DISCOURSE AND CONTEXT

Mohan Rao, Principal Director, Integrated Design INDÉ, Bengaluru | mohan@integrateddesign.org

Mohan Rao, Principal Director, Integrated Design INDÉ, Bengaluru | mohan@integrateddesign.org

FRAMING THE DISCOURSE CLIMATE CHANGE } }

This issue of the LA Journal is curated around the challenges of Climate Change; it is important to note the reason for such duration and at the time it is being done. Climate change is no longer merely a theory that one can postulate upon; Climate change is very real and increasingly manifest in the everyday. The phenomenon is increasingly referred to as Climate Crisis, given the extreme ramifications for the planet.

The idea of Climate Change as an anthropogenic phenomenon has been well established for several decades now. Some of the earliest research that dealt with the idea of human-induced Climate Change date back more than a century. Over the last three or four decades, scientists around the world have established beyond doubt that human actions – be it industrialization, burning of fossil fuels, land-use change, agricultural cropping patterns, and practices, or consumer lifestyles – all these and several other factors together have irreversibly changed the earth’s climate.

Any serious discussion on the issue of Climate Change should necessarily address the idea of denial – individuals and interest groups who deploy either pseudoscience or questionable logic to either completely deny human-induced Climate Change or play down its immediacy and criticality. Tragically, a crisis that needs an immediate and concrete response and action is mired in conspiracy theories, wasting precious resources and time. Equally important is the non-recognition of the impacts of the looming crisis as affecting every one of us inhabiting the planet. The great reluctance to effect any change in the status quo of development narratives or lifestyles is reflected in tokenisms that abound our practices. It is quite common for people to ask how one’s actions can make a difference in ocean acidification, for example. Or, to put it differently, how does a distant phenomenon like ocean acidification has any impact on our lives, far away from the oceans? It is crucial to understand the inter-relatedness of issues and the multiple cause and effects that have led to this climate crisis. It is for this reason that the very first article [Decoding Climate Change by H. S. Sudhira] is framed like a dummy’s guide; structured to answer frequently asked questions as well as demystify the many myths and misunderstandings around Climate Change.

The predicted outcome of Climate Change impacts every aspect of the biosphere we inhabit – it is not limited to a rise in the average global temperatures or the consequent rise in sea levels due to the melting polar caps. It goes well beyond these and includes complete disruption of biodiversity, food systems, soil moisture, disease vectors, etc.; every aspect that is critical to the existence of life on the planet and that of course includes humans.

While the audience of the LA Journal is largely landscape architects, architects, and planners, we need to understand and appreciate critical perspectives that emerge from varied fields such as science, agriculture, design, planning, academia, and even the arts. Each brings their perspectives in reading the challenges of Climate Change and the possible ways these could be addressed, whether through mitigation or adaptation. Either way, a proactive and immediate response is required of us; because we are the ones who have been the main drivers and causes of Climate Change on earth, and it is our moral responsibility to ensure future generations do not pay the price for our actions and inaction. Elaborating on the theme of alternative perspectives is the article India’s disembedded rural landscape by A. R. Vasavi, highlighting the impact of Climate Change on rural India as a narration of everyday, a distant experience from the urban.

The relevance of Climate Change to the profession of landscape architecture is critical since it deals with a wide array of systems and contexts – biotic and abiotic, urban and rural, and man-made and natural. Given the wide range of scales, contexts, and geographies the profession engages with, Landscape architects are possibly among the best suited to address the challenges of Climate Change.

The relevance of Climate Change to the profession of landscape architecture is critical since it deals with a wide array of systems and contexts – biotic and abiotic, urban and rural, and man-made and natural. Given the wide range of scales, contexts, and geographies the profession engages with, Landscape architects are possibly among the best suited to address the challenges of Climate Change.

While the best among the landscape architect community has always tried to create a balance between the natural world and the human world, it is now time to move this challenge up by several notches by not only addressing present-day challenges - be they environmental or developmental – to actively engage with critical challenges of the future. How landscape architects will proactively respond to this challenge will change the profession in profound ways. It will determine how we conceive of ourselves, frame the practice as well as shape the development discourse of the future. In this context, two interesting perspectives emerge; one is for the landscape profession to leverage technology as a way toward building resilience [Evolution of the Art and Science of Landscape Architecture and Design by Peter Head], while the other is more introspective [Landscape Architecture in the time of Climate Change by Krishnachandran Balakrishnan], questioning the role and responsibilities of the landscape discipline and speculating on its possible realignment to be future-ready.

Equally important is the way the trajectory of landscape academic programs is guided and informed by the challenges of Climate Change. Conventional educational patterns developed over the last hundred years will need to be severely challenged, driven as they were by visual and spatial design in its formative years to concerns of environment and development in the last decades of the 20th century. This needs to be challenged further to include not just current development challenges but future predictions driven by temperature rise, loss of biodiversity, and impact of extreme events, amongst others. We must prepare our student community to face these challenges of risks and vulnerabilities in the coming decades and foreground the idea of the resilience of all systems. The compilation of interviews [Climate Change in Academics by Geeta Wahi Dua] with several academicians of institutes running undergraduate post-graduate programs along with their studio works make for an interesting read in this context. The level of awareness and extent of engagement varies widely – from focused programs addressing resilience to a mere addendum to the conventional syllabus. These conversations take on a special import on the 50th anniversary of the Landscape program at the School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi, whose mandate laid a strong emphasis on active engagement with contemporary development issues. Whether an issue as vital as Climate Change finds a place in current academic discourse in architecture and landscape programs across the country remains to be seen.

One of the major challenges while dealing with Climate Change is the idea of extreme events versus gradual change. While it is relatively easy to react to extreme events such as floods or cyclones, it is the series of gradual changes that Climate Change is sure to bring upon us in the coming decades that makes it so much more challenging to respond to. While incremental changes provide us the opportunity to react, intervene and adapt, it also quite likely to make us complacent. The immediate and focused reaction to an extreme event such as the earthquake in Latur or the tsunami in Nicobar mobilized society as a whole – from fundraising to sustained action,

Conventional educational patterns developed over the last hundred years will need to be severely challenged, driven as they were by visual and spatial design in its formative years to concerns of environment and development in the last decades of the 20th century.

including design interventions by professionals. Unfortunately, slow and incremental changes do not elicit the same intensity of response. Added to this is the idea of disaster fatigue; repeated flooding of our cities is a classic example that makes us more accepting of the situation as the new normal. Rather than planning and undertaking concerted action to address the issue during its nascent stage, repeated incidents of cyclonic storms to heat waves only makes us more complacent and accepting. Developing coping mechanisms in place of active mitigation is a dangerous and slippery slope that can further exacerbate immense disparities in an already unequal world.

It is useful to use the analogy of a human body to better gauge our reactions to the climate crisis. Typical anomalies in the functioning of the human body – be it a sickness, an accident, or a kidney stone – have specific and immediate responses by the medical community and more importantly by the patients themselves. Compare this to lifestyle diseases that cause very gradual and sustained harm such as diabetes or cholesterol; these are not perceived as an immediate or grave enough threat. The urgency with which these are addressed is unfortunately quite similar to our reaction to Climate Change; while the dangers are well established, the threat is quite invisible in a seemingly distant future. The analogy when extended to our environment shows an immediate reaction to extreme events such as a cyclone or an earthquake while a gradual change such as soil erosion or loss of biodiversity fails to elicit the same degree of response.

A recurring question among the professionals and students is that of scale. I am often asked how one can make a difference in a global challenge such as the climate crisis when we are typically dealing with small projects of five to ten hectares. One way to think of this question is in terms of the accretive nature of actions; in how the present climate crisis is a result of thousands of small interventions over the last two centuries. In the same manner, the solution, or at least part of the solution, can also lie in small interventions whose collective value can impact the larger system. This includes a large menu of actions that can help address soil conservation, biodiversity management, climate-sensitive design, resource management, etc. A tangible engagement of these issues and the diverse actions they entail can be seen in the project section across different scales, geographies, and contexts. Be it the IIT Gandhinagar addressing food security [Designing for the Changing Climate by Vinod Gupta] or the Surat Safe Habitat [Towards a Positive and Transformative Process by Integrated Design INDÉ] addressing challenges of flood risks, what is notable is the foregrounding of critical global issues with context-specific responses. Moving beyond the tangible and spatial are urban and institutional strategies, amply demonstrated in articles [Socially Just and Adaptive Community Spaces by Anjali Karol Mohan, Gayathri Muraleedharan & Juliana Gomez Aristizabal, and Climate adaptation strategies for coastal fishing communities by Selco Foundation]. These highlights how the Climate crisis impacts the livelihood of the marginalized, whose narratives are often missed and overlooked in the design discourses, capturing a nuanced reading of our urban environments [Mental Health Resilience to Climate Change by Shobha Raja and Harini Nagendra].

One way to think of the question of scale is in terms of the accretive nature of actions; in how the present climate crisis is a result of thousands of small interventions over the last two centuries. In the same manner, the solution, or at least part of the solution, can also lie in small interventions whose collective value can impact the larger system.

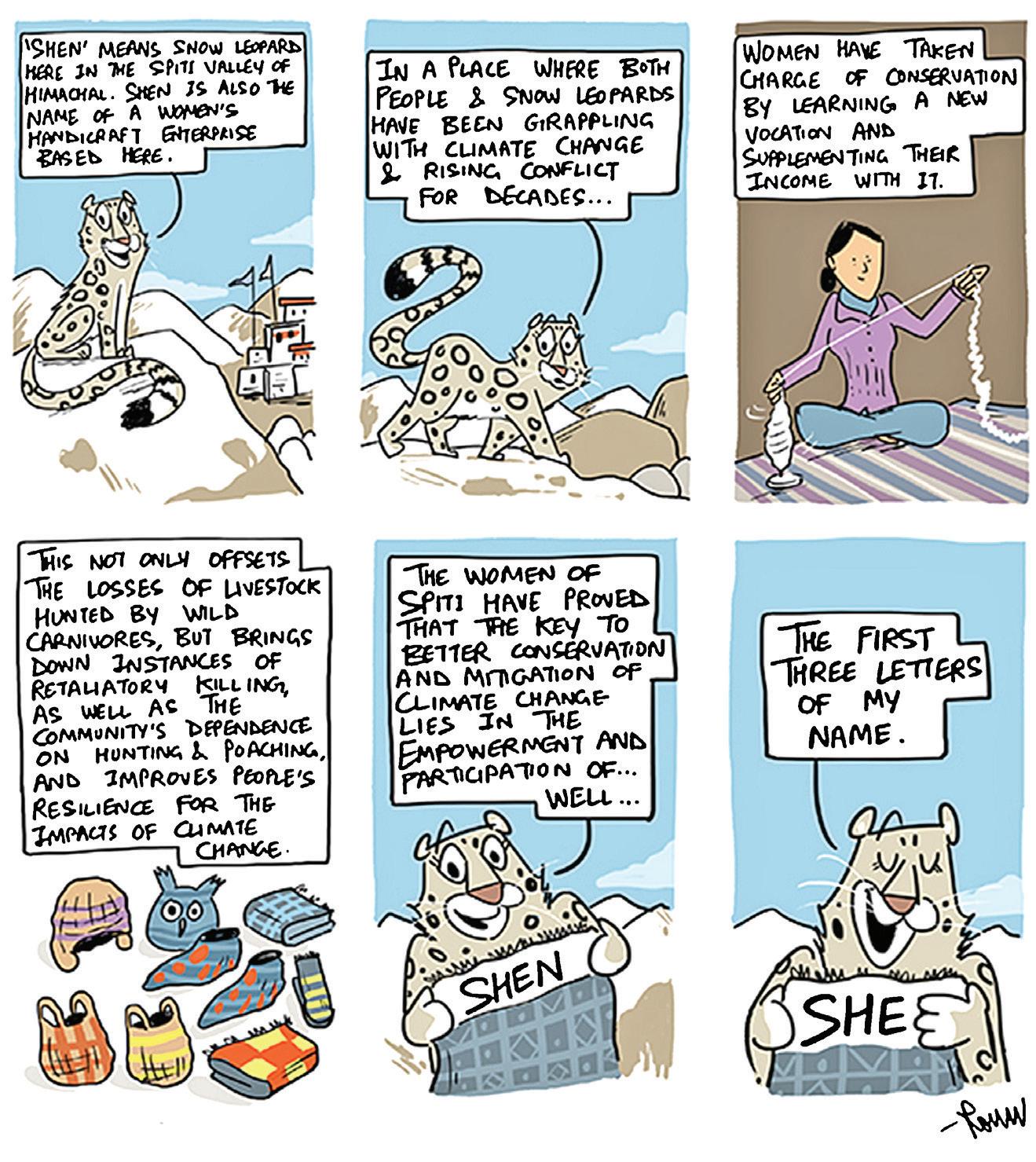

In addition to the technical understandings of the climate crisis – both academic and professional – from landscape architects, planners, and policymakers, we need to acknowledge and internalize the valuable insights from the thinkers in our society including journalists, writers, poets, and so on. The everyday media plays a critical role in how Climate Change is both understood and communicated beyond the formal structures of the profession and academic institutions as evidenced by thoughts on cinema [Climate Change in Cinema by Karishma Rao] and graphic art/ cartoons, which so very well championed by Rohan Chakravarty [Green Humour].

Over the past two to three decades there has been a lot of discussion on sustainable landscapes which is a very positive development. It is crucial to realize that the idea of sustainability as presently defined by various rating systems is largely driven by two issues; one, it is entirely focused on the built environment and its presumed efficiencies, and two, it is premised on the idea of maintaining the same ‘standards of development’. Such paradigms of sustainability neither recognize risks and vulnerabilities nor engage with the idea of resilience in the long term. They merely use the idea of sustainability to foster the efficiency of resourcesaddressing a demand-supply scenario to maintain the status quo of current ideas of development. In light of the climate crisis, what is imperative is the urgent need to develop a new paradigm of development that balances societal and environmental concerns effectively and equitably.