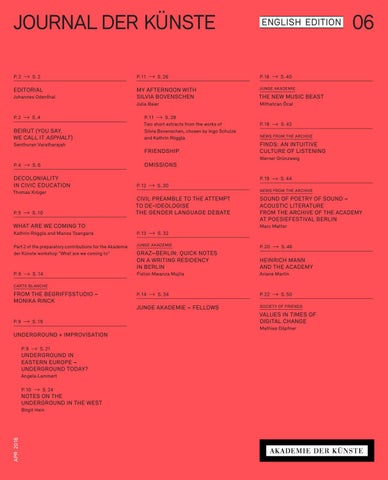

JOURNAL DER KÜNSTE P. 2

S. 2

EDITORIAL Johannes Odenthal

P. 2

S. 4

BEIRUT (YOU SAY, WE CALL IT ASPHALT )

P. 11

S. 26

ENGLISH EDITION

P. 16

S. 40

JUNGE AKADEMIE

MY AFTERNOON WITH SILVIA BOVENSCHEN

THE NEW MUSIC BEAST

Julia Baier

Mithatcan Öcal

P. 11 S. 28 Two short extracts from the works of Silvia Bovenschen, chosen by Ingo Schulze and Kathrin Röggla

Senthuran Varatharajah

FRIENDSHIP

06

P. 18

S. 42

NEWS FROM THE ARCHIVE

FINDS: AN INTUITIVE CULTURE OF LISTENING Werner Grünzweig

P. 4

S. 6

DECOLONIALITY IN CIVIC EDUCATION

OMISSIONS P. 19 P. 12

S. 30

Thomas Krüger

P. 5

S. 10

CIVIL PREAMBLE TO THE ATTEMPT TO DE-IDEOLOGISE THE GENDER LANGUAGE DEBATE

WHAT ARE WE COMING TO

S. 44

NEWS FROM THE ARCHIVE

SOUND OF POETRY OF SOUND – ACOUSTIC LITERATURE FROM THE ARCHIVE OF THE ACADEMY AT POESIEFESTIVAL BERLIN Marc Matter

Kathrin Röggla and Manos Tsangaris

P. 13

Part 2 of the preparatory contributions for the Akademie der Künste workshop “What are we coming to”

JUNGE AKADEMIE

P. 20

GRAZ–BERLIN: QUICK NOTES ON A WRITING RESIDENCY IN BERLIN

HEINRICH MANN AND THE ACADEMY

Fiston Mwanza Mujila

Ariane Martin

P. 14

P. 22

P. 6

S. 14

S. 32 S. 46

CARTE BLANCHE

FROM THE BEGRIFFSSTUDIO – MONIKA RINCK P. 9

S. 19

S. 34

JUNGE AKADEMIE – FELLOWS

S. 50

SOCIETY OF FRIENDS

VALUES IN TIMES OF DIGITAL CHANGE Mathias Döpfner

UNDERGROUND + IMPROVISATION P. 9

S. 21

UNDERGROUND IN EASTERN EUROPE – UNDERGROUND TODAY? Angela Lammert P. 10

S. 24

NOTES ON THE UNDERGROUND IN THE WEST

APR 2018

Birgit Hein