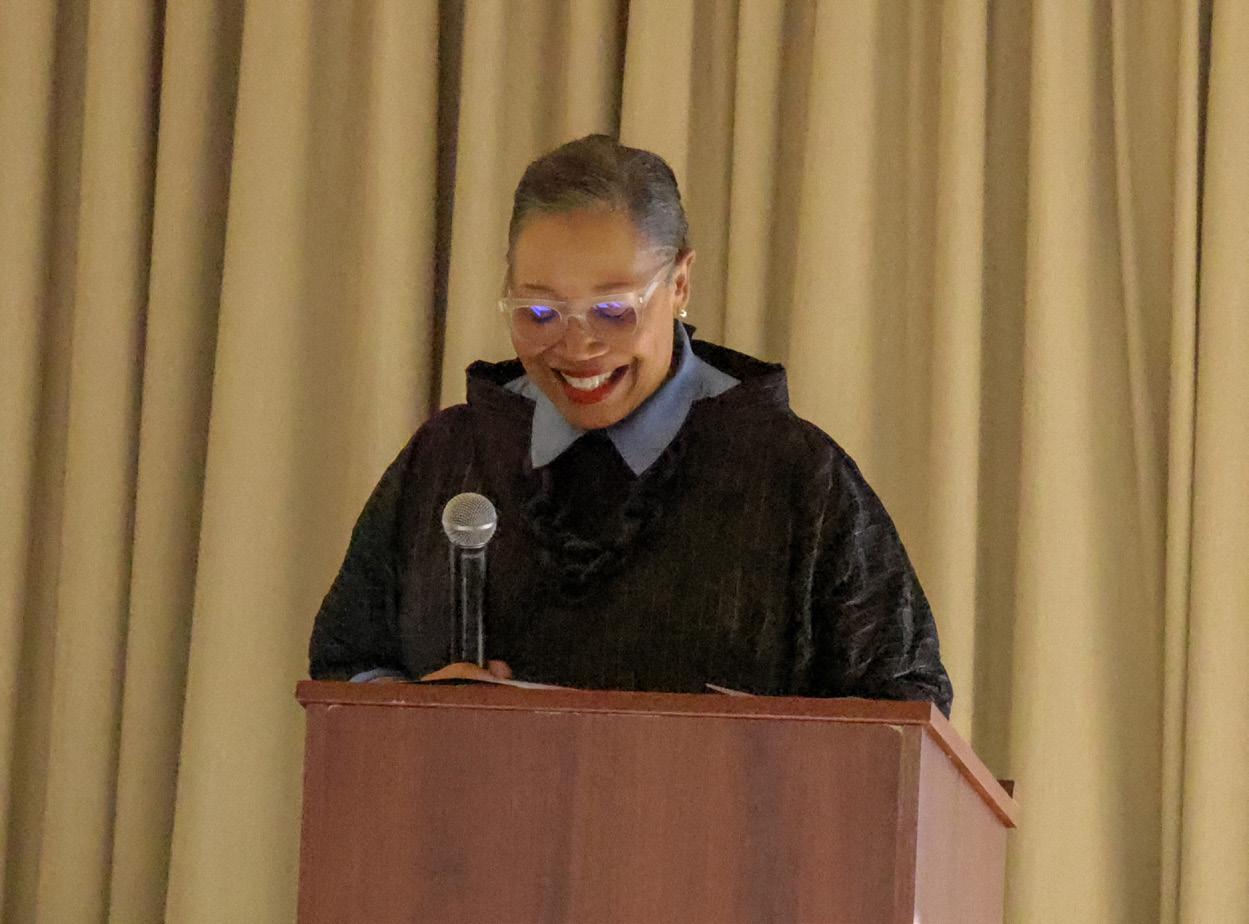

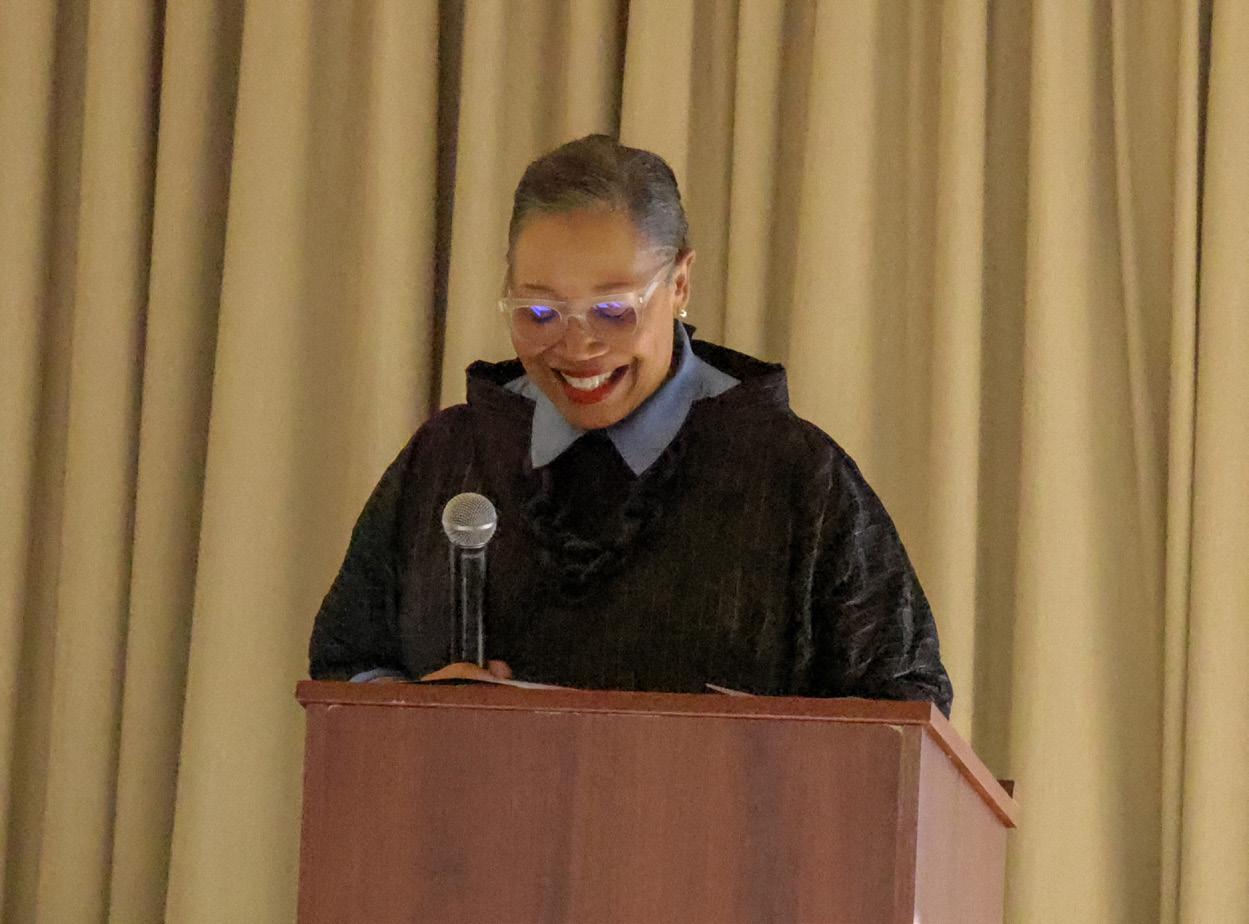

The Future Starts Now

THE FUTURE STARTS NOW INDUSTRY ROUNDTABLE 25

Twenty-five years is a long time — and as we gathered at this year’s Industry Roundtable, I thought about how we have spent it, and where the next 25 years might take this vital community of thinkers and doers in design. We’ve built a strong network of diverse viewpoints — we challenge each other, but we’re allied and united in our strong intention to build a better design industry and profession. We’ve equipped a generation of leaders with actionable plans and strategies — not to mention inspiration that sets the year-long tone and agenda for many of our participants. Undeniably, and importantly, we’ve had a lot of fun. Looking to the future, I’m impressed with the power of the IIDA community to set in motion a new kind of design industry that will open the door to a more diverse, technology-enabled, humanityfocused next generation of leaders. I’m excited by the vision of a preferred future — and the strategies for how to get there — that we share. I’m heartened by our continuing ability to fearlessly take on the challenges of our industry, and by our life-and-workenriching connection to each other.

The time we spend together has undoubtedly impacted our past and continues to impact our future. I can’t wait to see where next year, and the years to come, will take us!

2

Table of Contents

p3 Letter from cheryl S. Durst

p4 Time to connect/ Time to reflect

p6 Future Possible: Design, Time and the Shape of Things to Come

p8 Past, perfected: Problem Solving with Ray & Charles Eames

p10 Top of Mind: the big Qs we brought to IR, and a few emerging As

p14 Design thinking: Building better communities

3

Time to connect/ time to reflect

How the future of networking gets built at Industry Roundtable:

Over 25 years, the Industry Roundtable think tank has assembled design leadership to investigate, question, strategize and solve the most important issues facing our industry. But connection is our secret sauce. What makes those connections so strong?

• We drop the barriers: We come to the IR table with openness and eagerness to share ideas and solve problems for the industry — yes, even if we’re competitors in real life!

• We cultivate inspiration: We don’t just share deep discussions, we share cultural experiences that inspire and feed creativity.

• We get personal: We connect over meals and in between keynotes, exchanging viewpoints, dog stories, and tales of that design life. (Note: margaritas and queso didn’t hurt, either!)

4

“As long as I’m still learning I’m still growing as a designer, and as a human.”

— Bill Grant AIGAFellow Mayor, City of Canton, GA President & COO, Grant Design Collaborative

Bill Grant

Llisa Demetrios

Mark Bryan

“The new covetable is not what you can buy, but what you can learn.”

— Llisa Demetrios Chief Curator, Eames Institute

“The time is right for us to challenge those big assumptions we have about our design experience, process, and industry.”

5

— Mark Bryan Senior Foresight Associate, Future Today Institute

“The time is right for us to challenge the assumptions we have about our design experience, process, and industry.”

— Mark Bryan

Future Possible: Design, Time and the Shape of Things to Come

Designers are decision-makers and shapers.

But what happens when a constantly shifting societal landscape casts uncertainty on our ability to make choices that will serve us well in years to come?

Manufacturers’ forecasting depends on the reliability of supply chains; clients demand spaces that will serve current hybrid work patterns while remaining relevant for years or decades; sustainable design is an ever-more-urgent imperative that demands longevity in design.

Sure would be nice if we had a crystal ball. Luckily, Mark Bryan, IIDA’s Futurist in Residence, is the next best thing.

FUTURISM + DESIGN

In his Industry Roundtable presentation, Mark showed us not only how the techniques of futurism can be used to help us make predictive choices, but also how current forces shaping society and the business landscape impact design now and in the near future.

Mark, a senior futurist at the Future Today Institute, uses the techniques of futurism to help clients reduce uncertainty and make decisions. At Industry Roundtable, his role included astute observation as manufacturers and designers engaged in dialog around key industry issues. Among the topics the IR think tank was seeking clarity on:

What will happen if the traditional workplace goes away?

Who will our clients be in the future?

How will goods be sourced and made?

“When you face uncertainty,” Mark says, “make a list and start to do research around those areas — that will start to move you forward.” That research, he explains, should reveal both trends (not things that are “trendy” but things that show a societal direction emerging) and disruptors (things that are causing change.) Those trends and disruptors point to where things are headed next — reading them can provide a window into the likely near future, and possibly beyond.

9 Trends to watch for:

Mark’s

1

Next gen virtual drawing and collaboration tools

2

Additive manufacturing — materials evolution

3

The war on plastics and carbon

4

Shifting focus from time-based work to the expertise we bring

6

FACTORING IN TIME

As we look to the future, time is the factor that touches everything: time consciousness is everywhere. We are universally facing a shortage of time; we debate time at the office vs. time at home; we scrutinize commute times and their impact on employment and social mobility; a recent study recommended “time dosing” to measure exposure to nature for college students, in an effort to nurture their mental health.

This intense societal focus on time points the way to design questions for the future. Can design of cities address commute times, access to employment, and affordable housing? How can we design to make workplace time more valuable, efficient, and desirable? Can a focus on experiential design help alleviate the time crisis by gifting us new experiences? (The answer to that one, Mark says, is yes — humans perceive new experiences as “adding time” to their lives.)

A FOCUS ON LOCAL

Time and locality are inextricably linked, and future scenarios point toward ways in which locality will impact the way both business and daily life are designed. From “5-minute neighborhoods” where work, recreation, and home are all within a quick walk; to urban infill manufacturing and distribution facilities that rely on locally produced materials. Locality, of course, also intersects with climate change, and continued need for flexibility and movement of people and even entire communities means that modular designs which allow for climate responses including migration will be necessary.

A PERSONALLY CRAFTED LIFE

Future work life will no doubt continue to be impacted by remote work trends and the desire for autonomy. What comes next? A future in which working hours and styles are crafted for each person’s preference and physical and mental wellbeing; and dynamic, multidisciplinary project teams form and re-form for each project. Helping to craft that life plan might be a “time crafting coach.” A combination of a wellness coach and a career coach, this expert will work with clients to optimize their lifestyle to suit a range of factors that create an ideal schedule for both workplace success and personal health. AI assistants will likely take over some job functions to free up time for strategy and creative work; they’ll also help designers know when to power down for a walk outside. One drawback to this techforward life: it could exacerbate the current tech divide if access to technology is not provided for all.

A MATERIALS-DRIVEN INDUSTRY

The future search for new materials — as well as ways to create circularity and reuse of old ones — will center on regional or local availability. This not only solves for supply chain disruption, it adds incentive to create new streams of materials through upcycled goods. Limiting the amount of new materials in each project, as well as deconstruction and reuse plans for every project, will help to fuel a new paradigm for manufacturers.

SHAPING A PREFERRED FUTURE

Future scenarios, of course, are not set in stone. With every prediction comes a chance to envision a different outcome, and map steps to create it; in fact, futurism can be used to help us plan to redirect an outcome we’d like to avoid, as much as it can help us step into the future of our choosing. The real work comes from envisioning a preferred future and planning present-day actions that can move us toward it.

At IR, design leaders began to sketch a preferred future, one focused on the continued relevance of place and human connection. Among the priorities were equitable access to technology; educational infrastructure in rural locations; creating preferred work times for staff to increase engagement; building increased collaboration between firms, sharing industry intelligence; and maintaining human culture, boundaries, and privacy.

Given that set of goals and others that would reinforce the future we want to see, design professionals can focus their problem-solving skills on creating design solutions that, over time, bring the ideal closer to the here and now. The future is ours to create.

5

Work that makes the process more visible and inclusive

6 Compact/modular design applications

7 Introducing time dosing into spaces/ products

8 Design that adds gratitude and extends experiences

9

Offering new skills to reward time — a reward that’s not just about salary

7

Past, perfected: Problem Solving with Ray & Charles Eames

Llisa Demetrios’ childhood memories are a design junkie’s dream: she often found her grandfather, Charles Eames, up on a crane, figuring out shots for the iconic film “Powers of 10.” Grandmother Ray Eames, in a deep-pocketed dress of her own design, gave hugs that smelled like roses and had a workshop full of papers collected from around the world; objects and ephemera filling drawer after drawer. Endless iterations of furniture legs and seats — the designs that almost made it — were everywhere. / It was, undoubtedly, a magical glimpse into the world and creative process of two of design’s most revered figures. But within the fertile creative ecosystem of the Eames workshop, something else was at work: a system of imaginative problem-solving that has incredible resonance for designers and creatives working today. /As chief curator at the Eames Institute of Infinite Curiosity, Llisa both preserves her grandparents’ legacy and shares it within the context of their unique methods. “Our goal at the Institute today is really to unpack the way Ray and Charles solved problems,” she says, “the way they infused every one of their designs with discovery and curiosity at every turn.” /With thousands of artifacts from the Eames workshop to catalog, (work that is still ongoing today) Llisa has spent decades immersed in the clues Ray and Charles left behind. Based on her learnings and her own experiences with her grandparents, she has assembled lessons from their prolific process, to share with the world.

8

Image © Eames Office, LLC

Find knowledge (and inspiration) everywhere

Fueled by insatiable curiosity, the Eameses were continuously learning. Among the multitude of objects they studied as observers and collectors of design were kites and childrens’ toys, which exist today as part of their archive. They also sought knowledge of processes and technique from unlikely sources — including workmen who might have been called to repair something in the workshop, but found themselves walking “the long way to the kitchen sink.” A trip through the workshop, the Eameses reasoned, might prompt a discussion about their own projects in progress; and in turn an exchange of useful ideas from the repairman’s practical and experienced point of view.

Turn criticism into problem solving

Walking home from dinner with her grandfather, Llisa recalls being asked how she enjoyed her meal. The dinner, which included borscht, didn’t exactly rank high on an 8-year-old’s list of favorites. Charles’ response to her criticism? “He said ‘What would you have done differently?’” That question turned her dislike into an exploration of materials, techniques and possibilities, and aptly taught the lesson “don’t just complain, come with a solution.”

Design with iteration in mind

Good design remains responsive to changing needs and conditions; which is why the Eameses continued to refine even their most successful pieces, even after they entered production. For them, iteration was a key part of an open-ended design process, either used to take steps toward a better solution or to confirm that initial thinking was correct. Eight variations of a chair leg might be created, only to return to the first variation: “You had to make the other seven to know that the first one was the right one.”

Intend to inspire

Though the Eames brand is known for pieces of exquisite function as well as both visual and physical longevity, they also designed pieces intended exclusively to spark human curiosity, emotion, imagination, and a sense of play. Their Musical Tower, a 15-foot, vertical xylophone which plays when a marble is dropped into a slot in the top, was originally designed for the Time-Life Building. When it proved too popular with tenants, it found its way back to their studio. A design for an intended national aquarium in Washington, D.C. inspired the Eameses to create a design that they hoped would spark curiosity and empathy — allowing humans to see and want to protect the otherwise largely invisible inhabitants of the ocean. Eventually, though the original commission was never built, their plan for such an aquarium informed the design of several major aquariums in the United States, serving the Eameses’ intent by imparting a love of the ocean to millions of visitors.

9

© Nicholas Calcott for the Eames Institute

Top of Mind: the big Q’s we brought to Industry Roundtable, and a few emerging A’s

HOW DO WE SUPPORT AND SHAPE THE NEXT GENERATION OF TALENT?

Attracting and retaining talent is a key topic when design leaders gather, but this year’s IR revealed a new wrinkle: the current class of entry-level designers was in design school during the pandemic, meaning that their ability to gain invaluable experience through hands-on, in person work experience has been limited. “We don’t need to let them fall to the side because of all that,” says Tara Headley, IIDA, senior interior designer at IA Interior Architects. “Maybe you change how your internships work, make it about the social interaction, make them have those experiences they were unable to have in college. They’re going to need our help.”

But it’s not just designers at the entry level who are looking for more from firms; intentional, thoughtful support benefits junior designers across the board, and also is a crucial reinforcement for firms’ EDI efforts. “I don’t think we should just rely on people to come into this industry and figure it out,” says Nicola Casale, senior vice president at Yellow Goat Design. “We all have to ask ourselves, ‘What kind of a mentor are you?’ I feel optimistic about it because I feel like maybe this is just what we need to start to change that culture.”

That shift is exemplified by the concept of “sponsorship” rather than mentorship: a lead-by-example relationship that educates about the larger organization; encourages younger staff to talk about themselves and share opinions and ideas; and leans into the idea that there is more than one path to good design.

Incorporating in-person experiences into that sponsorship relationship is key, as is showing vulnerability and openness as leaders. Incorporating greater connection, next-level mentorship, and in-house education can help to set young designers up for success, paving the way for a strong design industry.

HOW CAN WE ELEVATE DESIGN’S PERCEIVED — AND PAID — VALUE?

Whether influenced by a continuing focus on attracting and retaining talent, or economic conditions beyond the labor market, the conversation around design fees and designer salaries was prevalent at this year’s IR. IIDA’s mission has always included elevation of the design industry and recognition of design’s inherent business value; this year’s IR discussions reiterated the importance of that goal in response to current and future business environments.

“I think we’ve probably operated too long from a place of ‘we do this for the love of design,’” says Erika Moody, FIIDA, president of Helix Architecture+Design. “There should also be some ambition that there is value, and this is a career we want people to go into in the future. We want to have more diversity — let’s make sure we are recruiting young people and setting those hires up for long, successful careers. I find it encouraging that we’re having this conversation now.”

“We’re in the position to reinvent ourselves and rethink what we’re doing,” says Ronnie Belizaire, FIIDA, vice president of project and development at Jones Lang Lasalle, “and with that comes real responsibility. How do we universally look at our fee structures and have more of that courage and audacity about how we value ourselves and our profession? How do we solve problems not just for clients but consider ourselves a client?”

10

CAN WE MOVE PAST “WORKPLACE” AND INTO “PLACEMAKING?”

“I’m so over the question: ‘Hybrid or non-hybrid?’” says Verda Alexander, IIDA, principal and co-founder at Studio O+A. At IR, the consensus was that the debate over workplace style has evolved beyond the binary — and that the true challenge for the design industry is to create a place that supersedes a sole function, a place that succeeds in its ability to create experience and human connection. Designers are also looking beyond the classic design brief, to expand design’s influence into the larger ecosystem of brand. “I really think the future of our industry … is the idea of brand and looking at the whole organization,” says Alexander. “We design experiences, and we need to take that out of the idea of space exclusively. We can help them create a story.”

Placemaking as part of brand building can communicate and amplify an organization’s values, as well as communicate ties to the larger community and local ecosystem. Design with human experience in mind can create connections to all of those things, and contribute to human as well as corporate wellbeing. “When we design spaces where people are happier and healthier than when they left home that morning, that is powerful,” says Ana Pinto-Alexander, FIIDA, principal and global sector director at Interiors HKS. “What is more powerful than that? We create emotions.”

WHAT’S THE NEXT STEP IN SUSTAINABLE PRACTICE — AND HOW CAN WE MAKE REUSE COOL?

The IR sustainability conversation took many forms this year, but an overarching theme was longevity. As the design industry continues its push toward a sustainable built environment, designing for longevity of products and projects is a priority, as is exploring new ways to create and renew spaces without creating waste. Designing for adaptability — building in the capacity for change without building in obsolescence — is one strategy that was part of the IR brainstorm. But another idea got attendees talking, too: reuse, and how designers can make it a badge of honor for clients. “I hope we start to see more innovation in the reuse space,” says Katy Mercer, IIDA, principal at Woods Bagot. “How do we take away that ickiness?”

One idea (and one designers are good at) — make it cool.

“As people look for authenticity in their lives, that can come into the workplace,” says Manuel Navarro, principal and design director at IA Interior Architects. “Coming in and seeing something that has patina, you’re going to have a different experience in that space.”

11

“When we design spaces where people are happier and healthier than when they left home that morning, that is powerful,” says Ana Pinto-Alexander, FIIDA

“I think we need to seek inspiration both digitally and physically; look for that balance. Seek out those days where you can walk around and see beautiful things.”

— Alan Almasy Director, Sales Enablement, Client Practice Group A+D and CRE MillerKnoll

“When we tie [design] to local culture and purpose, then employees are part of that story, too.”

— Ronnie Belizaire Vice President, Project & Development Jones Lang Lasalle

— Ronnie Belizaire Vice President, Project & Development Jones Lang Lasalle

“Clients are looking at pulling people back, not forcing them, and it makes our job a lot more fun.”

— Manuel Navarro Principal, Design Director, IA Interior Architects

“While it seems counterintuitive, I think that to remain relevant over the long term, we need to slow down and take a moment of pause to figure out how do we want to do this better.”

— Nita Posada Principal, Director of Interior Design, Skylab Architecture

12

“The more you look at the future, the more important it is for us to be grounded in the present and in the moment. We really have to inform ourselves about what is now so that we can really understand where it’s going.”

“If you can have a great conversation, there’s an opportunity to live outside your mind and into the mind of someone else. When you drop your own agenda, you just gain that perspective.”

— Mike Keilhauer President, Keilhauer

— Doug Shapiro, Ind. IIDA Vice President, Research & Insights Host, “Imagine a Place” OFS

“There is an interesting balance between fear of what the future might be and what might change, and, because we are designers, a healthy excitement for the unknown.”

Architecture+Design 13

— Erika Moody President, Helix

Design thinking: Building better communities

When Bill Grant took an unknown exit off the highway, he was just looking to cut his commute — but today he’s both a working designer who is president and chief creative officer of Grant Design Collaborative and the mayor of the town at the end of that highway exit, Canton, Georgia. Grant’s path, like that of many creatives, has been a winding and audacious one and has yielded unique insights that point to a pathway for designers to have greater impact on our shared future.

Perpetual learning is essential

Bill didn’t start with a design degree. Instead, he leaned into his ability as a writer and learned design along the way. Eventually, that skill-acquiring and building approach brought him to a leadership role in the design world, as past national president of AIGA. His practice blossomed as well, executing branding work for major corporations; approaching each project as a holistic exploration of the client’s brand ecosystem allowed him to use each project as a learning experience for himself and his team. “Clients ask us, ‘Have you done this before?’ I say ‘No, and that’s why you should hire us. We haven’t done it before, so we’ll ask better questions’”

Talent is where you find it

Dalton, Ga., where Bill grew up and started his career in the carpet industry, might seem like an unusual place to find world-class design talent. But his own small-town beginnings taught him, he says, that “talent has no zip code.” As the leader of a design studio, he still applies that thinking. Basing his business in Canton, Ga., in between the major market of Atlanta and the carpet industry in Dalton, allows him to draw on a talent pool and a client pool that is larger than either market. “I believe in surrounding myself with people who are smarter than I am, more talented than I am, and letting the teamwork,” he says, “assembling a great team.”

Design thinking brings perspective to the world beyond design

City government was never a part of Bill’s career plan. But when a zoning issue threatened the historic downtown residential district where he lives, he found himself running for city council, and then for mayor. He quickly discovered an advantage when it came to solving city issues: “As designers, we are able to visualize things, and I think that’s kind of what’s missing in government, those people are typically not visual people.”

The problem-solving skills innate to designers can pave the way for greater acceptance of change in the physical environment of the towns and neighborhoods where we live. “People hear change and they get freaked out,” Bill says, “but when they can actually see what can happen and feel how it impacts their lives, they are ok with it.” Over time, his ability to envision Canton’s future allowed Bill to implement a multi-year plan for success and transformation, including revitalizing a once-dying downtown and bringing housing that is not only affordable, it is well-designed and desirable for both residents and the community. Today, he says, “Canton is my biggest design project.”

His experiences in local government, he says, have convinced him that design thinking can have its greatest impact at the local level, where involvement shapes the world that most of us live in and the problems that most directly affect daily lives. “I’m an example of what can happen when design thinking is involved in local government,” he says. “That’s why we need more designers in local government — we think differently.”

14 Images courtesy of Bill Grant

15

DESIGN EXPERTS

Verda Alexander, IIDA Studio O+A

Phillip Barash Public Sphere Projects

Gabrielle Bullock, IIDA, FAIA, NOMAC Perkins&Will (Los Angeles)

Mark Bryan Future Today Institute

David Cordell Perkins&Will (D.C.)

Llisa Demetrios Eames Institute

Ray Ehscheid, IIDA, RID IA Interior Architects (New York)

Brian Graham, IIDA Graham Design, LLC

Mayor Bill Grant, AIGA Fellow City of Canton, GA and Grant Design Collaborative

Dina Griffin, IIDA, FAIA, NOMA Interactive Design Architects

Lance Hastings ZGF Architects

Tara Headley, IIDA IA Interior Architects (Atlanta)

SPONSORS AND INDUSTRY EXPERTS

Alan Almasy, Ind. IIDA MillerKnoll

Michelle Boolton, Ind. IIDA Kimball International

Nicola Casale Yellow Goat Design

Stacy Craig, Ind. IIDA, Aff. AIA USG

Jackie Dettmar, Ind. IIDA Mohawk Group

Victoria deVuono Bentley Mills

Carolyn Forbes, Ind. IIDA USG

Gavin Hendricks Mohawk Industries

Teresa Humphrey, Ind. IIDA Wilsonart

Roby Isaac, Ind. IIDA Mannington

IIDA INTERNATIONAL BOARD OF DIRECTORS

George Bandy, Ind. IIDA Fiber Industries LLC

Ronnie Belizaire, FIIDA JLL

Stacey Crumbaker, IIDA Mahlum Architects

Cheryl S. Durst, Hon. FIIDA IIDA Headquarters

Diana Farmer-Gonzalez, IIDA Design Director and Strategist

Fiona Grandowski, IIDA Collins Cooper Carusi Architects

Mike Johnson II, IIDA Hickok Cole

Samantha JosaphatMedina, RA, NOMA Studio 397 Architecture PLLC

James Kerrigan, FIIDA Jacobs (Dallas)

Katy Mercer, IIDA, AIA Woods Bagot (San Francisco)

Linda Mysliwiec, AIA, NOMA Gensler (Chicago)

Manuel Navarro IA Interior Architects (Austin, TX)

Ana Pinto-Alexander, FIIDA, RID HKS

Diana Pisone Stantec (Chicago)

Nita Posada, IIDA Skylab Architecture

Joey Shimoda, FIIDA, FAIA Shimoda Design Group

Abby Scott, IIDA HDR (Omaha)

Alissa Wehmueller, IIDA Helix Architecture+Design

Jim Williamson, FIIDA Gensler (D.C.)

Erin Jende, Ind. IIDA Interface

Mike Keilhauer Keilhauer

Steve Kinder Loftwall and GoodWork US

Kaelynn Reid, Ind. IIDA Kimball International

Mark Shannon Crossville

Doug Shapiro, Ind. IIDA OFS

Jeff West Shaw Contract

Paul Young Tarkett

Angie Lee, FIIDA, AIA Pembroke

Erika Moody, FIIDA Helix Architecture + Design

Jon Otis, IIDA O|A Agency

Jennifer Ruckel, Ind. IIDA 3form

Thanks to our sponsors, Mohawk, Kimball International and USG Ceilings

Special thanks to the Museum of International Folk Art and the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture, Santa Fe, New Mexico. Photography, DesignVox

Amy Storek, Ind. IIDA Arper USA

Sascha Wagner, FIIDA, AIA Huntsman Architectural Group

Scan to watch IR25’s highlights

information

as of May 16, 2023

All attendee

confirmed

— Ronnie Belizaire Vice President, Project & Development Jones Lang Lasalle

— Ronnie Belizaire Vice President, Project & Development Jones Lang Lasalle