SÁBÁT POETICS OF CARE

ILGHAR DADGOSTARI

M aster ´ s t hesis

i lghar dadgostari

acco M panied by :

dr . p rof . b onaventure soh bejeng ndikung

l erato shadi & t onderai k oschke

r au M strategien

W eissensee kunsthochschule

berlin a pril 2024

In an act of remembrance, in an effort to grasp my present, I resolve to release the bonds that have restrained me from writing and shaping my voice. The western academic traits has been, and continue to be, a force that colonizes the way I value my thoughts, emotions, and lived experiences. It took me a decade to recognize how I was subjugated by academic institutions that sought to consume my body and mind within its patriarchal capitalist structures. Yet, these pages recognize me as their subject, and I command their depths. This is a story of my transformation in a healing path I chose to take —not to conquer pain, but to embrace and honor it for the resilience it bestows.

I speak from a place of strength, as well as from weakness. My strength lies in my ancestors’ wisdom to confront life as it unfolds. My weakness lies in my desire to thrive within a community of care. My strength surrenders to the realities I witness, choosing neither to ignore nor to forget. My weakness resorts to the safety and comfort of intimacy and friendships.

Through juxtapositions of my existence in a white supremacist world of patriarchal capitalism, I repose myself as the alienated other, as the inferior in the eyes of those in power, as the non-human exotic barbarian being, conformed to the pitiful gazes, and reclaim my place in history as a human, as a non-binary gender-queer trans-woman and declare my role as a queer-feminist with kindness and honesty. I offer forgiveness to those who have wronged me and then embark on my chosen battle as an artist advocating for reparations.

In pursuit of a space in between the schools of hospitality and individualism, I beckon you to embark on this journey with me through the poetics of care, to reclaim a connection long forgotten yet never truly lost. Bear with the notion that the yawning gulf between us is just an illusion and to cling to its existence a tragedy.

This is an invitation for you to lend an ear, for me to unearth the barriers that have hindered our horses from galloping towards a radiant horizon. Together, we may seethe with passion, together we may reminisce and weep. Together, we may share laughter, together we may taste disappointment, yet never yield hope, for it is the final thread we may grasp onto. Together, we dream beneath a shared roof crafted by ancestral wisdom and sage; a heritage that I carry from my motherland to yours, from mine to ours, where we can gather and forge a path for healings.

It is but a fragment of a path, offering you and me a sanctuary to pause and rejuvenate.

A passageway crafted by the echoes of its surroundings, shielding the harshness of the hardships for a brief relief from the scorching heats of the day:

“SÁBÁT”, a structure commonly found in Yazd, Iran, series of interconnected arches or vaulted ceilings, harmonious blend of hospitality, grace, and cultural resonance. My legacy from ancient Persian architecture, guiding the passengers along a tranquil shaded poetic pathway into the fabric of a collective future.

The Joy I felt each time the school bell rang was indescribable. What did I imagine happening, or what did I see myself doing after stepping out of the classroom? The possibilities seemed limitless, as my imagination knew no boundaries. I was not yet informed or aware of the injustices the world was yet to unveil. Moreover, it took far less to satisfy my sense of wonder, as I had not yet been frequently disappointed by the adult world’s realities. Such reflections were just beginning to seep into my perception—and that of any other child navigating the more complex social landscapes.

I was born and raised until the age of five in the south of Iran, while registered in the northwest, where my mother was born, some 2000 kilometers away. The geographical divide between these two cities is marked by a difference of ten degrees in latitude and fifteen in longitude, a spatial gap that has historically set them on nuanced trajectories, further influenced by their distinct climates. Thus, my upbringing in the south was interwoven with experiences that often delineated me from others socially, by accent, skin color and culture.

I recall a time in kindergarten when six “girls” encircled me, along with another “boy” who, under their direction, exposed his genitals to me. Then, all eyes turned, expecting me to do the same so they may compare the color difference. It was only then that I became aware of my skin color and how it might mark me as peculiar and exotic, to my peers. Yet, in that moment, I still had control. I could choose not to join in this game of race, which seemed designed to single me out as an outsider, even within what I had believed to be a playful environment. It’s apparent today that the actions of my classmates then were not entirely of their own making and were not intended to be violent. Nonetheless, it was hurtful.

Some years later, in primary school in bustling city of Tehran, the joyful bell rang, and in the blink of an eye, everyone packed their belongings in their backpacks, and hurried out of the classroom. We raced down the stairs to the backyard to merge with the other students leaving. It was exclusively “boys” congregating on their way home, along with teachers and some parents picking up their children.

On this specific day there was one younger “girl” standing in front of a wall in the shadows, waiting to pick up “her” brother. “She” caught my attention with “her” colorful clothing, wearing a skirt that starkly contrasted with our dark blue uniforms. Directly in front of “her”, a group of three “boys” formed a circle and sang a song to “her”, one that demeaned “girls” as weak rabbits and praised “boys” as strong lions—a well-known childish song that consistently made any “girl” upset by its context. I remember how scared and alone “she” appeared as the “boys” continued to sing, until “her” brother, seemingly oblivious to the “boys”, arrived, took “her” hand, and led “her” away.

Unexpectedly this memory resurfaced while I was lying on the table of my somatic care practitioner, “Care,” while we delved into the root cause of my attempts to articulate to friends and colleagues the weight of pain carried by a marginalized body in a predominantly white society, that I am living in, since 2016 as I left Iran to Study art and Design in Switzerland and now in Berlin.

This recollection reminds me of a Persian myth from the mountainous regions of Iran. According to the story passed down by the elders, during the full moon, panthers climb to the summit of the tallest cliffs in a quest to get closer to the moon. Driven by a profound longing, they eventually make a daring leap towards the moon, only to descend and fall from the summit they had reached, and die.

Put me inside red earth // where my roots have entwined since birth // remind me of my cosmic essence // woven by my lineage and heritage // bring me back up // to the vast black sky // to the insanity of the stars // and grant me the grace, the moon and the sun.

What if I am this panther jumping over and over again in my attempts to be heard and to be seen for the stories, I carry to prevail a sense of love in a dark night that has light only by the reflection of a sun hiding on the other side?! What if the mystery to be revealed lies on the back of the moon, to be never seen but to be thought of?! What if my descent is not the fall of my dreams but the resilience my body seeks in each cascade for the possible human?!

At this juncture of understanding, it dawned on me that my endeavors to articulate my pain could, inadvertently, fortify yet the same power structures that oppress the marginalized— not through explicit dehumanization, but by neglecting to recognize their intrinsic humanity from the outset.

When was it for you to realize you were not seen as a human, but instead were reduced to your physical attributes? The color of your skin, the inexpensive fabric of your shirt, the holes in your shoes, the accent in your voice, your perceived gender, the shape of your face, the curves of your body, the sorrow in your eyes, the apparent need for help—One or all at once, could be the excuse for others to deem you inferior. You were faced with a choice:

Fight or flight! Perhaps your initial reaction was introspective; you questioned what you might have done to warrant such hostility. Why are they yelling at you? Why are they striking you? Why don’t they listen when you say no and plead for them to stop. Do you deserve respect, love, and kindness? To where can you flee to feel safe and respected? From what are you running? Where have you been that its very existence seems to deny and demean yours? What is home? What is happiness?

As the years go by, you grow older, and the search for answers that might offer some peace continues. The white lines on the road blend into the horizon, and the number of cities passed fades from your memory, as do the lovers and friendships. Each scar evolves into reminders of danger, manifesting the forms of fear, erupting in moments of anger, leading to your solitude. Yet, it is those treasured memories that can conjure hope—to dream of a place you may be able to call one day home.

Where our rage and pain are hidden, also lies our power. “They surface in our dreams.” We realize them in poetry that gives us the strength and courage to see, to feel, to speak, and to dare.1

Audre Lorde suggests that; “Poetry forms the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams towards survival and change: first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action. Poetry is the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought.”2

Nameless as love is. Nameless as the sensual feeling that touching hands transmit, and “let us know that this world is not enough, that indeed something is missing”. Whereas empty hands provoke a desire, a wanting of a better world, a rejection of the here and now.3

1 Lorde 2017, 11.

I plant my hands in the garden’s tender embrace, unfurling into green with a whisper, a knowing, a pulse, a grace! And in the inky cradle of my fingers the sparrows will nest and lay eggs.4

2 Ibid., 8.

3 Russel 2020, 22.

4 Another birth by Forough Farokhzad translated by Ilghar Dadgostari - Forough Farokhzad was an influential Iranian revolutionary modernist poet and an iconoclastic, feminist author, activist and film maker. 1934-1967 IN PURSUIT OF HOPE

Hands are delicate and strong. They are full of knowledge, motion, and emotion. Full of Memory and poetry. So, we make poems with them as we make love; “holding hands and loving each other as refusing the world that judges some of us to be unlovable; loving each other as a way of surviving the world.”5

Hold! Hold my body. travel with me to the neverlands and count my skin, one by one with your hands where you touch is where I grow what you seek is what you find

That is how history comes to be creating what you need to survive, where it has not yet been served. You ignite by refusing the reality oppressed to you and ought to imagine a new one. Poetry is a glitch of our hopes and imagination that we could use as a vehicle to move and rethink our physical selves and eventually be hospitable to our own body and its cosmic being.6

Our body becomes poetry as we breathe, and our senses emerge into existence as oxygen manifests its essence through metamorphosis of objects that travel along the line of breath. Without oxygen life becomes a mere abstraction, devoid of the substance that holds the knowledge to recreate the world as tangible material, turning it into a vector of energy - a living experience, a powerful force that can transcend the confines of this page and transport us elsewhere.

5 Lorde 2017, X.

6 Russel 2020, 30.

“well, I’m not a poet I’m just a girl and poets, I think are naïve to think we could exist in a world beyond this one they are hopeful, to say the least and me?

I’m hopeless this world is all I have and I have no dreams to follow in another world. love, anger, hurt, happy I’ve been all but I’m not a poet I’m just a girl a girl with words to express what a stranger could feel with imagination of that of the creator but this is my world and it is all I have”7

7 Aayushi Soni https://www.instagram.com/reel/C3QNEEZt0dO/?igsh=MXE2NXRxZ3EwZmh5Ng==

How could our imagination spring, surpassing the confines of our conventional perception of life? In what realm does our connection to the cores of our existence find its source? And how do community and heritage contribute to evoking the reservoir of knowledge inherent in the very tissues of our being?

When the elements of repression are at play, the potential for dialogue diminishes as the oppressor denies knowledge, comprehension, recollection, conviction, belief, and acceptance for the unpleasant realities that impede their transition from the unconscious to the conscious mind and action. And how could one envision a space for dialogue when the oppressor insists on maintaining control from a position of authority by dismissing one’s truth as a dubious interpretation of reality and labelling one’s resistance as a violent, dogmatic approach in negotiating a safer space?

Now listen to this reed-flute’s deep lament

About the heartache being apart has meant:

‘Since from the reed-bed they uprooted me

My song’s expressed each human’s agony,8

Within the vast expanse of the space, I hear the reed-flute’s deep lament; a transformative echo where the breakdown of limitations thrusts the emergence of possibilities. It is an uplifting resonance that encourages the spirit and empowering its innate capacity for healings. It is not a matter of ascending to a higher state, but rather shedding the imposed mental and spiritual pollutions. The power of imagination within the poetry of body and breath negotiates an alternation in the power structures of a society. Poetry activates elements of care within a community, advocating for reparations and healings within its space of creation.

Where does this space begin, and where does it end? Who hosts this space and opens the door for newcomers to arrive?”

8 JALAL AL-DIN RUMI (1207-1273),

In the pursuit of a safer space for dialogues and reparations, of one that Bell Hooks calls “space of radical openness”9 , the imperative lies in amplifying the power to defy oppression. In sparking a transformative change, it is urgent to dismantle the injustices embedded within society,10 by replacing hierarchies of pain with layers of empathy and hospitality, fostering a deeper understanding and connection among individuals. On this path of liberation, one must refuse the binary regulations in a society, that determines a hostile border between the host and the guest by denying their humanity. Humanity is that “unconditional readiness to share” that cosmos Philosophies of our ancestors demonstrate. This notion resonates their heritage and enlightens a path toward “personhood and communality”.11 The spirit of community is mirrored in the ancient teachings across civilizations and their cultural narratives:

In Greek mythology, we learn about the principles of Xenia, which praises the notions of hospitality. These principles teach us to greet guests with kindness and generosity, ensuring their comfort and safety, regardless of their social status or background. Similarly, in Zoroastrian system of ethics “whole existence becomes the appropriate sphere for the working of human sympathy.”12 One gets respect and glory through “charity”13 by which world becomes easy and happy.14

9 Hooks 1989, 149

10 Kilomba 2020, 36.

11 Bejeng Ndikung 2020, Contemplations on the Notions of Hospitality, 16.

12 Buch 1919, 134.

13 See Ibid., 135. “Charity” or good- will, active philanthropy in all its shapes and forms, large-mindedness are part and parcel of a virtuous organization.

14 Dustoor, Sanjana 1894, 468.

In Pahlavi writings the higher manifestation of the act of Benevolence shows itself “in different virtues such as generosity, sympathy, hospitality, peacefulness, patience, good temper, courtesy, and disinterestedness.”15 And goes on by placing the heart and conscience of the generous on top of the light of the holy fire.16 Moreover in the heterogeneous cosmos of African philosophies, “An unconditional readiness to share” is praised as the natural core of hospitality, inherited from the soil on which all life rises.17 It is considered a vital element in the conception of personhood and communality, as expressed in philosophies like Akan and Igbo.18

This concurrence is a form of refusal to borders, suggesting that the earth shall not be possessed, but cherished and shared.19 Sand as the righteous child of the sea floats in water, seats on the ground and flies by the wind, carrying this millennial scent around, with the message that no one has more right than another to a particular part of the earth and that our globe can host all beings together.20

These teachings serve as the oxygen for a community that opposes hostility and microspace nation-state mentalities, advocating for a global perspective that view the earth as a common space that has no end and no starting point. This mind-space promotes coexistential interconnectedness between beings as the essence of the divine - a concept that is absent in modern European philosophy,21 that initially approaches community-building from an individualistic standpoint rather than approaching individual autonomy from a communal framework.

15 Dastur, Sanjana 1885, Avestan-Pahlavi texts, 18.

16 West 1892, Pahlavi Texts, 555.

17 Echema 1995, 35.

18 Bejeng Ndikung 2020, Whose Land have I lit on now?, 16.

19 Minkkinen 2007, 53-60.

20 Miliopoulos 2007, Immanuel Kant, 341-386.

21 Bejeng Ndikung 2020, Whose Land have I lit on now?, 15.

A breast which separation’s split in two

Is what I seek, to share this pain with you:

When kept from their true origin, all yearn

For union on the day they can return.22

Given these insights, it is evident how ancestral rituals and practices could be a gateway to activate elements of hospitality and care within a community that sets a vision for honesty and healings in liberating the soul from the constraints of apathy toward pluralities of empathy. This notion ushers us into a realm where the archives of our heritage reveal spirits mingling with the elements—fire, water, and wind intertwine, each whispering tales steeped in the ages. The crackling fire, the tranquil water, and the gusts of wind that resonate the poetry of heritage and memory. Exploring the archives of collective memories through poetry paves the way for the conjuring of fictional worlds, blending history, fantasy, legend, folklore, and myth to craft intricate visions for the future.

On the other hand, military regimes of patriarchal capitalism systematically demolish protective territoriality of a hospitable space of home. Fear and anxieties compound in this cruel space and shift “social borders”. The tyrannical gladiators put their black military boots on and trap the citizens inside rural forms of brutality and agonize Memories to transform the society into solitary cells. They imprison bodies and thoughts and resolve them into domestic migrants, alienated from their shared heritage of oceans, and soil.

As these tyrannies of patriarchal capitalism forge a landscape of isolation and oppression within their context of fear and confinement, it is expected that such suppressive systematic structures contribute to the proliferation of toxic traits within societal norms. Building on the repercussions of binary methodologies of individualism, this environment perpetuates momentary fixations among individuals, leading to the development of passive and active forms of addiction, as well as fostering behaviors rooted in racism, sexism, classism, ableism, queerphobia, and body shaming that manifest sadomasochistic tendencies.23

Within the pages of “Plantation Memories,” Grada Kilomba articulates repreparation as the delicate negotiation of recognition within the complex interplay of contextual dynamics. She asserts that repreparation involves actively negotiating the multifaceted realities shaped by racism and sexism. Kilomba aptly argues that the pivotal act of surrendering privileges emerges as a transformative strategy in addressing the repercussions of groupbased misanthropies, entailing a comprehensive alteration of structures, agendas, spaces, positions, dynamics, subjective relations, and linguistic paradigms.25

Kilomba’s discourse on repreparation in negotiating a multiverse of realities, argues against the reduction of the elements of observation that consistently fail to recognize inherent disparities within the popular dichotomies of white-supremacist capitalism. Often perceived as a practical approach rooted in the notion of “less is more,” this espousal of minimalism veils a stark reality of exploitative practices deeply entrenched in neo-colonialism.

Amongst the crowd, alone I mourn my fate, With good and bad I’ve learnt to integrate, That we were friends each one was satisfied But none sought out my secrets from inside;24

In the shadow of unspoken secrets and solitary struggles, there lies an urgency to recognize the inner turmoil that bind us. We must move past the confines of individualism and navigate beyond the binaries of singularity and individualism, towards the ‘multiplicity of beings’ that resonate with the heritages of ancestral wisdom, envisioning a revitalized intuition for the future. This journey involves traversing triggers from an eventful past with a delicate gaze characterized by collective care, acceptance, and trust to foster healing and reparations within society. Whether stemming from conscious or subconscious, encompassing the echoes of generational and ancestral traumas interwoven within our tissues, these adversities serve as sources of wisdom and resilience, fortifying ethos of hope.

The exploitation of labor in countries like Bangladesh, Pakistan, Cambodia, India, and Vietnam, where predominantly women and children endure forced overtime, harassment, unsafe working conditions, and low wages to meet the global demand for fast mass-production, illustrates how capitalist enterprises perpetuate resource extraction and human rights abuses for economic profit. This exploitative cycle is replicated in countries such as Congo, Venezuela, Guinea, Nigeria, Bolivia, Indonesia, and many others, reflecting the oppressive power dynamics inherited from colonial legacies. In this cycle, individuals and communities are reduced to mere commodities for financial gain of those in power.

The systemic exploitation within extractive industries not only leads to environmental degradation and economic disparities but also reinforces systemic racial and gender inequalities and power imbalances. This perpetuation of inequality fuels the oppressive systems, sustaining racial and gender disparities as core components of their exploitative structures and localizing them within reinforced global financial and social principles.

25 Kilomba 2020, 22.

Then maybe it is not a mere approach after all, but more of a systematic strategy that aims to eliminate realities that does not fit its traits of exploiting the resources and individuals. It is a deliberate act of oppression, in which delicate matters in life are actively repressed, reduced, and simplified to align with the perspective of the white subject, affording them a sense of ease of the climate they cause. It is not a failure to recognize the intersection between things, but rather a conscious decision to ignore their livelihood from the outset to maintain a self-serving comfort zone. White feminism is an appropriate example for that, where the interlocking of race and gender in structures of identification26 within a white notion of womanhood and its false form of universality are actively dismissed.27

Moreover, the disregard of human and environmental well-being by modern capitalist architecture and design is also evident in its individualistic functionalism focusing solely on production and consumption. Along with these attitudes the intersection of science, AI Technology, capitalism, and its neglectful culture builds up the matrix of modern design. By neglecting spiritual aspects and the interconnected nature of existence, this approach perpetuates a cycle of materialistic pursuits that erode the fabric of society and foster a culture that prioritizes individual success over collective well-being.28

However the current entanglement of this matrix with social and cultural movements of the body in contemporary history of design leads the society to the key elements of its role orchestrating alternative forms of design, that acknowledge inherent raciosexist capitalist infrastructures of everyday life and design on a journey that contributes to more pluriverse Design assertations in building stronger relations between things and beings.29 Within this context Bachelard emphasizes on “poetics of home” and their oneiric function, which the concept of “modern living” have deviated from.30

Moreover, Juhani Pallasmaa demonstrates how spatial poetry intertwines memory, emotions, dreams, identity, and intimacy in forming a space that transcends physicality and acts as a catalyst that shapes and alters our perception of reality. He argues how a tectonic language within a space can be employed to either establish boundaries or shatter barriers, in forging connections that inspire a sense of unity.31

Yet, the rifts of modern architecture and design from such existential experiences hinders our capacity to envision alternative realities. Hence, it becomes imperative to craft methodologies that cultivate ecological awareness and a deep understanding of philosophical and cultural issues encompassing spatial dynamics, temporal dimensions, material essence, locality, and dynamics of agency in constructing different selves and societies.32

My deepest secret’s in this song I wail

But eyes and ears can’t penetrate the veil:

Body and soul are joined to form one whole

But no one is allowed to see the soul.’

It’s fire not just hot air the reed-flute’s cry, If you don’t have this fire then you should die.33

26 Ibid., 56

27 collins 2000; Fulani 1988; hooks 1992; Mirza 1997

28 Escobar 2018, 91.

29 Ibid., 30.

30 Bachelard 1969, 35.

31 Palasma 2016, 96-97

32 Escobar 2018, 38.

33 JALAL AL-DIN RUMI, Last Verse of The Song of the Reed

Reflecting on the symbiotic relationship between spatial dynamics and sensory perception as discussed by Pallasmaa, Rumi’s verse invites us to heed the reed’s lament, symbolizing a deep unity among all beings within the natural world. This motif resonates with Marx’s critique of commodity fetishism34, where the inherent worth of natural materials is eclipsed by capitalist valuations. Rumi’s poignant call urges us to acknowledge the foundational significance of the environment, prompting a critical revaluation of our ecological and philosophical stances.35

The materialist phenomenology inherent in these principles36 is beautifully exemplified in traditional temples like the 14th-Century Buddhist sanctuary located outside Kyoto, portrayed by anthropologist Norris Johnson. These temples, embody a philosophy where each element within the space coexists harmoniously, engaging with and responding to its environment, serving as communal sanctuaries for transitions and connections.37

This interplay gives rise to a rich spectrum of emotions and a multiverse of existences, contributing to a spatial narrative that cultivates the notions of interbeing, empathy and unity, as evidenced in the teachings of Buddhism, the Maya civilization, and the architectural marvels of ancient Iran. These monuments challenge the modern notion of independent and selfcontained existence,38 where the world is made structurally unsustainable, and destruction has become a norm in the hands of global experts, bureaucrats, and geoengineers who can only recommend the business-as-usual approaches that emerge from impoverished liberal mind-sets: The neoliberal globalization ideology adopted by Western modernists envisions a singular world where multitude of cultures coexist within the framework of a dominant reality, perceived as the sole nature. This imperialistic stance asserts the West’s entitlement to position itself as the epitome of “the world,” imposing its norms on other cultures, demanding their compliance with its standards, and overshadowing their unique identities.39

34 Marx 1992 (1867).

35 Ali, The Reed Laments: Ecology in Muslim Thought, 6.

36 Tanizaki 1994, 25.

37 Johnson 2012.

38 Escobar 2018, 84.

39 Ibid., 87.

In contrast, relational cultures recognize a dynamic world brimming with vitality, where humans and other entities share an intertwined existence. While modern societies merely occupy space, non-modern cultures forge deep connections with their environment by navigating elaborate relations and narratives that shape a sense of belonging.

In the pursuit of balance between the isolated and intertwined perceptions of individuals, novel ideas are emerging in the design world, propelled by networks of mutual agency, impact, and skill, making it increasingly challenging to uphold the illusion of the solitary self. This shift paves the way for the principles of co-creation and interactive collaborations, empowering designers, and the general populace to revive the power of collective engagement.40 Within this context, Manzini discerns a rising aspiration to depart from individualistic standards as a promising foundation for collaborative design41 through an Ecological awareness that recognizes sustainable interactions between entities and their environments, prompting shifts in individual and collective perspectives that dynamically introduce alternative paradigms of reality.42

This approach contributes to an ontological stance in design that Winograd and Flores encapsulate as an intervention in our cultural heritage, emerging from our current episteme. Ontologically oriented design anticipates potential breakdowns in our daily routines and tools by crafting vibrant artifacts, infrastructures, and organizational frameworks, that open up emergent spaces for renewed social and cultural engagements. They arguably draw from our ancestral roots while envisioning future transformations in our communal existence, by pioneering innovative tools, that guide a paradigm shift in understanding human nature and action, leading to technological advancements, and alternations for our societal fabric.43 Winograd and Flores highlight that such tools serve as the cornerstone of our actions, sculpting the world we inhabit, although the evolution we seek transcends mere technical advancements, encompassing a perpetual metamorphosis in our perception of our environment and selves—” of how we continue becoming the beings we are.”44

40 Manzini, Coad 2015, 24.

41 Manzini, Coad 2015, 94-98.

42 Escobar 2018, 116.

43 Winograd, Flores 1986, 163.

44 Ibid., 179.

As Tonkinwise notes ontologically oriented design plays a pivotal role within critical design studies, in reshaping societal organization, values, and economic models,45 by adopting a relational mind-space of materiality, and by employing a retro futuristic ecological awareness that unveils the vibrant agency of objects, contrasting with the conventional perception of “inert” objects.46 This approach recontextualizes materiality within the economic compasses of production and consumption, and implements principles of ecological economics, while repositioning design within larger contextual frameworks stemming from localities, mediums, and platforms, as in Architecture, Literature, and music.47

In a historical research, music and cultural theorist Ana María Ochoa Gautier unravels the connections between aurality and existence, blurring the traditional distinctions between epistemology and ontology. 48 Inspired by Stephen Feld’s acoustemology framework she reveals the emergence of relational aurality paradigms where sound physics, musical structure, (im)material essence, sound technology, and auditory perception converge. Ochoa Gautier challenges the notion that local sounds merely mirror specific localities, emphasizing instead the transcultural nature of sonic experiences that catalyze a pluriversal energy transcending the confines of sound domains.49 Within this multifaceted tapestry, musicians navigate cultural and political terrains, drawing insights from the interdependent fabric of relational existence and inspire ontological dialogues that initiate intrepistemic forms of collaboration in music production as well as in design and architecture.50

The themes of relational aurality and transcultural sonic experiences that Ochoa Gautier articulates resonate deeply when juxtaposed with specific cultural critiques of music, such as those expressed by Ahmad Shamlu. At a gathering at Berkeley University in New York, Shamlu critiqued traditional Iranian music for its melancholic overtones and its stagnation in the past, challenging it to meet the contemporary needs of Iranian communities.

45 Tonkinwise 2012, 8.

46 Bennett 2010, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things.

47 Escobar 2018, 32.

48 Gautier 2014, Aurality: Listening and Knowledge in Nineteenth-Century Colombia.

49 Gautier 2006, “Sonic Transculturation, Epistemologies of Purification and the Aural Public Sphere in Latin America.”

50 Manzini, Coad 2015, Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation.

This critique underscores the dynamic interplay between global musical expressions and their cultural receptions,51 as discussed in the broader framework of music’s ontological and epistemological impact.52

To fathom this argument, one should follow the origins of seven degrees generally used by musicians as scales in different areas. For example, scales of Persian Music are extracted from a pool containing seventeen to twenty-four notes compared to the Western scale extracted from only twelve notes. The Persian music system divides the whole tone into three or four parts, rather than two in the western music system.53

These additional divisions are referred as “Gusheh,” which is a melody type like Indian Raga, the Arabic maqam, and the echoes of Byzantine music. - “A traditional repertory of melodies, melodic formulae, stereotyped figures, tonal progressions, ornamentations, rhythmic patterns, etc., that serves as a model for the creation of new melodies.”54 Other genetic materials provided by “Gusheh” features mood, character, and indefinable ingredients such as extramusical associations.55 Associations which are related to old poems, some specific performers,56 and traditional motives and ornaments in the historic architecture of Iran.57

Inevitably melodies that are created relying on these parameters are well-attached to the stories of resistance in Iran and the middle east. That is how this piece of Land that always faced challenging times in history reflects its story through poetry, literature, architecture, and music.

51 Shamlu 1990, Q&A session with Berkeley University students, 50`- 58`.

52 Zonis 1973, 46.

53 Ibid., 53.

54 Apel 1969, s.v. “Melody type.” - The concept of maqam is discussed by Spector 1970.

55 Zonis 1973, 46.

56 Ibid., 48.

57 Tokhmechian, Gharehbaglou 2018, “Music, Architecture and Mathematics in Traditional Iranian Architecture.”

I would like to interpret these sub-divisions of tones in music, architecture and arguably poetry of Mediterranean cultural sphere as representatives of a world in between. The complexities of life in these geographic zones are deeply ingrained and reflected between the tones and are highly visible in different transitional forms in architecture. These complexities uphold anecdotes of resistance that carry sorrow throughout their fabrics of history. Considering the strong co-habitation of poetry, music and architecture in Iran, the melancholic quality of Persian music presents itself in different forms of grief also in Poems. Additionally, exerting oneself is demonstrated in literature as a unique way to show affection and love toward attainment of a desire. A clear example of this phenomenon in Persian poesy is an exceptional poem by prominent Persian Poet of the medieval period Saadi Shirazi (1210 -1292 AD) called “conversation between the candle and the moth”:58

“One night, as I lay awake, I heard a moth say to a candle: “I am thy lover; if I burn, it is proper. Why dost thou weep?” The candle replied: “O my poor friend! Love is not thy business. Thou fliest from before a flame; I stand erect until I am entirely consumed. If the fire of love has burned thy wings, regard me, who from head to foot must be destroyed.” Before the night had passed, someone put the candle out, exclaiming: “Such is the end of love!” Grieve not over the grave of one who lost his life for his friend; be glad of heart, for he was the chosen of Him. If thou art a lover, wash not thy head of the sickness of love; like Saadi, wash thy hands of selfishness. A devoted lover holds not back his hand from the object of his affections though arrows and stones may rain upon his head. Be cautious; if thou goest down to the sea, give thyself up to the storm.“59

58 Two important musical interpretations of this poem, reveals the cohabitation between Music and literature in Iran. The more traditional performance by Mohamadreza Shajarian (1940 - 2020): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_SpeVkq_AS0. A more contemporary approach by Shahrram Nazeri (1950 - now): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DKHM3FZnDdY. 59 Saadi: collected works, 2019, 53.

Offering one’s life is a way to praise the beloved in literature as well as in everyday life in Iran. One could say that Iranian minds tend to reify their endeavors in the form of death, suffering and grief. But there is more attached to the act of offering one’s life for love. But the question is how does this sacrificed body call its history and its path back to life?

A person´s body does not lose its value after death. There is always an urge to preserve their corpse from further violence,60 because this tormenting object establishes the destiny and the carnage of all beings in the end.61 This diminishing object in grave can no longer answer their expectations, but rather nourishes their fear of discontinuity and becoming nothing; and that is why the survivors are convinced that this lifeless body should carry on living 62

“Grieve not over the grave of one who lost his life for his friend; be glad of heart, for he was the chosen of Him. “

When the anecdote of a corpse reflects an act of resistance in a political manner, then fragility of life will be reinstated as “defiance in/as radical love.”63

“A devoted lover holds not back his hand from the object of his affections though arrows and stones may rain upon his head. “

On the subject sacrifice Georges Bataille indicates in his book Eroticism: “the victim dies, and the spectators share in what his death reveals. This sacramental element is the revelation of continuity through the death of discontinuous being to those who watch it as a solemn rite.”64

He goes on by emphasizing that “a sacrifice is a novel, a story, illustrated in a bloody fashion.”65 But how could this inversion transform the object of sacrifice and the surrounding world to create a life of its own?

This sacramental element as an active form of care needs a force capable of lifting off the page and carrying us away to recreate this brutal act of resistance as a material to shape a collective tale and turning it into a cautionary energy. In this regard Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung suggests, “Art spaces could become spaces of radical thinking. Of radical love. Of protest. So, the issue at stake is how can we create spaces where people and society could show and reveal their wounds?”66

This space has been practiced in Persian music, literature, and architecture for centuries, but it still has a long way to be actively acknowledged by societies out of Iran. In general, though it might seem like a platitude, but I believe that there is an emergence of bridges and transitions between worlds; and music, literature and architecture have the potential to Rearticulate the stories with an artistic approach to make cultural exchanges between nuanced communities more coherent and empowering.

Furthermore, it is crucial to narrate the stories of resistance for remembrance in a world prone to forgetfulness. Sharing our vulnerabilities and revealing our wounds as acts of protest not only facilitate individual and collective healing but also serve as a poignant reminder of shared wisdom. This collective wisdom, born from shared wounds, guides us in acknowledging harsh realities and challenging brutality. As we navigate storms together towards our aspirations, this shared wisdom bears witness to our compassion, prudence, and love.67 In this context Kilomba proposes acts of surrender as transformative strategies for altering structures, agendas, spaces, positions, dynamics, subjective relations, and linguistic paradigms,68 while Saadi Shirazi goes a step further by emphasizing the importance of sacrifice as a pathway to transformations.

60 Zonis 1973, 46.

61 Ibid., 44.

62 Ibid., 57.

63 Bejeng Ndikung 2021, The delusions of care, 68.

64 Zonis 1973, 82.

65 Ibid., 87.

66 Bejeng Ndikung, Bonaventure Soh 2018, Opening Keynote DEFIANCE IN/AS RADICAL LOVE: Soliciting Friction Zones and Healing Spaces

67 Bejeng Ndikung 2021, The delusions of care, 68.

68 22 plantation memories

„Be cautious; if thou goest down to the sea, give thyself up to the storm. “

The notions of storytelling and collective dreaming are powerful tools in transcending the individual boundaries and embracing the interdependency of all life forms. As Thomas Berry eloquently articulates, our historical mission in this pivotal moment is to reimagine humanity at a species level, engaging in critical reflection and forging deep connections with the community of life systems.69 This clarion call to usher in a new era, rooted in the principles of the Ecozoic age, finds resonance in Herman Greene’s assertion that the path to true progress lies in transitioning from an industrial-economic model to a harmonious ecological cultural age. In efforts to navigate such complex transitions in the climates of globalization of western civilization and the rulings of patriarchal capitalism, it is urgent to recognize the junctures of human history and natural history through the spectrum of cosmological investigations that are bedded within ancestral practices and rituals of life.70

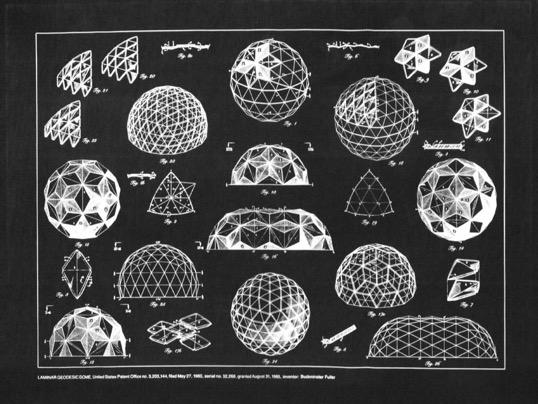

At this point of departure, and in a second act of remembrance and recognition I invite you to take part in a journey with me through cosmos of geometry as means of ancestral knowledge and heritage, shaping and manifesting the material world, a tool for realizing our desires and dreams, Which made it possible to create images of the imagination, to collect them, and to alter them.

69 Berry 1999, 159.

70 Green 2015, 8.

During Nowruz at the major holidays at the turn of the year, which in Iran occur in MidMarch, I went on an Iranian cultural journey with my family to ancient Babylon and Chogha Zanbil. In the southern part of the country, we visited the Ziggurat, one of the oldest pyramid structures in ancient Iran. The illuminated ruins of this pyramid in the evening reminded me, of the glass pyramid of the Louvre Museum in Paris - although the shapes only vaguely resemble each other. (Fig. 1) The structure evoked a feeling of ambivalence and ambiguity in me. I couldn’t explain what the difference between the two was. Was it the materiality or the context? My father explained to me that the temple city of Chogha Zanbil represents an image of the cosmos. The question grew within me whether this was the reason for my perception and resonance with this ancient pyramid.

The sensual experience of historical objects repeated itself on our journey from the west of Iran to the east, reflecting similar trajectories in my mind. The same sensation emerged in me as I observed the transitional hall of the Friday Mosque in Isfahan, which inevitably reminded me of the church hall nave of Notre Dame in Paris. This feeling of resonance was akin to a déjà vu, constantly narrating a timeless story; like a memory of the beginning of history.

The story starts with an initial curiosity about the world’s function. Human curiosity, a fundamental instinct, drives us to use geometric tools and explanations to make sense of our surroundings. Cosmological considerations highlighted geometry’s crucial role in simplifying natural forms into specific structures. About 7000 years before our current chronology, inspired by the mystical and supernatural, nuanced religious beliefs took shape. Ancient religions also sought to classify and comprehend the world. Yet, how can these insights explain the feelings I experienced in Chogha Zanbil and Friday Mosque in Isfahan?

Given the emotional depth of a setting can resonate with intuitive understanding, these pages aspire to uncover ancient architectural research findings that whisper of a universal intuition. Thus, I offer this exploration as a tribute to unraveling the essence of our world through the prism of geometric architectural viewpoints from ancient times. At the outset, my focus is on documenting the genesis of geometric structures and forms. Beginning with a historical and archaeological lens, I delve into the early strides in geometry as observed by ancient philosophers and mathematicians. Drawing from their insights, I aim to decipher the elements within these structures that guide space towards a harmonious alignment with its environment, achieved through the thoughtful application of specific design components.

The results of this exploration of geometry and spatial design are intended to recognize spatial structures as additions to non-tangible elements of care and community in a space and the way these corelate in evoking a sense of belonging and harmony.

// POETICS OF GEOMETRY

The first geometric representations were landscape and land maps on clay tablets. (Fig. 2) These also served to structure a community. They can be dated back to around the 9th millennium BC, roughly to the time when the first evidence of settled communities in Iran is recorded. They were widespread in Egypt and Babylon. With the help of such maps, the Egyptians developed the foundation of geometry, which brought a completely new theory of space to the awareness of ancient scientists.71

Figure 3: The ratios of the red segment to the green segment, the green segment to the blue segment, and the blue segment to the violet segment are based on the golden ration and all equal to Phi (Φ).

Another example of geometry in action is Pythagoras’ use of the pentagram, a five-pointed star where each line segment relates to others through the Golden Ratio. (Fig. 3) This principle, integral to mathematics, geometry, and nature, also reveals a pentagon at the star’s center.74 Plato (c. 427 BC - 347 BC) utilized this shape to symbolize the universe in Greek philosophy. He considered it a comprehensive representation of the cosmos and explored these ideas through a debate in a dialogue with Timaeus about the physical world and humanity’s nature:

Our current knowledge in geometry is though primarily owed to the ancient Greeks and the Pythagorean school.72 Pythagoras (c. 570 BC - 495 BC), the founder of the Pythagorean school, made seminal discoveries in arithmetic and geometry, in which he used music to determine the harmony of numbers and shapes. Pythagoras realized that the harmony of a tensioned and plucked string can only be achieved when a precise number of standing waves are induced, which became the first pillars of geometric studies.73

71 Mlodinow 2002, 69-73.

72 Dabbour 2012, 380-391.

73 Wilson 1997, 17.

Plato attributed the universe’s structure to four elements, aiming for proportionality. (Fig. 4) He posited that besides fire and earth, a third element was needed for visibility and tangibility. Asserting that the world, being a solid, required a fourth element for harmony, he introduced water and air to bridge fire and earth. These elements harmonized the world’s body through proportions.75 The dodecahedron, the fifth solid, composed of twelve pentagons, allowed the universe to be depicted in a way that aligned with the understanding of time and space.76

These investigations served as foundational mechanisms through which languages and initial social structures were developed, ultimately shaping the architectural culture of antiquity.77

74 Meisner 2018, 24.

75 Plato, Timaeus, 31b-33e.

76 Luminet 2003, 593-595.

77 Hejazi 2014, 7-22.

The invention of writing and the transcription of language around 3000 BC had a decisive influence on Sumerian society and culture. It enabled communication in larger human groupings in the city-states and the recording and transmission of knowledge about building techniques and architecture.78

The traditions of ancient religious prayer texts reveal this interplay of theological and cosmic perceptions in shaping the temples. In order to address pleas to God, ritual prayer forms and the deliberate design of a temple complex were considered as a form of connection to God and to the spiritual. This phenomenon is particularly evident in the development of the architectural culture of Babylon, one of the most influential cities in Mediterranean Cultural Sphere.79

After Ur, the homeland of Abraham, was conquered by the Elamites of Iranian descent around 2000 BC, the city transformed into one of the most powerful states known as Babylon (Babilu: Gate of God). In Babylon, gigantic buildings were constructed. The Elamites believed that their destiny was governed by the stars. In the temple, astronomical studies, such as those on propulsion, were conducted. These studies arose from the influence of the Zoroastrian religion, instructions from various gods, and the theories of the zodiac concept. The result of these studies was one of the earliest records of cosmological thought.80

In Mesopotamia, the city was not only the center of a geographical area but also the link between the divine and human worlds.81 The main deities of the pantheon had a city under their protection, whose prosperity depended on the relationships between the palace and the temple. The choice of location, the city plan, and the founding rites were the responsibility of the gods.82 By the first half of the first millennium BC, Babylon had become the spiritual and intellectual heart of ancient Mesopotamia. The city, heir to a thousand-year-old culture, shone brightly on the pre-classical civilized world.83

78 Wilson 1997, 7.

79 Ragavan 2013, 240.

80 Wilson 1997, 8.

81 Horowitz 1998, 208–20.

82 Ragavan 2013, 207.

83 Wilson 1997, 8.

The Babylonians were the inventors of the first mathematical problems and created the sexagesimal system of angle measurement. They developed a simple form of algebraic geometry that served as the basis for surveys and other practical applications. Babylon was the cosmic center, the symbol of the harmony of the world, created among other cities through the power of Marduk, the supreme god. He conquered the forces of chaos and organized the universe. This cosmological aspect is very prominent in the urban planning and architectural design of the city, where the famous towering ziggurat stood at the focal point.84

“Etemenaki” or the current interpretation of the classical Tower of

Structures similar to Ziggurat were constructed vastly in various regions of the cosmos to create religious representations, which served as backdrops for ritual practices. These ritual and religious spaces were created through permanent and also monumental architecture.85

84 Ragavan 2013, 1.

85 Ibid., 254.

Early Zoroastrian beliefs, which thrived in the eastern and northeastern regions of the Iranian linguistic area,86 were significantly influenced by the multicultural and polyethnic Arsacid Empire (559-323 BC). This empire, located just north of Egypt, synthesized Parthian, Achaemenid-Iranian, and Hellenistic-Seleucid elements, creating a cultural crossroads between the country’s east and west.87 Architecturally, during the Parthian period, Iranian buildings typically featured a simple square layout with a central courtyard. This space often included a square domed hall with a prominent Iwan—a raised wall on the façade— and a circular hall topped with an elliptical dome,88 which was highly influenced by Roman architectural traditions.89 (Fig. 6)

These developments continued to evolve, after Zoroastrianism was established as the state religion, and fire sanctuaries and ritual ceremonies became central to cultural expressions, prominently featuring in architectural designs. This era’s defining architectural forms included the enclosed fire temple—a square central chamber encircled by a corridor—and the open pavilion, known as Chahartaq.90

86 Ludwig 2013, 161.

87 Ibid., 36.

88 Ibid., 412.

89 Ellerbrock 2016, 207.

90 Ludwig 2013, 408.

The Chahartaq features a dome (Persian: Gombad) supported by four square corner pillars, designed to shelter the eternal fire, often referred to as the “Fire Temple” or “House of Fire.” This architectural innovation, was noted by scholar Huff for its significant structural and aesthetic characteristics, leading to its prominent role in traditional Iranian architecture.

Among these venerable structures, the Kuh-e-Khwaj (Fig. 7) built during the Sassanid Empire stands out, drawing parallels not only to Greek-Roman temples but also to Buddhist shrines, showcasing the eclectic influences that define Sassanid architectural style.91

Further examination of temple complexes reveals that all dome roofs were constructed using conical squinches (Persian Sehkonj, Filpush, and Gushvara), a technique from the Sassanian (Fig. 8, 11) This architectural method, which evolved into the refined muqarnas of the Islamic period, also influenced Christian church designs, including St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, reflecting elements of Parthian architectural principles.93

91 Ghanimati 2013, 894-6.

92 Ibid., 885.

93 Ellerbrock 2016, 284.

Islamic art flourished during the Umayyad rule (661 AD - 750 AD), as classical-antique traditions were blended with cosmic motifs from pre-Islamic cultures like Coptic Egypt and Sassanian Persia, influencing the design of architectural structures and decorations.94

In this arch, the ratio of height to span is 3/4, allowing it to achieve significant height with considerable load-bearing capacity.

This integration gave rise to distinctive architectural forms in mosque and palace construction, laying the foundation for subsequent architectural styles. The resulting new methods demonstrated refined geometric, floral, and epigraphic ornaments as central design elements.95 The Jamé Mosque of Isfahan is a prime example of this integration, combining beauty, significance, and function in architectural design by incorporating the Golden Ratio in structural elements like the “Chamaneh” arch. (Fig. 9) The dome’s structural behavior, illustrates the division ratio of a pentagon, (Fig. 10) showcasing the precision of proportional relationships between arches and other elements.96

94 Bonner 2016, 56.

95 Hillenbrand 2005, 37.

96 Zandiyehvakili 2019, 719.

These geometric features stem from a comprehensive consideration of harmony (balance and symmetry), proportionality, geometric motifs of two-dimensional and three-dimensional patterns, and the utilization of specific numbers and their dimensional modulation.97

12th century.

The squinches in this clay brick building have a staircase-like, arched design that was once widespread in Mediterranean. This building represents one of the last examples of pre-Islamic architecture.

These geometric principles enabled the calculation of unique connections between square floor plans and a circular base for the dome, marking significant innovations in Persian architecture. Squinches, Muqarnas, Karbandi, and other geometric patterns stand as iconic examples of these principles. We will explore how these unique structural and decorative elements in Persian architecture demonstrate the meticulous craftsmanship and complex geometry employed in shaping the spaces.98 (Fig. 11)

97 Necipoglu 1995, 71.

98 Zandiyehvakili 2019, 720.

The squinch refers to the “transition zone” that connects the round dome ceiling with the walls of a square room. The geometric relationship between square and circle leads, in the structure of the transition zone, to a regular polygon that serves as the base of the dome. The squinches are responsible for evenly distributing the load-bearing forces, making them a symbol of “problem-solving” in Iranian architectural history.99 (Fig. 12)

Rows of overlapping brick corbels were also utilized as a constructional solution in Persian architecture, forming the stalactite-like structures known as Muqarnas. These architectural elements allowed for the construction of various pointed arch variations through geometric calculations.100 The vestibule of the Jamé Mosque in Isfahan showcases a unique application of Muqarnas, where the structures served to soften sharp corners and edges. While not bearing loads, Muqarnas were structurally stable. The picture below demonstrates how Muqarnas transformed the octagonal floor plan into a circular shape, providing a stable foundation for the dome vault.101

“Rasmi-Karbandi” is another distinct technique for the transition zone. The Hashti-Pavilion in Yazd, Iran (Fig. 14) displays a unique configuration of arches that facilitate load transfer.102

“Karbandi” is a spatial system that emerges by projecting a star-shaped drawing onto a curved surface, which is characterized by a sophisticated use of geometry and repetitive symmetry.103 The technical term “Karbandi” was used for creating interlocking patterns in construction; a form of decoration on the intrados of a vault, formed by the overlapping of arches, which resolves the transition from a square floor plan to a circular dome.104

102 Zandiyehvakili 2019, 721.

103 Garofalo 2016, 169.

104 Ibid., 194.

The design concept of sacred buildings in Iran was interrelated to the notion and belief in the third dimension. As a result, the techniques of Muqarnas and Rasmi-Karbandi were predominantly utilized for the construction of the roof vaults. The belief in a third dimension and the reverence for the creation story of beauty, which, as per Ibn Al-Jaytham, commenced with the amalgamation of light, color, and harmony, gave rise to refined architectural designs. By employing these geometric interpretations of beauty, joy, and admiration, the viewer’s spirit is led into a realm beyond the material.105

15:

The spatial configuration at all levels of the vault system in the Karbandi.

Schematic depiction of the arrangement of Karbandi - Interlaced geometric patterns of Rasmi-Karbandi, projected into the Dome.

The Muqarnas drawings were complemented by scaled drawings on the construction site. The transfer of the drawing from the scaled drawing onto paper was accomplished through the use of tracing paper, which allowed for the passage of charcoal powder onto the plaster of the Dome. The powdery trace drawing was known as Hayula. The conventional use of the term is translated as “monster,” which could refer to the monstrous nature of this phase of drawing, and philosophically, Hayula was expressed as “formless substance.” The term “Hayula” is derived from the Greek/Latin term “HYLE” and is particularly associated with the Aristotelian concept of matter or the cause of matter. This intermediary presence of a substance without form corresponds to the description of the transitional stage from translating a sketch into a scaled drawing.106 (Fig. 15)

The composite radial patterns are upward-facing designs that transform the lower square structure into the upper circle. (Fig. 16) These astral drawings symbolize the celestial order.

A Persian archaeologist described this symbolism as follows: “The square is the most materialized form of creation and, as the Earth, represents the polar condition of quantity, while the circle, as Heaven, signifies quality; the integration of both is achieved through the triangle, which embodies both aspects. The square of the Earth is the foundation upon which the intellect acts to reintegrate the earthly back into the circle of Heaven.”107

Islamic thinkers, as well as Euclid and Pythagoras, viewed geometry as a means of shaping and manifesting the material world, a tool for realizing our desires and dreams. This made it possible to create images of the imagination, to collect them, or to alter them.108

The interior of the tomb is covered with a Muqarnas vault, in which layers of niches overlap, seemingly defying the laws of gravity and forming a dome. This effect is often compared to a honeycomb or the mentioned stalactites.

106 Ibid., 98.

107 Ardalan 1973, 29.

108 Koliji 2015, 21.