A publication of Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art

Volume 27 | Winter 2022/2023

THE INTUIT STORE T h u – S u n : 1 1 a . m . – 6 p . m . i n t u i t . g i v e c l o u d . c o / s t o r e P h o t o g r a p h b y C h e r i E i s e n b e r g

ABOUT INTUIT:

Founded in 1991, Intuit is a premier museum of outsider and self-taught art, defined as work created by artists who faced marginalization, overcame personal odds to make their artwork, or who did not, or sometimes could not, follow a traditional path of art making, often using materials at hand to realize their artistic vision. By presenting a diversity of artistic voices, Intuit builds a bridge from art to audiences. The museum’s mission—to celebrate the power of outsider art—is grounded in the ethos that powerful art can be found in unexpected places and made by unexpected creators.

INDEX

letter from the president by debra kerr

SUPPORTING ARTISTS WITH DISABILITIES

by vincent uribe

CREATIVE GROWTH ART CENTER by

tom di maria

AT HOME WITH ARTISTS: THE EDUCATION OF TED DEGENER

RECENT

ACQUISITIONS

SAFE SPACES: INTUITEENS 2022

by cielo aguilera and courtney thompson

by annalise flynn book reviews by william swislow support leadership contributors

Cover: Gregory Warmack (Mr. Imagination) in his home in Bethlehem, Pa., in 2007 by Ted Degener. Photo courtesy Ted Degener

Back Cover: Reverend Kornegay at his environment in Brent, Ala., in 1990 by Ted Degener. Photo courtesy Ted Degener

Above: Gregory Warmack (Mr. Imagination) (American, 1948–2012). Untitled (castings of the artist’s hands), 2009. Plaster, paint and wire, 10 3/4 x 4 1/2 x 3/4 in. Collection of Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, gift of Lisa Stone and Don Howlett in honor of Susann Craig, 2021.11. Photo by John Faier

ISBN 978-0-9990010-3-5

The Outsider is published once a year by Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, located at 756 N. Milwaukee Avenue, Chicago, IL 60642. Prior to Fall 1996, Volume 1, Issue 1, The Outsider was published as In'tuit.

05 06 12 16 31 35 38 22

28

4

Dear friends of Intuit,

People often ask me if there will still be outsider artists in the future of our increasingly connected society. Leaving aside, for now, whether the term outsider is viable, my answer is yes: Absolutely, there will be self-taught artists facing social, political and economic barriers to traditional paths of art making. Will those artists be free from influence of popular culture? Likely not, but many artists firmly placed in the genre were and are not free from influence. Henry Darger was a consumer of newspapers, magazines and fiction of his time. Lee Godie visited the Art Institute of Chicago and declared herself a French Impressionist. The edges of what constitutes such an artist are blurred and will continue to be so; John Maizels of Raw Vision described trying to define the edges as ripples moving outward from where the stone lands in the water.

This year’s Visionary Ball was one of Intuit’s most successful ever, thanks in large part to the outpouring of enthusiasm and support for our 2022 Visionary Award recipient, Frank Maresca, and his many contributions to the advancement of the field of self-taught art. In accepting the award, Frank said, “Supporting...non-academic artists— self-taught, outsider—has really been the privilege of my life. There’s nothing

more important to me than sharing what I love with others.” It was a great honor for Intuit friends to celebrate Frank and Intuit both in-person and online at the hybrid event.

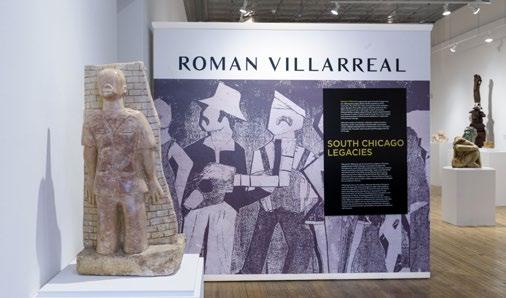

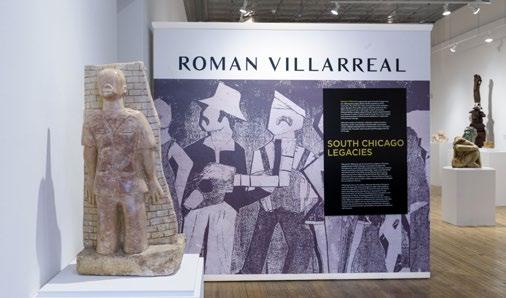

Throughout 2022, Intuit saw tremendous audience enthusiasm and media coverage for the exhibition Roman Villarreal: South Chicago Legacies. Audiences are consistently enthusiastic about the opportunity to interact in person and virtually with a living selftaught artist. Villarreal’s work reflects his perspective on his community and documents his lived experiences there: economic hardship, gangs, drugs, or the death of loved ones or comrades in arms.

You—our members, friends and readers— help Intuit find these artists and their art, through open eyes and minds. Thank you for your partnership with our team. In this issue, you will find artworks featured that have been recently added to Intuit’s collection through generous gifts, motivated by a desire to leave a legacy or, simply, needing to re-curate what is on one’s walls. Thank you for thinking of the museum and helping it grow.

Warm

THE PRESIDENT

LETTER FROM

regards,

Debra Kerr, President and CEO

5

LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT

Photo of Deb Kerr with artist Dr. Charles Smith courtesy Intuit

Opposite Page: Photographs by Cheri Eisenberg

By Vincent Uribe

By Vincent Uribe

Supporting Artists with Disabilities

What does it mean to be an artist with a disability? Should we look at artwork or value it differently when someone with a disability creates it? These questions are complicated by the fact that we live in a society that doesn’t fully appreciate, embrace or foster any artist to their full extent. I firmly believe that we should support all artists, including those with disabilities, and that making that possible is more nuanced than many may realize.

As an artist whose practice centers on social curation, I have worked with hundreds of artists over the past 12 years through a multitude of social events, from gallery exhibitions to creative workshops to late-night dance parties to benefit art auctions. I have dedicated my career to supporting emerging to mid-career artists’ professional development. The core of my practice is uplifting artists from a variety of backgrounds in order to promote integration, create dialogue and build a respectful, open community.

In many ways, supporting artists with disabilities is no different than supporting artists without disabilities. It takes time and a foundation of mutual respect to nurture a relationship with any artist. One likely wouldn’t ask a stranger a personal medical question without getting to know them first. When working with, admiring or collecting from artists, personal histories are just that—personal. Artists with disabilities deserve the same respect of privacy as anyone else, and whatever medical diagnosis they may have (mental, physical, developmental, emotional) should be left to the individual—

7 SUPPORTING ARTISTS WITH DISABILITIES

Photo of studio artist Jean Wilson with Vincent Uribe courtesy Arts of Life

without expectation—to disclose anything. Suppose an artist’s disability is not intrinsically part of their work, the same way an artist’s background or sexual orientation might not be. In that case, that information is presumed private and irrelevant to the value of the practice. Asking about an individual’s diagnosis is rude and insensitive and should not influence one’s perspective on the work.

Beyond relationship building, it also takes time and care to successfully incorporate many voices into the process. At Arts of Life, a creative collective for artists with intellectual and developmental disabilities, we are guided by a model of Collective Decision Making. Our artists have a voice in decisions both large and small—from strategic planning and staff hiring to party planning.

However, as our community has grown, it became increasingly untenable to offer every opportunity to every artist. So, we developed the Artist Enterprise Program to support our artists in their chosen professional development track. In my role, I work directly with the Curatorial Committee to plan our gallery exhibitions. In order to promote integration and increased exposure, I invite a guest curator— usually an emerging artist who has never curated before—to partner with our committee on an exhibition. The guest curator works with the committee to identify the theme, make final selections of artwork, and install the work. Bringing our artists into the process definitely elongates the timeline, but ultimately each exhibition is richer for it. And by creating a space to nurture these collaborations, guest curators and artists then carry those experiences into

Left: Photo of Vincent Uribe courtesy Arts of Life and Vincent Uribe

Right Top: Photo of an Arts of Life exhibition opening courtesy Arts of Life

Right Bottom: Photo of studio artist Christianne Msall courtesy Arts of Life

8 THE OUTSIDER

In many ways, supporting artists with disabilities is no different than supporting artists without disabilities.

10 THE OUTSIDER

future projects. So, our artists now are featured in exhibitions across the country beyond those we at Arts of Life directly coordinate.

At the same time, there are external forces that make supporting artists with disabilities different. The starving artist is real, and most artist funding is limited. For artists with disabilities, the challenges of receiving support are exacerbated by outdated and backward rules. In the U.S., people with disabilities must live in poverty to maintain their state disability benefits. If their income or savings exceed $2,000 a month, they risk no longer qualifying for necessary medical support. For an artist with intellectual or developmental disabilities, this could also threaten their housing. This keeps them tied to an unfortunate government system of suppression. As the visibility of our artists grows, so do their art sales. Our team plans creatively with our artists to ensure the payouts do not have an unintended cost.

Ultimately, what I have learned is that a one-size-fits all approach does not work in this sector. Regardless of our current disability status, we each bring our own life experiences and skills to the table. By getting to know artists as individuals, we can foster the trust and understanding needed to support them effectively and help the art world to thrive.

Vincent Uribe (@vcentu) is a creative community builder. As Founding Director of LVL3, he has organized hundreds of exhibitions featuring emerging and midcareer artists. At Arts of Life, he has launched the Circle Contemporary galleries and facilitated public exhibitions for artists with intellectual and developmental disabilities at the Chicago Cultural Center, Art on the MART and the Ukrainian Institute of Modern Art. Vincent serves as a founding board member for Equity Arts.

11

Photo of Vincent Uribe courtesy Arts of Life and Vincent Uribe

SUPPORTING ARTISTS WITH DISABILITIES

CREATIVE GROWTH

ART CENTER

By Tom di Maria

12 THE OUTSIDER

12

The late 1960s and ‘70s marked a time of enormous social and political change in America. Cultural shifts—linked to hippie culture, women’s rights, Black power and other such movements—empowered the advancement of people with disabilities. Often marginalized and placed in staterun institutions for their entire lives, people with developmental disabilities seized upon these changes and started an active disability justice movement that remains essential and vibrant today.

Dwight Mackintosh (American, 1906–2006). Untitled (Figures with Writings), n.d. Mixed media on paper, 22 x 28 in.

Collection of Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, gift of Creative Growth Art Center, 2004.6.2. Courtesy Creative Growth Art Center

Opposite Page: Judith Scott (American, 1943–2005). Blue Bird Pod, n.d. Mixed media and fibers, 13 1/2 x 22 x 17 in.

Collection of Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, gift of Creative Growth Art Center, 2004.6.4. Courtesy Creative Growth Art Center

13

GROWTH

CENTER

CREATIVE

ART

Donald Mitchell (American, b. 1951). Untitled, n.d. Marker on paper, 18 3/4 x 22 1/2 in.

Collection of Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, gift of Creative Growth Art Center, 2004.6.1.

Courtesy Creative Growth Art Center

14 THE OUTSIDER

14

This new social order allowed for the idea of disability as a culture to take form and set the stage for people with disabilities to have access to expressive activities outside an institutional setting for the very first time.

This movement has led to opportunities for artists like Tarik Echols, whose art Intuit will exhibit from December 2022 to May 2023, to emerge from and to develop a presence in the contemporary art world.

Creative Growth Art Center, founded in 1974, benefited from this social climate as its concept was a radical departure from the norms of the time. It was founded as an artist-led space with a hands-off approach to fostering the inherent creative potential of every individual. It includes an adjoining gallery where the artists’ work is professionally presented, viewed and sold. Creative Growth provides opportunities for the artists and the general public to engage in meaningful encounters about the art and the artists’ lives as people with disabilities.

For nearly 50 years, this model has led to the creation of dozens of similar centers worldwide and is now an international movement demonstrating that the culture of disability, and the art of people with developmental disabilities, is advancing in countries around the world.

As work by artists from such centers gain greater exposure and a larger audience, questions are raised about its relationship to the academic art world and the field of so-called outsider art. While the use of the term outsider art is not embraced by Creative Growth, there can be advantages for artists with disabilities to align themselves with collectors and galleries that support work with this label. The aesthetic similarities are often spot on, and the use of the word calls attention to an artist’s work by collectors who follow the field. That said, the term has negative connotations as it relates to how the maker, in this case a person with a disability, can be seen as being “other” and not a part of the contemporary social fabric. It also delegates the work to a niche market, where it might only be seen by a segment of art collectors and curators.

While the field continues to grow as a recognized force within the contemporary art world, additional efforts toward advancement and growth will continue to be required as we move forward. The number of people with disabilities who have access to creative expression is still exceedingly small. It is imperative to understand that creativity is a fundamental human right and a powerful tool for people with disabilities to find aesthetic, personal and communicative growth in the world today.

The advancement of this work needs to continue, and the results of those efforts will be powerful and rewarding for both artist and viewer alike.

15 CREATIVE GROWTH ART CENTER

Creative Growth provides opportunities for the artists and the general public to engage in meaningful encounters about the art and the artists’ lives as people with disabilities.

Ace Parson in the window of his Rainbow House in Vancouver, Wash., in 1995 by Ted Degener.

Photo courtesy Ted Degener

Ace Parson in the window of his Rainbow House in Vancouver, Wash., in 1995 by Ted Degener.

Photo courtesy Ted Degener

at home with artists:

The Education of Ted Degener

By Annalise Flynn

In January 2023, Intuit will present an exhibition of photography and film by Ted Degener, an artist who has spent countless hours traveling the United States to seek out creators of artist-built environments— personal spaces like homes, gardens and studios fully transformed into continually evolving, site-specific and life-encompassing works of art. Given the expansive, transformative and rooted qualities of artist-built

environments and that they are typically intended to be experienced as a single work rather than a collection of disparate objects, they are particularly difficult to share inside institutional walls. Oftentimes, pure documentation of sites fails to capture even a small fraction of the magic of experiencing the place in three dimensions—of finding your body enveloped by the creative work of another.

AT HOME

WITH ARTISTS: THE EDUCATION OF TED DEGENER

Mary Proctor’s Art Yard in Tallahassee, Fla., in 1997 by Ted Degener. Photo courtesy Ted Degener

Mary Proctor’s Art Yard in Tallahassee, Fla., in 1997 by Ted Degener. Photo courtesy Ted Degener

Degener’s photos, however, don’t attempt to merely document an artwork or transport a viewer to a place. These portraits capture the artist in their space, inhabiting their work— something many have done for a lifetime, growing with and within their work. They capture the joy of making and the pride of sharing it with the world. They reveal the one thing that many environments are incomplete without—the dynamic presence of their makers—something that can never be experienced or recreated once the artist has left the site or passed away. Degener’s collection of portraits comes together to reveal something like the lives of these artists themselves—a lifelong pursuit, an impassioned collecting and the making of something enormous that will never be quite complete. In this interview, I spoke with Degener to learn more about his practice.

Annalise Flynn: How did you first become interested in artist-built environments and road tripping?

Ted Degener: Right after college, I did construction in Woodstock, N.Y., and happened to visit Clarence Schmidt’s famous site, which was already in ruins. That was a big influence. I would go to New York and often visit the Strand Bookstore. I bought a book called Fantastic Architecture, Roger Cardinal’s book [Outsider Art], and Seymour Rosen’s book In Celebration of Ourselves; curiously, all on the discount racks. I became more and more interested in them. There was also a book called Amazing America, which made a huge impression on me. It included a guide to sometimes environments and sometimes quirky Americana. I became interested in both types of places at the same time, as well as festivals and religious sites in the United States— sort of as a way to understand our odd and beautiful country.

I became interested in the organizations SPACES, Kansas Grassroot Arts Association and The Orange Show. These associations would do a map every month. When the thing came out, I would be really psyched to see it…and I would often go on road trips to follow those maps. In the early days, there wasn’t much information about any of this stuff… Following the maps helped me find a bunch of places, and sometimes I also just wandered the back roads. That was the greatest thing, when you just went around a corner and found something that blew your mind.

AF: Why the focus on portraits versus photos of the environments alone?

TD: I do portraits because they capture an important moment in time. The work of environments has more power when the artist is alive, but I do believe in preservation of these sites. It’s a challenge to find a moment that tells the story or at least part of the story of a site or a person.

AF: What kind of relationship do you have with the artists? How have artists responded to your work?

TD: Some artists I’ve visited many times, some just once. I find that people are very happy to share their work as it is their passion. There are photographs I’ve never shared because the people were so fragile. Of course, everyone is different, and most people are more interested in what they’re doing than what I’m doing. I’m very open about what I tell the artist about their work, and I think they appreciate my enthusiasm. In a way, most environments are made as unfinanced public art, in my opinion, waiting for an appreciative audience.

AT HOME WITH ARTISTS: THE EDUCATION OF TED DEGENER

AF: Why do you take these photos? Is it primarily to share them with other people, to increase recognition of the artists, something you just do for yourself?

TD: I suppose, in some cases, I try to promote the artist’s work, and in some artist’s cases, I try to protect them. I think of myself as someone who just makes a historical record on people who might not be appreciated otherwise.

AF: How do you find out about environments?

TD : Now, through Facebook, dealers at the Outsider Art Fair. In the old days, it was much more difficult, but through the organizations I mentioned. By luck, I just happened onto Margaret’s Grocery. I missed Mary T. Smith because KGAA [Kansas Grassroots Art Association] gave the wrong town, and I spent three days asking for directions there.

AF: What about this work (artist-built environments) is important to you? What about your work is important to you?

TD: It [artist-built environments] tends to be made by self-educated people who are working things out as they go along. Be it the quality of their brushstrokes or their architectural ideas, they must really believe in what they’re doing to engage in a life’s work. I’ve always found self-educated people interesting. I think the real geniuses like Lonnie Holley even invent their own language. The best things about America are its individualism and diversity, and environment builders are sort of heroes on quest. It’s my quest to appreciate their contributions, and I am perhaps self-educated by them… It’s an art of generosity.

AF: Do you have any favorite memories of a particular trip or artist?

TD: Going around the corner and seeing Margaret’s Grocery, spending time with Leonard Knight, taking the comedy tour of Paul Hefti’s yard at sunset, Finster talking for four hours straight, Jimmie Sudduth playing harmonica like a train with his dogs howling along.

AF: What have decades of this pursuit taught you?

TD: A more democratic and open-minded appreciation of all art. High art—great. Vernacular art—great. As Seymour Rosen said: it’s a celebration of ourselves.

This interview with Ted Degener was performed by Annalise Flynn on September 12, 2022. It has been edited for length and clarity.

AT HOME WITH ARTISTS: THE EDUCATION OF TED DEGENER

21

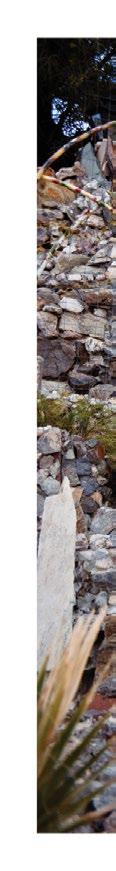

Louis Lee in his Rock Garden in Phoenix, Ariz., in 1995 by Ted Degener.

Photo courtesy Ted Degener

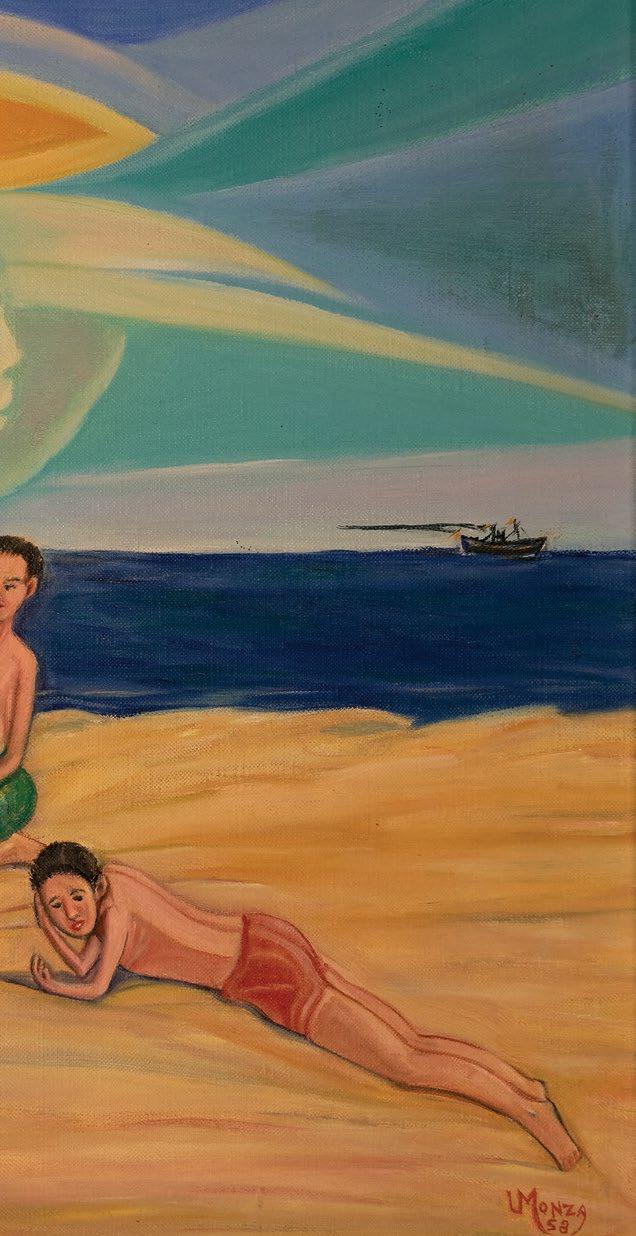

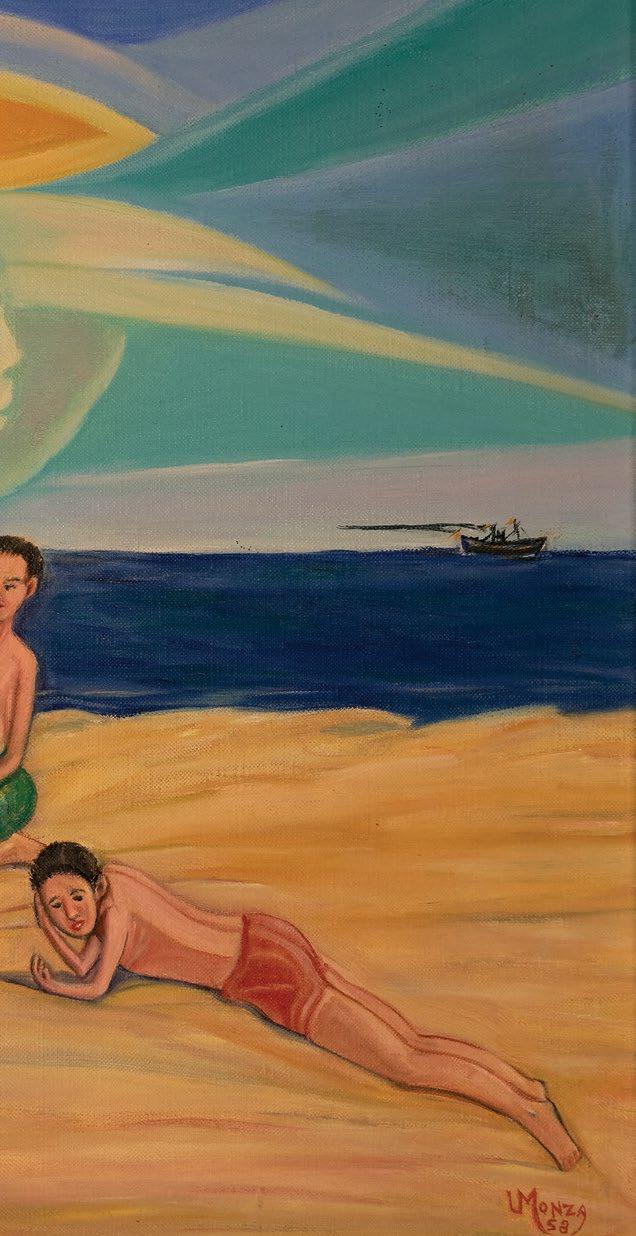

Louis B. Monza (b. Italy 1897–d. America 1984). Children on the Beach, 1985. Oil on canvas, 16 x 20 in.

Collection of Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, gift of Daniel Wojcik, 2021.13

Photo by John Faier

Photo by John Faier

recent acquisitions recent acquisitions recent acquisitions

23

William Dawson (American, 1901–1990). Untitled (Dawson and his family), c. late 1970s. Paint on paper, 17 x 21 in.

Collection of Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, gift of Iris Witkowsky, 2021.19

Photo by John Faier

Right: Mr. Imagination (Gregory Warmack) (American, 1948–2012). Untitled (castings of the artist’s hands), 2009. Plaster, paint and wire, 10 3/4 x 4 1/2 x 3/4 in.

Collection of Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, gift of Lisa Stone and Don Howlett in honor of Susann Craig, 2021.11

Photo by John Faier

Opposite page: The Peace Prophet (American, life dates unknown). Untitled, 2015. Mixed media, 28 x 22 in.

Collection of Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, 2022.15

24 THE OUTSIDER

In 2002, Intuit established a permanent collection. Now home to more than 1,300 works of art, the collection includes pieces by Aldobrando “Aldo” Piacenza, Pauline Simon, Mose Tolliver, Inez Nathaniel Walker and Purvis Young, among many other renowned outsider and self-taught artists. The collection continues to grow, thanks to the support of many generous donors. Between 2021 and 2022, Intuit accessed 35 works of art into its permanent collection, of which six pieces are spotlighted here in The Outsider.

25 25 RECENT ACQUISITIONS

Ionel B. Talpazan (b. Romania 1955–d. America 2015). Untitled (UFOs), 1999–2000. Crayon, marker and grease pencil on board, 18 x 24 in.

Collection of Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, gift of Daniel Wojcik, 2021.15

26 THE OUTSIDER

Photo by John Faier

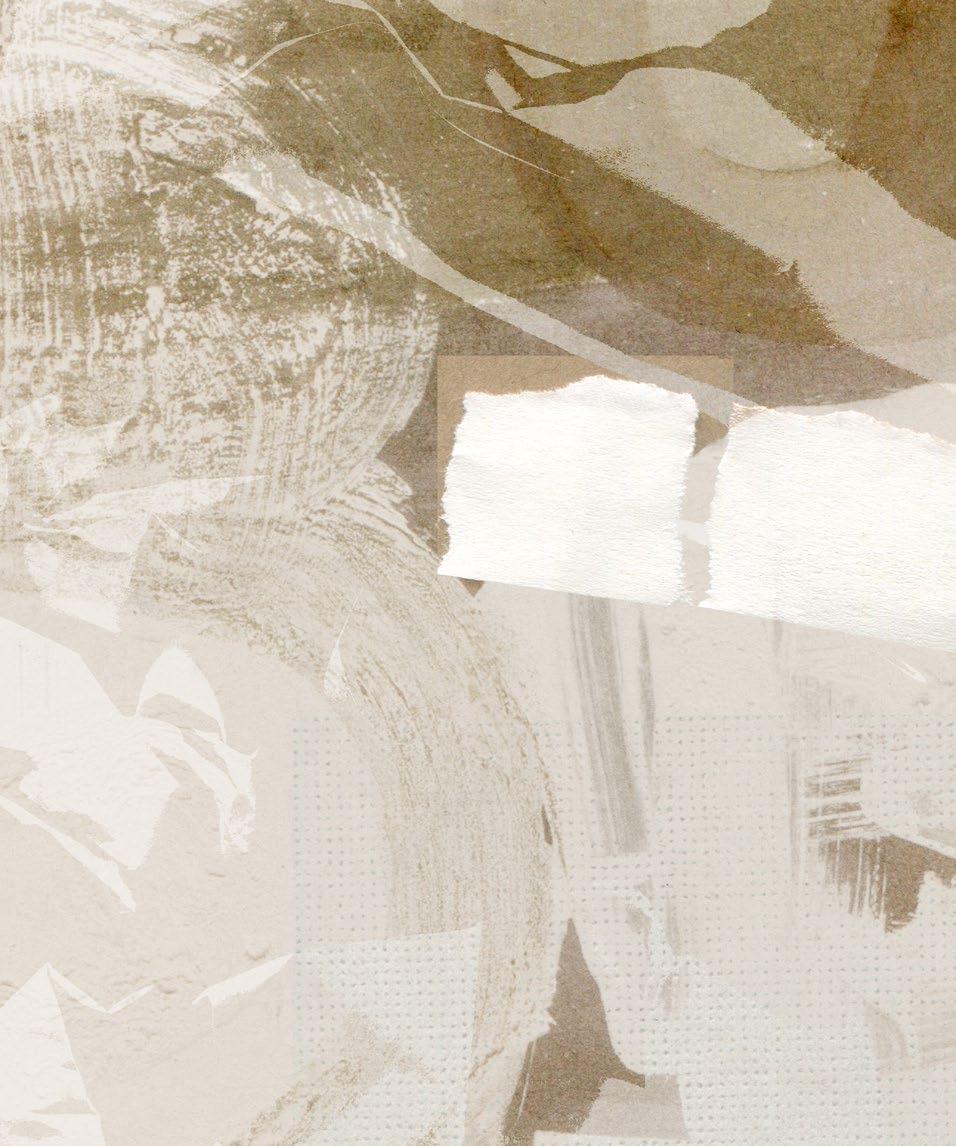

William Hawkins (American, 1895–1990). Untitled, 1988. Paper collage and enamel on Masonite, 39 1/2 x 48 in.

Collection of Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, gift of Frank Maresca, 2021.17

27 RECENT ACQUISITIONS

Safe Spaces: IntuiTeens 2022

By Cielo Aguilera and Courtney Thompson

This past summer, teens from across Chicagoland joined the IntuiTeens, the museum’s summer youth internship program that centers on creativity and celebrating the power of outsider art.

THE OUTSIDER

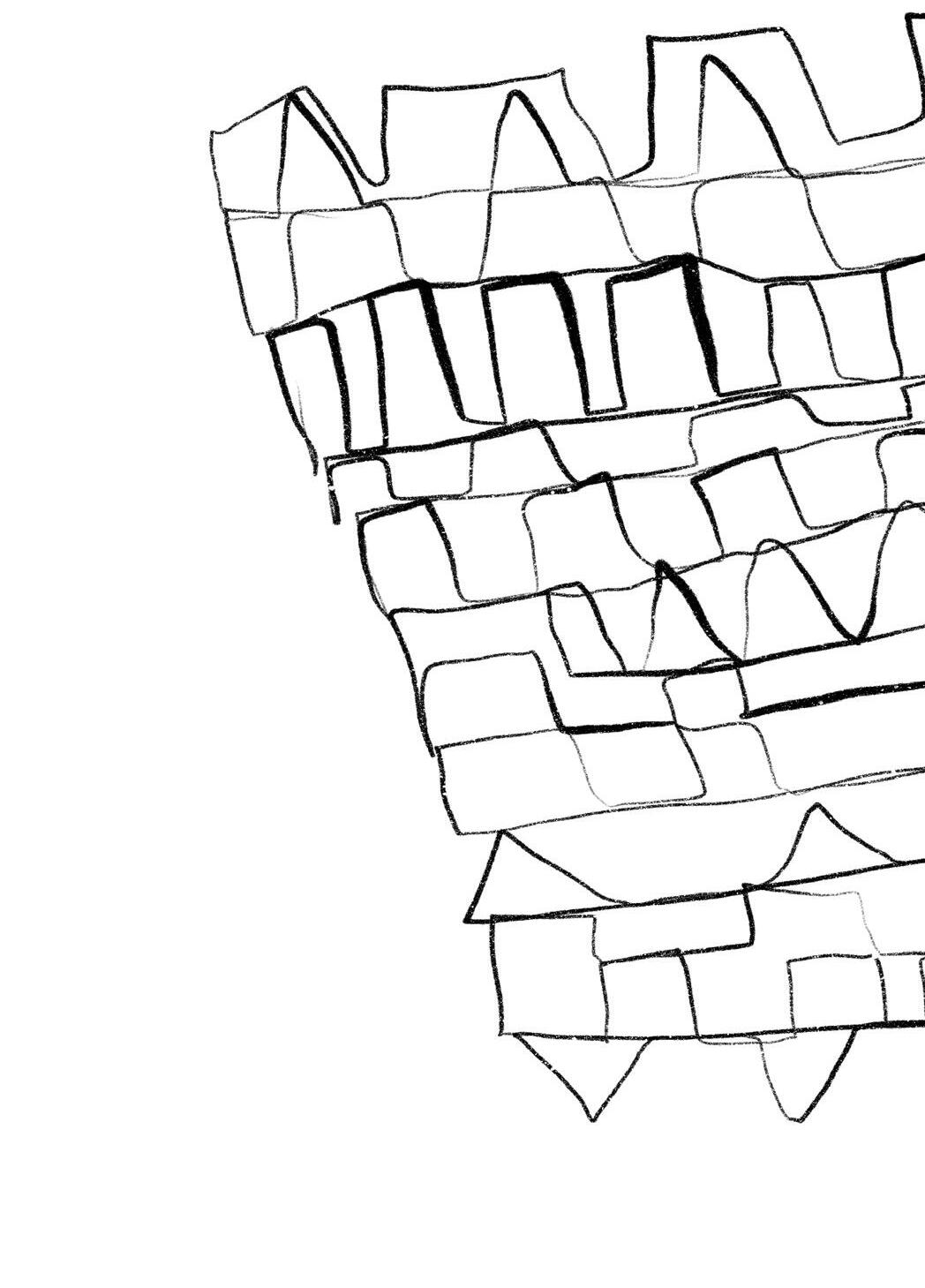

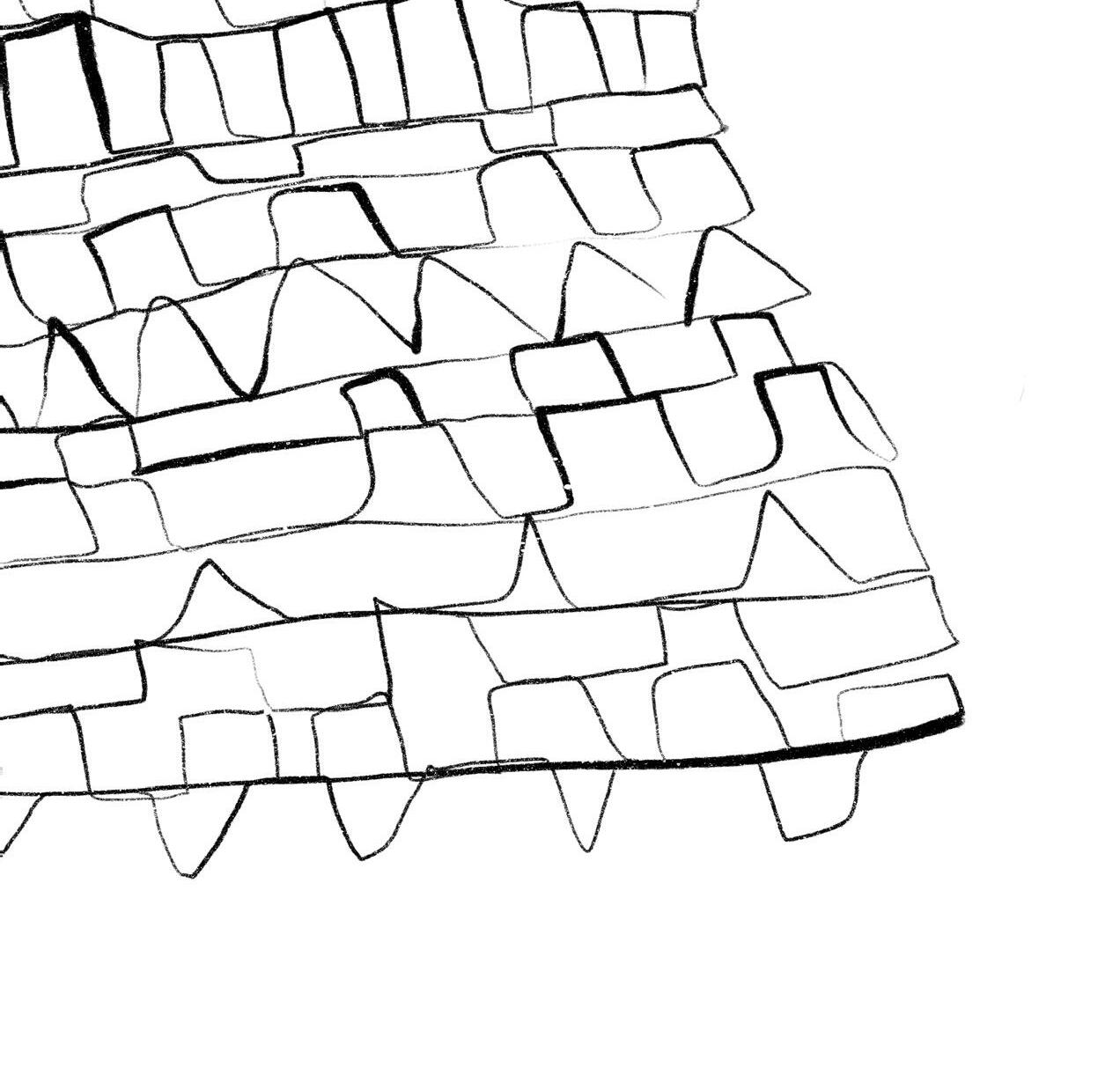

To kick off the program, the cohort reflected on the 2021 IntuiTeens Community Quilt, created in collaboration with the Social Justice Sewing Academy. This activity served as an entrance into the group’s discussions about current issues and the ways these issues connect to the lived experiences and backgrounds of outsider artists. After doing some research, the teens explored, through drawing, personal connections to an artist of their choice.

in these uncertain times, expanding on the idea of what makes a home “home” for them. They drew upon their knowledge of artists such as Wesley and Ricky Willis, Martín Ramírez, and Emery Blagdon, seeing how these artists focused their work on community, home and healing. The teens also considered the practices and mediums self-taught artists use and how to implement these techniques into their projects: three-dimensional, diorama-like pieces about comfort and healing. Some are based in reality and others are more imaginary, but they portray and reflect the teens’ hopes, desires and personal backgrounds. This project not only encouraged the teens to identify and produce safe spaces but fostered a sense of belonging, encouraging them to take up space, envisioning a future and imagining what is possible.

Next, the teens visited Weinberg/Newton Gallery to see Key Change, an exhibition focused on housing and land inequity. These activities served as catalysts for profound conversations pertaining to social justice issues, and the teens responded by reimagining their homes and rooms as a means to identify safe spaces for themselves and others

The concept of reimagining is also at the center of the work of William Estrada, an artist and art educator at the University of Illinois Chicago and Telpochcalli Elementary. Estrada addresses inequity, migration and community in his art—urgently calling for our re-examination of public and private spaces. The IntuiTeens had the opportunity to participate in a printmaking workshop with Estrada after listening to his story and learning more about his art practice.

“I learned that everyone has a different definition of a safe space.”

—Kanchi, 2022 IntuiTeen

Left: Photo of Juno’s Safe Space

SAFE SPACES: INTUITEENS 2022

Right: Photo of Deonna’s Safe Space

In continuation of the summer’s overarching theme of safe spaces, the teens collaborated with Dr. Blair Smith from the University of Illinois UrbanaChampaign, who led a virtual artist talk about what it means to listen as an art form by paying attention to the sounds and voices of a community. Dr. Smith introduced the IntuiTeens to work done by SOLHOT (Saving Our Lives, Hear Our Truths), a youth organization with whom she has performed. SOLHOT was founded by Dr. Ruth Nicole Brown, who had a “vision for a space where Black girls could express, create and make space to be free.” Dr. Smith then demonstrated how she approaches her sound-based work, and the teens formed responses to her “Just Because” prompt.

Here are some of their responses: “Just because I am transgender doesn’t mean I’m confused, my name is Juno, and I am an artist.”

“Just because I am Indian doesn’t mean I will fit your stereotype, my name is Samia, and I am a traveler.”

“Just because I am a girl doesn’t mean I exist for you, my name is Andrea, and I am a proud descendant of strong women.”

Later in the program, the teens traveled across town to explore the exhibition Nick Cave: Forothermore at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. Forothermore spans three decades of the artist’s career. The IntuiTeens immersed themselves in the exhibit, which touched on and amplified themes of civic engagement, current social impacts and social justice issues. To conclude the summer, the IntuiTeens participated in critique sessions and prepared artist statements in response to the program’s culminating project: Identifying and (Re)Imagining Safe Spaces: An Exploration of Home:

“I learned to express my art in a different way…I chose [to make] this to see how I would create a peaceful house.”

—Deonna

“Creating this piece allowed me to explore a place in my mind where I felt entirely safe… I learned how to use the materials I found to create an image that existed in my head.”

—Samia

“I made sure to add all of my comfort items… The ofrenda is a part of my culture and brings me comfort because I struggle coping with death.”

—Juno

Top: Photo of Samia’s Safe Space

Top: Photo of Samia’s Safe Space

THE OUTSIDER

Bottom: Photo of Kanchi’s Safe Space

If you follow the literature of the folk/ outsider/self-taught art field, then you know the name of Tom Patterson. He wrote the definitive book about Eddie Owens Martin/St. EOM and Pasaquan and, with John Turner, the first major book about Howard Finster, among other achievements.

Now he’s written a memoir that includes numerous interesting anecdotes from his encounters with Martin, Finster and other figures from the world of folk and outsider art, including the folklore professor who explained why

THE TOM PATTERSON YEARS: CULTURAL ADVENTURES OF A FLEDGLING SCRIBE

the outputs of creators like Martin and Finster weren’t folk art. That assessment is old hat now, but, for Patterson, his experience came before the term wars had worn themselves out.

The Martin stories are some of the best, making clear that weed was essential to managing one’s relationship with the Saint. Patterson shares lots of anecdotes, but no spoilers here.

BOOK REVIEWS

Photo / The Tom Patterson Years: Cultural Adventures of a Fledgling Scribe by Tom Patterson. Hiding Press/Jargon, 208 pages, 10 pages of photographs, 2021. ISBN 9781733709897. Paperback, $18

In any case, I can recommend this book with but a single reservation: While there is plenty of material about the world of self-taught art, the bulk of the volume really focuses on Patterson’s young adulthood in Atlanta. His account of early 1980s southern bohemianism is admirably detailed and well worth the read in its own right. It was an appealing world and an appealing life.

BOOK REVIEWS | THE TOM PATTERSON YEARS

31

His account of early 1980s southern bohemianism is admirably detailed and well worth the read in its own right.

BOOK REVIEWS

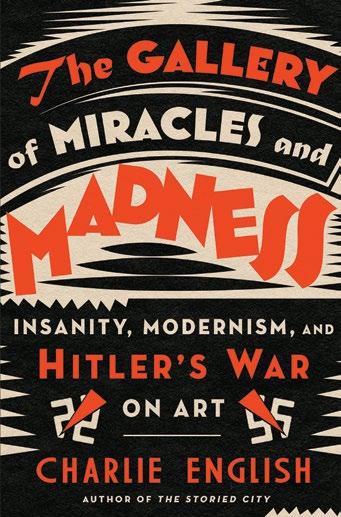

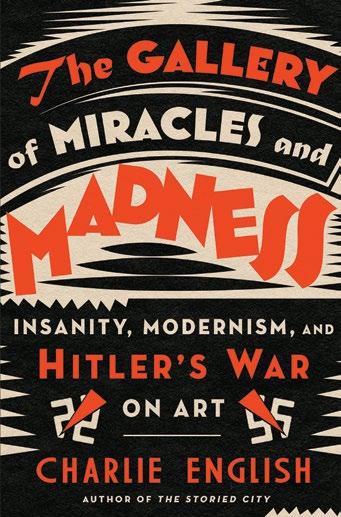

Charlie English begins his history of Nazi cultural preoccupations—and the genocides that followed—with the story of Franz Karl Buhler, a German blacksmith who turned painter after he was overtaken by mental illness and entered an asylum. He also was an artist collected by the pioneering psychiatrist Hans Prinzhorn (who gave him the pseudonym Franz Pohl), and he was as well an early victim of Nazi genocidal policies.

THE GALLERY OF MIRACLES AND MADNESS: INSANITY, MODERNISM, AND HITLER’S WAR ON ART

BY CHARLIE ENGLISH

BY CHARLIE ENGLISH

Prinzhorn, and his famous collection of art by asylum inmates, played a major role in Germany’s 20th-century culture wars, up to and including the Nazi’s assault on what they called “degenerate” art, an assault that ultimately included murder as well as ridicule.

I had viewed the Nazi concern with this art as a weird and unfortunate example of their bad taste and manipulative cultural policies—but not nearly as bad as what followed. English makes the case that Nazi art policies were a forerunner and, ultimately, an integral part of the Holocaust.

And for those of us whose interest in Prinzhorn has extended little beyond the art brut he championed, English supplies fascinating and horrifying context. That includes a good deal of detail on Prinzhorn’s life. Besides being a physician and earning a Ph.D. in art history, he was a

32 THE OUTSIDER

English makes the case that Nazi art policies were a forerunner and, ultimately, an integral part of the Holocaust.

professionally trained singer and translator, among other things. And a man who had his own stumbles. In 1921 he diagnosed himself as “an unstable psychopath with hysterical traits.” And in 1932 he evinced sympathy for Hitler and the Nazis, admiring Hitler’s leadership abilities, it seems, and the prospect of national renewal, though he appears to have repented of that view before his death in 1933 as the Nazis consolidated their power.

Whatever his own flaws, as English says, Prinzhorn “rescued art from the diagnostic clutches of psychiatry and placed the previously despised art of the mentally ill on a pedestal, equal to or higher than that of some of the most vaunted artists in German history.”

English, a former arts editor and head of international news for The Guardian, gives Prinzhorn and the power of the art he championed their due, but he devotes the rest of the book to the dark side of artistic engagement. Adolph Hitler, it seems, was just as passionate about art as Prinzhorn and his modernist admirers, and that passion fueled Hitler’s monomaniacal vision.

“Art gave Hitler a higher political purpose,” English writes, believing “the Germans would be judged by the quality of their cultural achievements and their monuments… From every platform, [Hitler] styled a culture war, exploited the widespread antipathy Germans felt for modernity and modernism.”

Carl Schneider, the Nazi psychiatrist who later headed the Heidelberg Clinic where Prinzhorn had worked, put the Nazi view this way: Prinzhorn, by putting art all on one level, “whether it was a Rembrandt or a child’s scribble … opened the door to ‘art for every good-for-nothing,’ as anyone, however inartistic, could claim metaphysical authority for his need for expression.”

We might take Schneider’s comments as something of a backhanded endorsement of what came to be called art brut. But that’s trivial compared with the upshot of this particular culture war. The Holocaust got underway with the murder—the Nazis called it euthanasia—of the disabled, a group that included at least 30 Prinzhorn artists (so far identified), including Franz Karl Buhler.

This is a book about art and culture, but the culture wars in Germany in the early 20th century were inseparable from politics— just as they seem today. English does not mention the current crop of aspiring authoritarian leaders around the world riding the wave of those wars, and comparisons of any of them to Hitler tend toward the facile. However, one of his main points is that Hitler’s passion for art was an engine of his charisma, which would have been nonetheless important if he hadn’t surrounded himself with a talented coterie of officials. That such a combination had devastating results for everyone and could again is the ultimate message of this book.

Swislow

Photo / The Gallery of Miracles and Madness: Insanity, Modernism, and Hitler’s War on Art by Charlie English. Random House, 336 pages, 16 pages of plates, 2021. ISBN: 9780525512059. Hardcover, $28

33

“From every platform, [Hitler] styled a culture war, exploited the wide-spread antipathy Germans felt for modernity and modernism.”

William

BOOK REVIEWS | THE GALLERY OF MIRACLES AND MADNESS

SYMPOSIUM

34

FIRST CONVERSATIONS

ARTISTS

SERIES INCLUSIVITY FOR ARTISTS WITH DISABILITIES All panels were held at the Chicago Cultural Center’s Claudia Cassidy Theater and on Zoom. If you missed the series or would like to watch again, you can find the recordings in the Artists First Conversations playlist on Intuit’s YouTube channel. October 15 The Relationship Between Art Making and Mental Health November 19 The Ethics of Exhibiting Artists with Neurodevelopmental and Mental Health Disabilities December 10 How Artists with Disabilities Fit into the Greater Art World SPONSORED BY KIYOKO LERNER & THE NATHAN AND KIYOKO LERNER FOUNDATION WITH ADDITIONAL SUPPORT FROM THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS AND INTUIT: THE CENTER FOR INTUITIVE AND OUTSIDER ART • HELD IN TANDEM WITH THE CHICAGO CULTURAL CENTER EXHIBITION ARTISTS FIRST: TWENTY-FIVE YEARS OF STUDIO ART AT THRESHOLDS • CO-PRESENTED BY THE DEPARTMENT OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS AND SPECIAL EVENTS

Thank you, donors! Mounting inspiring exhibitions, public programs, outreach initiatives and scholarship is made possible by a dedicated community of supporters.

SEPTEMBER 2021–AUGUST 2022

$50,000+

Robert A. Roth • Terra Foundation for American Art

$25,000–$49,999

Alphawood Foundation Anonymous Jean and Lewis Greenblatt ◊ Eugenie Johnson • Jeanne Ruddy and Victor F. Keen r Jan Petry ◊ Dorothea and Leo Rabkin Foundation

$15,000–$24,999 Janet and Craig Duchossois Illinois Arts Council Agency Ashley and Michael Joyce

$10,000–$14,999

John C. Jerit r Kelly Jones James Kaufmann

Debra Kerr ◌ and Steven D. Thompson Angela Lustig and Dale E. Taylor Angie Mills Stacy Wells ◊ and Rick Farrell Tom Yoder

$5,000–$9,999

Leslie Tcheyan and Edward V. Blanchard Community Foundation Santa Cruz County Josh Feldstein Ellen M. Glassmeyer Corvova Lee and Robert M. Greenberg Joan and Charles Gross William B. Hinchliff JoAnn Seagren and Scott Lang ◊ Stella Lee and Michael McCluggage Sherry Siegel and Robert Alter Nikki and Fredric Stein Michael Sullivan ◊ Minna and Charles Taylor Dr. David Walega

Planned gifts of assets, cash, art, stock and more help to inspire future audiences through outsider and selftaught art programs. Please let us know about your plans so you may receive Legacy Society benefits. Learn more by contacting Claire Fassnacht, development manager, at (312) 624-8000 or claire@art.org.

35

SUPPORT

SUPPORT

YOU ALREADY INCLUDED INTUIT IN YOUR WILL, TRUST OR IRA?

TIONS

HAVE

$1,000–$4,999

Bobette Ash

Susan Baerwald r

Judith and Patrick Blackburn ◊

Richard Bowen ◊

Leslie Kay Buchbinder

John Cain

Diane and Shev Ciral

Janet Williams and Ralph Concepcion • Deborah Doyle and David Kemerer

Sue Eleuterio and Tom Sourlis

Janet Franz and William Swislow ◊

Marjorie Freed •

Nancy Gerrie

The Joseph B. Glossberg Foundation

Jennifer and Scott Gordon

Shelley Gorson and Alan Salpeter

Moira Collins Griffin and Andrew Griffin

Robert Grossett ◊ and Christopher LaMorte

Madeleine Grynsztejn and Tom Shapiro

Carl Hammer •

Jill Heppenheimer

Tracy Holmes ◊

Marguerite Juliusson and David Montagano

Rob Lentz ◊ and MK Victorson

Sue and John Lowenberg

Frank Maresca r

Bonnie ◊ and Molly McGrath Gary Metzner and Scott Johnson César Montenegro ◊

Elizabeth Nelson ◊ and Adam Kallish Niner Foundation

Benedicta Badia ◊ and Martin Nordenstahl

Karen Patterson

Tynnetta Qaiyim ◊

Phyllis Rabineau ◊ and John Alderson

Jean Rundquist

Leisa Rundquist

Ruth Foundation for the Arts

Leslie Shad and Joseph Brennan

Eugenie Shields

Jennifer Siegenthaler and Philip Cable

Susan Manning Silverstein and Rob Silverstein

Toni Smith

Judy and Jerry Stefl ◊

Susan Stephenson

David Syrek ◊ and David Csicsko

Beverly Trier and Anthony Petullo

George Viener

Cleo Wilson ◊

Marsha Woodhouse Michelle Woods ◊

In-Kind

Paula and Gordon Addington Jean and Mike Ban

Richard Bowen ◊

Wallace Bowling and Douglas Dawson Kenneth Burkhart

Kevin Cole •

Harriet Finkelstein • Janet Franz and William Swislow ◊ Pat and Francis Fullam

Tim Garvey

Nancy Gorman

Joffrey Ballet

Eugenie Johnson • Nancy Josephson

David Kargl

Victor F. Keen r

Lookingglass Theatre Sue and John Lowenberg Angela Lustig and Dale E. Taylor

Frank Maresca r Jan Petry ◊ and Angie Mills Linda Reeves Remy Bumppo Theatre Sidra Stich

Lisa Stone • and Don Howlett Thomas McCormick Gallery Emily van der Harten p Iris Witkowsky Daniel Wojcik James Zanzi

Legacy Society

Harriet Finkelstein • Jan Petry ◊

Phyllis Rabineau ◊ and John Alderson Susan and Christopher Swales Cleo Wilson ◊ Karen Zupko

DONATIONS IN HONOR

Dana Boutin p Marsha and Edward Fogle Sean Fogle Susan Stephenson

Cheri Eisenberg ◊ Susan and Scott Glazer

Debra Kerr ◌ Gary Metzner and Scott Johnson

Scott Lang ◊ Shelley Gorson and Alan Salpeter Family Fund at The Chicago Community Foundation Maxine and Larry Snider

36 THE OUTSIDER

SUPPORT

Frank Maresca r

Janet and Craig Duchossois

The Greenberg Lee Family Charitable Fund

The Charles and Joan Gross Family Foundation Mary Anne Hunting and Thomas H. Remien

Molly McGrath

Bonnie McGrath ◊

Jan Petry ◊

Judith and Patrick Blackburn ◊ Joan and Hank Bliss Richard Bowen ◊

Wallace Bowling and Douglas Dawson

Dianne Bowman Mitchell Darch Angela D’Aversa Cheri Eisenberg ◊ Janet Franz and William Swislow ◊ Marjorie Freed • Charlotte Glashagel David Greene Karen Haring William B. Hinchliff Lois and James Darwin Hobart Tracy Holmes ◊ Marguerite Juliusson

Debra Kerr ◌ and Steven D. Thompson Susan Lane Jack Levin Sue and John Lowenberg Patricia Lunkes Nancy McDaniel Angie Mills David R. Montagano Virginia Nemmers Eve and Ed Noonan Lisa Zschunke and Aron Packer Barbara Provus Mary and Bruce Rigdon Laurie and Regan Romei Leisa Rundquist Keith Sadler Eugenie Shields Toni Smith

Judy and Jerry Stefl ◊ Susan Stephenson Michael Sullivan ◊ Minna and Charles Taylor Soraya and Robert Tonos Frederick Wackerle

Jan Petry ◊ and Angie Mills

Laurie Rosenow

Lisa Stone • Karen Patterson

William Swislow ◊ Lee Swislow

Dr. David Walega Leslie Kay Buchbinder

Cleo Wilson ◊ Kelly Jones Robert A. Roth • Tom Yoder

Cleo Wilson ◊ and Robert A. Roth • Stella Lee and Michael McCluggage

DONATIONS IN MEMORY Philip Carey Ian Carey

Susann Craig • Mary A. Allen Laurie Baskin and Steve Fadem Sharon Craig Carolyn Fineran Moira Collins Griffin and Andrew Griffin Martha Henry Jean Iker

Debra Kerr ◌ and Steven D. Thompson Barbara Manning Lois J. Mikos Mary and Bruce Rigdon Robert A. Roth • Gail and John Steffen Judy and Jerry Stefl ◊ Susan Stephenson Toko Enterprises, LLC Adriane and Scott Turow

William Fagaly Micki Beth Stiller

Norma Dlouhy Mantooth James and Anna McColl

Intuit strives to provide the most accurate information. Please notify Claire Fassnacht, development manager, at claire@art.org with any needed corrections.

Board of Directors ◊ Vivian Society • Strategic Advisory Council r

Staff ◌ Young Professionals Board p

37 SUPPORT

LEADERSHIP

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Tracy Holmes, President

Patrick Blackburn

Richard Bowen

Tim Bruce Robert Burnier

Cheri Eisenberg Lewis Greenblatt Rob Grossett Scott Lang Rob Lentz

Bonnie McGrath César Montenegro Elizabeth Nelson

Benedicta Badia Nordenstahl Jan Petry

VIVIAN SOCIETY (LIFE TRUSTEES)

Kevin Cole Ralph Concepcion Susann Craig • Harriet Finkelstein

Marjorie Freed Carl Hammer

Eugenie Johnson Ann Nathan Bob Roth Judy Saslow Lisa Stone

• Deceased

STAFF

Debra Kerr, President and CEO

Tynnetta Qaiyim Phyllis Rabineau Kevin Sampson Maya Sonal Patel, MBA board fellow Jerry Stefl Michael Sullivan William Swislow David Syrek Stacy Wells Cleo Wilson Zachary Wirsum Adam Wolford Michelle Woods Shawn Grenald, ex officio

YOUNG PROFESSIONALS BOARD

Shawn Grenald, President Isabel Axon-Sanchez Spencer Blaney Gabriella Bomben Dana Boutin

STRATEGIC ADVISORY COUNCIL

Scott Lang, Chair Susan Baerwald Michelle Boone John Jerit Victor F. Keen Ashley Smither Langley John Maizels Frank Maresca Douglas Robson Leslie Umberger

Teddy Braziunas Wyatt Buescher Jane Castro Sofia Coulson Marilyn Creswell Ben Fisher Katherine Gorman Payton Head Emma Kearney Catherine LaMendola Katherine Lelek Erin Madarieta Lail Marmor Jen Moss Tyler Roberts Khushi Suri Emily van der Harten Jessica Wain

Annaleigh Wetzel Fabiola Yep Leah Zuberer

Charlie Miller, Preparator

Alison Amick, Senior Manager of Exhibitions and Development, Chief Curator

Julie Blake, Special Projects and Merchandising Coordinator

William Deschler, Finance and Operations Manager

Claire Fassnacht, Development Manager

Tina Horton, Development Associate

Claire Renaud, Assistant Registrar

Christina Stavros, Registrar and Curatorial Assistant Larry (Tate) Tate, Guest Services Associate

Courtney Thompson, Senior Manager of Learning and Engagement

Joshua Willis, Guest Services Associate Lindsey Wurz, Marketing and Communications Manager

38 THE OUTSIDER

CIELO AGUILERA

Cielo Aguilera is a Chicago-born artist studying K–12 art education at the University of Illinois UrbanaChampaign. She is an alumna of Morton College in Cicero, Ill., where she earned her Associate in Fine Arts. Aguilera first joined Intuit in 2021 as the museum’s first Emerging Museum Professional Fellow, returning in 2022 as the Youth Programs Associate. Her teaching philosophy is centered around educational equity, diversity and inclusion.

TOM DI MARIA

Tom di Maria has served as Creative Growth Art Center’s director since 2000. As director, he develops partnerships with museums, galleries and international design companies to help bring Creative Growth’s artists with disabilities fully into the contemporary art world. He speaks around the world about the Center’s artists and their relationship to both outsider art and contemporary culture.

ANNALISE FLYNN

Annalise Flynn is an independent art historian and curator based in Sheboygan, Wisc. She manages SPACES (Saving and Preserving Arts and Cultural Environments), the world’s largest repository of archival documentation related to artist-built environments, on behalf of the Kohler Foundation in Kohler, Wisc.

CONTRIBUTORS

Bill Swislow is an Intuit board member and frequent contributor to The Outsider. He is a digital business consultant, a writer and the operator of www. interestingideas.com, a website dedicated to vernacular culture, outsider art and oddball ideas.

SPECIAL THANKS:

Elizabeth Nelson, Design Management

COURTNEY THOMPSON

Courtney Thompson is the senior manager of learning and engagement at Intuit. They have a bachelor’s in Spanish and master’s in higher education from James Madison University. Their love for intuitive art and education comes from their practice as a self-taught painter and mosaic tile teaching artist. Through educational programming, Thompson strives to create an environment and thriving community where individuals can be their authentic selves at Intuit and beyond.

VINCENT URIBE

Vincent Uribe (@vcentu) is a creative community builder. As Founding Director of LVL3, he’s organized hundreds of exhibitions featuring emerging and mid-career artists. At Arts of Life, he launched the Circle Contemporary galleries and facilitated exhibitions for artists with intellectual and developmental disabilities at the Chicago Cultural Center, Art on the MART and the Ukrainian Institute of Modern Art. Uribe serves as a founding board member for Equity Arts.

39

LEADERSHIP / CONTRIBUTORS

Jennifer Bennett Walker, Design Lindsey Wurz, Managing Editor of The Outsider

40 THE OUTSIDER (312) 624-9487 www.art.org @intuitartcenter 756 N. Milwaukee Avenue Chicago, IL 60642 intuit@art.org

By Vincent Uribe

By Vincent Uribe

Ace Parson in the window of his Rainbow House in Vancouver, Wash., in 1995 by Ted Degener.

Photo courtesy Ted Degener

Ace Parson in the window of his Rainbow House in Vancouver, Wash., in 1995 by Ted Degener.

Photo courtesy Ted Degener

Mary Proctor’s Art Yard in Tallahassee, Fla., in 1997 by Ted Degener. Photo courtesy Ted Degener

Mary Proctor’s Art Yard in Tallahassee, Fla., in 1997 by Ted Degener. Photo courtesy Ted Degener

Photo by John Faier

Photo by John Faier

Top: Photo of Samia’s Safe Space

Top: Photo of Samia’s Safe Space

BY CHARLIE ENGLISH

BY CHARLIE ENGLISH