VILNIAUS DAILĖS AKADEMIJOS

VILNIAUS FAKULTETO

INTERJERO DIZAINO KATEDRA

(su)augant. Alksnynės gynybinis kompleksas.

Justė Žvirblytė ir Goda Padvelskytė

Bakalauro baigiamasis darbas

Interjero dizaino studijų programa, valstybinis kodas 6121PX017

Bakalaurantės: Justė Žvirblytė, Goda Padvelskytė

Darbo vadovė: doc. Laura Malcaitė Tvirtinu, katedros vedėjas: doc. Rokas Kilčiauskas (parašas) (parašas) (parašas) (parašas) (parašas) (parašas) (parašas) (parašas)Įvadas

Tyrimas

Forma

Oras Tuštuma

Garsas

Bunkeris

Abjektas

Antrasis kūnas

Teritorija

Kompleksas

Jungtys

Dokumentika

Projektas

Oras Tuštuma

Vanduo

Abjektas

Pauzė

Garsas

Santrauka

Bibliografja

Introduction Research Form Weather Emptiness Sound

Bunker Abject The second body Territory

Complex Connectors Documentary

Project

Weather Emptiness

Water Abject Pause Sound

Summary

Bibliography

Projekte analizuojamas Kuršių Nerijoje esantis Alksnynės gynybinio komplekso teritorijos istorinis kontekstas, dabartinė padėtis ir galimos ateities perspektyvos. Ieškoma būdų kaip kalbėti apie karo žalą aplinkai, spręsti apleistos karinės inžinerijos išnaudojimo/ įveiklinimo klausimą. Projektu taip pat siekiama skatinti saugų ir tvarų požiūrį į žmogaus sąveiką su gamta, oro stichijomis ir mažiausiais gamtoje esančiais organizmais, pabrėžiant jų mąstymo ir veikimo svarbą, kuruojant ir keičiant kraštovaizdį.

Stebėjimas ir pojūčiai tampa šios erdvės formavimo ir suvokimo įrankiais, režisuojant antžeminių ir požeminių erdvių sistemą kaip nedalomą visumą - naratyvą, kurioje susijungia žmogus, ir kiti organizmai. Žmogaus kuruojamas kraštovaizdis ir sąveika tarp organizmų yra tiriami skirtingose altitudėse, įvairiais aspektais ir sluoksniais, įskaitant žmogaus sukurtas struktūras, gamtines struktūras, stichijas, cikliškumą ir laikinumą.

The project analyzes the historical context, current situation, and potential future perspectives of the Alksnynė defensive complex territory located on the Curonian Spit. It seeks ways to address the environmental damage caused by war and resolve the issue of abandoned military engineering. The project also aims to promote a safe and sustainable approach to human interaction with nature, natural elements, and the smallest organisms in the environment, emphasizing their signifcance in shaping and changing the landscape.

Observation and sensory experiences become tools for shaping and understanding this space, directing the system of underground and aboveground spaces as an integral whole - a narrative in which humans and other organisms merge. The human-curated landscape and the interaction between organisms are examined at diferent altitudes, various aspects, and layers, including human-created structures, natural formations, elements, cyclicality, and temporality.

Tai fragmentuota teritorija, persmelkta istorinės vertės, bet vis dėlto apleista, likutinė ir sustingusi laike. Kita vertus, tai vieta, kurioje žmogus ir gamta gali gyvuoti drauge, o ne vienas prieš kitą.

It is a fragmented territory, imbued with historical value, yet still abandoned, residual, and frozen in time. On the other hand, it is a place where humans and nature can coexist, rather than being at odds with each other.

Ieškant būdų atsakyti klausimus apie jungtis tarp laikotarpių ir gamtos, nagrinėjame šaltinius kurie įprasmintų juos per patirtis. Analizuojam šviesą per formą, tuštumą per nebūtį ir gamtą per gyvybę, todėl išskirtos patirtys įgauna sąvokas, referuojančias tam tikrą erdvės ir organizmų veiklos suvokimo formą.

In search of ways to address the connection between time periods and nature, we explore sources that give them meaning through experiences. We analyze light through form, emptiness through non-being, and nature through life. As a result, highlighted experiences acquire concepts that refer to a particular form of perception of space and organism activity.

Kūriniuose erdvė, kurioje gali jausti būtį per matymą, ne visai suprantamą polinkį tam tikrą judesį ar jausmą tampa vienu iš pagrindinių aspektų. Tai nepatogios formos ir padėtys, kurios atveria galimybę suvokti kūną kaip įrankį, siekiant naujų interpretacinių galimybių.

In these artworks, space becomes one of the main aspects where one can perceive existence through sight, with a tendency that is not entirely understandable toward a particular movement or sensation. It involves uncomfortable forms and positions that open up the possibility of perceiving the body as a tool, seeking new interpretative possibilities.

Anouk Vogel Architecture monogram #2

Nereferencinės formos turi savitą, unikalią išraišką, nes jos nebuvo tikslingai sukurtos.

Jos tarsi priklauso sau.

Formos, kaip ir gamtos peizažas, yra paruoštos atrasti, interpretuoti ir tapti dar nesuvokiamo objekto antspaudu.

Rasta forma yra kvietimas pakeisti projektavimo procesą, sužinoti, kokias netikėtas erdvines sąlygas galima sukurti pasąmoningų formų paieškoje.1

Non-referential forms have their own unique expression because they were not intentionally created with a specifc purpose in mind.

They belong to themselves, so to speak.

Forms, like the landscape of nature, are prepared to be discovered, interpreted, and become imprints of yet undiscovered objects.

A found form is an invitation to change the design process, to explore what unexpected spatial conditions can be created in the search for subconscious forms.1

Lundgaard & Tranberg Architects, Marianne Krogh CON-NECT-ED-NESS 2021

Danijos paviljone 17-oje Venecijos architektūros bienalėje, erdvė traktuojama kaip įrankis nematomą paverčiant matomu, siekiant atkreipti dėmesį nedalomą žmonių, organizmų ir elementų ryšį. Tai iliustruojama tiesiogiai sujungiant paviljono įrengimą su pačios planetos cikline sistema.

Projekte keliamas klausimas, kaip galime kurti naują, prasmingą santykį su pasauliu, kuriame atpažįstame, jog esame susiję – ne tik vienas su kitu, bet su visomis gyvomis būtybėmis?

In the Danish Pavilion at the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale, space is treated as a tool to transform the invisible into the visible, aiming to draw attention to the inseparable connection between humans, organisms, and elements. This is illustrated by directly linking the pavilion installation with the cyclical system of the planet itself.

The project raises the question of how we can create a new, meaningful relationship with the world in which we recognize that we are interconnected, not just with each other, but with all living beings.

James Turrell savo darbų serija “Skyspace” provokuoja žiūrovo juslinį suvokimą. įtraukianti instaliacija, siūlo unikalią šviesos ir erdvės patirtį, pamatyti dangų, jį įrėminant. Manipuliuodamas žmonių suvokimu, apdorojant šviesą ir erdvę, menininkas siekia priminti, kad iš esmės viskas, ką matome, yra iliuzija.

“Mano darbas labiau susijęs su jūsų matymu, o ne su mano matymu, nors tai yra mano matymo rezultatas. Mane taip pat domina erdvės buvimo jausmas; tai erdvė, kurioje jauti buvimą, beveik esybę – tą fzinį jausmą ir galią, kurią gali suteikti erdvė.”

James Turrell’s series of works called “Skyspace” provokes the viewer’s sensory perception. This engaging installation ofers a unique experience of light and space, inviting one to see the sky framed within it. By manipulating people’s perceptions, and manipulating light and space, the artist aims to remind us that fundamentally everything we see is an illusion.

“My work is more about your seeing than it is about my seeing, although it is a product of my seeing. I’m also interested in the presence of space; it’s a space where you feel the presence, almost an entity – that physical sense and power that space can give.”

“Architektūra turėtų būti saugi ir tikra. Ji turėtų apsaugoti: nuo oro sąlygų, nuo tamsos, nuo nežinomybės. Blind Light visa tai paneigia,”- taip savo darbą pristato Anthony Gormley, kuriuo jis priverčia lankytojus naudotis savo kūnais kaip įrankiais patiriant erdvę, metant iššūkį kasdieniškam žmogaus ir erdvės santykiui.2

Šis darbas tyrinėja mūsų orientaciją erdvėje, kaip mūsų kūnai reaguoja kai esame dezorientuoti, siekiant įveiklinti mūsų emocijas ir juslinius pojūčius. Taip jausmas tampa meno kūriniu.

“Architecture should be safe and certain. It should protect us from weather conditions, from darkness, and the unknown. Blind Light denies all of that,” explains Anthony Gormley as he presents his work. Through his artwork, he compels visitors to use their bodies as tools to experience space, challenging the everyday relationship between humans and space.2

This work explores our orientation in space and how our bodies react when we are disoriented, aiming to evoke our emotions and sensory perceptions. In this way, the sensation itself becomes the artwork.

Šis darbas tyrinėja mūsų orientavimasis erdvėje, ir kaip mūsų kūnai reaguoja kai esame dezorientuoti.

It challenges our sense of orientation and explores how our bodies react when we are disoriented.

Oro tema traktuojama kaip gamtos potyrio esmė organizmų gyvenime, kaip nevaldomą ir nesuvokiamą verčiame sukonstruotą ir atribotą. Elementų sąveika iš esmės keičia struktūros, vietos ar erdvės patirtį, o jos suvokimas kuria jungtis tarp kūno ir nematerialios realybės.

The theme of air is approached as the essence of the sensation of nature in organisms’ lives, transforming the uncontrollable and incomprehensible into something constructed and abstracted. The interaction of elements fundamentally alters the experience of structure, place, or space, and its perception creates a connection between the body and the immaterial reality.

„Architektūros nematerialumas... pabrėžia, kad pastatai yra ne tik fziniai objektai, bet ir dinamiški bei besikeičiantys subjektai, kurie daro įtaką aplinkai ir yra jos veikiami.” 3

“Nematerialūs gamtos aspektai, tokie kaip cikliški šviesos ir oro motyvai, taip pat gali būti įtraukti architektūrinį dizainą, sukuriant erdves, kurios reaguoja jų natūralią aplinką.” 4

Žmogaus patirtis objekte priklauso nuo visų pojūčių suvokimo, tačiau nemateriali architektūra gali kurti jausmą įprastai siejamą su nematerialia jausena, pavyzdžiui, kvapu. Nematerialumo patirtis priklauso nuo to, kaip vartotojas interpretuoja tai, kas yra matoma ir jaučiama.

Renesanso laikais gamta buvo vertinama dėl jos grožio, tačiau dažnai iš atstumo, vengiant nesuvaldytų ir nesuprantamų kalnų ir miškų. Kaip David Tuveson pabrėžia, “Nemateriali siela, kaip lankytoja materijoje, niekada negali jaustis namuose”. 5

Kartu su technologine raida ir mokslo pakilimu, instrumentai, tokie kaip mikroskopas ar teleskopas, sukūrė galimybes pamatyti nematomą, iki šiol nesuprastą pasaulį. Vis išsamesni stebėjimai, buvo labiau orientuoti gamtos objektų savybes ir mažiau jų tiesioginę vertę žmonėms.

Naujai atrastos augalų, gyvūnų ir vietovių rūšys, plėtė žmogaus supratimą apie mūsų jungtis su gamta, stimuliuojant pagarbą ir teigiamą požiūrį “Naujajam pasauliui”. Iš vienos pusės, mokslas atskyrė gamtą nuo žmogaus, skatinant susirūpinimą jos nenuspėjama didybe, tačiau kūrė naujas suvokimo prasmes paremtas faktais.

"The immateriality of architecture... emphasizes that buildings are not just physical objects but also dynamic and changing subjects that infuence the environment and are infuenced by it." 3

"Immaterial aspects of nature, such as cyclical motifs of light and air, can also be incorporated into architectural design, creating spaces that respond to their natural surroundings.” 4

The human experience of an object depends on the perception of all senses, but immaterial architecture can create a sense commonly associated with immaterial sensations, such as scent. The experience of immateriality depends on how the user interprets what is visible and felt.

During the Renaissance, nature was valued for its beauty but often from a distance, avoiding untamed and incomprehensible mountains and forests. As David Tuveson emphasizes, "The immaterial soul, as a visitor in the matter, can never feel at home.” 5

With the advancement of technology and the rise of science, instruments such as microscopes and telescopes created opportunities to see the invisible, previously incomprehensible world. More detailed observations were more focused on the properties of natural objects and less on their direct value to humans.

Newly discovered species of plants, animals, and locations expanded human understanding of our connections to nature, stimulating respect and a positive attitude towards the "New World." On one hand, science separated nature from humans, causing concern about its unpredictable magnitude, but it also created new meanings of perception based on facts.

Pastoraliniai paveikslai, iš esmės švenčia gamtos prisijaukinimą, užvaldymą, mūsų viešpatavimą gamtos pasauliui. John Constable “Flatfordo malūnas” įvaizdina vandens išnaudojimo galimybes, medinių įrankių galimybes ir gyvūnų (arklio) galią. Menininko švelnus spalvų naudojimas sukuria ramią, teigiamą atmosferą.

Priešingai, Philip James De Loutherbourg siekia parodyti neįtikėtiną dieviškąją gamtos galią. Romantiškas kraštovaizdžio menas didybę kelia kraštutinumų principu – įspūdingu aukščiu, sunkiomis formomis, tamsa ar stipria šviesa. Meno pagalba formuojamas perspėjimas tiems, kurie nori prieštarauti gamtai, joje įžvelgiama Dievo rūstybė. „Lavina Alpėse“ nurodo kontrastą tarp didžiulio, dantyto uolos veido ir mažų fgūrėlių, sukrėstų mirtinos lavinos grėsmės.

Pastoral paintings essentially celebrate the subjugation and mastery of nature, our dominion over the natural world. John Constable’s “Flatford Mill” portrays the possibilities of water utilization, the capabilities of wooden tools, and the power of animals (the horse). The artist’s subtle use of colors creates a calm, positive atmosphere.

In contrast, Philip James De Loutherbourg seeks to depict the incredible divine power of nature. Romantic landscape art evokes grandeur through the principle of extremes - impressive heights, heavy forms, darkness, or strong light. Through art, a warning is formed for those who wish to oppose nature, perceiving God’s wrath within it. “An Avalanche in the Alps” signifes the contrast between the vast, jagged face of the rock and the small fgures, shocked by the threat of a deadly avalanche.

John Constable, Flatford Mill (‘Scene on a Navigable River’), 1817

Philip James De Loutherbourg (‘An Avalanche in the Alps’), 1803

‘Sukurti meną, architektūrą ir gamtą vienoje erdvės kategorijoje.’

Create art, architecture, and nature in one category of space.

“Nemateriali architektūra, suformuota gamtos ir žmogaus jėgų, kurioje oras, dujos, ugnis, garsas, sąmoningai veikia su gamta nereikalaujant didelių dirbtinių modifkacijų. Tai savitai veikiantys elementai pilni gyvybės ir potyrio, kurių stebėjimas tampa erdvės įprasminimo būdu.” 6

Momento efemeriškumas

juntamas Yves Klein 1957 m. “Oro architektūroje”. Tai radikali architektūros vizija: lengva, erdvi ir nesvari, be fzinių kliūčių ar ribų.

Projekte išryškinama, jog architektūra turėtų būti ne tik funkcinė struktūra, bet ir eterinė, poetinė ir dvasinė patirtis, kuri įtrauktų ir transformuotų žiūrovą, galėtų sukurti nuostabos ir transcendencijos jausmą.

“Immaterial architecture is shaped by the forces of nature and human interaction, in which air, gases, fre, and sound consciously interact with nature without requiring signifcant artifcial modifcations. These self-acting elements are full of life and sensation, and observing them becomes a way of giving meaning to space.” 6

The ephemeral nature is felt in Yves Klein’s 1957 “Air Architecture”. It represents a radical vision of architecture: lightweight, spacious, and unsoiled, without physical barriers or limits.

The project highlights that architecture should not only be a functional structure but also an ethereal, poetic, and spiritual experience that engages and transforms the viewer, capable of creating a sense of wonder and transcendence.

Erdvei reikalinga gyvybė, kurioje ji galėtų egzistuoti kaip tuštumos forma.

Space requires vitality to exist as the form of emptiness.

Anish Kapoor Void feld 1954

„Tuštuma iš tikrųjų yra būsena viduje. [...] Man atrodo, kad grįžtu prie pasakojimo be pasakojimo idėjos, prie to, kas leidžia kiek įmanoma tiesiau įnešti psichologiją, baimę, mirtį ir meilę. Ši tuštuma nėra kažkas, kas nėra neištarta. Tai potenciali erdvė, o ne ne erdvė.” 7

Kūrinyje bandoma sukurti įtampą tarp masės ir tuštumos, sąveikaujančių kiekviename iš sunkiųjų blokų, tarp buvimo ir nebuvimo. Taigi kūrinys peržengia minimalizmo ribas, viena vertus, išlaikydamas ekspresyvų menininko nebuvimą, kita vertus, gilindamasis prasmės dvilypumus, suteikiančius kūriniui gebėjimą savyje talpinti psichologijos, minties ar sudėtingų kultūrinių nuorodų elementus.

“Emptiness is actually a state within. [...] feel that am returning to the idea of a narrative without a narrative, to what allows us to directly introduce psychology, fear, death, and love. This emptiness is not something unspoken. It is a potential space, not a non-space.” 7

The artwork attempts to create tension between the mass and emptiness, interacting within each of the heavy blocks, between existence and non-existence. Thus, the artwork transcends the boundaries of minimalism, on one hand maintaining the artist’s expressive absence, and on the other hand delving into the ambiguities of meaning, providing the artwork with the ability to contain elements of psychology, thought, or complex cultural references within itself.

“Tai potenciali erdvė, o ne ne erdvė.” 8

“It is a potential space, not a non-space.” 8

Projektas, semiasi energijos iš nematerialaus, nesugriaunamo Kultūros paveldo ir senovinių Bchaaleh alyvmedžių, medžių, kurie pasiekę savo mirties amžių, ilsisi uosto didžiulių kamienų įdubose. Gyvena ir siekia gyventi kartu reikalaudami teisės tylą.

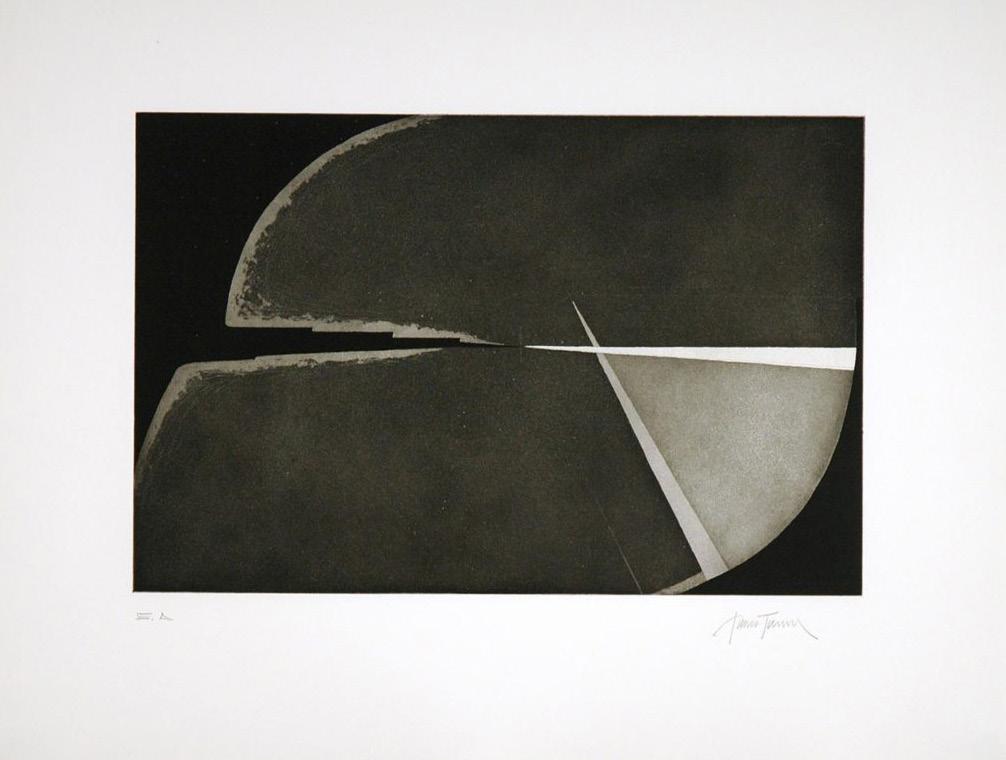

Užmezgant dialogą tarp kelių skirtingų epochų ir disciplinų, kūrinio dizainas buvo pagrįstas Etelio Adnano eilėraščiu, taip pat Paulo Virilio antiformomis, pakabintomis priešais šešiolikos senovinių Libano medžių seriją.

The project draws energy from the immaterial, indestructible Cultural Heritage and ancient Bchaaleh olive trees, trees that have reached their age of death and fnd rest in the hollows of massive stones by the port. They live and seek to coexist, demanding the right to silence.

By engaging in a dialogue between diferent epochs and disciplines, the design of the artwork was inspired by Etel Adnan’s poetry as well as the antiforms of Paul Virilio, displayed in front of a series of sixteen ancient Lebanese trees.

Garsai (kaip ir kiti nematerialūs objektai), yra neatsiejami nuo erdvės funkcijos ir patirties, todėl turi būti kruopščiai apgalvoti ir suprojektuoti, kaip ir bet kuris fzinis komponentas. Atsižvelgiant erdvės komponentus, galima sukurti aplinką, kuri būtų ne tik funkcionali, bet kūniškai prasminga bei emociškai rezonuojanti

Sounds (like other immaterial objects) are inseparable from the function and experience of space, so they need to be carefully considered and designed, just like any physical component. By taking into account the components of space, it is possible to create an environment that is not only functional but also physically meaningful and emotionally resonant.

Marco Barotti projektas MOSS yra kompleksiškas technologijų, meno ir gamtos sankirtos tyrinėjimas. Projektas susideda iš garso instaliacijos, renkant duomenis iš samanų, jas transliuojant gyvai verčiant garsu sukuriant įtaigų ir įtraukiantį “vaizdo” garsą.

Barotti kūrybą įkvėpė idėja, kad gamtos pasaulis yra sudėtinga sistema, o žmonės gali daug išmokti ją stebėdami ir sąveikaudami su juo. Projekte kuriamas tiltas tarp natūralaus ir dirbtinio pasaulių.

Instaliacijos centre - samanos. Kiekviename jų kupste įrengti jutikliai, stebintys jų pačių augimą ir aktyvumą. Šie duomenys apdorojami kompiuteriniu algoritmu, kuris generuoja unikalų garsą, pagrįstą samanų judesiais ir elgesiu. Gautas garso takelis gražus ir užvaldantis, kaip ir sudėtingo ir dažnai paslaptingo gamtos pasaulio veikimo atspindys.

Marco Barotti’s project MOSS is a complex exploration of the intersection of technology, art, and nature. The project consists of a sound installation that collects data from moss and translates it into live-generated sound, creating an immersive and captivating “sonic” experience.

Barotti’s work is inspired by the idea that the natural world is a complex system from which humans can learn by observing and interacting with it. The project aims to bridge the gap between the natural and artifcial worlds.

At the center of the installation are the mosses themselves. Each cluster of moss is equipped with sensors that monitor their growth and activity. These data are processed by a computer algorithm that generates a unique sound based on the movements and behavior of the moss. The resulting sound composition is beautiful and mesmerizing, refecting the intricate and often mysterious workings of the natural world.

Claudia Martinho Liminal 2021Verkadefabriek Serre, Den Bosch mieste, Nyderlanduose, sukurta garsinė instaliacija, leidžianti klausytis ne tik žmogaus, bet ir kasdien nepastebimo augalų ir gyvūnų pasaulio.

Šis garso peizažas atskleidžia ritmų, tonų, dronų ir melodijų moduliaciją keliais sluoksniais: aplinkos garsų įrašai parke aplink ežerą, povandeniniai, akustiniai instrumentai ir sintezatoriai. Garso peizažas buvo sukurtas taip, kad erdviškai rezonuotų su instaliacinės erdvės architektūra, su specifniais psichoakustiniais efektais.

Įtraukiantis kūrinys kvietė praeivius sulėtėti ir pasinerti aktyvų ir išplėstinį garsų spektrą, kalbantį apie tai, kas dažnai nematoma ir negirdima. Instaliacija buvo siekiama išplėsti žmogaus suvokimo ribas įvairiais vietinių ekosistemų balsais, siekiant akustinio jautrumo ir susiliejimo su aplinka.

The Verkadefabriek Serre in the city of Den Bosch, Netherlands, featured a sound installation that allowed visitors to listen not only to the human world but also to the often unnoticed world of plants and animals.

This sonic landscape revealed the modulation of rhythms, tones, drones, and melodies across multiple layers: recordings of environmental sounds in the park surrounding the lake, underwater sounds, acoustic instruments, and synthesizers. The sound landscape was designed to resonate spatially with the architecture of the installation space, incorporating specifc psychoacoustic efects.

This immersive artwork invited passersby to slow down and immerse themselves in an active and expanded spectrum of sounds, revealing what is often unseen and unheard. The installation aimed to expand the boundaries of human perception through the voices of local ecosystems, seeking acoustic sensitivity and merging with the environment.

„Antiform“, kūrinys, įkvėptas Paulo Virilio koncepcijos, primena dangų ir erdvės, antigravitacijos ir pakilimo idėją. Prisimename Virilio žodžius: „kur yra jaučiamas objektas, būtybė ar daiktas, erdvės nebėra, mes iš jos atimame tūrį, tuo pačiu veiksmu suteikiame jai formą: Antiformą“. Kaip ir bunkeriai praradę funkcija, išsivadavę iš esamų šablonų tampa neformalūs ir abstraktūs.

‘Antiform’, a piece inspired by Paul Virilio’s concept, evokes the sky and the idea of expanse, anti-gravity, and elevation. We remember Virilio’s words: “where there is a sentient object, being or thing, the space is no more, we take away a volume from it, by this very act we give it a shape: the Antiform.” Like bunkers that have lost their function, they become informal and abstract when freed from existing templates.

P. Virilio - kultūros teoretikas, architektas ir meno flosofas, dokumentavęs ir tyrinėjęs apleistus Antrojo pasaulinio karo nacistinės Vokietijos bunkerius Prancūzijos pakrantėje. Jų karybos pobūdį, geopolitinę padėtį ir estetinę vertę šiuolaikinėje to meto perspektyvoje. Daugelių atvejų bunkeris, pasak Virilio, yra XX amžiaus simbolis.

Bunkeris - nėra objektas, tai sąvoka, su kuria jis siejamas ir simbolizuojamas. Tai erdvė ir laikas, kuriame jis buvo pastatytas. Jungianti praeitį, dabartį ir ateitį. Pėdsakas kraštovaizdyje ir atmintyje, laukiantis laiko “kol galėsime iš naujo apsvarstyti šiuos karinius paminklus” 9

Tai “sunki pilka masė” 10, kuri “tapo mitu, esamu ir nesamu vienu metu. Esančiu kaip pasibjaurėjimo objektas, vietoje skaidrios ir atviros civilinės architektūros. Nesamu kaip naujosios tvirtovės esmė, po kojomis, nematoma mums. (...) Apleistas ant pamario smėlio kaip išnykusios rūšies oda.“ 11

Pro ventiliacijos angas ir netikėtus praėjimus, prasiskverbiantys saulės spinduliai ir žvilgsnis horizontąvienintelis sąlytis su išore, kuriantis fenomenalią patirtį ir viltį geresniam rytojui.

P. Virilio is a cultural theorist, architect, and philosopher of art who documented and studied the abandoned Nazi bunkers along the coast of France that were built during the Second World War. The nature of their warfare, geopolitical and aesthetic value in the modern perspective of that time. In many cases, the bunker, according to Virilio, is a symbol of the 20th century.

A bunker is not just an object, but a concept that it is associated with and symbolizes. It is an environment and a time in which it was constructed. Connecting the past, present, and future. A trace in the landscape and memory, waiting until “we are able to consider to anew these military monuments.” 9

It is a "heavy gray mass" 10 that “has become a myth, present and absent at the same time: present as an object of disgust instead of a transparent and open civilian architecture, absent insofar as the essence of the new fortress is elsewhere, underfoot, invisible from here on in. (…) Abandoned on the sand of the littoral like the skin of a species that has disappeared.” 11

Through the ventilation shafts and unexpected passages, the sunlight penetrates the bunker, and a glimpse into the horizon - the only contact with the outside world. Creating a phenomenal experience, and hope for a better tomorrow.

The Architecture of Ruins: Designs on the Past, Present and Future

„Architektūros ir kraštovaizdžio, gamtos ir kultūros hibridas, griuvėsiai reprezentuoja tai, kas nebaigta, ir tai, kas nepadaryta, tiek augimas, tiek nykimas, potencialas ir praradimas, ateitis, ir praeitis.“ 12

Griuvėsiai architektūroje yra daugiau, o ne mažiau. Dėl jau esamo santykio su tautiniu tapatumu, kultūra, gamta ir kt. Jie lyg statybos aikštelė - pilna potencialo, kurioje nėra aiškios funkcijos ar reikšmės. Tai skirtingų kontekstų kompozicija, kuri niekada nebus galutinė. Tačiau turinti atviras galimybes pritaikymui, išradimams ir kūrybai, tiesiogine prasme ir vaizduotėje.

Juose jau egzistuojantys, užmegzti simbioziniai ryšiai su nuolat besikeičiančiais gamtos ir visuomenės kontekstais. Architektūra natūralizavusi su kraštovaizdžiu - sužmogina gamtą, leidžia ją geriau suprasti, patirti ir pažinti. Ilgainiui tapdama nedalomų darinių, palengvinto lėto irimo, transformacijos procesų dalimi.

„Kaip istorinio mąstymo ir jo diskurso su atmintimi alegorija, dialogas tarp paminklo ir griuvėsių yra vis aktualesnis ir būtinas dvidešimt pirmojo amžiaus visuomenėje, kuri turi mokėti prisiminti ir prisiminti, kaip pamiršti.” 13

“A hybrid of architecture and landscape and nature and culture, the ruin represents the unfnished as well as the undone, growth as well as decay, potential as well as loss, and the future as well as the past.” 12

Ruins in architecture, are more, not less. Due to the already existing relationship with national identity, culture, nature, etc. They are like a construction site full of potential with no clear function or meaning. It is a composition of diferent contexts that will never be terminal. Therefore with the possibilities open to adaptation, invention and creativity, literally and imaginatively.

They establish symbiotic relationships with the ever-changing contexts of nature and society. Architecture naturalized with the landscapehumanizes nature, allowing it to be better understood, experienced and known. Eventually becoming indivisible formations, facilitating the process of slow decay and transformation.

“As an allegory of historical thinking and its discourse with memory, the dialogue between a monument and a ruin is evermore poignant and necessary in a twenty-frst-century society that needs to know how to remember and remember how to forget.” 13

Šis projektas jungia Naujosios Olandijos vandens ir karinės gynybos, naudotos nuo 1815 m. iki 1940 m., apsaugančios miestus nuo tyčinių potvynių, linijas. Iš pažiūros nesunaikinamas ir nepajudinamas, paminklo statusą turintis bunkeris yra atveriamas. Jis padalinamas per pusę mediniu lentų taku, vedančių apsemtą zoną ir gretimo gamtos rezervato pėsčiųjų taką. Tokiu būdu dizainas leidžia pažvelgti paprastai fziškai nesuvokiamo bunkerio vidų. Juntamas bunkerio “svoris” ir jo kuriama atskirtis nuo išorinio pasaulio. Šiuo projektu buvo kvestionuojama Nyderlandų paveldo politika, keičiant suvokimą apie karinės inžinerijos struktūras.

RAAAF 599

Tai vienas iš daugelio bunkerių esančių prie Naujosios Olandijos vandens linijos. Įtvirtinimas yra įtrauktas į Nyderlandų paveldo registrą, todėl architektai gerbdami jo istorinę ir kultūrinę vertę, naują funkciją, atostogų namai, organizavo siekdami minimalios intervencijos. Grubi ir sunki bunkerio estetika kontrastuoja su naujai projektuojamais mediniais baldais, kurie gražina dalelę gamtos. Šalia įtvirtinimo - terasa, kurios perimetras toks pat kaip ir išorinių bunkerio sienų, siekiant pabrėžti kiek ploto prarandama dėl monolitinių betono sienų.

This is one of the many bunkers located along the New Holland Water Line. The fortifcation is included in the Dutch heritage register, so architects, respecting its historical and cultural value, organized a new function for it as a holiday home, aiming for minimal intervention. The rugged and heavy aesthetics of the bunker contrast with newly designed wooden furniture, which brings a touch of nature. Adjacent to the fortifcation is a terrace, with a perimeter matching that of the external bunker walls, emphasizing the amount of space lost due to the monolithic concrete walls. B-ILD architects

CMK - architects Botos Collection

Pirminė pastato funkcija - bombų slėptuvė, įrengta nacistinėje Vokietijoje 1943 m. Bunkeris, su dviejų metrų storio sienomis, pastatytas siekiant apsaugoti iki trijų tūkstančių civilių. Vėliau SSRS naudotas kaip karo belaisvių stovykla, tekstilės ir atogrąžų vaisių saugykla, o vėliau ir kaip techno klubas. Šiuo metu II pasaulinio karo bunkeris - privatus šiuolaikinio meno muziejus, priklausantis kolekcionieriams Karen ir Christian Boros.

Naujai kuriama funkcija nesistengta paslėpti pastato ilgametės istorijos. Priešingai, palikta apleista ir gamtos veikiama, pakitusi erdvė jungiama su minimalia intervencija, kuri buvo reikalinga pastatą pritaikant muziejaus funkcijai. Todėl išsaugomi ilgametę bunkerio istoriją menantys bruožai: kulkų skylės fasade, užrašai ant sienų, telefonspynės, netolygūs sienoje suformuoti įėjimai, skirti įvežamoms prekėms ir net kažkada bunkerį užėmusios trumpalaikės reivo scenos likučiai.

This project brings together the New Holland Water Line, a series of military defense lines used from 1815 to 1940 to protect cities from artillery foods. Despite its seemingly indestructible and immovable appearance, this bunker, which holds monument status, is actually accessible. It is divided in half by a wooden plank pathway that leads into the covered area and connects to the adjacent nature reserve walking trail. This design allows visitors to glimpse into the typically physically inaccessible interior of the bunker. The “weight” of the bunker and its sense of separation from the outside world is palpable. With this project, the heritage policy of the Netherlands was challenged, altering perceptions of military engineering structures.

The primary function of the building was as a bomb shelter, built in Nazi Germany in 1943. The bunker, with its two-meter-thick walls, was designed to protect up to three thousand civilians. It was later used by the Soviet Union as a prisoner-of-war camp, a textile and tropical fruit storage facility, and eventually as a techno club. Currently, the World War II bunker has been transformed into a private contemporary art museum belonging to collectors Karen and Christian Boros.

The newly created function does not attempt to hide the building’s long history. On the contrary, it is left abandoned and infuenced by nature, connecting the transformed space with minimal intervention required for adapting the building to its museum function. Therefore, characteristic features that evoke the bunker’s history are preserved, such as bullet holes on the facade, inscriptions on the walls, telephone switches, uneven entrances in the walls for the transportation of goods, and even remnants of short-lived rave scenes that once occupied the bunker.

Terminai “objektas’ ir “subjektas” kartais naudojami apibendrinant santykį tarp stebėtojo ir stebimojo.

Objektu gali tapti viskas, pastatas, skulptūra ar kraštovaizdis. Tai matomas ir patiriamas kūnas.

Subjektas, tai objekto stebėtojas ir tyrinėtojas.

Abjekto sąvoka naudojama apibūdinti nepatogumo, šleikštulio ir atskirties jausmą.

The terms “object” and “subject” are sometimes used to generalize the relationship between the observer and the observed.

An object can be anything, a building, a sculpture, or a landscape. It is a visible and experiential entity.

The subject is the observer and explorer of the object.

The concept of the abject is used to describe feelings of discomfort, unease, and alienation.

Julia Kristeva Powers of Horror

An Essay on Abjection 1982

Kristeva teigia, kad abjekto patyrimas yra esminis žmogaus subjektyvumo aspektas, jis apima susidūrimą su tais dalykais, kurie mūsų manymu, kelia pyktį ar grėsmę savojo “aš” supratimui. Mūsų baimė ir pasibjaurėjimas abjektu, yra susiję su noru išlaikyti gamtos pasaulio ir savo kūno funkcijų kontrolę, kuri prieštarauja natūraliam pasaulio ir žmonių kismui. Abjektas primena apie mūsų materialumą ir pažeidžiamumą, atveria suvokimui, kad mūsų tapatybė nuolat kinta ir gali keistis.

14. p. 4

Pritariant abjektui ir pripažįstant savo ryšį su gamta, galima patirti išlaisvinimą, nes tai leidžia sugriauti tvirtas kategorijas ir ribas, susisiekti su kitais žmonėmis sklandžiai ir įtraukiau. Ji rašo:

15. p. 5

„Priimti abjektą reiškia, tiesiogiai susidurti su tuo, kas yra kitoks, išorinis, svetimas, ne vietinis“. 14

Susiduriant su abjektais gamtoje, pagal savo moralinius įsitikinimus ir vertybes, mes keliam klausimą sau, ar objektai svetimi mums, mūsų istorijai, svetimi teritorijai ar pačiai gamtai?

„Abjektas reprezentuoja tai, kas traumuoja, ko neįmanoma įsisavinti, kas yra išstumta iš mūsų ir socialinės santvarkos, bet taip pat ir tai, kas grasina sugrįžti ir tą tvarką suardyti“ 15

Kristeva argues that the experience of the abject is an essential aspect of human subjectivity, encompassing our encounter with those things that, in our perception, arouse anger or threaten our sense of self. Our fear and disgust of the abject are related to the desire to maintain control over the functions of the natural world and our bodies, which contradicts the natural order and human confict. The abject reminds us of our materiality and vulnerability, opening up the realization that our identity is constantly changing and can be altered.

By accepting the abject and acknowledging our connection to nature, we can experience liberation, as it allows us to break down rigid categories and boundaries, communicate with others smoothly and inclusively. She writes,

“To accept the abject is to confront directly that which is diferent, external, foreign, and non-local.” 14

In confronting abjects in nature, according to our moral beliefs and values, we ask ourselves whether objects are foreign to us, our history, foreign territory, or nature itself.

“The abject represents that which is traumatic, that which cannot be assimilated, that which is expelled from us and from social order, but also that which frightens us with the prospect of returning and disrupting that order.” 15

Marija Teresė Rožanskaitė, painting “The Wound” (1984-1987)

Primityvi fzinė erdvė - namai, ir jos dizainas, naudojami norint suprasti, žmogus egzistavimo pasaulyje ir jo supančios aplinkos santykyje su visata, kolektyvine sąmone ir pačiu savimi. O tam tikri dizaino elementai sukelia stiprias emocijas ir sujungdami žmogų su gilesnėmis jų pačių vaizduotės dalimis.

Bachelardo namų objektai yra kupini emocinės patirties. Atidaryta spintelė – tai atskleistas pasaulis, stalčiai –paslapčių vietos, o kiekvienu įprastu veiksmu atveriame begalines savo egzistencijos dimensijas.

“Stalčių, skrynių, užraktų, spintų tema - neišmatuojamas intymumo apmąstymų rezervas. […] Jie - sudėtingi objektai, objektaisubjektai. Kaip mes, per mus ir mums jie turi savąjį intymumą.” 16

Šie baldai tampa saugykla, žmogaus vaizduotei ir intymumui, tarp objekto ir žmogaus, kuri gali būti suprantamas tik jiems. Kadangi, kas “slapta žmoguje ir slapta daiktuose kyla toje pačioje toje pačioje topoanalizėje.”

17 Todėl, tai ką mato ir įsivaizduoja vienas, to negali suprasti kitas, nes tik “dvi uždaros būtybės bendrauja tuo pačiu simboliu.” 18

The primitive physical space of a house and its design are used to understand human existence in the world and its relationship with the universe, collective consciousness, and self. Certain design elements evoke strong emotions and connect individuals with deeper parts of their own imagination.

According to Bachelard, objects in the home are full of emotional experiences. An open shelf reveals a world, drawers are places of secrets, and through ordinary actions, we open up infnite dimensions of our existence.

"The topic of drawers, chests, locks, cabinets - an immeasurable reserve of thoughtfulness. […] They are complex objects, objects-subjects. Like us, through us and to them, they have their own intimacy.” 16

These pieces of furniture become a repository for human imagination and receptivity, between an object and a person that can only be understood by them. Because what is "secret in man and secret in things arises in that specialist topoanalysis". 17 Therefore, what one sees and imagines, cannot understand the other, because only "two closed beings communicate with the same symbol". 18

The Poetics of Space

Tema antrasis kūnas, sujungia visus anksčiau minėtus kūrinius, keičia žmogaus, kaip stebėtojo perspektyvą žmogaus, kaip dalyvio.

The theme of the second body, which unites all the previously mentioned works, changes the perspective of man as an observer to man as a participant.

Pūvantys gyvūnų kūnai Rotting animal carcasses

Apleisti ar griūvantys pastatai | Abandoned or decaying buildings

Šiukšlės, kurias palieka žmonės Trash and litter left behind by humans

Vabzdžiai, nešiojantys užkratą ar ligas | Insects, those that are perceived as pests or disease carriers

Teršalai, chemikalai ar atliekos miške | Pollution, such as chemicals or waste dumped in the forest

Negyvi medžiai ar šakos, jų pūviniai Dead trees or branches that have fallen and are decaying Gyvūnų išmatos | Animal feces

Abjektas

Gilles Clément Manifesto of the Third Landscape

Trečiasis kraštovaizdis - tai tarpinė erdvė tarp šviesos ir šešėlio, intersticinis peizažas. Tai likusi dalis, atskirta nuo niekada neeksploatuotų ir nuo saugomų žmogaus veiklos erdvių. Tai dykvietė, kupina simbolinės vertės, bet apleista ir neišnaudota. Joje aiškiai išryškėja erdvės įtraukimo ir išnaudojimo trūkumai, tačiau tuo pačiu tai yra erdvė, kuri tapo prieglobsčiu gamtos įvairovei ir regeneracijai. Trečiasis kraštovaizdis neigia prielaidą, jog natūralu yra tik tai, kas nėra žmogaus veikla. Vietoj to, jis prasideda įsitikinimu, jog reikia veikti kartu su gamta, o ne prieš ją.

The third landscape is an intermediate space between light and shadow, an interstitial landscape. It is the remaining part separated from never exploited and protected areas of human activity. It is a wilderness full of symbolic value, yet abandoned and unused. It clearly reveals the shortcomings of space inclusion and exploitation, but at the same time, it has become a refuge for nature’s diversity and regeneration. The third landscape denies the assumption that only what is untouched by human activity is natural. Instead, it begins with the belief that we need to act in harmony with nature rather than against it.

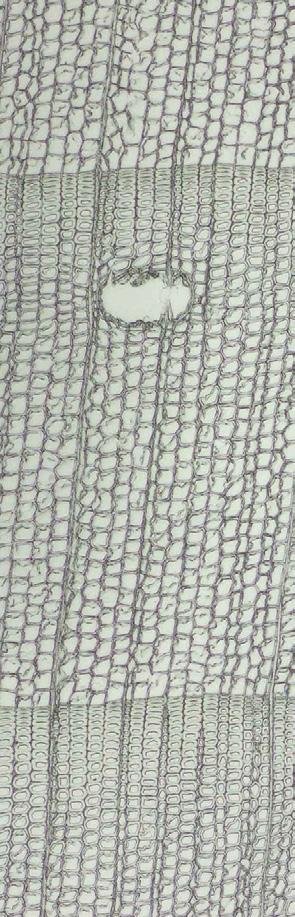

Porėtų ląstelių struktūra lemia, kad molekulinė sąveika tarp organizmų, supančios aplinkos, įskaitant orą, kuriuo kvėpuojame, ir maistą, kurį valgome, vyksta nuolatos. Tokiu būdu, ribos tarp kūnų, aplinkos tampa neaiškios, neapibrėžtos.

Hildyard teigimu, žmonės turėtų suprasti kūnus ne kaip atskirus subjektus, o kaip didžios ekosistemos dalį. Ši perspektyva padeda geriau suvokti žmogaus veiklos poveikį gamtos pasauliui.

The structure of porous cells determines that the molecular interaction between organisms and the surrounding environment, including the air we breathe and the food we consume, is constantly occurring. In this way, the boundaries between bodies and the environment become unclear and undefned.

According to Hildyard, people should perceive their bodies not as separate entities but as part of a vast ecosystem. This perspective helps to better understand the impact of human activities on the natural world.

Cambio

Projekte Formafantasma menininkai tiria medienos valdymo pramonę ir jos galimybes keisti ir pagerinti medienos valdymo praktikas.

Projekto tikslas pabrėžti medienos kaip gyvybingo ir ilgaamžio produkto vaidmenį, kurio panaudojimo ciklas yra nuolat keičiamas ir tobulinamas. Atkreipti dėmesį medienos prieinamumą ir jos reikšmę ekonomikai, aplinkai ir kultūrai.

Formafantasma įtraukė skirtingus medienos valdymo praktikos aspektus, įskaitant medienos gamybą, medienos pramonę ir medienos naudojimo procesus. Atlikti tyrimai apėmė skirtingas medienos rūšis ir panaudojimo galimybes, ieškant atsakymo valdant medienos išteklius ir atliekų kiekį.

,,Cambio” projektas pabrėžia svarbą keičiant esamas medienos valdymo praktikas, kuriant tvarų ir jautrų aplinkai gyvenimo būdą.

In their project “Formafantasma,” the artists explore the timber industry and its potential to change and improve timber management practices.

The goal of the project is to emphasize the role of timber as a sustainable and long-lasting product, with a constantly evolving and improving utilization cycle. It aims to draw attention to the accessibility of timber and its signifcance to the economy, the environment, and culture.

Formafantasma incorporates various aspects of timber management practices, including timber production, the timber industry, and the processes of timber utilization. The research conducted encompasses diferent types of timber and their potential uses, seeking solutions for managing timber resources and waste.

The “Cambio” project highlights the importance of transforming existing timber management practices and creating a sustainable and environmentally conscious way of life.

„... norint išlikti su problema, reikia išmokti būti iš tikrųjų dabartyje, o ne kaip nykstančiu tašku tarp baisios ar edeniškos praeities ir apokaliptinės ar išganingos ateities, bet kaip mirtingiems gyvūnams, susipynusiems daugybę nebaigtų vietų, laikų, dalykų, prasmių konfgūracijų.” 19

Knygos tikslas - paskatinti skaitytoją išeiti už tradicinių vakarietiškų mąstymo apie gamtą ribų ir atpažinti visų gyvų organizmų tarpusavio ryšius. Haraway teigia, kad turime atsiriboti nuo žmogų orientuotų perspektyvų ir pripažinti nežmogiškų būtybių, tokių kaip gyvūnai, augalai ir mikroorganizmai svarbą ir savarankiškumą.

Knygos pavadinimas “Staying with the Trouble” reiškia mintį, kad negalime tiesiog nusigręžti nuo problemų, su kuriomis susiduria pasaulis, ir tikėtis, kad jos išnyks savaime. Vietoj to turime aktyviai įsitraukti sudėtingą ir dažnai netvarkingą pasaulio realybę kuriant tvaresnius ir empatiškesnius gyvenimo būdus.

Išbūti su problema reikalauja priimti dviprasmiškumą ir neapibrėžtumą, pripažinti, kad nėra lengvų atsakymų ar greitų sprendimų, priimti, jog pažanga dažnai yra lėta. Suprasti, kad daugelis mūsų problemų yra giluminio pobūdžio ir kad vienos problemos sprendimas dažnai reikalauja kovos su kitomis.

“To stay with the trouble, one must learn to be truly present, not as a vanishingly small point between a dreadful or Edenic past and apocalyptic or salvifc futures, but as mortal critters entwined in myriad unfnished confgurations of places, times, matters, meanings.” 19

The aim of the book is to encourage the reader to go beyond traditional Western thinking about nature and recognize the interconnections among all living organisms. Haraway argues that we need to move away from human-centered perspectives and acknowledge the importance and autonomy of non-human beings, such as animals, plants, and microorganisms.

The title of the book, “Staying with the Trouble,” conveys the idea that we cannot simply turn away from the problems that the world is facing and hope that they will disappear on their own. Instead, we must actively engage with the complex and often messy reality of the world, creating more sustainable and empathetic ways of living.

Staying with the trouble requires embracing ambiguity and uncertainty, acknowledging that there are no easy answers or quick solutions, and accepting that progress is often slow. It means understanding that many of our problems are deeply rooted and that solving one problem often requires confronting others.

“Tai prasideda nuo įsitikinimo, kad visas natūralizmas yra iš tikrųjų humanizmas.”

“It begins, with conviction that all naturalism is really humanism”

Kuršių nerija ir Baltijos pakrantės lyguma – atskiras geografnis rajonas su savitomis geomorfologinėmis ir klimatinėmis sąlygomis. Stiprūs vėjai, pustymas, sausi ir greitai įkaistantys nederlingi dirvožemiai, druskingas vanduo, staigios ir dažnos oro permainos lemia nerijos augalijos išskirtinumą. Kuršių nerijos kraštovaizdis projekte tampa gamtos ir žmogaus sąveikos modeliu, kurio istorija glaudžiai susijusi su nerijos atsiradimu ir praeitimi.

The Curonian Spit and the Baltic Sea coastal plain are a distinct geographical region with unique geomorphological and climatic conditions. Strong winds, dunes, dry and quickly heating infertile soils, brackish water, and sudden and frequent weather changes contribute to the exceptional vegetation of the Spit. The landscape of the Curonian Spit becomes a model of the interaction between nature and humans, closely linked to the emergence and history of the Spit.

Baltijos jūros bangos ir srovės gabeno didžiules smėlio mases nuo ardomų pusiasalio krantų, iš kurių formavosi įvairios povandeninio reljefo formos, kurios pakitus jūros lygiui, išniro iš vandens.

Parabolinių kopų formavimosi metu vėjas buvo sąlyginai nestiprus, o didelis kiekis kritulių sudarė puikias sąlygas augalijos plitimui. Per keletą XVIII amžiaus dešimtmečių vėjas išpustė vakarinę pusiasalio dalį ir sunešė kopas link rytinio pusiasalio pakraščio. Šios kopos tapo svarbia apsauginės funkcijos dalimi, kuri padėjo apsaugoti Kuršių neriją nuo jūros audrų ir kitų gamtos reiškinių. Vėliau nuniokotus plotus siekta apželdinti ir atkurti apsauginę funkciją. Pradėti vykdyti krantotvarkos darbai.

The waves and currents of the Baltic Sea brought enormous amounts of sand from the eroded shores of the peninsula, forming various forms of submarine relief, which emerged from the water as the sea level changed.

During the formation of parabolic dunes, the wind was relatively weak, and a large amount of precipitation provided excellent conditions for the spread of vegetation. Over several decades in the 18th century, the wind blew away the western part of the peninsula and carried the dunes towards the eastern coast of the peninsula. These dunes became an important part of the protective function, helping to safeguard the Curonian Spit from sea storms and other natural phenomena. Later, eforts were made to aforest and restore the protective function of the devastated areas, and coastal management works were initiated.

Nerijos kraštovaizdis itin nukentėjo Pirmojo ir Antrojo pasaulinio karo metais.

Karo metais kasant apkasų tranšėjas, įrengiant žemines ar kitokius karinius įtvirtinimus buvo sunaikinti ir iškirsti didžiuliai miško plotai bei išardyta apie trečdalis apsauginio kopagūbrio ruožo pylimo, dar labiau suaktyvėjo smėlio pustymas. 1949 m. Lietuvoje organizuota Miškų ūkio ministerijos ekspedicija konstatavo, kad Kuršių nerijoje yra daugiau kaip 500 ha išdegusių želdinių, 800-900 ha beržynų užpulti miško kenkėjų ir daugiau kaip 2000 ha neapželdintų smėlynų. Dėl to, po Antrojo Pasaulinio karo keitėsi nerijos miškų rūšinė sudėtis. “Tuo metu medynuose didžiausią dalį sudarė kalninės pušys (44%), o maždaug po 17% buvo paprastųjų pušų ir beržų. Šiuo metu nerijos miškuose vyrauja paprastosios pušys (53%), o kalninių pušų sumažėjo iki 27%. Beržų skaičius pasikeitė nežymiai. Dabar jie sudaro 15% visų medynų.” 20

Žala buvo padaryta ne tik kraštovaizdžiui, bet ir visoms gyvenančioms rūšims nerijoje. Prieš Antrąjį pasaulinį karą Kuršių nerijoje buvo virš 200 šių stambių žinduolių. Po karo jų beveik neliko. Todėl pirmaisiais pokario metais kopose buvo galima aptikti tik baltas jų kaukoles. Dauguma Kuršių nerijos gyvenviečių buvo nuniokotos. Civilių gyventojų beveik neliko, išskyrus pavienius Kuršių nerijos senbuvius, kurie įsikūrė atokiose vietose - kopose ar miškuose. 1945 m. rugsėjo mėnesį „Valstiečių laikraštyje“ rašytojas Danas Pumputis dalinosi įspūdžiais iš kelionės į Pervalką: „Po kojų skundžiasi baltas smėlis – apkasai, spygliuotos vielos, mediniai bunkeriai... “. 21

Dabar Kuršių nerijos kraštovaizdis yra atsinaujinęs, nors iki šiol galima matyti sprogimų duobių ar rasti išmėtytas šovinių skeveldras visoje Neringoje. Fortifkacijos įtvirtinimai per daugiau nei 70 metų yra susitapatinę su gamta. Įtvirtinimai apaugę samanomis, medžiais ir kt. Juose galima rasti nemažai žiemojančių vabzdžių ir kitų rūšių. Todėl galima teigti, jog tokių statinių griovimas ir buvusio kraštovaizdžio atkūrimas padarytų tik didesnę žalą kraštovaizdžiui, gamtai, gyvūnams ir kt.

The landscape of the Curonian Spit sufered greatly during the First and Second World Wars.

During the wars, extensive forest areas were destroyed and cleared when digging trenches and constructing underground or other military fortifcations. Around one-third of the protective sand dune strip was dismantled, exacerbating the process of sand drifting. In 1949, an expedition organized by the Ministry of Forestry of Lithuania reported over 500 hectares of burned-out forests, 800-900 hectares of birch stands attacked by forest pests, and over 2000 hectares of unforested sandy areas in the Curonian Spit. As a result, the species composition of the forests in the Spit changed after the Second World War. “At that time, Scots pine dominated the forests (44%), while common pine and birch each accounted for approximately 17%. Currently, common pine dominates the Curonian Spit forests (53%), while the presence of Scots pine has decreased to 27%. The number of birch trees has changed insignifcantly and now represents 15% of all forest stands.” 20

The damage was not only inficted on the landscape but also on all the species inhabiting the Curonian Spit. Prior to World War II, there were over 200 of these large mammals in the area, but after the war, they were nearly extinct. Therefore, in the early post-war years, it was only possible to fnd their white skeletons in the dunes. Most of the settlements in the Curonian Spit were destroyed, and there were hardly any civilian inhabitants left, except for a few elderly residents who settled in remote areas such as the dunes or forests. In September 1945, the writer Danas Pumputis shared his impressions from a trip to Pervalka in the “Valstiečių laikraštis”: “White sand complains underfoot - trenches, barbed wire, wooden bunkers...”. 21

Nowadays, the landscape of the Curonian Spit has rejuvenated, although traces of explosion craters can still be seen, and scattered shell fragments can be found throughout the Neringa region. The fortifcation structures have become intertwined with nature over the course of more than 70 years. The fortifcations are covered with sand, vegetation, and other elements. They provide habitats for overwintering insects and various species. Therefore, it can be argued that the removal of such structures and the restoration of the former landscape would only cause greater harm to the landscape, nature, animals, and others.

bunkeriais Vakarų Europoje“, 2020 m.

21. Dikšaitė, L., Grigaitis, Ž., Juškevičienė, D., Piekienė, N., Žemaitienė, G., 2021, Didžiojo kopagūbrio kraštovaizdžio kaita ir apsauga grobšto gamtiniame rezervate ir parnidžio kraštovaizdžio draustinyje, Kuršių nerijos nacionalinio parko direkcija.

21. Dikšaitė, L., Grigaitis, Ž., Juškevičienė, D., Piekienė, N., Žemaitienė, G., 2021, Landscape change and protection of the Great Dune Ridge in the Grobsta nature reserve and Parnidis landscape reserve, Curonian Spit National Park Directorate.

XVII a. Kuršių Neriją dengia miškai.

XVII century. |The Curonian Spit is covered by forests.

1800 m. Pradedami kopų sutvirtinimo darbai.

1800 Dune reinforcement works are starting.

1939 m. Kovo 22 d. | Klaipėdos kraštas atitenka nacistinei Vokietijai.

In 1939, March 22nd Klaipėda region belongs to Nazi Germany.

1939 m. Kovo 24 d. | Klaipėda gauna tvirtovės statusą.

In 1939, March 24th Klaipėda gets the status of a fortress.

1939 m. Balandis Pradėtos statyti Mėmelio artilerijos baterijos etapas.

in 1939, April Construction of Memelis artillery battery phase started.

1939 m. Birželis Plataus masto pratybos.

in 1939, June Extensive exercises.

1942 m. Baigtos statyti visos numatytos artilerijos baterijos.

In 1942 All planned artillery batteries have been completed.

1944 m. Spalis SSRS pradeda puolimą Klaipėdos krašte.

In 1944, October USSR starts ofensive in Klaipėda region.

1945 m. Sausio 25 d. | Klaipėdos kraštas okupuotas SSRS.

In 1945, January 25th The Klaipėda region was occupied by the USSR.

1949 m. Lietuvoje organizuota miško - melioracinė ekspedicija.

In 1949 Forest reclamation expedition organized in Lithuania.

1951 - 1955 m. Pokaryje vykdyti sutvirtinimo darbai.

1951 - 1955 Reinforcement works were carried out after the war.

1955 m. Baterijų veikla sustabdyta.

In 1955 Battery operation stopped.

2000 m. Įkuriamas Kuršių Nerijos nacionalinis parkas.

In 2000 The Curonian Spit National Park is established.

2002 m. Pajūrio regiono parko iniciatyva dalinai sutvarkytas vienas artilerijos blokas.

In 2002 On the initiative of the coastal region park, one artillery block was partially repaired.

2006 m. Gaisras Smiltynėje.

In 2006 Fire in Smiltyne.

2009 m. Pradėtos kaupti relikvijos, atidarytas fortifkacijos muziejus Klaipėdoje.

In 2009 Relics began to be collected, the fortifcation museum was opened in Klaipėda.

2020 m. Rugsėjo 18 d. Kompleksas perduotas Kuršių nerijos parko direkcijai.

In 2020, September 18 The complex was handed over to the Curonian Spit Park Directorate.

2021 m. Pradėti tyrinėjimo darbai, atliktas vidaus lazerinis skenavimas.

In 2021 Exploration work has started, interior laser scanning has been carried out.

2022 m. Atidaryta laikina Rodion Petrov šviesų instaliacija „Grįžtamasis ryšys“.

In 2022 | Rodion Petrov‘s temporary light installation „The Return Connection“ has been opened.

Alksnynės gynybinis kompleksas (vok. Schweinsrücken) yra vienas iš šešių gynybinių įtvirtinimų, nacistinės Vokietijos pastatytų per II pasaulinį karą tarp 1939 - 1945 metų, siekiant apsaugoti Klaipėdos (tuo metu Memelio) miestą nuo priešininkų laivų ir lėktuvų atakų.

Komplekso teritorijoje yra išlikę penki betoniniai įtvirtinimai, apkasų tranšėjos, dvi nenustatyto kalibro pabūklų platformos, sprogimų išmuštos duobės bei iki šiol įvairiose vietose randamų sviedinių skeveldrų, šovinių ir gilzių.

Karo metu pabūklų ir šaudmenų transportavimui buvo naudojama nerijos miškų želdintojų nutiesta siaurojo geležinkelio trasa, jungusi Alksnynės bateriją su kitomis ant kopų įrengtomis laikinomis baterijomis. Šie įtvirtinimai yra vieni unikalesnių pavyzdžių vokiečių fortifkacijos istorijoje. Pagal savo originalią funkciją įtvirtinimai buvo naudojami iki 1955 metų.

The Alksnynė defensive complex (German: Schweinsrücken) is one of the six defensive fortifcations built by Nazi Germany during World War II between 1939 and 1945 to protect the city of Klaipėda (then called Memel) from attacks by enemy ships and aircraft.

Within the complex, there are fve remaining concrete fortifcations, trench excavations, two unidentifed caliber gun platforms, bomb craters, and various fragments of shells, bullets, and casings found in diferent locations.

During the war, the narrow-gauge railway built by the forest planters of the Spit was used for transporting guns and ammunition, connecting the Alksnynė battery with other temporary batteries installed on the dunes. These fortifcations are some of the most unique examples in the history of German fortifcations. According to their original function, the fortifcations were used until 1955 y.

Lietuvai atgavus nepriklausomybę karinius I ir II pasaulinio karo fortifkacijos įrenginius dėmesys nebuvo kreipiamas. 2005 metais kompleksas buvo įtrauktas Lietuvos kultūros paveldo sąrašą, nes buvo pripažintas vertingu architektūrai, istorijai ir kultūrai.

Tačiau jokie aplinkosauginiai ar atnaujinimo darbai nebuvo pradėti. 2020 metais kompleksas buvo perleistas Kuršių nerijos nacionalinio parko direkcijai. Atsirado informaciniai stendai šalia įtvirtinimų, bunkeriai buvo išvalyti ir paruošti pažintinėms ekskursijoms. 2022 m. rugsėjo mėn. pirmą kartą buvo atlikti Alksnynės gynybinio komplekso archeologiniai tyrinėjimai, kuriuos užsakė Kuršių nerijos nacionalinis parkas.

Tyrimus atliko archeologas dr. Klaidas Perminas. Tyrimo tikslai: nustatyti statinių būklę po žemės paviršiumi, kultūrinio sluoksnio storį, pobūdį, aptikti ir atidengti galimai po žemės paviršiumi esančius betoninius takus, rasti galimas inžinerines-architektūrines statinių dalis ir su jomis susijusius radinius (t.y. ginklus, amunicijas ar jų dalis/elementus ir pan.)

Vieta, kurioje išsidėstęs gynybinis kompleksas, yra miškingoje pakilumoje, apaugusioje daugiausiai pušimis, 200–300 m vakarus nuo Kuršių marių kranto. Tiriamų bunkerių stratigrafja panaši.

Beveik visi archeologinio tyrimo tikslai buvo pasiekti. Aptikti radiniai kultūrinį sluoksnį leidžia datuoti Antrojo pasaulinio karo metais ir sovietmečiu. Rastos gilzės rodo, kad šoviniai, naudoti komplekse veikusių Vokietijos kariuomenės karių, buvo pagaminti 1935–1940 m. įvairių šalių (Vokietijos, Italijos, Belgijos, Prancūzijos) gamyklose. Nors su kompleksu susiję radiniai didelės archeologinės ir istorinės vertės neturi, jie suteikia papildomos informacijos apie komplekso techninį-inžinerinį įrengimą, amuniciją bei karių buitį karo metais.

Šiuo metu gynybos kompleksą norima dar labiau pritaikyti naudojimui: renginiams, koncertams, ekskursijoms, stovykloms ir kita.

After regaining independence, Lithuania did not focus on the military fortifcations of World War I and II. In 2005, the complex was included in the List of Cultural Heritage of Lithuania, as it was recognized as valuable in terms of architecture, history, and culture.

However, no environmental or renovation works were initiated. In 2020, the complex was transferred to the management of the Curonian Spit National Park. Information boards were placed near the fortifcations, bunkers were cleaned and prepared for educational tours. In September 2022, archaeological research was conducted for the frst time at the Alksnynė defensive complex, commissioned by the Curonian Spit National Park. The research was conducted by archaeologist Dr. Klaidas Perminas. The research aims were to determine the condition of the structures below the ground surface, the thickness and nature of the cultural layer, to discover and uncover possible underground concrete paths, and to fnd possible engineering and architectural parts of the structures and related artifacts (such as weapons, ammunition, or their parts/elements, and etc.)

The location of defensive complex is situated in a wooded elevation, mostly covered by pine trees, approximately 200-300 meters west of the coast of the Curonian Sea. The stratigraphy of the studied bunkers is similar.

Nearly all the objectives of the archaeological research were achieved. The discovered artifacts allow dating to the years of World War II and the Soviet era. The found shells indicate that the ammunition used by the German army soldiers stationed in the complex was produced between 1935 and 1940 in various countries (Germany, Italy, Belgium, and France) factories. Although the artifacts related to the complex do not possess signifcant archaeological and historical value, they provide additional information about the technical and engineering features of the complex, as well as the military life during the war.

Currently, the defense complex is to be adapted even more for use: events, concerts, excursions, camping trips, etc.

Pietinė pabūklo platforma FLA 24a su kazematu

Southern gun platform

FLA 24a with casemate

Išlikę - 80% Po žeme - 50%

Remaining - 80%

Underground - 50%

Savybės:

Užpiltas dirbtinai suformuotu kalnu. Dalinai po žeme.

Vėjuota, atsiveria marių ir jūros horizontai.

Konstrukcija stipriai suniokota ir sugriuvusi.

Įėjimas įmanomas.

Features:

Filled with an artifcially formed mountain.

Partly underground. It is windy, and the horizons of the lagoon and the sea open up. The structure is heavily damaged. Entry is possible.

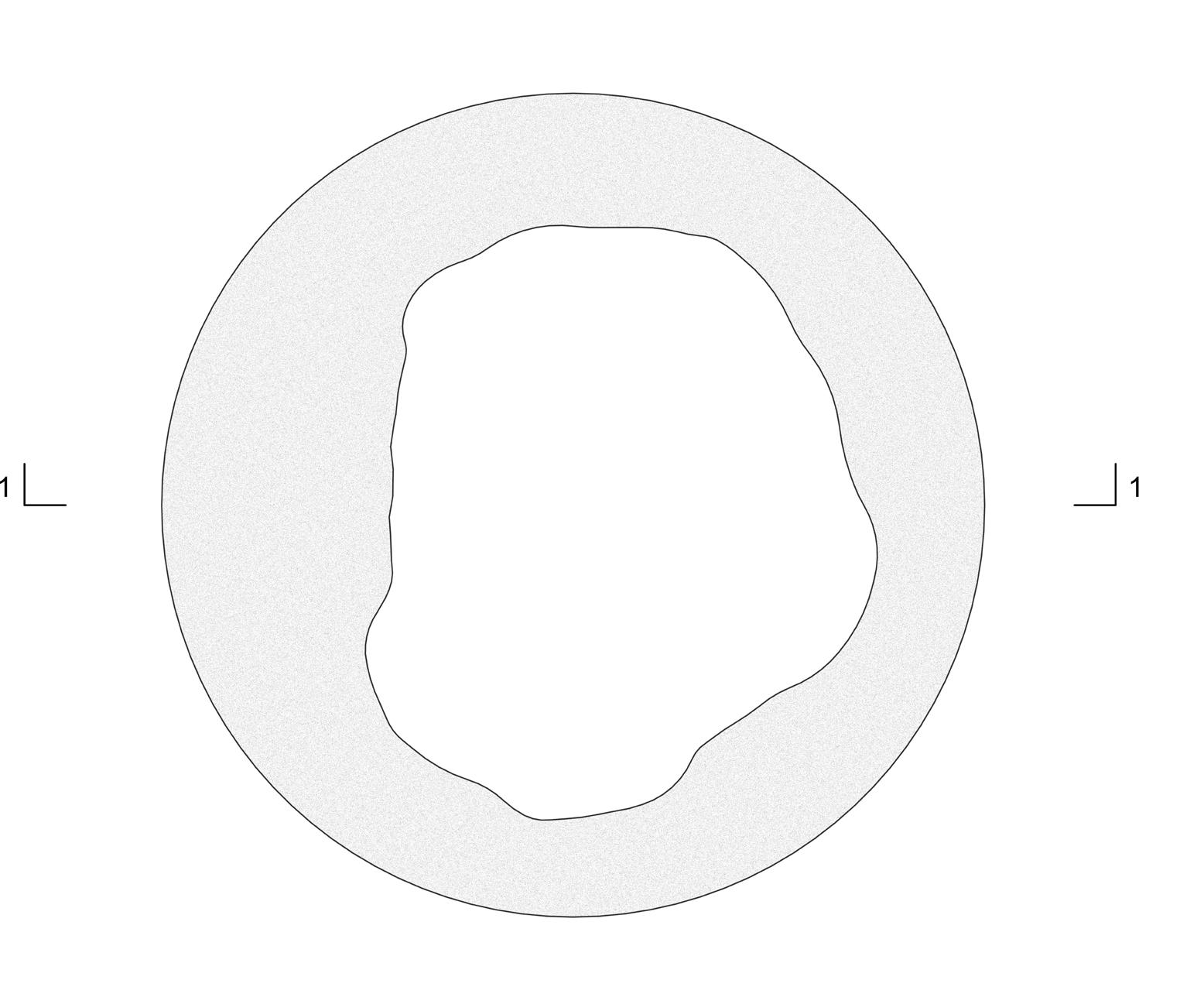

Platforma buvo pastatyta Flak 30 priešlėktuviniam pabūklui. Pabūklas turėjo vieną ar kelis vamzdžius, šaudančius 20 mm kalibro šoviniais. Kazematas įgulai buvo įrengtas požeminėje dalyje šalia pabūklo platformos. Kurio vidines pertvaras suniokojo po karo įvykdytas sprogimas siekiant sunaikinti platformos aplinkoje rastus pabūklų sviedinius. Į platformą ir kazematą buvo galima patekti vieninteliu išorėje įrengtu įėjimu.

The platform was built for the Flak 30 anti-aircraft gun. The cannon had one or more barrels fring 20 mm caliber cartridges. A casemate for the crew was installed in the underground part near the gun platform. The internal bulkheads of which were destroyed by a post-war explosion to destroy cannon shells found in the platform area. Access to the platform and casemate was provided by a single external entrance.

Užpiltas dirbtinai suformuotu kalnu. Didžioji dalis po žeme. Septyni įėjimai. Trūkumas natūralios šviesos.

Dezorientacija.

Features:

Filled with an artifcially formed mountain.

Most of it is underground. Seven entrances.

Lack of natural light. Disorientation.

Bateriją sudaryta iš keturių pabūklų platformų, su ginklais, įrengtais trapecijos kampuose su ugnies kontrolės postu centre. Juos jungė išilgai įrengti koridoriai, vedantys slėptuves, kazematus, šaudmenims skirtas patalpas, sanmazgus, generatorių patalpos, kurios turėjo autonominį šildymą, elektrą, oro slėgio rekuperacijos sistemą. Vienoje baterijos patalpoje (išdažytoje raudona spalva) buvo įrengta operacinė. Visos pabūklų platformos ir ugnies valdymo centras turėjo įrengtus požeminius įėjimus ir du atskirus įėjimus įrengtus tarp įgulos gyvenamųjų kazematų. Rytinės pusės dvi pabūklų platformos buvo pastatytos pagal tipinį projektą. Po karo jos buvo iš dalies išsprogdintos.

The battery consisted of four gun platforms, with guns mounted at the corners of a trapezoid with a fre control post in the center. They were connected by long corridors leading to hideouts, casemates, ammunition rooms, junctions, and generator rooms, which had autonomous heating, electricity, and an air pressure recovery system. An operating room was installed in one battery room (painted red). All gun platforms and the fre control center had underground entrances and two separate entrances between the crew housing casemates. The two gun platforms on the eastern side were built according to a typical design. After the war, they were partially exhausted.

Eastern gun platform FLA 24a with casemate

Remaining - 80%

Underground - 50%

Savybės:

Požeminė ir antžeminė erdvės.

Išėjimas ant stogo.

Vyrauja drėgmė ir vėsuma.

Yra natūraliai susiformavęs baseinas.

Pro lubose esanti pabūklo tvirtinimui skirta ertmė baseiną pildo vandens lašais.

Gausu įvairių ertmių, plyšių.

Features:

Underground and aboveground spaces.

Exit to the roof.

Humidity and coolness prevail.

There is a naturally formed pool.

Drops of water fll the pool through the cavity in the ceiling for the cannon attachment.

There are many cavities and cracks.

Platforma buvo pastatyta Flak 30 priešlėktuviniam pabūklui. Pabūklas turėjo vieną ar kelis vamzdžius, šaudančius 20 mm kalibro šoviniais. Po pabūklo platforma buvo įrengtas kazematas įgulai, kelios šovinių ir amunicijos sandėliavimo patalpos. Ši pabūklo platforma unikali tuo, kad vienintelė išsaugojo kamufiažinės dangos pėdsakus. Ant dviejų išorinių sienų išliko gelsvų ir žalsvų dažų daugiakampės fgūros bei metalinės kilputės, prie kurių tvirtinosi kamufiažinis tinklas, kurių dėka pabūklo platforma buvo sunkiai pastebima priešo aviacijai. platformą ir kazematą buvo galima patekti vieninteliu požeminiu įėjimu su laiptais.

The platform was built for the Flak 30 anti-aircraft gun.

The cannon had one or more barrels fring 20 mm caliber cartridges. A casemate for the crew, and several ammunition and ammunition storage rooms were installed under the gun platform. This gun platform is unique in that it is the only one that has preserved traces of its camoufage coating. Polygonal fgures of yellowish and greenish paint remained on the two outer walls and metal loops to which camoufage netting was attached, thanks to which the gun platform was difcult to see for enemy aviation. The platform and casemate were accessed by a single underground entrance with stairs.

Remaining - 99% Underground - 100% Ammunition storage FLA 22 Arsenal

Savybės:

Užpiltas dirbtinai suformuotu kalnu. Du požeminiai įėjimai.

Ritmiška. monotoniška erdvė.

Mažiausiai klaustrofobiška.

Features:

Filled with an artifcially formed mountain.

Two underground entrances. Rhythmic. monotonous space.

The least claustrophobic.

Bunkeryje buvo įrengta sunkiųjų priešlėktuvinių pabūklų šaudmenų saugykla su šešiomis šaudmenų sandėliavimo patalpomis ir sprogdiklių sandėliu. Keturios didžiosios patalpos buvo sujungtos trijų eilių arkinėmis durų angomis. Prie sienų buvo sumontuoti stelažai šaudmenų sandėliavimui. Patalpų vėdinimui buvo įrengtos ventiliacinės angos. Iš rytų pusės buvo įrengti du požeminiai įėjimai. Karo metu šaudmenų transportavimui šalia arsenalo galėjo būti naudojamas nerijos miškų želdintojų nutiestas siaurasis geležinkelis, kurio pylimas arsenalo šiaurinėje pusėje suardytas aviacinių bombų sprogimais.

The bunker was equipped with ammunition storage for heavy anti-aircraft guns six ammunition storage rooms and a warehouse for explosives. The four large rooms were connected by three rows of arched doorways. Racks for ammunition storage were installed along the walls. Ventilation holes were installed for ventilation of the premises. Two underground entrances were installed on the east side. During the war, a narrow railway built by the foresters of the Spit could have been used for the transportation of ammunition near the arsenal, whose embankment on the northern side of the arsenal was destroyed by aerial bomb explosions.

Remaining - 99%

Underground - 98%

Savybės:

Užpiltas dirbtinai suformuotu kalnu. Turi avarinis išėjimą. Labiausiai klaustrofobiškas.

Features:

Filled with an artifcially formed mountain.

Has an emergency exit. The most claustrophobic.

Kazematinis elektrinės bunkeris, kuris tiekė elektrą baterijų prožektoriams. Bunkeryje buvo įrengti variklių ir valdymo įrenginių kazematas, degalų ir vandens aušinimo rezervuarų kazematai, vandens atsargų ir dvi patalpos įgulai su avariniu išėjimu. Bunkerio kazematų durys buvo slankiojančios konstrukcijos, pagamintos iš armuoto betono. Valdymo įrenginių kazemato sienos buvo iškaltos medinėmis kartelėmis, prie kurių buvo tirtinamas metalinis tinklas, saugojęs įrenginius nuo betono atplaišų bunkerio apšaudymo metu.

A casemate power station bunker supplied electricity to the battery searchlights. The bunker was equipped with a casemate for engines and control devices, casemates for fuel and water cooling tanks, water reserves, and two rooms for the crew with an emergency exit. The bunker casemate doors were sliding structures made of reinforced concrete. The walls of the casemate of the control facilities were carved with wooden bars, to which a metal mesh was attached, which protected the facilities from concrete splinters during the shelling of the bunker.

Kalbant apie Kuršių nerijos unikalų kraštovaizdį, svarbu pastebėti žmogaus vaidmenį išsaugant ir apsaugant šią natūralią aplinką. Kai klimato kaitos poveikis tampa vis akivaizdesnis, būtina skatinti tvarumo ir konservacijos pastangas, kad užtikrintume šių pažeidžiamų ekosistemų tęstinumą. Be žmogaus intervencijos, tikėtina, kad daugelis augalų ir gyvūnų rūšių, dėl kurių Kuršių nerija yra tokia išskirtinė, būtų pavojuje arba visiškai nyktų. Pripažįstant visų gyvųjų organizmų sąveikų svarbą ir imantis proaktyvių žingsnių, galime padėti užtikrinti tvarią ateitį skatinant regeneraciją.

When considering the distinctive landscape of the Curonian Spit, it is important to acknowledge the human role in preserving and protecting this natural environment. As the efects of climate change become more apparent, it is imperative to promote sustainability and conservation eforts to ensure the continuity of these vulnerable ecosystems. Without human intervention, it is likely that many plant and animal species that make the Curonian Spit so unique would be endangered or even face extinction. By recognizing the importance of interactions between all living organisms and taking proactive steps, we can help ensure a sustainable future by promoting regeneration.

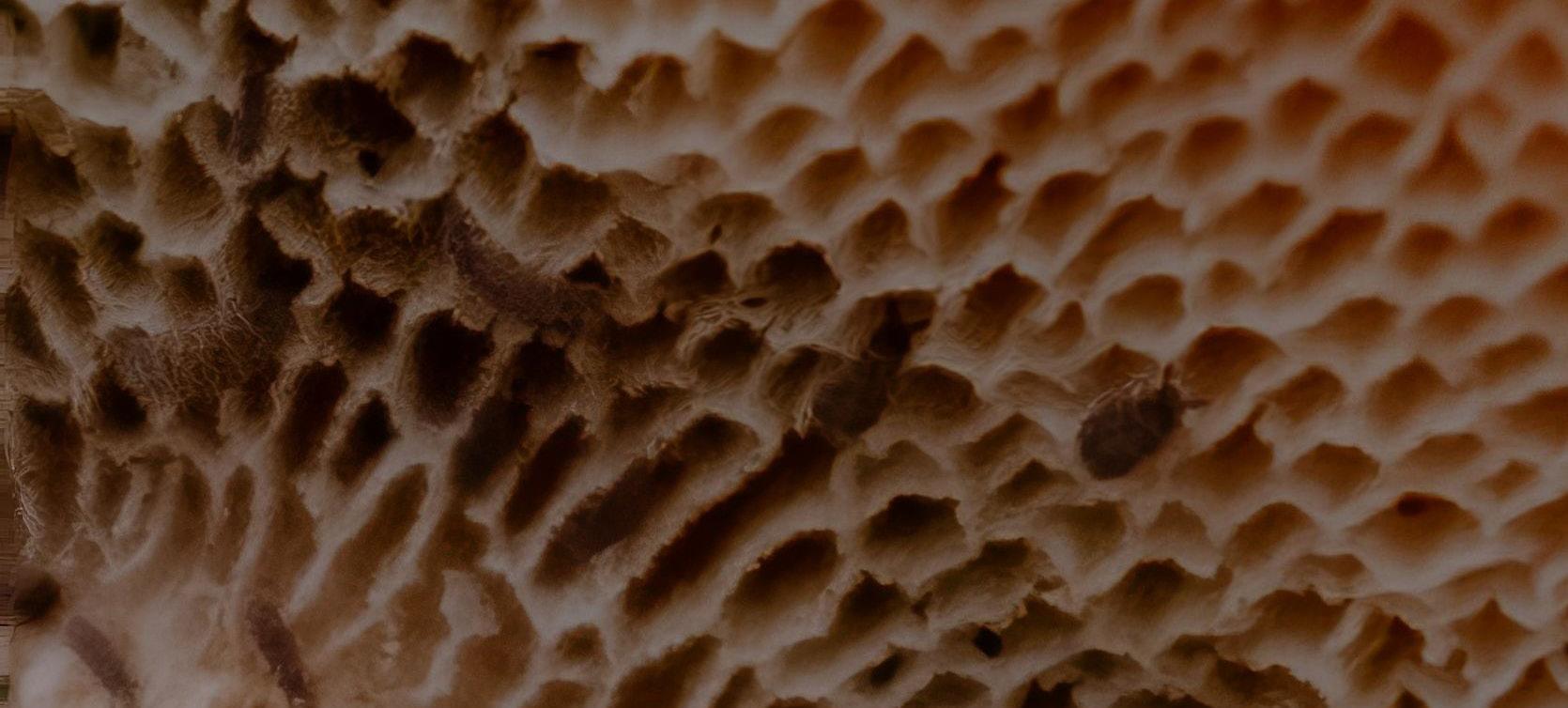

Miško sudėtinga ekosistema - įvairių augalų rūšių prieglobstis. Kai kurios augalų rūšys buvo žinomos kaip genius loci, įkūnijančios vietos dvasią ir prisidedančios prie jos unikalaus teritorijos charakterio. Viena iš tokių rūšių yra pušis, kurios dažnai siejamos su atsparumu ir tvirtumu. Jos gali išgyventi atšiauriomis aplinkos sąlygomis, pavyzdžiui, sausroje ar ekstremaliose temperatūrose. Pušis suteikia buveinę įvairiems gyvūnams ir grybams, tokiems kaip Phellinus pini, dažniausiai augantiems ant subrendusių medžių kamienų.

Abipusė tarpusavio priklausomybė. Kiekviena augalų rūšis tam tikru mastu priklauso nuo kitų, nesvarbu, ar tai yra apdulkinimas, sėklų sklaida ar maistinių medžiagų ciklas. Pavyzdžiui, Violo-Corynephoretum canescentis yra miško augalų bendrija, kuriai būdinga žibuoklių ir kitų augalų rūšių įvairovė. Ši bendruomenė atlieka svarbų vaidmenį palaikant dirvožemio derlingumą ir drėgmės lygį.

Arrhenia spathulata yra dar viena augalų rūšis, kuri yra tarpusavyje susijusi su aplinka r prisideda prie miško bendrystės jungčių. Tai mažas, medienoje gyvenantis grybas, dažniausiai randamas pušynuose. Jis vaidina svarbų vaidmenį skaidant organines medžiagas ir prisideda prie bendros miško ekosistemos sveikatos.

The forest is a complex ecosystem that serves as a habitat for various plant species. Some plant species are known as “genius loci,” embodying the spirit of a place and contributing to its unique character. One such species is the pine tree, often associated with resilience and strength. Pines can survive harsh environmental conditions such as drought or extreme temperatures. They provide a habitat for diverse animals and fungi, such as Phellinus pini, which commonly grows on mature tree trunks.

There is a mutual interdependence between diferent plant species, whether it’s through pollination, seed dispersal, or nutrient cycling. For example, Violo-Corynephoretum canescentis is a forest plant community characterized by the diversity of violets and other plant species. This community plays an important role in maintaining soil fertility and moisture levels.

Arrhenia spathulata is another plant species that is interconnected with its environment and contributes to the connectivity of the forest community. It is a small wood-dwelling fungus commonly found in pine forests. It plays a vital role in breaking down organic matter and contributes to the overall health of the forest ecosystem.

Įvairių gyvūnų rūšių buvimas miške rodo sveiką ir klestinčią ekosistemą, kiekviena jų atlieka unikalų vaidmenį, prisidedant prie viso miško pusiausvyros ir stabilumo kūrimo. Kuršių nerijos miškuose gyvenantys gyvūnai yra svarbus kraštovaizdžio formavimo veiksnys. Jų elgesys ir mityba gali paveikti žemės paviršiaus formą, prisidėti prie miško retinimo ir pakrantės formos kitimo.

Vienas iš būdingų gyvūnų Kuršių nerijos miškams yra stirnos. Jos ėda vaisius ir skleidžia sėklas visame miške, padedant naujiems augalams augti ir užtikrinant augalų rūšių tęstinumą.

Gyvūnai, tokie kaip bitės, drugeliai ir kolibridos, yra svarbūs apdulkintojai. Jie padeda apdulkinti gėles ir užtikrinti augalų reprodukciją, ir taip prisideda prie visos miško ekosistemos sveikatos ir įvairovės.

Kenkėjų kontrolė: Grobuonys, tokie kaip paukščiai, lapės ir gyvatės, padeda kontroliuoti kenkėjų, galinčių pažeisti miško ekosistemą, populiacijas, tokias kaip graužikai ir vabzdžiai.

Kitas svarbus gyvūnas, prisidedantis prie kraštovaizdžio formavimo, yra briedis. Briedžių ragai kabina medžių šakas, ir paviršiaus žievę. Tai lemia medžių degeneracines reakcijas, jų nykimą, bet kartu kuria ir vietas naujoms grybų populiacijoms.

Maistinių medžiagų apykaita: Gyvūnai, tokie kaip elniai ir stirnos, padeda perdirbti maistines medžiagas miške, ėsdami augalus ir tuomet pasišluodami savo atliekas, kurios suteikia svarbių maistinių medžiagų kitiems augalams augti.

Teritorijoje taip pat gyvena įvairūs graužikai ir šernai, kurie kasa žemę ir formuoja gruntinį paviršių.

The presence of various animal species in the forest indicates a healthy and thriving ecosystem. Each species plays a unique role in contributing to the overall balance and stability of the forest. Their behavior and diet can afect the surface form of the land, contribute to forest thinning, and shape the coastline.

One of the characteristic animals in the forests of the Curonian Spit is the deer. They eat fruits and spread seeds throughout the forest, helping new plants to grow and ensuring the continuity of plant species.

Animals such as bees, beetles, and hummingbirds are important pollinators. They help pollinate fowers and ensure plant reproduction, thus contributing to the overall health and diversity of the forest ecosystem.

Pest control: Predatory birds such as hawks, foxes, and snakes help control populations of pests that can damage the forest ecosystem, such as rodents and insects.

Another important animal that contributes to landscape formation is the moose. Moose antlers rub against tree branches and bark, resulting in degenerative reactions and the decline of trees, but at the same time creating habitats for new fungal populations.

Nutrient cycling: Animals such as elk and storks help recycle nutrients in the forest by consuming plants and depositing their waste, which provides important nutrients for the growth of other plants.

The territory is also inhabited by various rodents, which dig the ground and shape the soil surface.

landscape shaped by animals

Bunkeriai miškuose gali suteikti prieglaudą ir gyvenvietę įvairioms gyvūnų rūšims. Daugelis gyvūnų, tokių kaip žiurkės ir paukščiai, naudoja bunkerių erdves lizdams, guoliavimui ir žiemos miegui. Be to, apleisti bunkeriai gali tarnauti kaip maisto šaltinis kai kuriems gyvūnams. Pavyzdžiui, šikšnosparniai gali maitintis vabzdžiais, kuriuos traukia drėgna ir tamsi aplinka.

Intensyvėjant žemės ūkiui, iš dirbamos žemės pašalinama daug natūralių savybių, ko pasekoje mažėja ir laukinių rūšių buveinės. Tuo tarpu bunkeriai, kurie nėra paveikti žemės konsolidacijos, galėtų tapti potencialiu prieglobsčiu šioms rūšims. 2016 m. ,,Urban Ecosystems” žurnale publikuotas CNRS atliktas tyrimas. Jame buvo ištirti 182 apleisti antrojo pasaulinio karo bunkeriai, įrengti Rytų Prancūzijoje plytinčiuose pasėliuose, miškuose ar giraitėse,. Bunkeriuose buvo aptikta daugybė gyvūnų buvimo ženklų: 34% barsukų ir raudonųjų lapių pėdsakai, o urvelių - 24%. Pastebėta, jog gyvūnai dažniau nei požeminiuose ar antžeminiuose bunkeriuose prieglobsčio ieško dalinai požeminiuose . Taigi bunkeriai galėtų padėti sulėtinti nenumaldomą agrarinio kraštovaizdžio blogėjimą rūšių pasitraukimą iš šių kraštovaizdžių. 20

Lietuvoje bunkeriai tampa prieglobsčiu šikšnosparniams. Pavyzdžiui, Klaipėdoje esančioje antrojo pasaulinio karo priešlėktuvinės “Memel Nord” baterijos pietinė dalis yra žmonių lankoma ekspozicija, o šiaurinėje, kuri yra apleista, yra tapusi prieglobsčiu ten žiemojantiems šikšnosparniams, kurie yra įrašyti Lietuvos raudonąją knygą - Natererio pelėausis (Myotis nattereti). O tai tik trečias ar ketvirtas užfksuotas žiemojančio šios rūšies šikšnosparnio atvejis Lietuvoje.

Svarbu atkreipti dėmesį, kad seni bunkeriai taip pat gali kelti pavojų kai kurioms gyvūnų rūšims. Gyvūnai, kurie patenka į bunkerį lieka įkalinti, o tarša ar toksinai tampa kenksmingu elementu kai kurioms rūšims.