Karin Skousbøll

GREEK ARCHITECTURE NOW

STUDIO ART BOOKSHOP

Karin Skousbøll

GREEK ARCHITECTURE NOW

STUDIO ART BOOKSHOP

CREDITS: Published by: STUDIO ART BOOKSHOP By Elias Tsibouris 32, Tsakalof Street, 102 73 Athens, Greece +30 210 36 22 602 /36 00 647 mail: office@studiobookshop.com www.studiobookshop.com Author and editor: Karin Skousbøll Associate professor, Architect MAA The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts School of Architecture Study Department 8 & Institute 3 +45 3268 6304 / 2622 4054 mail: karin.skousboll@karch.dk Graphic design by: Jesper Jans www.j-grafik.dk English guidance and proofreading: Kirsten Rafn Fanøgade 1 DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark Print and reproduction: Athens, Greece

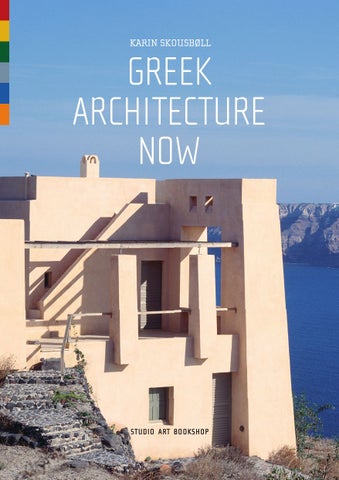

Typeface: Cholla/Emigre.com This publication is generously supported by Bergia Foundation Cover: Vacation House in Santorini, by architect Agnes Couvelas Photographer: Francesco Jodice Opening page: Overview of Daedalos Tourist complex at the island af Kos, by architect Nicos Valsamakis 1988–91. Illustration acknowledgements please see page 314-320. All rights reserved First edition – 2006 No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permisssion from the publisher except in the context of reviews.

Contents: Chapters: Preface

4

Past and present of Greek architecture

10

Essentials af Greek architecture

74

Athens – urban development, new perspectives

92

Attica and the sites of the Olympic games 2004

122

Thessaloniki – urban development and actual perspectives

170

Cases: Athens

182

Attica

250

Nothern Mainland

260

Middle Mainland

272

Southern Mainland

282

Islands: Cyclades and Crete

290

Index: Illustration index and credits

318

Index of names and institutions

325

Index of places, projects and special notions

333

Bibliography

345

About the author

349

CHAPTER 1

Past and present of greek architecture

Watercolour painting of the Danish architect Christian Hansen, 1836: Parthenon with the “intruding” mosque – the fatal explosion happened 26th of September 1687. Plan of Acropolis, showing the conscious spatial composition of the elements in order to emphasise their individual 3-dimensionality. Le Corbusier Sketch of Parthenon 1911 from his journey of study to the Mediterranean and Near Eastern.

16

mology through the dialogue with Timaios. He uses the notion Chora as neither a place nor space, but defined by “what is perceived, occupied by what stands out” (ref. Carsten Madsen & Henrik Oxvig: Arkitektonik, Filosofi, Arkitektur, KA Kbh. 1990 p.117) (About Chora, see further in chapter 2, pp. 90-91). This way of seeing buildings as individual elements which reciprocally create the spatial context between themselves was not based on a geometric axial or abstract system, but rather refined as a 3-dimensional scenography based on the ideal exposure of each sublime element. This is still a visible quality of perception in contemporary Greek architecture. During the 1920s-30s this idea also had a great impact on the whole modernist configuration of space based on a release of the symmetry and an emphasis of the object’s individual shape and sphere. (ref. Lars Marcussen: (Topology of Architecture, KA. Cph. 2003 p 40-42). The site-plan of Acropolis is a striking example of this exquisite composition of autonomous elements standing out and interacting in the spatial context. Whether participating in the former time’s Panathenaean processions or in today’s hobs of tourists, you yourself, as a moving body, contribute to the existing setting of the site. When entering through the Propylaia gate – intentionally erected in an oblique angle – you perceive an ever shifting scenery through your changing positions when you move.

Parthenon as it is perceived to day when entering Acropolis from Propyleia. The experience of Acropolis end Parthenon temple as spatial setting in the urban landscape of Athens – here from the pedestrian street, Dionissiou Areopagitou.

Strangely enough - almost as a contradiction – already in the 5th century ancient Greece was the inventor of the grid-pattern city, the so-called Hippodamian town plan. This has widely spread as a popular type of cityscape all over the world. In the following pages the urban planning will be examined as an issue providing a basis for understanding now-a-days Greek urbanity. The first Greek city planning The first Minoan civilisations from early Bronze Age (2800-1450 BC) were situated in Crete, the Cyclades and at Peloponnese. The city of Knossos seems to have been a centralised city governed totally from the palace complex. It did not need fortresses like Mycenae 17

Byzantine style is known from many churches – among them Church of the Holy Apostle in ancient agora area in Athens built 1000-1025 as one of the oldest ones above the ruins of a roman nymphaeon from the 2nd century. Roman influence in architecture: part of the inner 100 column-peristyle courtyard of Hadrian’s Library (N of Roman Agora, Athens) Constructed ca. 130 AD by the roman emperor, who settled in Athens for a period. Church of Panagia Parigoritissa (13th century) in Arta SW of Ioannina – the second city of Epirus, which has a wealth of Byzantine monuments

22

260 AD) Athens continued to be a major seat of learning, and Caesar Hadrian (76-138 AD), even moved his residence to Athens, built the famous library and several other public buildings there. Even after the division of the Roman Empire (end of 4th century) Athens remained an important intellectual and cultural centre, until Emperor Justinian closed the schools of philosophy and theology in 529 AD. The Greek language was still used for literature, history, philosophy and natural science, while matters of law, diplomacy and military followed roman nomenclature. Thessaloniki now came in focus of the Byzantine emperors as a Christian stronghold, and Athens hereafter became merely an outpost of the Byzantine Empire. Consequently the period 1200-1453 was another Dark Age of constant invasions – Francs, Catalans, Florentines, Venetians – violently usurped the power of Athens and other parts of Greece. But, to do them justice, they also left their marks in culture and architecture. This was an effect of the crusades launched from 1095 by the Franks. Later their deal with the mighty Venice resulted in the tragic sacking of Constantinople 1204. Subsequently Greece became the apple of discord in the constant war between the Latin and the Byzantine worlds. While Constantinople tried to regain its

23

Villa in Anavryta by architect Aris Zambicos (2005). The spatial concept is inspired by architect Oscar Niemeyer’s architecture. New addition to villa designed by architect Kyriakos Krokos (1991). The excellent interplay created by arch. Maria Kokkinou and Andreas Kourkoulas (2005).

74

of the contractors and builders using “the ones we know” and the EU pre-qualification system of inviting tenders for projects or competitions does not ease the break-through. The best way for young architects has always been going through projects of private villas, and as this tradition of individual building design particularly in Greece has been very strong, it is still a very good possibility. Fancy villas have found a renaissance especially now when the issue of trendy homes and personal life style has become so “hot”. Of course the competitions are important as well as the general promotion of modernist Greek architecture accomplished through exhibitions, journals and books. A revival of the interest in architecture has been noticeable since the competitions for the new Acropolis Museum, a series of Greek entries in the Venice Biennale since 1990 and the RIBA exhibition 2003 of contemporary architecture in Greece. Greek nominations for the Mies van der Rohe prize (Katerina Tsiagarida and Zoe Samourkas 2000) and Greek Euro-Pan-competitionwinners call for international attention. Finally the international competition of “Ephemeral structures” 2002-03-part of the Greek cultural Olympiad, aimed at new intermediate installations enriching the urban scene. This tempted a lot of young talents of architecture to come forward with new ideas. So gradually Greek architecture is finding its place in the international scene. Many Greek architects are still trained in Schools of architecture abroad. In Greece three new schools of architecture are challenging the two older ones in Athens and Thessaloniki. An international exchange of students and professionals does also develop the wider perspective and a shared knowledge. A lot of talents are found, but the week point is that architecture is considered as the production of individual artefacts, especially individual villas, which do often establish a strong relationship between nature and the given artefact. So the key problem which Greek architecture today faces is that the accumulation of individual successful buildings can hardly amount to

MOB architects, V. Baskozos, D. Tsagaraki and Assoc. created a colourful rebuilding of an existing villa of the artist Giorgos Kypris 1997-99 in Drossia, north of Athens.

a successful overall built environment. Yet the competitions for the four main squares in Athens and the harbour-front in Thessaloniki are positive signs of a growing interest in the physical shape of the public sphere. The immanent Greek notion of “Chora� may be heading at a strong come-back. No doubt the focus on Greece and Athens qua the Olympic Games in 2004 and the many architectural assignments connected to this giant tour de force has, like it happened for instance in Barcelona 2000, advanced the optimism and the courage of the whole architectural firmament. The mere attention Greek architecture attracted by the success of the Olympic Games will for certain accelerate its progress. 75

CHAPTER 3

Athens – urban development new perspectives

tably the Greek city, in particular Athens, constitutes a common field of reference for these architects, who undertake their individual trajectories within an urban condition which offers no concrete formal context for an architectural production. Therefore, any contextual affinity must be of a conceptual and not of a formal, visual character. (cf. Archis 7/2000 M. Theodorou: Athens 2000 AD: Forensic spacescape, p.76). Tendencies in the contemporary progressive architecture of the Athens region Many of the works/projects presented by this investigation in contemporary Greek architecture seem to profit from the relative vagueness of the context, which leaves it up to the architects to refer to selected, different constituting elements of the environment. This conceptual freedom opens for an abstract architectural form language, “an architecture of difference”, which rejects to establish any forged historic continuity. One may say that the absence of a readable context provokes a creative interpretation of the present banal, everyday elements and the potential flux of activities. Three tendencies prevail in the present Greek architecture – as reflected in the cases: 1. A number of architects respond to the formal bustle of the Greek urban landscape by presenting structures which are evidently ordered, abstract, yet with a touch of individual boldness. The projects are like islands of rest in the wavy urban sea – not detached from their environment, but rather in an interactive balanced situation. The single modern works differentiate from the surrounding urban context through subtle but determined moves, an extraordinary handling of the materiality of the volumes/structures and geometrical refinements of the design. Transparency and tectonics are important issues especially in relation to industrial buildings, office- and showroom spaces etc. Exponents of this stringent but inventive style are architects like Catherine Diacomidis & Nikos 112

Theme: Resistance and Topos. Double and triple residences in Papagou quarter by arch. Niokos Ktenas (1993-98, 1998-2000) The urban villas underline the interchange of external spaces and internal volumes. Papagou quarter of Athens (arch. Nikos Ktenas 1998-2000) – a three residence urban villa underlining the interchange of external spaces and internal volumes. (See also case pp. 244-45) Architects own house in Papagou (Kalliopi Kontozoglou, 1998-2001) – the design plays with the artistic movement and interaction of two prisms of different height on a narrow site with a slope. (see case pp. 238-39)

113

CHAPTER 4

Attica and the sites of the Olympic games 2004

Cape Sounion – one of the favourite attractions of Attica. Brauron/Vravrona ruins – famous for its Sanctuary of Artemis.

Attica Athens is a part of the Attica region (see p. 130), not only a central area for Greece but also for the events of Olympics 2004 – therefore these themes are coupled in this chapter. Nevertheless Attica comprises more than just the Olympic-sites and the capital. Among its attractions, well known by many tourists: are the large port of Piraeus and the famous Temple of Poseidon from 444 BC at Cape Sounion, a place which offers the splendid sunset panoramas. In antiquity Attica was the very centre of Greek culture. As history tells, until the 7th century Attica consisted of a number of small kingdoms like for instance Eleusis/Elefsina, Megara, Ramnous and Brauron/Vravrona. The ruins of these long lost cities and sanctuaries are still visible monuments. Attica also includes the famous plain of Marathon, where the Athenians under the command of Miltiades 490 BC defeated the Persians. In 2003-04 the memorial of the victory, the burial mound of the Greek heroes, and the surroundings have been partly reorganised. The Marathonrace commemorates the site. Besides these attractions, Attica has several beachresorts along the Southwest Apollo-coast, which for decades has been a very popular and fast-developing part of greater Athens. So far the East part of Attica has much more modest locations and beaches. The inland features characteristic landscapes with gorges 126

The Marathon Dam, constructed 1926, faced with Pendeli marble. Eleusis/ Elefsina relics of the Sanctuary of Demeter, dating back to Mycenaean time.

and forests around the peaks of Mt. Parnes (1430m) and Mt. Pendeli (1107 m), the latter famous for its marble quarries. The ancient quarries were in work already from 570 BC and in the 5th century they were the major source of material for the entire marble constructions, not only in Athens, but also in Eleusis, Delphi and Olympia. These quarries are still to be seen in the landscape (John L. Tomkinson: Attica, Athens 2002, p. 83-84) Attica does also offer Byzantine attractions like the Daphne monastery (damaged by earthquake 1999) and the monastery gardens at Kessariani. Once upon a time in 1841, when the Danish poet Hans Christian Andersen arrived to Piraeus, these sites were lovely rural idylls – now they are more or less engulfed in the greater Athens urbanised area. 127

184

Athens

185

186

GEK-TERNA Headquarters – Office 85, Mesogion Avenue, Neo Psychiko, Athens Architect: Sir Michael Hopkins, GB 2000-03 When the GEK-TERNA construction-company decided to relocate from the suburbs to central Athens, they were determined to make the new headquarters a distinguished modern addition to the extraordinary architectural heritage of Athens. The conditions for the invited architects of the limited international competition in year 2000 were not the easiest ones: The site was problematic, with the hectic Mesogion Avenue on one side and a much quieter residential street behind it, facing west. Another building occupies the wedge shape of the junction, leaving the site an irregular rhomboid with two street elevations. A level change of 3,6 m also exists between the two streets at significantly different angles.

The winning design of Hopkins Architects maximises the usable space up till a total of 11,000 m2, within the irregularly shaped site and the height limit of six storeys above ground. The architect has chosen to use a controlled palette of components and materials, using steel, concrete and timber, and responding to this formal discipline brushed stainless steel panels on the elevation, contrasting with the exposed concrete of the frames, cast in situ. However, the most important part of the idea concept concerns the spatial qualities of the complex. The roofed spaces surround an open double courtyard, in an attempt to temper the environment. The elevation and internal layout both reflect a desire to moderate the effect of the strong The main inner façade opening towards the triangular atrium.

athens

The triangular atrium is underlined by connecting bridges/balconies.

187

188

ATTICA

189

Office building “Zenon SA-Robotics Informatics” – II+III Address: 5, Kanari St., Glyka Nera, NE of Athens Attica Architect: DH-Architects, C. Diacomidis N. Haritos with T. Bessel, 2000-04 The building of the “Zenon SA-RoboticsInformatics” company is located in the north-eastern suburb of Athens, Glyka Nera, and situated next to an existing building belonging to the company and designed by the same architects in 1994. The company had an urgent need of office space, so the programme aimed at a maximum amount of m2 on the plot next to the already built up plot, + a new connection. The basic three floor plans are quite simple and functional with a service-circulation zone dividing the plan into two nearly identical spaces. The connecting section of the buildings has a lower ceiling to mark the entrance and reception area. The result is a split-level relation of the two sides of the building from the basement to the first floor, thus creating spaces of 1st floor height and an interesting variation of the spatial organism, see the section. The external appearance of the building is a simple cube, which has been unfolded or opened in a way that makes the initial volume still recognisable. Parts of the cube become walls, which 1: define the plot in relation to the neighbouring plots and the street or 2: modulate the garden spaces creating a continuous inside/outside contact. The interior profits from the green areas with fresh air, shadow and 190

attica

leisure spaces, which also adapt the complex to its context. The use of simple lightpainted plaster on the façades refers to the general building-fabric of the neighbouring area, but is contrasted by the metal appearing in all the different sun-protection systems. (cf. description by the DH-architects’ office) The interior of the building is generally characterised by the use of the white painted walls and the elegant appearance of the light-grey industrial floor matching the metal openings and creating a neutral and flexible office space. Natural wood is used for the steps of the metal staircases and the built-in lockers and some colour accents are added in the service and reception zone, underlining the public character of this area. The whole complex has a both relaxed and refined expression, which makes it a good example of an office architecture, which blends in a sensitive way with the environment adding new qualities by an understated corporate design image.

The external facades play with the simple cubic form.

Parts of the cube is carved out or become walls defining the plot.

Plan and section illustrate the simple but expressive concept.

attica

The interior continues the tone striken by the exterior design.

191