Building India’s Blue-Green Network: A Strategic Framework for Bengaluru

Study Report 2022

About this

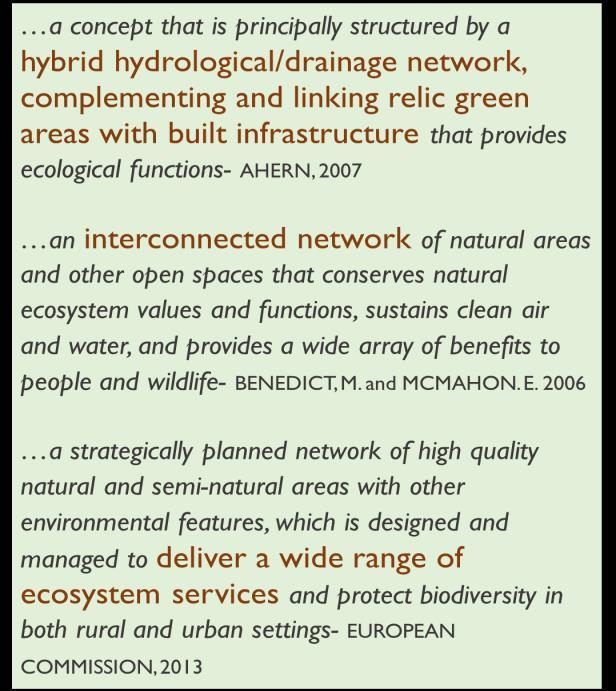

Global definitions ▪

Learning from global conceptual tenets

Blue-Green Infrastructure in the Global South

BGI in the Indian context

Gaps and Opportunities in the Indian policy ecosystem

▪ Pillars of the Strategic Framework

Natural Valleys and Lake System ▪

The Past of the Present: Socio-Ecological Functioning of Bangalore’s Blue-Green Network ▪

The Present of the Past: Fragmentation of the Blue-Green Network

▪

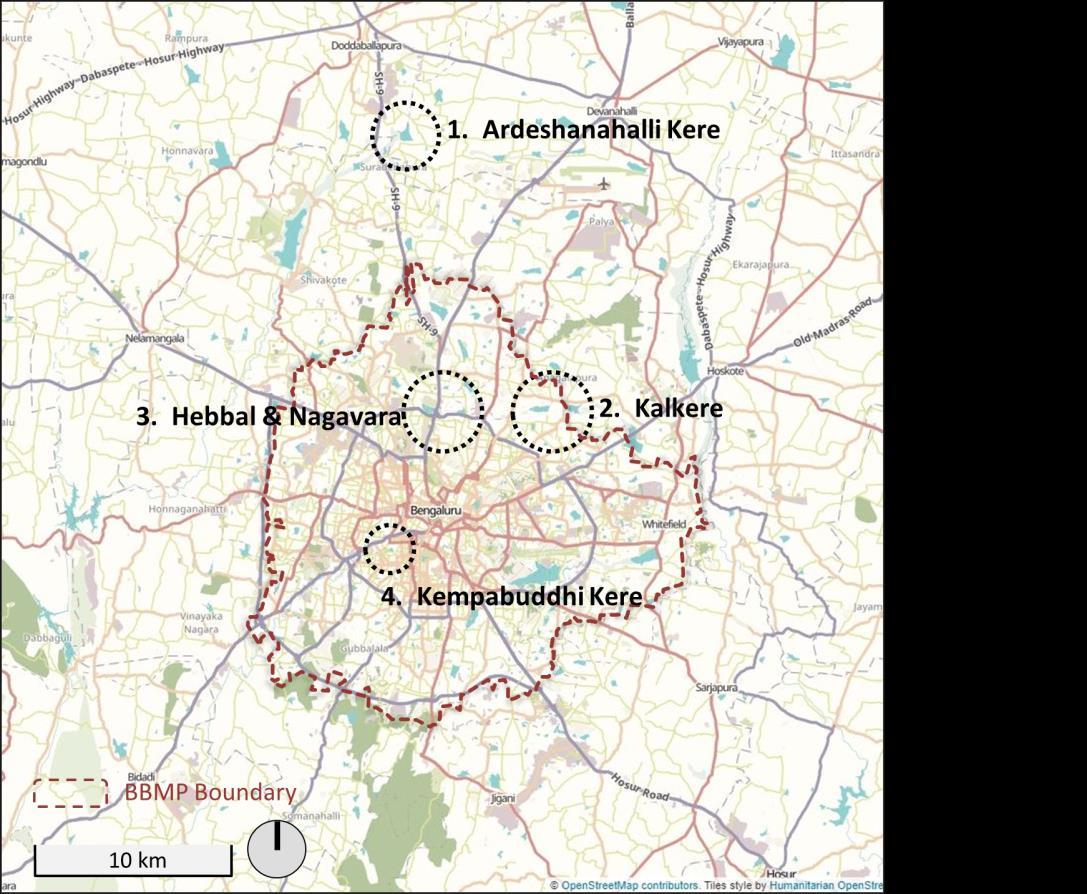

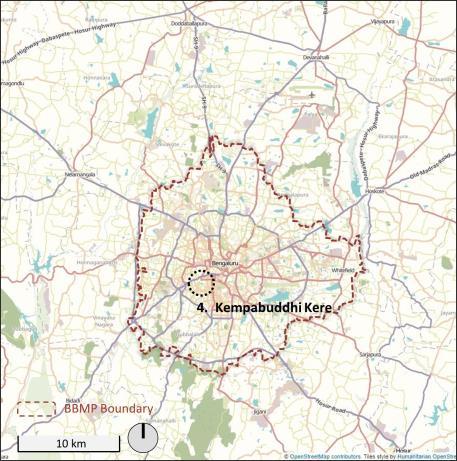

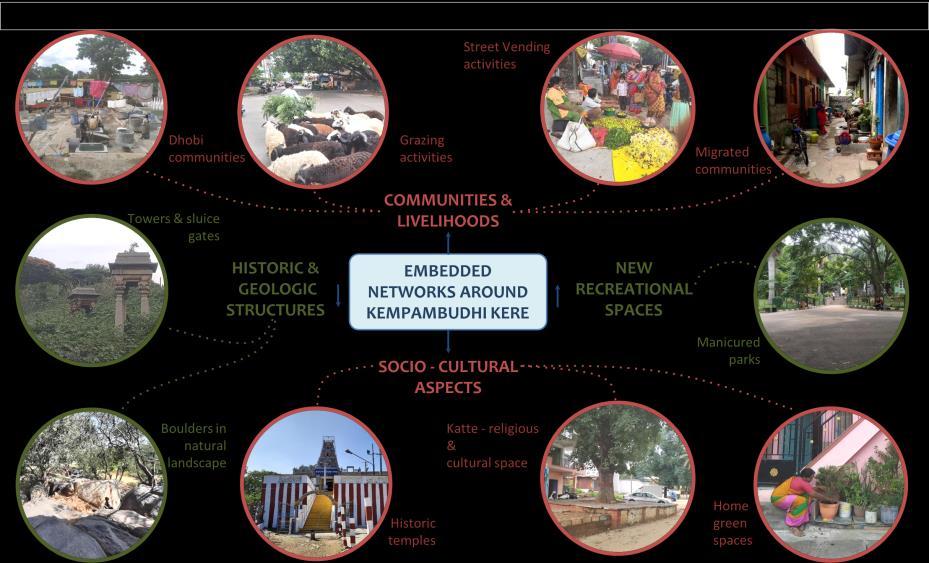

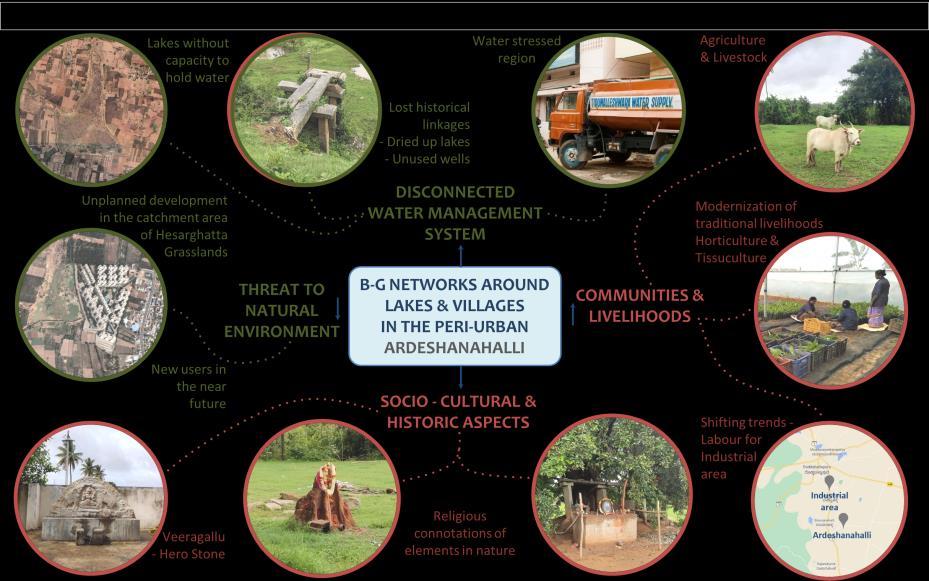

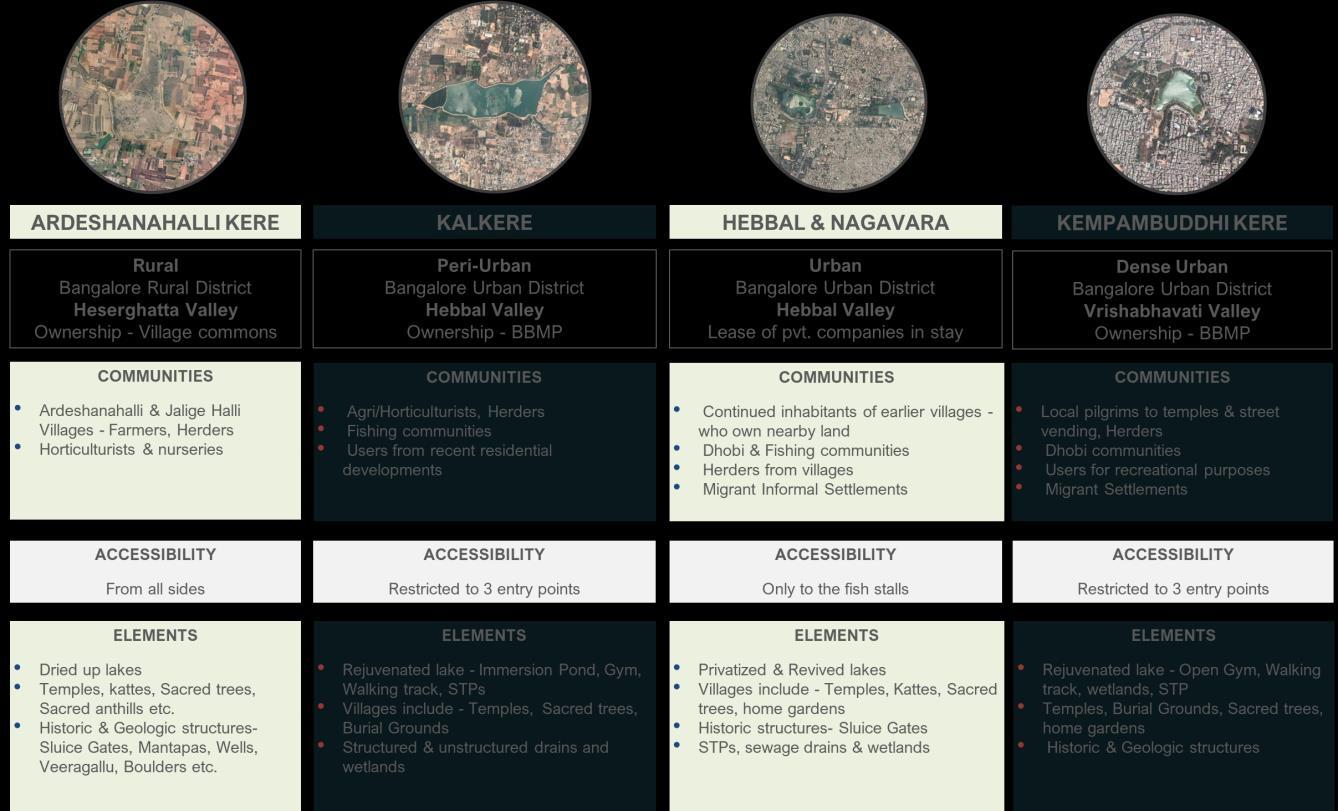

Identification of 3 scales within existing BGN ▪ Introducing study sites ▪ Site 1: Ardeshanahalli Kere ▪ Site 2: Kalkere ▪ Site 3: Kempabudhi Kere ▪ Site 4: Hebbal and Nagavara ▪ Site 5: Kempabudhi Kere ▪ Mapping and Foreground Associated Eco-system Services ▪

Comparative Summary of Blue-green Networks Across Sites

▪

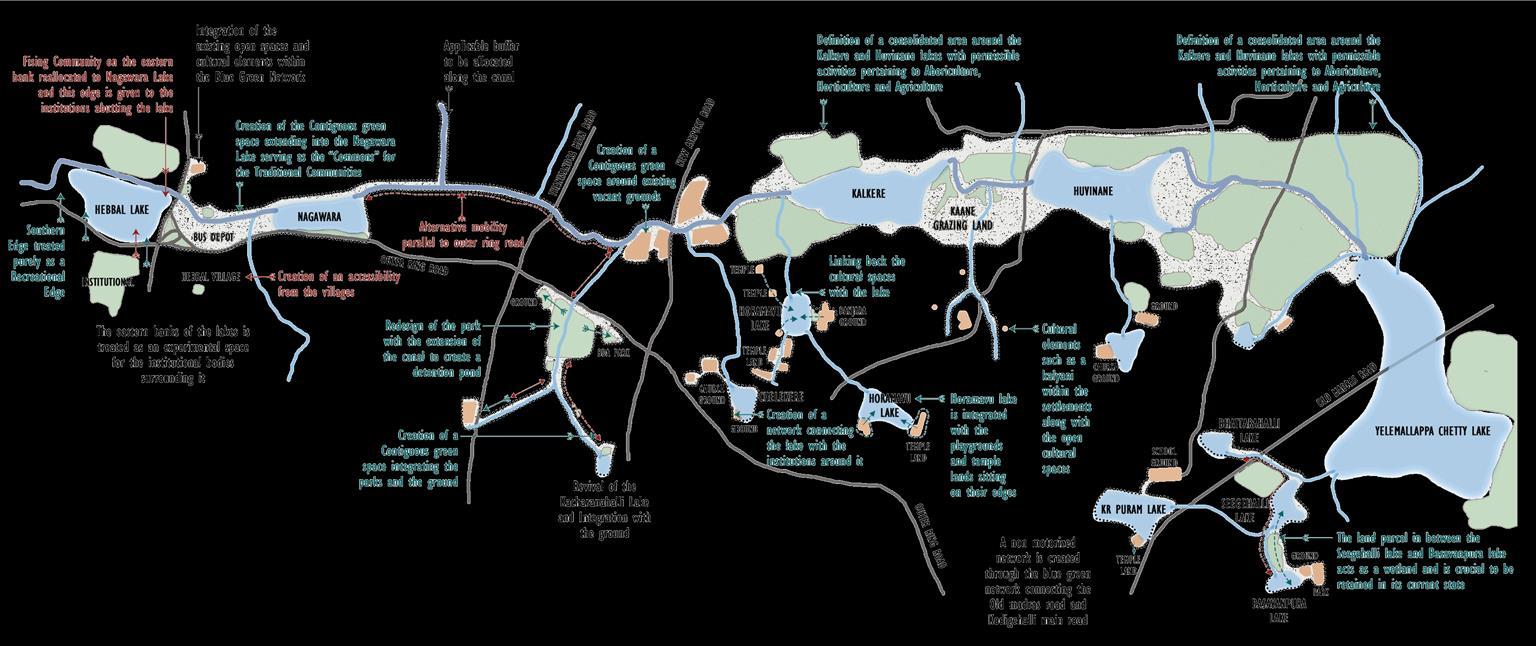

Demonstration strategies at Hebbal Valley (HebbalYelemallappa Lake Series) ▪

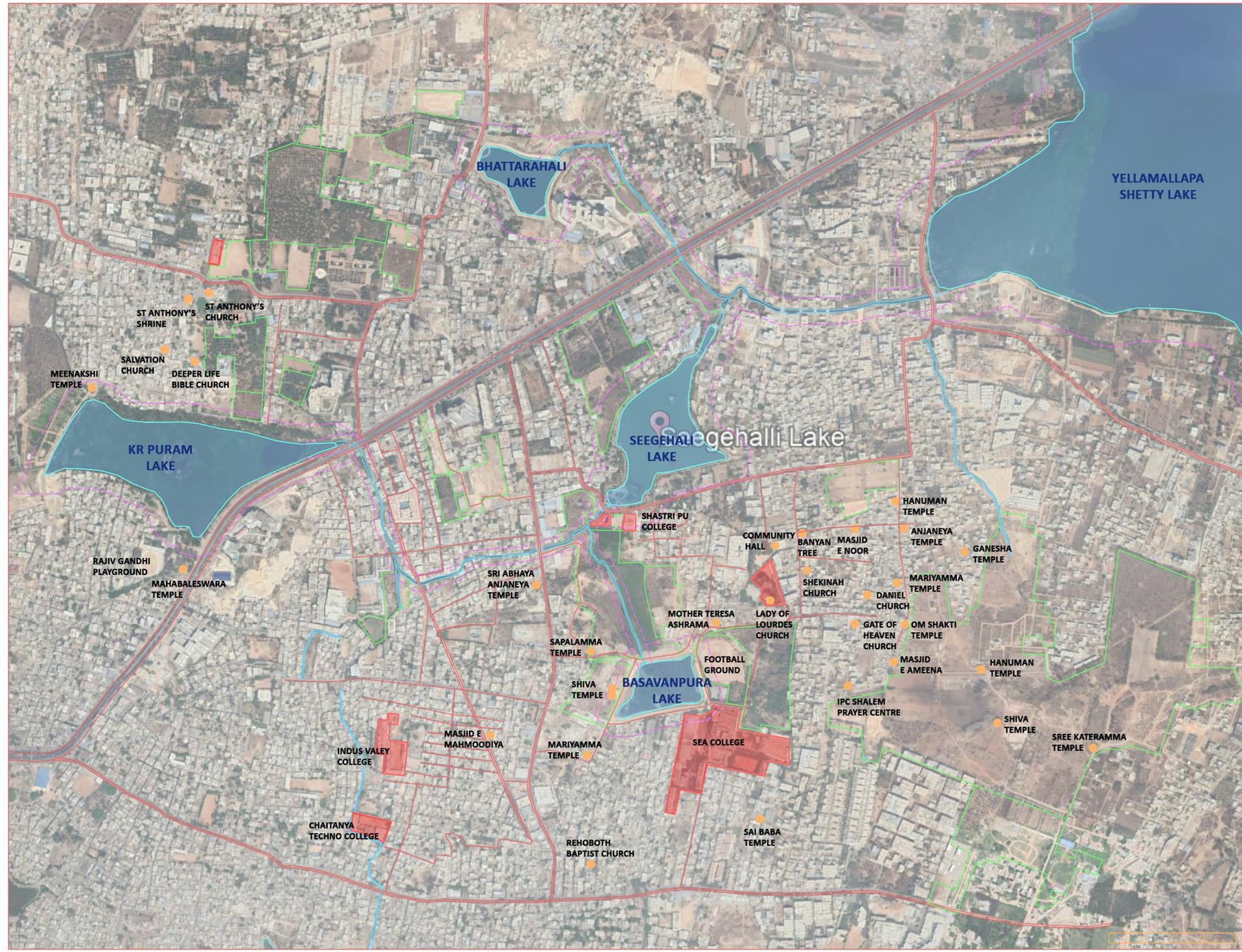

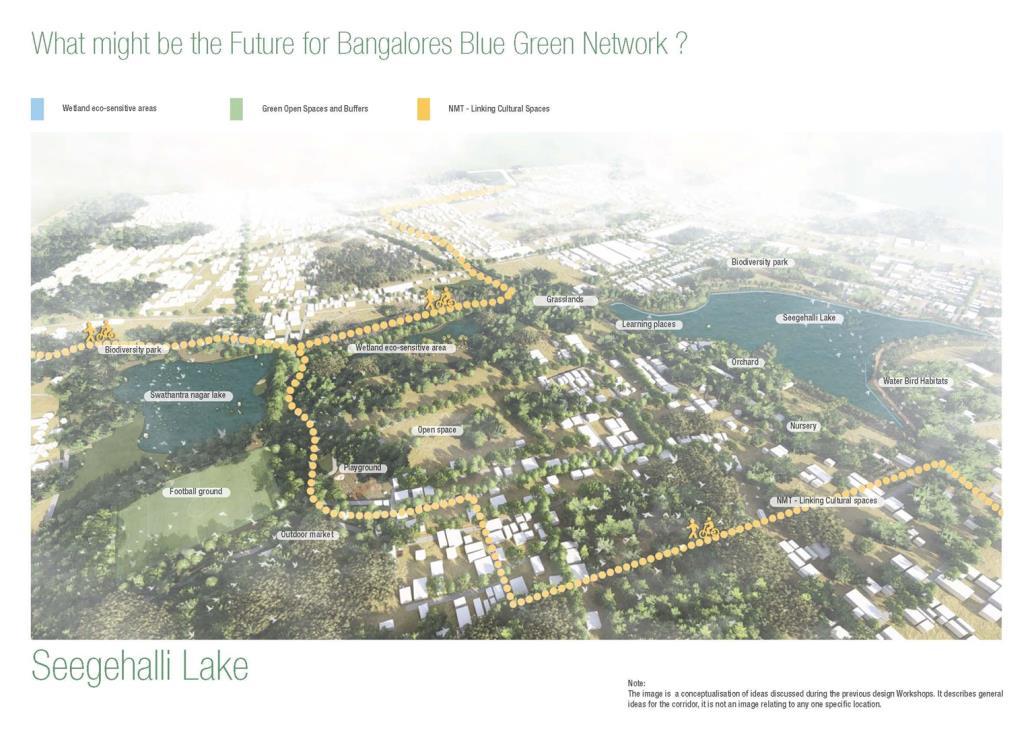

Demonstration strategies at Segehalli Lake ▪ Strategies at Precinct Level ▪

Demonstration strategies at precinct scale ▪

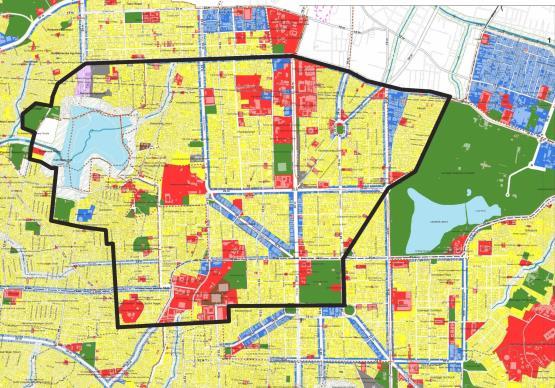

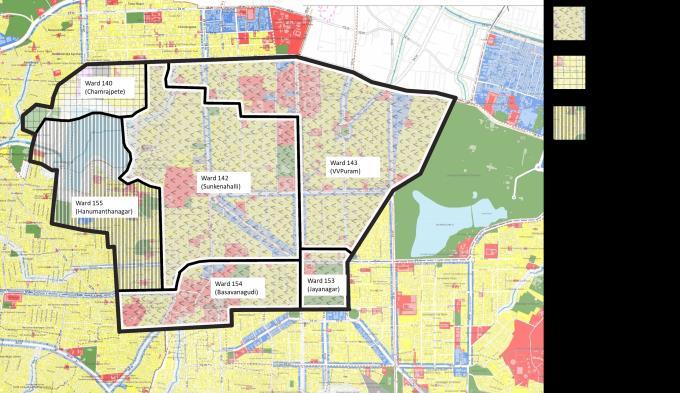

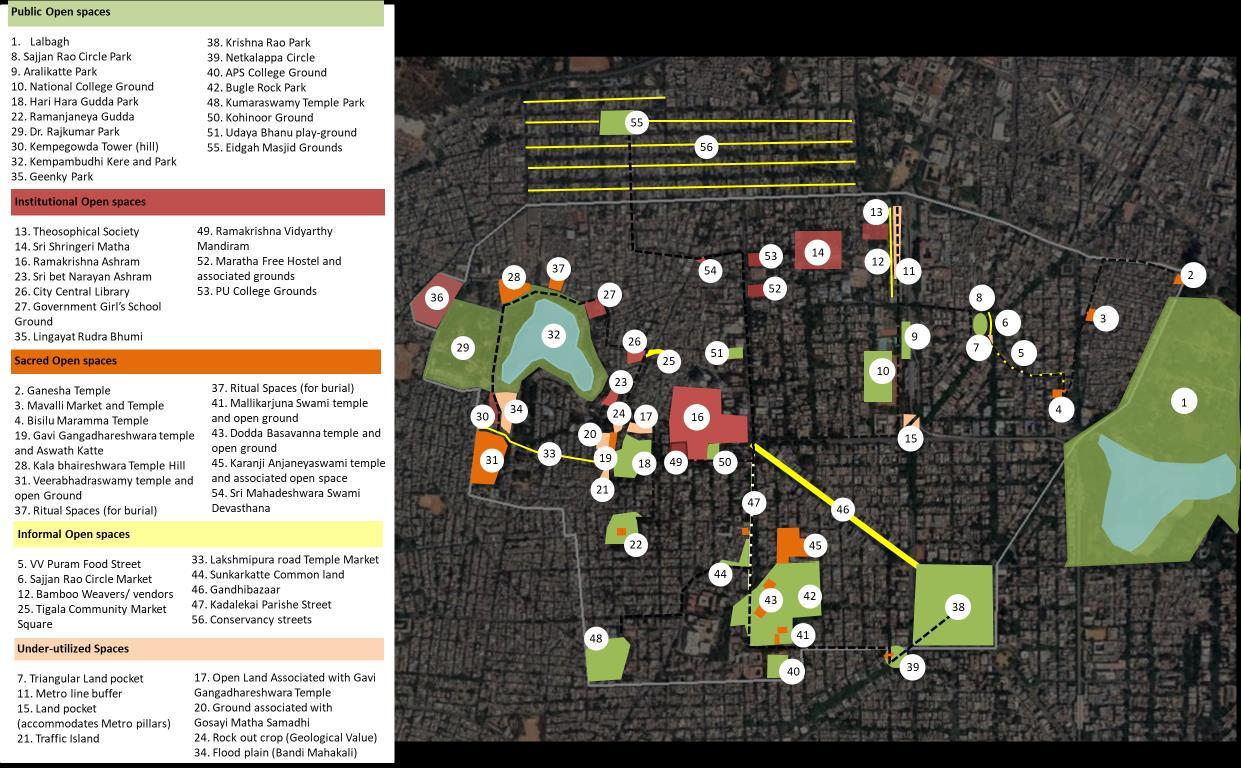

Selected Precinct: Basavanagudi, Gavipuram, VV Puram and Mavalli

SummaryBengaluru’s blue-green networks, when studied through an ecosystem services lens at multiple scales, embodying multiple functions appear networked at places and disaggregated at others. Understanding what constitutes the network – the elements of the network - as well as its interconnections (or lack thereof) is important to arrive at a comprehensive, yet nuanced understanding of the green and blue, one that takes into consideration social challenges, catalysts of development, cultural considerations and underlying environmental systems.

To facilitate this understanding Blue- Green spaces were identified, mapped and analysed across three scales: the neighborhood, the city, and the larger city region. The greens and blues at each of these scales provide specific and varied services to the city. Notably, care was taken to not force a blue-green co-existence of spaces, especially in the city center that is densely urbanized. At all three scales, to understand the Blue Green Networks (BGN), apart from identifying the blues and the attendant greens, a temporal understanding of the socio-economic, ecological, cultural and recreational linkages, functionalities and the attendant uses were comprehended, mapped and analysed.

As was evident from a detail reading at the three scales, the networks and functionalities that the blue- green spaces embody are diverse and complex. Identifying these functionalities and uses will allow, on one hand, for an integrated approach to enhance the socio-ecological and spatial functioning of green spaces in the city. On the other, it will contribute

This report begins by briefly tracing the conceptual evolution of blue-green systems, primarily through global definitions. The conceptual tracing reveals the need to move beyond a ‘blue green infrastructure’ approach towards one that acknowledges and foregrounds the blue green as a ‘networked and nested’ system. The section ascertains the need for such an approach in the context of the global South and traces the conceptual tenets of the blue- green in the Indian context. The report also engages with some of the existing and emerging policy narratives to understand the gaps and the opportunities.

strategic framework, the subsequent section attempts to understand the blue green networks in the city, and the aspects (like topography and development) that are shaping and re shaping these networks. This expanded understanding at the city scale revealed the insufficient comprehension of the manifestations and functionalities of blue-green spaces at various scales, which led to the conceptualization of these networks across three scales- the city region, the city, and the neighborhood.

towards enhancing social cohesion, equity and livability, integrating insights from diverse knowledge systems and incorporating the diversity and specificity of stakeholder relationship with BGN into strategies, and address the challenge of insufficient engagement with questions of power and access which results in projects reinforcing existing social inequalities.

The next section weighs on this conceptual understanding and puts forth a four-pillared strategic framework for the study of blue green networks for Bengaluru. Following this

Four sites across the city were selected to demonstrate the process of reading blue green networks in these sites, and mapping and foregrounding of eco-system-based services in them. This nuanced reading of the sites led to the framing of comprehensive strategies that are cognizant of the

networked and nested blue- green systems at various scales in the city. The regional strategies are demonstrated at the Hebbal- Yelemallapa lake series in the Hebbal valley. How these regional strategies talk to the smaller nested scales (like for a single lake and its surrounding) is demonstrated at Segehalli lake and its surrounding. By taking a case at the precinct scale (from Kempabudhi lake to Lalbagh), the report also demonstrates how alternate modes of enquiry emanating from a bottom up reading of spaces can reveal a nuanced understanding of everyday open spaces. This approach provides an alternative understanding of the public and semi-public green spaces, including the nuances that exist at street level/ at human experience level.

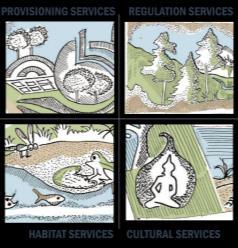

Initially articulated as green infrastructure, the concept adapts a landscape ecology understanding to spatial planning. Its first definition by Benedict and McMahon in 2002 highlighted how the interconnected system of green spaces constitutes a life support system to communities by providing clean air and water. While initial definitions conceptualized ‘green’ in terms of the colour of the spaces, as definitions evolved ‘green’ came to refer to an adjective of environmental friendliness and green infrastructure expanded to include a wide range of natural, seminatural and natural spaces within its ambit (Wright, 2011). In terms of functions too, from the initial focus on provisioning and regulation services, a wide range of cultural and habitat services came to be acknowledged.

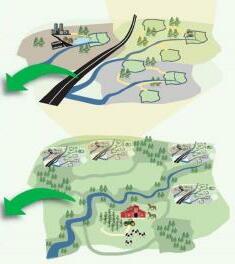

The adjacent box gives a chronological account of the evolving definitions of BGI. While varying in terminology these definitions largely highlight three main goals to which green infrastructure corresponds: climate response, health and urban resilience. Carrying over understanding of the dynamics that characterize flow of energy, materials, nutrients, species, and people across a landscape, the concept seeks to direct the strategic spatial organization and configuration of urban environments to achieve a range of biotic, abiotic and cultural goals (Ahern, 2007). It positions itself as an alternative to ‘grey infrastructure’ i.e. artificially engineered solutions that in addition to being capital intensive to build, operate, maintain and replace is seen to shift amplified risks to other locations (Brears, 2018).

These definitions highlight three aspects as definitive in the conceptualization and operationalization of blue-green infrastructure: Multi-scalarity, Multi-functionality, and Networks

• Landscapes as hierarchical nested systems with constraints and connections in ecological processes spread across multiple scales.

• Approached in policy and praxis at various geographic levels and overlapping jurisdictional boundaries.

• Compared to grey infrastructure that works by shifting amplified risks, green infrastructure seeks to move from damage control to contributive dimensions.

• Multi-dimensional benefits can be conceptualized through the ecosystem services concept as including the following services:

• It refers to the degree to which a landscape facilitates or impedes the flow of energy, materials, nutrients, species, and people across a landscape.

• Approaches focus on identifying key points for physical linkages, where important connections exist, or where connections should be made.

Existing definitions tend to embody an infrastructure-based understanding i.e., of discrete blue, green and grey elements performing in a multi-scalar, multi-functional and interconnected manner. However, this infrastructure-based understanding while useful in conceptualizing certain provisioning, regulation and habitat services, misses out especially on the cultural services. It also frames the relationship between natural elements and humans in an extractive manner, missing out on the co-production of ecosystem services by interlinked socio-ecological systems.

To address these insufficiencies, it is critical to move from an infrastructure-based understanding to a network-based understanding of blue green. The network-based understanding foregrounds the embedded functioning of the blue-green network within socio-cultural contexts. It allows for both a broadening and a deepening. It broadens the ambit of elements constitutive of the blue-green network from the conventionally considered blue, green and grey elements to other socio-cultural spaces that might straddle these categories in terms of typology. It also deepens understanding of the blue-green network to acknowledge the specificity of its manifestation and functioning in relation to socio-cultural fabrics and histories of the context.

The adoption and evidencing of the blue-green infrastructure concept remains absent or sparse in cities of the Global South. This has been linked to the presence of ‘more pressing concerns’ such as poverty, unemployment, housing inadequacies, infrastructure deficiencies and resource deprivations overlapping with and exacerbating risks associated with climate change and environmental degradation. Unfolding within weak regulatory and institutional contexts, urban planning frameworks and policies in these cities tend to embody a reactive rather than proactive stance towards challenges of urbanization and climate change.

These factors however do not preclude the potential relevance, applicability and adaptability of the blue-green infrastructure concept. Rather, they highlight the need to explore, align and embed it within larger calls to develop urban planning frameworks that respond to the stubborn realities of the Global South.

Marked by shared histories of colonial and post-colonial development trajectories, urban planning mechanisms in cities of the Global South largely exist as legacy instruments mismatched with contextual realities. Given the heterogeneity, complexity and temporality of South urbanism, there is a rising awareness that responding to these challenges will require a bottom-up and grounded reinterpretation of urban planning. This awareness provides an ideal context for mainstreaming understanding of the dependence of urban systems on ecosystems and reorienting urbanization patterns with natural cycles, limits and flows.

While blue-green infrastructure as a term has not found much representation in statutory frameworks of cities of the Global South, there have been policies and projects that seek to leverage blue-green networks towards various

socio-economic and environmental goals. With some of them at the national scale, such as China’s Sponge City program and some of them at the city scale, such as Singapore’s ABC Water program, these initiatives establish the applicability of the concept in the Global South. However, with the traditional focus on risk reduction, recreation and aesthetics dominating within these initiatives, the full range of applicability of the concept remains unexplored. It is vital that the potential of BGI as a strategy capable of articulating, engaging and responding to the trade-offs and linkages between the aims of equity, economy and sustainability be foregrounded while applying it to urban geographies of the Global South.

Adapting the blue-green infrastructure concept to the Global South will require recognizing that there exists an embedded understanding of BGI in cities of the Global South. This embedded understanding of BGI is often embodied in the traditional ecological knowledge systems, livelihoods and management practices that have been marginalized by formal planning frameworks. They have the potential to reveal the specificities, divergences and diversities in the conception of and relationship with BGI within cities of the Global South. For example, compared to the Global North, BGI in the Global South shares a more integral relationship with livelihoods especially of the urban poor in cities. Further, the productive landscape overlaps with the sacred landscapes contributing to the conservation and sustainable usage of natural resources. Eliciting and integrating insights from these grounded knowledge systems is essential not only for operationalization the BGI concept in Southern cities but also towards re-thinking global definitions and opening avenues for theoretical innovation.

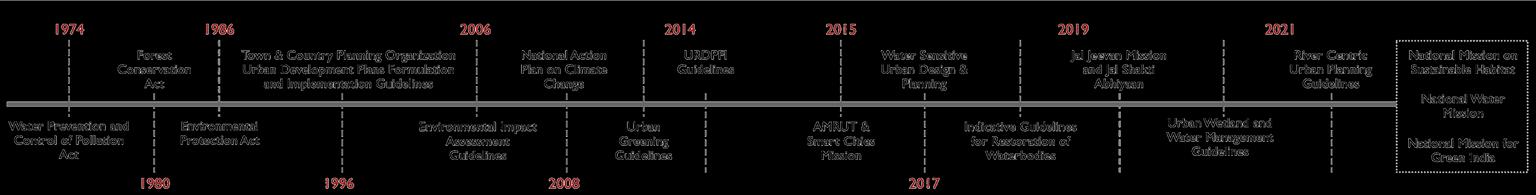

India has a strong ethos of nature conservation ingrained into its cultural system which has been given recognition in the Indian Constitution under Article 48(a), ‘the State shall endeavour to protect and improve the environment and to safeguard forests and wildlife in the country.’ However real orientation towards contemporary environmental issues began in the aftermath of the 1972 Stockholm Conference on Human Environment (Singh and Singh, 2021). In 1980, the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) was set up to be the apex institution for conservation of flora, fauna, forests and wildlife (Sandhu and Sidhu, 2015). Under the aegis of these institutions, the federal government began enacting more wide-ranging and comprehensive environmental laws. Currently India has enacted more than 200 laws for protecting the environment. In addition to this there have been a plethora of policies and programs that have been implemented over the years by central, state and local agencies for conservation and management of blue-green assets.

Institutional provisions in the Indian context

While there has been an institutionalization of the need for natural resource conservation and sustainable development patterns, there are certain gaps in this policy framework that need to be addressed.

Within natural resource conservation there has been inordinate focus on conservation of water resources. A similar bias is seen also with respect to the work on groundthere has been an influx of civil society initiatives and citizen activism around the protection and restoration of water resources. This focus, while definitely constituting a step forward from extractive development patterns, can turn out to be ineffectual or problematic, if water resource conservation is conceptualized in separation from its associated green spaces and integrated function with the ecosystem. There is a need to move beyond the water or blue-centric focus of policies to foreground both the blue

and the green in tandem. The question of decentralization and co-ordinated functioning remains a pain point within the existing policy framework. The plethora of guidelines that have been produced to guide municipalities to take action towards building urban resilience, have been of limited use in directing action on ground. Further, the policies and guidelines have insufficiently addressed how institutions in various sectors and tiers of government will coordinate action. The lack of such a coordination is especially problematic for natural resource management since the extents of ecological dynamics often transcends administrative boundaries. Keeping this in mind there is need for policies to specifically address how horizontal and vertical coordination can be fostered towards resilience building. The focus of policies tends to be on control and conservation, ignoring the performative dimensions of

blue-green assets. Such a myopic focus results in displacing, marginalizing and dis-incentivizing many embedded socio-ecological relationships which are critical to the ecosystem functioning. This regulatory and standardized approach manufactures a dissonance between conservation and developmental imperatives. It also manufactures informality, as communities whose lives and livelihoods depend on natural resources see a significant depreciation in the quality of their life. There is a need to move from a one-size-fit-all approach towards foregrounding the performative dimensions of natural resources and the socio-ecological relationships that characterize its functioning.

Characterized by tree-lined avenues and parks over lapping with IT hubs that house global industries, the city has come to be known by names such as ‘Garden City’ and ‘Silicon Valley’. From a small village in the 12th century, its growth to a mega-city with a population of 84.4 lakh (2011 census) and extent of 741 sq.km. is marked by a rich and contested history. The context for this history is set by the geological, topographical and hydrological characteristics of the region.

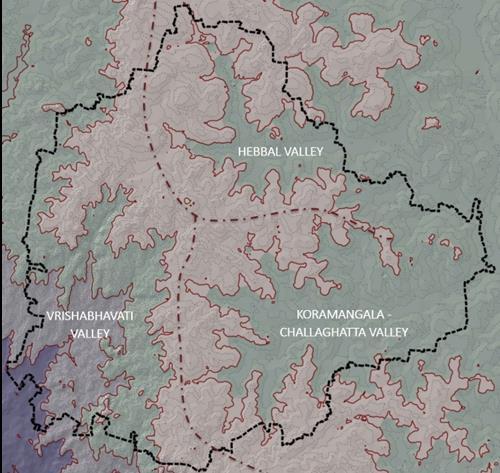

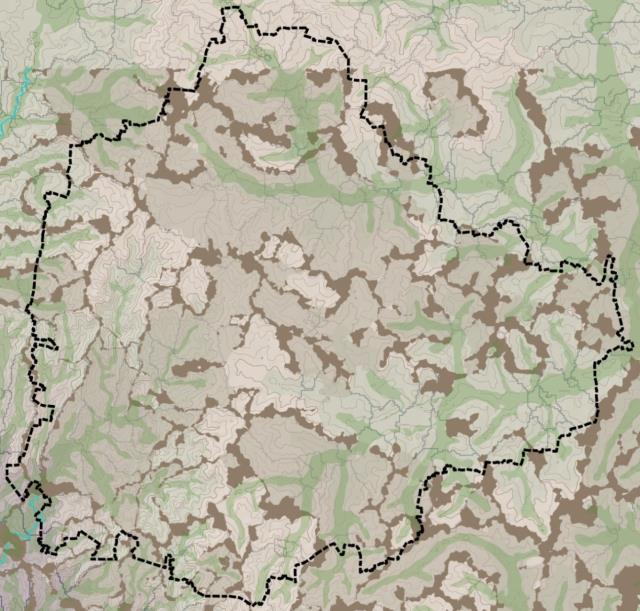

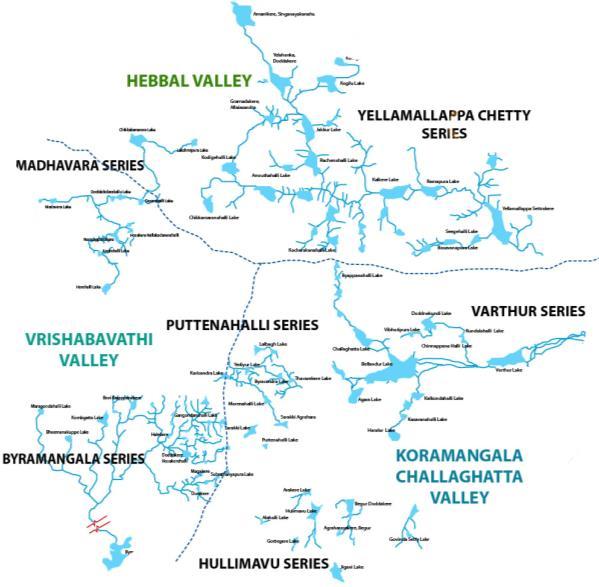

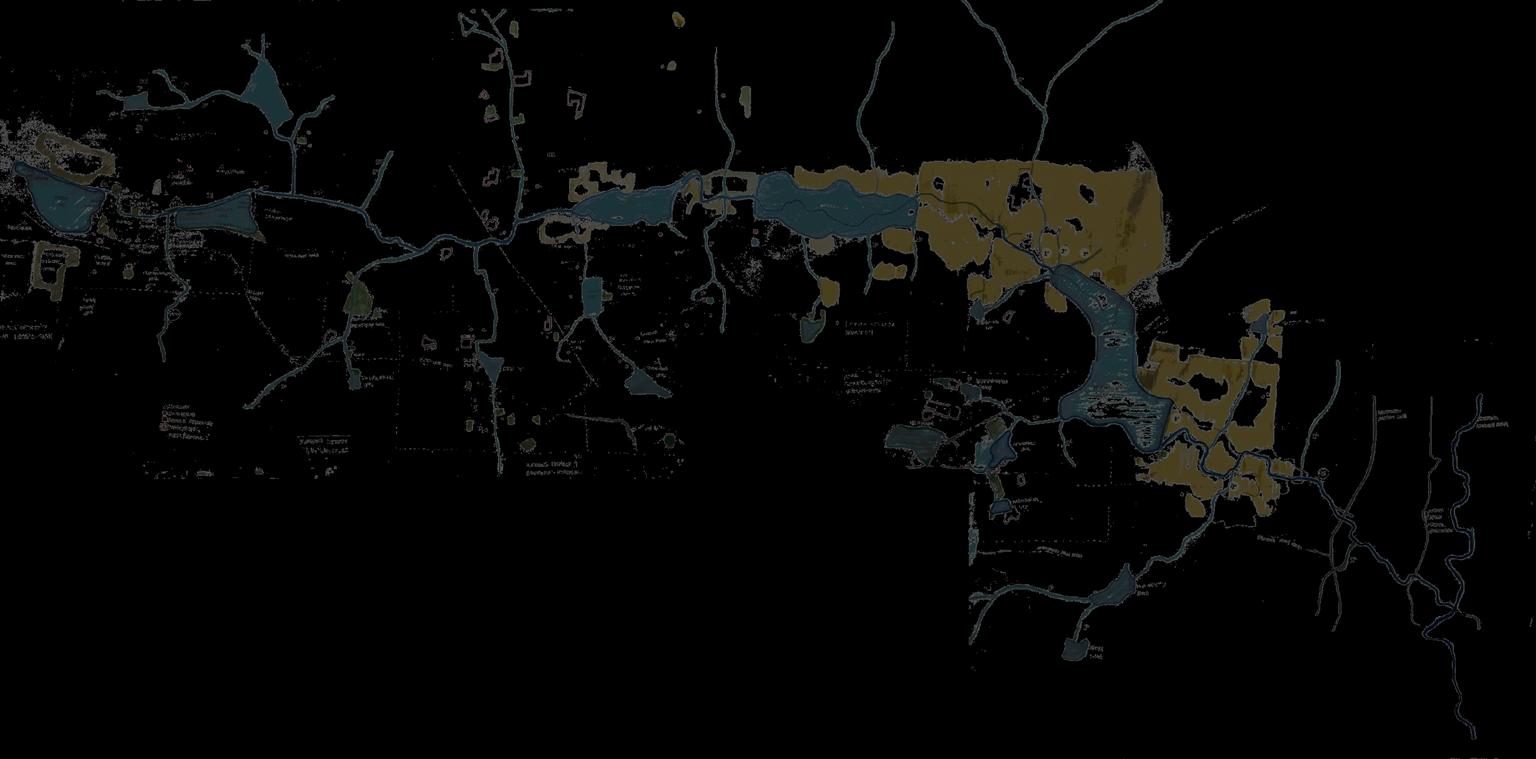

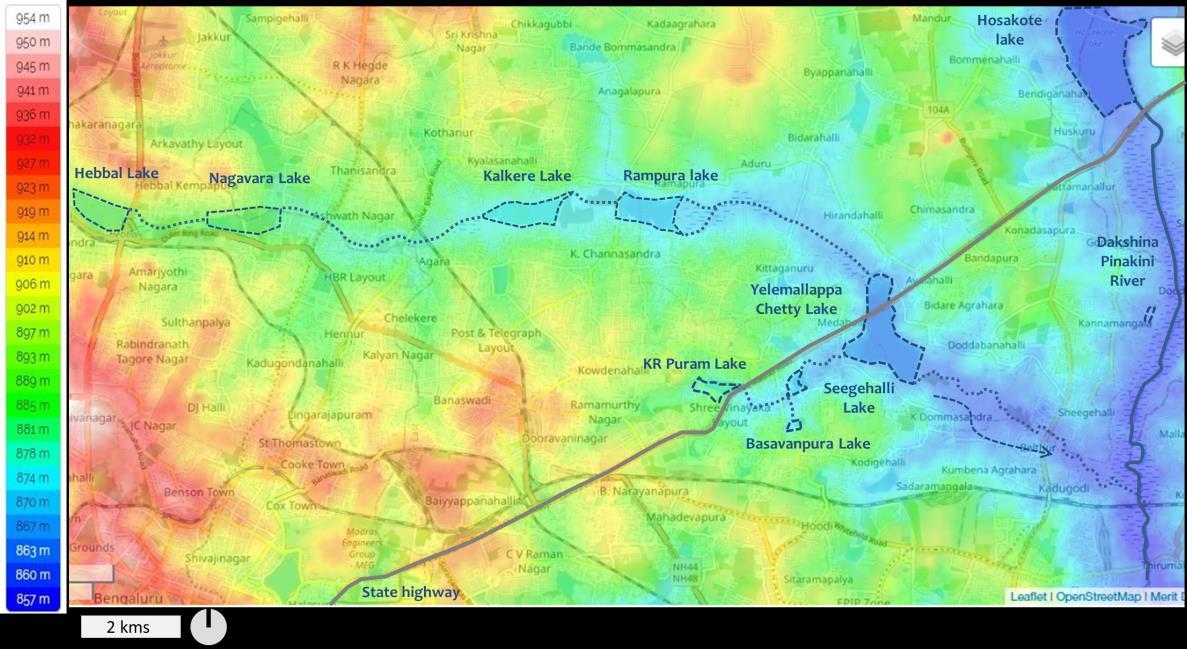

The characteristic topography of Bengaluru has been a critical determinant for its water systems and water flow dynamics which in turn has determined how human life and development aggregated. The topography takes the shape of a plateau that can be compared to an inverted saucer with the highest areas located in a flat center and gradual slopes towards the south-east and south-west. This terrain is further characterized by several interspersed ridges and valleys that delineate smaller watersheds in the land. A central ridge that runs from north to south marks the structure of the land morphology defining three major valley systems. These valley systems are the Koramangala - Challaghatta Valley, the Vrishabhavati Valley, and the Hebbal Valley Systems.

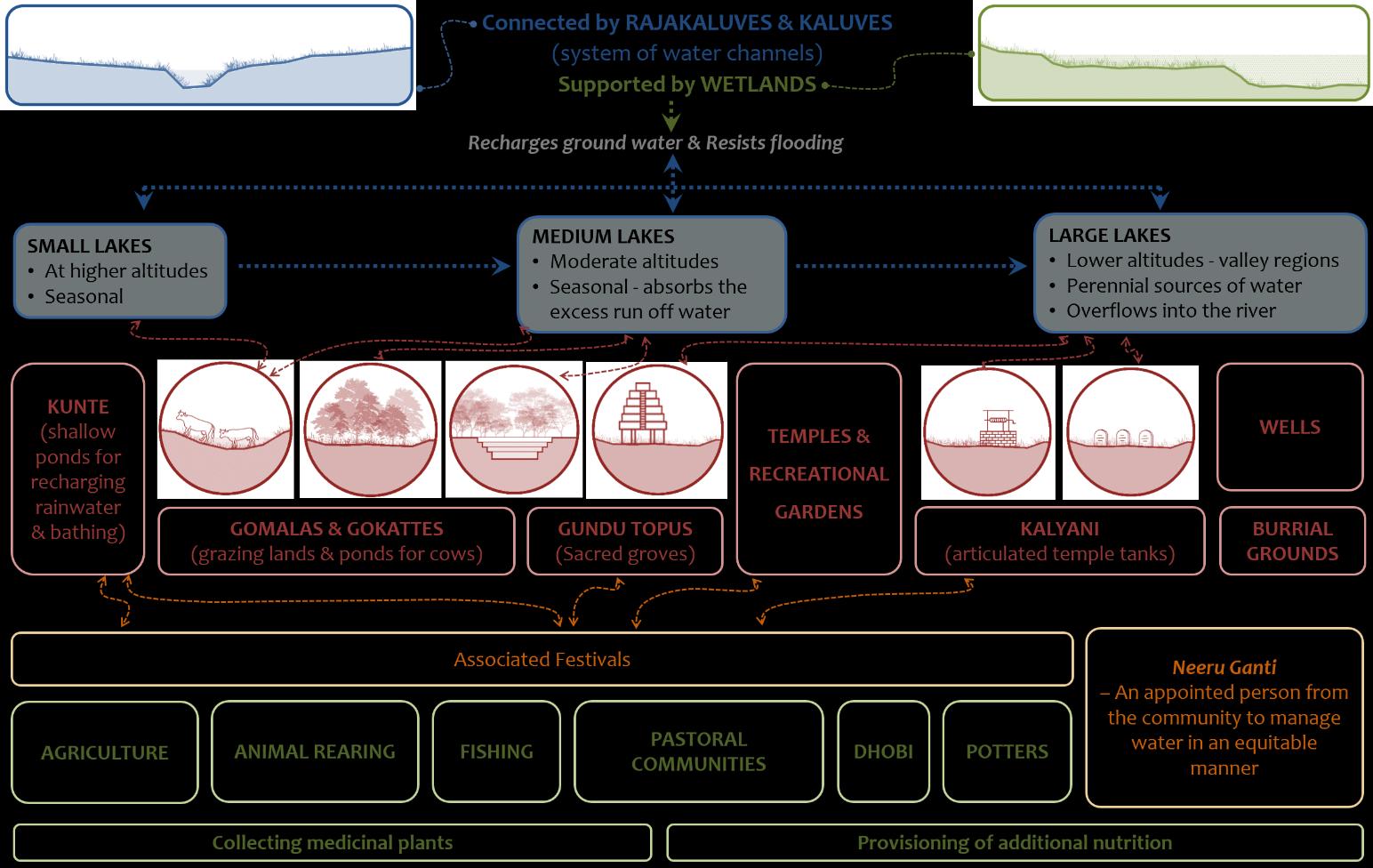

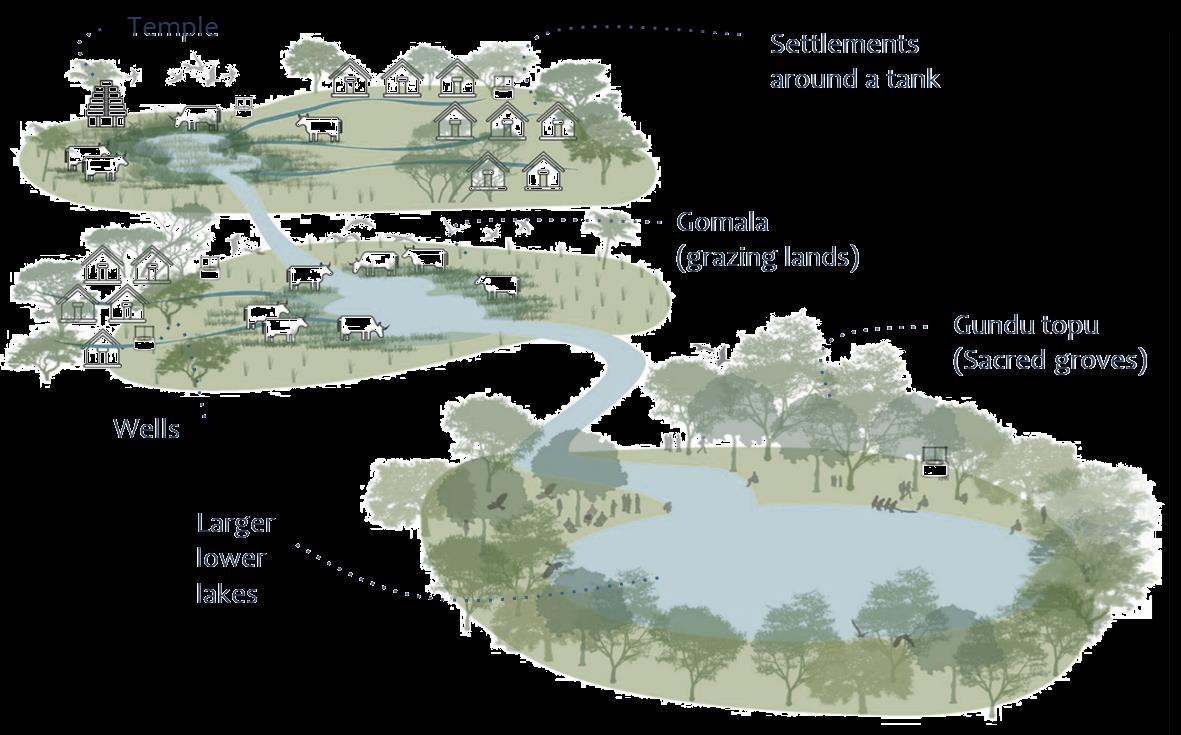

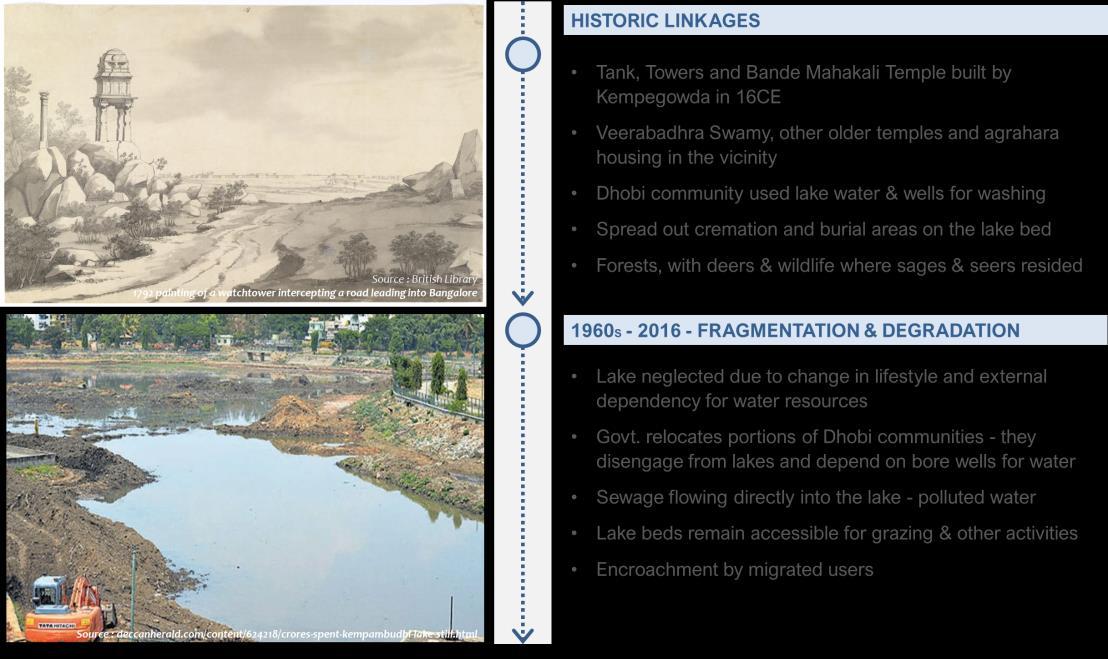

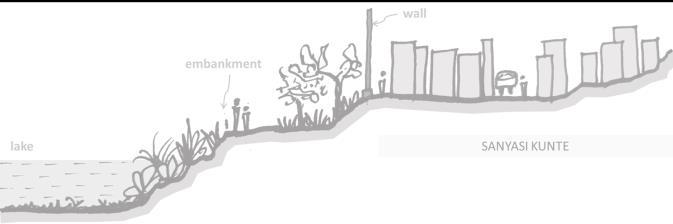

The historically developed lake networks essentially leveraged upon this ridge and valley system. Created by damming rain-fed streams, these lakes were envisioned as graded system with lakes of varying sizes and varying functions connected by drains known as rajakaluve. This downward flow of surplus water from one lake to the next was controlled by overflow weirs known as tabu that allowed equal distribution and perennial water supply. While many of these connections and systems that allowed the lake network to function as an integrated system have been lost over time, existing linkages allow us to identify 5 lake series in the 3 valley systems.

The historically developed lake and drainage systems of Bangalore stand as evidence of a now attenuated culture of environmental stewardship that balanced between conservation and sustainable usage. The lakes were constructed and managed by adjacent village communities with the support of local chieftains and rulers. While commoners built small water bodies for the benefit of the community, kings and rulers undertook large irrigation works as part of their religious and social obligations (Iyengar, 2007). Within the village communities, specific families and groups were responsible for particular maintenance tasks such as desilting and maintenance of canals and tank bunds. Further, access for various activities such as fishing, irrigation, grazing and collection of fodder was managed through set of spatio-temporal rules and arrangements (D’souza and Nagendra, 2011). The blue-green network therefore functioned as deeply embedded with the lives and livelihoods of communities

Illustration of interconnected socio-ecological systems in historic times

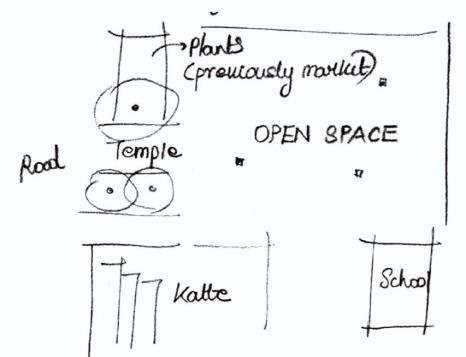

Located close to the settlements, Kunte is a seasonal shallow pond that behaves like a soak pit and recharges rainwater for the nearby wells. These were mostly used for domestic purposes. These were prominent location for village festivities with a temple on its banks and were built & maintained by a circling responsibility of individuals and families within the village.

Gomala were similar to kunte but were largely reserved for cattle use. After the cattle grazed in the outskirts of the town they would come back and drink from the gokkatte

Neeruganti - Neeruganti were persons who were charged with managing the control and distribution of water from the community tank for irrigation purposes.

Niru Bari - Niru bari was a system of land allotment and water distribution at various levels such that it was in the personal interest of the farmer to ensure water flow from one field to the next (Kalave, 2007).

The lakes and their wetlands were a resource base for various livelihoods such as fishing, livestock rearing, and agriculture. Towards supporting these livelihoods, the lakes existed as commons with fluid and temporal ownership, usage and management agreements that aligned with ecological dynamics.

The wetlands of the lake were a site for communities to grow various types of vegetables and greens along with providing fodder for livestock rearing.

Most common source of water in the Bangalore region up to the mid 19C. The cascading system of lakes & ponds would recharge the ground water for the wells. Apart from individual houses, villages had intricately designed common wells - 1,960 wells were recorded in 1885. They range from 1.5 ft to 20 ft wide wells.

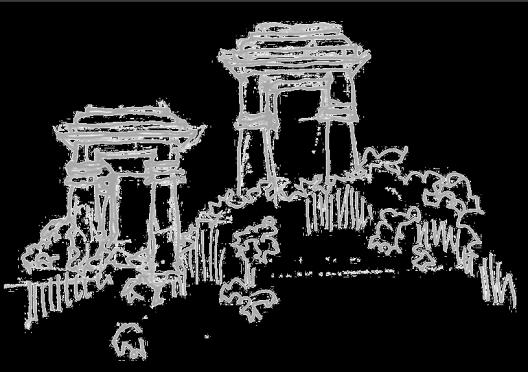

Devara Kadu / Gundu Topus

Protected wooded areas close to settlements that hosted the local village deities. Produce was shared from this commonly held land – Contained local revered trees as Banyan, Tamarind, Jackfruit, Peepal etc. Certain scared trees in the gundu topu or within the settlement are raised on a special platform called katte.

With a strong tradition of nature worship, ashwath katte were a predominant ordering element of village settlements that survived into the urban fabric. They were usually built around peepul (Ficus Religiosa) trees, which in addition to having multiple religious practices and beliefs associated with them, are known for their ecological importance as keystone species.

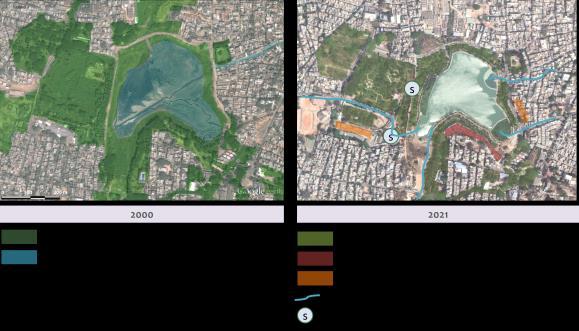

Bangalore’s population has shown a 10-fold increase between 1951-2011. This urban growth has been accompanied by significant environmental degradation (Ramachandra et.al., 2019). Between 1973 to 2016 there has been 1005 % increase in concretization or paved surfaces, 88 % decline in vegetation, 79 % decline in wetlands and drop in groundwater tables from 28 to 300 meters.

Once known as the ‘Garden City’ for its tree-lined avenues and landscaped gardens, the city now has only 1.5 million trees to support its population of 8.5 million. While in 1961 there were 262 lakes, official statistics today mention 114 lakes with only 33 of them being live lakes (Fernando, 2008). Much of the expansion of the city has been through conversion of rural geographies in its peripheries. As such the loss of blue-green assets is more pronounced in the city periphery than its core. While land-use conversion and ecosystem changes have been a constant feature of the city growth, what sets apart the environmental degradation in the recent years is its heightened scale and pace which has caused detrimental impacts on the well-being of people (Sudhira and Nagendra, 2013).

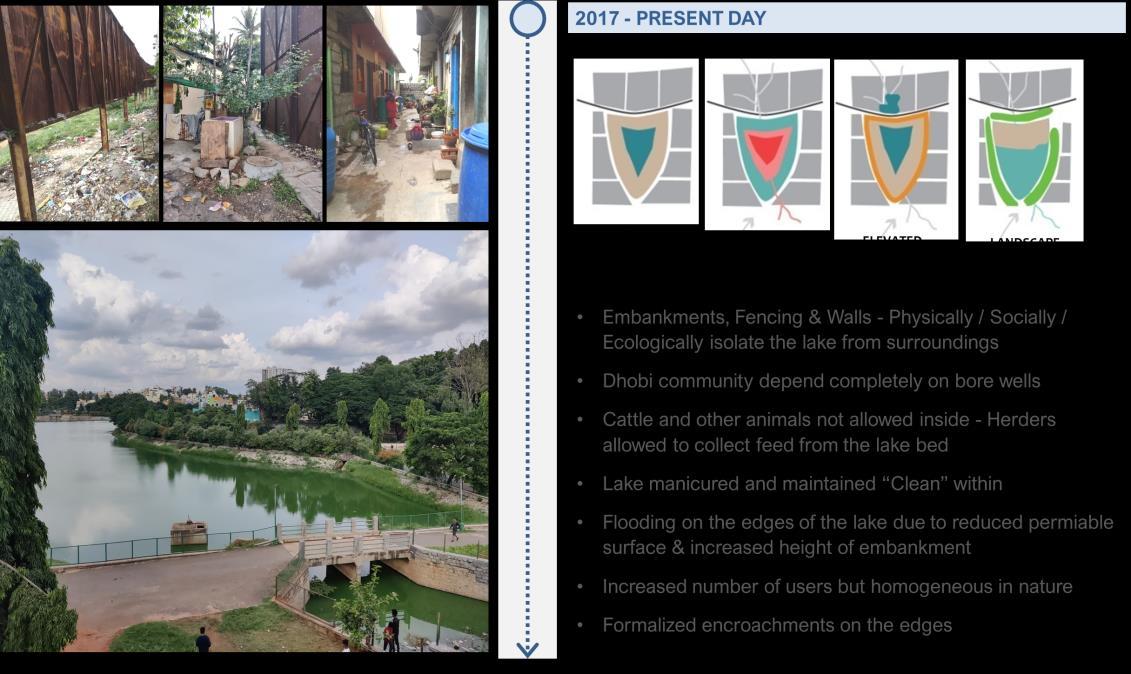

This homogenization of user groups, delinks local communities whose relationship with the lake was shaped by generational socio-cultural activities and marginalizes migrant informal communities who depend on the lake edges for additional income (Murphy et al., 2019)

Low-lying wetland areas of lakes have in many cases been used as land for development or remain as open public grounds. Some legally contested low-lying land areas are used as waste dumps or have been encroached by informal settlements. Such situations cause physical fragmentation of the larger lake and valley systems ingrained in the ecological fabric of the city.

Independent blue-green systems in the city

There has been extensive engagement by various actors with respect to the management of Blue-Green spaces in the recent years. From large scale projects and policies that apply to the regional context, to grass-root movements in neighborhood lakes, the engagement by multiple actors has brought about a momentum of change towards a sustainable future. Although, it can be observed that these multiple actors engage in different isolated parts of the overall Blue-Green network. The governmental and institutional frameworks are fragmented in their functionality too. While the BBMP is involved in lake rejuvenation projects, the BWSSB manages the STPs that feed these lakes. This fragmented approach is seen throughout the current processes of lake rejuvenation.

Lakes in the city are mostly viewed as an opportunity to beautify the neighborhood for middle/high-income residents.

In the socio-cultural front, linkages with native species of trees, stories and practices around katte, nagabana, gundu topu have slowly been reduced from its original multifunctional usages to religious usages on specific auspicious days alone. Community wells, old kalyani tanks are usually ignored and used as waste dumps unless linked to a religious space. Most such small nooks in the ecological character of the city are very easily liable to the dangers of encroachment and unplanned development. The value of such neighborhood spaces is not yet fully realized in the present conversations and planning practices.

On a regional scale, peripheries of the growing city are constantly at a clash with the regional environmental preserves. Turahalli forest, Bannarghatta National Park, Nandi Hills and Heserghatta grasslands are few of these havens which have been compromised in the name of development.

Analysis of the existing conversations around blue-green spaces reveals how there is an insufficient conceptualization of its varied manifestations and functionalities at various scales. State-led policies and guidelines tend to focus on the regional scale and in foregrounding regulatory functions of blue-green elements at that scale, tend to miss out on the interconnected blue-green elements at lower scales and their associated socio-cultural functions. The neighborhood scale design and rejuvenation projects on the other hand, tend to conceptualize blue-green elements in isolation and the focus on its recreation functions. This myopic focus of state, society and civil society actors at various scales needs to be remedied.

There is a need for an integrated approach that articulates specific strategies at the various scales while maintaining continuity and flow from one scale to the next. Towards articulating such an approach, it is necessary to define the various scales at which the analysis of the blue-green network will be distributed.

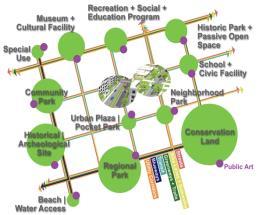

The blue-green elements at this scale will include but not be limited to: The blue-green elements at this scale will include but not be limited to: The blue-green elements at this scale will include but not be limited to:

• Rivers

• Reservoirs

• Forests

• Other bio-diversity hotspots.

The blue-green elements and ecosystem functioning at this scale are characterized by multiple interdependencies that abound urban-rural administrative boundaries. The investigation at this scale should focus on tracing these interdependencies and identifying alignment in management of natural resources by various agencies.

• Lake series

• Hierarchies of rajakaluve (drains)

• City level parks and

• Other green spaces

The ecological relationships with the blue-green elements at this scale will be oriented towards regulation and provisioning for the city as a whole The investigation at this scale should focus on the identifying practical ways in which the interconnectivity within the blue-green network can be improved to enhance urban ecosystems.

• Lakes and its immediate surroundings

• Specific sections of the rajakaluve (drains)

• Ashwatha katte and other socio-cultural spaces

• Individual and community wells

• Kitchen gardens, Neighborhood parks, Burial Grounds

The relationship between surrounding communities and the blue-green elements at this scale will include provisioning of basic needs such as food, water, fuel amongst others, livelihood dependencies and sociocultural activities. It will be critical to unpack these relationships as they existed before, the transformations and fragmentations that were brought about due to urbanization and the potential for ecological relationships to be revived within the current socio-political and economic circumstances.

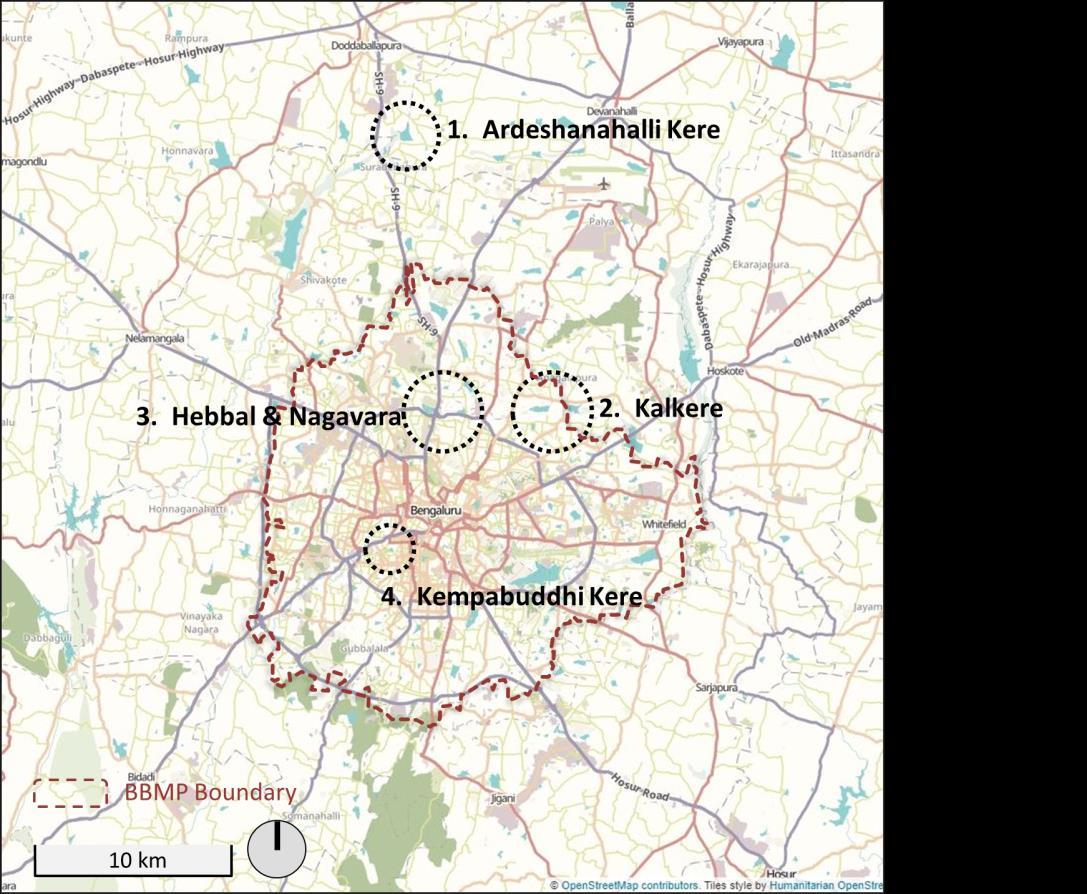

In carrying out the study, Blue- Green spaces were identified, mapped and analysed across three scales: the neighborhood, the city and the larger city region. The greens and blues at each of these scales provide specific and varied services to the city. Notably, care was taken to not force a blue-green co-existence of spaces, especially in the city center that is densely urbanized. The identified study areas included:

1. At the neighborhood level, the precinct bounded by Kempambudhi Kere on one end and Lalbagh at the other was taken. The focus at this scale is on the intermediate, disaggregated green spaces that are not necessarily anchored around a blue element.

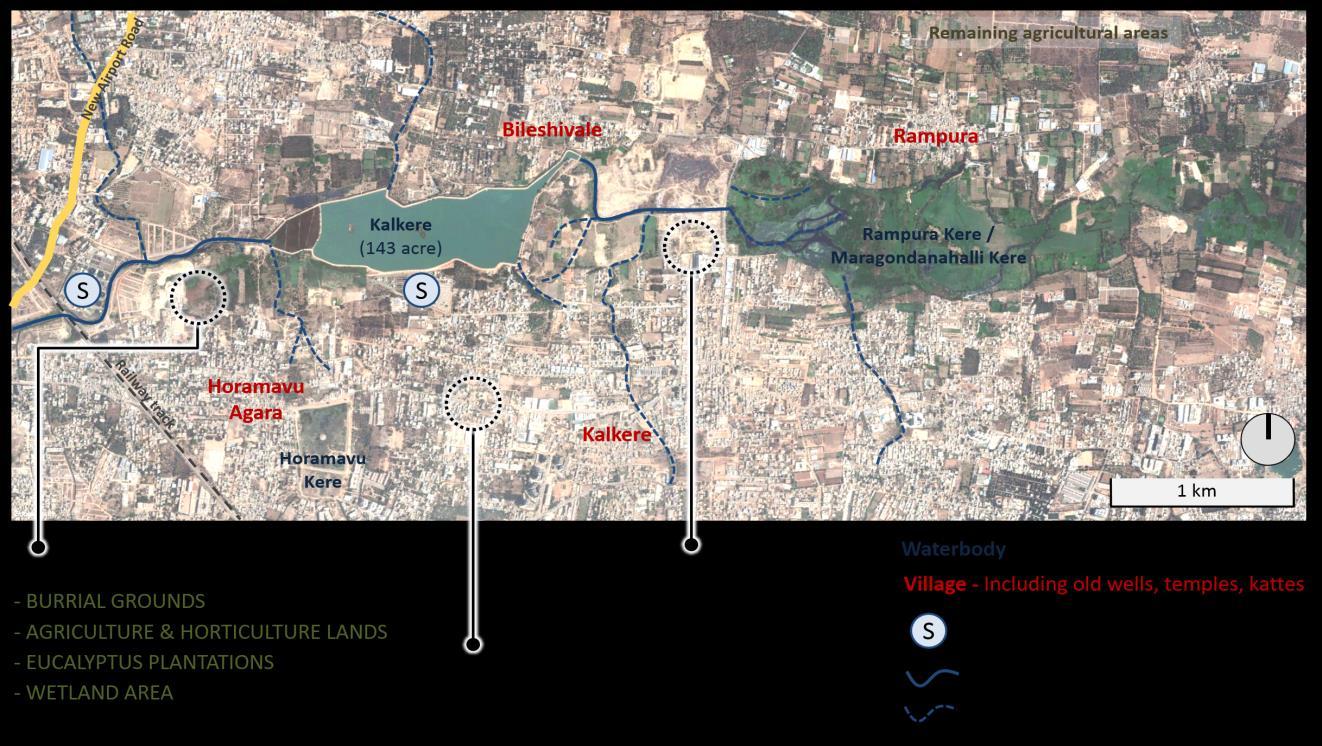

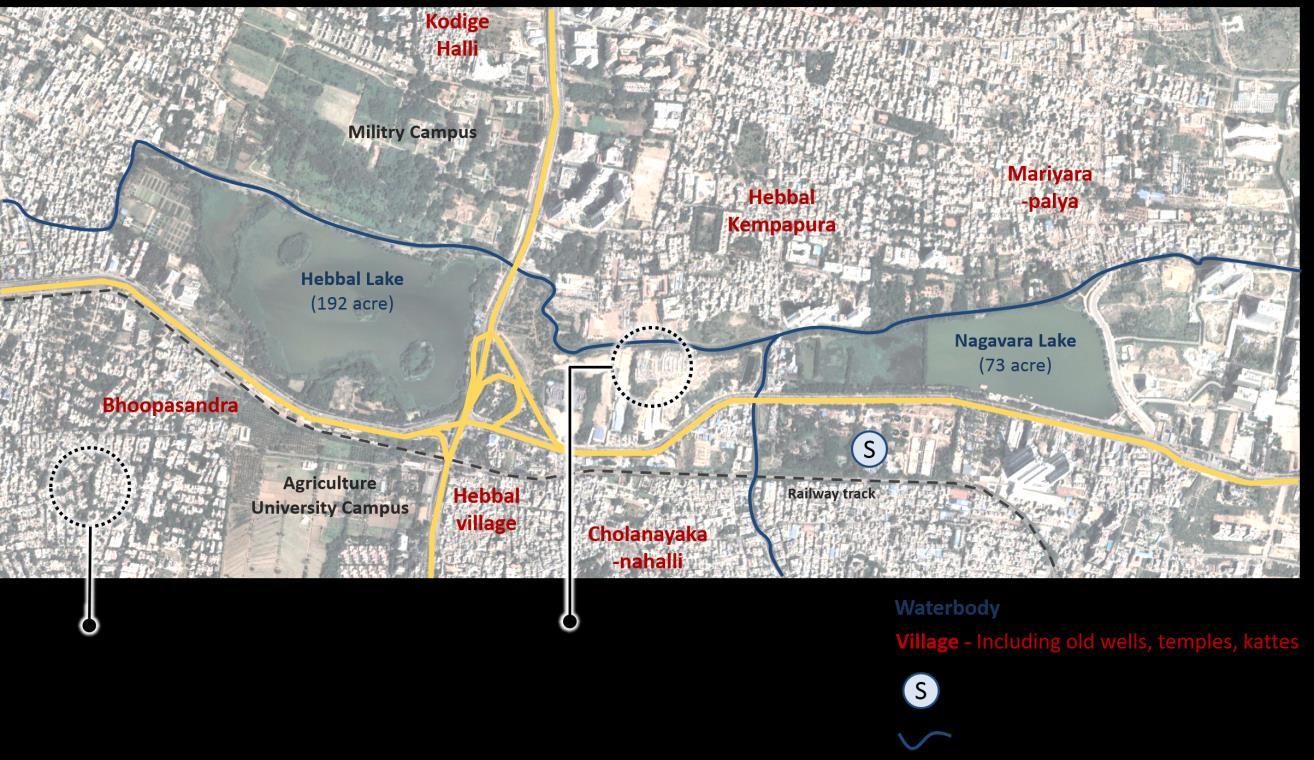

2. At the city scale, the kere overflow systems of Hebbal, Nagavara and Kalkere were studied.

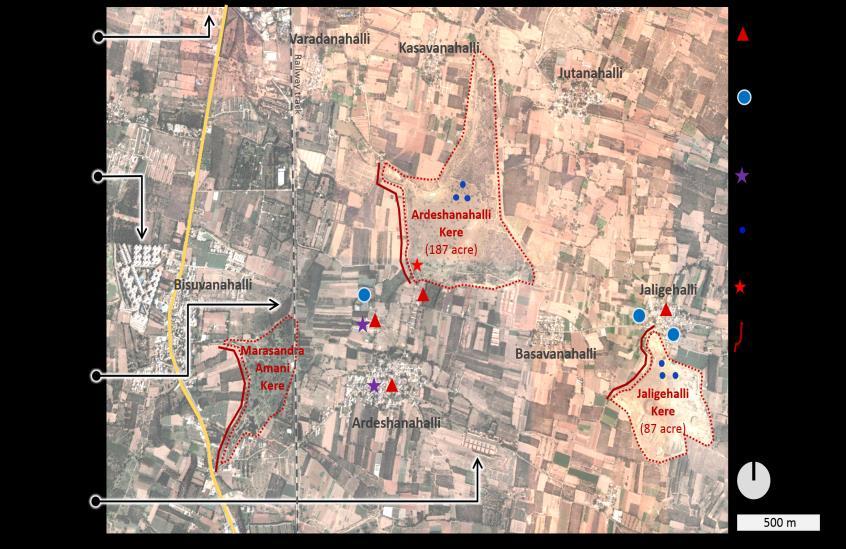

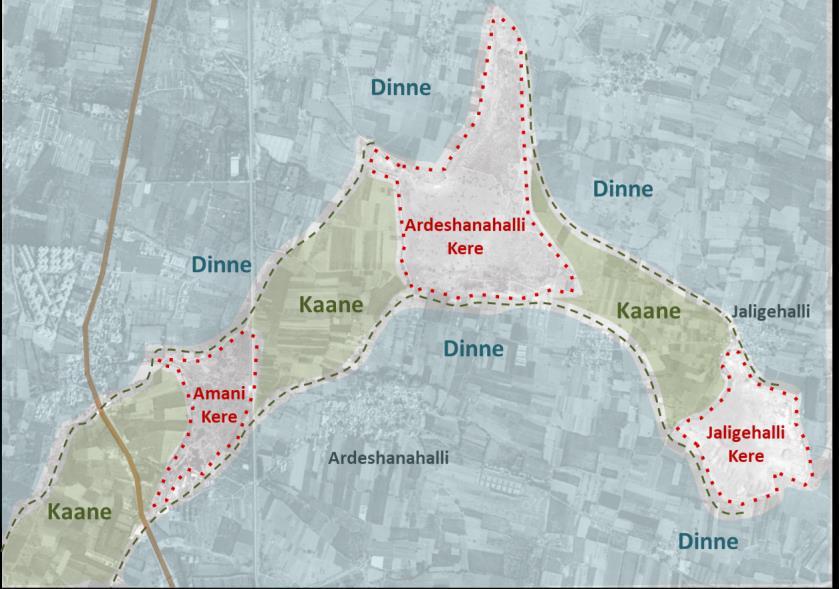

3. At the regional scale, the Ardeshanahalli lake was studied, to understand the catalysts and practices that influence the larger peri-urban region surrounding the city.

At all three scales, in an attempt to understand the BGN, apart from identifying the blues and the attendant greens, a temporal understanding of the socio-economic, ecological, cultural and recreational linkages, functionalities and the attendant uses were comprehended, mapped and analysed. Blue- green features at all the three scales are intrinsically connected and perform a role at all scales. For instance, Ardeshanahalli as a peri-urban lake that flow into Hesaraghatta valley has a defined neighbourhood that it services. The same holds true for the Hebbal- Nagavara lakes that are located within the Yellamallappa Chetty tank series in the Hebbal Valley also service the numerous villages within its vicinity.

As is evident from a detail reading at the three scales, the networks, functionalities that the blue- green spaces that these embody are diverse and complex. Identifying these functionalities and uses will allow, on one hand, for an integrated approach to enhance the socio-ecological and spatial functioning of green spaces in the city. On the other, it constitutes a proactive step towards addressing the three challenges of:

1. Enhancing social cohesion, equity and livability.

2. Integrating insights from diverse knowledge systems and incorporating the diversity and specificity of stakeholder relationship with BGI into strategies.

3. Insufficient engagement with question of power and access which results in projects reinforcing existing social inequalities

The next section discusses the three study areas and the strategic conclusions that the study offers.

Location of study sites in the city

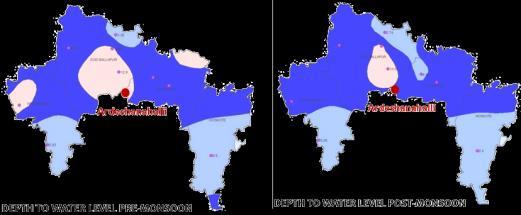

Covering an area of 187 acre and located within the Bangalore Development Authority boundary, Ardeshanahalli kere is one of the upstream lakes that flow into Hesaraghatta valley. On one hand, the increasing water stress in the region has been putting traditional livelihoods in jeopardy. One the other, the location of key city infrastructure such as the Kempegowda International Airport near these villages has been triggering urban transformation. Lakes that were once the major water source for the villages, now lie dry for most part of the year, with the villagers having to find alternate methods to meet their water requirements.

The villagers recounted how the lake and management practices developed around its sustainable usage, had once supported their livelihoods. ‘The neeruganti would decide how much water from the lake will be let out into the different fields. But, with the jodi grama (village council) breaking down, the neeruganti lost his power.’ The only remaining markers of these historically developed systems is a panikallu, a measuring stone that was used to monitor changes in water level and broken remains of the tabu, sluicegates that were used to let water from the lake into the agricultural fields. Today, the lake no longer supports agriculture livelihoods, instead it is the borewells constructed in the lakebed that communities depend on. Communities reported how the water table has receded to a depth of 1400 ft and how during summers they have to depend on municipal tankers to meet their water requirements. When asked how this situation of water stress came to be one of

the farmers replied,

‘The city continues to build, because of which water does not seep into the ground. On top that trees have been cut down. Due to all of these reasons, rains have reduced, and we have to depend on borewells for water.’

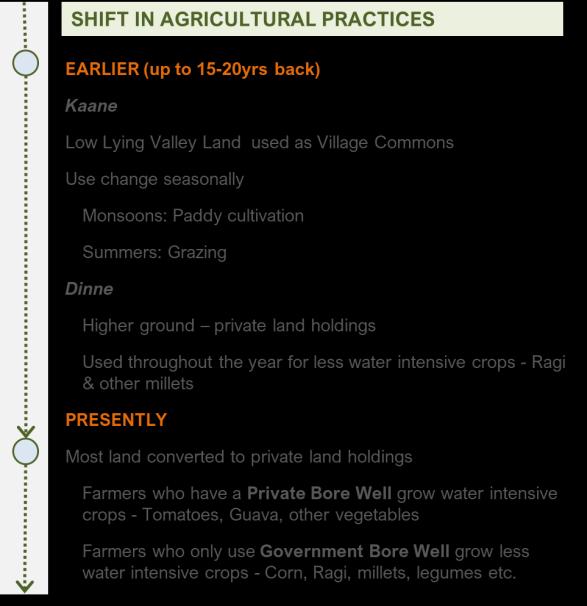

When the lake used to hold water, and the traditional water management systems were active, there used to be two types of land on which agriculture was done. One was the upstream land, called dinne, which had private land holdings on which less water intensive crops such as ragi and millets were grown all year round. The other was low lying land, called kanne, in the valley area between the lakes which acted as village commons. Some of the traditional livelihoods have acquired a modernized format, responding to the urban market demand. For example, the newer generations have set up nurseries and tissue-culture institutions, bringing together the traditional knowledge of their elders and the technical botanical training they have acquired.

The settlement structure and spatial practices in these villages revealed how productive and sacred landscapes overlap and support each other like within and along the edges of agricultural fields, socio-religious elements such as katte and nagabana. There were also some unique socio-religious elements that aren’t often spotted in urban environments. These included the veeragallu, an auspicious stone with a carved depiction of a significant story of bravery in the village’s history; anthills, which were protected and worshipped; and mandapas, a pillared pavilion that marked the village square. While these elements remained socio-culturally significant to the community and shaped their ecological relationships, some of the practices associated with them have attenuated as natural resources degraded. For example, while a few years the villagers used to celebrate Teppotsava, a festival that commemorates the sacred relationship with the lake, this practice has been discontinued since the lake no longer fills up with water.

The village revealed the dynamics of urban transformation occurring in real time. The attenuation of traditional water management practices and the water stress has led an agrarian crisis. It must be pointed out that the reasons for water stress are not purely urban in nature- starting from the colonial period, many farmers shifted to eucalyptus cultivation, which being a water intensive exotic species, contributed to ecological degradation. As the agrarian crisis intensifies the region has also begun to act as land bank for the city. As such, multiple industries such as tobacco, textile and automobile have set up in the area and villagers are shifting to employment in these factories. Many of the villagers have migrated from the village after selling off their land.

The 105-acre Kalkere Lake is the downstream lake from Nagawara located within the Yellamallappa Chetty tank series in the Hebbal Valley. Located right at the edge of municipal boundary, the lake and the surroundings starkly reveal peri-urban dynamics of shifting land use patterns, economies and cultural patterns. Until 2018, the lake frequently encountered problems of pollution, frothing and algae growth. It was then taken up for rejuvenation. Nearby residents spoke positively of the impacts of the rejuvenation, highlighting how water quality has tremendously improved since the lake doesn’t fill up with sewage anymore. The re-opened lake has a jogging path, park and kalyani (temple tank) and attracts residents from the nearby residential layouts.

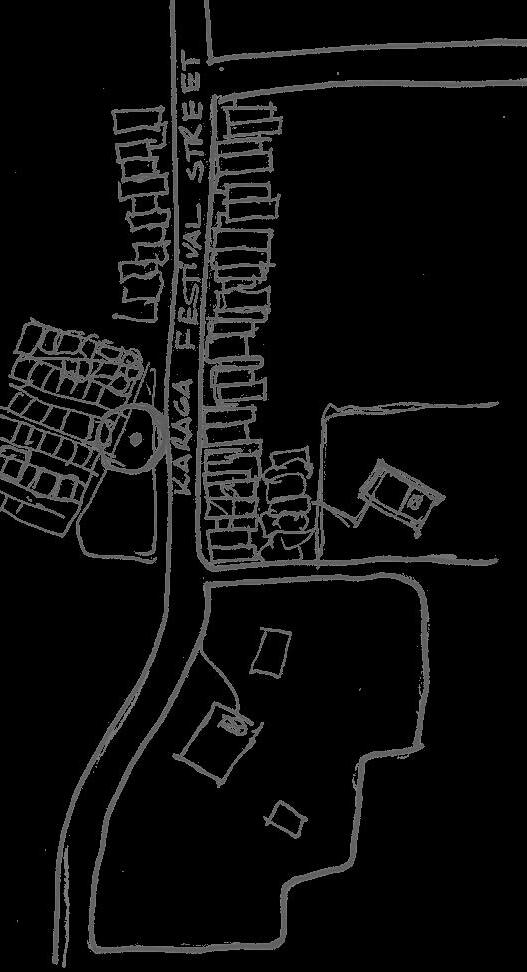

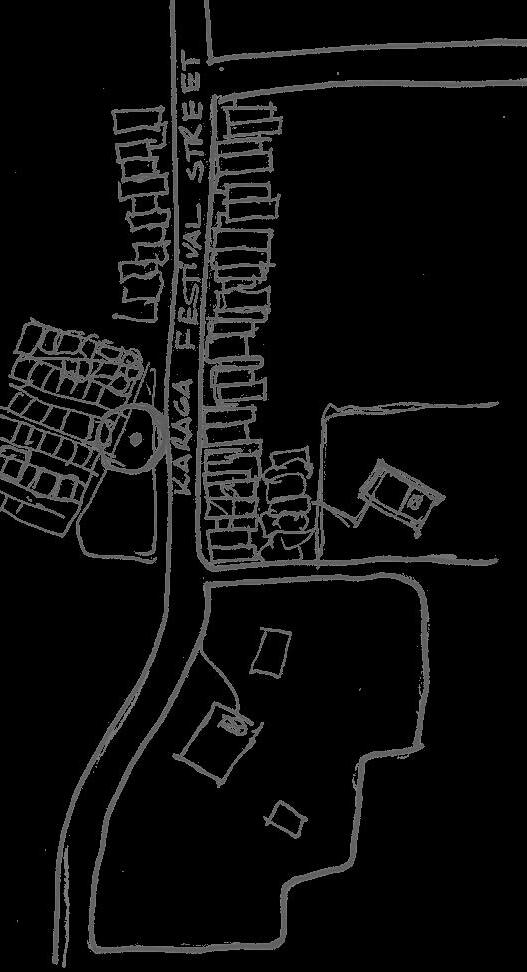

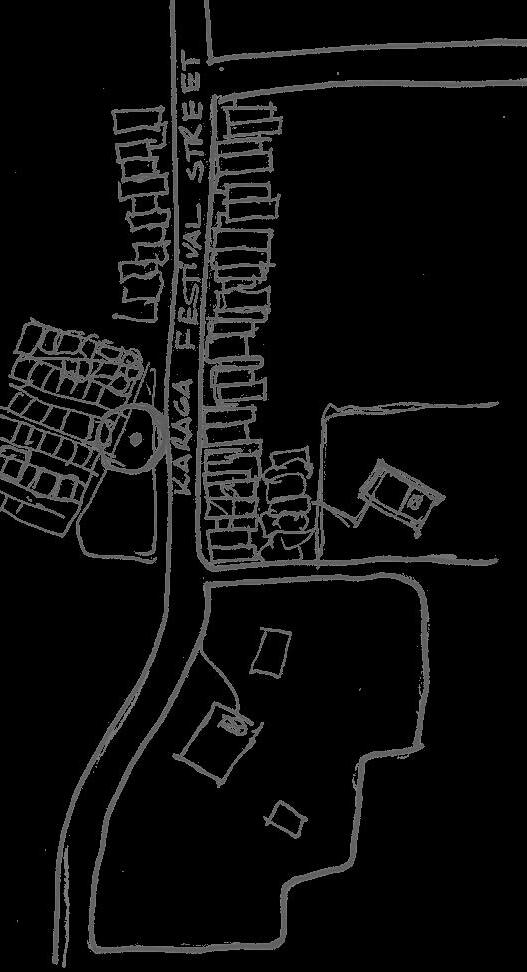

Map of Kalkere and Rampura Lake and surrounding area

Surrounding Kalkere Lake are villages such as Horamavu, Agara, Kalkere, Bileshivale, and Rampura. The urban transformation that these villages are now undergoing is revealed through the high prevalence of construction activities in these villages. The built fabric is also marked by sharp contrast with older housing typologies interspersed with newer detached housing and apartments. In addition to the old temples, burial grounds, and katte, new types of open spaces such as parks and open-air gyms have begun to come in the area to cater to the preferences of the shifting demographic.

Location of Kalkere in the city

The area had certain surviving pockets of agricultural and horticulture fields. These were mostly generational land holdings of the nearby villagers. The crops grown included ragi, banana, tomatoes, mango, chikoo, coconut, greens like pudina & palak. The farmers highlighted how agricultural livelihood has depreciated considerably and the way in which the livelihood is practiced has also had considerable shifts. The farmers now pump out water from the rajakaluve to meet their water requirements. Wells that they once depended on, are now filled with polluted water.

The fishing community is granted access to Kalkere by the Govt. Fisheries Department. They access one end of the rejuvenated lake to catch and sell fishes in the evening hours. Most customers come from the new residential layouts in the surrounding area. The fishes are then sent out to be sold in the markets outside.

A classic example of the tensions and conflicts between old and new land-uses that is bound to unfold in the area was seen with respect to the usage of the kaane (downstream) land between Kalkere and Rampura lakes. The livestock herders in the nearby villages depend on this land to graze their sheep, cows and goats. However, this land has now been taken over by a private developer to develop residential apartments. For the time being the developers have agreed to grant access to the herders and their animals to graze within their boundary. However, as construction picks up pace, the herders assert that without access to the grazing area, they will not be able to continue their livelihood and they have no alternate livelihood to fall back on.

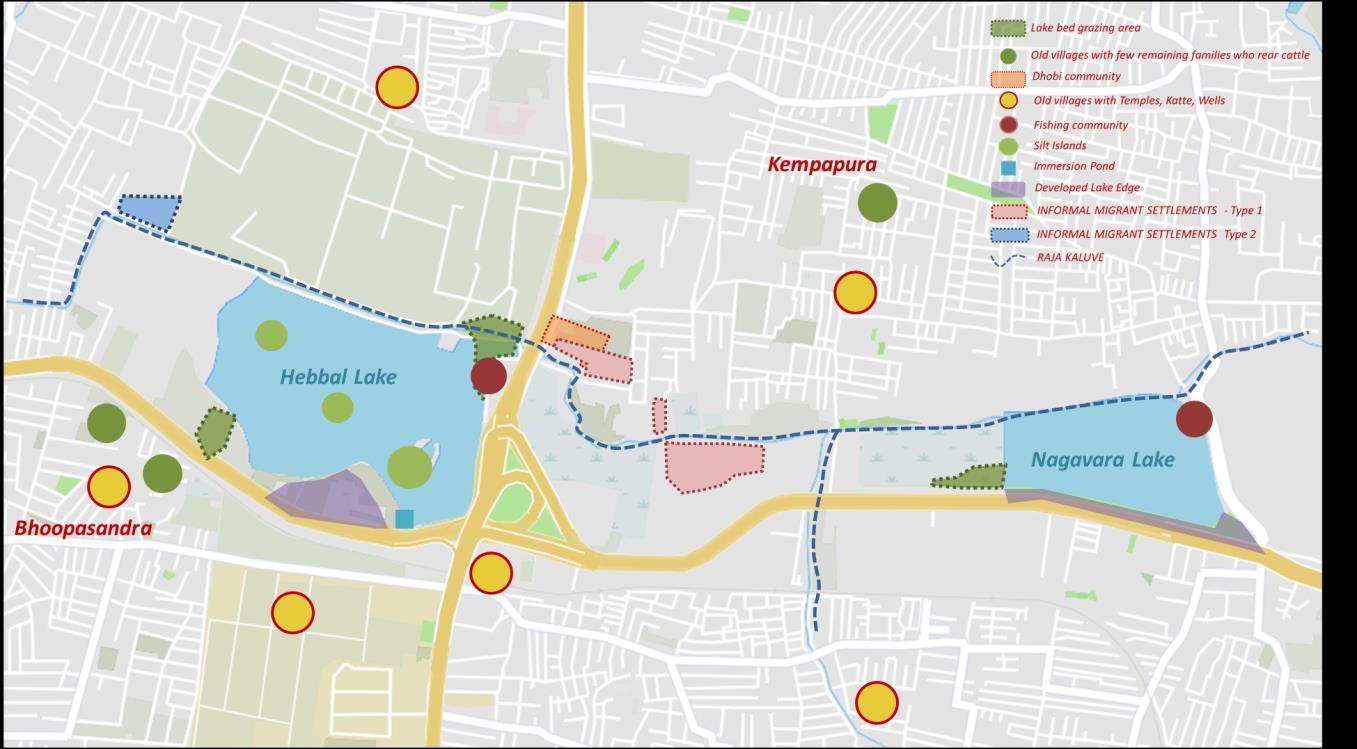

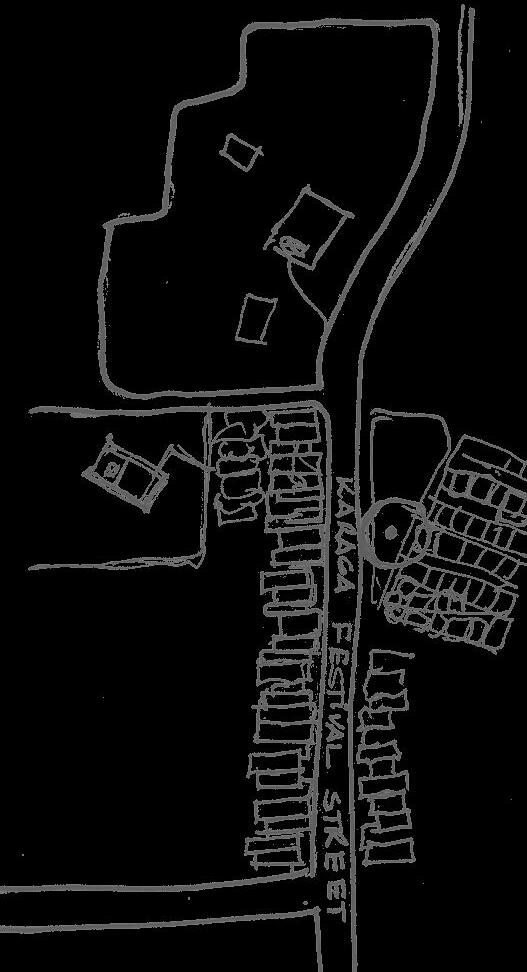

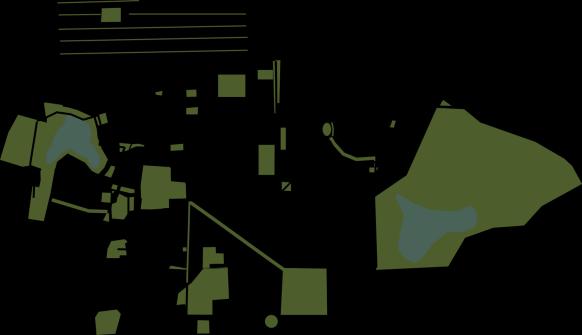

Hebbal Lake covers an area of 192 acres and Nagavara lake covers an area of 72 acres and both these lakes are located within the Yellamallappa Chetty tank series in the Hebbal Valley. In the past, the lakes used to be a nucleus for the agriculture driven economy of the region and the main source of drinking water. The settlements surrounding the lakes continue to retain certain characteristics and markers of ecological relationships that they once shared with the lakes and associated blue-green elements. As urban growth began to trigger economic and cultural shifts, these relationships attenuated resulting in an incremental degradation of the lakes with unchecked inflow of sewage, weed and algae growth. In 1998, there was a call to remedy this situation and accordingly Hebbal Lake was de-silted, islands were constructed to attract migratory birds and parks and jogging paths were constructed. In 2006, the lake was leased out to a private body, Oberoi Group under a develop-operate-transfer model. Around the same period, Nagawara Lake was also leased out to Lumbini Gardens Pvt. Ltd. While Hebbal Lake continues to be under the management of Oberoi Group, the management of Nagavara Lake by Lumbini Gardens Pvt. Ltd. has been called into question as the group has insufficiently dealt with sewage inflow management for the lake. The lakes which once used to be commons freely accessed by communities, have now become ticketed compounds that now, given the recent pandemic situation, is effectively abandoned. Map of Hebbal and Nagawara Lake and surrounding

Since the lakes were handed over to private bodies for management, access to it and usage of its resources has been controlled and monitored. Within the Hebbal Lake boundary there exists a park, nursery, a Kalyani (temple tank), and a space for fishermen to practice their livelihood. Within the Nagawara Lake boundary allotted uses are almost completely recreational in nature with a swimming pool, boating area and restaurant. Significant portions of the lake are cut off from access, as the abutting areas are owned by private bodies and government bodies such as the Forest Department and Fisheries Department.

Some of the old villages that surrounded Hebbal and Nagavara Lake have socio-spatial markers that indicate their historic relationship with the lake. These socio-spatial markers included religious infrastructure such as ashwath katte, naga bana, and temples around which the settlement was structured. The older inhabitants of the village recounted how the village had been urbanized- as primary livelihoods became less viable and land values increased, many of the villagers either sold off their land or developed their land into rental housing.

While the degradation of the ecological relationships with the lake was not the sole driver for the shift in livelihoods, it did play a significant role. Some of the major livelihoods that depended on the lake were agriculture, fishing, clothwashing and livestock rearing. Among these, agriculture has almost completely moved out, livestock rearing continues with difficulty, fishing and cloth-washing has acquired a morphed format. Fishermen are the only community with direct access to the lake both in Hebbal and Nagawara with their access rights determined by the Fisheries Department.

Hebbal-Nagawara lakes and surroundings

The agricultural fields that marked the Hebbal-Nagawara Valley as recently as 2000, have completely disappeared. In its place is an uneasy agglomeration of urban activities. The eastern portion of the valley area has become a major traffic junction marking the meeting of NH 44 and NH 75. The residual space the traffic junction was converted into the Kempegowda Park, but as of now, these recreational activity remains de-activated.

The starkest example of how terrains marked by ambiguous ownership patterns, attract and support activities that would otherwise be considered undesirable within the city, was revealed when we moved further north in the valley area, towards the rajakaluve Hidden almost entirely from the road, abutting the rajakaluve was a squatter settlement whose 100-200 household strong community were engaged in dry waste segregation and processing. This community was mostly made of migrants from West Bengal and Bangladesh. The houses were mostly made tin sheets and tarpaulin sheets, and the settlement was organized into different sectors based on the waste collection contractor they worked under. Beyond the rajakaluve that marked the northern edge of the settlement were high-rise residential apartments and institutional buildings, whose waste the informal settlement dwellers collected and processed. The vivid contrast in urban realities on either side of the rajakaluve presented a poignant spatial indication of urban inequality within the city.

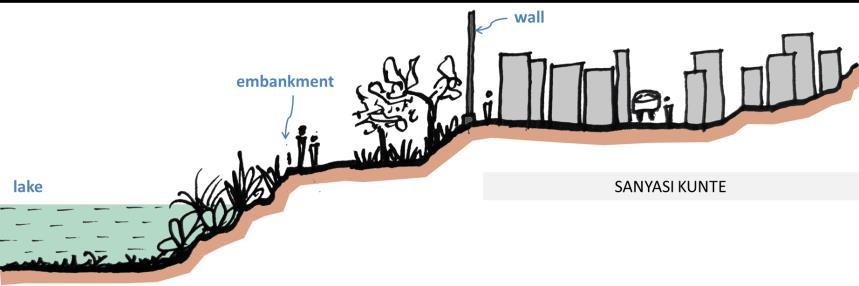

The origins of the Kempabudhi Lake can be traced back to the 16th century, when it was built by Kempe Gowda, the Vijayanagara chieftain who is credited with founding the city of Bengaluru in honor of his family deity Kempamma The lake developed to be a center for cultural, religious and economic activities in addition to provisioning water for the nearby localities. Some of major temples that developed in its surroundings include Gavi Gangadhareshwara temple, Pralaya Kala Veerabhadra Swamy temple and Bande Mahakali temple. Over the years, with urban growth resulting in discharge of untreated sewage, weed growth and encroachments, the provisioning and livelihood relationships with the lake degraded. In 2013, the lake was taken up for restoration by the BBMP and since then, the lake has transformed into an active recreational amenity with few surviving livelihood relationships.

Once functioning as a contiguous blue-green network, its physical linkage with the associated blue-green spaces such as wetlands, forests, burial grounds, grazing grounds had been cut off over the years. The severance of these linkages had impacted the ecological functioning of these spaces. While some of them degraded beyond use, others survived but with reduced or alternative functioning.

The temples that dot the lake periphery and the mythological origin stories attached to them indicate the sacral character of the landscape. The temples transform into a hub of activity especially during the early mornings and evenings as devotees from all over the city flock to the temple. Correspondingly the temple surroundings- roads and parking spaces temporally transform to accommodate street vending activities.

While the communities narrated about a time in which they actively frequented the lake and its buffer areas for their day-to-day needs and livelihoods. In the present day, the most accessible green element available to the community were the home gardens they had nurtured in their courtyards and terraces. The incidence of these green pockets seemed to be more evident in the older settlement areas as a surviving, manifestation of the culture.

The dhobi community spoke of a past when they could directly access the lake for the livelihood. However, as the lake water began to get polluted and their access to it was cut-off they had to come up with alternatives. Following the lake rejuvenation, the access of grazing community to the wetlands that they depended on for fodder was almost completely cut off on the pretext of keeping the lake ‘clean’. They were allowed only collect fodder but could not bring their animals inside the lake premises. This is a relevant example of how the highly regulatory approach of the state breeds informality.

Ecosystem Services are the benefits human populations derive, directly or indirectly, from ecosystem functions (COSTANZA ET AL. , 1997)

The study mapped the existing cultural ecosystem services provided by the blue-green networks in the study sites. This understanding of the cultural connect with open spaces is illustrated (for Kempabudhi Kere and Ardeshanahalli) below.

Aesthetic

Ecosystem services which enables the enjoyment of scenic landscapes and attractive landscape features.

Ecosystem services which serve as potential recreational places such as for eco-tourism and outdoor sports.

Spiritual Landscapes which symbolize spiritual and historic values.

This represents landscapes with cultural and artisitc value, where nature is used as a motive in books, painting , folklore for example.

Landscapes with scientific and educational value where nature is used for scientific research.

Demonstration Site: Hebbal Valley (Hebbal-Yelemallappa Lake Series)

Blue- green features are intrinsically connected at different scales and perform varied roles. For instance, the Hebbal- Yellamallappa lakes that are located within the Yellamallappa Chetty tank series in the Hebbal Valley also service the numerous villages within its vicinity. Following are the six key strategies suggested for the lake series.

1

Establishing the order of hierarchy for the water systems and incorporation of the applicable buffers.

Consolidation of the open spaces around the water systems to reclaim spaces for community usage and participation.

2

Revival of the defunct lakes and identification of the broken linkages in the series which strengthens the blue green network.

To create one contiguous blue green network integrating the cultural open spaces and opening up to the potential open spaces along this network.

Strengthen the link between the traditional communities dependent on the natural resources for their livelihood.

To create a network of alternative mobility for the heavy traffic roads by enabling a non motorized pedestrian friendly network along the Rajakaluves.

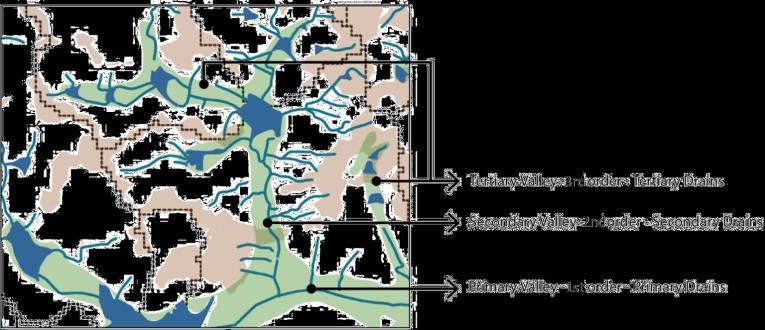

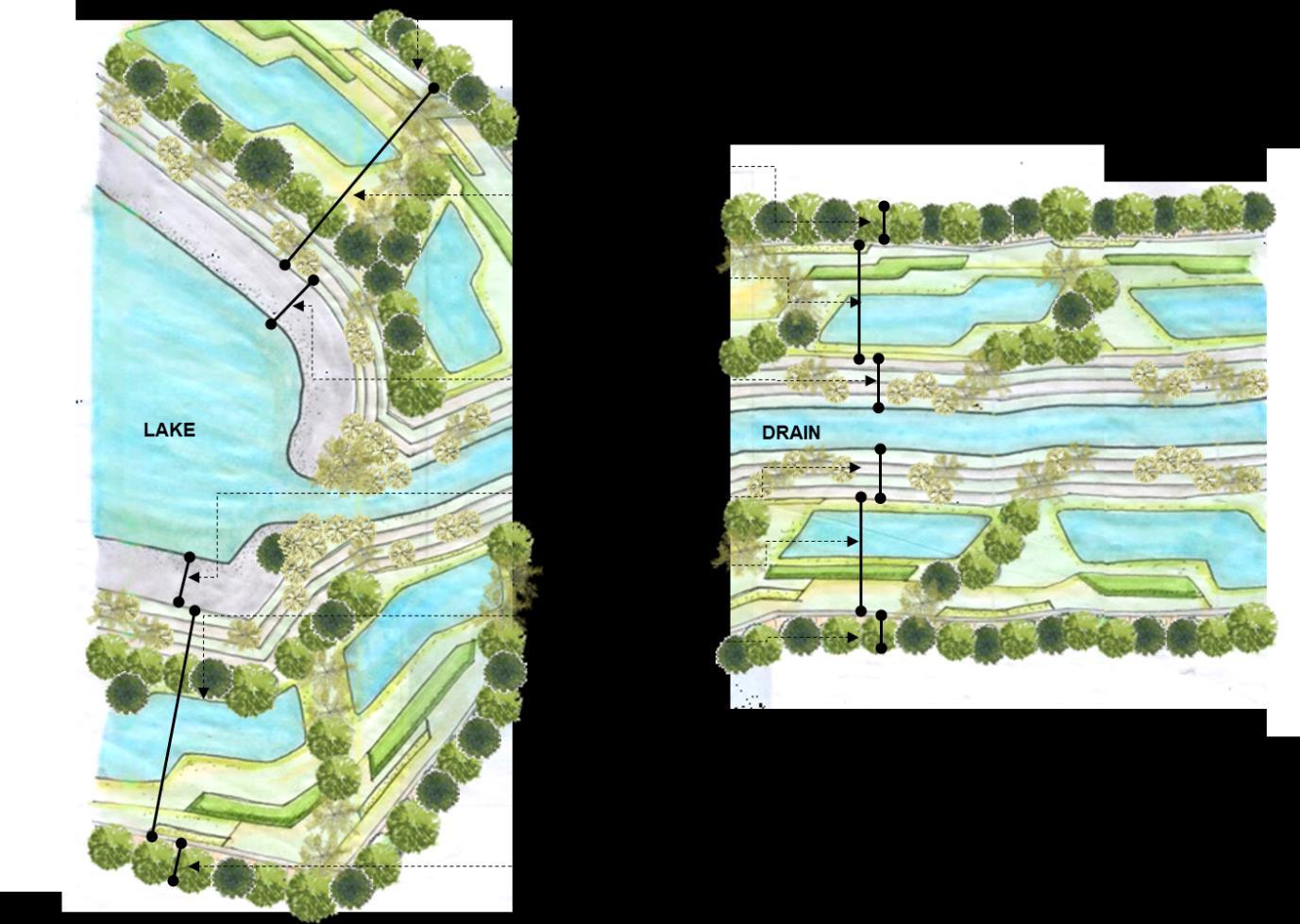

An overall understanding of the Yelemallappa chetty series was undertaken through the study of the lakes and the network of rajakaluves which connects them. The fist step was to establish the order of hierarchy for the water systems through the classification of the rajakaluves into stream orders

For the Hebbal- Yelemallappa lake series, the network of water systems has been categorized into primary, secondary and tertiary order of streams based on its location in the series as illustrated in the adjacent map. Buffers for each drain type (as indicated below) is also dependent on the density of urban fabric around the lakes (D1 –High density, D2- Moderate density, D3Low density)

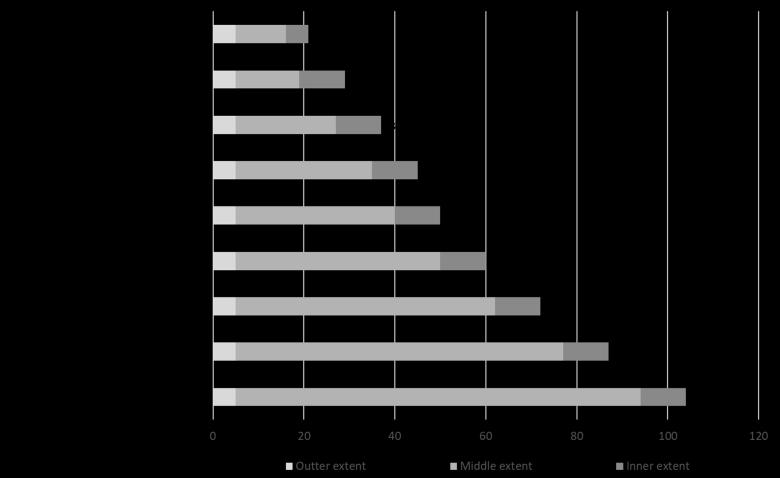

Extents of outer, middle and inner extents within buffers of each zone:

1st, 2nd, and 3rd order drains in Yelemallapa Chetty lake series

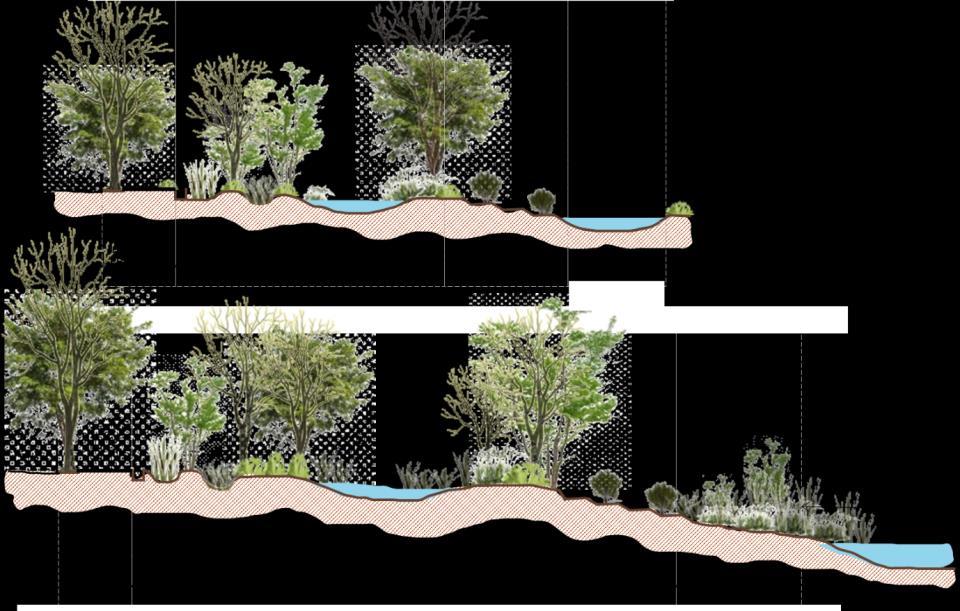

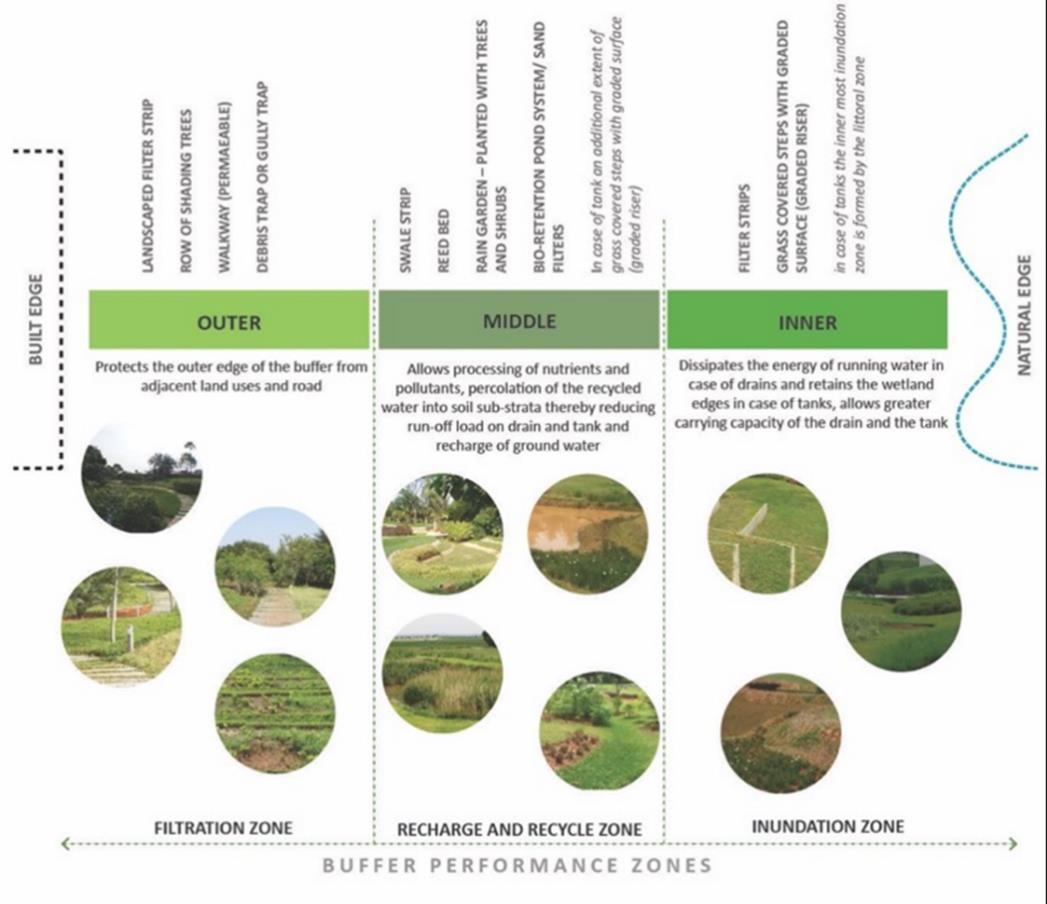

The extent of the buffers are prescribed for the tank and valley systems under normal rainfall events and the indicated in the graph are the absolute minimum. In case of extreme rainfall scenarios (worst case scenarios), the requirement of regulated buffers extent will be higher; these need to be arrived at based on inundation modelling for extreme events. The spatial character of the proposed buffer areas along the canals and the lakes have been illustrated through the schematic sections on the right. The actual widths of these zones will vary upon the order of the stream and the density of the settlement. A brief description of each buffer performance zone is shown below. Broadly the buffer zone is divided into three parts: filtration zone, recharge and recycle zone, and inundation zone.

• Filtration zone: Traps sediments and organic matter and protects outer buffer edge from adjacent land uses.

• Recharge and recycle zone: Allows processing of nutrients and pollutants, percolation of storm water into soil sub strata, helps reduce run off load in drain and tank, recharge of ground water.

• Inundation zone: Dissipates energy of running water in case of drains and retains the wetland edges, allows greater carrying capacity of drains and tanks.

The character of landuse across this stretch was documented based on the ward level landuse maps to understand the nature of the user groups. While the Hebbal lake was predominantly surrounded by institutional campuses, the dense urban village was spread across the regions surrounding the Hebbal and Nagawara lakes.

The secondary valley draining to the inlet of the Kalkere lake is dominated by school and colleges,while the region around the Kalkere and Huvinane lakes has the presence of agricultural and horticultural plantations. Further downstream of the Huvinane lake upto the Yelemallappa chetty lake is dominated by the sub-urban landscape and is lined with agricultural fields.

Strategies and Interventions

Based on the study undertaken, the first step was to apply the proposed buffer widths and regulations around the lakes and the canals connecting them.

At the regional scale, policy level strategies and interventions were explored based on the existing landuse character across this network as well as integrating the potential open spaces and the cultural elements sprewn across the landscape to create a consolidated blue green network. This stretch has been divided into 4 segments and the strategies for each have been elaborated in the following pages.

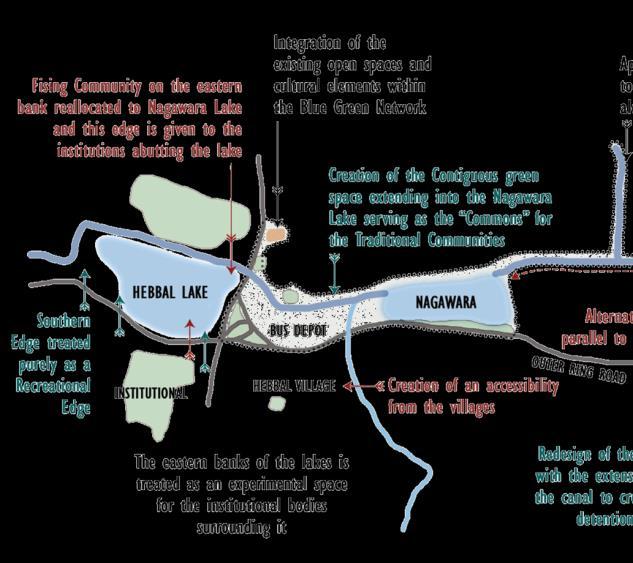

Interventions at the Hebbal valley

• Hebbal lake is cut off from the traditional communities with the advent of the outer ring road.

• It is surrounded by institutional lands, with the military campus on the North, the fisheries department on the West and the Agricultural GKVK campus on the South.

• The intent is to treat the banks of the lakes as experimental space for the institutional bodies surrounding it.

• The absence of open spaces in the dense urban villages around the lake, makes it crucial to retain the Southern periphery of the Hebbal lake, purely for recreational purposes.

• There is a potential to develop the land between the two lakes by creating a large open space between the canal edge and the outer ring road, extending into the Nagawara lake.

• This space will serve as the commons for the traditional communities such as the fishermen, dhobi and cow herders community, present in the urban village.

• The existing bus depot and the informal settlement currently existing in this pocket will be integrated within the open space.

• The idea is to also extend this network to integrate the Parsee tower of silence and the school ground across the other edge of the canal.

• A non motorized thoroughfare has been defined through the secondary valley draining into the primary valley, which links the old cultural remnants of the village with the commons.

• An alternative mobility network has been developed along the canal, extending from the Hebbal lake to the point where the canal intersects the new airport road. This has been perceived as a pedestrian cum cycle network, establishing a non motorized connect parallel to the outer ring road.

• The outlet from the Rachanahalli lake drains into the outlet from the Nagawara lake. It is essential to allocate the applicable buffers along this canal.

• The Hennur biodiversity park is the 3rd largest open space in Bangalore (Post Lalbagh and cubbon park). It has the potential to be reprogrammed and redesigned, by the expansion of the canal running across the park into a detention pond, which will filter the water before draining into the subsequent lakes. The presence of BDA parks and grounds around this space, has the potential to be to be integrated into this network.

• The Kacharanahalli lake towards the upstream of the Hennur biodiversity park needs to be revived, with the integration of the ground abutting it. Buffer regulations to be applicable to the existing development surronding this lake.

• The presence of numerous institutions along this network, creates a need to extend the alternative mobility network running along the primary valley, across this stretch.

• The existing vacant grounds along the prlmary valley has been consolidated into a one large open space.

• The chelekere lake has been similarly connected with the institutional open spaces around it.

• The existing land use around the Kalkere predominantly comprises of agriculture and horticultural lands with plantations. This along with the wetlands and the agricultural fields to the downstream of Huvinane has been defined as one large consolidated open space with policy regulations which permits activities related to arboriculture, horticulture and agriculture. This will enable in retaining the kaane grazing area along the canal edge and the peri-urban landscape around these lakes.

• To the upstream of Kalkere, is the secondary valley which drains from the Horamavu agara lake. This lake has the potential to be integrated with the large Banjara ground abutting it as well network the temple lands which is spread across the built fabric, as a part of this circuit.

• Further upstream of this, the tertiary valley and the Horamavu lake can similarly be integrated with the playgrounds and temple lands sitting on their edges.

• The large consolidated space around Kalkere and Huvinane extends upto the Yelemallappa chetty lake. Another inlet for this lake is from the Southern edge where it drains from Seegehalli lake which drains from Kr puram lake and Basavanpura lake.

• The land parcel in between the Seegehalli lake and the Basavanpura lake acts as a wetland and is crucial to be retained in its current state.

• While smaller culltural open spaces sitting along the secondary and tertiary valleys have been integrated along the circuit, the intent is to also create an alternative non motorized network along the canal edge, which would connect the heavy traffic old madras road to the Kodigehalli main road, to the south of Basavanpura lake.

A demonstration area has been selected in the downstream of the series around the Seegehalli lake, to further demonstrate the design proposal based on the regional level understanding across the Hebbal valley. The existing landuse, cultural open spaces and the canals connecting these lakes have been mapped to get a comprehensive understanding of this region.

Strategy 1

The applicable buffers around the canals and the lakes have been incorporated. The potential open spaces along this blue network has also been inegrated in the circuit to form a consolidated blue green network.

A non motorized network has been created along one stretch of the network, linking the Old madras road with the Kodigehalli main road. This network has been extended through the cultural markers of the village and connects to the Seegehalli main road.

The spaces along ths network have been accordingly programmed to cater to the existing landuse

Active spaces for the community have been strategically oriented along the NMT network while the ecological and productive spaces have been positioned across the rest of the network.

The wetland in between the Seegehalli lake and the Basavanpura lake has been declared as an eco sensitive area, with the canal expanded to create a detention pond. .

A few of the peripheral roads along the Basavanpura lake has been omitted to create one contiguous green space.

The inherent cultural, historical, sacred, ecological, architectural, social and economic value of all open spaces should be studied and recognized at the neighborhood and community scale. It is recommended that the mode of enquiry facilitating such a reading be institutionalized both as a process and a method within policy and plan.

Greening operations should essentially focus on a ‘functional and productive’ idea of green.

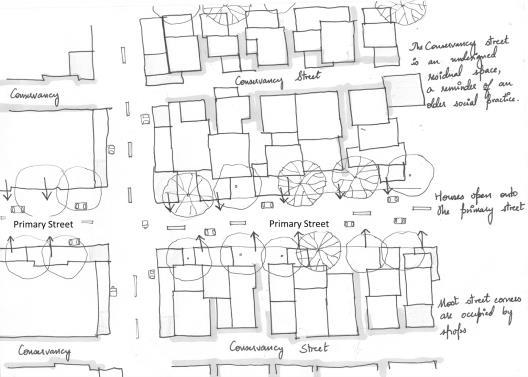

Standard planning criteria has a myopic definition of open spaces, that inhibits the potentials that these spaces hold. While the transect walk of the precint allowed for the following open spaces categorization: public, institutional, sacred, informal and under-utilized, other categories can emerge from varuing contexts and lenses

A one size fits all policy for planning for BGN should not be followed.

Attempts to formalize undefined public spaces usually run contrary to the idea of temporality and associated multifunctionality. In the case of undefined maidaan’s for example, the edges can be defined to protect them from encroachment. Similarly, the planting of trees along the interface of public spaces will provide much needed shade and seating space to visitors. Vending spaces can be incorporated through design that is premised on an understanding of temporal and associated functions.

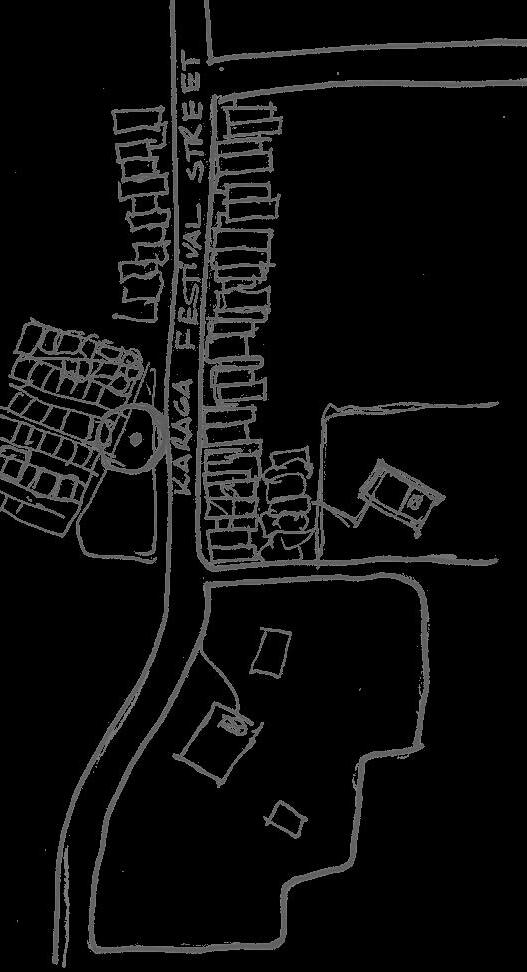

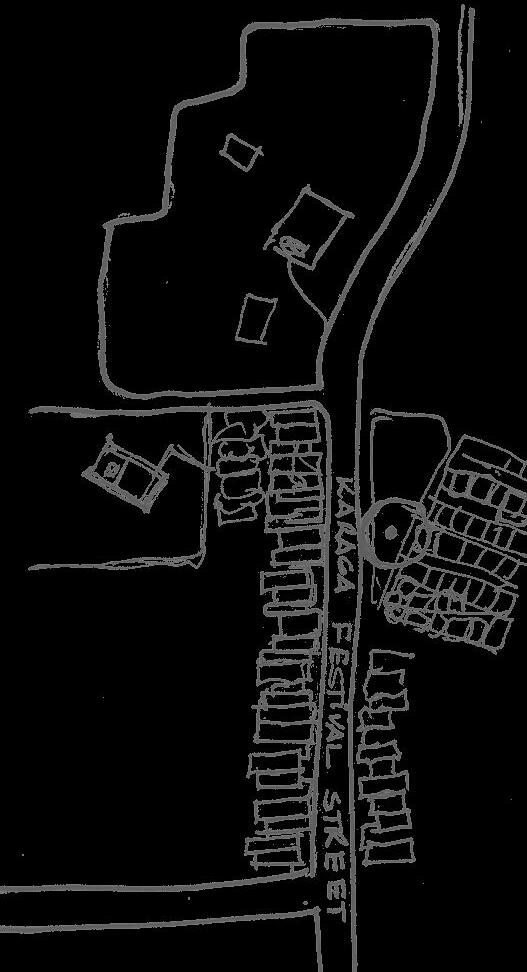

Some temporal functional linkages, like the Kadalekai Parishe, that have a strong spatial association can be enhanced using design interventions.

Some roads in the precinct, like Gandhi-bazaar, Lakshmipura road and the bamboo weaver’s street have permanent markets. Intelligent design can enhance userboth the consumer and the supplier - experience on these streets.

Participation with existing and future users of these spaces is critical to efficient design. This will ensure the building of a just, democratic urban space. It will also set the stage for managing green-blue systems as common property resources at the neighborhood scale.

These can be appropriated in some way, based on the existing context. In this precinct, intersections either housed small stalls, or functioned as small parks, based on their size. Arali katte park is a good model for the development of an under-utilized open space.

Squatter settlements often occupy unclaimed green spaces. The government policy of eviction is neither just nor effective as a means for obtaining public land. Sustained dialogue and rehabilitation can go a long way to stabilizing both the resource users and the system.

The topography and land character of these neighborhood scale spaces should be recognized. It is often easy to forget the underlying topography, amidst the urban fabric. However, the precinct has a unique undulating topography that should be kept in mind.

The ecological value of contiguous open spaces should be foregrounded at the precinct scale. Care should be taken to ensure that institutional fragmentation and road construction does not fragment these last remaining contiguous ecosystems.

The dissonance between administrative boundaries and ecological/ spatial extents should be addressed. Ward boundaries are not always a reflection of ecological/ social/ cultural systems. Recognizing contiguous open spaces and defining and foregrounding frameworks within plan and policy as non-negotiables is critical. Community and individual gardens can be promoted through plan regulations and implementation to be incentivized.

Resource management, including the management of waste, water and food should be incorporated into green infrastructure at the neighborhood scale. This will reduce pressure on city-scale infrastructure. Measures such as the encouragement of productive landscapes and decentralized waste management can improve resource management at the neighborhood scale..

Selected Precinct: Basavanagudi, Gavipuram, VV Puram and Mavalli

The precinct studied extends from Lalbagh to Kempambudhi Kere in Southern Bangalore. It bears a rich ecological history, with a range of features, from rocks of geological significance, to culturalhistorical elements. In the early years following independence, (led by Königsberger and Sir M. Visweswarayya), this area was also a testbed for modern planning theory. Basavanagudi, one of the earliest settlements in this area strongly resonates with Ebenezer Howard’s ‘Garden City Model.’ The site can therefore an interesting lab to derive conclusions about open space use.

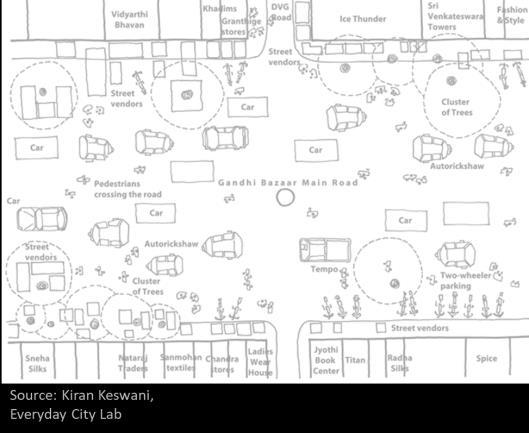

A bottom-up layered acknowledgment and mapping of a variety of public as well as sumi-public green spaces was attempted within the precinct. Such a mode of enquiry adopted called into question the popular idea of public green spaces, by studying these smaller community elements. In carrying out this exercise, the study successfully engages with the existence of the everyday open spaces, from temporal market streets to regularized public parks networked or otherwise with the tank ecologies and systems and associated socio-cultural open spaces.

Study Precinct: From Lalbagh to Kempambudhi Kere

Such a reading provided an alternative reading of the public and semi-public green spaces and their existing and potential role in the city fabric. 1

From Lalbagh to Kempambudhi Kere

Areas: Basavanagudi, Gavipuram, VV Puram and Mavalli

• Public Open Spaces

• Institutional Open spaces

• Sacred Open spaces

• Informal Open spaces

• Under-utilized Spaces

• Acknowledge and map varied uses of identified open spaces

Selected Precinct: Basavanagudi, Gavipuram, VV Puram and Mavalli

This study mapped a rich matrix of open spaces, and in doing so, called into question the very definition of what constitutes ‘public green.’ Standard planning practice has a regularized definition of green and blue. In land use plans these are categorized as open spaces In doing so, it often ignores the nuances that exist at street level/ at human experience level. Common imaginations of green spaces are recreation oriented, with a simplistic focus on cycle tracks and children’s parks.

What is also important to note is that many of these open spaces have more than one role. For example, sacred landscapes may be both culturally and ecologically rich while institutional open spaces (as in the case of the Ramakrishna and Shankar matha) may be productive landscapes. It is therefore important to take a holistic view of these neighborhood level spaces, as opposed to a myopic one. That is, even though these spaces function at smaller scales, they may very well be part of a larger system.

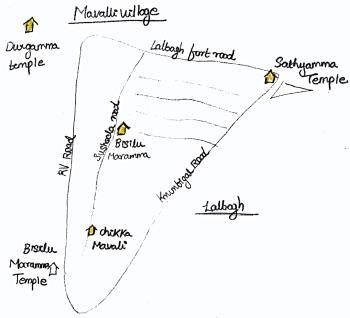

The following pages demonstrates the mapping of open spaces for two selected areas: Bisilu

• Malavalli, true to its name, comprised of mango groves and nurseries, inhabited by the Tigala community, who have now moved to Sidhapura, on the Eastern fringe of Lalbagh.

• Four main temples serve as markers of the traditional Mavalli village, which is now engulfed by the city.

• The Ooru habba, which happens once in 3 years, networks these temples, through the procession of the deity along these roads.

• Most of the streets have a temple.

• The Bisilu Maramma temple is an important religious node, with the Mavalli market abutting it.

• This is a large congregational space, which belongs to the temple trust, comprising of the temple, a large open space, a kalyana mandapam and an office building.

• The space transforms across the day to cater to a wide range of user groups.

• The main activities of the habba happens in this space, during which the market moves out to the road.

• There existed a government school in place of the kalyana mandapam and this space hosted vendors who sold mangoes during the summer. These have changed over time.

• KR Road was originally lined with banyan trees on both sides. In fact, the road had so many trees that it was called tree road. Later (1980) the banyan trees were cut (to widen the road) and replaced with Rain trees.

• A community of bamboo weavers has been using this road to sell their wares, first under the shade of the banyan trees and later under the shade of the rain trees. The trees and wide foot path were essential to their trade, as they had ample space to occupy.

• When the metro line was made these rain trees were cut. The pavement is much narrower now, leaving the vendors with reduced space to conduct their wares. The wide road, with the large divider and median also means that fewer customers approach the vendors. In taking away from the metro line, a large patch of unusable open space was created in the center of the road.

An underutilized space along the National grounds metro was converted into a park, which has a high footfall, due to its strategic location amidst colleges. The park is not fenced and the existing trees have been used to create seating spaces. It also has a dedicated play area for children and an open gym.

This study mapped a rich matrix of open spaces, and in doing so, called into question the very definition of what constitutes ‘public green.’ Standard planning practice has a regularized definition of green and blue. In land use plans these are categorized as open spaces In doing so, it often ignores the nuances that exist at street level/ at human experience level. Common imaginations of green spaces are recreation oriented, with a simplistic focus on cycle tracks and children’s parks.

From this study it is clear that public spaces in the city take on several forms, from residual open spaces to sacred spaces to Institutional spaces. The scales of spaces also vary, from the smaller ashwath kattes to large public grounds. Each of these spaces performs a service and is of value to the city. It is important that we recognize, optimize and leverage the value of each of these types of open spaces, as opposed to strait-jacketing them. What is also important to note is that many of these open spaces have more than one role.

For long this area has supported markets and temporal spaces. From the annual Kadalekai Parishe to VV Puram’s food street, the roads in this area are highly effective informal public spaces. When not used as markets, they continue to function as vehicular thoroughfares.

Urbanization has over-written many older spatial ecologies. However, memories of these systems still exist as functional linkages. These functional linkages are more often than not, closely linked to a cultural practice. They are important because they carry the memory of these embedded ecologies.

Similarly, public grounds and temple courts are also used temporally. The use of the Bisilu Maramma temple court is governed by several governing principles and rules that have evolved over the years while also having , transforming from a vegetable market to a clothes market to a festival ground, at different times of the day and year.

Many spaces are also used multi-functionally. In the case of Gandhi Bazaar, the road is simultaneously used as a market and a vehicular thoroughfare.

The formalization of city infrastructure and a lack of acknowledgement of these uses stand to threaten these fluidities and informal economies.

For example, the Karaga yatre continues to be performed in some of the city lakes, including Kempambudhi Kere All of these lakes were at some point dry, polluted or compromised to varying degrees. However, the yatra continued to be celebrated, in memory of the older association. Similarly, the lands around the bull temple were historically groundnut fields. Today the Kadalekai parishe (groundnut fair) continues as a functional linkage of this spatial history.

The spatial fragmentation of open spaces in Bangalore is a significant hurdle to their contiguous reading. This fragmentation occurs across scales, from the scale of an individual Ashwath Katte, to the larger ecology of the Kempambudhi lake system.

Once a part of a contiguous blue-green network, Kempambudhi’s physical linkage with the associated bluegreen spaces such as wetlands, forests, burial grounds, grazing grounds has been cut off over the years. The severance of these linkages has impacted the ecological functioning of these spaces. While some of them have degraded beyond use, others have survived with reduced or alternative functioning. For example, the lake that once supported livelihoods and provisioned water for nearby settlements, now functions primarily as a recreation space. Part of the forest area had been converted into a children’s park, while the rest has been cordoned off as Forest Department property. Informal settlements have come up on grazing grounds, and roads divide and separate contiguous ecologies.

Several natural-resource dependent livelihoods continue to survive in the city, to varying degrees. Their survival depends on a couple of factors, such as accessibility to the resource, and social-socio-economic factors. As green spaces in the city are formalized and fenced, these livelihoods slowly die out.

The survival of many of these livelihoods depends as much on social agency and community voice, as it does on anything else. Communities that have political clout and are able to make their case are often given special consideration, while others are ignored. The conversations with the dhobi community, for instance, revealed that they were in fact an exception. Unlike many other traditional livelihoods, they had been able to gain enough sociopolitical capital to leverage the required resource access and service provision for them to continue their livelihood. In comparison stands the grazing community. Following the lake rejuvenation, the access of this community to the wetlands that they depended on for fodder was almost completely cut off on the pretext of keeping the lake ‘clean’.

This precinct is marked by several temples and structures of historic value. In many cases, the landscapes around these structures have remained unchanged, and are important visual narrators of the city’s original landscape.

The topography of this precinct is also interesting. Made up of small ridges and valley systems, it has an interesting mix of natural features, from monolithic granite rocks, to fertile lake clay, to sacred landscapes and forests. Overwritten on the forests are cultivation landscapes of coconut groves or totas, and today there are parks and curated landscapes.

It is clear that open spaces in India are fragmented institutionally. Multiple administrative claims dis-associate contiguous landscapes and encourage their fragmentation. For example, Krishna Rao park was originally planned as a node of the Basavanagudi area. However, in administrative definition, Basavanagudi has been subdivided into four different wards. Of these, Krishna Rao Park comes under the jurisdiction of the Jayanagar ward. This dissonance between administrative units and original planning principles catalyzes fragmentation.

The starkest example of the how common property resources have degraded with the imposition of publicprivate property ownership regimes was a 100-year-old community well located near the Kempambudhi Kere where the dhobi community works. The water from this well was once used by the dhobi community to celebrate the Gange Pooja festival. Today, while water remains in the well is polluted beyond usability. Access to it has been cut off because a boundary wall segregating the property of the dhobi community and Forest Department has been built over it.

The diversity of socio-cultural backgrounds and community types in Indian cities, means that their patterns of occupation are very different. By extension, this also means that the types of open spaces required/ available to these communities can differ. For example, Mavalli village near Lalbagh has a unique spatial character, stitched together as it is, by several small temples and shrines. Of these, the Bisilu Maramma temple is the focus of the village, and the open space that it affords is the center of community activity. This is not to say that nearby public parks ae not visited, but that communities like these, which strongly resonate with a certain cultural history are also associated with specific types of spaces.

From our study it became clear that a space could be under used for one of two reasons. Firstly, the space may be poorly planned/ un-planned, with little or no regard for usability. Traffic islands and residual intersections fall into this category. Secondly, institutional barriers/ legal uncertainty may come in the way of a space’s usage. For example, the Maratha free hostel has a large open ground that is largely lying unused. Pre-covid, the land was used as a parking space for guests.

Similarly, in Chamarajapete, the conservancy streets are transforming into informal public spaces, used by children to play cricket, and as spill over spaces for small shops and trades. On the other hand, typical planned areas with higher income occupants, like Basavanagudi or Gavipuram, are more dependent on large parks and formal public spaces.

Unmanaged/ un-regularized open spaces in India are often used as dumping grounds for waste. Similarly, lakes in Bangalore are treated as receptacles for the city’s sewage. Therefore, responsible resource management is an important facet to consider while developing a blue green system In Bangalore. Open spaces in the city have the potential to manage neighborhood waste at decentralized scales. It is important to understand the potential of these systems.

• Ahern, J. (2007). Green infrastructure for cities: The spatial dimension. 17.

• Benedict, M. A., & McMahon, E. (2006). Green infrastructure: Linking landscapes and communities. Island Press.

• Brears, R. C. (2018). From Traditional Grey Infrastructure to Blue-Green Infrastructure. In R. C. Brears (Ed.), Blue and Green Cities: The Role of Blue-Green Infrastructure in Managing Urban Water Resources (pp. 1–41). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-59258-3_1

• Costanza, R., d'Arge, R., de Groot, R. et al. The value of the world's ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 387, 253–260 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1038/387253a0

• D’Souza, R., & Nagendra, H. (2011). Changes in public commons as a consequence of urbanization: The Agara lake in Bangalore, India. Environmental Management, 47(5), 840–850. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-011-9658-8

• European Commission. (2013). Green Infrastructure (GI)—Enhancing Europe’s Natural Capital. European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/ecosystems/docs/green_infrastructures/1_EN_ACT_part1_v5.pdf

• Iyengar, S. (2007). A collection of traditional practices for water conservation and management in Karnataka. 136.

• Kalave, S. (2007). Water tradition: The Malnad story- an article in Waternama | India Water Portal. https://www.indiawaterportal.org/articles/water-tradition-malnad-story-article-waternama

• Murphy, A., Enqvist, J. P., & Tengö, M. (2019). Place-making to transform urban social–ecological systems: Insights from the stewardship of urban lakes in Bangalore, India. Sustainability Science, 14(3), 607–623. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00664-1

• Ramachandra, T. V., Sellers, J., Bharath, H. A., & Setturu, B. (2020). Micro level analyses of environmentally disastrous urbanization in Bangalore. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 191(3), 787. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-019-7693-8

• Sandhu, Er. V., & Sidhu, Dr. A. S. (2015). Environmental Governance in India: A Systematic Review of the Initiatives (Volume 8, Issue 4). http://www.pbr.co.in/2015/2015_month/Oct/7.pdf

• Sudhira, H. S., & Nagendra, H. (2013). Local Assessment of Bangalore: Graying and Greening in Bangalore – Impacts of Urbanization on Ecosystems, Ecosystem Services and Biodiversity. In T. Elmqvist, M. Fragkias, J. Goodness, B. Güneralp, P. J. Marcotullio, R. I. McDonald, S. Parnell, M. Schewenius, M. Sendstad, K. C. Seto, & C. Wilkinson (Eds.), Urbanization, Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: Challenges and Opportunities: A Global Assessment (pp. 75–91). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7088-1_7

• Wright, H. (2011). Understanding green infrastructure: The development of a contested concept in England. Local Environment, 16(10), 1003–1019. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2011.631993

Building India’s Blue-Green Network: A Strategic Framework for Bengaluru is a project that brought together Australian and Indian firms, and academic and government actors via online platforms to develop a framework for enhancing Bengaluru’s BlueGreen Network. The project led to a more nuanced understanding of the Blue-Green networks in the city and more importantly, derived a framework to strengthen this natural system that has been an integral part in shaping socio-political geography of Bengaluru.

Building India’s Blue Green Network: A Strategic Framework for Bengaluru was one of the 12 projects selected for support by the Australian Government through the Australia-India Council (AIC) 2021 Grants Program and was implemented by McGregor Coxall (Australia) in collaboration Integrated Design (INDE; Bengaluru).