4 minute read

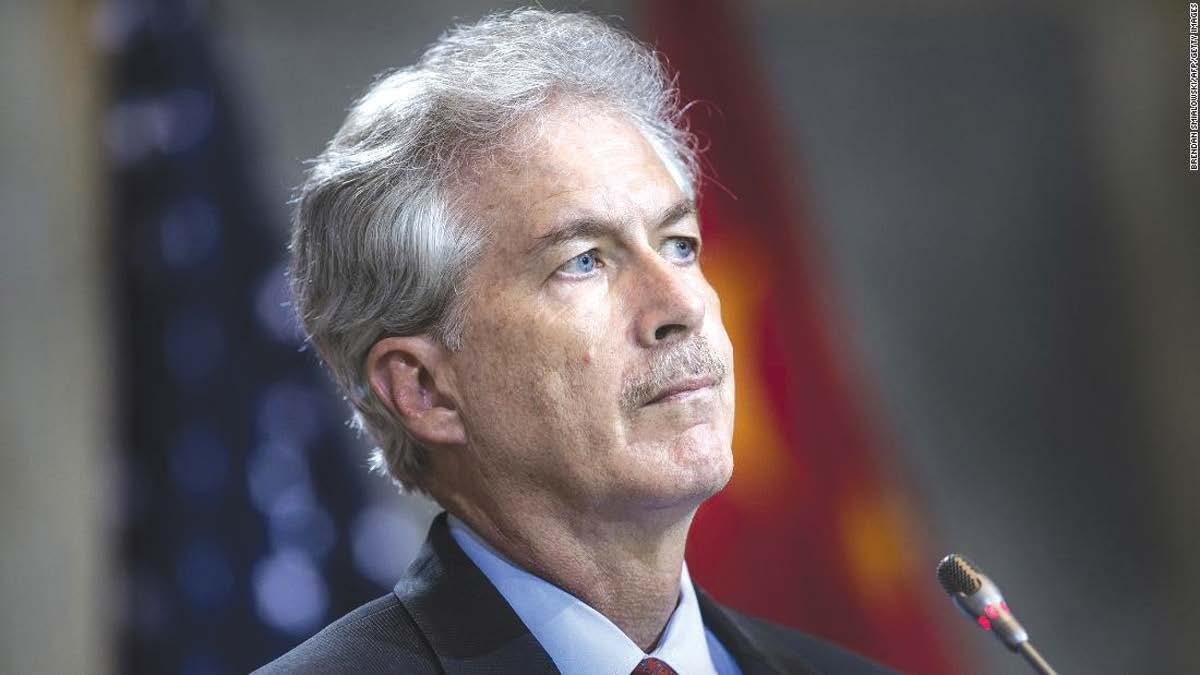

Biden Plans to Nominate William J. Burns by David Ignatius

By David Ignatius

President-elect Joe Biden plans to nominate William J. Burns, a former career diplomat who has served both parties and won respect at home and abroad, to run a CIA that has been badly battered by the Trump administration.

The choice of Burns is the incoming administration’s last major personnel decision, and it highlights the qualities that characterize Biden’s foreign policy team. Burns is an inside player – brainy, reserved, collegial – and loyal to his superiors, sometimes to a fault, as he conceded in his 2019 memoir.

Though a diplomat, not a spy, Burns is a classic “gray man” like those who populate the intelligence world. And he has often served as a secret emissary: The title of his memoir, “The Back Channel,” refers in part to his role as the covert intermediary in the initial contacts with Iran that led to the 2015 nuclear agreement.

For an agency that lives on personal trust, Burns is an apt choice. As I wrote nearly two years ago in reviewing the memoir, Burns “is widely viewed as the best Foreign Service officer of his generation.” His list of mentors is a “who’s who” of diplomacy, perhaps topped by James A. Baker III, who served as secretary of state for President George H.W. Bush in the closing days of the Cold War.

The choice of Burns will disappoint those who wanted a career intelligence officer to succeed Gina Haspel, the current director. Michael Morell, a career CIA analyst and former acting director, was popular among many CIA alumni, who argued that he knew the agency’s shortcomings well enough to oversee the overhaul that CIA needs for the 21st century.

Biden opted for an outsider who could bring independent judgment to running the agency. He is said to have offered the job initially to Thomas E. Donilon, a former national security adviser in the Obama administration and close Biden friend, and then to have considered David Cohen, a former Treasury official who worked for two years as CIA deputy director under President Barack Obama.

What’s likely to have appealed to Biden, in addition to his personal comfort level with Burns, is his reputation as a nonpartisan figure who served in hard places – Russia and the Middle East –and over the years developed close relationships with the countries that are the CIA’s key liaison partners.

His biggest challenge will be dealing with a quirky, cliquey CIA culture that is often resistant to change. CIA operatives have been masterful over the years at bending new directors to their priorities. Burns will have to surmount that – and encourage change in an agency whose fundamentals have been rocked by new technology.

The CIA has been hunkered down during the Trump years, with employees trying to stick to their jobs of collecting and analyzing secrets even as Trump made the intelligence agencies his personal punching bag. Trump’s first CIA director, Mike Pompeo, was seen by agency officers as smart and aggressive but also mercurial and temperamental.

Haspel dealt skillfully with Pompeo as his deputy, and she replaced him when he left to become secretary of state. She has kept an un-

usually low profile, disdaining media interviews and trying to avoid clashes with the volcanic Trump. Foreign intelligence chiefs came to see Haspel’s continued tenure as a key indicator that the United States was still a reliable secret partner, despite Trump’s machinations.

Haspel held her ground when it mattered. When journalist Jamal Khashoggi was murdered, she told Congress that the agency had relatively high confidence that Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman was responsible – even though the Saudi leader was a Trump favorite. Several weeks before the Nov. 3 election, Haspel signaled that she would resign if Trump and Director of National Intelligence John Ratcliffe released sensitive classified information about the origins of the Russia investigation whose disclosure she believed would seriously harm national security.

Burns will inherit the job of “telling truth to power,” as the CIA’s mission is often described. His record shows that he has been a perceptive critic of policy decisions but sometimes accommodated those he thought were mistaken. He warned privately of the “recklessly rosy assumptions” that underlay President George W. Bush’s decision to invade Iraq in 2003, but asked in his memoirs, “Why didn’t I go to the mat in my opposition or quit?”

Since leaving the State Department in 2014 after a 33-year diplomatic career, Burns has served as president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Fluent in Arabic and Russian, he has less experience in what’s arguably the biggest challenge for the next CIA director – understanding a China that poses a growing economic, political and military challenge. Burns will also need to focus on the rapidly changing technologies that support intelligence – and threaten the CIA’s ability to operate in a world where every movement leaves a digital exhaust and a DNA trace.

To succeed at the CIA, Burns will have to be undiplomatic. That may not be his natural instinct, but this job requires telling people, especially the boss, things they don’t want to hear. (c) 2020, Washington Post Writers Group