1997-1998

El comencament del curs coincidi amb la celehraci6 dels 90 anys de l'IEC, i la nostra Societat hi participa, coin les altres, amh una taula rodona intitulada Fls estudis classics a lc's portes del seis XXI, on es tractaren els aspectes principals dels reptes que tenim plantejats avui dia. Els principals Toren: ensenyament secundari, ensenyament superior i recerca, tradici6 recent i ideologia dels estudis classics a Catalunya, situaci6 del mon editorial i de les traduccions, projeccio internacional. La modern Caries Miralles, i hi parlaren Marc Mayer, Jaume P6rtulas i Antoni Seva, a part clef public que participa en el debat final. L'acte tingue Hoc el 31 d'octuhre. La resta de 1'any academic va ser ocupada em hona part per un curs de 30 hores reconegut pel I)epartament d'Ensenyament dintre del programa de formaci6 (.lei professorat. Es tituki Mitologia i Cieucies de l'Aaatlgaaitat i dura, en clues parts, del 4 de novemhre al 31 de mare, a rah de dues conferencies setmanals. Ileus-11C aqui la Ilista:

4 de novemhre: "Mite i pensament en la Grecia del S. V1,^, Prof. _Jaume P6rtulas.

6 de novemhre: "Mitologia Classica i Sants Pares", Prof. Josep O'Callaghan. 10 de novembre: „Copografia de Roma y textos literarios del s. I dG, Prof. Emilio Rodriguez.

13 de novembre: --La numismatica como fuente,,, Prof. Francisca Chaves. 18 de novemhre: "Les religions antiques de la peninsula", Prof. Javier Velaza.

20 de novemhre: „La literatura juridica romana en bronco"", Prof. Julian Gonzalez.

25 de novemhre: '^Esvaint ombres i sortint de la caverna. Lectura de La caverna de Rodolf Sirera^^, Prof. Pau Gilahert.

23 de fehrer: ,Plato's Quarrel with the Poets, Prof. Stanley Rosen. En col.lahoraci6 amb la Societat de Filosofia.

24 de fehrer: ,An Introduction to Plato's Philehus", Prof. Stanley Rosen. En col.laboracio amh la Societat de Filosofia.

3 Cie mare: literatura i mite,,, Prof. Caries Miralles.

5 de mare: Jradici6 classica i literatura.., Prof. iaume Juan. 10 de mar4: 4.3 suhstitucio Cie mitologies. El s. IV CdC, un segle frontissa.., Prof. Montserrat Camps.

12 de mar4: 4Historia i mite a Roma,, Prof. Marc Mayer. 17 de mar4: -Alguns temes mitologics a I'escultura", Prof. Eva Koppel. 19 de mare: -Paisatges deifies", Prof. Maite Clavo.

21 de mare: La epigrafia romana de la peninsula iberica: prohlemas, esfuerzos, resultados", Prof. G. Alfoldy.

31 de nlarc: ,Mosaicos de terra mitolbgico,,, Prof. Jose M. Alvarez.

A part d'aixb, ens visitaren alguns altres conferenciants, val a dir que alguns de gran prestigi. Fl 15 desembre. Victor Palleja ens parka de J'n altre hereu del pensament classic: i'Islam . I'll Cie febrer el professor Mikl(>s Szab( ens dihuixa un estat Cie la guestio sohre "Fis celtes del centre d'Europa,,. El 21 i el 22 d'abril, el professor Walter Burkert, de la Universitat Cie Zurich, pronuncia dues conferencies organitzades en col.lahoracioi amh la Societat d'Ilistoria Cie la Ciencia i de la Tccnica. Els titols foren:,Fitness or Opium: Biology, Sociobiology and Ancient Religions", i Purification in Ritual and 'T'heatre: From Selinus to Aeschylus". El 12 i el 13 de maig, ara en col.laboracio amb el Departaiuent Cie grec de la Universitat de Barcelona, la professora Suzanne Said, de la Universitat de Columbia, parka, a la nostra seu, de 4Famille et cite Clans les tragedies thebaines^,, i a Ia Facultat Cie Filologia de -L'identitC grecque Bans la rhetbrique de la democratie a I'Fmpire,^. Finalment, el professor Ernest Marcos, de la Universitat Cie Bar(elona, tanc:t CI curs parlant de ,."L'Emperador dell grecs" a l)esclot a Muntaner"; aixo fou el 10 Cie jury.

A part Cie les conferencies, i a mes del numero 12-13 d'Itaca, apareguC el primer annex de la nostra revista, un volum de 590 pagines. editat per M. Mayer, J.M. Nolla i J. Pardo, i titulat Dc' les c'sh-rrchircN i^tdt^c^re. a I'o ganiIzacio pro1'incial ro'naiia.

1998-1999

El professor Geza Alfoldy, bon conegut de la Societat i de I'Institut, del qual es memhre corresponent, inaugura el curs, el 15 d'octuhre, parlant de 'I'rajano padre y el ninfeo de Mileto-. Pere Canela, professor de la Universitat Aut<noma, el 20 de gener ens explica les Tarticularitats del Ilati hispanic,,. El 8 de gener, Ezio Pellizer, professor de la tniversitat de Trieste, ens il.lustra, amh diapositives, sobre ,La storia di Medusa: varianti iconiche e varianti narrative que, completat, sort en aquestes mateixes pagines. L' 11 i el 12 de mare, en col.laboracib amb la Societat d'Histbria de la Ciencia i de la Tecnica, organitzarem dues conferencies del professor Geoffrey

ii'

Activitats

E.R. Lloyd, de la Universitat de Camhridge, que tingueren Iloc a la sala d'actes del CSIC; una fou + ilosofia y medicina en la Grecia antigua: modelos de conocimiento y sus repercusiones": l'altra: la comparacion entre la ciencia griega y la china . El 14 d'ahril , Gloria Torres, professora a la Universitat de Barcelona ens vingue a parlar, a la Reial Academia de Medicina, de -La llegenda arturica a 1 ' hagiografia" Ja pet maig, el dia 3, Margaret Kenna professora a la Universitat de Swansea , del Pius de Gal. l.es, ens mostra un ,Pilgrimage to a Greek island from Argonauts to Athenian migrants^, ( aquesta conferencia fou organitzada en col.lahoracio amh el I)epartament d'Antropologia de la Universitat de Barcelona ); i el 18, C.indida Ferrero, de la Universitat Autonoma . parla de Juan Gil de Zamora v su okra cientifica^. Finalment el dia 17 de juny, el professor David Konstan, de la Brown University, amh una discussio sohre 4La misericordia diving (lei paganisnw al cristianism o,,, dams pas al petit refrigeri amh que sole111 tancar el curs.

I,a mort d ' Efialtcs

\I. 1'icaFam

Quant al v()stre conciutada Efialtes. encara no An estat descc)herts ,quells (lui Cl feren mo rir"".

Antifc)nt V 08 es la referencia mes acc)stada en el temps a i'assassinat d'Efialtes, eI ciutada atones el nom del (pal es assc)ciat a la retallada Cie poders s()ferta per 1-Arc6pag vet's l'anv 162-1 aC.

FA capitol \\V Cie I'aristc)telica C)nstiliwi(i (l'Alenes es fa tamhe ress<) de la mt)rt (I Hialtes. tot presentant aquest personatge c(nn a enemic inexorable Cie I'Arei)pag i recc)ilint Lill incident -en retire tins delegats Cie i'ArW)pag. I:fialtes, cctn eneut clue es dispc)sen a for-lc) agafar, cerca, espacn-dit, refugi en Lin altar- clue p()sa en evidencia la sera pOr davant dell are()pagites. Amh fajut cie 'i'emistc)cles, Efialtes ac()nsegueix desprc)veir del sell pcxler el COnsell vligarquic, pero, al cap cie pc)c- temps". rnu)r <<xcit arterOsament (c>C)Wg)ovtlOFL ) )Cl' Arist<xlic dc 'lanagra^^. Pkttarc' ahc)na la tesi de Fassassinat. a la vegada quo prep partit contra ids nt)eneu', clue atrihui;t el (Tint a on Pericles pie cIe gelosia i d'env eja contra Cl nc)stie pers()natge. Segt)ns Plutarc, la desaparicio d'I:fialtes, cie qui rent.a-ca la seVa actitud contra els c)ligargties i a favor del pc) ile. s'ltauria prOdtiit perdue eels enemies c(mspiraren contra ell i, d'amagat (xpuquiu);). el mat.urn per mitja (I Aristodic cie 'lanagra». I)i<)dOr dc Sicilia` emfasitra els danvs causats per Ffialtes a l'Arec)pag i expiica clue nc) se'n s<)rli impunemens' sinO que. "occit durant is nit. la sera Vida tingue Lill final c)hsrur.

I. l'rr. I)).

2. FOrllist 335F5. i. Xi "'.O ^1. Fis c(lito^cs hrrfcrcixcn Ia lectura ('t0(1c ) ;a aOFicu;.

IO M. 'feces, Fan

11.1.

Aquesta es tota la inf<)rmaciO que ens pan transmes els grecs sohre la nun-t del nostre personatge. Es evident que hi ha unaninlitat a 1'hora do, cOnsicletar que Efialtes fou assassinat. I aixt) mater opina Ia majoria (Tautots Contenlporanis`. Lcs fonts antigues, amh Tunica excepciO ci'Antifout, coincicieixen tamhe a menci mar la mart de I'atencs inunecliatanlent clespres cl'al itidir a ,quells que havien patit les conse(l encies de Ia seva activitat, tot possihilitant que horn arrihi a vincul:u' CI crint a una iniciativa (IC l'Are6pag. EI no stye article en vol cleixar constancia i, alhora, ,Want una mica mes enlla, es pr^)pc)sa cle criclar l'atenci() sohre certs elements que apareixen en les narracions del fet i (Iue, en altres contextos, serveixen per caracteritvar I'activitat cde la instituci(i areopagitic.i. E1 testin)oni de )i )dOr renlarca. Cam hem vist, que Ia mart c1'Efialtes es proclui ""durant Ia nit,,. I creiem que ,quest, no es una clacla irrellevant, ates que, en la tracliciO hel-lena. hi ha punts tie contacte entre ]a nocturnitat i 1'Areopag.

En efecte, a Les 1`11114'rtrcles ci'Iaquil, Atenea, en pronunciar el parlament que institueix ,quest consell, el clehneix corn a tUdOVTO)v iiJTEQ / ^YE)11Yo^)oc 4)(.)OUoi]p(t yljc»", paraules que Cl. Riha traclueix per guardia tie la terra, senlpre despert en clefensa clels qui clormen,, que, an)h una gran eficacia, apropen Ia instituci(> atenesa a imatges du vetlla i de salv,(guarcla^. Encara mts: en diversos passatges c1'aquesta n)ateixa ohra, cle la qual P. Vidal-Naquet° fa notar que es clou amh una processb nocturnal'' apareix la nit -i la negror (Iue Ii es PIC)pia- vinculada a uns essers que tenon molt a veure amh I'existencia de l'Are6pag. Em refereixo, naturalment. a les Erinies, Ies lilies de Ia nit'', vestides de tie-

Hi ha, per('), alguna veu discrepant: 1). SiocKloN (The death of Fphialtesn, (,'Q 32, 1982, pp. 227-8), hasant-se en elfet yue Ies fonts no esmenten la presencia de ferides en el cos ('Rialtos, dedueix yue ,quest podria haver n>rt de causes naturals. Corn a exernple representatiu de Ia postura contraria -4-o es, ayuella yue adnact yue, efectivament, hi hague un homicidi- cfr. C. Hip,,yry-r. A history of the Athenian constittttion to the end of the fifth century h.C.. Oxford 1952, p. 213. Quanta opinions sohre yui fou I'autor de 1'assas.sinat. vegeu el capitol Sete de I'ol^ra de L. Pu:cikn.H, hficrltr. Genova 1988.

6. Vv. 705-6. Cfr. v. 692.

7. Esyuil, /ra,^edies 111, FilM, Barcelona 1931, p. 163.

8. E.R. Doim,s ('Morals and Politics in the Oresteia», The ancient coucel)t of progress and other essays, Oxford 1973, pp. 45-63) posy en relaciO Ia frase d'Esyuil amh altres expressions (Arist. Ath. 1,-1 i 8,+, Plu. Sol. 19) yue atrihueixcn a I'Areoopag una actitud de vigilancia en el si de la polls.

9. Chasse et sacrifice Bans I'Orestic' d'Eschyle.., a J.-P. VFR.vAxr - P. S i)At-xAcx ttr, ,lt)the et tragedie en Grace aucienne, Paris 1982, pp. 133-58.

1(). Cfr. vv. 1022 10,0-2.

11. Cfr. vv. 321-2, 416. 745, 792-3, etc... Sohre Ies Frinies corn afilles do la nit. vegeu C. R.A.\lNU1''c, La unit (t lc's enfcuus de /a unit dons la tradition grecc/lie. Paris 1986. p. 103 ss.

LI lll()I-t CH"I'LlItcs

gre", yue e^l^erin^enten una f^>sra rancunia" i yue han rebut c1e Clitenu^esU-a sarrifiris n^x^turns^^

^CgUlnl en ayues[^l Illa^el\a Ilnla, CalClra yUe rerUll1111 Una lnfOr11Y1C1O se-

g^ms Ia dual l'Are^>^^^ig c^erci;i les se^^es funri^ms hrerisament ^iurant la nit.

Ik^s hassatgcs ale I,luria hi Ian rr•ferencia: 1'un'`, en una aferrissa^l^i argunu^ntari<"> a ta^^^^r cle la hre^°alen^.< <l'all^^ yue h^nn ^^eu ^lamunt cl'allo c{ue

h^nn esr^>It^i, ens f^n^nei^ la n^^tici,i clue la insti[uci<""> atenes^i relehra^^a aurli^nria cle nit, mewre yue I'altre"' rerun el c^msell cle n<^ tenir en c^m^hte

I'eclat, 1'aharrn^'a <> la h<ma an<>menacla cl'ayuell c{ue harl^i i cl'actuar rani h^^ fan els are<>^^agites, ^^yue jutgen cle nit i en la t^>srcn-, jeer tal cle n^^ h:u-^ir esnu^nt en els <>r«lc^rs, sine en les }^^u-aulrs que ayuests ^^ronuncien^^.

II.?.

'I'^n^nen^ cle hill n<ni a I'e^^is^xli de lei nun-t cl'l^:fialtes ^^er tal rle suhratilar-ne una alts r^u-arteristica. F.m referei^^^ al fet c{ue les f^>nts rer^>Ilicles a 1'inici cl'ayuest .u-ticle ens han inl<^rmat, successi^^ament, que «enr.u-a n<> han estat clesc^,hc^rts» ayuells yui m.narcn el n<^su-e herscmatge' . yue .uluest f^ni ,issussirrit ^^.u^terc^sament^^, yue uns enemies ^^ronshiraren r^^nu-a ell^^, yue el feren ^^rcir ^^c1'an^agat^^ i yue „la sera ^^iela tingut^ un Final ^^hscur»'^' ^lacles yue, nu^s enllii cle 1<< se^^<< -cliscutihle, <> no- ^°ersemhlanc^a, ens remeten ;i un mateix c^mtezt c1'^x^ultari<^ i c1e secret, c^^nteYt que, cl'alh-a hancla, escau cl'all^i mes, seg^ms la traclici6 cultural gre^;a, a la instituci^i are^^hagitica. l?Is r.^hit^>ls ,?. ^3 ^O ^lel cliscurs Cuith^u .A^c^c^rc^ ens assahenten cl'un inri^lent en el yu.^l 1'acniaci^^ ^>rulta juga un haher clestarat. L'atenes F.st^^fan ha cas;u la se^^a -sulx^sacla- filly Fan^^ amh 'he^^^enes, l'incli^^iclu ck^signat

I^er ^>ruh;u- el carver cl'^u-ront-rei. Artuant nisi, Estefan ha transgreclit les Reis c1r la ^x>lis, car la noia, filly c1e la c^n^tesana Neera, ^s una ^^vi^, rc>sa yue la inraharita her a c^>nh^eure ma[rinu>ni legitim amh un ciuta^l;i. 1'er^^ rl }^itjor ^lel vas ^^s yue, r^^m a miller cle 1'arc<>nt-rei, F:m^^ :u-riha a ar<»n}^lir ayuells antes sacrif^iri<<ls ^^yue n<^ han de sec cli^^ulgats^^ (u^^^^1u) i ^1uu a

I?. Cir. ^^. i^l i ^^'0. Als ^^^^. IHI-i, la negr^^r de les Erinirs rontrasta amh Ia I,Ian<<^r de ICs flrtses d'A}xil^lo: ho fa Constar P. A"n>^t.-'^:^C^t^sT (np. nil. a la n. 9. ^^. I^^,^, a yui hem m;mllev;it Li maj^^ria de ICs dadcs ex^osades en ayuest ^^aragraf.

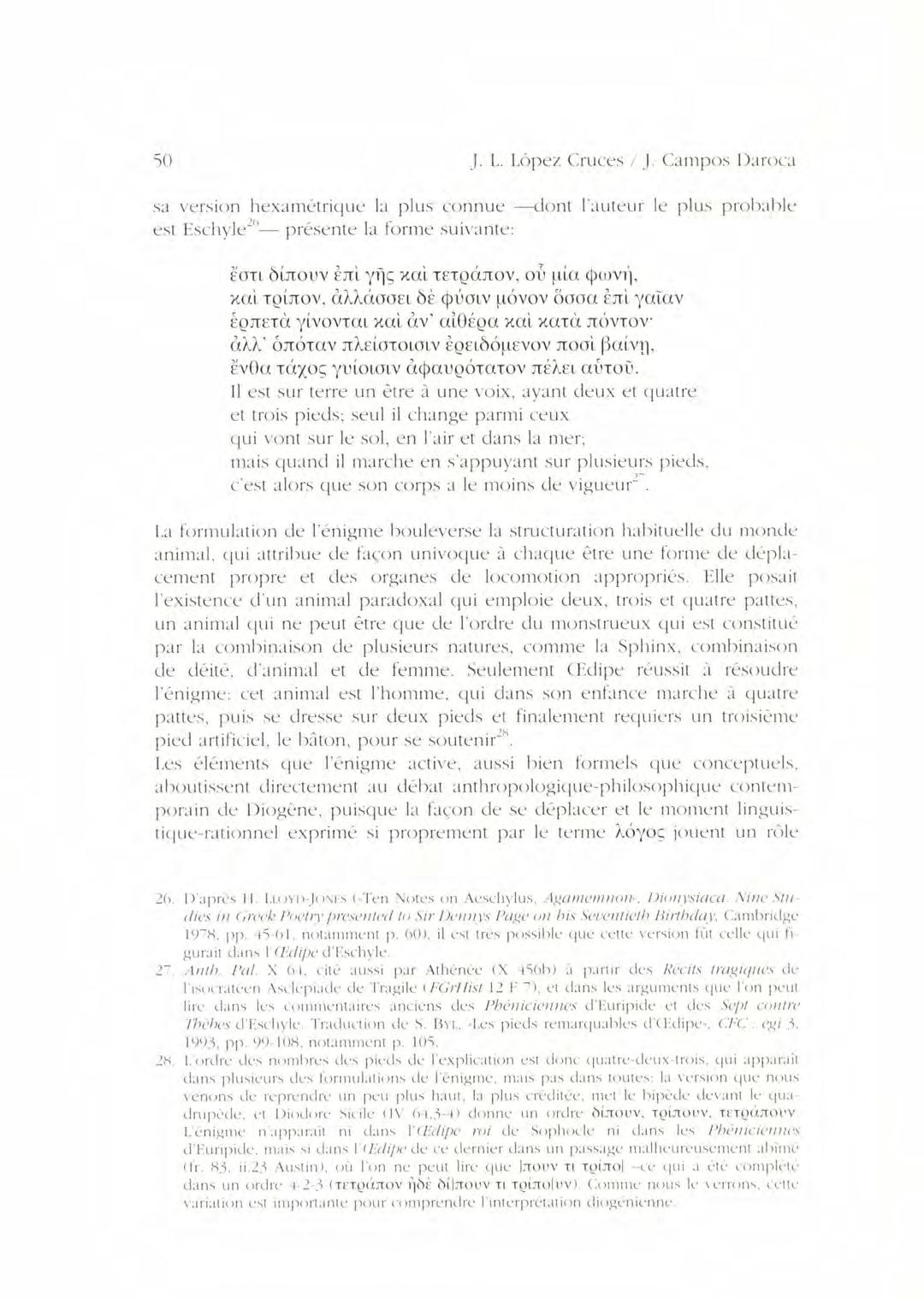

l3. Cfr. ^^. hi?.

I i. Cdr. ^^^^. l^Kr9. Sr>hre la relaci^3 existent rntre les Erinies i 1'aann^^liment de sacrifiris nocuu^ns, vegeu-ne els escolis ur/ l^^c.

I ^. 1)unt. Ili.

I6. llcv^nt. b^i.

I,. ^li•s enda^^ant tindrem ocasi6 d'oruE^ar-nos d'Aristbdic de Tanagra, assen}alat Baer dues fonts nom a Li m;i csrrutori del trim.

IH. t^a nut iidi^).ov -^^<>hscur•^, en la nostri versib- indueix G. H. Orr>F^:^riieit (I^iodorrrs

Srrulr^s 1V^, 'I'hc^ Loeb Classical Lihrar^^, Cambridge (\1ass.l - Londres 1956, ^. iZ^) a haduir la (rase de Li segiient manes: ^^none ever knew ho^^^ he lost his life.n

I?

M. "Teresa Fau

M. "Teresa Fau

terme rituals secruts- ((t1rOL)Q)1iTa) de gran transcenciei1 is per a la cOniunitat i permes()s unicament a domes ci'Ori en irrepr()txable. I,'acces de Fan() 11 a aiIO yue Ii era veciat mOtiva la intervenci6 dc I'Are)pag, yue f;l inciaga- cions sohre Li identitat cie la transgressors. En assahentar se dc Ia vernal, ci cOnsell (iccicieix castigar Te6genes, per(k), ai xO si, es prop(sa d e fe r-ho sell secrete (i'v etTrOQQ)'jT(1)).

Climent cl'Alexanclria'`', ficiel a una traclici("> segons la dual f?syuil hauria estat inciiscret en relaci6 an)h Fleusis" explica clue Cl c1ran)atur^,1 cOii ar ^ur• clavant I'Are6pag pel let cl haver dOnat a cOneixer en escena clacles referents als nlisteris eleusins. El mateix Climent tlegeix, per6, clue Is(luil acOnsegui Lill vereciicte ciahsOluci6 en I inifestar clue ell no havia estat mai iniciat As misteris.

I )inarc" afirma yue I'Arei)pag Custociiava Tai ( TOO(QljTOI', (t(AOljxu; -O arrOOtjxuc- yue garantien Li seguretat ci'Atenes. IZ.u". yV'allace" erica la nostra ate11ci6 SOhre el fet yue Wolf', el primer editor du i)inarc. havia prOpOsat OijxaC, mot (Iue IaOln pot traduir per "doml)es". Paut()r anlerica crew yue la hipotesi cie \V'Olf, acceptacia gels editors Cie la "1'euhner, es "attractivO^, ales yue I'Are6pag, yue assumeix la lases de presel^ ar ail6 secret, guarciava la tomha ci'Edip, la yual, situada en Lill indict clescOnegut per tt la majOria de cititaclans, assegurava la cOntinu'itat de la pOlis ,ttenes i. Es, clones, a t(luest fet yue s'estaria referint I)inarc -segueix Opinant \t'alla CC- hauria emprat la forma plural (h'lxu; per inotiuS meriment retorics. COmpromes en la preservaci6 d all6 yue es i yue, pel he tie la cOmunitat, ha cle continuer sent secret, i'Are6pag irriba a incOrpOrar I'actt aci() secreta a -almenvs algunes cie les seves intervencions. Hem tingut Ocasi6 cie veure-ho en la decisio de castigar -en secrete I'arcOnt-rei Te6genes, i ho pOCiem cOnstatar tatnhe en Ilegir is n )ticia yue ens i111 01-111A yue, en temps cie Sol(-), Yuan el consell areOpagitic exercia el seu caret a castigar alga amh una molts, n'ingressava l'impOrt al tresor public sense fer cOnstar per escrit la CauSa yue havla original la sanca). Mes ei)cal'a: ,selnbla (-()III SI, cie tint sovintejar la relacio amh al16 que pertany a 1'itmhit del secret, el taranna mateix dels areOpagites n'hagues yueclat afectat. COnsti yue hO diem amh Lill punt cl'irOniat, en la yual Cosa no ciiferim essencialnlent dTayuells actors yue, tot recOrrent a una expressi6 proverbial, atrihueixen ais membres dc l'Are6pag Lill caracter peculiarment reservat'', fins al punt d'afirmar la im-

19. Stroin. 11 1-0u.

20. Cfr. Arist. FA 1111x10, I leraclid. Pont. fr. 170 Wl;ntlrt Ael. 171\ 19. Vegcu tanthc Ri t)HLvRUI, I.e clelit cfimpiete cfapres la legislation attiyue-^, 1111 IT, 1960, pp. 8'-105. 21. 1 9.

22. TheAreo/)q^its (;'otutcil to _307 b. C., The johns i0Opkins I'niversity Press I0$5, p III) Sohre I us cle uToQQ)11T0; (IC uOO11TO; cn 1)ntext(5 miit^rir^. ^Ir A\ Iii sri i;i. I/„n), necans Berlin 19-2.

23. Arist. Ath. 8.4. '!(Ir 'l'lama ( )r \\I ','ITil_ In 4)l \ I^^I

L/ m.m Jl]iuk..^, |^

Ix>^sil^ilitat [ant cl'iclentifir^u^-ne al^;uns r^nn cl';u-rihar a r^mt^iXer el n^nnl^re e^arte ^I'inte^r:u^ts cle la institucic^'`.

I)'alh;i I^ancl,^, la ^l^°tiU^c•sa un^l^ yut^ 1'^r^°^^I^an ^°s n^^^u ^n ^I n^arr cl^all<^ ^^rult li al<>^;^a una inclisrutil^lc r<>mpct^ncia ^i 1'h^n^acle ^lirtaminar s^^l^re

^luelr^nn t.^n rec^^nclit r^nn s<">n les intenri<^ns cle I'^sser l^unl;i. tent p^^ssil^le, per ezemple, clue el c^^nsell al^s^>l^;ui la ^l<ma yue, amh t^^ta rertesa, ha nwt.u un lunne'" i clue, en can^^i, r<>nclumni per partiripari^i en un ^leli^^te cle s,u^^ I'incli^^i^lu glue n^^ cluia a Its mans rah element raha^ ale hro^^^x^ar la nun^t' ^. li at<>i^^,^ t.unhe r<^mpcti°nria a I^lu^raclr tr^^har Ia ^ t°ritat clu^• s'an^a^.< en un s<nnni, r^nuluint :Iixi ^^^°rs un ^1^°st^nlla^ Ix^sitiu un al^cr ^^n^^iUic^>Il,it yue sen^l^la^^a, en principi, destinut a n<> tenir s^^luri^r',

III. I.

l'n r^^p estal^lert <lue hi ha una relaci<> entre 1'Are^>p^ig i clues c:u-artrristi ^lucs -n<>rturnitat s^°rret- ass<>ria^l^, a l,i nu^rt cl'I^:f^i^ilt^s, h^issc^m a ^^rup.u--n^>s cl':lrist^xliccle 'I'ana^;ra, I'l^^^me a yui dues cle les I^^nts r^msi^nacles a 1'iniri cl'ayuest arti^^le (ens ret^^°rim ail t^°^t arist^^[^lic i ail hass;it^e hlut.^ryuii^) prescnten c^nn ^i actor material c1e I'assassinat.

La tra^iic^i<"> l^el^len.^ ^;u:u^cl,I, a hrol^<^sit ci'acluest personate, un silo°nri ez:^sper.ult i, fora cle I,^ notiria yue el relacion^i aml^ 1'acri^^ homiri^la, no ezisteiz rap alts rel^ercnria a I'incli^^i^lu en yiiesti^^, la clu^il cosy ens ol^li^;a a iniriar la rerer^^a prevent rom a Irise els testinumis clot ens infonnen sollfe la nun^t cl't?lialtes.

Ik>s [refs rararteritien Ia ^i^aneri ale ter d'Aristixlir cle "I'^in^igra: la se^^a ralxicitat per actuar^u-terosament (la ^^ic[ima nu>ri be^i^u^ov^^Oti^) i I;i se^^a ^^inrulari^"> :unh 1'an^hit ^I'all^> o^^ult (els enemirs ^I'El^ialtes sc'n sen^iren x(:^t+cp«u^^^). tii, a nits, pre stem ^uen^^i^i a la noticia cle I)icxi<>r se^ons Iii dual I'assassinat es prociui clurint la nit, resultara que Arist^>clic cle 'I'an^igra ti• ones c.u:^cteristiyut^^ (caparitat her al cl^^lc^s, relaci^i aml^ alli> clot is atoll una especial I^ahilitat per ^i 1'actuacib nocturna) yue c'I ronnotcn

?>. Cfr. Ath. ^'I ?>i tiff. L6. Arist. .1 /,1/ 110?. La nu^rt es pr^^clui clespres yue I'incli^^idu en yues[i^i hegues rl liltre am^>r^is yue,an^h ^^^^luntatn^> prcci.^an^cm h<m^icida, li ha^^ia Iliurat la ^I^ma. Cal ter c^mstar yue I'Are^^pa^; t^• tamhe jurisclicci^> en casos d'hrnnicieJi Per emrrin:unent, es a ^lir, cn situa^i^>ns en yur la nx^rt ha estat aciministrula ^1e manes ^^orulta ». Cil^. ll. \X111 ?E, :^1'ISI..9 /Lz ^,^ i I'^> II. ^^III 11. h. Cfr. I). LV'I ?^. I?s tracta clel pare cle la sacerclotessa cle 13raurci, yue f^^u I^instigack^r cfun a„ as,inat I?I text especifica yue el suhjecte retie el rastig, ^^t^^t n<^ ha^^er turat^^ la ^^ietima.

Zt^. Cicero ^Uc - /) trio. 15+l rerull un epis^xli, ^up^^sadament pr<xag^^nitzat per S^^f^^cles, el yual, arl^^crtit reiteracl . unent per un s^nnni satire la i^Icntitat c1e I'honu° yue ha^^ia rc^h:u un ^^alu<is ^ >I^jecte del temple d^licrarles, acudi a I'Arei^pag. EI consell prengue Ies mesures ^^p<n^tunes i cl cas f^xt feli^^ment result.

AI_I^ rc ^.I I,itl

cons a hersonatge m('lic, c's a (III-, posseidor d'a(luella [none de saviesa clue -tal coin denu)strenM. I)etienne i I.-P. Vernant"- tea v'eure amp la sagacitat, 1'astucia, la facilitat per a hre^ e ile alL) clue hot esdevenir-se, la cahacitat per a (lissintular i per a posar haranys, la suhtilesa i la facultat de mantenir-se en Lin estat de vetlla vigilant enfront de I'adversari. La melis d'Aristodic cle Tanagrt 1'ave'ina aLin altre hetsonatge, anontenat tainhe Aristodic, clue coneixem gravies a Lin relat &I lerodot"'. Fs tracta dun it-lustre riutada de Cinte, fill d'Heraclides, (ILIC gosa mcxlific.u- lee ronso (iUtnrics dung indicacio Oracul.u-. Fn efecte, 1'orarle (foie 13ranyuides havct or(Icnat el Iliurament als horses de Parties, Lin enemic (le (jr"yue s'11a0s rcfugiat a Cinte. Aristoclic ht)s<t en duhte la veraritat clef ntissatge rebut i assunteix la tusca de for, ell hersonalment, unasegong cOn.sulta a la divinitat. En refire una reshostg identica a la printera, (luu a [erne el hla yue, anti premeditacio ('xTrpovoi 1c) havia roncehut: CS h()sa a dollar V()ites entorn del temple i a exhulsar-ne lee gas yue hi hgvien let niu. Mientre esta realitzant ayuesta acciO, se sent una veu yue recrintina el sou captcni iient. Aristodic, hero, no Testa has sense recursos (OUX WTOLtt'lo(CVT(0, Sill() yue respon al clew: tienvt)r. tLi yue defenses iixi els teas suhlicgnts, ordenes, (Al canvi, ale cimeus yue Iliurin of sou suhlicant?-. L'estrategia toexit, glmenvs en Lin primer nu)ment", i el refugiat esenviat a Mitilene.

La metis d'Aristodic fill d'Heraclides es manifesta en Li seva capacilat per a posau- parallys, her a actuar 11111) hreineditgrio i her a [Taber sortida (aopoc) en mt)ntents dificils". A ell Ii Ila estat util a ]'bore d'ajudar la seva ciutat a afrontar una situaciO rompromesa, a Aristodic de "l'anagrt li hg servit per mater Efialtes. I. ;u-ringts a ayuest hunt, cal dir yue no es estranv de trohar, en Li literature grega, Ines personatgesanoincnats Aristodic yue, d'una manera o d'una altra, se situen en contextos de iiwlis". tna altrg rcntarca g hroposit d'ayuest nom. L'etiiiologia ci vincula a I'exercici de Nx11. I aixo ens fa pens:' en Lin text a yue al-ludient en comenc.n ayuest article. F:n efecte, a 1'hora de presenter els testinionis de 1'assassinat, recollient Lill pgssatge de Plutarc yue atrihu'ia a Aristndic de Tamagni I'exeruci(") delgrim.La ntateixa font fa Lin hreu romentari de 1'actuacio holitica d'I;lialtes, de yui afirnte yue inshir;tva terror als oligaryues i yue era inexorable contra ayuells yue havien faltat a cixil en relacio '11111) el Noble (TOV Tov bflitov (itO(XOeVTOV). Ayuest Ffigltes yue vetllg per tgl yue el pohle no es vegi privet de dix1I acaha sent neutrelittat per till

29. Les ruses de I'intclligenrc. La niiti' dc, Grcr^. t'.11i' I'1-i 31). i,-00.

31. I'acties sera finalntent Mural als perses pets habitants de Quios.

32. Fn I'olra citada a la n. 29 es fa pales yue Ia possessi() (rayuestes habilitate cs propia clc pcrsonatges metics.

33. AIgun d aquesre indivi(Ius fins tot arriba a aparcixcr con a victinrt cl'una situacio> clc nx'lis. Ayuest scria cl cas de I'Arist<dic pare d'Li0 not yue, (/' ail, es sorpres per Lill flop (anim al i0011(0nramrni (uclicI. on rcaliLlt Lill yci (1ue. 11111) Ice ^ccc^ aloil! II 11 11 [11 5. Li riun 111 c Ir,ir.nlc do I'i ,cclu<<ill t.ll'\II '5tii

L' m.`o Jl^]uhc^ |^

incli^^iclu yue h^>ssil^ilita yue els ^^li^;,u^yues -4^^ cs, els ^ipic3TO^- n^^ siguin hri^;us ^Ie la c^ixi^ yue creuen yue els r<^rresh^^n. Aixi, ^^^'ist<^cll^ lxxlri^i lien

I^t^ ser un „n^»i^ P^u-lant^^ yue, cl'un^i hancl,i. <xult:u-ia la iclentitat real de I'h^>miricla i, ^l'una alts, ex^^licitaria els m^xius cle 1'assassinat''.

III.?.

I'renem .u-a ^n c<^nsiderari^^ 1'alU^e element yue c<mfigura el n<m^ aml^ yue• c^mei^em l'assassi cl'Efialtes, ^^ull clir la refert^ncia a "['ana^ra`'. 1'in^lr^°t ^^n es hrexlui un fet yue su^x^sem cr^>n^>I^>^;icament ^^r^^^^er a 1'l^^nuiricli. En ef^ecte, I',m^^ ^+>^ aC hi tingue ll^>c una hatalla hr<^tag^mitracla her es^^artans i atenes<>s. La ^^ict<^ria t<ni clefs eshartans, }^er<^ aix^^ n<> imhe^li yue ac{ucsts <>htessin leer t<>rnar ail Pel^^h^mnes. Atones reacci<^na amh rahiclesa i, al cal cle h^x^ tombs, Ics s^^^^es tr<>^^es ol^tenien ^i F.n^^fita un tricnnf yue significa^^^i I^inic Tun Peri<>^le cl'ingerencia en t°ls afc rs c1^ l^t•^>c^ia'°. 1'el yue fa << les cirrumstancies yue em^^^lt^u^en la hatalla cle Tanagra, ^^^^1^Iriem assen^^al.u^ alguns Pets yue prc^^x^rci^men al c^mlhat ones c.u-acteristiyues,cliguem-ne, heculia^s. Tuciclicles`- ens informa yue ones l^^^rces eslxu^t:uu^s yue eren a i3e^x^ia i yue acalririrn lxu-[irihant en la Ixitalla rel^eren. ale n^anera ^>rulta (x^ri?^a), Iii ^^etiri^> ^l'ajut cl^uns atones<>s yue ^lesitja^^en en^lerr^>car el sistem;i clenu^critic c1e la sera lx>lis i atunu^-nc lei l^>rtificari^>. A Atones, mentrestant. Iii lea la creenGa yue les tr<>^^es es^^artanes n^^ trohen la n1an^°ra c1e s<^rtir (c^^r^^^tiv) ^1^^ ^i^^^cia en ^lirerci^"^ alI'el^^lx^nn^s, i aix<>, afe^it a la s<>sl^ita yue limn intenta acal^ar amh el ri^^;im clem^^rratic, fa yue s'inici^in les l^ostilitats. Durant la I^atalla, la ra^^alleria [essalia, alia^la clefs ^uen^s<>s, c^m^ i:^ cle h^m^l<>I i hren hartita f^iv^n- clefs eslru^tam.

I)i^^cl^^r`^ eshlica n^c's ^letallaclament I'artuaci^^ clefs tessalis. Ayuests, un c^^p s'I^a fetcle nit. clecicleixen atacar un c<^mh^^i c1e suhministram^°nt atones els ^^i^ilants clef yu<<I, i^;n^n^ants ale la ^leserci^i you s'ha hr^^clu^it, els rehen ccm^ a :unirs. I^:Is tessalis ahr^^fitenI'a^^inent^sa her a for un gran carnat^;e enh^e els sous antics ^iliats.

;i. I'renrni cum a base un [rxt cie (;re^;cn^i ^Ie A;izi:uv. (\I 3 ,, 1i^)ia) on Grist rs yuali^icat rlc «^>i^ftu^> ixo; ^^n ^^I sentit r1r^ ,^jut}^e i^ptim^^, hi ha tatnhe la possihilitat de ^curr rn el n^mi ^Ir I^^>ccicl^^r ^l h:fialte, una cLu;i refrri°niia a I'Areopag, la ins[ituri^> yue t^uu eml^lematicament ^erjurlicacla ^x^r I'es^aclista assassinat i yue, c<nn cs pr<ni salnu, cxcrria. Yuan s'csyucia, funci < ms juclic ials. "l:unl>i^ en ayuest cas ens u^^^haricm, cl^^n^ :^, ci;i^;u^t Tun ^^ n^^m ^^arlant^^ yue enti ini^^ecliria cle saber c^^m es cieia, en realitat, fh^^miricla.

^^. ha text arist^rii•lic ;in^nncna ^ris^ixlir ^I^uvu^(puio;: el ^rnsatge ^^lutaryuiu. ^I'u^'u7^^rx^'^;. ;^,_ Ar};ru I). llt,^n, JY^^rir^ (; rc^cn, Hama - 13.u^i I^)^)11, p^ 350 i». i'. IO,,^1-,. i^;. AI Nfl?-a.

I(, ^ ^ k ^,l

'I'^ml el testim^mi cle 'I'uriclicles c<nn el cle [)iocl^n- ens situen enun rontexl m^^lic. En efecte, pr^^^i.unent a Ia I^,uall^t hi ha I'nrhruciu ^^ct^hucl'uns atenes^>s glue s^^l^liriten 1'^ijut cle 1'enemic; h^u:^l^lelament, els r^>nriutaclans cl'ayuests c<>nshiracl^^rs .^^^s/^i/c^^t ^^ue j^assa yu^lc^ml i atrihutizen .^I^ es^xu-t^ms una situari^^ cl'u^o^^iu (^t^, tr^^hc^^t surlrc/n). Per arahar cle rehLu^ el rlau, els tessalis, rlc> grit, can^^ien ^Ie rengle, ^^^t^^^u^l^^c^^t els h<nnes yue els him ar^>Ilit c<n» <i amirs i en maten d^^lusnnt^^rrt un:^ h<>na muni^">. 'I'<^t hlegat cns remet a acluell ronte^t cle nrc^/is clue jai hem troh^it en la rererca a l^r^>h^^sit ciel n^nn cl'Arist^xlir.

I)'al[ra hanclu, la n^^tiria [uriclicle^i ele 1'intent cle c^^^ d'est^U hre^^i a la hatall.^ evoca el f^et clue ^i Atcnes hi ha^^ia un imlxn^t^u^t sect^^r c^ligiu^cluic n^^ Bens hostil a 1'Arebp^ig i raclirilment c<^ntru^i ,ils interessos rehresentats leer h:fi,iltt°s. [ cl',iyui neis un interr<^^;ant: c^uan tr^^h^^tn la r^°f^°r^^nria ^i un tal Arist^^cli^ ^^cle 'I',ina^ra>>, hem cl'entenclre necessiu-iament glue es tracta cl'un in^li^^iclu ^^oriiincl ^Ie "I'anagra^^? ti^> hi hauri,i lei lx>ssihilitat cle hensar glue som ela^^^mt ci'urri ^leterminacla aclscri^rio icle<^l^^gicu i yue la clen^^mina^ic> ^^cle '1'^magri^^ al^ludiria .^ alga romhr^mies .unh la lx^sici^^ p^^htirt yue ah<x^a ^i I'intent sc^lici<^s, es a ^lir, a ^tlgu ^^relaci^mat .unh^^ i n^> pas ^^pro^^inent cle^^ I'in^lret alt°I r^>mhat% La conjer^ura n^^ ens seml^la clel t<x rel^utjahle"' referm^u^ia la nosU^ahih^xesi glue les f^mts, en s^>hre el n^m^ c1e I^assassi cl'l^aialtes. ens han u-ansmcs. en realitat, un ^^nom h.u-I:m[^^.

I.I.

Creiem ^>hortu cle c^m^hlen^entar la rererca s<^hre el n^>m cl'Arist^xlic amh una inciagaci<i semhlant a hr<^h^>sit clel n<nn ^l'F.f^ialtes. La finalit^it ^s la mateiva: clenu>sU-ar yue els n<^stres testinu^nis hermeten cl'estahlir una relaci^i entre els Hams clels hr^xag^mistes --h^^txi ^^irtinw- c1e 1'acci^"^ h<>miricla i l^°s rirrun^stancics ^^n yu^. su^x^saclamcnt. c^s ^^r^>cl^u I'assassinat. f:fi,iltes^ ^°s. ^n Ia traclici<i cultur,il grega, el n^m^ glue r^^j^ un ^s^er yut• h^m^ ^^incula a una acti^^itat clue sal tenir liar clur.mt la nit: em referei^<^ al fet clr unni.u^.

Artemicl^n^"' esm^°nta I?f^ialtes (<<I c^^s[at cl'fl^°rat^^, Pan i asrie^^i) r^>n^ un c1^^ls ^^ssers sus^^ehtihles cl'ahartiter en els s^n^u^is ^lels nun-tals interhrt°ta el sentit clue lx^t tenir la see a hresenria .uenent a la m:mer,i ^'n yue es hr^>clueis.

i9. La nxn^^i^logia no hi esta Iris cn conh^tt. P. Cii ^^^nt,^i^e (liludc^s srn• Ic- tr,cnbtrlrrirc^,^r^^r. P:u^is 1^ ) ^(i, (^. 11)i) ussen}^ala yue cl suffix -ir.6; E^ot csscr ct^^lic;rt a rows i a I^crson^^s ^^yui se trou^^rnt en <luelyue ra^^^ort^^ amh un clctcrmin;it hol^le o ciut:u. (^u:m al suffix -uio^. rir In. Ln Jr,rmnlir, n rlc^c nuns ^°tt ,rrr nnrirnl I':uis l^)ii ^r^^ini^x - I^k^s^. I'I' ^(i ^^ iii II^

l.'I lll()Il d li'llw" F

F:ust:^ri' ^^^^ s'allun^^a ^air^^ cl^ac^ut^sta inti>rmari^">. Ut^sJ^ri^s ^I'inclic.u' ^^u^^ cl nu>t ^^^«^'r^1i^. ^xx ^^rrnclrr la's t<>rmes f=n^ui^n^e, i'^niui^o^ ^>, cnr;u,i. t'^^«>%^^^, t^^^^lira <^ur ^'^niu%o^ ^^s un tt^rm^ <^u^,ultra ,il^luclir a la ^^^hrc ^^u^ rs n^:^nif^^sta ^ic<nnE^an^^a^la c1c c^illr^cls, ^xx rcferir-sc• tamhe al cluintu^t ^^u^^ at:ua rls ^I^n^n^^^nts''

C^^n^ cl^i^•n^ su;u^a, els s<nnnis tamhe els malums s^>I^n t^nir II<x^ clurant

la nit. I n<^hi ha cluhtc ^^uc I,^ nit ^°^ tamhe ^I num^^nt E^ri^^ile^iat ^i^° lu f^<rsr^^r. l^na ti^sc^^r r^m^ Iii <^ut^ s^^hrt^^^e a un altr^° ^^c^rs<mat^t• :uunn^nut la^i.^ltrs. a^^u^^st r^>^^ n<>^xts un clctfntun. sing"> un r;^^;ant^^ue. atacat ^^^^r ^^^x^l^l^^ i I li•r.^cl^°^, ^•^ ^^crit Ex^r :uuh^l^"^s: ^^l tr^^t ^l'A}^<>I^I^> li f^n-acl^i full t•syuc^rr^•: t•I

^I'I li^rarl^^s, full clrct'`.

I^^?.

tii la traclici^^^ aE^r^^^ri ^^l^:fialtcs^ a I':unhit clr la nit ^^^r mitja ch^ la se^^a ^^inrulaci<"> als s^m^nis i a la <^hscuritat. tan^h^^, ^^cr una alts ^^ia, I'accnta al nx>n ci^^ Ia nt<^lla. I ^iis<> ^racies a una n^xicia se^cros la dual ^^I?fialt^^s^^ is el n<>m ^I^^ I'h^nn^ clue, :unh ^°I st•u raE^tcnim^^nt art^^r^">s, ^^^^rjuclica t•n^hlcmiiticanu^n[ cl ^x>hlr firer.

Ilerixi<>t" ^•^ unu h^>n^i f<>nt ^^er acreclir al E^ecs^mat^c^. E^r<>ta^<>nista Tun clelirte cic ua^iri<^> <^ue ral situur en la (^r^^ria cle It^^ :;uerres n^^clic^urs. just en el nu^nu^nt en <^ut° el rei ^Icls Exrses n^^ ^^eu la manes ale s^^rtir (um^ot^cwl^>^ ^^u« ^^,t'^^^) cle I'atiucar en clue es h^^>ha, r.u- n^> ^^<>[ t<>r:^^itar els r^^mhatents <^ue s'han fet farts .^ les "I'erm<>^^ilc•s. :^lesl^ores es ^^resenta un talI^a^ialtes i, ^unh I^es^^^ranta c1'^sser nx>It hen rerc^mpensat, li nu>su-a el r^uni <^u^^ cluu al r^^n^crit yue scr^i la^^ia ^^ue em^^r:u^an els }^erst^s Eger an^nrear uns resistenis<^ue ^^c>c cl^^^^ien t^°nu^r una esr<mlesa c<>n^ la <^ue ^^atiren. :^n^h ac^uesta acrid el u^a^i^l^^r E^r^^^^^^ca Li nx>rt -t ler^^ci<>t lug ^liu hcn rl.u:uuent: ^>^r^^^Of^^c^t' cl'a<^u^^lls lu^mcs <^ue. [^^t i acl<>n^u--s^• cl^• Ilur nx>rt inuninrnt, rchut:;cn la ^x^ssihilita^ cle fu^;ir. La f^ ^lels her^>is cle Irs '['erm<^^^iles ens renx•t, c<»n cl^•iem, a un c^mte^t cle nn-li.^. f^:n rfectc, c^uan l^encmir ^'s U-<>hu^a en una situaci^^ ^1e u^rc^^^i«, r^^n^j^ar^°i^ un in^li^^i^lu c^u<• c•s rr^ rla ra^^ac' ale tr^^hr^r suriirl^^ i cl^° matar ar^er<>s^u^n^nt, ^s a clir cle ^)c^i^cx^ovt^iv. [ amh aiz^^ es rl<xi el rerrlc t<>rnem altre c^^^^ a I'c^^is<x1i clr I^assassinat cle 1'estaclista atent•s. Fem menunia: la inert li arrih;t:u^t^^r<^samc°nt (f<>u ^^crit ^^o?.o^^o^^^^O^i^) i I'hc>miri^ii s'csclr^^in^ui^ ^lurant Ia nit..1'urlur^rrtul i t^i^tc^t^ht^i^, crnth clulus scin cl^^s frets <^uc la [racliri^"> rt•laci^^na .unh el n^nn ^^I:fialtes•^. .A^nc^trrr^rrlr^i i rinctrlucrri

^i. fi^^^,,. ^^^^ xi iii. i?. :Afirma^i<i <^ue, ^xiictiramen[, r^^incicl^'ix amh la que trohem a L:11 ^+ii. Per una rrfcrrncia a t';rui?,n^;-t'^Tir^^<r, c^^m a Zvi^cihunv, cfr. Eus[ari, I Ic^m. l/. A" ^h^. i^ A^uill^xl. (,?. ^if. A^II ?li-Ii.

is 11- Icrv..I Lill

troth d)los son, precisament clues caracteristiyues de la w rt de I'aleni'^l Efialtes.

Al llarg d'ayuestes pagines Item gnat tr<>Irtnt dives cS Jades clue ens Ilan pernes d'estahlir relacions i paral-lelismes eftre deterntinats elements. I)e primer, Item c()nstatat (1ue I'Arc)pag to unes formes d'actuaci(") Irelacionahles amh I'anthit de la nit i d'al16 (1ue oS secret i ocult) clue son tanthe presents en I'episodi Je I'assassinat d'ayuell yue fou considerat Cl sea acarnissat enemic. I)espros, hem tingut ocasi6 de polar de manifest yue aguestes maneres de fer no eren pas alienes aArisl6clic, el presuntpte homicicla, de yui hem suhratllAt la versant n/elic(d. a Li vegada yue ens dentanavem Si no ens trohent savant dun .nom parlant., vinculahle :tl sector oia aryuic i AS intents desestahilitzadors de la Jenu)cracia atenesa" cronol6gic:unent propers a la hatalla -tanthe ntc-licv- de "I'anagra. Finalntent, la nrelis -conjuntament anth la nocturnitat- ha tornat afer :tcte de pres(^ncia en la indagaci6 sohre ins del nom ,Efi:tltes" en els textos grecs. Potser alga pociria pensar yue aix6 (Inc. A t:111 de hrevissint resum, acal)ent d'expos:n- es Una simple enunteraci6 de coincidencies. No Os ]XIS A(jLIe.SllI la nostra opinit"). Bell al iontrari, soul del p:u-CT yue totes i cadascuna de Ies Jades -fins tot les aparentment rtes irrellevants- yue podent Ii'( en una narraci6 tenen tin sentit yue mereix de ser Jescohert i pies en consideraci6. 1, tornant al lc'il-n/oliv del nostre article, co es, la mart d'El'ialies, voldriem fer una darrera remarca. I es yue el testimoni cronol6gic:unent nte^ :tcoStat al succes (Antifont) es limita a esmentar 1'assassinat sense al-ludir a cap alts circurttstancia. Per a llegir details concrets, hens de rec6rrer :t fonts rues Illunvades (en algun cal, ntes Illunva(_les) en el temps. I no ens costa gaire de supusar yue, clu:m trohent referoncies a la nocturnitat de I'esdeveniment, al dolos :unh Clue es produio al font de I'homicida, no som, de fet, savant dunes Jades historujtics, sin6 clavant duns elements producte dun proces d'elahoraci6 ttrilbuihle a la mateixa tradici6 cultural grega.

). I'cr a una intin-n)acici gcncral sOhrc (lucstio)ns rclcridc s a alli) yue (0 ('S explicit l-ncl ruin e1' la pilitica hcl.lcna rtr. ("A" STARR, Political /u/e•lh;,Cur in (.ia,csiea / (; reert, Leiden 1971.

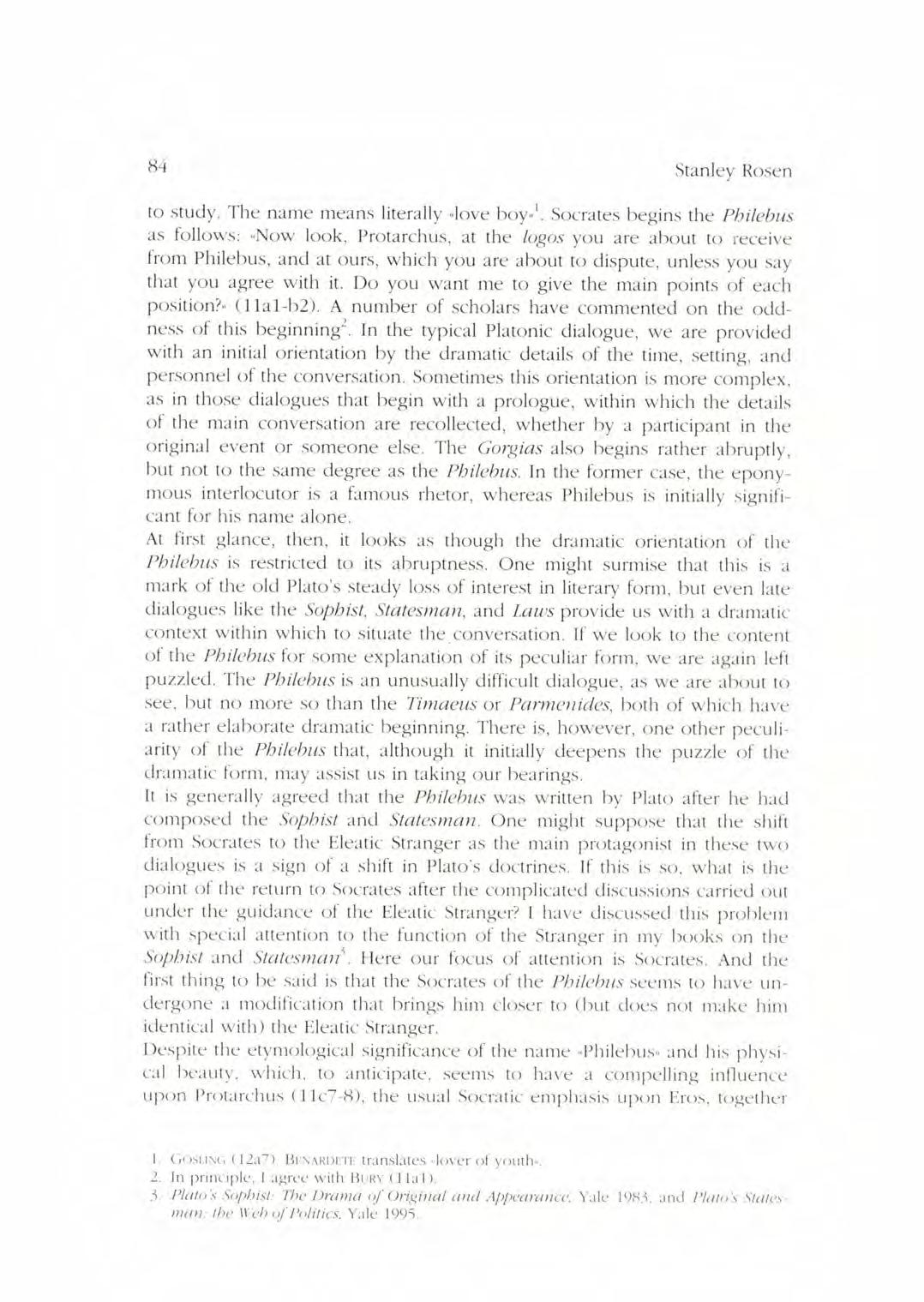

Storie di Medusa : varianti iconiche cvarianti discorsive

a.io I>cllizcr

(:crclicr) cli (lescrivere it funzionaullento clei ('Osi cietti ,scgni ic()nici,, o vistiali ncll'enunciarc scgmcnti narrativ i (o intcrc scclucnze) I)crtincnti alle StOric () ai rarcOnti the chiamiam() -mitici», ccrcanci() ch renciere onto clci ca aticri ch (Iucsto I).Irticolarc til)() Ch Cnunciazionc. Semhrano intcressanti, in I):urtic()larc, Ic I)r()ccclurc di idCntificazionc e ch intcl-prctazionc, Ia clcfinizionc d'iclentita clci ,,()ggetti delta narrazionc, e le c(>nciizioni ch ricnoscinuCnt() (ICllc se(ltiCn7( ra[)i)resentate come I)arte cli una struttura namitiv a Dill aI11I)ia.

Si ccrchcra anc he di idlers in cv iclenza (Iuanto sia im1)ortantc, c in nuxlo I)articolarc per inuliaoini chc rappresentano seclucnzc cli «racconti mitici-, la ,(onti)etcnza clcll'cnunciatari(r,, colleen() motto variahiie net temp() c nello slr,v.io, c(>mc conclizionc chc rends IN )s,ihile la ricc'Zinltc' e la lcttura di till racconto traclizionalc (o Ch una harts cli csso) raI)I)resentato in una o pit) inlnlagini.

AIcunc figure \ Crranno Csaniinate pur eviclcnziarc i prohlcmi teorici soggiaccnti, chc ai paiono motto c(ml)lessi ch I)cr ,c', c f()rse lo son() alldi I)iu I)cr nr.ltcriali chc I)roveng()no cia tin'CI)oca molt() ciistantc cia n()i, cii> chc c()nlI)()rta una grmd(2 stratificazionc c ciificrelvi:v.ionc (tells ron1i)ctcnzc nciscc()h e nclic culture. Si cCrcllcra cli cviclcnziarc it I).uticoLirc tip) ch C n(/)o 1 iur1C into)/)rdtutit'(I richicsto I)er la Icttura di immagini the ( i I)rov eng()n( ) cia tin Ix)sstto lontano, come c (luCilo clell'antichita ^^cLrssica^^.

It eliscussiexu' ua srmiol(wi sui I)rohlemi (ICII'iconisnu) in generale e seml)re v iv i, cfi-. \I V.UC>SADO ' t:c c>, in t:(^^ ), Knit c t'Oruih,riucu, Boml)iani, Milano 199,, cal)itolo 6, unismo e il)oico c-, I)i). 2 ) - i 06. Si V cdano an( he i lav on raccolti ch LuciaCorit:u\ e \ ^ir^n (i ur). h:L';ww l'('/)cru rCurlc. N)l(wti,i. I',^culal)i() I9OI. roll un;i I^Ut)Ii,I inU'O

'II I/II, I'l'III/k't

C,'ulnc h(uin0 Lent ' 111 SO ill c'r'i(1C'llzu ,[ li (1/il0rl ( IC'/ Gr(nthc Mu Cll L/C't;i', it

SC L lt0 ic01tic0 / ' iln'i(1 (1 Ogy'11i (7('77( 7 rc'(lll(l second( ill/ online minic tico. [ ')I i)ISiOmc d i stilllOIi vi s uafi , Ol lici, fi s ici, prn (lilc (' 1117(7 s c'17c ( I i (')i/nic/a/i, chc' CIC'l'OnO C'ssc ' rc ill (lil(1Icbc m0(10 inic'lprc ' l(lIi. Clc'c( ( li/icali (1(11l'c'liioici(11(1ri0, sit/Ii h(/S (' ( I i i1//C s tt(1 c O mpc' Ic'liz(1. (bc c o me 1'c'(1rc'll/O (' /1/1(1 (' 77/77[1 /i)7'1C' i/id/i/c ' 1 (li'1(lhilC'. Q i tesl 0 1 1p0 ( It c ' lllllt c iazi01 / C', C' i / 1751( / 1(110 (it 1111(1 11-iphcc r('l(l.ziOllc' fr( l In, C'lC'mc'1tti chc si j ) ussOlIO r'isna/izz( rc in 1111(1 surl a ( li Iria1i" u l0. /'Ossi a mo (lislin,tllc'rC' 1117 rcfcrcntu. till significa nt u c iln tip):

(1) it rcicrcutu (' it)/ dcsif;natunl till (lita/cosa Ch(' f(1 p(11/c' (IC'1 m0 /1( 1(1 11(1111r7lC'. c'(I C' c'shIunc 'O (111(1 sc'nliOSi C' (1l /iii riia t lO;

W it sionificantc C' 1111 ilisic'n/C' (Ii 51ln/0/i too! chC' currispoll(lun0 (1 till 11/10 51(1/)(7(', cl)c' p //(1 c'SSC'IC' (1ssocu/10 (7 tilt r4c' rC'lt1C' con/i/lu'; it re'li'rC'1ltC' l w//c cosi ricuilosci/il0 co//IC' /acc'11/C' p(UiC' (It till 11/10. 11 st,tilli /lca1Jlc. C hsc,cli0, pil1/i rl, fi)1C,("r(ffia, gra//il0, h(1ss0r7ic'r'0, c'/c.. si 1/7r'/ 1/C'i coil/r01/ti dc/ rc'/('rc'iilc' ill rc'/a2 iul/c di tl',lsfO1'IllaZl<)ilC:

c) it tip) c till(/ rupprC'sC'lrt(1zi0lic lllc'1/1((IC', tilt(/SC'riC' (II Ir(1lli (lislilllil'1 511711ll/r(ll7 ill 1110(10 cost(11l/C' C' 17co1/OscibilC''. is ciii pni.zioiu' C' (it ,1aralillrC' (ill C/nC/1c/u' 11/istira) 1111(1 Cc'lI( C'(1/iivaIC'llz(/ I1'(/ rc/c'7'C'l /lc' C' 11 st,clnpCa //lc, ill /110(10 (1(1 /)C'ril/C'l/C'i71c it ricolloscill/c'7110.

C,cn-bI(71) 1o (Ii 1' isi (alizz((11' (ln('sl(' rc'l(7._iOlti Cull Fail I lo t (/C '/ S cgIIc'1i/('"r(lli).

TIPO

stabilizzazione ricolloscimento corlforrnit (i cou f 0?' mil a

RF,FFRENTF_ trasfor mazioue

SIG,1'IFIC.A;NTE

_' (iruulx NH iJ. M. kIIyI<IyHIk(, I. I:ur:llye, I'II. 11iy<,I struclurc ct rlut„ri(luc (lu si ;nc iclmiyuc in: it. I'VtItI [ c II-G. Ri I'Rl ill ((ur .), Lv);Lcwcc's c'l /)c s/) c'c/ill's clc 1(1 'r miutic/ Ilc. Reci t ed cl'hunlmgr;cc purvr.1/,t;irclc( s Julien Grc'inms (? vOII.)..Amstcrcl : un I ', )I. I. hh. -4+9-(i I "cli , m :I^^unlcrc Ic raraltcri^ticilc - l ) r u c rlx I),,ir( -I1I , IILl111an -rl)il, lI II / u r u c tc 11 s ml, ( r e lx Ile cli I, 11, ,cr 11.[, Ic I IInI'11.1 k , t,

Stone di Alcdust: v,IIianti ic(nichc c varianti discoi^,kc )I

Su it t/csc' signific: mtc-rcfcrentc si cullncu1/H rc'1(1ziulli ( it u-asfinfnrtzi () nc, Cbr /)uss0110 (11 ( 1(1r'c (I(1 /111'c's1c' l lsi011c lllillilrl(1lc ( tilt r)1(1/licbirtu a tlil(1 st(1111(1 (It (('r(1. (Ill(1si i (lc')ttici (111(1 f1"11r/ r'(IJ)/)/Csc'nt(tcr tilt ,c'nt( ' llu a rrrr susicr) (r lir('iii 11/Ol1Oc/cl uli (/)cr c'sc'))l /) in 1'icunu bi(iilrlc'r/siul/(1I(' ru/)/)rc'u')ri(//( I (1(1Il(1

silbnr/c'lic ( It 11/1(1 n/(1rtu hylccialu curl /01(1 n1 (1tit(1 sit rrrr f ), liH). S?1ll'1lssc rclerentC-tip() si 51111(11/H rc'lu:iulti ( It stahilixzazi O n(2. /)c'1' ctrl t Iralli

Cuslil/11iri 17c d r(bili (1(111'u,g,t3c tl0 r(1/)/)rc'solliat( (u (1(1 rrr/(1 sc ' ric cu('rc'ilic (li o Lc'lli) si ir/lc;() r(1rto (1 St (1bi1Lz(1rc 1Ut p"nadigma di ric()nOscihilita cbc

ruppr-c'sc'nt(1 (1 /)/) rnrtn it tip). ntc'rrh'c' rrc'l sc ' rrsH irrr'Cr,ru si st(hiliscc tilt(/ rc'Iuzinl/C (It C()n1Ormita (ic/ rc'/('/'c '/ tlc' (1ll(1 5/1(1 r(1/)p resc'rlt(12iHrlc m('rtluIc.

Suull'(lssc' significantc-tip() si 1/Or (1/1O rc'lu2 inrli di C() nf Onnita ((1r/cbc ' ill /)rc-

Sc')1._(I ( I t ^r(1/l(li ( 1 /1'c lsita, /)c'r c 'c c'/1]pio ( It clin/c ' rtsiurri, a s t ili.<:d iurli, s('//1/) I I/1c(1z1H1/i, c'1C.) cbc /) c'rnrc'llc ' ruirnH U MC/I0 d i rurt'isu1'c' 1/c'/ Si,^Ili/!C(1lllc rill(/ m et ) /i/c'sl(1zit ) rrc del li/)O, i ll bu ss ' (1 Ilc (h1(1rrtit(1 c ( 111(1 butt/(/ (lci I lu/Il i (lisiirttir7 cbc si /)OSSUI1u curt /i) r'n/(rc (1d c'ss(, rc' l/(lc'/ulur/c pussibilc it riconOscimcntO.

1. i.c' n/c'tln/HJJOSi (It .llc(11ls(1

^'edi^uno ora una prim;( immaginc. Lin ''l, 11 C'1 l to (1 pOtrchhc csscrc riCOnosciuta Colic appartenentc a Lill cicl() narratM) bun precis)), alm(ullo per ipotesi. Cominccrenu) I'mmlisi partendo da una prima descrizionc ilk )1t() clcnuntare Fig. I, Fig. I his: Si Osserv i I'inunagine, da sinistrt verso dcstia. 1'n gross( pcscc C O )I.O a testa in giu. Poi ahhianu) una Ii Lira harhata (SI)0 dLincque maschille (a menO the non Si tratti di Lin tr:nestim(_,nto), Coi capelli lunghi c arricciati sully nuca, vestito con una sort.[ di pantaloni stretti (ultcriorc 1111(() anaschile ). Ouesto personaggio port.[ in0ltrc do li s1iv "Ili () catzari, ciascuno con una specie di sper()ne. una protuhcrania ^ isihilc in c()rrispondcni.a di cntramhi i tall()ni dei picdi. 11 c apo i' girato dal lato opposto, r1spett0 al c()rpO. Nclla man() (tests strings Lill ()ggetto ricuiVo, una sort.[ di falce; e r0n Lt sinistra after(.[ it pols0 di una second, figura. Ourst;t, chc chianfcrenu> ti?, si prescnta in pOsizi0nc fr )state. ma ha Ic g;unhc Orientate v crso Ia propria destra, le ginoccltia picgatc come per Lill hallo o una e()rsa. I capclli a rricciati ai Lui. di f<)ggia fcnnninitc, prescntano circa II ('SCICSCcnzc lunghc C s()ttili, ctisposte a Corona sully testa. II vOtto, Irontalc, c ,unpiO, toncleggiante. C piu grandc, rispett() a quell() Bella figura maschilc, c in (lualchc nu)do sproporzion-,tto al corp. t'n vcstit o sell/.[ nrulichc C una gonna (tratto fenuninilC" almeno in nx)lte culture del 1lcditcrranco) ())p(oll)) parzialmcnte it (torso c la meta inferiors del cOrpo. (Inurnagino the nx)Iti osscrv atori .[v ranno gum fo)rmulato ctualche idea, circa it riconoscimento di possihili pcrsonaggi a 1()r() gia noti).

Stone (Ii ..\lccIt sa: v ariIn ti ironichc c v arianti disc( rsi^ e )3

I hicdi di questa figura, the per altri versi (gigantism) d(Al, testa. escrescenie sul capo) semhranc> cliscc>starsi (It nu)lto da (lla ,normalc-- nu)rfologia del C()rho umano fenuninile, appaiono tratteggiati come artigli di uccelto napace (bird's clue's, cer1 .c). A\renu) dunque on ihrido donna-UCCell(), cioc una figura con tratti mostruosi. Si noti per) the quest, figura rtorr por1ct 1c ali.

I'er qualche ragione empiric,, (lie rileva di una logic, elementare (induttiva o analogic,?), I'atteggiamento di St semhra riflettere l'intenzione di aggredire S2, scrvendosi dell'arma da taglio the ugli stringe in pugno.

La seen, sen)hra dunque rahhresentare una mirtuccict, in parte mess, in alto con I'uso di un'arma. In tutti i casi, ahhiamo Lino scontro, Lin affrontan)into the vede hullo di fr()nte all'altro on Soggetto e Lin Antagonist,.

I)eI grande non saprei the Cosa dire. Andrm interpretato come segno di un',unhientaiionc marina Bella seen,? 0 sari da interpretare con criteri di 1Yrlio cli%%icilis, per esetnpio sit piano simholico o allegoric()? Allude a qualche altra Cosa, ( Ile her) non riuscianu) a comprendere? 0 si tratta di Lin n)osu-o marina, Lill hescecane, un'ora, Lin kelos, net qual caso sa nchhcro p)ssihili altre inferenze, attingendo a conoscenie the gia possedi;uno, 1_1,'l Live ad una struttura na rnativa a not gia not,?

App<<re cv ideate come sia ineVitahile. Come prima passo verso una inler/rrclel:laird, ric()rrcre ally ricers di possihili interterenze tra la tigurativita ironic, e quell, narrative (descrittiva), try Okun e logos, come ha di recente mess) ho-.11c in cv idcnia I<<cvntho Lins hrandao. Fer leggere un"immagine Came quest, (lohhianu) attingcre ally nostra cont/)crlceruzt rrurretlivn, in altri termini, (lohhiamo mettere a frutto la nostra conosceni,) dellenCiClohedia di riferin)ento. Siamo costretti a tare dcllc interenie, dclle illav.ioni, hasandoci so qualsiasi rasa sahhiamo in precedenia, chc sia sinrild a ci() chc vedian)o; qualcosa Chc ci richiami ally mcntc intormaziOni gi;i now, tratti clistinti^i, doll di cui gia dishoniamo. In altri termini, la scene non ci pu(')(lire null,, tranne the Si tratta di Lin affrontamento, di Lin incontno ostile. delta lotto tra due ters)naggi, uno masc hile e Lill() fenn)tinite, di rui it second() semhra (almeno in quest, imn)aginc) aggredire it primo, c questo semhra opp()rsi con It mono e ran un':u-ma. 'I'utto it rest( (individuazione degli attanti, riconoscimento di una scene o di Lill segm(Anto, suo possihile inserimento in una se(Iucnia narrative not,), dohhi.un() infcrinlo dally nostra competenia di osscrvatori, attimgendo a infornrv.ioni tipologiche di rui gig disponiamo. La frontalita, le escrescenie sot repo, interpretahili per ip()tesi Cone sc'r/)crtli, impongono a chiunque d()n(sca la morf()l(gia (lelle figure fcnuuinili

2 1 la.io I'elIizcr

nu)sLruOsc dell, rnitOIogi,t greca', 1'evocazionc di personaggi feniuninili anguicriniti», riot con dei scrpenti tra i capelli (o al posto di cssi): per esempi0 le Erinni o lc GOtgoni, cue risponclono a nu)Iti dei tratti the riconosrian)o in cluesta inun,tginc, ma non n lttlli. A (luc•sto panto, Vedianu) roc almciio per la second,( dcllc ipotesi (nlesse cfa parse Ic Frinni) scatty una c(rrispondenza tcrnlinc a (ermine, the e provocata cfa una struttura narrative hen precis,, the e in nostro possess(), e di rostra dOmpelenza. S1 (il s()ggctto niaschile) sotniglia nu)It() a an p(2t-SOMIggio the Si serve di una lake (101 j) ') per tf n)nt,II-C an figure nu>stru()sa cue aveva dci serpenti sal capo, una clelle tie GOt,goni (mostri tnguicriniti e capaci di volare), di Hoene Medusa: Si tratta evi(ientcmentc di Persco. ho stesso alto cli distOrccre la testa mentre aggredisce 1'antagOnista. C any sort, di epiteto fOrnlLilaft'", Lill tratto distintivo di (Iaesto croe, cioe" Lin elemento rostante deli,( tipologia l^gurativ,I stereOtipa cue to rigLi,u-da. Ala allora ai piedi non port, sper(ni, 111,1 si trattera di ali, i fumosi cal/ari alati c'he f1anno pane deli, sue attrezzatura ""canonic,, per ath-ontare it tcrrihilc nu>stro. ylancano altri clcmenti non second,u-i, altri ""cpitcti iconograhci come I,t hot:tia (i 1bisls) per ripOrre la testa di Medusa, 0 1'e1111) di Ilaci's. cue lo r'ndcva invisihilc, ma pazienia! M,mca anclie 10 scud() lucid() come Lill() specclhio rue compare in alcune varianti narrative` (rue c't per escmpi(> nel film -Cotta di "I'itani", di D(2smoncl Davis, con Laurence Olivier, 11,11-1-V I lamlin e Ursula Andress). M,t I'essenziale, sopraltutto gr /ie tl gusto cOmpiut0 (la dec01lazione di an nu)strO feniminile angui(rinitO), consente di rirOnOSccre in (ILiCSta imnrtgine an pOSSihile c1'(ttdr dcll'iIllpresa di PerseO, figliO di I)anae c di /(-'us, nip()te di Acrisio di Argo.

L'ipotesi tipologica the la niortologia di S2 corrisponda elfettiv,nncrite a una G0rg0ne, e in p,u-ticolare a Medusa, appare (ILiin(ii r,tffOrzata. :Mkt ill()1-"I, the ci fanno gli artigli di uccell0? Nell, descrizione d(!110 1'S. Apoll0d0to, per esempio, si pars, di mini di hnonzo c all ci oro, nia non si fa cenno ad artigli di uccellO da preda I? per tornare hrevenlente al grosso pescc, si Osservi I,I Fig. I ter, dove e rappresentata an',tltra not, impresa dcfl'eroc Persco. 11 K 'tn^ L a)0Ito differente, ma compare proprio an pescc veilicalc! Lc semi.' O Ic figure rappresentate in imm,tgini possono contencre enunciati, it cai algol-itillO difficilnnente pLl(') coinciclere con yuello Belle sequenze di enunciate del rarconto, a mono di non essere disposte intenzi0nalmente in «hancle" seyaenziali cocrenti. A volt(, posson0 invecc rappresentare scmplicemcnte

I. :Alasi pima clu' si tnuta di Lin sigillcp (Ii Baghdad, forsc di pr(pcrnicnza cipriOta, VII-VI xr. ad: Jr. W. Iii Rhrkr, in: Ian I W I y1y11 at (cur.), l I1c°rl)rei ItioIis o/'(;1-oc'k.llhibulnR1" Cro(nn Helm, 1.O1-16)n 195-, hp 31 c 39 n. ,'. ( , fr. in paiticolarc O id. .1lc'ta,u. IV ?H2-Ht: Pcrsc() stesso^, su richic',ta di Lint) (lull, (()rtc cli Cefc•O, Harr, - Sc tann•u hurrc'udac c//poi, (prod luc'ra,i 're'but. acre, rcywrctc.csu lrrrnnnn adcpci_Vissc .ilcdp,sac- cbnn(tmgravis sonatas coltrbras(rr(' ipsam(prc 1(wehat... h. Ps. Appll()(l. II 1,2 (1O).

titoriC (Ii Nleclusa: v;irianti iomiCI)c c Aarianti cliSC )i i^^

Fig. I to

dui tratti di <<cletiniiionc di sfrndo», <) clcll'amhicnte c irr( )-tante, in quest() casO marino. Ali nel nostr() esenipio, sv renxi un'ainhicnt,tiionc ni,u in sIasats, poichC Vorrchhc Connotare per l'affrontamento dells GorgonC Lino spario Chc inVCCC Ci risulta piuttost() adatto ally lotto Conti() it Kdtos. Conic si vide, in yuesta attivilat figurstiv a Ci pu<) essere molt() hriculait'.

2. ,Illira..iuoi iie/ lc'mpu c 11c'lly spazio

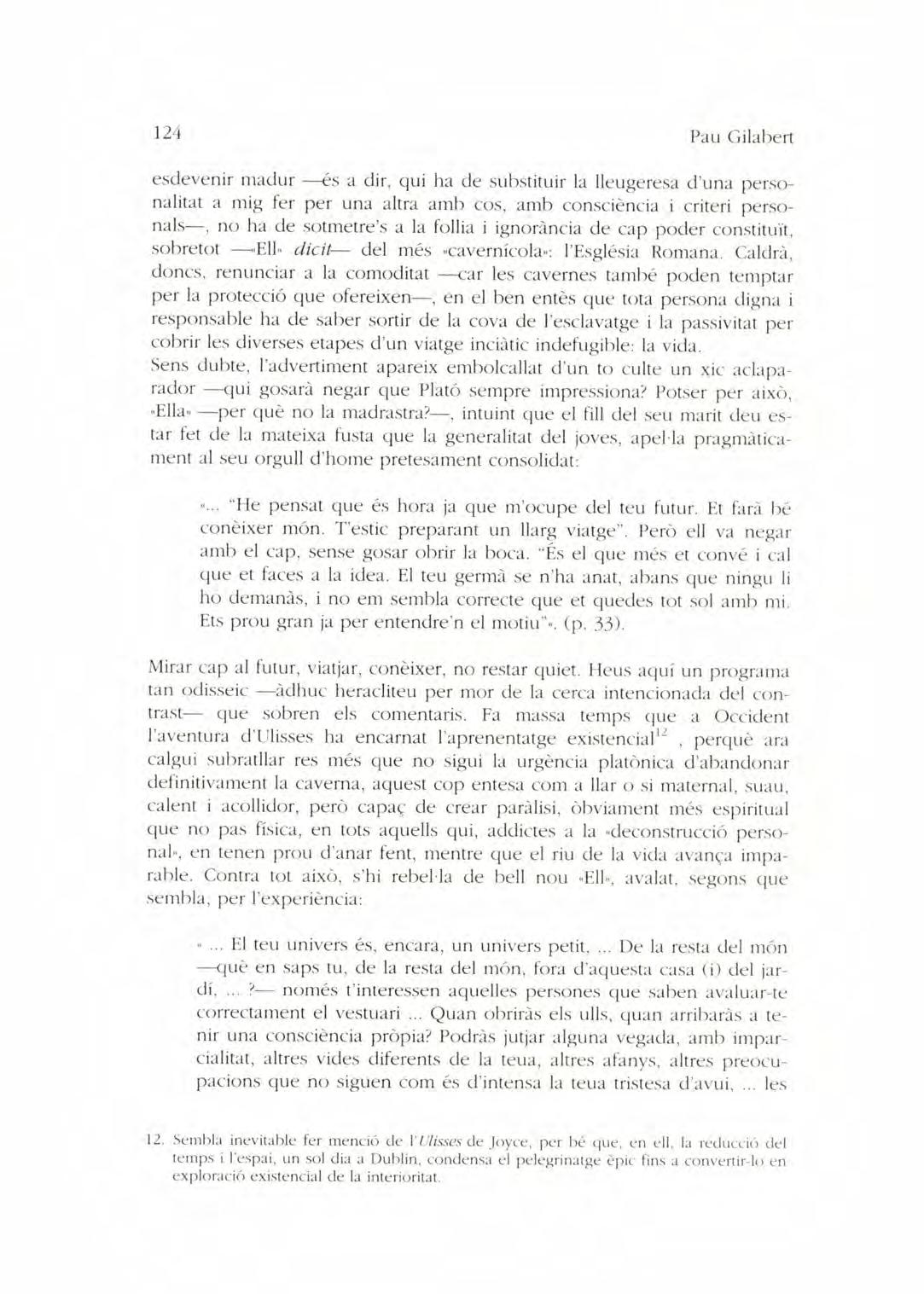

Walter I31,1rkert, in Lin ecccllcnte libro del 1992 - 1).11-la a quest() proposito cli crc'alir'c^ nlisrrnck'rstclltclin,, (o^vero ^traintenCliniento rreativo») e dice the (lUCSI( process( ) di interferenza intercultut'ale 1) 1.16 a v olte essere pin rid(() e piOdUttiV() dells niera trssmissionc (che pure, second() I() studios() sv'izzer(), rim,urc Lin facto). In elfetti, cluanto piu Ci si allontana nel tempo e nello sp,uio, tanto piu i moclelli icon()grafici, conic anche i temi narrativi, tendon() It essere faintCsi. all ,tssuniere forme anihiguc, ad animettere, o a gencrarc, varianti. burkert segnsls per csenipio alcune impressionanti analogic Cie si possono Lirmarc Ira la tipologia dells Got-gone C quells Ch Lin clenione Icgato ally niagia e all'uni^ erso dells paure intantili, Chi,umato Laniashtu (chc avrehhe forse altincnia perfino linguistics con i mostri greci ippartc-

\\ lit SKISI. Iiu' Oriciulcrlizillg Rc'rulrriicur..tic'ar I-astrru lu/lrrc'ucr on Greek Culhnr iu the 1:in l )' , l rcl)cric A p" I larv aid I ni'. Press, Cambridge (Mass. )-Loncl(m 1992.

1(' Lzio I'cllizcr

nenti ally tipologia di Lamia) (Fig. II). Questo mostro orrihile, come osserva hurkert, in effetti ha in comunc con la figura mostruosa (o ,gorgonica") clcll'iminagine precedents, oltrc ai serpenti, al volto frontalc ed orrihile, alle zanne ud ally (corsa trasversale,, ( hiiiclcatif, the compare in iltre immagini del demone), anche le zampc di uccello space".

Fig. If

Il facto c chc gli artigli ai piedi si ritrovano, pcr(> assai lontano clalla c'ultura cdella regions mcclioricntale, the ha conosciuto la tip(logia di Lamashtu, cioc in Itruria, duMluc in una rcgione assai lontana sia da Cipro o dalla ,AIesopotatnia, sia clalla Grecia. Si osservino per csempio ini nagini come

8. F pertino una rent, attinenza con it numcko equine, cfr I'inmaginc cli un'anto^ra heomci a niliev oo, di cui parlerenuu tra p)co, Fig. V (ca 660 aC ), Parigi, LaniV re. CA '')i.

tit^^ri^^ cli Al^•^lu.^a: ^.u^ianti ic^>ni^l^c c ^arianti ^lis^ui_^i^^^ )-

yu^•st:^: Fig. III (:^nne si ^'eclc•, Ali ^irti^li Ali urcell^> raE^are p<^ss<m<> liheran^entr i^^n^Exu-irc la cl^^^^e men<> re le as^^etta^^amo, e gli ^u^tisti j^<^te^^an^> ^^ern^euersi ihridazi^>ni ^ rir<nnjx>si^i^mi the e^^^^ran^^ un rert^^ sense ^lel h^^irulu,^c^.

1'i};. 111

I ^^r^^hlcmi n<m m.u^ran^^; iii fr<mtr a fen<nneni r^mu^ yuesti, si E^^^ss^nu^ r^^rrarc int^•r^^retai.i^mi ^liffusi^>nistc, ilic j^eri^ mi semhr;uu> sjx•ss<> ^liff^irili Ala cl^x^umrn^:u^^^. ^^^^hur^^ si ^^u<> ric^n^rcre ^i ijx>tcsi ^x^li^enetirl^e.

i..llc^clrrsu,^c^^mru rnr cc^rt^c^%

tii <>sscr^^i ^^ru yuest'alU;i int^t^.^;;in^°, s^^m^^re c1i tracli^i^^ne etrusra, Fig. IV^ ru^>li ^^rin^i^^ali s^>n^^ ,ihh;istanra rl^i:u^i, e alruni tritti clistinti^^i lei ^^^^i_^^>na^^i s^m^^ hen rir<m<>srihili, hennc^ nuu^rhin^^ le ali e i calru^i ulati. C'c in^^ec^^ la ^^fhisi.^, it cestin^^ the ^n^^>huhiln^ente c^>ntiene ^i^^ la testa c1i Ale^lusa. t^:^sa .^tessa ir^^n I^^i le ali, ^^rc>^^ri<^ c<nne la .Aleclusa cii 13a^^lacl, mentrc

9, '^t i c ('^[ I II )ml( ), II Illet ','I d( I 1\ A ]^ ( r. LINK 1, S. I,.

ii'' h Iii/

I•i}. IN

tassi ('he v'a ,t! di Ia delta mortologia: in altri termini, sc c'e tintalc, chc in hrescnza di unao hiu fiturc femminili, di cui una scnia testa, time in una nrtno un'au-ha da to(llio ricurv a, nell'altra till, hors,, chhen(. ndlc culture di tuttO it Mcditurranc( cl l hrinuo millennio (per restaue suite gcncrali) difficilc the )norr si tratti dell'eroc Persco, it (lecollatore di Medusa. Ricorrendo hoi ilia Stessa enciclohedia rniti(a (ai /ogol), sahhia llw anc he chc (l,tl hUSto, o dal calla, delta :%kdUSa de('ahitata nacquero clue hersonaOgi, tin certo "Spada d'oro,,, (Zirr,;(ior, e tin cavallo alato (le ali shariscono da una harte. e rist intano dall,;tltra, her ('osi dire) cue sari f.urnoso her^ glare fino at cielo e her far sgo n"Ire f<rnti ceiehri con tin calcio del suo zoccolo. Si trill, di Per;aso. Ala osserVianu> hens la tip ur,t: dal calla csce una testa di animate, chc ha tratti equini, ma qualcosa the seinhra fortemente a tin haio di coma! hon s'e hai Vista tin Pegaso con Ic coma. F liora? cos, Sara sticcesso? In effetti, sc ricorriamo agli specialisti, quell, chc dovreniirno suhhorre sia .Medusa. C interhretata come una «Figur hit cinem I iirschkohf», cioe una figura femhinile con la testa di cerv o, ohpure come till cerV o clue sta shtintando fuori dal pasta delta fign'at femminile ("odor IIir,sch. der aus ihrem Runnhf entshrinrt?»). Siunno di tt-onte a una "crVutrt'c nrlsrr^rclc^slu^trli^r^,' etrusca? I'n'ihotesi chc nii harrehhe sensata,

'St()oric (it :Medusa: v;u'ialit i ironichc e varianti (I iscorsivc

snrhhe (ii intcrprct.u-c Conic s/Ir1lzzi d i x111/sue queue the appaiono effettiv.unente come coma ignora re it particolare Bella pelle maculata, the p"11-la fortemente a favors del cervo, e pensare the quello the semhra stia nascendo dally testatagliata di Medusa sia effettivamente tin cavallo, cioe Pegaso.

t n'altra ipotesi non da scartare e la seguente un artigiano ceretano, cerrando di imitare un esemplare greco recante oily figurazione (, r(t/)hd') di cui non comprendcva hone it senso , perche non conosccva it mito di Persco, c it partirolarc Bella nascita di Pegaso dalla testa cli Medusa, avrchhe liher.unente interprctato tome ce1,1'0 qucllo the nell originale era un c(I1'ullo. Ma sappiamo the la conoscenza del ,mito,, greco era talmente Billow nella rultura etrusra , die i miti (compreso Perseo ) piu noti erano riprodotti in centinaia di esemplari persino nell'.urte ^,sacra^^ cioe in hassorilievi scolpiti su urns funcr.-ic.

-1. ['11(1 .l1('(Ills(1 c(ll'(l lh ll(1!

Vcdi.uno ora la Fig . V: l? un'anfora heotica lavorata a rilievo. c risale piu o nu'no al tempo di Archiloco. intorno al 660 aC. Si vedono con chiarezza la sp;i(la, anche se (11-1i non e ricurva, la l^ihisis portata a tracolla. i calzari roil

Fig. V

ill /I( I't'111/(

delle irricciatLirc, ('Ile sappi.uno di pater ricon()SCerc Come pi((()lC (Ili. t n rapricapo an(h'(SS() arricciato, (Iie p()trchhC CSSCrC Uni sort, di rappcIl() da Viaggio (hetasc)). Scmhncrchhs un'ultcriorc Variants: non e la famosa 4? 1'11cc, ";()I-ti di c'lnio fatt() di dcnti cfi Iupo, 1'clmO di Ades chc rends invisihili c. the permisc all'ci )C cfi avviciner:si Ale GOrgoni Selma Csserc natat(). .Ala si Osservi it sc((nd() s()ggettO (S?, o Ant: Medusa): fr()ntalita, dimensiani eeccssivc dell, testa, h()cca munita di z.ulnc, perfino dciscrpentc1li tracciati con ahilita al ccntro Bella cahigliatura,eattitudinc ,silit attica- di vittima di una decahitarione, n()n ci conscntono duhhi: e Medusa. Nla ,liana, pcr(he ha Lin Corp) di cavallo, quasi fosse Lill Centaur()? Che signihcat() pu(') vcic una variants cosi clanu)r()sa? Inv.tno posi qucsta damanda a P Irigi, pin di dodici anni fa, davanti agli amici c collcghi dcl Centre che sarehhe divcntat() it Centre Gernct, can Nic )lc L01-aux. F. Frantisi-I)ucroux, 1 " l.issarraguc, C altri Cspcrti i(()nol()gi, (he avrehher() pr()datto laVOri conk l.a cite clots intq(c'.c. Non ()ttcnni una risp)sta soddisfacentc, c non I'h0 ,mean, tr0Vata neppurc Oggi. Ma SC vedianx) l'imniaginc di1..uriashtu (-Ile sta su una sort, di cquin() (forsc Lin asino), c se ricordiam0 quclla di Medusa ('Ile produce dal Su() (()rp() Lin cat'al/o (alato), c per cscmpio ri(()rdianio anche (he Medusa fu Scciotta des Posidonc I IippiOS, ritn()Vi.uno tratti pertincnti the p)SS()n0 Iorse render (onto di (1UCSt.t 'cavallill itaa", dell, m)rf( )genesi di qucsta stran0 ihrid(), di quest, curios, Variants iconic, cue a prima Vista scmhrerehhc ahcrtante cprivy di una logic, plausihile. I)cr cli pin, stow Banda it LI\IC, ci si accorge (he qucsta morlolagia non isolata, ed esistono anticlu esempi ()ricntali, prima meta del VI sec01(), da 13ihlos, di qucsta "variantc morfologica"" (sir. la tigura V his.

Mesta Lin piccolo pr( )hlema, ahhastanza inquictantc: chc cosi ci I a quclla picc()I, lucertoli o salamandra, nel cimpo in alto a destra? Mi scnthra ancOra pin Oscura del grosses pcscc chc ihhiamo Vista ncl Sigillo orientalc di Bagdad. Sirchhc fOrsc Lill tritto ""pr()fstic()», chc intends anticipire una se(Iucnra ,Iquanta successive tic] temp() narrativ() di tutta Ia Viccnda di Persc(), cioe Li I()tta contra Lin mostr() marina, una specie di c/ra,r;o (il film chc ho citato, chi.una in sous, addirittura it h"rukeii, preso in prcstito dalla mit()logia sc,ncfinavi!) chianlato kelos, chc si iccingcvi a diVIrare la hell, Andromeda? Oppurc Si tract, scmpliccmcnte Ch Lill ricntpitiV(), till nu)tiV() )rnamentale per ()ccuparc Lin() Spazi() Vuoto sulk superficie dell'anf()ra? I ()r:Sc arrivi Lill momenta in cui e hens sipcrsi formers, pratic,nd() tin, prudente tits iiescicntli, per non corners it risrhio di c,derc inVece una Santa ch .%urorc iii%c'rc'itzicilc (/char iii%erentialis) (he p()u-ehbc p()rt:u-ci trope() l()ntan().

")tone di Medusa: v arianti iconi( h( - (- v,I rianti discor,iv (V

^. 1 'ur iu)rli hri//(nrc'c( /)('2

c(Iianu, (WI (Iucst'JItrt (linos, itumaginc. Fig. VI: h'on si:uno I)iu in un ;unhientc cu IturilnxCnte div-crso, come Bagdad o (:il)r oricntaleggiantc o c()IIIc it nuncio etruSCO, m;t Ci tlO iamo in anlhicntC (1rcco. Siam) (lunyuc costretti a nuovr inferenic, sull'ignoto autore di quest, ()r/p1)('. Si.( it hittor( cl)e it SL() puhhlico ( i 4ettori,, dell'inu11Iginc)• Si SuhPone. conoscono herfettatucnte it mito di I'ersco. Sc a Iui v icnc sostituito un AM WC di% ecso, (lohhianu> suhhorrc nc^ sia stato kltto a hello IN >sct, in till contesto connunicativ o C culnu-alc hen hreciso. II registro infatti. I ()nta delta scricta del Icrsonaggio (ma I'. Lissarrague Osseo, chc satin farmO riders. fill[ Sono semhrc terrihilmcntc Seri) e c(mlicO, "satires('(r: it pet:sonaggio the c()ntlpie testi formulari», Ia decollwione di un antagonist, die possic(lc tutti i trIt ti (Ii.stiIt iv i per essere ideIt ificat() con Certe/za assoluta come ,tiledusa. i caIII iat(): ha Ia coda, Ic orecchie Iongue e a punt,. C tutti i tratti cite not si:uno Ihituati a riconosccre come distintivi dell,ligurt di un tiileno"Inu(Iishonendo degli attrihuti tipici del notissimo erne Perseo, e dells p )siture.

Iu (:Ii K. 5( 1111(m) - I li y(,. 1)ic l )-,l:omt,c, Pc'r.wus. Bellerophon. IferaklcN uucl 7L,ewirs in cle-r klnssisclcu runt IV 1le,uisliscl,c n tiuus1, I firmerVertag, Munchen IUHH, I). 11 I: hlicgt sin alter 5ilcnmit si(I(clschm Cr!. ,,

Pig. V' his

\ I

dc,gli atteggiamenti gestuali the gli sono props, nella sequenza narrativa (,lie e caratteristica dell'erOC ergiv(). Isiamo intorno at -460, dunyue prima dci teatro a not natal I)ovrenimo per questo ricostruire Lill altro mitO". Lisa variance narrative in cui t'eroe the sconfisse :Medusa non e piu Pet:seo, ma Lill altro personaggio'', Lin essere ridic )lo dai tratti semi-animaleschi? Credo di no. Si Cleve tener canto delta destinazione, delta funzione, del contest() in cui foggetto the enuncia l'imniagine era impiegato. I)unyue, le varianti dovrehhero essere apprezzate, valutate, in base Al contestO, alle finality e alIc modality del lord impicgo. Qui Ia funzione e cambiata: l'efl'etto VOluto dall'enunciatore semhra essere di tipo comic(),parodistico, oserei dire 'paratragico(o se vogliamo, ^para-mitico"").

Ma e possihite una divers, interpretazione, di tipo pit, "serio-: per esempio, Karl S chef)td, it grande studios0 di artC figurative grcca, sostiene'' the I'im-

1 1. Fschilo scrisse Lin drunma (satiresco?) dal titolo Le Furcidi. Alla storia di Persco ahhartengono anche it cclchre l)ilatrudkui (sicuramente satiresco), e Lin dranuna dal that() I'ulI1(h" tes.

12. K. ti^.ner^)t.u, Gutter roil llc'ldensu^^)en der Griecheu, vol. II, 1978, lab. 85-80.

St0rie di Medusa \111-i;tnti icOnichc c varianti discOI Ivc 3

maginc pUO (sere ritcrita ad in «Nlvtll()S (rocs Kamptcs von Pcrscus and I )ionys()s- ( I)i(' I r(? )1lil c', p. 1 I l), una dhattaglia Ira Norse() c 1)ionis()"" chc ccrtamcntc ehhe pOCO Seguit() nell'aite tigurativa dells ep )Che successive.

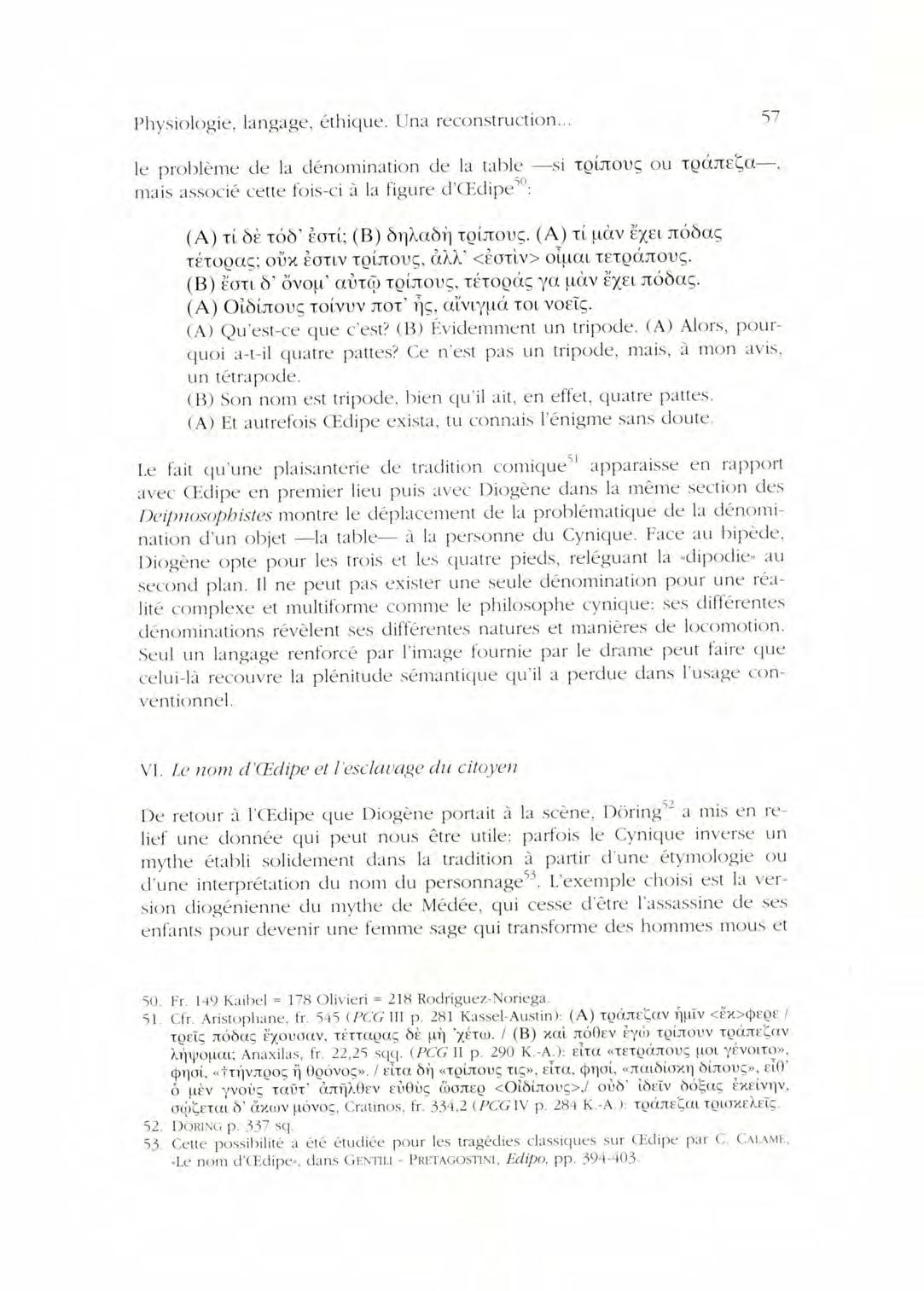

In effelti, n()i Sappiauno Che nel liter() XLVII clellc I)iunisiuc:ilc di Nonno di Iii )p()li, (53,-07^, Cfr. anche XXV, vv. 1O5-11O) CC' propri() una terrihilc hattaglia di I crseo c()ntr() I)iOniso, dei Micenei contra i Saliri c lc Menadi, chc Si cOnCludcra con la mane di Arianna, la duale verra adclirittura piciri/iccllu da11'croe con la testa di Medusa (vv. 005-08), mentre e anch'essa impegn.ua ncl comhattimento. Ma si tr^ltta di una Storia Che Compare verso Li second, meta del V secolo, dundue in migliaio di anni piu tardi. In effetti, la storia chhe poca fortuna anche Hell, tradizione Ietteraria, c non S()1() in duclla icon()gratica, tanto Che e p()CO nota anche agli spccialisti. ( )Itre a un paiO di cenni piuttosto espliciti in Pausania, ahl^iamo yualche n()tizia Che ci (lice the la hattaglia tra Argivi e corteo dionisiac() era state trattata, scmhra, da Lill Oscuro podia di Home Dinar(() (chi non C()nt()ndcre, scmhra, con altri (monimi), the avrchhc cantato la version(, inver() ISSai Curios,, dell, 111017( del di(), di (cii Si sarehhe mostrata la t()mha a I )elfi; col anche assai verisimilc Cho., IOstess() terra sia stato trattat() petsim) ncl I)iultisO del pact, [tilorionc, the taiito intlussO ehhe sui pocti Iatini". I.e f()nti lCItcrarie SO una hattaglia tra I)ioniso c Nose(), tra Sileni, Satiri e Menacli e Ari;ivi clique ci Sono. anche Sc per la Inaggi )r parts son() perdute. Le dittcrenzc, semmai, rigu.u-davan() la sea cofC IUSiOnc. Si va loll, sc()nf,itta, Che avrchhe conip)rtatopersino la nu)rte di 1)ioniso, fino illa distruzione e untiliazione di Perse() e di Argo, oppure alla pictrificazi()nc c catasterizzazione di Arianna, Seguita Ch una platealc riconciliazi()ne dei clue f'igli di Zeus. QueI ('lie e force innovative, e ('lie IC fonti iconografichc ,tttestano cluesta hattaglia tra I)ioniso e Persc() gianella prima meta del V secOlo, mentre Ic fonti scrittedi qucst'epoca tacciono C()mpletamente.

0. lil'C '1'1 cv11Cl11s1U111

COnu' Si vcde lO studio (Ic11c ,Ere/) i)iai iconiche present , piu pr()hlemi che (ertczzc, COmc hen Bann) gli st()rici dcll' artc antic, c gli :irclicOl()gi chc hannO affrontato un'impresa gigantcsca come it 1.INIC. Nia pr()prio grazic a strunlcnti come yuesto , I() StLIdioS() di rdCC()nti ^,mitici Oggi pui) cenuxlanu•nte attingerc a una yuantita di materiali iconografici tale da permcnet-gli di esten ( Icrc lc Sue analisi ai prod()tti di una modality enunciativa divdrSa nta strettamente correlate al racconto (o all'clahorazione letter.u - ia () tcatralc

(ti ad eti. .A. Iivitlc,v//I. --II 1)i<)ms s di F.ut()rione, in _17ucli Kusln,1911, IOrinu I% pp. )I(r-+, in panic. pl) 12l-25, c I'ampio) studio) di Giampicra AKIllooyI, 1'crsc<) cOntri) I)io nisO a Lema--, in F. (()\:A (cur.), Rico rclnuclo R(ill'n'lc C.wuttarelln. .110cu1lnncet eli sIiuli, Cisalpin<), Milano 1999, pp. 9-70.

cli Cs.( ) ). Orl/ic 111,1 clispOnihitita Cli tint' illunagini, Altr' S'(lucnzc, AltrC

Scglll('tIt ,t/1OIIi, aItl'i 1-it nll IYtrrativi, c SpesSO, Aallailtl lllotto sigIli flt,It lvc vengono in Iiuto allo Stt(lioSO Cli nlitOlOgia ciaSSica, c gli (Onscnt(mO di ,trriccllire Ic sue AnaliSi e di allart,u-C lc sue vcclute.I'erch0, c(nnc giust,tnlehte lla Osscrv,ito JatyntiiO Lins tirinciao, Li cultura greca ahtita ci ha LtsciatO si,t ciiStOrsi, 1o)(roi, the inlnlagini, ci/ Iles, c ,t volt' ci 1r()Vianl( no-Ala cOhCh/iOne (Ii aver' solo I'uno () solo I'altr(), a volt' possianx) clisporrc di entranlhi, a VOlte ancort ,thhi,unO una CI/J)hrusis, Lin 16gos hortato su tin'c'i(?O)l the magari non e piit visihilc''. Attic Volte infinc, ahhianl() soltanto till CI/?())/, un'inlnlagine chc ti racconta una Storia CIA SOIa:cos(, it hlit0 puO Viaggiare hello spazio c net tempo, c magari 1 irrivare lino a noi, inchc sen/,1 hisOgnn (Icltc p,ir01c. Ma tOSA s,u-chhci( it nletOC cfe11'llerrrioil scoperte vicino a I'osidOnia Paestum, o le magnifichc StUItun' clcll'Attare di I'erganx), se non conoscessiIll() IC aVVenturc Cli grief', la Storia Cli Sisih) 0 Lt conlplessa Icggcncla di 'i'ctcphos? F cosi inch' la leggencla di Pcl:sc() c (tell' Gorgoni, celehrata ct,ti pocti e clai tragici, ci Viene narrat,t per Ia prihla VOIta clai rahsocli ctelLI Scuola csioclea, come cl'stri/(one di uh'Opera d'art' the non csistepiu, nella fanl()S,t e1/)hrcLcis Clella Sten,t Scolhita c1,111'Artigiann Clivif() sotto Scuclu di la'id', the Si linlita a clescrivere it seghlent() finale CICII'chisoClio, la toga clcll'er0c", in Ilrecla a una grtnclc paura, inscguito c1a11t clue terrihiti Sorelle ilnnu)rtali. Al ternline Ch gLiclla fuga, cluanclo Ie Gorgon( si ritirerinno, caclru it homo clad scinlitarra (o clalla Spada, o (lalla talc') Cli PerscO, ' cial (lucl manico, cletto in grew m)'i(?o; (fungo, e Anthc inlpugnatura), Si sl^icghera it home ciellu famosa citta di :tiliccnc. Ma yu'st,t c Lin'altra storia ancora, (IelLi yUale hoSSCClianlo soltanto Li yersione Scritta (,tra/)ho): fors' essa attend' Lin pittore, Lin Veronese, Lin Vettsyoe/., Lill Picasso 0 (1tiatcun Iltt-O, the la sappia rtppresentare inLin yuaclr), Su una ('C0in Lill St',ItLKII_io.

L I sficla, () scnlpliccnlcnte it conlpit() the ti si presenta, e stinlolante: tohfront,o-e i moclclli di interpreta/ione (let ciistorsO narratiy() («nlitit'o O lion) the ahhiamo conlinciato ,t impiegarc, credo con hoohi riSUltati, per Ie figure distorsiVC (etunctue Verhali, linguistichc, Oral( o scrittc) ton quo.-Ili chc Lt SCnliotica visLi,tte ci t()I-niscC per I-,nl,ttisi dell'cnohtiazione per s'gni iconici, cioe per oggetti prodotti c'Oil I'intenzione Significare gU,tlcos,t, di proelurre cd enunci,u-c in scnso a Lin puhhtito di destinatari for" ancor piit Vasto di y1-1010 a cui Si rivolgc it clistOlsO Verh,ttC, soprattutto (Iuetto Scritto. Qucsti oggetti, duCSti ttlanufatti pt'odotti d,tll'arte figuratiV,t, prt5'ntall0 giit a una prima inalisi strutturC enunciatmyC peculiar(, hla atu-ettanto 'fticaci, chic vale Ii)rsc la pena di analizzare' c(miprcnclere piu t fond(). In (lucst,t

I I. i it rasa, per escmpi(. clclla prulalia lucianca su trarle-Ogmins, stucliata acutamcntc clan() stess( l iNs l3RAti1)nO in una ronferenza tenuta di recent' a "Trieste (21.12.98).

15. ,Ala si nnti, c scnlpito in nro con tutu gli oggetti chc to ca atterizzano, calzari, spada ((bur), laihisis d'argenio on fringe tt'oro, elmn ( klnde) cii Aries, Aspic, vv. 220-27.

ti t OO r c c l AIcclu"a: v;irianti icunichc c v a r a n t ( ) i \ ivC

hrc>shettiv : i,ii LC.ricu1t Icrntu,^raphiClrnt rahhrcu•nta Un<) strumenti> m( )ItO hrcziO O )Cl unc) studio ) auclio -viSiVO clIIIJrnitc>l()gia dell, Grccia Intica. Is-) ci hcrmettc infitti cii av v icinare C quasi Ch sOvrahhO>rrc ally figura clcl lc'c:lur ill / rrlurln (Iuclla non mcnc) imhc)rtantc dcl lcclor ill intc^^inc(<^ Icc/or ill tuhtclu), mcttenclc ) ci in gradO Ch ricc^struirc hiu cla vicinc) I'cshcricnza grcca nclla hcrccziOne c nclla ricc z ionc clci mcxlclli c clcllc strutturc narrativc -i 'initi- chc harmO fattc) granclc clucsta cultura (1c1 hassat^^, chc rahhrescnta ancc > ra Ia hiu ricra creclitit chc sc(,c>li hannc) lasciatc) ally nmstra cultura curc)hca.

Alcune osservazioni su xljb£µuly TUQ(itvvu)v ( Eur. Med. 990)

(iim'.111n;1 Priz%1

II (Iuint() ChI O(liO (kilt .1/:cl('rl (Ii LLiriI)iclc Si COnrl11(le Coll Lill ( l11t0 1101 (luai( Ic (l(tnnc clrl (01O cSllrill nl0 it 1)1-0hri0 cl0l0rc c la hr(thr11 an OSCia her it cicstiI1) rllc attcncle tutti (01010 rllc sOUO COinVOIti ncll"t vendetta Orga11izztlt:t chill, pro xag(>nista: Ia pieta (lei r(1rO ( infatti clirctta \ e1:s) i clue bambini, Glat. rc, (I iiS) nc c :tileclca. LO stasinlO C rOStruit0 a ChiasIIm: drilim it (010 Si sOffcrnla Sui IMIllhini, I)Oi su Glaurc. i)01 Su GiasOnC c infiliC

Su 1lecica, rllianlata TULUIVU MdbOV 11('(T11O (infelirc nlaclre di hinlhi. A \ OO(1-O^). Al CCntlO, clun(IliC, Si trOVa la (Ohhia GlasOnC - Glaurc. niCntrc all'inizi0 Ccl ally fine si UOv an0 rispcttiv anlCntc i hanlhini C AIcclCi. rliC Victic lit 1:111:1 n()Il ((n)e sh )Sa traclita. ma Csciusiv:ullente cO111c 111aClrc.

La Dicta clef roil) si Csi)rime attraVCrs() alruni a Cttiv i Cho-' Si ripet(mO Okni

Olta rllc v icnc nlcn/iOnat( ) Lino (lei hersOn:iggl rOinV OIti nClla \ cncletta clcllc hrOta^ Onista: Glaurc v iene (illinita clue Mile 0i'OTUVO, V. 996 - 9

Gias(nc C rhi:11lut10 T(ui,UZ (\ 991) C 6i10TUV0, (\'. O ). M(AIC.1 infifC riCc\C I'Chitet0 T((/JUIVU (V. 990). SC, heat. Lt pieta clcllc d(>nnC rOrinuiC nci COnfi-()nti clei hinlhi, cli McclCa c di GIauCC ah}^arc MALI Cd inC(ILii\0Cahi1C ( per Ia di CreOI1tC si 1 )SSOnO OSSCrV i1C s(tprattutt0 I'1C0e111O ad (iTi '. it lops clcllc nOz/C tic] 1-eg110 (lei nl0rti C la inCnzi(>ne dell, Sua hCllezza.

II tctlrlinc UTtl, come' c nol(), r:urltiuclc° in Sc Una Ill()ltchlicita cli contpIcssi signitirati, ccl c Pcrtantu clillirilnu•ntc u:utUCihilc con Lin 11111(0 vocaholo: it Strit:nltMo cvoca intatti una ;( iagura (IctinitiAa id irrcvocahilc. (lc•tcrnlinata in nu)clu sot)rannaturatc. Sul signiliOtto clcl tontine %. P.K. IS)IlI 7711 Gi'c'c''s (Old tbc' 10) U11, I rkcIcv' - Los .Angclcs 195I (it. it. I (;rc( i ( 7lrru_luttcvk', Fitcnzc 1959), pp. 51-00 clclLcctizionc it:tliana (divilta di vctgogna C. civilt;t di rnltpa t. ?. II /o/tos clcltt no//,c nc'I rcgno clci M01-ti to part( clcllc inunagini con cui ahitualntcntc Si esttrimc it rinthianto tter c'hi Inuorc giovane: cit. ad usemlvio tiohlt. :U^i, U -5 (ttr(Ir; Tit' T(u') i v "A(<lot1 nlvtlt- vItt(pi i`6Yty TIVi. lascia (ta Ia tanciulta %.tcla silos:t nclf:Ad in ttucao iasn it nlcttivo c inttlicgato cla (acontc con s.ncasmo). S-6-,S c 1 (I-11 (Tit vt^ttgtu('( Tt^iai i.u (irv (^rii.tW)Z riv "'At(lot' (111µ0t;. «ntiscro cclchrancio it tito nuzialc nctLa

/^^ (,i/^.xm./ |`n///

per Meclea it fatt^^ the l'accent^^ ven^;a p<^sto sully causa pii^ the sidle c^mseguen^e clell^i sua venclet[a ^, I'atte^;giament^^ verse Gias<>ne appare men<> line ire, p^^icht^ le cl^mne, riferencl^^si a lui, acl^xta^^<> si ^;li a^^;euivi the h^^ ric^^rclat<^ s^>pra, ma, c^mten^p^>raneamente, c^mtinuan<^ a mettere in eviclenz^i Ia sua c<>Ipev^^leizas. Il ^^uart^^ stasin^<> rappresenta anii un<> clei p<>chi punti clell^i tragedia in cui, accant^^ ally r^nulanna, c^>mpare un sentiment^^ cli comu^isera^i^>ne nei confr^mti di Gias^me', espress<^ attraveis^^ la c<^nstatazi^^ne ^lella spropc^rzione esistente fra le aspettative ^lell'u^mu^ e i risultati cla lui <rttenuti'.

I versi inrentrati su (^ias<>ne son^> i se^;uerni:

^i^ c^', ^^^ ta^av, ^;^ xaxovvµ^^^ x^^^t^<<uv Tt+^xivvwv, mx<<siv ou xaTr^^bci^C ^i^^rO^xw (iu^i^x ^oocfaYe^C a^,oxcu

Tt: ^j^x «n+^rt^p^w (1CCV(XTOV. 4i+^fT«vr^ µoi^x^^ ^^cxw mx^x^ixi^ (i+v. 991-95).

ll passe viene ahitualmente interpretat<> in c^uestc^ nxxl<r

clinu^ra cli Acle^^), Eur. O^^. ll(i9 ("'Au^rw vuµ^iov xrxn^µrvi^, ^^avenclo ottenuto cunx^ s^^oso Acle„), //^^rctrh^s ^EH(^-^;1, Ip[^. .9rJ. ^(,U-61 lTi nu^^Ut^vov; .,A^c1i^C viv ^uC tu^xe. vu^upeu^rEl ruxu, ..E^erchc ver^;inN Pres[o, a yuanto pam, Azle la s[^useru•^l. si pui^ anche ricor^lare Eur. llc^r. ^^ 16: Polissena, porn ^xima cli rssere s;icrific:^ta, I;imenta cli doversene andare nell'Acle fivvµ^<^c ^'wi^µtvuu^c ^uv fi' ^xEnjv n+xr^iv (^^senza nozZC, senza gli imcnei cui a^^evo diritto,^). Cfr. annc^ it lanu^nto the, in 1?ur. 7i•uurl. 116ti-7U, E?cuha fa sully some cli Astian.ute, the nun^ira ^^rima Ali av^'r k<xluto le gioie clclla ^io^^inezza, fra cui it m:urinumio. Qucsto [enri. inoltre, vicnc svolu> in nunu^rosi eE^i};rammi clcll'/l ulnlr{din /'r^lntir^tr: ^^. acl csen^^^iu A^II I i, IH?, IHi, 156, i i,. Sull':u^gomcrno ^^. C. Sec,.^i.. %iz^^^^'rh^ aucl (,'irilizu^ruu: m^ lu^c^i^^rc°talinu a/^ .^'uj^hnclc^s, London 19?il, E^^^. IS?-?Of^ (^^Antigone: 1)cath and Lovc, Il:ules anti Uion}^sus•), N. I ^^wv z. 1-'uEuus t^u,^iytrc's ^lc^ lrvcv^ tnu^ fenrmct Paris 1VN> tr it. (.i,^nc- urcrclcvc^ hz{^icantcvNc^ ^unr clnuuc^. Roma-Bari 19HH), ^h. ^9-^^^+ clclfcclizionc ilaliana. R.ti.A. sr^v^<^itn, ^^'I^he Tragic Wcclcling», /U.S' IU%, I^)H7, Pp. ll)6-il), IZ. ^21'llyI, .1/rn•rrr{^<^!u lJrcatl^. 7%u^ (,'un/lnlir^rt u% lk^^^^^lrliu,^ nud l^nue^rzr/ Rrhruls, Princeton l ^nivenity Press 199^^. i. s^,^^ranutt^^ cl^^^^o it ciisco^^u^ cli ^leciea sully conclizione fi•nuninile (^^^^. ?3U-bfi), la con Manna ^Icl r^,n^ nei confronti clell<> sE^^^so trick[ore c nu^ho neua, e si mantienr inalterata lino al tennine clclla tra};eclia; come esempi si possono citare i ^^^^. lil-37, l05 ((^iasone i^ clefinito zLxxl^in^, xuxcSvu^tgx^c^, ?(^,-(,t^ Ue donne affermano es^^licitamente Ia Ieginimitit clclla ^cn^lcna clclla E^n>[agonista), ^,6=H e, sopr:Ututu^, ILiI-iL (clo^x^ it rrsoc^mto clclla nu^rte cli Glauce ^• Creonte it coro esclama: ^^xx' t^uiµuw ^ru^?,f^ ri^^^' tv ^^µtLxG / xuxu ^rw«nrrrv fv^liru^,'lua^ivi, ,^semin^a the it dio in ^^uesto ^;iorno niol^i mali ^;iustamcn[c infli^;ga ;t Giasone^^).

i. Ally fine clclla trageelia, yu:nulo Giasone accorre ^x^r meuere i figli al ri^ru^o clclla vencleua clei Corinzi, senza suEx•re the in realty song gia niorti, it coro (^^^^. I i0h I ^I)') es cl:un:u w t^rjµov, of+r, oiafl' of xax^uv ^^r^^u^ac, / 'Idaov ... (^^:^9iscro. non s;ii a yual ^ninto clei mali sei giunto, Giasone...^^).

>. Lo stcsso nu^tivo comE^arc ncl ^^asso c'itato Welly no^;i +.

Al( Line osse1va/inAli su x) 1bt:IUuvTZ1^)( tvvmv Il :ur. filed. 99O) 1I

1. tu, n)iser (>, vile SOS(), inlparc ') llatO at re, senza saherl (> p(rti roving at tuni figli, alla lnrn vita, e ()dioSa finite ally tua SpOS:t. InfelicC , ( Iuant() It allontani dally sOrte lche immaginavil"".

I COnur)entatnri di (1UCSt() pass(), a partire cfall() scoliaste'', harm() interpretatO x)lov1t(i)V come sinOnimO cli ZIj6F(TT1lC. CiOe ^fparefte ac(JUiSito tramite nltttrinx)nio"" O, ancor piu specificaunente, ,genero" : Si tratterehhe dell'uniCO Gas() in cui it t(21-mine assume tale significato'. II tern)ine xll(>Flt(;)V, invece. significa prnprian)ente ^,COlui rite Si prende curt di uf:t persona", e viene usato s()prattutto (con)e it verh) xi16'u)) in riferin)ent() all' cure rile Si renclnf() a Lin nx)rt(': it significato piu generale e (luellO cli snllerit() nei Cnnfrnnti (Ii (IHaiCUnO o clualcnsa», oppure Ch ^,guardi:tnO, custOCle' I"gualmente, it verh) xq6tti(u significa anche -con tI'll rre matrinumin tranlite I1leanza,) e (luindi, per esteso, ,alle.u-si),".

Data la cnmplessita cdi significati del termine x)l)FItWV e degli altri ad esso Icgati, e ti)rse p()ssihile, pur setlZa esrluClere it significato di imparcntato-, tenere presenti and ie gli altri, che arricchiscono it C()ntcnuto clelle p:H- )he del corn. Innanzitutt() Si pun Osser\are come 1'espressione xt](FtRi)V TUQuVV(0V Si inserisct nell'anlhitn Belle nun)erose espressioni che, net core) Bella tragedia, vengnnO aclnperate dai vari personaggi per clefinire l'intento s)Ci:tle.- clelle nOZZe di GiasnneH vi Sono anti tre punti nei yu.(li, in c()ntesti sin)ili :t yuesto, COmpainno termini legati a X1j OC_, nei Sun signifiCato di parentela ". (dui

(^. Lo scoliast' (.Viol Ali For. .l/rcl 990) 5pi'ga it pass() in (lucsto nxxi): K1l(it ulv (li' ^uE>u Ti) xi1t)o;, ((vii ToC' yutll Litz. F. A1O^r:v^^FlI, l'nc'aholario (1('tln liliguei 1'r'cO. "Torino 1995, tr;ulucc x112)Fµarv liOnt(r. I'cr it 5ignifi(ato hiu g'ncralc (it xl1btOTllc cfr. ad esenlpio Plat. Lc,. 773h c Xcn. llem. 1. 1.8: per it 5ignificato piu specifico (it gencro'' cfr. Isocr. 10.+3. II sostantivo, Holt(( gcnerico, pui) assunu'r' (it volta in voila signilicui specilici: oltre al gig chain .gencro•, Si possono ricordarc (ludIli (Ii ^5uoccro (Aristoph. 7bc.cin. 7+1, «patrigno, (l)cmosth. 30.31 ), .ir;ucllasiru ( Fur. I/o. 831).

8. Cfr. ). L I' lira• pine's Ilc'clca. Oxti)r(I 1938, comm. it verso 990: -solo in ya'sto rasa xryc)rl(nn' = X!/Oi)TT!/

9. A'. I)/:L( s r zIjot'I1(uv. Con it signiticalo di ''colui che Si prendc cura di nn mono,, it t'rnlin' c ((Salo ad ('ticmpio in Ilom. Il. A\III 163 e Apoll. Rhod. Ill 12- 1. Per I'uso di xllhri'(u nil signifi(:Ito di rcndere onori funehri" cfr. Soph. L'l. 11 11. I-:ur. Kl). 983. I11. (1i. Ih'ogn. 0115, Adsch.S)(1)pl. 70, Soph. itut. 549 e Pb. 195. Aristoph. 2.12 e 731, \poll. Rind. III -31-32 c IV 91. Lo 51(55) significato ha it sost:mtivo Xllbnlu)vFiuc in \poII. Rho(I. 9--98 c I 2-1.

1 I_ Ch. ad cscn)pio Acsch. from. 890, Soph. 7)-acb. 1221, Fur. Hipp. 63-,.

I?. A IS c v. h 'l((IIOI JIAWI/.iXOi, A'. 13v I<FXTC-M TU9)UVVWV, v. 55-+ Jnuib(t 'tllhul (i(tollt'()c, v. 59I L1"XTU(L ^iU6ll.FUIV, A. 8_ ,'11f1((Z Tl'9(tVVOV.

13. V. ,6 flul.uut xuiV(0V ).FiJT`Ttti Xlt )l l`ti(/TOV (Li v'cclu parenteli (('(Ion() all' move. vv'. 3()O (1, 1.T FlO (C(WVFC TOIL VFIUOTI V11lt(PiOLc / x(d TOLOI Xll(Fl1O((RV Oil OliIx9)OI