54 minute read

FIGURE 3- VEGETATIVE COMMUNITIES

4.2- VEGETATIVE COMMUNITIES

The descriptions that follow provide a brief overview of the predominant vegetative communities and land uses found on the Island. Vegetative communities with similar structure and/or ecological characteristics, such as forested wetlands and herbaceous wetlands, have been grouped within these overviews. Several vegetative communities with smaller areal extent or ruderal characteristics were not included in this overview, but all the communities are described in information provided by GADNR in Appendix D.

Each of the following overviews includes:

vegetation classification description maintained by

• General Vegetation Category, including US Vegetation Classification designation(s) and corresponding number on Figure 3

• A brief Description of the current structure of each habitat

• Key Ecological Attributes that consist of ecological or biological characteristics on which the habitat a 50-year period

composition, structure, or aesthetic depends. Alteration of these characteristics could lead to the loss of the habitat type over time

• Underlying Soil types based on the mapping efforts included in the USDA Soil Survey of Camden and Glynn Counties, Georgia, 1980

• Acreage and Percentage that each vegetative community/land cover occurs on within the Island

• Dominant Vegetation (by stratum if appropriate)

• Other Typical Plant Species found within the • A description of the Current Conditions of the structure, diversity, hydrology, fuel loads, or other characteristics relevant to defining management goals

• Global Rarity Ranking based on the global ranks identified in the Conservation Status section of the NatureServe

• Threats and Stresses to the integrity, function, and/or aesthetic of each land use/vegetative community listed in order of priority to be addressed,

• Wetland Status based on Environmental Setting designations within the associated NatureServe vegetation classification

• Desired Future Conditions for the community that would be obtained with appropriate management over vegetation type

4.2.1- MARITIME HAMMOCKS

• MARITIME LIVE OAK HAMMOCK (1) • SOUTHEASTERN FLORIDA MARITIME HAMMOCK (2)

Description: Mature upland forests of mixed old-age canopy dominated by live oak, sand live oak, and other oak species, minimal (Live Oak Hammock) to moderately dense (Florida Maritime Hammock) mid-story, and diverse understories ranging from dense saw palmetto to open shrub layers with minimal herbaceous plants

Key Ecological Attributes:

Mature forest canopy composition and structure; broad areas with intact habitat; canopy species that are sensitive to fire

Underlying Soils:

Cainhoy fine sand, 0-5% slopes; Fripp-Duckston complex, 0-20% slopes; Mandarin fine sand; Meggett fine sandy loam; Pelham loamy sand

Acreage/Percentage of the Island: 1,160/19.8

Dominant Vegetation:

• Dominant Canopy/Subcanopy Vegetation: live oak, sand live oak (Florida Maritime Hammock), sand laurel oak, slash pine, red bay, cabbage palm

• Dominant Shrub Vegetation: saw palmetto, beauty berry, sparkleberry, eastern red cedar, wax myrtle, yaupon holly, rusty staggerbush (Florida Maritime Hammock), fetterbush (Florida Maritime Hammock)

• Dominant Herbaceous Vegetation: witchgrass, slender woodoats, foxtail, basketgrass, whip nutrush Other Typical Vegetation: blackberry, catbrier, American holly, Spanish moss, witchgrass, switchcane, resurrection fern, eastern gamagrass, muscadine, tough bully, pigeonwings

Current Conditions: Variable canopy characteristics and understory conditions range from mature canopies of pine and sand laurel oak, with frequently high fuel loads from leaf litter and saw palmetto, to mixed canopies of live oak and pine over an open shrub and groundcover layer, to multi-aged stands of large live oak over a dense understory composed almost exclusively of saw palmetto and rusty lyonia. Areas with saw palmetto exhibit other fire dependent/resilient herbaceous and shrub species. For most canopy areas, the canopy is primarily mature with few multi-aged saplings/young trees present, although the number of saplings is more pronounced in the southern portion of the Island within this habitat.

Threats and Stresses:

• Habitat fragmentation and loss from new development uses or modifications to existing uses

• High fuel loads and extensive fuel “laddering” on or adjacent to fire-sensitive canopy species that could expose the community to destructive, stand-altering fires • Undesirable fire applications due to factors such as campfires, discarded cigarettes, and improper fire prescription • Invasive floral and faunal exotic species infestations • Loss of red bay trees from laurel wilt • Limited regeneration of canopy species due to factors such as deer over-browsing and lack of appropriate recruitment conditions (e.g., open soils, fire)

Wetland Status: No

Global Rarity Ranking:

G1 Critically Imperiled

G2 Imperiled

G3 Vulnerable

G4 Apparently Secure

Desired Future Conditions: Intact aggregations of mature canopy supplemented by multi-aged saplings with a diversity and structure of native species, including epiphytes, and minimal fuel loads composed of duff, herbaceous, and low-growing shrub vegetation that reduce the potential for destructive, uncontrolled fires

4.2.2- PINE FORESTS

• MARITIME SLASH PINE UPLAND FLATWOODS (5) • MID- TO LATE- SUCCESSIONAL LOBLOLLY PINE - SWEETGUM FOREST (6)

Description: Mature upland forests of pine-dominated, typically old-age canopy, minimal midstory, and diverse understories

Key Ecological Attributes:

Mature pine canopies with scattered oaks; diverse understory of fire dependent/resilient species; habitat continuity with other vegetation types

Underlying Soils:

Mandarin fine sand; Mandarin-Urban Land Complex; Pelham loamy sand; Rutledge fine sand

Acreage/Percentage of the Island: 1,160/19.8

Dominant Vegetation:

• Dominant Canopy/Subcanopy Vegetation: slash pine, live oak, red/swamp bay, loblolly pine, sweetgum

• Dominant Shrub Vegetation: saw palmetto, wax myrtle, eastern red cedar, yaupon holly, fetterbush

• Dominant Herbaceous Vegetation: sparse; rockrose, silkgrass, brackenfern, goldenrod

Other Typical Vegetation: catbrier, Spanish moss, witchgrass, switchcane, prickly-pear, pigeonwings, deerberry, muscadine, sea oxeye, elephant’s foot, beautyberry, St. Andrews cross, coral bean, camphor tree, blackberry, Virginia chainfern Current Conditions: Pine dominates the canopy throughout with scattered occurrences of live oak and other canopy species. Understory conditions range from dense saw palmetto (less common) and yaupon holly to more open shrub-dominated areas with herbaceous species present. Portions have recently been burned, reducing fuel loads, but much of this type exhibits high fuel loads from leaf litter and saw palmetto. Pond pine is present as a sub-dominant pine forest canopy species in much of the Island’s central interior, generally in association with lower elevation.

Threats and Stresses:

• Habitat fragmentation and loss from new development uses or modifications to existing uses, • High fuel loads that could expose the community to destructive, stand altering fires, • Limited ability to apply prescribed fire due to restrictions such as smoke management and fire control measures posed by adjacent land uses, • Limited regeneration of canopy species due to factors such as lack of appropriate recruitment and seed production conditions (e.g., open soils, fire) and deer over-browsing, • Undesirable fire applications due to factors such as campfires, discarded cigarettes, and improper fire prescription, • Invasive floral and faunal exotic species infestations, and • Vulnerability to pest species such as southern pine beetle.

Wetland Status: No

Global Rarity Ranking:

G1 Critically Imperiled

G2 Imperiled

G3 Vulnerable

G4 Apparently Secure

Desired Future Conditions: A multi-age canopy composed of pine, live oak, and other native canopy species with a relatively open, diverse herbaceous and shrub layer characterized by low fuel loads that support occasional, low- intensity fires

4.2.3- FORESTED WETLANDS

• OUTER COASTAL PLAIN SWEETBAY SWAMP FOREST (7) • LOBLOLLY-BAY FOREST (8), RED MAPLE – TUPELO MARITIME SWAMP FOREST (9)

Description: Freshwater forested wetland systems with dense canopies, open shrub and herbaceous layers

Key Ecological Attributes:

Freshwater hydrology; diverse, mature canopy structure; hydric soils

Underlying Soils:

Rutledge fine sand

Acreage/Percentage of the Island: 72/1.2

Dominant Vegetation:

• Dominant Canopy/Subcanopy Vegetation: red maple, loblolly bay, slash pine, dahoon holly, black tupelo, swamp bay

• Dominant Shrub Vegetation: wax myrtle, swamp bay, buttonbush, fetterbush

• Dominant Herbaceous Vegetation: slender woodoats, sedges, lizard’s tail, cinnamon fern, Virginia chainfern

Wetland Status: Yes Other Typical Vegetation: peppervine, plume grass, muscadine, Spanish moss, Virginia creeper, hempweed, switchcane, cabbage palm, bluestem, netted chainfern, pennywort, blackberry

Current Conditions: Encroachment of transitional vegetation; death of wetland canopy species may be indicative of hydrological alteration; canopy composition changed by death of bay trees from redbay ambrosia beetle/laurel wilt fungus; herbaceous layer has grown densely in portions that have open canopies; large numbers of canopy trees have fallen and are lying on the ground in loblolly bay forest and red maple – swamp blackgum forest; golf course channels and pond systems along with regional groundwater changes may be affecting hydrology; upper reaches of systems have begun transition to upland vegetation

Threats and Stresses:

• Local and potentially, regional hydrology alterations due to groundwater withdrawals • Sensitive to brackish/freshwater input changes and sea level rise • Wetland exhibits encroachment of vegetation that typically occurs on the transition between wetland and upland • Canopy loss due to laurel wilt fungus and the uncertainty associated with the long-term viability of this genus (Persea) in the forested landscape on the Island • Exotic invasive plant species infestations • High fuel loads that could expose the community to destructive, stand-altering fires • Saltwater intrusion • Climate change induced extremes in drought and precipitation

Global Rarity Ranking:

G1 Critically Imperiled

G2 Imperiled

G3 Vulnerable

G4 Apparently Secure

G4 (Loblolly Bay Forest); G3 (Outer Coastal Plain Sweetbay Swamp Forest); G2 (Red Maple – Swamp Blackgum Maritime Swamp Forest)

Desired Future Conditions: Mature-canopy of native wetland species, with natural (dynamic) hydroperiods that support a diversity of multi-aged canopy species and appropriate understory, and herbaceous vegetation at densities that do not pose a risk for catastrophic fire

• ATLANTIC COAST INTERDUNE SWALE (11); LIVE OAK - YAUPON HOLLY • (WAX-MYRTLE) SHRUBLAND ALLIANCE (12)

Description: Mosaic of dune successional vegetation stages from backdune swales to shrub thickets

Key Ecological Attributes:

Salt tolerance; hydrological inundation regime; high species and habitat diversity; adapted to dynamic movements of sand from wind and wave transport

Underlying Soils:

Beaches

Acreage/Percentage of the Island: 128/2.2

Dominant Vegetation:

• Dominant Canopy/Subcanopy Vegetation: scattered live oak and cabbage palm • Dominant Shrub Vegetation: wax myrtle, swamp/red bay, eastern red cedar

• Dominant Herbaceous Vegetation: needle rush, saltmeadow cordgrass, bluestem, rush

Global Rarity Ranking:

G1 Critically Imperiled

G2 Imperiled

G3 Vulnerable

G4 Apparently Secure

G3 (Atlantic Coast Interdune Swale); G2/G3 (Live Oak-Yaupon holly holly-(Wax Myrtle) Shrubland Alliance)

Desired Future Conditions: A dynamic variety of successional stages ranging from herbaceous interdune swales to mature live oak forests with salt-tolerant shrubs that are allowed to undergo natural processes Other Typical Vegetation: peppervine, tough bully, groundsel, Hercules’-club, plume grass, saw palmetto, lantana, pigeonwings, butterfly pea, giant foxtail, knotweed, rustweed, dune prickly-pear, prickly-pear, ragweed

Current Conditions: Undulating landscape exhibits mosaic of shrub/oak thickets on dry areas and freshwater herbaceous marshes in depressions; system exhibits high diversity in herbaceous and shrub species on an overall basis, although upland areas can be low in vegetation cover; wetland depressions range from diverse freshwater systems to needle rush flats, in part due to successional status and distance from the primary dune (measured from the south)

Threats and Stresses:

• Soil openings within community or adjacent vegetation types may lead to wind erosion • Sensitive to overwash if adjacent dunes are altered • Habitat fragmentation and loss from new development uses or modifications to existing uses • Sea-level rise from climate change may alter vegetation composition and soils in recently established interdune swales, • Exotic species infestations, including pathogens (such as the fungus Raffaelea lauricola, which is transmitted by the invasive ambrosia beetle (Xyleborus glabratus) and has wreaked havoc on redbay trees across the Island) • Development in adjacent lands may limit seed sources for succession • Sensitive to alterations in the timing, salinity, and duration of water discharges from adjacent development • Early successional areas may be sensitive to recreation uses • Deer over-browsing may limit recruitment of shrub and canopy species • Unauthorized foot traffic • Lack of sediment deposition • Loss of habitat due to woody encroachment and lack of fire • Limitations to the landward migration of this community type associated with climate change and sea level rise due to adjacent development

Wetland Status: Yes

4.2.5- SALTMARSH ISLAND/ECOTONES

• RED-CEDAR - LIVE OAK - CABBAGE PALMETTO • MIDDEN WOODLAND (4); COASTAL SALT SHRUB THICKET (13)

Description: Isolated patches of live oak and cedar forest and/or shrubland with scattered palms and pines with dense, salttolerant understory vegetation on small islands or peninsulas surrounded by tidal marsh, some underlain by high-calcium soils enriched with oyster shell material

Key Ecological Attributes:

Salt tolerance and sensitivity to salinity changes

Underlying Soils:

Mandarin fine sand; Bohickets-Capers Association (including disposed dredged material)

Acreage/Percentage of the Island: 96/1.6

Dominant Vegetation:

• Dominant Canopy/Subcanopy Vegetation: live oak, southern red cedar, cabbage palm, slash pine (Shrub Thicket), black cherry (Shrub Thicket), Hercules-club (Shell Midden), sugarberry (Shell Midden)

• Dominant Shrub Vegetation: Marsh Hammock - saw palmetto; Shell Midden - Florida wild privet, climbing buckthorn, soapberry, saw palmetto, yaupon holly, erect prickly-pear, Spanish bayonet; Shrub Thicket - wax myrtle, red cedar, groundsel, marsh elder, yaupon holly, salt cedar, lantana

• Dominant Herbaceous Vegetation: sparse; rockrose, silkgrass, brackenfern, goldenrod

Other Typical Vegetation: coral bean, needle rush, trumpet vine, poison ivy, tough bully, muscadine, Virginia creeper, red/ swamp bay, Spanish moss Current Conditions: Occur on salt marsh ecotones as well as sand ridges and islands, including a shell midden and dredge spoil, surrounded by salt marshes in southern portions of Island; successional communities representing transition from highelevation areas in marsh communities to live oak hammocks as land and soil accretes around the vegetation; calcium-loving species occur as codominants in the canopy and/or shrub layers of the Shell Midden, including several Georgia Special Concern plant species; salt cedar (exotic) present in many locations; trees at lower elevation margins exhibiting decreased vigor, potentially due to hydrologic or salinity changes

Threats and Stresses:

• Invasion and expansion of area occupied by salt-tolerant exotic species • Potential declines in native cactus species from non-native cactus moth, • Succession to closed-canopy mixed pine and oak forest • Limited regeneration of canopy species due to factors such as lack of appropriate recruitment, seed production conditions (e.g., open soils, fire) and deer over-browsing • Wave erosion of dredge spoil island • Hydrological alterations in the adjacent marshes and rivers • Sea level rise impacts to community through inundation • Undesirable fire applications due to factors such as campfires and improper fire prescription

Wetland Status: Yes (Shrub Thicket) No (Marsh Hammock, Shell Midden)

Global Rarity Ranking:

G1 Critically Imperiled

G2 Imperiled

G3 Vulnerable

G4 Apparently Secure

G3 (Red Cedar – Live Oak – Cabbage Palmetto Marsh Hammock); G2 (South Atlantic Coastal Shell Midden Woodland); G4 (Coastal Shrub Thicket)

Desired Future Conditions: Multi-age canopy of native oak, cedar, and shrubs (Marsh Hammock), calcium-loving and other shrub species (Shell Midden), or a mixture of native pine and oak and salt-tolerant shrubs (Salt Shrub) that grade into the adjacent coastal marsh

4.2.6- DUNES

• SEA OATS TEMPERATE HERBACEOUS ALLIANCE (15)

Description: Primary dune dominated by sea oats

Key Ecological Attributes:

Salt tolerance; dune formation; vegetation composition and structure of species that contribute to dune formation/ stabilization

Underlying Soils:

Beaches

Acreage/Percentage of the Island: 66/1.1

Dominant Vegetation:

• Dominant Herbaceous Vegetation: sea oats

Other Typical Vegetation: bitter seabeach grass, southern saltwort, fleabane, butterfly pea, pigeonwings, dune primrose, largeleaf pennywort, sandspur, beach elder, saltmeadow cordgrass, railroad vine, beach croton, fiddleleaf morning-glory, yucca, seashore dropseed Current Conditions: Extensive natural primary dune in southern portions of Island; successful restoration of dunes has occurred in central portion of Island; variable degrees of disturbance occur throughout Island from pedestrian traffic and authorized motor vehicle use on beach

Threats and Stresses:

• Highly sensitive to human en croachment • Soil destabilization • Vegetation loss • Availability of native dune species propagules/plants for regeneration, including sea oats • Wave erosion • Vegetation re-establishment within restoration areas • Exotic species infestations such as salt cedar and beach vitex • Sea level rise may impact sea oats communities at lowest elevations of dunes or lead to dune erosion • Beach armoring or alterations may affect dune formation processes • Authorized beach driving • Deer grazing • Actions that alter natural patterns of sand transport and accretion

Wetland Status: No

Global Rarity Ranking:

G1 Critically Imperiled

G2 Imperiled

G3 Vulnerable

G4 Apparently Secure

Desired Future Conditions: Robust and continuous dunes steadily accreting following storm events, supporting stable or increasing populations of nesting sea turtles and shorebirds, and stabilized by a diverse dune plant assemblage free of nonnative, invasive species

4.2.7- FRESHWATER HERBACEOUS WETLANDS

(SOUTHERN ATLANTIC COASTAL PLAIN CAROLINA WILLOW DUNE SWALE (10), SAND CORDGRASS – SEASHORE MALLOW HERBACEOUS VEGETATION (16), SOUTHERN HAIRGRASS – SALTMEADOW CORDGRASS – DUNE FINGERGRASS HERBACEOUS VEGETATION (17), SOUTH ATLANTIC COASTAL POND (18), SAWGRASS HEAD (20)

Description: Freshwater herbaceous/shrub wetlands dominated by cordgrass or sawgrass in herbaceous wetlands and Carolina willow and large-flowered hibiscus in the shrub wetlands

Key Ecological Attributes:

Freshwater hydration sources; herbaceous community structure; inundation regimes

Underlying Soils: Rutledge fine sand

Acreage/Percentage of the Island: 29/0.5

• Carolina Willow Dune Swale: Carolina willow, large-flowered hibiscus, dotted smartweed, royal fern, peppervine, hemp weed, wax myrtle, lizard’s tail, pennywort, false nettle

• Cordgrass Communities - sand cordgrass, southern hair grass, saltmeadow cordgrass, dune fingergrass, wax myrtle, dog fennel, frog bit, fleabane, rush, bluestem, blackberry, ragweed, knotweed

• Sawgrass Head - sawgrass, Carolina willow, buttonbush, black tupelo, thistle, blackberry, dog fennel, peppervine, wax myrtle, cabbage palm, lizard’s tail

Wetland Status: Yes Current Conditions: Encroachment of transitional vegetation; death of wetland shrubs/decrease in area covered by wetland herbaceous species may be indicative of hydrological alteration in cordgrass and sawgrass head communities; staining on willows indicate periodic inundation for sawgrass head, but inundation length may not be sufficient to maintain historical wetland type; all communities except for Carolina willow dune swale appear to be transitioning to a different, potentially non-wetland, vegetation type; Carolina willow dune swale home to large-flowered hibiscus

Dominant Vegetation:

Threats and Stresses:

• Regional and local (on-Island) groundwater withdrawals • Encroachment of transitional and upland vegetation, development in adjacent uplands could alter surface water hydrology inputs • Excavated pond near landfill effects on surface hydrology of sawgrass head • Exotic species infestations • Sea level rise changes to salinity and tidal movement in freshwater marshes connected to coastal marsh • Shrub growth due to inundation regime alterations and/or altered fire patterns • Deer grazing.

Global Rarity Ranking:

G1 Critically Imperiled

G2 Imperiled

G3 Vulnerable

G4 Apparently Secure

G3/G4 (Southern Atlantic Coastal Plain Carolina Willow Dune Swale); G3 (Sand Cordgrass – Seashore Mallow Herbaceous Vegetation); G2 (Southern Hairgrass – Saltmeadow Cordgrass – Dune Fingergrass Herbaceous Vegetation); G3 (South Atlantic Coastal Pond); G2 (Sawgrass Head)

Desired Future Conditions: Freshwater marshes and/or prairies with appropriate shrub growth that exhibit natural (dynamic) hydroperiods and support a diversity of native understory and herbaceous vegetation and wildlife

4.2.8- TIDAL MARSHES

• SOUTHERN ATLANTIC COASTAL PLAIN SALT AND BRACKISH TIDAL MARSH (21)

Description: Herbaceous-dominated tidal marshes interspersed with creeks and saltpans

Key Ecological Attributes:

Tidal water fluctuations; water depth and residence time; salinity levels

Underlying Soils:

Bohicket – Capers Association

Acreage/Percentage of the Island: 1,755/30

Dominant Vegetation:

• Marsh: smooth cordgrass, glasswort, saltwort, salt grass, needle rush

• Marsh Border: sea oxeye, eastern red cedar, groundsel, marsh elder, salt cedar, cabbage palm, fleabane Current Conditions: Tidally influenced herbaceous systems often coupled with tidal channels/creeks; community type exhibits multiple plant zones depending on salinity/ inundation regimes; plant zones include creek levees, low and high marsh, needle rush and shrub marsh borders, saltpans with limited vegetation, and small shrub islands; portions of the habitat were impounded creating generally open water bodies with variable salinity levels; recreation trails occur on the margins of portions of this habitat; sensitive to brackish/freshwater input changes

Threats and Stresses:

• Alteration in tidal flow patterns, • New or altered freshwater, pollutant, and nutrient inputs • Historical impoundments • Incompatible recreation uses • Existing trail effects on hydrology • Development in adjacent uplands that alters surface water flow patterns • Historical channel dredge spoil deposition • Exotic species invasion including salt cedar on margins and low islands • Vegetation zonation changes from increased salinity and higher tidal reach resulting from sea level rise • Armoring of creek banks or channels with riprap or other hard surfaces • Broad-scale pesticide application to minimize mosquito growth may affect wildlife in upper trophic layers • Florida-native species, such as the mangrove tree crab migrating north as a result of climate change

Wetland Status: Yes

Global Rarity Ranking:

Common

Desired Future Conditions: Predominantly herbaceous communities characterized by multiple plant zones consistent with variable salinity and inundation from tidal fluctuations, dissected by natural creek channels

4.2.9- BEACH

• SOUTH ATLANTIC UPPER OCEAN BEACH (22)

Description: Open sand beaches including the upper beach and subtidal and intertidal sand shoals

Key Ecological Attributes:

Tidal cycle; sand movement; tidal wrack; erosion and accretion

Underlying Soils:

Beaches

Acreage/Percentage of the Island: 295/5

Dominant Vegetation:

• Dominant Herbaceous Vegetation: southeastern sea rocket and/or limited to no other vegetation

Other Typical Vegetation: csaltmeadow cordgrass, railroad vine, beach croton, southern saltwort, seacoast marshelder, shoreline seapurslane

Global Rarity Ranking:

G1 Critically Imperiled

G2 Imperiled

G3 Vulnerable

G4 Apparently Secure

Desired Future Conditions: Sand beaches and intertidal/ subtidal shoals constantly changing with tidal influences with scattered vegetation tolerant of high salinity, dynamic winds and moving sands providing sustained habitat value for nesting sea turtles and shorebirds. Undisturbed beaches are free of erosion control infrastructure. Engineered beaches are designed to accommodate and emulate natural processes. Current Conditions: Extensive natural primary dune in southern portions of Island; beach armoring occurs in north-central portions of historical beach; extensive areas of intertidal and subtidal sand shoals present, especially in the southern portion of the Island; variable degrees of disturbance occur throughout Island from pedestrian traffic; Generally, Driftwood Beach and northeast portion of Island exhibit reduction in width of beach due to erosional forces, while the beaches in the southern end of the Island are expanding due to accretion

Threats and Stresses:

• Requires unhindered longshore currents and up-current sand sources to naturally replenish sand • Conflicts between recreation and tourism and natural process of accretion and erosion • Installation of beach armoring such as bulkheads, groins, jetties, and rip rap that alter natural sand movements and erosion/accretion activities • Sea level rise will likely impact this community and may make it difficult for decision-makers to allow natural processes to run their course • Placement or location of structures within areas affected by predicted 100-year sea level rise • Exterior/visible lighting on buildings near sea turtle nesting areas • Motorized vehicles on the beach • Soil destabilization from pedestrian traffic • Trash associated with tidal wrack • Litter deposited by beach users and discarded by people in areas where debris can float onshore at Jekyll Island • Authorized beach driving • Human-caused disturbances for nesting and roosting shorebirds, sea turtles, and other beach inhabitants • Effects of fire ants, raccoons, and other native and invasive predators on nesting shorebirds, sea turtles, and other egg laying beach inhabitantsk

Wetland Status: No

4.2.10- URBAN DEVELOPED

• INCLUDES DEVELOPED, GOLF COURSE, PARKS & RECREATION, QUARRY/STRIPMINE/ EXCAVATED WATERBODY, TRANSPORTATION, AND OPEN FIELD DESIGNATIONS (24-29)

Description: Residential, commercial, golf course, excavated ponds, and infrastructure portions of the Island; includes open space for lawns, parks, and forested areas

Key Ecological Attributes:

Small pockets of natural vegetation; Wildland/Urban interface

Underlying Soils:

Carnhoy fine sand, 0-5% slopes; Fripp-Duckson complex, 0-20% slopes; Mandarin fine sand; Mandarin-Urban land complex; Rutledge fine sand

Acreage/Percent of the Island: 1,550/27 (not to be confused with the 1,675-acre limit on the area of developed land – see Section 2.2 of this report)

Dominant Vegetation:

• lawns; live oak, sand laurel oak, slash pine, landscape plantings

Current Conditions: Land use category includes lands currently used for residential uses, commercial and recreational elements, and supporting infrastructure; the historic district; developed areas typically include buildings, roads, lawns, and/or scattered landscape plantings; natural vegetative communities occur throughout land use type, including forested areas within the golf course, early successional dune communities within vacant lots, canopy tree structure on lots; pockets of natural vegetation areas within these designations provide important habitat for migratory species; refugia for larger wildlife species that occur or stray into developed lands, and territory for smaller resident wildlife species; exotic species such as tallow have been planted on some residential lots; roadways and trails cross wetland systems to provide access into the Island; excavated ponds occur within the golf course and other areas of the Island

Global Rarity Ranking:

Not ranked

Desired Future Conditions: Residential, commercial, and recreational uses with low-maintenance landscapes of native vegetation, effective storm water retention/detention infrastructure, and occupants that embrace natural resource protection on the Island

Threats and Stresses:

Threats have been identified most importantly for specific natural habitat conservation as opposed to human-made habitats. However, since natural system processes occur within human-made habitats and wildlife still use remnant natural systems within urban settings as well, management strategies and threat assessments are still warranted. The following list is identified for urban/developed lands:

• Habitat fragmentation and edge effects • Population-level impacts to wildlife species associated with vehicle-strikes on roadways • Altered wildlife diversity and movement patterns resulting from eradication and colonization • Exotic species infestations such as camphor tree and Cherokee rose • Pollution from oil, grease, and heavy metals from impervious surface run-off, and herbicide and pesticide treatments • Fire suppression • Installation of beach armoring such as bulkheads, groins, jetties, and rip-rap that alter natural sand movements and erosion/accretion activities • Alteration of natural wetlands due to ditching for drainage • Water source redistribution in stormwater lagoons • Construction related impacts, such as pollution related to construction waste and erosion/sedimentation concerns • Water withdrawals for potable use and irrigation • Light and noise pollution • Limited seed dispersal of native species due to patchiness of remaining natural habitat

Wetland Status: The majority of this category is not currently wetland. Historical wetlands within urban/developed land uses have been extensively altered through vegetation removal, drainage alterations, and fill/dredge activities. Remaining wetlands are typically small and altered in both vegetation composition and hydrology and may not be separately mapped on Figure 3, but may be candidates for future restoration and/or enhancement activities.

4.3 PLANTS

GADNR staff conducted plant surveys on Jekyll Island prior to 2012. Since 2012, JIA staff have conducted both structured and opportunistic plant inventories within the Park. Notable rare plants have included climbing buckthorn, large-flowered hibiscus, and Florida wild privet. Assuring their long-term viability is a key element in the management actions included in Section 5.0. They are indicators of ecosystem health in a variety of habitats across the Island, and their protection is essential to a successful conservation strategy. The JIA will work to build a digital and/or physical herbarium collection, and a GIS database of rare plant locations along with metadata describing most recent observations.

Many of the rare plants documented on the Island are associated two distinct types of soil and hydrologic characteristics:

Shell Midden / Calcium-Rich Soils

Florida wild privet, rouge plant, climbing buckthorn, and soapberry occur on shell middens along the causeway and along the marsh on the southwestern portion of the Island, as well as potentially other locations with abundant shell deposits. These areas have high-calcium soils typically associated with Native American middens. Red mulberry is a more common species that is associated with these deposits. Many of the locations that were home to this vegetation type have been lost or destroyed outside of the conservation areas. Latham’s hammock on the causeway is particularly important because it is the only sizeable area of this type within the Park that is not subjected to deer herbivory. However, it is threatened by sea-level rise. JIA will protect these plants by preventing any expansion of development from affecting Native American middens and by collecting seed from rare plant populations threatened with loss to be grown and planted to establish viable populations in relatively secure locations.

Brackish / Freshwater Wetland Soils

Several species are found in upper reaches of the coastal marsh or freshwater wetland systems, including powder-puff mimosa, saltmarsh mallow, and large-flowered hibiscus (also known as swamp hibiscus). The large-flowered hibiscus is a showy species characteristic of this group located within both freshwater marsh and freshwater wet grasslands in various spots through the Island. This species is sensitive to alterations in inundation regimes, salinity levels, and other disturbances. By protecting all remaining freshwater wetlands from the impacts of development, including sedimentation and nutrient pollution, and by strategically pursuing engineered protections for high-value freshwater wetlands to prevent contamination by saltwater intrusion through sea-level rise, JIA will strive to conserve these rare plants.

saltmarsh mallow

swamp hibiscus red mulberry

4.3.1 INVASIVE EXOTIC SPECIES

Since 2012, Jekyll Island has had an active invasive plant control program and JIA has participated as partners on the steering committee of the Coastal Georgia Cooperative Invasive Species Management Area (CG-CISMA). The CG-CISMA partners maintain a listing of invasive species organized into three priority levels based on the amount of resources that CISMA partners invest. This list can be found in Appendix E. Jekyll Island is unique in being the only barrier island on the coast of Georgia where mature stands of Chinese tallow tree were established but have now been ecologically eradicated, due to JIA efforts with the support of CG-CISMA partners. Other high-priority invasive plant species for Jekyll include salt cedar, Chinaberry, camphor tree, Japanese climbing fern, and Chinese privet.

The CG-CISMA also addresses invasive exotic animal species including feral pigs and Cuban treefrogs. Feral pigs have been documented on the Jekyll causeway but not yet on the Island. If established, they would impose heavy negative impacts on native plant and wildlife communities. Likewise, invasive Cuban treefrogs pose a severe threat to native treefrog populations.

A targeted control effort associated with a concentrated infestation of Cuban treefrogs at a hotel property on the Island has made progress, but isolated occurrences of the species continue to be documented at this location and have occurred at two other locations across the Island. Landscape material from Florida-based sources should be expected to be an ongoing source of invasion for both plants and animals. At this time, landscaping procurement for the island cannot feasibly be accomplished without utilizing Florida-based sources. Early detection and rapid response will continue to be an essential strategy.

Chinaberry

Cuban treefrog Chinese privet

4.3.2 PLANT PRIORITY SPECIES

Plant species listed in the table below have been identified as priorities for conservation because their persistence within Jekyll Island State Park faces potential challenges. Some priority species may need monitoring or research to maintain awareness of their local status, improve understanding of their ecological roles and prospects, and inform management action to mitigate identified threats. By limiting the amount of disturbance caused by development or acting to restore enhance ecological systems with the Park, the JIA can reduce threats and risks to the persistence of these species. The Environmental Assessment Procedure (Chapter 7) should be implemented for any projects with the potential to negatively impact priority species.

Priority species include federally listed species along with species identified in the most recent version (2015) of the Georgia SWAP as Coastal Plain High Priority Plants, provided these federal- and state-identified species have been documented within Jekyll Island State Park beyond an isolated, incidental occurrence.

Additionally, the List includes species not listed by federal or state authorities if JIA Conservation staff concluded that they were:

• Locally rare or at-risk in Jekyll Island State Park • Experiencing wide-range declines and either locally dependent on resources currently within the Park or with the potential to benefit from habitat restoration/enhancement within the Park • Particularly at risk of threat due to climate change or sea-level rise within the Park • Particularly well-suited to serve as an indicator of ecosystem health

Plant Priority Species are listed below and in more detail in Appendix B. Species highlighted below are watchlist species that could occur on Jekyll but have either never been documented, are unverified or documented by a single instance, or have not been documented in the past 20 years.

black tupelo button bush climbing buckthorn dwarf pawpaw Florida wild privet hop tree large-flowered hibiscus lime-fleeing sedge loblolly bay muhly grass pignut hickory rouge plant soapberry widgeon grass

Watchlist Species:

Bartram’s airplant greenfly orchid

Florida wild privet

loblolly bay

pignut hickory

4.4 WILDLIFE

Wildlife management is the act of deliberately influencing the trajectory of wildlife habitat, wildlife populations, and human/wildlife interactions for the benefit of both wildlife and people. Simply limiting disturbance is not always the most advantageous strategy, particularly in the context of substantial human influence over the landscape, both historic and current. The ecology of disturbance, caused by fire and storms for example, is critical to the life-history strategies of many wildlife species. Efforts should therefore be made to provide an appropriate array of early successional habitats throughout the areas covered under this plan. Considering the challenges posed by development to many wildlife species, the highly complex and dynamic nature of the underlying natural systems, widely varying social and cultural attitudes towards wildlife and the environment, and the highly visible nature of management on Jekyll Island, implementation of the goals articulated in this plan presents a constantly evolving challenge. Success depends upon intuitive and adaptive decision making, informed by familiarity with public values and the best available science.

Since the approval of the 2012 Conservation Plan, substantial efforts have been placed on monitoring, managing and conducting research on wildlife and their habitats across the Island. Numerous examples of these activities are cited in this chapter. Efforts include collaborative work with universities, agency research personnel and NGOs. Appendix G provides references for published works completed since 2010 that inform this Plan and are applicable to its implementation. Ongoing monitoring and research efforts will support management and operational decision making, development considerations, and techniques for ecological restoration.

Summary Wildlife Goals

The following goals provide an overarching framework to guide the development and evaluation of wildlife and habitat management, restoration, research, and outreach programs.

1. Actively enhance underperforming habitat to maximize the availability of food, water, space, and cover for Wildlife Priority Species. 2. The reintroduction and continued use of prescribed fire for wildlife habitat enhancement and human safety (including upkeep of buffer areas and firebreaks). 3. The restoration of connectivity to saltmarsh and brackish wetlands. 4. The restoration of the historical extent and vegetation diversity of freshwater wetlands. 5. The provision of supplemental recruits to the populations of rare or threatened plant species using local genotypes and selecting resilient locations, including reforestation of live oak. 6. The prevention of negative impacts from invasive species through prioritized removal or, if relevant, restoration of the habitat altered by the invasive species. 7. The increased connectivity of habitats on the Island that are safely navigable by all wildlife species. 8. The continuation of publicly available wildlife issue response service. 9. The prevention, deterrence, and elimination of wildlife feeding and disturbance/ harassment, especially with species that can injure or transmit disease to people. 10. The continuation of prioritized species monitoring to include keystone predators, migratory species, wetland-dependent species, species experiencing widespread decline, and locally rare species. 11. The development of strategies that minimize wildlife injury or mortality. 12. The continued evaluation and minimization of negative impacts of development or redevelopment to wildlife habitats. 13. Acknowledge that barrier islands are dynamic communities and that some external influences, such as shoreline processes and range shifts of regionally native species, should be allowed to proceed. 14. When appropriate, manage natural predators such as raccoons and coyotes to minimize impacts to Wildlife Priority Species including sea turtles and shorebirds.

4.4.1 RESTORATION

Ecological restoration involves active human intervention to influence the environmental trajectory of damaged, degraded, or destroyed habitats. Restoration can involve reintroducing a natural process to remediate an existing habitat, planting to recreate a habitat or conversion of one habitat to another. Degraded or diminished habitats identified in this Plan, are candidates for restoration. Restoration will prioritize the diversity and connectivity of high-value habitats available on the Island, such as the restoration effort for Fortson Pond, prospects for restoring connectivity among the other remaining fragments of the First Creek tidal system, or restoration of rare maritime grassland communities. Restoration projects may include recreating or reconnecting previously filled or fragmented wetlands, removing invasive exotic plants, the application of prescribed fire to promote diverse and productive fire-adapted or early successional plant communities, protection or creation of wildlife corridors, or using native seeds/seedlings to establish a desired plant community. Regardless, the guiding objectives will be to: 1) maximize native biodiversity; 2) support rare or threatened species; and 3) enhance ecosystem resiliency.

4.4.3 WILDLIFE RESPONSE

In 2012, a wildlife response program was initiated. Initially conceived as an opportunistic invitation to report sightings of species being researched, the influx of calls about injured or sick animals and safety concerns led to the evolution of a wildlife-response hotline available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The JIA Conservation Division operates this system with rotating on-call and manager-on-duty responsibilities.

With increased visitation to the Island, and more awareness of the hotline, call volumes have increased significantly. Call volume varies seasonally depending on both human and wildlife activities, with the highest volume of calls in the spring and early summer when visitation is high, and many animals are on the move.

The objectives of this program are to: 1) mitigate any immediate risk to people or to wildlife, especially priority species; 2) create an opportunity for informative engagement with visitors, residents, and staff; and 3) provide information about the location of human/ wildlife interactions and the nature of these interactions.

4.4.4 WILDLIFE MONITORING & RESEARCH

Following approval of the first iteration of this Plan in 2011, JIA began building a body of site-specific knowledge to support conservation efforts on Jekyll Island. The JIA now directly coordinates a strategic monitoring and research program for the Island to support the development of wildlife/habitat management efforts, operational best management practices, and communication/education strategies. This monitoring serves as a bellwether for sudden population fluctuations or more gradual trends that may call for management intervention. JIA staff also coordinate with other agencies and institutions to provide access to Jekyll Island State Park as a field site to do research. The overarching objective of conservation-oriented monitoring and research on Jekyll Island is to better understand the dynamics and needs associated with accommodating a diverse wildlife assemblage alongside human activity in the context of limited, sustainable development. JIA investment in research will encourage tightly focused questions, novel approaches, and research products that are likely to directly contribute to decisions of management, restoration, or sustainability in specific and foreseeable ways. Listed and summarized below are species that have been the subject of JIA-directed monitoring and research.

Keystone Predators

Predators are an indicator of a healthy ecosystem and contribute to stabilizing populations of prey species that can dominate and reduce the diversity of other communities when unchecked. Many predators need large home ranges to survive. Space can be limiting on a relatively small island like Jekyll. Species with small and/or isolated populations are at risk of extirpation from the Island due to factors such as disease, habitat loss due to storm or sea-level rise impacts, predation or competition by invasive species, or road-mortality. Predators are often the first species to disappear from a landscape that has been over-developed. Some predators exert such significant influence on the ecosystems they inhabit as to be classified as “keystone” species. JIA Conservation staff recognize the following species as keystone predators.

American alligator – The alligator population on Jekyll has been monitored since 2011 and has included routine population census counts and mark-recapture efforts. Academic research involving movement, toxicology, public education, and diet have been completed or are in progress. The alligator population on the Island appears to be stable with the age structure shifting to larger individuals that reduce the number of younger alligators through cannibalism. Movement research indicates that larger size classes of alligators move frequently across the Island, utilizing freshwater wetlands, artificial ponds, saltmarsh areas, and sometimes traveling to other islands or the mainland. Preliminary results from toxicology studies indicate that Jekyll-based alligators may carry less of a chemical pollution load than alligators studied elsewhere, implying that alligators on Jekyll Island are less exposed to pollutants that can bioaccumulate in the food chain. Ongoing population monitoring will continue, along with outreach and education to promote awareness, appreciation, and safety consciousness around Jekyll’s largest predator.

Bobcat – Bobcats were first confirmed on Jekyll in 2014 and have established a small, but apparently growing population. Genetic identification from scat has thus far only confirmed the presence of five individuals, but a population of between 5 and 10 individuals appears likely at the time of this Plan update. Monitoring includes movements and habitat use with cameras and GPS tracking, and scat collections for diet analysis and DNA identification of individuals. The aim of these efforts is to determine if the Jekyll bobcat population is likely to be self-sustaining. Bobcat reproduction on the Island appears to have occurred on multiple occasions since 2014, but survival and establishment rates are unknown. Inbreeding and its impact on fitness are a concern. If the population is deemed unlikely to sustain itself, discussions will be initiated with GADNR to explore possible interventions to sustain this species’ important role in the local, island ecosystem.

Eastern diamondback rattlesnake – The Eastern diamondback rattlesnake (EDB) is another rare predator on Jekyll Island and has been monitored since 2011 via radio tracking to gather information on survival, habitat use around development, basic life history, and population status. Results show that EDBs avoid areas that are used and maintained by people, including areas that are mowed and open or used regularly by pedestrians. They rarely cross roads and are most likely to do so prior to and after hibernation, and during the fall breeding season. Of 35 EDBs that were tracked, 52% have died, a quarter of those from human-caused mortality. Rattlesnakes rely on camouflage and are among the most difficult predator species to find and observe in nature without radio-telemetry. Assessing population size is a major challenge that is being addressed through a structured detectability assessment. Analysis of DNA as well as the chemical composition of venom indicates that the Jekyll EDB population is isolated from mainland populations and internally fragmented with no genetic exchange occurring between individuals on the south and north ends of the Island. In the future, continued radio-tracking is expected to provide information on average lifespan, demographic survival rates, and reproductive output. Monitoring can also reveal how individuals respond to extreme events like droughts, hurricanes, and over the long-term, climate-related changes in the environment.

Canebreak rattlesnake – Canebrake rattlesnakes appear a very rare predator on Jekyll Island, having only been observed on three occasions since 2011. A single adult was captured in early 2018 and subsequently equipped with a radio transmitter to track its movements. During the 16 months it was tracked, no other individuals of this species were discovered. A hybrid juvenile cross between an EDB and a Canebrake was also discovered on the Island in 2018 and is currently being tracked. This instance is one of only a few known occurrences in the wild of hybrid EDB/Canebrake individuals. The occurrence of a hybrid could indicate a lack of same-species mates for the adult known to be present on the Island.

OTHER SPECIES GROUPS RECEIVING SUSTAINED MONITORING AND RESEARCH EFFORT

Turtles

The Georgia Sea Turtle Center (GSTC) is the lead within the JIA for all turtle research, management, conservation and outreach. As a primary focus, the GSTC implements sea turtle monitoring and management protocols set forth by the Georgia Sea Turtle Cooperative, a GADNR-led program. Data are submitted annually to a central electronic repository to support collaborative research and conservation initiatives.

Nesting sea turtles have been studied since 1955 on Jekyll Island. The primary species that nests on Jekyll Island is the loggerhead sea turtle, although green sea turtles, and leatherback sea turtles have been observed. Sea turtle nest monitoring and research on Jekyll Island follows statewide management protocols, which involve identifying nests, protecting them from predators with wire mesh and monitoring incubation period and hatching success. The GSTC also performs overnight patrols to identify and tag as many nesting females as possible. In collaboration with a regional study led by University of Georgia researchers, one egg from every nest and one skin biopsy from every nesting female are collected to genetically assign nests to individual females. Additional sea turtle research led by the GSTC includes collaborations to study injury rates, environmental contaminants, behavior following abandoned nesting attempts, nest incubation temperature, disease monitoring, and a variety of other veterinary and health-related topics.

The diamond-backed terrapin is the only turtle species that exclusively inhabits estuarine environments. Its populations have suffered significant declines from coastal development and bycatch mortality in crab pots. Modeling efforts predict that the population around the Jekyll causeway faces decline if threats such as road mortality and nest predation are not reduced. Led by the GSTC, vehicular patrols on the causeway during peak nesting times have been very successful in reducing collisions by moving terrapins off the roadway. These patrols also allow timely rescue of injured terrapins and collection of viable eggs from deceased females for captive rearing and subsequent release. Each turtle is individually marked so that it can be identified if encountered in the future. Several mitigation strategies have been successfully implemented, including protected nest mounds to encourage the turtles to nest without crossing the road, flashing light signs to alert motorists to be on the lookout for terrapins, and education programs on the causeway and at the GSTC. Future efforts will focus on design, construction, and testing of barriers to prevent terrapins from accessing the roadway.

Box turtles have undergone significant declines throughout their range owing to habitat loss, road mortality and other threats. The GSTC has been radio-tracking box turtles on Jekyll Island since 2011. Data collected from radio-tracking provides information about box turtle survival around developed habitats, reproductive output, habitat preferences, population size and trajectory, and whether head-started juveniles can augment the population. Box turtle mortality due to vehicle strikes on roads has been observed, and head-started box turtles have proven to successfully establish and survive at high rates in the wild on Jekyll.

Shorebirds

Nesting Wilson’s plovers have been monitored on Jekyll Island since 2012. Because they use beach habitats during peak season when human visitation is highest, they face significant challenges when nesting and rearing young. Nest numbers on Jekyll are low relative to major nesting sites in Georgia, but Jekyll beaches have produced fledglings to bolster a species that is classified as Threatened by the State of Georgia. Jekyll’s nest numbers have been rising in recent years, likely due to an increase in early successional dune habitat recovering and expanding following hurricanes that modified the Jekyll shoreline in 2016 and 2017. Conservation strategies include roping off the most important habitat areas during nesting, limiting beach driving, prohibiting pets from core nesting areas, and strictly enforcing leash rules around nest/hatchlings outside of the no-pet zone. To evaluate management success and threats, JIA monitors nesting and rearing using cameras, surveys, and banding hatchlings. JIA Conservation staff also participate in annual migration and mid-winter shorebird surveys following International Shorebird Survey (ISS) protocols in coordination with other partners along the GA coast organized under the Georgia Shorebird Alliance, which is collaboratively led by GADNR and Manomet, Inc.

Migratory Butterflies

Jekyll Island provides important habitat for many species of butterflies. There are several species that migrate south in the fall season along the Atlantic Flyway. The importance of the Atlantic Flyway, migration rates, and habitat requirements for these species are currently unknown. A regional study in cooperation with other conservation organizations on the Georgia coast was initiated in 2018 to evaluate conservation opportunities and challenges for these species. Along with other partners in the Butterflies of the Atlantic Flyway Association (BAFA), JIA is monitoring three focal species annually during migration: monarchs, gulf fritillaries, and cloudless sulfurs.

Frogs

Frogs have been monitored on the Island since 2011. Because they rely on sensitive and ephemeral freshwater wetlands, they serve as indicator species for the health of these important habitats. The frogs of Jekyll Island have been monitored through passive artificial refugia and through frog call surveys following rain events. Eleven species of frogs have been documented on the Island since 2011. The gray treefrog was only observed three times, all between 2012 and 2013, indicating that they are very rare on the Island. They may be naturally rare, they may have declined due to disease, or they may have experienced declines from other pressures, human-induced or otherwise. Frog call monitoring will continue on a periodic basis.

Mammals

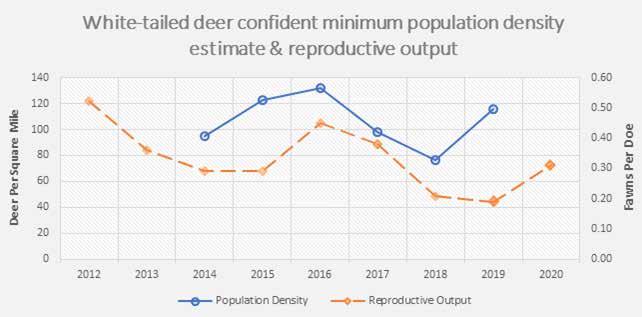

White-tailed deer are an abundant species found in all habitats on Jekyll Island. Annual assessments conducted since 2012 utilizing spotlight surveys, supplemented with photo surveys since 2014, indicate that the population has been generally stable at consistently high densities. Population density estimates have been produced by photo-identifying individual bucks based on unique antler morphology each year at bait stations distributed across representative habitats throughout the Island. Bucks that are not uniquely identifiable with confidence are not counted. The number of uniquely identified bucks is taken as a confident minimum number of adult bucks present on the island at that time. The ratio of bucks to non-bucks (does plus fawns) is averaged over three nights conducting spotlight count surveys along a standardized route across the island. The buck to non-buck ratio is applied to the number of confidently photo-identified bucks to produce a conservative estimate of total deer on the Island, which is divided by the area of the Island (excluding beach, marsh, and ponds) to present the result as density (deer per square mile). Jekyll Island’s unmanaged herd, based on this confident minimum estimation approach, has not fallen below 79 deer per square mile since 2014, the first year of buck photo-identification. GADNR advises landowners to manage for an average population size of 20-30 deer per square mile for a healthy herd in the Lower Coastal Plain region of the state. The average annual number of fawns per doe from 2012 – 2019 was 0.33, based on spotlight survey data. Assuming a typical doe is reproductive for five years during a lifespan, doe deer on Jekyll are producing approximately 1.67 offspring over the course of their lives on average. However, 2018 and 2019 spotlight surveys recorded the lowest average number of fawns per doe of any year since surveys began in 2012.

If the number of fawns produced per doe remains at 2018/2019 levels, or falls below, the typical doe may no longer produce enough offspring to replace herself in the population and density could begin decline. Though inconclusive at this stage, this reduction in the number of fawns per doe could prove to be an indicator that the significance of fawn predation, by the apparently establishing bobcat population, is increasing. Potential ecological consequences of what nonetheless remains a highly abundant large herbivore population include heavy deer parasite loads and susceptibility to disease in the population, as well as impacts to native plant community structure, diversity, and cover, including in sensitive habitats such as sand dunes and wetlands.

Bat surveys have been conducted each summer since 2015 on behalf of GADNR using “Anabat” technology that records bat calls while driving a standardized route around the Island. These surveys have documented five bat species, including northern yellow bats and tri-color bats, both listed by the State of Georgia as Species of Concern.

Raccoons are ubiquitous on the Island and are monitored for disease when an animal is near death due to illness or injury and must be euthanized. Rabies, distemper, and parvo are all known to occur in the Jekyll Island raccoon population based on the monitoring, conducted in partnership with the Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study. High raccoon populations have negative impacts on nesting sea turtles and shorebirds, and their influence on these priority species is monitored on the Island.

4.4.5 EXTERNAL RESEARCH APPLICATION REVIEW PROCESS

Jekyll Island offers a unique, and easily accessible, natural laboratory in a limited-development context that is attractive to researchers studying environmental systems, flora, fauna, and cultural resources. All research that takes place on Jekyll Island is subject to the approval of JIA. In 2017, JIA established a standing Research Committee to evaluate, furnish feedback, and consider approving proposed research projects led by external investigators. To do research on Jekyll, a brief proposal is required for evaluation. Principal investigators are required to submit a scope of work summarizing their proposed project, methodology, reasons for pursuing Jekyll as a study site, expected research products, and other collaborators. JIA reserves the right to deny research applications that may be deemed inappropriate for Jekyll, or to approve research with conditions or modifications. At the time of this update, the Research Committee includes the Director of Conservation, the GSTC Director, the GSTC Research Ecologist, the Director of Historic Resources, and the Conservation Division’s Wildlife Biologist. These roles may be delegated to others within the JIA structure as needed due to availability or expertise. A JIA point of contact for coordination and oversight is designated for each research project following approval.

4.4.6 WILDLIFE PRIORITY SPECIES

Wildlife species listed in the table below have been identified as priorities for conservation because their persistence within Jekyll Island State Park faces potential challenges. Some priority species may call for monitoring or research to maintain awareness of their local status, improve understanding of their ecological roles and prospects, and inform management action to mitigate identified threats to their local persistence. By limiting development disturbance or acting to restore or enhance ecological systems with the Park, the JIA can reduce risks to the persistence of these species. The Environmental Assessment Procedure (Chapter 7) should be implemented for any projects with the potential to negatively impact priority species.

Priority species include federally listed species along with species identified in the most recent (2015) version of the Georgia State Wildlife Action Plan (SWAP) as Coastal Plain High Priority Animals, provided these federal and state identified species also have been documented within Jekyll Island State Park beyond an isolated, incidental occurrence. Bird species included on the Watch List of the State of North America’s Birds 2016 Assessment by the Committee of the North American Bird Conservation Initiative (NABCI) have been incorporated as well. These are the bird species NABCI determined to be most at risk of extinction without significant conservation actions to reverse declines and reduce threats. https://www.stateofthebirds.org/2016/resources/species-assessments/

Additionally, the List includes species not listed by federal or state authorities, if JIA Conservation staff concluded that they were:

• Locally rare or at-risk in Jekyll Island State Park

• Experiencing range-wide declines and either locally dependent on resources currently within the Park or with the potential to benefit from habitat restoration/enhancement within the Park

• Particularly at risk of threat due to climate change or sea-level rise within the Park

• Particularly well-suited to serve as an indicator of ecosystem health

Wildlife Priority Species are listed below and in more detail in Appendix B. Species highlighted below are watchlist species that could occur on Jekyll but have either never been documented, are unverified or documented by a single instance, or have not been documented in the past 20 years.

Birds

American oystercatcher American woodcock bald eagle black-necked stilt bobolink cape may warbler chuck-will’s-widow common nighthawk Connecticut warbler eastern whip-poor-will gull-billed tern horned grebe Kentucky warbler king rail least bittern least tern lesser yellowlegs little blue heron loggerhead shrike long-billed curlew marbled godwit nelson’s sparrow painted bunting pectoral sandpiper peregrine falcon piping plover prairie warbler prothonotary warbler red knot reddish egret red-headed woodpecker American kestrel saltmarsh sparrow seaside sparrow semipalmated sandpiper short-billed dowitcher swallow-tailed kite tricolored heron willet Wilson’s plover whimbrel wood stork wood thrush

Watchlist Species:

American black duck Bachman’s sparrow barn owl black rail black-billed cuckoo Kirtland’s warbler northern bobwhite northern saw-whet owl Swainson’s warbler

Reptiles

box turtle canebrake rattlesnake green sea turtle Kemp’s ridley sea turtle leatherback sea turtle

Mammals

bobcat gray fox northern yellow bat tri-colored bat

Invertebrates

hummock crayfish mole crayfish monarch butterfly coachwhip diamondback terrapin loggerhead sea turtle eastern diamondback rattlesnake eastern kingsnake

Amphibians

barking treefrog eastern newt gray treefrog pinewoods treefrog

Watchlist Species:

two-toed amphiuma

Watchlist Species:

eastern coral snake island glass lizard pygmy rattlesnake

Fish

Watchlist Species:

bluefin killifish

4.4.7 ABUNDANT, POTENTIALLY PROBLEMATIC SPECIES

The Island is home to a variety of wildlife in addition to those designated as Wildlife Priority Species. Several of these species, including white-tailed deer and raccoon, are ubiquitous and often attracted to food resources within and surrounding developed areas. They may become a nuisance in developed landscapes where natural predators are reduced or absent. While sometimes desirable from a wildlife viewing perspective, these circumstances can adversely affect long-term conservation goals. For example, white-tailed deer may reduce the productivity or diversity of herbaceous vegetation in the understory. Raccoons may prey directly upon the eggs and young of Wildlife Priority Species, including sea turtles, diamondback terrapins, and wood storks. Large alligators may present real or perceived concerns for human safety, exacerbated by feeding. Management of these species requires an understanding of the population that can be supported by the natural systems with sustained habitat quality, the population that can coexist compatibly with human population, and the health of the population in question.

Other forms of wildlife, such as mosquitoes, ticks, and rodents, are more traditionally viewed as nuisance or pest species by humans, either because of the annoyance inflicted by the species or because of health concerns. Chemical applications associated with pest control can collaterally harm non-target species. JIA will continue to coordinate with Glynn County Mosquito Control to promote and facilitate maximized larvicide treatment to minimize the need for adulticide spraying. JIA will seek to collaboratively establish no-spray areas and routes where adulticide will not be used. Anticoagulant rodenticides can poison and kill predators or scavengers of exposed rodents, including some Wildlife Priority Species, such as bobcats. Regulatory tools, including prohibition through local ordinance, will be evaluated for advancement as needed to protect Wildlife Priority Species.

4.4.8 WILDLIFE DISEASE

Wildlife diseases can have major impacts on wildlife populations and may pose a risk of human infection. When wildlife species exhibit symptoms consistent with disease, appropriate experts, including the GSTC veterinarian will be consulted. The Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Survey (SCWDS) is an important partner in this regard. Provided approval from Georgia DNR, JIA has access to SCWDS resources such as testing racoon carcasses for rabies and deer herd health assessments. Notable wildlife diseases confirmed to be present in Jekyll Island wildlife populations include:

Rabies: Documented in racoons on Jekyll Island periodically since 2013 (Ortiz et al., 2018, Appendix G), rabies can be transmitted to other mammal species including humans, and it is suspected to have been a factor in the rapid decline of the Island’s gray fox population that occurred between 2014 and 2016.

Amphibian Diseases: Amphibians have been documented with ranavirus and chytrid fungus on Jekyll Island, but no significant declines appear to have resulted, perhaps indicating that these pathogens are not novel here.

Snake Fungal Disease: Snake fungal disease has been documented in five of 15 snake species on Jekyll and is apparently widespread, but unlike severe instances documented in more northern latitudes, no widespread mortality events have yet been linked to this disease on Jekyll Island. The disease has been successfully treated in an Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake by the GSTC Veterinarian.

The presence of Lyme Disease on Jekyll Island has not been confirmed through direct testing of ticks for the pathogen. However, ticks in the Southeast are known to carry numerous pathogens in addition to Lyme.

4.5 POTENTIAL IMPACTS TO WILDLIFE AND PLANTS FROM CLIMATE CHANGE

The following narrative draws from material in the 2015 Georgia SWAP. Also, a new overarching management objective for Jekyll Island State Park pertaining to climate adaptation has been added to this Plan in Chapter 5.

The complex set of consequences related to climate change are referenced in greater detail in Objective A in Chapter 5. These consequences, including warmer temperatures, sea-level rise, greater frequencies of extreme tides and the higher potential for extreme storms are impacting wildlife species, plant communities, and habitats, and these effects are projected to increase substantially over time. The impact of climate change reaches beyond local and state boundaries and affects each species differently. The impacts of climate change do not exist in isolation but combine with and exacerbate existing threats to wildlife and plants. Habitat protection, restoration, and connectivity enhancement can help mitigate the impacts of climate change.

Range shifts in response to climate change may affect wildlife and plants on Jekyll Island. A warming climate will likely cause the ranges of many species to shift northward, possibly leading to changes in ecological dominance and interactions between longestablished species on the Island and new arrivals. The timing of seasonal events, such as the arrival of migratory birds and the pulses of invertebrate production that supports them, could become asynchronous, leading to reduced bird fitness. Plant species that are reliant on isolated lowland habitats are threatened by sea-level rise and saltwater intrusion/inundation.

Climate change is likely to have adverse effects on herpetofauna. Effects on habitat suitability are the most wide ranging, but in the case of most turtle species and the American alligator, species that exhibit temperature-dependent sex determination, warming temperatures may skew sex ratios adversely. The GSTC will continue to monitor the length of incubation for all sea turtle nests, which is significantly correlated with incubation temperature and sex ratio. The Conservation Department will continue to monitor the island’s alligator population. Warming winters and heightened extremes of rainfall and drought could also impair the ability of rattlesnakes to hibernate in winter and affect the availability of their small-mammal prey.