Basco, Catangay, Evangelista, Maguddayao,Sabalza

December2024

Basco, Catangay, Evangelista, Maguddayao,Sabalza

December2024

ACountermappingofUPResidents’Spatial EmbodimentofLand

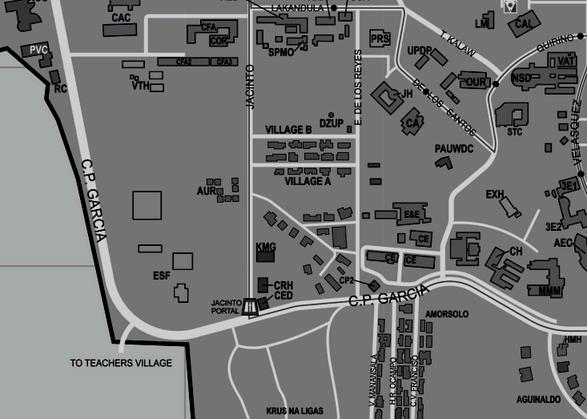

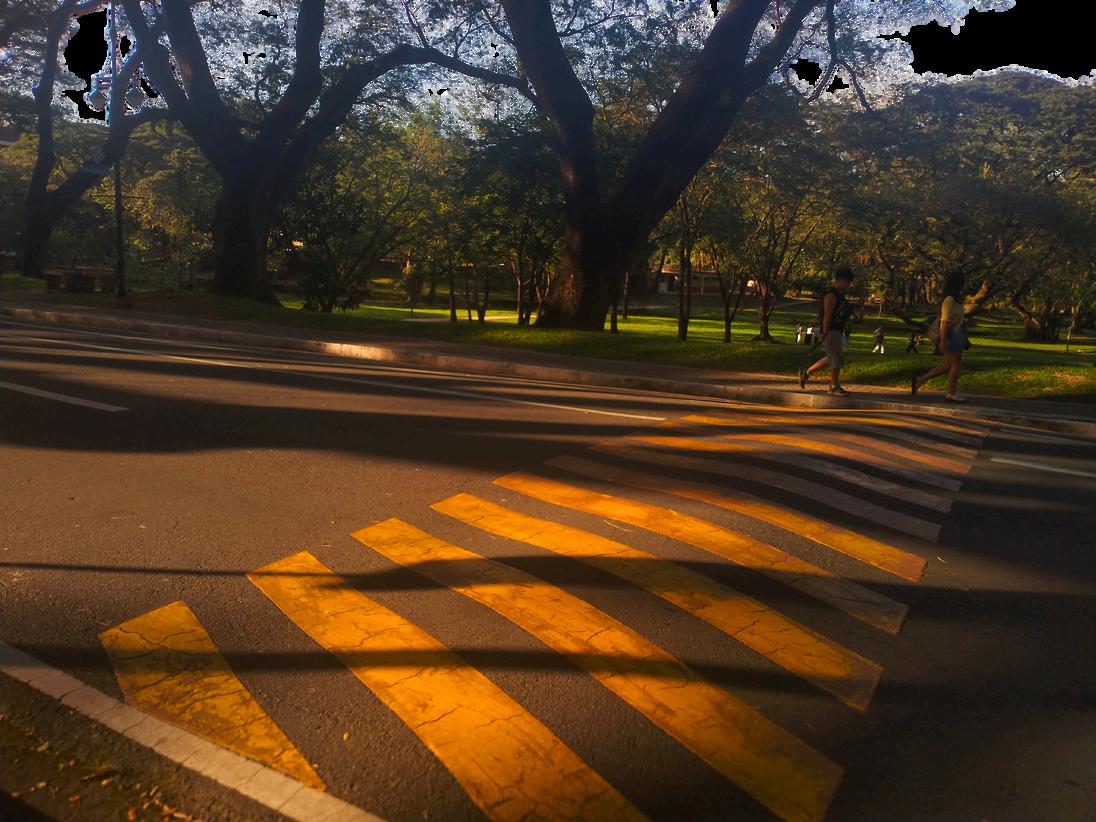

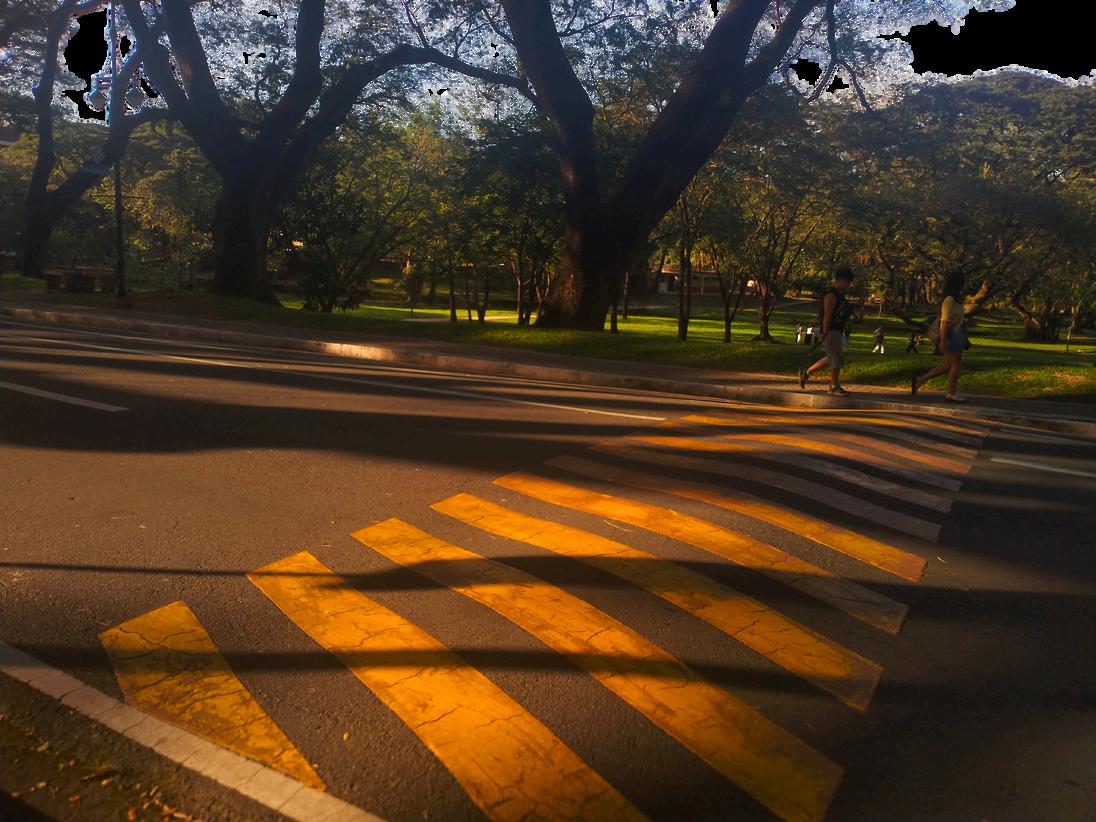

Cover:

A street view of Village B, with the image appearing torn or ripped, reveals the map used by the informants to create their counter-maps at the center. The map is prominently displayed, symbolizing the unearthing of hidden or overlooked narratives andspaceswithinthevillages

PhotobyKhristineMaguddayao

AllRightsReserved.2024

This zine is the intellectual property of the informants and authors No part of this zine, including text and photographs, may be reused,republished,orreproducedwithoutwrittenpermission.Allphotographsincludedinthiszineweretakenbytheauthors.

This zine was written and compiled with care and verified to the best of our abilities However, we acknowledge that some errors oromissionsmaystillbepresent.

Authors: JaneBasco,JohnRovicCatangay,JoanEvangelista,KhristineMaguddayao,FrancieSabalza

What do we know about space and place? Is it merely only movement and habitation? A destination? The GPS coordinates of landscape and location? More precisely, what does it mean to make space?

Perhaps, space lends itself to embodiment – shaped by human and subjective experiences constantly being (un)done by bodies that inhabit or trespass on it. At the same time, these bodies are under pressure. Policed within their constrained spaces by institutions and restrictions, they yield and contend with the ebb and flow of power, knowledge, and capital.

These tensions are not new to the communities living in UPD. They are, after all, straddling land renowned for upholding excellence and activism that is also deeply tied to their personal histories of identity and placemaking. Beneath its role as an educational institution, UP Diliman has long served as a contested site where issues of land ownership, occupation, and access play out, complicating its institutional identity. And already, these contestations, subtle or not, are marked by the moves and countermoves of its peoples – whether they be in the minute tinkering of their homes, the riots that take place in dissonance against displacement, or the reminiscent traces of belonging –altogether reconfiguring their own construction of their space.

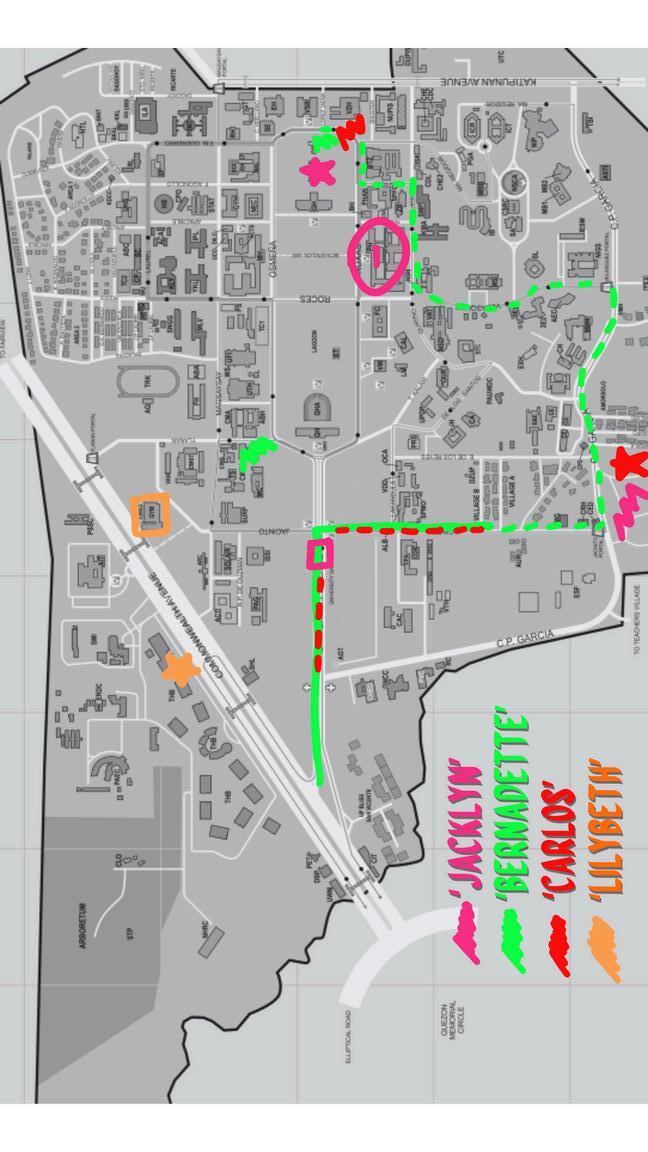

Combining countermapping and ethnographic interviews, the project aims to produce a map that represents how the residents of UP Village A, B, and C navigate through space, where emotions and memories are inscribed into the place itself. Maps are political, and Counter-mapping allows us to highlight spatial experiences alongside official maps and boundaries created by governing institutions. Narratives will also be analyzed next to the map’s representation of movement, paying particular attention to their narratives and as observed by the researchers.

This project is conducted by student researchers under Dr. Efenita May Taqueban’s Anthro 179 (Culture Change) class. As students studying within UP Diliman, we recognize that our construction of UP is influenced by our academic associations with the space next to our anthropological training. An awareness of reflexivity will be maintained throughout the process of writing and producing the results of our work.

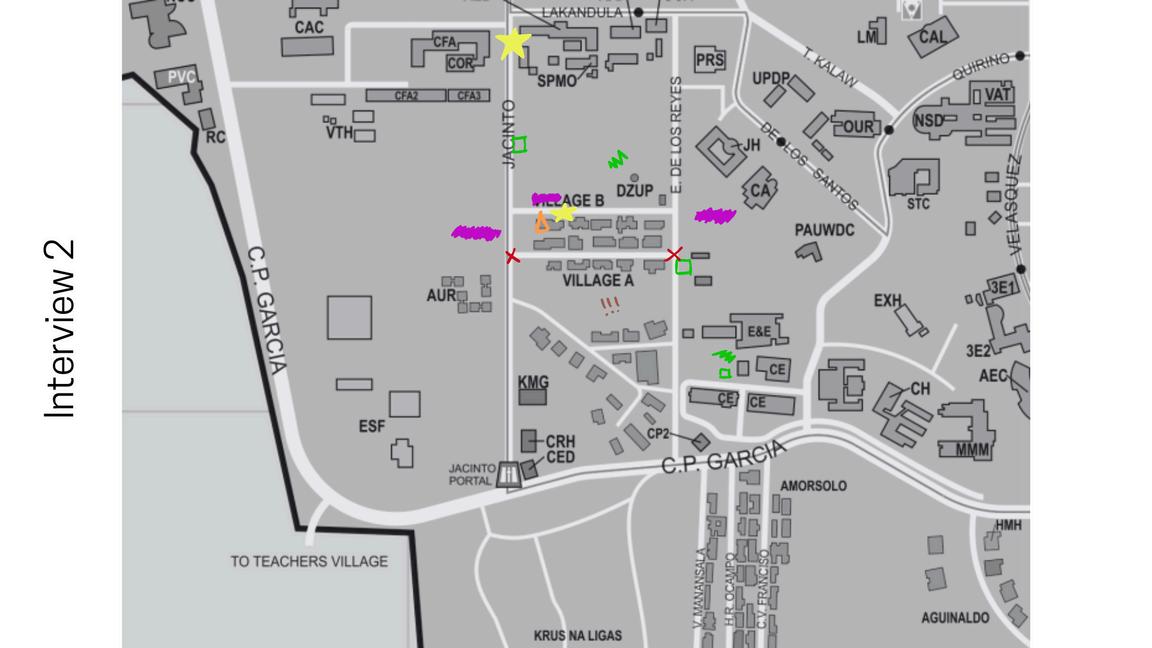

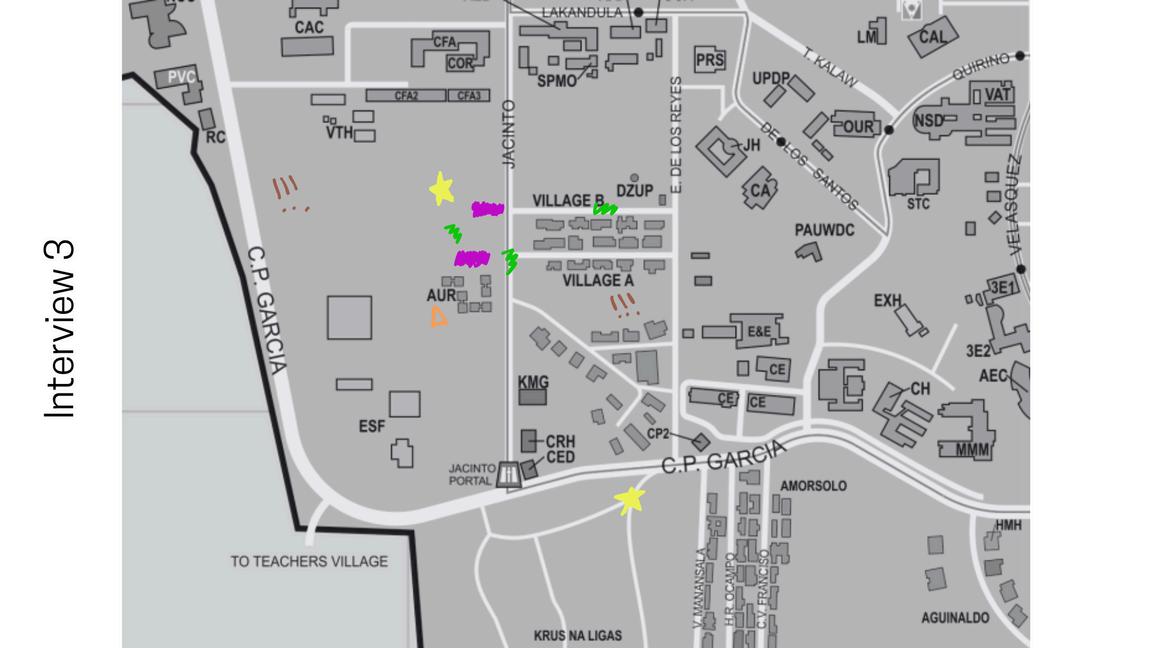

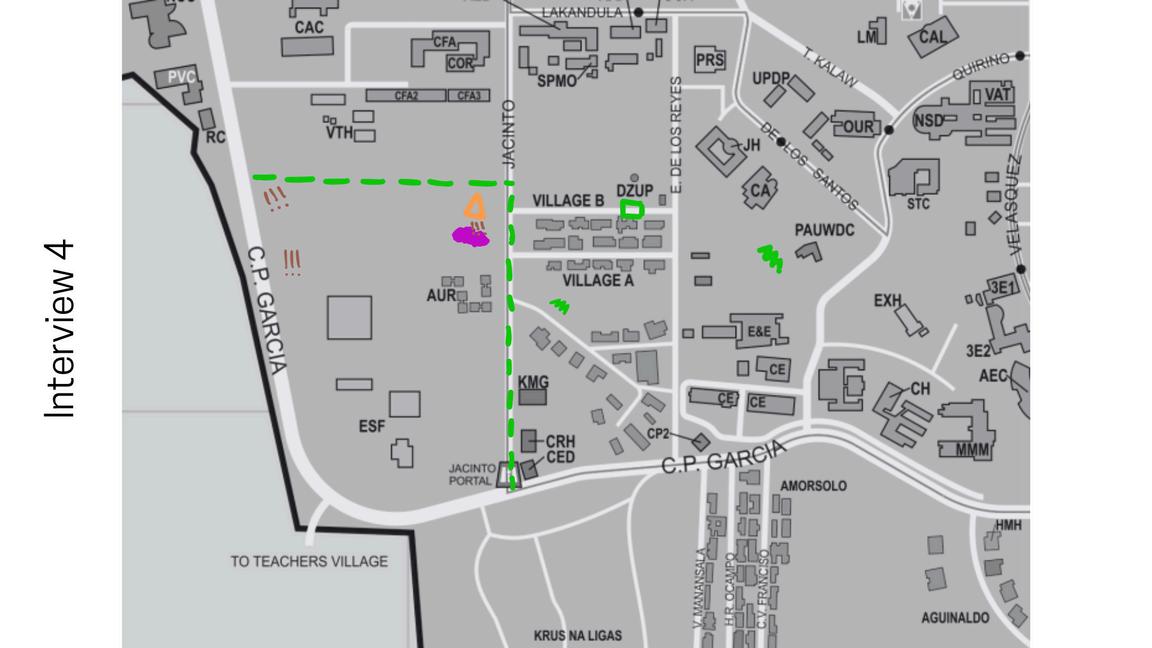

Upon being granted permission from the Barangay U.P. Campus, rapport was established through a series of field visits from November 18 - December 13. Four semi-structured interviews were conducted, thus providing us four maps that vary according to spatial relations. Boundary constructions and navigation will be highlighted in reference to the interviews conducted.

Counter-mapping serves as a powerful way for local people to further legitimate their claims of land and resources. Since its introduction to the social sciences, it has been used to produce counter-maps based on traditional and local knowledge as a way to explicate community and folk conceptions of space.

*All interviews conducted were done with the consent forms signed and clarified verbally before and after the interview. The anonymity of the interlocutors was maintained through the use of random name generators.

UP Diliman, the flagship campus of the University of the Philippines, stands as a vital intersection of academic excellence, activism, and contested histories. Built in 1949 after World War II left the original Manila campus in ruins, UP Diliman was designed to embody the ideals of “Honor, Excellence, and Service” for the nation. Yet, UP Diliman is more than its role as an educational institution; it is a "city within a city," where intellectual discourse, cultural shifts, and socio-political tensions unfold. Amid its green landscapes and historic landmarks, the campus tells a story of progress and , reflecting its historic role in shaping the nation's intellectual and cultural wever, UP Diliman is also a contested space, where questions about land and access continue to shape the lives of those who call it home.

Nestled within the bustling Barangay U.P. Campus, Villages A, B, and C reflect the complex dynamics of space and place in UP Diliman. These neighborhoods are home to a diverse community, including university staff, long-time residents, and informal settlers, all of whom navigate the shared yet stratified environment. Each village reveals the struggles and connections that shape life on contested grounds, balancing the push and pull between permanence and transience, formality and informality, and the strong ties that hold their communities together amidst constant change.

Village A is a tightly-knit community that embodies resilience and an enduring connection to the land. Once a neighborhood of orderly “white houses” built for UP staff, it has grown into the vibrant "looban," a maze of narrow alleys and overlapping homes shaped by generations of change. This transformation reflects the residents’ ability to adapt, balancing their personal histories with the institutional footprint of UP. Despite challenges, including a devastating fire in 2022, Village A continues to thrive. Its evolving landscape—marked by both permanence and impermanence—stands as a

Village B, located next to Village A, is a dynamic space shaped by constant movement and change. Originally part of the same housing plan, it has transformed into a hub for transient residents such as students, faculty, and short-term workers. This fluidity is reflected in its physical layout, where temporary adaptations blend with more permanent structures. Village B is also a functional center, with jeepneys and tricycle terminals along Jacinto Street and a southern edge bustling with businesses. From dry goods and school supplies to fresh food, vegetables, and restaurants, the variety of stores caters to the everyday needs of its diverse residents, making it a lively intersection of mobility and permanence.

Village C, in contrast, speaks to a story of erasure and resistance Unlike the more established Villages A and B, it has been both physically and symbolically erased from official maps, leaving its residents invisible and their existence unacknowledged. Despite this neglect, they persist, carving out a space built on collective action and unyielding community solidarity. The struggles of Village C highlight broader issues of marginalization, as its residents continue to assert their right to belong in a world that seeks to erase them. Village C stands as a powerful testament to survival, where resilience and resistance shape their ongoing fight for recognition.

Together, Villages A, B, and C reveal the layered narratives of placemaking and persistence in UP Diliman’s contested grounds.

House House Memory Memory

Changes Changes

Recreational RouteRecreational Route

Free time Spaces Free time Spaces

Routine SpacesRoutine Spaces

Danger/ CalamityDanger/ Calamity

Boundary/ LimitedBoundary/ Limited Space Space

‘jacklyn’ ‘jacklyn’

‘

‘Carlos’ ‘Carlos’

‘Lilybeth’ ‘Lilybeth’

Discourses regarding Village A, B, and C are a part of a historically changing construction of these spaces, instituted through emerging discourses of those that live within the villages. Such discourses produce knowledge that, when controlled, establishes power relations that subsequently produces a notion of ‘truth’ that society (or a subset of it) accepts. Two points are worth noting. First, the narrative construction of reality - revealed through the various discourses of knowledge - creates a sense of truth that relies on what makes narrative sense instead of what is actually observed. Second, the truths constructed appear in the mind but are nonetheless observable manifestations.

As one of the participants noted, they are unable to pin their specific location in ride-sharing and deliver applications due to the map’s inaccuracy. Another mapping discontinuity is the non-appearance of Village C in the map. In an interview with Jacklyn, they argue that Village C did not exist before. Unlike Villages A and B, Jacklyn accounts that Village C’s land was not a space for residencies but the early residents decided to build houses anyway. Meanwhile, participants from Village C have a different narrative to explain their non-existence on the map. In their accounts, a barangay chairperson had a disagreement with a village organizer.

“...,tinanggal kami sa mapa. ”

To “punish” them, the chairperson ‘removed Village C from the map’, telling everyone that there are no residents in Village C anymore. This was further perpetuated as the narrative that most residents of Village C were relocated after a fire that occurred in the area started to circulate. This caused the residents to receive fewer social services and benefits before and during the pandemic. The residents also had limited access to requesting documents needed for employment as barangay officials were reluctant to issue documents to those claiming to reside in Village C, believing that the area stopped being inhabited.

However, these maps do not reveal the actual constructions of spaces of the residents. These maps were referred to as wrong (‘mali’) and, for Village C residents, as an erasure of identities (‘tinanggal kami sa mapa’). These constructions find observable manifestations in the action of the residents.

Jacklyn’s partner, for instance, continuously removes the trash that clogs the creek in their area and maintains the makeshift bridge that allows them to cross the creek. According to Jacklyn, they do it to maintain their own space, regardless of whether UP recognizes their needs or not. Furthermore, Jacklyn, Carlos, and Lilybeth shared that despite the strictness of UP with construction noises and housing-dimension regulations, they still managed to enact their own spacemaking through designing their own spaces. In this sense, while the maps that contain them create constraints, their constructions of space continue to be reflected nonetheless.

These accounts reflect a degree of regimes of truths that existed among the participants’ residences. While maps hold power in dictating the ways in which spaces are perceived and interacted with by those in power , these truths do not exist in absolutes. Rather, through counter-mapping and constant conversations with residents, systems of truths that exist on-ground and contradict imposed truths can be unearthed. Moreover, these differing systems of truths manifest different observable manifestations. Here, power exists as ble of constructing systems of truth that can shape observable those who hold institutional power or those subjected to it.

The residents in the UP villages have embodied the standards set by the University of the Philippines regarding the spaces granted to them, eventually affecting how they navigate their social responsibilities, both within and beyond. Yet, despite it seeming as if the system is in control, this project explores the participants’ utilization of their agency drives the construction of self, despite the strict standards set by the institution. And other possible factors affect the construction of self and community.

blah

Jacklyn mentioned that the community is close-knit. Aside from years of mutual support, practical reasons imposed by the institution is the main reason, specifically new homes can't be built in the area. For instance, her neighbor from when she first moved in in 2008 is still their neighbor. The only time relocation occurs is when an uncontrollable occurrence takes place. Unique to Jacklyn is their partner’s initiative to clean the sewer so that the area is clean, perhaps for the benefit of people. Notably, construction for house expansion is rarely done, as there is a strict length and width need to be met. Aside from the need for extensive paperwork, construction work noises are considered a bother in the community. Yet, they emphasize that: “Kahit mag pukpok ka diyan, may blue guard na kaagad. Pero makakagawa ka, kung may kapitbahay ka na mababait.” providing an image that their community relies on each other, where as long as nobody reports, building can be achieved, without the need of time consuming permits.

“Mabasura kasi, siya lang naman naglilinisdiyane.”

“(Nakapaligid ang aking mga) kaibigan, parang lahat magkakakilala sa village. Masayarito.”

Bernadette backs the closeness of the UP Villages community. They use the space to play, building fond memories with the residents. Bernadette shared that they used the empty spot in front of the Fine Arts waiting shed (now Gyud food) before as an area to fly their saranggolas and play Chinese garter. Moreover, their house has been used not only as their livelihood area, but also a place to gather for casual hangouts. They also mentioned that the UP Villages’ accommodating if there are events such as birthdays, closing off the street to provide enough space for celebrations, as long as a permit is filed.

In contrast, Lilybeth and Carlos expressed disappointment with the politicians for forgetting the existence of UP Village C, that their village was removed from maps, and that they are even deprived of barangay IDs and government benefits, leading to embodied erasure. But now, it is back to normal. Both Carlos and Lilybeth acknowledge the independence of UP Village C, yet the people residing outside of it view it as an extension of UP Village B. Both of them expressed strong emotions in terms of being othered from the other villages, that they were kinawawa, kinalimutan, and felt insulted when the same organization president that deprived them of their identities as UP Village C residents ran again. Additionally, given the 60 residents in their area, Carlos notes that they know each other, regarding the crimes happening in the area as not of their causation but of intruders.

“Angsabisaamin"Aba wala nang Village C bakit kukuha pa kayo ng ID?". Kaya nawalan kami ng gana sa administrasyon na iyon, kase pinabayaan kami. Kahit noong pandemic halos wala kaming makuha na reliefdito.”

Despite having to follow the system s rules and regulations, the limited agency, community dynamics over the years, and even external factors all intertwined. Through their daily interactions with each other and the space provided, the UP villages residents create their sense of self, community and belonging that goes beyond the constraints of institutional control. Reminiscing the statements, it is home for them, where solidarity within the different spaces exist, and hope runs.

The University of the Philippines (UP), known for being “para sa bayan,” provides economic relief by allowing residents to have their houses inside the campus rent-free. However, it imposes strict control over their homes, for example, seeking approval from UP before making any changes to their homes. One participant shared: “Bawal kasi magpataas ng bahay dito… Papa-permit ka muna sa UP.” Even with simple construction noises, UP police or security personnel would visit their homes. While some restrictions such as allowing slightly higher (From 8 ft to 10 ft) houses have eased over time, strict limitations on home construction remain. One resident recounted an incident where armed authorities entered her house uninvited, traumatizing her children. This shows the aggressive enforcement of policies at UP. These strict rules led one resident to ask, “Private or public ba ang UP?... Mahigpit kase sila.” This confusion speaks about UP as a public institution that exercises private-like authority. With this authority, residents often feel they have no choice but to comply.

“PrivateorpublicbaangUP?...

“Malakingbagaynarinna nakakatirakamiritonglibre.”

However, UP’s control doesn’t stop at housing. They also have relocation policies which residents criticized because of its poor fairness and support. There is a story of buildings being constructed and displacement of families are common. One resident mentioned being offered a 4x5 land area and a small amount of money to relocate by the private company constructing the building: “Bibigay lang ng limang libo... tapos ikaw pa ang magpapagawa ng bahay mo.” For them, it would mean sacrificing their jobs, community, and stability. Another resident even described the fire that occurred a few years ago as a “favor” to UP, since it spared them the effort of forcibly evicting people.

Yet, when asked if they agree with UP’s decisions, one person admitted: “Oo kasi kumbaga wala naman kaming magagawa. Susunod na lang kami, kung ano… Malaking bagay na rin na nakakatira kami rito ng libre.”

This reflects resident’s acceptance of UP’s authority for its financial help by living rentfree, even with the restrictions. These challenges made the residents demand to be treated with dignity and recognized as fellow human beings, wanting their voices to be heard and their rights to be respected

Across different villages in UP, residents show how their resistance to institutional and spatial rules is often limited by systemic and physical constraints. For example, economic dependence, one resident acknowledged that, “Malaking bagay na rin na nakakatira kami rito ng libre.” This creates a power imbalance where residents feel constrained because resisting could mean losing their home or livelihood. There are also strict restrictions on building height and home modifications, requiring permits from UP, which further limit residents’ ability to adapt their spaces or resist institutional control. However, when institutional actions threatened their community’s stability, resistance sometimes escalated into direct action, such as riots. In Village C, some of the residents were relocated due to the construction of a new building. Many of them resisted the move because the relocation area lacked basic necessities like water, electricity, and proper housing which prompted an organized resistance. One participant explained “Sinasang ayunan namin kung sa makatao at binibigay din sa amin ang tamang karapatan pero kung hindi at maapakan kami syempre hindi kami basta bastang papayag dahil mayroon kaming pamilya.”

“...syemprehindikamibastabastang papayagdahilmayroonkaming pamilya.”

Beside these riots, they also indirectly resisted UP’s authority. Residents from Village C created an organization that works to assert their rights and demand fair treatment from the institution. They emphasize their willingness to comply with UP’s rules, showing that they are not engaging in outright defiance or confrontational resistance. Instead, they are strategically presenting themselves as cooperative participants who are still advocating for their rights. This organization was recognized by both the barangay and UP. The barangay supports community initiatives and serves as a mediator between the residents and UP. They coordinate consultations and to ensure the community's collective concerns are heard. However, its involvement is limited and dependent on the barangay captain's leadership and priorities.

Overall, these experiences reveal how systemic and physical constraints dictate the forms and limits of resistance across the villages. While institutional barriers often suppress direct opposition, residents find ways to adapt and push back, demonstrating resilience and agency in constrained spaces.

Through countermapping and ethnographic interviews, existing power relations and differences in spatial constructions between residents of different villages in UP, the university, and private capital were unearthed. Akin to Kusaka’s observations of Philippine politics, the arena of power in the university is one in which elite hegemony does not fully capture the cognition of the civil society, composed of differing groups which also hold constantly conflicting constructions of space. While UP sees the villages as sites in need of regulation and private companies see the lands as opportunities for capital, the residents have constructed such spaces as homes.

A sense of ownership was constructed, despite the lack of actual land ownership, and is reflected in modifications of spaces and resistances to encroachment. Moreover, the residents themselves have developed a sense of community, which differentiates the self from the Other, whether it be those with institutional and economic power or those that come from a different village. These constructions of identities - both communal and individual - clash with each other. These differences in constructions reveal different systems of truths that simultaneously exist with each other. Reflected in the countermapping and interview data, these different truths manifest themselves both in the cognition and in observable interactions with people and surroundings.

Any recommendation for the well-being of the residents of different UP villages requires a recognition of the spatial constructions of different UP villages. Jacklyn argues that the drainage in their space needs to be properly maintained, citing problems with the smell and its effects on the general hygiene of their neighborhood. In the same light, Bernadette argues that the lack of trash segregation on the side of villagers and sometimes the garbage collectors create lasting smells of trash around the neighborhood. It is Carlos and Lilybeth, both residents of Village C which experienced a sense of erasure from the barangay and repression from both the university and private companies, which had more to say.

On the surface, they mention the need to be provided with essential needs such as food and gas, along with street lights that they argue will alleviate the crime inside the village. However, at the heart of these concerns, Lilybeth mentions that the villagers simply want to be treated with dignity, like any other human being. They desire to be recognized as people that exist and deserve to be treated properly, without intimidation and threats of eviction.

In consideration of these needs, we recommend two general actions. First, there is a need for UP to refrain from merely being a regulatory institution. Instead, the university needs to take a more proactive approach in understanding the needs of the people that live under its lands. This includes a more grassroots dialogue with the residents instead of merely appearing when there are actions to be prevented. Second, any decision regarding the spaces that the villagers should occupy must include the voices of those residing in the spaces themselves. While the residents are capable of holding their own constructions of spaces, these constructions become null when they are unarticulated in proper deliberations of the future of such spaces. A recognition of these voices open the lands inside UP to be modified in ways that become mutually beneficial for the institution and the people.

"Bodies on Contested Grounds"

speaksoflivesembodiedinstruggle—fleshandspirit rootedinplacesofconflict,erasure,andpower.These arebodiesthatendure,resist,andreclaim,asserting theirpresenceinspacesthatneglectthem.