© 2022 Global Education Group and Integritas Communications.

All rights reserved. No part of this eHealth Source may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embedded in articles or reviews.

Integritas Communications

95 River Street, Suite 5B Hoboken, NJ 07030

www.integritasgrp.com www.exchangecme.com

FACULTY

Amy L. Lightner, MD

Director, Center for Regenerative Medicine and

Surgery

Associate Professor of Colorectal Surgery, Digestive Disease Institute

Associate Professor of Inflammation and Immunity

Lerner Research Institute

Core Member in the Center for Immunotherapy Cleveland Clinic Cleveland, Ohio

Dr. Amy Lightner is an Associate Professor of Surgery in the Department of Colon and Rectal Surgery at Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, the Associate Chair of Surgical Research, and an Associate Professor of Inflammation and Immunity with a focus on regenerative therapy for Crohn’s disease. Dr. Lightner received her undergraduate degree. in Human Biology from Stanford University in California and then obtained her medical degree from Boston University in Massachusetts. Dr. Lightner then completed her general surgery training at University of California at Los Angeles, during which time she spent 2 years at Stanford University doing full-time research in stem cell therapy for transplantation under a California Institute of Regenerative Medicine training grant. Following graduation from general surgery residency, she went to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, for a fellowship in colon and rectal surgery, and joined the clinic staff following her training. Dr. Lightner was then recruited to Cleveland Clinic for her surgical

expertise in inflammatory bowel disease and to initiate clinical trials in stem cell therapy.

Dr. Lightner has received extramural funding from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, Cure for IBD, Rainin Foundation, and American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgery. She is a member of the editorial boards of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, Colorectal Disease, British Journal of Surgery, Crohn’s and Colitis 360, and Diseases of the Colon and Rectum, and serves as surgical cochair for the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation's annual meeting and associate chair of the inflammatory bowel disease committee, clinical practice guidelines committee, and surgical research committee within the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons.

Dr. Lightner’s clinical interests include inflammatory bowel disease, in particular fistulizing disease and reconstructive pouch surgery. Her academic interests include stem cell-based therapy to treat the inflammatory bowel disease both locally and systemically. Dr. Lightner is currently doing laboratory-based research in this field under a career development regenerative medicine training grant and is conducting clinical trials to translate the bench work to the bedside.

Bruce E. Sands, MD, MS

Dr. Burrill B. Crohn Professor of Medicine Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Chief, Division of Gastroenterology Mount Sinai Health System New York, New York

Dr. Bruce Sands is an expert in the management of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) and has earned an international reputation for his care of patients with complex and refractory disease. Dr. Sands was awarded his undergraduate and medical degrees from Boston University in Massachusetts and trained in internal medicine at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. After completing his gastroenterology fellowship at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston, he joined the faculty of Harvard Medical School and served as the Acting Chief of the Gastrointestinal Unit at MGH before moving to Mount Sinai in 2010 as Chief of the Dr. Henry D. Janowitz Division of Gastroenterology.

Dr. Sands is widely recognized for his innovative treatment of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis and for his clinical investigations of new therapeutics. Dr. Sands’ research also explores IBD epidemiology and includes the creation of a population-based cohort of IBD patients in Rhode Island, a project funded by both the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Sands has served as an Associate Editor for the journal Gastroenterology and has published over 200 original manuscripts in leading journals such as Gut, Gastroenterology, and the American Journal of Gastroenterology. He was the lead investigator of the landmark

studies ACCENT 2, UNIFI, and VARSITY, published in the New England Journal of Medicine

.

Dr. Sands is a past chair of the Clinical Research Alliance of the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America and served as chair of the Immunology, Microbiology and Inflammatory Bowel Disease Section of the American Gastroenterological Association. Additionally, Dr. Sands was the chair of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD). In 2016 Dr. Sands was awarded the Dr. Henry Janowitz Lifetime Achievement Award from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America, that organization’s highest honor.

PREAMBLE

Target Audience

The educational design of this activity addresses the needs of gastroenterologists, colorectal surgeons, and specialist NPs and PAs.

Program Overview

The presence of fistulizing Crohn’s disease (FCD) reflects a distinct, aggressive phenotype of CD and indicates a challenging and complicated disease course necessitating an early, intense, and multidisciplinary approach to treatment. Compared with patients without perianal involvement, patients with perianal FCD have higher rates of hospitalization, surgery, and use of immunosuppressive medications and are at higher risk of complications, including anal and rectal cancer. Further, despite recent advances in pharmacologic therapies and surgical techniques, complete healing occurs in only half of cases. Even if healing is achieved, the risk of fistula recurrence remains high regardless of the treatment approach. This multimedia IBD eHealth Source™ activity, composed of 4 chapters, will provide published clinical evidence and guideline recommendations surrounding the evaluation, medical and surgical treatment, and longitudinal assessment of FCD. Clinical data will be augmented with insights from expert faculty to provide actionable recommendations for the multidisciplinary and shared decision-making approach to care.

Educational Objectives

After completing this activity, the participant should be better able to:

• Assess the type, severity, and disease burden of fistulizing Crohn’s disease (FCD)

• Compare and contrast the clinical trial data on current and emerging agents, including biologics and stem cells, for the medical treatment of perianal FCD (PFCD)

• Optimize the combination of medical therapy with surgical techniques to treat PFCD lesions of various types and severity with a goal of optimizing patient outcomes

• Employ a multidisciplinary and shared decision-making approach to managing patients with PFCD that includes medical therapy, surgical treatment approaches, as well as incorporation of patient preferences

Physician Accreditation Statement

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the accreditation requirements and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint providership of Global Education Group (Global) and Integritas Communications. Global is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Physician Credit Designation

Global Education Group designates this enduring material for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™. Physicians should

claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Nurse Practitioner Continuing Education

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Accreditation Standards of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP) through the joint providership of Global Education Group and Integritas Communications. Global Education Group is accredited by the American Association of Nurse Practitioners as an approved provider of nurse practitioner continuing education. Provider number: 110121. This activity is approved for 1.0 contact hour(s) (which includes 0.0 hour(s) of pharmacology).

Disclosures of Conflicts of Interest

Global adheres to the policies and guidelines, including the Standards for Integrity and Independence in Accredited CE, set forth to providers by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) and all other professional organizations, as applicable, stating those activities where continuing education credits are awarded must be balanced, independent, objective, and scientifically rigorous. All persons in a position to control the content of an accredited continuing education program provided by Global are required to disclose all financial relationships with any ineligible company within the past 24 months to Global. All financial relationships reported are identified as relevant and mitigated by Global in accordance with the Standards for Integrity and Independence in Accredited CE in

advance of delivery of the activity to learners. The content of this activity was vetted by Global to assure objectivity and that the activity is free of commercial bias.

All relevant financial relationships have been mitigated.

The faculty have the following relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies:

Amy

L. Lightner, MD

Consulting Fee(s): Boomerang Medical, Inc., Mesoblast Limited, Ossium Health, Inc., Takeda Pharmaceuticals U.S.A., Inc.

Bruce

E. Sands, MD, MS

Consulting Fee(s): AbbVie, Amgen, Arena Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celltrion Healthcare, Genentech, Glaxo SmithKline, Janssen, Lilly, Merck & Co., Pfizer, Sun Pharma Global, Takeda Pharmaceuticals International, Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D; Contracted Research: Arena Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Bristol Myers Squibb; Honoraria: Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda; Stock Option Holder: Ventyx Biosciences

The planners and managers at Global and Integritas Communications have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Disclosure of Unlabeled Use

This educational activity may contain discussion of published and/ or investigational uses of agents that are not indicated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Global and Integritas Communications do not recommend the use of any agent outside of the labeled indications.

The opinions expressed in the educational activity are those of the faculty and do not necessarily represent the views of any organization associated with this activity. Please refer to the official prescribing information for each product for discussion of approved indications, contraindications, and warnings.

Disclaimer

Participants have an implied responsibility to use the newly acquired information to enhance patient outcomes and their own professional development. The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. Any procedures, medications, or other courses of diagnosis or treatment discussed in this activity should not be used by clinicians without evaluation of patient conditions and possible contraindications on dangers in use, review of any applicable manufacturer’s product information, and comparison with recommendations of other authorities.

Instructions to Receive Credit

order to receive credit, participants must complete the following: 1. Read the

3.

and

In

educational objectives, accreditation information, and faculty disclosures at the beginning of this activity. 2. Complete the Preactivity Questions.

Review the activity content. 4. Achieve a grade of 70% on the Postactivity Test Questions

complete the Evaluation.

Fee Information & Refund/Cancellation Policy

There is no fee for this educational activity.

Global Contact Information

For information about the approval of this program, please contact Global at 303-395-1782 or cme@globaleducationgroup.com.

INTRODUCTION

This eHealth Source™ for fistulizing Crohn’s disease (FCD) will focus on topics related to the evaluation and classification of disease, patient assessment and management goals, as well as the clinical evidence for use of medical versus surgical therapies. Clinical data will be augmented with pertinent qualitative, research-derived insights—via video commentary—to provide actionable recommendations from experts to practicing clinicians. VIDEO 1: Meet the experts

CHAPTER 1: SNAPSHOT OF FISTULIZING CROHN’S DISEASE

Disease Burden

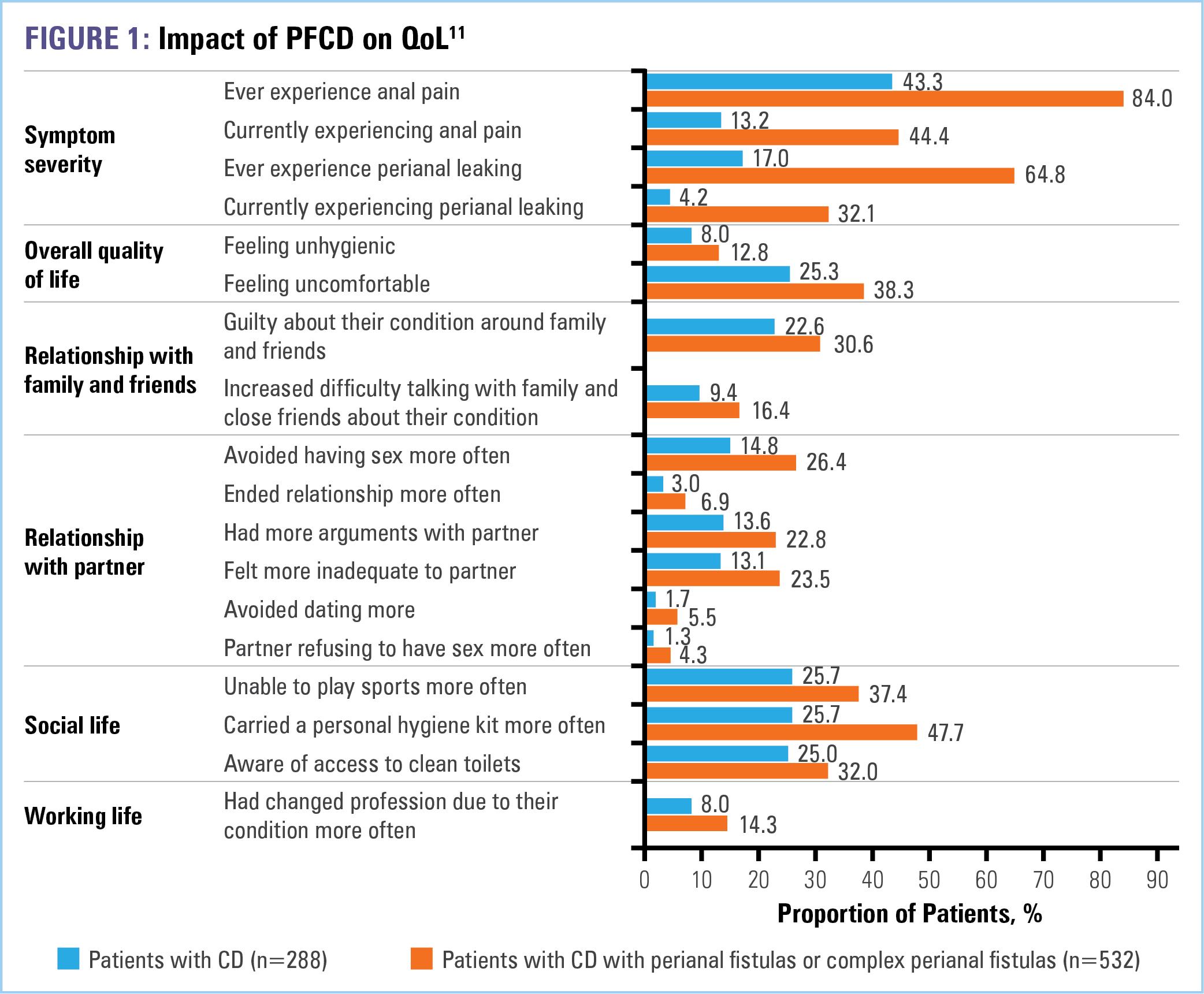

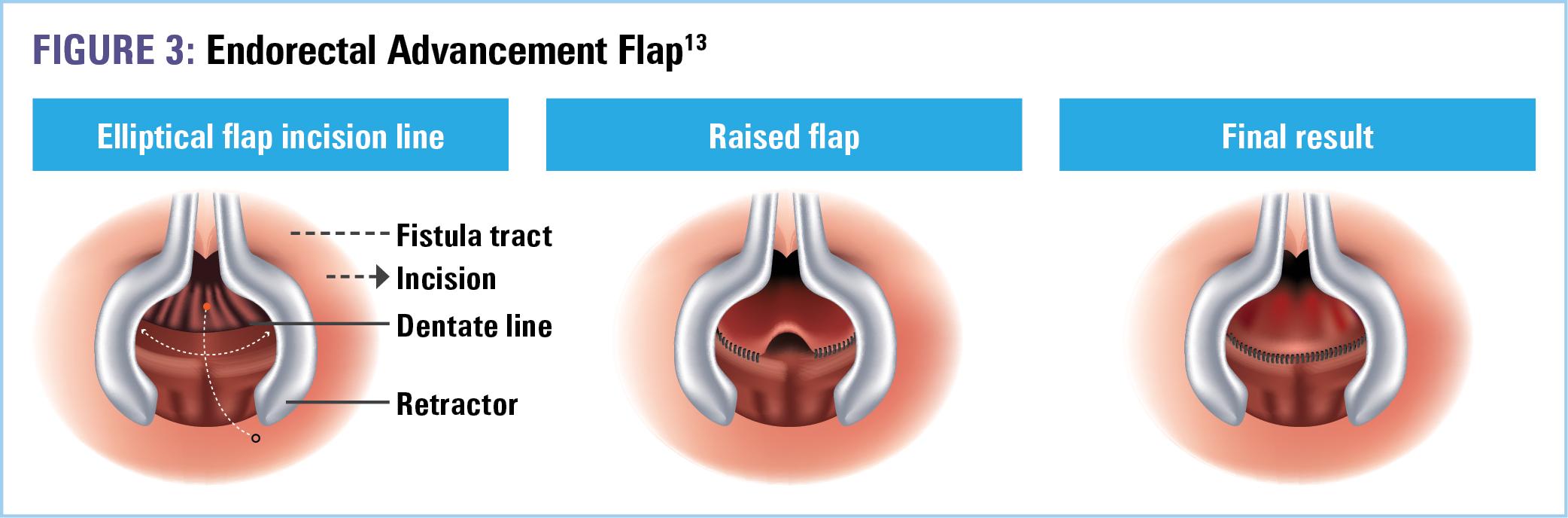

The prevalence of Crohn’s disease (CD) in the United States is approximately 200 per 100,000 adults and 46 per 100,000 children aged 2-17 years.1 One of the most severe manifestations of CD is fistulizing disease, which develops in up to 50% of patients.2-7 Fistulas can develop in any location within the gastrointestinal tract (Table 1). The most common phenotype is that of perianal fistulizing disease (PFCD).8 Complex cases may involve multiple structures of the anorectal anatomy and, therefore, are especially challenging to treat.9 Symptoms, which include anal pain, purulent discharge, and destruction of the anal sphincter and perineal tissue,10 can have a profound effect on patients’ quality of life (QOL), including social and sexual QOL (Figure 1). 11 Further, despite medical treatment, about one-third of patients suffer from recurring fistula and only one-third achieve permanent fistula closure with surgery.12

Pathophysiology

Although the specific etiology of FCD is unknown, the same multifactorial interplay of events that lead to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) underlie that of FCD: genetic susceptibility, immune dysregulation, environmental stress, and infectious triggers.8 Further, the transmural inflammation of CD predisposes patients to fistula formation.8 In fact, signs of moderate to severe inflammation are present in more than 80% of fistulas.12 This destructive inflammation is the prime source of epithelial barrier injury and defective wound healing that consequently lead to perpetual tissue damage and remodeling.12 Ultimately, deeper layers of the gut wall are penetrated, forming connections to other organs or the body surface.12 Figure 2 depicts the major players involved in this pathogenic process.12

VIDEO 2: Patient testimonial

VIDEO 2: Patient testimonial

1. Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs)—a diverse set of microbial molecules that share “patterns” or structures that alert immune cells to destroy intruding pathogens—invade the gut mucosa

2. Intestinal epithelial cells undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) for the purpose of wound healing

3. Presence of PAMPs induces an inflammatory reaction resulting in increased secretion of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)

4. TNF induces secretion of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and is a major inducer of EMT as well as increased expression of molecules associated with cell invasiveness, eg, β6-integrin

• TGF-β-induced interleukin (IL)-13 and increased activation of remodeling matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) critically contribute to invasive cell growth

5. EMT and MMP overactivation and increased expression of invasive molecules contribute to the development of fistulas

Diagnosis and Assessment

Because PFCD is a common manifestation of CD and its symptoms may be disproportionate compared with its anatomic aggressiveness, examination of the perianal region should be performed at initial CD diagnosis and repeated regularly, especially when new symptoms develop.14 Basic assessment of perianal fistula during an in-office visit include visual perianal inspection, digital rectal palpitation, and anoscopy. Eliciting a detailed history and asking specific questions during the patient interview is also imperative, as patients may be hesitant to disclose their symptoms.15 Typical symptoms include anal pain with defecation, perianal itching, bleeding, and drainage.14 Because the main symptom of perianal fistulas is drainage, patients may describe having to wear a pad due to ongoing discharge.15

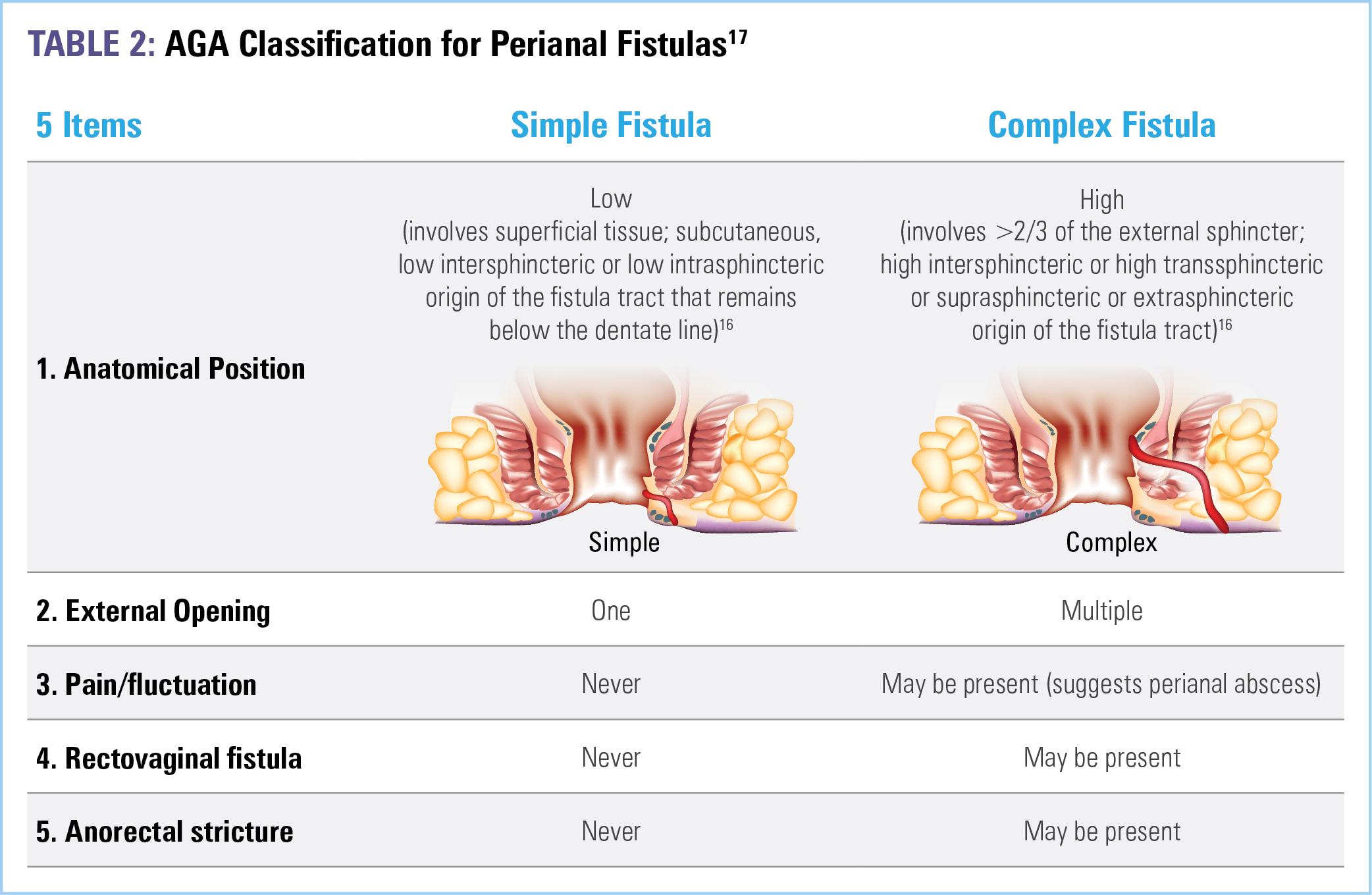

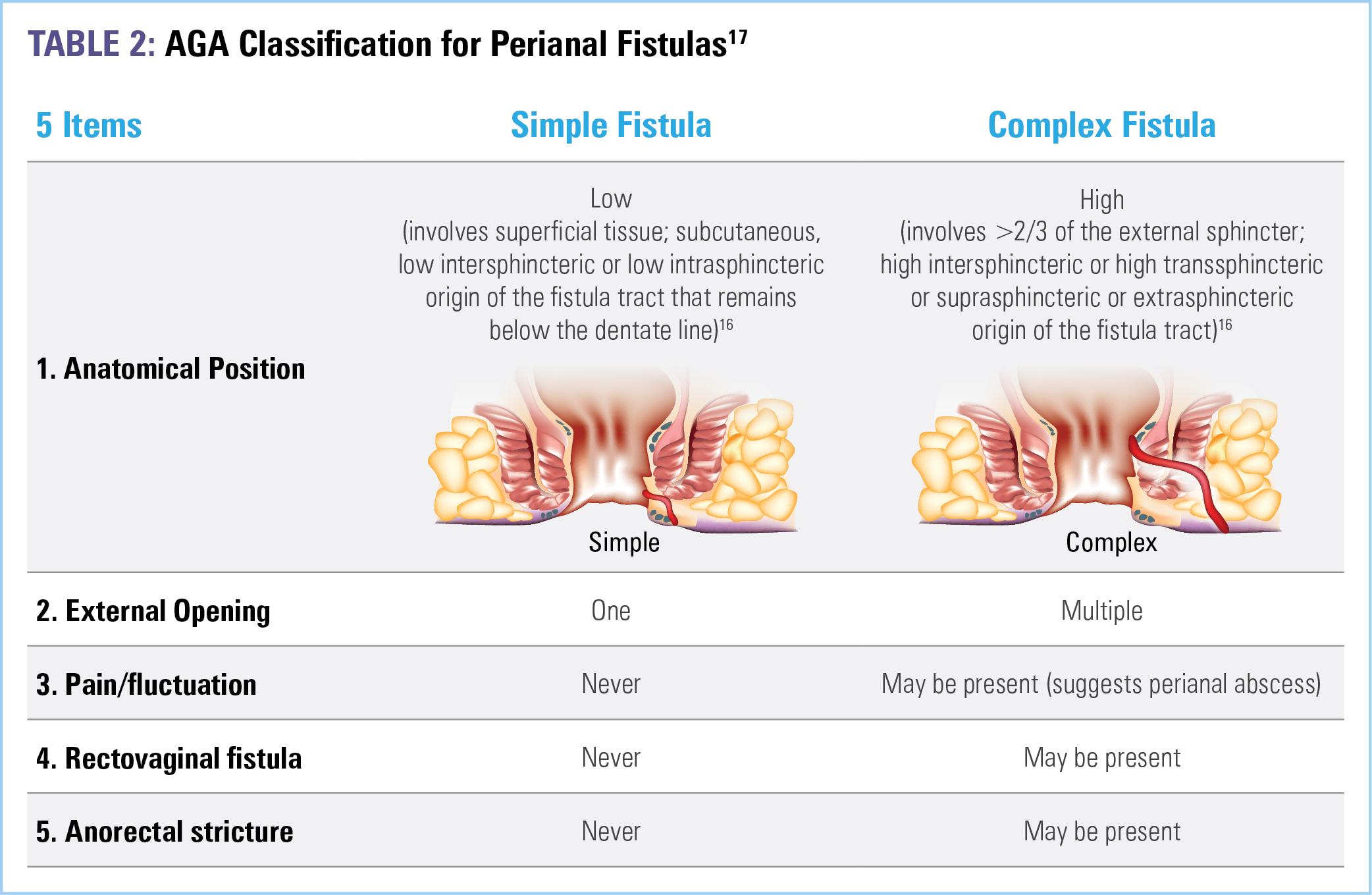

If fistula or perianal abscess is suspected (due to the presence of pain, fluctuance, or stricture) or identified, a comprehensive workup requires pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and examination under anesthesia (EUA)—with EUA being the gold standard for establishing diagnosis—to determine the extent and involvement with surrounding tissue.16,17 While endosonography, which requires anorectal ultrasound, may be done, it is not required as MRI plus EUA are highly sensitive and specific. Should perianal abscess be present, drainage must be performed to prevent local sepsis. Additionally, endoscopic assessment of active luminal disease should be performed, as treatment should be optimized with a goal of achieving and maintaining remission.16 Understanding of the exact anatomy of the fistula and accurately classifying disease is of major importance to the selection of treatment modalities.16 Table 2 outlines the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) 5-item classification system for perianal fistulas.17

Therapeutic management of perianal fistulas is informed by the presence of inflammation in the rectum, the location and type of fistulas present, and the severity of symptoms.17 Simple fistulas are not associated with macroscopic evidence of rectal inflammation or perianal complications and, therefore, have higher rates of healing compared with complex fistulas, 88.2% vs 64.6% respectively.14,17 Complex fistulas, conversely, may be associated with abscess, proctitis, rectal stricture, or connection with the bladder or vagina, and are major risk factors for poor prognosis— thus, they are more difficult to treat and necessitate aggressive therapy.16 Approximately 71% to 84% of anal fistulas are complex.18 Medical and surgical management of FCD will be discussed in the upcoming chapters.

VIDEO 3: Clinical pearls for the evaluation of PFCD

References

1. Ye Y, Manne S, Treem WR, et al. Prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in pediatric and adult populations: recent estimates from large national databases in the United States, 2007-2016. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26(4):619-625.

2. Adegbola SO, Dibley L, Sahnan K, et al. Development and initial psychometric validation of a patient-reported outcome measure for Crohn’s perianal fistula: the Crohn's anal fistula quality of life (CAF-QoL) scale. Gut. 2021;70(9):1649-1656.

3. Ayoub F, Odenwald M, Micic D, et al. Vedolizumab for perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Intest Res. 2022;20(2):240-250.

4. Brochard C, Rabilloud ML, Hamonic S, et al. Natural history of perianal Crohn’s disease: long-term follow-up of a population-based cohort. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(2):e102-e110.

5. Caron B, D'Amico F, Danese S, et al. Endpoints for perianal Crohn’s disease trials: past, present and future. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15(8):1387-1398.

6. Carr S, Velasco AL. Fistula in ano. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing;2022.

7. Pedersen KE, Lightner AL. Managing complex perianal fistulizing disease. J Laparoendosc Adv Surgl Tech A. 2021;31(8):890-897.

8. Lightner AL, Ashburn JH, Brar MS, et al. Fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Curr Probl Surg. 2020;57(11):100808.

9. Feroz SH, Ahmed A, Muralidharan A, et al Comparison of the efficacy of the various treatment modalities in the management of perianal Crohn’s fistula: a review. Cureus. 2020;12(12):e11882.

10. Rubbino F, Greco L, di Cristofaro A, et al. Journey through Crohn’s disease complication: from fistula formation to future therapies. J Clin Med. 2021;10(23):5548.

11. Spinelli A, Yanai H, Lonnfors S, et al. The impact of perianal fistula in Crohn’s disease on quality of life: results of a patient survey conducted in Europe. Paper presented at European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation Virtual Congress; July 2021.

12. Scharl M, Rogler G. Pathophysiology of fistula formation in Crohn’s disease. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2014;5(3):205-212.

13. Levy C, Tremaine WJ. Management of internal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2002;8(2):106-111.

14. Aguilera-Castro L, Ferre-Aracil C, Garcia-Garcia-de-Paredes A, et al. Management of complex perianal Crohn’s disease. Ann Gastroenterol. 2017;30(1):33-44.

15. Lightner A. Management of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;17(11):533-535.

16. Sulz MC, Burri E, Michetti P, et al. Treatment algorithms for Crohn’s disease. Digestion. 2020;101(suppl 1):43-57.

17. Sandborn WJ, Fazio VW, Feagan BG, et al. AGA technical review on perianal Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(5):1508-1530.

18. Schwartz DA, Tagarro I, Carmen Díez M, et al. Prevalence of fistulizing Crohn’s disease in the United States: estimate from a systematic literature review attempt and population-based database analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(11):1773-1779.

CHAPTER 2:

CONTEMPORARY MEDICAL THERAPY FOR FISTULIZING CROHN’S DISEASE TREATMENT SELECTION FOR INITIATION & SEQUENCING

There are 2 major components that must be addressed during the management of FCD. The first is the inflammatory component, which is addressed medically with pharmacologic therapy.1 The second is the mechanical component, which is addressed surgically with several options available depending on the severity of the fistula.1 Thus, it is important to emphasize that a combined medical and surgical approach yields the best patient outcomes— better than either modality alone.1 In this chapter, we will review medical therapies for FCD as well as the goals for treatment. Surgical strategies for FCD will be discussed in Chapter 3. 1

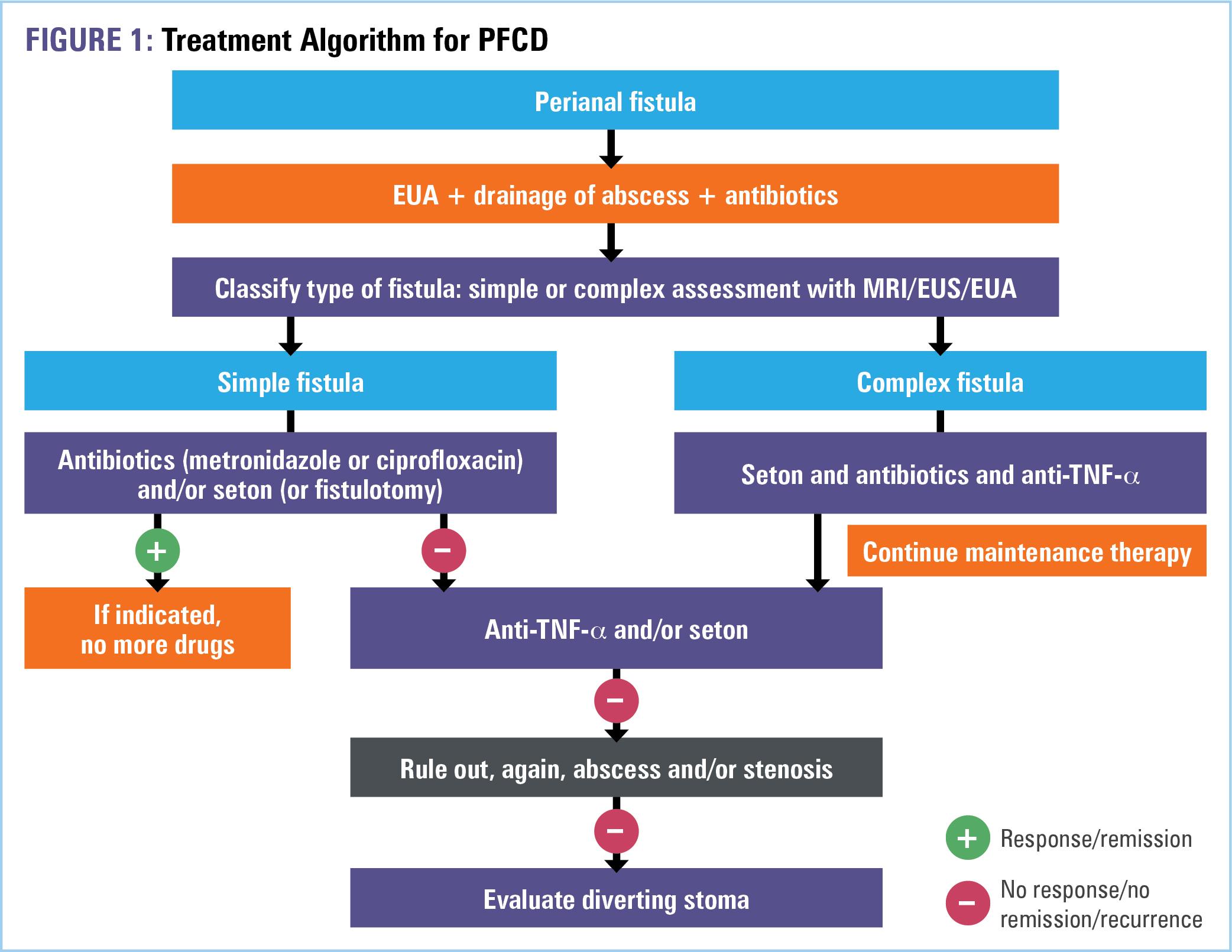

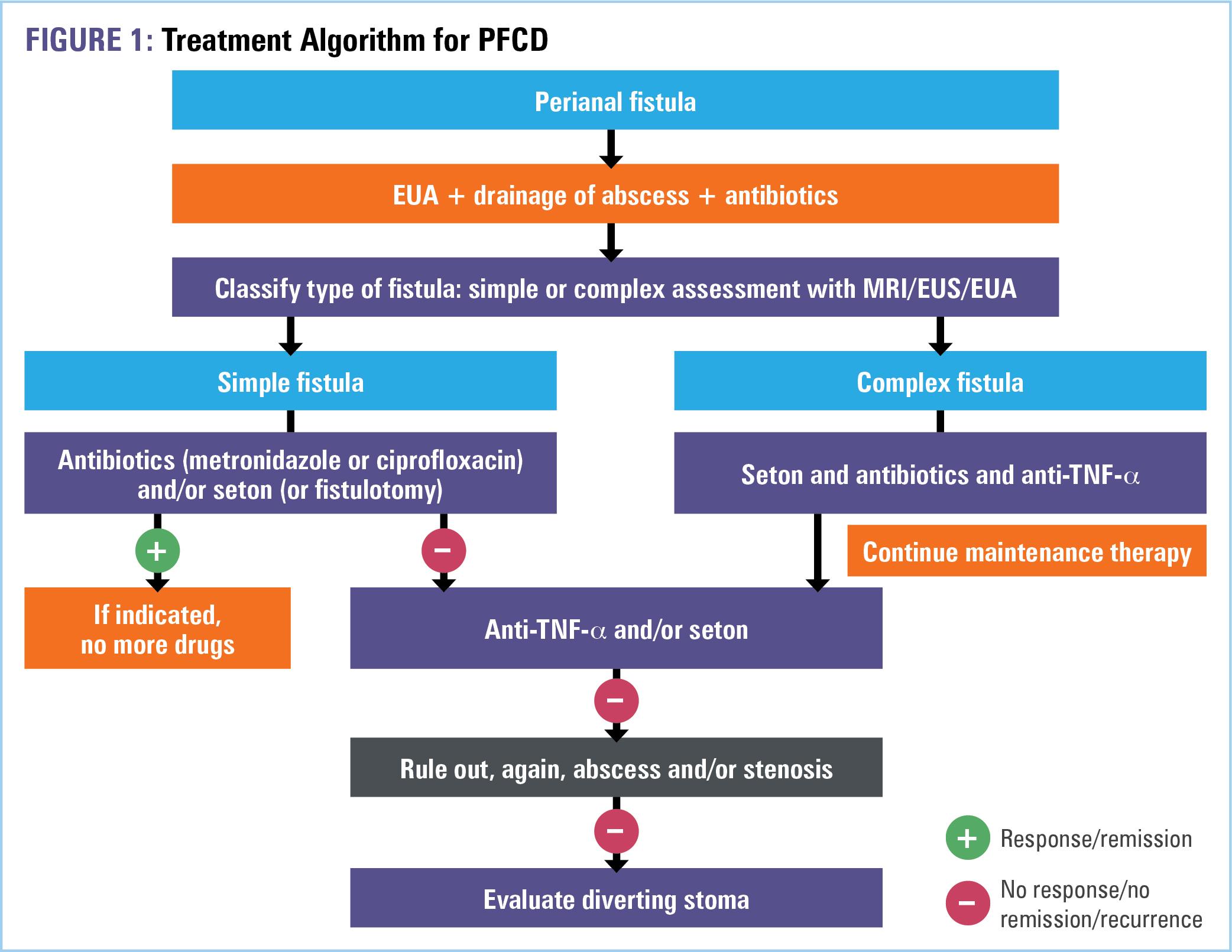

While treatment goals may vary by patient, the ultimate goal for all perianal fistulas is closure, healing, and reduction in symptoms.2 Whereas asymptomatic simple fistulas do not need treatment, symptomatic simple fistulas can be medically treated with antibiotics (for local infection), TNF-α antagonists, and/or by

surgical placement of a seton, fistulotomy, or fistulectomy. Notably, in almost all cases, a surgical consultation with examination under anesthesia (EUA) should be completed prior to initiation of medical therapy to ensure the absence of abscess and adequate control of local sepsis.3,4 Medical therapy for complex fistulas includes the same classes of agents as that for simple fistulas; however, due to their progressive behavior and poor prognosis, complex fistulas frequently necessitate surgery to accomplish disease control. In ultra-refractory disease, surgery is the last and only resort.3 A simplified treatment algorithm adapted from Sulz MC and colleagues is provided in Figure 1. 4

TNF-α antagonists are a first-line recommendation from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), frequently in combination with an immunomodulator (azathioprine/6-

mercaptopurine [AZA/6-MP] or methotrexate [MTX]) to increase their efficacy and mitigate immunogenicity.4,5 Supported by a “moderate certainty of evidence” the AGA specifically states:

• In adult outpatients with CD and active perianal fistula, the AGA recommends the use of infliximab over no treatment for the induction and maintenance of fistula remission.5

AND

• In adult outpatients with CD and active perianal fistula without perianal abscess, the AGA recommends the use of biologic agents in combination with an antibiotic over a biologic drug alone for the induction of fistula remission.

Infliximab (IFX) has the most robust data as a first-line agent for the management of PFCD; reflecting its US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved indication for “reducing the number of draining enterocutaneous and rectovaginal fistulas and maintaining fistula closure in adult patients with FCD.”6,7 Evidence includes a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of patients with symptomatic draining fistulas that found a greater rate of induction of remission of fistula closure with IFX therapy versus placebo, risk ratio (RR) 0.52.5 Another retrospective analysis found IFX to be statistically more effective in preventing recurrence when compared with adalimumab.7 Lastly, in RCTs, use of IFX or adalimumab in combination with the antibiotic ciprofloxacin was significantly more effective than using either TNF-α antagonist alone in achieving fistula closure, RR, 0.42. Thus, although placebo-controlled trials failed to demonstrate efficacy of antibiotic therapy alone for the induction of fistula remission,2,5 their use as adjunct therapy to treat infection and prevent abscess formation is associated with symptom improvement.1

For patients in whom treatment with one or more TNF-α antagonists has failed, ustekinumab (UST) and vedolizumab (VDZ) are available for use. While FDA-approved for “moderately to severely active CD or [ulcerative colitis] UC,” their efficacy for the treatment of CD-related fistulas is limited. Hence, the “low certainty of evidence” recommendation from the AGA:

• In adult outpatients with CD and active perianal fistula, the AGA recommends the use of adalimumab, ustekinumab, or vedolizumab over no treatment for the induction or maintenance of fistula remission.5

The clinical effectiveness of UST, an inhibitor of IL-12 and IL-23, for the treatment of PFCD was evaluated in a meta-analysis of 9 randomized studies that included 396 patients.8 After the first dose, 41% of pooled patients showed a response to therapy and 17% experienced remission.8 The response rate increased to 56% at 1 year.8 Another open-label study found clinical improvement in 50% of patients with perianal fistulas following UST treatment.1 VDZ, an antagonist of the α4β7 integrin receptor expressed by circulating T and B cells, was evaluated in a recent meta-analysis of 4 studies with a total of 198 patients with PFCD. Results of the study demonstrated a pooled complete healing rate of 27.6% in patients treated with VDZ.9 Another phase 4 study evaluating 2 VDZ dosing regimens (VDZ 300 mg intravenous [IV] at weeks 0, 2, 6, 14, and 22 and the same regimen plus an additional VDZ dose at week 10) in PFCD reported rates of 53.6% and 42.9%, respectively, in achieving ≥50% decrease in draining fistulas and 100% fistulae closure at week 30.10 While this study was prospective, sample size was small and it lacked a placebo arm.

Given that biologics generally have limited efficacy in PFCD and lose efficacy over time, there is a significant gap in the availability

of effective pharmacologic treatment options. Further, the best fistula healing rates reported with combined medical and surgical approaches are approximately 50%. To address this lack of effective treatment options, promising cell-based therapies as well as novel therapeutic targets are in development, offering encouraging data in fistula healing and patient outcomes.11

One novel approach to FCD treatment involves the use of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). In addition to being multipotent, MSCs act as immunomodulators to regulate T cell activity and promote tissue repair.12,13 MSCs are harvested from bone or from adipose tissue. Depending on the medical need, they can be collected from the patient’s own body (autologous) or from another donor (allogeneic). MSCs, however, have a short shelf life of cell viability—approximately 48 hours from the laboratory to the operating room—which adds to the complexity of the procedure.1 Darvadstrocel, an allogeneic adipose-derived MSC therapy, was approved in the European Union in 2018 and Japan in 2021 for the treatment of refractory complex PFCD in adults.14,15 In the pivotal phase 3 ADMIRE-CD trial of patients with nonactive or mildly active luminal CD and refractory complex perianal fistulas, treatment with an intralesional injection of darvadstrocel resulted in significantly greater rates of combined remission at week 24 compared with placebo, 50% (53 of 103 patients) vs 34% (36 of 101 patients) P=0.021, respectively.16 Clinical remission was defined as closure of all treated external openings that were draining at baseline, and absence of collections larger than 2 cm assessed by MRI. Longterm outcomes of 40 patients from the ADMIRE-CD study were reported after 104 weeks of follow-up via a retrospective chart review study (INSPECT). These data revealed higher rates of clinical remission with darvadstrocel, 56%, versus placebo, 40%.17 A postapproval, real-world observational study is ongoing in Europe. Interim analysis data were consistent with outcomes

from ADMIRE-CD, demonstrating a 65% rate of clinical remission at 6 months.18 Given its robust data, the US FDA granted regenerative medicine advanced therapy (RMAT) designation to darvadstrocel in May 2019 for complex perianal fistulas in adults with CD.

Other agents that are currently being studied in FCD include the selective antibodies to IL-23 and p19, risankizumab and mirikizumab, respectively, and an oral selective Janus kinase 1 inhibitor, filgotinib.4 Early areas of research centering on targeting MMP activity,19 combination biologic therapies,20 and hyperbaric oxygen therapy are also ongoing.20

VIDEO 4: Medical management of PFCD

References

1.

2020;57(11):100808.

Lightner AL, Ashburn JH, Brar MS, et al. Fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Curr Probl Surg.

2. Sandborn WJ, Fazio VW, Feagan BG, et al. AGA technical review on perianal Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(5):1508-1530.

3. Aguilera-Castro L, Ferre-Aracil C, Garcia-Garcia-de-Paredes A, et al. Management of complex perianal Crohn’s disease. Ann Gastroenterol. 2017;30(1):33-44.

4. Sulz MC, Burri E, Michetti P, et al. Treatment algorithms for Crohn’s disease. Digestion. 2020;101(suppl 1):43-57.

5. Feuerstein JD, Ho EY, Shmidt E, et al. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the medical management of moderate to severe luminal and perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(7):2496-2508.

6. Remicade [package insert]. Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech Inc.; 2013.

7. Ji CC, Takano S. Clinical efficacy of adalimumab versus infliximab and the factors associated with recurrence or aggravation during treatment of anal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Intest Res. 2017;15(2):182-186.

8. Attauabi M, Burisch J, Seidelin JB. Efficacy of ustekinumab for active perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the current literature. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2021;56(1):53-58.

9. Ayoub F, Odenwald M, Micic D, et al. Vedolizumab for perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Intest Res. 2022;20(2):240-250.

10. Schwartz DA, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Lasch K, et al. Efficacy and safety of 2 vedolizumab intravenous regimens for perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease: ENTERPRISE Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(5):1059-1067.

11. Kotze PG, Shen B, Lightner A, et al. Modern management of perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: future directions. Gut. 2018;67(6):1181-1194.

12. Gallo G, Tiesi V, Fulginiti S, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cell therapy in the management of perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: an up-to-date review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020;56(11):563.

13. Sebbagh AC, Rosenbaum B, Péré G, et al. Regenerative medicine for digestive fistulae therapy: benefits, challenges and promises of stem/stromal cells and emergent perspectives via their extracellular vesicles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021;179:113841.

14. European Medicines Agency. Human medicine European public assessment report (EPAR): alofisel. Last updated April 3, 2022. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/ medicines/human/EPAR/alofisel.

15. Pharma Japan. Alofisel approved in Japan. Last updated September 28, 2021. https:// pj.jiho.jp/article/245278

16. Panés J, García-Olmo D, Van Assche G, et al. Expanded allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (Cx601) for complex perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: a phase 3 randomised, double-blind controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1281-1290.

17. Garcia-Olmo D, Gilaberte I, Binek M, et al. Follow-up study to evaluate the long-term safety and efficacy of darvadstrocel (mesenchymal stem cell treatment) in patients

with perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease: ADMIRE-CD phase 3 randomized controlled trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022;65(5):713-720.

18. Zmora O, Baumgart DC, Faubion W, et al. P603 INSPIRE: 6-month interim analysis from an observational post-marketing registry on the effectiveness and safety of darvadstrocel in patients with Crohn’s disease and complex perianal fistulas. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2022;16(suppl 1):i536-i537.

19. Rubbino F, Greco L, di Cristofaro A, et al. Journey through Crohn’s disease complication: from fistula formation to future therapies. J Clin Med. 2021;10(23):5548.

20. Revés J, Ungaro RC, Torres J. Unmet needs in inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Res Pharmacol Drug Discov. 2021;2:100070.

CHAPTER 3: SURGICAL STRATEGIES FOR PFCD

While nearly 90% of patients with PFCD will undergo surgery to treat a perianal fistula, it is important to emphasize that a combined medical-surgical approach demonstrates improved efficacy when compared with either strategy alone.1 In all cases, the primary surgical goal for the treatment of PFCD is to preserve anal sphincter function while achieving closure of the internal opening(s) of the fistula tract(s).2,3

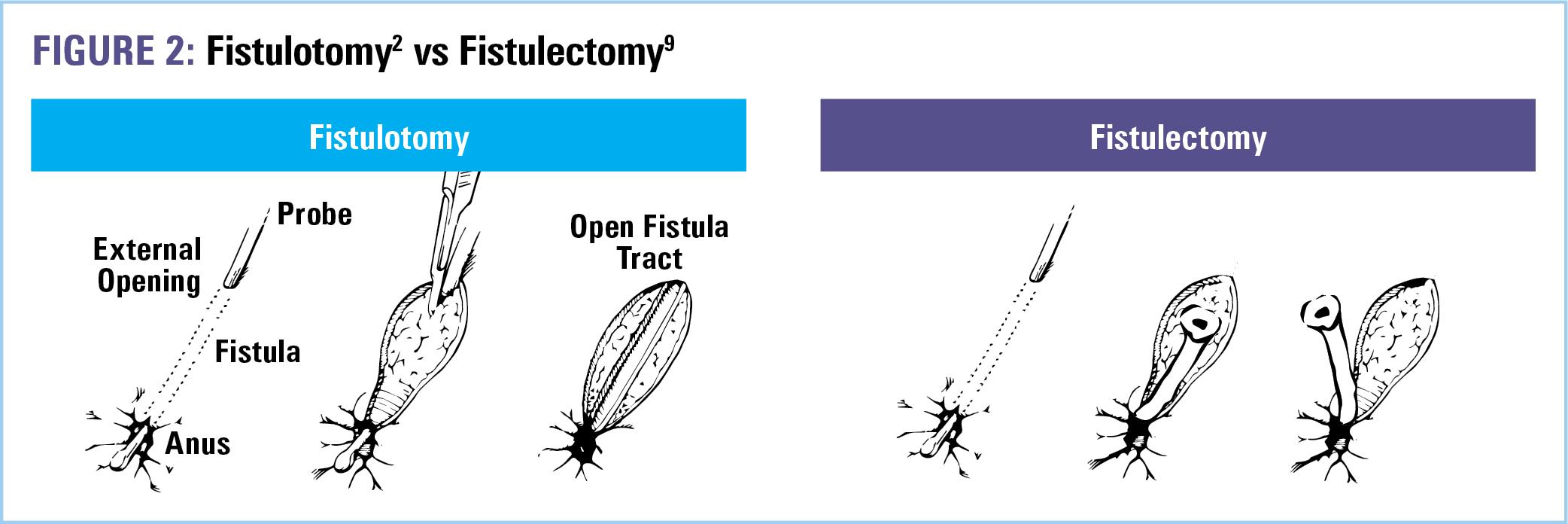

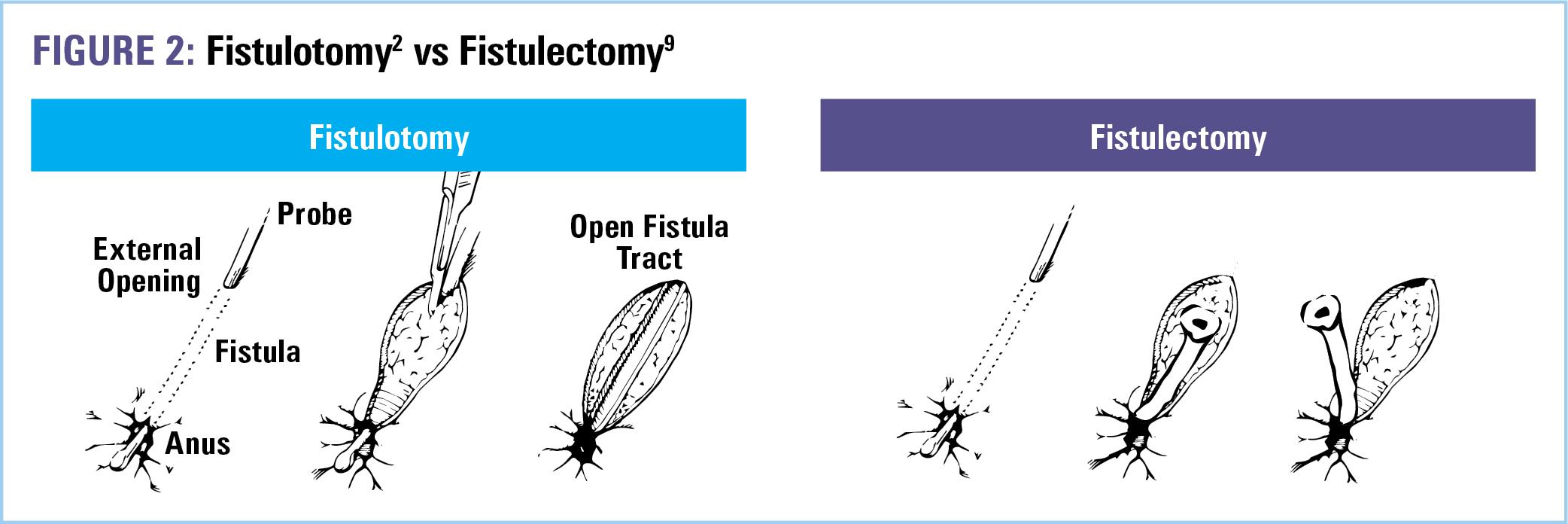

In the acute setting, the most common surgical approach to PFCD includes an examination under anesthesia (EUA), curettage of granulation tissue inside the fistula tracts, drainage of perianal abscess if present, and placement of noncutting setons.4,5 Simple fistulas, however—those that are superficial, characterized by a low anatomical position with little to no involvement of the sphincter muscles, one external opening, and no associated perianal complications—can be adequately treated with a fistulotomy.3 Fistulotomy lays open the tract from internal to external opening,6 allowing for drainage, preventing abscess formation, and promoting healing by secondary intention. Healing rates for fistulotomy range from 80% to 100% and are greater when active macroscopic inflammation is absent.2,4 In the presence of proctitis, fistulotomy healing rates drop to 27%.7 Therefore, the use of a noncutting seton (Figure 1) as the initial treatment for simple fistulas maybe be preferred prior to fistulotomy when active rectal inflammation is present.2

Another surgical option for simple fistulas presenting without proctitis is fistulectomy, the complete excision of the fistulous tract by sharp dissection or cautery (Figure 2). While procedure of choice depends on the surgeon, there have been comparative prospective clinical trials. One study randomized 30 patients (without CD) with simple perianal fistula to either fistulectomy or fistulotomy.8 Outcomes demonstrated shorter operating times, less postoperative pain, and less time needed for wound healing with fistulotomy. However, no difference in postoperative complications, incontinence, or fistula recurrence was found between groups.

Complex fistulas—characterized by high anatomical position, significant sphincter muscle involvement, multiple or branching tracts, and perianal inflammation—require a conservative surgical approach to treatment. This reduces the risk of postoperative incontinence, which is directly related to the thickness of

sphincter muscle divided.2,6 Thus fistulotomy or fistulectomy in patients with complex fistulas is not recommended, per American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS) Guidelines,3 as they are ineffective and associated with a high rate of proctectomy due to either incontinence or nonhealing.2 And while a number of other surgical strategies exist for complex cases, options are limited by the presence of active proctitis; emphasizing the need for optimal medical therapy prior to surgery.

Prior to any definitive surgical management, infection control with an incision and drainage (I&D) and noncutting seton should be the initial treatment for complex fistulas.10 Noncutting setons allow for abscess drainage, stimulation of fibrosis, and prevention of closure of the external opening—thereby avoiding recurrent perianal abscess.1,7 However, they are not a cure and should be removed following resolution of local infection and rectal mucosal healing.1 Rates of complete healing following seton withdrawal are approximately 50%.1 Thus, additional surgery is typically indicated to close the internal opening and achieve complete healing.

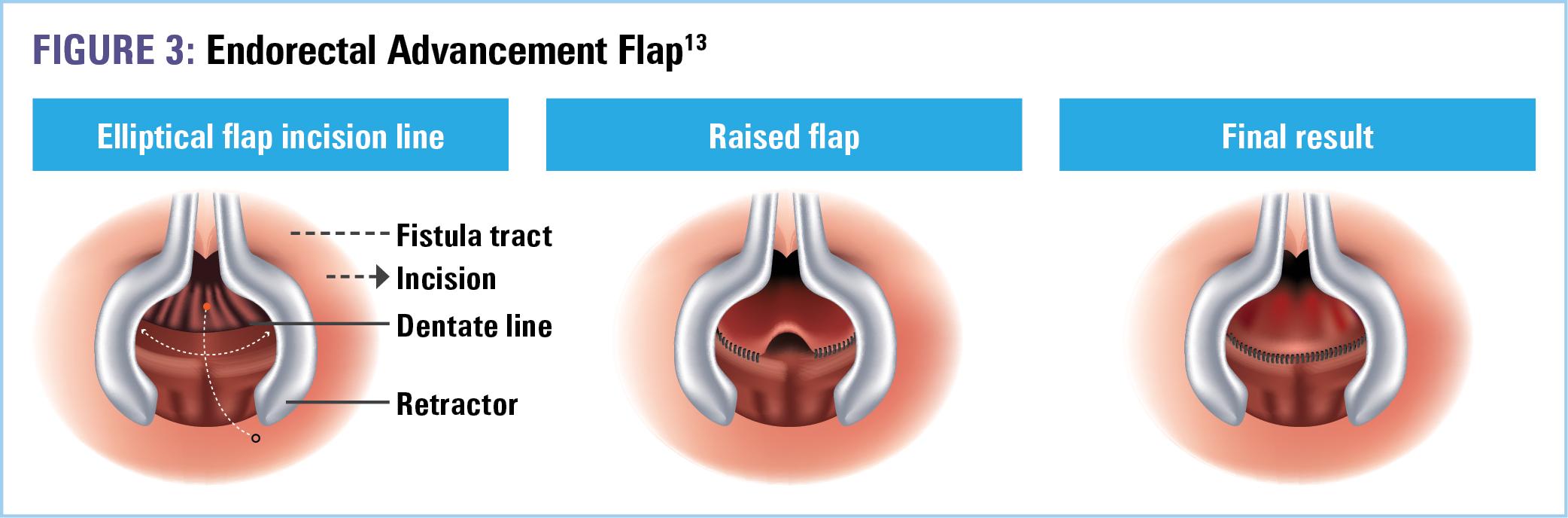

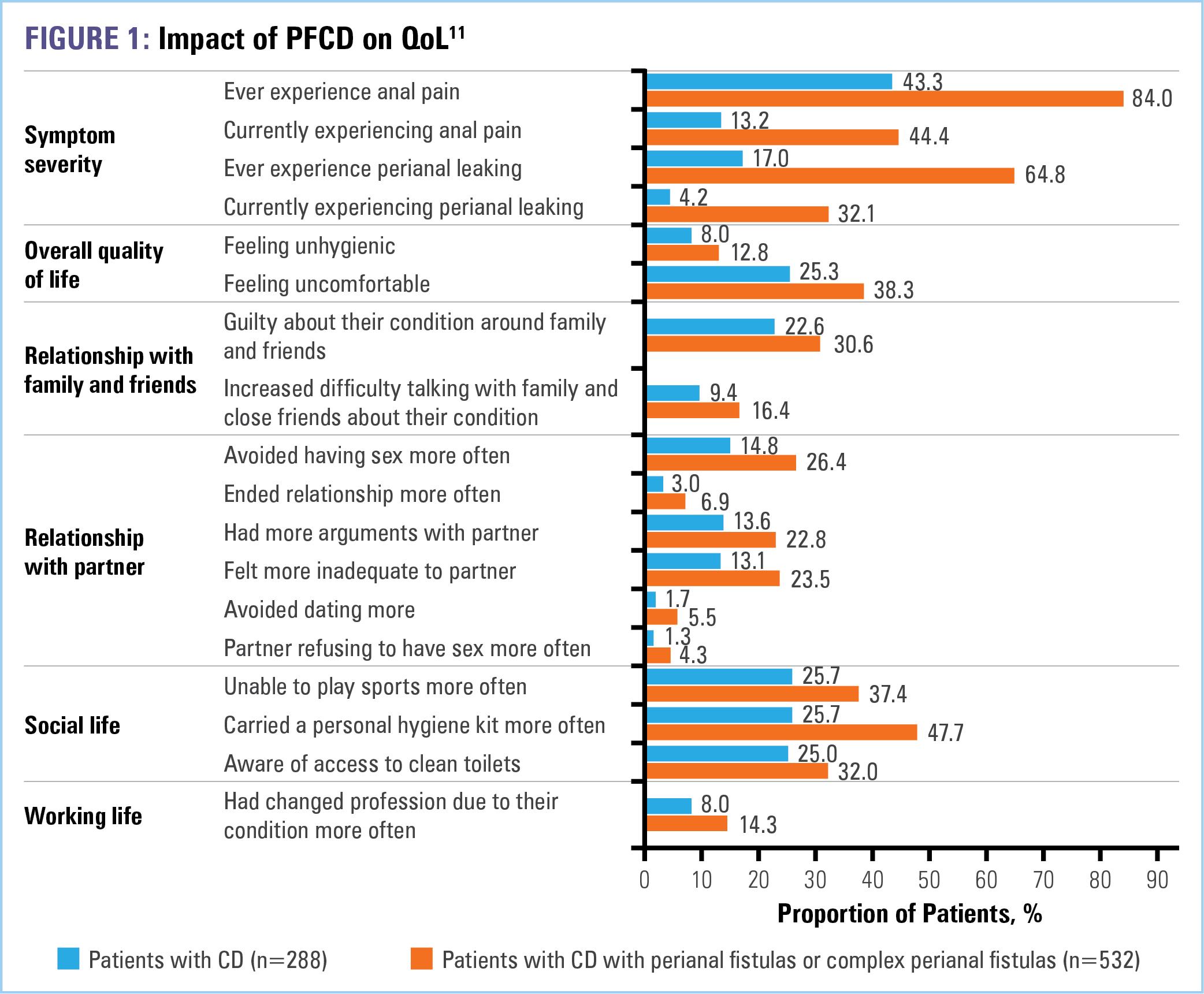

There is no universally accepted gold standard for the surgical treatment of PFCD; therefore, the choice of procedure(s) is assessed by a combination of patient and surgeon factors.11 Potential options following seton removal include endorectal advancement flap, ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT), and lastly, in refractory cases, proctectomy.1,7 Among these, the advancement flap (Figure 3) is the most common.12 During this procedure, a segment of healthy tissue proximal to the internal opening of the fistula is carefully dissected into a U-shaped flap.1 The wide pedicle maintains adequate blood supply to the flap, which is then used to cover the opening. The flap is secured to the anal canal with interrupted sutures.1 Complete healing rates are demonstrated in about 50% of patients.12

The LIFT procedure (Figure 4) shares comparable efficacy to the advancement flap with the exception of a lower rate of incontinence, 7.8% versus 1.6%.12 During this procedure, the intersphincteric groove is opened and the fistulous tract is dissected and isolated. The tract is then ligated with interrupted sutures, disconnecting the internal and external ends.1,7 Modifications of the LIFT procedure have also been implemented, including the incorporation of a biologic mesh or fistula plug.3 However, while the LIFT is safe and relatively effective, its precise indication and technical difficulties limit its wide adoption.1,7

With respect to emerging minimally invasive surgical techniques— including video-assisted anal fistula treatment VAAFT15 and fistula

laser closure (FiLaC)11—additional data are needed as none to date has shown much benefit for the treatment of perianal fistulas.3,4

Lastly, despite these advanced surgical procedures and persistent measures to preserve sphincter muscle function, and therefore continence, refractory PFCD is common. These severe cases do not respond to medical therapy, surgical intervention, or long-term seton drainage, and therefore often, approximately 40% of the time, require proctectomy with permanent fecal diversion.1 A promising option, however, for these complex PFCD cases, is mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) therapy. The latest 2022 ASCRS Guidelines recommend local administration of MSC in the setting of CD-related, refractory anorectal fistula (weak recommendation/ moderate quality evidence).3 Support for this recommendation is based on phase 3 data evaluating the effectiveness of darvadstrocel—a suspension of human allogeneic adiposederived mesenchymal stem cells extracted from the subdermal adipose tissue of healthy donors. While darvadstrocel has yet to receive FDA approval, it is currently approved for use in Europe and Japan. However, given its limited availability, it is likely to be utilized following failure of medical therapy in severe cases with multiple tracts in which surgical approaches, such as an advancement flap or LIFT, are not options.

VIDEO 5: Surgical management of PFCD

References

1. Lightner AL, Ashburn JH, Brar MS, et al. Fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Curr Probl Surg. 2020;57(11):100808.

2. Sandborn WJ, Fazio VW, Feagan BG, et al. AGA technical review on perianal Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(5):1508-1530.

3. Gaertner WB, Burgess PL, Davids JS, et al. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons clinical practice guidelines for the management of anorectal abscess, fistula-in-ano, and rectovaginal fistula. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022;65(8):964-985.

4. Lightner AL. Management of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 2021;17(11):533-535.

5. Aguilera-Castro L, Ferre-Aracil C, Garcia-Garcia-de-Paredes A, et al. Management of complex perianal Crohn’s disease. Ann Gastroenterol. 2017;30(1):33-44.

6. Ommer A, Herold A, Berg E, et al. Cryptoglandular anal fistulas. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108(42):707-713.

7. Pedersen KE, Lightner AL. Managing complex perianal fistulizing disease. J Laparoendoscop Adv Surg Tech A. 2021;31(8):890-897.

8. Elsebai O, Elsesy A, Ammar M, et al. Fistulectomy versus fistulotomy in the management of simple perianal fistula. Menoufia Med J. 2016;29(3):564-569.

9. Jain BK, Vaibhaw K, Garg PK, et al. Comparison of a fistulectomy and a fistulotomy with marsupialization in the management of a simple anal fistula: a randomized, controlled pilot trial. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2012;28(2):78-82.

10. Gold SL, Cohen-Mekelburg S, Schneider Y, et al. Perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease, part 2: surgical, endoscopic, and future therapies. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 2018;14(9):521-528.

11. Adegbola SO, Sahnan K, Tozer P, et al. Emerging data on fistula laser closure (FiLaC) for the treatment of perianal fistulas; patient selection and outcomes. Clin Exper Gastroenterol. 2021;14:467-475.

12. Rubbino F, Greco L, di Cristofaro A, et al. Journey through Crohn’s disease complication: from fistula formation to future therapies. J Clin Med. 2021;10(23):5548.

13. Yellinek S, Krizzuk D, Moreno Djadou T, et al. Endorectal advancement flap for complex anal fistula: does flap configuration matter? Colorectal Dis. 2019;21(5):581-587.

14. Romaniszyn M, Walega PJ, Nowak W. Efficacy of LIFT (ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract) for complex and recurrent anal fistulas – a single-center experience and a review of the literature. Pol J Surg. 2014;86(11):532-536.

15. Chase TJG, Quddus A, Selvakumar D, et al. VAAFT for complex anal fistula: a useful tool, however, cure is unlikely. Tech Coloproctol. 2021;25(10):1115-1121.

CHAPTER 4: MONITORING AND LONGTERM FOLLOW-UP OF PFCD

Assessment Tools and Indices

Recurrence rates of simple fistulas range from 0% to 20%.1 However, the risk of recurrence in complex PFCD is even higher, occurring in nearly two-thirds of patients. Thus, the best way to mitigate recurrence is to maintain disease control with appropriate and effective medical therapy.2

With respect to posttreatment monitoring, the simplest way to evaluate fistula activity is the Fistula Drainage Assessment This exam is based on clinician’s perception and classifies fistulas as active in the presence of purulent drainage following gentle digital compression.2 Clinical response is achieved if there is a reduction of 50% or more in the number of draining fistulas in 2 consecutive visits, and remission is established when draining fistulas are absent in 2 consecutive visits.3 The Fistula Drainage Assessment does not consider patient morbidity or perianal abscesses. Further, persistent fistula tracts as well as active inflammation may be present despite cessation of active drainage and healing of the external orifice.2,3 Thus, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also be implemented within the longitudinal monitoring strategy, particularly when used as a comparison to baseline studies in more aggressive cases.4

A more comprehensive assessment tool used to evaluate perianal disease activity and treatment efficacy is the Perianal Disease Activity Index (PDAI). The PDAI evaluates 5 elements (Table 1): 1) fistula discharge, 2) pain and activity restriction, 3) sexual activity restriction, 4) type of perianal disease, and 5) induration.3 Graded on a Likert scale, a score >4 suggests the need for additional medical or surgical treatment and has an accuracy of 87% when used to discriminate between active and inactive disease.2,3 However, no specific score or incremental differences in scores have been conclusively defined for remission or improvement.2 Further, only 1 of 5 categories, “type of perianal disease,” has potential implications for postsurgical outcomes. Therefore, the PDAI should not be used as a prognostic tool when deciding among surgical interventions.5

One proposed clinical index that may not only serve to evaluate postsurgical outcomes but also aid in prognosis is the Perianal Crohn's Disease Activity Index (PCDAI). The PCDAI (Table 2) is a 6item questionnaire that consists of easily identifiable and common features of PFCD—including 1) abscess, 2) fistula, 3) fissure and/or ulcer, 4) stenosis, 5) incontinence, and 6) concomitant disease.5 The scoring system was tested in a pilot study of 28 patients. Using the Spearman nonparametric correlation test (correlation coefficient, 0.78; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.57-0.89; P<0.001), results demonstrated that a PCDAI score ≤15 correlated with a good surgical outcome, whereas a score ≥20

accurately predicted failure of surgical intervention.5 Due to limited sample size, additional prospective studies are warranted to investigate its prognostic value.

Lastly, therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) offers an opportunity to improve patient outcomes in PFCD by optimizing the effectiveness of biologic treatment.6 Higher serum biologic concentrations are associated with improved therapeutic outcomes with respect to fistula healing and normalization of inflammatory markers. Thus, monitoring drug trough levels and modifying dosage accordingly may lead to improved efficacy.6 The greatest evidence supporting the use of TDM within management of PFCD is provided by several studies investigating infliximab (IFX). One retrospective study of 117 patients with PFCD found that fistula healing was associated with a significantly higher median serum IFX concentration of 15.8 μg/ mL, whereas active fistulas correlated with a median IFX concentration of 4.4 μg/mL (P<0.0001).6,7 Achieving an IFX concentration ≥10.1 µg/mL was also associated with fistula closure, with incremental gain in fistula healing demonstrated at higher IFX levels.7 A more recent study supporting TDM within the management of PFCD is a post hoc analysis of the ACCENT-II trial, which evaluated IFX induction and maintenance therapy. IFX concentrations ≥11.3 μg/mL were associated with the highest rate of long-term remission at week 14.8

With respect to TDM of newer biologics vedolizumab (VDZ) and ustekinumab (UST), studies are scarce. The ENTERPRISE phase 4 study, which evaluated VDZ dosing regimens in patients with PFCD, demonstrated that a small sample size of patients with fistula healing had higher pooled VDZ trough concentrations versus nonresponders from week 6 to week 22. This observation, however, was not maintained at week 30.9 Further, conclusions regarding the relationship between VDZ dosing and treatment response could not be drawn.6

Whether proactively increasing biologic therapy dosage to achieve higher serum concentrations improves short- or long-term

posttreatment outcomes is debatable. However, evidence does support the approach of optimizing drug levels to threshold prior to switching therapy in patients who have not experienced fistula healing at lower trough concentrations.7

The Patient Perspective on Long-term Outcomes

Patient quality of life (QOL) is “the ultimate measure of treatment effectiveness.”4 Consequently, designing therapeutic management plans that preserve the highest possible QOL is the goal of PFCD treatment.10,11 This includes educating patients on the potential outcomes of available treatment options, eliciting their personal goals for management, setting expectations, and then— based on informed discussions—selecting treatment(s) in partnership with the patient in a process commonly known as shared decision-making (SDM).11 A recent survey distributed to patients with PFCD revealed that the top 2 patient goals of treatment are decreasing pain and healing the fistula.12 Survey results also revealed that 43% of patients also prefer to make the final decision on treatment after considering their doctor’s opinion. Many patients are concerned about surgical complications (60%) or medication side effects (50%).12 These treatment concerns compound an already significant patient disease burden that is characterized, according to survey respondents, by increased stress (67%), financial strain (66%), and emotional distress (65%).12 Therefore, the patients’ perspective is an invaluable measurement of treatment success and should be utilized throughout the management of disease, especially when assessing long-term treatment outcomes.

VIDEO 6: Multidisciplinary management of PFCD for optimized outcomes

References

1. Gold SL, Cohen-Mekelburg S, Schneider Y, et al. Perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease, part 2: surgical, endoscopic, and future therapies. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 2018;14(9):521-528.

2. Losco A, Viganò C, Conte D, et al. Assessing the activity of perianal Crohn’s disease: comparison of clinical indices and computer-assisted anal ultrasound. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(5):742-749.

3. Aguilera-Castro L, Ferre-Aracil C, Garcia-Garcia-de-Paredes A, et al. Management of complex perianal Crohn’s disease. Ann Gastroenterol. 2017;30(1):33-44.

4. Lightner AL, Ashburn JH, Brar MS, et al. Fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Curr Prob Surg. 2020;57(11):100808.

5. Pikarsky AJ, Gervaz P, Wexner SD. Perianal Crohn disease: a new scoring system to evaluate and predict outcome of surgical intervention. Arch Surg. 2002;137(7):774-778.

6. Zulqarnain M, Deepak P, Yarur AJ. Therapeutic drug monitoring in perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease. J Clin Med. 2022;11(7):1813.

7. Yarur AJ, Kanagala V, Stein DJ, et al. Higher infliximab trough levels are associated with perianal fistula healing in patients with Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45(7):933-940.

8. Papamichael K, Vande Casteele N, Jeyarajah J, et al. Higher postinduction infliximab concentrations are associated with improved clinical outcomes in fistulizing Crohn’s disease: an ACCENT-II post hoc analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(5):1007-1014.

9. Schwartz DA, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Lasch K, et al. Efficacy and safety of 2 vedolizumab intravenous regimens for perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease: ENTERPRISE study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(5):1059-1067.

10. Pedersen KE, Lightner AL. Managing complex perianal fistulizing disease. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2021;31(8):890-897.

11. Feuerstein JD, Ho EY, Shmidt E, et al. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the medical management of moderate to severe luminal and perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(7):2496-2508.

12. Salinas GD, Belcher ED, Cazzetta SE, et al. S817 Patient and caregiver perspectives on management of Crohn’s-related perianal fistulas: results of a U.S. national survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:S378-S379.

CLINICAL RESOURCE CENTER™

Guidelines

AGA

Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Medical Management of Moderate to Severe Luminal and Perianal

Fistulizing Crohn’s Disease.

Feuerstein JD, Ho EY, Shmidt E, et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(7):2496-2508. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34051983/

ACG Clinical Guidelines: Management of Crohn’s Disease in Adults.

Lichtenstein GR, Loftus EV, Isaacs KL, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(4):481-517.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29610508

ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Crohn’s Disease: Medical Treatment.

Torres J, Bönovas S, Doherty G, et al. J Crohns Colitis 2020;14(1):4-22.

https://academic.oup.com/ecco-jcc/article/14/1/4/5620479

American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on Therapeutic Drug Monitoring in Inflammatory Bowel Disease.

Feuerstein JD, Nguyen GC, Kupfer SS, et al. Gastroenterology 2017;153(3):827-834.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28780013/

Suggested Reading

Managing complex perianal fistulizing disease.

Pederson KE, Lightner AL. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2021;31(8):890-897. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34314631/

Fistulizing Crohn’s disease.

Lightner AL, Ashburn JH, Brar MS, et al. Curr Probl Surg 2020;57(11):100808. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33187597/

Management of complex perianal Crohn’s disease.

Aguilera-Castro L, Ferre-Aracil C, Garcia-Garcia-de-Paredes A, et al. Ann Gastroenterol. 2017;30(1):33-44. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28042236/

Modern surgical strategies for perianal Crohn’s disease.

Zabot GP, Cassol O, Saad-Hossne R, et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2020; 26(42):6572-6581. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7673971/

Development and initial psychometric validation of a patient-reported outcome measure for Crohn’s perianal fistula: the Crohn’s anal fistula quality of life (CAF-QoL) scale.

Adegbola SO, Dibley L, Sahnan K, et al. Gut. 2021;70(9):1649-1656. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33272978/

Treatment algorithms for Crohn’s disease.

Sulz MC, Burri E, Michetti P, et al. Digestion. 2020;101(suppl 1):43-57. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32172251/

Approach to the management of recently diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease patients: a user's guide for adult and pediatric gastroenterologists.

Agrawal M, Spencer EA, Colombel JF, et al. Gastroenterology 2021;161(1):47-65. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33940007/

Clinical efficacy of adalimumab versus infliximab and the factors associated with recurrence or aggravation during treatment of anal fistulas in Crohn’s disease.

Ji CC, Takano S. Intest Res. 2017;15(2):182-186. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5430009/

Efficacy and safety of 2 vedolizumab intravenous regimens for perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease: ENTERPRISE Study.

Schwartz DA, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Lasch K, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(5):1059-1067. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34597729/

Vedolizumab for perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis.

Ayoub F, Odenwald M, Micic D, et al. Intest Res. 2022;20(2):240-250. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9081994/

Efficacy of ustekinumab for active perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the current literature.

Attauabi M, Burisch J, Seidelin JB. Scand J Gastroenterol 2021;56(1):53-58. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33264569/

Mesenchymal stromal cell therapy in the management of perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: an up-to-date review.

Gallo G, Tiesi V, Fulginiti S, et al. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020;56(11):563. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33121049/

Regenerative medicine for digestive fistulae therapy: benefits, challenges and promises of stem/stromal cells and emergent perspectives via their extracellular vesicles.

Sebbagh AC, Rosenbaum B, Péré G, et al. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2021;179:113841. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34175308/

Expanded allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (Cx601) for complex perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: a phase 3 randomised, double-blind controlled trial.

Panés J, García-Olmo D, Van Assche G, et al. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1281-1290. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27477896/

Follow-up study to evaluate the long-term safety and efficacy of darvadstrocel (mesenchymal stem cell treatment) in patients with perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease: ADMIRE-CD phase 3 randomized controlled trial.

Garcia-Olmo D, Gilaberte I, Binek M, et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022;65(5):713-720. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34890373/

P603 INSPIRE: 6-month interim analysis from an observational post-marketing registry on the effectiveness and safety of darvadstrocel in patients with Crohn’s disease and complex perianal fistulas. Zmora O, Baumgart DC, Faubion W, et al. J Crohn's Colitis 2022;16(suppl 1):i536-i537.

https://academic.oup.com/ecco-jcc/article/16/Supplement_1/i536/6513125

Patient Resources

American College of Gastroenterology

https://gi.org/topics/inflammatory-bowel-disease/

American Gastroenterological Association

https://gastro.org/practice-guidance/gi-patient-center/

Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation

http://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/ European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation https://www.ecco-ibd.eu/

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Health information for Crohn’s disease. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/crohnsdisease

VIDEO 2: Patient testimonial

VIDEO 2: Patient testimonial