the Heart of the Turf RACING’S BLACK PIONEERS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

28 THE EARLY 1900s

Raleigh Colston Jr.

Thomas Colston

John Buckner

Will Harbut

Cunningham Graves

46 LEXINGTON’S EAST END

Isaac Burns Murphy

Jimmy Winkfield

Ansel Williamson

Edward Dudley Brown

William Walker

Cato

Harry Lewis

William Bird

Ansel Williamson

Charles Stewart

14

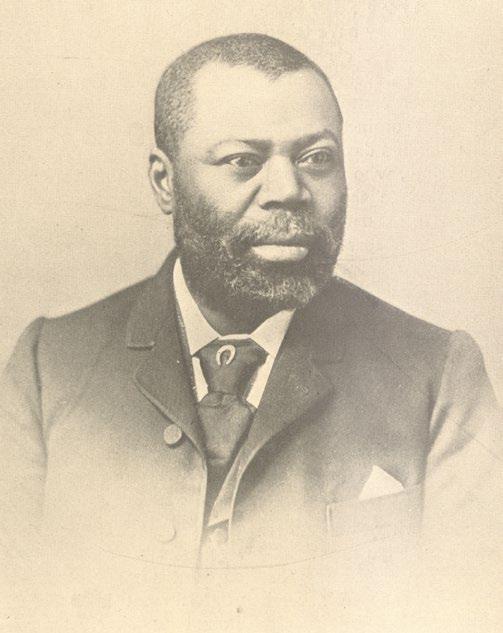

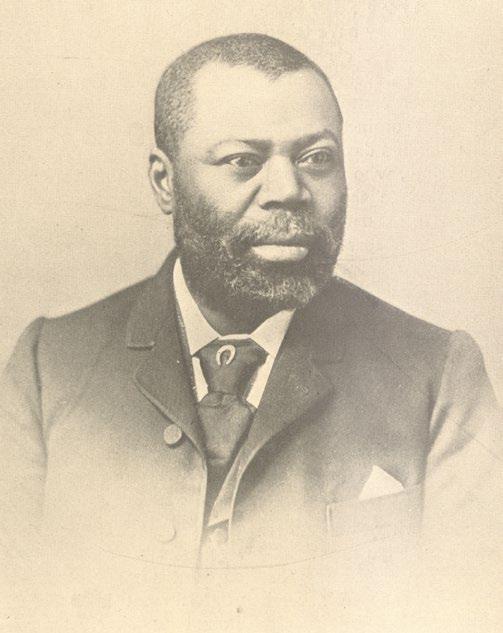

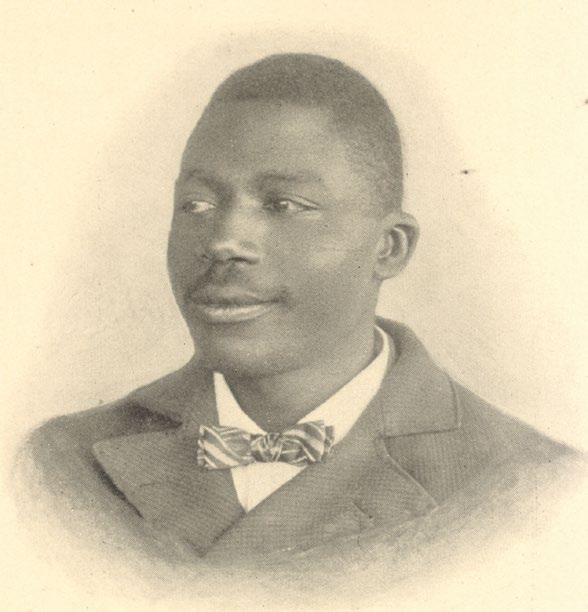

Raleigh Colston Sr.

Harry Colston

Joseph Colston

Dudley Allen

Eli Jordan

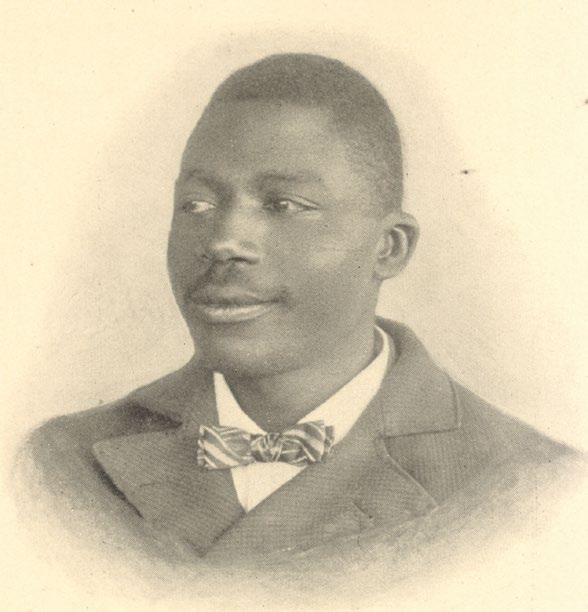

Edward Dudley Brown

Albert Cooper

Thomas Greene

Matthew Earley

Luther Carr

Lee Christy

Oliver Lewis

William Walker

Burns Murphy

Clemon Brooks

30 THE MID-1900s

Silvia Bishop

Theophilus Irvin Jr.

Marshall Lilly

Eugene Carter

Oscar Dishman Jr.

33 THE MID TO LATE 1900s

Dudley Sidney

Francis Carrol Wilson Sr.

Walter Edwards

John Joe Hughes Jr.

Archie R. Donaldson

Eddie Sweat

Cheryl White

Jonathan Figgs

Martin L. Brown

Sylvester Carmouche

40 THE 2000s

James Long

Charles Robinson

Phillip L. Jones

Cordell Anderson

Ron Hill

Shelby Pike Barnes

Bud Haggins

George Anderson

Henry J. Harris

William Porter

Alonzo Clayton

26 TURN OF THE 20TH CENTURY

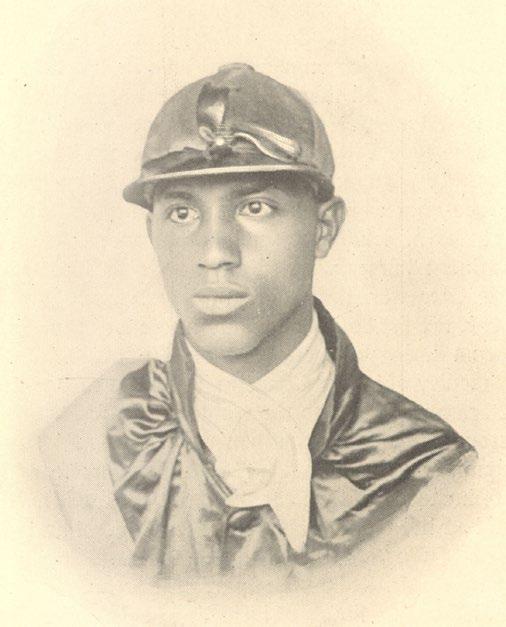

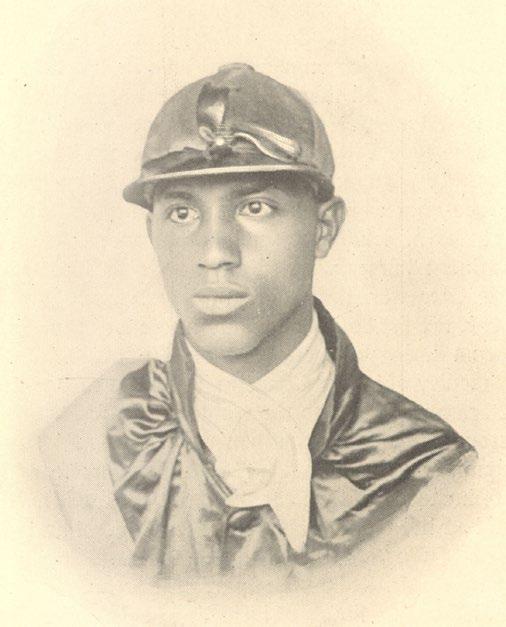

James “Soup” Perkins

Jimmy Winkfield

Jimmy Lee

Marlon St. Julien

DeShawn Parker

Kendrick Carmouche

Greg Harbut

44 KENTUCKY ASSOCIATION TRACK

History of racing in Lexington

James Carter

Isaac Burns Murphy

Anthony Hamilton

Isaac Lewis

James “Soup” Perkins

Thomas Britton

Raleigh Colston Sr.

Raleigh Colston Jr.

Abraham Perry

Eli Jordan

Lee Christy

Courtney Matthews

Mattie Perkins

John Jacob Perkins

William Perkins

Frank Perkins

James “Soup” Perkins

Dudley Allen

Alonzo Curtis

Clay Trotter

Oliver Lewis

James Carter

50 RACING’S BLACK PIONEERS: PHOTO GALLERY

Rosewood keepsake box with ornamental brass and copper inlays belonging to jockey William Walker (detail).

2 HISTORICAL HIGHLIGHTS 8 INTRODUCTION 10 YESTERDAY, TODAY & TOMORROW 12 THE ANTEBELLUM ERA

THE MID TO LATE 1800s

THE

18

RECONSTRUCTION ERA

Isaac

21 THE LATE 1800s Anthony Hamilton Willie Simms

7

GRACIOUSLY LOANED BY HANK AND MARY BROCKMAN PHOTO COURTESY JAMES SHAMBHU

8

Oscar Dishman Jr. (right) and Robert Turner (left) with Dust Wind, circa 1965 KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

FROM THE ERA of slavery to today, Kentucky has remained an industry hub for pioneering Black horsemen and women. The economy of the Bluegrass and viability of the Thoroughbred industry as a whole are rooted in their skill, hard work, knowledge, and tenacity.

From racetrack superstars to behind-the-scenes caretakers, The Heart of the Turf: Racing’s Black Pioneers highlights select stories of the countless African Americans who forged their way in Kentucky and beyond, making the racing industry what it is today.

We document and share their past and present stories with an eye toward the future. As our country continues to grapple with race and equity issues, finding ways to advance all areas of the workforce through diversity remains an ongoing challenge. By examining the obstacles, tragedies, and triumphs of successive generations of racing’s Black pioneers, we can inform today’s initiatives to create new, inclusive opportunities across the industry.

9

FROM THE AMERICAN Revolution through the Civil War, horse racing was the country’s sport of choice, and many of the sport’s best horsemen were enslaved. Living with the atrocities of slavery, Black grooms, farriers, stable managers, trainers, and riders tasked with the conditioning, and 24/7 care of racehorses passed down their hard-earned knowledge to the next generation, cultivating a continuum of outstanding horsemanship.

In the early years following the Civil War and the national abolition of slavery in 1865, African American stable managers, trainers, and jockeys continued to excel, as they owned, bred, conditioned, or rode some of the country’s top horses in prestigious races. Black jockeys, the sport’s most visible players, swept racing cards while headlines celebrated their skill in the saddle. The economic growth fueled by the country’s Industrial Revolution created a new workforce ready and willing to pay for entertainment. As racing fans packed track grandstands in the late 1800s to engage in the nation’s favorite pastime, Black jockeys shared the spotlight, often on mounts trained or owned by African Americans. At their collective height in 1892, Black jockeys occupied more than a third of the top 25 jockey positions in America.

Circumstances for Black horsemen would change dramatically by the late 1890s. Escalating legislation in many states barred African Americans from public spaces and facilities. Racing’s Black workforce experienced the same mounting violence, segregation and systemic discrimination that targeted all African Americans. Many former stars of the turf were forced to seek employment elsewhere, often flocking to urban centers in the North or to Europe for a shot in racing overseas.

YESTERDAY, TODAY & TOMORROW

Isaac Burns Murphy collectible cigarette card

IMAGE COURTESY LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

10

Willie Simms after winning the 1897 Suburban Handicap on Ben Brush KEENELAND LIBRARY HEMMENT COLLECTION

Although displaced to lower profile and less lucrative positions, many Black horsemen remained in the industry, particularly on Kentucky farms and tracks. Working for leading Bluegrass horse farms while living in proximity to each other, Black horsemen endured, honing and sharing their horsemanship with each other and their apprentices through the early 20th century.

Faced with system-wide, sustained barriers to licensure as trainers or jockeys, their successors secured work primarily as grooms, exercise riders, and backside workers through the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. The last half of the 20th century saw more Black racehorse owners, licensed jockeys and trainers, and women across industry roles. Moving forward, these pioneers’ vital strides continue to pave the way for African Americans seeking careers in the saddle or on the backside, and in equine science, veterinary medicine, industry organizational leadership, and farm or track promotion and management.

John Buckner with Man o’ War in 1922 KEENELAND LIBRARY JEFFORDS COLLECTION

Kendrick Carmouche in 2020

John Buckner with Man o’ War in 1922 KEENELAND LIBRARY JEFFORDS COLLECTION

Kendrick Carmouche in 2020

11

PHOTO COURTESY ADAM COGLIANESE

UP TO THE abolition of slavery in 1865 after the Civil War, countless enslaved boys and men were tasked with the daily maintenance of horses in the American South. Many enslaved boys grew up working with and caring for horses around the clock, often sleeping in the stables or fields. Selected for their small size or talent in the saddle, some became exercise riders and then jockeys as early as the age of 10.

One prominent jockey of this period was Cato, most remembered for his victory aboard Virginia-bred Wagner who contested and beat Kentucky-bred Grey Eagle in 1839 in one of the mid-19th century’s most epic match races. Cato, named after the Roman statesman in a common and cruelly ironic naming practice of slaveholders, overcame his enslaved name by becoming one of the few jockeys of the era to win his freedom. In most cases, despite their success, skilled enslaved jockeys were so valuable that their owners were unwilling to release them from enslavement.

Through a lifelong process of honing their instincts and gaining knowledge from their predecessors as prior stable hands or jockeys, some enslaved men went on to train horses and manage racing stables. Harry Lewis, born in Kentucky circa 1805, was a prominent trainer for horse owner Willa Viley, who purchased Lewis for $1,500.

By 1850, Harry Lewis was a free man with a reported $500 annual salary to train Viley’s horses. The success of racing stables hinged on the keen skills of African American horse trainers, whether enslaved or free, although training as a free Black man during the era of slavery was the exception to the rule. Lewis trained several prominent racehorses of the day, including Richard Singleton, Grey Eagle, and Dr. Elisha Warfield’s promising 3-year-old colt Darley. Darley was later renamed Lexington – winner of six of his seven starts and the most successful sire of the second half of the 19th century.

Another free Black trainer was William “Bill” Bird. Born in 1832, Bird apprenticed at age 10 with James and Jerry Haxall of Nashville, Tennessee. From age 16 to 19, he was employed by horse owners John Merrill, Tom Patterson, and Major Seagull. Richard Ten Broeck contracted Bird in 1856 to train his horses in England, including the great Pryor and Prioress.

IN THE ANTEBELLUM ERA

Trainer Harry Lewis with Richard Singleton Richard Singleton by Edward Troye IMAGE COURTESY VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS

12

The jockey Cato with Wagner ENGRAVING AFTER THE ORIGINAL PAINTING WAGNER BY EDWARD TROYE IN AMERICAN TURF REGISTER, JULY 1843

Ansel Williamson, born enslaved in Virginia circa 1806, became a top horseman at several Kentucky racing stables. Williamson established his reputation as an enslaved trainer while conditioning T.G. Goldsby’s Brown Dick to sweeping victories across Southern states. After his early success, Williamson was sold in succession to Kentucky owners A. Keene Richards and Robert A. Alexander, for whom he trained multiple prominent racehorses, including Australian, Glycera, Asteroid, and Norfolk. After the Civil War, Williamson trained as a free man for H.P. McGrath in Fayette County and Abe Buford in Woodford County. Although best remembered for training Aristides, the winner of the first Kentucky Derby in 1875, Williamson conditioned Travers, Belmont, Jerome, Phoenix, and Withers Stakes winners.

Another enslaved horseman who traveled across state lines acting as a racing stable agent was former prize-winning jockey Charles Stewart. Riding in his first race as a 70-pound 13-year-old, Stewart went on to establish himself as a trainer and stable foreman. Traveling as far as the free state of Pennsylvania on business for his owner Colonel William Ransom Johnson of Virginia, Stewart’s mobility between Southern states and free states in the North as an enslaved horseman speaks to his unique position within the confines of slavery and its myriad social and psychological complexities.

Trainer Ansel Williamson with Asteroid and jockey Edward Dudley Brown The Undefeated Asteroid by Edward Troye IMAGE COURTESY VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS

Trainer Ansel Williamson with Asteroid and jockey Edward Dudley Brown The Undefeated Asteroid by Edward Troye IMAGE COURTESY VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS

AFTER THE ORIGINAL PAINTING BY EDWARD TROYE IN AMERICAN TURF REGISTER, MAY 1833 13

Charles Stewart with Medley ENGRAVING

THE LEGACY OF the Colston family spanned almost a century from the mid-1800s to the early 1900s. Brothers Raleigh Sr. (b. 1837), Harry (b. 1845), and Joseph (b. 1853) were born enslaved on John Harper’s Nantura Stud in Woodford County, Kentucky. All three brothers were jockeys and trainers. Raleigh and Harry would also become racehorse owners.

Harry and Joseph Colston remained at Nantura after the Civil War, conditioning leading racehorses of the day, including Longfellow and Ten Broeck. Ten Broeck earned his place in history defeating the unstoppable Mollie McCarty in their 1878 legendary match race. Harry later sold one of Longfellow’s colts, Irish King, for $4,000 to start his own racing stable.

After emancipation, Raleigh Colston Sr. trained for several prominent Kentucky stables, including Robert A. Alexander’s Woodburn Stud and Daniel Swigert’s Stockwood Stud. Raleigh’s noteworthy horses include Kingfisher, the first horse trained by an African American to win the Belmont Stakes in 1870, and Leonatus, winner of the 1883 Kentucky, Illinois, and Latonia Derbys. Raleigh and his family moved to Lexington near the Kentucky Association Track in 1871, where he continued to train for leading stables in the area and established his own stable in 1879.

Dudley Allen was born enslaved in 1846 in Lexington, Kentucky. He gained his freedom in 1864 when he enlisted with the 5th Cavalry of the United States Colored Troops during the Civil War. After the war, he and his wife Margaret purchased a home in East Lexington where Allen launched a successful career training and owning racehorses that spanned four decades. Allen conditioned horses for Thomas J. Megibben, founder of Latonia Race Course in northern Kentucky, and worked as a trainer for several stables in the area, including Runnymede Stud and Jacobin Stable – a stable Allen co-owned with Kinzea Stone.

IN THE MID TO LATE 1800s

Leonatus, trained by Raleigh Colston Sr. KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

Kingman, trained and co-owned by Dudley Allen KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

14

Groom with Henry of Navarre, 1891 KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

When Kingman, a horse Allen trained and co-owned, won the 1891 Kentucky Derby with Isaac Murphy in the saddle, Allen became the first Black owner of a Derby winner. Allen and Murphy were the last African American owner-jockey pair to win the Derby, and Allen remains the most recent African American trainer to hold a Derby title. Allen apprenticed several young men for careers as jockeys or trainers, much like one of his contemporaries, Eli Jordan. A successful multiple stakes-winning trainer in his own right with his superstar and 1879 Horse of the Year, Falsetto, Jordan also mentored top jockeys of the day, including Thomas Britton, Isaac Murphy, and Shelby Barnes.

Separated from his family and sold at Lexington’s slave auction block at around age seven, Edward Dudley Brown was purchased by Robert A. Alexander of Woodburn Stud. Brown was trained as a stable hand before becoming a jockey in 1864 under Ansel Williamson’s tutelage. Brown rode Asteroid during his undefeated 1864 and 1865 seasons, and after the Civil War, he piloted Kingfisher (trained by African American Raleigh Colston Sr.) in his 1870 Belmont Stakes win. As Brown became too heavy to ride competitively, he transitioned into developing young horses, often selling them to prominent owners after their early success under his conditioning. His achievements as a trainer and owner positioned him as one of Kentucky’s wealthiest African Americans by the end of the 19th century. Among his many leading horses of the late 1800s, Brown trained multiple graded stakes winners Plaudit, Ben Brush, and Hindoo. His career highlights include 1877 Kentucky Derby winner Baden-Baden, 1893 Kentucky Oaks winner Monrovia, and 1900 Kentucky Oaks winner Etta –a filly he trained, owned, and later sold to John E. Madden of Hamburg Place.

1897 Suburban Handicap won by Ben Brush, Willie Simms up KEENELAND LIBRARY HEMMENT COLLECTION

1897 Suburban Handicap won by Ben Brush, Willie Simms up KEENELAND LIBRARY HEMMENT COLLECTION

15

Edward Dudley Brown KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

BORN DURING ENSLAVEMENT in Virginia in 1850, Albert Cooper worked his way from stable hand to foreman of the seven-time Preakness Stakes winning stable of R. Wyndham Walden. After nearly 20 years of overseeing racehorse care, Cooper began to train for several prominent owners across the country, including J.E. Brewster of Chicago’s Washington Park Race Track and E.J. “Lucky” Baldwin of California. After conditioning a string of successful runners for Baldwin, Cooper was contracted by California- and Kentucky-based James Ben Ali Haggin and New York-based Senator George Hearst. Following Hearst’s death, Cooper begin to purchase and train horses in his own stable, while also conditioning for James R. Keene. Over his long career, Cooper conditioned the great Mollie McCarty and claimed two American Derby wins with Volante in 1885 and Silver Cloud in 1886. While working for the Hough brothers, Cooper trained the Kentucky-bred Burlington who won the 1890 Brooklyn Derby, Great Tidal Stakes, and the Belmont Stakes at odds of 7-1 with African American Shelby “Pike” Barnes in the saddle.

Thomas Greene, born in 1859 during enslavement in Charleston, South Carolina, became an exercise rider in his youth before he began to work as a free man for Henry Horres, a Charleston-based breeder, for nearly ten years. Greene went on to train or manage stables for prominent owners W.C. Daly, E.R. Bradley, and the father-son team of James R. and Foxhall Keene. His stakes-winning horses at New York tracks included Fidelio, Prince George, and Count, while his best filly, Royal Rose, won the 1896 Gaiety Stakes at Morris Park in the Bronx, New York. By the end of the 19th century, Greene had charge of some of James R. Keene’s best performers, including the veterans Ben Brush and Rhodesia, as well as Keene’s up-and-coming 2- and 3-year-olds.

Other contemporaries of Greene, including Matthew Earley, trained horses for owners with stables based across the country. Born in Georgia in 1867, Earley joined the staff of Byron McClelland at age 15 as an exercise rider, working some of the best horses in McClelland’s stable. He became an assistant trainer for Edward Wall before taking charge of William R. Jones’s string, including the great runners Belwood, Satisfied, Babette, and Postmaster. The most notable horse under Earley’s care was Charade, winner of the 1892 Tidal Stakes and the 1893 Brookdale and Metropolitan Handicaps.

IN THE MID TO LATE 1800s

Albert Cooper KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

16

Matthew Earley KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

One of the many young men African American trainer Dudley Allen took under his wing was Luther Carr, Allen’s nephew through marriage. Described by the 1898 publication The American Turf as another “representative of that army of capable turfmen who have come out of Kentucky,” Carr began working for Allen as a stable hand in 1884. Over a seven-year period, Carr learned the ropes before assuming the role of assistant trainer under Allen.

Carr’s reputation for proficiency and professionalism landed him a training contract with the prominent African American turfman Lee Christy. During the late 1800s, Carr conditioned horses for James E. Pepper, B.J. Johnson, Charles Smith, and the stable of Bromley & Company. Some of the noteworthy horses under Carr’s management were two public favorite campaigners sired by Fonso –Rudolph and First Mate.

Lee Christy, born in 1859, was a native of Gallatin, Tennessee. He began his career as a jockey, coming to Kentucky to join the stable of Daniel Swigert. He later advanced to training for J. Allen & Company in Frankfort before working for Frank Harper at Nantura Farm in Woodford County from 1882 to 1884. In 1898, Christy announced the opening of his public training stable in Lexington, where he had purchased a home for his family.

Trainer Byron McClelland’s staff, circa 1895 KEENELAND LIBRARY HEMMENT COLLECTION

Thomas Greene KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

17

Luther Carr KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

FROM POLICY CHANGES that ushered in rights for former slaves to evolving social systems for race relations, the Reconstruction years following the Civil War’s end in the 1860s precipitated tremendous economic, social, and political changes for African Americans. Oliver Lewis was one of several jockeys who got their start during the Reconstruction era. Born in 1856 in Woodford County, Kentucky, Lewis was employed at a young age by H.P. McGrath, along with more than 20 other African Americans.

The inaugural Kentucky Derby was a comparatively small event in the racing world in 1875. By the time of its first running, ten years after slavery had legally ended, several of racing’s top jockeys and trainers were African

JOCKEYS IN THE RECONSTRUCTION ERA

Isaac Burns Murphy at the 1890 clambake celebrating Salvator, Murphy’s mount in the 1890 match race against Tenny KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

18

Americans. In the 1875 Kentucky Derby, all but two of the 15 jockeys were Black, and the race’s first winner, Aristides, was ridden by Oliver Lewis and trained by the prominent Black horseman Ansel Williamson. Black jockeys would win the Derby in 16 of its first 28 runnings, as the race continued to gain traction as a premier racing event in the region.

After winning the Derby at age 18, Lewis continued to ride primarily for McGrath. He later became a bookmaker and developed handicapping charts that paved the way for those eventually found in publications like the Daily Racing Form. Lewis is buried in African Cemetery No. 2 in Lexington’s East End.

William Walker was born enslaved in 1860 in Woodford County, Kentucky. By age 11, he had already won his first official race at Jerome Park in Westchester County, New York. His greatest triumph came while piloting the Kentucky-bred colt Ten Broeck to victory over the undefeated California mare Molly McCarty in their celebrated 1878 match race at the Louisville Jockey Club (now Churchill Downs).

Walker rode Baden-Baden to his Kentucky Derby victory in 1877, and he secured three other mounts in the Derby over his successful 21-year riding career. Claiming stakes wins across the country, Walker is often remembered as a long-standing fixture at Churchill Downs, where he was leading jockey during the 1876 spring meet and the fall meets of 1875 and 1876. Additionally, Walker tied as meet leader in the springs of 1877, 1878, and 1881.

Walker transitioned to training horses in 1905. Regarded as an expert on bloodlines, he provided pedigree analysis for prominent horse owners in the Bluegrass including John Madden of Hamburg Place, while also acting as a turf correspondent for several sporting publications. It is reported that Walker, either in an official capacity or as a spectator, saw 59 straight Kentucky Derbys before his death in Louisville in 1933.

Oliver Lewis KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

William Walker KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

Presentation watch, manufactured circa 1887, belonging to jockey William Walker.

Oliver Lewis KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

William Walker KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

Presentation watch, manufactured circa 1887, belonging to jockey William Walker.

19

GRACIOUSLY LOANED BY HANK AND MARY BROCKMAN PHOTO COURTESY JAMES SHAMBHU

One of William Walker’s many protégés was the great Isaac Burns Murphy . Known for his control in the saddle and light touch, Murphy outshone many of his peers through his consistent performance. No jockey of his time or since has matched his career winning percentage of at least 44 percent.

Born in 1861 in Bourbon County, Kentucky, Murphy learned his craft from several area Black horsemen, including his earliest tutelage under the trainer Eli Jordan. Making his start with Jordan as a stable hand, Murphy would go on to win four American Derbys between 1884 and 1888, five Latonia Derbys between 1883 and 1891, and

to be the first jockey in history to win three Kentucky Derbys (1884, 1890, 1891).

Given his reputation as a “wizard in the saddle” and an “excellent judge of pace,” Murphy was often offered the best horses to ride, and his services were sought by the most prominent racing stables in the country. The Californian owner E.J. “Lucky” Baldwin paid Murphy $10,000 a year for first call on his services. When the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame held its initial elections for inductees in 1955, Murphy was the first jockey voted into membership half a century after his death in 1896. Murphy was buried in Lexington’s African Cemetery No. 2, close to his home in the East End.

Isaac Burns Murphy KEENELAND LIBRARY HEMMENT COLLECTION

Isaac Burns Murphy on Salvator winning the 1890 match race against Tenny (Edward Garrison up) at Sheepshead Bay KEENELAND LIBRARY HEMMENT COLLECTION

Victorian cake basket used by Isaac Burns Murphy as a calling card tray for guests visiting his Lexington home.

KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

Isaac Burns Murphy KEENELAND LIBRARY HEMMENT COLLECTION

Isaac Burns Murphy on Salvator winning the 1890 match race against Tenny (Edward Garrison up) at Sheepshead Bay KEENELAND LIBRARY HEMMENT COLLECTION

Victorian cake basket used by Isaac Burns Murphy as a calling card tray for guests visiting his Lexington home.

KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

20

PHOTO COURTESY JAMES SHAMBHU

“FEW MEN KNOWN to the turf have had more rapid progress or more marked reputation at the age of 29 than Anthony Hamilton.” Earning this praise in the esteemed publication, The American Turf, Anthony Hamilton was born in South Carolina in 1869 or 1870. Experienced in the saddle from a young age, Hamilton began his jockey apprenticeship in the stable of one of the country’s leading trainers, William Lakeland. Hamilton paired his strength in the irons with his ability to read when to press his mount and when to hold back. His rare balance of athleticism and discernment catapulted him to early success, and his services were in high demand across the country with prominent owners like James Ben Ali Haggin, August Belmont Sr., Mike Dwyer, and Pierre Lorillard. Having ridden a winner in nearly every major race of his day in the U.S. and several in Europe, Hamilton is best remembered for his dominance at New York tracks. He was the only Black rider to score victories in four premier New York handicaps – the Manhattan (1891), Brooklyn (1889 and 1895), Suburban (1895), and Metropolitan (1896).

JOCKEYS IN THE LATE 1800s

Anthony Hamilton on Pickpocket in 1893

KEENELAND LIBRARY HEMMENT COLLECTION

21

Anthony Hamilton KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

His most notable mounts include Firenze, Potomac, and Lamplighter. Hamilton’s wedding reception was hosted by his friend and fellow jockey, Isaac Burns Murphy, in Murphy’s Lexington home. Earning a remarkable career winning percentage that approached Murphy’s, Hamilton was thrown from a horse in Russia in 1904, ending his brilliant career. He died in France shortly after, and his remains were returned to Queens County, New York, for burial.

Another top rider in the U.S. and Europe in the late 1800s was Willie Simms (alternate spelling, Sims). Simms, the only African American jockey to have won each of the future American Triple Crown events – the Kentucky Derby (1896 and 1898), the Preakness Stakes (1898), and the Belmont Stakes (1893 and 1894), was born in Georgia in 1870.

Riding early in his career for Congressman William Scott and Philip Dwyer, by 1893 at age 23, Simms had bested most of his competitors. Stables across the U.S., confident in his reputation for steady judgment in the saddle, placed him aboard their best runners. Simms won some of the era’s most competitive races, including the Champagne Stakes and the Jerome and Suburban Handicaps, before riding in England. He is credited with popularizing the “American” short-stirrup riding style in Europe.

Simms, along with other Black jockeys competing in the 1890s, continued to find mounts despite increasing systemic prejudice from the white racing establishment that amplified in the late 1800s and came to a head at the turn of the 20th century. Heralded in turf publications in the 1890s as “one of the greatest jockeys of the present age,” the Hall of Famer Simms remains firmly ranked as one of America’s best jockeys of all time.

Born in 1871 in Beaver Dam, Kentucky, Shelby “Pike” Barnes burst onto the racing scene in his teens, topping the country’s leading jockey standings in 1888 with 206 wins and an astounding winning percentage of 32.9 percent. He was also the country’s top jockey the following year, racking up 170 wins. In 1888, Barnes won the inaugural Futurity at Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn, New York, aboard Proctor Knott. Other highlights from his brief career include wins in the 1889 Latonia Oaks, Champagne Stakes, and Travers Stakes, as well as the 1890 Belmont Stakes and Brooklyn Derby. After piloting some of the premier runners of his time – Burlington, Long Dance, and Tenny, Barnes retired from riding at age 20 and later died from tuberculosis in 1908. He was the first jockey in history to surpass 200 wins in a year and was inducted into the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame in 2011.

Willie Simms

KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

Willie Simms

KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

22

Shelby “Pike” Barnes KEENELAND LIBRARY HEMMENT COLLECTION

Another Kentuckian who met success in the saddle was Bud Haggins. Born in 1870, Haggins began exercising horses at age 11. He was winning races by the age of 14, and his confidence in the saddle earned him a coveted position with William Stoops’ Kentucky-based stable. Haggins won 15 races in a row on Stoops’ Little Fred in 1884. His other winning mounts at Kentucky tracks include Templar, Warrenton, and Glenbrook.

Bud Haggins

KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

Sam Doggett, Willie Simms, and Fred Taral in the early 1890s

Bud Haggins

KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

Sam Doggett, Willie Simms, and Fred Taral in the early 1890s

23

KEENELAND LIBRARY HEMMENT COLLECTION

OFTEN REFERRED TO by his nickname of “Spider,” George Anderson was born in Baltimore in 1871. At age 17, he was the first African American jockey to win the Preakness Stakes, piloting Samuel Brown’s Buddhist to victory by eight lengths. Of the seven African American riders who had Preakness mounts in the race’s history, two visited the winner’s circle – Anderson in 1889 on Buddhist and Willie Simms in 1898 on Sly Fox. With his athletic capacity and solid reputation for what turf publications of his day referred to as “integrity and cleverness,” Anderson was sought out by some of the country’s most distinguished stables. After he established a noteworthy career on prominent runners of the late 1880s and early 1890s, Anderson struggled to make weight. His increased weight, coupled with heightening social and political challenges faced by Black jockeys in flat racing in the late 19th century, pressed Anderson to transition to riding in steeplechase events.

Another rider who got his start in the early 1890s was Virginia native Henry J. Harris. Born in 1876, Harris started exercising horses at 15. As a consistent lightweight jockey of his day, Harris accepted a riding contract early on with William Lakeland. Having established a reputation for cool adaptability and what turf writers deemed “a clear head,” Harris was riding for some of the country’s top owners by the mid-1890s.

One of Harris’s contemporaries, William Porter, was born in 1877 in Lexington, Kentucky. Porter attended local schools before taking on his first job at age 14 with the eminent African American horseman Edward Dudley Brown. After exercising horses for Brown in Chicago and Saratoga Springs, New York, Porter returned to Kentucky. In the fall of 1892, he was employed by E.J. “Lucky” Baldwin during the Latonia meet in northern Kentucky. While under Baldwin’s employ, Porter had his first mount, El Reno. They finished third. Porter was aboard El Reno again in the colt’s second start when Porter secured his first win. By the late 1890s, Porter was a regular rider for Foxhall Keene, William Landsberg, and William Daley. Some of his notable runners included Oracle, The Winner, Storm King, and Lady Bess.

Born in 1876 in Missouri, Alonzo “Lonnie” Clayton became an exercise rider for E.J. “Lucky” Baldwin in Chicago in the summer of 1888. At age 14, he began working with D.A. Honig’s string of horses at the Clifton Race Track in New Jersey. Clayton had his first mount at Clifton aboard Redstone,

George Anderson KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

William Porter KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

24

Henry J. Harris KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

and by age 15, he was winning major stakes races at tracks across the country.

Before he was 20, Clayton had victories on Azra in the 1891 Champagne Stakes and the 1892 Kentucky Derby, Clark Stakes, and Travers Stakes. He met tremendous success at Kentucky tracks, leading the 1893 Churchill Downs fall meet and winning two consecutive Kentucky Oaks – in 1894 aboard Selika and in 1895 aboard Voladara. Another noteworthy mount for Clayton was Ornament. Together in 1897, they won the St. Louis Derby, the Fall Handicap at Sheepshead Bay in New York, as well as the Clark Stakes and the Latonia Derby in Kentucky.

The 1890s was the last full decade in which African American jockeys dominated the track, but Clayton remained among the best in the saddle, claiming a brilliant win aboard Tillo in the 1898 Suburban Handicap as he neared the end of his riding career. When Clayton piloted Azra to an impressive nose victory in the 1892 Kentucky Derby at age 15, he became the youngest jockey in history to win the race.

Jockeys Alonzo Clayton (left) and L. Reiff (right) in 1894

KEENELAND LIBRARY HEMMENT COLLECTION

Jockeys Alonzo Clayton (left) and L. Reiff (right) in 1894

KEENELAND LIBRARY HEMMENT COLLECTION

25

Alonzo Clayton KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

BLACK JOCKEYS DOMINATED the country’s racing scene in the years following the Civil War. Turf publications and local newspapers celebrated their skill in the saddle, and racing fans, who burgeoned in the late 1800s as the national sport drew larger and larger crowds, elevated riders like Isaac Burns Murphy and Shelby “Pike” Barnes to superstar status. By 1890, the country’s top Black jockeys were earning up to $20,000 a year – an astronomical salary for the times.

The unparalleled success of Black jockeys from 1870 through the 1890s exposed a deep paradox. Tensions escalated around the reality that African Americans, who lived across the country as second-class citizens, could gain the status of national heroes on the track. Other than boxing, no other sport allowed the routine mixing of races. As Black jockeys continued to dominate the track, white jockeys and horsemen, fueled by systemic racism, became increasingly embittered.

Intensified racial tensions on the track came to a head following the Supreme Court’s 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson ruling that state-sponsored segregation laws were constitutional. Local and national racing governing boards began to revoke or withhold licenses for Black jockeys. The very publications and newspapers that praised the athleticism and reliability of Black jockeys began to defame their skill and character. Violence erupted on and off the track, with white jockeys whipping Black riders mid-race or intentionally boxing in their horses on the rails.

Despite these formidable challenges, many Black jockeys, like James , continued to ride. Born in 1880 in Lexington, Kentucky, Perkins began his jockey training at age 10, surrounded by a family of horsemen. After fellow Black jockey Alonzo Clayton, Perkins became the

JOCKEYS AT THE TURN OF THE 20TH CENTURY

Jimmy Winkfield working out 1902 Kentucky Derby winner Alan-a-Dale KEENELAND LIBRARY HEMMENT COLLECTION

COOK

26

Jimmy Winkfield KEENELAND LIBRARY

COLLECTION

second 15-year-old to win the Kentucky Derby with his victory aboard Halma in 1895. Leading the country as its winningest jockey in 1895 with 192 wins from 762 mounts, Perkins remained in the saddle through early 1903.

Born in 1882 near Lexington in Chilesburg, Kentucky, Jimmy Winkfield began exercising horses at age seven. His career as a jockey took off in 1899, and by 1901, Winkfield rode 161 winners, including runners who captured the Tennessee, Latonia, and Kentucky Derbys. Winning the Kentucky Derby on His Eminence in 1901, Winkfield claimed his second Derby win on Alan-a-Dale in 1902. He remains the last African American jockey to win the Kentucky Derby.

Winkfield continued to dominate jockey standings across U.S. tracks in 1902 and 1903. Faced with mounting discrimination and organized violence, Winkfield was one of several Black jockeys who were forced to seek work in Europe despite their accomplishments in this country. Winkfield met immediate success there, winning major races in Poland, Russia, Germany, and France.

Winkfield retired from riding at age 50, with roughly 2,500 wins in the U.S. and Europe to his name. He maintained a successful training career with a stable in MaisonsLaffitte, France, where he died in 1974. Winkfield was inducted into the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame in 2004 and is commemorated with the annual running of the Jimmy Winkfield Stakes at Aqueduct in Queens, New York.

Jimmy Lee, born in Louisiana, began exercising horses in 1901, after the many impacts of Jim Crow laws and their “separate but equal” policies had a strong foothold in the racing establishment. Black jockeys, the most publicly visible figures in the industry, felt the brunt of violence and disenfranchisement that forced them overseas or to abandon their careers entirely at the turn of the 20th century. Despite the seemingly insurmountable obstacles, Lee won the prestigious Latonia Derby in 1906 aboard The Abbott. During Churchill Downs’ 1907 meet, Lee rode 49 winners, setting a meet record for the track that he held until 1976. Although

Lee rode in two Kentucky Derbys in 1907 and 1909, the horses did not place. Turf writers described Lee as humble and unassuming, attributing his success to his solid understanding of the horse, fearless and adaptive riding, and attention to detail on and off the track.

Lee’s victories in the 1907 Kentucky Oaks aboard Wing Ting and Saratoga’s Travers

Stakes aboard Dorante in 1908 marked some of the last wins by an African American jockey in the country’s most prestigious racing events. Lee is best remembered for sweeping all six races on the Churchill Downs card on June 5, 1907, a feat that has never been repeated.

Jimmy Lee KEENELAND LIBRARY HEMMENT COLLECTION

27

James “Soup” Perkins KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

THE LOSS OF Black jockeys as the highest profile members of the turf at the turn of the 20th century was driven primarily by discrimination, but another national trend was also at play. The anti-gambling political movement that began to sweep the country in the late 1800s culminated in many states adopting legislation, such as New York’s 1908 HartAgnew Law, that made wagering on horses illegal. By the early 1910s, states like Maryland and Kentucky were some of the only jurisdictions that had not outlawed wagering on racehorses. The resulting loss of revenue from the era’s anti-gambling laws drove most tracks out of business across the country.

Racing began to rebound in New York in 1913 and in other states by the late 1910s, after significant hits to its workforce. Fewer operating tracks meant fewer races. Jockeys sought employment overseas or in other sectors of the economy. Many Black horsemen who had grown up in the South mentored by Black stable foremen, trainers, grooms, or farriers, began to seek work in the industrial urban centers of the North – the country’s growing employment hubs.

Despite economic and political shifts impacting much of the country, many Black horsemen remained in the Bluegrass during the early 1900s. In Kentucky, the horse industry still drove much of the state’s economy, yielding more job opportunities at tracks and farms for those looking to employ their hard-earned skills. Like their predecessors, turn-of-the-century Kentuckians passed on their knowledge to the next generation.

The Lexington-based Colston family is a prime example of the continuity of African American horsemanship passed through generations. Raleigh Colston Sr. trained prestigious stakes winners at tracks across the country in the late 1800s. His sons Raleigh Colston Jr. and Thomas Colston became trainers and owners, training their colt Colston to his third place finish in the 1911 Kentucky Derby. Colston was the last horse trained

IN THE EARLY 1900s

MCCLURE

28

John Buckner with Man o’ War, circa 1925

KEENELAND LIBRARY

COLLECTION

and owned by an African American to finish in the money in what is now the first leg of America’s Triple Crown.

Although ousted from more visible and lucrative careers as racehorse jockeys, owners, or trainers by the 1920s, African Americans continued to work in the industry in various capacities on and off the track, often caring for and conditioning horses on farms or the track’s backside.

John Buckner was the first of three Black grooms of the legendary Man o’ War. He was charged with Man o’ War’s care in 1921, when the future Racing Hall of Famer retired to stud at Hinata Farm in Lexington, Kentucky. Buckner accompanied Man o’ War during his move from Hinata to nearby Faraway Farm the following year. He remained Man o’ War’s groom until October 1930 when his employer, Elizabeth Daingerfield, resigned from Faraway. Having worked for the Daingerfield family for years and proven himself indispensable to stable operations, Buckner continued to work for Daingerfield at her Haylands Farm.

Will Harbut was Man o’ War’s groom from the fall of 1930 until the spring of 1946. Born in Lexington in 1883, Harbut worked for several local horsemen from a young age, including Harrie Scott at Glen-Helen Stud. When Scott became Faraway Farm’s new manager in 1930, he placed the farm’s valued stallion and one of racing’s most recognizable icons in Harbut’s care. Over time, Harbut began to incorporate Man o’ War’s accomplishments into a farm tour. Thousands of racing fans from across the country came to Faraway to see the pair and to experience firsthand the bond between the incomparable stud groom and one of the greatest horses in history. Featured in newspapers and turf publications nationwide, Harbut and Man o’ War made the cover of a 1941 edition of Saturday Evening Post

Cunningham Graves, born in 1899, worked with horses for much of his life. Before assuming the care of Man o’ War after Will Harbut’s health declined in the spring of 1946, Graves traveled to various tracks charged with around-the-clock care of horses. After Man o’ War’s death and burial in 1947, for which Graves helped prepare the horse’s body for a nationally broadcast funeral, he remained the stud groom for several of his former charge’s progeny when they retired from racing, including War Relic and Triple Crown winner War Admiral.

Clemon Brooks, born in 1907, cared for the great Nashua at Lexington’s Spendthrift Farm for 25 years. When Nashua arrived to stud duty at Spendthrift in 1956, he was only the second horse in history to have earned more than $1 million in his racing career. In addition to his responsibilities as a stud groom, Brooks began to create a compelling farm tour built around Nashua. Racing fans flocked to Spendthrift each year to see them in action, and the pairing of “Clem” and Nashua remain inseparable in industry memory. Having worked at farms and tracks in several states before he began working for Spendthrift in 1941, Brooks established a reputation as one of the best stud grooms in the country, remaining with Spendthrift for more than 40 years.

Will Harbut with Man o’ War, 1937 KEENELAND LIBRARY MEADORS COLLECTION

Will Harbut with Man o’ War, 1937 KEENELAND LIBRARY MEADORS COLLECTION

29

Clem Brooks with Nashua, 1964 KEENELAND LIBRARY FEATHERSTON COLLECTION

Born in 1920 to a West Virginia family as one of 17 children, Sylvia Bishop was an industry trailblazer who began working as a hot walker and groom at West Virginia’s Charles Town racetrack at age 14. Faced with race and gender barriers during the height of the nation’s Civil Rights movement, Bishop worked her way through the ranks to become the first African American woman licensed to train racehorses in the country. Though that tremendous feat and her trips to the winner’s circle with prominent owners did not elicit much fanfare in her day, Bishop’s record speaks to her achievements. She died in 2004 and is remembered for her passion for horses, diligence in monitoring her charges around the clock, and tireless work ethic on and off the track.

Theophilus Irvin Jr., another Black horseman with family roots in the Bluegrass horse industry, was born in 1915. Irvin’s father worked for the trainer William Perkins; his mother Ada was the daughter of trainer George Morton. The Irvin family home on Chestnut Street in Lexington, Kentucky, was in close vicinity to the Kentucky Association track, where the younger Irvin spent much of his childhood. After working for his father from a young age and breaking horses for nearby farms during his teens, Irvin was awarded his trainer’s license in 1947. He trained for prominent Kentucky owners such as J. Graham Brown and J. Keene Daingerfield Jr. With Daingerfield’s support, Irvin became the first African American employed by the Kentucky Racing Commission, working in licensure and horse drug testing from 1979 until his retirement in 1995.

IN THE MID-1900s

Eddie Arcaro presents the Iron Horse Mile trophy to Sylvia Bishop in the winner’s circle with Bright Gem and owner M. Tyson Gilpin at Shenandoah Downs on September 4, 1962

30

PHOTO COURTESY M. TYSON GILPIN JR.

Marshall Lilly, another esteemed Black horseman with Lexington roots, was born in Fayette County in 1885. Shadowing his father who worked for the breeder James A. Grinstead, Lilly laid the foundation for his success that would span the first half of the 20th century. He began exercising horses for Edward Dudley Brown in the late 1890s. Accompanying Brown to New York in 1901, Lilly remained in the Northeast, working for future Racing Hall of Fame trainer James Rowe Sr.

Lilly’s expertise and precision in the saddle made him one of the country’s most sought after exercise riders. He worked some of the premier early 20th century horses, including Sysonby, Peter Pan, Colin, Regret, Upset, Equipoise, and Twenty Grand. When anti-gambling laws sent Rowe’s Whitney-owned stable to England in 1911, Lilly accompanied the New Marketbased string overseas. When he returned to the Whitneys’ domestic operation, Greentree Stable in New Jersey, Lilly conditioned and managed Greentree’s horses for nearly four decades until his retirement in 1949.

Marshall Lilly working out Twenty Grand, Horse of the Year in 1931

KEENELAND LIBRARY COOK COLLECTION

Marshall Lilly KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

Marshall Lilly working out Twenty Grand, Horse of the Year in 1931

KEENELAND LIBRARY COOK COLLECTION

Marshall Lilly KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

31

Born in 1926, Eugene Carter was raised in Maddoxtown, a small African American community north of Lexington, Kentucky. Although his father was a tobacco farmer, many of the men living in Carter’s community worked at nearby horse farms. Carter chose to pursue working with horses over tobacco farming or a long bus ride into Lexington to attend segregated public school. He shadowed Will Harbut’s care of Man o’ War at Faraway Farm before becoming an exercise rider at Elsmeade Farm in 1941. In that same year, Carter broke yearlings for Cy White, trainer for Ogden Phipps’ stable. Denied the opportunity to become a licensed jockey, Carter continued to condition horses at tracks across the country before

settling into his 25-year employment at Saxony Farm. After his retirement in 2002, he began to work at the Kentucky Horse Park’s Hall of

Although Eugene Carter was never awarded a jockey license despite his skill in the saddle, trainer Oscar Dishman Jr. became one of the few licensed African American trainers in the country to run a longstanding stable in the mid-20th century. Born in Scott County, Kentucky, Dishman spent much of his childhood at his grandparents’ farm taking care of their horses, while his father worked at the C.V. Whitney Farm in Lexington. He got his start in the industry exercising horses at Keeneland and Latonia Downs. Dishman pursued a training career in the early 1960s during segregation, overcoming obstacles white trainers would never face. His wife was denied entry through the front gate of Cincinnati’s River Downs despite being married to the track’s leading trainer, and, at the outset of his career, he could not purchase horses outright. By the 1970s, Dishman was training more than 40 horses at a time, conditioning multiple runners who earned more than $100,000 a season. His top horse, Silver Series, won the 1977 Ohio Derby, the Hutcheson Stakes in Florida, and the American Derby in Chicago.

Champions, sharing the stories of the retired racing legends John Henry, Cigar, and Funny Cide with fans from around the world.

Eugene Carter KENTUCKY HORSE PARK

Champions, sharing the stories of the retired racing legends John Henry, Cigar, and Funny Cide with fans from around the world.

Eugene Carter KENTUCKY HORSE PARK

32

Oscar Dishman Jr. KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

EARNING THE MONIKER “Horse Whisperer,” Dudley Sidney spent his childhood working with horses at his grandfather’s livery stable in Georgetown, Kentucky. Born in 1929, Sidney would hone the horsemanship skills cultivated at his family’s business with some of the area’s most prestigious breeding and training farms of the mid-1900s, including Castleton, Dodge Stables, and Walnut Hall Stock Farm. In 1982, after his retirement from LexingtonFayette Urban County Government, Sidney became a ringman at Keeneland at age 52.

Ringmen, or horse handlers in the sales ring, play a critical role at horse auctions. As they take the lead of horses they have never met, they must anticipate horses’ behavior on an unfamiliar stage, handle them with a strong and calming command, and showcase them in the best possible light to potential buyers. Sidney showed thousands of horses, many of them sale toppers, in Keeneland’s ring over his long career. When he held the reins of a Mr. Prospector colt that sold for $2.1 million on opening day of the 1998 September Yearling Sale, a photo of the pair made the cover of The Blood-Horse magazine.

Only a select few skilled handlers make it to the world’s largest Thoroughbred auction house. Francis Carrol Wilson Sr., with 15 years’ experience, mentored his brother-in-law, Dudley Sidney, when Sidney joined Keeneland Sales as a ringman.

Born in 1928, Wilson, also a Scott County native, was one of 18 children. When offered part-time employment at Lexington’s Jonabell Farm in 1948 after graduating from high school, Wilson was told the work might last a month. From foaling and grooming to conditioning and sales preparation, Wilson worked with Jonabell until his retirement in 1993.

During many of his nearly 50 years at Jonabell, Wilson also worked for Keeneland Sales as a ringman. Assuming the role in 1967, he showed the first yearling ever sold for more than $1 million at the 1976 Keeneland July Selected Yearling Sale. By Secretariat out of Charming Alibi, the colt was sold by Nelson Bunker Hunt and purchased by a group of Canadians for $1.5 million. Wilson’s enduring contributions to Keeneland Sales are commemorated with a plaque that reads “Frankie’s Corner” in the area where he awaited horses before they entered the ring. After Wilson’s death in 2015, his grandson, Jermo Reese, founded the youth equine education program Frankie’s Corner Little Thoroughbred Crusade to honor his grandfather’s legacy.

IN THE MID TO LATE 1900s

Dudley Sidney with a yearling by Mr. Prospector out of Molly Girl, the 2000 Keeneland July Selected Yearling Sale topper KEENELAND ASSOCIATION BILL STRAUS

Jermo Reese accepting the 2021 Phoenix Rising Lex Horsemen Honoree Award on behalf of his grandfather, Francis Carrol Wilson Sr.

33

PHOTO COURTESY JAHARA MUNDY

As was the case for many Black horsemen of the Bluegrass, Walter Edwards got his start in the industry at a young age. As a stable hand and then groom, Edwards built his craft caring for horses of all ages around the clock. By 1970, he was conditioning horses for races at tracks in Kentucky, Indiana, Ohio, New Jersey, Illinois, and Canada. Edwards and his wife, Jo Carolyn, went on to train, own, and breed horses during their more than 50 years of working together. The couple maintained their training stable in Lexington, Kentucky, through 2020.

John Joe Hughes Jr., a Kentuckian and ever-adaptive horseman, was born in 1926. Hughes began working as a stable hand in the early 1940s. From working as a groom and exercise rider to handling horse transport for meets at various U.S. tracks, Hughes wore many hats in the industry through the mid-1970s. After working in New York and Florida, Hughes returned to Kentucky and joined John “Bud” Greely’s stable in 1960. In a 2019 interview, Hughes recalled life on the backside during segregation, noting while everyone worked together in the barns “tending the horses,” African Americans ate separately and sat in a designated “colored” area of the grandstand.

Walter Edwards accepting his 2019 Phoenix Rising Lex Horsemen Honoree Award

PHOTO COURTESY APRIL WILLIAMS

John Joe Hughes Jr., accepting his 2021 Phoenix Rising Lex Horsemen Honoree Award

Walter Edwards accepting his 2019 Phoenix Rising Lex Horsemen Honoree Award

PHOTO COURTESY APRIL WILLIAMS

John Joe Hughes Jr., accepting his 2021 Phoenix Rising Lex Horsemen Honoree Award

34

PHOTO COURTESY JAHARA MUNDY

Ohio Governor James A. Rhodes, owner Archie R. Donaldson, trainer Oscar Dishman Jr., and Edward J. DeBartolo Jr.

(left to right) after Silver Series won the 1977 Ohio Derby

Ohio Governor James A. Rhodes, owner Archie R. Donaldson, trainer Oscar Dishman Jr., and Edward J. DeBartolo Jr.

(left to right) after Silver Series won the 1977 Ohio Derby

35

KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

BORN IN 1938 in Holly Hill, South Carolina, Eddie Sweat left his family’s tenant farm in high school after future Racing Hall of Fame trainer Lucien Laurin offered him a job. Sweat traveled the racing circuit for much of his life, working as a hot walker, horse van driver, and groom for Lucien and then his son, Roger Laurin. While Secretariat, Sweat’s brilliant charge, rose to greatness and captivated the nation before and after his 1973 Triple Crown win, the horse’s many connections also made headlines. As a pair, Sweat and Secretariat were inseparable in the public eye and on the backside. Sweat shouldered the horse’s daily care, from mucking shedrow stalls at 4:30 every morning to tending to his needs around the clock, bunking nightly in a nearby tack room.

In a 1985 interview, Sweat told reporters that a “groom is everything to a racehorse. He’s a father, a mother. He’s a babysitter, a doctor. Most of all, though, you have to be a friend. You treat a horse with tenderness and kindness, and he’ll respect you.”

Characterized by his colleagues as an exemplary horseman and handler, Sweat died of leukemia in 1998. When Sweat’s family did not have the means to pay for his funeral services, the Jockey Club Foundation provided the needed funds. The fact that the caretaker of one of the greatest racehorses in history died without sufficient resources for his family and burial spotlighted the long-standing class and racial disparities faced by backside workers.

IN THE MID TO LATE 1900s

36

Eddie Sweat with Secretariat KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

Cheryl

At age 17, White secured her first mount at Thistledown Race Track in Ohio on June 15, 1971, just a few years after jockey licenses were first issued to women in America. Her mount that day, Ace Reward, was trained by her father. Despite their impressive initial sprint, the pair finished last. White rode her first winner, Jetolara, nearly three months later at West Virginia’s Waterford Park on September 2, 1971. Jetolara was trained and owned by White’s father and bred by White’s mother. White’s trailblazing rides over the

summer of 1971 made headlines and landed her on the cover of the July 29, 1971 issue of Jet magazine. Over her riding career that spanned more than 20 years, White accumulated 227 wins on Thoroughbreds at primarily Midwestern tracks before moving to California in 1974 to ride quarter horses and Appaloosas on the county fair circuit. White topped the Appaloosa Horse Club’s jockey standings in 1977, 1983, 1984, and 1985. After riding her last winner at California’s Los Alamitos Race Course on July 25, 1992, White retired with over 750 career wins. She became a racing steward in California before returning to Ohio to join the racing office at Mahoning Valley Race Course in 2014. She worked at Mahoning until her death in 2019.

Cheryl White (third from the right) with a group of female jockeys at the 1972 Boots and Bows Handicap, Atlantic City Race Course

KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

White , the country’s first Black female jockey to win a professional race, learned the ropes from her father, jockey and trainer Raymond White Sr., and her mother, Doris Gorske, a Polish breeder and owner.

Cheryl White (third from the right) with a group of female jockeys at the 1972 Boots and Bows Handicap, Atlantic City Race Course

KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

White , the country’s first Black female jockey to win a professional race, learned the ropes from her father, jockey and trainer Raymond White Sr., and her mother, Doris Gorske, a Polish breeder and owner.

37

Jonathan Figgs Jr., born in Lexington in 1955, spent much of his childhood in Maysville, Kentucky, on a cattle and tobacco farm owned by his maternal grandfather Charles A. Jordan. Fascinated with horses from his earliest memories, Figgs carried a toy horse in his pocket and a dream to become a jockey. Although his size kept him out of the saddle, Figgs worked with his grandfather’s horses as they plowed their family’s fields. As Figgs remarked in a 2019 oral history interview, horses were in “his blood,” and by 13, he was working at Castleton Farm near Lexington under the tutelage of his other grandfather, Luther W. Figgs, who had been a stud groom at the farm since 1917.

From his start in the industry at Castleton Farm in 1968 to today, Figgs has held several positions during his long career, including Stallion Manager, Yearling Manager, Broodmare Manager, and Assistant Trainer. He has worked with some of the country’s top Thoroughbreds across several leading Bluegrass farms, including the Hall of Fame horses Forego, Lure, Personal Ensign, and Alysheba. Figgs currently works for Godolphin as a night watchman.

KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

Group of jockeys at Evangeline Downs in 1978

Jonathan Figgs at Keeneland, in 2023

38

PHOTO COURTESY JONATHAN FIGGS

Black jockeys continued to ride throughout the 20th century, despite systemic prejudice that often impeded their ability to receive licensure and secure mounts. This group photograph taken at Louisiana’s Evangeline Downs in 1978 features jockeys (standing, left to right) Chester Colligan, Martin L. Brown, John D. Sam, Charles W. McMahan, James M. Sam, and (kneeling, left to right) Sylvester Carmouche, Donald Alexandra, and Darrel Volier. Martin L. Brown would remain in the saddle until age 67, mentoring several young Black jockeys over his long career. Sylvester Carmouche’s son, Kendrick, rides today.

39

ONCE JOCKEY JAMES Long got his start in the industry in the early 1970s, he remained in racing until his death in 2017. Long was born and raised in New York City. After his boss at a Brooklyn newspaper printing plant invited him to the races at Belmont Park, the 4’8” high school senior set out on a career path that spanned four decades. Getting his start as a hot walker in 1972, Long was given his first chance in the saddle by the Thoroughbred owner, breeder, and future Boston Celtics owner Harry T. Mangurian Jr. Winning his first race at Aqueduct Racetrack on July 4, 1974, Long would accumulate more than 4,000 career starts through 2008. While contending with multiple injuries and facing down stereotypes, he finished in the money 1,012 times, with career earnings of nearly $2.8 million. After he retired from riding, Long was a clerk of scales and then a steward at Michigan’s Hazel Park Raceway. Ever an advocate for sharing and promoting African Americans’ contributions to the sport, Long proclaimed in a 2011 speech in Lexington, “The very first professional athlete in America was not a basketball player, not a football player, not a baseball player. He rode horses, the sport of kings, and he was African American.”

Charles Robinson grew up in the industry, watching his father and grandfather exercise horses. Robinson began his apprenticeship with the African American trainer Richard Spiller at age 16, and he worked horses for several Bluegrass farms, including Saxony, Maine Chance, Heaven Hill, and Domino Stud. Robinson’s work took him to tracks on both coasts,

IN THE 2000s

James Long accepting his 2016 Phoenix Rising Lex Horsemen Honoree Award

PHOTO COURTESY RICHARD GREISSMAN

James Long on Valid Appeal winning the 1975 Dwyer Handicap at Belmont Park KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

Charles Robinson accepting his 2020 Phoenix Rising Lex Horsemen Honoree Award

40

PHOTO COURTESY APRIL WILLIAMS

the Midwest, and across Kentucky. He exercised hundreds of horses over his long career, including the 2001 Kentucky Derby winner Monarchos. Robinson retired in 2011, and Phoenix Rising Lex recognized his contributions to the industry with an African American Horsemen Honoree Award in 2020.

A native of Huntington, West Virginia, Phillip L. Jones moved to Lexington, Kentucky, to live with his grandparents at age 16. He fell into steady work under his grandfather who was a stud groom, farm manager, and trainer at various horse farms in and around Lexington. Although Jones’s elders discouraged him from pursuing a career in the industry, he followed in his grandfather’s footsteps as a trainer and eventually a breeder. Jones has trained runners at tracks in Kentucky, Virginia, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, Indiana, and Colorado. After selling his horse stock in September 2022, Jones continues to assist other owners at Lexington’s Thoroughbred Center.

Cordell Anderson was not raised around horses in his native Jamaica or brought up in a family with a history in horsemanship, but when he was offered a job at age 18 by Eileen Cliggott, a Jamaica-based trainer, it set him on a trajectory that continues more than 40 years later. While working for Cliggott, Anderson’s work started in the early morning hours, as he tended stalls and galloped horses. He moved to Kentucky to work at Taylor Made Farm in Jessamine County in the early 1980s, and his natural ease with horses and skill as a handler for Taylor Made drew the attention of Keeneland’s yearling inspection team. He joined Keeneland Sales in November 1988. Anderson’s cool responsiveness at the end of a horse’s shank in the sales ring has worked its magic over decades of showcasing horses to prospective buyers from around the world. When asked how to describe Anderson’s craft in September 2020, fellow African American ringman Ron Hill noted, “There’s no man alive that’s held as many million-dollar horses as Cordell Anderson. That kind of says it all.”

41

Cordell Anderson with an American Pharoah filly out of Leslie’s Lady at the 2019 Keeneland September Yearling Sale KEENELAND ASSOCIATION DAVID COYLE

MARLON ST. JULIEN, born in Louisiana in 1972, began riding professionally at Evangeline Downs in 1989. Following a long line of Black jockeys based at the Louisiana track, St. Julien began to secure rides at tracks across the country, earning leading rider titles at Delta Downs in 1993 and 1994, Lone Star Park in 1998, and Kentucky Downs in 1999. Winning his first graded stakes aboard Social Charter in the 1999 Fayette Stakes at Keeneland, St. Julien would retire in 2018 with 2,468 wins from 23,767 starts and career earnings of nearly $47 million. With his seventhplace finish on Curule in the 2000 Kentucky Derby, St. Julien was the first Black jockey to ride in the Derby since 1921, when Henry King placed tenth on Planet.

When DeShawn Parker scored his 6,000th win on June 21, 2022, he joined the ranks of only 20 other jockeys in Thoroughbred racing history to have reached that milestone. Born in Cincinnati in 1971 and raised with the indelible influence of his father, esteemed Midwestern racing steward Daryl Parker, DeShawn had his first start in 1988. Three decades later, Parker has finished in the money more than 16,000 times, with career earnings approaching $83 million as of December 2022. In 2010, Parker became the first Black jockey since 1895 to lead all American jockeys in races won, and he topped the country’s leading rider by wins standing again in 2011. Parker was selected by fellow jockeys as winner of the 2021 George Woolf Memorial Jockey Award that honors riders whose characters and careers advance the sport.

Kendrick Carmouche, a son and grandson of jockeys, remembers being on a horse as early as the age of seven. He had his first win at Louisiana’s Evangeline Downs in 2000 on a horse conditioned by Shelton Zenon, an African American trainer. After success riding at Texas and Mid-Atlantic tracks, Carmouche took on the New York circuit. He was part of a noteworthy 2017 Toboggan Stakes win at Aqueduct, in which the Jamaican-born owners Anthony and Gaston Grant, trainer Gaston Grant, and rider Carmouche, were all Black. The Toboggan Stakes was held on Martin Luther King Jr. Day that year, and Sentell Taylor Jr., an African American placing judge at New York Tracks for more than 50 years, presented the winner’s trophy. Carmouche also

IN THE 2000s

Marlon St. Julien KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

DeShawn Parker accepting the 2021 George Woolf Memorial Jockey Award

PHOTO COURTESY SANTA ANITA PARK/ BENOIT PHOTO COLLECTION

Kendrick Carmouche in July 2022

42

PHOTO COURTESY ADAM COGLIANESE

won the 2018 Jimmy Winkfield Stakes at Aqueduct – a stakes race named to commemorate the legendary Black jockey. As of December 2022, Carmouche has accumulated more than 3,600 wins with career earnings surpassing $134 million.

Greg Harbut’s multi-generational history in horsemanship dates to his great-grandfather, Will Harbut, the stud groom of Man o’ War. Greg’s grandfather, Tom Harbut, conditioned horses for owners Elizabeth Arden, Louie B. Mayer, and Harry F. Guggenheim, in addition to breeding and co-owning the 1962 Kentucky Derby entry Touch Bar. Although Churchill Downs officially desegregated the track in 1961, Tom Harbut’s name was not listed in the Derby program, and he was not permitted to sit in the stands to watch his entry run.

Greg Harbut developed the foundational knowledge passed on by his family while working at WinStar Farm in Versailles, Kentucky, during high school. He then engaged in international industry training programs before returning to Kentucky and founding Harbut Bloodstock Agency. In addition, he and partner Ray Daniels created the syndicate Living the Dream Stables in 2017 to attract minority Thoroughbred owners to the industry. Harbut, Daniels, and co-owner Wayne Scherr brought Necker Island to the Kentucky Derby in 2020. On the heels of these successes, Harbut and Daniels established the Ed Brown Society to support students of color pursuing work in the industry. Harbut remains an influential advocate for an inclusive industry workforce and honoring the legacy of African American predecessors in the sport.

The Heart of the Turf: Racing’s Black Pioneers presented by the Keeneland Library is one of several initiatives in Kentucky to record, preserve, and share the stories of past and present Black horsemen and women. Various grassroots community organizations, libraries, museums, and universities in our state and beyond have championed efforts to chronicle the African American experience in racing.

As of 2022, Lexingtonbased organizations, including the International Museum of the Horse,

Phoenix Rising Lex, Ed Brown Society, Legacy Equine Academy, African Cemetery No. 2, Frankie’s Corner Little Thoroughbred Crusade, and UK Libraries’ Notable Kentucky African Americans Database, work to recount the legacy of African Americans in racing and to expand current industry workforce opportunities. Several Louisville-based efforts are also underway, including the Project to Preserve African American Turf History (PPAATH) and the Kentucky Derby Museum’s Black Heritage in Racing exhibit and educational programs.

Greg Harbut at the 2017 Phoenix Rising Festival in Lexington, Kentucky

PHOTO COURTESY SUZIE PICOU-OLDHAM

2018 Phoenix Rising Festival in Lexington, Kentucky

PHOTO COURTESY JAMES SHAMBHU

Greg Harbut at the 2017 Phoenix Rising Festival in Lexington, Kentucky

PHOTO COURTESY SUZIE PICOU-OLDHAM

2018 Phoenix Rising Festival in Lexington, Kentucky

PHOTO COURTESY JAMES SHAMBHU

43

Promotional broadside for the Kentucky Association’s 1862 Spring Meet

HORSERACING HAS HAD a home in Lexington since the settlement’s founding. Quartermile sections of early roads, including a course on Main Cross (now South Broadway), were used as tracks for two-horse straight-line sprints. Known as quarter races, these sprints on public roads were banned by town trustees over safety concerns in 1793. Local horsemen also took their quarter races to a designated grassy lot known as The Commons through the early 1800s. By October 1789, three-mile heat purse races were run on the town’s first oval course, the Lexington Course. Also known as Race Field, the flat track was laid out on pastureland just east of Georgetown Road and north of Main Street. The Lexington Course was home to racing through 1811, when a course on William Williams’s property on the west side of Georgetown Road, nearly opposite the Lexington Course location, began operating through the late 1820s.

Members of the Lexington Jockey Club assembled at Mrs. Keen’s Inn, the longtime favored watering hole for area horsemen, in July 1826 to form the Kentucky Association for the Improvements of Breeds of Stock. The list of Kentucky Association subscribers included prominent Bluegrass citizens and politicians, most of whom were Thoroughbred breeders. Recognized as the oldest turf organization in America, the Kentucky Association would own 29 acres north of Winchester

THE KENTUCKY ASSOCIATION

KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

KEENELAND LIBRARY MCCLURE COLLECTION 44

Ashland Oaks at the Kentucky Association, circa 1920

Kentucky Association 1928 Fall Meet general admission ticket KEENELAND ASSOCIATION MATT ANDERSON

A day at the races, Kentucky Association KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

Road between 5th and 7th Streets by 1828, showcasing a new one-mile dirt racetrack, stables, and grandstand. The oval track at the east end of town, with its turf skinned and harrowed to create a bare dirt racing surface, was the second mile-long dirt track constructed in North America.

The era’s top Bluegrass Thoroughbred breeding farms were built concurrent with slavery. Enslaved Black grooms, trainers, and riders shouldered the breeding and racing operations for area stables during the Kentucky Association’s first four decades. After the national abolition of slavery in 1865, Black horsemen with multi-generational ties to the Lexington track remained a driving force of local racing stables during the late 1800s.

From its inaugural race meet in October 1828, the Kentucky Association hosted regular spring and fall meets through November 1897. In 1831, Association officers established an annual stakes race to honor their hallowed meeting place, the Phoenix Hotel, formerly Mrs. Keen’s Inn. The resulting Phoenix Stakes, now run at six furlongs at Keeneland every October, remains the country’s oldest stakes race. Black jockeys, including James Carter, Isaac Burns Murphy, Anthony Hamilton, Isaac Lewis Perkins, won the race 12 times between 1875 and 1895.

By the early 1870s, the Kentucky Association had grown its facility to 65 acres. Financial pressures, driven by anti-gambling lobbying in the state legislature and heightened competition from other tracks in Louisville and northern Kentucky, came to a head by the early 1900s. The Association faced a tumultuous first three decades of the 20th century, changing ownership multiple times and sustaining recurring losses to its physical plant. After the track celebrated its centennial anniversary in 1926, the catastrophic economic downturn of the Great Depression drove the Kentucky Association to close permanently. The track hosted its last race meet in the spring of 1933.

Bluegrass horsemen and business leaders rallied to restore Thoroughbred racing to Lexington. A committee appointed to determine a location for a new racing plant settled on John Oliver “Jack” Keene’s property on Versailles Road. Keene had nearly completed construction on a state-of-the art private racing facility five miles west of the city center. The newly formed Keeneland Association acquired the property, completed facilities construction, and opened on October 15, 1936. The two gateposts that once marked the Kentucky Association entrance now stand at Keeneland’s gates. Five of Keeneland’s premier stakes races – the Ben Ali, Phoenix, Ashland, Blue Grass, and Breeders’ Futurity, originated at the Kentucky Association track.

45

The Lexington Bowl, manufactured in 1854, depicts a mid-19th century race scene at the Kentucky

LEXINGTON’S AFRICAN AMERICAN population grew dramatically in the years immediately following the Civil War, more than doubling between 1860 and 1870. Before the war, the area now known as Lexington’s East End comprised large estates owned by a few families. After slavery was abolished in 1865, the tracts were divided into smaller lots to establish neighborhoods for newly freed African Americans.

The East End had been home to the Kentucky Association track since the late 1820s. Many recently freed Black horsemen, already based near the Association, maintained their track ties and settled their families in its surrounding neighborhoods. The track also provided opportunities for newcomers to the industry, as working in horse breeding and racing provided gainful income for many members of Lexington’s growing Black middle and professional classes.

By the late 1800s, four future Racing Hall of Fame horsemen lived in Lexington’s East End – jockeys Isaac Burns Murphy and Jimmy Winkfield, trainer Ansel Williamson, and trainer/owner Edward Dudley Brown. Countless other Black horsemen, including jockeys William Walker, Thomas Britton, and trainers/owners Raleigh Colston Sr. and Jr., Abraham Perry, Eli Jordan, Lee Christy, and Courtney Mathews bought their homes, built their businesses, and raised their families in surrounding neighborhoods. Their wives often handled accounts and real estate transactions while their husbands’ work on the racing circuit took them out of town for long periods.

Mattie Perkins, wife of trainer John Jacob Perkins and mother of horsemen William, Frank, and James, bought their family home on Thomas Street in 1890. During his nearly 20 years as a trainer, William Perkins conditioned more than 600 winners of major races. His home stood on the corner of Race and Third Streets. His brother, James “Soup” Perkins, once recounted jumping the fence behind their house to get to the Kentucky Association track. At age 13, he had mounts for 26 races at the track’s fall meet, and by 1895, he claimed the Phoenix Stakes and Kentucky Derby. He and his wife, Elenora

LEXINGTON’S EAST END

Kentucky Association track

46

KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

Saunders, lived on Wilson Street.

Isaac Burns Murphy purchased a 10-room, two-story home with his wife, Lucy Carr. With views of the Kentucky Association track from their roof observatory, the couple hosted community gatherings and social events through Murphy’s death in 1896. No other jockey in racing history has bested Murphy’s winning percentage of least 44 percent. His skill in the saddle and influence as a community pillar are commemorated in the Isaac Murphy Memorial Art Garden located on the site of his former home on East Third Street.

Jimmy Winkfield, the last Black jockey to win the Kentucky Derby in 1902, lived on Warnock Street in the neighborhood of Goodloetown. Winkfield pursued a riding career in Europe in the early 1900s when escalating discrimination forced him out of America. After accumulating more than 2,500 wins over his long career, Winkfield established a training stable in France.

Ansel Williamson, Hall of Fame trainer of Brown Dick, Asteroid, and the first Kentucky Derby winner, Aristides, built his home on what is now Florida Street. Edward Dudley Brown, a former enslaved jockey and trainer who became a prominent racehorse owner after emancipation, lived on Eastern Avenue and based his training and breeding operations in Lexington’s East End. Owner and trainer Dudley Allen, who won the 1891 Phoenix Stakes and Kentucky and Latonia Derbys with Kingman piloted by Isaac Burns Murphy, lived with his family and apprenticed several young horsemen from his home on Kinkead Street.

Kentucky Association track apron KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

Kentucky Association track apron KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

47

View of the Kentucky Association grandstand from the infield KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION

Many of the African Americans who called Lexington’s East End home lie in rest in African Cemetery No. 2 on East Seventh Street. The Cemetery was the first burial site of Isaac Burns Murphy and is the burial location of more than 175 identified horsemen, including trainer Abraham Perry, farriers Alonzo Curtis and Clay Trotter, and jockeys Oliver Lewis, James Carter, Thomas Britton, and James “Soup” Perkins, among many others.